| «The Stone Flower» | ||

|---|---|---|

| by Pavel Bazhov | ||

| Original title | Каменный цветок | |

| Translator | Alan Moray Williams (first), Eve Manning, et al. | |

| Country | Soviet Union | |

| Language | Russian | |

| Series | The Malachite Casket collection (list of stories) | |

| Genre(s) | skaz | |

| Published in | Literaturnaya Gazeta | |

| Publication type | Periodical | |

| Publisher | The Union of Soviet Writers | |

| Media type | Print (newspaper, hardback and paperback) | |

| Publication date | 10 May 1938 | |

| Chronology | ||

|

«The Stone Flower» (Russian: Каменный цветок, tr. Kamennyj tsvetok, IPA: [ˈkamʲənʲɪj tsvʲɪˈtok]), also known as «The Flower of Stone«, is a folk tale (also known as skaz) of the Ural region of Russia collected and reworked by Pavel Bazhov, and published in Literaturnaya Gazeta on 10 May 1938 and in Uralsky Sovremennik. It was later released as a part of the story collection The Malachite Box. «The Stone Flower» is considered to be one of the best stories in the collection.[1] The story was translated from Russian into English by Alan Moray Williams in 1944, and several times after that.

Pavel Bazhov indicated that all his stories can be divided into two groups based on tone: «child-toned» (e.g. «Silver Hoof») with simple plots, children as the main characters, and a happy ending,[2] and «adult-toned». He called «The Stone Flower» the «adult-toned» story.[3]

The tale is told from the point of view of the imaginary Grandpa Slyshko (Russian: Дед Слышко, tr. Ded Slyshko; lit. «Old Man Listenhere»).[4]

Publication[edit]

The Moscow critic Viktor Pertsov read the manuscript of «The Stone Flower» in the spring of 1938, when he traveled across the Urals with his literary lectures. He was very impressed by it and published the shortened story in Literaturnaya Gazeta on 10 May 1938.[5] His complimenting review The fairy tales of the Old Urals (Russian: Сказки старого Урала, tr. Skazki starogo Urala) which accompanied the publication.[6]

After the appearance in Literaturnaya Gazeta, the story was published in first volume of the Uralsky Sovremennik in 1938.[7][8] It was later released as a part of Malachite Box collection on 28 January 1939.[9]

In 1944 the story was translated from Russian into English by Alan Moray Williams and published by Hutchinson as a part of the collection The Malachite Casket: Tales from the Urals.[10] The title was translated as «The Stone Flower».[11] In the 1950s translation of The Malachite Casket was made by Eve Manning[12][13] The story was published as «The Flower of Stone».[14]

The story was published in the collection Russian Magic Tales from Pushkin to Platonov, published by Penguin Books in 2012. The title was translated by Anna Gunin as «The Stone Flower».[15]

Plot summary[edit]

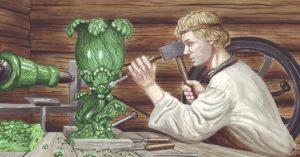

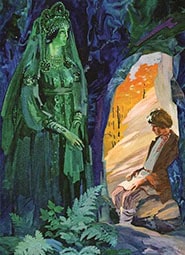

The main character of the story, Danilo, is a weakling and a scatterbrain, and people from the village find him strange. He is sent to study under the stone-craftsman Prokopich. One day he is given an order to make a fine-molded cup, which he creates after a thornapple. It turns out smooth and neat, but not beautiful enough for Danilo’s liking. He is dissatisfied with the result. He says that even the simplest flower «brings joy to your heart», but his stone cup will bring joy to no one. Danilo feels as if he just spoils the stone. An old man tells him the legend that a most beautiful Stone Flower grows in the domain of the Mistress of the Copper Mountain, and those who see it start to understand the beauty of stone, but «life loses all its sweetness» for them. They become the Mistress’s mountain craftsmen forever. Danilo’s fiancée Katyenka asks him to forget it, but Danilo longs to see the Flower. He goes to the copper mine and finds the Mistress of the Copper Mountain. He begs her to show him the Flower. The Mistress reminds him of his fiancée and warns Danilo that he would never want to go back to his people, but he insists. She then shows him the Malachite Flower. Danilo goes back to the village, destroys his stone cup and then disappears. «Some said he’d taken leave of his senses and died somewhere in the woods, but others said the Mistress had taken him to her mountain workshop forever».[16]

Sources[edit]

The main character of the story, Danilo the Craftsman, was based on the real miner Danila Zverev (Russian: Данила Кондратьевич Зверев, tr. Danila Kondratyevich Zverev; 1858–1938).[17] Bazhov met him at the lapidary studio in Sverdlovsk. Zverev was born, grew up and spent most of his life in Koltashi village, Rezhevsky District.[18] Before the October Revolution Zverev moved to Yekaterinburg, where he took up gemstone assessment. Bazhov later created another skaz about his life, «Dalevoe glyadeltse». Danila Zverev and Danilo the Craftsman share many common traits, e.g. both lost their parents early, both tended cattle and were punished for their dreaminess, both suffered from poor health since childhood. Danila Zverev was so short and thin that the villagers gave him the nickname «Lyogonkiy» (Russian: Лёгонький, lit. ‘»Lightweight»‘). Danilo from the story had another nickname «Nedokormysh» (Russian: Недокормыш, lit. ‘»Underfed» or «Famished»‘). Danila Zverev’s teacher Samoil Prokofyich Yuzhakov (Russian: Самоил Прокофьич Южаков) became the source of inpisration for Danilo the Craftsman’s old teacher Prokopich.[17]

Themes[edit]

During Soviet times, every edition of The Malachite Box was usually prefaced by an essay by a famous writer or scholar, commenting on the creativity of the Ural miners, cruel landlords, social oppression and the «great workers unbroken by the centuries of slavery».[19] The later scholars focused more on the relationship of the characters with nature, the Mountain and the mysterious in general.[20] Maya Nikulina comments that Danilo is the creator who is absolutely free from all ideological, social and political contexts. His talent comes from the connection with the secret force, which controls all his movements. Moreover, the local landlord, while he exists, is unimportant for Danilo’s story. Danilo’s issues with his employer are purely aesthetic, i.e., a custom-made vase was ordered, but Danilo, as an artist, only desires to understand the beauty of stone, and this desire takes him away from life.[21]

The Stone Flower is the embodiment of the absolute magic power of stone and the absolute beauty, which is beyond mortals’ reach.[22]

Many noted that the Mistress’ world represents the realm of the dead,[23][24] which is emphasized not only by its location underneath the human world but also mostly by its mirror-like, uncanny, imitation or negation of the living world.[23] Everything looks strange there, even the trees are cold and smooth like stone. The Mistress herself does not eat or drink, she does not leave any traces, her clothing is made of stone and so on. The Mountain connects her to the world of the living, and Danilo metaphorically died for the world, when we went to her.[24] Mesmerized by the Flower, Danilo feels at his own wedding as if he were at a funeral. A contact with the Mistress is a symbolic manifestation of death. Marina Balina noted that as one of the «mountain spirits», she does not hesitate to kill those who did not pass her tests, but even those who had been rewarded by her do not live happily ever after, as shown with Stepan in «The Mistress of the Copper Mountain».[23] The Mistress was also interpreted as the manifestation of female sexuality. «The Mistress exudes sexual attraction and appears as its powerful source».[25] Mark Lipovetsky commented that Mistress embodies the struggle and unity between Eros and Thanatos. The Flower is made of cold stone for that very reason: it points at death along with sexuality.[26] All sexual references in Pavel Bazhov’s stories are very subtle, owing to Soviet puritanism.[27]

Danilo is a classical Bazhov binary character. On the one hand, he is a truth seeker and a talented craftsman, on the other hand, he is an outsider, who violates social norms, destroys the lives of the loved ones and his own.[28] The author of The Fairy Tale Encyclopedia suggests that the Mistress represents the conflict between human kind and nature. She compares the character with Mephistopheles, because a human needs to wager his soul with the Mistress in order to get the ultimate knowledge. Danilo wagers his soul for exceptional craftsmanship skills.[29] However, the Mistress does not force anyone to abandon their moral values, and therefore «is not painted in dark colours».[30] Lyudmila Skorino believed that she represented the nature of the Urals, which inspires a creative person with its beauty.[31]

Denis Zherdev commented that the Mistress’s female domain is the world of chaos, destruction and spontaneous uncontrolled acts of creation (human craftsmen are needed for the controlled creation). Although the characters are so familiar with the female world that the appearance of the Mistress is regarded as almost natural and even expected, the female domain collides with the ordered factory world, and brings in randomness, variability, unpredictability and capriciousness. Direct contact with the female power is a violation of the world order and therefore brings destruction or chaos.[32]

One of the themes is how to become a true artist and the subsequent self-fulfillment. The Soviet critics’ point of view was that the drama of Danilo came from the fact that he was a serf, and therefore did not receive the necessary training to complete the task. However, modern critics disagree and state that the plot of the artist’s dissatisfaction is very popular in literature. Just like in the Russian poem The Sylph, written by Vladimir Odoyevsky, Bazhov raises the issue that the artist can reach his ideal only when he comes in with the otherworldly.[33]

Sequels[edit]

«The Master Craftsman»[edit]

«The Master Craftsman» redirects here. For a member of a guild, see Master craftsman.

«The Master Craftsman» (Russian: Горный мастер, tr. Gornyj master) was serialized in Na Smenu! from 14 to 26 January 1939, in Oktyabr (issues 5–6), and in Rabotnitsa magazine (issues 18–19).[34][35] In 1944 the story was translated from Russian into English by Alan Moray Williams and published by Hutchinson as a part of the collection The Malachite Casket: Tales from the Urals. The title was translated as «The Master Craftsman».[36] In the 1950s translation of The Malachite Casket, made by Eve Manning, the story was published as «The Mountain Craftsman«.[37] The story was published in the collection Russian Magic Tales from Pushkin to Platonov, published by Penguin Books in 2012. The title was translated by Anna Gunin as «The Mountain Master«.[38]

The story begins after the disappearance of Danilo. For several years Danilo’s betrothed Katyenka (Katya) waits for him and stays unmarried despite the fact that everyone laughs at her. She is the only person who believes that Danilo will return. She is quickly nicknamed «Dead Man’s Bride». When both of her parents die, she moves away from her family and goes to Danilo’s house and takes care of his old teacher Prokopich, although she knows that living with a man can ruin her reputation. Prokopich welcomes her happily. He earns some money by gem-cutting, Katya runs the house, cooks, and does the gardening. When Prokopich gets too old to work, Katya realizes that she cannot possibly support herself by needlework alone. She asks him to teach her some stone craft. Prokopich laughs at first, because he does not believe gem-cutting is a suitable job for a woman, but soon relents. He teaches her how to work with malachite. After he dies, Katya decides to live in the house alone. Her strange behaviour, her refusal to marry someone and lead a normal life cause people at the village to think that she is insane or even a witch, but Katya firmly believes that Danilo will «learn all he wants to know, there in the mountain, and then he’ll come».[39] She wants to try making medallions and selling them. There are no gemstones left, so she goes to the forest, finds an exceptional piece of gemstone and starts working. After the medallions are finished, she goes to the town to the merchant who used to buy Prokopich’s work. He reluctantly buys them all, because her work is very beautiful. Katya feels as if this was a token from Danilo. She runs back to the forest and starts calling for him. The Mistress of the Copper Mountain appears. Katya bravely demands that she gives Danilo back. The Mistress takes her to Danilo and says: «Well, Danilo the Master Craftsman, now you must choose. If you go with her you forget all that is mine, if you remain here, then you must forget her and all living people».[40] Danilo chooses Katya, saying that he thinks about her every moment. The Mistress is pleased with Katya’s bravery and rewards her by letting Danilo remember everything that he had learned in the Mountain. She then warns Danilo to never tell anyone about his life there. The couple thanks the Mistress and goes back to the village. When asked about his disappearance, Danilo claims that he simply left to Kolyvan to train under another craftsman. He marries Katya. His works is extraordinary, and everyone starts calling him «the mountain craftsman».

Other books[edit]

This family’s story continues in «A Fragile Twig», published in 1940.[41] «A Fragile Twig» focuses on Katyenka and Danilo’s son Mitya. This is the last tale about Danilo’s family. Bazhov had plans for the fourth story about Danilo’s family, but it was never written. In the interview to a Soviet newspaper Vechernyaya Moskva the writer said: «I am going to finish «The Stone Flower» story. I would like to write about the heirs of the protagonist, Danilo, [I would like] to write about their remarkable skills and aspirations for the future. I’m thinking about leading the story to the present day».[42] This plan was later abandoned.

Reception and legacy[edit]

The Stone Flower in the early design of Polevskoy’s coat of arms (1981).[43]

The current flag of Polevskoy features the Mistress of the Copper Mountain (depicted as a lizard) inside the symbolic representation of the Stone Flower.

Danilo the Craftsman became one of the best known characters of Bazhov’s tales.[21] The fairy tale inspired numerous adaptations, including films and stage adaptations. It is included in the school reading curriculum.[44] «The Stone Flower» is typically adapted with «The Master Craftsman».

- The Stone Flower Fountain at the VDNKh Center, Moscow (1953).

- The Stone Flower Fountain in Yekaterinburg (1960).[45] Project by Pyotr Demintsev.[46]

It generated a Russian catchphrase «How did that Stone Flower come out?» (Russian: «Не выходит у тебя Каменный цветок?», tr. Ne vykhodit u tebja Kamennyj tsvetok?, lit. «Naught came of your Stone Flower?»),[47] derived from these dialogue:

«Well, Danilo the Craftsman, so naught came of your thornapple?»

«No, naught came of it,» he said.[48]

The style of the story was praised.[49]

Films[edit]

- The Stone Flower, a 1946 Soviet film;[50] incorporates plot elements from the stories «The Mistress of the Copper Mountain» and «The Master Craftsman».

- The Stone Flower, a 1977 animated film;[51] based on «The Stone Flower» and «The Master Craftsman»

- The Master Craftsman, a 1978 animated film made by Soyuzmultfilm studio,[52] based on «The Stone Flower» and «The Master Craftsman».

- The Book of Masters, a 2009 Russian language fantasy film, is loosely based on Bazhov’s tales, including «The Stone Flower».[53][54]

- The Stone Flower (another title: Skazy), a television film of two-episodes that premiered on 1 January 1988. This film is a photoplay (a theatrical play that has been filmed for showing as a film) based on the 1987 play of the Maly Theatre. It was directed by Vitaly Ivanov, with the music composed by Nikolai Karetnikov, and released by Studio Ekran. It starred Yevgeny Samoylov, Tatyana Lebedeva, Tatyana Pankova, Oleg Kutsenko.[55]

Theatre[edit]

- The Stone Flower, the 1944 ballet composed by Alexander Fridlender.[8]

- Klavdiya Filippova combined «The Stone Flower» with «The Master Craftsman» to create the children’s play The Stone Flower.[56] It was published in Sverdlovsk as a part of the 1949 collection Plays for Children’s Theatre Based on Bazhov’s Stories.[56]

- The Stone Flower, an opera in four acts by Kirill Molchanov. Sergey Severtsev wrote the Russian language libretto. It was the first opera of Molchanov.[57] It premiered on 10 December 1950 in Moscow at the Stanislavski and Nemirovich-Danchenko Music Theatre.[58] The role of Danila (tenor) was sung by Mechislav Shchavinsky, Larisa Adveyeva sung the Mistress of the Copper Mountain (mezzo-soprano), Dina Potapovskaya sung Katya (coloratura soprano).[59][60]

- The Tale of the Stone Flower, the 1954 ballet composed by Sergei Prokofiev.[61]

- Skazy, also called The Stone Flower, the 1987 play of the Maly Theatre.[55]

Notes[edit]

- ^ «Bazhov Pavel Petrovitch». The Russian Academy of Sciences Electronic Library IRLI (in Russian). The Russian Literature Institute of the Pushkin House, RAS. pp. 151–152. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- ^ Litovskaya 2014, p. 247.

- ^ «Bazhov P. P. The Malachite Box» (in Russian). Bibliogid. 13 May 2006. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- ^ Balina, Marina; Goscilo, Helena; Lipovetsky, Mark (25 October 2005). Politicizing Magic: An Anthology of Russian and Soviet Fairy Tales. The Northwestern University Press. p. 115. ISBN 9780810120327.

- ^ Slobozhaninova, Lidiya (2004). «Malahitovaja shkatulka Bazhova vchera i segodnja» “Малахитовая шкатулка” Бажова вчера и сегодня [Bazhov’s Malachite Box yesterday and today]. Ural (in Russian). Yekaterinburg. 1.

- ^ Komlev, Andrey (2004). «Bazhov i Sverdlovskoe otdelenie Sojuza sovetskih pisatelej» Бажов и Свердловское отделение Союза советских писателей [Bazhov and the Sverdlovsk department of the Union of the Soviet writers]. Ural (in Russian). Yekaterinburg. 1.

- ^ Bazhov 1952, p. 243.

- ^ a b «Kamennyj tsvetok» (in Russian). FantLab. Retrieved 22 November 2015.

- ^ «The Malachite Box» (in Russian). The Live Book Museum. Yekaterinburg. Retrieved 22 November 2015.

- ^ The malachite casket; tales from the Urals, (Book, 1944). WorldCat. OCLC 1998181.

- ^ Bazhov 1944, p. 76.

- ^ «Malachite casket : tales from the Urals / P. Bazhov ; [translated from the Russian by Eve Manning ; illustrated by O. Korovin ; designed by A. Vlasova]». The National Library of Australia. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- ^ Malachite casket; tales from the Urals. (Book, 1950s). WorldCat. OCLC 10874080.

- ^ Bazhov 1950s, p. 9.

- ^ Russian magic tales from Pushkin to Platonov (Book, 2012). WorldCat.org. OCLC 802293730.

- ^ Bazhov 1950s, p. 67.

- ^ a b «Родина Данилы Зверева». А.В. Рычков, Д.В. Рычков «Лучшие путешествия по Среднему Уралу». (in Russian). geocaching.su. 28 July 2012. Retrieved 23 November 2015.

- ^ Dobrovolsky, Evgeni (1981). Оптимальный вариант. Sovetskaya Rossiya. p. 5.

- ^ Nikulina 2003, p. 76.

- ^ Nikulina 2003, p. 77.

- ^ a b Nikulina 2003, p. 80.

- ^ Prikazchikova, E. (2003). «Каменная сила медных гор Урала» [The Stone Force of The Ural Copper Mountains] (PDF). Izvestiya of the Ural State University (in Russian). The Ural State University (28): 16.

- ^ a b c Balina 2013, p. 273.

- ^ a b Shvabauer, Nataliya (10 January 2009). «Типология фантастических персонажей в фольклоре горнорабочих Западной Европы и России» [The Typology of the Fantastic Characters in the Miners’ Folklore of Western Europe and Russia] (PDF). Dissertation (in Russian). The Ural State University. p. 147. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- ^ Balina 2013, p. 270.

- ^ Lipovetsky 2014, p. 220.

- ^ Lipovetsky 2014, p. 218.

- ^ Zherdev, Denis (2003). «Binarnost kak element pojetiki bazhovskikh skazov» Бинарность как элемент поэтики бажовских сказов [Binarity as the Poetic Element in Bazhov’s Skazy] (PDF). Izvestiya of the Ural State University (in Russian). The Ural State University (28): 46–57.

- ^ Budur 2005, p. 124.

- ^ Budur 2005, p. 285.

- ^ Bazhov 1952, p. 232.

- ^ Zherdev, Denis. «Poetika skazov Bazhova» Поэтика сказов Бажова [The poetics of Bazhov’s stories] (in Russian). Research Library Mif.Ru. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

- ^ Sozina, E. «O nekotorykh motivah russkoj klassicheskoj literatury v skazah P. P. Bazhova o masterah О некоторых мотивах русской классической литературы в сказах П. П. Бажова о «мастерах» [On some Russian classical literature motives in P. P. Bazhov’s «masters» stories.]» in: P. P. Bazhov i socialisticheskij realizm.

- ^ «Горный мастер» [The Master Craftsman] (in Russian). FantLab. Retrieved 27 November 2015.

- ^ Bazhov 1952 (1), p. 243.

- ^ Bazhov 1944, p. 95.

- ^ Bazhov 1950s, p. 68.

- ^ Russian magic tales from Pushkin to Platonov (Book, 2012). WorldCat.org. OCLC 802293730.

- ^ Bazhov 1950s, p. 70.

- ^ Bazhov 1950s, p. 80.

- ^ Izmaylova, A. B. «Сказ П.П. Бажова «Хрупкая веточка» в курсе «Русская народная педагогика»» [P. Bazhov’s skaz A Fragile Twig in the course The Russian Folk Pedagogics] (PDF) (in Russian). The Vladimir State University. Retrieved 11 December 2015.

- ^ «The interview with P. Bazhov». Vechernyaya Moskva (in Russian). Mossovet. 31 January 1948.: «Собираюсь закончить сказ о «Каменном цветке». Мне хочется показать в нем преемников его героя, Данилы, написать об их замечательном мастерстве, устремлении в будущее. Действие сказа думаю довести до наших дней».

- ^ «Городской округ г. Полевской, Свердловская область» [Polevskoy Town District, Sverdlovsk Oblast]. Coats of arms of Russia (in Russian). Heraldicum.ru. Retrieved 9 December 2015.

- ^ Korovina, V. «Программы общеобразовательных учреждений» [The educational institutions curriculum] (in Russian). Retrieved 9 December 2015.

- ^ «Средний Урал отмечает 130-летие со дня рождения Павла Бажова» (in Russian). Yekaterinburg Online. 27 January 2009. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- ^ «Фонтан «Каменный цветок» на площади Труда в Екатеринбурге отремонтируют за месяц: Общество: Облгазета».

- ^ Kozhevnikov, Alexey (2004). Крылатые фразы и афоризмы отечественного кино [Catchphrases and aphorisms from Russian cinema] (in Russian). OLMA Media Group. p. 214. ISBN 9785765425671.

- ^ Bazhov 1950s, p. 231. In Russian: «Ну что, Данило-мастер, не вышла твоя дурман-чаша?» — «Не вышла, — отвечает.»

- ^ Eydinova, Viola (2003). «O stile Bazhova» О стиле Бажова [About Bazhov’s style]. Izvestiya of the Ural State University (in Russian). The Ural State University. 28: 40–46.

- ^ «The Stone Flower (1946)» (in Russian). The Russian Cinema Encyclopedia. Retrieved 23 November 2015.

- ^ «A Stone Flower». Animator.ru. Retrieved 22 November 2015.

- ^ «Mining Master». Animator.ru. Retrieved 22 November 2015.

- ^ Sakharnova, Kseniya (21 October 2009). ««Книга мастеров»: герои русских сказок в стране Disney» [The Book of Masters: the Russian fairy tale characters in Disneyland] (in Russian). Profcinema Co. Ltd. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- ^ Zabaluyev, Yaroslav (27 October 2009). «Nor have we seen its like before…» (in Russian). Gazeta.ru. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- ^ a b «Каменный цветок 1987» [The Stone Flower 1987] (in Russian). Kino-teatr.ru. Retrieved 9 December 2015.

- ^ a b Litovskaya 2014, p. 250.

- ^ Rollberg, Peter (7 November 2008). Historical Dictionary of Russian and Soviet Cinema. Scarecrow Press. p. 461. ISBN 9780810862685.

- ^ «Опера Молчанова «Каменный цветок»» [Molchanov’s opera The Stone Flower] (in Russian). Belcanto.ru. Retrieved 20 December 2015.

- ^ The Union of the Soviet Composers, ed. (1950). Советская музыка [Soviet Music] (in Russian). Vol. 1–6. Государственное Музыкальное издательство. p. 109.

- ^ Medvedev, A (February 1951). «Каменный цветок» [The Stone Flower]. Smena (in Russian). Smena Publishing House. 2 (570).

- ^ Balina 2013, p. 263.

References[edit]

- Bazhov, Pavel (1952). Valentina Bazhova; Alexey Surkov; Yevgeny Permyak (eds.). Sobranie sochinenij v trekh tomakh Собрание сочинений в трех томах [Works. In Three Volumes] (in Russian). Vol. 1. Moscow: Khudozhestvennaya Literatura.

- Bazhov, Pavel; translated by Alan Moray Williams (1944). The Malachite Casket: tales from the Urals. Library of selected Soviet literature. The University of California: Hutchinson & Co. ltd. ISBN 9787250005603.

- Bazhov, Pavel; translated by Eve Manning (1950s). Malachite Casket: Tales from the Urals. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House.

- Lipovetsky, Mark (2014). «The Uncanny in Bazhov’s Tales». Quaestio Rossica (in Russian). The University of Colorado Boulder. 2 (2): 212–230. doi:10.15826/qr.2014.2.051. ISSN 2311-911X.

- Litovskaya, Mariya (2014). «Vzroslyj detskij pisatel Pavel Bazhov: konflikt redaktur» Взрослый детский писатель Павел Бажов: конфликт редактур [The Adult-Children’s Writer Pavel Bazhov: The Conflict of Editing]. Detskiye Chteniya (in Russian). 6 (2): 243–254.

- Balina, Marina; Rudova, Larissa (1 February 2013). Russian Children’s Literature and Culture. Literary Criticism. Routledge. ISBN 978-1135865566.

- Budur, Naralya (2005). «The Mistress of the Copper Mountain». Skazochnaja enciklopedija Сказочная энциклопедия [The Fairy Tale Encyclopedia] (in Russian). Olma Media Group. ISBN 9785224048182.

- Nikulina, Maya (2003). «Pro zemelnye dela i pro tajnuju silu. O dalnikh istokakh uralskoj mifologii P.P. Bazhova» Про земельные дела и про тайную силу. О дальних истоках уральской мифологии П.П. Бажова [Of land and the secret force. The distant sources of P.P. Bazhov’s Ural mythology]. Filologichesky Klass (in Russian). Cyberleninka.ru. 9.

- P. P. Bazhov i socialisticheskij realizm // Tvorchestvo P.P. Bazhova v menjajushhemsja mire П. П. Бажов и социалистический реализм // Творчество П. П. Бажова в меняющемся мире [Pavel Bazhov and socialist realism // The works of Pavel Bazhov in the changing world]. The materials of the inter-university research conference devoted to the 125th birthday (in Russian). Yekaterinburg: The Ural State University. 28–29 January 2004. pp. 18–26.

| «The Stone Flower» | ||

|---|---|---|

| by Pavel Bazhov | ||

| Original title | Каменный цветок | |

| Translator | Alan Moray Williams (first), Eve Manning, et al. | |

| Country | Soviet Union | |

| Language | Russian | |

| Series | The Malachite Casket collection (list of stories) | |

| Genre(s) | skaz | |

| Published in | Literaturnaya Gazeta | |

| Publication type | Periodical | |

| Publisher | The Union of Soviet Writers | |

| Media type | Print (newspaper, hardback and paperback) | |

| Publication date | 10 May 1938 | |

| Chronology | ||

|

«The Stone Flower» (Russian: Каменный цветок, tr. Kamennyj tsvetok, IPA: [ˈkamʲənʲɪj tsvʲɪˈtok]), also known as «The Flower of Stone«, is a folk tale (also known as skaz) of the Ural region of Russia collected and reworked by Pavel Bazhov, and published in Literaturnaya Gazeta on 10 May 1938 and in Uralsky Sovremennik. It was later released as a part of the story collection The Malachite Box. «The Stone Flower» is considered to be one of the best stories in the collection.[1] The story was translated from Russian into English by Alan Moray Williams in 1944, and several times after that.

Pavel Bazhov indicated that all his stories can be divided into two groups based on tone: «child-toned» (e.g. «Silver Hoof») with simple plots, children as the main characters, and a happy ending,[2] and «adult-toned». He called «The Stone Flower» the «adult-toned» story.[3]

The tale is told from the point of view of the imaginary Grandpa Slyshko (Russian: Дед Слышко, tr. Ded Slyshko; lit. «Old Man Listenhere»).[4]

Publication[edit]

The Moscow critic Viktor Pertsov read the manuscript of «The Stone Flower» in the spring of 1938, when he traveled across the Urals with his literary lectures. He was very impressed by it and published the shortened story in Literaturnaya Gazeta on 10 May 1938.[5] His complimenting review The fairy tales of the Old Urals (Russian: Сказки старого Урала, tr. Skazki starogo Urala) which accompanied the publication.[6]

After the appearance in Literaturnaya Gazeta, the story was published in first volume of the Uralsky Sovremennik in 1938.[7][8] It was later released as a part of Malachite Box collection on 28 January 1939.[9]

In 1944 the story was translated from Russian into English by Alan Moray Williams and published by Hutchinson as a part of the collection The Malachite Casket: Tales from the Urals.[10] The title was translated as «The Stone Flower».[11] In the 1950s translation of The Malachite Casket was made by Eve Manning[12][13] The story was published as «The Flower of Stone».[14]

The story was published in the collection Russian Magic Tales from Pushkin to Platonov, published by Penguin Books in 2012. The title was translated by Anna Gunin as «The Stone Flower».[15]

Plot summary[edit]

The main character of the story, Danilo, is a weakling and a scatterbrain, and people from the village find him strange. He is sent to study under the stone-craftsman Prokopich. One day he is given an order to make a fine-molded cup, which he creates after a thornapple. It turns out smooth and neat, but not beautiful enough for Danilo’s liking. He is dissatisfied with the result. He says that even the simplest flower «brings joy to your heart», but his stone cup will bring joy to no one. Danilo feels as if he just spoils the stone. An old man tells him the legend that a most beautiful Stone Flower grows in the domain of the Mistress of the Copper Mountain, and those who see it start to understand the beauty of stone, but «life loses all its sweetness» for them. They become the Mistress’s mountain craftsmen forever. Danilo’s fiancée Katyenka asks him to forget it, but Danilo longs to see the Flower. He goes to the copper mine and finds the Mistress of the Copper Mountain. He begs her to show him the Flower. The Mistress reminds him of his fiancée and warns Danilo that he would never want to go back to his people, but he insists. She then shows him the Malachite Flower. Danilo goes back to the village, destroys his stone cup and then disappears. «Some said he’d taken leave of his senses and died somewhere in the woods, but others said the Mistress had taken him to her mountain workshop forever».[16]

Sources[edit]

The main character of the story, Danilo the Craftsman, was based on the real miner Danila Zverev (Russian: Данила Кондратьевич Зверев, tr. Danila Kondratyevich Zverev; 1858–1938).[17] Bazhov met him at the lapidary studio in Sverdlovsk. Zverev was born, grew up and spent most of his life in Koltashi village, Rezhevsky District.[18] Before the October Revolution Zverev moved to Yekaterinburg, where he took up gemstone assessment. Bazhov later created another skaz about his life, «Dalevoe glyadeltse». Danila Zverev and Danilo the Craftsman share many common traits, e.g. both lost their parents early, both tended cattle and were punished for their dreaminess, both suffered from poor health since childhood. Danila Zverev was so short and thin that the villagers gave him the nickname «Lyogonkiy» (Russian: Лёгонький, lit. ‘»Lightweight»‘). Danilo from the story had another nickname «Nedokormysh» (Russian: Недокормыш, lit. ‘»Underfed» or «Famished»‘). Danila Zverev’s teacher Samoil Prokofyich Yuzhakov (Russian: Самоил Прокофьич Южаков) became the source of inpisration for Danilo the Craftsman’s old teacher Prokopich.[17]

Themes[edit]

During Soviet times, every edition of The Malachite Box was usually prefaced by an essay by a famous writer or scholar, commenting on the creativity of the Ural miners, cruel landlords, social oppression and the «great workers unbroken by the centuries of slavery».[19] The later scholars focused more on the relationship of the characters with nature, the Mountain and the mysterious in general.[20] Maya Nikulina comments that Danilo is the creator who is absolutely free from all ideological, social and political contexts. His talent comes from the connection with the secret force, which controls all his movements. Moreover, the local landlord, while he exists, is unimportant for Danilo’s story. Danilo’s issues with his employer are purely aesthetic, i.e., a custom-made vase was ordered, but Danilo, as an artist, only desires to understand the beauty of stone, and this desire takes him away from life.[21]

The Stone Flower is the embodiment of the absolute magic power of stone and the absolute beauty, which is beyond mortals’ reach.[22]

Many noted that the Mistress’ world represents the realm of the dead,[23][24] which is emphasized not only by its location underneath the human world but also mostly by its mirror-like, uncanny, imitation or negation of the living world.[23] Everything looks strange there, even the trees are cold and smooth like stone. The Mistress herself does not eat or drink, she does not leave any traces, her clothing is made of stone and so on. The Mountain connects her to the world of the living, and Danilo metaphorically died for the world, when we went to her.[24] Mesmerized by the Flower, Danilo feels at his own wedding as if he were at a funeral. A contact with the Mistress is a symbolic manifestation of death. Marina Balina noted that as one of the «mountain spirits», she does not hesitate to kill those who did not pass her tests, but even those who had been rewarded by her do not live happily ever after, as shown with Stepan in «The Mistress of the Copper Mountain».[23] The Mistress was also interpreted as the manifestation of female sexuality. «The Mistress exudes sexual attraction and appears as its powerful source».[25] Mark Lipovetsky commented that Mistress embodies the struggle and unity between Eros and Thanatos. The Flower is made of cold stone for that very reason: it points at death along with sexuality.[26] All sexual references in Pavel Bazhov’s stories are very subtle, owing to Soviet puritanism.[27]

Danilo is a classical Bazhov binary character. On the one hand, he is a truth seeker and a talented craftsman, on the other hand, he is an outsider, who violates social norms, destroys the lives of the loved ones and his own.[28] The author of The Fairy Tale Encyclopedia suggests that the Mistress represents the conflict between human kind and nature. She compares the character with Mephistopheles, because a human needs to wager his soul with the Mistress in order to get the ultimate knowledge. Danilo wagers his soul for exceptional craftsmanship skills.[29] However, the Mistress does not force anyone to abandon their moral values, and therefore «is not painted in dark colours».[30] Lyudmila Skorino believed that she represented the nature of the Urals, which inspires a creative person with its beauty.[31]

Denis Zherdev commented that the Mistress’s female domain is the world of chaos, destruction and spontaneous uncontrolled acts of creation (human craftsmen are needed for the controlled creation). Although the characters are so familiar with the female world that the appearance of the Mistress is regarded as almost natural and even expected, the female domain collides with the ordered factory world, and brings in randomness, variability, unpredictability and capriciousness. Direct contact with the female power is a violation of the world order and therefore brings destruction or chaos.[32]

One of the themes is how to become a true artist and the subsequent self-fulfillment. The Soviet critics’ point of view was that the drama of Danilo came from the fact that he was a serf, and therefore did not receive the necessary training to complete the task. However, modern critics disagree and state that the plot of the artist’s dissatisfaction is very popular in literature. Just like in the Russian poem The Sylph, written by Vladimir Odoyevsky, Bazhov raises the issue that the artist can reach his ideal only when he comes in with the otherworldly.[33]

Sequels[edit]

«The Master Craftsman»[edit]

«The Master Craftsman» redirects here. For a member of a guild, see Master craftsman.

«The Master Craftsman» (Russian: Горный мастер, tr. Gornyj master) was serialized in Na Smenu! from 14 to 26 January 1939, in Oktyabr (issues 5–6), and in Rabotnitsa magazine (issues 18–19).[34][35] In 1944 the story was translated from Russian into English by Alan Moray Williams and published by Hutchinson as a part of the collection The Malachite Casket: Tales from the Urals. The title was translated as «The Master Craftsman».[36] In the 1950s translation of The Malachite Casket, made by Eve Manning, the story was published as «The Mountain Craftsman«.[37] The story was published in the collection Russian Magic Tales from Pushkin to Platonov, published by Penguin Books in 2012. The title was translated by Anna Gunin as «The Mountain Master«.[38]

The story begins after the disappearance of Danilo. For several years Danilo’s betrothed Katyenka (Katya) waits for him and stays unmarried despite the fact that everyone laughs at her. She is the only person who believes that Danilo will return. She is quickly nicknamed «Dead Man’s Bride». When both of her parents die, she moves away from her family and goes to Danilo’s house and takes care of his old teacher Prokopich, although she knows that living with a man can ruin her reputation. Prokopich welcomes her happily. He earns some money by gem-cutting, Katya runs the house, cooks, and does the gardening. When Prokopich gets too old to work, Katya realizes that she cannot possibly support herself by needlework alone. She asks him to teach her some stone craft. Prokopich laughs at first, because he does not believe gem-cutting is a suitable job for a woman, but soon relents. He teaches her how to work with malachite. After he dies, Katya decides to live in the house alone. Her strange behaviour, her refusal to marry someone and lead a normal life cause people at the village to think that she is insane or even a witch, but Katya firmly believes that Danilo will «learn all he wants to know, there in the mountain, and then he’ll come».[39] She wants to try making medallions and selling them. There are no gemstones left, so she goes to the forest, finds an exceptional piece of gemstone and starts working. After the medallions are finished, she goes to the town to the merchant who used to buy Prokopich’s work. He reluctantly buys them all, because her work is very beautiful. Katya feels as if this was a token from Danilo. She runs back to the forest and starts calling for him. The Mistress of the Copper Mountain appears. Katya bravely demands that she gives Danilo back. The Mistress takes her to Danilo and says: «Well, Danilo the Master Craftsman, now you must choose. If you go with her you forget all that is mine, if you remain here, then you must forget her and all living people».[40] Danilo chooses Katya, saying that he thinks about her every moment. The Mistress is pleased with Katya’s bravery and rewards her by letting Danilo remember everything that he had learned in the Mountain. She then warns Danilo to never tell anyone about his life there. The couple thanks the Mistress and goes back to the village. When asked about his disappearance, Danilo claims that he simply left to Kolyvan to train under another craftsman. He marries Katya. His works is extraordinary, and everyone starts calling him «the mountain craftsman».

Other books[edit]

This family’s story continues in «A Fragile Twig», published in 1940.[41] «A Fragile Twig» focuses on Katyenka and Danilo’s son Mitya. This is the last tale about Danilo’s family. Bazhov had plans for the fourth story about Danilo’s family, but it was never written. In the interview to a Soviet newspaper Vechernyaya Moskva the writer said: «I am going to finish «The Stone Flower» story. I would like to write about the heirs of the protagonist, Danilo, [I would like] to write about their remarkable skills and aspirations for the future. I’m thinking about leading the story to the present day».[42] This plan was later abandoned.

Reception and legacy[edit]

The Stone Flower in the early design of Polevskoy’s coat of arms (1981).[43]

The current flag of Polevskoy features the Mistress of the Copper Mountain (depicted as a lizard) inside the symbolic representation of the Stone Flower.

Danilo the Craftsman became one of the best known characters of Bazhov’s tales.[21] The fairy tale inspired numerous adaptations, including films and stage adaptations. It is included in the school reading curriculum.[44] «The Stone Flower» is typically adapted with «The Master Craftsman».

- The Stone Flower Fountain at the VDNKh Center, Moscow (1953).

- The Stone Flower Fountain in Yekaterinburg (1960).[45] Project by Pyotr Demintsev.[46]

It generated a Russian catchphrase «How did that Stone Flower come out?» (Russian: «Не выходит у тебя Каменный цветок?», tr. Ne vykhodit u tebja Kamennyj tsvetok?, lit. «Naught came of your Stone Flower?»),[47] derived from these dialogue:

«Well, Danilo the Craftsman, so naught came of your thornapple?»

«No, naught came of it,» he said.[48]

The style of the story was praised.[49]

Films[edit]

- The Stone Flower, a 1946 Soviet film;[50] incorporates plot elements from the stories «The Mistress of the Copper Mountain» and «The Master Craftsman».

- The Stone Flower, a 1977 animated film;[51] based on «The Stone Flower» and «The Master Craftsman»

- The Master Craftsman, a 1978 animated film made by Soyuzmultfilm studio,[52] based on «The Stone Flower» and «The Master Craftsman».

- The Book of Masters, a 2009 Russian language fantasy film, is loosely based on Bazhov’s tales, including «The Stone Flower».[53][54]

- The Stone Flower (another title: Skazy), a television film of two-episodes that premiered on 1 January 1988. This film is a photoplay (a theatrical play that has been filmed for showing as a film) based on the 1987 play of the Maly Theatre. It was directed by Vitaly Ivanov, with the music composed by Nikolai Karetnikov, and released by Studio Ekran. It starred Yevgeny Samoylov, Tatyana Lebedeva, Tatyana Pankova, Oleg Kutsenko.[55]

Theatre[edit]

- The Stone Flower, the 1944 ballet composed by Alexander Fridlender.[8]

- Klavdiya Filippova combined «The Stone Flower» with «The Master Craftsman» to create the children’s play The Stone Flower.[56] It was published in Sverdlovsk as a part of the 1949 collection Plays for Children’s Theatre Based on Bazhov’s Stories.[56]

- The Stone Flower, an opera in four acts by Kirill Molchanov. Sergey Severtsev wrote the Russian language libretto. It was the first opera of Molchanov.[57] It premiered on 10 December 1950 in Moscow at the Stanislavski and Nemirovich-Danchenko Music Theatre.[58] The role of Danila (tenor) was sung by Mechislav Shchavinsky, Larisa Adveyeva sung the Mistress of the Copper Mountain (mezzo-soprano), Dina Potapovskaya sung Katya (coloratura soprano).[59][60]

- The Tale of the Stone Flower, the 1954 ballet composed by Sergei Prokofiev.[61]

- Skazy, also called The Stone Flower, the 1987 play of the Maly Theatre.[55]

Notes[edit]

- ^ «Bazhov Pavel Petrovitch». The Russian Academy of Sciences Electronic Library IRLI (in Russian). The Russian Literature Institute of the Pushkin House, RAS. pp. 151–152. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- ^ Litovskaya 2014, p. 247.

- ^ «Bazhov P. P. The Malachite Box» (in Russian). Bibliogid. 13 May 2006. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- ^ Balina, Marina; Goscilo, Helena; Lipovetsky, Mark (25 October 2005). Politicizing Magic: An Anthology of Russian and Soviet Fairy Tales. The Northwestern University Press. p. 115. ISBN 9780810120327.

- ^ Slobozhaninova, Lidiya (2004). «Malahitovaja shkatulka Bazhova vchera i segodnja» “Малахитовая шкатулка” Бажова вчера и сегодня [Bazhov’s Malachite Box yesterday and today]. Ural (in Russian). Yekaterinburg. 1.

- ^ Komlev, Andrey (2004). «Bazhov i Sverdlovskoe otdelenie Sojuza sovetskih pisatelej» Бажов и Свердловское отделение Союза советских писателей [Bazhov and the Sverdlovsk department of the Union of the Soviet writers]. Ural (in Russian). Yekaterinburg. 1.

- ^ Bazhov 1952, p. 243.

- ^ a b «Kamennyj tsvetok» (in Russian). FantLab. Retrieved 22 November 2015.

- ^ «The Malachite Box» (in Russian). The Live Book Museum. Yekaterinburg. Retrieved 22 November 2015.

- ^ The malachite casket; tales from the Urals, (Book, 1944). WorldCat. OCLC 1998181.

- ^ Bazhov 1944, p. 76.

- ^ «Malachite casket : tales from the Urals / P. Bazhov ; [translated from the Russian by Eve Manning ; illustrated by O. Korovin ; designed by A. Vlasova]». The National Library of Australia. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- ^ Malachite casket; tales from the Urals. (Book, 1950s). WorldCat. OCLC 10874080.

- ^ Bazhov 1950s, p. 9.

- ^ Russian magic tales from Pushkin to Platonov (Book, 2012). WorldCat.org. OCLC 802293730.

- ^ Bazhov 1950s, p. 67.

- ^ a b «Родина Данилы Зверева». А.В. Рычков, Д.В. Рычков «Лучшие путешествия по Среднему Уралу». (in Russian). geocaching.su. 28 July 2012. Retrieved 23 November 2015.

- ^ Dobrovolsky, Evgeni (1981). Оптимальный вариант. Sovetskaya Rossiya. p. 5.

- ^ Nikulina 2003, p. 76.

- ^ Nikulina 2003, p. 77.

- ^ a b Nikulina 2003, p. 80.

- ^ Prikazchikova, E. (2003). «Каменная сила медных гор Урала» [The Stone Force of The Ural Copper Mountains] (PDF). Izvestiya of the Ural State University (in Russian). The Ural State University (28): 16.

- ^ a b c Balina 2013, p. 273.

- ^ a b Shvabauer, Nataliya (10 January 2009). «Типология фантастических персонажей в фольклоре горнорабочих Западной Европы и России» [The Typology of the Fantastic Characters in the Miners’ Folklore of Western Europe and Russia] (PDF). Dissertation (in Russian). The Ural State University. p. 147. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- ^ Balina 2013, p. 270.

- ^ Lipovetsky 2014, p. 220.

- ^ Lipovetsky 2014, p. 218.

- ^ Zherdev, Denis (2003). «Binarnost kak element pojetiki bazhovskikh skazov» Бинарность как элемент поэтики бажовских сказов [Binarity as the Poetic Element in Bazhov’s Skazy] (PDF). Izvestiya of the Ural State University (in Russian). The Ural State University (28): 46–57.

- ^ Budur 2005, p. 124.

- ^ Budur 2005, p. 285.

- ^ Bazhov 1952, p. 232.

- ^ Zherdev, Denis. «Poetika skazov Bazhova» Поэтика сказов Бажова [The poetics of Bazhov’s stories] (in Russian). Research Library Mif.Ru. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

- ^ Sozina, E. «O nekotorykh motivah russkoj klassicheskoj literatury v skazah P. P. Bazhova o masterah О некоторых мотивах русской классической литературы в сказах П. П. Бажова о «мастерах» [On some Russian classical literature motives in P. P. Bazhov’s «masters» stories.]» in: P. P. Bazhov i socialisticheskij realizm.

- ^ «Горный мастер» [The Master Craftsman] (in Russian). FantLab. Retrieved 27 November 2015.

- ^ Bazhov 1952 (1), p. 243.

- ^ Bazhov 1944, p. 95.

- ^ Bazhov 1950s, p. 68.

- ^ Russian magic tales from Pushkin to Platonov (Book, 2012). WorldCat.org. OCLC 802293730.

- ^ Bazhov 1950s, p. 70.

- ^ Bazhov 1950s, p. 80.

- ^ Izmaylova, A. B. «Сказ П.П. Бажова «Хрупкая веточка» в курсе «Русская народная педагогика»» [P. Bazhov’s skaz A Fragile Twig in the course The Russian Folk Pedagogics] (PDF) (in Russian). The Vladimir State University. Retrieved 11 December 2015.

- ^ «The interview with P. Bazhov». Vechernyaya Moskva (in Russian). Mossovet. 31 January 1948.: «Собираюсь закончить сказ о «Каменном цветке». Мне хочется показать в нем преемников его героя, Данилы, написать об их замечательном мастерстве, устремлении в будущее. Действие сказа думаю довести до наших дней».

- ^ «Городской округ г. Полевской, Свердловская область» [Polevskoy Town District, Sverdlovsk Oblast]. Coats of arms of Russia (in Russian). Heraldicum.ru. Retrieved 9 December 2015.

- ^ Korovina, V. «Программы общеобразовательных учреждений» [The educational institutions curriculum] (in Russian). Retrieved 9 December 2015.

- ^ «Средний Урал отмечает 130-летие со дня рождения Павла Бажова» (in Russian). Yekaterinburg Online. 27 January 2009. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- ^ «Фонтан «Каменный цветок» на площади Труда в Екатеринбурге отремонтируют за месяц: Общество: Облгазета».

- ^ Kozhevnikov, Alexey (2004). Крылатые фразы и афоризмы отечественного кино [Catchphrases and aphorisms from Russian cinema] (in Russian). OLMA Media Group. p. 214. ISBN 9785765425671.

- ^ Bazhov 1950s, p. 231. In Russian: «Ну что, Данило-мастер, не вышла твоя дурман-чаша?» — «Не вышла, — отвечает.»

- ^ Eydinova, Viola (2003). «O stile Bazhova» О стиле Бажова [About Bazhov’s style]. Izvestiya of the Ural State University (in Russian). The Ural State University. 28: 40–46.

- ^ «The Stone Flower (1946)» (in Russian). The Russian Cinema Encyclopedia. Retrieved 23 November 2015.

- ^ «A Stone Flower». Animator.ru. Retrieved 22 November 2015.

- ^ «Mining Master». Animator.ru. Retrieved 22 November 2015.

- ^ Sakharnova, Kseniya (21 October 2009). ««Книга мастеров»: герои русских сказок в стране Disney» [The Book of Masters: the Russian fairy tale characters in Disneyland] (in Russian). Profcinema Co. Ltd. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- ^ Zabaluyev, Yaroslav (27 October 2009). «Nor have we seen its like before…» (in Russian). Gazeta.ru. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- ^ a b «Каменный цветок 1987» [The Stone Flower 1987] (in Russian). Kino-teatr.ru. Retrieved 9 December 2015.

- ^ a b Litovskaya 2014, p. 250.

- ^ Rollberg, Peter (7 November 2008). Historical Dictionary of Russian and Soviet Cinema. Scarecrow Press. p. 461. ISBN 9780810862685.

- ^ «Опера Молчанова «Каменный цветок»» [Molchanov’s opera The Stone Flower] (in Russian). Belcanto.ru. Retrieved 20 December 2015.

- ^ The Union of the Soviet Composers, ed. (1950). Советская музыка [Soviet Music] (in Russian). Vol. 1–6. Государственное Музыкальное издательство. p. 109.

- ^ Medvedev, A (February 1951). «Каменный цветок» [The Stone Flower]. Smena (in Russian). Smena Publishing House. 2 (570).

- ^ Balina 2013, p. 263.

References[edit]

- Bazhov, Pavel (1952). Valentina Bazhova; Alexey Surkov; Yevgeny Permyak (eds.). Sobranie sochinenij v trekh tomakh Собрание сочинений в трех томах [Works. In Three Volumes] (in Russian). Vol. 1. Moscow: Khudozhestvennaya Literatura.

- Bazhov, Pavel; translated by Alan Moray Williams (1944). The Malachite Casket: tales from the Urals. Library of selected Soviet literature. The University of California: Hutchinson & Co. ltd. ISBN 9787250005603.

- Bazhov, Pavel; translated by Eve Manning (1950s). Malachite Casket: Tales from the Urals. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House.

- Lipovetsky, Mark (2014). «The Uncanny in Bazhov’s Tales». Quaestio Rossica (in Russian). The University of Colorado Boulder. 2 (2): 212–230. doi:10.15826/qr.2014.2.051. ISSN 2311-911X.

- Litovskaya, Mariya (2014). «Vzroslyj detskij pisatel Pavel Bazhov: konflikt redaktur» Взрослый детский писатель Павел Бажов: конфликт редактур [The Adult-Children’s Writer Pavel Bazhov: The Conflict of Editing]. Detskiye Chteniya (in Russian). 6 (2): 243–254.

- Balina, Marina; Rudova, Larissa (1 February 2013). Russian Children’s Literature and Culture. Literary Criticism. Routledge. ISBN 978-1135865566.

- Budur, Naralya (2005). «The Mistress of the Copper Mountain». Skazochnaja enciklopedija Сказочная энциклопедия [The Fairy Tale Encyclopedia] (in Russian). Olma Media Group. ISBN 9785224048182.

- Nikulina, Maya (2003). «Pro zemelnye dela i pro tajnuju silu. O dalnikh istokakh uralskoj mifologii P.P. Bazhova» Про земельные дела и про тайную силу. О дальних истоках уральской мифологии П.П. Бажова [Of land and the secret force. The distant sources of P.P. Bazhov’s Ural mythology]. Filologichesky Klass (in Russian). Cyberleninka.ru. 9.

- P. P. Bazhov i socialisticheskij realizm // Tvorchestvo P.P. Bazhova v menjajushhemsja mire П. П. Бажов и социалистический реализм // Творчество П. П. Бажова в меняющемся мире [Pavel Bazhov and socialist realism // The works of Pavel Bazhov in the changing world]. The materials of the inter-university research conference devoted to the 125th birthday (in Russian). Yekaterinburg: The Ural State University. 28–29 January 2004. pp. 18–26.

На чтение 14 мин Просмотров 6.9к. Опубликовано 13.11.2021

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ «Каменный цветок» за 4 минуты и подробно за 8 минут.

Очень краткий пересказ сказки «Каменный цветок»

На уральских заводах трудились камнерезы, которые делали из малахита красивые и нужные вещи: посуду, украшения, шкатулки. Был среди них Прокопьич, мастер славный, но человек уже пожилой.

Барин, на которого трудился Прокопьич, посчитал необходимым приставить к старику ученика, дабы тот успел перенять тайны мастерства. Приказчик много приводил к Прокопьичу мальчишек, но те оказывались не годны: отказывался Прокопьич передавать знания. Надавав ученикам тумаков за непонимание, выбраковывал всех.

Как-то приказчик заметил худенького, слабого мальчика-сироту, Данилку Недокормыша. Казалось, ни к чему у ребенка не было таланта: прислуживать в трактире у него не получалось, за стадом коров он уследить не мог – словом, бесполезен в хозяйстве. Хорошо Данилка разве что на дудочке играл. А еще он любил рассматривать цветы, травинки, слыл мечтательным парнишкой.

Раз Данилка подвергся страшному физическому наказанию за недогляд за коровами (нескольких утащили волки), после чего едва выжил. Приказчику и пришла на ум гениальная идея: раз парнишка сирота, можно отдать его в ученье к Прокопьичу: авось выживет после его суровой школы, а не выживет – все равно плакать по мальчику некому.

Прокопьич поначалу с неохотой принял мальчика, но в первый же вечер подросток покорил сердце старого мастера: указал ему, какой лучше на новом изделии делать узор. Прокопьич попробовал – и понял: у мальчика верный глаз. После этого Прокопьич потеплел, стал считать Данилку почти сыном, заботился о нем и от тяжелой работы берег.

Данилка между тем играючи перенял у старика секреты камнерезного мастерства. Приказчик испытал мальчика. Видит: Данилка справляется со сложной работой. Написал барину, а тот поручил Даниле и Прокопьичу выточить невероятной красоты каменную чашу. Дал время, деньги, материал – все, лишь бы работа вышла славная.

Данилка (к тому времени уже выросший, возмужавший, заимевший невесту) заказ барина выполнил. По этому случаю собрали они с Прокопьичем гостей.

На скромном пиру один совсем старый мастер, учивший еще Прокопьича, рассказал Даниле, как оживить камень и раскрыть всю его силу: для этого надо посмотреть на каменный цветок. Данила вместе с заказом барина еще и свою чашу делал. Сделал чудесную, да только никак не удавалось ему вдохнуть в камень жизнь.

Услышал он рассказ старого камнереза, загорелись у него глаза. Не испугался Данила ничего, даже когда ему сказали, что Хозяйка Медной горы, позволив взглянуть на каменный цветок, мастера от себя никогда не отпустит, и будет он вечно на нее работать глубоко под землей.

Пошел Данила к Змеиной горе, где брал недавно камень малахитовый для своей чаши, стал думать, как бы ему увидеть каменный цветок. Раскрылась гора, явилась юноше великолепная Хозяйка Медной горы, стала уговаривать не смотреть на цветок: это опасно.

Данила на все готов был, упросил Хозяйку показать цветок. Словно нехотя исполнила волшебница просьбу молодого мастера.

Бросился Данила, пораженный красотой цветка, домой. А там спал на лавке сильно сдавший за последние годы, ослабевший Прокопьич. Данила посмотрел на него, пожалел старика.

Вспомнил свою невесту, которая давно уже любила его и очень печалилась, потому что все ждала свадьбу, а Даниле было не до нее. От этих мыслей сердце юноши сжалось. Он понял, что не нужен ему Каменный цветок. Схватил молоток, разбил вдребезги чашу, которую для себя делал, с цветком, и бросился в лес.

С тех пор о нем никто ничего не слышал. Одни уверяют, что Данила ушел к Хозяйке Медной горы в работники. А другие полагают, что молодой мастер лишился рассудка и сгинул в лесу.

Главные герои и их характеристика:

- Данилка – в начале повествования это худенький, слабый, плохо приспособленный к жизни подросток, круглый сирота, «волоски кудрявеньки, глазки голубеньки». Высокий, гибкий как тростинка, Данила тем не менее оказался очень крепким силой духа: почти до смерти забил его палач, а он и не вскрикнул ни разу. Потом Данила вырос и стал «высокий да румяный, кудрявый да веселый», девушки на него заглядывались. Но Данила был поглощен одной страстью: из него вырос настоящий великий мастер-камнерез, и хотелось ему добиться в своем мастерстве истинного совершенства.

- Прокопьич – пожилой мастер, имевший исключительный талант камнереза, лучше всех в заводах. Одинокий, крутой нравом, но обладавший добрым сердцем. Полюбил Данилку, как сына.

- Хозяйка Медной горы – волшебная красавица в малахитовом платье, владелица сокровищ гор, обладательница каменного цветка. Коварно соблазняла мастеров каменным цветком, обещая открыть им дар оживления камня, и заманивала к себе в вечное рабство.

Второстепенные герои и их характеристика:

- Приказчик – грубый, жестокий человек. Он был поставлен барином для контроля над заводами, в которых работали камнерезы. Следил за тем, чтобы абсолютно все наказы барина исполнялись, руководствуясь принципом: «Заставь дурака молиться, он и лоб расшибет».

- Катя Летемина – невеста Данилы, красивая, добрая девушка.

- Барин – владелец малахитовых заводов и мастерских, ему принадлежали и крепостные, которые там трудились, в том числе Данилка с Прокопьичем. В сказке этот персонаж сам не появляется, только выражает свою волю через приказчика либо через письма. В отличие от приказчика, умел ценить крепостных, берег и создавал особые условия тем, которые трудились успешно и проявляли талант.

- Старичок мастер – «ветхий старичоночко», обучавший Прокопьича и других славных мастеров, глуховатый от старости, слабый. Отличался мудростью: именно он подсказал Даниле, как раскрыть полную силу камня, но предостерег: опасное это дело.

- Бабушка Вихориха – старушка-травница, сердобольная, мудрая, выходила Данилу после побоев, поставила на ноги. Впервые от нее мальчик узнал о каменном цветке.

Краткое содержание сказки «Каменный цветок» подробно

На уральских заводах в стародавние времена работали с малахитом крепостные мастера. Лучшим считался Прокопьич. Барин, зная, что Прокопьич уже в годах, велел приказчику подыскать для Прокопьича ученика, чтобы тот обучил его всем премудростям работы камнереза.

Приказчик честно пытался выполнить баринов наказ, но все ученики не нравились Прокопьичу: щедро «угостив» каждого мальчонку оплеухами, пожилой мастер возвращал его родителям. Приказчик злился, но не мог пойти против воли барина, а Прокопьич ни в ком из парнишек не замечал «верного глаза» и продолжал «браковать» потенциальных камнерезов.

В том же селе рос маленький Данилко Недокормыш. Лет ему было 12 или чуть большие, был он худенький, гибкий, высокого роста, с голубыми глазами. Мальчик рано остался сиротой, не помнил ни отца, ни матери.

Сначала приказчик пытался сделать из него дворового слугу, но ребенок оказался не редкость нерасторопным. Затем отдали его в подпаски. Большей частью Данилка любовался природой, рассматривал травинки и букашек, о чем-то мечтал, а за стадом следил плохо.

Правда, быстро освоил дудочку, на которой часто играл. За это женщины подкармливали мальчика, дарили ему рубашки да штаны.

Однажды Данилка отвлекся на свои думы, заигрался на рожке, а в это время подкрались волки и утащили несколько коров. Среди коров попалась одна со двора приказчика.

Последовало тяжелое наказание: старого пастуха и его помощника Данилку избили до полусмерти. Мальчик оказался на удивление стойким, проявил характер: как ни старался палач, ни единого вскрика, только слезки капали у ребенка.

Думали, что Данилка не выживет. Сердобольные люди отдали его знахарке Вихорихе, которая с помощью трав и настоек вылечила мальчика. Как только Данилке полегчало, он начал интересоваться травами, расспрашивал бабушку, какая из них как называется, как цветет.

Вихориха рассказала Данилке, что есть цветок «не открытый», которого она ни разу не видела, да и мало кто из людей видал его. Это каменный цветок, прячется он от людей. Всякий, кому доведется увидеть цветок, делается несчастным.

Когда Данилка немного пришел в себя, приказчик отдал его в ученье к Прокопьичу. Решил приказчик, что раз мальчик выжил после чудовищных побоев, значит, несмотря на внешнюю хрупкость, выдержит и суровую школу Прокопьича. А нет – так он сирота, плакать никто не будет.

Прокопьич очень неохотно взял мальчика. Попенял приказчику, что, мол, уж больно хлипкий ученик, как его учить? Стукнешь раз – из него и дух вон. Но приказчик оставался непреклонен.

Делать нечего – скрепя сердце согласился Прокопьич попытаться обучить Данилку. В первый же вечер паренек осмотрел работу Прокопьича и подсказал, как лучше сделать так, чтобы узор полностью раскрылся.

Прокопьич поворчал для виду, но попробовал сделать по словам мальчика – все получилось лучше некуда. Понял Прокопьич, что пришел к нему ученик, у которого «глаз верный» — очень талантливый мальчишка.

Сразу оттаял сердцем пожилой мастер. Справил Данилке шубенку, сапоги, стал хорошо кормить его, а учебой особо не мучал – решил, что мальчику надо сперва окрепнуть.

Данилка то калину собирал для пирогов, то за дровами ездил, то окуней ловил на пруду. И между делом потихоньку перенимал у Прокопьича азы мастерства: подходил, смотрел за работой, задавал вопросы, а то и сам принимался что-то вырезать.

Однажды приказчик увидел Данилку на пруду с удочкой. Разозлился: взрослый парнишка в рабочий день бездельничает! Взял Данилку за ухо и отвел к Прокопьичу. Старый мастер вступился за мальчика: дескать, я его сам на такую работу отправляю.

Приказчик начал экзаменовать Данилку, проверяя, чему он обучился у Прокопьича. Какой вопрос ни задаст – на все Данила легко отвечает.

Тогда приказчик задал Даниле уроки – велел выточить несколько простеньких вещиц. Мальчик справился. Приказчику изделия очень понравились. Он написал барину: так и так, объявился у нас молодой мастер, зовут Данила.

На уроках его оставить или на оброк отпустить, как Прокопьича? Барин задал Даниле работу – выточить чашу – и отписал, что пусть сначала сделает, а там он уже решит, как дальше с Данилой поступить.

Данилка тем временем уже вырос, возмужал, превратился в крепкого красивого парня. Теперь его уже звали не Недокормыш, а Данила-мастер. Работали они вместе с Прокопьичем, горя не знали. Юноша уже и жениться собирался, влюбился в красавицу Катю, односельчанку.

Выточил Данила по заданию барина чашу. Да не одну, а три. И барину так понравилась работа, что он решил оставить Данилку вместе с Прокопьичем на оброке (это было легче, чем на уроках), дал притом задание: еще одну чашу каменную изготовить. Чертеж точный прислал.

Работают Данила и Прокопьич, вот уже чаша баринова готова. Только Данила захотел еще и свою выточить, особую, чтобы была как настоящий каменный цветок. Ходил по лесу, искал цветок, который дал бы ему вдохновение, да все было не то.

По случаю завершения работы над бариновой чашей Прокопьич и Данила устроили скромную пирушку, позвали гостей: Катю Летемину с родителями и знакомых мастеров-камнерезов. Гости подивились тонкой работе, но Данила махнул рукой: работа-то, дескать, хорошая, да только неживая чаша. А хочется такую сделать, чтобы живой цветок получился.

Один старый-старый мастер, еще Прокопьича некогда обучавший, сказал: «Есть такой каменный цветок – если на него поглядеть, то всю силу и красоту камня сразу поймешь, и будут у тебя такие работы получаться – глаз не отвести».

И предупредил, что опасный это цветок: кто на него посмотрит, тому белый свет не мил станет, и он в мастера к Хозяйке Медной горы уйдет.

Данила загорелся: хочу цветок увидеть! Катя заплакала. Мастера стали стыдить дедушку, видя девичье горе: мол, совсем ты, старый, из ума выживаешь, заговариваться стал, парня с толку сбиваешь.

Но Даниле мысль запала в голову. На следующий день он отправился на Медный рудник, искать подходящий для своего будущего живого каменного цветка камень. Искал, искал, — все не то. Вдруг голос слышит: «Иди к Змеиной горке» и видит женский образ в голубой дымке.

Пошел Данила к указанному месту, а там прямо из горы огромный кусок малахита отломлен. Красивый, глаз не отвести. Данила понял: это и есть тот камень, который ему нужен. Доставил он камень домой, принялся за работу.

Выточил цветок – прямо живой, все, кто приходил смотреть, дивились. Но Данила остался своей работой недоволен: все чего-то недоставало в каменной чаше.

Махнул рукой: ладно, не дано мне силу камня открыть. Стал торопить невесту со свадьбой. Но так и тянуло его еще раз сходить к Змеиной горке, сам не знал, зачем. Не совладал с собой, пошел.

Нашел выбоину в скале, откуда камень для него выломан был, забрался внутрь, думает. Откуда ни возьмись – появилась красивая женщина в малахитовом платье. Это была Хозяйка Медной горы, как догадался Данила.

Стал просить Данила Хозяйку показать ему каменный цветок. Хитрая волшебница отговаривала парня, да только он на своем настоял. Уговорил.

После того, как Данила увидел сказочные каменные цветы на поляне в саду Хозяйки Медной горы, он лишился сна и покоя. Не в радость ему была и предстоящая свадьба. Ночью он поднялся, послушал, как тяжело кашляет старый Прокопьич, сердце его заболело от жалости.

Схватил Данила молоток и изо всех сил ударил по своей чаше, которую все хотел оживить. А в баринову чашу плюнул – и бросился бежать.

С той поры его больше не видели. Кто говорит, что парень с ума сошел и пропал в лесной чащобе, а кто уверяет, будто ушел он к Хозяйке Медной горы, день и ночь вытачивает для нее дивные поделки.

Кратко об истории создания произведения

Сказ П.П. Бажова «Каменный цветок» основан на старинных народных преданиях. Бажов родился на Урале в 1879 году, отец его работал в рудниках, поэтому быт горнорабочих и камнерезов был знаком будущему писателю не понаслышке. Сказы (сказки) об этих людях Бажов начал писать в 1920-х годах, когда судьба вновь забросила его на Урал после скитаний по другим землям.

«Каменный цветок» был впервые опубликован в 1938 году в «Литературной газете», а позже вошел в цикл сказок «Малахитовая шкатулка». Это история юноши, загубившего свой талант и себя из-за чрезмерного желания добиться вершин мастерства не с помощью усилий, а путем привлечения волшебных потусторонних сил.

Краткое содержание «Каменный цветок»

4.3

Средняя оценка: 4.3

Всего получено оценок: 1281.

Обновлено 13 Мая, 2022

О произведении

Сказ «Каменный цветок» Бажова написан в 1937 году. Произведение вошло в сборник сказов писателя «Малахитовая шкатулка». В основу легли старинные легенды и сказания горнорабочих Урала.

Как и в остальных сказах сборника, главный персонаж — человек творческий, Данила-мастер, который занимался обработкой камня и стремился создать прекрасную чашу в виде цветка.

Для читательского дневника и подготовки к уроку литературы в 5 классе рекомендуем читать онлайн краткое содержание «Каменный цветок».

Опыт работы учителем русского языка и литературы — 27 лет.

Место и время действия

События произведения происходят в конце XIX — начале XX века на Урале.

Главные герои

- Прокопьич – старый мастер малахитных дел, суровый, но добрый мужчина.

- Данилка Недокормыш – сирота, ученик Прокопьича, мечтавший познать красоту камня.

- Хозяйка – волшебница, обитающая в Змеиной горе, владычица самоцветов.

Другие персонажи

- Барин – богатый хозяин, которому принадлежали крупные залежи малахита.

- Приказчик – злобный и недалекий, но исполнительный помощник барина.

- Катя Летемина – невеста Данилки, милая, любящая девушка.

Краткое содержание

Старик Прокопьич имел славу самого лучшего, самого опытного мастера – резчика по малахиту. Ему присылали «парнишек на выучку»

, но по какой-то причине Прокопьич «учил шибко худо»

: то ли ему было жаль расставаться со своим мастерством, то ли не видел он в своих учениках способностей к этому деликатному делу. Одного за другим отправлял он их обратно с коротким пояснением: «Не гож этот…»

.

Так и оставался Прокопьич без ученика, пока не «дошло дело до Данилки Недокормыша»

. Сиротке было лет двенадцать, не больше. Из жалости его «взяли сперва в казачки при господском доме: табакерку, платок подать, сбегать куда и протча»

. Однако парнишка оказался не приспособлен к этому делу – с куда большим удовольствием он рассматривал картины или различные драгоценные поделки в барском доме. Не смог он работать и подпаском – из-за его невнимательности коровы разбредались, куда хотели. В результате было решено отдать мальчика на обучение Прокопьичу.

Узнав о горькой судьбе Данилушки, Прокопьич пожалел его, а вскоре так привязался, что «прямо сказать, за сына держал»

. Поначалу старик давал парнишке много свободы, но как узнал об этом приказчик, так стал сам контролировать обучение Данилки. Но это было лишним – мальчик был на удивление толковый и быстро учился всем премудростям малахитного дела.

Вырос Данилушка высоким, сильным, красивым парнем – «однем словом, сухота девичья»

. Прокопьич стал с ним и за невест разговоры вести, но парень мечтал стать настоящим мастером, а потом уж думать о семье.

Однажды барин, чтобы определить уровень мастерства Данилки, приказал ему сделать малахитовую чашу на ножке. Увидев его работу, барин был доволен – он сразу смекнул, что Прокопьич взрастил отличного мастера себе на смену. Он передал Данилке новые чертежи, по которым он должен был вырезать новую чашу со сложными, затейливыми узорами.

После этой проверки Данилка понял, что способен на многое. Вот тогда он и задумал самостоятельно, не по барским чертежам, вырезать редкой красоты чашу, «чтобы камень полную силу имел»

. Мысли о ней не давали ему покоя ни днем, ни ночью.

Видя, что парень сам не свой, старик решил его женить: «лишняя дурь из головы вылетит, как семьей обзаведется»

. У Данилки уже была на примете славная девушка – Катя Летемина, на которой он собирался жениться, как только выполнит заказ барина.

Чаша по барским чертежам вышла у Данилки знатная. По этому случаю позвал Прокопьич старых мастеров, и те одобрили работу Данилки. Вот только сам он был не очень доволен чашей, в которой не видел ни особой красоты, ни жизни.

Тогда самый старый мастер сказал, что тот, кто увидит каменный цветок, постигнет красоту камня и попадет «к Хозяйке в горные мастера»

. Услышав это, загорелся Данилка увидеть тот самый каменный цветок. Однажды, перед самой свадьбой, отправился он на Змеиную гору за малахитом – тут ему Хозяйка и явилась.

Данилка принялся умолять Хозяйку показать ему каменный цветок. Та долго отговаривала от этого: после не будет уж прежней жизни. Вот только Данилка настаивал на своем, и Хозяйка повела парня в свой сад, где он увидел неземной красоты каменный цветок.

Вернулся Данилка домой сам не свой. Он грустил весь вечер, а ночью убежал неизвестно куда. Одни говорили, «что он ума решился, в лесу загинул»

, а другие не сомневались, что Данилу взяла к себе в горные мастера сама Хозяйка…

И что в итоге?

Данилка Недокормыш — увидев каменный цветок в саду Хозяйки Медной горы, убегает из дома; вероятно, становится горным мастером у Хозяйки.

Хозяйка — не сумев отговорить Данилку, всё-таки показывает ему каменный цветок.

Заключение

Главная мысль произведения – истинное мастерство невозможно без полного самоотречения. Однако в погоне за идеалом не стоит забывать о любимых людях и приносить в жертву собственную жизнь.

После ознакомления с кратким пересказом «Каменного цветка» рекомендуем прочесть сказку в полной версии.

Тест по сказке

Проверьте запоминание краткого содержания тестом:

Доска почёта

Чтобы попасть сюда — пройдите тест.

-

Егор Малинин

10/10

-

Max-Play Yt

10/10

-

Настя Толпеева

10/10

-

Ольга Штыкова

10/10

-

Данила Сторожев

9/10

-

Маша Пешкова

10/10

-

Кактус Спайк

9/10

-

Ева Сухоруких

10/10

-

Кирилл Устинов

10/10

-

Дима Чашинов

8/10

Рейтинг пересказа

4.3

Средняя оценка: 4.3

Всего получено оценок: 1281.

А какую оценку поставите вы?

- Краткие содержания

- Бажов

- Каменный цветок

Краткое содержание Бажов Каменный цветок

Жил на Урале очень хороший, но уже не молодой мастер по малахиту. Поэтому решил хозяин, что бы мастер передал свое ремесло дальше. По этой причине наказал он своему показчику найти ученика этому мастеру. Много ребят приводил приказчик, однако не подходили они мастеру. Все мальчишки боялись мастера, а их родители не хотели свое чадо отправлять к мастеру. Так вот и попал Данила к мастеру. Мальчик был сиротой, поэтому заступиться за него было некому. Данила с первого дня удивил мастера, он указал ему на ошибку. Ведь глаз у мальчика, был точным, он мог чувствовать камень и то, как ложится на него узор, дабы показать его красоту.

Мастер жил один, так как жена у него умерла, а детей у него не было, поэтому и прикипел мастер к сироте.

Прослышал про молодого талантливого мастера сам хозяин. После этого Даниле начали доверять выделку не простых вещей из малахита.

Как-то ему дали рисунок особенной чаши и позволили изготавливать ее без ограничения времени. Но приказчик должен был присматривать за тем, чтобы мастер не помогал Даниле. Данила занялся чашей, но работа его не радовала. Чаша была ему не по душе – он не видел в ней блеска. Получив разрешение приказчика, надумал Данила-мастер сделать новую чашу по своему желанию, он хотел показать всю прелесть камня. Один старый мастер поведал историю о каменном цветке, который находиться в пещере у Хозяйки Медной горы. Кому удастся увидеть этот каменный цветок, понимают всю прелесть камня, но навсегда попадают в горные мастера к Хозяйке Медной горы.

Стал Данила-мастер бродить и искать такой цветок, чтобы по его аналогу изготовить свою чашу, которая сможет донести всю прелесть камня. Один раз, бродя по руднику и ища камень для своей чаши, Данила услышал женский голос, посоветовавший искать камень у Змеиной горы. Возле этой горы Данила нашел камень, который ему надо, и начал работу. Сразу работа над чашей шла хорошо, но вскоре остановилась. Не выходила верхняя часть цветка. Данила даже сказал своей невесте, что готов отложить свадьбу, настолько он увлекся работой.

Данила очень хотел посмотреть на этот безупречный, шикарный каменный цветок и вновь отправился к Змеиной горе. Там он увидел Хозяйку Медной горы. Услышав его рассказ о том, что чаша не получилась, она предложила взять новый камень, но чашу создавать самому. Не смотря ни на что, Данила, тем не менее, хотел посмотреть на этот прекрасный цветок. Хозяйка горы сказала Даниле о том, что увидев цветок, он не будет хотеть жить и трудиться промеж людей. Он возвратится назад в Медную гору. Но Данила был настойчив, и ему удалось посмотреть на прекрасный каменный цветок.

Вернувшись, домой он даже сказал своей невесте, что скоро они поженятся. Но как-то раз Данила-мастер стал грустить, и в один из дней взял свою чашу, которая как ему казалась не выходит, и разбил ее. После чего он пошел из дома и больше никогда никто его не видел.

Долго разыскивали Данилу. Одни сказывали, что он умом тронулся и погиб в лесу, а иные сказывали, что Хозяйка горы забрала мастера к себе в горные мастера.

Читая этот рассказ, осознаешь, что не надо искать сверхъестественного и сказочного богатства при этом гнаться за ним. Нужно ценить то, что есть. Надо уметь сочетать работу и жизнь.

Можете использовать этот текст для читательского дневника

Бажов. Все произведения

- Голубая змейка

- Горный мастер

- Две ящерки

- Железковы покрышки

- Каменный цветок

- Кошачьи уши

- Малахитовая шкатулка

- Медной горы Хозяйка

- Огневушка поскакушка

- Приказчиковы подошвы

- Про великого полоза

- Серебряное копытце

- Синюшкин колодец

- Таюткино зеркальце

- Травяная западенка

- Хрупкая веточка

Каменный цветок. Картинка к рассказу

Сейчас читают

- Краткое содержание Горький Бывшие люди

Произведение «Бывшие люди», написанное в одно тысячу восемьсот девяносто седьмом году представляет собой очерк, так как автор описывает личные впечатления и переживания, испивавшие в момент проживание

- Краткое содержание Куприн В цирке

Цирковой борец Арбузов пришел к доктору с недомоганиями: тяжесть в голове, слабость, плохой сон. Доктор Луховицын осмотрел больного и поставил диагноз: гипертрофия сердца. Такое заболевание было не редкостью для людей тяжелого физического труда

- Краткое содержание Проказы старухи зимы Ушинского

Жанровая направленность произведения представляет собой короткий сказочный рассказ о природе. Главной героиней рассказа является зима, представленная в образе злой старухи, отличающейся суровостью и морозным холодом.

- Краткое содержание Гоголь Портрет

Художник Чартков на Щукинском дворе разглядывал картины, и тут его взгляд упал на портрет старого мужчины в восточном одеянии. Отдав за картину последние деньги, Чартков идёт домой.

- Краткое содержание Гаршин Attalea princeps

В одном городе был большой ботанический сад с красивой оранжереей. Витые колонны держали узорчатые арки с паутиной металлических рам со стеклами. Сквозь стекла виднелись растения

Краткое содержание Бажов Каменный цветок для читательского дневника

Автор: Павел Бажов

Год написания: 1937

Жанр: сказка

Главные герои: мастер Прокопьич, ученик, сирота Данилка Недокормыш.

Сюжет:

Однажды появился у старого резчика по малахиту талантливый ученик. Старик радовался его способностям, приказчик радовался безупречно выполненной работе, а барин стал доверять самые дорогие заказы. Жить бы и жить молодому мастеру, да загрустил он и зачастил в гору. Все искал необыкновенный каменный цветок, чтобы постичь саму суть красоты и гармонии. Добился своего – встретил и Хозяйку горы, и каменный цветок повидал. Себе на беду.