Биография Чайковского

7 Мая 1840 – 6 Ноября 1893 гг. (53 года)

4.4

Средняя оценка: 4.4

Всего получено оценок: 4551.

Петр Ильич Чайковский (1840–1893 гг.) – знаменитый русский композитор, дирижер. Один из величайших композиторов мира, автор более 80 музыкальных произведений, среди которых известнейшие балеты «Щелкунчик» и «Лебединое озеро». Один из самых исполняемых композиторов во всем мире.

Опыт работы учителем русского языка и литературы — 27 лет.

Ранние годы

Родился Петр Ильич Чайковский 25 апреля (7 мая) 1840 года в городе Воткинск в многодетной семье инженера. В доме Чайковских часто звучала музыка. Его родители увлекались игрой на фортепиано, органе.

В биографии Чайковского важно отметить, что в возрасте пяти лет он уже умел играть на фортепиано, еще через три года превосходно играл по нотам. В 1849 году семья Чайковских переехала в Алапаевск, а затем в Санкт-Петербург.

Обучение

Первоначальное образование Чайковским было получено дома. Затем Петр два года занимался в пансионе, после чего – в училище правоведения Петербурга. Творчество Чайковского в этот период проявлялось в факультативных занятиях музыкой. Смерть матери в 1862 году сильно повлияла на ранимого ребенка. После окончания училища в 1859 году Петр стал служить в Департаменте юстиции.

В свободное время часто посещал оперный театр, особенно сильное впечатление на него оказали постановки опер Моцарта и Глинки.

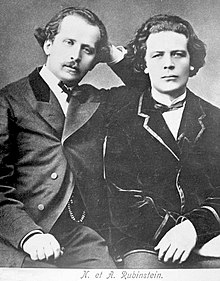

Проявив склонность к сочинению музыки, Чайковский становится студентом консерватории Петербурга. Дальнейшие занятия в жизни Петра Ильича у великолепных преподавателей Н. Зарембы, А. Рубинштейна во многом помогли формированию музыкальной личности. После окончания консерватории композитор Чайковский был приглашен Николаем Рубинштейном (братом преподавателя) в Московскую консерваторию на должность профессора.

Творческая и личная жизнь

Многие концерты Чайковского были написаны во время работы в консерватории. Опера «Ундина»(1869 г.) не была поставлена, автор уничтожил ее. Лишь небольшая часть ее позже была представлена как балет Чайковского «Лебединое озеро».

Стоит кратко отметить, что в 1877 году, чтобы избавиться от сплетен о своей нетрадиционной ориентации, Чайковский решил жениться на студентке консерватории Антонине Милюковой. Не испытывая к жене чувств, спустя несколько недель он навсегда уехал от нее. С тех пор супруги жили раздельно, они так и не смогли развестись в силу различных обстоятельств.

В 1878 году он покидает консерваторию и уезжает за границу. В то же время Чайковский близко общается с Надеждой фон Мекк – богатой поклонницей его музыки. Она ведет с ним переписку, поддерживает его материально и морально.

За двухлетнее время проживания в Италии, Швейцарии появляются новые великолепные произведения Чайковского: опера «Евгений Онегин», Четвертая симфония.

В мае 1878 года Чайковский делает вклад в детскую музыкальную литературу: пишет сборник пьес для детей под названием «Детский альбом».

После материальной помощи Надежды фон Мекк композитор много путешествует. С 1881 по 1888 год им было написано множество произведений. В частности, вальсы, симфонии, увертюры, сюиты.

Наконец в биографии Петра Чайковского установился спокойный творческий период, тогда же автор сам смог дирижировать на концертах.

Смерть и наследие

Умер Чайковский в Петербурге 25 октября (6 ноября) 1893 от холеры. Его похоронили в Александро-Невской лавре в Санкт-Петербурге.

Именем великого композитора названы улицы, консерватории в Москве и Киеве, а также прочие музыкальные учреждения (институты, колледжи, училища, школы) во многих городах бывшего СССР. В его честь установлены памятники, его именем назван театр и концертный зал, симфонический оркестр и международный музыкальный конкурс.

Другие варианты биографии

Более сжатая для доклада или сообщения в классе

Вариант 2

Интересные факты

- В семье Петра Ильича не было профессиональных музыкантов, но все очень любили музыку: глава семейства играл на флейте, мать – на арфе и фортепиано. Начальные уроки игры на рояле будущий композитор получил в возрасте пяти лет у Марии Марковны Пальчиковой.

Все интересные факты из жизни Чайковского

Тест по биографии

А вы хорошо запомнили краткую биографию Чайковского? Пройдите тест!

Доска почёта

Чтобы попасть сюда — пройдите тест.

-

Карина Козюлькина

11/11

-

Владислав Кейш

11/11

-

Александра Воронова

10/11

-

Екатерина Челядинова

10/11

-

Мария Дычинская

11/11

-

DELETED

10/11

-

Алмас Амир

10/11

-

Елена Наумцева

9/11

-

Виктория Анисимова

10/11

-

Ильсур Сайфутдинов

11/11

Оценка по биографии

4.4

Средняя оценка: 4.4

Всего получено оценок: 4551.

А какая ваша оценка за эту биографию?

Петр Чайковский — биография

Петр Ильич Чайковский – великий русский композитор, дирижер, педагог и критик. Его произведения известны всем соотечественникам, даже в том случае, если эти люди не являются приверженцами классической музыки.

Детство и юность

Петр Ильич Чайковский родился в поселке Воткинск (современная Удмуртия) 7 мая 1840 года. Отец будущего музыканта – представитель казачьего рода Чаек, хорошо известного на Украине. Илья Петрович служил инженером. Мама большого семейства тоже была образованной женщиной. В Училище женских сирот Александра Андреевна Ассиер изучила целый ряд предметов – литературу, географию, арифметику, иностранные языки, риторику.

В этом уральском поселке Чайковский-старший руководил Камско-Воткинским сталелитейным заводом. Это было крупнейшее предприятие Российской империи, руководитель которого получал прекрасное жалование и целый ряд преференций. Для жилья Чайковским предоставили огромный казенный дом, у директора завода было и собственное войско, которое состояло из сотни казаков. Семья жила на широкую ногу, часто принимала в своем доме гостей – местных дворян, иностранных инженеров, столичную молодежь.

Семейство Чайковских было большим, будущий композитор был вторым ребенком. Его старшего брата звали Николай, после Петра родился еще один мальчик – Ипполит, затем сестра Александра. Места в огромном доме хватало всем, вместе с Чайковскими жили и многочисленные родственники главы семейства. Родители очень заботились о воспитании и образовании своих детей, из Санкт-Петербурга они выписали гувернантку. Эта женщина, Фанни Дюрбах, была француженкой, она очень долго жила в семье Чайковских.

Родители будущего композитора очень любили музыку, они и сами были прекрасными музыкантами. Отец играл на флейте, мама – на арфе и фортепиано. У Александры Андреевны был сильный голос, она прекрасно исполняла романсы. Гувернантка музицировать не умела, но музыку тоже очень любила. Отец приобрел два музыкальных инструмента – рояль и оркестрион (так в те времена называли механический орган). Играть на рояле маленького Петрушу учила крепостная крестьянка Марья Пальчикова, владевшая музыкальной грамотой.

Юный Чайковский увлеченно изучал основы игры на рояле. В тот период им владела еще одна большая страсть – любовь к поэзии. Он не только с упоением читал стихи разных авторов, но и сам сочинял их на французском языке. Настоящим кумиром будущего композитора в то время был Людовик XVII. Молодой человек старательно изучал биографию французского короля, пытался отыскать в разных источниках как можно более фактов о жизни монарха. Эта историческая личность для Чайковского была и осталась примером для подражания.

Когда Петруше исполнилось восемь лет, их большое семейство переезжает в Москву. Илья Петрович в тот период вышел на пенсию, искал достойное место работы. Через два месяца Чайковские оказались в Санкт-Петербурге, где отец сразу же пристроил своих старших сыновей в пансион Шмеллинга. В северной столице Петруша продолжает обучаться музыке. Он знакомится с балетом, оперой, симфоническим оркестром. Мальчик долго привыкает к сырому климату Петербурга, часто болеет. В подростковом возрасте он перенес корь, тяжелый недуг не прошел бесследно. В течение всей жизни у композитора время от времени случались припадки.

Чайковские устроили старшего сына Николая в Институт Корпуса горных инженеров. Все остальное семейство отправилось в город Алапаевск. Здесь Илья Петрович занял должность руководителя завода наследников Яковлева. Гувернантку-француженку к тому времени сменила русская женщина, Анастасия Петрова, которая стала заниматься воспитанием и обучением юного Петра Ильича. В 1849 году семейство Чайковских увеличилось, родились два младших сына-близнеца Анатолий и Модест.

Образование и служба

Петруша с ранних лет увлекался музыкой, и родители прекрасно видели, что у него есть способности. Но они совсем не думали, что занятие музыкой может стать достойной профессией для их одаренного сына. Это выглядело как-то несерьезно. Самое интересное, что их мнение полностью разделял и сам будущий композитор. Он с удовольствием посещал оперу, балет, приходил в восторг от концертов выдающихся музыкантов, но не связывал свое будущее с музыкой.

Настало время определяться с местом учебы. Сначала у родителей была идея отправить Петрушу учиться на горного инженера, так же, как и старшего сына. Однако местом его учебы стало Императорское училище правоведения, находящееся в северной столице. С десятилетнего возраста Петруша обучается юриспруденции. Он учился здесь десять лет. Вначале мальчику было очень тяжело, он тосковал по родителям, привычной жизни. Его родители жили слишком далеко и не могли часто навещать ребенка.

В Петербурге у Чайковских был друг – Модест Вакар, он стал настоящим попечителем для малолетнего студента. Но для самого Вакара теплое отношение и участие к маленькому Чайковскому закончились настоящей трагедией. Малолетний студент совершенно случайно, непреднамеренно занес в дом Вакара скарлатину. Этой болезнью заразился маленький сынок Модеста, и спасти ребенка не удалось.

В 1852 году Илья Петрович оставил службу. Все большое семейство отправилось в Петербург. Петруше стало намного легче, теперь он не только виделся со своей семьей, но и часто посещал русский балет, оперу. У молодого Чайковского появился близкий друг, им стал одноклассник Алексей Апухтин, будущий поэт. Этот человек оказал большое влияние на формирование личности и взглядов Петра Ильича.

Молодому Чайковскому было только 14 лет, когда умерла его мама. Она скончалась от холеры, большое семейство осиротело. Всех старших детей Илья Петрович устроил в образовательные учреждения закрытого типа. С ним остались только близнецы, которым на тот момент не исполнилось и пяти лет. Втроем они временно поселились у брата Ильи Петровича.

В течение трех лет, с 1855 по 1858 год, Петр Ильич берет уроки игры на фортепиано у Рудольфа Кюндингера, известного немецкого пианиста. Отец будущего композитора нанял этого музыканта, но через три года занятия пришлось прекратить. Старший Чайковский вложил все свои средства в дело, которое принесло сплошные убытки. Музыканту было нечем заплатить за его работу. Но инженер Чайковский был на редкость удачлив, совсем скоро он стал главой Технологического института. Ему предложили хорошее жалование, огромную казенную квартиру.

Училище правоведения Петр окончил в 1859 году. Здесь его все любили – и педагоги, и сверстники. Чайковский всегда умел располагать людей к себе, привлекать их теплым отношением и добрым нравом.

Могут быть знакомы

Карьера юриста

Молодому человеку предложили место в Министерстве юстиции, он вел крестьянские дела. В часы досуга Петр Ильич посещает оперу, занимается музыкой. Когда молодому юристу исполнился 21 год, он впервые побывал за границей, посетил несколько европейских стран. Чайковский за границей выступал в качестве переводчика, он сопровождал инженера Писарева, приятеля своего отца. Будущий композитор к тому периоду прекрасно знал два языка – французский и итальянский.

Творчество

Молодой сотрудник Министерства Юстиции даже не помышляет о музыкальной карьере. Он не сознает силу своего дара, но отец будущего композитора к тому времени уже хорошо понимает, что у его сына – великий талант. Однажды Илья Петрович даже посетил Кюндингера, желая убедиться, что он не ошибается относительно большого дарования Петра.

Однако немецкий пианист не был в большом восторге от способностей молодого Чайковского, он отозвался о них весьма прохладно. Кроме того, его ученику уже исполнился 21 год, а в таком возрасте заниматься музыкой несколько поздно. Но Илья Петрович настаивал, чтобы сын совмещал работу с получением музыкального образования.

В этот период в Санкт-Петербурге открылась новая консерватория под руководством Антона Рубинштейна. Петр загорелся идеей учиться здесь, он стал одним из первых студентов этого учебного заведения по классу композиции. Юриспруденцию пришлось забросить, совмещать работу с учебой было невозможно.

Дипломной работой Чайковского стала кантата «К радости», созданная к русскоязычному переводу оды Шиллера с таким же названием. Петербургские музыканты не одобрили это музыкальное произведение. Самым резким был критик Цезарь Кюи, он назвал Чайковского слабым композитором, обвинил его в консерватизме. На самом деле это было совсем не так – для Чайковского музыка была и оставалась свободой, его кумирами были музыканты, не признававшие правил и авторитетов.

Молодой композитор выстоял под градом критики. Он окончил консерваторию с серебряной медалью, высшей наградой того времени, и сразу же принялся за работу. Николай Рубинштейн, брат знаменитого музыканта, предложил ему должность профессора в Московской консерватории.

Расцвет музыкальной карьеры

Молодой Чайковский стал замечательным педагогом. Он очень многое сделал для правильной организации учебного процесса. Учебников по профилю было очень мало, профессор сам пишет методические пособия, занимается переводами зарубежных учебников. В течение двух лет он успевает преподавать и занимается творчеством. Но это было очень нелегко, и Петр Ильич решил покинуть консерваторию.

В это время ему очень помогала богатая покровительница, вдова Надежда фон Мекк. Ежегодная сумма в шесть тысяч рублей позволяла молодому композитору не думать о хлебе насущном. Свое время он стал тратить только на творчество. В этот период он знакомится с композиторами из знаменитой «Могучей кучки». Главой содружества был Милий Балакирев, именно он посоветовал Чайковскому создать увертюру-фантазию по мотивам «Ромео и Джульетты» (1869).

После этого композитор пишет не менее знаменитое произведение — симфоническую фантазию «Буря» (1873), идея создания которой принадлежала музыкальному критику Владимиру Стасову. В этот период Петр Ильич много путешествует, набирается сил и вдохновения для творчества. 70-е годы можно с полным правом назвать периодом расцвета его музыкальной карьеры. Он создает балет «Лебединое озеро», оперу «Опричник», Вторую, Третью симфонию, Фантазию «Франческа да Римини», оперу «Евгений Онегин», фортепианный цикл «Времена года».

В следующее десятилетие он часто бывает за границей в рамках концертных поездок. Чайковский подружился со многими выдающимися музыкантами – Эдвардом Григом, Антонином Дворжаком, Густавом Малером. Во время концертов он выступает в качестве дирижера. Петр Ильич побывал и в Соединенных Штатах, где его ждал оглушительный успех. Теперь уже никто не сомневался в гениальности этого композитора.

В последние годы свой жизни он живет в подмосковном Клину, занимается благотворительностью, жертвует деньги на школу, помогает бороться с частыми пожарами. В этом городе он пишет балет «Щелкунчик», оперу «Пиковая дама», «Иоланту», Пятую симфонию, увертюру «Гамлет». Композитор получает международное признание, в 1892 году он избран членом-корреспондентом Академии изящных искусств в Париже, в 1893 году — почетным доктором Кембриджского университета.

Личная жизнь

Петр Ильич был очень дружелюбным человеком, у него сохранилось много фотографий с друзьями-мужчинами. И хотя это самые обычные фото, они вызывали жгучий интерес у определенных личностей, явно завидовавших композитору. Еще при жизни композитора общество часто обсуждало нетрадиционную ориентацию известного музыканта.

Ходили сплетни, что его мужчинами являются братья Сафроновы (Алексей и Михаил), Владимир Давыдов, Иосиф Котек. При этом в жизни знаменитого музыканта присутствовали и женщины. Об одной из них, Надежде фон Мекк, уже упоминалось выше. Француженку Арто Дезире все называли избранницей Петра. Но девушка вышла замуж за испанца Мариана Падилью. Официальной супругой композитора стала Антонина Милюкова. Она была младше своего гениального мужа на восемь лет. Этот союз был недолгим, через несколько недель супруги расстались, хотя развестись они так и не успели.

Злопыхатели говорили, что все связи с женщинами у Чайковского – обыкновенная фикция, которой он прикрывает свое влечение к мужчинам. Как было на самом деле – неизвестно, да это и не так важно, возможно, это просто выдумки завистников, пытающихся очернить личность великого музыканта. Маленький пример – тот же самый Рудольф Кюндингер, который по какой-то причине так яростно отрицал наличие таланта у Чайковского. Вряд ли опытный педагог мог так сильно ошибаться в степени одаренности своего подопечного. Скорее всего, здесь тоже взыграла обыкновенная зависть.

Что касается личной жизни музыканта, мы не имеем права судить его. Во главу угла здесь следует поставить другое – гениальность русского композитора, который оставил нам свои бессмертные творения.

Причина смерти

В ноябре 1893 года композитор умер от холеры. Его прах погребен в Некрополе мастеров искусств.

Слушать композиции

Ссылки

- Страница в Википедии

Для нас важна актуальность и достоверность информации. Если вы обнаружили ошибку или неточность, пожалуйста, сообщите нам. Выделите ошибку и нажмите сочетание клавиш Ctrl+Enter.

Пётр Ильич Чайковский. Биография

Пётр Ильич Чайковский родился 7 мая 1840 года в поселке Воткинск. Сейчас территория поселка относится к Удмуртии. Отец Петра Ильича, Илья Петрович Чайковский не владел музыкальной профессией. Он происходил от казачьего рода Чаек, который хорошо известен Украине и работал простым инженером. Мать Петра Ильича Чайковского, Александра Андреевна Ассиер окончила училище для сирот, где занималась литературой, географией, арифметикой, риторикой и иностранными языками.

В свое время отец Петра Ильича Чайковского получил хорошую должность, из-за чего переехал на Урал. Он стал руководителем Камско-Воткинского сталелитейного завода, одного из крупнейших предприятий. Ему предоставили не только большой дом с прислугой, но и войско, в котором служило сто казаков. Среди гостей большого дома бывали дворяне, столичная молодежь, английские инженеры и другие представители высшего общества.

В семье Чайковских было шестеро детей: старший — Николай, второй сын — Пётр (Пётр Ильич Чайковский), Ипполит и младшая сестра Александра, позже родились близнецы Модест и Анатолий. Кроме того, в большом доме всегда жили родственники Ильи Петровича Чайковского, а позже и гувернантка детей, француженка Фанни Дюрбах из Монбельяра, которую встретили как члена семьи.

Из воспоминаний М. И. Чайковского: «Навстречу выбежала масса людей, начались объятия и поцелуи, среди которых трудно было различить родных от прислуги, так ласковы и теплы были проявления всеобщей радости. Мой отец подошёл к молодой девушке и расцеловал её как родную. Эта простота, патриархальность отношений сразу ободрили и согрели молодую иностранку и поставили в положение почти члена семьи».

Несмотря на то, что родители Петра Ильича Чайковского не были профессиональными музыкантами, музыка всегда жила в их доме. Илья Петрович умел играть на флейте, Александра Андреевна – на фортепиано и арфе, говорили также, что она чудесно исполняет романсы, а гувернантка просто очень любила музыку.

В доме Чайковских стоял оркестрион (механический орган) и рояль. Пётр Ильич брал уроки игры на рояле у крепостной Марьи Пальчиковой. Он не только был талантлив в музыке, но и сочинял стихи.

Старшие дети Чайковских получили хорошее образование: они учились в Санкт-Петербурге в пансионе Шмеллинга. Здесь Пётр Ильич познакомился с балетом, оперой и симфоническим оркестром. В юном возрасте случилась беда: Пётр Чайковский переболел корью, от последствий которой страдал всю жизнь.

В 1850 году Пётр Ильич Чайковский поступил в Императорское училище правоведения, где проучился вплоть до 1859 года. До разорения отца и кончины матери Пётр Ильич также брал уроки игры на фортепиано у знаменитого немецкого пианиста Рудольфа Кюндингера. Из-за бедственного положения семьи их позже пришлось прекратить.

После окончания учёбы Пётр Ильич Чайковский работал в Министерстве юстиции, где вёл дела крестьян. В свободное время он ходил в театр и музицировал. В 1861 году Чайковский впервые побывал за границей, где посетил Гамбург, Берлин, Антверпен, Брюссель, Париж, Остенде и Лондон.

Пётр Ильич Чайковский. Музыкальная карьера

В 21 год юный Пётр Чайковский еще не думал о музыкальной карьере, а музыку считал лишь своим увлечением. Всё перевернуло открытие в Санкт-Петербурге новой консерватории, руководителем которой стал сам Антон Рубинштейн. Пётр Ильич Чайковский твёрдо решил туда поступать. Это ему удалось, он стал одним из первых студентов по классу компощиции и окончательно бросил юриспруденцию.

Впоследствии Пётр Ильич преподавал в Московской консерватории и даже сам переводил обучающую литературу для своих студентов. В Москве же начался подъем его творческой карьеры. В 1873 году Чайковский написал другое свое знаменитое произведение – симфоническую фантазию «Буря», снова начал путешествовать, учиться и искать вдохновение.

В 1870-ые годы родились другие великие произведения классика:

- балет «Лебединое озеро»,

- опера «Опричник»,

- Концерт для фортепиано с оркестром,

- Вторая и Третья симфонии,

- фантазия «Франческа да Римини»,

- опера «Евгений Онегин»,

- фортепианный цикл «Времена года» и многие другие.

Пётр Ильич Чайковский путешествовал с концертными гастролями, дружил со знаменитыми музыкантами Европы, перенимая их опыт. Незадолго до своей кончины он переехал в Клин, где много занимался благотворительностью. В 1885 году он помогал бороться с пожаром, из-за которого в городе сгорело несколько десятков домов.

Даже на закате жизненного пути Чайковский продолжал заниматься музыкой. В этот период он написа:

- балет «Щелкунчик»,

- оперу «Пиковая дама»,

- увертюру «Гамлет»,

- оперу «Иоланта»,

- Пятую симфонию.

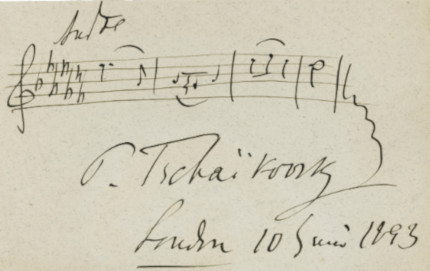

Пётр Ильич Чайковский получил международное признание. В 1892 году его избрали членом-корреспондентом Академии изящных искусств в Париже, а в 1893 году – почетным доктором университета в Кембридже.

Чайковский скончался 6 ноября 1893 года от холеры. Его отпевали в Казанском соборе, а похоронили в Некрополе мастеров искусств.

Творчество Петра Ильича Чайковского

Пётр Ильич Чайковский работал во всех известных музыкальных жанрах своего времени, но отдавал предпочтение масштабным: операм и симфониям. Его занимали глубокий внутренний мир человека, его душа и переживание драмы. Музыка Чайковского при этом очень тонкая, лирическая и певучая. Его произведения вызывают сильный эмоциональный отклик слушателя. Даже малые музыкальные жанры при этом Чайковский сопровождал симфонической масштабностью. Одной из главных тем творчества Петра Ильича Чайковского стали сострадание и любовь к людям.

Чайковский работал и в области хоровой духовной музыки. Продолжателями его музыкальных традиций считали С. Танеева, А. Глазунова, С. Рахманинова, А. Скрябина. Музыка Чайковского стала символом русской жизни и культуры XIX в. Благодаря наследию Чайковского мы смогли заново открыть для себя образы русской и мировой литературы — Пушкина и Гоголя, Шекспира и Данте, русской лирической поэзии второй половины XIX в. Чайковский заслуженно при жизни получил мировую известность и до сих пор считается одним из лучших отечественных композиторов.

Читайте также:

- За мелодией Чайковского я услышала: «Помилуй меня». И жизнь будто перевернулась

- Сэр Джон Тавенер — православный британский композитор

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hz3XaozGKDM

Поскольку вы здесь…

У нас есть небольшая просьба. Эту историю удалось рассказать благодаря поддержке читателей. Даже самое небольшое ежемесячное пожертвование помогает работать редакции и создавать важные материалы для людей.

Сейчас ваша помощь нужна как никогда.

Биография

Русскую культуру сегодня сложно представить без имени Петра Чайковского. Гениальный композитор успел создать множество ярких произведений, которые получили признание не только в России, но и далеко за пределами страны. Тонкий вкус, великолепное музыкальное чутье, идеальный слух позволили мастеру оставаться на вершине славы и после смерти.

Детство и юность

Петр Ильич родился 7 мая 1840 года в поселке Воткинске, расположенном на территории современной Удмуртии. Отец мальчика — Илья Петрович Чайковский, инженер, происходивший из казачьего рода Чаек, известного в Украине. Матерью будущего композитора стала Александра Андреевна Ассиер, выпускница училища женских сирот, где она получила знания по литературе, арифметике, риторике и иностранным языкам.

На Урале семейство оказалось из-за того, что Илье Петровичу предложили должность руководителя Камско-Воткинского сталелитейного завода. В Воткинске Чайковский-старший получил дом с прислугой, в который заглядывали дворяне, молодежь из столицы, английские инженеры и другие достопочтенные личности.

Петр оказался вторым ребенком. У него также был старший брат Николай, младший брат Ипполит и младшая сестра Александра. В доме Чайковских жила не только сама семейная чета с детьми, но и многочисленные родственники Ильи Петровича. Для обучения наследников из Санкт-Петербурга вызвали гувернантку-француженку Фанни Дюрбах, которая впоследствии стала практически членом семьи Чайковских.

Музыка была желанным гостем в родительском доме Петра. Отец умел играть на флейте, матушка — на фортепиано и арфе, а также умело исполняла романсы. Гувернантка музыкальным образованием была обделена, однако тоже питала страсть к творчеству. У Чайковских стоял оркестрион (механический орган) и рояль. В детстве Петя брал уроки игры на рояле у крепостной Марьи Пальчиковой, которая владела музыкальной грамотой.

В 1848 году Чайковские переехали в Москву, так как Илья Петрович ушел на пенсию и намеревался найти частную службу. Через пару месяцев семейство снова переехало, на этот раз — в Санкт-Петербург. Здесь Петр продолжал обучаться музыке, а также ближе познакомился с балетом, оперой и симфоническим оркестром.

В 1849 году Николая Чайковского, старшего брата Петра, определили в Институт Корпуса горных инженеров, а остальные дети вместе с родителями вернулись на Урал, в город Алапаевск. Там глава семейства занял пост руководителя завода наследников Яковлева. Фанни Дюрбах к тому времени покинула семью Чайковских, и для подготовки подросшего Петра к получению дальнейшего образования наняли другую гувернантку — Анастасию Петрову. В том же году у юного музыканта появились еще два младших брата — близнецы Модест и Анатолий.

Образование и госслужба

Родители не рассматривали музыку как достойную профессию для Петра. Поначалу его хотели отправить в Институт Корпуса горных инженеров, как и старшего сына Николая, но потом отдали предпочтение Императорскому училищу правоведения, располагавшемуся в Санкт-Петербурге. В подготовительный класс заведения Петя поступил в 1850 году.

Подростком Петр подружился с одноклассником, поэтом Алексеем Апухтиным, который оказал большое влияние на его взгляды и убеждения. В период с 1855 по 1858 годы Чайковский брал уроки игры на фортепиано у знаменитого немецкого пианиста Рудольфа Кюндингера. Педагога наследнику нанял отец, но весной 1858 года уроки пришлось прекратить: из-за аферы Илья Петрович потерял практически все деньги, и платить зарубежному музыканту стало нечем.

Училище правоведения Петр закончил в 1859 году. По завершении учебы молодой человек получил работу в министерстве юстиции, там он вел дела крестьян. В свободное время продолжал ходить в оперный театр и заниматься музыкой. В 1861 году Чайковский впервые побывал за границей, посетив Гамбург, Антверпен, Брюссель, Париж, Лондон. К тому времени он владел итальянским и французским.

Музыка

Как ни удивительно, даже в 21-летнем возрасте Петр, получивший образование и заступивший на государственную службу, еще не помышлял о музыкальной карьере. Свое увлечение он, как и некогда родители, не воспринимал всерьез. Но, к счастью, отец будущего композитора Илья Петрович все же чувствовал, что сыну суждено стать великим музыкантом.

Чайковский-старший даже сходил к Рудольфу Кюндингеру, чтобы узнать его мнение относительно таланта наследника. Немецкий пианист категорично заявил, что особых музыкальных способностей у Чайковского-младшего нет, да и 21 год не тот возраст, чтобы начинать творческую карьеру. И сам Петр предложение отца совместить работу с получением музыкального образования поначалу воспринял как шутку.

Но когда узнал, что в Санкт-Петербурге открывается новая консерватория, руководить которой будет знаменитый Антон Рубинштейн, все в корне изменилось. Чайковский решил во что бы то ни стало поступить туда, что и сделал, оказавшись в числе первых студентов этого образовательного учреждения по классу композиции. А вскоре после этого бросил юриспруденцию, решив, несмотря на появившиеся проблемы с деньгами, посвятить себя музыке.

В качестве дипломной работы Чайковский написал кантату «К радости» к русскоязычному переводу одноименной оды Фридриха Шиллера. На музыкантов Санкт-Петербурга кантата произвела плохое впечатление. Особенно резко выразился критик Цезарь Кюи, заявив, что как композитор Чайковский крайне слаб, а также обвинив его в консерватизме. И это при том, что для Петра кумирами стали Александр Бородин и Модест Мусоргский — композиторы, не признававшие авторитетов и правил.

Но подобная реакция вовсе не смутила молодого творца. Получив после успешного завершения Петербургской консерватории заслуженную серебряную медаль, бывшую тогда высшей наградой, он с еще большим рвением и азартом взялся за работу. В 1866 году композитор переехал в Москву по приглашению брата своего наставника. Николай Рубинштейн предложил Чайковскому работу профессора в Московской консерватории.

Расцвет карьеры

В Московской консерватории Чайковский показал себя как прекрасный преподаватель, приложив много усилий для организации образовательного процесса. Поскольку достойных учебников для студентов на тот момент существовало мало, композитор занялся переводами зарубежной литературы и даже созданием собственных методических материалов.

Впрочем, в 1878 году Петр Ильич, уставший разрываться между преподаванием и собственным творчеством, оставил должность. Его место занял Сергей Танеев, ставший самым любимым учеником Чайковского. Сводить концы с концами Чайковскому помогала богатая покровительница Надежда фон Мекк. Будучи обеспеченной вдовой, она боготворила композитора и ежегодно предоставляла музыканту субсидии в размере 6 тыс. рублей.

Именно после переезда в Москву начался настоящий подъем творческой карьеры Петра Ильича Чайковского и произошел существенный рост его как композитора. В это время он познакомился с композиторами — участниками творческого содружества «Могучая кучка». По совету Милия Балакирева, главы содружества, Чайковский в 1869 году создал увертюру-фантазию по мотивам произведения Уильяма Шекспира «Ромео и Джульетта».

В 1870-е годы композитор написал такие произведения, как балет «Лебединое озеро», оперы «Опричник» и «Евгений Онегин», концерт для фортепиано с оркестром, симфонии № 2 и № 3, фантазия «Франческа да Римини», фортепианный цикл «Времена года» и другие. В 1880–1890-е Петр Чайковский еще чаще, чем ранее, ездил за границу, причем в подавляющем большинстве случаев — в рамках гастролей.

Во время таких поездок музыкант познакомился и подружился с музыкантами из Западной Европы: Густавом Малером, Артуром Никишем, Эдвардом Григом, Антонином Дворжаком и другими. Сам композитор во время концертов выступал как дирижер. В начале 1890-х Чайковскому даже удалось побывать в США. Там его ждал ошеломляющий успех во время концерта, где Петр Ильич дирижировал при исполнении собственных произведений.

Последние годы перед кончиной Чайковский провел в окрестностях городка Клина под Москвой. Там же композитор, недовольный качеством жизни местных крестьян, договорился об открытии школы и жертвовал деньги на ее содержание. В 1885 году он помогал клинчанам бороться с пожаром, при котором в городе сгорело несколько десятков домов.

В этот период жизни композитор написал балет «Щелкунчик», оперы «Пиковая дама» и «Иоланта», увертюру «Гамлет», Пятую симфонию. Тогда же было подтверждено международное признание таланта Петра Ильича: в 1892 году его избрали членом-корреспондентом Академии изящных искусств в Париже, а в 1893 году — почетным доктором университета в Кембридже.

Личная жизнь

Сохранилось немало фото, где Петр Чайковский запечатлен в благопристойном виде с друзьями-мужчинами. Ориентация композитора еще при его жизни становилась предметом для пересудов: некоторые обвиняли музыканта в том, что тот гомосексуалист. Предполагалось, что мужчины, к которым мастер мог испытывать отнюдь не платоническую привязанность, — Иосиф Котек, Владимир Давыдов, братья Алексей и Михаил Сафроновы.

Сложно судить, есть ли доподлинные доказательства того, что композитор любил мужчин. Его связи с упомянутыми выше личностями могли быть и дружескими. Как бы то ни было, женщины в судьбе Чайковского тоже были, хотя некоторые исследователи утверждают, что так композитор пытался скрыть собственные пристрастия.

Так, несостоявшейся женой Петра Ильича стала молодая французская примадонна Арто Дезире, которая предпочла ему испанца Мариана Падилью. А в 1877 году его официальной супругой стала Антонина Милюкова, которая была младше новоиспеченного супруга на восемь лет. Впрочем, этот брак продлился всего несколько недель, хотя официально Антонина и Петр так и не развелись.

Стоит напомнить и о его связи с Надеждой фон Мекк, которая преклонялась перед талантом композитора и долгие годы поддерживала его материально.

Смерть

Композитора не стало 25 октября (6 ноября по новому стилю) 1893-го. Официальной причиной смерти Петра Ильича медики назвали холеру. В то время Санкт-Петербург оказался во власти эпидемии из-за плохого качества воды. Вечером 20 октября вместе с братом Модестом Чайковским и друзьями мастер посетил ресторан Ф. О. Лейнера на Невском проспекте. По свидетельству некоторых очевидцев, музыкант выпил стакан сырой воды, что и оказалось причиной заражения.

В рамках этого факта существовали и расхождения — приводились мнения о том, что вечером композитор пил белое вино, а некипяченую воду употребил дома, ночью. Также упоминалось, что еще до 20 октября музыкант уже был болен, но не мог распознать болезнь. Уже к утру 21-го у Петра Ильича появились признаки недомогания, которые он оставил без внимания (симптомы совпадали с теми, что уже случались у него в связи с катаром желудка).

Вечером того же дня состояние ухудшилось, прибывшие медики констатировали у больного холеру. В течение следующих дней врачи пытались облегчить страдания композитора, советовали принять горячую ванну с целью выведения токсинов, что ужаснуло Чайковского — ведь именно в ванне умерла его мать, так же заболевшая холерой. Однако медицинские манипуляции не увенчались успехом — время было упущено, и спасти мастера не представлялось возможным.

Нашлось место и альтернативным версиям. В основном они связывались с идеей «скрытого» самоубийства композитора — причины же для такого ухода из жизни (с помощью стакана зараженной воды или яда) назывались разные. Среди наиболее популярных — страх Петра Ильича перед преследованием за гомосексуализм (слух якобы распространили родственницы Николая Римского-Корсакова в отместку за нежелание Чайковского жениться на одной из них).

Существовала и версия об угрозах композитору от русской императорской семьи якобы за связь с одним из ее представителей. Также бытует мнение, что ориентация Петра Ильича стала камнем преткновения для выпускников училища правоведения, потребовавших от музыканта добровольного ухода из жизни. Однако эти домыслы опроверг биограф Чайковского Александр Познанский.

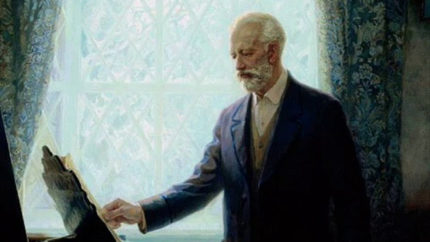

За несколько месяцев до смерти Петр Ильич, находясь на гастролях в Одессе, позировал художнику Николаю Дмитриевичу Кузнецову. Живописец вел работу в перерывах между репетициями и концертами — композитор представлял публике Шестую симфонию, драматизм которой многие позднее объяснили предчувствием скорого ухода. В 1984-м портрет выкупил Павел Михайлович Третьяков.

Память

Имя композитора увековечено не только на родине, но и далеко за ее пределами. Многие музыкальные школы, улицы городов и даже теплоход названы в честь великого творца. В Клину и Алапаевске открыты музеи, посвященные жизни и творчеству Петра Ильича. Нашлось место отражению личности русского гения и в кинематографе. Западных режиссеров в XX столетии (Карл Фрёлих, Кен Рассел) интересовали подробности личной жизни и смерти музыканта.

В 1970-м на советских экранах появился фильм «Чайковский» Игоря Таланкина, в котором главная роль досталась Иннокентию Смоктуновскому. Картина повествовала о биографии композитора с юных лет, а основной сюжетной линией выступила переписка Петра Ильича с Надеждой фон Мекк. В 2022-м Кирилл Серебренников представил на фестивале в Каннах ленту «Жена Чайковского», в центр которой поставил сложные отношения гения с юной женой Антониной Милюковой.

Произведения

- 1866 — Симфония № 1 «Зимние грёзы»

- 1868 — «Воевода»

- 1869 — «Ундина»

- 1872 — «Опричник»

- 1872 — Симфония № 2

- 1875 — Симфония № 3

- 1878 — «Евгений Онегин»

- 1877 — «Лебединое озеро»

- 1878 — Симфония № 4

- 1879 — «Орлеанская дева»

- 1883 — «Мазепа»

- 1885 — «Черевички»

- 1885 — «Манфред»

- 1887 — «Чародейка»

- 1888 — Симфония № 5

- 1889 — «Спящая красавица»

- 1890 — «Пиковая дама»

- 1891 — «Иоланта»

- 1892 — «Щелкунчик»

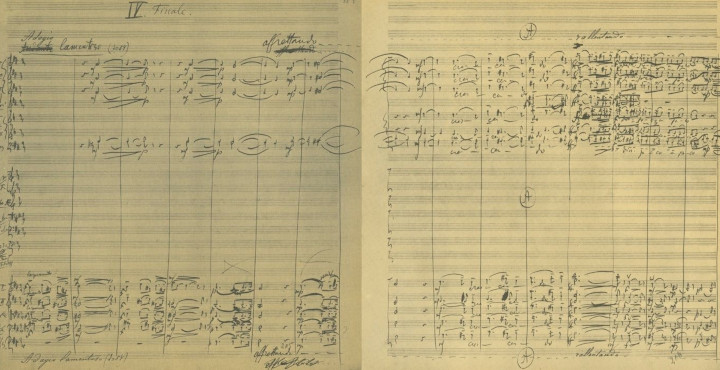

- 1893 — Симфония № 6 «Патетическая»

Интересные факты

- Петра Ильича связывали теплые приятельские отношения с Антоном Чеховым. Сам композитор приезжал в Таганрог, где родился автор «Вишневого сада», в особняк (сейчас — Дом Чайковского), где жил его брат Ипполит, но знакомство писателя и музыканта произошло в Санкт-Петербурге. Антон Павлович посвятил творцу сборник «Хмурые люди», а также собирался вместе с Чайковским написать оперу «Бэла» по мотивам книги Михаила Лермонтова «Герой нашего времени», но планы не удалось осуществить.

- В фильме «Талантливый мистер Рипли» Энтони Мингеллы герой Том Рипли попадает в оперу на постановку «Евгения Онегина» Чайковского. В картине изображается сцена из второго акта (убийство Владимира Ленского), и артисты исполняют арии на русском языке.

- Летом 1892 года, находясь во Франции во время концертной поездки, композитор впервые услышал звучание удивительного инструмента — челесты, клавишного металлофона. Петр Ильич был так очарован им, что тут же захотел его купить. Чарующую мелодию челесты публика вскоре услышала в балете «Щелкунчик», а именно в номере «Танец феи Драже».

Краткая биография Чайковского — 1 вариант

Чайковский Петр Ильич родился в 25 апреля 1840 году в поселке Воткинск. Жил он в семье, где было много детей. В его доме всегда играла музыка. Чайковские увлекались музыкой, поэтому он с ранних лет хорошо имел талант игры на фортепиано, а некоторое время спустя чудесно разбирался и играл по нотам.

Через 9 лет они переезжают в Алапаевск. Недолго пожив там, перебираются в Петербург.

Начальное образование Чайковский получил дома, последующее в пансионе, где проучился 2 года, а следом в школе правоведения.

С 1860 по 1865 обучался в консерватории, которую закончил с серебряной медалью (наивысшая награда тех времен). Позже уезжает в Москву, где ему предлагают место педагога по музыке. Пробыв в Москве 10 лет, он собирает вещи и перебирается за границу. Композитор очень тесно общается с Надеждой фон Мекк – его фанаткой, которая к тому же и очень богата.

За время путешествий он напишет много произведений. В основном, вальсы, увертюры, сюиты. Самые знаменитые постановки мы знаем и по сей день.

Ушел из жизни Петр Чайковский 25 октября 1893 в Петербурге от холеры. Похоронен там же.

Его именем названы улицы и консерватории в Киеве и Москве. Много памятников было установлено в его честь.

И сегодня Чайковского с удовольствием слушают во всем мире.

Краткая биография Чайковского — 2 вариант

Петр Ильич Чайковский известен как один из величайших композиторов не только в России, но и во всем мире. За свои 53 года жизни он написал более 80 музыкальных произведений, в том числе 10 опер и 3 балета.

Петр Ильич Чайковский родился 7 мая 1840 года в Вятской губернии Российской империи (современный город Воткинск в Удмуртии). Его отец – Илья Петрович Чайковский, выдающийся русский инженер. Мать – Александра Андреевна Ассиер, дочка крупного таможенного чиновника, который был родом из Франции.

Родители Петра Ильича любили музыку. Его мать играла на фортепиано и пела, в доме стоял механический орган — оркестрина, в исполнении которого маленький Пётр впервые услышал «Дон Жуана» Моцарта. Пока семья жила в Воткинске, им часто доводилось слышать по вечерам мелодичные народные песни рабочих завода и крестьян.

Детство Чайковского

Чувствительность натуры Петра Ильича проявилась в раннем детстве. Француженка гувернантка Фанни Дюрбах, которую он обожал, сразу заметила в 7-летнем мальчике нежную душу, тягу ко всему прекрасному. Она приоткрыла ему мир искусства, рассказывала о жизни композиторов.

В родительском доме в Воткинске был механический орган.

В него вставлялись валики с крючочками, заводилась пружина, и в комнате звучали отрывки из популярных опер Россини, Беллини, Моцарта.

Маленький Петя слушал оркестрино часами. Фанни не раз заставала мальчика в слезах. Втайне от взрослых он садился за фортепиано и повторял услышанное по памяти.

Учеба

В 1849 году семья переехала в город Алапаевск, а в 1850 году — в Санкт-Петербург. Там родители отправляют Чайковского в Императорское училище правоведения, находившееся вблизи от улицы, ныне носящей имя композитора.

Чайковский провёл 2 года за границей, в 1300 км от родного дома, так как возраст поступления в училище составлял 12 лет. Для Чайковского разлука с матерью была очень сильной душевной травмой. В 1852 году, поступив в училище, он начал серьёзно заниматься музыкой, которую преподавали факультативно.

Чайковский был известен как неплохой пианист и хорошо импровизировал. С 16 лет начал уделять большее внимание музыке, занимаясь у известного педагога Луиджи Пиччоли. Затем наставником будущего композитора стал Рудольф Кюндингер.

Окончив училище в 1859 году, Чайковский получил чин титулярного советника и начал работать в Министерстве юстиции. В свободное от службы время посещал оперный театр, где на него сильное впечатление оказывали постановки опер Моцарта и Глинки.

Музыкальная деятельность Петра Ильича

В 1862 году Петр Ильич оставил карьеру юриста и поступил в консерваторию в класс композиции Антона Рубинштейна. Курс он окончил с золотой медалью и вскоре переехал в Москву, став профессором вновь открытой консерватории.

После первого же исполнения сочиненной им кантаты на оду Фридриха Шиллера «К радости» к нему пришли известность и успех. Критики отмечали, что в России появился необыкновенно талантливый композитор. Следом Чайковский написал свою первую симфонию «Зимние грезы».

В 1868 году Чайковский неожиданно влюбился в итальянскую оперную певицу Дезире Арто, гастролировавшую в России. Он посвятил ей романс для фортепиано, сделал предложение. Но брак не состоялся по разным причинам. Дезире уехала из России, а Чайковский остался в расстроенных чувствах.

Музыкальные произведения

От мук неразделенной любви композитора спасло написание музыки. Он создал увертюру-фантазию «Ромео и Джульетта», за ней последовали симфоническая фантазия «Буря» по Шекспиру, «Франческа да Римини» по «Божественной комедии» Данте.

В 1875 году Петр Ильич Чайковский начал работать над балетом «Лебединое озеро», премьера которого состоялась через 2 года в Большом театре с большим успехом. Он продолжал творить в мире сказки, причудливых фантазий, написал новые балеты — «Спящая красавица», «Щелкунчик».

70-е годы XIX века в творчестве Чайковского ― период творческих исканий. Его привлекают историческое прошлое России, русский народный быт, тема человеческой судьбы. В это время он пишет такие сочинения, как оперы «Опричник» и «Кузнец Вакула», музыка к драме Островского «Снегурочка».

Личная жизнь

Творчество Чайковского сопровождал успех, чего нельзя было сказать о его личной жизни. Он совершил безрассудный поступок и женился на девушке, совершенно чуждой ему по духу, далекой от его музыки. Он и сам не знал, зачем это сделал. Начались новые переживания. Спасаясь от жены, он уехал за границу, потом ушел из консерватории. Он искал путь к самому себе. И не находил.

В 1876 году у Чайковского началась переписка с еще одной странной женщиной — богатой меценаткой Надеждой Филаретовной фон Мекк, вдовой, матерью 18 детей, старше его на 10 лет. Она поощряла творчество композитора, материально поддерживала, но они ни разу не встретились, хотя оба жили в Москве.

Последние годы жизни

До конца жизни Петр Ильич Чайковский сочинял оперы, симфонии, разъезжал по другим странам с концертами. Его музыка звучала во всем цивилизованном мире. В последние месяцы жизни он создал 6-ю «Патетическую симфонию». Она оказалась его завещанием.

Умер Петр Ильич 6 ноября 1893 года в возрасте 53-х лет от холеры. Все расходы на погребение великого композитора на себя взял сам император – Александр III. Петр Ильич Чайковский был похоронен в Александро-Невской лавре в Некрополе мастеров искусств.

Краткая биография Чайковского — 3 вариант

Петр Ильич Чайковский (1840–1893 гг.) – знаменитый русский композитор, дирижер. Один из величайших композиторов мира, автор более 80 музыкальных произведений, среди которых известнейшие балеты «Щелкунчик» и «Лебединое озеро». Один из самых исполняемых композиторов во всем мире.

Родился Петр Ильич Чайковский 25 апреля (7 мая) 1840 года в городе Воткинск в многодетной семье инженера. В доме Чайковских часто звучала музыка. Его родители увлекались игрой на фортепиано, органе.

В биографии Чайковского важно отметить, что в возрасте пяти лет он уже умел играть на фортепиано, еще через три года превосходно играл по нотам. В 1849 году семья Чайковских переехала в Алапаевск, а затем в Санкт-Петербург.

Обучение

Первоначальное образование Чайковским было получено дома. Затем Петр два года занимался в пансионе, после чего – в училище правоведения Петербурга. Творчество Чайковского в этот период проявлялось в факультативных занятиях музыкой. Смерть матери в 1862 году сильно повлияла на ранимого ребенка. После окончания училища в 1859 году Петр стал служить в Департаменте юстиции.

В свободное время часто посещал оперный театр, особенно сильное впечатление на него оказали постановки опер Моцарта и Глинки.

Проявив склонность к сочинению музыки, Чайковский становится студентом консерватории Петербурга. Дальнейшие занятия в жизни Петра Ильича у великолепных преподавателей Н. Зарембы, А. Рубинштейна во многом помогли формированию музыкальной личности. После окончания консерватории композитор Чайковский был приглашен Николаем Рубинштейном (братом преподавателя) в Московскую консерваторию на должность профессора.

Творческая и личная жизнь

Многие концерты Чайковского были написаны во время работы в консерватории. Опера «Ундина»(1869 г.) не была поставлена, автор уничтожил ее. Лишь небольшая часть ее позже была представлена как балет Чайковского «Лебединое озеро».

Стоит кратко отметить, что в 1877 году, чтобы избавиться от сплетен о своей нетрадиционной ориентации, Чайковский решил жениться на студентке консерватории Антонине Милюковой. Не испытывая к жене чувств, спустя несколько недель он навсегда уехал от нее. С тех пор супруги жили раздельно, они так и не смогли развестись в силу различных обстоятельств.

В 1878 году он покидает консерваторию и уезжает за границу. В то же время Чайковский близко общается с Надеждой фон Мекк – богатой поклонницей его музыки. Она ведет с ним переписку, поддерживает его материально и морально.

За двухлетнее время проживания в Италии, Швейцарии появляются новые великолепные произведения Чайковского: опера «Евгений Онегин», Четвертая симфония.

В мае 1878 года Чайковский делает вклад в детскую музыкальную литературу: пишет сборник пьес для детей под названием «Детский альбом».

После материальной помощи Надежды фон Мекк композитор много путешествует. С 1881 по 1888 год им было написано множество произведений. В частности, вальсы, симфонии, увертюры, сюиты.

Наконец в биографии Петра Чайковского установился спокойный творческий период, тогда же автор сам смог дирижировать на концертах.

Смерть и наследие

Умер Чайковский в Петербурге 25 октября (6 ноября) 1893 от холеры. Его похоронили в Александро-Невской лавре в Санкт-Петербурге.

Именем великого композитора названы улицы, консерватории в Москве и Киеве, а также прочие музыкальные учреждения (институты, колледжи, училища, школы) во многих городах бывшего СССР. В его честь установлены памятники, его именем назван театр и концертный зал, симфонический оркестр и международный музыкальный конкурс.

Она ведет с ним переписку, поддерживает его материально и морально.

За двухлетнее время проживания в Италии, Швейцарии появляются новые великолепные произведения Чайковского: опера «Евгений Онегин», Четвертая симфония.

В мае 1878 года Чайковский делает вклад в детскую музыкальную литературу: пишет сборник пьес для детей под названием «Детский альбом».

После материальной помощи Надежды фон Мекк композитор много путешествует. С 1881 по 1888 год им было написано множество произведений. В частности, вальсы, симфонии, увертюры, сюиты.

Наконец в биографии Петра Чайковского установился спокойный творческий период, тогда же автор сам смог дирижировать на концертах.

Смерть и наследие

Умер Чайковский в Петербурге 25 октября (6 ноября) 1893 от холеры. Его похоронили в Александро-Невской лавре в Санкт-Петербурге.

Именем великого композитора названы улицы, консерватории в Москве и Киеве, а также прочие музыкальные учреждения (институты, колледжи, училища, школы) во многих городах бывшего СССР. В его честь установлены памятники, его именем назван театр и концертный зал, симфонический оркестр и международный музыкальный конкурс.

Петр Ильич Чайковский

Один из самых лиричных композиторов, овеянный всемирной славой. Его именем в России названа главная вотчина, воспитывающая российских музыкантов – Московская государственная консерватория. А также престижный международный конкурс академических исполнителей, крупнейшее событие мирового масштаба. Пётр Ильич Чайковский – выдающий русский композитор, целиком отдававший себя миру вдохновения и создавший такие гениальные творения, что они во всём мире в нынешнее время являются самыми исполняемыми произведениями. Очаровывающий мелодизм, блестящее владение композиторской техникой, а также умение видеть в любом трагизме светлое и гармоничное делает Петра Ильича величайшей творческой личностью не только в отечественной, но и во всей мировой музыкальной культуре.

Краткую биографию Петра Ильича Чайковского и множество интересных фактов о композиторе читайте на нашей странице.

Краткая биография Чайковского

Петр Ильич родился в российской глубинке – селении Воткинск близ небольшого завода 7 мая 1840 года в семье горного инженера. С рождения мальчик впитал в себя исконный дух русской интеллигенции. Детство его прошло в родном имении под сенью деревенской природы, среди живописных видов и звуков народных песен. Все эти впечатления ранних лет позднее оформились в необыкновенную любовь к Родине, ее истории и культуре, ее такому творческому народу.

Образование детям в этой большой и дружной семье стремились дать лучшее. С ними всегда была гувернантка Фанни Дюрбах, которая, кстати, сохранила очень много воспоминаний о маленьком Петруше. С детства это был самый впечатлительный, тонко чувствующий, ранимый, талантливый ребенок с тончайшей нервной организацией. Няня называла его «фарфоровый мальчик». Такая хрупкая, неврастеничная психическая структура, такое острое восприятие жизни и чувствительность сохранились у него на всю жизнь.

Дом был наполнен музыкой, родители будущего композитора сами любили музицировать, они устраивали музыкальные вечера, в гостиной стоял механический орган (оркестрина). Любовь к занятиям на фортепиано ему привила горячо любимая матушка, и уже с 5 лет он довольно регулярно упражняется. Занятия музыкой захватывали его целиком, но, испугавшись за неустойчивую психику Пети, родители отправили его учиться в Императорское училище правоведения в Санкт-Петербурге, считая, что музыка ему во вред.

Биография Чайковского гласит, что по окончании учебы, в 1859 году Петр Ильич немного поработал в чине титулярного советника в Министерстве юстиции, продолжая факультативно заниматься музыкой, посещая музыкальные вечера и оперные спектакли. К тому моменту он уже считался хорошим пианистом и импровизатором. Благодаря службе он впервые попал за границу, поехав в трехмесячное турне с инженером Писаревым в качестве переводчика. Позднее поездки в Европу с гастрольными выступлениями или для отдыха станут для него важнейшей частью творческой деятельности. Сама возможность побывать в Европе, приобщиться к ее культурным памятникам будоражила его.

В 1862 году он окончательно решает связать свою жизнь с музыкой. Точнее, для себя он определил это как служение Музыке. Он поступает в только что открывшуюся Санкт-Петербургскую консерваторию, где обучается по классу композиции. Там он знакомится с Антоном Рубинштейном, который оказал значительное влияние на его жизнь. Так вскоре после окончания консерватории Чайковским (с большой серебряной медалью, высшей наградой), Рубинштейн приглашает его в Москву – теперь уже преподавать основы сочинения, гармонии, теории музыки и оркестровки.

Педагогическая деятельность Чайковского

Стоит отметить, что московская консерватория на тот момент (в 1866 году) тоже только начала существовать. По сути, на тот момент не было отечественной школы, обучающей исполнительскому или композиторскому мастерству. Были разрозненные переводы западных учебников, отдельные классы учителей, которые не стали концертирующими музыкантами, а передавали свои навыки ученикам по принципу «делай как я».

Чайковский не только читал лекции, многие учебные программы и пособия он написал непосредственно сам, что-то переводил из зарубежных источников. Остались записи лекций его ученика, выдающегося русского композитора Сергея Танеева, из которых можно судить о глубине познаний, способности вдумчиво анализировать музыку с точки зрения ее строения, формы, элементов. Это титанический методический труд, переоценить который невозможно.

Благодаря стараниям Петра Ильича обучение российских музыкантов и особенно композиторов приобрело систему, метод, цельность. Долгое время эта часть его биографии опускалась, ее считали незначительным эпизодом. Виной тому собственные высказывания Чайковского о том, что педагогическая работа его тяготит, ученики глупы и невежественны. Но все эти слова совершенно не отражают истину – явление Чайковского как педагога в тогдашней национальной музыкальной культуре предопределило на столетия (!) появление русской композиторской школы и уникальных, самобытных, гениальных композиторов. Это целая веха в отечественной музыкальной педагогике.

Примечательно, что такой серьезный вклад в преподавание и критику Чайковский внес, почти не уменьшая времени на собственные сочинения. Это характеризует его как человека чудовищной работоспособности, трудоголика, который бросил каждую минуту своего земного пребывания на алтарь Музыки.

Становление как композитора

Его творческий путь не был усыпан розами. В самом начале его часто резко критиковали за желание угодить слушателю. Затем, когда он уже часто бывал в Европе и пытался соединить лучшее от западной культуры с традиционными русскими чертами, ему трудно было встретить единодушие аудитории. По-настоящему его гений оценили лишь в конце.

Ранние сочинения Чайковского датируются 1854 годом. Это были небольшие пьесы — «Анастасия-вальс» и романс «Мой гений, мой ангел, мой друг…». Ученические его работы консерваторского периода уже выдают в нем мастера. Одна из работ – программное произведение к драме Н.А. Островского «Гроза». Со знаменитым драматургом впоследствии Петра Ильича связывала не только нежная дружба, но и творческие проекты. Так в 1873 году была написана музыка к сказке «Снегурочка», позднее на эту же тему написал оперу Николай Римский-Корсаков.

Это время (конец 60-х и начало 70-х) было для него творческим поиском, наиболее обращенным к народному искусству. Тогда же примерно был издан его сборник «50 русских народных песен для фортепиано в 4 руки». Сказочно-мифический сюжет, присущий фольклору, был воплощен в опере «Ундина». Первая постановка ее прошла с определенным успехом, но уже к концу сезона ее сняли из театрального репертуара. Рукопись композитор уничтожил. Лишь некоторые музыкальные фрагменты перешли позднее в «Снегурочку». По ним можно судить, что к тому моменту Петр Ильич владел техникой колористического письма.

За годы работы в консерватории он написал много произведений, из знаковых можно перечислить 4 симфонии, 5 опер, принесший ему мировую славу балет «Лебединое озеро», концерт для фортепиано с оркестром, 3 струнных квартета.

Постепенно он пришел к пониманию, что должен больше времени посвящать сочинению музыки. Изнуряющая работа в консерватории требовала очень много времени и сил. И в 1878 году Чайковский проводит последние свои занятия, но до конца жизни сохраняет переписку со многими учениками, ставшими потом маститыми исполнителями. В письмах он всегда оставался их педагогом и цензором, давал рекомендации.

В 1877 году композитор начинает работу над «Евгением Онегиным». Поглощенный сочинением, он как-то слишком поспешно женится на Антонине Милюковой. Брак развалился буквально через несколько недель. Все в молодой жене Чайковского раздражало. А совместная жизнь с ней стала серьезным испытанием для него. Душевные терзания этого периода привели к нервному срыву и сказались на музыке. Так совпало, что написанные в этот момент «Евгений Онегин» и 4-я симфония стали вершинами его творчества.

В 1878 году он уезжает оправиться от происшедших событий за границу. Тогда помощь ему стала оказывать Надежда Филаретовна фон Мекк, меценат и поклонница творчества Петра Ильича. В течение долгих 14 лет они переписывались, но так ни разу и не встретились. Тем не менее, ее моральная и материальная помощь позволяли Петру Ильичу заниматься творчеством относительно свободно, он мог не оглядываться на издателей или дирекцию театров.

С 1880-х годов он много гастролирует по миру. Он сводит личное знакомство с такими столпами европейской и русской культуры как Лев Толстой, Эдвард Григ, Антонин Дворжак и многими другими. Вся его такая сильная впечатлительность как губка впитывала богатство и разнообразие мира. Он один из немногих счастливчиков, кому удалось завоевать признание публики, критиков, коллег еще при жизни.

Согласно биографии Чайковского в последние годы его неизъяснимо потянуло на родину, композитору хотелось жить вдали от шумных городов, где на улице его мог узнать любой. Он признавался, что бесконечно устал от окружающей его суеты. Поэтому он выбирал небольшие дачные поселки под Москвой, где арендовал усадьбу. Последний дом, в котором он жил в подмосковном Клину, стал домом-музеем мемориальным заповедником имени композитора.

Умер он в 1893 году неожиданно. Врачи диагностировали холеру, которая развилась буквально за несколько дней. Незадолго до этого ему подали в одном из ресторанов стакан некипяченой воды. Хотя и существовали другие версии по поводу смерти Чайковского, доказательств их предоставлено не было.

Интересные факты о Чайковском

- Долгое время жизнеописание этого величайшего композитора, внесшего значительный вклад в мировую культуру, было окружено мифами и легендами. Галантный XIX век не допускал упоминания фактов, даже в малейшей степени компрометирующих столь выдающегося человека. Далее эту традицию подхватила советская идеология, привнесшая в образ композитора новые черты, отвечающие задачам построения нового общества. Начало XXI века принесло моду на обсуждение самого личного и интимного, и превратило внутренний мир Художника в большую проходную площадь.

- В ранней молодости Петр Ильич был влюблен в бельгийскую певицу Дезире Арто, он даже собирался сделать ей предложение. Но она внезапно уехала и вышла замуж за другого. Чайковский невероятно страдал, посвятил ей романс «Забыть так скоро». В фильме Игоря Таланкина 1970 года «Чайковский» этот эпизод показан выразительно. В главной роли блистательный Иннокентий Смоктуновский, а в роли Дезире – Майя Плисецкая в необычном для себя амплуа.

- Из биографии Чайковского мы знаем, что в 1893 году композитор был награжден почетной ученой степенью от Кембриджского Университета.

- В настоящее время ведутся судебные слушания по делу о праве на название. Балет «Спящая красавица» невольно стал предметом горячего спора с компанией «Уолт Дисней» за эмблему. Также ожидает вердикта заявка кинокомпании на патент имени «Принцесса Аврора», которая также является главной героиней произведения Чайковского. Примечательно, что Дисней воспользовался музыкой Петра Ильича при создании одноименного мультфильма 1959 года.

- Большую часть жизни Чайковский был подвержен депрессиям. С 14-ти лет по поводу рано ушедшей матери, чью потерю он долго оплакивал. Он также был ипохондриком. Больше всего он боялся оглохнуть как Бетховен.

- «Вдохновение — гость, который охотно не посещает ленивое». Этим принципом он руководствовался всю свою жизнь.

- В 1877 богатая предпринимательница Надежда фон Мек поддержала скрипача Иосифа Котека, который был бывшим студентом и другом Чайковского и был рекомендован ей пианистом Николаем Рубинштейном. Она была впечатлена композитором Чайковским, и расспрашивала Рубинштейна подробно о нем. Именно Котек, однако, убедил ее написать ему, после чего она представилась как “пылкий поклонник”. Таким образом, их отношения закрепились как эпистолярная дружба: между 1877 и 1890, они обменялись более чем 1200 письмами, и она была той, кто поддержал его после того, как критики разорвали его Пятую Симфонию. Она поощряла его упорно продолжать заниматься сочинениями. Они просто встретились лично однажды, случайно, в августе 1879.

Характерные особенности музыки Чайковского

Среди музыковедов нередко мнение, что Чайковский – великий оперный, симфонический, балетный композитор, но камерная или инструментальная музыка у него слабоваты, не столь интересны. Отмечают также его «нефортепианное мышление», мешающее создать малыми выразительными средствами нечто по-настоящему грандиозное. Это ошибочное мнение. Чего только стоят «6 пьес для фортепиано», это целый спектакль для исполнителя – спектакль одного актера, где он может показать все свое прекрасное чувствование и музыкальность.

Его мелодике свойственна невероятная интонационная тонкость. У него как у Баха в музыке закодированы интонации. Их тончайшие переливы и игра являются его индивидуальной композиторской чертой.

Критика Чайковского

Мимолетной считают писательскую деятельность композитора. Однако, несмотря на недолгий период, который Петр Ильич посвятил литературному опыту, его статьи в журналах «Русские ведомости» и газете «Современная летопись» имели важнейшее значение в культурной жизни России, так как помогали формировать мнение и видение музыки широким массам.

Его собственные высокие нравственные и эстетические идеалы, к которым он стремился осознанно всю свою жизнь, заставляли его размышлять о роли искусства в жизни общества и человека. Он испытывал острую потребность делиться подобными мыслями с соотечественниками. Во многом его взгляды тогда в отношении музыки определяли воззрения современников.

Последними публикациями, написанными Петром Ильичом в командировке в Баварии, стали отчеты о вагнеровских концертах в 1876 году. К концу его Чайковский уже стал символом русской истории, русской интеллигенции, русского духа.

Не Чайковский Чайковский

У Петра Ильича, как ни у какого более композитора, есть произведения, которые официально имеют 2 редакции – одна авторская, другая – с чужими правками. Причем, внесенные изменения значительны. Известно, что сегодня, в силу сложившейся исполнительской традиции, в некоторых произведениях чаще всего звучит не совсем Чайковский. Например, «Вариации на тему рококо» для оркестра и соло виолончели.

Концертных произведений для традиционно «оркестровых» инструментов не так много, любой музыкант-инструменталист мечтает показать красоту звучания своего инструмента отдельно от оркестра. В 1876-77 году появились на свет «Вариации». Это был давно ожидаемый подарок для московского виолончелиста Вильгельма Фитцегагена, близкого друга композитора, по совместительству – первой виолончели Русского Музыкального Общества. Он участвовал во всех премьерах музыки Чайковского как солист, исполнитель первой партии. Главный доверенный музыкант Петра Ильича.

Премьера «Вариаций» состоялась в ноябре 1877 года, она прошла без Чайковского, который в тот момент находился за границей на репетициях и исполнениях других своих сочинений. После премьеры Фитценгаген отнес ноты издателю Чайковского Петру Юргенсону со своими правками. Так он полностью убрал 1 из 8 вариаций, некоторые из них поменял местами и изменил коду. В таком виде ноты пошли в печать.

Изменения, на взгляд «редактора» Фитценгагена, позволили самую виртуозную часть произведения поставить в финал, где он мог блеснуть исполнительским мастерством. Петр Ильич тогда много гастролировал, на письма «редактора» не отвечал. Но не потому, что был согласен с редакцией. А в скором времени даже возражать некому стало – Николай Васильевич умер. Спустя еще несколько лет – и сам Петр Чайковский.

Долгие годы путаница с редакциями оставалась в неизвестности. Артисты за это время привыкли исполнять редактированный вариант. Именно в этой версии, начиная с 1962 года, «Вариации на тему рококо» становятся обязательным произведением на 3 туре конкурса им. Чайковского. Последние 3 десятка тактов для всех исполнителей технически очень трудны, чисто их сыграть практически не возможно. Но долгая практика исполнения именно этого нотного варианта создала произведению своеобразный ореол виртуозности, особой сложности, доступной не каждому исполнителю. Теперь, если кто-то пожелает исполнить его в авторской версии, немедленно будет признан струсившим или мало техничным.

Интерпретации и современные обработки произведений Чайковского

В современном исполнительском искусстве лучшим исполнителем музыки Чайковского считают Михаила Плетнева. В 20-м веке одной из ярчайших и точнейших интерпретаций считали технически совершенную и стилистически безупречную игру Святослава Рихтера. Среди симфонических исполнений выделяют трактовки дирижеров Леонарда Бернстайна, Евгения Мравинского, Евгения Светланова.

Романсная лирика Чайковского чрезвычайно привлекательна для артистов оперы и камерного жанра. Такие разноплановые вокалисты как Сергей Лемешев, Дмитрий Хворостовский, Галина Вишневская, каждый со своей уникальной певческой манерой, с блеском исполняли тонкие, полные невероятной эмоциональной насыщенности романсы Чайковского.

Есть и огромное количество обработок знаменитейших тем Чайковского на электронных инструментах и со спецэффектами:

- Фаустаса Латенаса;

- Клинта Мэнселла;

- Сергея Жилина;

- в джазовой обработке;

- рок-обработке;

- электропоп-обработке.

В 1945 Вере Мухиной торжественно поручили изготовить памятник Петру Ильичу Чайковскому. Задумка скульптуры не сразу была воплощена в жизнь, несколько раз ее приходилось полностью переделывать. В итоге автор не дожила до дня открытия памятника, это была ее последняя работа. Но в окончательной версии он являет собой символ творческого вдохновения. Символично и его расположение – во дворе Московской консерватории, где ежедневно проходят толпы спешащих студентов музыкальных факультетов и туристов, желающих приобщиться к источнику русской музыки.

Понравилась страница? Поделитесь с друзьями:

Фильм о Чайковском

|

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky |

|

|---|---|

| Пётр Ильич Чайковский | |

Portrait c. 1888 by Émile Reutlinger |

|

| Born | 7 May 1840

Votkinsk, Russian Empire |

| Died | 6 November 1893 (aged 53)

Saint Petersburg |

| Works | List of compositions |

| Signature | |

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky[n 2] ( chy-KOF-skee;[2] 7 May 1840 – 6 November 1893)[n 3] was a Russian composer of the Romantic period. He was the first Russian composer whose music would make a lasting impression internationally. He wrote some of the most popular concert and theatrical music in the current classical repertoire, including the ballets Swan Lake and The Nutcracker, the 1812 Overture, his First Piano Concerto, Violin Concerto, the Romeo and Juliet Overture-Fantasy, several symphonies, and the opera Eugene Onegin.

Although musically precocious, Tchaikovsky was educated for a career as a civil servant as there was little opportunity for a musical career in Russia at the time and no system of public music education. When an opportunity for such an education arose, he entered the nascent Saint Petersburg Conservatory, from which he graduated in 1865. The formal Western-oriented teaching that he received there set him apart from composers of the contemporary nationalist movement embodied by the Russian composers of The Five with whom his professional relationship was mixed.

Tchaikovsky’s training set him on a path to reconcile what he had learned with the native musical practices to which he had been exposed from childhood. From that reconciliation, he forged a personal but unmistakably Russian style. The principles that governed melody, harmony and other fundamentals of Russian music ran completely counter to those that governed Western European music, which seemed to defeat the potential for using Russian music in large-scale Western composition or for forming a composite style, and it caused personal antipathies that dented Tchaikovsky’s self-confidence. Russian culture exhibited a split personality, with its native and adopted elements having drifted apart increasingly since the time of Peter the Great. That resulted in uncertainty among the intelligentsia about the country’s national identity, an ambiguity mirrored in Tchaikovsky’s career.

Despite his many popular successes, Tchaikovsky’s life was punctuated by personal crises and depression. Contributory factors included his early separation from his mother for boarding school followed by his mother’s early death, the death of his close friend and colleague Nikolai Rubinstein, his failed marriage with Antonina Miliukova, and the collapse of his 13-year association with the wealthy patroness Nadezhda von Meck. His homosexuality, which he kept private,[3][4] has traditionally also been considered a major factor though some scholars have downplayed its importance.[5][6] Tchaikovsky’s sudden death at the age of 53 is generally ascribed to cholera, but there is an ongoing debate as to whether cholera was indeed the cause and whether the death was accidental or intentional.

While his music has remained popular among audiences, critical opinions were initially mixed. Some Russians did not feel it was sufficiently representative of native musical values and expressed suspicion that Europeans accepted the music for its Western elements. In an apparent reinforcement of the latter claim, some Europeans lauded Tchaikovsky for offering music more substantive than base exoticism and said he transcended stereotypes of Russian classical music. Others dismissed Tchaikovsky’s music as «lacking in elevated thought»[7] and derided its formal workings as deficient because they did not stringently follow Western principles.

Life[edit]

Childhood[edit]

Tchaikovsky’s birthplace in Votkinsk, now a museum

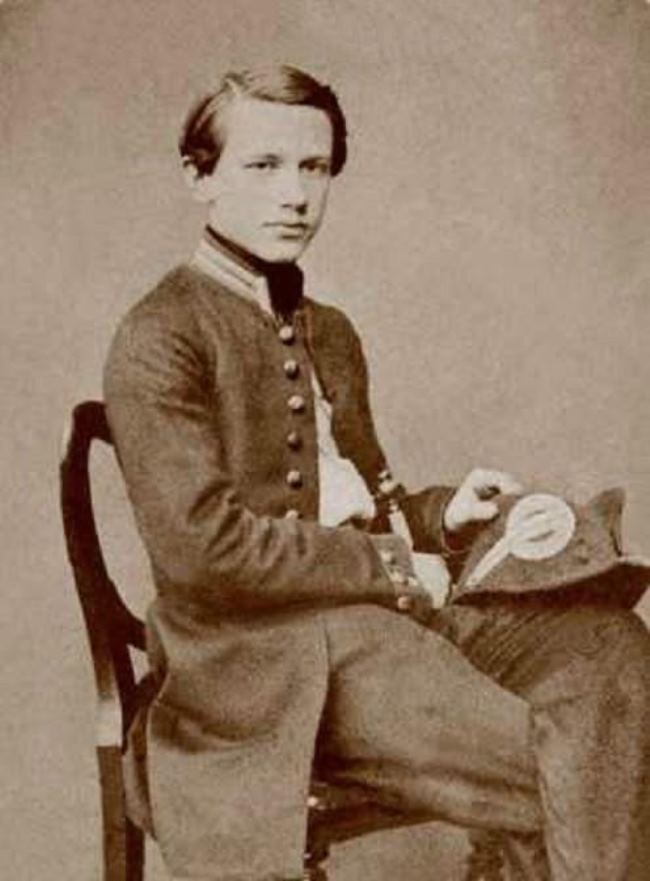

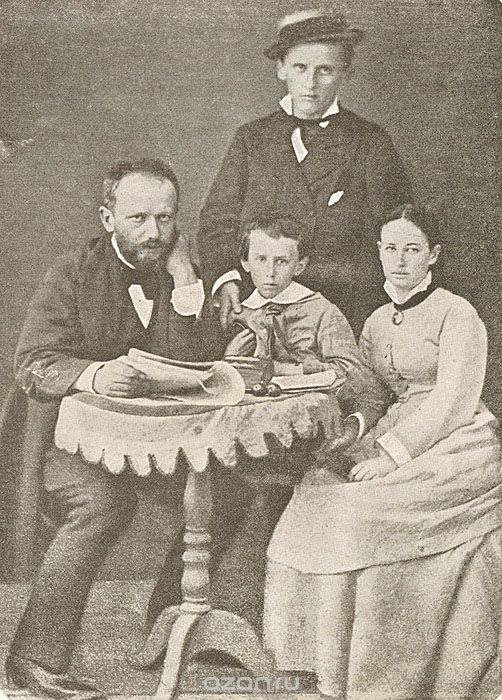

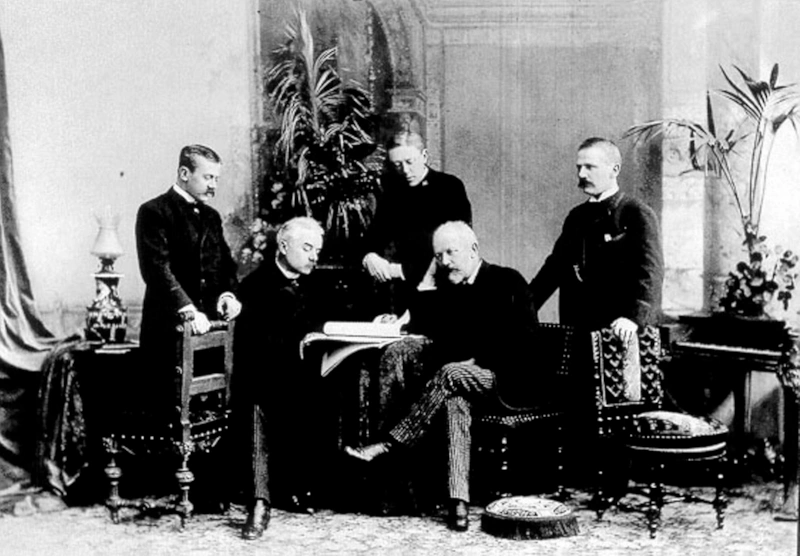

The Tchaikovsky family in 1848. Left to right: Pyotr, Alexandra Andreyevna (mother), Alexandra (sister), Zinaida, Nikolai, Ippolit, Ilya Petrovich (father)

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky was born on 7 May 1840 in Votkinsk,[8] a small town in Vyatka Governorate (present-day Udmurtia) in the Russian Empire, into a family with a long history of military service. His father, Ilya Petrovich Tchaikovsky, had served as a lieutenant colonel and engineer in the Department of Mines,[9] and would manage the Kamsko-Votkinsk Ironworks. His grandfather, Pyotr Fedorovich Tchaikovsky, was born in the village of Nikolaevka, Yekaterinoslav Governorate, Russian Empire (present-day Mykolaivka, Luhansk Oblast, Ukraine),[10] and served first as a physician’s assistant in the army and later as city governor of Glazov in Vyatka. His great-grandfather,[11][12] a Zaporozhian Cossack named Fyodor Chaika, distinguished himself under Peter the Great at the Battle of Poltava in 1709.[13][14]

Tchaikovsky’s mother, Alexandra Andreyevna (née d’Assier), was the second of Ilya’s three wives, 18 years her husband’s junior and French and German on her father’s side.[15] Both Ilya and Alexandra were trained in the arts, including music—a necessity as a posting to a remote area of Russia also meant a need for entertainment, whether in private or at social gatherings.[16] Of his six siblings,[n 4] Tchaikovsky was close to his sister Alexandra and twin brothers Anatoly and Modest. Alexandra’s marriage to Lev Davydov[17] would produce seven children[18] and lend Tchaikovsky the only real family life he would know as an adult,[19] especially during his years of wandering.[19] One of those children, Vladimir Davydov, who went by the nickname ‘Bob’, would become very close to him.[20]

In 1844, the family hired Fanny Dürbach, a 22-year-old French governess.[21] Four-and-a-half-year-old Tchaikovsky was initially thought too young to study alongside his older brother Nikolai and a niece of the family. His insistence convinced Dürbach otherwise.[22] By the age of six, he had become fluent in French and German.[16] Tchaikovsky also became attached to the young woman; her affection for him was reportedly a counter to his mother’s coldness and emotional distance from him,[23] though others assert that the mother doted on her son.[24] Dürbach saved much of Tchaikovsky’s work from this period, including his earliest known compositions, and became a source of several childhood anecdotes.[25]

Tchaikovsky began piano lessons at age five. Precocious, within three years he had become as adept at reading sheet music as his teacher. His parents, initially supportive, hired a tutor, bought an orchestrion (a form of barrel organ that could imitate elaborate orchestral effects), and encouraged his piano study for both aesthetic and practical reasons.

However, they decided in 1850 to send Tchaikovsky to the Imperial School of Jurisprudence in Saint Petersburg. They had both graduated from institutes in Saint Petersburg and the School of Jurisprudence, which mainly served the lesser nobility, and thought that this education would prepare Tchaikovsky for a career as a civil servant.[26] Regardless of talent, the only musical careers available in Russia at that time—except for the affluent aristocracy—were as a teacher in an academy or as an instrumentalist in one of the Imperial Theaters. Both were considered on the lowest rank of the social ladder, with individuals in them enjoying no more rights than peasants.[27]

His father’s income was also growing increasingly uncertain, so both parents may have wanted Tchaikovsky to become independent as soon as possible.[28] As the minimum age for acceptance was 12 and Tchaikovsky was only 10 at the time, he was required to spend two years boarding at the Imperial School of Jurisprudence’s preparatory school, 1,300 kilometres (800 mi) from his family.[29] Once those two years had passed, Tchaikovsky transferred to the Imperial School of Jurisprudence to begin a seven-year course of studies.[30]

Tchaikovsky’s early separation from his mother caused an emotional trauma that lasted the rest of his life and was intensified by her death from cholera in 1854, when he was fourteen.[31][n 5] The loss of his mother also prompted Tchaikovsky to make his first serious attempt at composition, a waltz in her memory. Tchaikovsky’s father, who had also contracted cholera but recovered fully, sent him back to school immediately in the hope that classwork would occupy the boy’s mind.[32] Isolated, Tchaikovsky compensated with friendships with fellow students that became lifelong; these included Aleksey Apukhtin and Vladimir Gerard.[33]

Music, while not an official priority at school, also bridged the gap between Tchaikovsky and his peers. They regularly attended the opera[34] and Tchaikovsky would improvise at the school’s harmonium on themes he and his friends had sung during choir practice. «We were amused,» Vladimir Gerard later remembered, «but not imbued with any expectations of his future glory».[35] Tchaikovsky also continued his piano studies through Franz Becker, an instrument manufacturer who made occasional visits to the school; however, the results, according to musicologist David Brown, were «negligible».[36]

In 1855, Tchaikovsky’s father funded private lessons with Rudolph Kündinger and questioned him about a musical career for his son. While impressed with the boy’s talent, Kündinger said he saw nothing to suggest a future composer or performer.[37] He later admitted that his assessment was also based on his own negative experiences as a musician in Russia and his unwillingness for Tchaikovsky to be treated likewise.[38] Tchaikovsky was told to finish his course and then try for a post in the Ministry of Justice.[39]

Civil service; pursuing music[edit]

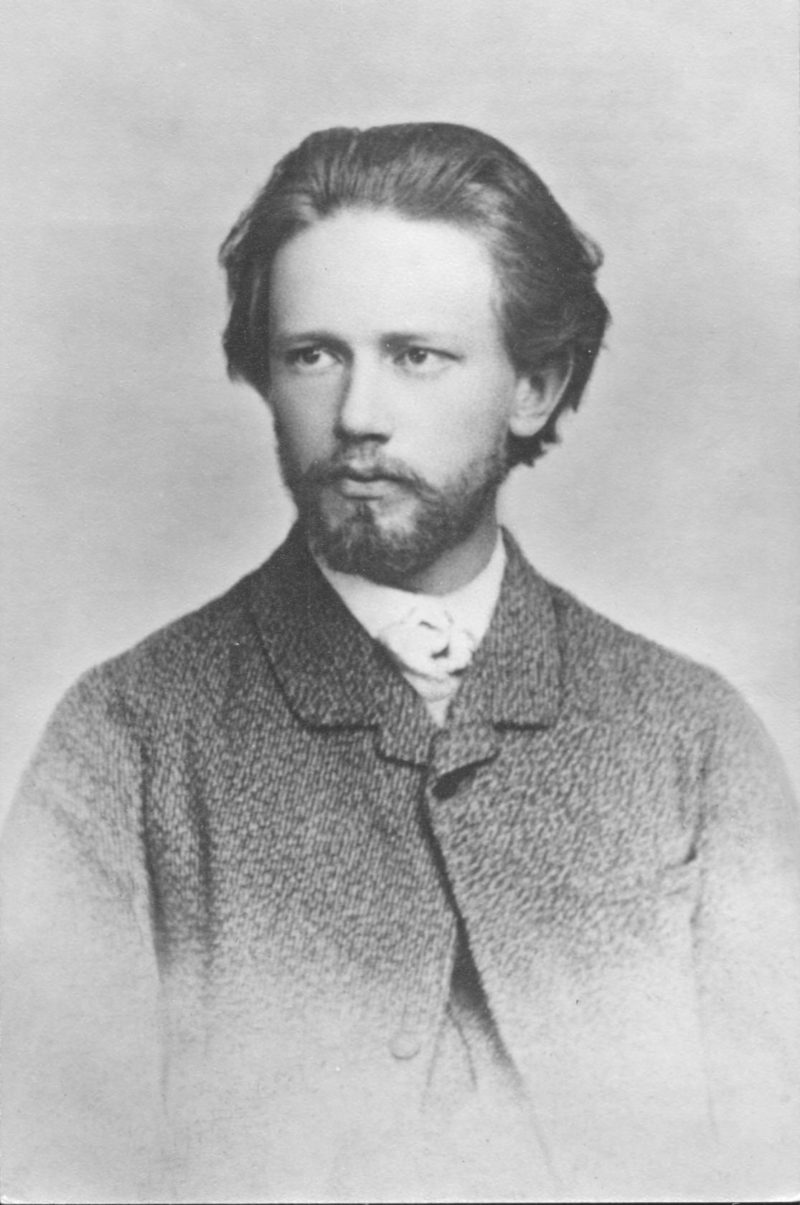

Tchaikovsky as a student at the Moscow Conservatory. Photo, 1863

On 10 June 1859, the 19-year-old Tchaikovsky graduated as a titular counselor, a low rung on the civil service ladder. Appointed to the Ministry of Justice, he became a junior assistant within six months and a senior assistant two months after that. He remained a senior assistant for the rest of his three-year civil service career.[40]