Птица додо или маврикийский дронт, одна из самых загадочных и интересных представителей пернатых, живших когда-либо на Земле. Маврикийскому дронту удалось выжить в доисторическом времени и дожить до наших времен, пока он не столкнулась, с главным врагом всех животных и птиц, с человеком. Последние представители этой уникальной птицы погибли более трёх веков назад, но к счастью многие интересные факты об их жизни сохранились и по сей день.

Происхождение вида и описание

Фото: Птица додо

Точной информации о происхождении птицы додо нет, однако ученые уверены, что Маврикийский дронт является далеким предком древних голубей, которые когда-то высадились на остров Маврикий.

Несмотря на существенные отличия внешнего вида причудливой птицы додо и голубя, пернатые имеют общие характеристики, как:

- голые участки вокруг кожи глаз, достигающие основания клюва;

- специфическое строение ног;

- отсутствие особой кости (сошник) в черепе;

- наличие расширенной части пищевода.

Найдя на острове достаточные комфортные условия для обитания и размножения, птицы стали постоянными жителями данной местности. В последствии эволюционируя в течении нескольких сотен лет, птицы видоизменились, увеличились в размерах и разучились летать. Сложно сказать, сколько веков птица додо мирно существовала в своём ареале обитания, однако первые упоминания о ней появились в 1598 году, когда впервые голландские моряки высадились на острова. Благодаря записям голландского адмирала, который описывал весь животным мир, встречающийся на его пути, Маврикийский дронт получил свою известность на весь мир.

Фото: Птица додо

Необыкновенная, нелетающая птица получила научное название дронт, но во всем мире её называют додо. История возникновения прозвища «додо» не точна, но существует версия, что из-за дружелюбного характера и отсутствия способностей летать, голландские моряки называли её глупой и вялой, что в переводе похоже на голландское слово «duodu». По другим версиям название связано с криками птицы или подражанием её голоса. Также сохранились исторические записи, где утверждается, что первоначально голландцы дали название птицам — валлоуберд, а португальцы называли их просто пингвинами.

Внешний вид и особенности

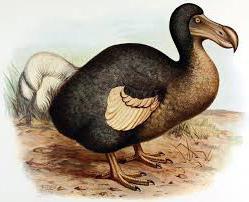

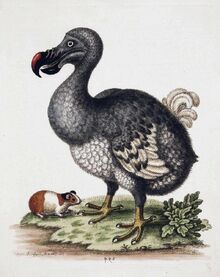

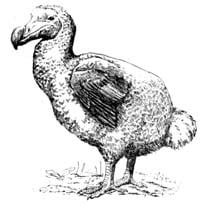

Фото: Птицы додо Маврикий

Несмотря на родственность с голубями, маврикийский дронт внешне больше напоминал упитанную индейку. Из-за огромного живота, который практически волочился по земле, птица не только не могла взлететь, но и не могла быстро бегать. Только благодаря историческим записям и картинам художников тех времен, удалось установить общее представление и внешний вид этой единственной в своём роде птицы. Длина туловища достигало до 1 метра, а средняя масса тела составляла 20 кг. Птица додо обладала мощным, красивым клювом, желто-зеленоватого оттенка. Голова была небольших размеров, с короткой немного изогнутой шеей.

Оперенье было нескольких видов:

- серого или коричневатого оттенка;

- былого цвета.

Желтые лапы были схожи с лапами современных домашних птиц, три пальца из которых были расположены впереди, а одина сзади. Когти были короткие, крюкообразной формы. Украшал птицу короткий, пушистый хвост, состоящий из изогнутых внутрь перьев, придающий маврикийскому дронту особую важность и элегантность. Птицы имели половой орган, различающий самок от самцов. Особь мужского пола, обычно был крупнее самки и имел больший клюв, который использовал в борьбе за самку.

Как свидетельствуют множество записей тех времен, все кому посчастливилось встретить додо, оставались под большим впечатлением от внешнего вида этой уникальной птицы. Создавалось впечатление, что у птицы нет совсем крыльев, так как они были небольших размеров и в соотношении с их мощным телом, были практически не заметны.

Где обитает птица додо?

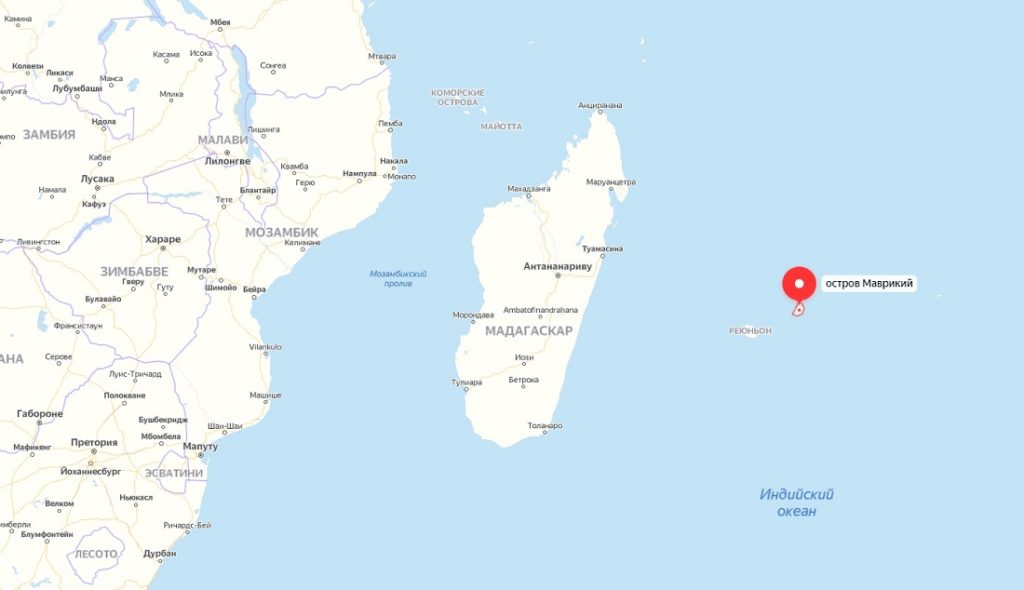

Фото: Вымершая птица додо

Птица додо, являлась жительницей архипелага Маскаренских островов, расположенных в Индийском океане, недалеко от Мадагаскара. Это были безлюдные и спокойные острова, свободные не только от людей, но и от возможных опасностей и хищников. Точно не известно от куда и почему прилетели предки маврикийских дронтов, однако птицы приземлившись в этот райский уголок, остались на островах до конца своих дней. Так как климат на острове жаркий и влажный, достаточно теплым в зимнее месяца и не очень жарким в летние, птицы чувствовали себя очень комфортно уютно весь год. А богатая флора и фауна острова позволяла жить сытой и спокойной жизнью.

Данный вид дронта обитал непосредственно на острове Маврикий, однако в состав архипелага входил остров Реюньон, который был домом белого дронта и остров Родригес, на котором обитали дронты отшельники. К сожалению, у всех них, как и у самого маврикийского дронта, была такая же печальная судьба, они были полностью истреблены людьми.

Интересный факт: Голанские мореплаватели пытались отправить на корабле несколько взрослых особей в Европу для его подробного изучения и размножения, однако практически никто не пережил долгого и тяжелого путешествия. Поэтому единственной средой обитания оставался остров Маврикий.

Теперь Вы знаете где жила птица додо. Давайте же посмотрим, чем она питалась.

Чем питается птица додо?

Фото: Птица додо

Додо была мирная птица питающаяся в основном пищей растительного происхождения. Остров был настолько богат всевозможной едой, что маврикийскому дронту, не нужно было делать никаких особых усилий для добычи себе еды, а просто подбирать все необходимое прямо с земли, что в дальнейшем и сказалось на его внешнем виде и размеренном образе жизни.

В ежедневный рацион птицы входили:

- спелые плоды пальмы латании, небольшие ягоды в виде горошин диаметров в несколько сантиметров;

- почки и листья деревьев;

- луковицы и коренья;

- всевозможная трава;

- ягоды и фрукты;

- мелкие насекомые;

- твердые семена деревьев.

Интересный факт: Для того чтобы зерно дерева Кальвария проросло и дало ростки, его необходимо было извлечь из твердой шкарлупы. Это как раз и происходило во время поедания зерен птицей додо, только благодаря своему клюву, птице удавалось раскрывать данные зерна. Поэтому из-за цепной реакции, после исчезновения птиц, со временем, деревья Кальвария также пропали с флоры острова.

Одной особенностью пищеварительной системы птицы додо, являлось то, что для переваривания твердой пищи, она специально глотала мелкие камешки, что способствовало лучшему перетиранию еды на мелкие частицы.

Особенности характера и образа жизни

Фото: Птица додо, или дронт

Из-за идеальных условий царивших на острове, для птиц не было никаких угроз со стороны. Чувствуя себя в полной безопасности, они обладали очень доверчивым и дружелюбным характером, что в дальнейшем сыграло фатальной ошибкой и привело к полному вымиранию вида. Приблизительная продолжительность жизни составляла около 10 лет.

В основном птицы держались небольшими стаями по 10-15 особей, в густых лесах, где было много растений и необходимой пищи. Размеренная и пассивная жизнь привела к образованию большого живота, который практически волочился по земле, сделав пернатых очень медлительными и неуклюжими.

Общались эти удивительные птицы, с помощью криков и громких звуков, которые можно было услышать на расстоянии больше 200 метров. Созывая друг друга, начинали активно махать своими маленькими крыльями, создавая громкий звук. С помощью этих движений и звуков, сопровождая всё это специальными танцами перед самкой, и проходил обряд выбора партнера.

Пара между особями создавалась на всю жизнь. Гнезда для своего будущего потомства, птицы сооружали очень тщательно и аккуратно, в виде небольшого холмика, добавляя туда пальмовые листья и всевозможные ветки. Процесс высиживания длился около двух месяцев, при этом родители очень яро охраняли свое единственное крупное яйцо.

Интересный факт: В процессе высиживания яйца, участвовали оба родителя по очереди, а если к гнезду подходила посторонняя особь додо, то выгонять шла особь соответствующего пола незваного гостя.

Социальная структура и размножение

Фото: Птицы додо

К сожалению, благодаря только современным исследованиям костных останков маврикийских дронтов, ученым удалось узнать больше информации о размножении этой птицы и её характере роста. До этого, об эти птицах практически ничего не было известно. Данные исследования показали, что птица размножалась в определенное время года, приблизительно в марте, при этом сразу полностью теряла свои перья, оставаясь в пушистом оперении. Данный факт подтверждался признаками потери большого количества минералов из организма птицы.

По характеру роста в костях было определенно, что птенцы, после вылупления из яиц, достаточно быстро вырастали до больших размеров. Однако, до полной половой зрелости им необходимо было несколько лет. Особым преимуществом для выживания служило, то что они вылуплялись в августе, в более спокойный и богатый пищей период. А в период с ноября по март на острове бушевали опасные циклоны, часто заканчивающиеся нехваткой еды.

Интересный факт: Самка додо откладывала только одно яйцо за раз, что и стало одной из причин их быстрого исчезновения.

Примечательно, что сведения полученные научными исследованиями, полностью соответствовали записям моряков, которым посчастливилось встретиться лично с этими уникальными птицами.

Естественные враги птиц додо

Фото: Исчезнувшая птица додо

Миролюбивые птицы жили в полном спокойствие и безопасности, на острове не было ни одного хищника, который бы мог охотиться за птицей. Всевозможные рептилии и насекомые, так же не несли никакой угрозы для безобидной додо. Поэтому в процессе многолетней эволюции птица додо не обзавелась никакими защитными приспособлениями или навыками, которые могли бы спасти её при нападении.

Всё резко поменялось с приходом человека на остров, будучи доверчивой и любопытной птицей, додо сама с интересом шла на контакт с голландскими колонистами, не подозревая всей опасности, став легкой добычей жестоких людей.

В начале моряки не знали, можно ли употреблять мясо этой птицы, да и на вкус оно оказалось жесткое и не очень приятное, однако голод и быстрый улов, птица практически не сопротивлялась, способствовало убийству додо. Да и мореплаватели поняли, что добыча дронта весьма выгода, ведь трёх забитых птиц, хватало на целую команду. Помимо этого, не малый ущерб принесли завезенные на острова звери.

А именно:

- кабаны давили яйца дронтов;

- козы съедали кустарники, где строили свои гнёзда птицы, делая их еще больше уязвимыми;

- собаки и кошки уничтожали старых и молодых птиц;

- крысы пожирали птенцов.

Охота была существенным фактором гибели додо, но обезьяны, олени, свиньи и крысы, выпущенные на остров с кораблей, во многом, определили их судьбу.

Популяция и статус вида

Фото: Голова птицы додо

Практически, всего за 65 лет, человеку удалось полностью уничтожить многовековую популяцию этого феноменального пернатого животного. К сожалению, люди не только варварски уничтожили всех представителей данного рода птицы, но и не сумели с достоинством сохранить её останки. Существуют сведения о нескольких случаев, перевезенных с островов птицы додо. Первая птица была перевезена в Нидерланды в 1599 году, где произвела фурор, особенно среди художников, которые часто изображали удивительную птицу в своих картинах.

Вторая особь была привезена в Англию, практически спустя 40 лет, где выставлялась на обозрения удивленной публике за деньги. Затем из измученной, умершей птицы сделали чучело и выставлять в Оксфордском музее. Однако данное чучело не удалось сохранить да наших дней, от него осталось в музее, только засушенная голова и нога. Несколько частей черепа дронта и останки лап можно также увидеть в Дании и Чехии. Также ученые смогли смоделировать полноценную модель птицы додо, чтобы люди увидели, как они выглядели до вымирания. Хотя многие экземпляры дронта оказались в европейских музеях, большинство из них были потеряны или уничтожены.

Интересный факт: Большую известность птица додо получила благодаря сказке «Алиса в стане чудес», где додо является одним из персонажей истории.

Птица додо переплетается с множеством научных факторов и необоснованных домыслов, однако истинным и неоспоримым аспектом, являются жестокие и неоправданные действия человека, ставшие главной причиной вымирания целого вида животного.

Дата публикации: 16.07.2019 года

Дата обновления: 25.09.2019 года в 20:43

Теги:

- Raphus Brisson

- Вторичноротые

- Вымершие животные

- Голубеобразные

- Голубиные

- Двусторонне-симметричные

- Дронтовые

- Животные Африки

- Животные Красной книги

- Животные леса

- Животные Мадагаскара

- Животные на букву Д

- Животные на букву П

- Животные смешанных и широколиственных лесов

- Животные Субтропического пояса Южного полушария

- Животные Тропического пояса Южного полушария

- Животные широколиственного леса

- Животные широколиственных лесов

- Исчезнувшие животные

- Лесные птицы

- Настоящие птицы

- Нелетающие птицы

- Необычные животные

- Необычные животные мира

- Необычные животные планеты

- Необычные птицы

- Новонёбные

- Позвоночные

- Птицы Африки

- Птицы Красной книги

- Птицы леса

- Самые необычные животные

- Самые необычные животные в мире

- Самые необычные животные мира

- Самые необычные птицы

- Уникальные животные

- Хордовые животные

- Челюстноротые

- Четвероногие

- Экзотические животные

- Экзотические птицы

- Эукариоты

- Эуметазои

На чтение 8 мин. Опубликовано 09.04.2021

Небольшой остров посреди Индийского океана, Маврикий, был необитаем в течение тысяч лет. Начиная с 1634 года, голландцы начали заселять местность, строить флот. Они вырубали леса, чтобы увеличить площадь для импортных товаров, принимали на свою территорию моряков, рабов, каторжников.

Распространение людского населения привело к заметному ухудшению флоры и фауны острова: снижению числа видов или полному их уничтожению. Поведение человека не обошло стороной и птицы додо, которая бесследно исчезла с маленького острова.

Содержание

- Происхождение вида

- Описание животного

- Как выглядит

- Отличие самки от самца

- Характер и образ жизни

- Где обитала

- Чем питалась

- Размножение

- Естественные враги

- Ближайшие родственники

- Взаимоотношения с людьми

- Птица додо в Красной Книге

- Основные причины исчезновения

- Есть ли потенциал возрождения вида

- Интересные факты о животном

Происхождение вида

Маврикийский дронт – это крупная птица, эндемик, существовавшая только на острове Маврикий. Додо причисляют к потомкам прилетевших на остров 4 миллиона лет назад голубей.

Вследствие отсутствия существенных врагов, наличия пищи на земле, они перестали летать, быстро приспособились к пассивному, наземному образу жизни. Птицы увеличились в размерах, полностью изменили свой внешний вид.

Что касается названия, то первоначально пернатых прозвали «вальгфогель», что в переводе означает «отвратительная птица». Такое имя дал голландский адмирал Вибранд ван Варвейк, которому был противен вкус мяса животного. Спустя 4 года Виллем ван Вестсанен дал дронту прозвище «додо».

Описание животного

Птица внешне напоминала индюка, однако отличалась весьма внушительным размером: волочившимся по земле брюхом, длинной шеей, массивным клювом. Такой вид создавал впечатление грозной и опасной особи, что никак не сочеталось с мирным и доверчивым характером.

Первые описания мореплавателей гласят о том, что они сравнивали дронта с большим голубем, лебедем или индейкой. Однако позже они утверждали, что это неведомый и крайне отвратительный на вкус вид.

Как выглядит

Додо достигал 1 метра роста и весил примерно 20 – 23 кг. Птица была медлительной, с короткими слаборазвитыми крыльями и малой грудной клеткой, из – за которых она не могла летать. Тело покрывали мягкие сероватые перья, напоминающие пух, короткий хвост выделялся белым окрасом. Благодаря характерному внешнему виду дронт выглядел весьма пушистым.

Лапки его были желтого цвета и непропорционально короткими. Три пальца с крюкообразными когтями располагались спереди, а один сзади. Голову частично покрывал пух, а пятнистый, желто – зеленый, клюв изгибался резко вниз, имел длину 21 – 23 см.

Отличие самки от самца

Среди популяции данного вида был заметен характерный половой диморфизм. Самцы были значительно крупнее самок, имели большой закругленный клюв длиной 23 см. Он служил своеобразным орудием в борьбе за самку.

Дополнительно, особи мужского пола имели крупные широкие тазовые кости, позволяющие носить на себе не малый вес.

Характер и образ жизни

Птицы жили, в основном, на фруктовых деревьях, держались небольшими стайками по 10 – 15 особей. Точного описания их поведения нет, за исключением заметок о дружелюбности, способах привлечения самки. Между собой дронты жили мирно. Записи биологов не дают сведений об агрессивном, хищническом поведении.

Где обитала

Согласно историческим данным, ареал дронта – леса окрестных районов юга, запада Маврикия. Климат на острове был влажным и, одновременно, жарким. Теплые зимние месяцы и прохладные летние создавали комфортные условия для существования животных.

Чем питалась

Описания, дошедшие до наших дней, свидетельствуют о том, что у птиц был зверский аппетит, а сами они не отличались питательностью, приятным вкусом. Утверждению о невыдающихся вкусовых качествах, противоречит характер питания додо:

- пальмовые плоды;

- почки, листья;

- луковицы, корни растений;

- орехи;

- моллюски;

- мелкие насекомые;

- семена деревьев.

При исследовании в желудке птиц были обнаружены мелкие камешки, которые они использовали для перетирания пищи.

Размножение

Дронты формировали гнезда на земле из пальмовых веток и листьев. Начиналось строительство в марте, а к августу на свет уже появлялся птенец. Откладывали птицы одно большое яйцо (данный факт считается одной из причин быстрого исчезновения).

При этом додо полностью сбрасывала перья, оставаясь покрытой пухом: будущему птенцу самка отдавала большое количество минеральных веществ, микроэлементов.

Яйцо поочередно высиживали самец и самка. Весь процесс вместе с вскармливанием птенца длился несколько месяцев. Додо были очень ответственными родителями, не подпускали других животных к гнезду.

После вылупления птенцы очень быстро достигали больших размеров. Приблизительная продолжительность жизни особей составляла 10 – 13 лет.

Естественные враги

Благодаря безопасной среде обитания у дронтов отсутствовали естественные враги. Даже насекомые или рептилии не представляли опасности. Единственным, по – настоящему губительным влиянием, обладал человек.

Почти за 65 лет он сумел истребить всех особей данного вида. Однако есть все же достойный отрывок печальной истории: люди сумели сохранить останки додо и подарить миру подробную информации об этих уникальных существах.

Ближайшие родственники

Близким, ныне живущим, родственником дронта считается Никобарский голубь, встречающийся на островах Юго – восточной Азии. Сородич также имеет неразвитые крылья, но может взлетать на невысокие деревья, если ему угрожает опасность.

Другим сородичем считается Родригесский дронт с острова Родригес, ставший жертвой людского «интереса». Вымер представитель к концу 1700 года.

Взаимоотношения с людьми

Для птиц на острове царили идеальные условия для мирного существования: отсутствие хищных животных, людей. Чувство полной безопасности сделало додо дружелюбными, весьма доверчивыми. Это послужило на руку жестоким морякам, заселившим остров.

Из документальных источников известно, что пришедшие на землю Маврикия голландцы легко приручили дронтов. Они без труда подходили к ним, дотрагивались до перьев, хвоста. Со временем, европейцы сменили интерес на наживу: они стали охотиться за безобидными животными, пока те полностью не исчезли.

Птица додо в Красной Книге

Маврикийский дронт был занесен в Красную книгу к1662 году согласно документальным изложениям Энтони Чика, британского биолога, орнитолога. Птице был присвоен статус – «вымерший вид».

Информацию о дронте несет также Черная книга. Она содержит список животных, существовавших не так давно и исчезнувших вследствие деятельности человека.

Основные причины исчезновения

Из – за своих коротких крыльев, громоздкого тела дронт не мог летать или спасаться бегом от опасности. Это делало его легко добычей. До прибытия поселенцев на остров додо не сталкивались с хищниками. Они без страха восприняли появление новых хозяев острова.

За короткий промежуток времени люди начали серьезно задумываться о своем дальнейшем пребывании на Маврикие. Потребление мяса дронта стало обычным явлением, даже несмотря на отвратительный вкус.

Однако люди были не единственной угрозой истребления додо. Крысы, обезьяны сбегали с кораблей, поедали яйца и птенцов дронта.

На остров были привезены олени, свиньи, козы, куры, собаки, кошки. Все это в значительной мере нарушило мирную жизнь его обитателей, превратив ее в борьбу за выживание.

Последнее зафиксированное наблюдение за дронтом датируется 1688 годом. Но дополнительный статистический анализ дает другую дату: 1693 год. Официально исчезновение додо признали только к 19 веку.

Существует еще одна теория исчезновения: ученые полагают, что причиной гибели послужил мощный циклон или наводнение. Однако она составляет всего 10 % от общего признания.

Есть ли потенциал возрождения вида

До конца 18 века в британском музее находились мумифицированные останки додо. Последнее чучело птицы находилось при Оксфордском университете, где сейчас от него остались лишь голова и лапка. В 1755 году испорченные временем, молью части чучела были сожжены.

Скелет животного есть в Американском музее естественной истории Нью – Йорка, который собран из костей нескольких птиц додо. Цельный туловище одного дронта, найденный близ болота, имеется в Музее естественной истории Маврикия.

Сохранившихся останков птицы может оказаться достаточно для восстановления мягких тканей и воссоздания фрагментов ДНК. Птица по генетическому коду близка к никобарским голубям, которые могут выступить «суррогатными» носителями. Однако эти факты не упрощают задачи возрождения маврикийского дронта.

Во всяком случае, додо стоит едва ли не последним в списке, кого ученые пожелают вернуть к жизни.

Интересные факты о животном

Несмотря на печальный исход, важные факты о жизни додо все же остались. Благодаря наличию записей моряков, путешественников биологи и антропологи могут составить полную картину жизни маврикийского дронта. Некоторые факты о додо:

- Других птиц от гнезда отгоняли представители того же пола: если во время насиживания к яйцу приближалась самка, то самец начинал размахивать крыльями, издавать громкие звуки, призывая «родительницу» к защите.

- Привлекали птицы друг друга особым образом: около 4 – 5 минут они воспроизводили 15 – 20 взмахов крыльями и танцевали перед самкой. Сопровождали пляску додо характерным криком. От этого гулкий шум был слышен на расстоянии 200 метров.

- Пару себе дронты выбирали один раз и на всю жизнь.

- Европейцы жестоко обходились с птицами, устраивая соревнования, целью которых было убить побольше дронтов. Многие пытались увезти додо с собой. Во время переезда птицы роняли слезы, отказывались от еды, погибали. Казалось, будто они понимали, что больше не вернуться на родину.

- Птицы питались зернами дерева Кальвария, твердую скорлупу которых они могли расколоть своим массивным клювом. Извлечение семян таким образом давало возможность появлению новых ростков дерева. С исчезновением додо, посредством цепной реакции, перестали расти и Кальвария.

До нашего времени дошли и несколько рисунков мореплавателей, которые первыми видели дронта. Благодаря им антропологи могли сделать относительно точные описания жизни животного. Трагическая судьба маврикийского дронта – еще одно доказательство бездумного поведения человека.

Как знак символизма и памяти, Джерсийский трест выбрал додо для своей эмблемы, а государственным символом Маврикия стал герб, увенчанный изображением птицы. Из – за медлительности и неповоротливости пернатых моряки считали их глупыми. Но ,может, все было наоборот?

| Dodo

Temporal range: Holocene |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Dodo skeleton cast (left) and model based on modern research (right), at Oxford University Museum of Natural History | |

|

Conservation status |

|

|

|

|

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Columbiformes |

| Family: | Columbidae |

| Subfamily: | †Raphinae |

| Genus: | †Raphus Brisson, 1760 |

| Species: |

†R. cucullatus |

| Binomial name | |

| †Raphus cucullatus

(Linnaeus, 1758) |

|

|

|

| Location of Mauritius (in blue) | |

| Synonyms | |

|

The dodo (Raphus cucullatus) is an extinct flightless bird that was endemic to the island of Mauritius, which is east of Madagascar in the Indian Ocean. The dodo’s closest genetic relative was the also-extinct Rodrigues solitaire. The two formed the subfamily Raphinae, a clade of extinct flightless birds that were a part of the family which includes pigeons and doves. The closest living relative of the dodo is the Nicobar pigeon. A white dodo was once thought to have existed on the nearby island of Réunion, but it is now believed that this assumption was merely confusion based on the also-extinct Réunion ibis and paintings of white dodos.

Subfossil remains show the dodo was about 1 metre (3 ft 3 in) tall and may have weighed 10.6–17.5 kg (23–39 lb) in the wild. The dodo’s appearance in life is evidenced only by drawings, paintings, and written accounts from the 17th century. Since these portraits vary considerably, and since only some of the illustrations are known to have been drawn from live specimens, the dodos’ exact appearance in life remains unresolved, and little is known about its behaviour. It has been depicted with brownish-grey plumage, yellow feet, a tuft of tail feathers, a grey, naked head, and a black, yellow, and green beak. It used gizzard stones to help digest its food, which is thought to have included fruits, and its main habitat is believed to have been the woods in the drier coastal areas of Mauritius. One account states its clutch consisted of a single egg. It is presumed that the dodo became flightless because of the ready availability of abundant food sources and a relative absence of predators on Mauritius. Though the dodo has historically been portrayed as being fat and clumsy, it is now thought to have been well-adapted for its ecosystem.

The first recorded mention of the dodo was by Dutch sailors in 1598. In the following years, the bird was hunted by sailors and invasive species, while its habitat was being destroyed. The last widely accepted sighting of a dodo was in 1662. Its extinction was not immediately noticed, and some considered it to be a myth. In the 19th century, research was conducted on a small quantity of remains of four specimens that had been brought to Europe in the early 17th century. Among these is a dried head, the only soft tissue of the dodo that remains today. Since then, a large amount of subfossil material has been collected on Mauritius, mostly from the Mare aux Songes swamp. The extinction of the dodo within less than a century of its discovery called attention to the previously unrecognised problem of human involvement in the disappearance of entire species. The dodo achieved widespread recognition from its role in the story of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, and it has since become a fixture in popular culture, often as a symbol of extinction and obsolescence.

Taxonomy

The dodo was variously declared a small ostrich, a rail, an albatross, or a vulture, by early scientists.[2] In 1842, Danish zoologist Johannes Theodor Reinhardt proposed that dodos were ground pigeons, based on studies of a dodo skull he had discovered in the collection of the Natural History Museum of Denmark.[3] This view was met with ridicule, but was later supported by English naturalists Hugh Edwin Strickland and Alexander Gordon Melville in their 1848 monograph The Dodo and Its Kindred, which attempted to separate myth from reality.[4] After dissecting the preserved head and foot of the specimen at the Oxford University Museum and comparing it with the few remains then available of the extinct Rodrigues solitaire (Pezophaps solitaria) they concluded that the two were closely related. Strickland stated that although not identical, these birds shared many distinguishing features of the leg bones, otherwise known only in pigeons.[5]

Strickland and Melville established that the dodo was anatomically similar to pigeons in many features. They pointed to the very short keratinous portion of the beak, with its long, slender, naked basal part. Other pigeons also have bare skin around their eyes, almost reaching their beak, as in dodos. The forehead was high in relation to the beak, and the nostril was located low on the middle of the beak and surrounded by skin, a combination of features shared only with pigeons. The legs of the dodo were generally more similar to those of terrestrial pigeons than of other birds, both in their scales and in their skeletal features. Depictions of the large crop hinted at a relationship with pigeons, in which this feature is more developed than in other birds. Pigeons generally have very small clutches, and the dodo is said to have laid a single egg. Like pigeons, the dodo lacked the vomer and septum of the nostrils, and it shared details in the mandible, the zygomatic bone, the palate, and the hallux. The dodo differed from other pigeons mainly in the small size of the wings and the large size of the beak in proportion to the rest of the cranium.[5]

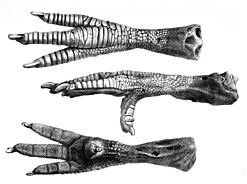

Sketch of the Oxford head made before it was dissected in 1848

1848 lithograph of the Oxford specimen’s foot, which has been sampled for DNA

Throughout the 19th century, several species were classified as congeneric with the dodo, including the Rodrigues solitaire and the Réunion solitaire, as Didus solitarius and Raphus solitarius, respectively (Didus and Raphus being names for the dodo genus used by different authors of the time). An atypical 17th-century description of a dodo and bones found on Rodrigues, now known to have belonged to the Rodrigues solitaire, led Abraham Dee Bartlett to name a new species, Didus nazarenus, in 1852.[6] Based on solitaire remains, it is now a synonym of that species.[7] Crude drawings of the red rail of Mauritius were also misinterpreted as dodo species; Didus broeckii and Didus herberti.[8]

For many years the dodo and the Rodrigues solitaire were placed in a family of their own, the Raphidae (formerly Dididae), because their exact relationships with other pigeons were unresolved. Each was also placed in its own monotypic family (Raphidae and Pezophapidae, respectively), as it was thought that they had evolved their similarities independently.[9] Osteological and DNA analysis has since led to the dissolution of the family Raphidae, and the dodo and solitaire are now placed in their own subfamily, Raphinae, within the family Columbidae.[10]

Evolution

In 2002, American geneticist Beth Shapiro and colleagues analysed the DNA of the dodo for the first time. Comparison of mitochondrial cytochrome b and 12S rRNA sequences isolated from a tarsal of the Oxford specimen and a femur of a Rodrigues solitaire confirmed their close relationship and their placement within the Columbidae. The genetic evidence was interpreted as showing the Southeast Asian Nicobar pigeon (Caloenas nicobarica) to be their closest living relative, followed by the crowned pigeons (Goura) of New Guinea, and the superficially dodo-like tooth-billed pigeon (Didunculus strigirostris) from Samoa (its scientific name refers to its dodo-like beak). This clade consists of generally ground-dwelling island endemic pigeons. The following cladogram shows the dodo’s closest relationships within the Columbidae, based on Shapiro et al., 2002:[11][12]

A similar cladogram was published in 2007, inverting the placement of Goura and Didunculus and including the pheasant pigeon (Otidiphaps nobilis) and the thick-billed ground pigeon (Trugon terrestris) at the base of the clade.[13] The DNA used in these studies was obtained from the Oxford specimen, and since this material is degraded, and no usable DNA has been extracted from subfossil remains, these findings still need to be independently verified.[14] Based on behavioural and morphological evidence, Jolyon C. Parish proposed that the dodo and Rodrigues solitaire should be placed in the subfamily Gourinae along with the Goura pigeons and others, in agreement with the genetic evidence.[15] In 2014, DNA of the only known specimen of the recently extinct spotted green pigeon (Caloenas maculata) was analysed, and it was found to be a close relative of the Nicobar pigeon, and thus also the dodo and Rodrigues solitaire.[16]

The 2002 study indicated that the ancestors of the dodo and the solitaire diverged around the Paleogene-Neogene boundary, about 23.03 million years ago. The Mascarene Islands (Mauritius, Réunion, and Rodrigues), are of volcanic origin and are less than 10 million years old. Therefore, the ancestors of both birds probably remained capable of flight for a considerable time after the separation of their lineage.[17] The Nicobar and spotted green pigeon were placed at the base of a lineage leading to the Raphinae, which indicates the flightless raphines had ancestors that were able to fly, were semi-terrestrial, and inhabited islands. This in turn supports the hypothesis that the ancestors of those birds reached the Mascarene islands by island hopping from South Asia.[16] The lack of mammalian herbivores competing for resources on these islands allowed the solitaire and the dodo to attain very large sizes and flightlessness.[18][19] Despite its divergent skull morphology and adaptations for larger size, many features of its skeleton remained similar to those of smaller, flying pigeons.[20] Another large, flightless pigeon, the Viti Levu giant pigeon (Natunaornis gigoura), was described in 2001 from subfossil material from Fiji. It was only slightly smaller than the dodo and the solitaire, and it too is thought to have been related to the crowned pigeons.[21]

Etymology

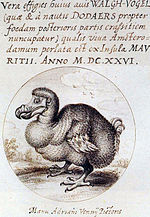

1601 engraving showing Dutch activities on the shore of Mauritius and the first published depiction of a dodo on the left (2, called «Walchvoghel«)

One of the original names for the dodo was the Dutch «Walghvoghel«, first used in the journal of Dutch Vice Admiral Wybrand van Warwijck, who visited Mauritius during the Second Dutch Expedition to Indonesia in 1598.[22] Walghe means «tasteless», «insipid», or «sickly», and voghel means «bird». The name was translated by Jakob Friedlib into German as Walchstök or Walchvögel.[23] The original Dutch report titled Waarachtige Beschryving was lost, but the English translation survived:[24]

On their left hand was a little island which they named Heemskirk Island, and the bay it selve they called Warwick Bay… Here they taried 12. daies to refresh themselues, finding in this place great quantity of foules twice as bigge as swans, which they call Walghstocks or Wallowbirdes being very good meat. But finding an abundance of pigeons & popinnayes [parrots], they disdained any more to eat those great foules calling them Wallowbirds, that is to say lothsome or fulsome birdes.[25][26]

Another account from that voyage, perhaps the first to mention the dodo, states that the Portuguese referred to them as penguins. The meaning may not have been derived from penguin (the Portuguese referred to those birds as «fotilicaios» at the time), but from pinion, a reference to the small wings.[22] The crew of the Dutch ship Gelderland referred to the bird as «Dronte» (meaning «swollen») in 1602, a name that is still used in some languages.[27] This crew also called them «griff-eendt» and «kermisgans», in reference to fowl fattened for the Kermesse festival in Amsterdam, which was held the day after they anchored on Mauritius.[28]

The etymology of the word dodo is unclear. Some ascribe it to the Dutch word dodoor for «sluggard», but it is more probably related to Dodaars, which means either «fat-arse» or «knot-arse», referring to the knot of feathers on the hind end.[29] The first record of the word Dodaars is in Captain Willem Van West-Zanen’s journal in 1602.[30] The English writer Sir Thomas Herbert was the first to use the word dodo in print in his 1634 travelogue claiming it was referred to as such by the Portuguese, who had visited Mauritius in 1507.[28] Another Englishman, Emmanuel Altham, had used the word in a 1628 letter in which he also claimed its origin was Portuguese. The name «dodar» was introduced into English at the same time as dodo, but was only used until the 18th century.[31] As far as is known, the Portuguese never mentioned the bird. Nevertheless, some sources still state that the word dodo derives from the Portuguese word doudo (currently doido), meaning «fool» or «crazy». It has also been suggested that dodo was an onomatopoeic approximation of the bird’s call, a two-note pigeon-like sound resembling «doo-doo».[32]

The Latin name cucullatus («hooded») was first used by Juan Eusebio Nieremberg in 1635 as Cygnus cucullatus, in reference to Carolus Clusius’s 1605 depiction of a dodo. In his 18th-century classic work Systema Naturae, Carl Linnaeus used cucullatus as the specific name, but combined it with the genus name Struthio (ostrich).[5] Mathurin Jacques Brisson coined the genus name Raphus (referring to the bustards) in 1760, resulting in the current name Raphus cucullatus. In 1766, Linnaeus coined the new binomial Didus ineptus (meaning «inept dodo»). This has become a synonym of the earlier name because of nomenclatural priority.[33]

Description

Right half of the Oxford specimen’s head (the left half is separate)

1848 lithograph of the Oxford specimen’s skull in multiple views

As no complete dodo specimens exist, its external appearance, such as plumage and colouration, is hard to determine.[22] Illustrations and written accounts of encounters with the dodo between its discovery and its extinction (1598–1662) are the primary evidence for its external appearance.[34] According to most representations, the dodo had greyish or brownish plumage, with lighter primary feathers and a tuft of curly light feathers high on its rear end. The head was grey and naked, the beak green, black and yellow, and the legs were stout and yellowish, with black claws.[35] A study of the few remaining feathers on the Oxford specimen head showed that they were pennaceous rather than plumaceous (downy) and most similar to those of other pigeons.[36]

Subfossil remains and remnants of the birds that were brought to Europe in the 17th century show that dodos were very large birds, up to 1 m (3 ft 3 in) tall. The bird was sexually dimorphic; males were larger and had proportionally longer beaks. Weight estimates have varied from study to study. In 1993, Bradley C. Livezey proposed that males would have weighed 21 kilograms (46 lb) and females 17 kilograms (37 lb).[37] Also in 1993, Andrew C. Kitchener attributed a high contemporary weight estimate and the roundness of dodos depicted in Europe to these birds having been overfed in captivity; weights in the wild were estimated to have been in the range of 10.6–17.5 kg (23–39 lb), and fattened birds could have weighed 21.7–27.8 kg (48–61 lb).[38] A 2011 estimate by Angst and colleagues gave an average weight as low as 10.2 kg (22 lb).[39] This has also been questioned, and there is still controversy over weight estimates.[40][41] A 2016 study estimated the weight at 10.6 to 14.3 kg (23 to 32 lb), based on CT scans of composite skeletons.[42] It has also been suggested that the weight depended on the season, and that individuals were fat during cool seasons, but less so during hot.[43]

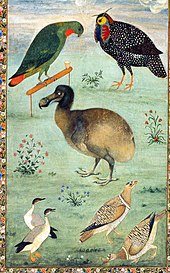

Dodo among Indian birds, by Ustad Mansur, c. 1625; perhaps the most accurate depiction of a live dodo

The skull of the dodo differed much from those of other pigeons, especially in being more robust, the bill having a hooked tip, and in having a short cranium compared to the jaws. The upper bill was nearly twice as long as the cranium, which was short compared to those of its closest pigeon relatives. The openings of the bony nostrils were elongated along the length of the beak, and they contained no bony septum. The cranium (excluding the beak) was wider than it was long, and the frontal bone formed a dome-shape, with the highest point above the hind part of the eye sockets. The skull sloped downwards at the back. The eye sockets occupied much of the hind part of the skull. The sclerotic rings inside the eye were formed by eleven ossicles (small bones), similar to the amount in other pigeons. The mandible was slightly curved, and each half had a single fenestra (opening), as in other pigeons.[20]

The dodo had about nineteen presynsacral vertebrae (those of the neck and thorax, including three fused into a notarium), sixteen synsacral vertebrae (those of the lumbar region and sacrum), six free tail (caudal) vertebrae, and a pygostyle. The neck had well-developed areas for muscle and ligament attachment, probably to support the heavy skull and beak. On each side, it had six ribs, four of which articulated with the sternum through sternal ribs. The sternum was large, but small in relation to the body compared to those of much smaller pigeons that are able to fly. The sternum was highly pneumatic, broad, and relatively thick in cross-section. The bones of the pectoral girdle, shoulder blades, and wing bones were reduced in size compared to those of flighted pigeon, and were more gracile compared to those of the Rodrigues solitaire, but none of the individual skeletal components had disappeared. The carpometacarpus of the dodo was more robust than that of the solitaire, however. The pelvis was wider than that of the solitaire and other relatives, yet was comparable to the proportions in some smaller, flighted pigeons. Most of the leg bones were more robust than those of extant pigeons and the solitaire, but the length proportions were little different.[20]

Many of the skeletal features that distinguish the dodo and the Rodrigues solitaire, its closest relative, from other pigeons have been attributed to their flightlessness. The pelvic elements were thicker than those of flighted pigeons to support the higher weight, and the pectoral region and the small wings were paedomorphic, meaning that they were underdeveloped and retained juvenile features. The skull, trunk and pelvic limbs were peramorphic, meaning that they changed considerably with age. The dodo shared several other traits with the Rodrigues solitaire, such as features of the skull, pelvis, and sternum, as well as their large size. It differed in other aspects, such as being more robust and shorter than the solitaire, having a larger skull and beak, a rounded skull roof, and smaller orbits. The dodo’s neck and legs were proportionally shorter, and it did not possess an equivalent to the knob present on the solitaire’s wrists.[37]

Contemporary descriptions

Most contemporary descriptions of the dodo are found in ship’s logs and journals of the Dutch East India Company vessels that docked in Mauritius when the Dutch Empire ruled the island. These records were used as guides for future voyages.[14] Few contemporary accounts are reliable, as many seem to be based on earlier accounts, and none were written by scientists.[22] One of the earliest accounts, from van Warwijck’s 1598 journal, describes the bird as follows:

Painting of a dodo head by Cornelis Saftleven from 1638, probably the latest original depiction of the species

Blue parrots are very numerous there, as well as other birds; among which are a kind, conspicuous for their size, larger than our swans, with huge heads only half covered with skin as if clothed with a hood. These birds lack wings, in the place of which 3 or 4 blackish feathers protrude. The tail consists of a few soft incurved feathers, which are ash coloured. These we used to call ‘Walghvogel’, for the reason that the longer and oftener they were cooked, the less soft and more insipid eating they became. Nevertheless their belly and breast were of a pleasant flavour and easily masticated.[44]

One of the most detailed descriptions is by Herbert in A Relation of Some Yeares Travaille into Afrique and the Greater Asia from 1634:

First here only and in Dygarrois [Rodrigues] is generated the Dodo, which for shape and rareness may antagonize the Phoenix of Arabia: her body is round and fat, few weigh less than fifty pound. It is reputed more for wonder than for food, greasie stomackes may seeke after them, but to the delicate they are offensive and of no nourishment. Her visage darts forth melancholy, as sensible of Nature’s injurie in framing so great a body to be guided with complementall wings, so small and impotent, that they serve only to prove her bird. The halfe of her head is naked seeming couered with a fine vaile, her bill is crooked downwards, in midst is the thrill [nostril], from which part to the end tis a light green, mixed with pale yellow tincture; her eyes are small and like to Diamonds, round and rowling; her clothing downy feathers, her train three small plumes, short and inproportionable, her legs suiting her body, her pounces sharpe, her appetite strong and greedy. Stones and iron are digested, which description will better be conceived in her representation.[45]

Contemporary depictions

Compilation of the Gelderland ship’s journal sketches from 1601 of live and recently killed dodos, attributed to Joris Laerle

The travel journal of the Dutch ship Gelderland (1601–1603), rediscovered in the 1860s, contains the only known sketches of living or recently killed specimens drawn on Mauritius. They have been attributed to the professional artist Joris Joostensz Laerle, who also drew other now-extinct Mauritian birds, and to a second, less refined artist.[46] Apart from these sketches, it is unknown how many of the twenty or so 17th-century illustrations of the dodos were drawn from life or from stuffed specimens, which affects their reliability.[22] Since dodos are otherwise only known from limited physical remains and descriptions, contemporary artworks are important to reconstruct their appearance in life. While there has been an effort since the mid-19 century to list all historical illustrations of dodos, previously unknown depictions continue to be discovered occasionally.[47]

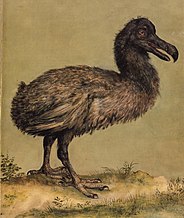

The traditional image of the dodo is of a very fat and clumsy bird, but this view may be exaggerated. The general opinion of scientists today is that many old European depictions were based on overfed captive birds or crudely stuffed specimens.[48] It has also been suggested that the images might show dodos with puffed feathers, as part of display behaviour.[39] The Dutch painter Roelant Savery was the most prolific and influential illustrator of the dodo, having made at least twelve depictions, often showing it in the lower corners. A famous painting of his from 1626, now called Edwards’s Dodo as it was once owned by the ornithologist George Edwards, has since become the standard image of a dodo. It is housed in the Natural History Museum, London. The image shows a particularly fat bird and is the source for many other dodo illustrations.[49][50]

An Indian Mughal painting rediscovered in the Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, in 1955 shows a dodo along with native Indian birds.[51] It depicts a slimmer, brownish bird, and its discoverer Aleksander Iwanow and British palaeontologist Julian Hume regarded it as one of the most accurate depictions of the living dodo; the surrounding birds are clearly identifiable and depicted with appropriate colouring.[52] It is believed to be from the 17th century and has been attributed to the Mughal painter Ustad Mansur. The bird depicted probably lived in the menagerie of the Mughal Emperor Jahangir, located in Surat, where the English traveller Peter Mundy also claimed to have seen two dodos sometime between 1628 and 1633.[53][22] In 2014, another Indian illustration of a dodo was reported, but it was found to be derivative of an 1836 German illustration.[54]

All post-1638 depictions appear to be based on earlier images, around the time reports mentioning dodos became rarer. Differences in the depictions led ornithologists such as Anthonie Cornelis Oudemans and Masauji Hachisuka to speculate about sexual dimorphism, ontogenic traits, seasonal variation, and even the existence of different species, but these theories are not accepted today. Because details such as markings of the beak, the form of the tail feathers, and colouration vary from account to account, it is impossible to determine the exact morphology of these features, whether they signal age or sex, or if they even reflect reality.[55] Hume argued that the nostrils of the living dodo would have been slits, as seen in the Gelderland, Cornelis Saftleven, Savery’s Crocker Art Gallery, and Ustad Mansur images. According to this claim, the gaping nostrils often seen in paintings indicate that taxidermy specimens were used as models.[22] Most depictions show that the wings were held in an extended position, unlike flighted pigeons, but similar to ratites such as the ostrich and kiwi.[20]

Behaviour and ecology

Savery paintings featuring dodos in the corners in various poses, painted approximately between 1625 and 1629

Little is known of the behaviour of the dodo, as most contemporary descriptions are very brief. Based on weight estimates, it has been suggested the male could reach the age of 21, and the female 17.[37] Studies of the cantilever strength of its leg bones indicate that it could run quite fast.[38] The legs were robust and strong to support the bulk of the bird, and also made it agile and manoeuvrable in the dense, pre-human landscape. Though the wings were small, well-developed muscle scars on the bones show that they were not completely vestigial, and may have been used for display behaviour and balance; extant pigeons also use their wings for such purposes.[20] Unlike the Rodrigues solitaire, there is no evidence that the dodo used its wings in intraspecific combat. Though some dodo bones have been found with healed fractures, it had weak pectoral muscles and more reduced wings in comparison. The dodo may instead have used its large, hooked beak in territorial disputes. Since Mauritius receives more rainfall and has less seasonal variation than Rodrigues, which would have affected the availability of resources on the island, the dodo would have less reason to evolve aggressive territorial behaviour. The Rodrigues solitaire was therefore probably the more aggressive of the two.[56] In 2016, the first 3D endocast was made from the brain of the dodo; the brain-to-body-size ratio was similar to that of modern pigeons, indicating that dodos were probably equal in intelligence.[57]

1601 map of a bay on Mauritius; the small D on the far right side marks where dodos were found

The preferred habitat of the dodo is unknown, but old descriptions suggest that it inhabited the woods on the drier coastal areas of south and west Mauritius. This view is supported by the fact that the Mare aux Songes swamp, where most dodo remains have been excavated, is close to the sea in south-eastern Mauritius.[58] Such a limited distribution across the island could well have contributed to its extinction.[59] A 1601 map from the Gelderland journal shows a small island off the coast of Mauritius where dodos were caught. Julian Hume has suggested this island was l’île aux Benitiers in Tamarin Bay, on the west coast of Mauritius.[60][46] Subfossil bones have also been found inside caves in highland areas, indicating that it once occurred on mountains. Work at the Mare aux Songes swamp has shown that its habitat was dominated by tambalacoque and Pandanus trees and endemic palms.[43] The near-coastal placement and wetness of the Mare aux Songes led to a high diversity of plant species, whereas the surrounding areas were drier.[61]

Many endemic species of Mauritius became extinct after the arrival of humans. So the ecosystem of the island is badly damaged and hard to reconstruct. Before humans arrived, Mauritius was entirely covered in forests, but very little remains of them today, because of deforestation.[62] The surviving endemic fauna is still seriously threatened.[63] The dodo lived alongside other recently extinct Mauritian birds such as the flightless red rail, the broad-billed parrot, the Mascarene grey parakeet, the Mauritius blue pigeon, the Mauritius scops owl, the Mascarene coot, the Mauritian shelduck, the Mauritian duck, and the Mauritius night heron. Extinct Mauritian reptiles include the saddle-backed Mauritius giant tortoise, the domed Mauritius giant tortoise, the Mauritian giant skink, and the Round Island burrowing boa. The small Mauritian flying fox and the snail Tropidophora carinata lived on Mauritius and Réunion, but vanished from both islands. Some plants, such as Casearia tinifolia and the palm orchid, have also become extinct.[64]

Diet

A 1631 Dutch letter (long thought lost, but rediscovered in 2017) is the only account of the dodo’s diet, and also mentions that it used its beak for defence. The document uses word-play to refer to the animals described, with dodos presumably being an allegory for wealthy mayors:[65]

The mayors are superb and proud. They presented themselves with an unyielding, stern face and wide open mouth, very jaunty and audacious of gait. They did not want to budge before us; their war weapon was the mouth, with which they could bite fiercely. Their food was raw fruit; they were not dressed very well, but were rich and fat, therefore we brought many of them on board, to the contentment of us all.[65]

In addition to fallen fruits, the dodo probably subsisted on nuts, seeds, bulbs, and roots.[66] It has also been suggested that the dodo might have eaten crabs and shellfish, like their relatives the crowned pigeons. Its feeding habits must have been versatile, since captive specimens were probably given a wide range of food on the long sea journeys.[67] Oudemans suggested that as Mauritius has marked dry and wet seasons, the dodo probably fattened itself on ripe fruits at the end of the wet season to survive the dry season, when food was scarce; contemporary reports describe the bird’s «greedy» appetite. The Mauritian ornithologist France Staub suggested in 1996 that they mainly fed on palm fruits, and he attempted to correlate the fat-cycle of the dodo with the fruiting regime of the palms.[30]

Skeletal elements of the upper jaw appear to have been rhynchokinetic (movable in relation to each other), which must have affected its feeding behaviour. In extant birds, such as frugivorous (fruit-eating) pigeons, kinetic premaxillae help with consuming large food items. The beak also appears to have been able to withstand high force loads, which indicates a diet of hard food.[20] Examination of the brain endocast found that though the brain was similar to that of other pigeons in most respects, the dodo had a comparatively large olfactory bulb. This gave the dodo a good sense of smell, which may have aided in locating fruit and small prey.[57]

Several contemporary sources state that the dodo used Gastroliths (gizzard stones) to aid digestion. The English writer Sir Hamon L’Estrange witnessed a live bird in London and described it as follows:

About 1638, as I walked London streets, I saw the picture of a strange looking fowle hung out upon a clothe and myselfe with one or two more in company went in to see it. It was kept in a chamber, and was a great fowle somewhat bigger than the largest Turkey cock, and so legged and footed, but stouter and thicker and of more erect shape, coloured before like the breast of a young cock fesan, and on the back of a dunn or dearc colour. The keeper called it a Dodo, and in the ende of a chymney in the chamber there lay a heape of large pebble stones, whereof hee gave it many in our sight, some as big as nutmegs, and the keeper told us that she eats them (conducing to digestion), and though I remember not how far the keeper was questioned therein, yet I am confident that afterwards she cast them all again.[68]

It is not known how the young were fed, but related pigeons provide crop milk. Contemporary depictions show a large crop, which was probably used to add space for food storage and to produce crop milk. It has been suggested that the maximum size attained by the dodo and the solitaire was limited by the amount of crop milk they could produce for their young during early growth.[69]

In 1973, the tambalacoque, also known as the dodo tree, was thought to be dying out on Mauritius, to which it is endemic. There were supposedly only 13 specimens left, all estimated to be about 300 years old. Stanley Temple hypothesised that it depended on the dodo for its propagation, and that its seeds would germinate only after passing through the bird’s digestive tract. He claimed that the tambalacoque was now nearly coextinct because of the disappearance of the dodo.[70] Temple overlooked reports from the 1940s that found that tambalacoque seeds germinated, albeit very rarely, without being abraded during digestion.[71] Others have contested his hypothesis and suggested that the decline of the tree was exaggerated or seeds were also distributed by other extinct animals such as Cylindraspis tortoises, fruit bats, or the broad-billed parrot.[72] According to Wendy Strahm and Anthony Cheke, two experts in the ecology of the Mascarene Islands, the tree, while rare, has germinated since the demise of the dodo and numbers several hundred, not 13 as claimed by Temple, hence, discrediting Temple’s view as to the dodo and the tree’s sole survival relationship.[73]

The Brazilian ornithologist Carlos Yamashita suggested in 1997 that the broad-billed parrot may have depended on dodos and Cylindraspis tortoises to eat palm fruits and excrete their seeds, which became food for the parrots. Anodorhynchus macaws depended on now-extinct South American megafauna in the same way, but now rely on domesticated cattle for this service.[74]

Reproduction and development

As it was flightless and terrestrial and there were no mammalian predators or other kinds of natural enemy on Mauritius, the dodo probably nested on the ground.[75] The account by François Cauche from 1651 is the only description of the egg and the call:

I have seen in Mauritius birds bigger than a Swan, without feathers on the body, which is covered with a black down; the hinder part is round, the rump adorned with curled feathers as many in number as the bird is years old. In place of wings they have feathers like these last, black and curved, without webs. They have no tongues, the beak is large, curving a little downwards; their legs are long, scaly, with only three toes on each foot. It has a cry like a gosling, and is by no means so savoury to eat as the Flamingos and Ducks of which we have just spoken. They only lay one egg which is white, the size of a halfpenny roll, by the side of which they place a white stone the size of a hen’s egg. They lay on grass which they collect, and make their nests in the forests; if one kills the young one, a grey stone is found in the gizzard. We call them Oiseaux de Nazaret. The fat is excellent to give ease to the muscles and nerves.[5]

Thin sections of hindlimb bones showing stages of the growth series

Diagram showing life history events of a dodo based on histology and accounts

Cauche’s account is problematic, since it also mentions that the bird he was describing had three toes and no tongue, unlike dodos. This led some to believe that Cauche was describing a new species of dodo («Didus nazarenus«). The description was most probably mingled with that of a cassowary, and Cauche’s writings have other inconsistencies.[76] A mention of a «young ostrich» taken on board a ship in 1617 is the only other reference to a possible juvenile dodo.[77] An egg claimed to be that of a dodo is stored in the East London Museum in South Africa. It was donated by the South African museum official Marjorie Courtenay-Latimer, whose great aunt had received it from a captain who claimed to have found it in a swamp on Mauritius. In 2010, the curator of the museum proposed using genetic studies to determine its authenticity.[78] It may instead be an aberrant ostrich egg.[32]

Because of the possible single-egg clutch and the bird’s large size, it has been proposed that the dodo was K-selected, meaning that it produced few altricial offspring, which required parental care until they matured. Some evidence, including the large size and the fact that tropical and frugivorous birds have slower growth rates, indicates that the bird may have had a protracted development period.[37] The fact that no juvenile dodos have been found in the Mare aux Songes swamp may indicate that they produced little offspring, that they matured rapidly, that the breeding grounds were far away from the swamp, or that the risk of miring was seasonal.[79]

A 2017 study examined the histology of thin-sectioned dodo bones, modern Mauritian birds, local ecology, and contemporary accounts, to recover information about the life history of the dodo. The study suggested that dodos bred around August, after having potentially fattened themselves, corresponding with the fat and thin cycles of many vertebrates of Mauritius. The chicks grew rapidly, reaching robust, almost adult, sizes, and sexual maturity before Austral summer or the cyclone season. Adult dodos which had just bred moulted after Austral summer, around March. The feathers of the wings and tail were replaced first, and the moulting would have completed at the end of July, in time for the next breeding season. Different stages of moulting may also account for inconsistencies in contemporary descriptions of dodo plumage.[80]

Relationship with humans

1648 engraving showing the killing of dodos (centre left, erroneously depicted as penguin-like) and other animals now extinct from Mauritius

Mauritius had previously been visited by Arab vessels in the Middle Ages and Portuguese ships between 1507 and 1513, but was settled by neither. No records of dodos by these are known, although the Portuguese name for Mauritius, «Cerne (swan) Island», may have been a reference to dodos.[81] The Dutch Empire acquired Mauritius in 1598, renaming it after Maurice of Nassau, and it was used for the provisioning of trade vessels of the Dutch East India Company henceforward.[82] The earliest known accounts of the dodo were provided by Dutch travellers during the Second Dutch Expedition to Indonesia, led by admiral Jacob van Neck in 1598. They appear in reports published in 1601, which also contain the first published illustration of the bird.[83] Since the first sailors to visit Mauritius had been at sea for a long time, their interest in these large birds was mainly culinary. The 1602 journal by Willem Van West-Zanen of the ship Bruin-Vis mentions that 24–25 dodos were hunted for food, which were so large that two could scarcely be consumed at mealtime, their remains being preserved by salting.[84] An illustration made for the 1648 published version of this journal, showing the killing of dodos, a dugong, and possibly Mascarene grey parakeets, was captioned with a Dutch poem,[85] here in Hugh Strickland’s 1848 translation:

For food the seamen hunt the flesh of feathered fowl,

They tap the palms, and round-rumped dodos they destroy,

The parrot’s life they spare that he may peep and howl,

And thus his fellows to imprisonment decoy.[86]

Some early travellers found dodo meat unsavoury, and preferred to eat parrots and pigeons; others described it as tough, but good. Some hunted dodos only for their gizzards, as this was considered the most delicious part of the bird. Dodos were easy to catch, but hunters had to be careful not to be bitten by their powerful beaks.[87]

The appearance of the dodo and the red rail led Peter Mundy to speculate, 230 years before Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution:

Of these 2 sorts off fowl afforementionede, For oughtt wee yett know, Not any to bee Found out of this Iland, which lyeth aboutt 100 leagues From St. Lawrence. A question may bee demaunded how they should bee here and Not elcewhere, beeing soe Farer From other land and can Neither fly or swymme; whither by Mixture off kindes producing straunge and Monstrous formes, or the Nature of the Climate, ayer and earth in alltring the First shapes in long tyme, or how.[27]

Dodos transported abroad

The dodo was found interesting enough that living specimens were sent to Europe and the East. The number of transported dodos that reached their destinations alive is uncertain, and it is unknown how they relate to contemporary depictions and the few non-fossil remains in European museums. Based on a combination of contemporary accounts, paintings, and specimens, Julian Hume has inferred that at least eleven transported dodos reached their destinations alive.[88]

Hamon L’Estrange’s description of a dodo that he saw in London in 1638 is the only account that specifically mentions a live specimen in Europe. In 1626 Adriaen van de Venne drew a dodo that he claimed to have seen in Amsterdam, but he did not mention if it were alive, and his depiction is reminiscent of Savery’s Edwards’s Dodo. Two live specimens were seen by Peter Mundy in Surat, India, between 1628 and 1634, one of which may have been the individual painted by Ustad Mansur around 1625.[22] In 1628, Emmanuel Altham visited Mauritius and sent a letter to his brother in England:

Right wo and lovinge brother, we were ordered by ye said councell to go to an island called Mauritius, lying in 20d. of south latt., where we arrived ye 28th of May; this island having many goates, hogs and cowes upon it, and very strange fowles, called by ye portingalls Dodo, which for the rareness of the same, the like being not in ye world but here, I have sent you one by Mr. Perce, who did arrive with the ship William at this island ye 10th of June. [In the margin of the letter] Of Mr. Perce you shall receive a jarr of ginger for my sister, some beades for my cousins your daughters, and a bird called a Dodo, if it live.[89]

Whether the dodo survived the journey is unknown, and the letter was destroyed by fire in the 19th century.[90]

The earliest known picture of a dodo specimen in Europe is from a c. 1610 collection of paintings depicting animals in the royal menagerie of Emperor Rudolph II in Prague. This collection includes paintings of other Mauritian animals as well, including a red rail. The dodo, which may be a juvenile, seems to have been dried or embalmed, and had probably lived in the emperor’s zoo for a while together with the other animals. That whole stuffed dodos were present in Europe indicates they had been brought alive and died there; it is unlikely that taxidermists were on board the visiting ships, and spirits were not yet used to preserve biological specimens. Most tropical specimens were preserved as dried heads and feet.[88]

One dodo was reportedly sent as far as Nagasaki, Japan, in 1647, but it was long unknown whether it arrived.[74] Contemporary documents first published in 2014 proved the story, and showed that it had arrived alive. It was meant as a gift, and, despite its rarity, was considered of equal value to a white deer and a bezoar stone. It is the last recorded live dodo in captivity.[91]

Extinction

Illustration of Dutch sailors pursuing dodos, by Walter Paget, 1914. Hunting by humans is not believed to have been the main cause of the bird’s extinction.

Like many animals that evolved in isolation from significant predators, the dodo was entirely fearless of humans. This fearlessness and its inability to fly made the dodo easy prey for sailors.[92] Although some scattered reports describe mass killings of dodos for ships’ provisions, archaeological investigations have found scant evidence of human predation. Bones of at least two dodos were found in caves at Baie du Cap that sheltered fugitive slaves and convicts in the 17th century, which would not have been easily accessible to dodos because of the high, broken terrain.[10] The human population on Mauritius (an area of 1,860 km2 or 720 sq mi) never exceeded 50 people in the 17th century, but they introduced other animals, including dogs, pigs, cats, rats, and crab-eating macaques, which plundered dodo nests and competed for the limited food resources.[43] At the same time, humans destroyed the forest habitat of the dodos. The impact of the introduced animals on the dodo population, especially the pigs and macaques, is today considered more severe than that of hunting.[93] Rats were perhaps not much of a threat to the nests, since dodos would have been used to dealing with local land crabs.[94]

It has been suggested that the dodo may already have been rare or localised before the arrival of humans on Mauritius, since it would have been unlikely to become extinct so rapidly if it had occupied all the remote areas of the island.[59] A 2005 expedition found subfossil remains of dodos and other animals killed by a flash flood. Such mass mortalities would have further jeopardised a species already in danger of becoming extinct.[95] Yet the fact that the dodo survived hundreds of years of volcanic activity and climatic changes shows the bird was resilient within its ecosystem.[61]

Some controversy surrounds the date of its extinction. The last widely accepted record of a dodo sighting is the 1662 report by shipwrecked mariner Volkert Evertsz of the Dutch ship Arnhem, who described birds caught on a small islet off Mauritius, now suggested to be Amber Island:

These animals on our coming up to them stared at us and remained quiet where they stand, not knowing whether they had wings to fly away or legs to run off, and suffering us to approach them as close as we pleased. Amongst these birds were those which in India they call Dod-aersen (being a kind of very big goose); these birds are unable to fly, and instead of wings, they merely have a few small pins, yet they can run very swiftly. We drove them together into one place in such a manner that we could catch them with our hands, and when we held one of them by its leg, and that upon this it made a great noise, the others all on a sudden came running as fast as they could to its assistance, and by which they were caught and made prisoners also.[96]

The dodos on this islet may not necessarily have been the last members of the species.[97] The last claimed sighting of a dodo was reported in the hunting records of Isaac Johannes Lamotius in 1688. A 2003 statistical analysis of these records by the biologists David L. Roberts and Andrew R. Solow gave a new estimated extinction date of 1693, with a 95% confidence interval of 1688–1715. These authors also pointed out that because the last sighting before 1662 was in 1638, the dodo was probably already quite rare by the 1660s, and thus a disputed report from 1674 by an escaped slave could not be dismissed out of hand.[98]

Pieter van den Broecke’s 1617 drawing of a dodo, a one-horned sheep, and a red rail; after the dodo became extinct, visitors may have confused it with the red rail

The British ornithologist Alfred Newton suggested in 1868 that the name of the dodo was transferred to the red rail after the former had gone extinct.[99] Cheke also pointed out that some descriptions after 1662 use the names «Dodo» and «Dodaers» when referring to the red rail, indicating that they had been transferred to it.[100] He therefore pointed to the 1662 description as the last credible observation. A 1668 account by English traveller John Marshall, who used the names «Dodo» and «Red Hen» interchangeably for the red rail, mentioned that the meat was «hard», which echoes the description of the meat in the 1681 account.[101] Even the 1662 account has been questioned by the writer Errol Fuller, as the reaction to distress cries matches what was described for the red rail.[102] Until this explanation was proposed, a description of «dodos» from 1681 was thought to be the last account, and that date still has proponents.[103]

Cheke stated in 2014 that then recently accessible Dutch manuscripts indicate that no dodos were seen by settlers in 1664–1674.[104] In 2020, Cheke and the British researcher Jolyon C. Parish suggested that all mentions of dodos after the mid-17th century instead referred to red rails, and that the dodo had disappeared due to predation by feral pigs during a hiatus in settlement of Mauritius (1658–1664). The dodo’s extinction therefore was not realised at the time, since new settlers had not seen real dodos, but as they expected to see flightless birds, they referred to the red rail by that name instead. Since red rails probably had larger clutches than dodos and their eggs could be incubated faster, and their nests were perhaps concealed, they probably bred more efficiently, and were less vulnerable to pigs.[105]

It is unlikely the issue will ever be resolved, unless late reports mentioning the name alongside a physical description are rediscovered.[94] The IUCN Red List accepts Cheke’s rationale for choosing the 1662 date, taking all subsequent reports to refer to red rails. In any case, the dodo was probably extinct by 1700, about a century after its discovery in 1598.[1][101] The Dutch left Mauritius in 1710, but by then the dodo and most of the large terrestrial vertebrates there had become extinct.[43]

Even though the rareness of the dodo was reported already in the 17th century, its extinction was not recognised until the 19th century. This was partly because, for religious reasons, extinction was not believed possible until later proved so by Georges Cuvier, and partly because many scientists doubted that the dodo had ever existed. It seemed altogether too strange a creature, and many believed it a myth. The bird was first used as an example of human-induced extinction in Penny Magazine in 1833, and has since been referred to as an «icon» of extinction.[106]

Physical remains

17th-century specimens

The only extant remains of dodos taken to Europe in the 17th century are a dried head and foot in the Oxford University Museum of Natural History, a foot once housed in the British Museum but now lost, a skull in the University of Copenhagen Zoological Museum, and an upper jaw in the National Museum, Prague. The last two were rediscovered and identified as dodo remains in the mid-19th century.[107] Several stuffed dodos were also mentioned in old museum inventories, but none are known to have survived.[108] Apart from these remains, a dried foot, which belonged to the Dutch professor Pieter Pauw, was mentioned by Carolus Clusius in 1605. Its provenance is unknown, and it is now lost, but it may have been collected during the Van Neck voyage.[22] Supposed stuffed dodos seen in museums around the world today have in fact been made from feathers of other birds, many of the older ones by the British taxidermist Rowland Ward’s company.[107]

Casts of the Oxford head before dissection and the lost London foot

The only known soft tissue remains, the Oxford head (specimen OUM 11605) and foot, belonged to the last known stuffed dodo, which was first mentioned as part of the Tradescant collection in 1656 and was moved to the Ashmolean Museum in 1659.[22] It has been suggested that this might be the remains of the bird that Hamon L’Estrange saw in London, the bird sent by Emanuel Altham, or a donation by Thomas Herbert. Since the remains do not show signs of having been mounted, the specimen might instead have been preserved as a study skin.[109] In 2018, it was reported that scans of the Oxford dodo’s head showed that its skin and bone contained lead shot, pellets which were used to hunt birds in the 17th century. This indicates that the Oxford dodo was shot either before being transported to Britain, or some time after arriving. The circumstances of its killing are unknown, and the pellets are to be examined to identify where the lead was mined from.[110]

Many sources state that the Ashmolean Museum burned the stuffed dodo around 1755 because of severe decay, saving only the head and leg. Statute 8 of the museum states «That as any particular grows old and perishing the keeper may remove it into one of the closets or other repository; and some other to be substituted.»[111] The deliberate destruction of the specimen is now believed to be a myth; it was removed from exhibition to preserve what remained of it. This remaining soft tissue has since degraded further; the head was dissected by Strickland and Melville, separating the skin from the skull in two-halves. The foot is in a skeletal state, with only scraps of skin and tendons. Very few feathers remain on the head. It is probably a female, as the foot is 11% smaller and more gracile than the London foot, yet appears to be fully grown.[112] The specimen was exhibited at the Oxford museum from at least the 1860s and until 1998, where-after it was mainly kept in storage to prevent damage.[113] Casts of the head can today be found in many museums worldwide.[109]

Coloured engraving of the now lost London foot from 1793 (left), and 1848 lithograph of same in multiple views

The dried London foot, first mentioned in 1665, and transferred to the British Museum in the 18th century, was displayed next to Savery’s Edwards’s Dodo painting until the 1840s, and it too was dissected by Strickland and Melville. It was not posed in a standing posture, which suggests that it was severed from a fresh specimen, not a mounted one. By 1896 it was mentioned as being without its integuments, and only the bones are believed to remain today, though its present whereabouts are unknown.[22]