- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Geography & Travel

- Health & Medicine

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Literature

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- Science

- Sports & Recreation

- Technology

- Visual Arts

- World History

- On This Day in History

- Quizzes

- Podcasts

- Dictionary

- Biographies

- Summaries

- Top Questions

- Week In Review

- Infographics

- Demystified

- Lists

- #WTFact

- Companions

- Image Galleries

- Spotlight

- The Forum

- One Good Fact

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Geography & Travel

- Health & Medicine

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Literature

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- Science

- Sports & Recreation

- Technology

- Visual Arts

- World History

- Britannica Classics

Check out these retro videos from Encyclopedia Britannica’s archives. - Demystified Videos

In Demystified, Britannica has all the answers to your burning questions. - #WTFact Videos

In #WTFact Britannica shares some of the most bizarre facts we can find. - This Time in History

In these videos, find out what happened this month (or any month!) in history. - Britannica Explains

In these videos, Britannica explains a variety of topics and answers frequently asked questions.

- Student Portal

Britannica is the ultimate student resource for key school subjects like history, government, literature, and more. - COVID-19 Portal

While this global health crisis continues to evolve, it can be useful to look to past pandemics to better understand how to respond today. - 100 Women

Britannica celebrates the centennial of the Nineteenth Amendment, highlighting suffragists and history-making politicians. - Britannica Beyond

We’ve created a new place where questions are at the center of learning. Go ahead. Ask. We won’t mind. - Saving Earth

Britannica Presents Earth’s To-Do List for the 21st Century. Learn about the major environmental problems facing our planet and what can be done about them! - SpaceNext50

Britannica presents SpaceNext50, From the race to the Moon to space stewardship, we explore a wide range of subjects that feed our curiosity about space!

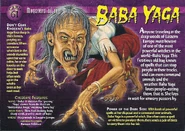

Baba Yaga is a witch, known in Eastern Slavic countries. In majority of tales, she is represented as an evil being who ride either broom or mortar, wields a pestle and scares and eat children, however in very few tales she gives her wisdom to protagonists. She lives in forest hut which has chicken legs.

Children are warned in Russia that Babayka (or Baba Yaga) will come for them at night if they behave badly.

Poland – «Baba Jaga» or «Muma» is a monster (often portrayed as a witch living in the forest) that kidnaps badly behaving children and presumably eats them. It is referenced in a children’s game of the same name, which involves one child being blindfolded, and other children trying to avoid being caught. [62]

Similar Hags

Babaroga (not to be mistaken with Baba Yaga!) is creature known among Southern Slavs. She is represented as very ugly, hunchbacked old woman with horn on head, who live in dark caves. According to folktales, Babaroga likes to steal naughty children and to bring them to her lair.

In Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Serbia, and Macedonia, the Bogeyman is called Babaroga, baba meaning old woman and rogovi meaning horns, literally meaning old woman with horns. The details vary from one household to another. In one version, babaroga takes children, puts them in a sack, and then, when it comes to its cave, eats them. In another version, it takes children and pulls them up through tiny holes in the ceiling. [26]

Iraq’s ancient folklore has the saalua, a half-witch half-demon ghoul that «is used by parents to scare naughty children». She is briefly mentioned in a tale of the 1001 Nights, and is known in some other Persian Gulf countries as well.[52]

Black Annis was a hag with a blue face and iron claws who lived in a cave in the Dane Hills of Leicestershire. She ventured forth at night in search of children to devour.[39 Briggs, Katharine (1976). An Encyclopedia of Fairies. Pantheon Books. pp. 24–25. ISBN 0394409183.][40 the Folklore Society (1895). County Folk-Lore (Vol. 1). «Leicestershire and Rutland» (Charles James Billson, ed.). pp. 4–9, 76–77.]

Grindylow, Jenny Greenteeth and Nelly Longarms were grotesque hags who lived in ponds and rivers and dragged children beneath the water if they got too close.[41 Wright, Elizabeth Mary (1913). Rustic Speech and Folk-Lore. Humphrey Milford, Oxford University Press. pp. 198–202.]

Peg Powler is a hag who inhabits the River Tees.

Popular Culture

In 2020 Baba Yaga was added as a playable character in the MOBA game Smite, the second for the Slavic pantheon after Chernobog. She appears as an old woman in a mortar and holding a pestle.

Gallery

Baba Yaga from the movie «Polish Legends: Jaga»

«Polish Legends: Jaga»

«Polish Legends: Jaga»

«Polish Legends: Jaga»

Baba Yaga in Smite.

Baba Yaga in Scooby-Doo! Mystery Incorporated.

Baba Yaga in Scribblenauts Unlimited.

Baba Yaga in Fortnite.

Baba Yaga Weird n’ Wild Creatures card.

This page uses content from Wikipedia. The original article was at Baba Yaga (view authors). As with Myths and Folklore Wiki, the text of Wikipedia is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike License 3.0 (Unported).

Светило науки — 46 ответов — 0 раз оказано помощи

In East Slavic tales of particular importance is the image of Baba Yaga. He goes back to the era of matriarchy and much remains mysterious (for example, there are several assumptions, but there is no convincing explanation of the name «witch»). To the witch at her call runs every animal that creeps every creeping thing, every bird flies. She is not only a lady living beings, but also the Keeper of the fire hearth (not accidentally tale connects with her utensils — the stupa, pomelo, poker).

The ancient roots of Baba Yaga says the ambivalence of its properties: it can be a helper and opponent. Yaga shows the way in Kasaeva Kingdom, from her hero gets a wonderful items and a magic horse. However, the witch acts as a warrior, avenger, the thief of children. In a patrimonial society Yaga personified mother ancestor, and the tale emphasized uterum her feminine characteristics, while doing this, because of the fall of the cult, already with a sneer: «Sitting witch of Aginine, Avdotya of Krzyminski, nose up at the ceiling, Tits across the threshold, snot through a flower bed, the language of soot raking».

The motive of the meeting of the hero with Baba Yaga known by many stories of fairy tales. Its origin Century. I. Propp explained in connection with the initiation rituals of tribal society, which have reached maturity, the young men were initiated into the hunter (warriors), and the girls were taken into the circle of mothers . In the basis of the rites was the fictional death, when a man allegedly visited the realm of the dead and got there wonderful properties, and then was reborn in a new capacity. In two books («the Morphology of the fairy tale» and «the Historical roots of fairy tales») Propp showed that the uniformity of the narrative structure of different works in this genre corresponds to such rites of antiquity. Summing up his investigations, he wrote: «We found that the compositional unity of the tale lies not in any peculiarities of the human psyche, not in the specifics of artistic creativity, it lies in the historical reality of the past. What now tell you once did, portrayed, and what did not, imagine» .

Inside the fairy story clearly allocated two spaces: the world of people and wonderful far far away Kingdom, trilisate the state is nothing like the mythical realm of the dead. In ancient times it was associated with the sun, so the tale portrays his gold. In different stories of the miraculous Kingdom situated under ground, under water, in the distant woods or on high mountains, in the sky. Therefore, it is very far removed from the people and moves, like the daily movement of the sun. There goes the hero of a fairy tale for the wonderful Golden wonders and for the bride, and then returns with prey in their home. From the real world far far away Kingdom always separated by some border: heavy stone pillar with an inscription of three roads, a high steep mountain, a river of fire, guelder rose bridge, but most often by Baba Yaga. C. J. Propp concluded that the witch is dead, the mother dead, the guide to the afterlife.

In the rites of the ancient people of the hut was zoomorphic image. Fabulous cottage retains the characteristics of a living creature: she hears addressed to her words («Hut, hut, turn to the forest, in front of me»), turns around, and finally she had the chicken legs. Zoomorphic image of the hut associated with chicken, and chicken in the entire system of Ethnography and folklore of the Eastern Slavs symbolized female fertility. Fairytale motif meeting with house Yaga told echoes the feminine initiation.

Story Reads: 79,381

This is a vintage fairy tale, and may contain violence. We would encourage parents to read beforehand if your child is sensitive to such themes.

There were once a man and wife who had no child, though they wished for one above all things.

One day, when the husband was away, the wife laid a big stick of wood in the cradle and began to rock it and sing to it. Presently she looked and saw that the stick had arms and legs. Filled with joy, she began to rock and sing to it again; she kept it up for a long time, and when she looked again, there, instead of the stick of wood, was a fine little boy in the cradle.

The woman took the child up and nursed him, and after that he was to her as her own son. She named him Peter, and made a little suit of clothes and a cloth cap for him to wear.

One day Peter put on his little coat and went out in a boat to fish on the river.

At noon his mother went down to the bank of the stream and called to him, “Peter, Peter, bring your boat to shore, for I have brought a little cake for you to eat.”

Then Peter said to his boat:

“Little boat, little boat, float a little nearer.

Little boat, little boat, float a little nearer.”

The boat floated up to the shore; Peter took the cake and went back to his fishing again.

Now it so happened that a Baba Yaga, a terrible witch, was hiding in the bushes near-by. She heard all that passed between the woman and the child. So after the woman had gone home, the Baba Yaga waited for a while, and then she went down to the edge of the river and hid herself there, and called out:

“Peter, Peter, bring your boat to the shore, for I have brought another little cake for you.”

But when Peter heard her voice, which was very coarse and loud, he knew it must be a Baba Yaga calling him, so he said:

“Little boat, little boat, float a little farther.

Little boat, little boat, float a little farther.”

Then the boat floated away still farther out of the Baba Yaga’s reach.

The old witch soon guessed what was the matter, and she rushed off to a blacksmith, who lived over beyond the forest.

“Blacksmith, blacksmith, forge me a little fine voice as quickly as you can,” she cried, “or I will put you in my mortar and grind you to pieces with my pestle.”

The blacksmith was frightened. He made her a little fine voice as quickly as he could, and the Baba Yaga took it and hastened back to the river.

There she hid herself close to the shore and called in her little new voice, “Peter, Peter, bring your boat to the shore, for I have brought another little cake for you to eat.”

When Peter heard the Baba Yaga calling him in her fine, small voice, he thought it was his mother, so he said to his boat:

“Little boat, little boat, float a little nearer.

Little boat, little boat, float a little nearer.”

Then the little boat came to the land. Peter looked all about, but saw no one. He wondered where his mother had gone, and stepped out of his boat to look for her.

Immediately the Baba Yaga seized him. Like a whirlwind she rushed away with him through the forest and never stopped till she reached her own house. There she shut him up in a cage behind the house to keep him until he grew fat.

After she had shut him up, she went back into the house, and her little cat was there.

“Mistress,” said the cat, “I have cooked the dinner for you, and I am very hungry. Will you not give me something to eat?”

“All that I leave, that you can have,” answered the Baba Yaga. She sat down at the table and ate up everything but one small bone. That was all the cat had.

Meanwhile at home the mother waited and waited for Peter to come back from the river with his fish. Then at last she went down to look for him. There was his boat drawn up on the shore empty, and all round it were marks of the Baba Yaga’s feet, and the trees and bushes were broken where she had rushed away through the forest. Then the mother knew that a witch had carried off the little boy.

She went back home, weeping and wailing.

Now the woman had a very faithful servant, and when this girl heard her mistress wailing, she asked her what the matter was.

The woman told her all that she had seen down at the river, and how she was sure a Baba Yaga had flown away with Peter.

“Mistress,” said the girl, “there is no reason for you to despair. Just give me a little wheaten cake to keep the life in me, and I will set out and find Peter, even though I have to travel to the end of the world.”

Then the woman was comforted. She gave the servant a cake, and the girl set out in search of Peter.

She went on and on, and after a while she came to the Baba Yaga’s house. It stood on fowls’ legs, and turned whichever way the wind blew. The girl knocked at the door, and the Baba Yaga opened it.

“What do you want here?” she asked. “Are you seeking work or shunning work?”

“I am seeking work,” answered the girl. “Can you give me anything to do?”

The witch scowled at her terribly. “You may come in,” she said, “and set my house in order, but do not go peeping and prying about, or it will be the worse for you.”

The girl went in and began to set the house in order, while the Baba Yaga flew away into the forest, riding in a mortar, urging it along with a pestle, and sweeping away the traces with a broom.

After the witch had gone, the little cat said to the girl, “Give me, I beg of you, a little food, for I am starving with hunger.”

“Here is a little cake; it is all I have, but I will give it to you in Heaven’s name.”

The little cat took the cake and ate it all up, every crumb.

“Now listen,” said the cat. “I know why you are here, and that you are searching for the little boy named Peter. He is in a cage behind the house, but you can do nothing to help him now. Wait until after dinner, when the Baba Yaga goes to sleep. Then rub her eyes with pitch so that she cannot get them open, and you may escape with the child through the forest.”

The girl thanked the little cat and promised to do in all things as it bade her.

When the Baba Yaga came home, “Well, have you been peeping and prying?” she asked.

“That I have not,” answered the girl.

The Baba Yaga sat down, ate everything there was on the table, bones and all. Then she lay down and went to sleep. She snored terribly.

The girl took some pitch and smeared the witch’s eyelids with it. Then she went out to where Peter was and let him out of the cage, and they ran away through the forest together.

The Baba Yaga slept for a long time. At last she yawned and woke, but she could not get her eyes open. They were stuck tight with pitch. She was in a terrible rage; she stamped about and roared terribly. “I know who has done this,” she cried, “and as soon as I get my eyes open, I will go after her and tear her to pieces.” Then she called to the cat to come and scratch her eyes open with its sharp little claws.

“That I will not,” answered the cat. “As long as I have been with you, you have given me nothing but hard words and bones to gnaw, but she stroked my fur, and gave me a cake to eat. Scratch your own eyes open, for you shall have no help from me.” And then the little cat ran away into the forest.

But the faithful servant and Peter journeyed safely on through the forest, and you may guess whether or not the mother was glad to have her little Peter safe home again.

As to the old Baba Yaga, she may be shouting and stamping and rubbing the pitch from her eyes yet, for all I know.

RUSSIAN FAIRY TALE BY KATHARINE PYLE

Vintage Illustration by Katharine Pyle

Header illustration from Pixabay, with thanks.

LET’S CHAT ABOUT THE STORY ~ IDEAS FOR TALKING WITH KIDS

Stranger Danger

1. Little Peter knew the first time that it was not his mother calling for him because she had a different voice. As a result, he decided not to bring the little boat in the first time. What kinds of things might make you feel uncomfortable about a stranger? What would you do if you felt uncomfortable about a stranger or what they were asking you?

Kindness

2. The cat helps the servant girl to free Peter. Why does she do this? What do you think this says about kindness?

Book Information!

No schema found.

This article is about the entity in Slavic folklore. For adaptations and other uses, see Baba Yaga (disambiguation).

In Slavic folklore, Baba Yaga, also spelled Baba Jaga (from Polish), is a supernatural being (or one of a trio of sisters of the same name) who appears as a deformed and/or ferocious-looking woman. In fairy tales Baba Yaga flies around in a mortar, wields a pestle, and dwells deep in the forest in a hut usually described as standing on chicken legs. Baba Yaga may help or hinder those that encounter or seek her out and may play a maternal role; she has associations with forest wildlife. According to Vladimir Propp’s folktale morphology, Baba Yaga commonly appears as either a donor or a villain, or may be altogether ambiguous.

Baba Yaga depicted in Tales of the Russian People (published by V. A. Gatsuk in Moscow in 1894)

Look up Baba Yaga in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

Dr. Andreas Johns identifies Baba Yaga as «one of the most memorable and distinctive figures in eastern European folklore», and observes that she is «enigmatic» and often exhibits «striking ambiguity».[1] Johns summarizes Baba Yaga as «a many-faceted figure, capable of inspiring researchers to see her as a Cloud, Moon, Death, Winter, Snake, Bird, Pelican or Earth Goddess, totemic matriarchal ancestress, female initiator, phallic mother, or archetypal image».[2]

EtymologyEdit

Variations of the name Baba Yaga are found in many East Slavic languages. The first element is a babble word which gives the word бабуся (babusya or ‘grandmother’) in modern Ukrainian, бабушка (babushka or ‘grandmother’) in modern Russian, and babcia (‘grandmother’) in Polish. In Serbo-Croatian, Bosnian, Macedonian, Bulgarian and Romanian baba means ‘grandmother’ or ‘old woman’. In contemporary Polish and Russian, baba is the pejorative synonym for ‘woman’, especially one that is old, dirty or foolish. As with other kinship terms in Slavic languages, baba may be used in other ways, potentially as a result of taboo; it may be applied to various animals, natural phenomena, and objects, such as types of mushrooms, cake or pears. In the Polesia region of Ukraine, the plural baby may refer to an autumn funeral feast. The element may appear as a means of glossing the second element, iaga, with a familiar component or may have also been applied as a means of distinguishing Baba Yaga from a male counterpart.[2]

Yaga is more etymologically problematic and there is no clear consensus among scholars about its meaning. In the 19th century, Alexander Afanasyev proposed the derivation of Proto-Slavic *ož and Sanskrit ahi (‘serpent’). This etymology has been explored by 20th-century scholars. Related terms appear in Serbo-Croatian jeza (‘horror’, ‘shudder’, ‘chill’), Slovene jeza (‘anger’), Old Czech jězě (‘witch’, ‘legendary evil female being’), modern Czech jezinka (‘wicked wood nymph’, ‘dryad’), and Polish jędza (‘witch’, ‘evil woman’, ‘fury’). The term appears in Old Church Slavonic as jęza/jędza (‘disease’). In other Indo-European languages the element iaga has been linked to Lithuanian engti (‘to abuse (continuously)’, ‘to belittle’, ‘to exploit’), Old English inca (‘doubt’, ‘worry», ‘pain’), and Old Norse ekki (‘pain’, ‘worry’).[3]

AttestationsEdit

The first clear reference to Baba Yaga (Iaga baba) occurs in 1755; Mikhail V. Lomonosov’s Russian Grammar [ru]. In Lomonosov’s grammar book, Baba Yaga is mentioned twice among other figures largely from Slavic tradition. The second of the two mentions occurs within a list of Slavic gods and beings next to their presumed equivalence in Roman mythology (the Slavic god Perun, for example, appears equated with the Roman god Jupiter). Baba Yaga, however, appears in a third section without an equivalence, highlighting her perceived uniqueness even in this first known attestation.[4]

In the narratives in which Baba Yaga appears, she displays a variety of typical attributes: a turning, chicken-legged hut; and a mortar, pestle, and/or mop or broom. Baba Yaga often bears the epithet Baba Yaga kostyanaya noga (‘bony leg’), or Baba Yaga s zheleznymi zubami (‘with iron teeth’) [5] and when inside her dwelling, she may be found stretched out over the stove, reaching from one corner of the hut to another. Baba Yaga may sense and mention the russkiy dukh (‘Russian scent’) of those that visit her. Her nose may stick into the ceiling. Particular emphasis may be placed by some narrators on the repulsiveness of her nose, breasts, buttocks, or vulva.[6]

In some tales a trio of Baba Yagas appear as sisters, all sharing the same name. For example, in a version of «The Maiden Tsar» collected in the 19th century by Alexander Afanasyev, Ivan, a handsome merchant’s son, makes his way to the home of one of three Baba Yagas:[7]

He journeyed onwards, straight ahead … and finally came to a little hut; it stood in the open field, turning on chicken legs. He entered and found Baba Yaga the Bony-legged. «Fie, fie,» she said, «the Russian smell was never heard of nor caught sight of here, but it has come by itself. Are you here of your own free will or by compulsion, my good youth?» «Largely of my own free will, and twice as much by compulsion! Do you know, Baba Yaga, where lies the thrice tenth kingdom [ru]?» «No, I do not,» she said, and told him to go to her second sister; she might know..

Ivan Bilibin, Baba Yaga, illustration in 1911 from «The tale of the three tsar’s wonders and of Ivashka, the priest’s son» (A. S. Roslavlev)

Ivan walks for some time before encountering a small hut identical to the first. This Baba Yaga makes the same comments and asks the same question as the first, and Ivan asks the same question. This second Baba Yaga does not know either and directs him to the third, but says that if she gets angry with him «and wants to devour you, take three horns from her and ask her permission to blow them; blow the first one softly, the second one louder, and third still louder.» Ivan thanks her and continues on his journey.

After walking for some time, Ivan eventually finds the chicken-legged hut of the youngest of the three sisters turning in an open field. This third and youngest of the Baba Yagas makes the same comment about «the Russian smell» before running to whet her teeth and consume Ivan. Ivan begs her to give him three horns and she does so. The first he blows softly, the second louder, and the third louder yet. This causes birds of all sorts to arrive and swarm the hut. One of the birds is the firebird, which tells him to hop on its back or Baba Yaga will eat him. He does so and the Baba Yaga rushes him and grabs the firebird by its tail. The firebird leaves with Ivan, leaving Baba Yaga behind with a fist full of firebird feathers.

In Afanasyev’s collection of tales, Baba Yaga also appears in «Baba Yaga and Zamoryshek», «By Command of the Prince Daniel», «Vasilisa the Fair», «Marya Moryevna», «Realms of Copper, Silver, and Gold» [fr], «The Sea Tsar and Vasilisa the Wise», and «Legless Knight and Blind Knight» (English titles from Magnus’s translation).[8]

Depiction on lubkiEdit

Baba Yaga appears on a variety of lubki (singular lubok), wood block prints popular in late 17th and early 18th century Russia. In some instances, Baba Yaga appears astride a pig going to battle against a reptilian entity referred to as «crocodile».

A lubok of «Iaga Baba» dancing with a bald old man with bagpipes

Some scholars interpret this scene as a political parody. Peter the Great persecuted Old Believers, who in turn referred to him as a crocodile. Some lubki feature a ship below the crocodile with Baba Yaga dressed in what has been identified as Finnish dress; Peter the Great’s wife Catherine I was sometimes derisively referred to as the chukhonka (‘Finnish woman’).[9] A lubok that features Baba Yaga dancing with a bagpipe-playing bald man has been identified as a merrier depiction of the home life of Peter and Catherine. Alternately, some scholars have interpreted these lubki motifs as reflecting a concept of Baba Yaga as a shaman. The crocodile would in this case represent a monster who fights witches, and the print would be something of a «cultural mélange» that «demonstrate[s] an interest in shamanism at the time».[10]

According to the Ph.D. dissertation of Andreas Johns, «Neither of these two interpretations significantly changes the image of Baba Yaga familiar from folktales. Either she can be seen as a literal evil witch, treated somewhat humorously in these prints, or as a figurative ‘witch’, an unpopular foreign empress. Both literal and figurative understandings of Baba Yaga are documented in the nineteenth century and were probably present at the time these prints were made.»[10]

Related figures and analoguesEdit

Ježibaba [cs], a figure closely related to Baba Yaga, occurs in the folklore of the West Slavic peoples. The two figures may originate from a common figure known during the Middle Ages or earlier; both figures are similarly ambiguous in character, but differ in appearance and the different tale types they occur in. Questions linger regarding the limited Slavic area—East Slavic nations, Slovakia, and the Czech lands—in which references to Ježibaba are recorded.[11] Jędza [pl], another figure related to Baba Yaga, appears in Polish folklore.[12]

Similarities between Baba Yaga and other beings in folklore may be due to either direct relation or cultural contact between the Eastern Slavs and other surrounding peoples. In Central and Eastern Europe, these figures include the Bulgarian gorska maika (Горска майка’, ‘Forest Mother’, also the name of a flower); the Hungarian vasorrú bába (‘Iron-nose Midwife’), the Serbian Baba Korizma, Gvozdenzuba (‘Iron-tooth’), Baba Roga (used to scare children in Bosnia, Croatia, Montenegro and Serbia), šumska majka (‘Forest Mother’), and the babice; and the Slovenian jaga baba or ježibaba, Pehta or Pehtra baba and kvatrna baba or kvatrnica. In Romanian folklore, similarities have been identified in several figures, including Mama padurii (‘Forest Mother’) or Baba Cloanta referring to the nose as a bird’s beak. In neighboring Germanic Europe, similarities have been observed between the Alpine Perchta and Holda or Holle in the folklore of Central and Northern Germany, and the Swiss Chlungeri.[13]

Some scholars have proposed that the concept of Baba Yaga was influenced by East Slavic contact with Finno-Ugric and Siberian peoples.[14] The Karelian Syöjätär has some aspects of Baba Yaga, but only the negative ones, while in other Karelian tales, helpful roles akin to those from Baba Yaga may be performed by a character called akka (‘old woman’).[15]

In modern cultureEdit

The character Valada Geloë, in Tad Williams’ ‘Memory, Sorrow, and Thorn’ trilogy, who is described as a «forest woman», has supernatural powers, can transform into a bird, and lives in a hut on a lake with bird feet which appears to move.

Voleth Meir, also known as the Deathless Mother in Season 2 of Netflix’s The Witcher, is based on Baba Yaga.

Baba Yaga, appearing as a grotesque, child-eating witch, features as a prominent character in Hellboy comics franchise, including its 2019 film installment.

The film character John Wick is referred to by his enemies as «Baba Yaga», the name used synonymously with the term «bogeyman».

Dragon Ball character Fortuneteller Baba is based on Baba Yaga, as is fellow anime character Yubaba from Hayao Miyazaki’s Spirited Away, while the titular object of Miyazaki’s Howl’s Moving Castle is modeled after her walking hut.

The ninth movement of Modest Mussorgsky’s suite Pictures at an Exhibition is titled «The Hut on Hen’s Legs (Baba Yaga)» and is inspired by a painting by Viktor Hartmann depicting the same.

Animated segments telling the story of Baba Yaga were used in the 2014 documentary The Vanquishing of the Witch Baba Yaga, directed by American filmmaker Jessica Oreck.[16]

In the animated movie Bartok the Magnificent (1998) by Fox Studios, Baba Yaga is portrayed as a false antagonist who gives Bartok quests to save the Czar of Russia.

The 1989 PC game Quest for Glory: So You Want to Be a Hero has the player undo curses cast by Baba Yaga, who serves as a main antagonist in the title.

She is a playable magical character in Smite.

Orson Scott Card’s 1999 fantasy novel, “Enchantment”, features Baba Yaga as the arch-villainess, in this modern take on the Ukrainian version of ‘Sleeping Beauty’.

The Track ‘Baba Yaga’ was released August 2021, on Slaughter to Prevail’s Kostolom Album.

See alsoEdit

- Morana (goddess)

- Babay, a night spirit in Slavic folklore who is also useful in scaring children.

- Hansel and Gretel

- Despoina / Persephone

- Hecate

- The Morrígan

- Yama-uba, a similar character to Baba Yaga, in Japanese folklore.

- Izanami

CitationsEdit

- ^ Johns 2004, p. 1–3.

- ^ a b Johns 2004, p. 9.

- ^ Johns 2004, p. 10.

- ^ Johns 2004, p. 12.

- ^ «Baba Yaga – Old Peter’s Russian tales». 1916.

- ^ Johns 1998, p. 21.

- ^ Afanasyev 1973, p. 231.

- ^ Afanasyev 1916, pp. .xiii–xv.

- ^ Johns 2004, p. 15.

- ^ a b Johns 2004, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Johns 2004, p. 61–66.

- ^ Hubbs 1993, p. 40.

- ^ Johns 2004, pp. 68–84.

- ^ Johns 2004, p. 61.

- ^ Johns 2004, pp. 80–82.

- ^ Hoad, Phil (29 September 2016). «The Vanquishing of the Witch Baba Yaga review – bewitching nature documentary». The Guardian. Guardian News & Media Limited. Retrieved 13 September 2022.

Cited and general sourcesEdit

- Afanasyev, Alexander (1916). Magnus, Leonard A. (ed.). Russian Folk-Tales. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co.

- Afanasyev, Alexander (1973) [1945]. Russian Fairy Tales. Translated by Guterman, Norbert. New York: Pantheon Books. ISBN 978-0-394-73090-5.

- Henry, C. (2022). Ryan, L. (ed.). Into the Forest: Tales of the Baba Yaga. Black Spot Books. ISBN 978-1-64548-123-2.

- Johns, Andreas (1998). «Baba Yaga and the Russian Mother». The Slavic and East European Journal. American Association of Teachers of Slavic and East European Languages. 42 (1): 21–36. doi:10.2307/310050. JSTOR 310050.

- Johns, Andreas (2004). Baba Yaga: The Ambiguous Mother and Witch of the Russian Folktale. New York: Peter Lang. ISBN 978-0-8204-6769-6.

- Hubbs, Joanna (1993). Mother Russia: The Feminine Myth in Russian culture (1st Midland Book ed.). Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-20842-2. OCLC 29539185.

External linksEdit

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Baba Yaga.

- Baba Yaga: The greatest ‘wicked witch’ of all?, BBC

In East Slavic tales of particular importance is the image of Baba Yaga. He goes back to the era of matriarchy and much remains mysterious (for example, there are several assumptions, but there is no convincing explanation of the name «witch»). To the witch at her call runs every animal that creeps every creeping thing, every bird flies. She is not only a lady living beings, but also the Keeper of the fire hearth (not accidentally tale connects with her utensils — the stupa, pomelo, poker).

The ancient roots of Baba Yaga says the ambivalence of its properties: it can be a helper and opponent. Yaga shows the way in Kasaeva Kingdom, from her hero gets a wonderful items and a magic horse. However, the witch acts as a warrior, avenger, the thief of children. In a patrimonial society Yaga personified mother ancestor, and the tale emphasized uterum her feminine characteristics, while doing this, because of the fall of the cult, already with a sneer: «Sitting witch of Aginine, Avdotya of Krzyminski, nose up at the ceiling, Tits across the threshold, snot through a flower bed, the language of soot raking».

The motive of the meeting of the hero with Baba Yaga known by many stories of fairy tales. Its origin Century. I. Propp explained in connection with the initiation rituals of tribal society, which have reached maturity, the young men were initiated into the hunter (warriors), and the girls were taken into the circle of mothers . In the basis of the rites was the fictional death, when a man allegedly visited the realm of the dead and got there wonderful properties, and then was reborn in a new capacity. In two books («the Morphology of the fairy tale» and «the Historical roots of fairy tales») Propp showed that the uniformity of the narrative structure of different works in this genre corresponds to such rites of antiquity. Summing up his investigations, he wrote: «We found that the compositional unity of the tale lies not in any peculiarities of the human psyche, not in the specifics of artistic creativity, it lies in the historical reality of the past. What now tell you once did, portrayed, and what did not, imagine» .

Inside the fairy story clearly allocated two spaces: the world of people and wonderful far far away Kingdom, trilisate the state is nothing like the mythical realm of the dead. In ancient times it was associated with the sun, so the tale portrays his gold. In different stories of the miraculous Kingdom situated under ground, under water, in the distant woods or on high mountains, in the sky. Therefore, it is very far removed from the people and moves, like the daily movement of the sun. There goes the hero of a fairy tale for the wonderful Golden wonders and for the bride, and then returns with prey in their home. From the real world far far away Kingdom always separated by some border: heavy stone pillar with an inscription of three roads, a high steep mountain, a river of fire, guelder rose bridge, but most often by Baba Yaga. C. J. Propp concluded that the witch is dead, the mother dead, the guide to the afterlife.

In the rites of the ancient people of the hut was zoomorphic image. Fabulous cottage retains the characteristics of a living creature: she hears addressed to her words («Hut, hut, turn to the forest, in front of me»), turns around, and finally she had the chicken legs. Zoomorphic image of the hut associated with chicken, and chicken in the entire system of Ethnography and folklore of the Eastern Slavs symbolized female fertility. Fairytale motif meeting with house Yaga told echoes the feminine initiation.