|

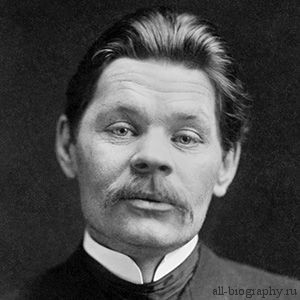

Maxim Gorky |

|

|---|---|

Gorky in 1926 at Posillipo |

|

| Born | Aleksey Maksimovich Peshkov 28 March [O.S. 16 March] 1868 Nizhny Novgorod, Nizhny Novgorod Governorate, Russian Empire |

| Died | 18 June 1936 (aged 68) Gorki-10, Moscow Oblast, Soviet Union |

| Occupation | Prose writer, dramatist, essayist, politician, poet |

| Period | 1892–1936 |

| Notable works | The Lower Depths (1902) Mother (1906) My Childhood. In the World. My Universities (1913–1923) The Life of Klim Samgin (1925–1936) |

| Signature | |

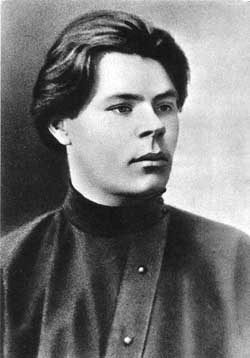

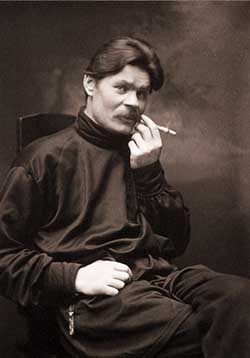

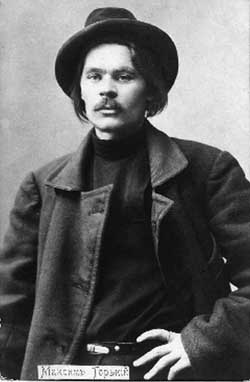

Alexei Maximovich Peshkov (Russian: Алексе́й Макси́мович Пешко́в;[a] 28 March [O.S. 16 March] 1868 – 18 June 1936), popularly known as Maxim Gorky (Russian: Макси́м Го́рький), was a Russian writer and socialist political thinker and proponent.[1] He was nominated five times for the Nobel Prize in Literature.[2] Before his success as an author, he travelled widely across the Russian Empire changing jobs frequently, experiences which would later influence his writing.

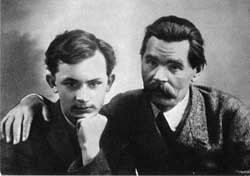

Gorky’s most famous works are his early short stories, written in the 1890s («Chelkash», «Old Izergil», and «Twenty-Six Men and a Girl»); plays The Philistines (1901), The Lower Depths (1902) and Children of the Sun (1905); a poem, «The Song of the Stormy Petrel» (1901); his autobiographical trilogy, My Childhood, In the World, My Universities (1913–1923); and a novel, Mother (1906). Gorky himself judged some of these works as failures, and Mother has been frequently criticized, and Gorky himself thought of Mother as one of his biggest failures.[3] However, there have been warmer judgements of some less-known post-revolutionary works such as the novels The Artamonov Business (1925) and The Life of Klim Samgin (1925–1936); the latter is considered Gorky’s masterpiece and has sometimes been viewed by critics as a modernist work. Unlike his pre-revolutionary writings (known for their «anti-psychologism») Gorky’s late works differ with an ambivalent portrayal of the Russian Revolution and «unmodern interest to human psychology» (as noted by D. S. Mirsky).[4] He had associations with fellow Russian writers Leo Tolstoy and Anton Chekhov, both mentioned by Gorky in his memoirs.

Gorky was active in the emerging Marxist communist and later in the Bolshevik movement. He publicly opposed the Tsarist regime, and for a time closely associated himself with Vladimir Lenin and Alexander Bogdanov’s Bolshevik wing of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party. For a significant part of his life, he was exiled from Russia and later the Soviet Union (USSR). In 1932, he returned to the USSR on Joseph Stalin’s personal invitation and lived there until his death in June 1936. After his return, he was officially declared the «founder of Socialist Realism». Despite his official reputation, Gorky’s relations with the Soviet regime were rather difficult. Modern scholars consider his ideology of God-Building as distinct from the official Marxism–Leninism, and his work fits uneasily under the «Socialist Realist» label. Gorky’s work still has a controversial reputation because of his political biography, although in the last years his works are returning to European stages and being republished.[5]

Life[edit]

Early years[edit]

Born as Alexei Maximovich Peshkov on 28 March [O.S. 16 March] 1868, in Nizhny Novgorod, Gorky became an orphan at the age of eleven. He was brought up by his maternal grandmother[1] and ran away from home at the age of twelve in 1880. After an attempt at suicide in December 1887, he travelled on foot across the Russian Empire for five years, changing jobs and accumulating impressions used later in his writing.[1]

As a journalist working for provincial newspapers, he wrote under the pseudonym Иегудиил Хламида (Jehudiel Khlamida).[6] He started using the pseudonym «Gorky» (from горький; literally «bitter») in 1892, when his first short story, «Makar Chudra», was published by the newspaper Kavkaz (The Caucasus) in Tiflis, where he spent several weeks doing menial jobs, mostly for the Caucasian Railway workshops.[8][9] The name reflected his simmering anger about life in Russia and a determination to speak the bitter truth. Gorky’s first book Очерки и рассказы (Essays and Stories) in 1898 enjoyed a sensational success, and his career as a writer began. Gorky wrote incessantly, viewing literature less as an aesthetic practice (though he worked hard on style and form) than as a moral and political act that could change the world. He described the lives of people in the lowest strata and on the margins of society, revealing their hardships, humiliations, and brutalisation, but also their inward spark of humanity.[1]

Political and literary development[edit]

Gorky’s reputation grew as a unique literary voice from the bottom stratum of society and as a fervent advocate of Russia’s social, political, and cultural transformation. By 1899, he was openly associating with the emerging Marxist social-democratic movement, which helped make him a celebrity among both the intelligentsia and the growing numbers of «conscious» workers. At the heart of all his work was a belief in the inherent worth and potential of the human person. In his writing, he counterposed individuals, aware of their natural dignity, and inspired by energy and will, with people who succumb to the degrading conditions of life around them. Both his writings and his letters reveal a «restless man» (a frequent self-description) struggling to resolve contradictory feelings of faith and scepticism, love of life and disgust at the vulgarity and pettiness of the human world.[citation needed]

In 1916, Gorky said that the teachings of the ancient Jewish sage Hillel the Elder deeply influenced his life: «In my early youth I read…the words of…Hillel, if I remember rightly: ‘If thou art not for thyself, who will be for thee? But if thou art for thyself alone, wherefore art thou’? The inner meaning of these words impressed me with its profound wisdom…The thought ate its way deep into my soul, and I say now with conviction: Hillel’s wisdom served as a strong staff on my road, which was neither even nor easy. I believe that Jewish wisdom is more all-human and universal than any other; and this not only because of its immemorial age…but because of the powerful humaneness that saturates it, because of its high estimate of man.»[10]

He publicly opposed the Tsarist regime and was arrested many times. Gorky befriended many revolutionaries and became a personal friend of Vladimir Lenin after they met in 1902. He exposed governmental control of the press (see Matvei Golovinski affair). In 1902, Gorky was elected an honorary Academician of Literature, but Tsar Nicholas II ordered this annulled. In protest, Anton Chekhov and Vladimir Korolenko left the Academy.[11]

From 1900 to 1905, Gorky’s writings became more optimistic. He became more involved in the opposition movement, for which he was again briefly imprisoned in 1901. In 1904, having severed his relationship with the Moscow Art Theatre in the wake of conflict with Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko, Gorky returned to Nizhny Novgorod to establish a theatre of his own.[b] Both Konstantin Stanislavski and Savva Morozov provided financial support for the venture.[13] Stanislavski believed that Gorky’s theatre was an opportunity to develop the network of provincial theatres which he hoped would reform the art of the stage in Russia, a dream of his since the 1890s.[13] He sent some pupils from the Art Theatre School—as well as Ioasaf Tikhomirov, who ran the school—to work there.[13] By the autumn, however, after the censor had banned every play that the theatre proposed to stage, Gorky abandoned the project.[13]

As a financially successful author, editor, and playwright, Gorky gave financial support to the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP), as well as supporting liberal appeals to the government for civil rights and social reform. The brutal shooting of workers marching to the Tsar with a petition for reform on 9 January 1905 (known as the «Bloody Sunday»), which set in motion the Revolution of 1905, seems to have pushed Gorky more decisively toward radical solutions. He became closely associated with Vladimir Lenin and Alexander Bogdanov’s Bolshevik wing of the party, with Bogdanov taking responsibility for the transfer of funds from Gorky to Vpered.[14] It is not clear whether he ever formally joined, and his relations with Lenin and the Bolsheviks would always be rocky. His most influential writings in these years were a series of political plays, most famously The Lower Depths (1902). While briefly imprisoned in Peter and Paul Fortress during the abortive 1905 Russian Revolution, Gorky wrote the play Children of the Sun, nominally set during an 1862 cholera epidemic, but universally understood to relate to present-day events. He was released from the prison after a European-wide campaign, which was supported by Marie Curie, Auguste Rodin and Anatole France, amongst others.[15]

Gorky assisted the Moscow uprising of 1905, and after its suppression his apartment was raided by the Black Hundreds. He subsequently fled to Lake Saimaa, Finland.[16] In 1906, the Bolsheviks sent him on a fund-raising trip to the United States with Ivan Narodny. When visiting the Adirondack Mountains, Gorky wrote Мать (Mat’, Mother), his notable novel of revolutionary conversion and struggle. His experiences in the United States—which included a scandal over his travelling with his lover (the actress Maria Andreyeva) rather than his wife—deepened his contempt for the «bourgeois soul.»

Capri years[edit]

Between 1909–1911 Gorky lived on the island of Capri in the burgundy-coloured «Villa Behring».

From 1906 to 1913, Gorky lived on the island of Capri in southern Italy, partly for health reasons and partly to escape the increasingly repressive atmosphere in Russia.[1] He continued to support the work of Russian social-democracy, especially the Bolsheviks and invited Anatoly Lunacharsky to stay with him on Capri. The two men had worked together on Literaturny Raspad which appeared in 1908. It was during this period that Gorky, along with Lunacharsky, Bogdanov and Vladimir Bazarov developed the idea of an Encyclopedia of Russian History as a socialist version of Diderot’s Encyclopédie.

In 1906, Maxim Gorky visited New York City at the invitation of Mark Twain and other writers. An invitation to the White House by President Theodore Roosevelt was withdrawn after the New York World reported that the woman accompanying Gorky was not his wife.[17] After this was revealed all of the hotels in Manhattan refused to house the couple, and they had to stay at an apartment in Staten Island.[16]

During a visit to Switzerland, Gorky met Lenin, who he charged spent an inordinate amount of his time feuding with other revolutionaries, writing: «He looked awful. Even his tongue seemed to have turned grey».[18] Despite his atheism,[19] Gorky was not a materialist.[20] Most controversially, he articulated, along with a few other maverick Bolsheviks, a philosophy he called «God-Building» (богостроительство, bogostroitel’stvo),[1] which sought to recapture the power of myth for the revolution and to create religious atheism that placed collective humanity where God had been and was imbued with passion, wonderment, moral certainty, and the promise of deliverance from evil, suffering, and even death. Though ‘God-Building’ was ridiculed by Lenin, Gorky retained his belief that «culture»—the moral and spiritual awareness of the value and potential of the human self—would be more critical to the revolution’s success than political or economic arrangements.

Return from exile[edit]

An amnesty granted for the 300th anniversary of the Romanov dynasty allowed Gorky to return to Russia in 1914, where he continued his social criticism, mentored other writers from the common people, and wrote a series of important cultural memoirs, including the first part of his autobiography.[1][21] On returning to Russia, he wrote that his main impression was that «everyone is so crushed and devoid of God’s image.» The only solution, he repeatedly declared, was «culture».

After the February Revolution, Gorky visited the headquarters of the Okhrana (secret police) on Kronversky Prospekt together with Nikolai Sukhanov and Vladimir Zenisinov.[22] Gorky described the former Okhrana headquarters, where he sought literary inspiration, as derelict, with windows broken, and papers lying all over the floor.[23] Having dinner with Sukhanov later the same day, Gorky grimly predicted that revolution would end in «Asiatic savagery».[24] Initially a supporter of the Socialist-Revolutionary Alexander Kerensky, Gorky switched over to the Bolsheviks after the Kornilov affair.[25] In July 1917, Gorky wrote his own experiences of the Russian working class had been sufficient to dispel any «notions that Russian workers are the incarnation of spiritual beauty and kindness».[26] Gorky admitted to feeling attracted to Bolshevism, but admitted to concerns about a creed that made the entire working class «sweet and reasonable — I had never known people who were really like this».[27] Gorky wrote that he knew the poor, the «carpenters, stevedores, bricklayers», in a way that the intellectual Lenin never did, and he frankly distrusted them.[27]

During World War I, his apartment in Petrograd was turned into a Bolshevik staff room, and his politics remained close to the Bolsheviks throughout the revolutionary period of 1917. On the day after the October Revolution of 7 November 1917, Gorky observed a gardener working the Alexander Park who had cleared snow during the February Revolution while ignoring the shots in the background, asked people during the July Days not to trample the grass and was now chopping off branches, leading Gorky to write that he was «stubborn as a mole, and apparently as blind as one too».[28] Gorky’s relations with the Bolsheviks became strained, however, after the October Revolution. One contemporary recalled how Gorky would turn «dark and black and grim» at the mere mention of Lenin.[29] Gorky wrote that Vladimir Lenin together with Leon Trotsky «have become poisoned with the filthy venom of power», crushing the rights of the individual to achieve their revolutionary dreams.[29] Gorky wrote that Lenin was a «cold-blooded trickster who spares neither the honor nor the life of the proletariat. … He does not know the popular masses, he has not lived with them».[29] Gorky went on to compare Lenin to a chemist experimenting in a laboratory with the only difference being the chemist experimented with inanimate matter to improve life while Lenin was experimenting on the «living flesh of Russia».[29] A further strain on Gorky’s relations with the Bolsheviks occurred when his newspaper Novaya Zhizn (Новая Жизнь, «New Life«) fell prey to Bolshevik censorship during the ensuing civil war, around which time Gorky published a collection of essays critical of the Bolsheviks called Untimely Thoughts in 1918. (It would not be re-published in Russia until after the collapse of the Soviet Union.) The essays call Lenin a tyrant for his senseless arrests and repression of free discourse, and an anarchist for his conspiratorial tactics; Gorky compares Lenin to both the Tsar and Nechayev.[citation needed]

- «Lenin and his associates,» Gorky wrote, «consider it possible to commit all kinds of crimes … the abolition of free speech and senseless arrests.»[30]

He was a member of the Committee for the Struggle against Antisemitism within the Soviet government.[31]

In 1921, he hired a secretary, Moura Budberg, who later became his mistress. In August 1921, the poet Nikolay Gumilev was arrested by the Petrograd Cheka for his monarchist views. There is a story that Gorky hurried to Moscow, obtained an order to release Gumilev from Lenin personally, but upon his return to Petrograd he found out that Gumilev had already been shot – but Nadezhda Mandelstam, a close friend of Gumilev’s widow, Anna Akhmatova wrote that: «It is true that people asked him to intervene. … Gorky had a strong dislike of Gumilev, but he nevertheless promised to do something. He could not keep his promise because the sentence of death was announced and carried out with unexpected haste, before Gorky had got round to doing anything.»[32] In October, Gorky returned to Italy on health grounds: he had tuberculosis.

Povolzhye famine[edit]

In July 1921, Gorky published an appeal to the outside world, saying that millions of lives were menaced by crop failure. The Russian famine of 1921–22, also known as Povolzhye famine, killed an estimated 5 million, primarily affecting the Volga and Ural River regions.[33]

Second exile[edit]

Gorky left Russia in September 1921, for Berlin. There he heard about the impending Moscow Trial of 12 Socialist Revolutionaries, which hardened his opposition to the Bolshevik regime. He wrote to Anatole France denouncing the trial as a «cynical and public preparation for the murder» of people who had fought for the freedom of the Russian people. He also wrote to the Soviet vice-premier, Alexei Rykov asking him to tell Leon Trotsky that any death sentences carried out on the defendants would be «premeditated and foul murder.»[34] This provoked a contemptuous reaction from Lenin, who described Gorky as «always supremely spineless in politics», and Trotsky, who dismissed Gorky as an «artist whom no-one takes seriously».[35] He was denied permission by Italy’s fascist government to return to Capri, but was permitted to settle in Sorrento, where he lived from 1922 to 1932, with an extended household that included Moura Budberg, his ex-wife Andreyeva, her lover, Pyotr Kryuchkov, who acted as Gorky’s secretary (initially a spy for Yagoda) for the remainder of his life, Gorky’s son Max Peshkov, Max’s wife, Timosha, and their two young daughters.

He wrote several successful books while there,[36] but by 1928 he was having difficulty earning enough to keep his large household, and began to seek an accommodation with the communist regime. The General Secretary of the Communist Party Joseph Stalin was equally keen to entice Gorky back to the USSR. He paid his first visit in May 1928 – at the very time when the regime was staging its first show trial since 1922, the so-called Shakhty Trial of 53 engineers employed in the coal industry, one of whom, Pyotr Osadchy, had visited Gorky in Sorrento. In contrast to his attitude to the trial of the Socialist Revolutionaries, Gorky accepted without question that the engineers were guilty, and expressed regret that in the past he had intervened on behalf of professionals who were being persecuted by the regime. During the visit, he struck up friendships with Genrikh Yagoda (deputy head of the OGPU) who vested interest in spying on Gorky, and two other OGPU officers, Semyon Firin and Matvei Pogrebinsky, who held high office in the Gulag. Pogrebinsky was Gorky’s guest in Sorrento for four weeks in 1930. The following year, Yagoda sent his brother-in-law, Leopold Averbakh to Sorrento, with instructions to induce Gorky to return to Russia permanently.[37]

Return to Russia[edit]

Gorky’s return from Fascist Italy was a major propaganda victory for the Soviets. He was decorated with the Order of Lenin and given a mansion (formerly belonging to the millionaire Pavel Ryabushinsky, which was for many years the Gorky Museum) in Moscow and a dacha in the suburbs. The city of Nizhni Novgorod, and the surrounding province were renamed Gorky. Moscow’s main park, and one of the central Moscow streets, Tverskaya, were renamed in his honour, as was the Moscow Art Theatre. The largest fixed-wing aircraft in the world in the mid-1930s, the Tupolev ANT-20 was named Maxim Gorky in his honour.

He was also appointed President of the Union of Soviet Writers, founded in 1932, to coincide with his return to the USSR. On 11 October 1931 Gorky read his fairy tale poem «A Girl and Death» (which he wrote in 1892) to his visitors Joseph Stalin, Kliment Voroshilov and Vyacheslav Molotov, an event that was later depicted by Viktor Govorov in his painting. On that same day Stalin left his autograph on the last page of this work by Gorky: «This piece is stronger than Goethe’s Faust (love defeats death)>» Voroshilov also left a «resolution»: «I am illiterate, but I think that Comrade Stalin more than correctly defined the meaning of A. Gorky’s poems. On my own behalf, I will say: I love M. Gorky as my and my class of writer, who correctly defined our forward movement.»[38]

As Vyacheslav Ivanov remembers, Gorky was very upset:

They wrote their resolution on his fairy tale «A Girl and Death». My father, who spoke about this episode with Gorky, insisted emphatically that Gorky was offended. Stalin and Voroshilov were drunk and fooling around.[39]

Apologist for the gulag[edit]

In 1933, Gorky co-edited, with Averbakh and Firin, an infamous book about the White Sea-Baltic Canal, presented as an example of «successful rehabilitation of the former enemies of proletariat». For other writers, he urged that one obtained realism by extracting the basic idea from reality, but by adding the potential and desirable to it, one added romanticism with deep revolutionary potential.[40] For himself, Gorky avoided realism. His denials that even a single prisoner died during the construction of the aforementioned canal was refuted by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn who claimed thousands of prisoners froze to death not only in the evenings from the lack of adequate shelter and food, but even in the middle of the day. Most tellingly, Solzhenitsyn and Dmitry Likhachov document a visit, on June 20, 1929 to Solovki, the “original” forced labour camp, and the model upon which thousands of others were constructed. Given Gorky’s reputation, (both to the authorities and to the prisoners), the camp was transformed from one where prisoners (Zeks) were worked to death to one befitting the official Soviet idea of “transformation through labour”. Gorky did not notice the relocation of thousands of prisoners to ease the overcrowding, the new clothes on the prisoners (used to labouring in their underwear), or even the hiding of prisoners under tarpaulins, and the removal of the torture rooms. The deception was exposed when Gorky was presented with children “model prisoners”, one of who challenged Gorky if he “wanted to know the truth”. On the affirmative, the room was cleared and the 14-year-old boy recounted the truth — starvation, men worked to death, and of the pole torture, of using men instead of horses, of the summary executions, of rolling prisoners, bound to a heavy pole down stairs with hundreds of steps, of spending the night, in underwear, in the snow. Gorky never wrote about the boy, or even asked to take the boy with him. The boy was executed after Gorky left.[41] Gorky left the room in tears, and wrote in the visitor book “I am not in a state of mind to express my impressions in just a few words. I wouldn’t want, yes, and I would likewise be ashamed to permit myself the banal praise of the remarkable energy of people who, while remaining vigilant and tireless sentinels of the Revolution, are able, at the same time, to be remarkably bold creators of culture”.[42]

On his definitive return to the Soviet Union in 1932, Maxim Gorky received the Ryabushinsky Mansion, designed in 1900 by Fyodor Schechtel for the Ryabushinsky family. The mansion today houses a museum about Gorky.

As Gorky’s biographer Pavel Basinsky notes, it was impossible for Gorky to «take the boy with him» even with his reputation of a «great proletarian writer». As he says, Gorky had to spend over 2 years to free Julia Danzas.[43] Some of the Solovki historians doubt that there was a boy.

Gorky also helped other political prisoners (not without the influence of his wife, Yekaterina Peshkova). For example, because of Gorky’s interference Mikhail Bakhtin’s initial verdict (5 years of Solovki) was changed to 6 years of exile.

D: Mikhail Mikhailovich, have you met Gorky in person?

B: With Gorky? No. I only saw him several times, and then (there is no need to write this down), when, therefore, I was imprisoned, Gorky even sent two telegrams to the appropriate institutions …

D: Gorky?

B: Yes. In my defence.

D: Well, it just needs to be written down.

B: He knew my first book and generally heard a lot about me, and we had mutual acquaintances…

<…>

B: Well, it was… 1929.

D: Yeees. And Gorky… Then he stopped interfering.

B: So in the case… yes, in my case there were Gorky’s telegrams, his two telegrams. <…>

D: A lot of good things was made by his wife, Yekaterina Pavlovna.

B: Yes. Yekaterina Pavlovna. I didn’t know her <…> She was then the chairman of the so-called …

D: Red Cross.B: Yes. Political Red Cross.

Hostility to homosexuality[edit]

Gorky strongly supported efforts in getting a law passed in 1934, making homosexuality a criminal offense. His attitude was coloured by the fact that some members of the Nazi Sturmabteilung were homosexual. The phrase «exterminate all homosexuals and fascism will vanish» is often attributed to him.[45][46] He was actually quoting a popular saying. Writing in Pravda on 23 May 1934, Gorky said: «There is already a sarcastic saying: Destroy homosexuality and fascism will disappear.»[47][48]

Gorky and the Soviet censorship[edit]

And in my opinion, he (Vladislav Khodasevich) is right when he says that the Soviet critics have made up an anti-Soviet play from The Turbin Brothers. Bulgakov is «not a brother» to me; I have not the slightest desire to defend him. But he is a talented writer, and we don’t have many people like that. So there’s no point in making them «martyrs for an idea.»

— Letter to Joseph Stalin, 1930[49]

Gorky was following Bulgakov’s literary career since 1925, when he first read The Fatal Eggs. According to his letters, even then he admired his talent. Partly because of Gorky Bulgakov’s plays The Cabal of Hypocrites and The Days of the Turbins were allowed for staging.[50] Gorky also tried to use his influence to allow the Moscow Art Theater production of Bulgakov’s other play, Flight.[51] However, it was banned because of Stalin’s personal reaction.[52]

…I strongly support the publication by Academia of the novel Demons and other contrrevolutionary novels, such as Pisemsky’s’ Troubled Seas, Leskov’s No Way Out and Krestovsky’s Marevo. I do this because I am against the transformation of legal literature into illegal literature, which is being sold «from under the counter» and which seduces young people with its «taboo»… You need to know the enemy, you need to know his ideology… The Soviet government is not afraid of anything, and least of all can frighten the publication an old novel. But … Comrade Zaslavsky with his article brought true pleasure to our enemies, and especially to the White émigrés. «They ban Dostoyevsky» they screech, grateful to Comrade Zaslavsky.

.

Gorky’ s article «On the issue of Demons»

Anti-formalist campaign[edit]

You have a big choice of weapons. Soviet literature has every opportunity to apply these types of weapons (genres, styles, forms and methods of literary creativity) in their diversity and completeness, selecting all the best that has been created in this area by all previous eras.[54]

Socialist realism provides artistic creativity with an exceptional opportunity for the manifestation of creative initiative, the choice of various forms, styles and genres.

Shostakovich is a young man, about 25 years old, undeniably talented, but very self-confident and very nervous. The article in Pravda hit him like a brick on the head, the guy is completely depressed. <…> «Muddle», but why? In what and how is it expressed — «muddle»? Critics must give a technical assessment of Shostakovich’s music. And what the Pravda article gave allowed a bunch of mediocre people, hack-workers, to attack Shostakovich in every possible way.

— Letter to Joseph Stalin, 1936[55]

Conflicts with Stalinism[edit]

Gorky’s relationship with the regime got colder after his return to the Soviet Union in 1933: the Soviet authorities would never let him out in Italy again. He continued to write the propagandist articles in Pravda and glorify Stalin. However, by 1934 his relationship with the regime was getting more and more distant. Leopold Averbakh, whom Gorky regarded as a protege, was denied a role in the newly created Writers Union, and objected to interference by the Central Committee staff in the affairs of the union[citation needed]; Gorky’s conception of «Socialist realism» and creation of the Writers Union, instead of ending the RAPP «literary dictatorship» and uniting the «proletarian» writers with the denounced «poputchicks» becomes a tool to increase the censorship. This conflict, which may have been exacerbated by Gorky’s despair over the early death of his son, Max, came to a head just before the first Soviet Writers Congress, in August 1934.

His meetings with Stalin were getting more rare. At that time he gets influenced by Lev Kamenev, who was made the director of Academia publishing House because of Gorky’s request, and Nikolai Bukharin, who had been Gorky’s friend since 1920s.[56] On 11 August, Gorky submitted an article for publication in Pravda which attacked the deputy head of the press department, Pavel Yudin with such intemperate language that Stalin’s deputy, Lazar Kaganovich ordered its suppression, but was forced to relent after hundreds of copies of the article circulated by hand.[citation needed] Gorky’s draft of the keynote speech he was due to give at the congress caused such consternation when he submitted it to the Politburo that four of its leading members – Kaganovich, Vyacheslav Molotov, Kliment Voroshilov, and Andrei Zhdanov – were sent to persuade him to make changes.[57]

Yesterday we, having familiarized ourselves with M. Gorky’s speech to the Congress of Writers, came to the conclusion that the speech is not suitable in this form. First of all — the very construction and arrangement of the material — 3/4, if not more, is occupied by general historical and philosophical reasoning, and even then incorrect. Primitive society is presented as the ideal, and capitalism at all of its stages is portrayed as a reactionary force that hindered the development of technology and culture. It is clear that this position is non-Marxist. Soviet literature is almost not covered, but the speech is called «On Soviet Literature.» <…> …after a long talk he agreed to make some edits and changes. It seems that he is in a bad mood. <…> The point, of course, is not what he says, but how he says it. These talks have reminded me of comrade Krupskaya. I think that Kamenev plays an important role in shaping these sentiments of Gorky. <…>

Today we exchanged views and think that it is better, after making some edits, to publish it than to allow it to be read as illegal.

In his speech he calls Fyodor Dostoevsky a «medieval inquisitor», however, he admires him for «having painted with the most vivid perfection of word portraiture a type of egocentrist, a type of social degenerate in the person of the hero of his Notes from Underground» and notes him as a major figure in Russian classic literature.[59] After the end of the congress Central Committee of the Party, in which maintained that writers the likes of Panferov, Ermilov, Fadeyev, Stavsky, and many other writers who were approved as the «masters of Socialist realism», were unworthy of membership in the Union of Soviet Writers, obviously preferring Boris Pasternak, Andrei Bely, Andrei Platonov and Artyom Vesyoly (Gorky took the latter two in his «writers brigade» because of their inability to be published,[60] although he criticized Bely and Platonov for their techniques). He also wrote an article about Panferov’s novel Brusski: «One could, of course, not note the verbal errors and careless technique of the gifted writer, but he acts as an adviser and teacher, and he teaches the production of literary waste».[61]

Gorky also tried to fight the Soviet censorship as it was growing more power. For example, he tried to defend an issue of Dostoevsky’s Demons.

As the conflict was becoming more visible, Gorky’s political and literary positions became weaker. Panferov wrote an answer to Gorky, in which he criticized him. David Zaslavsky published an ironical response to Gorky’s defense of Demons.

According to some sources (such as Romain Rolland’s diary), because of Gorky’s refusal to blindly obey the policies of Stalinism, he had lost the Party’ s goodwill and spent his last days under unannounced house arrest.[62]

Death[edit]

With the increase of Stalinist repression and especially after the assassination of Sergei Kirov in December 1934, Gorky was placed under unannounced house arrest in his house near Moscow in Gorki-10 (the name of the place is a completely different word in Russian unrelated to his surname). His long-serving secretary Pyotr Kryuchkov had been recruited by Yagoda as a paid informer.[63] Before his death from a lingering illness in June 1936, he was visited at home by Stalin, Yagoda, and other leading communists, and by Moura Budberg, who had chosen not to return to the USSR with him but was permitted to stay for his funeral.

The sudden death of Gorky’s son Maxim Peshkov in May 1934 was followed by the death of Maxim Gorky himself in June 1936 from pneumonia. Speculation has long surrounded the circumstances of his death. Stalin and Molotov were among those who carried Gorky’s urn during the funeral. During the Bukharin trial in 1938 (one of the three Moscow Trials), one of the charges was that Gorky was killed by Yagoda’s NKVD agents.[64]

In Soviet times, before and after his death, the complexities in Gorky’s life and outlook were reduced to an iconic image (echoed in heroic pictures and statues dotting the countryside): Gorky as a great Soviet writer who emerged from the common people, a loyal friend of the Bolsheviks, and the founder of the increasingly canonical «socialist realism».[65]

Bibliography[edit]

Source: Turner, Lily; Strever, Mark (1946). Orphan Paul; A Bibliography and Chronology of Maxim Gorky. New York: Boni and Gaer. pp. 261–270.

Novels[edit]

- Goremyka Pavel, (Горемыка Павел, 1894). Published in English as Orphan Paul[66]

- Foma Gordeyev (Фома Гордеев, 1899). Also translated as The Man Who Was Afraid

- Three of Them (Трое, 1900). Also translated as Three Men and The Three

- The Mother (Мать, 1906). First published in English, in 1906

- The Life of a Useless Man (Жизнь ненужного человека, 1908)

- A Confession (Исповедь, 1908)

- Gorodok Okurov (Городок Окуров, 1908), not translated

- The Life of Matvei Kozhemyakin (Жизнь Матвея Кожемякина, 1910)

- The Artamonov Business (Дело Артамоновых, 1925). Also translated as The Artamonovs and Decadence

- The Life of Klim Samgin (Жизнь Клима Самгина, 1925–1936). Published in English as Forty Years: The Life of Clim Samghin

- Volume I. Bystander (1930)

- Volume II. The Magnet (1931)

- Volume III. Other Fires (1933)

- Volume IV. The Specter (1938)

Novellas and short stories[edit]

- Sketches and Stories (Очерки и рассказы), 1899

- «Makar Chudra» (Макар Чудра), 1892

- «Old Izergil» (Старуха Изергиль), 1895

- «Chelkash» (Челкаш), 1895

- «Konovalov» (Коновалов), 1897

- The Orlovs (Супруги Орловы), 1897

- Creatures That Once Were Men (Бывшие люди), 1897

- «Malva» (Мальва), 1897

- Varenka Olesova (Варенька Олесова), 1898

- «Twenty-six Men and a Girl» (Двадцать шесть и одна), 1899

Plays[edit]

- The Philistines (Мещане), translated also as The Smug Citizens and The Petty Bourgeois (Мещане), 1901

- The Lower Depths (На дне), 1902

- Summerfolk (Дачники), 1904

- Children of the Sun (Дети солнца), 1905

- Barbarians (Варвары), 1905

- Enemies, 1906.

- The Last Ones (Последние), 1908. Translated also as Our Father[c]

- Reception (Встреча), 1910. Translated also as Children

- Queer People (Чудаки), 1910. Translated also as Eccentrics

- Vassa Zheleznova (Васса Железнова), 1910, 1935 (revised version)

- The Zykovs (Зыковы), 1913

- Counterfeit Money (Фальшивая монета), 1913

- The Old Man (Старик), 1915, Revised 1922, 1924. Translated also as The Judge

- Workaholic Slovotekov (Работяга Словотеков), 1920

- Egor Bulychev (Егор Булычов и другие), 1932

- Dostigayev and Others (Достигаев и другие), 1933

Non-fiction[edit]

- My Childhood. In the World. My Universities (1913–1923)

- Chaliapin, articles in Letopis, 1917[d]

- My Recollections of Tolstoy, 1919

- Reminiscences of Tolstoy, Chekhov, and Andreyev, 1920–1928

- Fragments from My Diary (Заметки из дневника), 1924

- V.I. Lenin (В.И. Ленин), reminiscence, 1924–1931

- The I.V. Stalin White Sea – Baltic Sea Canal, 1934 (editor-in-chief)

- Literary Portraits [c.1935].[68]

Essays[edit]

- O karamazovshchine (О карамазовщине, On Karamazovism/On Karamazovshchina), 1915, not translated

- Untimely Thoughts. Notes on Revolution and Culture (Несвоевременные мысли. Заметки о революции и культуре), 1918

- On the Russian Peasantry (О русском крестьянстве), 1922

Poems[edit]

- «The Song of the Stormy Petrel» (Песня о Буревестнике), 1901

- «Song of a Falcon» (Песня о Соколе), 1902. Also referred to as a short story

Autobiography[edit]

- My Childhood (Детство), Part I, 1913–1914

- In the World (В людях), Part II, 1916

- My Universities (Мои университеты), Part III, 1923

Collections[edit]

- Sketches and Stories, three volumes, 1898–1899

- Creatures That Once Were Men, stories in English translation (1905). This contained an introduction by G. K. Chesterton[69] The Russian title, Бывшие люди (literally «Former people») gained popularity as an expression in reference to people who severely dropped in their social status

- Tales of Italy (Сказки об Италии), 1911–1913

- Through Russia (По Руси), 1923

- Stories 1922-1924 (Рассказы 1922-1924 годов), 1925

Commemoration[edit]

Gorky memorial plaque on Glinka street in Smolensk

- In almost every large settlement of the states of the former USSR, there was[70] or is Gorky Street. In 2013, 2110 streets, avenues and lanes in Russia were named «Gorky», and another 395 were named «Maxim Gorky».[71]

- Gorky was the name of Nizhny Novgorod from 1932 to 1990.

- Gorkovsky suburban railway line, Moscow

- Gorkovskoye village of Novoorsky District of Orenburg Oblast

- Gorky village in the Leningrad oblast

- Gorkovsky village (Volgograd) (formerly Voroponovo)

- Village n.a. Maxim Gorky, Kameshkovsky District of Vladimir Oblast

- Gorkovskoye village is the district center of Omsk Oblast (formerly Ikonnikovo)

- Maxim Gorky village, Znamensky District of Omsk Oblast

- Village n.a. Maxim Gorky, Krutinsky District of Omsk Oblast

- In Nizhny Novgorod the Central District Children’s Library, the Academic Drama Theater, a street, as well as a square are named after Maxim Gorky. And the most important attraction there is the museum-apartment of Maxim Gorky

- Drama theaters in the following cities are named after Maxim Gorky: Moscow (MAT, 1932), Vladivostok (Primorsky Gorky Drama Theater — PGDT), Berlin (Maxim Gorki Theater), Baku (ASTYZ), Astana (Russian Drama Theater named after M. Gorky), Tula (Tula Academic Theatre), Minsk (Theater named after M. Gorky), Rostov-on-Don (Rostov Drama Theater named after M. Gorky), Krasnodar, Samara (Samara Drama Theater named after M. Gorky), Orenburg (Orenburg Regional Drama Theater), Volgograd (Volgograd Regional Drama Theater), Magadan (Magadan Regional Music and Drama Theater), Simferopol (KARDT), Kustanay, Kudymkar (Komi- Perm National Drama Theater), Young Spectator Theater in Lviv, as well as in Saint Petersburg from 1932 to 1992 (DB). Also, the name was given to the Interregional Russian Drama Theater of the Fergana Valley, the Tashkent State Academic Theater, the Tula Regional Drama Theater, and the Nur-Sultan Regional Drama Theater.

- Palaces of Culture n.a. Maxim Gorky were built in Nevinnomyssk, Rovenky, Novosibirsk and Saint Petersburg

- Universities: Maxim Gorky Literature Institute, Ural State University, Donetsk National Medical University, Minsk State Pedagogical Institute, Omsk State Pedagogical University, until 1993 Turkmen State University in Ashgabat was named after Maxim Gorky (now named after Magtymguly Pyragy), Sukhum State University was named after Maxim Gorky, National University of Kharkiv was named after Gorky in 1936–1999, Ulyanovsk Agricultural Institute, Uman Agricultural Institute, Kazan Order of the Badge of Honor The institute was named after Maxim Gorky until it was granted the status of an academy in 1995 (now Kazan State Agrarian University), the Mari Polytechnic Institute and Perm State University named after Maxim Gorky (1934–1993)

- The following cities have parks named after Maxim Gorky: Rostov-on-Don, Taganrog, Saratov, Minsk, Krasnoyarsk, Kharkiv, Odessa, Melitopol, Moscow, Alma-Ata

Monuments[edit]

Monuments of Maxim Gorky are installed in many cities. Among them:

- In Russia — Borisoglebsk, Arzamas, Volgograd, Voronezh, Vyborg, Dobrinka, Izhevsk, Krasnoyarsk, Moscow, Nevinnomyssk, Nizhny Novgorod, Orenburg, Penza, Pechora, Rostov-on-Don, Rubtsovsk, Rylsk, Ryazan, St. Petersburg, Sarov, Sochi, Taganrog, Khabarovsk, Chelyabinsk, Ufa, Yartsevo.

- In Belarus — Dobrush, Minsk. Mogilev, Gorky Park, bust.

- In Ukraine — Donetsk, Kryvyi Rih, Melitopol, Kharkiv, Yalta, Yasynuvata

- In Azerbaijan — Baku

- In Kazakhstan — Alma-Ata, Zyryanovsk, Kostanay

- In Georgia — Tbilisi

- In Moldova — Chisinaus, Leovo

- In Italy — Sorrento

- In India — Gorky Sadan,[72] Kolkata

On 6 December 2022 the City Council of the Ukrainian city Dnipro decided to remove from the city all monuments to figures of Russian culture and history, in particular it was mentioned that the monuments to Gorky, Alexander Pushkin and Mikhail Lomonosov would be removed from the public space of the city.[73] The monument of Gorky that been erected in 1977 was dismantled on 26 December 2022.[74]

-

-

-

-

Now dismantled monument in Dnipro as it was in 2021

Philately[edit]

Maxim Gorky is depicted on postage stamps: Albania (1986),[75] Vietnam (1968)[76] India (1968),[77] Maldives (2018),[78] and many more. Some of them can be found below.

- Maxim Gorky postage stamps

-

Postage stamp USSR, 1932

-

Postage stamp USSR, 1932

-

Postage stamp, the USSR, 1943

-

Postage stamp, the USSR, 1943

-

Postage stamp, the USSR, «10 years since the death of M. Gorky» (1946, 30 kopeeks)

-

Postage stamp, the USSR, «10 years since the death of M. Gorky» (1946, 60 kopeeks)

-

Postage stamp, GDR, 1953

-

Postage stamp, the USSR, 1956

-

Postage stamp, the USSR, 1958

-

Postage stamp, the USSR, 1959

-

Postage stamp, the USSR, 1968

-

Postage stamp, Russia, «Rusiia. XX век. Culture» (2000, 1,30 rubles)

In 2018, FSUE Russian Post released a miniature sheet dedicated to the 150th anniversary of the writer.

Numismatics[edit]

Silver commemorative coin, 2 rubles «Maxim Gorky», 2018

- In 1988, a 1 ruble coin was issued in the USSR, dedicated to the 120th anniversary of the writer.

- In 2018, on the 150th anniversary of the writer’s birthday, the Bank of Russia issued a commemorative silver coin with a face value of 2 rubles in the series “Outstanding Personalities of Russia”.

Depictions and adaptations[edit]

- In 1912, the Italian composer Giacomo Orefice based his opera Radda on the character of Radda in Gorky’s 1892 short story Makar Chudra.

- In 1932, German playwright Bertolt Brecht published his play The Mother, which was based on Gorky’s 1906 novel Mother. The same novel was also adapted for an opera by Valery Zhelobinsky in 1938.

- In 1938–1939, Gorky’s three-part autobiography was released by Soyuzdetfilm as three feature films: The Childhood of Maxim Gorky, My Apprenticeship and My Universities, all three directed by Mark Donskoy.

- In 1975, Gorky’s 1908 play The Last Ones (Последние), had its New York debut at the Manhattan Theater Club, under the alternative English title Our Father, directed by Keith Fowler.

- In 1985, Gorky’s 1906 play Enemies was translated by Kitty Hunter-Blair and Jeremy Brooks and directed in London by Ann Pennington in association with the Internationalist Theatre at the tail end of the British miners’ strike of 1984–1985. Gorky’s «pseudo-populism» is done away with in this production by the actors speaking «without distinctive accents and consequently without populist sentiment».[79]

See also[edit]

- FK Sloboda Tuzla football club from Bosnia and Herzegovina, originally called FK Gorki

- Gorky Park in Moscow and Park of Maxim Gorky in Kharkiv, Ukraine

- Maxim Gorky Literature Institute

- Palace of Culture named after Maxim Gorky, Novosibirsk

- Soviet cruiser Maxim Gorky, a Project 26bis (or Kirov-class) light cruiser, which served from 1940 to 1956 and was awarded the Order of the Red Banner in 1944

- Tupolev ANT-20 aircraft, nicknamed «Maxim Gorky»

- Znanie Publishers

Notes[edit]

- ^ His own pronunciation, according to his autobiography Detstvo (Childhood), was Пешко́в, but most Russians say Пе́шков, which is therefore found in reference books.

- ^ Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko had insulted Gorky with his critical assessment of Gorky’s new play Summerfolk, which Nemirovich described as shapeless and formless raw material that lacked a plot. Despite Stanislavski’s attempts to persuade him otherwise, in December 1904 Gorky refused permission for the MAT to produce his Enemies and declined «any kind of connection with the Art Theatre.»[12]

- ^ William Stancil’s English translation, titled Our Father, was premiered by the Virginia Museum Theater in 1975, under the direction of Keith Fowler. Its New York debut was at the Manhattan Theater Club.

- ^ The manuscript of this work, which Gorky wrote using information supplied by his friend Chaliapin, was translated, together with supplementary correspondence of Gorky with Chaliapin and others.[67]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g Liukkonen, Petri. «Maxim Gorky». Books and Writers (kirjasto.sci.fi). Finland: Kuusankoski Public Library. Archived from the original on 6 July 2009.

- ^ «Nomination Database». The Nobel Prize. Archived from the original on 28 June 2018. Retrieved 10 December 2018.

- ^ «Мать». Рассказы. Очерк. 1906—1910. Полное собрание сочинений. Художественные произведения в 25 томах (in Russian). Vol. Том 8. Moscow: Nauka. 1970.

- ^ Mirsky, D. S. (1925). Contemporary Russian Literature, 1881–1925. p. 120. Archived from the original on 1 October 2021.

- ^ Dege, Stefan (28 March 2018). «A portrait of Russian writer Maxim Gorky». Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 25 October 2022.

- ^ «Maxim Gorky». LibraryThing. Archived from the original on 29 November 2009. Retrieved 21 July 2009.

- ^ Commentaries to Makar Chudra // Горький М. Макар Чудра и другие рассказы. – М: Детская литература, 1970. – С. 195–196. – 207 с.

- ^ Isabella M. Nefedova. Maxim Gorky. The Biography // И.М.Нефедова. Максим Горький. Биография писателя Л.: Просвещение, 1971.

- ^ Herz, Joseph H., ed. (1920). A Book of Jewish Thoughts. Humphrey Milford, Oxford University Press. p. 138.

- ^ Handbook of Russian Literature, Victor Terras, Yale University Press, 1990.

- ^ Benedetti 1999, pp. 149–150.

- ^ a b c d Benedetti 1999, p. 150.

- ^ Biggart, John (1989), Alexander Bogdanov, Left-Bolshevism and the Proletkult 1904–1932, University of East Anglia

- ^ Figes, p. 181

- ^ a b Figes, pp. 200-202

- ^ Sorel, New York Times March 5, 2021

- ^ Moynahan 1992, p. 117.

- ^ Evgeniĭ Aleksandrovich Dobrenko (2007). Political Economy of Socialist Realism. Yale University Press. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-300-12280-0.

Gorky hated religion with all the passion of a former God-builder. Probably no other Russian writer (unless one considers Dem’ian Bednyi a writer) expressed so many angry words about God, religion, and the church. But Gorky’s atheism always fed on that same hatred of nature. He wrote about God and about nature in the very same terms.

- ^ Tova Yedlin (1999). Maxim Gorky: A Political Biography. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 86. ISBN 978-0-275-96605-8.

Gorky had long rejected all organized religions. Yet he was not a materialist, and thus he could not be satisfied with Marx’s ideas on religion. When asked to express his views about religion in a questionnaire sent by the French journal Mercure de France on April 15, 1907, Gorky replied that he was opposed to the existing religions of Moses, Christ, and Mohammed. He defined religious feeling as an awareness of a harmonious link that joins man to the universe and as an aspiration for synthesis, inherent in every individual.

- ^ Times, Marconi Transatlantic Wireless Telegraph To the New York (19 January 1914). «GORKY BACK IN RUSSIA.; Amnesty Permits His Return — Is Still In Ill Health. (Published 1914)». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 16 January 2021.

- ^ Moynahan 1992, p. 91 & 95.

- ^ Moynahan 1992, p. 91.

- ^ Moynahan 1992, p. 95.

- ^ Moynahan 1992, p. 246.

- ^ Moynahan 1992, p. 201.

- ^ a b Moynahan 1992, p. 202.

- ^ Moynahan 1992, p. 318.

- ^ a b c d Moynahan 1992, p. 330.

- ^ Harrison E. Salisbury, Black Night, White Snow, New York, 1978, p. 540.

- ^ Brendan McGeever. Antisemitism and the Russian Revolution. — Cambridge University Press, 2019. — p.p. 247.

- ^ Mandelstam, Nadezhda (1971). Hope Against Hope, a Memoir. London: Collins & Harvill. p. 110. ISBN 0-00-262501-6.

- ^ Courtois, Stéphane; Werth, Nicolas; Panné, Jean-Louis; Paczkowski, Andrzej; Bartošek, Karel; Margolin, Jean-Louis (1999). The Black Book of Communism: Crimes, Terror, Repression. Harvard University Press. p. 123. ISBN 9780674076082.

- ^ McSmith 2015, p. 86.

- ^ McSmith 2015, p. 82.

- ^ Tova Yedlin (1999). Maxim Gorky: A Political Biography. Praeger. p. 229.

- ^ McSmith 2015, pp. 84–88.

- ^ «Scan of the page from «A Girl And Death» with autograph by Stalin». Archived from the original on 7 September 2012. Retrieved 21 July 2009.

- ^ Basinsky, Pavel. Горький: страсти по Максиму. АСТ.

- ^ R. H. Stacy, Russian Literary Criticism p188 ISBN 0-8156-0108-5

- ^ Likhachov, Dmitry (1995). Воспоминания. Logos. pp. 183–188.

- ^ Solzhenitsyn, Alexander (2007). The Gulag Archepelago. Harper Perennial. pp. 199–205.

- ^ Basinsky, Pavel (18 February 2018). «Басинский: Правда истории не совпадает с нашими представлениями о ней». Российская газета (in Russian). Archived from the original on 24 January 2022.

- ^ Беседы В. Д. Дувакина с М. М. Бахтиным. Прогресс. 1996. pp. 113–114, 298.

- ^ McSmith 2015, p. 160.

- ^ Lingiardi, Vittorio (2002). «6. The Führer’s Eagle». Men in Love: Male Homosexualities from Ganymede to Batman. Translated by Hopcke, Robert H.; Schwartz, Paul. Chicago, IL, US: Open Court. p. 89. ISBN 9780812695151. OCLC 49421786.

- ^ Steakley, James. Gay Men and the Sexual History of the Political Left, Volume 29. p. 170.

- ^ Ginsberg, Terri; Mensch, Andrea (13 February 2012). A Companion to German Cinema. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4051-9436-5.

- ^ «14. М. Горький — И.В. Сталину. | Документы XX века». doc20vek.ru.

- ^ Полное собрание сочинений. Письма в 24 томах. Полное собрание сочинений. Письма в 24 томах (in Russian). Vol. Т. 15-20. Moscow: Nauka. 2012–2018.

- ^ «Театр, которого не было: «Бег» Михаила Булгакова во МХАТе». Коммерсантъ. 11 October 2019.

- ^ Сталин И. В. Сочинения. Ответ Билль-Белоцерковскому

- ^ ««Бесы»: «…под наблюдением Заславского». Издательство «Academia». Год 1935-й — Федор Михайлович Достоевский. Антология жизни и творчества». fedordostoevsky.ru.

- ^ a b Первый всесоюзный съезд советских писателей. Стенографический отчёт. — М.: Государственное издательство «Художественная литература», 1934. — 718 с.

- ^ Дворниченко, Оксана (13 August 2006). Дмитрий Шостакович: путешествие. Текст. ISBN 9785751605919 – via Google Books.

- ^ Время Горького и проблемы истории. М. Горький. Материалы и исследования (in Russian). Vol. 14. Moscow: Gorky Institute of World Literature. 2018. ISBN 978-5-9208-0515-7.

- ^ Davies, R.W. (2003). The Stalin-Kaganovich Correspondence 1931–36. New Haven: Yale U.P. pp. 249–253. ISBN 0-300-09367-5.

- ^ Составители: О. В.Хлевнюк, Р. У. Дэвис (13 August 2001). «Сталин и Каганович. Переписка. 1931 — 1936 гг» – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Gorky, Maxim. «Soviet Literature». Soviet Writers’ Congress 1934. Marxist Internet Archive. Archived from the original on 5 January 2019. Retrieved 4 January 2019.

- ^ «Introduction to Platonov». New Left Review. 69. 2011. Archived from the original on 27 June 2019.

- ^ Gorky, Maxim (1934). «Классика: Горький Максим. По поводу одной дискуссии». Maxim Moshkov Library (in Russian). Archived from the original on 2 November 2021. Retrieved 10 February 2022.

- ^ Yedlin, Tovah (1999). Maxim Gorky: A Political Biography. Westport, Connecticut, United States: Praeger Publishers. ISBN 0-275-96605-4.

- ^ McSmith 2015, p. 91.

- ^ Vyshinsky, Andrey (April 1938). «The Treason Case Summed Up» (PDF). neworleans.indymedia.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 March 2009. Retrieved 10 February 2022.

From Soviet Russia Today, April 1938 Vol. 7 No. 2. Transcribed by Red Flag Magazine.

- ^ Ellis, Andrew. Socialist Realisms: Soviet Painting 1920–1970. Skira Editore S.p.A., 2012, p. 22

- ^ Orphan Paul, Boni and Gaer, NY, 1946.

- ^ N. Froud and J. Hanley (Eds and translators), Chaliapin: An Autobiography as told to Maxim Gorky (Stein and Day, New York 1967) Library of Congress card no. 67-25616.

- ^ Gorky, Maxim (September 2001). Literary Portraits. The Minerva Group, Inc. ISBN 978-0-89875-580-0.

- ^ Gorky, Maksim. Creatures That Once Were Men, and other stories. Translated by Shirazi, J. M. – via National Library of Australia.

Translated from the Russian by J. M. Shirazi and others. With an introduction by G. K. Chesterton

- ^ «Bandera Street appeared in the liberated Izium». Ukrayinska Pravda (in Ukrainian). 3 December 2022. Retrieved 3 December 2022.

- ^ «Gorky Street». karta.tendryakovka.ru. Retrieved 13 February 2020.

- ^ https://www.gorkysadan.com/[bare URL]

- ^ «Monuments to Pushkin, Lomonosov, and Gorky will be removed from public space in Dnipro — city council». Ukrayinska Pravda (in Ukrainian). 6 December 2022. Retrieved 6 December 2022.

- ^ Oleh Bildin (26 December 2022). «Monuments to Gorky and Chkalov were dismantled in Dnipro». Informator (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 10 January 2023.

- ^ «Maxim Gorky (1868-1936), Russian and Soviet writer». colnect.com. Retrieved 13 February 2020.

- ^ ,«Portrait of Maxim Gorky». colnect.com. Retrieved 13 February 2020.

- ^ «Birth Centenary Maxim Gorky». colnect.com. Retrieved 13 February 2020.

- ^ «Leo Tolstoy (1828-1910); Maxim Gorky (1868-1936)». colnect.com. Retrieved 13 February 2020.

- ^ «Press File: Reviews of ‘Enemies’ by Maxim Gorky directed by Ann Penington in 12 pages» – via Internet Archive.

Sources[edit]

- Banham, Martin, ed. 1998. The Cambridge Guide to Theatre. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-43437-8.

- Benedetti, Jean (1999). Stanislavski : His Life and Art : a Biography (3rd, rev. and expanded ed.). London: Methuen. ISBN 0-413-52520-1. OCLC 1109272008.

- McSmith, Andy (2015). Fear and the Muse Kept Watch, The Russian Masters – from Akhmatova and Pasternak to Shostakovich and Eisenstein – under Stalin. New York: The New Press. ISBN 9781620970799. OCLC 907678164.

- Moynahan, Brian (1992). Comrades : 1917 — Russia in Revolution. Boston: Little, Brown. ISBN 978-0-316-58698-6. OCLC 1028562793 – via Internet Archvive.

- Worrall, Nick. 1996. The Moscow Art Theatre. Theatre Production Studies ser. London and NY: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-05598-9.

- Figes, Orlando: A People’s Tragedy: The Russian Revolution: 1891–1924 The Bodley Head, London. (2014) ISBN 978-0-14-024364-2

Further reading[edit]

- Figes, Orlando (June 1996). «Maxim Gorky and the Russian revolution». History Today. 46 (6): 16. ISSN 0018-2753. EBSCOhost 9606240213.

- Tovah Yedlin. Maxim Gorky: A Political Biography

External links[edit]

- Maxim Gorky Archive at marxists.org

- Works by Maxim Gorky at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Maxim Gorky at Internet Archive

- Works by Maxim Gorky at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Newspaper clippings about Maxim Gorky in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

|

Maxim Gorky |

|

|---|---|

Gorky in 1926 at Posillipo |

|

| Born | Aleksey Maksimovich Peshkov 28 March [O.S. 16 March] 1868 Nizhny Novgorod, Nizhny Novgorod Governorate, Russian Empire |

| Died | 18 June 1936 (aged 68) Gorki-10, Moscow Oblast, Soviet Union |

| Occupation | Prose writer, dramatist, essayist, politician, poet |

| Period | 1892–1936 |

| Notable works | The Lower Depths (1902) Mother (1906) My Childhood. In the World. My Universities (1913–1923) The Life of Klim Samgin (1925–1936) |

| Signature | |

Alexei Maximovich Peshkov (Russian: Алексе́й Макси́мович Пешко́в;[a] 28 March [O.S. 16 March] 1868 – 18 June 1936), popularly known as Maxim Gorky (Russian: Макси́м Го́рький), was a Russian writer and socialist political thinker and proponent.[1] He was nominated five times for the Nobel Prize in Literature.[2] Before his success as an author, he travelled widely across the Russian Empire changing jobs frequently, experiences which would later influence his writing.

Gorky’s most famous works are his early short stories, written in the 1890s («Chelkash», «Old Izergil», and «Twenty-Six Men and a Girl»); plays The Philistines (1901), The Lower Depths (1902) and Children of the Sun (1905); a poem, «The Song of the Stormy Petrel» (1901); his autobiographical trilogy, My Childhood, In the World, My Universities (1913–1923); and a novel, Mother (1906). Gorky himself judged some of these works as failures, and Mother has been frequently criticized, and Gorky himself thought of Mother as one of his biggest failures.[3] However, there have been warmer judgements of some less-known post-revolutionary works such as the novels The Artamonov Business (1925) and The Life of Klim Samgin (1925–1936); the latter is considered Gorky’s masterpiece and has sometimes been viewed by critics as a modernist work. Unlike his pre-revolutionary writings (known for their «anti-psychologism») Gorky’s late works differ with an ambivalent portrayal of the Russian Revolution and «unmodern interest to human psychology» (as noted by D. S. Mirsky).[4] He had associations with fellow Russian writers Leo Tolstoy and Anton Chekhov, both mentioned by Gorky in his memoirs.

Gorky was active in the emerging Marxist communist and later in the Bolshevik movement. He publicly opposed the Tsarist regime, and for a time closely associated himself with Vladimir Lenin and Alexander Bogdanov’s Bolshevik wing of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party. For a significant part of his life, he was exiled from Russia and later the Soviet Union (USSR). In 1932, he returned to the USSR on Joseph Stalin’s personal invitation and lived there until his death in June 1936. After his return, he was officially declared the «founder of Socialist Realism». Despite his official reputation, Gorky’s relations with the Soviet regime were rather difficult. Modern scholars consider his ideology of God-Building as distinct from the official Marxism–Leninism, and his work fits uneasily under the «Socialist Realist» label. Gorky’s work still has a controversial reputation because of his political biography, although in the last years his works are returning to European stages and being republished.[5]

Life[edit]

Early years[edit]

Born as Alexei Maximovich Peshkov on 28 March [O.S. 16 March] 1868, in Nizhny Novgorod, Gorky became an orphan at the age of eleven. He was brought up by his maternal grandmother[1] and ran away from home at the age of twelve in 1880. After an attempt at suicide in December 1887, he travelled on foot across the Russian Empire for five years, changing jobs and accumulating impressions used later in his writing.[1]

As a journalist working for provincial newspapers, he wrote under the pseudonym Иегудиил Хламида (Jehudiel Khlamida).[6] He started using the pseudonym «Gorky» (from горький; literally «bitter») in 1892, when his first short story, «Makar Chudra», was published by the newspaper Kavkaz (The Caucasus) in Tiflis, where he spent several weeks doing menial jobs, mostly for the Caucasian Railway workshops.[8][9] The name reflected his simmering anger about life in Russia and a determination to speak the bitter truth. Gorky’s first book Очерки и рассказы (Essays and Stories) in 1898 enjoyed a sensational success, and his career as a writer began. Gorky wrote incessantly, viewing literature less as an aesthetic practice (though he worked hard on style and form) than as a moral and political act that could change the world. He described the lives of people in the lowest strata and on the margins of society, revealing their hardships, humiliations, and brutalisation, but also their inward spark of humanity.[1]

Political and literary development[edit]

Gorky’s reputation grew as a unique literary voice from the bottom stratum of society and as a fervent advocate of Russia’s social, political, and cultural transformation. By 1899, he was openly associating with the emerging Marxist social-democratic movement, which helped make him a celebrity among both the intelligentsia and the growing numbers of «conscious» workers. At the heart of all his work was a belief in the inherent worth and potential of the human person. In his writing, he counterposed individuals, aware of their natural dignity, and inspired by energy and will, with people who succumb to the degrading conditions of life around them. Both his writings and his letters reveal a «restless man» (a frequent self-description) struggling to resolve contradictory feelings of faith and scepticism, love of life and disgust at the vulgarity and pettiness of the human world.[citation needed]

In 1916, Gorky said that the teachings of the ancient Jewish sage Hillel the Elder deeply influenced his life: «In my early youth I read…the words of…Hillel, if I remember rightly: ‘If thou art not for thyself, who will be for thee? But if thou art for thyself alone, wherefore art thou’? The inner meaning of these words impressed me with its profound wisdom…The thought ate its way deep into my soul, and I say now with conviction: Hillel’s wisdom served as a strong staff on my road, which was neither even nor easy. I believe that Jewish wisdom is more all-human and universal than any other; and this not only because of its immemorial age…but because of the powerful humaneness that saturates it, because of its high estimate of man.»[10]

He publicly opposed the Tsarist regime and was arrested many times. Gorky befriended many revolutionaries and became a personal friend of Vladimir Lenin after they met in 1902. He exposed governmental control of the press (see Matvei Golovinski affair). In 1902, Gorky was elected an honorary Academician of Literature, but Tsar Nicholas II ordered this annulled. In protest, Anton Chekhov and Vladimir Korolenko left the Academy.[11]

From 1900 to 1905, Gorky’s writings became more optimistic. He became more involved in the opposition movement, for which he was again briefly imprisoned in 1901. In 1904, having severed his relationship with the Moscow Art Theatre in the wake of conflict with Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko, Gorky returned to Nizhny Novgorod to establish a theatre of his own.[b] Both Konstantin Stanislavski and Savva Morozov provided financial support for the venture.[13] Stanislavski believed that Gorky’s theatre was an opportunity to develop the network of provincial theatres which he hoped would reform the art of the stage in Russia, a dream of his since the 1890s.[13] He sent some pupils from the Art Theatre School—as well as Ioasaf Tikhomirov, who ran the school—to work there.[13] By the autumn, however, after the censor had banned every play that the theatre proposed to stage, Gorky abandoned the project.[13]

As a financially successful author, editor, and playwright, Gorky gave financial support to the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP), as well as supporting liberal appeals to the government for civil rights and social reform. The brutal shooting of workers marching to the Tsar with a petition for reform on 9 January 1905 (known as the «Bloody Sunday»), which set in motion the Revolution of 1905, seems to have pushed Gorky more decisively toward radical solutions. He became closely associated with Vladimir Lenin and Alexander Bogdanov’s Bolshevik wing of the party, with Bogdanov taking responsibility for the transfer of funds from Gorky to Vpered.[14] It is not clear whether he ever formally joined, and his relations with Lenin and the Bolsheviks would always be rocky. His most influential writings in these years were a series of political plays, most famously The Lower Depths (1902). While briefly imprisoned in Peter and Paul Fortress during the abortive 1905 Russian Revolution, Gorky wrote the play Children of the Sun, nominally set during an 1862 cholera epidemic, but universally understood to relate to present-day events. He was released from the prison after a European-wide campaign, which was supported by Marie Curie, Auguste Rodin and Anatole France, amongst others.[15]

Gorky assisted the Moscow uprising of 1905, and after its suppression his apartment was raided by the Black Hundreds. He subsequently fled to Lake Saimaa, Finland.[16] In 1906, the Bolsheviks sent him on a fund-raising trip to the United States with Ivan Narodny. When visiting the Adirondack Mountains, Gorky wrote Мать (Mat’, Mother), his notable novel of revolutionary conversion and struggle. His experiences in the United States—which included a scandal over his travelling with his lover (the actress Maria Andreyeva) rather than his wife—deepened his contempt for the «bourgeois soul.»

Capri years[edit]

Between 1909–1911 Gorky lived on the island of Capri in the burgundy-coloured «Villa Behring».

From 1906 to 1913, Gorky lived on the island of Capri in southern Italy, partly for health reasons and partly to escape the increasingly repressive atmosphere in Russia.[1] He continued to support the work of Russian social-democracy, especially the Bolsheviks and invited Anatoly Lunacharsky to stay with him on Capri. The two men had worked together on Literaturny Raspad which appeared in 1908. It was during this period that Gorky, along with Lunacharsky, Bogdanov and Vladimir Bazarov developed the idea of an Encyclopedia of Russian History as a socialist version of Diderot’s Encyclopédie.

In 1906, Maxim Gorky visited New York City at the invitation of Mark Twain and other writers. An invitation to the White House by President Theodore Roosevelt was withdrawn after the New York World reported that the woman accompanying Gorky was not his wife.[17] After this was revealed all of the hotels in Manhattan refused to house the couple, and they had to stay at an apartment in Staten Island.[16]

During a visit to Switzerland, Gorky met Lenin, who he charged spent an inordinate amount of his time feuding with other revolutionaries, writing: «He looked awful. Even his tongue seemed to have turned grey».[18] Despite his atheism,[19] Gorky was not a materialist.[20] Most controversially, he articulated, along with a few other maverick Bolsheviks, a philosophy he called «God-Building» (богостроительство, bogostroitel’stvo),[1] which sought to recapture the power of myth for the revolution and to create religious atheism that placed collective humanity where God had been and was imbued with passion, wonderment, moral certainty, and the promise of deliverance from evil, suffering, and even death. Though ‘God-Building’ was ridiculed by Lenin, Gorky retained his belief that «culture»—the moral and spiritual awareness of the value and potential of the human self—would be more critical to the revolution’s success than political or economic arrangements.

Return from exile[edit]

An amnesty granted for the 300th anniversary of the Romanov dynasty allowed Gorky to return to Russia in 1914, where he continued his social criticism, mentored other writers from the common people, and wrote a series of important cultural memoirs, including the first part of his autobiography.[1][21] On returning to Russia, he wrote that his main impression was that «everyone is so crushed and devoid of God’s image.» The only solution, he repeatedly declared, was «culture».

After the February Revolution, Gorky visited the headquarters of the Okhrana (secret police) on Kronversky Prospekt together with Nikolai Sukhanov and Vladimir Zenisinov.[22] Gorky described the former Okhrana headquarters, where he sought literary inspiration, as derelict, with windows broken, and papers lying all over the floor.[23] Having dinner with Sukhanov later the same day, Gorky grimly predicted that revolution would end in «Asiatic savagery».[24] Initially a supporter of the Socialist-Revolutionary Alexander Kerensky, Gorky switched over to the Bolsheviks after the Kornilov affair.[25] In July 1917, Gorky wrote his own experiences of the Russian working class had been sufficient to dispel any «notions that Russian workers are the incarnation of spiritual beauty and kindness».[26] Gorky admitted to feeling attracted to Bolshevism, but admitted to concerns about a creed that made the entire working class «sweet and reasonable — I had never known people who were really like this».[27] Gorky wrote that he knew the poor, the «carpenters, stevedores, bricklayers», in a way that the intellectual Lenin never did, and he frankly distrusted them.[27]

During World War I, his apartment in Petrograd was turned into a Bolshevik staff room, and his politics remained close to the Bolsheviks throughout the revolutionary period of 1917. On the day after the October Revolution of 7 November 1917, Gorky observed a gardener working the Alexander Park who had cleared snow during the February Revolution while ignoring the shots in the background, asked people during the July Days not to trample the grass and was now chopping off branches, leading Gorky to write that he was «stubborn as a mole, and apparently as blind as one too».[28] Gorky’s relations with the Bolsheviks became strained, however, after the October Revolution. One contemporary recalled how Gorky would turn «dark and black and grim» at the mere mention of Lenin.[29] Gorky wrote that Vladimir Lenin together with Leon Trotsky «have become poisoned with the filthy venom of power», crushing the rights of the individual to achieve their revolutionary dreams.[29] Gorky wrote that Lenin was a «cold-blooded trickster who spares neither the honor nor the life of the proletariat. … He does not know the popular masses, he has not lived with them».[29] Gorky went on to compare Lenin to a chemist experimenting in a laboratory with the only difference being the chemist experimented with inanimate matter to improve life while Lenin was experimenting on the «living flesh of Russia».[29] A further strain on Gorky’s relations with the Bolsheviks occurred when his newspaper Novaya Zhizn (Новая Жизнь, «New Life«) fell prey to Bolshevik censorship during the ensuing civil war, around which time Gorky published a collection of essays critical of the Bolsheviks called Untimely Thoughts in 1918. (It would not be re-published in Russia until after the collapse of the Soviet Union.) The essays call Lenin a tyrant for his senseless arrests and repression of free discourse, and an anarchist for his conspiratorial tactics; Gorky compares Lenin to both the Tsar and Nechayev.[citation needed]

- «Lenin and his associates,» Gorky wrote, «consider it possible to commit all kinds of crimes … the abolition of free speech and senseless arrests.»[30]

He was a member of the Committee for the Struggle against Antisemitism within the Soviet government.[31]

In 1921, he hired a secretary, Moura Budberg, who later became his mistress. In August 1921, the poet Nikolay Gumilev was arrested by the Petrograd Cheka for his monarchist views. There is a story that Gorky hurried to Moscow, obtained an order to release Gumilev from Lenin personally, but upon his return to Petrograd he found out that Gumilev had already been shot – but Nadezhda Mandelstam, a close friend of Gumilev’s widow, Anna Akhmatova wrote that: «It is true that people asked him to intervene. … Gorky had a strong dislike of Gumilev, but he nevertheless promised to do something. He could not keep his promise because the sentence of death was announced and carried out with unexpected haste, before Gorky had got round to doing anything.»[32] In October, Gorky returned to Italy on health grounds: he had tuberculosis.

Povolzhye famine[edit]

In July 1921, Gorky published an appeal to the outside world, saying that millions of lives were menaced by crop failure. The Russian famine of 1921–22, also known as Povolzhye famine, killed an estimated 5 million, primarily affecting the Volga and Ural River regions.[33]

Second exile[edit]

Gorky left Russia in September 1921, for Berlin. There he heard about the impending Moscow Trial of 12 Socialist Revolutionaries, which hardened his opposition to the Bolshevik regime. He wrote to Anatole France denouncing the trial as a «cynical and public preparation for the murder» of people who had fought for the freedom of the Russian people. He also wrote to the Soviet vice-premier, Alexei Rykov asking him to tell Leon Trotsky that any death sentences carried out on the defendants would be «premeditated and foul murder.»[34] This provoked a contemptuous reaction from Lenin, who described Gorky as «always supremely spineless in politics», and Trotsky, who dismissed Gorky as an «artist whom no-one takes seriously».[35] He was denied permission by Italy’s fascist government to return to Capri, but was permitted to settle in Sorrento, where he lived from 1922 to 1932, with an extended household that included Moura Budberg, his ex-wife Andreyeva, her lover, Pyotr Kryuchkov, who acted as Gorky’s secretary (initially a spy for Yagoda) for the remainder of his life, Gorky’s son Max Peshkov, Max’s wife, Timosha, and their two young daughters.

He wrote several successful books while there,[36] but by 1928 he was having difficulty earning enough to keep his large household, and began to seek an accommodation with the communist regime. The General Secretary of the Communist Party Joseph Stalin was equally keen to entice Gorky back to the USSR. He paid his first visit in May 1928 – at the very time when the regime was staging its first show trial since 1922, the so-called Shakhty Trial of 53 engineers employed in the coal industry, one of whom, Pyotr Osadchy, had visited Gorky in Sorrento. In contrast to his attitude to the trial of the Socialist Revolutionaries, Gorky accepted without question that the engineers were guilty, and expressed regret that in the past he had intervened on behalf of professionals who were being persecuted by the regime. During the visit, he struck up friendships with Genrikh Yagoda (deputy head of the OGPU) who vested interest in spying on Gorky, and two other OGPU officers, Semyon Firin and Matvei Pogrebinsky, who held high office in the Gulag. Pogrebinsky was Gorky’s guest in Sorrento for four weeks in 1930. The following year, Yagoda sent his brother-in-law, Leopold Averbakh to Sorrento, with instructions to induce Gorky to return to Russia permanently.[37]

Return to Russia[edit]

Gorky’s return from Fascist Italy was a major propaganda victory for the Soviets. He was decorated with the Order of Lenin and given a mansion (formerly belonging to the millionaire Pavel Ryabushinsky, which was for many years the Gorky Museum) in Moscow and a dacha in the suburbs. The city of Nizhni Novgorod, and the surrounding province were renamed Gorky. Moscow’s main park, and one of the central Moscow streets, Tverskaya, were renamed in his honour, as was the Moscow Art Theatre. The largest fixed-wing aircraft in the world in the mid-1930s, the Tupolev ANT-20 was named Maxim Gorky in his honour.

He was also appointed President of the Union of Soviet Writers, founded in 1932, to coincide with his return to the USSR. On 11 October 1931 Gorky read his fairy tale poem «A Girl and Death» (which he wrote in 1892) to his visitors Joseph Stalin, Kliment Voroshilov and Vyacheslav Molotov, an event that was later depicted by Viktor Govorov in his painting. On that same day Stalin left his autograph on the last page of this work by Gorky: «This piece is stronger than Goethe’s Faust (love defeats death)>» Voroshilov also left a «resolution»: «I am illiterate, but I think that Comrade Stalin more than correctly defined the meaning of A. Gorky’s poems. On my own behalf, I will say: I love M. Gorky as my and my class of writer, who correctly defined our forward movement.»[38]

As Vyacheslav Ivanov remembers, Gorky was very upset:

They wrote their resolution on his fairy tale «A Girl and Death». My father, who spoke about this episode with Gorky, insisted emphatically that Gorky was offended. Stalin and Voroshilov were drunk and fooling around.[39]

Apologist for the gulag[edit]