Проклятие гробницы Тутанхамона

70 314

4.63

26

Надпись на стене гробницы Тутанхамона гласила: «Смерть скоро настигнет того, кто осмелится нарушить покой мёртвого правителя!» Интересно, что на протяжении следующих десяти лет, смерть тринадцати участников археологических раскопок и девяти близко общающихся с ними людей не могла не привлечь внимания общественности, особенно – журналистов, которые смогли сделать из этого события настоящую сенсацию.

Их не волновал тот факт, что возраст большинства умерших учёных значительно превышал семьдесят лет, а один из организаторов экспедиции, лорд Карнарвон, болел астмой, и воздух затхлой гробницы на пользу ему не пошёл. А вот на то, что присутствовавшая при вскрытии усыпальницы и саркофага дочь Карнарвона, леди Эвелин, прожила не один десяток лет, умерев в восьмидесятилетнем возрасте, пресса особого внимания не обратила.

Содержание:

- 1 Местонахождение гробницы

- 2 Тутанхамон, правитель Египта

- 3 Поиски потерянной гробницы

- 4 Первая комната

- 5 Усыпальница

- 6 Проклятье гробницы

Местонахождение гробницы

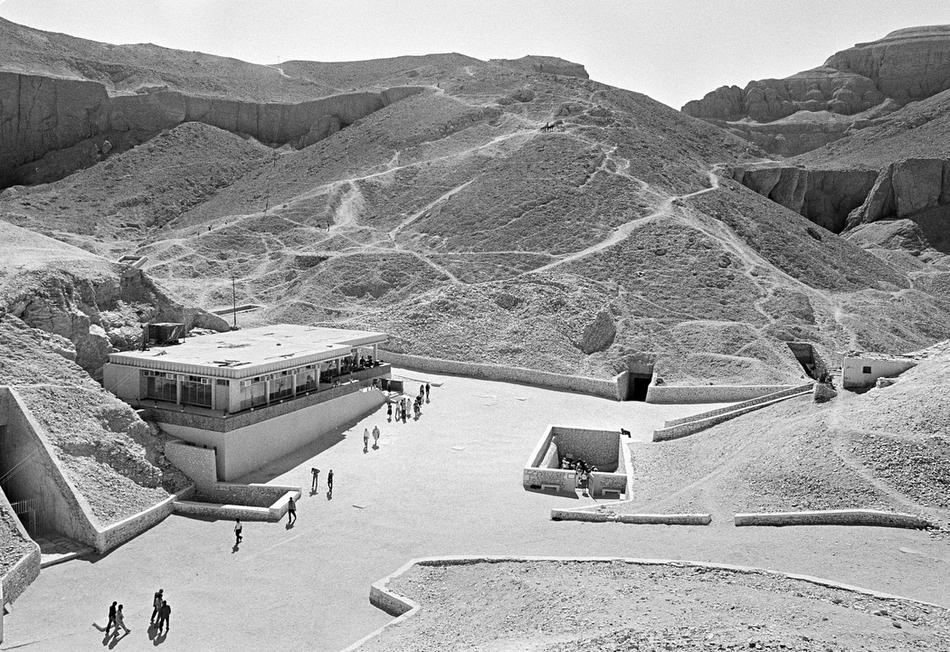

Одно из самых известных захоронений мира, гробница Тутанхамона или как её обозначают археологи, KV 62, находится в центре долины Царей на западном побережье Нила, недалеко от современного города Луксор (в древности – Фива). На географической карте эту территорию можно обнаружить по следующим координатам: 25° 44′ 27″ с. ш., 32° 36′ 7″ в. д.

На территории было обнаружено более шестидесяти могил, усопших правителей Египта и высокопоставленных чиновников, и состоит она из двух долин – восточной, где расположена большая часть гробниц, и западной. Долину Царей археологи — вот уже на протяжении двух веков прочесывают туда-сюда, перебирая каждый камешек и, казалось бы, новых находок на её территории обнаружено быть не должно.

Тем не менее в 2006 году удалось найти очередную нетронутую гробницу с пятью мумиями. Эта находка стала первой с 1922 года, когда Картером была обнаружена гробница Тутанхамона, наполненная золотом, драгоценными камнями, посудой, статуэтками и другими уникальными произведениями искусства, созданными в XIV ст. до н.э.

Тутанхамон, правитель Египта

До того момента, как была обнаружена гробница Тутанхамона, фараона, который правил с 1332 по 1323 год до нашей эры, в самом существовании этого правителя многие египтологи сомневались – слишком уж незначительный след в истории своей страны он оставил. Что, впрочем, не удивляет: Египтом он начал править в возрасте девяти лет, а умер, не дожив до двадцати. Он только успел возобновить культ бога Амона, который его отец, фараон Эхнатон, заменил Атоном.

В том, кто именно был его отец, учёные к единому мнению не пришли. Большинство египтологов, учитывая данные недавно проведённых анализов ДНК и радиологического исследования остатков фараона, сходятся на том, что родителями фараона были Эхнатон и его сестра. Среди правителей древнего Египта близкородственные браки были не редкость, поэтому не удивительно, что женой Тутанхамона также оказалась его сестра, Анхесенамон, от которой он имел двух мертворожденных детей (их остатки были обнаружены в его усыпальнице).

Одной из самых интригующих тайн Тутанхамона является вопрос: почему правитель умер, не дожив даже до двадцати лет (даже по тем временам смерть в девятнадцатилетнем возрасте считалась ранней). На этот счёт существует несколько версий:

- Тутанхамон умер из-за внезапной болезни;

- Юноша имел неизлечимые наследственные заболевания, которые бывают от близкородственных браков;

- Молодого правителя убили;

- Фараон умер, упав с колесницы и получив травмы, несовместимые с жизнью.

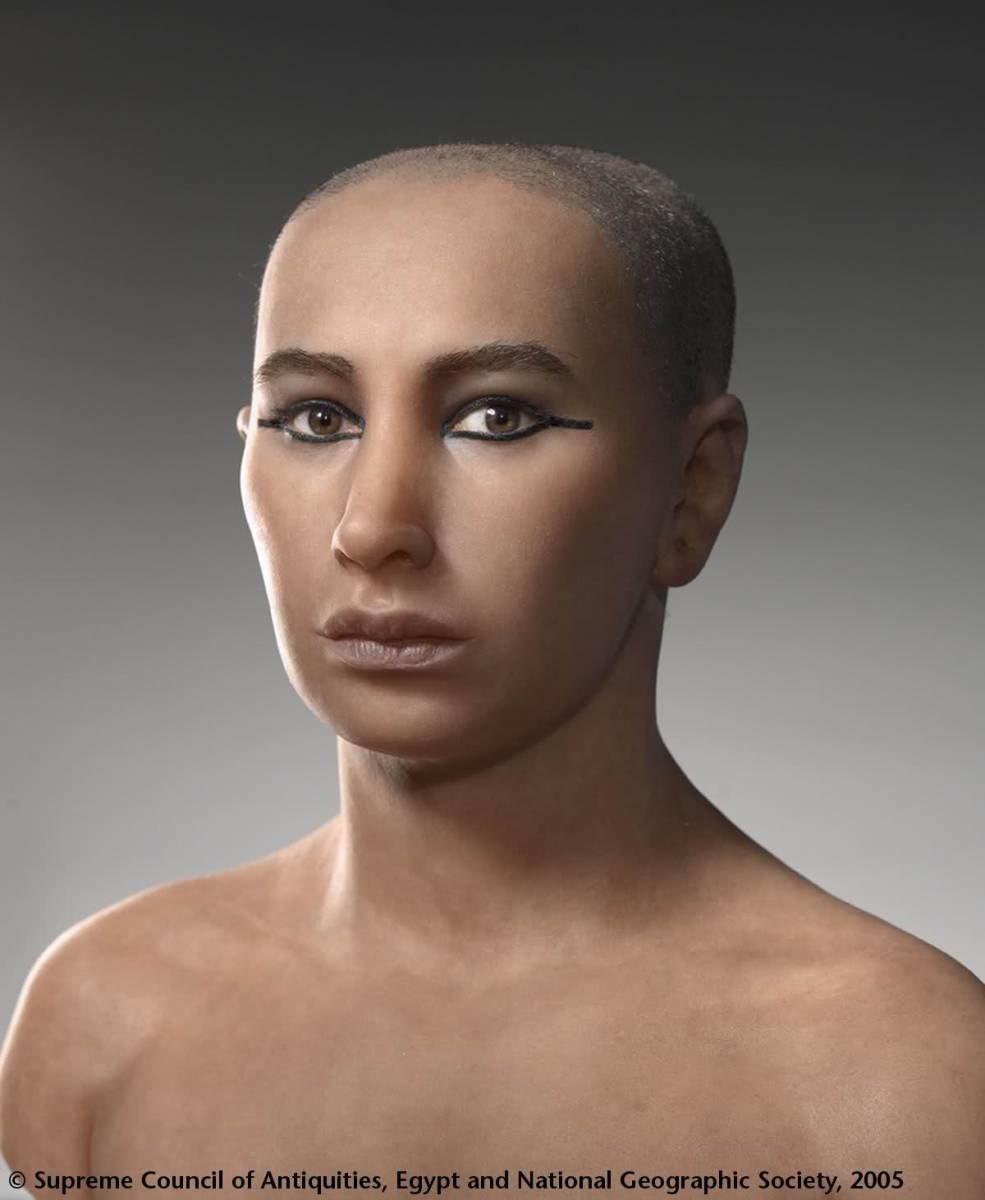

Современные исследования показали, что наследственными болезнями молодой фараон не страдал, поэтому никаких генетических заболеваний, тяжёлой формы сколиоза или болезни, которая придала его скелету женоподобную фигуру и т.п., у него не было. Единственными болезнями, которые выявили учёные, была так называемая «волчья пасть» и косолапость. Также ими была опровергнута гипотеза о том, что он скончался из-за несовместимой с жизнью травмы, поскольку подобных переломов у фараона обнаружено не было (трещина в черепе, судя по всему, появилась, когда жрецы бальзамировали тело).

Последние исследования показали, что смерть Тутанхамона вызвала тяжёлая форма малярии, чему свидетельствуют найденные в усыпальнице лекарства для лечения этого заболевания. Поскольку в саркофаге были обнаружены венки из цветущих васильков и ромашек, удалось установить, что похоронен он был в первой половине весны. На мумификацию уходит около семидесяти дней, следовательно молодой правитель должен был умереть в начале зимы (в это время в Древнем Египте был как раз разгар сезона охоты, из-за которого и появилось предположение, что он упал с колесницы).

Поиски потерянной гробницы

Искать усыпальницу Татанхамона археолог Картер и лорд Карнавон начали в 1916 году. Идея изначально казалась утопичной, поскольку в те годы эта территория была перерыта вдоль и поперёк и считалось, что здесь невозможно найти никаких значительных находок.

На поиски гробницы археологи потратили более шести лет, а обнаружили ее там, где ожидали найти меньше всего: перекопав все окрестности, они не тронули лишь небольшой участок, на котором находились хижины древних строителей усыпальниц (интересно, что именно отсюда они и начинали раскопки).

Уводящая вниз ступенька была обнаружена египтологами под первой же лачугой. Расчистив лестницу, археологи увидели внизу замурованную дверь – открытие гробницы Тутанхамона состоялось! Случилось это 3 ноября 1922 года. На этом этапе работы в гробнице фараона Тутанхамона были приостановлены: как раз в это время лорд Карнарвон находился в Лондоне. Картер, решив дождаться его, отправив телеграмму, что он нашел искомое, терпеливо ожидал друга в течение трёх недель. Тот приехал с дочерью, леди Эвелин – и 25 ноября 1922 года археологи спустились к гробнице.

Первая комната

Ещё не дойдя до двери, египтологи поняли, что грабители гробниц здесь уже побывали (вход не только вскрывали, но и обратно замуровывали и запечатывали). Это подтвердило и тот факт, что размуровав дверь, в коридоре были обнаруженные разбитые черепки, целые и битые кувшины, вазы и прочие осколки предметов – грабители явно уже уносили добычу, когда были остановлены, возможно, стражей.

Почему сокровища гробницы Тутанхамона оказались неразграбленными – одна из тайн, которая вот уже около столетия не даёт покоя учёным. Интересно, что в результате исследований египтологами было точно установлено, что грабежом усыпальниц занимались не только профессиональные расхитители гробниц, но и близкие к трону люди. Когда Египет переживал кризисные времена, пополнять казну за счёт вскрытия гробниц давно почивших фараонов не гнушались. То, что первая обнаруженная печать, которой запечатали усыпальницу молодого фараона, являлась лишь обыкновенной царской печаткой, а имя Тутанхамона находилось на печати, находящейся на нетронутой части двери, говорит само за себя.

Удивлению археологов не было пределов. После многочисленных работ им удалось добраться до комнаты, заставленной разнообразными предметами: здесь находился золотой трон, вазы, ларцы, светильники, письменные принадлежности, золотая колесница. А друг напротив друга стояли две чёрные скульптуры фараона, в золотых передниках и сандалиях, с булавами, жезлами и со священной коброй на лбу.

Также была обнаружена дыра, сделанная грабителями и ведущая в боковую комнату, которая была полностью забита золотыми украшениями, драгоценными камнями, предметами быта и даже находилось несколько распиленных кораблей, на одном из которых правитель после смерти должен был отправиться в загробный мир.

Придя в себя от увиденного обилия сокровищ, археологи поняли, что саркофаг в этих помещениях отсутствует, следовательно, должна быть ещё одна погребальная комната. Третье запечатанное помещение было обнаружено между двумя скульптурами. И вот тут исследования были остановлены: Картер решил закрыть гробницу и уехал в Каир для организационной работы (увидев такое количество драгоценностей и ценных экспонатов, он принял решение провести с египетским правительством переговоры).

Вернулся он в середине декабря, после чего к причалу была проведена железная дорога. А возле берега находился пароход, специально арендованный для того, чтобы вывезти сокровища гробницы Тутанхамона. Первая находка была извлечена из усыпальницы 27 декабря, а первую партию драгоценностей на судно доставили в середине марта (как раз в это время заболевает и умирает от воспаления лёгких лорд Карнарвон).

Вытаскивать наружу находки было непросто, тогда как часть вещей находилась в идеальном состоянии, другая часть — почти истлела ( это относится к тканным, кожаным и деревянным предметам). В качестве примера Картер наводит пару найденных вышитых бисером сандалий: одна сандалия буквально рассыпалась при малейшем прикосновении, и чтобы её кое-как собрать, пришлось приложить немалые усилия, а вот вторая оказалась довольно крепкой. Такая ситуация возникла из-за проникающей через известняковую стену влаги, из-за которой многие предметы в комнате покрылись желтоватым налётом, а кожаные вещи сильно размякли.

Усыпальница

Погребальную комнату, в которой был установлен обитый пластинами из золота и украшенный синей мозаикой огромный футляр, вскрыли в середине февраля. То, что воры сюда не забрались, стало понятно, когда Картер обнаружил, что печати на саркофаге оказались нетронуты. Размеры футляра, где находился саркофаг, поражали:

- Длина – 5,11 м;

- Ширина – 3,35 м;

- Высота – 2,74 м.

Футляр занимал практически всю усыпальницу (интересно, что из этой комнаты можно было попасть в ещё одну, которая была наполнена сокровищами). На одной из сторон футляра были установлены закрытые на засов створчатые двери без печати. За ними находился ещё один футляр, поменьше, без мозаики, но с печатью Тутанхамона. Над ним нависал прикреплённый к деревянным карнизам расшитый блёстками покров из льняной ткани (к сожалению, время его не пощадило: он стал бурым и во многих местах порвался из-за находящихся на нём позолоченных бронзовых маргариток).

Работы в очередной раз были остановлены. Нужно было убрать стену, которая отделяла усыпальницу от первой комнаты и разобрать четыре позолоченных погребальных футляра, между которыми были обнаружены булавы, стрелы, луки, золотые и серебряные жезлы, украшенные фигурками Тутанхамона. На эти работы у археологов ушло около 84 дней.

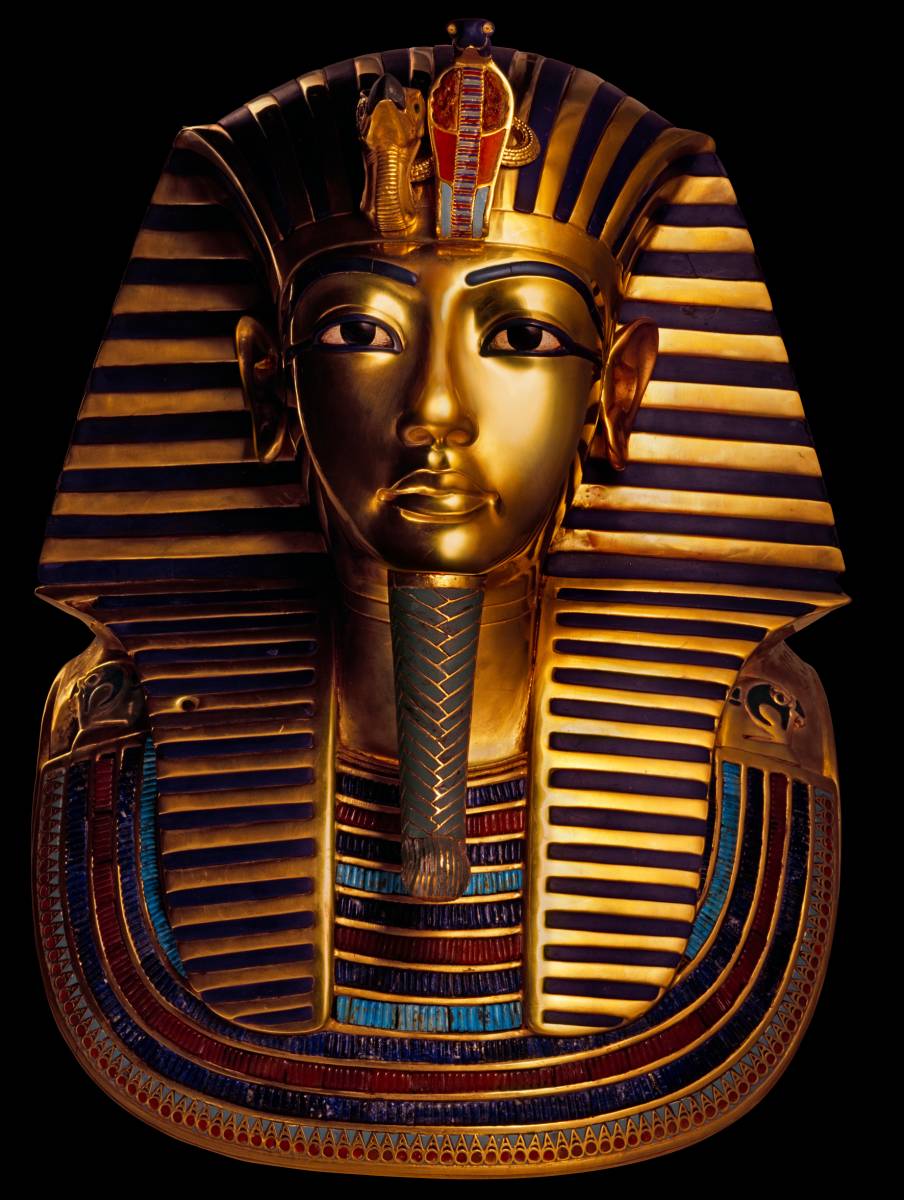

Разобрав последний футляр, перед египтологами оказалась крышка огромного саркофага из жёлтого кварцита, длина которого превышала 2,5 метра, а крышка весила более тонны. Открыв саркофаг, учёные обнаружили огромный позолоченный рельефный портрет Тутанхамона, который на деле оказался крышкой двухметрового гроба, повторяющей контуры мужской фигуры. На лбу крышки-портрета находились обвитые гирляндой из высохших цветов символы Нижнего и Верхнего Египта – Кобра и Ястреб.

В первом саркофаге размещался второй, где и был установлен основной золотой гроб и находилась окаменевшая и потемневшая от времени мумия Тутанхамона, лицо и грудь которого покрывала золотая маска (толщина стенки саркофага составляла около 3,5 мм).

Интересно, что статуи египетского правителя, найденные в первой комнате, как и золотые маски, обнаруженные на мумии и лицах на трех гробах, оказались точными копиями молодого правителя. Это дало возможность установить, что некоторые статуи Тутанхамона были присвоены некоторыми фараонами, например, Хоремхеб стёр на скульптуре его имя и написал своё.

Проклятье гробницы

Раскопки и исследования усыпальницы молодого фараона длились около пяти лет, а уже через год словосочетание «Тутанхамон проклятие гробницы» стали практически неотделимы друг от друга. Всё началось после того как через год после вскрытия гробницы от воспаления лёгких скончался лорд Карнарвон, далее, на протяжении нескольких лет ушли из жизни ещё около десяти участников раскопок.

Одной из самых популярных идей поклонников теории «Тутанхамон проклятие гробницы» (среди них был и Артур Конан Дойл) были гипотезы о вредном грибке, радиоактивных элементах или положенных в гробницу ядов. Сама картина смертей выглядит следующим образом:

- Карнарвон умирает в марте 1923 года (говорят, что в момент его смерти в Каире неожиданно исчезло электричество);

- Второй жертвой проклятья становится Дуглас-Рейд, который делал рентген мумии;

- Погибает А.К. Мейс. Он вскрывал с Картером погребальную комнату;

- В этом же году из-за заражения крови умирает брат Карнарвона, полковник Обри Герберт;

- Египетского принца, который был на раскопках при вскрытии гробницы, убивает собственная супруга;

- На следующий год в столице Египта от выстрела убийцы погибает генерал-губернатор Судана сэр Ли Стек;

- В 1928 г. внезапно умирает Ричард Бартель, секретарь Картера, а его отец два года спустя выпрыгивает из окна;

- В 1930 г. заканчивает жизнь самоубийством сводный брат лорда Карнарвона.

В прессе появились сообщения о смерти таких известных участников экспедиции, как Брэстеда, Гардинера, Дейвиса (они действительно умерли в это время, но на момент смерти их возраст превышал 70 лет, а Гардинеру было 84). К истории «Тутанхамон проклятие гробницы» относили и супругу Карнарвона, Альмины, о которой говорили, что она якобы скончалась на 61 году жизни от укуса насекомого, но слухи оказались ложными, она умерла значительно позже, в возрасте 93 лет.

А вот смерть главного участника экспедиции, Картера, к загадочным смертям, как не старались журналисты, приписать не смогли: он умер шестнадцать лет спустя после вскрытия гробницы – слишком уж велик оказался срок для того, чтобы его можно было привязать к столь популярной теме как «Тутанхамон проклятие гробницы».

Гробница Тутанхамона — от создания до находки: факты об усыпальнице египетского фараона

- Фараон Тутанхамон и его правление

- Гробница в Долине царей

- Великое археологическое открытие

- Историческое значение находки и ее культовый статус

- Интересные факты о гробнице Тутанхамона

- Мифы, загадки и тайны

Тутанхамон не дожил и до 20 лет, оставшись среди современников царем средней руки, который не успел реализовать задуманное. Имя молодого человека могло навеки раствориться в пучине истории, если бы не череда загадочных смертей, за которыми последовало возникновение понятия «проклятие фараонов». При жизни юный правитель ничем заметным не отличился. Но события, случившиеся 3 тыс. лет спустя, поставили его в топ-5 самых известных фараонов. Произошло это, когда была открыта гробница Тутанхамона. Подробнее о великой археологической находке и мистических тайнах усыпальницы царя – в материале 24СМИ.

Фараон Тутанхамон и его правление

В историографии Древнего Египта выделяют 18 хронологий нахождения юного правителя у власти. Исследователи полагают, что Тутанхамон занимал трон минимум 8 лет, максимум – 14. По усредненным прикидкам ученых, фараон руководил государством в 1332–1323 годах до н. э. Правление выпало на период Нового царства – «золотой эпохи» Древнего Египта, длившейся 500 лет – до 1069 года до н. э.

Историографы выдвинули теорию, согласно которой Тутанхамон – сын выдающегося фараона Эхнатона, известного своими реформами. Трон наследник занял примерно в 10 лет, но на ранних этапах правления судьбой государства ведали регенты из числа бывших приближенных отца.

Эхнатон – автор скандальной религиозной реформы, которая потрясла устои древнеегипетского общества. Царь заменил язычество монотеистической религией. Фараон решил, что подданные должны поклоняться единому богу Солнца – Атону, а затем и вовсе причислил себя к рангу высшего существа на Земле. Тутанхамон свернул реформу и вернул прежний пантеон богов. Наследник предал имя Эхнатона анафеме, а столичный город Ахетатон разрушили.

Умер правитель в 18 или 19 лет. Похоронили молодого человека в Долине царей. Обстоятельства смерти Тутанхамона вызывают не меньше споров, чем вопрос о происхождении.

Археологические исследования показали, что фараон был субтильным и болезненным подростком. Пропорции тела были далеки от идеала. В частности, царя отличали слишком длинные руки. В дополнение у правителя была «волчья пасть» и косолапость. Опираясь на эту информацию, ученые определили доминирующую версию смерти – тяжелая болезнь. Считается, что отец и мать фараона были близкими родственниками, что и привело к генетическим мутациям.

Альтернативная гипотеза гласит, что Тутанхамон, возможно, не обладал самым крепким здоровьем, но смерть не связана с каким-либо недугом. В 2005 году ученые опровергли теорию о наличии у царя тяжелой формы сколиоза. Некоторые исследователи уверены, что фараон погиб в результате несчастного случая под колесами повозки. Трагедия произошла во время охоты – гибель Тутанхамона пришлась на разгар охотничьего сезона в Египте.

В ходе осмотра мумии ученые обнаружили след колеса на левом боку, продавленную грудину и сломанные ребра. Незадолго до смерти фараон сломал ногу – кость срослась неправильно, что сделало юношу восприимчивым к инфекциям.

Третья теория утверждает, что молодой правитель умер от малярии. В 2010 году ученые обнаружили возбудители болезни в останках фараона в ходе ДНК-анализа. Это самое древнее доказательство заражения малярией, которое известно историографии.

По другой гипотезе, Тутанхамон пал жертвой заговора одного из регентов, который вскоре стал полноправным правителем. Сторонники теорий приводят свои доводы, и точно назвать причину смерти царя пока не выходит. Но нет сомнения, что правитель умер, не дожив до 20 лет, и был похоронен по всем традициям.

Гробница в Долине царей

Исследователи полагают, что усыпальницу для Тутанхамона начали строить еще в годы правления его отца. Предполагалось, что тело фараона после смерти найдет покой возле города Ахетатон, но столицу разрушили после возвращения к многобожию. Для молодого фараона запустили строительство новой гробницы в Фивах, но не успели ко дню смерти правителя. Поэтому для скоропостижно умершего царя спешно обустроили другую усыпальницу, которая в размерах уступает прочим пантеонам XVIII династии.

Гробница Тутанхамона расположена в Долине царей на юге Египта. Усыпальница высечена в белом известняке в одном из холмов. О гробнице Тутанхамона известно, что за основу строители взяли небольшую пещеру. Ее расширили для размещения нескольких прямоугольных помещений. Гробница расположена на глубине 8 м ниже поверхности земли. Площадь комплекса – 109,82 кв. м.

Гробницу размером с просторную квартиру возводили наспех. Процесс мумификации занимал 70 дней, поэтому рабочие спешили отправить царя в последний путь по всем традициям. Построили сооружение примерно в 1323 году до н. э. На поверхности виднеется вход, после которого идет лестница. Гробница Тутанхамона по плану выглядит как типичная усыпальница: коридор, передняя комната, погребальный зал, сокровищница, кладовая.

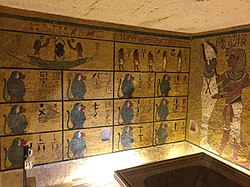

Подготовка к похоронам проходила в спешке, поэтому украсили только погребальную комнату. На фресках изображены этапы траурного мероприятия, боги и различные ритуальные процедуры. До 2018 года археологи были уверены, что в гробнице есть секретные помещения или тайники. Была надежда отыскать комнату с саркофагом царицы Нефертити – предполагаемой матери Тутанхамона. Но современные ученые доказали, что построенная наспех гробница не имеет тайных комнат.

Археологи в 1920-х убедились, что гробницу некто посещал до них. Но, вероятнее всего, в усыпальницу спускались древние грабители. Авантюристам XVIII–XIX веков имя Тутанхамона не было известно. О фараоне знали только египтологи, многие из которых считали его «самым бедным царем». Грабители, побывавшие в гробнице, вероятно, за тысячу лет до британских исследователей забрали часть украшений, предметы мебели, но 90% содержимого осталось под землей.

Ученые полагают, что в древности расхитители были более суеверными и каждый шорох или стук мог вызвать приступ паники. Возможно, грабителей спугнул кто-то из местных жителей. Шли времена, и гробница Тутанхамона утонула в песках Долины царей. Так как царь считался малоизвестным и «бедным», то никто особо и не старался найти утраченную усыпальницу, поэтому гробница осталась фактически неразграбленной.

Великое археологическое открытие

Интерес к древним артефактам и архитектурным памятникам, преобразовавшийся в археологию, возник из корыстных желаний. Во второй половине XVIII столетия путешественники и авантюристы ехали на раскопки не ради науки, а для личного обогащения. В XIX веке приоритеты изменились: появились состоятельные энтузиасты и увлеченные ученые, которые тратили состояния, время и силы на поиски уникальных артефактов и памятников, рассчитывая взамен обрести славу.

Китай, Индия, Аравийский полуостров, затерянные в лесах Южной и Центральной Америки пирамиды индейцев, как и легендарные сокровища тамплиеров привлекали исследователей. Но жемчужиной археологической карты в конце XIX и начале XX века был Египет. Пока ученые перекапывали тонны песка, на экраны выходили фильмы, посвященные Клеопатре. Западную Европу и США охватила египтомания.

На старте XX столетия Долина царей представляла собой хорошо изученную местность, где побывали и профессиональные археологи, и искатели сокровищ. Египетское правительство вплело в захватывающий процесс бюрократию. Для проведения раскопок исследователи получали специальное разрешение на поиски древностей в Долине царей.

С 1902 года здесь работала группа археологов эксцентричного американского миллионера Теодора Дэвиса. Поиски были результативными: нашли несколько гробниц, в том числе принадлежащую военачальнику и фараону Хоремхебу. Но Дэвис рассчитывал найти неразграбленную царскую усыпальницу. В 1914-м Дэвис потерял интерес, поэтому продал разрешение британскому археологу-любителю Джорджу Карнарвону.

К тому моменту сложилось мнение, что Долина царей больше ничем не может удивить. Но лорд Карнарвон в 1906 году познакомился с египтологом Говардом Картером. Британец был уверен, что гробница Тутанхамона скрыта под песками где-то на юге Египта, вероятнее всего, в Долине царей. Карнарвон доверился товарищу и с 1914 года начал финансировать поиски утраченной усыпальницы.

В те времена инструментарий археологии был скудным, и ученые годами работали без результатов, опираясь порой на интуицию. Карнарвон поначалу был воодушевлен, но последующие 8 лет не принесли плодов, и лорд, подобно миллионеру Дэвису, разочаровался в затее. В ноябре 1922 года спонсор объявил Картеру, что выдает деньги на последний сезон раскопок, который впоследствии отметился открытием века.

4 ноября 2022 года исполнилось 100 лет со дня, когда Говард Картер обнаружил гробницу Тутанхамона. В тот день команда нашла только вход в неизвестную усыпальницу, но на запечатанной двери стоял знак королевской крови. Накануне события произошел случай, который не показался Картеру странным, зато местные жители увидели мрачное знамение. В ходе раскопок Говарда сопровождала канарейка. Однажды в дом ученого пробралась кобра, которая убила птицу. А ведь ядовитая змея символизировала власть фараонов.

О находке ученый сообщил Карнарвону, который прибыл в Египет, чтобы поучаствовать во вскрытии гробницы. 24 ноября исследователи впервые заглянули внутрь, просунув лампу. Взору археологов предстало убранство усыпальницы. Но восторг сменился небольшим разочарованием. Картер и Карнарвон заметили, что они не первые посетители гробницы. Внутри был беспорядок, оставленный расхитителями, но сокровища остались на месте. Было очевидно, что воры приходили сюда неоднократно, но каждый раз по каким-то неведомым причинам уходили с пустыми руками.

Читайте такжеКлеопатра — легендарная царица Египта: факты и мифы о древней правительнице

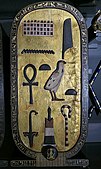

Из-за бюрократических проволочек работы в склепе стартовали только 16 февраля 1923 года. В гробнице Тутанхамона нашли золотые украшения, оружие, музыкальные инструменты, посуду, статуэтки, инсигнии – символы царской власти. Из ювелирных изделий ученые обнаружили золотую диадему, браслет со скарабеем, браслет-повязку со скарабеем, кулон с крылатым скарабеем Хепри.

Среди других находок – колесницы Тутанхамона, щит, бумеранг, меч, кинжал и ножны фараона, игровая доска, золотые сандалии, зонтик, золотые статуи, в том числе и та, которая изображает богиню, несущую царя на голове, детские игрушки.

Всего вещей из гробницы насчитали свыше 5,4 тыс. единиц. Макет корабля помог ученым сформировать представление о флоте Древнего Египта.

Историческое значение находки и ее культовый статус

Последний сезон, который Карнарвон обещал спонсировать, завершился великим археологическим открытием. Гробница Тутанхамона как архитектурный памятник мало чем выделяется из череды других усыпальниц обсуждаемой эпохи. Усопший как царь не успел оставить заметный след по причине ранней смерти. Но сложилось так, что захоронение дошло до XX–XXI веков в более сохранном виде, чем другие аналогичные объекты.

Особенность находки заключается в том, что археолог Картер смог впервые прикоснуться к декорациям древнеегипетской гробницы, сделал их фото и составил точное описание. Возникла вторая волна египтомании, которая характеризовалась не только притоком археологов в долину Нила, но и открытием новых музеев и выставок, на экраны вышли новые фильмы, а читатели знакомились с новыми произведениями о храбрых путешественниках и археологах, мумиях и проклятиях фараонов.

Предметы из гробницы находятся в Каирском египетском музее, в стенах которого собрано 150 тыс. экспонатов, связанных с историографией Египта. В середине 2022 года были обнародованы планы перевезти мумию Тутанхамона в Каир. Но ученые не спешат с реализацией плана. Есть сторонники того, чтобы останки царя продолжали храниться в усыпальнице. Тутанхамон – один из немногих фараонов, чья мумия пролежала 3 тыс. лет нетронутой.

Авторы вовсю эксплуатировали тему потревоженных мумий, которые насылали болезни на искателей приключений и их близких. Ожившие трупы египетских фараонов бродили по улицам Лондона или Каира и стремились вернуть утраченный облик, а храбрые герои пытались вернуть их в царство Анубиса. В 1932 году вышла картина «Мумия», в которой главную роль исполнил Борис Карлофф. Далее последовал фильм «Рука мумии», а за ним – «Гробница мумии», «Призрак мумии», «Проклятие мумии».

Интересные факты о гробнице Тутанхамона

1. В конце 1960-х ученые изучили фрагмент мумии фараона. Анализ показал, что останки царя подвергались воздействию температуры в 200 °C. Исследователи полагают, что причина в бальзамирующих средствах, которые могли «запечь» останки Тутанхамона.

2. Ученые объяснили природу «проклятия фараона». Умирали не только археологи, побывавшие в гробнице в 1920-х, но и современные туристы. Так, последней жертвой стала женщина, посетившая усыпальницу в 1990-х. Медики обнаружили в легких умершей грибок. Патогены могли попасть в воздух, когда, например, из саркофага извлекали тело фараона. Под действием высокой температуры и времени бальзамирующие масла приклеили останки ко дну гроба. Поэтому Картер разрезал мумию.

3. На стенах погребального зала содержатся предупреждения тем, кто потревожит покой фараона. Но в мировоззрении древних египтян нет описания, согласно которому проклятие должно настигнуть человека при жизни. Предостережения гласят, что расплата за осквернение захоронения ждет злоумышленника в загробном мире. Факт говорит о том, что даже египетская мифология дает понять: «проклятие фараона» – вымысел писателей и кинематографистов.

4. В центре погребальной комнаты стоял деревянный ящик, обитый листовым золотом и украшенный иероглифами. Длина футляра составляет 5,11 м, ширина – 3,35 м, а высота – 2,74 м. Интересный факт: в ящике располагался саркофаг, внутри которого по принципу матрешки хранились 3 гроба. Первые два были деревянные и обитые золотом. Третий гроб, в котором лежит мумия, выполнен из золота и весит 100 кг.

5. Кроме останков Тутанхамона, археологи нашли еще две мумии эмбрионов. Длина первой – 30 см, что соответствует плоду на пятом месяце развития, второй – 38,5 см, что является нормой для 8-месячного эмбриона. Но исследователи полагают, что мертворожденные дети были близнецами. Анализ ДНК показал, что они были дочерьми Тутанхамона.

Мифы, загадки и тайны

Борьба науки с псевдоисторическими теориями подобна поединку Геракла с гидрой. Один развеянный миф сменяется двумя новыми. Древнеегипетская культура не стала исключением, а история с гробницей Тутанхамона и вовсе возглавила список загадок и тайн Египта.

Все началось с «ничем не примечательного события», которое на сей раз случилось с Карнарвоном. Мецената экспедиции Картера укусил комар. Во время бритья лорд зацепил место укуса, которое превратилось в кровоточащую рану. Она долго не заживала и вызывала беспокойство аристократа.

Дурное предчувствие подтвердилось, когда Карнарвон не мог встать с кровати из-за лихорадки. Смерть 56-летнего лорда совпала с неполадками в электросети Каира, что только прибавило веса легенде о «проклятии фараона». Карнарвон умер через четыре месяца после того, как спустился в усыпальницу царя.

Подачу электричества восстановили, но причина поломки осталась загадкой. Еще одно мрачное совпадение: в один день с Карнарвоном, но в Англии, умерла собака лорда. Злые языки наперебой кричали: финансировал экспедицию, которая потревожила фараона, и умер первым. Действительно, смерть мецената – начало цепи зловещих событий.

Читайте такжеОстров Пасхи — земля брошенных истуканов: история освоения, география, природные условия и другие факты

Лорд скончался 5 апреля 1923 года. Ровно через пять лет в 53 года умер Артур Мейс, входивший в команду археологов. Причиной смерти ученого стало отравление мышьяком. Радиолог Арчибальд Рейд скончался вскоре после возвращения в Англию. В зоне раскопок находился финансист Джордж Гоулд, который умер через полгода от лихорадки.

Череда трагических событий не оставила семью Карнарвона. Сначала от укуса насекомого умерла жена лорда, а сводный брат аристократа свел счеты с жизнью. У Говарда Картера был молодой и здоровый секретарь Ричард Бартель, который внезапно умер в 1928 году от остановки сердца. Скорая смерть настигла некоторых ученых и медиков, которые работали с мумией или артефактами. Всего скоропостижно умерли 22–25 человек, непосредственно связанных с раскопками.

Приведенные факты являются главным аргументом сторонников эзотерического подхода. Но мистики упускают один важный нюанс. Главной целью «проклятия фараона» должен был стать Картер, который и потревожил покой мумии. Но археолог прожил еще 16 лет с момента открытия гробницы и умер в 64 года. Ученый в одном из последних интервью заявлял, что знает, где искать усыпальницу Александра Македонского. Но археолог не поделился наработками: «Тайна умрет со мной».

Сам Картер не верил в проклятия и мифы. «Человеческий разум должен с презрением отвергать такие выдумки», – говорил ученый. Археолог подчеркивал, что гробница Тутанхамона – «самое безобидное» место на планете. Средняя продолжительность жизни участников экспедиции составила 74 года. Большинство умерших вскоре после раскопок – пожилые люди, которые стоически выдерживали работу в жару при 50 °C, но становились жертвами инфекций или несчастных случаев.

Эта история началась с гибели подростка – правителя Древнего Египта. Его имя могло навсегда кануть в Лету, если бы не череда загадочных смертей, удивительным образом связанная с ним. Тутанхамон вовсе не был выдающимся царем, но события, которые произошли 3000 лет спустя, сделали его самым известным из когда-либо живших фараонов.

Жизнь и смерть фараона

Правление Тутанхамона приходится на период Нового царства – расцвета древнеегипетского государства. Он стал последним представителем XVIII династии, но управлял страной недолго – предположительно, с 1332 по 1323 гг. до н.э. Умер фараон в возрасте 19 или 18 лет, и был похоронен в Долине Царей.

Считается, что Тутанхамон был сыном Эхнатона, знаменитого фараона-реформатора. Египетский трон достался Тутанхамону, когда ему исполнилось девять лет. Как следствие, в период его правления судьбой страны распоряжался не столько сам правитель, сколько бывшие соратники Эхнатона.

Предыдущий фараон был автором религиозной реформы, потрясшей устои древнего общества – замены язычества монотеистической религией, поклонением единому богу Солнца – Атону, а потом и самому фараону. Тутанхамон же решил вернуться к старым богам. Имя Эхнатона предали анафеме, а его бывшая столица Ахетатон была полностью разрушена.

До сих пор не утихают споры о причинах смерти Тутанхамона. Данные археологических исследований показывают, что он был худым и болезненным юношей. Да, пропорции его тела далеки от совершенства: в частности, у него были слишком длинные руки. Именно поэтому одна из самых популярных версий смерти фараона – предполагаемое тяжелое заболевание. Некоторые исследователи, впрочем, категорически не согласны с такими выводами, настаивая на том, что правитель Египта был полностью здоровым человеком. Согласно данным некоторых последних исследований, фараон умер под колесами повозки – на левом боку его тела остался след колеса. Как бы то ни было, одно можно сказать с полной уверенностью: фараон умер в ранней молодости и был похоронен по всем традициям.

Удивительная находка Говарда Картера

Авторами находки, потрясшей весь научный мир, стали археолог Говард Картер и его коллега лорд Карнарвон. Последний не был профессиональным археологом, но взял на себя значительную часть финансирования раскопок, начавшихся в 1914 году. В те годы современных археологических приспособлений еще не существовало, поэтому ученым приходилось работать в очень непростых условиях – долго и часто безрезультатно. К 1922 году лорд и вовсе разочаровался в своих изысканиях, поэтому прекратил и выделение средств.

В то время Картер проводил раскопки в Долине Царей и 4 ноября совершенно случайно обнаружил вход в новую гробницу. На запечатанной двери стоял знак королевской крови – символ захоронения египетской знати. О своей находке археолог немедленно сообщил лорду Карнарвону, который в то время находился в Англии.

Тут надо остановиться и сказать, что еще до вскрытия гробницы с Картером произошел на первый взгляд ничем не примечательный случай. Дело в том, что при раскопках Картера сопровождал питомец – маленькая канарейка. И вот однажды в жилище ученого забралась кобра и съела птичку. Сам археолог не придал этому никакого значения, а вот его прислуга, состоявшая из местных жителей, восприняла это знаком надвигающейся беды. Кобра – один из символов египетских фараонов.

Но вернемся к обнаруженной Картером двери. 24 ноября Карнарвон и Картер решили поближе рассмотреть странную находку. Они просунули лампу в проделанное отверстие и — о, чудо! – увидели роскошную усыпальницу фараона. Увы, сразу стало ясно, что археологи были не первыми посетителями гробницы. Воры несколько раз наведывались сюда за сокровищами, однако каждый раз по какой-то неведомой причине они вынуждены были бежать. Это казалось очевидным: внутри все было перевернуто вверх дном, хотя сокровища фараона были на месте. Но исследовать обстоятельства попыток ограбления у археологов вышло далеко не сразу. Ученые долго дожидались разрешения властей на проведение работ в склепе.

Работы в нем начались 16 февраля 1923 года. Археологи увидели, что склеп состоял из четырех помещений, главным из которых была комната с мумией фараона. В гробнице ученые нашли многочисленные золотые украшения, оружие, посуду, статуэтки, символы царской власти. Потом среди содержимого гробницы обнаружатся еще два тела, принадлежавшие мертворожденным дочерям фараона.

Загадочная смерть

Новость об археологической сенсации всколыхнула весь научный мир. Это и понятно, ведь речь шла об одной из самых выдающихся находок за все время исследования Древнего Египта! Вряд ли Говард Картер мог тогда представить, что вскоре гробница Тутанхамона прославит его еще больше. Правда, подобной славы не пожелаешь никому.

Весной того же года другое «ничем не примечательное событие» произошло уже с Карнарвоном: его укусил комар. Спустя несколько дней лорд порезался в месте укуса, а вскоре обратил внимание, что небольшая царапина подозрительно долго не заживает. Опасения Карнарвона оправдались, когда у него началась лихорадка. Вскоре он скончался. Потом говорили, будто бы комар, укусивший лорда, был «ядовитым». Таинственности истории добавил тот факт, что в момент смерти лорда в Каире внезапно погас свет. Причину аварии установить так и не удалось, но и это еще не все загадочные совпадения. Примерно в то же время, когда сердце Карнарвона остановилось, умерла и его собака, находившаяся в этот момент у него дома в Англии. Конечно, все это можно объяснить обыкновенными совпадениями, раздутыми желтой прессой. Но смерть лорда и все, что было с ней связано, стала лишь первым звеном в цепи зловещих событий.

Лорд Карнарвон скончался 5 апреля 1923 года, спустя четыре месяца после посещения гробницы Тутанхамона. А уже через несколько дней умер Артур Мейс, один из археологов, входивших в экспедицию Картера. Насколько можно было судить, причиной гибели Мейса стало отравление мышьяком. По возвращении в Англию гибель настигла еще одного специалиста тех раскопок – радиолога Арчибальда Рейда. За раскопками гробницы наблюдал и американский финансист Джордж Гоулд. Он умер полгода спустя, подхватив лихорадку.

От укуса насекомого погибла жена лорда Карнарвона, а его сводный брат вскоре покончил жизнь самоубийством. Наконец, в 1928 году умер молодой секретарь Говарда Картера Ричард Бартель. Смерть наступила в результате остановки сердца, хотя Бартель не жаловался на свое здоровье. Все эти люди занимались исследованием мумии фараона. Кроме этого, жертвами «проклятия» стали профессор Ла Флер, рентгенолог Вид и некоторые другие ученые. Всего же в разное время скончались, по разным данным, от 22 до 25 человек, так или иначе связанных с захоронением египетского фараона. Казалось, будто отмщение Тутанхамона настигнет каждого, кто осмелится потревожить его покой…

Тем не менее, сторонники эзотерического подхода иногда упускают один важный момент: главная мишень «проклятия фараона», археолог Говард Картер, умер естественной смертью в 1939 году. На тот момент ему исполнилось 65 лет.

В 1980 году увидело свет интервью с Ричардом Адамсоном – последним живым исследователем из экспедиции Картера. Адамсон также решительно отверг миф о проклятии египетского царя. Строго говоря, почти все умершие ученые к моменту своей смерти находились в очень преклонном возрасте. Участники экспедиции Картера прожили в среднем 74 года.

Но нередко на счет египетского правителя записывают не только погибших ученых, но и простых туристов. Случаи необъяснимых смертей имеют место даже в наше время.

Истоки легенды

Для начала попробуем разобраться в том, откуда появился миф о проклятии. Это прозвучит странно, но сам по себе он является всего лишь газетной уткой. Стараясь обеспечить покой усопшим, древние египтяне, действительно, прибегали к всевозможным заклятиям и заговорам. По мнению современных специалистов, иероглифы содержат некоторые предостережения, но нередко они воспринимаются слишком буквально. С подачи журналистов трактовка некоторых предупреждений порой оказывается искажена до неузнаваемости.

Надписи в усыпальницах предостерегают незадачливого путника от осквернения гробницы или запрещают посещение усыпальницы человеку с дурной репутацией. В случае с Тутанхамоном исследователи установили лишь то, что здесь имеет место заклинание, оберегающее покой египетского царя и защищающее его от песков пустыни.

Автором сообщения о проклятии Тутанхамона стал один из журналистов Daily Express. Свою лепту внесла и писательница Мария Корелли, автор многочисленных произведений на тему мистики. Уже после гибели Карнарвона Мария Корелли и Артур Конан Дойл (тоже большой любитель мистики) утверждали, будто бы они предостерегали незадачливых археологов. Еще раньше к подобной тематике обратилась британская писательница Джейн Лоудон Вебб. Ее мистическое произведение «Мумия» увидело свет в далеком 1828 году. Впоследствии авторы художественной литературы и дальше будут эксплуатировать якобы ужасающие предостережения. Именно так в массовом сознании сформировался зловещий мистический образ египетских фараонов.

«Проклятие фараона Тутанхамона» сделало древнеегипетскую тематику одним из самых популярных мистических направлений в массовой культуре. Одним из последних художественных произведений на эту тему стал вышедший в 2006 году фантастический фильм «Тутанхамон: Проклятие гробницы».

Невидимый убийца

Несмотря на это, «проклятие фараона» действительно может существовать, и объясняется оно вполне естественными факторами.

Поначалу никто из участников экспедиции Картера не обратил внимания на странный налет на стенах усыпальницы. Вопреки первоначальной версии о потрескавшейся росписи, причиной настенных пятен был грибок. Спустя 30 лет после череды загадочных смертей медик Джоффри Дин обратил внимание, что симптомы заболевания ученых, посетивших гробницу, напоминают так называемую «пещерную болезнь». Ее причина – микроскопические грибки. Понятно, что сырые и темные помещения, вроде усыпальницы Тутанхамона, стали благодатной средой для их распространения. Позже египетский биолог Эззеддин Таха подтвердит справедливость этой догадки, обнаружив грибок в организме многих археологов, занятых исследованием Древнего Египта.

В наш век антибиотики сводят опасность таких микроорганизмов на нет. Но если иммунитет человека ослаблен, заражение грибком может иметь довольно тяжелые последствия. В 1990-е годы ученые взяли пробу выделений из легких туристки, умершей после посещения гробницы Тутанхамона. Было установлено, что в организме погибшей находился грибок, который и мог стать причиной ее гибели.

Участники экспедиции Картера тоже могли стать жертвами вредных микроорганизмов, которыми они заразились, находясь рядом с мумией. В пользу этой версии говорит одно важное обстоятельство. Спустя 3000 лет масла, которые использовались для мумификации, превратились в клей. Чтобы извлечь фараона из гроба, Картер пошел на решительный шаг – он разрезал мумию. В те годы египтологи редко использовали специальные защитные средства, и при контакте с мумией вредные микроорганизмы легко могли проникнуть в дыхательные пути, вызвав тяжелые заболевания.

Тутанхамон принадлежал к XVIII династии фараонов – одной из самых известных в истории Древнего Египта. Время ее правления приходится на эпоху Нового царства. Основатель династии Яхмос I объединил разрозненные территории Египта, и его потомки правили страной в 1550-1292 годах до н. э. Представителями династии были несколько могущественных правителей, изменивших историю своей страны, а также ряд женщин-фараонов.

Современные исследователи отмечают, что работа с мумией может быть опасна, поскольку мумифицированное тело может содержать вредоносные бактерии. Существует и обратная сторона вопроса: занесенные извне бактерии могут разрушить мумию.

На наш взгляд, версия о том, что причиной гибели посетителей гробницы Тутанхамона был грибок, звучит вполне правдоподобно. Но официальной точки зрения относительно череды загадочных смертей не существует до сих пор. Как не существует и доказательств того, что ученых и простых туристов убивали вредные микроорганизмы.

Отец Тутанхамона Эхнатон был одним из самых выдающихся религиозных реформаторов в истории. Именно он впервые ввел в Египте монотеизм, «отменив» весь пантеон египетских божеств и оставив лишь бога Солнца – Атона. Скорее всего, целью такого нововведения было укрепление личной власти фараона. Реформа могла быть использована и для централизации египетской державы.

С просьбой прокомментировать этот вопрос мы обратились к действительному члену Международной Ассоциации египтологов, президенту Ассоциации по изучению Древнего Египта Виктору Солкину. Он сказал:

– По сути, скоропостижной и отчасти странной можно назвать только смерть Джорджа Герберта Карнарвона, который был меценатом экспедиции. Срезав укус москита во время бритья, лорд скончался от сепсиса, после чего все, что связано с Египтом, стало восприниматься крайне негативно в его семье, а большая часть его превосходной коллекции была продана в США. Остальные смерти – вовсе не такие многочисленные, как об этом нередко пишут в прессе. Они были связаны, прежде всего, с тем, что после открытия гробницы юного царя члены экспедиции Картера работали в Долине царей, не покладая рук, в том числе и в летние месяцы, когда температура в Долине порой превосходит отметку 50 градусов жары. Умерло несколько членов экспедиции – все пожилые люди, которые просто физически с трудом переносили выпавшие на их долю испытания климатом и песками Египта. Сам Говард Картер, казалось бы, главный виновник открытия царской гробницы, скончался в преклонном возрасте и от естественных причин. С момента открытия гробницы прошло почти 17 лет. Кроме того, в первой трети XX века все «египетское» было по-прежнему связано с мистицизмом, спиритуализмом и другими явлениями, сопровождавшими европейский «египетский восторг». Пресса и салонное общество не удержалось от того, чтобы не увидеть в нескольких инфарктах пожилых ученых нечто потустороннее.

Нужно сказать, что в древнеегипетском мировоззрении вообще нет представлений о том, что проклятие грабителям гробниц должно вызвать скоропостижную смерть. Сохранившиеся образцы текстов, направленных против тех, кто угрожает умершему, наоборот, говорят о гневе богов в загробном мире. «Что до того, кто пальцем коснется пирамиды этой, и этого храма, принадлежащих мне и моему Ка (двойнику, жизненной силе) – будет он осужден девятью богами, и будет ему небытие, и дом его будет в небытии, будет он тем, кого осудили, тем, кто пожирает сам себя» – эта цитата, приведенная от имени царя, встречается в знаменитых «Текстах пирамид», которые появились на стенах царских гробниц в XXV веке до н.э. Посмертное воздаяние, небытие в мире богов было куда более серьезным наказанием в глазах египтян, чем банальная смерть физического тела – важной, но не главной составляющей сущности человека. В гробнице Тутанхамона вообще не было текстов проклятий. Пресловутая «глиняная табличка с проклятиями», якобы найденная археологами, газетная утка. Известен ее автор – археолог Артур Вейгалл, который испытывал неприязнь к Картеру и слухом о «проклятии» порядком усложнил жизнь выдающегося археолога, и так осаждаемого прессой. СМИ не имели достаточного количества информации, так как исключительное право на репортажи из гробницы получила по решению лорда Карнарвона лондонская Times.

Женой Тутанхамона была царица Анхесенамон, дочь того же Эхнатона. От нее Тутанхамон имел двух дочерей, родившихся мертвыми. Скорее всего, братом Тутанхамона был Сменхкара – еще один фараон из этой же династии. Сменхкара правил сразу после смерти своего отца вплоть до прихода к власти девятилетнего Тутанхамона.

Наш эксперт:

Виктор Солкин, действительный член Международной Ассоциации египтологов, президент Ассоциации по изучению Древнего Египта

Нашли опечатку? Выделите фрагмент и нажмите Ctrl + Enter.

| KV62 | |

|---|---|

| Burial site of Tutankhamun | |

The wall decorations in KV62’s burial chamber |

|

|

KV62 |

|

| Coordinates | 25°44′25.4″N 32°36′05.1″E / 25.740389°N 32.601417°ECoordinates: 25°44′25.4″N 32°36′05.1″E / 25.740389°N 32.601417°E |

| Location | East Valley of the Kings |

| Discovered | 4 November 1922 |

| Excavated by | Howard Carter |

| Decoration |

|

| Layout | Bent to the right |

|

← Previous Next → |

The tomb of Tutankhamun, also known by its tomb number, KV62, is the burial place of Tutankhamun (reigned c. 1334–1325 BC), a pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty of ancient Egypt, in the Valley of the Kings. The tomb consists of four chambers and an entrance staircase and corridor. It is smaller and less extensively decorated than other Egyptian royal tombs of its time, and it probably originated as a tomb for a non-royal individual that was adapted for Tutankhamun’s use after his premature death. Like other pharaohs, Tutankhamun was buried with a wide variety of funerary objects and personal possessions, such as coffins, furniture, clothing and jewellery, though in the unusually limited space these goods had to be densely packed. Robbers entered the tomb twice in the years immediately following the burial, but Tutankhamun’s mummy and most of the burial goods remained intact. The tomb’s low position, dug into the floor of the valley, allowed its entrance to be hidden by debris deposited by flooding and tomb construction. Thus, unlike other tombs in the valley, it was not stripped of its valuables during the Third Intermediate Period (c. 1070 – 664 BC).

Tutankhamun’s tomb was discovered in 1922 by excavators led by Howard Carter. As a result of the quantity and spectacular appearance of the burial goods, the tomb attracted a media frenzy and became the most famous find in the history of Egyptology. The death of Carter’s patron, the Earl of Carnarvon, in the midst of the excavation process inspired speculation that the tomb was cursed. The discovery produced only limited evidence about the history of Tutankhamun’s reign and the Amarna Period that preceded it, but it provided insight into the material culture of wealthy ancient Egyptians as well as patterns of ancient tomb robbery. Tutankhamun became one of the best-known pharaohs, and some artefacts from his tomb, such as his golden funerary mask, are among the best-known artworks from ancient Egypt.

Most of the tomb’s goods were sent to the Egyptian Museum in Cairo and are now in the Grand Egyptian Museum in Giza, although Tutankhamun’s mummy and sarcophagus are still on display in the tomb. Flooding and heavy tourist traffic have inflicted damage on the tomb since its discovery, and a replica of the burial chamber has been constructed nearby to reduce tourist pressure on the original tomb.

History[edit]

Burial and robberies[edit]

The central portion of the Valley of the Kings in 2012, with tomb entrances labeled. The covered entrance to KV62 is at centre right.

Tutankhamun reigned as pharaoh between c. 1334 and 1325 BC, towards the end of the Eighteenth Dynasty during the New Kingdom.[1][2] He took the throne as a child after the death of Akhenaten (who was probably his father) and the subsequent brief reigns of Neferneferuaten and Smenkhkare. Akhenaten had radically reshaped ancient Egyptian religion by worshipping a single deity, Aten, and rejecting other deities, a shift that began the Amarna Period.[3] One of Tutankhamun’s major acts was the restoration of traditional religious practice. His name was changed from Tutankhaten, referring to Akhenaten’s deity, to Tutankhamun, honouring Amun, one of the foremost deities of the traditional pantheon. Similarly, his queen’s name was changed from Ankhesenpaaten to Ankhesenamun.[4]

Shortly after he took power, he commissioned a full-size royal tomb, which was probably one of two tombs from the same era, WV23 or KV57.[5] KV62 is thought to have originally been a non-royal tomb, possibly intended for Ay, Tutankhamun’s advisor. After he died prematurely, KV62 was enlarged to accommodate his burial. Ay became pharaoh on Tutankhamun’s death and was buried in WV23. Ay was elderly when he came to the throne, and it is possible that he buried Tutankhamun in KV62 in order to usurp WV23 for himself and ensure that he would have a tomb of suitably royal proportions ready when he himself died. Pharaohs in Tutankhamun’s time also built mortuary temples where they would receive offerings to sustain their spirits in the afterlife. The Temple of Ay and Horemheb at Medinet Habu contained statues that were originally carved for Tutankhamun, suggesting either that Tutankhamun’s temple stood nearby or that Ay usurped Tutankhamun’s temple as his own.[6]

Ay was succeeded by Tutankhamun’s general Horemheb, although the transfer of power may have been contested and created a brief period of political instability.[7][8] As part of the continued reaction against Atenism, Horemheb tried to erase Akhenaten and his successors from the record, dismantling Akhenaten’s monuments and usurping those erected by Tutankhamun. Future king-lists skipped straight from Akhenaten’s father, Amenhotep III, to Horemheb.[7]

Within a few years of his burial, the tomb was robbed twice. After the first robbery, officials responsible for its security repaired and repacked some of the damaged goods before filling the outer corridor with chips of limestone, along with objects dropped by the thieves, to deter future thefts. Nevertheless, a second set of robbers burrowed through the corridor fill. This robbery too was detected, and after a second hasty restoration the tomb was once again sealed.[9]

The Valley of the Kings is subject to periodic flash floods that deposit alluvium.[10] Much of the valley, including the entrance to Tutankhamun’s tomb, was covered by a layer of alluvium over which huts were later built for the tomb workers who cut KV57, in which Horemheb was buried. The geologist Stephen Cross has argued that a major flood deposited this layer after KV62 was last sealed and before the huts were built, which would mean Tutankhamun’s tomb had been rendered inaccessible by the time Ay’s reign ended.[11] However, the Egyptologist Andreas Dorn suggests that this layer already existed during Tutankhamun’s reign, and workers dug through it to reach the bedrock into which they cut his tomb.[12]

More than 150 years after Tutankhamun’s burial, KV9, the tomb of Ramesses V and Ramesses VI, was cut into the rock to the west of his tomb.[13] The entrance of his tomb was further buried by mounds of debris from KV9’s excavation and by huts built by the tomb workers atop that debris. In subsequent years the tombs in the valley suffered major waves of robbery: first during the late Twentieth Dynasty by local gangs of thieves, then during the Twenty-first Dynasty by officials working for the High Priests of Amun, who stripped the tombs of their valuables and removed the royal mummies. Tutankhamun’s tomb, buried and forgotten, remained undisturbed.[14]

Discovery and clearance[edit]

Several tombs in the Valley of the Kings lay open continuously from ancient times onward, but the entrances to many others remained hidden until after the emergence of Egyptology in the early nineteenth century.[15] Many of the remaining tombs were found by a series of excavators working for Theodore M. Davis from 1902 to 1914. Under Davis most of the valley was explored, although he never found Tutankhamun’s tomb because he thought no tomb would have been cut into the valley floor.[16] Among his discoveries was KV54, a pit containing objects bearing Tutankhamun’s name; these objects are now thought to have been either burial goods that were originally stored in the corridor of Tutankhamun’s tomb, which were removed and reburied in KV54 when the restorers filled the corridor, or objects related to Tutankhamun’s funeral. Davis’s excavators also discovered a small tomb called KV58 that contained pieces of a chariot harness bearing the names of Tutankhamun and Ay. Davis was convinced that KV58 was Tutankhamun’s tomb.[17]

The northwest corner of the antechamber, as photographed in 1922. The plaster partition between the antechamber and burial chamber is on the right.

After Davis gave up work on the valley, the archaeologist Howard Carter and his patron George Herbert, 5th Earl of Carnarvon, made an effort to clear the valley of debris down to the bedrock. Davis’s finds of artefacts bearing Tutankhamun’s name gave them reason to hope they might find his tomb.[18] The discovery began on 4 November 1922 with a single step at the top of the entrance staircase.[19] When the excavators reached the antechamber, on 26 November, it exceeded all expectations, providing unprecedented insight into what a New Kingdom royal burial was like.[20]

The condition of the burial goods varied greatly; many had been profoundly affected by moisture, which probably derived from both the damp state of the plaster when the tomb was first sealed and from water seepage over the millennia until it was excavated.[21] Recording the tomb’s contents and conserving them so they could survive to be transported to Cairo proved to be an unprecedented task, lasting for ten digging seasons.[22][23] Although many others participated, the only members of the excavation team who worked throughout the process were Carter, Alfred Lucas (a chemist who was instrumental in the conservation effort), Harry Burton (who photographed the tomb and its artefacts) and four foremen: Ahmed Gerigar, Gad Hassan, Hussein Abu Awad and Hussein Ahmed Said.[24]

The spectacular nature of the tomb goods inspired a media frenzy, dubbed «Tutmania», that made Tutankhamun into one of the most famous pharaohs, often known by the nickname «King Tut».[25][26] In the Western world the publicity inspired a fad for ancient Egyptian-inspired design motifs.[27] In Egypt it reinforced the ideology of pharaonism, which emphasized modern Egypt’s connection to its ancient past and had risen to prominence during Egypt’s struggle for independence from British rule from 1919 to 1922.[28] The publicity increased when Carnarvon died of an infection in April 1923, inspiring rumours that he had been killed by a curse on the tomb. Other deaths or strange events connected with the tomb came to be attributed to the curse as well.[29]

After Carnarvon’s death, the tomb clearance continued under Carter’s leadership. In the second season of the process, in late 1923 and early 1924, the antechamber was emptied of artefacts and work began on the burial chamber.[30] The Egyptian government, which had become partially independent in 1922, fought with Carter over the question of access to the tomb; the government felt that Egyptians, and especially the Egyptian press, were given too little access. In protest of the government’s increasing restrictions, Carter and his associates stopped work in February 1924, beginning a legal dispute that lasted until January 1925. Under the agreement that resolved the dispute, the artefacts from the tomb would not be divided between the government and the dig’s sponsors, as had been standard practice on previous Egyptological digs.[31] Instead most of the tomb’s contents went to the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.[32]

The excavators opened and removed Tutankhamun’s coffins and mummy in 1925, then spent the next few seasons working on the treasury and annexe. The clearance of the tomb itself was completed in November 1930, though Carter and Lucas continued to work on conserving the remaining burial goods until February 1932, when the last shipment was sent to Cairo.[33]

Tourism and preservation[edit]

The tomb has been a popular tourist destination ever since the clearance process began.[34] Sometime after the mummy was reinterred in 1926, someone broke into the sarcophagus, stealing objects Carter had left in place. A likely time for the event is the Second World War, when a shortage of security workers led to widespread looting of Egyptian antiquities. The body was subsequently rewrapped, suggesting local officials may have done so after discovering the theft, but did not report it. The theft was not exposed until 1968, after the anatomist Ronald Harrison re-examined Tutankhamun’s remains.[35]

Each of the Valley of the Kings tombs were vulnerable to flash flooding.[36] When analysing Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1927, Lucas concluded that despite the moisture seepage, no significant liquid water had entered before its discovery.[37] In contrast, since the discovery water has periodically trickled in through the entrance, and on New Year’s Day in 1991 a rainstorm flooded the tomb through a fault in the burial chamber ceiling. The flood stained the painted chamber wall and left about 7 centimetres (2.8 in) of standing water on the floor.[38] Tombs are also threatened by the tourists who visit them, who may damage the wall decoration with their touch and with the moisture introduced by their breath.[36] The mummy is also vulnerable to this kind of damage, so in 2007 it was moved to a climate-controlled glass display case that was placed in the antechamber, allowing it to be displayed to the public while protecting it from humidity and mould.[39]

The Society of Friends of the Royal Tombs of Egypt suggested the idea of creating a replica of Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1988, so that tourists could see it without further damaging the original.[40] In 2009, Factum Arte, a workshop that specialises in replicas of large-scale artworks, took detailed scans of the burial chamber on which to base a replica,[40] while the Egyptian government and the Getty Conservation Institute launched a long-term project to assess the condition of the tomb and renovate it as needed.[41] The replica was completed in 2012 and opened to the public in 2014;[40] the renovation was completed in 2019.[42]

In 2015, the Egyptologist Nicholas Reeves argued, based on Factum Arte’s scans, that the west and north walls of the burial chamber included previously unnoticed plaster partitions. That would suggest the tomb contained two previously unknown chambers, one behind each partition, which Reeves suggested were the burial place of Neferneferuaten. The Ministry of Antiquities commissioned a ground-penetrating radar examination later that year, which seemed to show voids behind the chamber walls, but follow-up radar examinations in 2016 and 2018 determined that there are no such voids and therefore no hidden chambers.[43]

Tutankhamun’s tomb is in higher demand from tourists than any other in the Valley of the Kings. Up to 1,000 people pass through it on its busiest days.[44]

Architecture[edit]

Tutankhamun’s tomb lies in the eastern branch of the Valley of the Kings, where most tombs in the valley are located.[45] It is cut into the limestone bedrock in the valley floor, on the west side of the main path, and runs beneath a low foothill.[46] Its design is similar to those of non-royal tombs from its time, but elaborated so as to resemble the conventional plan of a royal tomb.[47] It consists of a westward-descending stairway (labeled A in the conventional Egyptological system for designating parts of royal tombs in the valley); an east–west descending corridor (B); an antechamber at the west end of the passage (I); an annexe adjoining the southwest corner of the antechamber (Ia); a burial chamber north of the antechamber (J); and a room east of the burial chamber (Ja), known as the treasury.[48] The burial chamber and treasury may have been added to the original tomb when it was adapted for Tutankhamun’s burial.[47] Most Eighteenth Dynasty royal tombs used a layout with a bent axis, so that a person moving from the entrance to the burial chamber would take a sharp turn to the left along the way. By placing Tutankhamun’s burial chamber north of the antechamber, the builders of KV62 gave it a layout with an axis bent to the right rather than the left.[49][50]

The entrance stair descends steeply beneath an overhang.[5] It originally consisted of sixteen steps. The lowest six were cut away during the burial to make room to maneuver the largest pieces of funerary furniture through the doorway, then rebuilt, then removed again 3,400 years later when the excavators removed that same furniture. The corridor is 8 metres (26 ft) long and 1.7 metres (5 ft 7 in) wide; the antechamber is 7.9 metres (26 ft) north–south by 3.6 metres (12 ft) east–west; the annexe is 4.4 metres (14 ft) north–south by 2.6 metres (8 ft 6 in) east–west; the burial chamber is 4 metres (13 ft) north–south by 6.4 metres (21 ft) east–west; and the treasury is 4.8 metres (16 ft) north–south by 3.8 metres (12 ft) east–west. The chambers range from 2.3 metres (7 ft 7 in) to 3.6 metres (12 ft) high, and the floors of the annexe, burial chamber and treasury are about 0.9 metres (2 ft 11 in) below the floor of the antechamber. In the west wall of the antechamber is a small niche for a beam that was used for manoeuvring the sarcophagus through the room.[51] The burial chamber contains four niches, one in each wall, in which were placed «magic bricks» inscribed with protective spells.[51][52]

Partitions constructed of limestone and plaster originally sealed the doorways between the stairway and the corridor; between the corridor and the antechamber; between the antechamber and the annexe; and between the antechamber and the burial chamber. All were breached by robbers. Most were resealed by the restorers, but the robbers’ hole in the annexe doorway was left open.[53]

There are several faults in the rock into which the tomb is cut, including a large one that runs south-southeast to north-northwest across the antechamber and burial chamber.[54] Although the workmen who cut the tomb sealed the fault in the burial chamber with plaster,[55] the faults are responsible for the water seepage that affects the tomb.[54]

Decoration[edit]

Scene from the north wall of the burial chamber, in which Tutankhamun, followed by his ka (an aspect of his soul), embraces the god Osiris[56]

The plaster partitions were marked with impressions from seals borne by various officials who oversaw Tutankhamun’s burial and the restoration efforts. These seals consist of hieroglyphic text that celebrates Tutankhamun’s services to the gods during his reign.[57]

Aside from these seal impressions, the only wall decoration in the tomb is in the burial chamber. This limited decorative programme contrasts with other royal tombs of the late Eighteenth Dynasty, in which two chambers in addition to the burial chamber often received decoration, and with the practice in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Dynasties, in which all parts of the tomb were decorated. None of the decoration is executed in relief, a technique that was not used in the Valley of the Kings until the reign of Horemheb.[58]

KV62’s burial chamber is painted with figures on a yellow background. The east wall portrays Tutankhamun’s funeral procession, a type of image that is common in private New Kingdom tombs but not found in any other royal tomb. The north wall shows Ay performing the Opening of the Mouth ritual upon Tutankhamun’s mummy, thus legitimising him as the king’s heir, and then Tutankhamun greeting the goddess Nut and the god Osiris in the afterlife. The south wall portrayed the king with the deities Hathor, Anubis and Isis. Part of the decoration of this wall was painted on the partition dividing the burial chamber from the antechamber, and thus the figure of Isis had to be destroyed when the partition was demolished during the tomb clearance. The west wall bears an image of twelve baboons, which is an extract from the first section of the Amduat, a funerary text that describes the journey of the sun god Ra through the netherworld. On three walls the figures are given the unusual proportions found in the art style of the Amarna Period, although the south wall reverts to the conventional proportions found in art before and after Amarna.[59]

Burial goods[edit]

The contents of the tomb are by far the most complete example of a royal set of burial goods in the Valley of the Kings,[60] numbered at 5,398 objects.[61] Some classes of object number in the hundreds: there are 413 shabtis (figurines intended to do work for the king in the afterlife) and more than 200 pieces of jewellery.[62] Objects were present in all four chambers in the tomb as well as the corridor.[63]

The efforts of the robbers, followed by the hasty restoration effort, left much of the tomb in disarray when it was last sealed.[64] By the time of the discovery, many of the objects had been damaged by alternating periods of humidity and dryness.[65] Nearly all leather in the tomb had dissolved into a pitch-like mass, and while the state of preservation of textiles was highly inconsistent, the worst-preserved had turned into a black powder.[66] Wooden objects were warped and their glues dissolved, leaving them in a very fragile state.[65] Every exposed surface was covered with an unidentified pink film;[67] Lucas suggested it was some kind of dissolved iron compound that came from the rock or the plaster.[68] In the process of cleaning, restoring and removing the damaged artefacts, the excavators labeled each object or group of objects with a number, from 1 to 620, appending letters to distinguish individual objects within a group.[69]

Outer chambers[edit]

The corridor may have contained miscellaneous materials, such as bags of natron, jars and flower garlands, that were moved to KV54 when the corridor was filled after the first robbery.[63] Other objects and fragments were incorporated into the corridor fill. One well-known artefact, a wooden bust of Tutankhamun, was apparently found in the corridor when it was excavated, but it was not recorded in Carter’s initial excavation notes.[70]

The antechamber contained 600 to 700 objects. Its west side was taken up by a tangled pile of furniture among which miscellaneous small objects, such as baskets of fruit and boxes of meat, were placed. Several dismantled chariots took up the southeast corner, while the northeast contained a collection of funerary bouquets and the north end of the chamber was dominated by two life-size statues of Tutankhamun that flanked the entrance to the burial chamber.[71] These statues are thought to have either served as guardians of the burial chamber or as figures representing the king’s ka, an aspect of his soul.[72] Among the significant objects in the antechamber were several funerary beds with animal heads, which dominated the cluster of furniture against the west wall; an alabaster lotus chalice; and a painted box depicting Tutankhamun in battle, which Carter regarded as one of the finest works of art in the tomb. Carter thought even more highly of a gilded and inlaid throne depicting Tutankhamun and Ankhesenamun in the art style of the Amarna Period; he called it «the most beautiful thing that has yet been found in Egypt».[73] Boxes in the antechamber contained most of the clothing in the tomb, including tunics, shirts, kilts, gloves and sandals, as well as cosmetics such as unguents and kohl.[74] Scattered in various places in the antechamber were pieces of gold and semiprecious stones from a corselet, a ceremonial version of the armor that Egyptian kings wore into battle. Reconstructing the corselet was one of the most complex tasks the excavators faced.[75] This room also contained a wooden dummy of Tutankhamun’s head and torso. Its purpose is uncertain, although it bears marks that may indicate it once wore a corselet, and Carter suggested it was a mannequin for the king’s clothes.[76]

The annexe contained more than 2,000 individual artefacts. Its original contents were jumbled together with objects that had been haphazardly replaced during the restoration after the robberies, including beds, stools, and stone and pottery vessels containing wine and oils.[77] The room housed most of the tomb’s foodstuffs, most of the shabtis and many of its wooden funerary models, such as models of boats.[78] Much of the weaponry in the tomb, such as bows, throwing sticks and khopesh-swords, as well as ceremonial shields, were found here.[79] Other objects in the annexe were personal possessions that Tutankhamun seemingly used as a child, such as toys, a box of paints and a fire-lighting kit.[80]

-

A painted chest from the antechamber

-

A chariot, reassembled from the pieces in the antechamber

-

Two of the embroidered gloves found in the antechamber and annexe[81]

-

Ceremonial shield from the annexe

-

A calcite model boat from the annexe

-

A senet game-board from the annexe

-

Shabtis, many of which were found in the annexe

Burial chamber[edit]

The shrines and the sarcophagus they enclosed, shown to scale

Most of the space in the burial chamber was taken up by the gilded wooden outer shrine enclosing three nested inner shrines and, within them, a stone sarcophagus containing three nested coffins. Also a wooden frame stood between the outermost and second shrines which was covered with a blue linen pall spangled with bronze rosettes. Yet even this chamber contained burial goods, including jars, religious objects such as imiut fetishes, oars, fans and walking sticks, some of which were inserted in the narrow gaps between shrines.[82] Each wall of the chamber bore a niche containing a brick,[83] of a type that Egyptologists call «magic bricks», because they are inscribed with passages from Spell 151 from the funerary text known as the Book of the Dead, and are intended to ward off threats to the dead.[52]

The decoration of the shrines, executed in relief, includes portions of several funerary texts. All four shrines bear extracts from the Book of the Dead, and further extracts from the Amduat are on the third shrine.[84] The outermost shrine is inscribed with the earliest known copy of the Book of the Heavenly Cow, which describes how Ra reshaped the world into its current form.[85] The second shrine bears a funerary text that is found nowhere else, although texts with similar themes are known from the tombs of Ramesses VI (KV9) and Ramesses IX (KV6). Like them, it describes the sun god and the netherworld using a cryptic form of hieroglyphic writing that uses non-standard meanings for each hieroglyphic sign. These three texts are sometimes labeled «enigmatic books» or «books of the solar-Osirian unity».[86][87]

The sarcophagus is made of quartzite but with a red granite lid, painted yellow to match the quartzite. It is carved with the images of four protective goddesses (Isis, Nephthys, Neith and Serqet), and contained a golden lion-headed bier on which rested three nested coffins in human shape.

The outer two coffins were made of gilded wood inlaid with glass and semiprecious stones, while the innermost coffin, though similarly inlaid, was primarily composed of 110.4 kilograms (243 lb) of solid gold.[88] Within it lay Tutankhamun’s mummified body. On the body, and contained within the layers of mummy wrappings, were 143 items, including articles of clothing such as sandals, a plethora of amulets and other jewellery and two daggers. Tutankhamun’s head bore a beaded skullcap and a gold diadem, all of which was encased in the golden mask of Tutankhamun, which has become one of the most iconic ancient Egyptian artefacts in the world.[89]

-

Diagram of shrines and coffins in the tomb

-

The middle coffin, from the burial chamber

-

The inner coffin, from the burial chamber

Treasury[edit]

In the doorway of the treasury stood a shrine on carrying poles topped by a statue of the jackal god Anubis, in front of which lay a fifth magic brick.[90] Against the east wall of the treasury was a tall gilded shrine containing the canopic chest, in which Tutankhamun’s internal organs were placed after mummification. Whereas most canopic chests contain separate jars, Tutankhamun’s consists of a single block of alabaster carved into four compartments, each covered by a human-headed stopper and containing an inlaid gold coffinette that housed one of the king’s organs.[91] Between the Anubis shrine and the canopic shrine stood a wooden sculpture of a cow’s head, representing the goddess Hathor. The treasury was the location of most of the tomb’s wooden models, including more boats and a model granary, as well as many of the shabtis.[92] Boxes in the treasury contained miscellaneous items, including much of the tomb’s jewellery.[93] A nested set of small coffins in the treasury contained a lock of hair belonging to Tiye, the wife of Amenhotep III, who is thought to have been Tutankhamun’s grandmother. One box contained two miniature coffins in which mummies of Tutankhamun’s stillborn daughters were interred.[94]

-

A box from the treasury shaped like the cartouche of Tutankhamun’s name

-

The canopic shrine from the treasury

-

The canopic chest from the treasury, with three of the four stoppers present

-

Figurines of deities, found in the treasury

Significance[edit]

The volume of goods in Tutankhamun’s tomb is often taken as a sign that longer-lived kings who had full-size tombs were buried with an even larger array of objects. Yet Tutankhamun’s burial goods barely fit into his tomb, so the Egyptologist Joyce Tyldesley argues that larger tombs in the valley may have contained assemblages of similar size that were arranged in a more orderly and spacious manner.[95]

This statuette of Tutankhamun standing on a panther closely resembles images from the tomb of Seti II.[96]

The fragmentary remains of burial goods in other tombs in the Valley of the Kings include many of the same objects found in Tutankhamun’s, implying that there was a somewhat standard set of object types for royal burials in this era. The life-size statues of Tutankhamun and the statuettes of deities have parallels in several other tombs in the valley, while the statuettes of Tutankhamun himself are closely paralleled by wall paintings in KV15, the tomb of Seti II. Funerary models, such as Tutankhamun’s model boats, were mainly a feature of burials in the Old and Middle Kingdoms and fell out of favour in non-royal burials in the New, but several royal tombs in the Valley of the Kings contained them. Conversely, Tutankhamun’s tomb contained no funerary texts on papyri, unlike private tombs from its era, but the existence of an excerpt of the Book of the Dead on a papyrus from KV35, the tomb of Amenhotep II, suggests that their absence in Tutankhamun’s tomb may have been unusual.[97]

No papyrus texts at all were among the burial goods—a disappointment to Egyptologists, who hoped to find documents that would clarify the history of the Amarna Period. Instead much of the value of the discovery was in the insight it provided into the material culture of ancient Egypt.[98] Among the furniture was a foldable bed, the only intact example known from ancient Egypt.[99] Some of the boxes could be latched with the turn of a knob, and Carter called them the oldest known examples of such a mechanism.[100] Other everyday items include musical instruments, such as a pair of trumpets; a variety of weapons, including a dagger made of iron, a rare commodity in Tutankhamun’s time; and about 130 staffs, including one bearing the label «a reed staff which His Majesty cut with his own hand.»[101]

Tutankhamun’s clothes—loose tunics, robes and sashes, often elaborately decorated with dye, embroidery or beadwork—exhibit more variety than the clothes depicted in art from his time, which consist largely of plain white kilts and tight sheaths. No crowns were found in the tomb, although crooks and flails, which also served as emblems of kingship, were stored there. Tyldesley suggests that crowns may have not been considered personal property of the king and were instead passed down from reign to reign.[102]