Диана Спенсер: история жизни, любви и разочарований принцессы людских сердец

Принцесса Диана погибла в автокатастрофе 31 августа 1997 года. Водитель не справился с управлением, пытаясь уйти от преследования папарацци. После трагического ухода про Диану Спенсер слагали песни и снимали фильмы. Королева людских сердец, для которой волшебная сказка обернулась крушением надежд, навсегда останется для своих поклонников воплощением красоты и добра. Вспомнили самые яркие и драматичные моменты из биографии принцессы Уэльской.

Леди Ди называли самой фотографируемой женщиной мира. Казалось, она излучала внутренний свет и очаровывала своим обаянием всех вокруг.

Не занимайтесь самолечением! В наших статьях мы собираем последние научные данные и мнения авторитетных экспертов в области здоровья. Но помните: поставить диагноз и назначить лечение может только врач.

Она не афишировала, что на самом деле происходило в её душе в период размолвки и последующего развода с принцем Чарльзом. Сила характера и умение дарить тепло сделали ее невероятно популярной. В 2002 году леди Диана, по результатам опроса, заняла третье место в списке великих британцев, опередив королеву и других британских монархов.

РЕКЛАМА – ПРОДОЛЖЕНИЕ НИЖЕ

Детство и юность Дианы

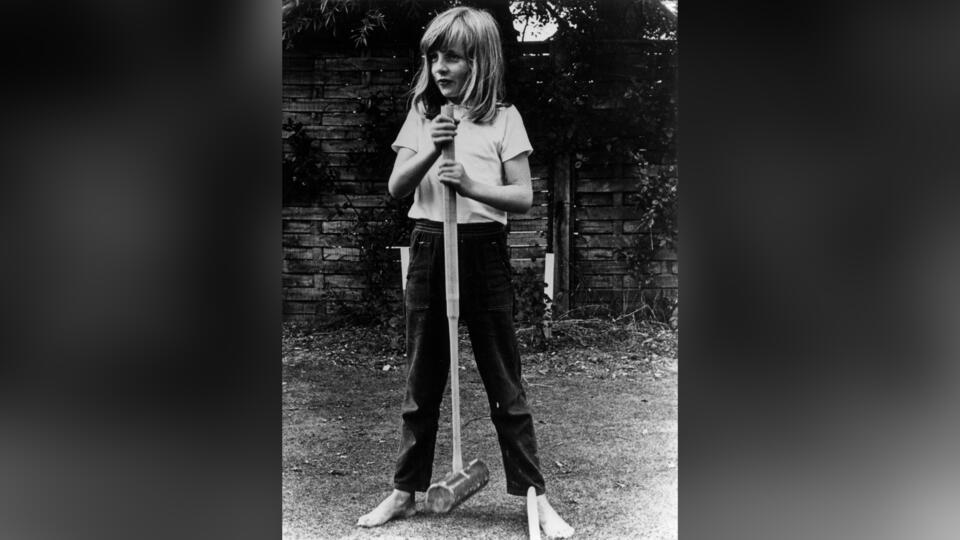

Диана Френсис Спенсер родилась 1 июля 1961 года. Третья девочка в семье, она стала очередным разочарованием графа Джона Спенсера, ожидавшего сына – наследника титулов и поместий. Но в детстве Диана была окружена любовью: как младшую, ее баловали и родные, и прислуга.

Если подробнее говорить о родословной Дианы Спенсер, ее отец являлся виконтом (дворянский титул, средний между графом и бароном) Элторпа, представителем одной из ветвей того же семейства Спенсер, что и Уинстон Черчилль. Графы Спенсеры не один век проживали в центре Лондона, в Спенсер-хаусе.

Принцесса Диана и другие звезды, известные своими скандальными высказываниями

Принцесса Диана в 1995 году пообщалась с журналистом BBC Мартином Баширом, что спровоцировало грандиозный скандал. Она заявила, что в их браке с Чарльзом изначально было три человека, намекнув на его давнюю любовницу Камиллу Паркер-Боулз. Принцесса Уэльская открыто рассказала о своей депрессии, булимии, тревоге и отчаянии — темах, которые по умолчанию были табуированными для членов королевской семьи.

РЕКЛАМА – ПРОДОЛЖЕНИЕ НИЖЕ

РЕКЛАМА – ПРОДОЛЖЕНИЕ НИЖЕ

Семейная идиллия родителей Дианы длилась недолго. Уличенная в супружеской измене, графиня Спенсер уехала в Лондон, забрав младших детей. Процесс развода сопровождался скандалом – на суде бабушка Дианы свидетельствовала против дочери. Семейный разлад навсегда остался связан для девочки со страшным словом «развод». Отношения с мачехой не сложились, и остаток детства будущая принцесса Диана металась между маминым особняком в Шотландии и папиным в Англии, нигде не чувствуя себя дома.

РЕКЛАМА – ПРОДОЛЖЕНИЕ НИЖЕ

Диана не отличалась особым прилежанием, и учителя отзывались о ней как о неглупой, но не очень одаренной девочке. Истинная же причина ее равнодушия к наукам была в том, что она уже была поглощена другой страстью – балетом. Но высокий рост помешал увлечению стать делом жизни. Лишенная возможности стать балериной, будущая принцесса Уэльская обратилась к общественной деятельности. Ее увлекающуюся натуру и способность заражать других своим энтузиазмом отмечали все вокруг.

Знакомство Дианы с Чарльзом

Биография 16-летней Дианы Спенсер откроется новой главой – судьбоносной встречей с принцем Чарльзом. Сестра Дианы Сара тогда встречалась с наследником британского престола, но роман прекратился после неосторожного интервью девушки. Вскоре после разрыва Чарльз стал приглядываться к той, в которой прежде видел лишь младшую сестру своей подружки. Вскоре сын королевы пришел к выводу: Диана – само совершенство! Девушка была польщена вниманием принца, и все шло к счастливой развязке.

РЕКЛАМА – ПРОДОЛЖЕНИЕ НИЖЕ

РЕКЛАМА – ПРОДОЛЖЕНИЕ НИЖЕ

За уик-эндом в загородном доме друзей последовал круиз на яхте «Британия», а затем приглашение в замок Балморал, летнюю резиденцию английских монархов, где Диану официально представили королевской семье. Для заключения брака будущему монарху требуется разрешение монарха действующего. Формально Диана Спенсер была идеальной кандидаткой на роль невесты. Обладая всеми достоинствами менее удачливой сестры (благородным происхождением, прекрасным воспитанием и привлекательной внешностью), она могла похвастаться невинностью и скромностью, чего явно не хватало бойкой Саре. И только одно смущало Елизавету II – Диана казалась слишком неприспособленной к дворцовой жизни. Но Чарльзу было за тридцать, поиски лучшей претендентки могли затянуться, и после долгих колебаний королева дала наконец благословение.

РЕКЛАМА – ПРОДОЛЖЕНИЕ НИЖЕ

РЕКЛАМА – ПРОДОЛЖЕНИЕ НИЖЕ

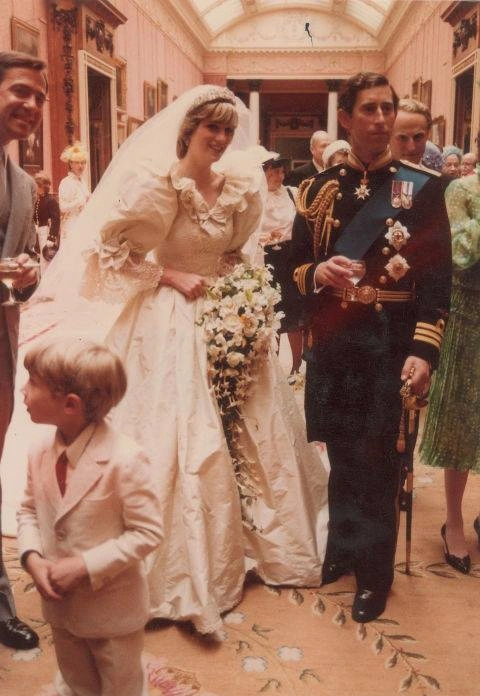

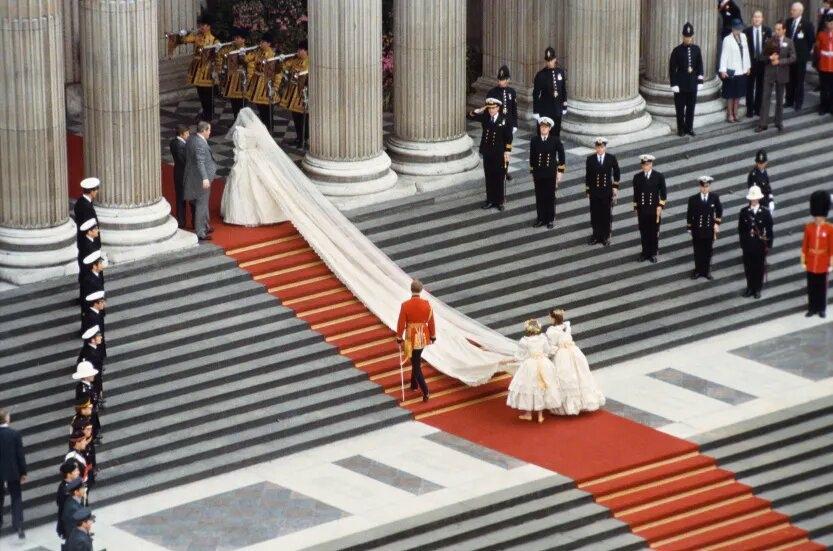

6 февраля 1981 года Диана приняла предложение принца. А уже 29 июля 20-летняя Спенсер обвенчалась с наследником престола и стала принцессой Уэльской, ее стали называть леди Ди. Церемония прошла в соборе Святого Павла. Трансляцию посмотрело 750 миллионов человек, еще 600 тысяч зрителей собрались на улице, чтобы увидеть свадебный кортеж.

РЕКЛАМА – ПРОДОЛЖЕНИЕ НИЖЕ

Сама свадьба была похожа на сказку. Фото Дианы Спенсер в пышном белом платье с восьмиметровым шлейфом опубликовали все местные издания. Она подъехала к церкви в карете, окруженной эскортом из офицеров королевской конной гвардии. Из брачных обетов было убрано слово «повиноваться», что произвело сенсацию – еще бы, ведь даже сама королева Англии обещала во всем слушаться мужа.

РЕКЛАМА – ПРОДОЛЖЕНИЕ НИЖЕ

Всего через год после свадьбы принцесса Диана укачивала сына и наследника — принца Уильяма. Через пару лет родился Гарри. Молодая мама позже призналась, что эти годы были в их с Чарльзом отношениях лучшими. Все свободное время они проводили с детьми. «Семья – самое важное», — говорила сияющая Диана журналистам.

РЕКЛАМА – ПРОДОЛЖЕНИЕ НИЖЕ

РЕКЛАМА – ПРОДОЛЖЕНИЕ НИЖЕ

В это время леди Ди впервые продемонстрировала решительный характер. Презрев обычаи, она сама выбрала имена для принцев, отказалась от помощи королевской няни (наняв свою) и всячески старалась оградить высочайшее вмешательство в жизнь ее семьи. Преданная и ласковая мама, она организовывала свои дела так, чтобы они не мешали ей встречать детей из школы. А дел было невероятное количество!

Королевские дела леди Ди

В оговоренные церемониалом обязанности принцессы Уэльской входило посещение благотворительных мероприятий. Традиционно благотворительность – занятие каждого члена королевской семьи. Принцы и принцессы издавна патронируют больницы, приюты, хосписы, детские дома и некоммерческие организации, но никто из британских монархов не занимался этим с такой страстью, как Диана.

РЕКЛАМА – ПРОДОЛЖЕНИЕ НИЖЕ

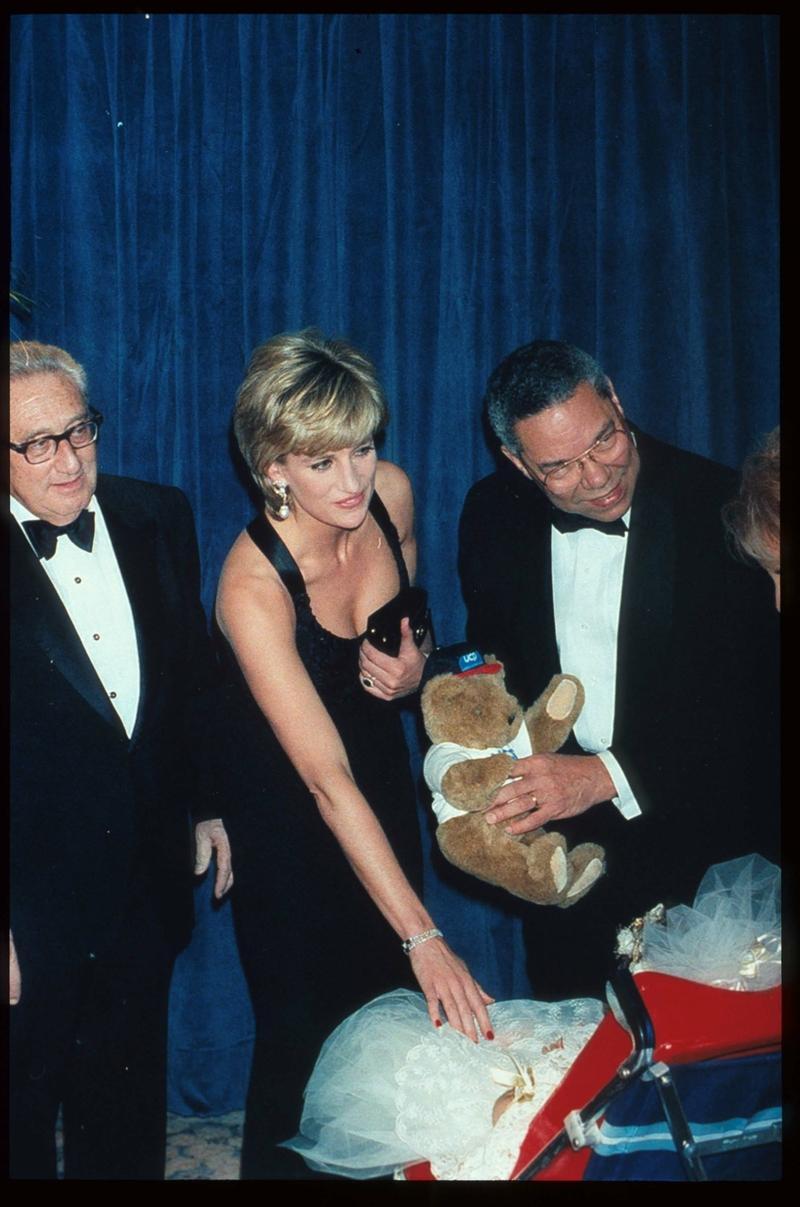

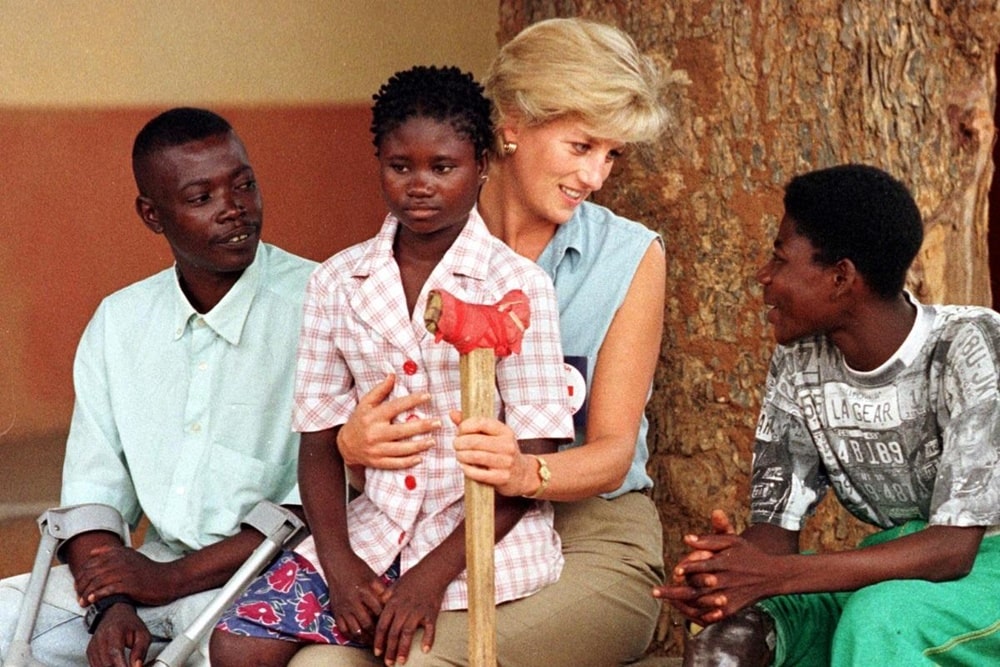

Она сильно расширила список посещаемых учреждений, включив в них госпитали для больных СПИДом и лепрозории. Принцесса посвящала много времени проблемам детей и молодежи, но среди ее подопечных числились и дома престарелых, и центры реабилитации алкоголиков и наркоманов. Леди Диана также поддерживала кампанию за запрещение применения противопехотных мин в Африке.

РЕКЛАМА – ПРОДОЛЖЕНИЕ НИЖЕ

РЕКЛАМА – ПРОДОЛЖЕНИЕ НИЖЕ

Принцесса Диана щедро тратила на добрые дела свои средства и богатство королевской семьи, а также привлекала в качестве спонсоров друзей из высшего общества. Сопротивляться ее мягкому, но несокрушимому обаянию было невозможно. Ее обожали все соотечественники, да и за границей у леди Ди было множество поклонников. «Самое тяжелое заболевание мира – это то, что в нем мало любви», — постоянно повторяла она. При этом Диана безуспешно боролась и с собственным наследственным заболеванием — булимией (пищевое расстройство), а на фоне нервных переживаний и стрессов сдерживать себя было пыткой.

РЕКЛАМА – ПРОДОЛЖЕНИЕ НИЖЕ

Семейные дела принцессы Уэльской

История семейной жизни принцессы Дианы чем-то напоминала трагедию союза родителей Спенсер. Молодая женщина была несчастна. Многолетний роман Чарльза с замужней женщиной – леди Камиллой Паркер-Боулз, о котором Диана узнала после свадьбы, возобновился в середине 80-х.

Оскорбленная Диана сблизилась с Джеймсом Хьюиттом, инструктором по верховой езде. Напряжение усилилось, когда в прессу просочились записи компрометирующих телефонных разговоров обоих супругов с любовниками. Последовали многочисленные интервью, в ходе которых Чарльз и Диана обвиняли друг друга в том, что их союз распался. «В моем браке было слишком много народу», — грустно шутила принцесса. Личная тайна принцессы Дианы, урожденной Спенсер, стала достоянием общественности. В 1994 году вышла книга под названием «Влюбленная принцесса», по которой даже был снят одноименный фильм.

РЕКЛАМА – ПРОДОЛЖЕНИЕ НИЖЕ

РЕКЛАМА – ПРОДОЛЖЕНИЕ НИЖЕ

Возмущенная королева постаралась ускорить развод сына. Бумаги были подписаны 28 августа 1996 года, и с этого момента принцесса Диана потеряла все права на обращение Ваше Королевское Высочество. Сама она всегда говорила, что хочет быть лишь королевой людских сердец, а не супругой правящего монарха. После развода Диана почувствовала себя немного свободнее, хотя ее жизнь все еще регулировалась протоколом: она была бывшей женой наследного принца и матерью двух наследников. Диана Спенсер была вынуждена хранить тайны и соблюдать приличия. Именно любовь к сыновьям заставляла ее сохранять видимость семьи и терпеть измены мужа: «Любая нормальная женщина ушла бы давно. Но я не могла. У меня сыновья». Даже в разгар скандала леди Ди не прекращала занятий благотворительностью.

РЕКЛАМА – ПРОДОЛЖЕНИЕ НИЖЕ

После развода леди Диана не оставила благотворительность, и ей действительно удавалось менять мир к лучшему. Она направляла свои силы на борьбу со СПИДом, раком, обращала свою помощь детям с пороками сердца.

РЕКЛАМА – ПРОДОЛЖЕНИЕ НИЖЕ

РЕКЛАМА – ПРОДОЛЖЕНИЕ НИЖЕ

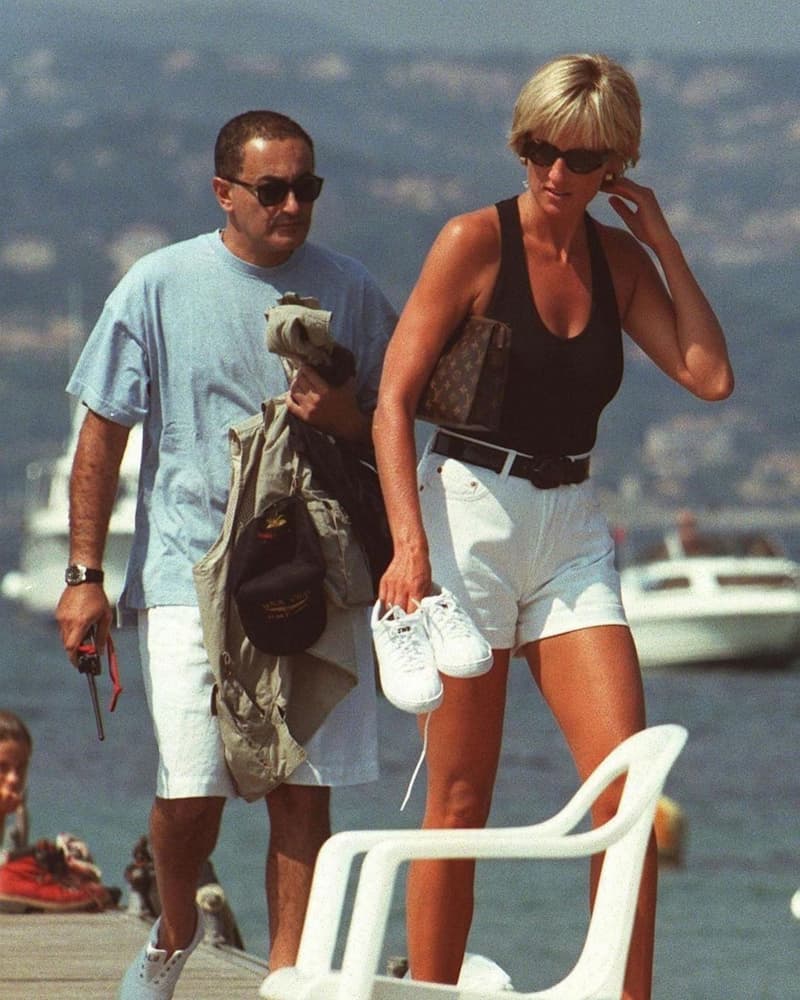

В это время принцесса Уэльская пережила страстный роман с хирургом пакистанского происхождения Хаснатом Ханом. Хан происходил из очень религиозной семьи, и влюбленная Диана всерьез рассматривала обращение в ислам, чтобы иметь возможность выйти замуж за возлюбленного. К сожалению, противоречия между двумя культурами были слишком велики, и в июне 1997 года пара рассталась. Всего через несколько недель леди Ди стала встречаться с Доди Аль-Файедом, продюсером и сыном египетского мультимиллионера.

РЕКЛАМА – ПРОДОЛЖЕНИЕ НИЖЕ

Национальная трагедия – гибель леди Дианы

31 августа 1997 года Диана и Доди находились в Париже. На автомобиле они покинули отель, когда за ними увязались машины с папарацци. Пытаясь уйти от погони, водитель не справился с управлением и врезался в бетонную опору моста. Он сам и Доди Аль-Файед погибли на месте, принцессу Диану доставили в больницу, где она скончалась через два часа после катастрофы. Единственный выживший в аварии, телохранитель Тревор Рис-Джонс не помнит событий.

РЕКЛАМА – ПРОДОЛЖЕНИЕ НИЖЕ

РЕКЛАМА – ПРОДОЛЖЕНИЕ НИЖЕ

Полиция провела тщательное расследование, в результате которого причиной смерти леди Дианы был объявлен несчастный случай, вызванный неосторожностью шофера и беспечностью пассажиров машины (никто из них не был пристегнут).

Елизавета II была против объявления национального траура, настаивая на том, что принцесса Уэльская уже не принадлежала к монаршей семье на момент гибели. Однако игнорирование смерти их любимицы вызвало народный гнев. Толпа желающих проститься с принцессой Дианой несколько дней держала оборону около Букингемского дворца, требуя приспустить флаги в знак национальной трагедии. Тогда Елизавета сдалась, но восстановить титул Дианы королева отказывается до сих пор, хотя на этом настаивают принцы Уильям и Гарри.

РЕКЛАМА – ПРОДОЛЖЕНИЕ НИЖЕ

Королева людских сердец

Места, где Диана чаще всего бывала при жизни, а также туннель, где она погибла, стали объектом паломничества ее поклонников. На похоронах леди Ди Элтон Джон, который был ее близким другом, исполнил версию песни «Свеча на ветру», в которой были слова: «Ты прожила жизнь, как свеча горит на ветру. // И пусть она сгорела слишком быстро, легенда о тебе не умрет никогда».

В 2021 году на экраны вышел драматический фильм «Спенсер: Тайна принцессы Дианы». Биографическую картину снял режиссер Пабло Ларраин. В ней описывается период, в котором леди Ди приняла решение расторгнуть брак с Чарльзом и покинуть королевскую семью.

В целом фильм «Спенсер» про принцессу Диану получил положительные отзывы критиков. В нем не показана ее трагическая гибель, но отражены душевные муки, которые испытывала королевская особа, когда ее брак терпел крах. В какой-то момент она едва не покончила жизнь самоубийством. Но вовремя одумалась.

Диану Спенсер сыграла Кристен Стюарт. Режиссер отмечал свой выбор уникальностью актрисы. За исполнение этой роли Кристен номинирована на премии «Оскар», «Золотой глобус», «Выбор критиков» как лучшая актриса.

Фото: Getty Images, Rex/Fotodom

Леди Ди – подлинная звезда британской монархии. Никто из членов королевской семьи не пользовался таким успехом в народе, как принцесса Диана. Несмотря на то, что с момента гибели женщины прошло уже больше 20 лет, интерес к ней не утихает.

Биография принцессы Дианы весьма занимательна, ведь на счету этой удивительной дамы множество замечательных поступков.

Будущая принцесса Уэльская родилась в семье британских аристократов. Дата рождения – 1 июля 1961 года. Диана Спенсер – именно так звали девочку – стала дочерью носителя титула виконта Элторпа, происходившего из древнего рода Спенсер-Черчиллей.

Мать Дианы по имени Фрэнсис Шанд Кайдд также была голубых кровей. Бабушка будущей принцессы Уэльской по материнской линии являлась фрейлиной королевы Елизаветы Боуз-Лайон.

Семья Дианы также включала двух старших сестер по имени Сара и Джейн. Спенсерам не повезло с сыновьями: единственный родившийся мальчик умер спустя 10 часов после появления на свет. Лишь после рождения третьей дочери у них родился долгожданный наследник Чарльз.

Диана в детстве

Первые уроки Диане давала Гертруда Аллен, гувернантка. Затем девочка посещала школу в Силфилде, позже получала образование в Ридлсуорт-Холл.

Ей нравилось рисовать и танцевать – в этих областях она достигла больших успехов. Все прочие предметы давались юной Диане с трудом – наука ее не слишком интересовала.

В конечном итоге девушке не удалось сдать выпускные экзамены и получить аттестат зрелости. Построить карьеру профессиональной балерины ей также было не суждено – помешал высокий рост.

До замужества она успела поработать воспитательницей в детском саду «Молодая Англия». Девушка вела довольно обычный для британской молодежи образ жизни. Отец подарил ей скромную квартиру, где она и проживала, избегая шумных лондонских вечеринок.

Знакомство с принцем

Судьбоносная встреча с суженым состоялась, когда прекрасной Диане было 16. Тогда принц ухаживал за ее сестрой Сарой, однако вскоре сменил предпочтения. Его выбор был одобрен и членами монаршей семьи.

Скромная симпатичная девушка без тянувшегося за ней шлейфа скандалов и с отличной родословной показалась королеве достойной партией для будущего наследника престола.

Чарльз пригласил Диану на королевскую яхту «Британия». Уже в 1980 году состоялось знакомство с членами королевской семьи, прошедшее в остановке фамильного замка Балморал.

Мать Чарльза не преминула отметить достоинства кандидатки в невестки. Ее смущала лишь кажущаяся неприспособленность Дианы к дворцовой жизни. Однако принцу было уже немало лет – тянуть с женитьбой не было времени.

По возвращении из военно-морского похода на корабле «Непобедимый» принц Чарльз не замедлил сделать Диане предложение сочетаться браком.

6 февраля 1981 года леди Ди ответила согласием, а уже спустя полгода состоялась свадебная церемония.

Свадебная церемония

Мероприятие было назначено на 29 июля 1981 года. Дату выбирали с учетом погодных условий, чтобы дождь не смог омрачить празднество.

Торжество проводилось в соборе святого Павла, выбранного в силу наличие большего числа мест для гостей.

Принцесса Уэльская Диана выглядела великолепно: шлейф ее свадебного платья имел длину 7,5 метров и стоимость в 10 тысяч фунтов. Церемония транслировалась всеми мировыми СМИ: ее просмотрели около 700 тысяч телезрителей. Почти такое же количество людей лично наблюдали за торжеством.

Свадьба с принцем

Не обошлось и без неловких моментов: во время произнесения традиционной клятвы у алтаря английская принцесса перепутала порядок имен принца Чарльза.

Это, вместе с отсутствием заверений в вечном повиновении, считалось нарушением этикета. Однако королевские пресс-атташе предпочли сделать вид, что все идет по плану – текст свадебного обета для членов британского двора был скорректирован.

Брак леди Ди

Поначалу личная жизнь венценосной семьи казалась безоблачной. Супруги поселились в Кенсингтонском дворце. Диана писала своей няне Мэри Кларк о том, как ей нравится быть замужней дамой.

Но счастье длилось недолго. Уже в середине 80-х Чарльз возобновил многолетний роман с Камиллой Паркер-Боулз. Сколько лет Диане пришлось терпеть связь мужа на стороне – сложно сказать. Однако она знала о Камилле еще в момент получения предложения.

Неверность мужа больно ранила принцессу. Нервное потрясение проявилось в виде булимии, приходилось пить успокоительные. Женщина не спешила разводиться из-за сыновей, однако нашла утешение в близком общении с инструктором по верховой езде Джеймсом Хьюиттом.

Обнародование телефонных бесед супругов со своими любовниками привело к скандалу. Возмущенная королева начала настаивать на разводе, чтобы сохранить репутацию монаршей семьи.

В 1992 году прозвучали первые заявления о расставании супругов. Однако после этого прошло еще несколько лет, на протяжении которых Диана и Чарльз формально продолжали оставаться женатыми.

«Брак втроем» — так именовала сложившуюся ситуацию сама леди Ди. Конец всему положило откровенное интервью ВВС, данное принцессой Уэльской в 1995 году.

На нее ополчились все вокруг, включая членов собственной семьи. Елизавета Вторая предложила сыну и его жене наконец оформить расставание.

Официальный развод состоялся в 1996 году, тогда же к Диане перестали обращаться «Ее королевское высочество». За деньги беспокоиться не пришлось: ей было выплачено 17 миллионов фунтов стерлингов, а также назначено 400 тысяч ежегодно.

Дополнительно супруги подписали соглашение о конфиденциальности: им было запрещено обсуждать на публике подробности супружеской жизни либо развода. От этого брака у леди Ди осталось двое сыновей: принц Гарри Уэльский и принц Уильям Уэльский.

После развода принцесса выставила принадлежавшие ей платья на аукционе, выручив за них около 3,5 миллионов фунтов.

Диана с детьми

Личная жизнь принцессы наладилась романом с хирургом Хаснатом Ханом родом из Пакистана. Влюбленные старались скрываться от вездесущих папарацци, хотя они подолгу жили вместе в Кенсингтонском дворце и лондонской квартире врача.

Головокружительный роман завершился расставанием летом 1997 года – сказались глубокие культурные различия и свободолюбивые взгляды принцессы.

Леди Ди глубоко переживала неудачу в личной жизни. Ей удалось найти утешение в объятиях сына миллиардера Мохаммеда Аль-Файеда Доди. Влюбленные даже собирались пожениться, однако их планам не суждено было сбыться.

Чем была знаменита

Краткая история благотворительной деятельности женщины включает многочисленные посещения больниц, неблагополучных стран и других мест, где требовалась помощь. Подобная активность входит в круг непосредственных обязанностей членов королевской семьи.

Годы жизни Дианы были отмечены участием в многочисленных благотворительных акциях по всему миру. Женщина занималась этим со всей страстью, от души. Ей удалось значительно расширить перечень посещаемых учреждений: в него вошли больницы для больных СПИДом, лепрозории.

Не меньшее внимание принцесса уделяла и проблемам детей, молодежи. В число подопечных вошли также дома престарелых, реабилитационные центры.

Ей принадлежит и заслуга поддержки кампании, нацеленной на запрет противопехотных мин в Африке. Смелая женщина прошла через минное поле, расположенное в Анголе, в защитном жилете, несмотря на обуявший ее страх. Именно так ей хотелось привлечь внимание к этой проблеме.

Благотворительная деятельность Дианы

Общественная деятельность стала увлечением принцессы. Она презирала условности и всегда стремилась оказать помощь нуждающимся.

Диана пожимала руки больным СПИДом, в то время как это считалось опасным. Обнимать зараженных проказой в Индии для нее также было в порядке вещей.

Настоящий ангел – именно так называли женщину. В число своих друзей Диану записала и мать Тереза.

За время своей активной деятельности в качестве жены Чарльза Диане были вручены многочисленные награды, среди которых:

- Орден королевы Елизаветы Второй;

- Египетский орден добродетельности;

- Большой крест ордена Короны (Нидерланды) и множество других.

История принцессы Дианы – повесть о женщине с открытым сердцем. Доброта и отзывчивость – вот чем была знаменита принцесса.

Число ее поклонников исчислялось миллионами. Ее любили не только в Англии, но и далеко за ее пределами.

Женщина всеми силами стремилась привнести в мир любовь.

Принцесса Уэльская – икона стиля

Среди представительниц прекрасного пола Диана пользовалась популярностью не только как ярая общественница. Ее быстро стали считать иконой стиля. Дамы Великобритании, а позже и всего мира, стремились подражать ей.

Принцесса одевалась со вкусом – ее стиль пытались копировать женщины со всех уголков света. Однако одежда от знаменитых кутюрье не каждому по карману, зато стрижка под Диану стала доступной всем.

Клиентки парикмахерских упрашивали мастеров сделать их прическу максимально схожей с укладкой принцессы. Волосы Дианы сначала были сравнительно длинными, однако за 2 года до развода она позволила себе укоротить пряди до стрижки под пажа.

Даме быстро удалось стать настоящей законодательницей моды. Любой выход в свет или поездка за границу привлекали пристальное внимание к жене Чарльза.

Обстоятельства трагедии

Леди Ди погибла 31 августа 1997 года.

В этот скорбный день королева людских сердец вместе со своим возлюбленным Доди находились в Париже. Сев в машину Мерседес-Бенц S280, они покинули гостиницу. За ними вслед выехали неугомонные папарацци. Водитель автомобиля, в котором находились леди Диана и Доди, всячески пытался уйти от погони репортеров.

Однако случилась беда: ему не удалось справиться с управлением – транспортное средство на скорости въехало в бетонную опору моста. Шофер и возлюбленный принцессы скончались сразу же, в то время как Диану успели довезти до медучреждения.

Однако спустя 2 часа ее не стало – полученные травмы оказались несовместимы с жизнью.

В этом ДТП удалось выжить лишь телохранителю Тревору Рис-Джонсу, однако в его памяти не осталось никаких воспоминаний о трагедии.

Обстоятельства случившегося были тщательно изучены – по результатам проверки сделан вывод о том, что причиной аварии стал банальный несчастный случай. Именно эта версия была озвучена как официальная.

Дата смерти принцессы стала черным днем в истории Великобритании.

Елизавета Вторая не хотела объявлять национальный траур, ведь на момент ужасной трагедии Диана уже не являлась членом монаршей семьи. Подобный подход к делу вызывал страшное возмущение у народа. Тысячи желающих проводить и Диану в последний путь толпились вокруг Букингемского дворца, выдвигая требование спустить флаги в знак национальной трагедии.

Королева пошла на уступки, однако споры касательно восстановления титула леди Ди ведутся и по сей день.

Место трагедии

Похороны, состоявшиеся 6 сентября 1997 года, ознаменовались выступлением Элтона Джона, дружившего с Дианой. Он спел собственную версию композиции «Сеча на ветру».

Место гибели бывшей Принцессы Уэльской стол объектом паломничества ее многочисленных поклонников. Тело женщины похоронено в Нортгемптоншире.

В настоящее время не утихают споры относительно обстоятельств смерти принцессы. Даже 23 года спустя после случившегося многие историки, конспирологи и другие неравнодушные продолжают строить гипотезы в поисках разгадки.

Звучали самые невероятные догадки. Спустя 10 лет с момента, когда умерла Диана, в отчете Скотланд-Ярда была опубликована информация о двукратном превышении допустимой скорости на отрезке дороги под мостом Альма. Также был достоверно установлен факт наличия алкоголя в крови шофера, который превышал норму в 3 раза.

Однако и сейчас не оставляются попытки доказать причастность к смерти дамы высших британских кругов. Сторонники подобных теорий не сомневаются в вине спецагентов.

И по сей день Диана Уэльская остается одним из наиболее популярных лиц в британской истории. Ей удалось обойти в рейтинге всех других английских монархов.

Биография

Ее называют принцессой сердец, народной принцессой, иконой стиля на все времена. Английские подданные ее боготворили, в других странах она вызывала восхищение и большую симпатию. Диана Спенсер, принцесса Уэльская — первая супруга принца Чарльза, подарившая британскому трону двух наследников. Согласно опросу BBC, принцесса Диана входит в число самых популярных лиц в истории Британии, опережая в этом рейтинге прочих английских монархов.

Детство и юность

Диана Фрэнсис Спенсер, ее высочество принцесса Уэльская, родилась 1 июля 1961 года в графстве Норфолк в английской аристократической семье. Ее отец Джон Спенсер, носитель титула виконта Элторпа, происходил из древнего рода Спенсер-Черчилей, носителей королевской крови, происходившей от Карла Второго, прославившегося как Веселый Король.

Династия, к которой принадлежала принцесса Диана, может гордиться такими именитыми сыновьями, как сэр Уинстон Черчилль и герцог Мальборо. Родовым владением семьи Спенсер является Спенсер-Хауз, расположенный в квартале Вестминстер в центре Лондона.

Мать Дианы Фрэнсис Шанд Кайдд тоже происходит из аристократического рода. Бабушка Дианы по материнской линии была фрейлиной королевы Елизаветы Боуз-Лайон.

Биография будущей принцессы также была вне претензий. Начальное образование Диана получила в Сандрингеме. В дальнейшем девочка посещала частную школу Силфилд, а позднее училась в Ридлсуорт-Холле. В детстве характер будущей венценосной особы не был трудным, но она всегда проявляла упрямство.

Родители Дианы развелись, когда ей было 8 лет, что стало сильным потрясением для ребенка. В результате бракоразводного процесса Диана осталась с отцом, а мать уехала в Шотландию, где жила с новым мужем.

Вместе с младшей Дианой в доме отца остались и ее старшие сестры и брат. А вскоре Джон Спенсер повторно женился на Рейн Маккордейл, графине Дартмут. Дети без особого энтузиазма восприняли мачеху — объявили женщине бойкот. И только спустя время Диана поняла, насколько мудрой и терпеливой была жена ее отца.

Следующим местом учебы будущей принцессы Уэльской становится привилегированная школа для девочек Уэст-Хилл в графстве Кент. Здесь Диана не проявила себя в качестве усердной ученицы, а ее увлечением стали музыка и танцы. По слухам, в молодости леди Ди не давались точные науки, она даже несколько раз провалила экзамены.

Личная жизнь

В 1977 году в Элторпе состоялось знакомство Дианы и принца Чарльза, однако в то время будущие супруги не обратили друг на друга серьезного внимания. Молодой человек был увлечен старшей сестрой девушки Сарой Спенсер, на которой намеревался жениться.

Дело шло к браку, но в одном из разговоров с журналистами Сара допустила грубую ошибку. В пылу влюбленности она сообщила, что для нее нет значения, кем будет ее муж — принцем или мусорщиком, главное — это чувство любви между супругами. Такое сравнение оскорбило королевскую семью, а Чарльз написал ей гневное прощальное письмо.

В этом же году Диана на протяжении короткого времени обучалась в Швейцарии, но вернулась домой из-за сильной тоски по родине. После окончания учебы девушка начала работать няней и воспитательницей в детском саду в престижном районе Лондона Найтсбридже.

В столице Великобритании она жила с матерью, затем переехала в собственную квартиру, которую ей подарили на 18-летие. Среди мест работы Дианы в это время числились также Young England School, хореографическая студия для подростков, где Спенсер преподавала танцы, фирма по организации праздников.

Свадьба с принцем Чарльзом

В возрасте 19 лет Диана вновь попала в круг общения принца Чарльза. Холостая жизнь наследника престола на тот момент являлась серьезным поводом для беспокойства его родителей.

Елизавету II волновала связь сына с Камиллой Паркер-Боулз, замужней дамой, отношения с которой принц даже не пытался скрывать. В сложившейся ситуации кандидатура Дианы Спенсер на роль принцессы была с радостью одобрена королевской семьей.

Принц пригласил Диану начала на королевскую яхту, после чего поступило приглашение в замок Балморал для знакомства с королевской семьей. Чарльз сделал предложение в замке Виндзор, но факт помолвки некоторое время держался в секрете. Официальное оглашение состоялось 24 февраля 1981 года. Символом этого события стало знаменитое кольцо с сапфиром в окружении 14 бриллиантов.

Леди Ди стала первой англичанкой за последние 300 лет, которая вышла замуж за наследника престола.

Свадьба принца Чарльза и Дианы Спенсер стала самой дорогой церемонией в истории Великобритании. Торжество состоялось в соборе Святого Павла в Лондоне 29 июля 1981 года. Венчанию предшествовали парадный проезд по улицам Лондона кареты с членами королевской семьи, марш полков содружества и Стеклянная карета, в которой прибыли Диана и ее отец.

Принц Чарльз был одет в парадную форму командира флота ее величества. На Диане было платье с 8-метровым шлейфом стоимостью 9 тыс. фунтов, разработанное молодыми английскими дизайнерами Элизабет и Дэвидом Эмануэль. Дизайн наряда хранился в строжайшей тайне от публики и прессы, платье доставили во дворец в запечатанном конверте. Голову будущей принцессы украшала семейная реликвия — тиара.

Брачный обряд Дианы и Чарльза был назван сказочной свадьбой и свадьбой века. По подсчетам специалистов, зрительская аудитория, следившая за трансляцией торжеств в прямом эфире по главным мировым телеканалам, составила более 750 млн человек.

После торжественного обеда в Букингемском дворце пара отправилась на королевском поезде в поместье Броадлендс, а затем вылетела в Гибралтар, откуда Чарльз и принцесса Диана начали круиз по Средиземному морю. По его окончании был дан еще один прием в Шотландии, где представители прессы получили разрешение сфотографировать новобрачных. Свадебные торжества обошлись налогоплательщикам почти в 3 млн фунтов стерлингов.

Развод

Уже во время медового месяца в отношениях пары наметилась трещина. Позднее в СМИ появились аудиозаписи, которые Диана отправляла писателю-биографу Эндрю Мортону. В них принцесса сообщала, что накануне бракосочетания пережила сильный приступ булимии, причиной которого стала ревность к Камилле Паркер-Боулз.

Диана так и не смогла справиться со своими чувствами в дальнейшем, что привело к двум попыткам суицида, одну из которых она предприняла, будучи беременной первым ребенком. Принцесса подчеркивала, что муж проявлял к ней равнодушие и называл ее депрессию манипуляцией. Личная жизнь венценосной семьи разрушалась на глазах.

По настоянию королевы Елизаветы после ряда скандальных событий состоялся развод Чарльза и Дианы. Это произошло спустя 4 года после фактического распада семьи. В браке с принцем родились двое сыновей, принц Уильям Уэльский и принц Гарри Уэльский.

Принцесса получила единоразовую выплату в размере 17 млн фунтов стерлингов ($ 22 млн) и ежегодное пополнение бюджета на 400 тыс. фунтов стерлингов ($ 519 тыс.) для оплаты жилья.

Слухи о романах принцессы

В 1995 году, по слухам, Диана встретила свою настоящую любовь. Навещая друга в больнице, принцесса случайно познакомилась с кардиохирургом Хаснатом Ханом. Чувства были взаимными. Однако постоянное внимание общественности, от которой пара даже сбежала на родину Хана, в Пакистан, и активное осуждение родителями Хана как его роли фактически любовника принцессы, так и свободолюбивых взглядов самой женщины, не дали роману развиться.

После развода Диана потеряла множество привилегий, которые дарила ей принадлежность к королевской семье. Прежде всего, она лишилась своего титула королевское высочество, превратившись в Диану, принцессу Уэльскую. Также с этого момента леди Ди обязана была содержать свою охрану, оплачивать все поездки.

В это время, как утверждают журналисты, Диана начала отношения с кинопродюсером, сыном египетского миллиардера Доди аль-Файедом. Их знакомство состоялось во время посещения принцессой Уэльской и ее сыновьями апартаментов отца Доди, Мохаммеда, на Лазурном берегу. Позднее пара уже самостоятельно совершила круиз по Средиземному морю.

Официально эта связь не была подтверждена никем из близких друзей принцессы, а в книге, написанной дворецким Дианы, факт их отношений прямо отрицается.

Стиль и внешность

Принцесса Диана родилась под знаком зодиака Рак. Таким людям свойственно наличие богатой фантазии, которую леди Ди с успехом применяла при создании своего образа. Она умело сочетала аристократичность и изысканность, добавляя к своему стилю нотку эпатажности.

В молодости гардероб Дианы Спенсер мало чем отличался от выбора соотечественниц. Тем не менее высокая девушка со стройной фигурой (рост Дианы — 178 см, вес — 56 кг) привлекала внимание своей красотой даже в скромных хлопковых и шерстяных нарядах.

Позднее, став супругой представителя королевской династии, путем проб и ошибок Диана выработала собственный стиль. Девушка испробовала все виды одежды, начиная от старомодных блуз и платьев в мелкий цветочек и заканчивая яркими нарядами, которые навсегда вошли в историю моды.

Это и белая блуза с воротником-лентой, в которой принцесса впервые появилась на обложке британского Vogue, и алый костюм, надетый Дианой для посещения центра больных СПИДом. Самым знаменитым на сегодня остается так называемое платье мести.

В черном мини-платье с открытым верхом и коротким шлейфом Диана дефилировала на вечеринке журнала Vanity Fair в 1994 году. Поговаривают, в этот день между супругами состоялся откровенный разговор, в котором принц Чарльз признался в связи с давней любовницей.

Из духов принцесса предпочитала любимый аромат Марии-Антуанетты, который использовался при создании парфюма Houbigant Quelques Fleurs L’Original.

Настоящим украшением внешности леди Ди всегда оставалась ее стрижка. Пышная копна светлых подстриженных слоями волос придавала облику принцессы беззащитный вид.

Благотворительность

Принцесса Диана пользовалась искренней любовью жителей Великобритании, ласково называвших ее леди Ди. Принцесса много занималась благотворительностью, жертвуя средства в различные фонды, была активисткой движения, добивавшегося запрета противопехотных мин, оказывала людям материальную и моральную помощь.

На попечении принцессы Дианы было 100 заведений, куда она регулярно наведывалась с гуманитарной помощью. Леди Ди поражала граждан Великобритании отсутствием брезгливости и искренним участием в решении проблем госпиталей, домов детей и престарелых.

Ее общественная деятельность простиралась за пределы Великобритании. В 1995 году Диана побывала в Москве, где посетила пациентов Тушинской детской больницы и учеников начальной общеобразовательной школы № 751.

Скандалы

Во время брака народной принцессе стало все труднее сдерживать ревность и беречь репутацию семьи, так как принц Чарльз не только не прервал внебрачную связь, но и открыто признавал ее. Ситуация осложнялась тем, что в лице королевы Елизаветы, принявшей в этом конфликте сторону сына, принцесса Диана получила влиятельного оппонента.

Усугубившая депрессия привела к тому, что принцессе было назначено лечение. Ее здоровьем занимались трое медиков. В ход шли таблетки, снотворное, гипноз и психологические техники. Помогало все это только отчасти.

В 1990 году деликатное положение семейной пары уже невозможно было скрывать, и ситуация получила огласку. В этот период принцесса Диана тоже призналась в своих связях с тренером по верховой езде и конюхом Джеймсом Хьюиттом.

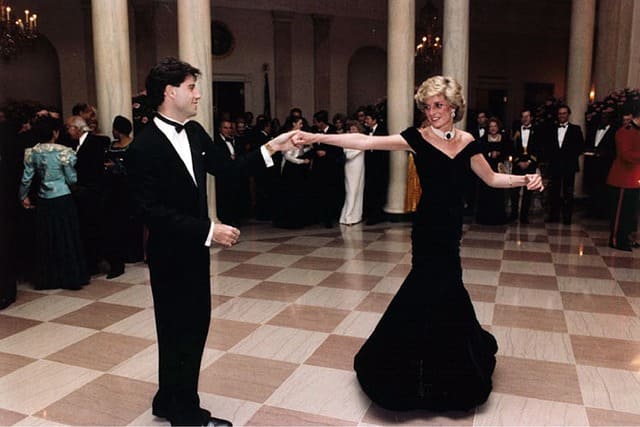

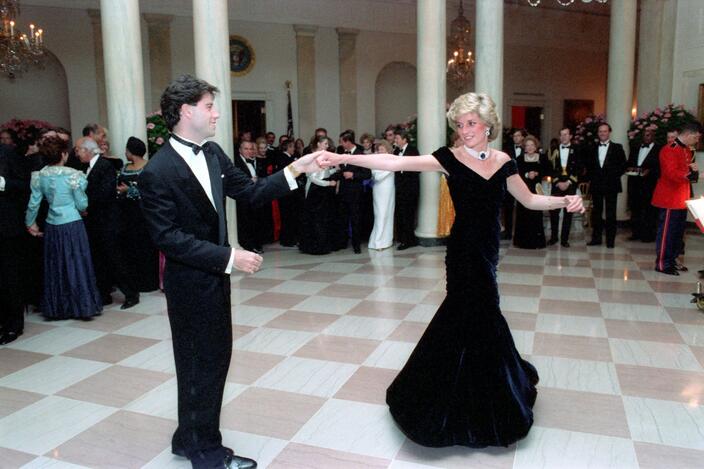

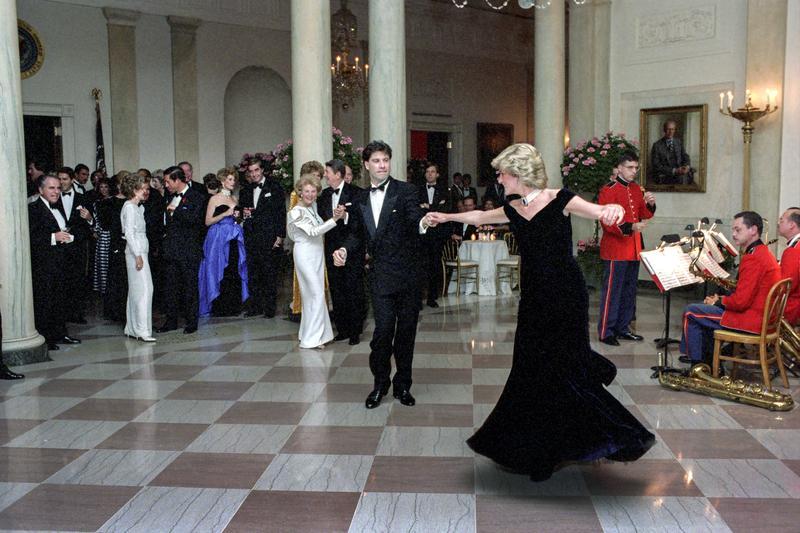

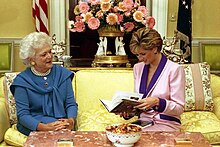

Внимание супруга Диана стремилась заполучить различными способами, начиная от банальных истерик и заканчивая эпатажными выходками и скандалами. По слухам, она, переодевшись в мужчину, посетила гей-бар в компании рок-звезды Фредди Меркьюри, о чем упоминает в своей книге британская комедийная актриса Клео Рокос. На встрече в Белом доме с Рейганами Диана исполнила танец вместе с актером Джоном Траволтой.

Окончательно точку во всей истории противостояния супругов поставило часовое интервью леди Ди, которое она дала телеведущему программы «Панорама» канала ВВС Мартину Бэширу. В беседе принцесса рассказала о всех проблемах, которые сопровождали ее брак, о депрессии, попытках самоубийства и даже о некоторых своих изменах, которые были вызваны поведением мужа. Передача вызвала эффект разорвавшейся бомбы.

В 2020 году для площадки Netflix началась работа над документальной лентой «Быть мной: Диана» (Being Me: Diana). Еще на этапе разработки сценария фильм вызвал возмущение у сыновей леди Ди. Проект познакомит зрителей с личной жизнью принцессы, а также приоткроет завесу тайны над многими неизвестными фактами.

Смерть

31 августа 1997 года Диана разбилась в автокатастрофе. Во время визита в Париж автомобиль, проезжая туннель под мостом Альма, столкнулся с бетонной опорой. В салоне, кроме принцессы, находились Доди аль-Файед, телохранитель Тревор Рис Джонс и водитель Анри Поль. Шофер и Доди аль-Файед скончались мгновенно на месте происшествия.

На момент обнаружения машины леди Ди была еще жива. Умирающая принцесса тихо произносила фразу «Боже мой», а на обращения доктора реагировала морганием. В госпитале ее пытались реанимировать, но сердце женщины от удара сильно сместилось в правую сторону, произошел разрыв легочной аорты. Полученные травмы оказались несовместимыми с жизнью.

Принцесса Диана умерла спустя 3,5 часа в больнице Сальпетриер. Телохранитель выжил, но получил тяжелые травмы головы, в результате которых ничего не помнил о моменте аварии. Позднее фото с места гибели леди Ди облетели все международные СМИ.

Смерть принцессы Дианы стала потрясением не только для жителей Великобритании, но и для всего мира. Во Франции в стихийный памятник Дианы скорбящие превратили парижскую копию факела статуи Свободы.

Расследование автокатастрофы

Среди причин автокатастрофы называют много факторов, начиная с версии, согласно которой машина принцессы пыталась оторваться от преследующего ее автомобиля с папарацци, и заканчивая заговором против Дианы.

Опубликованный через 10 лет отчет Скотланд-Ярда подтвердил факт обнаруженного в ходе расследования двукратного превышения скорости, допустимой для движения на участке дороги под мостом Альма, а также факт наличия алкоголя в крови водителя, превышавшего допустимую норму в 3 раза.

Многие последователи теории заговора причиной смерти принцессы Дианы называли ее убийство спецслужбами Великобритании. О том, что женщина была убита, заявлял впоследствии и ее телохранитель Алан Макгрегор. По его словам, в тот день он отметил множество нарушений правил безопасности. На конспирологической версии настаивал и Мохаммед аль-Файед, но его иск был отклонен французской стороной.

Похороны

Похороны принцессы состоялись 6 сентября. Проводить леди Ди пришли более миллиона человек. Люди стояли живым коридором от Сент-Джеймсского дворца до Вестминстерского аббатства и забрасывали процессию цветами, выкрикивая признания в любви.

Вслед за гробом шли родной брат Дианы граф Спенсер, ее сыновья и принцы Чарльз и Филипп. Впоследствии это получасовое шествие Чарльз Спенсер назвал самыми тяжелыми минутами своей жизни.

Могила леди Ди находится на уединенном острове в поместье Элторп (семейное поместье Спенсеров) в Нортгемптоншире.

После смерти Дианы было обнародовано ее завещание, согласно которому драгоценности принцессы отходили будущим невестам ее сыновей. Так, Кейт Миддлтон получила в дар от принца Уильяма знаменитое кольцо с сапфирами, а невеста принца Гарри Меган Маркл — кольцо с аквамарином и свадебное платье принцессы Уэльской.

Память

Народная принцесса после своей гибели оставила глубокий след в сердцах многих людей, в том числе и звезд шоу-бизнеса. Cэр Элтон Джон посвятил ее памяти песню «Свеча на ветру», а Майкл Джексон — композицию Privacy.

Через 10 лет после гибели был снят фильм о последних часах жизни принцессы. В год ее 50-летия вышла лента «Принцесса Диана. Последний день в Париже». Кроме этого, ей посвятили песни Леди Гага, Depeche mode и «Аквариум».

В честь принцессы Дианы в 2017 году у стен Кенсингтонского дворца в Лондоне был разбит Белый сад. Это большая цветочная композиция, состоящая из 12 тысяч белых цветов — тюльпанов, нарциссов и гиацинтов, которые высажены по периметру прямоугольного пруда.

В год 20-летия со дня гибели Дианы в резиденции принца Уильяма и Кейт Миддлтон в Кенсингтонском дворце был открыт Музей вещей леди Ди.

В 2019 году в сериале «Корона» роль принцессы исполнила Эмма Коррин. Фильм посвящен правлению королевы Великобритании Елизаветы II. Другой актрисой, удостоившейся чести воплотить образ легенды на экране, стала Кристен Стюарт. Лента Пабло Ларраина «Спенсер» рассказала зрителю о непростом периоде в жизни королевской семьи, когда Леди Ди решилась на развод. Супруга Чарльза сыграл Джек Фартинг.

Впрочем, не только актрисы старались в точности скопировать уникальный стиль Дианы. В 2022 году в СМИ заговорили о блогере Роуз ван Рейн, которая поразила аудиторию своей схожестью со знаменитостью. Девушка выставляла стилизованные фото, на которых можно было увидеть легендарную прическу Леди Ди.

Награды

- Королевский семейный орден королевы Елизаветы II

- Большой крест ордена Короны

- Орден Добродетельности специального класса

Интересные факты

- По материнской линии у принцессы Дианы есть армянские корни. Прапрабабушкой королевской особы была Элиза Кевар (Кеворкян), армянка из индийского города Гуджарата. В свое время она вышла замуж за шотландского купца и переехала в Великобританию.

- В честь принцессы названы такие растения, как клематис и гортензия. Они были введены в агротехнику британскими питомниками в середине 80-х годов.

- Часть приверженцев конспирологии утверждает, что до рождения принца Уильяма на свет появилась родная дочь леди Ди и принца Чарльза Сара. Во время планового осмотра гинекологом перед помолвкой у Дианы Спенсер якобы отобрали яйцеклетки, после чего доктор оплодотворил их клетками будущего мужа. Из полученных эмбрионов был сохранен один и тайно подсажен жене медика.

Народная принцесса, «английская роза» – леди Диану называли по-разному, но одно всегда было неизменным: ее харизма притягивала к ней, как магнитом, любовь миллионов людей во всем мире. В недавнем рейтинге 100 величайших британцев она заняла третье место, обогнав 11 особ королевских кровей. И в этом нет ничего удивительного: в многогранном образе Дианы каждый находил что-то свое, каждый видел частичку себя. Принцесса с простыми и понятными чувствами и эмоциями – такой она осталась в памяти и сегодня, спустя 25 лет после чудовищной аварии в центре Парижа. Об истории принцессы Дианы – в материале РЕН ТВ.

Аристократическое происхождение

Принцесса Уэльская, леди Диана Френсис Спенсер родилась 1 июля 1961 года в городе Сандрингем, в графстве Норфолк, в известной аристократической семье. Ее отец, Эдвард Джон Спенсер – виконт Элторп, представитель семейства Спенсер-Черчиллей, славу которого составил Уинстон Черчилль, герцог Мальборо. Мать Дианы Фрэнсис Рут Рош была младшей дочерью Эдмунда Мориса Берка Роше, 4-го барона Фермоя.

Говоря о чертах характера представителей семьи Спенсер, их биограф лестно отмечал: «В этой древней и родовитой крови счастливо сочетались гордость и честь, милосердие и достоинство, сознание долга и потребность идти собственною тропою. Всегда и всюду. Иметь в груди маленькое сердце и дух короля, переплетая в нем накрепко, неразрывно женственность и львиную отвагу, мудрость и хладнокровие».

Когда Диане было 6 лет, родители развелись. Мать девочки переехала в Лондон, оставив детей в Норфолке. Вспоминая то время, Диана говорила, что было тяжело: родители были заняты сведением счетов, мать часто плакала, а отец ничего даже не пытался объяснить детям.

Фото: © Global Look Press/imago stock&people

В 12 лет Диану приняли в привилегированную школу для девочек в графстве Кент. Учеба давалась ей нелегко, однако преподаватели отмечали безусловный талант Дианы к музыке и танцам. Она очень хотела стать балериной, но этому помешал ее высокий рост. На совершеннолетие отец подарил ей квартиру в Лондоне, а сама Диана устроилась на работу в детском саду.

Знакомство Дианы и принца Чарльза

Во второй половине 1970-х Диана познакомилась с принцем Чарльзом. Поначалу будущий наследник английского престола ухаживал за старшей сестрой Дианы Сарой. Однако в ноябре 1979 года Диану пригласили на королевскую охоту, где милая улыбчивая девушка привлекла внимание принца.

Чарльз был самым завидным женихом Великобритании и имел репутацию ловеласа, на счету которого было приличное количество романов и любовных интрижек. Разумеется, молодая Диана Спенсер идеально подходила на роль жены наследника британской короны не только благодаря своему происхождению, но и во многом за счет образа скромной, хорошо воспитанной и привлекательной девушки.

Свадьба Дианы и Чарльза

29 июля 1981 года 20-летняя Диана вышла замуж за 32-летнего принца Уэльского, получив титул принцессы. Бракосочетание должно было стать «свадьбой века», приготовления к которой начались задолго до назначенной даты. Кульминацией истории о Золушке стала шикарная церемония в Соборе святого Павла в Лондоне, телетрансляцию которой посмотрели 750 миллионов человек.

Фото: © Global Look Press via ZUMA Press/Ron Bull

Пышное свадебное платье Дианы из шелковой тафты с объемными рукавами и длинным, почти четырехметровым, шлейфом, украшенное ручной вышивкой, жемчугом и стразами, стало одним из самых знаменитых нарядов в истории.

Сейчас уже известно, что за считанные дни до торжества в правильности своего выбора сомневались оба супруга, но решения никто менять не стал. По словам Дианы, идя к алтарю, она чувствовала себя ягненком, которого ведут на убой. После церемонии молодожены вернулись во дворец и разошлись по отдельным комнатам.

Интересно, что выходя замуж, Диана поклялась Чарльзу «любить, поддерживать, уважать и дорожить». Но не поклялась «повиноваться мужу во всем». Она стала первой королевской невестой, которая убрала эту фразу из брачного обета.

Как Диана стала народной принцессой

Диану никто не учил тому, как должна вести себя принцесса Уэльская. Но она почти сразу стала популярнее своего мужа. Люди полюбили ее не только за красоту и обаяние, но и за непосредственность: она была живой. Она станцевала с Джоном Траволтой на приеме в Белом доме. Вместе с танцором Уэйном Слипом выступила на сцене Королевского театра. Номер принцессы понравился всем, кроме ее мужа. Зрители вызывали Диану и Уэйна на бис восемь раз. Чарльз тогда сказал супруге, что она выглядела неприлично.

Фото: © ТАСС/Pete Souza/CNP via ZUMA Wire

Сложно сказать, что сильнее злило принца – то, что пресса называет его жену «непозволительно фривольной», или то, что объективы всех камер направлены исключительно на нее. Диана и сама понимала, как сложно с этим было справиться ее мужу.

Рождение детей прибавило Диане еще больше популярности, и в первую очередь потому, что она безусловно и безоговорочно воспринималась британцами как своя. Принцесса родила Уильяма и Гарри в госпитале, а не во дворце, сама возила их на теннис, организовывала с ними вылазки в город, где совершенно запросто, без каких-либо церемоний ходила в зоопарк или в парк развлечений.

Диана часто устраивала неформальные встречи с журналистами, на которые брала старшего сына. Стремясь привить детям понимание важности борьбы за права человека, Диана водила сыновей на встречи с пациентами курируемых ею лечебных заведений и посещала ночлежки для бездомных.

Благотворительная деятельность принцессы Дианы

К концу 1980-х публичный образ принцессы Дианы стал меняться в сторону консервативности и традиционности, что совпало с ее занятиями благотворительностью и миротворческой деятельностью. Из легко смущающейся принцессы – репортеры даже называли ее «робкая Ди» – Диана превратилась в яркого общественного деятеля. Она, не стесняясь, вступала в диалог с представителями разных религиозных конфессий, национальностей, социальных слоев и политических партий.

Фото: © Global Look Press/e58/ZUMApress.com

Леди Ди курировала более 100 благотворительных организаций. А началось все с борьбы с ВИЧ и СПИДом. В апреле 1987 года в британской больнице открылось первое в стране отделение для пациентов с этой болезнью, и сотрудники клиники попросили кого-нибудь из королевской семьи присутствовать на церемонии открытия. Этим «кем-то» стала Диана.

ВИЧ до сих пор многие считают «болезнью наркоманов и проституток». А в 80-е годы большинство были уверены, что заразиться этим вирусом можно даже от прикосновения. Диана, придя в больницу, сняла перчатки и пожала руки всем пациентам отделения. Сегодня это кажется нормальным. Тогда это было подвигом и сенсацией.

В 1992 году она побывала в хосписе матери Терезы в Калькутте. А три года спустя – в Москве, в Тушинской детской больнице. Диана плохо произносила речи, но умела утешить прикосновением и взглядом. Те, кто ее знал, говорили: своей работой она хотела заслужить одобрение и любовь, которых ей так не хватало в королевской семье.

«Я думаю, что сегодня у мира есть одна большая болезнь – люди чувствуют, что страдают от большого недостатка любви. И я знаю, что если я могу дать любовь – пусть лишь на минуту, лишь на полчаса, лишь на день или на месяц – я буду счастлива сделать это», – сказала леди Диана в интервью в 1995 году.

Фото: © Global Look Press via ZUMA Press/Dinendra Haria

Последняя миссия принцессы Уэльской

Последней миссией Дианы стала программа по предотвращению гибели людей от противопехотных мин. Принцесса объездила много стран, от Анголы до Боснии, чтобы увидеть катастрофические последствия применения этого оружия.

Она не только разговаривала с людьми, потерявшими из-за мин ноги и руки, но и сама прошла по деактивированному минному полю.

«У меня душа ушла в пятки, челюсть свела судорога. Я еще никогда не делала шаги с такой осторожностью. Я отлично понимала, что малейшая ошибка, и твой следующий шаг может оказаться последним», – вспоминала принцесса Уэльская.

Один из фоторепортеров, не успевший снять ее путь на пленку, попросил Диану пройти по полю еще раз. Никто не ожидал, что она согласится. Но леди Ди повернулась и прошла по полю вновь. Ей было важно, чтобы эти снимки были сделаны и их увидели во всем мире.

Фото: © ТАСС/EPA/ANTONIO COTRIM

Леди Ди – икона стиля

С самого первого появления на публике Диана, формируя свой образ, делала ставку на классику, элегантность и выбирала только те вещи, которые безупречно сидели на ее ухоженной фигуре. Как и полагается жене наследника престола, Диана носила костюмы от британских дизайнеров. Но она нарушала много других правил королевской моды. Так она отказалась от перчаток и шляп, чем очень удивила придворных стилистов. Леди Ди не любила сложные прически, она не только коротко стриглась, но и делала жесткие укладки, как ни уговаривали ее те же стилисты отказаться от лака для волос. Кроме этого, Диана в браке не носила каблуки: она и так была чуть выше мужа.

Леди Ди всегда позволяла себе чуть больше, чем дозволено принцессе: смелые вырезы на спине, открытые плечи. Но самым откровенным стало платье, надетое ею в 1994 году, после того, как Чарльз официально объявил о своей связи с Камиллой Паркер Боулз, замужней женщиной, с которой принц встречался еще до свадьбы. Из черного бархата, не доходящее до колен, с открытыми плечами и глубоким декольте – его назвали «платьем мести». Таблоиды опубликовали фото леди Ди с подписью: «Красотка, от которой отказался принц Чарльз».

После официального развода Диана стала еще смелее. Она всегда выбирала наряды и марки сама, предпочитая Versace, Christian Lacroix, Ungaro и Chanel. Два платья тех лет вошли в историю моды – голубое асимметричное от Versace и платье-комбинация от Dior. Тогда, в 1996-м, оно выглядело по-настоящему дерзко.

Фото: © ТАСС/АР, Global Look Press

Развод принцессы Дианы и принца Чарльза

К началу 1990-х брак Дианы и Чарльза полностью изжил себя. Разлад между супругами произошел из-за многолетних интимных отношений Чарльза с Камиллой Паркер Боулз. Сама же Диана некоторое время поддерживала связь с Джеймсом Хьюиттом – своим инструктором по верховой езде.

В 1993 году премьер-министр Великобритании Джон Мейджор объявил о решении принца и принцессы Уэльских расстаться и вести раздельную жизнь. О разводе речь еще не шла, но в следующем году Чарльз признался телеведущему Джонатану Димблби, что неверен Диане. Он подтвердил свои отношения с Камиллой, заявив, что их роман возобновился в 1986-м. 28 августа 1996 года по инициативе королевы Елизаветы II был оформлен бракоразводный процесс, спровоцировавший серию откровенных интервью, в которых Диана в красках рассказывала о невыносимой жизни во дворце.

Гибель принцессы Дианы

В новую свободную жизнь Диана вступала с энтузиазмом. Закрутив роман с сыном египетского миллиардера Мохаммеда аль-Файеда, Доди, она почувствовала себя окрыленной, но судьба распорядилась иначе. 31 августа 1997 года Диана и Доди погибли в автокатастрофе. Их автомобиль врезался в одну из опор подземного тоннеля под мостом Альма в самом центре Парижа.

Фото: © REUTERS/Stringer

Новость, пришедшая из Парижа, повергла нацию в шок. Но в еще большем шоке британцы оказались от действий, а вернее, от бездействия королевского двора. Елизавета II молчала несколько дней. И все эти дни у ворот Букингемского дворца росла гора из цветов, свечей и трогательных записок. Диану любили как члена семьи, слезы скорбящих были абсолютно искренними. И таким же искренним было недоумение. «Они ведут себя так, как будто им все равно», – говорили люди. И добавляли: «Это типичная реакция королевской семьи – придерживаться протокола и плевать на человеческие чувства».

«Сначала народ возмущался тем, что над дворцом не приспущен флаг. Потом начались вопросы: где королевская семья? Почему они не приезжают?» – вспоминала руководитель службы взаимодействия с госструктурами в 1997–2001 годах Энжи Хантер.

Заголовки газет в первые дни после трагедии буквально кричали: «Покажите, что вам не все равно!», «Приспустите флаг», «Ваш народ страдает. Поговорите с нами, Ваше Величество!». На пятый день было решено, что королева и принц Филипп вернутся в Лондон из замка Балморал на сутки раньше, чем планировалось.

«В четверг я поговорил с королевой. В самом начале разговора я понял, что мы мыслим одинаково. Она понимала, что сейчас очень важно показать народу, что она испытывает те же чувства, что и он. Так что мне не пришлось ее убеждать. Она уже была готова», – вспоминал позднее Тони Блэр, премьер-министр Великобритании в 1997–2007 годах.

Фото: © REUTERS/Jasper Juinen

Принцессу Диану, королеву людских сердец, похоронили 6 августа. Флаг над Букингемским дворцом в этот день приспустили впервые в истории.

Репортеры однажды спросили принца Уильяма, старшего сына Дианы, что для него значит тот роковой день, 31 августа 1997 года. Уильям ответил:

«Когда в 15 лет с тобой случается такое потрясение – смерть матери, это или сломает тебя, или закалит. Я не позволил случившемуся меня сломать. Я сказал себе, что должен стать сильнее. Я хотел стать таким, чтобы мама мною гордилась. Я не хотел, чтобы она волновалась за нас или чтобы все думали, что ее смерть сломала Уильяма или Гарри. Я буду гордиться собой, если смогу хотя бы на одну тысячную долю стать таким же, как она».

Все о монархиях

Жизнь и смерть Леди Ди — все, что вы хотели знать о принцессе Уэльской

В новой еженедельной колонке HELLO.RU о монархах рассказываем, почему Леди Ди не стала балериной и как спасалась от папарацци.

Фото:

Getty Images, www.hrp.org.uk, royal.uk

Текст:

Ариадна Рокоссовская

01.07.2022 / 14:00

Еще больше новостей в нашем Telegram-канале, группе ВКонтакте и канале Яндекс.Дзен

______________________________

1 июля 1961 года в Сандрингеме родилась Диана Френсис Спенсер. Ей не суждено было стать королевой Британии, но она стала «королевой людских сердец». Несмотря на то, что ее нет уже почти 25 лет, принцесса Диана по сей день остается самым популярным членом британской королевской семьи. Ее жизнь проходила на глазах миллионов людей, но есть факты, которые известны далеко не всем.

- Бабушка Дианы по материнской линии, Рут Рош, баронесса Фермой, была фрейлиной королевы-матери Елизаветы Боуз-Лайон. Кроме того, она была близким другом королевы и организовывала для нее различные мероприятия.

- Диана родилась в Парк-Хаусе, то есть в парковом доме, на территории Сандрингемского дворца в Норфолке, которая является частным владением королевской семьи. Там же в 1936 году родилась мать принцессы Дианы Фрэнсис. Сейчас в этом здании находится отель.

- У Дианы было две сестры: Сара (ныне леди Сара МакКоркодейл) и Джейн (ныне леди Джейн Феллоуз), а также младший брат Чарльз (ныне граф Спенсер). Но был и еще один брат, Джон Спенсер, который умер через несколько часов после своего рождения в январе 1960 года. Это случилось за полтора года до рождения Дианы.

- В детстве Диана занималась балетом и мечтала о сцене, но в определенный момент стало понятно, что она выросла слишком высокой для балерины.

- Она стала леди Дианой Спенсер в 1975 году, когда ее отец унаследовал графский титул деда. Ее называли леди Ди даже после того, как она вышла замуж за принца Чарльза и стала принцессой.

- До того, как Диана встретила принца Чарльза, она перебивалась случайными заработками, в том числе, работала няней. Ей платили 5 долларов в час за игры с детьми, стирку и уборку. Она также работала воспитателем детского сада на полставки в лондонском районе Пимлико. Таким образом, после помолвки с принцем Уэльским Диана стала первой невестой наследника престола, имевшей до этого оплачиваемую работу.

- Своего будущего мужа Диана встретила, благодаря тому, что в конце 70-х он встречался с ее старшей сестрой Сарой. Позже это дало Саре повод говорить: «Я их познакомила. Я – Купидон». Сестры были очень близки, и Диана говорила о ней: «Это единственный человек, которому я могу доверять».

- Диана и Чарльз состояли в, пусть далеком, но родстве. Они приходились друг другу 16-юродными братом и сестрой. И оба — потомки короля Генриха VII из династии Тюдоров.

- До своей помолвки в 1981 году Диана и принц Уэльский встречались около 13 раз. Но отец Чарльза принц Филипп посоветовал ему «поступить правильно». И хотя королевские обручальные кольца обычно изготавливают на заказ, Диана выбрала себе кольцо из каталога коллекции ювелирной фирмы Garrard. Украшение из 18-каратного золота, с 14-ю бриллиантами, расположенными вокруг крупного цейлонского сапфира овальной формы, теперь принадлежит ее невестке Кейт Миддлтон. Принц Уильям подарил его ей, когда делал предложение руки и сердца.

- Свадебное платье леди Ди било рекорды сразу по нескольким пунктам: оно было украшено более чем десятью тысячами жемчужин, а длина шлейфа составила 25 футов (7,62 м), и это — один из самых длинных королевских шлейфов, которые когда-либо видел мир.

- Диана нарушила традицию обещать у алтаря «подчиняться» своему мужу. Вместо этого она пообещала «любить его, поддерживать, почитать и оберегать в болезни и здравии». Впоследствии Кейт Миддлтон и Меган Маркл, выходя замуж за ее сыновей — принцев Уильяма и Гарри, последовали ее примеру.

- По многовековой традиции наследники британского престола всегда появлялись на свет в королевском дворце. Но Диана решила, что будет рожать своих детей в частном отделении государственного госпиталя Святой Марии. Так принц Уильям стал первым будущим монархом, который родился в больнице, как простые смертные. И в своем подходе к воспитанию леди Ди не походила на других королевских матерей. Насколько можно судить, она была первой кормящей матерью наследника престола. И в целом Диана была полна решимости воспитать Уильяма и Гарри настолько «нормально», насколько это было возможно в ее ситуации. Руководитель персонала принцессы Дианы Патрик Джефсон вспоминал: «Она позаботилась о том, чтобы они попробовали такие вещи, как поход в кино, стояние в очереди в Макдональдсе, посещение парков развлечений, чтобы им было о чем говорить со сверстниками». Она отдала детей в обычную школу, потому что хотела социализировать их и это, по мнению многих экспертов в области монархии, ее главное наследство сыновьям.

- Леди Ди всегда благодарила тех, кто делал ей подарки. По данным СМИ, она написала благодарственные письма тысячам людей, которые прислали игрушки новорожденному принцу Уильяму. В последние годы некоторые из ее написанных от руки открыток были проданы с аукциона по цене от 2000 до 20000 долларов, в зависимости от их содержания и уникальности.

- У принцессы Дианы было много звездных друзей, в том числе Элтон Джон, Джордж Майкл, Тильда Суинтон и Лайза Минелли. Она также дружила с актерами Куртом Расселом и Голди Хоун и вместе с Уильямом и Гарри провела десять дней на их ранчо в Колорадо, спасаясь от папарацци.

- Кстати о папарацци. Как «самая фотографируемая женщина в мире», она знала, как нужно позировать перед камерами и, что еще важнее, как не нужно. На любом официальном мероприятии у нее в руке был небольшой атласный клатч, который сочетался с ее платьем. В эти крошечные сумочки помещалась только губная помада, но она носила их с другой целью. Поскольку камеры следовали за Дианой повсюду, ей приходилось следить за тем, что может попасть в кадр, например, когда она выходит из автомобиля. Сумочка была нужна для того, чтобы прикрывать декольте. На большинстве фотографий, снятых в тот момент, когда Диана выходит из машины, видно, что она использует клатч в качестве «щита». По словам дизайнера Анны Хиндмарч, которая часто работала с Дианой, принцесса так их и называла: «сумочки для декольте».

- После развода с принцем Чарльзом в 1996 году Диану лишили титула «ее королевское высочество» по настоянию бывшего мужа. Согласно условиям их развода, «она должна отказаться от права стать королевой Англии и называться ее королевским кысочеством», — сообщала газета New York Times. По информации этого издания «королева Елизавета II была готова позволить Диане сохранить почетный титул, но принц Чарльз был непреклонен».

- После того, как развод Дианы и принца Чарльза стал достоянием общественности и, прежде всего, таблоидов, она решила записать на пленку свою версию истории. Ее друг доставил эту запись британскому журналисту Эндрю Мортону, который много лет писал о королевской семье. Принцесса говорила о том, что несчастлива, что чувствует себя преданной, о попытках самоубийства и о двух обстоятельствах, о которых я до этого никогда не слышал: о расстройстве пищевого поведения, называемом булимией, и о женщине по имени Камилла», — рассказывал Мортон, в 1992 году выпустивший книгу «Диана. Ее истинная история». Эта книга стала бестселлером и навсегда изменила представление о жизни принцессы.

- После трагической смерти принцессы Дианы в автокатастрофе в 1997 году ее похоронили в поместье Элторп в Нортгемптоне. Это поместье принадлежит семье Спенсеров уже более 500 лет. Место захоронения принцессы Дианы — небольшой остров с часовней на Овальном озере – был назван ее именем.

Читайте также

Кто это? Биография принцессы Дианы Уэльской столь же яркая, как и она сама. Нежная и изящная воспитательница смогла не только покорить наследника британской короны, но и стать королевой людских сердец.

Как ей удалось? Чтобы понять, почему принцесса Диана навеки вошла в историю любимицей всего мира, нужно обратиться к ее биографии с самого детства и проследить до конца ее дней.

В статье мы расскажем:

- Биография принцессы Дианы Уэльской периода детства и юности

- Знакомство Дианы с принцем Чарльзом

- Свадьба Дианы и Чарльза

- Почему леди Диану называли королевой людских сердец

- Развод Чарльза и Дианы Уэльской

- Гибель принцессы Дианы

- Народная память о леди Ди

Биография принцессы Дианы Уэльской периода детства и юности

1 июля 1961 года на свет появилась девочка Диана Френсис Спенсер. Она стала третьей по счету дочкой в семье. Ее отец Джон Спенсер был очень расстроен, так как ждал сына, которому хотел передать свой титул и поместья. При этом Диану все очень любили – как родные, так и обслуживающий персонал – и баловали, потому что она была самой младшей.

Отец Дианы был виконтом Элторпа. Это дворянский титул, который занимает положение между бароном и графом. Джон Спенсер являлся представителем рода Спенсер. К одному из его ответвлений относился и Уинстон Черчилль. Спенсеры много веков жили в поместье в центре Лондона, которое называлось Спенсер-хаус.

Семейная жизнь родителей Дианы была недолгой. Графиня Спенсер изменила своему мужу и уехала, забрав с собой младших детей. Развод был очень тяжелым и скандальным. Собственная мать графини давала показания против дочери.

Для Дианы с раннего детства слово «развод» ассоциировалось с большими переживаниями. Позже отец будущей принцессы женился заново, но теплых отношений с мачехой у нее не сложилось. Поэтому в детстве Диане приходилось жить на два дома – в мамином особняке в Шотландии и папином в Англии. Но нигде она не чувствовала себя комфортно.

Диана не была отличницей и не обладала никакими феноменальными способностями. Учителя говорили, что она не глупая, но и не сверхспособная. На самом деле ее равнодушие к учебе объяснялось тем, что девочка была увлечена балетом. Однако из-за высокого роста ей не удалось посвятить свою жизнь этому искусству. Поэтому Диана решила попробовать себя в общественной деятельности. Если она чем-то начинала заниматься, то полностью погружалась в процесс и легко могла вести за собой других.

Знакомство Дианы с принцем Чарльзом

Согласно биографии принцессы леди Дианы, первая встреча будущих супругов состоялась в 1977 году в Элторпе. Но тогда они особо не обратили внимание друг на друга. Чарльзу больше нравилась старшая сестра Дианы Сара Спенсер, он даже хотел на ней жениться.

Дело близилось к свадьбе, но как-то в интервью Сара неосмотрительно высказалась, за что потом и поплатилась. Она была влюблена и сказала, что для нее совсем не имеет значения род деятельности будущего мужа, он может быть как принцем, так и мусорщиком, главное, чтобы они любили друг друга. Королевская семья была раздосадована таким заявлением, и вскоре девушка получила от Чарльза прощальное послание.

Бесплатно только до 14 января

ТОП-3 обязательных

материала, чтобы

быть счастливой

в 2023 году

Аника Снаговская

ТОП-5 по РФ среди авторов и ведущих женских тренингов

Эти методики проверены на 8500 моих учениц, 98% отмечают позитивные изменения в своей жизни.

-

Как выйти из отношений быстро и без боли

3 главных правила правильного окончания любых отношений -

5 правил счастливой и гармоничной жизни для каждой женщины

Практики, которые раскроют твою женственность и сексуальность -

Как полюбить себя: 7 простых шагов

Действенная аффирмация для

вхождения состояния любви к себе

Скачать их вы можете совершенно бесплатно:

Скачать материалы бесплатно

Уже скачали

В то время Диана находилась на обучении в Швейцарии, которое оказалось очень непродолжительным из-за того, что она сильно скучала по дому. После того, как учеба закончилась, она работала няней, а после воспитателем в детском саду, который находился в Найтсбридже (дорогой район Лондона).

Сначала в Лондоне она жила вместе с мамой. Когда ей исполнилось 18, переехала в свою квартиру, подаренную родителями. Также Диана работала в Young England School, в студии, где подростки занимались хореографией (давала уроки танцев), и в фирме, которая организовывала праздничные мероприятия.

В 19-летнем возрасте Диана попала в общую компанию с принцем Чарльзом. Его родители были очень обеспокоены жизнью сына, который до сих пор не определился с избранницей.

Особенно Елизавета II переживала за то, что сын встречается с замужней девушкой Камиллой Паркер-Боулз. Он открыто демонстрировал окружающим свой роман. Именно поэтому королевская семья быстро согласилась на брак между принцем Чарльзом и Дианой Спенсер.

Только до 11.01

10 простых способов сделать свою жизнь лучше

Павел Андреев

Основатель крупнейшей онлайн-школы астрологии «Лаборатория жизни»

Астрология — это наука, которая раскрывает нашу связь с небесными телами, позволяет заглянуть в будущее и принимать верные решения.

Мы подготовили документы, которые помогут разобраться в азах астрологии. Обладая данными знаниями, вы сможете улучшить не только свою жизнь, но и жизни других людей!

Скачивайте и используйте уже сегодня:

Каким будет 2023 год для знаков зодиака

Что ждет каждый знак зодиака в новом году, и как себя вести

5 шагов для составления индивидуального плана развития

Вы научитесь планировать и достигать то, чего хотите

Ваше кармическое предназначение по дате рождения

Какой жизненный путь вас ожидает в зависимости от даты рождения

Скачать бесплатно

Уже скачали

Сначала принц провел время с Дианой на яхте, которая принадлежала их семье, а позже пригласил девушку на знакомство с членами семьи в замок Балморал. Предложение руки и сердца было сделано в замке Виндзор, но некоторое время королевская семья держала это событие в тайне. Официально об этом было объявлено только 24 февраля 1981 года. Чарльз подарил Диане обручальное кольцо с крупным сапфиром, который был окружен 14 бриллиантами.

Свадьба Дианы и Чарльза

За предшествующие 300 лет Диана оказалась первой англичанкой по происхождению, которая стала женой наследного принца.

Свадебная церемония и само торжество Чарльза и Дианы были самыми дорогими в истории Великобритании. Бракосочетание состоялось 29 июля 1981 года в соборе Святого Павла. Сначала королевская семья парадно проехала в карете по улицам Лондона, затем прошел марш полков содружества, завершалось шествие стеклянной каретой, где сидели Диана и ее отец.

Принц Чарльз надел парадный мундир командирского флота Королевы. Платье Дианы имело 8-метровый шлейф и обошлось в 9 тысяч фунтов. Его разработкой занимались молодые дизайнеры английского происхождения Элизабет и Дэвид Эмануэль. До свадьбы о наряде невесты было совершенно ничего не известно. Его привезли во дворец запакованным настолько тщательно, чтобы никто не смог ничего разглядеть. На голове будущей принцессы была драгоценность, передающаяся по наследству, – тиара.

Церемония проходила как в сказке. Фото принцессы Дианы в платье с огромным шлейфом было опубликовано во всех местных изданиях. Ее стеклянная карета была окружена сопровождением из офицеров королевской конной гвардии. Из брачных клятв убрали фразу «повиноваться».

На тот момент это взбудоражило общественность, ведь даже сама королева Англии обещала во всем слушаться мужа. Специалисты подсчитали, что на тот момент за трансляцией свадьбы по всему миру следили более 750 миллионов зрителей.

Торжественный обед прошел в Букингемском дворце. После молодожены отправились на поезде королевской семьи в поместье Броадлендс, а затем улетели на Гибралтар. Именно оттуда началось их романтическое путешествие по Средиземному морю. Как только пара вернулась, был дан праздничный обед в Шотландии. На нем разрешили присутствовать прессе и делать фотографии. Налогоплательщики отдали за эти торжества порядка 3 миллионов фунтов стерлингов.

Уже через год у пары родился первенец – наследник принц Уильям. Через пару лет на свет появился второй ребенок – принц Гарри. Позже Диана говорила, что этот период был самым лучшим в их семейной жизни. Все свободное время они проводили в круг семьи и детей. «Семья – самое важное», — рассуждала счастливая Диана в интервью.

За это время стало понятно, что леди Ди особа очень решительная. Несмотря на то, что в королевской семье было принято по-другому, она сама дала имена своим сыновьям, наняла няню и старалась, чтобы представители королевской семьи как можно меньше вмешивались в ее жизнь. Она была прекрасной мамой и обязательно продумывала свой день так, чтобы встретить детей из школы. При том, что дел у нее всегда было очень много.

Почему леди Диану называли королевой людских сердец

Даже если прочитать краткую версию биографии принцессы Дианы, станет понятно, что она очень сильно повлияла на королевскую семью. Ее даже называли королевой людских сердец, потому что она заметно выделялась на фоне британской знати. В роли принцессы появились новшества, которые ранее не были свойственны для монархии.

Принцесса Уэльская по договоренности должна была посещать различные благотворительные мероприятия. Благотворительность – это традиционное занятие членов королевской семьи. Принцы и принцессы разных поколений брали под патронаж больницы, хосписы, приюты, детские дома и некоммерческие организации. Но Диана была буквально поглощена этим занятием.

Она добавила в список посещений больницы, где лежали больные СПИДом, и лепрозорий. Больше всего времени принцесса занималась проблемами молодежи и детей, но при этом не забывала и про дома престарелых, центры реабилитации наркоманов и алкоголиков. Леди Ди также выступала против применения противопехотных мин в странах Африки.

Она вела общественную деятельность далеко за пределами Великобритании. В 1995 году Диана даже побывала с визитом в Москве. Посетила там Тушинскую детскую больницу и начальную общеобразовательную школу № 751.

Принцесса Диана не скупилась на помощь и тратила как свои средства, так и наследие королевской семьи, а в качестве спонсоров подключала известных друзей. Своим обаянием покоряла всех вокруг. Ее очень любили не только соотечественники, но и люди за рубежом.

Она утверждала: «Самое тяжелое заболевание мира – это то, что в нем мало любви». При этом у самой принцессы Ди было наследственное заболевание – булимия (пищевое расстройство). Она испытывала много стрессов и переживаний и поэтому сдерживать себя ей удавалось с большим трудом.

Знак зодиака Дианы – Рак. Как правило, такие люди имеют очень развитую фантазию. Принцесса нашла ей прекрасное применение, создавая свои неповторимые образы. В них сочетались сдержанность, утонченность и нотки эпатажности.

Будучи супругой принца, путем проб и ошибок в итоге она нашла свой уникальный стиль. Девушка носила совершенно разную одежду: винтажные блузки, платья в цветочек и яркие наряды, которые остались в истории моды.

Например, всем запомнились ее белая блузка с воротником-лентой, которая была надета во время фотосессии для обложки британского журнала Vogue, или яркий костюм алого цвета во время посещения центра больных СПИДом.

Одним из самых знаменитых нарядов принцессы стало черное короткое платье с открытым верхом и небольшим шлейфом. Диана продемонстрировала его в 1994 году на вечеринке журнала Vanity Fair. Ходят слухи, что именно в этот день супруги серьезно поговорили и принц Чарльз рассказал жене о своих похождениях «налево».

Развод Чарльза и Дианы Уэльской

Семейная жизнь Дианы очень похожа на историю ее родителей. Девушка не была счастлива. В середине 80-х годов Чарльз вновь закрутил роман со своей давней любовницей Камиллой Паркер-Боулз. О том, что у них когда-то была связь, принцесса Ди узнала, будучи уже замужем.

Диана была унижена и раздавлена и поэтому вступила в отношения с Джеймсом Хьюиттом, ее инструктором по верховой езде. Ситуация стала еще хуже, когда у прессы оказались записи разговоров супругов со своими любовниками по телефону. Затем начались бесчисленные интервью, где они винили друг друга в неудачном супружестве.

Принцесса говорила: «В моем браке было слишком много народу». Именно тогда стали известны подробности личной жизни женщины. В 1994 году в свет вышла книга-биография о принцессе Диане «Влюбленная принцесса», позже по ней сняли фильм с таким же названием.

Елизавета II была возмущена и старалась скорее завершить бракоразводный процесс. Он состоялся 28 августа 1996 года. Диана уже не могла называться Ваше Королевское Высочество. Но ей это было совершенно не важно, ведь главное, что люди ее полюбили.

После развода жизнь Дианы стала проще, но она все равно должна была с гордостью носить звание бывшей жены наследного принца и матери его двоих детей. Она не могла жить свободно и обязана была соблюдать приличия. В своих интервью она говорила, что терпела все унижения только ради любимых сыновей: «Любая нормальная женщина ушла бы давно. Но я не могла. У меня сыновья». Даже в процессе развода леди Ди не прекращала заниматься благотворительностью.

Она посвятила ей и последующее время и старалась сделать жизнь нуждающихся людей гораздо лучше. Диана помогала больным СПИД, раком, детям с пороком сердца и многим другим.

В это время в ее личной жизни случился бурный роман с хирургом из Пакистана Хаснатом Ханом. У Хана была очень религиозная семья, поэтому Диана серьезно думала принять ислам и выйти замуж за любимого.

К сожалению, представителям разных культур редко удается создать счастливую семью из-за несходства менталитетов, они не стали исключением и разошлись в июне 1997 года. Но прошло всего несколько недель, и леди Ди встретила новую любовь – Доди Аль-Файеда, продюсера и сына одного из богатейших людей Египта. В официальной биографии принцессы Дианы есть фото ее личной жизни, сделанные за несколько лет до гибели.

Гибель принцессы Дианы

31 августа 1997 года влюбленные Диана и Доди проводили время в Париже. На своем автомобиле они уехали из отела и пытались скрыться от навязчивых папарацци.

В этот момент водитель не справился с управлением и на скорости въехал в бетонную опору моста. Он, как и Доди Аль-Файед, погиб мгновенно, за жизнь принцессы Дианы еще пытались бороться врачи. Но через несколько часов после катастрофы она тоже умерла. В аварии выжил лишь телохранитель Тревор Рис-Джонс, но он не помнит того, что случилось.

В биографии принцессы Дианы написано, что правоохранительными органами были изучены все факты, в результате которых установлено, что причиной смерти стали травмы, полученные пассажирами авто из-за того, что они не были пристегнуты, а водитель был неосторожен на дороге.