ЧЕЛЯБИНСКИЙ МЕТЕОРИТ

- Авторы

- Руководители

- Файлы работы

- Наградные документы

Текст работы размещён без изображений и формул.

Полная версия работы доступна во вкладке «Файлы работы» в формате PDF

Введение

15 февраля 2013 года над Челябинском пролетел метеорит, который упал в озеро Чебаркуль. Свидетелями падения метеорита стали тысячи жителей Казахстана, Тюменской, Курганской, Свердловской и Челябинской областей (см. приложение 1, 2). Из-за распространения ударной волны, образовавшейся при прохождении метеоритом плотных слоёв атмосферы со сверхзвуковой скоростью, в Челябинске около тысячи жителей были ранены осколками разбитых стёкол, пострадало около 7 тыс. 200 зданий.

Данное природное явление оставило след в летописи нашего края – как яркое природное событие, как природное событие катастрофического характера. Благодаря этому событию, о Челябинске заговорил весь мир, многие в мире узнали о нашем городе.

Это событие вызвало большой интерес науки и общественности. 21-22 июня в г.Чебаркуле прошла международная научно-практическая конференция, 20-22 мая 2014 года – III всероссийская научно-практическая конференция с международным участием. Поиск метеорита проводилось Челябинским региональным отделением Русского географического общества (С.Г.Захаров) совместно с коллегами из чешского Карлова Университета под руководством Г.Клеточки[2]. Дальнейшие исследования метеорита продолжались научно-исследовательскими институтами России и за рубежом.

усского

Цель работы: собрать материал о Челябинской метеорите.

Задачи:

-Описать процесс падения метеорных тел на Землю

-Дать классификацию метеоритов и следах внеземной органики в метеоритах

-Описать Челябинский метеорит.

-Ответить на вопрос: почему Жители Южного Урала — «счастливцы».

Объект исследования – метеорит, предмет исследования – Челябинский метеорит.

Гипотеза – Челябинский метеорит – космический странник, рождённый за пределами Солнечной системы. А жители Южного Урала — «счастливцы».

Глава 1.Метеориты. Процесс падения метеорных тел на Землю

Твёрдое тело космического происхождения, упавшее на поверхность Земли, называется метеоритом. Особо яркие метеоры называют болидами.

Изучением метеоритов занимались академики В. И. Вернадский, А. Е. Ферсман, известные энтузиасты исследования метеоритов П. Л. Драверт, Л. А. Кулик и многие другие.

В Российской академии наук сейчас есть специальный комитет, который руководит сбором, изучением и хранением метеоритов. При комитете есть большая метеоритная коллекция.

Метеорное тело входит в атмосферу Земли на скорости от 11 до 72 км/с. На такой скорости начинается его разогрев и свечение. За счёт обгорания вещества метеорного тела, масса тела, долетевшего до поверхности значительно меньше его массы на входе в атмосферу. Например, небольшое тело, вошедшее в атмосферу Земли на скорости 25 км/с и более, сгорает почти без остатка.

Если метеорное тело не сгорело в атмосфере, то по мере торможения оно теряет горизонтальную составляющую скорости. Это приводит к изменению траектории падения от часто почти горизонтальной в начале до практически вертикальной в конце. По мере торможения, свечение метеорного тела падает, оно остывает.

Кроме того, может произойти разрушение метеорного тела на фрагменты, что приводит к выпадению метеоритного дождя. Разрушение некоторых тел носит катастрофический характер, сопровождаясь мощными взрывами, и нередко не остаётся следов метеоритного вещества на земной поверхности, как это было в случае с Тунгусским болидом.

При соприкосновении метеорита с земной поверхностью на больших скоростях (порядка 2000-4000 м/с) происходит выделение большого количества энергии, в результате метеорит и часть горных пород в месте удара испаряются, что сопровождается мощными взрывными процессами, формирующими крупный округлый кратер, намного превышающий размеры метеорита. Примером этому служит Аризонский кратер.

Предполагается, что наибольший метеоритный кратер на Земле — Кратер Земли Уилкса (диаметр около 500 км) [4,5].

Крупные современные метеориты, обнаруженные на территории России

Тунгусский феномен (на данный момент неясно именно метеоритное происхождение тунгусского феномена. Подробно см. в статье Тунгусский метеорит[4]). Упал 30 июня 1908 года в бассейне реки Подкаменная Тунгуска в Сибири. Общая энергия оценивается в 40-50 мегатонн в тротиловом эквиваленте.

Метеорит Царёв (метеоритный дождь). Упал предположительно 6 декабря 1922 г. вблизи села Царёв (ныне — Волгоградской области). Каменный метеорит. Многочисленные осколки собраны на площади около 15 кв. км. Их общая масса 1,6 тонны. Самый крупный фрагмент весит 284 кг.

Сихотэ-Алинский метеорит (общая масса осколков 30 тонн, энергия оценивается в 20 килотонн). Железный метеорит. Упал в Уссурийской тайге 12 февраля 1947 г.

Витимский болид. Упал в районе посёлков Мама и Витимский Мамско-Чуйского района Иркутской области в ночь с 24 на 25 сентября 2002 года. Событие имело большой общественный резонанс, хотя общая энергия взрыва метеорита, по-видимому, сравнительно невелика (200 тонн тротилового эквивалента, при начальной энергии 2,3 килотонны), максимальная начальная масса (до сгорания в атмосфере) 160 тонн, а конечная масса осколков порядка нескольких сотен килограммов.

Находка метеорита — довольно редкое явление. Лаборатория метеоритики сообщает: «Всего на территории РФ за 250 лет было найдено только 125 метеоритов»[4,5].

Глава 2. Классификация метеоритов.«Организованные элементы»

Метеориты по составу делятся на три группы:

1. Каменные

2. Железные

3. Железо-каменные

Наиболее часто встречаются каменные метеориты (92,8 % падений).

Железные метеориты состоят из железо-никелевого сплава. Они составляют 5,7 % падений.

Железо — каменные метеориты имеют промежуточный состав между каменными и железными метеоритами. Они сравнительно редки (1,5 % падений).

При исследовании каменных метеоритов обнаруживаются так называемые «организованные элементы» — микроскопические (5-50 мкм) «одноклеточные» образования, часто имеющие явно выраженные двойные стенки, поры, шипы и т. д.[5]

На сегодняшний день не доказано, что эти окаменелости принадлежат останкам каких-либо форм внеземной жизни. Но эти образования имеют такую высокую степень организации, которую принято связывать с жизнью[5].

Кроме того, такие формы не обнаружены на Земле.

Особенностью «организованных элементов» является их многочисленность: на 1г. вещества углистого метеорита приходится примерно 1800 «организованных элементов» [4,5].

2.1. Челябинский метеорит

Паде́ние метеори́та в Челя́бинске — столкновение с земной поверхностью фрагментов небольшого астероида, разрушившегося в результате торможения в атмосфере Земли 15 февраля 2013 года примерно в 9 часов 20 минут по местному времени. Суперболид взорвался в окрестностях Челябинска на высоте 15—25 км[1].

В этот день астероид диаметром около 17 метров и массой порядка 10 тыс. тонн (по расчётам НАСА) вошёл в атмосферу Земли на скорости около 18 км/с. Судя по продолжительности атмосферного полёта, вход в атмосферу произошёл под очень острым углом. Спустя примерно 32,5 сек после этого небесное тело разрушилось. Разрушение представляло собой серию событий, сопровождавшихся распространением ударных волн. Общее количество высвободившейся энергии по оценкам НАСА составило около 440 килотонн в тротиловом эквиваленте. По оценкам НАСА это самое большое из известных небесных тел, падавших на Землю после Тунгусского метеорита в 1908 году, оно соответствует событию, происходящему в среднем раз в 100 лет.

Небесное тело не было обнаружено до его вхождения в атмосферу. Скорость метеорита при падении составила от 20 до 70 километров в секунду. Через 5 часов после события в СМИ появились сведения о предположительном месте падения метеорита — в озере Чебаркуль в 1 км от города Чебаркуль. Момент падения метеорита наблюдали рыбаки около озера Чебаркуль. По их словам, пролетело около 7 фрагментов метеорита, один из которых упал в озеро, взметнув столб воды 3—4 метров в высоту.

Первые осколки, в виде небольших метеоритов, были найдены несколькими днями позже. Власти Челябинской области выделили 3 миллиона рублей на поиск и подъем фрагментов метеорита из озера Чебаркуль. В сентябре 2013 года началась подготовка к подъёму основной части метеорита, покоящейся в озере Чебаркуль на глубине примерно 11 метров под пятиметровым слоем ила. 16 октября 2013 года он был поднят. Вес основного осколка челябинского метеорита, который был найден в озере Чебаркуль в октябре прошлого года, составил 654 кг. Однако при подъеме из озера и при взвешивании он раскололся на несколько частей. В итоге основным осколком принято считать самый крупный сохранившийся фрагмент весом 540 кг, который ныне хранится в Челябинском краеведческом музее. Более мелкие осколки находятся в различных исследовательских учреждениях, в частности, в ЧелГУ (см. приложение 3).

По данным Челябинского географического общества: «суперболид взорвался на высоте 23-26 км[2]. Взрывная волна до центра города (около 40 км по прямой линии) шла около трёх минут; основной и последующие взрывы (они практически сливались) были зафиксированы в 9-20. Ещё до того, как к Челябинску подошла ударная волна, ледовый покров озера Чебаркуль пробил самый «весомый «осколок весом от 800 кг до тонны (максимальный вес 1800 кг). Падение произошло в центральной части озера в зоне глубин 10±0,5 метров, в 150 м от восточного, вдающегося в озеро мыса полуострова Крутик[2].

Метеорит каменный с низким содержанием металлов. Есть цинк, вольфрам, никель. Больше всего меди. Основное вещество метеорита образовалось 4,5 млрд лет назад, около 300 млн лет назад метеорит откололся от материнского тела, а несколько тысяч лет назад в результате столкновения с третьим телом образовались трещины, заполненные расплавом, что не позволяет определить возраст однозначно[1,6].

2.2. Жители Южного Урала — «счастливцы»

Выдвигая гипотезу о том, что Челябинский метеорит – космический странник, рождённый за пределами Солнечной системы и мы – жители Южного Урала — счастливцы, я пользуюсь следующими данными:

В этот день астероид диаметром около 17 метров и массой порядка 10 тыс. тонн (по расчётам НАСА) вошёл в атмосферу Земли на скорости около 18 км/с[1,5].

Первая космическая скорость, или круговая скорость — скорость, необходимая для обращения спутника по круговой орбите вокруг Земли или другого космического объекта. Для Земли она равна 7.9 км/с. Вторая космическая скорость, называемая также скоростью убегания, или параболической скоростью — минимальная скорость, которую должно иметь свободно движущееся тело на расстоянии R от центра Земли или другого космического тела, чтобы, преодолев силу гравитационного притяжения, навсегда покинуть его. Для Земли равна 11.2 км/с.Кроме этих общепринятых существуют еще две редко употребимые величины: 3-я и 4-ая космические скорости — это скорости ухода, соответственно, из Солнечной системы и Галактики[3].

Если наш метеорит двигался со скоростью 18 км/с, что выше 2 космической скорости – значит он гость нашей Солнечной системы.

2. Второй интересный факт – почему заранее никто не обнаружил летевший к нам астероид и метеорит???

— «Небесное тело не было обнаружено до его вхождения в атмосферу». В этот день астероид диаметром около 17 метров и массой порядка 10 тыс. тонн (по расчётам НАСА) вошёл в атмосферу Земли. На уроках географии в 5 классе мы изучали, что ближайшей планета- гигант Юпитер – «Защитница Земли». Из-за большой массы она многие небесные тела небольших размеров, гостей Солнечной системы, притягивает и «поглощает». Но иногда она «выплёвывает» их обратно. И не известно, куда полетит это небесное тело. Может быть, никто не предполагал о нашем госте, т. к. его выплюнул Юпитер. И поэтому к нашему пришельцу никто не был готов?

3. Спустя примерно 32,5 сек после входа в атмосферу, небесное тело разрушилось на высоте 15—25 км. Мы «счастливцы, т.к. если бы оно не разрушилось на этой высоте, а упало на землю, то разрушения были бы очень значительные. «Общее количество высвободившейся энергии по оценкам НАСА составило около 440 килотонн в тротиловом эквиваленте, по оценкам РАН — 100−200 килотонн, по оценкам сотрудников ИНАСАН — от 0,4 до 1,5 Мт в тротиловом эквиваленте. Мощность взрыва была равносильна разрыву минимум двух десятков хиросимских бомб[1,5]. Самое счастливое, что не было человеческих жертв.

4. Что никто не пострадал – нас защитило озеро Чебаркуль – если бы осколок упал на землю – то последствия были бы больше, чем описано «Научный журнал Geophysical Research Letters (англ.), со ссылкой на результаты, полученные после анализа учёными французского Комиссариата атомной энергии данных сенсорных станций, дал оценку в 460 килотонн в тротиловом эквиваленте (самый высокий показатель за всё время наблюдений за ядерными испытаниями), и заявил, что ударная волна дважды обогнула Землю» [1,5].

5. С.Г. Зазаров, доцент ЧГПУ, участвующий в организации работ по подьёму осколка метеорита со дна озера Чебаркуль написал: «В связи с этим представляется рациональным организация на озере Чебаркуль первого в России метеоритного заказника, захватывающего самую восточную часть полуострова Крутик и прилегающий к нему с севера участок акватории примерно 300×300 м. В пределах этой зоны возможно плавание маломерных судов, проведение организованных экскурсий и свободный доступ граждан. В пределах территории и акватории заказника должны быть запрещены неорганизованные погружения с аквалангом и добыча метеоритного материала магнитами с плавсредств и ледового покрова.

Организация особо охраняемой природной территории — Чебаркульского метеоритного заказника послужит и делу привлечения в регион туристов; в пределах заказника можно поставить памятный знак (СТЕЛЛА, МАЯК)». С.Г. Зазаров предлагает организовывать экскурсии к месту падения небесного тела, второго по мощности после Тунгусского метеорита[2]. Я считаю, что создание заказника – это достойная дань уважения к нашему гостю Солнечной системы.

Заключение

Челябинский (чебаркульский) метеорит нанёс большой ущерб.

По сообщению губернатора Челябинской области Михаила Юревича, ущерб превысил миллиард рублей, из них ущерб наиболее пострадавшему ледовому дворцу «Уральская молния» составил 200 млн рублей. Разбилось минимум 200 тыс. квадратных метров стекла. Наиболее пострадали Челябинск и Копейск. Из бюджета области было выделено около 9 млн рублей (см. приложение 4).

Обломки челябинского метеорита вмонтированы в центр десяти золотых медалей для зимней олимпиады 2014 года в Сочи, которые разыграны в первую годовщину падения метеорита — 15 февраля 2014 года. В Челябинске, Чебаркуле, пос. Тимирязевский поставлены памятники в честь этого события (см. приложение 5-7).

«Сотрудники NASA назвали жителей Южного Урала «счастливцами», а Челябинск – самым везучим городом планеты, так как то, что произошло 15 февраля утром, можно объяснить лишь чудом. Метеорит разорвался на высоте 20-25 километров над городом-миллионером. Мощность взрыва была равносильна разрыву минимум двух десятков хиросимских бомб. Что еще удивило ученых из разных стран: несмотря на количество пострадавших, при ЧС никто не погиб» [1,5].

В своей работе:я собрала материал о Челябинской метеорите, описала процесс падения метеорных тел на Землю, дала классификацию метеоритов и следах внеземной органики в метеоритах, описала Челябинский метеорит.

На основе знаний ученицы 5 класса выдвинула гипотезу и сделав анализ фактов доказала, что Челябинский метеорит – космический странник, рождённый за пределами Солнечной системы, а жители Южного Урала — «счастливцы».

Список используемой литературы

Анфилогов, В. Н. Вещественный состав обломков Челябинского метеорита: доклад/ Анфилогов, В. Н. и др. — Миасс : Институт минералогии УрО РАН, 2013.

Захаров, С.Г. Экоститема озера Чебаркуль до и после падения метеорита/ С.Г. Захаров. — Челябинск : Край ра, 2014.

Космические скорости. Большая советская энциклопедия. — URL: http://bse.sci-lib.com/article065144.html.

Метеорит. Энциклопедия Кругосвет. — URL:http://www.krugosvet.ru/enc/nauka_i_tehnika/astronomiya/METEORIT.html.

Падение метеорита. Челябинск. — URL: https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/

Симоненко, А.Н. Метеориты – осколки астероидов/А.Н. Симоненко. — М.: Наука, 1979.

Челябинский метеорит Приложение 1

Фотография Марата Ахметвалеева

Взрыв метеорита Приложение 2

Приложение 3

Карта следа падения и воронка на озере Чебаркуль, в месте падения метеорита

Фотография Николая Середина

Подъём метеорита Приложение 4

Приложение 5

Памятник метеориту на оз.Чебаркуль открылся 15 февраля 2014 года, спустя год после падения земного тела на Землю. …

Фотография Евгения Архипова

Памятник метеориту в пос. Тимирязевский

Фотография Шкериной С.В.

Верблюд с метеоритом — новый памятник в Челябинске установлен в часть дня города в сентябре 2015 года (фотография нашего класса)

(Рафаэль Сайфулин, автор скульптуры, учился в Ленинградском высшем художественно-промышленном училище имени В. И. Мухиной и позднее переехал в Финляндию)

Просмотров работы: 5945

История падения Челябинского метеорита

Челябинский метеорит упал на Землю в начале дня 15 февраля 2013 года. Сразу же возникло множество версий происшедшего. Взрыв от падения небесного тела был такой силы, что в домах города оказались выбиты стекла, повреждены постройки, а более 1000 человек оказались в больницах с повреждениями различной степени тяжести.

При этой природной катастрофе столице Южного Урала пришлось пережить ударную волну огромной мощности. Спустя некоторое время ученые проанализировали данные и выяснили, что ударная волна от падения космического тела составила порядка 500 килотонн в тротиловом эквиваленте. Для сравнения: взрыв от приземления космического гостя в озеро оказался в двенадцать раз мощнее взрыва над Хиросимой. Масштаб силы природы поражает.

«Челябинск» опроверг ранее бытовавшее среди ученых мнение о том, что для человечества опасны только метеориты с диаметром свыше ста метров

Всего от падения метеорита пострадало полторы тысячи человек. В основном, ранения людям нанесли осколки выбитых стекол.

Почему метеорит стал полной неожиданностью для всех

Приборы не смогли зафиксировать полет Челябинского метеорита до того, как тот вошел в атмосферу. Причина проста: современная оптическая техника не в состоянии предсказать приближение подобного небесного тела раньше, чем за 2-3 часа до его падения. Этот простой факт показывает нам, как мало мы еще знаем о космическом пространстве, лежащем за пределами нашей родной планеты.

Внезапное появление метеорита, получившего в дальнейшем имя «Челябинск» стало серьезным напоминанием для людей о том, что падение крупных метеоритов является серьезной угрозой для населения Земли. И в настоящее время от нее не существует защиты. Именно поэтому это событие подтолкнуло ученых к более тщательным исследованиям метеоритов.

Изучение кратеров на Земле и Луне, химический анализ состава метеоритов позволили ученым создать теории об истории Солнечной системы и ее эволюции, а также причинах образования и разрушения небесных тел различного размера. Возможно, в далеком будущем человечество сможет защитить себя от космической угрозы.

Метеорит «Челябинск» вошел в атмосферу Земли с восточного направления. Первоначально его размеры составляли примерно девять-десять тысяч тонн, а диаметр — 17 м. «Челябинск» опроверг ранее бытовавшее среди ученых мнение о том, что для человечества опасны только метеориты с диаметром свыше ста метров.

Спустя короткое время после падения нашли частично оплавленные кусочки метеорита, общая масса которых составляла примерно 3,5 кг. Убедительным выглядит предположение, что «родиной» Челябинского метеорита является Главный пояс астероидов, а небесное тело, от которого он откололся, было диаметром в несколько сотен километров.

Хронология событий падения «Челябинска»

15 февраля 2013 года метеорит добрался до земной атмосферы. Примерно в 50-30 километрах от земной поверхности метеорное тело раскололось на множество кусков. Ударные волны, которые возникли из-за движения метеорного тела со скоростью, гораздо большей чем скорость звука, были похожи на несколько взрывов. Свидетелями подобного явления за много лет до этого стали люди, видевшие падение Тунгусского космического тела.

современная оптическая техника не в состоянии предсказать приближение подобного небесного тела раньше, чем за 2-3 часа до его падения

Частицы метеорита упали с неба, став метеоритным дождем. Фрагменты «Челябинска» еще долго находили по всей области.

Работами по исследованию упавшего метеорного тела занялись специалисты Уральского Федерального университета во главе с Михаилом Ларионовым. На следующий день после уникального природного явления ученые приступили к розыску обломков.

5 марта 2013 года ученые получили достоверные данные о нахождении самого крупного фрагмента метеорита — дно озера Чебаркуль.

18 марта метеорит официально получил название «Челябинск» — в честь города.

16 октября 2013 года из озера извлекли самый большой осколок весом более 570 кг.

Интересные факты о Челябинском метеорите

- Существует ни на что не похожая серия фотографий, на которых изображена последовательность вспышек болида, а также траектория падения. Их автором стал Марат Ахметвалеев, молодой фотограф из Челябинска.

- «Родительский» астероид, от которого откололся «Челябинск», скорей всего испытал столкновение с другим масштабным космическим объектом. Об этом свидетельствуют факты исследований: тело метеорита стало рыхлым, он покрыт множеством трещин, в которых есть следы застывшего ударного расплава.

- Кусок «Челябинска», с 2016 года выставленный в Государственном историческом музее Южного Урала, со временем становится легче и легче. Оказалось, что в метеорите существуют поры, которые при столкновении с водой озера Чебаркуль заполнились влагой. Она потихоньку испаряется.

- Челябинск — единственный город на планете и в истории человеческой расы, пострадавший от падения метеорита.

- Возраст Челябинского метеорита нельзя определить точно. Возраст метеора, от которого он откололся, превышает 4,5 млрд лет, возраст самого метеорита — примерно 300 млн лет, а несколько тысячелетий назад «Челябинск» столкнулся с еще одним небесным телом, из-за чего в нем образовались трещины.

- Мелкие осколки были использованы при изготовлении золотых олимпийских медалей и были вручены победителям Сочинских Олимпийских Игр в первую годовщину падения «Челябинска» — 15 февраля 2014 года. 20 коллекционных медалей с кусочками метеорита изготовили для того, чтобы продать коллекционерам.

- Первый вариант названия метеорита — «Чебаркуль» по имени озера, в которое упал самый крупный обломок.

«Russian meteor» redirects here. For the 1908 Tunguska explosion, see Tunguska event.

(video link) Location of the meteor |

|

| Date | 15 February 2013 |

|---|---|

| Time | 09:20:29 YEKT (UTC+06:00) |

| Location | Chebarkul, Chelyabinsk Oblast, Russia |

| Coordinates | 55°09′00″N 61°24′36″E / 55.150°N 61.410°ECoordinates: 55°09′00″N 61°24′36″E / 55.150°N 61.410°E[1] |

| Also known as | Chelyabinsk meteorite[2] |

| Cause | Meteor air burst |

| Non-fatal injuries | 1,491 indirect injuries[3] |

| Property damage | Over 7,200[4] buildings damaged, collapsed factory roof, shattered windows, $33 million (2013 USD) lost[5] |

The Chelyabinsk meteor was a superbolide that entered Earth’s atmosphere over the southern Ural region in Russia on 15 February 2013 at about 09:20 YEKT (03:20 UTC). It was caused by an approximately 20 m (66 ft) near-Earth asteroid that entered the atmosphere at a shallow 18.3 ± 0.4 degree angle with a speed relative to Earth of 19.16 ± 0.15 kilometres per second (69,000 km/h or 42,690 mph).[6][7] The light from the meteor was briefly brighter than the Sun, visible up to 100 km (62 mi) away. It was observed over a wide area of the region and in neighbouring republics. Some eyewitnesses also felt intense heat from the fireball.

The object exploded in a meteor air burst over Chelyabinsk Oblast, at a height of around 29.7 km (18.5 mi; 97,000 ft).[7][8] The explosion generated a bright flash, producing a hot cloud of dust and gas that penetrated to 26.2 km (16.3 mi), and many surviving small fragmentary meteorites. The bulk of the object’s energy was absorbed by the atmosphere, creating a large shock wave with a total kinetic energy before atmospheric impact estimated from infrasound and seismic measurements to be equivalent to the blast yield of 400–500 kilotons of TNT (about 1.4–1.8 PJ) range – 26 to 33 times as much energy as that released from the atomic bomb detonated at Hiroshima,[9] and the rough equivalent in energy output to the former Soviet Union’s own mid-August 1953 initial attempt at a thermonuclear device.

The object approached Earth undetected before its atmospheric entry, in part because its radiant (source direction) was close to the Sun. Its explosion created panic among local residents, and about 1,500 people were injured seriously enough to seek medical treatment. All of the injuries were due to indirect effects rather than the meteor itself, mainly from broken glass from windows that were blown in when the shock wave arrived, minutes after the superbolide’s flash. Some 7,200 buildings in six cities across the region were damaged by the explosion’s shock wave, and authorities scrambled to help repair the structures in sub-freezing temperatures.

With an estimated initial mass of about 12,000–13,000 tonnes[7][8][10] (13,000–14,000 short tons), and measuring about 20 m (66 ft) in diameter, it is the largest known natural object to have entered Earth’s atmosphere since the 1908 Tunguska event, which destroyed a wide, remote, forested, and very sparsely populated area of Siberia. The Chelyabinsk meteor is also the only meteor confirmed to have resulted in many injuries. No deaths were reported.

The earlier-predicted and well-publicized close approach of a larger asteroid on the same day, the roughly 30 m (98 ft) 367943 Duende, occurred about 16 hours later; the very different orbits of the two objects showed they were unrelated to each other.

Initial reports[edit]

The meteor’s path in relation to the ground.

Local residents witnessed extremely bright burning objects in the sky in Chelyabinsk, Kurgan, Sverdlovsk, Tyumen, and Orenburg Oblasts, Bashkortostan, and in neighbouring regions in Kazakhstan,[11][12][13] when the asteroid entered the Earth’s atmosphere over Russia.[14][15][16][17][18] Amateur videos showed a fireball streaking across the sky and a loud boom several minutes afterwards.[19][20][21] Some eyewitnesses claim they felt intense heat from the fireball.[22]

The event began at 09:20:21 Yekaterinburg time,[7][8] several minutes after sunrise in Chelyabinsk, and minutes before sunrise in Yekaterinburg. According to eyewitnesses, the bolide appeared brighter than the sun,[12] as was later confirmed by NASA.[23] An image of the object was also taken shortly after it entered the atmosphere by the weather satellite Meteosat 9.[24] Witnesses in Chelyabinsk said that the air of the city smelled like «gunpowder», «sulfur» and «burning odors» starting about 1 hour after the fireball and lasting all day.[8]

Atmospheric entry[edit]

Illustrating all «phases», from atmospheric entry to explosion.

The visible phenomenon due to the passage of an asteroid or meteoroid through the atmosphere is called a meteor.[25] If the object reaches the ground, then it is called a meteorite. During the Chelyabinsk meteoroid’s traversal, there was a bright object trailing smoke, then an air burst (explosion) that caused a powerful blast wave. The latter was the only cause of the damage to thousands of buildings in Chelyabinsk and its neighbouring towns. The fragments then entered dark flight (without the emission of light) and created a strewn field of numerous meteorites on the snow-covered ground (officially named Chelyabinsk meteorites).

The last time a similar phenomenon was observed in the Chelyabinsk region was the Kunashak meteor shower of 1949, after which scientists recovered about 20 meteorites weighing over 200 kg in total.[26] The Chelyabinsk meteor is thought to be the biggest natural space object to enter Earth’s atmosphere since the 1908 Tunguska event,[27][28][29] and the only one confirmed to have resulted in many injuries,[30][Note 1] although a small number of panic-related injuries occurred during the Great Madrid Meteor Event of 10 February 1896.[31]

Preliminary estimates released by the Russian Federal Space Agency indicated the object was an asteroid moving at about 30 km/s in a «low trajectory» when it entered Earth’s atmosphere. According to the Russian Academy of Sciences, the meteor then pushed through the atmosphere at a velocity of 15 km/s.[17][32] The radiant (the apparent position of origin of the meteor in the sky) appears from video recordings to have been above and to the left of the rising Sun.[33]

Early analysis of CCTV and dashcam video posted online indicated that the meteor approached from the southeast, and exploded about 40 km south of central Chelyabinsk above Korkino at a height of 23.3 kilometres (76,000 ft), with fragments continuing in the direction of Lake Chebarkul.[1][34][35][36] On 1 March 2013, NASA published a detailed synopsis of the event, stating that at peak brightness (at 09:20:33 local time), the meteor was 23.3 km high, located at 54.8°N, 61.1°E. At that time it was travelling at about 18.6 kilometres per second (67,000 km/h; 42,000 mph) – almost 60 times the speed of sound.[1][37] In November 2013, results were published based on a more careful calibration of dashcam videos in the field weeks after the event during a Russian Academy of Sciences field study, which put the point of peak brightness at 29.7 km altitude and the final disruption of the thermal debris cloud at 27.0 km, settling to 26.2 km, all with a possible systematic uncertainty of ± 0.7 km.[7][8]

The United States space agency NASA estimated the diameter of the bolide at about 17–20 m and has revised the mass several times from an initial 7,700 tonnes (7,600 long tons; 8,500 short tons),[14] until reaching a final estimate of 10,000 tonnes.[14][38][39][40][41] The air burst’s blast wave, when it hit the ground, produced a seismic wave which registered on seismographs at magnitude 2.7.[42][43][44]

The Russian Geographical Society said the passing of the meteor over Chelyabinsk caused three blasts of different energy. The first explosion was the most powerful, and was preceded by a bright flash, which lasted about five seconds. Initial newspaper altitude estimates ranged from 30–70 km, with an explosive equivalent, according to NASA, of roughly 500 kilotonnes of TNT (2,100 TJ), although there is some debate on this yield[45] (500 kt is exactly the same energy released by the Ivy King nuclear explosion in 1952). According to a paper in 2013, all these ~500 kiloton yield estimates for the meteor airburst are «uncertain by a factor of two because of a lack of calibration data at those high energies and altitudes».[7][8] Because of this, some studies have suggested the explosion to have been as powerful as 57 megatonnes of TNT (240 PJ), which would mean a more powerful explosion than Tunguska and comparable to the Tsar Bomba.[46]

The hypocentre of the explosion was to the south of Chelyabinsk, in Yemanzhelinsk and Yuzhnouralsk. Due to the height of the air burst, the atmosphere absorbed most of the explosion’s energy.[47] The explosion’s blast wave first reached Chelyabinsk and environs between less than 2 minutes 23 seconds[citation needed] and 2 minutes 57 seconds later.[48] The object did not release all of its kinetic energy in the form of a blast wave, as some 90 kilotons of TNT (about 3.75 × 1014 joules, or 0.375 PJ) of the total energy of the main airburst’s fireball was emitted as visible light according to NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory,[1][49] and two main fragments survived the primary airburst disruption at 29.7 kilometres (18.5 mi); they flared around 24 kilometres (15 mi), with

one falling apart at 18.5 kilometres (11.5 mi) and the other remaining luminous down to

13.6 kilometres (8.5 mi),[8] with part of the meteoroid continuing on its general trajectory to punch a hole in the frozen Lake Chebarkul, an impact that was fortuitously captured on camera and released in November 2013.[50]

This visualization shows the aftermath observations by NASA satellites and computer models projections of the plume and meteor debris trajectory around the atmosphere. The plume rose to an altitude of 35 km and once there, it was rapidly blown around the globe by the polar night jet.[51]

The infrasound waves given off by the explosions were detected by 20 monitoring stations designed to detect nuclear weapons testing run by the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty Organization (CTBTO) Preparatory Commission, including the distant Antarctic station, some 15,000 kilometres (9,300 mi) away. The blast of the explosion was large enough to generate infrasound returns, after circling the globe, at distances up to about 85,000 kilometres (53,000 mi). Multiple arrivals involving waves that travelled twice around the globe have been identified. The meteor explosion produced the largest infrasounds ever to be recorded by the CTBTO infrasound monitoring system, which began recording in 2001,[52][53][54] so great that they reverberated around the world several times, taking over a day to dissipate.[55] Additional scientific analysis of US military infrasound data was aided by an agreement reached with US authorities to allow its use by civilian scientists, implemented only about a month before the Chelyabinsk meteor event.[18][55]

A full view of the smoke trail with the bulbous section corresponding to a mushroom cloud’s cap.

A preliminary estimate of the explosive energy by astronomer Boris Shustov, director of the Russian Academy of Sciences Institute of Astronomy, was 200 kilotonnes of TNT (840 TJ),[56] another using empirical period-yield scaling relations and the infrasound records, by Peter Brown of the University of Western Ontario gave a value of 460–470 kilotonnes of TNT (1,900–2,000 TJ) and represents a best estimate for the yield of this airburst; there remains a potential «uncertainty [in the order of] a factor of two in this yield value».[57][58] Brown and his colleagues also went on to publish a paper in November 2013 which stated that the «widely referenced technique of estimating airburst damage does not reproduce the [Chelyabinsk] observations, and that the mathematical relations found in the book The Effects of Nuclear Weapons which are based on the effects of nuclear weapons – [which is] almost always used with this technique – overestimate blast damage [when applied to meteor airbursts]».[59] A similar overestimate of the explosive yield of the Tunguska airburst also exists; as incoming celestial objects have rapid directional motion, the object causes stronger blast wave and thermal radiation pulses at the ground surface than would be predicted by a stationary object exploding, limited to the height at which the blast was initiated-where the object’s «momentum is ignored».[60] Thus, a meteor airburst of a given energy is «much more damaging than an equivalent [energy] nuclear explosion at the same altitude».[61][62]

The seismic wave produced when the primary airburst’s blast struck the ground yields a rather uncertain «best estimate» of 430 kilotons (momentum ignored),[62] corresponding to the seismic wave which registered on seismographs at magnitude 2.7.[42][43][44]

A picture taken of the smoke trail with the double plumes visible either side of the bulbous «mushroom cloud» cap.

Brown also states that the double smoke plume formation, as seen in photographs, is believed to have coincided near the primary airburst section of the dust trail (as also pictured following the Tagish Lake fireball), and it likely indicates where rising air quickly flowed into the center of the trail, essentially in the same manner as a moving 3D version of a mushroom cloud.[63] Photographs of this smoke trail portion, before it split into two plumes, show this cigar-shaped region glowing incandescently for a few seconds.[64] This region is the area in which the maximum of material ablation occurred, with the double plume persisting for a time and then appearing to rejoin or close up.[65]

Injuries and damage[edit]

Shattered windows in the foyer of the Chelyabinsk Drama Theatre

The blast created by the meteor’s air burst produced extensive ground damage over an irregular elliptical area around a hundred kilometres wide, and a few tens of kilometres long,[66] with the secondary effects of the blast being the main cause of the considerable number of injuries. Russian authorities stated that 1,491 people sought medical attention in Chelyabinsk Oblast within the first few days.[3] Health officials reported 112 hospitalisations, including two in serious condition. A 52-year-old woman with a broken spine was flown to Moscow for treatment.[citation needed] Most of the injuries were caused by the secondary blast effects of shattered, falling or blown-in glass.[67] The intense light from the meteor, momentarily brighter than the Sun, also produced injuries, leading to over 180 cases of eye pain, and 70 people subsequently reported temporary flash blindness.[68] Twenty people reported ultraviolet burns similar to sunburn, possibly intensified by the presence of snow on the ground.[68] Vladimir Petrov, when meeting with scientists to assess the damage, reported that he sustained so much sunburn from the meteor that the skin flaked only days later.[69]

A fourth-grade teacher in Chelyabinsk, Yulia Karbysheva, was hailed as a hero after saving 44 children from imploding window glass cuts. Despite not knowing the origin of the intense flash of light, Karbysheva thought it prudent to take precautionary measures by ordering her students to stay away from the room’s windows and to perform a duck and cover maneuver and then to leave a building. Karbysheva, who remained standing, was seriously lacerated when the blast arrived and window glass severed a tendon in one of her arms and left thigh; none of her students, whom she ordered to hide under their desks, suffered cuts.[70][71] The teacher was taken to a hospital which received 112 people that day. The majority of the patients were suffering from cuts.[71]

The collapsed roof over the warehouse section of a zinc factory in Chelyabinsk

After the air blast, car alarms went off and mobile phone networks were overloaded with calls.[72] Office buildings in Chelyabinsk were evacuated. Classes for all Chelyabinsk schools were cancelled, mainly due to broken windows.[citation needed] At least 20 children were injured when the windows of a school and kindergarten were blown in at 09:22.[73] Following the event, government officials in Chelyabinsk asked parents to take their children home from schools.[74]

Approximately 600 m2 (6,500 sq ft) of a roof at a zinc factory collapsed during the incident.[75] Residents in Chelyabinsk whose windows were smashed quickly sought to cover the openings with anything available, to protect themselves against temperatures of −15 °C (5 °F).[76] Approximately 100,000 home-owners were affected, according to Chelyabinsk Oblast Governor Mikhail Yurevich.[77] He also said that preserving the water pipes of the city’s district heating was the primary goal of the authorities as they scrambled to contain further post-explosion damage.[citation needed]

By 5 March 2013, the number of damaged buildings was tallied at over 7,200, which included some 6,040 apartment blocks, 293 medical facilities, 718 schools and universities, 100 cultural organizations, and 43 sport facilities, of which only about 1.5% had not yet been repaired.[4] The oblast governor estimated the damage to buildings at more than 1 billion roubles[78] (approximately US$33 million [79]). Chelyabinsk authorities said that broken windows of apartment homes, but not the glazing of enclosed balconies, would be replaced at the state’s expense.[80] One of the buildings damaged in the blast was the Traktor Sport Palace, home arena of Traktor Chelyabinsk of the Kontinental Hockey League (KHL). The arena was closed for inspection, affecting various scheduled events, and possibly the postseason of the KHL.[81]

The irregular elliptical disk shape/»spread-eagled butterfly»[82] ground blast damage area, produced by the airburst,[83] is a phenomenon first noticed upon studying the other larger airburst event: Tunguska.[84]

Reactions[edit]

The Chelyabinsk meteor struck without warning. Dmitry Medvedev, the Prime Minister of Russia, confirmed a meteor had struck Russia and said it proved that the «entire planet» is vulnerable to meteors and a spaceguard system is needed to protect the planet from similar objects in the future.[19][85] Dmitry Rogozin, the deputy prime minister, proposed that there should be an international program that would alert countries to «objects of an extraterrestrial origin»,[86] also called potentially hazardous objects.

Colonel General Nikolay Bogdanov, commander of the Central Military District, created task forces that were directed to the probable impact areas to search for fragments of the asteroid and to monitor the situation. Meteorites (fragments) measuring 1 to 5 cm (0.39 to 1.97 in) were found 1 km (0.62 mi) from Chebarkul in the Chelyabinsk region.[87]

On the day of the impact, Bloomberg News reported that the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs had suggested the investigation of creating an «Action Team on Near-Earth Objects», a proposed global asteroid warning network system, in face of 2012 DA14‘s approach.[88][89] As a result of the impact, two scientists in California proposed directed-energy weapon technology development as a possible means to protect Earth from asteroids.[90][91] Furthermore, the NEOWISE satellite was brought out of hibernation for its second mission extension to scan for near-earth objects.[92] Later in 2013, NASA began annual asteroid impact simulation testing.[93]

Frequency[edit]

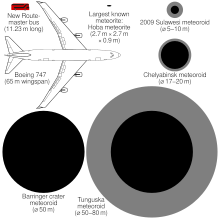

Comparison of approximate sizes of notable impactors with the Hoba meteorite, a Boeing 747 and a New Routemaster bus

It is estimated that the frequency of airbursts from objects 20 metres across is about once in every 60 years.[94] There have been incidents in the previous century involving a comparable energy yield or higher: the 1908 Tunguska event, and, in 1963 off the coast of the Prince Edward Islands in the Indian Ocean.[95] Two of those were over unpopulated areas; however, the 1963 event may not have been a meteor.[96]

Centuries before, the 1490 Ch’ing-yang event, of an unknown magnitude, apparently caused 10,000 deaths.[97] While modern researchers are sceptical about the 10,000 deaths figure, the 1908 Tunguska event would have been devastating over a highly populous district.[97]

Origin[edit]

Based on its entry direction and speed of 19 kilometres per second, the Chelyabinsk meteor apparently originated in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter. It was probably an asteroid fragment. The meteorite has veins of black material which had experienced high-pressure shock, and were once partly melted due to a previous collision. The metamorphism in the chondrules in the meteorite samples indicates the rock making up the meteor had a history of collisions and was once several kilometres below the surface of a much larger LL chondrite asteroid. The Chelyabinsk asteroid probably entered an orbital resonance with Jupiter (a common way for material to be ejected from the asteroid belt) which increased its orbital eccentricity until its perihelion was reduced enough for it to be able to collide with the Earth.[98]

Meteorites[edit]

Strewnfield map of recovered meteorites (253 documented find locations, status of 18 July 2013).

In the aftermath of the air burst of the body, many small meteorites fell on areas west of Chelyabinsk, generally at terminal velocity, about the speed of a piece of gravel dropped from a skyscraper.[99] Analysis of the meteor showed that all resulted from the main breakup at 27–34 km altitude.[7] Local residents and schoolchildren located and picked up some of the meteorites, many located in snowdrifts, by following a visible hole that had been left in the outer surface of the snow. Speculators were active in the informal market that emerged for meteorite fragments.[99]

A 112.2 gram (3.96 oz) Chelyabinsk meteorite specimen, one of many found within days of the airburst, this one between the villages of Deputatsky and Emanzhelinsk. The broken fragment displays a thick primary fusion crust with flow lines and a heavily shocked matrix with melt veins and planar fractures. Scale cube is 1 cm (0.39 in).

In the hours following the visual meteor sighting, a 6-metre (20 ft) wide hole was discovered on Lake Chebarkul’s frozen surface. It was not immediately clear whether this was the result of an impact; scientists from the Ural Federal University collected 53 samples from around the hole the same day it was discovered. The early specimens recovered were all under 1 centimetre (0.39 in) in size and initial laboratory analysis confirmed their meteoric origin. They are ordinary chondrite meteorites and contain 10 per cent iron. The fall is officially designated as the Chelyabinsk meteorite.[2] The Chelyabinsk meteor was later determined to come from the LL chondrite group.[100] The meteorites were LL5 chondrites having a shock stage of S4, and had a variable appearance between light and dark types. Petrographic changes during the fall allowed estimates that the body was heated between 65 and 135 degrees during its atmospheric entry.[101]

In June 2013, Russian scientists reported that further investigation by magnetic imaging below the location of the ice hole in Lake Chebarkul had identified a 60-centimetre (2.0-foot)-size meteorite buried in the mud at the bottom of the lake. Before recovery began, the chunk was estimated to weigh roughly 300 kilograms (660 lb).[102]

Following an operation lasting a number of weeks, it was raised from the bottom of the Chebarkul lake on 16 October 2013. With a total mass of 654 kg (1,442 lb), this is the largest found fragment of the Chelyabinsk meteorite. Initially, it tipped and broke the scales used to weigh it, splitting into three pieces.[103][104]

In November 2013, a video from a security camera was released showing the impact of the fragment at the Chebarkul lake.[7][105] This is the first recorded impact of a meteorite on video. From the measured time difference between the shadow generating meteor to the moment of impact, scientists calculated that this meteorite hit the ice at about 225 m (738 ft) per second, 64 per cent of the speed of sound.[7]

Media coverage[edit]

| External video |

|---|

| Meteor air burst |

The Russian government put out a brief statement within an hour of the event. Serendipitously the news in English was first reported by the hockey site Russian Machine Never Breaks before heavy coverage by the international media and the Associated Press ensued, with the Russian government’s confirmation less than two hours afterwards.[106][107][108] Less than 15 hours after the meteor impact, videos of the meteor and its aftermath had been viewed millions of times.[109]

The number of injuries caused by the asteroid led the Internet-search giant Google to remove a Google Doodle from their website, created for the predicted pending arrival of another asteroid, 2012 DA14.[110] New York City planetarium director Neil deGrasse Tyson stated the Chelyabinsk meteor was unpredicted because no attempt had been made to find and catalogue every 15-metre near-Earth object.[111] Doing so would be very difficult, and current efforts only aim at a complete inventory of 150-metre near-Earth objects. The Asteroid Terrestrial-impact Last Alert System, on the other hand, could now predict some Chelyabinsk-like events a day or so in advance, if and only if their radiant is not close to the Sun.

On 27 March 2013, a broadcast episode of the science television series Nova titled «Meteor Strike» documented the Chelyabinsk meteor, including the significant contribution to meteoritic science made by the numerous videos of the airburst posted online by ordinary citizens. The Nova program called the video documentation and the related scientific discoveries of the airburst «unprecedented». The documentary also discussed the much greater tragedy «that could have been» had the asteroid entered the Earth’s atmosphere more steeply.[55][112]

Impactor orbital parameters[edit]

| Source | Q | q | a | e | i | Ω | ω |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AU | (°) | ||||||

| Popova, Jenniskens, Emel’yanenko et al.; Science[7] | 2.78 ±0.20 |

0.74 ±0.02 |

1.76 ±0.16 |

0.58 ±0.02 |

4.93 ±0.48° |

326.442 ±0.003° |

108.3 ±3.8° |

| Lyytinen via Hankey; AMS[113] | 2.53 | 0.80 | 1.66 | 0.52 | 4.05° | 326.43° | 116.0° |

| Zuluaga, Ferrin; arXiv[114] | 2.64 | 0.82 | 1.73 | 0.51 | 3.45° | 326.70° | 120.6° |

| Borovicka, et al.; IAU[115] | 2.33 | 0.77 | 1.55 | 0.50 | 3.6° | 326.41° | 109.7° |

| Zuluaga, Ferrin, Geens; arXiv[116] | 1.816 | 0.716 | 1.26 ± 0.05 |

0.44 ± 0.03 |

2.984° | 326.5° ± 0.3° |

95.5° ± 2° |

| Chodas, Chesley; JPL via Sky and Telescope[117] | 2.78 | 0.75 | 1.73 | 0.57 | 4.2° | ||

| Insan[118] | 1.5 | 0.5 | 3° | ||||

| Proud; GRL[119] | 2.23 | 0.71 | 1.47 | 0.52 | 4.61° | 326.53° | 96.58° |

| de la Fuente Marcos; MNRAS: Letters[120] | 2.48 | 0.76 | 1.62 | 0.53 | 3.97° | 326.45° | 109.71° |

Multiple videos of the Chelyabinsk superbolide, particularly from the dashboard cameras and traffic cameras which are ubiquitous in Russia, helped to establish the meteor’s provenance as an Apollo asteroid.[115][121] Sophisticated analysis techniques included the subsequent superposition of nighttime starfield views over recorded daytime images of the same cameras, as well as the plotting of the daytime shadow vectors shown in several online videos.[55]

The radiant of the impacting asteroid was located in the constellation Pegasus in the Northern hemisphere.[114] The radiant was close to the Eastern horizon where the Sun was starting to rise.[114]

The asteroid belonged to the Apollo group of near-Earth asteroids,[114][122] and was roughly 40 days past perihelion[113] (closest approach to the Sun) and had aphelion (furthest distance from the Sun) in the asteroid belt.[113][114] Several groups independently derived similar orbits for the object, but with sufficient variance to point to different potential parent bodies of this meteoroid.[119][120][123] The Apollo asteroid 2011 EO40 is one of the candidates proposed for the role of the parent body of the Chelyabinsk superbolide.[120] Other published orbits are similar to the 2-kilometre-diameter asteroid (86039) 1999 NC43 to suggest they had once been part of the same object;[124] they may not be able to reproduce the timing of the impact.[120]

Coincidental asteroid approach[edit]

Comparison of the former orbit of the Chelyabinsk meteor (larger elliptical blue orbit) and asteroid 2012 DA14 (smaller circular blue orbit), showing that they are dissimilar.

Preliminary calculations rapidly showed that the object was unrelated to the long-predicted close approach of the asteroid 367943 Duende, that flew by Earth 16 hours later at a distance of 27,700 km.[14][125][126] The Sodankylä Geophysical Observatory,[33] Russian sources,[127] the European Space Agency,[128] NASA[14] and the Royal Astronomical Society[129] all concluded that the two asteroids had widely different trajectories and therefore could not have been related.

See also[edit]

- Tunguska event

- Asteroid impact avoidance

- Impact event

- List of meteor air bursts

- Near-Earth object

Notes[edit]

- ^ Historical, normally accurate, Chinese records of the 1490 Ch’ing-yang event describe over 10,000 deaths, but have never been confirmed.

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d Yeomans, Don; Chodas, Paul (1 March 2013). «Additional Details on the Large Fireball Event over Russia on Feb. 15, 2013». NASA/JPL Near-Earth Object Program Office. Archived from the original on 30 April 2013.

Note that [the] estimates of total energy, diameter and mass are very approximate.

NASA’s webpage in turn acknowledges credit for its data and visual diagrams to:- Peter Brown (University of Western Ontario); William Cooke (Marshall Space Flight Center); Paul Chodas, Steve Chesley and Ron Baalke (JPL); Richard Binzel (MIT); and Dan Adamo.

- ^ a b «Chelyabinsk». Meteoritical Bulletin Database. The Meteoritical Society. Archived from the original on 3 June 2013.

- ^ a b Число пострадавших при падении метеорита приблизилось к 1500 [The number of victims of the meteorite approached 1500] (in Russian). РосБизнесКонсалтинг [RBC]. 18 February 2013. Archived from the original on 2 May 2013. Retrieved 18 February 2013.

- ^ a b «Meteorite-caused emergency situation regime over in Chelyabinsk region». Russia Beyond The Headlines. Rossiyskaya Gazeta. Interfax. 5 March 2013.

- ^ Global Catastrophe Recap — February 2013, Aon, March 2013

- ^ «O. P. Popova, et al. «Chelyabinsk Airburst, Damage Assessment, Meteorite Recovery and Characterization.» Science 342, 1069–1073 (2013).» (PDF).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Popova, Olga P.; Jenniskens, Peter; Emel’yanenko, Vacheslav; et al. (2013). «Chelyabinsk Airburst, Damage Assessment, Meteorite Recovery, and Characterization». Science. 342 (6162): 1069–1073. Bibcode:2013Sci…342.1069P. doi:10.1126/science.1242642. hdl:10995/27561. PMID 24200813. S2CID 30431384. Archived from the original on 25 January 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g «O. P. Popova, et al. Chelyabinsk Airburst, Damage Assessment, Meteorite Recovery and Characterization. Science 342 (2013)» (PDF).

- ^ David, Leonard (7 October 2013). «Russian Fireball Explosion Shows Meteor Risk Greater Than Thought». www.space.com. New York: Wired Magazine/Conde Nast.best estimate of the equivalent nuclear blast yield of the Chelyabinsk explosion

- ^ Schiermeier, Quirin (6 November 2013). «Risk of massive asteroid strike underestimated». Nature News. Nature Publishing Group. doi:10.1038/nature.2013.14114. S2CID 131384120. Archived from the original on 7 November 2013.

- ^ Byford, Sam (15 February 2013). «Russia rocked by meteor explosion». The Verge. Archived from the original on 5 March 2013.

- ^ a b Kuzmin, Andrey (15 February 2013). «Meteorite explodes over Russia, more than 1,000 injured». Reuters. Archived from the original on 22 February 2013.

- ^ Shurmina, Natalia; Kuzmin, Andrey (15 February 2013). «Meteorite hits central Russia, more than 500 people hurt». Yahoo News. Archived from the original on 15 February 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Agle, D. C. (13 February 2013). «Russia Meteor Not Linked to Asteroid Flyby». NASA news. NASA. Archived from the original on 17 February 2013.

- ^ Arutunyan, Anna; Bennetts, Marc (15 February 2013). «Meteor in central Russia injures at least 500». USA Today.

- ^ Heintz, Jim; Isachenkov, Vladimir (15 February 2013). «100 injured by meteorite falls in Russian Urals». Mercury News. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 2 May 2013.

- ^ a b Major, Jason (15 February 2013). «Meteor Blast Rocks Russia». Universe Today. Archived from the original on 17 February 2013.

- ^ a b Fountain, Henry (25 March 2013). «A Clearer View of the Space Bullet That Grazed Russia». The New York Times. Archived from the original on 26 March 2013.

- ^ a b «PM Medvedev Says Russian Meteorite KEF-2013 Shows «Entire Planet» Vulnerable». Newsroom America. 15 February 2013. Archived from the original on 23 June 2013. Retrieved 15 February 2013.

- ^ Videos capture exploding meteor in sky (Television production). United States: CNN. 16 February 2013.

- ^ «Meteor shower over Russia sees meteorites hit Earth». The Sydney Morning Herald. 16 February 2013. Archived from the original on 23 June 2013.

- ^ «Russian Meteor strike eyewitnesses speak». YouTube. 15 February 2013.

In Russian, with translation voiceover in English

- ^ Mackey, Robert; Mullany, Gerry (15 February 2013). «Spectacular Videos of Meteor Over Siberia». The New York Times. Archived from the original on 30 April 2013.

- ^ «Meteor over Russia seen by Meteosat – EUMETSAT». eumetsat.int. EUMETSAT. Archived from the original on 6 September 2020. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- ^ Rubin, Alan E.; Grossman, Jeffrey N. (January 2010). «Meteorite and meteoroid: New comprehensive definitions». Meteoritics & Planetary Science. 45 (1): 114–122. Bibcode:2010M&PS…45..114R. doi:10.1111/j.1945-5100.2009.01009.x. S2CID 129972426.

- ^ Grady, Monica M (31 August 2000). Catalogue of Meteorites. London: Natural History Museum, Cambridge University Press. p. 285. ISBN 978-0-521-66303-8.

- ^ Brumfiel, Geoff (15 February 2013). «Russian meteor largest in a century». Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2013.12438. S2CID 131657241. Archived from the original on 20 February 2013.

- ^ T.C. (15 February 2013). «Asteroid impacts – How to avert Armageddon». The Economist. Archived from the original on 19 February 2013.

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (15 February 2013). «Size of Blast and Number of Injuries Are Seen as Rare for a Rock From Space». The New York Times. Archived from the original on 20 February 2013.

- ^ Ewalt, David M (15 February 2013). «Exploding Meteorite Injures A Thousand People in Russia». Forbes. Archived from the original on 8 April 2013.

- ^ S.F. Chronicle (1896). «Explosion of an Aerolite in Madrid (10 February 1896)». Notices from the Lick Observatory. Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 8 (47): 86–87. Bibcode:1896PASP….8…86C. doi:10.1086/121074.

Many injuries resulted from the panic which broke out… Much damage was done by the force of the concussion.

- ^ Heintz, Jim (15 February 2013). «500 injured by blasts as meteor falls in Russia». Yahoo News. Archived from the original on 24 June 2013.

- ^ a b «Are 2012 DA14 and the Chelyabinsk meteor related?». Kilpisjärvi Atmospheric Imaging Receiver Array. Finland: Sodankylä Geophysical Observatory. 15 February 2013. Archived from the original on 23 June 2013.

- ^ Barstein, Geir (18 February 2013). «Kan koste flere tusen grammet» [(Meteorite) can cost several thousand dollars per gram]. Dagbladet (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 1 May 2013.

- ^ ssvilponis (16 February 2013). Chelyabinsk meteorite, 2013 February 15th (Map). Google Maps.

- ^ Geens, Stefan (16 February 2013). «Reconstructing the Chelyabinsk meteor’s path, with Google Earth, YouTube and high-school math». Ogle Earth. Archived from the original on 28 February 2013.

- ^ Fazekas, Andrew (1 July 2013). «Russian Meteor Shockwave Circled Globe Twice». Newswatch. National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 13 July 2013.

- ^ Cooke, William (15 February 2013). «Orbit of the Russian Meteor». NASA blogs. Archived from the original on 7 March 2013.

- ^ Malik, Tariq (17 February 2013). «Russian Meteor Blast Bigger Than Thought, NASA Says». Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 18 February 2013.

- ^ Black, Phil; Smith-Spark, Laura (18 February 2013). «Russia starts cleanup after meteor strike». CNN. Archived from the original on 17 February 2013.

- ^ Sreeja, VN (4 March 2013). «New Asteroid ‘2013 EC’ Similar To Russian Meteor To Pass Earth At A Distance Less Than Moon’s Orbit». International Business Times. Archived from the original on 30 April 2013.

- ^ a b «Meteor Explosion near Chelyabinsk, Russia». US Geological Survey. 15 February 2013. Archived from the original on 19 February 2013.

- ^ a b «Magnitude ? (Uncertain Or Not Yet Determined) – URAL MOUNTAINS REGION, RUSSIA». National Earthquake Information Center. U.S. Geological Survey. 15 February 2013. Archived from the original on 18 February 2013.

- ^ a b Oskin, Becky (15 February 2013). «Russia meteor blast produced 2.7 magnitude earthquake equivalent». The Christian Science Monitor. ISSN 0882-7729. Archived from the original on 16 February 2013.

- ^ Sample, Ian (7 November 2013). «Scientists reveal the full power of the Chelyabinsk meteor explosion». The Guardian. Archived from the original on 9 November 2013.

- ^ Lobanovsky, Yury. «Parameters of Chelyabinsk and Tunguska Meteoroids» (PDF). Retrieved 26 November 2022.

- ^ «Russian meteor hit atmosphere with force of 30 Hiroshima bombs». The Telegraph. 16 February 2013. Archived from the original on 18 February 2013.

- ^ Метеорит в Челябинске [Meteorite in Chelyabinsk] (in Russian). YouTube. 15 February 2013.

- ^ Brown, P.; Spalding, R. E.; ReVelle, D. O.; Tagliaferri, E.; Worden, S. P. (2002). «The flux of small near-Earth objects colliding with the Earth» (PDF). Nature. 420 (6913): 294–296. Bibcode:2002Natur.420..294B. doi:10.1038/nature01238. PMID 12447433. S2CID 4380864. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 April 2013. Retrieved 20 March 2013.

- ^ «Newly Released Security Cam Video Shows Chelyabinsk Meteorite Impact in Lake Chebarkul by Bob King on November 7, 2013». 7 November 2013.

- ^ «Fallout from the Russian fireball encircled Earth, research shows». The Christian Science Monitor. 19 August 2013.

- ^ «Russian Fireball Largest Ever Detected by CTBTO’s Sensors». CTBTO. 18 February 2013. Archived from the original on 27 October 2017. Retrieved 19 February 2013.

- ^ Harper, Paul (20 February 2013). «Meteor explosion largest infrasound recorded». The New Zealand Herald. APN Holdings NZ.

- ^ Schiermeier, Quirin (10 June 2013). «Russian meteor blast was the largest ever recorded by CTBTO». Nature News Blog. Macmillan Publishers Limited.

- ^ a b c d «Meteor Strike». NOVA. PBS. 27 March 2013. Archived from the original on 21 April 2013.

- ^ «Оценка мощности взрыва Челябинского болида в 500 килотонн завышена в 3-4 раза» (in Russian). 19 February 2013. Retrieved 25 July 2021.

- ^ «Fireball Events Chelyabinsk Meteor of 15 Feb. 2013 – Preliminary results as of Feb 16, 2013. Dr. Peter Brown».

- ^ Le Pichon, Alexis; Ceranna, L.; Pilger, C.; Mialle, P.; Brown, D.; Herry, P.; Brachet, N. (2013). «2013 Russian Fireball largest ever detected by CTBTO infrasound sensors». Geophysical Research Letters. 40 (14): 3732. Bibcode:2013GeoRL..40.3732L. doi:10.1002/grl.50619. S2CID 129384715.

- ^ Brown, PG; Assink, JD; Astiz, L; Blaauw, R; Boslough, MB; et al. (2013). «A 500-kiloton airburst over Chelyabinsk and an enhanced hazard from small impactors». Nature. 503 (7475): 238–41. Bibcode:2013Natur.503..238B. doi:10.1038/nature12741. hdl:10125/33201. PMID 24196713. S2CID 4450349.

- ^ «Sandia supercomputers offer new explanation of Tunguska disaster». Sandia National Laboratories. 17 December 2007. Retrieved 22 December 2007.

- ^ «Research to Address Near-Earth Objects Remains Critical, Experts Say».

- ^ a b Kelly Beatty (7 November 2013). «New Chelyabinsk Results Yield Surprises». Archived from the original on 6 August 2014.

- ^ «WGN, the Journal of the IMO 41:1 (2013) A Preliminary Report on the Chelyabinsk Fireball/Airburst Peter Brown» (PDF).

- ^ «O. P. Popova, et al. Chelyabinsk Airburst, Damage Assessment, Meteorite Recovery and Characterization.Science 342 (2013). FIGURE 1» (PDF).

- ^ «Postcards from Chelyabinsk – SETI Institute Colloquium Series (Peter Jenniskens) 15:10 on». YouTube.

- ^ «Map of glass damage in Chelyabinsk Oblast. From: Popova et al. Science Science Vol. 42 (2013)».

- ^ Heintz, Jim; Isachenkov, Vladimir (15 February 2013). «Meteor explodes over Russia’s Ural Mountains; 1,100 injured as shock wave blasts out windows». Postmedia Network Inc. The Associated Press. Archived from the original on 13 May 2013. Retrieved 5 March 2013.

Emergency Situations Ministry spokesman Vladimir Purgin said many of the injured were cut as they flocked to windows to see what caused the intense flash of light, which was momentarily brighter than the sun.

- ^ a b Grossman, Lisa (6 November 2013). «CSI Chelyabinsk: 10 insights from Russia’s meteorite». New Scientist. Archived from the original on 9 November 2013.

- ^ «Cameras for Allsky Meteor Surveillance (CAMS)».

- ^ Kramer, Andrew E. (17 February 2013). «After Assault From the Heavens, Russians Search for Clues and Count Blessings». The New York Times. Archived from the original on 17 February 2013.

- ^ a b «Челябинская учительница спасла при падении метеорита более 40 детей». Интерфакс-Украина (in Russian). Retrieved 28 September 2018.

- ^ «Meteorite explosion over Russia injures hundreds». The Guardian. 15 February 2013. Archived from the original on 18 February 2013.

- ^ Bidder, Benjamin (15 February 2013). «Meteoriten-Hagel in Russland: «Ein Knall, Splittern von Glas»» [Meteorite hail in Russia: «A blast, splinters of glass»]. Der Spiegel (in German). Archived from the original on 18 February 2013.

- ^ «Central Russia hit by meteor shower in Ural region». BBC News. 15 February 2013. Archived from the original on 18 February 2013.

- ^ Campbell, Charlie (15 February 2013). «Meteorite injures hundreds in Russia». Time. Archived from the original on 15 February 2013.

- ^ «Chelyabinsk Station history». Weather Underground. 15 February 2013. Archived from the original on 30 April 2013.

- ^ Zhang, Moran (16 February 2013). «Russia Meteor 2013: Damage To Top $33 Million; Rescue, Cleanup Team Heads To Meteorite-Hit Urals». International Business Times. Archived from the original on 30 April 2013.

- ^ Ущерб от челябинского метеорита превысит миллиард рублей [Damage from Chelyabinsk meteorite exceeds one billion rubles] (in Russian). Lenta.ru. 15 February 2013. Archived from the original on 13 May 2013.

- ^ «Russian meteor damage estimated at over $30 million».

- ^ Сергей Давыдов: жертв и серьезных разрушений нет [Sergei Davydov: casualties and no serious damage]. Chelad (in Russian). 15 February 2013. Archived from the original on 17 February 2013.

- ^ Gretz, Adam (15 February 2013). «KHL arena among buildings damaged in Russian meteorite strike». CBS Sports. Archived from the original on 1 May 2013.

- ^ «NASA and International Researchers Collect Clues to Meteoroid Science November 6, 2013». 6 November 2013.

- ^ «Map of glass damage in Chelyabinsk Oblast. From: Popova et al. Science Science Vol. 42 (2013)».

- ^ Boyarkina, A. P., Demin, D. V., Zotkin, I. T., Fast, W. G. Estimation of the blast wave of the Tunguska meteorite from the forest destruction. – Meteoritika, Vol. 24, 1964, pp. 112–128 (in Russian).

- ^ Agencies, News (15 February 2013). «400 injured by meteorite falls in Russian Urals». Ynetnews. Y net news. Archived from the original on 18 February 2013.

- ^ Amos, Howard (15 February 2013). «Meteorite explosion over Chelyabinsk injures hundreds». The Guardian. Archived from the original on 18 February 2013.

- ^ В полынье в Чебаркульском районе Челябинской области, возможно, найдены обломки метеорита – МЧС [In the ice-hole in Chebarkulsky district of Chelyabinsk region, possibly found fragments of the meteorite – MOE] (in Russian). Interfax. 15 February 2013. Archived from the original on 23 June 2013.

- ^ Drajem, Mark; Weber, Alexander (15 February 2013). «Asteroid Passes Earth as UN Mulls Monitoring Network». Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 18 February 2013.

- ^ David, Leonard (18 February 2013). «United Nations reviewing asteroid impact threat». CBS News. Archived from the original on 18 February 2013.

- ^ Villamarin, Jenalyn (22 February 2013). «End of the World 2013: DE-STAR Project Proposed after Asteroid 2012 DA14 Flyby, Russian Meteor Blast». International Business Times. Archived from the original on 30 April 2013. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- ^ Barrie, Allison (19 February 2013). «Massive, orbital laser blaster could defend against asteroid threats». Fox News. Archived from the original on 21 February 2013.

- ^ «The WISE in NEOWISE: How a Hibernating Satellite Awoke to Discover the Comet». 22 July 2020.

- ^ «NASA has led 7 asteroid-impact simulations. Only once did experts figure out how to stop the space rock from hitting Earth». Business Insider. 20 May 2021. Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- ^ Robert Marcus; H. Jay Melosh; Gareth Collins (2010). «Earth Impact Effects Program». Imperial College London / Purdue University. Retrieved 4 February 2013. (solution using 2600kg/m^3, 17 km/s, 45 degrees)

- ^ Wayne Edwards; Peter G. Brown; Douglas O. ReVelle (2006). «Estimates of meteoroid kinetic energies from observations of infrasonic airwaves» (PDF). Journal of Atmospheric and Solar-Terrestrial Physics. 68 (10): 1136–1160. Bibcode:2006JASTP..68.1136E. doi:10.1016/j.jastp.2006.02.010.

- ^ Silber, Elizabeth A.; Revelle, Douglas O.; Brown, Peter G.; Edwards, Wayne N. (2009). «An estimate of the terrestrial influx of large meteoroids from infrasonic measurements». Journal of Geophysical Research. 114 (E8). Bibcode:2009JGRE..114.8006S. doi:10.1029/2009JE003334.

- ^ a b Yau, K., Weissman, P., & Yeomans, D. Meteorite Falls In China And Some Related Human Casualty Events, Meteoritics, Vol. 29, No. 6, pp. 864–871, ISSN 0026-1114, bibliographic code: 1994Metic..29..864Y.

- ^ Kring, David A.; Boslough, Mark (1 September 2014). «Chelyabinsk: Portrait of an asteroid airburst». Physics Today. 67 (9): 32–37. Bibcode:2014PhT….67i..32K. doi:10.1063/PT.3.2515. ISSN 0031-9228.

- ^ a b Kramer, Andrew E. (18 February 2013). «Russians Wade into the Snow to Seek Treasure From the Sky». The New York Times.

- ^ «NASA (YouTube) – Dr. David Kring – Asteroid Initiative Workshop Cosmic Explorations Speakers Session». YouTube. 21 November 2013.

- ^ Badyukov, D.D.; Raitala, J.; Kostama, P.; Ignatiev, A.V. (March 2015). «Chelyabinsk meteorite: Shock metamorphism, black veins and impact melt dikes, and the Hugoniot». Petrology. 23 (2): 103–115. doi:10.1134/S0869591115020022. S2CID 140628758.

- ^ «Huge Chunk of Meteorite Located in Urals Lake – Scientist». RIA Novosti. 22 June 2013. Archived from the original on 23 June 2013.

- ^ Весы не выдержали тяжести челябинского метеорита [Weighing scales couldn’t withstand the heft of the Chelyabinsk meteorite] (in Russian). NTV. 16 October 2013. Archived from the original on 17 October 2013.

- ^ Herszenhorn, David M. (16 October 2013). «Lifted From a Russian Lake, a Big, if Fragile, Space Rock». The New York Times. Archived from the original on 17 October 2013.

- ^ King, Bob (7 November 2013). «Newly Released Security Cam Video Shows Chelyabinsk Meteorite Impact in Lake Chebarkul». Universe Today. Archived from the original on 9 November 2013.

- ^ Franke-Ruta, Garance (15 February 2013). «How a D.C. Hockey Fan Site Got the Russian Meteorite Story Before the AP». The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 17 February 2013.

- ^ Челябинский метеорит стал одной из самых популярных тем в мире [Chelyabinsk meteorite has become one of the hottest topics in the world]. Federal Press World News (in Russian). Federal Press. 15 February 2013. Archived from the original on 23 June 2013.

- ^ «How A Hockey Blog Got The Scoop on Russia’s Meteorite». NPR.org. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- ^ «Meteor Over Russia Hits Internet with 7.7 Million Video Views». Visible Measures. Visible Measures. Archived from the original on 12 April 2013.

- ^ Stern, Joanna (15 February 2013). «Asteroid 2012 DA14 Google Doodle Removed After Russian Meteor Shower Injuries». ABC News. Archived from the original on 16 February 2013.

- ^ «Neil deGrasse Tyson: Radar could not detect meteor». Today. 15 February 2013. Archived from the original on 9 May 2013.

- ^ Kaplan, Karen (27 March 2013). «Russian meteor, a ‘death rock from space,’ stars on ‘Nova’«. Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 28 March 2013.

- ^ a b c Hankey, Mike (15 February 2013). «Large Daytime Fireball Hits Russia». American Meteor Society. Archived from the original on 21 May 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Zuluaga, Jorge I.; Ferrin, Ignacio (2013). «A preliminary reconstruction of the orbit of the Chelyabinsk Meteoroid». arXiv:1302.5377 [astro-ph.EP].

We use this result to classify the meteoroid among the near Earth asteroid families finding that the parent body belonged to the Apollo asteroids.

- ^ a b «CBET 3423 : 20130223 : Trajectory and Orbit of the Chelyabinsk Superbolide». Astronomical Telegrams. International Astronomical Union. 23 February 2013. Archived from the original on 23 April 2013. (registration required)

- ^ Zuluaga, Jorge I.; Ferrin, Ignacio; Geens, Stefan (2013). «The orbit of the Chelyabinsk event impactor as reconstructed from amateur and public footage». arXiv:1303.1796 [astro-ph.EP].

- ^ Beatty, Kelly (6 March 2013). «Update on Russia’s Mega-Meteor». Sky and Telescope. Sky Publishing Corp. Archived from the original on 23 June 2013. Retrieved 26 June 2013.

- ^ Вибе, Дмитрий (25 March 2013). Семинар по Челябинскому метеориту: российская наука выдала «официальную» информацию [Seminar in Chelyabinsk meteorite: Russian science has given «official» information] (in Russian). Компьютерра [Computerra]. Archived from the original on 23 June 2013.

- ^ a b Proud, S. R. (16 July 2013). «Reconstructing the orbit of the Chelyabinsk meteor using satellite observations». Geophysical Research Letters. 40 (13): 3351–3355. Bibcode:2013GeoRL..40.3351P. doi:10.1002/grl.50660.

- ^ a b c d de la Fuente Marcos, C.; de la Fuente Marcos, R. (1 September 2014). «Reconstructing the Chelyabinsk event: pre-impact orbital evolution». Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society: Letters. 443 (1): L39–L43. arXiv:1405.7202. Bibcode:2014MNRAS.443L..39D. doi:10.1093/mnrasl/slu078. S2CID 118417667.

- ^ «Astronomers Calculate Orbit of Chelyabinsk Meteorite». The Physics arXiv Blog. MIT Technology Review. 25 February 2013.

Their conclusion is that the Chelyabinsk meteorite is from a family of rocks that cross Earth’s orbit called Apollo asteroids.

- ^ Rincon, Paul (26 February 2013). «Russia meteor’s origin tracked down». BBC News. Archived from the original on 26 February 2013.

- ^ Geens, Stefan (9 March 2013). «Chelyabinsk meteoroid trajectories compared using Google Earth and YouTube». YouTube.

- ^ Borovička, Jiří; Spurný, Pavel; Brown, Peter; Wiegert, Paul; Kalenda, Pavel; Clark, David; Shrbený, Lukáš (6 November 2013). «The trajectory, structure and origin of the Chelyabinsk asteroidal impactor». Nature. 503 (7475): 235–7. Bibcode:2013Natur.503..235B. doi:10.1038/nature12671. PMID 24196708. S2CID 4399008.

- ^ Plait, Phil (15 February 2013). «Breaking: Huge Meteor Explodes Over Russia». Slate. Archived from the original on 16 February 2013.

- ^ Уральский метеорит отвлек научный мир от знаменитого астероида [Ural meteorite distracted (sic) from the scientific world famous asteroid] (in Russian). Moscow: РИА Новости (RIA Novosti). 15 February 2013. Archived from the original on 17 March 2013.

- ^ Elenin, Leonid (15 February 2013). «Siberian fireball (video)». SpaceObs (in Russian). Archived from the original on 4 March 2013.

- ^ «Russian Asteroid Strike». ESA.int. European Space Agency. 15 February 2013. Archived from the original on 21 February 2013.

- ^ Marson, James; Naik, Gautam (15 February 2013). «Falling Meteor Explodes Over Russia». The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 15 February 2013.

- Attribution

- This article contains portions of text translated from the corresponding article of the Russian Wikipedia. A list of contributors can be found there in its history section.

Further reading[edit]

- Balcerak, E. (2013). «Nuclear test monitoring system detected meteor explosion over Russia». Eos, Transactions American Geophysical Union. 94 (42): 384. Bibcode:2013EOSTr..94S.384B. doi:10.1002/2013EO420010.

- Barry, Ellen; Kramer, Andrew E. (15 February 2013). «Shock Wave of Fireball Meteor Rattles Siberia, Injuring 1,200». NYTimes.com. (website).

Also published as «Meteor Explodes, Injuring Over 1,000 in Siberia». The New York Times (New York ed.). 16 February 2013. p. A1. (print). - Borovička, J.; Spurný, P.; Brown, P.; Wiegert, P.; Kalenda, P.; Clark, D.; Shrbený, L. (2013). «The trajectory, structure and origin of the Chelyabinsk asteroidal impactor». Nature. 503 (7475): 235–237. Bibcode:2013Natur.503..235B. doi:10.1038/nature12671. PMID 24196708. S2CID 4399008.

- Brown, P. G.; Assink, J. D.; Astiz, L.; Blaauw, R.; Boslough, M. B.; et al. (2013). «A 500-kiloton airburst over Chelyabinsk and an enhanced hazard from small impactors». Nature. 503 (7475): 238–241. Bibcode:2013Natur.503..238B. doi:10.1038/nature12741. hdl:10125/33201. PMID 24196713. S2CID 4450349.

- Gorkavyi, N.; Rault, D. F.; Newman, P. A.; Da Silva, A. M.; Dudorov, A. E. (2013). «New stratospheric dust belt due to the Chelyabinsk bolide». Geophysical Research Letters. 40 (17): 4728–4733. Bibcode:2013GeoRL..40.4728G. doi:10.1002/grl.50788. hdl:2060/20140016772. S2CID 129408498.

- Gorkavyi, N. N.; Taidakova, T. A.; Provornikova, E. A.; Gorkavyi, I. N.; Akhmetvaleev, M. M. (2013). «Aerosol plume after the Chelyabinsk bolide». Solar System Research. 47 (4): 275–279. Bibcode:2013SoSyR..47..275G. doi:10.1134/S003809461304014X. S2CID 123632925.

- Kohout, Tomas; Gritsevich, Maria; Grokhovsky, Victor I.; Yakovlev, Grigoriy A.; Haloda, Jakub; et al. (2013). «Mineralogy, reflectance spectra, and physical properties of the Chelyabinsk LL5 chondrite – Insight into shock-induced changes in asteroid regoliths». Icarus. 228 (1): 78–85. arXiv:1309.6081. Bibcode:2014Icar..228…78K. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2013.09.027. S2CID 59359694.

- Le Pichon, A.; Ceranna, L.; Pilger, C.; Mialle, P.; Brown, D.; Herry, P.; Brachet, N. (2013). «The 2013 Russian fireball largest ever detected by CTBTO infrasound sensors». Geophysical Research Letters. 40 (14): 3732–3737. Bibcode:2013GeoRL..40.3732L. doi:10.1002/grl.50619. S2CID 129384715.

- Miller, Steven D.; Straka, William; Bachmeier, Scott (5 November 2013). «Earth-viewing satellite perspectives on the Chelyabinsk meteor event». Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 110 (45): 18092–18097. Bibcode:2013PNAS..11018092M. doi:10.1073/pnas.1307965110. PMC 3831432. PMID 24145398.