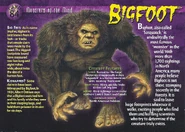

Bigfoot is an ape-human type creature that many believe lives mostly in forests in the Pacific Northwest region of the North American continent. He is also often referred to as Sasquatch. He is often described as a large and hairy, resembling a half-man, half-ape creature in folklore and myths. Many of those who have reported seeing Bigfoot describe him with large eyes, a low-set forehead, large brow-ridge, and having enormous footprints. He is believed to be upwards of 500 pounds and anywhere from two to three meters tall. He is also reported to be rather smelly, and he is mainly nocturnal.

| Interesting Bigfoot Facts: |

|---|

|

The Bigfoot mystery has existed for hundreds of years in different countries around the world. |

|

Bigfoot is the most famous cryptid (unidentified creature that’s existence has not been proven). |

|

Russia, France and Germany have all placed Bigfoot on the endangered species list. |

|

Some believe that David Thompson was the first to discover Bigfoot in 1811 when he found a set of his footprints. |

|

Many believe that Bigfoot is vegetarian while others believe that he is a meat and plant eater. |

|

Early Native Americans believed that Bigfoot was a spiritual creature. |

|

Reports suggest that Bigfoot is brown, although many have also reported black, gray, white and greenish-blue Bigfoots. |

|

There have been too many eyewitness accounts of Bigfoot sightings for researchers to dismiss the idea of the possibility of Bigfoot’s existence. |

|

Many of the eyewitnesses who have reported to have seen Bigfoot are credible people, not those looking to gain fame or fortune or attention. |

|

There is DNA evidence to date to prove that Bigfoot exists. |

|

Bigfoot has many nicknames including Jacko, Jingera, Monkey Man, Old Skunky Bill, Rugaru, Tree Men, Windego, Wigidokowok, and Yeti (its Himilayan cousin), among many others. |

|

The first person to capture footage of Bigfoot was Roger Patterson. |

|

Some believe that Bigfoot makes howling sounds, and that he lives in swampy forests and near mountains. |

|

There is an Algonquin legend that a female Bigfoot named Yeahoh that fell in love with a lost hunter. It ended badly when he wanted to return home. |

|

It has been reported that Bigfoot is not bothered by pepper spray. It has also been reported that Bigfoots are not capable of sneezing. |

|

Some believe that Bigfoots are not ape-human creatures at all. They believe that they are extra-terrestrials. Nobody has been able to prove either theory because of the lack of DNA evidence. |

|

A Brazilian legend says that Bigfoot was captured in Brazil in 1867. It was fed berries, nuts, and bananas but didn’t like the bananas. It escaped soon after. |

|

Native Americans believed in Bigfoot long before the Europeans came to north America. |

|

Some believe that no remains of a Bigfoot have ever been found because Bigfoots bury their dead the same as humans do. |

|

Bigfoot hair samples have not been able to provide conclusive evidence because they do not match any other hair samples on record. |

|

Many Bigfoot tracks have been found in the Bluff Creek area. This is the same area where Roger Patterson would shoot his famous Bigfoot film footage. |

|

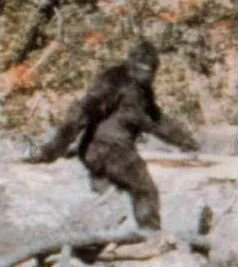

Frame 352 of the Patterson–Gimlin film, alleged to depict a female Bigfoot.[1] |

|

| Other name(s) | Sasquatch Other names |

|---|---|

| Country |

|

| Region | North America |

Bigfoot, also commonly referred to as Sasquatch, is a purported ape-like creature said to inhabit the forests of North America. Many dubious articles have been offered in attempts to prove the existence of Bigfoot, including anecdotal claims of sightings as well as alleged video and audio recordings, photographs, and casts of large footprints.[2] Some of which are known or admitted hoaxes.[3]

Tales of wild, hairy humanoids exist throughout the world,[4] and such creatures appear in the folklore of North America,[5] including the mythologies of indigenous people.[6][7] Bigfoot is an icon within the fringe subculture of cryptozoology,[8] and an enduring element of popular culture.[9]

The majority of mainstream scientists have historically discounted the existence of Bigfoot, considering it to be the result of a combination of folklore, misidentification, and hoax, rather than a living animal.[10][11] Folklorists trace the phenomenon of Bigfoot to a combination of factors and sources including indigenous cultures, the European wild man figure, and folk tales.[12] Wishful thinking, a cultural increase in environmental concerns, and overall societal awareness of the subject have been cited as additional factors.[13]

Other creatures of relatively similar descriptions are alleged to inhabit various regions throughout the world, such as the Skunk ape of the southeastern United States; the Almas, Yeren, and Yeti in Asia; and the Australian Yowie; all of which are also engrained in the cultures of their regions.[14]

Description

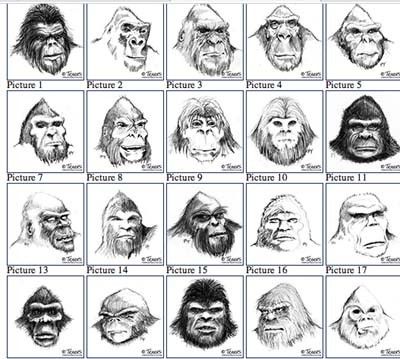

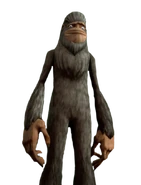

Bigfoot is most often described as a large, muscular, and bipedal ape-like creature covered in black, dark brown, or dark reddish hair.[16][17] Anecdotal descriptions estimate a height of roughly 1.8–2.7 metres (6–9 ft), with some descriptions having the creatures standing as tall as 3.0–4.6 metres (10–15 ft).[18] Some alleged observations describe Bigfoot as more «man-like»,[19] with reports of a human-like face.[20][21] In 1971, multiple people in The Dalles, Oregon, filed a police report describing an «overgrown ape», and one of the men claimed to have sighted the creature in the scope of his rifle, but could not bring himself to shoot it because, «It looked more human than animal».[22]

Common descriptions also include broad shoulders, no visible neck, and long arms, which skeptics describe as likely misidentification of a bear standing upright.[23] Some alleged nighttime sightings have stated the creature’s eyes «glowed» yellow or red.[24] However, eyeshine is not present in humans or any other known apes and so proposed explanations for observable eyeshine off of the ground in the forest include owls, raccoons, or opossums perched in foliage.[25]

Michael Rugg, owner of the Bigfoot Discovery Museum in Northern California, claims to have smelled Bigfoot, stating, «Imagine a skunk that had rolled around in dead animals and had hung around the garbage pits».[26]

The enormous footprints for which the creature is named are claimed to be as large as 610 millimetres (24 in) long and 200 millimetres (8 in) wide.[17] Some footprint casts have also contained claw marks, making it likely that they came from known animals such as bears, which have five toes and claws.[27][28]

History

Indigenous and early records

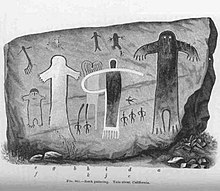

A reproduction of the petroglyphs at Painted Rock.

Many of the indigenous cultures across the North American continent include tales of mysterious hair-covered creatures living in forests,[29] and according to anthropologist David Daegling, these legends existed long before contemporary reports of «Bigfoot». These stories differed in their details both regionally and between families in the same community.[30]

On the Tule River Indian Reservation in Central California, petroglyphs created by a tribe of Yokuts at a site called Painted Rock are alleged by some to depict a group of Bigfoot called «the Family».[31] The local tribespeople call the largest of the glyphs «Hairy Man» and they are estimated to be between 500 and 1000 years old.[32] 16th century Spanish explorers and Mexican settlers in California told tales of the los Vigilantes Oscuros, or «Dark Watchers», large creatures alleged to stalk their camps at night.[33] In the region that is now Mississippi, a French Jesuit priest was living with the Natchez in 1721 and reported stories of hairy creatures in the forest known to scream loudly and steal livestock.[34]

Ecologist Robert Pyle argues that most cultures have accounts of human-like giants in their folk history, expressing a need for «some larger-than-life creature».[35] Each language had its own name for the creature featured in the local version of such legends. Many names mean something along the lines of «wild man» or «hairy man», although other names describe common actions that it was said to perform, such as eating clams or shaking trees.[36] Chief Mischelle of the Nlaka’pamux at Lytton, British Columbia told such a story to Charles Hill-Tout in 1898.[37]

The Sts’ailes people tell stories about sasq’ets, a shapeshifting creature that protects the forest. The name «Sasquatch» is the anglicized version of sasq’ets (sas-kets), roughly translating to «hairy man» in the Halq’emeylem language.[38]

Members of the Lummi tell tales about creatures known as Ts’emekwes. The stories are similar to each other in the general descriptions of Ts’emekwes, but details differed among various family accounts concerning the creature’s diet and activities.[39] Some regional versions tell of more threatening creatures: the stiyaha or kwi-kwiyai were a nocturnal race, and children were warned against saying the names so that the «monsters» would not come and carry them off to be killed.[40] The Iroquois tell of an aggressive, hair covered giant with rock-hard skin known as the Ot ne yar heh or «Stone Giant», more commonly referred to as the Genoskwa.[41] In 1847, Paul Kane reported stories by the natives about skoocooms, a race of cannibalistic wild men living on the peak of Mount St. Helens in southern Washington state. Also related to this area was an alleged incident in 1924 in which a violent encounter between a group of gold prospectors and a group of «ape-men» occurred. These allegations were reported in the July 16, 1924, issue of The Oregonian and have become a popular piece of Bigfoot lore, with the area now being referred to as Ape Canyon.[42] U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt, in his 1893 book, The Wilderness Hunter, writes of a story he was told by an elderly mountain man named Bauman in which a foul smelling, bipedal creature ransacked his beaver trapping camp, stalked him, and later became hostile when it fatally broke his companion’s neck in the wilderness near the Idaho-Montana border.[43] Roosevelt notes that Bauman appeared fearful while telling the story, but attributed the trapper’s folkloric German ancestry to have potentially influenced him.[44]

Less-menacing versions have also been recorded, such as one by Reverend Elkanah Walker from 1840. Walker was a Protestant missionary who recorded stories of giants among the natives living near Spokane, Washington. These giants were said to live on and around the peaks of the nearby mountains, stealing salmon from the fishermen’s nets.[45]

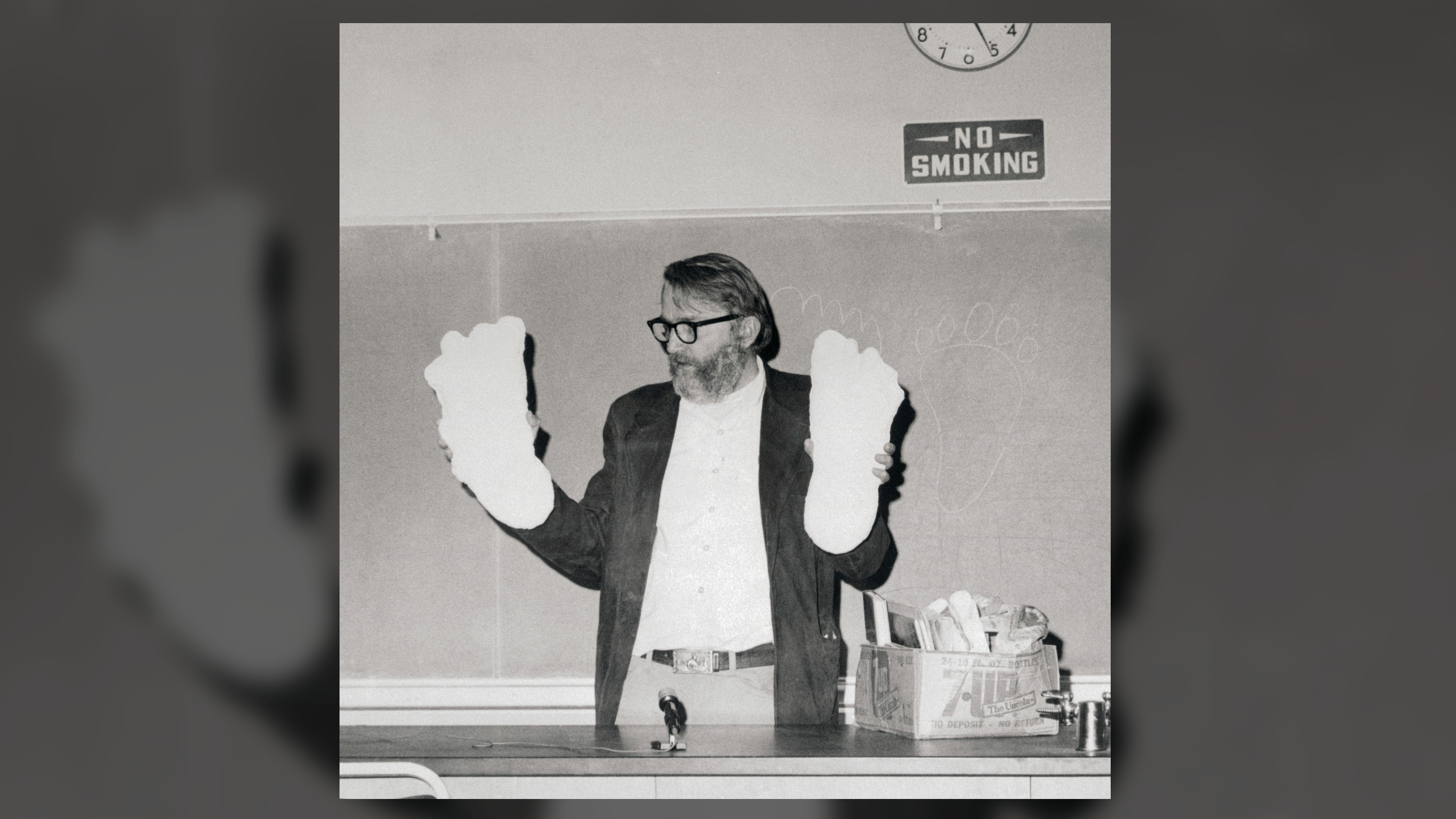

Origin of the «Bigfoot» name

In 1958, Jerry Crew, a logging company bulldozer operator in Humboldt County, California, discovered a set of large, 410 millimetres (16 in) human-like footprints sunk deep within the mud in the Six Rivers National Forest.[46] Upon informing his coworkers, many claimed to have seen similar tracks on previous job sites as well as telling of odd incidents such as an oil drum weighing 450 pounds (200 kg) having been moved without explanation. The logging company men soon began utilizing the term «Bigfoot» to describe the mysterious culprit.[47] Crew, who initially believed someone was playing a prank on them, once again observed more of these numerous, massive footprints and contacted reporter Andrew Genzoli of the Humboldt Times newspaper. Genzoli interviewed lumber workers and wrote articles about the mysterious footprints, introducing the name «Bigfoot» in relation to the tracks and the local tales of large, hairy wild men.[48] A plaster cast was made of the footprints and Crew appeared, holding one of the casts, on the front page of the newspaper on October 6, 1958. The story spread rapidly as Genzoli began to receive correspondence from major media outlets including the New York Times and Los Angeles Times.[49] As a result, the term «Bigfoot» became widespread as a reference to an apparently large, unknown creature leaving massive footprints in Northern California.[50]

In 2002, the family of Crew’s deceased coworker Ray Wallace stated that their father had been secretly making the large footprints with carved, wooden feet and that he was responsible for the tracks.[51] Despite the Wallace family’s statement, Willow Creek and Humboldt County are considered by some to be the «Bigfoot Capital of the World».[52]

Other historic uses of «Bigfoot»

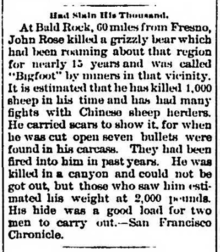

1895 article describing a giant grizzly bear named «Bigfoot».[53]

In the 1830s, a Wyandot chief was nicknamed «Big Foot» due to his significant size, strength and large feet.[54] Potawatomi Chief Maumksuck, known as Chief «Big Foot», is today synonymous with the area of Walworth County, Wisconsin and has a state park and school named for him.[55] William A. A. Wallace, a famous 19th century Texas Ranger, was nicknamed «Bigfoot» due to his large feet and today has a town named for him: Bigfoot, Texas.[56] Lakota leader Spotted Elk was also called «Chief Big Foot». In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, at least two enormous marauding grizzly bears were widely noted in the press and each nicknamed «Bigfoot». The first grizzly bear called «Bigfoot» was reportedly killed near Fresno, California in 1895 after killing sheep for 15 years; his weight was estimated at 2,000 pounds (900 kg).[53] The second one was active in Idaho in the 1890s and 1900s between the Snake and Salmon rivers, and supernatural powers were attributed to it.[57]

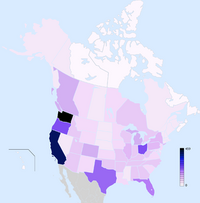

Sightings

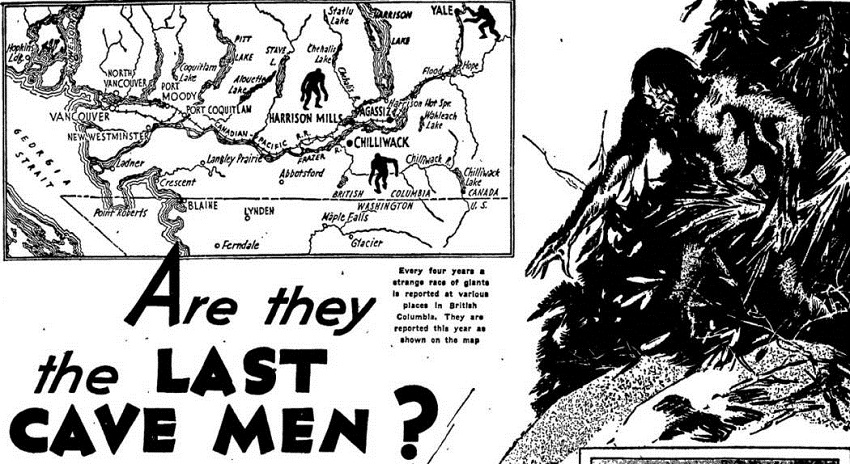

According to Live Science, there have been over 10,000 reported Bigfoot sightings in the continental United States.[58] About one-third of all claims of Bigfoot sightings are located in the Pacific Northwest, with the remaining reports spread throughout the rest of North America.[27][59][60] Most reports are considered mistakes or hoaxes, even by those researchers who claim Bigfoot exists.[61]

Sightings predominantly occur in the northwestern region of Washington, Oregon, Northern California, and British Columbia. Other prominent areas of supposed sightings include the rural areas of the Great Lakes region and the southeastern United States. According to data collected from the Bigfoot Field Researchers Organization’s (BFRO) Bigfoot sightings database in 2019, Washington has over 2,000 reported sightings, California over 1,600, Pennsylvania over 1,300, New York and Oregon over 1,000, and Texas has just over 800.[62] The debate over the legitimacy of Bigfoot sightings reached a peak in the 1970s, and Bigfoot has been regarded as the first widely popularized example of pseudoscience in American culture.[63]

Regional and other names

Many regions have differentiating names for the creatures.[64] In Canada, the name Sasquatch is widely used although often interchangeably with the name Bigfoot.[65] The United States uses both of these names but also has numerous names and descriptions of the creatures depending on the region and area in which they are allegedly sighted.[66] These include the Skunk ape in Florida and other southern states,[67] Grassman in Ohio,[68] Fouke Monster in Arkansas,[69] Wood Booger in Virginia,[70] the Monster of Whitehall in Whitehall, New York,[71] Momo in Missouri,[72] Honey Island Swamp Monster in Louisiana,[73] Dewey Lake Monster in Michigan,[74] Mogollon Monster in Arizona,[75] the Big Muddy Monster in southern Illinois,[76] and The Old Men of the Mountain in West Virginia.[77] The term Wood Ape is also used by some as a means to deviate from the perceived mythical connotation surrounding the name «Bigfoot».[78] Other names include Bushman, Treeman, and Wildman.[79]

Alleged behavior

Some Bigfoot researchers allege that Bigfoot throws rocks as territorial displays and for communication.[80][81][82] Other alleged behaviors include audible blows struck against trees or «wood knocking», further alleged to be communicative.[83][84][85]

Skeptics argue that these behaviors are easily hoaxed.[86]

Additionally, structures of broken and twisted foliage seemingly placed in specific areas have been attributed by some to Bigfoot behavior.[87] In some reports, lodgepole pine and other small trees have been observed bent, uprooted, or stacked in patterns such as weaved and crisscrossed, leading some to theorize that they are potential territorial markings.[88] Some instances have also included entire deer skeletons being suspended high in trees.[89] In Washington state, a team of amateur Bigfoot researchers called the Olympic Project claimed to have discovered a collection of nests, and they had primatologists study them, with the conclusion being that they appear to have been created by a primate.[90]

Many alleged sightings are reported to occur at night leading to some speculations that the creatures may possess nocturnal tendencies.[91] However, experts find such behavior untenable in a supposed ape- or human-like creature, as all known apes, including humans, are diurnal, with only lesser primates exhibiting nocturnality.[92] Most anecdotal sightings of Bigfoot describe the creatures allegedly observed as solitary, although some reports have described groups being allegedly observed together.[93]

Alleged vocalizations

Alleged vocalizations such as howls, screams, moans, grunts, whistles, and even a form of supposed language have been reported and allegedly recorded.[94][95] Some of these alleged vocalization recordings have been analyzed by individuals such as retired U.S. Navy cryptologic linguist Scott Nelson. He analyzed audio recordings from the early 1970s said to be recorded in the Sierra Nevada mountains dubbed the «Sierra Sounds» and stated, «It is definitely a language, it is definitely not human in origin, and it could not have been faked».[96] Les Stroud has spoken of a strange vocalization he heard in the wilderness while filming Survivorman that he stated sounded primate in origin.[97] The majority of mainstream scientists maintain that the source of the sounds often attributed to Bigfoot are either hoaxes, anthropomorphization, or likely misidentified and produced by known animals such as owl, wolf, coyote, and fox.[98][99][100]

Alleged encounters

A story from 1924, often referred to as the «Battle of Ape Canyon», presents miners being attacked by large, hairy «ape men» that threw rocks onto their cabin roof from a nearby cliff after one of the miners allegedly shot one with a rifle.[101] In Fouke, Arkansas in 1971, a family reported that a large, hair-covered creature startled a woman after reaching through a window. This alleged incident was later deemed a hoax.[102]

In 1974, the New York Times presented the dubious tale of Albert Ostman, a Canadian prospector, who stated that he was kidnapped and held captive by a family of Bigfoot for six days in 1924 in Toba Inlet, British Columbia.[103]

The 2021 Hulu documentary series, Sasquatch, describes marijuana farmers telling stories of Bigfoots harassing and killing people within the Emerald Triangle region in the 1970s through the 1990s; and specifically the alleged murder of three migrant workers in 1993.[104] Investigative journalist David Holthouse attributes the stories to illegal drug operations using the local Bigfoot lore to scare away competition, specifically superstitious immigrants, and that the high rate of murder and missing persons in the area is attributed to human actions.[105]

There have also been reports of dogs allegedly being killed by a Bigfoot. In the early 1990s, 9-1-1 audio recordings were made public in which a homeowner in Kitsap County, Washington called law enforcement for assistance with a large subject, described by him as being «all in black», having entered his backyard. He previously reported to law enforcement that his dog was killed recently when it was thrown over his fence.[106][107] Anthropologist Jeffrey Meldrum notes that any large predatory animal is potentially dangerous to humans, specifically if provoked, but indicates that most anecdotal accounts of Bigfoot encounters result in the creatures hiding or fleeing from people.[108] Some amateur researchers have reported the creatures moving or taking possession of intentional «gifts» left by humans such as food and jewelry, and leaving items in their place such as rocks and twigs.[109] Skeptics argue that many of these alleged human interactions are easily hoaxed, the result of misidentification, or are outright fabrications.[110]

Proposed explanations

A black bear showcasing its ability to sit in a human-like fashion.

Various explanations have been suggested for sightings and to offer conjecture on what existing animal has been misidentified in supposed sightings of Bigfoot. Scientists typically attribute sightings either to hoaxes or to misidentification of known animals and their tracks, particularly black bears.[111][112]

Misidentification

The 2007 photo of an unidentified creature captured on a trail camera.

Bears

Mainstream scientists theorize that American black bears are a likely culprit for most Bigfoot sightings, particularly when observers view a subject from afar, are in dense foliage or there are poor lighting conditions.[113] Additionally, black bears have been observed and recorded walking upright, often as the result of an injury.[114] While upright, adult black bears stand roughly 1.5–2.1 metres (5–7 ft),[115] and grizzly bears roughly 2.4–2.7 metres (8–9 ft),[116] both within the range of anecdotal Bigfoot reports.

In 2007, the Bigfoot Field Researchers Organization put forward photos which they stated showed a juvenile Bigfoot. The Pennsylvania Game Commission, however, stated that the photos were of a bear with mange.[117] The Pennsylvania Game Commission unsuccessfully attempted to locate the suspected mangey bear. Scientist Vanessa Woods, after estimating that the subject in the photo had approximately 560 millimetres (22 in) long arms and a 476 millimetres (18.75 in) torso, concluded it was more comparable to a chimpanzee.[118]

Escaped apes

Some have proposed that sightings of Bigfoot may simply be people observing and misidentifying known great apes such as chimpanzees, gorillas, and orangutans that have escaped from captivity such as zoos, circuses, and exotic pets belonging to private owners.[119] This explanation is often proposed in relation to the Bigfoot-like Skunk ape, as some argue the humid subtropical climate of the southeastern United States could potentially support a population of escaped apes.[120]

Humans

Humans have been mistaken for Bigfoot, with some incidents leading to injuries. In 2013, a 21-year-old man in Oklahoma was arrested after he told law enforcement he accidentally shot his friend in the back while their group was allegedly hunting for Bigfoot.[121] In 2017, a shamanist wearing clothing made of animal furs was vacationing in a North Carolina forest when local reports of alleged Bigfoot sightings flooded in. The Greenville Police Department issued a public notice not to shoot Bigfoot in fear of someone in a fur suit mistakenly being injured or killed.[122] In 2018, a person was shot at multiple times by a hunter near Helena, Montana who claimed he mistook him for a Bigfoot.[123]

Additionally, some have attributed feral humans or hermits living in the wilderness as being another explanation for alleged Bigfoot sightings.[124][125] One famous story, the Wild Man of the Navidad, tells of a wild ape-man who roamed the wilderness of eastern Texas in the mid-19th century, stealing food and goods from local residents. A search party allegedly captured an escaped African slave who was attributed to the story.[126] During the 1980s, a number of psychologically damaged American Vietnam veterans were stated by the state of Washington’s veterans’ affairs director, Randy Fisher, to have been living in remote wooded areas of the state.[127]

Pareidolia

Some have proposed that pareidolia may explain Bigfoot sightings, specifically the tendency to observe human-like faces and figures within the natural environment.[128][129] Photos and videos of poor quality alleged to depict Bigfoots are often attributed to this phenomenon and commonly referred to as «Blobsquatch».[130]

Hoaxes

Both Bigfoot believers and non-believers agree that many of the reported sightings are hoaxes or misidentified animals.[131] Author Jerome Clark argues that the Jacko Affair was a hoax, involving an 1884 newspaper report of an ape-like creature captured in British Columbia. He cites research by John Green, who found that several contemporaneous British Columbia newspapers regarded the alleged capture as highly dubious, and notes that the Mainland Guardian of New Westminster, British Columbia wrote, «Absurdity is written on the face of it.»[132]

In 1968, the frozen corpse of a supposed hair covered hominid measuring 5 feet 11 inches (1.8 m) was paraded around the United States as part of a traveling exhibition. Many stories surfaced as to its origin such as it having been killed by hunters in Minnesota or killed by American soldiers near Da Nang during the Vietnam War. It was attributed by some to be proof of Bigfoot-like creatures. Primatologist John R. Napier studied the subject and concluded it was a hoax made of latex. Others disputed this, claiming Napier did not study the original subject. As of 2013, the subject, dubbed the Minnesota Iceman, is on display at the «Museum of the Weird» in Austin, Texas.[133]

Tom Biscardi, long-time Bigfoot enthusiast and CEO of «Searching for Bigfoot, Inc.», appeared on the Coast to Coast AM paranormal radio show on July 14, 2005, and said that he was «98% sure that his group will be able to capture a Bigfoot which they had been tracking in the Happy Camp, California area.»[134] A month later, he announced on the same radio show that he had access to a captured Bigfoot and was arranging a pay-per-view event for people to see it. He appeared on Coast to Coast AM again a few days later to announce that there was no captive Bigfoot. He blamed an unnamed woman for misleading him, and said that the show’s audience was gullible.[134]

On July 9, 2008, Rick Dyer and Matthew Whitton posted a video to YouTube, claiming that they had discovered the body of a dead Bigfoot in a forest in northern Georgia. Tom Biscardi was contacted to investigate. Dyer and Whitton received $50,000 from «Searching for Bigfoot, Inc.»[135] The story was covered by many major news networks, including BBC,[136] CNN,[137] ABC News,[138] and Fox News.[139] Soon after a press conference, the alleged Bigfoot body was delivered in a block of ice in a freezer with the Searching for Bigfoot team. When the contents were thawed, observers found that the hair was not real, the head was hollow, and the feet were rubber.[140] Dyer and Whitton admitted that it was a hoax after being confronted by Steve Kulls, executive director of SquatchDetective.com.[141]

In August 2012, a man in Montana was killed by a car while perpetrating a Bigfoot hoax using a ghillie suit.[142][143]

In January 2014, Rick Dyer, perpetrator of a previous Bigfoot hoax, said that he had killed a Bigfoot in September 2012 outside San Antonio. He claimed to have had scientific tests conducted on the body, «from DNA tests to 3D optical scans to body scans. It is the real deal. It’s Bigfoot, and Bigfoot’s here, and I shot it, and now I’m proving it to the world.»[144][145] He said that he had kept the body in a hidden location, and he intended to take it on tour across North America in 2014. He released photos of the body and a video showing a few individuals’ reactions to seeing it,[146] but never released any of the tests or scans. He refused to disclose the test results or to provide biological samples. He said that the DNA results were done by an undisclosed lab and could not be matched to identify any known animal.[147] Dyer said that he would reveal the body and tests on February 9, 2014, at a news conference at Washington University,[148] but he never made the test results available.[149] After the Phoenix tour, the Bigfoot body was taken to Houston.[150]

On March 28, 2014, Dyer admitted on his Facebook page that his «Bigfoot corpse» was another hoax. He had paid Chris Russel of «Twisted Toybox» to manufacture the prop from latex, foam, and camel hair, which he nicknamed «Hank». Dyer earned approximately US$60,000 from the tour of this second fake Bigfoot corpse. He stated that he did kill a Bigfoot, but did not take the real body on tour for fear that it would be stolen.[151][152]

In April 2022, a man in Mobile, Alabama posted photos he claimed were of a Bigfoot to his Facebook page, indicating the Mobile County Sheriff’s Office validated their authenticity and the team from Finding Bigfoot was being dispatched. The photos circulated on social media, attracting the attention of NBC 15. The man admitted the photos were an April Fools’ Day hoax.[153]

On July 7, 2022, wildlife educator and media personality Coyote Peterson released a post on Facebook in which he claimed to have discovered a large primate skull in British Columbia, indicating that he had excavated and smuggled the skull into the United States for primatologist review. He further claimed to have initially hidden the discovery due to concerns that government agencies may intervene. The post went viral, quickly garnering the attention of multiple scientists who dismissed the skull as likely a replica of a gorilla skull. Darren Naish, a vertebrate paleontologist, stated, «I’m told that Coyote Peterson does this sort of thing fairly often as clickbait, and that this is a stunt done to promote an upcoming video. Maybe this is meant to be taken as harmless fun. But in an age where anti-scientific feelings and conspiracy culture are a serious problem it—again—really isn’t a good look. I think this stunt has backfired».[154]

Gigantopithecus

Fossil jaw of the extinct primate Gigantopithecus blacki

Bigfoot proponents Grover Krantz and Geoffrey H. Bourne both believed that Bigfoot could be a relict population of the extinct southeast Asian ape species Gigantopithecus blacki. According to Bourne, G. blacki may have followed the many other species of animals that migrated across the Bering land bridge to the Americas.[155] To date, no Gigantopithecus fossils have been found in the Americas. In Asia, the only recovered fossils have been of mandibles and teeth, leaving uncertainty about G. blacki‘s locomotion. Krantz has argued that G. blacki could have been bipedal, based on his extrapolation from the shape of its mandible. However, the relevant part of the mandible is not present in any fossils.[156] The more popular view is that G. blacki was quadrupedal, as its enormous mass would have made it difficult for it to adopt a bipedal gait.

Matt Cartmill criticizes the G. blacki hypothesis:

The trouble with this account is that Gigantopithecus was not a hominin and maybe not even a crown group hominoid; yet the physical evidence implies that Bigfoot is an upright biped with buttocks and a long, stout, permanently adducted hallux. These are hominin autapomorphies, not found in other mammals or other bipeds. It seems unlikely that Gigantopithecus would have evolved these uniquely hominin traits in parallel.[157]

Bernard G. Campbell writes: «That Gigantopithecus is in fact extinct has been questioned by those who believe it survives as the Yeti of the Himalayas and the Sasquatch of the north-west American coast. But the evidence for these creatures is not convincing.»[158]

Extinct hominidae

Primatologist John R. Napier and anthropologist Gordon Strasenburg have suggested a species of Paranthropus as a possible candidate for Bigfoot’s identity, such as Paranthropus robustus, with its gorilla-like crested skull and bipedal gait[159] —despite the fact that fossils of Paranthropus are found only in Africa.

Michael Rugg of the Bigfoot Discovery Museum presented a comparison between human, Gigantopithecus, and Meganthropus skulls (reconstructions made by Grover Krantz) in episodes 131 and 132 of the Bigfoot Discovery Museum Show.[160] Bigfoot enthusiasts that think Bigfoot may be the «missing link» between apes and humans have promoted the idea that Bigfoot is a descendent of Gigantopithecus blacki, but that ape diverged from orangutans around 12 million years ago and is not related to humans.[161]

Some suggest Neanderthal, Homo erectus, or Homo heidelbergensis to be the creature, but, like all other great apes, no remains of any of those species have been found in the Americas.[162]

Scientific view

Expert consensus is that allegations of the existence of Bigfoot are not credible science.[163] Belief in the existence of such a large, ape-like creature is more often attributed to hoaxes, confusion, or delusion rather than to sightings of a genuine creature.[16] In a 1996 USA Today article, Washington State zoologist John Crane said, «There is no such thing as Bigfoot. No data other than material that’s clearly been fabricated has ever been presented.»[35]

As with other similar beings, climate and food supply issues would make such a creature’s survival in reported habitats unlikely.[164] Bigfoot is alleged to live in regions unusual for a large, nonhuman primate, i.e., temperate latitudes in the northern hemisphere; all recognized nonhuman apes are found in the tropics of Africa and Asia. Great apes have not been found in the fossil record in the Americas, and no Bigfoot remains are known to have been found. Phillips Stevens, a cultural anthropologist at the University at Buffalo, summarized the scientific consensus as follows:

It defies all logic that there is a population of these things sufficient to keep them going. What it takes to maintain any species, especially a long-lived species, is you gotta have a breeding population. That requires a substantial number, spread out over a fairly wide area where they can find sufficient food and shelter to keep hidden from all the investigators.[165]

In the 1970s, when Bigfoot «experts» were frequently given high-profile media coverage, McLeod writes that the scientific community generally avoided lending credence to such fringe theories by refusing even to debate them.[63]

Primatologist Jane Goodall was asked for her personal opinion of Bigfoot in a 2002 interview on National Public Radio’s «Science Friday». She joked, «Well, now you will be amazed when I tell you that I’m sure that they exist.»[166]

She later added, chuckling, «Well, I’m a romantic, so I always wanted them to exist», and finally, «You know, why isn’t there a body? I can’t answer that, and maybe they don’t exist, but I want them to.»[167] In 2012, when asked again by the Huffington Post, Goodall said «I’m fascinated and would actually love them to exist,» adding, «Of course, it’s strange that there has never been a single authentic hide or hair of the Bigfoot, but I’ve read all the accounts.»[168]

Paleontologist and author Darren Naish states in a 2016 article for Scientific American that if «Bigfoot» existed, an abundance of evidence would also exist that cannot be found anywhere today, making the existence of such a creature exceedingly unlikely.[169]

Naish summarizes the evidence for «Bigfoot» that would exist if the creature itself existed:

- If «Bigfoot» existed, so would consistent reports of uniform vocalizations throughout North America as can be identified for any existing large animal in the region, rather than the scattered and widely varied «Bigfoot» sounds haphazardly reported;

- If «Bigfoot» existed, so would many tracks that would be easy for experts to find, just as they easily find tracks for other rare megafauna in North America, rather than a complete lack of such tracks alongside «tracks» that experts agree are fraudulent;

- Finally, if «Bigfoot» existed, an abundance of «Bigfoot» DNA would already have been found, again as it has been found for similar animals, instead of the current state of affairs, where there is no confirmed DNA for such a creature whatsoever.[169]

«DeNovo: Journal of Science» article

A request to register the species name Homo sapiens cognatus was made by veterinarian Melba S. Ketchum,[170] lead of The Sasquatch Genome Project, following publication of «Novel North American Hominins, Next Generation Sequencing of Three Whole Genomes and Associated Studies», Ketchum, M. S., et al., in the DeNovo: Journal of Science, 13 Feb 2013.[171] The article examined 111 samples of blood, tissue, hair, and other specimens «characterized and hypothesized» to have been «obtained from elusive hominins in North America commonly referred to as Sasquatch.»

The title «DeNovo: Journal of Science» in which the paper was published was later found to be a Web site—registered only nine days before the paper was announced—whose first and only «journal» issue contained nothing but the «Sasquatch» article described above.[172][173]

In 2013, ZooBank, the non-governmental organization that is generally accepted by zoologists to assign species names, approved the registration request for the subspecies name Homo sapiens cognatus to be used for the reputed hominid more familiarly known as Bigfoot or Sasquatch.[174] «Cognatus» is a Latin term meaning «related by blood.»

According to a statement by an ICZN associate scientist, «ZooBank and the ICZN do not review evidence for the legitimacy of organisms to which names are applied – that is outside our mandate, and is really the job of the relevant taxonomic/biological community (in this case, primatologists) to do that. When H. s. cognatus was first registered, needless to say we received a lot of inquiry about it. We scrutinized the original description and registration of this name as best as we could, and as far as we can determine, all the requirements were fulfilled for establishing the new name. Thus, at the moment, we have no grounds to reject the scientific name. This says nothing about the legitimacy of the taxon concept – it’s just about whether the name was established according to the rules.»

Opinions of primatologists are generally against the existence of the purported species, as described above.

Researchers

Ivan T. Sanderson and Bernard Heuvelmans, founders of the subculture and pseudoscience of cryptozoology, have spent parts of their career searching for Bigfoot.[175] Later scientists who researched the topic included Jason Jarvis, Carleton S. Coon, George Allen Agogino and William Charles Osman Hill, though they later stopped their research due to lack of evidence for the alleged creature.[176]

John Napier asserts that the scientific community’s attitude towards Bigfoot stems primarily from insufficient evidence.[177] Other scientists who have shown varying degrees of interest in the creature are Grover Krantz, Jeffrey Meldrum, John Bindernagel, David J. Daegling,[178] George Schaller,[35][179][180] Russell Mittermeier, Daris Swindler, Esteban Sarmiento,[181] and Mireya Mayor.[182]

Formal studies

One study was conducted by John Napier and published in his book Bigfoot: The Yeti and Sasquatch in Myth and Reality in 1973.[183][better source needed] Napier wrote that if a conclusion is to be reached based on scant extant «‘hard’ evidence,» science must declare «Bigfoot does not exist.»[184] However, he found it difficult to entirely reject thousands of alleged tracks, «scattered over 125,000 square miles» (325,000 km2) or to dismiss all «the many hundreds» of eyewitness accounts. Napier concluded, «I am convinced that Sasquatch exists, but whether it is all it is cracked up to be is another matter altogether. There must be something in north-west America that needs explaining, and that something leaves man-like footprints.»[185]

In 1974, the National Wildlife Federation funded a field study seeking Bigfoot evidence. No formal federation members were involved and the study made no notable discoveries.[186] Also in 1974, the now defunct North American Wildlife Research Team constructed a «Bigfoot trap» in the Rogue River–Siskiyou National Forest in Jackson County, Oregon. It was baited with animal carcasses and captured multiple bears, but no Bigfoot.[187] Upkeep of the trap ended in the early 1980s, but in 2006 the United States Forest Service repaired the trap, which today is a tourist destination along the Collings Mountain hiking trail.[188]

Beginning in the late 1970s, physical anthropologist Grover Krantz published several articles and four book-length treatments of Sasquatch. However, his work was found to contain multiple scientific failings including falling for hoaxes.[189]

A study published in the Journal of Biogeography in 2009 by J.D. Lozier et al. used ecological niche modeling on reported sightings of Bigfoot, using their locations to infer preferred ecological parameters. They found a very close match with the ecological parameters of the American black bear, Ursus americanus. They also note that an upright bear looks much like a Bigfoot’s purported appearance and consider it highly improbable that two species should have very similar ecological preferences, concluding that Bigfoot sightings are likely misidentified sightings of black bears.[190]

In the first systematic genetic analysis of 30 hair samples that were suspected to be from Bigfoot-like creatures, only one was found to be primate in origin, and that was identified as human. A joint study by the University of Oxford and Lausanne’s Cantonal Museum of Zoology and published in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B in 2014, the team used a previously published cleaning method to remove all surface contamination and the ribosomal mitochondrial DNA 12S fragment of the sample. The sample was sequenced and then compared to GenBank to identify the species origin. The samples submitted were from different parts of the world, including the United States, Russia, the Himalayas, and Sumatra. Other than one sample of human origin, all but two are from common animals. Black and brown bears accounted for most of the samples, other animals include cow, horse, dog/wolf/coyote, sheep, goat, deer, raccoon, porcupine, and tapir. The last two samples were thought to match a fossilized genetic sample of a 40,000 year old polar bear of the Pleistocene epoch;[191] a second test identified the hairs as being from a rare type of brown bear.[192][193]

In 2019, the FBI declassified an analysis it conducted on alleged Bigfoot hairs in 1976. Amateur Bigfoot researcher Peter Byrnes sent the FBI 15 hairs attached to a small skin fragment and asked if the bureau could assist him in identifying it. Jay Cochran, Jr., assistant director of the FBI’s Scientific and Technical Services division responded in 1977 that the hairs were of deer family origin.[194][195]

Claims

An artist’s impression of the creature

After what The Huffington Post described as «a five-year study of purported Bigfoot (also known as Sasquatch) DNA samples»,[196] but prior to peer review of the work, DNA Diagnostics, a veterinary laboratory headed by veterinarian Melba Ketchum issued a press release on November 24, 2012, claiming that they had found proof that the Sasquatch «is a human relative that arose approximately 15,000 years ago as a hybrid cross of modern Homo sapiens with an unknown primate species.» Ketchum called for this to be recognized officially, saying that «Government at all levels must recognize them as an indigenous people and immediately protect their human and Constitutional rights against those who would see in their physical and cultural differences a ‘license’ to hunt, trap, or kill them.»[172] Failing to find a scientific journal that would publish their results, Ketchum announced on February 13, 2013, that their research had been published in the DeNovo Journal of Science. The Huffington Post discovered that the journal’s domain had been registered anonymously only nine days before the announcement. This was the only edition of DeNovo and was listed as Volume 1, Issue 1, with its only content being the Ketchum paper.[172][197][173] Shortly after publication, the paper was analyzed and outlined by Sharon Hill of Doubtful News for the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry. Hill reported on the questionable journal, mismanaged DNA testing and poor quality paper, stating that «The few experienced geneticists who viewed the paper reported a dismal opinion of it noting it made little sense.»[198] The Scientist magazine also analyzed the paper, reporting that:

Geneticists who have seen the paper are not impressed. «To state the obvious, no data or analyses are presented that in any way support the claim that their samples come from a new primate or human-primate hybrid,» Leonid Kruglyak of Princeton University told the Houston Chronicle. «Instead, analyses either come back as 100 percent human, or fail in ways that suggest technical artifacts.» The website for the DeNovo Journal of Science was setup [sic] on February 4, and there is no indication that Ketchum’s work, the only study it has published, was peer reviewed.[199]

A body print taken in the year 2000 from the Gifford Pinchot National Forest in Washington state dubbed the Skookum cast is also believed by some to have been made by a Bigfoot that sat down in the mud to eat fruit left out by researchers during the filming of an episode of the Animal X television show. Skeptics believe the cast to have been made by a known animal such as an elk.[200]

Anthropologist Jeffrey Meldrum, who specializes in the study of primate bipedalism, possesses over 300 footprint casts that he maintains could not be made by wood carvings or human feet based on their anatomy, but instead are evidence of a large, non-human primate present today in America.[201]

Image of Florida Bigfoot created with command prompts describing such a creature in an AI program

In 2005, Matt Crowley obtained a copy of an alleged Bigfoot footprint cast, called the «Onion Mountain Cast», and was able to painstakingly recreate the dermal ridges. Michael Dennett of the Skeptical Inquirer spoke to police investigator and primate fingerprint expert Jimmy Chilcutt in 2006 for comment on the replica and he stated, «Matt has shown artifacts can be created, at least under laboratory conditions, and field researchers need to take precautions».[202] Chilcutt had previously stated that some of the alleged Bigfoot footprint plaster casts he examined were genuine due to the presence of «unique dermal ridges».[203] Dennett states that Chilcutt had published nothing on the statements about «unique dermal ridges» that Chilcutt states prove authenticity, nor had anyone else published anything on that topic, with Chilcutt making his statements solely through a posting on the Internet.[202] Dennett states further that no reviews on Chilcutt’s statements had been performed beyond those by what Dennett states to be «other Bigfoot enthusiasts».[202]

In 2015, Centralia College professor Michael Townsend claimed to have discovered prey bones with «human-like» bite impressions on the southside of Mount St. Helens. Townsend claimed the bites were over two times wider than a human bite, and that he and two of his students also found 16-inch footprints in the area.[204]

Jeremiah Byron, host of the Bigfoot Society Podcast, believes Bigfoot are omnivores, stating, «They eat both plants and meat. I’ve seen accounts that they eat everything from berries, leaves, nuts, and fruit to salmon, rabbit, elk, and bear. Ronny Le Blanc, host of Expedition Bigfoot on the Travel Channel indicated he has heard anecdotal reports of Bigfoot allegedly hunting and consuming deer.[205]

Claims about the origins and characteristics of Bigfoot have also crossed over with other paranormal claims, including that Bigfoot, extraterrestrials, and UFOs are related or that Bigfoot creatures are psychic, can cross into different dimensions, or are completely supernatural in origin.[50] Additionally, claims regarding Bigfoot have been associated with conspiracy theories including a government cover-up.[206]

Patterson-Gimlin film

The most well-known video of an alleged Bigfoot, the Patterson-Gimlin film, was recorded on October 20, 1967, by Roger Patterson and Robert «Bob» Gimlin as they explored an area called Bluff Creek in Northern California. The 59.5-second-long video has become an iconic piece of Bigfoot lore, and continues to be a highly scrutinized, analyzed, and debated subject.[207]

Academic experts from related fields have typically judged the film as providing «no supportive data of any scientific value»[208] with perhaps the most common proposed explanation being that it was a hoax.[209]

Organizations and events

There are several organizations dedicated to the research and investigation of Bigfoot sightings in the United States. The oldest and largest is the Bigfoot Field Researchers Organization (BFRO).[210] The BFRO also provides a free database to individuals and other organizations. Their website includes reports from across North America that have been investigated by researchers to determine credibility.[211] Another includes the North American Wood Ape Conservancy (NAWAC), a nonprofit organization.[212] Other similar organizations exist throughout many U.S. states and their members come from a variety of backgrounds.[213][214]

Some organizations, as well as private researchers and enthusiasts own and operate Bigfoot museums.[215][216] In 2022, The Bigfoot Crossroads of America Museum and Research Center in Hastings, Nebraska was selected for addition into the archives of the U.S. Library of Congress.[217]

Conferences and festivals dedicated to Bigfoot are attended by thousands of people.[218][219] These events commonly include guest speakers, research and lore presentations, and sometimes live music, vendors, food trucks, and other activities such as costume contests and «Bigfoot howl» competitions.[220][221] The Chamber of Commerce in Willow Creek, California has hosted the «Bigfoot Daze» festival annually since the 1960s, drawing on the popularity of the local lore.[222] Some receive collaboration between local government and corporations, such as the Smoky Mountain Bigfoot Festival in Townsend, Tennessee which is sponsored by Monster Energy.[223] The 2022 Bigfoot Festival in Marion, North Carolina saw tens of thousands in attendance, resulting in a large economic boost for the small town of less than 8,000 residents.[224]

In February 2016, the University of New Mexico at Gallup held a two-day Bigfoot conference at a cost of $7,000 in university funds.[225]

In popular culture

Bigfoot has a demonstrable impact in popular culture,[226] and has been compared to Michael Jordan as a cultural icon.[227] In 2018, Smithsonian magazine declared «Interest in the existence of the creature is at an all-time high».[228] According to a poll taken in May 2020, about 1 in 10 American adults believe that Bigfoot is a real animal.[229] The creature has inspired the naming of a medical company, music festival, sports mascot, amusement park ride, monster truck, a Marvel Comics superhero and more. In 2022, A Bigfoot named «Legend» was selected as the official mascot for the World Athletics Championships being held in Eugene, Oregon.[230] October 20, the anniversary of the Patterson-Gimlin film recording, is considered by some as «National Sasquatch Awareness Day».[231]

Laws and ordinances exist regarding harming or killing a Bigfoot, specifically in the state of Washington. In 1969 in Skamania County, a law was passed making killing a Bigfoot punishable by a felony conviction resulting in a monetary fine up to $10,000 or five years imprisonment. In 1984, the law was amended to a misdemeanor and the entire county was declared a «Sasquatch refuge». Whatcom County followed suit in 1991, declaring the county a «Sasquatch Protection and Refuge Area».[232][233] In 2022, Grays Harbor County, Washington, passed a similar resolution after a local elementary school in Hoquiam submitted a classroom project asking for a «Sasquatch Protection and Refuge Area» to be granted.[234] In 2021, Rep. Justin Humphrey, in an effort to bolster tourism, proposed an official Bigfoot hunting season in Oklahoma, indicating that the Wildlife Conservation Commission would regulate permits and the state would offer a $3 million bounty if such a creature was captured alive and unharmed.[235][236]

In 2015, World Champion taxidermist Ken Walker completed what he believes to be a lifelike Bigfoot model based on the subject in the Patterson–Gimlin film.[237] He entered it into the 2015 World Taxidermy & Fish Carving Championships in Springfield, Missouri and was the subject of Dan Wayne’s 2019 documentary Big Fur.[238]

Some have been critical of Bigfoot’s rise to fame, arguing that the appearance of the creatures in cartoons, reality shows, and advertisements further reduces the potential validity of serious scientific research.[239] Others propose that society’s fascination with the concept of Bigfoot stems from human interest in mystery, the paranormal, and loneliness.[240] In a 2022 article discussing recent Bigfoot sightings, journalist John Keilman of the Chicago Tribune states, «As UFOs have gained newfound respect, becoming the subject of a Pentagon investigative panel, the alleged Bigfoot sighting is a reminder that other paranormal phenomena are still out there, entrancing true believers and amusing skeptics».[241]

In the 2018 podcast Wild Thing, creator and journalist Laura Krantz argues that the concept of Bigfoot can be an important part of environmental interest and protection, stating, «If you look at it from the angle that Bigfoot is a creature that has eluded capture or hasn’t left any concrete evidence behind, then you just have a group of people who are curious about the environment and want to know more about it, which isn’t that far off from what naturalists have done for centuries».[242][243] Bigfoot has been used in official government environmental protection campaigns, albeit comedically, by entities such as the U.S. Forest Service in 2015.[244]

The act of searching for or researching the creatures is often referred to as «Squatching» or «Squatch’n»,[245] popularized by the Animal Planet reality series, Finding Bigfoot.[246] Bigfoot researchers and believers are often called «Squatchers».[247]

During the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, Bigfoot became a part of many North American social distancing promotion campaigns, with the creature being referred to as the «Social Distancing Champion» and as the subject of various internet memes related to the pandemic.[248][249]

See also

- Bigfoot: The Life and Times of a Legend – 2009 book published by University of Chicago Press

- Sasquatch: Legend Meets Science – 2003 film documentary aired on Discovery Channel

- Sasquatch: Legend Meets Science – 2006 book published by Forge

Citations

- ^ «DNA tests to help crack mystery of Bigfoot or Yeti existence». The Australian. Associated Press. May 24, 2012. Retrieved May 21, 2014.

- ^ Daegling, David J. (2004). Bigfoot exposed: an anthropologist examines America’s enduring legend. Rowman Altamira. ISBN 0-7591-0538-3. Retrieved March 16, 2021.

- ^ Pappas, Evan (April 7, 2014). «Bigfoot hoax exposed (again) and other infamous hoaxes». seattlepi.com. Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Retrieved March 16, 2021.

- ^ McClelland, John (October 2011). «Tracking the Legend of Bigfoot». statemuseum.arizona.edu. Arizona State Museum. Retrieved January 3, 2022.

- ^ McNeill, Lynne (March 8, 2012). «Using Folklore to Tackle Bigfoot: ‘Animal Planet’ Comes to USU». usu.edu. Utah State University. Retrieved December 27, 2021.

- ^ Jilek-Aall, Louise (June 1972). «What is a Sasquatch — or, the Problematics of Reality Testing». Canadian Psychiatric Association Journal. 17 (3): 243–247. doi:10.1177/070674377201700312. S2CID 3205204. Retrieved January 11, 2022.

- ^ Munro, Kate (May 14, 2019). «North America’s Sasquatch: finding fact within the fable». sbs.com. NITV. Retrieved December 27, 2021.

- ^ Eliot, Krissy (June 28, 2018). «So, Why Do People Believe In Bigfoot Anyway?». alumni.berkeley.edu. Cal Alumni Association. Archived from the original on March 2, 2021. Retrieved March 16, 2021.

- ^ «Bigfoot’s pop culture footprint». Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 16, 2021.

- ^ Tracking key trends in biodiversity science and policy: based on the proceedings of a UNESCO International Conference on Biodiversity Science and Policy. UNESCO. 2013. pp. 50–. ISBN 978-92-3-001118-5.

- ^ B. Regal (April 11, 2011). Searching for Sasquatch: Crackpots, Eggheads, and Cryptozoology. Springer. ISBN 978-0-230-11829-4.

- ^ Blitz, Matt (August 5, 2021). «People Say They’ve Seen Bigfoot — Can We Really Rule Out That Possibility?». yahoo.com. Yahoo!. Retrieved August 6, 2021.

- ^ Walls, Robert E. 1996. «Bigfoot» in Brunvand, Jan Harold (editor). American Folklore: An Encyclopedia, p. 158–159. Garland Publishing, Inc.

- ^ «Beyond Bigfoot». amnh.org. American Museum of Natural History. Retrieved March 18, 2021.

- ^ «Shawnee Forest Bigfoot». enjoyillinois.com. Retrieved April 12, 2021.

- ^ a b «Bigfoot [a.k.a. Abominable Snowman of the Himalayas, Mapinguari (the Amazon), Sasquatch, Yowie (Australia) and Yeti (Asia)]». The Skeptic’s Dictionary. Archived from the original on September 14, 2008. Retrieved August 17, 2008.

- ^ a b «Sasquatch». Encyclopædia Britannica. 2008.

- ^ «Sasquatch». merriam-webster.com. Merriam-Webster. Retrieved May 11, 2021.

- ^ Boivin, John (January 16, 2021). «Bigfoot or moose? Possible sighting shocks, excites residents of small B.C. community». globalnews.ca. Global News. Retrieved December 21, 2021.

- ^ Aziz, Saba (August 14, 2021). «Bigfoot in Canada: Inside the hunt for proof — or at least a good photo». globalnews.ca. Global News. Retrieved December 21, 2021.

- ^ «‘No joke’: B.C. minister laughs off lawsuit claiming proof of Bigfoot». ctvnews.ca. CTV News. October 31, 2017. Retrieved December 21, 2021.

- ^ Cahill, Tim (May 10, 1973). «Giant Hairy Apes in the North Woods: A Bigfoot Study». rollingstone.com. Rolling Stone. Retrieved February 25, 2022.

- ^ Brulliard, Karin (July 5, 2016). «Is bigfoot just an upright-walking bear? We asked the experts». The Washington Post. Retrieved March 18, 2021.

- ^ Hodgin, Carrie (January 11, 2019). «Glowing Red-Eyes: Bigfoot Sightings Reported At Night In Mocksville». CBS News. WFMY-TV. Retrieved March 18, 2021.

- ^ Nickell, Joe (September 28, 2017). «Bigfoot Eyeshine: A Contradiction». centerforinquiry.org. Center for Inquiry. Retrieved March 18, 2021.

- ^ Robertson, Michelle (December 20, 2021). «‘We know it’s a Bigfoot because of the scream and the smell’: The man who saw Sasquatch». sfgate.com. SFGate. Retrieved December 21, 2021.

- ^ a b Nickell, Joe (January 2007). «Investigative Files: Mysterious Entities of the Pacific Northwest, Part I». Skeptical Inquirer. Retrieved October 20, 2009.

- ^ «SDNHM – Black Bear Sign». May 24, 2010. Archived from the original on May 24, 2010. Retrieved January 25, 2022.

- ^ «Sasquatch». oregonwild.org. Retrieved November 26, 2021.

- ^ Daegling 2004, p. 28

- ^ «Was Big Foot at the Reservation?». recorderonline.com. Porterville Recorder. November 14, 2013. Retrieved May 10, 2021.

- ^ Moskowitz, Kathy (August 13, 2004). «Mayak datat: An Archaeological Viewpoint of the Hairy Man Pictographs». bigfootproject.org. Retrieved May 4, 2021.

- ^ Almond, Elliott (January 31, 2022). «Trekking California’s mysterious Bigfoot trail». The Mercury News. Retrieved February 3, 2022.

- ^ Grayson, Walt (November 1, 2021). «Focused on Mississippi: «Bigfoot Bash» to be held in Natchez on November 4th». wjtv.com. WJTV. Retrieved November 26, 2021.

- ^ a b c Goodavage, Maria (May 24, 1996). «Hunt for Bigfoot Attracts True Believers». USA Today. Archived from the original on March 14, 2017. Retrieved July 19, 2007.

- ^ Meldrum, Jeff (2007). Sasquatch: Legend Meets Science. Macmillan. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-7653-1217-4. Retrieved February 19, 2010.

- ^ Chandler, Nathan (April 9, 2020). «What’s the Difference Between Sasquatch and Bigfoot?». science.howstuffworks.com. HowStuffWorks. Retrieved January 3, 2022.

- ^ Kadane, Lisa (July 21, 2022). «The true origin of Sasquatch». bbc.com. BBC. Retrieved August 10, 2022.

- ^ Rasmus, Stacy M. (2002). «Repatriating Words: Local Knowledge in a Global Context». American Indian Quarterly. 26 (2): 286–307. doi:10.1353/aiq.2003.0018. JSTOR 4128463. S2CID 163062209.

- ^ Rigsby, Bruce. «Some Pacific Northwest Native Language Names for the Sasquatch Phenomenon». Bigfoot: Fact or Fantasy?. Archived from the original on December 5, 2008. Retrieved August 18, 2008.

- ^ Mart, T.S.; Cabre, Mel (October 13, 2020). The Legend of Bigfoot: Leaving His Mark on the World. Red Lightning Books. pp. 24–25. ISBN 978-1684351398. Retrieved March 22, 2021.

- ^ Pyle, Robert Michael (1995), Where Bigfoot Walks: Crossing the Dark Divide, Houghton Mifflin Books, 1995, p. 131, ISBN 0-395-85701-5

- ^ «Roosevelt Relates ‘Bigfoot Story’«. tampabay.com. July 27, 2010. Retrieved March 18, 2021.

- ^ «Teddy Roosevelt Wrote About A Fatal Bigfoot Encounter». bearstatebooks.com. Bear State Books. Retrieved March 18, 2021.

- ^ «The Diary of Elkanah Walker». Bigfoot Encounters. Retrieved August 1, 2007.

- ^ Bailey, Eric (April 19, 2003). «Bigfoot’s Big Feat: New Life». Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ Flight, Tim (November 9, 2018). «The Hairy History of Bigfoot in 20 Intriguing Events». historycollection.com. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ McPhate, Mike (August 7, 2018). «When California introduced Bigfoot to the world». California Sun. Retrieved March 18, 2021.

- ^ Blu Buhs, Joshua (September 1, 2010). Bigfoot: The Life and Times of a Legend. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226079790. Retrieved March 18, 2021.

- ^ a b Nickell, Joe (2017). «Bigfoot As Big Myth: 7 Phases of Mythmaking». Skeptical Inquirer. 41 (5): 52–57. Archived from the original on August 26, 2018. Retrieved August 26, 2018.

- ^ «The enduring legend of Bigfoot». theweek.com. The Week. April 6, 2019. Retrieved March 18, 2021.

- ^ Eliot, Krissy. «Greetings from Willow Creek, Bigfoot Capital of the World». alumni.berkeley.edu. UC Berkeley. Retrieved March 18, 2021.

- ^ a b «Had Slain His Thousand». Placerville Mountain Democrat. No. p. 7. February 9, 1895. Retrieved October 22, 2016.

- ^ «Sketches of Western Adventure». Newbern Sentinel. No. p. 1. May 3, 1833. Retrieved May 8, 2018.

- ^ «Why is your high school named Big Foot?». bigfoot.k12.wi.us. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ «Texas Ranger «Big Foot» Wallace born». history.com. A&E Television Networks. November 16, 2009. Retrieved April 14, 2021.

- ^ «A Terror to Ranchmen. «Bigfoot,» the Giant Grizzly, and his Costly Depredations». Goshen Daily Democrat. No. p. 8. May 24, 1902. Retrieved October 22, 2016.

- ^ Radford, Benjamin; Patrick Pester (January 14, 2022). «Bigfoot: Is the Sasquatch real?». livescience.com. LiveScience. Retrieved February 25, 2022.

- ^ «Geographical Database of Bigfoot/Sasquatch Sightings and Reports». Bigfoot Field Research Organization. Archived from the original on August 19, 2008. Retrieved August 19, 2008.

- ^ Cartmill, Matt (January 2008). «Bigfoot Exposed: An Anthropologist Examines America’s Enduring Legend/Sasquatch: Legend Meets Science». American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 135 (1): 118. doi:10.1002/ajpa.20691.

- ^ Radford, Benjamin (November 6, 2012). «Bigfoot: Man-Monster or Myth?». Live Science. Retrieved January 2, 2016.

- ^ «Where has Bigfoot Been Sighted the Most? Washington, California, Pennsylvania Among Top States». Newsweek. May 9, 2019. Retrieved March 23, 2021.

- ^ a b McLeod, Michael (2009). Anatomy of a Beast: Obsession and Myth on the Trail of Bigfoot. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-520-25571-5.

- ^ «AKA Bigfoot World Map». google.com. Retrieved April 4, 2021.

- ^ Thomas, Nicki (January 26, 2018). «Sasquatch». thecanadianencyclopedia.ca. Retrieved April 4, 2021.

- ^ Walls, Robert (January 22, 2021). «Bigfoot (Sasquatch) legend». oregonencyclopedia.org. Retrieved April 4, 2021.

- ^ «Geographical Database of Bigfoot/Sasquatch Sightings & Reports». Bigfoot Field Researchers Organization. Archived from the original on February 28, 2009. Retrieved April 10, 2009.

- ^ Keating, Don (February 10, 2017). «The Legend of Bigfoot at Salt Fork State Park». visitguernseycounty.com. Guernsey County. Retrieved March 23, 2021.

- ^ Thompson, Amy Michelle (February 28, 2017). «Fouke Monster». encyclopediaofarkansas.net. Retrieved March 23, 2021.

- ^ Sorrell, Robert (August 26, 2016). «Fans, experts assemble for first ever Virginia Bigfoot Conference». richmond.com. Richmond Times. Retrieved April 4, 2021.

- ^ Price, Mark (July 16, 2018). «NY town proclaims Bigfoot its official animal. ‘It can’t hurt,’ town official says». The Charlotte Observer. Retrieved April 4, 2021.

- ^ Banias, MJ (September 30, 2019). «The Missouri Monster ‘Momo’ Is the Cryptid Time Forgot». Vice. Retrieved March 11, 2021.

- ^ «Big Foot». honeyislandswamp.com. Retrieved March 10, 2021.

- ^ Dimick, Aaron (May 30, 2016). «Michigan Monsters: Dewey Lake Monster legend comes to the surface». WWMT. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- ^ Ford, Erin (October 24, 2017). «Searching for the Mogollon Monster». Grand Canyon News. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- ^ Cates, Kristen (October 26, 2005). «Chasing Monsters: Big Muddy Monster still has Murphysboro residents wondering». The Southern Illinoisan. Retrieved April 9, 2021.

- ^ Todd, Roxy (October 29, 2021). «New W.Va. Bigfoot Museum Highlights A Local Take On The Mountain State’s Sasquatch». wvpublic.org. West Virginia Public Broadcasting. Retrieved December 21, 2021.

- ^ Bozek, Rachel. «Habitat Of The Wood Ape». aetv.com. A&E. Retrieved April 1, 2021.

- ^ Chandler, Nathan (April 9, 2020). «What’s the Difference Between Sasquatch and Bigfoot?». howstuffworks.com. Retrieved June 24, 2021.

- ^ Kimmick, Ed (August 19, 2012). «‘Sasquatch Watch’ researcher keeps on looking for rock-throwing beast». missoulian.com. Missoulian. Retrieved May 10, 2021.

- ^ Enzastiga, Adrian (September 20, 2018). «The hunt to prove the existence of Sasquatch». dailyiowan.com. The Daily Iowan. Retrieved May 18, 2021.

- ^ Bryan, Saint (August 20, 2019). «Real or hoax? A new Bigfoot exhibit is drawing standing-room crowds in Lacey». king5.com. KING-TV. Retrieved May 18, 2021.

- ^ Meier, Eric (September 27, 2016). «Wood knock warning». wrkr.com. WRKR. Retrieved August 31, 2021.

- ^ Sain, Johnny Carrol (September 25, 2020). «Finding bigfoot – In the woods in search of North America’s great, wild ape». hatchmag.com. Hatch Magazine. Retrieved August 31, 2021.

- ^ «Do Squatches Go Knock in the Night?». animalplanet.com. Animal Planet. Retrieved August 31, 2021.

- ^ Carlisle, John (December 27, 2016). «On the trail of Bigfoot in an Upper Peninsula Michigan forest». wusa9.com. WUSA. Retrieved May 18, 2021.

- ^ «Behavior». Bigfoot Field Researchers Organization. Retrieved November 16, 2020.

- ^ Carey, Liz (March 19, 2021). «Could Kentucky’s Deep Forests Hide a Piece of the ‘Bigfoot Puzzle’«. dailyyonder.com. Daily Yonder. Retrieved May 10, 2021.

- ^ Therriault, Ednor. «In Search of Bigfoot». mtoutlaw.com. Mountain Outlaw magazine. Retrieved March 24, 2021.

- ^ Neuharth, Spencer (September 2, 2020). «What’s the Best Evidence Bigfoot Exists?». themeateater.com. Jeremiah Byron, Bigfoot Society Podcast: MeatEater. Retrieved March 18, 2021.

- ^ Harrison, Shawn (July 23, 2020). «Hiker believes he might have found evidence of Bigfoot». The Herald Journal. Idaho State Journal. Retrieved March 18, 2021.

- ^ Martin, Robert (September 25, 2009). «Primates». Current Biology. 22 (18): R785–R790. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2012.07.015. PMID 23017987. S2CID 235311971.

- ^ Kelley, Michael (May 18, 2021). «Portland author explores lore of Bigfoot in Maine». pressherald.com. The Forecaster. Retrieved May 18, 2021.

- ^ Weisberger, Mindy (December 8, 2019). «‘Expedition Bigfoot’ Scours Oregon Woods for Signs of the Mythical and Elusive Beast». livescience.com. Live Science. Retrieved March 18, 2021.

- ^ Mullane, JD (November 25, 2021). «A scream in the night, but was it Bigfoot in that PA forest?». Courier Times. Retrieved November 26, 2021.

- ^ «Retired Navy man studies Bigfoot sounds». The Hastings Tribune. February 18, 2019. Retrieved November 17, 2020.

- ^ Cleary, Tom (March 21, 2021). «Joe Rogan Says These Sounds Are the ‘Weirdest S*** Ever’«. heavy.com. Heavy. Retrieved March 24, 2021.

- ^ Cockle, Richard (January 20, 2013). «Bigfoot or animals? Strange sounds coming from swamp on Umatilla Indian Reservation». The Oregonian. Retrieved March 24, 2021.

- ^ Stollznow, Karen. «(Big)foot in Mouth: Bigfoot Language». scientificamerican.com. Scientific American. Retrieved March 24, 2021.

- ^ Tuggle, Zach (August 2, 2022). «An Ohio woman is convinced she recorded Bigfoot. Experts say it could be something else». USA Today. Mansfield News Journal. Retrieved August 8, 2022.

- ^ Perry, Douglas (May 17, 2019). «How a 1924 Bigfoot battle on Mt. St. Helens helped launch a legend: Throwback Thursday». oregonlive.com. The Oregonian. Retrieved March 31, 2021.

- ^ Charton, Scott (July 20, 1986). «15 Summers After Tracks Found, Fouke Monster Called Hoax». apnews.com. Associated Press. Retrieved March 31, 2021.

- ^ Anderson, David (January 20, 1974). «It’s hard to prove that something, even a monster, does not exist». The New York Times. Retrieved December 22, 2021.

- ^ Ali, Lorraine (April 20, 2021). «Weed culture. True crime. Bigfoot lore. ‘Sasquatch’ has something for everyone». Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 21, 2021.

- ^ White, Peter (April 20, 2021). «‘Sasquatch’: Director Joshua Rofé On Bringing Together Bigfoot, Weed & Murder In Hulu Doc Series». deadline.com. Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved April 21, 2021.

- ^ «Bigfoot 911 Call in Washington State». youtube.com. Archived from the original on November 23, 2021. Retrieved March 31, 2021.

- ^ «1990 Bigfoot 911 calls in (HD)». youtube.com. Archived from the original on November 23, 2021. Retrieved March 31, 2021.

- ^ Neuharth, Spencer (September 16, 2020). «Is Bigfoot Dangerous?». themeateater.com. MeatEater. Retrieved March 31, 2021.

- ^ «Gifts From The Other Side». sasquatchinvestigations.org. Sasquatch Investigations of The Rockies. January 24, 2013. Retrieved March 31, 2021.

- ^ Judd, Ron (September 30, 2019). «The legend of Sasquatch won’t die. (But if just one Bigfoot would — die, that is — Ron Judd would become a believer.)». The Seattle Times. Retrieved March 31, 2021.

- ^ Holmes, Bob (July 6, 2009). «Bigfoot’s likely haunts ‘revealed’«. New Scientist. Retrieved January 2, 2016.

- ^ Price, Mark (November 10, 2021). «Images of beast on 2 feet inspires talk of Bigfoot in North Carolina. It’s a bear». The Sacramento Bee. Retrieved November 22, 2021.

- ^ Nickell, Joe (October 2013). «Bigfoot Lookalikes: Tracking Hairy Man-Beasts». skepticalinquirer.com. Skeptical Inquirer. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ Handwerk, Brian (July 7, 2016). «Watch: Tough Bear Powers Through Injury by Walking Upright». nationalgeographic.com. National Geographic. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ «Facts about Black Bears» (PDF). njfishandwildlife.com. New Jersey Fish and Wildlife. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved April 21, 2021.

- ^ «Brown Bears». nps.gov. National Park Service. Retrieved April 21, 2021.

- ^ «Hunter’s pics revive lively Bigfoot debate». MSNBC. October 29, 2007. Retrieved February 16, 2011.

- ^ «Bigfoot Science Fiction Or Science Fact?». Scientriffic (58): 17. November 2008.

- ^ Radford, Ben (August 14, 2012). «Could Escaped Animals Account for Bigfoot Reports?». seeker.com. Seeker. Retrieved April 21, 2021.

- ^ Poling, Dean (September 11, 2014). «Planet of the Skunk Apes». valdostadailytimes.com. Valdosta Daily Times. Retrieved April 21, 2021.

- ^ Jauregui, Andres (December 6, 2017). «‘Bigfoot Hunt’ Goes Wrong, Ends With Man Shot, Three Arrested». HuffPost. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ «Man in suit believes he may have been mistaken as Bigfoot in NC». WTVD. ABC News. August 10, 2017. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ Casiano, Louis (December 19, 2018). «Hunter thought he was firing at Bigfoot, ‘victim’ tells police». Fox News. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ Cooke, Bruno (March 31, 2021). «Are there feral people in national parks? Behind TikTok’s cannibal claims». thefocus.news. Retrieved April 21, 2021.

- ^ Jones, Terry (April 14, 2017). «Louisiana’s Wild Men». countryroadsmagazine.com. Retrieved April 21, 2021.

- ^ Reese, Randy (July 23, 2002). «Wildman of the Navidad: Truth or Tall Tale?». bfro.net. Retrieved April 21, 2021.

- ^ «U.S Wilds Hide Scars of Vietnam». The New York Times. December 31, 1983. Retrieved April 21, 2021.

- ^ «When it looks like aliens but it’s just Nature!». yankeeskeptic.com. September 11, 2016. Retrieved May 11, 2021.

- ^ Plait, Phil (October 9, 2011). «Sunsquatch». discovermagazine.com. Discover Magazine. Retrieved May 11, 2021.

- ^ Klee, Miles (November 6, 2012). «America, Meet ‘Blobsquatch’«. blackbookmag.com. BlackBook. Retrieved May 11, 2021.

- ^ Radford, Benjamin (March–April 2002). «Bigfoot at 50 Evaluating a Half-Century of Bigfoot Evidence». Skeptical Inquirer. Retrieved August 17, 2008.

- ^ Clark, Jerome (1993). Unexplained! 347 Strange Sightings, Incredible Occurrences and Puzzling Physical Phenomena. Visible Ink. p. 195. ISBN 978-0-8103-9436-0.

- ^ Naish, Darren (January 2, 2017). «The Strange Case of the Minnesota Iceman». scientificamerican.com. Scientific American. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ a b «Georgia Bigfoot body in freezer». Retrieved March 30, 2010.

- ^ Boone, Christian; Kathy Jefcoats (August 20, 2008). «Searching for Bigfoot group to sue Georgia hoaxers». The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Archived from the original on December 6, 2008.

- ^ «Americans ‘find body of Bigfoot’«. BBC News. August 15, 2008. Retrieved March 31, 2010.

- ^ «Body proves Bigfoot no myth, hunters say». CNN. August 15, 2008. Archived from the original on March 18, 2010. Retrieved March 31, 2010.

- ^ Ki Mae Heusser (August 15, 2008). «Legend of Bigfoot: Discovery or Hoax?». ABC News. Archived from the original on February 11, 2017. Retrieved March 30, 2010.

- ^ Wollan, Malia (September 16, 2008). «Georgia men claim hairy, frozen corpse is Bigfoot». Fox News. Retrieved April 1, 2010.

- ^ Keefe, Bob (August 19, 2008). «Bigfoot’s body a hoax, California site reveals». Cox News Service. Archived from the original on December 6, 2008. Retrieved April 1, 2010.

- ^ Ki Mae Heusser (August 19, 2008). «A Monster Discovery? It Was Just a Costume». ABC News. Archived from the original on September 29, 2008. Retrieved October 22, 2008.

- ^ Lynch, Rene (August 28, 2012). «Bigfoot hoax ends badly: Montana jokester hit, killed by car». Los Angeles Times. Retrieved December 24, 2013.

- ^ Skeptical Inquirer, Vol. 36 #6, Nov. 2012, p. 9

- ^ Lee Speigel (January 5, 2014). «Bigfoot Hunter Rick Dyer Claims He Killed The Hairy Beast And Will Take It On Tour». The Huffington Post. Retrieved January 7, 2014.

- ^ Tim Gerber (January 2, 2014). «Bigfoot hunter shares pictures of dead creature». KSAT-TV. Archived from the original on January 8, 2014. Retrieved January 7, 2014.

- ^ Rick Dyer. People’s Reactions Seeing a Real Bigfoot. YouTube. Archived from the original on January 6, 2014.

- ^ Zoe Mintz (January 29, 2014). «Rick Dyer, Bigfoot Hunter, Shares New Photos Of Alleged ‘Monster’ Sasquatch». International Business Times. Retrieved February 1, 2014.

- ^ Mucha, Peter (January 15, 2014). «Bigfoot Revealed February 9, 2014». Philly.com. Retrieved January 17, 2014.

- ^ «Bigfoot On Tour». WGHP. February 8, 2014. Retrieved February 10, 2014.

- ^ Uhl, Norm (February 5, 2014). «Bigfoot On Tour in Houston». Interactive One. Archived from the original on February 11, 2014. Retrieved February 10, 2014.

- ^ «Bigfoot Killed in San Antonio?». Snopes.com. March 31, 2014. Retrieved April 2, 2014.

- ^ Landau, Joel (March 31, 2014). «Bigfoot hunter Rick Dyer admits he lied about killing the beast». Daily News. Retrieved April 2, 2014.

- ^ Lane, Keith (April 15, 2022). «First the leprechaun and now this? Photos of Wilmer Bigfoot hoax go viral». WPMI-TV. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- ^ Lanese, Nicoletta (July 8, 2022). «Scientists dismiss Coyote Peterson’s ‘large primate skull’ discovery as fake». livescience.com. Live Science. Retrieved July 11, 2022.

- ^ Bourne, Geoffrey H.; Cohen, Maury (1975). The Gentle Giants: The Gorilla Story. G.P. Putnam’s Sons. pp. 296–300. ISBN 978-0-399-11528-8.

- ^ Daegling 2004, p. 14

- ^ Cartmill 2008, p. 117

- ^ Campbell, Bernard G. (1979). Humankind Emerging. Little, Brown and Company. p. 100. ISBN 978-0-673-52170-5. Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 78-78234.

- ^ Coleman, Loren. «Scientific Names for Bigfoot». BFRO. Archived from the original on September 9, 2008. Retrieved August 19, 2008.

- ^ «Bigfoot Discovery Project Media». Archived from the original on April 19, 2010. Retrieved April 4, 2010.

- ^ Ciaccia, Chris (November 14, 2019). «Missing link found? ‘Original Bigfoot’ was close relative of orangutan, study says». foxnews.com. Fox News. Retrieved February 8, 2022.

- ^ Daegling 2004, p. 16

- ^ Robert B. Stewart (2007). Intelligent design: William A. Dembski & Michael Ruse in dialogue. p. 83. ISBN 9780800662189.

- ^ Sjögren, Bengt (1980). Berömda vidunder (in Swedish). Settern. ISBN 978-91-7586-023-7.

- ^ Earls, Stephanie. «Bigfoot hunting». Archived from the original on January 29, 2010. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ^ «Sasquatch: Legend Meets Science». NPR.

- ^ Flatow, Ira (September 27, 2002). «Transcript of Dr. Jane Goodall’s Comments on NPR Regarding Sasquatch». Bigfoot Field Researchers Organization. Retrieved October 14, 2016 – via National Public Radio’s Science Friday.