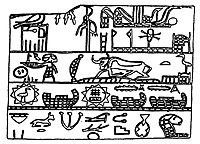

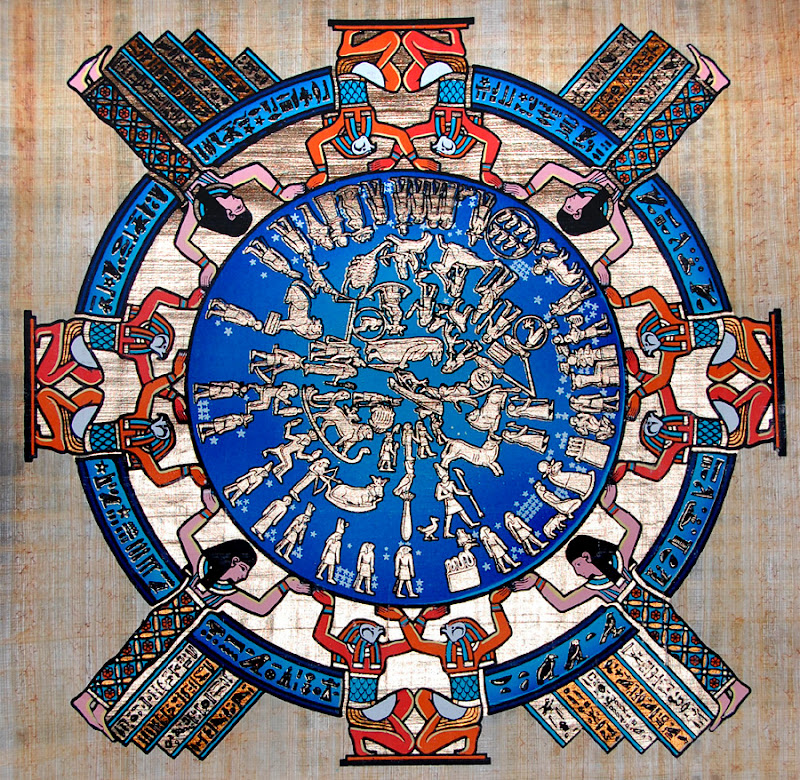

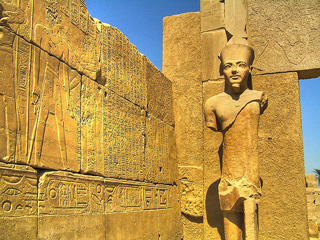

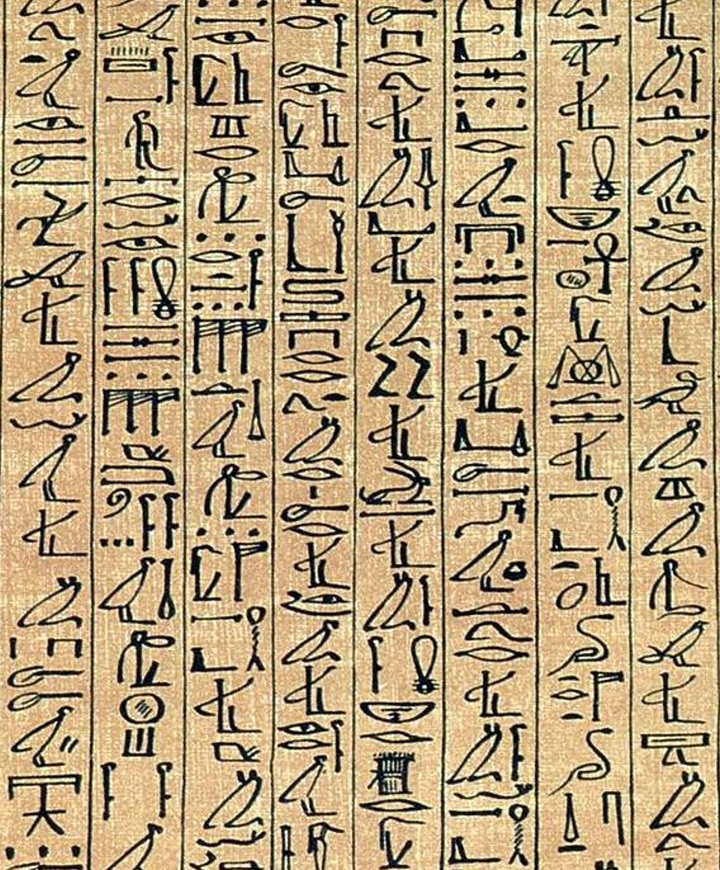

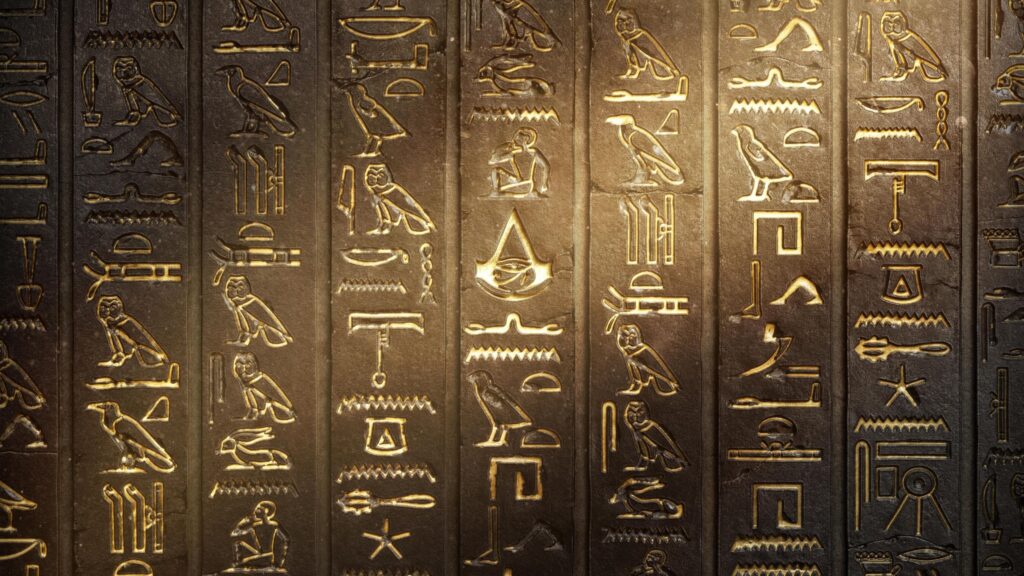

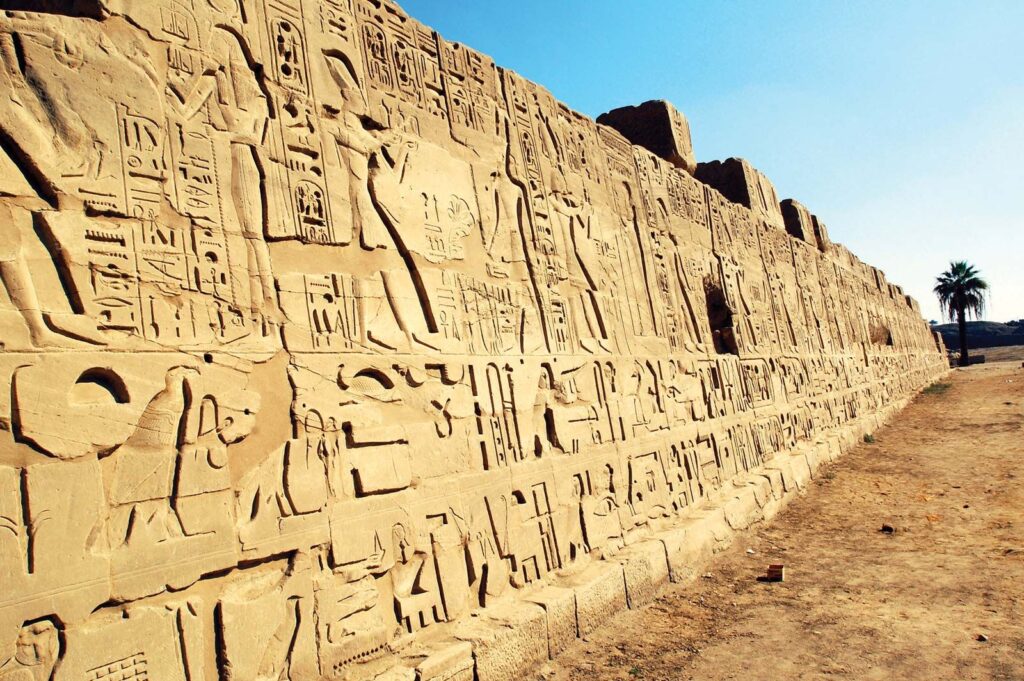

В Древнем Египте письменность возникла на стыке IV-III тыс. до н.э. Древняя письменность Египта представлена в виде изображений и текстов на стенах гробниц и пирамид.

Ключ к разгадке истории письменности Древнего Египта

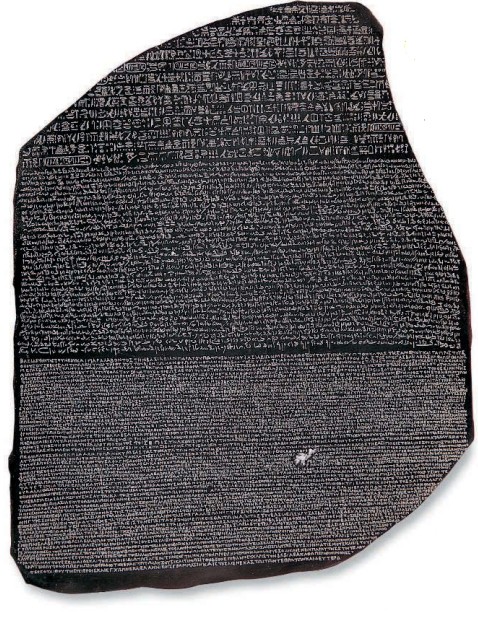

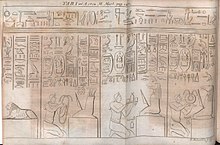

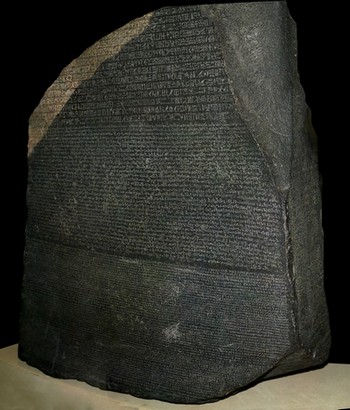

Тексты египетского письма стойко хранили тайны. Ключом к разгадке древней письменности Египта стал Розеттский камень, найденный в 1799 году при Розетте недалеко от Александрии. На фрагменте увесистой плиты в 760 кг, высотой 1,2 м, шириной около 1 м и толщиной 30 см разместились три идентичных текста на разных языках письменности Древнего Египта. В верхней части на 14 строках расположились древнеегипетские иероглифы, в середине камня 34 строки занимало демотическое письмо, а в нижней части вытесаны 14 строк текста на древнегреческом языке. Находка стала отправной точкой для исследований истории древней письменности Египта. С 1822 года лингвисты смогли расшифровать надписи на стенах гробниц.

Письменность древнего Египта: иероглифы

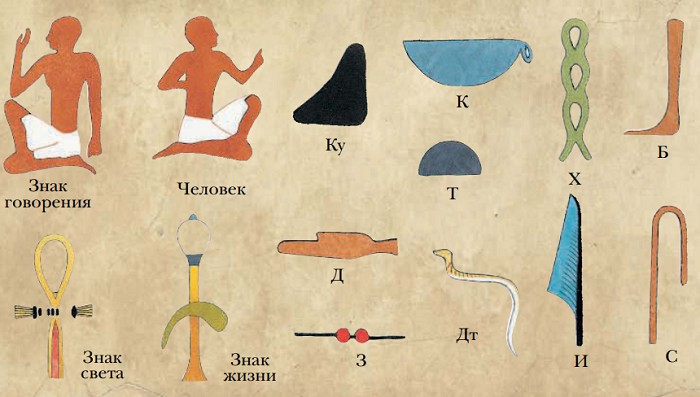

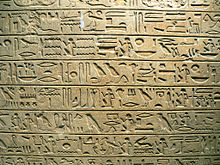

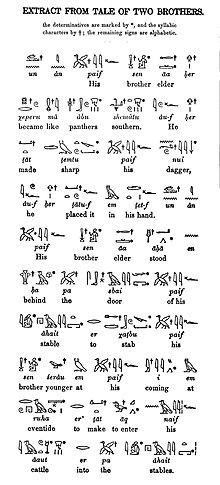

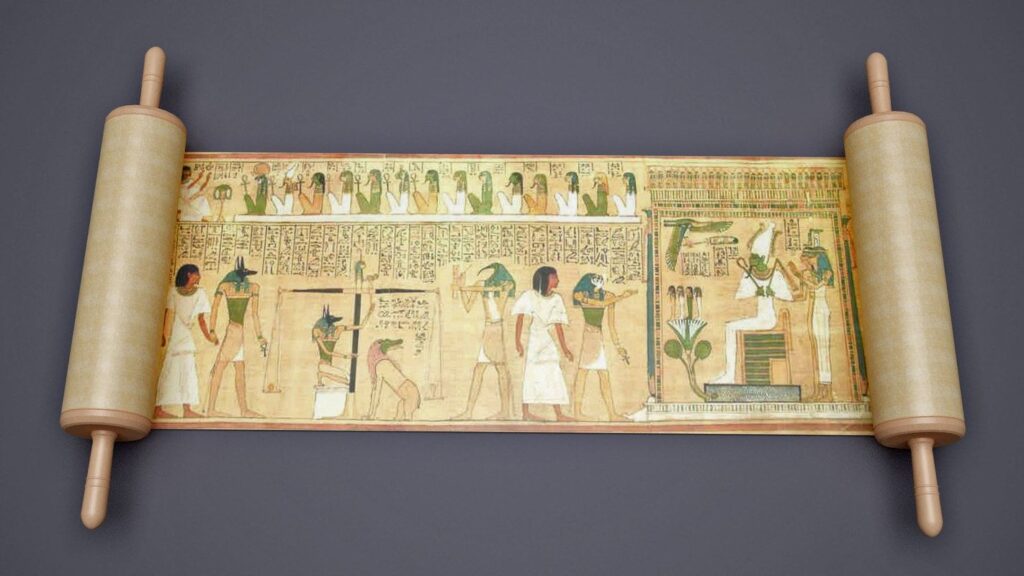

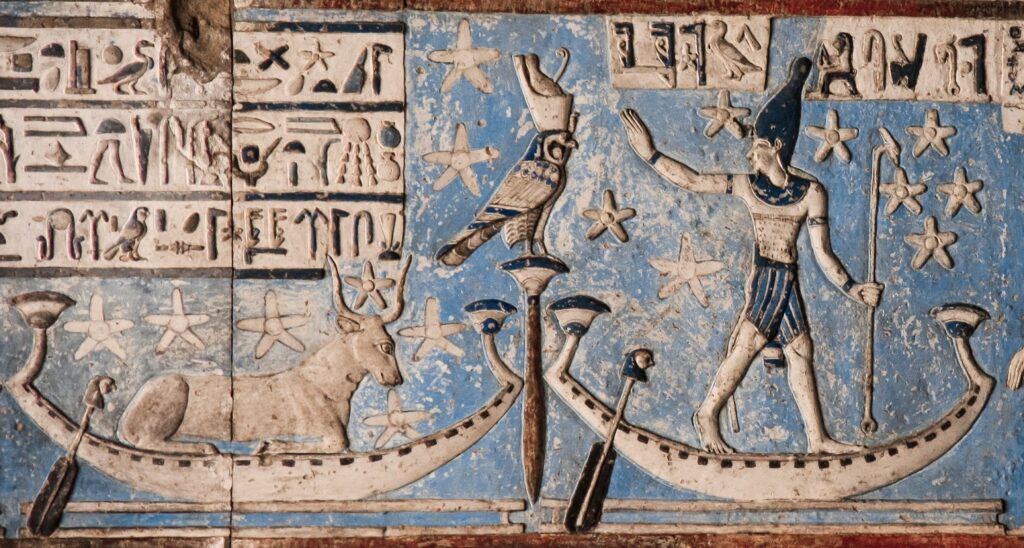

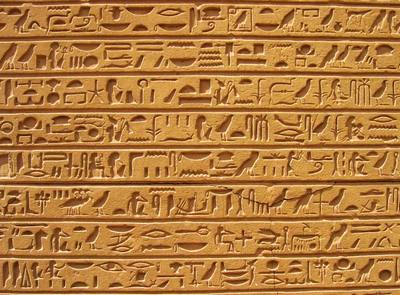

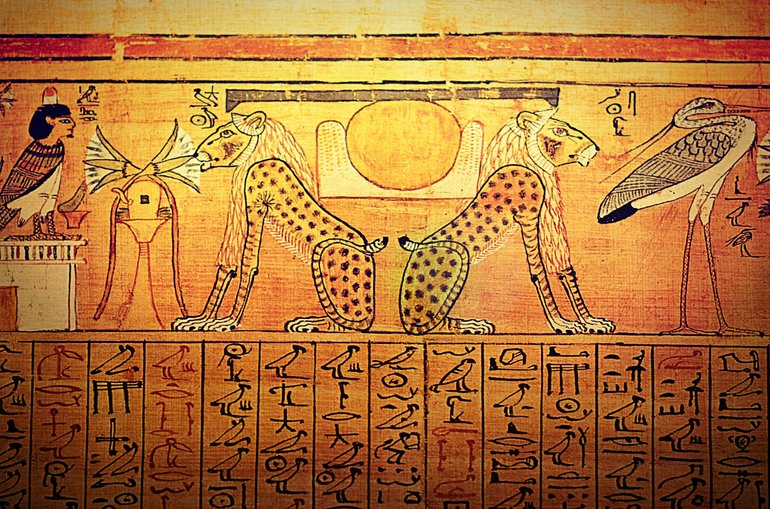

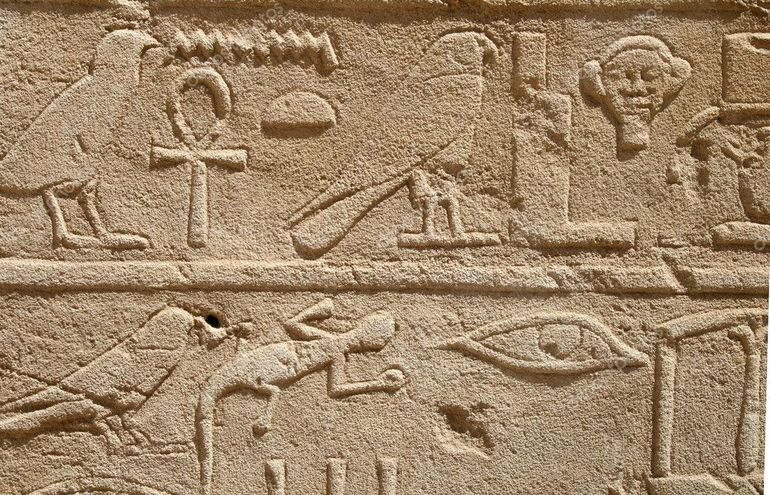

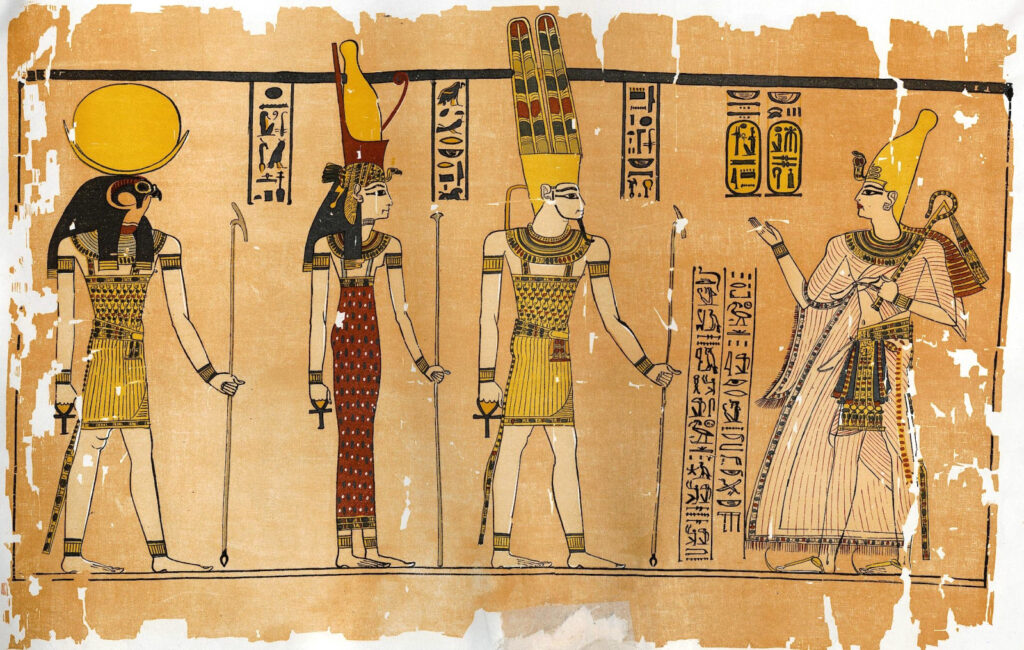

Египтяне считали, что письмо было изобретено богом мудрости Тота. «Божественное слово» передавалось в виде иероглифов. Понятие иероглифа происходит от греческого hieros (священная) и glypho.(надпись). «Священное письмо» исследователи-египтологи определили как рисуночное письмо с дополнением фонетических знаков. Иероглифы писали в колонках слева направо. Иероглифические знаки высекали на камнях, вырезали на коже, наносили кисточкой на папирус. Иероглифические письма использовали в гробницах и для религиозных целей до IV века н.э.

Древний Египет и история письменности: иератические знаки

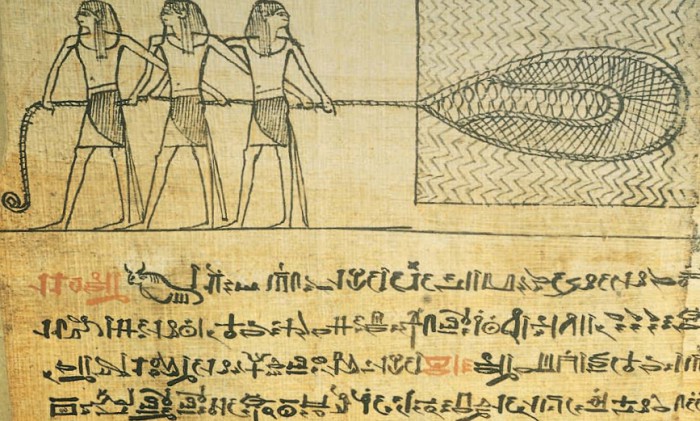

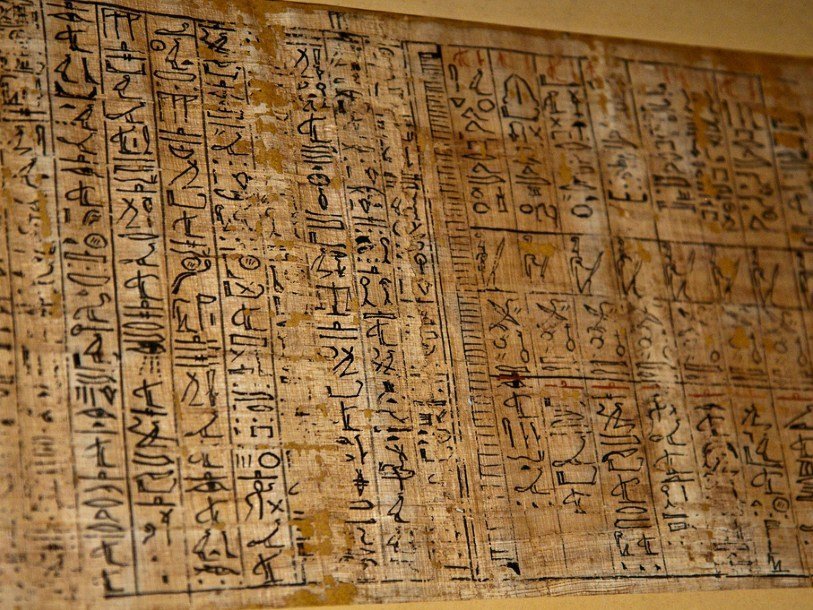

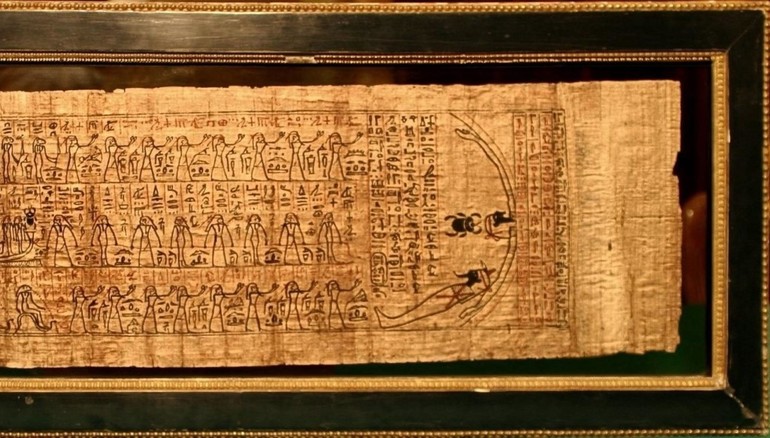

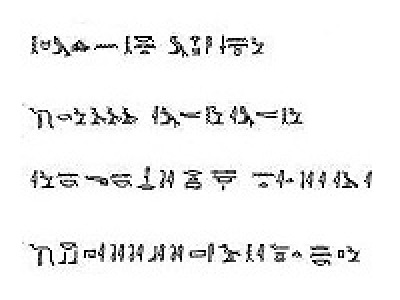

В истории письменности древнего Египта одновременно с иероглифическим письмом существовало иератическое. Этот вид древнеегипетской письменности, как и демотическое письмо в дальнейшем, было скорописным письмом. Для письма использовали папирус, кожу, глиняные черепки, ткани, дерево. Пометки делали чернилами. Употреблялись иератические знаки для написания хозяйственных документов и литературных трактатов древнеегипетскими жрецами. Письмо «иератика» просуществовало до III века н.э. и отличалось по способу написания: справа налево.

История письменности древнего Египта: демотические символы

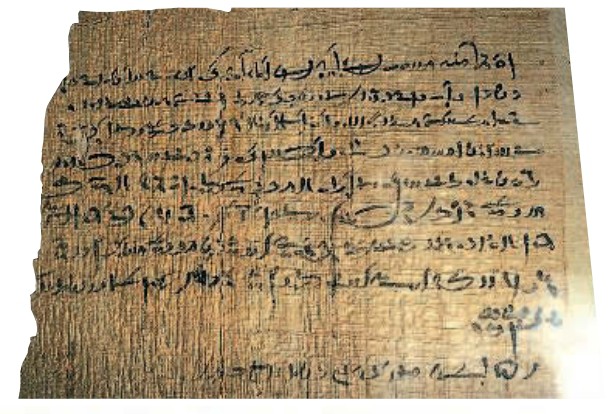

Постепенно иератическое письмо развилось в демотическое. Это была упрощенная форма иероглифической письменности периода поздней иератики. Дематика считалась народным письмом. Демотические тексты описывали разные сферы деятельности египтян. Периодизации использования демотической письменности датируется VII веком до н.э. — V века н.э. Демотическая письменность – это наиболее прогрессивный вид древней египетской письменности. Постепенно появилось демотическое «слоговое письмо». Сложность демотической письменности заключалась в многозначной трактовке знаков.

Проект история письменности Древнего Египта в видео:

Смотрите также:

Иероглифы Древнего Египта

Что означают древние буквы Египта

Письменность в Древнем Египте

Слово «папирус» происходит от названия тростника, который произрастает на берегах реки Нил. Для изготовления папируса (бумаги) египтяне снимали верхний слой со стволов тростника. Сердцевину нарезали полосками, мочили в воде, а затем укладывали слоями крест-накрест. Их плющили молотком, пока они не образовывали однородную массу. После этого поверхность папируса полировали деревянным инструментом. В числе других писчих материалов были глиняные черепки, дощечки из кожи или гипса.

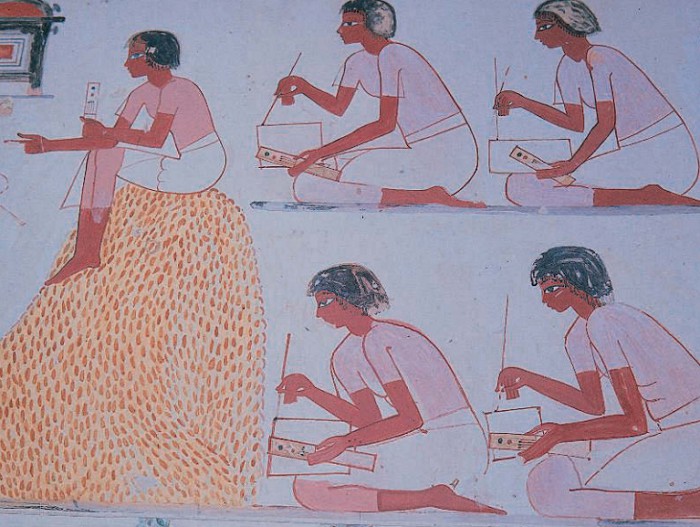

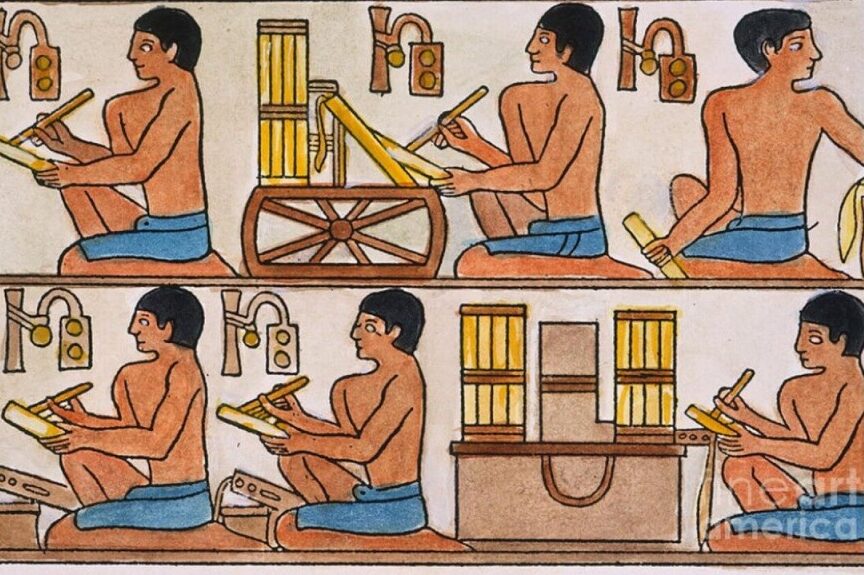

Считается, что примерно лишь четверо из тысячи египтян умели читать или писать. Писцы являлись профессиональными писарями, которые занимались переписыванием официальных документов и указов, писем, стихов и историй. Обучение юных писцов отличалось основательностью, строгостью и суровостью. Один из наставников, Аменемоп, так обращался к своим ученикам: «Не проводи ни дня в лености, иначе ты будешь бит». Однако большинство рабочего люда завидовали легкой жизни писцов. Их хорошо вознаграждали за работу.

Этот красивый инструмент был найден в гробнице Тутанхамона. Он сделан из слоновой кости, отделанной на конце золотой фольгой. Полировальные лопатки использовались писцами для шлифовки поверхности свежеизготовленного папируса.

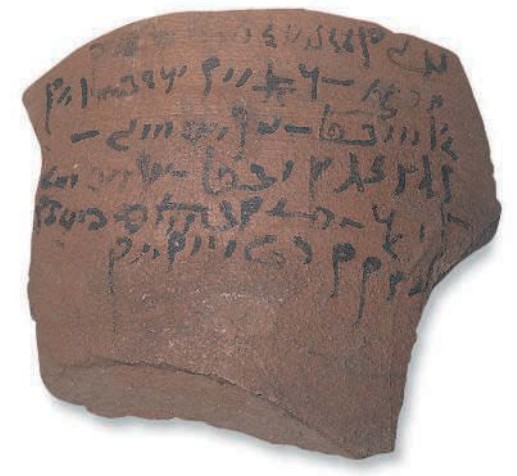

Школьные упражнения нередко записывались на выброшенных осколках камня или глины. Эти осколки известны как остраконы. Юные писцы переписывали упражнения на остраконе, а затем отдавали их на проверку учителю. В Египте было обнаружено множество образцов исправленных упражнений.

Сидящие на коленях писцы ведут учет размера урожая зерновых. Земледелец после этого должен был отдать часть зерна фараону в качестве подати, или налога. Многие писцы состояли при правительстве и переписывали отчеты, налоги, приказы и законы. Они были чем-то вроде государственных служащих.

Этот письменный прибор писца датируется примерно 3000 г. до н. э. Он состоит из тростниковых перьев и чернильницы. Чернила делали из древесного угля или сажи, смешанных с водой. Писцы носили с собой дробилку для того, чтобы сначала измельчать красители. Нередко на письменном приборе гравировалось имя писца и имя его работодателя или фараона.

В Древнем Египте кисточки и перья делались из тростника. Куски чернил смешивались с водой на специальной палитре. Черные чернила изготавливались из древесного угля, а красные чернила делались из охры (составной части железа). То и другое смешивали с камедью.

Работа писца нередко означала, что ему приходилось отправляться в деловые путешествия, чтобы фиксировать официальные документы. У большинства имелась переносная палитра вроде этой на случай разъездов. Писцы нередко также имели при себе портфель или сумку для документов, чтобы уберечь сведения, которые они записывали.

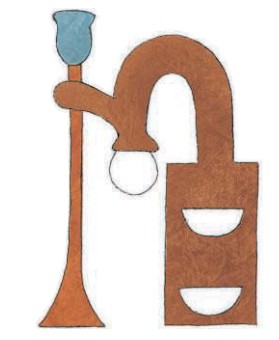

Иероглиф, обозначающий писца, состоит из водяного сосуда, держателя для кисточки и палитры с кусками чернил. Египетским словом для обозначения писца или чиновника было слово «сеш».

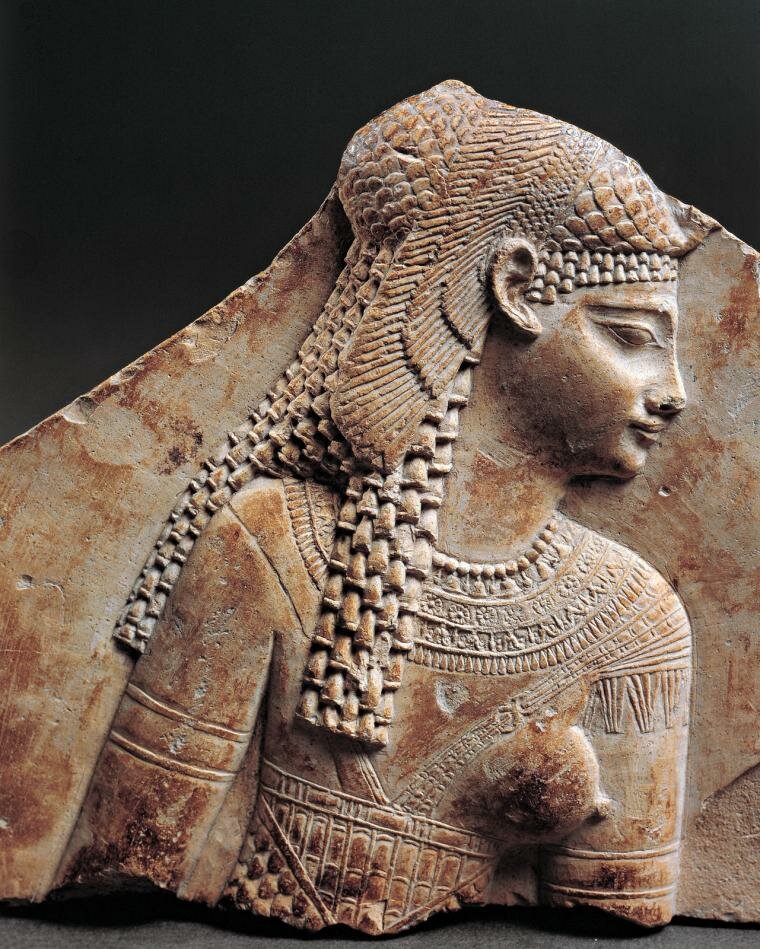

Аккроупи сидит, скрестив ноги, и держит в руках папирус и письменный прибор. Аккроупи был знаменитым писцом, жившим в Египте во времена Древнего царства. Писцы нередко считались влиятельными людьми в Древнем Египте, и до наших дней дошли их многочисленные статуи. Высокое положение писцов подтверждается в тексте «Сатира о профессиях», в котором говорится: «Заметь, что ни один писец не лишен пищи и богатств от царя».

Способы письма

Нам известно так много о древних египтянах благодаря письменному языку, который они оставили после себя. Надписи, сообщающие подробные сведения о их жизни, встречаются на всем – от обелисков до гробниц. Начиная примерно с 3100 г. до н. э. они использовали пиктограммы, называющиеся иероглифами. Каждая пиктограмма могла обозначать предмет, идею или звук. Изначальный вариант насчитывал около 100 иероглифических символов. Иероглифы использовались тысячелетиями, однако с 1780 г. до н. э. было популярно также и иератическое письмо. В поздний период Древнего Египта наряду с иероглифами использовалось и еще одно письмо – демотическое.

Впрочем, к 600 г. н. э., когда давно канул в историю последний фараон, никто уже не понимал иероглифы. Секреты Древнего Египта были утрачены на 1200 лет, до обнаружения Розеттского камня.

Обнаружение Розеттского камня явилось счастливой случайностью. В 1799 году французский солдат нашел кусок камня в египетской деревушке под названием Рашид – или Розетта. На этом камне одни и те же слова были написаны тремя способами, представляющими два языка. Иероглифический текст вверху, демотический текст в центре, а греческий – внизу.

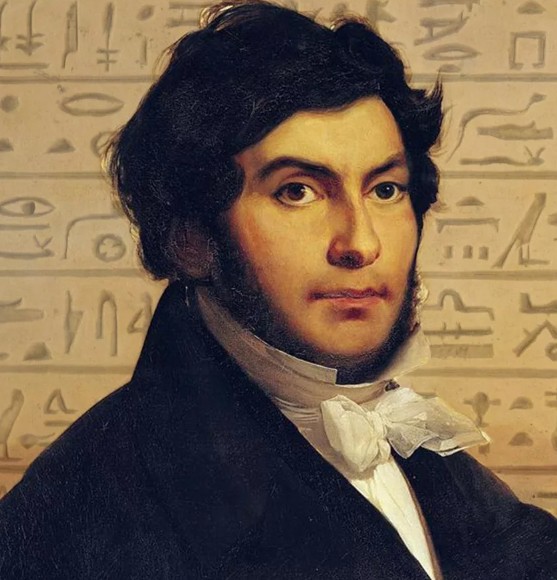

В 1822 году французский ученый Жан-Франсуа Шампольон расшифровал надписи Розеттского камня. На камне запечатлен царский указ, написанный в 196 г. до н. э., когда у власти в Египте был греческий царь Птолемей V. Греческий текст на камне позволил Шампольону перевести иероглифы. Это открытие стало краеугольным для нашего понимания того, как жили древние египтяне.

Иератическое письмо использовало рисуночные символы (пиктограммы) и делало их очертания более похожими на буквы. Этот вид письма был менее отрывистым и позволял писать быстро. Им пользовались для изложения историй, писем и деловых соглашений. Его всегда читали справа налево.

Демотическое письмо (слева) было введено к концу Позднего царства. Оно позволяло писать еще быстрее, чем иератическое письмо. Первоначально им пользовались в деловых целях, но вскоре оно стало применяться и для религиозных и научных записей. Это письмо исчезло, когда Египет попал под власть римлян.

Иероглифы состояли из небольших рисунков. Эти рисунки базировались на упрощенном изображении птиц и змей, растений, частей тела, лодок и домов. Одни иероглифы выражали сложные идеи, как то: свет, путешествие или жизнь. Другие означали буквы или звуки, которые можно было комбинировать для получения слов.

Поделиться ссылкой

Древнеегипетский язык — язык, на котором говорили древние египтяне,

населявшие долину Нила к северу от первого из нильских порогов.

Образует одну из ветвей афразийских

языков, носящую название египетской.

Имеет ряд схождений в фонетике и морфологии с

семитской

ветвью афразийской семьи, в связи с чем в свое время некоторые авторы относили его к семитским.

Другая достаточно популярная в свое время точка зрения заключалась в признании его промежуточным звеном

между семитской, берберо-ливийской

и кушитской ветвями.

Обе эти трактовки в настоящее время отвергнуты.

Крупная надпись, высеченная на скале к северу от древнеегипетского города Эль-Каб, проливает свет

на становление письменности этой цивилизации.

Четыре иероглифа появились около 3250 г. до н.э., в период так называемой Нулевой династии,

когда долина Нила была разделена на несколько царств, а письменность только-только зарождалась.

Исследователи разглядели четыре символа: голову быка на шесте, двух аистов и ибиса.

В более поздних надписях такая последовательность связывалась с солнечным циклом.

Она также могла выражать власть фараона над упорядоченным космосом.

Известные до 2017 года надписи периода Нулевой династии носили исключительно деловой характер

и были небольшими по размеру (не больше 2,5 см). Высота новооткрытых знаков – около полуметра.

Древнейшие из известных нам документов на древнеегипетском языке

относятся ко времени правления I династии и датируются концом 4 – началом 3 тысячелетия до н.э.

Почти все каменные памятники этого периода покрыты иероглифическими словесно-слоговыми письменами,

в которых сохранились черты пиктографического письма.

В деловой документации со времен глубокой древности использовалась особого рода иероглифическая скоропись;

после периода правления V династии (около 2500 до н.э.), к которому относятся древнейшие записи на папирусе,

эта скоропись стала называться иератическим письмом.

После 7 в. до н.э. на основе иератического письма сформировалась сверхскорописная форма –

демотическое письмо, остававшееся в употреблении вплоть до конца 5 в. н.э.

Монументальная (рисуночная) форма египетского письма после появления иератики использовалась редко.

В истории древнеегипетского языка принято выделять несколько периодов.

-

Древнейший, называемый староегипетским языком, датируется 32–22 веками до н.э.;

он представлен в записанных в соответствии с их фонетическим звучанием гимнах и заклинаниях, найденных в пирамидах;

в течение веков эти тексты передавались изустно. -

Следующий период истории древнеегипетского языка – среднеегипетский язык,

который оставался литературным языком Египта с 22 по 14 век до н.э.;

для некоторых целей он продолжал употребляться и во времена римского правления. -

После примерно 1350 года до н.э. среднеегипетский уступает место позднеегипетскому

(или новоегипетскому) языку как в литературных текстах, так и в официальных документах.

Позднеегипетский оставался в употреблении до тех пор, пока его приблизительно в 7 в. до н.э.

не сменил демотический египетской – язык демотических текстов. -

Примерно во 2 в. н.э. для записи древнеегипетских текстов стал применяться

греческий алфавит,

и начиная с этого времени древнеегипетский язык стал называться коптским.

Последняя известная запись иератическим письмом датируется 3 в. н.э.; демотическим – 5 в. н.э.;

с этого момента древнеегипетский язык принято считать мертвым.

В период Средневековья древнеегипетские иероглифы были забыты, но с развитием науки

стали предприниматься многочисленные усилия по их дешифровке.

Все эти попытки, основывавшиеся главным образом на трактате Гораполло (ок. 5 в. н.э.), не имели успеха.

В 1799 был обнаружен Розеттский камень, содержавший надписи 3 в. до н.э.

на греческом,

древнеегипетском иероглифическом и демотическом языках.

Эта надпись стала солидной основой для дешифровки, которая была немедленно начата

и в 1822 доведена до завершения французским ученым Ж.Ф.Шампольоном.

С тех пор египтологи последовательно работали над реконструкцией древнеегипетской грамматики и лексики,

в результате чего большинство древнеегипетских документов всех периодов поддается переводу.

Элементы фонографии в древнеегипетской письменности

В первых же доступных прочтению и интерпретации образцах собственно письма, помимо логограмм и детерминативов,

обнаруживается вполне развитая система фонетического письма, причем в том же виде,

в каком она сохранялась на протяжении тысячелетий ее употребления в Египте.

Бросающейся в глаза особенностью фонетических знаков является то, что они несут информацию

только о согласных звуках текста и об их расположении относительно друг друга,

но ничего не сообщают нам о гласных, которые тоже не могли не присутствовать в воспроизводимой данным письмом речи.

Многие ученые утверждают, что эти знаки применялись для распознавания только согласных звуков,

однако другие настаивают на том, что они, подобно клинописным знакам, обозначали слоги,

но в отличие от клинописи, где каждый знак, как правило, обозначал только один слог,

в египетском письме каждый знак обозначал целый ряд слогов, содержавших одни и те же согласные, но разные гласные.

В египетском письме имелось три вида фонетических знаков:

- примерно 24 знака, обозначавших только один согласный,

- примерно 70 знаков, обозначавших два согласных,

- и несколько знаков, обозначавших три согласных.

Когда использовался двух- или трехсогласный знак, при нем почти всегда имелся один или более односогласный знак,

повторявший частично или полностью его фонетическое значение [странно, зачем?].

Фонетические знаки, как и в случае клинописи, безусловно, произошли от логограмм.

Египетский фонетический знак – это зачастую рисунок какого-то предмета, для которого в языке имеется короткое слово,

содержащее тот же согласный, который обозначается данным знаком.

Детерминативы в египетском письме

Детерминативы появились в египетском письме довольно поздно.

В конце концов почти каждое слово стало на письме сопровождаться детерминативом.

Исключения составляют слова, записываемые с помощью вышеприведенных самостоятельных логограмм,

и кое-какие слова, записываемые фонетическими знаками, – например, слова со значением ‘имя’ и ‘хороший’,

личные и указательные местоимения, предлоги и несколько часто встречающихся глаголов.

Египетские детерминативы отличаются от клинописных и в некоторых других отношениях.

Они всегда стоят после написания слова, и при одном слове может быть употреблено более одного детерминатива.

Количество различных детерминативов в египетском письме намного больше, чем в клинописи:

в египетском имеется по меньшей мере 100 широкоупотребительных детерминативов и еще несколько сотен более редких.

Египетские детерминативы бывают трех видов:

специфические – те, что встречаются с одним-единственным словом,

родовые – те, что встречаются с более чем одним словом,

и фонетические детерминативы.

Специфические детерминативы обычно рассматриваются как логограммы, несмотря на то,

что они, как правило, сопровождаются фонетическим отображением самого слова.

За таким комплексом знаков может следовать родовой детерминатив.

Каждый родовой детерминатив сочетается с большим числом слов и, подобно клинописным детерминативам,

указывает на тот класс объектов, к которому принадлежит объект, обозначаемый конкретным словом.

Только немногие египетские логограммы употреблялись самостоятельно, при большинстве же из них

имелись детерминативы и фонетические знаки, передававшие частично или полностью звучание слова.

Когда логограмма встречалась в самостоятельном употреблении, то под ней стояла маленькая черточка.

[Может быть, т.н. «вирамы» в Фестском диске тоже означают смену типа знака?]

Примеры таких самостоятельных логограмм – знаки для слов со значением ‘лицо’, ‘сердце’, ‘дом’, ‘гора’ и ‘глаз’.

Литература об истории египетской иероглифики её расшифровке

-

Baines, J. 2004. The Earliest Egyptian Writing: Development, context, purpose. In Houston, S. D. (ed.),

The First Writing: Script Invention as History and Process. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 150–189.

Применение древнеегипетского письма другими народами

Семитские надписи древнеегипетскими иероглифами (XXIV в. до н.э.)

Древние записи, сделанные египетскими иероглифами на подземных частях стен пирамиды фараона Униса

(последний из V династии: правил приблизительно в 2375 — 2345 годах до н. э.) в Саккаре,

долгое время представляли собой большую проблему для науки: ни у кого не получалось их расшифровать.

Дешифровку выполнил профессор Ричард Штайнер из нью-йоркского университета Ешивы.

Оказалось, что эти тексты написаны на языке древних ханаанцев, на котором они говорили 5000 лет назад

[III тысячелетие до нашей эры].

Точной датировки этих надписей нет, но египтологи полагают, что они были нанесены в период с 30 по 25 век до нашей эры.

[почему они гадают, если это произошло при Унисе в 24 веке от Р.Х.?]

Текст содержит заклятья, которые были должны защищать мумии фараонов от ядовитых змей.

Интересно, что для этого египтянам пришлось прибегнуть именно к семитской магии.

Сам фараон Унис известен жестокой войной с ханаанцами. Вероятно, пленные ханаанеяне и строили ему пирамиду.

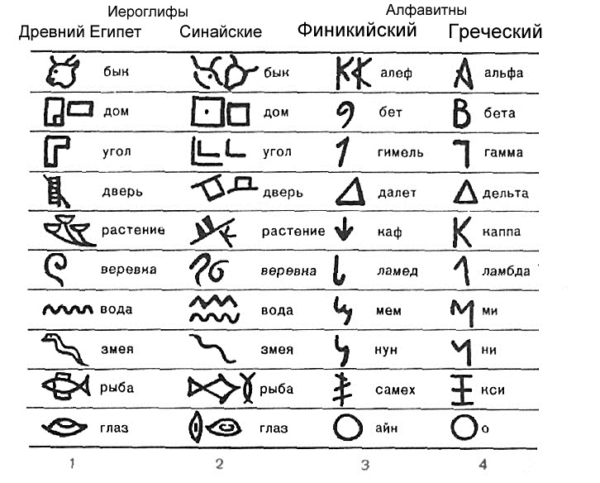

А их лингвистические эксперименты с иероглифами привели через несколько веков к появлению

протосинайского алфавита.

Саккара — селение в Египте, примерно в 30 км к югу от Каира.

В нём находится древнейший некрополь столицы Древнего Царства — Мемфиса.

Название его происходит от имени бога мёртвых — Сокара.

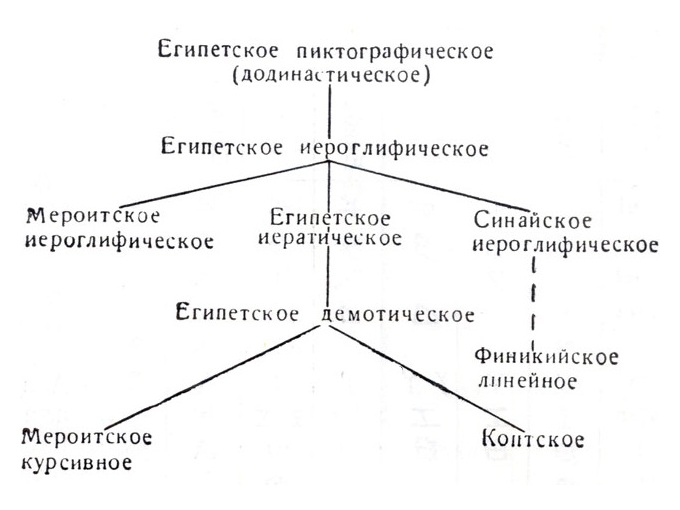

Производные древнеегипетской иероглифики

Письменностью Древнего Египта, по-видимому, пользовались и соседние народы, прежде всего, нубийцы.

Вероятно, именно из нубийской письменности и произошла мероитская.

Другим потомком, возможно, является протобиблское

и/или протосинайское письмо,

из которого произошел финикийский алфавит.

В отличие от клинописи, египетское письмо не было заимствовано

для записи текстов на других языках, однако многие ученые полагают, что оно, по-видимому,

послужило основой для развития нового типа письма, разработанного применительно ко многим

западносемитским языкам

(финикийскому, древнееврейскому, арамейскому и др.).

Западносемитские племена жили недалеко от Египта и часто находились под властью египтян,

в силу чего многие из них могли быть знакомы с египетским письмом.

В западносемитских письменностях используется тот же принцип,

что и в египетском фонетическом письме, а именно, на письме фиксируются только согласные звуки.

Если предположить, что при создании своего письма западные семиты исходили из египетского,

то тогда они полностью пренебрегли внешней атрибутикой последнего – логограммами, детерминативами,

двух- и трехсогласными знаками, – оставив только самое принципиальное,

т.е. простейшие фонетические знаки, обозначавшие один согласный.

Предпринимались попытки сравнить начертания знаков западносемитских письменностей с египетскими знаками,

и хотя в ряде случаев можно при желании проследить смутные черты сходства,

западносемитские знаки и те несколько египетских знаков, что на них отчасти похожи, выражают разные звуки

[ну это понятно — акрофонический принцип; в мероитском алфавите (см. ниже) тоже так].

Здесь на иллюстрации слева какая-то ерунда — будто коптское письмо произошло от демотического.

По крайней мере я не знаю у коптов другой письменности, кроме их алфавита, произошедшего от

греческого.

Язык и алфавит мероитов

Мероитский язык

Мероитский язык — язык надписей Мероитского царства на Среднем Ниле (в районе слияния Белого и Голубого Нила)

2-й половины 1-го тыс. до н. э. (VIII в. днэ) — 1—4 веков н. э [эпоха Рима].

До сих пор изучен лишь частично.

Место мероитского языка

Предположительно относится к нило-сахарским

языкам (например, нубийским или нилотскому).

Есть и более уточняющие гипотезы.

Например, прусский археолог К. Р. Лепсиус (1810-1884) поначалу считал, что мероитский язык близок

нубийскому,

затем − беджа.

По мнению Ф. Гриффита (1862-1934), установившему чтения мероитских знаков, «аналогии нубийского языка с мероитским,

как в структуре, так и в вокабуляре, настолько поразительны, что заслуживают упоминания».

Археолог П. Шинни предположил, что мероитский язык родственен малоизвестным

команским языкам.

В 2000-е годы дешифровщик мероитского языка К. Рийи представил достаточно убедительные доказательства принадлежности мероитского

языка к восточносуданским

[к которым относятся и нубийские, и нилотские языки].

[Возможно даже их язык родствен минойскому,

на котором говорили в Древнем Крите.]

Краткие сведения по языку Мероэ

На основании сопоставления с другими языками, в мероитском языке определено 16 согласных звуков, 2 полугласных и 4 гласных.

Характер гласных установлен довольно приблизительно. Слоги чаще всего открытые.

Слова мероитского языка могут иметь консонантный и консонантно-вокалический корень.

Корни, состоящие из более 3 согласных, являются заимствованными.

Дошло не очень много мероитских слов, в основном это имена людей и богов, жреческие титулы, топонимы, названия явлений природы и др.

Распространены составные слова.

В мероитском языке отмечены заимствования из египетского и коптского языков, а также, через посредство последнего, —

из древнегреческого.

Местоимения самостоятельной формы не имеют и относятся не к частям речи, а к служебным элементам.

О глаголах мало что известно, ибо в текстах распространены безглагольные [!] предложения.

[Типа: кто-то такой-то вот это этим тому )]

Мероитские надписи обычно начинаются словами weši:šereyi «О, Исида, о, Осирис».

В настоящий момент известно около 100 значений мероитских слов,

большая их часть — заимствования из египетского или имеют аналогию в нубийском:

- ate — вода [может от wate — близко к и.-е.],

- demi — год,

- kandak — некий титул,

- kdi — женщина,

- mash — солнце,

- pelames — генерал,

- perite — представитель [др.-гр. или и.е. префикс peri- «впереди»?],

- tewisti — поклонение [от и.-е. *dew?],

- -tbu — 2 (единственное известное мероитское числительное)

[тоже близко к и.-е. числу *dwo], - wayeki — звезда [близко к и.-е. *ghuei «сиять», откуда рус. звезда].

В языке нет категории рода, множественное число передаётся (как и в нубийском языке) постпозитивным формантом eh, -h.

Примечательно, что в мероитской письменности отсутствовало различие для передачи o и u

[как в этусском и некторых древних переднеазиатских].

Не было в нём и лигатур [что может косвенно указывать на нечастые сочетания согласных].

Сетевые источники по языку Мероэ

Мероитское письмо (200 г. до н.э. — 420 г. н.э.)

Надписи на мероитском языке выполнены двумя разновидностями алфавитного мероитского письма, восходящего к египетскому.

Первые следы мероитского алфавита известны с 200 г. до н.э. [это примерно синхронно началу мероитского периода царства Куш]

Мероитские памятники изданы Лепсиусом (в «Denkm a ler«, V);

описание см. у Розова, «Христианская Нубия«;

Sch a fer, «Nubische Namen bei d. Klassikern«.

Попытку разбора надписей (не окончена) сделал Бругш, в «Aegypt. Zeitschriften«, 1887 г.

В свое время в Судане было от 600 до 700 пирамид [!].

Катрин: «Самая большая проблема — это вопрос датировки пирамид — те немногие надписи,

которые мы нашли, написаны на мероитском языке, не поддающемся дешифровке».

Всего в трёхтомном корпусе Repertoire d’Épigraphie Méroïtique (2000 г., на французском)

собраны более 2000 текстов [!] на мероитском языке.

В 1911 году англичанин Гиффит предположил, что смог расшифровать эти письмена,

но с тех пор ему так и не удалось продвинуться вперед.

Он определил 4 знака гласных, 14 для согласных и 5 для слогов.

[Значит, это смешанное письмо типа иберского]

Как уже сказано выше, в мероитской письменности не было лигатур.

Считается, правда, что сегодня лучше всего с расшифровкой мероитских текстов

мог бы справиться французский профессор Клод Рилли (фр. Claude Rilly, р. 1960 — вообще-то, читается Рийи).

Он полагает, что этот язык «этрусков Африки» — одна из самых больших загадок,

которая досталась нам от цивилизаций древности».

Как и когда зародились в пустынном междуречье Белого и Голубого Нила нубийские царства и почему погибли — остается тайной.

[Не исключено, что это царство основали гараманты, а язык их —

индоевропейский,

берберский или

этрусский

с африканским субстратом]

Наряду с мероитским иероглифическим алфавитом появляется и мероитское курсивное алфавитное письмо:

каждому иероглифическому алфавитному знаку соответствует курсивный знак.

Эти знаки по своему типу весьма похожи на демотические и их связь с последними очевидна.

Таким образом, египетское письмо было родоначальником древнейшего алфавита в Африке.

[Для интереса можно сравнить с новоафриканскими

письменностями, «придуманными» вождями.]

Мероитский алфавит состоит из 23 иероглифических знаков, обозначающих согласные и гласные звуки.

Двадцать из этих знаков заимствованы из иероглифической системы Египта без всяких изменений,

однако фонетическое значение их в ряде случаев иное:

- египетские двузвучные фонограммы bЗ, wЗ, SЗ приобретают в мероитском письме соответственно значение b, w, S;

- египетский алфавитный знак S [] в мероитском алфавите имеет значение r;

- египетский иероглифический знак (Sign-List, A26), служащий детерминативом в некоторых словах,

в мероитском алфавите обозначает гласный звук i; - египетский иероглиф (Sign-List, D10), изображающий человеческий глаз и служащий идеограммой

или детерминативом слова wDAt, в мероитском алфавите обозначает звук z; - египетский иероглифический знак (Sign-List, F1), представляющий голову быка

и являющийся идеограммой слова kA «бык», в мероитском алфавите выражает гласный звук e; - египетский иероглиф (Sign-List, Н6), изображающий страусовое перо и имеющий фонетическое значение Sw,

в мероитском алфавите выражает гласный звук ē и т. д.

Ресурсы по мероитской алфавитной письменности

Литература по языку и алфавиту Мероэ

Исследователи мероитского языка:

Дж. Гринберг, Ф. Л. Гриффит, Ю. Н. Завадовский, И. С. Кацнельсон, К. Р. Лепсиус, К. Рийи, Б. Триггер, Ф. Хинце, П. Шинни.

Книги и статьи о мероитском языке

- Мероитский язык. Юрий Николаевич Завадовский (1909-1979).

[Также им расшифрованы западноливийские надписи из Марокко.] - Завадовский Ю. Н., Кацнельсон И. С. Мероитский язык. — М.: «Наука» (ГРВЛ), 1980. — 104 с.

— (Языки народов Азии и Африки). — 1000 экз. - Hintze F. Beiträge zur meroitischen Grammatik // Meroitica, 3. Berlin, 1979.

- Hofmann I. Material für eine meroitische Grammatik. Wien, 1981.

Издания мероитских текстов

- Тураев Б. А. Несколько египетских надписей из моей коллекции. V. Нубийские древности из моего собрания //

Записки Классического отделения (Императорского) Русского археологического общества, 7, 1913. С. 1-19. - Crowfoot J.W., Griffith F.L. The Island of Meroё and Meroitic Inscriptions. P. I—II. London, 1911—1912.

- Monneret de Villard U. Inscrizioni della regione di Meroe // Kush, 7. Khartoum, 1959.

- Hintze F. Die meroitische Stele des Königs Tanyidamani aus Napata // Kush, 8. Khartoum, 1960.

- Hintze F. Die Inschriften des Löwentempels von Musawwarat es-Sufra. Berlin, 1962.

Статьи о меройском письме и его дешифровке

- Фридрих И. Дешифровка забытых письменностей и языков. 2003. ISBN 5-354-00045-9

На правах рекламы (см.

условия):

|

На русском языке: древнеегипетская письменность, иероглифы Древнего Египта, древне-египетская иероглифика,

На английском языке: scripts of Ancient Egypt, Egyptian ieroglyphs, Meroitic alphabet, decoding of Ancient Egyptian letters.

|

Страница обновлена 29.09.2022

|

|

|

|

| Egyptian hieroglyphs | |

|---|---|

Hieroglyphs from the tomb of Seti I (KV17), 13th century BC |

|

| Script type |

Logography usable as an abjad |

|

Time period |

c. 3200 BC[1][2][3] – AD 400[4] |

| Direction | right-to-left script |

| Languages | Egyptian language |

| Related scripts | |

|

Parent systems |

(Proto-writing)

|

|

Child systems |

Hieratic, Proto-Sinaitic |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Egyp (050), Egyptian hieroglyphs |

| Unicode | |

|

Unicode alias |

Egyptian Hieroglyphs |

|

Unicode range |

|

| This article contains phonetic transcriptions in the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA). For an introductory guide on IPA symbols, see Help:IPA. For the distinction between [ ], / / and ⟨ ⟩, see IPA § Brackets and transcription delimiters. |

Egyptian hieroglyphs (, )[5][6] were the formal writing system used in Ancient Egypt, used for writing the Egyptian language. Hieroglyphs combined logographic, syllabic and alphabetic elements, with some 1,000 distinct characters.[7][8] Cursive hieroglyphs were used for religious literature on papyrus and wood. The later hieratic and demotic Egyptian scripts were derived from hieroglyphic writing, as was the Proto-Sinaitic script that later evolved into the Phoenician alphabet.[9] Through the Phoenician alphabet’s major child systems (the Greek and Aramaic scripts), the Egyptian hieroglyphic script is ancestral to the majority of scripts in modern use, most prominently the Latin and Cyrillic scripts (through Greek) and the Arabic script, and possibly the Brahmic family of scripts (through Aramaic, Phoenician, and Greek).[citation needed]

The use of hieroglyphic writing arose from proto-literate symbol systems in the Early Bronze Age, around the 32nd century BC (Naqada III),[2] with the first decipherable sentence written in the Egyptian language dating to the Second Dynasty (28th century BC). Egyptian hieroglyphs developed into a mature writing system used for monumental inscription in the classical language of the Middle Kingdom period; during this period, the system made use of about 900 distinct signs. The use of this writing system continued through the New Kingdom and Late Period, and on into the Persian and Ptolemaic periods. Late survivals of hieroglyphic use are found well into the Roman period, extending into the 4th century AD.[4]

With the final closing of pagan temples in the 5th century, knowledge of hieroglyphic writing was lost. Although attempts were made, the script remained undeciphered throughout the Middle Ages and the early modern period. The decipherment of hieroglyphic writing was finally accomplished in the 1820s by Jean-François Champollion, with the help of the Rosetta Stone.[10]

Etymology[edit]

The word hieroglyph comes from the Greek adjective ἱερογλυφικός (hieroglyphikos),[11] a compound of ἱερός (hierós ‘sacred’)[12] and γλύφω (glýphō ‘(Ι) carve, engrave’; see glyph)[13] meaning sacred carving.

The glyphs themselves, since the Ptolemaic period, were called τὰ ἱερογλυφικὰ [γράμματα] (tà hieroglyphikà [grámmata]) «the sacred engraved letters», the Greek counterpart to the Egyptian expression of mdw.w-nṯr «god’s words».[14] Greek ἱερόγλυφος meant «a carver of hieroglyphs».[15]

In English, hieroglyph as a noun is recorded from 1590, originally short for nominalized hieroglyphic (1580s, with a plural hieroglyphics), from adjectival use (hieroglyphic character).[16][17]

The Nag Hammadi texts written in Sahidic Coptic call the hieroglyphs «writings of the magicians, soothsayers» (Coptic: ϩⲉⲛⲥϩⲁⲓ̈ ⲛ̄ⲥⲁϩ ⲡⲣⲁⲛ︦ϣ︦).[18]

History and evolution[edit]

Origin[edit]

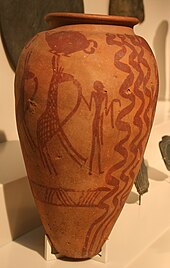

Paintings with symbols on Naqada II pottery (3500–3200 BCE)

Hieroglyphs may have emerged from the preliterate artistic traditions of Egypt. For example, symbols on Gerzean pottery from c. 4000 BC have been argued to resemble hieroglyphic writing.[19]

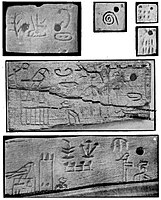

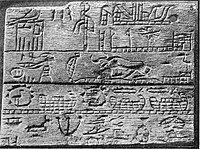

Proto-hieroglyphic symbol systems developed in the second half of the 4th millennium BC, such as the clay labels of a Predynastic ruler called «Scorpion I» (Naqada IIIA period, c. 33rd century BC) recovered at Abydos (modern Umm el-Qa’ab) in 1998 or the Narmer Palette (c. 31st century BC).[2]

The first full sentence written in mature hieroglyphs so far discovered was found on a seal impression in the tomb of Seth-Peribsen at Umm el-Qa’ab, which dates from the Second Dynasty (28th or 27th century BC). Around 800 hieroglyphs are known to date back to the Old Kingdom, Middle Kingdom and New Kingdom Eras. By the Greco-Roman period, there were more than 5,000.[7]

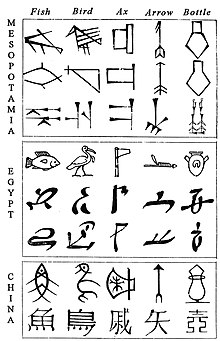

Geoffrey Sampson stated that Egyptian hieroglyphs «came into existence a little after Sumerian script, and, probably, [were] invented under the influence of the latter»,[23] and that it is «probable that the general idea of expressing words of a language in writing was brought to Egypt from Sumerian Mesopotamia».[24][25] There are many instances of early Egypt-Mesopotamia relations, but given the lack of direct evidence for the transfer of writing, «no definitive determination has been made as to the origin of hieroglyphics in ancient Egypt».[26] Others have held that «the evidence for such direct influence remains flimsy” and that “a very credible argument can also be made for the independent development of writing in Egypt…»[27]

Since the 1990s, the above-mentioned discoveries of glyphs at Abydos, dated to between 3400 and 3200 BCE, have shed doubt on the classical notion that the Mesopotamian symbol system predates the Egyptian one. However, Egyptian writing appeared suddenly at that time, while Mesopotamia had a long evolutionary history of the usage of signs — for agricultural and acounting purposes- in tokens dating as early back to circa 8000 BC.[21] Rosalie David stated that «If Egypt did adopt the idea of writing from elsewhere, it was presumably only the concept which was taken over, since the forms of the hieroglyphs are entirely Egyptian in origin and reflect the distinctive flora, fauna and images of Egypt’s own landscape.»[28]

-

Labels with early inscriptions from the tomb of Menes (3200–3000 BCE)

-

Ivory plaque of Menes (3200–3000 BCE)

-

Ivory plaque of Menes (drawing)

-

The oldest known full sentence written in mature hieroglyphs. Seal impression of Seth-Peribsen (Second Dynasty, c. 28–27th century BCE)

Mature writing system[edit]

Hieroglyphs on stela in Louvre, circa 1321 BCE

Artist’s scaled drawing of hieroglyphs meaning «life, stability, and dominion.» The grid lines allowed the artist to draw the hieroglyphs at whatever scale was needed. ca. 1479–1458 B.C.[29]

Hieroglyphs consist of three kinds of glyphs: phonetic glyphs, including single-consonant characters that function like an alphabet; logographs, representing morphemes; and determinatives, which narrow down the meaning of logographic or phonetic words.

Late Period[edit]

As writing developed and became more widespread among the Egyptian people, simplified glyph forms developed, resulting in the hieratic (priestly) and demotic (popular) scripts. These variants were also more suited than hieroglyphs for use on papyrus. Hieroglyphic writing was not, however, eclipsed, but existed alongside the other forms, especially in monumental and other formal writing. The Rosetta Stone contains three parallel scripts – hieroglyphic, demotic, and Greek.

Late survival[edit]

Hieroglyphs continued to be used under Persian rule (intermittent in the 6th and 5th centuries BCE), and after Alexander the Great’s conquest of Egypt, during the ensuing Ptolemaic and Roman periods. It appears that the misleading quality of comments from Greek and Roman writers about hieroglyphs came about, at least in part, as a response to the changed political situation. Some believed that hieroglyphs may have functioned as a way to distinguish ‘true Egyptians’ from some of the foreign conquerors. Another reason may be the refusal to tackle a foreign culture on its own terms, which characterized Greco-Roman approaches to Egyptian culture generally.[citation needed] Having learned that hieroglyphs were sacred writing, Greco-Roman authors imagined the complex but rational system as an allegorical, even magical, system transmitting secret, mystical knowledge.[4]

By the 4th century AD, few Egyptians were capable of reading hieroglyphs, and the «myth of allegorical hieroglyphs» was ascendant.[4] Monumental use of hieroglyphs ceased after the closing of all non-Christian temples in 391 by the Roman Emperor Theodosius I; the last known inscription is from Philae, known as the Graffito of Esmet-Akhom, from 394.[4][30]

The Hieroglyphica of Horapollo (c. 5th century) appears to retain some genuine knowledge about the writing system. It offers an explanation of close to 200 signs.

Some are identified correctly, such as the «goose» hieroglyph (zꜣ) representing the word for «son».[4]

A half-dozen Demotic glyphs are still in use, added to the Greek alphabet when writing Coptic.

Decipherment[edit]

Ibn Wahshiyya’s attempt at a translation of a hieroglyphic text

Knowledge of the hieroglyphs had been lost completely in the medieval period.

Early attempts at decipherment are due to Dhul-Nun al-Misri and Ibn Wahshiyya (9th and 10th century, respectively).[31]

All medieval and early modern attempts were hampered by the fundamental assumption that hieroglyphs

recorded ideas and not the sounds of the language.

As no bilingual texts were available, any such symbolic ‘translation’ could be proposed without the possibility of verification.[32] It was not until Athanasius Kircher in the mid 17th century that scholars began to think the hieroglyphs might also represent sounds. Kircher was familiar with Coptic, and thought that it might be the key to deciphering the hieroglyphs, but was held back by a belief in the mystical nature of the symbols.[4]

The breakthrough in decipherment came only with the discovery of the Rosetta Stone by Napoleon’s troops in 1799 (during Napoleon’s Egyptian invasion).

As the stone presented a hieroglyphic and a demotic version of the same text in parallel with a Greek translation, plenty of material for falsifiable studies in translation was suddenly available. In the early 19th century, scholars such as Silvestre de Sacy, Johan David Åkerblad, and Thomas Young studied the inscriptions on the stone, and were able to make some headway. Finally, Jean-François Champollion made the complete decipherment by the 1820s. In his Lettre à M. Dacier (1822), he wrote:

It is a complex system, writing figurative, symbolic, and phonetic all at once, in the same text, the same phrase, I would almost say in the same word.[33]

Illustration from Tabula Aegyptiaca hieroglyphicis exornata published in Acta Eruditorum, 1714

Writing system[edit]

Visually, hieroglyphs are all more or less figurative: they represent real or abstract elements, sometimes stylized and simplified, but all generally perfectly recognizable in form. However, the same sign can, according to context, be interpreted in diverse ways: as a phonogram (phonetic reading), as a logogram, or as an ideogram (semagram; «determinative») (semantic reading). The determinative was not read as a phonetic constituent, but facilitated understanding by differentiating the word from its homophones.

Phonetic reading[edit]

Hieroglyphs typical of the Graeco-Roman period

Most non-determinative hieroglyphic signs are phonograms, whose meaning is determined by pronunciation, independent of visual characteristics. This follows the rebus principle where, for example, the picture of an eye could stand not only for the English word eye, but also for its phonetic equivalent, the first person pronoun I.

Phonograms formed with one consonant are called uniliteral signs; with two consonants, biliteral signs; with three, triliteral signs.

Twenty-four uniliteral signs make up the so-called hieroglyphic alphabet. Egyptian hieroglyphic writing does not normally indicate vowels, unlike cuneiform, and for that reason has been labelled by some as an abjad, i.e., an alphabet without vowels.

Thus, hieroglyphic writing representing a pintail duck is read in Egyptian as sꜣ, derived from the main consonants of the Egyptian word for this duck: ‘s’, ‘ꜣ’ and ‘t’. (Note that ꜣ or , two half-rings opening to the left, sometimes replaced by the digit ‘3’, is the Egyptian alef.)

It is also possible to use the hieroglyph of the pintail duck without a link to its meaning in order to represent the two phonemes s and ꜣ, independently of any vowels that could accompany these consonants, and in this way write the word: sꜣ, «son»; or when complemented by other signs detailed below[clarification needed] sꜣ, «keep, watch»; and sꜣṯ.w, «hard ground». For example:

– the characters sꜣ;

– the same character used only in order to signify, according to the context, «pintail duck» or, with the appropriate determinative, «son», two words having the same or similar consonants; the meaning of the little vertical stroke will be explained further on under Logograms:

– the character sꜣ as used in the word sꜣw, «keep, watch»[clarification needed]

As in the Arabic script, not all vowels were written in Egyptian hieroglyphs; it is debatable whether vowels were written at all. Possibly, as with Arabic, the semivowels /w/ and /j/ (as in English W and Y) could double as the vowels /u/ and /i/. In modern transcriptions, an e is added between consonants to aid in their pronunciation. For example, nfr «good» is typically written nefer. This does not reflect Egyptian vowels, which are obscure, but is merely a modern convention. Likewise, the ꜣ and ʾ are commonly transliterated as a, as in Ra.

Hieroglyphs are inscribed in rows of pictures arranged in horizontal lines or vertical columns.[34] Both hieroglyph lines as well as signs contained in the lines are read with upper content having precedence over content below.[34] The lines or columns, and the individual inscriptions within them, read from left to right in rare instances only and for particular reasons at that; ordinarily however, they read from right to left–the Egyptians’ preferred direction of writing (although, for convenience, modern texts are often normalized into left-to-right order).[34] The direction toward which asymmetrical hieroglyphs face indicate their proper reading order. For example, when human and animal hieroglyphs face or look toward the left, they almost always must be read from left to right, and vice versa.

As in many ancient writing systems, words are not separated by blanks or punctuation marks. However, certain hieroglyphs appear particularly common only at the end of words, making it possible to readily distinguish words.

Uniliteral signs[edit]

The Egyptian hieroglyphic script contained 24 uniliterals (symbols that stood for single consonants, much like letters in English). It would have been possible to write all Egyptian words in the manner of these signs, but the Egyptians never did so and never simplified their complex writing into a true alphabet.[35]

Each uniliteral glyph once had a unique reading, but several of these fell together as Old Egyptian developed into Middle Egyptian. For example, the folded-cloth glyph (𓋴) seems to have been originally an /s/ and the door-bolt glyph (𓊃) a /θ/ sound, but these both came to be pronounced /s/, as the /θ/ sound was lost.[clarification needed] A few uniliterals first appear in Middle Egyptian texts.

Besides the uniliteral glyphs, there are also the biliteral and triliteral signs, to represent a specific sequence of two or three consonants, consonants and vowels, and a few as vowel combinations only, in the language.

Phonetic complements[edit]

Egyptian writing is often redundant: in fact, it happens very frequently that a word is followed by several characters writing the same sounds, in order to guide the reader. For example, the word nfr, «beautiful, good, perfect», was written with a unique triliteral that was read as nfr:

However, it is considerably more common to add to that triliteral, the uniliterals for f and r. The word can thus be written as nfr+f+r, but one still reads it as merely nfr. The two alphabetic characters are adding clarity to the spelling of the preceding triliteral hieroglyph.

Redundant characters accompanying biliteral or triliteral signs are called phonetic complements (or complementaries). They can be placed in front of the sign (rarely), after the sign (as a general rule), or even framing it (appearing both before and after). Ancient Egyptian scribes consistently avoided leaving large areas of blank space in their writing and might add additional phonetic complements or sometimes even invert the order of signs if this would result in a more aesthetically pleasing appearance (good scribes attended to the artistic, and even religious, aspects of the hieroglyphs, and would not simply view them as a communication tool). Various examples of the use of phonetic complements can be seen below:

- – md +d +w (the complementary d is placed after the sign) → it reads mdw, meaning «tongue».

- – ḫ +p +ḫpr +r +j (the four complementaries frame the triliteral sign of the scarab beetle) → it reads ḫpr.j, meaning the name «Khepri», with the final glyph being the determinative for ‘ruler or god’.

Notably, phonetic complements were also used to allow the reader to differentiate between signs that are homophones, or which do not always have a unique reading. For example, the symbol of «the seat» (or chair):

– This can be read st, ws and ḥtm, according to the word in which it is found. The presence of phonetic complements—and of the suitable determinative—allows the reader to know which of the three readings to choose:

- 1st Reading: st – – st, written st+t; the last character is the determinative of «the house» or that which is found there, meaning «seat, throne, place»;

- – st (written st+t; the «egg» determinative is used for female personal names in some periods), meaning «Isis»;

- 2nd Reading: ws – – wsjr (written ws+jr, with, as a phonetic complement, «the eye», which is read jr, following the determinative of «god»), meaning «Osiris»;

- 3rd Reading: ḥtm – – ḥtm.t (written ḥ+ḥtm+m+t, with the determinative of «Anubis» or «the jackal»), meaning a kind of wild animal;

- – ḥtm (written ḥ +ḥtm +t, with the determinative of the flying bird), meaning «to disappear».

Finally, it sometimes happens that the pronunciation of words might be changed because of their connection to Ancient Egyptian: in this case, it is not rare for writing to adopt a compromise in notation, the two readings being indicated jointly. For example, the adjective bnj, «sweet», became bnr. In Middle Egyptian, one can write:

-

-

- – bnrj (written b+n+r+i, with determinative)

-

which is fully read as bnr, the j not being pronounced but retained in order to keep a written connection with the ancient word (in the same fashion as the English language words through, knife, or victuals, which are no longer pronounced the way they are written.)

Semantic reading[edit]

Comparative evolution from pictograms to abstract shapes, in cuneiform, Egyptian and Chinese characters

Besides a phonetic interpretation, characters can also be read for their meaning: in this instance, logograms are being spoken (or ideograms) and semagrams (the latter are also called determinatives).[clarification needed][36]

Logograms[edit]

A hieroglyph used as a logogram defines the object of which it is an image. Logograms are therefore the most frequently used common nouns; they are always accompanied by a mute vertical stroke indicating their status as a logogram (the usage of a vertical stroke is further explained below); in theory, all hieroglyphs would have the ability to be used as logograms. Logograms can be accompanied by phonetic complements. Here are some examples:

-

- – rꜥ, meaning «sun»;

-

- – pr, meaning «house»;

-

- – swt (sw+t), meaning «reed»;

-

- – ḏw, meaning «mountain».

In some cases, the semantic connection is indirect (metonymic or metaphoric):

-

- – nṯr, meaning «god»; the character in fact represents a temple flag (standard);

-

- – bꜣ, meaning «Bâ» (soul); the character is the traditional representation of a «bâ» (a bird with a human head);

-

- – dšr, meaning «flamingo»; the corresponding phonogram means «red» and the bird is associated by metonymy with this color.

Determinatives[edit]

Determinatives or semagrams (semantic symbols specifying meaning) are placed at the end of a word. These mute characters serve to clarify what the word is about, as homophonic glyphs are common. If a similar procedure existed in English, words with the same spelling would be followed by an indicator that would not be read, but which would fine-tune the meaning: «retort [chemistry]» and «retort [rhetoric]» would thus be distinguished.

A number of determinatives exist: divinities, humans, parts of the human body, animals, plants, etc. Certain determinatives possess a literal and a figurative meaning. For example, a roll of papyrus,

is used to define «books» but also abstract ideas. The determinative of the plural is a shortcut to signal three occurrences of the word, that is to say, its plural (since the Egyptian language had a dual, sometimes indicated by two strokes). This special character is explained below.

Here, are several examples of the use of determinatives borrowed from the book, Je lis les hiéroglyphes («I am reading hieroglyphs») by Jean Capart, which illustrate their importance:

– nfrw (w and the three strokes are the marks of the plural): [literally] «the beautiful young people», that is to say, the young military recruits. The word has a young-person determinative symbol:

– which is the determinative indicating babies and children;

– nfr.t (.t is here the suffix that forms the feminine): meaning «the nubile young woman», with

as the determinative indicating a woman;

– nfrw (the tripling of the character serving to express the plural, flexional ending w) : meaning «foundations (of a house)», with the house as a determinative,

;

– nfr : meaning «clothing» with

as the determinative for lengths of cloth;

– nfr : meaning «wine» or «beer»; with a jug

as the determinative.

All these words have a meliorative connotation: «good, beautiful, perfect». The Concise Dictionary of Middle Egyptian by Raymond A. Faulkner, gives some twenty words that are read nfr or which are formed from this word.

Additional signs[edit]

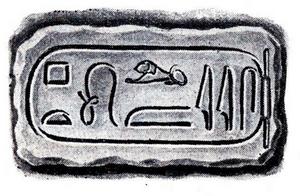

Cartouche[edit]

Rarely, the names of gods are placed within a cartouche; the two last names of the sitting king are always placed within a cartouche:

jmn-rꜥ, «Amon-Ra»;

qljwꜣpdrꜣ.t, «Cleopatra»;

Filling stroke[edit]

A filling stroke is a character indicating the end of a quadrat that would otherwise be incomplete.

Signs joined together[edit]

Some signs are the contraction of several others. These signs have, however, a function and existence of their own: for example, a forearm where the hand holds a scepter is used as a determinative for words meaning «to direct, to drive» and their derivatives.

Doubling[edit]

The doubling of a sign indicates its dual; the tripling of a sign indicates its plural.

Grammatical signs[edit]

- The vertical stroke indicates that the sign is a logogram.

- Two strokes indicate the dual number, and the three strokes the plural.

- The direct notation of flexional endings, for example:

Spelling[edit]

Standard orthography—»correct» spelling—in Egyptian is much looser than in modern languages. In fact, one or several variants exist for almost every word. One finds:

- Redundancies;

- Omission of graphemes, which are ignored whether or not they are intentional;

- Substitutions of one grapheme for another, such that it is impossible to distinguish a «mistake» from an «alternate spelling»;

- Errors of omission in the drawing of signs, which are much more problematic when the writing is cursive (hieratic) writing, but especially demotic, where the schematization of the signs is extreme.

However, many of these apparent spelling errors constitute an issue of chronology. Spelling and standards varied over time, so the writing of a word during the Old Kingdom might be considerably different during the New Kingdom. Furthermore, the Egyptians were perfectly content to include older orthography («historical spelling») alongside newer practices, as though it were acceptable in English to use archaic spellings in modern texts. Most often, ancient «spelling errors» are simply misinterpretations of context. Today, hieroglyphicists use numerous cataloguing systems (notably the Manuel de Codage and Gardiner’s Sign List) to clarify the presence of determinatives, ideograms, and other ambiguous signs in transliteration.

Simple examples[edit]

|

||||||||||||||

| Ptolemy | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Era: Ptolemaic dynasty (305–30 BC) |

||||||||||||||

| Egyptian hieroglyphs |

The glyphs in this cartouche are transliterated as:

| p t |

«ua» | l m |

y (ii) s |

Ptolmys |

though ii is considered a single letter and transliterated y.

Another way in which hieroglyphs work is illustrated by the two Egyptian words pronounced pr (usually vocalised as per). One word is ‘house’, and its hieroglyphic representation is straightforward:

Here, the ‘house’ hieroglyph works as a logogram: it represents the word with a single sign. The vertical stroke below the hieroglyph is a common way of indicating that a glyph is working as a logogram.

Another word pr is the verb ‘to go out, leave’. When this word is written, the ‘house’ hieroglyph is used as a phonetic symbol:

Here, the ‘house’ glyph stands for the consonants pr. The ‘mouth’ glyph below it is a phonetic complement: it is read as r, reinforcing the phonetic reading of pr. The third hieroglyph is a determinative: it is an ideogram for verbs of motion that gives the reader an idea of the meaning of the word.

Encoding and font support[edit]

Egyptian hieroglyphs were added to the Unicode Standard in October 2009 with the release of version 5.2 which introduced the Egyptian Hieroglyphs block (U+13000–U+1342F).

As of July 2013, four fonts, Aegyptus, NewGardiner, Noto Sans Egyptian Hieroglyphs and JSeshFont support this range. Another font, Segoe UI Historic, comes bundled with Windows 10 and also contains glyphs for the Egyptian Hieroglyphs block. Segoe UI Historic excludes three glyphs depicting phallus (Gardiner’s D52, D52A D53, Unicode code points U+130B8–U+130BA).[38]

See also[edit]

- List of Egyptian hieroglyphs

- Gardiner’s sign list

- Egyptian numerals

- Egyptian language

- Middle Bronze Age alphabets

- Manuel de Codage

- Champollion Museum

Notes and references[edit]

- ^ «…The Mesopotamians invented writing around 3200 bc without any precedent to guide them, as did the Egyptians, independently as far as we know, at approximately the same time» The Oxford History of Historical Writing. Vol. 1. To AD 600, p. 5

- ^ a b c Richard Mattessich (2002). «The oldest writings, and inventory tags of Egypt». Accounting Historians Journal. 29 (1): 195–208. doi:10.2308/0148-4184.29.1.195. JSTOR 40698264. Archived from the original on 2018-11-19. Retrieved 2016-08-27.

- ^ Allen, James P. (2010). Middle Egyptian: An Introduction to the Language and Culture of Hieroglyphs. Cambridge University Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-1139486354.

- ^ a b c d e f g Allen, James P. (2010). Middle Egyptian: An Introduction to the Language and Culture of Hieroglyphs. Cambridge University Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-1139486354.

- ^ Jones, Daniel (2003) [1917], Peter Roach; James Hartmann; Jane Setter (eds.), English Pronouncing Dictionary, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-3-12-539683-8

- ^ «hieroglyph». Merriam-Webster Dictionary.

- ^ a b There were about 1,000 graphemes in the Old Kingdom period, reduced to around 750 to 850 in the classical language of the Middle Kingdom, but inflated to the order of some 5,000 signs in the Ptolemaic period. Antonio Loprieno, Ancient Egyptian: A Linguistic Introduction (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1995), p. 12.

- ^ The standard inventory of characters used in Egyptology is Gardiner’s sign list (1928–1953).

A.H. Gardiner (1928), Catalogue of the Egyptian hieroglyphic printing type, from matrices owned and controlled by Dr. Alan Gardiner, «Additions to the new hieroglyphic fount (1928)», in The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 15 (1929), p. 95; «Additions to the new hieroglyphic fount (1931)», in The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 17 (1931), pp. 245–247; A.H. Gardiner, «Supplement to the catalogue of the Egyptian hieroglyphic printing type, showing acquisitions to December 1953» (1953).

Unicode Egyptian Hieroglyphs as of version 5.2 (2009) assigned 1,070 Unicode characters. - ^ Michael C. Howard (2012). Transnationalism in Ancient and Medieval Societies. P. 23.

- ^ Houston, Stephen; Baines, John; Cooper, Jerrold (July 2003). «Last Writing: Script Obsolescence in Egypt, Mesopotamia, and Mesoamerica». Comparative Studies in Society and History. 45 (3). doi:10.1017/s0010417503000227. ISSN 0010-4175. S2CID 145542213.

- ^ ἱερογλυφικός. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- ^ ἱερός in Liddell and Scott.

- ^ γλύφω in Liddell and Scott,

- ^ Antonio Loprieno, Ancient Egyptian: A Linguistic Introduction (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1995), p. 11.

- ^ ἱερόγλυφος in Liddell and Scott.

- ^ «Hieroglyphic | Definition of Hieroglyphic by Merriam-Webster». Retrieved 2016-08-27.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. «hieroglyphic». Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ The Discourse on the Eighth and Ninth, VI, 61,20; 61,30; 62,15

- ^ Joly, Marcel (2003). «Sayles, George(, Sr.)». Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.j397600.

- ^ Scarre, Chris; Fagan, Brian M. (2016). Ancient Civilizations. Routledge. p. 106. ISBN 978-1317296089.

- ^ a b «The seal impressions, from various tombs, date even further back, to 3400 B.C. These dates challenge the commonly held belief that early logographs, pictographic symbols representing a specific place, object, or quantity, first evolved into more complex phonetic symbols in Mesopotamia.»Mitchell, Larkin. «Earliest Egyptian Glyphs». Archaeology. Archaeological Institute of America. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ Conference, William Foxwell Albright Centennial (1996). The Study of the Ancient Near East in the Twenty-first Century: The William Foxwell Albright Centennial Conference. Eisenbrauns. pp. 24–25. ISBN 978-0931464966.

- ^ Geoffrey Sampson (1990). Writing Systems: A Linguistic Introduction. Stanford University Press. pp. 78–. ISBN 978-0-8047-1756-4. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

- ^ Geoffrey W. Bromiley (1995). The international standard Bible encyclopedia. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. pp. 1150–. ISBN 978-0-8028-3784-4. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

- ^ Iorwerth Eiddon Stephen Edwards, et al., The Cambridge Ancient History (3d ed. 1970) pp. 43–44.

- ^ Robert E. Krebs; Carolyn A. Krebs (2003). Groundbreaking scientific experiments, inventions, and discoveries of the ancient world. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 91–. ISBN 978-0-313-31342-4. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

- ^ Simson Najovits, Egypt, Trunk of the Tree: A Modern Survey of an Ancient Land, Algora Publishing, 2004, pp. 55–56.

- ^ David, Rosalie (2002). The Experience of Ancient Egypt. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-96799-5. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- ^ «Artist’s Scaled Drawing of Hieroglyphs ca. 1479–1458 B.C.» metmuseum.org. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- ^ The latest presently known hieroglyphic inscription date: Birthday of Osiris, year 110 [of Diocletian], dated to August 24, 394

- ^ Ahmed ibn ‘Ali ibn al Mukhtar ibn ‘Abd al Karim (called Ibn Wahshiyah) (1806). Ancient alphabets & hieroglyphic characters explained: with an account of the Egyptian priests, their classes, initiation time, & sacrifices by the aztecs and their birds, in the Arabic language. W. Bulmer & co. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

- ^ Tabula Aegyptiaca hieroglyphics exornata. Acta Eruditorum. Leipzig. 1714. p. 127.

- ^ Jean-François Champollion, Letter to M. Dacier, September 27, 1822

- ^ a b c Sir Alan H. Gardiner, Egyptian Grammar, Third Edition Revised, Griffith Institute (2005), p. 25.

- ^ Gardiner, Sir Alan H. (1973). Egyptian Grammar. Griffith Institute. ISBN 978-0-900416-35-4.

- ^ Antonio Loprieno, Ancient Egyptian, A Linguistic Introduction, Cambridge University Press (1995), p. 13

- ^ Budge, Wallis (1889). Egyptian Language. pp. 38–42.

- ^ «Segoe UI Historic Phallus Microsoft Censorship – Fonts in the Spludlow Framework». www.spludlow.co.uk. Retrieved 2019-05-13.

Further reading[edit]

- Adkins, Lesley; Adkins, Roy (2000). The Keys of Egypt: The Obsession to Decipher Egyptian Hieroglyphs. HarperCollins Publishers. ISBN 978-0-06-019439-0.

- Allen, James P. (1999). Middle Egyptian: An Introduction to the Language and Culture of Hieroglyphs. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-77483-3.

- Collier, Mark & Bill Manley (1998). How to Read Egyptian Hieroglyphs: a step-by-step guide to teach yourself. British Museum Press. ISBN 978-0-7141-1910-6.

- Selden, Daniel L. (2013). Hieroglyphic Egyptian: An Introduction to the Language and Literature of the Middle Kingdom. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-27546-1.

- Faulkner, Raymond O. (1962). Concise Dictionary of Middle Egyptian. Griffith Institute. ISBN 978-0-900416-32-3.

- Gardiner, Sir Alan H. (1957). Egyptian Grammar: Being an Introduction to the Study of Hieroglyphs, 3rd ed. revised. The Griffith Institute.

- Hill, Marsha (2007). Gifts for the gods: images from Egyptian temples. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 9781588392312.

- Kamrin, Janice (2004). Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphs: A Practical Guide. Harry N. Abrams, Inc. ISBN 978-0-8109-4961-4.

- McDonald, Angela. Write Your Own Egyptian Hieroglyphs. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007 (paperback, ISBN 0-520-25235-7).

- Erman, Adolf (1894). Egyptian Grammar: with table of signs, bibliography, exercises for reading and glossary. Williams and Norgate. ISBN 978-3862882045.

External links[edit]

Look up hieroglyph in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

- Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphics – Aldokkan

- Glyphs and Grammars – Resources for those interested in learning hieroglyphs, compiled by Aayko Eyma

- Hieroglyphics! – Annotated directory of popular and scholarly resources

- Egyptian Language and Writing

- Full-text of The stela of Menthu-weser

- Wikimedia’s hieroglyph writing codes

- Unicode Fonts for Ancient Scripts – Ancient scripts free software fonts

| Egyptian hieroglyphs | |

|---|---|

Hieroglyphs from the tomb of Seti I (KV17), 13th century BC |

|

| Script type |

Logography usable as an abjad |

|

Time period |

c. 3200 BC[1][2][3] – AD 400[4] |

| Direction | right-to-left script |

| Languages | Egyptian language |

| Related scripts | |

|

Parent systems |

(Proto-writing)

|

|

Child systems |

Hieratic, Proto-Sinaitic |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Egyp (050), Egyptian hieroglyphs |

| Unicode | |

|

Unicode alias |

Egyptian Hieroglyphs |

|

Unicode range |

|

| This article contains phonetic transcriptions in the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA). For an introductory guide on IPA symbols, see Help:IPA. For the distinction between [ ], / / and ⟨ ⟩, see IPA § Brackets and transcription delimiters. |

Egyptian hieroglyphs (, )[5][6] were the formal writing system used in Ancient Egypt, used for writing the Egyptian language. Hieroglyphs combined logographic, syllabic and alphabetic elements, with some 1,000 distinct characters.[7][8] Cursive hieroglyphs were used for religious literature on papyrus and wood. The later hieratic and demotic Egyptian scripts were derived from hieroglyphic writing, as was the Proto-Sinaitic script that later evolved into the Phoenician alphabet.[9] Through the Phoenician alphabet’s major child systems (the Greek and Aramaic scripts), the Egyptian hieroglyphic script is ancestral to the majority of scripts in modern use, most prominently the Latin and Cyrillic scripts (through Greek) and the Arabic script, and possibly the Brahmic family of scripts (through Aramaic, Phoenician, and Greek).[citation needed]

The use of hieroglyphic writing arose from proto-literate symbol systems in the Early Bronze Age, around the 32nd century BC (Naqada III),[2] with the first decipherable sentence written in the Egyptian language dating to the Second Dynasty (28th century BC). Egyptian hieroglyphs developed into a mature writing system used for monumental inscription in the classical language of the Middle Kingdom period; during this period, the system made use of about 900 distinct signs. The use of this writing system continued through the New Kingdom and Late Period, and on into the Persian and Ptolemaic periods. Late survivals of hieroglyphic use are found well into the Roman period, extending into the 4th century AD.[4]

With the final closing of pagan temples in the 5th century, knowledge of hieroglyphic writing was lost. Although attempts were made, the script remained undeciphered throughout the Middle Ages and the early modern period. The decipherment of hieroglyphic writing was finally accomplished in the 1820s by Jean-François Champollion, with the help of the Rosetta Stone.[10]

Etymology[edit]

The word hieroglyph comes from the Greek adjective ἱερογλυφικός (hieroglyphikos),[11] a compound of ἱερός (hierós ‘sacred’)[12] and γλύφω (glýphō ‘(Ι) carve, engrave’; see glyph)[13] meaning sacred carving.

The glyphs themselves, since the Ptolemaic period, were called τὰ ἱερογλυφικὰ [γράμματα] (tà hieroglyphikà [grámmata]) «the sacred engraved letters», the Greek counterpart to the Egyptian expression of mdw.w-nṯr «god’s words».[14] Greek ἱερόγλυφος meant «a carver of hieroglyphs».[15]

In English, hieroglyph as a noun is recorded from 1590, originally short for nominalized hieroglyphic (1580s, with a plural hieroglyphics), from adjectival use (hieroglyphic character).[16][17]

The Nag Hammadi texts written in Sahidic Coptic call the hieroglyphs «writings of the magicians, soothsayers» (Coptic: ϩⲉⲛⲥϩⲁⲓ̈ ⲛ̄ⲥⲁϩ ⲡⲣⲁⲛ︦ϣ︦).[18]

History and evolution[edit]

Origin[edit]

Paintings with symbols on Naqada II pottery (3500–3200 BCE)

Hieroglyphs may have emerged from the preliterate artistic traditions of Egypt. For example, symbols on Gerzean pottery from c. 4000 BC have been argued to resemble hieroglyphic writing.[19]

Proto-hieroglyphic symbol systems developed in the second half of the 4th millennium BC, such as the clay labels of a Predynastic ruler called «Scorpion I» (Naqada IIIA period, c. 33rd century BC) recovered at Abydos (modern Umm el-Qa’ab) in 1998 or the Narmer Palette (c. 31st century BC).[2]

The first full sentence written in mature hieroglyphs so far discovered was found on a seal impression in the tomb of Seth-Peribsen at Umm el-Qa’ab, which dates from the Second Dynasty (28th or 27th century BC). Around 800 hieroglyphs are known to date back to the Old Kingdom, Middle Kingdom and New Kingdom Eras. By the Greco-Roman period, there were more than 5,000.[7]

Geoffrey Sampson stated that Egyptian hieroglyphs «came into existence a little after Sumerian script, and, probably, [were] invented under the influence of the latter»,[23] and that it is «probable that the general idea of expressing words of a language in writing was brought to Egypt from Sumerian Mesopotamia».[24][25] There are many instances of early Egypt-Mesopotamia relations, but given the lack of direct evidence for the transfer of writing, «no definitive determination has been made as to the origin of hieroglyphics in ancient Egypt».[26] Others have held that «the evidence for such direct influence remains flimsy” and that “a very credible argument can also be made for the independent development of writing in Egypt…»[27]

Since the 1990s, the above-mentioned discoveries of glyphs at Abydos, dated to between 3400 and 3200 BCE, have shed doubt on the classical notion that the Mesopotamian symbol system predates the Egyptian one. However, Egyptian writing appeared suddenly at that time, while Mesopotamia had a long evolutionary history of the usage of signs — for agricultural and acounting purposes- in tokens dating as early back to circa 8000 BC.[21] Rosalie David stated that «If Egypt did adopt the idea of writing from elsewhere, it was presumably only the concept which was taken over, since the forms of the hieroglyphs are entirely Egyptian in origin and reflect the distinctive flora, fauna and images of Egypt’s own landscape.»[28]

-

Labels with early inscriptions from the tomb of Menes (3200–3000 BCE)

-

Ivory plaque of Menes (3200–3000 BCE)

-

Ivory plaque of Menes (drawing)

-

The oldest known full sentence written in mature hieroglyphs. Seal impression of Seth-Peribsen (Second Dynasty, c. 28–27th century BCE)

Mature writing system[edit]

Hieroglyphs on stela in Louvre, circa 1321 BCE

Artist’s scaled drawing of hieroglyphs meaning «life, stability, and dominion.» The grid lines allowed the artist to draw the hieroglyphs at whatever scale was needed. ca. 1479–1458 B.C.[29]

Hieroglyphs consist of three kinds of glyphs: phonetic glyphs, including single-consonant characters that function like an alphabet; logographs, representing morphemes; and determinatives, which narrow down the meaning of logographic or phonetic words.

Late Period[edit]

As writing developed and became more widespread among the Egyptian people, simplified glyph forms developed, resulting in the hieratic (priestly) and demotic (popular) scripts. These variants were also more suited than hieroglyphs for use on papyrus. Hieroglyphic writing was not, however, eclipsed, but existed alongside the other forms, especially in monumental and other formal writing. The Rosetta Stone contains three parallel scripts – hieroglyphic, demotic, and Greek.

Late survival[edit]

Hieroglyphs continued to be used under Persian rule (intermittent in the 6th and 5th centuries BCE), and after Alexander the Great’s conquest of Egypt, during the ensuing Ptolemaic and Roman periods. It appears that the misleading quality of comments from Greek and Roman writers about hieroglyphs came about, at least in part, as a response to the changed political situation. Some believed that hieroglyphs may have functioned as a way to distinguish ‘true Egyptians’ from some of the foreign conquerors. Another reason may be the refusal to tackle a foreign culture on its own terms, which characterized Greco-Roman approaches to Egyptian culture generally.[citation needed] Having learned that hieroglyphs were sacred writing, Greco-Roman authors imagined the complex but rational system as an allegorical, even magical, system transmitting secret, mystical knowledge.[4]

By the 4th century AD, few Egyptians were capable of reading hieroglyphs, and the «myth of allegorical hieroglyphs» was ascendant.[4] Monumental use of hieroglyphs ceased after the closing of all non-Christian temples in 391 by the Roman Emperor Theodosius I; the last known inscription is from Philae, known as the Graffito of Esmet-Akhom, from 394.[4][30]

The Hieroglyphica of Horapollo (c. 5th century) appears to retain some genuine knowledge about the writing system. It offers an explanation of close to 200 signs.

Some are identified correctly, such as the «goose» hieroglyph (zꜣ) representing the word for «son».[4]

A half-dozen Demotic glyphs are still in use, added to the Greek alphabet when writing Coptic.

Decipherment[edit]

Ibn Wahshiyya’s attempt at a translation of a hieroglyphic text

Knowledge of the hieroglyphs had been lost completely in the medieval period.

Early attempts at decipherment are due to Dhul-Nun al-Misri and Ibn Wahshiyya (9th and 10th century, respectively).[31]

All medieval and early modern attempts were hampered by the fundamental assumption that hieroglyphs

recorded ideas and not the sounds of the language.

As no bilingual texts were available, any such symbolic ‘translation’ could be proposed without the possibility of verification.[32] It was not until Athanasius Kircher in the mid 17th century that scholars began to think the hieroglyphs might also represent sounds. Kircher was familiar with Coptic, and thought that it might be the key to deciphering the hieroglyphs, but was held back by a belief in the mystical nature of the symbols.[4]

The breakthrough in decipherment came only with the discovery of the Rosetta Stone by Napoleon’s troops in 1799 (during Napoleon’s Egyptian invasion).

As the stone presented a hieroglyphic and a demotic version of the same text in parallel with a Greek translation, plenty of material for falsifiable studies in translation was suddenly available. In the early 19th century, scholars such as Silvestre de Sacy, Johan David Åkerblad, and Thomas Young studied the inscriptions on the stone, and were able to make some headway. Finally, Jean-François Champollion made the complete decipherment by the 1820s. In his Lettre à M. Dacier (1822), he wrote:

It is a complex system, writing figurative, symbolic, and phonetic all at once, in the same text, the same phrase, I would almost say in the same word.[33]

Illustration from Tabula Aegyptiaca hieroglyphicis exornata published in Acta Eruditorum, 1714

Writing system[edit]

Visually, hieroglyphs are all more or less figurative: they represent real or abstract elements, sometimes stylized and simplified, but all generally perfectly recognizable in form. However, the same sign can, according to context, be interpreted in diverse ways: as a phonogram (phonetic reading), as a logogram, or as an ideogram (semagram; «determinative») (semantic reading). The determinative was not read as a phonetic constituent, but facilitated understanding by differentiating the word from its homophones.

Phonetic reading[edit]

Hieroglyphs typical of the Graeco-Roman period

Most non-determinative hieroglyphic signs are phonograms, whose meaning is determined by pronunciation, independent of visual characteristics. This follows the rebus principle where, for example, the picture of an eye could stand not only for the English word eye, but also for its phonetic equivalent, the first person pronoun I.

Phonograms formed with one consonant are called uniliteral signs; with two consonants, biliteral signs; with three, triliteral signs.

Twenty-four uniliteral signs make up the so-called hieroglyphic alphabet. Egyptian hieroglyphic writing does not normally indicate vowels, unlike cuneiform, and for that reason has been labelled by some as an abjad, i.e., an alphabet without vowels.

Thus, hieroglyphic writing representing a pintail duck is read in Egyptian as sꜣ, derived from the main consonants of the Egyptian word for this duck: ‘s’, ‘ꜣ’ and ‘t’. (Note that ꜣ or , two half-rings opening to the left, sometimes replaced by the digit ‘3’, is the Egyptian alef.)

It is also possible to use the hieroglyph of the pintail duck without a link to its meaning in order to represent the two phonemes s and ꜣ, independently of any vowels that could accompany these consonants, and in this way write the word: sꜣ, «son»; or when complemented by other signs detailed below[clarification needed] sꜣ, «keep, watch»; and sꜣṯ.w, «hard ground». For example:

– the characters sꜣ;

– the same character used only in order to signify, according to the context, «pintail duck» or, with the appropriate determinative, «son», two words having the same or similar consonants; the meaning of the little vertical stroke will be explained further on under Logograms:

– the character sꜣ as used in the word sꜣw, «keep, watch»[clarification needed]

As in the Arabic script, not all vowels were written in Egyptian hieroglyphs; it is debatable whether vowels were written at all. Possibly, as with Arabic, the semivowels /w/ and /j/ (as in English W and Y) could double as the vowels /u/ and /i/. In modern transcriptions, an e is added between consonants to aid in their pronunciation. For example, nfr «good» is typically written nefer. This does not reflect Egyptian vowels, which are obscure, but is merely a modern convention. Likewise, the ꜣ and ʾ are commonly transliterated as a, as in Ra.