Королева Кровавая Мэри

18 Февраля 1516 – 17 Ноября 1558 гг. (42 года)

4.6

Средняя оценка: 4.6

Всего получено оценок: 132.

Мария I Тюдор (1516–1558 гг.) — первая коронованная королева Англии, дочь Генриха 8, которая вошла в историю как Мария Кровавая. Ее имя всегда ассоциировалось с многочисленными жестокими расправами, а день ее смерти в Англии отмечался как национальный праздник. Биография Кровавой Марии богата интересными фактами. Рассмотрим кратко самые важные из них, которые позволят лучше узнать личность королевы Англии.

Детство и юность

Мария I Тюдор родилась 18 февраля 1516 года в Лондоне. Ее отцом был король Англии Генрих VIII, а матерью — младшая принцесса Испании Екатерина Арагонская. Она оказалась первым ребенком королевской четы, который смог выжить: до ее рождения королева шесть раз беременела, но так и не смогла подарить супругу наследника.

С юных лет принцесса обладала твердым, сдержанным характером, которым восхищался отец. Девочка прилежно училась и уже в раннем возрасте прекрасно владела латынью и греческим языком, была очень образованной, играла на клавесине и танцевала.

Жизнь с мачехами

Генрих VIII, потеряв надежду получить законного наследника от королевы Екатерины, решил аннулировать брак с ней. Но в результате подобного решения Мария автоматически бы становилась незаконнорожденной дочерью и теряла все права на корону.

Екатерина не давала согласие на расторжение брака, и тогда Генрих VIII самовольно женился на Анне Болейн. Мачеха пыталась наладить хорошие отношения с Марией, но та категорически отказывалась идти на контакт. После казни Анны Болейн по обвинению в супружеской измене король взял в жены Джейн Сеймур, которая родила ему сына Эдуарда, но сама умерла после родов.

Отныне Генрих VIII менял жен, как перчатки, и Марии Тюдор приходилось каждый раз привыкать к новой мачехе. Когда умер король Генрих, Марии исполнился 31 год, и она еще не была замужем. Наследником становился болезненный Эдуард, который скончался в юном возрасте от туберкулеза. Перед смертью его заставили подписать указ о престолонаследии, по которому Мария Тюдор лишалась возможности взойти на престол. Однако подобное решение вызвало негодование у народа, и в 1553 году Мария стала королевой Англии.

Правление

После правления Генриха VIII, отлученного папой римским от церкви, в Англии было разрушено немало монастырей и церквей. Свита короля Эдуарда полностью разворовала королевскую казну. Перед новой королевой стояла непростая задача: возродить из пепла бедную страну, которая ей досталась по наследству.

В первые полгода правления Мария Тюдор отправила на плаху всех тех, кто строил против нее интриги и заговоры и у кого был хоть малейший шанс свергнуть ее с престола. Вместе с тем королева приблизила к себе людей, которые еще вчера были против нее, но могли оказать существенную помощь в управлении страной.

Будучи глубоко верующей католичкой, Мария начала восстановительные работы в стране с реконструкции монастырей и укрепления католической веры. При этом она безжалостно отправляла на казнь протестантов: за годы правления Марии Тюдор было убито около трехсот иноверцев. Именно тогда за ней закрепилось прозвище королева Кровавая Мэри.

Личная жизнь

Еще в детстве Мария I Тюдор была помолвлена с юным императором Священной Римской империи Карлом V Габсбургом. Однако этот брак так и не состоялся из-за испорченных отношений Генриха с Римской Церковью.

Бесконечная череда мачех не давала Марии возможность устроить свою личную жизнь, и потому на момент коронации она все еще оставалась незамужней женщиной.

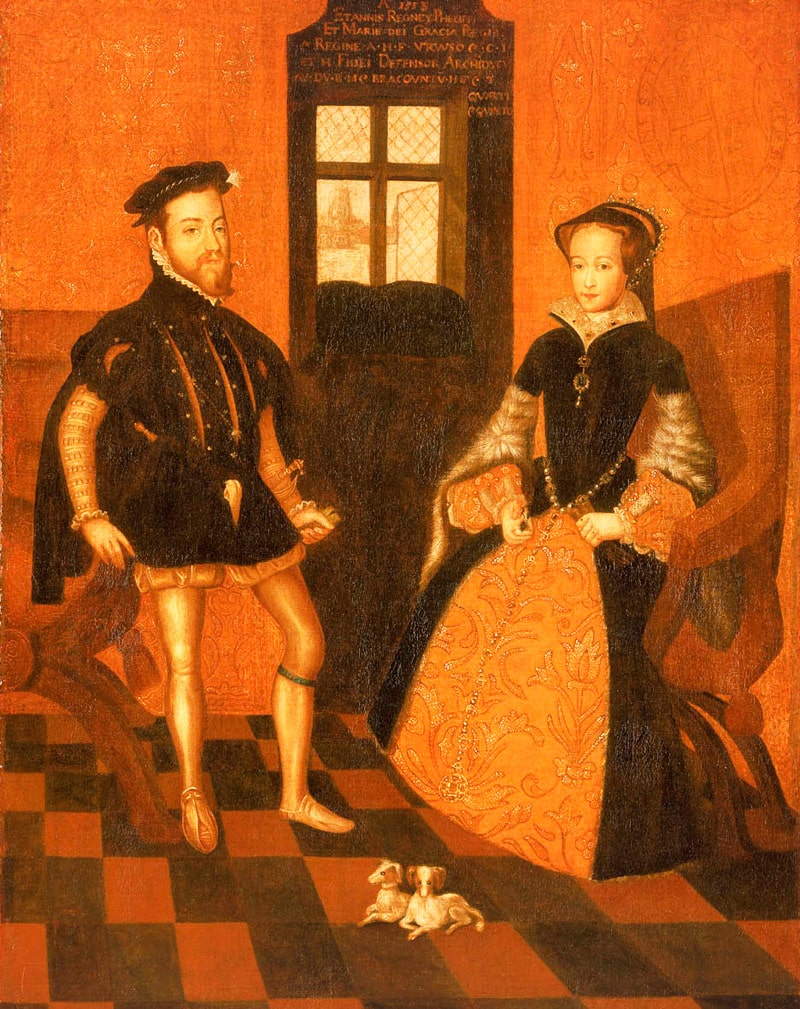

В 1554 году Тюдор все же связала себя узами брака с королем Испании из династии Габсбургов Филиппом II. Она настояла на том, чтобы супруг подписал договор, согласно которому не смел вмешиваться в управление Англией. Вскоре королева объявила о беременности, но она оказалась ложной.

Народ сразу невзлюбил высокомерного короля Филиппа, чья свита вела себя крайне вызывающе. На улицах Англии нередкими стали стычки между испанцами и местными жителями.

Последние годы жизни

В 1558 году Англию накрыла эпидемия лихорадки, от которой страдала вся Европа. В августе того же года опасной болезнью заразилась и Мария Тюдор. Осознавая всю серьезность ситуации, она лишила супруга каких-либо прав на британскую корону и написала завещание в пользу Елизаветы — дочери Генриха VIII и Анны Болейн. Скончалась Мария I Тюдор 17 ноября 1558 года, причиной смерти стала лихорадка, с которой она так и не смогла справиться.

Тест по биографии

Доска почёта

Чтобы попасть сюда — пройдите тест.

-

Сережа Фролов

6/10

Оценка по биографии

4.6

Средняя оценка: 4.6

Всего получено оценок: 132.

А какая ваша оценка за эту биографию?

Детство и юность Марии

Мария родилась 18 февраля 1516 года в семье Генриха VIII и Екатерины Арагонской. Хотя ребёнок и не стал долгожданным наследником мужского пола, король искренне обрадовался появлению на свет здоровой и крепкой девочки. К тому моменту Екатерина уже перенесла несколько выкидышей, а единственный сын, рождённый в 1511 году, скончался всего через 7 недель. Следующая беременность королевы последовала в 1518 году, однако ребёнок, ещё одна девочка, не прожил и нескольких часов. Для Екатерины Арагонской эта беременность стала последней. К концу 1510-х в отношениях пары наметился разлад: у короля появилась фаворитка Бесси Блаунт. В 1519 году Бесси родила Генриху мальчика, названного Генри Фицроем. Хотя официально рождение бастарда не пошатнуло позиций принцессы Марии, Екатерина Арагонская опасалась, что Фицрой станет наследником в обход её дочери.

В истории Англии до обозначенных событий лишь однажды женщина восседала на престоле: Матильда, дочь Генриха I, которая так никогда и не была коронована. Будучи не в состоянии удержать власть, Матильда лишилась трона, а страна погрузилась в затяжную гражданскую войну.

Для Генриха VIII идея женщины во главе Англии была на тот момент неприемлема. И всё же Мария, за которой числился свой собственный двор, неформально носила звание принцессы Уэльской — титул, которым могла обладать лишь супруга наследника престола, принца Уэльского. Официально Мария так никогда этот титул не получила, однако Генрих VIII, скорее всего, оставил этот вопрос открытым, дабы иметь пространство для манёвра.

Мария получила образование, достойное истинной наследницы престола, как если бы она и вправду рассматривалась на эту роль. И всё же для Генриха VIII, ещё надеявшегося обзавестись законным сыном, дочь была, прежде всего, инструментом в политических играх. На протяжении детских и юношеских лет Марию много раз сватали за наследников то французского, то испанского престолов — в зависимости от того, с кем Англия на тот момент искала альянса.

Мария Тюдор в детстве. (wikipedia.org)

Примерно в середине 1520-х король начал задумываться о разводе. Непосредственно процесс начался только в 1529 году и растянулся на несколько лет. Главным аргументом Генриха VIII в пользу развода с первой женой было то обстоятельство, что её предыдущий брак с его покойным старшим братом Артуром всё же был консумирован. Доказать или опровергнуть данный прецедент у историков не получилось до сих пор. Скорее всего, для короля именно такой аргумент представлялся наиболее весомым, способным обеспечить ему разрешение Папы Римского разойтись с Екатериной по-хорошему. Не получив желаемого ответа от Рима, Генрих VIII взял дело в свои руки: последующая религиозная реформация и назначение короля главой церкви Англии позволили монарху творить всё, что душе угодно. Екатерину удалили от двора, король больше не считал её своей супругой, а обращаться к ней отныне полагалось как к «вдовствующей принцессе Уэльской». Всё это, разумеется, повлияло и на положение принцессы Марии.

Опала, потеря статуса и конфликт с отцом

В 1533-м Генрих женился на Анне Болейн, а уже в в сентябре того же года родилась их дочь принцесса Елизавета. Марию признали незаконнорождённой, и своё место в очереди на престол она уступила Елизавете. Всё это сказалось на здоровье Марии: у неё начались проблемы с репродуктивной системой, возможно, вызванные тяжёлым стрессом. Ещё будучи совсем юной девушкой, она страдала от депрессии. Причиной тому был не только развод родителей, но также государственные и религиозные реформы, последовавшие за ним. Выращенная истовой католичкой Екатериной, Мария признавала только эту веру, а потому реформацию, затеянную отцом, не могла принять. Ко всему прочему, протестантство было верованием новой жены Генриха, ненавистной Анны Болейн, которую Мария отказывалась признавать королевой.

Напряжение в отношениях Генриха VIII со старшей дочерью нарастало. Личный двор Марии упразднили, а её саму отправили жить в резиденцию, где воспитывалась Елизавета. Согласно некоторым свидетельствам, по распоряжению Анны Болейн, Марию унижали, оскорбляли и даже применяли к ней физическое наказание в случае непослушания, однако как таковых подтверждений этому нет.

До самой смерти Екатерины Арагонской в 1536 году Марии было отказано в возможности не только навещать мать, но и обмениваться письмами (впрочем, они вели тайную корреспонденцию при помощи доверенных слуг). После кончины матери девушка долгое время пребывала в отчаянии. Некоторое облегчение ей принесла казнь Анны Болейн: у Марии появилась надежда на воссоединение с отцом. Кроме того, теперь она была не единственным «бастардом»: из порядка престолонаследия исключили и маленькую Елизавету.

В том же 1536 году Генрих VIII снова женился — на леди Джейн Сеймур. Она предприняла осторожную попытку помирить Марию с отцом, однако король отказывался общаться с дочерью до тех пор, пока та не подпишет документ с признанием, во-первых, что главой церкви отныне считается сам монарх, а, во-вторых, что брак её родителей был нелегитимным. Таким образом, Марии предстояло расписаться в том, что она — незаконнорождённая дочь. Опасаясь преследования и казни, девушка со скрипом подписала бумагу, даже толком её не прочитав. При этом она призналась, что никогда не сможет простить себя за эту сделку с совестью. И всё же её роспись на документе смягчила сердце Генриха VIII: Марию пригласили ко двору, где и произошло воссоединение отца и дочери.

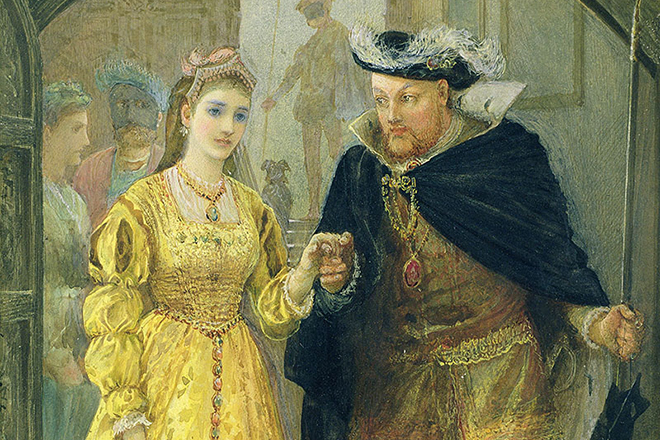

Портрет семьи Генриха VIII. Мария — по правую руку от него. (rct.uk)

В 1537 году родился долгожданный законный наследник — принц Эдуард. О восстановлении Марии в порядке престолонаследия речи не шло, однако её положение значительно улучшилось. Принцесса стала крёстной матерью для брата, которого сердечно полюбила. Вскоре Джейн Сеймур скончалась, и Мария искренне горевала после смерти мачехи.

Впоследствии не со всеми новыми жёнами отца у неё складывались дружеские отношения. Так, например, к протестантке Анне Клевской, четвёртой супруге короля, она поначалу относилась с подозрением из-за религиозных противоречий, однако всё же прониклась к ней доверием. Брак Анны и Генриха VIII продлился очень недолго, и вот уже новая королева, Екатерина Говард, сменила Клевскую. С Говард, которая была примерно на 9 лет младше самой Марии, взаимопонимания не вышло. Старшая дочь Генриха относилась к новой мачехе презрительно, полагая её слишком молодой, глупой и необразованной пустышкой.

Говард тоже недолго проходила в королевах, примерно полтора года. На следующий год после её казни король женился в шестой и последний раз — на Екатерине Парр. Хотя Парр, как и Клевская, была известна своими протестантскими взглядами, ей удалось добиться расположения Марии. Новая мачеха была всего на три года старше принцессы и до брака с королём находилась в свите Марии.

В 1544 году Генрих VIII подписал новый указ о престолонаследии, согласно которому обе дочери, Мария и Елизавета, восстанавливались в праве претендовать на престол, но только после Эдуарда и в случае отсутствия у него потомков. Это подарило Марии надежду.

Старшая сестра непреклонного брата

Генрих VIII скончался в 1547 году, оставив после себя малолетнего Эдуарда королём. Мальчику на тот момент было всего 9 лет, и правил он при содействии регента. Недолгое царствование Эдуарда VI стало тяжёлым периодом для Марии: сын превзошёл отца в его самых смелых мечтах о реформации церкви. В отличие от Генриха VIII, который опасался радикальных перемен и сохранил множество истинно католических обрядов, Эдуард желал полного «очищения» церкви от всего, что напоминало «старую» веру. Мария всё так же продолжала служить мессу — во времена Эдуарда VI это было строго-настрого запрещено. Отказ принцессы подчиниться требованиям брата отречься от католичества привёл к конфликту. Устранить Марию он не мог — она значилась наследницей престола после него. Своих детей у Эдуарда по юности лет ещё не было. И всё же за свою безопасность принцесса опасалась, а потому обратилась к двоюродному брату императору Священной Римской империи Карлу V с просьбой защитить её интересы. Тот пригрозил Эдуарду войной, если Марии не будет позволено по-прежнему служить мессу и придерживаться тех католических обрядов, к которым она привыкла. Принцесса даже планировала бежать из страны при содействии Карла V, однако Эдуард VI не собирался отпускать сестру. Кроме того, приближённые Марии докладывали ей об ослаблении здоровья короля и его потенциально скорой смерти. В случае побега за границу до его кончины она рисковала потерять права на престол.

Эдуард VI. (npg.org.uk)

Эдуард VI умер в 1553 году, в возрасте всего лишь 15 лет. Незадолго до этого он, желая защитить свои протестантские реформы, назначил в обход сестер наследницей молодую Джейн Грей, внучку Генриха VII. Грей объявили королевой 10 июля 1553 года. К этому моменту Мария, покинувшая столицу незадолго до смерти Эдуарда, активно собирала сторонников, чтобы взять власть. Ей оказали поддержку как знать, так и простой народ, желавший видеть на троне дочь Генриха VIII. 19 июля Джейн Грей низложили, а Марию объявили новой королевой. 3 августа 1553 года, сопровождаемая огромной свитой, которая включала и принцессу Елизавету, Мария с триумфом проехала по улицам Лондона — Грей к этому времени уже 2 недели как находилась в Тауэре под арестом. Поначалу Мария не собиралась казнить леди Джейн, понимая, что та оказалась пешкой в руках своего свёкра Джона Дадли, бывшего регента Эдуарда. Решение о судьбе девушки было отложено, однако её всё так же содержали под стражей.

Королева-католичка

Мария определила для себя две главнейшие цели, которых необходимо было достигнуть в её правление: вернуть Англию в лоно католичества и родить наследника. Обе задачи представлялись крайне трудными. В своих шагах по восстановлению католической религии в стране Мария была не слишком радикальна, например, возвращать земли, отнятые у монастырей в годы правления её отца, она не стала — их новые богатые хозяева ополчились бы против короны. Мария восстановила многие католические обряды, включая ту же мессу, главным языком на службе вновь стала латынь, а не английский, кроме того, священнослужителям вновь запретили жениться, а уже женатым приказали отречься либо от супружества, либо от сана.

Более всего новая королева желала воссоединения с Римом и восстановления Папы в роли главы церкви, однако даже английские католики со скептицизмом отреагировали на эти планы. Возрождение связей с Римом означало бы не только формальное подчинение воле Папы, но и финансовое бремя в виде налоговых отчислений. Однако ресторация Папы как главы церкви была необходима Марии для подтверждения законности брака её родителей и, соответственно, собственного статуса легитимного потомка (именно Папа гарантировал Генриху и Екатерине разрешение жениться, несмотря на предыдущий брак Арагонской с принцем Артуром).

Мария с триумфом прибывает в Лондон. (elizabethi.org)

В первый год на троне Мария объявила, что не будет заставлять своих субъектов обращаться в католичество, однако её заверения в гарантии безопасности протестантам оказались ложными. После восшествия дочери Генриха VIII на престол около 800 человек покинули страну. В каком-то смысле это даже воодушевило Марию: она ожидала, что число окажется куда более значительным. Вскоре, несмотря на обещания королевы, были арестованы виднейшие фигуры реформации, в их числе Томас Кранмер, духовный наставник Эдуарда VI и один из основных деятелей эпохи Генриха VIII, обеспечивший решение вопроса о разводе короля. К Кранмеру у Марии была персональная неприязнь: именно его она считала виновным в падении матери и потере собственного статуса 20 лет назад. В заточении Кранмер, наблюдавший за сожжением еретиков, отрёкся от протестантства и объявил, что готов принять католичество, рассчитывая на помилование, однако Мария лично вмешалась в процесс, и Кранмера приговорили к смерти на костре.

В 1554 году были восстановлены Акты о ереси, что означало неминуемое преследование протестантов. Всего за 5 лет у власти Мария отправила на костёр 283 человека. Для сравнения, в годы правления Генриха VIII (почти 40 лет) были казнены около 80 еретиков. Именно по причине столь жёстких мер по отношению к протестантам Мария заработала себе прозвище «кровавой». В народе массовые сожжения встретили противоречиво, и даже советники Марии предупреждали её о непопулярности подобной жестокости. Смерть на костре полагали одной из самых страшных. Впоследствии многие жертвы, казнённые в годы правления Марии, попали в список мучеников.

Королевы тоже плачут

Что же до личной жизни королевы? Учитывая, что Мария взошла на престол в возрасте 37 лет, вопрос о замужестве необходимо было решить как можно скорее. В самой Англии оказалось мало кандидатов, обладавших достаточно высоким статусом, чтобы свататься к самой королеве. Искать мужа нужно было за границей, однако парламент опасался, что заморский принц или король сделают Англию зависимой от другой державы. И тот же Парламент настаивал, что королеве необходимы муж и наследник.

Карл V предложил своего сына Филиппа II. Он был на 11 лет младше Марии и обладал весьма приятной наружностью. Увидев портрет Филиппа кисти Тициана, королева загорелась желанием непременно заполучить принца в качестве супруга. Переговоры о свадьбе начались уже в конце 1553 года. Парламент решил, что Филипп и Мария будут носить титулы короля и королевы, однако править Мария продолжит самостоятельно, а после её смерти Филиппа лишат всякой власти в Англии. Советники рассчитывали, что супруг окажет влияние на политические решения королевы, но последнее слово останется за ней.

Мария и Филипп (collections.rmg.co.uk)

Когда новости о свадьбе стали известны широкой публике, послышались недовольные голоса. Мало кто из англичан желал видеть рядом со своей королевой иностранца. Опасались вовлечения Англии в политические игры и войны чужой державы, в особенности потому что Филипп был наследником трона Карла V. В 1554 году вспыхнуло восстание под предводительством Томаса Уайатта: несколько тысяч человек отправились в Лондон с целью свергнуть Марию и поставить на её место всё ту же Джейн Грей, которая по-прежнему содержалась в Тауэре. В восстании принимал участие её отец Генри Грей. Мария быстро собрала сторонников, готовых выступить против мятежа, и обратилась с речью к народу. В своём послании она убеждала англичан, что её брак поможет укрепить мир и порядок в государстве и что она руководствуется всеобщим благом, а не личными мотивами. В этом, конечно, была доля лукавства: Мария по-настоящему жаждала брака с Филиппом. Восстание подавили, а Джейн Грей казнили — королева опасалась последующих мятежей в поддержку протестантской кандидатки.

Свадьба состоялась 25 июля 1554 года. В отличие от Марии, Филипп не желал этого союза, но подчинился воле отца. Королева ему не понравилась: он полагал её откровенно некрасивой. Их союз вряд ли можно назвать счастливым — Филипп проводил много времени вне Англии, занимаясь государственными делами у себя на родине и готовясь в скором времени наследовать трон.

В сентябре 1554 года Мария предположила, что ожидает ребёнка. Она стала заметно набирать в весе, её живот округлился, пришла утренняя тошнота. Парламент принял акт, согласно которому Филипп становился регентом будущего наследника или наследницы престола в случае смерти Марии. Предполагаемой датой рождения ребёнка назвали июнь 1555 года. Девять месяцев Мария демонстрировала все признаки обычной беременности, однако уже к июлю 1555 года стало очевидно, что никакого наследника не будет. Беременность оказалась ложной. Подобное расстройство часто является следствием самовнушения, ложная беременность имеет все «симптомы» настоящей, притом что фактическое зачатие так и не состоялось. Большие надежды как самой Марии, так и всего королевства, не оправдались: она ощущала себя посрамлённой в глазах народа. Эта трагедия укрепила Марию в вере, что бог посылает ей наказание за слишком толерантное отношение к еретикам-протестантам, и она ужесточила их преследование.

Бесславный конец

Помимо религиозной войны и отсутствия наследника Мария столкнулась с ещё одной проблемой — пустой королевской казной. Гигантские траты её предшественников, порча монеты в период правления Генриха VIII и Эдуарда VI, наводнения, неурожай и голод привели к истощению запасов золота. Мария строила планы по проведению денежной реформы, однако не успела их воплотить. Она попыталась расширить международную торговлю, отыскать новые ресурсы и рынки, в частности, выдала патент на работу «Московской компании» — английского торгового предприятия, — но столкнулась с противостоянием со стороны испанцев, ревностно оберегавших свои судоходные торговые пути. Подобные меры должны были способствовать постепенной перестройке денежной системы в пользу поиска новых источников дохода в противовес привычному повышению налогов в случае дефицита государственного бюджета. Впоследствии по этому пути пойдет её сестра Елизавета.

Сара Болгер в роли Марии в «Тюдорах». (tudorsandotherhistories.com)

В 1557 году Мария вновь объявила о беременности. Но и на этот раз ожидания не оправдались: по прошествии 9 месяцев ребёнок так и не появился на свет. Эта беременность также оказалась ложной. Плохое самочувствие королевы объяснялось её болезнью. Первые признаки серьёзного недомогания проявились весной 1558 года, а к осени королева совсем ослабла. Она умерла 17 ноября 1558 года в возрасте 42 лет. Преемницей Марии, согласно акту о престолонаследии, стала Елизавета, и именно её последующее долгое правление вошло в историю как «золотой век» Англии. За Марией же, возможно, не вполне справедливо, закрепилась исключительно репутация «кровавой» — её помнят только как безумную католичку, безжалостно уничтожавшую еретиков.

Может ли женщина, которая априори рождена для любви и нежности, стать жестокой без причины? А если есть повод, в чём её вина? Эти вопросы возникают невольно, как только речь заходит о королеве Марии. События тех лет оставили кровавый след в истории страны.

Английская королева Мария I Тюдор была дочерью Екатерины Арагонской и Генриха VIII. Так же, как и отец, она оставила после себя не самые приятные воспоминания.

Но что должна была сделать женщина, чтобы день её смерти стал для Англии национальным праздником? И заслуженно ли королева была прозвана Кровавой Мэри?

Читать еще: история еще одной известной в истории Марии (Гамильтон). Трагическая судьба и короткая яркая жизнь.

Содержание

- 1 Краткая биография Марии Тюдор: детство

- 2 Восшествие на престол

- 3 Годы правления кровавой Мэри

- 4 Замужество и ложная беременность

- 5 Почему Марию называли «кровавой»

- 6 Когда и как умерла английская королева

Краткая биография Марии Тюдор: детство

Родилась царственная малышка 18 февраля 1516 года. Детство Марии было счастливым, хоть и длилось оно недолго. После развода короля с ее матерью, Екатериной, он объявил дочь незаконнорожденной, и стал менять жен с большой скоростью.

Девочке приходилось приноравливаться к каждой из жен, чтобы не потерять своего статуса. После свадьбы Генриха и Анны Болейн девочка была отправлена из дворца. Отношения с новой женой отца у Марии совсем не сложились, впрочем, как и со всеми последующими.

Начиная с 6 лет, ей попеременно назначали каких-то вельможных женихов из политических соображений, но потом Генрих все помолвки отменял. Таким образом, до 31 года Мария все еще не была замужем.

С детства, благодаря матери, девочка воспитывалась в строгой католической вере. Это и стало причиной того, что Генрих не хотел видеть её подле себя, тем более на престоле. Однако судьба распорядилась иначе.

Восшествие на престол

Наследников престола был стать Эдуард, рожденный от Генриха и его очередной жены Джейн Сеймур. Он взошел на престол в малолетнем возрасте 9 лет. Мальчик рос слабым, особых надежд не подавал, а принцессу держали вдали от дворца, опасаясь, что она выйдет замуж и силой захватит престол, свергнув Эдуарда.

После смерти Эдуарда его преемницей стала Джейн Грей, а Мария была вынуждена бегать подальше из страны. Но всего 9 дней продлилось ее правление — поддержки у народа она не получила, и на престол взошла Мария.

Годы правления кровавой Мэри

Мария была провозглашена королевой Англии в 37 лет (19 июля 1553 года). Разворованная казна и непрекращающиеся религиозные распри – вот что ей досталось от Эдуарда в наследство. Королева казнила свою предшественницу и всю ее родню, и стала восстанавливать монастыри и храмы, разрушенные предыдущими правителями, отошедшими от веры.

На костер пошли толпами протестанты, она стала возвращать католическую веру предков. . Все те, кто не хотел подчиняться вере, провозглашались еретиками. Мария реконструировала монастыри и вместе с этим приближала к себе людей, которые могли помочь ей в восстановлении страны.

Поскольку в Англии нашлось много людей, противившихся вере, Мария решила начать применять крайние меры. Не смотря на угрожающее прозвище королевы, она сделала много для страны. Историки того времени писали:

«Достижения Марии часто недооценены. Она провела успешный переворот в Англии 16-го века. В моменты кризиса она показывала себя мужественной, решительной и политически грамотной».

В 1955 году молодая королева издала закон, что власть правительницы женского пола, так же, как мужского, является полной, целостной и абсолютной, чем уравняла права в королевском наследовании трона.

Замужество и ложная беременность

Мужем королевы стал испанский наследник Филипп Баварский, которого Мария очень любила. Молодой супруг был намного младше и не питал никаких чувств к королеве. Всё, чего он хотел получить – это деньги и статус. Муж Марии был напыщенным и самовлюбленным, народ его не любил, как и его свиту, и это постоянно вызывало кровавые стычки на улицах.

Однако Мария не хотела признавать очевидное.

Королева даже объявила о беременности, которая впоследствии оказалась ложной. Мэри сложно переживала этот период и несколько месяцев не выходила из дворца. Вот что об этом писали современники:

30 апреля 1555 года «колокола звонили по всей стране, запускались фейерверки, на улицах проходили массовые гулянья – а все это после новостей о том, что Мария I произвела на свет здорового сына. Но никакого сына не было. Надежда произвести наследника вскоре угасла.

Почему Марию называли «кровавой»

В феврале 1555 года Англия превратилась в один большой костёр для иноверцев. Мария казнила протестантов по всей стране. За годы правления королевы было сожжено порядка трёхсот человек. По этой причине Марию и называли не иначе как Кровавая Мэри.

Но королева по своему была предана своей стране. Когда Англию охватила смертельная лихорадка, унесшая множество жизней, Мария также заболела. Зная, что исход может быть скорым и непредсказуемым, она составила завещание в пользу сестры Елизаветы, тем самым отстранив от престола ненавистного английскому люду Филиппа, который был занят только своими грязными делишками, и думал лишь о своей корысти.

На заметку!

Во время Варфоломеевской ночи погибло более 2-х тысяч протестантов, но почему-то Карла 9-го Валуа, одобрившего эту резню, никто не прозвал «кровавым»?!

Когда и как умерла английская королева

Мария I умерла 17 ноября 1558 года, не оставив наследников. Согласно основной версии, причиной смерти королевы была лихорадка, однако историки пришли к другому выводу. Ложные симптомы, указывающие на беременность, не могли появиться сами по себе. Скорее всего, у королевы была киста яичника или рак матки. Это и могло стать причиной её смерти.

Преемницей Марии стала её сестра Елизавета, дочь Генриха VIII и Анны Болейн. Вместе со смертью Кровавой Мэри в Англии закончился и век инквизиции. Несмотря на то, что у власти Мария была недолго, годы её правления стали важным периодом в жизни Англии.

Но — страна вздохнула с облегчением после ухода из жизни кровавой правительницы.

Елизавета, поддерживаемая знатью, быстро взошла на престол, и стала управлять страной. Марию похоронили лишь 13 декабря в капелле Генриха VII. Там же после смерти была похоронена и Елизавета. Надгробие венчает памятник второй сестре, и надпись, которая гласит:

«Союзницы на троне и в могиле, сёстры Елизавета и Мария лежат здесь в надежде на воскрешение».

Памятник Марии Первой Тюдор был поставлен лишь на родине мужа, в Испании, в Англии ни одного нет.

Обновлено: 10.01.2023

Мария I Тюдор (1516–1558 гг.) — первая коронованная королева Англии, дочь Генриха 8, которая вошла в историю как Мария Кровавая. Ее имя всегда ассоциировалось с многочисленными жестокими расправами, а день ее смерти в Англии отмечался как национальный праздник. Биография Кровавой Марии богата интересными фактами. Рассмотрим кратко самые важные из них, которые позволят лучше узнать личность королевы Англии.

Детство и юность

Мария I Тюдор родилась 18 февраля 1516 года в Лондоне. Ее отцом был король Англии Генрих VIII, а матерью — младшая принцесса Испании Екатерина Арагонская. Она оказалась первым ребенком королевской четы, который смог выжить: до ее рождения королева шесть раз беременела, но так и не смогла подарить супругу наследника.

С юных лет принцесса обладала твердым, сдержанным характером, которым восхищался отец. Девочка прилежно училась и уже в раннем возрасте прекрасно владела латынью и греческим языком, была очень образованной, играла на клавесине и танцевала.

Жизнь с мачехами

Генрих VIII, потеряв надежду получить законного наследника от королевы Екатерины, решил аннулировать брак с ней. Но в результате подобного решения Мария автоматически бы становилась незаконнорожденной дочерью и теряла все права на корону.

Екатерина не давала согласие на расторжение брака, и тогда Генрих VIII самовольно женился на Анне Болейн. Мачеха пыталась наладить хорошие отношения с Марией, но та категорически отказывалась идти на контакт. После казни Анны Болейн по обвинению в супружеской измене король взял в жены Джейн Сеймур, которая родила ему сына Эдуарда, но сама умерла после родов.

Отныне Генрих VIII менял жен, как перчатки, и Марии Тюдор приходилось каждый раз привыкать к новой мачехе. Когда умер король Генрих, Марии исполнился 31 год, и она еще не была замужем. Наследником становился болезненный Эдуард, который скончался в юном возрасте от туберкулеза. Перед смертью его заставили подписать указ о престолонаследии, по которому Мария Тюдор лишалась возможности взойти на престол. Однако подобное решение вызвало негодование у народа, и в 1553 году Мария стала королевой Англии.

Правление

После правления Генриха VIII, отлученного папой римским от церкви, в Англии было разрушено немало монастырей и церквей. Свита короля Эдуарда полностью разворовала королевскую казну. Перед новой королевой стояла непростая задача: возродить из пепла бедную страну, которая ей досталась по наследству.

В первые полгода правления Мария Тюдор отправила на плаху всех тех, кто строил против нее интриги и заговоры и у кого был хоть малейший шанс свергнуть ее с престола. Вместе с тем королева приблизила к себе людей, которые еще вчера были против нее, но могли оказать существенную помощь в управлении страной.

Будучи глубоко верующей католичкой, Мария начала восстановительные работы в стране с реконструкции монастырей и укрепления католической веры. При этом она безжалостно отправляла на казнь протестантов: за годы правления Марии Тюдор было убито около трехсот иноверцев. Именно тогда за ней закрепилось прозвище королева Кровавая Мэри.

Личная жизнь

Еще в детстве Мария I Тюдор была помолвлена с юным императором Священной Римской империи Карлом V Габсбургом. Однако этот брак так и не состоялся из-за испорченных отношений Генриха с Римской Церковью.

Бесконечная череда мачех не давала Марии возможность устроить свою личную жизнь, и потому на момент коронации она все еще оставалась незамужней женщиной.

В 1554 году Тюдор все же связала себя узами брака с королем Испании из династии Габсбургов Филиппом II. Она настояла на том, чтобы супруг подписал договор, согласно которому не смел вмешиваться в управление Англией. Вскоре королева объявила о беременности, но она оказалась ложной.

Народ сразу невзлюбил высокомерного короля Филиппа, чья свита вела себя крайне вызывающе. На улицах Англии нередкими стали стычки между испанцами и местными жителями.

Последние годы жизни

Может ли женщина, которая априори рождена для любви и нежности, стать жестокой без причины? А если есть повод, в чём её вина? Эти вопросы возникают невольно, как только речь заходит о королеве Марии. События тех лет оставили кровавый след в истории страны .

Английская королева Мария I Тюдор была дочерью Екатерины Арагонской и Генриха VIII. Так же, как и отец, она оставила после себя не самые приятные воспоминания.

Но что должна была сделать женщина, чтобы день её смерти стал для Англии национальным праздником? И заслуженно ли королева была прозвана Кровавой Мэри?

Читать еще: история еще одной известной в истории Марии (Гамильтон). Трагическая судьба и короткая яркая жизнь.

Краткая биография Марии Тюдор: детство

Родилась царственная малышка 18 февраля 1516 года. Детство Марии было счастливым, хоть и длилось оно недолго. После развода короля с ее матерью, Екатериной, он объявил дочь незаконнорожденной, и стал менять жен с большой скоростью.

Девочке приходилось приноравливаться к каждой из жен, чтобы не потерять своего статуса. После свадьбы Генриха и Анны Болейн девочка была отправлена из дворца. Отношения с новой женой отца у Марии совсем не сложились, впрочем, как и со всеми последующими.

Начиная с 6 лет, ей попеременно назначали каких-то вельможных женихов из политических соображений, но потом Генрих все помолвки отменял. Таким образом, до 31 года Мария все еще не была замужем.

С детства, благодаря матери, девочка воспитывалась в строгой католической вере. Это и стало причиной того, что Генрих не хотел видеть её подле себя, тем более на престоле. Однако судьба распорядилась иначе.

Восшествие на престол

Наследников престола был стать Эдуард, рожденный от Генриха и его очередной жены Джейн Сеймур. Он взошел на престол в малолетнем возрасте 9 лет. Мальчик рос слабым, особых надежд не подавал, а принцессу держали вдали от дворца, опасаясь, что она выйдет замуж и силой захватит престол, свергнув Эдуарда.

После смерти Эдуарда его преемницей стала Джейн Грей, а Мария была вынуждена бегать подальше из страны. Но всего 9 дней продлилось ее правление — поддержки у народа она не получила, и на престол взошла Мария.

Годы правления кровавой Мэри

Мария была провозглашена королевой Англии в 37 лет (19 июля 1553 года). Разворованная казна и непрекращающиеся религиозные распри – вот что ей досталось от Эдуарда в наследство. Королева казнила свою предшественницу и всю ее родню, и стала восстанавливать монастыри и храмы, разрушенные предыдущими правителями, отошедшими от веры.

На костер пошли толпами протестанты, она стала возвращать католическую веру предков. . Все те, кто не хотел подчиняться вере, провозглашались еретиками. Мария реконструировала монастыри и вместе с этим приближала к себе людей, которые могли помочь ей в восстановлении страны.

Поскольку в Англии нашлось много людей, противившихся вере, Мария решила начать применять крайние меры. Не смотря на угрожающее прозвище королевы, она сделала много для страны. Историки того времени писали:

В 1955 году молодая королева издала закон, что власть правительницы женского пола, так же, как мужского, является полной, целостной и абсолютной, чем уравняла права в королевском наследовании трона.

Замужество и ложная беременность

Мужем королевы стал испанский наследник Филипп Баварский, которого Мария очень любила. Молодой супруг был намного младше и не питал никаких чувств к королеве. Всё, чего он хотел получить – это деньги и статус. Муж Марии был напыщенным и самовлюбленным, народ его не любил, как и его свиту, и это постоянно вызывало кровавые стычки на улицах.

Королева даже объявила о беременности, которая впоследствии оказалась ложной. Мэри сложно переживала этот период и несколько месяцев не выходила из дворца. Вот что об этом писали современники:

30 апреля 1555 года «колокола звонили по всей стране, запускались фейерверки, на улицах проходили массовые гулянья – а все это после новостей о том, что Мария I произвела на свет здорового сына. Но никакого сына не было. Надежда произвести наследника вскоре угасла.

В феврале 1555 года Англия превратилась в один большой костёр для иноверцев. Мария казнила протестантов по всей стране. За годы правления королевы было сожжено порядка трёхсот человек. По этой причине Марию и называли не иначе как Кровавая Мэри.

Но королева по своему была предана своей стране . Когда Англию охватила смертельная лихорадка, унесшая множество жизней, Мария также заболела. Зная, что исход может быть скорым и непредсказуемым, она составила завещание в пользу сестры Елизаветы, тем самым отстранив от престола ненавистного английскому люду Филиппа, который был занят только своими грязными делишками, и думал лишь о своей корысти.

На заметку!

Когда и как умерла английская королева

Мария I умерла 17 ноября 1558 года, не оставив наследников. Согласно основной версии, причиной смерти королевы была лихорадка, однако историки пришли к другому выводу. Ложные симптомы, указывающие на беременность, не могли появиться сами по себе. Скорее всего, у королевы была киста яичника или рак матки. Это и могло стать причиной её смерти.

Преемницей Марии стала её сестра Елизавета, дочь Генриха VIII и Анны Болейн. Вместе со смертью Кровавой Мэри в Англии закончился и век инквизиции. Несмотря на то, что у власти Мария была недолго, годы её правления стали важным периодом в жизни Англии.

Но — страна вздохнула с облегчением после ухода из жизни кровавой правительницы.

Елизавета, поддерживаемая знатью, быстро взошла на престол, и стала управлять страной. Марию похоронили лишь 13 декабря в капелле Генриха VII. Там же после смерти была похоронена и Елизавета. Надгробие венчает памятник второй сестре, и надпись, которая гласит:

Памятник Марии Первой Тюдор был поставлен лишь на родине мужа, в Испании, в Англии ни одного нет.

Мария I Тюдор (годы ее жизни — 1516-1558) — английская королева, известная также как Мария Кровавая. Ей не поставили на родине ни одного памятника (он есть только в Испании, где родился ее муж). Сегодня имя этой королевы ассоциируется в первую очередь с расправами. Действительно, их было множество в годы, когда на престоле находилась Мария Кровавая. По истории ее царствования написано множество книг, а интерес к ее личности не угасает и по сей день. Несмотря на то что в Англии день ее смерти (тогда же Елизавета I взошла на престол) отмечали как национальный праздник, эта женщина не была такой уж жестокой, как многие ее представляли. Прочитав статью, вы убедитесь в этом.

Родители Марии, ее детство

Родители Марии — английский король Генрих VIII Тюдор и Екатерина Арагонская, младшая испанская принцесса. Династия Тюдоров в то время была еще очень молодой, и Генрих был только вторым правителем Англии, относящимся к ней.

В 1516 году королева Екатерина родила дочь Марию, единственного своего жизнеспособного ребенка (у нее до этого было несколько неудачных родов). Отец девочки был разочарован, однако надеялся на появление в будущем наследников. Марию он любил, называл жемчужиной в своей короне. Он восхищался твердым и серьезным характером своей дочери. Девочка плакала очень редко. Она прилежно училась. Преподаватели обучали ее латыни, английскому, музыке, греческому, игре на клавесине и танцам. Будущая королева Мария Первая Кровавая интересовалась христианской литературой. Ее очень привлекали рассказы о древних девах-воительницах и женщинах-мученицах.

Кандидаты в мужья

Принцессу окружала многочисленная свита, соответствующая ее положению: придворный штат, капеллан, служанки и няни, леди-наставница. Повзрослев, Мария Кровавая начала заниматься соколиной охотой и верховой ездой. Хлопоты о ее замужестве, как это водится у королей, начались еще с младенчества. Девочке было 2 года, когда ее отец заключил договор о помолвке своей дочери с сыном Франциска I, французским дофином. Договор, однако, был расторгнут. Другим кандидатом в мужья 6-летней Марии был Карл V Габсбург, император Священной Римской империи, который был старше своей невесты на 16 лет. Однако принцесса не успела созреть для замужества.

Екатерина оказалась неугодна Генриху

На 16-м году супружества Генрих VIII, у которого до сих пор не было наследников мужского пола, решил, что его брак с Екатериной неугоден Богу. Появление на свет внебрачного сына свидетельствовало о том, что тому виной был не Генрих. Дело, оказывается, было в его супруге. Король назвал своего бастарда Генрихом Фицроем. Он подарил сыну поместья, замки и герцогский титул. Однако сделать Генриха наследником он не мог, учитывая то, что легитимность создания династии Тюдоров была сомнительна.

Развод, новая жена Генриха

А теперь, в 1525 году, король попросил у папы разрешения на развод. Климент VII не отказал, однако и не предоставил своего согласия. Он распорядился как можно дольше затягивать «дело короля». Генрих изложил своей супруге свое мнение по поводу бесплодности и греховности их брака. Он попросил ее согласиться на развод и уйти в монастырь, однако женщина ответила решительным отказом. Этим она обрекла себя на весьма незавидную участь — прозябание в захолустных замках под надзором и разлучение со своей дочерью. Несколько лет тянулось «дело короля». Архиепископ Кентерберийский, а также назначенный Генрихом примас церкви наконец объявили брак недействительным. Король был обвенчан с Анной Болейн, своей фавориткой.

Объявление Марии незаконнорожденной

Тогда Климент VII решил отлучить от церкви Генриха. Он объявил его дочь от новой королевы Елизавету незаконнорожденной. Т. Кранбер в ответ на это объявил по приказу короля незаконнорожденной и Марию, дочь Екатерины. Она была лишена всех привилегий, полагающихся наследнице.

Генрих становится главой англиканской церкви

Парламент в 1534 году подписал «Акт о супремации», по которому король возглавил англиканскую церковь. Некоторые догматы религии были пересмотрены и отменены. Так возникла англиканская церковь, которая находилась как бы посередине между протестантством и католичеством. Те, кто отказался ее принять, были объявлены изменниками и подвергнуты суровым наказаниям. Отныне конфисковывалось имущество, принадлежавшее католической церкви, а церковные поборы начали поступать в королевскую казну.

Тяжелое положение Марии

Мария Кровавая со смертью своей матери осиротела. Она стала всецело зависеть от жен своего отца. Анна Болейн ее ненавидела, всячески над ней издевалась и даже применяла рукоприкладство. Сам факт того, что в апартаментах, принадлежавших когда-то ее матери, теперь проживала эта женщина, которая носила драгоценности и корону Екатерины, причинял большие страдания Марии. За нее бы заступились испанские бабушка с дедом, однако к этому времени они уже умерли, а их наследнику хватало проблем и в своей стране.

Недолгим было счастье Анны Болейн — до того как на свет появилась дочь вместо сына, ожидаемого королем и обещанного ею. Всего 3 года она пробыла королевой и пережила Екатерину только на 5 месяцев. Анна была обвинена в государственной и супружеской измене. Женщина взошла на эшафот в мае 1536 г., а Елизавета, ее дочь, была объявлена незаконнорожденной, как прежде будущая Мария Кровавая Тюдор.

Другие мачехи Марии

И лишь когда скрепя сердце наша героиня согласилась признать Генриха VIII главой англиканской церкви, в душе своей оставаясь католичкой, ей наконец вернули свиту и доступ во дворец короля. Мария Кровавая Тюдор, однако, не вышла замуж.

Генрих через несколько дней после смерти Болейн женился на фрейлине Джейн Сеймур. Она пожалела Марию и уговорила своего мужа возвратить ее во дворец. Сеймур родила Генриху VIII, которому к тому времени было уже 46 лет, долгожданного сына Эдуарда VI, а сама умерла от родильной горячки. Известно, что король ценил и любил третью жену больше других и завещал похоронить себя возле ее могилы.

Четвертый брак для короля сложился неудачно. Увидев Анну Клевскую, свою супругу, в натуре, он пришел в ярость. Генрих VIII после развода с ней казнил Кромвеля, своего первого министра, который был организатором сватовства. С Анной он развелся через полгода, в соответствии с брачным договором, не вступая с ней в плотские отношения. Он дал ей после развода титул приемной сестры, а также небольшое владение. Отношения между ними были практически родственными, как и отношения Клевской с детьми короля.

Кэтрин Готвард, следующая мачеха Марии, была обезглавлена в Тауэре, после 1,5 лет брака, за супружескую измену. За 2 года до кончины короля был заключен шестой брак. Екатерина Парр заботилась о детях, ухаживала за своим больным супругом, была хозяйкой двора. Эта женщина убедила короля быть более доброжелательным к своим дочерям Елизавете и Марии. Екатерина Парр пережила короля и избежала казни лишь из-за собственной находчивости и по счастливой случайности.

Смерть Генриха VIII, признание Марии законнорожденной

Генрих VIII скончался в январе 1547 г., завещав Эдуарду, своему малолетнему сыну, корону. В случае если его потомок умрет, она должна была достаться дочерям — Елизавете и Марии. Эти принцессы были наконец признаны законнорожденными. Это давало им возможность рассчитывать на корону и достойное замужество.

Правление Эдуарда и его смерть

Мария из-за приверженности к католичеству терпела гонения. Она даже хотела покинуть Англию. Для короля Эдуарда была нестерпима мысль о том, что она вступит на престол после него. По совету лорда-протектора он решил переписать отцовское завещание. Наследницей была объявлена 16-летняя Джейн Грей, троюродная сестра Эдуарда и внучка Генриха VII. Она была протестанткой, а также невесткой Нортумберленда.

Эдуард VI вдруг заболел спустя 3 дня после утверждения составленного им завещания. Это произошло летом 1553 года. Вскоре он скончался. Согласно одной из версий, смерть наступила от туберкулеза, поскольку он с самого детства был слаб здоровьем. Однако есть и другая версия. Герцог Нортумберленд при подозрительных обстоятельствах удалил от короля лечащих врачей. У его постели появилась знахарка. Она якобы дала Эдуарду дозу мышьяка. После этого король почувствовал себя хуже и испустил дух в возрасте 15 лет.

Мария становится королевой

После его смерти королевой стала Джейн Грей, которой было в то время 16 лет. Однако народ взбунтовался, не признав ее. Через месяц Мария взошла на престол. Ей было к этому времени уже 37 лет. После царствования Генриха VIII, который провозгласил себя главой Церкви и был отлучен от нее папой римским, в государстве было разрушено около половины всех монастырей и церквей. Непростую задачу должна была решить после смерти Эдуарда Мария Кровавая. Англия, которая ей досталась, была разорена. Ее нужно было срочно возрождать. За первые полгода она казнила Джейн Грей, ее супруга Гилфорда Дадли, а также свекра Джона Дадли.

Казнь Джейн и ее мужа

Правление Марии Кровавой

Мария снова приблизила к себе тех, кто еще недавно был в числе ее противников. Она понимала, что они могут помочь ей в управлении государством. Восстановление страны началось с возрождения католической веры, которое предприняла Мария Кровавая. Попытка контрреформации — так называется оно на научном языке. Были реконструированы многие монастыри. Однако на период правления Марии пришлось множество казней протестантов. Костры запылали с февраля 1555 г. Сохранилось много свидетельств о том, как люди мучились, умирая за веру. Около 300 человек были сожжены. Среди них были Латимер, Ридли, Крамнер и другие иерархи церкви. Королева распорядилась не щадить и тех, кто был согласен стать католиком, оказавшись перед костром. За все эти жестокости Мария и получила свое прозвище Кровавая.

Замужество Марии

Королева вышла замуж за сына Карла V Филиппа (летом 1554 г.). Супруг был на 12 лет моложе Марии. Согласно брачному договору, он не мог вмешиваться в управление страной, а рожденные от брака дети должны были стать наследниками английского трона. Филипп в случае преждевременной кончины Марии должен был возвратиться в Испанию. Англичане невзлюбили супруга королевы. Хотя Мария делала попытки через парламент утвердить решение о том, чтобы Филипп считался королем Англии, ей было отказано в этом. Сын Карла V был высокомерен и напыщен. Прибывшая вместе с ним свита вела себя вызывающе.

Кровавые стычки между испанцами и англичанами начали происходить на улицах после прибытия Филиппа.

Болезнь и смерть

У Марии в сентябре были обнаружены признаки беременности. Составили завещание, согласно которому Филипп должен был стать регентом ребенка до его совершеннолетия. Однако ребенок не появился на свет. Мария назначила преемником Елизавету, свою сестру.

В мае 1558 г. стало ясно, что мнимая беременность на самом деле была симптомом болезни. Мария страдала от лихорадки, головной боли, бессонницы. Она начала терять зрение. Летом королева заразилась гриппом. Елизавета была официально назначена преемницей 6 ноября 1558 г. Мария умерла 17 ноября этого же года. Историки считают, что болезнь, от которой скончалась королева — киста яичника или рак матки. Останки Марии покоятся в Вестминстерском аббатстве. Престол после ее смерти унаследовала Елизавета I.

Мария I Тюдор (1516-1558) – первая коронованная королева Англии, старшая дочь Генриха 8 и Екатерины Арагонской. Также известна под прозвищами Мария Кровавая (Кровавая Мэри) и Мария Католичка. В ее честь не было установлено ни одного памятника на родине.

С именем этой королевы ассоциируются жестокие и кровавые расправы. День ее смерти (и одновременно день восхождения на трон Елизаветы 1) отмечали в государстве как национальный праздник.

В биографии Марии Тюдор есть много интересных фактов, о которых мы расскажем в данной статье.

Итак, перед вами краткая биография Марии I Тюдор.

Биография Марии Тюдор

Мария Тюдор появилась на свет 18 февраля 1516 году в Гринвиче. У своих родителей она была долгожданным ребенком, поскольку все предыдущие дети английского короля Генриха 8 и его супруги Екатерины Арагонской, умирали еще в утробе, либо сразу после рождения.

Девочка отличалась серьезностью и ответственностью, вследствие чего уделяла большое внимание учебе. Благодаря этим качествам, Мария овладела греческим и латинским языками, а также хорошо танцевала и играла на клавесине.

В подростковом возрасте Тюдор увлекалась чтением христианских книг. В это время биографии она обучалась верховой езде и соколиной охоте. Поскольку Мария была единственным ребенком у своего отца, именно ей должен был перейти престол.

В 1519 г. девушка могла лишиться этого права, так как любовница монарха, Элизабет Блаунт, родила ему сына Генриха. И хотя мальчик был рожден вне брака, он все же имел королевское происхождение, вследствие чего к нему приставили свиту и удостоили соответствующих титулов.

Правление

Спустя какое-то время король начал рассуждать над тем, кому должна перейти власть. В результате, он решил сделать Марию принцессой Уэльской. Стоит отметить, что тогда Уэльс еще не был частью Англии, но находился у нее в подчинении.

В 1525 г. Мария Тюдор обосновалась в своих новых владениях, взяв с собой многочисленную свиту. Ей предстояло следить за правосудием и выполнением церемониальных мероприятий. Интересен факт, что на тот момент ей было всего 9 лет.

Спустя 2 года произошли серьезные перемены, которые круто повлияли на биографию Тюдор. После продолжительного брака Генрих аннулировал отношения с Екатериной, вследствие чего Мария автоматически признавалась незаконной дочерью, что грозило ей потерей права на престолонаследие.

Однако оскорбленная супруга не признала фиктивность брака. Это привело к тому, что король стал угрожать Екатерине и запрещать видеться с дочкой. Жизнь Марии еще больше ухудшилась, когда у отца появились новые жены.

Первой избранницей Генриха 8 была Анна Болейн, родившая ему девочку Елизавету. Но когда монарх узнал об изменах Анны, он распорядился казнить ее.

После этого он взял в жены более покладистую Джейн Сеймур. Именно она родила мужу первого законного сына, умерев от послеродовых осложнений.

Следующими женами английского правителя становились Анна Клевская, Екатерина Говард и Екатерина Парр. Имея брата Эдуарда по отцовской линии, который в возрасте 9 лет сел на трон, Мария теперь была второй претенденткой на престол.

Мальчик не отличался хорошим здоровьем, поэтому его регенты опасались, что если Мария Тюдор выйдет замуж, она устремит все силы для свержения Эдуарда. Слуги настраивали юношу против сестры и мотивацией для этого была фанатичная приверженность девушки к католичеству, тогда как Эдуард являлся протестантом.

К слову, именно по этой причине Тюдор получила прозвище – Мария Католичка. В 1553 г. у Эдуарда обнаружили туберкулез, от которого тот и скончался. Накануне смерти он подписал указ, согласно которому его преемницей становилась Джейн Грей из рода Тюдоров.

В итоге, Мария и ее сестра по отцу – Елизавета, лишались права на корону. Но когда 16-летняя Джейн стала главой государства, она не имела поддержки со стороны подданных.

Это привело к тому, что всего через 9 дней ее сместили с престола, а ее место заняла Мария Тюдор. Новоизбранной королеве пришлось управлять странной сильно пострадавшей от рук ее предшественников, которые разграбили казну и разрушили более половины храмов.

Биографы Марии характеризует ее как не жестокого человека. Стать такой ее скорее побудили сложившиеся обстоятельства, требующие жестких решений. За первые 6 месяцев нахождения у власти, она казнила Джейн Грей и некоторых своих родственников.

Массовые казни при правлении Марии Тюдор

При этом изначально королева хотела помиловать всех осужденных, однако после восстания Уайетта в 1554 г. она не смогла этого сделать. В последующие годы биографии Мария Тюдор активно отстраивала церкви и монастыри, делая все возможное для возрождения и развития католицизма.

Вместе с тем по ее распоряжению казнили множество протестантов. На кострах было сожжено примерно 300 человек. Интересен факт, что на пощаду не могли надеяться даже те, кто оказавшись перед костром, соглашались принять католичество.

По этой и другим причинам, королеву начали называть – Мария Кровавая или Кровавая Мэри.

Личная жизнь

Родители выбрали для Марии жениха, когда ей едва исполнилось 2 года. Генрих договорился о помолвке дочери с сыном Франциска 1, но позже помолвка была расторгнута.

Спустя 4 года отец вновь договаривается о женитьбе девочки с императором Священной Римской империи Карлом 5 Габсбургом, который был старше Марии на 16 лет. Но когда в 1527 г. английский король пересмотрел свое отношение к Риму, его симпатия к Карлу улетучилась.

Генрих задался целью выдать дочь замуж за кого-нибудь из высокопоставленных королевских особ Франции, коими могли стать Франциск 1 или его сын.

Однако, когда отец решил бросить мать Марии, все изменилось. В итоге, девушка оставалась незамужней вплоть до смерти короля. К слову, на тот момент ей исполнился уже 31 год.

В 1554 г. Тюдор вступила в брак с монархом Испании Филиппом 2. Интересно, что она была на 12 лет старше своего избранника. Детей в этом союзе так и не родилось. Народ не любил Филиппа за его чрезмерную гордость и тщеславие.

Мария Тюдор и ее муж Филипп 2

Свита, приехавшая с ним, вела себя недостойным образом. Это привело к тому, что на улицах начали происходить кровавые столкновения между англичанами и испанцами. Филипп не скрывал, что не испытывал к Марии никаких чувств.

Испанец был увлечен сестрой супруги – Елизаветой Тюдор. Он питал надежды, что со временем престол перейдет к ней, вследствие чего поддерживал с девушкой дружеские отношения.

Смерть

В 1557 г. Европу поглотила лихорадка вирусной породы, которая привела к смертям большого количества людей. Летом следующего года Мария также заболела лихорадкой осознав, что ей вряд ли удастся выжить.

Королева переживала за будущее государства, поэтому не теряя времени составила документ, лишавший Филиппа прав на Англию. Она сделала своей преемницей сестру Елизавету, несмотря на то, что при жизни они часто конфликтовали.

Фото Марии Тюдор

Мария Тюдор и ее отец Генрих 8

18 Февраля 1516 – 17 Ноября 1558 гг. (42 года)

Мария I Тюдор (1516–1558 гг.) — первая коронованная королева Англии, дочь Генриха 8, которая вошла в историю как Мария Кровавая. Ее имя всегда ассоциировалось с многочисленными жестокими расправами, а день ее смерти в Англии отмечался как национальный праздник. Биография Кровавой Марии богата интересными фактами. Рассмотрим кратко самые важные из них, которые позволят лучше узнать личность королевы Англии.

Детство и юность

Мария I Тюдор родилась 18 февраля 1516 года в Лондоне. Ее отцом был король Англии Генрих VIII, а матерью — младшая принцесса Испании Екатерина Арагонская. Она оказалась первым ребенком королевской четы, который смог выжить: до ее рождения королева шесть раз беременела, но так и не смогла подарить супругу наследника.

С юных лет принцесса обладала твердым, сдержанным характером, которым восхищался отец. Девочка прилежно училась и уже в раннем возрасте прекрасно владела латынью и греческим языком, была очень образованной, играла на клавесине и танцевала.

Жизнь с мачехами

Генрих VIII, потеряв надежду получить законного наследника от королевы Екатерины, решил аннулировать брак с ней. Но в результате подобного решения Мария автоматически бы становилась незаконнорожденной дочерью и теряла все права на корону.

Екатерина не давала согласие на расторжение брака, и тогда Генрих VIII самовольно женился на Анне Болейн. Мачеха пыталась наладить хорошие отношения с Марией, но та категорически отказывалась идти на контакт. После казни Анны Болейн по обвинению в супружеской измене король взял в жены Джейн Сеймур, которая родила ему сына Эдуарда, но сама умерла после родов.

Отныне Генрих VIII менял жен, как перчатки, и Марии Тюдор приходилось каждый раз привыкать к новой мачехе. Когда умер король Генрих, Марии исполнился 31 год, и она еще не была замужем. Наследником становился болезненный Эдуард, который скончался в юном возрасте от туберкулеза. Перед смертью его заставили подписать указ о престолонаследии, по которому Мария Тюдор лишалась возможности взойти на престол. Однако подобное решение вызвало негодование у народа, и в 1553 году Мария стала королевой Англии.

Правление

После правления Генриха VIII, отлученного папой римским от церкви, в Англии было разрушено немало монастырей и церквей. Свита короля Эдуарда полностью разворовала королевскую казну. Перед новой королевой стояла непростая задача: возродить из пепла бедную страну, которая ей досталась по наследству.

В первые полгода правления Мария Тюдор отправила на плаху всех тех, кто строил против нее интриги и заговоры и у кого был хоть малейший шанс свергнуть ее с престола. Вместе с тем королева приблизила к себе людей, которые еще вчера были против нее, но могли оказать существенную помощь в управлении страной.

Будучи глубоко верующей католичкой, Мария начала восстановительные работы в стране с реконструкции монастырей и укрепления католической веры. При этом она безжалостно отправляла на казнь протестантов: за годы правления Марии Тюдор было убито около трехсот иноверцев. Именно тогда за ней закрепилось прозвище королева Кровавая Мэри.

Личная жизнь

Еще в детстве Мария I Тюдор была помолвлена с юным императором Священной Римской империи Карлом V Габсбургом. Однако этот брак так и не состоялся из-за испорченных отношений Генриха с Римской Церковью.

Бесконечная череда мачех не давала Марии возможность устроить свою личную жизнь, и потому на момент коронации она все еще оставалась незамужней женщиной.

В 1554 году Тюдор все же связала себя узами брака с королем Испании из династии Габсбургов Филиппом II. Она настояла на том, чтобы супруг подписал договор, согласно которому не смел вмешиваться в управление Англией. Вскоре королева объявила о беременности, но она оказалась ложной.

Народ сразу невзлюбил высокомерного короля Филиппа, чья свита вела себя крайне вызывающе. На улицах Англии нередкими стали стычки между испанцами и местными жителями.

Последние годы жизни

Читайте также:

- Сообщение о лиственном дереве 1 класс окружающий мир

- Сообщение моя бабушка строитель

- Сообщение о андреевича крылова где он учился

- Сообщение о жизнедеятельности клетки

- Сообщение про санки 2 класс

| Mary I | |

|---|---|

Portrait by Antonis Mor, 1554 |

|

| Queen of England and Ireland

(more…) |

|

| Reign | July 1553[a] – 17 November 1558 |

| Coronation | 1 October 1553 |

| Predecessor | Jane (disputed) or Edward VI |

| Successor | Elizabeth I |

| Co-monarch | Philip (1554–1558) |

| Queen consort of Spain | |

| Tenure | 16 January 1556 – 17 November 1558 |

| Born | 18 February 1516 Palace of Placentia, Greenwich, England |

| Died | 17 November 1558 (aged 42) St James’s Palace, London, England |

| Burial | 14 December 1558

Westminster Abbey, London |

| Spouse |

Philip II of Spain (m. ) |

| House | Tudor |

| Father | Henry VIII |

| Mother | Catherine of Aragon |

| Religion | Roman Catholicism |

| Signature |

Mary I (18 February 1516 – 17 November 1558), also known as Mary Tudor, and as «Bloody Mary» by her Protestant opponents, was Queen of England and Ireland from July 1553 and Queen of Spain from January 1556 until her death in 1558. She is best known for her vigorous attempt to reverse the English Reformation, which had begun during the reign of her father, Henry VIII. Her attempt to restore to the Church the property confiscated in the previous two reigns was largely thwarted by Parliament, but during her five-year reign, Mary had over 280 religious dissenters burned at the stake in the Marian persecutions.

Mary was the only child of Henry VIII by his first wife, Catherine of Aragon, to survive to adulthood. Her younger half-brother, Edward VI, succeeded their father in 1547 at the age of nine. When Edward became terminally ill in 1553, he attempted to remove Mary from the line of succession because he supposed, correctly, that she would reverse the Protestant reforms that had taken place during his reign. Upon his death, leading politicians proclaimed Lady Jane Grey as queen. Mary speedily assembled a force in East Anglia and deposed Jane, who was ultimately beheaded. Mary was—excluding the disputed reigns of Jane and the Empress Matilda—the first queen regnant of England. In July 1554, Mary married Philip of Spain, becoming queen consort of Habsburg Spain on his accession in January 1556.

After Mary’s death in 1558, her re-establishment of Roman Catholicism was reversed by her younger half-sister and successor, Elizabeth I.

Birth and family[edit]

Mary was born on 18 February 1516 at the Palace of Placentia in Greenwich, England. She was the only child of King Henry VIII and his first wife, Catherine of Aragon, to survive infancy. Her mother had suffered many miscarriages and stillbirths.[3] Before Mary’s birth, four previous pregnancies had resulted in a stillborn daughter and three short-lived or stillborn sons, including Henry, Duke of Cornwall.[4]

Mary was baptised into the Catholic faith at the Church of the Observant Friars in Greenwich three days after her birth.[5] Her godparents included Lord Chancellor Thomas Wolsey; her great-aunt Catherine, Countess of Devon; and Agnes Howard, Duchess of Norfolk.[6] Henry VIII’s first cousin once removed, Margaret Pole, Countess of Salisbury, stood sponsor for Mary’s confirmation, which was conducted immediately after the baptism.[7] The following year, Mary became a godmother herself when she was named as one of the sponsors of her cousin Frances Brandon.[8] In 1520, the Countess of Salisbury was appointed Mary’s governess.[9] Sir John Hussey (later Lord Hussey) was her chamberlain from 1530, and his wife Lady Anne, daughter of George Grey, 2nd Earl of Kent, was one of Mary’s attendants.[10]

Childhood[edit]

Mary at the time of her engagement to Emperor Charles V. She is wearing a rectangular brooch inscribed with «The Emperour».[11]

Mary was a precocious child.[12] In July 1520, when scarcely four and a half years old, she entertained a visiting French delegation with a performance on the virginals (a type of harpsichord).[13] A great part of her early education came from her mother, who consulted the Spanish humanist Juan Luis Vives for advice and commissioned him to write De Institutione Feminae Christianae, a treatise on the education of girls.[14] By the age of nine, Mary could read and write Latin.[15] She studied French, Spanish, music, dance, and perhaps Greek.[16] Henry VIII doted on his daughter and boasted to the Venetian ambassador Sebastian Giustiniani that Mary never cried.[17] Mary had a fair complexion with pale blue eyes and red or reddish-golden hair. She was ruddy-cheeked, a trait she inherited from her father.[18]

Despite his affection for Mary, Henry was deeply disappointed that his marriage had produced no sons.[19] By the time Mary was nine years old, it was apparent that Henry and Catherine would have no more children, leaving Henry without a legitimate male heir.[20] In 1525, Henry sent Mary to the border of Wales to preside, presumably in name only, over the Council of Wales and the Marches.[21] She was given her own court based at Ludlow Castle and many of the royal prerogatives normally reserved for a Prince of Wales. Vives and others called her the Princess of Wales, although she was never technically invested with the title.[22] She appears to have spent three years in the Welsh Marches, making regular visits to her father’s court, before returning permanently to the home counties around London in mid-1528.[23]

Emperor Charles V, Mary’s cousin and later father-in-law

Throughout Mary’s childhood, Henry negotiated potential future marriages for her. When she was only two years old, Mary was promised to Francis, Dauphin of France, the infant son of King Francis I, but the contract was repudiated after three years.[24] In 1522, at the age of six, she was instead contracted to marry her 22-year-old cousin Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor.[25] However, Charles broke off the engagement within a few years with Henry’s agreement.[26] Cardinal Wolsey, Henry’s chief adviser, then resumed marriage negotiations with the French, and Henry suggested that Mary marry the French king Francis I, who was eager for an alliance with England.[27] A marriage treaty was signed which provided that Mary marry either Francis I or his second son Henry, Duke of Orleans,[28] but Wolsey secured an alliance with France without the marriage.

In 1528, Wolsey’s agent Thomas Magnus discussed the idea of her marriage to her cousin James V of Scotland with the Scottish diplomat Adam Otterburn.[29] According to the Venetian Mario Savorgnano, by this time Mary was developing into a pretty, well-proportioned young lady with a fine complexion.[30]

Adolescence[edit]

Although these various possibilities for Mary’s marriage had been considered, the marriage of Mary’s parents was itself in jeopardy, which threatened her status. Disappointed at the lack of a male heir, and eager to remarry, Henry attempted to have his marriage to Catherine annulled, but Pope Clement VII refused his request. Henry claimed, citing biblical passages (Leviticus 20:21), that the marriage was unclean because Catherine was the widow of his brother Arthur, Prince of Wales (Mary’s uncle). Catherine claimed that her marriage to Arthur was never consummated and so was not a valid marriage. Pope Julius II had issued a dispensation on that basis. Clement VII may have been reluctant to act because he was influenced by Charles V, Catherine’s nephew and Mary’s former betrothed, whose troops had surrounded and occupied Rome in the War of the League of Cognac.[31]

From 1531, Mary was often sick with irregular menstruation and depression, although it is not clear whether this was caused by stress, puberty or a more deep-seated disease.[32] She was not permitted to see her mother, whom Henry had sent to live away from court.[33] In early 1533, Henry married Anne Boleyn, and in May, Thomas Cranmer, the Archbishop of Canterbury, formally declared the marriage with Catherine void and the marriage to Anne valid. Henry repudiated the pope’s authority, declaring himself Supreme Head of the Church of England. Catherine was demoted to Dowager Princess of Wales (a title she would have held as Arthur’s widow), and Mary was deemed illegitimate. She was styled «The Lady Mary» rather than Princess, and her place in the line of succession was transferred to Henry and Anne’s newborn daughter, Elizabeth.[34] Mary’s household was dissolved;[35] her servants (including the Countess of Salisbury) were dismissed and, in December 1533, she was sent to join her infant half-sister’s household at Hatfield, Hertfordshire.[36]

Mary determinedly refused to acknowledge that Anne was the queen or that Elizabeth was a princess, further enraging King Henry.[37] Under strain and with her movements restricted, Mary was frequently ill, which the royal physician attributed to her «ill treatment».[38] The Imperial ambassador Eustace Chapuys became her close adviser, and interceded, unsuccessfully, on her behalf at court.[39] The relationship between Mary and her father worsened; they did not speak to each other for three years.[40] Although both she and her mother were ill, Mary was refused permission to visit Catherine.[41] When Catherine died in 1536, Mary was «inconsolable».[42] Catherine was interred in Peterborough Cathedral, while Mary grieved in semi-seclusion at Hunsdon in Hertfordshire.[43]

Adulthood[edit]

In 1536, Queen Anne fell from the king’s favour and was beheaded. Elizabeth, like Mary, was declared illegitimate and stripped of her succession rights.[44] Within two weeks of Anne’s execution, Henry married Jane Seymour, who urged her husband to make peace with Mary.[45] Henry insisted that Mary recognise him as head of the Church of England, repudiate papal authority, acknowledge that the marriage between her parents was unlawful, and accept her own illegitimacy. She attempted to reconcile with Henry by submitting to his authority as far as «God and my conscience» permitted, but was eventually bullied into signing a document agreeing to all of Henry’s demands.[46] Reconciled with her father, Mary resumed her place at court.[47] Henry granted her a household, which included the reinstatement of Mary’s favourite, Susan Clarencieux.[48] Mary’s privy purse accounts for this period, kept by Mary Finch, show that Hatfield House, the Palace of Beaulieu (also called Newhall), Richmond and Hunsdon were among her principal places of residence, as well as Henry’s palaces at Greenwich, Westminster and Hampton Court.[49] Her expenses included fine clothes and gambling at cards, one of her favourite pastimes.[50] Rebels in the North of England, including Lord Hussey, Mary’s former chamberlain, campaigned against Henry’s religious reforms, and one of their demands was that Mary be made legitimate. The rebellion, known as the Pilgrimage of Grace, was ruthlessly suppressed.[51] Along with other rebels, Hussey was executed, but there is no suggestion that Mary was directly involved.[52] In 1537, Queen Jane died after giving birth to a son, Edward. Mary was made godmother to her half-brother and acted as chief mourner at the queen’s funeral.[53]

1545 painting showing left to right ‘Mother Jak’, Mary, Edward, Henry VIII, Jane Seymour (posthumous), Elizabeth and Will Somers (court fool)

Mary was courted by Philip, Duke of Bavaria, from late 1539, but he was Lutheran and his suit for her hand was unsuccessful.[54] Over 1539, the king’s chief minister, Thomas Cromwell, negotiated a potential alliance with the Duchy of Cleves. Suggestions that Mary marry William I, Duke of Cleves, who was the same age, came to nothing, but a match between Henry and the Duke’s sister Anne was agreed.[55] When the king saw Anne for the first time in late December 1539, a week before the scheduled wedding, he found her unattractive but was unable, for diplomatic reasons and without a suitable pretext, to cancel the marriage.[56] Cromwell fell from favour and was arrested for treason in June 1540; one of the unlikely charges against him was that he had plotted to marry Mary himself.[57] Anne consented to the annulment of the marriage, which had not been consummated, and Cromwell was beheaded.[58]

In 1541, Henry had the Countess of Salisbury, Mary’s old governess and godmother, executed on the pretext of a Catholic plot in which her son Reginald Pole was implicated.[59] Her executioner was «a wretched and blundering youth» who «literally hacked her head and shoulders to pieces».[60] In 1542, following the execution of Henry’s fifth wife, Catherine Howard, the unmarried Henry invited Mary to attend the royal Christmas festivities.[61] At court, while her father was between marriages and thus without a consort, Mary acted as hostess.[62] In 1543, Henry married his sixth and last wife, Catherine Parr, who was able to bring the family closer together.[63] Henry returned Mary and Elizabeth to the line of succession through the Act of Succession 1544 (also known as the Third Succession Act), placing them after Edward – though both remained legally illegitimate.[64]

Henry VIII died in 1547, and Edward succeeded him. Mary inherited estates in Norfolk, Suffolk and Essex, and was granted Hunsdon and Beaulieu as her own.[65] Since Edward was still a child, rule passed to a regency council dominated by Protestants, who attempted to establish their faith throughout the country. For example, the Act of Uniformity 1549 prescribed Protestant rites for church services, such as the use of Thomas Cranmer’s Book of Common Prayer. Mary remained faithful to Roman Catholicism and defiantly celebrated traditional Mass in her own chapel. She appealed to her cousin Emperor Charles V to apply diplomatic pressure demanding that she be allowed to practise her religion.[66]

For most of Edward’s reign, Mary remained on her own estates and rarely attended court.[67] A plan between May and July 1550 to smuggle her out of England to the safety of the European mainland came to nothing.[68] Religious differences between Mary and Edward continued. Mary attended a reunion with Edward and Elizabeth for Christmas 1550, where the 13-year-old Edward embarrassed Mary, then 34, and reduced both her and himself to tears in front of the court, by publicly reproving her for ignoring his laws regarding worship.[69] Mary repeatedly refused Edward’s demands that she abandon Catholicism, and Edward persistently refused to drop his demands.[70]

Accession[edit]

On 6 July 1553, at the age of 15, Edward VI died of a lung infection, possibly tuberculosis.[71] He did not want the crown to go to Mary because he feared she would restore Catholicism and undo his and their father’s reforms, and so he planned to exclude her from the line of succession. His advisers told him that he could not disinherit only one of his half-sisters: he would have to disinherit Elizabeth as well, even though she was a Protestant. Guided by John Dudley, 1st Duke of Northumberland, and perhaps others, Edward excluded both from the line of succession in his will.[72]

Contradicting the Act of Succession 1544, which restored Mary and Elizabeth to the line of succession, Edward named Northumberland’s daughter-in-law Lady Jane Grey, the granddaughter of Henry VIII’s younger sister Mary, as his successor. Lady Jane’s mother was Frances Brandon, Mary’s cousin and goddaughter. Just before Edward’s death, Mary was summoned to London to visit her dying brother, but was warned that the summons was a pretext on which to capture her and thereby facilitate Jane’s accession to the throne.[73] Therefore, instead of heading to London from her residence at Hunsdon, Mary fled to East Anglia, where she owned extensive estates and Northumberland had ruthlessly put down Kett’s Rebellion. Many adherents to the Catholic faith, opponents of Northumberland, lived there.[74] On 9 July, from Kenninghall, Norfolk, she wrote to the privy council with orders for her proclamation as Edward’s successor.[75]

On 10 July 1553, Lady Jane was proclaimed queen by Northumberland and his supporters, and on the same day Mary’s letter to the council arrived in London. By 12 July, Mary and her supporters had assembled a military force at Framlingham Castle, Suffolk.[76] Northumberland’s support collapsed,[77] and Jane was deposed on 19 July.[78] She and Northumberland were imprisoned in the Tower of London. Mary rode triumphantly into London on 3 August 1553, on a wave of popular support. She was accompanied by her half-sister Elizabeth and a procession of over 800 nobles and gentlemen.[79]

Reign[edit]

One of Mary’s first actions as queen was to order the release of the Roman Catholic Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk, and Stephen Gardiner from imprisonment in the Tower of London, as well as her kinsman Edward Courtenay.[80] Mary understood that the young Lady Jane was essentially a pawn in Northumberland’s scheme, and Northumberland was the only conspirator of rank executed for high treason in the immediate aftermath of the attempted coup. Lady Jane and her husband, Lord Guildford Dudley, though found guilty, were kept under guard in the Tower rather than immediately executed, while Lady Jane’s father, Henry Grey, 1st Duke of Suffolk, was released.[81] Mary was left in a difficult position, as almost all the Privy Counsellors had been implicated in the plot to put Lady Jane on the throne.[82] She appointed Gardiner to the council and made him both Bishop of Winchester and Lord Chancellor, offices he held until his death in November 1555. Susan Clarencieux became Mistress of the Robes.[83] On 1 October 1553, Gardiner crowned Mary at Westminster Abbey.[84]

Spanish marriage[edit]