Тип Кольчатые черви (Кольчецы) включает животных, у которых вытянутое тело поделено на кольца, или сегменты.

Кольчатые черви — наиболее прогрессивная группа червей. У этих животных впервые появилась кровеносная система, сегментация тела, а также парные органы движения и вторичная полость тела.

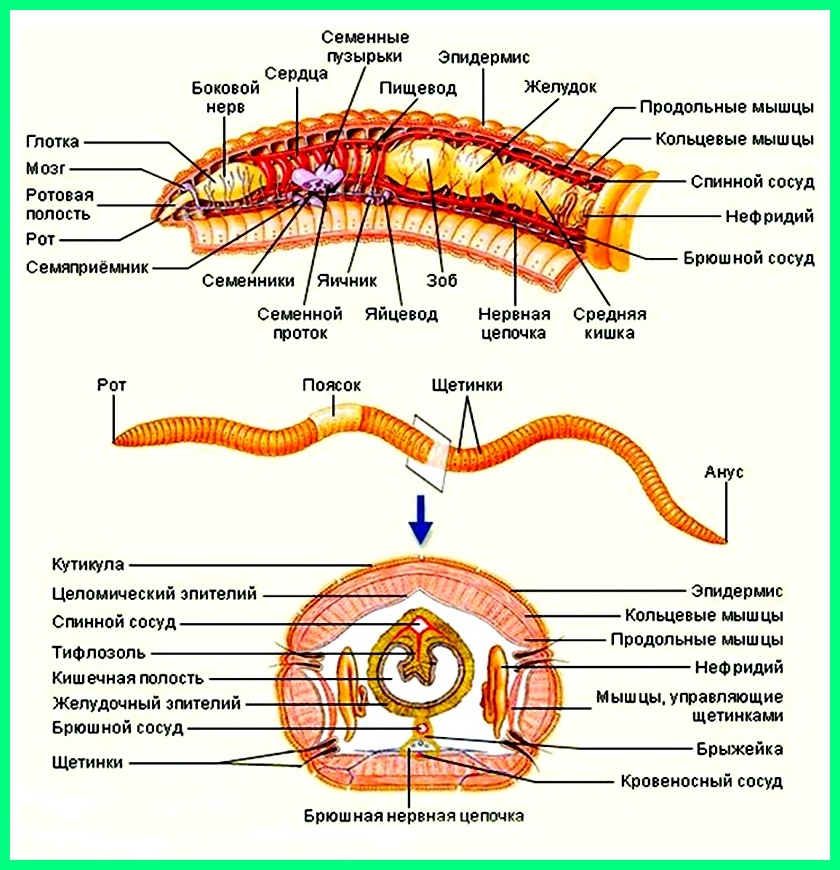

В типе Кольчатые черви выделяют несколько классов. Мы рассмотрим три из них: Многощетинковые, Малощетинковые и Пиявки.

Рис. (1). Классы Кольчатых червей

Особенности строения тела

Тело Кольчатых червей состоит из трёх слоёв клеток: эктодермы, энтодермы и мезодермы (т. е. они трёхслойные животные).

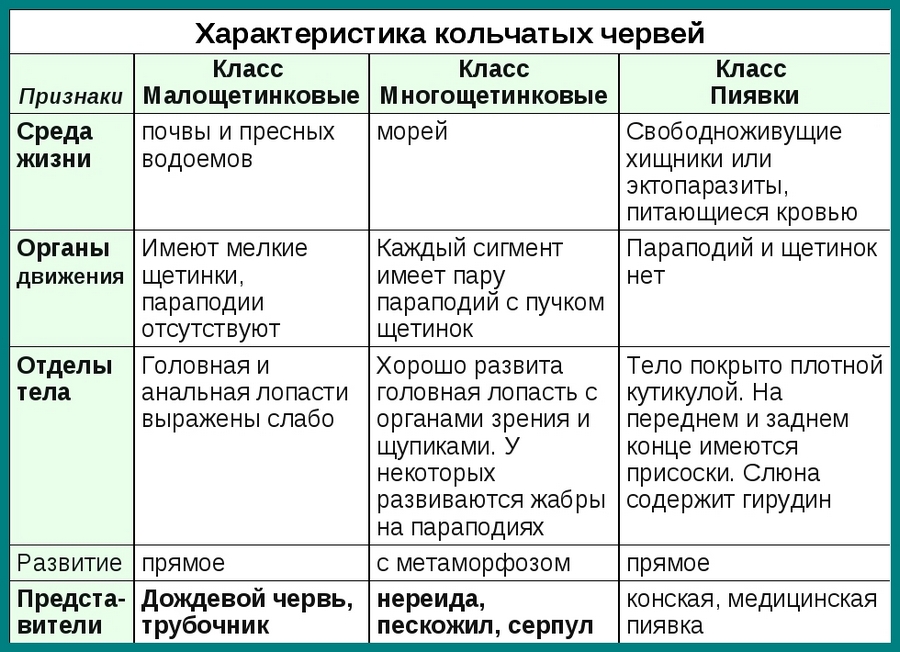

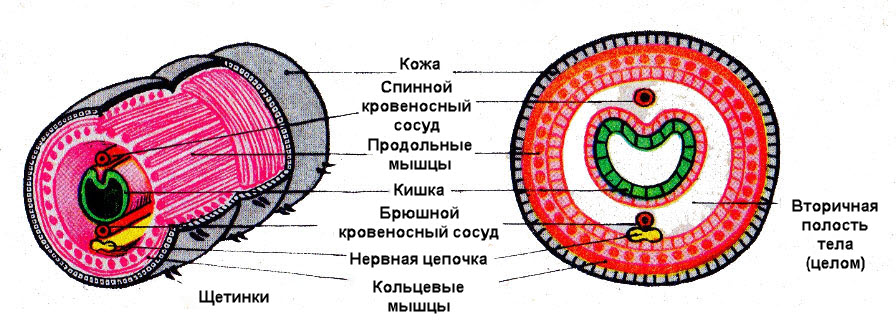

Рис. (2). Поперечный разрез тела

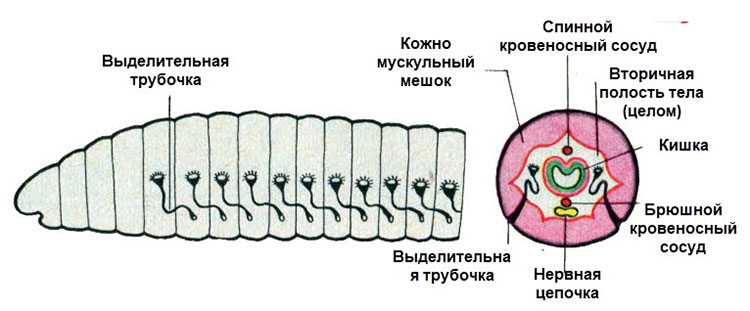

Вторичная полость тела (целом) развивается из клеток мезодермы. Вторичная полость выстлана эпителием и заполнена полостной жидкостью, обеспечивающей постоянство внутренней среды организма. Жидкость служит гидроскелетом (т. е. является опорой тела и поддерживает его форму), а также участвует в транспорте питательных веществ и газов, в выведении вредных продуктов обмена.

Кольчатые черви — в основном свободноживущие животные, они имеют двустороннюю симметрию.

Всё тело кольчецов делится на кольца (сегменты). Их число у разных видов отличается — может быть несколько сегментов, а может быть несколько сотен. Сегменты имеют сходное строение: в каждом есть нервные узлы, пара органов выделения и половые железы, а снаружи располагаются выросты. Немного отличаются сегменты передней и задней частей тела, поэтому у червей выделяют головной отдел, туловище и хвостовой отдел.

Рис. (3). Первые сегменты тела

Передвигаются черви за счёт сокращения кольцевых и продольных мышц. У некоторых есть параподии — особые парные выросты, которые располагаются на каждом сегменте.

Внутреннее строение

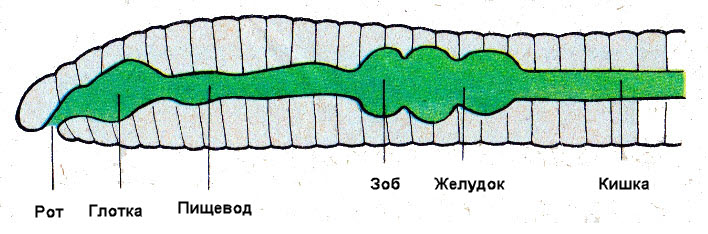

У кольчецов сквозная пищеварительная система. Она состоит из дифференцированной на отделы передней кишки (в которой выделяются рот, глотка, пищевод и желудок, а у некоторых видов — зоб), средней кишки и задней кишки, заканчивающейся анальным отверстием.

Рис. (4). Пищеварительная система

У морских многощетинковых кольчатых червей впервые появляются органы дыхания — жабры. У других представителей типа газообмен происходит через влажную поверхность тела.

У кольчатых червей более сложное по сравнению с круглыми червями строение нервной системы и органов чувств.

Нервные узлы у кольчецов объединены в окологлоточное кольцо и брюшную нервную цепочку. От узлов в каждом сегменте ответвляются нервы.

Рис. (5). Нервная система

У кольчатых червей есть органы чувств: светочувствительные клетки или глаза, щупальца и щетинки, органы химического чувства и равновесия.

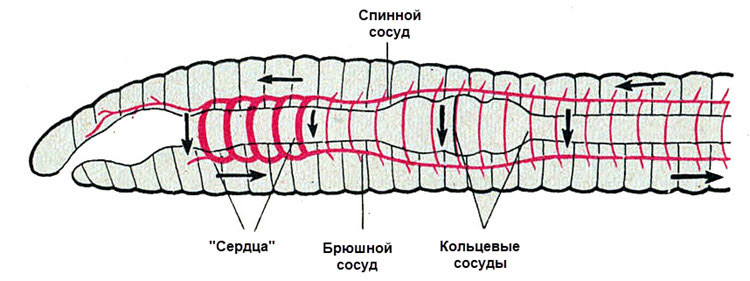

У кольчецов есть кровь и замкнутая кровеносная система.

Рис. (6). Кровеносная система

Выделительная система находится в каждом сегменте тела. Она образована метанефридиями, состоящими из воронок с ресничками, выделительных канальцев, и выделительных пор.

Рис. (7). Метанефридии

Размножение

Животные могут размножаться половым и бесполым способами. Среди Кольчатых червей встречаются раздельнополые виды и гермафродиты. Половое размножение даже у гермафродитов происходит с участием двух особей. При бесполом размножении тело червя делится на несколько частей и происходит регенерация, т. е. достраивание недостающих отделов.

От примитивных животных, похожих на плоских ресничных червей, произошли многощетинковые кольчатые черви. У них сформировалась вторичная полость тела, появилась кровеносная система, а тело дифференцировалось (разделилось) на сегменты. От многощетинковых произошли более прогрессивные малощетинковые черви.

Источники:

Рис. 1. Классы Кольчатых червей. https://image.shutterstock.com/image-vector/illustration-shows-three-types-segmented-600w-1732064596.

Рис. 2. Поперечный разрез тела. © ЯКласс.

Рис. 3. Первые сегменты тела. https://image.shutterstock.com/image-illustration/zoology-animal-morphology-internal-anatomy-600w-1981622696.

Рис. 4. Пищеварительная система. https://image.shutterstock.com/z/stock-vector-vector-schematic-illustration-of-very-basic-earthworm-anatomy-infographic-2041917095.

Рис. 5. Нервная система. https://image.shutterstock.com/z/stock-vector-vector-schematic-illustration-of-very-basic-earthworm-anatomy-infographic-2041917095.

Рис. 6. Кровеносная система. https://image.shutterstock.com/z/stock-vector-vector-schematic-illustration-of-very-basic-earthworm-anatomy-infographic-2041917095.

Рис. 7. Метанефридии. © ЯКласс.

- Энциклопедия

- Насекомые

- Кольчатые черви

Кольчатые черви являются организмами, у которых нет позвоночника. Обычно они находятся в пресных и соленых водоемах, а также в почве. Размеры червей могут быть от нескольких миллиметров до шести метров. У каждого червя на теле имеется несколько колец. Если он вдруг порвется и потеряет несколько колец, то спустя некоторое время они сами восстановятся.

Снаружи все тело червя покрыто специальной кутикулой, которая не смывается и находится постоянно на теле. А под кожей находятся мышцы. Одни мышцы продольные, а другие кольцевые. Кроме этого у некоторых из них имеются небольшие выросты по бокам. И на этих выростах имеются жабры и щетинки. Вот при помощи данных щетинок они и передвигаются по земле.

Внутри червя имеется жидкость, которая захватывает весь организм. И при помощи этой воды они дышат, а еще им дышать помогают жабры. У многих червей кровь только движется по сосудам. Сердца у червей вообще нет, из-за этого мышцы сокращаются.

В земле или в любой другой почве можно встретить около пятисот различных видов червей.

Размножаются черви бесполым, а также и половым путем. Если размножение происходит в бесполом виде, то червь при этом распадается на несколько частей. А спустя некоторое время они соединяются. Если размножение происходит половое, то здесь уже участие принимают обе самки. Они обмениваются половыми клетками.

Кроме этого можно встретить и многощетинковых червей. Обычно они обитают в морской или пресной воде. И при этом вода может быть как теплой, так и холодной. На сегодняшний день вычисляется около десяти тысяч различных видов многощетинковых червей.

Вариант №2

Кольчатые черви, прародителями которых были плоские черви, имеют другое, менее распространенное, название кольчецы — известны как самый прогрессивный вид червей. Объясняется это тем, что у них впервые были обнаружены кровеносная система, до этого у других червей она отсутствовала, а органы движения парные, представляют собой кожные отростки с щетинками — параподии.

Свое название кольчатые черви получили благодаря туловищу, состоящему из сегментов в виде множества колец. Они, как бы, нанизаны друг на друга, а внутри проходит кишечник, оплетенный стволами кровеносной и нервной системы. Для кольчатых червей характерен ускоренный рост, благодаря вновь образующимся кольцам у анальной лопасти. В зависимости от вида длина их туловища может достигать от пары миллиметров до, более чем, шести метров.

Кольчатые черви — трехслойные животные, так как на эмбриональном этапе закладываться развитие трёх слоев:

- эктодерма

- мезодерма

- энтодерма

Традиционная классификация частично утратила свою объективность благодаря новым открытиям и исследования. В настоящее время опираются на результаты новой классификации, согласно которой выделяют два основных класса:

- Многощетинковые

- Поясковые

Вторые, в свою очередь, подразделяются на подклассы:

- Малощетинковые

- Пиявки и другие.

Эволюционируя, тело червей подверглось существенным изменениям, впервые появилась вторичная полость, целом, заполненная жидкостью, главная функция которой транспортировка питательных веществ, и, как следствие, освобождение от продуктов жизнедеятельности, отсюда и название — вторичнополостные. Жидкость, оказывая давление на эпителий, определяет форму тела, то есть служит, своего рода, каркасом или гидроскелетом. Сокращаясь, мышечный скелет позволяет червю активно перемещаться.

Особенности систем жизнеобеспечения:

- Замкнутый тип кровеносной системы. Функцию крови выполняет жидкость, которой заполнен целом.

- Пищеварительная система. Из ротовой полости, мышечными сокращениями пища попадает через глотку в кишечник, затем переваривание пищи продолжается в средней кишке, далее задняя кишка и анальное отверстие имея дыхательной системы, транспортировку кислорода берет на себя кровеносная система.

- Нервная система — это подобие головного мозга и нервные узлы.

- Выделительная система. За выведение продуктов жизнедеятельности отвечают метанефридии , это микро воронки усыпанные ресничками, движением которых вытесняются продукты обмена.

Кольчатые черви важный элемент биологической цепочки. Доказано их благотворное влияние на почвообразование и, как результат, более высокая урожайность.

7 класс по биологии

Кольчатые черви

Популярные темы сообщений

- Монитор

Монитор – это устройство вывода компьютера, которое отображает графическую информацию и текст. Монитор состоит из экрана, блока питания, электронной схемы, кнопок для настройки параметров экрана и корпуса,

- Комнатная роза

Самым прекрасным и любимым цветком человека по праву можно назвать розу. И правда нет более восхитительного и элегантного растения на нашей планете. Цветок принадлежащий к роду шиповников семейству розовых,

- Докучаев Василий Васильевич

Докучаев Василий Васильевич — великий русский ученый, географ. Жил и занимался изучением почв на нашей Земле. Он создал такую науку, как почвоведение. Докучаев родился в многодетной семье священника. У него было четыре сестры и два брата.

- Дерево (Лиственное)

Деревья — это самые большие растения на земле. У всех деревьев, как и у растений есть корни, ствол и листья. Лиственные деревья так и называются, потому что покрыты листьями.

- Творчество Саша Чёрный

Саша Чёрный – самый известный из псевдонимов Александра Михайловича Гликберга. Творчество Чёрного началось с рассказа «Дневник резонера», появившегося на страницах житомирской газеты

Содержание

- Описание

- Размножение

- Питание

- Классификация

Кольчатые черви (Annelida) – тип беспозвоночных, который насчитывает около 12000 известных науке видов многощетинковых и малощетинковых червей, пиявок и мизостомид. Кольчатые черви обитают в морской среде, как правило, приливно-отливной зоне и вблизи гидротермальных жерл, пресноводных водоемах, а также на суше.

Описание

Кольчатые черви имеют билатеральную симметрию. Их тело состоит из области головы, области хвоста и средней области многочисленных повторных сегментов.

Сегменты отделяются друг от друга перегородками. Каждый сегмент содержит полный набор органов и имеет пару хитиновых щетинок, а морские виды параподии (мускулистые придатки, используемые для передвижения). Рот расположен на первом сегменте в области головы, кишечник проходит через все тело до ануса, расположенного в хвостом сегменте. У многих видов кровь циркулирует по кровеносным сосудам. Тело кольчатых червей наполнено жидкостью, которая создает гидростатическое давление и придает животным форму. Большинство кольчатых червей обитают в почвах или илистых отложениях на дне пресноводных или морских водоемов.

Наружный слой тела кольчатых червей состоит из двух слоев мышц, один слой имеет волокна, работающие в продольном направлении, а второй слой, из мышечных волокон, работающих по круговой схеме. Кольчатые черви передвигаются путем координации своих мышц по всей длине своего тела.

Два слоя мышц (продольные и кольцевые) способны работать таким образом, что части тела кольчатых червей могут быть попеременно длинными и тонкими или короткими и толстыми. Это позволяет кольчатым червям создавать волну движения вдоль всего тела, что позволяет им перемещаться по рыхлой земле (в случае дождевого червя). Они вытягиваются, чтобы проникать через почву и строить новые подземные ходы и пути.

Размножение

Многие виды кольчатых червей используют бесполую форму размножения, но есть виды размножающие половым путем. Большинство видов развиваются из личинок.

Питание

Питаются кольчатые черви разлагающимися растительными материалами. Исключением являются пиявки, группа кольчатых червей, паразитирующих на других животных. Пиявки имеют две присоски, по одной на обоих концах тела при помощи которых они присасываются к хозяину и питаются его кровью. Они производят антикоагулянты, чтобы предотвратить свертывание во время питания. Многие пиявки также глотают мелкую беспозвоночную добычу целиком.

Классификация

Кольчатые черви делятся на следующие таксономические группы:

- Многощетинковые черви (Polychaeta);

- Поясковые черви (Clitellata);

- Мизостомиды (Myzostomida).

Погонофоры (Pogonophora) и эхиуры или эхиуриды (Echiura или Echiurida) считаются близкими родственниками кольчатых червей. Кольчатые черви наряду с погонофорами и эхиуридами относятся к группе трохозойные (Trochozoa).

Гугломаг

Спрашивай! Не стесняйся!

Задать вопрос

Не все нашли? Используйте поиск по сайту

Тип КОЛЬЧАТЫЕ ЧЕРВИ

Кольчатые черви (другие названия: кольчецы, аннелиды) — тип беспозвоночных из группы первичноротых. Тип насчитывает около 18 тысяч видов. Одни из наиболее известных представителей данного типа — дождевые черви.

Среда обитания: водная, почвенная (моря, пресные водоёмы, почва). Образ жизни: в основном свободноживущие, реже — паразиты. Развитие происходит из трёх зародышевых листков. Первичноротые животные — первичный рот зародыша (бластопор) преобразуется в ротовое отверстие взрослого организма.

Систематика. Тип Кольчатые черви включает классы: Малощетинковые, Многощетинковые и Пиявки.

Общая характеристика типа Кольчатые черви

Строение. Двусторонняя симметрия тела. Размеры тела от 0,5 мм до 3 м. Тело подразделяется на головную лопасть, туловище и анальную лопасть. У многощетинковых обособлена голова с глазами, щупальцами и усиками. Тело сегментировано (внешняя и внутренняя сегментация). Туловище содержит от 5 до 800 одинаковых сегментов, имеющих форму колец. Сегменты имеют одинаковое внешнее и внутреннее строение (метамерия) и выполняют сходные функции. Метамерное строение тела определяет высокую способность к регенерации.

Стенка тела образована кожно-мускульным мешком, состоящим из однослойного эпителия, покрытого тонкой кутикулой, двух слоёв гладких мышц: наружного кольцевого и внутреннего продольного, и однослойного эпителия вторичной полости тела. При сокращении кольцевых мышц тело червя становится длинным и тонким, при сокращении продольных мышц оно укорачивается и утолщается.

Органы движения — параподии (имеются у многощетинковых). Это выросты кожно-мускульного мешка на каждом сегменте с пучками щетинок. У малощетинковых сохраняются только пучки щетинок.

Полость тела вторичная — целом (имеет эпителиальную выстилку, покрывающую кожно-мускульный мешок изнутри и органы пищеварительной системы снаружи). У большинства представителей полость тела разделена поперечными перегородками, соответственно сегментам тела. Полостная жидкость является гидроскелетом и внутренней средой, она участвует в транспорте продуктов обмена, питательных веществ и половых продуктов.

Пищеварительная система состоит из трёх отделов: переднего (рот, мускулистая глотка, пищевод, зоб), среднего (трубчатый желудок и средняя кишка) и заднего (задняя кишка и анальное отверстие). Железы пищевода и средней кишки выделяют ферменты для переваривания пищи. Всасывание питательных веществ происходит в средней кишке.

Кровеносная система замкнутая. Имеется два главных сосуда: спинной и брюшной, соединённые в каждом сегменте кольцевидными сосудами. По спинному сосуду кровь движется от заднего конца тела к переднему, по брюшному — спереди назад. Движение крови осуществляется благодаря ритмичным сокращениям стенок спинного сосуда и кольцевых сосудов («сердца») в области глотки, имеющих толстые мышечные стенки. Кровь у многих красная.

Дыхание. У большинства кольчатых червей дыхание кожное. У многощетинковых имеются органы дыхания — перистые или листовидные жабры. Это видоизменённые спинные усики параподий или головной лопасти.

Выделительная система метанефридиального типа. Метанефридии имеют вид трубочек с воронками. По две в каждом сегменте. Воронка, окруженная ресничками, и извитые трубочки находятся в одном сегменте, а короткий каналец, открывающийся наружу отверстием — выделительной порой, в соседнем сегменте.

Нервная система представлена надглоточным и подглоточным узлами (ганглиями), окологлоточным нервным кольцом (соединяет надглоточный и подглоточный ганглии) и брюшной нервной цепочкой, состоящей из парных нервных узлов в каждом сегменте, соединённых продольными и поперечными нервными стволами.

Органы чувств. У многощетинковых есть органы равновесия и зрения (2 или 4 глаза). Но у большинства имеются только отдельные обонятельные, осязательные, вкусовые и светочувствительные клетки.

Размножение и развитие. Почвенные и пресноводные формы в основном гермафродиты. Половые железы развиваются только в определённых сегментах. Осеменение внутреннее. Тип развития — прямой. Кроме полового размножения характерно и бесполое (почкование и фрагментация). Фрагментация осуществляется благодаря регенерации — восстановлению утраченных тканей и частей тела. Морские представители типа раздельнополые. Половые железы у них развиваются во всех или в определённых сегментах тела. Развитие с метаморфозом, личинка — трохофора.

Происхождение и ароморфозы. К возникновению типа привели следующие ароморфозы: органы движения, органы дыхания, замкнутая кровеносная система, вторичная полость тела, сегментация тела.

Значение. Дождевые черви улучшают структуру и повышают плодородие почвы. Океанический червь палоло употребляется в пищу человеком. Медицинские пиявки используются для кровопускания.

Класс Малощетинковые (Олигохеты)

Представители: дождевые черви, трубочники и др. Большинство малощетинковых обитают в почве и пресных водах. Детритофаги (питаются полуразложившимися остатками растений и животных). Параподии отсутствуют. Щетинки отходят непосредственно от стенки тела. Головная лопасть выражена слабо. Органы чувств часто отсутствуют, но имеются обонятельные, осязательные, вкусовые, светочувствительные клетки. Гермафродиты. Осеменение внутреннее, перекрестное. Развитие прямое, проходит в коконе, который после оплодотворения образуется на теле червя в виде пояска, а затем сползает с него.

Огромна роль дождевых червей в почвообразовании. Они способствуют накоплению гумуса и улучшают структуру почвы, тем самым повышая плодородие почвы.

Класс Многощетинковые (Полихеты)

Представители: нереиды, пескожилы, палоло и др. Обитают главным образом в морях, преимущественно донные формы, ползают или зарываются в грунт. Некоторым свойственно свечение. Среди многощетинковых встречаются свободноживущие и паразитические формы. Многие хищники. Длина тела от 2 мм до 3 м. На каждом сегменте расположена пара параподий с многочисленными щетинками. Хорошо развита головная лопасть, на которой расположены органы зрения. У многих на параподиях расположены жабры. Кровь часто окрашена в красный цвет. Большинство многощетинковых раздельнополы. Осеменение наружное. Развитие с метаморфозом (личинка трохофора).

Класс Пиявки

Пиявки — свободноживущие хищники или эктопаразиты, питающиеся кровью. Параподии и щетинки отсутствуют. Тело снаружи покрыто плотной кутикулой. Наружная кольчатость не соответствует внутренней сегментации. На переднем и заднем концах тела имеются присоски. Головная и анальная лопасти не выражены. Полость тела редуцирована. В ротовой полости есть хитиновые зубцы, разрезающие кожу жертвы при питании пиявки. Слюна содержит гирудин — вещество, препятствующее свертыванию крови. Средняя кишка образует карманы, которые при питании заполняются кровью. Метанефридии находятся лишь в нескольких сегментах. Гермафродиты. Осеменение внутреннее. Развитие прямое.

Это конспект по биологии для 6-9 классов по теме «Кольчатые черви». Выберите дальнейшие действия:

- Перейти к следующему конспекту: Тип Моллюски

- Вернуться к списку конспектов по Биологии.

- Проверить знания по Биологии.

| Annelida

Temporal range: Early Cambrian– Recent PreꞒ Ꞓ O S D C P T J K Pg N |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Glycera sp. | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Clade: | Bilateria |

| Clade: | Nephrozoa |

| (unranked): | Protostomia |

| (unranked): | Spiralia |

| Superphylum: | Lophotrochozoa |

| Phylum: | Annelida Lamarck, 1809 |

| Classes and subclasses | |

|

Cladistic view

Traditional view

|

The annelids (Annelida , from Latin anellus, «little ring»[1][a]), also known as the segmented worms, are a large phylum, with over 22,000 extant species including ragworms, earthworms, and leeches. The species exist in and have adapted to various ecologies – some in marine environments as distinct as tidal zones and hydrothermal vents, others in fresh water, and yet others in moist terrestrial environments.

The Annelids are bilaterally symmetrical, triploblastic, coelomate, invertebrate organisms. They also have parapodia for locomotion. Most textbooks still use the traditional division into polychaetes (almost all marine), oligochaetes (which include earthworms) and leech-like species. Cladistic research since 1997 has radically changed this scheme, viewing leeches as a sub-group of oligochaetes and oligochaetes as a sub-group of polychaetes. In addition, the Pogonophora, Echiura and Sipuncula, previously regarded as separate phyla, are now regarded as sub-groups of polychaetes. Annelids are considered members of the Lophotrochozoa, a «super-phylum» of protostomes that also includes molluscs, brachiopods, and nemerteans.

The basic annelid form consists of multiple segments. Each segment has the same sets of organs and, in most polychates, has a pair of parapodia that many species use for locomotion. Septa separate the segments of many species, but are poorly defined or absent in others, and Echiura and Sipuncula show no obvious signs of segmentation. In species with well-developed septa, the blood circulates entirely within blood vessels, and the vessels in segments near the front ends of these species are often built up with muscles that act as hearts. The septa of such species also enable them to change the shapes of individual segments, which facilitates movement by peristalsis («ripples» that pass along the body) or by undulations that improve the effectiveness of the parapodia. In species with incomplete septa or none, the blood circulates through the main body cavity without any kind of pump, and there is a wide range of locomotory techniques – some burrowing species turn their pharynges inside out to drag themselves through the sediment.

Earthworms are oligochaetes that support terrestrial food chains both as prey and in some regions are important in aeration and enriching of soil. The burrowing of marine polychaetes, which may constitute up to a third of all species in near-shore environments, encourages the development of ecosystems by enabling water and oxygen to penetrate the sea floor. In addition to improving soil fertility, annelids serve humans as food and as bait. Scientists observe annelids to monitor the quality of marine and fresh water. Although blood-letting is used less frequently by doctors than it once was, some leech species are regarded as endangered species because they have been over-harvested for this purpose in the last few centuries. Ragworms’ jaws are now being studied by engineers as they offer an exceptional combination of lightness and strength.

Since annelids are soft-bodied, their fossils are rare – mostly jaws and the mineralized tubes that some of the species secreted. Although some late Ediacaran fossils may represent annelids, the oldest known fossil that is identified with confidence comes from about 518 million years ago in the early Cambrian period. Fossils of most modern mobile polychaete groups appeared by the end of the Carboniferous, about 299 million years ago. Palaeontologists disagree about whether some body fossils from the mid Ordovician, about 472 to 461 million years ago, are the remains of oligochaetes, and the earliest indisputable fossils of the group appear in the Paleogene period, which began 66 million years ago.[3]

Classification and diversity[edit]

There are over 22,000 living annelid species,[4][5] ranging in size from microscopic to the Australian giant Gippsland earthworm and Amynthas mekongianus, which can both grow up to 3 meters (9.8 ft) long [5][6][7] to the largest annelid, Microchaetus rappi which can grow up to 6.7 m (22 ft). Although research since 1997 has radically changed scientists’ views about the evolutionary family tree of the annelids,[8][9] most textbooks use the traditional classification into the following sub-groups:[6][10]

- Polychaetes (about 12,000 species[4]). As their name suggests, they have multiple chetae («hairs») per segment. Polychaetes have parapodia that function as limbs, and nuchal organs that are thought to be chemosensors.[6] Most are marine animals, although a few species live in fresh water and even fewer on land.[11]

- Clitellates (about 10,000 species [5]). These have few or no chetae per segment, and no nuchal organs or parapodia. However, they have a unique reproductive organ, the ring-shaped clitellum («pack saddle») around their bodies, which produces a cocoon that stores and nourishes fertilized eggs until they hatch [10][12] or, in moniligastrids, yolky eggs that provide nutrition for the embryos.[5] The clitellates are sub-divided into:[6]

- Oligochaetes («with few hairs»), which includes earthworms. Oligochaetes have a sticky pad in the roof of the mouth.[6] Most are burrowers that feed on wholly or partly decomposed organic materials.[11]

- Hirudinea, whose name means «leech-shaped» and whose best known members are leeches.[6] Marine species are mostly blood-sucking parasites, mainly on fish, while most freshwater species are predators.[11] They have suckers at both ends of their bodies, and use these to move rather like inchworms.[13]

The Archiannelida, minute annelids that live in the spaces between grains of marine sediment, were treated as a separate class because of their simple body structure, but are now regarded as polychaetes.[10] Some other groups of animals have been classified in various ways, but are now widely regarded as annelids:

- Pogonophora / Siboglinidae were first discovered in 1914, and their lack of a recognizable gut made it difficult to classify them. They have been classified as a separate phylum, Pogonophora, or as two phyla, Pogonophora and Vestimentifera. More recently they have been re-classified as a family, Siboglinidae, within the polychaetes.[11][14]

- The Echiura have a checkered taxonomic history: in the 19th century they were assigned to the phylum «Gephyrea», which is now empty as its members have been assigned to other phyla; the Echiura were next regarded as annelids until the 1940s, when they were classified as a phylum in their own right; but a molecular phylogenetics analysis in 1997 concluded that echiurans are annelids.[4][14][15]

- Myzostomida live on crinoids and other echinoderms, mainly as parasites. In the past they have been regarded as close relatives of the trematode flatworms or of the tardigrades, but in 1998 it was suggested that they are a sub-group of polychaetes.[11] However, another analysis in 2002 suggested that myzostomids are more closely related to flatworms or to rotifers and acanthocephales.[14]

- Sipuncula was originally classified as annelids, despite the complete lack of segmentation, bristles and other annelid characters. The phylum Sipuncula was later allied with the Mollusca, mostly on the basis of developmental and larval characters. Phylogenetic analyses based on 79 ribosomal proteins indicated a position of Sipuncula within Annelida.[16] Subsequent analysis of the mitochondrion’s DNA has confirmed their close relationship to the Myzostomida and Annelida (including echiurans and pogonophorans).[17] It has also been shown that a rudimentary neural segmentation similar to that of annelids occurs in the early larval stage, even if these traits are absent in the adults.[18]

Distinguishing features[edit]

No single feature distinguishes Annelids from other invertebrate phyla, but they have a distinctive combination of features. Their bodies are long, with segments that are divided externally by shallow ring-like constrictions called annuli and internally by septa («partitions») at the same points, although in some species the septa are incomplete and in a few cases missing. Most of the segments contain the same sets of organs, although sharing a common gut, circulatory system and nervous system makes them inter-dependent.[6][10] Their bodies are covered by a cuticle (outer covering) that does not contain cells but is secreted by cells in the skin underneath, is made of tough but flexible collagen[6] and does not molt[19] – on the other hand arthropods’ cuticles are made of the more rigid α-chitin,[6][20] and molt until the arthropods reach their full size.[21] Most annelids have closed circulatory systems, where the blood makes its entire circuit via blood vessels.[19]

| Annelida[6] | Recently merged into Annelida[8] | Closely related | Similar-looking phyla | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Echiura[22] | Sipuncula[23] | Nemertea[24] | Arthropoda[25] | Onychophora[26] | |

| External segmentation | Yes | No | Only in a few species | Yes, except in mites | No |

| Repetition of internal organs | Yes | No | Yes | In primitive forms | Yes |

| Septa between segments | In most species | No | |||

| Cuticle material | Collagen | None | α-chitin | ||

| Molting | Generally no;[19] but some polychaetes molt their jaws, and leeches molt their skins[27] | No[28] | Yes[21] | ||

| Body cavity | Coelom; but this is reduced or missing in many leeches and some small polychaetes[19] | Two coelomata, main and in proboscis | Two coelomata, main and in tentacles | Coelom only in proboscis | Hemocoel |

| Circulatory system | Closed in most species | Open outflow, return via branched vein | Open | Closed | Open |

Description[edit]

Segmentation[edit]

Prostomium

Peristomium

O Mouth

Growth zone

Pygidium

O Anus

Diagram of segments of an annelid[6][10]

Most of an annelid’s body consists of segments that are practically identical, having the same sets of internal organs and external chaetae (Greek χαιτη, meaning «hair») and, in some species, appendages. The frontmost and rearmost sections are not regarded as true segments as they do not contain the standard sets of organs and do not develop in the same way as the true segments. The frontmost section, called the prostomium (Greek προ- meaning «in front of» and στομα meaning «mouth») contains the brain and sense organs, while the rearmost, called the pygidium (Greek πυγιδιον, meaning «little tail») or periproct contains the anus, generally on the underside. The first section behind the prostomium, called the peristomium (Greek περι- meaning «around» and στομα meaning «mouth»), is regarded by some zoologists as not a true segment, but in some polychaetes the peristomium has chetae and appendages like those of other segments.[6]

The segments develop one at a time from a growth zone just ahead of the pygidium, so that an annelid’s youngest segment is just in front of the growth zone while the peristomium is the oldest. This pattern is called teloblastic growth.[6] Some groups of annelids, including all leeches,[13] have fixed maximum numbers of segments, while others add segments throughout their lives.[10]

The phylum’s name is derived from the Latin word annelus, meaning «little ring».[4]

Body wall, chaetae and parapodia[edit]

Annelids’ cuticles are made of collagen fibers, usually in layers that spiral in alternating directions so that the fibers cross each other. These are secreted by the one-cell deep epidermis (outermost skin layer). A few marine annelids that live in tubes lack cuticles, but their tubes have a similar structure, and mucus-secreting glands in the epidermis protect their skins.[6] Under the epidermis is the dermis, which is made of connective tissue, in other words a combination of cells and non-cellular materials such as collagen. Below this are two layers of muscles, which develop from the lining of the coelom (body cavity): circular muscles make a segment longer and slimmer when they contract, while under them are longitudinal muscles, usually four distinct strips,[19] whose contractions make the segment shorter and fatter.[6] But several families have lost the circular muscles, and it has been suggested that the lack of circular muscles is a plesiomorphic character in Annelida.[29] Some annelids also have oblique internal muscles that connect the underside of the body to each side.[19]

The setae («hairs») of annelids project out from the epidermis to provide traction and other capabilities. The simplest are unjointed and form paired bundles near the top and bottom of each side of each segment. The parapodia («limbs») of annelids that have them often bear more complex chetae at their tips – for example jointed, comb-like or hooked.[6] Chetae are made of moderately flexible β-chitin and are formed by follicles, each of which has a chetoblast («hair-forming») cell at the bottom and muscles that can extend or retract the cheta. The chetoblasts produce chetae by forming microvilli, fine hair-like extensions that increase the area available for secreting the cheta. When the cheta is complete, the microvilli withdraw into the chetoblast, leaving parallel tunnels that run almost the full length of the cheta.[6] Hence annelids’ chetae are structurally different from the setae («bristles») of arthropods, which are made of the more rigid α-chitin, have a single internal cavity, and are mounted on flexible joints in shallow pits in the cuticle.[6]

Nearly all polychaetes have parapodia that function as limbs, while other major annelid groups lack them. Parapodia are unjointed paired extensions of the body wall, and their muscles are derived from the circular muscles of the body. They are often supported internally by one or more large, thick chetae. The parapodia of burrowing and tube-dwelling polychaetes are often just ridges whose tips bear hooked chetae. In active crawlers and swimmers the parapodia are often divided into large upper and lower paddles on a very short trunk, and the paddles are generally fringed with chetae and sometimes with cirri (fused bundles of cilia) and gills.[19]

Nervous system and senses[edit]

The brain generally forms a ring round the pharynx (throat), consisting of a pair of ganglia (local control centers) above and in front of the pharynx, linked by nerve cords either side of the pharynx to another pair of ganglia just below and behind it.[6] The brains of polychaetes are generally in the prostomium, while those of clitellates are in the peristomium or sometimes the first segment behind the prostomium.[30] In some very mobile and active polychaetes the brain is enlarged and more complex, with visible hindbrain, midbrain and forebrain sections.[19] The rest of the central nervous system, the ventral nerve cord, is generally «ladder-like», consisting of a pair of nerve cords that run through the bottom part of the body and have in each segment paired ganglia linked by a transverse connection. From each segmental ganglion a branching system of local nerves runs into the body wall and then encircles the body.[6] However, in most polychaetes the two main nerve cords are fused, and in the tube-dwelling genus Owenia the single nerve chord has no ganglia and is located in the epidermis.[10][31]

As in arthropods, each muscle fiber (cell) is controlled by more than one neuron, and the speed and power of the fiber’s contractions depends on the combined effects of all its neurons. Vertebrates have a different system, in which one neuron controls a group of muscle fibers.[6] Most annelids’ longitudinal nerve trunks include giant axons (the output signal lines of nerve cells). Their large diameter decreases their resistance, which allows them to transmit signals exceptionally fast. This enables these worms to withdraw rapidly from danger by shortening their bodies. Experiments have shown that cutting the giant axons prevents this escape response but does not affect normal movement.[6]

The sensors are primarily single cells that detect light, chemicals, pressure waves and contact, and are present on the head, appendages (if any) and other parts of the body.[6] Nuchal («on the neck») organs are paired, ciliated structures found only in polychaetes, and are thought to be chemosensors.[19] Some polychaetes also have various combinations of ocelli («little eyes») that detect the direction from which light is coming and camera eyes or compound eyes that can probably form images.[31] The compound eyes probably evolved independently of arthropods’ eyes.[19] Some tube-worms use ocelli widely spread over their bodies to detect the shadows of fish, so that they can quickly withdraw into their tubes.[31] Some burrowing and tube-dwelling polychaetes have statocysts (tilt and balance sensors) that tell them which way is down.[31] A few polychaete genera have on the undersides of their heads palps that are used both in feeding and as «feelers», and some of these also have antennae that are structurally similar but probably are used mainly as «feelers».[19]

Coelom, locomotion and circulatory system[edit]

Most annelids have a pair of coelomata (body cavities) in each segment, separated from other segments by septa and from each other by vertical mesenteries. Each septum forms a sandwich with connective tissue in the middle and mesothelium (membrane that serves as a lining) from the preceding and following segments on either side. Each mesentery is similar except that the mesothelium is the lining of each of the pair of coelomata, and the blood vessels and, in polychaetes, the main nerve cords are embedded in it.[6] The mesothelium is made of modified epitheliomuscular cells;[6] in other words, their bodies form part of the epithelium but their bases extend to form muscle fibers in the body wall.[32] The mesothelium may also form radial and circular muscles on the septa, and circular muscles around the blood vessels and gut. Parts of the mesothelium, especially on the outside of the gut, may also form chloragogen cells that perform similar functions to the livers of vertebrates: producing and storing glycogen and fat; producing the oxygen-carrier hemoglobin; breaking down proteins; and turning nitrogenous waste products into ammonia and urea to be excreted.[6]

Many annelids move by peristalsis (waves of contraction and expansion that sweep along the body),[6] or flex the body while using parapodia to crawl or swim.[33] In these animals the septa enable the circular and longitudinal muscles to change the shape of individual segments, by making each segment a separate fluid-filled «balloon».[6] However, the septa are often incomplete in annelids that are semi-sessile or that do not move by peristalsis or by movements of parapodia – for example some move by whipping movements of the body, some small marine species move by means of cilia (fine muscle-powered hairs) and some burrowers turn their pharynges (throats) inside out to penetrate the sea-floor and drag themselves into it.[6]

The fluid in the coelomata contains coelomocyte cells that defend the animals against parasites and infections. In some species coelomocytes may also contain a respiratory pigment – red hemoglobin in some species, green chlorocruorin in others (dissolved in the plasma)[19] – and provide oxygen transport within their segments. Respiratory pigment is also dissolved in the blood plasma. Species with well-developed septa generally also have blood vessels running all long their bodies above and below the gut, the upper one carrying blood forwards while the lower one carries it backwards. Networks of capillaries in the body wall and around the gut transfer blood between the main blood vessels and to parts of the segment that need oxygen and nutrients. Both of the major vessels, especially the upper one, can pump blood by contracting. In some annelids the forward end of the upper blood vessel is enlarged with muscles to form a heart, while in the forward ends of many earthworms some of the vessels that connect the upper and lower main vessels function as hearts. Species with poorly developed or no septa generally have no blood vessels and rely on the circulation within the coelom for delivering nutrients and oxygen.[6]

However, leeches and their closest relatives have a body structure that is very uniform within the group but significantly different from that of other annelids, including other members of the Clitellata.[13] In leeches there are no septa, the connective tissue layer of the body wall is so thick that it occupies much of the body, and the two coelomata are widely separated and run the length of the body. They function as the main blood vessels, although they are side-by-side rather than upper and lower. However, they are lined with mesothelium, like the coelomata and unlike the blood vessels of other annelids. Leeches generally use suckers at their front and rear ends to move like inchworms. The anus is on the upper surface of the pygidium.[13]

Respiration[edit]

In some annelids, including earthworms, all respiration is via the skin. However, many polychaetes and some clitellates (the group to which earthworms belong) have gills associated with most segments, often as extensions of the parapodia in polychaetes. The gills of tube-dwellers and burrowers usually cluster around whichever end has the stronger water flow.[19]

Feeding and excretion[edit]

Feeding structures in the mouth region vary widely, and have little correlation with the animals’ diets. Many polychaetes have a muscular pharynx that can be everted (turned inside out to extend it). In these animals the foremost few segments often lack septa so that, when the muscles in these segments contract, the sharp increase in fluid pressure from all these segments everts the pharynx very quickly. Two families, the Eunicidae and Phyllodocidae, have evolved jaws, which can be used for seizing prey, biting off pieces of vegetation, or grasping dead and decaying matter. On the other hand, some predatory polychaetes have neither jaws nor eversible pharynges. Selective deposit feeders generally live in tubes on the sea-floor and use palps to find food particles in the sediment and then wipe them into their mouths. Filter feeders use «crowns» of palps covered in cilia that wash food particles towards their mouths. Non-selective deposit feeders ingest soil or marine sediments via mouths that are generally unspecialized. Some clitellates have sticky pads in the roofs of their mouths, and some of these can evert the pads to capture prey. Leeches often have an eversible proboscis, or a muscular pharynx with two or three teeth.[19]

The gut is generally an almost straight tube supported by the mesenteries (vertical partitions within segments), and ends with the anus on the underside of the pygidium.[6] However, in members of the tube-dwelling family Siboglinidae the gut is blocked by a swollen lining that houses symbiotic bacteria, which can make up 15% of the worms’ total weight. The bacteria convert inorganic matter – such as hydrogen sulfide and carbon dioxide from hydrothermal vents, or methane from seeps – to organic matter that feeds themselves and their hosts, while the worms extend their palps into the gas flows to absorb the gases needed by the bacteria.[19]

Annelids with blood vessels use metanephridia to remove soluble waste products, while those without use protonephridia.[6] Both of these systems use a two-stage filtration process, in which fluid and waste products are first extracted and these are filtered again to re-absorb any re-usable materials while dumping toxic and spent materials as urine. The difference is that protonephridia combine both filtration stages in the same organ, while metanephridia perform only the second filtration and rely on other mechanisms for the first – in annelids special filter cells in the walls of the blood vessels let fluids and other small molecules pass into the coelomic fluid, where it circulates to the metanephridia.[34] In annelids the points at which fluid enters the protonephridia or metanephridia are on the forward side of a septum while the second-stage filter and the nephridiopore (exit opening in the body wall) are in the following segment. As a result, the hindmost segment (before the growth zone and pygidium) has no structure that extracts its wastes, as there is no following segment to filter and discharge them, while the first segment contains an extraction structure that passes wastes to the second, but does not contain the structures that re-filter and discharge urine.[6]

Reproduction and life cycle[edit]

Asexual reproduction[edit]

Polychaetes can reproduce asexually, by dividing into two or more pieces or by budding off a new individual while the parent remains a complete organism.[6][35] Some oligochaetes, such as Aulophorus furcatus, seem to reproduce entirely asexually, while others reproduce asexually in summer and sexually in autumn. Asexual reproduction in oligochaetes is always by dividing into two or more pieces, rather than by budding.[10][36] However, leeches have never been seen reproducing asexually.[10][37]

Most polychaetes and oligochaetes also use similar mechanisms to regenerate after suffering damage. Two polychaete genera, Chaetopterus and Dodecaceria, can regenerate from a single segment, and others can regenerate even if their heads are removed.[10][35] Annelids are the most complex animals that can regenerate after such severe damage.[38] On the other hand, leeches cannot regenerate.[37]

Sexual reproduction[edit]

Apical tuft (cilia)

Prototroch (cilia)

Stomach

Mouth

Metatroch (cilia)

Mesoderm

Anus

/// = cilia

It is thought that annelids were originally animals with two separate sexes, which released ova and sperm into the water via their nephridia.[6] The fertilized eggs develop into trochophore larvae, which live as plankton.[40] Later they sink to the sea-floor and metamorphose into miniature adults: the part of the trochophore between the apical tuft and the prototroch becomes the prostomium (head); a small area round the trochophore’s anus becomes the pygidium (tail-piece); a narrow band immediately in front of that becomes the growth zone that produces new segments; and the rest of the trochophore becomes the peristomium (the segment that contains the mouth).[6]

However, the lifecycles of most living polychaetes, which are almost all marine animals, are unknown, and only about 25% of the 300+ species whose lifecycles are known follow this pattern. About 14% use a similar external fertilization but produce yolk-rich eggs, which reduce the time the larva needs to spend among the plankton, or eggs from which miniature adults emerge rather than larvae. The rest care for the fertilized eggs until they hatch – some by producing jelly-covered masses of eggs which they tend, some by attaching the eggs to their bodies and a few species by keeping the eggs within their bodies until they hatch. These species use a variety of methods for sperm transfer; for example, in some the females collect sperm released into the water, while in others the males have a penis that inject sperm into the female.[40] There is no guarantee that this is a representative sample of polychaetes’ reproductive patterns, and it simply reflects scientists’ current knowledge.[40]

Some polychaetes breed only once in their lives, while others breed almost continuously or through several breeding seasons. While most polychaetes remain of one sex all their lives, a significant percentage of species are full hermaphrodites or change sex during their lives. Most polychaetes whose reproduction has been studied lack permanent gonads, and it is uncertain how they produce ova and sperm. In a few species the rear of the body splits off and becomes a separate individual that lives just long enough to swim to a suitable environment, usually near the surface, and spawn.[40]

Most mature clitellates (the group that includes earthworms and leeches) are full hermaphrodites, although in a few leech species younger adults function as males and become female at maturity. All have well-developed gonads, and all copulate. Earthworms store their partners’ sperm in spermathecae («sperm stores») and then the clitellum produces a cocoon that collects ova from the ovaries and then sperm from the spermathecae. Fertilization and development of earthworm eggs takes place in the cocoon. Leeches’ eggs are fertilized in the ovaries, and then transferred to the cocoon. In all clitellates the cocoon also either produces yolk when the eggs are fertilized or nutrients while they are developing. All clitellates hatch as miniature adults rather than larvae.[40]

Ecological significance[edit]

Charles Darwin’s book The Formation of Vegetable Mould Through the Action of Worms (1881) presented the first scientific analysis of earthworms’ contributions to soil fertility.[41] Some burrow while others live entirely on the surface, generally in moist leaf litter. The burrowers loosen the soil so that oxygen and water can penetrate it, and both surface and burrowing worms help to produce soil by mixing organic and mineral matter, by accelerating the decomposition of organic matter and thus making it more quickly available to other organisms, and by concentrating minerals and converting them to forms that plants can use more easily.[42][43] Earthworms are also important prey for birds ranging in size from robins to storks, and for mammals ranging from shrews to badgers, and in some cases conserving earthworms may be essential for conserving endangered birds.[44]

Terrestrial annelids can be invasive in some situations. In the glaciated areas of North America, for example, almost all native earthworms are thought to have been killed by the glaciers and the worms currently found in those areas are all introduced from other areas, primarily from Europe, and, more recently, from Asia. Northern hardwood forests are especially negatively impacted by invasive worms through the loss of leaf duff, soil fertility, changes in soil chemistry and the loss of ecological diversity. Especially of concern is Amynthas agrestis and at least one state (Wisconsin) has listed it as a prohibited species.

Earthworms migrate only a limited distance annually on their own, and the spread of invasive worms is increased rapidly by anglers and from worms or their cocoons in the dirt on vehicle tires or footwear.

Marine annelids may account for over one-third of bottom-dwelling animal species around coral reefs and in tidal zones.[41] Burrowing species increase the penetration of water and oxygen into the sea-floor sediment, which encourages the growth of populations of aerobic bacteria and small animals alongside their burrows.[45]

Although blood-sucking leeches do little direct harm to their victims, some transmit flagellates that can be very dangerous to their hosts. Some small tube-dwelling oligochaetes transmit myxosporean parasites that cause whirling disease in fish.[41]

Interaction with humans[edit]

Earthworms make a significant contribution to soil fertility.[41] The rear end of the Palolo worm, a marine polychaete that tunnels through coral, detaches in order to spawn at the surface, and the people of Samoa regard these spawning modules as a delicacy.[41] Anglers sometimes find that worms are more effective bait than artificial flies, and worms can be kept for several days in a tin lined with damp moss.[46] Ragworms are commercially important as bait and as food sources for aquaculture, and there have been proposals to farm them in order to reduce over-fishing of their natural populations.[45] Some marine polychaetes’ predation on molluscs causes serious losses to fishery and aquaculture operations.[41]

Scientists study aquatic annelids to monitor the oxygen content, salinity and pollution levels in fresh and marine water.[41]

Accounts of the use of leeches for the medically dubious practise of blood-letting have come from China around 30 AD, India around 200 AD, ancient Rome around 50 AD and later throughout Europe. In the 19th century medical demand for leeches was so high that some areas’ stocks were exhausted and other regions imposed restrictions or bans on exports, and Hirudo medicinalis is treated as an endangered species by both IUCN and CITES. More recently leeches have been used to assist in microsurgery, and their saliva has provided anti-inflammatory compounds and several important anticoagulants, one of which also prevents tumors from spreading.[41]

Ragworms’ jaws are strong but much lighter than the hard parts of many other organisms, which are biomineralized with calcium salts. These advantages have attracted the attention of engineers. Investigations showed that ragworm jaws are made of unusual proteins that bind strongly to zinc.[47]

Evolutionary history[edit]

Fossil record[edit]

Since annelids are soft-bodied, their fossils are rare.[48] Polychaetes’ fossil record consists mainly of the jaws that some species had and the mineralized tubes that some secreted.[49] Some Ediacaran fossils such as Dickinsonia in some ways resemble polychaetes, but the similarities are too vague for these fossils to be classified with confidence.[50] The small shelly fossil Cloudina, from 549 to 542 million years ago, has been classified by some authors as an annelid, but by others as a cnidarian (i.e. in the phylum to which jellyfish and sea anemones belong).[51][52] Until 2008 the earliest fossils widely accepted as annelids were the polychaetes Canadia and Burgessochaeta, both from Canada’s Burgess Shale, formed about 505 million years ago in the early Cambrian.[53] Myoscolex, found in Australia and a little older than the Burgess Shale, was possibly an annelid. However, it lacks some typical annelid features and has features which are not usually found in annelids and some of which are associated with other phyla.[53] Then Simon Conway Morris and John Peel reported Phragmochaeta from Sirius Passet, about 518 million years old, and concluded that it was the oldest annelid known to date.[50] There has been vigorous debate about whether the Burgess Shale fossil Wiwaxia was a mollusc or an annelid.[53] Polychaetes diversified in the early Ordovician, about 488 to 474 million years ago. It is not until the early Ordovician that the first annelid jaws are found, thus the crown-group cannot have appeared before this date and probably appeared somewhat later.[54] By the end of the Carboniferous, about 299 million years ago, fossils of most of the modern mobile polychaete groups had appeared.[53] Many fossil tubes look like those made by modern sessile polychaetes,[55] but the first tubes clearly produced by polychaetes date from the Jurassic, less than 199 million years ago.[53] In 2012, a 508 million year old species of annelid found near the Burgess shale beds in British Columbia, Kootenayscolex, was found that changed the hypotheses about how the annelid head developed. It appears to have bristles on its head segment akin to those along its body, as if the head simply developed as a specialized version of a previously generic segment.

The earliest good evidence for oligochaetes occurs in the Tertiary period, which began 65 million years ago, and it has been suggested that these animals evolved around the same time as flowering plants in the early Cretaceous, from 130 to 90 million years ago.[56] A trace fossil consisting of a convoluted burrow partly filled with small fecal pellets may be evidence that earthworms were present in the early Triassic period from 251 to 245 million years ago.[56][57] Body fossils going back to the mid Ordovician, from 472 to 461 million years ago, have been tentatively classified as oligochaetes, but these identifications are uncertain and some have been disputed.[56][58]

Internal relationships[edit]

Traditionally the annelids have been divided into two major groups, the polychaetes and clitellates. In turn the clitellates were divided into oligochaetes, which include earthworms, and hirudinomorphs, whose best-known members are leeches.[6] For many years there was no clear arrangement of the approximately 80 polychaete families into higher-level groups.[8] In 1997 Greg Rouse and Kristian Fauchald attempted a «first heuristic step in terms of bringing polychaete systematics to an acceptable level of rigour», based on anatomical structures, and divided polychaetes into:[59]

| Morphological phylogeny of Annelida (1997)[59] |

- Scolecida, less than 1,000 burrowing species that look rather like earthworms.[60]

- Palpata, the great majority of polychaetes, divided into:

- Canalipalpata, which are distinguished by having long grooved palps that they use for feeding, and most of which live in tubes.[60]

- Aciculata, the most active polychaetes, which have parapodia reinforced by internal spines (aciculae).[60]

Annelida

some «Scolecida» and «Aciculata»

some «Canalipalpata»

Sipuncula, previously a separate phylum

some «Scolecida» and «Canalipalpata»

some «Scolecida»

Echiura, previously a separate phylum

some «Scolecida»

some «Canalipalpata»

Siboglinidae, previously phylum Pogonophora

some «Canalipalpata»

some «Scolecida», «Canalipalpata» and «Aciculata»

Annelid groups and phyla incorporated into Annelida (2007; simplified).[8]

Highlights major changes to traditional classifications.

Also in 1997 Damhnait McHugh, using molecular phylogenetics to compare similarities and differences in one gene, presented a very different view, in which: the clitellates were an offshoot of one branch of the polychaete family tree; the pogonophorans and echiurans, which for a few decades had been regarded as a separate phyla, were placed on other branches of the polychaete tree.[62] Subsequent molecular phylogenetics analyses on a similar scale presented similar conclusions.[63]

In 2007 Torsten Struck and colleagues compared three genes in 81 taxa, of which nine were outgroups,[8] in other words not considered closely related to annelids but included to give an indication of where the organisms under study are placed on the larger tree of life.[64] For a cross-check the study used an analysis of 11 genes (including the original 3) in ten taxa. This analysis agreed that clitellates, pogonophorans and echiurans were on various branches of the polychaete family tree. It also concluded that the classification of polychaetes into Scolecida, Canalipalpata and Aciculata was useless, as the members of these alleged groups were scattered all over the family tree derived from comparing the 81 taxa. It also placed sipunculans, generally regarded at the time as a separate phylum, on another branch of the polychaete tree, and concluded that leeches were a sub-group of oligochaetes rather than their sister-group among the clitellates.[8] Rouse accepted the analyses based on molecular phylogenetics,[10] and their main conclusions are now the scientific consensus, although the details of the annelid family tree remain uncertain.[9]

In addition to re-writing the classification of annelids and three previously independent phyla, the molecular phylogenetics analyses undermine the emphasis that decades of previous writings placed on the importance of segmentation in the classification of invertebrates. Polychaetes, which these analyses found to be the parent group, have completely segmented bodies, while polychaetes’ echiurans and sipunculan offshoots are not segmented and pogonophores are segmented only in the rear parts of their bodies. It now seems that segmentation can appear and disappear much more easily in the course of evolution than was previously thought.[8][62] The 2007 study also noted that the ladder-like nervous system, which is associated with segmentation, is less universal than previously thought in both annelids and arthropods.[8][b]

The updated phylogenetic tree of the Annelid phylum is comprised by a grade of basal groups of polychaetes: Palaeoannelida, Chaetopteriformia and the Amphinomida/Sipuncula/Lobatocerebrum clade. This grade is followed by Pleistoannelida, the clade containing nearly all of annelid diversity, divided into two highly diverse groups: Sedentaria and Errantia. Sedentaria contains the clitellates, pogonophorans, echiurans and some archiannelids, as well as several polychaete groups. Errantia contains the eunicid and phyllodocid polychaetes, and several archiannelids. Some small groups, such as the Myzostomida, are more difficult to place due to long branching, but belong to either one of these large groups.[65][66][67][68][69]

External relationships[edit]

Annelids are members of the protostomes, one of the two major superphyla of bilaterian animals – the other is the deuterostomes, which includes vertebrates.[63] Within the protostomes, annelids used to be grouped with arthropods under the super-group Articulata («jointed animals»), as segmentation is obvious in most members of both phyla. However, the genes that drive segmentation in arthropods do not appear to do the same in annelids. Arthropods and annelids both have close relatives that are unsegmented. It is at least as easy to assume that they evolved segmented bodies independently as it is to assume that the ancestral protostome or bilaterian was segmented and that segmentation disappeared in many descendant phyla.[63] The current view is that annelids are grouped with molluscs, brachiopods and several other phyla that have lophophores (fan-like feeding structures) and/or trochophore larvae as members of Lophotrochozoa.[70] Meanwhile, arthropods are now regarded as members of the Ecdysozoa («animals that molt»), along with some phyla that are unsegmented.[63][71]

The «Lophotrochozoa» hypothesis is also supported by the fact that many phyla within this group, including annelids, molluscs, nemerteans and flatworms, follow a similar pattern in the fertilized egg’s development. When their cells divide after the 4-cell stage, descendants of these four cells form a spiral pattern. In these phyla the «fates» of the embryo’s cells, in other words the roles their descendants will play in the adult animal, are the same and can be predicted from a very early stage.[72] Hence this development pattern is often described as «spiral determinate cleavage».[73]

Phylogenetic tree of early lophophorates

Fossil discoveries lead to the hypothesis that Annelida and the lophophorates are more closely related to each other than any other phyla. Because of the body plan of lophotrochozoan fossils, a phylogenetic analysis found the lophophorates as the sister group of annelids. Both groups share in common: the presence of chaetae secreted by microvilli; paired, metameric coelomic compartments; and a similar metanephridial structure.[74]

Notes[edit]

- ^ The term originated from Jean-Baptiste Lamarck’s annélides.[1][2]

- ^ Note that since this section was written, a new paper has revised the 2007 results: Struck, T. H.; Paul, C.; Hill, N.; Hartmann, S.; Hösel, C.; Kube, M.; Lieb, B.; Meyer, A.; Tiedemann, R.; Purschke, G. N.; Bleidorn, C. (2011). «Phylogenomic analyses unravel annelid evolution». Nature. 471 (7336): 95–98. Bibcode:2011Natur.471…95S. doi:10.1038/nature09864. PMID 21368831. S2CID 4428998.

References[edit]

- ^ a b McIntosh, William Carmichael (1878). «Annelida» . In Baynes, T. S. (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 2 (9th ed.). New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons. pp. 65–72.

- ^ Mitchell, Peter Chalmers (1911). «Annelida» . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 2 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 72–73.

- ^ Renne, Paul R.; Deino, Alan L.; Hilgen, Frederik J.; Kuiper, Klaudia F.; Mark, Darren F.; Mitchell, William S.; Morgan, Leah E.; Mundil, Roland; Smit, Jan (7 February 2013). «Time Scales of Critical Events Around the Cretaceous-Paleogene Boundary» (PDF). Science. 339 (6120): 684–687. Bibcode:2013Sci…339..684R. doi:10.1126/science.1230492. PMID 23393261. S2CID 6112274.

- ^ a b c d Rouse, G. W. (2002). «Annelida (Segmented Worms)». Encyclopedia of Life Sciences. John Wiley & Sons. doi:10.1038/npg.els.0001599. ISBN 978-0470016176.

- ^ a b c d Blakemore, R.J. (2012). Cosmopolitan Earthworms. VermEcology, Yokohama.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak Ruppert, E. E.; Fox, R. S. & Barnes, R. D. (2004). «Annelida». Invertebrate Zoology (7th ed.). Brooks / Cole. pp. 414–420. ISBN 978-0-03-025982-1.

- ^ Lavelle, P. (July 1996). «Diversity of Soil Fauna and Ecosystem Function» (PDF). Biology International. 33. Retrieved 2009-04-20.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Struck, T.H.; Schult, N.; Kusen, T.; Hickman, E.; Bleidorn, C.; McHugh, D.; Halanych, K.M. (5 April 2007). «Annelid phylogeny and the status of Sipuncula and Echiura». BMC Evolutionary Biology. 7: 57. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-7-57. PMC 1855331. PMID 17411434.

- ^ a b Hutchings, P. (2007). «Book Review: Reproductive Biology and Phylogeny of Annelida». Integrative and Comparative Biology. 47 (5): 788–789. doi:10.1093/icb/icm008.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Rouse, G. (1998). «The Annelida and their close relatives». In Anderson, D. T. (ed.). Invertebrate Zoology. Oxford University Press. pp. 176–179. ISBN 978-0-19-551368-4.

- ^ a b c d e Rouse, G. (1998). «The Annelida and their close relatives». In Anderson, D.T. (ed.). Invertebrate Zoology. Oxford University Press. pp. 179–183. ISBN 978-0-19-551368-4.

- ^ Ruppert, E. E.; Fox, R. S. & Barnes, R. D. (2004). «Annelida». Invertebrate Zoology (7th ed.). Brooks / Cole. p. 459. ISBN 978-0-03-025982-1.

- ^ a b c d Ruppert, E. E.; Fox, R. S. & Barnes, R.D. (2004). «Annelida». Invertebrate Zoology (7th ed.). Brooks / Cole. pp. 471–482. ISBN 978-0-03-025982-1.

- ^ a b c Halanych, K. M.; Dahlgren, T. G.; McHugh, D. (2002). «Unsegmented Annelids? Possible Origins of Four Lophotrochozoan Worm Taxa». Integrative and Comparative Biology. 42 (3): 678–684. doi:10.1093/icb/42.3.678. PMID 21708764. S2CID 14782179.

- ^ McHugh, D. (July 1997). «Molecular evidence that echiurans and pogonophorans are derived annelids». Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 94 (15): 8006–8009. Bibcode:1997PNAS…94.8006M. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.15.8006. PMC 21546. PMID 9223304.

- ^ Hausdorf, B.; et al. (2007). «Spiralian Phylogenomics Supports the Resurrection of Bryozoa Comprising Ectoprocta and Entoprocta». Molecular Biology and Evolution. 24 (12): 2723–2729. doi:10.1093/molbev/msm214. PMID 17921486.

- ^ Shen, X.; Ma, X.; Ren, J.; Zhao, F. (2009). «A close phylogenetic relationship between Sipuncula and Annelida evidenced from the complete mitochondrial genome sequence of Phascolosoma esculenta». BMC Genomics. 10: 136. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-10-136. PMC 2667193. PMID 19327168.

- ^ Wanninger, Andreas; Kristof, Alen; Brinkmann, Nora (Jan–Feb 2009). «Sipunculans and segmentation». Communicative and Integrative Biology. 2 (1): 56–59. doi:10.4161/cib.2.1.7505. PMC 2649304. PMID 19513266.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Rouse, G. (1998). «The Annelida and their close relatives». In Anderson, D. T. (ed.). Invertebrate Zoology. Oxford University Press. pp. 183–196. ISBN 978-0-19-551368-4.

- ^ Cutler, B. (August 1980). «Arthropod cuticle features and arthropod monophyly». Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 36 (8): 953. doi:10.1007/BF01953812. S2CID 84995596.

- ^ a b Ruppert, E. E.; Fox, R. S. & Barnes, R. D. (2004). «Introduction to Arthropoda». Invertebrate Zoology (7th ed.). Brooks / Cole. pp. 523–524. ISBN 978-0-03-025982-1.

- ^ Ruppert, E. E.; Fox, R. S. & Barnes, R. D. (2004). «Echiura and Sipuncula». Invertebrate Zoology (7th ed.). Brooks / Cole. pp. 490–495. ISBN 978-0-03-025982-1.

- ^ Anderson, D. T. (1998). «The Annelida and their close relatives». In Anderson, D.T. (ed.). Invertebrate Zoology. Oxford University Press. pp. 183–196. ISBN 978-0-19-551368-4.

- ^ Ruppert, E. E.; Fox, R. S. & Barnes, R. D. (2004). «Nemertea». Invertebrate Zoology (7th ed.). Brooks / Cole. pp. 271–282. ISBN 978-0-03-025982-1.

- ^ Ruppert, E. E.; Fox, R. S. & Barnes, R. D. (2004). «Arthropoda». Invertebrate Zoology (7th ed.). Brooks / Cole. pp. 518–521. ISBN 978-0-03-025982-1.

- ^ Ruppert, E. E.; Fox, R. S. & Barnes, R. D. (2004). «Onychophora and Tardigrada». Invertebrate Zoology (7th ed.). Brooks / Cole. pp. 505–510. ISBN 978-0-03-025982-1.

- ^ Paxton, H. (June 2005). «Molting polychaete jaws—ecdysozoans are not the only molting animals». Evolution & Development. 7 (4): 337–340. doi:10.1111/j.1525-142X.2005.05039.x. PMID 15982370. S2CID 22020406.

- ^ Nielsen, C. (September 2003). «Proposing a solution to the Articulata–Ecdysozoa controversy» (PDF). Zoologica Scripta. 32 (5): 475–482. doi:10.1046/j.1463-6409.2003.00122.x. S2CID 1416582. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 March 2009. Retrieved 2009-03-11.

- ^ Minelli, Alessandro (2009), «Chapter 6. A gallery of the major bilaterian clades», Perspectives in Animal Phylogeny and Evolution, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-856620-5, p. 82:

This is the case for circular muscles, which have been reported as absent in many families (Opheliidae, Protodrilidae, Spionidae, Oweniidae, Aphroditidae, Acoetidae, Polynoidae, Sigalionidae, Phyllodocidae, Nephtyidae, Pisionidae, and Nerillidae; Tzetlin et al. 2002). Tzetlin and Filippova (2005) suggest that absence of circular muscles is possibly plesiomorphic in the Annelida.

- ^ Jenner, R. A. (2006). «Challenging received wisdoms: Some contributions of the new microscopy to the new animal phylogeny». Integrative and Comparative Biology. 46 (2): 93–103. doi:10.1093/icb/icj014. PMID 21672726.

- ^ a b c d Ruppert, E. E.; Fox, R. S. & Barnes, R. D. (2004). «Annelida». Invertebrate Zoology (7th ed.). Brooks / Cole. pp. 425–429. ISBN 978-0-03-025982-1.

- ^ Ruppert, E.E.; Fox, R.S. & Barnes, R.D. (2004). «Introduction to Metazoa». Invertebrate Zoology (7th ed.). Brooks / Cole. pp. 103–104. ISBN 978-0-03-025982-1.

- ^ Ruppert, E.E.; Fox, R.S. & Barnes, R.D. (2004). «Annelida». Invertebrate Zoology (7th ed.). Brooks / Cole. pp. 423–425. ISBN 978-0-03-025982-1.

- ^ Ruppert, E.E.; Fox, R.S. & Barnes, R.D. (2004). «Introduction to Bilateria». Invertebrate Zoology (7th ed.). Brooks / Cole. pp. 196–224. ISBN 978-0-03-025982-1.

- ^ a b Ruppert, E. E.; Fox, R. S. & Barnes, R. D. (2004). «Annelida». Invertebrate Zoology (7th ed.). Brooks / Cole. pp. 434–441. ISBN 978-0-03-025982-1.

- ^ Ruppert, E. E.; Fox, R. S. & Barnes, R. D. (2004). «Annelida». Invertebrate Zoology (7th ed.). Brooks / Cole. pp. 466–469. ISBN 978-0-03-025982-1.

- ^ a b Ruppert, E. E.; Fox, R. S. & Barnes, R. D. (2004). «Annelida». Invertebrate Zoology (7th ed.). Brooks / Cole. pp. 477–478. ISBN 978-0-03-025982-1.

- ^ Hickman, Cleveland; Roberts, L.; Keen, S.; Larson, A.; Eisenhour, D. (2007). Animal Diversity (4th ed.). New York: Mc Graw Hill. p. 204. ISBN 978-0-07-252844-2.

- ^ Ruppert, E.E.; Fox, R.S. & Barnes, R.D. (2004). «Mollusca». Invertebrate Zoology (7th ed.). Brooks / Cole. pp. 290–291. ISBN 0030259827.

- ^ a b c d e Rouse, G. (1998). «The Annelida and their close relatives». In Anderson, D. T. (ed.). Invertebrate Zoology. Oxford University Press. pp. 196–202. ISBN 978-0-19-551368-4.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Siddall, M. E.; Borda, E.; Rouse, G. W. (2004). «Towards a tree of life for Annelida». In Cracraft, J.; Donoghue, M. J. (eds.). Assembling the tree of life. Oxford University Press. pp. 237–248. ISBN 978-0-19-517234-8.

- ^ New, T. R. (2005). Invertebrate conservation and agricultural ecosystems. Cambridge University Press. pp. 44–46. ISBN 978-0-521-53201-3.

- ^ Nancarrow, L.; Taylor, J. H. (1998). The worm book. Ten Speed Press. pp. 2–6. ISBN 978-0-89815-994-3. Retrieved 2009-04-02.

- ^ Edwards, C. A.; Bohlen, P. J. (1996). «Earthworm ecology: communities». Biology and ecology of earthworms. Springer. pp. 124–126. ISBN 978-0-412-56160-3. Retrieved 2009-04-12.

- ^ a b Scaps, P. (February 2002). «A review of the biology, ecology and potential use of the common ragworm Hediste diversicolor«. Hydrobiologia. 470 (1–3): 203–218. doi:10.1023/A:1015681605656. S2CID 22669841.

- ^ Sell, F. E. (2008). «The humble worm – with a difference». Practical Fresh Water Fishing. Read Books. pp. 14–15. ISBN 978-1-4437-6157-4.

- ^ «Rags to riches». The Economist. July 2008. Retrieved 2009-04-20.

- ^ Rouse, G. (1998). «The Annelida and their close relatives». In Anderson, D. T. (ed.). Invertebrate Zoology. Oxford University Press. p. 202. ISBN 978-0-19-551368-4.

- ^ Briggs, D. E. G.; Kear, A. J. (1993). «Decay and preservation of polychaetes; taphonomic thresholds in soft-bodied organisms». Paleobiology. 19 (1): 107–135. doi:10.1017/S0094837300012343.

- ^ a b Conway Morris, Simon; Pjeel, J.S. (2008). «The earliest annelids: Lower Cambrian polychaetes from the Sirius Passet Lagerstätte, Peary Land, North Greenland» (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 53 (1): 137–148. doi:10.4202/app.2008.0110. S2CID 35811524.

- ^ Miller, A. J. (2004). «A Revised Morphology of Cloudina with Ecological and Phylogenetic Implications» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 March 2009. Retrieved 2009-04-12.

- ^ Vinn, O.; Zatoń, M. (2012). «Inconsistencies in proposed annelid affinities of early biomineralized organism Cloudina (Ediacaran): structural and ontogenetic evidences». Carnets de Géologie (CG2012_A03): 39–47. doi:10.4267/2042/46095. Archived from the original on 2013-07-11. Retrieved 2012-08-29.

- ^ a b c d e Dzik, J. (2004). «Anatomy and relationships of the Early Cambrian worm Myoscolex«. Zoologica Scripta. 33 (1): 57–69. doi:10.1111/j.1463-6409.2004.00136.x. S2CID 85216629.

- ^ Budd, G. E.; Jensen, S. (May 2000). «A critical reappraisal of the fossil record of the bilaterian phyla». Biological Reviews of the Cambridge Philosophical Society. 75 (2): 253–95. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.1999.tb00046.x. PMID 10881389. S2CID 39772232.

- ^ Vinn, O.; Mutvei, H. (2009). «Calcareous tubeworms of the Phanerozoic» (PDF). Estonian Journal of Earth Sciences. 58 (4): 286–296. doi:10.3176/earth.2009.4.07.

- ^ a b c Humphreys, G.S. (2003). «Evolution of terrestrial burrowing invertebrates» (PDF). In Roach, I.C. (ed.). Advances in Regolith. CRC LEME. pp. 211–215. ISBN 978-0-7315-5221-4. Retrieved 2009-04-13.

- ^ Retallack, G.J. (1997). «Palaeosols in the upper Narrabeen Group of New South Wales as evidence of Early Triassic palaeoenvironments without exact modern analogues» (PDF). Australian Journal of Earth Sciences. 44 (2): 185–201. Bibcode:1997AuJES..44..185R. doi:10.1080/08120099708728303. Retrieved 2009-04-13.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Conway Morris, S.; Pickerill, R.K.; Harland, T.L. (1982). «A possible annelid from the Trenton Limestone (Ordovician) of Quebec, with a review of fossil oligochaetes and other annulate worms». Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 19 (11): 2150–2157. Bibcode:1982CaJES..19.2150M. doi:10.1139/e82-189.

- ^ a b Rouse, G. W.; Fauchald, K. (1997). «Cladistics and polychaetes». Zoologica Scripta. 26 (2): 139–204. doi:10.1111/j.1463-6409.1997.tb00412.x. S2CID 86797269.

- ^ a b c Rouse, G. W.; Pleijel, F.; McHugh, D. (August 2002). «Annelida. Annelida. Segmented worms: bristleworms, ragworms, earthworms, leeches and their allies». The Tree of Life Web Project. Tree of Life Project. Archived from the original on 12 April 2009. Retrieved 2009-04-13.

- ^ A group of worms classified by some as polychaetes and by others as clitellates, see Rouse & Fauchald (1997) «Cladistics and polychaetes»

- ^ a b McHugh, D. (1997). «Molecular evidence that echiurans and pogonophorans are derived annelids». Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 94 (15): 8006–8009. Bibcode:1997PNAS…94.8006M. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.15.8006. PMC 21546. PMID 9223304.

- ^ a b c d Halanych, K.M. (2004). «The new view of animal phylogeny» (PDF). Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics. 35: 229–256. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.35.112202.130124. Retrieved 2009-04-17.

- ^ «Reading trees: A quick review». University of California Museum of Paleontology. Archived from the original on 15 April 2009. Retrieved 2009-04-13.

- ^ Struck, T.; Golombek, Anja; et al. (2015). «The Evolution of Annelids Reveals Two Adaptive Routes to the Interstitial Realm». Current Biology. 25 (15): 1993–1999. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2015.06.007. PMID 26212885. S2CID 12919216.

- ^ Weigert, Anne; Bleidorn, Christoph (2015). «Current status of annelid phylogeny». Organisms Diversity & Evolution. 16 (2): 345–362. doi:10.1007/s13127-016-0265-7. S2CID 5353873.

- ^ Marotta, Roberto; Ferraguti, Marco; Erséus, Christer; Gustavsson, Lena M. (2008). «Combined-data phylogenetics and character evolution of Clitellata (Annelida) using 18S rDNA and morphology». Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 154: 1–26. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2008.00408.x.

- ^ Christoffersen, Martin Lindsey (1 January 2012). «Phylogeny of basal descendants of cocoon-forming annelids (Clitellata)». Turkish Journal of Zoology. 36 (1): 95–119. doi:10.3906/zoo-1002-27. S2CID 83066199.

- ^ Struck TH (2019). «Phylogeny». In Purschke G, Böggemann M, Westheide W (eds.). Handbook of Zoology: Annelida. Vol. 1: Annelida Basal Groups and Pleistoannelida, Sedentaria I. De Gruyter. doi:10.1515/9783110291582-002. ISBN 9783110291469.

- ^ Dunn, CW; Hejnol, A; Matus, DQ; Pang, K; Browne, WE; Smith, SA; Seaver, E; Rouse, GW; Obst, M (2008). «Broad phylogenomic sampling improves resolution of the animal tree of life». Nature. 452 (7188): 745–749. Bibcode:2008Natur.452..745D. doi:10.1038/nature06614. PMID 18322464. S2CID 4397099.

- ^ Aguinaldo, A. M. A.; J. M. Turbeville; L. S. Linford; M. C. Rivera; J. R. Garey; R. A. Raff; J. A. Lake (1997). «Evidence for a clade of nematodes, arthropods and other moulting animals». Nature. 387 (6632): 489–493. Bibcode:1997Natur.387R.489A. doi:10.1038/387489a0. PMID 9168109. S2CID 4334033.