|

Lewis Carroll |

|

|---|---|

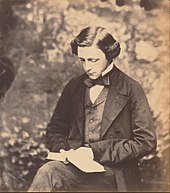

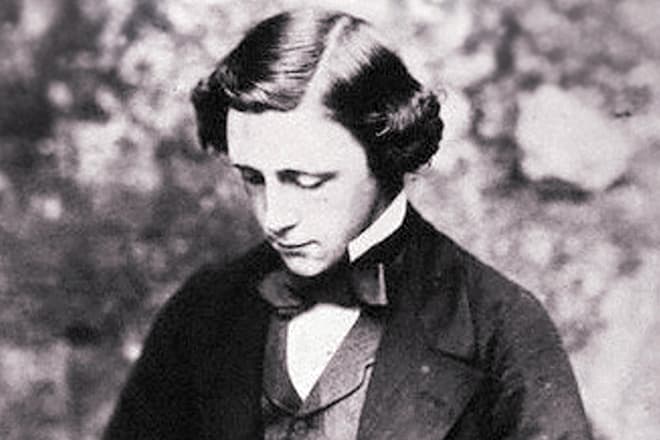

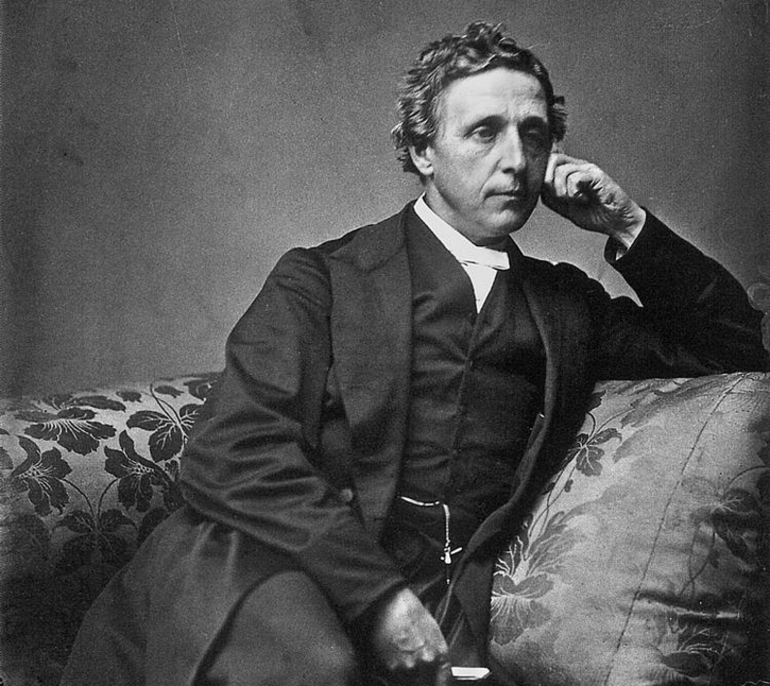

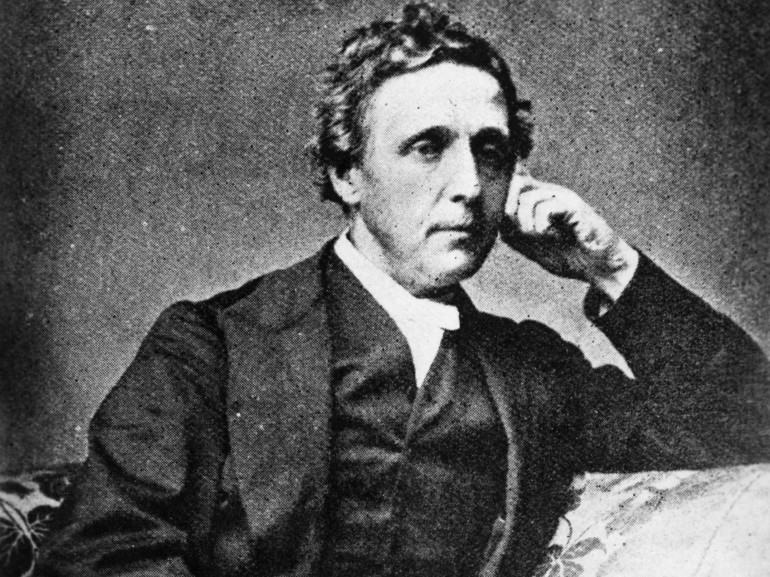

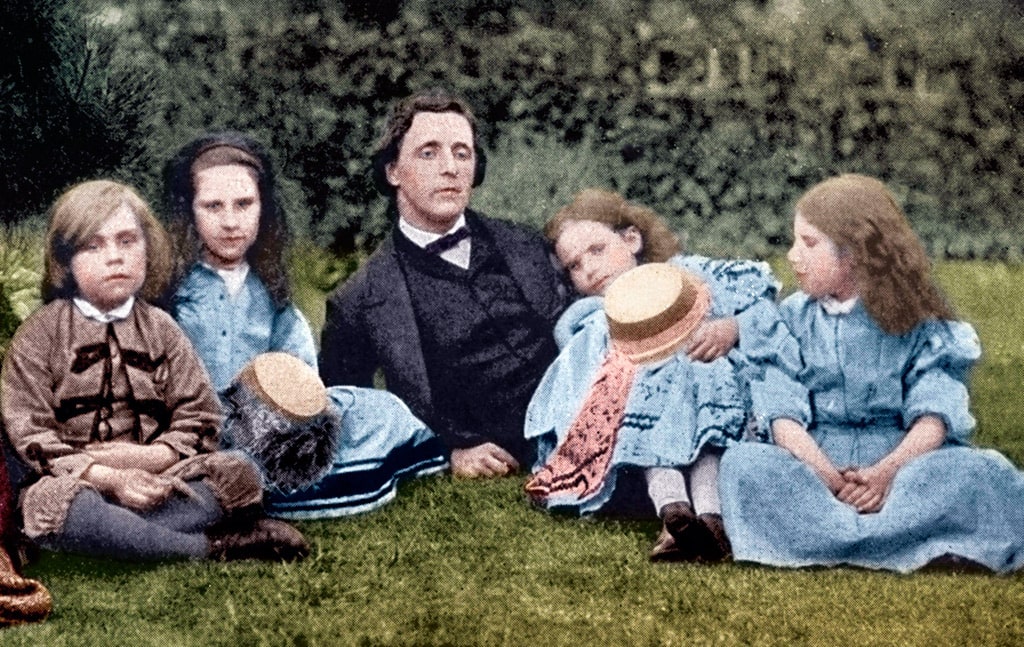

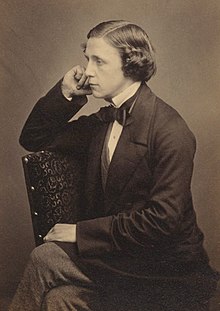

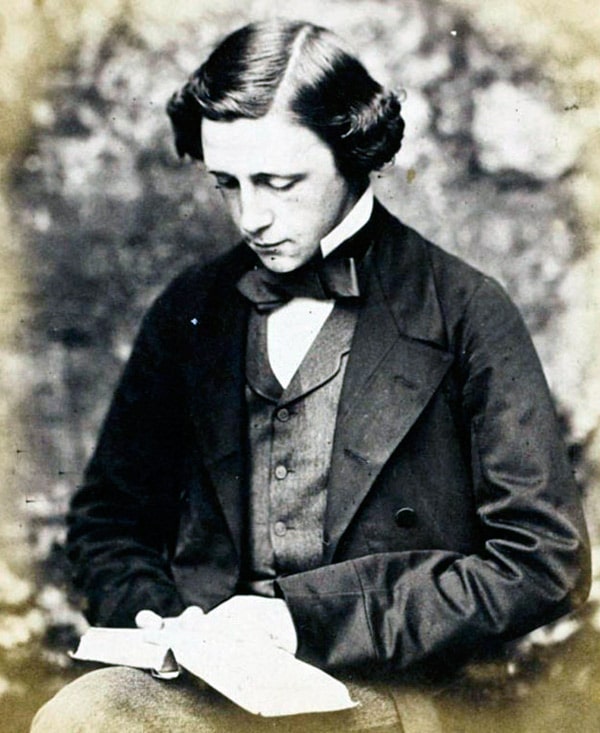

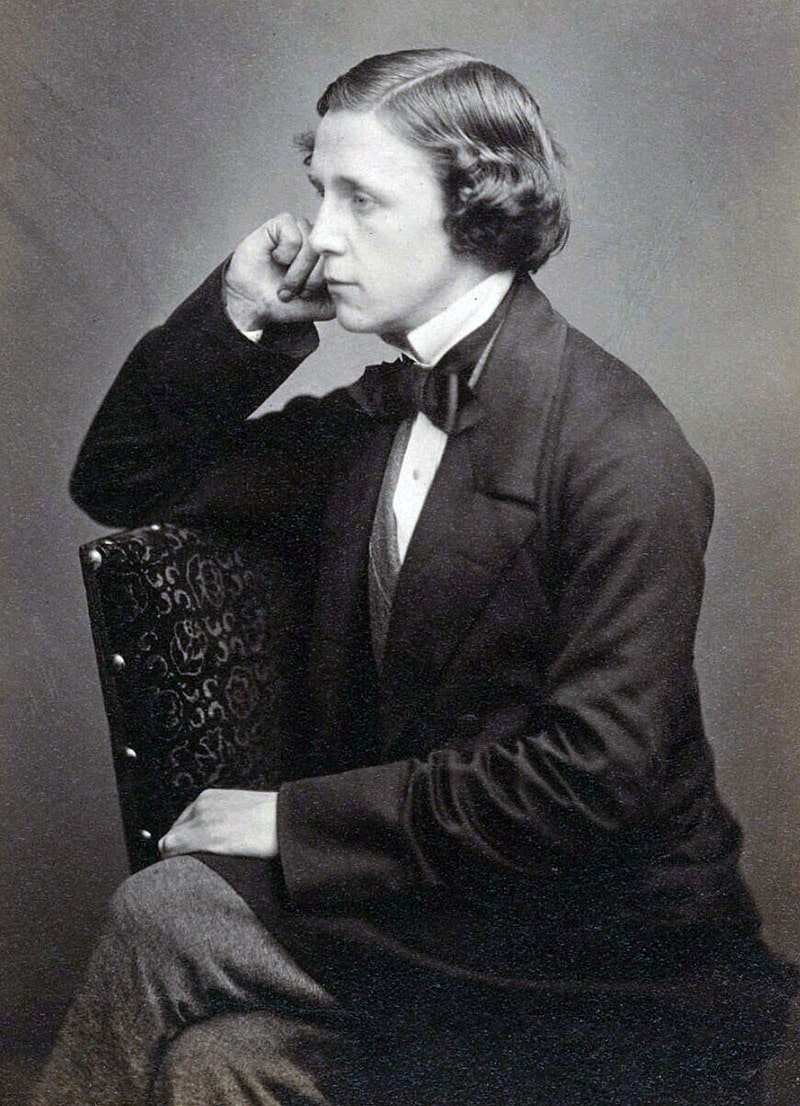

Carroll in June 1857 |

|

| Born | Charles Lutwidge Dodgson 27 January 1832 Daresbury, Cheshire, England |

| Died | 14 January 1898 (aged 65) Guildford, Surrey, England |

| Resting place | Mount Cemetery, Guildford, Surrey, England |

| Occupation |

|

| Education |

|

| Genre |

|

| Relatives |

|

| Signature | |

Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (; 27 January 1832 – 14 January 1898), better known by his pen name Lewis Carroll, was an English author, poet and mathematician. His most notable works are Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and its sequel Through the Looking-Glass (1871). He was noted for his facility with word play, logic, and fantasy. His poems Jabberwocky (1871) and The Hunting of the Snark (1876) are classified in the genre of literary nonsense.

Carroll came from a family of high-church Anglicans, and developed a long relationship with Christ Church, Oxford, where he lived for most of his life as a scholar and teacher. Alice Liddell, the daughter of Christ Church’s dean Henry Liddell, is widely identified as the original inspiration for Alice in Wonderland, though Carroll always denied this.

An avid puzzler, Carroll created the word ladder puzzle (which he then called «Doublets»), which he published in his weekly column for Vanity Fair magazine between 1879 and 1881. In 1982 a memorial stone to Carroll was unveiled at Poets’ Corner in Westminster Abbey. There are societies in many parts of the world dedicated to the enjoyment and promotion of his works.[1][2]

Early life[edit]

Dodgson’s family was predominantly northern English, conservative, and high-church Anglican. Most of his male ancestors were army officers or Anglican clergymen. His great-grandfather, Charles Dodgson, had risen through the ranks of the church to become the Bishop of Elphin in rural Ireland.[3] His paternal grandfather, another Charles, had been an army captain, killed in action in Ireland in 1803, when his two sons were hardly more than babies.[4] The older of these sons, yet another Charles Dodgson, was Carroll’s father. He went to Rugby School and then to Christ Church, Oxford.[5] He reverted to the other family tradition and took holy orders. He was mathematically gifted and won a double first degree, which could have been the prelude to a brilliant academic career. Instead, he married his first cousin Frances Jane Lutwidge in 1830 and became a country parson.[6][7]

Dodgson was born on 27 January 1832 at All Saints’ Vicarage in Daresbury, Cheshire,[8] the oldest boy and the third oldest of 11 children. When he was 11, his father was given the living of Croft-on-Tees, Yorkshire, and the whole family moved to the spacious rectory. This remained their home for the next 25 years. Charles’ father was an active and highly conservative cleric of the Church of England who later became the Archdeacon of Richmond[9] and involved himself, sometimes influentially, in the intense religious disputes that were dividing the church. He was high-church, inclining toward Anglo-Catholicism, an admirer of John Henry Newman and the Tractarian movement, and did his best to instil such views in his children. However, Charles developed an ambivalent relationship with his father’s values and with the Church of England as a whole.[10]

During his early youth, Dodgson was educated at home. His «reading lists» preserved in the family archives testify to a precocious intellect: at the age of seven, he was reading books such as The Pilgrim’s Progress. He also spoke with a stammer – a condition shared by most of his siblings[11] – that often inhibited his social life throughout his years. At the age of twelve he was sent to Richmond Grammar School (now part of Richmond School) in Richmond, North Yorkshire.

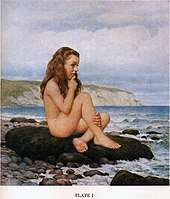

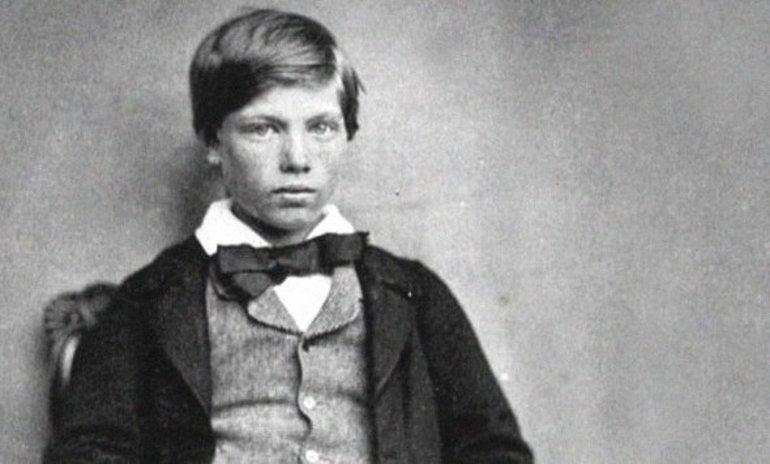

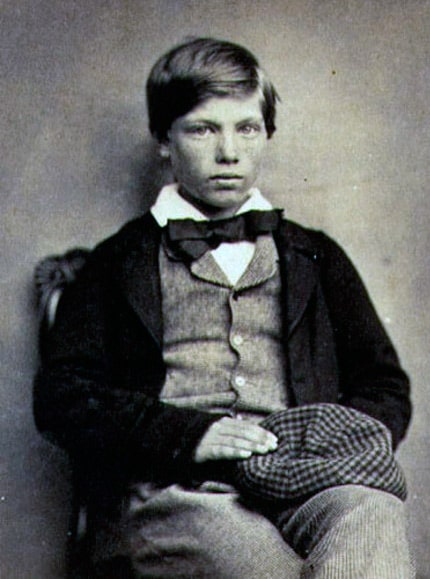

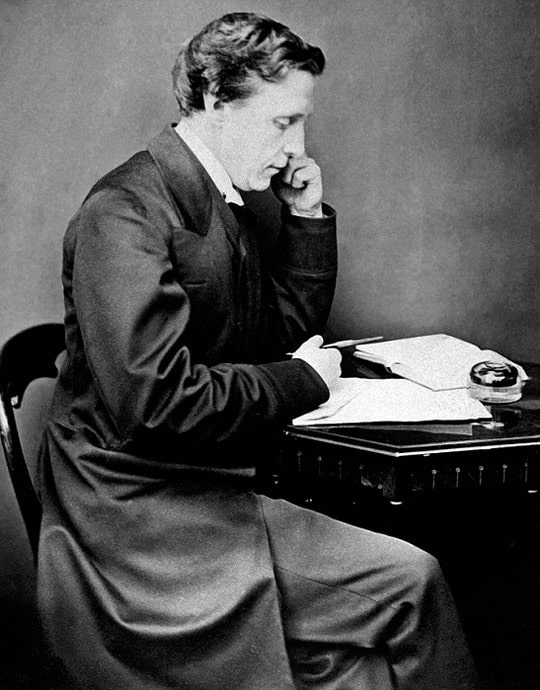

Lewis Carroll self-portrait c. 1856, aged 24 at that time

In 1846 Dodgson entered Rugby School, where he was evidently unhappy, as he wrote some years after leaving: «I cannot say … that any earthly considerations would induce me to go through my three years again … I can honestly say that if I could have been … secure from annoyance at night, the hardships of the daily life would have been comparative trifles to bear.»[12] He did not claim he suffered from bullying, but cited little boys as the main targets of older bullies at Rugby.[13] Stuart Dodgson Collingwood, Dodgson’s nephew, wrote that «even though it is hard for those who have only known him as the gentle and retiring don to believe it, it is nevertheless true that long after he left school, his name was remembered as that of a boy who knew well how to use his fists in defence of a righteous cause», which is the protection of the smaller boys.[13]

Scholastically, though, he excelled with apparent ease. «I have not had a more promising boy at his age since I came to Rugby», observed mathematics master R. B. Mayor.[14] Francis Walkingame’s The Tutor’s Assistant; Being a Compendium of Arithmetic – the mathematics textbook that the young Dodgson used – still survives and it contained an inscription in Latin, which translates to: «This book belongs to Charles Lutwidge Dodgson: hands off!»[15] Some pages also included annotations such as the one found on p. 129, where he wrote «Not a fair question in decimals» next to a question.[16]

He left Rugby at the end of 1849 and matriculated at the University of Oxford in May 1850 as a member of his father’s old college, Christ Church.[17] After waiting for rooms in college to become available, he went into residence in January 1851.[18] He had been at Oxford only two days when he received a summons home. His mother had died of «inflammation of the brain» – perhaps meningitis or a stroke – at the age of 47.[18]

His early academic career veered between high promise and irresistible distraction. He did not always work hard, but was exceptionally gifted, and achievement came easily to him. In 1852, he obtained first-class honours in Mathematics Moderations and was soon afterwards nominated to a Studentship by his father’s old friend Canon Edward Pusey.[19][20] In 1854, he obtained first-class honours in the Final Honours School of Mathematics, standing first on the list, and thus graduated as Bachelor of Arts.[21][22] He remained at Christ Church studying and teaching, but the next year he failed an important scholarship exam through his self-confessed inability to apply himself to study.[23][24] Even so, his talent as a mathematician won him the Christ Church Mathematical Lectureship in 1855,[25] which he continued to hold for the next 26 years.[26] Despite early unhappiness, Dodgson remained at Christ Church, in various capacities, until his death, including that of Sub-Librarian of the Christ Church library, where his office was close to the Deanery, where Alice Liddell lived.[27]

Character and appearance[edit]

Health problems[edit]

The young adult Charles Dodgson was about 6 feet (1.83 m) tall and slender, and he had curly brown hair and blue or grey eyes (depending on the account). He was described in later life as somewhat asymmetrical, and as carrying himself rather stiffly and awkwardly, although this might be on account of a knee injury sustained in middle age. As a very young child, he suffered a fever that left him deaf in one ear. At the age of 17, he suffered a severe attack of whooping cough, which was probably responsible for his chronically weak chest in later life. In early childhood, he acquired a stammer, which he referred to as his «hesitation»; it remained throughout his life.[27]

The stammer has always been a significant part of the image of Dodgson. While one apocryphal story says that he stammered only in adult company and was free and fluent with children, there is no evidence to support this idea.[28] Many children of his acquaintance remembered the stammer, while many adults failed to notice it. Dodgson himself seems to have been far more acutely aware of it than most people whom he met; it is said that he caricatured himself as the Dodo in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, referring to his difficulty in pronouncing his last name, but this is one of the many supposed facts often repeated for which no first-hand evidence remains. He did indeed refer to himself as a dodo, but whether or not this reference was to his stammer is simply speculation.[27]

Dodgson’s stammer did trouble him, but it was never so debilitating that it prevented him from applying his other personal qualities to do well in society. He lived in a time when people commonly devised their own amusements and when singing and recitation were required social skills, and the young Dodgson was well equipped to be an engaging entertainer. He could reportedly sing at a passable level and was not afraid to do so before an audience. He was also adept at mimicry and storytelling, and reputedly quite good at charades.[27]

[edit]

In the interim between his early published writings and the success of the Alice books, Dodgson began to move in the pre-Raphaelite social circle. He first met John Ruskin in 1857 and became friendly with him. Around 1863, he developed a close relationship with Dante Gabriel Rossetti and his family. He would often take pictures of the family in the garden of the Rossetti’s house in Chelsea, London. He also knew William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais, and Arthur Hughes, among other artists. He knew fairy-tale author George MacDonald well – it was the enthusiastic reception of Alice by the young MacDonald children that persuaded him to submit the work for publication.[27][29]

Politics, religion, and philosophy[edit]

In broad terms, Dodgson has traditionally been regarded as politically, religiously, and personally conservative. Martin Gardner labels Dodgson as a Tory who was «awed by lords and inclined to be snobbish towards inferiors».[30] William Tuckwell, in his Reminiscences of Oxford (1900), regarded him as «austere, shy, precise, absorbed in mathematical reverie, watchfully tenacious of his dignity, stiffly conservative in political, theological, social theory, his life mapped out in squares like Alice’s landscape».[31] Dodgson was ordained a deacon in the Church of England on 22 December 1861. In The Life and Letters of Lewis Carroll, the editor states that «his Diary is full of such modest depreciations of himself and his work, interspersed with earnest prayers (too sacred and private to be reproduced here) that God would forgive him the past, and help him to perform His holy will in the future.»[32] When a friend asked him about his religious views, Dodgson wrote in response that he was a member of the Church of England, but «doubt[ed] if he was fully a ‘High Churchman'». He added:

I believe that when you and I come to lie down for the last time, if only we can keep firm hold of the great truths Christ taught us—our own utter worthlessness and His infinite worth; and that He has brought us back to our one Father, and made us His brethren, and so brethren to one another—we shall have all we need to guide us through the shadows. Most assuredly I accept to the full the doctrines you refer to—that Christ died to save us, that we have no other way of salvation open to us but through His death, and that it is by faith in Him, and through no merit of ours, that we are reconciled to God; and most assuredly I can cordially say, «I owe all to Him who loved me, and died on the Cross of Calvary.»

— Carroll (1897)[33]

Dodgson also expressed interest in other fields. He was an early member of the Society for Psychical Research, and one of his letters suggests that he accepted as real what was then called «thought reading».[34] Dodgson wrote some studies of various philosophical arguments. In 1895, he developed a philosophical regressus-argument on deductive reasoning in his article «What the Tortoise Said to Achilles», which appeared in one of the early volumes of Mind.[35] The article was reprinted in the same journal a hundred years later in 1995, with a subsequent article by Simon Blackburn titled «Practical Tortoise Raising».[36]

Artistic activities[edit]

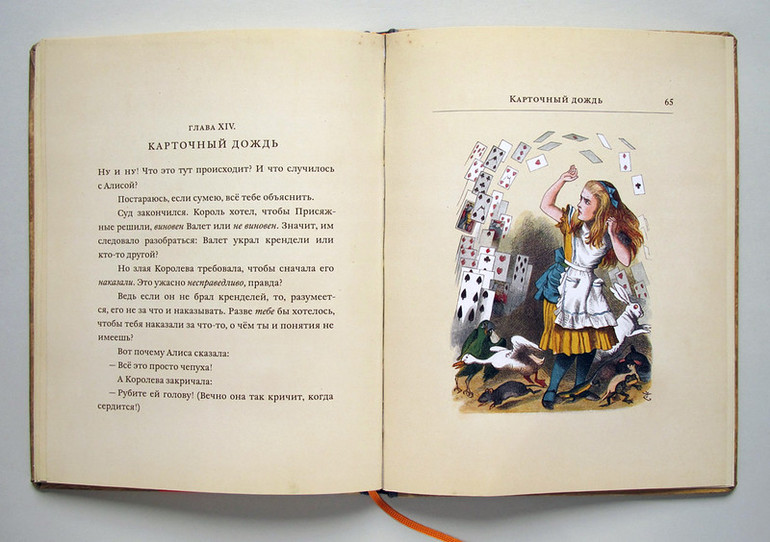

One of Carroll’s own illustrations

Literature[edit]

From a young age, Dodgson wrote poetry and short stories, contributing heavily to the family magazine Mischmasch and later sending them to various magazines, enjoying moderate success. Between 1854 and 1856, his work appeared in the national publications The Comic Times and The Train, as well as smaller magazines such as the Whitby Gazette and the Oxford Critic. Most of this output was humorous, sometimes satirical, but his standards and ambitions were exacting. «I do not think I have yet written anything worthy of real publication (in which I do not include the Whitby Gazette or the Oxonian Advertiser), but I do not despair of doing so someday,» he wrote in July 1855.[27] Sometime after 1850, he did write puppet plays for his siblings’ entertainment, of which one has survived: La Guida di Bragia.[37]

In March 1856, he published his first piece of work under the name that would make him famous. A romantic poem called «Solitude» appeared in The Train under the authorship of «Lewis Carroll». This pseudonym was a play on his real name: Lewis was the anglicised form of Ludovicus, which was the Latin for Lutwidge, and Carroll an Irish surname similar to the Latin name Carolus, from which comes the name Charles.[7] The transition went as follows:

«Charles Lutwidge» translated into Latin as «Carolus Ludovicus». This was then translated back into English as «Carroll Lewis» and then reversed to make «Lewis Carroll».[38] This pseudonym was chosen by editor Edmund Yates from a list of four submitted by Dodgson, the others being Edgar Cuthwellis, Edgar U. C. Westhill, and Louis Carroll.[39]

Alice books[edit]

«The chief difficulty Alice found at first was in managing her flamingo». Illustration by John Tenniel, 1865.

The Jabberwock, as illustrated by John Tenniel for Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking-Glass, including the poem «Jabberwocky».

In 1856, Dean Henry Liddell arrived at Christ Church, bringing with him his young family, all of whom would figure largely in Dodgson’s life over the following years, and would greatly influence his writing career. Dodgson became close friends with Liddell’s wife Lorina and their children, particularly the three sisters Lorina, Edith, and Alice Liddell. He was widely assumed for many years to have derived his own «Alice» from Alice Liddell; the acrostic poem at the end of Through the Looking-Glass spells out her name in full, and there are also many superficial references to her hidden in the text of both books. It has been noted that Dodgson himself repeatedly denied in later life that his «little heroine» was based on any real child,[40][41] and he frequently dedicated his works to girls of his acquaintance, adding their names in acrostic poems at the beginning of the text. Gertrude Chataway’s name appears in this form at the beginning of The Hunting of the Snark, and it is not suggested that this means that any of the characters in the narrative are based on her.[41]

Information is scarce (Dodgson’s diaries for the years 1858–1862 are missing), but it seems clear that his friendship with the Liddell family was an important part of his life in the late 1850s, and he grew into the habit of taking the children on rowing trips (first the boy, Harry, and later the three girls) accompanied by an adult friend[42] to nearby Nuneham Courtenay or Godstow.[43]

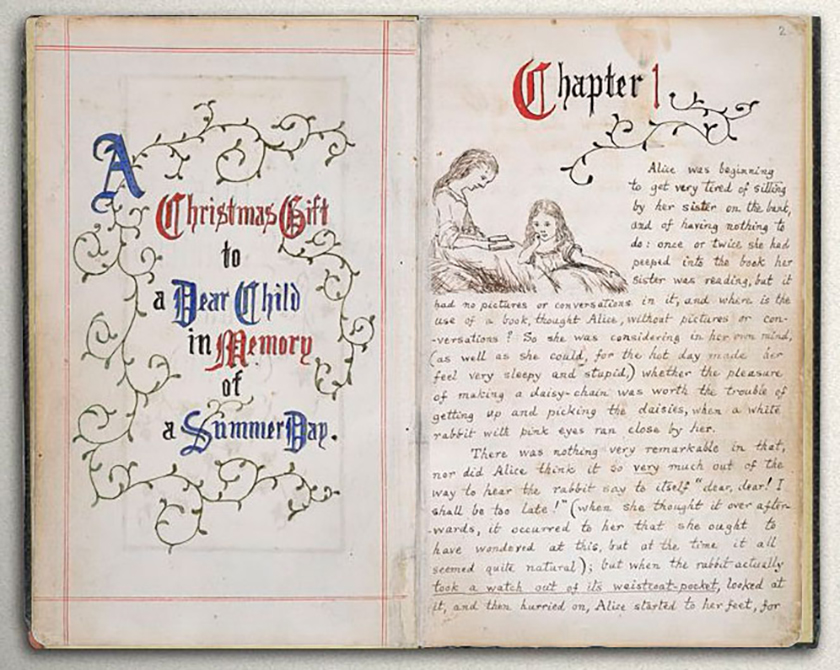

It was on one such expedition on 4 July 1862 that Dodgson invented the outline of the story that eventually became his first and greatest commercial success. He told the story to Alice Liddell and she begged him to write it down, and Dodgson eventually (after much delay) presented her with a handwritten, illustrated manuscript entitled Alice’s Adventures Under Ground in November 1864.[43]

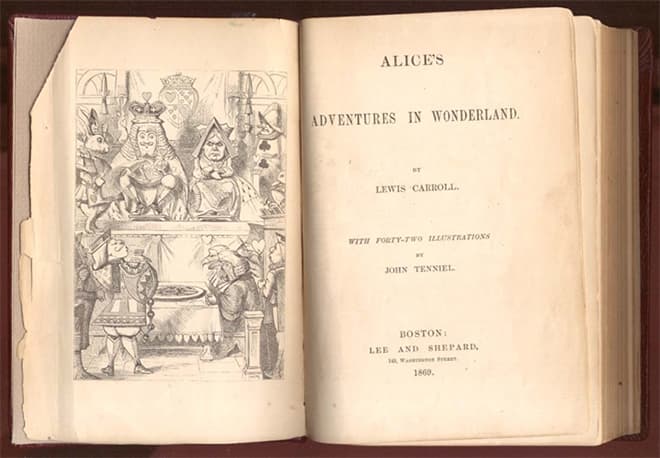

Before this, the family of friend and mentor George MacDonald read Dodgson’s incomplete manuscript, and the enthusiasm of the MacDonald children encouraged Dodgson to seek publication. In 1863, he had taken the unfinished manuscript to Macmillan the publisher, who liked it immediately. After the possible alternative titles were rejected – Alice Among the Fairies and Alice’s Golden Hour – the work was finally published as Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland in 1865 under the Lewis Carroll pen-name, which Dodgson had first used some nine years earlier.[29] The illustrations this time were by Sir John Tenniel; Dodgson evidently thought that a published book would need the skills of a professional artist. Annotated versions provide insights into many of the ideas and hidden meanings that are prevalent in these books.[44][45] Critical literature has often proposed Freudian interpretations of the book as «a descent into the dark world of the subconscious», as well as seeing it as a satire upon contemporary mathematical advances.[46][47]

The overwhelming commercial success of the first Alice book changed Dodgson’s life in many ways.[48][49][50] The fame of his alter ego «Lewis Carroll» soon spread around the world. He was inundated with fan mail and with sometimes unwanted attention. Indeed, according to one popular story, Queen Victoria herself enjoyed Alice in Wonderland so much that she commanded that he dedicate his next book to her, and was accordingly presented with his next work, a scholarly mathematical volume entitled An Elementary Treatise on Determinants.[51][52] Dodgson himself vehemently denied this story, commenting «… It is utterly false in every particular: nothing even resembling it has occurred»;[52][53] and it is unlikely for other reasons. As T. B. Strong comments in a Times article, «It would have been clean contrary to all his practice to identify [the] author of Alice with the author of his mathematical works».[54][55] He also began earning quite substantial sums of money but continued with his seemingly disliked post at Christ Church.[29]

Late in 1871, he published the sequel Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There. (The title page of the first edition erroneously gives «1872» as the date of publication.[56]) Its somewhat darker mood possibly reflects changes in Dodgson’s life. His father’s death in 1868 plunged him into a depression that lasted some years.[29]

The Hunting of the Snark[edit]

In 1876, Dodgson produced his next great work, The Hunting of the Snark, a fantastical «nonsense» poem, with illustrations by Henry Holiday, exploring the adventures of a bizarre crew of nine tradesmen and one beaver, who set off to find the snark. It received largely mixed reviews from Carroll’s contemporary reviewers,[57] but was enormously popular with the public, having been reprinted seventeen times between 1876 and 1908,[58] and has seen various adaptations into musicals, opera, theatre, plays and music.[59] Painter Dante Gabriel Rossetti reputedly became convinced that the poem was about him.[29]

Sylvie and Bruno[edit]

In 1895, 30 years after the publication of his masterpieces, Carroll attempted a comeback, producing a two-volume tale of the fairy siblings Sylvie and Bruno. Carroll entwines two plots set in two alternative worlds, one set in rural England and the other in the fairytale kingdoms of Elfland, Outland, and others. The fairytale world satirizes English society, and more specifically the world of academia. Sylvie and Bruno came out in two volumes and is considered a lesser work, although it has remained in print for over a century.

Photography (1856–1880)[edit]

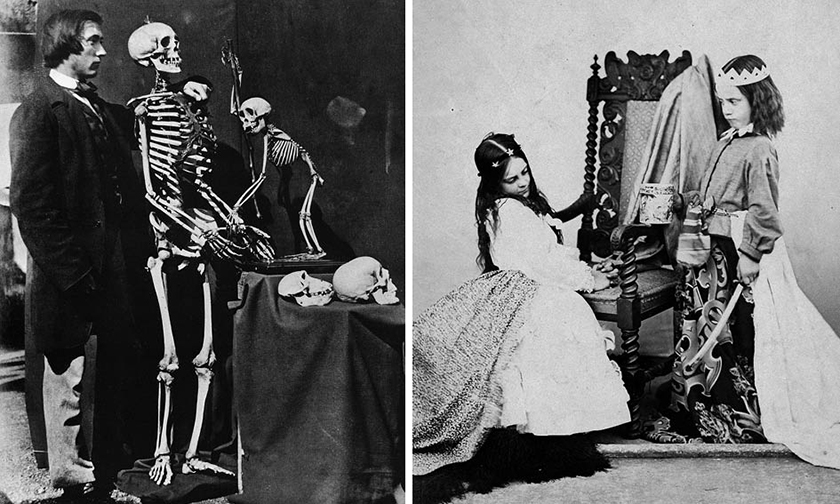

In 1856, Dodgson took up the new art form of photography under the influence first of his uncle Skeffington Lutwidge, and later of his Oxford friend Reginald Southey.[60] He soon excelled at the art and became a well-known gentleman-photographer, and he seems even to have toyed with the idea of making a living out of it in his very early years.[29]

A study by Roger Taylor and Edward Wakeling exhaustively lists every surviving print, and Taylor calculates that just over half of his surviving work depicts young girls, though about 60% of his original photographic portfolio is now missing.[61] Dodgson also made many studies of men, women, boys, and landscapes; his subjects also include skeletons, dolls, dogs, statues, paintings, and trees.[62] His pictures of children were taken with a parent in attendance and many of the pictures were taken in the Liddell garden because natural sunlight was required for good exposures.[42]

He also found photography to be a useful entrée into higher social circles.[63] During the most productive part of his career, he made portraits of notable sitters such as John Everett Millais, Ellen Terry, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Julia Margaret Cameron, Michael Faraday, Lord Salisbury, and Alfred Tennyson.[29]

By the time that Dodgson abruptly ceased photography (1880, after 24 years), he had established his own studio on the roof of Tom Quad, created around 3,000 images, and was an amateur master of the medium, though fewer than 1,000 images have survived time and deliberate destruction. He stopped taking photographs because keeping his studio working was too time-consuming.[64] He used the wet collodion process; commercial photographers who started using the dry-plate process in the 1870s took pictures more quickly.[65] Popular taste changed with the advent of Modernism, affecting the types of photographs that he produced.

Inventions[edit]

To promote letter writing, Dodgson invented «The Wonderland Postage-Stamp Case» in 1889. This was a cloth-backed folder with twelve slots, two marked for inserting the most commonly used penny stamp, and one each for the other current denominations up to one shilling. The folder was then put into a slipcase decorated with a picture of Alice on the front and the Cheshire Cat on the back. It intended to organize stamps wherever one stored their writing implements; Carroll expressly notes in Eight or Nine Wise Words about Letter-Writing it is not intended to be carried in a pocket or purse, as the most common individual stamps could easily be carried on their own. The pack included a copy of a pamphlet version of this lecture.[66][67]

Reconstructed nyctograph, with scale demonstrated by a 5 euro cent.

Another invention was a writing tablet called the nyctograph that allowed note-taking in the dark, thus eliminating the need to get out of bed and strike a light when one woke with an idea. The device consisted of a gridded card with sixteen squares and a system of symbols representing an alphabet of Dodgson’s design, using letter shapes similar to the Graffiti writing system on a Palm device.[68]

He also devised a number of games, including an early version of what today is known as Scrabble. Devised some time in 1878, he invented the «doublet» (see word ladder), a form of brain-teaser that is still popular today, changing one word into another by altering one letter at a time, each successive change always resulting in a genuine word.[69] For instance, CAT is transformed into DOG by the following steps: CAT, COT, DOT, DOG.[29] It first appeared in the 29 March 1879 issue of Vanity Fair, with Carroll writing a weekly column for the magazine for two years; the final column dated 9 April 1881.[70] The games and puzzles of Lewis Carroll were the subject of Martin Gardner’s March 1960 Mathematical Games column in Scientific American.

Other items include a rule for finding the day of the week for any date; a means for justifying right margins on a typewriter; a steering device for a velociman (a type of tricycle); fairer elimination rules for tennis tournaments; a new sort of postal money order; rules for reckoning postage; rules for a win in betting; rules for dividing a number by various divisors; a cardboard scale for the Senior Common Room at Christ Church which, held next to a glass, ensured the right amount of liqueur for the price paid; a double-sided adhesive strip to fasten envelopes or mount things in books; a device for helping a bedridden invalid to read from a book placed sideways; and at least two ciphers for cryptography.[29]

He also proposed alternative systems of parliamentary representation. He proposed the so-called Dodgson’s method, using the Condorcet method.[71] In 1884, he proposed a proportional representation system based on multi-member districts, each voter casting only a single vote, quotas as minimum requirements to take seats, and votes transferable by candidates through what is now called Liquid democracy.[72]

Mathematical work[edit]

Within the academic discipline of mathematics, Dodgson worked primarily in the fields of geometry, linear and matrix algebra, mathematical logic, and recreational mathematics, producing nearly a dozen books under his real name. Dodgson also developed new ideas in linear algebra (e.g., the first printed proof of the Kronecker–Capelli theorem),[73][74] probability, and the study of elections (e.g., Dodgson’s method) and committees; some of this work was not published until well after his death. His occupation as Mathematical Lecturer at Christ Church gave him some financial security.[75]

Mathematical logic[edit]

His work in the field of mathematical logic attracted renewed interest in the late 20th century. Martin Gardner’s book on logic machines and diagrams and William Warren Bartley’s posthumous publication of the second part of Dodgson’s symbolic logic book have sparked a reevaluation of Dodgson’s contributions to symbolic logic.[76][77][78] It is recognized that in his Symbolic Logic Part II, Dodgson introduced the Method of Trees, the earliest modern use of a truth tree.[79]

Algebra[edit]

Robbins’ and Rumsey’s investigation[80] of Dodgson condensation, a method of evaluating determinants, led them to the alternating sign matrix conjecture, now a theorem.

Recreational mathematics[edit]

The discovery in the 1990s of additional ciphers that Dodgson had constructed, in addition to his «Memoria Technica», showed that he had employed sophisticated mathematical ideas in their creation.[81]

Correspondence[edit]

Dodgson wrote and received as many as 98,721 letters, according to a special letter register which he devised. He documented his advice about how to write more satisfying letters in a missive entitled «Eight or Nine Wise Words about Letter-Writing».[82]

Later years[edit]

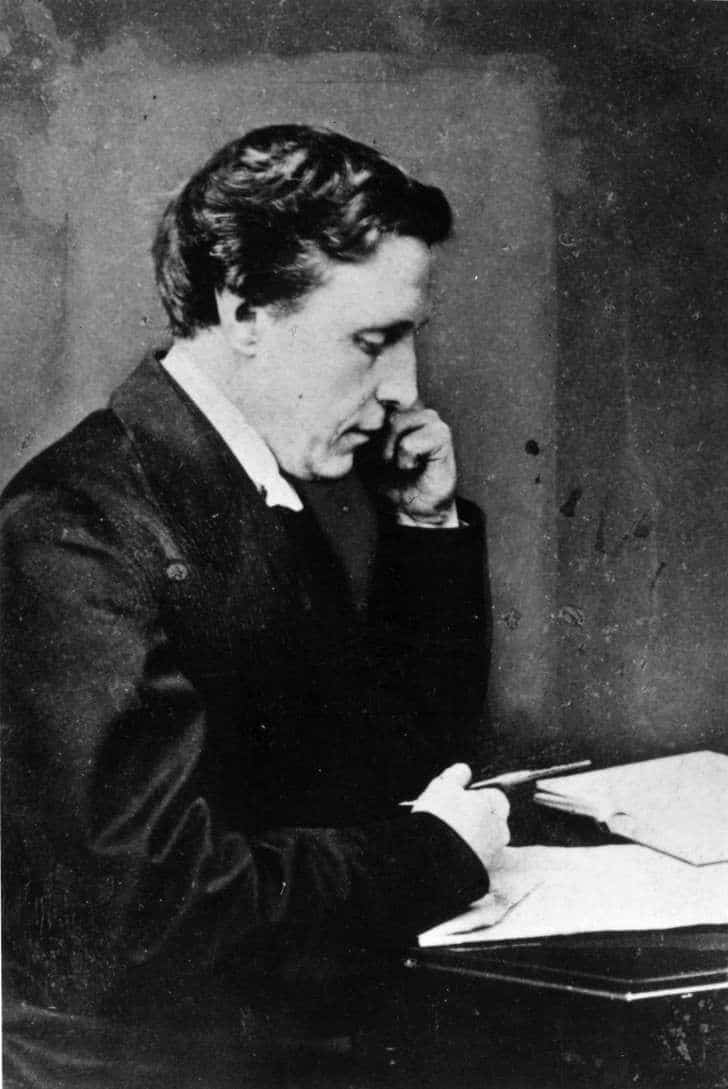

Lewis Carroll in later life

Dodgson’s existence remained little changed over the last twenty years of his life, despite his growing wealth and fame. He continued to teach at Christ Church until 1881 and remained in residence there until his death. Public appearances included attending the West End musical Alice in Wonderland (the first major live production of his Alice books) at the Prince of Wales Theatre on 30 December 1886.[83] The two volumes of his last novel, Sylvie and Bruno, were published in 1889 and 1893, but the intricacy of this work was apparently not appreciated by contemporary readers; it achieved nothing like the success of the Alice books, with disappointing reviews and sales of only 13,000 copies.[84][85]

The only known occasion on which he travelled abroad was a trip to Russia in 1867 as an ecclesiastic, together with the Reverend Henry Liddon. He recounts the travel in his «Russian Journal», which was first commercially published in 1935.[86] On his way to Russia and back, he also saw different cities in Belgium, Germany, partitioned Poland, and France.

Death[edit]

Dodgson died of pneumonia following influenza on 14 January 1898 at his sisters’ home, «The Chestnuts», in Guildford in the county of Surrey, just four days before the death of Henry Liddell. He was two weeks away from turning 66 years old. His funeral was held at the nearby St Mary’s Church.[87] His body was buried at the Mount Cemetery in Guildford.[29]

He is commemorated at All Saints’ Church, Daresbury, in its stained glass windows depicting characters from Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland.

Controversies and mysteries[edit]

Sexuality[edit]

Some late twentieth-century biographers have suggested that Dodgson’s interest in children had an erotic element, including Morton N. Cohen in his Lewis Carroll: A Biography (1995),[88] Donald Thomas in his Lewis Carroll: A Portrait with Background (1995), and Michael Bakewell in his Lewis Carroll: A Biography (1996).

Cohen, in particular, speculates that Dodgson’s «sexual energies sought unconventional outlets», and further writes:

We cannot know to what extent sexual urges lay behind Charles’s preference for drawing and photographing children in the nude. He contended the preference was entirely aesthetic. But given his emotional attachment to children as well as his aesthetic appreciation of their forms, his assertion that his interest was strictly artistic is naïve. He probably felt more than he dared acknowledge, even to himself.[89]

Cohen goes on to note that Dodgson «apparently convinced many of his friends that his attachment to the nude female child form was free of any eroticism», but adds that «later generations look beneath the surface» (p. 229). He argues that Dodgson may have wanted to marry the 11-year-old Alice Liddell and that this was the cause of the unexplained «break» with the family in June 1863,[29] an event for which other explanations are offered. Biographers Derek Hudson and Roger Lancelyn Green stop short of identifying Dodgson as a paedophile (Green also edited Dodgson’s diaries and papers), but they concur that he had a passion for small female children and next to no interest in the adult world.[citation needed] Catherine Robson refers to Carroll as «the Victorian era’s most famous (or infamous) girl lover».[90]

Several other writers and scholars have challenged the evidential basis for Cohen’s and others’ views about Dodgson’s sexual interests. Hugues Lebailly has endeavoured to set Dodgson’s child photography within the «Victorian Child Cult», which perceived child nudity as essentially an expression of innocence.[91] Lebailly claims that studies of child nudes were mainstream and fashionable in Dodgson’s time and that most photographers made them as a matter of course, including Oscar Gustave Rejlander and Julia Margaret Cameron. Lebailly continues that child nudes even appeared on Victorian Christmas cards, implying a very different social and aesthetic assessment of such material. Lebailly concludes that it has been an error of Dodgson’s biographers to view his child-photography with 20th- or 21st-century eyes, and to have presented it as some form of personal idiosyncrasy, when it was a response to a prevalent aesthetic and philosophical movement of the time.

Karoline Leach’s reappraisal of Dodgson focused in particular on his controversial sexuality. She argues that the allegations of paedophilia rose initially from a misunderstanding of Victorian morals, as well as the mistaken idea – fostered by Dodgson’s various biographers – that he had no interest in adult women. She termed the traditional image of Dodgson «the Carroll Myth». She drew attention to the large amounts of evidence in his diaries and letters that he was also keenly interested in adult women, married and single, and enjoyed several relationships with them that would have been considered scandalous by the social standards of his time. She also pointed to the fact that many of those whom he described as «child-friends» were girls in their late teens and even twenties.[92] She argues that suggestions of paedophilia emerged only many years after his death, when his well-meaning family had suppressed all evidence of his relationships with women in an effort to preserve his reputation, thus giving a false impression of a man interested only in little girls. Similarly, Leach points to a 1932 biography by Langford Reed as the source of the dubious claim that many of Carroll’s female friendships ended when the girls reached the age of 14.[93]

In addition to the biographical works that have discussed Dodgson’s sexuality, there are modern artistic interpretations of his life and work that do so as well – in particular, Dennis Potter in his play Alice and his screenplay for the motion picture Dreamchild, and Robert Wilson in his musical Alice.

Ordination[edit]

Dodgson had been groomed for the ordained ministry in the Church of England from a very early age and was expected to be ordained within four years of obtaining his master’s degree, as a condition of his residency at Christ Church. He delayed the process for some time but was eventually ordained as a deacon on 22 December 1861. But when the time came a year later to be ordained as a priest, Dodgson appealed to the dean for permission not to proceed. This was against college rules and, initially, Dean Liddell told him that he would have to consult the college ruling body, which would almost certainly have resulted in his being expelled. For unknown reasons, Liddell changed his mind overnight and permitted him to remain at the college in defiance of the rules.[94] Dodgson never became a priest, unique amongst senior students of his time.

There is currently no conclusive evidence about why Dodgson rejected the priesthood. Some have suggested that his stammer made him reluctant to take the step because he was afraid of having to preach.[95] Wilson quotes letters by Dodgson describing difficulty in reading lessons and prayers rather than preaching in his own words.[96] But Dodgson did indeed preach in later life, even though not in priest’s orders, so it seems unlikely that his impediment was a major factor affecting his choice.[citation needed] Wilson also points out that the Bishop of Oxford, Samuel Wilberforce, who ordained Dodgson, had strong views against clergy going to the theatre, one of Dodgson’s great interests. He was interested in minority forms of Christianity (he was an admirer of F. D. Maurice) and «alternative» religions (theosophy).[97] Dodgson became deeply troubled by an unexplained sense of sin and guilt at this time (the early 1860s) and frequently expressed the view in his diaries that he was a «vile and worthless» sinner, unworthy of the priesthood and this sense of sin and unworthiness may well have affected his decision to abandon being ordained to the priesthood.[98]

Missing diaries[edit]

At least four complete volumes and around seven pages of text are missing from Dodgson’s 13 diaries.[99] The loss of the volumes remains unexplained; the pages have been removed by an unknown hand. Most scholars assume that the diary material was removed by family members in the interests of preserving the family name, but this has not been proven.[100] Except for one page, material is missing from his diaries for the period between 1853 and 1863 (when Dodgson was 21–31 years old).[101][102][failed verification] During this period , Dodgson began experiencing great mental and spiritual anguish and confessing to an overwhelming sense of his own sin. This was also the period of time when he composed his extensive love poetry, leading to speculation that the poems may have been autobiographical.[103][104]

Many theories have been put forward to explain the missing material. A popular explanation for one missing page (27 June 1863) is that it might have been torn out to conceal a proposal of marriage on that day by Dodgson to the 11-year-old Alice Liddell. However, there has never been any evidence to suggest that this was so, and a paper offers some evidence to the contrary which was discovered by Karoline Leach in the Dodgson family archive in 1996.[105]

The «cut pages in diary» document, in the Dodgson family archive in Woking

This paper is known as the «cut pages in diary» document, and was compiled by various members of Carroll’s family after his death. Part of it may have been written at the time when the pages were destroyed, though this is unclear. The document offers a brief summary of two diary pages that are missing, including the one for 27 June 1863. The summary for this page states that Mrs. Liddell told Dodgson that there was gossip circulating about him and the Liddell family’s governess, as well as about his relationship with «Ina», presumably Alice’s older sister Lorina Liddell. The «break» with the Liddell family that occurred soon after was presumably in response to this gossip.[106][107] An alternative interpretation has been made[by whom?] regarding Carroll’s rumoured involvement with «Ina»: Lorina was also the name of Alice Liddell’s mother. What is deemed most crucial and surprising is that the document seems to imply that Dodgson’s break with the family was not connected with Alice at all; until a primary source is discovered, the events of 27 June 1863 will remain in doubt.

Migraine and epilepsy[edit]

In his diary for 1880, Dodgson recorded experiencing his first episode of migraine with aura, describing very accurately the process of «moving fortifications» that are a manifestation of the aura stage of the syndrome.[108] Unfortunately, there is no clear evidence to show whether this was his first experience of migraine per se, or if he may have previously had the far more common form of migraine without aura, although the latter seems most likely, given the fact that migraine most commonly develops in the teens or early adulthood. Another form of migraine aura called Alice in Wonderland syndrome has been named after Dodgson’s little heroine because its manifestation can resemble the sudden size-changes in the book. It is also known as micropsia and macropsia, a brain condition affecting the way that objects are perceived by the mind. For example, an afflicted person may look at a larger object such as a basketball and perceive it as if it were the size of a golf ball. Some authors have suggested that Dodgson may have experienced this type of aura and used it as an inspiration in his work, but there is no evidence that he did.[109][110]

Dodgson also had two attacks in which he lost consciousness. He was diagnosed by a Dr. Morshead, Dr. Brooks, and Dr. Stedman, and they believed the attack and a consequent attack to be an «epileptiform» seizure (initially thought to be fainting, but Brooks changed his mind). Some have concluded from this that he had this condition for his entire life, but there is no evidence of this in his diaries beyond the diagnosis of the two attacks already mentioned.[108] Some authors, Sadi Ranson in particular, have suggested that Carroll may have had temporal lobe epilepsy in which consciousness is not always completely lost but altered, and in which the symptoms mimic many of the same experiences as Alice in Wonderland. Carroll had at least one incident in which he suffered full loss of consciousness and awoke with a bloody nose, which he recorded in his diary and noted that the episode left him not feeling himself for «quite sometime afterward». This attack was diagnosed as possibly «epileptiform» and Carroll himself later wrote of his «seizures» in the same diary.

Most of the standard diagnostic tests of today were not available in the nineteenth century. Yvonne Hart, consultant neurologist at the John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, considered Dodgson’s symptoms. Her conclusion, quoted in Jenny Woolf’s 2010 The Mystery of Lewis Carroll, is that Dodgson very likely had migraine and may have had epilepsy, but she emphasises that she would have considerable doubt about making a diagnosis of epilepsy without further information.[111]

Legacy[edit]

There are societies in many parts of the world dedicated to the enjoyment and promotion of his works and the investigation of his life.[112]

Copenhagen Street in Islington, north London is the location of the Lewis Carroll Children’s Library.[113]

In 1982, his great-nephew unveiled a memorial stone to him in Poets’ Corner, Westminster Abbey.[114] In January 1994, an asteroid, 6984 Lewiscarroll, was discovered and named after Carroll. The Lewis Carroll Centenary Wood near his birthplace in Daresbury opened in 2000.[115]

Born in All Saints’ Vicarage, Daresbury, Cheshire, in 1832, Lewis Carroll is commemorated at All Saints’ Church, Daresbury in its stained glass windows depicting characters from Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. In March 2012, the Lewis Carroll Centre, attached to the church, was opened.[116]

Works[edit]

Literary works[edit]

- La Guida di Bragia, a Ballad Opera for the Marionette Theatre (around 1850)

- «Miss Jones», comic song (1862)[117]

- Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865)

- Phantasmagoria and Other Poems (1869)

- Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There (includes «Jabberwocky» and «The Walrus and the Carpenter») (1871)

- The Hunting of the Snark (1876)

- Rhyme? And Reason? (1883) – shares some contents with the 1869 collection, including the long poem «Phantasmagoria»

- A Tangled Tale (1885)

- Sylvie and Bruno (1889)

- The Nursery «Alice» (1890)

- Sylvie and Bruno Concluded (1893)

- Pillow Problems (1893)

- What the Tortoise Said to Achilles (1895)

- Three Sunsets and Other Poems (1898)

- The Manlet (1903)[118]

Mathematical works[edit]

- A Syllabus of Plane Algebraic Geometry (1860)

- The Fifth Book of Euclid Treated Algebraically (1858 and 1868)

- An Elementary Treatise on Determinants, With Their Application to Simultaneous Linear Equations and Algebraic Equations

- Euclid and his Modern Rivals (1879), both literary and mathematical in style

- Symbolic Logic Part I

- Symbolic Logic Part II (published posthumously)

- The Alphabet Cipher (1868)

- The Game of Logic (1887)

- Curiosa Mathematica I (1888)

- Curiosa Mathematica II (1892)

- A discussion of the various methods of procedure in conducting elections (1873), Suggestions as to the best method of taking votes, where more than two issues are to be voted on (1874), A method of taking votes on more than two issues (1876), collected as The Theory of Committees and Elections, edited, analysed, and published in 1958 by Duncan Black

Other works[edit]

- Some Popular Fallacies about Vivisection

- Eight or Nine Wise Words About Letter-Writing

- Notes by an Oxford Chiel

- The Principles of Parliamentary Representation (1884)

See also[edit]

- Lewis Carroll identity

- Lewis Carroll Shelf Award

- RGS Worcester and The Alice Ottley School – Miss Ottley, the first Headmistress of The Alice Ottley School, was a friend of Lewis Carroll. One of the school’s houses was named after him.

- Carroll diagram

- Origins of a Story

- The White Knight

References[edit]

- ^ «Lewis Carroll Societies». Lewiscarrollsociety.org.uk. Archived from the original on 29 March 2016. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ^ Lewis Carroll Society of North America Inc. Archived 26 March 2022 at the Wayback Machine Charity Navigator. Retrieved 7 October

- ^ Clark, p. 10

- ^ Collingwood, pp. 6–7

- ^ Bakewell, Michael (1996). Lewis Carroll: A Biography. London: Heinemann. p. 2. ISBN 9780434045792.

- ^ Collingwood, p. 8

- ^ a b Cohen, pp. 30–35

- ^ «Google map of Daresbury, UK». Retrieved 22 October 2011.[dead link]

- ^ «Charles Lutwidge Dodgson». The MacTutor History of Mathematics archive. Archived from the original on 5 July 2011. Retrieved 8 March 2011.

- ^ Cohen, pp. 200–202

- ^ Cohen, p. 4

- ^ Collingwood, pp. 30–31

- ^ a b Woolf, Jenny (2010). The Mystery of Lewis Carroll: Discovering the Whimsical, Thoughtful, and Sometimes Lonely Man Who Created «Alice in Wonderland». New York: St. Martin’s Press. pp. 24. ISBN 9780312612986.

- ^ Collingwood, p. 29

- ^ Carroll, Lewis (1995). Wakeling, Edward (ed.). Rediscovered Lewis Carroll Puzzles. New York City: Dover Publications. pp. 13. ISBN 0486288617.

- ^ Lovett, Charlie (2005). Lewis Carroll Among His Books: A Descriptive Catalogue of the Private Library of Charles L. Dodgson. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers. p. 329. ISBN 0786421053.

- ^ Clark, pp. 63–64

- ^ a b Clark, pp. 64–65

- ^ Collingwood, p. 52

- ^ Clark, p. 74

- ^ Collingwood, p. 57

- ^ Wilson, p. 51

- ^ Cohen, p. 51

- ^ Clark, p. 79

- ^ Flood, Raymond; Rice, Adrian; Wilson, Robin (2011). Mathematics in Victorian Britain. Oxfordshire, England: Oxford University Press. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-19-960139-4. OCLC 721931689.

- ^ Cohen, pp. 414–416

- ^ a b c d e f Leach, Ch. 2.

- ^ Leach, p. 91

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Cohen, pp. 100–4

- ^ Gardner, Martin (2000). Introduction to The annotated Alice: Alice’s adventures in Wonderland & Through the looking glass. W. W. Norton & Company. p. xv. ISBN 0-517-02962-6.

- ^ Gardner, Martin (2009). Introduction to Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass. Oxford University Press. p. xvi. ISBN 978-0-517-02962-6.

- ^ Collingwood

- ^ Collingwood, Chapter IX

- ^ Hayness, Renée (1982). The Society for Psychical Research, 1882–1982 A History. London: Macdonald & Co. pp. 13–14. ISBN 0-356-07875-2.

- ^ Carroll, L. (1895). «What the Tortoise Said to Achilles». Mind. IV (14): 278–280. doi:10.1093/mind/IV.14.278.

- ^ Blackburn, S. (1995). «Practical Tortoise Raising». Mind. 104 (416): 695–711. doi:10.1093/mind/104.416.695.

- ^ Heath, Peter L. (2007). «Introduction». La Guida Di Bragia, a Ballad Opera for the Marionette Theatre. Lewis Carroll Society of North America. pp. vii–xvi. ISBN 978-0-930326-15-9.

- ^ Roger Lancelyn Green On-line Encyclopædia Britannica Archived 9 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Thomas, p. 129

- ^ Cohen, Morton N. (ed) (1979) The Letters of Lewis Carroll, London: Macmillan.

- ^ a b Leach, Ch. 5 «The Unreal Alice»

- ^ a b Winchester, Simon (2011). The Alice Behind Wonderland. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-539619-5. OCLC 641525313.

- ^ a b Leach, Ch. 4

- ^ Gardner, Martin (2000). «The Annotated Alice. The Definitive Edition». New York: W.W. Norton.

- ^ Heath, Peter (1974). «The Philosopher’s Alice». New York: St. Martin’s Press.

- ^ «Algebra in Wonderland». The New York Times. 7 March 2010. Archived from the original on 12 March 2010. Retrieved 10 February 2017.

- ^ Bayley, Melanie. «Alice’s adventures in algebra: Wonderland solved». New Scientist. Archived from the original on 25 January 2022. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- ^ Elster, Charles Harrington (2006). The big book of beastly mispronunciations: the complete opinionated guide for the careful speaker. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. pp. 158–159. ISBN 061842315X. Archived from the original on 3 January 2017. Retrieved 3 August 2016.

- ^ Emerson, R. H. (1996). «The Unpronounceables: Difficult Literary Names 1500–1940». English Language Notes. 34 (2): 63–74. ISSN 0013-8282.

- ^ «Lewis Carroll». Biography in Context. Gale. Archived from the original on 26 March 2022. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- ^ Wilson

- ^ a b «Lewis Carroll – Logician, Nonsense Writer, Mathematician and Photographer». The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. BBC. 26 August 2005. Archived from the original on 3 February 2009. Retrieved 12 February 2009.

- ^ Dodgson, Charles (1896). Symbolic Logic.

- ^ Strong, T. B. (27 January 1932). «Mr. Dodgson: Lewis Carroll at Oxford». [The Times].

- ^ «Fit for a Queen». Snopes. 26 March 1999. Archived from the original on 26 March 2022. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- ^ Cohen, Morton (24 June 2009). Introduction to «Alice in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass». Random House. ISBN 978-0-553-21345-4.

- ^ Cohen, Morton N. (1976). «Hark the Snark». In Guilano, Edward (ed.). Lewis Carroll Observed. New York: Clarkson N. Potter, Inc. pp. 92–110. ISBN 0-517-52497-X.

- ^ Williams, Sidney Herbert; Madan, Falconer (1979). Handbook of the literature of the Rev. C.L. Dodgson. Folkestone, England: Dawson. p. 68. ISBN 9780712909068. OCLC 5754676.

- ^ Greenarce, Selwyn (2006) [1876]. «The Listing of the Snark». In Martin Gardner (ed.). The Annotated Hunting of the Snark (Definitive ed.). W. W. Norton. pp. 117–147. ISBN 0-393-06242-2.

- ^ Clark, p. 93

- ^ Taylor, Roger; Wakeling, Edward (25 February 2002). Lewis Carroll, Photographer. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-07443-6.

- ^ Cohen, Morton (1999). «Reflections in a Looking Glass.» New York: Aperture.

- ^ Thomas, p. 116

- ^ Thomas, p. 265

- ^ Wakeling, Edward (1998). «Lewis Carroll’s Photography». An Exhibition From the Jon A. Lindseth Collection of C. L. Dodgson and Lewis Carroll. New York, NY: The Grolier Club. pp. 55–67. ISBN 0-910672-23-7.

- ^ Flodden W. Heron, «Lewis Carroll, Inventor of Postage Stamp Case» in Stamps, vol. 26, no. 12, 25 March 1939

- ^ «Carroll Related Stamps». The Lewis Carroll Society. 28 April 2005. Archived from the original on 21 March 2012. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- ^ Everson, Michael. (2011) «Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland: An edition printed in the Nyctographic Square Alphabet devised by Lewis Carroll». Foreword by Alan Tannenbaum, Éire: Cathair na Mart. ISBN 978-1-904808-78-7

- ^ Gardner, Martin. «Word Ladders: Lewis Carroll’s Doublets». No. Vol. 80, No. 487, Centenary Issue (Mar. 1996). The Mathematical Gazette. JSTOR 3620349. Archived from the original on 20 April 2021. Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- ^ Deanna Haunsperger, Stephen Kennedy (31 July 2006). The Edge of the Universe: Celebrating Ten Years of Math Horizons. Mathematical Association of America. p. 22. ISBN 0-88385-555-0.

- ^ Black, Duncan; McLean, Iain; McMillan, Alistair; Monroe, Burt L.; Dodgson, Charles Lutwidge (1996). A Mathematical Approach to Proportional Representation. ISBN 978-0-7923-9620-8. Archived from the original on 4 February 2021. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- ^ Charles Dodgson, Principles of Parliamentary Representation (1884)

- ^ Seneta, Eugene (1984). «Lewis Carroll as a Probabilist and Mathematician» (PDF). The Mathematical Scientist. 9: 79–84. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 January 2016. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- ^ Abeles, Francine F. (1998) Charles L. Dodgson, Mathematician». An Exhibition From the Jon A. Lindseth Collection of C.L. Dodgson and Lewis Carroll». New York: The Grolier Club, pp. 45–54.

- ^ Wilson, p. 61

- ^ Gardner, Martin. (1958) «Logic Machines and Diagrams». Brighton, Sussex: Harvester Press

- ^ Bartley, William Warren III, ed. (1977) «Lewis Carroll’s Symbolic Logic». New York: Clarkson N. Potter, 2nd ed 1986.

- ^ Moktefi, Amirouche. (2008) «Lewis Carroll’s Logic», pp. 457–505 in British Logic in the Nineteenth Century, Vol. 4 of Handbook of the History of Logic, Dov M. Gabbay and John Woods (eds.) Amsterdam: Elsevier.

- ^ «Modern Logic: The Boolean Period: Carroll – Encyclopedia.com». Archived from the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 22 July 2020.

- ^ Robbins, D. P.; Rumsey, H. (1986). «Determinants and alternating sign matrices». Advances in Mathematics. 62 (2): 169. doi:10.1016/0001-8708(86)90099-X.

- ^ Abeles, F. F. (2005). «Lewis Carroll’s ciphers: The literary connections». Advances in Applied Mathematics. 34 (4): 697–708. doi:10.1016/j.aam.2004.06.006.

- ^ Clark, Dorothy G. (April 2010). «The Place of Lewis Carroll in Children’s Literature (review)». The Lion and the Unicorn. 34 (2): 253–258. doi:10.1353/uni.0.0495. S2CID 143924225. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 21 January 2014.

- ^ Carroll, Lewis (1979). The Letters of Lewis Carroll, Volumes 1–2. Oxford University Press. p. 657.

Dec. 30th.—To London with M—, and took her to «Alice in Wonderland,» Mr. Savile Clarke’s play at the Prince of Wales’s Theatre… as a whole, the play seems a success.

- ^ Angelica Shirley Carpenter (2002). Lewis Carroll: Through the Looking Glass. Lerner. p. 98.ISBN 978-0822500735.

- ^ Christensen, Thomas (1991). «Dodgson’s Dodges» Archived 15 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine. rightreading.com.

- ^ «Chronology of Works of Lewis Carroll». Archived from the original on 20 February 2009. Retrieved 20 February 2009.

- ^ «Lewis Carroll and St Mary’s Church – Guildford: This Is Our Town website». 30 October 2013. Archived from the original on 11 November 2016. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- ^ Cohen, pp. 166–167, 254–255

- ^ Cohen, p. 228

- ^ Robson, Catherine (2001). Men in Wonderland: The Lost Girlhood of the Victorian Gentlemen. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. p. 137. ISBN 978-0691004228.

- ^ «Association for new Lewis Carroll studies». Contrariwise.wild-reality.net. Archived from the original on 7 February 2012. Retrieved 19 October 2019.

- ^ Leach, pp. 16–17

- ^ Leach, p. 33

- ^ Dodgson’s MS diaries, volume 8, 22–24 October 1862

- ^ Cohen, p. 263

- ^ Wilson, pp. 103–104

- ^ Leach, p. 134

- ^ Dodgson’s MS diaries, volume 8, see prayers scattered throughout the text

- ^ Leach, pp. 48, 51

- ^ Leach, pp. 48–51

- ^ Leach, p. 52

- ^ Wakeling, Edward (April 2003). «The Real Lewis Carroll / A Talk given to the Lewis Carroll Society». 1855 … 1856 … 1857 … 1858 … 1862 … 1863. Archived from the original on 22 August 2016. Retrieved 14 September 2009.

- ^ Leach p. 54

- ^ «The Dodgson Family and Their Legacy». Archived from the original on 14 January 2011. Retrieved 5 January 2011.

- ^ Dodgson Family Collection, Cat. No. F/17/1. «Cut Pages in Diary». (For an account of its discovery see The Times Literary Supplement, 3 May 1996.)

- ^ Leach, pp. 170–2.

- ^ «Text available on-line». Looking for Lewis Carroll. Archived from the original on 16 November 2018. Retrieved 4 May 2007.

- ^ a b Wakeling, Edward (Ed.) «The Diaries of Lewis Carroll», Vol. 9, p. 52

- ^ Maudie, F.W. «Migraine and Lewis Carroll». The Migraine Periodical. 17.

- ^ Podoll, K; Robinson, D (1999). «Lewis Carroll’s migraine experiences». The Lancet. 353 (9161): 1366. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)74368-3. PMID 10218566. S2CID 5082284.

- ^ Woolf, Jenny (4 February 2010). The Mystery of Lewis Carroll. St. Martin’s Press. pp. 298–9. ISBN 978-0-312-67371-0.

- ^ «Lewis Carroll Societies». Lewiscarrollsociety.org.uk. Archived from the original on 29 March 2016. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- ^ «‘A most curious thing’ / Lewis Carroll Library». www.designbybeam.com. Archived from the original on 3 April 2015. Retrieved 15 March 2013.

- ^ «LEWIS CARROLL IS HONORED ON 150TH BIRTHDAY». The New York Times. 18 December 1982. Archived from the original on 5 May 2015. Retrieved 30 January 2015.

- ^ «Lewis Carroll Centenary Wood near Daresbury Runcorn». www.woodlandtrust.org.uk. Archived from the original on 5 August 2020. Retrieved 27 November 2019.

- ^ About Us, Lewis Carroll Centre & All Saints Daresbury PCC, archived from the original on 14 April 2012, retrieved 11 April 2012

- ^ The Carrollian. Lewis Carroll Society. Issue 7–8. p. 7. 2001: «In 1862 when Lewis Carroll sent to Yates the manuscript of the words of a ‘melancholy song’, entitled ‘Miss Jones’, he hoped that it would be published and performed by a comedian on a London music-hall stage.» Archived 4 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ The Hunting of the Snark and Other Poems and Verses, New York: Harper & Brothers, 1903

Bibliography[edit]

- Clark, Ann (1979). Lewis Carroll: A Biography. London: J. M. Dent. ISBN 0-460-04302-1.

- Cohen, Morton (1996). Lewis Carroll: A Biography. Vintage Books. pp. 30–35. ISBN 0-679-74562-9.

- Collingwood, Stuart Dodgson (1898). The Life and Letters of Lewis Carroll. London: T. Fisher Unwin.

- Leach, Karoline (1999). In the Shadow of the Dreamchild: A New Understanding of Lewis Carroll. London: Peter Owen.

- Pizzati, Giovanni: «An Endless Procession of People in Masquerade». Figure piane in Alice in Wonderland. 1993, Cagliari.

- Reed, Langford: The Life of Lewis Carroll (1932. London: W. and G. Foyle)

- Taylor, Alexander L., Knight: The White Knight (1952. Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd)

- Taylor, Roger & Wakeling, Edward: Lewis Carroll, Photographer. 2002. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-07443-7. (Catalogues nearly every Carroll photograph known to be still in existence.)

- Thomas, Donald (1996). Lewis Carroll: A Biography. Barnes and Noble, Inc. ISBN 978-0-7607-1232-0.

- Wilson, Robin (2008). Lewis Carroll in Numberland: His Fantastical Mathematical Logical Life. London: Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0-7139-9757-6.

- Woolf, Jenny: The Mystery of Lewis Carroll. 2010. New York: St Martin’s Press. ISBN 978-0-312-61298-6

Further reading[edit]

- Black, Duncan (1958). The Circumstances in which Rev. C. L. Dodgson (Lewis Carroll) wrote his Three Pamphlets and Appendix: Text of Dodgson’s Three Pamphlets and of ‘The Cyclostyled Sheet’ in The Theory of Committees and Elections, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- Bowman, Isa (1899). The Story of Lewis Carroll: Told for Young People by the Real Alice in Wonderland, Miss Isa Bowman. London: J.M. Dent & Co.

- Carroll, Lewis: The Annotated Alice: 150th Anniversary Deluxe Edition. Illustrated by John Tenniel. Edited by Martin Gardner & Mark Burstein. W. W. Norton. 2015. ISBN 978-0-393-24543-1

- Dodgson, Charles L.: Euclid and His Modern Rivals. Macmillan. 1879.

- Dodgson, Charles L.: The Pamphlets of Lewis Carroll

- Vol. 1: The Oxford Pamphlets. 1993. ISBN 0-8139-1250-4

- Vol. 2: The Mathematical Pamphlets. 1994. ISBN 0-9303-26-09-1

- Vol. 3: The Political Pamphlets. 2001. ISBN 0-930326-14-8

- Vol. 4: The Logic Pamphlets. 2010 ISBN 978-0-930326-25-8.

- Douglas-Fairhurst, Robert (2016). The Story of Alice: Lewis Carroll and the Secret History of Wonderland. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674970762.

- Goodacre, Selwyn (2006). All the Snarks: The Illustrated Editions of the Hunting of the Snark. Oxford: Inky Parrot Press.

- Graham-Smith, Darien (2005). Contextualising Carroll, University of Wales, Bangor. PhD thesis.

- Huxley, Francis: The Raven and the Writing Desk. 1976. ISBN 0-06-012113-0.

- Kelly, Richard: Lewis Carroll. 1990. Boston: Twayne Publishers.

- Kelly, Richard (ed.): Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. 2000. Peterborough, Ontario: Broadviewpress.

- Lovett, Charlie: Lewis Carroll Among His Books: A Descriptive Catalogue of the Private Library of Charles L. Dodgson. 2005. ISBN 0-7864-2105-3

- Waggoner, Diane (2020). Lewis Carroll’s Photography and Modern Childhood. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-19318-2.

- Wakeling, Edward (2015). The Photographs of Lewis Carroll: A Catalogue Raisonné. Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-76743-0.

- Wullschläger, Jackie: Inventing Wonderland. ISBN 0-7432-2892-8. — Also looks at Edward Lear (of the «nonsense» verses), J. M. Barrie (Peter Pan), Kenneth Grahame (The Wind in the Willows), and A. A. Milne (Winnie-the-Pooh).

- N.N.: Dreaming in Pictures: The Photography of Lewis Carroll. Yale University Press & SFMOMA, 2004. (Places Carroll firmly in the art photography tradition.)

External links[edit]

- Digital collections

- Works by Lewis Carroll in eBook form at Standard Ebooks

- Works by Lewis Carroll at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Lewis Carroll at Internet Archive

- Works by Lewis Carroll at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Works by Lewis Carroll at Open Library

- The Poems of Lewis Carroll

- [1] First Editions

- Physical collections

- Guide to Harcourt Amory collection of Lewis Carroll at Houghton Library, Harvard University

- Lewis Carroll at the British Library

- Lewis Carroll online exhibition at the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin

- Lewis Carroll Scrapbook Collection at the Library of Congress

- «Archival material relating to Lewis Carroll». UK National Archives.

- Biographical information and scholarship

- Lewis Carroll at victorianweb.org

- Contrariwise: the Association for New Lewis Carroll Studies — articles by leading members of the ‘new scholarship’

- Lewis Carroll’s Shifting Reputation

- Lewis Carroll: Logic, Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Other links

- Lewis Carroll at the Internet Book List

- Lewis Carroll at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Newspaper clippings about Lewis Carroll in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

- The Lewis Carroll Society

|

Lewis Carroll |

|

|---|---|

Carroll in June 1857 |

|

| Born | Charles Lutwidge Dodgson 27 January 1832 Daresbury, Cheshire, England |

| Died | 14 January 1898 (aged 65) Guildford, Surrey, England |

| Resting place | Mount Cemetery, Guildford, Surrey, England |

| Occupation |

|

| Education |

|

| Genre |

|

| Relatives |

|

| Signature | |

Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (; 27 January 1832 – 14 January 1898), better known by his pen name Lewis Carroll, was an English author, poet and mathematician. His most notable works are Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and its sequel Through the Looking-Glass (1871). He was noted for his facility with word play, logic, and fantasy. His poems Jabberwocky (1871) and The Hunting of the Snark (1876) are classified in the genre of literary nonsense.

Carroll came from a family of high-church Anglicans, and developed a long relationship with Christ Church, Oxford, where he lived for most of his life as a scholar and teacher. Alice Liddell, the daughter of Christ Church’s dean Henry Liddell, is widely identified as the original inspiration for Alice in Wonderland, though Carroll always denied this.

An avid puzzler, Carroll created the word ladder puzzle (which he then called «Doublets»), which he published in his weekly column for Vanity Fair magazine between 1879 and 1881. In 1982 a memorial stone to Carroll was unveiled at Poets’ Corner in Westminster Abbey. There are societies in many parts of the world dedicated to the enjoyment and promotion of his works.[1][2]

Early life[edit]

Dodgson’s family was predominantly northern English, conservative, and high-church Anglican. Most of his male ancestors were army officers or Anglican clergymen. His great-grandfather, Charles Dodgson, had risen through the ranks of the church to become the Bishop of Elphin in rural Ireland.[3] His paternal grandfather, another Charles, had been an army captain, killed in action in Ireland in 1803, when his two sons were hardly more than babies.[4] The older of these sons, yet another Charles Dodgson, was Carroll’s father. He went to Rugby School and then to Christ Church, Oxford.[5] He reverted to the other family tradition and took holy orders. He was mathematically gifted and won a double first degree, which could have been the prelude to a brilliant academic career. Instead, he married his first cousin Frances Jane Lutwidge in 1830 and became a country parson.[6][7]

Dodgson was born on 27 January 1832 at All Saints’ Vicarage in Daresbury, Cheshire,[8] the oldest boy and the third oldest of 11 children. When he was 11, his father was given the living of Croft-on-Tees, Yorkshire, and the whole family moved to the spacious rectory. This remained their home for the next 25 years. Charles’ father was an active and highly conservative cleric of the Church of England who later became the Archdeacon of Richmond[9] and involved himself, sometimes influentially, in the intense religious disputes that were dividing the church. He was high-church, inclining toward Anglo-Catholicism, an admirer of John Henry Newman and the Tractarian movement, and did his best to instil such views in his children. However, Charles developed an ambivalent relationship with his father’s values and with the Church of England as a whole.[10]

During his early youth, Dodgson was educated at home. His «reading lists» preserved in the family archives testify to a precocious intellect: at the age of seven, he was reading books such as The Pilgrim’s Progress. He also spoke with a stammer – a condition shared by most of his siblings[11] – that often inhibited his social life throughout his years. At the age of twelve he was sent to Richmond Grammar School (now part of Richmond School) in Richmond, North Yorkshire.

Lewis Carroll self-portrait c. 1856, aged 24 at that time

In 1846 Dodgson entered Rugby School, where he was evidently unhappy, as he wrote some years after leaving: «I cannot say … that any earthly considerations would induce me to go through my three years again … I can honestly say that if I could have been … secure from annoyance at night, the hardships of the daily life would have been comparative trifles to bear.»[12] He did not claim he suffered from bullying, but cited little boys as the main targets of older bullies at Rugby.[13] Stuart Dodgson Collingwood, Dodgson’s nephew, wrote that «even though it is hard for those who have only known him as the gentle and retiring don to believe it, it is nevertheless true that long after he left school, his name was remembered as that of a boy who knew well how to use his fists in defence of a righteous cause», which is the protection of the smaller boys.[13]

Scholastically, though, he excelled with apparent ease. «I have not had a more promising boy at his age since I came to Rugby», observed mathematics master R. B. Mayor.[14] Francis Walkingame’s The Tutor’s Assistant; Being a Compendium of Arithmetic – the mathematics textbook that the young Dodgson used – still survives and it contained an inscription in Latin, which translates to: «This book belongs to Charles Lutwidge Dodgson: hands off!»[15] Some pages also included annotations such as the one found on p. 129, where he wrote «Not a fair question in decimals» next to a question.[16]

He left Rugby at the end of 1849 and matriculated at the University of Oxford in May 1850 as a member of his father’s old college, Christ Church.[17] After waiting for rooms in college to become available, he went into residence in January 1851.[18] He had been at Oxford only two days when he received a summons home. His mother had died of «inflammation of the brain» – perhaps meningitis or a stroke – at the age of 47.[18]

His early academic career veered between high promise and irresistible distraction. He did not always work hard, but was exceptionally gifted, and achievement came easily to him. In 1852, he obtained first-class honours in Mathematics Moderations and was soon afterwards nominated to a Studentship by his father’s old friend Canon Edward Pusey.[19][20] In 1854, he obtained first-class honours in the Final Honours School of Mathematics, standing first on the list, and thus graduated as Bachelor of Arts.[21][22] He remained at Christ Church studying and teaching, but the next year he failed an important scholarship exam through his self-confessed inability to apply himself to study.[23][24] Even so, his talent as a mathematician won him the Christ Church Mathematical Lectureship in 1855,[25] which he continued to hold for the next 26 years.[26] Despite early unhappiness, Dodgson remained at Christ Church, in various capacities, until his death, including that of Sub-Librarian of the Christ Church library, where his office was close to the Deanery, where Alice Liddell lived.[27]

Character and appearance[edit]

Health problems[edit]

The young adult Charles Dodgson was about 6 feet (1.83 m) tall and slender, and he had curly brown hair and blue or grey eyes (depending on the account). He was described in later life as somewhat asymmetrical, and as carrying himself rather stiffly and awkwardly, although this might be on account of a knee injury sustained in middle age. As a very young child, he suffered a fever that left him deaf in one ear. At the age of 17, he suffered a severe attack of whooping cough, which was probably responsible for his chronically weak chest in later life. In early childhood, he acquired a stammer, which he referred to as his «hesitation»; it remained throughout his life.[27]

The stammer has always been a significant part of the image of Dodgson. While one apocryphal story says that he stammered only in adult company and was free and fluent with children, there is no evidence to support this idea.[28] Many children of his acquaintance remembered the stammer, while many adults failed to notice it. Dodgson himself seems to have been far more acutely aware of it than most people whom he met; it is said that he caricatured himself as the Dodo in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, referring to his difficulty in pronouncing his last name, but this is one of the many supposed facts often repeated for which no first-hand evidence remains. He did indeed refer to himself as a dodo, but whether or not this reference was to his stammer is simply speculation.[27]

Dodgson’s stammer did trouble him, but it was never so debilitating that it prevented him from applying his other personal qualities to do well in society. He lived in a time when people commonly devised their own amusements and when singing and recitation were required social skills, and the young Dodgson was well equipped to be an engaging entertainer. He could reportedly sing at a passable level and was not afraid to do so before an audience. He was also adept at mimicry and storytelling, and reputedly quite good at charades.[27]

[edit]

In the interim between his early published writings and the success of the Alice books, Dodgson began to move in the pre-Raphaelite social circle. He first met John Ruskin in 1857 and became friendly with him. Around 1863, he developed a close relationship with Dante Gabriel Rossetti and his family. He would often take pictures of the family in the garden of the Rossetti’s house in Chelsea, London. He also knew William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais, and Arthur Hughes, among other artists. He knew fairy-tale author George MacDonald well – it was the enthusiastic reception of Alice by the young MacDonald children that persuaded him to submit the work for publication.[27][29]

Politics, religion, and philosophy[edit]

In broad terms, Dodgson has traditionally been regarded as politically, religiously, and personally conservative. Martin Gardner labels Dodgson as a Tory who was «awed by lords and inclined to be snobbish towards inferiors».[30] William Tuckwell, in his Reminiscences of Oxford (1900), regarded him as «austere, shy, precise, absorbed in mathematical reverie, watchfully tenacious of his dignity, stiffly conservative in political, theological, social theory, his life mapped out in squares like Alice’s landscape».[31] Dodgson was ordained a deacon in the Church of England on 22 December 1861. In The Life and Letters of Lewis Carroll, the editor states that «his Diary is full of such modest depreciations of himself and his work, interspersed with earnest prayers (too sacred and private to be reproduced here) that God would forgive him the past, and help him to perform His holy will in the future.»[32] When a friend asked him about his religious views, Dodgson wrote in response that he was a member of the Church of England, but «doubt[ed] if he was fully a ‘High Churchman'». He added:

I believe that when you and I come to lie down for the last time, if only we can keep firm hold of the great truths Christ taught us—our own utter worthlessness and His infinite worth; and that He has brought us back to our one Father, and made us His brethren, and so brethren to one another—we shall have all we need to guide us through the shadows. Most assuredly I accept to the full the doctrines you refer to—that Christ died to save us, that we have no other way of salvation open to us but through His death, and that it is by faith in Him, and through no merit of ours, that we are reconciled to God; and most assuredly I can cordially say, «I owe all to Him who loved me, and died on the Cross of Calvary.»

— Carroll (1897)[33]

Dodgson also expressed interest in other fields. He was an early member of the Society for Psychical Research, and one of his letters suggests that he accepted as real what was then called «thought reading».[34] Dodgson wrote some studies of various philosophical arguments. In 1895, he developed a philosophical regressus-argument on deductive reasoning in his article «What the Tortoise Said to Achilles», which appeared in one of the early volumes of Mind.[35] The article was reprinted in the same journal a hundred years later in 1995, with a subsequent article by Simon Blackburn titled «Practical Tortoise Raising».[36]

Artistic activities[edit]

One of Carroll’s own illustrations

Literature[edit]

From a young age, Dodgson wrote poetry and short stories, contributing heavily to the family magazine Mischmasch and later sending them to various magazines, enjoying moderate success. Between 1854 and 1856, his work appeared in the national publications The Comic Times and The Train, as well as smaller magazines such as the Whitby Gazette and the Oxford Critic. Most of this output was humorous, sometimes satirical, but his standards and ambitions were exacting. «I do not think I have yet written anything worthy of real publication (in which I do not include the Whitby Gazette or the Oxonian Advertiser), but I do not despair of doing so someday,» he wrote in July 1855.[27] Sometime after 1850, he did write puppet plays for his siblings’ entertainment, of which one has survived: La Guida di Bragia.[37]

In March 1856, he published his first piece of work under the name that would make him famous. A romantic poem called «Solitude» appeared in The Train under the authorship of «Lewis Carroll». This pseudonym was a play on his real name: Lewis was the anglicised form of Ludovicus, which was the Latin for Lutwidge, and Carroll an Irish surname similar to the Latin name Carolus, from which comes the name Charles.[7] The transition went as follows:

«Charles Lutwidge» translated into Latin as «Carolus Ludovicus». This was then translated back into English as «Carroll Lewis» and then reversed to make «Lewis Carroll».[38] This pseudonym was chosen by editor Edmund Yates from a list of four submitted by Dodgson, the others being Edgar Cuthwellis, Edgar U. C. Westhill, and Louis Carroll.[39]

Alice books[edit]

«The chief difficulty Alice found at first was in managing her flamingo». Illustration by John Tenniel, 1865.

The Jabberwock, as illustrated by John Tenniel for Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking-Glass, including the poem «Jabberwocky».

In 1856, Dean Henry Liddell arrived at Christ Church, bringing with him his young family, all of whom would figure largely in Dodgson’s life over the following years, and would greatly influence his writing career. Dodgson became close friends with Liddell’s wife Lorina and their children, particularly the three sisters Lorina, Edith, and Alice Liddell. He was widely assumed for many years to have derived his own «Alice» from Alice Liddell; the acrostic poem at the end of Through the Looking-Glass spells out her name in full, and there are also many superficial references to her hidden in the text of both books. It has been noted that Dodgson himself repeatedly denied in later life that his «little heroine» was based on any real child,[40][41] and he frequently dedicated his works to girls of his acquaintance, adding their names in acrostic poems at the beginning of the text. Gertrude Chataway’s name appears in this form at the beginning of The Hunting of the Snark, and it is not suggested that this means that any of the characters in the narrative are based on her.[41]

Information is scarce (Dodgson’s diaries for the years 1858–1862 are missing), but it seems clear that his friendship with the Liddell family was an important part of his life in the late 1850s, and he grew into the habit of taking the children on rowing trips (first the boy, Harry, and later the three girls) accompanied by an adult friend[42] to nearby Nuneham Courtenay or Godstow.[43]

It was on one such expedition on 4 July 1862 that Dodgson invented the outline of the story that eventually became his first and greatest commercial success. He told the story to Alice Liddell and she begged him to write it down, and Dodgson eventually (after much delay) presented her with a handwritten, illustrated manuscript entitled Alice’s Adventures Under Ground in November 1864.[43]

Before this, the family of friend and mentor George MacDonald read Dodgson’s incomplete manuscript, and the enthusiasm of the MacDonald children encouraged Dodgson to seek publication. In 1863, he had taken the unfinished manuscript to Macmillan the publisher, who liked it immediately. After the possible alternative titles were rejected – Alice Among the Fairies and Alice’s Golden Hour – the work was finally published as Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland in 1865 under the Lewis Carroll pen-name, which Dodgson had first used some nine years earlier.[29] The illustrations this time were by Sir John Tenniel; Dodgson evidently thought that a published book would need the skills of a professional artist. Annotated versions provide insights into many of the ideas and hidden meanings that are prevalent in these books.[44][45] Critical literature has often proposed Freudian interpretations of the book as «a descent into the dark world of the subconscious», as well as seeing it as a satire upon contemporary mathematical advances.[46][47]

The overwhelming commercial success of the first Alice book changed Dodgson’s life in many ways.[48][49][50] The fame of his alter ego «Lewis Carroll» soon spread around the world. He was inundated with fan mail and with sometimes unwanted attention. Indeed, according to one popular story, Queen Victoria herself enjoyed Alice in Wonderland so much that she commanded that he dedicate his next book to her, and was accordingly presented with his next work, a scholarly mathematical volume entitled An Elementary Treatise on Determinants.[51][52] Dodgson himself vehemently denied this story, commenting «… It is utterly false in every particular: nothing even resembling it has occurred»;[52][53] and it is unlikely for other reasons. As T. B. Strong comments in a Times article, «It would have been clean contrary to all his practice to identify [the] author of Alice with the author of his mathematical works».[54][55] He also began earning quite substantial sums of money but continued with his seemingly disliked post at Christ Church.[29]