Вормсский Рейхстаг: общеимперское дело

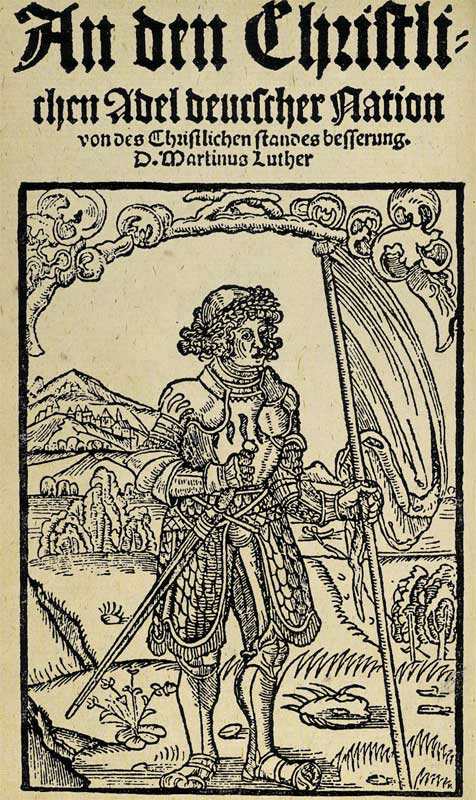

Октябрь 1517 года стал отправной точкой в истории Реформации в Германии — это был пролог непростого процесса борьбы ряда общественных групп внутри империи. По сути, 31 октября 1517 года — формальная дата, обросшая красивой легендой, которую, скорее всего, придумал соратник и ученик Лютера Филипп Меланхтон. Якобы к стенам Виттенбергского кафедрального собора доктор богословия прибил открытое письмо архиепископу Майнца Альбрехту Бранденбургскому — 95 тезисов. Сам Лютер никогда не вспоминал об этом событии как о публичной демонстрации своих идей. Период с 1517-го по 1521-й пройдёт в спорах с видными интеллектуалами от церкви, а также в процессе публикации самых известных трактатов. Получат своё распространение такие произведения, как «К христианскому дворянству немецкой нации», «О свободе христианина» и «О вавилонском пленении пап». Апостольский престол был обеспокоен распространением учения бывшего августинского монаха, но в немецких землях пока ещё не случилось бурной реакции.

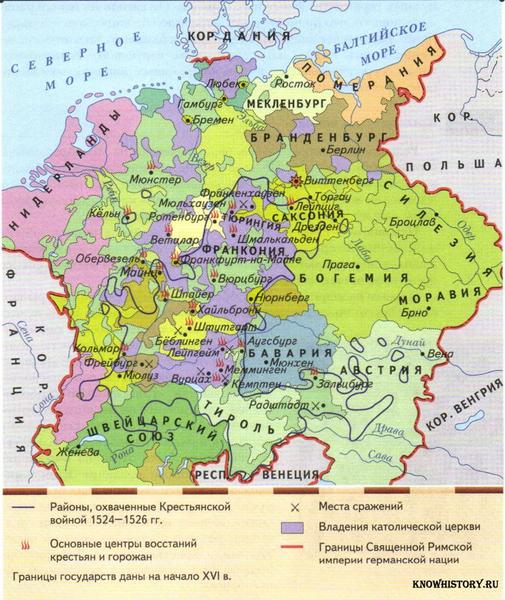

«К христианскому дворянству немецкой нации». (pinterest)

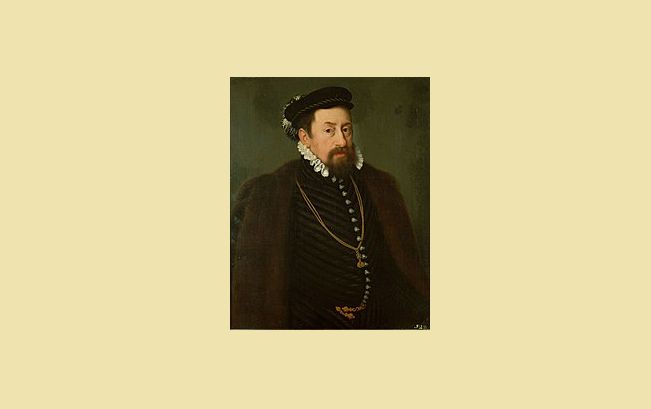

Однако ситуация внутри империи менялась: в 1519 году Максимилиан I ушёл в лучший из миров, и княжеская ассамблея во Франкфурте выбрала государем Карла V. Ревностный католик, негативно относившийся к опусам Лютера, был обязан избранию на престол голосу протектора богослова, саксонского курфюрста Фридриха III Мудрого. После того как мятежный доктор из Виттенбергского университета сжёг папскую буллу об отлучении его от церкви, верховная власть империи намеревалась выдворить еретика за границу. Но по личной просьбе курфюрста Фридриха Мудрого император Карл V даёт возможность выступить богослову на Вормсском рейхстаге в первой половине 1521 года.

Центральным вопросом рейхстага стала турецкая проблема, далее — жалобы князей на церковную юстицию. Элита хотела разграничения сфер влияния церковной и светской юстиций, так как обе соприкасались слишком часто. Самый главный пункт — право суда над духовными лицами.

17 апреля Мартину Лютеру предоставили возможность выступить. Ему предстояло произнести свою речь в очень непростых условиях. Разбор его дела шёл 3 дня: говорил он путано, очень стеснялся княжеской ассамблеи, чувствовал себя некомфортно. Позднее доктор богословия не любил вспоминать Вормсский съезд, ибо, как сам считал, выглядел он там очень неубедительно. Император не воспринял речь реформатора, но часть князей всё же обратила внимание на его высказывания, ведь он защищал те же постулаты, что выдвигали и они.

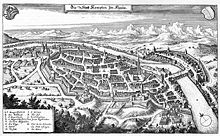

В итоге в майские дни 1521 года были приняты два серьёзных решения. Первое — Лютер покидал в 20-дневный срок территорию Священной Римской империи. Второе — ему и его сторонникам запрещалась проповедь, а также решение по его делу откладывалось до следующего вселенского собора. Многие князья, даже архиепископ Майнца, не осмелились подписать это постановление. Официально Лютер — изгой. Он торопится в Саксонию, где попадает в руки местного дворянства: реформатора якобы похищают. Появляется некий рыцарь Георг в замке Вартбург, что в Тюрингии, который занимается переводом Библии на немецкий язык. Эта хитрая операция была подготовлена не без помощи курфюрста Фридриха Мудрого.

Замок Вартбург. (Wikimedia Commons)

Фактически с 1521 года о себе официально заявляет Реформация в Германии: общественные массы начинают включаться в спор Лютера с Римом. Теперь это общеимперское дело.

Крестьянская война в Германии

Отец немецкой Реформации на время отошёл от дел: у движения нет лидера. Оно постепенно распадается на два течения. Первое — откровенно радикальное, которое выступало за немедленные преобразования в церкви, зачастую выливавшиеся в погромы монастырей, соборов и иконоборческое движение.

У «анархистов» было два лидера — импульсивный Андреас Карлштадт и энергичный Томас Мюнцер. Их идеи являлись максимальным упрощением лютеровской риторики. Немедленные действия без чёткого плана были обречены на потерю контроля над движением.

Второе — умеренное, которым руководил ученик Лютера, интеллектуал, преподаватель древнегреческого языка Виттенбергского университета Филипп Меланхтон. Но с простым народом сторонники нейтрального направления не нашли общего языка.

В 1522 году Лютер выходит из тени и выдворяет радикалов из Виттенберга. В землях курфюршества Саксония появляются первые лютеранские общины. Тем не менее до конца не было ясно, как должны существовать сообщества нового вероисповедания. Было необходимо организованное управление и власть.

Но на юго-западе Германии под знамёнами новой веры начинаются волнения. В 1522—1523 гг. в Эльзасе и Швабии прогремело рыцарское восстание. Интересы мелкого дворянства не особенно волновали новоиспечённого императора, а вот братья по Евангелию могли помочь в борьбе за права военной элиты. Но, к несчастью, евангелических сторонников было мало, а имперский Швабский союз городов и дворян дал отпор рыцарям под предводительством Франца фон Зиккенгена и Гёца фон Берлихингена.

Рыцарское восстание 1522−1523 гг. (pinterest)

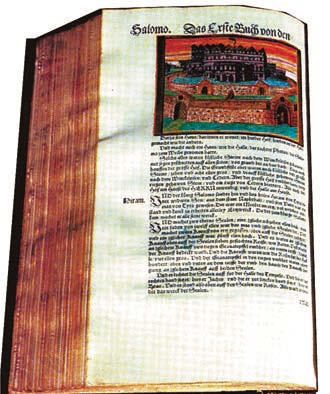

Через год после провала рыцарского мятежа поднимают головы крестьяне. Их интересуют вопросы общинных прав и церковная реформа. Так и началась Крестьянская война на юге Германии, которая гремела с 1524-го по 1525-й. Стихийный бунт простого люда сильно ударил по дворянским поместьям и церковным землям. Расправы были неминуемы. Во главе отрядов восставших землепашцев были и рыцари, и народные проповедники. Лютера сильно опечалило такое положение дел: он хоть и призывал к борьбе, но не через насилие.

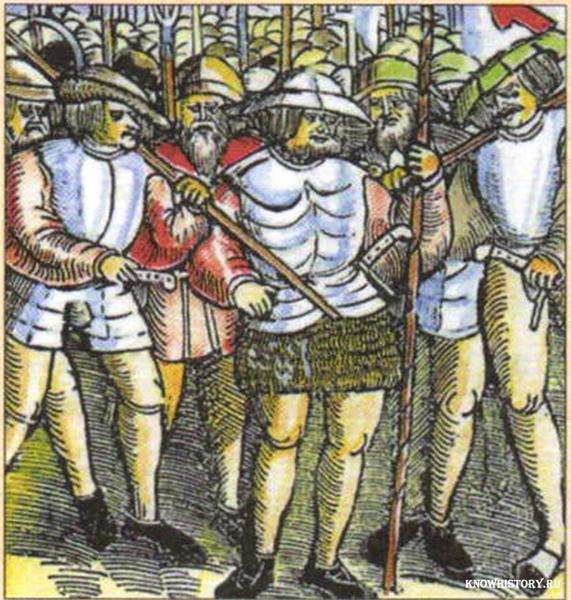

Восставшие крестьяне. (pinterest)

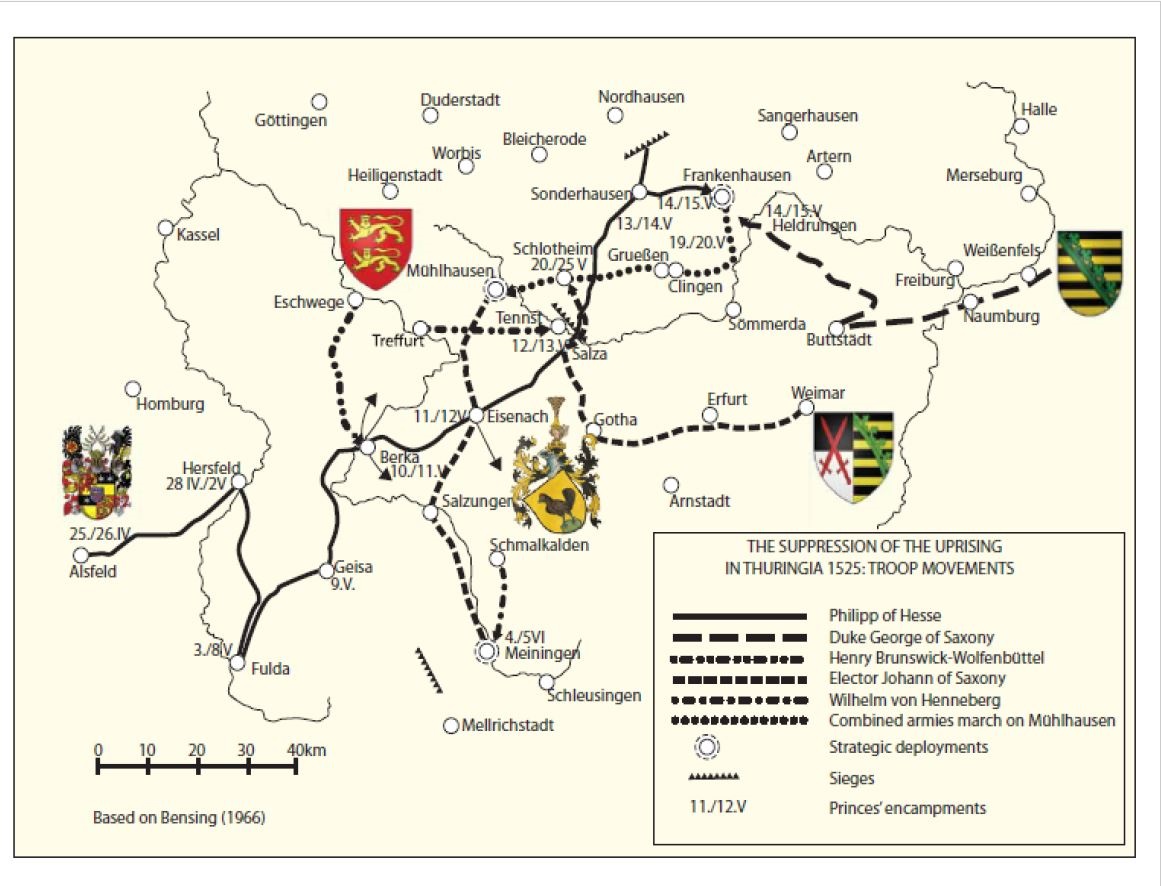

В начале 1525 года Швабский союз подавляет большинство крестьянских бунтов на юго-западе немецких земель. Весной и летом идёт зачистка Тюрингии: в битве под Франкенхаузеном 14−15 мая закончится история Томаса Мюнцера.

Битва под Франкенхаузеном. (pinterest)

Он спрячется в городе и объявит себя пророком. Однако войска ландграфа Гессенского Филиппа Великодушного и Георга Трухзеса фон Вальдбурга найдут главаря мятежников и обезглавят его. Хаос Крестьянской войны оставил сильный отпечаток не только в душе Мартина Лютера, но и на состоянии империи. Число жертв было колоссальным.

Карта восстания в Тюрингии. (pinterest)

После подобных социальных катаклизмов княжеская власть внедряется в реформационное движение. Элита начинает реагировать на посылы Лютера и видеть в них свою выгоду: курфюршество Саксония, ландграфство Гессен, земли Немецкого ордена в Пруссии и Прибалтике принимают учение виттенбергского богослова. Городские общины и мелкие владения дворян на юге и западе Германии также перенимают лютеранство.

Двор Габсбургов откровенно не справлялся с такой диффузией Реформации в Германии. Пока Карл V был занят итальянскими делами, его брат эрцгерцог Фердинанд на рейхстаге в Шпейре 1526 года пошёл на компромисс: к постановлениям Вормсского рейхстага добавилась ещё одна строка: каждый чин империи в своих владениях справляет богослужение, как велит его совесть. Фактически развитию идей Лютера дали зелёный свет. Однако в 1529 году император Карл V потребовал от эрцгерцога добиться признания князьями статей Вормсского рейхстага. Но дворянство ответило протестом.

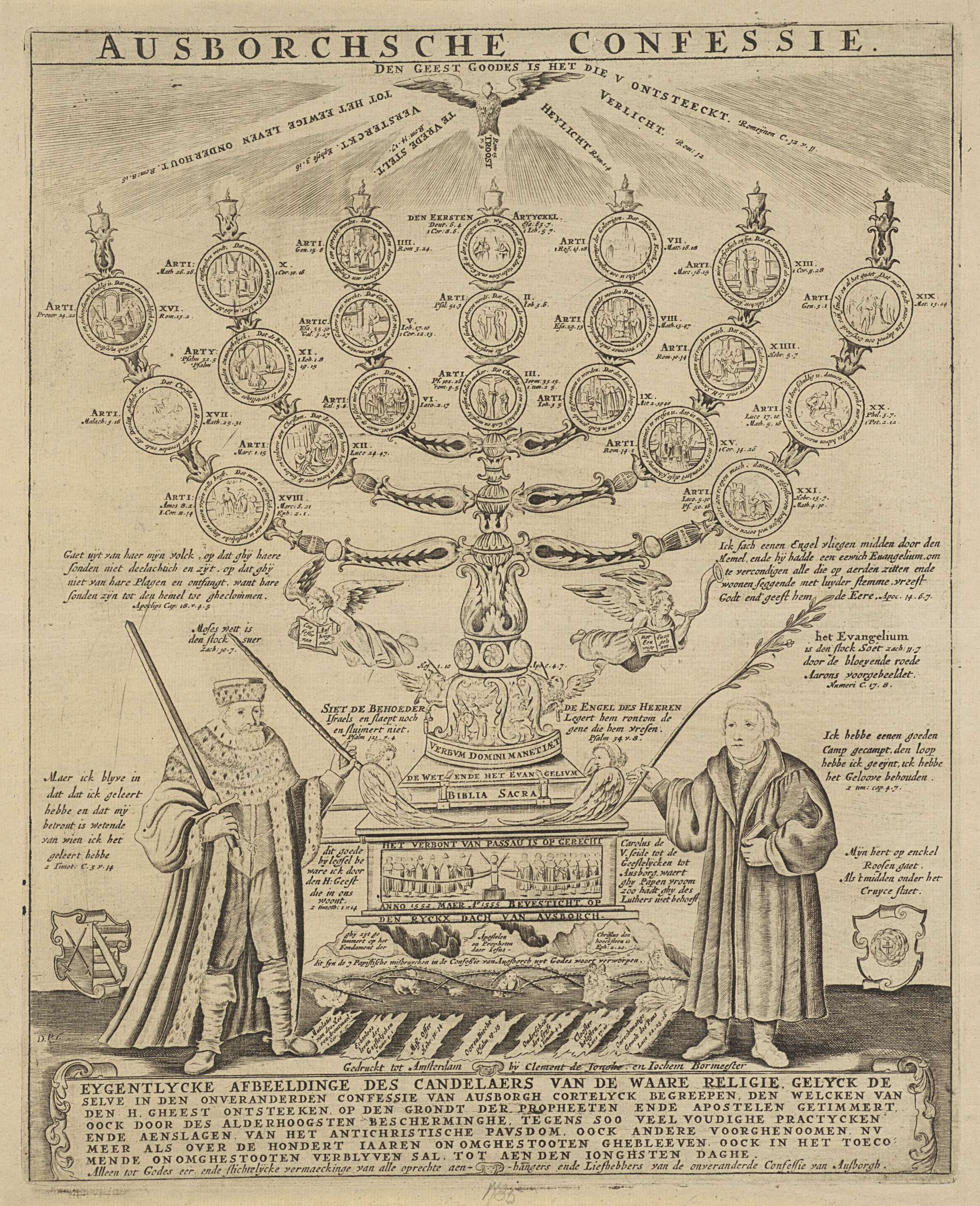

В 1530 году в Аугсбурге «протестанты» во главе с Меланхтоном представили свою формулу вероисповедания. Карл решительно не соглашался с протестантским крылом княжеской ассамблеи и дал год на пересмотр своего мнения. Государь открыто угрожал опалой и репрессиями.

Шмалькальденская война

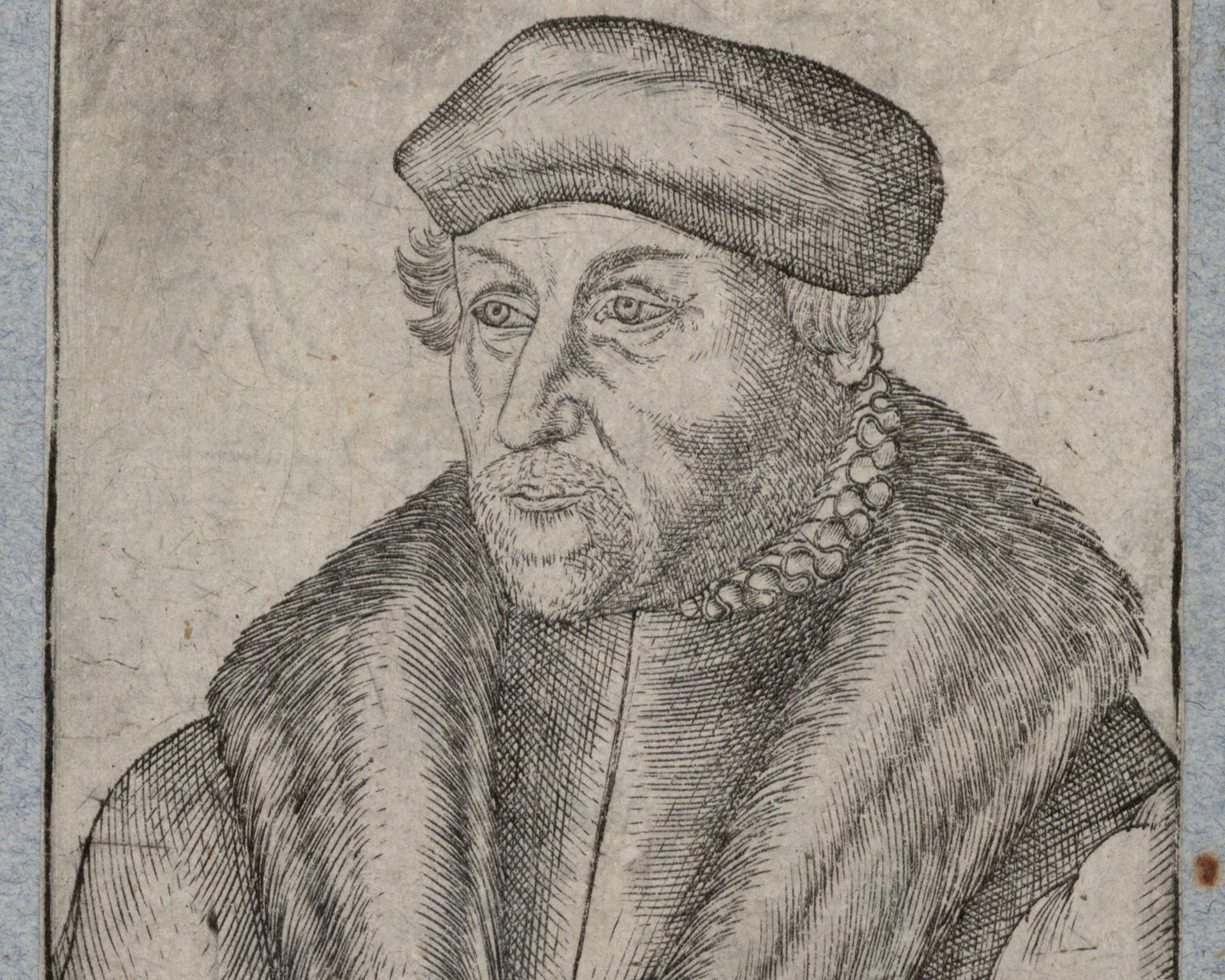

Напуганная протестантская знать и города в феврале 1531 года создают своё объединение — Шмалькальденский союз. Во главе стояли две важные для немецкой истории фигуры — Филипп Гессенский и Иоганн-Фридрих Саксонский. У союза сформировалась своя казна и свои вооружённые силы. В управлении объединением протестантов главную роль играл ландграф Гессена Филипп Великодушный — энергичный и деятельный князь, который думал о всеевропейском союзе протестантов. Он искал контакты с французскими, швейцарскими и нидерландскими братьями по вере. Вскоре к союзу примыкают реформаторские Вюртемберг и Брауншвейг.

Филипп Великодушный — ландграф Гессенан. (Wikimedia Commons)

Спустя почти 15 лет император Карл V и его сторонники начали борьбу против окрепшего союза протестантов. В 1545 году в Италии открылся Тридентский собор, который был собран в ответ на реформационное движение. Карл наконец разобрался с турецкой опасностью и заключил перемирие с Францией. Империя решила нанести ответный удар: в феврале 1546 года, когда уже не стало Лютера, на рейхстаге в Регенсбурге вождей Шмалькальденского союза провозгласили мятежниками.

Начались открытые боевые действия. На первых порах протестанты одержали ряд побед, но не смогли со временем закрепить свой успех. Военные советники мятежников предупреждали князей о перекрытии альпийских перевалов, через которые император мог получить подкрепление из Италии. Но лидеры союза больше пеклись о своих наследственных землях. Сторонники Карла собрали сильную группировку в Баварии и к осени 1546 года перешли в наступление. Армия протестантов распалась весной 1547 года в Саксонии и в апреле того же года была наголову разбита под Мюльбергом.

Шмалькальденская война. (Wikimedia Commons)

Император молниеносно развернул кампанию по реставрации католических порядков в Германии. Лютеровское вероучение возбранялось, вожди протестантского союза были помещены в тюрьму в Ингольштадте. Триумф Карла не оказался долгоиграющим: северные города и княжества решительно выступили против консервативных мер имперской власти, а союзники Габсбургов были напуганы — они считали, что император откровенно превышает свои полномочия.

На волне столкновений с Францией в 1551—1552 гг. разыгралась вторая Шмалькальденская война. Первой скрипкой протестантов стал курфюрст Мориц Саксонский. Мятежники решили не повторять старых ошибок и захватили альпийские перевалы, заставив имперское войско бежать в глубь Тироля. Потерявший всякое желание беседовать с протестантами, Карл делегировал полномочия Фердинанду: эрцгерцог пошёл на диалог и подписал с мятежниками в марте 1552 года Пассаутский мир. Союз протестантов распускался при условии вывода всех иностранных формирований с территории империи и освобождения всех пленных вождей объединения. Также гарантировалась свобода лютеранскому вероисповедованию.

Аугсбургский религиозный мир: уязвимое согласие

В 1555 году имперские чины наконец собрались в Аугсбурге, чтобы выработать новую формулу взаимодействия власти и протестантских князей. Напряжённые переговоры всё-таки закончились подписанием 25 октября 1555 года Аугсбургского религиозного мира.

Документ способствовал полному восстановлению земского мира в империи, концу смут и реорганизации имперской юстиции. Также было окончательно узаконено лютеранское вероисповедание, но при этом кальвинисты, баптисты, адвентисты и прочие протестантские движения объявлялись вне закона. Все дела по преследованию лютеран и католиков прекращались.

Аугсбургский религиозный мир. (pinterest)

Казалось, в империи воцарился мир и порядок, но, к сожалению, существовали важные обстоятельства, которые делали Аугсбургское согласие очень уязвимым. Любое появление нового течения протестантизма в немецких землях ставило под угрозу баланс сил. Существовала также проблема трактовки формулировок документа. Несмотря на всю стойкость имперских порядков и соглашений, последствия Аугсбургского мира сыграют важную роль в дестабилизации религиозного климата в Священной Римской империи начала 17-го столетия.

Эта

война – одна из ранних форм буржуазной

революции.

Причины

крестьянской войны,

две главные: 1) кризис феодальной системы

в XVI в.; 2) раскол в реформационном

движении. Крестьянской войне предшествовало

появление различных сект, ересиархи

которых предсказывали грядущую великую

войну. Среди этих сект наиболее значимой

была секта анабаптистов.

Своими действиями и идеологически

анабаптисты в дальнейшем вольются в

крестьянскую войну. В 20-х гг. XVI в. во

главе анабаптистов стоял подмастерье

Николай

Шторх.

Анабаптисты отрицали церковную

организацию и считали, что каждый

верующий обладает даром Божественного

откровения. На кого снизошла Божественная

благодать, тот становится пророком,

вещает «живое Евангелие», поэтому,

проповедовали анабаптисты, не нужен

институт священства. Анабаптисты

возвещали скорое наступление тысячелетнего

царства Христова на земле и предрекали,

что будут низвергнуты все земные троны

и бедные будут возвышены, а богатые

унижены. Реальными действиями анабаптисты

сыграли заметную роль в крестьянской

войне, которая началась в германских

землях в 20-х гг. XVI в.

Основоположником

реформационного народного направления

явился Томас

Мюнцер

(1490-1525). В качестве реформатора он начинал

как единомышленник и соратник Лютера,

но Мюнцер встает во главе

крестьянско-плебейского крыла Реформации,

с его идеями немедленных революционных

действий. Центром соратников Мюнцера

и центром будущей войны становится

город Цвиккау,

к ним присоединяются анабаптисты.

Идеологическое

обоснование

крестьянской войны базировалось

Мюнцером на его понимании Реформации

прежде всего как социально-политического

переворота, должны произвести самые

обездоленные слои населения – крестьяне

и городская беднота. В результате победы

должны установить новый общественный

строй без классовых различий, эксплуатации,

частной собственности. Бог для Мюнцера

не творец, стоящий над миром, а сам мир

в его единстве, высшая идея интегрального,

объединяющего отдельные части. Служение

Богу это, прежде всего, активная

деятельность человечества на общее

благо. Народ, считал Мюнцер, является

ревнителем дела Бога. «Богатые безбожники

будут низвергнуты, униженные возвышены»,

– писал Мюнцер.

Крестьянской

войне под руководством Мюнцера

предшествовали многочисленные волнения

в Германии, где революционная обстановка

к 20-м годам чрезвычайно накалилась.

Первыми выступили рыцари во главе с

Францем

фон Зиккенгеном.

Идеологом рыцарского выступления, как

пролога Крестьянской войны, был

знаменитый немецкий гуманист Ульрих

фон Гуттен.

Крестьянская

война началась в 1524

г. и закончилась в 1525

г. Развернулась она в юго-западных

немецких землях, где было распространено

реформационное религиозное учение

Цвингли. Война под руководством Мюнцера

началась на верхнем Рейне, затем охватила

регионы между верхним Рейном и верхним

Дунаем. Первым требованием, которое

выдвинули восставшие крестьяне, была

отмена феодальных поборов. Но цели и

задачи войны под руководством Мюнцера

не сводилась только к этому положению.

Восстание приобретало организованный

характер. В конце 1524 – нач. 1525 г. появляется

первая общереволюционная программа

«Статейное

письмо»,

открыто провозглашающее необходимость

коренного социального и политического

переворота и создания общества социальной

справедливости. Однако эта программа

не стала общей программой войны. Ряд

руководителей восстания не были столь

революционно настроены и склонялись

к переговорам с властями и с феодалами,

т.е. готовы были занять компромиссные

позиции, далекие от революционных.

Великая

Крестьянская война под руководством

Томаса Мюнцера, началось в феврале 1525

г.

в Швабии,

откуда она перебросилась в другие

немецкие земли. Руководители отдельных

военных отрядов по-разному понимали

«божественное право»: одни понимали

его как установление полного социального

равенства, другие – как ликвидацию

крепостной зависимости. Весной 1525 г.

создается в Швабии крестьянская

организация «Христианское

объединение».

В Швабии действует и враждебное ему

объединение – бюргерский «Швабский

союз».

Поскольку «Швабский союз» был гораздо

сильнее «Христианского объединения»,

представители последнего решили пойти

на переговоры со «Швабским союзом»,

подготовив для этого идейную платформу

– знаменитые «Двенадцать

статей». Эта программа была разработана

цвинглианскими реформаторами.

«Двенадцать статей», обоснованные Св.

Писанием, подчеркивали мирный характер

намерений и требований крестьян. В этот

документ были включены реформационные

статьи: необходимость Реформы Церкви,

обязательная выборность и сменяемость

священников.

Экономические

требования:

отмены крепостного права, требования

«Двенадцати статей» касались самых

злободневных вопросов крестьянской

жизни и стали общей программой восставшего

немецкого крестьянства. А наиболее

революционно настроенная часть крестьян

не была удовлетворена этой программой

и отказалась от нее, начав действовать

и бороться за революционные преобразования

в Германии в духе «Статейного письма»,

более революционной по характеру

программы Крестьянской войны. «Швабский

союз» не смог уничтожить «Христианское

объединение» в Швабии. В германских

землях все более сгущалась грозовая

атмосфера, назревала необходимость

вооруженной борьбы, которую и начал

«Швабский союз» весной 1525 г. Основные

силы восставших крестьян в Швабии были

разбиты. Тогда «Швабский союз» перенес

свои действия в другие немецкие земли,

где бушевала Крестьянская война – во

Франконию. Отношение князей к Реформации

менялось. Сначала они все были на стороне

оппозиции Риму. В отсутствие Карла V во

главе Германии находилось имперское

правление состоявшее из курфюрстов и

из уполномоченных от отдельных округов

Германии. В 1522 оно пригласило саксонских

епископов принять меры против

виттенбергских беспорядков, но когда

Лютер успокоил смуту, курфюрсту

саксонскому удалось склонить имперское

правление к тому, чтобы Вормский эдикт

был оставлен без последствий. Само

управление благосклонно относилось к

Реформации, надеясь посредством нее

освободить Германию от папских поборов.

В 1523 новому папе (Адриану VI) имперское

правление и собравшийся в Нюрнберге

сейм прямо отказали привести в исполнение

церковное отлучение и государственную

опалу, тяготевшие над Лютером. Сейм

выставил целый ряд жалоб против курии.

К 1526 у Лютера окончательно сложились

виттенбергские церковные порядки, т.е.

главным образом богослужение на народном

языке, заменившее католическую мессу.

Согласившись на ограничение прежнего

произвола курии, папа Климент VII расширил

вместе с тем власть князей над местным

духовенством и даже отдал им часть

церковных имуществ и доходов, за что

князья обязывались преследовать

лютеранство в своих владениях. Такое

соглашение курии с южными немецкими

князьями было оформлено на Регенсбургском

съезде в июне 1524 г. после чего в Австрии,

Баварии и Зальцбурге начались гонения

на приверженцев Реформация. В 1529 г. был

созван сейм в Шпеере и императором было

предложено восстановить Вормский эдикт

ввиду возникновения разных ужасных

сект. Большинство прямо выразило

согласие подчиниться Вормскому эдикту;

меньшинство составило протест,

подписанную

пятью князьями (в том числе курфюрстом

саксонским и ландграфом гессенским) и

уполномоченными 14 имперских городов.

Они получили название «протестантов»,

распространившееся впоследствии на

всех оставивших католическую церковь.

Протест был актом неповиновения

императору: князья и имперские города

становились в положение подданных и

заявляли, что во всем остальном они

готовы повиноваться императору, но

только не в том, что касается славы

Божией и спасения души. В связи с

протестом 1529 ставился уже, таким образом,

вопрос о праве с оружием в руках

отстаивать свободу совести. В 1530 Карл

V после девятилетнего отсутствия приехал

в Германию, назначив собрание имперского

сейма в Аугсбурге. Во время Аугсбургского

сейма 1530 Карл V выразил желание

познакомиться с учением лютеран,

Меланхтон составил знаменитое

Аугсбургское

исповедание

в духе сближения протестантского учения

с католическим и во время дальнейших

переговоров с богословами Карла V охотно

шел на уступки, так что его поведение

даже вызвало протесты со стороны Лютера

и лютеранских князей. Документ был

подписан всеми лютеранскими князьями

и представителями двух имперских

городов. Протестантские чины (в том

числе лютеранские и цвинглианские

города) протестовали против такого

решения, и ответом их на угрозы императора

и католиков было заключение ими в самом

конце 1530 г. Шмалькальденского

союза.

В 1532 г. в Нюрнберге состоялось соглашение,

в силу которого князья и города, принявшие

уже аугсбургское исповедание, оставались

при нем, но отказывались от зашиты его

последователей в других землях.

Огражденная Нюрнбергским трактатом,

Реформация могла спокойно утверждаться

и даже распространяться на новые земли,

хотя по смыслу соглашения 1532 должен

был поддерживаться status quo. В 1534 введена

была Реформация в Вюртемберге, куда

возвратился изгнанный оттуда раньше

герцог Ульрих. В 1538 главные католические

князья с королем Фердинандом во главе

заключили между собой союз в Нюрнберге.

В 1539 г. Реформация сделала новые важные

приобретения. Когда умер саксонский

герцог Георг, его преемник Генрих,

поддерживаемый Шмалькальденским

союзом, ввел Реформацию и в альбертинской

Саксонии при содействии светских

сословий ландтага. Иоахим II, курфюрст

бранденбургский, уступая народному

желанию, также ввел у себя лютеранство,

хотя и с некоторыми особенностями. В

1542 Шмалькальденский

союз

напал на герцога брауншвейгского и

заставил его бежать из его владений, в

которых курфюрст саксонский и Филипп

Гессенский ввели протестантизм.

В

1545 при посредстве Франции был заключен

Карлом мир и с турками. Первым результатом

нового мира было подавление кельнской

Реформации. В 1545 по настоянию Карла V

папа Павел III созвал собор в Триденте,

но протестанты отказались в нем

участвовать. В 1546 г., в год смерти Лютера,

началась война между императором и

Шмалькальденским союзом, окончившаяся

поражением и пленом курфюрста саксонского

и ландграфа гессенского. Это была победа

иностранного государя, завоевание

Германии иноземным войском. Папа боялся

усиления императорской власти,

утверждения Карла V в Италии в его планов

на счет собора. Франция была также в

числе врагов Карла V: новый французский

король Генрих II продолжал политику

своего отца. Изменивший шмалькальденцам

герцог саксонский Мориц был недоволен

Карлом V за неисполнение обещаний и

чувствовал себя крайне неловко, так

как все называли его изменником. В

чувстве негодования на императора

нация была солидарна с князьями. В 1552

князья обнародовали манифест, объявляя,

что они берутся за оружие для освобождения

Германии от скотского рабства. Быстрое

движение Морица на Тироль, где находился

не ожидавший нападения император,

заставило его искать спасения в бегстве.

Пассауским соглашением было постановлено

(1552), что имперские чины, держащиеся

Аугсбургского исповедания, будут

пользоваться свободой до восстановления

религиозного единства Германии

вселенским или национальным собором,

совещанием богословов или сеймом.

В

1555

был заключен Аугсбургский

религиозный мир

прекративший религиозную борьбу в

Германии и санкционировавший все

главные приобретения князей за

реформационный период. Наиболее

существенные постановления этого мира

были следующие. Князья и вольные города,

державшиеся Аугсбургского исповедания,

ограждались от притеснения за веру, но

пвинглианцы и кальвинисты (сильно уже

распространившиеся в то время) исключались

из этого правила. Далее провозглашался

принцип в силу которого подданные

должны были следовать вере своего

правительства; в пользу протестантских

подданных в духовных княжествах сделана

была, впрочем, оговорка. Другой оговоркой

постановлялось, что если бы епископ

задумал перейти в протестантизм, то

ему нельзя было секуляризировать свой

лен. Обе эти оговорки не были, однако,

утверждены формально. Политические

итоги немецкой Реформация:

Реформация содействовала начавшемуся

гораздо раздроблению Германии, разделив

страну на два враждебных лагеря, лишь

одну часть нации освободив от Рима,

ослабив власть императора и усилив,

наоборот, власть князей. Сокрушив

рыцарей и крестьян и победив императора,

князья стали в более или менее независимое

положение по отношению к папе, подчинили

себе местное духовенство, секуляризировали

церковную собственность и сделались

господами в религиозных делах своих

княжеств.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

Реформация XVI века — это ключевой этап в истории Европы. Реформация — это движение за обновление католической церкви и пересмотр религиозных догм. Это движение привело к появлению новых конфессиональных течений и к потере католической церковью монополии.

Предпосылки к реформации

Важнейшими предпосылками реформации были, прежде всего:

- распространения философии гуманизма, провозгласивший человека хозяином своей судьбы и связанная с ней обмирщение сознания;

- также к предпосылкам следует отнести распространение новых религиозных учений — ереси, с точки зрения официальной церкви, в которых основной акцент делался на внутреннее стремление человека к богу, а не на религиозные обряды;

- также к предпосылкам реформации можно отнести распространение книгопечатания и подъем образования.

К причинам реформации следует отнести:

- во-первых, богатство церкви и вызывающее поведение священников. Нередко их критиковали за чревоугодие, корыстолюбие и невежество. Такое поведение вызывало недовольство всех социальных слоев;

- также стремление светских властей подчинить себе церковь на своих территориях и секуляризировать церковные земли;

- недовольство бюргерства и крестьянства церковной десятиной и другими церковными поборами тоже является одной из причин реформации;

- ну и, наконец, следует назвать продажу индульгенций.

Начало реформации

Реформация началась в Германии. В XV-XVI веках Германия представляла собой конгломерат земель: курфюршество, герцогство, маркграфство и так далее, которые управлялись фактически независимыми князьями. Власть императора над ними была весьма условна. Хотя имперская корона и оставалась у дома Габсбургов, но ее судьбу решали курфюрсты, поскольку они имели право выбирать императора. Также часть германских земель принадлежала церкви и управлялась независимыми духовными князьями.

Короли Англии и Франции, которые управляли централизованными монархическими государствами, укрепляли свою власть и боролись со стремлениями Папы Римского к верховенству над светскими властями. Германия же, составлявшая большую часть священной Римской империи, продолжала отправлять в Рим большие деньги, что вызывало недовольство, как горожан и крестьян, так и части князей.

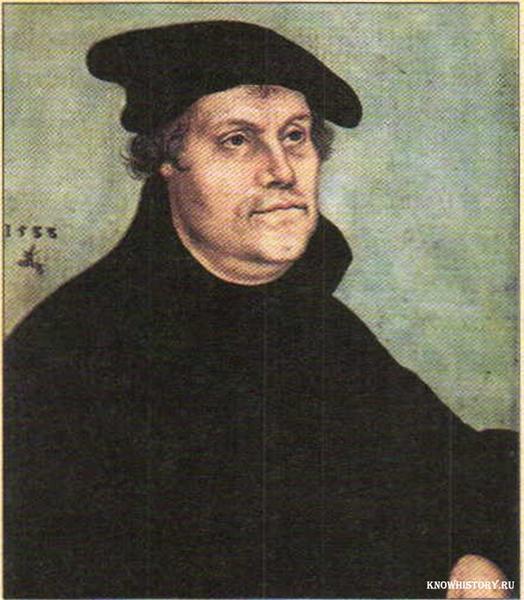

Мартин Лютер

Лидером реформации стал Мартин Лютер, католический священник и преподаватель теологии в Виттенбергском университете. 31 октября 1517 года он прибил к дверям Виттенбергского собора свои знаменитые 95 тезисов против индульгенции. Мартин Лютер утверждал, что покупка индульгенции освобождает лишь от наказания, наложенного церковью, а искупление греха возможно только покаянием и добрыми делами. Священники, злоупотребляющие продажей индульгенцией и богатство церкви, по мнению Лютера, подрывает не только авторитет самой церкви, но и авторитет Папы Римского.

Следует отметить, что Мартин Лютер критиковал не столько Папу Римского, хотя и отмечал недопустимость его богатства, вызывающее недовольство паствы. Он критиковал скорее священников, злоупотребляющих своей властью.

Давайте прочтем несколько отрывков из этого произведения: «Поэтому ошибаются те проповедники индульгенций, которые объявляют, что посредством Папских индульгенций, человек избавляется от всякого наказания и спасается. Если кому-нибудь может быть дано полное прощение всех наказаний, то несомненно, что она дается наиправеднейшим, то есть немногим.

Должно учить христиан: Папа не считает покупку индульгенции, даже в малой степени сопоставимой с делами милосердия.

Должно учить христиан: тот, кто, видя нищего и пренебрегая им, покупает индульгенцию, не получит Папского прощения, но гнев Божий навлечет на себя.

Должно учить христиан: если они не обладают достатком, им вменяется в обязанность оставлять необходимое в своем доме и ни в коем случае не тратить достояние на индульгенции.

Должно учить христиан: покупка индульгенции — дело добровольное, а не принудительные.

Должно учить христиан: если бы папа узнал о злоупотреблениях проповедников отпущений, он счел бы за лучше сжечь дотла храм святого Петра, чем возводить его из кожи, мяса и костей своих овец».

Тезисы Мартина Лютера были признаны в то время ересью, и в 1520 году Папа издал буллу об отречении священника от церкви. Но он сжёг это папское послание на глазах у своих студентов. Вступив в полемику с Папой Римским, Мартин Лютер издал несколько сочинений, в которых изложил свои взгляды на религию и церковь. У него появилось много последователей среди немецкого бюргерства и дворянства, поскольку его учение отвечало их утилитарным интересам. Речь идет о желании бюргерства освободиться от церковных поборов и желание князей секуляризировать церковные земли и укрепить собственную власть.

Главная идея учения Мартина Лютера

Главная идея учения Мартина Лютера заключалась в том, что человек спасается только верой в Бога и не нуждается при этом в посредничестве церкви.

Спасение только верой — вот ключевой тезис его учения.

Католическая же церковь утверждала, что человек может получить прощение только при помощи церкви. Мартин Лютер считал, что церковь не должна быть богатой, и поэтому поддерживал идею секуляризации церковных земель. Из семи христианских таинств он предлагал оставить только два: крещение и причастие, поскольку только они упоминаются в Библии, а остальные пять он считал изобретением католической церкви.

Мартин Лютер выступал за перевод Библии с латыни, на которой не говорила паства на национальные языки. Это давало возможность верующим самостоятельно изучать Библию, при этом на священников возлагалась задача помощи в чтении Библии. На национальных языках должно было идти и богослужение. Пышность церковных обрядов, почитание икон, святых и мощей Мартин Лютер объявил идолопоклонством.

Преследования Мартина Лютера

В 1521 году император священной Римской империи Карл V вызвал Мартина Лютера на Вормсский рейхстаг. Туда же прибыли и посланники Папы Римского, которые требовали от Лютера отречения от его еретических взглядов. Но Лютера поддержала группа северо-германских князей, которая желала разрыва с Римом и укрепления собственной власти.

По легенде Мартин Лютер заявил: «Я на том стою и не могу иначе».

Над ним нависла реальная угроза ареста, но его спасли северо-германские князья, которые спрятали священника в одной из крепостей саксонского курфюрста Фридриха. Таковы были ключевые положения религиозного учения Мартина Лютера. Основанная на его учении церковь получила название лютеранская.

Последователи Мартина Лютера

Между тем последователи Мартина Лютера перешли к действию. В Саксонии и некоторых других немецких княжествах католическую мессу заменили проповедью. Из церквей выбрасывали иконы, таким образом, было уничтожено множество предметов средневекового искусства. В борьбу постепенно вовлекались крестьянства, бюргерства и разорившиеся рыцарства.

Появилось и желание политической реформации. Тяжелое социально-экономическое положение немецкого крестьянства обусловило столь быстрое распространение в его среде учений о справедливом политическом переустройстве. Зарождение капиталистических отношений в деревне привели к захвату дворянством христианских общинных земель, а также к увеличению налогов и к разорению и закрепощению части германского крестьянства.

Крестьянские восстания в Германии

Летом 1524 года на юге Германии вспыхнули крестьянские восстания. Идейно это движение возглавил священник Томас Мюнцер. Он призывал не только к реформации церкви, но и к установлению царства Божьего на земле. Восставшие составили программу, которая вошла в историографию под названием «12 статей». В этом документе крестьяне требовали права избирать священника и смещать его с должности. Также они считали, что десятина должна тратится только на содержание священника и его семьи и на помощь бедным членам общины. Также крестьяне требовали личной свободы и права пользоваться лесами, ловить дичь, рыбу и зверей. Леса и пашни должны были быть возвращены в общинное пользование.

Крестьяне требовали установления оброка и барщины по справедливости и отмены всех дополнительных поборов, в частности, отмены штрафов. Особой статьей они требовали отмены, так называемого, посмертного побора, который взимался с семьи умершего крестьянина и к которому, как правило, добавлялся и побор за право пользования наследством.

Постепенно восстание переместилась с юго-запада в центральные земли Германии. Наиболее организованным оно было в Тюрингии. Горожане и разорившееся рыцарства, примкнувшие к крестьянам, составили свою программу. Это, так называемая, Гейльброннская программа. Она ограничивала власть князей, и предусматривала централизацию страны.

Согласно этому документу в стране должны были быть созданы единые органы управления, подчиненные императору. Власть духовенства была ограничена и церковь лишалась собственности. Также документ предусматривал отмену внутренних таможен и введение единой денежной системы, и единой системы мер и весов. Программа практически не учитывала интересы крестьянства, в частности, указывалось, что крестьяне могут освободиться от феодальных повинностей путем выкупа феода в 20 кратном размере. Несмотря на то, что эта программа могла стать базой для объединения немецкого общества, крестьяне так и не смогли созвать съезд, чтобы обсудить ее. Хорошо вооруженные армии князей довольно быстро разбили разрозненные отряды крестьян. К концу 1525 года восстание было полностью подавлено.

Появление протестантизма

После окончания крестьянской войны часть германских князей продолжила секуляризацию церковных земель. Некоторые духовные князья отказывались от своего сана и объявляли себя государями своих прежних духовных княжеств. Так, например, поступил великий магистр Тевтонского ордена, который в 1525 году принял титул герцога Прусского. Другая часть князей, напуганная крестьянской войной и видевшая ее причины в реформации, осталась верной католицизму.

Император Карл V, отстаивая интересы католической церкви, в 1529 году созвал рейхстаг, на котором потребовал от князей прекратить секуляризацию церковных земель. Князья, сторонники учения Мартина Лютера, заявили протест. Так появилось слово протестантизм, обозначающее одно из направлений в христианстве. Основные положения лютеранства были изложены в документе под названием «Апология Аугсбургского вероисповедания».

Противостояние князей протестантов и князей католиков

Противостояние князей протестантов и князей католиков, которых поддерживал император, вылилось в две войны. Это так называемые Шмалькальденские войны. Но боевые действия не привели к перевесу ни одной из сторон и в 1555 году в Аугсбурге был заключен религиозный мир. Император признал право князей самостоятельно решать, какой будет религия в их государстве. Таким образом, восторжествовал принцип: чья земля, того и вера. Подданные же должны были исповедовать ту религию, к которой принадлежал их князь.

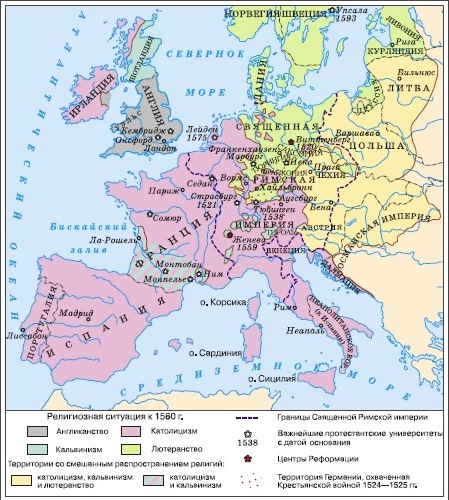

Северные и северо-восточные земли Германии, а также некоторые центральные княжества, приняли лютеранство. Юг остался католическим. Аугсбургский религиозный мир закрепил политическую раздробленность Германии. Постепенно в XVI веке лютеранство распространилось в Европе. Оно стало официальной религией в Дании, Норвегии, Финляндии и прибалтийских землях.

Аугсбургский религиозный мир

4.4

Средняя оценка: 4.4

Всего получено оценок: 156.

4.4

Средняя оценка: 4.4

Всего получено оценок: 156.

Заключение Аугсбургского религиозного мира в 1555 году стало одним из этапов Реформации в Европе XVI века. Согласно договору, лютеранство становилось официальной религией и у людей появилось право на его вероисповедание.

Предыстория

Реформация в Европе, а точнее на территории Священной Римской империи, началась в 1517 году с деятельности Мартина Лютера. В этом специфическом государстве, состоявшем из множества княжеств и отдельных городов, произошел религиозный раскол.

В 1524-1526 годах империя пережила крестьянскую войну. У протестантов в 1527 году появился первый собственный университет в Марбурге. Католических князей в противостоянии с протестантами поддержал император Карл V Габсбург. В результате, первым крупным военным конфликтом между католиками и протестантами стала Шмалькальденская война 1546-1547 годов. В ходе нее Мориц Саксонский, хоть и являлся сам протестантом, поддержал Карла V. Победителями в войне вышли католики, но из-за угрозы коллапса империи участники конфликта вынуждены были пойти на компромисс как в религиозной, так и в политической сфере.

Поискам компромисса способствовало ряд обстоятельств. Например, у императора Священной Римской империи ухудшились отношения с папой римским. Немецкие князья не хотели, чтобы престол императора достался наследнику по испанской линии Габсбургов – Филиппу II.

Переговоры и подписание

После очередного выступления князей-протестантов в 1552 году состоялись переговоры в городе Пассау. На них впервые образовалась нейтральная группа из князей, которых возглавил брат Карла V, эрцгерцог Австрии и король Чехии – Фердинанд I. Он изъявил готовность признать лютеранство и провести реформу Священной Римской империи.

В марте 1555 года было подписано соглашение между княжествами Саксония, Гессен и Бранденбург. Они согласовали свои позиции на переговорах с императором Карлом V, который от них отказался и переложил это на своего брата Фердинанда.

Датой подписания Аугсбургского мира стало 25 сентября 1555 года. Его условия были таковы:

- Лютеранство признавалось легитимным вероисповеданием.

- Признания не получили следующие направления протестантизма, например, цвинглианство и анабаптизм.

- Амнистия всем, кто был осужден из-за принадлежности к лютеранству.

- Принцип свободы вероисповедания для светских и духовных князей, рыцарей и вольных городов. Любой субъект империи мог перейти в лютеранство или вернуться в католичество.

- Протестанты сохранили земли, которые они успели секуляризировать до 1552 года.

- За католиками сохранялись их земельные владения в случае перехода епископа или аббата в лютеранство.

Религиозный мир восстановил единство Священной Римской империи и установил мир на ее территории. Была восстановлена деятельность ее институтов. Согласно условиям договора, подданные князей не имели права на выбор вероисповедания. Каждый князь сам решал лютеранство или католичество будет в его владениях. Этот принцип получил наименование “Чья страна, того и вера”.

19 сентября 1555 года Карл Габсбург отрекся от престола и выразил в тексте отречения несогласие с Аугсбургским договором, текст которого уже был готов. Следовательно, договор вступил в силу только с 1556 года, после передачи императорского престола Фердинанду I.

Что мы узнали?

Кратко об Аугсбургском мирном договоре можно узнать из школьного курса истории 6-7 класса, когда проходят Реформацию. Он стал важнейшим событием в религиозной и политической жизни Центральной Европы XVI века.

Тест по теме

Доска почёта

Чтобы попасть сюда — пройдите тест.

Пока никого нет. Будьте первым!

Оценка доклада

4.4

Средняя оценка: 4.4

Всего получено оценок: 156.

А какая ваша оценка?

§ 4. Реформация и крестьянская война в Германии

Причины Реформации

XV–XVI века были для Европы временем религиозных исканий. В результате изобретения книгопечатания Библия и комментарии к ней стали доступными не только для священнослужителей, но и для многих грамотных людей. Находилось всё больше смельчаков, склонных к самостоятельным размышлениям, к сомнениям во всём, что ещё недавно казалось незыблемым, в том числе и в вопросах веры. Этих энергичных и предприимчивых людей не устраивали средневековые идеалы смирения и аскетизма, они не хотели смотреть на земную жизнь лишь как на приготовление к жизни загробной. Оставаясь верующими, они испытывали потребность в вероучении, которое оправдывало бы такую позицию. А католические идеалы вызывали всё больше критики, нередко продолжавшей и развивавшей традиции средневековых ересей.

Карикатура на Католическую церковь. Изображающая Антихриста в папской тиаре. XVI в.

Католическую церковь было за что критиковать. Современники высмеивали и обличали корыстолюбие, невежество, чревоугодие священников и монахов. Всеобщее недовольство вызывали огромные богатства Церкви. Предметом зависти дворян были её обширные земельные владения. Экономным горожанам всё меньше нравились пышное церковное убранство и дорогостоящие церковные обряды. Правители хотели установить в своих государствах контроль над Церковью и воспользоваться её богатствами. Этому противились папы, претендовавшие на главенство над светской властью. Кроме того, в Рим поступали колоссальные доходы, получаемые со всех католиков Европы: плата за церковные должности, десятина, плата за исполнение обрядов… Папский двор купался в роскоши, папы и кардиналы пировали, охотились. Многие брали взятки, за деньги в Риме можно было приобрести любую должность и получить отпущение любых грехов. Несоответствие между образом жизни служителей Церкви и тем, что они проповедовали, вызывало возмущение верующих и части духовенства.

Религиозная процессия на площади Св. Марка в Венеции. Художник Д. Беллини

Католическая церковь учила, что даже самый добродетельный христианин греховен по самой своей природе, в силу первородного греха Адама. Он не способен собственными силами «спастись», т. е. искупить свои грехи. Только Церковь, являясь посредницей между верующим и Богом, может обеспечить человеку вечное спасение. Для этого нужно следовать всем её предписаниям, жертвовать деньги, признавать семь церковных таинств – обрядов, выполняемых священниками. Считалось, что в момент совершения таинства верующему передаётся Божественная благодать. Церковь учила, что страдания Христа, заслуги апостолов и святых создали как бы «запас» благодати. Распоряжаясь им, Папа Римский имеет право прощать верующим любые грехи. Выданные от его лица письменные отпущения грехов назывались индульгенциями. Огромные доходы от их продажи должны были использоваться на благочестивые цели. Торговля индульгенциями не нравилась наиболее совестливым верующим, а то обстоятельство, что эти деньги тратились на личные нужды священнослужителей, лишь подливало масло в огонь.

Какие семь таинств признаёт католицизм? (Вспомните из курса истории Средних веков или выясните из литературы.)

Недовольство Церковью нарастало по всей Европе. Началась Реформация – широкое движение за реформу (обновление) Католической церкви, охватившее в XVI в. многие европейские страны.

Реформация зародилась в Германии, и это не случайно. Ни в одной другой стране Европы к началу XVI в. не накопилось столько противоречий. В отличие от многих европейских стран (Англии, Франции, Испании), в Германии, составлявшей основную часть Священной Римской империи, в это время сохранялась политическая раздробленность. Раннее развитие капитализма во многих отраслях промышленности причудливо сочеталось здесь с отсталостью деревни, в которой сохранялись традиционные отношения между крестьянами и сеньорами.

Идеи объединения страны, ограничения произвола князей, усиления императорской власти и других перемен буквально витали в воздухе. Но многочисленным проектам реформ неизменно противостояли те силы, которые не были в них заинтересованы, и прежде всего семь курфюрстов – наиболее могущественных князей, имевших право выбирать императора. По сути, в стране все враждовали со всеми. Князья не давали усилиться императору и в то же время притесняли простых дворян; дворяне, бессильные перед волей князей, отыгрывались на крестьянах и горожанах, жестоко страдавших от их произвола. И только в одном – в недовольстве Католической церковью – сходились все слои немецкого общества. В раздробленной Германии у слабой императорской власти не было сил противиться притязаниям пап. В немецких землях Церковь сильно зависела от Рима и отправляла туда огромные суммы.

Всеобщее недовольство Римом и обострение всех других общественных противоречий сделало обстановку в Германии взрывоопасной. Воспламеняющее действие, подобно удару молнии в бочку пороха, оказали «95 тезисов» Ма?ртина Лю?тера, с которыми он выступил 31 октября 1517 г.

Папа Римский Лев Х – противник Реформации. Художник Рафаэль

Мартин Лютер против Папы Римского

Сын разбогатевшего рудокопа Мартин Лютер (1483–1546) учился в университете и подавал блестящие надежды, но затем бросил учёбу и ушёл в монастырь, стремясь найти там путь к спасению души. Позже он стал священником и доктором теоло?гии, проповедовал в церкви города Ви?ттенберга. После долгих размышлений Лютер пришёл к выводу, что милостью Божьей будет оправдан лишь искренне верующий, а те внешние проявления благочестия, которых Церковь требует от верующих, не имеют никакого значения для спасения души.

Мартин Лютер. Художник Л. Кранах Старший

Придя к своей главной идее об оправдании верой, Лютер не мог не обратить внимания на продажу индульгенций недалеко от Ви?ттенберга. Его уже давно возмущала идея спасения за деньги, и теперь он решился действовать. В считаные недели «95 тезисов» против индульгенций стали известны всей Германии. Не помышляя о разрыве с Римом, Лютер думал лишь убедить Папу отказаться от продажи индульгенций. Однако в Риме в этих тезисах усмотрели ересь. От Лютера требовали отречься от своего учения, грозя отлучением от Церкви. Но он упорно стоял на своём и даже дерзал дальше развивать свои взгляды.

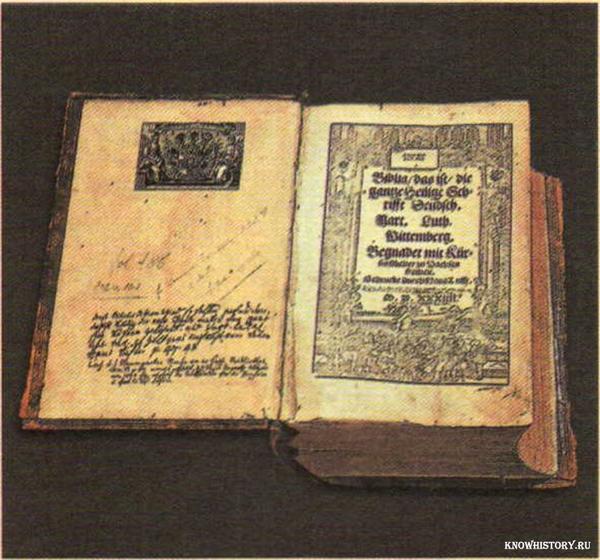

Страница из Библии в переводе Мартина Лютера

Идея Лютера об оправдании верой имела важные последствия, которые он и сам осознал не сразу. Ведь если человека спасает вера, то нужно ли посредничество Церкви во главе с Папой? Церковь должна лишь наставлять людей в религиозной жизни, помогать им понять Библию. Имущества у неё быть не должно, а то, что есть, следует секуляризи?ровать, т. е. передать светским властям. Священники, по Лютеру, ничем не отличаются от обычных людей, и в их безбрачии нет никакого смысла. И тем более не нужны монахи…

Признавая в делах веры авторитет только Священного Писания, Лютер, вопреки нормам католицизма, подчёркивал, что сочинения отцов Церкви, решения пап и соборов не имеют обязательной силы. Зато Библия должна быть доступна каждому христианину, а не только священнику, знающему латынь. Лютер перевёл Библию на немецкий язык, и его перевод считается замечательным памятником немецкой словесности XVI столетия.

Церковь в Виттенберге, где проповедовал Мартин Лютер

Свой идеал Церкви Лютер видел в раннем христианстве и предлагал отказаться от церковных таинств и ритуалов, не присущих ему изначально. Он выступил против пышного богослужения на латыни, причём особенно важным был отказ от торжественной мессы (ит. messa – основная католическая церковная служба); именно отношением к мессе католики и в дальнейшем отличались от сторонников Реформации. Лютер осуждал паломничество, почитание икон и мощей святых, а из семи церковных таинств предлагал оставить лишь те два, которые упоминаются в Библии, – крещение и причащение. Со временем он «добрался» и до центра Католической церкви – Святого Престола, подвергнув резкой критике его пороки и претензии.

Взгляды Лютера, и особенно его идея оправдания верой, легли в основу различных религиозных реформаторских направлений в Германии и за её пределами.

Чем отличается лютеровское понимание путей спасения души от католического?

В 1520 г. Папа Римский издал особый документ – бу?ллу с угрозой отлучить немецкого бунтаря от Церкви. В ответ Лютер публично сжёг один из экземпляров буллы. Множилось число сторойников реформ и среди бюргеров, и среди дворян, и даже среди князей. Их поддержал и саксонский курфюрст Фридрих Мудрый, во владениях которого жил Лютер.

Весной 1521 г. дело Лютера рассматривалось на Во?рмском рейхстаге в присутствии императора Карла V. Лютер вновь отказался отречься от своих взглядов. Император встал на сторону Папы и добился того, что рейхстаг (парламент) резко осудил новую ересь.

Между тем сторонники Лютера от слов переходили к делу. Возбуждённые проповедниками толпы уничтожали в церквах иконы – в результате погибли многие шедевры средневекового искусства. Лютер осудил такие действия: он считал, что Реформацию следует проводить только мирными средствами и что заниматься этим должны власти, а не простой народ.

Однако Лютер не мог контролировать события. Начатое им дело привлекло очень многих, но каждый понимал его учение по-своему. В Реформации появились разные направления, выражавшие интересы различных слоев общества. Сам Лютер оказался сторонником умеренного течения, стремясь опереться на князей и городские власти. Но были и приверженцы решительных действий, связывавшие реформу Церкви с переустройством общества в целом.

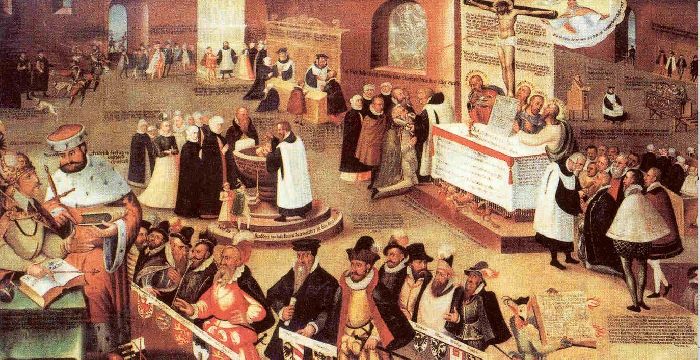

Мартин Лютер перед императором Карлом V на рейхстаге в Вормсе

Крестьянская война в Германии

Идеи Реформации быстро распространялись в народе. Многие считали, что земные порядки, противоречащие Божественным установлениям, следует изменить. Среди сторонников народной Реформации выделялся То?мас Мю?нцер (ок. 1490–1525). Сначала он поддержал Мартина Лютера, но затем стал его непримиримым врагом.

Томас Мюнцер

Мюнцер полагал, что частные интересы людей должны быть подчинены целому – Божественному замыслу. Понять его способны лишь те, кто действует в интересах всего общества. Это – трудовой народ, ремесленники и пахари. Взяв власть в свои руки, они установят на земле царство справедливости. А раз мирным путём им власть не отдают, значит, надо вести вооружённую борьбу против препятствующих воплощению Божественного замысла господ и властей.

Эта проповедь прозвучала на фоне резкого обострения отношений между сеньорами и крестьянами. Сеньоры в это время стремились повысить свои доходы за счёт простых земледельцев, возрождая старые повинности и вводя новые. В ответ крестьяне организовывали заговоры против господ. Все заговоры были раскрыты, но сыграли немаловажную роль в подготовке нового восстания, самого крупного в истории страны.

Крестьянская война началась на юго-западе Германии летом 1524 г. Крестьяне вооружались и собирались в отряды. Они отстаивали «старые обычаи», протестовали против ограничения их личной свободы и увеличения барщины. Восприняв некоторые идеи Реформации, крестьяне всё чаще соглашались признать только такие светские порядки, которые можно обосновать текстом Библии.

Восставшие составили несколько программ, в которых сформулировали свои требования. В одной из них – «Статейном письме» – всем дворянам и служителям Церкви предлагалось отказаться от своих привилегий и начать жить и трудиться как обычные люди. В противном случае они будут поставлены вне общества, а замки и монастыри – разрушены. На практике это выливалось в жестокие казни наиболее ненавистных сеньоров. Составители ещё одной программы – «Двенадцать статей» – требовали отмены личной зависимости крестьян, ограничения церковной десятины, барщины и штрафов. Они выступали за облегчение повинностей, но не за их уничтожение.

Между тем восстание с юго-запада страны распространилось на Франко?нию, Тюри?нгию и Тиро?ль. Во Франконии его поддержали многие горожане. Восставшие хотели обсудить дальнейшие действия и общую программу на съезде своих представителей в городе Хайльбро?нне. «Хайльброннская программа» предусматривала ограничение власти князей и централизацию страны. Все органы управления должны были подчиниться императору. Предусматривались секуляризация церковного имущества, закрытие монастырей, лишение духовенства светской власти, выборность пастырей самими общинами. Намечалось введение равенства всех перед законом, отмена таможен, чеканка единой для всей страны монеты, введение единой системы мер и весов. Предполагалось, что крестьяне смогут выкупить свои повинности путём единовременной уплаты ежегодного взноса в двадцатикратном размере, хотя для большинства крестьян собрать деньги на выкуп было нереально.

Как вы думаете, как развивались бы события, если бы «Хайльброннскую программу» удалось провести в жизнь?

Однако созвать съезд и обсудить эту программу крестьянам не удалось. Оправившись от первоначальной растерянности, власти разбили повстанцев и во Франконии, и в Тюрингии, где восставших возглавлял сам Мюнцер. В мае 1525 г. превосходящие силы князей взяли штурмом укреплённый лагерь восставших у Франкенха?узена. За подавлением восстания последовали жестокие расправы над его участниками, был казнён и Мюнцер. Считается, что в Крестьянской войне погибло около 100 тыс. человек. Положение крестьянства в целом ухудшилось, его сословное неравенство сохранилось.

Подавление крестьянского восстания стало поражением народной Реформации, а также сторонников реформ среди бюргерства и части рыцарства. Было закреплено всевластие князей, и объединение Германии надолго отодвинулось. И всё же Крестьянская война осталась в истории как символ борьбы народа за свободу.

Дальнейшие судьбы лютеранства

Мартин Лютер резко осудил повстанцев и Томаса Мюнцера, закрепив свой союз с князьями и городской верхушкой. Теперь, после поражения народной Реформации, многие князья больше не считали поддержку Лютера опасным делом. В то же время их чрезвычайно привлекали идеи секуляризации и главенства государя над Церковью. Они перешли на сторону Реформации и присвоили себе церковные владения. Даже великий магистр Тевтонского ордена распустил орден, секуляризировал его земли и принял титул герцога Прусского. Главой Церкви в каждом княжестве становился его государь.

Когда на рейхстаге 1529 г. католики оказались в большинстве и потребовали отменить завоевания Реформации, сторонники Лютера – лютеране – заявили протест. Они утверждали, что в делах веры мнение большинства не может быть навязано меньшинству. С этого времени их стали называть также протеста?нтами. Позже этот термин распространился на всех сторонников Реформации в Европе.

Достичь компромисса между протестантами и католиками так и не удалось, но и военные действия не дали перевеса ни одной из сторон. Заключённый в Аугсбурге в 1555 г. религиозный мир признал равноправие католицизма и лютеранства. Князья получили право определять религию своих подданных, руководствуясь принципом «чья власть, того и вера». В Германии образовались две группировки княжеств: на юге и западе страны преобладали католики, на севере и востоке – протестанты. Отношения между ними оставались напряжёнными.

К тому времени Реформация давно перешагнула границы Германии. Число сторонников Лютера множилось всюду. По инициативе королевской власти Реформация по лютеранскому образцу была проведена в Англии, в Дании с подвластными ей Норвегией и Исландией, в Швеции с подвластной Финляндией. В каждой из этих стран Церковь возглавил монарх. Таким образом, к середине XVI в. лютеранство возобладало в нескольких европейских странах.

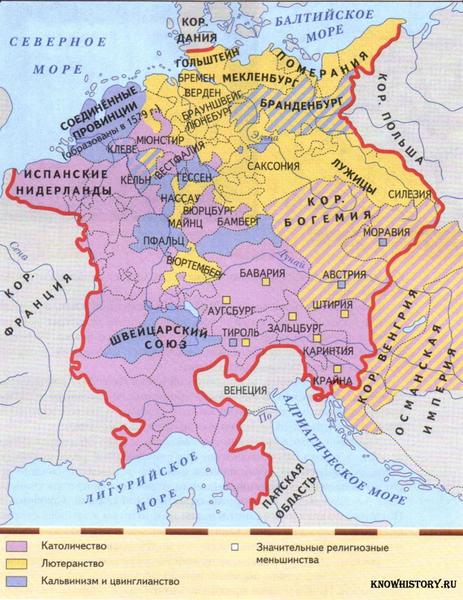

Реформация в Европе в XVI в. и крестьянская война в Германии

Найдите на карте основные области Крестьянской войны: юго-запад (Швабию), Франконию, Тюрингию, Тироль. Найдите города Хайльбронн и Франкенхаузен. Найдите страны и области, где победило лютеранство.

Подведём итоги

В первой половине XVI в. в Европе началась Реформация – широкое движение за обновление Католической церкви, охватившее почти всю Европу. Расколов Церковь, Реформация дала начало новым направлениям в христианстве. Народная Реформация потерпела поражение в ходе Крестьянской войны в Германии, лютеранство же победило в ряде стран Европы.

Теология (от гр. theo?s – Бог и l?gos – слово) – то же, что богословие: систематизированное изложение вероучения, обосновывающее его истинность и необходимость для человека.

• 1517 – начало Реформации в Германии.

• 1524–1525 – Крестьянская война в Германии.

• 1555 – Аугсбургский религиозный мир.

«Я не могу и не хочу отрекаться, потому что действовать вразрез с совестью тяжело, неблагочестиво и опасно».

(Из речи Мартина Лютера на Вормском рейхстаге)

Вопросы

1*. Как вы думаете, почему Реформация началась именно в Германии?

2. Можно ли считать случайностью то, что Реформация началась с тезисов против индульгенций?

3. Почему в Реформации появились разные направления?

4. Какие положения программ Крестьянской войны говорят о влиянии Реформации на их составителей?

5. Почему сторонников Реформации стали называть протестантами?

6. Каковы были итоги Реформации к середине XVI в.?

Задания

1. Опираясь на материал учебника, докажите, что Реформация назревала во всей Европе, а не только в Германии.

2. Определите, как связаны с идеей Лютера об оправдании верой следующие положения его тезисов:

1) требование секуляризации церковного имущества;

2) осуждение монашества;

3) осуждение паломничества;

4) сокращение числа церковных таинств;

5) отрицание авторитета папских булл и церковных соборов.

3. Определите, какие из приведённых высказываний принадлежат М. Лютеру, а какие – Т. Мюнцеру. Найдите различия во взглядах двух реформаторов.

1) «Когда, какой заповедью Бог дал князьям такую власть, что мы, бедняки, должны проводить на барщине все хорошие дни и можем работать у себя на поле только в дождь, обливаясь кровавым потом? В своей справедливости Бог не потерпит, чтобы нас постоянно заставляли косить их луга, возделывать пашни…»

2) «Каждый христианин, если только он истинно раскаивается, получает полное отпущение вины и без индульгенции».

3) «Если мы на законном основании вешаем воров и обезглавливаем грабителей, то почему мы должны потакать римскому корыстолюбию – величайшему вору и разбойнику изо всех существовавших или могущих существовать на Земле, – которое прикрывается священными именами Христа и святого Петра?»

4) «Бороться против власти Папы, не признавать отпущения грехов, чистилища, панихид и других злоупотреблений – значит проводить реформу только наполовину».

5) «Беритесь за дело Божие и выходите на борьбу. Время настало!.. Господь хочет приняться за дело, злодеи должны погибнуть».

6) «Всякий, кто может, должен их [крестьян] бить, душить, колоть тайно или явно и помнить, что не может быть ничего ядовитее, вреднее, ничего более дьявольского, чем мятежник. Его надо убивать, как бешеную собаку: если ты его не убьёшь, то он убьёт тебя и вместе с тобою целую страну».

Данный текст является ознакомительным фрагментом.

Читайте также

§ 4. Реформация и крестьянская война в Германии

§ 4. Реформация и крестьянская война в Германии

Причины РеформацииXV–XVI века были для Европы временем религиозных исканий. В результате изобретения книгопечатания Библия и комментарии к ней стали доступными не только для священнослужителей, но и для многих грамотных

§ 55. Крестьянская война 1773 – 1775 гг

§ 55. Крестьянская война 1773 – 1775 гг

Положение крестьян. Известно стремление императрицы убедить всех, особенно иностранных корреспондентов, что страна при её правлении процветает, а народ живет в достатке и благоденствии. Показательны два письма Екатерины: одно

Вторая Крестьянская война

Вторая Крестьянская война

Формально она началась в 1930 году – ответ крестьян на проводимую Иосифом Сталиным политику коллективизации. О ее масштабах и количестве активных участников журналисты и историки спорят до сих пор. Одни утверждают, что она представляла большую

Крестьянская война

Крестьянская война

Война «красных и белых», регулярной Красной армии и регулярных белых армий была лишь частью гражданской войны. Второй ее частью была война крестьянская. История России знает большие крестьянские войны, в 17-м веке — восстание Степана Разина, и в 18-м —

Крестьянская война тайпинов

Крестьянская война тайпинов

Эта форма вначале оказалась традиционной для Китая, т.е. такой, в которой почти не была заметной антииностранная, антизападная линия недовольства. Даже напротив, чуждые традиционной структуре западные христианские идеи сыграли чуть ли не

§2. КРЕСТЬЯНСКАЯ ВОЙНА ПОД ПРЕДВОДИТЕЛЬСТВОМ И.И. БОЛОТНИКОВА

§2. КРЕСТЬЯНСКАЯ ВОЙНА ПОД ПРЕДВОДИТЕЛЬСТВОМ И.И. БОЛОТНИКОВА

Если о Василии Шуйском практически нет солидных работ, поскольку основные события шли как бы без него и часто против него, то о крестьянской войне и Иване Исаевиче Болотникове (ум. в 1608) написано много книг и

Крестьянская война в Германии

Крестьянская война в Германии

Протестное общественное движение, вызванное обострением социально-экономических и политических противоречий в Германии на протяжении XV – начала XVI в., достигло своей кульминации во время крестьянской войны 1524–1525 гг. Первые выступления

КРЕСТЬЯНСКАЯ ВОЙНА В ГЕРМАНИИ

КРЕСТЬЯНСКАЯ ВОЙНА В ГЕРМАНИИ

Нападение крестьян на рыцаряРеформация, начатая Лютером, нашла своих сторонников во всех слоях населения Германии. Интересно, что каждый находил в ней что-то свое и подстраивал религиозные идеи Лютера, зачастую искажая их, под свои чаяния.

Крестьянская война (1524—1525 гг.)

Крестьянская война (1524—1525 гг.)

Общественное движение и социальная борьба в Германии конца XV — начала XVI в. достигли своей кульминации в Крестьянской войне 1524—1525 гг. Одна из ее причин — ухудшение экономического,социального и правового статуса крестьян, особенное

Коллективизация и крестьянская война

Коллективизация и крестьянская война

Распространенное в массовом историческом сознании и в работах многих историков и публицистов жесткое противопоставление «программ» Сталина и «правых» — «программ» индустриального скачка и продолжения нэпа, — как правило,

24. К чему привела Реформация в Германии?

24. К чему привела Реформация в Германии?

Реформация была первым актом выступления нового, зародившегося в недрах феодального общества буржуазного сословия против феодальных порядков.Реформация началась в духовной сфере, с выступления буржуазии против католицизма –

31. Крестьянская война под руководством Пугачева

31. Крестьянская война под руководством Пугачева

Начало и ход крестьянской войны. Первыми восстали казаки на реке Яик (теперь река Урал). Царское правительство лишало уральских казаков их вольностей, облагало их обременительными налогами, стремясь превратить казаков в

6. РЕФОРМАЦИЯ В ГЕРМАНИИ

6. РЕФОРМАЦИЯ В ГЕРМАНИИ

Великие географические открытия изменили жизнь европейского общества, причем были опровергнуты некоторые церковные догмы. Открытия ученых также вносили свой вклад в опровержение церковных учений о мироздании. В XVI в. под влиянием открытий,

7. КРЕСТЬЯНСКАЯ ВОЙНА В ГЕРМАНИИ 7 (1524–1526 ГГ.)

7. КРЕСТЬЯНСКАЯ ВОЙНА В ГЕРМАНИИ 7 (1524–1526 ГГ.)

Уровень социально—экономического и политического развития Германии к началу XVI в. уступал только Нидерландам и Англии. Рост городов обусловливал интенсивную деятельность сельского хозяйства, которое стало приносить больше

§ 4. Реформация и крестьянская война в Германии

§ 4. Реформация и крестьянская война в Германии

Причины РеформацииXV–XVI вв. были для Европы временем духовного обновления. В результате изобретения книгопечатания Библия и комментарии к ней стали доступными не только для священнослужителей, но и для многих грамотных

Вслед за началом эпохи культурного возрождения, Великих географических открытий и острого международного соперничества в Европе начался грандиозный переворот в духовной сфере, принявший форму религиозной Реформации.

Содержание

- 1 Предпосылки Реформации

- 2 Германия накануне Реформации

- 3 Начало Реформации в Германии

- 4 Крестьянская война

- 5 Княжеская реформация и итоги Реформации в Германии

- 6 Итоги Реформации в Германии

Предпосылки Реформации

Понятие «Реформация» обозначает широкое движение за обновление католической церкви, развернувшееся по всей Европе, которое в итоге привело к образованию новых, так называемых «протестантских» церквей. Реформация происходила в самый разгар Итальянских войн, в которые были вовлечены практически все государства Европы, что сказалось на ходе и особенностях Реформации в разных странах.

Гуманизм эпохи Возрождения ставил в центр внимания человека с его земными, повседневными интересами, что проявилось даже в поведении первосвященников католической церкви. В конце XV — первой половине XVI в. римский престол один за другим занимали папы, отличавшиеся стремлением к роскоши, военной славе и другим далёким от служения Богу делам. Эти «ренессансные папы» славились беспринципностью и неразборчивостью в средствах, не останавливаясь перед убийством и другими преступлениями ради достижения своих целей. Понятно, что их поведение ослабляло авторитет церкви и усиливало стремление к её реформе.

Дж. Беллини. Процессия с реликвией Св. Креста на площади Св. Марка. Венеция. 1496 г.

Основной причиной Реформации стал внутренний кризис самой католической церкви. Протест против официальной церкви проистекал из глубины религиозного чувства. Необходимо учитывать, что религия имела первостепенное значение в духовной жизни средневекового человека, определяя всё его мировоззрение, а через него — повседневное поведение. Именно поэтому любые перемены в этой области имели большие последствия и оказывали влияние буквально на все стороны жизни.

На протяжении всего позднего Средневековья в европейском обществе, которое считалось единой «христианской республикой», распространялись религиозные течения, сторонники которых делали основной акцент не на соблюдении церковных обрядов и формальных проявлениях веры, а на внутреннем, индивидуальном общении человека с Богом. Реальная жизнь церкви, как им казалось, вступала в явное противоречие с христианским вероучением. Особое возмущение вызывало несоответствие образа жизни служителей церкви тому, что они проповедовали. Их поведение и политика, проводимая Римом, спровоцировали в итоге такую острую реакцию, которая привела к расколу католического мира. Реформационное движение, таким образом, носило не антирелигиозный, а антицерковный характер. Оно ставило целью укрепить истинную веру в противовес испорченной вере католического духовенства.

Неприятие вызывали, прежде всего, растущие материальные запросы римской церкви. Все верующие платили десятину — особый налог в размере 1/10 всех доходов. Велась открытая торговля церковными должностями, усилившаяся в начале XVI в. в связи с Итальянскими войнами. Умение верхушки католической церкви находить всё новые и новые источники богатств казалось неисчерпаемым. По всей Европе существовало огромное количество монастырей, имевших обширные земельные владения и иные богатства, с многочисленным населением, образ жизни которого давал повод для упрёков в праздности.

Важнейшую роль в успехе Реформации сыграло стремительное развитие книгопечатания, позволившее сделать Библию более доступной, что и создавало условия для широкого распространения новых религиозных идей.

Германия накануне Реформации

Родиной Реформации стала Германия, где все накопившиеся к началу XVI в. проблемы ощущались особенно остро. Большое значение имело и то, что на протяжении веков в Германии складывались своеобразные традиции религиозной мысли, которые отличали её от всей остальной Европы. Именно здесь возникло народное движение за «новое благочестие», участники которого пытались самостоятельно изучать Священное Писание. В это же время в Германии появились проповедники, призывавшие к простой жизни в евангельской нищете, они собирали вокруг себя многочисленных последователей.

Католическая церковь в Германии занимала исключительно привилегированное положение по сравнению с другими странами. Она владела почти третью всей германской земли и распоряжалась огромным количеством крестьян. Церковь в Германии больше, чем любая другая, зависела от Рима. Упадок императорской власти давал папам возможность практически бесконтрольно действовать на территории Священной Римской империи германской нации.

Сатирическая гравюра, разоблачающая папскую торговлю индульгенциями

Самой распространённой формой извлечения доходов была продажа индульгенций — специальных свидетельств об «отпущении» грехов. В XVI в. торговля индульгенциями стала совсем уж беззастенчивой. За деньги церковь готова была простить не только прошлые прегрешения, но и будущие, гарантируя верующим безнаказанность и фактически поощряя их жить во грехе.

Начало Реформации в Германии

Продажа индульгенций, начатая для финансирования строительства собора Св. Петра в Риме, приобрела особенно широкий размах при папе Льве X (1513-1521 гг.). Человеком, бросившим ему вызов, стал саксонский монах Мартин Лютер (1483—1546).

М. Лютер

Будущий реформатор родился в семье рудокопа, ставшего впоследствии владельцем небольшого медеплавильного предприятия. Он сумел получить университетское образование, несколько лет провёл в монастыре, а затем начал преподавать богословие в университете г. Виттенберга, расположенного во владениях герцога Саксонского. Хорошее знание церковной жизни и многолетние размышления над религиозными проблемами привели Лютера к мысли о необходимости очистить католическую церковь от пороков, вызывавших всеобщее возмущение. Средство к достижению этой цели он видел в возврате к идеалам раннего христианства, когда единственным авторитетом для христиан был текст Библии в его первозданной чистоте.

31 октября 1517 г. в соответствии с принятым в те времена обычаем Лютер прибил к дверям церкви в Виттенберге знаменитые «95 тезисов» — свои возражения против торговли индульгенциями. Это событие считается началом Реформации.

Переведённые с латыни на немецкий язык тезисы Лютера стремительно распространялись по всей Германии, заставляя миллионы его соотечественников задуматься над сложившимся в их стране положением. Попытка папы опровергнуть опасные мысли привела лишь к тому, что внимание народа ещё более сосредоточилось на Лютере.

В 1520 г. Лютер сделал следующий, ещё более решительный шаг, опубликовав обращение «К христианскому дворянству германской нации об исправлении христианства» и ряд других сочинений, в которых опровергал основные догматы католической церкви и осуждал господствовавшие в ней нравы. В доказательство серьёзности своих намерений Лютер демонстративно сжёг папскую буллу об отлучении его от церкви.

В 1521 г. Лютер был вызван на рейхстаг в Вормсе, где предстал перед судом императора Карла V. Согласно легенде, в ответ на предъявленные ему обвинения непреклонный реформатор решительно заявил: «На том стою и не могу иначе». Императору в тот момент было не до Германии. Назревала война с Францией, поэтому едва ли не в самую критическую минуту истории Германии он спешил оставить её для осуществления своих внешнеполитических замыслов. Карл V издал эдикт об осуждении Лютера, но тот вовремя скрылся во владениях герцога Саксонского Фридриха Мудрого, который первым из крупных германских князей встал на сторону Реформации.

Реформация в Германии

Лютер подготовил перевод Библии на немецкий язык, который сыграл колоссальную роль в истории германской культуры, дав импульс к формированию немецкого литературного языка. Перевод Лютера лёг в основу всей системы немецкого образования, которой он всегда придавал большое значение.

Мартин Лютер за переводом Библии в замке в Вартбурге. Гравюра. 1530 г.

Библия в переводе Мартина Лютера

Религиозное учение, основанное на идеях Лютера, получило название лютеранство. В настоящее время оно насчитывает десятки миллионов последователей во многих странах мира (их называют также евангельскими христианами, или евангелистами).

Основной смысл лютеранства сводится к идее об «оправдании верой», что означает отказ от внешних проявлений религиозности в пользу внутренних переживаний каждого человека. Спасение души провозглашалось индивидуальным делом верующего, не требующим вмешательства со стороны официальной церкви. Священное Писание объявлялось единственным авторитетом в вопросах веры, который не нуждался ни в каких толкованиях, а тем более — в формальных решениях церкви для своего подтверждения.

Лютеранство утверждало ненужность посредника между человеком и Богом — и, таким образом, ненужность церкви как особой организации. Новое учение предполагало отказ от монашества и церковного имущества. На место роскошных, богато декорированных католических храмов приходила «дешёвая церковь», лишённая ненужных украшений и пышных обрядов. От католичества сохранялось лишь то, что прямо не противоречило Писанию: крест, алтарь, орган. Важнейшее значение имело и то, что вместо латыни богослужение велось теперь на родном языке верующего. Религиозная жизнь сосредоточивалась теперь в церковных общинах, возглавляемых проповедниками — пасторами.

Крестьянская война

Реформация породила всеобщие надежды на преобразование германского общества. По всей стране распространялось убеждение, что мир находится накануне переворота, подготовленного всем ходом истории. Никогда ранее Германия не переживала такой поры надежд, энтузиазма, веры в быстрое обновление.

Ненависть к Риму на какое-то время заставила немцев забыть о различии интересов, но чем шире становился круг вовлечённых в движение социальных сил, тем явственнее давали знать о себе их противоречия и несхожие цели.

Первым на защиту своих интересов выступило германское рыцарство. Однако поднятое рыцарями восстание потерпело неудачу, что привело к его ослаблению как самостоятельной общественной силы и постепенному исчезновению с исторической арены.

Широкие народные массы по-своему истолковывали «христианскую свободу» и требовали решительным образом изменить условия своей жизни. Результатом стала «народная Реформация». К 1525 г. вся Германия была охвачена восстаниями, получившими название Крестьянской войны. Эти события заняли важное место в истории Германии в период перехода к Новому времени. Они стали следствием резкого ухудшения условий существования крестьянства, а Реформация подвела под требования крестьян идейную основу.

Вооружённые крестьяне. Гравюра XVI в.

Крестьянская война в Германии

В важнейшем доку менте Крестьянской войны — «12 статьях» — подчеркивалось: «сущность всех крестьянских статей (как ясно видно дальше) направлена к тому, чтобы понять это Евангелие и жить согласно с ним».

Эти выступления наглядно показали, что события стали развиваться не так, как предполагал инициатор Реформации. Лютер осудил восставших, опубликовав воззвание «Против разбойных крестьянских орд».

Борьба носила крайне ожесточённый характер, в ходе подавления крестьянских восстаний погибло около 100 тыс. человек.

Княжеская реформация и итоги Реформации в Германии

После окончания Крестьянской войны дело Реформации взяли в свои руки князья, занявшие отныне ведущее положение в происходящих событиях. Начинался период Реформации, который получил название «княжеская» Реформация. Включение владетельных князей в реформационное движение поднимало его на новый уровень.

В Германской империи существовали две категории князей: князья светские и князья церковные. Между ними существовали серьёзные противоречия. Реформация открывала перед светскими князьями возможности для расширения своих владений за счёт владений церковных князей.

Стремительному распространению Реформации по всей империи способствовала также борьба за власть между императором и князьями. Реформация позволяла светским князьям укрепить своё положение в Империи за счёт ослабления власти монарха.

Главным содержанием «княжеской» Реформации стал захват монастырских земель и секуляризация церковных владений, то есть обращение церковной собственности (преимущественно земли) в светскую. Карл V не сразу вмешался в конфликт между князьями и церковью. Всё это время его отвлекали войны в Италии. В 1529 г., после подписания мира в Каморе, Карл V получил, наконец, возможность заняться германскими делами. Первым делом император запретил захваты монастырского и церковного имущества и восстановил императорский эдикт 1521 г. о запрете лютеранства. Эти решения вызвали знаменитый протест пяти князей и 14 имперских городов — сторонников Реформации. Отсюда происходят понятия протестантизм и протестант, которые стали общими названиями для всего реформационного движения и его последователей.

Попытка Карла V восстановить церковное единство Германии не удалась. Обстоятельства, связанные с внешней политикой, вынудили императора надолго отложить борьбу против протестантов. Только заключённый в 1544 г. мир с Францией развязал Карлу V руки для борьбы с протестантами. Первая религиозная война в Германии (1546-1547 гг.) завершилась решительной победой императора. Однако в ходе второй войны 1552 г. протестанты выступили в союзе с королём Франции и быстро добились победы.

Между тем Германия находилась в состоянии почти полного хаоса. В 1555 г. в Аугсбурге был созван рейхстаг, которому суждено было подвести черту под религиозными войнами в Германии. Заключённый в Аугсбурге религиозный мир был основан на принципе: «Чья страна, того и вера» (то есть в каждом княжестве правитель имел право установить вероисповедание, которое выбрал сам). В Империи отныне признавались два христианских вероисповедания, одинаково равных перед законом, — католическое и лютеранское.

Видя крушение своих идеалов, Карл V отрёкся от всех титулов, чтобы закончить свою жизнь в одном из испанских монастырей.

Итоги Реформации в Германии