Ганс Кристиан Андерсен — биография

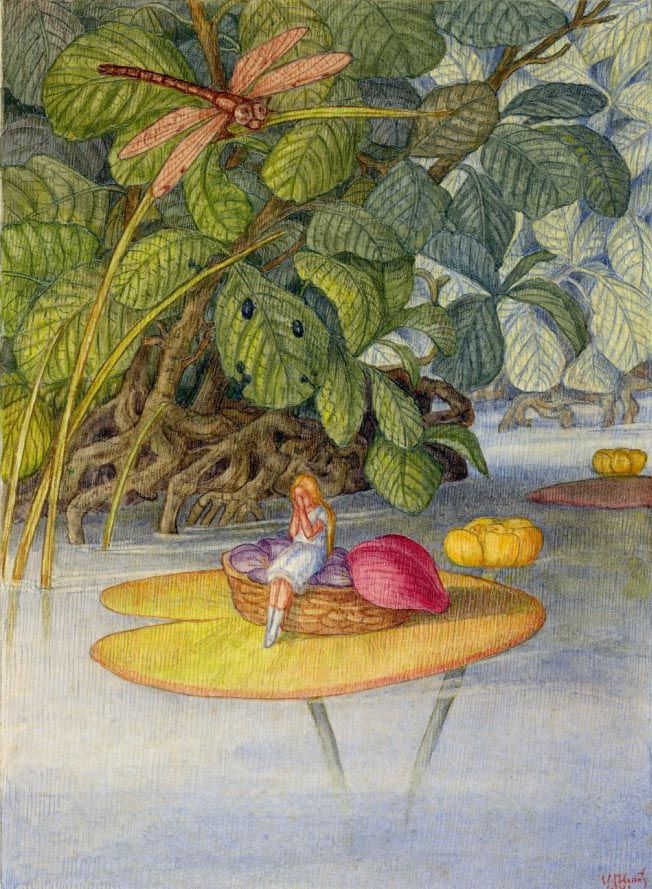

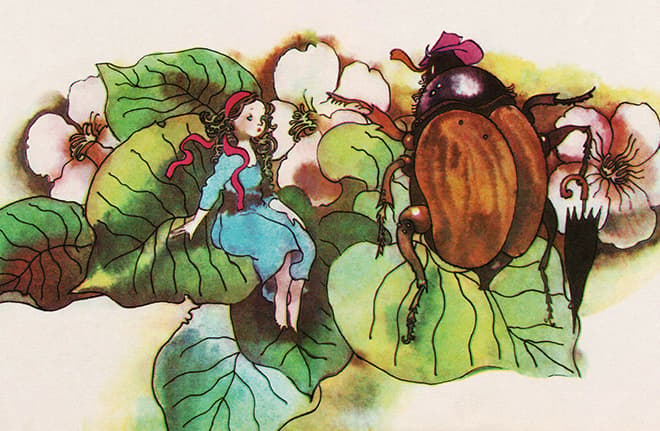

Ганс Христиан Андерсен — известный на весь мир писатель из Дании, подаривший читателю такие популярные во все времена сказки, как Гадкий утенок, Принцесса на горошине, Снежная королева, Дюймовочка и другие.

Дети и взрослые по всему миру отлично знают имя известного писателя из Дании Ганса Христиана Андерсена, произведения которого можно читать на 150 разных языках. Не в одном поколении дети с удовольствием слушают, как родители им читают интересные сказки популярного мастера пера. Достаточно вспомнить Принцессу на горошине или Дюймовочку, мультики о Герде или Русалочке.

Увлекательный мир, описанный автором в сказках, знакомясь с которым можно проследить и актуальные философские мысли, притягателен для читателей самых разных возрастов. Специалисты уже не раз отмечали, что, на первый взгляд, легкий стиль повествования в произведениях таит в себе глубокий смысл, помогающий задуматься над важными в жизни человека вещами.

Детство

В оригинале имя писателя, родившегося 2 апреля 1805 года в городе Оденсе, звучит как Ханс Кристиан. В некоторых источниках можно встретить версию, что он был внебрачным сыном короля Дании Кристиана VIII, однако будущий гений пера с раннего детства жил с родителями в бедных условиях. Отец по имени Ганс был башмачником, малограмотная мать Анна Мари — прачкой.

По мнению главы семейства, корнями его происхождения были представители знатной династии. Так, бабушка по отцу однажды поведала внуку, что их семья относится к привилегированному социальному классу, но в последствии эти данные не подтвердились. Много разных слухов ходило вокруг родственников Андерсена — они и в настоящее время не дают поклонникам его таланта покоя. Так, некоторые утверждают, что дедушка писателя, работавший резчиком, слыл сумасшедшим, так как делал странные поделки людей с крыльями, напоминающими ангельские.

С литературой Ганс познакомился благодаря отцу, часто читавшему сыну арабскую сказку «1001 ночь». Перед сном ежедневно маленький мальчик погружался в волшебный мир красочных восточных историй о красавице Шахерезаде. Папа любил гулять с отпрыском по городскому парку, изредка они даже бывали в театре, который оставил самые яркие впечатления у ребенка.

Ганс-старший скончался, когда младшему было 11 лет. В детском возрасте он погрузился в непростой мир окружающей реальности, где далеко не всегда приходилось испытывать только положительные эмоции. Нервничать Андерсена заставлял местный задира и учителя, запросто применяющие розги с воспитательной целью, так что школу мальчик воспринимал как пытку.

Чувствительный Ганс не выдержал и отказался ходить на учебу, и родители устроили его в специальную благотворительную школу, предназначенную для бедняков.

По окончании заведения юноша стал учеником ткача, потом переквалифицировался в портного, а затем работал на табачной фабрике.

Отношения с коллективом не заладились с самого начала. Андерсен не воспринимал глупые шутки и пошлые анекдоты коллег, которые в один прекрасный день под общий гогот стянули штаны с него, чтобы проверить, мальчик перед ними или девочка. Смущал их тонкий голос мальчика, который любил спеть во время работы. После злой шутки он совсем замкнулся, а единственными друзьями стали сделанные отцом деревянные куклы.

В возрасте 14 лет подросток отправляется в Копенгаген, называемый тогда «скандинавским Парижем». Мать ждала скорого возвращения сына, так что с легкостью его отпустила. У него же были большие планы стать знаменитым, получить актерское образование и играть в театре классические постановки. К тому времени это был высокорослый юноша с длинными конечностями и носом, благодаря которым был прозван «фонарным столбом» и «аистом».

В детстве мальчика также дразнили «писателем пьес» за игрушечный театр в доме с тряпочными «лицедеями».

Прилежный Ганс с неординарной внешностью был похож на гадкого утенка на службе в Королевском театре, куда был принят из жалости, а не по причине ярких способностей. На сцене ему доставались только второстепенные роли, а вскоре у юноши еще стал ломаться голос. Коллеги по цеху, чаще воспринимавшие Андерсена в качестве поэта, порекомендовали молодому человеку заняться литературой.

Датскому чиновнику Йонасу Коллину, отвечавшему за финансы в годы правления Фредерика VI, непохожий на других молодой человек был по душе, так что он смог добиться разрешения от короля оплаты стоимости образования молодого писателя. Благодаря этому Ганс смог пройти обучение в престижных школах Эльсинора и Слагельсе, правда учиться приходилось вместе с младшими на 6 лет учениками. Прилежным слушателем он так и не стал, поэтому не овладел в совершенстве грамотой, делая всю жизнь множество ошибок в письме. Будучи зрелым, сказочник признавался, что студенческие годы приходили к нему в кошмарных снах, ведь ректор много раз высказывал свое негативное отношение к студенту Андерсену, а критику он воспринимал плохо.

Творческие годы

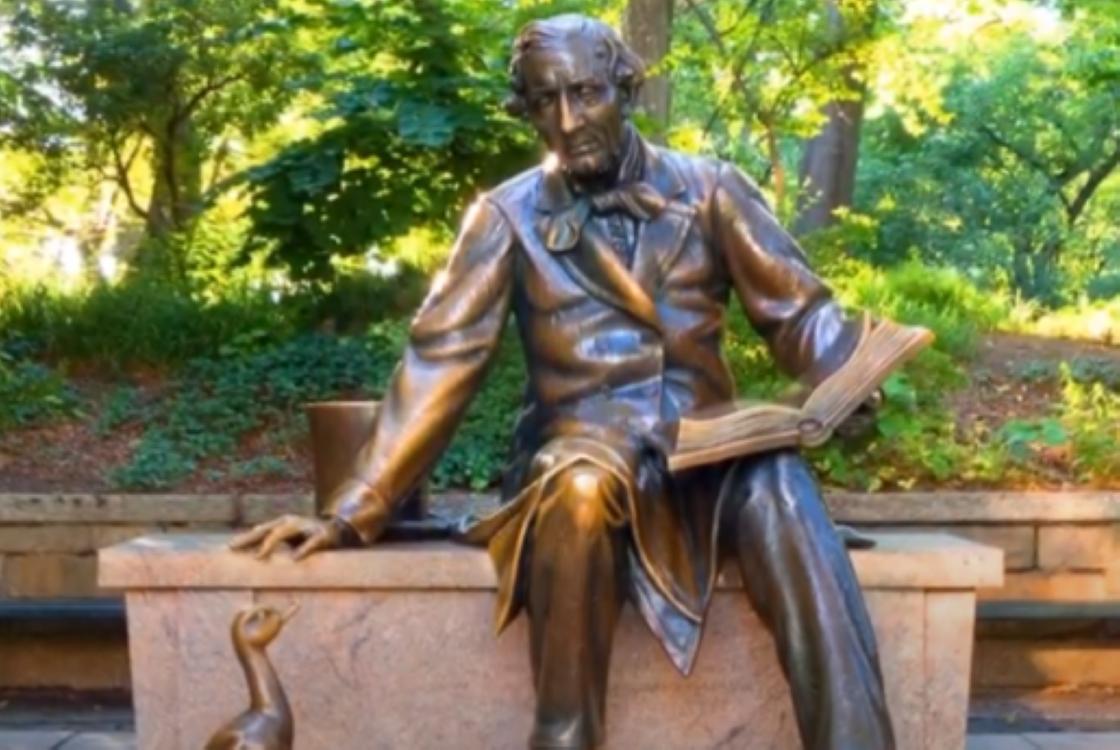

Ганс Христиан Андерсен занимался написанием повестей, стихов, баллад, романов, однако большая часть почитателей его таланта связывают свою любовь со сказками талантливого писателя, которых выпущено было общим числом 156. При этом он не любил, чтобы его воспринимали как детского писателя, и говорил, что пишет с одинаковой частотой для маленьких читателей и взрослых. Он даже приказал не размещать детей на своем памятнике, хотя проект подразумевал изначально монумент в детском окружении.

Общая слава и признание пришли к Андерсену в 24 года после публикации «Пешего путешествия от канала Холмен к восточной оконечности Амагера» — увлекательного приключенческого рассказа. После этого новые литературные произведения автора стали появляться одно за другим. Среди них оказались и великие сказочные произведения, послужившие зарождением системы высоких жанров. Тяжелее давались ему новеллы, романы, водевили, при написании которых автора словно настигал творческий кризис.

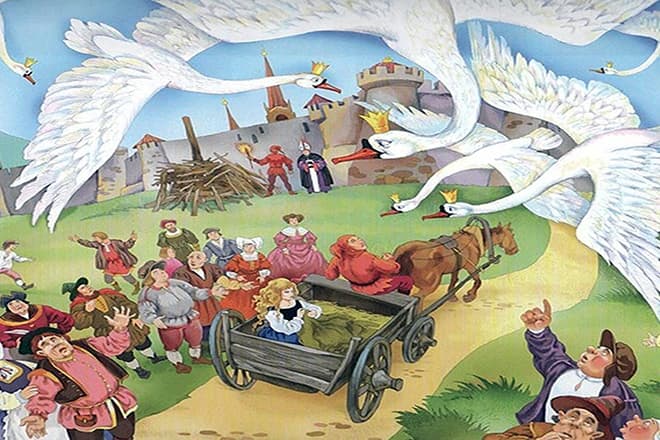

Поводом для вдохновения публициста была повседневная жизнь, где он радовался и маленькому жучку, и цветочному лепестку, и катушке с нитками. Стоит только вспомнить, с какой обстоятельностью в его работах описаны биографии горошинки из стручка или калоши. Добавляя элементы своей фантазии, элементы народного эпоса автор написал «Дикие лебеди», «Огниво», «Свинопас» и многие другие произведения, вошедшие в сборник от 1837 года «Сказки, рассказанные детям».

Ганс Христиан с радостью делал персонажей протагонистами, ищущими свое место в обществе. Это можно сказать про Русалочку, Дюймовочку, Гадкого утенка — положительных героев, симпатичных читателю. В каждой истории легко найти глубокий философский смысл, достаточно прочитать «Новое платье короля» — сказку, где император поручил сшить себе дорогое платье двум проходимцам. Наряд сшили из «невидимых нитей», которые не смогут заметить только глупцы. И король в голом виде щеголял по двору.

Конечно, никто вокруг и не видел тончайших нитей, однако все молчали, боясь показаться в глазах короля глупцами. Сказка стала настоящей притчей, а в обиход прочно вошло выражение «А король-то голый», которое существует до настоящих дней. Что характерно, с удачным исходом можно назвать не все сказки Андерсена, когда спасение главного героя приходило неожиданно из ниоткуда.

Взрослая публика любила писателя за реальность в своих произведениях. Он не описывал утопический мир с долго и счастливо живущими людьми. Автор легко мог отправить в камин стойкого оловянного солдатика, посылая маленького героя на верную смерть. В 35 лет из под пера мастера начинают выходить новеллы-миниатюры, выходит сборник под названием «Книга с картинками без картинок». В 44 года он публикует роман «Две баронессы», в 48 — произведение «Быть или не быть», однако они не дали ему такого успеха, как сказки

Могут быть знакомы

Личная жизнь

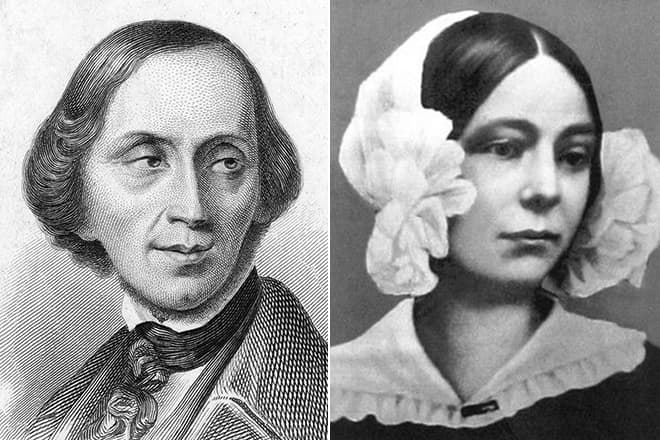

Как актер Ганс не состоялся, однако стал великим писателем, личная жизнь которого полна недосказанностей и сейчас. Ходят слухи, без интимной близости с противоположным полом он оставался продолжительное время. Некоторые убеждают в латентном гомосексуализме, о котором говорит эпистолярное наследие. Андерсен находился в тесных дружеских отношениях с Эдвардом Коллином, танцовщиком Харальдом Шраффом, наследным герцогом Веймара.

В его жизни присутствовало три женщины, однако все ограничивалось лишь непродолжительной симпатией, без женитьбы.

Первой его девушкой была сестра школьного друга Риборг Войгт, с которой он из-за скромности даже не решился заговорить. Другую звали Луиза Коллин, не желавшая принимать знаки внимания со стороны Ганса, в том числе многочисленные любовные письма. Она выбрала в итоге состоятельного юриста.

В 41 год уже многим известному писателю очень понравилась оперная певица Женни Линд, имевшая прозвище «шведский соловей» за необычайно звучный голос. Ганс не один раз караулил предмет своего обожания за кулисами сцены, дарил даме щедрые подарки, писал любовные послания в стихах. Однако приятная девушка тоже не торопилась отвечать взаимностью, относясь к писателю, как к брату. И она вышла за муж не за него, а за композитора из Англии Отто Гольдшмидта, чем вызвала у сказочника глубокую депрессию. Певица стала прототипом героини Снежная королева.

Так получилось, что Андерсену патологически не везло на личном фронте, поэтому вполне понятно, почему он после прибытия в Париж был нередким гостем кварталов красных фонарей. Только на встречах с фривольными дамами Ганс занимался тем, что разговаривал о своей несчастной жизни. Когда же приятель упрекнул его за использование подобного рода заведений не по назначению, писатель брезгливо поморщился в ответ.

Ганс Андерсен являлся настоящим почитателем таланта Чарьлза Диккенса, с которым он познакомился во время литературного собрания, организованного в своем салоне графиней Блессингтон. Позже он отметил в своем личном дневнике, что был безмерно счастлив поговорить с живущим ныне популярным английским писателем, которого любит больше всех остальных.

Сказочник вновь побывал после той встречи в Англии, посетив без приглашения Диккенса в его доме, не доставив радости семье писателя при этом. Со временем Чарльз перестал отвечать на письма Ганса, вызвав у него искреннее недоумение.

Последние годы и смерть

После падения с постели в возрасте 67 лет, писатель получил серьезные травмы, с которыми в итоге организм не смог справиться.

Затем у Андерсена был диагностирован рак печени. Умер Ганс 4 августа 1875 года и похоронен в Копенгагене на кладбище Ассистэнс.

Ссылки

- Страница в Википедии

Для нас важна актуальность и достоверность информации. Если вы обнаружили ошибку или неточность, пожалуйста, сообщите нам. Выделите ошибку и нажмите сочетание клавиш Ctrl+Enter.

|

Hans Christian Andersen |

|

|---|---|

Andersen in 1869 |

|

| Born | 2 April 1805 Odense, Funen, Denmark–Norway |

| Died | 4 August 1875 (aged 70) Østerbro, Copenhagen, Denmark |

| Resting place | Assistens Cemetery, Copenhagen (København) |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Period | Danish Golden Age |

| Genres | Children’s literature, travelogue |

| Notable works | «The Little Mermaid» «The Ugly Duckling» «The Snow Queen» «The Emperor’s New Clothes» |

| Signature | |

| Website | |

| Hans Christian Andersen Centre |

Hans Christian Andersen ( AN-dər-sən, Danish: [ˈhænˀs ˈkʰʁestjæn ˈɑnɐsn̩] (listen); 2 April 1805 – 4 August 1875) was a Danish author. Although a prolific writer of plays, travelogues, novels, and poems, he is best remembered for his literary fairy tales.

Andersen’s fairy tales, consisting of 156 stories across nine volumes[1] and translated into more than 125 languages,[2] have become culturally embedded in the West’s collective consciousness, readily accessible to children but presenting lessons of virtue and resilience in the face of adversity for mature readers as well.[3] His most famous fairy tales include «The Emperor’s New Clothes», «The Little Mermaid», «The Nightingale», «The Steadfast Tin Soldier», «The Red Shoes», «The Princess and the Pea», «The Snow Queen», «The Ugly Duckling», «The Little Match Girl», and «Thumbelina». His stories have inspired ballets, plays, and animated and live-action films.[4]

Early life[edit]

Andersen’s childhood home in Odense

Hans Christian Andersen was born in Odense, Denmark on 2 April 1805. He had a stepsister named Karen.[5] His father, also named Hans, considered himself related to nobility (his paternal grandmother had told his father that their family had belonged to a higher social class,[6] but investigations have disproved these stories).[6][7] Although it has been challenged,[6] a persistent speculation suggests that Andersen was an illegitimate son of King Christian VIII. Danish historian Jens Jørgensen supported this idea in his book H.C. Andersen, en sand myte [a true myth].[8]

Hans Christian Andersen was baptised on 15 April 1805 in Saint Hans Church (St John’s Church) in Odense, Denmark. His certificate of birth was not drafted until November 1823, according to which six Godparents were present at the baptising ceremony: Madam Sille Marie Breineberg, Maiden Friederiche Pommer, shoemaker Peder Waltersdorff, journeyman carpenter Anders Jørgensen, hospital porter Nicolas Gomard, and royal hatter Jens Henrichsen Dorch.

Andersen’s father, who had received an elementary school education, introduced his son to literature, reading to him the Arabian Nights.[9] Andersen’s mother, Anne Marie Andersdatter, was an illiterate washerwoman. Following her husband’s death in 1816, she remarried in 1818.[9] Andersen was sent to a local school for poor children where he received a basic education and had to support himself, working as an apprentice to a weaver and, later, to a tailor. At fourteen, he moved to Copenhagen to seek employment as an actor. Having an excellent soprano voice, he was accepted into the Royal Danish Theatre, but his voice soon changed. A colleague at the theatre told him that he considered Andersen a poet. Taking the suggestion seriously, Andersen began to focus on writing.

Jonas Collin, director of the Royal Danish Theatre, held great affection for Andersen and sent him to a grammar school in Slagelse, persuading King Frederick VI to pay part of the youth’s education.[10] Andersen had by then published his first story, «The Ghost at Palnatoke’s Grave» (1822). Though not a stellar pupil, he also attended school at Elsinore until 1827.[11]

He later said that his years at this school were the darkest and most bitter years of his life. At one particular school, he lived at his schoolmaster’s home. There he was abused and was told that it was done in order «to improve his character». He later said that the faculty had discouraged him from writing, which then resulted in a depression.[12]

Career[edit]

Early work[edit]

It doesn’t matter about being born in a duckyard, as long as you are hatched from a swan’s egg

«The Ugly Duckling»

A very early fairy tale by Andersen, «The Tallow Candle» (Danish: Tællelyset), was discovered in a Danish archive in October 2012. The story, written in the 1820s, is about a candle that did not feel appreciated. It was written while Andersen was still in school and dedicated to one of his benefactors. The story remained in that family’s possession until it turned up among other family papers in a local archive.[13]

In 1829, Andersen enjoyed considerable success with the short story «A Journey on Foot from Holmen’s Canal to the East Point of Amager.» Its protagonist meets characters ranging from Saint Peter to a talking cat. Andersen followed this success with a theatrical piece, Love on St.Nicholas Church Tower, and a short volume of poems. He made little progress in writing and publishing immediately following the issue of these poems but he did receive a small travel grant from the king in 1833. This enabled him to set out on the first of many journeys throughout Europe. At Jura, near Le Locle, Switzerland, Andersen wrote the story «Agnete and the Merman». The same year he spent an evening in the Italian seaside village of Sestri Levante, the place which inspired the title of «The Bay of Fables».[14] He arrived in Rome in October 1834. Andersen’s travels in Italy were reflected in his first novel, a fictionalized autobiography titled The Improvisatore (Improvisatoren), published in 1835 to instant acclaim.[15][16]

Literary fairy tales[edit]

A paper chimney sweep cut by Andersen

Fairy Tales Told for Children. First Collection. (Danish: Eventyr, fortalt for Børn. Første Samling.) is a collection of nine fairy tales by Hans Christian Andersen. The tales were published in a series of three installments by C. A. Reitzel in Copenhagen, Denmark between May 1835 and April 1837, and represent Andersen’s first venture into the fairy tale genre.

The first installment of sixty-one unbound pages was published 8 May 1835 and contained «The Tinderbox», «Little Claus and Big Claus», «The Princess and the Pea» and «Little Ida’s Flowers». The first three tales were based on folktales Andersen had heard in his childhood while the last tale was completely Andersen’s creation and created for Ida Thiele, the daughter of Andersen’s early benefactor, the folklorist Just Mathias Thiele. Reitzel paid Andersen thirty rixdollars for the manuscript, and the booklet was priced at twenty-four shillings.[17][18]

The second booklet was published on 16 December 1835 and contained «Thumbelina», «The Naughty Boy» and «The Traveling Companion». «Thumbelina» was completely Andersen’s creation although inspired by «Tom Thumb» and other stories of miniature people. «The Naughty Boy» was based on a poem by Anacreon about Cupid, and «The Traveling Companion» was a ghost story Andersen had experimented with in the year 1830.[17]

The third booklet contained «The Little Mermaid» and «The Emperor’s New Clothes», and it was published on 7 April 1837. «The Little Mermaid» was completely Andersen’s creation though influenced by De la Motte Fouqué’s «Undine» (1811) and the lore about mermaids. This tale established Andersen’s international reputation.[19] The only other tale in the third booklet was «The Emperor’s New Clothes», which was based on a medieval Spanish story with Arab and Jewish sources. On the eve of the third installment’s publication, Andersen revised the conclusion of his story, (the Emperor simply walks in procession) to its now-familiar finale of a child calling out, «The Emperor is not wearing any clothes!»[20]

Danish reviews of the first two booklets first appeared in 1836 and were not enthusiastic. The critics disliked the chatty, informal style and immorality that flew in the face of their expectations. Children’s literature was meant to educate rather than to amuse. The critics discouraged Andersen from pursuing this type of style. Andersen believed that he was working against the critics’ preconceived notions about fairy tales, and he temporarily returned to novel-writing. The critics’ reaction was so severe that Andersen waited a full year before publishing his third installment.[21]

The nine tales from the three booklets were combined and then published in one volume and sold at seventy-two shillings. A title page, a table of contents, and a preface by Andersen were published in this volume.[22]

In 1868 Horace Scudder, the editor of Riverside Magazine For Young People, offered Andersen $500 for a dozen new stories. Sixteen of Andersen’s stories were published in the American magazine, and ten of them appeared there before they were printed in Denmark.[23]

Travelogues[edit]

In 1851 he published In Sweden, a volume of travel sketches. The publication received wide acclaim. A keen traveler, Andersen published several other long travelogues: Shadow Pictures of a Journey to the Harz, Swiss Saxony, etc. etc. in the Summer of 1831, A Poet’s Bazaar, In Spain and A Visit to Portugal in 1866. (The last describes his visit with his Portuguese friends Jorge and José O’Neill, who were his friends in the mid-1820s while he was living in Copenhagen.) In his travelogues, Andersen took heed of some of the contemporary conventions related to travel writing but he always developed the style to suit his own purpose. Each of his travelogues combines documentary and descriptive accounts of his experiences, adding additional philosophical passages on topics such as what it is to be an author, general immortality, and the nature of fiction in literary travel reports. Some of the travelogues, such as In Sweden, even contain fairy-tales.

In the 1840s, Andersen’s attention again returned to the theatre stage, but with little success. He had better luck with the publication of the Picture-Book without Pictures (1840). A second series of fairy tales was started in 1838 and a third series in 1845. Andersen was now celebrated throughout Europe although his native Denmark still showed some resistance to his pretensions.

Between 1845 and 1864, H. C. Andersen lived at Nyhavn 67, Copenhagen, where a memorial plaque is placed on a building.[24]

The works of Hans Andersen became known throughout the world. Rising from a poor social class, the works made him into an acclaimed author. Royal families of the world were patrons of the writings including the monarchy of Denmark, the House of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg. An unexpected invitation from King Christian IX to the royal palace would not only entrench the Andersen folklore in Danish royalty but would inexplicably be transmitted to the Romanov dynasty in Russia.[25]

Personal life[edit]

Søren Kierkegaard[edit]

In ‘Andersen as a Novelist’, Søren Kierkegaard remarks that Andersen is characterized as, “…a possibility of a personality, wrapped up in such a web of arbitrary moods and moving through an elegiac duo-decimal scale [i.e., a chromatic scale including sharps and flats, associated more with lament or elegy than an ordinary scale] of almost echoless, dying tones just as easily roused as subdued, who, in order to become a personality, needs a strong life-development.”

Meetings with Charles Dickens[edit]

In June 1847, Andersen paid his first visit to England, enjoying a triumphal social success during this summer. The Countess of Blessington invited him to her parties where intellectual people would meet, and it was at one of such parties where he met Charles Dickens for the first time. They shook hands and walked to the veranda, which Andersen wrote about in his diary: «We were on the veranda, and I was so happy to see and speak to England’s now-living writer whom I do love the most.»[26]

The two authors respected each other’s work and as writers, they shared something important in common: depictions of the poor and the underclass who often had difficult lives affected both by the Industrial Revolution and by abject poverty. In the Victorian era there was a growing sympathy for children and an idealization of the innocence of childhood.

Ten years later, Andersen visited England again, primarily to meet Dickens. He extended the planned brief visit to Dickens’ home at Gads Hill Place into a five-week stay, much to the distress of Dickens’s family. After Andersen was told to leave, Dickens gradually stopped all correspondence between them, this to the great disappointment and confusion of Andersen, who had quite enjoyed the visit and could never understand why his letters went unanswered.[26]

Love life[edit]

In Andersen’s early life, his private journal records his refusal to have sexual relations.[27][28]

Andersen experienced same-sex attraction;[29] he wrote to Edvard Collin:[30] «I languish for you as for a pretty Calabrian wench … my sentiments for you are those of a woman. The femininity of my nature and our friendship must remain a mystery.»[31] Collin, who preferred women, wrote in his own memoir: «I found myself unable to respond to this love, and this caused the author much suffering.» Andersen’s infatuation for Carl Alexander, the young hereditary duke of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach,[32] did result in a relationship:

The Hereditary Grand Duke walked arm in arm with me across the courtyard of the castle to my room, kissed me lovingly, asked me always to love him though he was just an ordinary person, asked me to stay with him this winter … Fell asleep with the melancholy, happy feeling that I was the guest of this strange prince at his castle and loved by him … It is like a fairy tale.[29]

There is a sharp division in opinion over Andersen’s physical fulfillment in the sexual sphere. The Hans Christian Andersen Center of University of Southern Denmark and biographer Jackie Wullschlager hold contradictory views.[33]

Wullschlager’s biography maintains he was possibly lovers with Danish dancer Harald Scharff[34] and Andersen’s «The Snowman» was inspired by their relationship.[35] Scharff first met Andersen when the latter was in his fifties. Andersen was clearly infatuated, and Wullschlager sees his journals as implying that their relationship was sexual.[36] Scharff had various dinners alone with Andersen and his gift of a silver toothbrush to Andersen on his fifty-seventh birthday marked their relationship as incredibly close.[37] Wullschlager asserts that in the winter of 1861–62 the two men entered a full-blown love affair that brought «him joy, some kind of sexual fulfillment, and a temporary end to loneliness.»[38] He was not discreet in his conduct with Scharff, and displayed his feelings much too openly. Onlookers regarded the relationship as improper and ridiculous. In his diary for March 1862, Andersen referred to this time in his life as his «erotic period».[39] On 13 November 1863, Andersen wrote, «Scharff has not visited me in eight days; with him it is over.»[40] Andersen took the end calmly and the two thereafter met in overlapping social circles without bitterness, though Andersen attempted to rekindle their relationship a number of times without success.[41][note 1][note 2][42]

In contrast to Wullschlager’s assertions are Klara Bom and Anya Aarenstrup from the H. C. Andersen Centre of University of Southern Denmark. They state «it is correct to point to the very ambivalent (and also very traumatic) elements in Andersen’s emotional life concerning the sexual sphere, but it is decidedly just as wrong to describe him as homosexual and maintain that he had physical relationships with men. He did not. Indeed, that would have been entirely contrary to his moral and religious ideas, aspects that are quite outside the field of vision of Wullschlager and her like.»[43]

Andersen also fell in love with unattainable women, and many of his stories are interpreted as references.[44] At one point, he wrote in his diary: «Almighty God, thee only have I; thou steerest my fate, I must give myself up to thee! Give me a livelihood! Give me a bride! My blood wants love, as my heart does!»[45] A girl named Riborg Voigt was the unrequited love of Andersen’s youth. A small pouch containing a long letter from Voigt was found on Andersen’s chest when he died several decades after he first fell in love with her, and after, he presumably fell in love with others. Other disappointments in love included Sophie Ørsted, the daughter of the physicist Hans Christian Ørsted, and Louise Collin, the youngest daughter of his benefactor Jonas Collin. One of his stories, «The Nightingale», was written as an expression of his passion for Jenny Lind and became the inspiration for her nickname, the «Swedish Nightingale».[46] Andersen was often shy around women and had extreme difficulty in proposing to Lind. When Lind was boarding a train to go to an opera concert, Andersen gave Lind a letter of proposal. Her feelings towards him were not the same; she saw him as a brother, writing to him in 1844: «farewell … God bless and protect my brother is the sincere wish of his affectionate sister, Jenny».[47] It is suggested that Andersen expressed his disappointment by portraying Lind as the eponymous anti-heroine of his Snow Queen.[48]

Death[edit]

Andersen at Rolighed: Israel Melchior (c. 1867)

In early 1872, at age 67, Andersen fell out of his bed and was severely hurt; he never fully recovered from the resultant injuries. Soon afterward, he started to show signs of liver cancer.[49]

He died on 4 August 1875, in a house called Rolighed (literally: calmness), near Copenhagen, the home of his close friends, the banker Moritz G. Melchior and his wife.[49] Shortly before his death, Andersen had consulted a composer about the music for his funeral, saying: «Most of the people who will walk after me will be children, so make the beat keep time with little steps.»[49]

His body was interred in the Assistens Kirkegård in the Nørrebro area of Copenhagen, in the family plot of the Collins. In 1914, however, the stone was moved to another cemetery (today known as «Frederiksbergs ældre kirkegaard»), where younger Collin family members were buried. For a period, his, Edvard Collin’s and Henriette Collin’s graves were unmarked. A second stone has been erected, marking H.C. Andersen’s grave, now without any mention of the Collin couple, but all three still share the same plot.[50]

At the time of his death, Andersen was internationally revered, and the Danish Government paid him an annual stipend as a «national treasure».[51]

Legacy and cultural influence[edit]

Archives, collections and museums[edit]

- The Hans Christian Andersen Museum or H.C. Andersens Odense, is a set of museums/buildings dedicated to the famous author Hans Christian Andersen in Odense, Denmark, some of which, at various times in history, have functioned as the main Odense-based museum on the author.

- The Hans Christian Andersen Museum in Solvang, California, a city founded by Danes, is devoted to presenting the author’s life and works. Displays include models of Andersen’s childhood home and of «The Princess and the Pea». The museum also contains hundreds of volumes of Andersen’s works, including many illustrated first editions and correspondence with Danish composer Asger Hamerik.[52]

- The Library of Congress Rare Book and Special Collections Division was bequeathed an extensive collection of Andersen materials by the Danish-American actor Jean Hersholt.[53][54]

Art, entertainment and media[edit]

Denmark, 1935

Films and TV series[edit]

- La petite marchande d’allumettes (1928; in English: The Little Match Girl), film by Jean Renoir, based on «The Little Match Girl»

- The Ugly Duckling (1931) and its’ 1939 remake of the same name, two animated Silly Symphonies cartoon shorts produced by Walt Disney Productions, based on The Ugly Duckling.

- Andersen was played by Joachim Gottschalk in the German film The Swedish Nightingale (1941), which portrays his relationship with the singer Jenny Lind.

- The Red Shoes (1948) British drama film written, directed, and produced by the team of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger based on «The Red Shoes».

- Hans Christian Andersen (1952), an American musical film starring Danny Kaye that, though inspired by Andersen’s life and literary legacy, was meant to be neither historically nor biographically accurate; it begins by saying, «This is not the story of his life, but a fairy tale about this great spinner of fairy tales»

- The Snow Queen (1957), a Soviet Union animated film based on The Snow Queen by Lev Atmanov of Soyuzmultfilm, authentic depiction of the fairy tale that garnered critical acclaim[55][56]

- Carevo novo ruho (The emperor’s new clothes), a 1961 Croatian film, directed by Ante Babaja.

- The Wild Swans (1962), Sovietic animated adapatation of The Wild Swans, by Soyuzmultfilm

- The Rankin/Bass Productions-produced fantasy film, The Daydreamer (1966), depicts the young Hans Christian Andersen imaginatively conceiving the stories he would later write.

- The Little Mermaid (1968) 30-minute faithful Sovietic animated adaptation of The Little Mermaid by Soyuzmultfilm

- The World of Hans Christian Andersen (1968), a Japanese anime fantasy film from Toei Doga, based on the works of Danish author Hans Christian Andersen

- Andersen Monogatari (1971), a Japanese animated anthology series prodused by Mushi Production.

- The Pine Tree (c1974) 23 mins, colour. Commentary by Liz Lochhead[57]

- Hans Christian Andersen’s The Little Mermaid (1975) Japanese anime film from Toei quite faithfully based on The Little Mermaid

- The Little Mermaid (1976) Czech fantasy film based on The Little Mermaid

- The Wild Swans (1977), Japanese animated adaptation of The Wild Swans by Toei

- Thumbelina (1978), Japanese anime film from Toei based on Thumbelina

- The Little Mermaid (1989), an animated film based on The Little Mermaid created and produced at Walt Disney Feature Animation in Burbank, CA

- Thumbelina (1994), an animated film based on the «Thumbelina» created and produced at Sullivan Bluth Studios Dublin, Ireland

- One segment in Fantasia 2000 is based on «The Steadfast Tin Soldier», against Shostakovich’s Piano Concerto No. 2, Movement #1: «Allegro».

- Hans Christian Andersen: My Life as a Fairytale (2003), a British made-for-television film directed by Philip Saville, a fictionalized account of Andersen’s early successes, with his fairy stories intertwined with events in his own life.[58][59]

- The Fairytaler (2003), Danish-British animated series based on several Andersen fairy tales

- The Little Matchgirl (2006), an animated short film by the Walt Disney Animation Studios directed by Roger Allers and produced by Don Hahn

- The Snow Queen (2012), a Russian 3D animated film based on The Snow Queen, the first film of The Snow Queen series produced by Wizart Animation[60]

- Frozen (2013), a 3D computer-animated musical film produced by Walt Disney Animation Studios that is loosely inspired by The Snow Queen.

- Ginger’s Tale (2020), a Russian 2D traditional animated film loosely based on The Tinderbox, produced at Vverh Animation Studio in Moscow[61]

Video games[edit]

- Andersen appears as a Caster-class Servant in Fate/EXTRA CCC (2013), and Fate/Grand Order (2015).

Literature[edit]

Andersen’s stories laid the groundwork for other children’s classics, such as The Wind in the Willows (1908) by Kenneth Grahame and Winnie-the-Pooh (1926) by A. A. Milne. The technique of making inanimate objects, such as toys, come to life («Little Ida’s Flowers») would later also be used by Lewis Carroll and Beatrix Potter.[62][63]

Monuments and sculptures[edit]

One of Copenhagen’s widest and busiest boulevards, skirting Copenhagen City Hall Square at the corner of which Andersen’s larger-than-life bronze statue sits, is named «H. C. Andersens Boulevard.»[64]

- Hans Christian Andersen (1880), even before his death, steps had already been taken to erect, in Andersen’s honour, a large statue by sculptor August Saabye, which can now be seen in the Rosenborg Castle Gardens in Copenhagen.[4]

- Hans Christian Andersen (1896) by the Danish sculptor Johannes Gelert, at Lincoln Park in Chicago, on Stockton Drive near Webster Avenue[65]

- Hans Christian Andersen (1956), a statue by sculptor Georg J. Lober and designer Otto Frederick Langman, at Central Park Lake in New York City, opposite East 74th Street (40.7744306°N, 73.9677972°W)

- Hans Christian Andersen (2005) Plaza de la Marina in Malaga, Spain

-

Statue in Central Park, New York commemorating Andersen and The Ugly Duckling

-

Statue in Odense being led out to the harbour during a public exhibition

-

-

Portrait bust in Sydney unveiled by the Crown Prince and Princess of Denmark in 2005

Music[edit]

- Hans Christian Andersen (album), a 1994 album by Franciscus Henri

- The Song is a Fairytale (Sangen er et Eventyr), a song cycle based on fairy tales by Hans Christian Andersen, composed by Frederik Magle

- Atonal Fairy Tale[66] music composed by Gregory Reid Davis Jr. and the fairy tale, The Elfin Mound, by Hans Christian Andersen is read by Smart Dad Living

Stage productions[edit]

For opera and ballet see also List of The Little Mermaid Adaptations

- Little Hans Andersen (1903), a children’s pantomime at the Adelphi Theatre

- Sam the Lovesick Snowman at the Center for Puppetry Arts: a contemporary puppet show by Jon Ludwig inspired by The Snow Man.[67]

- Striking Twelve, a modern musical take on «The Little Match Girl», created and performed by GrooveLily.[68]

- The musical comedy Once Upon a Mattress is based on Andersen’ work ‘The Princess and the Pea’.[69]

Awards[edit]

- Hans Christian Andersen Awards, prizes awarded annually by the International Board on Books for Young People to an author and illustrator whose complete works have made lasting contributions to children’s literature.[70]

- Hans Christian Andersen Literature Award, a Danish literary award established in 2010

- Andersen’s fable «The Emperor’s New Clothes» was inducted in 2000 into the Prometheus Hall of Fame for Best Classic Fiction [71]

Events and holidays[edit]

- Andersen’s birthday, 2 April, is celebrated as International Children’s Book Day.[72]

- The year 2005, designated «Andersen Year» in Denmark,[73] was the bicentenary of Andersen’s birth, and his life and work was celebrated around the world.

- In Denmark, a well-attended «once in a lifetime» show was staged in Copenhagen’s Parken Stadium during «Andersen Year» to celebrate the writer and his stories.[73]

- The annual H.C. Andersen Marathon, established in 2000, is held in Odense, Denmark

Places named after Andersen[edit]

- H. C. Andersens Boulevard, a major road in Copenhagen formerly known as Vestre Boulevard (Western Boulevard), received its current name in 1955 to mark the 150-year anniversary of the writer’s birth

- Hans Christian Andersen Airport, small airport servicing the Danish city of Odense

- Instituto Hans Christian Andersen, Chilean high school located in San Fernando, Colchagua Province, Chile

- Hans Christian Andersen Park, Solvang, California

- CEIP Hans Christian Andersen Archived 1 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Primary Education School in Malaga, Spain.

Theme parks[edit]

- In Japan, the city of Funabashi has a children’s theme park named after Andersen.[74] Funabashi is a sister city to Odense, the city of Andersen’s birth.

- In China, a US$32 million theme park based on Andersen’s tales and life was expected to open in Shanghai’s Yangpu District in 2017.[75] Construction on the project began in 2005.[76]

Works[edit]

Andersen’s fairy tales include:

- «The Angel» (1843)

- «The Bell» (1845)

- «Blockhead Hans» (1855)

- «The Elf Mound» (1845)

- «The Emperor’s New Clothes» (1837)

- «The Fir-Tree» (1844)

- «The Flying Trunk» (1839)

- «The Galoshes of Fortune» (1838)

- «The Garden of Paradise» (1839)

- «The Goblin and the Grocer» (1852)

- «Golden Treasure» (1865)

- «The Happy Family» (1847)

- «The Ice-Maiden» (1861)

- «It’s Quite True» (1852)

- «The Jumpers» (1845)

- «Little Claus and Big Claus» (1835)

- «Little Ida’s Flowers» (1835)

- «The Little Match Girl» (1845)

- «The Little Mermaid» (1837)

- «Little Tuk» (1847)

- «The Most Incredible Thing» (1870)

- «The Naughty Boy» (1835)

- «The Nightingale» (1843)

- «The Old House» (1847)

- «Ole Lukoie» (1841)

- «The Philosopher’s Stone» (1858)

- «The Princess and the Pea» (1835)

- «The Red Shoes» (1845)

- «The Rose Elf» (1839)

- «The Shadow» (1847)

- «The Shepherdess and the Chimney Sweep» (1845)

- «The Snow Queen» (1844)

- «The Snowman» (1861)

- «The Steadfast Tin Soldier» (1838)

- «The Storks» (1839)

- «The Story of a Mother» (1847)

- «The Sweethearts; or, The Top and the Ball» (1843)

- «The Swineherd» (1841)

- «The Tallow Candle» (1820s)

- «The Teapot» (1863)

- «Thumbelina» (1835)

- «The Tinderbox» (1835)

- «The Traveling Companion» (1835)

- «The Ugly Duckling» (1843)

- «What the Old Man Does is Always Right» (1861)

- «The Wild Swans» (1838)

The Hans Christian Andersen Museum in Odense has a large digital collection of Hans Christian Andersen papercuts,[77] drawings,[78] and portraits.[79]

See also[edit]

- Kjøbenhavnsposten, a Danish newspaper in which Andersen published one of his first poems

- Pleated Christmas hearts, invented by Andersen

- Vilhelm Pedersen, the first illustrator of Andersen’s fairy tales

- Collastoma anderseni sp. nov. (Rhabdocoela: Umagillidae: Collastominae), an endosymbiont from the intestine of the sipunculan Themiste lageniformis, for a species named after Andersen.

- List of The Little Mermaid Adaptations

Explanatory notes[edit]

- ^ While on holiday, for example, Andersen and Scharff were forced to spend the night in Helsingør. Andersen reserved a double room for them both but Scharff insisted upon having his own.

- ^ Andersen continued to follow Scharff’s career with interest but in 1871 an injury during rehearsal forced Scharff permanently from the ballet stage. Scharff tried acting without success, married a ballerina in 1874, and died in the St. Hans insane asylum in 1912.

Citations[edit]

- ^ «Hans Christian Andersen : Fairy tales». andersen.sdu.dk.

- ^ Wenande, Christian (13 December 2012). «Unknown Hans Christian Andersen fairy tale discovered». The Copenhagen Post. Archived from the original on 14 December 2012. Retrieved 15 December 2012.

- ^ Wullschläger 2002

- ^ a b Bredsdorff 1975

- ^ «Life». SDU Hans Christian Andersen Centret. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ a b c Rossel 1996, p. 6

- ^ Askgaard, Ejnar Stig. «The Lineage of Hans Christian Andersen». Odense City Museums. Archived from the original on 4 May 2012.

- ^ H.C. Andersen, en sand myte, Hovedland (1 January 1987)

- ^ a b Rossel 1996, p. 7

- ^ Hans Christian Andersen — Childhood and Education. Danishnet.

- ^ «H.C. Andersens skolegang i Helsingør Latinskole». Hcandersen-homepage.dk. Retrieved 2 April 2010.

- ^ Wullschläger 2002, p. 56.

- ^ «Local historian finds Hans Christian Andersen’s first fairy tale». Politiken.dk. 12 December 2012. Retrieved 2 June 2013.

- ^ «Andersen Festival, Sestri Levante». Andersen Festival. Retrieved 2 June 2013.

- ^ Christopher John Murray (13 May 2013). Encyclopedia of the Romantic Era, 1760-1850. Routledge. p. 20. ISBN 978-1-135-45579-8.

- ^ Jan Sjåvik (19 April 2006). Historical Dictionary of Scandinavian Literature and Theater. Scarecrow Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-8108-6501-3.

- ^ a b Wullschläger 2002, p. 150

- ^ Frank 2005, p. 13

- ^ Wullschläger 2002, p. 174

- ^ Wullschläger 2002, p. 176

- ^ Wullschläger 2002, pp. 150, 165

- ^ Wullschläger 2002, p. 178

- ^ Rossel, Sven Hakon, Hans Christian Anderson, Writer and Citizen of the World, Rodopi, 1996

- ^ «Official Tourism Site of Copenhagen». Visitcopenhagen.com. Archived from the original on 25 July 2008. Retrieved 2 April 2010.

- ^ Кудряшов, Константин (25 November 2017). «Дагмар — принцесса на русской горошине. Как Андерсен вошёл у нас в моду». aif.ru. Retrieved 20 December 2020.

- ^ a b «H.C. Andersen og Charles Dickens 1857». Hcandersen-homepage.dk. 31 March 2012. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- ^ Lepage, Robert (18 January 2006). «Bedtime stories». The Guardian. Retrieved 19 July 2006.

- ^ Recorded using «special Greek symbols».Garfield, Patricia (21 June 2004). «The Dreams of Hans Christian Andersen» (PDF). p. 29. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 March 2012. Retrieved 19 August 2020.

- ^ a b Booth, Michael (2005). Just As Well I’m Leaving: To the Orient With Hans Christian Andersen. London: Vintage. pp. Pos. 2226. ISBN 978-1-44648-579-8.

- ^ Hans Christian Andersen’s correspondence, ed. Frederick Crawford6, London. 1891.

- ^ Seriality and Texts for Young People: The Compulsion to Repeat edited by M. Reimer, N. Ali, D. England, M. Dennis Unrau, Melanie Dennis Unrau

- ^ Pritchard, Claudia (27 March 2005). «His dark materials». The Independent. Archived from the original on 14 March 2007. Retrieved 23 July 2006.

- ^ «Hans Christian Andersen | Research and Knowledge».

- ^ de Mylius, Johan. «The Life of Hans Christian Andersen. Day By Day». Hans Christian Andersen Center. Retrieved 22 July 2006.

- ^ Wullschläger 2002, pp. 373, 379

- ^ «Hans Christian Andersen: The Life of a Storyteller». Gay & Lesbian Review Worldwide. 1 November 2001. Retrieved 10 June 2009.

- ^ «Andersen’s Fairy Tales». The Advocate. 26 April 2005. Retrieved 10 June 2009.

- ^ Wullschläger 2002, pp. 387–389

- ^ Andersen 2005b, pp. 475–476Wullschlager

- ^ Andersen 2005b, p. 477Wullschlager

- ^ Wullschläger 2002, pp. 392–393

- ^ Andersen 2005b, pp. 477–479Wullschlager

- ^ Hans Christian Andersen Center, Hans Christian Andersen – FAQ

- ^ Hastings, Waller (4 April 2003). «Hans Christian Andersen». Northern State University. Archived from the original on 23 November 2007. Retrieved 15 December 2012.

- ^ «The Tales of Hans Christian Andersen». Scandinavian.wisc.edu. Archived from the original on 12 March 2012. Retrieved 2 April 2010.

- ^ «H.C. Andersen og Jenny Lind». 2 July 2014.

- ^ «H.C. Andersen homepage (Danish)». Hcandersen-homepage.dk. Retrieved 2 April 2010.

- ^ Charlie Connelly, Great European Lives #219 Jenny Lind, The New European 18 October – 5 November 2021. page 47.

- ^ a b c Bryant, Mark: Private Lives, 2001, p. 12.

- ^ in Danish, http://www.hcandersen-homepage.dk/?page_id=6226

- ^ «Hans Christian Andersen». Biography.

- ^ «The Hans Christian Andersen Museum». SolvangCA.com. Archived from the original on 29 November 2010. Retrieved 16 September 2010.

- ^ «Jean Hersholt Collections». Loc.gov. 15 April 2009. Retrieved 2 April 2010.

- ^ «Billedbog til Jonas Drewsen». (15 April 2009) Retrieved 2 November 2009.

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (14 April 1960). «Screen: Disney ala Soviet: The Snow Queen’ at Neighborhood Houses (Published 1960)». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 22 November 2020.

- ^ Weiler, A. H. (7 June 1959). «By Way of Report; Soviet ‘Snow Queen,’ Other Animated Features Due — ‘Snowman’s’ Story (Published 1959)». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 22 November 2020.

- ^ «The Pine Tree». National Library of Scotland. Moving Image Archive.

- ^ Moore, Frazier (6 September 2002). «Upcoming TV schedules focus on events of 9/11». Chillicothe Gazette (Ohio). p. 13.

- ^ Greenhill, Pauline (2015). ««The Snow Queen»: Queer Coding in Male Directors’ Films». Marvels & Tales. Vol. 29, no. 1. ProQuest 1663315597.

- ^ Milligan, Mercedes (2 June 2012). «Russian Animation on Ice». Animation Magazine. Retrieved 22 November 2020.

- ^ «Annecy 2020, Ginger’s Tale, recensione, un principe da salvare — Cineblog». Cineblog (in Italian). 22 June 2020. Retrieved 22 November 2020.

- ^ Sherry, Clifford J. (2009). Animal Rights: A Reference Handbook. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-59884-191-6.

- ^ «Ledger Legends: J. M. Barrie, Beatrix Potter and Lewis Carroll | Barclays». home.barclays. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ Google Maps, by City Hall Square (Rådhuspladsen), continues eastbound as the bridge «Langebro»

- ^ «The Hans Christian Andersen Statue». Skandinaven. 17 September 1896. Archived from the original on 4 September 2014. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- ^ Atonal Fairy Tale; From the album It Is What It Isn’t, Too!, (2020) by Smart Dad Living]

- ^ «Jon Ludwig’s Sam the Lovesick Snowman«. Puppet.org. Archived from the original on 3 February 2009. Retrieved 2 April 2010.

- ^ Blankenship, Mark (13 November 2006). «Striking 12».

- ^ Ross Griffel, Margaret (2013). Operas in English: A Dictionary. Scarecrow Press. p. 393. ISBN 978-0-8108-8325-3.

- ^ «Hans Christian Andersen Awards». International Board on Books for Young People. Archived from the original on 4 July 2017. Retrieved 19 March 2014.

- ^ «Libertarian Futurist Society». www.lfs.org.

- ^ «International Children’s Book Day». International Board on Books for Young People. Retrieved 17 December 2012.

Since 1967, on or around Hans Christian Andersen’s birthday, 2 April, International Children’s Book Day (ICBD) is celebrated to inspire a love of reading and to call attention to children’s books.

- ^ a b Brabant, Malcolm (1 April 2005). «Enduring Legacy of Author Andersen». BBC News. BBC. Retrieved 17 December 2012.

- ^ «H.C. Andersen Park — Funabashi». City of Funabashi Tourism. Retrieved 12 April 2017.

- ^ Fan, Yanping (11 November 2016). «安徒生童话乐园明年开园设七大主题区» [Andersen fairy tales opening next year to set up seven theme areas]. Sina Corp. Retrieved 12 April 2017.

- ^ Zhu, Shenshen (16 July 2013). «Fairy-tale park takes shape in city». Shanghai Daily. Retrieved 12 April 2017.

- ^ papercuts[permanent dead link]

- ^ drawings

- ^ portraits

General bibliography[edit]

- Andersen, Hans Christian (2005a) [2004]. Jackie Wullschläger (ed.). Fairy Tales. Tiina Nunnally. New York: Viking. ISBN 0-670-03377-4.

- Andersen, Jens (2005b) [2003]. Hans Christian Andersen: A New Life. Tiina Nunnally. New York, Woodstock, and London: Overlook Duckworth. ISBN 978-1-58567-737-5.

- Binding, Paul (2014). Hans Christian Andersen : European witness. Yale University Press.

- Bredsdorff, Elias (1975). Hans Christian Andersen: the story of his life and work 1805–75. Phaidon. ISBN 0-7148-1636-1. Retrieved 4 April 2012.

- Stig Dalager, Journey in Blue, historical, biographical novel about H.C.Andersen, Peter Owen, London 2006, McArthur & Co., Toronto 2006.

- Gosse, Edmund William (1911). «Andersen, Hans Christian» . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 1 (11th ed.). pp. 958–959.

- Roes, André, Kierkegaard en Andersen, Uitgeverij Aspekt, Soesterberg (2017) ISBN 978-94-6338-215-1

- Ruth Manning-Sanders, Swan of Denmark: The Story of Hans Christian Andersen, Heinemann, 1949

- Rossel, Sven Hakon (1996). Hans Christian Andersen: Danish Writer and Citizen of the World. Rodopi. ISBN 90-5183-944-8.

- Stirling, Monica (1965). The Wild Swan: The Life and Times of Hans Christian Andersen. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc.

- Terry, Walter (1979). The King’s Ballet Master. New York: Dodd, Mead & Company. ISBN 0-396-07722-6.

- Wullschläger, Jackie (2002) [2000]. Hans Christian Andersen: The Life of a Storyteller. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-91747-9.

- Zipes, Jack (2005). Hans Christian Andersen: The Misunderstood Storyteller. New York and London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-97433-X.

External links[edit]

- Works by or about Hans Christian Andersen at Internet Archive

- Works by Hans Christian Andersen at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- The Story of My Life (1871) by Hans Christian Andersen — English

- Electronic collection of H. C. Andersen’s Fairy Tales

- The Orders and Medals Society of Denmark has descriptions of Hans Christian Andersen’s Medals and Decorations.

- Hans Christian Andersen at IMDb

|

Hans Christian Andersen |

|

|---|---|

Andersen in 1869 |

|

| Born | 2 April 1805 Odense, Funen, Denmark–Norway |

| Died | 4 August 1875 (aged 70) Østerbro, Copenhagen, Denmark |

| Resting place | Assistens Cemetery, Copenhagen (København) |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Period | Danish Golden Age |

| Genres | Children’s literature, travelogue |

| Notable works | «The Little Mermaid» «The Ugly Duckling» «The Snow Queen» «The Emperor’s New Clothes» |

| Signature | |

| Website | |

| Hans Christian Andersen Centre |

Hans Christian Andersen ( AN-dər-sən, Danish: [ˈhænˀs ˈkʰʁestjæn ˈɑnɐsn̩] (listen); 2 April 1805 – 4 August 1875) was a Danish author. Although a prolific writer of plays, travelogues, novels, and poems, he is best remembered for his literary fairy tales.

Andersen’s fairy tales, consisting of 156 stories across nine volumes[1] and translated into more than 125 languages,[2] have become culturally embedded in the West’s collective consciousness, readily accessible to children but presenting lessons of virtue and resilience in the face of adversity for mature readers as well.[3] His most famous fairy tales include «The Emperor’s New Clothes», «The Little Mermaid», «The Nightingale», «The Steadfast Tin Soldier», «The Red Shoes», «The Princess and the Pea», «The Snow Queen», «The Ugly Duckling», «The Little Match Girl», and «Thumbelina». His stories have inspired ballets, plays, and animated and live-action films.[4]

Early life[edit]

Andersen’s childhood home in Odense

Hans Christian Andersen was born in Odense, Denmark on 2 April 1805. He had a stepsister named Karen.[5] His father, also named Hans, considered himself related to nobility (his paternal grandmother had told his father that their family had belonged to a higher social class,[6] but investigations have disproved these stories).[6][7] Although it has been challenged,[6] a persistent speculation suggests that Andersen was an illegitimate son of King Christian VIII. Danish historian Jens Jørgensen supported this idea in his book H.C. Andersen, en sand myte [a true myth].[8]

Hans Christian Andersen was baptised on 15 April 1805 in Saint Hans Church (St John’s Church) in Odense, Denmark. His certificate of birth was not drafted until November 1823, according to which six Godparents were present at the baptising ceremony: Madam Sille Marie Breineberg, Maiden Friederiche Pommer, shoemaker Peder Waltersdorff, journeyman carpenter Anders Jørgensen, hospital porter Nicolas Gomard, and royal hatter Jens Henrichsen Dorch.

Andersen’s father, who had received an elementary school education, introduced his son to literature, reading to him the Arabian Nights.[9] Andersen’s mother, Anne Marie Andersdatter, was an illiterate washerwoman. Following her husband’s death in 1816, she remarried in 1818.[9] Andersen was sent to a local school for poor children where he received a basic education and had to support himself, working as an apprentice to a weaver and, later, to a tailor. At fourteen, he moved to Copenhagen to seek employment as an actor. Having an excellent soprano voice, he was accepted into the Royal Danish Theatre, but his voice soon changed. A colleague at the theatre told him that he considered Andersen a poet. Taking the suggestion seriously, Andersen began to focus on writing.

Jonas Collin, director of the Royal Danish Theatre, held great affection for Andersen and sent him to a grammar school in Slagelse, persuading King Frederick VI to pay part of the youth’s education.[10] Andersen had by then published his first story, «The Ghost at Palnatoke’s Grave» (1822). Though not a stellar pupil, he also attended school at Elsinore until 1827.[11]

He later said that his years at this school were the darkest and most bitter years of his life. At one particular school, he lived at his schoolmaster’s home. There he was abused and was told that it was done in order «to improve his character». He later said that the faculty had discouraged him from writing, which then resulted in a depression.[12]

Career[edit]

Early work[edit]

It doesn’t matter about being born in a duckyard, as long as you are hatched from a swan’s egg

«The Ugly Duckling»

A very early fairy tale by Andersen, «The Tallow Candle» (Danish: Tællelyset), was discovered in a Danish archive in October 2012. The story, written in the 1820s, is about a candle that did not feel appreciated. It was written while Andersen was still in school and dedicated to one of his benefactors. The story remained in that family’s possession until it turned up among other family papers in a local archive.[13]

In 1829, Andersen enjoyed considerable success with the short story «A Journey on Foot from Holmen’s Canal to the East Point of Amager.» Its protagonist meets characters ranging from Saint Peter to a talking cat. Andersen followed this success with a theatrical piece, Love on St.Nicholas Church Tower, and a short volume of poems. He made little progress in writing and publishing immediately following the issue of these poems but he did receive a small travel grant from the king in 1833. This enabled him to set out on the first of many journeys throughout Europe. At Jura, near Le Locle, Switzerland, Andersen wrote the story «Agnete and the Merman». The same year he spent an evening in the Italian seaside village of Sestri Levante, the place which inspired the title of «The Bay of Fables».[14] He arrived in Rome in October 1834. Andersen’s travels in Italy were reflected in his first novel, a fictionalized autobiography titled The Improvisatore (Improvisatoren), published in 1835 to instant acclaim.[15][16]

Literary fairy tales[edit]

A paper chimney sweep cut by Andersen

Fairy Tales Told for Children. First Collection. (Danish: Eventyr, fortalt for Børn. Første Samling.) is a collection of nine fairy tales by Hans Christian Andersen. The tales were published in a series of three installments by C. A. Reitzel in Copenhagen, Denmark between May 1835 and April 1837, and represent Andersen’s first venture into the fairy tale genre.

The first installment of sixty-one unbound pages was published 8 May 1835 and contained «The Tinderbox», «Little Claus and Big Claus», «The Princess and the Pea» and «Little Ida’s Flowers». The first three tales were based on folktales Andersen had heard in his childhood while the last tale was completely Andersen’s creation and created for Ida Thiele, the daughter of Andersen’s early benefactor, the folklorist Just Mathias Thiele. Reitzel paid Andersen thirty rixdollars for the manuscript, and the booklet was priced at twenty-four shillings.[17][18]

The second booklet was published on 16 December 1835 and contained «Thumbelina», «The Naughty Boy» and «The Traveling Companion». «Thumbelina» was completely Andersen’s creation although inspired by «Tom Thumb» and other stories of miniature people. «The Naughty Boy» was based on a poem by Anacreon about Cupid, and «The Traveling Companion» was a ghost story Andersen had experimented with in the year 1830.[17]

The third booklet contained «The Little Mermaid» and «The Emperor’s New Clothes», and it was published on 7 April 1837. «The Little Mermaid» was completely Andersen’s creation though influenced by De la Motte Fouqué’s «Undine» (1811) and the lore about mermaids. This tale established Andersen’s international reputation.[19] The only other tale in the third booklet was «The Emperor’s New Clothes», which was based on a medieval Spanish story with Arab and Jewish sources. On the eve of the third installment’s publication, Andersen revised the conclusion of his story, (the Emperor simply walks in procession) to its now-familiar finale of a child calling out, «The Emperor is not wearing any clothes!»[20]

Danish reviews of the first two booklets first appeared in 1836 and were not enthusiastic. The critics disliked the chatty, informal style and immorality that flew in the face of their expectations. Children’s literature was meant to educate rather than to amuse. The critics discouraged Andersen from pursuing this type of style. Andersen believed that he was working against the critics’ preconceived notions about fairy tales, and he temporarily returned to novel-writing. The critics’ reaction was so severe that Andersen waited a full year before publishing his third installment.[21]

The nine tales from the three booklets were combined and then published in one volume and sold at seventy-two shillings. A title page, a table of contents, and a preface by Andersen were published in this volume.[22]

In 1868 Horace Scudder, the editor of Riverside Magazine For Young People, offered Andersen $500 for a dozen new stories. Sixteen of Andersen’s stories were published in the American magazine, and ten of them appeared there before they were printed in Denmark.[23]

Travelogues[edit]

In 1851 he published In Sweden, a volume of travel sketches. The publication received wide acclaim. A keen traveler, Andersen published several other long travelogues: Shadow Pictures of a Journey to the Harz, Swiss Saxony, etc. etc. in the Summer of 1831, A Poet’s Bazaar, In Spain and A Visit to Portugal in 1866. (The last describes his visit with his Portuguese friends Jorge and José O’Neill, who were his friends in the mid-1820s while he was living in Copenhagen.) In his travelogues, Andersen took heed of some of the contemporary conventions related to travel writing but he always developed the style to suit his own purpose. Each of his travelogues combines documentary and descriptive accounts of his experiences, adding additional philosophical passages on topics such as what it is to be an author, general immortality, and the nature of fiction in literary travel reports. Some of the travelogues, such as In Sweden, even contain fairy-tales.

In the 1840s, Andersen’s attention again returned to the theatre stage, but with little success. He had better luck with the publication of the Picture-Book without Pictures (1840). A second series of fairy tales was started in 1838 and a third series in 1845. Andersen was now celebrated throughout Europe although his native Denmark still showed some resistance to his pretensions.

Between 1845 and 1864, H. C. Andersen lived at Nyhavn 67, Copenhagen, where a memorial plaque is placed on a building.[24]

The works of Hans Andersen became known throughout the world. Rising from a poor social class, the works made him into an acclaimed author. Royal families of the world were patrons of the writings including the monarchy of Denmark, the House of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg. An unexpected invitation from King Christian IX to the royal palace would not only entrench the Andersen folklore in Danish royalty but would inexplicably be transmitted to the Romanov dynasty in Russia.[25]

Personal life[edit]

Søren Kierkegaard[edit]

In ‘Andersen as a Novelist’, Søren Kierkegaard remarks that Andersen is characterized as, “…a possibility of a personality, wrapped up in such a web of arbitrary moods and moving through an elegiac duo-decimal scale [i.e., a chromatic scale including sharps and flats, associated more with lament or elegy than an ordinary scale] of almost echoless, dying tones just as easily roused as subdued, who, in order to become a personality, needs a strong life-development.”

Meetings with Charles Dickens[edit]

In June 1847, Andersen paid his first visit to England, enjoying a triumphal social success during this summer. The Countess of Blessington invited him to her parties where intellectual people would meet, and it was at one of such parties where he met Charles Dickens for the first time. They shook hands and walked to the veranda, which Andersen wrote about in his diary: «We were on the veranda, and I was so happy to see and speak to England’s now-living writer whom I do love the most.»[26]

The two authors respected each other’s work and as writers, they shared something important in common: depictions of the poor and the underclass who often had difficult lives affected both by the Industrial Revolution and by abject poverty. In the Victorian era there was a growing sympathy for children and an idealization of the innocence of childhood.

Ten years later, Andersen visited England again, primarily to meet Dickens. He extended the planned brief visit to Dickens’ home at Gads Hill Place into a five-week stay, much to the distress of Dickens’s family. After Andersen was told to leave, Dickens gradually stopped all correspondence between them, this to the great disappointment and confusion of Andersen, who had quite enjoyed the visit and could never understand why his letters went unanswered.[26]

Love life[edit]

In Andersen’s early life, his private journal records his refusal to have sexual relations.[27][28]

Andersen experienced same-sex attraction;[29] he wrote to Edvard Collin:[30] «I languish for you as for a pretty Calabrian wench … my sentiments for you are those of a woman. The femininity of my nature and our friendship must remain a mystery.»[31] Collin, who preferred women, wrote in his own memoir: «I found myself unable to respond to this love, and this caused the author much suffering.» Andersen’s infatuation for Carl Alexander, the young hereditary duke of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach,[32] did result in a relationship:

The Hereditary Grand Duke walked arm in arm with me across the courtyard of the castle to my room, kissed me lovingly, asked me always to love him though he was just an ordinary person, asked me to stay with him this winter … Fell asleep with the melancholy, happy feeling that I was the guest of this strange prince at his castle and loved by him … It is like a fairy tale.[29]

There is a sharp division in opinion over Andersen’s physical fulfillment in the sexual sphere. The Hans Christian Andersen Center of University of Southern Denmark and biographer Jackie Wullschlager hold contradictory views.[33]

Wullschlager’s biography maintains he was possibly lovers with Danish dancer Harald Scharff[34] and Andersen’s «The Snowman» was inspired by their relationship.[35] Scharff first met Andersen when the latter was in his fifties. Andersen was clearly infatuated, and Wullschlager sees his journals as implying that their relationship was sexual.[36] Scharff had various dinners alone with Andersen and his gift of a silver toothbrush to Andersen on his fifty-seventh birthday marked their relationship as incredibly close.[37] Wullschlager asserts that in the winter of 1861–62 the two men entered a full-blown love affair that brought «him joy, some kind of sexual fulfillment, and a temporary end to loneliness.»[38] He was not discreet in his conduct with Scharff, and displayed his feelings much too openly. Onlookers regarded the relationship as improper and ridiculous. In his diary for March 1862, Andersen referred to this time in his life as his «erotic period».[39] On 13 November 1863, Andersen wrote, «Scharff has not visited me in eight days; with him it is over.»[40] Andersen took the end calmly and the two thereafter met in overlapping social circles without bitterness, though Andersen attempted to rekindle their relationship a number of times without success.[41][note 1][note 2][42]

In contrast to Wullschlager’s assertions are Klara Bom and Anya Aarenstrup from the H. C. Andersen Centre of University of Southern Denmark. They state «it is correct to point to the very ambivalent (and also very traumatic) elements in Andersen’s emotional life concerning the sexual sphere, but it is decidedly just as wrong to describe him as homosexual and maintain that he had physical relationships with men. He did not. Indeed, that would have been entirely contrary to his moral and religious ideas, aspects that are quite outside the field of vision of Wullschlager and her like.»[43]

Andersen also fell in love with unattainable women, and many of his stories are interpreted as references.[44] At one point, he wrote in his diary: «Almighty God, thee only have I; thou steerest my fate, I must give myself up to thee! Give me a livelihood! Give me a bride! My blood wants love, as my heart does!»[45] A girl named Riborg Voigt was the unrequited love of Andersen’s youth. A small pouch containing a long letter from Voigt was found on Andersen’s chest when he died several decades after he first fell in love with her, and after, he presumably fell in love with others. Other disappointments in love included Sophie Ørsted, the daughter of the physicist Hans Christian Ørsted, and Louise Collin, the youngest daughter of his benefactor Jonas Collin. One of his stories, «The Nightingale», was written as an expression of his passion for Jenny Lind and became the inspiration for her nickname, the «Swedish Nightingale».[46] Andersen was often shy around women and had extreme difficulty in proposing to Lind. When Lind was boarding a train to go to an opera concert, Andersen gave Lind a letter of proposal. Her feelings towards him were not the same; she saw him as a brother, writing to him in 1844: «farewell … God bless and protect my brother is the sincere wish of his affectionate sister, Jenny».[47] It is suggested that Andersen expressed his disappointment by portraying Lind as the eponymous anti-heroine of his Snow Queen.[48]

Death[edit]

Andersen at Rolighed: Israel Melchior (c. 1867)

In early 1872, at age 67, Andersen fell out of his bed and was severely hurt; he never fully recovered from the resultant injuries. Soon afterward, he started to show signs of liver cancer.[49]

He died on 4 August 1875, in a house called Rolighed (literally: calmness), near Copenhagen, the home of his close friends, the banker Moritz G. Melchior and his wife.[49] Shortly before his death, Andersen had consulted a composer about the music for his funeral, saying: «Most of the people who will walk after me will be children, so make the beat keep time with little steps.»[49]

His body was interred in the Assistens Kirkegård in the Nørrebro area of Copenhagen, in the family plot of the Collins. In 1914, however, the stone was moved to another cemetery (today known as «Frederiksbergs ældre kirkegaard»), where younger Collin family members were buried. For a period, his, Edvard Collin’s and Henriette Collin’s graves were unmarked. A second stone has been erected, marking H.C. Andersen’s grave, now without any mention of the Collin couple, but all three still share the same plot.[50]

At the time of his death, Andersen was internationally revered, and the Danish Government paid him an annual stipend as a «national treasure».[51]

Legacy and cultural influence[edit]

Archives, collections and museums[edit]

- The Hans Christian Andersen Museum or H.C. Andersens Odense, is a set of museums/buildings dedicated to the famous author Hans Christian Andersen in Odense, Denmark, some of which, at various times in history, have functioned as the main Odense-based museum on the author.

- The Hans Christian Andersen Museum in Solvang, California, a city founded by Danes, is devoted to presenting the author’s life and works. Displays include models of Andersen’s childhood home and of «The Princess and the Pea». The museum also contains hundreds of volumes of Andersen’s works, including many illustrated first editions and correspondence with Danish composer Asger Hamerik.[52]

- The Library of Congress Rare Book and Special Collections Division was bequeathed an extensive collection of Andersen materials by the Danish-American actor Jean Hersholt.[53][54]

Art, entertainment and media[edit]

Denmark, 1935

Films and TV series[edit]

- La petite marchande d’allumettes (1928; in English: The Little Match Girl), film by Jean Renoir, based on «The Little Match Girl»

- The Ugly Duckling (1931) and its’ 1939 remake of the same name, two animated Silly Symphonies cartoon shorts produced by Walt Disney Productions, based on The Ugly Duckling.

- Andersen was played by Joachim Gottschalk in the German film The Swedish Nightingale (1941), which portrays his relationship with the singer Jenny Lind.

- The Red Shoes (1948) British drama film written, directed, and produced by the team of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger based on «The Red Shoes».

- Hans Christian Andersen (1952), an American musical film starring Danny Kaye that, though inspired by Andersen’s life and literary legacy, was meant to be neither historically nor biographically accurate; it begins by saying, «This is not the story of his life, but a fairy tale about this great spinner of fairy tales»

- The Snow Queen (1957), a Soviet Union animated film based on The Snow Queen by Lev Atmanov of Soyuzmultfilm, authentic depiction of the fairy tale that garnered critical acclaim[55][56]

- Carevo novo ruho (The emperor’s new clothes), a 1961 Croatian film, directed by Ante Babaja.

- The Wild Swans (1962), Sovietic animated adapatation of The Wild Swans, by Soyuzmultfilm

- The Rankin/Bass Productions-produced fantasy film, The Daydreamer (1966), depicts the young Hans Christian Andersen imaginatively conceiving the stories he would later write.

- The Little Mermaid (1968) 30-minute faithful Sovietic animated adaptation of The Little Mermaid by Soyuzmultfilm

- The World of Hans Christian Andersen (1968), a Japanese anime fantasy film from Toei Doga, based on the works of Danish author Hans Christian Andersen

- Andersen Monogatari (1971), a Japanese animated anthology series prodused by Mushi Production.

- The Pine Tree (c1974) 23 mins, colour. Commentary by Liz Lochhead[57]

- Hans Christian Andersen’s The Little Mermaid (1975) Japanese anime film from Toei quite faithfully based on The Little Mermaid

- The Little Mermaid (1976) Czech fantasy film based on The Little Mermaid

- The Wild Swans (1977), Japanese animated adaptation of The Wild Swans by Toei

- Thumbelina (1978), Japanese anime film from Toei based on Thumbelina

- The Little Mermaid (1989), an animated film based on The Little Mermaid created and produced at Walt Disney Feature Animation in Burbank, CA

- Thumbelina (1994), an animated film based on the «Thumbelina» created and produced at Sullivan Bluth Studios Dublin, Ireland

- One segment in Fantasia 2000 is based on «The Steadfast Tin Soldier», against Shostakovich’s Piano Concerto No. 2, Movement #1: «Allegro».

- Hans Christian Andersen: My Life as a Fairytale (2003), a British made-for-television film directed by Philip Saville, a fictionalized account of Andersen’s early successes, with his fairy stories intertwined with events in his own life.[58][59]

- The Fairytaler (2003), Danish-British animated series based on several Andersen fairy tales

- The Little Matchgirl (2006), an animated short film by the Walt Disney Animation Studios directed by Roger Allers and produced by Don Hahn

- The Snow Queen (2012), a Russian 3D animated film based on The Snow Queen, the first film of The Snow Queen series produced by Wizart Animation[60]

- Frozen (2013), a 3D computer-animated musical film produced by Walt Disney Animation Studios that is loosely inspired by The Snow Queen.

- Ginger’s Tale (2020), a Russian 2D traditional animated film loosely based on The Tinderbox, produced at Vverh Animation Studio in Moscow[61]

Video games[edit]

- Andersen appears as a Caster-class Servant in Fate/EXTRA CCC (2013), and Fate/Grand Order (2015).

Literature[edit]

Andersen’s stories laid the groundwork for other children’s classics, such as The Wind in the Willows (1908) by Kenneth Grahame and Winnie-the-Pooh (1926) by A. A. Milne. The technique of making inanimate objects, such as toys, come to life («Little Ida’s Flowers») would later also be used by Lewis Carroll and Beatrix Potter.[62][63]

Monuments and sculptures[edit]

One of Copenhagen’s widest and busiest boulevards, skirting Copenhagen City Hall Square at the corner of which Andersen’s larger-than-life bronze statue sits, is named «H. C. Andersens Boulevard.»[64]

- Hans Christian Andersen (1880), even before his death, steps had already been taken to erect, in Andersen’s honour, a large statue by sculptor August Saabye, which can now be seen in the Rosenborg Castle Gardens in Copenhagen.[4]

- Hans Christian Andersen (1896) by the Danish sculptor Johannes Gelert, at Lincoln Park in Chicago, on Stockton Drive near Webster Avenue[65]

- Hans Christian Andersen (1956), a statue by sculptor Georg J. Lober and designer Otto Frederick Langman, at Central Park Lake in New York City, opposite East 74th Street (40.7744306°N, 73.9677972°W)

- Hans Christian Andersen (2005) Plaza de la Marina in Malaga, Spain

-

Statue in Central Park, New York commemorating Andersen and The Ugly Duckling

-

Statue in Odense being led out to the harbour during a public exhibition

-

-

Portrait bust in Sydney unveiled by the Crown Prince and Princess of Denmark in 2005

Music[edit]

- Hans Christian Andersen (album), a 1994 album by Franciscus Henri

- The Song is a Fairytale (Sangen er et Eventyr), a song cycle based on fairy tales by Hans Christian Andersen, composed by Frederik Magle

- Atonal Fairy Tale[66] music composed by Gregory Reid Davis Jr. and the fairy tale, The Elfin Mound, by Hans Christian Andersen is read by Smart Dad Living

Stage productions[edit]

For opera and ballet see also List of The Little Mermaid Adaptations

- Little Hans Andersen (1903), a children’s pantomime at the Adelphi Theatre

- Sam the Lovesick Snowman at the Center for Puppetry Arts: a contemporary puppet show by Jon Ludwig inspired by The Snow Man.[67]

- Striking Twelve, a modern musical take on «The Little Match Girl», created and performed by GrooveLily.[68]

- The musical comedy Once Upon a Mattress is based on Andersen’ work ‘The Princess and the Pea’.[69]

Awards[edit]

- Hans Christian Andersen Awards, prizes awarded annually by the International Board on Books for Young People to an author and illustrator whose complete works have made lasting contributions to children’s literature.[70]

- Hans Christian Andersen Literature Award, a Danish literary award established in 2010

- Andersen’s fable «The Emperor’s New Clothes» was inducted in 2000 into the Prometheus Hall of Fame for Best Classic Fiction [71]

Events and holidays[edit]

- Andersen’s birthday, 2 April, is celebrated as International Children’s Book Day.[72]

- The year 2005, designated «Andersen Year» in Denmark,[73] was the bicentenary of Andersen’s birth, and his life and work was celebrated around the world.

- In Denmark, a well-attended «once in a lifetime» show was staged in Copenhagen’s Parken Stadium during «Andersen Year» to celebrate the writer and his stories.[73]

- The annual H.C. Andersen Marathon, established in 2000, is held in Odense, Denmark

Places named after Andersen[edit]

- H. C. Andersens Boulevard, a major road in Copenhagen formerly known as Vestre Boulevard (Western Boulevard), received its current name in 1955 to mark the 150-year anniversary of the writer’s birth

- Hans Christian Andersen Airport, small airport servicing the Danish city of Odense

- Instituto Hans Christian Andersen, Chilean high school located in San Fernando, Colchagua Province, Chile