Химическая формула: SiO2 (диоксид кремния).

- Структура

- Свойства

- Морфология

- Разновидности

- Происхождение

- Применение

- Классификация

- Физические свойства

- Оптические свойства

- Кристаллографические свойства

СТРУКТУРА

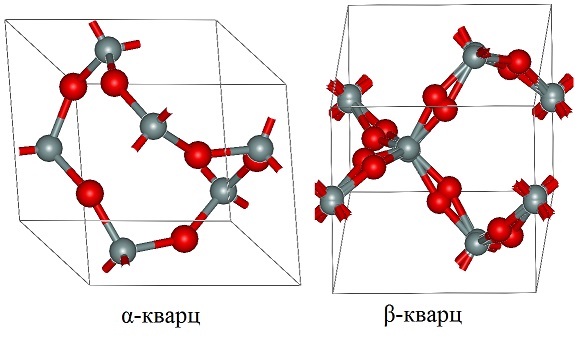

Две основные полиморфные кристаллические модификации двуокиси кремния: гексагональный β-кварц, устойчивый при давлении в 1 атм. (или 100 кн/м2) в интервале температур 870-573°С, и тригональный α-кварц, устойчивый при температуре ниже 573°С. В природе широко распространён именно α-кварц, эту устойчивую при низких температурах модификацию обычно называют просто кварцем. Все гексагональные кристаллы кварца, находимые в обычных условиях, являются параморфозами α-кварца по β-кварцу. α-кварц кристаллизуется в классе тригонального трапецоэдра тригональной сингонии. Кристаллическая структура – каркасного типа, построена из кремне-кислородных тетраэдров, расположенных винтообразно (с правым или левым ходом винта) по отношению к главной оси кристалла. В зависимости от этого различают правые и левые структурно-морфологические формы кристаллов кварца, отличимые внешне по симметрии расположения некоторых граней (например, трапецоэдра и др.). Отсутствие плоскостей и центра симметрии у кристаллов α-кварца обусловливает наличие у него пьезоэлектрических и пироэлектрических свойств.

СВОЙСТВА

Часто образует двойники. Растворяется в плавиковой кислоте и расплавах щелочей. Температура плавления 1713—1728 °C (из-за высокой вязкости расплава определение температуры плавления затруднено, существуют различные данные). Диэлектрик и пьезоэлектрик.

Относится к группе стеклообразующих оксидов, то есть может быть главной составляющей стекла. Однокомпонентное кварцевое стекло из чистого оксида кремния получают плавлением горного хрусталя, жильного кварца и кварцевого песка. Диоксид кремния обладает полиморфизмом. Стабильная при нормальных условиях полиморфная модификация — α-кварц (низкотемпературный). Соответственно β-кварцем называют высокотемпературную модификацию.

МОРФОЛОГИЯ

В магматических и метаморфических горных породах кварц образует неправильные изометричные зерна, сросшиеся с зернами других минералов, его кристаллами часто инкрустированы пустоты и миндалины в эффузивах.

В осадочных породах – конкреции, прожилки, секреции(жеоды), щётки мелких короткопризматических кристаллов на стенках пустот в известняках и др. Также обломки различной формы и размеров, галька, песок.

РАЗНОВИДНОСТИ КВАРЦА

Авантюрин — желтоватый или мерцающий буровато-красный кварцит (в связи с включениями слюды и железной слюдки).

Агат— слоисто-полосчатая разновидность халцедона.

Аметист— фиолетовый.

Бингемит — иризирующий кварц с включениями гётита.

Бычий глаз – густо-малиновый, бурый

Волосатик — горный хрусталь с включениями тонкоигольчатых кристаллов рутила, турмалина и/или других минералов, образующих игольчатые кристаллы.

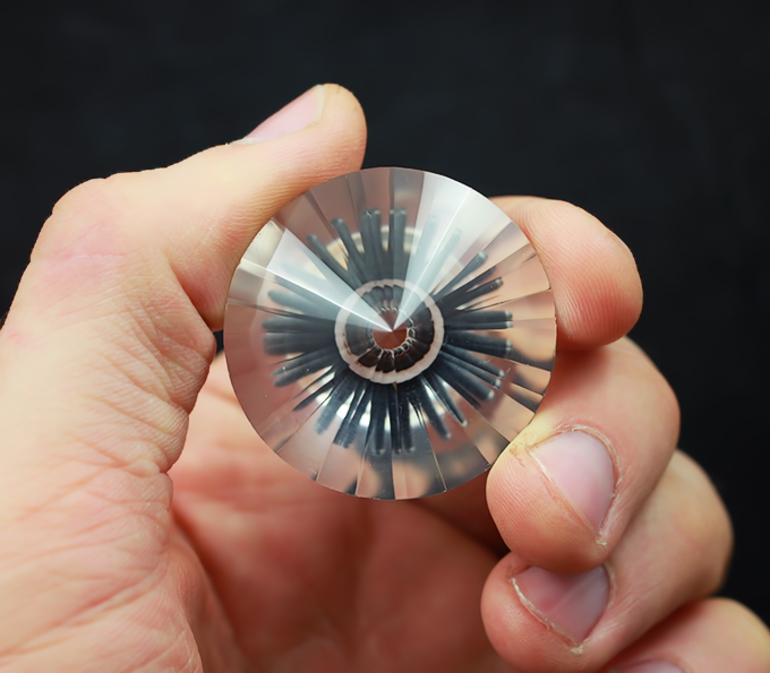

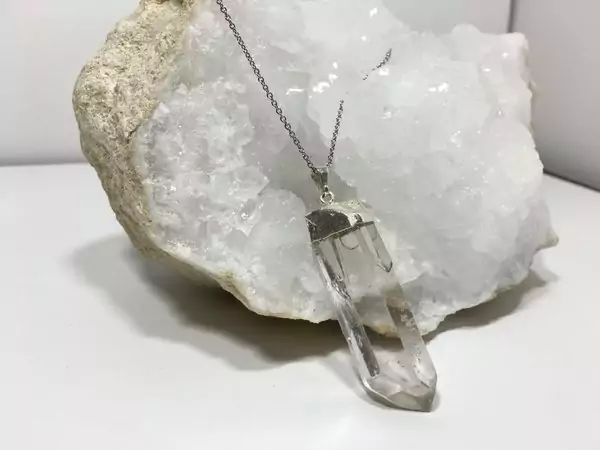

Горный хрусталь — кристаллы бесцветного прозрачного кварца.

Кремень — тонкозернистые скрытокристаллические агрегаты кремнезёма непостоянного состава, состоящие в основном из кварца и в меньшей степени халцедона, кристобалита, иногда с присутствием небольшого количества опала. Обычно находятся в виде конкреций или гальки, возникающей при их разрушении.

Морион — чёрный.

Переливт — cостоят из перемежающихся слоев микрокристаллов кварца и халцедона, никогда не бывают прозрачными.

Празем — зелёный (из-за включений актинолита).

Празиолит — луково-зелёный, получается искусственно прокаливанием жёлтого кварца.

Раухтопаз (дымчатый кварц) — светло-серый или светло-бурый.

Розовый кварц — розовый.

Халцедон— скрытокристаллическая тонковолокнистая разновидность. Полупрозрачен или просвечивает, цвет от белого до медово-жёлтого. Образует сферолиты, сферолитовые корки, псевдосталактиты или сплошные массивные образования.

Цитрин— лимонно-жёлтый.

Сапфировый кварц — синеватый, грубозернистый агрегат кварца.

Кошачий глаз — белый, розоватый, серый кварц с эффектом светового отлива.

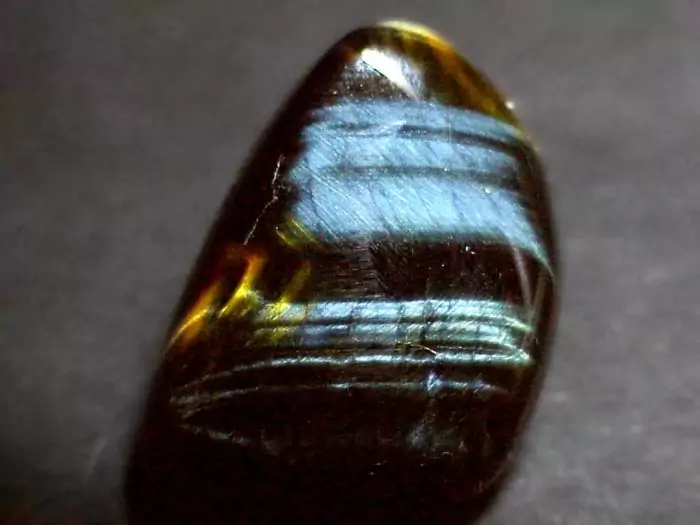

Соколиный глаз — окварцованный агрегат синевато-серого амфибола.

Тигровый глаз — аналогичен соколиному глазу, но золотисто-коричневого цвета.

Оникс— коричневый с белыми и чёрными узорами, красно-коричневый, коричнево-жёлтый, медовый, белый с желтоватыми или розоватыми прослоями. Для оникса особо характерны плоско-параллельные слои разного цвета.

Гелиотроп – непрозрачная тёмно-зелёная разновидность скрытокристалического кремнезема, по большей части тонкозернистого кварца, иногда с примесью халцедона, оксидов и гидроксидов железа и других второстепенных минералов, с ярко-красными пятнами и полосами.

ПРОИСХОЖДЕНИЕ

Непосредственно кристаллизуется из магмы кислого состава. Кварц содержат как интрузивные (гранит, диорит), так и эффузивные (риолит, дацит) породы кислого и среднего состава, может встречаться в магматических породах основного состава (кварцевое габбро).

В вулканических породах кислого состава нередко образует порфировые вкрапленники.

Кварц кристаллизуется из обогащенных флюидами пегматитовых магм и является одним из главных минералов гранитных пегматитов. В пегматитах кварц образует срастания с калиевым полевым шпатом (собственно пегматит), внутренние части пегматитовых жил нередко сложены чистым кварцем (кварцевое ядро). Кварц является главным минералов апогранитных метасоматитов – грейзенов.

При гидротермальном процессе образуются кварцевые и хрусталеносные жилы, особое значение имеют кварцевые жилы альпийского типа.

В поверхностных условиях кварц устойчив, накапливается в россыпях различного генезиса (прибрежно-морских, эоловых, аллювиальных и др.). В зависимости от различных условий образования кварц кристаллизуется в различных полиморфных модификациях.

ПРИМЕНЕНИЕ

Монокристаллы кварца применяются в оптическом приборостроении для изготовления фильтров, призм для спектрографов, монохроматоров, линз для Уф-оптики. Плавленый кварц применяют для изготовления специальной химической посуды. Кварц также используется для получения химически чистого кремния. Прозрачные, красивоокрашенные разновидности кварца являются полудрагоценными камнями и широко применяются в ювелирном деле. Кварцевые пески и кварциты используются в керамической и стекольной промышленности

Кварц (англ. Quartz) – SiO2

| Молекулярный вес | 60.08 г/моль |

| Происхождение названия | от стар. нем. “Querklufter” – “руда секущих жил”, или от нем “quarz”. |

| IMA статус | действителен, описан впервые до 1959 (до IMA) |

КЛАССИФИКАЦИЯ

| Strunz (8-ое издание) | 4/D.01-10 |

| Nickel-Strunz (10-ое издание) | 4.DA.05 |

| Dana (7-ое издание) | 75.1.3.1 |

| Dana (8-ое издание) | 75.1.3.1 |

| Hey’s CIM Ref. | 7.8.1 |

ФИЗИЧЕСКИЕ СВОЙСТВА

| Цвет минерала | сам по себе бесцветный или белый за счет трещиноватости, примесями может быть окрашен в любые цвета (пурпурный, розовый, чёрный, жёлтый, коричневый, зелёный, оранжевый, и т д.) |

| Цвет черты | белый |

| Прозрачность | полупрозрачный,прозрачный |

| Блеск | стеклянный |

| Спайность | весьма несовершенная ромбоэдрическая спайность по {1011} наблюдается наиболее часто, имеется по меньшей мере шесть других направлений |

| Твердость (шкала Мооса) | 7 |

| Излом | неровный, раковистый |

| Прочность | хрупкий |

| Плотность (измеренная) | 2.65 г/см3 |

| Радиоактивность (GRapi) | 0 |

ОПТИЧЕСКИЕ СВОЙСТВА

| Тип | одноосный (+) |

| Показатели преломления | nω = 1.543 – 1.545 nε = 1.552 – 1.554 |

| Максимальное двулучепреломление | δ = 0.009 |

| Оптический рельеф | низкий |

| Плеохроизм | не плеохроирует |

| Рассеивание | низкое, 0,009 |

| Люминесценция в ультрафиолетовом излучении | флюоресцентный и триболюминесценый, при УФ – желто-оранжевый |

КРИСТАЛЛОГРАФИЧЕСКИЕ СВОЙСТВА

| Точечная группа | 3 2 – трапецоэдрический |

| Пространственная группа | P31 2 1 |

| Сингония | Тригональная |

| Параметры ячейки | a = 4.9133Å, c = 5.4053Å |

| Двойникование | по дофинейскому закону, по бразильскому закону, по японскому закону |

Интересные статьи:

Как образуется, происхождение

Кварц известен людям с древнейших времён. Его легко обнаружить и добыть даже без применения специальной техники. Кроме того, он прочен и красив. Древние люди изготавливали из него не только украшения, но и орудия труда — топоры, ножи, отбойники.

Условия образования минерала различны. Он является породообразующим для большинства метаморфических и магматических пород. Может кристаллизоваться непосредственно из кислых магм. Встречается кварц и в составе осадочных пород: доломитов, известняков и пр. В них он имеет формы жеод (замкнутых полостей), конкреций (шаровидных минеральных агрегатов), прожилок и мелкокристаллических корок. В виде смесей и силикатов может сам входить в состав других минералов.

Относится к группе стеклообразующих оксидов, то есть стекло может состоять главным образом из этого минерала.

Состав, общие свойства

В переводе со средневерхненемецкого языка название кварц означает «твёрдый». Этот минерал представляет собой оксид кремния. Химическая формула кварца — SiO2 (оксид кремния). Температура плавления — около +1728 градусов. В разных источниках эти сведения могут отличаться, так как расплав минерала характеризуется повышенной вязкостью и в точности определить температуру сложно. Кварц — диэлектрик, то есть он не проводит или практически не проводит электрический ток. Плотность минерала — в пределах от 2,6 до 2,65 г/см³. Его твёрдость по 10-балльной шкале Мооса равна 7.

Кристаллы имеют характерное шестигранное псевдогексагональное призматическое строение. Они чаще всего бесцветны, но могут иметь белую окраску из-за большого количества трещин. Благодаря различным примесям, в том числе включениям других минералов (например, оксидов железа) могут приобретать и другие цвета.

Для кварца характерен полиморфизм, то есть при одной и той же химической формуле минерал может иметь различное строение кристаллической решётки. Благодаря её разной структуре в природе встречаются коэсит, тридимит, кристобалит.

Ещё одна полиморфная модификация, стишовит, была сначала получена искусственным путём при очень высоком давлении, а затем обнаружена в составе горных пород в Аризонском метеоритном кратере.

Для детей 2 класса описание минерала кварца должно быть более простым. Можно дать лишь его краткую характеристику, в соответствии с возрастными особенностями учащихся. Сведения о химической формуле и составе минерала для них ещё сложны, они изучаются в старших классах. В рамках курса «Окружающий мир» сообщение может включать, например, информацию о разновидностях полезного ископаемого. Этот минерал имеет много видов и внешне они довольно привлекательны. Поэтому у детей 7—8 лет такая информация вызывает большой интерес.

Разновидности, их разнообразие

Интересный факт: существует множество разновидностей кварца (более двух десятков), которые отличаются друг от друга прежде всего цветом. Так, этот минерал может выглядеть как бесцветные, прозрачные кристаллы (горный хрусталь), тёмный непрозрачный полудрагоценный камень коричневого или красно-коричневого цвета с белыми и чёрными или розоватыми и желтоватыми узорами соответственно (оникс).

И это далеко не все примеры. Дополнительный материал для детей 2 класса о свойствах камня кварца может включать краткие сведения о таких его разновидностях, как халцедон, цитрин, а также кошачий, тигровый и соколиный глаз. Названия последних видов вызывают живой интерес у учеников. В докладе могут содержаться сведения о том, что из многих разновидностей минерала делают ювелирные украшения. Дополнить информацию и сделать тему по-настоящему интересной для детей помогут тщательно подобранные иллюстрации.

Как и где добывают кварц

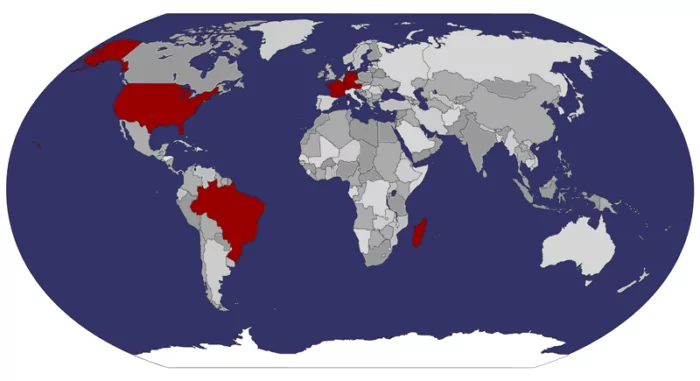

Это очень распространённый минерал, его месторождения не редкость. Залежи пока не обнаружены только в Антарктиде, но это лишь вопрос времени.

Однако далеко не все они имеют промышленное значение. На мировой рынок минерал в основном поставляют такие государства:

- США.

- Бразилия.

- Австралия.

- Шри-Ланка.

- Мадагаскар.

Кроме того, многие страны являются признанными лидерами в добыче какой-то одной разновидности минерала. Так, в России на Южном Урале добывают самые качественные в мире авантюрины. Это разновидность кварца зеленоватого цвета без искр. Прекрасные кристаллы горного хрусталя добывают в Италии, Франции. Помимо австралийских и бразильских, востребованы у ювелиров и аметисты из Германии, Армении.

Добыча кварца может вестись тремя способами, в зависимости от особенностей месторождения:

- Взрывным. Это наименее эффективный способ, который к тому же вредит окружающей среде. В результате получают, как правило, кристаллы невысокого качества, в виде обломков, с трещинами и сколами. Однако этот метод по-прежнему актуален из-за его дешевизны.

- Методом воздушной подушки. Он заключается в том, что порода раскалывается под действием высокого давления. Оно образуется путём нагнетания воздуха в специальную ёмкость, помещённую в скважину месторождения. При таком способе повреждения породы незначительны.

- Метод камнереза. Самый щадящий, но и наиболее дорогостоящий. Предусматривает использование специальной техники, стоимость которой довольно высока.

Кроме того, кварц синтезируют искусственным путём.

Применение минерала

Он относится к широко распространенным полезным ископаемым. Искусственный и натуральный кварц применение находят в следующих сферах:

- Оптика (в различных приборах).

- Производство (керамическая, стекольная промышленность). Благодаря пьезоэлектрическим свойствам они также используются в радио- и телефонной аппаратуре. Применяются в генераторах ультразвука. Большое количество кварцевого сырья используется для производства огнеупорных материалов, а также кварцевого стекла, из которого изготавливают изделия, стойкие к колебаниям температуры. Это лабораторная посуда, изоляторы, тигли и т. д. Из кварцевого стекла производят оптические волокна.

- Ювелирное дело. В сфере повышения в последние годы интереса к эзотерическим знаниям большую популярность приобрели амулеты с разными видами кварца, которые подбираются исходя из даты рождения человека и других параметров.

Искусственные кристаллы

Искусственный кварц имеет ряд преимуществ перед природным: это и более высокая химическая чистота, и однородная структура, вызванная более равномерным распределением примесей. Кроме того, промышленным образом выращивают монокристаллы, в природе же распространены сдвойникованные. Монокристаллы более пригодны для использования в оптической и радиоэлектронной промышленности.

Для ювелирного дела искусственные кристаллы кварца тоже удобнее, так как в процессе выращивания им можно придать практически любой цвет и насыщенность оттенка. Можно также вырастить кристаллы с задуманными плавными переходами одного цвета в другой. Интересно, что промышленным образом можно получить и такие цвета, которые в природе не встречаются или очень редки. Это синий, голубой и зелёный кварц. Для детей 2 класса эта информация тоже, несомненно, будет интересной.

Интересные факты

С элементарными сведениями о минералах ученики знакомятся уже в начальных классах. Учитель может сообщить на уроке следующие интересные сведения о кварце:

- Минерал может по-разному реагировать на колебания температуры. Так, чёрный кварц, нагретый до +300 градусов, приобретает золотистый цвет, а до +400 — прозрачность.

- Многим известно выражение «кварцевые часы». Для контроля за точностью хода в них используются кристаллы этого минерала. Часы с кварцевыми кристаллами считаются самым точными.

- Линзы из кварца намного прочнее, чем стеклянные.

Эти интересные факты вполне доступны для понимания детям 2 класса. Использование таких сведений на уроке поможет оживить восприятие и будет способствовать лучшему усвоению материала.

| Quartz | |

|---|---|

Quartz crystal cluster from Tibet |

|

| General | |

| Category | silicate mineral[1] |

| Formula (repeating unit) |

SiO2 |

| IMA symbol | Qz[2] |

| Strunz classification | 4.DA.05 (oxides) |

| Dana classification | 75.01.03.01 (tectosilicates) |

| Crystal system | α-quartz: trigonal β-quartz: hexagonal |

| Crystal class | α-quartz: trapezohedral (class 3 2) β-quartz: trapezohedral (class 6 2 2)[3] |

| Space group | α-quartz: P3221 (no. 154)[4] β-quartz: P6222 (no. 180) or P6422 (no. 181)[5] |

| Unit cell | a = 4.9133 Å, c = 5.4053 Å; Z=3 |

| Identification | |

| Formula mass | 60.083 g·mol−1 |

| Color | Colorless through various colors to black |

| Crystal habit | 6-sided prism ending in 6-sided pyramid (typical), drusy, fine-grained to microcrystalline, massive |

| Twinning | Common Dauphine law, Brazil law and Japan law |

| Cleavage | {0110} Indistinct |

| Fracture | Conchoidal |

| Tenacity | Brittle |

| Mohs scale hardness | 7 – lower in impure varieties (defining mineral) |

| Luster | Vitreous – waxy to dull when massive |

| Streak | White |

| Diaphaneity | Transparent to nearly opaque |

| Specific gravity | 2.65; variable 2.59–2.63 in impure varieties |

| Optical properties | Uniaxial (+) |

| Refractive index | nω = 1.543–1.545 nε = 1.552–1.554 |

| Birefringence | +0.009 (B-G interval) |

| Pleochroism | None |

| Melting point | 1670 °C (β tridymite) 1713 °C (β cristobalite)[3] |

| Solubility | Insoluble at STP; 1 ppmmass at 400 °C and 500 lb/in2 to 2600 ppmmass at 500 °C and 1500 lb/in2[3] |

| Other characteristics | lattice: hexagonal, Piezoelectric, may be triboluminescent, chiral (hence optically active if not racemic) |

| References | [6][7][8][9] |

Quartz is a hard, crystalline mineral composed of silica (silicon dioxide). The atoms are linked in a continuous framework of SiO4 silicon-oxygen tetrahedra, with each oxygen being shared between two tetrahedra, giving an overall chemical formula of SiO2. Quartz is the second most abundant mineral in Earth’s continental crust, behind feldspar.[10]

Quartz exists in two forms, the normal α-quartz and the high-temperature β-quartz, both of which are chiral. The transformation from α-quartz to β-quartz takes place abruptly at 573 °C (846 K; 1,063 °F). Since the transformation is accompanied by a significant change in volume, it can easily induce microfracturing of ceramics or rocks passing through this temperature threshold.

There are many different varieties of quartz, several of which are classified as gemstones. Since antiquity, varieties of quartz have been the most commonly used minerals in the making of jewelry and hardstone carvings, especially in Eurasia.

Quartz is the mineral defining the value of 7 on the Mohs scale of hardness, a qualitative scratch method for determining the hardness of a material to abrasion.

Etymology[edit]

The word «quartz» is derived from the German word «Quarz», which had the same form in the first half of the 14th century in Middle High German and in East Central German[11] and which came from the Polish dialect term kwardy, which corresponds to the Czech term tvrdý («hard»).[12]

The Ancient Greeks referred to quartz as κρύσταλλος (krustallos) derived from the Ancient Greek κρύος (kruos) meaning «icy cold», because some philosophers (including Theophrastus) apparently believed the mineral to be a form of supercooled ice.[13] Today, the term rock crystal is sometimes used as an alternative name for transparent coarsely crystalline quartz.[14][15]

Crystal habit and structure[edit]

Quartz belongs to the trigonal crystal system at room temperature, and to the hexagonal crystal system above 573 °C (846 K; 1,063 °F). The ideal crystal shape is a six-sided prism terminating with six-sided pyramids at each end. In nature quartz crystals are often twinned (with twin right-handed and left-handed quartz crystals), distorted, or so intergrown with adjacent crystals of quartz or other minerals as to only show part of this shape, or to lack obvious crystal faces altogether and appear massive.[16][17] Well-formed crystals typically form as a druse (a layer of crystals lining a void), of which quartz geodes are particularly fine examples.[18] The crystals are attached at one end to the enclosing rock, and only one termination pyramid is present. However, doubly terminated crystals do occur where they develop freely without attachment, for instance, within gypsum.[19]

A chiral pair of alpha quartz.

α-quartz crystallizes in the trigonal crystal system, space group P3121 or P3221 (space group 152 or 154 resp.) depending on the chirality. Above 573 °C (846 K; 1,063 °F), α-quartz in P3121 becomes the more symmetric hexagonal P6422 (space group 181), and α-quartz in P3221 goes to space group P6222 (no. 180).[20] These space groups are truly chiral (they each belong to the 11 enantiomorphous pairs). Both α-quartz and β-quartz are examples of chiral crystal structures composed of achiral building blocks (SiO4 tetrahedra in the present case). The transformation between α- and β-quartz only involves a comparatively minor rotation of the tetrahedra with respect to one another, without a change in the way they are linked.[16][21] However, there is a significant change in volume during this transition, and this can result in significant microfracturing in ceramics[22] and in rocks of the Earth’s crust.[23]

-

Crystal structure of α-quartz (red balls are oxygen, grey are silicon)

-

β-quartz

Varieties (according to microstructure)[edit]

Although many of the varietal names historically arose from the color of the mineral, current scientific naming schemes refer primarily to the microstructure of the mineral. Color is a secondary identifier for the cryptocrystalline minerals, although it is a primary identifier for the macrocrystalline varieties.[24]

| Major varieties of quartz | ||

|---|---|---|

| Type | Color & Description | Transparency |

| Herkimer diamond | Colorless | Transparent |

| Rock crystal | Colorless | Transparent |

| Amethyst | Purple to violet colored quartz | Transparent |

| Citrine | Yellow quartz ranging to reddish-orange or brown (Madera quartz), and occasionally greenish yellow | Transparent |

| Ametrine | A mix of amethyst and citrine with hues of purple/violet and yellow or orange/brown | Transparent |

| Rose quartz | Pink, may display diasterism | Transparent |

| Chalcedony | Fibrous, variously translucent, cryptocrystalline quartz occurring in many varieties. The term is often used for white, cloudy, or lightly colored material intergrown with moganite. Otherwise more specific names are used. |

|

| Carnelian | Reddish orange chalcedony | Translucent |

| Aventurine | Quartz with tiny aligned inclusions (usually mica) that shimmer with aventurescence | Translucent to opaque |

| Agate | Multi-colored, curved or concentric banded chalcedony (cf. Onyx) | Semi-translucent to translucent |

| Onyx | Multi-colored, straight banded chalcedony or chert (cf. Agate) | Semi-translucent to opaque |

| Jasper | Opaque cryptocrystalline quartz, typically red to brown but often used for other colors | Opaque |

| Milky quartz | White, may display diasterism | Translucent to opaque |

| Smoky quartz | Light to dark gray, sometimes with a brownish hue | Translucent to opaque |

| Tiger’s eye | Fibrous gold, red-brown or bluish colored chalcedony, exhibiting chatoyancy. | |

| Prasiolite | Green | Transparent |

| Rutilated quartz | Contains acicular (needle-like) inclusions of rutile | |

| Dumortierite quartz | Contains large amounts of blue dumortierite crystals | Translucent |

Varieties (according to color)[edit]

Pure quartz, traditionally called rock crystal or clear quartz, is colorless and transparent or translucent, and has often been used for hardstone carvings, such as the Lothair Crystal. Common colored varieties include citrine, rose quartz, amethyst, smoky quartz, milky quartz, and others.[25] These color differentiations arise from the presence of impurities which change the molecular orbitals, causing some electronic transitions to take place in the visible spectrum causing colors.

The most important distinction between types of quartz is that of macrocrystalline (individual crystals visible to the unaided eye) and the microcrystalline or cryptocrystalline varieties (aggregates of crystals visible only under high magnification). The cryptocrystalline varieties are either translucent or mostly opaque, while the transparent varieties tend to be macrocrystalline. Chalcedony is a cryptocrystalline form of silica consisting of fine intergrowths of both quartz, and its monoclinic polymorph moganite.[26] Other opaque gemstone varieties of quartz, or mixed rocks including quartz, often including contrasting bands or patterns of color, are agate, carnelian or sard, onyx, heliotrope, and jasper.[16]

Amethyst[edit]

Clear (regular) quartz

Amethyst

Blue quartz

Dumortierite quartz

Citrine quartz (natural)

Citrine quartz (heat-altered amethyst)

Milky quartz

Rose quartz

Smoky quartz

Prasiolite

Amethyst is a form of quartz that ranges from a bright vivid violet to a dark or dull lavender shade. The world’s largest deposits of amethysts can be found in Brazil, Mexico, Uruguay, Russia, France, Namibia, and Morocco. Sometimes amethyst and citrine are found growing in the same crystal. It is then referred to as ametrine. Amethyst derives its color from traces of iron in its structure.[27]

Blue quartz[edit]

Blue quartz contains inclusions of fibrous magnesio-riebeckite or crocidolite.[28]

Dumortierite quartz[edit]

Inclusions of the mineral dumortierite within quartz pieces often result in silky-appearing splotches with a blue hue. Shades of purple or grey sometimes also are present. «Dumortierite quartz» (sometimes called «blue quartz») will sometimes feature contrasting light and dark color zones across the material.[29][30] «Blue quartz» is a minor gemstone.[29][31]

Citrine[edit]

Citrine is a variety of quartz whose color ranges from pale yellow to brown due to a submicroscopic distribution of colloidal ferric hydroxide impurities.[32] Natural citrines are rare; most commercial citrines are heat-treated amethysts or smoky quartzes. However, a heat-treated amethyst will have small lines in the crystal, as opposed to a natural citrine’s cloudy or smoky appearance. It is nearly impossible to differentiate between cut citrine and yellow topaz visually, but they differ in hardness. Brazil is the leading producer of citrine, with much of its production coming from the state of Rio Grande do Sul. The name is derived from the Latin word citrina which means «yellow» and is also the origin of the word «citron». Sometimes citrine and amethyst can be found together in the same crystal, which is then referred to as ametrine.[33] Citrine has been referred to as the «merchant’s stone» or «money stone», due to a superstition that it would bring prosperity.[34]

Citrine was first appreciated as a golden-yellow gemstone in Greece between 300 and 150 BC, during the Hellenistic Age. Yellow quartz was used prior to that to decorate jewelry and tools but it was not highly sought after.[35]

Milky quartz[edit]

Milk quartz or milky quartz is the most common variety of crystalline quartz. The white color is caused by minute fluid inclusions of gas, liquid, or both, trapped during crystal formation,[36] making it of little value for optical and quality gemstone applications.[37]

Rose quartz[edit]

Rose quartz is a type of quartz that exhibits a pale pink to rose red hue. The color is usually considered as due to trace amounts of titanium, iron, or manganese, in the material. Some rose quartz contains microscopic rutile needles that produce asterism in transmitted light. Recent X-ray diffraction studies suggest that the color is due to thin microscopic fibers of possibly dumortierite within the quartz.[38]

Additionally, there is a rare type of pink quartz (also frequently called crystalline rose quartz) with color that is thought to be caused by trace amounts of phosphate or aluminium. The color in crystals is apparently photosensitive and subject to fading. The first crystals were found in a pegmatite found near Rumford, Maine, US and in Minas Gerais, Brazil.[39]

Smoky quartz[edit]

Smoky quartz is a gray, translucent version of quartz. It ranges in clarity from almost complete transparency to a brownish-gray crystal that is almost opaque. Some can also be black. The translucency results from natural irradiation acting on minute traces of aluminum in the crystal structure.[40]

Prasiolite[edit]

Prasiolite, also known as vermarine, is a variety of quartz that is green in color. Since 1950, almost all natural prasiolite has come from a small Brazilian mine, but it is also seen in Lower Silesia in Poland. Naturally occurring prasiolite is also found in the Thunder Bay area of Canada. It is a rare mineral in nature; most green quartz is heat-treated amethyst.[41]

Synthetic and artificial treatments[edit]

A synthetic quartz crystal grown by the hydrothermal method, about 19 cm long and weighing about 127 grams

Not all varieties of quartz are naturally occurring. Some clear quartz crystals can be treated using heat or gamma-irradiation to induce color where it would not otherwise have occurred naturally. Susceptibility to such treatments depends on the location from which the quartz was mined.[42]

Prasiolite, an olive colored material, is produced by heat treatment;[43] natural prasiolite has also been observed in Lower Silesia in Poland.[44] Although citrine occurs naturally, the majority is the result of heat-treating amethyst or smoky quartz.[43] Carnelian has been heat-treated to deepen its color since prehistoric times.[45]

Because natural quartz is often twinned, synthetic quartz is produced for use in industry. Large, flawless, single crystals are synthesized in an autoclave via the hydrothermal process.[46][16][47]

Like other crystals, quartz may be coated with metal vapors to give it an attractive sheen.[48][49]

Occurrence[edit]

Granite rock in the cliff of Gros la Tête on Aride Island, Seychelles. The thin (1–3 cm wide) brighter layers are quartz veins, formed during the late stages of crystallization of granitic magmas. They are sometimes called «hydrothermal veins».

Quartz is a defining constituent of granite and other felsic igneous rocks. It is very common in sedimentary rocks such as sandstone and shale. It is a common constituent of schist, gneiss, quartzite and other metamorphic rocks.[16] Quartz has the lowest potential for weathering in the Goldich dissolution series and consequently it is very common as a residual mineral in stream sediments and residual soils. Generally a high presence of quartz suggests a «mature» rock, since it indicates the rock has been heavily reworked and quartz was the primary mineral that endured heavy weathering.[50]

While the majority of quartz crystallizes from molten magma, quartz also chemically precipitates from hot hydrothermal veins as gangue, sometimes with ore minerals like gold, silver and copper. Large crystals of quartz are found in magmatic pegmatites.[16] Well-formed crystals may reach several meters in length and weigh hundreds of kilograms.[51]

Elemental impurity incorporation strongly influences the ability to process and utilize quartz. Naturally occurring quartz crystals of extremely high purity, necessary for the crucibles and other equipment used for growing silicon wafers in the semiconductor industry, are expensive and rare. These high-purity quartz are defined containing less than 50 ppm of impurity elements.[52] A major mining location for high purity quartz is the Spruce Pine Gem Mine in Spruce Pine, North Carolina, United States.[53] Quartz may also be found in Caldoveiro Peak, in Asturias, Spain.[54]

The largest documented single crystal of quartz was found near Itapore, Goiaz, Brazil; it measured approximately 6.1×1.5×1.5 m and weighed 39,916 kilograms.[55]

Mining[edit]

Quartz is extracted from open pit mines. Miners occasionally use explosives to expose deep pockets of quartz. More frequently, bulldozers and backhoes are used to remove soil and clay and expose quartz veins, which are then worked using hand tools. Care must be taken to avoid sudden temperature changes that may damage the crystals.[56][57]

Almost all the industrial demand for quartz crystal (used primarily in electronics) is met with synthetic quartz produced by the hydrothermal process. However, synthetic crystals are less prized for use as gemstones.[58] The popularity of crystal healing has increased the demand for natural quartz crystals, which are now often mined in developing countries using primitive mining methods, sometimes involving child labor.[59]

[edit]

Tridymite and cristobalite are high-temperature polymorphs of SiO2 that occur in high-silica volcanic rocks. Coesite is a denser polymorph of SiO2 found in some meteorite impact sites and in metamorphic rocks formed at pressures greater than those typical of the Earth’s crust. Stishovite is a yet denser and higher-pressure polymorph of SiO2 found in some meteorite impact sites.[60] Lechatelierite is an amorphous silica glass SiO2 which is formed by lightning strikes in quartz sand.[61]

Safety[edit]

As quartz is a form of silica, it is a possible cause for concern in various workplaces. Cutting, grinding, chipping, sanding, drilling, and polishing natural and manufactured stone products can release hazardous levels of very small, crystalline silica dust particles into the air that workers breathe.[62] Crystalline silica of respirable size is a recognized human carcinogen and may lead to other diseases of the lungs such as silicosis and pulmonary fibrosis.[63][64]

History[edit]

The word «quartz» comes from the German Quarz (help·info),[65] which is of Slavic origin (Czech miners called it křemen). Other sources attribute the word’s origin to the Saxon word Querkluftertz, meaning cross-vein ore.[66]

Quartz is the most common material identified as the mystical substance maban in Australian Aboriginal mythology. It is found regularly in passage tomb cemeteries in Europe in a burial context, such as Newgrange or Carrowmore in Ireland. The Irish word for quartz is grianchloch, which means ‘sunstone’. Quartz was also used in Prehistoric Ireland, as well as many other countries, for stone tools; both vein quartz and rock crystal were knapped as part of the lithic technology of the prehistoric peoples.[67]

While jade has been since earliest times the most prized semi-precious stone for carving in East Asia and Pre-Columbian America, in Europe and the Middle East the different varieties of quartz were the most commonly used for the various types of jewelry and hardstone carving, including engraved gems and cameo gems, rock crystal vases, and extravagant vessels. The tradition continued to produce objects that were very highly valued until the mid-19th century, when it largely fell from fashion except in jewelry. Cameo technique exploits the bands of color in onyx and other varieties.

Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder believed quartz to be water ice, permanently frozen after great lengths of time.[68] (The word «crystal» comes from the Greek word κρύσταλλος, «ice».) He supported this idea by saying that quartz is found near glaciers in the Alps, but not on volcanic mountains, and that large quartz crystals were fashioned into spheres to cool the hands. This idea persisted until at least the 17th century. He also knew of the ability of quartz to split light into a spectrum.[69]

In the 17th century, Nicolas Steno’s study of quartz paved the way for modern crystallography. He discovered that regardless of a quartz crystal’s size or shape, its long prism faces always joined at a perfect 60° angle.[70]

Quartz’s piezoelectric properties were discovered by Jacques and Pierre Curie in 1880.[71][72] The quartz oscillator or resonator was first developed by Walter Guyton Cady in 1921.[73][74] George Washington Pierce designed and patented quartz crystal oscillators in 1923.[75][76][77] Warren Marrison created the first quartz oscillator clock based on the work of Cady and Pierce in 1927.[78]

Efforts to synthesize quartz began in the mid-nineteenth century as scientists attempted to create minerals under laboratory conditions that mimicked the conditions in which the minerals formed in nature: German geologist Karl Emil von Schafhäutl (1803–1890) was the first person to synthesize quartz when in 1845 he created microscopic quartz crystals in a pressure cooker.[79] However, the quality and size of the crystals that were produced by these early efforts were poor.[80]

By the 1930s, the electronics industry had become dependent on quartz crystals. The only source of suitable crystals was Brazil; however, World War II disrupted the supplies from Brazil, so nations attempted to synthesize quartz on a commercial scale. German mineralogist Richard Nacken (1884–1971) achieved some success during the 1930s and 1940s.[81] After the war, many laboratories attempted to grow large quartz crystals. In the United States, the U.S. Army Signal Corps contracted with Bell Laboratories and with the Brush Development Company of Cleveland, Ohio to synthesize crystals following Nacken’s lead.[82][83] (Prior to World War II, Brush Development produced piezoelectric crystals for record players.) By 1948, Brush Development had grown crystals that were 1.5 inches (3.8 cm) in diameter, the largest to date.[84][85] By the 1950s, hydrothermal synthesis techniques were producing synthetic quartz crystals on an industrial scale, and today virtually all the quartz crystal used in the modern electronics industry is synthetic.[47]

-

Synthetic quartz crystals produced in the autoclave shown in Western Electric’s pilot hydrothermal quartz plant in 1959

-

Fatimid ewer in carved rock crystal (clear quartz) with gold lid, c. 1000.

Piezoelectricity[edit]

Quartz crystals have piezoelectric properties; they develop an electric potential upon the application of mechanical stress.[87] An early use of this property of quartz crystals was in phonograph pickups. One of the most common piezoelectric uses of quartz today is as a crystal oscillator. The quartz clock is a familiar device using the mineral. The resonant frequency of a quartz crystal oscillator is changed by mechanically loading it, and this principle is used for very accurate measurements of very small mass changes in the quartz crystal microbalance and in thin-film thickness monitors.[88]

See also[edit]

- Fused quartz

- List of minerals

- Quartz fiber

- Quartz reef mining

- Quartzolite

- Shocked quartz

References[edit]

- ^ «Quartz». A Dictionary of Geology and Earth Sciences. Oxford University Press. 19 September 2013. ISBN 978-0-19-965306-5.

- ^ Warr, L.N. (2021). «IMA–CNMNC approved mineral symbols». Mineralogical Magazine. 85 (3): 291–320. Bibcode:2021MinM…85..291W. doi:10.1180/mgm.2021.43. S2CID 235729616.

- ^ a b c Deer, W. A.; Howie, R.A.; Zussman, J. (1966). An introduction to the rock-forming minerals. New York: Wiley. pp. 340–355. ISBN 0-582-44210-9.

- ^ Antao, S. M.; Hassan, I.; Wang, J.; Lee, P. L.; Toby, B. H. (1 December 2008). «State-Of-The-Art High-Resolution Powder X-Ray Diffraction (HRPXRD) Illustrated with Rietveld Structure Refinement of Quartz, Sodalite, Tremolite, and Meionite». The Canadian Mineralogist. 46 (6): 1501–1509. doi:10.3749/canmin.46.5.1501.

- ^ Kihara, K. (1990). «An X-ray study of the temperature dependence of the quartz structure». European Journal of Mineralogy. 2 (1): 63–77. Bibcode:1990EJMin…2…63K. doi:10.1127/ejm/2/1/0063. hdl:2027.42/146327.

- ^ Quartz Archived 14 December 2005 at the Wayback Machine. Mindat.org. Retrieved 2013-03-07.

- ^ Anthony, John W.; Bideaux, Richard A.; Bladh, Kenneth W.; Nichols, Monte C. (eds.). «Quartz» (PDF). Handbook of Mineralogy. Vol. III (Halides, Hydroxides, Oxides). Chantilly, VA: Mineralogical Society of America. ISBN 0962209724. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 April 2010. Retrieved 21 October 2009.

- ^ Quartz Archived 12 November 2006 at the Wayback Machine. Webmineral.com. Retrieved 2013-03-07.

- ^ Hurlbut, Cornelius S.; Klein, Cornelis (1985). Manual of Mineralogy (20 ed.). ISBN 0-471-80580-7.

- ^ Anderson, Robert S.; Anderson, Suzanne P. (2010). Geomorphology: The Mechanics and Chemistry of Landscapes. Cambridge University Press. p. 187. ISBN 978-1-139-78870-0.

- ^ Digitales Wörterbuch der deutschen Sprache Archived 1 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine (in German)

- ^ «Quartz | Definition of quartz by Lexico». Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 26 November 2017.

- ^ Tomkeieff, S.I. (1942). «On the origin of the name ‘quartz’» (PDF). Mineralogical Magazine. 26 (176): 172–178. Bibcode:1942MinM…26..172T. doi:10.1180/minmag.1942.026.176.04. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- ^ Morgado, Antonio; Lozano, José Antonio; García Sanjuán, Leonardo; Triviño, Miriam Luciañez; Odriozola, Carlos P.; Irisarri, Daniel Lamarca; Flores, Álvaro Fernández (December 2016). «The allure of rock crystal in Copper Age southern Iberia: Technical skill and distinguished objects from Valencina de la Concepción (Seville, Spain)». Quaternary International. 424: 232–249. Bibcode:2016QuInt.424..232M. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2015.08.004.

- ^ Nesse, William D. (2000). Introduction to mineralogy. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 205. ISBN 9780195106916.

- ^ a b c d e f Hurlbut & Klein 1985.

- ^ Nesse 2000, p. 202-204.

- ^ Sinkankas, John (1964). Mineralogy for amateurs. Princeton, N.J.: Van Nostrand. pp. 443–447. ISBN 0442276249.

- ^ Tarr, W. A (1929). «Doubly terminated quartz crystals occurring in gypsum». American Mineralogist. 14 (1): 19–25. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- ^ Crystal Data, Determinative Tables, ACA Monograph No. 5, American Crystallographic Association, 1963

- ^ Nesse 2000, p. 201.

- ^ Knapek, Michal; Húlan, Tomáš; Minárik, Peter; Dobroň, Patrik; Štubňa, Igor; Stráská, Jitka; Chmelík, František (January 2016). «Study of microcracking in illite-based ceramics during firing». Journal of the European Ceramic Society. 36 (1): 221–226. doi:10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2015.09.004.

- ^ Johnson, Scott E.; Song, Won Joon; Cook, Alden C.; Vel, Senthil S.; Gerbi, Christopher C. (January 2021). «The quartz α↔β phase transition: Does it drive damage and reaction in continental crust?». Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 553: 116622. Bibcode:2021E&PSL.55316622J. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2020.116622. S2CID 225116168.

- ^ «Quartz Gemstone and Jewelry Information: Natural Quartz – GemSelect». www.gemselect.com. Archived from the original on 29 August 2017. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ «Quartz: The gemstone Quartz information and pictures». www.minerals.net. Archived from the original on 27 August 2017. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ Heaney, Peter J. (1994). «Structure and Chemistry of the low-pressure silica polymorphs». Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry. 29 (1): 1–40. Archived from the original on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 26 October 2009.

- ^ Lehmann, G.; Moore, W. J. (20 May 1966). «Color Center in Amethyst Quartz». Science. 152 (3725): 1061–1062. Bibcode:1966Sci…152.1061L. doi:10.1126/science.152.3725.1061. PMID 17754816. S2CID 29602180.

- ^ «Blue Quartz». Mindat.org. Archived from the original on 24 February 2017. Retrieved 24 February 2017.

- ^ a b Oldershaw, Cally (2003). Firefly Guide to Gems. Firefly Books. pp. 100. ISBN 9781552978146. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- ^ «The Gemstone Dumortierite». Minerals.net. Archived from the original on 6 May 2017. Retrieved 23 April 2017.

- ^ Friedman, Herschel. «THE GEMSTONE DUMORTIERITE». Minerals.net. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ^ Deer, Howie & Zussman, p. 350.

- ^ Citrine Archived 2 May 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Mindat.org (2013-03-01). Retrieved 2013-03-07.

- ^ Webster, Richard (8 September 2012). «Citrine». The Encyclopedia of Superstitions. p. 59. ISBN 9780738725611.

- ^ «Citrine Meaning». 7 January 2016. Archived from the original on 18 August 2017. Retrieved 18 August 2017.

- ^ Hurrell, Karen; Johnson, Mary L. (2016). Gemstones: A Complete Color Reference for Precious and Semiprecious Stones of the World. Book Sales. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-7858-3498-4.

- ^ Milky quartz at Mineral Galleries Archived 19 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Galleries.com. Retrieved 2013-03-07.

- ^ Rose Quartz Archived 1 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Mindat.org (2013-02-18). Retrieved 2013-03-07.

- ^ Colored Varieties of Quartz Archived 19 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Caltech

- ^ Fridrichová, Jana; Bačík, Peter; Illášová, Ľudmila; Kozáková, Petra; Škoda, Radek; Pulišová, Zuzana; Fiala, Anton (July 2016). «Raman and optical spectroscopic investigation of gem-quality smoky quartz crystals». Vibrational Spectroscopy. 85: 71–78. doi:10.1016/j.vibspec.2016.03.028.

- ^ «Prasiolite». quarzpage.de. 28 October 2009. Archived from the original on 13 July 2011. Retrieved 28 November 2010.

- ^ Liccini, Mark, Treating Quartz to Create Color Archived 23 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine, International Gem Society website. Retrieved 22 December 2014

- ^ a b Henn, U.; Schultz-Güttler, R. (2012). «Review of some current coloured quartz varieties» (PDF). J. Gemmol. 33: 29–43. doi:10.15506/JoG.2012.33.1.29. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- ^ Platonov, Alexej N.; Szuszkiewicz, Adam (1 June 2015). «Green to blue-green quartz from Rakowice Wielkie (Sudetes, south-western Poland) – a re-examination of prasiolite-related color varieties of quartz». Mineralogia. 46 (1–2): 19–28. Bibcode:2015Miner..46…19P. doi:10.1515/mipo-2016-0004.

- ^ Groman-Yaroslavski, Iris; Bar-Yosef Mayer, Daniella E. (June 2015). «Lapidary technology revealed by functional analysis of carnelian beads from the early Neolithic site of Nahal Hemar Cave, southern Levant». Journal of Archaeological Science. 58: 77–88. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2015.03.030.

- ^ Walker, A. C. (August 1953). «Hydrothermal Synthesis of Quartz Crystals». Journal of the American Ceramic Society. 36 (8): 250–256. doi:10.1111/j.1151-2916.1953.tb12877.x.

- ^ a b Buisson, X.; Arnaud, R. (February 1994). «Hydrothermal growth of quartz crystals in industry. Present status and evolution» (PDF). Le Journal de Physique IV. 04 (C2): C2–25–C2-32. doi:10.1051/jp4:1994204. S2CID 9636198.

- ^ Robert Webster, Michael O’Donoghue (January 2006). Gems: Their Sources, Descriptions and Identification. ISBN 9780750658560.

- ^ «How is Aura Rainbow Quartz Made?». Geology In. 2017. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- ^ Boggs, Sam (2006). Principles of sedimentology and stratigraphy (4th ed.). Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Pearson Prentice Hall. p. 130. ISBN 0131547283.

- ^ Jahns, Richard H. (1953). «The genesis of pegmatites: I. Occurrence and origin of giant crystals». American Mineralogist. 38 (7–8): 563–598. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- ^ Götze, Jens; Pan, Yuanming; Müller, Axel (October 2021). «Mineralogy and mineral chemistry of quartz: A review». Mineralogical Magazine. 85 (5): 639–664. Bibcode:2021MinM…85..639G. doi:10.1180/mgm.2021.72. ISSN 0026-461X. S2CID 243849577.

- ^ Nelson, Sue (2 August 2009). «Silicon Valley’s secret recipe». BBC News. Archived from the original on 5 August 2009. Retrieved 16 September 2009.

- ^ «Caldoveiro Mine, Tameza, Asturias, Spain». mindat.org. Archived from the original on 12 February 2018. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- ^ Rickwood, P. C. (1981). «The largest crystals» (PDF). American Mineralogist. 66: 885–907 (903). Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 August 2013. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- ^ McMillen, Allen. «Quartz Mining». Encyclopedia of Arkansas. Central Arkansas Library System. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ^ Eleanor McKenzie (25 April 2017). «How Is Quartz Extracted?». sciencing.com. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

- ^ «Hydrothermal Quartz». Gem Select. GemSelect.com. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ^ McClure, Tess (17 September 2019). «Dark crystals: the brutal reality behind a booming wellness craze». The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 25 September 2019.

- ^ Nesse 2000, pp. 201–202.

- ^ «Lechatelierite». Mindat.org. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- ^ Hazard Alert — Worker Exposure to Silica during Countertop Manufacturing, Finishing and Installation (PDF). DHHS (NIOSH). p. 2. Retrieved 27 November 2019.

- ^ «Silica (crystalline, respirable)». OEHHA. California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment. Retrieved 27 November 2019.

- ^ Arsenic, Metals, Fibres and Dusts. A Review of Human Carcinogens (PDF) (100C ed.). International Agency for Research on Cancer. 2012. pp. 355–397. ISBN 978-92-832-1320-8. Retrieved 27 November 2019.

- ^ German Loan Words in English Archived 21 August 2007 at the Wayback Machine. German.about.com (2012-04-10). Retrieved 2013-03-07.

- ^ Mineral Atlas Archived 4 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine, Queensland University of Technology. Mineralatlas.com. Retrieved 2013-03-07.

- ^ «Driscoll, Killian. 2010. Understanding quartz technology in early prehistoric Ireland». Archived from the original on 25 June 2017. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- ^ Pliny the Elder, The Natural History, Book 37, Chapter 9. Available on-line at: Perseus.Tufts.edu Archived 9 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Tutton, A.E. (1910). «Rock crystal: its structure and uses». RSA Journal. 59: 1091. JSTOR 41339844.

- ^ Nicolaus Steno (Latinized name of Niels Steensen) with John Garrett Winter, trans., The Prodromus of Nicolaus Steno’s Dissertation Concerning a Solid Body Enclosed by Process of Nature Within a Solid (New York, New York: Macmillan Co., 1916). On page 272 Archived 4 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Steno states his law of constancy of interfacial angles: «Figures 5 and 6 belong to the class of those which I could present in countless numbers to prove that in the plane of the axis both the number and the length of the sides are changed in various ways without changing the angles; … «

- ^ Curie, Jacques; Curie, Pierre (1880). «Développement par compression de l’électricité polaire dans les cristaux hémièdres à faces inclinées» [Development, via compression, of electric polarization in hemihedral crystals with inclined faces]. Bulletin de la Société minéralogique de France. 3 (4): 90–93. doi:10.3406/bulmi.1880.1564.. Reprinted in: Curie, Jacques; Curie, Pierre (1880). «Développement, par pression, de l’électricité polaire dans les cristaux hémièdres à faces inclinées». Comptes rendus. 91: 294–295. Archived from the original on 5 December 2012. Retrieved 17 December 2013.

- ^ Curie, Jacques; Curie, Pierre (1880). «Sur l’électricité polaire dans les cristaux hémièdres à faces inclinées» [On electric polarization in hemihedral crystals with inclined faces]. Comptes rendus. 91: 383–386. Archived from the original on 5 December 2012. Retrieved 17 December 2013.

- ^ Cady, W. G. (1921). «The piezoelectric resonator». Physical Review. 17: 531–533. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.17.508.

- ^ «The Quartz Watch – Walter Guyton Cady». The Lemelson Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on 4 January 2009.

- ^ Pierce, G. W. (1923). «Piezoelectric crystal resonators and crystal oscillators applied to the precision calibration of wavemeters». Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. 59 (4): 81–106. doi:10.2307/20026061. hdl:2027/inu.30000089308260. JSTOR 20026061.

- ^ Pierce, George W. «Electrical system,» U.S. Patent 2,133,642, filed: 25 February 1924; issued: 18 October 1938.

- ^ «The Quartz Watch – George Washington Pierce». The Lemelson Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on 4 January 2009.

- ^ «The Quartz Watch – Warren Marrison». The Lemelson Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on 25 January 2009.

- ^ von Schafhäutl, Karl Emil (10 April 1845). «Die neuesten geologischen Hypothesen und ihr Verhältniß zur Naturwissenschaft überhaupt (Fortsetzung)» [The latest geological hypotheses and their relation to science in general (continuation)]. Gelehrte Anzeigen. München: im Verlage der königlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften, in Commission der Franz’schen Buchhandlung. 20 (72): 577–584. OCLC 1478717. From page 578: 5) Bildeten sich aus Wasser, in welchen ich im Papinianischen Topfe frisch gefällte Kieselsäure aufgelöst hatte, beym Verdampfen schon nach 8 Tagen Krystalle, die zwar mikroscopisch, aber sehr wohl erkenntlich aus sechseitigen Prismen mit derselben gewöhnlichen Pyramide bestanden. ( 5) There formed from water in which I had dissolved freshly precipitated silicic acid in a Papin pot [i.e., pressure cooker], after just 8 days of evaporating, crystals, which albeit were microscopic but consisted of very easily recognizable six-sided prisms with their usual pyramids.)

- ^ Byrappa, K. and Yoshimura, Masahiro (2001) Handbook of Hydrothermal Technology. Norwich, New York: Noyes Publications. ISBN 008094681X. Chapter 2: History of Hydrothermal Technology.

- ^ Nacken, R. (1950) «Hydrothermal Synthese als Grundlage für Züchtung von Quarz-Kristallen» (Hydrothermal synthesis as a basis for the production of quartz crystals), Chemiker Zeitung, 74 : 745–749.

- ^ Hale, D. R. (1948). «The Laboratory Growing of Quartz». Science. 107 (2781): 393–394. Bibcode:1948Sci…107..393H. doi:10.1126/science.107.2781.393. PMID 17783928.

- ^ Lombardi, M. (2011). «The evolution of time measurement, Part 2: Quartz clocks [Recalibration]» (PDF). IEEE Instrumentation & Measurement Magazine. 14 (5): 41–48. doi:10.1109/MIM.2011.6041381. S2CID 32582517. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 May 2013. Retrieved 30 March 2013.

- ^ «Record crystal,» Popular Science, 154 (2) : 148 (February 1949).

- ^ Brush Development’s team of scientists included: Danforth R. Hale, Andrew R. Sobek, and Charles Baldwin Sawyer (1895–1964). The company’s U.S. patents included:

- Sobek, Andrew R. «Apparatus for growing single crystals of quartz,» U.S. Patent 2,674,520; filed: 11 April 1950; issued: 6 April 1954.

- Sobek, Andrew R. and Hale, Danforth R. «Method and apparatus for growing single crystals of quartz,» U.S. Patent 2,675,303; filed: 11 April 1950; issued: 13 April 1954.

- Sawyer, Charles B. «Production of artificial crystals,» U.S. Patent 3,013,867; filed: 27 March 1959; issued: 19 December 1961. (This patent was assigned to Sawyer Research Products of Eastlake, Ohio.)

- ^ The International Antiques Yearbook. Studio Vista Limited. 1972. p. 78.

Apart from Prague and Florence, the main Renaissance centre for crystal cutting was Milan.

- ^ Saigusa, Y. (2017). «Chapter 5 — Quartz-Based Piezoelectric Materials». In Uchino, Kenji (ed.). Advanced Piezoelectric Materials. Woodhead Publishing in Materials (2nd ed.). Woodhead Publishing. pp. 197–233. doi:10.1016/B978-0-08-102135-4.00005-9. ISBN 9780081021354.

- ^ Sauerbrey, Günter Hans (April 1959) [1959-02-21]. «Verwendung von Schwingquarzen zur Wägung dünner Schichten und zur Mikrowägung» (PDF). Zeitschrift für Physik (in German). Springer-Verlag. 155 (2): 206–222. Bibcode:1959ZPhy..155..206S. doi:10.1007/BF01337937. ISSN 0044-3328. S2CID 122855173. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 February 2019. Retrieved 26 February 2019. (NB. This was partially presented at Physikertagung in Heidelberg in October 1957.)

External links[edit]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Quartz.

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

- Quartz varieties, properties, crystal morphology. Photos and illustrations

- Gilbert Hart, «Nomenclature of Silica», American Mineralogist, Volume 12, pp. 383–395. 1927

- «The Quartz Watch – Inventors». The Lemelson Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on 7 January 2009.

- Terminology used to describe the characteristics of quartz crystals when used as oscillators

- Quartz use as prehistoric stone tool raw material

| Quartz | |

|---|---|

Quartz crystal cluster from Tibet |

|

| General | |

| Category | silicate mineral[1] |

| Formula (repeating unit) |

SiO2 |

| IMA symbol | Qz[2] |

| Strunz classification | 4.DA.05 (oxides) |

| Dana classification | 75.01.03.01 (tectosilicates) |

| Crystal system | α-quartz: trigonal β-quartz: hexagonal |

| Crystal class | α-quartz: trapezohedral (class 3 2) β-quartz: trapezohedral (class 6 2 2)[3] |

| Space group | α-quartz: P3221 (no. 154)[4] β-quartz: P6222 (no. 180) or P6422 (no. 181)[5] |

| Unit cell | a = 4.9133 Å, c = 5.4053 Å; Z=3 |

| Identification | |

| Formula mass | 60.083 g·mol−1 |

| Color | Colorless through various colors to black |

| Crystal habit | 6-sided prism ending in 6-sided pyramid (typical), drusy, fine-grained to microcrystalline, massive |

| Twinning | Common Dauphine law, Brazil law and Japan law |

| Cleavage | {0110} Indistinct |

| Fracture | Conchoidal |

| Tenacity | Brittle |

| Mohs scale hardness | 7 – lower in impure varieties (defining mineral) |

| Luster | Vitreous – waxy to dull when massive |

| Streak | White |

| Diaphaneity | Transparent to nearly opaque |

| Specific gravity | 2.65; variable 2.59–2.63 in impure varieties |

| Optical properties | Uniaxial (+) |

| Refractive index | nω = 1.543–1.545 nε = 1.552–1.554 |

| Birefringence | +0.009 (B-G interval) |

| Pleochroism | None |

| Melting point | 1670 °C (β tridymite) 1713 °C (β cristobalite)[3] |

| Solubility | Insoluble at STP; 1 ppmmass at 400 °C and 500 lb/in2 to 2600 ppmmass at 500 °C and 1500 lb/in2[3] |

| Other characteristics | lattice: hexagonal, Piezoelectric, may be triboluminescent, chiral (hence optically active if not racemic) |

| References | [6][7][8][9] |

Quartz is a hard, crystalline mineral composed of silica (silicon dioxide). The atoms are linked in a continuous framework of SiO4 silicon-oxygen tetrahedra, with each oxygen being shared between two tetrahedra, giving an overall chemical formula of SiO2. Quartz is the second most abundant mineral in Earth’s continental crust, behind feldspar.[10]

Quartz exists in two forms, the normal α-quartz and the high-temperature β-quartz, both of which are chiral. The transformation from α-quartz to β-quartz takes place abruptly at 573 °C (846 K; 1,063 °F). Since the transformation is accompanied by a significant change in volume, it can easily induce microfracturing of ceramics or rocks passing through this temperature threshold.

There are many different varieties of quartz, several of which are classified as gemstones. Since antiquity, varieties of quartz have been the most commonly used minerals in the making of jewelry and hardstone carvings, especially in Eurasia.

Quartz is the mineral defining the value of 7 on the Mohs scale of hardness, a qualitative scratch method for determining the hardness of a material to abrasion.

Etymology[edit]

The word «quartz» is derived from the German word «Quarz», which had the same form in the first half of the 14th century in Middle High German and in East Central German[11] and which came from the Polish dialect term kwardy, which corresponds to the Czech term tvrdý («hard»).[12]

The Ancient Greeks referred to quartz as κρύσταλλος (krustallos) derived from the Ancient Greek κρύος (kruos) meaning «icy cold», because some philosophers (including Theophrastus) apparently believed the mineral to be a form of supercooled ice.[13] Today, the term rock crystal is sometimes used as an alternative name for transparent coarsely crystalline quartz.[14][15]

Crystal habit and structure[edit]

Quartz belongs to the trigonal crystal system at room temperature, and to the hexagonal crystal system above 573 °C (846 K; 1,063 °F). The ideal crystal shape is a six-sided prism terminating with six-sided pyramids at each end. In nature quartz crystals are often twinned (with twin right-handed and left-handed quartz crystals), distorted, or so intergrown with adjacent crystals of quartz or other minerals as to only show part of this shape, or to lack obvious crystal faces altogether and appear massive.[16][17] Well-formed crystals typically form as a druse (a layer of crystals lining a void), of which quartz geodes are particularly fine examples.[18] The crystals are attached at one end to the enclosing rock, and only one termination pyramid is present. However, doubly terminated crystals do occur where they develop freely without attachment, for instance, within gypsum.[19]

A chiral pair of alpha quartz.

α-quartz crystallizes in the trigonal crystal system, space group P3121 or P3221 (space group 152 or 154 resp.) depending on the chirality. Above 573 °C (846 K; 1,063 °F), α-quartz in P3121 becomes the more symmetric hexagonal P6422 (space group 181), and α-quartz in P3221 goes to space group P6222 (no. 180).[20] These space groups are truly chiral (they each belong to the 11 enantiomorphous pairs). Both α-quartz and β-quartz are examples of chiral crystal structures composed of achiral building blocks (SiO4 tetrahedra in the present case). The transformation between α- and β-quartz only involves a comparatively minor rotation of the tetrahedra with respect to one another, without a change in the way they are linked.[16][21] However, there is a significant change in volume during this transition, and this can result in significant microfracturing in ceramics[22] and in rocks of the Earth’s crust.[23]

-

Crystal structure of α-quartz (red balls are oxygen, grey are silicon)

-

β-quartz

Varieties (according to microstructure)[edit]

Although many of the varietal names historically arose from the color of the mineral, current scientific naming schemes refer primarily to the microstructure of the mineral. Color is a secondary identifier for the cryptocrystalline minerals, although it is a primary identifier for the macrocrystalline varieties.[24]

| Major varieties of quartz | ||

|---|---|---|

| Type | Color & Description | Transparency |

| Herkimer diamond | Colorless | Transparent |

| Rock crystal | Colorless | Transparent |

| Amethyst | Purple to violet colored quartz | Transparent |

| Citrine | Yellow quartz ranging to reddish-orange or brown (Madera quartz), and occasionally greenish yellow | Transparent |

| Ametrine | A mix of amethyst and citrine with hues of purple/violet and yellow or orange/brown | Transparent |

| Rose quartz | Pink, may display diasterism | Transparent |

| Chalcedony | Fibrous, variously translucent, cryptocrystalline quartz occurring in many varieties. The term is often used for white, cloudy, or lightly colored material intergrown with moganite. Otherwise more specific names are used. |

|

| Carnelian | Reddish orange chalcedony | Translucent |

| Aventurine | Quartz with tiny aligned inclusions (usually mica) that shimmer with aventurescence | Translucent to opaque |

| Agate | Multi-colored, curved or concentric banded chalcedony (cf. Onyx) | Semi-translucent to translucent |

| Onyx | Multi-colored, straight banded chalcedony or chert (cf. Agate) | Semi-translucent to opaque |

| Jasper | Opaque cryptocrystalline quartz, typically red to brown but often used for other colors | Opaque |

| Milky quartz | White, may display diasterism | Translucent to opaque |

| Smoky quartz | Light to dark gray, sometimes with a brownish hue | Translucent to opaque |

| Tiger’s eye | Fibrous gold, red-brown or bluish colored chalcedony, exhibiting chatoyancy. | |

| Prasiolite | Green | Transparent |

| Rutilated quartz | Contains acicular (needle-like) inclusions of rutile | |

| Dumortierite quartz | Contains large amounts of blue dumortierite crystals | Translucent |

Varieties (according to color)[edit]

Pure quartz, traditionally called rock crystal or clear quartz, is colorless and transparent or translucent, and has often been used for hardstone carvings, such as the Lothair Crystal. Common colored varieties include citrine, rose quartz, amethyst, smoky quartz, milky quartz, and others.[25] These color differentiations arise from the presence of impurities which change the molecular orbitals, causing some electronic transitions to take place in the visible spectrum causing colors.

The most important distinction between types of quartz is that of macrocrystalline (individual crystals visible to the unaided eye) and the microcrystalline or cryptocrystalline varieties (aggregates of crystals visible only under high magnification). The cryptocrystalline varieties are either translucent or mostly opaque, while the transparent varieties tend to be macrocrystalline. Chalcedony is a cryptocrystalline form of silica consisting of fine intergrowths of both quartz, and its monoclinic polymorph moganite.[26] Other opaque gemstone varieties of quartz, or mixed rocks including quartz, often including contrasting bands or patterns of color, are agate, carnelian or sard, onyx, heliotrope, and jasper.[16]

Amethyst[edit]

Clear (regular) quartz

Amethyst

Blue quartz

Dumortierite quartz

Citrine quartz (natural)

Citrine quartz (heat-altered amethyst)

Milky quartz

Rose quartz

Smoky quartz

Prasiolite

Amethyst is a form of quartz that ranges from a bright vivid violet to a dark or dull lavender shade. The world’s largest deposits of amethysts can be found in Brazil, Mexico, Uruguay, Russia, France, Namibia, and Morocco. Sometimes amethyst and citrine are found growing in the same crystal. It is then referred to as ametrine. Amethyst derives its color from traces of iron in its structure.[27]

Blue quartz[edit]

Blue quartz contains inclusions of fibrous magnesio-riebeckite or crocidolite.[28]

Dumortierite quartz[edit]

Inclusions of the mineral dumortierite within quartz pieces often result in silky-appearing splotches with a blue hue. Shades of purple or grey sometimes also are present. «Dumortierite quartz» (sometimes called «blue quartz») will sometimes feature contrasting light and dark color zones across the material.[29][30] «Blue quartz» is a minor gemstone.[29][31]

Citrine[edit]

Citrine is a variety of quartz whose color ranges from pale yellow to brown due to a submicroscopic distribution of colloidal ferric hydroxide impurities.[32] Natural citrines are rare; most commercial citrines are heat-treated amethysts or smoky quartzes. However, a heat-treated amethyst will have small lines in the crystal, as opposed to a natural citrine’s cloudy or smoky appearance. It is nearly impossible to differentiate between cut citrine and yellow topaz visually, but they differ in hardness. Brazil is the leading producer of citrine, with much of its production coming from the state of Rio Grande do Sul. The name is derived from the Latin word citrina which means «yellow» and is also the origin of the word «citron». Sometimes citrine and amethyst can be found together in the same crystal, which is then referred to as ametrine.[33] Citrine has been referred to as the «merchant’s stone» or «money stone», due to a superstition that it would bring prosperity.[34]

Citrine was first appreciated as a golden-yellow gemstone in Greece between 300 and 150 BC, during the Hellenistic Age. Yellow quartz was used prior to that to decorate jewelry and tools but it was not highly sought after.[35]

Milky quartz[edit]

Milk quartz or milky quartz is the most common variety of crystalline quartz. The white color is caused by minute fluid inclusions of gas, liquid, or both, trapped during crystal formation,[36] making it of little value for optical and quality gemstone applications.[37]

Rose quartz[edit]

Rose quartz is a type of quartz that exhibits a pale pink to rose red hue. The color is usually considered as due to trace amounts of titanium, iron, or manganese, in the material. Some rose quartz contains microscopic rutile needles that produce asterism in transmitted light. Recent X-ray diffraction studies suggest that the color is due to thin microscopic fibers of possibly dumortierite within the quartz.[38]

Additionally, there is a rare type of pink quartz (also frequently called crystalline rose quartz) with color that is thought to be caused by trace amounts of phosphate or aluminium. The color in crystals is apparently photosensitive and subject to fading. The first crystals were found in a pegmatite found near Rumford, Maine, US and in Minas Gerais, Brazil.[39]

Smoky quartz[edit]

Smoky quartz is a gray, translucent version of quartz. It ranges in clarity from almost complete transparency to a brownish-gray crystal that is almost opaque. Some can also be black. The translucency results from natural irradiation acting on minute traces of aluminum in the crystal structure.[40]

Prasiolite[edit]

Prasiolite, also known as vermarine, is a variety of quartz that is green in color. Since 1950, almost all natural prasiolite has come from a small Brazilian mine, but it is also seen in Lower Silesia in Poland. Naturally occurring prasiolite is also found in the Thunder Bay area of Canada. It is a rare mineral in nature; most green quartz is heat-treated amethyst.[41]

Synthetic and artificial treatments[edit]

A synthetic quartz crystal grown by the hydrothermal method, about 19 cm long and weighing about 127 grams

Not all varieties of quartz are naturally occurring. Some clear quartz crystals can be treated using heat or gamma-irradiation to induce color where it would not otherwise have occurred naturally. Susceptibility to such treatments depends on the location from which the quartz was mined.[42]

Prasiolite, an olive colored material, is produced by heat treatment;[43] natural prasiolite has also been observed in Lower Silesia in Poland.[44] Although citrine occurs naturally, the majority is the result of heat-treating amethyst or smoky quartz.[43] Carnelian has been heat-treated to deepen its color since prehistoric times.[45]

Because natural quartz is often twinned, synthetic quartz is produced for use in industry. Large, flawless, single crystals are synthesized in an autoclave via the hydrothermal process.[46][16][47]

Like other crystals, quartz may be coated with metal vapors to give it an attractive sheen.[48][49]

Occurrence[edit]

Granite rock in the cliff of Gros la Tête on Aride Island, Seychelles. The thin (1–3 cm wide) brighter layers are quartz veins, formed during the late stages of crystallization of granitic magmas. They are sometimes called «hydrothermal veins».

Quartz is a defining constituent of granite and other felsic igneous rocks. It is very common in sedimentary rocks such as sandstone and shale. It is a common constituent of schist, gneiss, quartzite and other metamorphic rocks.[16] Quartz has the lowest potential for weathering in the Goldich dissolution series and consequently it is very common as a residual mineral in stream sediments and residual soils. Generally a high presence of quartz suggests a «mature» rock, since it indicates the rock has been heavily reworked and quartz was the primary mineral that endured heavy weathering.[50]

While the majority of quartz crystallizes from molten magma, quartz also chemically precipitates from hot hydrothermal veins as gangue, sometimes with ore minerals like gold, silver and copper. Large crystals of quartz are found in magmatic pegmatites.[16] Well-formed crystals may reach several meters in length and weigh hundreds of kilograms.[51]

Elemental impurity incorporation strongly influences the ability to process and utilize quartz. Naturally occurring quartz crystals of extremely high purity, necessary for the crucibles and other equipment used for growing silicon wafers in the semiconductor industry, are expensive and rare. These high-purity quartz are defined containing less than 50 ppm of impurity elements.[52] A major mining location for high purity quartz is the Spruce Pine Gem Mine in Spruce Pine, North Carolina, United States.[53] Quartz may also be found in Caldoveiro Peak, in Asturias, Spain.[54]

The largest documented single crystal of quartz was found near Itapore, Goiaz, Brazil; it measured approximately 6.1×1.5×1.5 m and weighed 39,916 kilograms.[55]

Mining[edit]

Quartz is extracted from open pit mines. Miners occasionally use explosives to expose deep pockets of quartz. More frequently, bulldozers and backhoes are used to remove soil and clay and expose quartz veins, which are then worked using hand tools. Care must be taken to avoid sudden temperature changes that may damage the crystals.[56][57]

Almost all the industrial demand for quartz crystal (used primarily in electronics) is met with synthetic quartz produced by the hydrothermal process. However, synthetic crystals are less prized for use as gemstones.[58] The popularity of crystal healing has increased the demand for natural quartz crystals, which are now often mined in developing countries using primitive mining methods, sometimes involving child labor.[59]

[edit]

Tridymite and cristobalite are high-temperature polymorphs of SiO2 that occur in high-silica volcanic rocks. Coesite is a denser polymorph of SiO2 found in some meteorite impact sites and in metamorphic rocks formed at pressures greater than those typical of the Earth’s crust. Stishovite is a yet denser and higher-pressure polymorph of SiO2 found in some meteorite impact sites.[60] Lechatelierite is an amorphous silica glass SiO2 which is formed by lightning strikes in quartz sand.[61]

Safety[edit]

As quartz is a form of silica, it is a possible cause for concern in various workplaces. Cutting, grinding, chipping, sanding, drilling, and polishing natural and manufactured stone products can release hazardous levels of very small, crystalline silica dust particles into the air that workers breathe.[62] Crystalline silica of respirable size is a recognized human carcinogen and may lead to other diseases of the lungs such as silicosis and pulmonary fibrosis.[63][64]

History[edit]

The word «quartz» comes from the German Quarz (help·info),[65] which is of Slavic origin (Czech miners called it křemen). Other sources attribute the word’s origin to the Saxon word Querkluftertz, meaning cross-vein ore.[66]

Quartz is the most common material identified as the mystical substance maban in Australian Aboriginal mythology. It is found regularly in passage tomb cemeteries in Europe in a burial context, such as Newgrange or Carrowmore in Ireland. The Irish word for quartz is grianchloch, which means ‘sunstone’. Quartz was also used in Prehistoric Ireland, as well as many other countries, for stone tools; both vein quartz and rock crystal were knapped as part of the lithic technology of the prehistoric peoples.[67]

While jade has been since earliest times the most prized semi-precious stone for carving in East Asia and Pre-Columbian America, in Europe and the Middle East the different varieties of quartz were the most commonly used for the various types of jewelry and hardstone carving, including engraved gems and cameo gems, rock crystal vases, and extravagant vessels. The tradition continued to produce objects that were very highly valued until the mid-19th century, when it largely fell from fashion except in jewelry. Cameo technique exploits the bands of color in onyx and other varieties.

Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder believed quartz to be water ice, permanently frozen after great lengths of time.[68] (The word «crystal» comes from the Greek word κρύσταλλος, «ice».) He supported this idea by saying that quartz is found near glaciers in the Alps, but not on volcanic mountains, and that large quartz crystals were fashioned into spheres to cool the hands. This idea persisted until at least the 17th century. He also knew of the ability of quartz to split light into a spectrum.[69]

In the 17th century, Nicolas Steno’s study of quartz paved the way for modern crystallography. He discovered that regardless of a quartz crystal’s size or shape, its long prism faces always joined at a perfect 60° angle.[70]

Quartz’s piezoelectric properties were discovered by Jacques and Pierre Curie in 1880.[71][72] The quartz oscillator or resonator was first developed by Walter Guyton Cady in 1921.[73][74] George Washington Pierce designed and patented quartz crystal oscillators in 1923.[75][76][77] Warren Marrison created the first quartz oscillator clock based on the work of Cady and Pierce in 1927.[78]

Efforts to synthesize quartz began in the mid-nineteenth century as scientists attempted to create minerals under laboratory conditions that mimicked the conditions in which the minerals formed in nature: German geologist Karl Emil von Schafhäutl (1803–1890) was the first person to synthesize quartz when in 1845 he created microscopic quartz crystals in a pressure cooker.[79] However, the quality and size of the crystals that were produced by these early efforts were poor.[80]