Доброго времени суток, дорогие читатели. Сегодня мы продолжаем путешествие по древнегреческой мифологии, а остановиться мы хотим на Аполлоне (Фебе) – невероятно красивом боге, златокудром и сребролуким, который олицетворял собой мужскую красоту и делает это по сей день. В греческой мифологии Аполлон был покровителем искусств, предводителем Муз, предсказателем, врачевателем и покровителем переселенцев, а в более поздней мифологии – Аполлон был еще и богом солнца. Но как, столь юный бог, сумел получить столько ответственных «должностей»? Об этом вы и узнаете в нашей статье.

Рождение

К сожалению, рождение одного из величайших сыновей верховного бога Олимпа проходило отнюдь не так радужно, каким оно могло бы быть. История Аполлона начинается с того, что отец его – громовержец Зевс, полюбил прекрасную красавицу, богиню Лето. К сожалению, на тот момент он находился в официальном браке с богиней Герой. И когда она узнала, что Зевс ей в очередной раз изменил, и, более того, любовница собирается подарить ему сына, то верховная богиня невероятно разозлилась.

Против мужа, верховного бога, Гера физически не могла ничего предпринять, т.к. однажды подняв бунт, она была жестоко наказана своим мужем и давала ему клятву никогда не поднимать восстание против Зевса. А вот отомстить сопернице – пожалуйста. И мщение ее было страшным. Гера запретила земле принимать Лето, а точнее – предоставлять ей место для родов. Более того, она наслала не незадачливую любовницу грозного и ужасного змея Пифона, порождение Геи, который обитал вблизи горы Парнас.

Ни на минуту Лето не могла присесть и отдохнуть. Могучий змей, по наущению Геры, постоянно ее преследовал и всячески ей досаждал. Долго скиталась любовница Зевса. Она исходила всю Элладу, но ни один клочок земли не соглашался приютить незадачливую богиню, ибо месть Геры была страшна.

В конце концов, Лето сумела найти пристанище. Им стал плавучий остров Делос, который и землей-то назвать нельзя было. Однако мщение Геры на этом не закончилось. Она запретила своей дочери Илифии, отвечающей за роды, помогать Лето. Долгих девять дней мучилась Лето, ибо без Илифии на свет не появлялся ни один младенец, будь он хоть человеком, хоть богом.

И только спустя эти долгие девять дней, другие олимпийцы сумели убедить Илифию помочь Лето. Как только Илифия спустилась на Делос, едва только она прикоснулась к Лето, как последняя, в тот же момент, родила двух прекрасных близнецов, которые получили имена: Аполлон и Артемида. При этом, хмурый и неприветливый дотоле остров, мгновенно расцвел и засиял совершенно новыми красками.

Детство и юность

Лето и ее новорожденные дети продолжают укрываться на острове от мщения Геры и Пифона, преследовавшего богиню. Однако Лето действительно родила прекрасных детей, будущих богов. Мифология гласит, что росли они не по дням, а по часам. Так, на седьмые сутки, Аполлон покинул пеленки. Уже тогда он был невероятно красивым и даже великолепным, а главное – безумно сильным.

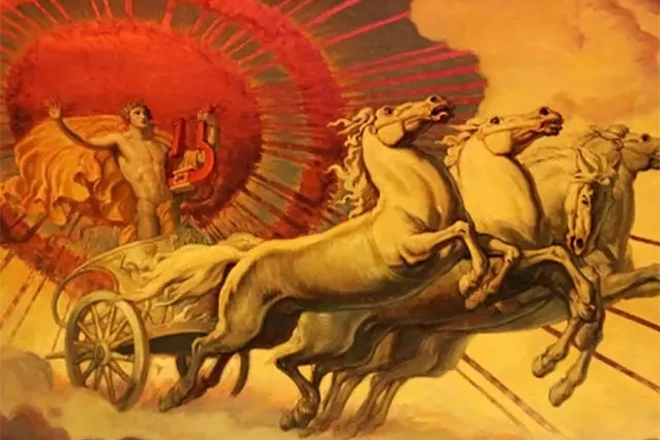

Зевс, видя, какого прекрасного сына подарила ему Лето, не сдерживает своего восхищения его могуществом и красотой. Отец дарит сыну семиструнную лиру, колесницу в которую, вместо коней, были запряжены два могучих лебедя, серебряный лук и стрелы, которые, специально для Аполлона, по указанию Зевса, изготовил сам Гефест.

Аполлон принимает подарки отца и сразу же отправляется в путь, на своей колеснице. Т.к. он был еще совсем юным, и даже маленьким, единственной его целью было доказать всем, что он не просто так пришел в этот мир. Но больше всего на свете он хочет постичь искусство прорицания, дабы открывать людям их путь. Для этого он направляет своих лебедей в прекрасную страну – Гиперборею, невероятно богатую и счастливую, где жители никогда не стареют и всегда ходят веселые и радостные. Там Аполлон и постигает искусство прорицания.

Жители Гипербореи обучают хорошо, а Аполлон – способный ученик. Он быстро добивается того, чего хотел, после чего задумывает вернуться на родину, дабы возвести собственный храм. Место для своего храма он находит очень быстро. Это площадка, около прекрасного источника, посреди лесной чащи. Однако в этих местах обитала нимфа Тельфуса. И ей совсем не понравилось то, что Аполлон нагрянул в ее владения.

Задать вопрос

Почему Гера не мстила Аполлону также, как и другим детям Зевса?

Мифология умалчивает об этом, но, скорее всего, она, как и другие олимпийцы, прониклась красотой и силой юного бога и признала в нем равного (как случилось и с Гераклом, впоследствии).

Победа над Пифоном

Однако противостоять сыну громовержца было не в ее власти, поэтому она решила действовать хитростью. Она убедила юного бога, что в этих местах слишком шумно, и что совсем рядом есть отличное тихое место, где он сможет возвести свой храм. Аполлон поверил нимфе, и отправился к подножью горы Парнас. Аполлон не ожидал подвоха, однако едва он уселся готовить чертежи, для собственного храма, как сзади него нависает огромная змеиная тень, тень Пифона.

По преданиям, Пифон был настолько огромным, что способен был обернуться вокруг горы Парнас 9 раз. Достаточно долго ждал он своего часа, часа мщения за то, что не сумел полноценно выполнить требование Геры, однако теперь у него есть полноценная возможность исправиться. Долго длилась битва, между божествами. Однако юный, прыткий и стреляющий без промаха сын Зевса сумел победить змея. Правда, для этого ему пришлось выпустить тысячу стрел. Так Аполлон сумел отомстить и за мать, и за себя, за то, что змей преследовал его, пока он еще находился в материнской утробе.

Гее, богине земли, совсем не понравилось, что ее дитя было убито. Смерть своего порождения она воспринимает как личное оскорбление и отправляется жаловаться самому Зевсу. Зевс, хоть он и покровительствовал Аполлону, все же выслушал жалобу Геи и предпринял меры. Он направил Аполлона в храм, дабы смыть со своих рук кровь убийства.

Аполлон выполняет просьбу отца, однако радость победы над столь грозным существом обуяло его, и в честь этой победы, Аполлон учреждает Пифийские игры – религиозные и спортивные состязания. Кроме того, он немного оскорбил Эрота, за что впоследствии поплатился, но об этом чуть позже.

Молодые годы

Аполлон построил свой храм, свое святилище. Но пока там не было жрецов, это было всего лишь здание. Долго сидел он на берегу моря и думал, где же ему достать жрецов, верных и честных. В этот момент, вдалеке на море, он увидел корабль, который вот-вот должен был затонуть. Не раздумывая, он превращается в дельфина и мигом доплывает до корабля.

На борту он обнаруживает голодных, усталых, ослабших и едва живых моряков, плывущих из Крита. Аполлон обещает спасти их, если они согласятся до конца жизни остаться жрецами в его храме. Моряки дают ему клятву, и Аполлон быстро приводит корабль к берегу. Так он получил жрецов, которых и обучил божественным таинствам.

Оставалось лишь дать месту имя. Моряки, помня, что Аполлон спас их, будучи в образе дельфина, прозвали святилище Дельфами, которое станет самым почитаемым святилищем Древней Греции. Именно тут простые смертные могли узнать свою судьбу, уготованную им богами. Жрецы же стали дельфийскими оракулами.

Аполлон на Олимпе

Достигнув совершеннолетия, Аполлон с триумфом попадает на Олимп, вместе с сестрой Артемидой и матерью Лето. Все поражены могуществом и красотой юного бога. Игрой на своей лире он услаждал слух бессмертных и смертных, но лук его – был грозным оружием, которое не щадило никого. Кроме того, Аполлон жестоко мстил тем, кто осмеливался оскорблять людей и божеств, находящихся под его покровительством. Стрелы его не знали пощады…

Месть за мать

По одной из легенд, Аполлон совершенствовал свое искусство прорицания, обучаясь у бога пастухов – Пана. Когда он в совершенстве овладел им, то пригласил к себе в храм Артемиду и Лето. К сожалению Лето, будучи в храме, была замечена великаном Титием. Мстительная Гера не забыла измены мужа, которая стала еще тяжелее из-за того, насколько блистательными оказались Аполлон и Афродита.

Рекомендуем по теме

Гера внушила страсть Титию к Лето. В результате, обезумевший великан, попытался схватить Лето и изнасиловать ее. Однако Аполлон и Артемида вовремя подоспели и расстреляли Тития из своих луков, защитив честь матери.

Во второй раз Аполлон заступился за Лето, из-за царицы Ниобы. По преданию она была любовницей самого Зевса, однако совместных детей у них не было. Но царица славилась своей плодовитостью. Своему супругу, Амфиону, царица подарила целых 14 детей. Из-за этого она стала насмехаться над Лето, у которой было всего двое детей, Аполлон и Артемида. Разгневанная богиня пожаловалась детям.

Аполлон не стал мириться с оскорблением матери. По легенде он спустился на землю к Ниобе и ее детям, и перестрелял их всех из лука (по другой легенде – они сделали это вместе с Артемидой). Горе Ниобы было неописуемым, и Зевс, видя ее страдания, превратил ее в камень. Так он и остался камнем, источающим слезы…

Месть Зевсу

У Аполлона был невероятно талантливый сын, Асклепий – великий врачеватель (подробнее о нем немного дальше). Он достиг настолько высоких успехов в медицине, что обрел способность возвращать людей к жизни, чем он и занимался без зазрения совести. Однако это безумное открытие, о котором мечтало все человечество, отнюдь не понравилось богам.

Взбешенный Аид, правитель царства мертвых, явился к Зевсу на Олимп и потребовал у него справедливости. Зевс также разделял мнение Аида, да и как могло быть иначе, когда Асклепий нарушал порядок, установленный между людьми и богами. Верховный бог принимает жалобу брата и поражает великого целителя молнией.

Аполлон был до предела поражен поступком отца. Он был в отчаянии, как же так, за что отец его поразил его сына? Почему нельзя было решить вопрос иначе? И Аполлон находит решение. И решение это – месть отцу. В качестве своей цели он выбирает тех самых циклопов, которых Зевс некогда освободил из Тартара, и которые ковали ему молнии. Аполлон перестрелял их всех до единого.

Сказать, что Зевс был в ярости – не сказать ничего. Аполлон совсем вышел из-под контроля и нужно было его как-то приструнить. В приступе безумной злобы, Зевс придумывает для Аполлона страшнейшее наказание. Он свергает его в Тартар. Но не долго был там прекрасный бог. Зевс позволил богине Лето уговорить себя и смягчил наказание сыну. За убийство циклопов тот должен был девять лет служить пастухом у простого смертного, у Адмета.

Отнюдь не суровым была служба Аполлона, однако и приятной ее не назовешь. Аполлон бы пастухов, и пас стада Адмета на берегу реки Амфис. Под началом Аполлона, коровы Адмета стали прекрасными, как и все, с чем сталкивался бог-красавец. Так продолжалось до тех пор, пока не родился маленький прохвост Гермес. В младенчестве он выбрался из колыбели, нашел место, где Аполлон пас стадо, и увел его к себе в пещеру.

С превеликим трудом Аполлону удалось выяснить личность похитителя. И несмотря на уверение малыша-Гермеса, он понял всю глубину его хитрости и вместе с ним отправился к Зевсу, дабы тот рассудил их. В этот раз верховный бог был на стороне Аполлона. Он приказал Гермесу вернуть брату коров.

Но когда они вернулись в пещеру с коровами, Гермес достал прекрасную лиру, которую он смастерил из панциря черепахи. Инструмент показался Аполлону настолько очаровательным, что он сам предложил Гермесу оставить коров себе, в обмен на эту прекрасную лиру. На этом они и расстались друзьями, а Гермес поклялся, что больше никогда ничего не украдет у брата.

Покровительство Адмету

Мифология об этом умалчивает, но, по всей видимости, Адмет не осмелился наказать Аполлона за пропавших коров. Кроме того, они были достаточно дружны. Можно даже сказать, что Аполлон любил Адмета, насколько мог любить эгоистичный бог одного из смертных.

Однажды Аполлон заметил, что Адмет чем-то опечален. Причина выяснилась достаточно скоро. Правитель Фер безумно влюбился в красавицу Алкесту, дочь царя Пелия. Девушка тоже любила Адмета, но вот отец ее не собирался просто так отдавать дочь кому попало. Он пообещал выдать дочь замуж за того, кто приедет на колеснице, запряженной львом и диким вепрем одновременно. Адмет был сильным и могучим, но поручение было просто невыполнимым.

Однако Аполлон решил помочь ему. По одной из легенд он наделил Адмета нечеловеческой силой (по другой – Аполлон уговорил Геракла помочь укротить диких животных). В любом случае Адмет выполнил требование Пелия, и тот сдержал обещание и женил его на своей дочери.

Помог Аполлон царю и на свадьбе, когда тот попросту забыл преподнести дары и жертвы сестре Аполлона – Артемиде. Возмущенная богиня собралась уже натравить на незадачливого царя огромного змея, однако Аполлон вступился за Адмета. Тот искупил вину, а Артемида настолько к нему прониклась, что обещала пощадить царя в день смерти, но при условии, если он найдет вместо себя человека, который отправится в Аид.

Через много лет спустя, неожиданно настал день смерти Адмета, причем настолько неожиданно, что он просто не успел подготовить вместо себя человека. Но и тут к нему на помощь пришел Аполлон. Он опоил Мойр, и те просто не успели обрезать нить жизни царя. Тот воспользовался полученным временем и побежал к своим старым родителям, дабы они согласились отправиться в Аид, вместо него. Но родители ему отказали. Тогда место Адмета в Аиде согласилась занять его любимая Алкеста. Позднее ее освободит Геракл (по другой легенде – Персефона, потрясенная ее смелостью).

Второе наказание

Аполлон был одним из тех богов, которые осмелились поднять восстание, против самого Зевса. Надо отдать ему должное, у него было множество причин быть недовольным властью отца. Тем не менее, если вы читали нашу статьи о Зевсе и Гере, то наверняка уже знаете, что попытка переворота была провальной.

Союзникам удалось сковать спящего Зевса цепями, и они уже собрались отправить его в Тартар, однако в дело вмешалась богиня Фетида, первая возлюбленная Зевса. Она призвала Бриарея, который освободил Зевса из оков. Разгневанный Зевс жестоко наказал Геру, которая организовала восстание, а Аполлона и Посейдона Зевс превратил в смертных и отправил на службу к Троянскому царю, строить знаменитые стены.

Жизнь после наказания

По-разному складывались у Аполлона отношения с другими богами. Однажды один из его сыновей, Эриманф, подглядел за обнаженной Афродитой, когда она купалась в источниках. Однако ему не хватило ловкости, чтобы остаться незамеченным. Возмущенная богиня навсегда ослепила юношу. В отместку, Аполлон превратил его в дикого вепря, который впоследствии убьет единственного счастливчика, кого по-настоящему любила прекрасная богиня любви – Адониса.

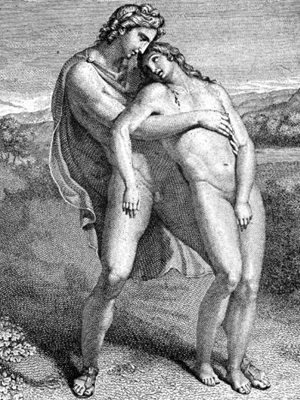

История Гиацинта

Мифология гласит, что существовал когда-то прекрасный принц Спарты, звали которого Гиацинтом. Но красота его мало ему послужила. В него влюбился Аполлон, а также Фамирид, известный певец того времени. Фамирид был искусным певцом, но и крайне самолюбивым. Возгордившись, он вызвал на состязание Муз, за что был лишен зрения. Таким образом, Аполлон избавился от первого соперника.

Почему Аполлон всегда убивал своих соперников. Ведь он доказывал, что лучше их?

Скорее всего за дерзость, за то, что они посмели бросить вызов самому богу. Мы уже сказали, что Аполлон был крайне самолюбивым, и даже простые попытки смертных превзойти его, жестоко карались.

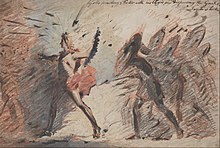

Но не долго наслаждался он своей победой. К спартанскому принцу воспылал страстью один из богов ветра, Зефир. По легенде, Аполлон играл с Гиацинтом в диск. Они бросали его друг другу, и когда Аполлон делал бросок, Зефир усилил его при помощи ветра. Принц пытался поймать диск, но тот попросту его убил. Из крови юноши вырос одноименный цветок.

Соперники Аполлона

Как мы уже рассказывали ранее, Аполлон был крайне самолюбив. Любую критику в свою сторону, или в сторону своих близких, он принимал как личное оскорбление. Так и случилось с сатиром Марсием, который нашел авлос (что-то вроде старинной флейты), выброшенный Афиной и действительно достиг в игре на нем небывалых высот. Однако этого сатиру было мало. Он возгордился и вызвал на музыкальную дуэль самого Аполлона.

Рассудить соперников должны были музы. Аполлон играл на знаменитой лире, а Марсий – на авлосе. По началу они никак не могли определиться, кто же из них более искусный музыкант, тогда Аполлон предложил выход. Он заключался в том, что к игре добавлялось и пение. Марсий запротестовал, т.к. играя на духовом инструменте, он физически не мог петь. Но Музам идея понравилась.

Само собой, очаровательная игра на лире, в сочетании с приятным и мелодичным голосом Аполлона произвели на муз более глубокое впечатление, и они отдали победу ему. Аполлон, в наказание за дерзость Марсия, содрал с последнего шкуру и подвесил на дереве.

Подобные истории постигли и других выскочек, решивших посоревноваться с Аполлоном в том или ином виде искусства. Например, Лин, знаменитый певец, также возгордился и вызвал Аполлона на состязание по пению, за что и был наказан. Или Иврит, который вызвал Аполлона на состязание по стрельбе из лука, где также был побежден и убит. Не менее трагическая судьба постигла и Форбанта, который признал себя равным Аполлону в кулачном бою, но также был побежден и уничтожен.

Соперничество с Гераклом

Рекомендуем по теме

Аполлон был крайне себялюбивым, и он очень ревновал и людей и богов к славе Геракла. Несколько раз они сталкивались в драках. Первая стычка у них случилась, когда Геракл отправился к оракулам в Дельфы, дабы испросить у них совета и предсказания. Однако оракулы молчали. Разгневанный Геракл забрал у предсказателей их треножник, но Аполлон, видя такое святотатство, вмешался.

Между ними завязалась драка, однако определенного исхода не было, т.к. вмешался Зевс. Он ударил молнией, между братьями и они помирились. Геракл вернул оракулам треножник, а Аполлон заставил оракулов дать ему предсказание.

Еще один раз Аполлон превратил в камень судью Крагелая, славившегося своей справедливостью. Спор был между Гераклом, Афиной и Аполлоном за город Амбракия, а точнее за то, кто должен был им обладать. Судья выбрал Геракла. И поплатился за это.

Также Аполлон застрелил правителя Спарты, Аристодема за то, что тот попросил Геракла, а не Аполлона, дать ему совет.

Аполлон в Троянской Войне

Аполлону в Троянской Войне выделена значимая роль. Возможно, благодаря Гомеру, мы и узнали все эти подробности, о боге-красавце. Согласно легендам, именно потомок Аполлона создал Трою. Да и сам он, отбывая наказание, строил для нее стены, вместе с Посейдоном. Поговаривают, что знаменитый герой Трои – Гектор, был не сыном Приама, а сыном Аполлона.

Именно Аполлон спас Энея (будущего основателя Рима), во время битвы с Диомедом, именно он помогает троянцам отбивать атаки Патрокла (практически брата Ахилла), именно он направляет стрелу Париса, которая ранила неуязвимого Ахилла в его пяту.

Возлюбленные Аполлона

Аполлон был достаточно противоречив, в любовных связях. Он не брезговал ни женщинами, ни мужчинами. В этом он был крайне похож на своего отца. Однако настоящую любовь он познал только в юности, и все из-за глупого бахвальства. А вот та самая история с Эросом, о которой мы обещали вам рассказать в начале нашей статьи.

Дафна

Когда Аполлон победил Пифона, он заметил подле себя маленького Эроса, с его миниатюрным золотым луком и стрелами. Аполлон стал над ним насмехаться, издеваясь, что такой маленький лук ни на что не пригоден. Эрос не стал сильно спорить с Аполлоном. Вместо этого он достал 2 стрелы (одну – вызывающую любовь, другую – вызывающую отвращение).

Первую стрелу он пустил в сердце Аполлона, а вторую – в сердце речной нимфы Дафны. Долгое время они и не подозревали о существовании друг друга, однако Дафна, пораженная обратной стрелой Эроса, всегда отказывала своим ухажерам. Но вот однажды Аполлон повстречал прекрасную Дафну. Сердце его безжалостно ухнуло вниз, однако нимфа попросту начала от него убегать.

Аполлон, в порыве безумной страсти, погнался за ней. Нимфа, не в силах больше убегать, попросила отца, бога реки, Пенея, помочь ей. И отец услышал мольбы девушки. Он превратил ее в великолепное дерево лавр, и Аполлон не успел даже притронуться к красавице. Не в силах завладеть девушкой, Аполлон решил забрать себе дерево. Он сделал лавровый венок, который всегда в будущем украшал его лиру. Именно поэтому лавровый венок возлагался на голову победителям в Пифийских Играх, а также такой венок красовался на головах протекторов Рима, потомков троянцев.

Кипарис

Кипарис – это еще один возлюбленный Аполлона, мужского пола. Однажды ему удалось приручить оленя, невероятной красоты. Но случилось несчастье, и молодой человек смертельно ранил своего любимца. Не в силах побороть свои чувства, он упросил Аполлона превратить его в дерево. Так и появилось одноименное дерево.

Кассандра

Кассандра – дочь троянского царя Приама. Однажды она пообещала отдаться Аполлону, а он, в награду за это, научил ее искусству прорицания. Однако девушка обманула бога и не сдержала обещания. В отместку Аполлон сделал так, чтобы предсказаниям провидицы никто больше не верил. Именно поэтому никто не стал ее слушать, когда она предсказывала гибель Трои, если троянцы заведут на территорию царства знаменитого коня, оставленного греками.

Коронида

А вот еще одна возлюбленная Аполлона с историю, которую мы обещали закончить в середине статьи. Собственно, Коронида – мать Асклепия. Однако, будучи уже им беременной, она не удержалась и полюбила смертного, Исхия. Разгневанный и преданный Аполлон убил обоих любовников. На погребальном костре он разрезал живот Корониды и достал оттуда Асклепия, которого отдал на воспитание мудрому кентавру Хирону.

Позднее отец Корониды, Флегий, решил отомстить богу за смерть дочери и сжег один из его храмов. В отместку, Аполлон попросту его убил.

Много еще у Аполлона было возлюбленных, как среди божеств и магических существ, так и среди людей, как среди мужчин, так и среди женщин. Однако ни с кем более Аполлон не был счастлив. Вот такой он, бог солнца и света, целителя и пророка, архитектора и строителя, великолепного стрелка из лука и олицетворение мужской красоты.

Часто задаваемые вопросы

Почему безумно красивый Аполлон отвергал любовь и почему часто отвергали его?

Насколько могущественным и значимым был Аполлон?

Почему сильный, смелый и умелый Аполлон часто избегал серьезной опасности?

Аполлон (др. -греч. Ἀπόλλων, лат. Apollo) — в древнегреческой и древнеримской мифологиях бог света (отсюда его прозвище Феб — «лучезарный», «сияющий»), покровитель искусств, предводитель и покровитель муз, предсказатель будущего, бог-врачеватель, покровитель переселенцев, олицетворение мужской красоты.

Согласно мифологии, Аполлон — сын громовержца Зевса, царя богов, и океаниды Лето (Латоны у римлян), его предыдущей жены или одной из его любовниц. Когда ревнивая супруга и одновременно сестра Тучегонителя — Гера — узнала о том браке, то запретила Лето рожать на твёрдой земле. Также она наслала на несчастную змея Пифона, чтобы убить пассию мужа. Убежище океанида в итоге нашла на плавучем острове Делос и родила своих детей под пальмой. Согласно Гомеру, сам Аполлон столкнулся с Пифоном и убил его, когда искал место для своего святилища. Лук же и стрелы ему выковал бог-кузнец Гефест. Все олимпийские богини, кроме Геры, присутствовали, чтобы стать свидетелями этого события. Также утверждается, что Гера похитила Илифию, богиню деторождения, чтобы предотвратить роды у Лето. Другие боги обманом заставили Геру отпустить ее, предложив ей янтарное ожерелье длиной 9 ярдов (8,2 м).

В детстве Аполлона вскормили нимфы Кориталия и Алетейя, олицетворение истины. Когда он появился на свет, сжимая в руках золотой меч, все на Делосе превратилось в золото, и остров наполнился амброзиальным благоуханием. Лебеди семь раз кружили над островом, и нимфы пели от восторга. Аполлон был омыт богинями, которые затем покрыли его белой одеждой и закрепили вокруг него золотые ленты. Поскольку Лето не могла накормить его, то это сделала Фемида, богиня божественного закона, давшая Аполлону нектар или амброзию. Отведав божественной пищи, Аполлон освободился от наложенных на него уз и объявил, что он будет мастером игры на лиреи стрельбе из лука и будет исполнять волю Зевса перед человечеством. Зевс, успокоивший к тому времени Геру, пришел и украсил сына золотой повязкой.

Рождение Аполлона привязало парящий Делос к земле. Океанида Лето пообещала, что ее сын всегда будет благосклонен к делосцам. По некоторым данным, через некоторое время Аполлон закрепил Делос на дне океана.Этот остров стал священным для Аполлона и был одним из главных культовых центров бога. Аполлон родился в седьмой день ( ἑβδομαγενής , hebdomagenes ) месяца Таргелион — согласно делосскому преданию — или месяца Бизиос — согласно дельфийскому преданию. Седьмой и двадцатый дни новолуния и полнолуния навсегда стали для него священными.

Мифографы сходятся во мнении, что сестра Аполлона — Артемида, богиня охоты, родилась первой и впоследствии помогла рождению Аполлона или родилась на острове Ортиглия, а затем помогла Лето пересечь море на Делос на следующий день, чтобы родить Аполлона. Единственное место, где особенно чтили Аполлона — это Гиперборея. Жители города устраивали в честь бога Пифийские игры и посвятили ему одну из своих рощ. Аполлон провел зимние месяцы среди гипербореев. Его отсутствие в мире вызвало холодность, и это было отмечено как его ежегодная смерть. Никаких пророчеств за это время не было. Он вернулся в мир в начале весны. В честь его возвращения в Дельфахпрошел праздник Феофании .

Говорят, что океанида Лето прибыла на Делос из Гипербореи в сопровождении стаи волков. Отныне Гиперборея стала зимним домом Аполлона, а волки стали для него священными. Его тесная связь с волками очевидна из его эпитета Lyceus/Ликеус, что означает «подобный волку» . Но Аполлон также был и убийцей волков в роли бога, защищавшего стада от хищников. Гиперборейское поклонение Аполлону несет в себе сильнейшие следы поклонения Аполлону как богу Солнца. Именно здесь, согласно мифам, Аполлон оплакивал своего сына Асклепия, и янтарные слёзы его стали водами реки Эридан, окружавшей Гиперборею. Аполлон также зарыл в Гиперборее стрелу, которой он убил киклопов — одноглазых великанов, которые во времена Титаномахии ковали Зевсу молнии. Позже он отдал эту стрелу Абарису.

В детстве Аполлон построил фундамент и жертвенник на Делосе, используя рога коз, на которых охотилась его сестра Артемида. Поскольку в молодости он научился строительному искусству, позже он стал известен как Архегет, основатель городов и бог, который руководил людьми при строительстве новых городов. От своего отца Зевса Аполлон также получил золотую колесницу, запряженную лебедями. В ранние годы, когда Аполлон пас коров, его воспитывали Трии, нимфы-пчелы, которые обучали его и укрепляли его пророческие способности. По мифам, это были странные существа, имевшие женские головы и туловища, а также нижняя часть тела и крылья пчелы.

Их звали Мелаина («Черная»), Клеодора («Известная своим даром») и Дафна («Лавр»). В их список также входит Корикия, в честь которой была названа Корикийская пещера. Тип гадания, которому Трии научили Аполлона, был гаданием с мантической галькой, бросанием камней, а не типом гадания, связанным с Девами-пчелами и Гермесом: клеромантией, бросанием жребия. Позже Трии сочетались любовными узами с Аполлоном и его дядей, богом морей Посейдоном. От брака с Корикией Аполлон породил сына Ликорея. Её сестра — Мелаина — родила от Аполлона Дельфа. Вскоре оба сына Аполлона стали основателями одноимённых городов. Третья же сестра из Трий — Клеодора — была любима Посейдоном и была матерью от него (или Клеопомпа) Парнаса, который основал греческий город Парнас.

Говорят также, что Аполлон изобрел лиру, а вместе с Артемидой — искусство стрельбы из лука. Затем он научил людей искусству врачевания и стрельбе из лука. Титанида Феба/Фиби, его бабушка, подарила Аполлону святилище оракула в Дельфах в качестве подарка на день рождения. Богиня Фемида вдохновила его стать там пророческим голосом Дельф. Также по мифам, подобно Гераклу, Аполлон был вынужден находиться в рабстве, чтобы очиститься от преступления.

В первый раз Аполлон совершил кровавое убийство Пифона, насланного Герой на его мать Лето. Поскольку Пифон являлся порождением богини Земли, Гея хотела, чтобы Аполлон был изгнан в Тартар в качестве наказания, однако Зевс не согласился и вместо этого изгнал своего сына с Олимпа и поручил ему очиститься. Аполлону пришлось девять лет служить пастухом у царя Адмета. Согласно иному варианту мифа, Аполлон путешествовал на Крит, где священник Карманор очистил его.

Второй раз Аполлон был наказан Зевсом за то, что застрелил киклопов в отместку за смерть своего сына Асклепия. Асклепий был искуснейшим врачом, и до того преуспел в своём мастерстве, что научился воскрешать мёртвых, чем нарушил заведённый богами порядок. Бог подземного царства Аид возмутился подобного рода вещами и нажаловался брату Зевсу на Асклепия. Громовержец тут же и поразил его молнией. После убийства киклопов бог Аполлон был сослан в Тартар, но океанида Лето вступилась за сына, и Зевс приговорил ещё к году каторжных работ у Адмета. Именно Аполлон помог Адмету жениться на Алкестиде, приручив льва и вепря, чтобы тянуть колесницу Адмета. Он присутствовал на их свадьбе, чтобы дать свое благословение. За годы служения Аполлон и Адмет стали близкими друзьями. Но римские писатели Овидий и Сервий описывали их отношения, как романтические.

Также Аполлон со своей сестрой Артемидой по мифам убили всех детей царицы Ниобы, которых у неё было то семеро, то двенадцать по разным версиям. В первой версии мифа, рассказанной Николаем Куном в переводе, Ниоба просто хвастается количеством своих детей по сравнению с детьми океаниды Латоны/Лето, что приводит к жестокой и бессмысленной расправе. Согласно второму варианту, Ниоба заходит ещё дальше — она ыысмеивала женоподобную внешность Аполлона и мужественную внешность Артемиды. Лето, оскорбленная этим, велела своим детям наказать Ниобу.

Соответственно, Аполлон убил сыновей Ниобы, а Артемиду — ее дочерей. По некоторым версиям мифа, Ниобиды — Хлорида/Хлорис и ее брат Амиклас не были убиты за то, что молились Лето. Их отец — Амфион — при виде своих мертвых сыновей либо покончил с собой, либо был убит Аполлоном после того, как поклялся отомстить. Опустошенная Ниоба бежала на гору Сипил в Малой Азии и обратилась в камень, когда плакала. Ее слезы образовали реку Ахелой . Зевс обратил всех жителей Фив в камень, и поэтому никто не хоронил ниобидов до девятого дня после их смерти, когда их погребали сами боги. Когда Хлорис вышла замуж и родила детей, Аполлон подарил ее сыну Нестору годы, которые он отнял у Ниобидов. Следовательно, Нестор смог прожить 3 поколения.

Когда-то Аполлон и бог Посейдон служили при троянском царе Лаомедонте, по словам Зевса. Аполлодор утверждает, что боги добровольно пришли к королю, замаскированному под людей, чтобы обуздать его высокомерие. Аполлон охранял скот Лаомедонта в долинах горы Ида, в то время как Посейдон строил стены Трои. Другие версии делают Аполлона и Посейдона строителями стены. По словам Овидия, Аполлон завершает свою задачу, играя свои мелодии на своей лире. Однако, царь не только отказался дать богам обещанную им плату, но и пригрозил связать им ноги и руки и продать в рабство. Возмущенный неоплачиваемым трудом и оскорблениями, Аполлон заразил город мором, а Посейдон наслал морское чудовище. Чтобы избавить от него город, Лаомедону пришлось принести в жертву свою дочь Гесиону (которую позже спасёт Геракл, тоже сын Зевса).

Во время своего пребывания в Трое у Аполлона была возлюбленная по имени Орея, нимфа и дочь Посейдона. У них родился сын по имени Илеус, которого очень любил Аполлон. Также Аполлон принимал участие в Троянской войне на стороне троянцев. После того, как Геракл (тогда его звали Алкидес) сошёл с ума и убил свою семью, он попытался очиститься и посоветовался с оракулом Аполлона. Аполлон через Пифию приказал ему служить царю Эврисфею в течение двенадцати лет и выполнить десять заданий, которые царь даст ему. Только тогда Алкидес получит прощение своего греха. Аполлон также переименовал его в Геракла.

Чтобы выполнить свою третью задачу, Геракл должен был поймать Керинейскую лань, священную лань Артемиды, и вернуть ее живой. Преследуя лань в течение года, животное в конце концов устало, и когда оно попыталось пересечь реку Ладон, Геракл поймал его. Пока он забирал его, ему противостояли Аполлон и Артемида, которые были возмущены Гераклом за этот поступок. Однако Геракл успокоил богиню и объяснил ей свое положение. После долгих уговоров Артемида разрешила ему взять лань и велела вернуть ее позже.

Сразу после своего рождения Аполлон потребовал лиру и изобрел пэан , став таким образом богом музыки. Как божественный певец, он покровитель поэтов, певцов и музыкантов. Ему приписывают изобретение струнной музыки. Философ Платон говорил, что врожденная способность людей получать удовольствие от музыки, ритма и гармонии — это дар Аполлона и муз. Согласно Сократу, древние греки верили, что Аполлон — это бог, который направляет гармонию и заставляет все вещи двигаться вместе, как для богов, так и для людей. По этой причине его называли Homopolon до того, как Homo заменили на A.

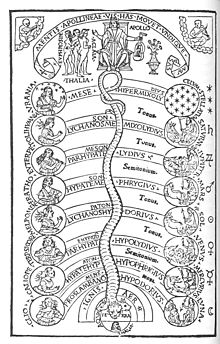

Гармоничная музыка Аполлона избавляла людей от их страданий, поэтому, как и Диониса, его также называют освободителем. Лебеди, которые считались самыми музыкальными среди птиц, считались «певцами Аполлона». Они являются священными птицами Аполлона и служили ему средством передвижения во время его путешествия в Гиперборею. Аполлон получил эпитет Мусагет («вождь муз») ведет их в танце. Они проводят свое время на Парнасе, который является одним из их священных мест. Аполлон также является любовником муз, и благодаря им он стал отцом известных музыкантов, таких как Орфей и Линус, бог лирической песни. Аполлон часто услаждает бессмертных богов своими песнями и игрой на лире, он появляется на банкете, чтобы сыграть на свадьбе таких божеств, как Пелий и Фетида или Эрос и Психея.

Когда сатиры Пан и Марсий возгордились своей игрой на дудке и аулосе и вызвали бога Аполлона на состязание, тот жестоко покарал обоих. С Марсия Аполлон нещадно содрал шкуру живьём. Кровь Марсия превратилась в реку, названную в честь сатира. Но Аполлон вскоре раскаялся и, огорченный содеянным, порвал струны своей лиры и выбросил ее. Позже лира была обнаружена музами и сыновьями Аполлона.

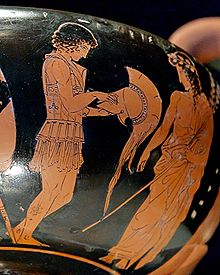

Аполлон в мифах действует и как покровитель и защитник моряков, и это одна из обязанностей, которую он разделяет с Посейдоном. В мифах он помогает героям, которые молятся ему о благополучном путешествии. Когда Аполлон заметил корабль критских моряков, попавший в шторм, он быстро принял форму дельфина и благополучно направил их корабль в Дельфы. Аргонавт Ясон, попав в шторм, молился своему покровителю Аполлону о помощи. Аполлон использовал свой лук и золотую стрелу, чтобы пролить свет на остров, где вскоре укрылись аргонавты. Этот остров был переименован в «Анафе», что означает «Он открыл его».

Также Аполлон разделял свои обязанности с Гелиосом в качестве бога Солнца, за что и получил эпитет Феб («лучезарный»). Но это отождествление началось гораздо позднее — в V веке до нашей эры. На первых Олимпийских играх Аполлон победил бога войны Ареса в борьбе. Он также обогнал Гермеса в гонке и занял первое место. Аполлон делит месяцы на лето и зиму. Он едет на спине лебедя в страну гипербореев в зимние месяцы, и отсутствие тепла зимой связано с его уходом. Во время его отсутствия Дельфы находились под опекой бога виноделия Диониса, и зимой пророчества не давались.

Из любовных похождений Аполлона нам по мифам известен только один эпизод, когда наяда Дафна отвергла бога, и тот пустился за ней в погоню. она превратилась в лавровое дерево. По другим версиям, она звала на помощь во время погони, и богиня Земли Гея помогла ей, взяв ее к себе и поставив на ее место лавровое дерево.

Согласно римскому поэту Овидию, преследование было вызвано богом эротической любви Купидоном/Эросом, который в отместку за оскорбление поразил Аполлона золотой стрелой любви и Дафну свинцовой стрелой ненависти. Миф объясняет происхождение лавра и связь Аполлона с лавром и его листьями, которыми его жрица пользовалась в Дельфах. Листья стали символом победы, а победителям Пифийских игр вручали лавровые венки. Похожая история случилась и с нимфой Сирингой, двойника богини Артемиды, в которую влюбился лесной бог-сатир Пан. Нимфа отвергла его любовь, и Пан начал преследовать её. Спас Сирингу какой-то речной бог и превратил девушку в тростник, из которого Пан смастерил свирель, названную её именем.

Мифы также приписывают Аполлону роман с Музами. От брака с Каллиопой, музой эпической поэзии и красноречия, у Аполлона родились сыновья сын Орфей и Линус Фракийский. Другая муза по имени Талия, муза идиллической поэзии и комедии, родила от Аполлона вооруженных и хохлатых танцоров Корибантов.

Кирена была фессалийской принцессой, которую любил Аполлон. В ее честь он построил город Кирену и сделал ее своей правительницей. Позже Аполлон даровал ей долголетие, превратив ее в нимфу. У пары было двое сыновей, Аристей и Идмон. Другая пассия Аполлона — Эвадна — была нимфой, дочерью Посейдона. Она родила ему сына Иамоса. Во время родов Аполлон послал ей в помощь Эйлитию, богиню деторождения. Рео, принцесса острова Наксос, была любима Аполлоном. Из любви к ней Аполлон превратил ее сестер в богинь. На острове Делос она родила Аполлону сына по имени Аний. Не желая иметь ребенка, она доверила младенца Аполлону и ушла. Аполлон воспитывал и воспитывал ребенка самостоятельно.

Орея, ещё одна дочь Посейдона, влюбилась в Аполлона, когда он и Посейдон служили троянскому царю Лаомедонту. Они оба объединились в день, когда были построены стены Трои. Она родила Аполлону сына, которого Аполлон назвал Илеем, в честь города его рождения, Илион ( Троя ). Илей был очень дорог Аполлону. Прекрасная, как лунный свет, дева Теро была любима лучезарным Аполлоном, и она любила его в ответ. От их союза она стала матерью Херона, прославившегося как «укротительница лошадей». Позже он построил город Херонея. Хирия или Тирия была матерью Цикна. Аполлон превратил мать и сына в лебедей, когда они прыгнули в озеро и попытались покончить с собой.

Ещё одна пассия — Гекуба — была женой царя Трои Приама, и у Аполлона от нее был сын по имени Троил. Оракул предсказал, что Троя не будет побеждена, пока Троил не достигнет двадцатилетнего возраста. Он попал в засаду и был убит Ахиллом, а Аполлон отомстил за его смерть, убив самого Ахиллеса. После разграбления Трои Гекуба была доставлена Аполлоном в Ликию. Также вторым сыном от Гекубы у Аполлона был Гектор, убитый во время Троянской войны.

Красавица Коронида была дочерью Флегия, царя лапифов. Будучи беременной богом врачевания Асклепием , Коронида влюбилась в другого парня — Исхия и переспала с ним. Когда Аполлон узнал о ее неверности благодаря своим пророческим силам, он послал свою сестру Артемиду убить Корониду. Аполлон спас младенца, разрезав живот Корониды и отдав его кентавру Хирону, чтобы тот поднял его. Аполлон полюбил и похитил океанидскую нимфу Мелию. Ее отец — титан Океан — послал одного из своих сыновей, Каанта, чтобы найти ее, но Каант не смог забрать ее у Аполлона, поэтому он сжег святилище Аполлона. В отместку Аполлон застрелил Каанта. Мелия родила от Аполлона Исменуса и Тенеруса.

Также Аполлону приписывается романтическая связь и с мужскими персонажами мифов. Адонис, который олицетворял смену времен года до Персефоны и был возлюбленным Афродиты, вел себя, как женщина, с Аполлоном. Гиацинт, красивый и спортивный спартанский принц, был одним из любовников Аполлона. Пара практиковалась в метании диска, когда диск, брошенный Аполлоном, был сбит с курса ревнивым богом легкого ветра Зефиром и попал Гиацинту в голову, мгновенно убив его. Говорят, что Аполлон полон горя. Из крови Гиацинта Аполлон создал цветок, названный в его честь, в память о его смерти, и его слезы окрасили лепестки цветка междометием αἰαῖ , что означает «увы».

Другим любовником был юноша Кипарис, потомок самого Геракла. Аполлон дал ему в компаньоны ручного оленя, но Кипарис случайно убил его дротиком, когда он спал в подлеске. Кипарис был так опечален его смертью, что попросил Аполлона, чтобы его слезы лились вечно. Аполлон удовлетворил просьбу, превратив его в кипарис, названный в его честь, который, как говорили, был грустным деревом, потому что сок образует капли, похожие на слезы, на стволе.

Аполлон произвел на свет много детей от смертных женщин и нимф, а также от богинь. Его дети выросли и стали врачами, музыкантами, поэтами, провидцами или лучниками. Многие из его сыновей основали новые города и стали королями. Все они обычно были очень красивы. Также чудовище Сцилла, согласно некоторым источникам, является порождением Аполлона от богини колдовства Гекаты. Знаменитая Кассандра была дочерью Гекубы и Приама. Аполлон хотел ухаживать за ней. Кассандра пообещала вернуть его любовь при одном условии — он должен дать ей силу видеть будущее. Аполлон исполнил ее желание, но она отказалась от своего слова и вскоре отвергла его. Разгневанный тем, что она нарушила свое обещание, Аполлон проклял ее тем, что, хотя она и увидит будущее, никто никогда не поверит ее пророчествам.

История персонажа

Повелитель солнца, покровитель музыкантов, талантливый предсказатель, врачеватель, отважный герой, многодетный отец – греческий Аполлон включает в себя множество образов. Вечно молодой и амбициозный бог честно завоевал собственное место на Олимпе. Любимец женщин и смелых мужчин занимает второе место в пантеоне божественных правителей.

История создания

По мнению современных исследователей, образ Аполлона зародился вовсе не на территории Греции. Мифы и легенды о лучезарном боге пришли в страну из Малой Азии. Подтверждает теорию необычное имя божества.

Значение имени бога стало загадкой не только для современных ученых, но и для философов Древней Греции. Плутарх выдвигал версию, что «Аполлон» переводится как «собрание». Теория не имеет под собой основы, так как имя нигде не упоминается в подобном контексте.

Вторым доказательством теории о заимствовании Аполлона у Азии является сочетание в одном лице противоречивых функций. Аполлон предстает перед людьми и положительным персонажем, и карающим богом. Подобный образ не характерен для мифологии Древней Греции. В любом случае, златокудрый бог занял почетное место на Олимпе, уступив в величии только собственному отцу – Зевсу.

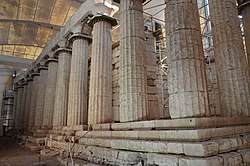

Культ Аполлона начал шествие с острова Делос и постепенно захватил всю страну, в том числе и итальянские колонии Греции. Уже оттуда власть бога солнца распространилась на Рим. Но, несмотря на огромную территорию влияния, именно Делос и город Дельфы стали центром служения божеству. На территории последнего греки возвели Дельфийский храм, где восседал оракул, толкование снов которым открывало тайны будущего.

Биография и образ

Греческий бог родился на берегу острова Делос. Одновременно с мальчиком на свет появилась сестра-близнец Артемида. Дети – плод любви Зевса-Громовержца и титаниды Лето (в другой версии Латоны). Женщине пришлось скитаться по небу и воде, так как Гера, официальная жена Зевса, запретила титаниде ступать на твердую почву.

Как и все дети Зевса, Аполлон быстро вырос и возмужал. Боги Олимпа, гордые и довольные пополнением, преподнесли юному божеству и его сестре подарки. Самым запоминающимся стал дар Гефеста – серебряный лук и золотые стрелы. С помощью этого оружия Аполлон совершит немало подвигов.

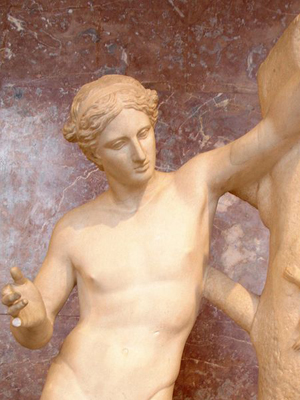

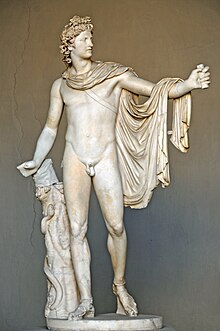

Описание внешности вечно юного божества своеобразно. В отличие от большинства героев Греции Аполлон не носил бороды, предпочитая открывать лицо окружающему миру. Метафора «златовласый», часто используемая в отношении бога, позволяет сделать вывод, что Аполлон – блондин.

Юноша среднего роста и среднего телосложения быстро и бесшумно передвигается по свету, с легкостью догоняя спортивную сестру. Нигде не упоминается обескураживающая красота бога, но количество любовных побед подсказывает, что Аполлон излучает магнетизм и обаяние.

Впрочем, в жизни бога была и несчастная любовь. Дафна, миф о которой отлично характеризует юность Аполлона, стала жертвой неприятной истории. Юный бог, уверенный в собственных силах, высмеял Эрота (бога любви), за что получил в сердце любовную стрелу. А стрела отвращения полетела прямиком в сердце нимфы Дафны.

Влюбленный Аполлон бросился за девушкой, которая решила спрятаться от настойчивого поклонника. Бог солнца не отступал, поэтому отец нимфы, видевший мучения дочери, превратил Дафну в лавровое дерево. Юноша украсил листвой лавра собственную одежду и колчан для стрел.

Свободное от подвигов и забот время юноша проводит за музыкой. Любимым инструментом для Аполлона стала кифара. Молодой бог гордится собственными успехами в музыке и часто покровительствует талантливым музыкантам. А чего не терпит Аполлон, так это хвастовства.

Весельчак-сатир Марсий, подобравший флейту Афины, однажды вызвал юного бога на состязание. Мужчина недооценил талант сына Зевса. Марсий проиграл состязание, а гордый и своенравный Аполлон в наказание за дерзость содрал с сатира шкуру.

Молодому богу бывает скучно на Олимпе, поэтому Аполлон часто спускается на землю, чтобы пообщаться с друзьями. Однажды приятельская встреча закончилась смертью. Сын Зевса и Гиацинт, сын местного царя, запускали в небо металлический диск. Аполлон не рассчитал силы, и снаряд угодил Гиацинту в голову. Любимец бога погиб, Аполлон не смог спасти друга. На месте трагедии расцвел цветок. Теперь каждую весну распускает бутон растение гиацинт, напоминающее о дружбе бога и человека.

Отличительная характеристика Аполлона – всепоглощающая любовь к матери и сестре. Ради благополучия близких женщин герой идет наперекор грозному отцу. Вскоре после рождения Аполлон убивает Пифона – могучего змея, преследующего Лето. За несогласованный акт мести Зевс свергает бога Солнца, и Аполлон должен восемь лет прослужить пастухом, чтобы загладить вину.

Второй раз Аполлон заступается за мать, когда Лето оскорбляет царица Ниоба. Подруги поспорили, кто из них более плодовит. Чтобы отстоять честь матери, Аполлон и Артемида перестреляли всех детей Ниобы.

Несмотря на часты стычки, за Аполлоном закрепилось звание любимчика отца. Такое расположение угнетает Геру – жену владыки Олимпа. Богиня прикладывает максимум усилий, чтобы причинить вред Аполлону. Впрочем, солнечный бог только посмеивается над проделками мачехи.

На божестве лежит серьезная обязанность – Аполлон с колесницей, в которую запряжена четверка лошадей, проезжает по небу, освещая Землю. Часто в путешествии златокудрого бога сопровождают нимфы и музы.

Возмужавший Аполлон часто заводит романы. В отличие от отца, мужчина предстает перед возлюбленными в истинном обличии. Исключением стали Антенора (принял облик собаки) и Дриопа (приходил дважды в виде змеи и черепахи). Несмотря на внушительный любовный стаж, Аполлон так и не женился. Более того, зачастую возлюбленные бога не хранили мужчине верность.

Зато собственных сыновей Аполлон опекает чрезмерно. Среди отпрысков бога значатся Еврипид, Пифагор, Янус, Орфей и Асклепий. Последний сильно прогневал дедушку, за что был убит Зевсом. Оскорбленный Аполлон в отместку перебил циклопов, которые создавали для владыки Олимпа волшебные молнии.

Интересные факты

- Ницше утверждал, что Аполлон – олицетворение порядка и света, а противоположные качества в мифологии представляет Дионис. Бог виноделия призывает сторонников нарушать правила, которые навязывает сын Зевса.

- Аполлон имеет хорошую физическую подготовку. Юноша с легкостью победил бога войны Ареса в кулачном бою.

- Писатель Рик Риордан представил собственное видение персонажа. В книге «Перси Джексон и Олимпийцы» читатель знакомится с современным бесшабашным сыном Зевса.

| Apollo | |

|---|---|

|

God of oracles, healing, archery, music and arts, sunlight, knowledge, herds and flocks, and protection of the young |

|

| Member of the Twelve Olympians and the Dii Consentes | |

Apollo Belvedere, c. 120–140 CE |

|

| Abode | Mount Olympus |

| Planet | Sun Mercury[1] (antiquity) |

| Animals | Raven, swan, wolf |

| Symbol | Lyre, laurel wreath, python, bow and arrows, sword |

| Tree | laurel, cypress |

| Day | Sunday (hēmérā Apóllōnos) |

| Mount | A chariot drawn by swans |

| Personal information | |

| Born |

Delos |

| Parents | Zeus and Leto |

| Siblings | Artemis (twin), Aeacus, Angelos, Aphrodite, Ares, Athena, Dionysus, Eileithyia, Enyo, Eris, Ersa, Hebe, Helen of Troy, Hephaestus, Heracles, Hermes, Minos, Pandia, Persephone, Perseus, Rhadamanthus, the Graces, the Horae, the Litae, the Muses, the Moirai |

| Children | Asclepius, Aristaeus, Corybantes, Hymenaeus, Apollonis, Amphiaraus, Anius, Apis, Cycnus, Eurydice, Hector, Linus of Thrace, Lycomedes, Melaneus, Melite, Miletus, Mopsus, Oaxes, Oncius, Orpheus, Troilus, Phemonoe, Philammon, Tenerus, Trophonius, and various others |

Apollo[a] is one of the Olympian deities in classical Greek and Roman religion and Greek and Roman mythology. The national divinity of the Greeks, Apollo has been recognized as a god of archery, music and dance, truth and prophecy, healing and diseases, the Sun and light, poetry, and more. One of the most important and complex of the Greek gods, he is the son of Zeus and Leto, and the twin brother of Artemis, goddess of the hunt. Seen as the most beautiful god and the ideal of the kouros (ephebe, or a beardless, athletic youth), Apollo is considered to be the most Greek of all the gods.[citation needed] Apollo is known in Greek-influenced Etruscan mythology as Apulu.[2]

As the patron deity of Delphi (Apollo Pythios), Apollo is an oracular god—the prophetic deity of the Delphic Oracle. Apollo is the god who affords help and wards off evil; various epithets call him the «averter of evil».

Medicine and healing are associated with Apollo, whether through the god himself or mediated through his son Asclepius. Apollo delivered people from epidemics, yet he is also a god who could bring ill-health and deadly plague with his arrows. The invention of archery itself is credited to Apollo and his sister Artemis. Apollo is usually described as carrying a silver or golden bow and a quiver of silver or golden arrows. Apollo’s capacity to make youths grow is one of the best attested facets of his panhellenic cult persona. As a protector of the young (kourotrophos), Apollo is concerned with the health and education of children. He presided over their passage into adulthood. Long hair, which was the prerogative of boys, was cut at the coming of age (ephebeia) and dedicated to Apollo.

Apollo is an important pastoral deity, and was the patron of herdsmen and shepherds. Protection of herds, flocks and crops from diseases, pests and predators were his primary duties. On the other hand, Apollo also encouraged founding new towns and establishment of civil constitution. He is associated with dominion over colonists. He was the giver of laws, and his oracles were consulted before setting laws in a city.

As the god of mousike,[b] Apollo presides over all music, songs, dance and poetry. He is the inventor of string-music, and the frequent companion of the Muses, functioning as their chorus leader in celebrations. The lyre is a common attribute of Apollo. In Hellenistic times, especially during the 5th century BCE, as Apollo Helios he became identified among Greeks with Helios, the personification of the Sun.[3] In Latin texts, however, there was no conflation of Apollo with Sol among the classical Latin poets until 1st century CE.[4] Apollo and Helios/Sol remained separate beings in literary and mythological texts until the 5th century CE.

Etymology

Apollo, fresco from Pompeii, 1st century AD

Apollo (Attic, Ionic, and Homeric Greek: Ἀπόλλων, Apollōn (GEN Ἀπόλλωνος); Doric: Ἀπέλλων, Apellōn; Arcadocypriot: Ἀπείλων, Apeilōn; Aeolic: Ἄπλουν, Aploun; Latin: Apollō)

The name Apollo—unlike the related older name Paean—is generally not found in the Linear B (Mycenean Greek) texts, although there is a possible attestation in the lacunose form ]pe-rjo-[ (Linear B: ]𐀟𐁊-[) on the KN E 842 tablet,[5][6][7] though it has also been suggested that the name might actually read «Hyperion» ([u]-pe-rjo-[ne]).[8]

The etymology of the name is uncertain. The spelling Ἀπόλλων (pronounced [a.pól.lɔːn] in Classical Attic) had almost superseded all other forms by the beginning of the common era, but the Doric form, Apellon (Ἀπέλλων), is more archaic, as it is derived from an earlier *Ἀπέλjων. It probably is a cognate to the Doric month Apellaios (Ἀπελλαῖος),[9] and the offerings apellaia (ἀπελλαῖα) at the initiation of the young men during the family-festival apellai (ἀπέλλαι).[10][11] According to some scholars, the words are derived from the Doric word apella (ἀπέλλα), which originally meant «wall,» «fence for animals» and later «assembly within the limits of the square.»[12][13] Apella (Ἀπέλλα) is the name of the popular assembly in Sparta,[12] corresponding to the ecclesia (ἐκκλησία). R. S. P. Beekes rejected the connection of the theonym with the noun apellai and suggested a Pre-Greek proto-form *Apalyun.[14]

Several instances of popular etymology are attested from ancient authors. Thus, the Greeks most often associated Apollo’s name with the Greek verb ἀπόλλυμι (apollymi), «to destroy».[15] Plato in Cratylus connects the name with ἀπόλυσις (apolysis), «redemption», with ἀπόλουσις (apolousis), «purification», and with ἁπλοῦν ([h]aploun), «simple»,[16] in particular in reference to the Thessalian form of the name, Ἄπλουν, and finally with Ἀειβάλλων (aeiballon), «ever-shooting». Hesychius connects the name Apollo with the Doric ἀπέλλα (apella), which means «assembly», so that Apollo would be the god of political life, and he also gives the explanation σηκός (sekos), «fold», in which case Apollo would be the god of flocks and herds.[17] In the ancient Macedonian language πέλλα (pella) means «stone,»[18] and some toponyms may be derived from this word: Πέλλα (Pella,[19] the capital of ancient Macedonia) and Πελλήνη (Pellēnē/Pellene).[20]

The Hittite form Apaliunas (dx-ap-pa-li-u-na-aš) is attested in the Manapa-Tarhunta letter.[21] The Hittite testimony reflects an early form *Apeljōn, which may also be surmised from comparison of Cypriot Ἀπείλων with Doric Ἀπέλλων.[22] The name of the Lydian god Qλdãns /kʷʎðãns/ may reflect an earlier /kʷalyán-/ before palatalization, syncope, and the pre-Lydian sound change *y > d.[23] Note the labiovelar in place of the labial /p/ found in pre-Doric Ἀπέλjων and Hittite Apaliunas.

A Luwian etymology suggested for Apaliunas makes Apollo «The One of Entrapment», perhaps in the sense of «Hunter».[24]

Greco-Roman epithets

Apollo’s chief epithet was Phoebus ( FEE-bəs; Φοῖβος, Phoibos Greek pronunciation: [pʰó͜i.bos]), literally «bright».[25] It was very commonly used by both the Greeks and Romans for Apollo’s role as the god of light. Like other Greek deities, he had a number of others applied to him, reflecting the variety of roles, duties, and aspects ascribed to the god. However, while Apollo has a great number of appellations in Greek myth, only a few occur in Latin literature.

Sun

- Aegletes ( ə-GLEE-teez; Αἰγλήτης, Aiglētēs), from αἴγλη, «light of the sun»[26]

- Helius ( HEE-lee-əs; Ἥλιος, Helios), literally «sun»[27]

- Lyceus ( ly-SEE-əs; Λύκειος, Lykeios, from Proto-Greek *λύκη), «light». The meaning of the epithet «Lyceus» later became associated with Apollo’s mother Leto, who was the patron goddess of Lycia (Λυκία) and who was identified with the wolf (λύκος).[28]

- Phanaeus ( fə-NEE-əs; Φαναῖος, Phanaios), literally «giving or bringing light»

- Phoebus ( FEE-bəs; Φοῖβος, Phoibos), literally «bright», his most commonly used epithet by both the Greeks and Romans

- Sol (Roman) (), «sun» in Latin

Wolf

- Lycegenes ( ly-SEJ-ən-eez; Λυκηγενής, Lukēgenēs), literally «born of a wolf» or «born of Lycia»

- Lycoctonus ( ly-KOK-tə-nəs; Λυκοκτόνος, Lykoktonos), from λύκος, «wolf», and κτείνειν, «to kill»

Origin and birth

Apollo’s birthplace was Mount Cynthus on the island of Delos.

- Cynthius ( SIN-thee-əs; Κύνθιος, Kunthios), literally «Cynthian»

- Cynthogenes ( sin-THOJ-in-eez; Κυνθογενής, Kynthogenēs), literally «born of Cynthus»

- Delius ( DEE-lee-əs; Δήλιος, Delios), literally «Delian»

- Didymaeus ( DID-im-EE-əs; Διδυμαῖος, Didymaios) from δίδυμος, «twin», as the twin of Artemis

Partial view of the temple of Apollo Epikurios (healer) at Bassae in southern Greece

Place of worship

Delphi and Actium were his primary places of worship.[29][30]

- Acraephius ( ə-KREE-fee-əs; Ἀκραίφιος, Akraiphios, literally «Acraephian») or Acraephiaeus ( ə-KREE-fee-EE-əs; Ἀκραιφιαίος, Akraiphiaios), «Acraephian», from the Boeotian town of Acraephia (Ἀκραιφία), reputedly founded by his son Acraepheus.[31]

- Actiacus ( ak-TY-ə-kəs; Ἄκτιακός, Aktiakos), literally «Actian», after Actium (Ἄκτιον)

- Delphinius ( del-FIN-ee-əs; Δελφίνιος, Delphinios), literally «Delphic», after Delphi (Δελφοί). An etiology in the Homeric Hymns associated this with dolphins.

- Epactaeus, meaning «god worshipped on the coast», in Samos.[32]

- Pythius ( PITH-ee-əs; Πύθιος, Puthios, from Πυθώ, Pythō), from the region around Delphi

- Smintheus ( SMIN-thewss; Σμινθεύς, Smintheus), «Sminthian»—that is, «of the town of Sminthos or Sminthe»[33] near the Troad town of Hamaxitus[34]

- Napaian Apollo (Ἀπόλλων Ναπαῖος), from the city of Nape at the island of Lesbos[35]

Temple of the Delians at Delos, dedicated to Apollo (478 BC). 19th-century pen-and-wash restoration.

William Birnie Rhind, Apollo (1889–1894), pediment sculpture, former Sun Life Building, Renfield Street Glasgow

Healing and disease

- Acesius ( ə-SEE-zhəs; Ἀκέσιος, Akesios), from ἄκεσις, «healing». Acesius was the epithet of Apollo worshipped in Elis, where he had a temple in the agora.[36]

- Acestor ( ə-SESS-tər; Ἀκέστωρ, Akestōr), literally «healer»

- Culicarius (Roman) ( KEW-lih-KARR-ee-əs), from Latin culicārius, «of midges»

- Iatrus ( eye-AT-rəs; Ἰατρός, Iātros), literally «physician»[37]

- Medicus (Roman) ( MED-ik-əs), «physician» in Latin. A temple was dedicated to Apollo Medicus at Rome, probably next to the temple of Bellona.

- Paean ( PEE-ən; Παιάν, Paiān), physician, healer[38]

- Parnopius ( par-NOH-pee-əs; Παρνόπιος, Parnopios), from πάρνοψ, «locust»

Founder and protector

- Agyieus ( ə-JUY-ih-yooss; Ἀγυιεύς, Aguīeus), from ἄγυια, «street», for his role in protecting roads and homes

- Alexicacus ( ə-LEK-sih-KAY-kəs; Ἀλεξίκακος, Alexikakos), literally «warding off evil»

- Apotropaeus ( ə-POT-rə-PEE-əs; Ἀποτρόπαιος, Apotropaios), from ἀποτρέπειν, «to avert»

- Archegetes ( ar-KEJ-ə-teez; Ἀρχηγέτης, Arkhēgetēs), literally «founder»

- Averruncus (Roman) ( AV-ə-RUNG-kəs; from Latin āverruncare), «to avert»

- Clarius ( KLARR-ee-əs; Κλάριος, Klārios), from Doric κλάρος, «allotted lot»[39]

- Epicurius ( EP-ih-KURE-ee-əs; Ἐπικούριος, Epikourios), from ἐπικουρέειν, «to aid»[27]

- Genetor ( JEN-ih-tər; Γενέτωρ, Genetōr), literally «ancestor»[27]

- Nomius ( NOH-mee-əs; Νόμιος, Nomios), literally «pastoral»

- Nymphegetes ( nim-FEJ-ih-teez; Νυμφηγέτης, Numphēgetēs), from Νύμφη, «Nymph», and ἡγέτης, «leader», for his role as a protector of shepherds and pastoral life

- Patroos from πατρῷος, «related to one’s father,» for his role as father of Ion and founder of the Ionians, as worshipped at the Temple of Apollo Patroos in Athens

- Sauroctunos, «lizard killer», possibly a reference to his killing of Python

Prophecy and truth

- Coelispex (Roman) ( SEL-isp-eks), from Latin coelum, «sky», and specere «to look at»

- Iatromantis ( eye-AT-rə-MAN-tis; Ἰατρομάντις, Iātromantis,) from ἰατρός, «physician», and μάντις, «prophet», referring to his role as a god both of healing and of prophecy

- Leschenorius ( LESS-kin-OR-ee-əs; Λεσχηνόριος, Leskhēnorios), from λεσχήνωρ, «converser»

- Loxias ( LOK-see-əs; Λοξίας, Loxias), from λέγειν, «to say»,[27] historically associated with λοξός, «ambiguous»

- Manticus ( MAN-tik-əs; Μαντικός, Mantikos), literally «prophetic»

- Proopsios (Προόψιος), meaning «foreseer» or «first seen»[40]

Music and arts

- Musagetes ( mew-SAJ-ih-teez; Doric Μουσαγέτας, Mousāgetās), from Μούσα, «Muse», and ἡγέτης «leader»[41]

- Musegetes ( mew-SEJ-ih-teez; Μουσηγέτης, Mousēgetēs), as the preceding

Archery

- Aphetor ( ə-FEE-tər; Ἀφήτωρ, Aphētōr), from ἀφίημι, «to let loose»

- Aphetorus ( ə-FET-ər-əs; Ἀφητόρος, Aphētoros), as the preceding

- Arcitenens (Roman) ( ar-TISS-in-ənz), literally «bow-carrying»

- Argyrotoxus ( AR-jər-ə-TOK-səs; Ἀργυρότοξος, Argyrotoxos), literally «with silver bow»

- Clytotoxus ( KLY-toh-TOK-səs; Κλυτότοξος, Klytótoxos), «he who is famous for his bow», the renowned archer.[42]

- Hecaërgus ( HEK-ee-UR-gəs; Ἑκάεργος, Hekaergos), literally «far-shooting»

- Hecebolus ( hiss-EB-əl-əs; Ἑκηβόλος, Hekēbolos), «far-shooting»

- Ismenius ( iz-MEE-nee-əs; Ἰσμηνιός, Ismēnios), literally «of Ismenus», after Ismenus, the son of Amphion and Niobe, whom he struck with an arrow

Appearance

- Acersecomes (Ακερσεκόμης, Akersekómēs), «he who has unshorn hair», the eternal ephebe.[43]

- Chrysocomes ( cry-SOH-koh-miss; Χρυσοκόμης, Khrusokómēs), literally «he who has golden hair.»

Amazons

- Amazonius (Ἀμαζόνιος), Pausanias at the Description of Greece writes that near Pyrrhichus there was a sanctuary of Apollo, called Amazonius (Ancient Greek: Ἀμαζόνιος) with image of the god said to have been dedicated by the Amazons.[44]

Other

- Patroos (Πατρώος, ancestral), there is the Temple of Apollo Patroos at the Ancient Agora of Athens

Celtic epithets and cult titles

Apollo was worshipped throughout the Roman Empire. In the traditionally Celtic lands, he was most often seen as a healing and sun god. He was often equated with Celtic gods of similar character.[45]

- Apollo Atepomarus («the great horseman» or «possessing a great horse»). Apollo was worshipped at Mauvières (Indre). Horses were, in the Celtic world, closely linked to the sun.[46]

- Apollo Belenus («bright» or «brilliant»). This epithet was given to Apollo in parts of Gaul, Northern Italy and Noricum (part of modern Austria). Apollo Belenus was a healing and sun god.[47]

- Apollo Cunomaglus («hound lord»). A title given to Apollo at a shrine at Nettleton Shrub, Wiltshire. May have been a god of healing. Cunomaglus himself may originally have been an independent healing god.[48]

- Apollo Grannus. Grannus was a healing spring god, later equated with Apollo.[49][50][51]

- Apollo Maponus. A god known from inscriptions in Britain. This may be a local fusion of Apollo and Maponus.

- Apollo Moritasgus («masses of sea water»). An epithet for Apollo at Alesia, where he was worshipped as god of healing and, possibly, of physicians.[52]

- Apollo Vindonnus («clear light»). Apollo Vindonnus had a temple at Essarois, near Châtillon-sur-Seine in present-day Burgundy. He was a god of healing, especially of the eyes.[50]

- Apollo Virotutis («benefactor of mankind»). Apollo Virotutis was worshipped, among other places, at Fins d’Annecy (Haute-Savoie) and at Jublains (Maine-et-Loire).[51][53]

Origins

The cult centers of Apollo in Greece, Delphi and Delos, date from the 8th century BCE. The Delos sanctuary was primarily dedicated to Artemis, Apollo’s twin sister. At Delphi, Apollo was venerated as the slayer of the monstrous serpent Python. For the Greeks, Apollo was the most Greek of all the gods, and through the centuries he acquired different functions. In Archaic Greece he was the prophet, the oracular god who in older times was connected with «healing». In Classical Greece he was the god of light and of music, but in popular religion he had a strong function to keep away evil.[54] Walter Burkert discerned three components in the prehistory of Apollo worship, which he termed «a Dorian-northwest Greek component, a Cretan-Minoan component, and a Syro-Hittite component.»[55]

Healer and god-protector from evil

In classical times, his major function in popular religion was to keep away evil, and he was therefore called «apotropaios» (ἀποτρόπαιος, «averting evil») and «alexikakos» (ἀλεξίκακος «keeping off ill»; from v. ἀλέξω + n. κακόν).[57] Apollo also had many epithets relating to his function as a healer. Some commonly-used examples are «paion» (παιών literally «healer» or «helper»)[58] «epikourios» (ἐπικούριος, «succouring»), «oulios» (οὔλιος, «healer, baleful»)[59] and «loimios» (λοίμιος, «of the plague»). In later writers, the word, «paion», usually spelled «Paean», becomes a mere epithet of Apollo in his capacity as a god of healing.[60]

Apollo in his aspect of «healer» has a connection to the primitive god Paean (Παιών-Παιήων), who did not have a cult of his own. Paean serves as the healer of the gods in the Iliad, and seems to have originated in a pre-Greek religion.[61] It is suggested, though unconfirmed, that he is connected to the Mycenaean figure pa-ja-wo-ne (Linear B: 𐀞𐀊𐀺𐀚).[62][63][64] Paean was the personification of holy songs sung by «seer-doctors» (ἰατρομάντεις), which were supposed to cure disease.[65]

Homer illustrated Paeon the god and the song both of apotropaic thanksgiving or triumph.[66] Such songs were originally addressed to Apollo and afterwards to other gods: to Dionysus, to Apollo Helios, to Apollo’s son Asclepius the healer. About the 4th century BCE, the paean became merely a formula of adulation; its object was either to implore protection against disease and misfortune or to offer thanks after such protection had been rendered. It was in this way that Apollo had become recognized as the god of music. Apollo’s role as the slayer of the Python led to his association with battle and victory; hence it became the Roman custom for a paean to be sung by an army on the march and before entering into battle, when a fleet left the harbour, and also after a victory had been won.

In the Iliad, Apollo is the healer under the gods, but he is also the bringer of disease and death with his arrows, similar to the function of the Vedic god of disease Rudra.[67] He sends a plague (λοιμός) to the Achaeans. Knowing that Apollo can prevent a recurrence of the plague he sent, they purify themselves in a ritual and offer him a large sacrifice of cows, called a hecatomb.[68]

Dorian origin

The Homeric Hymn to Apollo depicts Apollo as an intruder from the north.[69] The connection with the northern-dwelling Dorians and their initiation festival apellai is reinforced by the month Apellaios in northwest Greek calendars.[70] The family-festival was dedicated to Apollo (Doric: Ἀπέλλων).[71] Apellaios is the month of these rites, and Apellon is the «megistos kouros» (the great Kouros).[72] However it can explain only the Doric type of the name, which is connected with the Ancient Macedonian word «pella» (Pella), stone. Stones played an important part in the cult of the god, especially in the oracular shrine of Delphi (Omphalos).[73][74]

Minoan origin

George Huxley regarded the identification of Apollo with the Minoan deity Paiawon, worshipped in Crete, to have originated at Delphi.[75] In the Homeric Hymn, Apollo appeared as a dolphin and carried Cretan priests to Delphi, where they evidently transferred their religious practices. Apollo Delphinios or Delphidios was a sea-god especially worshipped in Crete and in the islands.[76] Apollo’s sister Artemis, who was the Greek goddess of hunting, is identified with Britomartis (Diktynna), the Minoan «Mistress of the animals». In her earliest depictions she was accompanied by the «Master of the animals», a bow-wielding god of hunting whose name has been lost; aspects of this figure may have been absorbed into the more popular Apollo.[77]

Anatolian origin

Illustration of a coin of Apollo Agyieus from Ambracia

A non-Greek origin of Apollo has long been assumed in scholarship.[9] The name of Apollo’s mother Leto has Lydian origin, and she was worshipped on the coasts of Asia Minor. The inspiration oracular cult was probably introduced into Greece from Anatolia, which is the origin of Sibyl, and where some of the oldest oracular shrines originated. Omens, symbols, purifications, and exorcisms appear in old Assyro-Babylonian texts. These rituals were spread into the empire of the Hittites, and from there into Greece.[78]

Homer pictures Apollo on the side of the Trojans, fighting against the Achaeans, during the Trojan War. He is pictured as a terrible god, less trusted by the Greeks than other gods. The god seems to be related to Appaliunas, a tutelary god of Wilusa (Troy) in Asia Minor, but the word is not complete.[79] The stones found in front of the gates of Homeric Troy were the symbols of Apollo. A western Anatolian origin may also be bolstered by references to the parallel worship of Artimus (Artemis) and Qλdãns, whose name may be cognate with the Hittite and Doric forms, in surviving Lydian texts.[80] However, recent scholars have cast doubt on the identification of Qλdãns with Apollo.[81]

The Greeks gave to him the name ἀγυιεύς agyieus as the protector god of public places and houses who wards off evil and his symbol was a tapered stone or column.[82] However, while usually Greek festivals were celebrated at the full moon, all the feasts of Apollo were celebrated at the seventh day of the month, and the emphasis given to that day (sibutu) indicates a Babylonian origin.[83]

The Late Bronze Age (from 1700 to 1200 BCE) Hittite and Hurrian Aplu was a god of plague, invoked during plague years. Here we have an apotropaic situation, where a god originally bringing the plague was invoked to end it. Aplu, meaning the son of, was a title given to the god Nergal, who was linked to the Babylonian god of the sun Shamash.[84] Homer interprets Apollo as a terrible god (δεινὸς θεός) who brings death and disease with his arrows, but who can also heal, possessing a magic art that separates him from the other Greek gods.[85] In Iliad, his priest prays to Apollo Smintheus,[86] the mouse god who retains an older agricultural function as the protector from field rats.[33][87][88] All these functions, including the function of the healer-god Paean, who seems to have Mycenean origin, are fused in the cult of Apollo.

Proto-Indo-European

The Vedic Rudra has some similar functions with Apollo. The terrible god is called «the archer» and the bow is also an attribute of Shiva.[89] Rudra could bring diseases with his arrows, but he was able to free people of them and his alternative Shiva is a healer physician god.[90] However the Indo-European component of Apollo does not explain his strong relation with omens, exorcisms, and with the oracular cult.

Oracular cult

Unusually among the Olympic deities, Apollo had two cult sites that had widespread influence: Delos and Delphi. In cult practice, Delian Apollo and Pythian Apollo (the Apollo of Delphi) were so distinct that they might both have shrines in the same locality.[91] Lycia was sacred to the god, for this Apollo was also called Lycian.[92][93] Apollo’s cult was already fully established when written sources commenced, about 650 BCE. Apollo became extremely important to the Greek world as an oracular deity in the archaic period, and the frequency of theophoric names such as Apollodorus or Apollonios and cities named Apollonia testify to his popularity. Oracular sanctuaries to Apollo were established in other sites. In the 2nd and 3rd century CE, those at Didyma and Claros pronounced the so-called «theological oracles», in which Apollo confirms that all deities are aspects or servants of an all-encompassing, highest deity. «In the 3rd century, Apollo fell silent. Julian the Apostate (359–361) tried to revive the Delphic oracle, but failed.»[9]

Oracular shrines

Apollo had a famous oracle in Delphi, and other notable ones in Claros and Didyma. His oracular shrine in Abae in Phocis, where he bore the toponymic epithet Abaeus (Ἀπόλλων Ἀβαῖος, Apollon Abaios), was important enough to be consulted by Croesus.[94]

His oracular shrines include:

- Abae in Phocis.

- Bassae in the Peloponnese.

- At Clarus, on the west coast of Asia Minor; as at Delphi a holy spring which gave off a pneuma, from which the priests drank.

- In Corinth, the Oracle of Corinth came from the town of Tenea, from prisoners supposedly taken in the Trojan War.

- At Khyrse, in Troad, the temple was built for Apollo Smintheus.

- In Delos, there was an oracle to the Delian Apollo, during summer. The Hieron (Sanctuary) of Apollo adjacent to the Sacred Lake, was the place where the god was said to have been born.

- In Delphi, the Pythia became filled with the pneuma of Apollo, said to come from a spring inside the Adyton.

- In Didyma, an oracle on the coast of Anatolia, south west of Lydian (Luwian) Sardis, in which priests from the lineage of the Branchidae received inspiration by drinking from a healing spring located in the temple. Was believed to have been founded by Branchus, son or lover of Apollo.

- In Hierapolis Bambyce, Syria (modern Manbij), according to the treatise De Dea Syria, the sanctuary of the Syrian Goddess contained a robed and bearded image of Apollo. Divination was based on spontaneous movements of this image.[95]

- At Patara, in Lycia, there was a seasonal winter oracle of Apollo, said to have been the place where the god went from Delos. As at Delphi the oracle at Patara was a woman.

- In Segesta in Sicily.

Oracles were also given by sons of Apollo.

- In Oropus, north of Athens, the oracle Amphiaraus, was said to be the son of Apollo; Oropus also had a sacred spring.

- in Labadea, 20 miles (32 km) east of Delphi, Trophonius, another son of Apollo, killed his brother and fled to the cave where he was also afterwards consulted as an oracle.

Temples of Apollo

Many temples were dedicated to Apollo in Greece and the Greek colonies. They show the spread of the cult of Apollo and the evolution of the Greek architecture, which was mostly based on the rightness of form and on mathematical relations. Some of the earliest temples, especially in Crete, do not belong to any Greek order. It seems that the first peripteral temples were rectangular wooden structures. The different wooden elements were considered divine, and their forms were preserved in the marble or stone elements of the temples of Doric order. The Greeks used standard types because they believed that the world of objects was a series of typical forms which could be represented in several instances. The temples should be canonic, and the architects were trying to achieve this esthetic perfection.[96] From the earliest times there were certain rules strictly observed in rectangular peripteral and prostyle buildings. The first buildings were built narrowly in order to hold the roof, and when the dimensions changed some mathematical relations became necessary in order to keep the original forms. This probably influenced the theory of numbers of Pythagoras, who believed that behind the appearance of things there was the permanent principle of mathematics.[97]

The Doric order dominated during the 6th and the 5th century BC but there was a mathematical problem regarding the position of the triglyphs, which couldn’t be solved without changing the original forms. The order was almost abandoned for the Ionic order, but the Ionic capital also posed an insoluble problem at the corner of a temple. Both orders were abandoned for the Corinthian order gradually during the Hellenistic age and under Rome.

The most important temples are:

Greek temples

- Thebes, Greece: The oldest temple probably dedicated to Apollo Ismenius was built in the 9th century B.C. It seems that it was a curvilinear building. The Doric temple was built in the early 7th century B.C., but only some small parts have been found[98] A festival called Daphnephoria was celebrated every ninth year in honour of Apollo Ismenius (or Galaxius). The people held laurel branches (daphnai), and at the head of the procession walked a youth (chosen priest of Apollo), who was called «daphnephoros».[99]

- Eretria: According to the Homeric hymn to Apollo, the god arrived to the plain, seeking for a location to establish its oracle. The first temple of Apollo Daphnephoros, «Apollo, laurel-bearer», or «carrying off Daphne», is dated to 800 B.C. The temple was curvilinear hecatombedon (a hundred feet). In a smaller building were kept the bases of the laurel branches which were used for the first building. Another temple probably peripteral was built in the 7th century B.C., with an inner row of wooden columns over its Geometric predecessor. It was rebuilt peripteral around 510 B.C., with the stylobate measuring 21,00 x 43,00 m. The number of pteron column was 6 x 14.[100][101]

- Dreros (Crete). The temple of Apollo Delphinios dates from the 7th century B.C., or probably from the middle of the 8th century B.C. According to the legend, Apollo appeared as a dolphin, and carried Cretan priests to the port of Delphi.[102] The dimensions of the plan are 10,70 x 24,00 m and the building was not peripteral. It contains column-bases of the Minoan type, which may be considered as the predecessors of the Doric columns.[103]

- Gortyn (Crete). A temple of Pythian Apollo, was built in the 7th century B.C. The plan measured 19,00 x 16,70 m and it was not peripteral. The walls were solid, made from limestone, and there was single door on the east side.

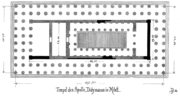

- Thermon (West Greece): The Doric temple of Apollo Thermios, was built in the middle of the 7th century B.C. It was built on an older curvilinear building dating perhaps from the 10th century B.C., on which a peristyle was added. The temple was narrow, and the number of pteron columns (probably wooden) was 5 x 15. There was a single row of inner columns. It measures 12.13 x 38.23 m at the stylobate, which was made from stones.[104]

Floor plan of the temple of Apollo, Corinth

- Corinth: A Doric temple was built in the 6th century B.C. The temple’s stylobate measures 21.36 x 53.30 m, and the number of pteron columns was 6 x 15. There was a double row of inner columns. The style is similar with the Temple of Alcmeonidae at Delphi.[105] The Corinthians were considered to be the inventors of the Doric order.[104]

- Napes (Lesbos): An Aeolic temple probably of Apollo Napaios was built in the 7th century B.C. Some special capitals with floral ornament have been found, which are called Aeolic, and it seems that they were borrowed from the East.[106]