Содержание

- Гробницы правителей архаичного периода

- Мастабы

- Пирамида Джосера

- Медумская пирамида

- Ломаная пирамида

- Розовая пирамида

- Великие пирамиды

- Пирамиды V и VI династий Древнего царства

- Пирамиды Среднего царства

- Долина Царей

- Долина Цариц

Гробница фараона в соответствии с религиозными представлениями Древнего Египта строилась как жилище умершего правителя. Гробницы фараонов играли огромную роль в истории Древнего Египта, в жизни египтян того времени. Порой на их строительство уходили громадные силы и средства всего государства. История строительства гробниц фараонов Египта является важной частью истории всего древнеегипетского государства.

По представлениям обитавшего в долине Нила первобытного человека, загробная жизнь являлась подобием земной, и умерший человек так же нуждался в жилище и еде, как и живой; гробница мыслилась домом умершего, что и определило ее первоначальную форму. Из этого же родилось стремление сохранить тело умершего или хотя бы голову. Так как в начале способы бальзамирования были несовершенными, в гробницы ставили статуи умершего как замену тела в случае его порчи. Итак, гробница- дом умершего- должна была служить таким помещением, где была бы в полной сохранности мумия, где помещалась бы статуя умершего и куда его родные могли приносить все необходимое для его питания. Эти требования и определили структуру гробниц Древнего царства.

Гробницы правителей архаичного периода

В конце доисторических времен не было специальных мест для захоронений, мертвых хоронили обычно рядом с поселениями и деревнями. Их закапывали в землю недалеко от хижин.

С появлением медных инструментов и орудий груда обряду похорон и местам захоронений стали уделять больше внимания.

В Бадари (Верхний Египет) стенки могил стали выкладывать циновками, в отдельных могилах над телом умершего сооружали навес. Могилы, выложенные кирпичом и состоящие из нескольких помещений, появились впервые в культуре Негада .

После объединения северных и южных земель фараоны I и II династий стали специально подчеркивать свое богатство и власть. Они строили огромные гробницы, устраивали пышные похороны. Примеру фараонов следовали высокопоставленные вельможи. Археологи нашли и раскопали царские захоронения архаичного периода в Саккаре – «городе мертвых» первой столицы объединенного Египта – Мемфиса. Такие же могилы были найдены в Абидосе, в районе верхнеегипетского города Тхис. Согласно предположениям в Абидосе находились символические могилы и гробницы древних правителей. Обе части государства несмотря на то, что правил ими один фараон, были еще достаточно самостоятельными, поэтому фараона нужно было хоронить в двух местах – естественно, одно из захоронений было символическим.

Город мертвых

«Город мертвых», как и город живых, располагался на границе пустыни и плодородной земли, даже гробницы напоминали своей формой жилые дома. Гробницы в Абидосе и Саккаре представляют два основных типа погребальных построек. Разница между ними хорошо видна на примере подлинной гробницы царицы Мернетх в Саккаре и ее символическим захоронением в Абидосе.

Гробница фараона в соответствии с религиозными представлениями Древнего Египта строилась как жилище умершего правителя. Гробницы фараонов играли огромную роль в истории Древнего Египта, в жизни египтян того времени. Порой на их строительство уходили громадные силы и средства всего государства. История строительства гробниц фараонов Египта является важной частью истории всего древнеегипетского государства.

Мастабы

В результате развития формы могил и усыпальниц правителей архаичных времен появились мастабы. Это самый ранний тип гробниц фараонов периода Древнего царства. Мастаба имеет форму усечённой пирамиды с несколькими помещениями внутри и подземной погребальной камерой

Мастабы состояли из подземной части, где ставили гроб с мумией, и массивной надземной постройки. Подобные постройки времени I династии имели вид дома с двумя ложными дверьми и двором, где приносились жертвы. Этот «дом» представлял собой облицованный кирпичом холм из песка и обломков камней. К такому зданию затем стали пристраивать кирпичную молельню с жертвенником. Для гробниц высшей знати уже при I династии применялся известняк. Постепенно мастаба усложнялась; молельни, и помещения для статуи устраивались уже внутри надземной части, сплошь сложенной из камня. По мере развития жилищ знати увеличивалось и количество помещений в мастаба, где к концу Древнего царства появляются коридоры, залы и кладовые.

Пирамида Джосера

Такие гробницы строили фараоны I и II династий Древнего царства. Всё изменилось при первом фараоне III династии Джосере. Для своей усыпальницы он поставил всё убывающие в размерах мастабы друг на друга, получив ступенчатую пирамиду.

Пирамида Джосера

Другим новшеством стало то, что фараон отказался от недолговечного необожженного кирпича, и приказал построить свою гробницу из камня. Таким образом, ступенчатая пирамида в Саккаре стала первым в мире каменным архитектурным сооружением. Её же считают первой египетской пирамидой.

Пирамида Джосера предназначалась для всей семьи усопшего, как и мастабы, возводимые до этого. В более поздних пирамидах хоронили только одного фараона. Для членов семьи в пирамиде Джосера было приготовлено в тоннелях пирамиды 11 погребальных камер. Там были похоронены все его жены и дети, в том числе была найдена мумия ребенка приблизительно восьми лет.

Пирамида была ограблена в древности, причем имеется несколько разных лазов, пробитых грабителями. Поэтому не удивительно, что мумию самого Джосера не нашли (вероятно, от него сохранилась лишь мумифицированная пятка).

Территория для строительства комплекса пирамиды Джосера, выбранная Имхотепом, находится на краю плоскогорья, откуда открывался прекрасный вид на Мемфис.

Медумская пирамида

Сначала фараон Снофру, осуществил переход к правильной форме пирамиды, перестроил ступенчатую пирамиду в Медуме, заложив ступени каменной кладкой, и придав пирамиде правильную геометрическую форму. Со временем эта кладка обвалилась, засыпав нижние ступени, и пирамида приобрела совершенно необычную форму.

Форма правильной пирамиды, т. е. имеющей квадратное основание, может быть изучена не только с технической стороны. На развитии формы пирамиды сказались изменения общественной структуры Древнего Египта и религиозных концепций.

Новые идеи изменили не только форму пирамиды, они привели к созданию целых комплексов культовых сооружений, необходимых для проведения ритуальных церемоний. Комплекс пирамиды в Медуме, ставший классическим, был построен в одно время с самой пирамидой. Он был возведен на границе пустыни и плодородной земли и состоял из двух храмов — нижнего и заупокойного. Оба храма были соединены дорогой восхождения. Главным элементом комплекса была пирамида — гробница фараона.

Маленький заупокойный храм находился у восточного склона медумской пирамиды. Дорога в него проходила через два полностью закрытых, темных и длинных помещения, расположенных у самого подножия пирамиды. Во дворике заупокойного храма стояли две каменные стелы без надписей, между ними находился жертвенный алтарь. Сюда приносили жертвенные дары, еду и питье для умершего фараона: От нижнего храма остались лишь незначительные следы, дорога восхождения хорошо сохранилась на всем своем протяжении. К комплексу пирамиды фараона Снофу в Медуме принадлежат и маленькие пирамиды-спутницы.

Ломаная пирамида

Две другие пирамиды фараона Снофру находятся к западу от нынешней деревни Дашур. Первая — это пирамида с ломаными гранями, или Ломаная пирамида. Стены ее нижней части наклонены под углом 54° ЗГ к линии горизонта, примерно с середины высоты пирамиды наклон стен становился 43° 21′. Для объяснения причин, вызвавших строительство пирамиды с такими ломаными гранями, существует несколько теорий. Одни специалисты считают, что во время строительства пирамиды произошло землетрясение, ее верхняя часть была слишком отвесной и была разрушена. Поэтому строители продолжили работы под другим, более пологим углом. Другие ученые видят здесь одно из доказательств взаимосвязи обелиска и пирамиды Нижний храм Ломаной пирамиды — самый древний из известных нам. Он расположен не на краю плодородных земель, как другие, более поздние храмы, а построен в пустыне. Дорога восхождения, соединяя его с культовыми постройками у пирамиды, продолжается дальше на восток, в сторону реки. Многие египтологи считают, что существовал еще один, настоящий нижний храм, построенный на границе пустыни и плодородной земли, но он не сохранился. Сохранившийся нижний храм, имея прямоугольник в плане, состоит из трех основных частей: входного зала-вестибюля, четырех помещений рядом с ним и большого двора, в глубине которого стояли две колоннады (по 10 колонн пятиметровой высоты в каждой). Они образовывали открытый дворик. За ним находились шесть камер со статуями фараона Снофру больше натуральной величины. Стены храма были украшены прекрасными барельефами.

Розовая пирамида

Вторая пирамида Снофру в Дашуре называется Розовой пирамидой. Этот цвет придает ей камень, из которого она построена. Угол наклона пирамиды примерно такой же, как в верхней части Ломаной пирамиды.

До сих пор остается неясным, для чего фараону Снофру потребовались сразу две рядом стоящие гробницы? Этот факт, как и многие другие, подтверждает гипотезу о том, что самые грандиозные пирамиды никогда не были гробницами фараонов.

Великие пирамиды

Самыми грандиозными гробницами фараонов были три пирамиды в Гизе, которые получили название Великих. Их считают одним из Семи чудес света. Они расположены на кромке пустынного плато Гиза, на границе с зеленой долиной Нила, на окраине Каира.

Этот древнеегипетский некрополь состоит из пирамиды Хеопса, несколько меньшей по размерам пирамиды Хефрена и относительно скромных размеров пирамиды Микерина, а также ряда менее крупных пирамид-спутников.

Пирамида Микерина ознаменовала конец эпохи больших пирамид. Все последующие сооружение были небольших размеров.

Во времена пятой династии в Египте пирамиды строились намного меньшего размера. Их возводили из каменных блоков меньшего размера и недорогих строительных материалов. Намного короче оказалось и время их существования. Большинство из них сейчас в руинах.

Пирамиды V и VI династий Древнего царства

Фараоны пятой династии построили пять относительно небольших пирамид в Абусире, примерно в девяти километрах южнее Гизы, а кроме них ещё три пирамиды в Саккаре. Рядом с пирамидой Джосера, с восточной стороны, фараон Усеркаф возвел свою пирамиду. Она была сооружена из огромных блоков грубо отесанного известняка.

Пирамида Унаса

Пирамида Унаса – последнего фараона пятой династии – была возведена к юго-западу от пирамиды Джосера. В настоящее время она довольно сильно разрушена.

В Саккаре во времена шестой династии было построено четыре небольшие пирамиды, но они сейчас имеют еще более плачевный вид.

Пирамиды Среднего царства

В период Среднего царства произошли значительные изменения в строительстве пирамид. В качестве строительного материала стали использовать не камень, а необожженный кирпич. Пирамиды опять увеличились в размерах, сложнее стала архитектура погребальной камеры, и заупокойный храм достиг максимальных размеров.

Правители тринадцатой династии прекратили строить этот тип усыпальниц для фараонов. Вместо пирамид в Древнем Египте стали возводиться гробницы, которые вырубались в скалах.

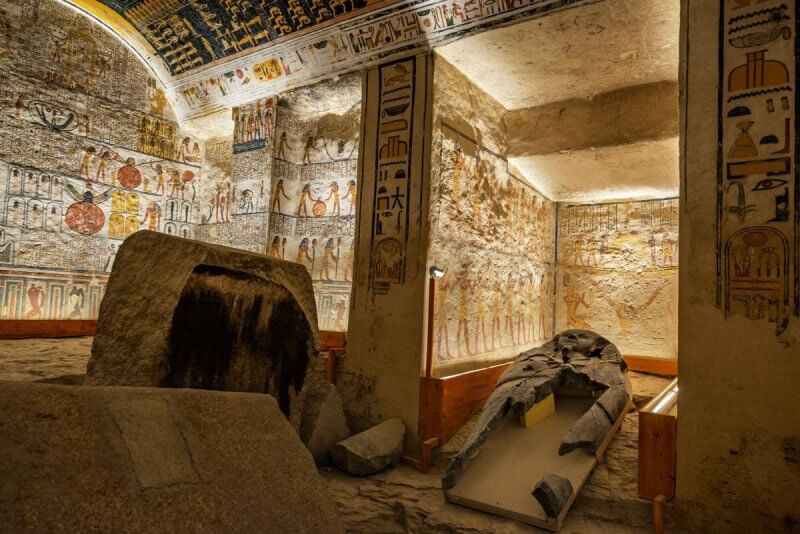

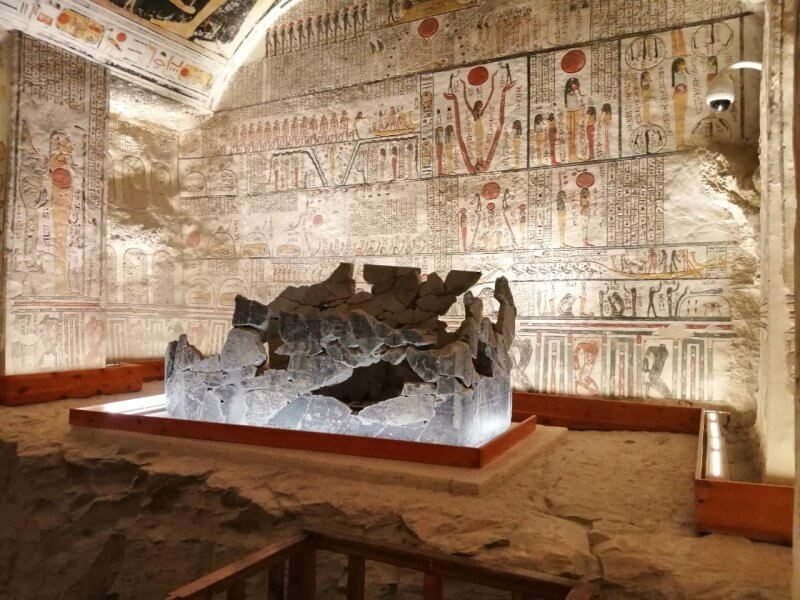

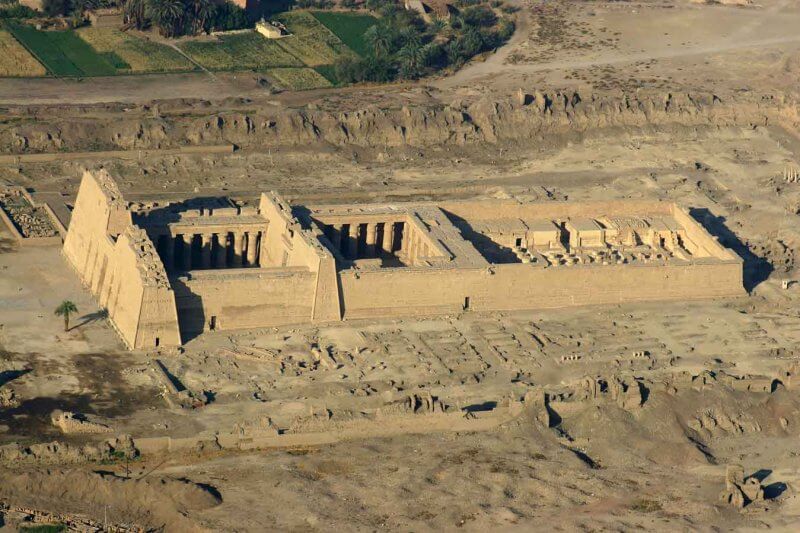

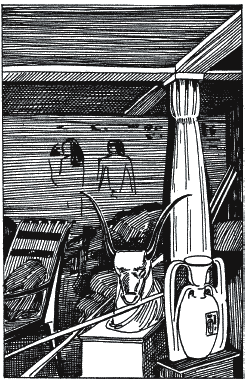

Долина Царей

Долина Царей — отдаленная и бесплодная местность неподалеку от реки Нил, стала некрополем для погребения египетских фараонов «Нового царства». В этой долине расположено, более чем шестьдесят гробниц фараонов, сделанных в течении пятисот лет, с шестнадцатого по одиннадцатый века до нашей эры.

Все началось с пожелания фараона Тутмоса Первого о тайном захоронении его тела, так как он знал о разграблениях других королевских усыпальниц и хотел избежать подобной участи. Он приказал отыскать для своего захоронения тайное место, которое имело бы скрытый вход от посторонних глаз. Его захоронение, в отличие от пышных традиционных царских погребений, было выполнено в форме колодца, в совершенно пустынном ущелье, названном «Долина Царей». С тех пор, появилась новая традиция оформления могил правителей – их вырезали в скальной породе, входом являлся длинный наклонный туннель, уходящий глубоко в недра скалы, снаружи тщательно замаскированный. Стены украшали яркими и красочными резными барельефами, рассказывающими о славной жизни и о многочисленных подвигах покойного. Нужно отметить, что фараон Тутмос I, не зря беспокоился о целостности своей гробницы и ее расхищения нечистыми на руку людьми, мечтающими в один день сказочно разбогатеть: подобные воры, захватив драгоценности, во избежание кары за свои проступки, сжигали останки мумий, что навсегда лишало усопшего возможности перехода души к новой загробной жизни.

Новый тайный способ захоронений оказался малоэффективным, так как множество гробниц фараонов все равно были разграблены, хотя, некоторые из них смогли сохранить египетские жрецы, успевшие перепрятать мумии царей и их сокровища, в новые тайники. Большинство таких захоронений фараонов были перенесены в местность около Дейр- эль- Бахри. Не были ограблены лишь гробницы фараонов Юйи и Туйи.

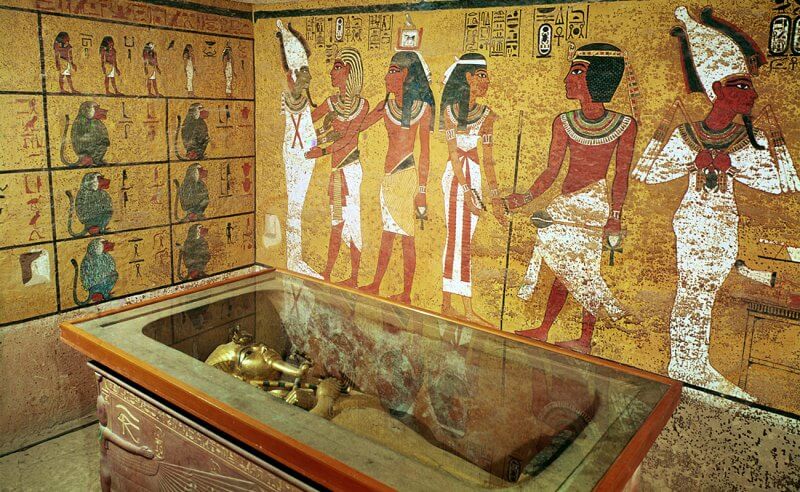

Гробница фараона Тутанхамона

Гробница фараона Тутанхамона — самая знаменитая из всех гробниц в «Долине царей» в Фивах, обнаруженная в 1922 году Говардом Картером — ученым-археологом из Англии. Эта гробница, в свое время, тоже была частично разграблена, но жрецам удалось спасти многие ее сокровища и останки Тутанхамона. Богатство и многочисленность сокровищ гробницы Тутанхамона потрясли мировое сообщество, ведь большая часть предметов состояла из золота, в том числе и роскошный гроб фараона. А вот сама гробница выглядела довольно скромно, в результате чего, ученые сделали вывод, что ее строили наспех, потому что молодой фараон умер внезапно. Кстати, в 2006 году, американскими археологами была обнаружена гробница эпохи восемнадцатой династии фараонов, расположенная около склепа фараона Тутанхамона. Тут нашли пять мумий, лежавших в саркофагах, на лице которых находились нетронутые погребальные маски, а вокруг стояли двадцать ларцов с деньгами и печатью фараона.

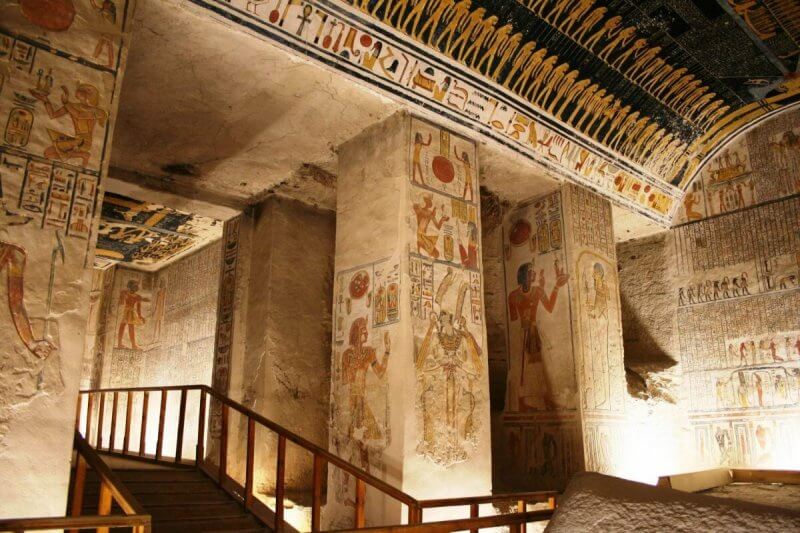

Гробница фараона Сети I.

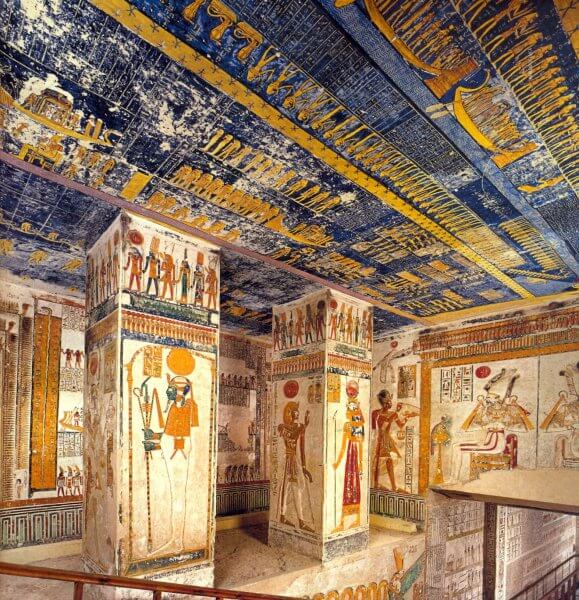

Стоит упомянуть о величии и поразительной красоте гробницы фараона Сети I, о ее искусно выполненных барельефах, прекрасных золотых росписях и изумительной погребальной камере, оформленной потолком — «звездное небо». Эта гробница имеет невероятно сложную конструкцию и подразделяется на множество залов, лестниц, галерей. А вот мумии фараона в гробнице обнаружено не было, ее перенесли в тайное место, чтобы уберечь от вандалов.

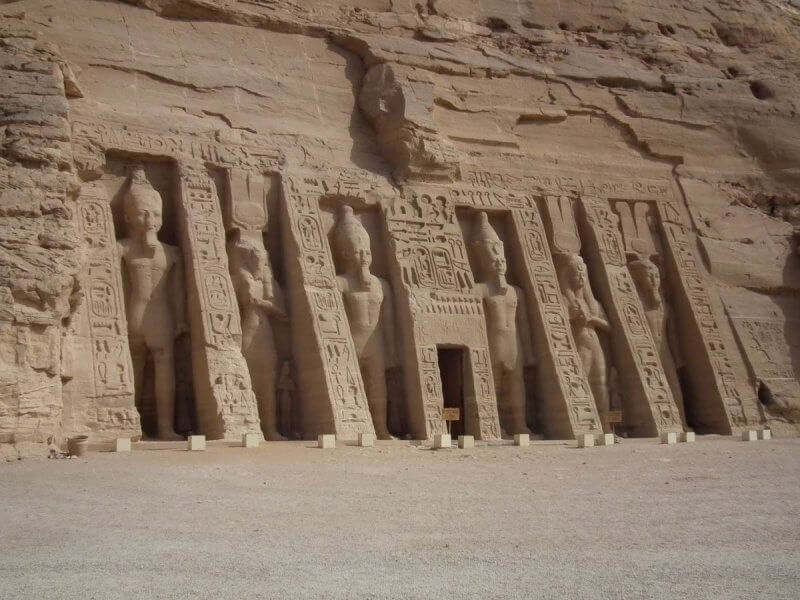

Долина Цариц

Долина Цариц — располагается в Фиванской долине, юго-западнее «Долины Царей». Этот некрополь появился во времена правления фараона Рамзеса I, примерно в 1300 году до нашей эры. Здесь начали возводить склепы для женщин царской половины династии и их детей, но некоторых цариц продолжали хоронить вместе с мужьями-фараонами.

Долина Цариц

На сегодняшний день в «Долине Цариц» найдено семьдесят девять гробниц и помещений культового назначения, в том числе комнат для мумифицирования тел усопших. Некрополь царских жен и детей изучен не так хорошо, как «Долина Царей». К сожалению, тут не сохранилось нетронутых гробницы, потому что эти захоронения не пытались тщательно прятать, как могилы фараонов. Тут отсутствовали ложные ходы, коварные ловушки, лабиринты, поэтому все захоронения «Долины Цариц» ограбили еще в древности.

В «Долине Цариц» находятся захоронения супруг фараонов, их отпрыски, некоторые высокопоставленные сановники Древнего Египта. Но их усыпальницы – это гробницы, вырубленные в скальных породах, в большинстве своем, довольно скромные и небольшие. Гробница включает небольшую прихожую на уровне поверхности, узкий наклонный ход, ведущий в погребальную камеру. Сейчас не распознана и половина гробниц «Долины Цариц». Посетить туристам можно лишь несколько из них.

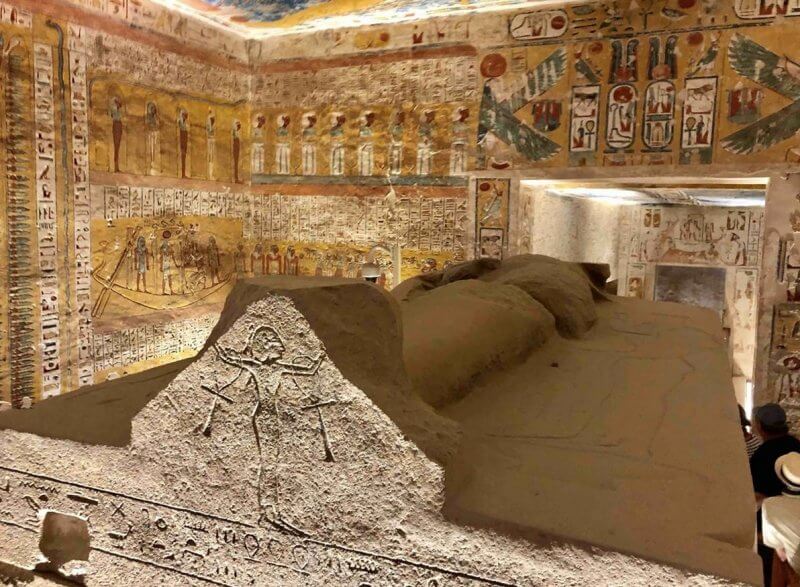

Гробница царицы Нефертари

Самое впечатляющее захоронение принадлежит царице Нефертари — любимой супруги фараона Рамзеса Второго. Оно устроено сложней прочих гробниц «Долины Цариц» и включает семь залов. Прекрасные фрески, покрывающие стены гробницы, заставили говорить о ней, как о «Сикстинской капелле Древнего Египта». Стены гробницы украшены изображениями самой царицы в разные моменты ее жизни, но всегда в окружении египетских богов. Погребальная камера Нефертари имеет четыре колонны, и все здесь расписано сюжетами «Книги мертвых». Несколько лет назад тут провели реставрацию и строго ограничили доступ посетителей. Яркие настенные фрески, по сей день выглядят свежими и яркими. Изображения исполнены согласно древней традиции Египта: все портреты написаны в профиль. Над мощным гранитным саркофагом царицы, находится роспись «звездное небо». На поверхностях стен лестницы, коридора тоже находятся росписи со сценами «Книги мертвых», начертаны сакральные тексты, советы, заклинания, чтобы усопший смог быстро попасть в царство Осириса.

Нефертари

Здесь часто встречаются изображения богов Осириса и Анубиса, сопровождавших души умерших в путешествии по чертогам загробного мира. Усыпальницу Нефертари обнаружили в 1904 году, под руководством Эрнесто Скиапарелли — директора «Египетского музея» итальянского города Турина. Росписи гробницы стали важным историческим источником, который может рассказать о мироощущениях и познаниях древних египтян о загробной жизни. Кстати, на стенах этой гробницы вырезано собственное стихотворение фараона Рамзеса II к любимой, но рано его покинувшей жене, трогающее до глубины души:

«Любовь моя единственная! Никто ей не соперник, она – красивейшая из живших на земле женщин, за мгновение укравшая мое сердце! »

Гробница царицы Тити

Славится очень колоритными и красочными росписями. Стены погребальной камеры украшены изображениями египетской богини Хатор – в обличье коровы на фоне гор, и она же, но уже в человеческом облике, оживляющая царицу Тити в водах Нила. Могилу украшают изображения самой царицы двадцатой династии Древнего Египта, а также изображения божественных представителей, самых распространенных в то время религиозных культов: Тот, Атум, Исида, Нефтида, Нейт, Осирис, Селкуит.

Египет – загадочная и таинственная страна Африки, привлекающая людей своими грандиозными архитектурными сооружениями и гигантскими некрополями. Особенно интересными с этой точки зрения для туристов являются «Долина Царей» и «Долина Цариц», расположенные рядом с современным городом Луксор. И

Древние гробницы в Египте имели большое значение для уже утерянной эпохи. Большой интерес, который испытывают к подобным местам археологи и не только весьма оправдан. Ведь такое захоронение хранит в себе великую историю, множество тайн, немного мистики и даже невероятные техники, которые использовались египтянами для такого процесса. Понятное дело простым людям больших гробниц не строили и предназначались они для особых персон, в частности царей и труды в это вкладывались не малые. К тому же вы должны были слышать об удивительных вещах, которые могли сделать египтяне, имея минимум знания и приспособлений. Чего только стоят пирамиды, которые даже для современного человека остаются загадкой, что уж говорить о сакральных планах этой эпохи.

Взгляд египетской религии на мир с одной стороны был очень практичным с другой же это полностью мифологическое сознание, которое нам сейчас трудно понять. И что касается таких масштабных захоронений, так это сплошная иррациональность в плане прилагаемых усилий, хотя напомним, хоронили знатную особу, которая была чуть ли не сыном великого божества. Тела не сжигали и хоронили в песках, так как это было невозможно. Но вот гробницы были отличным решение, и так как мир мертвых был фактически реален, как и других потом народов, место захоронения было для человека практически еще одним дома, там хранились не только его личные вещи, но и вся семья.

В разное время положение и основы гробницы менялись, кто-то строили подземные захоронения, другие создавали что-то наподобие храма, но смысл и технологии применялись удивительные. Что же касается того, что именно должно быть в гробнице имелся четкий план, который, скорее всего, заключался в нескольких основных сакральных элементов сооружения. Так египетская гробница классически всегда имеет погребальную камеру для саркофага, отдельное помещение для обрядов. Камера скорее напоминает склеп или старые захоронения, где умершего провожали и оставляли все важные для него вещи. В святилище же проводили обряды и важные процедуры при похоронах.

Гробниц было найдено довольно много, все они постепенно изучаются. Так как трудно разобрать древние письмена, не всегда понятно какое именно захоронение было открыто. Но для удобства все они пронумерованы, а уже после соотнесения всех исторических сводок можно примерно отдать место какой-то исторической личности Египта.

Список гробниц:

KV1 — гробница Рамсеса VII.

KV2 — гробница Рамсеса IV.

KV3 — гробница безымянного сына Рамсеса III.

KV4 — гробница Рамсеса XI.

KV6 — гробница Рамсеса IX.

KV5 — гробница некоторых из сыновей Рамсеса II.

KV7 — гробница Рамсеса II.

KV8 — гробница Мернептаха.

KV9 —известна как «Гробница Мемнона».

KV10 — гробница Аменмеса.

KV11 — гробница Рамсеса III .

Содержание

- Описание

- Местонахождение

- История

Описание

Большинство гробниц расположена в так называемой Долине царей, они открыты для туристов и вы можете посетить их и прослушать ряд интереснейших экскурсий. Понять иерархию каждого места будет проще понять, когда вы ближе узнаете историю Египта. Так как власть переходила по наследству, история каждого сына очень интересна, начало правления и конец требуют особого внимания в этом вопросе. Нельзя забывать, что каждое такое место имело большое сакральное значение и хранит в себе множество тайн. Особенно занимательно становится, когда рассказывают о проклятии фараона. Эта древняя байка ходит среди археологов и даже стала очень популярна для сюжетов различного кино. Но вся мистика кроется именно в мощи и труде, которая была вложена в такое сооружение.

Фактически жилище для умершего имеет внушительный вид, и даже если забыть о личности, которая здесь захоронена, вы все равно сможете разглядеть много всего интересного и получить много новых впечатлений. Также вы уже не раз могли встречать с описанием саркофага или элементов отделки гробниц в музеях и прочее, но увидеть подобное в той самой обстановке будет намного интереснее. Ведь такие храмы возводили всеми силами в течение многих лет и тратили громадные средства. Поэтому именно захоронениям уделяют, так много внимания, в его стенах хранится большая часть истории этих мест.

Местонахождение

Как уже говорилось выше, большая часть гробниц располагается в «Долине Царей». Вы можете найти ее на карте по точным координатам: 25°44′25″ с. ш. 32°36′08″ в. д. Со стороны это место совсем не примечательно, всего лишь ущелье со скалистой местностью, но какие богатства оно хранит внутри. Именно здесь строились гробницы для самых великих людей древнего Египта, а именно царей. Так же тут модно встретить и другие захоронения, важных чиновников и родственников.

История

Археологами Долина Царей была обнаружена всего лишь в 18 веке и сразу, привлекла огромнейший интерес, такое важное место стало фактически центром всех работ. Исследования еще не закончены и все также в стадии раскопок. Но многие из гробниц открыты для посещения и готовы рассказать вам свою историю. Самый большой интерес вызывает именно история о проклятии, которая появилась только после открытия гробницы Тутанхамонов в прошлом веке. Конечно, такое место внесено в список всемирного наследия.

Для ученых египетские пирамиды это настоящая кладовая, по которой они изучают историю, традиции, религию древних египтян. По найдены в гробницах вещам можно судить о развитии ремесла и искусства.

Содержание

- Египетские гробницы – интересные факты о самых знаковых достопримечательностях страны

- История египетских гробниц

- Особенности архитектуры

- Мистические свойства пирамид

- Самые популярные гробницы Египта

Египетские гробницы – интересные факты о самых знаковых достопримечательностях страны

История египетских гробниц

Гробницы строили инопланетяне – это самая популярная версии среди сторонников теорий заговора и уфологов. Сложно поверить, что древние люди в одних набедренных повязках таскали тяжелые каменные блоки, поднимали их на высоту.

Однако официальная наука утверждает, что даже в те древние времена это было возможным. Хоть и до сих пор неизвестно каким образом.

Считается, что пирамиды строились рабами, которых постоянно били и морили голодом. Египтологи утверждают, что это не так. Последние раскопки нашли предполагаемые дома рабочих, которые доказывают, что они содержались в довольно приличных условиях и получали достаточно пищи.

Египетские пирамиды – великие сооружения древнего мира. Они относятся к семи чудесам света. Ученые считают, что им около 5 тысяч лет.

ИНТЕРЕСНО! Некоторые ученые считаю, что египетские пирамиды намного старше своего официального возраста. Археологи нашли у основания пирамид следы грунта, который был вымыт осадками. Таких осадков не было по меньшей мере 10 тысяч лет.

Особенности архитектуры

Возводить себе гробницу египетские фараоны начинали еще при жизни. Это занимало много времени. Например, на строительство знаменитой пирамиды Хеопса ушло 20 лет.

Гробницу египетских фараонов строили по строгим геометрическим правилам. Угол наклона сторон всегда был от 53 до 73 градусов. При этом внешняя облицовка могла быть идеально гладкой или иметь выступы, что напоминала ступеньки.

Все блоки для строительства пирамид имели точную форму и идеально подходили друг другу. Они крепились между собой специальным раствором, формулу которого учены до сих пор так и не могут разгадать.

Внутри каждый пирамиды было множество помещений. Главной была непосредственно гробница, где находилось тело покойного фараона. Рядом было помещение кладовой – там собирали все вещи, которые могут понадобиться фараону в загробной жизни. В этих комнатах было множество статуй, которые описывали земную жизнь фараона.

СПРАВКА! Внутри гробницы было множество ложных коридоров и комнат. Это было сделано для того, чтобы оградить ценности от разграбления. К сожалению, это не спасло многие пирамиды от набегов варваров.

Пирамиды всегда строили на западном берегу Нила. Рядом с ними находилось еще два сооружения – заупокойный храм и гробница жены фараона.

Мистические свойства пирамид

Пресса уже десятки лет обсуждает необычные мистические свойства пирамид. Одни пишут о том, что в гробницах семена растут быстрей, а продукты не портятся. Другие снимают документальные фильмы о том, как люди, побывавшие в пирамидах, излечиваются от всех болезней.

В альтернативной науке есть даже такое направление – пирамидология. «Ученые» изучают свойства и энергетику древнеегипетских усыпальниц.

Они считают, что идеально правильная геометрическая форма египетской гробницы была сделана специально, чтобы накапливать энергию из космоса. При этом она фильтровалась – в пирамидах задерживается только положительная. А жрицы Древнего Египта впитывали ее и применяли на практике. По мнению пиромидологов, они лечили людей, предсказывали будущие и даже влияли на погоду.

Самая большая мистическая загадка пирамид – проклятие египетских гробниц. Считается, что любой, кто прикоснется к останкам фараона, погибнет страшной смертью. А самой опасной считается пирамида Тутанхамона.

ИНТЕРЕСНО! После вскрытия пирамиды Тутанхамона погибли все члены экспедиции. Но стоит критически относится к этой информации – ученые были уже не молоды и погибли не все сразу.

Важно отметит, что ни одно мистическое свойство, приписываемое пирамидам, не было подтверждено учеными и исследованиями.

Самые популярные гробницы Египта

До наших дней дошли 118 египетских пирамид. Самые популярные места у туристов — это Гиза, некрополь Саккары и Луксор.

Самой древней считается пирамида Джосера. Она находится в Саккаре. А самой большой пирамида Хеопса в Гизе. Интересна также Розовая пирамида в Дахшуре. Это была первая пирамида правильной геометрической формы.

Ко всем пирамидам можно купить организованные экскурсии из Каира или прибрежных городов. Или же добраться самостоятельно.

ВАЖНО! Все пирамиды находятся далеко от курорта Шарм-Эль-Шейх. Поэтому придется ли несколько часов добираться на автобусе, либо заплатить за билет на самолет до Каира.

Пирамиды – это визитная карточка Египта. Приехав в эту страну стоит обязательно посетить самые знаковые из них.

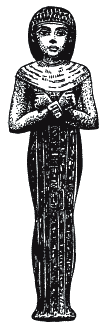

Смерть знатного египтянина

Когда, несмотря на все усилия врачевателей и молитвы жрецов, знатный египтянин умирал, его тело бальзамировали, чтобы предотвратить разложение. Сначала бальзамировщик извлекал мозг и внутренние органы умершего и складывал их в специальные сосуды, или каноны. Затем он обрабатывал труп бальзамирующими веществами. Забальзамированный труп заворачивали во много слоев полосками льняной ткани, а на лицо надевали погребальную маску. Обработанный таким образом труп называют мумией. Процесс бальзамирования знатного покойника длился 70 дней, затем его хоронили. Погребальная процессия переправлялась через Нил и двигалась к гробнице. Носилки с саркофагом сопровождали плакальщики, жрецы и слуги, несшие погребальные дары. Заключительные погребальные обряды исполнялись перед входом в гробницу. Церемония «отверзания уст», по поверью египтян, возвращала покойному способность есть, дышать и двигаться. Все, что должно было понадобиться умершему в царстве мертвых, помещали рядом с саркофагом внутри гробницы. Затем жрецы удалялись, заметая свои следы на полу гробницы.

В период Древнего царства (2686-2181гг. до н.э.) знатных египтян хоронили в склепах, над которыми строили огромные прямоугольные каменные гробницы — мастабы. Внутри некоторых гробниц были комнаты, стены которых расписывали сценами из повседневной жизни египтян.

Могилы бедняков

Умерших бедняков хоронили в ямах, вырытых в песке. Скорбящие родственники складывали в могилу все самое ценное из того, что имели, чтобы умершему лучше жилось в царстве мертвых.

Пирамиды

Царей Древнего и Среднего царств (2636—1633 гг. до н.э.) нередко хоронили под огромными каменными пирамидами. В Египте существует около 100 пирамид, самые знаменитые из них— пирамиды Гизы—показаны на этом рисунке. В них похоронены три царя и их главные жены. Первоначально они были облицованы сверкавшим на солнце белым известняком, но облицовка не сохранилась. Сфинкс, стерегущий пирамиды Гизы, был одним из воплощений древнеегипетского бога солнца. Не исключено, что моделью для лица этого сфинкса послужил фараон Хафра.

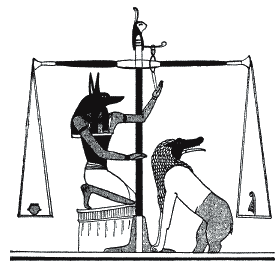

Древние египтяне верили в то, что души умерших переправляются на лодке через реку и попадают в царство мертвых. Там они должны держать ответ за свои поступки при жизни. Чтобы люди знали, как отвечать богам и как себя вести в их присутствии, жрецы написали Книгу мертвых. В ней говорилось, что перед лицом бога мертвых Осириса сердце умершего кладут на весы, на другой чаше которых лежит перышко— символ истины. Если чаши весов уравновесят друг друга, это означает, что человек вел добропорядочную жизнь и ему было уготовано вечное блаженство после смерти. Если же чаша с сердцем перевесит, это означает, что оно несет бремя греха и человека отдадут на съедение чудовищу.

Если вам посчастливилось бывать в Египте, вы наверняка согласитесь, что здесь, неподалеку от города Луксор, находится грандиозный некрополь – это Долина Царей. Пять веков местные жители хоронили тут древнеегипетских правителей. По мнению многих туристов, это место однозначно заслуживает внимания.

Фото: Долина Царей, Египет

Общая информация

Сегодня Долина Царей в Египте насчитывает около шести десятков гробниц, некоторые вырезаны в скале, а некоторые находятся на глубине ста метров. Чтобы добраться до места назначения – погребальной комнаты, приходится пройти по туннелю протяженностью 200 метров. Сохранившиеся до наших дней древние захоронения подтверждают, что фараоны готовились к своей смерти основательно. Каждая гробница – это несколько помещений, стены украшены изображениями из жизни египетского правителя. Не удивительно, что Долина Царей – одна из наиболее популярных достопримечательностей в Египте.

Захоронения здесь велись в период с 16 по 11 столетия до н.э. За пять веков на берегах Нила появился Город Мертвых. И сегодня в этой части Египта ведутся раскопки, во время которых ученые находят новые захоронения.

Интересный факт! В отдельных гробницах обнаруживают двух правителей – предшественника, а также его преемника.

Для захоронения была выбрана территория, расположенная рядом с городом Луксор в Египте. Пустыня будто создана природой для такого места как Долина Царей. Поскольку египетских правителей хоронили со всем богатством, в Город Мертвых часто приходили грабители, более того, в Египте появлялись целые города, жители которых промышляли кражами из гробниц.

Исторический экскурс

Решение организовать усыпальницу не в храме, а в другом месте принадлежит фараону Тутмосу. Таким образом, он хотел уберечь накопленные сокровища от грабителей. Долина Фив расположена в сложно доступном месте, поэтому мошенникам добраться сюда было не так просто. Усыпальница Тутмоса напоминала колодец, а помещение, где непосредственно захоронили фараона, находилось в скале. К этой комнате вела крутая лестница.

После Тутмоса I других фараонов стали хоронить по такой же схеме – под землей или в скале, кроме этого, к помещению с мумией вели запутанные лабиринты, устанавливались хитрые, опасные ловушки.

Интересный факт! Вокруг саркофага с мумией обязательно складывали погребальные дары, которые могли понадобиться в загробной жизни.

Полезно знать! У Тутмоса I была дочь Хатшепсут, которая вышла замуж за своего брата, а после смерти отца стала править Египтом. Храм, посвященный ей, находится близ Луксора. Справка о достопримечательности представлена на этой странице.

Гробницы

Долина Царей в Луксоре – это разветвленный каньон в Египте, на дальнем краю раздваивается в виде буквы «Т». Популярные и посещаемые усыпальницы – Тутанхамона, а также Рамсеса II.

Для посещения египетской достопримечательности необходимо купить билет, который дает право посетить три усыпальницы. Делать это лучше зимой, так как летом воздух прогревается до +50 градусов.

Внутреннее устройство гробниц приблизительно идентичное – лестница, ведущая вниз, коридор, затем снова лестница вниз и непосредственно место захоронения. Конечно, мумий в усыпальницах нет, посмотреть можно только росписи на стенах.

Важно! Внутри гробниц категорически запрещено фотографировать с вспышкой, так как краска, за столько веков привыкшая к темноте, от света быстро портится.

Наиболее интересными для посетителей являются следующие гробницы.

Гробница Рамсеса II

Это самая крупная скальная усыпальница, обнаружили ее в 1825 году, однако археологические раскопки начались только в конце 20 века. Гробница Рамсеса II была разграблена одной из первых, так как находится у входа в Долину Царей, кроме этого, часто затапливалась во время паводков.

После первого осмотра ученые не смогли открыть двери в другие помещения и использовали гробницу как склад. Первые значимые археологические находки были обнаружены в 1995 году, когда археолог Кент Уикс открыл и расчистил все погребальные комнаты, которых оказалось около семи десятков (по количеству главных сыновей Рамсеса I). В дальнейшем ученым удалось установить, что это не просто гробница, так как в 2006 году было обнаружено еще около 130 комнат. Работы по их расчистке ведутся до сих пор.

На заметку: величественный храм Рамзеса II есть и в Абу-Симбеле. Подробные сведения и любопытные факты о нем собраны в этой статье.

Гробница Рамсеса III

Считается, что эта усыпальница предназначалась для захоронения сына Рамсеса III, однако, археологи полагают, что помещение не использовалось по прямому назначению. Об этом свидетельствует незаконченное состояние некоторых помещений, а также небогатое оформление комнат. Здесь должны были похоронить Рамсеса IV, но он при жизни начал строить свою собственную гробницу.

Интересный факт! В период Византийской империи помещение использовалось в качестве часовни.

Несмотря на то, что гробница известна уже долгое время, к ее исследованию приступили только в начале 20 столетия. Раскопки финансировались юристом из Америки Теодором Дэвисом.

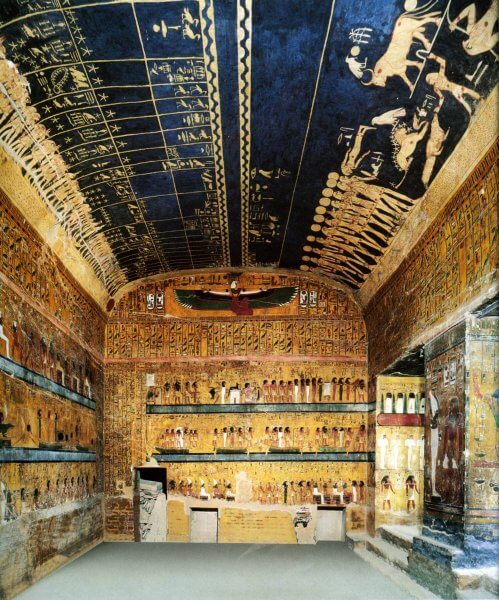

Гробница Рамзеса VI

Эта гробница известна как KV9, здесь похоронены два правителя – Рамсес V, а также Рамсес VI. Тут собрана заупокойная литература, написанная в годы Нового царства. Были обнаружены: Книга пещер, Книга Небесной Коровы, Книга земли, Книга врат, Амдуат.

Первые посетители появились здесь в период античности, об этом свидетельствуют наскальные рисунки. Завалы были расчищены в конце 19 столетия.

Интересный факт! Годы, когда строилась эта гробница, считаются периодом упадка в Египте. Это отразилось и на внутреннем убранстве – оно достаточно сдержанное в сравнении с усыпальницами других правителей.

Гробница Тутанхамона

Наиболее значимым открытием признана усыпальница Тутанхамона, ее обнаружили в 1922 году. Руководителю экспедиции удалось найти ступень лестницы, проход, который был запечатан. Когда в Египет прибыл лорд, финансировавший раскопки, удалось открыть проход и попасть в первую комнату. К счастью, она не была разграблена и сохранилась в первоначальном виде. Во время раскопок ученые обнаружили более 5 тысяч предметов, их тщательно переписали, затем направили в музей в Каире. Среди прочего – золотой саркофаг, украшения, посмертная маска, посуда, колесница. Саркофаг с мумифицированным телом фараона располагался в другом помещении, куда удалось попасть только спустя три месяца.

Интересный факт! Ученые и сегодня не могут прийти к единому мнению – был ли похоронен Тутанхамон с особенной пышностью, ведь многие гробницы на момент обнаружения были разграблены.

Долгое время считалось, что в гробнице Тутанхамона есть тайные помещения. Ученые полагали, что в одном из них похоронена Нефертити, которую называли матерью Тутанхамона. Однако с 2017 года поиски прекратили, так как результаты сканирования показали, что тайных комнат тут нет. Тем не менее, археологические исследования проводятся до сих пор, открываются новые факты о древнеегипетской цивилизации.

В результате исследований удалось определить, что Тутанхамон имел не типичную для мужчины фигуру, кроме этого, он передвигался с палочкой, так как имел врожденную травму — вывих стопы. Тутанхамон умер, едва достигнув зрелого возраста (19 лет), причина – малярия.

Интересный факт! В гробнице обнаружено 300 палок, их положили рядом с фараоном, чтобы он не испытывал трудностей во время ходьбы.

Кроме этого, в гробнице рядом с мумией Тутанхамона обнаружены две мумии-эмбриона — предположительно, это нерожденные дочери фараона.

Саркофаг, где был захоронен Тутанхамон, имел такие размеры:

- длина — 5,11 м;

- ширина — 3,35 м;

- высота — 2,75 м;

- вес крышки — более 1 тонны.

Из этого помещения можно было попасть в другое, наполненное сокровищами. Почти три месяца потратили археологи, чтобы разобрать стену между первой комнатой и усыпальницей, за время работ было обнаружено много ценных вещей, оружие.

Внутри саркофага находился портрет Тутанхамона, покрытый позолотой. В первом саркофаге специалисты обнаружили второй саркофаг, в котором и находилась мумия фараона. Его лицо и грудь покрывала маска из золота. Рядом с саркофагом ученые обнаружили небольшой букет сухих цветов. По одному из предположений, их оставила супруга Тутанхамона.

Интересный факт! Ученые обнаружили, что некоторые фараоны присвоили себе внешний облик Тутанхамона. Подписывали его изображения своими именами.

В 2019 году гробница была отреставрирована, внутри установили современную систему вентиляции, удалили царапины с изображений на стенах, заменили освещение.

Выбирайте жилье и узнавайте Цены с помощью этой формы

Booking.com

Гробница Тутмоса III

Возведена по характерному для египетской гробницы плану, но есть один необычный нюанс – вход расположен на высоте, прямо в скале. К сожалению, она была разграблена, только в конце 19 века ее вновь открыли.

Гробница начинается галереей, за которой следует шахта, после – зал с колоннами, здесь есть проход в погребальное помещение, стены декорированы рисунками, надписями, фресками.

Размеры:

- длина – 76,1 м;

- площадь – почти 311 м2;

- объем – 792,7 м3.

На заметку

Гробница Сети I

Это самая изысканная и протяженная гробница в Долине Царей в Египте, ее длина 137,19 м. Внутри есть 6 лестниц, колонные залы и более полутора десятков других помещений, где во всей красе проявляется египетское зодчество. К сожалению, к моменту открытия гробницу уже разграбили, и мумии в саркофаге не было, но в 1881 году останки Сети I были найдены в тайнике.

В погребальной комнате установлено шесть колон, к этому помещению примыкает еще одно, на потолке которого сохранились астрономические фигуры. По соседству находятся еще две комнаты с изображениями на религиозную тематику, созвездий, планет.

Усыпальница является одним из наиболее весомых религиозных памятников, который отражает представление древних египтян о смерти и возможной жизни после смерти.

Расхитители гробниц

Многие местные жители на протяжении тысячелетий промышляли расхищением гробниц, для некоторых этот род деятельности становился семейным. Это неудивительно, ведь в одной усыпальнице было столько сокровищ и богатств, что на них безбедно могли прожить несколько поколений одной семьи.

Конечно, местные власти всячески пытались остановить и предотвратить кражи, Долину Царей охраняли вооруженные военные, но многочисленные исторические документы подтверждают, что зачастую организаторами преступлений являлись сами представители власти.

Интересный факт! Среди местных жителей было немало людей, которые хотели сохранить историческое наследие, поэтому они брали мумии, сокровища и переносили их в безопасные места. Например, во второй половине 19 века в горах было обнаружено подземелье, где ученые нашли более десяти мумий, и пришли к выводу, что их перепрятали.

Проклятие фараонов

Исследования гробницы фараона Тутанхамона длилось пять лет, за это время трагически погибло много людей. С тех пор с усыпальницей связано проклятие гробницы. Всего умерло более десяти человек, связанных с раскопками и исследованиями. Первым ушел из жизни лорд Карнарвон, который спонсировал раскопки, причина – воспаление легких. Гипотез о причине столь многочисленных смертей было много – опасный грибок, радиация, яды, хранившиеся в саркофаге.

Интересный факт! В список поклонников версии проклятия гробницы также входил Артур Конан Дойл.

Вслед за лордом Карнарвоном умер специалист, проводивший рентген мумии, затем погибает археолог, вскрывавший погребальную комнату, спустя некоторое время скончались родной брат Карнарвона и полковник, сопровождавший раскопки. Во время раскопок в Египте присутствовал принц, его убила супруга, а через год был застрелен генерал-губернатор Судана. Внезапно погибают личный секретарь археолога Картера, его отец. Последний в списке трагических смертей – сводный брат Карнарвона.

В прессе были сообщения о гибели других участников раскопок, однако их смерти не связывают с проклятием гробницы, так как все они были в почтенном возрасте и, вероятнее всего, умерли по естественным причинам. Примечательно, но что проклятие не коснулось главного археолога – Картера. После экспедиции он прожил еще 16 лет.

До сих пор ученые не пришли к единому мнению – существует ли проклятие гробницы, ведь такое количество смертей – явление незаурядное.

Полезно знать! Неподалеку от Долины Царей расположена Долина Цариц, здесь хоронили жен и других членов семей. Их усыпальницы были скромнее, в них находили гораздо меньше предметов.

Экскурсии в Долину Царей

Самый простой способ посетить Долину Царей, сохранившуюся со времен Древнего Египта – купить экскурсию в Хургаде у туристического оператора или в отеле.

Экскурсионная программа выглядит следующим образом: группу туристов автобусом привозят к Городу Мертвых, у входа находится стоянка автобусов. По территории Долины Царей пешком ходить сложно и утомительно, поэтому гостей катает паровозик.

Еще один способ посетить достопримечательность – взять такси. Учитывая расценки на этот вид транспорта, лучше арендовать машину вскладчину.

Стоимость экскурсии из Хургады 55 евро для взрослых, детям до 10 лет – 25 евро. В эту цену входит обед, а вот напитки нужно брать с собой.

Полезно знать! Как правило, в рамках экскурсии туристы посещают также другие интересные места, например, фабрику парфюмерных масел или фабрику алебастра.

Полезные рекомендации

- Съемка разрешена, но исключительно снаружи, внутри гробниц использовать технику нельзя.

- Бберите с собой головной убор, а также больше воды, поскольку и зимой температура в пустыне не опускается ниже +40 градусов.

- Выбирайте комфортную обувь, так как придется ходить в туннелях.

- Маленьким детям и людям со слабым здоровьем лучше отказаться от такой экскурсии.

- В Долине Царей есть туристическая зона, где работают кафе и сувенирные лавки.

- Будьте осторожны – в сувенирных магазинах часто обманывают туристов – человек оплачивает каменную статуэтку, а продавец упаковывает глиняную, которая стоит на порядок меньше.

- Неподалеку от города Луксор находятся: храмовый комплекс Мединет-Абу с дворцом; Карнакский храм, строительство которого велось на протяжении 2 тысяч лет; Луксорский храм с колоннами, скульптурами, барельефами.

- График работы Долины Царей: в теплое время года с 06-00 до 17-00, в зимние месяцы – с 6-00 до 16-00.

- Цена билетов для тех, кто приезжает самостоятельно, — 10 евро. Если вы хотите посетить гробницу Тутанхамона, придется заплатить еще 10 евро.

Полезная весомая археологическая находка в Городе Мертвых датируется 2006 годом – археологи открыли гробницу с пятью саркофагами. Тем не менее, Долина Царей еще досконально не изучена. Вероятнее всего, здесь еще много тайн, мистических загадок, над которыми еще будут работать специалисты.

Новые открытия в гробнице Тутанхамона:

Автор: Юлия Матюхина

The ancient Egyptians had an elaborate set of funerary practices that they believed were necessary to ensure their immortality after death. These rituals included mummifying the body, casting magic spells, and burials with specific grave goods thought to be needed in the afterlife.[1][2]

The ancient burial process evolved over time as old customs were discarded and new ones adopted, but several important elements of the process persisted. Although specific details changed over time, the preparation of the body, the magic rituals, and grave goods were all essential parts of a proper Egyptian funeral.

History[edit]

Although no writing survived from the Predynastic period in Egypt (c. 6000 – 3150 BCE ), scholars believe the importance of the physical body and its preservation originated during that time. This likely explains why people of that time did not follow the common practice of cremation among neighboring cultures, but rather buried the dead. Some of the scholars believe the Predynastic-era Egyptians may have feared the bodies would rise again if mistreated after death.[3](p 9)

Early burials were in simple, shallow oval pits, with a few burial goods. Sometimes multiple people and animals were placed in the same grave. Over time, graves became more complex. At one point, bodies were placed in a wicker basket, but eventually bodies were placed in wooden or terracotta coffins. The latest tombs Egyptians made were sarcophagi. These graves contained burial goods such as jewellery, food, games, and sharpened splint.[3](p 7)

From the Predynastic period through the final Ptolemaic dynasty, there was a constant cultural focus on eternal life and the certainty of personal existence beyond death. This belief in an afterlife is reflected in the burial of grave goods in tombs. The Egyptian beliefs in an afterlife became known throughout the ancient world by way of trade and cultural transmission and had an influence on other civilizations and religions. Notably, this belief became well known by way of the Silk Road. Egyptians believed that individuals were admitted into the afterlife on the basis of being able to serve a purpose there. For example, the king was thought to be allowed into the afterlife because of the role as a ruler of Ancient Egypt, which would be a purpose translated into qualification for admission to the afterlife.

Human sacrifices found in early royal tombs reinforce the idea of serving a purpose in the afterlife. Those sacrificed were probably meant to serve the king in the afterlife. Eventually, figurines and wall paintings begin to replace human victims.[4] Some of these figurines may have been created to resemble certain people, so they could follow the king after their own lives ended.

Not only did the lower classes rely on the king’s favor, but also the noble classes. They believed that upon death, kings became deities who could bestow upon certain individuals the ability to have an afterlife. This belief existed from the predynastic period through the Old Kingdom.

Although many spells from the predeceasing texts were carried over, the new Coffin Texts also had new spells added, along with slight changes made to make the new funerary text more relatable to the nobility.[5] In the First Intermediate period, however, the importance of the king declined. Funerary texts, previously restricted to royal use, became more widely available. The kings no longer were god-kings in the sense that admission to the next life was allowed in the next life only due to the royal status, the role of kings changed, becoming merely the rulers of the population who upon death, would be leveled down toward the plane of the mortals.[6]

Prehistory, earliest burials[edit]

The first funerals in Egypt are known from the villages of Omari and Maadi in the north, near present-day Cairo. The people of these villages buried their dead in a simple, round grave with a pot. The body was neither treated nor arranged in a particular way as these aspects would change later in the historical period. Without any written evidence, except for the regular inclusion of a single pot in the grave,

there is little to provide information about contemporary beliefs concerning the afterlife during that period. Given later customs, the pot was probably intended to hold food for the deceased.[7](p 71)

Predynastic period, development of customs[edit]

Funerary customs were developed during the Predynastic period from those of the Prehistoric period. At first, people excavated round graves with one pot in the Badarian period (4400–3800 BCE), continuing the tradition of Omari and Maadi cultures. By the end of the Predynastic period, there were increasing numbers of objects deposited with the body in rectangular graves, and there is growing evidence of rituals practiced by Egyptians of the Naqada II period (3650–3300 BCE). At this point, bodies were regularly arranged in a crouched, compact position, with the face pointing toward either the east and the rising sun or the west that in this historical period was the land of the dead. Artists painted jars with funeral processions and perhaps images of ritual dancing. Figures of bare-breasted women with birdlike faces and their legs concealed under skirts also appeared. Some graves were much richer in goods than others, demonstrating the beginnings of social stratification. Gender differences in burials emerged with the inclusion of weapons in men’s graves and cosmetic palettes in women’s graves.[7](pp 71–72)

By 3600 BCE, Egyptians had begun to mummify the dead, wrapping them in linen bandages with embalming oils (conifer resin and aromatic plant extracts).[8][9]

Early Dynastic period, tombs and coffins[edit]

By the First Dynasty, some Egyptians were wealthy enough to build tombs over their burials rather than placing their bodies in simple pit graves dug into the sand. The rectangular, mudbrick tomb with an underground burial chamber called a mastaba developed in the early dynastic period. These tombs had niched walls, a style of building called the palace-façade motif because the walls imitated those surrounding the palace of the king. Since commoners as well as kings, however, had such tombs, the architecture suggests that in death, some wealthy people did achieve an elevated status. Later in the historical period, it is certain that the deceased was associated with the god of the dead, Osiris.

Grave goods expanded to include furniture, jewelry, and games as well as the weapons, cosmetic palettes, and food supplies in decorated jars known earlier, in the Predynastic period. In the richest tombs, grave goods then numbered in the thousands. Only the newly invented coffins for the body were made specifically for the tomb. Some inconclusive evidence exists for mummification. Other objects in the tombs that had been used during daily life suggest that in the First Dynasty Egyptians already anticipated needing such objects in the next life. Further continuity from this life into the next can be found in the positioning of tombs: those persons who served the king during their lifetimes chose burials close to their king. The use of stela in front of the tomb began in the First Dynasty, indicating a desire to individualize the tomb with the deceased’s name.[7](pp 72–73)

Old Kingdom, pyramids and mummification[edit]

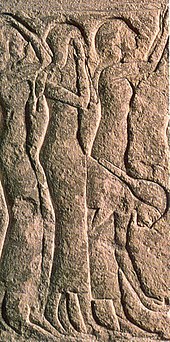

Relief of Men Presenting Oxen, c. 2500–2350 BCE Limestone. In this relief, three men bring cattle to the tomb owner, «from the towns of the estate», as the inscription says. Two of these balding, rustic laborers wear kilts of coarse material and the other wears nothing at all. A fragmentary scene below shows men bringing cranes, which Egyptians penned and raised for food. Artisans carved images of live food animals in tombs to supply the deceased with an eternal source of provisions. Brooklyn Museum

In the Old Kingdom, kings first built pyramids for their tombs surrounded by stone mastaba tombs for their high officials. The fact that most high officials were also royal relatives suggests another motivation for such placement: these complexes were also family cemeteries.

Among the elite, bodies were mummified, wrapped in linen bandages, sometimes covered with molded plaster, and placed in stone sarcophagi or plain wooden coffins. At the end of the Old Kingdom, mummy masks in cartonnage (linen soaked in plaster, modeled, and painted) also appeared. Canopic jars became used to hold their internal organs. Amulets of gold, faience, and carnelian first appeared in various shapes to protect different parts of the body. There is also the first evidence of inscriptions inside the coffins of the elite during the Old Kingdom. Often, reliefs of everyday items were etched onto the walls to supplement grave goods, which made them available through their representation.

The new false door was a non-functioning stone sculpture of a door, found either inside the chapel or on the outside of the mastaba; it served as a place to make offerings and recite prayers for the deceased. Statues of the deceased were being included in tombs and used for ritual purposes. Burial chambers of some private people received their first decorations in addition to the decoration of the chapels. At the end of the Old Kingdom, the burial chamber decorations depicted offerings, but not people.[7](pp 74–77)

First Intermediate period, regional variation[edit]

The political situation in the First Intermediate period, with its many centers of power, is reflected in the many local styles of art and burial at that time. The many regional styles for decorating coffins make their origins easy to distinguish from each other. For example, some coffins have one-line inscriptions and many styles include the depiction of Wadjet eyes (the human eye with the markings of a falcon). There are also regional variations in the hieroglyphs used to decorate coffins.

Occasionally men had tools and weapons placed in their graves, while some women had jewelry and cosmetic objects, such as mirrors. Grindstones were sometimes included in women’s tombs, perhaps to be considered a tool for food preparation in the next world, just as the weapons in men’s tombs imply men’s assignment to a role in fighting.[7](p 77)

Middle Kingdom, new tomb contents[edit]

Burial customs in the Middle Kingdom reflect some of the political trends of that period. During the Eleventh Dynasty, tombs were cut into the mountains of Thebes surrounding the king’s tomb or, in local cemeteries in Upper and Middle Egypt; Thebes was the native city of the Eleventh Dynasty kings, and they preferred to be buried there. But the Twelfth Dynasty high officials served the kings of a new family now ruling from the north in Lisht; these kings and their high officials preferred burial in a mastaba near the pyramids belonging to their masters. Moreover, the difference in topography between Thebes and Lisht led to a difference in tomb type: In the north, nobles built mastaba tombs on the flat desert plains, while in the south, local dignitaries continued to excavate tombs into the mountain.

For those of ranks lower than royal courtiers during the Eleventh Dynasty, tombs were simpler. Coffins could be simple wooden boxes with the body either mummified and wrapped in linen or simply wrapped without mummification, and the addition of a cartonnage mummy mask, a custom that continued until the Graeco-Roman period. Some tombs included wooded shoes and a simple statue near the body. In one burial there were only twelve loaves of bread, a leg of beef, and a jar of beer for food offerings. Jewelry could be included but only rarely were objects of great value found in non-elite graves. Some burials continued to include the wooden models that were popular during the First Intermediate period. Wooden models of boats, scenes of food production, craftsmen and workshops, and professions such as scribes or soldiers have been found in the tombs of this period.

Some rectangular coffins of the Twelfth Dynasty have short inscriptions and representations of the most important offerings the deceased required. For men, the objects depicted were weapons and symbols of office as well as food. Women’s coffins depicted mirrors, sandals, and jars containing food and drink. Some coffins included texts that were later versions of the royal Pyramid Texts.

Another kind of faience model of the deceased as a mummy seems to anticipate the use of shabti figurines (also called shawabti or an ushabti) later in the Twelfth Dynasty. These early figurines do not have the text directing the figure to work in the place of the deceased that is found in later figurines. The richest people had stone figurines that seem to anticipate shabtis, though some scholars have seen them as mummy substitutes rather than servant figures.

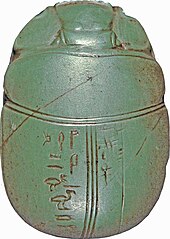

In the later Twelfth Dynasty, significant changes occurred in burials, perhaps reflecting administrative changes enacted by King Senwosret III (1836–1818 BCE). The body was now regularly placed on its back, rather than its side as had been traditional for thousands of years. Coffin texts and wooden models disappeared from new tombs of the period while heart scarabs and figurines shaped as mummies were now often included in burials, as they would be for the remainder of Egyptian history. Coffin decoration was simplified. The Thirteenth Dynasty saw another change in decoration. Different motifs were found in the north and south, a reflection of decentralized government power at the time. There was also a marked increase in the number of burials in one tomb, a rare occurrence in earlier periods. The reuse of one tomb by a family over generations seems to have occurred when wealth was more equitably spread.[7](pp 77–86)

Second Intermediate period, foreigner burials[edit]

Known graves from the Second Intermediate period reveal the presence of non-Egyptians buried in the country. In the north, graves associated with the Hyksos, a western Semitic people ruling the north from the northeast delta, include small mudbrick structures containing the body, pottery vessels, a dagger in a men’s graves, and often a nearby donkey burial. Simple pan-shaped graves in various parts of the country are thought to belong to Nubian soldiers. Such graves reflect very ancient customs and feature shallow, round pits, bodies contracted, and minimal food offerings in pots. The occasional inclusion of identifiable Egyptian materials from the Second Intermediate period provides the only marks distinguishing these burials from those of Predynastic and even earlier periods.[7](pp 86–89)

New Kingdom, new object purposes[edit]

The majority of elite tombs in the New Kingdom were rock-cut chambers. Kings were buried in multi-roomed, rock-cut tombs in the Valley of the Kings and no longer in pyramids. Priests conducted funerary rituals for them in stone temples built on the west bank of the Nile opposite of Thebes.

From the current evidence, the Eighteenth Dynasty appears to be the last period in which Egyptians regularly included multiple objects from their daily lives in their tombs; beginning in the Nineteenth Dynasty, tombs contained fewer items from daily life and included objects made especially for the next world. Thus, the change from the Eighteenth to the Nineteenth Dynasties formed a dividing line in burial traditions: the Eighteenth Dynasty more closely remembered the immediate past in its customs, whereas, the Nineteenth Dynasty anticipated the customs of the Late period.

Gilded bier fashioned to resemble the goddess Sekhmet, the lioness who was the fierce protector of the kings in life and death, from the Eighteenth Dynasty tomb of Tutankhamun, (fourteenth century BC), Cairo Museum

People of the elite ranks in the Eighteenth Dynasty placed furniture as well as clothing and other items in their tombs, objects they undoubtedly used during life on earth. Beds, headrests, chairs, stools, leather sandals, jewelry, musical instruments, and wooden storage chests were present in these tombs. While all of the objects listed were for the elite, many poor people did not put anything beyond weapons and cosmetics into their tombs.

No elite tombs are known to have survived unplundered from the Ramesside period. In that period, artists decorated tombs belonging to the elite with more scenes of religious events, rather than the everyday scenes that had been popular since the Old Kingdom. The funeral ceremony, the funerary meal with multiple relatives, the worshipping of the deities, even figures in the underworld were subjects in elite tomb decorations. The majority of objects found in the Ramesside period tombs were made for the afterlife. Aside from the jewelry, which could have been used also during life, objects in Ramesside tombs were manufactured for the next world.[7](pp 89–100)

Third Intermediate period[edit]

Although the political structure of the New Kingdom collapsed at the end of the Twentieth Dynasty, the majority of burials in the Twenty-first Dynasty directly reflect developments from the earlier period. At the beginning of that time, reliefs resembled those from the Ramesside period. Only at the very end of the Third Intermediate period did new funerary practices of the Late period begin to be seen.

Little is known of tombs from that period. The very lack of decorations in tombs seems to have led to much more elaborate decoration of coffins. The remaining grave goods of the period show fairly cheaply made shabtis, even when the owner was a queen or a princess.[7](pp 100–103)

Late period, monumentality and return to traditions[edit]

Burials in the Late period could make use of large-scale, temple-like tombs built for the non-royal elite for the first time. But the majority of tombs in this period were in shafts sunk into the desert floor. In addition to fine statuary and reliefs reflecting the style of the Old Kingdom, the majority of grave goods were specially made for the tomb. Coffins continued to bear religious texts and scenes. Some shafts were personalized by the use of stela with personal prayers of and the name of the deceased on it. Shabtis in faience for all classes are known. Canopic jars, although often nonfunctional, continued to be included. Staves and scepters representing the deceased’s office in life were often present as well. A wooden figure of either the god Osiris[10] or of the composite deity Ptah-Sokar-Osiris could be found,[11][12][13] along with heart scarabs, both gold and faience examples of djed-columns, Eye of Horus amulets, figures of deities, and images of the deceased’s ba. Tools for the tomb’s ritual called the «opening of the mouth» as well as «magical bricks» at the four compass points, could be included.[7](p 103)

Ptolemaic period, Hellenistic influences[edit]

Following the conquest of Egypt by Alexander the Great, the country was ruled by the descendants of Ptolemy, one of his generals. His Macedonian Greek family fostered a culture that promoted both Hellenistic and ancient Egyptian ways of life: many of the Greek-speaking people living in Alexandria followed the customs of mainland Greece, others adopted Egyptian customs, and indigenous Egyptians continued to follow their own already ancient customs.

Very few Ptolemaic tombs are known. Fine temple statuary of the period suggests the possibility of tomb sculpture and offering tables. Egyptian elite burials still made use of stone sarcophagi. The traditional Books of the Dead and amulets were also still popular.[7](p 103)

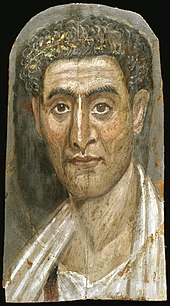

Roman period, Roman influences[edit]

The Romans conquered Egypt in 30 BCE, ending the rule of the last and most famous member of the Ptolemaic dynasty, Cleopatra VII. During Roman rule, an elite hybrid burial style developed that incorporated both Egyptian and Roman elements.

Some people were mummified and wrapped in linen bandages. The front of the mummy was often painted with a selection of traditional Egyptian symbols. Mummy masks, in cartonnage, plaster, or stucco, in either traditional Egyptian style or Roman style, might be added to the mummies.[14] Another possibility was a Roman-style mummy portrait, executed in encaustic (pigment suspended in wax) on a wooden panel. Sometimes the feet of the mummy were covered. An alternative to this was a complete shroud with Egyptian motifs, but a portrait in the Roman style. Tombs of the elite could also include fine jewelry.[7](pp 103–106)

Funerary rituals[edit]

Greek historians Herodotus (5th century BC) and Diodorus Siculus (1st century BC) provide the most complete surviving evidence of how ancient Egyptians approached the preservation of a dead body.[15] Before embalming, or preserving the dead body as to delay or prevent decay, mourners, especially if the deceased had high status, covered their faces with mud, and paraded around town while beating their chests.[15] If the wife of a high-status male died, her body was not embalmed until three or four days have passed, because this prevented abuse of the corpse.[15] In the case that someone drowned or was attacked, embalming was carried out immediately on their body, in a sacred and careful manner. This kind of death was viewed as venerated, and only priests were permitted to touch the body.[15]

After embalming, the mourners may have carried out a ritual involving an enactment of judgment during the Hour Vigil, with volunteers to play the role of Osiris and his enemy brother Set, as well as the deities Isis, Nephthys, Horus, Anubis, and Thoth.[16] As the tale goes, Set was envious of his brother Osiris for being granted the throne before him, so he plotted to kill him. Osiris’s wife, Isis, battled back and forth with Set to gain possession of Osiris’s body, and through this struggle, Osiris’s spirit was lost.[17] Nonetheless, Osiris resurrected and was reinstated as a god.[18] In addition to the reenactment of the judgment of Osiris, numerous funeral processions were conducted throughout the nearby necropolis, which symbolized different sacred journeys.[16]

The funeral procession to the tomb generally included cattle pulling the body in a sledge-type of carrier, with friends and family to follow. During the procession, the priest burned incense and poured milk before the dead body.[16] Upon arrival to the tomb, and essentially the next life, the priest performed the Opening of the mouth ceremony on the deceased. The deceased’s head was turned toward the south, and the body was imagined to be a statue replica of the deceased. Opening the mouth of the deceased symbolized allowing the person to speak and defend themselves during the judgment process. Goods were then offered to the deceased to conclude the ceremony.[16]

Mummification[edit]

Embalming[edit]

The preservation of a dead body was critical if the deceased wanted a chance at acceptance into the afterlife. Within the Ancient Egyptian concept of the soul, ka, which represented vitality, leaves the body once the person dies.[19] Only if the body is embalmed in a specific fashion will ka return to the deceased body, and rebirth will take place.[15] The embalmers received the body after death, and in a systematized manner, prepared it for mummification. The family and friends of the deceased had a choice of options that ranged in price for the preparation of the body, similar to the process at modern funeral homes. Next, the embalmers escorted the body to ibw, translated to “place of purification”, a tent in which the body was washed, and then per nefer, “the House of Beauty”, where mummification took place.[15]

Mummification process[edit]

Simplistic representation of the Ancient Egyptian mummification process

In order to live for all eternity and be presented in front of Osiris, the body of the deceased had to be preserved by mummification, so that the soul could reunite with it, and take pleasure in the afterlife. The main process of mummification was preserving the body by dehydrating it using natron, a natural salt found in Wadi Natrun. The body was drained of any liquids and left with the skin, hair, and muscles preserved.[20][full citation needed] The mummification process is said to have taken up to seventy days. During this process, special priests worked as embalmers as they treated and wrapped the body of the deceased in preparation for burial.

The process of mummification was available for anyone who could afford it. It was believed that even those who could not afford this process could still enjoy the afterlife with the recitation of the correct spells. Mummification existed in three different processes, ranging from most expensive, moderately expensive, and most simplistic, or least expensive.[15] The most classic, common, and most expensive method of mummification dates back to the eighteenth dynasty. The first step was to remove the internal organs and liquid so that the body would not decay. After being laid out on a table, the embalmers took out the brain through a process named excerebration by inserting a metal hook through the nostril, breaking through it into the brain. They removed as much as they could with the hook, and the rest they liquefied with drugs and drained out.[15] They threw out the brain because they thought that the heart did all the thinking. The next step was to remove the internal organs, the lungs, liver, stomach, and intestines, and to place them in canopic jars with lids shaped as the heads of the protective deities, the four sons of Horus: Imsety, Hapy, Duamutef, and Qebhseneuf. Imsety was human-headed and guarded the liver; Hapy was ape-headed and guarded the lungs; Duamutef was jackal-headed and guarded the stomach; Qebhseneuf was hawk-headed and guarded the small and large intestines.[25] Sometimes the four canopic jars were placed into a canopic chest and buried with the mummified body. A canopic chest resembled a «miniature coffin» and was intricately painted. The Ancient Egyptians believed that by burying their organs with the deceased, they may rejoin in the afterlife.[26] Other times, the organs were cleaned and cleansed, and then returned into the body.[15] The body cavity was then rinsed and cleaned with wine and an array of spices. The body was sewn up with aromatic plants and spices left inside.[15] The heart stayed in the body, because in the hall of judgment, it would be weighed against the feather of Maat. After the body was washed with wine, it was stuffed with bags of natron. The dehydration process took 40 days.[27]

The second part of the process took 30 days. This was the time when the deceased turned into a semi divine being, and all that was left in the body from the first part was removed, followed by applying first wine and then oils. The oils were for ritual purposes, as well as for preventing the limbs and bones from breaking while being wrapped. The body was sometimes colored with a golden resin, which protected the body from bacteria and insects. Additionally, this practice was based on the belief that divine beings had flesh of gold. Next, the body was wrapped in linen cut into strips with amulets while a priest recited prayers and burned incense. The linen was adhered to the body using gum, opposed to a glue.[15] The dressing provided the body physical protection from the elements, and depending on how wealthy the deceased’s family was, the deceased could be dressed with an ornamented funeral mask and shroud.[15] Special care was given to the head, hands, feet, and genitals, as contemporary mummies reveal extra wrappings and paddings in these areas.[21] Mummies were identified via small, wooden name-tags tied typically around the deceased’s neck.[15] The 70-day process is connected to Osiris and the length the star Sothis was absent from the sky.[28]

The second, moderately expensive option for mummification did not involve an incision into the abdominal cavity or the removal of the internal organs. Instead, the embalmers injected the oil of a cedar tree into the body, which prevented liquid from leaving the body. The body was then laid in natron for a specific number of days. The oil was then drained out of the body, and with it came the internal organs, the stomach and the intestines, which were liquefied by the cedar oil. The flesh dissolved in the natron, which left only skin and bones left of the deceased body. The remains are given back to the family.[15] The cheapest, most basic method of mummification, which was often chosen by the poor, involved purging out the deceased’s internal organs, and then laying the body in natron for 70 days. The body was then given back to the family.[15]

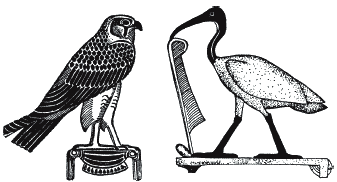

Animal mummification[edit]

Animals were mummified in Ancient Egypt for many reasons. Household pets that held a special importance to their owners were buried alongside them. However, animals were not only viewed as pets, but as incarnations of the deities. Most Ancient Egyptian dieties were associated with particular animals, frequently being depicted as such animals or as humans with the heads of such animals. Therefore, animals associated with particular gods were buried to honor those deities. Some animal mummifications were performed to serve as sacred offerings to the deities who often took the form of animals such as cats, frogs, cows, baboons, and vultures. Other animals were mummified with the intention of being a food offering to humans in the afterlife.

Mummy of a peregrine falcon c. 2000–1001 BCE

Several kinds of animal remains have been discovered in tombs in the area of Dayr al-Barsha, a Coptic village in Middle Egypt. The remains found in the shafts and burial chambers included dogs, foxes, eagle owls, bats, rodents, and snakes. These were determined to be individuals that had entered the deposits by accident, however.

Other animal remains that were found were more common and recurred more than those individuals who wound up accidentally trapped in these tombs. These remains included numerous gazelle and cattle bones, as well as calves and goats that were believed to have been as a result of human behavior. This was due to finding that some remains had fragments altered, missing, or separated from their original skeletons. These remains also had traces of paint and cut marks on them, seen especially with cattle skulls and feet.

Based on this, the natural environment of the Dayr al-Barsha tombs, and the fact that only some parts of these animals were found, the possibility of natural deposition can be ruled out, and the cause of these remains in fact are most likely caused by animal sacrifices, as only the head, foreleg, and feet were apparently selected for deposition within the tombs. According to a study by Christopher Eyre,[citation needed] cattle meat was not a part of the daily diet in Ancient Egypt, as the consumption of meat only took place during celebrations, including funerary and mortuary rituals, and the practice of providing the deceased with offerings of cattle as early as the Predynastic period.[22]

Burial rituals[edit]

After the mummy was prepared, it would need to be re-animated, symbolically, by a priest. The opening of the mouth ceremony was conducted by a priest who would utter a spell and touch the mummy or sarcophagus with a ceremonial adze – a copper or stone blade. This ceremony ensured that the mummy could breathe and speak in the afterlife. In a similar fashion, the priest could utter spells to reanimate the mummy’s arms, legs, and other body parts.

The priests, maybe even the king’s successor, proceeded to move the body of the embalmed dead king through the causeway to the mortuary temple. This is where prayers were recited, incense was burned, and more rituals were performed to help prepare the king for the final journey. The king’s mummy was then placed inside the pyramid along with enormous amount of food, drink, furniture, clothes, and jewelry that were to be used in the afterlife. The pyramid was sealed so that no one would ever enter it again. However, the king’s soul could move through the burial chamber at will. After the funeral kings become deities and could be worshipped in the temples beside their pyramid.[23]

In ancient times Egyptians were buried directly in the ground. Since the weather was so hot and dry, it was easy for the bodies to remain preserved. Usually the bodies would be buried in a compact position.[24] Ancient Egyptians believed the burial process to be an important part in sending humans to a comfortable afterlife.