| Буква | Название буквы | Звук, транскрипция | Произношение буквы |

|---|---|---|---|

| A a | a | [a] | |

| B b | bi | [b] | |

| C c | ci | [k] [t∫] | |

| D d | di | [d] | |

| E e | e | [e] | |

| F f | effe | [f] | |

| G g | gi | [g] [dg] | |

| H h | acca | не произносится вообще никак | |

| I i | i | [i] | |

| L l | elle | [l] | |

| M m | emme | [m] | |

| N n | enne | [n] | |

| O o | o | [o] | |

| P p | pi | [p] | |

| Q q | qu | [k] | |

| R r | erre | [r] | |

| S s | esse | [s] | |

| T t | ti | [t] | |

| U u | u | [u] | |

| V v | vu | [v] | |

| Z z | zeta | [z] | |

| Следующие пять букв не входят в итальянский алфавит. Они встречаются только в заимствованных иностранных словах. | |||

| J j | i lungа | [j] (i долгое) | |

| K k | cappa | [ k ] | |

| W w | doppiа vu | [v] (v двойное) | |

| X x | ics | [ ks ] | |

| Y y | ipsilon | [i] |

В отличие от русского языка все звуки итальянского языка произносятся очень отчётливо с большим напряжением рта. Итальянские гласные без ударения произносятся также чётко и разборчиво, как без ударения. Гласные могут быть открытыми, закрытыми и долгими (в открытом слоге под ударением.

Итальянские согласные звуки не смягчаются перед гласными e и i. Двойные согласные (например, в слове piccolo, маленький) произносятся очень чётко.

Буквенные сочетания

| gl | — перед i читается примерно как [лльи]: | |

|---|---|---|

| gn | — читается примерно как [нь]: signore — синьор | |

| sc | — перед i, e читается примерно как [ши], [ше]: uscire — выходить | |

| ch | — перед i, e читается как [к]: forchetta — вилка | |

| gh | — перед i, e читается как [г]: ghirigoro — закорючка, каракуля | |

| ci | — перед a, o, u читается примерно как [ч]: ciao | |

| gi | — перед a, o, u читается примерно как [дьж]: buongiorno — добрый день |

Ударение

Почти все итальянские слова заканчиваются на гласные, поэтому речь звучит очень мелодично. Как правило, ударение в итальянских словах падает на предпоследний слог: prego [прéго] — пожалуйста, часто на третий слог от конца: tavolo [тàволо] — стол; иногда — на последний слог: felicità [феличитà] — счастье; редко — на четвёртый слог от конца: mescolano [мéсколано] — перемешивают.

Ударение обозначают апострофом (`):

a) когда оно падает на конечную гласную: felicità

б) в некоторых односложных словах, которые звучат одинаково, для того чтобы отличать их при письме.

| è [э] — есть* dà [да] — даёт tè [тэ] — чай |

е [э] — и (союз) dа [да] — от, из (предлог) te [тэ] — тебя (местоимение) |

* — 3-е лицо, ед. числа глагола essere [эссере], в переводе с итальянского быть.

На артикли, предлоги и местоимения в итальянском языке ударение не падает, они произносятся слитно со следующим за ним словом, образуя с ним одно целое в звуковом отношении:

la luna [лялюна] — луна

ti vedo [тивэдо]- я тебя вижу (в переводе с итальянского)

Примечание: далее в уроках ударение будет обозначаться апострофом, только если оно падает на 3-й или 4-й слог.

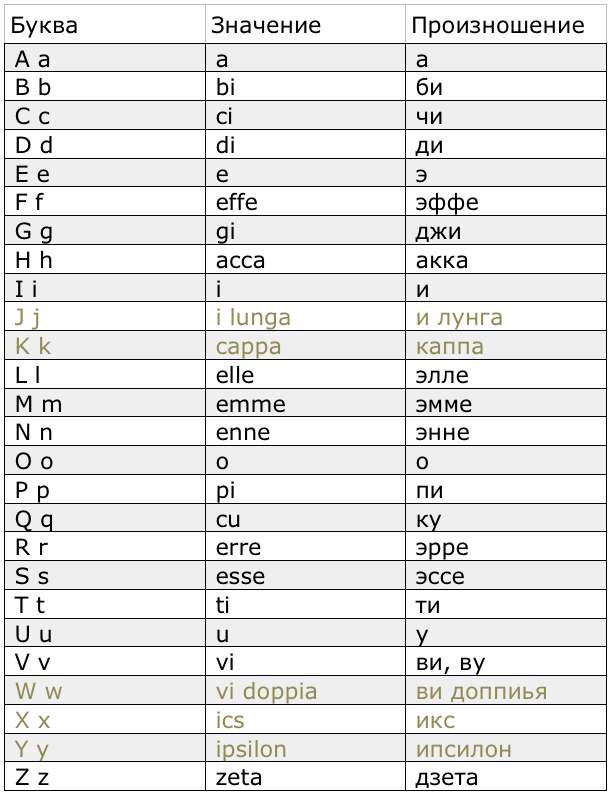

Итальянский алфавит состоит из 21 буквы + 5 дополнительных, которые употребляются в словах иностранного происхождения.

* J j i lunga «и» лунга (длинная)

** W w vi doppia ви доппиья (двойная)

Звуки.

Гласные: A, O, U и E, I.

A ◦ произносится как «а» и после gli, gn как «я»

O ◦ произносится как «о», может обозначать как более закрытый звук [o], так и более открытый звук [ɔ]

U ◦ произносится как «у» и после chi, gli, gn как «ю»

E ◦ произносится как «е» [e] или как «э» [ɛ]; после гласных (кроме i) как правило «э» [ɛ]

I ◦ в большинстве случаев произносится как «и», в нисходящих дифтонгах (как второй элемент, между гласной и согласной) как «й». Не произносится перед гласной после c, g, sc, если не стоит под ударением, а также в сочетаниях ci, cci, chi, gi, gli, sci + гласные a, o, u

Система гласных звуков в итальянском языке

Il sistema vocalico della lingua italiana

Согласные: B, C, D, F, G, H, L, M, N, P, Q, R, S, T, V, Z.

B ◦ произносится как «б»

C ◦ произносится как «к» после согласных и после гласных a, o, u; после гласных e, i читается как «ч»; в сочетаниях sci, sce — как «ш»

D ◦ произносится как «д»

F ◦ произносится как «ф»

G ◦ произносится как «г» после согласных и после гласных a, o, u; после гласных e, i читается как «дж»

H ◦ не произносится

L ◦ произносится как «л», но мягче чем в русском (е смягчается после e, i)

M ◦ произносится как «м»

N ◦ произносится как «н»

P ◦ произносится как «п»

Q ◦ используется только в сочетании qu [kw] и произносится как «ку», причем «у» звечит не так отчетливо. Исключения: soqquadro — беспорядок и biqquadro — бекар.

R ◦ произносится как «р»

S ◦ в начале слов перед глухими согласными и гласными — как «с», перед звонкими согласными как «з», между двумя гласными — как «з»

T ◦ произносится как «т»

V ◦ произносится как «в»

Z ◦ как правило, в начале слов произносится как «дз» (некоторые исключения — zio/zia [цио/циа] — дядя, тетя); а в середине слов как «ц»

Двойные согласные всегда произносятся как двойные.

Произношение иностранных слов близко к произношению оригинала.

Буква «L» перед «A, O, U» произносится более мягко, чем в русском, а перед «E, I» не так смягчается.

Итальянские слова большей частью произносятся так же, как и пишутся. В итальянском языке нет редукции и гласные, которые находятся в безударном положении, всегда звучат отчетливо. Произношение согласных букв тоже происходит гораздо напряженнее и четче, чем в русском языке, а перед такими гласными, как «E, I» согласные не намного смягчаются.

Особенно важно произношение гласных на конце слов, поскольку многие слова имеют одну основу, но в зависимости от окончания могут быть как женского, так и мужского рода или менять значение более кардинально.

Дифтонги — это слияние двух гласных звуков

нисходящие

/ai/ как в слове avrai

/ei/ как в слове dei

/ɛi/ как в слове direi

/oi/ как в слове voi

/ɔi/ как в слове poi

/au/ как в слове pausa

/eu/ как в слове Europa

/ɛu/ как в слове feudo

* e — «е»

* ɛ — «э»

* ɔ — долгий звук «о»

восходящие

/ja/ как в слове piano — йа

/je/ как в слове ateniese — йе

/jɛ/ как в слове piede — йэ

/jo/ как в слове fiore — йо

/jɔ/ как в слове piove — йО

/ju/ как в слове più — йу

/wa/ как в слове guado — уа

/we/ как в слове quello — уе

/wɛ/ как в слове guerra — уэ

/wi/ как в слове qui — уи

/wo/ как в слове liquore — уо

/wɔ/ как в слове nuoto — уО

Трифтонги — это три гласные, стоящие рядом, которые образуют один звук.

Пример: aiutare, aiola, paio, miei, tuoi, suoi

Полифтонги — четыре и более гласные, образующие один звук.

Примеры: gioiello, cuoio, gioia

Диакрити́ческие знаки в итальянском языке.

à, è, é, ì, í, î, ò, ó, ù, ú

«´» Аку́т (l’accento acuto) — острое ударение, наклон вправо. В словах с ударением на последнем слоге и в нескольких служебных односложных словах.

Примеры: perché, affinché, poiché, benché, cosicché, nonché, purché…

«`» Гра́вис (l’accento grave) — низкое (слабое или обратное) ударение, наклон влево. Указывает на открытость гласного и подчеркивает что слог ударный. Такие слова не меняют окончания во множественном числе и, для того, чтобы обозначить множественное число, перед словом ставится артикль. Используется также в середине слов в географических названиях.

Примеры: città, caffè, capacità, verità; окончания глаголов в простом будущем времени в ед.ч. 1-го и 3-го лица — sarò/sarà, potrò/potrà, ecc.; Mònako (di Baviera) — Мюнхен (как ни странно), Княжество Монако — Monaco.

« Î, î » («острая шапочка») — используется в формировании множественного числа существительных мужского рода, оканчивающихся на «-io», чтобы избежать омографии. Использование устаревает, пишут окончание «-i» и в случае единственного числа «-io» и «-e». Пример: principio — начало, основа, мн.ч. principî, principe – князь, принц, мн.ч. principi.

« ’ » Апостроф в итальянском ставится на месте элизии, в некоторых случаях усечения закодированных слов и при написании дат, если из контекста ясно о каком периоде идёт речь (напр. ’68). Подробно об элизии.

Ударение

Ударение, в итальянском языке, как правило, падает в словах на предпоследний слог. Такие слова в итальянской грамматике называются «parole piane». Но это правило имеет довольно много исключений.

В многосложных словах, насчитывающих 4 слога — «parole sdrucciole» (sdrucciole — скользящий, покатый) — ударение, как правило, падает на второй слог: meccanico (механик), interprete (переводчик).

В многосложных словах, состоящих из более 4-х и более слогов — «parole bisdrucciole» (bis — дважды, вторично + brucatura — сбор листев, оливок…) — ударение, как правило, падает на первый слог или слово имеет несколько ударений.

Есть небольшая группа слов, состоящих только из корня — «parole tronche» (усечённые слова) — ударение в данном случае показывает знак «´» (акут), но не все слова произносятся с ударением на этом слоге. Примеры: perché (почему, потому что), affinché (чтобы, для того), poiché (поскольку, потому что), benché (хотя, несмотря на то, что), cosicché (так что), nonché (не то чтобы не только…), purché (лишь бы, только бы), и т.д.

Полезные слова и выражения

Ciao [di incontro] – Привет

Salve – Здравствуйте / Здравствуй

Buongiorno – Добрый день (также утром)

Buona sera – Добрый вечер (после 16:00)

Buona notte – Доброй ночи

Buona giornata – Хорошего дневного времени Buona serata – Хорошего вечернего времени Buona notata – Хорошего ночного времени

Buon pomeriggio – Хорошего времени после обеда

Ciao, ciao-ciao [di congedo] – Пока

Arrivederci – До свидания (когда на «ты»)

ArrivederLa – До свидания (когда на «Вы»)

Ci vediamo – Увидимся (букв. «мы видимся»)

A presto – До скорого (когда неизвестно когда увидятся в следующий раз)

A dopo – букв. До «после» (когда планируют встретится в ближайшее или запланированное время)

A più tardi – букв. До «позднее» (когда планируют встретиться чуть позднее, в этот же день)

Часто при прощании желают хорошего времяпровождения в определённое время суток, то есть «Buona giornata», «Buona serata», «Buon pomeriggio».

Упражнения на чтение.

[К]: ca/co/cu // [Ч]: ce/ci

[Ча, Чо, Чу]: cia/cio/ciu // [Кья, Кье, Кьё, Кью]: chia/chie/chio/chiu

caro/cara; cari/care — дорогой/дорогая; дорогие

comodo — удобный

cura — забота

centro — центр

cibo — пища

ciao — привет, пока

ciò — это, то

ciuco — осёл (больше в переносном)

chiaro/chiara; chiari/chiare — ясный/ясная; ясные

chiesa — церковь

chiuso — закрытый

chioccia — наседка

[Г]: ga/go/gu // [ДЖ]: ge/gi

[ДЖа, ДЖо, ДЖу]: gia/gio/giu // [Гья, Гьё]: ghia/ghio

gallo — петух

gola — горло

gufo — филин

gelato — мороженое

gita — прогулка

giallo — жёлтый

giorno — день

giuba — грива

ghiaccio — лёд

ghiotta — противень

s+ звонкая согласная [З]:

svago — веселье, развлечение (процесс)

sdraiarsi — лежать

sdraio — лежание, шезлонг

s+ глухая согласная [С]:

storia — история

scala — лестница

sport — спорт

s между гласными [З]:

sposo/sposa — жених/невеста

casa — дом

ss между гласными [СС]:

spesso — часто

cassa — касса

[Ш,Щ]: sce/sci // [СК]: sche/schi

scena — сцена, подмостки

sci — лыжный спорт (лыжное катание)

schema — схема

schizzo — брызганье

-о/-а/-i/-e на конце слов (не редуцировать!):

bambino — мальчик, ребёнок

bambina — девочка

bambini — мальчики, дети

bambine — девочки

двойные согласные:

sabbia — песок

abbraccio — объятие

succo — сок

addio — пока, в смысле «прощай»

offerta — предложение, оферта

aggancio — связь, сцепка

oggi — сегодня

ballo — танец, балет

mamma — мама

sonno — сон

cappello/cappella/capello — шляпа/капелла/волос

soqquadro — беспорядок

arrivo — прибытие

massa — масса

mattino/mattina — утро

avvocato — адвокат, юрист, защитник

pizza — пицца

macchina — машина

macchiato — пятнистый, чуть приправленный

(например: caffè macchiato/latte macchiato — кофе с каплей молока/молоко с каплей кофе)

дифтонги:

восходящие

guida [уИ] — проводник, гид, путеводитель

suono [уО] — звук

uomo [уО] — мужчина

paese [аЭ] — страна, местность, место

cuore [уО] — сердце

нисходящие

pausa [Ау] — пауза, затишье

causa [Ау] — причина, дело

feudo [Эу] — феодальное владение (также переносно)

гласная + i

dei [эй] — неопр. (частичный) артикль (м.р. мн.ч.)

direi [эй] — сказал(-а) бы

poi [ой] — потом

questo/questa [уЭ] — этот/эта

quello/quella [уЭ] — тот/та

трифтонги:

paio [Аио] — пара

aiuto [айУ] — помошь

aiola [айО] — газон с цветами

miei/tuoi/suoi [иЭи/уОи/уОи] — мои/твои/свои

полифтонги:

gioiello [ойе] — украшение, драгоценность

gioia [Ойа] — радость

aiuola [айуО] — клумба

cuoio [уОйо] — выделанная кожа

cuoiaio [уОйАйо] — кожевник

stuoia [уОйа] — циновка

stuoiaio [уОайо] — циновщик

© Lara Leto (Ci Siciliano), 2016

© Италия и итальянский язык. Путешествуй красиво, учись легко, 2016

Наше знакомство с итальянским алфавитом начинается сразу с двух приятных новостей. Первая – это самый короткий алфавит из распространенных языков – всего 21 буква! И вторая — те, кто знает хоть один из европейских языков или начинал его изучать, вряд ли испытает трудности в усвоении итальянского алфавита – вы уже почти все знаете!

Я все-таки считаю, что недостаточно понимать, как читаются и звучат слова, нужно еще запомнить итальянский алфавит с произношением – это поможет избежать многих недоразумений. Например, когда вы диктуете свое имя или электронный адрес – их нужно называть по буквам. Итальянцам не очень легко воспринимать и правильно писать иностранные имена, они часто допускают ошибки, особенно, при передаче таких русских букв, как «е», «ю», «я». Для отображения этих звуков на письме они будут использовать две буквы.

Почти каждый учебник итальянского языка, в том числе и выбранный мной — Практический курс от Langenscheidt, начинается с алфавита. Но не во всех описывается звучание буквы достаточно четко, поэтому советую посмотреть видео в конце урока. Это позволит вам заучить звуки правильно сразу, и не нужно будет переучивать себя в дальнейшем.

Ниже я привожу итальянский алфавит с транскрипцией, буквы расположены по следующей схеме:

написание – итальянское название – русское соответствие

Aa — a [a] — а

Bb — bi [би] — б

Cc — сi [чи] — к, ч

Dd — di [ди] — д

Ee — e [э] — э

Ff — effe [эффэ] — ф

Gg — gi [джи] — г, дж

Hh — acca [акка] – немая, не прозносится

Ii — i [и] — и

Ll — elle [эллэ] — ль

Mm — emme [эммэ] — м

Nn — enne [эннэ] -н

Oo — о [о] — о

Pp — pi [пи] — п

Qq — qu [ку] — к

Rr — erre [эррэ] — р

Ss — esse [эссэ] — с, з

Tt — ti [ти] — т

Uu — u [у] — у

Vv — vu [ву] — в

Zz — zeta [дзета] — ц, дз

По традиции в языках, использующих латинскую письменность, слова иностранного происхождения пишут также как на исходном языке. Это немного неудобно для определения правильного произношения и не только. В итальянском языке возникает необходимость употреблять дополнительные буквы для сохранения оригинального написания. Для этой цели итальянцы используют пять «неитальянских» букв. Это:

Jj – i lunga [и лунга]

Kk – cappa [каппа]

Ww – vu doppia[ву доппья]

Xx – ics [икс]

Yy – ipsilon [ипсилон]

На следующей картинке можно увидеть итальянские буквы прописью. Возможно, вы встретитесь не только с печатным текстом, поэтому обратите особое внимание на те буквы, которые на письме отличаются. Конечно же, написание будет зависеть и от почерка, и от характера человека, но общий вид сохранится, и вы сможете прочитать послание – а это главное. Попробуйте сами что-то написать.

Открыв любой текст на итальянском, можно увидеть над гласными буквами диакритические знаки: à, è, é, ì, í, î, ò, ó, ù, ú. Они используются для:

1) указания, что ударение падает на последний слог, например, città, perché;

2) в односложных словах, когда ударение будет на втором слоге, например, già, può;

3) в односложных омонимах, чтобы различить смысл, например, da ( с ) – dà (он, она дает), e (и) – è (он, она является), se (если бы) – sé (себя).

Острое (привычное нам) ударение (акут) – указывает на закрытый гласный, а обратное ударение (гравис) – ставят над гласными, чтобы показать их открытость.

Ниже размещаю два интересных видео, которые могут помочь запомнить алфавит. Первое видео содержит название букв и примеры со словами и картинками, второе – детскую песенку про алфавит, спетую носителями языка. Очень жаль, что я пока не могу разобрать слова. Кто знает итальянский — отзовитесь, напишите в комментариях, что поют и как это переводится.

Чтобы быть в курсе самого интересного, подпишитесь на рассылку:

Italian orthography (the conventions used in writing Italian) uses 21 letters of the 26-letter Latin alphabet to write the Italian language. This article focuses on the writing of Standard Italian, based historically on the Florentine dialect,[1] and not the other Italian dialects.

Written Italian is very regular and almost completely phonemic – having an almost one-to-one correspondence between letters (or sequences of letters) and sounds (or sequences of sounds). The main exceptions are that stress placement and vowel quality (for ⟨e⟩ and ⟨o⟩) are not notated, ⟨s⟩ and ⟨z⟩ may be voiced or not, ⟨i⟩ and ⟨u⟩ may represent vowels or semivowels, and a silent ⟨h⟩ is used in a very few cases other than the digraphs ⟨ch⟩ and ⟨gh⟩ (used for the hard ⟨c⟩ and ⟨g⟩ sounds before ⟨e⟩ and ⟨i⟩).

Alphabet[edit]

The base alphabet consists of 21 letters: five vowels (A, E, I, O, U) and 16 consonants. The letters J, K, W, X and Y are not part of the proper alphabet, and appear only in loanwords (e.g. ‘jeans’, ‘weekend’),[2] foreign names, and in a handful of native words—such as the names Jesolo, Bettino Craxi, and Walter, which all derive from regional languages. In addition, grave and acute accents may modify vowel letters; circumflex accent is much rarer and is found only in older texts.

An Italian computer keyboard layout

An Italian handwriting script, taught in primary school

| Letter | Name | IPA | Diacritics |

|---|---|---|---|

| A, a | a [ˈa] | /a/ | à |

| B, b | bi [ˈbi] | /b/ | |

| C, c | ci [ˈtʃi] | /k/ or /tʃ/ | |

| D, d | di [ˈdi] | /d/ | |

| E, e | e [ˈe] | /e/ or /ɛ/ | è, é |

| F, f | effe [ˈɛffe] | /f/ | |

| G, g | gi [ˈdʒi] | /ɡ/ or /dʒ/ | |

| H, h | acca [ˈakka] | ∅ silent | |

| I, i | i [ˈi] | /i/ or /j/ | ì, í, [î] |

| L, l | elle [ˈɛlle] | /l/ | |

| M, m | emme [ˈɛmme] | /m/ | |

| N, n | enne [ˈɛnne] | /n/ | |

| O, o | o [ˈɔ] | /o/ or /ɔ/ | ò, ó |

| P, p | pi [ˈpi] | /p/ | |

| Q, q | cu (qu) [ˈku] | /k/ | |

| R, r | erre [ˈɛrre] | /r/ | |

| S, s | esse [ˈɛsse] | /s/ or /z/ | |

| T, t | ti [ˈti] | /t/ | |

| U, u | u [ˈu] | /u/ or /w/ | ù, ú |

| V, v | vi [ˈvi], vu [ˈvu] | /v/ | |

| Z, z | zeta [ˈdzɛːta] | /ts/ or /dz/ |

Consonants written double represent true geminates and are pronounced as such: anno ‘year’, pronounced [ˈanno] (cf. English ten nails). The short–long length contrast is phonemic, e.g. ritto [ˈritto] ‘upright’ vs. rito [ˈriːto] ‘rite, ritual’, carro [ˈkarro] ‘cart, wagon’ vs. caro [ˈkaːro] ‘dear, expensive’.

Vowels[edit]

The Italian alphabet has five vowel letters, ⟨a e i o u⟩. Of those, only ⟨a⟩ represents one sound value, while all others have two. In addition, ⟨e⟩ and ⟨i⟩ indicate a different pronunciation of a preceding ⟨c⟩ or ⟨g⟩ (see below).

In stressed syllables, ⟨e⟩ represents both open /ɛ/ and close /e/. Similarly, ⟨o⟩ represents both open /ɔ/ and close /o/ (see Italian phonology for further details on those sounds). There is typically no orthographic distinction between the open and close sounds represented, though accent marks are used in certain instances (see below). There are some minimal pairs, called heteronyms, where the same spelling is used for distinct words with distinct vowel sounds. In unstressed syllables, only the close variants occur.

In addition to representing the respective vowels /i/ and /u/, ⟨i⟩ and ⟨u⟩ also typically represent the semivowels /j/ and /w/, respectively, when unstressed and occurring before another vowel. Many exceptions exist (e.g. attuale, deciduo, deviare, dioscuro, fatuo, iato, inebriare, ingenuo, liana, proficuo, riarso, viaggio). An ⟨i⟩ may indicate that a preceding ⟨c⟩ or ⟨g⟩ is ‘soft’ (ciao).

C and G[edit]

The letters ⟨c⟩ and ⟨g⟩ represent the plosives /k/ and /ɡ/ before ⟨r⟩ and before the vowels ⟨a⟩, ⟨o⟩, ⟨u⟩. They represent the affricates /tʃ/ and /dʒ/ respectively when they precede a front vowel (⟨i⟩ or ⟨e⟩).

The letter ⟨i⟩ can also function within digraphs (two letters representing one sound) ⟨ci⟩ and ⟨gi⟩ to indicate «soft» (affricate) /tʃ/ or /dʒ/ before another vowel. In these instances, the vowel following the digraph is stressed, and ⟨i⟩ represents no vowel sound: ciò (/tʃɔ/), giù (/dʒu/). An item such as CIA ‘CIA’, pronounced /ˈtʃi.a/ with /i/ stressed, contains no digraph.

For words of more than one syllable, stress position must be known in order to distinguish between digraph ⟨ci⟩ or ⟨gi⟩ containing no actual phonological vowel /i/ and sequences of affricate and stressed /i/. For example, the words camicia «shirt» and farmacia «pharmacy» share the spelling ⟨-cia⟩, but contrast in that only the first ⟨i⟩ is stressed in camicia, thus ⟨-cia⟩ represents /tʃa/ with no /i/ sound (likewise, grigio ends in /dʒo/ and the names Gianni and Gianna contain only two actual vowels: /ˈdʒanni/, /ˈdʒanna/). In farmacia /i/ is stressed, so that ⟨ci⟩ is not a digraph, but represents two of the three constituents of /ˈtʃi.a/.

When the «hard» (plosive) pronunciation /k/ or /ɡ/ occurs before a front vowel ⟨i⟩ or ⟨e⟩, digraphs ⟨ch⟩ and ⟨gh⟩ are used, so that ⟨che⟩ represents /ke/ or /kɛ/ and ⟨chi⟩ represents /ki/ or /kj/. The same principle applies to ⟨gh⟩: ⟨ghe⟩ and ⟨ghi⟩ represent /ɡe/ or /ɡɛ/ and /ɡi/ or /ɡj/.

In the evolution from Latin to Italian, the postalveolar affricates /tʃ/ and /dʒ/ were contextual variants of the velar consonants /k/ and /ɡ/. They eventually came to be full phonemes, and orthographic adjustments were introduced to distinguish them. The phonemicity of the affricates can be demonstrated with minimal pairs:

| Plosive | Affricate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before ⟨i⟩, ⟨e⟩ | ch | china /ˈkina/ ‘India ink’ | c | Cina /ˈtʃina/ ‘China’ |

| gh | ghiro /ˈɡiro/ ‘dormouse’ | g | giro /ˈdʒiro/ ‘lap’, ‘tour’ | |

| Elsewhere | c | caramella /karaˈmɛlla/ ‘candy’ | ci | ciaramella /tʃaraˈmɛlla/ ‘shawm’ |

| g | gallo /ˈɡallo/ ‘rooster’ | gi | giallo /ˈdʒallo/ ‘yellow’ |

The trigraphs ⟨cch⟩ and ⟨ggh⟩ are used to indicate geminate /kk/ and /ɡɡ/, respectively, when they occur before ⟨i⟩ or ⟨e⟩; e.g. occhi /ˈɔkki/ ‘eyes’, agghindare /aɡɡinˈdare/ ‘to dress up’. The double letters ⟨cc⟩ and ⟨gg⟩ before ⟨i⟩ or ⟨e⟩ and ⟨cci⟩ and ⟨ggi⟩ before other vowels represent the geminated affricates /ttʃ/ and /ddʒ/, e. g. riccio ‘hedgehog’, peggio ‘worse’.

⟨g⟩ joins with ⟨l⟩ to form a digraph representing palatal /ʎ/ before ⟨i⟩, and with ⟨n⟩ to represent /ɲ/ with any vowel following. Between vowels these are pronounced phonetically long, as in /ˈaʎʎo/ aglio ‘garlic’, /ˈoɲɲi/ ogni ‘each’. By way of exception, ⟨gl⟩ before ⟨i⟩ represents /ɡl/ in some words derived from Greek, such as glicine ‘wisteria’, from learned Latin, such as negligente ‘negligent’, and in a few adaptations from other languages such as glissando [ɡlisˈsando], partially italianised from French glissant. ⟨gl⟩ before vowels other than ⟨i⟩ represents straightforward /ɡl/.

The digraph ⟨sc⟩ is used before ⟨e⟩ and ⟨i⟩ to represent /ʃ/; before other vowels, ⟨sci⟩ is used for /ʃ/. Otherwise, ⟨sc⟩ represents /sk/, the ⟨c⟩ of which follows the normal orthographic rules explained above.

| /sk/ | /ʃ/ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before ⟨i e⟩ | sch | scherno /ˈskɛrno/ | sc | scerno /ˈʃɛrno/ |

| Elsewhere | sc | scalo /ˈskalo/ | sci | scialo /ˈʃalo/ |

Intervocalic /ʎ/, /ɲ/, and /ʃ/ are always geminated and no orthographic distinction is made to indicate this.[3]

C and Q[edit]

Normally /kw/ is represented by ⟨qu⟩, but it is represented by ⟨cu⟩ in some words, such as cuoco, cuoio, cuore, scuola, scuotere and percuotere. These words all contain a /kwɔ/ sequence derived from an original /kɔ/ which was subsequently diphthongised. The sequence /kkw/ is always spelled ⟨cqu⟩ (e.g. acqua), with exceptions being spelled ⟨qqu⟩ in the words soqquadro, its derivation soqquadrare, and beqquadro and biqquadro, two alternative forms of bequadro or biquadro.[4]

S and Z[edit]

⟨s⟩ and ⟨z⟩ are ambiguous to voicing.

⟨s⟩ represents a dental sibilant consonant, either /s/ or /z/. However, these two phonemes are in complementary distribution everywhere except between two vowels in the same word and, even with such words, there are very few minimal pairs.

- The voiceless /s/ occurs:

- At the start of a word before a vowel (e.g. Sara /ˈsara/) or a voiceless consonant (e.g. spuntare /spunˈtare/)

- After any consonant (e.g. transitare /transiˈtare/)

- Before a voiceless consonant (e.g. raspa /ˈraspa/)

- At the start of the second part of a compound word (e.g. affittasi, disotto, girasole, prosegue, risaputo, reggiseno). These words are formed by adding a prefix to a word beginning with /s/

- The voiced /z/ occurs before voiced consonants (e.g. sbranare /zbraˈnare/).

- It can be either voiceless or voiced (/s/ or /z/) between vowels; in standard Tuscany-based pronunciation some words are pronounced with /s/ between vowels (e.g. casa, cosa, così, mese, naso, peso, cinese, piemontese, goloso); in Northern Italy (and also increasingly in Tuscany) ⟨s⟩ between vowels is always pronounced with /z/ whereas in Southern Italy ⟨s⟩ between vowels is always pronounced /s/.

⟨ss⟩ always represents voiceless /ss/: grosso /ˈɡrɔsso/, successo /sutˈtʃɛsso/, passato /pasˈsato/, etc.

⟨z⟩ represents a dental affricate consonant; either /dz/ (zanzara /dzanˈdzara/) or /ts/ (canzone /kanˈtsone/), depending on context, though there are few minimal pairs.

- It is normally voiceless /ts/:[5]

- At the start of a word in which the second syllable starts with a voiceless consonant (zampa /ˈtsampa/, zoccolo /ˈtsɔkkolo/, zufolo /ˈtsufolo/)

- Exceptions (because they are of Greek origin): zaffiro, zefiro, zotico, zeta, zafferano, Zacinto

- When followed by an ⟨i⟩ which is followed, in turn, by another vowel (e.g. zio /ˈtsi.o/, agenzia /adʒenˈtsi.a/, grazie /ˈɡratsje/)

- Exceptions: azienda /aˈdzjɛnda/, all words derived from words obeying other rules (e.g. romanziere /romanˈdzjɛre/, which is derived from romanzo)

- After the letter ⟨l⟩ (e.g. alzare /alˈtsare/)

- Exceptions: elzeviro /eldzeˈviro/ and Belzebù /beldzeˈbu/

- In the suffixes -anza, -enza and -onzolo (e.g. usanza /uˈzantsa/, credenza /kreˈdɛntsa/, ballonzolo /balˈlontsolo/)

- At the start of a word in which the second syllable starts with a voiceless consonant (zampa /ˈtsampa/, zoccolo /ˈtsɔkkolo/, zufolo /ˈtsufolo/)

- It is normally voiced /dz/:

- At the start of a word in which the second syllable starts with a voiced consonant or ⟨z⟩ (or ⟨zz⟩) itself (e.g. zebra /ˈdzɛbra/, zuzzurellone /dzuddzurelˈlone/)

- Exceptions: zanna /ˈtsanna/, zigano /tsiˈɡano/

- At the start of a word when followed by two vowels (e.g. zaino /ˈdzaino/)

- Exceptions: zio and its derived terms (see above)

- If it is single (not doubled) and between two single vowels (e.g. azalea /addzaˈlɛa/)

- Exceptions: nazismo /natˈtsizmo/ (from the German pronunciation of ⟨z⟩)

- At the start of a word in which the second syllable starts with a voiced consonant or ⟨z⟩ (or ⟨zz⟩) itself (e.g. zebra /ˈdzɛbra/, zuzzurellone /dzuddzurelˈlone/)

Between vowels and/or semivowels (/j/ and /w/), ⟨z⟩ is pronounced as if doubled (/tts/ or /ddz/, e.g. vizio /ˈvittsjo/, polizia /politˈtsi.a/). Generally, intervocalic z is written doubled, but it is written single in most words where it precedes ⟨i⟩ followed by any vowel and in some learned words.

⟨zz⟩ may represent either a voiceless alveolar affricate /tts/ or its voiced counterpart /ddz/:[6] voiceless in e.g. pazzo /ˈpattso/, ragazzo /raˈɡattso/, pizza /ˈpittsa/, grandezza /ɡranˈdettsa/, voiced in razzo /ˈraddzo/, mezzo /ˈmɛddzo/, azzardo /adˈdzardo/, azzurro /adˈdzurro/, orizzonte /oridˈdzonte/, zizzania /dzidˈdzanja/. Most words are consistently pronounced with /tts/ or /ddz/ throughout Italy in the standard language (e.g. gazza /ˈgaddza/ ‘magpie’, tazza /ˈtattsa/ ‘mug’), but a few words, such as frizzare ‘effervesce, sting’, exist in both voiced and voiceless forms, differing by register or by geographic area, while others have different meanings depending on whether they are pronounced in voiced or voiceless form (e.g. razza: /ˈrattsa/ (race, breed) or /ˈraddza/ (ray, skate)).[7][8] The verbal ending -izzare from Greek -ίζειν is always pronounced /ddz/ (e.g. organizzare /orɡanidˈdzare/), maintained in both inflected forms and derivations: organizzo /orɡaˈniddzo/ ‘I organise’, organizzazione /orɡaniddzatˈtsjone/ ‘organisation’. Like frizzare above, however, not all verbs ending in —izzare continue suffixed Greek -ίζειν), having instead —izz— as part of the verb stem. Indirizzare, for example, of Latin origin reconstructed as *INDIRECTIARE, has /tts/ in all forms containing the root indirizz-.

Silent H[edit]

In addition to being used to indicate a hard ⟨c⟩ or ⟨g⟩ before front vowels (see above), ⟨h⟩ is used to distinguish ho, hai, ha, hanno (present indicative of avere, ‘to have’) from o (‘or’), ai (‘to the’, m. pl.), a (‘to’), anno (‘year’); since ⟨h⟩ is always silent, there is no difference in the pronunciation of such words. The letter ⟨h⟩ is also used in some interjections, where it always comes immediately after the first vowel in the word (e.g. eh, boh, ahi, ahimè), as well as in some loanwords (e.g. hotel).[4] In filler words ehm and uhm both ⟨h⟩ and the preceding vowel are silent.[9][10]

J, K, W, X and Y[edit]

The letters J (I lunga ‘long I’), K (cappa), W (V doppia or doppia V ‘double V’), X (ics) and Y (ipsilon or I greca ‘Greek I’) are used only in loanwords, proper names and archaisms, with few exceptions.[citation needed]

In modern standard Italian spelling, the letter ⟨j⟩ is used only in Latin words, proper nouns (such as Jesi, Letojanni, Juventus etc.) and words borrowed from foreign languages. Until the 19th century, ⟨j⟩ was used instead of ⟨i⟩ in diphthongs, as a replacement for final -ii, and in vowel groups (as in Savoja); this rule was quite strict in official writing. ⟨j⟩ is also used to render /j/ in dialectal spelling, e.g. Romanesco dialect ajo /ˈajjo/ («garlic»; cf. Italian aglio /ˈaʎʎo/).

The letter ⟨k⟩ is not in the standard alphabet and exists only in unassimilated loanwords, although it is often used informally among young people as a replacement for ⟨ch⟩, paralleling the use of ⟨k⟩ in English (for example, ke instead of che).

Also ⟨w⟩ is only used in loanwords, mainly of Germanic origin. A capital W is used as an abbreviation of viva or evviva («long live»).

In Italian, ⟨x⟩ represents either /ks/, as in extra, uxorio, xilofono, or /ɡz/, as exoterico, when it is preceded by ⟨e⟩ and followed by a vowel.[11] In several related languages, notably Venetian, it represents the voiced sibilant /z/. It is also used, mainly amongst the young people, as a short written form for per, meaning «for» (for example x sempre, meaning «forever»): this is because in Italian the multiplication sign (similar to ⟨x⟩) is called per. However, ⟨x⟩ is found only in loanwords, as it is not part of the standard Italian alphabet; in most words with ⟨x⟩, this letter may be replaced with ‘s’ or ‘ss’ (with different pronunciation: xilofono/silofono, taxi/tassì) or, rarely, by ‘cs’ (with the same pronunciation: claxon/clacson).

Diacritics[edit]

The acute accent (´) may be used on ⟨é⟩ and ⟨ó⟩ to represent close-mid vowels when they are stressed in a position other than the default second-to-last syllable. This use of accents is generally mandatory only to indicate stress on a word-final vowel; elsewhere, accents are generally found only in dictionaries. Since final ⟨o⟩ is hardly ever close-mid, ⟨ó⟩ is very rarely encountered in written Italian (e.g. metró ‘subway’, from the original French pronunciation of métro with a final-stressed /o/).

The grave accent (`) is found on ⟨à⟩, ⟨è⟩, ⟨ì⟩, ⟨ò⟩, ⟨ù⟩. It may be used on ⟨è⟩ and ⟨ò⟩ when they represent open-mid vowels. The accents may also be used to differentiate minimal pairs within Italian (for example pèsca ‘peach’ vs. pésca ‘fishing’), but in practice this is limited to didactic texts. In the case of final ⟨ì⟩ and ⟨ù⟩, both possibilities are encountered. By far the most common option is the grave accent, ⟨ì⟩ and ⟨ù⟩, though this may be due to the rarity of the acute accent to represent stress; the alternative of employing the acute, ⟨í⟩ and ⟨ú⟩, is in practice limited to erudite texts, but can be justified as both vowels are high (as in Catalan). However, since there are no corresponding low (or lax) vowels to contrast with in Italian, both choices are equally acceptable.

The circumflex accent (^) can be used to mark the contraction of two unstressed vowels /ii/ ending a word, normally pronounced [i], so that the plural of studio ‘study, office’ may be written ⟨studi⟩, ⟨studii⟩ or ⟨studî⟩. The form with circumflex is found mainly in older texts, though it may still appear in contexts where ambiguity might arise from homography. For example, it can be used to differentiate words like geni (‘genes’, plural of gene) and genî (‘geniuses’, plural of genio). In general, current usage usually prefers a single ⟨i⟩ instead of a double ⟨ii⟩ or an ⟨î⟩ with circumflex.[12]

Monosyllabic words generally lack an accent (e.g. ho, me). The accent is written, however, if there is an ⟨i⟩ or a ⟨u⟩ preceding another vowel (più, può). This applies even if the ⟨i⟩ is «silent», i.e. part of the digraphs ⟨ci⟩ or ⟨gi⟩ representing /tʃ/ and /dʒ/ (ciò, giù). It does not apply, however, if the word begins with ⟨qu⟩ (qua, qui). Many monosyllabic words are spelled with an accent in order to avoid ambiguity with other words (e.g. là, lì versus la, li). This is known as accento distintivo and also occurs in other Romance languages (e.g. the Spanish tilde diacrítica).

Sample text[edit]

«Nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita

mi ritrovai per una selva oscura

ché la diritta via era smarrita.»

Lines 1–3 of Canto 1 of the Inferno, Part 1 of the Divina Commedia by Dante Alighieri, a highly influential poem. Translation (Longfellow): «Midway upon the journey of our life I found myself in a dark wood for the straight way was lost.»[13]

See also[edit]

- Gian Giorgio Trissino, humanist who proposed an orthography in 1524. Some of his proposals were taken.

- Claudio Tolomei, humanist who proposed an orthography in 1525.

Notes[edit]

- ^ Maiden & Robustelli 2014, p. 4.

- ^ «Italian Extraction Guide – Section A: Italian Handwriting» (PDF). Brigham Young University. 1981. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

The letters J, K, W, X, and Y appear in the Italian alphabet, but are used mainly in foreign words adopted into the Italian vocabulary.

- ^ Maiden & Robustelli 2014, p. 10.

- ^ a b Maiden & Robustelli 2014, p. 5.

- ^ Dizionario d’ortografia e di pronunzia.

- ^ Dizionario d’ortografia e di pronunzia.

- ^ Dizionario d’ortografia e di pronunzia.

- ^ Dizionario di pronuncia italiana online.

- ^ Dizionario d’ortografia e di pronunzia

- ^ Dizionario d’ortografia e di pronunzia

- ^ «x, X in Vocabolario — Treccani» [x, X in Vocabulary — Treccani]. Treccani (in Italian). Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- ^ Maiden & Robustelli 2014, pp. 4–5.

- ^ «Inferno 1». Digital Dante. Retrieved April 22, 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link)

References[edit]

- Maiden, Martin; Robustelli, Cecilia (2014). A Reference Grammar of Modern Italian (2nd ed.). Routledge. ISBN 9781444116786. Retrieved June 19, 2021.

External links[edit]

- Danesi, Marcel (1996). Italian the Easy way.

Italian orthography (the conventions used in writing Italian) uses 21 letters of the 26-letter Latin alphabet to write the Italian language. This article focuses on the writing of Standard Italian, based historically on the Florentine dialect,[1] and not the other Italian dialects.

Written Italian is very regular and almost completely phonemic – having an almost one-to-one correspondence between letters (or sequences of letters) and sounds (or sequences of sounds). The main exceptions are that stress placement and vowel quality (for ⟨e⟩ and ⟨o⟩) are not notated, ⟨s⟩ and ⟨z⟩ may be voiced or not, ⟨i⟩ and ⟨u⟩ may represent vowels or semivowels, and a silent ⟨h⟩ is used in a very few cases other than the digraphs ⟨ch⟩ and ⟨gh⟩ (used for the hard ⟨c⟩ and ⟨g⟩ sounds before ⟨e⟩ and ⟨i⟩).

Alphabet[edit]

The base alphabet consists of 21 letters: five vowels (A, E, I, O, U) and 16 consonants. The letters J, K, W, X and Y are not part of the proper alphabet, and appear only in loanwords (e.g. ‘jeans’, ‘weekend’),[2] foreign names, and in a handful of native words—such as the names Jesolo, Bettino Craxi, and Walter, which all derive from regional languages. In addition, grave and acute accents may modify vowel letters; circumflex accent is much rarer and is found only in older texts.

An Italian computer keyboard layout

An Italian handwriting script, taught in primary school

| Letter | Name | IPA | Diacritics |

|---|---|---|---|

| A, a | a [ˈa] | /a/ | à |

| B, b | bi [ˈbi] | /b/ | |

| C, c | ci [ˈtʃi] | /k/ or /tʃ/ | |

| D, d | di [ˈdi] | /d/ | |

| E, e | e [ˈe] | /e/ or /ɛ/ | è, é |

| F, f | effe [ˈɛffe] | /f/ | |

| G, g | gi [ˈdʒi] | /ɡ/ or /dʒ/ | |

| H, h | acca [ˈakka] | ∅ silent | |

| I, i | i [ˈi] | /i/ or /j/ | ì, í, [î] |

| L, l | elle [ˈɛlle] | /l/ | |

| M, m | emme [ˈɛmme] | /m/ | |

| N, n | enne [ˈɛnne] | /n/ | |

| O, o | o [ˈɔ] | /o/ or /ɔ/ | ò, ó |

| P, p | pi [ˈpi] | /p/ | |

| Q, q | cu (qu) [ˈku] | /k/ | |

| R, r | erre [ˈɛrre] | /r/ | |

| S, s | esse [ˈɛsse] | /s/ or /z/ | |

| T, t | ti [ˈti] | /t/ | |

| U, u | u [ˈu] | /u/ or /w/ | ù, ú |

| V, v | vi [ˈvi], vu [ˈvu] | /v/ | |

| Z, z | zeta [ˈdzɛːta] | /ts/ or /dz/ |

Consonants written double represent true geminates and are pronounced as such: anno ‘year’, pronounced [ˈanno] (cf. English ten nails). The short–long length contrast is phonemic, e.g. ritto [ˈritto] ‘upright’ vs. rito [ˈriːto] ‘rite, ritual’, carro [ˈkarro] ‘cart, wagon’ vs. caro [ˈkaːro] ‘dear, expensive’.

Vowels[edit]

The Italian alphabet has five vowel letters, ⟨a e i o u⟩. Of those, only ⟨a⟩ represents one sound value, while all others have two. In addition, ⟨e⟩ and ⟨i⟩ indicate a different pronunciation of a preceding ⟨c⟩ or ⟨g⟩ (see below).

In stressed syllables, ⟨e⟩ represents both open /ɛ/ and close /e/. Similarly, ⟨o⟩ represents both open /ɔ/ and close /o/ (see Italian phonology for further details on those sounds). There is typically no orthographic distinction between the open and close sounds represented, though accent marks are used in certain instances (see below). There are some minimal pairs, called heteronyms, where the same spelling is used for distinct words with distinct vowel sounds. In unstressed syllables, only the close variants occur.

In addition to representing the respective vowels /i/ and /u/, ⟨i⟩ and ⟨u⟩ also typically represent the semivowels /j/ and /w/, respectively, when unstressed and occurring before another vowel. Many exceptions exist (e.g. attuale, deciduo, deviare, dioscuro, fatuo, iato, inebriare, ingenuo, liana, proficuo, riarso, viaggio). An ⟨i⟩ may indicate that a preceding ⟨c⟩ or ⟨g⟩ is ‘soft’ (ciao).

C and G[edit]

The letters ⟨c⟩ and ⟨g⟩ represent the plosives /k/ and /ɡ/ before ⟨r⟩ and before the vowels ⟨a⟩, ⟨o⟩, ⟨u⟩. They represent the affricates /tʃ/ and /dʒ/ respectively when they precede a front vowel (⟨i⟩ or ⟨e⟩).

The letter ⟨i⟩ can also function within digraphs (two letters representing one sound) ⟨ci⟩ and ⟨gi⟩ to indicate «soft» (affricate) /tʃ/ or /dʒ/ before another vowel. In these instances, the vowel following the digraph is stressed, and ⟨i⟩ represents no vowel sound: ciò (/tʃɔ/), giù (/dʒu/). An item such as CIA ‘CIA’, pronounced /ˈtʃi.a/ with /i/ stressed, contains no digraph.

For words of more than one syllable, stress position must be known in order to distinguish between digraph ⟨ci⟩ or ⟨gi⟩ containing no actual phonological vowel /i/ and sequences of affricate and stressed /i/. For example, the words camicia «shirt» and farmacia «pharmacy» share the spelling ⟨-cia⟩, but contrast in that only the first ⟨i⟩ is stressed in camicia, thus ⟨-cia⟩ represents /tʃa/ with no /i/ sound (likewise, grigio ends in /dʒo/ and the names Gianni and Gianna contain only two actual vowels: /ˈdʒanni/, /ˈdʒanna/). In farmacia /i/ is stressed, so that ⟨ci⟩ is not a digraph, but represents two of the three constituents of /ˈtʃi.a/.

When the «hard» (plosive) pronunciation /k/ or /ɡ/ occurs before a front vowel ⟨i⟩ or ⟨e⟩, digraphs ⟨ch⟩ and ⟨gh⟩ are used, so that ⟨che⟩ represents /ke/ or /kɛ/ and ⟨chi⟩ represents /ki/ or /kj/. The same principle applies to ⟨gh⟩: ⟨ghe⟩ and ⟨ghi⟩ represent /ɡe/ or /ɡɛ/ and /ɡi/ or /ɡj/.

In the evolution from Latin to Italian, the postalveolar affricates /tʃ/ and /dʒ/ were contextual variants of the velar consonants /k/ and /ɡ/. They eventually came to be full phonemes, and orthographic adjustments were introduced to distinguish them. The phonemicity of the affricates can be demonstrated with minimal pairs:

| Plosive | Affricate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before ⟨i⟩, ⟨e⟩ | ch | china /ˈkina/ ‘India ink’ | c | Cina /ˈtʃina/ ‘China’ |

| gh | ghiro /ˈɡiro/ ‘dormouse’ | g | giro /ˈdʒiro/ ‘lap’, ‘tour’ | |

| Elsewhere | c | caramella /karaˈmɛlla/ ‘candy’ | ci | ciaramella /tʃaraˈmɛlla/ ‘shawm’ |

| g | gallo /ˈɡallo/ ‘rooster’ | gi | giallo /ˈdʒallo/ ‘yellow’ |

The trigraphs ⟨cch⟩ and ⟨ggh⟩ are used to indicate geminate /kk/ and /ɡɡ/, respectively, when they occur before ⟨i⟩ or ⟨e⟩; e.g. occhi /ˈɔkki/ ‘eyes’, agghindare /aɡɡinˈdare/ ‘to dress up’. The double letters ⟨cc⟩ and ⟨gg⟩ before ⟨i⟩ or ⟨e⟩ and ⟨cci⟩ and ⟨ggi⟩ before other vowels represent the geminated affricates /ttʃ/ and /ddʒ/, e. g. riccio ‘hedgehog’, peggio ‘worse’.

⟨g⟩ joins with ⟨l⟩ to form a digraph representing palatal /ʎ/ before ⟨i⟩, and with ⟨n⟩ to represent /ɲ/ with any vowel following. Between vowels these are pronounced phonetically long, as in /ˈaʎʎo/ aglio ‘garlic’, /ˈoɲɲi/ ogni ‘each’. By way of exception, ⟨gl⟩ before ⟨i⟩ represents /ɡl/ in some words derived from Greek, such as glicine ‘wisteria’, from learned Latin, such as negligente ‘negligent’, and in a few adaptations from other languages such as glissando [ɡlisˈsando], partially italianised from French glissant. ⟨gl⟩ before vowels other than ⟨i⟩ represents straightforward /ɡl/.

The digraph ⟨sc⟩ is used before ⟨e⟩ and ⟨i⟩ to represent /ʃ/; before other vowels, ⟨sci⟩ is used for /ʃ/. Otherwise, ⟨sc⟩ represents /sk/, the ⟨c⟩ of which follows the normal orthographic rules explained above.

| /sk/ | /ʃ/ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before ⟨i e⟩ | sch | scherno /ˈskɛrno/ | sc | scerno /ˈʃɛrno/ |

| Elsewhere | sc | scalo /ˈskalo/ | sci | scialo /ˈʃalo/ |

Intervocalic /ʎ/, /ɲ/, and /ʃ/ are always geminated and no orthographic distinction is made to indicate this.[3]

C and Q[edit]

Normally /kw/ is represented by ⟨qu⟩, but it is represented by ⟨cu⟩ in some words, such as cuoco, cuoio, cuore, scuola, scuotere and percuotere. These words all contain a /kwɔ/ sequence derived from an original /kɔ/ which was subsequently diphthongised. The sequence /kkw/ is always spelled ⟨cqu⟩ (e.g. acqua), with exceptions being spelled ⟨qqu⟩ in the words soqquadro, its derivation soqquadrare, and beqquadro and biqquadro, two alternative forms of bequadro or biquadro.[4]

S and Z[edit]

⟨s⟩ and ⟨z⟩ are ambiguous to voicing.

⟨s⟩ represents a dental sibilant consonant, either /s/ or /z/. However, these two phonemes are in complementary distribution everywhere except between two vowels in the same word and, even with such words, there are very few minimal pairs.

- The voiceless /s/ occurs:

- At the start of a word before a vowel (e.g. Sara /ˈsara/) or a voiceless consonant (e.g. spuntare /spunˈtare/)

- After any consonant (e.g. transitare /transiˈtare/)

- Before a voiceless consonant (e.g. raspa /ˈraspa/)

- At the start of the second part of a compound word (e.g. affittasi, disotto, girasole, prosegue, risaputo, reggiseno). These words are formed by adding a prefix to a word beginning with /s/

- The voiced /z/ occurs before voiced consonants (e.g. sbranare /zbraˈnare/).

- It can be either voiceless or voiced (/s/ or /z/) between vowels; in standard Tuscany-based pronunciation some words are pronounced with /s/ between vowels (e.g. casa, cosa, così, mese, naso, peso, cinese, piemontese, goloso); in Northern Italy (and also increasingly in Tuscany) ⟨s⟩ between vowels is always pronounced with /z/ whereas in Southern Italy ⟨s⟩ between vowels is always pronounced /s/.

⟨ss⟩ always represents voiceless /ss/: grosso /ˈɡrɔsso/, successo /sutˈtʃɛsso/, passato /pasˈsato/, etc.

⟨z⟩ represents a dental affricate consonant; either /dz/ (zanzara /dzanˈdzara/) or /ts/ (canzone /kanˈtsone/), depending on context, though there are few minimal pairs.

- It is normally voiceless /ts/:[5]

- At the start of a word in which the second syllable starts with a voiceless consonant (zampa /ˈtsampa/, zoccolo /ˈtsɔkkolo/, zufolo /ˈtsufolo/)

- Exceptions (because they are of Greek origin): zaffiro, zefiro, zotico, zeta, zafferano, Zacinto

- When followed by an ⟨i⟩ which is followed, in turn, by another vowel (e.g. zio /ˈtsi.o/, agenzia /adʒenˈtsi.a/, grazie /ˈɡratsje/)

- Exceptions: azienda /aˈdzjɛnda/, all words derived from words obeying other rules (e.g. romanziere /romanˈdzjɛre/, which is derived from romanzo)

- After the letter ⟨l⟩ (e.g. alzare /alˈtsare/)

- Exceptions: elzeviro /eldzeˈviro/ and Belzebù /beldzeˈbu/

- In the suffixes -anza, -enza and -onzolo (e.g. usanza /uˈzantsa/, credenza /kreˈdɛntsa/, ballonzolo /balˈlontsolo/)

- At the start of a word in which the second syllable starts with a voiceless consonant (zampa /ˈtsampa/, zoccolo /ˈtsɔkkolo/, zufolo /ˈtsufolo/)

- It is normally voiced /dz/:

- At the start of a word in which the second syllable starts with a voiced consonant or ⟨z⟩ (or ⟨zz⟩) itself (e.g. zebra /ˈdzɛbra/, zuzzurellone /dzuddzurelˈlone/)

- Exceptions: zanna /ˈtsanna/, zigano /tsiˈɡano/

- At the start of a word when followed by two vowels (e.g. zaino /ˈdzaino/)

- Exceptions: zio and its derived terms (see above)

- If it is single (not doubled) and between two single vowels (e.g. azalea /addzaˈlɛa/)

- Exceptions: nazismo /natˈtsizmo/ (from the German pronunciation of ⟨z⟩)

- At the start of a word in which the second syllable starts with a voiced consonant or ⟨z⟩ (or ⟨zz⟩) itself (e.g. zebra /ˈdzɛbra/, zuzzurellone /dzuddzurelˈlone/)

Between vowels and/or semivowels (/j/ and /w/), ⟨z⟩ is pronounced as if doubled (/tts/ or /ddz/, e.g. vizio /ˈvittsjo/, polizia /politˈtsi.a/). Generally, intervocalic z is written doubled, but it is written single in most words where it precedes ⟨i⟩ followed by any vowel and in some learned words.

⟨zz⟩ may represent either a voiceless alveolar affricate /tts/ or its voiced counterpart /ddz/:[6] voiceless in e.g. pazzo /ˈpattso/, ragazzo /raˈɡattso/, pizza /ˈpittsa/, grandezza /ɡranˈdettsa/, voiced in razzo /ˈraddzo/, mezzo /ˈmɛddzo/, azzardo /adˈdzardo/, azzurro /adˈdzurro/, orizzonte /oridˈdzonte/, zizzania /dzidˈdzanja/. Most words are consistently pronounced with /tts/ or /ddz/ throughout Italy in the standard language (e.g. gazza /ˈgaddza/ ‘magpie’, tazza /ˈtattsa/ ‘mug’), but a few words, such as frizzare ‘effervesce, sting’, exist in both voiced and voiceless forms, differing by register or by geographic area, while others have different meanings depending on whether they are pronounced in voiced or voiceless form (e.g. razza: /ˈrattsa/ (race, breed) or /ˈraddza/ (ray, skate)).[7][8] The verbal ending -izzare from Greek -ίζειν is always pronounced /ddz/ (e.g. organizzare /orɡanidˈdzare/), maintained in both inflected forms and derivations: organizzo /orɡaˈniddzo/ ‘I organise’, organizzazione /orɡaniddzatˈtsjone/ ‘organisation’. Like frizzare above, however, not all verbs ending in —izzare continue suffixed Greek -ίζειν), having instead —izz— as part of the verb stem. Indirizzare, for example, of Latin origin reconstructed as *INDIRECTIARE, has /tts/ in all forms containing the root indirizz-.

Silent H[edit]

In addition to being used to indicate a hard ⟨c⟩ or ⟨g⟩ before front vowels (see above), ⟨h⟩ is used to distinguish ho, hai, ha, hanno (present indicative of avere, ‘to have’) from o (‘or’), ai (‘to the’, m. pl.), a (‘to’), anno (‘year’); since ⟨h⟩ is always silent, there is no difference in the pronunciation of such words. The letter ⟨h⟩ is also used in some interjections, where it always comes immediately after the first vowel in the word (e.g. eh, boh, ahi, ahimè), as well as in some loanwords (e.g. hotel).[4] In filler words ehm and uhm both ⟨h⟩ and the preceding vowel are silent.[9][10]

J, K, W, X and Y[edit]

The letters J (I lunga ‘long I’), K (cappa), W (V doppia or doppia V ‘double V’), X (ics) and Y (ipsilon or I greca ‘Greek I’) are used only in loanwords, proper names and archaisms, with few exceptions.[citation needed]

In modern standard Italian spelling, the letter ⟨j⟩ is used only in Latin words, proper nouns (such as Jesi, Letojanni, Juventus etc.) and words borrowed from foreign languages. Until the 19th century, ⟨j⟩ was used instead of ⟨i⟩ in diphthongs, as a replacement for final -ii, and in vowel groups (as in Savoja); this rule was quite strict in official writing. ⟨j⟩ is also used to render /j/ in dialectal spelling, e.g. Romanesco dialect ajo /ˈajjo/ («garlic»; cf. Italian aglio /ˈaʎʎo/).

The letter ⟨k⟩ is not in the standard alphabet and exists only in unassimilated loanwords, although it is often used informally among young people as a replacement for ⟨ch⟩, paralleling the use of ⟨k⟩ in English (for example, ke instead of che).

Also ⟨w⟩ is only used in loanwords, mainly of Germanic origin. A capital W is used as an abbreviation of viva or evviva («long live»).

In Italian, ⟨x⟩ represents either /ks/, as in extra, uxorio, xilofono, or /ɡz/, as exoterico, when it is preceded by ⟨e⟩ and followed by a vowel.[11] In several related languages, notably Venetian, it represents the voiced sibilant /z/. It is also used, mainly amongst the young people, as a short written form for per, meaning «for» (for example x sempre, meaning «forever»): this is because in Italian the multiplication sign (similar to ⟨x⟩) is called per. However, ⟨x⟩ is found only in loanwords, as it is not part of the standard Italian alphabet; in most words with ⟨x⟩, this letter may be replaced with ‘s’ or ‘ss’ (with different pronunciation: xilofono/silofono, taxi/tassì) or, rarely, by ‘cs’ (with the same pronunciation: claxon/clacson).

Diacritics[edit]

The acute accent (´) may be used on ⟨é⟩ and ⟨ó⟩ to represent close-mid vowels when they are stressed in a position other than the default second-to-last syllable. This use of accents is generally mandatory only to indicate stress on a word-final vowel; elsewhere, accents are generally found only in dictionaries. Since final ⟨o⟩ is hardly ever close-mid, ⟨ó⟩ is very rarely encountered in written Italian (e.g. metró ‘subway’, from the original French pronunciation of métro with a final-stressed /o/).

The grave accent (`) is found on ⟨à⟩, ⟨è⟩, ⟨ì⟩, ⟨ò⟩, ⟨ù⟩. It may be used on ⟨è⟩ and ⟨ò⟩ when they represent open-mid vowels. The accents may also be used to differentiate minimal pairs within Italian (for example pèsca ‘peach’ vs. pésca ‘fishing’), but in practice this is limited to didactic texts. In the case of final ⟨ì⟩ and ⟨ù⟩, both possibilities are encountered. By far the most common option is the grave accent, ⟨ì⟩ and ⟨ù⟩, though this may be due to the rarity of the acute accent to represent stress; the alternative of employing the acute, ⟨í⟩ and ⟨ú⟩, is in practice limited to erudite texts, but can be justified as both vowels are high (as in Catalan). However, since there are no corresponding low (or lax) vowels to contrast with in Italian, both choices are equally acceptable.

The circumflex accent (^) can be used to mark the contraction of two unstressed vowels /ii/ ending a word, normally pronounced [i], so that the plural of studio ‘study, office’ may be written ⟨studi⟩, ⟨studii⟩ or ⟨studî⟩. The form with circumflex is found mainly in older texts, though it may still appear in contexts where ambiguity might arise from homography. For example, it can be used to differentiate words like geni (‘genes’, plural of gene) and genî (‘geniuses’, plural of genio). In general, current usage usually prefers a single ⟨i⟩ instead of a double ⟨ii⟩ or an ⟨î⟩ with circumflex.[12]

Monosyllabic words generally lack an accent (e.g. ho, me). The accent is written, however, if there is an ⟨i⟩ or a ⟨u⟩ preceding another vowel (più, può). This applies even if the ⟨i⟩ is «silent», i.e. part of the digraphs ⟨ci⟩ or ⟨gi⟩ representing /tʃ/ and /dʒ/ (ciò, giù). It does not apply, however, if the word begins with ⟨qu⟩ (qua, qui). Many monosyllabic words are spelled with an accent in order to avoid ambiguity with other words (e.g. là, lì versus la, li). This is known as accento distintivo and also occurs in other Romance languages (e.g. the Spanish tilde diacrítica).

Sample text[edit]

«Nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita

mi ritrovai per una selva oscura

ché la diritta via era smarrita.»

Lines 1–3 of Canto 1 of the Inferno, Part 1 of the Divina Commedia by Dante Alighieri, a highly influential poem. Translation (Longfellow): «Midway upon the journey of our life I found myself in a dark wood for the straight way was lost.»[13]

See also[edit]

- Gian Giorgio Trissino, humanist who proposed an orthography in 1524. Some of his proposals were taken.

- Claudio Tolomei, humanist who proposed an orthography in 1525.

Notes[edit]

- ^ Maiden & Robustelli 2014, p. 4.

- ^ «Italian Extraction Guide – Section A: Italian Handwriting» (PDF). Brigham Young University. 1981. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

The letters J, K, W, X, and Y appear in the Italian alphabet, but are used mainly in foreign words adopted into the Italian vocabulary.

- ^ Maiden & Robustelli 2014, p. 10.

- ^ a b Maiden & Robustelli 2014, p. 5.

- ^ Dizionario d’ortografia e di pronunzia.

- ^ Dizionario d’ortografia e di pronunzia.

- ^ Dizionario d’ortografia e di pronunzia.

- ^ Dizionario di pronuncia italiana online.

- ^ Dizionario d’ortografia e di pronunzia

- ^ Dizionario d’ortografia e di pronunzia

- ^ «x, X in Vocabolario — Treccani» [x, X in Vocabulary — Treccani]. Treccani (in Italian). Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- ^ Maiden & Robustelli 2014, pp. 4–5.

- ^ «Inferno 1». Digital Dante. Retrieved April 22, 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link)

References[edit]

- Maiden, Martin; Robustelli, Cecilia (2014). A Reference Grammar of Modern Italian (2nd ed.). Routledge. ISBN 9781444116786. Retrieved June 19, 2021.

External links[edit]

- Danesi, Marcel (1996). Italian the Easy way.