Морские ежи

Это донные животные, относящиеся к классу иглокожих. Они обитают практически во всех морях и океанах. Главное условие их существования — это очень соленая вода, поэтому в морях с невысоким содержанием соли, таких как Черное, Каспийское и Балтийское, их практически нет. Самые опасные виды ядовитых морских ежей встречаются в тропических водах Атлантического, Индийского и Тихого океанов.

Внешний вид

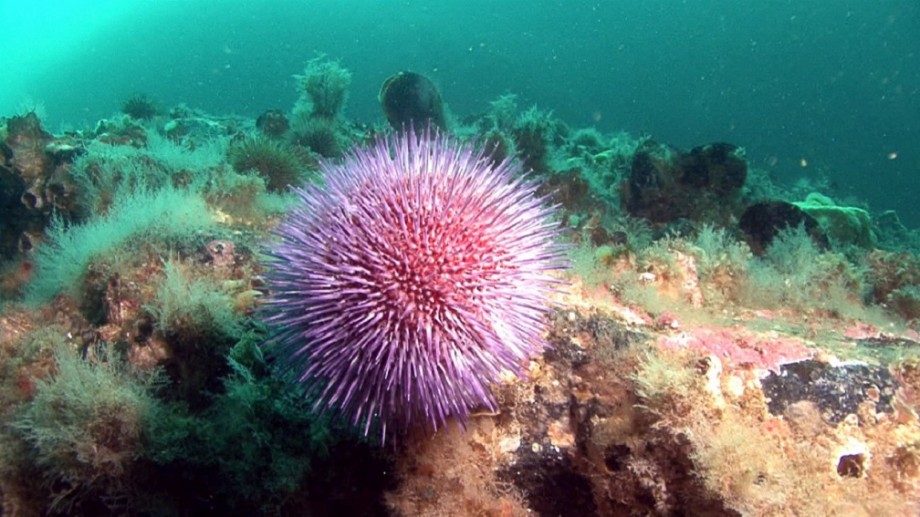

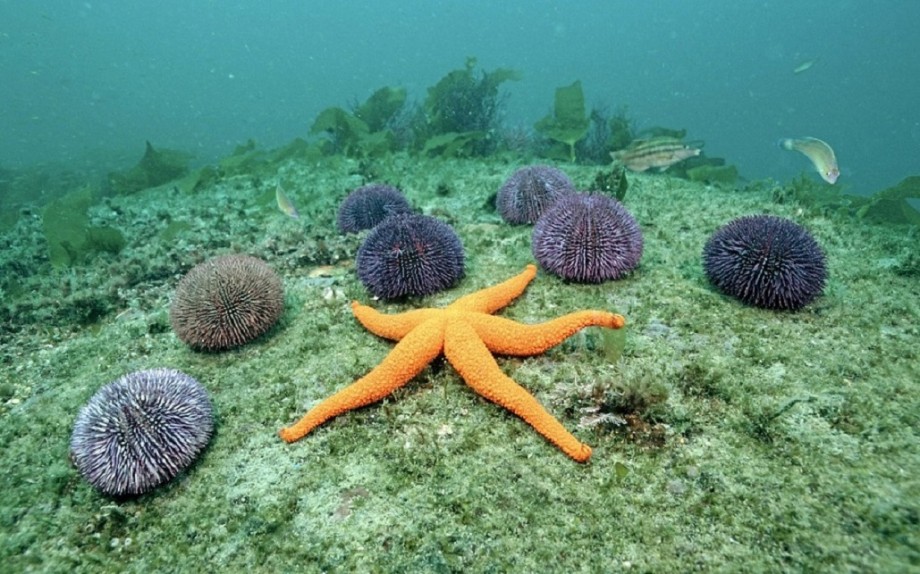

Пурпурный морской еж обитает вдоль Тихоокеанского побережья Северной Америки. Название получил за фиолетовый оттенок окраски тела. Диаметр его панциря составляет от 5 до 10 см

В настоящее время известно более 900 различных видов морских ежей, объединенных в 2 подкласса: правильные и неправильные. Правильные имеют круглый симметричный панцирь, а неправильные — уплощенный. К панцирю крепятся иглы, способные двигаться в различных направлениях и выполняющие сразу несколько функций: с их помощью ежи перемещаются, защищаются от хищников и добывают пищу. У одних видов иглы почти незаметные — не больше 2 мм, у других — длинные, около 30 см, иногда ядовитые. В основном морские ежи бывают пурпурными и розовыми, реже встречаются коричневые, зеленые, черные, белые, красные.

Ножки-трубочки

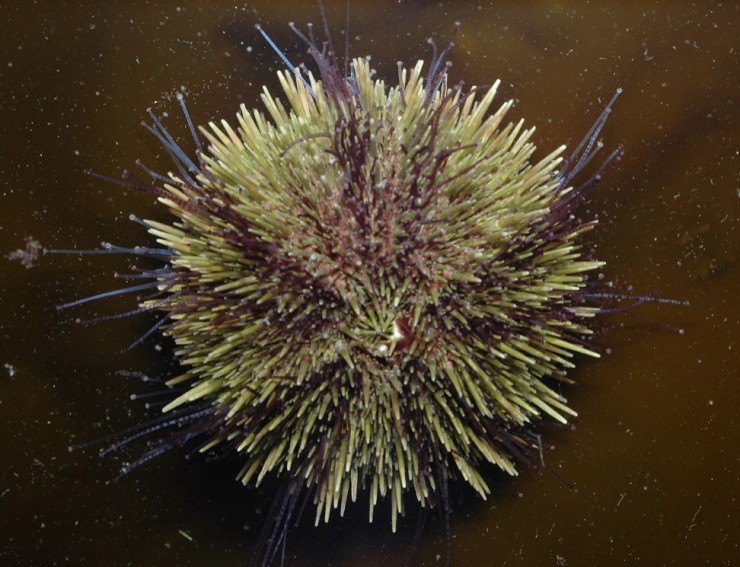

Зеленый морской еж обитает в морях Атлантического и Тихого океанов. Поверхность его панциря покрыта многочисленными подвижными иглами и педицелляриями

Панцирь морского ежа пронизывают сотни цилиндрических трубочек с присосками на конце. Наполняясь водой, эти ножки-трубочки растягиваются и крепятся к ближайшей поверхности, затем за счет изменения давления снова сокращаются, так животное передвигается. При помощи нижних ножек морские ежи зарываются в песок или очищают панцирь от остатков пищи, а верхние служат в качестве органов осязания и дыхания.

Огненный морской еж

Один из самых опасных ежей на нашей планете. Это агрессивный охотник, обладающий ядовитыми иглами и клешнями на кончиках педицеллярий. Стоит человеку наступить на такого ежа, шипы и челюсти тут же выпустят сильнодействующий парализующий яд.

Педицеллярии

Это особые органы, разбросанные среди игл морских ежей. Они находятся на гибких стебельках или непосредственно на поверхности тела и, словно клешни, снабжены несколькими хватательными створками. У некоторых морских ежей педицеллярии наполнены еще и ядовитыми железами.

Как и чем питаются морские ежи

Коричневый мирской еж. Такие в изобилии водятся в Адриатическом море у берегов Хорватии

Рот морского ежа расположен на нижней стороне туловища. Он снабжен сразу 5 челюстями, каждая из которых увенчана прочным острым зубом, растущим в течение всей жизни морского ежа. Свои уникальные челюсти эти животные используют в качестве скребка, отслаивая водоросли от камней, для размельчения добычи или рытья нор. Морские ежи всеядны. Они едят водоросли, моллюсков, губок, разнообразную падаль, а также мелких морских ежей и морских звезд.

Враги морских ежей

Морской бобр, или калан, — главный враг морских ежей. Большую части жизни он проводит в воде, на сушу выходит только для отдыха

Морских ежей поедают некоторые виды рыб, птиц, а также крабы и омары. Но самый главный охотник на этих колючих животных — морской бобр. Чтобы не пораниться острыми иглами, он заворачивает ежа в водоросли и разбивает его камнем прямо у себя на груди. Прячась от хищников, морские ежи забираются в узкие щели между камнями, увеличивая их до нужной глубины при помощи игл и зубов.

Опасность для человека

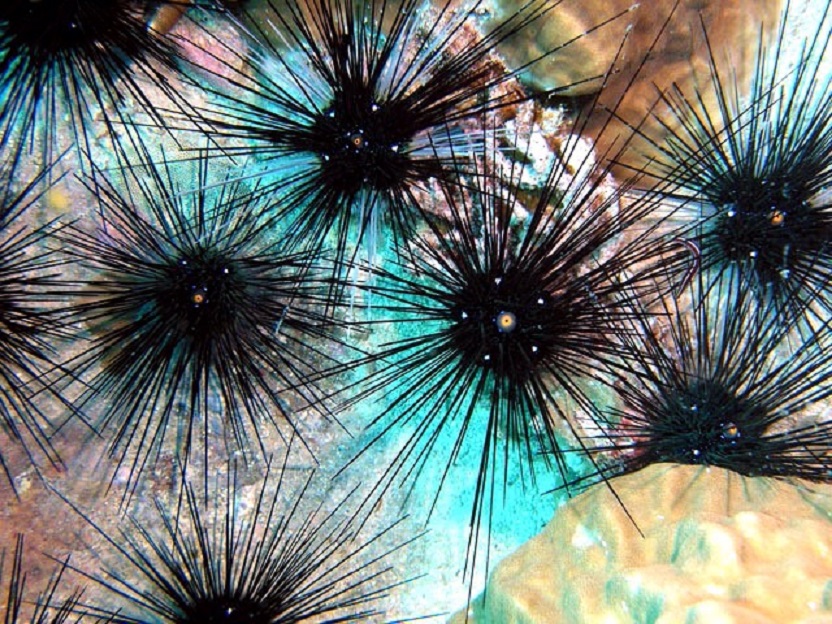

Черный морской еж с длинными иглами. Такие встречаются на побережье Таиланда

Яд многих морских ежей очень токсичен: даже сильно разведенный в воде он может оказать на человека губительное, в худшем случае даже смертельное воздействие. Кроме того, ежи вооружены длинными и очень тонкими иглами. Протыкая кожу человека, иглы ломаются и оставляют в теле кончики. Обычно возникает сильная боль, которая может продлиться несколько часов.

Красивые, но ядовитые

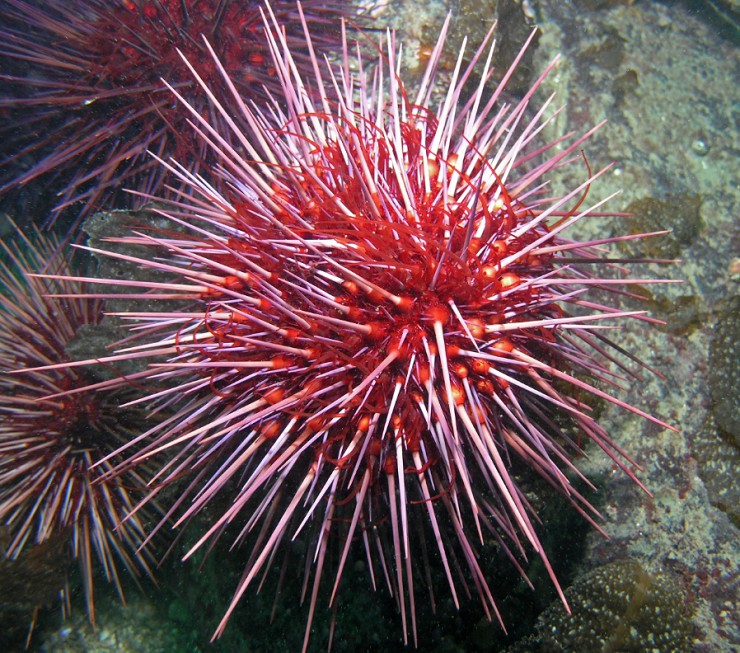

Гигантские красные морские ежи являются обладателями яркой окраски и острых ядовитых игл. Размер этих ежей достигает в диаметре до 20 см, а с иглами — до 45 см. Обитают они возле восточного побережья Африки, в водах Индонезии и Океании. Встречаются в больших количествах на глубине от 10 до 40 м.

Поделиться ссылкой

Изобретательность природы безгранична. Внешний облик каждой группы родственных видов живых существ — чаще всего вариация на какую-либо одну тему. Морских ежей можно назвать «вариацией на тему шара с иглами».

Возможно, именно из-за трудностей варьирования столь простой формы видов ежей сравнительно немного — всего около 850. Но если видовое разнообразие этих животных и не очень велико, зато численность их на многих участках дна поистине огромна.

В тех морях, где они обитают (морским ежам, как и другим иглокожим, необходима высокая соленость воды), это всегда одна из наиболее обычных групп донных животных. Можно было бы даже сказать, что их почти перестаешь замечать, если бы они не относились к таким существам, которые довольно энергично напоминают о своем присутствии. Живут морские ежи как у самого уреза воды, так и на больших глубинах. Недавно научно-исследовательским судном «Витязь» в желобе Банда с глубины 7340 м был поднят их новый вид, названный Пурталезия хептнери,— наиболее глубоководный из известных науке видов.

2. Пурталезия указана стрелкой.

Морских ежей делят на две основные группы — правильных и неправильных (заметим, кстати, что эти же термины использовал небезызвестный Винни-пух для классификации пчел, когда пытался полакомиться медом с помощью воздушного шарика). Форма тела правильных ежей наиболее близка к шару, у неправильных она может довольно значительно отклоняться от нее. Морские ежи достигают очень крупных размеров — до 16 сантиметров в диаметре тела, а учитывая длину игл — до 50 сантиметров и больше.

3. Все тело ежей заключено в панцирь (или скорлупу) из известковых пластинок.

У подавляющего большинства видов пластинки скреплены неподвижно и тело имеет постоянную форму. Только у представителей одного отряда скорлупа состоит из отдельных, не скрепленных друг с другом пластин; тело таких ежей, шарообразное в естественной обстановке, сплющивается при извлечении животных на поверхность. Даже у самых «правильных» ежей скорлупа не вполне шарообразна, а имеет уплощенную нижнюю сторону и куполообразную вершину. Именно такая форма обеспечивает наибольшую прочность панцирю при надавливании сверху. У разных видов пластинки панциря значительно различаются по толщине. У ежей, обитающих на небольших глубинах, особенно в тропических морях, панцирь чрезвычайно прочен, тогда как глубоководные виды и закапывающиеся ежи имеют обычно очень тонкую скорлупу, легко повреждаемую даже пальцами при неосторожном обращении.

4. Если очистить панцирь ежа от игл, обнаруживается, что пластинки располагаются двадцатью меридиональными рядами.

Пластинки пяти двойных рядов пронизаны несколькими парами отверстий; эти пластинки называются амбулакральными. Через отверстия в них проходят каналы амбулакральных ножек. Если посадить морского ежа в аквариум, видно, что ножки его очень длинные, тонкие и подвижные, в вытянутом состоянии их длина может превышать поперечник панциря. Этим амбулакральные ножки ежей отличаются от ножек морских звезд и голотурий, обычно довольно коротких. Вообще может создаться впечатление, что общий план строения морских ежей и звезд имеет очень мало общего. Но если представить звезду, лучи которой загнуты на спинную сторону (кстати, при действии некоторых химических веществ морские звезды действительно могут принимать такую позу), то она по форме тела и расположению амбулакральных ножек будет очень похожа на ежа.

5.

6.

Ножек у ежей очень много, иногда больше тысячи. Они имеют на конце хорошо развитую присоску и играют большую роль при движении по вертикальным поверхностям. При движении по горизонтали многие ежи пользуются иглами, переставляя которые, они двигаются, как на ходулях. К пластинкам панциря прикрепляются иглы, количество, форма и размер которых чрезвычайно разнообразны. Иглы соединены с пластинками не неподвижно, а с помощью шарового шарнира. Мышцы, окружающие этот шарнир, позволяют ему менять направление иглы. Некоторые ежи способны на очень энергичные движения иглами. Между иглами на пластинках размещаются особые хватательные органы — педицеллярии,— представляющие собой сильно видоизмененные иглы. Они делятся на несколько типов и могут быть похожи на клешни, пинцеты и др. Педицеллярии играют чрезвычайно важную роль в жизни ежей. Они очищают тело от попавших на него инородных частиц, участвуют в питании, защищают ежа от врагов. Педицеллярии — очень совершенные устройства для захвата и удерживания. Еще издавна внимание ученых привлекал вопрос, каким образом ежи, несмотря на небольшие размеры и слабые приводные мышцы, способны удерживать очень крупных животных, например рыб. Недавно проведенные исследования «челюстных» педицеллярий одного из видов ежей с помощью сканирующего электронного микроскопа показали, что конструкция их шарнирного механизма и зубчатого сочленения створок обеспечивает очень точное их смыкание.

Конфигурация створок такова, что чем сильнее вырывается жертва, тем сильнее сжимаются створки. Таким образом, удерживание добычи осуществляется за счет ее собственных мышечных усилий! Створки педицеллярий имеют острые зубцы и снабжены ядовитыми железами. Педицеллярии при удалении их с тела ежа способны автономно функционировать в течение многих часов, поэтому удалось изучить их реакцию на присутствие злейших врагов морских ежей — морских звезд. Если прикоснуться к педицеллярии или добавить в воду экстракт из ножек морской звезды (но не любой, а относящейся к виду, с которым еж может столкнуться в реальной обстановке), створки приоткроются на 90 градусов. Чтобы они разошлись еще больше, нужно воздействовать на нервные окончания у наружного края створок; при полном раскрытии (створки располагаются в одной плоскости, под углом 180 градусов друг к другу) в их основании открывается чувствительный бугорок. Прикосновение к бугорку каким-нибудь предметом, например пинцетом, вызывает смыкание створок, но яд при этом не выпрыскивается. А вот если прикоснуться к бугорку ножкой морской звезды, то действие произойдет по «полной программе» — створки захлопнутся и в жертву впрыснется яд из железы. После этого педицеллярия отмирает и заменяется новой.

7. Наиболее примечательной особенностью внутреннего строения ежей является их жевательный аппарат, так называемый Аристотелев фонарь (название это очень древнее, его употреблял еще Плиний).

Аристотелев фонарь (он действительно похож на подвесной фонарь, применявшийся в старину) — геометрически правильное и чрезвычайно рационально сконструированное устройство, состоящее из двадцати пяти известковых «косточек» сложной конфигурации и соединяющих их мышц. Его основная часть — пять дугообразных двойных пирамидок, служащих как бы держателями для зубов.

8. Зубы имеют вид длинного стержня, в сечении обычно грибовидного, один конец зуба (плюмула) виден в верхней части фонаря, второй торчит из ротового отверстия.

С помощью сканирующего электронного микроскопа удалось установить, что зубы ежей имеют уникальное по своей сложности строение и представляют собой как бы пакет, набранный из огромного числа тонких, изогнутых особым образом пластинок. При питании ежа крайние пластинки стираются, а на их место выдвигаются новые. Таким образом, зубы ежей самозатачиваются и растут в течение всей жизни (подобное же явление мы встречаем на суше у мышей, белок и других грызунов, но способ достижения самозатачивания там совсем иной). Зубы морских ежей чрезвычайно прочны, ими они сокрушают известняк, скалы и даже стальные конструкции. Некоторые ежи используют зубы не только по прямому назначению, но и для передвижения — резко смыкая и размыкая их, они отталкиваются от дна. Как уже говорилось, ежи очень различаются по строению и образу жизни. В морях нашей страны на доступных спортсмену-подводнику глубинах живут представители только одного рода правильных ежей — Стронгилоцентротус.

9. Очень много ежей в Японском море.

10. Наиболее обычный вид здесь — Стронгилоцентротус нудус, или невооруженный морской еж.

Научное название «невооруженный» этого шара с многочисленными длинными и прочными иглами может вызвать недоумение, но назван он так потому, что лишен ядовитых глобиферных педицеллярий. Нудусов не спутаешь с другими видами ежей как из-за большой длины игл, так и из-за окраски — темнофиолетовой, почти черной. Живут они как у самого уреза воды, иногда даже обсыхая, так и на глубинах до 180 метров. Невооруженные ежи медленно двигаются по камням и песку, соскребая своими долотообразными зубами слой обрастаний. Эти ежи поедают и мелких животных, встречающихся на камнях, но основная их пища — водоросли. Пока водорослей много, ежи живут рассредоточенно. При нехватке пищи они могут собираться огромными скоплениями. Мне приходилось встречать на скалах у самой поверхности воды полосы нудусов шириной около метра, в которых животные, располагаясь в два-три слоя, доедали остатки водорослей ламинарий и костарий. Ежи едят не все водоросли без разбора: некоторые виды привлекают их очень сильно, на другие они почти не обращают внимания.

11. Другой наиболее обычный на Дальнем Востоке вид ежей — промежуточный еж.

Он достигает размера 8 сантиметров. Тело ежа покрыто многочисленными, но короткими и довольно тонкими иглами. Цвет значительно варьирует, но обычно — сероватый или зеленоватый. Если невооруженные ежи живут совершенно открыто, то промежуточные всегда покрыты камешками, кусочками водорослей, створками раковин, которые прочно удерживают амбулакральными ножками. Такое «украшение» широко распространено у разных видов ежей. О его значении ученые до сих пор спорят. Одно из предположений, что таким образом ежи защищают себя от излишнего света (органов зрения у этих животных нет, но они ощущают свет всей поверхностью тела). Это в какой-то степени подтверждается тем, что большинство видов, применяющих «украшения», сбрасывают их на ночь и вновь «одеваются» с рассветом. В то же время встречаются и виды, которые не сбрасывают маскировочное покрытие даже ночью.

12. Обычные обитатели самой прибрежной полосы — ежи эхинометры.

Это относительно небольшие ежики с короткими конусообразными и довольно тупыми иглами, светлыми на концах, Эхинометры живут везде, где есть твердый известковый или скальный грунт. Один из широко распространенных типов берега в тропических районах — полого уходящая в воду известковая плита. Начиная с уреза воды такая плита бывает сплошь источена овальными ямками, в каждой из которых сидит эхинометра.

13. Ежи могут использовать уже готовые углубления, а могут высверливать гнезда и на гладком грунте.

При этом вначале они выгрызают породу зубами, а по мере углублении норы все большую роль начинают играть иглы. Ежи постоянно поворачиваются вокруг своей оси и многочисленные иглы, работая как фреза, постепенно углубляют и расширяют норку. Ежи не покидают своих гнезд в течение всей жизни, питаясь тем, что принесет с собой вода. Основная функция норы — не защита ежа от врагов, как иногда полагают, а предохранение от действия прибоя и высыхания в отлив. Эхинометры, поселившись в тихих бухтах, нор не строят.

14. Мест, пригодных для поселения эхинометр, не так уж много, поэтому каждый еж энергично защищает свою нору.

При попытках захватить чужое жилище между ежами происходят настоящие сражения, в ходе которого соперники толкают друг друга и иногда пускают в ход зубы Продолжительность схватки — от нескольких минут до 5 часов. При этом хозяин норы имеет как бы моральное преимущество перед чужаком и при прочих равных условиях наверняка выигрывает схватку. Если хозяина удалить из норы и поместить туда другого ежа такого же размера, то хозяин обязательно вернет себе законное убежище. Эхинометры и многие другие виды сверлящих ежей живут в местах, где прибой не достигает максимальной силы. Там, где на открытый берег обрушиваются огромные океанские волны, им не выстоять. Но ежи живут и здесь, правда, совсем другие — крупные коричневые «грифельные ежи» — гетероцентротусы.

15.

Иглы этих ежей вообще трудно назвать иглами — это толстые стержни до 1—1,5 сантиметра в поперечнике круглого или треугольного сечения с закругленными концами. По размерам и форме иглы гетероцентротусов больше всего напоминают авторучку. Конечно, использовать такие иглы для защиты — дело безнадежное. Но гетероцентротусам это и не к чему — в тех местах, где они обитают, никакие хищники жить не могут.

16.

Зато иглы прекрасно выполняют ту функцию, для которой они и предназначены — расклинивать тело ежа в глубокой пещерке. Еж благодаря им сидит в норе настолько прочно, что вытащить его, не повредив, очень трудно. Как и эхинометры, гетероцентротусы — добровольные узники и живут в норе всю жизнь, расширяя и углубляя ее по мере своего роста.

Самые заметные тропические ежи — несомненно диадемы. Это очень красивые животные с бархатистым на вид панцирем иссиня-черного цвета, на котором переливаются и как бы светятся пять ярко-синих треугольных пятен, иногда отороченных белой каймой.

17.

Самое интересное у диадем — их иглы. Они чрезвычайно длинные (до 30 сантиметров и более) и тонкие и острые настолько, что так и хочется сказать: «как иголка», но это сравнение здесь не подходит — иглы диадем значительно тоньше и острей швейной иглы. Иглы диадем очень подвижны. Когда подплываешь к такому ежу, он еще на расстоянии начинает шевелить ими, направляя их в сторону источника беспокойства.

18.

Диадемы живут обычно группами, часто образуя настоящие ежиные «поселки», и когда проплываешь над ними, внизу шевелится целый лес черных, серых или полосатых игл и сверкают голубые пятна — очень красивое зрелище. Диадемы отправляются на кормежку в заросли водорослей и морских трав ночью, а целый день отсиживаются в углублениях и пещерках коралловых рифов, выставив наружу иглы. Казалось бы, с их мощным оружием бояться некого, но это не так. Несколько видов рыб из спинороговых приспособились охотиться на этих ежей. Схватив ежа за иглы, рыба вытаскивает его на ровное место, несколькими толчками переворачивает на спину, и затем пробивает нижнюю, незащищенную длинными иголками, часть панциря. Но у диадем есть и друзья, постоянно живущие вместе с ними. Разные ежиные сожители принимают среди игл разные позы. Креветки располагаются головой вверх, рыбки кривохвостки — головой вниз, рыбки сифамии — горизонтально. Немецкий ученый X. Фрике провел на рифах Красного моря подводные наблюдения, чтобы выяснить, какие стимулы привлекают рыб и креветок к ежам. Для этого ежиным спутникам под водой предлагали пластмассовые шары с воткнутыми в них штырями или спицами. Оказалось, что и креветки, и рыбы предпочитали черный цвет белому, толстые иглы — тонким, многочисленные — редким, стоящие вертикально и параллельно — беспорядочно разбросанным. Не все морские ежи вегетарианцы. Так, копьеносные ежи (названные так из-за немногочисленных, но мощных игл, напоминающих копья) питаются в основном губками, мягкими кораллами и другими прикрепленными животными.

19.

20.

Большинство правильных морских ежей, относящихся к «мирным» видам, поедают мертвых животных, а многие при случае ловят и подвижных животных, даже креветок и рыб. Жертва чаще всего схватывается педицелляриями, но иногда в ее захвате и удерживании принимают участие и иглы. Убитая ядом добыча передается, как по эстафете, от одной педицеллярии к другой, пока не достигнет ротового отверстия. После этого еж, придерживая околоротовыми иглами, отрывает от нее кусочки зубами. Сами ежи также служат пищей разнообразным животным, их поедают и рыбы, и птицы, и млекопитающие, но чаще всего они становятся жертвами своих родственников — морских звезд.

До сих пор речь шла преимущественно о правильных или шаровидных ежах. Неправильные ежи значительно отличаются от них как строением, так и образом жизни. Наиболее сильно уклонилась от шара форма панциря представителей отряда плоских ежей. Многие виды этого отряда действительно совершенно плоские — как монета. Недаром американцы называют их «долларами» и «центами».

21.

Плоские ежи не всегда дисковидные, среди них встречаются виды, панцирь которых имеет глубокие боковые вырезы и даже сквозные отверстия; они чрезвычайно напоминают печенье, вырезанное фигурной формой изобретательной хозяйкой.

22.

Конечно, такая форма не для красоты. Большинство видов плоских ежей — закапывающиеся животные, а вырезы и прорези помогают ежу «тонуть» в песке. Конечно, природа могла бы поступить проще — просто уменьшить диаметр тела ежа, но это невыгодно — чем относительно шире поперечник панциря, тем волнам труднее перевернуть ежа — а это для ежей равносильно гибели, так как большинство видов не способны потом самостоятельно перевернуться «на живот».

23.

Тело плоских ежей сплошь покрыто короткими иголочками, которые правильнее бы назвать щетинками — уколоться такими иглами нельзя. Панцирь их сверху не гладкий, а имеет рисунок, обычно в виде пятилепесткового цветка.

Среди плоских ежей есть и не совсем плоские. В наших дальневосточных морях у открытых песчаных пляжей, начиная с глубины 1—1,5 метра, можно встретить целые поля крупных темно-малиновых ежей Скафехинус необыкновенный. Здесь же обычно живут и вдвое меньшие, величиной с металлический полтинник ежи — Скафехинус серый.

24.

Заметить их труднее, так как они закапываются в песок, правда, неглубоко. Закапывающиеся плоские ежи питаются органическими частицами, содержащимися в грунте, а живущие на поверхности — приносимыми водой. Форма панциря плоских ежей и степень его выпуклости имеет большое значение при их питании. Панцирь плоского ежа — гидродинамическое устройство, воздействующее на характер обтекающего его водного потока.

25.

Панцирь действует подобно крылу самолета, только с другой целью. За счет разницы в давлениях воды у выпуклой верхней и плоской нижней стороны происходит оседание взвешенных пищевых частиц, которые затем по пищевым желобкам направляются ко рту. Поселение плоских ежей — в целом единая гидродинамическая система, чутко реагирующая на скорость и направление преобладающих течений. Подводные фотографии, сделанные на значительных глубинах, показали, что на некоторых участках дна плоские ежи образуют сплошные «мостовые», а иногда даже располагаются в несколько слоев. Это не случайно — расстояние между особями выбирается таким образом, чтобы животные могли использовать токи воды, отклоняемые соседями. Пространственная решетка, образованная лежащими друг на друге дисками ежей, и обеспечивает максимально полное использование ресурсов придонных течений. Некоторые виды плоских ежей, например дендрастеры, для лучшего улавливания взвеси располагаются на дне в вертикальном положении, как бы воткнутыми ребром в песок. При этом угол наклона тела ежа к горизонту и положение в плане соответствуют направлению и силе течений.

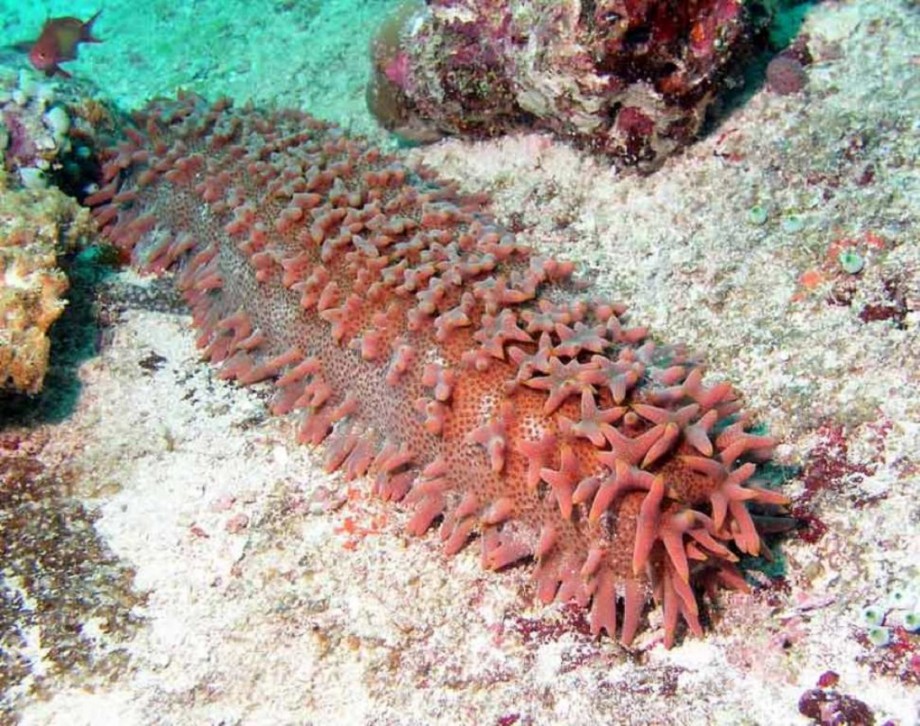

Плавая в зарослях зостеры в Японском море, на песчаных полянках можно увидеть круглые отверстия, как будто проколотые спицей; они не сопровождаются ни воронками, ни конусами, характерными для закапывающихся червей и моллюсков. Если рукой копнуть рыхлый песок, на поверхности окажется симпатичное яйцевидное существо, покрытое как бы шерсткой белесоватожелтоватого цвета — сердцевидный еж, представитель второго отряда неправильных ежей.

26.

Сердцевидные ежи живут, закопавшись на 5—10 сантиметров в песок. Они медленно движутся, раскапывая перед собой грунт и отталкиваясь уплощенными веслообразными иглами на нижней стороне тела.

27. Скелеты сердцевидных ежей.

28.

29. Пищу эти ежи получают с поверхности грунта, высовывая через уже виденный нами круглый вертикальный ход чрезвычайно длинные ножки с кисточкой на конце.

По мере продвижения в грунте вертикальный ход разрушается, и еж строит новый. Морские ежи имеют большое значение как в жизнедеятельности донных сообществ, так и в жизни человека.

О неприятностях, доставляемых ежами человеку. С возможностью наступить или столкнуться с ежами все время приходится считаться, когда работаешь в прибрежной зоне морей с океанической соленостью. Иглы ежей, водящихся в морях нашей страны, не ядовиты, но, проникнув в кожу, обычно обламываются и могут вызвать нагноение. Ласты, даже с закрытой подошвой, к сожалению, не предохраняют от уколов черными ежами. В тропиках постоянно приходится сталкиваться с уколами игл диадем, от которых не защищает ни гидрокостюм, ни даже толстые кожаные перчатки.

30.

В литературе можно встретить рекомендации извлекать иглы после укола диадемой хирургическим путем, но их явно разрабатывали люди, видевшие этих ежей только на картинках. Мне пришлось несколько раз «познакомиться вплотную» с диадемами. Нога или рука после этого похожа на фиолетовую подушку, сплошь нашпигованную обломками игл. О том, чтобы извлекать их, не может быть и речи, кажется проще просто отрезать поврежденную конечность. К счастью, этого делать не приходится, так как, вопреки распространенному мнению, иглы диадем не ядовиты и без всякого вмешательства обычно за сутки-двое полностью рассасываются (чего, к сожалению, нельзя сказать о толстых иглах других ежей, в том числе и живущих в наших морях). Конечно, уколы диадемами очень болезненны, пораженное место сильно опухает, иногда теряет чувствительность. Как и во всех случаях, когда в тело попадают нестерильные инородные тела, возможна вторичная инфекция. В то же время несколько видов ежей, и в первую очередь живущие в прибрежных водах Японии короткоиглые ежи, имеют иглы, снабженные ядовитыми железами. Очень опасен яд, содержащийся в глобиферных педицелляриях многих видов морских ежей. Укус педицеллярии вызывает сильную боль, расстройство речи и дыхания; известны случаи со смертельным исходом. К счастью, из-за того что педицелпярии имеют небольшие размеры и располагаются в гуще игл, укусы ими очень редки. Если все же такой случай произошел, необходимо прежде всего удалить из ранки оторванную педицеллярию, чтобы прекратить поступление новых порций яда, и обратиться за медицинской помощью.

Ещё несколько красавцев:

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

Как уже говорилось, численность ежей в прибрежной зоне может быть очень велика и соответственно велико их влияние на другие организмы. Особенно значительна роль ежей как регуляторов роста водорослей. Выедая огромные количества водорослей, в том числе и промысловых, ежи являются во многих районах одним из основных факторов, влияющих на их количество. Сами ежи также служат пищей для некоторых ценных промысловых организмов — птиц, рыб, крабов, омаров. Очень важную роль играют ежи в питании ценнейшего пушного зверя — калана, или морской выдры. Поведение каланов при питании очень интересно. Нырнув (иногда на несколько десятков метров), калан схватывает передними лапами и зубами несколько ежей и, прижав их к груди, поднимается на поверхность.

37. Здесь он переворачивается на спину и укладывает добычу в обширные складки шкуры на животе.

Затем зверь по очереди извлекает ежей, зубами и лапами обламывает иглы, прогрызает панцирь и съедает внутренности. Калифорнийские каланы для разбивания панцирей ежей и раковин моллюсков используют камни. Захватив такой камень (весом иногда более трех килограммов), калан укладывает его на груди и, ударяя по нему как по наковальне добычей, разбивает ее твердые покровы. Интересно, что хищническое истребление каланов у калифорнийского побережья привело к массовому размножению ежей, которые уничтожили на больших пространствах заросли самых крупных в мире водорослей макроцистис. Сейчас, после успешного проведения мероприятий по охране и переселению каланов, численность ежей вновь снизилась и равновесие восстанавливается.

38. Человек довольно широко использует ежей в пищу. Едят у них только зрелые половые продукты — икру и молоки.

39.

Вот как описывает один гурман это не совсем обычное блюдо: «Какой восхитительный аромат! Это гораздо вкуснее, чем лучшие устрицы, чувствуется неповторимое своеобразие океана, каждый кусок словно освежает рот, в памяти встает чистое, волшебное существо, проведшее жизнь в коралловых заводях, в прозрачной и искрящейся морской воде. Это блюдо можно есть лишь с чувством искреннего восхищения и благодарности за доставленные им новые, совершенно необычные ощущения». Действительно, морские ежи очень вкусны, но обязательно свежие и умело приготовленные.

Не следует думать, что ежей ловят только для удовлетворения прихоти небольшой кучки гурманов. Цифры говорят о другом — по данным ФАО (продовольственной и сельскохозяйственной организации ООН), ежегодно в мире добывается от 40 до 50 тысяч тонн этих животных. Наиболее широко развит промысел ежей в Японии, Чили и США. Но икра ежей имеет и другое, гораздо более важное значение. Морской еж стал и остается до сих пор одним из важнейших лабораторных животных. Половые продукты и зародыши ежей широко используются для решения различных проблем биологии развития, молекулярной биологии и цитологии. Ежи являются уникальным объектом для проведения таких работ и в этом качестве их ничем нельзя заменить. Морские ежи обладают очень важными достоинствами — от них возможно получать большие партии половых продуктов, у них строго синхронное развитие зародышей, проста инкубация в контролируемых условиях. Поэтому делящиеся яйца морских ежей все шире используются для массовых токсикологических и фармакологических испытаний новых медицинских препаратов. Человек очень многим обязан своему колючему «меньшому брату» — благодаря ему постигнуты многие тайны живого, созданы и создаются ценнейшие лекарственные препараты.

В.С. ЛЕВИН, кандидат биологических наук.

Это копия статьи, находящейся по адресу https://masterokblog.ru/?p=63176.

| Sea Urchin

Temporal range: Ordovician–Present PreꞒ Ꞓ O S D C P T J K Pg N |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Tripneustes ventricosus and Echinometra viridis | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Echinodermata |

| Subphylum: | Echinozoa |

| Class: | Echinoidea Leske, 1778 |

| Subclasses | |

|

Sea urchins () are spiny, globular echinoderms in the class Echinoidea. About 950 species of sea urchin live on the seabed of every ocean and inhabit every depth zone from the intertidal seashore down to 5,000 meters (16,000 ft; 2,700 fathoms).[1] The spherical, hard shells (tests) of sea urchins are round and covered in spines, ranging in length from 3 to 10 cm (1 to 4 in), though the black sea urchin can have spines as long as 30 cm (12 in). Sea urchins move slowly, crawling with tube feet, and also propel themselves with their spines. Although algae are the primary diet, sea urchins also eat slow-moving (sessile) animals. Predators that eat sea urchins include a wide variety of fish, starfish, crabs, marine mammals. Sea urchins are also used as food especially in Japan.

Like all echinoderms, adult sea urchins have fivefold symmetry, but their pluteus larvae feature bilateral (mirror) symmetry, indicating that the sea urchin belongs to the Bilateria group of animal phyla, which also comprises the chordates and the arthropods, the annelids and the molluscs, and are found in every ocean and in every climate, from the tropics to the polar regions, and inhabit marine benthic (sea bed) habitats, from rocky shores to hadal zone depths. The fossil record of the Echinoids dates from the Ordovician period, some 450 million years ago. The closest echinoderm relatives of the sea urchin are the sea cucumbers (Holothuroidea), both of which are deuterostomes, a clade that includes the chordates. (Sand dollars are a separate order in the sea urchin class Echinoidea.)

The animals have been studied since the 19th century as model organisms in developmental biology, as their embryos were easy to observe. That has continued with studies of their genomes because of their unusual fivefold symmetry and relationship to chordates. Species such as the slate pencil urchin are popular in aquariums, where they are useful for controlling algae. Fossil urchins have been used as protective amulets.

Diversity[edit]

Sea urchins are members of the phylum Echinodermata, which also includes sea stars, sea cucumbers, sand dollars, brittle stars, and crinoids. Like other echinoderms, they have five-fold symmetry (called pentamerism) and move by means of hundreds of tiny, transparent, adhesive «tube feet». The symmetry is not obvious in the living animal, but is easily visible in the dried test.[2]

Specifically, the term «sea urchin» refers to the «regular echinoids», which are symmetrical and globular, and includes several different taxonomic groups, with two subclasses : Euechinoidea («modern» sea urchins, including irregular ones) and Cidaroidea or «slate-pencil urchins», which have very thick, blunt spines, with algae and sponges growing on them. The «irregular» sea urchins are an infra-class inside the Euechinoidea, called Irregularia, and include Atelostomata and Neognathostomata. Irregular echinoids include: flattened sand dollars, sea biscuits, and heart urchins.[3]

Together with sea cucumbers (Holothuroidea), they make up the subphylum Echinozoa, which is characterized by a globoid shape without arms or projecting rays. Sea cucumbers and the irregular echinoids have secondarily evolved diverse shapes. Although many sea cucumbers have branched tentacles surrounding their oral openings, these have originated from modified tube feet and are not homologous to the arms of the crinoids, sea stars, and brittle stars.[2]

Description[edit]

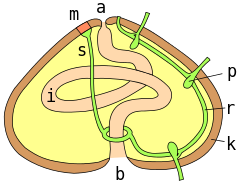

Sea urchin anatomy based on Arbacia sp.

Urchins typically range in size from 3 to 10 cm (1 to 4 in), although the largest species can reach up to 36 cm (14 in).[4] They have a rigid, usually spherical body bearing moveable spines, which gives the class the name Echinoidea (from the Greek ἐχῖνος ekhinos ‘spine’).[5] The name urchin is an old word for hedgehog, which sea urchins resemble; they have archaically been called sea hedgehogs.[6][7] The name is derived from Old French herichun, from Latin ericius (‘hedgehog’).[8]

Like other echinoderms, sea urchin early larvae have bilateral symmetry,[9] but they develop five-fold symmetry as they mature. This is most apparent in the «regular» sea urchins, which have roughly spherical bodies with five equally sized parts radiating out from their central axes. The mouth is at the base of the animal and the anus at the top; the lower surface is described as «oral» and the upper surface as «aboral».[a][2]

Several sea urchins, however, including the sand dollars, are oval in shape, with distinct front and rear ends, giving them a degree of bilateral symmetry. In these urchins, the upper surface of the body is slightly domed, but the underside is flat, while the sides are devoid of tube feet. This «irregular» body form has evolved to allow the animals to burrow through sand or other soft materials.[4]

Systems[edit]

Musculoskeletal[edit]

The internal organs are enclosed in a hard shell or test composed of fused plates of calcium carbonate covered by a thin dermis and epidermis. The test is referred to as an endoskeleton rather than exoskeleton even though it encloses almost all of the urchin. This is because it is covered with a thin layer of muscle and skin; sea urchins also do not need to molt the way invertebrates with true exoskeletons do, instead the plates forming the test grow as the animal does.

The test is rigid, and divides into five ambulacral grooves separated by five wider interambulacral areas. Each of these ten longitudinal columns consists of two sets of plates (thus comprising 20 columns in total). The ambulacral plates have pairs of tiny holes through which the tube feet extend.[10]

All of the plates are covered in rounded tubercles to which the spines are attached. The spines are used for defence and for locomotion and come in a variety of forms.[11] The inner surface of the test is lined by peritoneum.[4] Sea urchins convert aqueous carbon dioxide using a catalytic process involving nickel into the calcium carbonate portion of the test.[12]

Most species have two series of spines, primary (long) and secondary (short), distributed over the surface of the body, with the shortest at the poles and the longest at the equator. The spines are usually hollow and cylindrical. Contraction of the muscular sheath that covers the test causes the spines to lean in one direction or another, while an inner sheath of collagen fibres can reversibly change from soft to rigid which can lock the spine in one position. Located among the spines are several types of pedicellaria, moveable stalked structures with jaws.[2]

Sea urchins move by walking, using their many flexible tube feet in a way similar to that of starfish; regular sea urchins do not have any favourite walking direction.[13] The tube feet protrude through pairs of pores in the test, and are operated by a water vascular system; this works through hydraulic pressure, allowing the sea urchin to pump water into and out of the tube feet. During locomotion, the tube feet are assisted by the spines which can be used for pushing the body along or to lift the test off the substrate. Movement is generally related to feeding, with the red sea urchin (Mesocentrotus franciscanus) managing about 7.5 cm (3 in) a day when there is ample food, and up to 50 cm (20 in) a day where there is not. An inverted sea urchin can right itself by progressively attaching and detaching its tube feet and manipulating its spines to roll its body upright.[2] Some species bury themselves in soft sediment using their spines, and Paracentrotus lividus uses its jaws to burrow into soft rocks.[14]

-

Test of black sea urchin, showing tubercles and ambulacral plates (on right)

-

Inner surface of test, showing pentagonal interambulacral plates on right, and holes for tube feet on left.

-

-

Close-up of the test showing an ambulacral groove with its two rows of pore-pairs, between two interambulacra areas (green). The tubercles are non-perforated.

-

Close-up of a cidaroid sea urchin apical disc: the 5 holes are the gonopores, and the central one is the anus («periproct»). The biggest genital plate is the madreporite.[15]

Feeding and digestion[edit]

Dentition of a sea urchin

The mouth lies in the centre of the oral surface in regular urchins, or towards one end in irregular urchins. It is surrounded by lips of softer tissue, with numerous small, embedded bony pieces. This area, called the peristome, also includes five pairs of modified tube feet and, in many species, five pairs of gills.[4] The jaw apparatus consists of five strong arrow-shaped plates known as pyramids, the ventral surface of each of which has a toothband with a hard tooth pointing towards the centre of the mouth. Specialised muscles control the protrusion of the apparatus and the action of the teeth, and the animal can grasp, scrape, pull and tear.[2] The structure of the mouth and teeth have been found to be so efficient at grasping and grinding that similar structures have been tested for use in real-world applications.[16]

On the upper surface of the test at the aboral pole is a membrane, the periproct, which surrounds the anus. The periproct contains a variable number of hard plates, five of which, the genital plates, contain the gonopores, and one is modified to contain the madreporite, which is used to balance the water vascular system.[2]

Aristotle’s lantern in a sea urchin, viewed in lateral section

The mouth of most sea urchins is made up of five calcium carbonate teeth or plates, with a fleshy, tongue-like structure within. The entire chewing organ is known as Aristotle’s lantern from Aristotle’s description in his History of Animals (translated by D’Arcy Thompson):

… the urchin has what we mainly call its head and mouth down below, and a place for the issue of the residuum up above. The urchin has, also, five hollow teeth inside, and in the middle of these teeth a fleshy substance serving the office of a tongue. Next to this comes the esophagus, and then the stomach, divided into five parts, and filled with excretion, all the five parts uniting at the anal vent, where the shell is perforated for an outlet … In reality the mouth-apparatus of the urchin is continuous from one end to the other, but to outward appearance it is not so, but looks like a horn lantern with the panes of horn left out.

However, this has recently been proven to be a mistranslation. Aristotle’s lantern is actually referring to the whole shape of sea urchins, which look like the ancient lamps of Aristotle’s time.[17][18]

Heart urchins are unusual in not having a lantern. Instead, the mouth is surrounded by cilia that pull strings of mucus containing food particles towards a series of grooves around the mouth.[4]

Digestive and circulatory systems of a regular sea urchin:

a = anus ; m = madreporite ; s = aquifer canal ; r = radial canal ; p = podial ampulla ; k = test wall ; i = intestine ; b = mouth

The lantern, where present, surrounds both the mouth cavity and the pharynx. At the top of the lantern, the pharynx opens into the esophagus, which runs back down the outside of the lantern, to join the small intestine and a single caecum. The small intestine runs in a full circle around the inside of the test, before joining the large intestine, which completes another circuit in the opposite direction. From the large intestine, a rectum ascends towards the anus. Despite the names, the small and large intestines of sea urchins are in no way homologous to the similarly named structures in vertebrates.[4]

Digestion occurs in the intestine, with the caecum producing further digestive enzymes. An additional tube, called the siphon, runs beside much of the intestine, opening into it at both ends. It may be involved in resorption of water from food.[4]

Circulation and respiration[edit]

The water vascular system leads downwards from the madreporite through the slender stone canal to the ring canal, which encircles the oesophagus. Radial canals lead from here through each ambulacral area to terminate in a small tentacle that passes through the ambulacral plate near the aboral pole. Lateral canals lead from these radial canals, ending in ampullae. From here, two tubes pass through a pair of pores on the plate to terminate in the tube feet.[2]

Sea urchins possess a hemal system with a complex network of vessels in the mesenteries around the gut, but little is known of the functioning of this system.[2] However, the main circulatory fluid fills the general body cavity, or coelom. This coelomic fluid contains phagocytic coelomocytes, which move through the vascular and hemal systems and are involved in internal transport and gas exchange. The coelomocytes are an essential part of blood clotting, but also collect waste products and actively remove them from the body through the gills and tube feet.[4]

Most sea urchins possess five pairs of external gills attached to the peristomial membrane around their mouths. These thin-walled projections of the body cavity are the main organs of respiration in those urchins that possess them. Fluid can be pumped through the gills’ interiors by muscles associated with the lantern, but this does not provide a continuous flow, and occurs only when the animal is low in oxygen. Tube feet can also act as respiratory organs, and are the primary sites of gas exchange in heart urchins and sand dollars, both of which lack gills. The inside of each tube foot is divided by a septum which reduces diffusion between the incoming and outgoing streams of fluid.[2]

Nervous system and senses[edit]

The nervous system of sea urchins has a relatively simple layout. With no true brain, the neural center is a large nerve ring encircling the mouth just inside the lantern. From the nerve ring, five nerves radiate underneath the radial canals of the water vascular system, and branch into numerous finer nerves to innervate the tube feet, spines, and pedicellariae.[4]

Sea urchins are sensitive to touch, light, and chemicals. There are numerous sensitive cells in the epithelium, especially in the spines, pedicellaria and tube feet, and around the mouth.[2] Although they do not have eyes or eye spots (except for diadematids, which can follow a threat with their spines), the entire body of most regular sea urchins might function as a compound eye.[19] In general, sea urchins are negatively attracted to light, and seek to hide themselves in crevices or under objects. Most species, apart from pencil urchins, have statocysts in globular organs called spheridia. These are stalked structures and are located within the ambulacral areas; their function is to help in gravitational orientation.[4]

Life history[edit]

Reproduction[edit]

Male flower urchin (Toxopneustes roseus) releasing milt, November 1, 2011, Lalo Cove, Sea of Cortez

Sea urchins are dioecious, having separate male and female sexes, although no distinguishing features are visible externally. In addition to their role in reproduction, the gonads are also nutrient storing organs, and are made up of two main type of cells: germ cells, and somatic cells called nutritive phagocytes.[20] Regular sea urchins have five gonads, lying underneath the interambulacral regions of the test, while the irregular forms mostly have four, with the hindmost gonad being absent; heart urchins have three or two. Each gonad has a single duct rising from the upper pole to open at a gonopore lying in one of the genital plates surrounding the anus. Some burrowing sand dollars have an elongated papilla that enables the liberation of gametes above the surface of the sediment.[2] The gonads are lined with muscles underneath the peritoneum, and these allow the animal to squeeze its gametes through the duct and into the surrounding sea water, where fertilization takes place.[4]

Development[edit]

During early development, the sea urchin embryo undergoes 10 cycles of cell division,[21] resulting in a single epithelial layer enveloping the blastocoel. The embryo then begins gastrulation, a multipart process which dramatically rearranges its structure by invagination to produce the three germ layers, involving an epithelial-mesenchymal transition; primary mesenchyme cells move into the blastocoel[22] and become mesoderm.[23] It has been suggested that epithelial polarity together with planar cell polarity might be sufficient to drive gastrulation in sea urchins.[24]

The development of a regular sea urchin

An unusual feature of sea urchin development is the replacement of the larva’s bilateral symmetry by the adult’s broadly fivefold symmetry. During cleavage, mesoderm and small micromeres are specified. At the end of gastrulation, cells of these two types form coelomic pouches. In the larval stages, the adult rudiment grows from the left coelomic pouch; after metamorphosis, that rudiment grows to become the adult. The animal-vegetal axis is established before the egg is fertilized. The oral-aboral axis is specified early in cleavage, and the left-right axis appears at the late gastrula stage.[25]

Life cycle and development[edit]

In most cases, the female’s eggs float freely in the sea, but some species hold onto them with their spines, affording them a greater degree of protection. The unfertilized egg meets with the free-floating sperm released by males, and develops into a free-swimming blastula embryo in as few as 12 hours. Initially a simple ball of cells, the blastula soon transforms into a cone-shaped echinopluteus larva. In most species, this larva has 12 elongated arms lined with bands of cilia that capture food particles and transport them to the mouth. In a few species, the blastula contains supplies of nutrient yolk and lacks arms, since it has no need to feed.[4]

Several months are needed for the larva to complete its development, the change into the adult form beginning with the formation of test plates in a juvenile rudiment which develops on the left side of the larva, its axis being perpendicular to that of the larva. Soon, the larva sinks to the bottom and metamorphoses into a juvenile urchin in as little as one hour.[2] In some species, adults reach their maximum size in about five years.[4] The purple urchin becomes sexually mature in two years and may live for twenty.[26]

Ecology[edit]

Trophic level[edit]

Sea urchin in natural habitat

Sea urchins feed mainly on algae, so they are primarily herbivores, but can feed on sea cucumbers and a wide range of invertebrates, such as mussels, polychaetes, sponges, brittle stars, and crinoids, making them omnivores, consumers at a range of trophic levels.[27]

Predators, parasites, and diseases[edit]

Mass mortality of sea urchins was first reported in the 1970s, but diseases in sea urchins had been little studied before the advent of aquaculture. In 1981, bacterial «spotting disease» caused almost complete mortality in juvenile Pseudocentrotus depressus and Hemicentrotus pulcherrimus, both cultivated in Japan; the disease recurred in succeeding years. It was divided into a cool-water «spring» disease and a hot-water «summer» form.[28] Another condition, bald sea urchin disease, causes loss of spines and skin lesions and is believed to be bacterial in origin.[29]

Adult sea urchins are usually well protected against most predators by their strong and sharp spines, which can be venomous in some species.[30] The small urchin clingfish lives among the spines of urchins such as Diadema; juveniles feed on the pedicellariae and sphaeridia, adult males choose the tube feet and adult females move away to feed on shrimp eggs and molluscs.[31]

Sea urchins are one of the favourite foods of many lobsters, crabs, triggerfish, California sheephead, sea otter and wolf eels (which specialise in sea urchins). All these animals carry particular adaptations (teeth, pincers, claws) and a strength that allow them to overcome the excellent protective features of sea urchins. Left unchecked by predators, urchins devastate their environments, creating what biologists call an urchin barren, devoid of macroalgae and associated fauna.[32] Sea urchins graze on the lower stems of kelp, causing the kelp to drift away and die. Loss of the habitat and nutrients provided by kelp forests leads to profound cascade effects on the marine ecosystem. Sea otters have re-entered British Columbia, dramatically improving coastal ecosystem health.[33]

-

Wolf eel, a highly specialized predator of sea urchins

-

Anti-predator defences[edit]

The flower urchin is a dangerous, potentially lethally venomous species.

The spines, long and sharp in some species, protect the urchin from predators. Some tropical sea urchins like Diadematidae, Echinothuriidae and Toxopneustidae have venomous spines. Other creatures also make use of these defences; crabs, shrimps and other organisms shelter among the spines, and often adopt the colouring of their host. Some crabs in the Dorippidae family carry sea urchins, starfish, sharp shells or other protective objects in their claws.[34]

Pedicellaria[35] are a good means of defense against ectoparasites, but not a panacea as some of them actually feed on it.[36] The hemal system defends against endoparasites.[37]

Range and habitat[edit]

Sea urchins are established in most seabed habitats from the intertidal downwards, at an extremely wide range of depths.[38] Some species, such as Cidaris abyssicola, can live at depths of several kilometres. Many genera are found in only the abyssal zone, including many cidaroids, most of the genera in the Echinothuriidae family, and the «cactus urchins» Dermechinus. One of the deepest-living families is the Pourtalesiidae,[39] strange bottle-shaped irregular sea urchins that live in only the hadal zone and have been collected as deep as 6850 metres beneath the surface in the Sunda Trench.[40] Nevertheless, this makes sea urchin the class of echinoderms living the least deep, compared to brittle stars, starfish and crinoids that remain abundant below 8,000 m (26,250 ft) and sea cucumbers which have been recorded from 10,687 m (35,100 ft).[40]

Population densities vary by habitat, with more dense populations in barren areas as compared to kelp stands.[41][42] Even in these barren areas, greatest densities are found in shallow water. Populations are generally found in deeper water if wave action is present.[42] Densities decrease in winter when storms cause them to seek protection in cracks and around larger underwater structures.[42]

The shingle urchin (Colobocentrotus atratus), which lives on exposed shorelines, is particularly resistant to wave action. It is one of the few sea urchin that can survive many hours out of water.[43]

Sea urchins can be found in all climates, from warm seas to polar oceans.[38] The larvae of the polar sea urchin Sterechinus neumayeri have been found to use energy in metabolic processes twenty-five times more efficiently than do most other organisms.[44] Despite their presence in nearly all the marine ecosystems, most species are found on temperate and tropical coasts, between the surface and some tens of meters deep, close to photosynthetic food sources.[38]

-

The shape of the shingle urchin allows it to stay on wave-beaten cliffs.

Evolution[edit]

Fossil history[edit]

The thick spines (radiola) of Cidaridae were used for walking on the soft seabed.

The earliest echinoid fossils date to the Middle Ordovician period (circa 465 Mya).[45][46][47] There is a rich fossil record, their hard tests made of calcite plates surviving in rocks from every period since then.[48]

Spines are present in some well-preserved specimens, but usually only the test remains. Isolated spines are common as fossils. Some Jurassic and Cretaceous Cidaroida had very heavy, club-shaped spines.[49]

Most fossil echinoids from the Paleozoic era are incomplete, consisting of isolated spines and small clusters of scattered plates from crushed individuals, mostly in Devonian and Carboniferous rocks. The shallow-water limestones from the Ordovician and Silurian periods of Estonia are famous for echinoids.[50] Paleozoic echinoids probably inhabited relatively quiet waters. Because of their thin tests, they would certainly not have survived in the wave-battered coastal waters inhabited by many modern echinoids.[50] Echinoids declined to near extinction at the end of the Paleozoic era, with just six species known from the Permian period. Only two lineages survived this period’s massive extinction and into the Triassic: the genus Miocidaris, which gave rise to modern cidaroida (pencil urchins), and the ancestor that gave rise to the euechinoids. By the upper Triassic, their numbers increased again. Cidaroids have changed very little since the Late Triassic, and are the only Paleozoic echinoid group to have survived.[50]

The euechinoids diversified into new lineages in the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods, and from them emerged the first irregular echinoids (the Atelostomata) during the early Jurassic.[51]

Some echinoids, such as Micraster in the chalk of the Cretaceous period, serve as zone or index fossils. Because they are abundant and evolved rapidly, they enable geologists to date the surrounding rocks.[52]

In the Paleogene and Neogene periods (circa 66 to 1.8 Mya), sand dollars (Clypeasteroida) arose. Their distinctive, flattened tests and tiny spines were adapted to life on or under loose sand in shallow water, and they are abundant as fossils in southern European limestones and sandstones.[50]

Phylogeny[edit]

External[edit]

Echinoids are deuterostome animals, like the chordates. A 2014 analysis of 219 genes from all classes of echinoderms gives the following phylogenetic tree.[53] Approximate dates of branching of major clades are shown in millions of years ago (mya).

Internal[edit]

The phylogeny of the sea urchins is as follows:[54][55]

The phylogenetic study from 2022 presents a different topology of the Euechinoidea phylogenetic tree. Irregularia are sister group of Echinacea (including Salenioida) forming a common clade Carinacea, basal groups Aspidodiadematoida, Diadematoida, Echinothurioida, Micropygoida, and Pedinoida are comprised in a common basal clade Aulodonta.[56]

Relation to humans[edit]

Injuries[edit]

Sea urchin injury on the top side of the foot. This injury resulted in some skin staining from the natural purple-black dye of the urchin.

Sea urchin injuries are puncture wounds inflicted by the animal’s brittle, fragile spines.[57]

These are a common source of injury to ocean swimmers, especially along coastal surfaces where coral with stationary sea urchins are present. Their stings vary in severity depending on the species. Their spines can be venomous or cause infection. Granuloma and staining of the skin from the natural dye inside the sea urchin can also occur. Breathing problems may indicate a serious reaction to toxins in the sea urchin.[58] They inflict a painful wound when they penetrate human skin, but are not themselves dangerous if fully removed promptly; if left in the skin, further problems may occur.[59]

Science[edit]

Sea urchins are traditional model organisms in developmental biology. This use originated in the 1800s, when their embryonic development became easily viewed by microscopy. The transparency of the urchin’s eggs enabled them to be used to observe that sperm cells actually fertilize ova.[60] They continue to be used for embryonic studies, as prenatal development continues to seek testing for fatal diseases. Sea urchins are being used in longevity studies for comparison between the young and old of the species, particularly for their ability to regenerate tissue as needed.[61] Scientists at the University of St Andrews have discovered a genetic sequence, the ‘2A’ region, in sea urchins previously thought to have belonged only to viruses that afflict humans like foot-and-mouth disease virus.[62]

More recently, Eric H. Davidson and Roy John Britten argued for the use of urchins as a model organism due to their easy availability, high fecundity, and long lifespan. Beyond embryology, urchins provide an opportunity to research cis-regulatory elements.[63]

Oceanography has taken an interest in monitoring the health of urchins and their populations as a way to assess overall ocean acidification,[64] temperatures, and ecological impacts.

The organism’s evolutionary placement and unique embryology with five-fold symmetry were the major arguments in the proposal to seek the sequencing of its genome. Importantly, urchins act as the closest living relative to chordates and thus are of interest for the light they can shed on the evolution of vertebrates.[65] The genome of Strongylocentrotus purpuratus was completed in 2006 and established homology between sea urchin and vertebrate immune system-related genes. Sea urchins code for at least 222 Toll-like receptor genes and over 200 genes related to the Nod-like-receptor family found in vertebrates.[66] This increases its usefulness as a valuable model organism for studying the evolution of innate immunity. The sequencing also revealed that while some genes were thought to be limited to vertebrates, there were also innovations that have previously never been seen outside the chordate classification, such as immune transcription factors PU.1 and SPIB.[65]

As food[edit]

The gonads of both male and female sea urchins, usually called sea urchin roe or corals,[67] are culinary delicacies in many parts of the world, especially Japan.[68][69][70] In Japan, sea urchin is known as uni (うに), and its roe can retail for as much as ¥40,000 ($360) per kilogram;[71] it is served raw as sashimi or in sushi, with soy sauce and wasabi. Japan imports large quantities from the United States, South Korea, and other producers. Japan consumes 50,000 tons annually, amounting to over 80% of global production.[72] Japanese demand for sea urchins has raised concerns about overfishing.[73]

In Mediterranean cuisines, Paracentrotus lividus is often eaten raw, or with lemon,[74] and known as ricci on Italian menus where it is sometimes used in pasta sauces. It can also flavour omelettes, scrambled eggs, fish soup,[75] mayonnaise, béchamel sauce for tartlets,[76] the boullie for a soufflé,[77] or Hollandaise sauce to make a fish sauce.[78] In Chilean cuisine, it is served raw with lemon, onions, and olive oil. Though the edible Strongylocentrotus droebachiensis is found in the North Atlantic, it is not widely eaten. However, sea urchins (called uutuk in Alutiiq) are commonly eaten by the Alaska Native population around Kodiak Island. It is commonly exported, mostly to Japan.[79]

In the West Indies, slate pencil urchins are eaten.[68]

On the Pacific Coast of North America, Strongylocentrotus franciscanus was praised by Euell Gibbons; Strongylocentrotus purpuratus is also eaten.[68]

Native Americans in California are also known to eat sea urchins.[80] The coast of Southern California is known as a source of high quality uni, with divers picking sea urchin from kelp beds in depths as deep as 24 m/80 ft.[81] As of 2013, the state was limiting the practice to 300 sea urchin diver licenses.[81]

In New Zealand, Evechinus chloroticus, known as kina in Māori, is a delicacy, traditionally eaten raw. Though New Zealand fishermen would like to export them to Japan, their quality is too variable.[82]

-

Japanese uni-ikura don, sea urchin egg and salmon egg donburi

-

Open sea urchins in Sicily

Aquaria[edit]

A fossil sea urchin found on a Middle Saxon site in Lincolnshire, thought to have been used as an amulet[83]

Some species of sea urchins, such as the slate pencil urchin (Eucidaris tribuloides), are commonly sold in aquarium stores. Some species are effective at controlling filamentous algae, and they make good additions to an invertebrate tank.[84]

Folklore[edit]

A folk tradition in Denmark and southern England imagined sea urchin fossils to be thunderbolts, able to ward off harm by lightning or by witchcraft, as an apotropaic symbol.[85] Another version supposed they were petrified eggs of snakes, able to protect against heart and liver disease, poisons, and injury in battle, and accordingly they were carried as amulets. These were, according to the legend, created by magic from foam made by the snakes at midsummer.[86]

Explanatory notes[edit]

- ^ The tube feet are present in all parts of the animal except around the anus, so technically, the whole surface of the body should be considered to be the oral surface, with the aboral (non-mouth) surface limited to the immediate vicinity of the anus.[2]

References[edit]

- ^ «Animal Diversity Web – Echinoidea». University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Ruppert, Edward E.; Fox, Richard, S.; Barnes, Robert D. (2004). Invertebrate Zoology, 7th edition. Cengage Learning. pp. 896–906. ISBN 978-81-315-0104-7.

- ^ Kroh, A.; Hansson, H. (2013). «Echinoidea (Leske, 1778)». WoRMS. World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved 2014-01-04.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Barnes, Robert D. (1982). Invertebrate Zoology. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. pp. 961–981. ISBN 0-03-056747-5.

- ^ Guill, Michael. «Taxonomic Etymologies EEOB 111». Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- ^ Wright, Anne. 1851. The Observing Eye, Or, Letters to Children on the Three Lowest Divisions of Animal Life. London: Jarrold and Sons, p. 107.

- ^ Soyer, Alexis. 1853. The Pantropheon Or History of Food, And Its Preparation: From The Earliest Ages Of The World. Boston: Ticknor, Reed, and Fields,, p. 245.

- ^ «urchin (n.)». Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- ^ Stachan and Read, Human Molecular Genetics, p. 381: «What Makes Us Human»

- ^ «The Echinoid Directory — Natural History Museum». www.nhm.ac.uk. Natural History Museum, UK. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- ^ «The Echinoid Directory — Natural History Museum». www.nhm.ac.uk. Natural History Museum, UK. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- ^ «Sea urchins reveal promising carbon capture alternative». Gizmag. 4 February 2013. Retrieved 2013-02-05.

- ^ Kazuya Yoshimura, Tomoaki Iketani et Tatsuo Motokawa, «Do regular sea urchins show preference in which part of the body they orient forward in their walk ?», Marine Biology, vol. 159, no 5, 2012, p. 959–965.

- ^ Boudouresque, Charles F.; Verlaque, Marc (2006). «13: Ecology of Paracentrotus lividus«. In Lawrence, John, M. (ed.). Edible Sea Urchins: Biology and Ecology. Elsevier. p. 243. ISBN 978-0-08-046558-6.

- ^ «Apical disc and periproct». Natural History Museum, London. Retrieved 2 November 2019.

- ^ Claw inspired by sea urchins’ mouth can scoop up Martian soil

- ^ Voultsiadou, Eleni; Chintiroglou, Chariton (2008). «Aristotle’s lantern in echinoderms: an ancient riddle» (PDF). Cahiers de Biologie Marine. Station Biologique de Roscoff. 49 (3): 299–302.

- ^ Choi, Charles Q. (29 December 2010). «Rock-Chewing Sea Urchins Have Self-Sharpening Teeth». National Geographic News. Retrieved 2017-11-12.

- ^ Knight, K. (2009). «Sea Urchins Use Whole Body As Eye». Journal of Experimental Biology. 213 (2): i–ii. doi:10.1242/jeb.041715.

- Charles Q. Choi (December 28, 2009). «Body of Sea Urchin is One Big Eye». LiveScience (Press release).

- ^ Gaitán-Espitia, J. D.; Sánchez, R.; Bruning, P.; Cárdenas, L. (2016). «Functional insights into the testis transcriptome of the edible sea urchin Loxechinus albus». Scientific Reports. 6: 36516. Bibcode:2016NatSR…636516G. doi:10.1038/srep36516. PMC 5090362. PMID 27805042.

- ^ A. Gaion, A. Scuderi; D. Pellegrini; D. Sartori (2013). «Arsenic Exposure Affects Embryo Development of Sea Urchin, Paracentrotus lividus (Lamarck, 1816)». Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology. 39 (2): 124–8. doi:10.3109/01480545.2015.1041602. PMID 25945412. S2CID 207437380.

- ^ Kominami, Tetsuya; Takata, Hiromi (2004). «Gastrulation in the sea urchin embryo: a model system for analyzing the morphogenesis of a monolayered epithelium». Development, Growth & Differentiation. 46 (4): 309–26. doi:10.1111/j.1440-169x.2004.00755.x. PMID 15367199. S2CID 23988213.

- ^ Shook, D; Keller, R (2003). «Mechanisms, mechanics and function of epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in early development». Mechanisms of Development. 120 (11): 1351–83. doi:10.1016/j.mod.2003.06.005. PMID 14623443. S2CID 15509972.; Katow, Hideki; Solursh, Michael (1980). «Ultrastructure of primary mesenchyme cell ingression in the sea urchinLytechinus pictus». Journal of Experimental Zoology. 213 (2): 231–246. doi:10.1002/jez.1402130211.; Balinsky, BI (1959). «An electro microscopic investigation of the mechanisms of adhesion of the cells in a sea urchin blastula and gastrula». Experimental Cell Research. 16 (2): 429–33. doi:10.1016/0014-4827(59)90275-7. PMID 13653007.; Hertzler, PL; McClay, DR (1999). «alphaSU2, an epithelial integrin that binds laminin in the sea urchin embryo». Developmental Biology. 207 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1006/dbio.1998.9165. PMID 10049560.; Fink, RD; McClay, DR (1985). «Three cell recognition changes accompany the ingression of sea urchin primary mesenchyme cells». Developmental Biology. 107 (1): 66–74. doi:10.1016/0012-1606(85)90376-8. PMID 2578117.; Burdsal, CA; Alliegro, MC; McClay, DR (1991). «Tissue-specific, temporal changes in cell adhesion to echinonectin in the sea urchin embryo». Developmental Biology. 144 (2): 327–34. doi:10.1016/0012-1606(91)90425-3. PMID 1707016.; Miller, JR; McClay, DR (1997). «Characterization of the Role of Cadherin in Regulating Cell Adhesion during Sea Urchin Development». Developmental Biology. 192 (2): 323–39. doi:10.1006/dbio.1997.8740. PMID 9441671.; Miller, JR; McClay, DR (1997). «Changes in the pattern of adherens junction-associated beta-catenin accompany morphogenesis in the sea urchin embryo». Developmental Biology. 192 (2): 310–22. doi:10.1006/dbio.1997.8739. PMID 9441670.; Anstrom, JA (1989). «Sea urchin primary mesenchyme cells: ingression occurs independent of microtubules». Developmental Biology. 131 (1): 269–75. doi:10.1016/S0012-1606(89)80058-2. PMID 2562830.; Anstrom, JA (1992). «Microfilaments, cell shape changes, and the formation of primary mesenchyme in sea urchin embryos». The Journal of Experimental Zoology. 264 (3): 312–22. doi:10.1002/jez.1402640310. PMID 1358997.

- ^ Nissen, Silas Boye; Rønhild, Steven; Trusina, Ala; Sneppen, Kim (November 27, 2018). «Theoretical tool bridging cell polarities with development of robust morphologies». eLife. 7: e38407. doi:10.7554/eLife.38407. PMC 6286147. PMID 30477635.

- ^ Warner, Jacob F.; Lyons, Deirdre C.; McClay, David R. (2012). «Left-Right Asymmetry in the Sea Urchin Embryo: BMP and the Asymmetrical Origins of the Adult». PLOS Biology. 10 (10): e1001404. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001404. PMC 3467244. PMID 23055829.

- ^ Worley, Alisa (2001). «Strongylocentrotus purpuratus«. Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 2016-12-05.

- ^ Baumiller, Tomasz K. (2008). «Crinoid Ecological Morphology». Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences. 36: 221–49. Bibcode:2008AREPS..36..221B. doi:10.1146/annurev.earth.36.031207.124116.

- ^ Lawrence, John M. (2006). Edible Sea Urchins: Biology and Ecology. Elsevier. pp. 167–168. ISBN 978-0-08-046558-6.

- ^ Jangoux, Michel (1987). «Diseases of Echinodermata. I. Agents microorganisms and protistans». Diseases of Aquatic Organisms. 2: 147–162. doi:10.3354/dao002147.

- ^ «Defence – spines». Echinoid Directory. Natural History Museum.

- ^ Sakashita, Hiroko (1992). «Sexual dimorphism and food habits of the clingfish, Diademichthys lineatus, and its dependence on host sea urchin». Environmental Biology of Fishes. 34 (1): 95–101. doi:10.1007/BF00004787. S2CID 32656986.

- ^ Terborgh, John; Estes, James A (2013). Trophic Cascades: Predators, Prey, and the Changing Dynamics of Nature. Island Press. p. 38. ISBN 978-1-59726-819-6.

- ^ «Aquatic Species at Risk – Species Profile – Sea Otter». Fisheries and Oceans Canada. Archived from the original on 2008-01-23. Retrieved 2007-11-29.

- ^ Thiel, Martin; Watling, Les (2015). Lifestyles and Feeding Biology. Oxford University Press. pp. 200–202. ISBN 978-0-19-979702-8.

- ^ «Defence – pedicellariae». Echinoid Directory. Natural History Museum.

- ^ Hiroko Sakashita, » Sexual dimorphism and food habits of the clingfish, Diademichthys lineatus, and its dependence on host sea urchin «, Environmental Biology of Fishes, vol. 34, no 1, 1994, p. 95–101

- ^ Jangoux, M. (1984). «Diseases of echinoderms» (PDF). Helgoländer Meeresuntersuchungen. 37 (1–4): 207–216. Bibcode:1984HM…..37..207J. doi:10.1007/BF01989305. S2CID 21863649. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- ^ a b c Kroh, Andreas (2010). «The phylogeny and classification of post-Palaeozoic echinoids». Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 8 (2): 147–212. doi:10.1080/14772011003603556..

- ^ Mah, Christopher (April 12, 2011). «Sizes and Species in the Strangest of the Strange : Deep-Sea Pourtalesiid Urchins». The Echinoblog..

- ^ a b Mah, Christopher (8 April 2014). «What are the Deepest known echinoderms?». The Echinoblog. Retrieved 22 March 2018..

- ^ Mattison, J.E.; Trent, J.D.; Shanks, AL; Akin, T.B.; Pearse, J.S. (1977). «Movement and feeding activity of red sea urchins (Strongylocentrotus franciscanus) adjacent to a kelp forest». Marine Biology. 39 (1): 25–30. doi:10.1007/BF00395589. S2CID 84338735.

- ^ a b c Konar, Brenda (2000). «Habitat influences on sea urchin populations». In: Hallock and French (Eds). Diving for Science…2000. Proceedings of the 20th Annual Scientific Diving Symposium. American Academy of Underwater Sciences. Archived from the original on April 15, 2013. Retrieved 7 January 2011.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ ChrisM (2008-04-21). «The Echinoblog». echinoblog.blogspot.com.

- ^ Antarctic Sea Urchin Shows Amazing Energy-Efficiency in Nature’s Deep Freeze 15 March 2001 University of Delaware. Retrieved 22 March 2018

- ^ Botting, Joseph P.; Muir, Lucy A. (March 2012). «Fauna and ecology of the holothurian bed, Llandrindod, Wales, UK (Darriwilian, Middle Ordovician), and the oldest articulated holothurian» (PDF). Palaeontologia Electronica. 15 (1): 1–28. doi:10.26879/272. S2CID 55716313. Retrieved 29 October 2022.

- ^ Thompson, Jeffrey R.; Cotton, Laura J.; Candela, Yves; Kutscher, Manfred; Reich, Mike; Bottjer, David J. (14 April 2022). «The Ordovician diversification of sea urchins: systematics of the Bothriocidaroida (Echinodermata: Echinoidea)». Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 19 (20): 1395–1448. doi:10.1080/14772019.2022.2042408. S2CID 248192052. Retrieved 29 October 2022.

- ^ «Echinoids». British Geological Survey. 2017. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- ^ «The Echinoid Directory | Introduction». Natural History Museum. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ^ «The Echinoid Directory | Spines». Natural History Museum. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ^ a b c d Kirkaldy, J. F. (1967). Fossils in Colour. London: Blandford Press. pp. 161–163.

- ^ Schultz, Heinke A.G. (2015). Echinoidea: with pentameral symmetry. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 36 ff, section 2.4. ISBN 978-3-11-038601-1.

- ^ Wells, H. G.; Huxley, Julian; Wells, G. P. (1931). The Science of life. pp. 346–348.

- ^ Telford, M. J.; Lowe, C. J.; Cameron, C. B.; Ortega-Martinez, O.; Aronowicz, J.; Oliveri, P.; Copley, R. R. (2014). «Phylogenomic analysis of echinoderm class relationships supports Asterozoa». Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 281 (1786): 20140479. doi:10.1098/rspb.2014.0479. PMC 4046411. PMID 24850925.

- ^ Planet, Paul J.; Ziegler, Alexander; Schröder, Leif; Ogurreck, Malte; Faber, Cornelius; Stach, Thomas (2012). «Evolution of a Novel Muscle Design in Sea Urchins (Echinodermata: Echinoidea)». PLOS ONE. 7 (5): e37520. Bibcode:2012PLoSO…737520Z. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0037520. PMC 3356314. PMID 22624043.

- ^ Kroh, Andreas; Smith, Andrew B. (2010). «The phylogeny and classification of post-Palaeozoic echinoids». Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 8 (2): 147–212. doi:10.1080/14772011003603556.

- ^ Koch, Nicolás Mongiardino; Thompson, Jeffrey R; Hiley, Avery S; McCowin, Marina F; Armstrong, A Frances; Coppard, Simon E; Aguilera, Felipe; Bronstein, Omri; Kroh, Andreas; Mooi, Rich; Rouse, Greg W (Mar 22, 2022). «Phylogenomic analyses of echinoid diversification prompt a re-evaluation of their fossil record». eLife. 11: e72460. doi:10.7554/eLife.72460. PMC 8940180. PMID 35315317.

- ^ James, William D.; Berger, Timothy G.; et al. (2006). Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: clinical Dermatology. Saunders Elsevier. p. 431. ISBN 0-7216-2921-0.

- ^ Gallagher, Scott A. «Echinoderm Envenomation». eMedicine. Retrieved 12 October 2010.

- ^ Matthew D. Gargus; David K. Morohashi (2012). «A sea-urchin spine chilling remedy». New England Journal of Medicine. 30 (19): 1867–1868. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1209382. PMID 23134402.

- ^ «Insight from the Sea Urchin». Microscope Imaging Station. Exploratorium. Archived from the original on 2017-03-12. Retrieved 2018-03-07.

- ^ Bodnar, Andrea G.; Coffman, James A. (2016-08-01). «Maintenance of somatic tissue regeneration with age in short- and long-lived species of sea urchins». Aging Cell. 15 (4): 778–787. doi:10.1111/acel.12487. ISSN 1474-9726. PMC 4933669. PMID 27095483.

- ^ Roulston, C.; Luke, G.A.; de Felipe, P.; Ruan, L.; Cope, J.; Nicholson, J.; Sukhodub, A.; Tilsner, J.; Ryan, M.D. (2016). «‘2A‐Like’ Signal Sequences Mediating Translational Recoding: A Novel Form of Dual Protein Targeting» (PDF). Traffic. 17 (8): 923–39. doi:10.1111/tra.12411. PMC 4981915. PMID 27161495.

- ^ «Sea Urchin Genome Project». sugp.caltech.edu. Archived from the original on 2016-12-20. Retrieved 2016-12-05.

- ^ «Stanford seeks sea urchin’s secret to surviving ocean acidification | Stanford News Release». news.stanford.edu. 2013-04-08. Retrieved 2016-12-05.

- ^ a b Sodergren, E; Weinstock, GM; Davidson, EH; et al. (2006-11-10). «The Genome of the Sea Urchin Strongylocentrotus purpuratus». Science. 314 (5801): 941–952. Bibcode:2006Sci…314..941S. doi:10.1126/science.1133609. PMC 3159423. PMID 17095691.

- ^ Rast, JP; Smith, LC; Loza-Coll, M; Hibino, T; Litman, GW (2006). «Genomic Insights into the Immune System of the Sea Urchin». Science. 314 (5801): 952–6. Bibcode:2006Sci…314..952R. doi:10.1126/science.1134301. PMC 3707132. PMID 17095692.

- ^ Laura Rogers-Bennett, «The Ecology of Strongylocentrotus franciscanus and Strongylocentrotus purpuratus» in John M. Lawrence, Edible sea urchins: biology and ecology, p. 410

- ^ a b c Davidson, Alan (2014) Oxford Companion to Food. Oxford University Press, 3rd edition. pp. 730–731.

- ^ John M. Lawrence, «Sea Urchin Roe Cuisine» in John M. Lawrence, Edible sea urchins: biology and ecology

- ^ «The Rise of the Sea Urchin», Franz Lidz July 2014, Smithsonian

- ^ Macey, Richard (November 9, 2004). «The little urchins that can command a princely price». The Sydney Morning Herald.

- ^ Zatylny, Jane (6 September 2018). «Searchin’ for Urchin: A Culinary Quest». Hakai Magazine. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- ^ «Sea Urchin Fishery and Overfishing», TED Case Studies 296, American University full text

- ^ for Puglia, Italy: Touring Club Italiano, Guida all’Italia gastronomica, 1984, p. 314; for Alexandria, Egypt: Claudia Roden, A Book of Middle Eastern Food, p. 183

- ^ Alan Davidson, Mediterranean Seafood, p. 270

- ^ Larousse Gastronomique[page needed]

- ^ Curnonsky, Cuisine et vins de France, nouvelle édition, 1974, p. 248

- ^ Davidson, Alan (2014) Oxford Companion to Food. Oxford University Press, 3rd edition. p. 280

- ^ Kleiman, Dena (October 3, 1990). «Scorned at Home, Maine Sea Urchin Is a Star in Japan». The New York Times. p. C1.

- ^ Martin, R.E.; Carter, E.P.; Flick, G.J.; Davis, L.M. (2000). Marine and Freshwater Products Handbook. Taylor & Francis. p. 268. ISBN 978-1-56676-889-4. Retrieved 2014-12-03.

- ^ a b Lam, Francis (2014-03-14). «California Sea Urchin Divers, Interviewed by Francis Lam». Bon Appetit. Retrieved 2017-03-26.

- ^ Wassilieff, Maggy (March 2, 2009). «sea urchins». Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

- ^ «Amulet | LIN-B37563». Portable Antiquities Scheme. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- ^ Tullock, John H. (2008). Your First Marine Aquarium: Everything about Setting Up a Marine Aquarium, Including Conditioning, Maintenance, Selecting Fish and Invertebrates, and More. Barron’s Educational Series. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-7641-3675-7.

- ^ McNamara, Ken (2012). «Prehistoric fossil collectors». The Geological Society. Retrieved 14 March 2018.