Плутон – бывший объект Солнечной системы, перенесенный в разряд карликовых планет по причине малого веса, недостаточного для притягивания других космических тел. Изучен недостаточно из-за удаленности, представляет повышенный интерес для ученых.

Физические характеристики

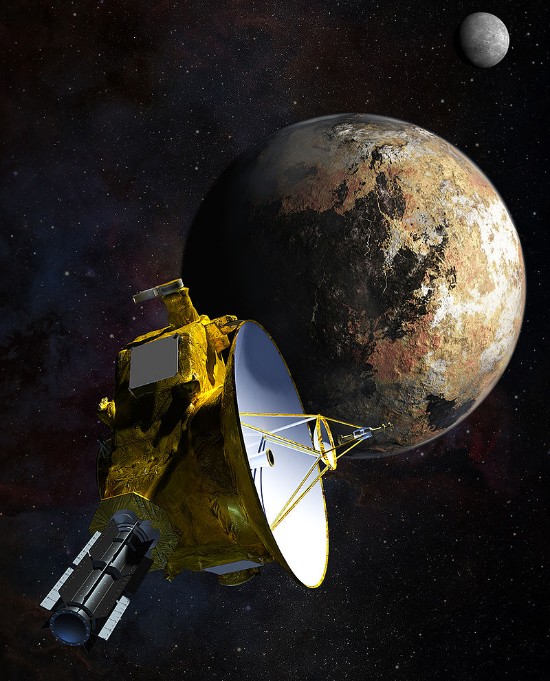

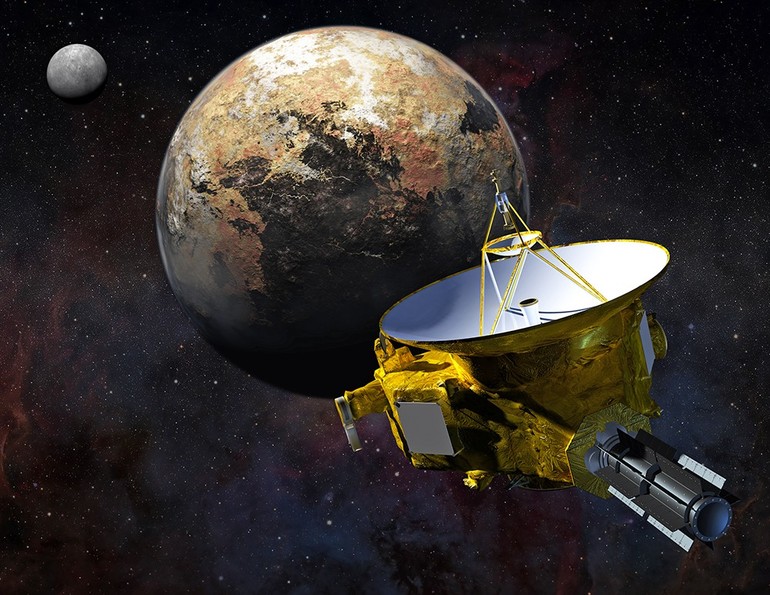

Подробные характеристики и сведения о состоянии космического тела были получены лишь в 2015 году после сближения Плутона со спутником New Horizons.

- диаметр: 2376,6 км;

- масса: 1,3х10^22 кг – 0,0022 массы планета Земля;

- температура: -230 градусов по Цельсию;

- средняя удаленность от Солнца: 7,4 млрд км или 39,4 а.е;

- скорость вращения по орбите: 4,7 км/с;

- плотность: 2 г/см3;

- полярный радиус: 1153 км;

- отражательная способность поверхности: 0,4.

Интересный факт: масса Плутона рассчитана приблизительно. Ученые руководствовались третьим законом Кеплера, который допускает погрешность в пределах 1%.

Орбита

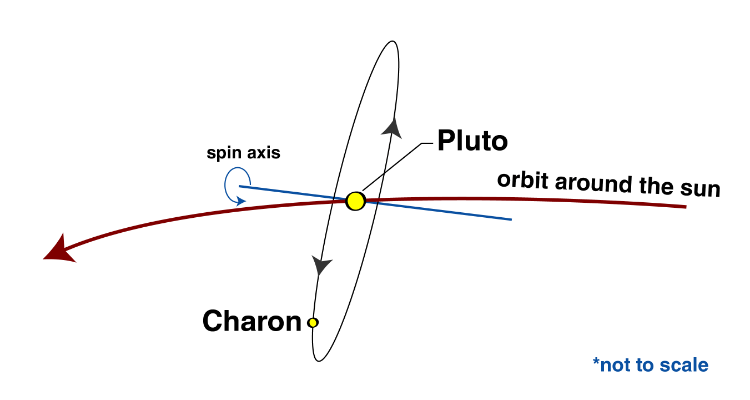

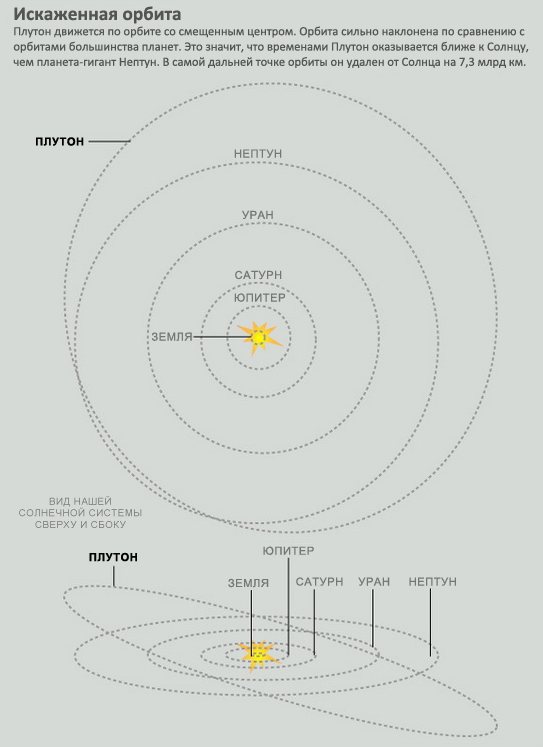

Орбита имеет форму вытянутого эллипса. На один оборот вокруг звезды Плутон тратит 248 лет. За этот период расстояние до Солнца постоянно меняется: уменьшается до 30 а.е (астрономических единиц) и удаляется до 39 а.е., где 1 а.е. равна 150 млн км. Наклон плоскости вращения составляет угол в 17 градусов относительно других планет.

Поскольку положение орбиты непостоянно: в одних случаях ниже плоскости эклиптики, в других выше, то Плутон время от времени меняется местами с Нептуном, находящимся ближе к Солнцу. Предположение о том, что карликовый объект был его спутником, было опровергнуто лишь по той причине, что уже несколько миллионов лет их орбиты находятся в постоянном резонансе в соотношении 3:2. Это значит, что за одно и тоже время одна из планет обращается вокруг Солнца три раза, а другая всего лишь два. Пока ученым удается прогнозировать поведение орбит Нептуна и Плутона, но на перспективу этот вопрос остается открытым

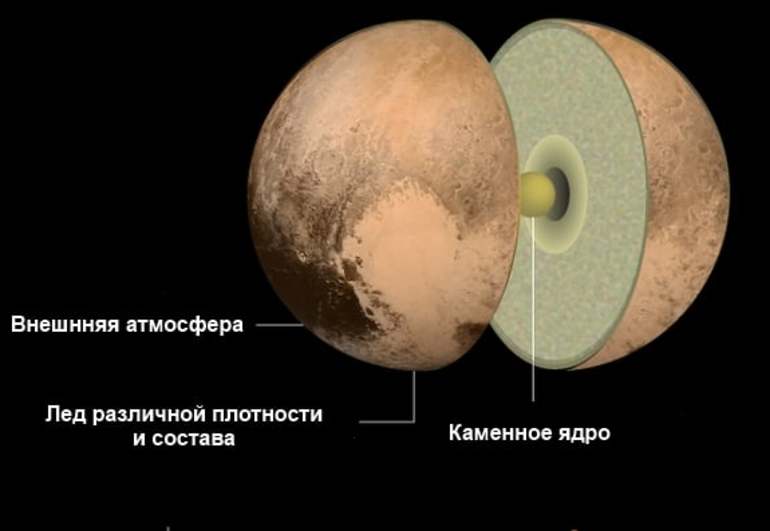

Внутреннее строение

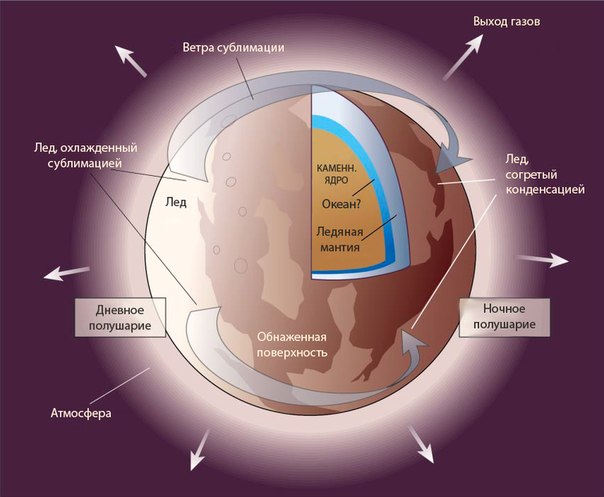

Планета состоит из трех составляющих элементов:

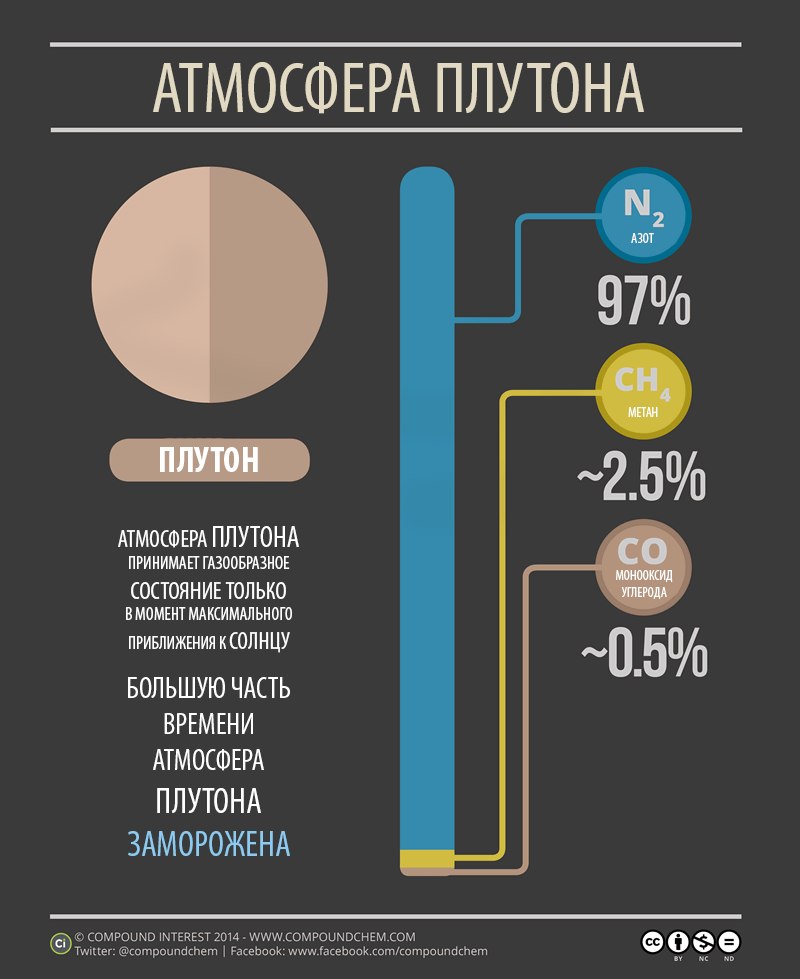

- атмосферы, представленной тонким слоем метана, азота и окиси углерода;

- мантии, толщиной в 250 км, состоящей из воды и льда;

- ядра диаметром в 1772 км, представляющего смесь камней и льда.

Выводы предположительные, сделаны на основе спектрального анализа, поскольку планета мало изучена.

Интересный факт: лед на Плутоне значительно прочнее, чем закаленная сталь, и составляет третью часть всей планеты.

Атмосфера и поверхность

Несмотря на то, что большая часть поверхности Плутона покрыта льдами, мощные телескопы зафиксировали неоднородную по цветовой гамме поверхность. На снимках были обнаружены:

- кратеры;

- углубления;

- равнины;

- ледяные глыбы.

В 2015 году обнаружена горная цепь, представляющая собой замерзшую смесь метана, азота и окиси углерода. На Плутоне есть газообразная атмосфера. Ее большая часть состоит из азота. В меньшей степени присутствуют метан и окись углерода. Такой состав исключает зарождение жизни даже в самой примитивной форме.

В период нахождения планеты в максимальной близости к Солнцу лед принимает иное состояние: газообразное. После удаления от небесного светила он превращается в кристаллы, опускающиеся на поверхность и образующие своеобразную корку.

Температура

До перехода в разряд карликовых небесных тел Плутон считали самой холодной планетой. Температура здесь опускается до -230-240 градусов по Цельсию. Сильные морозы обусловлены огромной удаленностью от Солнца: 7,4 миллиарда км, но из-за характерного строения орбиты атмосфера иногда становится газом, а затем замерзает и выпадает на поверхность.

Однако температурный режим не везде одинаков. Метан способен создавать парниковый эффект, поэтому на некоторой высоте от поверхности показатели повышаются, но незначительно: на 10 – 20 градусов по Цельсию.

Цвет

До 2015 года относительно окраса поверхности Плутона были только предположения. Поскольку большая часть планеты состоит изо льда, то и цвет должен быть соответствующий: белый с серыми и светло-синими оттенками. Однако на фотографиях, которые удалось сделать с помощью телескопа, явно просматривается иная палитра: светло-желтая, местами переходящая в более темные тона.

Есть ли жизнь на Плутоне

Для зарождения жизни на планете нет никаких условий:

- огромная удаленность от Солнца;

- низкая температура, при которой превращается в лед не только вода, но и газы: метан, азот и окись углерода;

- давление на поверхности в миллион с лишним раз ниже земного;

- газообразный атмосферный слой;

- поверхность, покрытая ледяной коркой.

Атмосфера постоянно меняется в зависимости от приближения или удаления от Солнца. В подобной среде невозможно даже предположить зарождение, а уж тем более существование жизни.

Интересный факт: если на Земле вес человека составляет 90 кг, то на Плутоне всего лишь 5,5 кг.

Спутники Плутона

Спутники Плутона

Спутники Плутона

Спутники Плутона

Спутники Плутона

Спутники Плутона

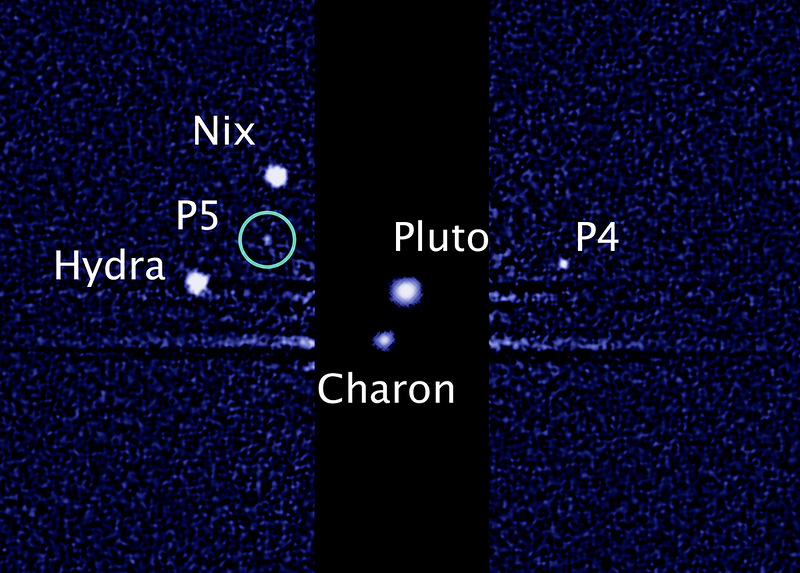

У Плутона пять спутников:

- Харон – открыт в 1978 году, в два раза меньше Плутона, диаметр – 1212 км, значительно отличается по составу. Предположительно, спутник является осколками самой планеты, выброшенными при столкновении, а потому и габариты более скромные.

- Никта – обнаружен в 2005 году при помощи телескопа Хаббл, первоначальный диаметр – 45 км. Перемещается по орбите с той же скоростью, что и Харон, а с Гидрой находится в резонансном соотношении 3:2. Длительность одного витка вокруг Плутона составляет 25 дней.

- Гидра – открыт в 2005 году, удален от Плутона на 65 000 км. Диаметр, исходя из уровня яркости, варьируется от 40 до 60 км, на орбитальный путь уходит 32 дня. Данных о составе спутника нет, но есть предположение о ледяной мантии и каменном ядре.

- Кербер – обнаружен в 2011 году, располагается между Гидрой и Никтой. Предположительная причина образования – столкновение Плутона с более крупным космическим телом, диаметр – 13-34 км, большая полуось – 59 000 км, время обращения – 32 дня.

- Стикс – открыт в 2012 году, самый маленький из пяти. От Плутона удален на 58 000 миль, диаметр – 10-25 км, один оборот преодолевает за 19 дней, большая полуось – 42 000 км. Иные физические данные не установлены.

Интересный факт: систему Плутон-Харон некоторые астрономы считают двойной планетой, поскольку они вращаются вокруг одной точки центра масс планет.

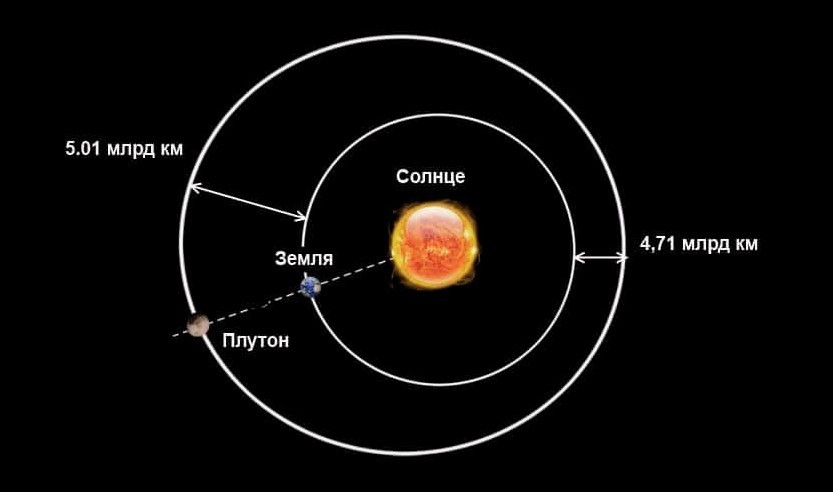

Сколько лететь до Плутона

Скорость света составляет почти 300 000 м/с. Чтобы ему преодолеть расстояние от Плутона до Земли, понадобится 4,6 часа. Скорость космического корабля «Новые Горизонты» составляла 58 000 км/ч. Это в два раза больше обычного ускорения для подобных аппаратов. Расчет времени, затраченного на полет, простой: старт кораблю был дан в 2006 году, а максимальное сближение с Плутоном было только в 2015 году. Если более точно, то время полета составило 9 лет, 5 месяцев, 24 дня.

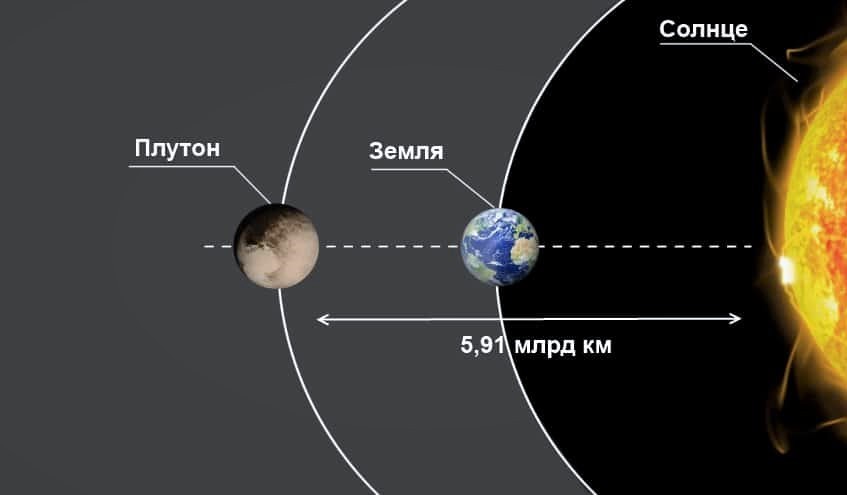

Расстояние от Земли до Плутона

По земным меркам оно составляет 4,4 млрд км или 29 астрономических единиц, но это при максимальном приближении Плутона к третьей планете от Солнца. При удалении расстояние увеличивается до 7,3 млрд км или 49 а.е. При расчете требуется брать во внимание орбитальный наклон в 17 градусов. С учетом всех особенностей, среднее расстояние определяется показателем в 5,91 млрд км или 40 а.е.

Интересный факт: солнечный свет добирается до Плутона за 5 ч, тогда как на Землю он падает через 7 мин.

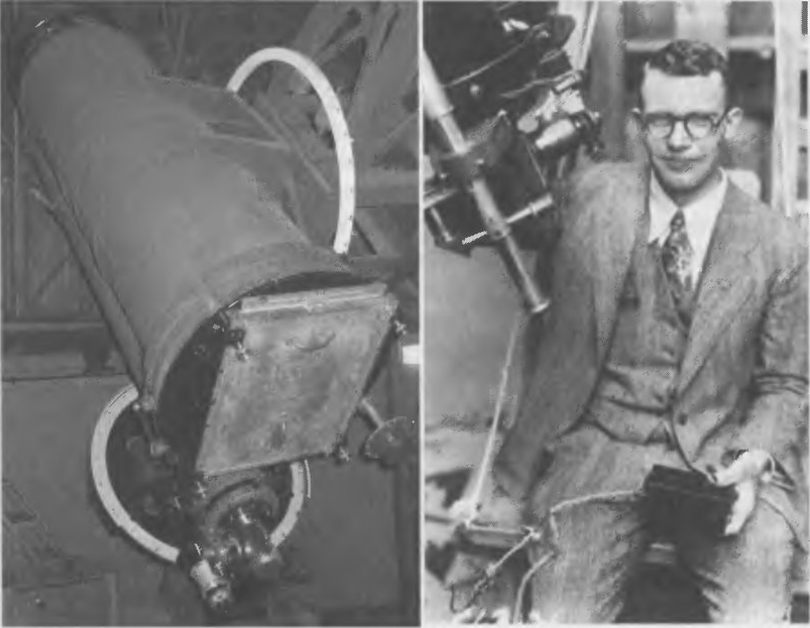

История открытия

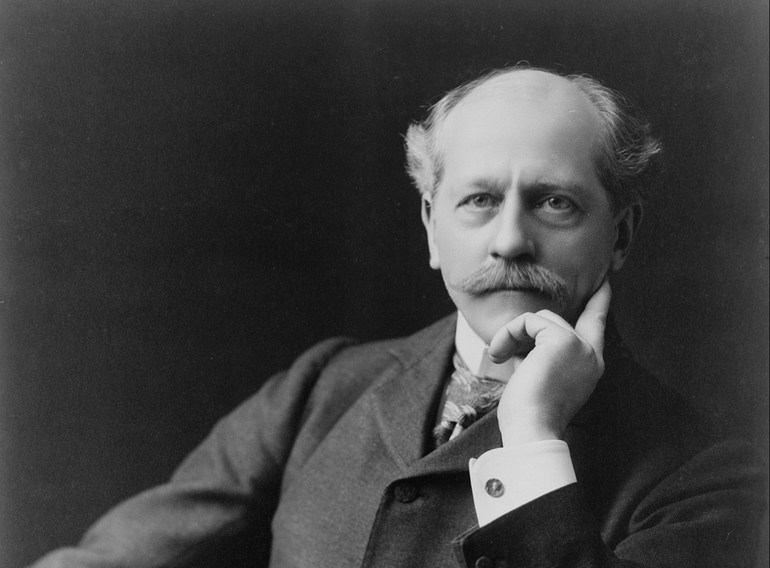

Французский математик, занимающийся небесной механикой, Урбен Леверье, провел исследование орбиты Урана. Он выявил определенные волнения, натолкнувшие на мысль, что именно какая-то неизвестная близлежащая планета является их причиной. В 1894 году американский бизнесмен, астроном и математик Персиваль Лоуэлл основал на собственные средства обсерваторию. Также стал инициатором проекта, в рамках которого осуществлялся поиск девятой планеты. Длительное время исследования были безуспешными. Энтузиасты сделали множество фотоснимков с многочисленными небесными телами, но искомое там никто не увидел.

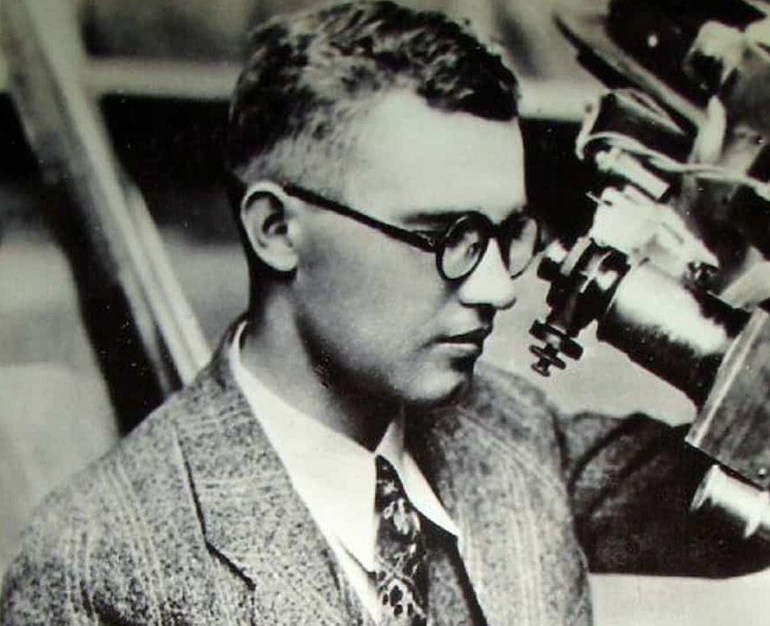

Плутон был открыт 18 февраля 1930 года американским астрономом Клайдом Томбо. Будучи принятым на работу в обсерваторию, он делал фотографии и вдруг заметил на снимках движущийся объект (из нескольких фотокарточек была сделана простейшая анимация). Это и был Плутон. Лоуэлловская обсерватория 13 марта этого же года сделала заявление об открытии новой планеты.

Почему Плутон так называется?

После открытия девятой планеты у астрономов появился логичный вопрос: какое название ей дать? Такое право предоставлялось первооткрывателю. Не самому Клайду Томбо, а месту, где он работал – обсерватории Лоуэлла. Жена уже давно почившего Лоуэлла, Констанция, предложила несколько названий. Первое название планеты – «Персиваль», в честь ее мужа, затем – «Зевс», а после и вовсе свое же имя. Однако научное сообщество проигнорировало ее предложения.

Ныне используемое название придумала Венеция Берни – обыкновенная оксфордская школьница. Дело в том, что Плутон – это бог из древнеримской мифологии, который правил подземным царством. Это отлично подходило для холодной и мрачной поверхности планеты.

Свою версию девочка озвучила дедушке, который тогда работал в библиотеке Оксфордского университета. Он передал предложение профессору Тернеру, отправившему сообщение в США своим коллегам. Всего было предложено 3 варианта: «Минерва», «Кронос» и «Плутон». Первые два отклонили, и официально планета получила название 1 мая 1930 года.

Исследование

В период с 1906 по 1916 год американские ученые впервые заговорили о случайном открытии еще одной планеты, девятой, которую нарекли «Планета Х». Далее исследования проводились в такой хронологии:

- в 1930 году сотрудник Лоуэлльского центра зафиксировал небесный объект, схожий по параметрам с «Планетой Х» исключительно благодаря зоркости зрения;

- в этом же году он официально получил название – «Плутон»;

- в 2006 году девятую планету перевели в статус карликовых небесных тел, лишив прежнего титула, поскольку за орбитой Нептуна находились иные объекты Вселенной;

- в 2006 году стартовал аппарат «Новые горизонты», основной целью которого было изучение Плутона и Харона, его спутника;

- в 2015 году спутник максимально сблизился с планетой (удаление составляло всего 12 500 км).

Аппарат предоставил данные, по которым удалось сделать спектральный анализ поверхности. В разное время делались снимки, появилась возможность сравнить геологическую активность.

Интересный факт: один день на Плутоне равен земной неделе.

Кольца Плутона

Изначально считалось, что вокруг Плутона должны быть кольца, которые могли образоваться в результате столкновений. При приближении к планете спутник «Новые горизонты» отправлял сделанные фотографии на Землю. На них колец обнаружено не было, более того, аппарат обязательно столкнулся бы с ними. После тщательного анализа полученных данных ученые единогласно пришли к выводу, что они вокруг планеты отсутствуют.

Статус Плутона сейчас

В 1930 году Плутон признали планетой – 9-ой по счету от Солнца, однако сравнительно недавно он потерял свой статус. Ученые начали сомневаться, что небесное тело соразмерно параметрам Земли. В результате исследований его определили в разряд карликовых планет. По данному поводу несколько раз устраивали дебаты, и окончательное решение приняли в 2006 году. Ученые выделили несколько критериев для определения статуса планеты:

- Космическое тело должно вращаться по орбите вокруг Солнца, а также быть спутником одной из звезд, а не какой-либо планеты.

- Объект должен иметь такую массу, которая позволит ему под действием гравитации обрести форму сферы.

- Размеры тела должны быть настолько большими, чтобы в пределах его орбиты не было более крупных объектов. Исключением являются только его спутники или объекты под действием гравитации.

Таким образом, после проверки этих факторов ученые установили, что называть Плутон планетой нельзя из-за третьего критерия. Поскольку он находится в поясе Койпера, его массу сравнили с близлежащими объектами. Выяснилось, что Плутон занимает всего 7% массы остальных космических тел.

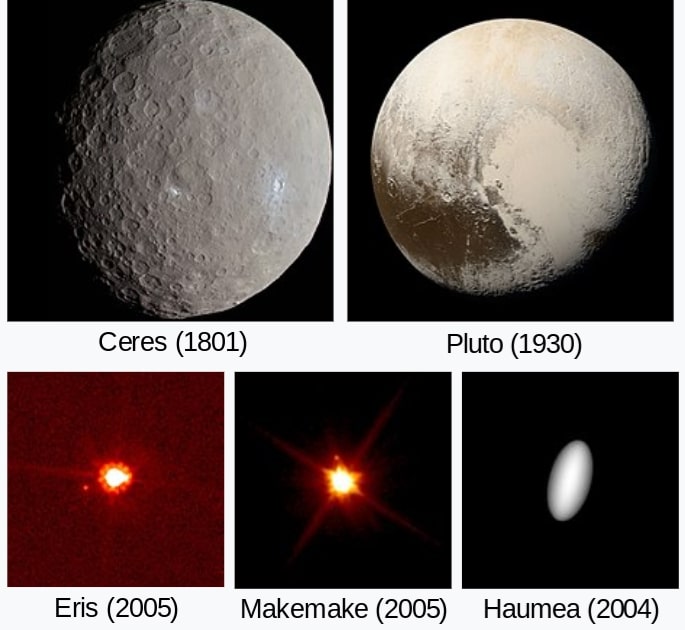

Другие карликовые планеты

Поскольку Плутон удовлетворял первым двум критериям, его определили в категорию карликовых планет, а также отнесли к классу плутоидов. Такими небесными телами считаются сферические объекты с небольшой массой. Они должны вращаться вокруг Солнца. При этом, орбите необходимо иметь больший радиус, чем у Нептуна. Кроме Плутона считаются плутоидами: Эрида, Макемаке и Хаумеа.

Интересный факт: на Плутоне одни сутки соответствуют шести земным, а одно полноценное вращение вокруг Солнца по земным меркам занимает целых 248 лет.

Официально Плутон внесли в список малых планет под номером 134340 (7 сентября 2006). Интересно, что если бы ученые с самого начала правильно охарактеризовали этот объект, то в каталоге он бы занимал место в первых тысячах. Единственное отличие между обычной планетой и карликовой теперь заключается только в размере объектов. По остальным параметрам они совпадают.

Интересное видео о Плутоне

Если Вы нашли ошибку, пожалуйста, выделите фрагмент текста и нажмите Ctrl+Enter.

Солнечная система > Карликовые планеты > Плутон

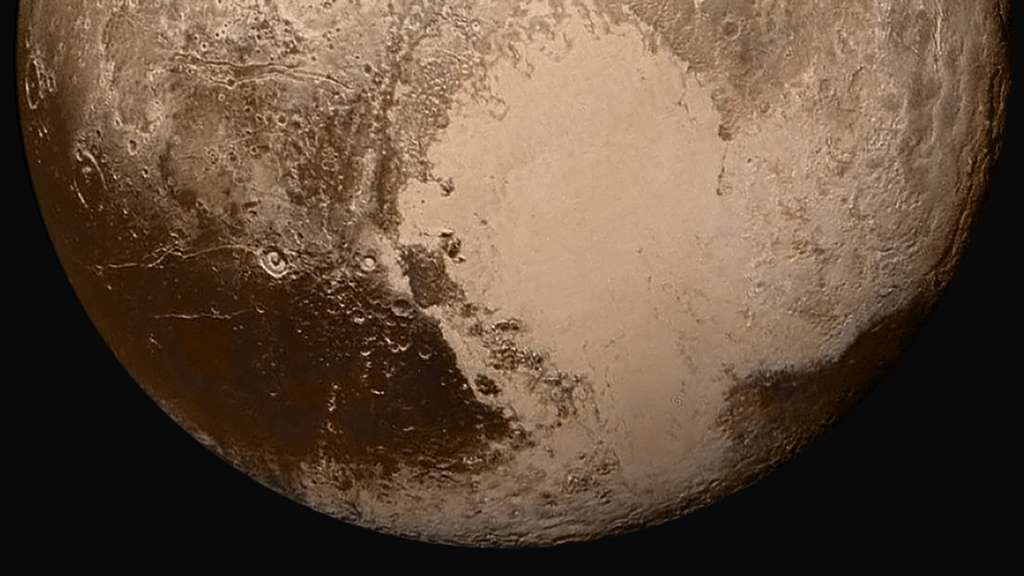

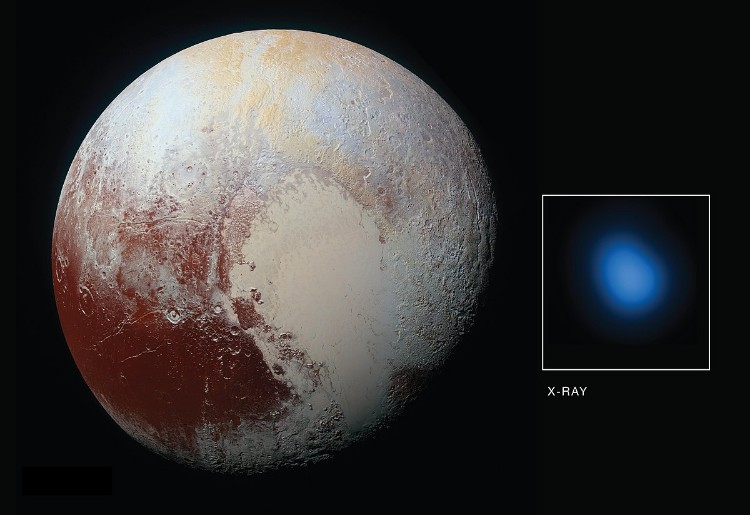

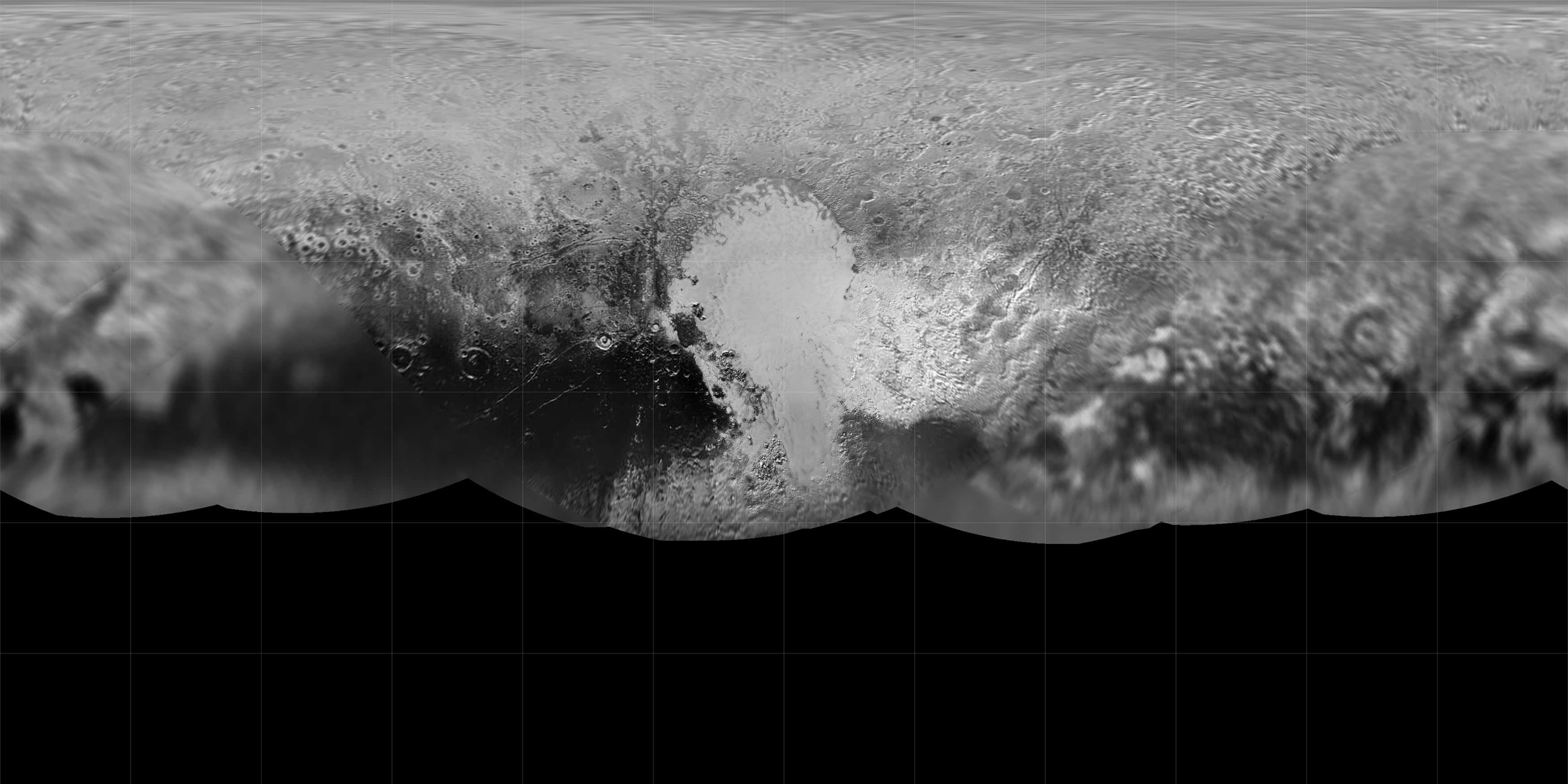

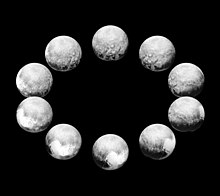

Плутон, снятый в высоком разрешении миссией Новые Горизонты в 2015 году

- Введение

- Открытие

- Название

- Размер, масса и орбита

- Состав и атмосфера

- Спутники Плутона

- Классификация

- Исследование

Плутон – карликовая планета Солнечной системы: открытие, название, размер, масса, орбита, состав, атмосфера, спутники, какая Плутон планета, исследования, фото.

Плутон — девятая или бывшая планета Солнечной системы, перешедшая в разряд карликовых.

В 1930 году Клайд Томб произвел открытие Плутона, ставшего на целый век 9-й планетой. Но в 2006 году его перенесли в семейство карликовых планет, потому что за чертой Нептуна нашли множество подобных объектов. Но это не отменяет его ценности, ведь теперь стоит на первом месте по крупности среди карликовых планет в нашей системе.

В 2015 году к нему добрался аппарат Новые Горизонты, и мы получили не только приближенные фото Плутона, но и много полезной информации. Давайте рассмотрим интересные факты о планете Плутон для детей и взрослых.

Интересные факты о планете Плутон

Название досталось в честь властелина подземного мира

- Это более поздняя вариация имя Аида. Ее предложила 11-летняя девочка Венеция Бруней.

В 2006 году стал карликовой планетой

- В этот момент МАС выдвигает новое определение «планеты» – небесный объект, пребывающий на орбитальном пути вокруг Солнца, обладает необходимой массой для сферической формы и очистил окрестности от посторонних тел.

Нашли 18 февраля 1930 года

- За 76 лет между обнаружением и смещением в карликовый тип Плутон успел пройти лишь треть орбитального маршрута.

Есть 5 спутников

- В лунном семействе числятся Харон (1978), Гидра и Никта (2005), Кербер (2011) и Стикс (2012).

Наибольшая карликовая планета

- Ранее полагали, что это звание заслуживает Эрида. Но сейчас мы знаем, что ее диаметр достигает 2326 км, а у Плутона – 2372 км.

На 1/3 состоит из воды

- Состав Плутона представлен водяным льдом, где воды в 3 раза больше, чем в земных океанах. Поверхность укрыта ледяной коркой. Заметны хребты, светлые и темные участки, а также цепь кратеров.

Уступает по размеру некоторым спутникам

- Более крупными считаются луны Гинимед, Титан, Ио, Каллисто, Европа, Тритон и земной спутник. Плутон достигает 66% лунного диаметра и 18% массы.

Наделен эксцентричной и наклонной орбитой

- Плутон проживает на расстоянии в 4.4-7.3 млрд. км от нашей звезды Солнца, а значит иногда подходит ближе Нептуна.

Принимал одного посетителя

- В 2006 году к Плутону отправился аппарат Новые Горизонты, прибывший к объекту 14 июля 2015 года. С его помощью удалось получить первые приближенные изображения. Сейчас аппарат движется к поясу Койпера.

Позицию Плутона предсказали математически

- Это случилось в 1915 году благодаря Персивалю Лоуэллу, который основывался на орбитах Урана и Нептуна.

Периодически возникает атмосфера

- Когда Плутон приближается к Солнцу, то поверхностный лед начинает таять и формирует тонкий атмосферный слой. Он представлен азотом и метановой дымкой с высотой в 161 км. Солнечные лучи разбивают метан на углеводороды, покрывающие лед темным слоем.

Открытие планеты Плутон

Присутствие Плутона предсказывали еще до того, как найти его в обзоре. В 1840-х гг. Урбен Верьер применил механику Ньютона, чтобы высчитать позицию Нептуна (тогда еще не был найден), базируясь на смещении орбитального пути Урана. В 19-м веке пристальное изучение Нептуна показало то, что его покой также нарушается (транзит Плутона).

В 1906 году Персиваль Лоуэлл основал поиск Планеты X. К сожалению, его не стало в 1916 году и не дождался открытия. И он даже не подозревал, что на двух его пластинах отобразился Плутон.

Фото Плутона 23 и 29 января 1930 года

В 1929 году поиски возобновились, и проект доверили Клайду Томбу. 23-летний парень провел целый год, делая снимки небесных участков, а потом анализируя их, чтобы отыскать моменты смещения объектов.

В 1930-м году он нашел возможного кандидата. Обсерватория запросила дополнительные фотографии и подтвердила наличие небесного тела. 13 марта 1930-го года открыли новую планету Солнечной системы.

Название планеты Плутон

После объявления обсерватория Лоуэлла начала получать огромное количество писем с предложением имен. Плутон был римским божеством, отвечающим за подземный мир. Это название поступило от 11-летней Венеции Берни, которой подсказал ее дедушка–астроном. Ниже представлены фото Плутона от космического телескопа Хаббл.

Плутон, наблюдаемый телескопом Хаббл в 2002-2003 гг

Официально его наименовали 24 марта 1930 года. Среди конкурентов фигурировали Миневра и Кронус. Но Плутон подходил идеально, так как первые буквы отражали инициалы Персиваля Лоуэлла.

К имени быстро привыкли. А в 1930 году Уолт Дисней даже назвал пса Микки Мауса Плуто в честь объекта. В 1941 году появился элемент плутоний от Гленна Сиборга.

Размер, масса и орбита планеты Плутон

При массе 1.305 х 1022 кг Плутон занимает вторую позицию по массивности среди карликовых планет. Показатель площади – 1.765 х 107 км, а объем – 6.97 х 109 км3.

Физические характеристики Плутона |

|

| Экваториальный радиус | 1153 км |

|---|---|

| Полярный радиус | 1153 км |

| Площадь поверхности | 1,6697·107 км² |

| Объём | 6,39·109 км³ |

| Масса | (1,305 ± 0,007)·1022 кг |

| Средняя плотность | 2,03 ± 0,06 г/см³ |

| Ускорение свободного падения на экваторе | 0,658 м/с² (0,067g) |

| Первая космическая скорость | 1,229 км/c |

| Экваториальная скорость вращения | 0,01310556 км/с |

| Период вращения | 6,387230 сид. дней |

| Наклон оси | 119,591 ± 0,014° |

| Склонение северного полюса | −6,145 ± 0,014° |

| Альбедо | 0,4 |

| Видимая звёздная величина | до 13,65 |

| Угловой диаметр | 0,065—0,115″ |

Теперь вы знаете, какая планета Плутон, но давайте изучим ее вращение. Карликовая планета движется по умеренному эксцентричному орбитальному пути, приближаясь к Солнцу на 4.4 млрд. км и отдаляясь на 7.3 млрд. км. Это говорит о том, что он иногда подходит ближе к Солнцу, чем Нептун. Но они обладают устойчивым резонансом, поэтому избегают столкновения.

Орбита и вращение Плутона |

|

| Перигелий | 29,65834067 а. е. |

|---|---|

| Афелий | 49,30503287 а. е. |

| Большая полуось | 39,48168677 а. е. |

| Эксцентриситет орбиты | 0,24880766 |

| Сидерический период обращения | 90 613,3055 дней (248,09 лет) |

| Синодический период обращения | 366,73 дней |

| Орбитальная скорость | 4,666 км/с |

| Наклонение | 17°,14175 |

| Долгота восходящего узла | 113,642 811° |

| Аргумент перицентра | 113,76329° |

| Спутники | 5 |

На проход вокруг звезды тратит 250 лет, а осевой оборот выполняет за 6.39 дней. Наклон составляет 120°, что приводит к примечательным сезонным колебаниям. В период солнцестояния ¼ поверхности непрерывно прогревается, а остальная находится во тьме.

Эта анимация наглядно показывает на какую высоту смог бы подпрыгнуть человек, находясь на поверхности Плутона

Состав и атмосфера планеты Плутон

С показателем плотности в 1.87 г/см3 Плутон обладает каменным ядром и ледяной мантией. Состав поверхностного слоя на 98% представлен азотным льдом с небольшим объемом метана и окиси углерода. Интересным формированием выступает Сердце Плутона (Область Томбо). Ниже представлена схема строения Плутона.

Теоретическая структура Плутона: замороженный азот, водный лед и камень

Исследователи думают, что внутри объект делится на слои, а плотное ядро наполнено каменистым материалом и окружено мантией из водяного льда. В диаметре ядро простирается на 1700 км, что охватывает 70% всей карликовой планеты. Распад радиоактивных элементов указывает на возможный подповерхностный океан с толщиной в 100-180 км.

Тонкий атмосферный слой представлен азотом, метаном и окисью углерода. Но объект такой холодный, что атмосфера застывает и падает на поверхность. Средний температурный показатель достигает -229°С.

Спутники Плутона

У карликовой планеты Плутон есть 5 спутников. Крупнейшим и ближайшим выступает Харон. Его нашел в 1978 году Джеймс Кристи, рассматривавший старые снимки. За ним скрываются остальные луны: Стикс, Никта, Кербер и Гидра.

Спутники Плутона

| Наименование | Диаметр (км) | Масса (×1021 кг) | Большая полуось (км) |

Период обращения (дней) | Угол наклона (к экватору Плутона) |

Открыт(год) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Плутон | 2306 ± 20 | 13,05 ± 0,07 | 2390 | 6,387230 | — | 1930 | |

| Плутон I | Харон | 1212 ± 3 | 1,52 ± 0,06 | 19 571 ± 4 | 6,387230 | 0,00° ± 0,014° | 1978 |

| Плутон V | Стикс | 10-25 | ? | 42 000 | 19 | ~0° | 2012 |

| Плутон II | Никта | 45 ? | < 0,002 | 48 675 ± 120 | 24,856 ± 0,001 | 0,04° ± 0,22° | 2005 |

| Плутон IV | Кербер | 13-34 | ? | 59 000 | 32,1 ± 0,3 | ~0° | 2011 |

| Плутон III | Гидра | 45-60 ? | < 0,002 | 64 780 ± 90 | 38,206 ± 0,001 | 0,22° ± 0,12° | 2005 |

В 2005 году телескоп Хаббл нашел Никс и Гидру, а в 2011-м – Кербер. Стикс заметили уже при полете миссии Новые Горизонты в 2012 году.

Харон, Стикс и Кербер обладают необходимой массой, чтобы сформироваться в виде сфероидов. А вот Никс и Гидра кажутся вытянутыми. Система Плутон-Харон интересная тем, что их центр масс расположен вне планеты. Из-за этого некоторые склоняются к мнению о двойной карликовой системе.

Сравнение размеров Харона и малых спутников Плутона

К тому же пребывают в приливном блоке и повернуты всегда одним боком. В 2007 году на Хароне заметили кристаллы воды и гидраты аммиака. Это говорит о том, что на Плутоне есть активные криогейзеры и океан. Спутники могли сформироваться из-за удара Платона и крупного тела в самом начале зарождения Солнечной системы.

Плутон и Харон

Астрофизик Валерий Шематович о ледяном спутнике Плутона, миссии New Horizons и океане Харона:

Классификация планеты Плутон

Почему Плутон не считается планетой? На орбите с Плутоном в 1992 году начали замечать похожие объекты, что навело на мысль о принадлежности карлика к поясу Койпера. Это заставило задуматься над истинной природой объекта.

В 2005 году ученые нашли транс-нептуновый объект – Эрида. Оказалось, что он больше Плутона, но никто не знал, можно ли назвать его планетой. Однако это стало толчком к тому, что в планетарной природе Плутона стали сомневаться.

В 2006 году в МАС развернули спор по поводу классификации Плутона. Новые критерии требовали пребывания на солнечной орбите, наличия достаточной гравитации для формирования сферы и очистки орбиты от остальных объектов.

Плутон провалился по третьему пункту. На собрании решили, что подобные планеты следует именовать карликами. Но не все поддержали это решение. Против активно выступали Алан Стерн и Марк Бай.

В 2008 году провели еще одну научную дискуссию, которая не привела к единому мнению. Но МАС утвердило официальную классификацию Плутона как карликовой планеты. Теперь вы знаете, почему Плутон больше не планета.

Исследование планеты Плутон

За Плутоном сложно наблюдать, потому что он крошечные и расположен сильно далеко. В 1980-х гг. НАСА начали планировать отправку миссии Вояджер-1. Но они все же ориентировались на спутник Сатурна Титан, поэтому не смогли наведаться к планете. Вояджер-2 также не рассматривал эту траекторию.

Но в 1977 году подняли вопрос о достижении Плутона и транс-нептуновых объектов. Создалась программа Плутон-Койпер Экспресс, которую отменили в 2000-м году, так как закончилось финансирование. В 2003 году стартовал проект Новые Горизонты, который отправился в 2006 году. В том же году появились первые фото объекта при тестировании инструмента LORRI.

Аппарат начал приближаться в 2015 году и присылал фото карликовой планеты Плутон на удаленности в 203 000 000 км. На них отобразились Плутон и Харон.

Плутон и Харон в обзоре аппарата Новые Горизонты

Ближайший подход случился 14 июля, когда получилось добыть самые лучшие и детальные кадры. Сейчас аппарат движется на скорости в 14.52 км/с. С этой миссией мы получили огромное количество информации, которую еще предстоит переварить и осознать. Но важно, что мы также лучше понимаем процесс формирования системы и другие подобные объекты. Далее можете внимательно изучить карту Плутона и фото особенностей его поверхности.

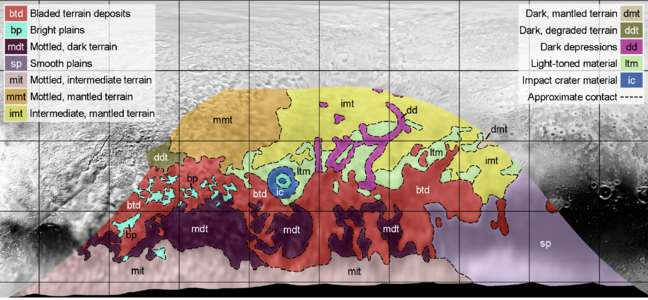

Карта поверхности карликовой планеты Плутон

Нажмите на изображение, чтобы его увеличить

Фотографии карликовой планеты Плутон

Полюбившаяся малютка больше не выступает планетой и заняла свое место в разряде карликовых. Но фотографии Плутона в высоком разрешении демонстрируют интереснейший мир. Прежде всего, нас встречает «сердце» – равнина, запечатленная Вояджером. Это кратерный мир, который ранее считали самой морозной, отдаленной и маленькой 9-й планетой. Снимки Плутона также продемонстрируют крупный спутник Харон, с которыми они напоминают двойную планету. Но космос на этом не заканчивается, ведь далее располагается еще много ледяных объектов.

«Бесплодные земли» Плутона

Снимок в высоком разрешении от Новых Горизонтов демонстрирует как эрозия и разломы создали узоры на ледяной корке Плутона. Утес возвышается на 1.2 мили, переходя слева направо. Выступает частью большей системы каньонов, вытягивающихся на сотни миль в северном полушарии. Участники миссии считают, что центральные горы выполнены из водяного льда, но прошли сквозь перемены из-за перемещения азота и прочих экзотических ледников. Это вызвало приглушенный ландшафт округлых пиков и коротких гребней. Снизу захватили часть Равнины Спутника. Сверху – северо-запад карликовой планеты.

Великолепный полумесяц Плутона

Кадр получили через 15 минут после максимального сближения аппарата 14 июля 2015 года. Перед вами глубинные слои тумана атмосферной дымки. Она простирается по всему объекту и отображает различные поверхностные формирования на ночной стороне (левой). Тень от карликовой планеты отбрасывается на самую верхнюю часть диска. На осветленной стороне (справа) находится гладкая территория – Равнина Спутника, чьи горы возвышаются на 3500 м. Подсветка выделяет более 12 слоев дымки в тонкой планетарной атмосфере. Горизонтальные небесные полосы – звезды, размытые из-за движения камеры. Кадр сняли на камеру MVIC при удаленности в 18000 км. Разрешение – 700 м на пиксель.

Голубое небо Плутона

Пылевидный слой дымки показывает синее сияние, запечатленное камерой MVIC на аппарате Новые Горизонты. Полагают, что формирование напоминает то, что видели на спутнике Сатурна Титане. Источником может служить активированные солнечными лучами химические реакции между азотом и метаном. Это вызывает создание небольших сажеподобных частичек (толины), которые растут при сближении с поверхностью. Для снимка использовали программное обеспечение, учитывающее сведения синих, красных и ближних ИК-изображений, чтобы создать цвет, доступный человеческому глазу.

Горные массивы, равнины и туманные дымки

14 июля 2015 года Новые Горизонты максимально сократил дистанцию к Плутону. Через четверть часа он оглянулся назад и запечатлел этот вид на закате, отобразив горы и плоские ледяные равнины. Неофициально гладкую территорию наименовали Равниной Спутника (справа). Рядом есть горы (слева), простирающиеся на 3500 м – Норгей Монтес (спереди) и Хиллари Монтес (на горизонте). С восточной стороны от Равнины – грубая местность, покрытая ледниками. Подсветка демонстрирует 12 слоев в дымке. Снимок выполнили на удаленности в 18000 км, а охват – 1250 км в ширину.

Дымовые слои над Плутоном

Этот образ удалось зафиксировать при помощи камеры MVIC аппарата Новые Горизонты. Можно различить примерно 20 шаров, простирающихся на сотни километров. Но они не идут строго параллельно поверхности. К примеру, ближе всех к поверхности расположен 5-километровый отсек (снизу слева). Ученые выяснили, что атмосфера наделена подобными слоями и они намного прохладней и компактней, чем полагали. Верхняя часть простирается в пространство из-за контакта с солнечными частичками.

Ледяные равнины в высоком разрешении

Это фото в высоком разрешении Новые Горизонты добыл 24 декабря 2015 году, где показана территория Равнины Спутника. Это часть изображения, где разрешение составляет 77-85 м на пиксель. Можно заметить клеточную структуру равнин, к чему мог привести конвективный взрыв в азотном льду. На изображении вместилась полоса с шириной в 80 км и длиной – 700 км, простирающаяся от северо-западной части Равнины Спутника к ледяной части. Выполнено с помощью инструмента LORRI на удаленности в 17000 км.

Найден второй горный хребет в «сердце» Плутона

Находка проживает недалеко от юго-запада Области Томбо, расположенной между территорией ярких ледяных равнин и темным кратерным ландшафтом. Обзор выполнили на удаленности в 77000 км, с особенностями, вытягивающимися на 1 км. Найденные замерзлые пики возвышаются на 1-1.5 км и располагаются на 110 км северо-западнее Норгей Монтес. Также снимок крайне четко передает топографию вдоль западного края Области Томбо. Прослеживается разница в фактуре между молодыми восточными равнинами и мрачным кратерным ландшафтом на севере. Между ними происходит сложный контакт, который все еще изучают. Полагают, что Равнина Спутника появилась менее 100 млн. лет назад, а значит более мрачные участки должны обладать возрастом в миллиарды лет. Снимок выполнен прибором LORRI на удаленности в 77000 км.

Плавающие холмы на Равнине Спутник

Азотные ледники могут переносить интересный груз – огромное количество изолированных холмов, способных выступать частями водяного льда из планетарных окрестностей. Каждый вытягивается на несколько километров. Холмы проживают на обширной Равнине Спутник или в «сердце» Плутона. Это пример удивительной геологической активности на планете.

Разнообразие ландшафта Плутона

Аппарат Новые Горизонты добыл это фото Плутона в высоком разрешении (14 июля 2015 год), что считается наилучшим увеличением с масштабом до 270 м. Секция простирается на 120-километров и взята с крупной мозаики. Видно, как поверхность равнины окружила две изолированные ледяные горы.

Райт Монс в цвете

Исследователи Новых Горизонтов предоставили цветной снимок в высоком разрешении одного из двух потенциальных криовулканов, замеченных в июле 2015 года. Райт Монс получил свое имя в честь изобретателей самолета – братьев Райт. Простирается на 150 км и возвышается на 4 км. Перед вами ледяной вулкан, который может быть крупнейшим подобным формированием. Ученые заинтригованы непривычным распределением красного материала и удивляются, почему он не пошел дальше. Также один кратер намекает на то, что удар произошел сравнительно недавно. А значит криовулкан был активным в недалеком прошлом. Составной кадр вмещает снимки от 14 августа 2015 года, выполненные инструментом LORRI на отдаленности в 48000 км. Цвет улучшен камерой MVIC при диапазоне 34000 км и расширении в 650 м на пиксель. Всего изображение охватило 230 км.

Реакция команды Новых Горизонтов на последний снимок Плутона

Участники исследовательской команды Новых Горизонтов видят последний и детальный снимок карликовой планеты, добытый 14 июля 2015 года. Расположены в Лаборатории прикладной физики Университета Джона Хопкинса (Мэриленд).

Сердце Плутона

Равнина Спутника – неофициальное наименование гладкой и светлой территории (слева), запечатленной Новыми Горизонтами. Блестящая белая часть нагорья (справа) может быть укрыта азотным льдом, попавшим с атмосферного слоя. Ниже находятся детали ледника.

Сложные поверхностные особенности Равнины Спутник

Масштабные азотные ледяные Равнины Спутника охватывают западную сторону «сердца» планеты. Команда Новых Горизонтов обработала снимки территории, чтобы отыскать узоры в поверхностной структуре. Ледяная вставка отображает расширенный цвет в крупном плане центра Равнины. Справа – карта рассеяния той же части. Она формируется через слияние двух кадров Равнины Спутника, взятых с разной геометрией и углом обзора. Яркие участки отражают солнечные лучи, потому что поверхность преимущественно гладкая. Более темные территории наделены грубой структурой. Карта демонстрирует, что центры клеток по большей части плавные, а края – грубые и острые. Границы между ними еще ярче, а значит еще более плавные. К этой закономерности мог привести конвективный поток в азотном льду (теплый лед поднимается в центре и опускается на краях, словно лава). Данные получили камерой MVIC. Левая вставка расширена до 680 м на пиксель и выполнена на удаленности в 33900 км. Правая – 495 м на пиксель и при отдалении в 24750 км. Центральная – 320 м на пиксель и при 16000 км отстраненности.

Читайте также:

- Интересные факты о Плутоне;

- Когда был открыт Плутон;

- Кто открыл Плутон;

- Почему Плутон больше не планета;

- Есть ли жизнь на Плутоне;

- Меркурий и Плутон

- Миссия Новые Горизонты к Плутону

- Как Плутон получил свое имя?

Строение Плутона

- Размеры Плутона;

- Состав Плутона;

- Масса Плутона;

- Кольца Плутона

Ссылки

История открытия

В середине XIX века математик из Франции У. Леверье с помощью классической механики, основанной на законах Ньютона, предсказал существование планеты Нептун. Выводы он сделал на основе возмущения орбиты Урана. К концу XIX века ученые пришли к единому мнению, что на Уран оказывает влияние еще одна планета.

В начале XX века ее поисками занялся исследователь Марса американец П. Лоуэл. Предварительно он рассчитал возможные места в Солнечной системе, где могло находиться новое небесное тело, которое он назвал «Планета X». Но Лоуэлу так и не удалось ее обнаружить, поскольку в 1916 году он умер.

Через три года после его смерти специалистам обсерватории повезло запечатлеть Плутон на четырех фотографических пластинках, но в этот период планета находилась очень далеко и практически не просматривалась. На несколько лет поиски были приостановлены. Только в 1929 году директор обсерватории Слайфер поручил новичку К. Томбо возобновить их.

Для этого молодой специалист по ночам проводил съемки звездного неба. При этом он каждый участок фиксировал три раза с перерывом в несколько дней, а затем с помощью блинк-компаратора получал информацию о небесных телах, которые меняли свое положение.

Только через год ему удалось обнаружить небесное тело, которое двигалось по звездному небу. В марте 1930 года новость об открытии Плутона была передана по телеграфу в обсерваторию Гарвардского колледжа, а Томбо наградили медалью имени Ханны Джексон-Гвилт.

Присвоение названия

Так как первооткрывателями планеты считались специалисты обсерватории Лоуэлла, им было предоставлено право присвоить название новому небесному телу. Всем желающим предложили присылать в обсерваторию свои варианты, после чего письма стали поступать со всех уголков мира.

Название «Плутон» первой предложила ученица из Оксфорда В. Берни, которой было 11 лет. Помимо астрономии школьница увлекалась изучением древней мифологии, поэтому она посчитала, что имя греческого бога как раз подойдет для новой планеты.

Работникам обсерватории было предложено выбрать из трех названий (Миневра, Кронос, Плутон) более подходящее для небесного тела. После недолгих обсуждений единогласно было выбрано имя греческого бога, которое впервые официально было представлено в печати 1 мая 1930 года.

В качестве награды за предложенный вариант девочка получила 5 фунтов стерлингов.

Физические характеристики

Из-за довольно большого расстояния между Землей и Плутоном очень сложно проводить качественное исследование планеты. Последнюю обширную информацию удалось получить совсем недавно, когда искусственный спутник New Horizons смог долететь в область небесного тела. Список физических параметров планеты:

- экваториальный и полярный радиусы — 1153 км;

- площадь — 1,6697·107 км²;

- масса Плутона — (1,305 ± 0,007)·1022 кг;

- первая космическая скорость — 1,23 км/с;

- время полного оборота вокруг оси — 6,39 дней;

- звездная величина — до 13,65;

- ускорение свободного падения — 0,658 м/с² (0,067 g).

Угловой диаметр планеты составляет около 0,11″, поэтому ее очень сложно увидеть даже в мощный телескоп. Выглядит Плутон как обыкновенная звезда. На снимках, сделанных космическим телескопом Хаббл, заметны только детали альбедо.

Описание строения планеты

На фотографиях, которые удалось сделать во время затмения Плутона его спутником, хорошо видно, что поверхность транснептунового объекта красноватого цвета и неоднородна. Из-за этого при обращении планеты периодически меняются ее яркость и спектр.

Высокая плотность небесного тела говорит, что, скорей всего, оно на 50—70% состоит из камня и на 30—50% — изо льда. Геологическое строение недр Плутона представлено плотным каменным ядром, окруженным слоем льда толщиной около 300 км. На поверхности планеты обнаружены:

- азотные летучие льды — 97—98%;

- замерзший метан — 1,5—3%;

- монооксид углерода — 0,01—0,5%;

- другие химические соединения.

Перечисленные вещества существуют в летучем состоянии. В зависимости от сезона они могут перемещаться по поверхности. На снимках, сделанных в 2015 году, были обнаружены возвышающиеся над ледяной поверхностью горы высотой до 3,5 км, которые, вероятней всего, состоят изо льда, а также большая светлая площадь в форме сердца. У Плутона есть своя атмосфера, в которую входят:

- азот — 90%;

- оксид углерода — 5%;

- метан — 4%.

Остальной объем состоит из соединения азота и углерода. В зависимости от расстояния до Солнца меняются плотность и температура атмосферы, а когда Плутон удаляется на значительное расстояние, последняя полностью вымерзает.

Спутники Плутона

У планеты насчитывается пять спутников, первый из которых, Харон, считается самым крупным. Он был обнаружен в семидесятых годах прошлого века. Его диаметр составляет 1212 км (35% Луны). Остальные спутники открыли гораздо позже, использовав телескоп «Хаббл». Все они обращаются в одну сторону практически по круговым орбитам. От Плутона они располагаются в следующей последовательности:

- Харон;

- Стикс;

- Никта;

- Кербер;

- Гидра.

Карликовая планета вместе со спутниками занимает небольшой объем, а максимальный радиус орбиты равен 2,2 млн км. Все сателлиты малого размера обладают неправильной формой, но у них высокое альбедо (0,5), так как лед на поверхности более чистый. Ученые предположили, что открытие небольших спутников говорит о наличии у Плутона колец, которые образуются в результате выбросов от ударов метеоритов и астероидов.

Исследования космическими аппаратами

Большую часть исследований планеты проводили с помощью американского телескопа «Хаббл». Только в начале XXI века, получив финансирование от правительства, к Плутону была направлен исследовательский аппарат New Horizons. В январе 2006 года стартовала ракета-носитель «Атлас-5».

Кроме того, на станцию поместили часть пепла К. Томбо, который умер в конце XX века. Ровно через год, пролетая рядом с Юпитером, станция получила дополнительное ускорение — она должна была сблизиться с Плутоном в 2015 году. На борту космического корабля установили специальную аппаратуру, а для проверки камеры первый снимок был сделан за 4,2 млрд км до планеты.

На станции были установлены спектроскопы и устройства для получения изображений, которые предназначались как для связи с Землей, так и для создания качественных карт поверхности планеты. Планировалось также обследовать атмосферу, обратные стороны Плутона и его спутника Харона. Летом 2015 года исследовательский аппарат приблизился на 12,5 тыс. км к планете и сделал качественные снимки высокого разрешения.

Занимательные факты

Хотя планета и открыта в 1930 году, о ней до сих пор очень мало информации. Она практически толком не исследована человечеством, но существует много интересных фактов о планете Плутон. К ним относятся:

- Полный круг по орбите осуществляется за 248 лет.

- В 2006 году ученые, проанализировав физические параметры Плутона, исключили его из семейства планет, переведя в разряд карликовых.

- Транснептуновый объект обладает самой вытянутой орбитой.

- Атмосфера на Плутоне непригодна для жизни.

- Оборот вокруг оси длится почти семь дней.

- Солнце на Плутоне перемещается с запада на восток.

- По сравнению с Землей планета вращается в обратную сторону.

- Средняя температура на поверхности составляет -229 °C.

- По размерам Плутон считается вторым маленьким транснептуновым объектом.

- В его честь назвали химический элемент плутоний.

- С момента открытия Плутона его круг по орбите закончится в 2178 году.

- Если смотреть на Солнце с поверхности, то это будет маленькая точка.

- Плутон легче Луны в 6 раз.

- Предполагается, что атмосфера планеты и его спутника Харона одна на двоих.

После получения последних фотографий со станции New Horizons специалисты НАСА до сих пор проводят их детальное изучение. Возможно, скоро человечество узнает много новой информации о Плутоне.

Northern hemisphere of Pluto in true color, taken by NASA’s New Horizons probe in 2015[a] |

||||||||

| Discovery | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discovered by | Clyde W. Tombaugh | |||||||

| Discovery site | Lowell Observatory | |||||||

| Discovery date | February 18, 1930 | |||||||

| Designations | ||||||||

|

Designation |

(134340) Pluto | |||||||

| Pronunciation | ( |

|||||||

|

Named after |

Pluto | |||||||

|

Minor planet category |

|

|||||||

| Adjectives | Plutonian [1] | |||||||

| Orbital characteristics[4][b] | ||||||||

| Epoch J2000 | ||||||||

| Earliest precovery date | August 20, 1909 | |||||||

| Aphelion |

|

|||||||

| Perihelion |

|

|||||||

|

Semi-major axis |

|

|||||||

| Eccentricity | 0.2488 | |||||||

|

Orbital period (sidereal) |

|

|||||||

|

Orbital period (synodic) |

366.73 days[2] | |||||||

|

Average orbital speed |

4.743 km/s[2] | |||||||

|

Mean anomaly |

14.53 deg | |||||||

| Inclination |

|

|||||||

|

Longitude of ascending node |

110.299° | |||||||

|

Argument of perihelion |

113.834° | |||||||

| Known satellites | 5 | |||||||

| Physical characteristics | ||||||||

| Dimensions | 2,376.6±1.6 km (observations consistent with a sphere, predicted deviations too small to be observed)[5] | |||||||

|

Mean radius |

|

|||||||

| Flattening | <1%[7] | |||||||

|

Surface area |

|

|||||||

| Volume |

|

|||||||

| Mass |

|

|||||||

|

Mean density |

1.854±0.006 g/cm3[6][7] | |||||||

|

Surface gravity |

|

|||||||

|

Escape velocity |

1.212 km/s[f] | |||||||

|

Synodic rotation period |

[8] |

|||||||

|

Sidereal rotation period |

|

|||||||

|

Equatorial rotation velocity |

47.18 km/h | |||||||

|

Axial tilt |

122.53° (to orbit)[2] | |||||||

|

North pole right ascension |

132.993°[9] | |||||||

|

North pole declination |

−6.163°[9] | |||||||

| Albedo | 0.52 geometric[2] 0.72 Bond[2] |

|||||||

|

||||||||

|

Apparent magnitude |

13.65[2] to 16.3[10] (mean is 15.1)[2] |

|||||||

|

Absolute magnitude (H) |

−0.44[11] | |||||||

|

Angular diameter |

0.06″ to 0.11″[2][g] | |||||||

| Atmosphere | ||||||||

|

Surface pressure |

1.0 Pa (2015)[7][13] | |||||||

| Composition by volume | Nitrogen, methane, carbon monoxide[12] |

Pluto compared in size to the Earth and Moon

Pluto (minor-planet designation: 134340 Pluto) is a dwarf planet in the Kuiper belt, a ring of bodies beyond the orbit of Neptune. It is the ninth-largest and tenth-most-massive known object to directly orbit the Sun. It is the largest known trans-Neptunian object by volume, by a small margin, but is slightly less massive than Eris. Like other Kuiper belt objects, Pluto is made primarily of ice and rock and is much smaller than the inner planets. Compared to Earth’s moon, Pluto has only one sixth its mass and one third its volume.

Pluto has a moderately eccentric and inclined orbit, ranging from 30 to 49 astronomical units (4.5 to 7.3 billion kilometers; 2.8 to 4.6 billion miles) from the Sun. Light from the Sun takes 5.5 hours to reach Pluto at its average distance (39.5 AU [5.91 billion km; 3.67 billion mi]). Pluto’s eccentric orbit periodically brings it closer to the Sun than Neptune, but a stable orbital resonance prevents them from colliding.

Pluto has five known moons: Charon, the largest, whose diameter is just over half that of Pluto; Styx; Nix; Kerberos; and Hydra. Pluto and Charon are sometimes considered a binary system because the barycenter of their orbits does not lie within either body, and they are tidally locked. The New Horizons mission was the first spacecraft to visit Pluto and its moons, making a flyby on July 14, 2015 and taking detailed measurements and observations.

Pluto was discovered in 1930, the first object in the Kuiper belt. It was immediately hailed as the ninth planet, but its planetary status was questioned when it was found to be much smaller than expected. These doubts increased following the discovery of additional objects in the Kuiper belt starting in the 1990s, and particularly the more massive scattered disk object Eris in 2005. In 2006 the International Astronomical Union (IAU) formally redefined the term planet to exclude dwarf planets such as Pluto. Many planetary astronomers, however, continue to consider Pluto and other dwarf planets to be planets.

History

Discovery

Discovery photographs of Pluto

Clyde Tombaugh, in Kansas

In the 1840s, Urbain Le Verrier used Newtonian mechanics to predict the position of the then-undiscovered planet Neptune after analyzing perturbations in the orbit of Uranus. Subsequent observations of Neptune in the late 19th century led astronomers to speculate that Uranus’s orbit was being disturbed by another planet besides Neptune.[14]

In 1906, Percival Lowell—a wealthy Bostonian who had founded Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona, in 1894—started an extensive project in search of a possible ninth planet, which he termed «Planet X».[15] By 1909, Lowell and William H. Pickering had suggested several possible celestial coordinates for such a planet.[16] Lowell and his observatory conducted his search until his death in 1916, but to no avail. Unknown to Lowell, his surveys had captured two faint images of Pluto on March 19 and April 7, 1915, but they were not recognized for what they were.[16][17] There are fourteen other known precovery observations, with the earliest made by the Yerkes Observatory on August 20, 1909.[18]

Percival’s widow, Constance Lowell, entered into a ten-year legal battle with the Lowell Observatory over her husband’s legacy, and the search for Planet X did not resume until 1929.[19] Vesto Melvin Slipher, the observatory director, gave the job of locating Planet X to 23-year-old Clyde Tombaugh, who had just arrived at the observatory after Slipher had been impressed by a sample of his astronomical drawings.[19]

Tombaugh’s task was to systematically image the night sky in pairs of photographs, then examine each pair and determine whether any objects had shifted position. Using a blink comparator, he rapidly shifted back and forth between views of each of the plates to create the illusion of movement of any objects that had changed position or appearance between photographs. On February 18, 1930, after nearly a year of searching, Tombaugh discovered a possible moving object on photographic plates taken on January 23 and 29. A lesser-quality photograph taken on January 21 helped confirm the movement.[20] After the observatory obtained further confirmatory photographs, news of the discovery was telegraphed to the Harvard College Observatory on March 13, 1930.[16]

As one Plutonian year corresponds to 247.94 Earth years,[2] Pluto will complete its first orbit since its discovery in 2178.

Name and symbol

Mosaic of best-resolution images of Pluto from different angles

The discovery made headlines around the globe.[21] Lowell Observatory, which had the right to name the new object, received more than 1,000 suggestions from all over the world, ranging from Atlas to Zymal.[22] Tombaugh urged Slipher to suggest a name for the new object quickly before someone else did.[22] Constance Lowell proposed Zeus, then Percival and finally Constance. These suggestions were disregarded.[23]

The name Pluto, after the Greek/Roman god of the underworld, was proposed by Venetia Burney (1918–2009), an eleven-year-old schoolgirl in Oxford, England, who was interested in classical mythology.[24] She suggested it in a conversation with her grandfather Falconer Madan, a former librarian at the University of Oxford’s Bodleian Library, who passed the name to astronomy professor Herbert Hall Turner, who cabled it to colleagues in the United States.[24]

Each member of the Lowell Observatory was allowed to vote on a short-list of three potential names: Minerva (which was already the name for an asteroid), Cronus (which had lost reputation through being proposed by the unpopular astronomer Thomas Jefferson Jackson See), and Pluto. Pluto received a unanimous vote.[25] The name was published on May 1, 1930.[24][26] Upon the announcement, Madan gave Venetia £5 (equivalent to £336 in 2021[27], or US$394 in 2021[28][29]) as a reward.[24]

The final choice of name was helped in part by the fact that the first two letters of Pluto are the initials of Percival Lowell. Pluto’s planetary symbol ⟨⟩ was then created as a monogram of the letters «PL» (in Unicode: U+2647 ♇ PLUTO),[30] though it is rarely used in astronomy today. For example, ⟨♇⟩ occurs in a table of the planets identified by their symbols in a 2004 article written before the 2006 IAU definition,[31] but not in a graph of planets, dwarf planets and moons from 2016, where only the eight IAU planets are identified by their symbols.[32]

(Planetary symbols in general are uncommon in astronomy, and are discouraged by the IAU.)[33] The ♇ monogram is also used in astrology, but the most-common astrological symbol for Pluto, at least in English-language sources, is an orb over Pluto’s bident ⟨⟩ (U+2BD3 ⯓ PLUTO FORM TWO). The bident symbol has seen some astronomical use as well since the IAU decision on dwarf planets, for example in a public-education poster on dwarf planets published by the NASA/JPL Dawn mission in 2015, in which each of the five dwarf planets announced by the IAU receives a symbol.[34] There are in addition several other symbols for Pluto found in European astrological sources, including three accepted by Unicode:

, U+2BD4 ⯔ PLUTO FORM THREE;

, U+2BD5 ⯕ PLUTO FORM FOUR, used in Uranian astrology; and

/

, U+2BD6 ⯖ PLUTO FORM FIVE, found in various orientations, showing Pluto’s orbit cutting across that of Neptune.[35]

The name ‘Pluto’ was soon embraced by wider culture. In 1930, Walt Disney was apparently inspired by it when he introduced for Mickey Mouse a canine companion named Pluto, although Disney animator Ben Sharpsteen could not confirm why the name was given.[36] In 1941, Glenn T. Seaborg named the newly created element plutonium after Pluto, in keeping with the tradition of naming elements after newly discovered planets, following uranium, which was named after Uranus, and neptunium, which was named after Neptune.[37]

Most languages use the name «Pluto» in various transliterations.[h] In Japanese, Houei Nojiri suggested the calque Meiōsei (冥王星, «Star of the King (God) of the Underworld»), and this was borrowed into Chinese and Korean. Some languages of India use the name Pluto, but others, such as Hindi, use the name of Yama, the God of Death in Hinduism.[38] Polynesian languages also tend to use the indigenous god of the underworld, as in Māori Whiro.[38]

Vietnamese might be expected to follow Chinese, but does not because the Sino-Vietnamese word 冥 minh «dark» is homophonous with 明 minh «bright». Vietnamese instead uses Yama, which is also a Buddhist deity, in the form of Sao Diêm Vương 星閻王 «Yama’s Star», derived from Chinese 閻王 Yán Wáng / Yìhm Wòhng «King Yama».[39][38][40]

Planet X disproved

Once Pluto was found, its faintness and lack of a viewable disc cast doubt on the idea that it was Lowell’s Planet X.[15] Estimates of Pluto’s mass were revised downward throughout the 20th century.[41]

Astronomers initially calculated its mass based on its presumed effect on Neptune and Uranus. In 1931, Pluto was calculated to be roughly the mass of Earth, with further calculations in 1948 bringing the mass down to roughly that of Mars.[43][45] In 1976, Dale Cruikshank, Carl Pilcher and David Morrison of the University of Hawaii calculated Pluto’s albedo for the first time, finding that it matched that for methane ice; this meant Pluto had to be exceptionally luminous for its size and therefore could not be more than 1 percent the mass of Earth.[46] (Pluto’s albedo is 1.4–1.9 times that of Earth.[2])

In 1978, the discovery of Pluto’s moon Charon allowed the measurement of Pluto’s mass for the first time: roughly 0.2% that of Earth, and far too small to account for the discrepancies in the orbit of Uranus. Subsequent searches for an alternative Planet X, notably by Robert Sutton Harrington,[49] failed. In 1992, Myles Standish used data from Voyager 2′s flyby of Neptune in 1989, which had revised the estimates of Neptune’s mass downward by 0.5%—an amount comparable to the mass of Mars—to recalculate its gravitational effect on Uranus. With the new figures added in, the discrepancies, and with them the need for a Planet X, vanished.[50] Today, the majority of scientists agree that Planet X, as Lowell defined it, does not exist.[51] Lowell had made a prediction of Planet X’s orbit and position in 1915 that was fairly close to Pluto’s actual orbit and its position at that time; Ernest W. Brown concluded soon after Pluto’s discovery that this was a coincidence.[52]

Classification

Artistic comparison of Pluto, Eris, Haumea, Makemake, Gonggong, Quaoar, Sedna, Orcus, Salacia, 2002 MS4, and Earth along with the Moon

- v

- t

- e

From 1992 onward, many bodies were discovered orbiting in the same volume as Pluto, showing that Pluto is part of a population of objects called the Kuiper belt. This made its official status as a planet controversial, with many questioning whether Pluto should be considered together with or separately from its surrounding population. Museum and planetarium directors occasionally created controversy by omitting Pluto from planetary models of the Solar System. In February 2000 the Hayden Planetarium in New York City displayed a Solar System model of only eight planets, which made headlines almost a year later.[53]

Ceres, Pallas, Juno and Vesta lost their planet status after the discovery of many other asteroids. Similarly, objects increasingly closer in size to Pluto were discovered in the Kuiper belt region. On July 29, 2005, astronomers at Caltech announced the discovery of a new trans-Neptunian object, Eris, which was substantially more massive than Pluto and the most massive object discovered in the Solar System since Triton in 1846. Its discoverers and the press initially called it the tenth planet, although there was no official consensus at the time on whether to call it a planet.[54] Others in the astronomical community considered the discovery the strongest argument for reclassifying Pluto as a minor planet.[55]

IAU classification

The debate came to a head in August 2006, with an IAU resolution that created an official definition for the term «planet». According to this resolution, there are three conditions for an object in the Solar System to be considered a planet:

- The object must be in orbit around the Sun.

- The object must be massive enough to be rounded by its own gravity. More specifically, its own gravity should pull it into a shape defined by hydrostatic equilibrium.

- It must have cleared the neighborhood around its orbit.[56][57]

Pluto fails to meet the third condition.[58] Its mass is substantially less than the combined mass of the other objects in its orbit: 0.07 times, in contrast to Earth, which is 1.7 million times the remaining mass in its orbit (excluding the moon).[59][57] The IAU further decided that bodies that, like Pluto, meet criteria 1 and 2, but do not meet criterion 3 would be called dwarf planets. In September 2006, the IAU included Pluto, and Eris and its moon Dysnomia, in their Minor Planet Catalogue, giving them the official minor-planet designations «(134340) Pluto», «(136199) Eris», and «(136199) Eris I Dysnomia».[60] Had Pluto been included upon its discovery in 1930, it would have likely been designated 1164, following 1163 Saga, which was discovered a month earlier.[61]

There has been some resistance within the astronomical community toward the reclassification.[62][63][64] Alan Stern, principal investigator with NASA’s New Horizons mission to Pluto, derided the IAU resolution, stating that «the definition stinks, for technical reasons».[65] Stern contended that, by the terms of the new definition, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, and Neptune, all of which share their orbits with asteroids, would be excluded[66] (even though he had himself previously suggested a criterion for clearing the neighbourhood, which considered all four of them to have done so).[67] He argued that all big spherical moons, including the Moon, should likewise be considered planets.[68] He also stated that because less than five percent of astronomers voted for it, the decision was not representative of the entire astronomical community.[66] Marc W. Buie, then at the Lowell Observatory, petitioned against the definition.[69] Others have supported the IAU. Mike Brown, the astronomer who discovered Eris, said «through this whole crazy, circus-like procedure, somehow the right answer was stumbled on. It’s been a long time coming. Science is self-correcting eventually, even when strong emotions are involved.»[70]

Public reception to the IAU decision was mixed. A resolution introduced in the California State Assembly facetiously called the IAU decision a «scientific heresy».[71] The New Mexico House of Representatives passed a resolution in honor of Tombaugh, a longtime resident of that state, that declared that Pluto will always be considered a planet while in New Mexican skies and that March 13, 2007, was Pluto Planet Day.[72][73] The Illinois Senate passed a similar resolution in 2009, on the basis that Clyde Tombaugh, the discoverer of Pluto, was born in Illinois. The resolution asserted that Pluto was «unfairly downgraded to a ‘dwarf’ planet» by the IAU.»[74] Some members of the public have also rejected the change, citing the disagreement within the scientific community on the issue, or for sentimental reasons, maintaining that they have always known Pluto as a planet and will continue to do so regardless of the IAU decision.[75]

In 2006, in its 17th annual words-of-the-year vote, the American Dialect Society voted plutoed as the word of the year. To «pluto» is to «demote or devalue someone or something».[76]

Researchers on both sides of the debate gathered in August 2008, at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory for a conference that included back-to-back talks on the current IAU definition of a planet.[77] Entitled «The Great Planet Debate»,[78] the conference published a post-conference press release indicating that scientists could not come to a consensus about the definition of planet.[79] In June 2008, the IAU had announced in a press release that the term «plutoid» would henceforth be used to refer to Pluto and other planetary-mass objects that have an orbital semi-major axis greater than that of Neptune, though the term has not seen significant use.[80][81][82]

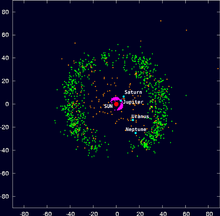

Orbit

Pluto was discovered in 1930 near the star δ Geminorum, and merely coincidentally crossing the ecliptic at this time of discovery. Pluto moves about 7 degrees east per decade with small apparent retrograde motion as seen from Earth. Pluto was closer to the Sun than Neptune between 1979 and 1999.

Animation of Pluto‘s orbit from 1850 to 2097

Sun ·

Saturn ·

Uranus ·

Neptune ·

Pluto

Pluto’s orbital period is currently about 248 years. Its orbital characteristics are substantially different from those of the planets, which follow nearly circular orbits around the Sun close to a flat reference plane called the ecliptic. In contrast, Pluto’s orbit is moderately inclined relative to the ecliptic (over 17°) and moderately eccentric (elliptical). This eccentricity means a small region of Pluto’s orbit lies closer to the Sun than Neptune’s. The Pluto–Charon barycenter came to perihelion on September 5, 1989,[3][i] and was last closer to the Sun than Neptune between February 7, 1979, and February 11, 1999.[83] Detailed calculations indicate that the previous such occurrence lasted only fourteen years, from July 11, 1735 to September 15, 1749, whereas between April 30, 1483 and July 23, 1503, it had also lasted 20 years. [84]

Although the 3:2 resonance with Neptune (see below) is maintained, Pluto’s inclination and eccentricity behave in a chaotic manner. Computer simulations can be used to predict its position for several million years (both forward and backward in time), but after intervals much longer than the Lyapunov time of 10–20 million years, calculations become unreliable: Pluto is sensitive to immeasurably small details of the Solar System, hard-to-predict factors that will gradually change Pluto’s position in its orbit.[85][86]

The semi-major axis of Pluto’s orbit varies between about 39.3 and 39.6 au with a period of about 19,951 years, corresponding to an orbital period varying between 246 and 249 years. The semi-major axis and period are presently getting longer.[87]

Orbit of Pluto – ecliptic view. This «side view» of Pluto’s orbit (in red) shows its large inclination to the ecliptic.

Orbit of Pluto – polar view. This «view from above» shows how Pluto’s orbit (in red) is less circular than Neptune’s (in blue), and how Pluto is sometimes closer to the Sun than Neptune. The darker sections of both orbits show where they pass below the plane of the ecliptic.

Relationship with Neptune

Despite Pluto’s orbit appearing to cross that of Neptune when viewed from directly above, the two objects’ orbits do not intersect. When Pluto is closest to the Sun, and close to Neptune’s orbit as viewed from above, it is also the farthest above Neptune’s path. Pluto’s orbit passes about 8 AU above that of Neptune, preventing a collision.[88][89][90][j]

This alone is not enough to protect Pluto; perturbations from the planets (especially Neptune) could alter Pluto’s orbit (such as its orbital precession) over millions of years so that a collision could be possible. However, Pluto is also protected by its 2:3 orbital resonance with Neptune: for every two orbits that Pluto makes around the Sun, Neptune makes three. Each cycle lasts about 495 years. (There are many other objects in this same resonance, called plutinos.) This pattern is such that, in each 495-year cycle, the first time Pluto is near perihelion, Neptune is over 50° behind Pluto. By Pluto’s second perihelion, Neptune will have completed a further one and a half of its own orbits, and so will be nearly 130° ahead of Pluto. Pluto and Neptune’s minimum separation is over 17 AU, which is greater than Pluto’s minimum separation from Uranus (11 AU).[90] The minimum separation between Pluto and Neptune actually occurs near the time of Pluto’s aphelion.[87]

The 2:3 resonance between the two bodies is highly stable and has been preserved over millions of years.[92] This prevents their orbits from changing relative to one another, and so the two bodies can never pass near each other. Even if Pluto’s orbit were not inclined, the two bodies could never collide.[90] The long term stability of the mean-motion resonance is due to phase protection. When Pluto’s period is slightly shorter than 3/2 of Neptune, its orbit relative to Neptune will drift, causing it to make closer approaches behind Neptune’s orbit. The gravitational pull between the two then causes angular momentum to be transferred to Pluto, at Neptune’s expense. This moves Pluto into a slightly larger orbit, where it travels slightly more slowly, according to Kepler’s third law. After many such repetitions, Pluto is sufficiently slowed that Pluto’s orbit relative to Neptune drifts in the opposite direction until the process is reversed. The whole process takes about 20,000 years to complete.[90][92][93]

Other factors

Numerical studies have shown that over millions of years, the general nature of the alignment between the orbits of Pluto and Neptune does not change.[88][87] There are several other resonances and interactions that enhance Pluto’s stability. These arise principally from two additional mechanisms (besides the 2:3 mean-motion resonance).

First, Pluto’s argument of perihelion, the angle between the point where it crosses the ecliptic and the point where it is closest to the Sun, librates around 90°.[87] This means that when Pluto is closest to the Sun, it is at its farthest above the plane of the Solar System, preventing encounters with Neptune. This is a consequence of the Kozai mechanism,[88] which relates the eccentricity of an orbit to its inclination to a larger perturbing body—in this case, Neptune. Relative to Neptune, the amplitude of libration is 38°, and so the angular separation of Pluto’s perihelion to the orbit of Neptune is always greater than 52° (90°–38°). The closest such angular separation occurs every 10,000 years.[92]

Second, the longitudes of ascending nodes of the two bodies—the points where they cross the ecliptic—are in near-resonance with the above libration. When the two longitudes are the same—that is, when one could draw a straight line through both nodes and the Sun—Pluto’s perihelion lies exactly at 90°, and hence it comes closest to the Sun when it is highest above Neptune’s orbit. This is known as the 1:1 superresonance. All the Jovian planets, particularly Jupiter, play a role in the creation of the superresonance.[88]

Quasi-satellite

In 2012, it was hypothesized that 15810 Arawn could be a quasi-satellite of Pluto, a specific type of co-orbital configuration.[94] According to the hypothesis, the object would be a quasi-satellite of Pluto for about 350,000 years out of every two-million-year period.[94][95] Measurements made by the New Horizons spacecraft in 2015 made it possible to calculate the orbit of Arawn more accurately.[96] These calculations confirm the overall dynamics described in the hypothesis.[97] However, it is not agreed upon among astronomers whether Arawn should be classified as a quasi-satellite of Pluto based on this motion, since its orbit is primarily controlled by Neptune with only occasional smaller perturbations caused by Pluto.[98][96][97]

Rotation

Pluto’s rotation period, its day, is equal to 6.387 Earth days.[2][99] Like Uranus, Pluto rotates on its «side» in its orbital plane, with an axial tilt of 120°, and so its seasonal variation is extreme; at its solstices, one-fourth of its surface is in continuous daylight, whereas another fourth is in continuous darkness.[100] The reason for this unusual orientation has been debated. Research from the University of Arizona has suggested that it may be due to the way that a body’s spin will always adjust to minimise energy. This could mean a body reorienting itself to put extraneous mass near the equator and regions lacking mass tend towards the poles. This is called polar wander.[101] According to a paper released from the University of Arizona, this could be caused by masses of frozen nitrogen building up in shadowed areas of the dwarf planet. These masses would cause the body to reorient itself, leading to its unusual axial tilt of 120°. The buildup of nitrogen is due to Pluto’s vast distance from the Sun. At the equator, temperatures can drop to −240 °C (−400.0 °F; 33.1 K), causing nitrogen to freeze as water would freeze on Earth. The same effect seen on Pluto would be observed on Earth were the Antarctic ice sheet is several times larger.[102]

Geology

Surface

High-resolution MVIC image of Pluto in enhanced color to bring out differences in surface composition

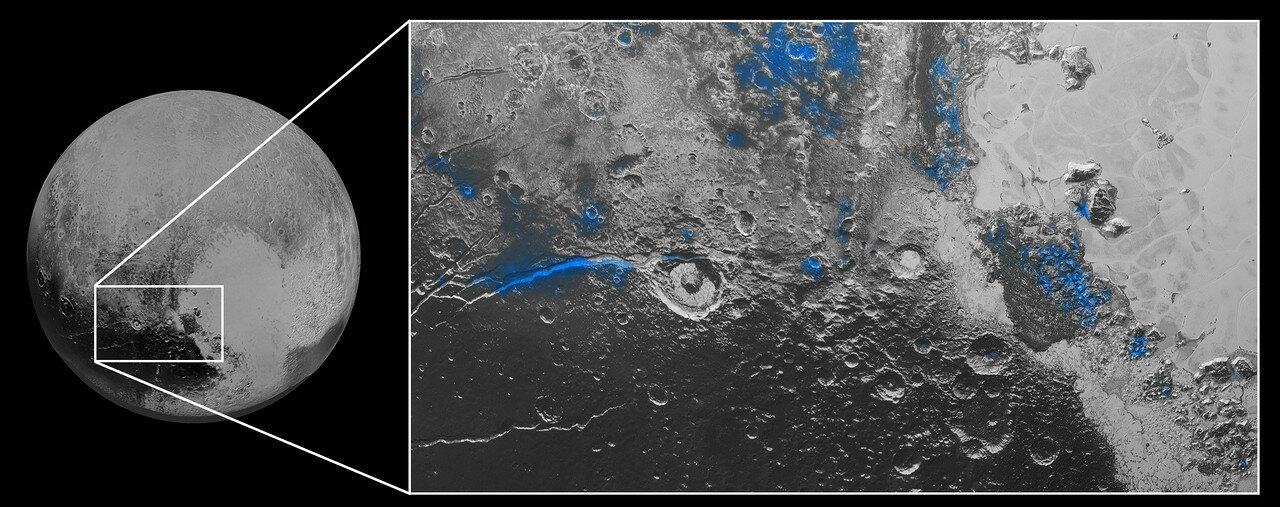

Regions where water ice has been detected (blue regions)

The plains on Pluto’s surface are composed of more than 98 percent nitrogen ice, with traces of methane and carbon monoxide.[103] Nitrogen and carbon monoxide are most abundant on the anti-Charon face of Pluto (around 180° longitude, where Tombaugh Regio’s western lobe, Sputnik Planitia, is located), whereas methane is most abundant near 300° east.[104] The mountains are made of water ice.[105] Pluto’s surface is quite varied, with large differences in both brightness and color.[106] Pluto is one of the most contrastive bodies in the Solar System, with as much contrast as Saturn’s moon Iapetus.[107] The color varies from charcoal black, to dark orange and white.[108] Pluto’s color is more similar to that of Io with slightly more orange and significantly less red than Mars.[109] Notable geographical features include Tombaugh Regio, or the «Heart» (a large bright area on the side opposite Charon), Cthulhu Macula,[6] or the «Whale» (a large dark area on the trailing hemisphere), and the «Brass Knuckles» (a series of equatorial dark areas on the leading hemisphere).

Sputnik Planitia, the western lobe of the «Heart», is a 1,000 km-wide basin of frozen nitrogen and carbon monoxide ices, divided into polygonal cells, which are interpreted as convection cells that carry floating blocks of water ice crust and sublimation pits towards their margins;[110][111][112] there are obvious signs of glacial flows both into and out of the basin.[113][114] It has no craters that were visible to New Horizons, indicating that its surface is less than 10 million years old.[115] Latest studies have shown that the surface has an age of 180000+90000

−40000 years.[116]

The New Horizons science team summarized initial findings as «Pluto displays a surprisingly wide variety of geological landforms, including those resulting from glaciological and surface–atmosphere interactions as well as impact, tectonic, possible cryovolcanic, and mass-wasting processes.»[7]

Distribution of over 1000 craters of all ages in the northern anti-Charon quadrant of Pluto. The variation in density (with none found in Sputnik Planitia) indicates a long history of varying geological activity. The lack of crater on the left and right of the map is due to low-resolution coverage of those sub-Charon regions.

Sputnik Planitia is covered with churning nitrogen ice «cells» that are geologically young and turning over due to convection.

In Western parts of Sputnik Planitia there are fields of transverse dunes formed by the winds blowing from the center of Sputnik Planitia in the direction of surrounding mountains. The dune wavelengths are in the range of 0.4–1 km and they are likely consists of methane particles 200–300 μm in size.[117]

Internal structure

Model of the internal structure of Pluto[118]

- Water ice crust

- Liquid water ocean

- Silicate core

Pluto’s density is 1.860±0.013 g/cm3.[7] Because the decay of radioactive elements would eventually heat the ices enough for the rock to separate from them, scientists expect that Pluto’s internal structure is differentiated, with the rocky material having settled into a dense core surrounded by a mantle of water ice. The pre–New Horizons estimate for the diameter of the core is 1700 km, 70% of Pluto’s diameter.[118] Pluto has no magnetic field.[119]

It is possible that such heating continues today, creating a subsurface ocean of liquid water 100 to 180 km thick at the core–mantle boundary.[118][120][121] In September 2016, scientists at Brown University simulated the impact thought to have formed Sputnik Planitia, and showed that it might have been the result of liquid water upwelling from below after the collision, implying the existence of a subsurface ocean at least 100 km deep.[122] In June 2020, astronomers reported evidence that Pluto may have had a subsurface ocean, and consequently may have been habitable, when it was first formed.[123][124] In March 2022, they concluded that peaks on Pluto are actually a merger of «ice volcanoes», suggesting a source of heat on the body at levels previously thought not possible.[125]

Mass and size

Pluto (bottom right) compared in size to the largest satellites in the solar system (from left to right and top to bottom): Ganymede, Titan, Callisto, Io, the Moon, Europa, and Triton

Pluto’s diameter is 2376.6±3.2 km[5] and its mass is (1.303±0.003)×1022 kg, 17.7% that of the Moon (0.22% that of Earth).[126] Its surface area is 1.774443×107 km2, or just slightly bigger than Russia. Its surface gravity is 0.063 g (compared to 1 g for Earth and 0.17 g for the Moon).[2]

The discovery of Pluto’s satellite Charon in 1978 enabled a determination of the mass of the Pluto–Charon system by application of Newton’s formulation of Kepler’s third law. Observations of Pluto in occultation with Charon allowed scientists to establish Pluto’s diameter more accurately, whereas the invention of adaptive optics allowed them to determine its shape more accurately.[127]

With less than 0.2 lunar masses, Pluto is much less massive than the terrestrial planets, and also less massive than seven moons: Ganymede, Titan, Callisto, Io, the Moon, Europa, and Triton. The mass is much less than thought before Charon was discovered.[128]

Pluto is more than twice the diameter and a dozen times the mass of Ceres, the largest object in the asteroid belt. It is less massive than the dwarf planet Eris, a trans-Neptunian object discovered in 2005, though Pluto has a larger diameter of 2,376.6 km[5] compared to Eris’s approximate diameter of 2,326 km.[129]

Determinations of Pluto’s size have been complicated by its atmosphere[130] and hydrocarbon haze.[131] In March 2014, Lellouch, de Bergh et al. published findings regarding methane mixing ratios in Pluto’s atmosphere consistent with a Plutonian diameter greater than 2,360 km, with a «best guess» of 2,368 km.[132] On July 13, 2015, images from NASA’s New Horizons mission Long Range Reconnaissance Imager (LORRI), along with data from the other instruments, determined Pluto’s diameter to be 2,370 km (1,470 mi),[129][133] which was later revised to be 2,372 km (1,474 mi) on July 24,[134] and later to 2374±8 km.[7] Using radio occultation data from the New Horizons Radio Science Experiment (REX), the diameter was found to be 2376.6±3.2 km.[5]

The masses of Pluto and Charon compared to other dwarf planets (Eris, Haumea, Makemake, Gonggong, Quaoar, Orcus, Ceres) and to the icy moons Triton (Neptune I), Titania (Uranus III), Oberon (Uranus IV), Rhea (Saturn V) and Iapetus (Saturn VIII). The unit of mass is ×1021 kg.

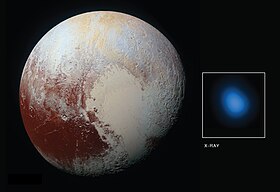

Atmosphere

A near-true-color image taken by New Horizons after its flyby. Numerous layers of blue haze float in Pluto’s atmosphere. Along and near the limb, mountains and their shadows are visible.

Image of Pluto in X-rays by Chandra X-ray Observatory (blue spot). The X-rays are probably created by interaction of the gases surrounding Pluto with solar wind, although details of their origin are not clear.

Pluto has a tenuous atmosphere consisting of nitrogen (N2), methane (CH4), and carbon monoxide (CO), which are in equilibrium with their ices on Pluto’s surface.[138][139] According to the measurements by New Horizons, the surface pressure is about 1 Pa (10 μbar),[7] roughly one million to 100,000 times less than Earth’s atmospheric pressure. It was initially thought that, as Pluto moves away from the Sun, its atmosphere should gradually freeze onto the surface; studies of New Horizons data and ground-based occultations show that Pluto’s atmospheric density increases, and that it likely remains gaseous throughout Pluto’s orbit.[140][141] New Horizons observations showed that atmospheric escape of nitrogen to be 10,000 times less than expected.[141] Alan Stern has contended that even a small increase in Pluto’s surface temperature can lead to exponential increases in Pluto’s atmospheric density; from 18 hPa to as much as 280 hPa (three times that of Mars to a quarter that of the Earth). At such densities, nitrogen could flow across the surface as liquid.[141] Just like sweat cools the body as it evaporates from the skin, the sublimation of Pluto’s atmosphere cools its surface.[142] Pluto has no or almost no troposphere; observations by New Horizons suggest only a thin tropospheric boundary layer. Its thickness in the place of measurement was 4 km, and the temperature was 37±3 K. The layer is not continuous.[143]