«Принцесса на горошине» читательский дневник

4.3

Средняя оценка: 4.3

Всего получено оценок: 78.

Обновлено 6 Августа, 2021

4.3

Средняя оценка: 4.3

Всего получено оценок: 78.

Обновлено 6 Августа, 2021

«Принцесса на горошине» — замечательная сказка Х.К. Андерсена, в которой принцессе удалось доказать своё знатное происхождение при помощи обычной горошины.

Краткое содержание сказки «Принцесса на горошине» для читательского дневника

ФИО автора: Андерсен Ханс Кристиан

Название: Принцесса на горошине

Число страниц: 2. Андерсен Ханс Кристиан. «Принцесса на горошине и другие сказки». Издательство «Эксмодетство». 2014 год

Жанр: Сказка

Год написания: 1835 год

Опыт работы учителем русского языка и литературы — 36 лет.

Главные герои

Принц – красивый юноша, который очень хотел жениться на настоящей принцессе.

Король – отец принца, пожилой, добродушный.

Королева – мать принца, мудрая, дальновидная.

Принцесса – красивая, нежная девушка.

Обратите внимание, ещё у нас есть:

Сюжет

В одном королевстве жил молодой красивый принц, который надумал жениться. Вот только он хотел взять в жёны непременно самую настоящую принцессу. Он отправился на поиски суженой, но никак не мог найти ту единственную, которая была бы истинной принцессой – принц всё время находил в невестах какие-то изъяны и сомневался, настоящие ли они особы королевской крови. Принц вернулся домой и очень горевал оттого, что никак не может жениться.

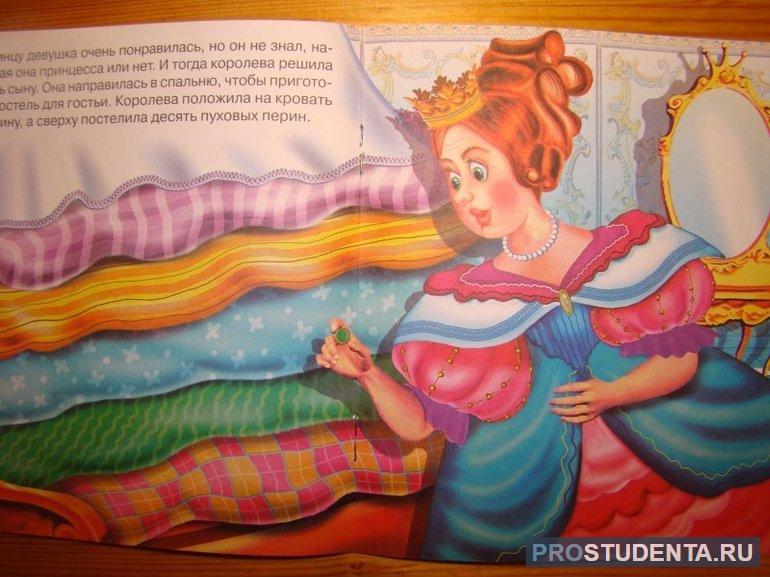

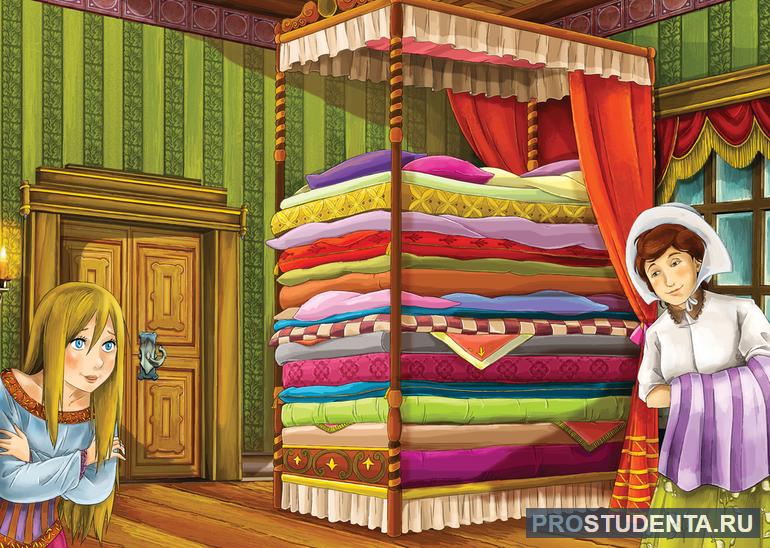

Как-то разбушевалась гроза: сверкала молния, гремел гром и дождь лил как из ведра. Неожиданно в ворота замка кто-то постучал, и старый король пошёл отворять. На пороге стояла промокшая насквозь девушка, которая утверждала, что она принцесса. Услышав это, королева промолчала и решила проверить слова незнакомки. Она прошла в опочивальню, сняла с кровати все тюфяки и подушки и положила на голые доски одну-единственную горошину, а затем уложила сверху многочисленные перины.

Королева привела девушку в опочивальню и уложила спать на кровать с горошиной. Утром она поинтересовалась, хорошо ли ей спалось, но девушка отвечала, что всю ночь не сомкнула глаз – она лежала на чём-то таком твердом и неудобном, что намяла себе бока. Тут все поняли, что перед ними самая настоящая принцесса, ведь только принцесса могла почувствовать крошечную горошину через пуховые перины и подушки.

Принц с радостью взял девушку в жёны, потому что в этот раз у него не было никаких сомнений, что принцесса настоящая. А горошина с тех пор хранится в музее.

План пересказа

- Принц хочет жениться.

- Неудачные поиски принцессы.

- Страдания принца.

- Сильная гроза.

- Появление принцессы.

- Горошина под перинами.

- Плохой сон.

- Проверка пройдена.

- Свадьба.

Главная мысль

Внешность обманчива, и о человеке нужно судить по его поступкам.

Чему учит

Сказка учит быть терпеливым, настойчивым в достижении цели. Учит не делать поспешных выводов о человеке, не испытав его в делах.

Отзыв

Истинную сущность ничем не скроешь, и даже промокшая под дождем принцесса, несчастная и продрогшая, всё равно остаётся принцессой, как бы она ни выглядела. Это смог понять принц, наконец нашедший именно ту невесту, которую так долго искал.

Пословицы

- Отведаешь сам — поверишь и нам.

- Не испытав — не узнаешь.

Что понравилось

Понравилось, что у королевы хватило мудрости не прогнать девушку или обвинить в обмане, а ловко проверить её при помощи горошины.

Тест по сказке

Доска почёта

Чтобы попасть сюда — пройдите тест.

-

Наталья Зеленова

10/10

-

Анастасия Солнцева

10/10

-

Кирилл Бычков

9/10

-

Наталья Михайлина

9/10

-

Что То

8/10

-

Инна Николаенко

9/10

-

Дамба-Сенги Тюлюш

10/10

-

Екатерина Тимченко

10/10

-

Роман Смирнов

10/10

-

Светлана Тарасова

10/10

Рейтинг читательского дневника

4.3

Средняя оценка: 4.3

Всего получено оценок: 78.

А какую оценку поставите вы?

Сказочная история про скромную девушку, которая оказалась настоящей принцессой рассказывается в одном из небольших произведений Ганса Христиана Андерсена. На уроках литературы школьники изучают эту сказку и анализируют. Считается, что это произведение самое короткое, поэтичное и популярное, поэтому следует ребятам предложить записать сказку «Принцесса на горошине» в читательский дневник, чтобы потом использовать для пересказа и написания сочинения.

Оглавление:

- История создания

- Характеристика героев

- Проблематика и жанровое своеобразие

- Краткий сюжет

- Художественные особенности

- Пересказ для читательского дневника

- Образец сочинения

- Анализ произведения

- Отзывы читателей

История создания

В сказочном сочинении Андерсена так много забавных деталей, что его содержание всегда нравится детям, поэтому при изучении следует не только говорить, как создавалось произведение, но и обязательно остановиться на том, чему же учит сказка «Принцесса на горошине».

Известно, что сказка была написана автором в 1835 году. Но литературные критики Дании не приняли её, осудив Андерсена за его легкомысленное произведение, в котором был не только простой язык народа, но и отсутствовала мораль. Один из критиков даже советовал автору больше не тратить своё время на написание сказок для детей, так как в ней не было никакой мысли и логики. Но после этого отзыва известный писатель создал более 170 сказочных историй.

Характеристика героев

Автор «Принцессы на горошине» так задумал своё произведение, что имён у персонажей нет. К тому же героев по сюжету немного:

- принц;

- король;

- королева;

- принцесса.

Принц очень нравится читателям, так как он молод и красив. Но у него была мечта — жениться на настоящей принцессе. И вся его семья тоже хорошая, так как король очень добрый, а королева — мудрая женщина, поэтому и находится невеста для принца тоже красивая и нежная, да ещё и настоящая принцесса.

Проблематика и жанровое своеобразие

Главная мысль «Принцесса на горошине» заключена в том, что не стоит принимать человека только по его внешности, а судить о нём следует по поступкам, которые он совершает. Идея сказочной истории — счастье не стоит искать, так как оно может появиться внезапно, когда его совсем не ждёшь.

Основная проблема заключается в том, что искать человека нужно не по его внешнему виду, а по тому, насколько он благороден. Смысл произведения заключён в последних строчках, когда герои становятся счастливыми. Но чтобы стать счастливым, нужно быть терпеливым и настойчивым.

Краткий сюжет

В одном из королевств жил прекрасный принц, которому пришло время жениться. Но вот только он решил, что его женой должна стать настоящая принцесса. Он стал искать такую девушку, но никак не мог найти. Невесты, которых он встречал на своём пути, всегда были с какими-то изъянами, которые заставляли юношу сомневаться, что они были королевской крови.

Так ни с чем и вернулся принц домой. И стал он ходить печальным и грустным, так как никак не мог выбрать себе невесту и жениться. Однажды очень сильно испортилась погода. Гроза так сильно разбушевалась, что страшно было находиться в доме: гремел гром и начался сильный дождь.

И вдруг неожиданно в ворота замка кто-то постучал, и старый король сразу же пошёл открывать. Он увидел девушку, которая уже насквозь промокла и с трудом разговаривала. Она сообщила, что принцесса, хотя внешне совсем не выглядела, как королевская особа. Королева промолчала, но решила проверить слова незнакомки.

Королева решила сама приготовить постель для девушки. Для этого она прошла в её спальню и сняла все тюфяки, а затем на голые доски положила одну маленькую горошину. Затем она снова сложила все перины назад и привела сюда девушку, оставив её одну в комнате до утра. Когда рассвело, и принцесса вышла из своей комнаты, королева поинтересовалась, как той спалось. И девушка честно призналась, что она так и не смогла заснуть, так как лежала на чём-то твёрдом и неудобном.

Так выяснилось, что незнакомка и на самом деле была настоящей принцессой, так как она смогла через множество пуховых перин почувствовать горошину. Вскоре принц женился на этой девушке, так как теперь у него не было никаких сомнений. А горошина с тех пор хранится в музее.

Художественные особенности

Особое место занимает горошина из сказки «Принцесса на горошине». Именно она смогла подтвердить правду, рассказанную незнакомкой, которая была бедно одета, голодна и до ниточки вымокшей.

Несмотря на то что девушка многое пережила, она не утратила своей внутренней красоты. Она по-прежнему остаётся доброй и терпеливой, умеет сострадать и стойко выносить все удары судьбы. Её душа прекрасна. Горошина в этой сказке является метафорой, так как истинное душевное благородство невозможно получить по рождению, а можно лишь только доказать поступками, поэтому в конце произведения она и получает самую лучшую награду — семейное счастье с прекрасным мужем.

Андерсен показывает, что горошина позволяет проверить чувственность и эмоциональность, которые как раз и помогают понять, насколько человек отзывчивый и внимательный к деталям и мелочам.

Пересказ для читательского дневника

В классе со школьниками можно не только делать анализ этого известного произведения, но и предложить ребятам создать свой рисунок. Это могут быть герои сказки либо иллюстрация к понравившемуся эпизоду. Можно в читательский дневник записать краткий пересказ или план. Он помог бы более точно передать основное содержание сказочного сочинения. План может выглядеть так:

- Принц собирается жениться.

- Поиски невесты оказались неудачными.

- Юноша страдает, что не может найти настоящую принцессу.

- Сильная гроза.

- Вымокшая девушка.

- Горошина для принцессы.

- Плохой сон.

- Успешная проверка.

- Долгожданная свадьба.

Если необходимо, можно в читательский дневник записать и понравившийся эпизод. Так, это может быть небольшой рассказ, как проходила испытания принцесса. Ей под огромное количество перин и пуховиков положили горошину. И, кажется, что её просто невозможно было почувствовать, так как она была очень маленькая. Но девушка плохо из-за горошины спала, так как она давила героине бока. Это и доказало, что принцесса всё-таки настоящая.

Образец сочинения

Сказки Андерсена знакомы мне с раннего детства, и всегда восхищали тем, что так интересно описывали самые обычные вещи. Но особенно выделяется из всех невероятно прекрасное волшебное произведение про принцессу, принца и горошину.

Главный герой — прекрасный юноша, который у меня не вызывает отрицательных эмоций. Он прекрасен и честно говорит о своём желании непросто жениться, а на благородной девушке. Но вот только не может такую найти, ведь ни одну из избранниц он так и не смог полюбить.

Зато ненастье всегда наступает неожиданно, и, как оказывается, не всегда это к несчастью. Вот и в сказке Андерсена в дом к грустному принцу постучалась прекрасная девушка, которая внешне не была похожа на принцессу, но утверждала, что относится к благородному и знатному роду. И хорошо, что родители у принца такие мудрые и хорошие люди. Они не выгнали её на улицу, ведь ей нужна была помощь. Но всё-таки решили устроить небольшую проверку, чтобы проверить правдивость слов девушки.

Сказка заканчивается хорошо и показывает всем, что никогда не стоит отчаиваться, а следует надеяться на лучшее. Такие литературные примеры помогают лучше понять жизнь и научиться поступать правильно.

Анализ произведения

Если человек благородный, это невозможно скрыть. И даже попав под дождь, вся несчастная, принцесса выглядит не очень привлекательно, но при этом всё равно остаётся прекрасной и благородной, душевной и искренней. Смог это увидеть и принц, который так долго искал её. Сказка показывает, что внешность в человеке не самое главное, ведь истинные душевные качества всё равно в нём проявятся и тогда можно будет понять, насколько он хорош или плох.

Писатель Андерсен показывает, что любой человек может оказаться в сложной ситуации, когда ему потребуется помощь, поэтому нужно быть отзывчивыми и доброжелательными. И в этом заключена главная мысль всего произведения. Часто люди в простой одежде оказываются и воспитанными, и благородными, и душевными. А нарядные одежды могут скрывать и подлого человека, у которого будет чёрствая душа и сердце, и который легко пройдёт мимо чужой беды, не оказав даже посильной помощи.

Отзывы читателей

Мне жалко было в начале принца, но он всё равно стал счастливым!

Мне принцесса очень понравилась! Я пробовала класть горошину, но, увы, ничего не почувствовала.

Настя, 11 лет

А мне родители принца понравились! Они очень добрые и хорошие!

Костя, 10 лет

| «The Princess and the Pea» | |

|---|---|

| by Hans Christian Andersen | |

1911 Illustration by Edmund Dulac |

|

| Original title | Prinsessen paa Ærten |

| Translator | Charles Boner |

| Country | Denmark |

| Language | Danish |

| Genre(s) | Literary fairy tale |

| Published in | Tales, Told for Children. First Collection. First Booklet. 1835. |

| Publication type | Fairy tale collection |

| Publisher | C.A. Reitzel |

| Media type | |

| Publication date | 8 May 1835 |

| Published in English | 1846 in A Danish Story-Book |

| Full text | |

«The Princess and the Pea» (Danish: «Prinsessen paa Ærten»; direct translation: «The Princess on the Pea»)[1] is a literary fairy tale by Hans Christian Andersen about a young woman whose royal ancestry is established by a test of her sensitivity. The tale was first published with three others by Andersen in an inexpensive booklet on 8 May 1835 in Copenhagen by C. A. Reitzel.

Andersen had heard the story as a child, and it likely has its source in folk material, possibly originating from Sweden, as it is unknown in the Danish oral tradition.[1] Neither «The Princess and the Pea» nor Andersen’s other tales of 1835 were well received by Danish critics, who disliked their casual, chatty style and their lack of morals.[2]

The tale is classified in the Aarne–Thompson–Uther Index as ATU 704, «The Princess and the Pea».[3]

Plot[edit]

The story tells of a prince who wants to marry a princess but is having difficulty finding a suitable wife. Something is always wrong with those he meets and he cannot be certain they are real princesses because they have bad table manners or they are not his type. One stormy night, a young woman drenched with rain seeks shelter in the prince’s castle. She claims to be a princess, but no one believes her because of the way she looks. The prince’s mother decides to test their unexpected guest by placing a pea in the bed she is offered for the night, covered by twenty mattresses and twenty eider-down beds on top of the mattresses.

In the morning, the princess tells her hosts that she endured a sleepless night, kept awake by something hard in the bed that she is certain has bruised her. With the proof of her bruised back, the princess passes the test and the prince rejoices happily, for only a real princess would have the sensitivity to feel a pea through such a quantity of bedding. The two are happily married, and the story ends with the pea being placed in a museum, where, according to the story, it can still be seen today unless someone has stolen it.

Sources[edit]

In his preface to the second volume of Tales and Stories (1863), Andersen claims to have heard the story in his childhood,[4][5] but the tale has never been a traditional one in Denmark.[6] He may as a child have heard a Swedish version, «Princess Who Lay on Seven Peas» («Princessa’ som lå’ på sju ärter»), which tells of an orphan girl who establishes her identity after a sympathetic helper (a cat or a dog) informs her that an object (a bean, a pea or a straw) had been placed under her mattress.[1]

Composition[edit]

Andersen deliberately cultivated a funny and colloquial style in the tales of 1835, reminiscent of oral storytelling techniques rather than the sophisticated literary devices of the fairy tales written by les précieuses, E. T. A. Hoffmann and other precursors. The earliest reviews criticized Andersen for not following such models. In the second volume of the 1863 edition of his collected works, Andersen remarked in the preface: «The style should be such that one hears the narrator. Therefore, the language had to be similar to the spoken word; the stories are for children but adults too should be able to listen in.»[4] Although no materials appear to exist specifically addressing the composition of «The Princess and the Pea», Andersen does speak to the writing of the first four tales of 1835 of which «The Princess on the Pea» is one. On New Year’s Day 1835, Andersen wrote to a friend: «I am now starting on some ‘fairy tales for children.’ I am going to win over future generations, you may want to know» and, in a letter dated February 1835 he wrote to the poet Bernhard Severin Ingemann: «I have started some ‘Fairy Tales Told for Children and believe I have succeeded. I have told a couple of tales which as a child I was happy about and which I do not believe are known and have written them exactly the way I would tell them to a child.» Andersen had finished the tales by March 1835 and told Admiral Wulff’s daughter, Henriette: «I have also written some fairy tales for children; Ørsted says about them that if The Improvisatore makes me famous then these will make me immortal, for they are the most perfect things I have written; but I myself do not think so.»[7] On 26 March, he observed that «[the fairy tales] will be published in April, and people will say: the work of my immortality! Of course, I shan’t enjoy the experience in this world.»[7]

Publication[edit]

«The Princess and the Pea» was first published in Copenhagen, Denmark by C.A. Reitzel on 8 May 1835 in an unbound 61-page booklet called Tales, Told for Children. First Collection. First Booklet. 1835. (Eventyr, fortalte for Børn. Første Samling. Første Hefte. 1835.). «The Princess and the Pea» was the third tale in the collection, with «The Tinderbox» («Fyrtøiet«), «Little Claus and Big Claus» («Lille Claus og store Claus«) and «Little Ida’s Flowers» («Den Lille Idas Blomster«). The booklet was priced at twenty-four shillings (the equivalent of 25 Dkr. or approximately US$5 as of 2009),[4] and the publisher paid Andersen 30 rixdollars (US$450 as of 2009).[7] A second edition was published in 1842 and a third in 1845.[4] «The Princess and the Pea» was reprinted on 18 December 1849 in Tales. 1850. with illustrations by Vilhelm Pedersen. The story was published again on 15 December 1862, in Tales and Stories. First Volume. 1862.The first Danish reviews of Andersen’s 1835 tales appeared in 1836 and were hostile. Critics disliked the informal, chatty style and the lack of morals,[2] and offered Andersen no encouragement. One literary journal failed to mention the tales at all, while another advised Andersen not to waste his time writing «wonder stories». He was told he «lacked the usual form of that kind of poetry … and would not study models». Andersen felt he was working against their preconceived notions of what a fairy tale should be and returned to writing novels, believing it to be his true calling.[8]

English translation[edit]

Charles Boner was the first to translate «The Princess and the Pea» into English, working from a German translation that had increased Andersen’s lone pea to a trio of peas in an attempt to make the story more credible, an embellishment also added by another early English translator, Caroline Peachey.[9] Boner’s translation was published as «The Princess on the Peas» in A Danish Story-Book in 1846.[6] Boner has been accused of missing the satire of the tale by ending with the rhetorical question, «Now was not that a lady of exquisite feeling?» rather than Andersen’s joke of the pea being placed in the Royal Museum.[9] Boner and Peachey’s work established the standard for English translations of the fairy tales, which, for almost a century, as Wullschlager notes, «continued to range from the inadequate to the abysmal».[10]

An alternate translation to the title was The Princess and the Bean, in The Birch-Tree Fairy Book.[11]

[edit]

Wullschlager observes that in «The Princess and the Pea» Andersen blended his childhood memories of a primitive world of violence, death and inexorable fate, with his social climber’s private romance about the serene, secure and cultivated Danish bourgeoisie, which did not quite accept him as one of their own. Researcher Jack Zipes said that Andersen, during his lifetime, «was obliged to act as a dominated subject within the dominant social circles despite his fame and recognition as a writer»; Andersen, therefore, developed a feared and loved the view of the aristocracy. Others have said that Andersen constantly felt as though he did not belong, and longed to be a part of the upper class.[12] The nervousness and humiliations Andersen suffered in the presence of the bourgeoisie were mythologized by the storyteller in the tale of «The Princess and the Pea», with Andersen himself the morbidly sensitive princess who can feel a pea through 20 mattresses.[13] Maria Tatar notes that, unlike the folk heroine of his source material for the story, Andersen’s princess has no need to resort to deceit to establish her identity; her sensitivity is enough to validate her nobility. For Andersen, she indicates, «true» nobility is derived not from an individual’s birth but from their sensitivity. Andersen’s insistence upon sensitivity as the exclusive privilege of nobility challenges modern notions about character and social worth. The princess’s sensitivity, however, may be a metaphor for her depth of feeling and compassion.[1]

While a 1905 article in the American Journal of Education recommended the story for children aged 8–10,[14] «The Princess and the Pea» was not uniformly well received by critics. Toksvig wrote in 1934, «[the story] seems to the reviewer not only indelicate but indefensible, in so far as the child might absorb the false idea that great ladies must always be so terribly thin-skinned.»[15] Tatar notes that the princess’s sensitivity has been interpreted as poor manners rather than a manifestation of noble birth, a view said to be based on «the cultural association between women’s physical sensitivity and emotional sensitivity, specifically, the link between a woman reporting her physical experience of touch and negative images of women who are hypersensitive to physical conditions, who complain about trivialities, and who demand special treatment».[1]

Researcher Jack Zipes notes that the tale is told tongue-in-cheek, with Andersen poking fun at the «curious and ridiculous» measures taken by the nobility to establish the value of bloodlines. He also notes that the author makes a case for sensitivity being the decisive factor in determining royal authenticity and that Andersen «never tired of glorifying the sensitive nature of an elite class of people».[16]

“The Princess and the Pea” spurred on positive criticism, as well. In fact, critic Paul Hazard pointed out the realistic aspects of the fairy tale that make it easily relatable to all people. He believed that «the world Andersen witnessed—which encompassed sorrow, death, evil and man’s follies—is reflected in his tales,» and most evidently in «The Princess and the Pea.» Another scholar, Niels Kofoed, noticed that “since they involve everyday-life themes of love, death, nature, injustice, suffering and poverty, they appeal to all races, ideologies, classes and genders.” Moreover, Celia Catlett Anderson realized that one of the things that makes this story so appealing and relatable is that optimism prevails over pessimism, especially for the main character of the princess. This inspires hope in the readers for their own futures and strength within themselves.[17]

Adaptations[edit]

In 1927, German composer Ernst Toch published an opera based on «The Princess and the Pea», with a libretto by Benno Elkan.[18] Reportedly this opera was very popular in the American student repertoires;[19] the music, as well as the English translation (by Marion Farquhar), were praised in a review in Notes.[18] The story was adapted to the musical stage in 1959 as Once Upon a Mattress, with comedian Carol Burnett playing the play’s heroine, Princess Winnifred the Woebegone. The musical was revived in 1997 with Sarah Jessica Parker in the role. A television adaptation of «The Princess and the Pea» starred Liza Minnelli in a Faerie Tale Theatre episode in 1984. The story has been adapted into three films, a six-minute IMAX production in 2001, one full-length animation film in 2002 and the 2005 feature-length movie featuring Carol Burnett and Zooey Deschanel.[1] The tale was the basis for a story in The Stinky Cheese Man and Other Fairly Stupid Tales by Jon Scieszka[20] and Lane Smith, wherein the prince decides to slip a bowling ball underneath one hundred mattresses after three years of unsuccessful attempts with the pea. In the morning, the princess comes downstairs and tells the queen, «This might sound odd but I think you need another mattress. I felt like I was sleeping on a lump as big as a bowling ball.» satisfying the king and the queen. The princess marries the prince and they live happily, though maybe not entirely honestly, ever after.[21] American poet Jane Shore published a poem, «The Princess and the Pea», in the January 1973 issue of Poetry, in which a close dependency between princess and pea is posited: «I lie in my skin as in an ugly coat: / my body owned by the citizens / who ache and turn whenever I turn / on the pea on which so much depends» (13-16).[22] Russian writer Evgeny Shvarts incorporates the story, with two other Andersen stories, in his Naked King.[23] In 2019, Simon Hood published a contemporary version of the story with animated illustrations.[24] Both the language and the illustrations modernised the story, while the plot itself remained close to traditional versions.

Similar tales[edit]

The Princess and the Pea in the Danish floral park Jesperhus

Tales of extreme sensitivity are infrequent in world culture but a few have been recorded. As early as the 1st century, Seneca the Younger had mentioned a legend about a Sybaris native who slept on a bed of roses and suffered due to one petal folding over.[25] Also similar is the medieval Perso-Arabic legend of al-Nadirah.[26] The 11th-century Kathasaritsagara by Somadeva tells of a young man who claims to be especially fastidious about beds. After sleeping in a bed on top of seven mattresses newly made with clean sheets, the young man rises in great pain. A crooked red mark is discovered on his body and upon investigation, a hair is found on the bottom-most mattress of the bed.[6] An Italian tale called «The Most Sensitive Woman» tells of a woman whose foot is bandaged after a jasmine petal falls upon it. The Brothers Grimm included a «Princess on the Pea» tale in an edition of their Kinder- und Hausmärchen but removed it after they discovered that it belonged to the Danish literary tradition.[1]

A few folk tales feature a boy discovering a pea or a bean assumed to be of great value. After the boy enters a castle and is given a bed of straw for the night he tosses and turns in his sleep, attempting to guard his treasure. Some observers are persuaded that the boy is restless because he is unaccustomed to sleeping on straw and is therefore of aristocratic blood.[1] In the more popular versions of the tale, only one pea is used. However, Charles Boner added in two more peas in his translation of the story upon which Andersen based his tale. Other differences amongst versions can be seen in various numbers of mattresses as well as feather beds. Versions of the story differ based on whether or not the character of the helper is included. The helper, in some cases, tells the princess to pretend she slept badly. In other versions, the helper does not appear at all and the princess decides to lie all on her own.[27]

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h Tatar (2008), pp. 70–77

- ^ a b Wullschlager (2000), pp. 159–160

- ^ Haase, Donald. The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Folktales and Fairy Tales: Q-Z. Greenwood Publishing Group. 2008. p. 798.

- ^ a b c d de Mylius (2009)

- ^ Holbek, Bengt (1990), «Hans Christian Andersen’s Use of Folktales», Merveilles et Contes, 4 (2): 220–32, JSTOR 41380775

- ^ a b c Opie & Opie (1974), p. 216

- ^ a b c Wullschlager (2000), p. 144

- ^ Andersen (2000), p. 135

- ^ a b Wullschlager (2000), p. 290

- ^ Wullschlager (2000), pp. 290–291

- ^ Johnson, Clifton. The Birch-tree Fairy Book: Favorite Fairy Tales. Boston: Little, Brown, & Company, 1906. p. 28=32.

- ^ Dewsbury, Suzanne, «Hans Christian Andersen- Introduction», Nineteenth-Century Literary Criticism, Gale Cengage, retrieved 3 May 2012

- ^ Wullschlager (2000), p. 151

- ^ «Readings from Andersen», The Journal of Education, 61 (6): 146, 1905, JSTOR 42806381

- ^ Toksvig (1934), p. 179

- ^ Zipes (2005), p. 35

- ^ Dewsbury, Suzanne, «Hans Christian Andersen—Introduction», Nineteenth-Century Literary Criticism, Gale Cengage, retrieved 3 May 2012

- ^ a b Cohen, Frederic (1954), «The Princess and the Pea. A Fairy Tale in One Act, Op. 43 by Ernst Toch», Notes, Second series, 11 (4): 602, doi:10.2307/893051, JSTOR 893051

- ^ «Obituary: Ernst Toch», The Musical Times, 105 (1461): 838, 1964, JSTOR 950468

- ^ Sipe, Lawrence R. (1993), «Using Transformations of Traditional Stories: Making the Reading-Writing Connection», The Reading Teacher, 47 (1): 18–26, JSTOR 20201188

- ^ Scieszka, John and Lane Smith (1992), The Stinky Cheese Man and Other Fairly Stupid Tales, Viking Press, ISBN 978-0-670-84487-6

- ^ Shore, Jane (January 1973), «The Princess and the Pea», Poetry, 121 (4): 190, JSTOR 20595894

- ^ Corten, Irina H.; Shvarts, Evgeny (1978), «Evgenii Shvarts as an Adapter of Hans Christian and Charles Perrault», Russian Review, 37 (1): 51–67, doi:10.2307/128363, JSTOR 128363

- ^ «The Princess And The Pea». Sooper Books. 2021-07-13.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ A Bed of Roses

- ^ Donzel, E. J. Van (1994). Islamic Desk Reference. BRILL. p. 122. ISBN 9789004097384.

- ^ Heiner, Heidi Anne, «History of The Princess and the Pea», SurLaLune Fairy Tales, retrieved 3 May 2012

Bibliography[edit]

- Andersen, Hans Christian (2000) [1871], The Fairy Tale of My Life: An Autobiography, Cooper Square Press, ISBN 0-8154-1105-7

- de Mylius, Johan (2009), «The Timetable Year By Year, 1835: The First Collection of Fairy-Tales», H.C. Andersens liv. Dag for dag. (The Life of Hans Christian Andersen. Day By Day.), The Hans Christian Andersen Center, retrieved 8 February 2009

- Opie, Iona; Opie, Peter (1974), The Classic Fairy Tales, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-211559-6

- Tatar, Maria (2008), The Annotated Hans Christian Andersen, W.W. Norton & Company, ISBN 978-0-393-06081-2

- Toksvig, Signe (1934) [1933], The Life of Hans Christian Andersen, Macmillan and Co.

- Wullschlager, Jackie (2000), Hans Christian Andersen: The Life of a Storyteller, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0-7139-9325-1

- Zipes, Jack (2005), Hans Christian Andersen, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-97433-X

Further reading[edit]

- Bataller Català, Alexandre. (2018). «La princesa i el pèsol» (ATU 704): de les reescriptures escolars a la construcció identitària. Estudis de Literatura Oral Popular / Studies in Oral Folk Literature. 27. 10.17345/elop201827-46.

- Shojaei Kawan, Christine. (2005). The Princess on the Pea: Andersen, Grimm and the Orient. Fabula. 46. 89-115. 10.1515/fabl.2005.46.1-2.89.

External links[edit]

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

- «Prinsessen på Ærten» Original Danish text

- «The Princess and the Pea» English translation by Jean Hersholt

- Archived audio version of the story

The Princess and the Pea public domain audiobook at LibriVox

| «The Princess and the Pea» | |

|---|---|

| by Hans Christian Andersen | |

1911 Illustration by Edmund Dulac |

|

| Original title | Prinsessen paa Ærten |

| Translator | Charles Boner |

| Country | Denmark |

| Language | Danish |

| Genre(s) | Literary fairy tale |

| Published in | Tales, Told for Children. First Collection. First Booklet. 1835. |

| Publication type | Fairy tale collection |

| Publisher | C.A. Reitzel |

| Media type | |

| Publication date | 8 May 1835 |

| Published in English | 1846 in A Danish Story-Book |

| Full text | |

«The Princess and the Pea» (Danish: «Prinsessen paa Ærten»; direct translation: «The Princess on the Pea»)[1] is a literary fairy tale by Hans Christian Andersen about a young woman whose royal ancestry is established by a test of her sensitivity. The tale was first published with three others by Andersen in an inexpensive booklet on 8 May 1835 in Copenhagen by C. A. Reitzel.

Andersen had heard the story as a child, and it likely has its source in folk material, possibly originating from Sweden, as it is unknown in the Danish oral tradition.[1] Neither «The Princess and the Pea» nor Andersen’s other tales of 1835 were well received by Danish critics, who disliked their casual, chatty style and their lack of morals.[2]

The tale is classified in the Aarne–Thompson–Uther Index as ATU 704, «The Princess and the Pea».[3]

Plot[edit]

The story tells of a prince who wants to marry a princess but is having difficulty finding a suitable wife. Something is always wrong with those he meets and he cannot be certain they are real princesses because they have bad table manners or they are not his type. One stormy night, a young woman drenched with rain seeks shelter in the prince’s castle. She claims to be a princess, but no one believes her because of the way she looks. The prince’s mother decides to test their unexpected guest by placing a pea in the bed she is offered for the night, covered by twenty mattresses and twenty eider-down beds on top of the mattresses.

In the morning, the princess tells her hosts that she endured a sleepless night, kept awake by something hard in the bed that she is certain has bruised her. With the proof of her bruised back, the princess passes the test and the prince rejoices happily, for only a real princess would have the sensitivity to feel a pea through such a quantity of bedding. The two are happily married, and the story ends with the pea being placed in a museum, where, according to the story, it can still be seen today unless someone has stolen it.

Sources[edit]

In his preface to the second volume of Tales and Stories (1863), Andersen claims to have heard the story in his childhood,[4][5] but the tale has never been a traditional one in Denmark.[6] He may as a child have heard a Swedish version, «Princess Who Lay on Seven Peas» («Princessa’ som lå’ på sju ärter»), which tells of an orphan girl who establishes her identity after a sympathetic helper (a cat or a dog) informs her that an object (a bean, a pea or a straw) had been placed under her mattress.[1]

Composition[edit]

Andersen deliberately cultivated a funny and colloquial style in the tales of 1835, reminiscent of oral storytelling techniques rather than the sophisticated literary devices of the fairy tales written by les précieuses, E. T. A. Hoffmann and other precursors. The earliest reviews criticized Andersen for not following such models. In the second volume of the 1863 edition of his collected works, Andersen remarked in the preface: «The style should be such that one hears the narrator. Therefore, the language had to be similar to the spoken word; the stories are for children but adults too should be able to listen in.»[4] Although no materials appear to exist specifically addressing the composition of «The Princess and the Pea», Andersen does speak to the writing of the first four tales of 1835 of which «The Princess on the Pea» is one. On New Year’s Day 1835, Andersen wrote to a friend: «I am now starting on some ‘fairy tales for children.’ I am going to win over future generations, you may want to know» and, in a letter dated February 1835 he wrote to the poet Bernhard Severin Ingemann: «I have started some ‘Fairy Tales Told for Children and believe I have succeeded. I have told a couple of tales which as a child I was happy about and which I do not believe are known and have written them exactly the way I would tell them to a child.» Andersen had finished the tales by March 1835 and told Admiral Wulff’s daughter, Henriette: «I have also written some fairy tales for children; Ørsted says about them that if The Improvisatore makes me famous then these will make me immortal, for they are the most perfect things I have written; but I myself do not think so.»[7] On 26 March, he observed that «[the fairy tales] will be published in April, and people will say: the work of my immortality! Of course, I shan’t enjoy the experience in this world.»[7]

Publication[edit]

«The Princess and the Pea» was first published in Copenhagen, Denmark by C.A. Reitzel on 8 May 1835 in an unbound 61-page booklet called Tales, Told for Children. First Collection. First Booklet. 1835. (Eventyr, fortalte for Børn. Første Samling. Første Hefte. 1835.). «The Princess and the Pea» was the third tale in the collection, with «The Tinderbox» («Fyrtøiet«), «Little Claus and Big Claus» («Lille Claus og store Claus«) and «Little Ida’s Flowers» («Den Lille Idas Blomster«). The booklet was priced at twenty-four shillings (the equivalent of 25 Dkr. or approximately US$5 as of 2009),[4] and the publisher paid Andersen 30 rixdollars (US$450 as of 2009).[7] A second edition was published in 1842 and a third in 1845.[4] «The Princess and the Pea» was reprinted on 18 December 1849 in Tales. 1850. with illustrations by Vilhelm Pedersen. The story was published again on 15 December 1862, in Tales and Stories. First Volume. 1862.The first Danish reviews of Andersen’s 1835 tales appeared in 1836 and were hostile. Critics disliked the informal, chatty style and the lack of morals,[2] and offered Andersen no encouragement. One literary journal failed to mention the tales at all, while another advised Andersen not to waste his time writing «wonder stories». He was told he «lacked the usual form of that kind of poetry … and would not study models». Andersen felt he was working against their preconceived notions of what a fairy tale should be and returned to writing novels, believing it to be his true calling.[8]

English translation[edit]

Charles Boner was the first to translate «The Princess and the Pea» into English, working from a German translation that had increased Andersen’s lone pea to a trio of peas in an attempt to make the story more credible, an embellishment also added by another early English translator, Caroline Peachey.[9] Boner’s translation was published as «The Princess on the Peas» in A Danish Story-Book in 1846.[6] Boner has been accused of missing the satire of the tale by ending with the rhetorical question, «Now was not that a lady of exquisite feeling?» rather than Andersen’s joke of the pea being placed in the Royal Museum.[9] Boner and Peachey’s work established the standard for English translations of the fairy tales, which, for almost a century, as Wullschlager notes, «continued to range from the inadequate to the abysmal».[10]

An alternate translation to the title was The Princess and the Bean, in The Birch-Tree Fairy Book.[11]

[edit]

Wullschlager observes that in «The Princess and the Pea» Andersen blended his childhood memories of a primitive world of violence, death and inexorable fate, with his social climber’s private romance about the serene, secure and cultivated Danish bourgeoisie, which did not quite accept him as one of their own. Researcher Jack Zipes said that Andersen, during his lifetime, «was obliged to act as a dominated subject within the dominant social circles despite his fame and recognition as a writer»; Andersen, therefore, developed a feared and loved the view of the aristocracy. Others have said that Andersen constantly felt as though he did not belong, and longed to be a part of the upper class.[12] The nervousness and humiliations Andersen suffered in the presence of the bourgeoisie were mythologized by the storyteller in the tale of «The Princess and the Pea», with Andersen himself the morbidly sensitive princess who can feel a pea through 20 mattresses.[13] Maria Tatar notes that, unlike the folk heroine of his source material for the story, Andersen’s princess has no need to resort to deceit to establish her identity; her sensitivity is enough to validate her nobility. For Andersen, she indicates, «true» nobility is derived not from an individual’s birth but from their sensitivity. Andersen’s insistence upon sensitivity as the exclusive privilege of nobility challenges modern notions about character and social worth. The princess’s sensitivity, however, may be a metaphor for her depth of feeling and compassion.[1]

While a 1905 article in the American Journal of Education recommended the story for children aged 8–10,[14] «The Princess and the Pea» was not uniformly well received by critics. Toksvig wrote in 1934, «[the story] seems to the reviewer not only indelicate but indefensible, in so far as the child might absorb the false idea that great ladies must always be so terribly thin-skinned.»[15] Tatar notes that the princess’s sensitivity has been interpreted as poor manners rather than a manifestation of noble birth, a view said to be based on «the cultural association between women’s physical sensitivity and emotional sensitivity, specifically, the link between a woman reporting her physical experience of touch and negative images of women who are hypersensitive to physical conditions, who complain about trivialities, and who demand special treatment».[1]

Researcher Jack Zipes notes that the tale is told tongue-in-cheek, with Andersen poking fun at the «curious and ridiculous» measures taken by the nobility to establish the value of bloodlines. He also notes that the author makes a case for sensitivity being the decisive factor in determining royal authenticity and that Andersen «never tired of glorifying the sensitive nature of an elite class of people».[16]

“The Princess and the Pea” spurred on positive criticism, as well. In fact, critic Paul Hazard pointed out the realistic aspects of the fairy tale that make it easily relatable to all people. He believed that «the world Andersen witnessed—which encompassed sorrow, death, evil and man’s follies—is reflected in his tales,» and most evidently in «The Princess and the Pea.» Another scholar, Niels Kofoed, noticed that “since they involve everyday-life themes of love, death, nature, injustice, suffering and poverty, they appeal to all races, ideologies, classes and genders.” Moreover, Celia Catlett Anderson realized that one of the things that makes this story so appealing and relatable is that optimism prevails over pessimism, especially for the main character of the princess. This inspires hope in the readers for their own futures and strength within themselves.[17]

Adaptations[edit]

In 1927, German composer Ernst Toch published an opera based on «The Princess and the Pea», with a libretto by Benno Elkan.[18] Reportedly this opera was very popular in the American student repertoires;[19] the music, as well as the English translation (by Marion Farquhar), were praised in a review in Notes.[18] The story was adapted to the musical stage in 1959 as Once Upon a Mattress, with comedian Carol Burnett playing the play’s heroine, Princess Winnifred the Woebegone. The musical was revived in 1997 with Sarah Jessica Parker in the role. A television adaptation of «The Princess and the Pea» starred Liza Minnelli in a Faerie Tale Theatre episode in 1984. The story has been adapted into three films, a six-minute IMAX production in 2001, one full-length animation film in 2002 and the 2005 feature-length movie featuring Carol Burnett and Zooey Deschanel.[1] The tale was the basis for a story in The Stinky Cheese Man and Other Fairly Stupid Tales by Jon Scieszka[20] and Lane Smith, wherein the prince decides to slip a bowling ball underneath one hundred mattresses after three years of unsuccessful attempts with the pea. In the morning, the princess comes downstairs and tells the queen, «This might sound odd but I think you need another mattress. I felt like I was sleeping on a lump as big as a bowling ball.» satisfying the king and the queen. The princess marries the prince and they live happily, though maybe not entirely honestly, ever after.[21] American poet Jane Shore published a poem, «The Princess and the Pea», in the January 1973 issue of Poetry, in which a close dependency between princess and pea is posited: «I lie in my skin as in an ugly coat: / my body owned by the citizens / who ache and turn whenever I turn / on the pea on which so much depends» (13-16).[22] Russian writer Evgeny Shvarts incorporates the story, with two other Andersen stories, in his Naked King.[23] In 2019, Simon Hood published a contemporary version of the story with animated illustrations.[24] Both the language and the illustrations modernised the story, while the plot itself remained close to traditional versions.

Similar tales[edit]

The Princess and the Pea in the Danish floral park Jesperhus

Tales of extreme sensitivity are infrequent in world culture but a few have been recorded. As early as the 1st century, Seneca the Younger had mentioned a legend about a Sybaris native who slept on a bed of roses and suffered due to one petal folding over.[25] Also similar is the medieval Perso-Arabic legend of al-Nadirah.[26] The 11th-century Kathasaritsagara by Somadeva tells of a young man who claims to be especially fastidious about beds. After sleeping in a bed on top of seven mattresses newly made with clean sheets, the young man rises in great pain. A crooked red mark is discovered on his body and upon investigation, a hair is found on the bottom-most mattress of the bed.[6] An Italian tale called «The Most Sensitive Woman» tells of a woman whose foot is bandaged after a jasmine petal falls upon it. The Brothers Grimm included a «Princess on the Pea» tale in an edition of their Kinder- und Hausmärchen but removed it after they discovered that it belonged to the Danish literary tradition.[1]

A few folk tales feature a boy discovering a pea or a bean assumed to be of great value. After the boy enters a castle and is given a bed of straw for the night he tosses and turns in his sleep, attempting to guard his treasure. Some observers are persuaded that the boy is restless because he is unaccustomed to sleeping on straw and is therefore of aristocratic blood.[1] In the more popular versions of the tale, only one pea is used. However, Charles Boner added in two more peas in his translation of the story upon which Andersen based his tale. Other differences amongst versions can be seen in various numbers of mattresses as well as feather beds. Versions of the story differ based on whether or not the character of the helper is included. The helper, in some cases, tells the princess to pretend she slept badly. In other versions, the helper does not appear at all and the princess decides to lie all on her own.[27]

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h Tatar (2008), pp. 70–77

- ^ a b Wullschlager (2000), pp. 159–160

- ^ Haase, Donald. The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Folktales and Fairy Tales: Q-Z. Greenwood Publishing Group. 2008. p. 798.

- ^ a b c d de Mylius (2009)

- ^ Holbek, Bengt (1990), «Hans Christian Andersen’s Use of Folktales», Merveilles et Contes, 4 (2): 220–32, JSTOR 41380775

- ^ a b c Opie & Opie (1974), p. 216

- ^ a b c Wullschlager (2000), p. 144

- ^ Andersen (2000), p. 135

- ^ a b Wullschlager (2000), p. 290

- ^ Wullschlager (2000), pp. 290–291

- ^ Johnson, Clifton. The Birch-tree Fairy Book: Favorite Fairy Tales. Boston: Little, Brown, & Company, 1906. p. 28=32.

- ^ Dewsbury, Suzanne, «Hans Christian Andersen- Introduction», Nineteenth-Century Literary Criticism, Gale Cengage, retrieved 3 May 2012

- ^ Wullschlager (2000), p. 151

- ^ «Readings from Andersen», The Journal of Education, 61 (6): 146, 1905, JSTOR 42806381

- ^ Toksvig (1934), p. 179

- ^ Zipes (2005), p. 35

- ^ Dewsbury, Suzanne, «Hans Christian Andersen—Introduction», Nineteenth-Century Literary Criticism, Gale Cengage, retrieved 3 May 2012

- ^ a b Cohen, Frederic (1954), «The Princess and the Pea. A Fairy Tale in One Act, Op. 43 by Ernst Toch», Notes, Second series, 11 (4): 602, doi:10.2307/893051, JSTOR 893051

- ^ «Obituary: Ernst Toch», The Musical Times, 105 (1461): 838, 1964, JSTOR 950468

- ^ Sipe, Lawrence R. (1993), «Using Transformations of Traditional Stories: Making the Reading-Writing Connection», The Reading Teacher, 47 (1): 18–26, JSTOR 20201188

- ^ Scieszka, John and Lane Smith (1992), The Stinky Cheese Man and Other Fairly Stupid Tales, Viking Press, ISBN 978-0-670-84487-6

- ^ Shore, Jane (January 1973), «The Princess and the Pea», Poetry, 121 (4): 190, JSTOR 20595894

- ^ Corten, Irina H.; Shvarts, Evgeny (1978), «Evgenii Shvarts as an Adapter of Hans Christian and Charles Perrault», Russian Review, 37 (1): 51–67, doi:10.2307/128363, JSTOR 128363

- ^ «The Princess And The Pea». Sooper Books. 2021-07-13.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ A Bed of Roses

- ^ Donzel, E. J. Van (1994). Islamic Desk Reference. BRILL. p. 122. ISBN 9789004097384.

- ^ Heiner, Heidi Anne, «History of The Princess and the Pea», SurLaLune Fairy Tales, retrieved 3 May 2012

Bibliography[edit]

- Andersen, Hans Christian (2000) [1871], The Fairy Tale of My Life: An Autobiography, Cooper Square Press, ISBN 0-8154-1105-7

- de Mylius, Johan (2009), «The Timetable Year By Year, 1835: The First Collection of Fairy-Tales», H.C. Andersens liv. Dag for dag. (The Life of Hans Christian Andersen. Day By Day.), The Hans Christian Andersen Center, retrieved 8 February 2009

- Opie, Iona; Opie, Peter (1974), The Classic Fairy Tales, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-211559-6

- Tatar, Maria (2008), The Annotated Hans Christian Andersen, W.W. Norton & Company, ISBN 978-0-393-06081-2

- Toksvig, Signe (1934) [1933], The Life of Hans Christian Andersen, Macmillan and Co.

- Wullschlager, Jackie (2000), Hans Christian Andersen: The Life of a Storyteller, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0-7139-9325-1

- Zipes, Jack (2005), Hans Christian Andersen, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-97433-X

Further reading[edit]

- Bataller Català, Alexandre. (2018). «La princesa i el pèsol» (ATU 704): de les reescriptures escolars a la construcció identitària. Estudis de Literatura Oral Popular / Studies in Oral Folk Literature. 27. 10.17345/elop201827-46.

- Shojaei Kawan, Christine. (2005). The Princess on the Pea: Andersen, Grimm and the Orient. Fabula. 46. 89-115. 10.1515/fabl.2005.46.1-2.89.

External links[edit]

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

- «Prinsessen på Ærten» Original Danish text

- «The Princess and the Pea» English translation by Jean Hersholt

- Archived audio version of the story

The Princess and the Pea public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Содержание статьи

- В чем смысл сказки?

- Чему учит?

- Мораль

- Пословицы

- В чем суть: краткое содержание

- Главные герои

- Пересказ сказки в вопросах и ответах (план пересказа)

- Что захотел сделать принц?

- Как он искал настоящую принцессу?

- Что случилось однажды вечером?

- Как выглядела принцесса, когда ее впервые увидел принц?

- Как встретили девушку в замке? Что предложили?

- О чем спросили у принцессы утром?

- Как поняли, что принцесса настоящая?

- Чем закончилась сказка?

- Выводы о сказке в вопросах и ответах

- Как ты думаешь, почему под тюфяки и пуховики положили именно горошину?

- Что тебе больше всего понравилось в сказке?

- Вопросы на внимательность

- Кто положил горошину в кровать принцессы?

- Сколько тюфяков и пуховиков было на постели девушки?

- Для любознательных

- Когда и кем была написана сказка?

- Встречал ли ты выражение «принцесса на горошине»? Кого так называют?

Главный смысл сказки «Принцесса на горошине» в том, что настоящее благородство невозможно утратить. Человек может выглядеть убого, жалко, но его доброе сердце и благодарная душа все равно проявят себя. Нужно судить человека по его поступкам, а не по внешности.

В чем смысл сказки?

Незнакомка, постучавшая в двери замка, выглядела ужасно. Гроза и ливень промочили ее одежду насквозь. Ее прическа распалась, с нее текла вода. Окружающие и подумать не могли, что перед ними принцесса. Девушке не поверили, но не стали ее обличать. Вместо этого королевская семья провела тест с горошиной в кровати. Незнакомка его прошла, и оказалась и вправду принцессой. После этого принц женился на ней.

Чему учит?

Не судить человека по его внешнему виду. Первое впечатление часто ошибочное. Чему еще учит сказка «Принцесса на горошине»:

- Быть терпеливым и настойчиво идти к цели.

- Проверять человека делом.

- Не обижаться, если тебя проверяют, а отнестись с пониманием. Быть искренним и открытым.

Мораль

Внешность обманчива, о человеке говорят его поступки.

Пословицы

Смысл произведения хорошо отражают следующие пословицы:

- «По одежке встречают – по уму провожают».

- «Суди дерево по плодам, а человека по делам».

- «Доверяй, но проверяй».

- «Сказка – ложь, да в ней намек, добрым молодцам урок».

В чем суть: краткое содержание

Сказка Ганса Христиана Андерсена «Принцесса на горошине» рассказывает о поиске достойной невесты для принца. Юноша захотел жениться, но не на первой попавшейся принцессе, а на самой настоящей. Он объехал весь мир и встретил много принцесс, но не мог понять, какая из них настоящая. Принц сильно горевал.

В один ненастный день, уже поздно вечером в дверь постучали. На пороге стояла девушка. Она ужасно выглядела, была вся мокрая от сильного ливня. Девушка представилась настоящей принцессой. Королева, мама принца, ничего не сказала, а решила проверить, так ли это.

Она подготовила очень мягкую королевскую постель. Только под самый низ тюфяков положила маленькую твердую горошинку. Утром девушку спросили, как она спала ночью. Та ответила, что очень плохо. Все ее тело покрылось синяками из-за того, что она спала на чем-то твердом. Тогда-то все и поняли, что принцесса перед ними самая настоящая. И принц женился на ней.

Видео: Принцесса на горошине сказка для детей

Главные герои

Чтобы понять, в чем суть сказки и кратко ее пересказать, будет полезно определить количество и характеры главных героев. Всего в произведении 3 действующих лица:

- Принц – целеустремленный юноша, захотевший жениться на настоящей принцессе.

- Принцесса – настоящая, по-королевски изнеженная, добрая, открытая и не злопамятная.

- Королева – мать принца, мудрая женщина.

Пересказ сказки в вопросах и ответах (план пересказа)

В младшей школе дети учатся слушать, читать и понимать прочитанное, а также пересказывать. Составить грамотный пересказ помогают наводящие вопросы, которые также могут использоваться как план пересказа.

Что захотел сделать принц?

Жениться на настоящей принцессе.

Как он искал настоящую принцессу?

Ездил по всему свету. Принцесс было много, но принц никак не мог узнать, настоящие они, или нет.

Что случилось однажды вечером?

Началась гроза. Сверкали молнии, гремел гром. Шел сильный ливень. В дверь замка постучала девушка, которая назвалась настоящей принцессой.

Как выглядела принцесса, когда ее впервые увидел принц?

Она была насквозь промокшей. С волос и одежды текла вода, затекала ей в башмаки, и вытекала из пяток. Принцесса выглядела ужасно.

Как встретили девушку в замке? Что предложили?

Ее пожалели и провели в спальню. Незнакомке предложили провести ночь на очень мягкой постели с одной только маленькой горошиной.

О чем спросили у принцессы утром?

Королевская семья поинтересовалась у девушки, как ей спалось ночью.

Как поняли, что принцесса настоящая?

Девушка ответила, что спала очень дурно. Она почти не сомкнула глаз из-за того, что постель у нее была очень твердой. Еще она пожаловалась на синяки на теле. Тогда все поняли, что она и вправду принцесса, если смогла почувствовать маленькую горошинку под целой горой тюфяков с пуховиками.

Чем закончилась сказка?

Свадьбой, и словами, что эта история правдивая.

Выводы о сказке в вопросах и ответах

Чтобы понять смысл произведения, нужно над ним размышлять. Сделать собственные выводы помогут вопросы о том, почему герои поступили так, а не иначе.

Как ты думаешь, почему под тюфяки и пуховики положили именно горошину?

Потому что горошинка маленькая. Ее невозможно почувствовать под тюфяками и пуховиками, если ты обычный человек. Только принцесса могла ее ощутить, потому что в замке она всегда спала на самой лучшей и мягкой постели.

Что тебе больше всего понравилось в сказке?

Находчивость королевы. Она нашла способ проверить, была ли незнакомка вправду принцессой, и не обидеть ее. По ее мнению, почувствовать горошину могла только нежная и деликатная особа королевских кровей.

Вопросы на внимательность

Читая или слушая сказку, дети не всегда обращают внимание на детали. Вопросы на внимательность помогают развить этот важный навык. Если ребенок затрудняется ответить, нужно прочитать ответ.

Кто положил горошину в кровать принцессы?

Это сделала мама принца, старая королева.

Сколько тюфяков и пуховиков было на постели девушки?

Двадцать тюфяков и двадцать пуховиков.

Для любознательных

Произведение достаточно короткое. Школьник во втором классе может прочесть его за 3-5 минут. Особенно любознательные дети могут задать дополнительные вопросы.

Когда и кем была написана сказка?

«Принцесса на горошине» была написана больше 150 лет назад, в 1835 году ее автором, известным писателем Гансом (Хансом) Кристианом Андерсеном.

Встречал ли ты выражение «принцесса на горошине»? Кого так называют?

Девочек и женщин, которые слишком изнеженные, преувеличивают твердость постели, кресла, которым «все не так, и недостаточно хорошо».

«Принцесса на горошине» – произведение не только для детей. В 3 года дети знакомятся с ним, как с интересной историей. В 5 лет начинают понимать смысл. В младшей школе уделяется больше внимания пересказу, анализу и выводам.

В чем смысл сказки «Принцесса на горошине» для взрослых, чему учит произведение? Счастливый финал напоминает, что добро всегда побеждает зло. Принцесса, которая выглядела из-за непогоды совсем неприглядно, все же была оценена по достоинству. Она продемонстрировала свои лучшие качества: благородство, благодарность за приют, доброту. Горошина символизирует отношение к неудачам, боли и трудностям. Не все могут почувствовать болезненный комок под толстым слоем «мягкого пуха», а только утонченная и чуткая душа.

Перечитав, точнее сказать — пересмотрев датскую адаптацию в виде пятнадцатиминутного мультика (кроме которого существует советская версия + полнометражный мультфильм 2002 года), я внезапно — и в этом давно нет ничего удивительного, — начал размышлять. Так бывает, когда в детстве смотришь, и даже мысли не возникает о подтексте и вменяемости сюжета. А тут видишь ли, задумался, в чём же смысл столь странной истории о принцессе, которая под перинами почувствовала сухую горошинку? Как оказалось, не я один задавался этим вопросом. Ниже представлены (от обстоятельных до кратких) мнения из комментариев, не все — но этих достаточно.

(1) Не всё золото, что блестит.

Встречают по одежке, провожают по уму.

Никогда не верь первому впечатлению, оно всегда обманчиво.

Только немного больше узнав о человеке, можно делать какие-либо выводы.

Так и в этой сказке: просто одетую девушку нельзя было сразу назвать принцессой, однако жизненные привычки в любой ситуации расскажут сами все о человеке, ведь то, к чему человек привык, как он сформировался умственно, трудно скрывать.

(2) Смысл сказки в том, что люди, оказывается, не все одинаковы, а отличаются друг от друга своим уровнем интеллигентности, развития нравственности, природной мудрости. Всего на одной странице, Андерсен определил всю философию нового времени. Принцесса пришла в рубищах, босая и замерзшая. За ней стелется шлейф необыкновенной истории, которую мы не знаем. Но она принцесса, и в этом ее суть. И достаточно всего одной горошины, чтобы понять это.

(3) Способ проверки подлинности принцессы всего лишь образ. Очарование принцессой происходит ещё до проверки горошиной. Если бы она не понравилась королевскому семейству, королева не пошла бы на такой риск — вручить судьбу сына и свою воле случая. То есть, мнение о незнакомке сперва таково: девушка хороша, но не обманулись ли мы? Чтобы удостовериться в том, что избранница действительно достойная, в жизни понадобились бы годы жизни с ней. В сказке же всё можно проверить горошиной. Сказочное свойство горошины — дать подтверждение — да, это именно та. А коль подтверждение получено, вот вам и доказательство, что и в лохмотьях может быть золотая, благородная, чистая душа.

(4) Принцесса не замуж шла, просто попросилась на ночлег, голодная и холодная, а коварная королева подсунула ей горошину в виде испытания. Принцесса утром разохалась от синяков, оставленных градинами (накануне она забегалась, промокла, разволновалась + твёрдые осадки побили), а потенциальная свекруха решила, что заполучила невестку голубых кровей. Сказка на внимательность.

(5) Способность почувствовать горошину дает право предполагать в человеке возможность почувствовать и состояние находящегося рядом человека, его боль, радость, сомнения. А там рядом и сочувствие, и соучастие. А еще и то, что принцесса сказала о том, что ей плохо спалось — это же ведь открытость!

(6) Главный смысл сказки состоит в том, что, если человек хочет что-то узнать, он обязательно придумает, как это сделать. Сказка учит быть сообразительным и находчивым, придумывать оригинальные решения для достижения цели.

(7) Смысл в том, что люди высшего общества привыкли к самому лучшему. Это стиль жизни принцессы не спят на тюфяках они не служанки. Поэтому и подвох чувствуют сразу. Без таких принцесс в реальной жизни не было бы класса люкс.

(8) Сказка учит нас не подразделять людей на нищих и богатых, то есть учит тому, что все люди равны. А встречать всегда людей лишь по одёжке — неправильно, нужно учиться доверять людям. Ведь суть человека в его внутреннем мире.

(9) Данная сказка — насмешка над королевскими кровями. Автор высмеивает знать, ржет над родителями принца и их критериями поиска жены своему сыну.

(10) Смысл в том, что сейчас принцесс настоящих не осталось. Спим на своих жестких кроватях с ортопедическим матрацем и ни одного синяка с утра.

(11) Горошина символизирует нечистую совесть.

Как ее не прикрывай, настоящая принцесса не сможет спать спокойно.

(12) Конечно же, всё может быть, но вот для меня мораль сказки такая: если чувствуешь себя принцессой, даже драные лохмотья тебе не будут помехой.

(13) Мне кажется… просто им нужна была «породистая» жена, а не какая-нить самозванка деревенская с улицы, вот в этом смысл, наверное.

(14) Мораль — оказаться в нужное время в нужном месте, подслушать и подсмотреть, как тебя будут испытывать. PS: Добавил не знаю зачем… а вдруг?

(15) У сказки нет морали. Мораль бывает у БАСНИ! Для этого данный жанр и создавался. А сказка — это отражение действительности, созданное творчеством. И Андерсен не морализирует, он показывает мир во всем его многообразии.

Такие дела, некоторые мнения в чём-то похожи, многие чисто домыслы — воображение рисует детали. Вы как думаете, какой номер близок к истине? Возможно, у кого-то включился СПГС. Что касается меня, то я склоняюсь к варианту 15 и 9.