Королева Виктория — биография

Виктория – королева Англии и Ирландии, при крещении получила имя Александрина Виктория. Находилась на престоле 63 года, семь месяцев и два дня, до сих пор осталась монархом, дольше всех занимавшим трон.

Правление королевы Виктории было таким долгим, что ее именем назвали целую эпоху. Зародилась викторианская мораль, литература, музыка, архитектура, и как ни странно, даже мебель. В годы ее правления Великобритания полностью расцвела – развивалась промышленность, политика, наука, культура. С тех пор над землями Британской империи всегда светило солнце, хотя королева не обладала реальной политической властью, монархия воспринималась просто как символ доброй старой Англии, одной из славных традиций, сохранившихся до сегодняшнего дня.

Детство

Виктория стала последней представительницей династии Ганноверов, которой очень нужен был наследник. У короля Вильгельма IV было двое детей, потенциальных кандидатов на трон, но они умерли еще младенцами. Претендентов на престол оказалось предостаточно – четыре престарелых брата Вильгельма IV и Шарлотта Уэльская, которая приходилась единственной внучкой Георгу III. Но Шарлотте не судилось оказаться на троне, в 1817-м во время родов она умерла. Шанс появился у сыновей Георга III, поэтому они срочно начали жениться. Не стал исключением и отец Виктории – герцог Кентский- Эдуард.

На тот момент ему перевалило за 50, он женился на немецкой принцессе Виктории Саксен-Кобург-Заальфельдской из рода Ветинов . До этого Виктория уже побывала в браке, осталась вдовой принца Лейнингенского, с двумя детьми на руках – Карлом и Феодорой. После свадьбы молодожены немного прожили в Германии, а когда герцогиня Кентская оказалась в интересном положении, Эдуард перевез всех в Англию. Он понимал, что ребенок должен родиться в Англии, чтобы иметь законные права на британский трон. 24 мая 1819-го крик новорожденной принцессы Виктории Кентской раздался в Кенсингтонском дворце Лондона.

Девочка абсолютно не помнила своего отца, потому что он умер, когда она была восьмимесячным младенцем. Причиной смерти Эдуарда назвали пневмонию. На должность принца-регента назначили бездетного Вильгельма IV. Викторию воспитывали во дворце, по специальной системе, разработанной ее матерью. Девочка ни на минуту не оставалась в одиночестве, даже спала вместе с мамой в одной спальне. Ее обучением занималась гувернантка, баронесса Лезен. Благодаря ей, девочка в совершенстве выучила языки – английский, немецкий, французский, латынь, знала арифметику, разбиралась в живописи и музыке. Мать запрещала ей всяческие контакты с незнакомыми людьми, а плакать в присутствии людей вообще считала дурным тоном.

Управление финансовыми вопросами герцогини кентской занимался бывший слуга Эдуарда – Джон Конрой. В 1832-м Виктория, ее мать и душеприказчик начали осуществлять ежедневные поездки по стране, чтобы девочка могла увидеть своих будущих подданных.

Начало правления

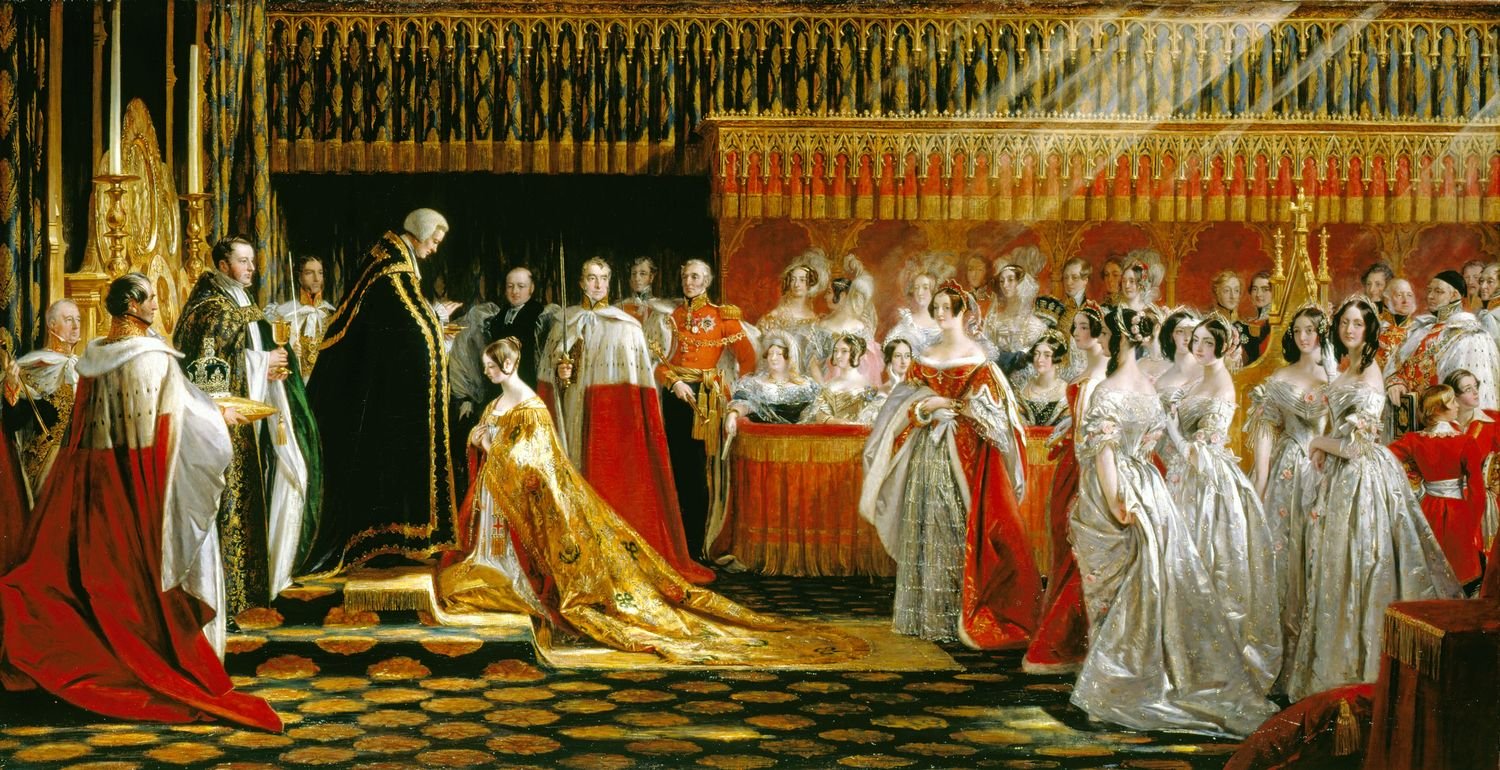

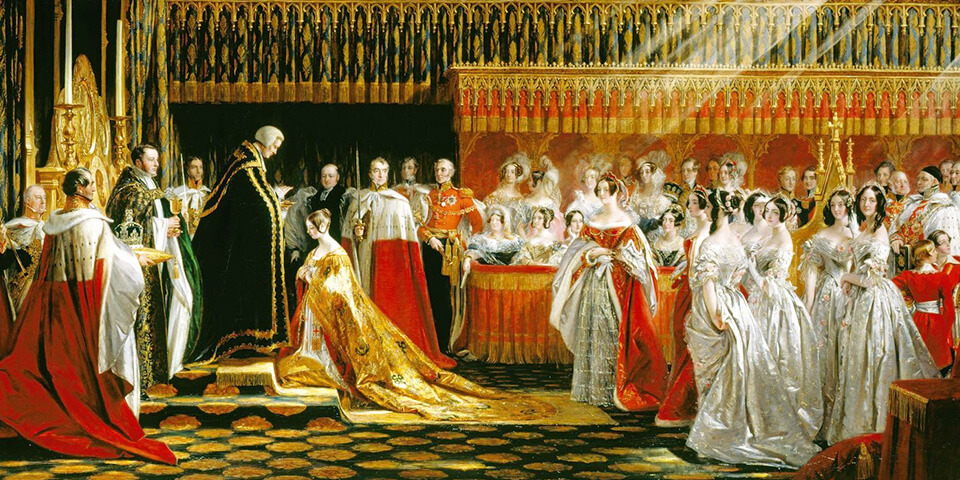

Крутой поворот в биографии принцессы случился 20 июня 1837-го года, когда ее разбудила мать и сообщила, что Вильгельм IV умер. Виктория, как единственная наследница, приняла присягу архиепископа Кентерберийского и лорда Конингема. Первое распоряжение новоиспеченного монарха могло показаться достаточно странным – она попросила оставить ее одну на час. Коронация проходила в Вестминстерском аббатстве, на нее собралось невероятное количество подданных – четыреста тысяч. Затем Виктория поселяется в Букингемском дворце, отстраняет от дел Джона Конроя и собственную мать, и отселяет их в дальнюю часть дворца.

В том же, 1837-м в казначействе выпустили монету, на которой красовалась новая правительница. Виктория приблизила к себе премьер-министра лорда Мельбурна. В начале своего правления королева получала ежегодную ренту, сумма которой равнялась 385-ти тысячам фунтов стерлингов. Юная монархиня сразу погасила все долги отца, оставшиеся после его смерти.

На тот момент в стране законодательную власть осуществлял парламент и кабинет министров. Спустя немного времени Виктория начала принимать участие в управлении государством, она назначала достойных на министерские посты, влияла на работу политических сил и партий. Когда в 1842-м в Ирландии начался голод, королева за счет личных средств поддерживала голодающих, спустя четыре года отменила пошлину на импортируемый хлеб, и мучные изделия стали более доступными для всех.

Могут быть знакомы

Внутренняя и внешняя политика

За годы правления Виктории Великобритания расцвела. Развивалась промышленность, научная и культурная деятельность, укреплялась армия. Статус королевы заметно повысился, тогда как роль монархии постепенно снижалась. Виктория приобрела статус символа власти, подданные доверяли ей безраздельно. Именно она сформировала пуританскую систему воспитания, отношение к семье стало более уважительным. Этим молодая королева очень отличалась от предыдущих монархов, которые придерживались аморального поведения.

Эпоха ее правления ознаменовалась появлением строгих правил поведения в обществе, возникли ограничения для вступающих в брак. Впоследствии число девушек, не вышедших замуж и не родивших детей, заметно увеличилось. Согласно правилам приличия, не разрешалось разнополым людям находиться вдвоем в одном помещении, даже отец не мог жить вместе со своей взрослой дочкой, если у нее не было матери. Молоденькие девушки не имели права говорить с незнакомыми людьми. Женщины не должны были обращаться за помощью к медикам-мужчинам, из-за чего увеличилось число летальных исходов. Доктор не имел возможности провести нормальный осмотр, ему не дозволялось обращаться к пациентке с неловкими вопросами, касающимися здоровья.

Но наряду с этим Викторианская эпоха стала временем расцвета моды, литературы, архитектуры, музыки, живописи. В 1851-м Лондон принимал первую Международную промышленную выставку, вскоре началось строительство Музея науки и Инженерного музея. За годы правления Виктории железнодорожные пути протянулись на 14,5 мили. Люди начали переезжать в города, и вскоре на одного сельского жителя приходилось два горожанина. Развитие коснулось и городской инфраструктуры – улицы мегаполисов теперь имели освещение, дома оборудовали водопроводами, канализацией, вдоль дорог тянулись тротуары, открылось первое метро. Именно в Англии впервые опубликовали книгу Карла Маркса «Капитал» и труд Чарльза Дарвина «Происхождение видов».

В 50-е годы Виктория назначила ответственным за внешнюю политику виконта Палмерстона. Он смог добиться того, что Британия стала мировым арбитром в рассмотрении спорных ситуаций. Несомненной победой премьер-министра стало провозглашение независимости Бельгии, которая до этого была колонией Голландии, он сумел ограничить влияние России в Черном и Средиземном море. Таким образом, британские корабли смогли добираться до Индии более коротким путем. Когда разразился опиумный конфликт, Великобритания сумела подавить Китай, и сама стала торговать опиумом на его территории. В 50-е годы Британия ввязалась в Крымскую войну против России.

Ирландия предпринимала множество попыток отделиться от Британии с помощью организации восстаний. Виктория пресекла эти попытки, ввела на ее территорию большое количество своих войск. В 1856-м британские правительственные войска пресекли повстанческую деятельность в Индии, усилив позиции правящего режима. В 1876-м премьер-министр Бенджамин Дизраэли выступил с предложением назначить Викторию императрицей Индии. Великобритания вела военные действия в африканских и азиатских странах, в 80-е годы ей удалось захватить Египет, а вскоре и Судан.

Личная жизнь

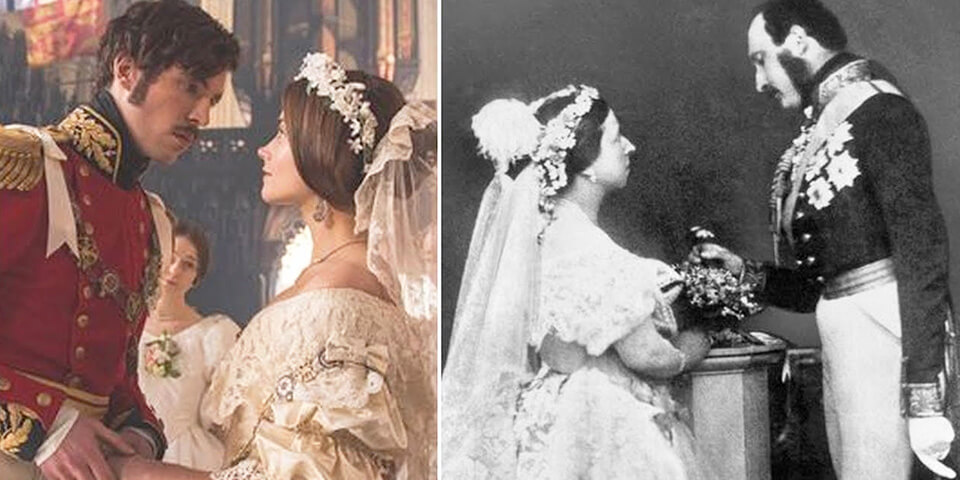

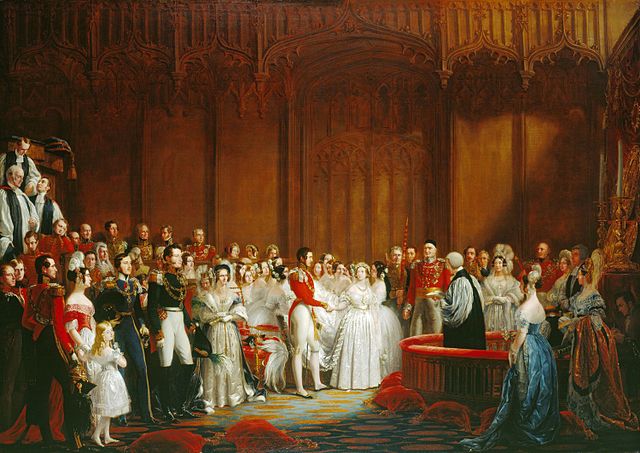

Своего будущего мужа, а заодно и кузена – Альберта, Виктория впервые увидела в 1836-м. Второй раз они встретились только спустя три года, в 1839-м. На тот момент она уже два года находилась на престоле. Юная королева не собиралась замуж, но ей пришлось решиться на такой шаг, потому что в противном случае она должна была разделить трон с матерью. Во время второй встречи девушка поняла, что Альберт ей глубоко симпатичен, она сама сделала ему предложение. 10 февраля 1840 года королева Виктория стала женой Альберта Саксен-Кобург-Готского. Местом проведения церемонии выбрали капеллу лондонского Сент-Джеймского дворца. На церемонии венчания на королеве было белое платье и фата, она и здесь установила новые порядки. Раньше невесты выходили замуж в красных или черных платьях.

Супруги любили другу друга, их отношения были теплыми и доверительными. Об этом королева часто писала в письмах, называя себя счастливейшей из всех женщин. Принца Альберта вполне устраивало такое положение дел. Вначале он оставался в тени своей властной супруги, выполнял только функции секретаря при ней. Но с каждым годом его полномочия расширялись, Альберт начал вести международную переписку.

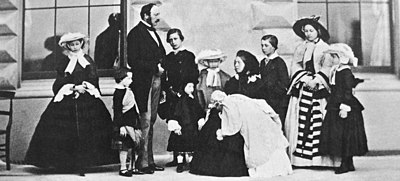

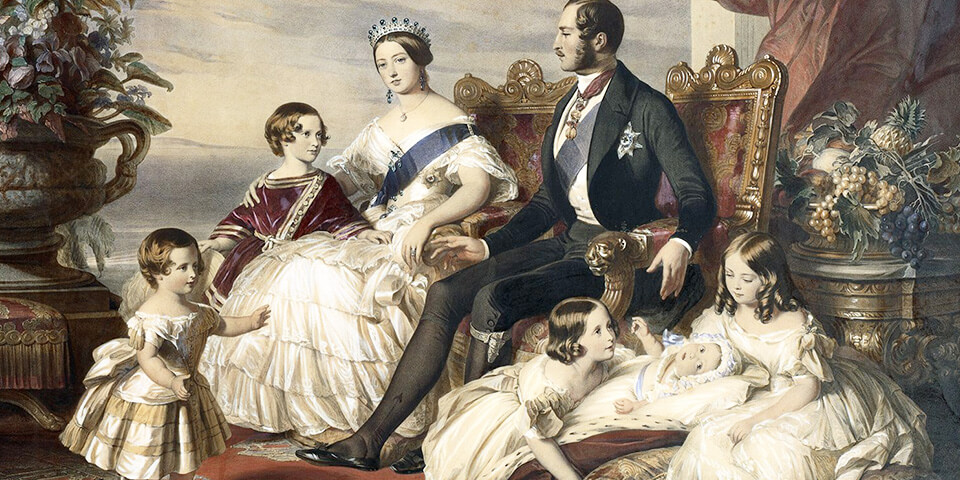

Королевская чета пользовалась любовью и уважением соотечественников. А когда они выпустили подарочный набор, состоявший из 14 снимков супружеской пары, то популярность Виктории и Альберта выросла неимоверно.

Весь тираж этого набора, который состоял из 60 тысяч экземпляров, был раскуплен. Таким образом, королева зародила еще одну традицию – семейное фото. Из десертов Виктория отдавала предпочтение ванильному бисквиту с клубникой и цедрой лимона, который сейчас носит ее имя.

В 1840 году в королевской семье родился первенец – дочь, по традиции получившая имя Виктория. Королева была счастлива в личной жизни, любила своего мужа, но терпеть не могла ходить беременной и рожать детей. Новорожденные вызывали у нее чувство брезгливости, после каждых родов она пребывала в депрессии. Несмотря на эти обстоятельства, Виктория родила еще восьмерых детей. В 1841 году родился сын Эдуард, в 1843-м — дочь Алиса, в 1844-м — сын Альфред, в 1846-м — дочь Елена, в 1848-м — дочь Луиза, в 1850-м — сын Артур, в 1853-м — сын Леопольд, в 1857-м — дочь Беатрис. Британская королева так грамотно женила и отдала замуж своих детей, что добилась не только их счастья в личной жизни, но и укрепления связей европейских правящих династий. За это она получила звание «бабушка Европы».

Альберта не стало в 1861-м, его унес брюшной тиф. Несколько лет королева пребывала в трауре. Справившись с потерей, Виктория включилась в решение государственных дел Великобритании. К середине 60-х у нее появился поверенный во всех делах – Джон Браун. Считалось, что он состоял с королевой в близкой связи. В 1887 году, в честь пятидесятой годовщины пребывания на троне, Виктория выписала себе несколько индийских слуг. Королева так пленилась экзотикой, что сделала индуса Абдула Карима своим фаворитом. Он также выполнял функции личного учителя и эксперта в вопросах ведической культуры.

Все дети Виктории прожили достойную жизнь, умерли в глубокой старости. Королева становилась бабушкой 42 раза, и прабабушкой 85 раз. У Виктории проявился ген гемофилии, который от нее получили в «наследство» дочери Алиса и Беатрис. Женщины являются носительницами гена, а мужчины болеют этим серьезным заболеванием. Из всех сыновей королевы, гемофилия проявилась у принца Леопольда. Этой же болезнью страдал и правнук Виктории – царевич Алексей, рождению которого так радовались российский император Николай II и его жена Александра Федоровна, дочь принцессы Алисы.

Смерть

В 90-е годы Виктория начала серьезно болеть. У нее нашли ревматизм, из-за которого она оказалась в каталке. Доктора обнаружили у королевы катаракту и афазию. В январе 1901-го Виктория уже не поднималась с постели, а 22 января того же года она скончалась.

Рядом с ней находились сын Эдуард и внук Вильгельм II, император Германии. Для подданных ее смерть стала тяжелым ударом. Вместе с ней уходила целая эпоха, которая в истории Великобритании до сих пор носит название «Золотой век».

Память

Память о величайшей из королев Британии продолжает жить. В ее честь снимаются фильмы, основой которых служит биография императрицы – «Молодая Виктория», «Мисс Браун», «Молодые годы королевы». Викторианскую эпоху в своих трудах воспевали Эвелин Энтони, Кристофер Хибберт, Литтон Стрэйч. Написано невероятное количество картин и музыкальных произведений.

Именем королевы Виктории названы географические объекты, города, штаты. В Канаде 24 мая (день рождения Виктории) до сих пор отмечается, как национальный праздник. Имя британской королевы использовали астрономы, ботаники, архитекторы.

Ссылки

- Страница в Википедии

Для нас важна актуальность и достоверность информации. Если вы обнаружили ошибку или неточность, пожалуйста, сообщите нам. Выделите ошибку и нажмите сочетание клавиш Ctrl+Enter.

«Victoria I» redirects here. For historical grand strategy game developed by Paradox Interactive, see Victoria: An Empire Under the Sun.

| Victoria | |

|---|---|

Photograph by Alexander Bassano, 1882 |

|

| Queen of the United Kingdom | |

| Reign | 20 June 1837 – 22 January 1901 |

| Coronation | 28 June 1838 |

| Predecessor | William IV |

| Successor | Edward VII |

| Empress of India | |

| Reign | 1 May 1876 – 22 January 1901 |

| Imperial Durbar | 1 January 1877 |

| Successor | Edward VII |

| Born | Princess Alexandrina Victoria of Kent 24 May 1819 Kensington Palace, London, England |

| Died | 22 January 1901 (aged 81) Osborne House, Isle of Wight, England |

| Burial | 4 February 1901

Royal Mausoleum, Frogmore, Windsor |

| Spouse |

Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (m. ; died ) |

| Issue |

|

| House | Hanover |

| Father | Prince Edward, Duke of Kent and Strathearn |

| Mother | Princess Victoria of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld |

| Religion | Protestant[a] |

| Signature |  |

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 216 days was longer than that of any previous British monarch and is known as the Victorian era. It was a period of industrial, political, scientific, and military change within the United Kingdom, and was marked by a great expansion of the British Empire. In 1876, the British Parliament voted to grant her the additional title of Empress of India.

Victoria was the daughter of Prince Edward, Duke of Kent and Strathearn (the fourth son of King George III), and Princess Victoria of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld. After the deaths of her father and grandfather in 1820, she was raised under close supervision by her mother and her comptroller, John Conroy. She inherited the throne aged 18 after her father’s three elder brothers died without surviving legitimate issue. Victoria, a constitutional monarch, attempted privately to influence government policy and ministerial appointments; publicly, she became a national icon who was identified with strict standards of personal morality.

Victoria married her first cousin Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha in 1840. Their children married into royal and noble families across the continent, earning Victoria the sobriquet «the grandmother of Europe» and spreading haemophilia in European royalty. After Albert’s death in 1861, Victoria plunged into deep mourning and avoided public appearances. As a result of her seclusion, British republicanism temporarily gained strength, but in the latter half of her reign, her popularity recovered. Her Golden and Diamond jubilees were times of public celebration. Victoria died aged 81 in 1901 at Osborne House on the Isle of Wight. The last British monarch of the House of Hanover, she was succeeded by her son Edward VII of the House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha.

Birth and family

Victoria’s father was Prince Edward, Duke of Kent and Strathearn, the fourth son of the reigning King of the United Kingdom, George III. Until 1817, the only legitimate grandchild of George III was Edward’s niece, Princess Charlotte of Wales, who was the daughter of George, Prince Regent (who would become George IV). Charlotte’s death in 1817 precipitated a succession crisis that brought pressure on the Duke of Kent and his unmarried brothers to marry and have children. In 1818, the Duke of Kent married Princess Victoria of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld, a widowed German princess with two children—Carl (1804–1856) and Feodora (1807–1872)—by her first marriage to Emich Carl, 2nd Prince of Leiningen. Her brother Leopold was Princess Charlotte’s widower and later the first king of Belgium. The Duke and Duchess of Kent’s only child, Victoria, was born at 4:15 a.m. on 24 May 1819 at Kensington Palace in London.[1]

Victoria was christened privately by the Archbishop of Canterbury, Charles Manners-Sutton, on 24 June 1819 in the Cupola Room at Kensington Palace.[b] She was baptised Alexandrina after one of her godparents, Tsar Alexander I of Russia, and Victoria, after her mother. Additional names proposed by her parents—Georgina (or Georgiana), Charlotte, and Augusta—were dropped on the instructions of Kent’s eldest brother, the Prince Regent.[2]

At birth, Victoria was fifth in the line of succession after the four eldest sons of George III: George, Prince Regent (later George IV); Frederick, Duke of York; William, Duke of Clarence (later William IV); and Victoria’s father, Edward, Duke of Kent.[3] The Prince Regent had no surviving children, and the Duke of York had no children; further, both were estranged from their wives, who were both past child-bearing age, so the two eldest brothers were unlikely to have any further legitimate children. William and Edward married on the same day in 1818, but both of William’s legitimate daughters died as infants. The first of these was Princess Charlotte, who was born and died on 27 March 1819, two months before Victoria was born. Victoria’s father died in January 1820, when Victoria was less than a year old. A week later her grandfather died and was succeeded by his eldest son as George IV. Victoria was then third in line to the throne after Frederick and William. William’s second daughter, Princess Elizabeth of Clarence, lived for twelve weeks from 10 December 1820 to 4 March 1821, and for that period Victoria was fourth in line.[4]

The Duke of York died in 1827, followed by George IV in 1830; the throne passed to their next surviving brother, William, and Victoria became heir presumptive. The Regency Act 1830 made special provision for Victoria’s mother to act as regent in case William died while Victoria was still a minor.[5] King William distrusted the Duchess’s capacity to be regent, and in 1836 he declared in her presence that he wanted to live until Victoria’s 18th birthday, so that a regency could be avoided.[6]

Heir presumptive

Portrait of Victoria with her spaniel Dash by George Hayter, 1833

Victoria later described her childhood as «rather melancholy».[7] Her mother was extremely protective, and Victoria was raised largely isolated from other children under the so-called «Kensington System», an elaborate set of rules and protocols devised by the Duchess and her ambitious and domineering comptroller, Sir John Conroy, who was rumoured to be the Duchess’s lover.[8] The system prevented the princess from meeting people whom her mother and Conroy deemed undesirable (including most of her father’s family), and was designed to render her weak and dependent upon them.[9] The Duchess avoided the court because she was scandalised by the presence of King William’s illegitimate children.[10] Victoria shared a bedroom with her mother every night, studied with private tutors to a regular timetable, and spent her play-hours with her dolls and her King Charles Spaniel, Dash.[11] Her lessons included French, German, Italian, and Latin,[12] but she spoke only English at home.[13]

In 1830, the Duchess of Kent, and Conroy, took Victoria across the centre of England to visit the Malvern Hills, stopping at towns and great country houses along the way.[14] Similar journeys to other parts of England and Wales were taken in 1832, 1833, 1834 and 1835. To the King’s annoyance, Victoria was enthusiastically welcomed in each of the stops.[15] William compared the journeys to royal progresses and was concerned that they portrayed Victoria as his rival rather than his heir presumptive.[16] Victoria disliked the trips; the constant round of public appearances made her tired and ill, and there was little time for her to rest.[17] She objected on the grounds of the King’s disapproval, but her mother dismissed his complaints as motivated by jealousy and forced Victoria to continue the tours.[18] At Ramsgate in October 1835, Victoria contracted a severe fever, which Conroy initially dismissed as a childish pretence.[19] While Victoria was ill, Conroy and the Duchess unsuccessfully badgered her to make Conroy her private secretary.[20] As a teenager, Victoria resisted persistent attempts by her mother and Conroy to appoint him to her staff.[21] Once queen, she banned him from her presence, but he remained in her mother’s household.[22]

By 1836, Victoria’s maternal uncle Leopold, who had been King of the Belgians since 1831, hoped to marry her to Prince Albert,[23] the son of his brother Ernest I, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. Leopold arranged for Victoria’s mother to invite her Coburg relatives to visit her in May 1836, with the purpose of introducing Victoria to Albert.[24] William IV, however, disapproved of any match with the Coburgs, and instead favoured the suit of Prince Alexander of the Netherlands, second son of the Prince of Orange.[25] Victoria was aware of the various matrimonial plans and critically appraised a parade of eligible princes.[26] According to her diary, she enjoyed Albert’s company from the beginning. After the visit she wrote, «[Albert] is extremely handsome; his hair is about the same colour as mine; his eyes are large and blue, and he has a beautiful nose and a very sweet mouth with fine teeth; but the charm of his countenance is his expression, which is most delightful.»[27] Alexander, on the other hand, she described as «very plain».[28]

Victoria wrote to King Leopold, whom she considered her «best and kindest adviser»,[29] to thank him «for the prospect of great happiness you have contributed to give me, in the person of dear Albert … He possesses every quality that could be desired to render me perfectly happy. He is so sensible, so kind, and so good, and so amiable too. He has besides the most pleasing and delightful exterior and appearance you can possibly see.»[30] However at 17, Victoria, though interested in Albert, was not yet ready to marry. The parties did not undertake a formal engagement, but assumed that the match would take place in due time.[31]

Accession

Victoria turned 18 on 24 May 1837, and a regency was avoided. Less than a month later, on 20 June 1837, William IV died at the age of 71, and Victoria became Queen of the United Kingdom.[c] In her diary she wrote, «I was awoke at 6 o’clock by Mamma, who told me the Archbishop of Canterbury and Lord Conyngham were here and wished to see me. I got out of bed and went into my sitting-room (only in my dressing gown) and alone, and saw them. Lord Conyngham then acquainted me that my poor Uncle, the King, was no more, and had expired at 12 minutes past 2 this morning, and consequently that I am Queen.»[32] Official documents prepared on the first day of her reign described her as Alexandrina Victoria, but the first name was withdrawn at her own wish and not used again.[33]

Since 1714, Britain had shared a monarch with Hanover in Germany, but under Salic law, women were excluded from the Hanoverian succession. While Victoria inherited the British throne, her father’s unpopular younger brother, Ernest Augustus, Duke of Cumberland, became King of Hanover. He was Victoria’s heir presumptive until she had a child.[34]

At the time of Victoria’s accession, the government was led by the Whig prime minister Lord Melbourne. He at once became a powerful influence on the politically inexperienced monarch, who relied on him for advice.[35] Charles Greville supposed that the widowed and childless Melbourne was «passionately fond of her as he might be of his daughter if he had one», and Victoria probably saw him as a father figure.[36] Her coronation took place on 28 June 1838 at Westminster Abbey. Over 400,000 visitors came to London for the celebrations.[37] She became the first sovereign to take up residence at Buckingham Palace[38] and inherited the revenues of the duchies of Lancaster and Cornwall as well as being granted a civil list allowance of £385,000 per year. Financially prudent, she paid off her father’s debts.[39]

At the start of her reign Victoria was popular,[40] but her reputation suffered in an 1839 court intrigue when one of her mother’s ladies-in-waiting, Lady Flora Hastings, developed an abdominal growth that was widely rumoured to be an out-of-wedlock pregnancy by Sir John Conroy.[41] Victoria believed the rumours.[42] She hated Conroy, and despised «that odious Lady Flora»,[43] because she had conspired with Conroy and the Duchess of Kent in the Kensington System.[44] At first, Lady Flora refused to submit to an intimate medical examination, until in mid-February she eventually acquiesced, and was found to be a virgin.[45] Conroy, the Hastings family, and the opposition Tories organised a press campaign implicating the Queen in the spreading of false rumours about Lady Flora.[46] When Lady Flora died in July, the post-mortem revealed a large tumour on her liver that had distended her abdomen.[47] At public appearances, Victoria was hissed and jeered as «Mrs. Melbourne».[48]

In 1839, Melbourne resigned after Radicals and Tories (both of whom Victoria detested) voted against a bill to suspend the constitution of Jamaica. The bill removed political power from plantation owners who were resisting measures associated with the abolition of slavery.[49] The Queen commissioned a Tory, Robert Peel, to form a new ministry. At the time, it was customary for the prime minister to appoint members of the Royal Household, who were usually his political allies and their spouses. Many of the Queen’s ladies of the bedchamber were wives of Whigs, and Peel expected to replace them with wives of Tories. In what became known as the «bedchamber crisis», Victoria, advised by Melbourne, objected to their removal. Peel refused to govern under the restrictions imposed by the Queen, and consequently resigned his commission, allowing Melbourne to return to office.[50]

Marriage

Though Victoria was now queen, as an unmarried young woman she was required by social convention to live with her mother, despite their differences over the Kensington System and her mother’s continued reliance on Conroy.[51] Her mother was consigned to a remote apartment in Buckingham Palace, and Victoria often refused to see her.[52] When Victoria complained to Melbourne that her mother’s proximity promised «torment for many years», Melbourne sympathised but said it could be avoided by marriage, which Victoria called a «schocking [sic] alternative».[53] Victoria showed interest in Albert’s education for the future role he would have to play as her husband, but she resisted attempts to rush her into wedlock.[54]

Victoria continued to praise Albert following his second visit in October 1839. Albert and Victoria felt mutual affection and the Queen proposed to him on 15 October 1839, just five days after he had arrived at Windsor.[55] They were married on 10 February 1840, in the Chapel Royal of St James’s Palace, London. Victoria was love-struck. She spent the evening after their wedding lying down with a headache, but wrote ecstatically in her diary:

I NEVER, NEVER spent such an evening!!! MY DEAREST DEAREST DEAR Albert … his excessive love & affection gave me feelings of heavenly love & happiness I never could have hoped to have felt before! He clasped me in his arms, & we kissed each other again & again! His beauty, his sweetness & gentleness – really how can I ever be thankful enough to have such a Husband! … to be called by names of tenderness, I have never yet heard used to me before – was bliss beyond belief! Oh! This was the happiest day of my life![56]

Albert became an important political adviser as well as the Queen’s companion, replacing Melbourne as the dominant influential figure in the first half of her life.[57] Victoria’s mother was evicted from the palace, to Ingestre House in Belgrave Square. After the death of Victoria’s aunt, Princess Augusta, in 1840, Victoria’s mother was given both Clarence and Frogmore Houses.[58] Through Albert’s mediation, relations between mother and daughter slowly improved.[59]

Contemporary lithograph of Edward Oxford’s attempt to assassinate Victoria, 1840

During Victoria’s first pregnancy in 1840, in the first few months of the marriage, 18-year-old Edward Oxford attempted to assassinate her while she was riding in a carriage with Prince Albert on her way to visit her mother. Oxford fired twice, but either both bullets missed or, as he later claimed, the guns had no shot.[60] He was tried for high treason, found not guilty by reason of insanity, committed to an insane asylum indefinitely, and later sent to live in Australia.[61] In the immediate aftermath of the attack, Victoria’s popularity soared, mitigating residual discontent over the Hastings affair and the bedchamber crisis.[62] Her daughter, also named Victoria, was born on 21 November 1840. The Queen hated being pregnant,[63] viewed breast-feeding with disgust,[64] and thought newborn babies were ugly.[65] Nevertheless, over the following seventeen years, she and Albert had a further eight children: Albert Edward (b. 1841), Alice (b. 1843), Alfred (b. 1844), Helena (b. 1846), Louise (b. 1848), Arthur (b. 1850), Leopold (b. 1853) and Beatrice (b. 1857).

The household was largely run by Victoria’s childhood governess, Baroness Louise Lehzen from Hanover. Lehzen had been a formative influence on Victoria[66] and had supported her against the Kensington System.[67] Albert, however, thought that Lehzen was incompetent and that her mismanagement threatened his daughter’s health. After a furious row between Victoria and Albert over the issue, Lehzen was pensioned off in 1842, and Victoria’s close relationship with her ended.[68]

Years with Albert

On 29 May 1842, Victoria was riding in a carriage along The Mall, London, when John Francis aimed a pistol at her, but the gun did not fire. The assailant escaped; the following day, Victoria drove the same route, though faster and with a greater escort, in a deliberate attempt to bait Francis into taking a second aim and catch him in the act. As expected, Francis shot at her, but he was seized by plainclothes policemen, and convicted of high treason. On 3 July, two days after Francis’s death sentence was commuted to transportation for life, John William Bean also tried to fire a pistol at the Queen, but it was loaded only with paper and tobacco and had too little charge.[69] Edward Oxford felt that the attempts were encouraged by his acquittal in 1840. Bean was sentenced to 18 months in jail.[70] In a similar attack in 1849, unemployed Irishman William Hamilton fired a powder-filled pistol at Victoria’s carriage as it passed along Constitution Hill, London.[71] In 1850, the Queen did sustain injury when she was assaulted by a possibly insane ex-army officer, Robert Pate. As Victoria was riding in a carriage, Pate struck her with his cane, crushing her bonnet and bruising her forehead. Both Hamilton and Pate were sentenced to seven years’ transportation.[72]

Melbourne’s support in the House of Commons weakened through the early years of Victoria’s reign, and in the 1841 general election the Whigs were defeated. Peel became prime minister, and the ladies of the bedchamber most associated with the Whigs were replaced.[73]

In 1845, Ireland was hit by a potato blight.[75] In the next four years, over a million Irish people died and another million emigrated in what became known as the Great Famine.[76] In Ireland, Victoria was labelled «The Famine Queen».[77][78] In January 1847 she personally donated £2,000 (equivalent to between £178,000 and £6.5 million in 2016[79]) to the British Relief Association, more than any other individual famine relief donor,[80] and supported the Maynooth Grant to a Roman Catholic seminary in Ireland, despite Protestant opposition.[81] The story that she donated only £5 in aid to the Irish, and on the same day gave the same amount to Battersea Dogs Home, was a myth generated towards the end of the 19th century.[82]

By 1846, Peel’s ministry faced a crisis involving the repeal of the Corn Laws. Many Tories—by then known also as Conservatives—were opposed to the repeal, but Peel, some Tories (the free-trade oriented liberal conservative «Peelites»), most Whigs and Victoria supported it. Peel resigned in 1846, after the repeal narrowly passed, and was replaced by Lord John Russell.[83]

| Victoria’s British prime ministers | |

| Year | Prime Minister (party) |

|---|---|

| 1835 | Viscount Melbourne (Whig) |

| 1841 | Sir Robert Peel (Conservative) |

| 1846 | Lord John Russell (W) |

| 1852 (Feb) | Earl of Derby (C) |

| 1852 (Dec) | Earl of Aberdeen (Peelite) |

| 1855 | Viscount Palmerston (Liberal) |

| 1858 | Earl of Derby (C) |

| 1859 | Viscount Palmerston (L) |

| 1865 | Earl Russell [Lord John Russell] (L) |

| 1866 | Earl of Derby (C) |

| 1868 (Feb) | Benjamin Disraeli (C) |

| 1868 (Dec) | William Gladstone (L) |

| 1874 | Benjamin Disraeli [Ld Beaconsfield] (C) |

| 1880 | William Gladstone (L) |

| 1885 | Marquess of Salisbury (C) |

| 1886 (Feb) | William Gladstone (L) |

| 1886 (Jul) | Marquess of Salisbury (C) |

| 1892 | William Gladstone (L) |

| 1894 | Earl of Rosebery (L) |

| 1895 | Marquess of Salisbury (C) |

| See List of prime ministers of Queen Victoria for details of her British and overseas premiers |

Internationally, Victoria took a keen interest in the improvement of relations between France and Britain.[84] She made and hosted several visits between the British royal family and the House of Orleans, who were related by marriage through the Coburgs. In 1843 and 1845, she and Albert stayed with King Louis Philippe I at Château d’Eu in Normandy; she was the first British or English monarch to visit a French monarch since the meeting of Henry VIII of England and Francis I of France on the Field of the Cloth of Gold in 1520.[85] When Louis Philippe made a reciprocal trip in 1844, he became the first French king to visit a British sovereign.[86] Louis Philippe was deposed in the revolutions of 1848, and fled to exile in England.[87] At the height of a revolutionary scare in the United Kingdom in April 1848, Victoria and her family left London for the greater safety of Osborne House,[88] a private estate on the Isle of Wight that they had purchased in 1845 and redeveloped.[89] Demonstrations by Chartists and Irish nationalists failed to attract widespread support, and the scare died down without any major disturbances.[90] Victoria’s first visit to Ireland in 1849 was a public relations success, but it had no lasting impact or effect on the growth of Irish nationalism.[91]

Portrait by Herbert Smith, 1848

Russell’s ministry, though Whig, was not favoured by the Queen.[92] She found particularly offensive the Foreign Secretary, Lord Palmerston, who often acted without consulting the Cabinet, the Prime Minister, or the Queen.[93] Victoria complained to Russell that Palmerston sent official dispatches to foreign leaders without her knowledge, but Palmerston was retained in office and continued to act on his own initiative, despite her repeated remonstrances. It was only in 1851 that Palmerston was removed after he announced the British government’s approval of President Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte’s coup in France without consulting the Prime Minister.[94] The following year, President Bonaparte was declared Emperor Napoleon III, by which time Russell’s administration had been replaced by a short-lived minority government led by Lord Derby.

Albert, Victoria and their nine children, 1857. Left to right: Alice, Arthur, Prince Albert, Albert Edward, Leopold, Louise, Queen Victoria with Beatrice, Alfred, Victoria, and Helena.

In 1853, Victoria gave birth to her eighth child, Leopold, with the aid of the new anaesthetic, chloroform. She was so impressed by the relief it gave from the pain of childbirth that she used it again in 1857 at the birth of her ninth and final child, Beatrice, despite opposition from members of the clergy, who considered it against biblical teaching, and members of the medical profession, who thought it dangerous.[95] Victoria may have had postnatal depression after many of her pregnancies.[96] Letters from Albert to Victoria intermittently complain of her loss of self-control. For example, about a month after Leopold’s birth Albert complained in a letter to Victoria about her «continuance of hysterics» over a «miserable trifle».[97]

In early 1855, the government of Lord Aberdeen, who had replaced Derby, fell amidst recriminations over the poor management of British troops in the Crimean War. Victoria approached both Derby and Russell to form a ministry, but neither had sufficient support, and Victoria was forced to appoint Palmerston as prime minister.[98]

Napoleon III, Britain’s closest ally as a result of the Crimean War,[96] visited London in April 1855, and from 17 to 28 August the same year Victoria and Albert returned the visit.[99] Napoleon III met the couple at Boulogne and accompanied them to Paris.[100] They visited the Exposition Universelle (a successor to Albert’s 1851 brainchild the Great Exhibition) and Napoleon I’s tomb at Les Invalides (to which his remains had only been returned in 1840), and were guests of honour at a 1,200-guest ball at the Palace of Versailles.[101] This marked the first time that a reigning British monarch had been to Paris in over 400 years.[102]

Portrait by Winterhalter, 1859

On 14 January 1858, an Italian refugee from Britain called Felice Orsini attempted to assassinate Napoleon III with a bomb made in England.[103] The ensuing diplomatic crisis destabilised the government, and Palmerston resigned. Derby was reinstated as prime minister.[104] Victoria and Albert attended the opening of a new basin at the French military port of Cherbourg on 5 August 1858, in an attempt by Napoleon III to reassure Britain that his military preparations were directed elsewhere. On her return Victoria wrote to Derby reprimanding him for the poor state of the Royal Navy in comparison to the French Navy.[105] Derby’s ministry did not last long, and in June 1859 Victoria recalled Palmerston to office.[106]

Eleven days after Orsini’s assassination attempt in France, Victoria’s eldest daughter married Prince Frederick William of Prussia in London. They had been betrothed since September 1855, when Princess Victoria was 14 years old; the marriage was delayed by the Queen and her husband Albert until the bride was 17.[107] The Queen and Albert hoped that their daughter and son-in-law would be a liberalising influence in the enlarging Prussian state.[108] The Queen felt «sick at heart» to see her daughter leave England for Germany; «It really makes me shudder», she wrote to Princess Victoria in one of her frequent letters, «when I look round to all your sweet, happy, unconscious sisters, and think I must give them up too – one by one.»[109] Almost exactly a year later, the Princess gave birth to the Queen’s first grandchild, Wilhelm, who would become the last German Emperor.

Widowhood

In March 1861, Victoria’s mother died, with Victoria at her side. Through reading her mother’s papers, Victoria discovered that her mother had loved her deeply;[110] she was heart-broken, and blamed Conroy and Lehzen for «wickedly» estranging her from her mother.[111] To relieve his wife during her intense and deep grief,[112] Albert took on most of her duties, despite being ill himself with chronic stomach trouble.[113] In August, Victoria and Albert visited their son, Albert Edward, Prince of Wales, who was attending army manoeuvres near Dublin, and spent a few days holidaying in Killarney. In November, Albert was made aware of gossip that his son had slept with an actress in Ireland.[114] Appalled, he travelled to Cambridge, where his son was studying, to confront him.[115] By the beginning of December, Albert was very unwell.[116] He was diagnosed with typhoid fever by William Jenner, and died on 14 December 1861. Victoria was devastated.[117] She blamed her husband’s death on worry over the Prince of Wales’s philandering. He had been «killed by that dreadful business», she said.[118] She entered a state of mourning and wore black for the remainder of her life. She avoided public appearances and rarely set foot in London in the following years.[119] Her seclusion earned her the nickname «widow of Windsor».[120] Her weight increased through comfort eating, which reinforced her aversion to public appearances.[121]

Victoria’s self-imposed isolation from the public diminished the popularity of the monarchy, and encouraged the growth of the republican movement.[122] She did undertake her official government duties, yet chose to remain secluded in her royal residences—Windsor Castle, Osborne House, and the private estate in Scotland that she and Albert had acquired in 1847, Balmoral Castle. In March 1864 a protester stuck a notice on the railings of Buckingham Palace that announced «these commanding premises to be let or sold in consequence of the late occupant’s declining business».[123] Her uncle Leopold wrote to her advising her to appear in public. She agreed to visit the gardens of the Royal Horticultural Society at Kensington and take a drive through London in an open carriage.[124]

Victoria and John Brown at Balmoral, 1863. Photograph by G. W. Wilson.

Through the 1860s, Victoria relied increasingly on a manservant from Scotland, John Brown.[125] Rumours of a romantic connection and even a secret marriage appeared in print, and some referred to the Queen as «Mrs. Brown».[126] The story of their relationship was the subject of the 1997 movie Mrs. Brown. A painting by Sir Edwin Henry Landseer depicting the Queen with Brown was exhibited at the Royal Academy, and Victoria published a book, Leaves from the Journal of Our Life in the Highlands, which featured Brown prominently and in which the Queen praised him highly.[127]

Palmerston died in 1865, and after a brief ministry led by Russell, Derby returned to power. In 1866, Victoria attended the State Opening of Parliament for the first time since Albert’s death.[128] The following year she supported the passing of the Reform Act 1867 which doubled the electorate by extending the franchise to many urban working men,[129] though she was not in favour of votes for women.[130] Derby resigned in 1868, to be replaced by Benjamin Disraeli, who charmed Victoria. «Everyone likes flattery,» he said, «and when you come to royalty you should lay it on with a trowel.»[131] With the phrase «we authors, Ma’am», he complimented her.[132] Disraeli’s ministry only lasted a matter of months, and at the end of the year his Liberal rival, William Ewart Gladstone, was appointed prime minister. Victoria found Gladstone’s demeanour far less appealing; he spoke to her, she is thought to have complained, as though she were «a public meeting rather than a woman».[133]

In 1870 republican sentiment in Britain, fed by the Queen’s seclusion, was boosted after the establishment of the Third French Republic.[134] A republican rally in Trafalgar Square demanded Victoria’s removal, and Radical MPs spoke against her.[135] In August and September 1871, she was seriously ill with an abscess in her arm, which Joseph Lister successfully lanced and treated with his new antiseptic carbolic acid spray.[136] In late November 1871, at the height of the republican movement, the Prince of Wales contracted typhoid fever, the disease that was believed to have killed his father, and Victoria was fearful her son would die.[137] As the tenth anniversary of her husband’s death approached, her son’s condition grew no better, and Victoria’s distress continued.[138] To general rejoicing, he recovered.[139] Mother and son attended a public parade through London and a grand service of thanksgiving in St Paul’s Cathedral on 27 February 1872, and republican feeling subsided.[140]

On the last day of February 1872, two days after the thanksgiving service, 17-year-old Arthur O’Connor, a great-nephew of Irish MP Feargus O’Connor, waved an unloaded pistol at Victoria’s open carriage just after she had arrived at Buckingham Palace. Brown, who was attending the Queen, grabbed him and O’Connor was later sentenced to 12 months’ imprisonment,[141] and a birching.[142] As a result of the incident, Victoria’s popularity recovered further.[143]

Empress

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

After the Indian Rebellion of 1857, the British East India Company, which had ruled much of India, was dissolved, and Britain’s possessions and protectorates on the Indian subcontinent were formally incorporated into the British Empire. The Queen had a relatively balanced view of the conflict, and condemned atrocities on both sides.[144] She wrote of «her feelings of horror and regret at the result of this bloody civil war»,[145] and insisted, urged on by Albert, that an official proclamation announcing the transfer of power from the company to the state «should breathe feelings of generosity, benevolence and religious toleration».[146] At her behest, a reference threatening the «undermining of native religions and customs» was replaced by a passage guaranteeing religious freedom.[146]

Victoria admired Heinrich von Angeli’s 1875 portrait of her for its «honesty, total want of flattery, and appreciation of character».[147]

In the 1874 general election, Disraeli was returned to power. He passed the Public Worship Regulation Act 1874, which removed Catholic rituals from the Anglican liturgy and which Victoria strongly supported.[148] She preferred short, simple services, and personally considered herself more aligned with the presbyterian Church of Scotland than the episcopal Church of England.[149] Disraeli also pushed the Royal Titles Act 1876 through Parliament, so that Victoria took the title «Empress of India» from 1 May 1876.[150] The new title was proclaimed at the Delhi Durbar of 1 January 1877.[151]

On 14 December 1878, the anniversary of Albert’s death, Victoria’s second daughter Alice, who had married Louis of Hesse, died of diphtheria in Darmstadt. Victoria noted the coincidence of the dates as «almost incredible and most mysterious».[152] In May 1879, she became a great-grandmother (on the birth of Princess Feodora of Saxe-Meiningen) and passed her «poor old 60th birthday». She felt «aged» by «the loss of my beloved child».[153]

Between April 1877 and February 1878, she threatened five times to abdicate while pressuring Disraeli to act against Russia during the Russo-Turkish War, but her threats had no impact on the events or their conclusion with the Congress of Berlin.[154] Disraeli’s expansionist foreign policy, which Victoria endorsed, led to conflicts such as the Anglo-Zulu War and the Second Anglo-Afghan War. «If we are to maintain our position as a first-rate Power», she wrote, «we must … be Prepared for attacks and wars, somewhere or other, CONTINUALLY.»[155] Victoria saw the expansion of the British Empire as civilising and benign, protecting native peoples from more aggressive powers or cruel rulers: «It is not in our custom to annexe countries», she said, «unless we are obliged & forced to do so.»[156] To Victoria’s dismay, Disraeli lost the 1880 general election, and Gladstone returned as prime minister.[157] When Disraeli died the following year, she was blinded by «fast falling tears»,[158] and erected a memorial tablet «placed by his grateful Sovereign and Friend, Victoria R.I.»[159]

Later years

On 2 March 1882, Roderick Maclean, a disgruntled poet apparently offended by Victoria’s refusal to accept one of his poems,[160] shot at the Queen as her carriage left Windsor railway station. Gordon Chesney Wilson and another schoolboy from Eton College struck him with their umbrellas, until he was hustled away by a policeman.[161] Victoria was outraged when he was found not guilty by reason of insanity,[162] but was so pleased by the many expressions of loyalty after the attack that she said it was «worth being shot at—to see how much one is loved».[163]

On 17 March 1883, Victoria fell down some stairs at Windsor, which left her lame until July; she never fully recovered and was plagued with rheumatism thereafter.[164] John Brown died 10 days after her accident, and to the consternation of her private secretary, Sir Henry Ponsonby, Victoria began work on a eulogistic biography of Brown.[165] Ponsonby and Randall Davidson, Dean of Windsor, who had both seen early drafts, advised Victoria against publication, on the grounds that it would stoke the rumours of a love affair.[166] The manuscript was destroyed.[167] In early 1884, Victoria did publish More Leaves from a Journal of a Life in the Highlands, a sequel to her earlier book, which she dedicated to her «devoted personal attendant and faithful friend John Brown».[168] On the day after the first anniversary of Brown’s death, Victoria was informed by telegram that her youngest son, Leopold, had died in Cannes. He was «the dearest of my dear sons», she lamented.[169] The following month, Victoria’s youngest child, Beatrice, met and fell in love with Prince Henry of Battenberg at the wedding of Victoria’s granddaughter Princess Victoria of Hesse and by Rhine to Henry’s brother Prince Louis of Battenberg. Beatrice and Henry planned to marry, but Victoria opposed the match at first, wishing to keep Beatrice at home to act as her companion. After a year, she was won around to the marriage by their promise to remain living with and attending her.[170]

Victoria was pleased when Gladstone resigned in 1885 after his budget was defeated.[171] She thought his government was «the worst I have ever had», and blamed him for the death of General Gordon at Khartoum.[172] Gladstone was replaced by Lord Salisbury. Salisbury’s government only lasted a few months, however, and Victoria was forced to recall Gladstone, whom she referred to as a «half crazy & really in many ways ridiculous old man».[173] Gladstone attempted to pass a bill granting Ireland home rule, but to Victoria’s glee it was defeated.[174] In the ensuing election, Gladstone’s party lost to Salisbury’s and the government switched hands again.

Golden Jubilee

Victoria and the Munshi Abdul Karim

In 1887, the British Empire celebrated Victoria’s Golden Jubilee. She marked the fiftieth anniversary of her accession on 20 June with a banquet to which 50 kings and princes were invited. The following day, she participated in a procession and attended a thanksgiving service in Westminster Abbey.[175] By this time, Victoria was once again extremely popular.[176] Two days later on 23 June,[177] she engaged two Indian Muslims as waiters, one of whom was Abdul Karim. He was soon promoted to «Munshi»: teaching her Urdu and acting as a clerk.[178][179][180] Her family and retainers were appalled, and accused Abdul Karim of spying for the Muslim Patriotic League, and biasing the Queen against the Hindus.[181] Equerry Frederick Ponsonby (the son of Sir Henry) discovered that the Munshi had lied about his parentage, and reported to Lord Elgin, Viceroy of India, «the Munshi occupies very much the same position as John Brown used to do.»[182] Victoria dismissed their complaints as racial prejudice.[183] Abdul Karim remained in her service until he returned to India with a pension, on her death.[184]

Victoria’s eldest daughter became empress consort of Germany in 1888, but she was widowed a little over three months later, and Victoria’s eldest grandchild became German Emperor as Wilhelm II. Victoria and Albert’s hopes of a liberal Germany would go unfulfilled, as Wilhelm was a firm believer in autocracy. Victoria thought he had «little heart or Zartgefühl [tact] – and … his conscience & intelligence have been completely wharped [sic]».[185]

Gladstone returned to power after the 1892 general election; he was 82 years old. Victoria objected when Gladstone proposed appointing the Radical MP Henry Labouchère to the Cabinet, so Gladstone agreed not to appoint him.[186] In 1894, Gladstone retired and, without consulting the outgoing prime minister, Victoria appointed Lord Rosebery as prime minister.[187] His government was weak, and the following year Lord Salisbury replaced him. Salisbury remained prime minister for the remainder of Victoria’s reign.[188]

Diamond Jubilee

On 23 September 1896, Victoria surpassed her grandfather George III as the longest-reigning monarch in British history. The Queen requested that any special celebrations be delayed until 1897, to coincide with her Diamond Jubilee,[189] which was made a festival of the British Empire at the suggestion of the Colonial Secretary, Joseph Chamberlain.[190] The prime ministers of all the self-governing Dominions were invited to London for the festivities.[191] One reason for including the prime ministers of the Dominions and excluding foreign heads of state was to avoid having to invite Victoria’s grandson Wilhelm II of Germany, who, it was feared, might cause trouble at the event.[192]

The Queen’s Diamond Jubilee procession on 22 June 1897 followed a route six miles long through London and included troops from all over the empire. The procession paused for an open-air service of thanksgiving held outside St Paul’s Cathedral, throughout which Victoria sat in her open carriage, to avoid her having to climb the steps to enter the building. The celebration was marked by vast crowds of spectators and great outpourings of affection for the 78-year-old Queen.[193]

Queen Victoria in Dublin, 1900

Victoria visited mainland Europe regularly for holidays. In 1889, during a stay in Biarritz, she became the first reigning monarch from Britain to set foot in Spain when she crossed the border for a brief visit.[194] By April 1900, the Boer War was so unpopular in mainland Europe that her annual trip to France seemed inadvisable. Instead, the Queen went to Ireland for the first time since 1861, in part to acknowledge the contribution of Irish regiments to the South African war.[195]

Death and succession

In July 1900, Victoria’s second son, Alfred («Affie»), died. «Oh, God! My poor darling Affie gone too», she wrote in her journal. «It is a horrible year, nothing but sadness & horrors of one kind & another.»[196]

Following a custom she maintained throughout her widowhood, Victoria spent the Christmas of 1900 at Osborne House on the Isle of Wight. Rheumatism in her legs had rendered her disabled, and her eyesight was clouded by cataracts.[197] Through early January, she felt «weak and unwell»,[198] and by mid-January she was «drowsy … dazed, [and] confused».[199] She died on 22 January 1901, at half past six in the evening, at the age of 81.[200] Her eldest son, Albert Edward, succeeded her as Edward VII. Edward and his nephew Wilhelm II were at Victoria’s deathbed.[201] Her favourite pet Pomeranian, Turi, was laid upon her deathbed as a last request.[202]

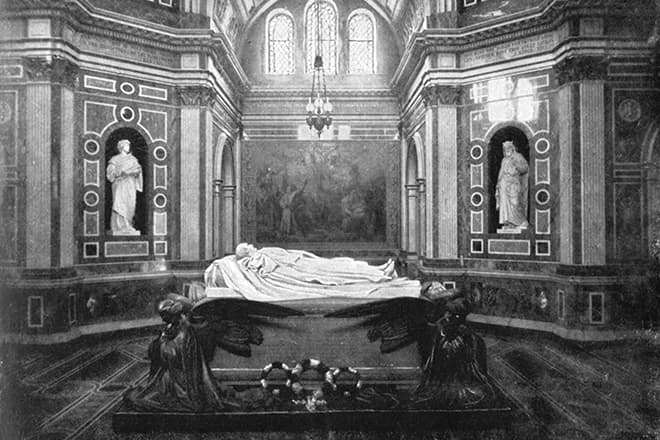

In 1897, Victoria had written instructions for her funeral, which was to be military as befitting a soldier’s daughter and the head of the army,[96] and white instead of black.[203] On 25 January, her sons Edward and Arthur and her grandson Wilhelm helped lift her body into the coffin.[204] She was dressed in a white dress and her wedding veil.[205] An array of mementos commemorating her extended family, friends and servants were laid in the coffin with her, at her request, by her doctor and dressers. One of Albert’s dressing gowns was placed by her side, with a plaster cast of his hand, while a lock of John Brown’s hair, along with a picture of him, was placed in her left hand concealed from the view of the family by a carefully positioned bunch of flowers.[96][206] Items of jewellery placed on Victoria included the wedding ring of John Brown’s mother, given to her by Brown in 1883.[96] Her funeral was held on Saturday 2 February, in St George’s Chapel, Windsor Castle, and after two days of lying-in-state, she was interred beside Prince Albert in the Royal Mausoleum, Frogmore, at Windsor Great Park.[207]

With a reign of 63 years, seven months, and two days, Victoria was the longest-reigning British monarch and the longest-reigning queen regnant in world history, until her great-great-granddaughter Elizabeth II surpassed her on 9 September 2015.[208] She was the last monarch of Britain from the House of Hanover; her son Edward VII belonged to her husband’s House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha.

Legacy

Victoria amused. The remark «We are not amused» is attributed to her but there is no direct evidence that she ever said it,[96][209] and she denied doing so.[210] Her staff and family recorded that Victoria «was immensely amused and roared with laughter» on many occasions.[211]

According to one of her biographers, Giles St Aubyn, Victoria wrote an average of 2,500 words a day during her adult life.[212] From July 1832 until just before her death, she kept a detailed journal, which eventually encompassed 122 volumes.[213] After Victoria’s death, her youngest daughter, Princess Beatrice, was appointed her literary executor. Beatrice transcribed and edited the diaries covering Victoria’s accession onwards, and burned the originals in the process.[214] Despite this destruction, much of the diaries still exist. In addition to Beatrice’s edited copy, Lord Esher transcribed the volumes from 1832 to 1861 before Beatrice destroyed them.[215] Part of Victoria’s extensive correspondence has been published in volumes edited by A. C. Benson, Hector Bolitho, George Earle Buckle, Lord Esher, Roger Fulford, and Richard Hough among others.[216]

Victoria was physically unprepossessing—she was stout, dowdy and only about five feet (1.5 metres) tall—but she succeeded in projecting a grand image.[217] She experienced unpopularity during the first years of her widowhood, but was well liked during the 1880s and 1890s, when she embodied the empire as a benevolent matriarchal figure.[218] Only after the release of her diary and letters did the extent of her political influence become known to the wider public.[96][219] Biographies of Victoria written before much of the primary material became available, such as Lytton Strachey’s Queen Victoria of 1921, are now considered out of date.[220] The biographies written by Elizabeth Longford and Cecil Woodham-Smith, in 1964 and 1972 respectively, are still widely admired.[221] They, and others, conclude that as a person Victoria was emotional, obstinate, honest, and straight-talking.[222]

Through Victoria’s reign, the gradual establishment of a modern constitutional monarchy in Britain continued. Reforms of the voting system increased the power of the House of Commons at the expense of the House of Lords and the monarch.[223] In 1867, Walter Bagehot wrote that the monarch only retained «the right to be consulted, the right to encourage, and the right to warn».[224] As Victoria’s monarchy became more symbolic than political, it placed a strong emphasis on morality and family values, in contrast to the sexual, financial and personal scandals that had been associated with previous members of the House of Hanover and which had discredited the monarchy. The concept of the «family monarchy», with which the burgeoning middle classes could identify, was solidified.[225]

Descendants and haemophilia

Victoria’s links with Europe’s royal families earned her the nickname «the grandmother of Europe».[226] Of the 42 grandchildren of Victoria and Albert, 34 survived to adulthood. Their living descendants include Charles III of the United Kingdom; Harald V of Norway; Carl XVI Gustaf of Sweden; Margrethe II of Denmark; and Felipe VI of Spain.

Victoria’s youngest son, Leopold, was affected by the blood-clotting disease haemophilia B and at least two of her five daughters, Alice and Beatrice, were carriers. Royal haemophiliacs descended from Victoria included her great-grandsons, Alexei Nikolaevich, Tsarevich of Russia; Alfonso, Prince of Asturias; and Infante Gonzalo of Spain.[227] The presence of the disease in Victoria’s descendants, but not in her ancestors, led to modern speculation that her true father was not the Duke of Kent, but a haemophiliac.[228] There is no documentary evidence of a haemophiliac in connection with Victoria’s mother, and as male carriers always had the disease, even if such a man had existed he would have been seriously ill.[229] It is more likely that the mutation arose spontaneously because Victoria’s father was over 50 at the time of her conception and haemophilia arises more frequently in the children of older fathers.[230] Spontaneous mutations account for about a third of cases.[231]

Namesakes

Around the world, places and memorials are dedicated to her, especially in the Commonwealth nations. Places named after her include Africa’s largest lake, Victoria Falls, the capitals of British Columbia (Victoria) and Saskatchewan (Regina), two Australian states (Victoria and Queensland), and the capital of the island nation of Seychelles.

The Victoria Cross was introduced in 1856 to reward acts of valour during the Crimean War,[232] and it remains the highest British, Canadian, Australian, and New Zealand award for bravery. Victoria Day is a Canadian statutory holiday and a local public holiday in parts of Scotland celebrated on the last Monday before or on 24 May (Queen Victoria’s birthday).

Titles, styles, honours, and arms

Titles and styles

At the end of her reign, the Queen’s full style was: «Her Majesty Victoria, by the Grace of God, of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland Queen, Defender of the Faith, Empress of India».[233]

Honours

British honours

- Royal Family Order of King George IV, 1826[234]

- Founder and Sovereign of the Order of the Star of India, 25 June 1861[235]

- Founder and Sovereign of the Royal Order of Victoria and Albert, 10 February 1862[236]

- Founder and Sovereign of the Order of the Crown of India, 1 January 1878[237]

- Founder and Sovereign of the Order of the Indian Empire, 1 January 1878[238]

- Founder and Sovereign of the Royal Red Cross, 27 April 1883[239]

- Founder and Sovereign of the Distinguished Service Order, 6 November 1886[240]

- Albert Medal of the Royal Society of Arts, 1887[241]

- Founder and Sovereign of the Royal Victorian Order, 23 April 1896[242]

Foreign honours

- Spain:

- Dame of the Order of Queen Maria Luisa, 21 December 1833[243]

- Grand Cross of the Order of Charles III[244]

- Portugal:

- Dame of the Order of Queen Saint Isabel, 23 February 1836[245]

- Grand Cross of the Order of the Immaculate Conception of Vila Viçosa[244]

- Russia: Grand Cross of St. Catherine, 26 June 1837[246]

- France: Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour, 5 September 1843[247]

- Mexico/Mexican Empire:

- Grand Cross of the National Order of Guadalupe, 1854[248]

- Grand Cross of the Imperial Order of San Carlos, 1866[249]

- Prussia: Dame of the Order of Louise, 1st Division, 11 June 1857[250]

- Brazil: Grand Cross of the Order of Pedro I, 3 December 1872[251]

- Persia:[252]

- Order of the Sun, 1st Class in Diamonds, 20 June 1873

- Order of the August Portrait, 20 June 1873

- Siam:

- Grand Cross of the White Elephant, 1880[253]

- Dame of the Order of the Royal House of Chakri, 1887[254]

- Hawaii: Grand Cross of the Order of Kamehameha I, with Collar, July 1881[255]

- Serbia:[256][257]

- Grand Cross of the Cross of Takovo, 1882

- Grand Cross of the White Eagle, 1883

- Grand Cross of St. Sava, 1897

- Hesse and by Rhine: Dame of the Golden Lion, 25 April 1885[258]

- Bulgaria: Order of the Bulgarian Red Cross, August 1887[259]

- Ethiopia: Grand Cross of the Seal of Solomon, 22 June 1897 – Diamond Jubilee gift[260]

- Montenegro: Grand Cross of the Order of Prince Danilo I, 1897[261]

- Saxe-Coburg and Gotha: Silver Wedding Medal of Duke Alfred and Duchess Marie, 23 January 1899[262]

Arms

As Sovereign, Victoria used the royal coat of arms of the United Kingdom. Before her accession, she received no grant of arms. As she could not succeed to the throne of Hanover, her arms did not carry the Hanoverian symbols that were used by her immediate predecessors. Her arms have been borne by all of her successors on the throne.

Outside Scotland, the blazon for the shield—also used on the Royal Standard—is: Quarterly: I and IV, Gules, three lions passant guardant in pale Or (for England); II, Or, a lion rampant within a double tressure flory-counter-flory Gules (for Scotland); III, Azure, a harp Or stringed Argent (for Ireland). In Scotland, the first and fourth quarters are occupied by the Scottish lion, and the second by the English lions. The crests, mottoes, and supporters also differ in and outside Scotland.

|

|

|

|---|---|

| Royal arms (outside Scotland) | Royal arms (in Scotland) |

Family

Issue

| Name | Birth | Death | Spouse and children[233][263] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Victoria, Princess Royal | 21 November 1840 |

5 August 1901 |

Married 1858, Frederick, later German Emperor and King of Prussia (1831–1888); 4 sons (including Wilhelm II, German Emperor), 4 daughters (including Queen Sophia of Greece) |

| Edward VII | 9 November 1841 |

6 May 1910 |

Married 1863, Princess Alexandra of Denmark (1844–1925); 3 sons (including King George V of the United Kingdom), 3 daughters (including Queen Maud of Norway) |

| Princess Alice | 25 April 1843 |

14 December 1878 |

Married 1862, Louis IV, Grand Duke of Hesse and by Rhine (1837–1892); 2 sons, 5 daughters (including Empress Alexandra Feodorovna of Russia) |

| Alfred, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha | 6 August 1844 |

31 July 1900 |

Married 1874, Grand Duchess Maria Alexandrovna of Russia (1853–1920); 2 sons (1 stillborn), 4 daughters (including Queen Marie of Romania) |

| Princess Helena | 25 May 1846 |

9 June 1923 |

Married 1866, Prince Christian of Schleswig-Holstein (1831–1917); 4 sons (1 stillborn), 2 daughters |

| Princess Louise | 18 March 1848 |

3 December 1939 |

Married 1871, John Campbell, Marquess of Lorne, later 9th Duke of Argyll (1845–1914); no issue |

| Prince Arthur, Duke of Connaught and Strathearn | 1 May 1850 |

16 January 1942 |

Married 1879, Princess Louise Margaret of Prussia (1860–1917); 1 son, 2 daughters (including Crown Princess Margaret of Sweden) |

| Prince Leopold, Duke of Albany | 7 April 1853 |

28 March 1884 |

Married 1882, Princess Helena of Waldeck and Pyrmont (1861–1922); 1 son, 1 daughter |

| Princess Beatrice | 14 April 1857 |

26 October 1944 |

Married 1885, Prince Henry of Battenberg (1858–1896); 3 sons, 1 daughter (Queen Victoria Eugenie of Spain) |

Ancestry

Family tree

- Red borders indicate British monarchs

- Bold borders indicate children of British monarchs

| Family of Queen Victoria, spanning the reigns of her grandfather, George III, to her grandson, George V | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Notes

- ^ As monarch, Victoria was Supreme Governor of the Church of England. She was also a member of the Church of Scotland.

- ^ Her godparents were Tsar Alexander I of Russia (represented by her uncle Frederick, Duke of York), her uncle George, Prince Regent, her aunt Queen Charlotte of Württemberg (represented by Victoria’s aunt Princess Augusta) and Victoria’s maternal grandmother the Dowager Duchess of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld (represented by Victoria’s aunt Princess Mary, Duchess of Gloucester and Edinburgh).

- ^ Under section 2 of the Regency Act 1830, the Accession Council’s proclamation declared Victoria as the King’s successor «saving the rights of any issue of His late Majesty King William the Fourth which may be borne of his late Majesty’s Consort». «No. 19509». The London Gazette. 20 June 1837. p. 1581.

References

Citations

- ^ Hibbert, pp. 3–12; Strachey, pp. 1–17; Woodham-Smith, pp. 15–29

- ^ Hibbert, pp. 12–13; Longford, p. 23; Woodham-Smith, pp. 34–35

- ^ Longford, p. 24

- ^ Worsley, p. 41.

- ^ Hibbert, p. 31; St Aubyn, p. 26; Woodham-Smith, p. 81

- ^ Hibbert, p. 46; Longford, p. 54; St Aubyn, p. 50; Waller, p. 344; Woodham-Smith, p. 126

- ^ Hibbert, p. 19; Marshall, p. 25

- ^ Hibbert, p. 27; Longford, pp. 35–38, 118–119; St Aubyn, pp. 21–22; Woodham-Smith, pp. 70–72. The rumours were false in the opinion of these biographers.

- ^ Hibbert, pp. 27–28; Waller, pp. 341–342; Woodham-Smith, pp. 63–65

- ^ Hibbert, pp. 32–33; Longford, pp. 38–39, 55; Marshall, p. 19

- ^ Waller, pp. 338–341; Woodham-Smith, pp. 68–69, 91

- ^ Hibbert, p. 18; Longford, p. 31; Woodham-Smith, pp. 74–75

- ^ Longford, p. 31; Woodham-Smith, p. 75

- ^ Hibbert, pp. 34–35

- ^ Hibbert, pp. 35–39; Woodham-Smith, pp. 88–89, 102

- ^ Hibbert, p. 36; Woodham-Smith, pp. 89–90

- ^ Hibbert, pp. 35–40; Woodham-Smith, pp. 92, 102

- ^ Hibbert, pp. 38–39; Longford, p. 47; Woodham-Smith, pp. 101–102

- ^ Hibbert, p. 42; Woodham-Smith, p. 105

- ^ Hibbert, p. 42; Longford, pp. 47–48; Marshall, p. 21

- ^ Hibbert, pp. 42, 50; Woodham-Smith, p. 135

- ^ Marshall, p. 46; St Aubyn, p. 67; Waller, p. 353

- ^ Longford, pp. 29, 51; Waller, p. 363; Weintraub, pp. 43–49

- ^ Longford, p. 51; Weintraub, pp. 43–49

- ^ Longford, pp. 51–52; St Aubyn, p. 43; Weintraub, pp. 43–49; Woodham-Smith, p. 117

- ^ Weintraub, pp. 43–49

- ^ Victoria quoted in Marshall, p. 27 and Weintraub, p. 49

- ^ Victoria quoted in Hibbert, p. 99; St Aubyn, p. 43; Weintraub, p. 49 and Woodham-Smith, p. 119

- ^ Victoria’s journal, October 1835, quoted in St Aubyn, p. 36 and Woodham-Smith, p. 104

- ^ Hibbert, p. 102; Marshall, p. 60; Waller, p. 363; Weintraub, p. 51; Woodham-Smith, p. 122

- ^ Waller, pp. 363–364; Weintraub, pp. 53, 58, 64, and 65

- ^ St Aubyn, pp. 55–57; Woodham-Smith, p. 138

- ^ Woodham-Smith, p. 140

- ^ Packard, pp. 14–15

- ^ Hibbert, pp. 66–69; St Aubyn, p. 76; Woodham-Smith, pp. 143–147

- ^ Greville quoted in Hibbert, p. 67; Longford, p. 70 and Woodham-Smith, pp. 143–144

- ^ Queen Victoria’s Coronation 1838, The British Monarchy, archived from the original on 3 February 2016, retrieved 28 January 2016

- ^ St Aubyn, p. 69; Waller, p. 353

- ^ Hibbert, p. 58; Longford, pp. 73–74; Woodham-Smith, p. 152

- ^ Marshall, p. 42; St Aubyn, pp. 63, 96

- ^ Marshall, p. 47; Waller, p. 356; Woodham-Smith, pp. 164–166

- ^ Hibbert, pp. 77–78; Longford, p. 97; St Aubyn, p. 97; Waller, p. 357; Woodham-Smith, p. 164

- ^ Victoria’s journal, 25 April 1838, quoted in Woodham-Smith, p. 162

- ^ St Aubyn, p. 96; Woodham-Smith, pp. 162, 165

- ^ Hibbert, p. 79; Longford, p. 98; St Aubyn, p. 99; Woodham-Smith, p. 167

- ^ Hibbert, pp. 80–81; Longford, pp. 102–103; St Aubyn, pp. 101–102

- ^ Longford, p. 122; Marshall, p. 57; St Aubyn, p. 104; Woodham-Smith, p. 180

- ^ Hibbert, p. 83; Longford, pp. 120–121; Marshall, p. 57; St Aubyn, p. 105; Waller, p. 358

- ^ St Aubyn, p. 107; Woodham-Smith, p. 169

- ^ Hibbert, pp. 94–96; Marshall, pp. 53–57; St Aubyn, pp. 109–112; Waller, pp. 359–361; Woodham-Smith, pp. 170–174

- ^ Longford, p. 84; Marshall, p. 52

- ^ Longford, p. 72; Waller, p. 353

- ^ Woodham-Smith, p. 175

- ^ Hibbert, pp. 103–104; Marshall, pp. 60–66; Weintraub, p. 62

- ^ Hibbert, pp. 107–110; St Aubyn, pp. 129–132; Weintraub, pp. 77–81; Woodham-Smith, pp. 182–184, 187

- ^ Hibbert, p. 123; Longford, p. 143; Woodham-Smith, p. 205

- ^ St Aubyn, p. 151

- ^ Hibbert, p. 265, Woodham-Smith, p. 256

- ^ Marshall, p. 152; St Aubyn, pp. 174–175; Woodham-Smith, p. 412

- ^ Charles, p. 23

- ^ Hibbert, pp. 421–422; St Aubyn, pp. 160–161

- ^ Woodham-Smith, p. 213

- ^ Hibbert, p. 130; Longford, p. 154; Marshall, p. 122; St Aubyn, p. 159; Woodham-Smith, p. 220

- ^ Hibbert, p. 149; St Aubyn, p. 169

- ^ Hibbert, p. 149; Longford, p. 154; Marshall, p. 123; Waller, p. 377

- ^ Woodham-Smith, p. 100

- ^ Longford, p. 56; St Aubyn, p. 29

- ^ Hibbert, pp. 150–156; Marshall, p. 87; St Aubyn, pp. 171–173; Woodham-Smith, pp. 230–232

- ^ Charles, p. 51; Hibbert, pp. 422–423; St Aubyn, pp. 162–163

- ^ Hibbert, p. 423; St Aubyn, p. 163

- ^ Longford, p. 192

- ^ St Aubyn, p. 164

- ^ Marshall, pp. 95–101; St Aubyn, pp. 153–155; Woodham-Smith, pp. 221–222

- ^ Queen Victoria and the Princess Royal, Royal Collection, archived from the original on 17 January 2016, retrieved 29 March 2013

- ^ Woodham-Smith, p. 281

- ^ Longford, p. 359

- ^ The title of Maud Gonne’s 1900 article upon Queen Victoria’s visit to Ireland

- ^ Harrison, Shane (15 April 2003), «Famine Queen row in Irish port», BBC News, archived from the original on 19 September 2019, retrieved 29 March 2013

- ^ Officer, Lawrence H.; Williamson, Samuel H. (2018), Five Ways to Compute the Relative Value of a UK Pound Amount, 1270 to Present, MeasuringWorth, archived from the original on 6 April 2018, retrieved 5 April 2018

- ^ Kinealy, Christine, Private Responses to the Famine, University College Cork, archived from the original on 6 April 2013, retrieved 29 March 2013

- ^ Longford, p. 181