Фрэнсис Дрейк биография

13 Июля 1540 – 28 Января 1596 гг. (55 лет)

4.3

Средняя оценка: 4.3

Всего получено оценок: 167.

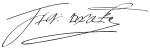

Френсис Дрейк (1540–1596) — английский военно-морской офицер, первооткрыватель и любимый корсар королевы Елизаветы I. Вошёл в историю как первый британский мореплаватель, совершивший кругосветное путешествие. Фрэнсис Дрейк, биография которого стала олицетворением мужества и отваги, является национальным героем Англии. Доклад на тему открытий и самых важных событий из жизни мореплавателя будет особенно полезен для детей, учеников 5 класса.

Ранние годы

Фрэнсис Дрейк родился в 1540 году в графстве Девон, став старшим из 12 детей протестантского фермера.

Из-за религиозных преследований в 1549 году семья была вынуждена покинуть Девон, и поселиться в порту Кент. Отец стал наместником местной церкви, а юный Фрэнсис стал обучаться тонкостям мореплавания.

Спустя несколько лет Дрейк отправился в своё первое плавание на торговом барке. Владелец барка настолько привязался к исполнительному и старательному юноше, что после смерти завещал ему своё судно. Так в возрасте 18 лет Фрэнсис Дрейк стал капитаном собственного корабля «Юдифь».

Первые экспедиции

Поначалу Дрейк занимался перевозкой различных торговых грузов. Однако подобная деятельность не приносила хорошего заработка.

В 1567 году Фрэнсис и его двоюродный брат Джон Хокинс решили провернуть авантюру с торговлей темнокожими рабами. Однако братьев поджидала неудача: с трюмами, полными «живым товаром», они оказались в западне у испанцев. Многие их товарищи были убиты, Дрейку и Хокинсу лишь чудом удалось выжить. Ненависть к Испании оказалась настолько сильна, что Фрэнсис поклялся обязательно отомстить обидчикам.

Последующие две экспедиции в Вест-Индию оказались очень успешными, благодаря чему Дрейк привлёк внимание королевы Елизаветы I. От неё он получил лицензию капера, которая, по сути, разрешала грабить испанские порты на Карибах. Фрэнсис Дрейк был рад воспользоваться случаем отомстить испанцам и спустя время вернулся в Англию с огромным количеством испанских сокровищ. За Дрейком закрепилась репутация самого успешного пирата своего времени.

Кругосветное плаванье

Довольная успехами Дрейка на море, королева Елизавета поручила ему пройти вдоль тихоокеанского побережья, атакуя все встречные испанские суда. Кроме того, корсар получил тайное поручение — тщательно исследовать побережье Северной Америки и отыскать пролив.

Получив в своё распоряжение 5 кораблей и сотню человек экипажа, 13 декабря 1577 года Дрейк покинул Плимут и отправился в путешествие. Разграбив испанские порты, расположенные вдоль западного побережья Южной Америки, Дрейк отправился на поиски пути в Атлантику. Он причалил возле берегов нынешнего Сан-Франциско, объявив королеву Елизавету правительницей этих земель.

Чтобы добраться до Тихого океана, капитан провёл флотилию через Магелланов пролив. Обогнув мыс Доброй надежды, в сентябре 1580 года он вернулся в Плимут. Таким образом, Фрэнсис Дрейк со своей командой совершил кругосветное путешествие, которое длилось 2 года и 9 месяцев. Его основным вкладом в пользу Англии стало не только испанское золото, но и ряд важных географических открытий.

Спустя несколько месяцев королева пожаловала Фрэнсису Дрейку рыцарский титул. Капитан также получил должность мэра города Плимут и членство в Палате Общин.

Непобедимая армада

В 1585 году между Англией и Испанией вспыхнула война. Получив в своё распоряжение флотилию из 20 кораблей, Дрейк принялся захватывать испанские колонии.

Спустя 2 года Дрейк с 30 судами вошёл в Лиссабон, где узнал, что в Кадисе собрано много кораблей испанской Непобедимой армады. Недолго думая, Дрейк тут же вошёл в порт и сжёг 22 суда своего давнего противника. Этот поступок имел важное стратегическое значение — испанцы получили серьёзный урон, в то время как боевой дух англичан значительно окреп. Спустя год Дрейк принял участие в окончательном уничтожении Великой армады.

При изучении краткой биографии Фрэнсиса Дрейка стоит упомянуть и о его неудачах. В 1596 году королева направила флотилию во главе со своим любимцем в Вест-Индию. Однако в этот раз военный поход оказался неудачным: испанцам удалось отбить атаку, а Дрейк тяжело заболел лихорадкой и дизентерией.

Неудача сломила Дрейка, ослабленного тяжёлой болезнью. Скончался мореплаватель в январе 1596 года в возрасте 55 лет. Френсис Дрейк был дважды женат, но оба брака оказались бездетными. В итоге огромное состояние Френсиса Дрейка унаследовал его племянник.

Тест по биографии

Доска почёта

Чтобы попасть сюда — пройдите тест.

-

Август Мандаринский

10/10

-

Alejandro Sailtramp

10/10

-

Sabina Mukhtarova

6/10

Оценка по биографии

4.3

Средняя оценка: 4.3

Всего получено оценок: 167.

А какая ваша оценка за эту биографию?

Он привез из Нового Света картофель, табак и сокровищ ценой в несколько годовых бюджетов английского королевства. Как было не восхищаться Фрэнсисом Дрейком? Его имя не забыто и сейчас: его можно встретить на географических картах и в рассказах о благородных пиратах прошлого.

А знаете ли вы, Почему моряк Фрэнсис Дрейк герой для англичан и пират для остального мира?

Как сын фермера стал пиратом

Будущий пират и вице-адмирал Королевского флота родился в 1540 году в семье фермера Эдмунда Дрейка, который был из младших сыновей, а значит, не понаслышке знал о том, что значит быть стесненным в средствах. В бедности проходили детство, а затем отрочество и Фрэнсиса, первенца. К тому же, его родителям, протестантам, пришлось страдать за свою веру – эпоха была неспокойной, и за свои религиозные воззрения часто приходилось бороться.

Баклендское аббатство — его Дрейк приобрел после того, как был посвящен в рыцари

Спасаясь от гонений со стороны католиков, Дрейки были вынуждены бежать из Девоншира, и фермерство осталось в прошлом. Отец был вынужден устроиться корабельным священником – так жизнь Фрэнсиса Дрейка оказалась связана с морем. Уже в двенадцать он был юнгой на торговом корабле, а в восемнадцать благодаря завещанию прежнего владельца получил судно в наследство и стал капитаном.

Приличного образования Дрейк так и не получил, до конца жизни он весьма неохотно читал и писал, зато он был решителен, самостоятелен и умел обращать себе на пользу любые повороты судьбы. Пусть первый корабль был небольшим, водоизмещением всего в 15 тонн, зато это было его, Дрейка, собственное дело, открывавшее широкие возможности. В 1558 году случилось и другое удачное для Дрейка событие: на престол, сменив умершую королеву Марию, вступила Елизавета.

Елизавета I

В 1567 году Фрэнсис Дрейк отправился в дальнее плавание, через океан – к берегам американского континента, не так давно открытого, но уже ставшего предметом территориальных споров.

Это была совместная экспедиция молодого капитана и его дяди, Джона Хокинса, который был старше Дрейка всего на восемь лет. Хокинс еще за несколько лет до этого путешествия открыл для себя способ хорошо заработать: он отправлялся к берегам Африки, там его целью становился захват чернокожих рабов, которые затем переправлялись в Новый Свет, чтобы быть проданными на невольничьем рынке. Работорговля была исключительно прибыльным занятием, несмотря на то, что мореплавателям постоянно угрожали самые разнообразные опасности – шторм, бунты собственных команд, эпидемии, набеги африканских племен, нападения испанцев.

Фрэнсис Дрейк и Джон Хокинс (в центре и справа)

Отношения английских и испанских мореплавателей были напряженными – виной тому была поддержка английской королевой голландских повстанцев, стремившихся освободиться от испанского владычества. Да и насчет колонизации американских земель вопрос стоял остро: Елизавете было интересно разбавить это испано-португальское представительство в Новом Свете, но англичанам там рады не были. Интересно, что испанские инквизиторы, поощрявшие истребление индейских племен, осуждали работорговлю как нечто не согласующееся с католическим вероучением.

В 2006 году во время визита в африканскую Гамбию потомок Хокинса принес публичные извинения за деятельность своего предка

Во время экспедиции Хокинса и Дрейка пять их кораблей подверглись нападению испанцев, в результате осталось два судна. Именно тогда Дрейк и поставит своей целью взять у испанцев все, что только возможно, – не только в стремлении отомстить за причиненные убытки, но и найдя наконец реального врага, которому можно было предъявить давние счеты: за детство, полное лишений, за преследования католиками родителей.

Король Испании Филипп II

С тех пор Фрэнсис Дрейк стал для испанского короля Филиппа II кошмаром наяву. Его называли Эль Драке, то есть «Дракон». Следующая экспедиция отправилась в Вест-Индию в 1572 году, тогда были захвачены и разграблены суда и испанские владения на суше, корабли англичанина ломились от золота и серебра. В Англию Фрэнсис Дрейк возвратился национальным героем.

Глава «пиратского флота» королевы Елизаветы

Фрэнсис Дрейк был человеком не только богатым, но и щедрым, а кроме того, он с большим почтением и галантностью относился к королеве. Существует даже легенда, что именно благодаря этому английскому пирату возникла традиция отдавать честь – якобы при первой встрече с Елизаветой он, сделав вид, что ослеплен ее красотой, заслонил глаза рукой. Дрейка заметили при дворе, да не просто заметили – ему была предложена служба на благо королевства. Бравый капитан был направлен в Ирландию для подавления восстания. А в 1577 году Елизавета поручила Дрейку возглавить экспедицию к тихоокеанскому побережью Америки.

М. Гирартс-мл. Портрет Фрэнсиса Дрейка

Формально плавание затевалось ради исследования новых земель и открытия Terra Australis Incognita – неизвестной южной земли, то есть Антарктиды. О том, что Южный полюс окружает материк, догадывались задолго до появления в тех широтах европейских мореплавателей. Забегая вперед, нужно сказать, что официальной цели путешествия Дрейк так и не достиг, правда, именно его имя получил широкий пролив между Антарктидой и архипелагом Огненная Земля.

Истинной же целью экспедиции было отобрать у испанцев столько богатств, сколько представится возможным, ради пополнения английской казны. Дрейк стал, таким образом, не пиратом, а капером – то есть действовал с санкции своего правителя против кораблей вражеского государства. Соглашение между королевой и капером носило конфиденциальный характер – только лишь им двоим была известна точная сумма награбленного и привезенного в Англию испанского добра.

Копия галеона «Золотая лань» в Лондоне

Тихого океана достигло только одно из судов экспедиции – галеон под названием «Пеликан», который был переименован в «Золотую лань» и под этим названием вошел в историю. На этом небольшом корабле (длина его составляла всего 36 метров) Дрейк и его команда провели без малого три года, поднявшись вдоль западного американского побережья до самого Ванкувера. Берег неподалеку от Сан-Франциско был объявлен английским и получил название Новый Альбион. Залив на калифорнийском побережье – там, где высадился Дрейк – носит его имя.

Обогнув африканский континент, Дрейк вернулся в Англию, совершив кругосветное путешествие и, кстати, доставил на родину огромное количество ценностей. По всей видимости, оно в разы превышало бюджет государства, а тем, кто инвестировал в это путешествие, все предприятие принесло более 4000 процентов прибыли.

Ф.Я. Лютербург «Разгром испанской армады»

Дрейк был встречен как национальный герой, он получил от королевы рыцарское звание. Испанцы были в ярости. Тем более, что на этом Дрейк не остановился и спустя несколько лет вернулся в воды Вест-Индии, разорив еще несколько испанских городов. Говорили, правда, что нападения английского капера использовались испанскими колонистами в собственных целях: на грабежи Дрейка списывали пропажу гораздо большего количества золота, чем англичанин мог увезти в реальности.

В 1585 году началась англо-испанская война, а в 1586 Испания начала снаряжать Непобедимую армаду – флот, который должен был дать отпор английским кораблям, а кроме того, помочь британским католикам в борьбе с протестантской церковью. Спустя два года состоялся поход Армады, и от испанцев отвернулась удача: больше половины судов были потеряны в боях или потонули в результате шторма, который разыгрался у британских берегов. Вице-адмирал флота, сэр Фрэнсис Дрейк отличился и тут, приняв в разгроме Непобедимой армады непосредственное участие.

Последняя экспедиция

А вот в последние годы жизни Дрейка удача как будто изменила ему. Планы захватить Лиссабон, на что очень рассчитывала Елизавета, провалились, нападения на испанские колонии уже не приносили того впечатляющего результата: неприятели извлекали уроки из прошлых поражений. Елизавета относилась к своему корсару куда прохладнее, чем прежде. В последнюю свою экспедицию к американскому берегу Дрейк отправился в 1595 году, снова с Джоном Хокинсом. Там, вблизи Панамы, он скончался, попросив перед смертью надеть на него доспехи.

Дж. Бем «Похороны Дрейка в море»

Фрэнсиса Дрейка похоронили в море в свинцовом гробу. Для короля Испании известие о смерти давнего врага стало настоящим праздником.

Детей у Дрейка, несмотря на два брака, не было, состояние перешло племяннику. До сих пор, как и полагается в таких случаях, ходят слухи о кладах с несметными сокровищами, спрятанными перед смертью английским пиратом, да еще – о карте, которая была якобы положена в гроб вместе с телом Дрейка.

Дрейк оставил в истории след не только как корсар на службе Ее Величества. Вместе с Хокинсом в 1590 году он основал в Лондоне богадельню для отставных моряков, чей возраст или здоровье не позволяли самостоятельно добиться достойных условий жизни.

Слева — памятник Дрейку в немецком Оффенбурге, уничтожен нацистами в 1939 г.; справа — памятник в Плимуте

Англичанин внес коррективы в военную науку; раньше считалось, что преимущество в морском бою дает количество орудий на борту, Дрейк же продемонстрировал, что куда большую значимость имеют скорость и маневренность судна – эта тактика оправдала себя во время боев против Непобедимой армады.

Если сам капер не был любителем брать в руки перо и чернила, то среди его окружения находилось немало тех, кто брался увековечить события его жизни на бумаге. Да и испанская инквизиция подробно документировала все, что относилось к Эль Драке. А потому о жизни Фрэнсиса Дрейка сейчас известно довольно много, несмотря на то, что после его смерти прошло уже более четырех веков. Правда, легенд и слухов остается предостаточно.

Фрэнсис Дрейк никогда не поднимал над своими судами черный пиратский флаг, а вот некоторые его коллеги это практиковали – с совершенно конкретными целями.

[источники]

Источник: https://kulturologia.ru/blogs/090920/47494/

Это копия статьи, находящейся по адресу https://masterokblog.ru/?p=73370.

Имя Фрэнсиса Дрейка, пирата XVI века, носит пролив между Антарктидой и Огненной землёй, пролив, соединяющий Атлантический и Тихий океан. И это одна из причин, почему его можно назвать самым известным реальным пиратом. Дрейк прославился тем, что осуществил кругосветное путешествие (второе в истории!) и принял активное участие в разгромлении испанского флота, который тогда называли Непобедимой Армадой. Одно время Дрейк был очень полезен британской короне, и поэтому в итоге даже смог получить титулы рыцаря и адмирала. В жизни пирата Её Величества было действительно много крутых штормов и поворотов…

Содержание

- 1 Дрейк в роли работорговца и его первые приключения

- 2 Путешествие Дрейка за сокровищами «Серебряного каравана»

- 3 Начало кругосветного путешествия английского корсара

- 4 «Золотая лань» идёт на север

- 5 Встреча Дрейка с индейцами и возвращение домой

- 6 Дрейк в роли адмирала и его последние годы жизни

- 7 Мифы и достопримечательности, связанные с личностью Дрейка

Дрейк в роли работорговца и его первые приключения

Фрэнсис Дрейк родился в семье корабельного священника в 1540 или 1541 году. Ещё будучи ребёнком (в возрасте от 10 до 13 лет), он завербовался юнгой на торговый корабль. Старик-капитан был впечатлён усердием юноши в морском деле, и поэтому решил завещать своё судно именно Дрейку. Таким образом, уже в 1561 году у Дрейка появился собственный корабль.

А когда Фрэнсис стал чуть постарше, его взял в своё плавание родственник — известный к тому времени моряк Джон Хокинс. Хокинс и Дрейк хотели нажиться на контрабандной работорговле. Схема «бизнеса» была незатейлива: взять рабов в Африке, а затем перевезти их в трюмах и продать в одной из колоний Испании в Вест-Индии (на островах Карибского моря).

Это знаменитый английский моряк Джон Хокинс — в каком-то смысле он являлся учителем Дрейка

Одна из экспедиций под руководством Хокинса, в которой участвовал Дрейк, состоялась в 1567 году. И так вышло, что около берегов Мексики английские суда подверглись вероломной атаке со стороны испанцев. Значительная часть этих судов ушла на дно, спастись смогли только два судна — Дрейка и Хокинса. Британские власти впоследствии требовали у короля Испанской империи (тогда им был Филипп II), чтобы он возместил ущерб за утраченные суда, но получили отказ. Узнав об этом, Дрейк сообщил, что сам заберёт всё, что сможет, у испанской короны.

Пират Фрэнсис Дрейк собственной персоной

То есть Дрейком во многих случаях двигала не только жажды наживы, но и желание отомстить. В скором времени он начинает действовать уже не как работорговец, но как пират — пускает ко дну и десятками грабит торговые корабли под испанскими флагами, попутно принося разрушения в прибрежные порты.

Путешествие Дрейка за сокровищами «Серебряного каравана»

Достаточно известна и подробно описана современниками экспедиция Дрейка 1572–1573 годов. Пират посетил испанские владения в Вест-Индии, захватил порт Номбре-де-Дьос, что находился на территории современной Панамы, и затопил некоторое количество судов неподалёку от гавани Картахены (порт Картахена в Карибском море ныне принадлежит Колумбии).

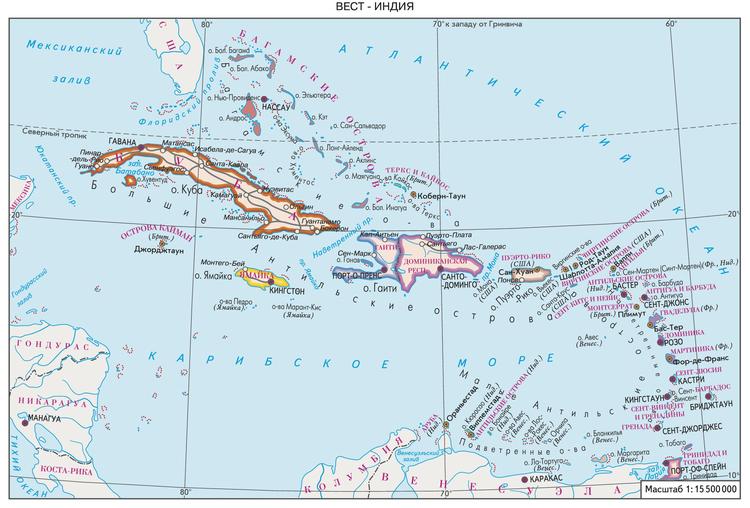

Вест-Индия на современной карте: в XVI веке практически все эти острова была испанскими

Кроме того, на Панамском перешейке ему удалось перехватить испанскую эскадру «Серебряный караван» — эта эскадра называлась так, потому что она перевозила около тридцати тонн серебра. Причём в ходе операции по захвату богатств с «Серебряного каравана» Дрейк проявил недюжинную изобретательность. Например, ему и его команде удалось прорваться сквозь кордон кораблей колониальных властей, которые патрулировали побережье, на обычном деревянном плоту. Сокровища же Дрейк заранее спрятал на берегу и вернулся за ними на следующую ночь. Это был настоящий успех для английского «джентельмена удачи».

9 августа 1573 года Дрейк вернулся в Плимут. И в результате стал известным на всю Англию корсаром (именно так в те времена называли пиратов, которые имели своеобразную лицензию от государства на захватывание и разграбление вражеских судов). Финансовое положение Дрейка значительно улучшилось — теперь он стал богатым и перестал зависеть от спонсоров и судовладельцев.

Начало кругосветного путешествия английского корсара

С годами репутация Дрейка как «железного пирата» и, одновременно, умелого военно-морского тактика, лишь крепла. И не удивительно, что при подготовке к морской войне с Испанией Фрэнсиса Дрейка вызвали для консультаций. Он сказал, что хорошим вариантом в данном случае стала бы атака на испанские территории и земли в Америке. Спустя какое-то время после этого Дрейк был приглашён на тайную аудиенцию к королеве Елизавете I. Их встреча состоялась в середине ноября 1577 года — пират и монаршая особа нашли что сказать друг другу.

Королева Елизавета I, которая негласно поддерживала пирата Дрейка

В итоге Елизавета I дала добро корсару на экспедицию к тихоокеанскому побережью Южной Америки. Кроме того, негласно Её Величество, как и ещё ряд почтенных джентельменов, стала спонсором этой экспедиции. Известно также, что Дрейку в ходе аудиенции королева подарила шёлковый шарфик с вышитыми золотом напутственными словами.

Вскоре для Дрейка построили шикарную флотилию из пяти кораблей. Кораблём-флагманом стал «Пеликан» с водоизмещением в сто тонн. Именно здесь располагалась каюта Фрэнсиса, которая также была обставлена очень богато. Вообще Дрейк даже во время путешествий предпочитал вести роскошный образ жизни — он ел из серебряной посуды, и во время трапезы его развлекали музыканты. Кроме того, рядом всегда стоял паж, готовый исполнить любое поручение.

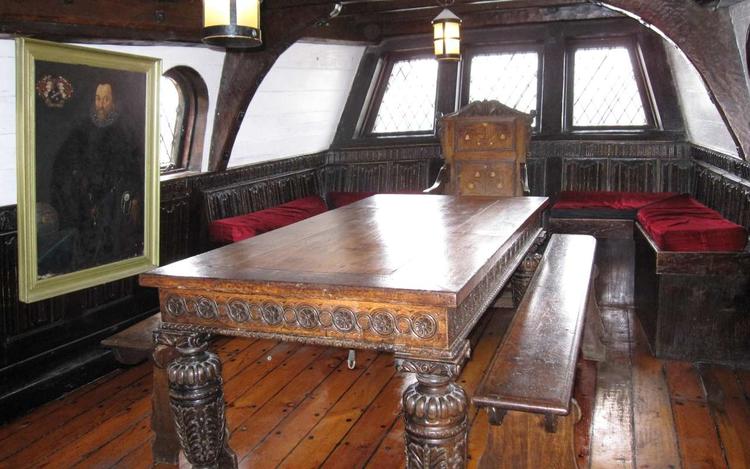

Предположительно, так выглядела каюта Фрэнсиса Дрейка

13 декабря 1577 года флотилия Дрейка выдвинулась из Плимута и отправилась в далёкий и долгий путь. Сначала Дрейк и его команда (всего на всех кораблях — порядка 160 человек) совершили несколько разбоев в отношении испанских и португальских судов с ценными грузами у африканских берегов. Вдобавок ко всему команде удалось взять в плен португальского лоцмана, который хорошо знал безопасные морские дороги к Южной Америке.

В июне 1578-го флотилия Дрейка подошла к бухте Сан-Хулиан, расположенной сравнительно близко к Магелланову проливу. Во время зимовки здесь на одном из судов разразился бунт, который поддержала некоторая часть команды. Но этот бунт был подавлен, и Дрейк в итоге даже повелел казнить зачинщика по фамилии Доути — за предательство.

После зимовки и перед тем, как направиться непосредственно в Магелланов пролив, команда Дрейка перетащила на другие корабли всё ценное с двух самых малых судов флотилии, которые оказались сильно повреждены — их решено было оставить в порту.

Дальнейшее путешествие преподнесло очередной неприятный сюрприз. На выходе из Магелланова пролива все три корабля флотилии Дрейка попали в шторм — в результате один из них напоролся на скалы и утонул, а второй вышвырнуло обратно в пролив (его капитан впоследствии предпочёл уплыть обратно в Англию). И только «Пеликан» каким-то чудом смог пробиться к Тихому океану, после чего его отнесло очень сильно на юг. Таким образом, кстати, команде Дрейка удалось выяснить, что Огненная земля — это остров, а не часть какого-то неведомого материка.

В честь того что «Пеликану» удалось пережить столь сильный шторм, Дрейк переименовал его в «Золотую лань». И фигурку на носу корабля тоже приказал заменить.

Одна из существующих сегодня больших копий корабля «Золотая лань» («Пеликан»)

«Золотая лань» идёт на север

Итак, в распоряжении пирата остался всего один корабль. Но Дрейк как настоящий авантюрист решил не отступать и продолжил миссию. Судно направилось на север, к берегам Чили.

А Дальше Дрейку начинает очень сильно везти как пирату. В портах на западном побережье Южной Америки он не встречал практически никакого сопротивления (испанцы просто не думали, что кто-то может туда добраться), и это позволяло легко получать добычу.

В частности, был разграблен порт Вальпараисо (находится на территории современной Чили). В этом порту пиратам достался особенно большой куш — корабль, нагруженный золотом и дорогостоящими предметами. И в самом городе тоже был обнаружен солидный запас золота.

Но всё же через какое-то время реакция на действия Дрейка последовала: правитель Перу направил два корабля в погоню за «Золотой Ланью». Также был выставлен патруль в Карибском море — на случай, если Дрейк с командой попытается перебраться через Панамский перешеек. Но всё это не помогло — Дрейк ушёл от возможных преследователей на север, и уже там продолжил грабить суда с драгоценностями. Число кораблей, попавших под горячую руку корсара, точно установить нереально, но ясно, что добыча была поистине огромной.

Дрейк не скрывал свою принадлежность к Англии — он грабил под английскими флагами

План Дрейка был таким — найти где-нибудь на севере пролив, ведущий на восток, и по этому проливу добраться до Атлантики. Впрочем, вскоре Дрейк понял, что вернуться прежним путём домой вряд ли удастся. Чем дальше плыло судно, тем больше беспокоились члены экипажа. Линия берега всё отклонялась и отклонялась к северо-западу — прохода на восток так и не обнаружилось.

Невесёлому настрою моряков соответствовали ухудшающиеся погодные условия. Становилось всё холоднее, с неба зачастили дожди со снегом. В определённый момент снасти даже покрылись слоем льда, и это осложнило управление кораблём.

Встреча Дрейка с индейцами и возвращение домой

Экспедиции Дрейка, по-видимому, всё же удалось достичь 48 параллели северной широты — и в этих местах Северной Америки ранее не бывал ещё ни один европейский корабль. Но здесь Дрейк понял, что дальше идти нет смысла. Поэтому Корабль повернул обратно на юг и спустился обратно, в более тёплые широты.

В июне 1579 года в районе 38° северной широты (то есть неподалёку от нынешнего Сан-Франциско) команда «Золотой Лани» высадились на берег с целью отдохнуть и отремонтировать корабль. Тут их встретили местные индейцы. Причём какого-либо враждебного отношения туземцы не проявили — они приняли странных пришельцев за богов. Осознав это, «боги» не растерялись и обменяли некоторые вещи с «Золотой лани» на еду и воду.

Фрэнсис Дрейк и члены его команды высаживаются в неведомых землях

Англичане провели здесь ещё несколько недель. И индейцы, чем больше общались с путешественниками, тем больше верили в то, что встретились с богами. Согласно описанию корабельного священника, в какой-то момент индейский вождь без всякого насилия передал власть «главному из богов» — Дрейку.

Пират захотел присоединить к Соединённому королевству открытую им землю. Он дал ей название «Новый Альбион». Для подтверждения права на владение землёй была изготовлена специальная пластина из меди с соответствующим текстом. Пластину закрепили на столбе, а вместо печати Дрейк якобы оставил серебряную монетку с портретом королевы.

Отдохнув и взвесив все «за» и «против», Дрейк решил поплыть на запад. Тем более, что ещё у побережья Никарагуа команде удалось взять с собой в качестве добычи испанские карты Тихого океана.

От берегов Америки судно «Золотая лань» отплыло на запад в июле 1579 года. И всё получилось в общем-то так, как и задумывалось. Сначала команда Дрейка остановилась на Филлипинах, затем на Моллукском архипелаге, а затем на острове Ява. Дальше уже были относительно знакомые места — корабль обогнул мыс Доброй Надежды и сделал по дороге домой только ещё одну остановку — в Сьерра-Леоне.

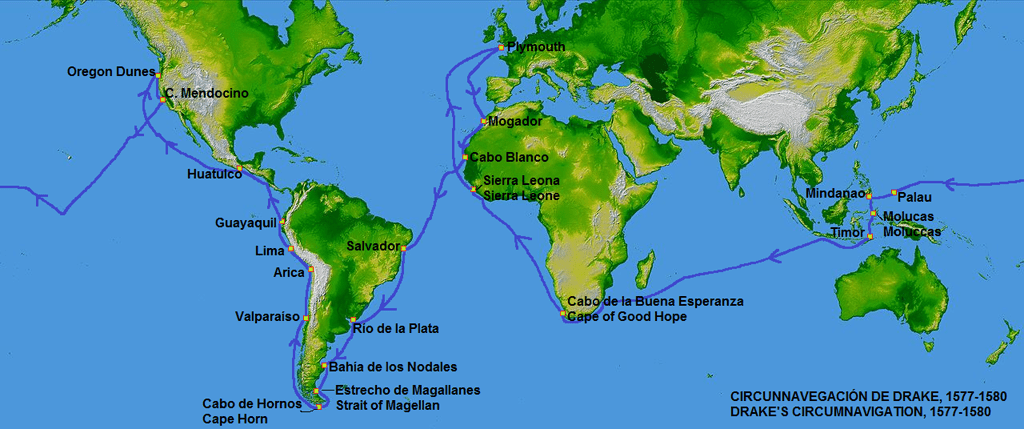

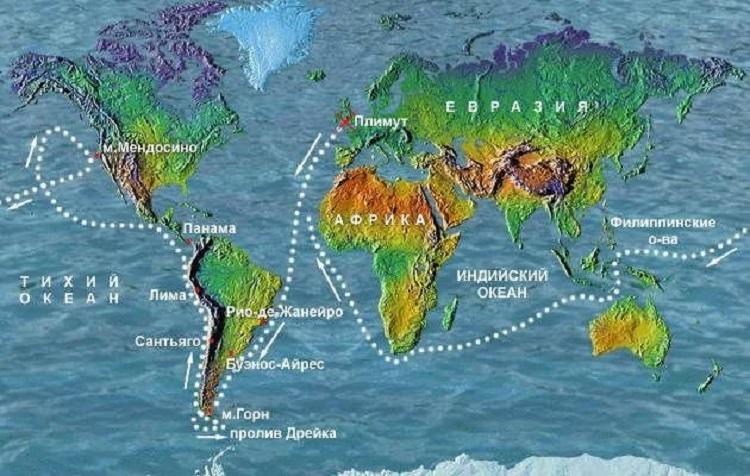

Маршрут кругосветного путешествия Дрейка на карте

Итак, в сентябре 1580 года Дрейк триумфально прибыл в Плимут. Его корабль был набит сокровищами на сумму 600000 фунтов, что равнялось размеру доходов Британского королевства за два года. Королева сразу же наградила Дрейка рыцарским титулом. Фактически Дрейк стал первым человеком, который осуществил кругосветку от начала и до конца (Магеллан, как известно, умер в пути).

Елизавета I прямо на корабле посвящает Дрейка в рыцари

Дрейк в роли адмирала и его последние годы жизни

Став дворянином, Дрейк приобрёл для себя уютное поместье и сыграл свадьбу – его женой стала девушка из богатой семьи. Также он одно время выполнял обязанности мэра Плимута и заседал в парламенте. Но всё же размеренная жизнь ему не слишком-то нравилась. Поэтому он организовал ещё несколько экспедиций в Карибский бассейн.

А в 1588 году Дрейк уже являлся британским адмиралом. В победе над «Непобедимой армадой» он сыграл роль, которую трудно переоценить. Строго говоря, сэр Фрэнсис Дрейк внёс очень эффективные новшества в тактику ведения морских сражений. Он делал ставку прежде всего на скорость кораблей, и поэтому смог победить испанский флот, который в целом был вооружён более мощными орудиями. Новая тактика англичан выглядела так: сначала книппелями портились паруса вражеского судна — это обездвиживало его и превращало стоячую мишень, а затем использовались все имеющиеся в арсенале средства для его разрушения.

Дрейк отличился, в том числе, и в Гравелинском морском сражении, в котором Непобедимая Армада проиграла

А в 1589 году Дрейк практически командовал объединёнными силами английского флота, в его распоряжении находилось более 150 боевых судов — удивительная карьера для бывшего пирата-корсара!

Но даже после этого он не успокоился — ему захотелось совершить ещё одну экспедицию к островам Центральной и Южной Америки за золотом и сокровищами. В это плавание легендарный корсар отправился в 1595 году, и оно стало, к сожалению, для него роковым.

Экспедиция с самого начала не задалась: погода за бортом была отвратительная, среди членов экипажей кораблей (а под руководством Дрейка, между прочим, была целая эскадра) стали распространяться дизентерия и тропическая лихорадка. К тому же Дрейк завёл корабли в неблагоприятное из-за гуляющих вокруг сильных ветров место у островка Эскудо-ле-Верагуа. Шло время, продовольственные запасы на судах стали подходить к концу, и это, конечно, тоже не прибавляло радости матросам…

А потом дизентерией заразился сэр Дрейк. С этим недугом он справиться уже не смог. Умер легендарный пират 28 января 1596 года — корабль в это время находился в пути. Прославленного «морского волка» похоронили под залпы пушек прямо в море, в специальном свинцовом гробу. В Плимут эскадра (точнее, то, что от неё осталось) возвратилась уже без капитана.

Картина художника Томаса Дэвидсона «Похороны адмирала Дрейка»

Мифы и достопримечательности, связанные с личностью Дрейка

Как свидетельствуют те, кто знал Фрэнсиса Дрейка, он был раздражительным, жадным, властолюбивым и весьма суеверным человеком. И уже при его жизни появилась испанская легенда о том, что в молодости Дрейк продал душу дьяволу и взамен получил удачливость в морских сражениях и приключениях. Также существовало поверье, что именно Дрейк навлёк жуткие штормы на «Непобедимую Армаду», и якобы ему в этом помогли ведьмы, с которыми он довольно близко общался с детства. Конечно, это всего лишь слухи и мифы.

С другой стороны, многим экспертам-историкам очевидно, что «жадный» Дрейк отнюдь не только ради несметных сокровищ предпринимал рискованные экспедиции. Как и всех великих мореплавателей, его влекли неизведанные земли, стремление побывать в местах, где до него не был ещё никто. И мореходы следующих поколений обязаны многими значимыми уточнениями на мировой карте именно этому корсару.

Кстати, есть версия, что картошку в Европу впервые привёз именно Дрейк, но, скорее всего, она не соответствует действительности. Вероятно, это всё-таки было сделано раньше испанцами. Однако в германском городке Оффенбург, в середине XIX века была установлена каменная статуя великого корсара с цветком картофеля в ладони – её автором был скульптор Андре Фридрих.

Памятник Фрэнсису Дрейку с картофелем (к сожалению, не сохранился до наших дней)

Сегодня Дрейка больше всего чтут и помнят, конечно, в Британии. Его портрет даже в 1973 году красовался на одной из марок Соединённого Королевства.

Марка 1973 года с пиратом Дрейком

И особенно много памятных мест, связанных с Дрейком, есть в городе Плимуте. Здесь стоит его памятник и работает музей Дрейка. А в Лондоне на южном берегу Темзы можно увидеть воссозданное судно «Золотая лань» — сегодня оно является туристической достопримечательностью. Впрочем, как и усадебный дом, в котором когда-то жил Дрейк — Бакленд-Эбби.

Вход в поместье Бакленд-Эбби сегодня

Этот дом давным-давно уже превращён в музей. И одним из самых важных его экспонатов является барабан Дрейка. Говорят, он начинает звучать сам по себе в дни знаменательных и судьбоносных для Великобритании событий…

Докуметальный фильм «Фрэнсис Дрейк. Покорение семи морей»

|

Sir Francis Drake |

|

|---|---|

Portrait by Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger |

|

| Born | c. 1540

Tavistock, Devon, England |

| Died | 28 January 1596 (aged 56)

Portobelo, Colón, Panama |

| Spouses |

|

| Piratical career | |

| Nickname | El Draque (Spanish, «The Dragon») |

| Type | Privateer |

| Allegiance | Kingdom of England |

| Years active | 1563–1596 |

| Rank | Vice admiral |

| Base of operations | Caribbean Sea |

| Commands |

Golden Hind (previously known as Pelican) |

| Battles/wars |

|

| Wealth | Est. Equiv. US$144.7 million in 2021;[1] #2 Forbes top-earning pirates[2] |

| Signature | |

|

Sir Francis Drake (c. 1540 – 28 January 1596)[3] was an English explorer, sea captain, privateer, naval officer, and politician. Drake is best known for his circumnavigation of the world in a single expedition, from 1577 to 1580 (the first English circumnavigation, the second carried out in a single expedition, and third circumnavigation overall). This included his incursion into the Pacific Ocean, until then an area of exclusive Spanish interest, and his claim to New Albion for England, an area in what is now the U.S. state of California. His expedition inaugurated an era of conflict with the Spanish on the western coast of the Americas,[4] an area that had previously been largely unexplored by Western shipping.[5] He was Member of Parliament (MP) for three constituencies; Camelford in 1581, Bossiney in 1584, and Plymouth in 1593.

Elizabeth I awarded Drake a knighthood in 1581 which he received on the Golden Hind in Deptford. In the same year, he was appointed mayor of Plymouth. As a vice admiral, he was second-in-command of the English fleet in the victorious battle against the Spanish Armada in 1588. After unsuccessfully attacking San Juan, Puerto Rico, he died of dysentery in January 1596.[6]

Drake’s exploits made him a hero to the English, but his privateering led the Spanish to brand him a pirate, known to them as El Draque, «The Dragon».[7] King Philip II of Spain allegedly offered a reward of 20,000 ducats for his capture or death,[8] equivalent to around £7,207,135.56 in 2022.[9]

Birth and early years[edit]

Francis Drake was born at Crowndale Farm in Tavistock, Devon, England. Although his birth date is not formally recorded, it is known that he was born while the Six Articles of 1539 were in force. His birth date is estimated from contemporary sources such as: «Drake was two and twenty when he obtained the command of the Judith«[10] (1566). This would date his birth to 1544. A date of c. 1540 is suggested from two portraits: one a miniature painted by Nicholas Hilliard in 1581 when he was allegedly 42, so born c. 1539, while the other, painted in 1594 when he was said to be 52,[11] would give a birth year of c. 1541. Lady Elliott-Drake, the collateral descendant, and final holder of the Drake Baronetcy, argued in her book on ‘The Family and Heirs of Sir Francis Drake’ that Drake’s birth year was 1541.[12]

He was the eldest of the twelve sons[13] of Edmund Drake (1518–1585), a Protestant farmer, and his wife, Mary Mylwaye. The first son was alleged to have been named after his godfather Francis Russell, 2nd Earl of Bedford.[14][unreliable source][15]

Due to religious persecution during the Prayer Book Rebellion in 1549, the Drake family fled from Devon to Kent. There Drake’s father obtained an appointment to minister the men in the King’s Navy. He was ordained deacon and was made vicar of Upnor Church on the Medway.[16] Drake’s father apprenticed him to his neighbour, the master of a barque used for coastal trade transporting merchandise to France.[16] The ship’s master was so satisfied with the young Drake’s conduct that, being unmarried and childless at his death, he bequeathed the barque to Drake.[when?] [16]

Marriage and family[edit]

Francis Drake married Mary Newman at St. Budeaux church, Plymouth, in July 1569. She died 12 years later, in 1581. In 1585, Drake married Elizabeth Sydenham—born c. 1562, the only child of Sir George Sydenham, of Combe Sydenham,[17] who was the High Sheriff of Somerset.[18]

Early career at sea[edit]

At an early age Drake was placed into the household of a relative, William Hawkins of Plymouth, and began his seagoing training as an apprentice on Hawkins’ boats.[19] By 18, he was a bursar,[20] and in the 1550s, Drake’s father found the young man a position with the owner and master of a small barque, one of the small traders plying between the Medway River and the Dutch coast. Drake likely engaged in commerce along the coast of England, the Low Countries and France.[21]

Slave trade[edit]

Sir John Hawkins (left) with Sir Francis Drake (centre) and Sir Thomas Cavendish

Between 1560 and 1568 Drake served as a seaman on a series of voyages on the ships of his second cousin, Sir John Hawkins, with whom he had been brought up.[22][19] On these voyages Hawkins is widely acknowledged to have begun the English slave trade. The West African slave trade was at this time a Portuguese and Spanish monopoly, but John Hawkins devised a plan to break into that trade, and in 1562, enlisted the aid of colleagues and family to finance his first slave voyage.[23] Drake, 12 years junior to Hawkins, was part of the crew and is mentioned by name in the records.[19][better source needed] They carried slaves, cloth, manufactured goods and contraband.[24]

For his second slave voyage Hawkins gained Queen Elizabeth I’s support, she allowed him to charter one of her ships, Jesus of Lübeck, and the rest of his needed capital came from a consortium of investors from her court.[25] Drake was twenty (c. 1563–1564),[20][26] and not a member of that consortium but the crew would have received a share in the profits.[27][28] Based on this association, scholar Kris Lane lists Drake as one of the first English slave traders.[29]

The Spanish and Portuguese were aggrieved that the English had entered into the slave trade and were selling slaves to their colonies, despite being forbidden from doing so. Queen Elizabeth I, under pressure to avoid an armed conflict, forbade Hawkins from going to sea for a third slave voyage. In response he set up a new slave voyage with a relative of his, John Lovell, in command.[25] Drake accompanied Lovell on this voyage.[25] In 1566–1567, Lovell attacked Portuguese settlements and slave ships on the coast of West Africa and then sailed to the Americas and sold the captured cargoes of enslaved Africans onto Spanish plantations.[30] The voyage was unsuccessful and more than 90 enslaved Africans were released without payment.[31][32]

Drake accompanied Hawkins on his next slave voyage. The crew attempted to capture and kidnap the inhabitants of a village near Cape Verde, but had to retreat. Hawkins recruited a local king in Sierra Leone to help him forcibly kidnap people, capturing and enslaving over 500 people before setting sail for the Spanish West Indies.[33] The voyage went badly, there were storms, Spanish hostility, armed conflict, and finally a hurricane separated one ship from the fleet to find its own way home.[34] The remaining ships were forced into the port of Vera Cruz in San Jan de Ulna where they could make repairs. Soon after the newly appointed viceroy of New Spain arrived with a fleet of ships. While still negotiating to resupply and repair, Hawkins’ ships were attacked by the fleet of Spanish ships in what became known as the Battle of San Juan de Ulúa.[35][36][37] The battle ended in defeat, with all but two of the English ships lost. The Jesus de Lubeck was set on fire. Drake fled on Judith leaving Hawkins behind, Hawkins escaped on Minion and limped back to England. Hundreds of English seamen were abandoned.[38]

After arriving back in England, Hawkins accused Drake of desertion and of stealing the treasure they had accumulated. Drake denied both accusations asserting he had distributed all profits among the crew and that he had believed Hawkins was lost when he left.[28][39] Other eyewitness accounts seem to exonerate Drake.[40] Drake’s hostility towards the Spanish is said to have started with the battle and its aftermath.[41] This was Drake’s last slave voyage, his seafaring life remained intertwined with that of his cousin, Hawkins, until death.[42]

Drake’s expedition of 1572–1573[edit]

In 1572, Drake embarked on his first major independent enterprise. He planned an attack on the Isthmus of Panama, known to the Spanish as Tierra Firme and the English as the Spanish Main. This was the point at which the silver and gold treasure of Peru had to be landed and sent overland to the Caribbean Sea, where galleons from Spain would pick it up at the town of Nombre de Dios. Drake left Plymouth on 24 May 1572, with a crew of 73 men in two small vessels, the Pascha (70 tons) and the Swan (25 tons), to capture Nombre de Dios.[43]

Drake’s first raid was late in July 1572. Drake formed an alliance with the Cimarrons. Drake and his men captured the town and its treasure. When his men noticed that Drake was bleeding profusely from a wound, they insisted on withdrawing to save his life and left the treasure.[citation needed] Drake stayed in the area for almost a year, raiding Spanish shipping and attempting to capture a treasure shipment.

The most celebrated of Drake’s adventures along the Spanish Main was his capture of the Spanish Silver Train at Nombre de Dios in March 1573. He raided the waters around Darien (in modern Panama) with a crew including many French privateers including Guillaume Le Testu, a French buccaneer, and Maroons, enslaved Africans who had escaped from their Spanish slaveowners. One of these men was Diego, who under Drake became a free man; Diego was also a capable ship builder.[44] Drake tracked the Silver Train to the nearby port of Nombre de Dios. After their attack on the richly laden mule train, Drake and his party found that they had captured around 20 tons of silver and gold. They buried much of the treasure, as it was too much for their party to carry, and made off with a fortune in gold.[45][46] (An account of this may have given rise to subsequent stories of pirates and buried treasure). Wounded, Le Testu was captured and later beheaded. The small band of adventurers dragged as much gold and silver as they could carry back across some 18 miles of jungle-covered mountains to where they had left the raiding boats. When they got to the coast, the boats were gone. Drake and his men, downhearted, exhausted and hungry, had nowhere to go and the Spanish were not far behind.

At this point, Drake rallied his men, buried the treasure on the beach, and built a raft to sail with two volunteers ten miles along the surf-lashed coast to where they had left the flagship. When Drake finally reached its deck, his men were alarmed at his bedraggled appearance. Fearing the worst, they asked him how the raid had gone. Drake could not resist a joke and teased them by looking downhearted. Then he laughed, pulled a necklace of Spanish gold from around his neck and said «Our voyage is made, lads!»[citation needed] By 9 August 1573, he had returned to Plymouth.[citation needed]

It was during this expedition that Drake climbed a high tree in the central mountains of the Isthmus of Panama and thus became the first Englishman to see the Pacific Ocean, mirroring the achievement of the Spaniard Vasco Núñez de Balboa in 1513. Drake remarked as he saw the Pacific Ocean that he hoped one day an Englishman would be able to sail it – which he would do years later as part of his circumnavigation of the world.[47]

When Drake returned to Plymouth after the raids, the government signed a temporary truce with King Philip II of Spain and so was unable to acknowledge Drake’s accomplishment officially. Drake was considered a hero in England and a pirate in Spain for his raids.[48]

Rathlin Island massacre[edit]

Drake was present at the 1575 Rathlin Island massacre in Ireland. Acting on the instructions of Sir Henry Sidney and the Earl of Essex, Sir John Norreys and Drake laid siege to Rathlin Castle. Despite their surrender, Norreys’ troops killed all the 200 defenders and more than 400 civilian men, women and children of Clan MacDonnell.[49] Meanwhile, Drake was given the task of preventing any Gaelic Irish or Scottish reinforcements reaching the island. Therefore, the remaining leader of the Gaelic defence against English power, Sorley Boy MacDonnell, was forced to stay on the mainland. Essex wrote in his letter to Queen Elizabeth’s secretary, that following the attack Sorley Boy «was likely to have run mad for sorrow, tearing and tormenting himself and saying that he there lost all that he ever had.»[50]

Circumnavigation (1577–1580)[edit]

A map of Drake’s route around the world. The northern limit of Drake’s exploration of the Pacific coast of North America is still in dispute. Drake’s Bay is south of Cape Mendocino.

With the success of the Panama isthmus raid, in 1577 Elizabeth I of England sent Drake to start an expedition against the Spanish along the Pacific coast of the Americas. Drake acted on the plan authored by Sir Richard Grenville, who had received royal patent for it in 1574. Just a year later the patent was rescinded after protests from Philip of Spain.

Diego was once again employed under Drake; his fluency in Spanish and English would make him a useful interpreter when Spaniards or Spanish-speaking Portuguese were captured. He was employed as Drake’s servant and was paid wages, just like the rest of the crew.[44] Drake and the fleet set out from Plymouth on 15 November 1577, but bad weather threatened him and his fleet. They were forced to take refuge in Falmouth, Cornwall, from where they returned to Plymouth for repair.[51]

After this major setback, Drake set sail again on 13 December aboard Pelican with four other ships and 164 men. He soon added a sixth ship, Mary (formerly Santa Maria), a Portuguese merchant ship that had been captured off the coast of Africa near the Cape Verde Islands. He also added its captain, Nuno da Silva, a man with considerable experience navigating in South American waters.

Drake’s fleet suffered great attrition; he scuttled both Christopher and the flyboat Swan due to loss of men on the Atlantic crossing. He made landfall at the gloomy bay of San Julian, in what is now Argentina. Ferdinand Magellan had called here half a century earlier, where he put to death some mutineers. Drake’s men saw weathered and bleached skeletons on the grim Spanish gibbets. Following Magellan’s example, Drake tried and executed his own «mutineer» Thomas Doughty. The crew discovered that Mary had rotting timbers, so they burned the ship. Drake decided to remain the winter in San Julian before attempting the Strait of Magellan.[52]

Execution of Thomas Doughty[edit]

On his voyage to interfere with Spanish treasure fleets, Drake had several quarrels with his co-commander Thomas Doughty and on 3 June 1578, accused him of witchcraft and charged him with mutiny and treason in a shipboard trial.[53] Drake claimed to have a (never presented) commission from the Queen to carry out such acts and denied Doughty a trial in England. The main pieces of evidence against Doughty were the testimony of the ship’s carpenter, Edward Bright, who after the trial was promoted to master of the ship Marigold, and Doughty’s admission of telling Lord Burghley, a vocal opponent of agitating the Spanish, of the intent of the voyage. Drake consented to his request of Communion and dined with him, of which Francis Fletcher had this strange account:

And after this holy repast, they dined also at the same table together, as cheerfully, in sobriety, as ever in their lives they had done aforetime, each cheering up the other, and taking their leave, by drinking each to other, as if some journey only had been in hand.[54]

Drake had Thomas Doughty beheaded on 2 July 1578. When the ship’s chaplain, Francis Fletcher, in a sermon suggested that the woes of the voyage in January 1580 were connected to the unjust demise of Doughty, Drake chained the clergyman to a hatch cover and pronounced him excommunicated.

Entering the Pacific (1578)[edit]

The three remaining ships of his convoy departed for the Magellan Strait at the southern tip of South America. A few weeks later (September 1578) Drake made it to the Pacific, but violent storms destroyed one of the three ships, the Marigold (captained by John Thomas) in the strait and caused another, the Elizabeth captained by John Wynter, to return to England, leaving only the Pelican. After this passage, the Pelican was pushed south and discovered an island that Drake called Elizabeth Island. Drake, like navigators before him, probably reached a latitude of 55°S (according to astronomical data quoted in Hakluyt’s The Principall Navigations, Voiages and Discoveries of the English Nation of 1589) along the Chilean coast.[55] In the Magellan Strait Francis and his men engaged in skirmish with local indigenous people, becoming the first Europeans to kill indigenous peoples in southern Patagonia.[56] During the stay in the strait, crew members discovered that an infusion made of the bark of Drimys winteri could be used as remedy against scurvy. Captain Wynter ordered the collection of great amounts of bark – hence the scientific name.[56]

Despite popular lore, it seems unlikely that Drake reached Cape Horn or the eponymous Drake Passage,[55] because his descriptions do not fit the first and his shipmates denied having seen an open sea.[citation needed] Historian Mateo Martinic, who examined his travels, credits Drake with the discovery of the «southern end of the Americas and the oceanic space south of it».[57] The first report of his discovery of an open channel south of Tierra del Fuego was written after the 1618 publication of the voyage of Willem Schouten and Jacob le Maire around Cape Horn in 1616.[58]

Drake pushed onwards in his lone flagship, now renamed the Golden Hind in honour of Sir Christopher Hatton (after his coat of arms). The Golden Hind sailed north along the Pacific coast of South America, attacking Spanish ports and pillaging towns. Some Spanish ships were captured, and Drake used their more accurate charts. Before reaching the coast of Peru, Drake visited Mocha Island, where he was seriously injured by hostile Mapuche. Later he sacked the port of Valparaíso further north in Chile, where he also captured a ship full of Chilean wine.[59]

Capture of Spanish treasure ships[edit]

Near Lima, Drake captured a Spanish ship with 25,000 pesos of Peruvian gold, amounting in value to 37,000 ducats of Spanish money (about £7m by modern standards). Drake also discovered news of another ship, Nuestra Señora de la Concepción, which was sailing west towards Manila. It would come to be called the Cacafuego. Drake gave chase and eventually captured the treasure ship, which proved his most profitable capture.

Aboard Nuestra Señora de la Concepción, Drake found 36 kilograms (80 lb) of gold, a golden crucifix, jewels, 13 chests full of royals of plate[clarification needed] and 26 thousand kilograms (26 long tons) of silver. Drake was naturally pleased at his good luck in capturing the galleon, and he showed it by dining with the captured ship’s officers and gentleman passengers. He offloaded his captives a short time later, and gave each one gifts appropriate to their rank, as well as a letter of safe conduct.

Coast of California: Nova Albion (1579)[edit]

Drake’s landing in California, engraving published 1590 by Theodor de Bry

Prior to Drake’s voyage, the western coast of North America had only been partially explored in 1542 by Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo who sailed for Spain.[61] So, intending to avoid further conflict with Spain, Drake navigated northwest of Spanish presence and sought a discreet site at which the crew could prepare for the journey back to England.[62][63]

On 5 June 1579, the ship briefly made first landfall at what is now South Cove, Cape Arago, just south of Coos Bay, Oregon, and then sailed south while searching for a suitable harbour to repair his ailing ship.[64][65][66][67][68] On 17 June, Drake and his crew found a protected cove when they landed on the Pacific coast of what is now Northern California.[69][70] While ashore, he claimed the area for Queen Elizabeth I as Nova Albion or New Albion.[71] To document and assert his claim, Drake posted an engraved plate of brass to claim sovereignty for Elizabeth and every successive English monarch.[72]

After erecting a fort and tents ashore, the crew labored for several weeks as they prepared for the circumnavigating voyage ahead by careening their ship, Golden Hind, so to effectively clean and repair the hull.[73] Drake had friendly interactions with the Coast Miwok and explored the surrounding land by foot.[74] When his ship was ready for the return voyage, Drake and the crew left New Albion on 23 July and paused his journey the next day when anchoring his ship at the Farallon Islands where the crew hunted seal meat.[75][76][77]

Across the Pacific and around Africa[edit]

Drake left the Pacific coast, heading southwest to catch the winds that would carry his ship across the Pacific, and a few months later reached the Moluccas, a group of islands in the western Pacific, in eastern modern-day Indonesia. At this time Diego died from wounds he had sustained earlier in the voyage, Drake was saddened at his death having become a good friend.[44] Golden Hind later became caught on a reef and was almost lost. After the sailors waited three days for convenient tides and had dumped cargo. Befriending Sultan Babullah of Ternate in the Moluccas, Drake and his men became involved in some intrigues with the Portuguese there. He made multiple stops on his way toward the tip of Africa, eventually rounded the Cape of Good Hope, and reached Sierra Leone by 22 July 1580.

Return to Plymouth (1580)[edit]

The «Drake Jewel» as painted by Gheeraerts the Younger in a 1591 portrait of Drake

On 26 September, Golden Hind sailed into Plymouth with Drake and 59 remaining crew aboard, along with a rich cargo of spices and captured Spanish treasures. The Queen’s half-share of the cargo surpassed the rest of the crown’s income for that entire year. Drake was hailed as the first Englishman to circumnavigate the Earth (and the second such voyage arriving with at least one ship intact, after Elcano’s in 1520).[78]

The Queen declared that all written accounts of Drake’s voyages were to become the Queen’s secrets of the Realm, and Drake and the other participants of his voyages on the pain of death sworn to their secrecy; she intended to keep Drake’s activities away from the eyes of rival Spain. Drake presented the Queen with a jewel token commemorating the circumnavigation. Taken as a prize off the Pacific coast of Mexico, it was made of enamelled gold and bore an African diamond and a ship with an ebony hull.[78]

For her part, the Queen gave Drake a jewel with her portrait, an unusual gift to bestow upon a commoner, and one that Drake sported proudly in his 1591 portrait by Marcus Gheeraerts now at the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich. On one side is a state portrait of Elizabeth by the miniaturist Nicholas Hilliard, on the other a sardonyx cameo of double portrait busts, a regal woman and an African male. The «Drake Jewel», as it is known today, is a rare documented survivor among sixteenth-century jewels; it is conserved at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London.[78]

Knighthood and arms[edit]

Queen Elizabeth awarded Drake a knighthood aboard Golden Hind in Deptford on 4 April 1581; the dubbing being performed by a French diplomat, Monsieur de Marchaumont, who was negotiating for Elizabeth to marry the King of France’s brother, Francis, Duke of Anjou.[79][80] By getting the French diplomat involved in the knighting, Elizabeth was gaining the implicit political support of the French for Drake’s actions.[81][82][83] During the Victorian era, in a spirit of nationalism, the story was promoted that Elizabeth I had done the knighting.[80]

After receiving his knighthood Drake unilaterally adopted the armorials of the ancient Devon family of Drake of Ash, near Musbury, to whom he claimed a distant but unspecified kinship. These arms were: Argent, a wyvern wings displayed and tail nowed gules,[84] and the crest, a dexter arm Proper grasping a battle axe Sable, headed Argent. The head of that family, also a distinguished sailor, Sir Bernard Drake (d. 1586), angrily refuted Sir Francis’s claimed kinship and his right to bear his family’s arms. That dispute led to «a box on the ear» being given to Sir Francis by Sir Bernard at court, as recorded by John Prince (1643–1723) in his «Worthies of Devon», first published in 1701.[85] Queen Elizabeth, to assuage matters, awarded Sir Francis his own coat of arms, blazoned as follows:

Sable a fess wavy between two pole-stars [Arctic and Antarctic] argent; and for his crest, a ship on a globe under ruff, held by a cable with a hand out of the clouds; over it this motto, Auxilio Divino; underneath, Sic Parvis Magna; in the rigging whereof is hung up by the heels a wivern, gules, which was the arms of Sir Bernard Drake.[86]

The motto, Sic Parvis Magna, translated literally, is: «Thus great things from small things (come)». The hand out of the clouds, labelled Auxilio Divino, means «With Divine Help». The full achievement is depicted in the form of a large, coloured plaster overmantel in the Lifetimes Gallery at Buckland Abbey[87]

Nevertheless, Drake continued to quarter his new arms with the wyvern gules.[88] The arms adopted by his nephew Sir Francis Drake, 1st Baronet (1588–1637) of Buckland were the arms of Drake of Ash, but the wyvern without a «nowed» (knotted) tail.[89]

-

Arms of Sir Francis Drake: Sable, a fess wavy between two pole-stars Arctic and Antarctic argent

-

Arms of Drake of Ash: Argent, a wyvern wings displayed and tail nowed gules.[84] The Drake family of Crowndale and Buckland Abbey used the same arms but the tail of the wyvern is not nowed (knotted)[89]

-

Sir Francis Drake with his new heraldic achievement, with motto: Sic Parvis Magna, translated literally: «Thus great things from small things (come)». The hand out of the clouds is labelled Auxilio Divino, or «With Divine Help»[87]

-

1577 engraving of Admiral Sir Francis Drake showing both Drake of Buckland and Drake of Ash Coat of arms quartered together

Purchase of Buckland Abbey[edit]

In 1580, Drake purchased Buckland Abbey, a large manor house near Yelverton, Devon, via intermediaries from Sir Richard Greynvile. He lived there for fifteen years, until his final voyage, and it remained in his family for several generations. Buckland Abbey is now in the care of the National Trust and a number of mementos of his life are displayed there.

Political career[edit]

Drake was politically astute, and although known for his private and military endeavours, he was an influential figure in politics during the time he spent in Britain. Often abroad, there is little evidence to suggest he was active in Westminster, despite being a member of parliament on three occasions.

After returning from his voyage of circumnavigation, Drake became the Mayor of Plymouth, in September 1581.[13] He became a member of parliament during a session of the 4th Parliament of Elizabeth I,[90] on 16 January 1581, for the constituency of Camelford. He did not actively participate at this point, and on 17 February 1581 he was granted leave of absence «for certain his necessary business in the service of Her Majesty».[91]

Drake became a member of parliament again in 1584 for Bossiney[13] on the forming of the 5th Parliament of Elizabeth I.[92] He served the duration of the parliament and was active in issues regarding the navy, fishing, early American colonisation, and issues related chiefly to Devon. He spent the time covered by the next two parliamentary terms engaged in other duties and an expedition to Portugal.[91]

He became a member of parliament for Plymouth in 1593.[91] He was active in issues of interest to Plymouth as a whole, but also to emphasise defence against the Spanish.[91][93]

Great Expedition to America[edit]

War had already been declared by Phillip II after the Treaty of Nonsuch, so the Queen through Francis Walsingham ordered Sir Francis Drake to lead an expedition to attack the Spanish colonies in a kind of pre-emptive strike. An expedition left Plymouth in September 1585 with Drake in command of twenty-one ships with 1,800 soldiers under Christopher Carleill. He first attacked Vigo in Spain and held the place for two weeks ransoming supplies. He then plundered Santiago in the Cape Verde islands after which the fleet then sailed across the Atlantic, sacked the port of Santo Domingo, and captured the city of Cartagena de Indias in present-day Colombia. At Cartagena, Drake released one hundred Turks who were enslaved.[94] On 6 June 1586, during the return leg of the voyage, he raided the Spanish fort of San Agustín in Spanish Florida.[95]

After the raids he then went on to find Sir Walter Raleigh’s settlement much further north at Roanoke which he replenished and also took back with him all of the original colonists before Sir Richard Greynvile arrived with supplies and more colonists. He finally reached England on 22 July, when he sailed into Portsmouth, England to a hero’s welcome.[95]

Spanish Armada[edit]

Angered by these acts, Philip II ordered a planned invasion of England.

Cádiz raid[edit]

On 15 March 1587, Drake accepted a new commission with several purposes: to disrupt the shipping routes in order to slow supplies from Italy and Andalusia to Lisbon, to trouble enemy fleets that were in their own ports, and to capture Spanish ships laden with treasure. Drake was also to confront and attack the Spanish Armada had it already sailed for England.[96] When arriving at Cadiz on 19 April, Drake found the harbour packed with ships and supplies as the Armada was readying and waiting for a fair wind to launch the fleet to attack.[97] In the early hours of the next day, Drake pressed his attack into the inner harbour and inflicted heavy damage.[98] Claims of the Spanish ship losses vary. Drake claimed he had sunk 39 ships, but other contemporary sources are lower, specifically some Spanish sources which suggest losses as low as 25 ships.[99] The attack became known as the «singeing of the King’s beard» and delayed the Spanish invasion by a year.[100]

Over the next month, Drake patrolled the Iberian coasts between Lisbon and Cape St. Vincent, intercepting and destroying ships on the Spanish supply lines. Drake estimated that he had captured around 1600–1700 tons of barrel staves, enough to make 25,000 to 30,000 barrels (4,800 m3) for containing provisions.[101]

Defeat of the Spanish Armada[edit]

Drake was vice admiral in command of the English fleet (under Lord Howard of Effingham) when it overcame the Spanish Armada that was attempting to invade England in 1588. As the English fleet pursued the Armada up the English Channel in closing darkness, Drake broke off and captured the Spanish galleon Nuestra Señora del Rosario, along with Admiral Pedro de Valdés and all his crew. The Spanish ship was known to be carrying substantial funds to pay the Spanish Army in the Low Countries. Drake’s ship had been leading the English pursuit of the Armada by means of a lantern. By extinguishing this for the capture, Drake put the fleet into disarray overnight.

On the night of 29 July, along with Howard, Drake organised fire-ships, causing the majority of the Spanish captains to break formation and sail out of Calais into the open sea. The next day, Drake was present at the Battle of Gravelines. He wrote as follows to Admiral Henry Seymour after coming upon part of the Spanish Armada, whilst aboard Revenge on 31 July 1588 (21 July 1588 OS):[102]

Coming up to them, there has passed some common shot between some of our fleet and some of them; and as far as we perceive, they are determined to sell their lives with blows.

The most famous (but probably apocryphal) anecdote about Drake relates that, prior to the battle, he was playing a game of bowls on Plymouth Hoe. On being warned of the approach of the Spanish fleet, Drake is said to have remarked that there was plenty of time to finish the game and still beat the Spaniards, perhaps because he was waiting for high tide. There is no known eyewitness account of this incident and the earliest retelling of it was printed 37 years later.[52] Adverse winds and currents caused some delay in the launching of the English fleet as the Spanish drew nearer,[52] perhaps prompting a popular myth of Drake’s cavalier attitude to the Spanish threat. It might also have been later ascribed to the stoic attribute of British culture.

-

Sir Francis Drake whilst playing bowls on Plymouth Hoe is informed of the approach of the Spanish Armada. Bronze plaque by Joseph Boehm, 1883, base of Drake statue, Tavistock

-

Drake–Norris Expedition[edit]

The people of quality dislike him for having risen so high from such a lowly family; the rest say he is the main cause of wars.

— Gonzalo González del Castillo, letter to King Philip II, 1592[103]

In 1589, the year after the failure of the Spanish Armada the English sent their own armada to attack Spain. Drake and Sir John Norreys were given three tasks:

- Destroy the battered Spanish Atlantic fleet, which was being repaired in ports of northern Spain

- Make a landing at Lisbon, Portugal and raise a revolt there against King Philip II (Philip I of Portugal) installing the pretender Dom António, Prior of Crato to the Portuguese throne

- Take the Azores if possible so as to establish a permanent base.

In the siege of Coruña, Drake and Norreys destroyed a few ships in the harbour of A Coruña in Spain but were repelled. This defeat in all fronts delayed Drake for two weeks, and he was forced to forgo hunting the rest of the surviving ships and head on to Lisbon.[101]

In Lisbon, he anchored the fleet in the Tagus estuary while Norris attempted to arouse a Portuguese rebellion with Dom António in the lead. The rebellion never materialized and the ground campaign was a total failure, so Norris, with his army and António, reembarked to make an attempt at capturing the treasure fleet. The weather was not in their favor so they eventually sailed for home.

However, Drake wanted to atone for such a bitter setback and, in order not to return empty-handed and with the morale of his troops sunk, he made a fleeting stop in the Galician rías, razing the defenseless town of Vigo to the ground without mercy for four days. Even this abusive demonstration of power did not leave the corsair unharmed, as he lost some five hundred more men on land, in addition to as many wounded. The growing defenses of the inhabitants, and the arrivals of militias from Portugal, put the ships in retreat again. Two of the vessels sailing back to Plymouth were captured in the Bay of Biscay by a squadron of zabras led by Captain Diego de Aramburu.[104][105]

The failure cost more than 12,000 lives and 20 ships.[106][107] After an investigation was opened in England to try to clarify the causes of the disaster, Drake, whose behavior was harshly criticized by his comrades in arms, was relegated to the modest post of commander of the coastal defenses of Plymouth, being denied the command of any naval expedition for the next six years.

Defeats and death[edit]

Drake’s seafaring career continued into his mid-fifties. In 1595, he failed to conquer the port of Las Palmas, and following a disastrous campaign against Spanish America, where he suffered a number of defeats, he unsuccessfully attacked San Juan de Puerto Rico, eventually losing the Battle of San Juan.

The Spanish gunners from El Morro Castle shot a cannonball through the cabin of Drake’s flagship, but he survived. He attempted to attack over land in an effort to capture the rich port of Panamá but was defeated again. A few weeks later, on 28 January 1596, he died (aged about 56) of dysentery, a common disease in the tropics at the time, while anchored off the coast of Portobelo where some Spanish treasure ships had sought shelter.[108] Following his death, the English fleet withdrew defeated.[109]

Before dying, he asked to be dressed in his full armour. He was buried at sea in a sealed lead-lined coffin, near Portobelo, a few miles off the coastline. It is supposed that his final resting place is near the wrecks of two British ships, the Elizabeth and the Delight, scuttled in Portobelo Bay. Divers continue to search for the coffin.[110][111]

Cultural impact[edit]

In Valparaíso, Chile, folklore associates a cave known as Cueva del Pirata (lit. «Cave of the Pirate») with Francis Drake. A legend says that when Drake sacked the port, he became disappointed over the scant plunder. Drake proceeded to enter the churches in fury to sack them and urinate on the goblets.[112] However he still found the plunder to be not worth enough to take it on board his galleon, hiding it in the cave.[112] Another version of the legend says a treasure was left in the cave because the plunder had been more than he could take on board.[112] Together with the treasure Drake would have left a man chained or a sentry to wait for them to return, which they did not.[112] The treasure is said to still be there, but those who approach it drown.[112]

Further north in Chile a tale says that because Drake feared falling prisoner to the Spanish he buried his treasure near Arica, these being one of many Chilean stories about entierros («burrowings»).[112][113]

In the UK there are various places named after him, especially in Plymouth, Devon. Places there carrying his name include the naval base HMS Drake, Drake’s Island, and a shopping centre and roundabout named Drake Circus. Plymouth Hoe is also home to a statue of Drake. The Sir Francis Drake Channel is located in the British Virgin Islands.

Several landmarks in northern California were named after Drake, beginning in the late 19th century and continuing into the 20th century. American historian Richard White has claimed that these commemorations have origins in Anglo-Saxonism,[114] a racist ideology that was variously used to justify manifest destiny, imperialism, slavery, nativism, and the genocide of indigenous peoples.[115] Public scrutiny of these memorials intensified after the murder of George Floyd, when protests against police brutality and racism drew critical attention to place names and monuments connected to white supremacy. Several California landmarks that commemorated Drake were removed or renamed. Citing Drake’s associations with the transatlantic slave trade, colonialism and piracy,[116][117] Sir Francis Drake High School, in San Anselmo, California, changed its name to Archie Williams High School, after former teacher and Olympic athlete Archie Williams. A statue of Drake in Larkspur, California was also removed by the city authorities.[118][119] Multiple jurisdictions in Marin County considered renaming Sir Francis Drake Boulevard, one of its major thoroughfares, but left the name intact when they failed to reach a consensus.[120] In San Francisco, the Sir Francis Drake Hotel was renamed the Beacon Grand Hotel.[121]

In British Columbia, Canada, where some theorise he may also have landed to the north of the usual site considered to be Nova Albion, various mountains were named in the 1930s for him, or in connection with Elizabeth I or other figures of that era, including Mount Sir Francis Drake, Mount Queen Bess, and the Golden Hinde, the highest mountain on Vancouver Island.

Drake’s will was the focus of a vast confidence scheme which Oscar Hartzell perpetrated in the 1920s and 1930s. He convinced thousands of people, mostly in the American Midwest, that Drake’s fortune was being held by the British government, and had compounded to a huge amount. If their last name was Drake they might be eligible for a share if they paid Hartzell to be their agent. The swindle continued until a copy of Drake’s will was brought to Hartzell’s mail fraud trial and he was convicted and imprisoned.[122]

Drake’s Drum has become an icon of English folklore with its variation of the classic King asleep in mountain story motif.

Drake was a major focus in the video game series Uncharted, specifically its first and third instalments, Uncharted: Drake’s Fortune and Uncharted 3: Drake’s Deception, respectively. The series follows Nathan Drake, a self-proclaimed descendant of Drake who retraces his ancestor’s voyages.

Drake was the subject of a TV series, Sir Francis Drake (1961-1962). Terence Morgan played Drake in the 26-episode adventure drama.

-

This portrait, c. 1581, may have been copied from Hilliard’s miniature—note the similar shirt—and the somewhat oddly-proportioned body, added by an artist who did not have access to Drake. National Portrait Gallery, London.

-

Bronze statue in Tavistock, in the parish of which he was born, by Joseph Boehm, 1883.

See also[edit]

- Francis William Drake, relative of Sir Francis Drake

- Drake’s Leat, a water supply for Plymouth, promoted by Drake

References[edit]

- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. «Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–». Retrieved 16 April 2022.

- ^ Woolsey, Matt (19 September 2008). «Top-Earning Pirates». Forbes.com. Forbes Magazine. Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- ^ Paris Profiles. Bibliothéque Nationale, Paris. pp. Portfolio 17.

- ^ Wallis, Helen (1984). «The Cartography of Drake’s Voyage». In Norman J. W. Thrower (ed.). Sir Francis Drake and the Famous Voyage, 1577–1580: Essays Commemorating the Quadricentennial of Drake’s Circumnavigation of the Earth. University of California Press. p. 143. ISBN 978-0-520-04876-8.

- ^ Soto Rodríguez, José Antonio (2006). «La defensa hispana del Reino de Chile» (PDF). Tiempo y Espacio (in Spanish). 16. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 January 2017. Retrieved 30 January 2016.

- ^ According to the English calendar then in use, Drake’s date of death was 28 January 1595, as the new year began on 25 March.

- ^ His name in Latinised form was Franciscus Draco («Francis the Dragon»). See Theodor de Bry Archived 22 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Cummins, John (1997). Francis Drake: The Lives of a Hero. St. Martin’s Press. p. 126. ISBN 978-0-312-16365-5.

- ^ Hanna, Mark G. (22 October 2015). Pirate Nests and the Rise of the British Empire, 1570-1740. UNC Press Books. p. 46. ISBN 978-1-4696-1795-4.

- ^ Campbell, John (1841). Lives of the British Admirals and Naval History of Great Britain from the Time of Caesar to the Chinese War of 1841 Chiefly Abridged from the work of Dr. John Campbell. Glasgow: Richard Griffin & Co. p. 104. ISBN 9780665347566. OCLC 12129656. Archived from the original on 25 November 2015. Retrieved 30 August 2012. Direct quote is followed by «this carries back his birth to 1544, at which time the six articles were in force, and Francis Russell was seventeen years of age.»

- ^ 1921/22 edition of the Dictionary of National Biography, which quotes Barrow’s Life of Drake (1843) p. 5.

- ^ Fuller-Elliot-Drake, Elisabeth (1911). The Family and Heirs of Sir Francis Drake. London: Smith, Elder & co. pp. 2, 21–22.

- ^ a b c Thomson, George Malcolm (1972), ‘Sir Francis Drake’, William Morrow & Company Inc. ISBN 978-0-436-52049-5

- ^ «Francis Drake bio». Tudor Place. Archived from the original on 29 November 2010. Retrieved 25 February 2010.

- ^ Froude, James Anthony (1896). English Seamen in the Sixteenth Century. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons. Quote: «He told Camden that he was of mean extraction. He meant merely that he was proud of his parents and made no idle pretensions to noble birth. His father was a tenant of the Earl of Bedford, and must have stood well with him, for Francis Russell, the heir of the earldom, was the boy’s godfather.»

- ^ a b c Southey, Robert (1897). English Seamen: Howard, Clifford, Hawkins, Drake, Cavendish. London: Methuen and Co.

- ^ Warren, Derrick (2005). Curious Somerset. Stroud: Sutton Publishing. pp. 90–91. ISBN 978-0-7509-4057-3.

- ^ «The Occupants of the ancient office of High Sheriff of Somerset». Tudor Court. Archived from the original on 13 May 2011. Retrieved 30 March 2011.

- ^ a b c Loades 2007.

- ^ a b Mill, James (1840). The History of British India, Volume 1. London: James Madden and Co. p. 9.

- ^ Sugden (2006), pp. 8–9.

- ^ Whitfield 2004, p. 17.

- ^ Whitfield 2004, p. 20.

- ^ Whitfield 2004, p. 19.

- ^ a b c Whitfield 2004, p. 21.

- ^ Sources vary on the dates and the age of Drake.

- ^ Sugden (2006), p. 9.

- ^ a b Kelsey (2000), p. 43.

- ^ Lane, Kris E.; Levine, Robert M. (2015). Pillaging the empire: piracy in the Americas, 1500-1750. Routledge. p. 34. ISBN 9781317462798.

- ^ Sauer, Carl Ortwin (1975). Sixteenth Century North America: The Land and the People as Seen by the Europeans. University of California Press. p. 235. ISBN 978-0-520-02777-0.

- ^ Sugden (2006), pp. 19–22.

- ^ Benezet, Anthony (1788). Some historical account of Guinea, : its situation, produce, and the general disposition of its inhabitants, with an inquiry into the rise and progress of the slave trade, its nature and lamentable effects. London: J. Phillips.

- ^ «Hawkins, Sir John (1532–1595), merchant and naval commander». Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. 2004. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/12672. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Whitfield 2004, p. 22.

- ^ Strickrodt, Silke (1 February 2006). «The British Transatlantic Slave Trade (4 vols.)». The English Historical Review. CXXI (490): 226–230. doi:10.1093/ehr/cej026.

- ^ Vicary, Tim (4 October 2012). «Sir Francis Drake and the African Slaves». English Historical Fiction Authors. Archived from the original on 22 August 2017. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- ^ «England’s first slave trader». BBC. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- ^ «Drake escaped during the attack and returned to England in command of a small vessel, the Judith, with an even greater determination to have his revenge upon Spain and the Spanish king, Philip II.»—»Sir Francis Drake» article in online Britannica Library. Retrieved 14 January 2016

- ^ Whitfield 2004, p. 24.

- ^ Lace 2009, p. 17.