The Nutcracker (Russian: Щелкунчик[a], tr. Shchelkunchik listen (help·info)) is an 1892 two-act «fairy ballet» (Russian: балет-феерия, balet-feyeriya) set on Christmas Eve at the foot of a Christmas tree in a child’s imagination. The music is by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, his Opus 71. The plot is an adaptation of E. T. A. Hoffmann’s 1816 short story The Nutcracker and the Mouse King. The ballet’s first choreographer was Marius Petipa, with whom Tchaikovsky had worked three years earlier on The Sleeping Beauty, assisted by Lev Ivanov. Although the complete and staged The Nutcracker ballet was not as successful as the 20-minute Nutcracker Suite Tchaikovsky had premiered nine months earlier, The Nutcracker soon became popular.

Since the late 1960s, it has been danced by countless ballet companies, especially in North America.[1] Major American ballet companies generate around 40% of their annual ticket revenues from performances of The Nutcracker.[2][3] The ballet’s score has been used in several film adaptations of Hoffmann’s story.

Tchaikovsky’s score has become one of his most famous compositions. Among other things, the score is noted for its use of the celesta, an instrument the composer had already employed in his much lesser known symphonic ballad The Voyevoda (1891).

Composition[edit]

After the success of The Sleeping Beauty in 1890, Ivan Vsevolozhsky, the director of the Imperial Theatres, commissioned Tchaikovsky to compose a double-bill program featuring both an opera and a ballet. The opera would be Iolanta. For the ballet, Tchaikovsky would again join forces with Marius Petipa, with whom he had collaborated on The Sleeping Beauty. The material Vsevolozhsky chose was an adaptation of E. T. A. Hoffmann’s story «The Nutcracker and the Mouse King», by Alexandre Dumas called «The Story of a Nutcracker».[4] The plot of Hoffmann’s story (and Dumas’ adaptation) was greatly simplified for the two-act ballet. Hoffmann’s tale contains a long flashback story within its main plot titled «The Tale of the Hard Nut», which explains how the Prince was turned into the Nutcracker. This had to be excised for the ballet.[5]

Petipa gave Tchaikovsky extremely detailed instructions for the composition of each number, down to the tempo and number of bars.[4] The completion of the work was interrupted for a short time when Tchaikovsky visited the United States for twenty-five days to conduct concerts for the opening of Carnegie Hall.[6] Tchaikovsky composed parts of The Nutcracker in Rouen, France.[7]

History[edit]

Saint Petersburg premiere[edit]

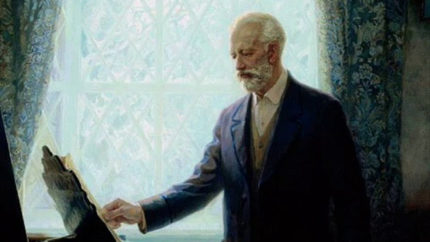

(Left to right) Lydia Rubtsova as Marianna, Stanislava Belinskaya as Clara and Vassily Stukolkin as Fritz, in the original production of The Nutcracker (Imperial Mariinsky Theatre, Saint Petersburg, 1892)

Varvara Nikitina as the Sugar Plum Fairy and Pavel Gerdt as the Cavalier, in a later performance in the original run of The Nutcracker, 1892

The first performance of The Nutcracker was not deemed a success.[8] The reaction to the dancers themselves was ambivalent. Although some critics praised Dell’Era on her pointework as the Sugar Plum Fairy (she allegedly received five curtain-calls), one critic called her «corpulent» and «podgy». Olga Preobrajenskaya as the Columbine doll was panned by one critic as «completely insipid» and praised as «charming» by another.[9]

Alexandre Benois described the choreography of the battle scene as confusing: «One can not understand anything. Disorderly pushing about from corner to corner and running backwards and forwards – quite amateurish.»[9]

The libretto was criticized as «lopsided»[10] and for not being faithful to the Hoffmann tale. Much of the criticism focused on the featuring of children so prominently in the ballet,[11] and many bemoaned the fact that the ballerina did not dance until the Grand Pas de Deux near the end of the second act (which did not occur until nearly midnight during the program).[10] Some found the transition between the mundane world of the first scene and the fantasy world of the second act too abrupt.[4] Reception was better for Tchaikovsky’s score. Some critics called it «astonishingly rich in detailed inspiration» and «from beginning to end, beautiful, melodious, original, and characteristic».[12] But this also was not unanimous, as some critics found the party scene «ponderous» and the Grand Pas de Deux «insipid».[13]

Subsequent productions[edit]

In 1919, choreographer Alexander Gorsky staged a production which eliminated the Sugar Plum Fairy and her Cavalier and gave their dances to Clara and the Nutcracker Prince, who were played by adults instead of children. This was the first production to do so. An abridged version of the ballet was first performed outside Russia in Budapest (Royal Opera House) in 1927, with choreography by Ede Brada.[14][unreliable source?] In 1934, choreographer Vasili Vainonen staged a version of the work that addressed many of the criticisms of the original 1892 production by casting adult dancers in the roles of Clara and the Prince, as Gorsky had. The Vainonen version influenced several later productions.[4]

The first complete performance outside Russia took place in England in 1934,[8] staged by Nicholas Sergeyev after Petipa’s original choreography. Annual performances of the ballet have been staged there since 1952.[15] Another abridged version of the ballet, performed by the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, was staged in New York City in 1940,[16] Alexandra Fedorova – again, after Petipa’s version.[8] The ballet’s first complete United States performance was on 24 December 1944 by the San Francisco Ballet, staged by its artistic director, Willam Christensen, and starring Gisella Caccialanza as the Sugar Plum Fairy, and Jocelyn Vollmar as the Snow Queen.[17][8] After the enormous success of this production, San Francisco Ballet has presented Nutcracker every Christmas Eve and throughout the winter season, debuting new productions in 1944, 1954, 1967, and 2004. The original Christensen version continues in Salt Lake City, where Christensen relocated in 1948. It has been performed every year since 1963 by the Christensen-founded Ballet West.[18]

The New York City Ballet gave its first annual performance of George Balanchine’s reworked staging of The Nutcracker in 1954.[8] The performance of Maria Tallchief in the role of the Sugar Plum Fairy helped elevate the work from obscurity into an annual Christmas classic and the industry’s most reliable box-office draw. Critic Walter Terry remarked that «Maria Tallchief, as the Sugar Plum Fairy, is herself a creature of magic, dancing the seemingly impossible with effortless beauty of movement, electrifying us with her brilliance, enchanting us with her radiance of being. Does she have any equals anywhere, inside or outside of fairyland? While watching her in The Nutcracker, one is tempted to doubt it.»[19]

Since Gorsky, Vainonen and Balanchine’s productions, many other choreographers have made their own versions. Some institute the changes made by Gorsky and Vainonen while others, like Balanchine, utilize the original libretto. Some notable productions include Rudolf Nureyev’s 1963 production for the Royal Ballet, Yury Grigorovich for the Bolshoi Ballet, Mikhail Baryshnikov for the American Ballet Theatre, Fernand Nault for Les Grands Ballets Canadiens starting in 1964, Kent Stowell for Pacific Northwest Ballet starting in 1983, and Peter Wright for the Royal Ballet and the Birmingham Royal Ballet. In recent years, revisionist productions, including those by Mark Morris, Matthew Bourne, and Mikhail Chemiakin have appeared; these depart radically from both the original 1892 libretto and Vainonen’s revival, while Maurice Béjart’s version completely discards the original plot and characters. In addition to annual live stagings of the work, many productions have also been televised or released on home video.[1]

Roles[edit]

The following extrapolation of the characters (in order of appearance) is drawn from an examination of the stage directions in the score.[20]

Act I[edit]

- Herr Stahlbaum

- His wife

- His children, including:

- Clara, his daughter, sometimes known as Marie or Masha

- Fritz, his son

- Louise, his daughter

- Children Guests

- Parents dressed as incroyables

- Herr Drosselmeyer

- His nephew (in some versions) who resembles the Nutcracker Prince and is played by the same dancer

- Dolls (spring-activated, sometimes all three dancers instead):

- Harlequin and Columbine, appearing out of a cabbage (1st gift)

- Vivandière and a Soldier (2nd gift)

- Nutcracker (3rd gift, at first a normal-sized toy, then full-sized and «speaking», then a Prince)

- Owl (on clock, changing into Drosselmeyer)

- Mice

- Sentinel (speaking role)

- The Bunny

- Soldiers (of the Nutcracker)

- Mouse King

- Snowflakes (sometimes Snow Crystals, sometimes accompanying a Snow Queen and King)

Act II[edit]

Ivan Vsevolozhsky’s original costume sketch for The Nutcracker (1892)

- Angels and/or Fairies

- Sugar Plum Fairy

- Clara/Marie

- The Nutcracker Prince

- 12 Pages

- Eminent members of the court

- Spanish dancers (Chocolate)

- Arabian dancers (Coffee)

- Chinese dancers (Tea)

- Russian dancers (Candy Canes)

- Danish shepherdesses / French mirliton players (Marzipan)

- Mother Ginger

- Polichinelles (Mother Ginger’s Children)

- Dewdrop

- Flowers

- Sugar Plum Fairy’s Cavalier

Plot [edit]

Below is a synopsis based on the original 1892 libretto by Marius Petipa. The story varies from production to production, though most follow the basic outline. The names of the characters also vary. In the original Hoffmann story, the young heroine is called Marie Stahlbaum and Clara (Klärchen) is her doll’s name. In the adaptation by Dumas on which Petipa based his libretto, her name is Marie Silberhaus.[5] In still other productions, such as Baryshnikov’s, Clara is Clara Stahlbaum rather than Clara Silberhaus.

Act I[edit]

Scene 1: The Stahlbaum Home

Konstantin Ivanov’s original sketch for the set of The Nutcracker (1892)

The ballet is set on Christmas Eve, where family and friends have gathered in the parlor to decorate the beautiful Christmas tree in preparation for the party. Once the tree is finished, the children are summoned. They stand in awe of the tree sparkling with candles and decorations.

The party begins.[21] A march is played.[22] Presents are given out to the children. Suddenly, as the owl-topped grandfather clock strikes eight, a mysterious figure enters the room. It is Drosselmeyer— a local councilman, magician, and Clara’s godfather. He is also a talented toymaker who has brought with him gifts for the children, including four lifelike dolls who dance to the delight of all.[23] He then has them put away for safekeeping.

Clara and her brother Fritz are sad to see the dolls being taken away, but Drosselmeyer has yet another toy for them: a wooden nutcracker carved in the shape of a little man, which the other children ignore. Clara immediately takes a liking to it, but Fritz accidentally breaks it. Clara is heartbroken, but Drosselmeyer fixes the nutcracker, much to everyone’s relief.

During the night, after everyone else has gone to bed, Clara returns to the parlor to check on her beloved nutcracker. As she reaches the little bed, the clock strikes midnight and she looks up to see Drosselmeyer perched atop it. Suddenly, mice begin to fill the room and the Christmas tree begins to grow to dizzying heights. The nutcracker also grows to life size. Clara finds herself in the midst of a battle between an army of gingerbread soldiers and the mice, led by their king. The mice begin to eat the gingerbread soldiers.

The nutcracker appears to lead the soldiers, who are joined by tin soldiers, and by dolls who serve as doctors to carry away the wounded. As the seven-headed Mouse King advances on the still-wounded nutcracker, Clara throws her slipper at him, distracting him long enough for the nutcracker to stab him.[24]

Scene 2: A Pine Forest

The mice retreat and the nutcracker is transformed into a handsome Prince.[25] He leads Clara through the moonlit night to a pine forest in which the snowflakes dance around them, beckoning them on to his kingdom as the first act ends.[26][27]

Act II[edit]

The Land of Sweets

Ivan Vsevolozhsky’s original costume designs for Mother Gigogne and her Polichinelle children, 1892

Clara and the Prince travel to the beautiful Land of Sweets, ruled by the Sugar Plum Fairy in the Prince’s place until his return. He recounts for her how he had been saved from the Mouse King by Clara and transformed back into himself.

In honor of the young heroine, a celebration of sweets from around the world is produced: chocolate from Spain, coffee from Arabia,[28][29] tea from China,[30] and candy canes from Russia[31] all dance for their amusement; Danish shepherdesses perform on their flutes;[32] Mother Ginger has her children, the Polichinelles, emerge from under her enormous hoop skirt to dance; a string of beautiful flowers perform a waltz.[33][34] To conclude the night, the Sugar Plum Fairy and her Cavalier perform a dance.[35][36]

A final waltz is performed by all the sweets, after which the Sugar Plum Fairy ushers Clara and the Prince down from their throne. He bows to her, she kisses Clara goodbye, and leads them to a reindeer-drawn sleigh. It takes off as they wave goodbye to all the subjects who wave back.

In the original libretto, the ballet’s apotheosis «represents a large beehive with flying bees, closely guarding their riches».[37] Just like Swan Lake, there have been various alternative endings created in productions subsequent to the original.

Musical sources and influences[edit]

The Nutcracker is one of the composer’s most popular compositions. The music belongs to the Romantic period and contains some of his most memorable melodies, several of which are frequently used in television and film. (They are often heard in TV commercials shown during the Christmas season.[38])

Tchaikovsky is said to have argued with a friend who wagered that the composer could not write a melody based on a one-octave scale in sequence. Tchaikovsky asked if it mattered whether the notes were in ascending or descending order and was assured it did not. This resulted in the Adagio from the Grand pas de deux, which, in the ballet, nearly always immediately follows the «Waltz of the Flowers». A story is also told that Tchaikovsky’s sister Alexandra (9 January 1842 — 9 April 1891[39]) had died shortly before he began composition of the ballet and that his sister’s death influenced him to compose a melancholy, descending scale melody for the adagio of the Grand Pas de Deux.[40] However, it is more naturally perceived as a dreams-come-true theme because of another celebrated scale use, the ascending one in the Barcarolle from The Seasons.[41]

Danse de la Fée-Dragée (Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy) is the third pas de deux in Act II

Tchaikovsky was less satisfied with The Nutcracker than with The Sleeping Beauty. (In the film Fantasia, commentator Deems Taylor observes that he «really detested» the score.) Tchaikovsky accepted the commission from Vsevolozhsky but did not particularly want to write the ballet[42] (though he did write to a friend while composing it, «I am daily becoming more and more attuned to my task»).[43]

Instrumentation[edit]

The music is written for an orchestra with the following instrumentation.

Musical scenes[edit]

From the Imperial Ballet’s 1892 program[edit]

Titles of all of the numbers listed here come from Marius Petipa’s original scenario as well as the original libretto and programs of the first production of 1892. All libretti and programs of works performed on the stages of the Imperial Theatres were titled in French, which was the official language of the Imperial Court, as well as the language from which balletic terminology is derived.

Casse-Noisette. Ballet-féerie in two acts and three tableaux with apotheosis.

|

Act I

|

Act II

Grand divertissement—

|

Structure[edit]

List of acts, scenes (tableaux) and musical numbers, along with tempo indications. Numbers are given according to the original Russian and French titles of the first edition score (1892), the piano reduction score by Sergei Taneyev (1892), both published by P. Jurgenson in Moscow, and the Soviet collected edition of the composer’s works, as reprinted Melville, New York: Belwin Mills [n.d.][44]

| Scene | No. | English title | French title | Russian title | Tempo indication | Notes | Listen |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Act I | |||||||

| Miniature Overture | Ouverture miniature | Увертюра | Allegro giusto | ||||

| Tableau I | 1 | Scene (The Christmas Tree) | Scène (L’arbre de Noël) | Сцена (Сцена украшения и зажигания ёлки) | Allegro non troppo – Più moderato – Allegro vivace | scene of decorating and lighting the Christmas tree | |

| 2 | March (also March of the Toy Soldiers) | Marche | Марш | Tempo di marcia viva | |||

| 3 | Children’s Gallop and Dance of the Parents | Petit galop des enfants et Entrée des parents | Детский галоп и вход (танец) родителей | Presto – Andante – Allegro | |||

| 4 | Dance Scene (Arrival of Drosselmeyer) | Scène dansante | Сцена с танцами | Andantino – Allegro vivo – Andantino sostenuto – Più andante – Allegro molto vivace – Tempo di Valse – Presto | Drosselmeyer’s arrival and distribution of presents | ||

| 5 | Scene and Grandfather Waltz | Scène et danse du Gross-Vater | Сцена и танец Гросфатер | Andante – Andantino – Moderato assai – Andante – L’istesso tempo – Tempo di Gross-Vater – Allegro vivacissimo | |||

| 6 | Scene (Clara and the Nutcracker) | Scène | Сцена | Allegro semplice – Moderato con moto – Allegro giusto – Più allegro – Moderato assai | departure of the guests | ||

| 7 | Scene (The Battle) | Scène | Сцена | Allegro vivo | |||

| Tableau II | 8 | Scene (A Pine Forest in Winter) | Scène | Сцена | Andante | a.k.a. «Journey through the Snow» | |

| 9 | Waltz of the Snowflakes | Valse des flocons de neige | Вальс снежных хлопьев | Tempo di Valse, ma con moto – Presto | |||

| Act II | |||||||

| Tableau III | 10 | Scene (The Magic Castle in the Land of Sweets) | Scène | Сцена | Andante | introduction | |

| 11 | Scene (Clara and Nutcracker Prince) | Scène | Сцена | Andante con moto – Moderato – Allegro agitato – Poco più allegro – Tempo precedente | arrival of Clara and the Prince | ||

| 12 | Divertissement | Divertissement | Дивертисмент | ||||

| a. Chocolate (Spanish Dance) | a. Le chocolat (Danse espagnole) | a. Шоколад (Испанский танец) | Allegro brillante | ||||

| b. Coffee (Arabian Dance) | b. Le café (Danse arabe) | b. Кофе (Арабский танец) | Commodo | ||||

| c. Tea (Chinese Dance) | c. Le thé (Danse chinoise) | c. Чай (Китайский танец) | Allegro moderato | ||||

| d. Trepak (Russian Dance) | d. Trépak (Danse russe) | d. Трепак (русский танец, карамельная трость)[45] | Tempo di Trepak, Presto | ||||

| e. Dance of the Reed Flutes | e. Les Mirlitons (Danse des Mirlitons) | e. Танец пастушков (Датский марципан)[45] | Andantino | ||||

| f. Mother Ginger and the Polichinelles | f. La mère Gigogne et les polichinelles | f. Полишинели | Allegro giocoso – Andante – Allegro vivo | ||||

| 13 | Waltz of the Flowers | Valse des fleurs | Вальс цветов | Tempo di Valse | |||

| 14 | Pas de Deux | Pas de deux | Па-де-дё | ||||

| a. Intrada (Sugar Plum Fairy and Her Cavalier) | a. La Fée-Dragée et le Prince Orgeat | a. Танец принца Оршада и Феи Драже | Andante maestoso | ||||

| b. Variation I: Tarantella | b. Variation I: Tarantelle (Pour le danseur) | b. Вариация I: Тарантелла | Tempo di Tarantella | ||||

| c. Variation II: Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy | c. Variation II: Danse de la Fée-Dragée (Pour la danseuse) | c. Вариация II: Танец Феи Драже | Andante ma non troppo – Presto | ||||

| d. Coda | d. Coda | d. Кода | Vivace assai | ||||

| 15 | Final Waltz and Apotheosis | Valse finale et Apothéose | Финальный вальс и Апофеоз | Tempo di Valse – Molto meno |

Concert excerpts and arrangements[edit]

Tchaikovsky: The Nutcracker Suite, Op. 71a[edit]

Tchaikovsky made a selection of eight of the numbers from the ballet before the ballet’s December 1892 première, forming The Nutcracker Suite, Op. 71a, intended for concert performance. The suite was first performed, under the composer’s direction, on 19 March 1892 at an assembly of the Saint Petersburg branch of the Musical Society.[46] The suite became instantly popular, with almost every number encored at its premiere,[47] while the complete ballet did not begin to achieve its great popularity until after the George Balanchine staging became a hit in New York City.[48] The suite became very popular on the concert stage, and was excerpted in Disney’s Fantasia, omitting the two movements prior to the Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy . The outline below represents the selection and sequence of the Nutcracker Suite made by the composer:

- Miniature Overture

- Characteristic Dances

- March

- Dance of the Sugar-Plum Fairy [ending altered from ballet version]

- Russian Dance (Trepak)

- Arabian Dance (coffee)

- Chinese Dance (tea)

- Dance of the Reed Flutes (Mirlitons)

- Waltz of the Flowers

Grainger: Paraphrase on Tchaikovsky’s Flower Waltz, for solo piano[edit]

The Paraphrase on Tchaikovsky’s Flower Waltz is a successful piano arrangement from one of the movements from The Nutcracker by the pianist and composer Percy Grainger.

Pletnev: Concert suite from The Nutcracker, for solo piano[edit]

The pianist and conductor Mikhail Pletnev adapted some of the music into a virtuosic concert suite for piano solo:

- March

- Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy

- Tarantella

- Intermezzo (Journey through the Snow)

- Russian Trepak

- Chinese Dance

- Andante maestoso (Pas de Deux)

Contemporary arrangements[edit]

- In 1942, Freddy Martin and his orchestra recorded The Nutcracker Suite for Dance Orchestra on a set of 4 10-inch 78-RPM records. An arrangement of the suite that lay between dance music and jazz, it was released by RCA Victor.[49]

- In 1947, Fred Waring and His Pennsylvanians recorded «The Nutcracker Suite» on a two-part Decca Records 12-inch 78 RPM record with one part on each side as Decca DU 90022,[50] packaged in a picture sleeve. This version had custom lyrics written for Waring’s chorus by among others, Waring himself. The arrangements were by Harry Simeone.

- In 1952, the Les Brown big band recorded a version of the Nutcracker Suite, arranged by Frank Comstock, for Coral Records.[51] Brown rerecorded the arrangement in stereo for his 1958 Capitol Records album Concert Modern.

- In 1960, Duke Ellington and Billy Strayhorn composed jazz interpretations of pieces from Tchaikovsky’s score, recorded and released on LP as The Nutcracker Suite.[52] In 1999, this suite was supplemented with additional arrangements from the score by David Berger for The Harlem Nutcracker, a production of the ballet by choreographer Donald Byrd (born 1949) set during the Harlem Renaissance.[53]

- In 1960, Shorty Rogers released The Swingin’ Nutcracker, featuring jazz interpretations of pieces from Tchaikovsky’s score.

- In 1962, American poet and humorist Ogden Nash wrote verses inspired by the ballet,[54] and these verses have sometimes been performed in concert versions of the Nutcracker Suite. It has been recorded with Peter Ustinov reciting the verses, and the music is unchanged from the original.[55]

- In 1962 a novelty boogie piano arrangement of the «Marche», titled «Nut Rocker», was a No.1 single in the UK, and No.21 in the USA. Credited to B. Bumble and the Stingers, it was produced by Kim Fowley and featured studio musicians Al Hazan (piano), Earl Palmer (drums), Tommy Tedesco (guitar) and Red Callender (bass). «Nut Rocker» has subsequently been covered by many others including The Shadows, Emerson, Lake & Palmer, The Ventures, Dropkick Murphys, The Brian Setzer Orchestra, and the Trans-Siberian Orchestra. The Ventures’ own instrumental rock cover of «Nut Rocker», known as «Nutty», is commonly connected to the NHL team, the Boston Bruins, from being used as the theme for the Bruins’ telecast games for over two decades, from the late 1960s. In 2004, The Invincible Czars arranged, recorded, and now annually perform the entire suite for rock band.

- The Trans-Siberian Orchestra’s first album, Christmas Eve and Other Stories, includes an instrumental piece titled «A Mad Russian’s Christmas», which is a rock version of music from The Nutcracker.

- On the other end of the scale is the comedic Spike Jones version released in December 1945 as «Spike Jones presents for the Kiddies: The Nutcracker Suite (With Apologies to Tchaikovsky)», featuring humorous lyrics by Foster Carling and additional music by Joe «Country» Washburne. An abridged version was released in 1971 as part of the long play record Spike Jones is Murdering the Classics, one of the rare comedic pop records to be issued on the prestigious RCA Red Seal label.

- International choreographer Val Caniparoli has created several versions of The Nutcracker ballet for Louisville Ballet, Cincinnati Ballet, Royal New Zealand Ballet, and Grand Rapids Ballet.[56] While his ballets remain classically rooted, he has contemporarized them with changes such as making Marie an adult instead of a child, or having Drosselmeir emerges through the clock face during the overture making «him more humorous and mischievous.»[57] Caniparoli has been influenced by his simultaneous career as a dancer, having joined San Francisco Ballet in 1971 and performing as Drosselmeir and other various Nutcracker roles ever since that time.[58]

- The Disco Biscuits, a trance-fusion jam band from Philadelphia, have performed «Waltz of the Flowers» and «Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy» on multiple occasions.

- The Los Angeles Guitar Quartet (LAGQ) recorded the Suite arranged for four acoustic guitars on their CD recording Dances from Renaissance to Nutcracker (1992, Delos).

- In 1993, guitarist Tim Sparks recorded his arrangements for acoustic guitar on The Nutcracker Suite.

- The Shirim Klezmer Orchestra released a klezmer version, titled «Klezmer Nutcracker,» in 1998 on the Newport label. The album became the basis for a December 2008 production by Ellen Kushner, titled The Klezmer Nutcracker and staged off-Broadway in New York City.[59]

- In 2002, The Constructus Corporation used the melody of Sugar Plum Fairy for their track «Choose Your Own Adventure».

- In 2009, Pet Shop Boys used a melody from «March» for their track «All Over the World», taken from their album Yes.

- In 2012, jazz pianist Eyran Katsenelenbogen released his renditions of Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy, Dance of the Reed Flutes, Russian Dance and Waltz of the Flowers from the Nutcracker Suite.

- In 2014, Pentatonix released an a cappella arrangement of «Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy» on the holiday album That’s Christmas to Me and received a Grammy Award on 16 February 2016 for best arrangement.

- In 2016, Jennifer Thomas included an instrumental version of «Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy» on her album Winter Symphony.

- In 2017, Lindsey Stirling released her version of «Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy» on her holiday album Warmer in the Winter.[60]

- In 2018, Pentatonix released an a cappella arrangement of «Waltz of the Flowers» on the holiday album Christmas Is Here!.

- In 2019, Madonna sampled a portion on her song «Dark Ballet» from her Madame X album.[61]

- In 2019, Mariah Carey released a normal and an a cappella version of ‘Sugar Plum Fairy’ entitled the ‘Sugar Plum Fairy Introlude’ to open and close her 25th Deluxe Anniversary Edition of Merry Christmas.[62]

- In 2020, Coone made a hardstyle cover version titled «The Nutcracker».[63]

Selected discography[edit]

Many recordings have been made since 1909 of the Nutcracker Suite, which made its initial appearance on disc that year in what is now historically considered the first record album.[64] This recording was conducted by Herman Finck and featured the London Palace Orchestra.[65] But it was not until the LP album was developed that recordings of the complete ballet began to be made. Because of the ballet’s approximate hour and a half length when performed without intermission, applause, or interpolated numbers, it fits very comfortably onto two LPs. Most CD recordings take up two discs, often with fillers. An exception is the 81-minute 1998 Philips recording by Valery Gergiev that fits onto one CD because of Gergiev’s somewhat brisker speeds.

- In 1954, the first complete recording of the ballet was released, a 2-LP set in mono sound released by Mercury Records. The cover design was by George Maas with illustrations by Dorothy Maas.[66] The music was performed by the Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Antal Doráti. Doráti later re-recorded the complete ballet in stereo, with the London Symphony Orchestra in 1962 for Mercury and with the Amsterdam Concertgebouw Orchestra in 1975 for Philips Classics. According to Mercury Records, the 1962 recording was made on 35mm magnetic film rather than audio tape, and used album cover art identical to that of the 1954 recording.[67][68] Dorati is the only conductor so far to have made three different recordings of the complete ballet. Some have hailed the 1975 recording as the finest ever made of the complete ballet.[69] It is also faithful to the score in employing a boys’ choir in the Waltz of the Snowflakes. Many other recordings use an adult or mixed choir.

- In 1956, Artur Rodziński and the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra made a complete recording of the ballet in stereo for Westminster Records.

- In 1959, the first stereo LP album set of the complete ballet, with Ernest Ansermet conducting the Orchestre de la Suisse Romande, appeared on Decca Records in the UK and London Records in the US.

- The first complete stereo Nutcracker with a Russian conductor and a Russian orchestra appeared in 1960, when Gennady Rozhdestvensky’s recording of it, with the Bolshoi Theatre Orchestra, was issued first in the Soviet Union on Melodiya, then imported to the U.S. on Columbia Masterworks. It was also Columbia Masterworks’ first complete Nutcracker.[70]

With the advent of the stereo LP coinciding with the growing popularity of the complete ballet, many other complete recordings of it have been made. Notable conductors who have done so include Maurice Abravanel, André Previn, Michael Tilson Thomas, Mariss Jansons, Seiji Ozawa, Richard Bonynge, Semyon Bychkov, Alexander Vedernikov, Ondrej Lenard, Mikhail Pletnev, and most recently, Simon Rattle.[71] A CD of excerpts from the Tilson Thomas version had as its album cover art a painting of Mikhail Baryshnikov in his Nutcracker costume; perhaps this was due to the fact that the Tilson Thomas recording was released by CBS Masterworks, and CBS had first telecast the Baryshnikov «Nutcracker».[72]

- The soundtrack of the 1977 television production with Mikhail Baryshnikov and Gelsey Kirkland, featuring the National Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Kenneth Schermerhorn, was issued in stereo on a CBS Masterworks 2 LP-set, but it has not appeared on CD. The LP soundtrack recording was, for a time, the only stereo version of the Baryshnikov Nutcracker available, since the show was originally telecast only in mono, and it was not until recently that it began to be telecast with stereo sound. The sound portion of the DVD is also in stereo.

- The first complete recording of the ballet in digital stereo was issued in 1985, on a two-CD RCA set featuring Leonard Slatkin conducting the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra. This album originally had no «filler», but it has recently been re-issued on a multi-CD set containing complete recordings of Tchaikovsky’s two other ballets, Swan Lake and The Sleeping Beauty. This three-ballet album has now gone out of print.

There have been two major theatrical film versions of the ballet, made within seven years of each other, and both were given soundtrack albums.

- The first theatrical film adaptation, made in 1985, is of the Pacific Northwest Ballet version, and was conducted by Sir Charles Mackerras. The music is played in this production by the London Symphony Orchestra. The film was directed by Carroll Ballard, who had never before directed a ballet film (and has not done so since). Patricia Barker played Clara in the fantasy sequences, and Vanessa Sharp played her in the Christmas party scene. Wade Walthall was the Nutcracker Prince.

- The second film adaptation was a 1993 film of the New York City Ballet version, titled George Balanchine’s The Nutcracker, with David Zinman conducting the New York City Ballet Orchestra. The director was Emile Ardolino, who had won the Emmy, Obie, and Academy Awards for filming dance, and was to die of AIDS later that year. Principal dancers included the Balanchine muse Darci Kistler, who played the Sugar Plum Fairy, Heather Watts, Damian Woetzel, and Kyra Nichols. Two well-known actors also took part: Macaulay Culkin appeared as the Nutcracker/Prince, and Kevin Kline served as the offscreen narrator. The soundtrack features the interpolated number from The Sleeping Beauty that Balanchine used in the production, and the music is heard on the album in the order that it appears in the film, not in the order that it appears in the original ballet.[73]

- Notable albums of excerpts from the ballet, rather than just the usual Nutcracker Suite, were recorded by Eugene Ormandy conducting the Philadelphia Orchestra for Columbia Masterworks, and Fritz Reiner and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra for RCA Victor. Arthur Fiedler and the Boston Pops Orchestra (for RCA), as well as Erich Kunzel and the Cincinnati Pops Orchestra (for Telarc) have also recorded albums of extended excerpts. The original edition of Michael Tilson Thomas’s version with the Philharmonia Orchestra on CBS Masterworks was complete, but is out of print;[74] the currently available edition is abridged.[75]

Neither Ormandy, Reiner, nor Fiedler ever recorded a complete version of the ballet; however, Kunzel’s album of excerpts runs 73 minutes, containing more than two-thirds of the music. Conductor Neeme Järvi has recorded act 2 of the ballet complete, along with excerpts from Swan Lake. The music is played by the Royal Scottish National Orchestra.[76]

- Many famous conductors of the twentieth century made recordings of the suite, but not of the complete ballet. These include Arturo Toscanini, Sir Thomas Beecham, Claudio Abbado, Leonard Bernstein, Herbert von Karajan, James Levine, Sir Neville Marriner, Robert Shaw, Mstislav Rostropovich, Sir Georg Solti, Leopold Stokowski, Zubin Mehta, and John Williams.

- In 2007, Josh Perschbacher recorded an organ transcription of the Nutcracker Suite.

Ethnic stereotypes and US activism[edit]

In 2013, Dance Magazine printed the opinions of three directors. Ronald Alexander of Steps on Broadway and The Harlem School of the Arts said the characters in some of the dances were «borderline caricatures, if not downright demeaning». He also said some productions had made changes to improve this. In the Arabian dance, for example, it was not necessary to portray a woman as a «seductress», showing too much skin. Alexander tried a more positive portrayal of the Chinese, but this was replaced by the more traditional version, despite positive reception. Stoner Winslett of the Richmond Ballet said The Nutcracker was not racist and that her productions had a «diverse cast». Donald Byrd of Spectrum Dance Theater saw the ballet as Eurocentric and not racist.[77] Chloe Angyal, in Feministing, referred to «unbelievably offensive racial and ethnic stereotypes». Some people who have performed in productions of the ballet do not see a problem because they are continuing what is viewed as «a tradition».[78] According to George Balanchine, «Coffee» was a sensuous belly dance intended for the fathers, not the children.[79]

In The New Republic in 2014, Alice Robb described white people wearing «harem pants and a straw hat, eyes painted to look slanted» and «wearing chopsticks in their black wigs» in the Chinese dance. The Arabian dance, she said, has a woman who «slinks around the stage in a belly shirt, bells attached to her ankles».[78] One of the problems, Robb said, was the use of white people to play ethnic roles, because of the directors’ desire for everyone to look the same.[78]

Among the attempts to change the dances were Austin McCormick making the Arabian dance into a pole dance, and San Francisco Ballet and Pittsburgh Ballet Theater changing the Chinese dance to a dragon dance.[78]

Alastair Macaulay of The New York Times defended Tchaikovsky, saying he «never intended his Chinese and Arabian music to be ethnographically correct».[80] He said, «their extraordinary color and energy are far from condescending, and they make the world of ‘The Nutcracker’ larger.»[80] To change anything is to «unbalance The Nutcracker» with music the author did not write. If there were stereotypes, Tchaikovsky also used them in representing his own country of Russia.[80] Moreover, the Votkinsk-born composer is perceived as a part of cultural heritage of Finnic peoples (non-Indo-European).[81][82][failed verification]

University of California, Irvine professor Jennifer Fisher said in 2018 that a two-finger salute[which?] used in the Chinese dance was not a part of the culture. Though it might have had its source in a Mongolian chopstick dance, she called it «heedless insensitivity to stereotyping». She also complained about the use in the Chinese dance of «bobbing, subservient ‘kowtow’ steps, Fu Manchu mustaches, and … yellowface» makeup, compared to blackface. One concern she had was that dancers believed they were learning about Asian culture, when they were really experiencing a cartoon version.[83]

Fisher went on to say some ballet companies were recognizing that change had to happen. Georgina Pazcoguin of the New York City Ballet and former dancer Phil Chan started the «Final Bow for Yellowface» movement and created a web site which explained the history of the practices and suggested changes. One of their points was that only the Chinese dance made dancers look like an ethnic group other than the one they belonged to. The New York City Ballet went on to drop geisha wigs and makeup and change some dance moves. Some other ballet companies followed.[83]

In popular culture[edit]

Film[edit]

Several films having little or nothing to do with the ballet or the original Hoffmann tale have used its music:

- The 1940 Disney animated film Fantasia features a segment using The Nutcracker Suite. This version was also included both as part of the 3-LP soundtrack album of Fantasia (since released as a 2-CD set), and as a single LP, with Dance of the Hours, another Fantasia segment, on the reverse side.[84][85]

- The Spirit of Christmas, a 1950 marionette made-for-TV featurette in color narrated by Alexander Scourby, utilizes the poem A Visit from St. Nicholas, and this sequence also includes music from The Nutcracker.

- A 1951 thirty-minute short, Santa and the Fairy Snow Queen, issued on DVD by Something Weird Video, features several dances from The Nutcracker.[86]

- The Nutcracker (1973) features a nameless girl (slightly similar to Clara) who works as a maid. She befriends and falls in love with a nutcracker ornament, who was a young prince cursed by the three headed Mouse King.

- Sanrio released a stop-motion adaptation of The Nutcracker entitled Nutcracker Fantasy in 1979.

- In 1988, Care Bears Nutcracker Suite was produced by the Canadian animation studio Nelvana and featured the Care Bears characters.

- A 1990 animated film titled The Nutcracker Prince was released and distributed by Warner Brothers Pictures and uses cuts of the music throughout and its story is based heavily on that of the ballet.

- A 1999 animated film titled The Nuttiest Nutcracker featured the voices of Cheech Marin, Jim Belushi, and Phyllis Diller, and followed a group of anthropomorphic fruits and vegetables.

- In 2001, Barbie appeared in her first film, Barbie in the Nutcracker. It used excerpts by Tchaikovsky, which were performed by the London Symphony Orchestra. Though it heavily altered the story, it still made use of ballet sequences which had been rotoscoped using real ballet dancers.[87]

- In 2007, Tom and Jerry: A Nutcracker Tale also used The Nutcracker excerpts, which were performed by the Chamber Orchestra of Philadelphia.

- Disney announced that a remake of The Nutcracker would be directed by Robert Zemeckis through the use of motion capture, a technique that was used in The Polar Express, Monster House, Beowulf, and A Christmas Carol. The film was cancelled following the box office disappointment of Mars Needs Moms.

- In 2010, The Nutcracker in 3D with Elle Fanning abandoned the ballet and most of the story, retaining much of Tchaikovsky’s music with lyrics by Tim Rice. The $90 million film became the year’s biggest box office bomb.

- In 2016, the Hallmark Channel presented A Nutcracker Christmas; a tele-film that contains a number of selected scenes of the 1892 two-act Nutcracker ballet.

- In 2017, the Athens State Orchestra in collaboration with Cinecreed productions (former name: 1895 cinematic creations) presented «A Different Nutcracker» animation film, directed by Yiorgos Molvalis. At the premiere (Chr. Lamprakis, Athens Concert Hall, December 26, 2017) as Silent animation, the film was recorded live by the Athens State Orchestra. In 2020 the official recording was integrated in to the film marking its completion and making it available for screenings without the need to have the orchestra present.

- In 2018, the Disney live-action film The Nutcracker and the Four Realms was released with Lasse Hallström and Joe Johnston as directors and a script by Ashleigh Powell.[88][89]

Television[edit]

- A 1954 Christmas episode of General Electric Theater featured Fred Waring and his choral group, the Pennsylvanians, singing excerpts from The Nutcracker with specially written lyrics. While the music was being sung, the audience saw ballet dancers performing.[90] The episode was hosted by Ronald Reagan.

- The 1987 true crime miniseries Nutcracker: Money, Madness and Murder opens every episode with the first notes of the ballet amid scenes of Frances Schreuder’s daughter dancing to it in ballet dress.

- «Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy» plays in the gabian dubbing version of El Chapulín Colorado episode «El Mistério Del Hombre De Las Nieves» while Chapolin and his friends Carlos and Florinda use sleeping bags for themselves to sleep at home until the music is interrupted after a fake yeti invades the house to scare them.

- Garfield and Friends episode, «Caped Avenger», «Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy» plays briefly while a shadow kidnaps Pooky.

- The «Toon TV» episode of Tiny Toon Adventures features an arcade-themed song called «Video Game Blues», set to «Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy» and «The Russian Dance».

- Batman: The Animated Series episode, «Christmas with the Joker», The Joker plays, «Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy», and later, «The Russian Dance» on a record player to distract Batman and Robin.

- A 1996 episode of The Magic School Bus («Holiday Special», season 3, episode 39), Wanda is planning to see a performance of The Nutcracker. Some of the music for this episode was based on the score of the ballet.[91]

- The Mickey Mouse Works «MouseTales» segment, the House of Mouse episode, «Pete’s Christmas Caper», and the feature film, Mickey’s Magical Christmas: Snowed in at the House of Mouse, with Mickey Mouse playing the role of the Nutcraker, Minnie Mouse as Maria, Donald Duck as the King Mouse, Goofy as the Magical Snow Fairy, and Ludwig Von Drake as Godpapa Drosselmeyer.

- The Barney & Friends TV Christmas episode features its own version of the Nutcracker with Barney the Dinosaur as the narrator, dressed up in a tuxedo vest and matching cuffs.

- Princess Tutu, a 2002 anime series that uses elements from many ballets as both music and as part of the storyline, uses the music from The Nutcracker in many places throughout its run, including using an arranged version of the overture as the theme for the main character. Both the first and last episodes feature The Nutcracker as their ‘theme’, and one of the main characters is named Drosselmeyer.

- An arrangement of this the Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy can be heard in Episode 8 of Girls und Panzer.

- Arrangements of the Waltz of the flowers can be heard in Episode 7 of Guilty Crown.

- The 2015 Canadian television film The Curse of Clara: A Holiday Tale, based on an autobiographical short story by onetime Canadian ballet student Vickie Fagan, centres on a young ballet student preparing to dance the role of Clara in a production of The Nutcracker.

Video games[edit]

- In the NES version of Tetris, the «Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy» is available as background music (referred to in the settings as «Music 1»), and the same arrangement was later remixed for the Game Boy Advance version of Tetris Worlds.

- In the NES game Winter Games, «Waltz of the Flowers» is used as the music for the figure skating event.

- In the game BioShock, the main character Jack meets an insane musician named Sander Cohen who tasks Jack with killing and photographing four of Sander’s ex-disciples. When the third photograph is given to Sander, in a fit of pique he unleashes waves of splicer enemies to attack Jack while playing «Waltz of the Flowers» from speakers in the area.

- In the original Lemmings «Dance of the Reed Flutes» and «Miniature Overture» is used in several levels.

- In Weird Dreams, there is also a plus sized ballerina dancing to the «Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy» in the Hall of Tubes.

- In the Baby Bowser levels of Yoshi’s Story, a variation of the «Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy» is used as the background music.

- In Mega Man Legends, the «Waltz of the Flowers» can be heard in the Balloon Fantasy minigame.

- In Crash Tag Team Racing, the «Trepak» are the background themes played during Tire & Ice track as a part with «Kalinka» and «Hungarian Dance No. 5».

- In the Wii version of Mario & Sonic at the Olympic Winter Games, «Waltz of the Flowers» is used as optional background music for the figure skating event. In the Nintendo DS version, the «Marche» and «Trepak» are used.[92]

- In Kingdom Hearts 3D: Dream Drop Distance the «Waltz of Flowers», «The Arabian Dance», «The Russian Dance», «The Dance of the Reed Flutes» and «The Chinese Dance» are the background themes that play when Riku is in the world based on Disney’s Fantasia.

- In Hatoful Boyfriend, the «Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy» is used as the character theme for Iwamine Shuu.

- In a TV advertisement for Army Men: Sarge’s Heroes 2, the plastic army men work together using a train playset to move a firecracker under the Christmas tree and place it between the Nutcracker doll’s legs, while «Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy» plays.

- In Fantasia: Music Evolved, a medley of «The Nutcracker» is listed and consists of the «Marche», «Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy», and «Trepak»; besides the original mix, there is also the «D00 BAH D00» mix and the «DC Breaks» mix.

- In Dynamite Headdy, the «March» is used in the Mad Dog boss battle.

- In Grand Theft Auto V one of the classical horns, that can be bought for cars, plays the «Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy».[93]

- The «Waltz of the Flowers» appears during a baby’s death scene in What Remains of Edith Finch.

- In the game «Cell to Singularity,» «Waltz of the Flowers» is heard in the background when new creatures are created.

- In LittleBigPlanet 3, a remix of «Waltz of the Flowers» is used as background music in the level «Tutu Tango» and is an unlockable music track in Create Mode.

- The «Kids Mode» of Just Dance 2021 and Just Dance 2022 features the song «Dance of the Mirlitons» on the soundtrack.

Children’s recordings[edit]

There have been several recorded children’s adaptations of the E.T.A. Hoffmann story (the basis for the ballet) using Tchaikovsky’s music, some quite faithful, some not. One that was not was a version titled The Nutcracker Suite for Children, narrated by Metropolitan Opera announcer Milton Cross, which used a two-piano arrangement of the music. It was released as a 78-RPM album set in the 1940s.[94] For the children’s label Peter Pan Records, actor Victor Jory narrated a condensed adaptation of the story with excerpts from the score. It was released on one side of a 45-RPM disc.[95] A later version, titled The Nutcracker Suite, starred Denise Bryer and a full cast, was released in the 1960s on LP and made use of Tchaikovsky’s music in the original orchestral arrangements. It was quite faithful to Hoffmann’s story The Nutcracker and the Mouse King, on which the ballet is based, even to the point of including the section in which Clara cuts her arm on the glass toy cabinet, and also mentioning that she married the Prince at the end. It also included a less gruesome version of «The Tale of the Hard Nut», the tale-within-a-tale in Hoffmann’s story. It was released as part of the Tale Spinners for Children series.[96]

Spike Jones produced a 78 rpm record set «Spike Jones presents for the kiddies The Nutcracker Suite (with Apologies to Tchaikovsky)» in 1944. It includes the tracks: «The Little Girl’s Dream», «Land of the Sugar Plum Fairy», «The Fairy Ball», «The Mysterious Room», «Back to the Fairy Ball» and «End of the Little Girl’s Dream». This is all done in typical Spike Jones style, with the addition of choruses and some swing music. The entire recording is available at archive.com [97]

Journalism[edit]

- In 2009, Pulitzer Prize–winning dance critic Sarah Kaufman wrote a series of articles for The Washington Post criticizing the primacy of The Nutcracker in the American repertory for stunting the creative evolution of ballet in the United States:[98][99][100]

That warm and welcoming veneer of domestic bliss in The Nutcracker gives the appearance that all is just plummy in the ballet world. But ballet is beset by serious ailments that threaten its future in this country… companies are so cautious in their programming that they have effectively reduced an art form to a rotation of over-roasted chestnuts that no one can justifiably croon about… The tyranny of The Nutcracker is emblematic of how dull and risk-averse American ballet has become. There were moments throughout the 20th century when ballet was brave. When it threw bold punches at its own conventions. First among these was the Ballets Russes period, when ballet—ballet—lassoed the avant-garde art movement and, with works such as Michel Fokine’s fashionably sexy Scheherazade (1910) and Léonide Massine’s Cubist-inspired Parade (1917), made world capitals sit up and take notice. Afraid of scandal? Not these free-thinkers; Vaslav Nijinsky’s rough-hewn, aggressive Rite of Spring famously put Paris in an uproar in 1913… Where are this century’s provocations? Has ballet become so entwined with its «Nutcracker» image, so fearfully wedded to unthreatening offerings, that it has forgotten how eye-opening and ultimately nourishing creative destruction can be?[99]

- In 2010, Alastair Macaulay, dance critic for The New York Times (who had previously taken Kaufman to task for her criticism of The Nutcracker[101]) began The Nutcracker Chronicles, a series of blog articles documenting his travels across the United States to see different productions of the ballet.[102]

Act I of The Nutcracker ends with snow falling and snowflakes dancing. Yet The Nutcracker is now seasonal entertainment even in parts of America where snow seldom falls: Hawaii, the California coast, Florida. Over the last 70 years this ballet—conceived in the Old World—has become an American institution. Its amalgam of children, parents, toys, a Christmas tree, snow, sweets and Tchaikovsky’s astounding score is integral to the season of good will that runs from Thanksgiving to New Year… I am a European who lives in America, and I never saw any Nutcracker until I was 21. Since then I’ve seen it many times. The importance of this ballet to America has become a phenomenon that surely says as much about this country as it does about this work of art. So this year I’m running a Nutcracker marathon: taking in as many different American productions as I can reasonably manage in November and December, from coast to coast (more than 20, if all goes well). America is a country I’m still discovering; let The Nutcracker be part of my research.[103]

- In 2014, Ellen O’Connell, who trained with the Royal Ballet in London, wrote, in Salon (website), on the darker side of The Nutcracker story. In E.T.A. Hoffmann’s original story, the Nutcracker and Mouse King, Marie’s (Clara’s), journey becomes a fevered delirium that transports her to a land where she sees sparkling Christmas Forests and Marzipan Castles, but in a world populated with dolls.[104] Hoffmann’s tales were so bizarre, Sigmund Freud wrote about them in The Uncanny.[105][106]

E.T.A. Hoffmann’s 1816 fairy tale, on which the ballet is based, is troubling: Marie, a young girl, falls in love with a nutcracker doll, whom she only sees come alive when she falls asleep. …Marie falls, ostensibly in a fevered dream, into a glass cabinet, cutting her arm badly. She hears stories of trickery, deceit, a rodent mother avenging her children’s death, and a character who must never fall asleep (but of course does, with disastrous consequences). While she heals from her wound, the mouse king brainwashes her in her sleep. Her family forbids her from speaking of her «dreams» anymore, but when she vows to love even an ugly nutcracker, he comes alive and she marries him.

Popular music[edit]

- The song «Dance Mystique» (track B1) on the studio album Bach to the Blues (1964) by the Ramsey Lewis Trio is a jazz adaptation of Coffee (Arabian Dance).

- The song «Fall Out» by English band Mansun from their 1998 album Six heavily relies on the celesta theme from the Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy.

- The song «Dark Ballet» by American singer-songwriter Madonna samples the melody of Dance of the Reed Flutes (Danish Marzipan) which is often mistaken for Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy. The song also relied on the lesser-known harp cadenza from Waltz of the Flowers. The same Tchaikovsky sample was earlier used in internationally famous 1992 ads for Cadbury Dairy Milk Fruit & Nut with ‘Madonna’ as the singing chocolate bar (in Russian version the subtitles «‘This Is Madonna'» (Russian: Это Мадонна, tr. Eto Madonna) were displayed on a screen.[107]

See also[edit]

- Parade of the Wooden Soldiers

Notes[edit]

- ^ Щелкунчикъ in Russian pre-revolutionary script.

References[edit]

- ^ a b Fisher, J. (2003). Nutcracker Nation: How an Old World Ballet Became a Christmas Tradition in the New World. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- ^ Agovino, Theresa (23 December 2013). «The Nutcracker brings big bucks to ballet companies». Crain’s New York Business. Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- ^ Wakin, Daniel J. (30 November 2009). «Coming Next Year: Nutcracker Competition». The New York Times.

- ^ a b c d Anderson, J. (1958). The Nutcracker Ballet, New York: Mayflower Books.

- ^ a b Hoffmann, E. T. A., Dumas, A., Neugroschel, J. (2007). Nutcracker and Mouse King, and the Tale of the Nutcracker, New York

- ^ Rosenberg, Donald (22 November 2009). «Tchaikovsky’s ‘Nutcracker’ a rite of winter thanks to its glorious music and breathtaking dances». Cleveland.com. Cleveland. Retrieved 4 November 2010.

- ^ «Tchaikovsky». Balletalert.com. Archived from the original on 16 March 2012. Retrieved 10 December 2012.

- ^ a b c d e «Nutcracker History». Balletmet.org. Archived from the original on 10 December 2008. Retrieved 18 December 2008.

- ^ a b Fisher 2003, p. 15

- ^ a b Fisher 2003, p. 16

- ^ Fisher 2003, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Fisher 2003, p. 17.

- ^ Wiley, Roland John (1991). Tchaikovsky’s Ballets: Swan Lake, The Sleeping Beauty, The Nutcracker. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ^ «Ballet Talk [Powered by Invision Power Board]». Ballettalk.invisionzone.com. 26 November 2008. Archived from the original on 17 September 2009. Retrieved 7 January 2009.

- ^ Craine, Debra (8 December 2007). «Christmas cracker». The Times. London.

- ^ «Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo. Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo records, 1935–1968 (MS Thr 463): Guide». Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- ^ «Remembering Jocelyn Vollmar (1925-2018): SF Ballet’s 1st Snow Queen sparkled on- and offstage».

- ^ «About : Ballet West».

- ^ «Maria Tallchief». The Kennedy Center. The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts. Archived from the original on 8 July 2015. Retrieved 15 November 2020.

- ^ Soviet ed., where they are printed in the original French with added Russian translation in editorial footnotes

- ^ Maximova, Yekaterina; Vasiliev, Vladimir (1967). Nutcracker Suite Performed By The Bolshoi (1967). Moscow, Russia: British Pathé.

- ^ The Nutcracker at the Royal Ballet: «March of the Toy Soldiers». London: Playbill Video. 1967. Archived from the original on 30 October 2021.

- ^ Dancers of the Moscow Ballet (2017). Doll Dance. Moscow, Russia: Moscow Ballet. Archived from the original on 30 October 2021.

- ^ Dancers of the Moscow Ballet (2017). The Rat King Appears. Moscow, Russia: Moscow Ballet. Archived from the original on 30 October 2021.

- ^ Dancers of the SemperOperBallett (2016). Snow Pas de Deux. Dresden, Germany: SemperOperBallett. Archived from the original on 30 October 2021.

- ^ Bolshoi Ballet (2015). The Nutcracker (Casse-Noisette) – Bolshoi Ballet in Cinema (Preview 1). Moscow, Russia: Pathé Live. Archived from the original on 30 October 2021.

- ^ Dancers of the Perm Opera Ballet Theatre (2017). Вальс снежинок из балета «Щелкунчик». Russia: Perm Opera Ballet Theatre. Archived from the original on 30 October 2021.

- ^ Dancers of the SemperOperBallett. The Nutcracker – Arabian Divertissement. Dresden, Germany: SemperOperBallett. Archived from the original on 15 January 2020.

- ^ Cecilia Iliesiu (2017). Arabian Coffee/Peacock. Pacific Northwest Ballet.

- ^ Dancers of the Mariinsky ballet (2012). The Nutcracker – Tea (Chinese Dance). Mariinsky Ballet. Archived from the original on 30 October 2021.

- ^ Dancers of the Boston Ballet (2017). SPOTLIGHT The Nutcracker’s Russian Dance. Boston Ballet. Archived from the original on 30 October 2021.

- ^ Dancers of the SemperOperBallett. The Nutcracker – Mirlitons Divertissement. Dresden, Germany: SemperOperBallett.

- ^ Kyra Nichols and the NYCB Corps de Ballet (2015). New York City Ballet: Waltz of the Flowers. New York City: Lincoln Center.

- ^ PNB dancers. Nutcracker Flowers Excerpt. Pacific Northwest Ballet. Archived from the original on 30 October 2021.

- ^ Alina Somova & Vladimir Shklyarov (2012). Sugarplum and Cavalier variations. St Petersburg, Russia: Ovation.

- ^ Darci Kistler. Dance of the Sugarplum Fairy. New York City: Ovation. Archived from the original on 30 October 2021.

- ^ Wiley 1991, p. 220.

- ^ Schwarm, Betsy. «The Nutcracker, OP. 71». Encyclopaedia Britannica. The Music Alliance. Retrieved 20 January 2017.

- ^ «Tchaikovskaya (Davydova) Alexandra Ilinichna». chaiklib.permculture.ru (in Russian). Chaykovsky Centralized Library System. Archived from the original on 24 October 2020. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ^ Jennifer Fisher (2004). ‘Nutcracker’ Nation: How an Old World Ballet Became a Christmas Tradition in the New World. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-10599-5.

- ^ «Шесть шедевров Чайковского, сделанных из обычной гаммы» [Six masterpieces by Tchaikovsky created from the usual scale]. kultspargalka.ru (in Russian). 4 April 2020. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

1. June. Barcarole from The Seasons 2. ‘Adagio’ from The Nutcracker 3. Lensky’s aria from Eugene Onegin 4. Serenade for Strings Waltz 5. ‘Melodrama’ from the music to the play by A. Ostrovsky The Snow Maiden 6. Yeletsky’s aria from The Queen of Spades

- ^ Tchaikovsky By David Brown W. W. Norton & Company, 1992 page 332

- ^ Appleford, David (19 December 2008). «The KEZ Christmas Countdown: Day 19 – The Nutcracker». Kfyi.com. Archived from the original on 12 January 2012. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- ^ Tchaikovsky, P. (2004). The Nutcracker: Complete Score, Dover Publications.

- ^ a b «Ballet and Food». art-eda.ru (in Russian). Artoteka of Food. 21 November 2018. Retrieved 4 December 2020.

Russian trepak «Candy Cane» and dance of sugar shepherds «Danish Marzipan»

- «Russian Seasons in Monaco». rusmonaco.fr (in Russian). Monaco and Cote D’Azur (printed Russian-language newspaper and magazine in Monaco and France). Retrieved 4 December 2020.

- «П.Чайковский. Щелкунчик. Дивертисмент. Большой театр. Tchaikovsky. The Nutcracker (1980)». YouTube. Official channel «Soviet Television» by the State TV and Radio Fund of Russia. 11 December 2018. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

The second title is «Датский марципан» – Danish marzipan. In the Grigorovich version for Bolshoi Theatre the idea of Europe is represented by dance with a marzipan sheep on wheels; Russian dance «Cancy Cane» combines the colors of candy canes and folklore heroes Ivan Tsarevich and Vasilisa the Wise

- ^ Alexander Poznansky, Tchaikovsky: The Quest for the Inner Man, p. 544

- ^ Brown, David. Tchaikovsky: The Final Years, 1885-1893. London, 1991; corrected edition 1992: p. 386

- ^ «The Nutcracker Profile: The History of The Nutcracker». Classicalmusic.about.com. 11 June 2010. Retrieved 1 July 2011.

- ^ «Freddy Martin And His Orchestra – Tschaikowsky’s Nutracker Suite In Dance Tempo». Discogs.

- ^ «Fred Waring & the Pennsylvanians – Nutcracker Suite«. Discogs.

- ^ «Discography of American Historical Recordings, s.v. «Decca matrix L 6763. Nutcracker suite, part 1 / Les Brown and his Band of Renown,» accessed December 19, 2020″.

- ^ «A Duke Ellington Panorama». Depanorama.net. Retrieved 1 July 2011.

- ^ «The Harlem Nutcracker». Susan Kuklin. Archived from the original on 11 June 2011. Retrieved 1 July 2011.

- ^ The New Nutcracker Suite and Other Innocent Verses: Ogden Nash, Ivan Chermayeff. Little, Brown and Company. January 1962 – via Amazon.com.

- ^ Ogden Nash. «The New Nutcracker Suite & Other Innocent Verses». Kirkus Reviews.

- ^ Cooper, Antonio. «Nutcracker Brings Magic to DeVos». The Oakland Press. Retrieved 1 October 2019.

- ^ Scher, Avichai (3 December 2018). «What’s it like to choreograph Nutcracker four different times». Dance Magazine. Dance Magazine. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

- ^ Merrell, Sue (30 November 2017). ««Nutcracker» Choreographer Makes GR Stop Ahead of Opening». grand rapids magazine. Retrieved 3 October 2019.

- ^ «blogcritics.org». blogcritics.org. Archived from the original on 11 July 2012. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- ^ «Lindsey Stirling Talks Joining ‘Dancing With the Stars’ & Shares First Holiday Album Track: Premiere». Billboard. 14 September 2017. Retrieved 23 October 2017.

- ^ Alexeyev, Alexander (5 August 2019). «Баян для Мадонны. Чайковский в новом альбоме Madame X» [Bayan [also a slang word for anything related to media content: videos, pictures, news, and an old post as fresh news] for Madonna. Tchaikovsky on the new Madame X album] (in Russian). Rossiyskaya Gazeta. Archived from the original on 2 September 2019. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ Van Horn, Charisse (19 November 2019). «Mariah Carey Shows Off Her Whistle Register In New Sugar Plum Fairy Acapella Rendition». celebrityinsider.org. Celebrity Insider. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ «Ho Ho, whatever! Got some jolly news for you… Proud to be part of the @smashthehouse Christmas album dropping 27/12. Swipe left to witness «The Nutcracker»!». Twitter. Retrieved 26 November 2020.

- ^ «Recording Technology History». History.sandiego.edu. Archived from the original on 12 March 2010. Retrieved 18 December 2008.

- ^ Macaulay, Alastair (31 December 2010). «‘The Nutcracker’ Chronicles: Listening to the Score».

- ^ «Tchaikovsky: The Nutcracker (Complete Ballet); Serenade for Strings – Credits on MSN Music». Music.msn.com. Archived from the original on 8 June 2013. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- ^ «Pyotr Il’yich Tchaikovsky, Antal Dorati, Harold Lawrence, London Symphony Orchestra, Philharmonia Hungarica, London Symphony Orchestra Chorus – Tchaikovsky: The Nutcracker (Complete Ballet); Serenade in C Major – Amazon.com Music». Amazon.

- ^ Styrous® (10 December 2012). «The Styrous® Viewfinder».

- ^ «Nutcracker». Classicalcdreview.com. Retrieved 18 December 2008.

- ^ «Tchaikovsky, Gennady Rozhdestvensky, Bolshoi Theater Orchestra – Tchaikovsky: The Nutcracker (Complete) – Amazon.com Music». Amazon.

- ^ «Tchaikovsky: the Nutcracker: Sir Simon Rattle, Tchaikovsky, Berliner Philharmoniker: Music». Amazon. Retrieved 1 July 2011.

- ^ «Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky, Michael Tilson Thomas, The Philharmonia Orchestra, Ambrosian Singers – Tchaikovsky: Music From The Nutcracker (Highlights) – Amazon.com Music». Amazon.

- ^ «The Nutcracker (1993 Motion Picture Soundtrack): Pyotr Il’yich Tchaikovsky, David Zinman, New York City Ballet Orchestra: Music». Amazon. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- ^ «Archived copy» (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 March 2014. Retrieved 2 November 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ «Tchaikovsky: The Nutcracker (Complete): Music». Amazon. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- ^ «Tchaikovsky: Nutcracker, Act II/ Swan Lake». AllMusic.

- ^ «Burning Question: Is Nutcracker Racist?». Dance Magazine. 1 December 2013. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- ^ a b c d Robb, Alice (24 December 2014). «Sorry, ‘The Nutcracker’ Is Racist». The New Republic. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- ^ Dunning, Jennifer (26 November 2004). «Staying on Their Toes for ‘The Nutcracker,’ Show After Show». The New York Times. Retrieved 13 February 2020.

- ^ a b c Macaulay, Alastair (6 September 2012). «Stereotypes in Toeshoes». The New York Times. Retrieved 13 February 2020.

- ^ «Tchaikovsky Museum-Estate» (in Russian). Finno-Ugric World. Retrieved 15 September 2020.

- ^ «Udmurtia to Host a Conference ‘Tchaikovsky: a Son of Udmurtia, the Genius of Man!’» (in Russian). Regnum. 5 October 2007. Retrieved 15 September 2020.

- ^ a b Fisher, Jennifer (11 December 2018). «Op-Ed: ‘Yellowface’ in ‘The Nutcracker’ isn’t a benign ballet tradition, it’s racist stereotyping». Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 13 February 2020.

- ^ «Disney (All) The Nutcracker Suite/Dance of the Hours – Sealed USA LP RECORD (284287)». Eil.com. 21 April 2004. Retrieved 1 July 2011.

- ^ «Tchaikovsky’s The Nutcracker Suite Also Ponchielli’s Dance of the Hours Philadelphia Orchestra Leopold Stokowski Conducting: Leopold Stokowski: Music». Amazon. 9 September 2009. Retrieved 1 July 2011.

- ^ «Santa and the Fairy Snow Queen : A Sid Davis Production : Free Download & Streaming : Internet Archive». 10 March 2001. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- ^ daflauta (2 October 2001). «Barbie in the Nutcracker (Video 2001)». IMDb.

- ^ Kit, Borys (4 March 2016). «Lasse Hallstrom to Direct Live-Action ‘Nutcracker’ for Disney». The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- ^ «The Nutcracker and the Four Realms (2018)». Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 1 November 2018.

- ^ ««General Electric Theater» Music for Christmas (TV Episode 1954)». IMDb. 19 December 1954.

- ^ ««The Magic School Bus» The Family Holiday Special (TV Episode 1996)». IMDb. 25 December 1996.

- ^ «Super Mario Wiki/Figure Skating». Mariowiki.com. 10 September 2012. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- ^ «GTA5 Classical horn 3». youtube.com. 8 May 2015. Archived from the original on 30 October 2021. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- ^ «Week 50». Kiddierecords.com. Archived from the original on 13 July 2011. Retrieved 1 July 2011.

- ^ «11 The Nutcracker Suite : Victor Jory». SoundCloud.

- ^ «Tale Spinners for Children». Artsreformation.com. 14 May 2008. Archived from the original on 13 August 2013. Retrieved 1 July 2011.

- ^ Spike Jones and his City Slickers. «Spike Jones presents for the kiddies The Nutcracker Suite with Apologies to Tchaikovsky«. archive.org. Retrieved 29 December 2022.

- ^ Kaufman, Sarah (13 September 2009). «Here Come Those Sugar Plums and Chestnuts». The Washington Post. Retrieved 26 November 2010.

- ^ a b Kaufman, Sarah (22 November 2009). «Breaking pointe: ‘The Nutcracker’ takes more than it gives to world of ballet». The Washington Post. Retrieved 26 November 2010.

- ^ Itzkoff, Dave (14 December 2009). «Sugar Plum Overdose: The Case Against ‘The Nutcracker’«. The Washington Post. Retrieved 26 November 2010.

- ^ Macaulay, Alastair (16 November 2010). «A ‘Nutcracker’ Lover Explains Himself». The New York Times. Retrieved 20 November 2010.

- ^ Macaulay, Alastair (10 November 2010). «The ‘Nutcracker’ Chronicles: The Marathon Begins». The New York Times. Retrieved 15 November 2010.

- ^ Macaulay, Alastair (10 November 2010). «The Sugarplum Diet». The New York Times. Retrieved 15 November 2010.

- ^ O’Connell, Ellen (25 December 2014). ««The Nutcracker’s» disturbing origin story: Why this was once the world’s creepiest ballet». Solon. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- ^ Freud, Sigmund (1919). «The Uncanny» (PDF).

- ^ «Nutcracker Ballet 101». Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- ^ «Reklamka Vimto i Frut’n’Nuts (1994)» (in Russian). YouTube channel «towaroved». Retrieved 24 September 2019.

External links[edit]

- The Nutcracker (ballet): Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- The Nutcracker (suite): Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- Tchaikovsky Research

- The Nutcracker ballet

The Nutcracker (Russian: Щелкунчик[a], tr. Shchelkunchik listen (help·info)) is an 1892 two-act «fairy ballet» (Russian: балет-феерия, balet-feyeriya) set on Christmas Eve at the foot of a Christmas tree in a child’s imagination. The music is by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, his Opus 71. The plot is an adaptation of E. T. A. Hoffmann’s 1816 short story The Nutcracker and the Mouse King. The ballet’s first choreographer was Marius Petipa, with whom Tchaikovsky had worked three years earlier on The Sleeping Beauty, assisted by Lev Ivanov. Although the complete and staged The Nutcracker ballet was not as successful as the 20-minute Nutcracker Suite Tchaikovsky had premiered nine months earlier, The Nutcracker soon became popular.

Since the late 1960s, it has been danced by countless ballet companies, especially in North America.[1] Major American ballet companies generate around 40% of their annual ticket revenues from performances of The Nutcracker.[2][3] The ballet’s score has been used in several film adaptations of Hoffmann’s story.

Tchaikovsky’s score has become one of his most famous compositions. Among other things, the score is noted for its use of the celesta, an instrument the composer had already employed in his much lesser known symphonic ballad The Voyevoda (1891).

Composition[edit]

After the success of The Sleeping Beauty in 1890, Ivan Vsevolozhsky, the director of the Imperial Theatres, commissioned Tchaikovsky to compose a double-bill program featuring both an opera and a ballet. The opera would be Iolanta. For the ballet, Tchaikovsky would again join forces with Marius Petipa, with whom he had collaborated on The Sleeping Beauty. The material Vsevolozhsky chose was an adaptation of E. T. A. Hoffmann’s story «The Nutcracker and the Mouse King», by Alexandre Dumas called «The Story of a Nutcracker».[4] The plot of Hoffmann’s story (and Dumas’ adaptation) was greatly simplified for the two-act ballet. Hoffmann’s tale contains a long flashback story within its main plot titled «The Tale of the Hard Nut», which explains how the Prince was turned into the Nutcracker. This had to be excised for the ballet.[5]

Petipa gave Tchaikovsky extremely detailed instructions for the composition of each number, down to the tempo and number of bars.[4] The completion of the work was interrupted for a short time when Tchaikovsky visited the United States for twenty-five days to conduct concerts for the opening of Carnegie Hall.[6] Tchaikovsky composed parts of The Nutcracker in Rouen, France.[7]

History[edit]

Saint Petersburg premiere[edit]

(Left to right) Lydia Rubtsova as Marianna, Stanislava Belinskaya as Clara and Vassily Stukolkin as Fritz, in the original production of The Nutcracker (Imperial Mariinsky Theatre, Saint Petersburg, 1892)

Varvara Nikitina as the Sugar Plum Fairy and Pavel Gerdt as the Cavalier, in a later performance in the original run of The Nutcracker, 1892

The first performance of The Nutcracker was not deemed a success.[8] The reaction to the dancers themselves was ambivalent. Although some critics praised Dell’Era on her pointework as the Sugar Plum Fairy (she allegedly received five curtain-calls), one critic called her «corpulent» and «podgy». Olga Preobrajenskaya as the Columbine doll was panned by one critic as «completely insipid» and praised as «charming» by another.[9]

Alexandre Benois described the choreography of the battle scene as confusing: «One can not understand anything. Disorderly pushing about from corner to corner and running backwards and forwards – quite amateurish.»[9]

The libretto was criticized as «lopsided»[10] and for not being faithful to the Hoffmann tale. Much of the criticism focused on the featuring of children so prominently in the ballet,[11] and many bemoaned the fact that the ballerina did not dance until the Grand Pas de Deux near the end of the second act (which did not occur until nearly midnight during the program).[10] Some found the transition between the mundane world of the first scene and the fantasy world of the second act too abrupt.[4] Reception was better for Tchaikovsky’s score. Some critics called it «astonishingly rich in detailed inspiration» and «from beginning to end, beautiful, melodious, original, and characteristic».[12] But this also was not unanimous, as some critics found the party scene «ponderous» and the Grand Pas de Deux «insipid».[13]

Subsequent productions[edit]

In 1919, choreographer Alexander Gorsky staged a production which eliminated the Sugar Plum Fairy and her Cavalier and gave their dances to Clara and the Nutcracker Prince, who were played by adults instead of children. This was the first production to do so. An abridged version of the ballet was first performed outside Russia in Budapest (Royal Opera House) in 1927, with choreography by Ede Brada.[14][unreliable source?] In 1934, choreographer Vasili Vainonen staged a version of the work that addressed many of the criticisms of the original 1892 production by casting adult dancers in the roles of Clara and the Prince, as Gorsky had. The Vainonen version influenced several later productions.[4]

The first complete performance outside Russia took place in England in 1934,[8] staged by Nicholas Sergeyev after Petipa’s original choreography. Annual performances of the ballet have been staged there since 1952.[15] Another abridged version of the ballet, performed by the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, was staged in New York City in 1940,[16] Alexandra Fedorova – again, after Petipa’s version.[8] The ballet’s first complete United States performance was on 24 December 1944 by the San Francisco Ballet, staged by its artistic director, Willam Christensen, and starring Gisella Caccialanza as the Sugar Plum Fairy, and Jocelyn Vollmar as the Snow Queen.[17][8] After the enormous success of this production, San Francisco Ballet has presented Nutcracker every Christmas Eve and throughout the winter season, debuting new productions in 1944, 1954, 1967, and 2004. The original Christensen version continues in Salt Lake City, where Christensen relocated in 1948. It has been performed every year since 1963 by the Christensen-founded Ballet West.[18]

The New York City Ballet gave its first annual performance of George Balanchine’s reworked staging of The Nutcracker in 1954.[8] The performance of Maria Tallchief in the role of the Sugar Plum Fairy helped elevate the work from obscurity into an annual Christmas classic and the industry’s most reliable box-office draw. Critic Walter Terry remarked that «Maria Tallchief, as the Sugar Plum Fairy, is herself a creature of magic, dancing the seemingly impossible with effortless beauty of movement, electrifying us with her brilliance, enchanting us with her radiance of being. Does she have any equals anywhere, inside or outside of fairyland? While watching her in The Nutcracker, one is tempted to doubt it.»[19]

Since Gorsky, Vainonen and Balanchine’s productions, many other choreographers have made their own versions. Some institute the changes made by Gorsky and Vainonen while others, like Balanchine, utilize the original libretto. Some notable productions include Rudolf Nureyev’s 1963 production for the Royal Ballet, Yury Grigorovich for the Bolshoi Ballet, Mikhail Baryshnikov for the American Ballet Theatre, Fernand Nault for Les Grands Ballets Canadiens starting in 1964, Kent Stowell for Pacific Northwest Ballet starting in 1983, and Peter Wright for the Royal Ballet and the Birmingham Royal Ballet. In recent years, revisionist productions, including those by Mark Morris, Matthew Bourne, and Mikhail Chemiakin have appeared; these depart radically from both the original 1892 libretto and Vainonen’s revival, while Maurice Béjart’s version completely discards the original plot and characters. In addition to annual live stagings of the work, many productions have also been televised or released on home video.[1]

Roles[edit]