Создание союза

Халифат состоял из множества стран, отличающихся высоким развитием культуры: Сирия, Египет, Средняя Азия, Месопотамия. Арабы занимали нижнюю ступень по качеству образования в сравнении с другими народами. Из-за неграмотности они уничтожали памятники культуры на завоеванных территориях. Когда халиф приказал сжечь библиотеку в Александрии, он сказал: «Если в книгах указано не то, что написано в Коране, то их нужно уничтожить. А если сказано то же самое, то они и не нужны».

Постепенно арабы переняли наследие своих соседей, они воспользовались их достижениями в искусстве и науках. Все страны союза заговорили на одном языке, на котором писали новые авторы и переводили старые произведения. Культура создавалась всеми народами мусульманского государства.

Причины подъема

Еще в восьмом веке арабы из Китая на свои территории завезли бумагу — новый для них материал. Он оказался прочнее и долговечнее папируса, дешевле пергамента, его легко производить. Чернила в бумагу впитывались быстрее, что значительно сократило временные затраты на создание рукописей и книг.

В тот период Халифатом правила династия Аббасидов. Они поддерживали распространение грамотности, ссылаясь на изречения Мухаммеда. Пророк Аллаха говорил, что чернила ученого ценнее и священнее крови мученика.

Основные причины высокого развития культуры в арабском Халифате — это использование достижения ранних цивилизаций и привоз новых материалов для учебы из других государств. Классические литературные произведения были переведены на арабский и иврит, турецкий и персидский. Мудрецы Халифата извлекали знания из разных источников — книг и дневников, таблиц, дощечек, рукописей и коротких сообщений, пергаментов и карт, живописи и даже музыки.

Развитие хозяйства

Сначала страны Халифата раскинулись на бескрайних степях. Позже они занялись разным хозяйством:

- земледелие;

- садоводство;

- виноградарство;

- животноводство.

Долины Сирии покрылись виноградниками и плодовыми садами, на берегах рек сеяли пшеницу, ячмень, сахарный тростник и финики. Путешественники привезли из Индии и Китая другие культуры — рис, хлопок, цитрусовые.

С этого начался расцвет ремесел. Мастера научились изготавливать прочные и легкие ткани из хлопка и шерсти, шелковые изделия, ткать ковры. Прославились арабы своими стеклянными изделиями и оружием. Такие изделия из дамасской стали, как защитные панцири, сабли и кинжалы, пользовались популярностью в европейских странах.

Халифат наладил торговые отношения с Китаем и Индией. Товары арабы провозили через пустыни на лошадях и верблюдах, а по морям доставляли их кораблями и лодками. Из Индии поставляли драгоценные камни и дорогие ткани, специи. Эти товары Халифат продавал в Европе. Во время торговли в разных государствах арабы устанавливали с ними деловые отношения.

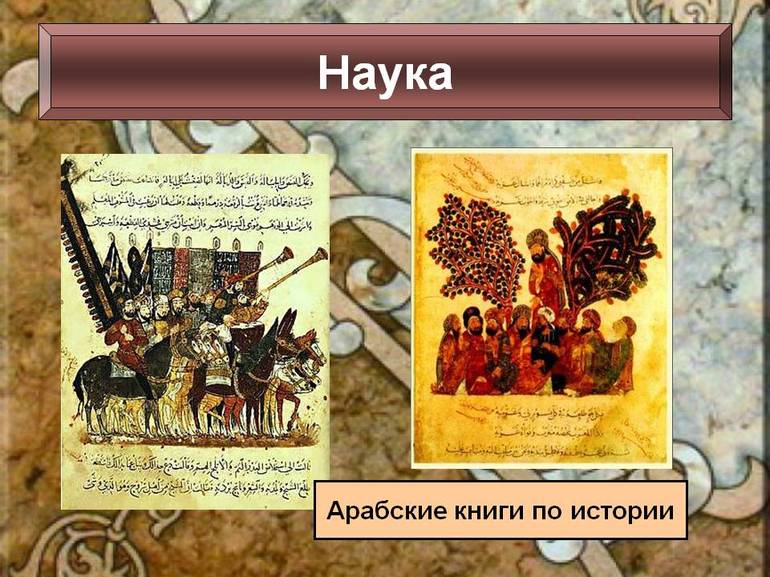

Философия и наука

Культура Халифата состояла из традиций ислама и античных идей. Арабам нравились работы Платона и Аристотеля, но и у самого государства были великие мыслители. Их записи даже переводили на европейские языки.

Больших успехов арабские ученые достигли в математике. Они первыми систематизировали алгебраическую науку. За основу они взяли исследования Архимеда и Евклида. Европа позаимствовала у мусульман десятичные дроби и индийские числа.

В городе Марокко — Фес — в 859 году основали первый университет, позже учебные заведения появились и в Багдаде, Каире. Здесь преподавали сразу несколько дисциплин:

- исламскую историю;

- религию (богословие);

- право.

Благодаря культурным достижениям арабского Халифата новые знания стали доступны разным странам. В университетах появились иностранные преподаватели, среди которых были представители других религий.

Достижения в медицине

В девятом веке началось развитие медицины, основной движущей силой стали наблюдения и анализ. Знания о болезнях и их лечении были изложены в книгах мыслителями Ибн Сина и Ар-Рази. Позже эти собрания попали в Европу, где получили широкую известность. Христиане узнали о медицинских исследованиях Галена и Гиппократа именно благодаря арабам.

Религия мусульман предписывает безвозмездную помощь бедным и нуждающимся. В крупных городах власти построили бесплатные больницы, куда могли обратиться для лечения все слои населения. Здесь же выдавали лекарства на дом и кормили бедняков. Их финансировали специальные благотворительные фонды. А в столицах Халифата появились и первые в мире заведения по уходу за душевнобольными.

Искусства и ремесла

Особенно ярко проявилась арабская культура в живописи, графике и других видах искусства. Мусульманские орнаменты нельзя перепутать с работами других мастеров. В исламе не принято изображать людей, поэтому распространенными были растительные узоры. Подобные орнаменты встречались на коврах, мебели, одежде, посуде. Резной лепниной украшали фасады и своды зданий. Хотя было довольно много текстильных изделий, скульптура практически не развивалась. А в живописи преобладали пейзажи и натюрморты.

Развивались и разные ремесла:

- стекольная промышленность;

- изготовление косметики;

- гончарство и плетение;

- ювелирное дело;

- производство кожаных изделий.

Сирия и Египет в то время были центрами производства товаров из стекла. Именно у арабов венецианцы позаимствовали технологию изготовления тончайшей посуды и других изделий. Первую подводку для глаз также изобрели арабы. Прославились они и своей глиняной и плетеной посудой — расписными тарелками, кувшинами, корзинами.

Были в Халифате и искусные ювелиры. Они мастерски обрабатывали драгоценные металлы и камни, создавали ожерелья, серьги, браслеты, головные уборы. Бриллиантами, рубинами и изумрудами украшали одежду, обувь и посуду. Известны и кожаные изделия мусульман. Они производили качественную обувь, ножны, плащи.

Литература и каллиграфия

Направлением всей культуры мусульман можно назвать стремление к красоте и совершенству. Поступки арабы оценивали по Корану, а характеристику человеку давали по его делам и отношению к окружающим. Их мудрые изречения записаны в книгах, сборниках стихов.

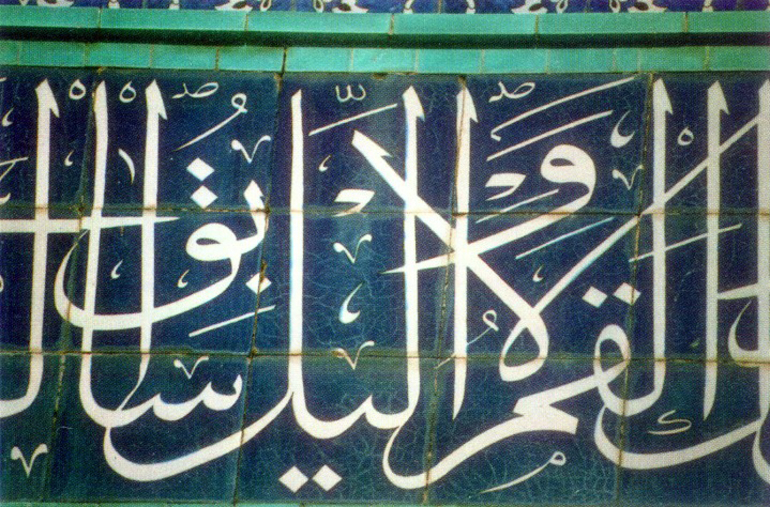

Много внимания на уроках в классах учителя уделяли каллиграфии. Дети и взрослые учились красиво писать, это умение считалось настоящим искусством. Религиозные фразы наносили на разные предметы:

- монеты;

- керамические плитки;

- стены;

- тарелки;

- деревянные и металлические пластины.

Литература авторов из Халифата стала известной за пределами государства. Преобладала религиозная тема, а все региональные языки вытеснял арабский. Позже стали популярными и персидские писатели.

Наиболее известной является поэзия мусульман. Почти все книги состоят из стихотворений. Даже научные труды по медицине, экономике, математике и философии содержат рифмованные строки. Популярными стали панегирики и эпическая поэзия. В этом государстве создали знаменитый сборник сказок Шахерезады «Тысяча и одна ночь».

Архитектурные сооружения

На архитектурную культуру Халифата повлияли доисламские цивилизации и соседние народы государства. Раннее зодчество напоминает сирийский и византийский стиль. Большинство архитекторов были христианами, а знаменитую мечеть в Дамаске построили по примеру базилики Иоанна Крестителя.

Позже развился собственный стиль арабов. В Тунисе возвели мечеть Кейруна. Она стала примером для остальных религиозных построек. У нее квадратная форма, а на территории расположены минарет, молитвенный зал с большими куполами и двор, окруженный портиками. Персидская архитектура немного отличается. Ее арки имели стрельчатую и подковообразную форму. Проекты зданий в османском стиле имели множество куполов. Ни один дворец Магрибской области не обошелся без огромных колонн. Арабский стиль получил распространение по всей территории Халифата.

Мировое значение

Переоценить значение культуры Халифата практически невозможно. Если говорить кратко, то большинство научных трудов, известных в мусульманских странах, стали основой образования европейцев. Их переводили на латинский язык, чтобы было проще изучать в христианском мире.

Огромный вклад арабского Халифата в мировую культуру отразился в литературе, искусстве, архитектуре, ремеслах. Европейцы знакомились с арабскими трудами в мусульманской Испании. Ее столица, Кордова, славилась большим количеством школ, где преподавали учителя разного происхождения.

В этом городе были огромные библиотеки. Здесь хранились старинные рукописи, исторические документы, каждый год мусульмане переводили тут по 16 000 книг, собранных по всему миру. Затем эти работы распространялись по разным странам.

Ученые, ремесленники и художники Халифата сделали довольно много для улучшения уровня образования по всему миру. Именно мусульмане заложили основы большинства наук, стали основоположниками нового стиля в архитектуре, создали великолепные образцы ювелирных изделий.

На чтение 7 мин Просмотров 1.3к. Опубликовано 27.09.2020

Мир арабов в VII – XIII веках был настоящей космополитической цивилизацией, объединяющей большое количество народов, живших в Испании, Северной Африке, в древних землях Египта, Сирии, Месопотамии. Сплотил эти все народы ислам. Было заключено множество союзов, открылись новые торговые пути, земли. Связь между народами обеспечивал арабский язык. Именно там зародилась общая арабская культура.

Арабская цивилизация объединила не только мусульман, но и христиан и евреев. Её представителями стали арабы, африканцы, берберы, египтяне, потомки финикийцев и хананеев, а также другие народы. Они «плавились» в одном большом котле. Динамичная цивилизация внесла в мир замечательные достижения. Между VII и XIII веками в арабском мире процветали культура и обучение, что способствовало развитию искусства и наук. Арабская цивилизация сохранила библиотеки древних греков, римлян, византийцев. Те знания, которые получила средневековая Европа, были взяты из арабского мира.

Математика

Арабы внесли в цифру 0, что дало возможность решать сложные математические задачи. 0 стал усовершенствованием индуистской концепции. Также арабская десятичная система счисления облегчила курс математики. Большая роль арабов в разработке алгебры и тригонометрии, отцом которых считают Аль-Хорезми. Он нашёл более точный и всеобъемлющий метод точного деления земель, чтобы можно тщательнее соблюдать Коран. Арабские математические исследования стали проходить в европейских университетах. Арабы реформировали календарь, в результате этого за пять тысяч лет произошла погрешность лишь в 1 день.

Астрономия

Как и математика, астрономия в древнем арабском мире усовершенствовалась, опираясь на религию. В ней учитывалось точное время восходов и закатов Солнца. Это нужно было для определения Уразы (мусульманского поста) во время Рамадана. Средневековые арабские астрономы создали карты звёздного неба в обсерваториях в Пальмире и Мараге. Им удалось определить длину градуса.

Арабские учёные установили долготу и широту. Они исследовали относительные скорости света и звука. Аль-Бируни даже обсуждал теорию вращения Земли вокруг собственной оси ещё задолго до Галилея. Аль-Фазари, аль-Фергани, аз-Заркали занимались разработкой магнитного компаса и построения знаков Зодиака. Большое количество арабских астрономов в XIII веке работали в Мараге.

Медицина

Большие достижения были достигнуты арабами в медицине. За основу они взяли методы врачевания Древней Месопотамии и Древнего Египта. В IX веке был арабский врач Ар-Рази. Он работал в области заражений инфекциями. В Европе вплоть до XVI века пользовались работами «Китаб аль-Мансури».

Аль-Рази первым удалось диагностировать оспу и корь. Он провёл связь между этими болезнями и заражением. Арабский врач разработал ртутную мазь и хирургические нитки из кишечника животных. В Европе хорошо известен Авиценна (Ибн Сина). Он стал пионером в области психиатрии. Ибн Хатиб и Ибн Хатима в XIV веке сделали вывод, что чума распространяется посредством заражения. А другой арабский врач, Китабул Малики аль-Маглуси работал над концепцией капиллярной системы. Сириец Ибн ан-Нафис открыл принципы малого круга кровообращения. Арабы для лечения широко применяли травы.

Архитектура

Арабы своей архитектурой прославляли Ислам. В первую очередь они строили мечети и мавзолеи. Научившись у римлян строить арки, они развили этот стиль в своём строительстве, сделав его образцом архитектуры. В Дамаске находится Большая Мечеть, которую построили ещё в VIII веке. В её архитектуру прекрасно вписалась подковообразная арка. Остроконечные арки можно увидеть в старинных мечетях Каира.

Такой стиль был перенят европейскими зодчими, строивших соборы в Англии, Франции, Италии. Прекрасные мечети были построены в Иерусалиме, Мекке, Триполи, Каире, Дамаске, Константинополе. Кубические арабские переходные опоры под куполами были применены в строительстве соборов и дворцов в Палермо в XI и XII веках. Очень много архитектурных сооружений арабского заимствования находится в России. Они пришли туда с завоеваниями Тамерлана. Старинная красота поражает своей элегантностью.

Навигация и география

Хананеи разработали первые в мире навигационные карты, возможно, это они сделали одновременно с египтянами, открывшими Атлантический океан.

В IX веке средневековые арабы изобрели магнитную стрелку компаса. Самым известным географом арабского Средневековья был аль-Идриси. Этот учёный XII века жил на Сицилии. Он составил атлас мира, состоящий из семидесяти карт. Но не все территории были нанесены на них. В своё время атлас Идриси, Китабал-Руджари, был самым лучшим спутником путешественников.

Его использовал в своих путешествиях Ибн Баттута, который проехал на лошадях, верблюдах и парусных кораблях более 75 тысяч миль. Он изучал Турцию, Болгарию, Россию, Персию, среднеазиатские страны. Ибн Баттута провёл несколько лет в Индии, а затем был послом в Китае.

Известный арабский путешественник написал о своих поездках книгу «Рихла». В ней он описал социальные условия, экономику, политику стран, которые посетил. Другой араб, Хасан аль-Ваззан, ставший христианином, получившим имя Лев Африканский, написал книгу о своих путешествиях по Африке.

Его труд перевели на несколько языков. Два столетия работы Льва Африканского считались самыми авторитетными исследованиями Африки.

Садоводство

Арабы очень любили землю. Они считали её источником жизни и даром Аллаха. Основателем ботаники считается живший в XII веке Ибн аль-Аввам. Он написал справочник, в который вошли более 500 различных растений. Учёным был описан метод прививки, кондиционирования почвы, лечения больных растений. Арабы внесли большой вклад в производство пищевых продуктов.

Им удалось прививать лозу, что стало основой в дальнейшем виноградарства в Европе. Арабы перевезли хлопок на европейский рынок из Египта. Кофе тоже пришёл в Европу из арабского мира. Арабы подарили миру разнообразные цветы и травы, из которых делались духи. Многие продукты питания, например, такие как рис, цитрусовые и другие, попали на европейскую кухню от арабов через восточные торговые караваны. Косметика, которую стали использовать европейки, тоже пришла к ним из арабского мира.

Разные науки

Большой вклад арабы внесли в инженерное дело, например, это были водяное колесо, цистерны, ирригация, водяные колодцы на фиксированных уровнях, водяные часы. Аль-Хайсам (Альхазен) описал оптические иллюзии, такие как радуга и миражи, что дало толчок к появлению фотографических инструментов. Велик вклад арабских учёных и в другие науки: физику, анатомию, химию.

Ремёсла

Малые художественные произведения были подняты арабами на высокий уровень. Их стеклянная посуда, керамика, текстиль прославились на весь мир. Стены зданий арабские мастера покрывали сложной мозаикой, плиткой, резьбой. В Европе очень любили сирийские мензурки и изделия из горного хрусталя. В Валенсии использовали мавританские обжиговые печи.

Арабским стеклодувам удалось получить синий цвет стекла, который в Европе стали называть мусульманским блюзом. Получив шёлк из Китая, арабские мастерицы научились делать прекрасные ткани. Кроме шёлка, ткачихи изготавливали хлопковый муслин, дамасский лён, шерсть Шираз. Всё это пользовалось большим спросом в Европе. Дубильщики из Марокко научились выделывать шкуры до мягкости шёлка. Марокканская кожа отличается высоким качеством. Прославилось на весь мир и калёное дамасское холодное оружие.

Каллиграфия

Арабская каллиграфия – настоящий вид искусства. Ею украшены все мечети. Очень красив и арабский язык. На нём написано большое количество поэтических и драматических произведений. Арабы очень много переводили на свой язык трудов учёных и философов древнего мира, таких как Аристотель, Платон, Гиппократ и других. «Тысяча и одна ночь» и «Рубайят» Омара Хайяма – самые любимые произведения арабской литературы. Арабами была разработана система историографии.

Музыка

Большое количество музыкальных инструментов пришло к нам из арабского мира, это арфа, лира, цитра, барабаны, флейта, гобой, тамбурин. Некоторые из них стали прародителями известных ныне инструментов, таких как гитара и мандолина. Волынка тоже была завезена в Европу из Палестины. Её привезли британские военные. Арабские лады звучат в музыкальных произведениях.

Философия

Прославились на весь мир и арабские философы, открывшие заново для мира труды Аристотеля и Платона. Они пытались найти ответы на вопросы сотворения Вселенной. Самыми известными из них стали Авиценна и Ибн Хальдун. Их мысли были сформированы многими древними цивилизациями – Древней Греции, Древнего Рима, Древнего Китая, Индии, Византии, Египта и других. Из арабской культуры родились три самые распространённые религии – Ислам, Христианство, Иудаизм.

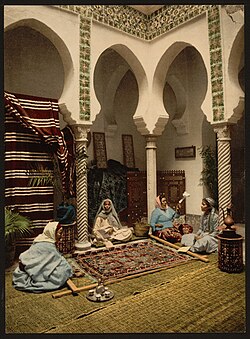

Making Arab carpets in Algiers, 1899

Arab culture is the culture of the Arabs, from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the Arabian Sea in the east, and from the Mediterranean Sea in the north to the Horn of Africa and the Indian Ocean in the southeast. The various religions the Arabs have adopted throughout their history and the various empires and kingdoms that have ruled and took lead of the Arabian civilization have contributed to the ethnogenesis and formation of modern Arab culture. Language, literature, gastronomy, art, architecture, music, spirituality, philosophy and mysticism are all part of the cultural heritage of the Arabs.[1]

The Arab world is sometimes divided into separate regions depending on different cultures, dialects and traditions including:

• The Levant: Lebanon, Syria, Palestine and Jordan.

• Egypt

• Mesopotamia (Iraq).

• The Arabian Peninsula: Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Oman, Yemen and the United Arab Emirates.

• Sudan

• The Maghreb: Libya, Tunisia, Algeria, Morocco and Mauritania.

Literature[edit]

Arabic literature is the writing produced, both prose and poetry, by speakers of the Arabic language. The Arabic word used for literature is adab which is derived from a word meaning «to invite someone for a meal» and implies politeness, culture and enrichment. Arabic literature emerged in the 6th century, with only fragments of the written language appearing before then. The Qur’an, from the 7th century, had the greatest and longest-lasting effect on Arabic culture and literature. Al-Khansa, a female contemporary of Muhammad, was an acclaimed Arab poet.

Mu’allaqat[edit]

The Mu’allaqat (Arabic: المعلقات, [al-muʕallaqaːt]) is the name given to a series of seven Arabic poems or qasida that originated before the time of Islam. Each poem in the set has a different author, and is considered to be their best work. Mu’allaqat means «The Suspended Odes» or «The Hanging Poems,» and comes from the poems being hung on the wall in the Kaaba at Mecca.

The seven authors, who span a period of around 100 years, are Imru’ al-Qais, Tarafa, Zuhayr, Labīd, ‘Antara Ibn Shaddad, ‘Amr ibn Kulthum, and Harith ibn Hilliza. All of the Mu’allaqats contain stories from the authors’ lives and tribe politics. This is because poetry was used in pre-Islamic time to advertise the strength of a tribe’s king, wealth and people.

The One Thousand and One Nights (Arabic: أَلْف لَيْلَة وَلَيْلَة ʾAlf layla wa-layla[2]), is a medieval folk tale collection which tells the story of Scheherazade, a Sassanid queen who must relate a series of stories to her malevolent husband, King Shahryar (Šahryār), to delay her execution. The stories are told over a period of one thousand and one nights, and every night she ends the story with a suspenseful situation, forcing the King to keep her alive for another day. The individual stories were created over several centuries, by many people from a number of different lands.

During the reign of the Abbasid Caliph Harun al-Rashid in the 8th century, Baghdad had become an important cosmopolitan city. Merchants from Persia, China, India, Africa, and Europe were all found in Baghdad. During this time, many of the stories that were originally folk stories are thought to have been collected orally over many years and later compiled into a single book. The compiler and ninth-century translator into Arabic is reputedly the storyteller Abu Abd-Allah Muhammad el-Gahshigar. The frame story of Shahrzad seems to have been added in the 14th century.

Music[edit]

Arabic music is the music of Arab people, especially those centered around the Arabian Peninsula. The world of Arab music has long been dominated by Cairo, a cultural center, though musical innovation and regional styles abound from Tunisia to Saudi Arabia. Beirut has, in recent years, also become a major center of Arabic music. Classical Arab music is extremely popular across the population, especially a small number of superstars known throughout the Arab world. Regional styles of popular music include Iraqi el Maqaam, Algerian raï, Kuwaiti sawt and Egyptian el gil.

«The common style that developed is usually called ‘Islamic’ or ‘Arab’, though in fact it transcends religious, ethnic, geographical, and linguistic boundaries» and it is suggested that it be called the Near East (from Morocco to India) style (van der Merwe, Peter 1989, p. 9).

Habib Hassan Touma (1996, p.xix-xx) lists «five components» which «characterize the music of the Arabs:

- The Arab tone system (a musical tuning system) with specific interval structures, invented by al-Farabi in the 10th century (p. 170).

- Rhythmic-temporal structures that produce a rich variety of rhythmic patterns, awzan, used to accompany the metered vocal and instrumental genres and give them form.

- Musical instruments that are found throughout the Arabian world and that represent a standardized tone system, are played with standardized performance techniques, and exhibit similar details in construction and design.

- Specific social contexts for the making of music, whereby musical genres can be classified as urban (music of the city inhabitants), rural (music of the country inhabitants), or Bedouin (music of the desert inhabitants).

- A musical mentality that is responsible for the aesthetic homogeneity of the tonal-spatial and rhythmic-temporal structures in Arabian music, whether composed or improvised, instrumental or vocal, secular or sacred. The Arab’s musical mentality is defined by:

- The maqām phenomenon.

- The predominance of vocal music.

- The predilection for small instrumental ensembles.

- The mosaiclike stringing together of musical form elements, that is, the arrangement in a sequence of small and smallest melodic elements, and their repetition, combination, and permutation within the framework of the tonal-spatial model.

- The absence of polyphony, polyrhythm, and motivic development. Arabian music is, however, very familiar with the ostinato, as well as with a more instinctive heterophonic way of making music.

- The alternation between a free rhythmic-temporal and fixed tonal-spatial organization on the one hand and a fixed rhythmic-temporal and free tonal-spatial structure on the other. This alternation… results in exciting contrasts.»

Much Arab music is characterized by an emphasis on melody and rhythm rather than harmony. Thus much Arabic music is homophonic in nature. Some genres of Arab music are polyphonic—as the instrument Kanoun is based upon the idea of playing two-note chords—but quintessentially, Arabic music is melodic.

It would be incorrect though to call it modal, for the Arabic system is more complex than that of the Greek modes. The basis of the Arabic music is the maqam (pl. maqamat), which looks like the mode, but is not quite the same. The maqam has a «tonal» note on which the piece must end (unless modulation occurs).

The riq is widely used in Arabic music

The maqam consists of at least two jins, or scale segments. «Jins» in Arabic comes from the ancient Greek word «genus,» meaning type. In practice, a jins (pl. ajnas) is either a trichord, a tetrachord, or a pentachord. The trichord is three notes, the tetrachord four, and the pentachord five. The maqam usually covers only one octave (two jins), but sometimes it covers more than one octave. Like the melodic minor scale and Indian ragas, some maqamat have different ajnas, and thus notes, while descending or ascending. Because of the continuous innovation of jins and because most music scholars don’t agree on the existing number anyway, it’s hard to give an accurate number of the jins. Nonetheless, in practice most musicians would agree on the 8 most frequently used ajnas: Rast, Bayat, Sikah, Hijaz, Saba, Kurd, Nahawand, and Ajam — and a few of the most commonly used variants of those: Nakriz, Athar Kurd, Sikah Beladi, Saba Zamzama. Mukhalif is a rare jins used exclusively in Iraq, and it does not occur in combination with other ajnas.

The main difference between the western chromatic scale and the Arabic scales is the existence of many in-between notes, which are sometimes referred to as quarter tones for the sake of practicality. However, while in some treatments of theory the quarter tone scale or all twenty four tones should exist, according to Yūsuf Shawqī (1969) in practice there are many fewer tones (Touma 1996, p. 170).

In fact, the situation is much more complicated than that. In 1932, at International Convention on Arabic music held in Cairo, Egypt (attended by such Western luminaries as Béla Bartók and Henry George Farmer), experiments were done which determined conclusively that the notes in actual use differ substantially from an even-tempered 24-tone scale, and furthermore that the intonation of many of those notes differ slightly from region to region (Egypt, Turkey, Syria, Iraq). The commission’s recommendation is as follows: «The tempered scale and the natural scale should be rejected. In Egypt, the Egyptian scale is to be kept with the values, which were measured with all possible precision. The Turkish, Syrian, and Iraqi scales should remain what they are…» (translated in Maalouf 2002, p. 220). Both in modern practice, and based on the evidence from recorded music over the course of the last century, there are several differently tuned «E»s in between the E-flat and E-natural of the Western Chromatic scale, depending on the maqam or jins in use, and depending on the region.

Musicians and teachers refer to these in-between notes as «quarter-tones» («half-flat» or «half-sharp») for ease of nomenclature, but perform and teach the exact values of intonation in each jins or maqam by ear. It should also be added, in reference to Touma’s comment above, that these «quarter-tones» are not used everywhere in the maqamat: in practice, Arabic music does not modulate to 12 different tonic areas like the Well-Tempered Klavier, and so the most commonly used «quarter tones» are on E (between E-flat and E-natural), A, B, D, F (between F-natural and F-sharp) and C.

The prototypical Arab ensemble in Egypt and Syria is known as the takht, which includes, (or included at different time periods) instruments such as the ‘oud, qanún, rabab, nay, violin (which was introduced in the 1840s or 50s), riq and dumbek. In Iraq, the traditional ensemble, known as the chalghi, includes only two melodic instruments—the jowza (similar to the rabab but with four strings) and santur—with riq and dumbek.

Dance[edit]

Arab folk dances also referred to as Oriental dance, Middle-Eastern dance and Eastern dance, refers to the traditional folk dances of the Arabs in Arab world (Middle East and North Africa).[3][4] The term «Arabic dance» is often associated with the belly dance. However, there are many styles of traditional Arab dance,[5] and many of them have a long history.[6] These may be folk dances, or dances that were once performed as rituals or as entertainment spectacle, and some may have been performed in the imperial court.[7] Coalescence of oral storytelling, poetry recital, and performative music and dance as long-standing traditions in Arab history.[8] Among the best-known of the Arab traditional dances are the belly dance and the Dabke.[9]

Belly dance also referred to as Arabic dance (Arabic: رقص شرقي, romanized: Raqs sharqi is an Arab expressive dance,[10][11][12][13] which emphasizes complex movements of the torso.[14] Many boys and girls in countries where belly dancing is popular will learn how to do it when they are young. The dance involves movement of many different parts of the body; usually in a circular way.

Media[edit]

Prior to the Islamic Era, poetry was regarded as the main means of communication on the Arabian Peninsula.[citation needed] It related the achievements of tribes and defeats of enemies and also served as a tool for propaganda. After the arrival of Islam, Imams (preachers) played a role in disseminating information and relating news from the authorities to the people. The suq or marketplace gossip and interpersonal relationships played an important role in the spreading of news, and this form of communication among Arabs continues today. Before the introduction of the printing press Muslims obtained most of their news from the imams at the mosque, friends or in the marketplace. Colonial powers and Christian Missionaries in Lebanon were responsible for the introduction of the printing press. It was not until the 19th century that the first newspapers began to appear, mainly in Egypt and Lebanon, which had the most newspapers per capita.

During French rule in Egypt in the time of Napoleon Bonaparte the first newspaper was published, in French. There is debate over when the first Arabic language newspaper was published; according to Arab scholar Abu Bakr, it was Al Tanbeeh (1800), published in Egypt, or it was Junral Al Iraq (1816), published in Iraq, according to other researchers. In the mid-19th century the Turkish Empire dominated the first newspapers.

The first newspapers were limited to official content and included accounts of relations with other countries and civil trials. In the following decades Arab media blossomed due to journalists mainly from Syria and Lebanon, who were intellectuals and published their newspapers without the intention of making a profit. Because of the restrictions by most governments, these intellectuals were forced to flee their respective countries but had gained a following and because of their popularity in this field of work other intellectuals began to take interest in the field.

The first émigré Arab newspaper, Mar’at al Ahwal, was published in Turkey in 1855 by Rizqallah Hassoun Al Halabi. It was criticized by the Ottoman Empire and shut down after only one year. Intellectuals in the Arab world soon realized the power of the press. Some countries’ newspapers were government-run and had political agendas in mind. Independent newspapers began to spring up which expressed opinions and were a place for the public to out their views on the state. Illiteracy rates in the Arab world played a role in the formation of media, and due to the low reader rates newspapers were forced to get political parties to subsidize their publications, giving them input to editorial policy.

Freedoms that have branched through the introduction of the Internet in Middle East are creating a stir politically, culturally, and socially. There is an increasing divide between the generations. The Arab world is in conflict internally. The internet has brought economic prosperity and development, but bloggers have been incarcerated all around in the Middle East for their opinions and views on their regimes, the same consequence which was once given to those who publicly expressed themselves without anonymity. But the power of the internet has provided also a public shield for these bloggers since they have the ability to engage public sympathy on such a large scale. This is creating a dilemma that shakes the foundation of Arab culture, government, religious interpretation, economic prosperity, and personal integrity.

Each country or region in the Arab world has varying colloquial languages which are used for everyday speech, yet its presence in the media world is discouraged. Prior to the establishment of Modern Standard Arabic (MSA), during the 19th century, the language of the media was stylized and resembled literary language of the time, proving to be ineffective in relaying information. Currently MSA is used by Arab media, including newspapers, books and some television stations, in addition to all formal writing. Vernaculars are however present in certain forms of media including satires, dramas, music videos and other local programs.

Media values[edit]

Journalism ethics is a system of values that determines what constitutes «good» and «bad» journalism.[15] A system of media values consists of and is constructed by journalists’ and other actors’ decisions about issues like what is «newsworthy,» how to frame the news, and whether to observe topical «red lines.»[16] Such a system of values varies over space and time, and is embedded within the existing social, political, and economic structures in a society. William Rugh states, «There is an intimate, organic relationship between media institutions and society in the way that those institutions are organized and controlled. Neither the institution nor the society in which it functions can be understood properly without reference to the other. This is certainly true in the Arab world.»[17] Media values in the Arab world therefore vary between and within countries. In the words of Lawrence Pintak and Jeremy Ginges (2008), “The Arab media are not a monolith.”[18]

Journalists in the Arab world hold many of the same values with their news generation as do journalists in the Western world. Journalists in the Arab world often aspire to Western norms of objectivity, impartiality, and balance. Kuldip Roy Rampal’s study of journalist training programs in North Africa leads him to the conclusion that, «the most compelling dilemma faced by professional journalists, increasingly graduates of journalism degree programs, in the four Maghreb states is how to reconcile their preference for press freedom and objectivity with constraints imposed by political and legal factors that point to a pro-government journalism.»[19] Iyotika Ramaprasad and Naila Nabil Hamdy state, “A new trend toward objectivity and impartiality as a value in Arab journalism seems to be emerging, and the values of Arab and Western journalism in this field have started to converge.”[20] Further, many journalists in the Arab world express their desires for the media to become a fourth estate akin to the media in the West. In a survey of 601 journalists in the Arab world, 40% of them viewed investigation of the government as part of their job.[18]

Important differences between journalists in the Arab world and their Western counterparts are also apparent. Some journalists in the Arab world see no conflict between objectivity and support for political causes.[21] Ramprasad and Hamdy’s sample of 112 Egyptian journalists gave the highest importance to supporting Arabism and Arab values, which included injunctions such as “defend Islamic societies, traditions and values” and “support the cause of the Palestinians.” Sustaining democracy through “examining government policies and decisions critically,” ranked a close second.[20]

Other journalists reject the notion of media ethics altogether because they see it as a mechanism of control. Kai Hafez states, “Many governments in the Arab world have tried to hijack the issue of media ethics and have used it as yet another controlling device, with the result that many Arab journalists, while they love to speak about the challenges of their profession, hate performing under the label of media ethics.”[15]

Historically, news in the Arab world was used to inform, guide, and publicize the actions of political practitioners rather than being just a consumer product. The power of news as political tool was discovered in the early 19th century, with the purchase of shares from Le Temps a French newspaper by Ismail the grandson of Muhammad Ali. Doing so allowed Ismail to publicize his policies.[22] Arab Media coming to modernity flourished and with it its responsibilities to the political figures that have governed its role. Ami Ayalon argues in his history of the press in the Arab Middle East that, “Private journalism began as an enterprise with very modest objectives, seeking not to defy authority but rather to serve it, to collaborate and coexist cordially with it. The demand for freedom of expression, as well as for individual political freedom, a true challenge to the existing order, came only later, and hesitantly at that, and was met by a public response that can best be described as faint.»[22]

Media researchers stress that the moral and social responsibility of newspeople dictates that they should not agitate public opinion, but rather should keep the status quo. It is also important to preserve national unity by not stirring up ethnic or religious conflict.[23]

The values of media in the Arab world have started to change with the emergence of “new media.» Examples of new media include news websites, blogs, and satellite television stations like Al Arabiya. The founding of the Qatari Al Jazeera network in 1996 especially affected media values. Some scholars believe that the network has blurred the line between private- and state- run news. Mohamed Zayani and Sofiane Sabraoui state, “Al Jazeera is owned by the government, but has an independent editorial policy; it is publicly funded, but independent minded.”[24] The Al Jazeera media network espouses a clear mission and strategy, and was one of the first news organizations in the Arab world to release a code of ethics.[25] Despite its government ties, it seeks to “give no priority to commercial or political over professional consideration” and to “cooperate with Arab and international journalistic unions and associations to defend freedom of the press.” With a motto of “the view and the other view,” it purports to “present the diverse points of view and opinions without bias and partiality.” It has sought to fuse these ostensibly Western media norms with a wider “Arab orientation,” evocative of the social responsibility discussed by scholars such as Noha Mellor above.

Some more recent assessments of Al Jazeera have criticized it for a lack of credibility in the wake of the Arab Spring. Criticism has come from within the Arab Middle East, including from state governments.[26] Independent commentators have criticized its neutrality vis-a-vis the Syrian Civil War.[citation needed]

Media values are not the only variable that affects news output in Arab society. Hafez states, “The interaction of political, economic, and social environments with individual and collective professional ethics is the driving force behind journalism.”[15] In most Arab countries, newspapers cannot be published without a government-issued license. Most Arab countries also have press laws, which impose boundaries on what can and cannot be said in print.

Censorship plays a significant role in journalism in the Arab world. Censorship comes in a variety of forms: Self-censorship, Government Censorship (governments struggle to control through technological advances in ex. the internet), Ideology/Religious Censorship, and Tribal/Family/Alliances Censorship. Because Journalism in the Arab world comes with a range of dangers – journalists throughout the Arab world can be imprisoned, tortured, and even killed in their line of work – self-censorship is extremely important for many Arab journalists. A study conducted by the Center for Defending Freedom of Journalists (CDFJ) in Jordan, for example, found that the majority of Jordanian journalists exercise self-censorship.[27] CPJ found that 34 journalists were killed in the region in 2012, 72 were imprisoned on December 1, 2012, and 126 were in exile from 2007 to 2012.[28]

A related point is that media owners and patrons have effects on the values of their outlets. Newspapers in the Arab world can be divided into three categories: government owned, partisan owned, and independently owned. Newspaper, radio, and television patronization in the Arab world has heretofore been primarily a function of governments.[29] «Now, newspaper ownership has been consolidated in the hands of powerful chains and groups. Yet, profit is not the driving force behind the launching of newspapers; publishers may establish a newspaper to ensure a platform for their political opinions, although it is claimed that this doesn’t necessarily influence the news content».[30] In the Arab world, as far as content is concerned, news is politics. Arab states are intimately involved in the economic well-being of many Arab news organizations so they apply pressure in several ways, most notably through ownership or advertising.[31]

Some analysts hold that cultural and societal pressures determine journalists’ news output in the Arab world. For example, to the extent that family reputation and personal reputation are fundamental principles in Arabian civilization, exposes of corruption, examples of weak moral fiber in governors and policy makers, and investigative journalism may have massive consequences. In fact, some journalists and media trainers in the Arab world nevertheless actively promote the centrality of investigative journalism to the media’s larger watchdog function. In Jordan, for example, where the degree of government and security service interference in the media is high, non-governmental organizations such as the Center for Defending the Freedom of Journalists (CDFJ) and Arab Reporters for Investigative Journalism (ARIJ) train journalists to undertake investigative journalism projects.[32]

The Jordanian Center for Defending Freedom of Journalists (CDFJ) posted this sign in protest of the country’s 2012 Press and Publications law. It reads, «The right to obtain information is a right for all people».

Some Saudi journalists stress the importance of enhancing Islam through the media. The developmental role of media was acknowledged by an overwhelming majority of Saudi journalists, while giving the readers what they want was not regarded as a priority.[33] However, journalism codes, as an important source for the study of media values, complicate this notion. Kai Hafez states, “The possible hypothesis that Islamic countries might not be interested in ‘truth’ and would rather propagate ‘Islam’ as the single truth cannot be verified completely because even a code that limits journalists’ freedom of expression to Islamic objectives and values, the Saudi Arabian code, demands that journalists present real facts.”[15] In addition, Saudi journalists operate in an environment in which anti-religious talk is likely to be met with censorship.

Patterns of consumption also affect media values. People in the Arab world rely on newspapers, magazines, radio, television, and the Internet to differing degrees and to meet a variety of ends. For Rugh, the proportion of radio and television receivers to Arab populations relative to UNESCO minimum standards suggests that radio and television are the most widely consumed media. He estimates that television reaches well over 100 million people in the region, and this number has likely grown since 2004. By contrast, he supposes that Arab newspapers are designed more for elite-consumption on the basis of their low circulation. He states, «Only five Arab countries have daily newspapers which distribute over 60,000 copies and some have dailies only in the under-10,000 range. Only Egypt has dailies which distribute more than a half million copies.»[34] Estimating newspaper readership is complicated, however, by the fact that single newspapers can change hands many times in a day. Finally, the internet continues to be a fairly common denominator in Arab societies. A report by the Dubai School of Government and Bayt.com estimates that there are more than 125 million Internet users in the region, and that more than 53 million of them actively use social media. They caution, however, that while «the internet has wide-ranging benefits, these benefits do not reach large segments of societies in the Arab region. The digital divide remains a significant barrier for many people. In many parts of the Arab world levels of educational attainment, economic activity, standards of living and internet costs still determine a person’s access to life-changing technology.[35] Further, according to Leo Gher and Hussein Amin, the Internet and other modern telecommunication services may serve to counter the effects of private and public ownership and patronage of the press. They state, «Modern international telecommunications services now assist in the free flow of information, and neither inter-Arab conflicts nor differences among groups will affect the direct exchange of services provided by global cyberspace networks.»[36]

Magazines[edit]

In most Arabian countries, magazines cannot be published without a government-issued license. Magazines in the Arabian world, like many of the magazines in the Western world, are geared towards women. However, the number of magazines in the Arab world is significantly smaller than that of the Western world. The Arab world is not as advertisement driven as the Western world. Advertisers fuel the funding for most Western magazines to exist. Thus, a lesser emphasis on advertisement in the Arabian world plays into the low number of magazines.

Radio[edit]

There are 40 private radio stations throughout the Middle East (list of private radio stations in the Arab world)

Arab radio broadcasting began in the 1920s, but only a few Arab countries had their own broadcasting stations before World War II. After 1945, most Arab states began to create their own radio broadcasting systems, although it was not until 1970, when Oman opened its radio transmissions, that every one of them had its own radio station.

Among Arab countries, Egypt has been a leader in radio broadcasting from the beginning. Broadcasting began in Egypt in the 1920s with private commercial radio. In 1947, however, the Egyptian government declared radio a government monopoly and began investing in its expansion.

By the 1970s, Egyptian radio had fourteen different broadcast services with a total air time of 1,200 hours per week. Egypt is ranked third in the world among radio broadcasters. The programs were all government controlled, and much of the motivation for the government’s investment in radio was due to the aspirations of President Gamal Abdel Nasser to be the recognized leader of the Arab world.

Egypt’s «Voice of the Arabs» station, which targeted other Arab countries with a constant stream of news and political features and commentaries, became the most widely heard station in the region. Only after the June 1967 war, when it was revealed that this station had misinformed the public about what was happening, did it lose some credibility; nevertheless it retained a large listenership.

On the Arabian Peninsula, radio was slower to develop. In Saudi Arabia, radio broadcasts started in the Jidda-Mecca area in 1948, but they did not start in the central or eastern provinces until the 1960s. Neighboring Bahrain had radio by 1955, but Qatar, Abu Dhabi, and Oman did not start indigenous radio broadcasting until nearly a quarter century later.

Television[edit]

Almost all television channels in the Arab world were government-owned and strictly controlled prior to the 1990s. In the 1990s the spread of satellite television began changing television in Arab countries. Often noted as a pioneer, Al Jazeera represents a shift towards a more professional approach to news and current affairs.[37] Financed by the Qatar government and established in 1996, Al Jazeera was the first Arabic channel to deliver extensive live news coverage, going so far as to send reporters to «unthinkable» places like Israel. Breaking the mold in more ways than one, Al Jazeera’s discussion programs raised subjects that had long been prohibited. However, in 2008, Egypt and Saudi Arabia called for a meeting to approve a charter to regulate satellite broadcasting. The Arab League Satellite Broadcasting Charter (2008) lays out principles for regulating satellite broadcasting in the Arab world.[38][39]

Other satellite channels:

- Al Arabiya: established in 2003; based in Dubai; offshoot of MBC

- Alhurra («The Free One»): established in 2004 by the United States; counter-perceives biases in Arab news media

- Al Manar: owned by Hezbollah; Lebanese-based; highly controversial

«Across the Middle East, new television stations, radio stations and websites are sprouting like incongruous electronic mushrooms in what was once a media desert. Meanwhile, newspapers are aggressively probing the red lines that have long contained them».[40] Technology is playing a significant role in the changing Arab media. Pintak furthers, «Now, there are 263 free-to-air (FTA) satellite television stations in the region, according to Arab Advisors Group. That’s double the figure as of just two years ago».[40] Freedom of speech and money have little to do with why satellite television is sprouting up everywhere. Instead, «A desire for political influence is probably the biggest factor driving channel growth. But ego is a close second».[40] The influence of the West is very apparent in Arab media, especially in television. Arab soap operas and the emerging popularity of reality TV are evidence of this notion.

«In the wake of controversy triggered by Super Star and Star Academy, some observers have hailed reality television as a harbinger of democracy in the Arab world.»[41] Star Academy in Lebanon is strikingly similar to American Idol mixed with The Real World. Star Academy began in 2003 in the Arab world. «Reality television entered Arab public discourse in the last five years at a time of significant turmoil in the region: escalating violence in Iraq, contested elections in Egypt, the struggle for women’s political rights in Kuwait, political assassinations in Lebanon, and the protracted Arab–Israeli conflict. This geo-political crisis environment that currently frames Arab politics and Arab–Western relations is the backdrop to the controversy surrounding the social and political impact of Arab reality television, which assumes religious, cultural or moral manifestations.»[42]

Cinema[edit]

Most Arab countries did not produce films before independence. In Sudan, Libya, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates, production is even now confined to short films or television. Bahrain witnessed the production of its first and only full-length feature film in 1989. In Jordan, national production has barely exceeded half a dozen feature films. Iraq has produced approximately 100 films and Syria some 150. Lebanon, owing to an increased production during the 1950s and 1960s, has made some 180 feature films. Only Egypt has far exceeded these countries, with a production of more than 2,500 feature films (all meant for cinema, not television).[43] As with most aspects of Arab media, censorship plays a large art of creating and distributing films. «In most Arab countries, film projects must first pass a state committee, which grants or denies permission to shoot. Once this permission is obtained, another official license, a so-called visa, is necessary in order to exploit the film commercially. This is normally approved by a committee of the Ministry of Information or a special censorship authority».[43] The most significant taboo topics under state supervision are consistent with those of other forms of media: religion, sex, and politics.

Internet[edit]

The Internet in the Arab world is powerful source of expression and information as it is in other places in the world. While some believe that it is the harbinger of freedom in media to the Middle East, others think that it is a new medium for censorship. Both are true. The Internet has created a new arena for discussion and the dissemination of information for the Arab world just as it has in the rest of the world. The youth in particular are accessing and utilizing the tools. People are encouraged and enabled to join in political discussion and critique in a manner that was not previously possible. Those same people are also discouraged and blocked from those debates as the differing regimes try to restrict access based on religious and state objections to certain material.

This was posted on a website operated by the Muslim Brotherhood:

The internet in the Arab world has a snowball effect; now that the snowball is rolling, it can no longer be stopped. Getting bigger and stronger, it is bound to crush down all obstacles. In addition, to the stress caused by the Arab bloggers, a new forum was opened for Arab activists; Facebook. Arab activists have been using Facebook in the utmost creative way to support the democracy movement in the region, a region that has one of the highest rates of repression in the world. Unlike other regions where oppressive countries (like China, Iran and Burma) represent the exception, oppression can be found everywhere in the Arab world. The number of Arab internet users interested in political affairs does not exceed a few thousands, mainly represented by internet activists and bloggers, out of 58 million internet users in the Arab world. As few as they are, they have succeeded in shedding some light on the corruption and repression of the Arab governments and dictatorships.[44]

Public Internet use began in the US in the 1980s. Internet access began in the early 1990s in the Arab world, with Tunisia being first in 1991 according to Dr. Deborah L. Wheeler. The years of the Internet’s introduction in the various Arab countries are reported differently. Wheeler reports that Kuwait joined in 1992, and in 1993, Turkey, Iraq and the UAE came online. In 1994 Jordan joined the Internet, and Saudi Arabia and Syria followed in the late 1990s. Financial considerations and the lack of widespread availability of services are factors in the slower growth in the Arab world, but taking into consideration the popularity of internet cafes, the numbers online are much larger than the subscription numbers would reveal.[45]

The people most commonly utilizing the Internet in the Arab world are youths. The café users in particular tend to be under 30, single and have a variety of levels of education and language proficiency. Despite reports that use of the internet was curtailed by lack of English skills, Dr. Wheeler found that people were able to search with Arabic. Searching for jobs, the unemployed frequently fill cafes in Egypt and Jordan. They are men and women equally. Most of them chat and they have email. In a survey conducted by Dr. Deborah Wheeler, she found them to almost all to have been taught to use the Internet by a friend or family member. They all felt their lives to have been significantly changed by the use of the Internet. The use of the Internet in the Arab world is very political in the nature of the posts and of the sites read and visited. The Internet has brought a medium to Arabs that allows for a freedom of expression not allowed or accepted before. For those who can get online, there are blogs to read and write and access to worldwide outlets of information once unobtainable. With this access, regimes have attempted to curtail what people are able to read, but the Internet is a medium not as easily manipulated as telling a newspaper what it can or cannot publish. The Internet can be reached via proxy server, mirror, and other means. Those who are thwarted with one method will find 12 more methods around the blocked site. As journalists suffer and are imprisoned in traditional media, the Internet is no different with bloggers regularly being imprisoned for expressing their views for the world to read. The difference is that there is a worldwide audience witnessing this crackdown and watching as laws are created and recreated to attempt to control the vastness of the Internet.[46]

Jihadists are using the Internet to reach a greater audience. Just as a simple citizen can now have a worldwide voice, so can a movement. Groups are using the Internet to share video, photos, programs and any kind of information imaginable. Standard media may not report what the Muslim Brotherhood would say on their site. However, for the interested, the Internet is a tool that is utilized with great skill by those who wish to be heard. A file uploaded to 100 sites and placed in multiple forums will reach millions instantly. Information on the Internet can be thwarted, slowed, even redirected, but it cannot be stopped if someone wants it out there on the Internet.

The efforts by the various regimes to control the information are all falling apart gradually. Those fighting crime online have devised methods of tracking and catching criminals. Unfortunately those same tools are being used to arrest bloggers and those who would just wish to be heard. The Internet is a vast and seemingly endless source of information. Arabs are using it more than perhaps the world is aware and it is changing the media.

Society[edit]

A Bedouin warrior, pictured between 1898 and 1914

Social loyalty is of great importance in Arab culture. Family is one of the most important aspects of the Arab society. While self-reliance, individuality, and responsibility are taught by Arabic parents to their children, family loyalty is the greatest lesson taught in Arab families. «Unlike the extreme individualism we see in North America (every person for him or herself, individual rights, families living on their own away from relatives, and so on), Arab society emphasizes the importance of the group. Arab culture teaches that the needs of the group are more important than the needs of one person.»[47] In the Bedouin tribes of Saudi Arabia, «intense feelings of loyalty and dependence are fostered and preserved»[48] by the family.[49] Margaret Nydell, in her book Understanding Arabs: A Guide for Modern Times, writes «family loyalty and obligations take precedence over loyalty to friends or demands of a job.»[50] She goes on to state that «members of a family are expected to support each other in disputes with outsiders. Regardless of personal antipathy among relatives, they must defend each other’s honor, counter criticism, and display group cohesion…»[50] Of all members of the family, however, the most revered member is the mother.

Family honor is one of the most important characteristics in the Arab family. According to Margaret Nydell, social exchanges between men and women happen very seldom outside of the work place.[50] Men and women refrain from being alone together. They have to be very careful in social situations because those interactions can be interpreted negatively and cause gossip, which can tarnish the reputation of women. Women are able to socialize freely with other women and male family members, but have to have family members present to socialize with men that are not part of the family.[50] These conservative practices are put into place to protect the reputation of women. Bad behavior not only affects women but her family’s honor. Practices differ between countries and families. Saudi Arabia has stricter practices when it comes to men and women and will even require marriage documents if a woman and man are seen together alone.[50]

Arab values

One of the characteristics of Arabs is generosity and they usually show it by being courteous with each other. Some of the most important values for Arabs are honor and loyalty. Margaret Nydell, in her book Understanding Arabs: A Guide for Modern Times’ [50] says that Arabs can be defined as, humanitarian, loyal and polite. Tarek Mahfouz explains in the book «Arab Culture» [51] that it is common for Arabs in dinner situations to insist on guests to eat the last piece of the meal or to fight over who will pay the bill at a restaurant for generosity.

Sports[edit]

Pan Arab Games[edit]

The Pan Arab Games are a regional multi-sport event held between nations from the Arab world. The first Games were held in 1953 in Alexandria, Egypt. Intended to be held every four years since, political turmoil as well as financial difficulties has made the event an unstable one. Women were first allowed to compete in 1985. By the 11th Pan Arab Games, the number of countries participating reached all 22 members of the Arab League, with roughly over 8,000 Arab athletes participating, it was considered the largest in the Games’ history, with the Doha Games in 2011 expected to exceed that number.

Cuisine[edit]

Originally, the Arabs of the Arabian Peninsula relied heavily on a diet of dates, wheat, barley, rice and meat, with little variety, with a heavy emphasis on yoghurt products, such as leben (لبن) (yoghurt without butterfat). Arabian cuisine today is the result of a combination of richly diverse cuisines, spanning the Arab world and incorporating Levantine, Egyptian, and others. It has also been influenced to a degree by the cuisines of India, Turkey, Berber, and others. In an average Arab household in Eastern Arabia, a visitor might expect a dinner consisting of a very large platter, shared commonly, with a vast mountain of rice, incorporating lamb or chicken, or both, as separate dishes, with various stewed vegetables, heavily spiced, sometimes with a tomato sauce. Most likely, there would be several other items on the side, less hearty. Tea would certainly accompany the meal, as it is almost constantly consumed. Coffee would be included as well.

Tea culture[edit]

Tea is a very important drink in the Arab world, it is usually served with breakfast, after lunch, and with dinner. For Arabs tea is a hospitality drink that is served to guests. It is also common for Arabs to drink tea with dates.

Dress[edit]

Men[edit]

Arab dress for men ranges from the traditional flowing robes to blue jeans, T-shirts and business suits. The robes allow for maximum circulation of air around the body to help keep it cool, and the head dress provides protection from the sun. At times, Arabs mix the traditional garb with western clothes.[52]

Thawb:

In the Arabian Peninsula men usually wear their national dress that is called «thawb» or «thobe» but can be also called «Dishdasha» in Kuwait or «Kandoura» (UAE). Thawbs differ slightly from state to state within the Gulf, but the basic ones are white. This is the traditional attire that Arabs wear in formal occasions.

Headdress:

The male headdress is known as a keffiyeh. In the Arabian Peninsula it is known as a guthra. It is usually worn with a black cord called an «agal», which keeps it on the wearer’s head.

- The Qatari guthra is heavily starched and it is known for its «cobra» shape.

- The Saudi guthra is a square shaped cotton fabric. The traditional is white but the white and red (shemagh) is also very common in Saudi Arabia.

- The Emirati guthra is usually white and can be used as a wrapped turban or traditionally with the black agal.

Headdress pattern might be an indicator of which tribe, clan, or family the wearer comes from. However, this is not always the case. While in one village, a tribe or clan might have a unique headdress, in the next town over an unrelated tribe or clan might wear the same headdress.

- Checkered headdresses relate to type and government and participation in the Hajj, or a pilgrimage to Mecca.

- Red and white checkered headdress – Generally of Jordanian origin. Wearer has made Hajj and comes from a country with a Monarch.

- Black and white checkered headdress – The pattern is historically of Palestinian origin.

- Black and grey represent Presidential rule and completion of the Hajj.

Women[edit]

Adherence to traditional dress varies across Arab societies. Saudi Arabia is more traditional, while Egypt is less so. Traditional Arab dress features the full length body cover (abaya, jilbāb, or chador) and veil (hijab). Women are only required to wear abayas in Saudi Arabia, although that restriction has been eased since 2015. The veil is not as prevalent in most countries outside the Arabian peninsula.

See also[edit]

- Culture of Eastern Arabia

- Culture of Palestine

- Culture of Syria

- Culture of Iraq

- Culture of Somalia

- Culture of Egypt

- Culture of Lebanon

- Arabian mythology

- Arabic miniature

References[edit]

- ^ Doris, Behrens-Abouseif (1999-01-01). Beauty in Arabic culture. Markus Wiener Publishers. ISBN 978-1558761995. OCLC 40043536.

- ^ Marzolph, Ulrich (2007). «Arabian Nights». In Kate Fleet; Gudrun Krämer; Denis Matringe; John Nawas; Everett Rowson (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (3rd ed.). doi:10.1163/1573-3912_ei3_COM_0021.

Arabian Nights, the work known in Arabic as Alf layla wa-layla

- ^ Hammond, Andrew (2007). Popular culture in the Arab world : arts, politics, and the media. Cairo, Egypt: American University in Cairo Press. ISBN 978-9774160547. OCLC 148667773.

- ^ Snodgrass, Mary Ellen (2016-08-08). The Encyclopedia of World Folk Dance. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9781442257498.

- ^ «The Traditional Arabic Dance». Our Pastimes.

- ^ Kashua, Sayed (2007-12-01). Dancing Arabs. Grove/Atlantic, Inc. ISBN 9781555846619.

- ^ Mason, Daniel Gregory (1916). The Art of Music: The dance. National Society of Music.

- ^ Khouri, Malek (2010). The Arab National Project in Youssef Chahine’s Cinema. American Univ in Cairo Press. ISBN 9789774163548.

- ^ Buonaventura, Wendy (2010). Serpent of the Nile : women and dance in the Arab world (Updated and rev. ed.). Northampton, Mass.: Interlink Books. ISBN 978-1566567916. OCLC 320803968.

- ^ Snodgrass, Mary Ellen (2016). The Encyclopedia of World Folk Dance. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9781442257498.

- ^ Reel, Justine J. (2013). Eating disorders : an encyclopedia of causes, treatment, and prevention. Santa Barbara, Calif.: Greenwood. ISBN 978-1440800580.

- ^ Buonaventura, Wendy (2010). Serpent of the Nile : women and dance in the Arab world ([Newly updated ed.] ed.). London: Saqi. ISBN 978-0863566288.

- ^ Hammond, Andrew (2007). Popular culture in the Arab world : arts, politics, and the media (1. publ. ed.). Cairo, Egypt: American University in Cairo Press. ISBN 978-9774160547.

- ^ Deagon, Andrea. «Andrea Deagon’s Raqs Sharqi».

- ^ a b c d Kai Hafez (ed.). Arab Media: Power and Weakness. New York: Continuum. pp. 147–64.

- ^ Bruce Itule; Douglas Anderson (2007). News Writing and Reporting for Today’s Media. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- ^ William Rugh (2004). Arab Mass Media: Newspapers, Radio, and Television in Arab Politics. Westport, CT: Praeger. ISBN 9780275982126.

- ^ a b Pintak, Lawrence; Jeremy Ginges (2008). «The Mission of Arab Journalism: Creating Change in a Time of Turmoil». The International Journal of Press/Politics. 13 (3): 219. doi:10.1177/1940161208317142. S2CID 145067689.

- ^ Rampal, Kuldip Roy (1996). «Professionals in Search of Professionalism: Journalists’ Dilemma in Four Maghreb States». International Communication Gazette. 58 (1): 25–43. doi:10.1177/001654929605800102. S2CID 220900576.

- ^ a b Ramaprasad, Jyotika; Naila Nabil Hamdy (2006). «Functions of Egyptian Journalists: Perceived Importance and Actual Importance». International Communication Gazette. 68 (2): 167–85. doi:10.1177/1748048506062233. S2CID 144729341.

- ^ Pintak, Lawrence; Jeremy Ginges (2009). «Inside the Arab Newsroom». Journalism Studies. 10 (2): 173. doi:10.1080/14616700802337800. S2CID 96478415.

- ^ a b Ayalon, Ami (1995). The Press in the Arab Middle East: A History. New York: Oxford UP.

- ^ Mellor, Noha. The Making of Arab News. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2005. Print.

- ^ Zayani, Mohamed; Sofiane Sahroui (2007). The Culture of Al Jazeera: Inside an Arab Media Giant. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company.

- ^ Code of Ethics Al Jazeera English. Al Jazeera Media Network, 7 November 2010. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- ^ Dunham, Jillian (14 September 2011). «Syrian TV Station Accuses Al Jazeera of Fabricating Uprising». The New York Times. Retrieved 22 March 2014.

- ^ Hazaimeh, Hani. «Majority of Jordanian Journalists Exercise Self-censorship – Survey». The Jordan Times. Archived from the original on 8 July 2014. Retrieved 22 March 2014.

- ^ «Attacks on the Press: Journalism on the Front Lines in 2012». Committee for the Protection of Journalists. 14 February 2013. Retrieved 22 March 2014.

- ^ Rugh, William (2004). Arab Mass Media: Newspapers, Radio, and Television in Arab Politics. Westport, CT: Praeger. p. 9. ISBN 9780275982126.

- ^ Pintak, Lawrence. «Arab Media: Not Quite Utopia»

- ^ Martin, Justin D. «)nvestigative Journalism in the Arab World». Nieman Reports. Retrieved 5 April 2011.

- ^ Pies, Judith (2008). «Agents of Change? Journalism Ethics in Lebanese and Jordanian Journalism Education». In Kai Hafez (ed.). Arab Media: Power and Weakness. New York: Continuum. pp. 165–81.

- ^ Tash, Abdulkader. A Profile of Professional Journalists Working in the Saudi Arabian Daily Press. Diss. Southern Illinois University, 1983. Print.

- ^ Rugh, William (2004). Arab Mass Media: Newspapers, Radio, and Television in Arab Politics. Westport, CT: Praeger. pp. 4–5. ISBN 9780275982126.

- ^ «The Arab World Online: Trends in Internet Usage in the Arab Region» (PDF). The Dubai School of Government with Bayt.com. Retrieved 9 April 2014.

- ^ Gher, Leo A.; Hussein Y. Amin (1999). «New and Old Media Access and Ownership in the Arab World». International Communication Gazette. 1. 61: 59–88. doi:10.1177/0016549299061001004. S2CID 144676746.

- ^ «Arab media: television». Al-bab.com. Archived from the original on 2011-05-05. Retrieved 2011-04-05.

- ^ Arab Media & Society (March, 2008):Arab Satellite Broadcasting Charter (Unofficial Translation) Archived 2012-10-21 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 6 February 2013

- ^ Arab Media & Society (March, 2008): Arab Satellite Broadcasting Charter (in Arabic) Archived 2012-10-21 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 6 February 2013

- ^ a b c Pintak, Lawrence. «Reporting a Revolution: the Changing Arab Media Landscape.» Arab Media & Society (February, 2007)

- ^ Kraidy, Marwan. «Arab Media & Society». Arabmediasociety.com. Archived from the original on 5 April 2011. Retrieved 2011-04-05.

- ^ Kraidy, Marwan M. Reality Television and Politics in the Arab World: Preliminary Observations. Transnational Broadcasting Studies, 15 (Fall/ Winter, 2006)

- ^ a b Shafik, Viola. Arab Cinema: History and Cultural Identity.

- ^ How the Internet has snowballed in the Arab world Archived 29 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Hofheinz, Albrecht. «The Internet in the Arab World: Playground for Political Liberalization.» (n.d.): 96

- ^ Rinnawi, Khalil. «The Internet and the Arab world as a virtual public shpere.» (n.d.): 23.

- ^ J. Esherick, Women in the Arab World (Philadelphia: Mason Crest Publishers, 2006), 68

- ^ M. J. Gannon, Understanding Global Culture: Metaphorical Journeys Through 28 Nations, 3rd Edition, (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2004), 70

- ^ L. A. Samovar, et al., Communication Between Cultures, 7th Ed., (Boston: Wadsworth, Cengage Learning, 2010), 70

- ^ a b c d e f M. Nydell, Understanding Arabs: A Guide for Modern Times, 4th Ed., (Boston: Intercultural Press, 2006), 71

- ^ Mahfouz, Tarek. Arab Culture, Vol. 1: An In-depth Look at Arab Culture Through Cartoons and Popular Art (English and Arabic Edition). Ed. Thane Floreth. 2011 ed. Vol. 1. N.p.: n.p., n.d. Print.

- ^ «Arab cultural awareness: 58 factsheets» (PDF). Leawenport, KY: US Army. Intelligence Unit. January 2006.

Further reading[edit]

- Mahfouz, Tarek (2011). Floreth, Thane (ed.). Arab Culture, Vol. 1: An In-depth Look at Arab Culture Through Cartoons and Popular Art (English and Arabic ed.).

Making Arab carpets in Algiers, 1899

Arab culture is the culture of the Arabs, from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the Arabian Sea in the east, and from the Mediterranean Sea in the north to the Horn of Africa and the Indian Ocean in the southeast. The various religions the Arabs have adopted throughout their history and the various empires and kingdoms that have ruled and took lead of the Arabian civilization have contributed to the ethnogenesis and formation of modern Arab culture. Language, literature, gastronomy, art, architecture, music, spirituality, philosophy and mysticism are all part of the cultural heritage of the Arabs.[1]

The Arab world is sometimes divided into separate regions depending on different cultures, dialects and traditions including:

• The Levant: Lebanon, Syria, Palestine and Jordan.

• Egypt

• Mesopotamia (Iraq).

• The Arabian Peninsula: Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Oman, Yemen and the United Arab Emirates.

• Sudan

• The Maghreb: Libya, Tunisia, Algeria, Morocco and Mauritania.

Literature[edit]

Arabic literature is the writing produced, both prose and poetry, by speakers of the Arabic language. The Arabic word used for literature is adab which is derived from a word meaning «to invite someone for a meal» and implies politeness, culture and enrichment. Arabic literature emerged in the 6th century, with only fragments of the written language appearing before then. The Qur’an, from the 7th century, had the greatest and longest-lasting effect on Arabic culture and literature. Al-Khansa, a female contemporary of Muhammad, was an acclaimed Arab poet.

Mu’allaqat[edit]

The Mu’allaqat (Arabic: المعلقات, [al-muʕallaqaːt]) is the name given to a series of seven Arabic poems or qasida that originated before the time of Islam. Each poem in the set has a different author, and is considered to be their best work. Mu’allaqat means «The Suspended Odes» or «The Hanging Poems,» and comes from the poems being hung on the wall in the Kaaba at Mecca.

The seven authors, who span a period of around 100 years, are Imru’ al-Qais, Tarafa, Zuhayr, Labīd, ‘Antara Ibn Shaddad, ‘Amr ibn Kulthum, and Harith ibn Hilliza. All of the Mu’allaqats contain stories from the authors’ lives and tribe politics. This is because poetry was used in pre-Islamic time to advertise the strength of a tribe’s king, wealth and people.

The One Thousand and One Nights (Arabic: أَلْف لَيْلَة وَلَيْلَة ʾAlf layla wa-layla[2]), is a medieval folk tale collection which tells the story of Scheherazade, a Sassanid queen who must relate a series of stories to her malevolent husband, King Shahryar (Šahryār), to delay her execution. The stories are told over a period of one thousand and one nights, and every night she ends the story with a suspenseful situation, forcing the King to keep her alive for another day. The individual stories were created over several centuries, by many people from a number of different lands.

During the reign of the Abbasid Caliph Harun al-Rashid in the 8th century, Baghdad had become an important cosmopolitan city. Merchants from Persia, China, India, Africa, and Europe were all found in Baghdad. During this time, many of the stories that were originally folk stories are thought to have been collected orally over many years and later compiled into a single book. The compiler and ninth-century translator into Arabic is reputedly the storyteller Abu Abd-Allah Muhammad el-Gahshigar. The frame story of Shahrzad seems to have been added in the 14th century.

Music[edit]

Arabic music is the music of Arab people, especially those centered around the Arabian Peninsula. The world of Arab music has long been dominated by Cairo, a cultural center, though musical innovation and regional styles abound from Tunisia to Saudi Arabia. Beirut has, in recent years, also become a major center of Arabic music. Classical Arab music is extremely popular across the population, especially a small number of superstars known throughout the Arab world. Regional styles of popular music include Iraqi el Maqaam, Algerian raï, Kuwaiti sawt and Egyptian el gil.

«The common style that developed is usually called ‘Islamic’ or ‘Arab’, though in fact it transcends religious, ethnic, geographical, and linguistic boundaries» and it is suggested that it be called the Near East (from Morocco to India) style (van der Merwe, Peter 1989, p. 9).

Habib Hassan Touma (1996, p.xix-xx) lists «five components» which «characterize the music of the Arabs:

- The Arab tone system (a musical tuning system) with specific interval structures, invented by al-Farabi in the 10th century (p. 170).

- Rhythmic-temporal structures that produce a rich variety of rhythmic patterns, awzan, used to accompany the metered vocal and instrumental genres and give them form.

- Musical instruments that are found throughout the Arabian world and that represent a standardized tone system, are played with standardized performance techniques, and exhibit similar details in construction and design.

- Specific social contexts for the making of music, whereby musical genres can be classified as urban (music of the city inhabitants), rural (music of the country inhabitants), or Bedouin (music of the desert inhabitants).

- A musical mentality that is responsible for the aesthetic homogeneity of the tonal-spatial and rhythmic-temporal structures in Arabian music, whether composed or improvised, instrumental or vocal, secular or sacred. The Arab’s musical mentality is defined by:

- The maqām phenomenon.

- The predominance of vocal music.

- The predilection for small instrumental ensembles.

- The mosaiclike stringing together of musical form elements, that is, the arrangement in a sequence of small and smallest melodic elements, and their repetition, combination, and permutation within the framework of the tonal-spatial model.