Сказка про детей бедного дровосека — Жана и Мари. Их родители работали до изнеможения, чтобы прокормить семью, но денег не было. Малыши по ночам мечтали о шоколадных пряниках и конфетах. Однажды дети пошли в лес за грибами, заблудились и наткнулись на пряничный домик. Садик вокруг домика был их конфет, крыша из марципана. Но тут вернулась хозяйка этого чуда – злая ведьма…

Пряничный домик читать

Давным-давно жили-были брат и сестра, Жан и Мари. Родители их были очень бедны, и жили они в старом домишке на опушке леса. Дети с утра до ночи работали, помогая отцу-дровосеку. Часто они возвращались домой такие усталые, что у них даже не было сил поужинать. Впрочем, нередко случалось, что ужина у них вообще не было, и вся семья ложилась спать голодной.

– Мари, – говорил иногда Жан, когда, голодные, они лежали в темной комнате и не могли заснуть, – мне так хочется шоколадного пряничка.

– Спи, Жан, – отвечала Мари, которая была старше и умнее своего брата.

– Ох, как хочется съесть большой шоколадный пряник с изюмом! – громко вздыхал Жан.

Но шоколадные пряники с изюмом не росли на деревьях, а у родителей Мари и Жана не было денег, чтобы поехать в город и купить их детям. Лишь только воскресные дни были для детей радостными. Тогда Жан и Мари брали корзинки и отправлялись в лес по грибы и ягоды.

– Не уходите далеко, – всегда напоминала мать.

– Да ничего с ними не случится, – успокаивал ее отец. – Им каждое дерево в лесу знакомо.

Однажды в воскресенье дети, собирая грибы и ягоды, так увлеклись, что не заметили, как наступил вечер.

Солнце быстро скрылось за темными тучами, а ветки елей зловеще зашумели. Мари и Жан в страхе огляделись вокруг. Лес уже не казался им таким знакомым.

–Мари, мне страшно – шепотом сказал Жан.

– А мне тоже, – ответила Мари. – Кажется, мы заблудились.

Большие, незнакомые деревья были похожи на немых великанов с широкими плечами. То там, то здесь в чаще сверкали огоньки – чьи-то хищные глаза.

– Мари, я боюсь, – снова прошептал Жан.

Стало совсем темно. Дрожащие от холода дети прижались друг к другу. Где-то вблизи ухала сова, а издалека доносился вой голодного волка. Страшная ночь длилась бесконечно. Дети, прислушиваясь к зловещим голосам, так и не сомкнули глаз. Наконец между густыми кронами деревьев блеснуло солнце, и постепенно лес перестал казаться мрачным и страшным. Жан и Мари поднялись и пошли искать дорогу домой.

Шли они, шли по незнакомым местам. Кругом росли громадные грибы, намного больше тех, что они обычно собирали. И вообще все было каким-то необычным и странным. Когда солнце было уже высоко, Мари и Жан вышли на поляну, посреди которой стоял домик. Необычный домик.

Крыша у него была из шоколадных пряников, стены – из розового марципана, а забор – из больших миндальных орехов. Вокруг него был сад, и росли в нем разноцветные конфеты, а на маленьких деревцах висели большие изюмины. Жан не верил собственным глазам. Он посмотрел на Мари, глотая слюнки.

– Пряничный домик! – радостно воскликнул он.

– Садик из конфет! – вторила ему Мари.

Не теряя ни минуты, изголодавшиеся дети бросились к чудесному домику. Жан отломил от крыши кусок пряника и принялся уплетать его. Мари зашла в садик и стала лакомиться то марципановыми морковками, то миндалем с забора, то изюмом с деревца.

– Какая вкусная крыша! – радовался Жан.

– А попробуй кусочек забора, Жан, – предложила ему Мари.

Когда дети наелись необычных лакомств, им захотелось пить. К счастью, посреди садика был фонтан, в котором, переливаясь всеми цветами, журчала вода. Жан отхлебнул из фонтана и удивленно воскликнул:

– Да это же лимонад!

Обрадованные дети жадно пили лимонад, как вдруг из-за угла пряничного домика появилась сгорбленная старушка. В руке у нее была палка, а на носу сидели очень толстые очки.

– Вкусный домик, не правда ли, детки? – спросила она.

Дети молчали. Испуганная Мари пролепетала:

– Мы потерялись в лесу… мы так проголодались…

Старушка, казалось, совсем не рассердилась.

– Что вы, не бойтесь, ребятки. Входите в дом. Я дам вам лакомства повкуснее, чем эти.

Как только дверь домика захлопнулась за Мари и Жаном, старушка изменилась до неузнаваемости. Из доброй и приветливой она превратилась в злую ведьму.

– Вот вы и попались! – прохрипела она, потрясая своей клюкой. – Разве это хорошо, есть чужой дом? Вы мне заплатите за это!

Дети задрожали и в страхе прижались друг к дружке.

– А что вы за это с нами сделаете? Наверное, вы все расскажете нашим родителям? – испуганно спросила Мари.

Ведьма расхохоталась.

– Ну, уж только не это! Я очень люблю детей. Очень!

И прежде чем Мари опомнилась, ведьма схватила Жана, втолкнула его в темный чулан и закрыла за ним тяжелую дубовую дверь.

– Мари, Мари! – слышались возгласы мальчика. – Мне страшно!

– Сиди тихо, негодник! – прикрикнула ведьма. – Ты ел мой дом, теперь я съем тебя! Но сначала мне надо немножко откормить тебя, а то ты слишком худенький.

Жан и Мари громко заплакали. Сейчас они готовы были отдать все пряники на свете за то, чтобы опять очутиться в бедном, но родном домике. Но и дом и родители были далеко, и никто не мог прийти им на помощь.

Тут злая хозяйка пряничного домика подошла к чулану.

– Эй, мальчик, просунь-ка палец через щелку в двери, – приказала она.

Жан послушно просунул через щелку самый тонкий пальчик. Ведьма пощупала его и недовольно сказала:

– Да, одни кости. Ничего, через недельку ты у меня будешь толстеньким-претолстеньким.

И ведьма начала усиленно кормить Жана. Каждый день она готовила для него вкусные блюда, приносила из садика целые охапки марципановых, шоколадных и медовых лакомств. А вечером приказывала ему просовывать в щелку пальчик и ощупывала его.

– Ой, мой золотой, ты толстеешь прямо на глазах.

И действительно, Жан быстро толстел. Но однажды Мари придумала вот что.

– Жан, в следующий раз, покажи ей эту палочку, – сказала она и просунула в чулан тоненькую палочку.

Вечером ведьма как обычно обратилась к Жану:

– А ну-ка, покажи пальчик, сладенький ты мой.

Жан просунул палочку, которую дала ему сестра. Старуха потрогала ее и отскочила как ошпаренная:

– Опять одни кости! Не для того я тебя кормлю, дармоед, чтобы ты был худой, как палка!

На следующий день, когда Жан снова просунул палочку, ведьма не на шутку рассердилась.

– Не может быть, чтобы ты был все еще такой худой! Покажи-ка еще раз палец.

И Жан снова просунул палочку. Старуха потрогала ее и вдруг дернула изо всей силы. Палочка и осталась у нее в руке.

– Что это? Что это? – крикнула она в ярости. – Палка!Ах ты, негодный обманщик! Ну,теперь твоя песенка спета!

Она открыла чулан и вытащила оттуда перепуганного Жана, который растолстел и стал, как бочка.

– Ну вот, мой дорогой, – злорадствовала старуха. – Вижу, что из тебя получится отличное жаркое!

Дети оцепенели от ужаса. А ведьма затопила печь, и через минуту она уже разгорелась. От нее так и шел жар.

– Видишь это яблоко? – спросила старуха Жана. Она взяла со стола спелое сочное яблоко и кинула его в печку. Яблоко зашипело в огне, сморщилось, а потом и вовсе исчезло. – То же самое будет и с тобой!

Ведьма схватила большую деревянную лопату, на которой обычно кладут в печь хлеб, посадила на нее пухленького Жана и сунула в нее. Однако мальчик настолько растолстел, что не пролезал в печку, как ведьма ни пыталась впихнуть его туда.

– А ну, слезай! – приказала старуха. – Попробуем иначе. Ложись-ка на лопату.

– Но я не знаю, как мне лечь, – захныкал Жан.

– Вот дурень! – буркнула ведьма. – Я тебе покажу!

И она легла на лопату. Мари только этого и надо было. В тот же миг она схватила лопату и сунула ведьму прямо в печь. Потом быстро закрыла железную дверцу и, схватив перепуганного брата за руку, крикнула:

– Бежим, скорее!

Дети выбежали из пряничного домика и помчались без оглядки в сторону темного леса.

Не разбирая дороги, они долго бежали по лесу и замедлили шаг только тогда, когда на небе появились первые звезды, а лес понемногу начал редеть.

Вдруг вдали они заметили слабый мерцающий огонек.

– Это наш дом! – крикнул запыхавшийся Жан.

Действительно, это был их старый, покосившийся домик. На его пороге стояли обеспокоенные родители и с тревогой и надеждой вглядывались в темноту. Как же они обрадовались, когда увидели бегущих к ним детей – Мари и Жана! А о злой ведьме, что жила в глухом лесу, никто больше не слыхал. Наверное, она сгорела в своей печке, а ее сказочный домик развалился на тысячи пряничных и марципановых крошек, которые склевали лесные птицы.

❤️ 187

🔥 110

😁 102

😢 55

👎 57

🥱 69

Добавлено на полку

Удалено с полки

Достигнут лимит

Время чтения: 10 мин.

Давным-давно жили-были брат и сестра, Жан и Мари. Родители их были очень бедны, и жили они в старом домишке на опушке леса. Дети с утра до ночи работали, помогая отцу-дровосеку. Часто они возвращались домой такие усталые, что у них даже не было сил поужинать. Впрочем, нередко случалось, что ужина у них вообще не было, и вся семья ложилась спать голодной.

– Мари, – говорил иногда Жан, когда, голодные, они лежали в темной комнате и не могли заснуть, – мне так хочется шоколадного пряничка.

– Спи, Жан, – отвечала Мари, которая была старше и умнее своего брата.

– Ох, как хочется съесть большой шоколадный пряник с изюмом! – громко вздыхал Жан.

Но шоколадные пряники с изюмом не росли на деревьях, а у родителей Мари и Жана не было денег, чтобы поехать в город и купить их детям. Лишь только воскресные дни были для детей радостными. Тогда Жан и Мари брали корзинки и отправлялись в лес по грибы и ягоды.

– Не уходите далеко, – всегда напоминала мать.

– Ничего с ними не случится, – успокаивал ее отец. – Им каждое дерево в лесу знакомо.

Однажды в воскресенье дети, собирая грибы и ягоды, так увлеклись, что не заметили, как наступил вечер.

Солнце быстро скрылось за темными тучами, а ветки елей зловеще зашумели. Мари и Жан в страхе огляделись вокруг. Лес уже не казался им таким знакомым.

– Мне страшно, Мари, – шепотом сказал Жан.

– Мне тоже, – ответила Мари. – Кажется, мы заблудились.

Большие, незнакомые деревья были похожи на немых великанов с широкими плечами. То там, то здесь в чаще сверкали огоньки – чьи-то хищные глаза.

– Мари, я боюсь, – снова прошептал Жан.

Стало совсем темно. Дрожащие от холода дети прижались друг к другу. Где-то вблизи ухала сова, а издалека доносился вой голодного волка.

Страшная ночь длилась бесконечно. Дети, прислушиваясь к зловещим голосам, так и не сомкнули глаз. Наконец между густыми кронами деревьев блеснуло солнце, и постепенно лес перестал казаться мрачным и страшным. Жан и Мари поднялись и пошли искать дорогу домой.

Шли они, шли по незнакомым местам. Кругом росли громадные грибы, намного больше тех, что они обычно собирали. И вообще все было каким-то необычным и странным.

Когда солнце было уже высоко, Мари и Жан вышли на поляну, посреди которой стоял домик. Необычный домик. Крыша у него была из шоколадных пряников, стены – из розового марципана, а забор – из больших миндальных орехов. Вокруг него был сад, и росли в нем разноцветные конфеты, а на маленьких деревцах висели большие изюмины. Жан не верил собственным глазам. Он посмотрел на Мари, глотая слюнки.

– Пряничный домик! – радостно воскликнул он.

– Садик из конфет! – вторила ему Мари.

Не теряя ни минуты, изголодавшиеся дети бросились к чудесному домику. Жан отломил от крыши кусок пряника и принялся уплетать его. Мари зашла в садик и стала лакомиться то марципановыми морковками, то миндалем с забора, то изюмом с деревца.

– Какая вкусная крыша! – радовался Жан.

– Попробуй кусочек забора, Жан, – предложила ему Мари.

Когда дети наелись необычных лакомств, им захотелось пить. К счастью, посреди садика был фонтан, в котором, переливаясь всеми цветами, журчала вода. Жан отхлебнул из фонтана и удивленно воскликнул:

– Да это же лимонад!

Обрадованные дети жадно пили лимонад, как вдруг из-за угла пряничного домика появилась сгорбленная старушка. В руке у нее была палка, а на носу сидели очень толстые очки.

– Вкусный домик, не правда ли, детки? – спросила она.

Дети молчали. Испуганная Мари пролепетала:

– Мы… мы потерялись в лесу… мы так проголодались…

Старушка, казалось, совсем не рассердилась.

– Не бойтесь, ребятки. Входите в дом. Я вам дам лакомства повкуснее, чем эти.

Как только дверь домика захлопнулась за Мари и Жаном, старушка изменилась до неузнаваемости. Из доброй и приветливой она превратилась в злую ведьму.

– Вот вы и попались! – прохрипела она, потрясая своей клюкой. – Разве это хорошо, есть чужой дом? Вы мне заплатите за это!

Дети задрожали и в страхе прижались друг к дружке.

– А что вы за это с нами сделаете? Наверное, вы все расскажете нашим родителям? – испуганно спросила Мари.

Ведьма расхохоталась.

– Ну уж только не это! Я очень люблю детей. Очень!

И прежде чем Мари опомнилась, ведьма схватила Жана, втолкнула его в темный чулан и закрыла за ним тяжелую дубовую дверь.

– Мари! – слышались возгласы мальчика. – Мне страшно!

– Сиди тихо, негодник! – прикрикнула ведьма. – Ты ел мой дом, теперь я съем тебя! Но сначала мне надо немножко откормить тебя, а то ты слишком худенький.

Жан и Мари громко заплакали. Сейчас они готовы были отдать все пряники на свете за то, чтобы опять очутиться в бедном, но родном домике. Но дом и родители были далеко, и никто не мог прийти им на помощь.

Тут злая хозяйка пряничного домика подошла к чулану.

– Эй, мальчик, просунь-ка палец через щелку в двери, – приказала она.

Жан послушно просунул через щелку самый тонкий пальчик. Ведьма пощупала его и недовольно сказала:

– Одни кости. Ничего, через недельку ты у меня будешь толстеньким-претолстеньким.

И ведьма начала усиленно кормить Жана. Каждый день она готовила для него вкусные блюда, приносила из садика целые охапки марципановых, шоколадных и медовых лакомств. А вечером приказывала ему просовывать в щелку пальчик и ощупывала его.

– Мой золотой, ты толстеешь прямо на глазах.

И действительно, Жан быстро толстел. Но однажды Мари придумала вот что.

– Жан, в следующий раз, покажи ей эту палочку, – сказала она и просунула в чулан тоненькую палочку.

Вечером ведьма как обычно обратилась к Жану:

– А ну, покажи-ка пальчик, сладенький ты мой.

Жан просунул палочку, которую дала ему сестра. Старуха потрогала ее и отскочила как ошпаренная:

– Опять одни кости! Не для того я тебя кормлю, дармоед, чтобы ты был худой, как палка!

На следующий день, когда Жан снова просунул палочку, ведьма не на шутку рассердилась.

– Не может быть, чтобы ты был все еще такой худой! Покажи еще раз палец.

И Жан снова просунул палочку. Старуха потрогала ее и вдруг дернула изо всей силы. Палочка и осталась у нее в руке.

– Что это? – крикнула она в ярости. – Палка! Ах ты, негодный обманщик! Ну, теперь твоя песенка спета!

Она открыла чулан и вытащила оттуда перепуганного Жана, который растолстел и стал, как бочка.

– Ну вот, мой дорогой, – злорадствовала старуха. – Вижу, что из тебя получится отличное жаркое!

Дети оцепенели от ужаса. А ведьма затопила печь, и через минуту она уже разгорелась. От нее так и шел жар.

– Видишь это яблоко? – спросила старуха Жана. Она взяла со стола спелое сочное яблоко и кинула его в печку. Яблоко зашипело в огне, сморщилось, а потом и вовсе исчезло. – То же самое будет и с тобой!

Ведьма схватила большую деревянную лопату, на которой обычно кладут в печь хлеб, посадила на нее пухленького Жана и сунула в нее. Однако мальчик настолько растолстел, что не пролезал в печку, как ведьма ни пыталась впихнуть его туда.

– А ну, слезай! – приказала старуха. – Попробуем иначе. Ложись-ка на лопату.

– Но я не знаю, как мне лечь, – захныкал Жан.

– Вот дурень! – буркнула ведьма. – Я тебе покажу!

И она легла на лопату. Мари только этого и надо было. В тот же миг она схватила лопату и сунула ведьму прямо в печь. Потом быстро закрыла железную дверцу и, схватив перепуганного брата за руку, крикнула:

– Бежим, скорее!

Дети выбежали из пряничного домика и помчались без оглядки в сторону темного леса.

Не разбирая дороги, они долго бежали по лесу и замедлили шаг только тогда, когда на небе появились первые звезды, а лес понемногу начал редеть.

Вдруг вдали они заметили слабый мерцающий огонек.

– Это наш дом! – крикнул запыхавшийся Жан.

Действительно, это был их старый, покосившийся домик. На его пороге стояли обеспокоенные родители и с тревогой и надеждой вглядывались в темноту.

Как же они обрадовались, когда увидели бегущих к ним детей – Мари и Жана!

А о злой ведьме, что жила в глухом лесу, никто больше не слыхал. Наверное, она сгорела в своей печке, а ее сказочный домик развалился на тысячи пряничных и марципановых крошек, которые склевали лесные птицы.

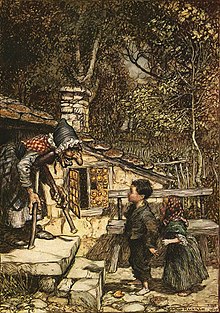

| Hansel and Gretel | |

|---|---|

The witch welcomes Hansel and Gretel into her hut. Illustration by Arthur Rackham, 1909. |

|

| Folk tale | |

| Name | Hansel and Gretel |

| Aarne–Thompson grouping | ATU 327A |

| Region | German |

| Published in | Kinder- und Hausmärchen, by the Brothers Grimm |

«Hansel and Gretel» (; German: Hänsel und Gretel [ˈhɛnzl̩ ʔʊnt ˈɡʁeːtl̩])[a] is a German fairy tale collected by the German Brothers Grimm and published in 1812 in Grimm’s Fairy Tales (KHM 15).[1][2] It is also known as Little Step Brother and Little Step Sister.

Hansel and Gretel are a brother and sister abandoned in a forest, where they fall into the hands of a witch who lives in a house made of gingerbread, cake, and candy. The cannibalistic witch intends to fatten Hansel before eventually eating him, but Gretel pushes the witch into her own oven and kills her. The two children then escape with their lives and return home with the witch’s treasure.[3]

«Hansel and Gretel» is a tale of Aarne–Thompson–Uther type 327A.[4][5] It also includes an episode of type 1121 (‘Burning the Witch in Her Own Oven’).[2][6] The story is set in medieval Germany. The tale has been adapted to various media, most notably the opera Hänsel und Gretel (1893) by Engelbert Humperdinck.[7][8]

Origin[edit]

Sources[edit]

Although Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm credited «various tales from Hesse» (the region where they lived) as their source, scholars have argued that the brothers heard the story in 1809 from the family of Wilhelm’s friend and future wife, Dortchen Wild, and partly from other sources.[9] A handwritten note in the Grimms’ personal copy of the first edition reveals that in 1813 Wild contributed to the children’s verse answer to the witch, «The wind, the wind,/ The heavenly child,» which rhymes in German: «Der Wind, der Wind,/ Das himmlische Kind.»[2]

According to folklorist Jack Zipes, the tale emerged in the Late Middle Ages Germany (1250–1500). Shortly after this period, close written variants like Martin Montanus’ Garten Gesellschaft (1590) began to appear.[3] Scholar Christine Goldberg argues that the episode of the paths marked with stones and crumbs, already found in the French «Finette Cendron» and «Hop-o’-My-Thumb» (1697), represents «an elaboration of the motif of the thread that Ariadne gives Theseus to use to get out of the Minoan labyrinth».[10] A house made of confectionery is also found in a 14th-century manuscript about the Land of Cockayne.[7]

Editions[edit]

From the pre-publication manuscript of 1810 (Das Brüderchen und das Schwesterchen) to the sixth edition of Kinder- und Hausmärchen (Grimm’s Fairy Tales) in 1850, the Brothers Grimm made several alterations to the story, which progressively gained in length, psychological motivation, and visual imagery,[11] but also became more Christian in tone, shifting the blame for abandonment from a mother to a stepmother associated with the witch.[1][3]

In the original edition of the tale, the woodcutter’s wife is the children’s biological mother,[12] but she was also called «stepmother» from the 4th edition (1840).[5][13] The Brothers Grimm indeed introduced the word «stepmother», but retained «mother» in some passages. Even their final version in the 7th edition (1857) remains unclear about her role, for it refers to the woodcutter’s wife twice as «the mother» and once as «the stepmother».[2]

The sequence where the duck helps them across the river is also a later addition. In some later versions, the mother died from unknown causes, left the family, or remained with the husband at the end of the story.[14] In the 1810 pre-publication manuscript, the children were called «Little Brother» and «Little Sister», then named Hänsel and Gretel in the first edition (1812).[11] Wilhelm Grimm also adulterated the text with Alsatian dialects, «re-appropriated» from August Ströber’s Alsatian version (1842) in order to give the tale a more «folksy» tone.[5][b]

Goldberg notes that although «there is no doubt that the Grimms’ Hänsel und Gretel was pieced together, it was, however, pieced together from traditional elements,» and its previous narrators themselves had been «piecing this little tale together with other traditional motifs for centuries.»[6] For instance, the duck helping the children cross the river may be the remnant of an old traditional motif in the folktale complex that was reintroduced by the Grimms in later editions.[6]

Plot[edit]

Hansel and Gretel are the young children of a poor woodcutter. When a famine settles over the land, the woodcutter’s second wife tells the woodcutter to take the children into the woods and leave them there to fend for themselves, so that she and her husband do not starve to death. The woodcutter opposes the plan, but his wife claims that maybe a stranger will take the children in and provide for them, which the woodcutter and she simply cannot do. With the scheme seemingly justified, the woodcutter reluctantly is forced to submit to it. They are unaware that in the children’s bedroom, Hansel and Gretel have overheard them. After the parents have gone to bed, Hansel sneaks out of the house and gathers as many white pebbles as he can, then returns to his room, reassuring Gretel that God will not forsake them.

The next day, the family walk deep into the woods and Hansel lays a trail of white pebbles. After their parents abandon them, the children wait for the moon to rise and then follow the pebbles back home. They return home safely, much to their stepmother’s rage. Once again, provisions become scarce and the stepmother angrily orders her husband to take the children further into the woods and leave them there. Hansel and Gretel attempt to gather more pebbles, but find the front door locked.

The following morning, the family treks into the woods. Hansel takes a slice of bread and leaves a trail of bread crumbs for them to follow to return back home. However, after they are once again abandoned, they find that the birds have eaten the crumbs and they are lost in the woods. After days of wandering, they follow a beautiful white bird to a clearing in the woods, and discover a large cottage built of gingerbread, cookies, cakes, and candy, with window panes of clear sugar. Hungry and tired, the children begin to eat the rooftop of the house, when the door opens and a «very old woman» emerges and lures the children inside with the promise of soft beds and delicious food. They enter without realizing that their hostess is a bloodthirsty witch who built the gingerbread house to waylay children to cook and eat them.

The next morning, the witch locks Hansel in an iron cage in the garden and forces Gretel into becoming a slave. The witch feeds Hansel regularly to fatten him up, but serves Gretel nothing but crab shells. The witch then tries to touch Hansel’s finger to see how fat he has become, but Hansel cleverly offers a thin bone he found in the cage. As the witch’s eyes are too weak to notice the deception, she is fooled into thinking Hansel is still too thin to eat. After weeks of this, the witch grows impatient and decides to eat Hansel, «be he fat or lean«.

She prepares the oven for Hansel, but decides she is hungry enough to eat Gretel, too. She coaxes Gretel to the open oven and asks her to lean over in front of it to see if the fire is hot enough. Gretel, sensing the witch’s intent, pretends she does not understand what the witch means. Infuriated, the witch demonstrates, and Gretel instantly shoves her into the hot oven, slams and bolts the door shut, and leaves «the ungodly witch to be burned in ashes«. Gretel frees Hansel from the cage and the pair discover a vase full of treasure, including precious stones. Putting the jewels into their clothing, the children set off for home. A swan ferries them across an expanse of water, and at home they find only their father; his wife having died from an unknown cause. Their father had spent all his days lamenting the loss of his children, and is delighted to see them safe and sound. With the witch’s wealth, they all live happily ever after.

Variants[edit]

Folklorists Iona and Peter Opie indicate that «Hansel and Gretel» belongs to a group of European tales especially popular in the Baltic regions, about children outwitting ogres into whose hands they have involuntarily fallen.[7]

ATU 327A tales[edit]

«Hansel and Gretel» is the prototype for the fairy tales of the type Aarne–Thompson–Uther (ATU) 327A. In particular, Gretel’s pretense of not understanding how to test the oven («Show Me How») is characteristic of 327A, although it also appears traditionally in other sub-types of ATU 327.[15] As argued by Stith Thompson, the simplicity of the tale may explain its spread into several traditions all over the world.[16]

A closely similar version is «Finette Cendron», published by Marie-Catherine d’Aulnoy in 1697, which depicts an impoverished king and queen deliberately losing their three daughters three times in the wilderness. The cleverest of the girls, Finette, initially manages to bring them home with a trail of thread, and then a trail of ashes, but her peas are eaten by pigeons during the third journey. The little girls then go to the mansion of a hag, who lives with her husband the ogre. Finette heats the oven and asks the ogre to test it with his tongue, so that he falls in and is incinerated. Thereafter, Finette cuts off the hag’s head. The sisters remain in the ogre’s house, and the rest of the tale relates the story of «Cinderella».[7][10]

In the Russian Vasilisa the Beautiful, the stepmother likewise sends her hated stepdaughter into the forest to borrow a light from her sister, who turns out to be Baba Yaga, a cannibalistic witch. Besides highlighting the endangerment of children (as well as their own cleverness), the tales have in common a preoccupation with eating and with hurting children: The mother or stepmother wants to avoid hunger, and the witch lures children to eat her house of candy so that she can then eat them.[17]

In a variant from Flanders, The Sugar-Candy House, siblings Jan and Jannette get lost in the woods and sight a hut made of confectionary in the distance. When they approach, a giant wolf named Garon jumps out of the window and chases them to a river bank. Sister and brother ask a pair of ducks to help them cross the river and escape the wolf. Garon threatens the ducks to carry him over, to no avail; he then tries to cross by swimming. He sinks and surfaces three times, but disappears in the water on the fourth try. The story seems to contain the «child/wind» rhyming scheme of the German tale.[18]

In a French fairy tale, La Cabane au Toit de Fromage («The Hut with the Roof made of Cheese»), the brother is the hero who deceives the witch and locks her up in the oven.[19]

In the first Puerto Rican variant of «The Orphaned Children,» the brother pushes the witch into the oven.[20]

Other folk tales of ATU 327A type include the French «The Lost Children», published by Antoinette Bon in 1887,[21][22] or the Moravian «Old Gruel», edited by Maria Kosch in 1899.[22]

The Children and the Ogre (ATU 327)[edit]

Structural comparisons can also be made with other tales of ATU 327 type («The Children and the Ogre»), which is not a simple fairy tale type but rather a «folktale complex with interconnected subdivisions» depicting a child (or children) falling under the power of an ogre, then escaping by their clever tricks.[23]

In ATU 327B («The Brothers and the Ogre»), a group of siblings come to an ogre’s house who intends to kill them in their beds, but the youngest of the children exchanges the visitors with the ogre’s offspring, and the villain kills his own children by mistake. They are chased by the ogre, but the siblings eventually manage to come back home safely.[24] Stith Thompson points the great similarity of the tales types ATU 327A and ATU 327B that «it is quite impossible to disentangle the two tales».[25]

ATU 327C («The Devil [Witch] Carries the Hero Home in a Sack») depicts a witch or an ogre catching a boy in a sack. As the villain’s daughter is preparing to kill him, the boy asks her to show him how he should arrange himself; when she does so, he kills her. Later on, he kills the witch and goes back home with her treasure. In ATU 327D («The Kiddlekaddlekar»), children are discovered by an ogre in his house. He intends to hang them, but the girl pretends not to understand how to do it, so the ogre hangs himself to show her. He promises his kiddlekaddlekar (a magic cart) and treasure in exchange for his liberation; they set him free, but the ogre chases them. The children eventually manage to kill him and escape safely. In ATU 327F («The Witch and the Fisher Boy»), a witch lures a boy and catches him. When the witch’s daughter tries to bake the child, he pushes her into the oven. The witch then returns home and eats her own daughter. She eventually tries to fell the tree in which the boy is hiding, but birds fly away with him.[24]

Further comparisons[edit]

The initial episode, which depicts children deliberately lost in the forest by their unloving parents, can be compared with many previous stories: Montanus’s «The Little Earth-Cow» (1557), Basile’s «Ninnillo and Nennella» (1635), Madame d’Aulnoy’s «Finette Cendron» (1697), or Perrault’s «Hop-o’-My-Thumb» (1697). The motif of the trail that fails to lead the protagonists back home is also common to «Ninnillo and Nennella», «Finette Cendron» and «Hop-o’-My-Thumb»,[26] and the Brothers Grimm identified the latter as a parallel story.[27]

Finally, ATU 327 tales share a similar structure with ATU 313 («Sweetheart Roland», «The Foundling», «Okerlo») in that one or more protagonists (specifically children in ATU 327) come into the domain of a malevolent supernatural figure and escape from it.[24] Folklorist Joseph Jacobs, commenting on his reconstructed proto-form of the tale (Johnnie and Grizzle), noticed the «contamination» of the tale with the story of The Master Maid, later classified as ATU 313.[28] ATU 327A tales are also often combined with stories of ATU 450 («Little Brother and Sister»), in which children run away from an abusive stepmother.[3]

Analysis[edit]

According to folklorist Jack Zipes, the tale celebrates the symbolic order of the patriarchal home, seen as a haven protected from the dangerous characters that threaten the lives of children outside, while it systematically denigrates the adult female characters, which are seemingly intertwined between each other.[8][29] The mother or stepmother indeed dies just after the children kill the witch, suggesting that they may metaphorically be the same woman.[30] Zipes also argues that the importance of the tale in the European oral and literary tradition may be explained by the theme of child abandonment and abuse. Due to famines and lack of birth control, it was common in medieval Europe to abandon unwanted children in front of churches or in the forest. The death of the mother during childbirth sometimes led to tensions after remarriage, and Zipes proposes that it may have played a role in the emergence of the motif of the wicked stepmother.[29]

Linguist and folklorist Edward Vajda has proposed that these stories represent the remnant of a coming-of-age, rite of passage tale extant in Proto-Indo-European society.[31][32] Psychologist Bruno Bettelheim argues that the main motif is about dependence, oral greed, and destructive desires that children must learn to overcome, after they arrive home «purged of their oral fixations». Others have stressed the satisfying psychological effects of the children vanquishing the witch or realizing the death of their wicked stepmother.[8]

Cultural legacy[edit]

Stage and musical theater[edit]

The fairy tale enjoyed a multitude of adaptations for the stage, among them the opera Hänsel und Gretel by Engelbert Humperdinck—one of the most performed operas.[33] It is principally based upon the Grimm’s version, although it omits the deliberate abandonment of the children.[7][8]

A contemporary reimagining of the story, Mátti Kovler’s musical fairytale Ami & Tami, was produced in Israel and the United States and subsequently released as a symphonic album.[34][35]

Literature[edit]

Several writers have drawn inspiration from the tale, such as Robert Coover in «The Gingerbread House» (Pricks and Descants, 1970), Anne Sexton in Transformations (1971), Garrison Keillor in «My Stepmother, Myself» in «Happy to Be Here» (1982), and Emma Donoghue in «A Tale of the Cottage» (Kissing the Witch, 1997).[8] Adam Gidwitz’s 2010 children’s book A Tale Dark & Grimm and its sequels In a Glass Grimmly (2012), and The Grimm Conclusion (2013) are loosely based on the tale and show the siblings meeting characters from other fairy tales.

Terry Pratchett mentions gingerbread cottages in several of his books, mainly where a witch had turned wicked and ‘started to cackle’, with the gingerbread house being a stage in a person’s increasing levels of insanity. In The Light Fantastic the wizard Rincewind and Twoflower are led by a gnome into one such building after the death of the witch and warned to be careful of the doormat, as it is made of candy floss.

Film[edit]

- Hansel and Gretel: An Opera Fantasy, a 1954 stop-motion animated theatrical feature film directed by John Paul and released by RKO Radio Pictures.

- A 1983 episode of Shelley Duvall’s Faerie Tale Theatre starred Ricky Schroder as Hansel and Joan Collins as the stepmother/witch.

- Hansel and Gretel, a 1983 TV special directed by Tim Burton.

- Hansel and Gretel, a 1987 American/Israeli musical film directed by Len Talan with David Warner, Cloris Leachman, Hugh Pollard and Nicola Stapleton. Part of the 1980s film series Cannon Movie Tales.

- Elements from the story were used in the 1994 horror film Wes Craven’s New Nightmare for its climax.

- «Hänsel und Gretel»[36] by 2012 German Broadcaster RBB released as part of its series Der rbb macht Familienzeit.

- Hansel & Gretel: Witch Hunters (2013) by Tommy Wirkola with Jeremy Renner and Gemma Arterton, (USA, Germany). The film follows the adventures of Hansel & Gretel who became adults.

- Gretel & Hansel, a 2020 American horror film directed by Oz Perkins in which Gretel is a teenager while Hansel is still a little boy.

- Secret Magic Control Agency (2021) is an animated retelling of the fairy tale by incorporating comedy and family genres[37]

Computer programming[edit]

Hansel and Gretel’s trail of breadcrumbs inspired the name of the navigation element «breadcrumbs» that allows users to keep track of their locations within programs or documents.[38]

Video games[edit]

- Hansel & Gretel and the Enchanted Castle (1995) by Terraglyph Interactive Studios is an adventure and hidden object game. The player controls Hansel, tasked with finding Prin, a forest imp, who holds the key to saving Gretel from the witch.[39]

- Gretel and Hansel (2009) by Mako Pudding is a browser adventure game. Popular on Newgrounds for its gruesome reimagining of the story, it features hand painted watercolor backgrounds and characters animated by Flash.[40]

- Fearful Tales: Hansel and Gretel Collector’s Edition (2013) by Eipix Entertainment is a HOPA (hidden object puzzle adventure) game. The player, as Hansel and Gretel’s mother, searches the witch’s lair for clues.[41]

- In the online role-playing game Poptropica, the Candy Crazed mini-quest (2021) includes a short retelling of the story. The player is summoned to the witch’s castle to free the children, who have been imprisoned after eating some of the candy residents.[42]

See also[edit]

- «Brother and Sister»

- «Esben and the Witch»

- Gingerbread house

- «Hop-o’-My-Thumb» (French fairy tale by Charles Perrault)

- «The Hut in the Forest»

- «Jorinde and Joringel»

- «Molly Whuppie»

- «Thirteenth»

- The Truth About Hansel and Gretel

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ In German, the names are diminutives of Johannes (John) and Margarete (Margaret).

- ^ Zipes words it as «re-appropriated» because Ströber’s Alsatian informant who provided «Das Eierkuchenhäuslein (The Little House of Pancakes)» had probably read Grimm’s «Hansel and Gretel».

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ a b Wanning Harries 2000, p. 225.

- ^ a b c d Ashliman, D. L. (2011). «Hansel and Gretel». University of Pittsburgh.

- ^ a b c d Zipes 2013, p. 121.

- ^ Goldberg 2008, p. 440.

- ^ a b c Zipes 2013, pp. 121–122.

- ^ a b c Goldberg 2000, p. 51.

- ^ a b c d e Opie & Opie 1974, p. 236.

- ^ a b c d e Wanning Harries 2000, p. 227.

- ^ Opie & Opie 1974, p. 236; Goldberg 2000, p. 42; Wanning Harries 2000, p. 225; Zipes 2013, p. 121

- ^ a b Goldberg 2008, p. 439.

- ^ a b Goldberg 2008, p. 438.

- ^ Zipes (2014) tr. «Hansel and Gretel (The Complete First Edition)», pp. 43–48; Zipes (2013) tr., pp. 122–126; Brüder Grimm, ed. (1812). «15. Hänsel und Grethel» . Kinder- und Haus-Märchen (in German). Vol. 1 (1 ed.). Realschulbuchhandlung. pp. 49–58 – via Wikisource.

- ^ Goldberg 2008, p. 438: «in the fourth edition, the woodcutter’s wife (who had been the children’s own mother) was first called a stepmother.»

- ^ Tatar 2002, p. 45

- ^ Goldberg 2008, pp. 439–440.

- ^ Thompson 1977, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Tatar 2002, p. 54

- ^ Bosschère, Jean de. Folk tales of Flanders. New York: Dodd, Mead. 1918. pp. 91-94.

- ^ Guerber, Hélène Adeline. Contes et légendes. 1ere partie. New York, Cincinnati [etc.] American book company. 1895. pp. 64-67.

- ^ Ocasio, Rafael (2021). Folk stories from the hills of Puerto Rico = Cuentos folklóricos de las montañas de Puerto Rico. New Brunswick. pp. 175–176. ISBN 978-1978823013.

- ^ Delarue 1956, p. 365.

- ^ a b Zipes 2013, pp. 146, 150.

- ^ Goldberg 2000, pp. 43.

- ^ a b c Goldberg 2008, p. 441.

- ^ Thompson 1977, p. 37.

- ^ Goldberg 2000, p. 44.

- ^ Tatar 2002, p. 72

- ^ Jacobs 1916, pp. 255–256.

- ^ a b Zipes 2013, p. 122.

- ^ Lüthi 1970, p. 64

- ^ Vajda 2010

- ^ Vajda 2011

- ^ Upton, George Putnam (1897). The Standard Operas (Google book) (12th ed.). Chicago: McClurg. pp. 125–129. ISBN 1-60303-367-X. Retrieved 15 October 2007.

- ^ «Composer Matti Kovler realizes dream of reviving fairy-tale opera in Boston». The Boston Globe. Retrieved 2019-10-31.

- ^ Schwartz, Penny. «Boston goes into the woods with Israeli opera ‘Ami and Tami’«. Times of Israel. Retrieved 2019-10-31.

- ^ «Hänsel und Gretel | Der rbb macht Familienzeit — YouTube». www.youtube.com. Archived from the original on 2021-10-30. Retrieved 2020-08-26.

- ^ Milligan, Mercedes (2019-11-01). «Wizart Reveals ‘Hansel and Gretel’ Poster Art Ahead of AFM». Animation Magazine. Retrieved 2020-11-07.

- ^ Mark Levene (18 October 2010). An Introduction to Search Engines and Web Navigation (2nd ed.). Wiley. p. 221. ISBN 978-0470526842. Retrieved June 24, 2016.

- ^ «Hansel & Gretel and the Enchanted Castle for Windows (1995)».

- ^ «Gretel and Hansel».

- ^ «Fearful Tales: Hansel and Gretel Collector’s Edition for iPad, iPhone, Android, Mac & PC! Big Fish is the #1 place for the best FREE games».

- ^ «The Candy Crazed Mini Quest is NOW LIVE!! 🍬🏰 | poptropica».

Bibliography[edit]

- Delarue, Paul (1956). The Borzoi Book of French Folk-Tales. Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.

- Goldberg, Christine (2000). «Gretel’s Duck: The Escape from the Ogre in AaTh 327». Fabula. 41 (1–2): 42–51. doi:10.1515/fabl.2000.41.1-2.42. S2CID 163082145.

- Goldberg, Christine (2008). «Hansel and Gretel». In Haase, Donald (ed.). The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Folktales and Fairy Tales. Greenwood. ISBN 978-0-313-04947-7.

- Jacobs, Joseph (1916). European Folk and Fairy Tales. G. P. Putnam’s sons.

- Lüthi, Max (1970). Once Upon A Time: On the Nature of Fairy Tales. Frederick Ungar Publishing Co. ISBN 9780804425650.

- Opie, Iona; Opie, Peter (1974). The Classic Fairy Tales. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-211559-1.

- Tatar, Maria (2002). The Annotated Classic Fairy Tales. BCA. ISBN 978-0-393-05163-6.

- Thompson, Stith (1977). The Folktale. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-03537-9.

- Vajda, Edward (2010). The Classic Russian Fairy Tale: More Than a Bedtime Story (Speech). The World’s Classics. Western Washington University.

- Vajda, Edward (2011). The Russian Fairy Tale: Ancient Culture in a Modern Context (Speech). Center for International Studies International Lecture Series. Western Washington University.

- Wanning Harries, Elizabeth (2000). «Hansel and Gretel». In Zipel, Jack (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Fairy Tales. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-968982-8.

- Zipes, Jack (2013). «Abandoned Children ATU 327A―Hansel and Gretel». The Golden Age of Folk and Fairy Tales: From the Brothers Grimm to Andrew Lang. Hackett Publishing. pp. 121ff. ISBN 978-1-624-66034-4.

Primary sources[edit]

- Zipes, Jack (2014). «Hansel and Gretel (Hänsel und Gretel)». The Original Folk and Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm: The Complete First Edition. Jacob Grimm; Wilhelm Grimm (orig. eds.); Andrea Dezsö (illustr.) (Revised ed.). Princeton University Press. pp. 43–48. ISBN 978-0-691-17322-1.

Further reading[edit]

- de Blécourt, Willem. «On the Origin of Hänsel und Gretel». In: Fabula 49, 1-2 (2008): 30-46. doi: https://doi.org/10.1515/FABL.2008.004

- Böhm-Korff, Regina (1991). Deutung und Bedeutung von «Hänsel und Gretel»: eine Fallstudie (in German). P. Lang. ISBN 978-3-631-43703-2.

- Freudenburg, Rachel. «Illustrating Childhood—»Hansel and Gretel».» Marvels & Tales 12, no. 2 (1998): 263-318. www.jstor.org/stable/41388498.

- Gaudreau, Jean. «Handicap et sentiment d’abandon dans trois contes de fées: Le petit Poucet, Hansel et Gretel, Jean-mon-Hérisson». In: Enfance, tome 43, n°4, 1990. pp. 395–404. [DOI: https://doi.org/10.3406/enfan.1990.1957]; www.persee.fr/doc/enfan_0013-7545_1990_num_43_4_1957

- Harshbarger, Scott. «Grimm and Grimmer: “Hansel and Gretel” and Fairy Tale Nationalism.» Style 47, no. 4 (2013): 490-508. www.jstor.org/stable/10.5325/style.47.4.490.

- Mieder, Wolfgang (2007). Hänsel und Gretel: das Märchen in Kunst, Musik, Literatur, Medien und Karikaturen (in German). Praesens. ISBN 978-3-7069-0469-8.

- Taggart, James M. «»Hansel and Gretel» in Spain and Mexico.» The Journal of American Folklore 99, no. 394 (1986): 435-60. doi:10.2307/540047.

- Zipes, Jack (1997). «The rationalization of abandonment and abuse in fairy tales: The case of Hansel and Gretel». Happily Ever After: Fairy Tales, Children, and the Culture Industry. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-25296-0.

External links[edit]

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

- Hansel and Gretel at Project Gutenberg

- The complete set of Grimms’ Fairy Tales, including Hansel and Gretel at Standard Ebooks

- Hansel and Gretel fairy tale

- Original versions and psychological analysis of classic fairy tales, including Hansel and Gretel

- The Story of Hansel and Gretel

- Collaboratively illustrated story on Project Bookses

- https://www.grimmstories.com/en/grimm_fairy-tales/hansel_and_gretel

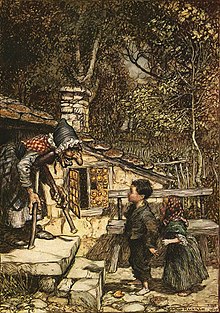

| Hansel and Gretel | |

|---|---|

The witch welcomes Hansel and Gretel into her hut. Illustration by Arthur Rackham, 1909. |

|

| Folk tale | |

| Name | Hansel and Gretel |

| Aarne–Thompson grouping | ATU 327A |

| Region | German |

| Published in | Kinder- und Hausmärchen, by the Brothers Grimm |

«Hansel and Gretel» (; German: Hänsel und Gretel [ˈhɛnzl̩ ʔʊnt ˈɡʁeːtl̩])[a] is a German fairy tale collected by the German Brothers Grimm and published in 1812 in Grimm’s Fairy Tales (KHM 15).[1][2] It is also known as Little Step Brother and Little Step Sister.

Hansel and Gretel are a brother and sister abandoned in a forest, where they fall into the hands of a witch who lives in a house made of gingerbread, cake, and candy. The cannibalistic witch intends to fatten Hansel before eventually eating him, but Gretel pushes the witch into her own oven and kills her. The two children then escape with their lives and return home with the witch’s treasure.[3]

«Hansel and Gretel» is a tale of Aarne–Thompson–Uther type 327A.[4][5] It also includes an episode of type 1121 (‘Burning the Witch in Her Own Oven’).[2][6] The story is set in medieval Germany. The tale has been adapted to various media, most notably the opera Hänsel und Gretel (1893) by Engelbert Humperdinck.[7][8]

Origin[edit]

Sources[edit]

Although Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm credited «various tales from Hesse» (the region where they lived) as their source, scholars have argued that the brothers heard the story in 1809 from the family of Wilhelm’s friend and future wife, Dortchen Wild, and partly from other sources.[9] A handwritten note in the Grimms’ personal copy of the first edition reveals that in 1813 Wild contributed to the children’s verse answer to the witch, «The wind, the wind,/ The heavenly child,» which rhymes in German: «Der Wind, der Wind,/ Das himmlische Kind.»[2]

According to folklorist Jack Zipes, the tale emerged in the Late Middle Ages Germany (1250–1500). Shortly after this period, close written variants like Martin Montanus’ Garten Gesellschaft (1590) began to appear.[3] Scholar Christine Goldberg argues that the episode of the paths marked with stones and crumbs, already found in the French «Finette Cendron» and «Hop-o’-My-Thumb» (1697), represents «an elaboration of the motif of the thread that Ariadne gives Theseus to use to get out of the Minoan labyrinth».[10] A house made of confectionery is also found in a 14th-century manuscript about the Land of Cockayne.[7]

Editions[edit]

From the pre-publication manuscript of 1810 (Das Brüderchen und das Schwesterchen) to the sixth edition of Kinder- und Hausmärchen (Grimm’s Fairy Tales) in 1850, the Brothers Grimm made several alterations to the story, which progressively gained in length, psychological motivation, and visual imagery,[11] but also became more Christian in tone, shifting the blame for abandonment from a mother to a stepmother associated with the witch.[1][3]

In the original edition of the tale, the woodcutter’s wife is the children’s biological mother,[12] but she was also called «stepmother» from the 4th edition (1840).[5][13] The Brothers Grimm indeed introduced the word «stepmother», but retained «mother» in some passages. Even their final version in the 7th edition (1857) remains unclear about her role, for it refers to the woodcutter’s wife twice as «the mother» and once as «the stepmother».[2]

The sequence where the duck helps them across the river is also a later addition. In some later versions, the mother died from unknown causes, left the family, or remained with the husband at the end of the story.[14] In the 1810 pre-publication manuscript, the children were called «Little Brother» and «Little Sister», then named Hänsel and Gretel in the first edition (1812).[11] Wilhelm Grimm also adulterated the text with Alsatian dialects, «re-appropriated» from August Ströber’s Alsatian version (1842) in order to give the tale a more «folksy» tone.[5][b]

Goldberg notes that although «there is no doubt that the Grimms’ Hänsel und Gretel was pieced together, it was, however, pieced together from traditional elements,» and its previous narrators themselves had been «piecing this little tale together with other traditional motifs for centuries.»[6] For instance, the duck helping the children cross the river may be the remnant of an old traditional motif in the folktale complex that was reintroduced by the Grimms in later editions.[6]

Plot[edit]

Hansel and Gretel are the young children of a poor woodcutter. When a famine settles over the land, the woodcutter’s second wife tells the woodcutter to take the children into the woods and leave them there to fend for themselves, so that she and her husband do not starve to death. The woodcutter opposes the plan, but his wife claims that maybe a stranger will take the children in and provide for them, which the woodcutter and she simply cannot do. With the scheme seemingly justified, the woodcutter reluctantly is forced to submit to it. They are unaware that in the children’s bedroom, Hansel and Gretel have overheard them. After the parents have gone to bed, Hansel sneaks out of the house and gathers as many white pebbles as he can, then returns to his room, reassuring Gretel that God will not forsake them.

The next day, the family walk deep into the woods and Hansel lays a trail of white pebbles. After their parents abandon them, the children wait for the moon to rise and then follow the pebbles back home. They return home safely, much to their stepmother’s rage. Once again, provisions become scarce and the stepmother angrily orders her husband to take the children further into the woods and leave them there. Hansel and Gretel attempt to gather more pebbles, but find the front door locked.

The following morning, the family treks into the woods. Hansel takes a slice of bread and leaves a trail of bread crumbs for them to follow to return back home. However, after they are once again abandoned, they find that the birds have eaten the crumbs and they are lost in the woods. After days of wandering, they follow a beautiful white bird to a clearing in the woods, and discover a large cottage built of gingerbread, cookies, cakes, and candy, with window panes of clear sugar. Hungry and tired, the children begin to eat the rooftop of the house, when the door opens and a «very old woman» emerges and lures the children inside with the promise of soft beds and delicious food. They enter without realizing that their hostess is a bloodthirsty witch who built the gingerbread house to waylay children to cook and eat them.

The next morning, the witch locks Hansel in an iron cage in the garden and forces Gretel into becoming a slave. The witch feeds Hansel regularly to fatten him up, but serves Gretel nothing but crab shells. The witch then tries to touch Hansel’s finger to see how fat he has become, but Hansel cleverly offers a thin bone he found in the cage. As the witch’s eyes are too weak to notice the deception, she is fooled into thinking Hansel is still too thin to eat. After weeks of this, the witch grows impatient and decides to eat Hansel, «be he fat or lean«.

She prepares the oven for Hansel, but decides she is hungry enough to eat Gretel, too. She coaxes Gretel to the open oven and asks her to lean over in front of it to see if the fire is hot enough. Gretel, sensing the witch’s intent, pretends she does not understand what the witch means. Infuriated, the witch demonstrates, and Gretel instantly shoves her into the hot oven, slams and bolts the door shut, and leaves «the ungodly witch to be burned in ashes«. Gretel frees Hansel from the cage and the pair discover a vase full of treasure, including precious stones. Putting the jewels into their clothing, the children set off for home. A swan ferries them across an expanse of water, and at home they find only their father; his wife having died from an unknown cause. Their father had spent all his days lamenting the loss of his children, and is delighted to see them safe and sound. With the witch’s wealth, they all live happily ever after.

Variants[edit]

Folklorists Iona and Peter Opie indicate that «Hansel and Gretel» belongs to a group of European tales especially popular in the Baltic regions, about children outwitting ogres into whose hands they have involuntarily fallen.[7]

ATU 327A tales[edit]

«Hansel and Gretel» is the prototype for the fairy tales of the type Aarne–Thompson–Uther (ATU) 327A. In particular, Gretel’s pretense of not understanding how to test the oven («Show Me How») is characteristic of 327A, although it also appears traditionally in other sub-types of ATU 327.[15] As argued by Stith Thompson, the simplicity of the tale may explain its spread into several traditions all over the world.[16]

A closely similar version is «Finette Cendron», published by Marie-Catherine d’Aulnoy in 1697, which depicts an impoverished king and queen deliberately losing their three daughters three times in the wilderness. The cleverest of the girls, Finette, initially manages to bring them home with a trail of thread, and then a trail of ashes, but her peas are eaten by pigeons during the third journey. The little girls then go to the mansion of a hag, who lives with her husband the ogre. Finette heats the oven and asks the ogre to test it with his tongue, so that he falls in and is incinerated. Thereafter, Finette cuts off the hag’s head. The sisters remain in the ogre’s house, and the rest of the tale relates the story of «Cinderella».[7][10]

In the Russian Vasilisa the Beautiful, the stepmother likewise sends her hated stepdaughter into the forest to borrow a light from her sister, who turns out to be Baba Yaga, a cannibalistic witch. Besides highlighting the endangerment of children (as well as their own cleverness), the tales have in common a preoccupation with eating and with hurting children: The mother or stepmother wants to avoid hunger, and the witch lures children to eat her house of candy so that she can then eat them.[17]

In a variant from Flanders, The Sugar-Candy House, siblings Jan and Jannette get lost in the woods and sight a hut made of confectionary in the distance. When they approach, a giant wolf named Garon jumps out of the window and chases them to a river bank. Sister and brother ask a pair of ducks to help them cross the river and escape the wolf. Garon threatens the ducks to carry him over, to no avail; he then tries to cross by swimming. He sinks and surfaces three times, but disappears in the water on the fourth try. The story seems to contain the «child/wind» rhyming scheme of the German tale.[18]

In a French fairy tale, La Cabane au Toit de Fromage («The Hut with the Roof made of Cheese»), the brother is the hero who deceives the witch and locks her up in the oven.[19]

In the first Puerto Rican variant of «The Orphaned Children,» the brother pushes the witch into the oven.[20]

Other folk tales of ATU 327A type include the French «The Lost Children», published by Antoinette Bon in 1887,[21][22] or the Moravian «Old Gruel», edited by Maria Kosch in 1899.[22]

The Children and the Ogre (ATU 327)[edit]

Structural comparisons can also be made with other tales of ATU 327 type («The Children and the Ogre»), which is not a simple fairy tale type but rather a «folktale complex with interconnected subdivisions» depicting a child (or children) falling under the power of an ogre, then escaping by their clever tricks.[23]

In ATU 327B («The Brothers and the Ogre»), a group of siblings come to an ogre’s house who intends to kill them in their beds, but the youngest of the children exchanges the visitors with the ogre’s offspring, and the villain kills his own children by mistake. They are chased by the ogre, but the siblings eventually manage to come back home safely.[24] Stith Thompson points the great similarity of the tales types ATU 327A and ATU 327B that «it is quite impossible to disentangle the two tales».[25]

ATU 327C («The Devil [Witch] Carries the Hero Home in a Sack») depicts a witch or an ogre catching a boy in a sack. As the villain’s daughter is preparing to kill him, the boy asks her to show him how he should arrange himself; when she does so, he kills her. Later on, he kills the witch and goes back home with her treasure. In ATU 327D («The Kiddlekaddlekar»), children are discovered by an ogre in his house. He intends to hang them, but the girl pretends not to understand how to do it, so the ogre hangs himself to show her. He promises his kiddlekaddlekar (a magic cart) and treasure in exchange for his liberation; they set him free, but the ogre chases them. The children eventually manage to kill him and escape safely. In ATU 327F («The Witch and the Fisher Boy»), a witch lures a boy and catches him. When the witch’s daughter tries to bake the child, he pushes her into the oven. The witch then returns home and eats her own daughter. She eventually tries to fell the tree in which the boy is hiding, but birds fly away with him.[24]

Further comparisons[edit]

The initial episode, which depicts children deliberately lost in the forest by their unloving parents, can be compared with many previous stories: Montanus’s «The Little Earth-Cow» (1557), Basile’s «Ninnillo and Nennella» (1635), Madame d’Aulnoy’s «Finette Cendron» (1697), or Perrault’s «Hop-o’-My-Thumb» (1697). The motif of the trail that fails to lead the protagonists back home is also common to «Ninnillo and Nennella», «Finette Cendron» and «Hop-o’-My-Thumb»,[26] and the Brothers Grimm identified the latter as a parallel story.[27]

Finally, ATU 327 tales share a similar structure with ATU 313 («Sweetheart Roland», «The Foundling», «Okerlo») in that one or more protagonists (specifically children in ATU 327) come into the domain of a malevolent supernatural figure and escape from it.[24] Folklorist Joseph Jacobs, commenting on his reconstructed proto-form of the tale (Johnnie and Grizzle), noticed the «contamination» of the tale with the story of The Master Maid, later classified as ATU 313.[28] ATU 327A tales are also often combined with stories of ATU 450 («Little Brother and Sister»), in which children run away from an abusive stepmother.[3]

Analysis[edit]

According to folklorist Jack Zipes, the tale celebrates the symbolic order of the patriarchal home, seen as a haven protected from the dangerous characters that threaten the lives of children outside, while it systematically denigrates the adult female characters, which are seemingly intertwined between each other.[8][29] The mother or stepmother indeed dies just after the children kill the witch, suggesting that they may metaphorically be the same woman.[30] Zipes also argues that the importance of the tale in the European oral and literary tradition may be explained by the theme of child abandonment and abuse. Due to famines and lack of birth control, it was common in medieval Europe to abandon unwanted children in front of churches or in the forest. The death of the mother during childbirth sometimes led to tensions after remarriage, and Zipes proposes that it may have played a role in the emergence of the motif of the wicked stepmother.[29]

Linguist and folklorist Edward Vajda has proposed that these stories represent the remnant of a coming-of-age, rite of passage tale extant in Proto-Indo-European society.[31][32] Psychologist Bruno Bettelheim argues that the main motif is about dependence, oral greed, and destructive desires that children must learn to overcome, after they arrive home «purged of their oral fixations». Others have stressed the satisfying psychological effects of the children vanquishing the witch or realizing the death of their wicked stepmother.[8]

Cultural legacy[edit]

Stage and musical theater[edit]

The fairy tale enjoyed a multitude of adaptations for the stage, among them the opera Hänsel und Gretel by Engelbert Humperdinck—one of the most performed operas.[33] It is principally based upon the Grimm’s version, although it omits the deliberate abandonment of the children.[7][8]

A contemporary reimagining of the story, Mátti Kovler’s musical fairytale Ami & Tami, was produced in Israel and the United States and subsequently released as a symphonic album.[34][35]

Literature[edit]

Several writers have drawn inspiration from the tale, such as Robert Coover in «The Gingerbread House» (Pricks and Descants, 1970), Anne Sexton in Transformations (1971), Garrison Keillor in «My Stepmother, Myself» in «Happy to Be Here» (1982), and Emma Donoghue in «A Tale of the Cottage» (Kissing the Witch, 1997).[8] Adam Gidwitz’s 2010 children’s book A Tale Dark & Grimm and its sequels In a Glass Grimmly (2012), and The Grimm Conclusion (2013) are loosely based on the tale and show the siblings meeting characters from other fairy tales.

Terry Pratchett mentions gingerbread cottages in several of his books, mainly where a witch had turned wicked and ‘started to cackle’, with the gingerbread house being a stage in a person’s increasing levels of insanity. In The Light Fantastic the wizard Rincewind and Twoflower are led by a gnome into one such building after the death of the witch and warned to be careful of the doormat, as it is made of candy floss.

Film[edit]

- Hansel and Gretel: An Opera Fantasy, a 1954 stop-motion animated theatrical feature film directed by John Paul and released by RKO Radio Pictures.

- A 1983 episode of Shelley Duvall’s Faerie Tale Theatre starred Ricky Schroder as Hansel and Joan Collins as the stepmother/witch.

- Hansel and Gretel, a 1983 TV special directed by Tim Burton.

- Hansel and Gretel, a 1987 American/Israeli musical film directed by Len Talan with David Warner, Cloris Leachman, Hugh Pollard and Nicola Stapleton. Part of the 1980s film series Cannon Movie Tales.

- Elements from the story were used in the 1994 horror film Wes Craven’s New Nightmare for its climax.

- «Hänsel und Gretel»[36] by 2012 German Broadcaster RBB released as part of its series Der rbb macht Familienzeit.

- Hansel & Gretel: Witch Hunters (2013) by Tommy Wirkola with Jeremy Renner and Gemma Arterton, (USA, Germany). The film follows the adventures of Hansel & Gretel who became adults.

- Gretel & Hansel, a 2020 American horror film directed by Oz Perkins in which Gretel is a teenager while Hansel is still a little boy.

- Secret Magic Control Agency (2021) is an animated retelling of the fairy tale by incorporating comedy and family genres[37]

Computer programming[edit]

Hansel and Gretel’s trail of breadcrumbs inspired the name of the navigation element «breadcrumbs» that allows users to keep track of their locations within programs or documents.[38]

Video games[edit]

- Hansel & Gretel and the Enchanted Castle (1995) by Terraglyph Interactive Studios is an adventure and hidden object game. The player controls Hansel, tasked with finding Prin, a forest imp, who holds the key to saving Gretel from the witch.[39]

- Gretel and Hansel (2009) by Mako Pudding is a browser adventure game. Popular on Newgrounds for its gruesome reimagining of the story, it features hand painted watercolor backgrounds and characters animated by Flash.[40]

- Fearful Tales: Hansel and Gretel Collector’s Edition (2013) by Eipix Entertainment is a HOPA (hidden object puzzle adventure) game. The player, as Hansel and Gretel’s mother, searches the witch’s lair for clues.[41]

- In the online role-playing game Poptropica, the Candy Crazed mini-quest (2021) includes a short retelling of the story. The player is summoned to the witch’s castle to free the children, who have been imprisoned after eating some of the candy residents.[42]

See also[edit]

- «Brother and Sister»

- «Esben and the Witch»

- Gingerbread house

- «Hop-o’-My-Thumb» (French fairy tale by Charles Perrault)

- «The Hut in the Forest»

- «Jorinde and Joringel»

- «Molly Whuppie»

- «Thirteenth»

- The Truth About Hansel and Gretel

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ In German, the names are diminutives of Johannes (John) and Margarete (Margaret).

- ^ Zipes words it as «re-appropriated» because Ströber’s Alsatian informant who provided «Das Eierkuchenhäuslein (The Little House of Pancakes)» had probably read Grimm’s «Hansel and Gretel».

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ a b Wanning Harries 2000, p. 225.

- ^ a b c d Ashliman, D. L. (2011). «Hansel and Gretel». University of Pittsburgh.

- ^ a b c d Zipes 2013, p. 121.

- ^ Goldberg 2008, p. 440.

- ^ a b c Zipes 2013, pp. 121–122.

- ^ a b c Goldberg 2000, p. 51.

- ^ a b c d e Opie & Opie 1974, p. 236.

- ^ a b c d e Wanning Harries 2000, p. 227.

- ^ Opie & Opie 1974, p. 236; Goldberg 2000, p. 42; Wanning Harries 2000, p. 225; Zipes 2013, p. 121

- ^ a b Goldberg 2008, p. 439.

- ^ a b Goldberg 2008, p. 438.

- ^ Zipes (2014) tr. «Hansel and Gretel (The Complete First Edition)», pp. 43–48; Zipes (2013) tr., pp. 122–126; Brüder Grimm, ed. (1812). «15. Hänsel und Grethel» . Kinder- und Haus-Märchen (in German). Vol. 1 (1 ed.). Realschulbuchhandlung. pp. 49–58 – via Wikisource.

- ^ Goldberg 2008, p. 438: «in the fourth edition, the woodcutter’s wife (who had been the children’s own mother) was first called a stepmother.»

- ^ Tatar 2002, p. 45

- ^ Goldberg 2008, pp. 439–440.

- ^ Thompson 1977, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Tatar 2002, p. 54

- ^ Bosschère, Jean de. Folk tales of Flanders. New York: Dodd, Mead. 1918. pp. 91-94.

- ^ Guerber, Hélène Adeline. Contes et légendes. 1ere partie. New York, Cincinnati [etc.] American book company. 1895. pp. 64-67.

- ^ Ocasio, Rafael (2021). Folk stories from the hills of Puerto Rico = Cuentos folklóricos de las montañas de Puerto Rico. New Brunswick. pp. 175–176. ISBN 978-1978823013.

- ^ Delarue 1956, p. 365.

- ^ a b Zipes 2013, pp. 146, 150.

- ^ Goldberg 2000, pp. 43.

- ^ a b c Goldberg 2008, p. 441.

- ^ Thompson 1977, p. 37.

- ^ Goldberg 2000, p. 44.

- ^ Tatar 2002, p. 72

- ^ Jacobs 1916, pp. 255–256.

- ^ a b Zipes 2013, p. 122.

- ^ Lüthi 1970, p. 64

- ^ Vajda 2010

- ^ Vajda 2011

- ^ Upton, George Putnam (1897). The Standard Operas (Google book) (12th ed.). Chicago: McClurg. pp. 125–129. ISBN 1-60303-367-X. Retrieved 15 October 2007.

- ^ «Composer Matti Kovler realizes dream of reviving fairy-tale opera in Boston». The Boston Globe. Retrieved 2019-10-31.

- ^ Schwartz, Penny. «Boston goes into the woods with Israeli opera ‘Ami and Tami’«. Times of Israel. Retrieved 2019-10-31.

- ^ «Hänsel und Gretel | Der rbb macht Familienzeit — YouTube». www.youtube.com. Archived from the original on 2021-10-30. Retrieved 2020-08-26.

- ^ Milligan, Mercedes (2019-11-01). «Wizart Reveals ‘Hansel and Gretel’ Poster Art Ahead of AFM». Animation Magazine. Retrieved 2020-11-07.

- ^ Mark Levene (18 October 2010). An Introduction to Search Engines and Web Navigation (2nd ed.). Wiley. p. 221. ISBN 978-0470526842. Retrieved June 24, 2016.

- ^ «Hansel & Gretel and the Enchanted Castle for Windows (1995)».

- ^ «Gretel and Hansel».

- ^ «Fearful Tales: Hansel and Gretel Collector’s Edition for iPad, iPhone, Android, Mac & PC! Big Fish is the #1 place for the best FREE games».

- ^ «The Candy Crazed Mini Quest is NOW LIVE!! 🍬🏰 | poptropica».

Bibliography[edit]

- Delarue, Paul (1956). The Borzoi Book of French Folk-Tales. Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.

- Goldberg, Christine (2000). «Gretel’s Duck: The Escape from the Ogre in AaTh 327». Fabula. 41 (1–2): 42–51. doi:10.1515/fabl.2000.41.1-2.42. S2CID 163082145.

- Goldberg, Christine (2008). «Hansel and Gretel». In Haase, Donald (ed.). The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Folktales and Fairy Tales. Greenwood. ISBN 978-0-313-04947-7.

- Jacobs, Joseph (1916). European Folk and Fairy Tales. G. P. Putnam’s sons.

- Lüthi, Max (1970). Once Upon A Time: On the Nature of Fairy Tales. Frederick Ungar Publishing Co. ISBN 9780804425650.

- Opie, Iona; Opie, Peter (1974). The Classic Fairy Tales. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-211559-1.

- Tatar, Maria (2002). The Annotated Classic Fairy Tales. BCA. ISBN 978-0-393-05163-6.

- Thompson, Stith (1977). The Folktale. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-03537-9.

- Vajda, Edward (2010). The Classic Russian Fairy Tale: More Than a Bedtime Story (Speech). The World’s Classics. Western Washington University.

- Vajda, Edward (2011). The Russian Fairy Tale: Ancient Culture in a Modern Context (Speech). Center for International Studies International Lecture Series. Western Washington University.

- Wanning Harries, Elizabeth (2000). «Hansel and Gretel». In Zipel, Jack (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Fairy Tales. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-968982-8.

- Zipes, Jack (2013). «Abandoned Children ATU 327A―Hansel and Gretel». The Golden Age of Folk and Fairy Tales: From the Brothers Grimm to Andrew Lang. Hackett Publishing. pp. 121ff. ISBN 978-1-624-66034-4.

Primary sources[edit]

- Zipes, Jack (2014). «Hansel and Gretel (Hänsel und Gretel)». The Original Folk and Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm: The Complete First Edition. Jacob Grimm; Wilhelm Grimm (orig. eds.); Andrea Dezsö (illustr.) (Revised ed.). Princeton University Press. pp. 43–48. ISBN 978-0-691-17322-1.

Further reading[edit]

- de Blécourt, Willem. «On the Origin of Hänsel und Gretel». In: Fabula 49, 1-2 (2008): 30-46. doi: https://doi.org/10.1515/FABL.2008.004

- Böhm-Korff, Regina (1991). Deutung und Bedeutung von «Hänsel und Gretel»: eine Fallstudie (in German). P. Lang. ISBN 978-3-631-43703-2.

- Freudenburg, Rachel. «Illustrating Childhood—»Hansel and Gretel».» Marvels & Tales 12, no. 2 (1998): 263-318. www.jstor.org/stable/41388498.

- Gaudreau, Jean. «Handicap et sentiment d’abandon dans trois contes de fées: Le petit Poucet, Hansel et Gretel, Jean-mon-Hérisson». In: Enfance, tome 43, n°4, 1990. pp. 395–404. [DOI: https://doi.org/10.3406/enfan.1990.1957]; www.persee.fr/doc/enfan_0013-7545_1990_num_43_4_1957

- Harshbarger, Scott. «Grimm and Grimmer: “Hansel and Gretel” and Fairy Tale Nationalism.» Style 47, no. 4 (2013): 490-508. www.jstor.org/stable/10.5325/style.47.4.490.

- Mieder, Wolfgang (2007). Hänsel und Gretel: das Märchen in Kunst, Musik, Literatur, Medien und Karikaturen (in German). Praesens. ISBN 978-3-7069-0469-8.

- Taggart, James M. «»Hansel and Gretel» in Spain and Mexico.» The Journal of American Folklore 99, no. 394 (1986): 435-60. doi:10.2307/540047.

- Zipes, Jack (1997). «The rationalization of abandonment and abuse in fairy tales: The case of Hansel and Gretel». Happily Ever After: Fairy Tales, Children, and the Culture Industry. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-25296-0.

External links[edit]

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

- Hansel and Gretel at Project Gutenberg

- The complete set of Grimms’ Fairy Tales, including Hansel and Gretel at Standard Ebooks

- Hansel and Gretel fairy tale

- Original versions and psychological analysis of classic fairy tales, including Hansel and Gretel

- The Story of Hansel and Gretel

- Collaboratively illustrated story on Project Bookses

- https://www.grimmstories.com/en/grimm_fairy-tales/hansel_and_gretel

Пряничный домик (сказка братьев Гримм)

Пряничный домик — сказка про братика и стестричку Жана и Мари. Родители детей были очень бедными, и они и дети целыми днями работали до изнеможения. Иной раз даже на ужин не хватало сил, а даже если бы и хватало, ужинать часто было нечем. Дети ночами мечтали о чем-нибудь сладеньком, особенно младшенький Жан. Пошли они как-то в лес по грибы и ягоды, заблудились и забрели в самую чащу, а там — чудо. Дети не верили своим глазам. Пряничный домик и конфетный садик, ручеёк из лимонада и другие сладости. Наелись дети, но тут вернулась хозяйка домика — злобная ведьма…

Данные о сказке

-

Категория

-

В аудио формате

-

Другие сказки братьев Гримм

Распечатать или скачать текст сказки

Пряничный домик: краткое содержание

Воскресенье – любимый день недели Жана и Мари. Именно в этот день можно погулять по лесу, собирать грибы и ягоды, отдохнуть немножко от изнуряющей ежедневной работы, ведь семья детей очень бедная. Вот в один из воскресных дней дети заблудились в лесу и им пришлось ночевать в самой глуши. Всю ночь они не спали, еле-еле перетерпели жуткий страх, ведь в лесу ночью очень-очень страшно маленьким детям.

Поутру они принялись искать дорогу домой, и набрели на чей-то домик. И вот удивление! Пряничный домик, заборчик из миндаля, изюминки на деревьях и к тому же лимонадный ручеек. Дети наелись сладостей, но тут вернулась хозяйка домика. Поначалу она показалась им доброй старушкой, но как только они по её приглашению зашли в дом – старуха превратилась в ведьму. Заперла она Жана и решила откормить его и съесть. Каждый день готовила ему всякие вкусности, и мальчик толстел прямо на глазах.

Мари решила обмануть старушку, дала брату тоненькую палочку, чтобы он её показывал вместо своего растолстевшего пальчика ведьме. Но старуху провести не удалось, она решила в тот же день съесть мальчика. Тогда Мари организовала всё так, чтобы ведьма сама села на лопату, показать, как именно она будет готовить мальчика, а потом взяла, да и засунула её в печь. Дети бежали. Долго-долго они бродили по лесу и тут увидели огонек родного дома. Там их уже ждали родители.