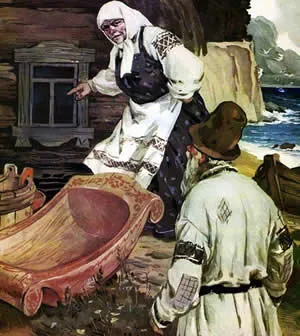

Придя домой, он видит новое корыто своей жены. Но желание старухи становится все сильнее — она заставляет мужа вернуться. к рыбке снова и снова, требуя все больше и больше (сначала для них обоих, потом только для себя):

Содержание

- Сказка о рыбаке и рыбке

- История создания сказки Пушкина о рыбаке и рыбке

- Сказка о рыбаке и рыбке

- Сказка О рыбаке и рыбке

Сказка о рыбаке и рыбке

Стихотворная сказка За жадную старуху и волшебство. рыбке, Он может исполнять желания. Сюжет основан на западнославянском сказкой из коллекции Братьев Гримм. Фраза «остановиться на сломе» — то есть искать большего и не останавливаться ни на чем — стала расхожим высказыванием.

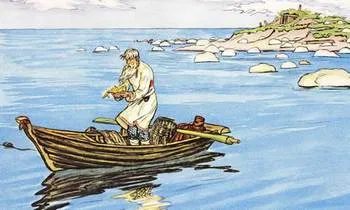

Старик и его старая жена прожили в жалкой землянке-каноэ у самого синего моря ровно тридцать лет и три года. Старик ловил рыбу неводом, а старуха вязала пряжу. Когда он бросил своего теленка в море, тот вернулся только с грязью. Когда он выбросил невод в другой раз, он вернулся с морем травы. Когда он выкинул теленка в третий раз, тот вернулся с сетью. рыбкой, С непростою рыбкой, — золотою. Как взмолится золотая рыбка! Он сказал человеческим голосом: «Отпусти меня, старик, в море; я заплачу себе высокую цену: я верну тебе все, что ты хочешь». Старик был поражен и испуган: он рыбачил тридцать три года и никогда не слышал, чтобы рыба что-то говорила.

Отпустил он рыбку золотую И сказал Она замолвила за него словечко: «Да пребудет с тобой Бог, золотая рыбка! Мне не нужно твое приданое,

«Иди к синему морю и гуляй там на свежем воздухе.

Старик вернулся к старухе и сказал ей.сказал «Я видел сегодня великое чудо. «Сегодня я поймал рыбку, Золотую рыбку, «Я застал женщину, говорящую на нашем языке. рыбка, Она хотела вернуться домой, к синему морю, и дорого за это заплатила: она заплатила за это тем, чего хотел я. Я не посмел выкупить ее и отпустить к синему морю». Старуха отругала старика: «Дурак, дурак, дурак! Вы не знали, как получить выкуп. с рыбки! «Жаль, что вы не взяли ее корыто, наше было разбито.

Тогда она пошла к синему морю и увидела, что море немного неспокойное. И она закричала. золотую рыбку, Приплыла к нему рыбка И сказал: «Что тебе нужно, старик?».

Старик поклонился и сказал: «Пощадите, госпожа. рыбка, Моя старуха меня разозлила, не дает мне покоя: ей нужно новое корыто, наше разбилось». Ей нужна новая кормушка. золотая рыбка»Не волнуйся, иди с Богом, и ты получишь новое корыто». Старик возвращается к старухе, а у старухи появляется новое корыто. Старуха ругает его еще больше: «Дурак, дурак, дурак! Ты умолял о корыте, дурак! Не слишком ли много эго в корыте? Вернись, дурак, ты! к рыбкеПоклонись ей и умоляй о доме».

Она отправилась к синему морю. золотую рыбку, Приплыла к нему рыбка, Она спросила: «Что тебе нужно, старик?». Старик поклонился и сказал: «Пощадите, госпожа. рыбка! Старуха еще больше рассердилась, не оставляет старика в покое: ворчливая женщина просится в дом». Ответить золотая рыбка»Не волнуйся, иди с Богом, ты найдешь хижину». Он отправился в свой приют, но приют исчез, и от него не осталось и следа. Перед ним — навес с побеленными кирпичными воротами и дубовыми воротами и створками.

Старуха сидит под окном и ругает своего мужа. «Ты дурак, глупый дурак! Ты выпросил дом, дурак! Вернитесь и поклонитесь. рыбке»Я не хочу быть черным крестьянином, я хочу быть аристократом».

Старик отправился к синему морю. (Синее море не спокойно). золотую рыбку. Приплыла к нему рыбка, Он спросил: «Что тебе нужно, старик?». Старик поклонился и сказал: «Пощадите, госпожа. рыбка! «Старуха злее, чем когда-либо, она не оставляет меня в покое: она не хочет быть крестьянкой, она хочет быть деревенской дворянкой. Ответы. золотая рыбка»Не волнуйся, иди с Богом».

Старик вернулся в дом старухи. У старухи новое корыто. Старуха ругает его еще больше: «Дурак ты, бездельник! «Дурак, дурак, взятку за корыто даешь! Не слишком ли много эгоизма в кормушке? Вернись, дурак, ты! к рыбкеПоклонись ей и умоляй о доме».

История создания сказки Пушкина о рыбаке и рыбке

«Сказка о рыбаке и рыбке» была написана Стихотворение было написано Александром Сергеевичем Пушкиным 2 октября 1833 года, во время второй Болдинской осени.

Болдинская осень — один из самых ярких творческих периодов в жизни поэта.

Эта эпоха характеризовалась невероятным творческим подъемом, который привел к созданию большого количества прекрасных произведений за относительно короткое время.

Первая «Осень» Болдино состоялась в 1831 году и подарила миру более 40 завершенных работ.

Вторая «Осень» Болдино была в два раза длиннее первой и породила более 10 невероятных работ. Среди них была «Сказка о рыбаке и рыбке».

Известно, что Пушкин при создании сказки по мотивам пьесы братьев Гримм». О рыбаке и его жене «.

Согласно этому источнику, в первой версии пьесы старуха должна была стать Папой и в конце пожелала стать богом.

Однако автор отказался от этой версии, чтобы сохранить русскую народную направленность. сказки.

В конце концов, Пушкин черпал из русского народа. сказку «Жадная старуха», в котором вместо рыбки появилось волшебное дерево.

Произведение было написано Осенью 1833 г. Через два года (1835) он был впервые опубликован в журнале «Библиотека для чтения».

Старик вернулся в дом старухи. У старухи новое корыто. Старуха ругает его еще больше: «Дурак ты, бездельник! «Дурак, дурак, взятку за корыто даешь! Не слишком ли много эгоизма в кормушке? Вернись, дурак, ты! к рыбкеПоклонись ей и умоляй о доме».

Сказка о рыбаке и рыбке

В Сказке о рыбаке и рыбке Старик и старуха живут на берегу синего моря. Однажды старик отправился на рыбалку и поймал золотую рыбку. Рыба попросила старика отпустить ее в обмен на желание. Рыбак пожалел ее и отпустил, ничего не заплатив. Когда он вернулся домой, он сказал своей женесказал об этом своей жене. Старуха назвала его дураком и отправила обратно просить хотя бы новое корыто. Рыба исполнила ее желание, но старуха не была удовлетворена и несколько раз посылала мужа обратно просить добавки. Когда она хотела стать владычицей морской, рыбка Все предыдущие чудеса были отменены, и старуха осталась со сломанным корытом. Эта история показывает, к чему приводит жадность.

У самого синего моря жили старик и старуха; тридцать лет прожили они в убогой хижине. Старик ловил рыбу неводом, а старуха вязала пряжу. Однажды он бросил своего теленка в море, и оттуда выплыла только грязь.

В другой раз он закинул невод, который всплыл с теленком травы. В третий раз, когда он выбросил теленка, появился теленок. рыбкой, С не простою рыбкой — золотою. Как взмолится золотая рыбка! Он сказал человеческим голосом: «Отпусти меня, старик, в море! Я дорого заплачу за себя: Я заплачу все, что вы пожелаете».

Старик был удивлен и испуган: он рыбачил тридцать три года и никогда не слышал, чтобы рыба говорила. Он отпустил. он рыбку золотую И сказал «Да пребудет с вами Бог, золотая рыбка! Мне не нужно твое жалованье; иди к синему морю и гуляй там на свежем воздухе».

Старик вернулся к старухе.сказал «Я видел сегодня великое чудо. рыбку, Золотую рыбку, «Я не прост; он говорил на нашем языке. рыбка, Она хотела вернуться домой, к синему морю, и дорого за это заплатила: Я не посмел выкупить ее на свободу и отпустил ее в синее море».

Старуха отругала старика: «Дурак, дурак, дурак! Вы не знали, как получить выкуп. с рыбки! «Вы должны хотя бы купить ей отдельное корыто, наше разбито».

Тогда она пошла к синему морю и увидела, что море немного неспокойное. Она плакала золотую рыбку. Приплыла к нему рыбка и спросил: «Что тебе нужно, старик?». Старик поклонился и сказал: «Пощадите, госпожа. рыбка, Моя старуха разозлила меня. Она не дает старику покоя: ему нужно новое корыто, наше разбито». Ответы. золотая рыбка»Не волнуйся, иди с Богом. Вы получите новое корыто».

Старик возвращается к старухе, а у старухи появляется новое корыто.

Старуха ругает его еще больше: «Дурак ты, бездельник! «Дурак, дурак, взятку за корыто даешь! Не слишком ли много эго в корыте? Вернись, дурак, ты! к рыбкеПоклонись ей и попроси у нее дом».

И она отправилась к синему морю. Она начала звонить золотую рыбку. Приплыла к нему рыбка, он спросил: «Что тебе нужно, старик?». Старик поклонился ей: «Пощадите, мадам. рыбка! Старуха еще больше злится, не оставляет старика в покое: ворчливая женщина просится в дом». Старуха не оставит старика в покое. золотая рыбка»Не волнуйся, иди с Богом, ты найдешь дом».

Старик вернулся в дом старухи. У старухи новое корыто. Старуха ругает его еще больше: «Дурак ты, бездельник! «Дурак, дурак, взятку за корыто даешь! Не слишком ли много эгоизма в кормушке? Вернись, дурак, ты! к рыбкеПоклонись ей и умоляй о доме».

Сказка О рыбаке и рыбке

Старик и его жена живут у моря. Старик зарабатывает на жизнь рыбалкой, а старуха вяжет пряжу. Однажды в сети старика попалась необычная женщина. золотая рыбка, который может говорить человеческим голосом (языком). Она обещает любой выкуп и просит отпустить ее в море, но старик отпускает ее. рыбку, Он оставляет старика, не требуя вознаграждения. Вернувшись домой в приют для бедных, он рассказывает жене о случившемся.сказываОн рассказывает жене, что произошло. Поругав мужа, она заставляет его вернуться к морю за помощью. рыбку и хотя бы попросить новое корыто взамен разбитого. У моря старик зовет рыбку, который появляется и обещает исполнить его желание, говоря: «Не волнуйся, иди с Богом».

Придя домой, он видит новое корыто своей жены. Но желание старухи становится все сильнее — она заставляет мужа вернуться. к рыбке снова и снова, требуя все больше и больше (сначала для них обоих, потом только для себя):

Получить новую избу; стать аристократической столбовой женщиной; стать «свободной царевной».

Море, в которое приходит старик, постепенно превращается из спокойного и синего в черное и бурное. Меняется и отношение старухи к старику: сначала она продолжает ругать его, затем, став хозяйкой, отправляет его в хлев, и, наконец, став королевой, прогоняет его совсем. В конце концов, она перезванивает мужу и требует, чтобы он вернулся. рыбка чтобы сделать ее «Владычицей морей», и что она сама рыбка чтобы стать ее слугой. На следующую просьбу старика Рыбка не отвечает, а когда возвращается домой, видит старуху, сидящую перед старой бадьей рядом со старым разбитым корытом.

В русской культуре есть поговорка «остаться у разбитого корыта», которая означает, что вы стремитесь к большему и в итоге остаетесь ни с чем.

Тогда она пошла к синему морю и увидела, что море немного неспокойное. И она закричала. золотую рыбку, Приплыла к нему рыбка И сказал: «Что тебе нужно, старик?».

The fairy tale commemorated on a Soviet Union stamp

The Tale of the Fisherman and the Fish (Russian: «Сказка о рыбаке и рыбке», romanized: Skazka o rybake i rybke) is a fairy tale in verse by Alexander Pushkin, published 1835.

The tale is about a fisherman who manages to catch a «Golden Fish» which promises to fulfill any wish of his in exchange for its freedom.

Textual notes[edit]

Pushkin wrote the tale in autumn 1833[1] and it was first published in the literary magazine Biblioteka dlya chteniya in May 1835.

English translations[edit]

Robert Chandler has published an English translation, «A Tale about a Fisherman and a Fish» (2012).[2][3]

Grimms’ Tales[edit]

It has been believed that Pushkin’s is an original tale based on the Grimms’ tale,[4] «The Fisherman and his Wife».[a]

Azadovsky wrote monumental articles on Pushkin’s sources, his nurse «Arina Rodionovna», and the «Brothers Grimm» demonstrating that tales recited to Pushkin in his youth were often recent translations propagated «word of mouth to a largely unlettered peasantry», rather than tales passed down in Russia, as John Bayley explains.[6]

Still, Bayley»s estimation, the derivative nature does not not diminish the reader’s ability to appreciate «The Fisherman and the Fish» as «pure folklore», though at a lesser scale than other masterpieces.[6] In a similar vein, Sergei Mikhailovich Bondi [ru] emphatically accepted Azadovsky’s verdict on Pushkin’s use of Grimm material, but emphasized that Pushkin still crafted Russian fairy tales out of them.[7]

In a draft version, Pushkin has the fisherman’s wife wishing to be the Roman Pope,[8] thus betraying his influence from the Brother Grimms’ telling, where the wife also aspires to be a she-Pope.[9]

Afanasyev’s collection[edit]

The tale is also very similar in plot and motif to the folktale «The Goldfish» Russian: Золотая рыбка which is No. 75 in Alexander Afanasyev’s collection (1855–1867), which is obscure as to its collected source.[7]

Russian scholarship abounds in discussion of the interrelationship between Pushkin’s verse and Afanasyev’s skazka.[7] Pushkin had been shown Vladimir Dal’s collection of folktales.[7] He seriously studied genuine folktales, and literary style was spawned from absorbing them, but conversely, popular tellings were influenced by Pushkin’s published versions also.[7]

At any rate, after Norbert Guterman’s English translation of Asfaneyev’s «The Goldfish» (1945) appeared,[10] Stith Thompson included it in his One Hundred Favorite Folktales, so this version became the referential Russian variant for the ATU 555 tale type.[11]

Plot summary[edit]

In Pushkin’s poem, an old man and woman have been living poorly for many years. They have a small hut, and every day the man goes out to fish. One day, he throws in his net and pulls out seaweed two times in succession, but on the third time he pulls out a golden fish. The fish pleads for its life, promising any wish in return. However, the old man is scared by the fact that a fish can speak; he says he does not want anything, and lets the fish go.

When he returns and tells his wife about the golden fish, she gets angry and tells her husband to go ask the fish for a new trough, as theirs is broken, and the fish happily grants this small request. The next day, the wife asks for a new house, and the fish grants this also. Then, in succession, the wife asks for a palace, to become a noble lady, to become the ruler of her province, to become the tsarina, and finally to become the Ruler of the Sea and to subjugate the golden fish completely to her boundless will. As the man goes to ask for each item, the sea becomes more and more stormy, until the last request, where the man can hardly hear himself think. When he asks that his wife be made the Ruler of the Sea, the fish cures her greed by putting everything back to the way it was before, including the broken trough.

Analysis[edit]

The Afanasiev version «The Goldfish» is catalogued as type ATU 555, «(The) Fisherman and his Wife», the type title deriving from the representative tale, Brothers Grimm’s tale The Fisherman and His Wife.[11][12][13]

The tale exhibits the «function» of «lack» to use the terminology of Vladimir Propp’s structural analysis, but even while the typical fairy tale is supposed to «liquidate’ the lack with a happy ending, this tale type breaches the rule by reducing the Russian couple back to their original state of dire poverty, hence it is a case of «lack not liquidated».[13] The Poppovian structural analysis sets up «The Goldfish» tale for comparison with a similar Russian fairy tale, «The Greedy Old Woman (Wife)».[13]

Adaptations[edit]

- 1866 — Le Poisson doré (The Golden Fish), «fantastic ballet», choreography by Arthur Saint-Léon, the music by Ludwig Minkus.

- 1917 — The Fisherman and the Fish by Nikolai Tcherepnin, op. 41 for orchestra

- 1937 — The Tale of the Fisherman and the Fish, USSR, animated film by Aleksandr Ptushko.[14]

- 1950 — The Tale of the Fisherman and the Fish, USSR, classic traditionally animated film by Mikhail Tsekhanovsky.,[15]

- 2002 — About the Fisherman and the Goldfish, Russia, stop-motion film by Nataliya Dabizha.[16]

See also[edit]

- Odnoklassniki.ru: Click for luck, comedy film (2013)

Explanatory notes[edit]

- ^ D. N. Medrish [ru] also opining that «we have folklore texts that arose under the indisputable Pushkin influence».[5]

References[edit]

- Citations

- ^ Chandler (2012), Alexander Pushkin, introduction.

- ^ Chandler (2012).

- ^ Pilinovsky (2014), pp. 396–397.

- ^ Chandler (2012), Alexander Pushkin, introduction and Pilinovsky (2014), pp. 396–397.

- ^ Medrish, D. N. (1980) Literatura i fol’klornaya traditsiya. Voprosy poetiki Литература и фольклорная традиция. Вопросы поэтики [Literature and folklore tradition. Questions of poetics]. Saratov University p. 97. apud Sugino (2019), p. 8

- ^ a b Bayley, John (1971). «2. Early Poems». Pushkin: A Comparative Commentary. Cambridge: CUP Archive. p. 53. ISBN 0521079543.

- ^ a b c d e Sugino (2019), p. 8.

- ^ Akhmatova, Anna Andreevna (1997). Meyer, Ronald (ed.). My Half Century: Selected Prose. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press. p. 387, n38. ISBN 0810114852.

- ^ Sugino (2019), p. 10.

- ^ Guterman (2013). Title page (pub. years). «The Goldfish» pp. 528–532.

- ^ a b Thompson (1974). Title page (pub. years). «The Goldfish». pp. 241–243. Endnote, p. 437 «Type 555».

- ^ Uther, Hans-Jörg (2004). The types of international folktales. Vol. 1. Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia, Academia Scientiarum Fennica. p. 273. ISBN 9789514109638.

- ^ a b c Somoff, Victoria (2019), Canepa, Nancy L. (ed.), «Morals and Miracles: The Case of ATU 555 ‘The Fisherman and His Wife’«, Teaching Fairy Tales, Wayne State University Press, ISBN 0814339360

- ^ «The Tale About the Fisherman and the Fish (1937)». Animation.ru. Retrieved 1 May 2017.

- ^ «The Tale About the Fisherman and the Fish (1950)». Animation.ru. Retrieved 1 May 2017.

- ^ «About the Fisherman and the Fish (2002)». Animation.ru. Retrieved 1 May 2017.

- Bibliography

- Briggs, A. D. P. (1982). Alexander Pushkin: A Critical Study. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Chandler, Robert, ed. (2012). «A Tale about a Fisherman and a Fish». Russian Magic Tales from Pushkin to Platonov. Penguin UK. ISBN 0141392541.

- Guterman, Norbert, tr., ed. (2013) [1945]. «The Goldfish». Russian Fairy Tales. The Pantheon Fairy Tale and Folklore Library. Aleksandr Afanas’ev (orig. ed.). Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. pp. 528–532. ISBN 0307829766.

- Sugino, Yuri (2019), «Pushkinskaya «Skazka o rybake i rybke» v kontekste Vtoroy boldinskoy oseni» Пушкинская «Сказка о рыбаке и рыбке» в контексте Второй болдинской осени [Pushkin’s“The Tale of the Fisherman and the Fish”in the Context of the Second Boldin Autumn], Japanese Slavic and East European Studies, 39: 2–25, doi:10.5823/jsees.39.0_2

- Thompson, Stith, ed. (1974) [1968]. «51. The Goldfish». One Hundred Favorite Folktales. Indiana University Press. pp. 241–243, endnote p. 437. ISBN 0253201721.

- Pilinovsky, Helen (2014), «(Review): Russian Magic Tales from Pushkin to Platonov by Robert Chandler», Marvels & Tales, 28 (2): 395–397, doi:10.13110/marvelstales.28.2.0395

External links[edit]

The fairy tale commemorated on a Soviet Union stamp

The Tale of the Fisherman and the Fish (Russian: «Сказка о рыбаке и рыбке», romanized: Skazka o rybake i rybke) is a fairy tale in verse by Alexander Pushkin, published 1835.

The tale is about a fisherman who manages to catch a «Golden Fish» which promises to fulfill any wish of his in exchange for its freedom.

Textual notes[edit]

Pushkin wrote the tale in autumn 1833[1] and it was first published in the literary magazine Biblioteka dlya chteniya in May 1835.

English translations[edit]

Robert Chandler has published an English translation, «A Tale about a Fisherman and a Fish» (2012).[2][3]

Grimms’ Tales[edit]

It has been believed that Pushkin’s is an original tale based on the Grimms’ tale,[4] «The Fisherman and his Wife».[a]

Azadovsky wrote monumental articles on Pushkin’s sources, his nurse «Arina Rodionovna», and the «Brothers Grimm» demonstrating that tales recited to Pushkin in his youth were often recent translations propagated «word of mouth to a largely unlettered peasantry», rather than tales passed down in Russia, as John Bayley explains.[6]

Still, Bayley»s estimation, the derivative nature does not not diminish the reader’s ability to appreciate «The Fisherman and the Fish» as «pure folklore», though at a lesser scale than other masterpieces.[6] In a similar vein, Sergei Mikhailovich Bondi [ru] emphatically accepted Azadovsky’s verdict on Pushkin’s use of Grimm material, but emphasized that Pushkin still crafted Russian fairy tales out of them.[7]

In a draft version, Pushkin has the fisherman’s wife wishing to be the Roman Pope,[8] thus betraying his influence from the Brother Grimms’ telling, where the wife also aspires to be a she-Pope.[9]

Afanasyev’s collection[edit]

The tale is also very similar in plot and motif to the folktale «The Goldfish» Russian: Золотая рыбка which is No. 75 in Alexander Afanasyev’s collection (1855–1867), which is obscure as to its collected source.[7]

Russian scholarship abounds in discussion of the interrelationship between Pushkin’s verse and Afanasyev’s skazka.[7] Pushkin had been shown Vladimir Dal’s collection of folktales.[7] He seriously studied genuine folktales, and literary style was spawned from absorbing them, but conversely, popular tellings were influenced by Pushkin’s published versions also.[7]

At any rate, after Norbert Guterman’s English translation of Asfaneyev’s «The Goldfish» (1945) appeared,[10] Stith Thompson included it in his One Hundred Favorite Folktales, so this version became the referential Russian variant for the ATU 555 tale type.[11]

Plot summary[edit]

In Pushkin’s poem, an old man and woman have been living poorly for many years. They have a small hut, and every day the man goes out to fish. One day, he throws in his net and pulls out seaweed two times in succession, but on the third time he pulls out a golden fish. The fish pleads for its life, promising any wish in return. However, the old man is scared by the fact that a fish can speak; he says he does not want anything, and lets the fish go.

When he returns and tells his wife about the golden fish, she gets angry and tells her husband to go ask the fish for a new trough, as theirs is broken, and the fish happily grants this small request. The next day, the wife asks for a new house, and the fish grants this also. Then, in succession, the wife asks for a palace, to become a noble lady, to become the ruler of her province, to become the tsarina, and finally to become the Ruler of the Sea and to subjugate the golden fish completely to her boundless will. As the man goes to ask for each item, the sea becomes more and more stormy, until the last request, where the man can hardly hear himself think. When he asks that his wife be made the Ruler of the Sea, the fish cures her greed by putting everything back to the way it was before, including the broken trough.

Analysis[edit]

The Afanasiev version «The Goldfish» is catalogued as type ATU 555, «(The) Fisherman and his Wife», the type title deriving from the representative tale, Brothers Grimm’s tale The Fisherman and His Wife.[11][12][13]

The tale exhibits the «function» of «lack» to use the terminology of Vladimir Propp’s structural analysis, but even while the typical fairy tale is supposed to «liquidate’ the lack with a happy ending, this tale type breaches the rule by reducing the Russian couple back to their original state of dire poverty, hence it is a case of «lack not liquidated».[13] The Poppovian structural analysis sets up «The Goldfish» tale for comparison with a similar Russian fairy tale, «The Greedy Old Woman (Wife)».[13]

Adaptations[edit]

- 1866 — Le Poisson doré (The Golden Fish), «fantastic ballet», choreography by Arthur Saint-Léon, the music by Ludwig Minkus.

- 1917 — The Fisherman and the Fish by Nikolai Tcherepnin, op. 41 for orchestra

- 1937 — The Tale of the Fisherman and the Fish, USSR, animated film by Aleksandr Ptushko.[14]

- 1950 — The Tale of the Fisherman and the Fish, USSR, classic traditionally animated film by Mikhail Tsekhanovsky.,[15]

- 2002 — About the Fisherman and the Goldfish, Russia, stop-motion film by Nataliya Dabizha.[16]

See also[edit]

- Odnoklassniki.ru: Click for luck, comedy film (2013)

Explanatory notes[edit]

- ^ D. N. Medrish [ru] also opining that «we have folklore texts that arose under the indisputable Pushkin influence».[5]

References[edit]

- Citations

- ^ Chandler (2012), Alexander Pushkin, introduction.

- ^ Chandler (2012).

- ^ Pilinovsky (2014), pp. 396–397.

- ^ Chandler (2012), Alexander Pushkin, introduction and Pilinovsky (2014), pp. 396–397.

- ^ Medrish, D. N. (1980) Literatura i fol’klornaya traditsiya. Voprosy poetiki Литература и фольклорная традиция. Вопросы поэтики [Literature and folklore tradition. Questions of poetics]. Saratov University p. 97. apud Sugino (2019), p. 8

- ^ a b Bayley, John (1971). «2. Early Poems». Pushkin: A Comparative Commentary. Cambridge: CUP Archive. p. 53. ISBN 0521079543.

- ^ a b c d e Sugino (2019), p. 8.

- ^ Akhmatova, Anna Andreevna (1997). Meyer, Ronald (ed.). My Half Century: Selected Prose. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press. p. 387, n38. ISBN 0810114852.

- ^ Sugino (2019), p. 10.

- ^ Guterman (2013). Title page (pub. years). «The Goldfish» pp. 528–532.

- ^ a b Thompson (1974). Title page (pub. years). «The Goldfish». pp. 241–243. Endnote, p. 437 «Type 555».

- ^ Uther, Hans-Jörg (2004). The types of international folktales. Vol. 1. Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia, Academia Scientiarum Fennica. p. 273. ISBN 9789514109638.

- ^ a b c Somoff, Victoria (2019), Canepa, Nancy L. (ed.), «Morals and Miracles: The Case of ATU 555 ‘The Fisherman and His Wife’«, Teaching Fairy Tales, Wayne State University Press, ISBN 0814339360

- ^ «The Tale About the Fisherman and the Fish (1937)». Animation.ru. Retrieved 1 May 2017.

- ^ «The Tale About the Fisherman and the Fish (1950)». Animation.ru. Retrieved 1 May 2017.

- ^ «About the Fisherman and the Fish (2002)». Animation.ru. Retrieved 1 May 2017.

- Bibliography

- Briggs, A. D. P. (1982). Alexander Pushkin: A Critical Study. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Chandler, Robert, ed. (2012). «A Tale about a Fisherman and a Fish». Russian Magic Tales from Pushkin to Platonov. Penguin UK. ISBN 0141392541.

- Guterman, Norbert, tr., ed. (2013) [1945]. «The Goldfish». Russian Fairy Tales. The Pantheon Fairy Tale and Folklore Library. Aleksandr Afanas’ev (orig. ed.). Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. pp. 528–532. ISBN 0307829766.

- Sugino, Yuri (2019), «Pushkinskaya «Skazka o rybake i rybke» v kontekste Vtoroy boldinskoy oseni» Пушкинская «Сказка о рыбаке и рыбке» в контексте Второй болдинской осени [Pushkin’s“The Tale of the Fisherman and the Fish”in the Context of the Second Boldin Autumn], Japanese Slavic and East European Studies, 39: 2–25, doi:10.5823/jsees.39.0_2

- Thompson, Stith, ed. (1974) [1968]. «51. The Goldfish». One Hundred Favorite Folktales. Indiana University Press. pp. 241–243, endnote p. 437. ISBN 0253201721.

- Pilinovsky, Helen (2014), «(Review): Russian Magic Tales from Pushkin to Platonov by Robert Chandler», Marvels & Tales, 28 (2): 395–397, doi:10.13110/marvelstales.28.2.0395