ЕСТЬ ЛИ ЭМОЦИИ У ЖИВОТНЫХ?

- Авторы

- Руководители

- Файлы работы

- Наградные документы

Игнатенко Д.С. 1

1МБОУ СОШ п.Дуки

Калинина А.Н. 1

1Никифорова 11

Текст работы размещён без изображений и формул.

Полная версия работы доступна во вкладке «Файлы работы» в формате PDF

Введение

Я часто бываю в гостях у своих подруг. Почти у всех есть домашние питомцы: кошки, собаки, попугаи, хомяки, рыбки и даже лягушки. У меня тоже есть домашние животные. Я часто играю с ними и с интересом наблюдаю за их поведением. Мне не раз приходилось наблюдать, как радуется приходу хозяина собака, как она рычит на чужого, как довольно урчит кошка после сытного обеда или ужина или когда её ласкают. Я считаю, что у животных есть такие эмоции, как гнев, радость, страх, обида. Так ли это? Мне захотелось узнать об эмоциях у животных и провести исследование на эту тему. Тема моей работы так и звучит «Есть ли эмоции у животных?»

Перед собой я поставила цель: узнать есть ли эмоции у животных.

Для достижения этой цели мне надо было решить следующие задачи:

— изучить и проанализировать литературу по данной теме;

— провести личные наблюдения за эмоциями собаки, кошки, попугая;

— составить творческий отчет о поведении домашних животных в разных жизненных ситуациях и выступить с ним в классе.

Объект исследования — животные.

Предмет исследования – эмоции животных.

Гипотеза: я предполагаю, что у животных есть эмоции, поэтому они могут страдать, радовать и любить.

Методы исследования:

— изучение;

— наблюдение;

— фоторепортаж.

Практическая значимость: материалы исследования можно использовать при проведении классного часа, в ходе которого ученики могут приобрести новые знания об эмоциях животных. Данная работа поможет сформировать доброе отношение к животным, мотивирует к наблюдению за поведением животных.

-

Глава. Эмоции.

-

Что такое эмоция?

-

Из словаря Ефремовой я узнала, что эмоция – это душевное переживание, чувство.

В словаре Даля написано, что эмоции – это состояния души; импульсивная реакция, отражающая отношение индивида к значимости воспринимаемого им явления; переживания, отражающие потребности организма и активизирующие или тормозящие деятельность; непосредственное переживание (протекание) чувства; не очень длительные переживания сменяющие друг друга вслед за изменением ситуации. Д.Н.Ушаков указал, что эмоции это — душевное переживание, волнение, чувство (часто сопровождаемое какими-нибудь инстинктивными выразительными движениями).

Прочитав много толкований из различных источников, я пришла к выводу, что эмоции – это душевное состояние. Эмоции должны соответствовать ситуациям и чувствам.

Если хочется смеяться — смейтесь, если плакать — плачьте. Выражение эмоций — это правильный путь к гармонии. (автор Маэстро «Психология человека»)

-

-

Какие же бывают эмоции?

-

Эмоции делятся на:

1) положительные эмоции — это удовольствие, восторг, радость. Примерами положительных эмоций могут быть уверенность, симпатия, любовь, нежность, блаженство.

2) отрицательные — это эмоции, которые проявляются в результате неудач или потерь. Примерами отрицательных эмоций могут быть грусть, печаль, расстройство, чувство утраты, гнев, тревога, отчаяние.

3) нейтральными можно назвать: любопытство, изумление, безразличие.

Вывод: Эмоции позволяют живому существу давать оценку всему, что происходит вокруг и внутри. Жизнь без эмоций невозможна!

-

-

«Язык эмоций» у животных.

-

Все звери – умные и быстро учатся. Они не умеют лгать, и не ведут войн, в которых гибнут миллионы существ. Если попадаются среди них злые создания, то такими их сделали люди. Не было надобности изучать язык людей, зато они прекрасно понимают, что происходит с человеком, просто наблюдая за ним, «считывая» его эмоции.

В моей подборке фотографий животных можно увидеть их эмоции. (Приложение 1, фото животных).

На странице журнала «ЗооМедВет» в рубрике «Чувствуют ли эмоции животные?» я прочитала, что в зоопарке одного китайского города слониха – мать отказалась от недавно родившегося слонёнка. Слонёнок плакал пять часов без перерыва, а в июле 2014 года в индийском городе спасли слона, который попал в руки к браконьерам и провёл в неволе 50 лет. Над ним всё время издевались: били и даже тыкали в него копьями, чтобы он вёл себя послушно. Когда спасатели прибыли на место и начали вызволять слона из цепей, он заплакал от радости. Учёные также считают, что слоны могут радоваться встрече с сородичем, рождению детёныша, а также хоронить других слонов и скорбеть по умершим. [2]

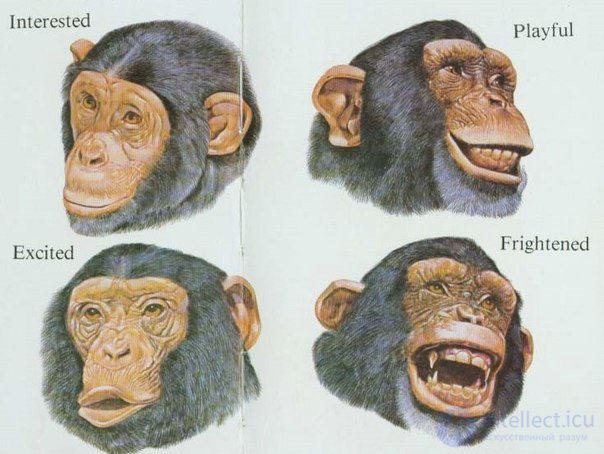

В книге «Письма» П. Скорука я прочитала, что шимпанзе это самые эмоциональные существа. Они умеют радоваться, печалиться. Также могут испытывать: злобу, страх, удивление, ярость, отвращение, любопытство, огорчение. Главное «орудие» для выражения эмоций — лицо. Самое выразительное на лице шимпанзе — губы и глаза. Иногда достаточно взглянуть только на губы, чтобы понять, что происходит с ним. Свои эмоции это животное внешне проявляет так, как это делает человек: раздраженно кричит, когда злится, гневно жестикулирует. Радость и любовь шимпанзе тоже проявляет, подобно нам: прыгает, танцует, весело скалится, облизывает партнера, дерет его за волосы, дает тумаки, потом жалеет и голубит. [3]

Учёным Барышниковым Н.С установлено, что у дельфинов также есть эмоции. Вот некоторые факты из жизни дельфинов: «Если дельфин злится, то глаза у него округляются, часто при этом бывает приоткрыта пасть. Обиженный дельфин поворачивается хвостом или боком, не теряя все же из вида обидчика, будь то другое животное или человек. Дельфины, как и слоны, способны долго помнить обиду, иногда месяцами отказываясь от контактов с человеком, причинившим им боль. «Гордое» или «самодовольное» выражение проявляется у них, когда они находятся в свободном плавании и не обращают внимания на окружающих. Эмоции у дельфинов хотя и менее ярко выражены, чем у наземных животных, но всё равно весьма характерны и разнообразны.

Совсем недавно мы читали произведение Л.Н.Толстого «Лев и собачка», основанное на реальных событиях. В рассказе описывается, как от тоски по умершей собачке погиб лев. Лев переживал эмоцию горя и скорби.

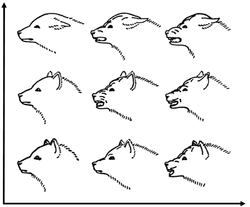

На сайте www.zoopicture.ru/pravda-o-volke я узнала, что настоящее достояние волка – это хвост, который позволяет выражать эмоции и демонстрировать широкую гамму намерений. Длинный и толстый хвост, на языке охотников – полено, у серых хищников опущен вниз, но даже по неуловимым движениям этой части тела можно определить неуверенность хищника, разглядеть агрессию или распознать игривое настроение. Впрочем, для проявления эмоций хищники активно используют и мимику, которая отличается богатством и выразительностью. Используя широкий арсенал средств – от оскаленной пасти и развернутых вперед ушей до своеобразной улыбки в сочетании с ушами, крепко прижатыми к голове, – волки без труда передают необъятную гамму чувств. [4]

Из разных источников я узнала, что чем более развитый организм, тем больше у него эмоций. Эмоции развиваются в первую очередь у стадных животных, так как выполняют в первую очередь функцию общения. Эмоции обезьян вполне развиты, у них живая мимика и богатый интонационный арсенал, а вот эмоции, например у лося не выражены, поскольку он, как одиночное животное, общается преимущественно с соседней осиной. Кошки, собаки и лошади, особенно живущие вместе с человеком, чаще всего проявляют эмоции. [1]

Вывод: изучая различную литературу, я поняла, что почти у всех животных есть эмоции, а особенно у тех, кто живёт стадом или семьёй и они им нужны для общения друг с другом или с человеком. У животных одиночек эмоции есть, но они выражены не ярко и не заметны человеческому глазу. [3]

Глава 2 . Мои наблюдения

Мне стало интересно, а знают ли мои одноклассники что-либо об эмоциях животных. С целью выяснения я провела анкетирование, в котором приняли участие учащиеся 3 класса. По результатам анкетирования, в котором приняли участие 20 учащихся, я пришла к следующим выводам:

-

У большинства опрошенных учащихся (77%) есть домашние животные.

-

Все опрошенные (100 %) любят животных.

-

3 % учащихся никогда не наблюдали эмоции у животных.

(Приложение 2, Диаграмма)

За всеми переживаниями своих питомцев стала наблюдать я. И выяснила, что всё же они испытывают эмоции, такие как: азарт, безразличие, благодарность, стыд, злость, радость и сейчас я о них расскажу.

2.1. Собака Джек.

Два года назад мне подарили прекрасного щенка. Я назвала его Джек. Пока был маленький жил в доме. А когда подрос, мы его переселили на улицу. Это обычный пес, без родословной, да и это не главное.

Не зря говорят, что собака друг человека. Джек очень веселый и игривый пес. По утрам он провожает меня в школу, а потом встречает веселым лаем. Он очень любит детей, звонко лает и прыгает, когда мы гуляем с друзьями. Он везде меня сопровождает. Джек всегда мне радуется и готов постоять за меня в любой момент. В эти моменты он как и я испытывает эмоцию радости.

Джек очень добрая собака, у него умные глаза. Он – мой самый верный друг. Я люблю его и рассказываю секреты, и он их верно хранит. Когда мне грустно, Джек кладет свою голову мне на колени и грустит вместе со мною. А когда мне радостно он ставит лапки на мои колени и радуется вместе со мной. А когда иду на прогулку, он с радостью меня сопровождает, виляя хвостом. Я иногда жалею, что собаки не умеют разговаривать. Мой песик во многом похож на меня. У него, как и у меня часто меняется настроение.

Вывод: наблюдая за своей собакой, теперь я точно знаю, что у собак есть эмоции и все они проявляются внешне и тоска, и радость, и гнев. Если вы любите собаку, то и она будет чувствовать любовь и получать удовольствие в вашей компании. (Приложение 3, Фото Джек)

2.2. Кошка Леди.

Моей кошке уже 1 год. Я с детства приучила её к ласкам и точно знаю, что она хочет в данный момент.

Моя кошка очень чувствительна и свои чувства выражает через эмоции. Когда я замечаю, что она сидит ко мне спиной и не откликается на своё имя, то лучше её не трогать, значит у неё плохое настроение, безразличие и состояние полного равнодушия.

Бывает так, когда она ложится рядом со мной и переворачивается животом кверху, значит, настроение у неё хорошее и игривое и она разрешает себя гладить и ласкать. Она громко мурлычет, выражая, таким образом, благодарность и любовь.

Когда я с ней играю, она машет хвостом из стороны в сторону, притаившись в укромном месте, и внезапно прыгает на предмет. От этого она испытывает счастье и радость.

Моя кошка очень ласковая и умеет сочувствовать. Как – то на репетиции танца я подвернула ногу и она очень болела. Моя Леди запрыгнула на постель и легла рядом возле ноги, а голову положила на больное место. Мурлыкала и урчала совсем по – другому не от удовольствия, а от сочувствия, что мне было больно.

Леди любит покушать и больше всего на свете предпочитает свежую рыбку. Когда папа ходит на рыбалку, обязательно приносит ей гостинец. Она благодарно мурчит в ответ. Моя кошка стала моим настоящим другом и думаю, моя жизнь была бы намного скучнее и обыденней, не будь рядом пушистой и доброй Леди.

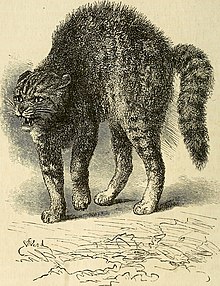

Леди никогда не будет общаться с теми, кто ей не нравится. Если с ней неучтиво обращаться, она может зашипеть или даже оцарапать. Она поднимает лапы, замахиваясь ими, грозно шипит, шерсть встает дыбом, особенно на спине, голове и хвосте кошки, спина изгибается, этим она пытается запугать недруга и показать свое превосходство, в том числе и по размерам. Так она выражает эмоцию злости.

Вывод: наблюдая за соей питомицей, я поняла, что кошки очень общительны, они становятся прекрасными компаньонами. Ни один человек не почувствует себя одиноким, если в его доме появилась кошка. Но кошки, привыкшие к общению, чахнут и умирают, когда лишаются его. Любите и заботьтесь о своих подопечных, а уж они вас отблагодарят! (Приложение 4, Фото Леди)

2.3. Попугай Чика

Я хорошо понимаю свою пернатую питомицу Чику, чего она от меня ждёт. Состояние птицы легко прочитывается по ее внешности и поведению. Она встречает меня с радостью, когда я сажусь к клетке. Моя птица хороший компаньон, дружна и любвеобильна, охотно подставляет шею, чтобы ее почесали, может часами сидеть на руке или плече. К человеку, которого видит в первый раз, никогда не подлетит, если летает по квартире, а если сидит в клетке, то забьётся в самый дальний угол. В этот момент он точно испытывает эмоцию страха.

Также попугай демонстрируют свою любовь ко мне с помощью отрыжки.

Чика — любопытная птица. Ей обязательно нужно быть в курсе всех событий на кухне и знать, чем заняты хозяева. Если мама готовит завтрак и режет что-нибудь на разделочной доске, Чика непременно утащит кусочек.

У моего попугая в клетке висят игрушки. Она ими играет, но иногда я вижу, что она заскучала, то вешаю в клетку новую игрушку, Чика испытывает большую радость.

Если мой питомец хорошо провёл день, то довольный перед сном скрежещет клювом. (Приложение 5, Фото Чика)

Вывод: я точно могу сказать вам, счастлив или печален мой питомец, испуган или доволен, а эмоции влияют на поведение попугаев.

ЗАКЛЮЧЕНИЕ

При подготовке работы и во время ее написания был собран и изучен материал с помощью интернета, энциклопедий, различных печатных изданий.

Я узнала, что такое эмоции, какие есть эмоции. В научной литературе, из анкеты учеников и по своим собственным наблюдениям нашла подтверждение своей гипотезе. Многие животные открыто, публично выражают свои эмоции, их моно увидеть. И если мы внимательны, то все, что мы видим снаружи, расскажет нам о том, что происходит в голове и сердце любого живого существа.

Я пришла к выводу, что животные, большие и маленькие такие же как мы живые существа, у каждого свой характер, свои мысли и мечты, и все хотят, чтобы к ним относились с пониманием и теплотой. Я очень счастлива, что рядом со мной всегда находятся мои друзья, которые любят меня.

Список источников:

- «Выражение эмоций. Мимика» Барышников Н.С.

- «Животные эмоции»Петр Скорук

-

«Литературное чтение. Христоматия» ч. 1

Интернет источники:

-

https://www.psychologos.ru/articles/view/emocii_u_zhivotnyh «Эмоции животных»

- www.lookatme.ru/mag/how-to/inspiration…/206127-animal-emotions

-

www.biofine.ru/bfins-1072-1.html

-

https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Эмоций

Приложение 1

«Язык эмоций» у животных.

Приложение 2

Анкета для учащихся.

-

Есть ли у вас домашние животные?

-

Любите ли вы животных?

-

Наблюдали ли вы эмоции у животных?

Приложение 3

Фото Джек.

Приложение 4

Фото Леди.

Приложение 6

Фото Чика.

Приложение 5

Попугай Чика

Просмотров работы: 7811

Множество

фактов и наблюдений, говорящих о богатой

палитре эмоций в животном мире, множество.

И,

в конечном счете, дело сводится к

обобщению этих фактов, к научным

умозаключениям. Разумеется, из одних и

тех же фактов нередко делаются самые

различные выводы. Увы, не последнюю роль

играет здесь и известный афоризм:

“Результат

зависит от точки зрения”.

От утвердившихся взглядов, от общепринятого

мнения. А порой и от ложной исходной

позиции ученого. “Нет

ничего опасней для новой истины, как

старое заблуждение”.

Наверное,

эти слова Гете всегда будут справедливы

и в познании в психике представителей

животного мира. В основе психической

деятельности животных лежит механизм

рефлекса — инстинктивная ответная

реакция организма на какие-то воздействия.

Но разве мы не видим во многих случаях

того, что выходит за рамки инстинкта?

Нередко на этот вопрос следует привычный

отрицательный ответ. Необычный факт

отвергается только потому, что противоречит

традиционному взгляду. А сомнения

остаются, поскольку утвердившиеся

объяснения необычных случаев поведения

животных далеко не всегда убеждают.

Исследование,

проведенное учеными из Оксфордского

университета, показало, что

высокоорганизованные животные способны

испытывать различные эмоции.

В

2007 году молодые люди решили на Рождество

подразнить амурскую тигрицу в Зоопарке

Сан-Франциско. Сейчас уже не важно, что

именно они там наговорили тигрице. Важно

то, что в её звериную душу запала глубокая

обида. Спустя несколько минут после

того, как обидчики ушли, она выбралась

за ограждение, сея ужас, пробралась

через открытые вольеры других зверей,

проложила путь через людскую толпу, и

отыскала тех самых троих лиходеев, чтобы

свести с ними кровавый счёт.

Тигры

умеют мстить (Источникперевод дляmixstuff– plagioclase)

Однако,

на самом деле — это «мелочь» в сравнении

с историей Владимира Маркова — россиянина,

промышлявшего браконьерством. В один

роковой день в 1997 году Маркову удалось

ранить тигра и, в качестве дополнительного

унижения, присвоить часть тигриной

добычи. Тигру, не смотря ни на что, удалось

спастись. При этом глубокие раны остались

не только на теле хищника, но и в его

душе.

Позже

тигр отыскал в лесу охотничью избушку

Маркова. Не застав хозяина, зверь обрушил

свою ярость на всё, что пахло браконьером,

и залёг в предвкушении мести у входа.

Дождавшись браконьера, тигр растерза

его и съел.

Слово

“крыса”

квалифицируется людьми, как оскорбление,

вне зависимости от их возраста и

социального положения. Назовите

кого-нибудь крысой на работе и убедитесь

сами. Никто не обрадуется.

Причина

кроется не только в том, что грязные

крысы разносят различные заболевания,

но и в их вопиющем несоответствии

стандартам людской добродетели. Крысам

неведома взаимопомощь, они не способны

к организации социальных групп. Всё,

что они могут — это безумный бег наперегонки

к любому гниющему мусору с последующим

его пожиранием, хождением по головам

друг друга и испражнением прямо на лицо

соседа в оголтелой, эгоистичной схватке

во имя еды и размножения.

Тем

не менее, многовековой научный опыт

говорит нам, что поведение животных,

кажущееся бессистемным и ужасным на

первый взгляд, может предстать в новом

свете при продолжительном наблюдении.

Исследователи крысиного поведения

столкнулись с примерами альтруизма и

преданности крыс по отношению друг к

другу.

Одну

из двух крыс, проживавших некоторое

время совместно, поместили в замкнутое

пространство, а другую оставили снаружи

наблюдать за пойманной в ловушку

подругой. Как и следовало ожидать, крыса,

оказавшаяся в неволе, стала подавать

сигналы о бедствии, побуждая другую

крысу немедленно принять меры по

спасению. Ярко проявив способность к

сопереживанию, свободная крыса бросилась

на помощь подруге, проигнорировав даже

специально приготовленную гору лакомств.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

A drawing of a cat by T. W. Wood in Charles Darwin’s book The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, described as acting «in an affectionate frame of mind».

Emotion is defined as any mental experience with high intensity and high hedonic content.[1] The existence and nature of emotions in non-human animals are believed to be correlated with those of humans and to have evolved from the same mechanisms. Charles Darwin was one of the first scientists to write about the subject, and his observational (and sometimes anecdotal) approach has since developed into a more robust, hypothesis-driven, scientific approach.[2][3][4][5] Cognitive bias tests and learned helplessness models have shown feelings of optimism and pessimism in a wide range of species, including rats, dogs, cats, rhesus macaques, sheep, chicks, starlings, pigs, and honeybees.[6][7][8] Jaak Panksepp played a large role in the study of animal emotion, basing his research on the neurological aspect. Mentioning seven core emotional feelings reflected through a variety of neuro-dynamic limbic emotional action systems, including seeking, fear, rage, lust, care, panic and play.[9] Through brain stimulation and pharmacological challenges, such emotional responses can be effectively monitored.[9]

Emotion has been observed and further researched through multiple different approaches including that of behaviourism, comparative, anecdotal, specifically Darwin’s approach and what is most widely used today the scientific approach which has a number of subfields including functional, mechanistic, cognitive bias tests, self-medicating, spindle neurons, vocalizations and neurology.

While emotions in nonhuman animals is still quite a controversial topic, it has been studied in an extensive array of species both large and small including primates, rodents, elephants, horses, birds, dogs, cats, honeybees and crayfish.

Etymology, definitions, and differentiation[edit]

The word «emotion» dates back to 1579, when it was adapted from the French word émouvoir, which means «to stir up». However, the earliest precursors of the word likely date back to the very origins of language.[10]

Emotions have been described as discrete and consistent responses to internal or external events which have a particular significance for the organism. Emotions are brief in duration and consist of a coordinated set of responses, which may include physiological, behavioural, and neural mechanisms.[11] Emotions have also been described as the result of evolution because they provided good solutions to ancient and recurring problems that faced ancestors.[12]

Laterality[edit]

It has been proposed that negative, withdrawal-associated emotions are processed predominantly by the right hemisphere, whereas the left hemisphere is largely responsible for processing positive, approach-related emotions. This has been called the «laterality-valence hypothesis».[13]

Basic and complex human emotions[edit]

In humans, a distinction is sometimes made between «basic» and «complex» emotions. Six emotions have been classified as basic: anger, disgust, fear, happiness, sadness and surprise.[14] Complex emotions would include contempt, jealousy and sympathy. However, this distinction is difficult to maintain, and animals are often said to express even the complex emotions.[15]

Background[edit]

Behaviourist approach[edit]

Prior to the development of animal sciences such as comparative psychology and ethology, interpretation of animal behaviour tended to favour a minimalistic approach known as behaviourism. This approach refuses to ascribe to an animal a capability beyond the least demanding that would explain a behaviour; anything more than this is seen as unwarranted anthropomorphism. The behaviourist argument is, why should humans postulate consciousness and all its near-human implications in animals to explain some behaviour, if mere stimulus-response is a sufficient explanation to produce the same effects?

Some behaviourists, such as John B. Watson, claim that stimulus–response models provide a sufficient explanation for animal behaviours that have been described as emotional, and that all behaviour, no matter how complex, can be reduced to a simple stimulus-response association.[16] Watson described that the purpose of psychology was «to predict, given the stimulus, what reaction will take place; or given the reaction, state what the situation or stimulus is that has caused the reaction».[16]

The cautious wording of Dixon exemplifies this viewpoint:[17]

Recent work in the area of ethics and animals suggests that it is philosophically legitimate to ascribe emotions to animals. Furthermore, it is sometimes argued that emotionality is a morally relevant psychological state shared by humans and non-humans. What is missing from the philosophical literature that makes reference to emotions in animals is an attempt to clarify and defend some particular account of the nature of emotion, and the role that emotions play in a characterization of human nature. I argue in this paper that some analyses of emotion are more credible than others. Because this is so, the thesis that humans and nonhumans share emotions may well be a more difficult case to make than has been recognized thus far.

Moussaieff Masson and McCarthy describe a similar view (with which they disagree):[18]

While the study of emotion is a respectable field, those who work in it are usually academic psychologists who confine their studies to human emotions. The standard reference work, The Oxford Companion to Animal Behaviour, advises animal behaviourists that «One is well advised to study the behaviour, rather than attempting to get at any underlying emotion. There is considerable uncertainty and difficulty related to the interpretation and ambiguity of emotion: an animal may make certain movements and sounds, and show certain brain and chemical signals when its body is damaged in a particular way. But does this mean an animal feels—is aware of—pain as we are, or does it merely mean it is programmed to act a certain way with certain stimuli? Similar questions can be asked of any activity an animal (including a human) might undertake, in principle. Many scientists regard all emotion and cognition (in humans and animals) as having a purely mechanistic basis.

Because of the philosophical questions of consciousness and mind that are involved, many scientists have stayed away from examining animal and human emotion, and have instead studied measurable brain functions through neuroscience.

Comparative approach[edit]

In 1903, C. Lloyd Morgan published Morgan’s Canon, a specialised form of Occam’s razor used in ethology, in which he stated:[19][20]

In no case is an animal activity to be interpreted in terms of higher psychological processes,

if it can be fairly interpreted in terms of processes which stand lower in the scale of psychological evolution and development.

Darwin’s approach[edit]

Charles Darwin initially planned to include a chapter on emotion in The Descent of Man but as his ideas progressed they expanded into a book, The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals.[21] Darwin proposed that emotions are adaptive and serve a communicative and motivational function, and he stated three principles that are useful in understanding emotional expression: First, The Principle of Serviceable Habits takes a Lamarckian stance by suggesting that emotional expressions that are useful will be passed on to the offspring. Second, The Principle of Antithesis suggests that some expressions exist merely because they oppose an expression that is useful. Third, The Principle of the Direct Action of the Excited Nervous System on the Body suggests that emotional expression occurs when nervous energy has passed a threshold and needs to be released.[21]

Darwin saw emotional expression as an outward communication of an inner state, and the form of that expression often carries beyond its original adaptive use. For example, Darwin remarks that humans often present their canine teeth when sneering in rage, and he suggests that this means that a human ancestor probably utilized their teeth in aggressive action.[22] A domestic dog’s simple tail wag may be used in subtly different ways to convey many meanings as illustrated in Darwin’s The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals published in 1872.

- Examples of tail position indicating different emotions in dogs

-

«Small dog watching a cat on a table»

-

«Dog approaching another dog with hostile intentions»

-

«Dog in a humble and affectionate frame of mind»

-

«Half-bred shepherd dog»

-

«Dog caressing his master»

Anecdotal approach[edit]

Evidence for emotions in animals has been primarily anecdotal, from individuals who interact with pets or captive animals on a regular basis. However, critics of animals having emotions often suggest that anthropomorphism is a motivating factor in the interpretation of the observed behaviours. Much of the debate is caused by the difficulty in defining emotions and the cognitive requirements thought necessary for animals to experience emotions in a similar way to humans.[15] The problem is made more problematic by the difficulties in testing for emotions in animals. What is known about human emotion is almost all related or in relation to human communication.

Scientific approach[edit]

In recent years, the scientific community has become increasingly supportive of the idea of emotions in animals. Scientific research has provided insight into similarities of physiological changes between humans and animals when experiencing emotion.[23]

Much support for animal emotion and its expression results from the notion that feeling emotions doesn’t require significant cognitive processes,[15] rather, they could be motivated by the processes to act in an adaptive way, as suggested by Darwin. Recent attempts in studying emotions in animals have led to new constructions in experimental and information gathering. Professor Marian Dawkins suggested that emotions could be studied on a functional or a mechanistic basis. Dawkins suggests that merely mechanistic or functional research will provide the answer on its own, but suggests that a mixture of the two would yield the most significant results.

Functional[edit]

Functional approaches rely on understanding what roles emotions play in humans and examining that role in animals. A widely used framework for viewing emotions in a functional context is that described by Oatley and Jenkins[24] who see emotions as having three stages: (i) appraisal in which there is a conscious or unconscious evaluation of an event as relevant to a particular goal. An emotion is positive when that goal is advanced and negative when it is impeded (ii) action readiness where the emotion gives priority to one or a few kinds of action and may give urgency to one so that it can interrupt or compete with others and (iii) physiological changes, facial expression and then behavioural action. The structure, however, may be too broad and could be used to include all the animal kingdom as well as some plants.[15]

Mechanistic[edit]

The second approach, mechanistic, requires an examination of the mechanisms that drive emotions and search for similarities in animals.

The mechanistic approach is utilized extensively by Paul, Harding and Mendl. Recognizing the difficulty in studying emotion in non-verbal animals, Paul et al. demonstrate possible ways to better examine this. Observing the mechanisms that function in human emotion expression, Paul et al. suggest that concentration on similar mechanisms in animals can provide clear insights into the animal experience. They noted that in humans, cognitive biases vary according to emotional state and suggested this as a possible starting point to examine animal emotion. They propose that researchers may be able to use controlled stimuli which have a particular meaning to trained animals to induce particular emotions in these animals and assess which types of basic emotions animals can experience.[25]

Cognitive bias test[edit]

Is the glass half empty or half full?

A cognitive bias is a pattern of deviation in judgment, whereby inferences about other animals and situations may be drawn in an illogical fashion.[26] Individuals create their own «subjective social reality» from their perception of the input.[27] It refers to the question «Is the glass half empty or half full?», used as an indicator of optimism or pessimism.

To test this in animals, an individual is trained to anticipate that stimulus A, e.g. a 20 Hz tone, precedes a positive event, e.g. highly desired food is delivered when a lever is pressed by the animal. The same individual is trained to anticipate that stimulus B, e.g. a 10 Hz tone, precedes a negative event, e.g. bland food is delivered when the animal presses a lever. The animal is then tested by being played an intermediate stimulus C, e.g. a 15 Hz tone, and observing whether the animal presses the lever associated with the positive or negative reward, thereby indicating whether the animal is in a positive or negative mood. This might be influenced by, for example, the type of housing the animal is kept in.[28]

Using this approach, it has been found that rats which are subjected to either handling or tickling showed different responses to the intermediate stimulus: rats exposed to tickling were more optimistic.[6] The authors stated that they had demonstrated «for the first time a link between the directly measured positive affective state and decision making under uncertainty in an animal model».

Cognitive biases have been shown in a wide range of species including rats, dogs, rhesus macaques, sheep, chicks, starlings and honeybees.[6]

Self-medication with psychoactive drugs[edit]

Humans can have a range of emotional or mood disorders such as depression, anxiety, fear and panic.[29] To treat these disorders, scientists have developed a range of psychoactive drugs such as anxiolytics. Many of these drugs are developed and tested by using a range of laboratory species. It is inconsistent to argue that these drugs are effective in treating human emotions whilst denying the experience of these emotions in the laboratory animals on which they have been developed and tested.

Standard laboratory cages prevent mice from performing several natural behaviours for which they are highly motivated. As a consequence, laboratory mice sometimes develop abnormal behaviours indicative of emotional disorders such as depression and anxiety. To improve welfare, these cages are sometimes enriched with items such as nesting material, shelters and running wheels. Sherwin and Ollson[30] tested whether such enrichment influenced the consumption of Midazolam, a drug widely used to treat anxiety in humans. Mice in standard cages, standard cages but with unpredictable husbandry, or enriched cages, were given a choice of drinking either non-drugged water or a solution of the Midazolam. Mice in the standard and unpredictable cages drank a greater proportion of the anxiolytic solution than mice from enriched cages, indicating that mice from the standard and unpredictable laboratory caging may have been experiencing greater anxiety than mice from the enriched cages.

Spindle neurons[edit]

Spindle neurons are specialised cells found in three very restricted regions of the human brain – the anterior cingulate cortex, the frontoinsular cortex and the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex.[31] The first two of these areas regulate emotional functions such as empathy, speech, intuition, rapid «gut reactions» and social organization in humans.[32] Spindle neurons are also found in the brains of humpback whales, fin whales, killer whales, sperm whales,[32][33] bottlenose dolphin, Risso’s dolphin, beluga whales,[34] and the African and Asian elephants.[35]

Whales have spindle cells in greater numbers and are maintained for twice as long as humans.[32] The exact function of spindle cells in whale brains is still not understood, but Hof and Van Der Gucht believe that they act as some sort of «high-speed connections that fast-track information to and from other parts of the cortex».[32] They compared them to express trains that bypass unnecessary connections, enabling organisms to instantly process and act on emotional cues during complex social interactions. However, Hof and Van Der Gucht clarify that they do not know the nature of such feelings in these animals and that we cannot just apply what we see in great apes or ourselves to whales. They believe that more work is needed to know whether emotions are the same for humans and whales.

Vocalizations[edit]

Though non-human animals cannot provide useful verbal feedback about the experiential and cognitive details of their feelings, various emotional vocalizations of other animals may be indicators of potential affective states.[9] Beginning with Darwin and his research, it has been known that chimpanzees and other great apes perform laugh-like vocalizations, providing scientists with more symbolic self-reports of their emotional experiences.[1]

Research with rats has revealed that under particular conditions, they emit 50-kHz ultrasonic vocalisations (USV) which have been postulated to reflect a positive affective state (emotion) analogous to primitive human joy; these calls have been termed «laughter».[36][37] The 50 kHz USVs in rats are uniquely elevated by hedonic stimuli—such as tickling, rewarding electrical brain stimulation, amphetamine injections, mating, play, and aggression—and are suppressed by aversive stimuli.[6] Of all manipulations that elicit 50 kHz chirps in rats, tickling by humans elicits the highest rate of these calls.[38]

Some vocalizations of domestic cats, such as purring, are well known to be produced in situations of positive valence, such as mother kitten interactions, contacts with familiar partner, or during tactile stimulation with inanimate objects as when rolling and rubbing. Therefore, purring can be generally considered as an indicator of «pleasure» in cats.[39]

Low pitched bleating in sheep has been associated with some positive-valence situations, as they are produced by males as an estrus female is approaching or by lactating mothers while licking and nursing their lambs.[39]

Neurological[edit]

Neuroscientific studies based on the instinctual, emotional action tendencies of non-human animals accompanied by the brains neurochemical and electrical changes are deemed to best monitor relative primary process emotional/affective states.[9] Predictions based on the research conducted on animals is what leads analysis of the neural infrastructure relevant in humans. Psycho-neuro-ethological triangulation with both humans and animals allows for further experimentation into animal emotions. Utilizing specific animals that exhibit indicators of emotional states to decode underlying neural systems aids in the discovery of critical brain variables that regulate animal emotional expressions. Comparing the results of the animals converse experiments occur predicting the affective changes that should result in humans.[9] Specific studies where there is an increase or decrease of playfulness or separation distress vocalizations in animals, comparing humans that exhibit the predicted increases or decreases in feelings of joy or sadness, the weight of evidence constructs a concrete neural hypothesis concerning the nature of affect supporting all relevant species.[9]

Criticism[edit]

The argument that animals experience emotions is sometimes rejected due to a lack of higher quality evidence, and those who do not believe in the idea of animal intelligence often argue that anthropomorphism plays a role in individuals’ perspectives. Those who reject that animals have the capacity to experience emotion do so mainly by referring to inconsistencies in studies that have endorsed the belief emotions exist. Having no linguistic means to communicate emotion beyond behavioral response interpretation, the difficulty of providing an account of emotion in animals relies heavily on interpretive experimentation, that relies on results from human subjects.[25]

Some people oppose the concept of animal emotions and suggest that emotions are not universal, including in humans. If emotions are not universal, this indicates that there is not a phylogenetic relationship between human and non-human emotion. The relationship drawn by proponents of animal emotion, then, would be merely a suggestion of mechanistic features that promote adaptivity, but lack the complexity of human emotional constructs. Thus, a social life-style may play a role in the process of basic emotions developing into more complex emotions.

Darwin concluded, through a survey, that humans share universal emotive expressions and suggested that animals likely share in these to some degree. Social constructionists disregard the concept that emotions are universal. Others hold an intermediate stance, suggesting that basic emotional expressions and emotion are universal but the intricacies are developed culturally. A study by Elfenbein and Ambady indicated that individuals within a particular culture are better at recognising other cultural members’ emotions.[40]

Examples[edit]

Primates[edit]

Primates, in particular great apes, are candidates for being able to experience empathy and theory of mind. Great apes have complex social systems; young apes and their mothers have strong bonds of attachment and when a baby chimpanzee[41] or gorilla[42] dies, the mother will commonly carry the body around for several days. Jane Goodall has described chimpanzees as exhibiting mournful behavior.[43] Koko, a gorilla trained to use sign language, was reported to have expressed vocalizations indicating sadness after the death of her pet cat, All Ball.[44]

Beyond such anecdotal evidence, support for empathetic reactions has come from experimental studies of rhesus macaques. Macaques refused to pull a chain that delivered food to themselves if doing so also caused a companion to receive an electric shock.[45][46] This inhibition of hurting another conspecific was more pronounced between familiar than unfamiliar macaques, a finding similar to that of empathy in humans.

Furthermore, there has been research on consolation behavior in chimpanzees. De Waal and Aureli found that third-party contacts attempt to relieve the distress of contact participants by consoling (e.g. making contact, embracing, grooming) recipients of aggression, especially those that have experienced more intense aggression.[47] Researchers were unable to replicate these results using the same observation protocol in studies of monkeys, demonstrating a possible difference in empathy between apes and other monkeys.[48]

Other studies have examined emotional processing in the great apes.[49] Specifically, chimpanzees were shown video clips of emotionally charged scenes, such as a detested veterinary procedure or a favorite food, and then were required to match these scenes with one of two species-specific facial expressions: «happy» (a play-face) or «sad» (a teeth-baring expression seen in frustration or after defeat). The chimpanzees correctly matched the clips to the facial expressions that shared their meaning, demonstrating that they understand the emotional significance of their facial expressions. Measures of peripheral skin temperature also indicated that the video clips emotionally affected the chimpanzees.

Rodents[edit]

In 1998, Jaak Panksepp proposed that all mammalian species are equipped with brains capable of generating emotional experiences.[50] Subsequent work examined studies on rodents to provide foundational support for this claim.[51] One of these studies examined whether rats would work to alleviate the distress of a conspecific.[52] Rats were trained to press a lever to avoid the delivery of an electric shock, signaled by a visual cue, to a conspecific. They were then tested in a situation in which either a conspecific or a Styrofoam block was hoisted into the air and could be lowered by pressing a lever. Rats that had previous experience with conspecific distress demonstrated greater than ten-fold more responses to lower a distressed conspecific compared to rats in the control group, while those who had never experienced conspecific distress expressed greater than three-fold more responses to lower a distressed conspecific relative to the control group. This suggests that rats will actively work to reduce the distress of a conspecific, a phenomenon related to empathy. Comparable results have also been found in similar experiments designed for monkeys.[53]

Langford et al. examined empathy in rodents using an approach based in neuroscience.[54] They reported that (1) if two mice experienced pain together, they expressed greater levels of pain-related behavior than if pain was experienced individually, (2) if experiencing different levels of pain together, the behavior of each mouse was modulated by the level of pain experienced by its social partner, and (3) sensitivity to a noxious stimulus was experienced to the same degree by the mouse observing a conspecific in pain as it was by the mouse directly experiencing the painful stimulus. The authors suggest this responsiveness to the pain of others demonstrated by mice is indicative of emotional contagion, a phenomenon associated with empathy, which has also been reported in pigs.[55] One behaviour associated with fear in rats is freezing. If female rats experience electric shocks to the feet and then witness another rat experiencing similar footshocks, they freeze more than females without any experience of the shocks. This suggests empathy in experienced rats witnessing another individual being shocked. Furthermore, the demonstrator’s behaviour was changed by the behaviour of the witness; demonstrators froze more following footshocks if their witness froze more creating an empathy loop.[56]

Several studies have also shown rodents can respond to a conditioned stimulus that has been associated with the distress of a conspecific, as if it were paired with the direct experience of an unconditioned stimulus.[57][58][59][60][61] These studies suggest that rodents are capable of shared affect, a concept critical to empathy.

Horses[edit]

Although not direct evidence that horses experience emotions, a 2016 study showed that domestic horses react differently to seeing photographs of positive (happy) or negative (angry) human facial expressions. When viewing angry faces, horses look more with their left eye which is associated with perceiving negative stimuli. Their heart rate also increases more quickly and they show more stress-related behaviours. One rider wrote, ‘Experienced riders and trainers can learn to read the subtle moods of individual horses according to wisdom passed down from one horseman to the next, but also from years of trial-and-error. I suffered many bruised toes and nipped fingers before I could detect a curious swivel of the ears, irritated flick of the tail, or concerned crinkle above a long-lashed eye.’ This suggests that horses have emotions and display them physically but is not concrete evidence.[62]

Birds[edit]

Marc Bekoff reported accounts of animal behaviour which he believed was evidence of animals being able to experience emotions in his book The Emotional Lives of Animals.[63] The following is an excerpt from his book:

A few years ago my friend Rod and I were riding our bicycles around Boulder, Colorado, when we witnessed a very interesting encounter among five magpies. Magpies are corvids, a very intelligent family of birds. One magpie had obviously been hit by a car and was laying dead on the side of the road. The four other magpies were standing around him. One approached the corpse, gently pecked at it-just as an elephant noses the carcass of another elephant- and stepped back. Another magpie did the same thing. Next, one of the magpies flew off, brought back some grass, and laid it by the corpse. Another magpie did the same. Then, all four magpies stood vigil for a few seconds and one by one flew off.

Bystander affiliation is believed to represent an expression of empathy in which the bystander tries to console a conflict victim and alleviate their distress. There is evidence for bystander affiliation in ravens (e.g. contact sitting, preening, or beak-to-beak or beak-to-body touching) and also for solicited bystander affiliation, in which there is post-conflict affiliation from the victim to the bystander. This indicates that ravens may be sensitive to the emotions of others, however, relationship value plays an important role in the prevalence and function of these post-conflict interactions.[64]

The capacity of domestic hens to experience empathy has been studied. Mother hens show one of the essential underpinning attributes of empathy: the ability to be affected by, and share, the emotional state of their distressed chicks.[65][66][67] However, evidence for empathy between familiar adult hens has not yet been found.[68]

Dogs[edit]

Some research indicates that domestic dogs may experience negative emotions in a similar manner to humans, including the equivalent of certain chronic and acute psychological conditions. Much of this is from studies by Martin Seligman on the theory of learned helplessness as an extension of his interest in depression:

A dog that had earlier been repeatedly conditioned to associate an audible stimulus with inescapable electric shocks did not subsequently try to escape the electric shocks after the warning was presented, even though all the dog would have had to do is jump over a low divider within ten seconds. The dog didn’t even try to avoid the «aversive stimulus»; it had previously «learned» that nothing it did would reduce the probability of it receiving a shock. A follow-up experiment involved three dogs affixed in harnesses, including one that received shocks of identical intensity and duration to the others, but the lever which would otherwise have allowed the dog a degree of control was left disconnected and didn’t do anything. The first two dogs quickly recovered from the experience, but the third dog suffered chronic symptoms of clinical depression as a result of this perceived helplessness.

A further series of experiments showed that, similar to humans, under conditions of long-term intense psychological stress, around one third of dogs do not develop learned helplessness or long-term depression.[69][70] Instead these animals somehow managed to find a way to handle the unpleasant situation in spite of their past experience. The corresponding characteristic in humans has been found to correlate highly with an explanatory style and optimistic attitude that views the situation as other than personal, pervasive, or permanent.

Since these studies, symptoms analogous to clinical depression, neurosis, and other psychological conditions have also been accepted as being within the scope of emotion in domestic dogs. The postures of dogs may indicate their emotional state.[71][72] In some instances, the recognition of specific postures and behaviors can be learned.[73]

Psychology research has shown that when humans gaze at the face of another human, the gaze is not symmetrical; the gaze instinctively moves to the right side of the face to obtain information about their emotions and state. Research at the University of Lincoln shows that dogs share this instinct when meeting a human, and only when meeting a human (i.e. not other animals or other dogs). They are the only non-primate species known to share this instinct.[74][75]

The existence and nature of personality traits in dogs have been studied (15,329 dogs of 164 different breeds). Five consistent and stable «narrow traits» were identified, described as playfulness, curiosity/fearlessness, chase-proneness, sociability and aggressiveness. A further higher order axis for shyness–boldness was also identified.[76][77]

Dogs presented with images of either human or dog faces with different emotional states (happy/playful or angry/aggressive) paired with a single vocalization (voices or barks) from the same individual with either a positive or negative emotional state or brown noise. Dogs look longer at the face whose expression is congruent to the emotional state of the vocalization, for both other dogs and humans. This is an ability previously known only in humans.[78] The behavior of a dog can not always be an indication of its friendliness. This is because when a dog wags its tail, most people interpret this as the dog expressing happiness and friendliness. Though indeed tail wagging can express these positive emotions, tail wagging is also an indication of fear, insecurity, challenging of dominance, establishing social relationships or a warning that the dog may bite.[79]

Some researchers are beginning to investigate the question of whether dogs have emotions with the help of magnetic resonance imaging.[80]

Elephants[edit]

Elephants are known for their empathy towards members of the same species as well as their cognitive memory. While this is true scientists continuously debate the extent to which elephants feel emotion. Observations show that elephants, like humans, are concerned with distressed or deceased individuals, and render assistance to the ailing and show a special interest in dead bodies of their own kind,[81] however this view is interpreted by some as being anthropomorphic.[82]

Elephants have recently been suggested to pass mirror self-recognition tests, and such tests have been linked to the capacity for empathy.[83] However, the experiment showing such actions did not follow the accepted protocol for tests of self-recognition, and earlier attempts to show mirror self-recognition in elephants have failed, so this remains a contentious claim.[84]

Elephants are also deemed to show emotion through vocal expression, specifically the rumble vocalization. Rumbles are frequency modulated, harmonically rich calls with fundamental frequencies in the infrasonic range, with clear formant structure. Elephants exhibit negative emotion and/or increased emotional intensity through their rumbles, based on specific periods of social interaction and agitation.[85]

Cats[edit]

Cat’s response to a fear inducing stimulus.

It has been postulated that domestic cats can learn to manipulate their owners through vocalizations that are similar to the cries of human babies. Some cats learn to add a purr to the vocalization, which makes it less harmonious and more dissonant to humans, and therefore harder to ignore. Individual cats learn to make these vocalizations through trial-and-error; when a particular vocalization elicits a positive response from a human, the probability increases that the cat will use that vocalization in the future.[86]

Growling can be an expression of annoyance or fear, similar to humans. When annoyed or angry, a cat wriggles and thumps its tail much more vigorously than when in a contented state. In larger felids such as lions, what appears to be irritating to them varies between individuals. A male lion may let his cubs play with his mane or tail, or he may hiss and hit them with his paws.[87] Domestic male cats also have variable attitudes towards their family members, for example, older male siblings tend not to go near younger or new siblings and may even show hostility toward them.

Hissing is also a vocalization associated with either offensive or defensive aggression. They are usually accompanied by a postural display intended to have a visual effect on the perceived threat. Cats hiss when they are startled, scared, angry, or in pain, and also to scare off intruders into their territory. If the hiss and growl warning does not remove the threat, an attack by the cat may follow. Kittens as young as two to three weeks will potentially hiss when first picked up by a human.[88]

Honeybees[edit]

Honeybees become pessimistic after being shaken

Honeybees («Apis mellifera carnica») were trained to extend their proboscis to a two-component odour mixture (CS+) predicting a reward (e.g., 1.00 or 2.00 M sucrose) and to withhold their proboscis from another mixture (CS−) predicting either punishment or a less valuable reward (e.g., 0.01 M quinine solution or 0.3 M sucrose). Immediately after training, half of the honeybees were subjected to vigorous shaking for 60 s to simulate the state produced by a predatory attack on a concealed colony. This shaking reduced levels of octopamine, dopamine, and serotonin in the hemolymph of a separate group of honeybees at a time point corresponding to when the cognitive bias tests were performed. In honeybees, octopamine is the local neurotransmitter that functions during reward learning, whereas dopamine mediates the ability to learn to associate odours with quinine punishment. If flies are fed serotonin, they are more aggressive; flies depleted of serotonin still exhibit aggression, but they do so much less frequently.

Within 5 minutes of the shaking, all the trained bees began a sequence of unreinforced test trials with five odour stimuli presented in a random order for each bee: the CS+, the CS−, and three novel odours composed of ratios intermediate between the two learned mixtures. Shaken honeybees were more likely to withhold their mouthparts from the CS− and from the most similar novel odour. Therefore, agitated honeybees display an increased expectation of bad outcomes similar to a vertebrate-like emotional state. The researchers of the study stated that, «Although our results do not allow us to make any claims about the presence of negative subjective feelings in honeybees, they call into question how we identify emotions in any non-human animal. It is logically inconsistent to claim that the presence of pessimistic cognitive biases should be taken as confirmation that dogs or rats are anxious but to deny the same conclusion in the case of honeybees.»[8][89]

Crayfish[edit]

Crayfish naturally explore new environments but display a general preference for dark places. A 2014 study[90] on the freshwater crayfish Procambarus clarkii tested their responses in a fear paradigm, the elevated plus maze in which animals choose to walk on an elevated cross which offers both aversive and preferable conditions (in this case, two arms were lit and two were dark). Crayfish which experienced an electric shock displayed enhanced fearfulness or anxiety as demonstrated by their preference for the dark arms more than the light. Furthermore, shocked crayfish had relatively higher brain serotonin concentrations coupled with elevated blood glucose, which indicates a stress response.[91] Moreover, the crayfish calmed down when they were injected with the benzodiazepine anxiolytic, chlordiazepoxide, used to treat anxiety in humans, and they entered the dark as normal. The authors of the study concluded «…stress-induced avoidance behavior in crayfish exhibits striking homologies with vertebrate anxiety.»

A follow-up study using the same species confirmed the anxiolytic effect of chlordiazepoxide, but moreover, the intensity of the anxiety-like behaviour was dependent on the intensity of the electric shock until reaching a plateau. Such a quantitative relationship between stress and anxiety is also a very common feature of human and vertebrate anxiety.[92]

See also[edit]

- Altruism in animals

- Animal cognition

- Animal communication

- Animal consciousness

- Animal faith

- Animal sexual behaviour § Sex for pleasure

- Empathy § In animals

- Evolution of emotion

- Fear § In animals

- Monkey painting

- Neuroethology

- Pain in animals

- Reward system § Animals vs. humans

- Self-awareness § In animals

- Thomas Nagel (seminal paper, «What is it like to be a bat?»)

References[edit]

- ^ a b Cabanac, Michel (2002). «What is emotion?». Behavioural Processes. 60 (2): 69–83. doi:10.1016/S0376-6357(02)00078-5. PMID 12426062. S2CID 24365776.

- ^ Panksepp, J. (1982). «Toward a general psychobiological theory of emotions». Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 5 (3): 407–422. doi:10.1017/S0140525X00012759. S2CID 145746882.

- ^ «Emotions help animals to make choices (press release)». University of Bristol. 2010. Retrieved October 26, 2013.

- ^ Jacky Turner; Joyce D’Silva, eds. (2006). Animals, Ethics and Trade: The Challenge of Animal Sentience. Earthscan. ISBN 9781844072545. Retrieved October 26, 2013.

- ^ Wong, K. (2013). «How to identify grief in animals». Scientific American. Retrieved October 26, 2013.

- ^ a b c d Rygula, R; Pluta, H; P, Popik (2012). «laughing rats are optimistic». PLOS ONE. 7 (12): e51959. Bibcode:2012PLoSO…751959R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0051959. PMC 3530570. PMID 23300582.

- ^ Douglas, C.; Bateson, M.last2=Bateson; Walsh, C.; Béduéc, A.; Edwards, S.A. (2012). «Environmental enrichment induces optimistic cognitive biases in pigs». Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 139 (1–2): 65–73. doi:10.1016/j.applanim.2012.02.018.

- ^ a b Bateson, M.; Desire, S.; Gartside, S.E.; Wright, G.A. (2011). «Agitated honeybees exhibit pessimistic cognitive biases». Current Biology. 21 (12): 1070–1073. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2011.05.017. PMC 3158593. PMID 21636277.

- ^ a b c d e f Panksepp, Jaak (2005). «Affective consciousness: Core emotional feelings in animals and humans». Consciousness and Cognition. 14 (1): 30–80. doi:10.1016/j.concog.2004.10.004. PMID 15766890. S2CID 8416255.

- ^ Merriam-Webster (2004). The Merriam-Webster dictionary (11th ed.). Springfield, MA: Author.

- ^ Fox, E. (2008). Emotion Science: An Integration of Cognitive and Neuroscientific Approaches. Palgrave MacMillan. pp. 16–17. ISBN 978-0-230-00517-4.

- ^ Ekman, P. (1992). «An argument for basic emotions». Cognition and Emotion. 6 (3): 169–200. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.454.1984. doi:10.1080/02699939208411068.

- ^ Barnard, S.; Matthews, L.; Messori, S.; Podaliri-Vulpiani, M.; Ferri, N. (2015). «Laterality as an indicator of emotional stress in ewes and lambs during a separation test». Animal Cognition. 19 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1007/s10071-015-0928-3. PMID 26433604. S2CID 7008274.

- ^ Handel, S. (2011-05-24). «Classification of Emotions». Retrieved 30 April 2012.

- ^ a b c d Dawkins, M. (2000). «Animal minds and animal emotions». American Zoologist. 40 (6): 883–888. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.596.3220. doi:10.1668/0003-1569(2000)040[0883:amaae]2.0.co;2. S2CID 86157681.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b Watson, J. B. (1930). Behaviorism (Revised Ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 11.

- ^ Dixon, B. (2001). «Animal emotions». Ethics and the Environment. 6 (2): 22–30. doi:10.2979/ete.2001.6.2.22.

- ^ Moussaieff Masson, J.; McCarthy, S. (1996). When Elephants Weep: The Emotional Lives of Animals. Delta. ISBN 978-0-385-31428-2.

- ^ D.S. Mills; J.N. Marchant-Forde, eds. (2010). The Encyclopedia of Applied Animal Behaviour and Welfare. CABI. ISBN 978-0851997247.

- ^ Morgan, C.L. (1903). An Introduction to Comparative Psychology (2nd ed.). W. Scott, London. pp. 59.

- ^ a b Darwin, C. (1872). The Expression Of The Emotions In Man And Animals. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

- ^ Hess, U. and Thibault, P., (2009). Darwin and emotion expression. American Psychological Association, 64(2): 120-128.[1]

- ^ Scruton, R; Tyler, A. (2001). «Debate: Do animals have rights?». The Ecologist. 31 (2): 20–23. ProQuest 234917337.

- ^ Oately, K.; Jenkins, J.M. (1996). Understanding Emotions. Blackwell Publishers. Malden, MA. ISBN 978-1-55786-495-6.

- ^ a b Paul, E; Harding, E; Mendl, M (2005). «Measuring emotional processes in animals: the utility of a cognitive approach». Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 29 (3): 469–491. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.01.002. PMID 15820551. S2CID 14127825.

- ^ Haselton, M. G.; Nettle, D. & Andrews, P. W. (2005). The evolution of cognitive bias. In D. M. Buss (Ed.), The Handbook of Evolutionary Psychology: Hoboken, NJ, US: John Wiley & Sons Inc. pp. 724–746.

- ^ Bless, H.; Fiedler, K. & Strack, F. (2004). Social cognition: How individuals construct social reality. Hove and New York: Psychology Press. p. 2.

- ^ Harding, EJ; Paul, ES; Mendl, M (2004). «Animal behaviour: cognitive bias and affective state». Nature. 427 (6972): 312. Bibcode:2004Natur.427..312H. doi:10.1038/427312a. PMID 14737158. S2CID 4411418.

- ^ Malhi, Gin S; Baune, Berhard T; Porter, Richard J (December 2015). «Re-Cognizing mood disorders». Bipolar Disorders. 17: 1–2. doi:10.1111/bdi.12354. ISSN 1398-5647. PMID 26688286.

- ^ Sherwin, C.M.; Olsson, I.A.S. (2004). «Housing conditions affect self-administration of anxiolytic by laboratory mice». Animal Welfare. 13: 33–38.

- ^ Fajardo, C.; et al. (4 March 2008). «Von Economo neurons are present in the dorsolateral (dysgranular) prefrontal cortex of humans». Neuroscience Letters. 435 (3): 215–218. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2008.02.048. PMID 18355958. S2CID 8454354.

- ^ a b c d Hof, P.R.; Van Der Gucht, E. (2007). «Structure of the cerebral cortex of the humpback whale, Megaptera novaeangliae (Cetacea, Mysticeti, Balaenopteridae)». Anatomical Record Part A. 290 (1): 1–31. doi:10.1002/ar.20407. PMID 17441195. S2CID 15460266.

- ^ Coghlan, A. (27 November 2006). «Whales boast the brain cells that ‘make us human’«. New Scientist. Archived from the original on 16 April 2008. Retrieved 27 August 2017.

- ^ Butti, C; Sherwood, CC; Hakeem, AY; Allman, JM; Hof, PR (July 2009). «Total number and volume of Von Economo neurons in the cerebral cortex of cetaceans». The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 515 (2): 243–59. doi:10.1002/cne.22055. PMID 19412956. S2CID 6876656.

- ^ Hakeem, A. Y.; Sherwood, C. C.; Bonar, C. J.; Butti, C.; Hof, P. R.; Allman, J. M. (2009). «Von Economo neurons in the elephant brain». The Anatomical Record. 292 (2): 242–8. doi:10.1002/ar.20829. PMID 19089889. S2CID 12131241.

- ^ Panksepp, J; Burgdorf, J (2003). ««Laughing» rats and the evolutionary antecedents of human joy?». Physiology and Behavior. 79 (3): 533–547. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.326.9267. doi:10.1016/s0031-9384(03)00159-8. PMID 12954448. S2CID 14063615.

- ^ Knutson, B; Burgdorf, J; Panksepp, J (2002). «Ultrasonic vocalizations as indices of affective states in rats» (PDF). Psychological Bulletin. 128 (6): 961–977. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.128.6.961. PMID 12405139. S2CID 4660938. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-02-28.

- ^ Panksepp, J; Burgdorf, J (2000). «50-kHz chirping (laughter?) in response to conditioned and unconditioned tickle-induced reward in rats: effects of social housing and genetic variables». Behavioural Brain Research. 115 (1): 25–38. doi:10.1016/s0166-4328(00)00238-2. PMID 10996405. S2CID 29323849.

- ^ a b Boissy, A.; et al. (2007). «Assessment of positive emotions in animals to improve their welfare». Physiology & Behavior. 92 (3): 375–397. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.02.003. PMID 17428510. S2CID 10730923.

- ^ Elfenbein, H.A.; Ambady, N. (2002). «On the universality and cultural specificity of emotion recognition: A meta-analysis». Psychological Bulletin. 128 (2): 203–235. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.128.2.203. PMID 11931516. S2CID 16073381.

- ^ Winford, J.N. (2007). «Almost human, and sometimes smarter». New York Times. Retrieved October 26, 2013.

- ^ «Mama gorilla won’t let go of her dead baby». Associated Press. 2008. Retrieved October 26, 2013.

- ^ Bekoff, Marc (2007). The Emotional Lives of Animals: A Leading Scientist Explores Animal Joy, Sorrow, and Empathy—and why They Matter. New World Library. ISBN 9781577315025.

- ^ McGraw, C. (1985). «Gorilla’s Pets: Koko Mourns Kittens Death». Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 26, 2013.

- ^ Wechkin, S.; Masserman, J.H.; Terris, W. (1964). «Shock to a conspecific as an aversive stimulus». Psychonomic Science. 1 (1–12): 47–48. doi:10.3758/bf03342783.

- ^ Masserman, J.; Wechkin, M.S.; Terris, W. (1964). «Altruistic behavior in rhesus monkeys». American Journal of Psychiatry. 121 (6): 584–585. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.691.4969. doi:10.1176/ajp.121.6.584. PMID 14239459.

- ^ De Waal, F.B.M. & Aureli, F. (1996). Consolation, reconciliation, and a possible cognitive difference between macaques and chimpanzees. In A.E. Russon, K.A. Bard, and S.T. Parker (Eds.), Reaching Into Thought: The Minds Of The Great Apes (pp. 80-110). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Watts, D.P., Colmenares, F., & Arnold, K. (2000). Redirection, consolation, and male policing: How targets of aggression interact with bystanders. In F. Aureli and F.B.M. de Waal (Eds.), Natural Conflict Resolution (pp. 281-301). Berkeley: University of California Press.

- ^ Parr, L.A. (2001). «Cognitive and physiological markers of emotional awareness in chimpanzees». Animal Cognition. 4 (3–4): 223–229. doi:10.1007/s100710100085. PMID 24777512. S2CID 28270455.

- ^ Panksepp, J. (1998). Affective. Neuroscience: The Foundation of Human and Animal Emotions. Oxford University Press, New York. p. 480.

- ^ Panksepp, J.B.; Lahvis, G.P. (2011). «Rodent empathy and affective neuroscience». Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 35 (9): 1864–1875. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2011.05.013. PMC 3183383. PMID 21672550.

- ^ Rice, G.E.; Gainer, P (1962). «Altruism in the albino rat». Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology. 55: 123–125. doi:10.1037/h0042276. PMID 14491896.

- ^ Mirsky, I.A.; Miller, R.E.; Murphy, J.B. (1958). «The communication of affect in rhesus monkeys I. An experimental method». Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association. 6 (3): 433–441. doi:10.1177/000306515800600303. PMID 13575267. S2CID 2646373.

- ^ Langford, D.J.; Crager, S.E.; Shehzad, Z.; Smith, S.B.; Sotocinal, S.G.; Levenstadt, J.S.; Mogil, J.S. (2006). «Social modulation of pain as evidence for empathy in mice». Science (Submitted manuscript). 312 (5782): 1967–1970. Bibcode:2006Sci…312.1967L. doi:10.1126/science.1128322. PMID 16809545. S2CID 26027821.

- ^ Reimerta, I.; Bolhuis, J.E; Kemp, B.; Rodenburg., T.B. (2013). «Indicators of positive and negative emotions and emotional contagion in pigs». Physiology and Behavior. 109: 42–50. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2012.11.002. PMID 23159725. S2CID 29192088.

- ^ Atsak, P.; Ore, M; Bakker, P.; Cerliani, L.; Roozendaal, B.; Gazzola, V.; Moita, M.; Keysers, C. (2011). «Experience modulates vicarious freezing in rats: a model for empathy». PLOS ONE. 6 (7): e21855. Bibcode:2011PLoSO…621855A. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0021855. PMC 3135600. PMID 21765921.

- ^ Kavaliers, M.; Colwell, D.D.; Choleris, E. (2003). «Learning to fear and cope with a natural stressor: individually and socially acquired corticosterone and avoidance responses to biting flies». Hormones and Behavior. 43 (1): 99–107. doi:10.1016/s0018-506x(02)00021-1. PMID 12614639. S2CID 24961207.

- ^ Kim, E.J.; Kim, E.S.; Covey, E.; Kim, J.J. (2010). «Social transmission of fear in rats: the role of 22-kHz ultrasonic distress vocalization». PLOS ONE. 5 (12): e15077. Bibcode:2010PLoSO…515077K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0015077. PMC 2995742. PMID 21152023.

- ^ Bruchey, A.K.; Jones, C.E.; Monfils, M.H. (2010). «Fear conditioning by-proxy: social transmission of fear during memory retrieval». Behavioural Brain Research. 214 (1): 80–84. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2010.04.047. PMC 2975564. PMID 20441779.

- ^ Jeon, D.; Kim, S.; Chetana, M.; Jo, D.; Ruley, H.E.; Lin, S.Y.; Shin, H.S.; Kinet, Jean-Pierre; Shin, Hee-Sup (2010). «Observational fear learning involves affective pain system and Cav1.2 Ca2+ channels in ACC». Nature Neuroscience. 13 (4): 482–488. doi:10.1038/nn.2504. PMC 2958925. PMID 20190743.

- ^ Chen, Q.; Panksepp, J.B.; Lahvis, G.P. (2009). «Empathy is moderated by genetic background in mice». PLOS ONE. 4 (2): e4387. Bibcode:2009PLoSO…4.4387C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0004387. PMC 2633046. PMID 19209221.

- ^ Smith, A.V.; Proops, L.; Grounds, K.; Wathan, J.; McComb, K. (2016). «Functionally relevant responses to human facial expressions of emotion in the domestic horse (Equus caballus)». Biology Letters. 12 (2): 20150907. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2015.0907. PMC 4780548. PMID 26864784.

- ^ Bekoff, Marc (2007). The Emotional Lives of Animals. Novato, California: New World Library. p. 1.

- ^ Orlaith, N.F.; Bugnyar, T. (2010). «Do Ravens Show Consolation? Responses to Distressed Others». PLOS ONE. 5 (5): e10605. Bibcode:2010PLoSO…510605F. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0010605. PMC 2868892. PMID 20485685.

- ^ Edgar, J.L.; Paul, E.S.; Nicol, C.J. (2013). «Protective mother hens: Cognitive influences on the avian maternal response». Animal Behaviour. 86 (2): 223–229. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2013.05.004. ISSN 0003-3472. S2CID 53179718.

- ^ Edgar, J.L.; Lowe, J.C.; Paul, E.S.; Nicol, C.J. (2011). «Avian maternal response to chick distress». Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 278 (1721): 3129–3134. doi:10.1098/rspb.2010.2701. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 3158930. PMID 21389025.

- ^ Broom, D.M.; Fraser, A.F. (2015). Domestic Animal Behaviour and Welfare (5 ed.). CABI Publishers. pp. 42, 53, 188. ISBN 978-1780645391.

- ^ Edgar, J.L.; Paul, E.S.; Harris, L.; Penturn, S.; Nicol, C.J. (2012). «No evidence for emotional empathy in chickens observing familiar adult conspecifics». PLOS ONE. 7 (2): e31542. Bibcode:2012PLoSO…731542E. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0031542. PMC 3278448. PMID 22348100.

- ^ Seligman, M. E. (1972). Learned helplessness. Annual Review of Medicine, 207-412.

- ^ Seligman, M. E.; Groves, D. P. (1970). «Nontransient learned helplessness». Psychonomic Science. 19 (3): 191–192. doi:10.3758/BF03335546.

- ^ «How to Avoid a Dog Bite -Be polite and pay attention to body language». The Humane Society of the United States. 2017. Retrieved April 28, 2017.

- ^ «Dog bite prevention & canine body language» (PDF). San Diego Humane Society. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 6, 2017. Retrieved April 30, 2017.

- ^ «New Bill In California to Protect Dogs in Police Altercations — PetGuide». PetGuide. 2017-02-22. Retrieved 2017-06-22.

- ^ Guo, K.; Hall, C.; Hall, S.; Meints, K.; Mills, D. (2007). «Left gaze bias in human infants, rhesus monkeys, and domestic dogs». Perception. 3. Archived from the original on 2011-07-15. Retrieved 2010-06-24.

- ^ Alleyne, R. (2008-10-29). «Dogs can read emotion in human faces». Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 2011-01-11. Retrieved 2010-06-24.

- ^ Svartberg, K.; Tapper, I.; Temrin, H.; Radesäter, T.; Thorman, S. (2004). «Consistency of personality traits in dogs». Animal Behaviour. 69 (2): 283–291. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2004.04.011. S2CID 53154729.

- ^ Svartberga, K.; Forkman, B. (2002). «Personality traits in the domestic dog (Canis familiaris)» (PDF). Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 79 (2): 133–155. doi:10.1016/S0168-1591(02)00121-1.

- ^ Albuquerque, N.; Guo, K.; Wilkinson, A.; Savalli, C.; Otta, E.; Mills, D. (2016). «Dogs recognize dog and human emotions». Biology Letters. 12 (1): 20150883. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2015.0883. PMC 4785927. PMID 26763220.

- ^ Coren, Stanley (December 5, 2011). «What a Wagging Dog Tail Really Means: New Scientific Data Specific tail wags provide information about the emotional state of dogs». Psychology Today. Retrieved April 30, 2017.

- ^ Berns, G. S.; Brooks, A. M.; Spivak, M. (2012). «Functional MRI in Awake Unrestrained Dogs». PLOS ONE. 7 (5): e38027. Bibcode:2012PLoSO…738027B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0038027. PMC 3350478. PMID 22606363.

- ^ Douglas-Hamilton, Iain; Bhalla, Shivani; Wittemyer, George; Vollrath, Fritz (2006). «Behavioural reactions of elephants towards a dying and deceased matriarch». Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 100 (1–2): 87–102. doi:10.1016/j.applanim.2006.04.014. ISSN 0168-1591.

- ^ Plotnik, Joshua M.; Waal, Frans B. M. de (2014-02-18). «Asian elephants (Elephas maximus) reassure others in distress». PeerJ. 2: e278. doi:10.7717/peerj.278. ISSN 2167-8359. PMC 3932735. PMID 24688856.

- ^ Bates, L, A. (2008). «Do Elephants Show Empathy?». Journal of Consciousness Studies. 15: 204–225.

- ^ Gallup, Gordon G.; Anderson, James R. (March 2020). «Self-recognition in animals: Where do we stand 50 years later? Lessons from cleaner wrasse and other species». Psychology of Consciousness: Theory, Research, and Practice. 7 (1): 46–58. doi:10.1037/cns0000206. ISSN 2326-5531. S2CID 204385608.

- ^ Altenmüller, Eckart; Schmidt, Sabine; Zimmermann, Elke (2013). Evolution of emotional communication from sounds in nonhuman mammals to speech and music in man. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-174748-9. OCLC 940556012.

- ^ «Cats do control humans, study finds». LiveScience.com. 2009. Retrieved 2009-07-20.

- ^ Lion#cite ref-105

- ^ Wikipedia, Source. (2013). Cat behavior : cats and humans, cat communication, cat intelligence, cat pheromone, cat. University-Press Org. ISBN 978-1-230-50106-2. OCLC 923780361.

- ^ Gorvett, Zaria (2021-11-29). «Why insects are more sensitive than they seem». BBC Future. Retrieved 2022-01-03.

- ^ Fossat, P.; Bacqué-Cazenave, J.; De Deurwaerdère, P.; Delbecque, J.-P.; Cattaert, D. (2014). «Anxiety-like behavior in crayfish is controlled by serotonin». Science. 344 (6189): 1293–1297. Bibcode:2014Sci…344.1293F. doi:10.1126/science.1248811. PMID 24926022. S2CID 43094402.

- ^ Sneddon, L.U. (2015). «Pain in aquatic animals». Journal of Experimental Biology. 218 (7): 967–976. doi:10.1242/jeb.088823. PMID 25833131.

- ^ Fossat, P.; Bacqué-Cazenave, J.; De Deurwaerdère, P.; Cattaert, D.; Delbecque, J.P. (2015). «Serotonin, but not dopamine, controls the stress response and anxiety-like behavior in the crayfish Procambarus clarkii». Journal of Experimental Biology. 218 (17): 2745–2752. doi:10.1242/jeb.120550. PMID 26139659.

Further reading[edit]

- Bekoff, M.; Jane Goodall (2007). The Emotional Lives of Animals. ISBN 978-1-57731-502-5.

- Holland, J. (2011). Unlikely Friendships: 50 Remarkable Stories from the Animal Kingdom.

- Swirski, P. (2011). «You’ll Never Make a Monkey Out of Me or Altruism, Proverbial Wisdom, and Bernard Malamud’s God’s Grace.» American Utopia and Social Engineering in Literature, Social Thought, and Political History. New York, Routledge.

- Mendl, M.; Burman, O.H.P.; Paul, E.S. (2010). «An integrative and functional framework for the study of animal emotion and mood». Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 277 (1696): 2895–2904. doi:10.1098/rspb.2010.0303. PMC 2982018. PMID 20685706.

- Anderson, D. J.; Adolphs, R. (2014). «A framework for studying emotions across species». Cell. 157 (1): 187–200. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.003. PMC 4098837. PMID 24679535.

- Wohlleben, Peter (2017-11-07). The Inner Life of Animals: Love, Grief, and Compassion — Surprising Observations of a Hidden World. Translated by Jane Billinghurst. Greystone Books Ltd. ISBN 9781771643023. Foreword by Jeffrey Moussaieff Masson. First published in 2016 in German, under the title Das Seelenleben der Tiere.

- «Sensitivity of pigs and the thieving of squirrels — all part of animals’ inner lives». The Washington Post. 2017-12-08.