The Osiris myth is the most elaborate and influential story in ancient Egyptian mythology. It concerns the murder of the god Osiris, a primeval king of Egypt, and its consequences. Osiris’s murderer, his brother Set, usurps his throne. Meanwhile, Osiris’s wife Isis restores her husband’s body, allowing him to posthumously conceive their son, Horus. The remainder of the story focuses on Horus, the product of the union of Isis and Osiris, who is at first a vulnerable child protected by his mother and then becomes Set’s rival for the throne. Their often violent conflict ends with Horus’s triumph, which restores maat (cosmic and social order) to Egypt after Set’s unrighteous reign and completes the process of Osiris’s resurrection.

The myth, with its complex symbolism, is integral to ancient Egyptian conceptions of kingship and succession, conflict between order and disorder, sexuality and rebirth, and especially death and the afterlife. It also expresses the essential character of each of the four deities at its center, and many elements of their worship in ancient Egyptian religion were derived from the myth.

The Osiris myth reached its basic form in or before the 24th century BCE. Many of its elements originated in religious ideas, but the struggle between Horus and Set may have been partly inspired by a regional conflict in Egypt’s Early Dynastic or Prehistoric Egypt. Scholars have tried to discern the exact nature of the events that gave rise to the story, but they have reached no definitive conclusions.

Parts of the myth appear in a wide variety of Egyptian texts, from funerary texts and magical spells to short stories. The story is, therefore, more detailed and more cohesive than any other ancient Egyptian myth. Yet no Egyptian source gives a full account of the myth, and the sources vary widely in their versions of events. Greek and Roman writings, particularly On Isis and Osiris by Plutarch, provide more information but may not always accurately reflect Egyptian beliefs. Through these writings, the Osiris myth persisted after knowledge of most ancient Egyptian beliefs was lost, and it is still well known today.

Sources[edit]

The myth of Osiris was deeply influential in ancient Egyptian religion and was popular among ordinary people.[1] One reason for this popularity is the myth’s primary religious meaning, which implies that any dead person can reach a pleasant afterlife.[2] Another reason is that the characters and their emotions are more reminiscent of the lives of real people than those in most Egyptian myths, making the story more appealing to the general populace.[3] In particular, the myth conveys a «strong sense of family loyalty and devotion», as the Egyptologist J. Gwyn Griffiths puts it, in the relationships between Osiris, Isis, and Horus.[4]

With this widespread appeal, the myth appears in more ancient texts than any other myth and in an exceptionally broad range of Egyptian literary styles.[1] These sources also provide an unusual amount of detail.[2] Ancient Egyptian myths are fragmentary and vague; the religious metaphors contained within the myths were more important than coherent narration.[5] Each text that contains a myth, or a fragment of one, may adapt the myth to suit its particular purposes, so different texts can contain contradictory versions of events.[6] Because the Osiris myth was used in such a variety of ways, versions often conflict with each other. Nevertheless, the fragmentary versions, taken together, give it a greater resemblance to a cohesive story than most Egyptian myths.[7]

The earliest mentions of the Osiris myth are in the Pyramid Texts, the first Egyptian funerary texts, which appeared on the walls of burial chambers in pyramids at the end of the Fifth Dynasty, during the 24th century BCE. These texts, made up of disparate spells or «utterances», contain ideas that are presumed to date from still earlier times.[8] The texts are concerned with the afterlife of the king buried in the pyramid, so they frequently refer to the Osiris myth, which is deeply involved with kingship and the afterlife.[9] Major elements of the story, such as the death and restoration of Osiris and the strife between Horus and Set, appear in the utterances of the Pyramid Texts.[10] Funerary texts written in later times, such as the Coffin Texts from the Middle Kingdom (c. 2055–1650 BCE) and the Book of the Dead from the New Kingdom (c. 1550–1070 BCE), also contain elements of the myth.[11]

Other types of religious texts give evidence for the myth, such as two Middle Kingdom texts: the Dramatic Ramesseum Papyrus and the Ikhernofret Stela. The papyrus describes the coronation of Senusret I, whereas the stela alludes to events in the annual festival of Khoiak. Rituals in both these festivals reenacted elements of the Osiris myth.[12] The most complete ancient Egyptian account of the myth is the Great Hymn to Osiris, an inscription from the Eighteenth Dynasty (c. 1550–1292 BCE) that gives the general outline of the entire story but includes little detail.[13] Another important source is the Memphite Theology, a religious narrative that includes an account of Osiris’s death as well as the resolution of the dispute between Horus and Set. This narrative associates the kingship that Osiris and Horus represent with Ptah, the creator deity of Memphis.[14] The text was long thought to date back to the Old Kingdom (c. 2686–2181 BCE) and was treated as a source for information about the early stages in the development of the myth. Since the 1970s, however, Egyptologists have concluded that the text dates to the New Kingdom at the earliest.[15]

Rituals in honor of Osiris are another major source of information. Some of these texts are found on the walls of temples that date from the New Kingdom, the Ptolemaic era (323–30 BCE), or the Roman era (30 BCE to the fourth century AD).[16] Some of these late ritual texts, in which Isis and Nephthys lament their brother’s death, were adapted into funerary texts. In these texts, the goddesses’ pleas were meant to rouse Osiris—and thus the deceased person—to live again.[17]

Magical healing spells, which were used by Egyptians of all classes, are the source for an important portion of the myth, in which Horus is poisoned or otherwise sickened, and Isis heals him. The spells identify a sick person with Horus so that he or she can benefit from the goddess’s efforts. The spells are known from papyrus copies, which serve as instructions for healing rituals, and from a specialized type of inscribed stone stela called a cippus. People seeking healing poured water over these cippi, an act that was believed to imbue the water with the healing power contained in the text, and then drank the water in hope of curing their ailments. The theme of an endangered child protected by magic also appears on inscribed ritual wands from the Middle Kingdom, which were made centuries before the more detailed healing spells that specifically connect this theme with the Osiris myth.[18]

Episodes from the myth were also recorded in writings that may have been intended as entertainment. Prominent among these texts is «The Contendings of Horus and Set», a humorous retelling of several episodes of the struggle between the two deities, which dates to the Twentieth Dynasty (c. 1190–1070 BCE).[19] It vividly characterizes the deities involved; as the Egyptologist Donald B. Redford says, «Horus appears as a physically weak but clever Puck-like figure, Seth [Set] as a strong-man buffoon of limited intelligence, Re-Horakhty [Ra] as a prejudiced, sulky judge, and Osiris as an articulate curmudgeon with an acid tongue.»[20] Despite its atypical nature, «Contendings» includes many of the oldest episodes in the divine conflict, and many events appear in the same order as in much later accounts, suggesting that a traditional sequence of events was forming at the time that the story was written.[21]

Ancient Greek and Roman writers, who described Egyptian religion late in its history, recorded much of the Osiris myth. Herodotus, in the 5th century BCE, mentioned parts of the myth in his description of Egypt in the Histories, and four centuries later, Diodorus Siculus provided a summary of the myth in his Bibliotheca historica.[22] In the early 2nd century AD,[23] Plutarch wrote the most complete ancient account of the myth in On Isis and Osiris, an analysis of Egyptian religious beliefs.[24] Plutarch’s account of the myth is the version that modern popular writings most frequently retell.[25] The writings of these classical authors may give a distorted view of Egyptian beliefs.[24] For instance, On Isis and Osiris includes many interpretations of Egyptian belief that are influenced by various Greek philosophies, and its account of the myth contains portions with no known parallel in Egyptian tradition. Griffiths concluded that several elements of this account were taken from Greek mythology, and that the work as a whole was not based directly on Egyptian sources.[26] His colleague John Baines, on the other hand, says that temples may have kept written accounts of myths that were later lost, and that Plutarch could have drawn on such sources to write his narrative.[27]

Synopsis[edit]

Death and resurrection of Osiris[edit]

At the start of the story, Osiris rules Egypt, having inherited the kingship from his ancestors in a lineage stretching back to the creator of the world, Ra or Atum. His queen is Isis, who, along with Osiris and his murderer, Set, is one of the children of the earth god Geb and the sky goddess Nut. Little information about the reign of Osiris appears in Egyptian sources; the focus is on his death and the events that follow.[28] Osiris is connected with life-giving power, righteous kingship, and the rule of maat, the ideal natural order whose maintenance was a fundamental goal in ancient Egyptian culture.[29] Set is closely associated with violence and chaos. Therefore, the slaying of Osiris symbolizes the struggle between order and disorder, and the disruption of life by death.[30]

Some versions of the myth provide Set’s motive for killing Osiris. According to a spell in the Pyramid Texts, Set is taking revenge for a kick Osiris gave him,[31] whereas in a Late Period text, Set’s grievance is that Osiris had sex with Nephthys, who is Set’s consort and the fourth child of Geb and Nut.[2] The murder itself is frequently alluded to, but never clearly described. The Egyptians believed that written words had the power to affect reality, so they avoided writing directly about profoundly negative events such as Osiris’s death.[32] Sometimes they denied his death altogether, even though the bulk of the traditions about him make it clear that he has been murdered.[33] In some cases the texts suggest that Set takes the form of a wild animal, such as a crocodile or bull, to slay Osiris; in others they imply that Osiris’s corpse is thrown in the water or that he is drowned. This latter tradition is the origin of the Egyptian belief that people who had drowned in the Nile were sacred.[34] Even the identity of the victim can vary, as it is sometimes the god Haroeris, an elder form of Horus, who is murdered by Set and then avenged by another form of Horus, who is Haroeris’s son by Isis.[35]

By the end of the New Kingdom, a tradition had developed that Set had cut Osiris’s body into pieces and scattered them across Egypt. Cult centers of Osiris all over the country claimed that the corpse, or particular pieces of it, were found near them. The dismembered parts could be said to number as many as forty-two, each piece being equated with one of the forty-two nomes, or provinces, in Egypt.[36] Thus the god of kingship becomes the embodiment of his kingdom.[34]

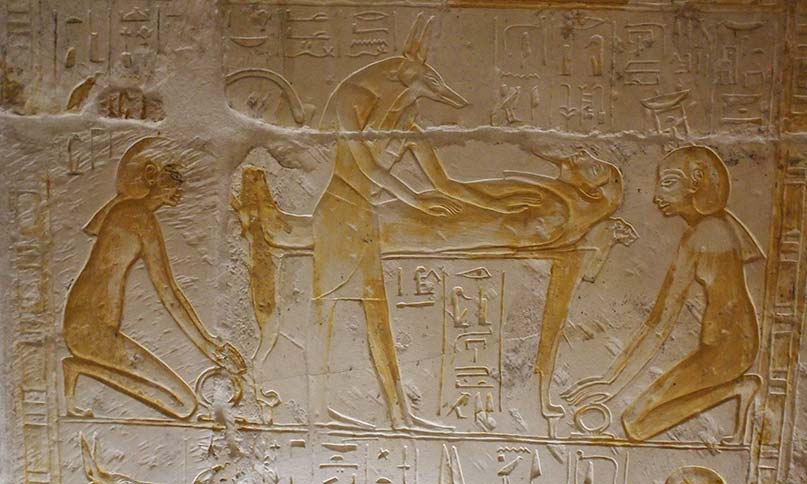

Isis, in the form of a bird, copulates with the deceased Osiris. At either side are Horus, although he is as yet unborn, and Isis in human form.[37]

Osiris’s death is followed either by an interregnum or by a period in which Set assumes the kingship. Meanwhile, Isis searches for her husband’s body with the aid of Nephthys.[36] When searching for or mourning Osiris, the two goddesses are often likened to falcons or kites,[38] possibly because kites travel far in search of carrion,[39] because the Egyptians associated their plaintive calls with cries of grief, or because of the goddesses’ connection with Horus, who is often represented as a falcon.[38] In the New Kingdom, when Osiris’s death and renewal came to be associated with the annual flooding of the Nile that fertilized Egypt, the waters of the Nile were equated with Isis’s tears of mourning[40] or with Osiris’s bodily fluids.[41] Osiris thus represented the life-giving divine power that was present in the river’s water and in the plants that grew after the flood.[42]

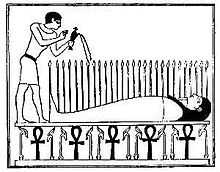

The goddesses find and restore Osiris’s body, often with the help of other deities, including Thoth, a deity credited with great magical and healing powers, and Anubis, the god of embalming and funerary rites. Osiris becomes the first mummy, and the gods’ efforts to restore his body are the mythological basis for Egyptian embalming practices, which sought to prevent and reverse the decay that follows death. This part of the story is often extended with episodes in which Set or his followers try to damage the corpse, and Isis and her allies must protect it. Once Osiris is made whole, Isis conceives his son and rightful heir, Horus.[43] One ambiguous spell in the Coffin Texts may indicate that Isis is impregnated by a flash of lightning,[44] while in other sources, Isis, still in bird form, fans breath and life into Osiris’s body with her wings and copulates with him.[36] Osiris’s revival is apparently not permanent, and after this point in the story he is only mentioned as the ruler of the Duat, the distant and mysterious realm of the dead. Although he lives on only in the Duat, he and the kingship he stands for will, in a sense, be reborn in his son.[45]

The cohesive account by Plutarch, which deals mainly with this portion of the myth, differs in many respects from the known Egyptian sources. Set—whom Plutarch, using Greek names for many of the Egyptian deities, refers to as «Typhon»—conspires against Osiris with seventy-two unspecified accomplices, as well as a queen from ancient Aethiopia (Nubia). Set has an elaborate chest made to fit Osiris’s exact measurements and then, at a banquet, declares that he will give the chest as a gift to whoever fits inside it. The guests, in turn, lie inside the coffin, but none fit inside except Osiris. When he lies down in the chest, Set and his accomplices slam the cover shut, seal it, and throw it into the Nile. With Osiris’s corpse inside, the chest floats out into the sea, arriving at the city of Byblos, where a tree grows around it. The king of Byblos has the tree cut down and made into a pillar for his palace, still with the chest inside. Isis must remove the chest from within the tree in order to retrieve her husband’s body. Having taken the chest, she leaves the tree in Byblos, where it becomes an object of worship for the locals. This episode, which is not known from Egyptian sources, gives an etiological explanation for a cult of Isis and Osiris that existed in Byblos in Plutarch’s time and possibly as early as the New Kingdom.[46]

Plutarch also states that Set steals and dismembers the corpse only after Isis has retrieved it. Isis then finds and buries each piece of her husband’s body, with the exception of the penis, which she has to reconstruct with magic, because the original was eaten by fish in the river. According to Plutarch, this is the reason the Egyptians had a taboo against eating fish. In Egyptian accounts, however, the penis of Osiris is found intact, and the only close parallel with this part of Plutarch’s story is in «The Tale of Two Brothers», a folk tale from the New Kingdom with similarities to the Osiris myth.[47]

A final difference in Plutarch’s account is Horus’s birth. The form of Horus that avenges his father has been conceived and born before Osiris’s death. It is a premature and weak second child, Harpocrates, who is born from Osiris’s posthumous union with Isis. Here, two of the separate forms of Horus that exist in Egyptian tradition have been given distinct positions within Plutarch’s version of the myth.[48]

Birth and childhood of Horus[edit]

In Egyptian accounts, the pregnant Isis hides from Set, to whom the unborn child is a threat, in a thicket of papyrus in the Nile Delta. This place is called Akh-bity, meaning «papyrus thicket of the king of Lower Egypt» in Egyptian.[49] Greek writers call this place Khemmis and indicate that it is near the city of Buto,[50] but in the myth, the physical location is less important than its nature as an iconic place of seclusion and safety.[51] The thicket’s special status is indicated by its frequent depiction in Egyptian art; for most events in Egyptian mythology, the backdrop is minimally described or illustrated. In this thicket, Isis gives birth to Horus and raises him, and hence it is also called the «nest of Horus».[36] The image of Isis nursing her child is a very common motif in Egyptian art.[49]

There are texts such as the Metternich Stela that date to the Late Period in which Isis travels in the wider world. She moves among ordinary humans who are unaware of her identity, and she even appeals to these people for help. This is another unusual circumstance, for in Egyptian myth, gods and humans are normally separate.[52] As in the first phase of the myth, she often has the aid of other deities, who protect her son in her absence.[36] According to one magical spell, seven minor scorpion deities travel with and guard Isis as she seeks help for Horus. They even take revenge on a wealthy woman who has refused to help Isis by stinging the woman’s son, making it necessary for Isis to heal the blameless child.[52] This story conveys a moral message that the poor can be more virtuous than the wealthy and illustrates Isis’s fair and compassionate nature.[53]

In this stage of the myth, Horus is a vulnerable child beset by dangers. The magical texts that use Horus’s childhood as the basis for their healing spells give him different ailments, from scorpion stings to simple stomachaches,[54] adapting the tradition to fit the malady that each spell was intended to treat.[55] Most commonly, the child god has been bitten by a snake, reflecting the Egyptians’ fear of snakebite and the resulting poison.[36] Some texts indicate that these hostile creatures are agents of Set.[56] Isis may use her own magical powers to save her child, or she may plead with or threaten deities such as Ra or Geb, so they will cure him. As she is the archetypal mourner in the first portion of the story, so during Horus’s childhood she is the ideal devoted mother.[57] Through the magical healing texts, her efforts to heal her son are extended to cure any patient.[51]

Conflict of Horus and Set[edit]

The next phase of the myth begins when the adult Horus challenges Set for the throne of Egypt. The contest between them is often violent but is also described as a legal judgment before the Ennead, an assembled group of Egyptian deities, to decide who should inherit the kingship. The judge in this trial may be Geb, who, as the father of Osiris and Set, held the throne before they did, or it may be the creator gods Ra or Atum, the originators of kingship.[58] Other deities also take important roles: Thoth frequently acts as a conciliator in the dispute[59] or as an assistant to the divine judge, and in «Contendings», Isis uses her cunning and magical power to aid her son.[60]

The rivalry of Horus and Set is portrayed in two contrasting ways. Both perspectives appear as early as the Pyramid Texts, the earliest source of the myth. In some spells from these texts, Horus is the son of Osiris and nephew of Set, and the murder of Osiris is the major impetus for the conflict. The other tradition depicts Horus and Set as brothers.[61] This incongruity persists in many of the subsequent sources, where the two gods may be called brothers or uncle and nephew at different points in the same text.[62]

Horus spears Set, who appears in the form of a hippopotamus, as Isis looks on

The divine struggle involves many episodes. «Contendings» describes the two gods appealing to various other deities to arbitrate the dispute and competing in different types of contests, such as racing in boats or fighting each other in the form of hippopotami, to determine a victor. In this account, Horus repeatedly defeats Set and is supported by most of the other deities.[63] Yet the dispute drags on for eighty years, largely because the judge, the creator god, favors Set.[64] In late ritual texts, the conflict is characterized as a great battle involving the two deities’ assembled followers.[65] The strife in the divine realm extends beyond the two combatants. At one point Isis attempts to harpoon Set as he is locked in combat with her son, but she strikes Horus instead, who then cuts off her head in a fit of rage.[66] Thoth replaces Isis’s head with that of a cow; the story gives a mythical origin for the cow-horn headdress that Isis commonly wears.[67]

In a key episode in the conflict, Set sexually abuses Horus. Set’s violation is partly meant to degrade his rival, but it also involves homosexual desire, in keeping with one of Set’s major characteristics, his forceful and indiscriminate sexuality.[68] In the earliest account of this episode, in a fragmentary Middle Kingdom papyrus, the sexual encounter begins when Set asks to have sex with Horus, who agrees on the condition that Set will give Horus some of his strength.[69] The encounter puts Horus in danger, because in Egyptian tradition semen is a potent and dangerous substance, akin to poison. According to some texts, Set’s semen enters Horus’s body and makes him ill, but in «Contendings», Horus thwarts Set by catching Set’s semen in his hands. Isis retaliates by putting Horus’s semen on lettuce-leaves that Set eats. Set’s defeat becomes apparent when this semen appears on his forehead as a golden disk. He has been impregnated with his rival’s seed and as a result «gives birth» to the disk. In «Contendings», Thoth takes the disk and places it on his own head; other accounts imply that Thoth himself was produced by this anomalous birth.[70]

Another important episode concerns mutilations that the combatants inflict upon each other: Horus injures or steals Set’s testicles and Set damages or tears out one, or occasionally both, of Horus’s eyes. Sometimes the eye is torn into pieces.[71] Set’s mutilation signifies a loss of virility and strength.[72] The removal of Horus’s eye is even more important, for this stolen Eye of Horus represents a wide variety of concepts in Egyptian religion. One of Horus’s major roles is as a sky deity, and for this reason his right eye was said to be the sun and his left eye the moon. The theft or destruction of the Eye of Horus is therefore equated with the darkening of the moon in the course of its cycle of phases, or during eclipses. Horus may take back his lost Eye, or other deities, including Isis, Thoth, and Hathor, may retrieve or heal it for him.[71] The Egyptologist Herman te Velde argues that the tradition about the lost testicles is a late variation on Set’s loss of semen to Horus, and that the moon-like disk that emerges from Set’s head after his impregnation is the Eye of Horus. If so, the episodes of mutilation and sexual abuse would form a single story, in which Set assaults Horus and loses semen to him, Horus retaliates and impregnates Set, and Set comes into possession of Horus’s Eye when it appears on Set’s head. Because Thoth is a moon deity in addition to his other functions, it would make sense, according to te Velde, for Thoth to emerge in the form of the Eye and step in to mediate between the feuding deities.[73]

In any case, the restoration of the Eye of Horus to wholeness represents the return of the moon to full brightness,[74] the return of the kingship to Horus,[75] and many other aspects of maat.[76] Sometimes the restoration of Horus’s eye is accompanied by the restoration of Set’s testicles, so that both gods are made whole near the conclusion of their feud.[77]

Resolution[edit]

As with so many other parts of the myth, the resolution is complex and varied. Often, Horus and Set divide the realm between them. This division can be equated with any of several fundamental dualities that the Egyptians saw in their world. Horus may receive the fertile lands around the Nile, the core of Egyptian civilization, in which case Set takes the barren desert or the foreign lands that are associated with it; Horus may rule the earth while Set dwells in the sky; and each god may take one of the two traditional halves of the country, Upper and Lower Egypt, in which case either god may be connected with either region. Yet in the Memphite Theology, Geb, as judge, first apportions the realm between the claimants and then reverses himself, awarding sole control to Horus. In this peaceable union, Horus and Set are reconciled, and the dualities that they represent have been resolved into a united whole. Through this resolution, order is restored after the tumultuous conflict.[78]

A different view of the myth’s end focuses on Horus’s sole triumph.[79] In this version, Set is not reconciled with his rival but utterly defeated,[80] and sometimes he is exiled from Egypt or even destroyed.[81] His defeat and humiliation is more pronounced in sources from later periods of Egyptian history, when he was increasingly equated with disorder and evil, and the Egyptians no longer saw him as an integral part of natural order.[80]

With great celebration among the gods, Horus takes the throne, and Egypt at last has a rightful king.[82] The divine decision that Set is in the wrong corrects the injustice created by Osiris’s murder and completes the process of his restoration after death.[83] Sometimes Set is made to carry Osiris’s body to its tomb as part of his punishment.[84] The new king performs funerary rites for his father and gives food offerings to sustain him—often including the Eye of Horus, which in this instance represents life and plenty.[85] According to some sources, only through these acts can Osiris be fully enlivened in the afterlife and take his place as king of the dead, paralleling his son’s role as king of the living. Thereafter, Osiris is deeply involved with natural cycles of death and renewal, such as the annual growth of crops, that parallel his own resurrection.[86]

Origins[edit]

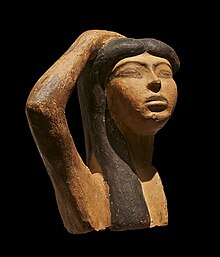

As the Osiris myth first appears in the Pyramid Texts, most of its essential features must have taken shape sometime before the texts were written down. The distinct segments of the story—Osiris’s death and restoration, Horus’s childhood, and Horus’s conflict with Set—may originally have been independent mythic episodes. If so, they must have begun to coalesce into a single story by the time of the Pyramid Texts, which loosely connect those segments. In any case, the myth was inspired by a variety of influences.[3] Much of the story is based in religious ideas[87] and the general nature of Egyptian society: the divine nature of kingship, the succession from one king to another,[88] the struggle to maintain maat,[89] and the effort to overcome death.[3] For instance, the lamentations of Isis and Nephthys for their dead brother may represent an early tradition of ritualized mourning.[90]

There are, however, important points of disagreement. The origins of Osiris are much debated,[41] and the basis for the myth of his death is also somewhat uncertain.[91] One influential hypothesis was given by the anthropologist James Frazer, who in 1906 said that Osiris, like other «dying and rising gods» across the ancient Near East, began as a personification of vegetation. His death and restoration, therefore, were based on the yearly death and re-growth of plants.[92] Many Egyptologists adopted this explanation. But in the late 20th century, J. Gwyn Griffiths, who extensively studied Osiris and his mythology, argued that Osiris originated as a divine ruler of the dead, and his connection with vegetation was a secondary development.[93] Meanwhile, scholars of comparative religion have criticized the overarching concept of «dying and rising gods», or at least Frazer’s assumption that all these gods closely fit the same pattern.[92] More recently, the Egyptologist Rosalie David maintains that Osiris originally «personified the annual rebirth of the trees and plants after the [Nile] inundation.»[94]

Horus and Set as supporters of the king

Another continuing debate concerns the opposition of Horus and Set, which Egyptologists have often tried to connect with political events early in Egypt’s history or prehistory. The cases in which the combatants divide the kingdom, and the frequent association of the paired Horus and Set with the union of Upper and Lower Egypt, suggest that the two deities represent some kind of division within the country. Egyptian tradition and archaeological evidence indicate that Egypt was united at the beginning of its history when an Upper Egyptian kingdom, in the south, conquered Lower Egypt in the north. The Upper Egyptian rulers called themselves «followers of Horus», and Horus became the patron god of the unified nation and its kings. Yet Horus and Set cannot be easily equated with the two halves of the country. Both deities had several cult centers in each region, and Horus is often associated with Lower Egypt and Set with Upper Egypt.[35] One of the better-known explanations for these discrepancies was proposed by Kurt Sethe in 1930. He argued that Osiris was originally the human ruler of a unified Egypt in prehistoric times, before a rebellion of Upper Egyptian Set-worshippers. The Lower Egyptian followers of Horus then forcibly reunified the land, inspiring the myth of Horus’s triumph, before Upper Egypt, now led by Horus worshippers, became prominent again at the start of the Early Dynastic Period.[95]

In the late 20th century, Griffiths focused on the inconsistent portrayal of Horus and Set as brothers and as uncle and nephew. He argued that, in the early stages of Egyptian mythology, the struggle between Horus and Set as siblings and equals was originally separate from the murder of Osiris. The two stories were joined into the single Osiris myth sometime before the writing of the Pyramid Texts. With this merging, the genealogy of the deities involved and the characterization of the Horus–Set conflict were altered so that Horus is the son and heir avenging Osiris’s death. Traces of the independent traditions remained in the conflicting characterizations of the combatants’ relationship and in texts unrelated to the Osiris myth, which make Horus the son of the goddess Nut or the goddess Hathor rather than of Isis and Osiris. Griffiths therefore rejected the possibility that Osiris’s murder was rooted in historical events.[96] This hypothesis has been accepted by more recent scholars such as Jan Assmann[62] and George Hart.[97]

Griffiths sought a historical origin for the Horus–Set rivalry, and he posited two distinct predynastic unifications of Egypt by Horus worshippers, similar to Sethe’s theory, to account for it.[98] Yet the issue remains unresolved, partly because other political associations for Horus and Set complicate the picture further.[99] Before even Upper Egypt had a single ruler, two of its major cities were Nekhen, in the far south, and Naqada, many miles to the north. The rulers of Nekhen, where Horus was the patron deity, are generally believed to have unified Upper Egypt, including Naqada, under their sway. Set was associated with Naqada, so it is possible that the divine conflict dimly reflects an enmity between the cities in the distant past. Much later, at the end of the Second Dynasty (c. 2890–2686 BCE), King Peribsen used the Set animal in writing his serekh-name, in place of the traditional falcon hieroglyph representing Horus. His successor Khasekhemwy used both Horus and Set in the writing of his serekh. This evidence has prompted conjecture that the Second Dynasty saw a clash between the followers of the Horus-king and the worshippers of Set led by Peribsen. Khasekhemwy’s use of the two animal symbols would then represent the reconciliation of the two factions, as does the resolution of the myth.[35]

Noting the uncertainty surrounding these events, Herman te Velde argues that the historical roots of the conflict are too obscure to be very useful in understanding the myth and are not as significant as its religious meaning. He says that «the origin of the myth of Horus and Seth is lost in the mists of the religious traditions of prehistory.»[87]

Influence[edit]

The effect of the Osiris myth on Egyptian culture was greater and more widespread than that of any other myth.[1] In literature, the myth was not only the basis for a retelling such as «Contendings»; it also provided the basis for more distantly related stories. «The Tale of Two Brothers», a folk tale with human protagonists, includes elements similar to the myth of Osiris.[100] One character’s penis is eaten by a fish, and he later dies and is resurrected.[101] Another story, «The Tale of Truth and Falsehood», adapts the conflict of Horus and Set into an allegory, in which the characters are direct personifications of truth and lies rather than deities associated with those concepts.[100]

Osiris and funerary ritual[edit]

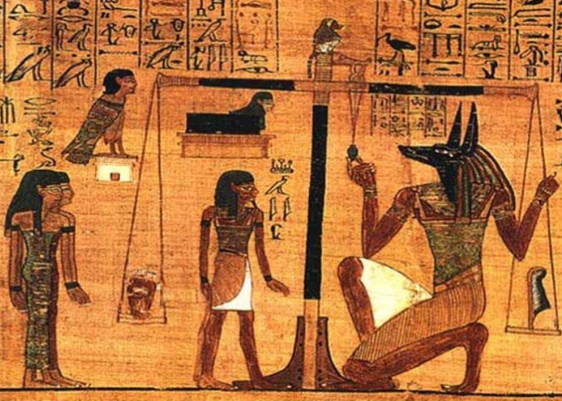

From at least the time of the Pyramid Texts, kings hoped that after their deaths they could emulate Osiris’s restoration to life and his rule over the realm of the dead. By the early Middle Kingdom (c. 2055–1650 BCE), non-royal Egyptians believed that they, too, could overcome death as Osiris had, by worshipping him and receiving the funerary rites that were partly based on his myth. Osiris thus became Egypt’s most important afterlife deity.[103] The myth also influenced the notion, which grew prominent in the New Kingdom, that only virtuous people could reach the afterlife. As the assembled deities judged Osiris and Horus to be in the right, undoing the injustice of Osiris’s death, so a deceased soul had to be judged righteous in order for his or her death to be undone.[83] As ruler of the land of the dead and as a god connected with maat, Osiris became the judge in this posthumous trial, offering life after death to those who followed his example.[104] New Kingdom funerary texts such as the Amduat and the Book of Gates liken Ra himself to a deceased soul. In them, he travels through the Duat and unites with Osiris to be reborn at dawn.[105] Thus, Osiris was not only believed to enable rebirth for the dead; he renewed the sun, the source of life and maat, and thus renewed the world itself.[106]

As the importance of Osiris grew, so did his popularity. By late in the Middle Kingdom, the centuries-old tomb of the First Dynasty ruler Djer, near Osiris’s main center of worship in the city of Abydos, was seen as Osiris’s tomb. Accordingly, it became a major focus of Osiris worship. For the next 1,500 years, an annual festival procession traveled from Osiris’s main temple to the tomb site. [107] Kings and commoners from across Egypt built chapels, which served as cenotaphs, near the processional route. In doing so they sought to strengthen their connection with Osiris in the afterlife.[108]

Another major funerary festival, a national event spread over several days in the month of Khoiak in the Egyptian calendar, became linked with Osiris during the Middle Kingdom.[109] During Khoiak the djed pillar, an emblem of Osiris, was ritually raised into an upright position, symbolizing Osiris’s restoration. By Ptolemaic times (305–30 BCE), Khoiak also included the planting of seeds in an «Osiris bed», a mummy-shaped bed of soil, connecting the resurrection of Osiris with the seasonal growth of plants.[110]

Horus, the Eye of Horus, and kingship[edit]

The myth’s religious importance extended beyond the funerary sphere. Mortuary offerings, in which family members or hired priests presented food to the deceased, were logically linked with the mythological offering of the Eye of Horus to Osiris. By analogy, this episode of the myth was eventually equated with other interactions between a human and a being in the divine realm. In temple offering rituals, the officiating priest took on the role of Horus, the gifts to the deity became the Eye of Horus, and whichever deity received these gifts was momentarily equated with Osiris.[111]

The myth influenced popular religion as well. One example is the magical healing spells based on Horus’s childhood. Another is the use of the Eye of Horus as a protective emblem in personal apotropaic amulets. Its mythological restoration made it appropriate for this purpose, as a general symbol of well-being.[112]

The ideology surrounding the living king was also affected by the Osiris myth. The Egyptians envisioned the events of the Osiris myth as taking place sometime in Egypt’s dim prehistory, and Osiris, Horus, and their divine predecessors were included in Egyptian lists of past kings such as the Turin Royal Canon.[113] Horus, as a primeval king and as the personification of kingship, was regarded as the predecessor and exemplar for all Egyptian rulers. His assumption of his father’s throne and pious actions to sustain his spirit in the afterlife were the model for all pharaonic successions to emulate.[114] Each new king was believed to renew maat after the death of the preceding king, just as Horus had done. In royal coronations, rituals alluded to Osiris’s burial, and hymns celebrated the new king’s accession as the equivalent of Horus’s own.[82]

Set[edit]

The Osiris myth contributed to the frequent characterization of Set as a disruptive, harmful god. Although other elements of Egyptian tradition credit Set with positive traits, in the Osiris myth the sinister aspects of his character predominate.[115] He and Horus were often juxtaposed in art to represent opposite principles, such as good and evil, intellect and instinct, and the different regions of the world that they rule in the myth. Egyptian wisdom texts contrast the character of the ideal person with the opposite type—the calm and sensible «Silent One» and the impulsive, disruptive «Hothead»—and one description of these two characters calls them the Horus-type and the Set-type. Yet the two gods were often treated as part of a harmonious whole. In some local cults they were worshipped together; in art they were often shown tying together the emblems of Upper and Lower Egypt to symbolize the unity of the nation; and in funerary texts they appear as a single deity with the heads of Horus and Set, apparently representing the mysterious, all-encompassing nature of the Duat.[116]

Overall Set was viewed with ambivalence, until during the first millennium BCE he came to be seen as a totally malevolent deity. This transformation was prompted more by his association with foreign lands than by the Osiris myth.[115] Nevertheless, in these late times, the widespread temple rituals involving the ceremonial annihilation of Set were often connected with the myth.[117]

Isis, Nephthys, and the Greco-Roman world[edit]

Both Isis and Nephthys were seen as protectors of the dead in the afterlife because of their protection and restoration of Osiris’s body.[118] The motif of Isis and Nephthys protecting Osiris or the mummy of the deceased person was very common in funerary art.[119] Khoiak celebrations made reference to, and may have ritually reenacted, Isis’s and Nephthys’s mourning, restoration, and revival of their murdered brother.[120] As Horus’s mother, Isis was also the mother of every king according to royal ideology, and kings were said to have nursed at her breast as a symbol of their divine legitimacy.[121] Her appeal to the general populace was based in her protective character, as exemplified by the magical healing spells. In the Late Period, she was credited with ever greater magical power, and her maternal devotion was believed to extend to everyone. By Roman times she had become the most important goddess in Egypt.[122] The image of the goddess holding her child was used prominently in her worship—for example, in panel paintings that were used in household shrines dedicated to her. Isis’s iconography in these paintings closely resembles and may have influenced the earliest Christian icons of Mary holding Jesus.[123]

In the late centuries BCE, the worship of Isis spread from Egypt across the Mediterranean world, and she became one of the most popular deities in the region. Although this new, multicultural form of Isis absorbed characteristics from many other deities, her original mythological nature as a wife and mother was key to her appeal. Horus and Osiris, being central figures in her story, spread along with her.[124] The Greek and Roman cult of Isis developed a series of initiation rites dedicated to Isis and Osiris, based on earlier Greco-Roman mystery rites but colored by Egyptian afterlife beliefs.[125] The initiate went through an experience that simulated descent into the underworld. Elements of this ritual resemble Osiris’s merging with the sun in Egyptian funerary texts.[126] Isis’s Greek and Roman devotees, like the Egyptians, believed that she protected the dead in the afterlife as she had done for Osiris,[127] and they said that undergoing the initiation guaranteed to them a blessed afterlife.[128] It was to a Greek priestess of Isis that Plutarch wrote his account of the myth of Osiris.[129]

Through the work of classical writers such as Plutarch, knowledge of the Osiris myth was preserved even after the middle of the first millennium AD, when Egyptian religion ceased to exist and knowledge of the writing systems that were originally used to record the myth were lost. The myth remained a major part of Western impressions of ancient Egypt. In modern times, when understanding of Egyptian beliefs is informed by the original Egyptian sources, the story continues to influence and inspire new ideas, from works of fiction to scholarly speculation and new religious movements.[130]

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ a b c Assmann 2001, p. 124.

- ^ a b c Smith 2008, p. 2.

- ^ a b c O’Connor 2009, pp. 37–40.

- ^ Griffiths 1970, pp. 344–345.

- ^ Tobin 1989, pp. 21–25.

- ^ Goebs 2002, pp. 38–45.

- ^ Tobin 1989, pp. 22–23, 104.

- ^ David 2002, pp. 92–94.

- ^ Griffiths 1980, pp. 7–8, 41.

- ^ Griffiths 1960, pp. 1, 4–7.

- ^ Pinch 2004, pp. 15, 78.

- ^ Griffiths 1980, pp. 107, 233–234.

- ^ Lichtheim 2006b, pp. 81–85.

- ^ Lichtheim 2006a, pp. 51–57.

- ^ David 2002, p. 86.

- ^ David 2002, p. 156.

- ^ Smith 2009, pp. 54–55, 61–62.

- ^ Pinch 2004, pp. 18, 29, 39.

- ^ Lichtheim 2006b, pp. 197, 214.

- ^ Redford 2001, p. 294.

- ^ Redford 2001, pp. 294–295.

- ^ Pinch 2004, pp. 34–35, 39–40.

- ^ Griffiths 1970, pp. 16–17.

- ^ a b Tobin 1989, p. 22.

- ^ Pinch 2004, p. 41.

- ^ Griffiths 1970, pp. 51–52, 98.

- ^ Baines 1996, p. 370.

- ^ Pinch 2004, pp. 75–78.

- ^ Pinch 2004, pp. 159–160, 178–179.

- ^ te Velde 1967, pp. 81–83.

- ^ Pinch 2004, p. 78.

- ^ Pinch 2004, pp. 6, 78.

- ^ Griffiths 1960, p. 6.

- ^ a b Griffiths 2001, pp. 615–619.

- ^ a b c Meltzer 2001, p. 120.

- ^ a b c d e f Pinch 2004, pp. 79–80.

- ^ Meeks & Favard-Meeks 1996, p. 37.

- ^ a b Griffiths 1980, pp. 49–50.

- ^ Wilkinson 2003, pp. 147–148.

- ^ Tobin 2001, p. 466.

- ^ a b Pinch 2004, pp. 178–179.

- ^ Tobin 1989, pp. 110–112.

- ^ Pinch 2004, pp. 80–81, 178–179.

- ^ Faulkner 1973, pp. 218–219.

- ^ Assmann 2001, pp. 129–130.

- ^ Griffiths 1970, pp. 137–143, 319–322.

- ^ Griffiths 1970, pp. 145, 342–343.

- ^ Griffiths 1970, pp. 147, 337–338.

- ^ a b Hart 2005, pp. 80–81.

- ^ Griffiths 1970, p. 313.

- ^ a b Assmann 2001, p. 133.

- ^ a b Meeks & Favard-Meeks 1996, pp. 82, 86–87.

- ^ Baines 1996, pp. 371–372.

- ^ Meeks & Favard-Meeks 1996, p. 73.

- ^ Pinch 2004, p. 39.

- ^ Griffiths 1960, p. 50.

- ^ Pinch 2004, pp. 147, 149–150, 185.

- ^ Griffiths 1960, pp. 58–59.

- ^ Griffiths 1960, p. 82.

- ^ Assmann 2001, pp. 135, 139–140.

- ^ Griffiths 1960, pp. 12–16.

- ^ a b Assmann 2001, pp. 134–135.

- ^ Lichtheim 2006b, pp. 214–223.

- ^ Hart 2005, p. 73.

- ^ Pinch 2004, p. 83.

- ^ Lichtheim 2006b, pp. 218–219.

- ^ Griffiths 2001, pp. 188–190.

- ^ te Velde 1967, pp. 55–56, 65.

- ^ Griffiths 1960, p. 42.

- ^ te Velde 1967, pp. 38–39, 43–44.

- ^ a b Pinch 2004, pp. 82–83, 91.

- ^ te Velde 1967, pp. 42–43.

- ^ te Velde 1967, pp. 43–46, 58.

- ^ Kaper 2001, p. 481.

- ^ Griffiths 1960, p. 29.

- ^ Pinch 2004, p. 131.

- ^ te Velde 1967, pp. 56–57.

- ^ te Velde 1967, pp. 59–63.

- ^ Pinch 2004, p. 84.

- ^ a b te Velde 1967, pp. 66–68.

- ^ Meeks & Favard-Meeks 1996, p. 29.

- ^ a b Assmann 2001, pp. 141–144.

- ^ a b Smith 2008, p. 3.

- ^ te Velde 1967, pp. 97–98.

- ^ Assmann 2001, pp. 49–50, 144–145.

- ^ Pinch 2004, pp. 84, 179.

- ^ a b te Velde 1967, pp. 76–80.

- ^ Griffiths 1980, pp. 185–186, 206.

- ^ Tobin 1989, p. 92.

- ^ Tobin 1989, p. 120.

- ^ Griffiths 1980, pp. 5–6.

- ^ a b Mettinger 2001, pp. 15–18, 40–41.

- ^ Griffiths 1980, pp. 158–162, 185.

- ^ David 2002, p. 157.

- ^ Griffiths 1960, pp. 131, 145–146.

- ^ Griffiths 1980, pp. 14–17.

- ^ Hart 2005, p. 72.

- ^ Griffiths 1960, pp. 141–142.

- ^ David 2002, p. 160.

- ^ a b Baines 1996, pp. 372–374.

- ^ Lichtheim 2006b, pp. 206–209.

- ^ Roth 2001, pp. 605–608.

- ^ David 2002, pp. 154, 158.

- ^ Griffiths 1980, pp. 181–184, 234–235.

- ^ Griffiths 1975, pp. 303–304.

- ^ Assmann 2001, pp. 77–80.

- ^ O’Connor 2009, pp. 90–91, 114, 122.

- ^ O’Connor 2009, pp. 92–96.

- ^ Graindorge 2001, pp. 305–307, vol. III.

- ^ Mettinger 2001, pp. 169–171.

- ^ Assmann 2001, pp. 49–50.

- ^ Meltzer 2001, p. 122.

- ^ Meeks & Favard-Meeks 1996, pp. 29–32.

- ^ Pinch 2004, pp. 84–87, 143.

- ^ a b te Velde 1967, pp. 137–142.

- ^ Englund 1989, pp. 77–79, 81–83.

- ^ Pinch 2004, pp. 193–194.

- ^ Pinch 2004, p. 171.

- ^ Wilkinson 2003, p. 160.

- ^ Smith 2009, pp. 96–99.

- ^ Assmann 2001, p. 134.

- ^ Wilkinson 2003, p. 146.

- ^ Mathews & Muller 2005, pp. 5–9.

- ^ David 2002, pp. 326–327.

- ^ Bremmer 2014, pp. 116, 123.

- ^ Griffiths 1975, pp. 296–298, 303–306.

- ^ Brenk 2009, pp. 228–229.

- ^ Bremmer 2014, pp. 121–122.

- ^ Griffiths 1970, pp. 16, 45.

- ^ Pinch 2004, pp. 45–47.

Works cited[edit]

- Assmann, Jan (2001) [German edition 1984]. The Search for God in Ancient Egypt. Translated by David Lorton. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-3786-1.

- Baines, John (1996). «Myth and Literature». In Loprieno, Antonio (ed.). Ancient Egyptian Literature: History and Forms. Cornell University Press. pp. 361–377. ISBN 978-90-04-09925-8.

- Bremmer, Jan N. (2014). Initiation into the Mysteries of the Ancient World. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-029955-7.

- Brenk, Frederick (2009). «‘Great Royal Spouse Who Protects Her Brother Osiris’: Isis in the Isaeum at Pompeii». In Casadio, Giovanni; Johnston, Patricia A. (eds.). Mystic Cults in Magna Graecia. University of Texas Press. pp. 217–234. ISBN 978-0-292-71902-6.

- David, Rosalie (2002). Religion and Magic in Ancient Egypt. Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-026252-0.

- Englund, Gertie (1989). «The Treatment of Opposites in Temple Thinking and Wisdom Literature». In Englund, Gertie (ed.). The Religion of the Ancient Egyptians: Cognitive Structures and Popular Expressions. S. Academiae Ubsaliensis. pp. 77–87. ISBN 978-91-554-2433-6.

- Faulkner, Raymond O. (August 1973). «‘The Pregnancy of Isis’, a Rejoinder». The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 59: 218–219. doi:10.2307/3856116. JSTOR 3856116.

- Goebs, Katja (2002). «A Functional Approach to Egyptian Myth and Mythemes». Journal of Ancient Near Eastern Religions. 2 (1): 27–59. doi:10.1163/156921202762733879.

- Graindorge, Catherine (2001). «Sokar». In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Vol. 3. Oxford University Press. pp. 305–307. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.

- Griffiths, J. Gwyn (1960). The Conflict of Horus and Seth. Liverpool University Press.

- Griffiths, J. Gwyn, ed. (1970). Plutarch’s De Iside et Osiride. University of Wales Press.

- Griffiths, J. Gwyn, ed. (1975). Apuleius, the Isis-book (Metamorphoses, book XI). E. J. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-04270-4.

- Griffiths, J. Gwyn (1980). The Origins of Osiris and His Cult. E. J. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-06096-8.

- Griffiths, J. Gwyn (2001). «Osiris». In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Vol. 2. Oxford University Press. pp. 615–619. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.

- Hart, George (2005). The Routledge Dictionary of Egyptian Gods and Goddesses, Second Edition. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-203-02362-4.

- Kaper, Olaf E. (2001). «Myths: Lunar Cycle». In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Vol. 2. Oxford University Press. pp. 480–482. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.

- Lichtheim, Miriam (2006a) [First edition 1973]. Ancient Egyptian Literature, Volume I: The Old and Middle Kingdoms. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-24842-7.

- Lichtheim, Miriam (2006b) [First edition 1976]. Ancient Egyptian Literature, Volume II: The New Kingdom. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-24843-4.

- Mathews, Thomas F.; Muller, Norman (2005). «Isis and Mary in Early Icons». In Vassiliaki, Maria (ed.). Images of the Mother of God: Perceptions of the Theotokos in Byzantium. Ashgate Publishing. pp. 3–11. ISBN 978-0-7546-3603-8.

- Meeks, Dimitri; Favard-Meeks, Christine (1996) [French 1993]. Daily Life of the Egyptian Gods. Translated by G. M. Goshgarian. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-8248-9.

- Meltzer, Edmund S. (2001). «Horus». In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Vol. 2. Oxford University Press. pp. 119–122. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.

- Mettinger, Tryggve N. D. (2001). The Riddle of Resurrection: «Dying and Rising Gods» in the Ancient Near East. Almqvist & Wiksell. ISBN 978-91-22-01945-9.

- O’Connor, David (2009). Abydos: Egypt’s First Pharaohs and the Cult of Osiris. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-39030-6.

- Pinch, Geraldine (2004) [First edition 2002]. Egyptian Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Goddesses, and Traditions of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-517024-5.

- Redford, Donald B. (2001). «The Contendings of Horus and Seth». In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. pp. 294–295. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.

- Roth, Ann Macy (2001). «Opening of the Mouth». In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Vol. 2. Oxford University Press. pp. 605–609. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.

- Smith, Mark (2008). Wendrich, Willeke (ed.). Osiris and the Deceased. UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology. Department of Near Eastern Languages and Cultures, UC Los Angeles. ISBN 978-0615214030. Retrieved June 5, 2012.

- Smith, Mark (2009). Traversing Eternity: Texts for the Afterlife from Ptolemaic and Roman Egypt. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-815464-8.

- te Velde, Herman (1967). Seth, God of Confusion. Translated by G. E. Van Baaren-Pape. E. J. Brill.

- Tobin, Vincent Arieh (1989). Theological Principles of Egyptian Religion. P. Lang. ISBN 978-0-8204-1082-1.

- Tobin, Vincent Arieh (2001). «Myths: An Overview». In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Vol. 2. Oxford University Press. pp. 464–469. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.

- Wilkinson, Richard H. (2003). The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-05120-7.

Further reading[edit]

- Borghouts, J. F. (1978). Ancient Egyptian Magical Texts. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-05848-4.

- Broze, Michèle (1996). Mythe et roman en Egypte Ancienne: les aventures d’Horus et Seth dans le Papyrus Chester Beatty I (in French). Peeters. ISBN 978-9068318906.

External links[edit]

- Plutarch: Isis and Osiris, on LacusCurtius. Full text of On Isis and Osiris as translated by Frank Cole Babbitt.

The Osiris myth is the most elaborate and influential story in ancient Egyptian mythology. It concerns the murder of the god Osiris, a primeval king of Egypt, and its consequences. Osiris’s murderer, his brother Set, usurps his throne. Meanwhile, Osiris’s wife Isis restores her husband’s body, allowing him to posthumously conceive their son, Horus. The remainder of the story focuses on Horus, the product of the union of Isis and Osiris, who is at first a vulnerable child protected by his mother and then becomes Set’s rival for the throne. Their often violent conflict ends with Horus’s triumph, which restores maat (cosmic and social order) to Egypt after Set’s unrighteous reign and completes the process of Osiris’s resurrection.

The myth, with its complex symbolism, is integral to ancient Egyptian conceptions of kingship and succession, conflict between order and disorder, sexuality and rebirth, and especially death and the afterlife. It also expresses the essential character of each of the four deities at its center, and many elements of their worship in ancient Egyptian religion were derived from the myth.

The Osiris myth reached its basic form in or before the 24th century BCE. Many of its elements originated in religious ideas, but the struggle between Horus and Set may have been partly inspired by a regional conflict in Egypt’s Early Dynastic or Prehistoric Egypt. Scholars have tried to discern the exact nature of the events that gave rise to the story, but they have reached no definitive conclusions.

Parts of the myth appear in a wide variety of Egyptian texts, from funerary texts and magical spells to short stories. The story is, therefore, more detailed and more cohesive than any other ancient Egyptian myth. Yet no Egyptian source gives a full account of the myth, and the sources vary widely in their versions of events. Greek and Roman writings, particularly On Isis and Osiris by Plutarch, provide more information but may not always accurately reflect Egyptian beliefs. Through these writings, the Osiris myth persisted after knowledge of most ancient Egyptian beliefs was lost, and it is still well known today.

Sources[edit]

The myth of Osiris was deeply influential in ancient Egyptian religion and was popular among ordinary people.[1] One reason for this popularity is the myth’s primary religious meaning, which implies that any dead person can reach a pleasant afterlife.[2] Another reason is that the characters and their emotions are more reminiscent of the lives of real people than those in most Egyptian myths, making the story more appealing to the general populace.[3] In particular, the myth conveys a «strong sense of family loyalty and devotion», as the Egyptologist J. Gwyn Griffiths puts it, in the relationships between Osiris, Isis, and Horus.[4]

With this widespread appeal, the myth appears in more ancient texts than any other myth and in an exceptionally broad range of Egyptian literary styles.[1] These sources also provide an unusual amount of detail.[2] Ancient Egyptian myths are fragmentary and vague; the religious metaphors contained within the myths were more important than coherent narration.[5] Each text that contains a myth, or a fragment of one, may adapt the myth to suit its particular purposes, so different texts can contain contradictory versions of events.[6] Because the Osiris myth was used in such a variety of ways, versions often conflict with each other. Nevertheless, the fragmentary versions, taken together, give it a greater resemblance to a cohesive story than most Egyptian myths.[7]

The earliest mentions of the Osiris myth are in the Pyramid Texts, the first Egyptian funerary texts, which appeared on the walls of burial chambers in pyramids at the end of the Fifth Dynasty, during the 24th century BCE. These texts, made up of disparate spells or «utterances», contain ideas that are presumed to date from still earlier times.[8] The texts are concerned with the afterlife of the king buried in the pyramid, so they frequently refer to the Osiris myth, which is deeply involved with kingship and the afterlife.[9] Major elements of the story, such as the death and restoration of Osiris and the strife between Horus and Set, appear in the utterances of the Pyramid Texts.[10] Funerary texts written in later times, such as the Coffin Texts from the Middle Kingdom (c. 2055–1650 BCE) and the Book of the Dead from the New Kingdom (c. 1550–1070 BCE), also contain elements of the myth.[11]

Other types of religious texts give evidence for the myth, such as two Middle Kingdom texts: the Dramatic Ramesseum Papyrus and the Ikhernofret Stela. The papyrus describes the coronation of Senusret I, whereas the stela alludes to events in the annual festival of Khoiak. Rituals in both these festivals reenacted elements of the Osiris myth.[12] The most complete ancient Egyptian account of the myth is the Great Hymn to Osiris, an inscription from the Eighteenth Dynasty (c. 1550–1292 BCE) that gives the general outline of the entire story but includes little detail.[13] Another important source is the Memphite Theology, a religious narrative that includes an account of Osiris’s death as well as the resolution of the dispute between Horus and Set. This narrative associates the kingship that Osiris and Horus represent with Ptah, the creator deity of Memphis.[14] The text was long thought to date back to the Old Kingdom (c. 2686–2181 BCE) and was treated as a source for information about the early stages in the development of the myth. Since the 1970s, however, Egyptologists have concluded that the text dates to the New Kingdom at the earliest.[15]

Rituals in honor of Osiris are another major source of information. Some of these texts are found on the walls of temples that date from the New Kingdom, the Ptolemaic era (323–30 BCE), or the Roman era (30 BCE to the fourth century AD).[16] Some of these late ritual texts, in which Isis and Nephthys lament their brother’s death, were adapted into funerary texts. In these texts, the goddesses’ pleas were meant to rouse Osiris—and thus the deceased person—to live again.[17]

Magical healing spells, which were used by Egyptians of all classes, are the source for an important portion of the myth, in which Horus is poisoned or otherwise sickened, and Isis heals him. The spells identify a sick person with Horus so that he or she can benefit from the goddess’s efforts. The spells are known from papyrus copies, which serve as instructions for healing rituals, and from a specialized type of inscribed stone stela called a cippus. People seeking healing poured water over these cippi, an act that was believed to imbue the water with the healing power contained in the text, and then drank the water in hope of curing their ailments. The theme of an endangered child protected by magic also appears on inscribed ritual wands from the Middle Kingdom, which were made centuries before the more detailed healing spells that specifically connect this theme with the Osiris myth.[18]

Episodes from the myth were also recorded in writings that may have been intended as entertainment. Prominent among these texts is «The Contendings of Horus and Set», a humorous retelling of several episodes of the struggle between the two deities, which dates to the Twentieth Dynasty (c. 1190–1070 BCE).[19] It vividly characterizes the deities involved; as the Egyptologist Donald B. Redford says, «Horus appears as a physically weak but clever Puck-like figure, Seth [Set] as a strong-man buffoon of limited intelligence, Re-Horakhty [Ra] as a prejudiced, sulky judge, and Osiris as an articulate curmudgeon with an acid tongue.»[20] Despite its atypical nature, «Contendings» includes many of the oldest episodes in the divine conflict, and many events appear in the same order as in much later accounts, suggesting that a traditional sequence of events was forming at the time that the story was written.[21]

Ancient Greek and Roman writers, who described Egyptian religion late in its history, recorded much of the Osiris myth. Herodotus, in the 5th century BCE, mentioned parts of the myth in his description of Egypt in the Histories, and four centuries later, Diodorus Siculus provided a summary of the myth in his Bibliotheca historica.[22] In the early 2nd century AD,[23] Plutarch wrote the most complete ancient account of the myth in On Isis and Osiris, an analysis of Egyptian religious beliefs.[24] Plutarch’s account of the myth is the version that modern popular writings most frequently retell.[25] The writings of these classical authors may give a distorted view of Egyptian beliefs.[24] For instance, On Isis and Osiris includes many interpretations of Egyptian belief that are influenced by various Greek philosophies, and its account of the myth contains portions with no known parallel in Egyptian tradition. Griffiths concluded that several elements of this account were taken from Greek mythology, and that the work as a whole was not based directly on Egyptian sources.[26] His colleague John Baines, on the other hand, says that temples may have kept written accounts of myths that were later lost, and that Plutarch could have drawn on such sources to write his narrative.[27]

Synopsis[edit]

Death and resurrection of Osiris[edit]

At the start of the story, Osiris rules Egypt, having inherited the kingship from his ancestors in a lineage stretching back to the creator of the world, Ra or Atum. His queen is Isis, who, along with Osiris and his murderer, Set, is one of the children of the earth god Geb and the sky goddess Nut. Little information about the reign of Osiris appears in Egyptian sources; the focus is on his death and the events that follow.[28] Osiris is connected with life-giving power, righteous kingship, and the rule of maat, the ideal natural order whose maintenance was a fundamental goal in ancient Egyptian culture.[29] Set is closely associated with violence and chaos. Therefore, the slaying of Osiris symbolizes the struggle between order and disorder, and the disruption of life by death.[30]

Some versions of the myth provide Set’s motive for killing Osiris. According to a spell in the Pyramid Texts, Set is taking revenge for a kick Osiris gave him,[31] whereas in a Late Period text, Set’s grievance is that Osiris had sex with Nephthys, who is Set’s consort and the fourth child of Geb and Nut.[2] The murder itself is frequently alluded to, but never clearly described. The Egyptians believed that written words had the power to affect reality, so they avoided writing directly about profoundly negative events such as Osiris’s death.[32] Sometimes they denied his death altogether, even though the bulk of the traditions about him make it clear that he has been murdered.[33] In some cases the texts suggest that Set takes the form of a wild animal, such as a crocodile or bull, to slay Osiris; in others they imply that Osiris’s corpse is thrown in the water or that he is drowned. This latter tradition is the origin of the Egyptian belief that people who had drowned in the Nile were sacred.[34] Even the identity of the victim can vary, as it is sometimes the god Haroeris, an elder form of Horus, who is murdered by Set and then avenged by another form of Horus, who is Haroeris’s son by Isis.[35]

By the end of the New Kingdom, a tradition had developed that Set had cut Osiris’s body into pieces and scattered them across Egypt. Cult centers of Osiris all over the country claimed that the corpse, or particular pieces of it, were found near them. The dismembered parts could be said to number as many as forty-two, each piece being equated with one of the forty-two nomes, or provinces, in Egypt.[36] Thus the god of kingship becomes the embodiment of his kingdom.[34]

Isis, in the form of a bird, copulates with the deceased Osiris. At either side are Horus, although he is as yet unborn, and Isis in human form.[37]

Osiris’s death is followed either by an interregnum or by a period in which Set assumes the kingship. Meanwhile, Isis searches for her husband’s body with the aid of Nephthys.[36] When searching for or mourning Osiris, the two goddesses are often likened to falcons or kites,[38] possibly because kites travel far in search of carrion,[39] because the Egyptians associated their plaintive calls with cries of grief, or because of the goddesses’ connection with Horus, who is often represented as a falcon.[38] In the New Kingdom, when Osiris’s death and renewal came to be associated with the annual flooding of the Nile that fertilized Egypt, the waters of the Nile were equated with Isis’s tears of mourning[40] or with Osiris’s bodily fluids.[41] Osiris thus represented the life-giving divine power that was present in the river’s water and in the plants that grew after the flood.[42]

The goddesses find and restore Osiris’s body, often with the help of other deities, including Thoth, a deity credited with great magical and healing powers, and Anubis, the god of embalming and funerary rites. Osiris becomes the first mummy, and the gods’ efforts to restore his body are the mythological basis for Egyptian embalming practices, which sought to prevent and reverse the decay that follows death. This part of the story is often extended with episodes in which Set or his followers try to damage the corpse, and Isis and her allies must protect it. Once Osiris is made whole, Isis conceives his son and rightful heir, Horus.[43] One ambiguous spell in the Coffin Texts may indicate that Isis is impregnated by a flash of lightning,[44] while in other sources, Isis, still in bird form, fans breath and life into Osiris’s body with her wings and copulates with him.[36] Osiris’s revival is apparently not permanent, and after this point in the story he is only mentioned as the ruler of the Duat, the distant and mysterious realm of the dead. Although he lives on only in the Duat, he and the kingship he stands for will, in a sense, be reborn in his son.[45]

The cohesive account by Plutarch, which deals mainly with this portion of the myth, differs in many respects from the known Egyptian sources. Set—whom Plutarch, using Greek names for many of the Egyptian deities, refers to as «Typhon»—conspires against Osiris with seventy-two unspecified accomplices, as well as a queen from ancient Aethiopia (Nubia). Set has an elaborate chest made to fit Osiris’s exact measurements and then, at a banquet, declares that he will give the chest as a gift to whoever fits inside it. The guests, in turn, lie inside the coffin, but none fit inside except Osiris. When he lies down in the chest, Set and his accomplices slam the cover shut, seal it, and throw it into the Nile. With Osiris’s corpse inside, the chest floats out into the sea, arriving at the city of Byblos, where a tree grows around it. The king of Byblos has the tree cut down and made into a pillar for his palace, still with the chest inside. Isis must remove the chest from within the tree in order to retrieve her husband’s body. Having taken the chest, she leaves the tree in Byblos, where it becomes an object of worship for the locals. This episode, which is not known from Egyptian sources, gives an etiological explanation for a cult of Isis and Osiris that existed in Byblos in Plutarch’s time and possibly as early as the New Kingdom.[46]

Plutarch also states that Set steals and dismembers the corpse only after Isis has retrieved it. Isis then finds and buries each piece of her husband’s body, with the exception of the penis, which she has to reconstruct with magic, because the original was eaten by fish in the river. According to Plutarch, this is the reason the Egyptians had a taboo against eating fish. In Egyptian accounts, however, the penis of Osiris is found intact, and the only close parallel with this part of Plutarch’s story is in «The Tale of Two Brothers», a folk tale from the New Kingdom with similarities to the Osiris myth.[47]

A final difference in Plutarch’s account is Horus’s birth. The form of Horus that avenges his father has been conceived and born before Osiris’s death. It is a premature and weak second child, Harpocrates, who is born from Osiris’s posthumous union with Isis. Here, two of the separate forms of Horus that exist in Egyptian tradition have been given distinct positions within Plutarch’s version of the myth.[48]

Birth and childhood of Horus[edit]

In Egyptian accounts, the pregnant Isis hides from Set, to whom the unborn child is a threat, in a thicket of papyrus in the Nile Delta. This place is called Akh-bity, meaning «papyrus thicket of the king of Lower Egypt» in Egyptian.[49] Greek writers call this place Khemmis and indicate that it is near the city of Buto,[50] but in the myth, the physical location is less important than its nature as an iconic place of seclusion and safety.[51] The thicket’s special status is indicated by its frequent depiction in Egyptian art; for most events in Egyptian mythology, the backdrop is minimally described or illustrated. In this thicket, Isis gives birth to Horus and raises him, and hence it is also called the «nest of Horus».[36] The image of Isis nursing her child is a very common motif in Egyptian art.[49]

There are texts such as the Metternich Stela that date to the Late Period in which Isis travels in the wider world. She moves among ordinary humans who are unaware of her identity, and she even appeals to these people for help. This is another unusual circumstance, for in Egyptian myth, gods and humans are normally separate.[52] As in the first phase of the myth, she often has the aid of other deities, who protect her son in her absence.[36] According to one magical spell, seven minor scorpion deities travel with and guard Isis as she seeks help for Horus. They even take revenge on a wealthy woman who has refused to help Isis by stinging the woman’s son, making it necessary for Isis to heal the blameless child.[52] This story conveys a moral message that the poor can be more virtuous than the wealthy and illustrates Isis’s fair and compassionate nature.[53]

In this stage of the myth, Horus is a vulnerable child beset by dangers. The magical texts that use Horus’s childhood as the basis for their healing spells give him different ailments, from scorpion stings to simple stomachaches,[54] adapting the tradition to fit the malady that each spell was intended to treat.[55] Most commonly, the child god has been bitten by a snake, reflecting the Egyptians’ fear of snakebite and the resulting poison.[36] Some texts indicate that these hostile creatures are agents of Set.[56] Isis may use her own magical powers to save her child, or she may plead with or threaten deities such as Ra or Geb, so they will cure him. As she is the archetypal mourner in the first portion of the story, so during Horus’s childhood she is the ideal devoted mother.[57] Through the magical healing texts, her efforts to heal her son are extended to cure any patient.[51]

Conflict of Horus and Set[edit]

The next phase of the myth begins when the adult Horus challenges Set for the throne of Egypt. The contest between them is often violent but is also described as a legal judgment before the Ennead, an assembled group of Egyptian deities, to decide who should inherit the kingship. The judge in this trial may be Geb, who, as the father of Osiris and Set, held the throne before they did, or it may be the creator gods Ra or Atum, the originators of kingship.[58] Other deities also take important roles: Thoth frequently acts as a conciliator in the dispute[59] or as an assistant to the divine judge, and in «Contendings», Isis uses her cunning and magical power to aid her son.[60]

The rivalry of Horus and Set is portrayed in two contrasting ways. Both perspectives appear as early as the Pyramid Texts, the earliest source of the myth. In some spells from these texts, Horus is the son of Osiris and nephew of Set, and the murder of Osiris is the major impetus for the conflict. The other tradition depicts Horus and Set as brothers.[61] This incongruity persists in many of the subsequent sources, where the two gods may be called brothers or uncle and nephew at different points in the same text.[62]

Horus spears Set, who appears in the form of a hippopotamus, as Isis looks on

The divine struggle involves many episodes. «Contendings» describes the two gods appealing to various other deities to arbitrate the dispute and competing in different types of contests, such as racing in boats or fighting each other in the form of hippopotami, to determine a victor. In this account, Horus repeatedly defeats Set and is supported by most of the other deities.[63] Yet the dispute drags on for eighty years, largely because the judge, the creator god, favors Set.[64] In late ritual texts, the conflict is characterized as a great battle involving the two deities’ assembled followers.[65] The strife in the divine realm extends beyond the two combatants. At one point Isis attempts to harpoon Set as he is locked in combat with her son, but she strikes Horus instead, who then cuts off her head in a fit of rage.[66] Thoth replaces Isis’s head with that of a cow; the story gives a mythical origin for the cow-horn headdress that Isis commonly wears.[67]

In a key episode in the conflict, Set sexually abuses Horus. Set’s violation is partly meant to degrade his rival, but it also involves homosexual desire, in keeping with one of Set’s major characteristics, his forceful and indiscriminate sexuality.[68] In the earliest account of this episode, in a fragmentary Middle Kingdom papyrus, the sexual encounter begins when Set asks to have sex with Horus, who agrees on the condition that Set will give Horus some of his strength.[69] The encounter puts Horus in danger, because in Egyptian tradition semen is a potent and dangerous substance, akin to poison. According to some texts, Set’s semen enters Horus’s body and makes him ill, but in «Contendings», Horus thwarts Set by catching Set’s semen in his hands. Isis retaliates by putting Horus’s semen on lettuce-leaves that Set eats. Set’s defeat becomes apparent when this semen appears on his forehead as a golden disk. He has been impregnated with his rival’s seed and as a result «gives birth» to the disk. In «Contendings», Thoth takes the disk and places it on his own head; other accounts imply that Thoth himself was produced by this anomalous birth.[70]

Another important episode concerns mutilations that the combatants inflict upon each other: Horus injures or steals Set’s testicles and Set damages or tears out one, or occasionally both, of Horus’s eyes. Sometimes the eye is torn into pieces.[71] Set’s mutilation signifies a loss of virility and strength.[72] The removal of Horus’s eye is even more important, for this stolen Eye of Horus represents a wide variety of concepts in Egyptian religion. One of Horus’s major roles is as a sky deity, and for this reason his right eye was said to be the sun and his left eye the moon. The theft or destruction of the Eye of Horus is therefore equated with the darkening of the moon in the course of its cycle of phases, or during eclipses. Horus may take back his lost Eye, or other deities, including Isis, Thoth, and Hathor, may retrieve or heal it for him.[71] The Egyptologist Herman te Velde argues that the tradition about the lost testicles is a late variation on Set’s loss of semen to Horus, and that the moon-like disk that emerges from Set’s head after his impregnation is the Eye of Horus. If so, the episodes of mutilation and sexual abuse would form a single story, in which Set assaults Horus and loses semen to him, Horus retaliates and impregnates Set, and Set comes into possession of Horus’s Eye when it appears on Set’s head. Because Thoth is a moon deity in addition to his other functions, it would make sense, according to te Velde, for Thoth to emerge in the form of the Eye and step in to mediate between the feuding deities.[73]

In any case, the restoration of the Eye of Horus to wholeness represents the return of the moon to full brightness,[74] the return of the kingship to Horus,[75] and many other aspects of maat.[76] Sometimes the restoration of Horus’s eye is accompanied by the restoration of Set’s testicles, so that both gods are made whole near the conclusion of their feud.[77]

Resolution[edit]

As with so many other parts of the myth, the resolution is complex and varied. Often, Horus and Set divide the realm between them. This division can be equated with any of several fundamental dualities that the Egyptians saw in their world. Horus may receive the fertile lands around the Nile, the core of Egyptian civilization, in which case Set takes the barren desert or the foreign lands that are associated with it; Horus may rule the earth while Set dwells in the sky; and each god may take one of the two traditional halves of the country, Upper and Lower Egypt, in which case either god may be connected with either region. Yet in the Memphite Theology, Geb, as judge, first apportions the realm between the claimants and then reverses himself, awarding sole control to Horus. In this peaceable union, Horus and Set are reconciled, and the dualities that they represent have been resolved into a united whole. Through this resolution, order is restored after the tumultuous conflict.[78]

A different view of the myth’s end focuses on Horus’s sole triumph.[79] In this version, Set is not reconciled with his rival but utterly defeated,[80] and sometimes he is exiled from Egypt or even destroyed.[81] His defeat and humiliation is more pronounced in sources from later periods of Egyptian history, when he was increasingly equated with disorder and evil, and the Egyptians no longer saw him as an integral part of natural order.[80]