Древний Египет является одной из первых мировых цивилизаций в истории человечества. Египтяне создали сложно устроенное стратифицированное общество, развитый государственный аппарат, систему налогов и отработочных повинностей, а также регулярную армию, осуществлявшую целенаправленную экспансию в земли соседей. Благодаря её эффективности в эпоху Нового царства границы египетских владений простирались от берега Евфрата в Сирии до территории современного Судана.

Географическое положение

По сравнению с другими цивилизациями Старого света Египет занимал особенное положение благодаря исключительным условиям своего существования: благодатному климату, плодородной почве и орошающим её водам Нила, которые обеспечивали обитателей страны всем необходимым для жизни. Со всех сторон Египет отрезан от соседей чётко очерченными естественными границами: Средиземным морем на севере, речными порогами на юге, скалистыми горами и труднопроходимыми пустынями на западе и востоке. Эти препятствия существенно затрудняли проникновение в Египет нежелательных гостей и в то же время изолировали страну от остального мира. Изоляцией объясняется внутренняя гомогенность египетского общества и своеобразие здешней культуры в сравнении с культурой соседних стран.

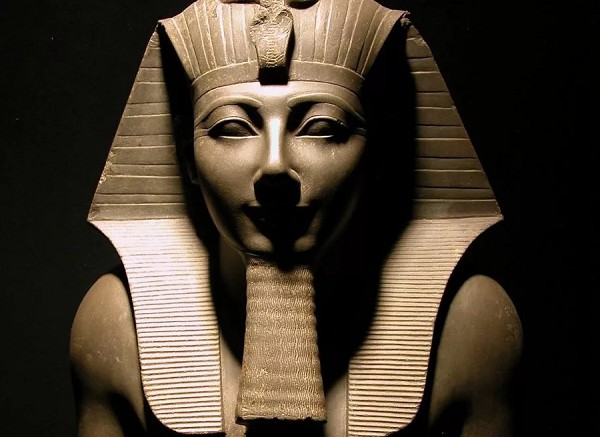

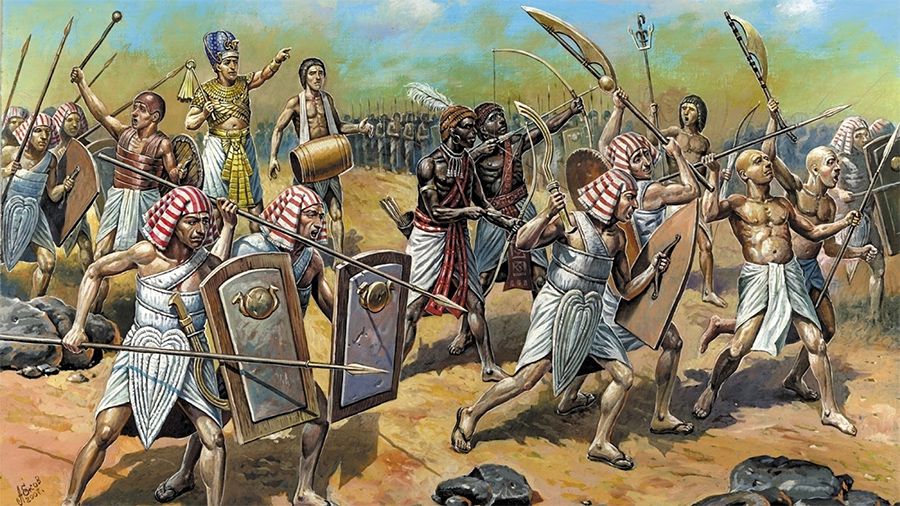

Насколько силён был контраст между старательно возделываемыми полями их собственной страны и пустынными землями за её границами, настолько же чётко мировоззрение египтян делило окружающий мир на две части. Внутри Египта находился упорядоченный мир богопочитания, порядка и справедливости, а за его пределами властвовал жестокий хаос. Себя египтяне воспринимали как единственный цивилизованный народ, а всех других, кто жил за пределами их страны, считали дикарями и варварами. Эта двойственная концепция мировосприятия наиболее наглядно выражается в излюбленном египетскими художниками мотиве царя, поражающего своих врагов. На протяжении тысячелетней истории Египта этот образ превосходства над остальным человечеством являлся стереотипным украшением артефактов, стел и стен храмов.

Объединение Египта

В географическом отношении Египет делится на две части: Верхний Египет — узкую и длинную долину, протянувшуюся приблизительно на 700 км от первых нильских порогов до вершины Дельты, и Нижний Египет, который большим треугольником, напоминающим греческую букву Δ, открывается к Средиземному морю. Первые политические образования на территории Древнего Египта возникали в пределах небольших областей (номов), которые охватывали несколько поселений, группировавшихся вокруг храмового святилища или городского центра. Каждый ном был самодостаточен в хозяйственном отношении, имел собственную систему религиозных культов и собственного независимого правителя, носившего титул номарха. В Верхнем Египте насчитывалось 22 нома, в Нижнем Египте — 20 номов. Отношения между соседними номами нередко бывали враждебными. Время от времени то одному, то другому из них удавалось получить преимущество над другими.

commons.wikimedia.org

Около 3500–3200 годов до н.э. из общей массы номов выдвинулись сильнейшие политические центры: Тинис, со временем подчинивший себе области Нижнего Египта, и Иераконполь, властвовавший над Верхним Египтом. Примерно в 3000 году до н.э. тинисский царь Нармер объединил бо́льшую часть страны под своей властью. Об этом рассказывают триумфальные сцены и пиктографические записи его знаменитой палетки, хранящейся в Каирском музее. Сами египтяне считали объединителем страны и основателем I династии царей сына Нармера Менеса. Он построил новую столицу Мемфис («Белая стена») в стратегически важном месте, на границе Верхнего и Нижнего Египта. Опираясь на ресурсы объединённой под их властью страны, потомки Менеса смогли с новыми силами приступить к завоеванию Дельты и лежащих к западу от неё ливийских областей.

Древнее царство

В эпоху Древнего царства (2707–2150 годы до н.э.) Египет находился в изоляции от внешнего мира. Поскольку внутри страны не было очевидной необходимости в постоянной армии, египетские военные силы в это время ограничивались царской вооружённой охраной и отрядами номархов, которые использовались для поддержания полицейского порядка. Ежегодно собиравшиеся по номам отряды юношей находили применение в различных трудовых повинностях, включая добычу и доставку строительного камня, разработку рудников и т.д. Время от времени фараоны отправляли военно-торговые экспедиции на Синай или в Нубию, откуда в страну поступали пленники и большое количество крупного рогатого скота, а также экзотические товары вроде слоновой кости, страусовых перьев и чёрного дерева.

memphistours.com

Автобиография царского вельможи и военачальника Уны, найденная в его гробнице из Абидоса времён правления V династии (2400–2250 годы до н.э.), содержит описание пяти возглавленных им экспедиций в Палестину. «Многие десятки тысяч солдат» в армии Уны были собраны из множества местных отрядов, мобилизованных провинциальными чиновниками в рамках трудовой повинности населения. Экспедиции могли насчитывать от нескольких сотен до 20 000 участников — цифра, которая не кажется запредельной для общества, способного осуществлять крупномасштабные строительные проекты. Бо́льшую часть этих людей составляли рабочие, носильщики и другой вспомогательный персонал, которых сопровождало сравнительно небольшое число вооружённых воинов. Один из документов Среднего царства насчитывает в составе экспедиции, отправленной на юг страны для добычи камня, 17 000 строительных рабочих и всего 1030 солдат.

pinterest.com

Среднее царство

Всё изменилось, когда в эпоху Среднего царства (2055–1650 годы до н.э.) Египет оказался втянут в международную политику. Фараоны этого времени были полны решимости держать страну в режиме изоляции, однако им приходилось уделять значительно больше внимания военным делам и границам, чем их предшественникам. Правители XII династии (1991−1783 годы до н.э.), в особенности воинственный Сенусерт III (1878–1841 годы до н.э.) и его преемник Аменемхет III (1844–1797 годы до н.э.), сумели превратить Египет в сильное государство, обладавшее мощным военным и экономическим потенциалом. Благодаря многочисленной постоянной армии, в которую теперь входили иноземные наёмники, египтяне проводили успешную завоевательную политику в Нубии. Стремясь обеспечить своё господство в золотоносных районах северной части страны, они прокладывали здесь дороги и возводили мощные укрепления, в которых держали постоянные гарнизоны.

Целую цепь из 17 крепостей возвёл Сенусерт III между 1-м порогом в районе современного Асуана и низовьями 2-го порога в стратегически важных местах, чтобы контролировать торговый маршрут вдоль Нила. Самые южные из этих крепостей располагались примерно в 50 км к югу от 2-го порога на наиболее узком участке вдоль всего течения Нила, где ширина реки не превышала 360 м. Далее к северу вниз по течению на западном берегу и прилегающих островах находились форты меньшего размера. В районе 2-го порога были воздвигнуты две огромные крепости Миргисса и Бухен, являвшиеся центрами местной администрации и служившие также складами снабжения. Хотя все эти укрепления были построены лишь из высушенного на солнце сырцового кирпича и брёвен, они представляли собой впечатляющие образцы египетской военной архитектуры, тщательно спланированные снаружи и внутри, превосходно защищённые массивными стенами, башнями и рвами.

Как и в эпоху Древнего царства, ядром армии являлся элитный корпус царской стражи. Он состоял из добровольцев и наёмников нубийцев, иногда бывших военнопленных, которые получали за свою службу продовольственные пайки и другое довольствие. Подобные отряды — правда, меньшей численности — состояли на службе правителей отдельных номов. Номинально они также подчинялись царю и должны были участвовать в военных походах. Основной состав армии набирался путём военной мобилизации молодёжи. Чтобы иметь сведения о количестве рекрутов, раз в несколько лет проводилась перепись населения. Численность жителей Египта в эпоху Древнего и Среднего царства следует оценивать в пределах от 1 до 1,5 млн человек с увеличением до 2 или даже 3 млн в эпоху Нового царства. Это обстоятельство позволяло фараонам при необходимости набирать большие армии, численность которых многократно превосходила все возможности их соседей.

egyptopedia.info

Армейское командование преимущественно состояло из вельмож и высокопоставленных чиновников, которые на определённом этапе своей карьеры занимали военные должности в силу имевшегося у них опыта. Иерархии и общей карьеры в привычном нам смысле слова не существовало. От военачальников ожидалось, что они будут выступать скорее в качестве администраторов и организаторов, способных обеспечить мобилизацию, транспортировку и последующее развёртывание больших масс солдат и рабочих. Многочисленная администрация, состоявшая из царских чиновников, распорядителей и писцов, обеспечивала снабжение армии продовольствием и всеми необходимыми ресурсами. Для строительства укреплений, заготовки продовольствия и транспортировки грузов использовались всё те же мобилизованные резервисты.

smarts-ef.org

Новое царство

Изгнание из Египта гиксосов и воссоединение всей страны под властью фараонов XVIII династии (1550–1292 годы до н.э.) способствовали укреплению египетской военной мощи и возобновлению экспансионистской политики по традиционным путям: на юг — в Нубию, на запад — в Ливию, на северо-восток — в область Палестины и Сирии. Уже в правление основателя династии Яхмоса I (1550–1525 годы до н.э.) египтяне полностью изгнали гиксосов из страны и сами перешли в наступление, захватив их оплот Шарухен. Преемники Яхмоса фараоны Аменхотеп I (1525–1504 годы до н.э.) и Тутмос I (1504–1492 годы до н.э.) совершали многочисленные походы в Нубию и Сирию и вернули Египет в границы, какими они были при Сенусерте III. Максимума своей территориальной протяжённости Египетская держава достигла в правление Тутмоса III (1479–1425 годы до н.э.), когда её границы простирались от берега Евфрата до пограничной стелы между 4-м и 5-м порогами Нила.

Новшеством Нового царства были централизованный административный аппарат и профессиональная армия, полностью организованная и контролируемая государством. Главой государства и главнокомандующим армией и флотом являлся фараон, обладавший абсолютной властью и единолично распоряжавшийся всеми ресурсами. Структура военной администрации Нового царства копировала гражданскую структуру. По главным направлениям военной политики вся страна была разделена на два военных округа. Штаб северной армии находился в Мемфисе, штаб южной — в Фивах. Позже появился третий штаб в Гелиополисе, а при Рамсесе II — и четвёртый. Начальники каждого из штабов были обязаны набирать и готовить рекрутов в своих округах и снабжать военные части и гарнизоны всем необходимым. С этой целью в штабах велись бесконечные списки. Составлявшие их многочисленные писцы подчинялись царскому писцу и главе военной службы писцов. В свою очередь, оба они подчинялись визирю.

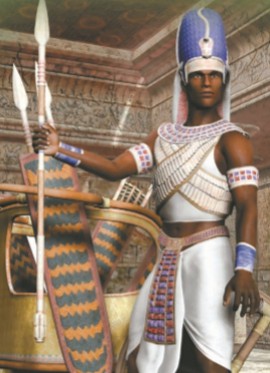

Произошли весьма существенные изменения в организации армии, которая приобрела более сложную структуру. Армейский командный состав существенно увеличился за счёт ряда офицерских должностей, таких как знаменосец, командир лучников или начальник форта. Дети знати наряду с традиционными профессиями жрецов или писцов всё чаще стали выбирать для себя военную карьеру. Для многих простолюдинов армия превратилась в социальный лифт, поскольку на командные должности нередко назначали людей, выдвинувшихся снизу, если они обладали подходящими качествами. Хорошей иллюстрацией служит биография фараона Хоремхеба (1319–1292 годы до н.э.), который начинал службу простым писцом, а затем стал военачальником. Фараоны Тутмос I (1504–1492 годы до н.э.) и Рамсес I (1295–1294 годы до н.э.) также были военачальниками прежде чем заняли трон. Таким образом, опыт военного командования и поддержка армии становились всё более значимыми факторами при выборе следующего правителя.

pinterest.es

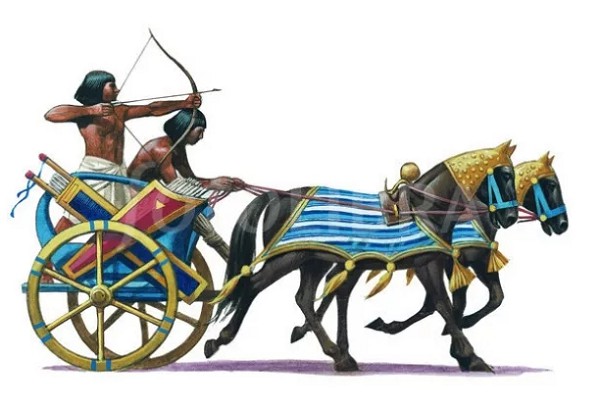

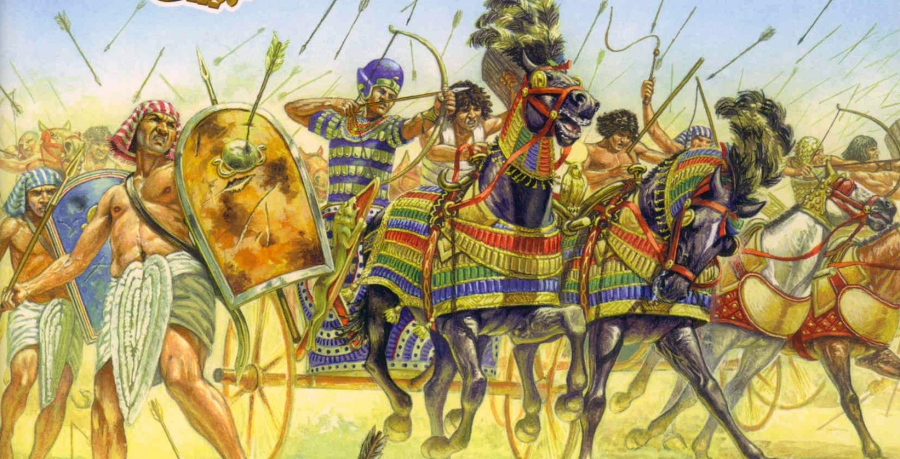

Частью общей «модернизации» египетской армии эпохи Нового царства стало появление новых разновидностей оружия. Наиболее значительным из этих нововведений было начало использования лошадей и колесниц, конструкцию которых египтяне заимствовали у гиксосов. Появление колесниц позволило армии вести совершенно новый манёвренный тип боя. Колесницы искали врага на широкой территории, нарушали его коммуникационные линии, атаковали его на марше, преследовали бегущих и т.д. Колесничие вооружались более мощным сложносоставным луком и носили тяжёлый доспех из бронзовых пластин. Умение метко стрелять с быстро движущейся платформы и сражаться в тяжёлом доспехе требовало длительного обучения, что, в свою очередь, имело важное социальное и политическое значение, поскольку привело к формированию нового профессионального класса воинов.

pinterest.com

Набор в армию и её структура

Как и в эпоху Среднего царства, основная часть египетской армии набиралась по призыву. Военная обязанность для египетских юношей начиналась в 17 лет. Существовали два класса солдат, набранных из общего числа призывников (djamu). Во-первых, это добровольцы и потомственные профессиональные солдаты (ahautyu — «воины»), служившие на протяжении многих лет и получавшие за свою службу землю от царской казны. Именно эти люди составляли ядро постоянной армии. Во-вторых, это новобранцы из числа крестьян (hewenu-nefru — «молодой новобранец»), которые должны были служить на протяжении установленного срока, по истечении которого получали возможность вернуться к обычной жизни. Как долго продолжалась их служба, не вполне ясно, однако представляется возможным, что она определялась теми же 10-месячными циклами, которые со времён Древнего царства регулировали трудовую повинность всего населения.

supersoldierproject.com

Имена юношей, достигших призывного возраста, заносились в особые списки. В определённый день от них требовалось явиться ко двору номарха, где из всех призывников отбирали наиболее крепких. Пропорция призывников в эпоху Нового царства значительно выросла в сравнении с более ранним временем. Если во времена Древнего или Среднего царства служить в армии приходилось, быть может, одному из сотни призывников, то теперь такая участь выпадала одному из десяти. Роспись в фиванской гробнице Усерхата, офицера времён правления Аменхотепа II (1427–1401 годы до н.э.), изображает сцены зачисления новобранцев в армию: парикмахеров, стригущих им волосы, и квартирмейстеров, выдающих пайки. Другие изображения воспроизводят что-то вроде физических упражнений на развитие выносливости, а также приёмы силовой борьбы и обучение владению оружием. После завершения начальной подготовки новобранцы зачислялись в свой полк.

pinterest.com

Армия Рамсеса II (1279–1213 годы до н.э.), сражавшаяся против хеттов в битве при Кадеше в 1274 году до н.э., состояла из четырёх полков, каждый из которых носил имена египетских божеств: Амона, Ра, Птаха и Сета. Каждый полк имел собственного военачальника — как правило, из числа царских сыновей или других близких родственников — и действовал в ходе кампании вполне самостоятельно. Символом полка был его штандарт с изображением божества. По штату каждый полк насчитывал приблизительно 5000 солдат, которые делились на 20 «рот» по 200–250 человек в каждой. «Рота» также имела своего командира и штандарт. К ней был приписан военный писец, отвечавший за снабжение солдат провизией и материально-техническим обеспечением. В свою очередь, «рота» состояла из пяти «взводов» по 50 пехотинцев в каждом под командованием «начальника пятидесяти». Такой «взвод» являлся низшей тактической единицей египетской армии.

Тактика

Египетская пехота делилась на тяжеловооружённых бойцов (nakhtu-aa) и лучников (megau) в пропорции, возможно, 50 на 50. Лучники вооружались простыми или сложносоставными луками и действовали в свободных порядках перед главными силами. При столкновении с лёгкой пехотой противника, например, с ливийскими ополченцами, для победы иной раз было достаточно расстрелять противника из луков. Против более устойчивых противников египтяне ставили свою тяжеловооружённую пехоту, построенную в плотные колонны по несколько человек в глубину строя. Эти воины были вооружены главным образом копьями, а также секирами и кинжалами. Защитой им служили большие щиты, которые изготавливались из высушенной на солнце воловьей кожи. Задача этих солдат на поле боя состояла в том, чтобы сокрушить сопротивление противника решительным натиском. Когда враг обращался в бегство, его преследовали и истребляли легковооружённые воины и колесницы.

pinterest.com

В эпоху Нового царства с ростом армий и увеличением интенсивности военных столкновений крупномасштабные сражения в открытом поле стали главным способом преодоления вражеского сопротивления и уничтожения его живых ресурсов. В битве при Кадеше в 1274 году до н.э. армия фараона Рамсеса II насчитывала от 20 000 до 30 000 пехотинцев и 1500 колесниц. Войска хеттов даже превосходили египтян по своей численности. Столкновения столь многочисленных сил ознаменовались высокими потерями с обеих сторон. Можно предположить, что при Кадеше египтяне потеряли от 3000 до 5000 воинов. С другой стороны, Рамсес III в 1180 году до н.э. сообщает о 12 500 ливийцах, погибших в ходе одной из предпринятых им кампаний. Чтобы подсчитать потери противника, обычной у египтян практикой было отрубать павшим врагам правые руки, а позже ещё и пенис. Церемония торжественного подношения отрубленных рук фараону запечатлена на многих рельефах.

world-archaeology.com

Условия службы

Жёлчный и реалистичный взгляд на армейскую жизнь содержит написанный около 1200 года до н.э. папирус Анастази III, автор которого стремится объяснить своему сыну преимущества профессии писца и отбить у него охоту к военной карьере:

«Слушай, я опишу тебе участь солдата: его воспитывают как непослушного ребёнка и заключают в казарму. Ему наносят болезненные удары по всему телу, жестокий удар по глазам и сокрушительный удар по лбу. Его голова расколота раной. Его растягивают и избивают, словно кусок папируса. Его избивают до полусмерти. Слушай, я опишу тебе его путешествие в страну Хару и поход по холмам: он несёт свой хлеб и воду на собственных плечах, словно осёл. Его шея становится мозолистой, как у осла, а хребет спины изгибается. Он пьёт отвратительную на вкус воду и останавливается только, чтобы постоять на страже. Когда он настигает врага, он подобен привязанной птице, у которой уже нет сил в конечностях. Если ему удастся вернуться в Египет, он подобен палке, которую съел древоточец, — он полон болезней. Его везут домой в состоянии паралича на спине осла. Его одежду украли, а слуга сбежал».

Несомненно, египетскому солдату, как и всякому другому, приходилось претерпевать лишения и сносить тяготы военной службы, однако те, кто оставался в живых, могли рассчитывать на поощрение. Им были доступны взятые у врага трофеи, награды за храбрость в виде ценных пожалований или продвижение по службе. По выходу в отставку им часто предоставлялась земля и скот, с которых они могли жить в старости.

Литература:

- Авдиев, В.И. Военная история Древнего Египта. — Т. II. — М: АН СССР, 1959.

- Энглим С., Джестис Ф. Дж., Райс Р. С. и др. Войны и сражения Древнего Мира. 3000 год до н.э. — 500 год н.э. / Пер. с англ. Т. Сенькиной, Т. Баракиной, С. Самуенко и др. — М.: Эксмо, 2007.

- Spalinger, A.J. War in Ancient Egypt. New Kingdom. — Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2005.

- Shaw, I. Egyptian warfare and weapons. — Shire Publications, 1991.

- Morkot, R.G. Historical dictionary of ancient Egyptian warfare. — Oxford, 2003.

- Healy, M. New Kingdom Egypt. — Osprey Publishing, Elite 40, 1992.

- Fields, N. Soldiers of Pharaoh. Middle Kingdom Egypt 2055–1065 BC. — Osprey Publishing, Warrior 121, 2007.

Армия Древнего Египта

На военную службу в Древнем Египте призывали 1 мужчину из 10-ти, но многие вступали в армию по собственному желанию, чтобы сделать карьеру. Крестьян и ремесленников набирали в армию только во время войны. Верховным главнокомандующим был сам фараон или назначенный им человек. Собственные военные отряды были в распоряжении номархов, правителей номов, но фараон мог призвать их в любой момент во время войны.

В период Нового царства египтяне начали разводить лошадей, и в армии появились отряды колесниц. Колесницей управлял возничий, а рядом с ним стоял воин, обычно лучник. Пехотинцы начали одеваться в пластинчатые панцири, на смену короткому мечу пришли массивный прямой меч и меч в виде серпа. Военные стали отдельной кастой и делились на группы по возрасту и сроку военной службы.

У египтян был свой сильный военно-морской флот, хорошо было развито фортификационное искусство (строительство крепостей). При штурме крепостей египтяне применяли тараны, а ворвавшись в чужую крепость, делали из своих щитов навес, чтобы избежать нападений лучников со стен крепости. Эту тактику впоследствии использовали римские легионеры.

Больше всего победоносных войн пришлось на время правления фараона Тутмоса III (1505-1450 гг. до н.э.). Он расширил границы Египта до 4-го порога Нила на юге и до Северной Сирии на севере.

Что представляла собой главная ударная сила Египетской армии?

Древнеегипетские воины на колеснице

У пеших древнеегипетских воинов было вполне обычное для того времени оружие. Часть из них была вооружена луком и стрелами (таких называли лучниками), а другая часть имела при себе боевые топоры и копья с бронзовыми наконечниками. Однако главной ударной силой армии Египта являлись боевые колесницы. В двухместную повозку запрягали пару лошадей. Один из воинов на колеснице поражал противника стрельбой из лука, а другой в это время направлял лошадей прямо в скопление вражеской пехоты. Сотни боевых колесниц сеяли панику и смерть, разрушая стройные ряды войска противника и заставляя его бросаться наутек.

В древнеегипетской армии существовали также одноместные колесницы, в которых воин-универсал одновременно мог вести лошадей и стрелять по врагу из лука.

Кто был самым удачливым древнеегипетским полководцем?

Таковым можно считать фараона Тутмоса III, правившего Египтом в 1479—1425 годах до нашей эры. Тутмос III успешно завершил пятнадцать военных походов на земли соседей и расширил пределы своего государства до невиданных доселе размеров. Ему удалось завоевать Нубию, Финикию, Палестину и Сирию, а Вавилония и Хеттское царство вынуждены были платить дань Египту и на время забыть о своих территориальных претензиях к этой державе. Надо отметить, что Тутмос III не только лично руководил своей армией в сражениях, но и принимал активное участие в баталиях, находясь на боевой колеснице.

Зачем Древнему Египту была нужна наемная армия?

Древнеегипетский воин

Более 5 тысяч лет назад на северо-востоке Африки в долине реки Нил возник Древний Египет. Это было самое цивилизованное государство своего времени. Здесь прекрасно развивались земледелие, строительство, письменность, науки. Египетские города были богаты, и поэтому являлись объектом нападений со стороны хеттов, нубийцев, эфиопов и других соседних племен. Кроме того, египтяне и сами были не прочь расширить свои территории за счет других народов и заставить соседей платить им дань. Для этих целей Египет и использовал регулярную армию. А чтобы солдаты были заинтересованы в успешном ведении боевых действий, их нанимали и платили им за несение воинской службы.

Поделиться ссылкой

Содержание

- 1 Военное дело Древнего Египта периода Древнего Царства

- 1.1 Организация армии периода Древнего Царства

- 1.2 Вооружение и состав войска периода Древнего Царства

- 2 Военное дело Древнего Египта периода Среднего Царства

- 2.1 Расцвет Египта периода Среднего царства и совершенствование военного дела египтян

- 2.2 Военные походы фараонов периода Среднего Царства

- 3 Военное дело Древнего Египта периода Нового Царства

- 3.1 Организация войска периода Нового царства

- 3.2 Военные походы Египта периода Нового царства

- 3.3 Related Posts:

Военное дело Древнего Египта периода Древнего Царства

Началом периода Древнего царства на территории современного Египта, считается объединение северного и южного египетских государств, сложившихся в Верхнем и Нижнем Египте к концу IV тысячелетия до н.э. Эта централизация имела важные последствия — расширение и совершенствование оросительной системы, обеспечившие развитие земледелия. Развивались ремесла, появились целые ремесленные мастерские, в которых, в частности, изготовлялось оружие. Расширялась торговля, а это, в свою очередь, способствовало развитию кораблестроения.

Древнеегипетская пехота

Организация армии периода Древнего Царства

Воины находились на службе у фараона, правителей округов и храмов. За свою службу они получали участки земли, которые обрабатывались рабами. Войско было организовано в форме военных поселений, расположенных в центре страны и на наиболее угрожаемых направлениях; главные силы находились в Нижнем Египте, который часто подвергался нападениям; меньше поселений было в Верхнем Египте, так как соседние нубийские племена не могли быть серьезным противником египтян вследствие своей раздробленности.

Больше того, покоренные нубийские племена были обязаны давать Египту определенное количество воинов для несения внутренней “полицейской” службы.

Во время больших походов фараоны усиливали свое войско за счет покоренных соседних племен. Этих воинов нельзя считать наемниками, так как нет никаких данных о том, что за участие в походе они получали какую-либо плату. Можно лишь предположить о праве их на какую-то долю в военной добыче.

Политическая централизация была основой военной централизации. Верховная власть принадлежала фараону, который назначал начальника войска, а также начальников отрядов или флотов. В документах времен Древнего царства упоминается “дом оружия” — своего рода военное ведомство, в ведении которого находилось изготовление оружия, постройка кораблей, снабжение войска и постройка оборонительных сооружений. Данных о численности египетского войска периода Древнего царства нет. В отношении флота имеется лишь одно упоминание об отряде из 40 кораблей, посланном за кедрами.

Вооружение и состав войска периода Древнего Царства

На вооружении воинов Древнего царства были: булава с каменным наконечником, боевой топор из меди, копье с каменным наконечником, боевой кинжал из камня или меди. В более ранний период широко применялся бумеранг.

Основным оружием служили лук и боевой топор. В качестве защитного оружия воины имели деревянный щит, обтянутый мехом. В войске, собранном для похода, часто возникали внутренние распри, причиной которых были сохранившиеся пережитки прежней политической раздробленности Египта, и это говорит о том, что военная дисциплина в египетском войске была слабой.

Войско состояло из отрядов. Дошедшие до нас источники говорят о том, что воины занимались боевой подготовкой, которой ведал специальный начальник военного обучения. Уже в период Древнего царства египтяне применяли построение шеренгами. Все воины в строю имели однообразное оружие.

Крепости периода Древнего царства были различной формы, встречались тут и круг, и овал и прямоугольник — никаких сведений о том, что их строительство регламентировалось, у нас нет. Крепостные стены иногда имели круглые башни в форме усеченного конуса с площадкой наверху и бруствером. Так, крепость около Абидоса построена в форме прямоугольника; длина ее сторон достигала 125 и 68 м, высота стен — 7—11 м, толщина в верхней части — 2 м. У крепости были один главный и два дополнительных входа. Крепости в Семнэ и Куммэ были уже сложными оборонительными сооружениями имевшими выступы, стены и башню.

Корабля египтян были гребные, но на них имелись паруса. На каждом корабле находилась постоянная команда с начальником во главе. Отряд кораблей возглавлял начальник флота. Постройкой кораблей ведал так называемый строитель кораблей. Всего египтяне располагали двумя «большими флотами» одним — в Верхнем, другим — в Нижнем Египте.

При штурме крепостей египтяне применят штурмовые лестницы с деревянными дисковыми колесиками, облегчавшими их остановку и передвижение вдоль крепостной стены и таранами.

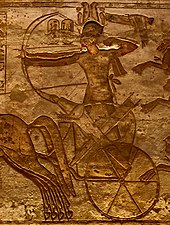

Фараон на боевой колеснице в бою

Военное дело Древнего Египта периода Среднего Царства

В период Среднего царства происходил быстрый рост производительных сил страны. В связи с улучшением ирригационной системы резко повысилась производительность сельского хозяйства, в стране появилось изобилие зерна, молочных и мясных продуктов, фруктов, сырья для ткацкого производства. С развитием ремесла увеличивалось производство орудий труда, предметов домашнего обихода, предметов роскоши, совершенствовалось оружие.

Расцвет Египта периода Среднего царства и совершенствование военного дела египтян

Непрерывно возрастало количество рабов, число порабощенных и зависимых соседних племен, труд рабов обогащал Египет и, прежде всего, его знать. Развивалась внутренняя и внешняя торговля, для обеспечения последней необходимо было развивать, прежде всего, флот. Завоевательная политика фараонов Среднего царства определила и дальнейшее усовершенствование военной организации.Одной из основных причин восстановления политического единства страны в конце III тысячелетия до н. э. была необходимость централизованного руководства ирригационной системой.

Воссоединение Египта происходило в процессе ожесточенной борьбы двух крупных его центров — Фив на юге и Гераклеополя на севере. Гераклеополь занимал выгодное географическое положение, что способствовало превращению его в экономический и политический центр Египта. Начался период Среднего царства — время расцвета древнего Египта

Территория Египта в период Среднего царства составляла примерно 35 тысяч кв. км. Численность населения его, по данным древних авторов и современным исчислениям, равнялась приблизительно 7 миллионам человек. Судя по имеющимся данным о наборе в одном из номов (один воин от ста мужчин), египетское войско могло состоять из нескольких десятков тысяч воинов. В поход обычно выступало несколько тысяч воинов, в надписях фараонов упоминаются отряды в 3 и 10 тысяч человек. В состав египетского войска входили значительные отряды наемников, завербованных в Нубии.

Фараон имел при себе “людей свиты”, составлявших его личную охрану, и “спутников правителя” — группу преданных ему знатных воинов, из состава которой назначались военачальники “начальник войска”, “начальник новобранцев”, “военный начальник Среднего Египта” и другие начальствующие лица.

В период Среднего царства была усовершенствована организация войска. Подразделения теперь имели определенную численность: 6, 40, 60, 100, 400, 600 воинов. Отряды насчитывали 2, 3, 10 тысяч воинов. Появились подразделения однообразно вооруженных воинов — копейщиков и лучников, которые имели порядок построения для движения; двигались колонной в четыре ряда по фронту и в десять шеренг глубиной.

Вооружение египетских воинов периода Среднего царства по сравнению с прошлым периодом несколько улучшилось, так как обработка металла стала более совершенной. Копья и стрелы имели теперь наконечники из бронзы. Оружие ударного действия оставалось прежним: боевой топор, копье до 2 м длиной, булава и кинжал. В качестве метательного оружия применялись копье для метания, бумеранг, праща для метания камней, лук.

Появился усиленный лук, который повышал дальность полета стрелы и точность ее попадания. Стрелы имели наконечники различной формы и оперение; длина их колебалась от 55 до 100 см. Обычные для Древнего Востока стрелы с листовидным наконечником, первоначально кремневым, а затем медным и бронзовым, были менее эффективным оружием, чем введенные скифами во второй четверти I тысячелетия до н. э. стрелы с граненым наконечником — костяным или бронзовым. Прицельный выстрел из лука, дистанция полета бумеранга и метательного копья были примерно одинаковы: 150—180 м; наилучшая меткость бумеранга и метательного копья достигалась на дистанции в 50 м. Щит, обитый мехом, высотой в половину человеческого роста продолжал оставаться единственным защитным снаряжением.

Имеются данные о поощрении рядовых воинов за выслугу лет путем выделения им небольших участков земли. Начальствующие лица за свои заслуги продвигались по службе, получая землю, скот, рабов или же награждались “золотом похвалы” (вроде ордена) и украшенным боевым оружием.

Военные походы фараонов периода Среднего Царства

Фараоны Среднего царства уделяли большое внимание обеспечению границ Египта. Появились системы оборонительных сооружений. Так, например, для защиты южной границы было построено три линии крепостей в районе первого и второго порогов Нила. Крепости стали более совершенными, они теперь имели зубцы, которые прикрывали оборонявшихся воинов, выступавшие башни для обстрела подступов к стене, ров, затруднявший подход к стене. Крепостные ворота были защищены башнями. Для вылазок устраивались небольшие выходы. Большое внимание уделялось снабжению гарнизона крепости водой, устраивались колодцы или скрытые выходы к реке.

Из сохранившихся остатков древнеегипетских крепостей этого периода наиболее характерной является крепость в Миргиссе, построенная в форме прямоугольника. Эта крепость имеет внутреннюю стену высотой в 10 м с выступающими башнями, расположенными на расстоянии 30 м одна от другой на противоположном от реки фасе, и ров шириной в 8 м. В 25 м от внутренней стены построена внешняя стена, которая охватывает крепость с трех сторон; с четвертой стороны круто обрывается к реке скала. Внешняя стена окружена рвом шириной 36 м.

Кроме того, на скалистых выступах были построены выдвинутые вперед стенки, примыкающие к углам крепости и позволяющие фланкировать подступы со стороны реки. Две другие стенки защищали главный вход в крепость. Крепость в Миргиссе являлась уже сложным оборонительным сооружением, в основу которого было положено требование фланкирования подступов. Это было шагом вперед в развитии фортификации — одной из отраслей военного искусства.

Фараоны и их военачальники предпринимали многочисленные походы в Нубию, Сирию и другие страны с целью их грабежа. При организации походов большое внимание обращалось на снабжение. Так, например, в одной надписи мы читаем: “Я пошел с войсками в 3000 человек… для каждого было два сосуда воды и 20 хлебцев на каждый день. Ослы были нагружены сандалиями”. На походе этому отряду пришлось вырыть 20 колодцев, чтобы обеспечить себя водой.

Некоторые сохранившиеся надписи показывают отдельные детали боя. Так, во время одного похода в Нубию произошел бой на Ниле и его берегах. Египтяне имели 20 кораблей, которые хорошо маневрировали, пользуясь, как говорится в источнике, “южным и северным, восточным и западным ветрами”. Корабли противника были уничтожены, а его сухопутное войско в беспорядке бежало. Эти данные говорят о некоторых моментах взаимодействия флотилии и сухопутного войска.

В XVIII веке до н. э. в Египет вторглись азиатские племена — гиксосы, которые владели страной до 1580 года. Египтяне заимствовали у них боевую колесницу.

Военное дело Древнего Египта периода Нового Царства

Период Нового царства, был характерен бурным ростом производительных сил египетского государства. Усовершенствовалась ирригационная система, что способствовало развитию земледелия. Расширялась торговля, вследствие чего в Египет в большом количестве ввозилась медь; развивалось ремесло.

В XVI веке до н. э. население Египта начало войну за освобождение от власти гиксосов. Возглавивший эту борьбу фиванский царь Камее говорил: “Я все же буду сражаться с азиатами… плачет вся страна. В Фивах обо мне скажут: “Камее —защитник Египта”. Из этого ясно, что Камее понимал освободительный характер войны. Борьба имела затяжной характер и закончилась изгнанием гиксосов из Египта.

В период Нового царства в Египте окончательно сложился кастовый строй, в целом повторяющий индийский: жрецы, воины, земледельцы и ремесленники. Рабы стояли вне кастового деления.

Военная каста делилась по возрасту или по продолжительности службы на две группы, различавшиеся по одежде, которую они носили. Первая группа, по данным Геродота, насчитывала до 160 тысяч человек, вторая — до 250 тысяч. Надо полагать, что эти цифры дают численность всей военной касты, включая стариков и детей, а возможно, и женщин. Так что в поход, в лучшем случае, могли выступить лишь десятки тысяч воинов.

При этом не следует забывать, что сообщения Геродота относятся к более позднему времени (500—600 лет после периода Нового царства). Египетское войско периода Нового царства представляло собой касту, воспитываемую в духе презрения к простому народу.

Один из гераклеопольских фараонов более позднего времени поучал своего сына: “Сгибай толпу. Уничтожай пыл, исходящий от нее. Не поддерживай человека, который враждебен в качестве простолюдина. Он всегда враждебен. Бедный человек—смута в войске… Берегись. Сделай конец его… Кротость — это преступление. Наказывай”.

Армия древнего Египта в бою

Организация войска периода Нового царства

Большая часть воинов Нового царства была вооружена мечами, значительную роль в бою играл лук. Улучшилось защитное вооружение: воин, кроме щита, имел еще шлем и панцирь из кожи с прикрепленными бронзовыми пластинками. Важной частью войска были боевые колесницы. Колесница представляла собой деревянную площадку (1 м х 0,5 м) на двух колесах, к которой наглухо прикреплялось дышло. Передняя часть и борта колесницы обшивались кожей, что защищало от стрел ноги боевого экипажа, который состоял из возницы и одного бойца. В колесницу впрягали двух лошадей.

Главную силу египетского войска составляла пехота, которая после введения однообразного вооружения состояла из лучников, пращников, копейщиков, воинов с мечами. Наличие одинаково вооруженной пехоты поставило вопрос о порядке ее построения. Появился строй пехоты, движения ее стали ритмичными, что резко бросается в глаза во всех изображениях египетских воинов периода Нового царства.

Во время похода египетское войско делилось на несколько отрядов, которые двигались колоннами. Вперед обязательно высылалась разведка. При остановках египтяне устраивали укрепленный лагерь из щитов. При штурме городов они применяли построение, называемое “черепахой” (навес из щитов, прикрывавший воинов сверху), таран, винею (низкий навес из виноградных лоз, покрытых дерном для защиты воинов при осадных работах) и штурмовую лестницу.

Снабжением войск ведал специальный орган. Продукты выдавались со складов по определенным нормам. Существовали специальные мастерские по изготовлению и ремонту оружия.

В период Нового царства египтяне имели сильный флот. Корабли оснащались парусами и большим количеством весел. По некоторым данным, носовая часть корабля была приспособлена для нанесения таранного удара вражескому кораблю. В египетском войске Нового царства можно уже видеть относительно хорошую организацию, но источники скупо освещают подробности его боевых действий. Сохранились отрывки из военных хроник фараона Тутмоса III (1525—1491 гг. до н. э.), которые вел писец, находившийся при египетском войске. По этим отрывкам можно составить некоторое представление о том, как решались отдельные стратегические и тактические вопросы.

Военные походы Египта периода Нового царства

Объектом завоевательных войн египтян в период правления Тутмоса III были богатые страны — Палестина и Сирия, куда египетское войско совершило 17 походов. Имеются данные о том, что в это же самое время египтяне совершали походы в Нубию. Таким образом, походы в Палестину и Сирию обеспечивались активными действиями против племен Нубии.

Как видно, основной стратегический объект действий намечался в Передней Азии, а вспомогательные удары — по Нубии, которые должны были обеспечить глубокий тыл египетского войска и безопасность страны с угрожаемого направления. Завоевательные походы в Переднюю Азию осуществлялись под личным командованием Тутмоса, походы в Нубию происходили под командованием его лучших военачальников.

В Северной Палестине и Сирии в период правления Тутмоса III сложилась антиегипетская коалиция с целью борьбы за независимость. Возглавлял эту коалицию царь Кадеша. Тутмос имел против себя серьезного противника, у которого опорными пунктами были сильные крепости — Мегиддо и Кадеш. Крепость Мегиддо имела важное стратегическое значение, так как преграждала путь из Египта в долину реки Оронта. Кадеш был политическим центром племен, восставших против Египта.

Походы египтян в период правления Тутмоса отличались целеустремленностью. Египтяне не распыляли своих сил, а наносили сосредоточенные и последовательные удары по важным стратегическим пунктам. Первые пять походов создали необходимую базу для наступления на Кадеш, овладение которым позволили бы предпринять походы вглубь Передней Азии, а последние должны были закрепить первоначальные успехи. Для решения этих задач имелось сильное, по тому времени, египетское войско, численность которого, по некоторым данным, доходила до 20 тысяч воинов. Большой египетский флот обеспечивал переброску войска в любой пункт побережья Палестины и Сирии, где были созданы базы с запасами продовольствия.

До нас дошли некоторые тактические подробности о походе египтян в Сирию в 1503 году или в 1504 году до н. э., в конце 22 года правления Тутмоса III. Египетское войско около 19 апреля выступило из северо-восточной пограничной крепости Джару и через девять дней достигло Газы (250 км от исходного пункта). 10 мая египтяне уже находились на южных склонах Кармельских гор (130—145 км от Газы). В это время войско антиегипетской коалиции сосредоточилось в Мегиддо, намереваясь удержать в своих руках этот важный пункт, находившийся на северных склонах Кармельских гор. Египетскому войску предстояло форсировать горный хребет.

Для выбора маршрута движения в Мегиддо был созван военный совет. Через Кармельокий хребет имелось три дороги: средняя представляла собой тропу, но это был кратчайший путь, вправо и влево от нее шли широкие дороги, которые выходили: одна к юго-восточной, другая — к северо-западной окраинам Мегиддо. Военачальники египетского войска возражали против использования тропы, заявляя: “Разве лошадь не будет идти за лошадью, а также и человек за человекам? Не должен ли будет наш авангард сражаться в то время, как наш арьергард еще будет стоять в Аруне?” Но Тутмос приказал идти прямым путем и лично встал во главе колонны, заявив, что пойдет “сам во главе своей армии, указывая путь собственными своими шагами”

13 мая голова колонны египетского войска достигла Аруна — пункта, расположенного на горном хребте. 14 мая египтяне двинулись дальше, сбили передовые части противника и вышли в долину Ездраелон, где могли развернуться для боя. Противник держал себя пассивно, а Тутмос, по совету своих военачальников, приказал не вступать в бой до полною сосредоточения египетского войска. Можно предполагать, что главные силы антиегипетской коалиции находились в районе Таанах, преграждая наиболее удобный подступ к Мегиддо. Форсирование горного хребта египтянами по тропе для них оказались неожиданным, и поэтому была упущена возможность уничтожения египетского войска по частям.

Выйдя к Мегиддо, Тутмос приказал разбить лагерь на берегу ручья Кины и готовиться к бою, который он решил дать на следующий день, т. е. 15 мая. В ночь на 15 мая он улучшил группировку своего войска, продвинув его левое крыло к дороге на Зефти, и перерезал этим противнику путь отступления на север.

Утром 15 мая египетское войско построилось для боя. Боевой порядок его состоял из трех частей, центр находился на левом берегу ручья Кины, правое крыло — на высоте, расположенной на правом берегу того же ручья, левое крыло — на высотах северо-западнее Мегиддо. Противник развернул свои силы на подступах к Мегиддо, юго-западнее города

Тутмос на боевой колеснице встал в центре и первый бросался на врага. “Фараон сам вел свою армию, мощный во главе ее, подобный языку пламени, фараон, работающий своим мечом. Он двинулся вперед, ни с кем несравнимый, убивая варваров”. Египетское войско атаковало противника и затем обратило его в бегство. Египтяне могли бы ворваться в город, если бы энергично преследовали бегущего врага. Но победоносное войско было занято грабежом захваченного богатого лагеря и дележом добычи. В это время ворота города были заперты, царей Кадеша, Мегиддо, их союзников, а также отдельных воинов, спасшихся бегством, гарнизон крепости и жители юрода втащили на крепостную стену.

Как только египетское войско разбило своего противника на подступах к Мегиддо, Тутмос приказал немедленно обложить город. “Они измерили город, окружив его оградой, возведенной из зеленых стволов всех излюбленных ими деревьев; его величество находился сам на укреплении, к востоку от города, осматривая, что было сделано”. Однако царь Кадеша сумел бежать из города. После нескольких недель осады город Мегиддо капитулировал. Оценивая значение своего успеха, Тутмос говорил: “Амон отдал мне все союзные области Джахи, заключенные в одном городе… Я словил в одном городе их, я окружил их толстой стеной”.

Трофеями Тутмоса были: 924 колесницы, 2238 лошадей, 200 комплектов оружия, жатва в долине Ездраелона, снятая египетским войском, 2000 голов крупного и 22500 голов мелкого скота. Перечень трофеев показывает, что египтяне снабжались за счет местных средств.

Для закрепления своего успеха египтяне двинулись дальше, взяли еще три города и построили крепость, которая была названа “Тутмос — связывающий варваров”. Теперь египтяне владели всей Палестиной. Но для упрочения египетского господства и подготовки базы на побережье потребовалось еще четыре похода. Шестой по счету поход имел целью взятие сильной крепости Кадеш. “Его величество прибыл к городу Кадешу, разрушил его, вырубил его леса, сжал его посевы”. Так была решена вторая стратегическая задача.

За время 17 походов, длившихся 19 лет, египтяне овладели сотнями городов, закрепили за собой Палестину и Сирию и вторглись в центральные районы Передней Азии.

Тутмос III — первый известный в истории полководец, который осуществлял планомерное наступление. Он намечал стратегические объекты и настойчиво добивался овладения ими. Так, например, в отношении Мегиддо фараон говорил: “…взятие тысячи городов — вот что такое пленение Мегиддо”, так как “вождь каждой страны, которая восстала, находится в нем”. Для обеспечения продвижения вглубь территории противника египтяне расширяли свои базы, проявляя заботу о тыле. Наконец, стратегия египтян этого периода характеризуется стремлением закрепить достигнутый успех путем устройства укрепленных пунктов на завоеванной территории и организацией многократных походов с целью полного подчинения покоренных племен. Походы для достижения поставленной цели, определение стратегического объекта действий для каждого похода, подготовка баз, закрепление успеха — все это существенные моменты стратегического руководства.

Как походный, так и боевой порядки были расчленены на три составные части, которые имели определенные частные задачи, вообще, и в выборе маршрутов передвижения войск и в организации промежуточных баз и укрепленных опорных пунктов, египтяне того времени показали достаточно высокий уровень понимания тактики и стратегии ведения войны, что в конечном итоге, и позволило фараонам значительно расширить свои владения и закрепиться далеко за пределами «домашней» территории по берегам Нила.

В период правления Рамсеса III (1204—1173 гг. до н. э.) египетское войско подверглось реорганизации. Было распределено несение службы в пехоте и в отрядах колесниц и организованы отряды наемников из иноземцев. Укрепилась дисциплина, повысилась требовательность начальствующего состава и, в то же время, были упразднены применявшиеся телесные наказания воинов, их заменили лишением чести, которую воин мог вернуть, проявив храбрость в бою.

Для борьбы с “морскими народами” египтяне создали сильный флот. Бой у Мигдола (около 1200 года до н. э.) в войне египтян с ливийцами и “морскими народами” характерен организацией взаимодействия флота и войска. Египетское войско заняло позиции у Мигдола, где правый фланг был усилен укреплениями, а левый обеспечен флотом. Исход боя решил египетский флот, который разбил флот “морских народов”, после чего бежало и их сухопутное войско. В одной из своих надписей Рамсес III сообщает, что в результате его побед “лук и оружие мирно лежали в арсеналах, воины могли есть досыта и пить в свое удовольствие; их жены и дети были при них”.

В целом надо сказать, что именно в войнах фараонов древнего Египта зарождалось военное искусство, с достижениями которого хорошо были знакомы греки, служившие наемниками у египетских фараонов уже в VII веке до н. э. Поэтому никак нельзя считать родоначальниками военного искусства именно греков — они действительно развили и во многом обогатили военную науку, однако не были её создателями и зачинателями.

[sign author=»ageageiron.ru» source=»компиляция на основе сведений находящихся в открытом доступе сети интернет»]

Ancient Egyptian War Wheels

Ancient Egypt was an ancient civilization of eastern North Africa, concentrated along the northern reaches of the Nile River in Egypt. The civilization coalesced around 3150 BC[1] with the political unification of Upper and Lower Egypt under the first pharaoh, and it developed over the next three millennia.[2] Its history occurred in a series of stable kingdoms, separated by periods of relative instability known as intermediate periods. Ancient Egypt reached its pinnacle during the New Kingdom, after which it entered a period of slow decline. Egypt was conquered by a succession of foreign powers in the late period, and the rule of the pharaohs officially ended in 31 BC, when the early Roman Empire conquered Egypt and made it a province.[3] Although the Egyptian military forces in the Old and Middle kingdoms were well maintained, the new form that emerged in the New Kingdom showed the state becoming more organized to serve its needs.[4]

For most parts of its long history, ancient Egypt was unified under one government. The main military concern for the nation was to keep enemies out. The arid plains and deserts surrounding Egypt were inhabited by nomadic tribes who occasionally tried to raid or settle in the fertile Nile River valley. Nevertheless, the great expanses of the desert formed a barrier that protected the river valley and was almost impossible for massive armies to cross. The Egyptians built fortresses and outposts along the borders east and west of the Nile Delta, in the Eastern Desert, and in Nubia to the south. Small garrisons could prevent minor incursions, but if a large force was detected a message was sent for the main army corps. Most Egyptian cities lacked city walls and other defenses.

The history of ancient Egypt is divided into three kingdoms and two intermediate periods. During the three kingdoms, Egypt was unified under one government. During the intermediate periods (the periods of time between kingdoms) government control was in the hands of the various nomes (provinces within Egypt) and various foreigners. The geography of Egypt served to isolate the country and allowed it to thrive. This circumstance set the stage for many of Egypt’s military conquests. They enfeebled their enemies by using small projectile weapons, like bows and arrows. They also had chariots which they used to charge at the enemy.

The Old Kingdom (2686–2181 BC)[edit]

The Old Kingdom was one of the greatest times in Egypt’s history. Because of this affluence, it allowed the government to stabilize and in turn organize a functioning military. During this period, most military conflict was limited to the consolidation of power within Egypt.[5]

During the Old Kingdom, there was no professional army in Egypt; the governor of each nome (administrative division) had to raise his own volunteer army.[6] Then, all the armies would come together under the Pharaoh to battle. Because military service was not considered prestigious, the army was mostly made up of lower-class men, who could not afford to train in other jobs.[7]

Old Kingdom soldiers were equipped with many types of weapons, including shields, spears, cudgels, maces, daggers, and bows and arrows. The most common Egyptian weapon was the bow and arrow. During the Old Kingdom, a single-arched bow was often used. This type of bow was difficult to draw, and there was less draw length. After the composite bow was introduced by the Hyksos, Egyptian soldiers used this weapon, as well.[8]

The First Intermediate Period (2181–2055 BC) and Middle Kingdom (2055–1650 BC)[edit]

The pharaoh Mentuhotep II commanded military campaigns south as far as the Second Cataract in Nubia, which had gained its independence during the First Intermediate Period. He also restored Egyptian hegemony over the Sinai region, which had been lost to Egypt since the end of the Old Kingdom.[9]

From the Twelfth Dynasty onwards, pharaohs often kept well-trained standing armies, which formed the basis of larger forces raised for defense against invasion. Under the rule of Senusret I, Egyptian armies built a border fort at Buhen and incorporated all of lower Nubia as an Egyptian colony.[10]

The Second Intermediate Period (1650–1550 BC)[edit]

After Merneferre Ay of the mid-13th dynasty fled his palace, a Canaanite tribe called the Hyksos sacked Memphis (the Egyptians’ capital city) and claimed dominion over Upper and Lower Egypt. After the Hyksos took control, many Egyptians fled to Thebes, where they eventually began to oppose the Hyksos rule.[11]

The Hyksos, Asiatics from the Northeast, set up a fortified capital at Avaris. The Egyptians were trapped at this time; their government had collapsed. They were sandwiched between the Hyksos in the north and the Kushite Nubians in the south. This period marked a great change for Egypt’s military. The Hyksos have been credited with bringing to Egypt the horse, the Ourarit (chariot), and the composite bow—tools that drastically altered the way Egypt’s military functioned. (Some evidence suggests that horses and chariots were present earlier.)[12][13][14] The composite bow, which allowed for more accuracy and greater kill distance with arrows, along with horses and chariots eventually assisted the Egyptian military in ousting the Hyksos from Egypt, beginning when Seqenenre Tao became ruler of Thebes and opened a struggle that claimed his own life in battle. Seqenenre was succeeded by Kamose, who continued to battle the Hyksos before his brother Ahmose finally succeeded in driving them out.[11] This marked the beginning of the New Kingdom.

The New Kingdom (1550–1069 BC)[edit]

In the New Kingdom new threats emerged. However, the military contributions of the Hyksos allowed Egypt to defend themselves from these foreign invasions successfully. The Hittites hailed from further northeast than had been previously encountered. They attempted to conquer Egypt, but were defeated and a peace treaty was made. Also, the mysterious Sea Peoples invaded the entire ancient Near East during this time. The Sea Peoples caused many problems, but ultimately the military was strong enough at this time to prevent a collapse of the government. The Egyptians were strongly vested in their infantry, unlike the Hittites who were dependent on their chariots. It is in this way the New Kingdom army was different than its two preceding kingdoms.[15]

Old and Middle Kingdom armies[edit]

Before the New Kingdom, the Egyptian armies were composed of conscripted peasants and artisans, who would then mass under the banner of the pharaoh.[6] During the Old and Middle Kingdom Egyptian armies were very basic. The Egyptian soldiers carried a simple armament consisting of a spear with a copper spearhead and a large wooden shield covered by leather hides. A stone mace was also carried in the Archaic period, though later this weapon was probably only in ceremonial use, and was replaced with the bronze battle axe. The spearmen were supported by archers carrying a simple curved bow and arrows with arrowheads made of flint or copper. No armor was used during the 3rd and early 2nd Millennium BC.[citation needed] Foreigners were also incorporated into the army, Nubians (Medjay), entered Egyptian armies as mercenaries and formed the best archery units.[8]

New Kingdom armies[edit]

The major advance in weapons technology and warfare began around 1600 BC when the Egyptians fought and finally defeated the Hyksos people who had made themselves lords of Lower Egypt.[6] It was during this period the horse and chariot were introduced into Egypt, which the Egyptians had no answer to until they introduced their own version of the war chariot at the beginning of the 18th Dynasty.[6] The Egyptians then improved the design of the chariot to suit their own requirements. That made the Egyptian chariots lighter and faster than those of other major powers in the Middle East. Egyptian war chariots were manned by a driver holding a whip and the reins and a fighter, generally wielding a composite bow or, after spending all his arrows, a short spear of which he had a few.[8] The charioteers wore occasionally scale armor, but many preferred broad leather bands crossed over the chest or carried a shield. Their torso was thus more or less protected, while the lower body was shielded by the chariot itself. The pharaohs often wore scale armour with inlaid semi-precious stones, which offered better protection, the stones being harder than the metal used for arrow tips.[16]

The principal weapon of the Egyptian army was the bow and arrow; it was transformed into a formidable weapon with the introduction by the Hyksos of the composite bow. These bows, combined with the war chariot, enabled the Egyptian army to attack quickly and from a distance.[citation needed]

Other new technologies included the khopesh,[citation needed] which temple scenes show being presented to the king by the gods with a promise of victory, body armour and improved bronze casting; in the 18th Dynasty soldiers began wearing helmets and leather or cloth tunics with metal scale coverings].[17][citation needed]

These changes also caused changes in the role of the military in Egyptian society, and so during the New Kingdom, the Egyptian military changed from levy troops into a firm organization of professional soldiers.[6][18] Conquests of foreign territories, like Nubia, required a permanent force to be garrisoned abroad. The encounter with other powerful Near Eastern kingdoms like the Mitanni, the Hittites, and later the Assyrians and Babylonians, made it necessary for the Egyptians to conduct campaigns far from home. Over 4,000 infantry of an army corps were organized into 20 companies between 200 and 250 men each.[19] The Egyptian army is estimated to have had over 100,000 soldiers at the time of Ramesses II c. 1300 BC.[20] There were also companies of Libyans, Nubians, Canaanite and Sherdens (Greeks) who served in the Egyptian army. They were often described as mercenaries but they were most likely impressed prisoners who preferred the life of a soldier instead of slavery.[21]

Late Period armies[edit]

The next leap forward came in the Late Period (712–332 BC), when mounted troops and weapons made of iron came into use. After the conquest by Alexander the Great, Egypt was heavily hellenised and the main military force became the infantry phalanx. The ancient Egyptians were not great innovators in weapons technology, and most weapons technology innovation came from Western Asia and the Greek world.

Military organization[edit]

As early as the Old Kingdom (c.2686–2160 BC) Egypt used specific military units, with military hierarchy appearing in the Middle Kingdom (c.2055–1650 BC). By the New Kingdom (c.1550–1069 BC), the Egyptian military consisted of three major branches: the infantry, the chariotry, and the navy.[22]

Soldiers of Egypt[edit]

During the Egyptian conquest, the Pharaoh would divide his army into two parts, the North and the South. They would then be further divided into four more armies named after the Egyptian god’s Ra, Amen, Ptah, Sutekh (of all the armies the Pharaoh would align himself with Amen). From there he would pick a commander in chief, generally princes of the royal house who would then pick captains to enforce orders given down the chain of command. During war times, the commander in chief was given the job of selecting their captains, who were usually lower-ranking princes of the royal house. They generally achieved these positions using tools of bribery and appealing to the interest courts. Another major factor of choosing both officers and captains was the degree of education they received; most officials were oftentimes diplomatists with extensive educational backgrounds. Later, after receiving the official position, the divided armies would ally themselves with mercenaries who would be trained with them as one of their own but never a part of the native Egyptian military.

Each regiment in the Egyptian army could have been identified by the weapon they carried: archers, lancers, spearmen, and infantry. The lancers not only carried their long-range weapon, the lance, but also a dagger on their belt and a short-curved sword. Depicted in Egyptian art is a cane or wand-type object that has been assigned to each fifth member in a group. This may indicate that the man carrying the cane or wand was in charge of a unit of men beside him (Girard).

Military standards

A military standard is the code or sign used to signify a standard among a group of militarized individuals to show distinction from other groups but not from one another. This only became prevalent in armies that were large enough to require division to be better controlled. This recognized division started as early as the Unification period in Egypt in the Proto-dynastic period (Faulkner). The most common symbol in Egyptian military history would be the semi-circular fan sitting on top of a large, long staff as shown by the sunshade hieroglyph 𓋺. This symbol represented the Egyptian naval fleet. During later dynasties, such as the 18th dynasty, it was the most common military standard symbol—particularly under the reign of Queen Hatshepsut. Another type of standard was the rectangular mounted on a long and large staff. The staff may have been decorated with ornaments such as ostrich feathers.[23]

Infantry[edit]

Infantry troops were partially conscripted, partially voluntary.[24] Egyptian soldiers worked for pay, both natives and mercenaries.[25] Of mercenary troops, Nubians were used beginning in the late Old Kingdom, Asiatic maryannu troops were used in the Middle and New Kingdoms, the Sherden, Libyans, and the «Na’arn» were used in the Ramesside Period,[26] (New Kingdom, Dynasties XIX and XX, c.1292-1075 BC[27]) and Phoenicians, Carians, and Greeks were used during the Late Period.[28]

Chariotry[edit]

The pharaoh on a Hittite war chariot

Leader riding a chariot holding a bow.

Chariotry, the backbone of the Egyptian army, was introduced into ancient Egypt from Western Asia at the end of the Second Intermediate Period (c.1650–1550 BC) / the beginning of the New Kingdom (c.1550–1069 BC).[29] Charioteers were drawn from the upper classes in Egypt. Chariots were generally used as a mobile platform from which to use projectile weapons, and were generally pulled by two horses[30] and manned by two charioteers; a driver who carried a shield, and a man with a bow or javelin. Chariots also had infantry support.[31] By the time of Qadesh, the chariot arm was at the height of its development. It was designed for speed and maneuverability, being lightweight and delicate in appearance. Its offensive power was in its capacity to rapidly turn, wheel and repeatedly charge, penetrating the enemy line and functioning as a mobile firing platform that afforded the fighting crewmen the opportunity to shoot many arrows from the composite bow. The chariot corps served as an independent arm but were attached to the infantry corps. At Qadesh, there were 25 vehicles per company. Many of the lighter vehicles were retained for scouting and communication duties. In combat, the chariots were deployed in troops of 10, squadrons of 50 and the larger unit was called the pedjet, commanded by an officer with the title ‘Commander of a chariotry host’ and numbering about 250 chariots.[32]

Chariots are best defined as horsedrawn vehicles with two spoked wheels that require their drivers and passengers to stand whilst in motion’ (Archer 1). Simply described, the chariot has been around for centuries in the near East not only showing the owners status in societies but also in times of war. This became the most predominate in the time of the 16th century when the chariot was introduced to the Egyptians during a war with the Hyksos army (Shulman). The chariot aided in many battles, they could be used in a multitude of ways from, a glorified product mover or transportation for soldiers to be moved to and from the battle fields in a ‘battle taxi’ type manner and a variety of other ways (Archer 2). A weapon that accompanied the soldiers and their passengers were objects such as the composite bows, arrows and a variety of other object such as spears and swords. The role of an archer was one of value when place on the back of a chariot, literally making this a target almost unable to hit due to the amount of movement. ‘Chariots were used to ferry bowmen to suitable firing positions, where they dismounted and fired their bows on foot, climbing back into their chariots and speeding away when threatened’ (Archer 6). One major usage of the chariot was to ram into the front lines of the enemy to scare them into breaking formation, giving the army the opportunity to get behind their lines and start fighting. Due to the fact that war horses, although trained, still became scared. ‘Horses will not willingly charge into massed ranks of infantry, always preferring to pull up and stop just short of their lines regardless of the intentions of the riders and handlers’ (Archer 4). Even if the horse-drawn chariot did follow through and attempt to break the enemy’s lines would have been a terrible idea if they were using the lighter Bronze Age type war chariots. The chariots proved themselves most useful on flat unbroken ground, this is where their speed and maneuvering capabilities were at their height. This did however become a thorn in the side of Egyptians during the eighth and ninth centuries when the battle between Egypt and Syria, Palestine Empire broke out, causing the Egyptian chariots to become virtually incapable of performing its intended duties due to the very nature of the landscape; mountainous and rocky. There are many theories as to how chariots aided in the rise and fall of Egypt, the most prominent of these was created by Robert Drews. He claims that chariots were responsible for the end of the Late Bronze Age. His claim is that the mercenaries in the area at this time spent a great amount of effort and time watching and learning the strength and weaknesses of the warfare styles of the Egyptian military to aid in the future rebellions they would hold to overthrow the government.[33]

Navy[edit]

Before the New Kingdom, the Egyptian military was mainly aquatic, and the high ranks were composed of elite middle-class Egyptians.[34] Egyptian troops were transported by naval vessels as early as the Late Old Kingdom.[35] By the later intermediate period, the navy was highly sophisticated and used complicated naval maneuvers, such as Kamose’s campaign against the Hyksos in the harbor of Avaris (c.1555–1550 BC)[36]

There were two different types of ship in Ancient Egypt: the reed boat and the vessel made from large wooden planks. The planked ships created the naval fleet and gave it its fierce reputation. These early ships lacked an internal rib for support. Each boat had a designated section, generally under the main deck, where the slave rowers would sit. The steering oar was operated by one man.[37]

Projectile weapons[edit]

Projectile weapons were used by the ancient Egyptians to weaken the enemy before an infantry assault. Slings, throw sticks, spears, and javelins were used, but the bow and arrow was the primary projectile weapon for most of Egypt’s history. A catapult dating to the 19th century BC. was found on the walls of the fortress of Buhen.[38]

Throw stick[edit]

The throw stick does appear to have been used to some extent during Egypt’s pre-dynastic period as a weapon, but it seems to have not been very effective for this purpose. Because of their simplicity, skilled infantry continued to use this weapon at least with some regularity through the end of the New Kingdom. It was used extensively for hunting fowl through much of Egypt’s dynastic period. Most of the Egyptians were intent on using this weapon for it had a holy effect as well.

Spear[edit]

The spear does not fit comfortably into either the close combat class or the projectile type of weapons. It could be either. During the Old and Middle Kingdom of Egypt’s Dynastic period, it typically consisted of a pointed blade made of copper or flint that was attached to a long wooden shaft by a tang. Conventional spears were made for throwing or thrusting, but there was also a form of a spear (halberd) which was fitted with an axe blade and thus used for cutting and slashing.

The spear was used in Egypt since the earliest times for hunting larger animals, such as lions. In its form of javelin (throwing spears) it was replaced early on by the bow and arrow. Because of its greater weight, the spear was better at penetration than the arrow, but in a region where armour consisted mostly of shields, this was only a slight advantage. On the other hand, arrows were much easier to mass-produce.

In battle, it never gained the importance among Egyptians which it was to have in classical Greece, where phalanxes of spear-carrying citizens fought each other. During the New Kingdom, it was often an auxiliary weapon of the charioteers, who were thus not left unarmed after spending all their arrows. It was also most useful in their hands when they chased down fleeing enemies stabbing them in their backs. Amenhotep II’s victory at Shemesh-Edom in Canaan is described at Karnak:

… Behold His Majesty was armed with his weapons, and His Majesty fought like Set in his hour. They gave way when His Majesty looked at one of them, and they fled. His majesty took all their goods himself, with his spear…

The spear was appreciated enough to be depicted in the hands of Ramesses III killing a Libyan. It remained short and javelin-like, just about the height of a man.[39]

Bow and arrow[edit]

Egyptian archer on a chariot, from an ancient engraving at Thebes

The bow and arrow is one of ancient Egypt’s most crucial weapons, used from Predynastic times through the Dynastic age and into the Christian and Islamic periods. The first bows were commonly «horn bows», made by joining a pair of antelope horns with a central piece of wood.

By the beginning of the Dynastic Period, bows were made of wood. They had a single curvature and were strung with animal sinews or strings made of plant fiber. In the pre-dynastic period, bows often had a double curvature, but during the Old Kingdom a single-arched bow, known as a self (or simple) bow, was adopted. These were used to fire reed arrows fletched with three feathers and tipped with flint or hardwood, and later, bronze. The bow itself was usually between one and two meters in length and made up of a wooden rod, narrowing at either end. Some of the longer self bows were strengthened at certain points by binding the wooden rod with cord. Drawing a single-arched bow was harder and one lost the advantage of draw-length double curvature provided.

During the New Kingdom the composite bow came into use, having been introduced by the Asiatic Hyksos. Often these bows were not made in Egypt itself but imported from the Middle East, like other ‘modern’ weapons. The older, single-curved bow was not completely abandoned, however. For example, it would appear that Tuthmosis III and Amenhotep II continued to use these earlier-styled bows. A difficult weapon to use successfully, it demanded strength, dexterity and years of practice. The experienced archer chose his weapon with care.

The Egyptian craftsmen never limited themselves to one type of wood, it was very common for them to be using woods both foreign and domestic to their lands. The handmade arrows we created using mature branches or twigs and in some rare cases some immature pieces of wood that would have its bark scraped off. Each arrow was built with consisted of a reed main shaft, with a wooden fore shift attached to the distal end. The arrow head was either attached or was already in place without the help of an outside stabilizer. The size of the arrows were .801 to .851 meters or 31.5 to 33.5 inches. There are four types of arrow that are further categorized under two groups: stone heads, which consisted of the chisel-ended and leaf shaped, and the wooden heads under which the pointed and blunt or flaring arrows have been categorized.[40]

Composite bow[edit]

The composite bow achieved the greatest possible range with a bow as small and light as possible. The maximum draw length was that of the archer’s arm. The bow, while unstrung, curved outward and was under an initial tension, dramatically increasing the draw weight. A simple wooden bow was no match for the composite bow in range or power. The wood had to be supported, otherwise it would break. This was achieved by adding horn to the belly of the bow (the part facing the archer) which would be compressed during the draw. Sinew was added to the back of the bow, to withstand the tension. All these layers were glued together and covered with birch bark.

Composite bows needed more care than simple basic bows, and were much more difficult and expensive to produce. They were more vulnerable to moisture, requiring them to be covered. They had to be unstrung when not in use and re-strung for action, a feat which required not a little force and generally the help of a second person.

As a result, they were not used as much as one might expect. The simple stave bow never disappeared from the battlefield, even in the New Kingdom. The simpler bows were used by the bulk of the archers, while the composite bows went first to the chariots, where their penetrative power was needed to pierce scale armor.

The first arrow-heads were flint, which was replaced by bronze in the 2nd millennium. Arrow-heads were mostly made for piercing, having a sharp point. However, the arrow heads could vary considerably, and some were even blunt (probably used more for hunting small game).

Sling[edit]

Hurling stones with a sling demanded little equipment or practice in order to be effective. Secondary to the bow and arrow in battle, the sling was rarely depicted. The first drawings date to the 20th century BC. Made of perishable materials, few ancient slings have survived. It relied on the impact the missile made and like most impact weapons was relegated to play a subsidiary role. In the hands of lightly armed skirmishers it was used to distract the attention of the enemy. One of its main advantages was the easy availability of ammunition in many locations. When lead became more widely available during the Late Period, sling bullets were cast. These were preferred to pebbles because of their greater weight which made them more effective.[41] They often bore a mark.

Notes and references[edit]

- ^ Only after 664 BC are dates secure. See Egyptian chronology for details. «Chronology». Digital Egypt for Universities, University College London. Retrieved 2008-03-25.

- ^ Dodson (2004) p. 46

- ^ Clayton (1994) p. 217

- ^ Healy, Mark (2005). Qadesh 1300 BC. London: Osprey. pp. 27–28.

- ^ «Ancient Egyptian Warfare». World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2020-12-07.

- ^ a b c d e Egyptology Online Archived 2007-10-20 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Benson, Douglas S. “Ancient Egypt’s Warfare: A survey of armed conflict in the chronology of ancient Egypt, 1600 BC-30 BC”, Bookmasters Inc., Ashland, Ohio, 1995

- ^ a b c «Ancient Egyptian Weapons». Archived from the original on 2018-02-10. Retrieved 2008-01-06.

- ^ Grimal, Nicolas (1988). A History of Ancient Egypt. Librairie Arthéme Fayard.

- ^ Shaw, Ian (2000). The Oxford history of ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-280458-8.

- ^ a b Tyldesley, Joyce A. “Egypt’s Golden Empire”, Headline Book Publishing, London, 2001. ISBN 0-7472-5160-6

- ^ W. Helck «Ein indirekter Beleg für die Benutzung des leichten Streitwagens in Ägypten zu Ende der 13. Dynastie», in JNES 37, pp. 337-40

- ^ see Egyptian Archaeology 4, 1994

- ^ see KMT 1:3 (1990), p. 5

- ^ Healy, Mark (2005). Qadesh 1300 BC. London: Osprey. p. 35.

- ^ «Body armour». Archived from the original on 2018-02-15. Retrieved 2008-01-06.

- ^ Pollastrini, A. M. (2017). «Some remarks on the Egyptian reception of foreign military technology during the 18th Dynasty: a brief survey of the armour». Proceedings of the XI International Congress of Egyptologists. Florence Egyptian Museum. Florence, 23-30 August 2015: 513–518. ISBN 978-1-78491-600-8.

- ^ Ancient Egyptian Army

- ^ Healy, Mark (2005). Qadesh 1300 BC. London: Osprey. p. 37.

- ^ Gabriel, Richard A. (2002). The Great Armies of Antiquity. ISBN 9780275978099.

- ^ Healy, Mark (2005). Qadesh 1300 BC. London: Osprey. pp. 37–38.

- ^ Darnell, John Colemen; Menassa, Colleen. Tutankhamun’s Armies. John Wiley and Sons Inc., New Jersey: 2007. p.60

- ^ Faulkner, R. O. (1941-01-01). «Egyptian Military Standards». The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 27: 12–18. doi:10.2307/3854558. JSTOR 3854558.

- ^ Darnell, John Colemen; Menassa, Colleen. TutanKhamun’s Armies. John Wiley and Sons Inc., New Jersey: 2007. pp.60-63

- ^ Spalinger, Anthony J.. War in Ancient Egypt. Blackwell Publishing, Malden, MA: 2005. p.7

- ^ Spalinger, Anthony J.. War in Ancient Egypt. Blackwell Publishing, Malden, MA: 2005. pp.6-7

- ^ Hornung, Erik. History of Ancient Egypt. trans. Lorton, David. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, New York: 1999. p.xvii

- ^ Allen, James; Hill, Marsha (October 2004). «Egypt in the Late Period (ca. 712–332 B.C.)». Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- ^ Spalinger, Anthony J.. War in Ancient Egypt. Blackwell Publishing, Malden, Massachusetts: 2005. p.8

- ^ Spalinger, Anthony J.. War in Ancient Egypt. Blackwell Publishing, Malden, Massachusetts: 2005. p.36

- ^ Darnell, John Colemen; Menassa, Colleen. TutanKhamun’s Armies. John Wiley and Sons Inc., New Jersey: 2007. pp.63-65

- ^ Healy, Mark (2005). Qadesh 1300 BC. London: Osprey. p. 39.

- ^ Archer, Robin (2010). «Chariotry to Cavalry: Developments in the Early First Millennium». History of Warfare.

- ^ Spalinger, Anthony J.. War in Ancient Egypt. Blackwell Publishing, Malden, MA: 2005. p.6

- ^ Darnell, John Colemen; Menassa, Colleen. TutanKhamun’s Armies. John Wiley and Sons Inc., New Jersey: 2007. p.65