Пожалуй, если бы провести конкурс среди древних цивилизаций мира на звание самой загадочной, то древняя цивилизация майя уверенно бы заняла в нем первое место. Народ, не знавший колеса, строил пирамиды, могущие по красоте и долговечности соревноваться с египетскими, а знаменитый календарь майя один из самых точных среди когда-либо созданных. И по сей день много тайн майя так и остались нераскрытыми, а историки все еще строят гипотезы о жизни этого одного из самых интересных племен доколумбовой Америки. Об истории индейцев майя, их культуре, религии наша сегодняшняя статья.

Где жили майя

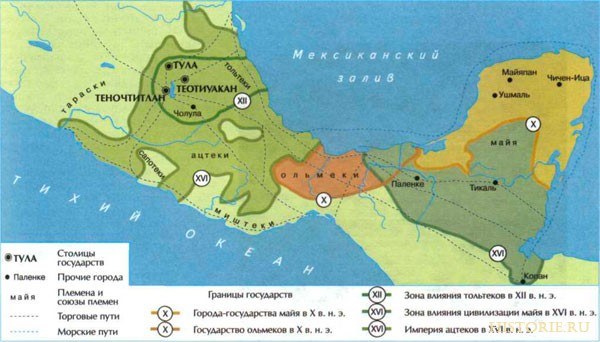

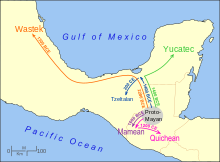

Но сперва ответим на вопрос, где жили племя майя, попробуем поискать их родину на карте Америке. А жили они в одном из самых теплых и комфортных в плане климата уголков нашей планеты, а именно на территории современной Мексике и ряда стран Центральной Америке: Панамы, Гватемалы, Белиза, Гондураса. Очень много культурных центров майя находилось на полуострове Юкатан.

Карта расположения цивилизации майя.

История

История цивилизации майя, как впрочем, и вопрос об их происхождении имеет, к сожалению, очень много темных пятен. Да что там говорить, даже подлинное название этого народа нам не известно, так как вошедшему в обиход слову «майя» мы обязаны Христофору Колумбу. А дело было так: во время своего четвертого плавания к американскому континенту (сам Колумб был искренне уверен, что плавал к берегам Индии и Китая) великий мореплаватель пристал к небольшому островку, расположенному недалеко от современного Гондураса. Там он повстречал индейских купцов, которые плыли на большой лодке. Колумб спросил их, откуда они, на что последовал ответ «из провинции Майан», вот отсюда и пошло название этого народа – майя.

Это то что касается их название, а вот насчет истории этого народа, то на момент прибытия европейцев цивилизация майя уже клонилась к упадку. Удивленным взорам европейцев предстали отличные каменные города, построенные майя, но была одна загвоздка, города эти оказались покинутыми и заброшенными. Что подвигло индейцев майя покинуть свои города и по сей день является одной из загадок этого народа и предметом дискуссии ученых историков-американистов. Быть может какие-то внутренние конфликты в их обществе, или вспышка эпидемии некой болезни, племенные войны или апокалипсические ожидания конца света (индейца майя были очень суеверными) или еще что-то? Гипотез по этому поводу есть немало, но точного подтверждения увы нет.

Также в том, что мы так мало знаем об истории народа майя есть вина и испанский конкистадоров. Некто Диего де Ландо, испанский инквизитор, прибивший в Новый свет обращать индейцев-язычников в христианскую веру, приказал сжечь все письмена майя, где хранилось немало ценных исторических сведений об этом народе. Так по приказу одного религиозного фанатика была практически стерта история целого народа.

Культура

А вот об особенностях культуры майя мы знаем куда больше, ведь сохранилось множество следов их деятельности, начиная от знаменитых пирамид майя в Чичен-Ице (полуостров Юкатан, Мексика).

Пирамиды майя в Чичен-Ице.

Руины некогда великого культурного и политического центра майя, города Чичен-Ица (переводится как «в устье колодца Ица») и по сей день привлекают толпы туристов со всего мира и являются свидетельством высокой культуры этого народа, особенно в градостроительстве (ведь до конца не понятно как майя строили свои пирамиды, современной строительной технике тогда и близко не было) и конечно же астрономии.

Это руины древней обсерватории майя, они были отличными астрономами, умевшими наблюдать за звездами, предсказывать солнечные и лунные затмения и составившими очень точный календарь, который как мы помним, заканчивается на 2012 году, что стало источником слухов о конце света в том году. Но скорее всего какому-то майянскому астроному просто надоело дальше составлять свой календарь, и он остановился на 2012 году.

Большие достижения майя имели не только в сфере астрономии, но и в математике, майянцы издревле в своих вычислениях использовали понятие нуля. К слову в Европе ноль стали использовать лишь после 1228 года с подачи итальянского математика Леонардо Пизанского, более известного как Фибоначчи.

Медицина майя также была весьма продвинутой, в частности они умели пломбировать зубы, делать протезы, зашивать раны с помощью человеческих волос и даже проводить хирургические операции с использованием наркотических обезболивающих средств в качестве анестезии.

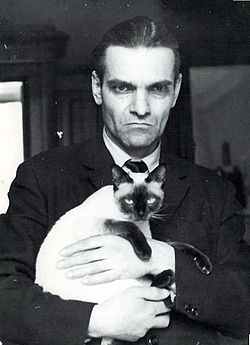

Письменность майя были иероглифической, и что стоит знать, помнить и гордится, расшифрована она была впервые нашим соотечественником, украинцем из Харьковской области, Юрием Кнорозовым.

Юрий Кнорозов, человек дешифровавший письмена майя.

Религия

Религия служила основным нравственным компасом индейцев майя, в целом они были очень набожными. За десятки веков у них образовались сложные религиозные ритуалы и церемонии, которые играли в их жизни решающую роль. Религия майя менялась и усложнялась в ходе их эволюции, перехода от кочевого к оседлому образу жизни. Первые майя (впрочем, как и любые другие народы) обожествляли солнце, луну, ветер, дождь, молнии, горы, леса, реки и озера и другие силы природы. Постепенно сложился развитый пантеон богов.

Верования индейцев майя были тесно связаны с другими сферами их деятельности, особенно хозяйством. Так, основным блюдом пищевого рациона майя была кукуруза, поэтому не удивительно, что по майянской мифологии бог-творец Хунаб свое время создал человечество именно с початков кукурузы. «Пополь-Вух» религиозный эпос майя выделяет в процессе перевоплощения кукурузы на человека большую роль не только Бога-творца Хунаб, но и богини Тепе – Великой Матери.

«Из теста кукурузы были созданы первые четыре человека Балам-кошкой, Балам-Акаба, Махукутах и Ики-Балам. Они стали предками всего человечества (видимо, первые четыре человека символизировали четыре основные расы нашей планеты)» – так рассказывает нам священный эпос майя «Пополь-Вух», и далее продолжает: «И были созданы для них женщины. Так божество показало свои намерения. Поистине прекрасными были женщины, вот имена их: Каха-Палун, Чомиха, Цунумиха и Какишака… Вместе с мужчинами они зачали людей больших и малых племен и нас самих». Вот такой майянский миф о сотворении мира.

По верованиям майя, уходящим корнями в седую глубину, мир наш создавался уже четыре раза и трижды разрушался всемирным потопом. Здесь мифы майя перекликаются и с индийским учением о 4 югах, о разных периодах существования человечества, которые составляют один день Брахмы и с христианской библейской легендой о всемирном потопе, только по версии майя всемирных потопов было не 1, а целых 3.

Первым был мир карликов, которые существовали еще до того как было создано солнце, когда же солнце наконец появилось оно превратилось в камень, а их города залило первым потопом. Второй мир был заселен различными преступниками и просто невеждами, которых успешно смыло следующим потопом, третий же мир был заселен уже майя, но и они утонули, наш же современный настоящий мир был создан в результате смешения всех трех предыдущих и его также ожидает четвертый потоп.

Цивилизация индейцев майя запомнилась в веках не только своим легендарным календарем и апокалиптическими настроениями ожидания конца света, но и чрезвычайно кровавыми ритуалами человеческих жертвоприношений, когда жестокие жрецы на вершинах своих величественных пирамид-храмов вырывали у несчастных жертв сердца в честь своих богов. Хотя, на самом деле человеческие жертвоприношения у индейцев майя появились не сразу. Долгое время первые индейцы майя вообще не приносили человеческих жертв, ограничиваясь жертвоприношением цветов, фруктов, различных украшений и, в крайнем случае, животных. Что же случилось такое с индейцами майя? Откуда появилась эта кровожадность?

Видимо ответ на этот вопрос опять же надо искать в религии майя, их богатой мифологии и в определенных исторических и культурных предпосылках. Так как индейцы майя были чрезвычайно набожными, а религиозные ритуалы и церемонии играли в их мире особую, даже решающую роль. Дело в том, что с какого-то времени в религиозном эпосе индейцев Мезоамерики, причем не только майя, но и ацтеков появилось представление, что солнце и жизнь вообще существуют только благодаря жертве. И только благодаря жертве солнце может сохраниться и продолжать свои функции, а кровь принесенных в жертву для него как будто горючее, такой себе бензин для автомобиля. Правда сперва солнце «удовлетворяли» жертвенной кровью животных, и очевидно позже на территории майя стали происходить определенные катаклизмы (мысль о которых потерялась в сумерках истории) и жрецы решили, что горючего в качестве жертвенной крови животных для солнышка мало, нужно что-то более действеннее – люди.

Так начались массовые человеческие жертвоприношения, как правило, в качестве «горючего» для солнца служили пленные индейцы из других племен, захваченные в результате какой-то маленькой (или большой) войны. Хотя бывало, что в жертву приносили и своих.

Боги

И давайте вспомним о богах майя, которых на самом деле было очень много, среди них были и такие экзотические боги, как бог полярной звезды, бог луны, покровительница медицинских знаний и деторождения – богиня Ишчель и богиня самоубийств (!) Иштаб. К слову, в религии майя самоубийство не считалось чем-то плохим (как скажем в большинстве религиях, особенно в христианстве) и было даже почетным делом. Особенно почетным считалось самоубийство через повешение, ведь саму богиню самоубийства Иштаб изображали не иначе, как в петле. В конце концов, самоубийство в религии майя приравнивалось к добровольному жертвоприношению и этим можно объяснить такое большое уважение к нему.

Бог-создатель майя Хунаба, который создал людей из початков кукурузы, как не странно, но почитался значительно меньше своего сына – бога небес Итсамана. Последний же фактически был верховным богом майя, легенды и мифы делают его первым жрецом, покровителем дня и ночи и изобретателем иероглифов и вообще письменности как таковой. «Сначала было слово» так начинаете Евангелие от Иоанна, индейцам майя тоже была знакома эта формула, сначала было слово, которое дал им бог Итсамана.

Также большим почетом пользовался бог дождя Чак который в религиозных мифах майя упоминается даже чаще, чем сам владыка небес итсамана. Может потому, что от Чака самым непосредственным образом зависело хозяйство майя и урожай кукурузы. В позднюю эпоху богу Чаку тоже приносились и человеческие жертвы, особенно когда долгое время не было дождя, надо же было отправить посланника, чтобы умилостивить Чака. Из жертв богу дождя Чаку не вынимали сердца на вершине пирамиды, их сбрасывали на дно большого ритуального колодца.

Третьим по значимости был сам загадочный бог-покровитель кукурузы, но почему загадочный? Ибо история не донесла нам его имени, некоторые исследователи считают, что им был бог лесов Йум Ках. Во всех упоминаниях этот самый молодой бог изображается с сильно деформированной головой, она (голова) обремененная многочисленными заботами о хорошем урожае.

Верования майя о загробной жизни не слишком отличаются скажем от верований, которые есть в христианстве или в исламе. Души праведников, и принесенных в жертву богам людей попадают в аналог Рая, прекрасное красочное место полное цветов и бабочек. Души же нечестивых людей попадают в подземное царство Шибальду (аналог Ада) где несут искупление за свои греховные поступки.

Старая английская поговорка гласит: «Если зеркала перестало отражать человека, значит, он близок к смерти». В конце Х-го века зеркало вечности уже почти перестало отражать культуру майя, пришло начало ее конца. Именно в это время оказались полностью покинутыми многие города майя, а что стало причиной этого как мы писали выше, так и остается неизвестным.

Интересные факты

- Пожалуй, самым удивительным является то, что народ строивший величественные пирамиды, имеющий точный календарь, обладающий многими познаниями в разных науках, так и не изобрел колеса. Да, индейцы майя (впрочем как и инки с ацтеками) не знали колес.

- Многие лингвисты считают, что слово «акула» майянского происхождения.

- У майя были весьма своеобразные представления о красоте, матери специально прижимали досочки ко лбам своих детей, делая их кость более плоской, считалось, что так красиво.

- Майя играли в футбол, только футбол у них был, разумеется, не такой как сейчас, каучуковый мяч нужно было забить в круглый обруч, а проигравшая команда в полном складе приносилась в жертву.

- Имена своим детям майя давали в зависимости от дня, когда те народились.

- Около 7 миллионов потомков майя и по сей день живут на территории Мексики и соседних стран, и даже практикуют жертвоприношения, правда, в качестве жертв выступают уже не люди, а куры.

Видео

И в завершение познавательный документальный фильм «Тайна цивилизации майя».

Автор: Павел Чайка, главный редактор исторического сайта Путешествия во времени

При написании статьи старался сделать ее максимально интересной, полезной и качественной. Буду благодарен за любую обратную связь и конструктивную критику в виде комментариев к статье. Также Ваше пожелание/вопрос/предложение можете написать на мою почту pavelchaika1983@gmail.com или в Фейсбук, с уважением автор.

Майя, пожалуй, самая известная цивилизация Мезоамерики, которая прославилась благодаря своей письменности, архитектуре, математике, астрологии, и вообще богатой культурой. Чего стоит только календарь майя, который своей последней датой многих людей довел до паники. В то же время майя является и одной из самых загадочных цивилизаций. К примеру, до сих пор не ясно ее происхождение. Тем не менее, в последнее время ученым удалось раскрыть многие секреты этой цивилизации. Поэтому предлагаем далее подробнее ознакомиться со всеми известными на сегодняшний день фактами о том, как она возникла, каких достижений добилась, а также как и почему пришла в упадок.

В последнее время ученым удалось раскрыть много секретов цивилизации Майя

Содержание

- 1 Как и когда произошла цивилизация майя

- 2 Как развивалась культура майя

- 3 Календарь майя

- 4 Пик развития цивилизации майя

- 5 Политическое устройство и религия

- 6 Как погибла цивилизация майя

Как и когда произошла цивилизация майя

Как мы уже сказали, происхождение культуры майя до конца ученым неизвестно. Считается, что она возникла в промежутке от 7000 г. до нашей эры и до 2000 г. до нашей эры. В этот период охотники-собиратели стали постепенно отказываться от своего привычного промысла, и вместо этого создавать постоянные поселения.

Как показали последние исследования, опубликованные в журнале Nature, первые поселенцы пришли из Южной Америки. Предположительно их основным продуктом питания стала кукуруза, которую они выращивали уже к 4000 году до нашей эры. По мнению ученых, именно кукуруза дала толчок развитию цивилизации майя.

Майя были большими любителями кукурузы, они начали ее выращивать уже к 4000 году до нашей эры

Как развивалась культура майя

Майя научились не только выращивать кукурузу, но и готовить ее для употребления с помощью никстамализации. Это довольно сложный процесс, который состоит из нескольких этапов — вначале кукурузу высушивают, затем замачивают, после чего готовят в щелочном растворе. В результате она становится мягкой и пригодной для еды. Также земледельцы выращивали другие некоторые овощи, такие как кабачки, бобы и пр.

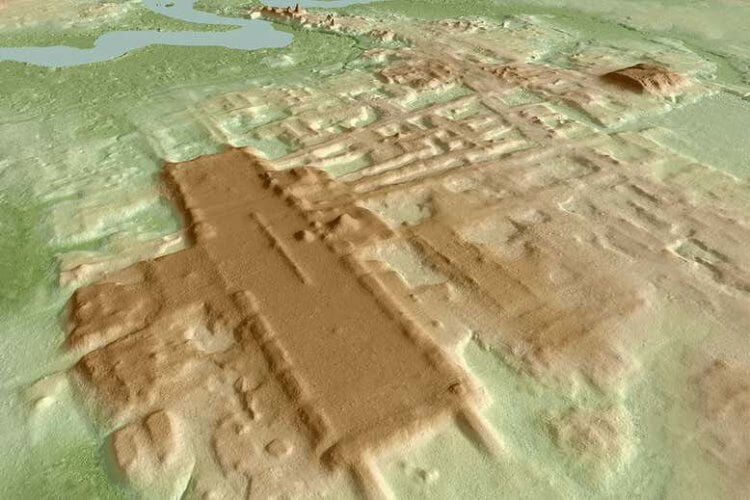

По мнению некоторых ученых, майя развивались вместе с соседней цивилизацией ольмеков, которая, возможно, была одной из самых развитых в те времена. По мнению ряда экспертов, именно после тесного контакта с ольмеками майя начали строить ритуальные комплексы, часть из которых сохранилась и до наших дней. В частности, в этот период был построен Агуада-Феникс, самое большое и древнее сооружение цивилизации майя.

Агуада-Феникс — самое крупное и древнее сооружение майя, которое сохранилось до наших дней

Переняв многое из культуры ольмеков, майя в какой-то момент начали активно возводить города вокруг своих территорий. В период с 1500 до 200 года до нашей эры племя развивалось очень быстро. Индейцы добились успехов в сельском хозяйстве, совершенствовали города, строили свое общество и создавали основы сложных торговых сетей. При этом они освоили эффективные методы очистки воды, создали письменность, развивали спорт и военное искусство.

Так как майя были земледельцами, долгое время считалось, что этот народ был достаточно мирным. Данное представление отображено в литературе и кинематографе. Однако, как показало последнее исследование, майя были достаточно воинственными и жестокими по отношению к врагам.

Календарь майя

Одно из самых известных достижений древних индейцев — это, конечно, календарь майя. Он включал три системы датирования — одна для богов, другая для гражданской жизни, а третья астрономическая. Как правило, когда говорят о календаре майя, имею в виду астрономический календарь, который еще называется долгим. Согласно ему, человечество было сотворено 11 августа 3114 г. до нашей эры.

Календарь майя напугал многих людей, но конца света не случилось

Новый цикл этого календаря начинался 21 декабря 2012 года. Это породило миф о том, что данная дата является последним днем человечества. Причем, этот миф был настолько популярным, что многие люди на полном серьезе готовились к концу света. Но он, как известно, так и не наступил.

Пик развития цивилизации майя

Расцвет цивилизации майя пришелся на период от 200 до 900 года нашей эры. Это хорошо заметно даже по архитектуре. Майя строили более совершенные ритуальные сооружения, похожие на пирамиды, а также величественные здания, которые выглядят как дворцы. Правда, неясно для чего использовались эти строения — служили местом жительства для элиты общества или выполняли другую задачу.

Более того, в этот период майя строили дороги, соединявшие города. Одна из них имеет длину 100 километров, и считается инженерным чудом. Посудите сами — дорога была сделана из камня и покрыта штукатуркой. Но самое главное, что она светилась в темноте.

Великую дорогу майя, протяжностью в 100 км, называют инженерным чудом

В период своего рассвета майя населяли центральную Америку. Они построили ряд гигантских по тем временам городов, таких как Паленке, Чичен-Ица, Копан, Калакмуль и Тикаль. К примеру, численность населения Тикаль составляла более 100 тысячи человек. Правда, впоследствии этот город индейцам пришлось покинуть из-за отравленной воды, о чем мы рассказывали ранее.

Политическое устройство и религия

Майя не были империей или единым государством. Вместо этого они строили автономные города, то есть каждый город был отдельным государством со своим правителем. Поэтому в истории городов были как периоды мирного сосуществования, так и борьбы за власть. Некоторые деревни, к примеру, Хойя-де-Серен, управлялись вообще коллективно, а не одним правителем.

Майя были глубоко религиозным обществом, как и многие другие цивилизации того времени. Поэтому религия отражена в архитектуре и искусстве. Главным божеством майя был Хун Хунакпу, бог кукурузы. Согласно верованиям майя, божества создали людей сначала из грязи, затем из дерева, а потом из кукурузы.

Для поклонения божествам майя практиковали жестокие ритуалы с жертвоприношениями

Майя для поклонения своим божествам практиковали различные ритуалы, среди которых были и очень жестокие — кровопускания и даже человеческие жертвоприношения. Даже спорт у майя был весьма своеобразным. После игры, напоминавшую футбол, проигравших приносили в жертву богам солнца и луны. Согласно мифам индейцев, боги тоже играли в эту игру.

Надо сказать, что различных жестоких ритуалов у майя было много. Не так давно археологи обнаружили затопленную лодку. По мнению экспертов ее тоже использовали вовсе не для ловли рыбы. Подробнее об этой находке можно почитать по этой ссылке.

Многие города майя были брошены из-за засухи

Как погибла цивилизация майя

Большинство центров майя стали приходить в упадок в IX и X веках нашей эры. Причина во многом связана с политическим устройством. Отношения между городами портились, в результате чего торговля прекращалась, регулярно велись изнурительные и кровопролитные войны.

Правда, единой теории гибели цивилизации нет. Согласно одной из основных гипотез, основная причина заключается в сильной засухе, а также уничтожении индейцами лесов. Поэтому некогда многолюдные и развитые городские центры превратились в заброшенные пустоши. Одна часть людей попросту погибла, а другая занимала плодородные земли на юге.

Потомки майя по сей день хранят культуру предков

Также свою роль в падение цивилизации майя внесли и европейские колонизаторы в 1500-х годах. Но, к тому времени, когда Испания захватила земли индейцев, большинство крупных поселений майя уже пустовали. Однако, вопреки распространенному мнению, сами майя не исчезли и по сей день. Рухнула лишь некогда могучая их цивилизация. Более шести миллионов потомков этого народа живут в современной Центральной Америке. Более того, они даже говорят на древних языках своих предков.

Обязательно подписывайтесь на ЯНДЕКС.ДЗЕН КАНАЛ, где вас ожидают поистине захватывающие и увлекательные материалы.

Кроме более 30 древних языков, потомкам племени удалось сохранить многие традиции, среди которых религиозные, сельскохозяйственные и землеустроительные. Да, стойкость культуры у майя не отнять. Ее не погубили ни войны, ни природные катаклизмы, ни европейская цивилизация на континенте.

Древний народ

История – наука, позволяющая заглянуть в самые загадочные и неизвестные уголки далёких миров, культур, народов. Она открывает новый таинственный мир, полный интересных фактов. А изучение отдельных народов, живших в давние времена, погружает и захватывает, насыщая воображение удивительными картинами прошлого.

Одной из таких уникальных древних цивилизаций была цивилизация Майя, потомков которой можно встретить и в наши дни. Это глубоко древний народ, берущий своё начало в 2000 году до н. э.

Где же жили Майя?

Территория проживания этого народа – юго-восток центрально-американского региона, сейчас это страны:

- Мексика (Юкатан, Табаско, Чьяпас, Кампече, Кинтана-Роо);

- Сальвадор;

- Гондурас (западная часть);

- Гватемала;

- Белиз.

Площадь проживания насчитывала около 350 тыс. км2.

Исторически принято делить всю историю Майя на 3 периода:

- I период начинался с зарождения до 317 года;

- II период с 317 года до 987 года;

- III период 987 года по XVI век.

Чем занимались Майя?

Майя занимались различными видами деятельности: строительство, письменность, земледелие, охота и рыболовство, астрономия, ремесло. Стоит рассмотреть эти виды деятельности подробнее.

Строительство

Историки пирамиды Майя ставят на один уровень с пирамидами Египта. Это не менее впечатляющие постройки. Самая известная пирамида Кукулькана. Выполнена в виде храмового сооружения, располагается в древнем городе Чичен-Ица, п-ова Юкатан. Постройка в виде трапеции, с 4-х сторон имеются лестницы, высота пирамиды 55 м. На вершине расположен храм, где совершались жертвоприношения.

Помимо пирамид, сами города представляют собой памятники архитектуры. Строительство их велось на протяжении 2-х исторических периодов (I и II).

Города представляли собой отдельные государства. Во главе каждого находился халач-виник, который назначал возглавлять селения, принадлежавшие данному городу, своим родственникам – батабам. Власть халач-виника передавалась по наследству, от отца к старшему сыну.

Для строительства использовали известняк. Для укрепления плит между собой использовали цемент – смесь из извести, песка и воды. Что удивительно у них не было колеса и вьючных животных для перевозки грузов, но их дороги были столь качественные, что многие современные строители могли бы позавидовать такому мастерству.

Письменность

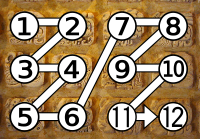

Для письма Майя использовали кору деревьев (фикусов), изготовленную специальным способом. Это что-то между папирусом и бумагой. Писали иероглифами, по количеству их было около нескольких сотен. Знаки иероглифов были 3-х видов:

- Фонетические, алфавитные и слоговые:

- Идеографические, т. е. целые слова;

- Ключевые, поясняющие значение слова.

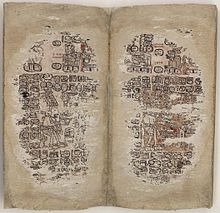

Также у них имелись книги, но «благодаря» конкистадорам, выжегшим все письменные носители, до настоящего времени сохранились только 3 книги. Каждая книга находится в разных городах Европы: Париже, Мадриде и Дрездене.

К письменности можно отнести и специальную систему счёта, придуманную этим народом. Эта система двадцатиричная. Она означала, что знак 0 увеличивает сочетающуюся с ним цифру в 20 раз. Если взять, в пример, нашу систему счёта, то она состоит из 9 цифр и 0, а у Майя она состояла из точки с чертой и 0.

Земледелие

На данном виде деятельности основывалась вся экономика цивилизации. Вид земляделия был подсечно-огневой. Принцип заключался в том, что на новых территориях вырубался лес, с больших деревьев сдиралась кора, и они сами засыхали на корню. Далее всё выжигалось, обязательно до наступления сезона дождей. После чего производился посев. Земля не обрабатывалась, посадка семян производилась по-простому: в небольшую ямку высыпались семена, и всё. Посевы охранялись от птиц и зверей. Выращивали: кукурузу, фасоль, тыкву, томаты, перец, табак. Была развита система орошения.

Рацион состоял не только из растительной пищи, употребляли мясо, добытое на охоте, разводили индюшек, кур. Занимались рыболовством. Добывали дикий мёд, соль. Изготавливали напиток из какао-бобов.

Земледелием занимались люди, находящиеся на 3 ступени иерархии – общинники. Их называли соседской общиной, т. к. все жили в одном поселении. У каждой семьи был свой участок земли, спустя 3 года этот участок заменялся другим. Плодородность почвы иссякало, и земле необходим был отдых. Такие общины выполняли повинности по отношению к высшим сословиям. Выплачивали дань, подносили подати.

Астрономия

Этой наукой занимались специальные люди – жрецы. Они предсказывали затмения, являлись хранителями знаний о движении звёзд, Солнца, Луны, Венеры. Были построены обсерватории для наблюдения за звёздами.

Был разработан календарь, точность которого для того времени была очень высока. Количество дней в году составляло 365, месяцев 18, дней в 1 месяце было 20. Чтобы выровнять солнечный год добавляли 5 дней, называя их неблагоприятными, в эти дни ничего не делали.

Религия

Религия имела свой определённый характер. Почиталось небо. Был развит культ божества природы. Им (божествам) приносились дары и жертвоприношения. Жертвой ритуала мог стать любой будь то пленник, либо представитель знати. Но этого не боялись, полагая, что умерев во время ритуала, ты точно окажешься в раю.

Ремесло

Помимо сельского хозяйства было развито и ремесло. Этим делом занималось то же сословие, что и земледелием. Изготавливали инструменты из камня, ткали ткани, изготавливали драгоценные украшения. Единственное, чего не было развито — это металлургия, по причине, отсутствия месторождений железных руд. Орудия труда и оружие изготавливали из дерева и камня. Только намного позже были найдены залежи меди, золота и серебра.

Развлечения

Одним из популярных развлечений была игра в мяч. Мяч изготавливали из каучука. Цель этой игры была в том, что мяч нужно забросить в кольцо, прикреплённое к стене на высоте 6 м., использовать для удара можно было только колено или локоть. Проигравшая команда должна была выбрать жертву для подношения. Такие были правила.

Спад цивилизации

Почему произошёл упадок такой развитой цивилизации? До сих пор учёные и исследователи ведут спор, и однозначный ответ не найден. Существуют 2 официальные версии:

- Экологическая. Разрушения равновесия между человеком и природой. Нехватка питьевой воды, вырождение плодородного слоя почв;

- Неэкологическая. Нарушение климата – засуха. Завоевание другим народом – Тольтеками.

В современном мире потомки майя проживают на полуострове Юкатан, в Белизе, в Гватемале, в Гондурасе, их численность около 6 млн. человек. Они придерживаются своей этнической направленности, сочетая это с современными направлениями в жизни.

Древняя цивилизация Майя остаётся загадкой, так как не все вопросы имеют четкие ответы. Ещё много предстоит выяснить и проработать, чтобы разобраться в истории этого народа. А, возможно, это останется тайной на долгое время.

Цивилизация майя овеяна множеством тайн и загадок. На сегодняшний день потомки индейцев – простые жители Мексики, особо не выделяющиеся среди других рас и народов. Но древняя история майя не дает покоя многим исследователям. Откуда у обычных земледельцев, которыми являлись племена майя, появились поразительные познания в математике, астрономии, письменности и физике? Каким образом они смогли изготовить невероятно сложные предметы или установить огромные мегалиты? Тайны всегда пленили умы людей. Давайте совершим захватывающее путешествие в таинственную историю майя.

Содержание

- 1 Цивилизация Майя и другие племена Мексики

- 2 История майя

- 3 Заказать археологическую экскурсию

- 4 Загадки майя

- 4.1 Хрустальный череп майя

- 4.2 Саркофаг Пакаля

- 4.3 Календарь майя

- 4.4 Храм надписей в Паленке

- 4.5 Пирамида Кукулькана в Чичен-Ице

- 4.6 Пирамида Волшебника в Ушмале

- 4.7 Тулум

- 4.8 Коба

- 4.9 Священный сенот Чичен-Ицы

- 5 История открытий и загадок Мексики

Цивилизация Майя и другие племена Мексики

Археологи находят артефакты, свидетельствующие о том, что территория Мексики была населена за несколько тысячелетий до н.э. Мнения историков по поводу точной датировки этих находок разнятся. Во всяком случае, очевидно, что древние народы перебрались на северо-американский материк еще в глубокой древности.

Официально признанная история считает первой индейской цивилизацией ольмеков, которые проживали на берегах Мексиканского залива со 2-го тысячелетия до н.э. по 5 век н.э. Им приписывается изобретение сложной письменности, солнечного календаря, двадцатилетнего отсчета, спортивно-религиозной игры в мяч и др. Также считается, что ольмеки смогли построить пирамиды и вытесать из камня знаменитые пятиметровые головы воинов.

Индейская цивилизация сапотеков малоизучена. Историки предполагают, что она возникла в 5 веке до н.э. Столица располагалась в Монте-Альбане, известном своим удивительным Храмом танцующих с нерасшифрованными до сих пор надписями. Загадочная культура Исапы, следы которой найдены в штате Чьяпас, оставила историкам множество артефактов для исследований. В их числе необычные стелы с изображениями божеств и людей, монументы, алтари.

Культура ацтеков относится к более позднему периоду истории Мексики вплоть до ее завоевания испанцами. Столицей ацтекского государства был Теночтитлан, ставший впоследствии городом Мехико. Ацтеки поклонялись различным божествам, главным из которых считался бог войны Уицилопочтли. Это племя было очень воинственным: многотысячные жертвоприношения людей были в порядке вещей. Они постоянно враждовали с окружавшими их племенами и совершали набеги на чужие территории. Последний правитель ацтеков Куаутемок был свергнут конкистадорами в 1521 году.

Среди множества других индейских племен, населявших Мексику, можно выделить тарасков, миштеков, тольтеков, тотонаков, чичимеков. Племена цивилизации майя заслужили особое положение среди своих собратьев благодаря невероятно сложным историческим памятникам и высокоразвитой культуре, которую им приписывает официальная история.

История майя

Рассматривая историю народов майя, следует отметить, что существует несколько теорий развития этой цивилизации. По официальной – той, которую преподают в университетах и публикуют в учебниках, – культура майя появилась около 3-х тысяч лет назад. Она обладала настолько высоким уровнем технологий, научных знаний и развития, что превосходила нынешнюю цивилизацию в несколько раз.

Существует и другая теория, альтернативная, но набирающая все большее число сторонников. Согласно этой теории, в древности существовала некая высокоразвитая цивилизация, которая исчезла за несколько тысячелетий до н.э. Она и оставила после себя удивительные исторические памятники, письмена и артефакты, свидетельствующие о невероятном уровне развития. Это, кстати, согласуется с библейской хронологией времен до Всемирного потопа. Похоже, что эта цивилизация была уничтожена в Потопе.

Индейцы майя появились на территориях древней цивилизации намного позже. Они стали осваивать, как могли, найденные постройки и применять в своем обиходе календари, статуи и другие предметы доисторической культуры. Сами же майя признают, что получили свои знания от «богов», а не приобрели их самостоятельно. Да и что можно было бы ожидать от цивилизации, главным занятием которой было выращивание кукурузы? Зачем индейцам глубокие познания в астрономии, если они не совершали космических полетов? Каким образом майя смогли построить огромные пирамиды, если у них даже не было колеса?

Какой теории придерживаться, решать вам. Давайте рассмотрим некоторые официальные даты из истории майя.

1000-400 годы до н.э. – появление незначительных поселений майя в северной части Белиза.

400-250 годы до н.э. – быстрый рост городов на обширных территориях полуострова Юкатан, Гватемалы, Белиза и Сальвадора. Археологи находят большое число произведений из нефрита, обсидиана и драгоценных металлов.

250 г. до н.э. – 600 г. н.э. – народы майя формируются в города-государства, постоянно воюющие друг с другом за территории.

600-950 годы н.э. – рассвет и последующий упадок многих майянских городов. Для историков пока неясны причины такого запустения. Одни приводят в качестве объяснения какое-то стихийное бедствие, например, сильную засуху. Другие утверждают, что это могли быть захватнические войны или эпидемии.

950-1500 годы н.э. – возникают новые города на севере Юкатана, особое значение придается морской торговле с ацтеками.

1517 год – первый задокументированный контакт племен майя с европейцами на полуострове Юкатан. Тогда индейцы потерпели поражение в сражении с хорошо вооруженными испанцами. Но еще на протяжении нескольких десятков лет они отчаянно боролись за независимость от захватчиков.

Во времена испанской конкисты колонизаторы беспощадно уничтожали культурные особенности майя, стремясь обратить их в католическую веру. Известно, что католический священник Диего де Ланда сжег собрание книг майя в целях борьбы с шаманизмом.

Заказать археологическую экскурсию

Загадки майя

На территориях, где проживали народы майя, найдено огромное количество предметов, которые поражают современных исследователей. Некоторые можно рассмотреть в музеях Мексики, например, в Музее антропологии в Мехико, другие рассеяны в музеях по всему миру. А сколько еще не получило всеобщую огласку!

Хрустальный череп майя

Как утверждают археологи, разноцветные черепа из кварца были не редки среди сокровищ майя. Установить их точную датировку пока невозможно. Еще сложнее определить, каким образом они были выполнены и, главное, для чего. Один из таких черепов – легендарный череп Митчеллс-Хэджесс. Он был найден по сообщениям самого исследователя, в честь которого получил свое название, при раскопках в джунглях полуострова Юкатан. Череп поражает совершенством линий. Он имеет удивительное свойство: при попадании на него лучей света под определенным углом глазницы черепа начинают светиться. Применялся ли этот череп в поклонении божествам при каких-то религиозных ритуалах или же он просто служил украшением интерьера? Точных ответов пока нет, зато существует множество предположений.

Современные исследователи похожи на африканских аборигенов, которые нашли в пустыне стеклянную бутылку и пытаются определить ее предназначение, направляя на нее лучи солнца. Скорее всего, древние применяли хрустальные черепа так, как мы и представить себе не можем.

В современном мире не существует технологий, которые смогли бы повторить подобный шедевр. А ведь на древнем хрустальном черепе нет ни единого следа от инструментов. Так что пока этот удивительный предмет остается одной из самых больших загадок прошлого.

Саркофаг Пакаля

В мексиканском штате Чьяпас находится знаменитый археологический комплекс Паленке. В расположенном в нем Храме надписей был найден загадочный саркофаг. Ученые приписывают его существование правителю майя Пакалю, который был в нем похоронен. Удивительные изображения на крышке саркофага до сих пор вызывают споры в ученых кругах. Некоторые видят на рисунке самого Пакаля, воскресшего из царства мертвых. Другие предполагают, что это вовсе не Пакаль, а некий доисторический астронавт в кабине космолета. Невозможно что-либо утверждать наверняка. Поэтому саркофаг овеян тайной.

Интересна не только каменная крышка, но и сам саркофаг. Он просто огромен. Его размеры 3,8 м на 2,2 м. Саркофаг вытесан из цельного камня весом 15 тонн и имеет точную прямоугольную форму. Крышка весит 5 с половиной тонн. Каким образом он мог быть выполнен? Трудно представить древних индейцев, разбивающих каменную глыбу примитивными орудиями. Еще сложнее предположить, как и кто установил этого гиганта в пирамиде.

Календарь майя

Приписываемый культуре майя календарь поражает ученых своей сложностью и точностью. По утверждениям исследователей он состоит из двух календарей: солнечного и священного (галактического). Первый включал в себя 365 дней, второй – 260. Священный календарь (цолькин) – это система исчисления из 13 чисел и 20 символов. Многие претендуют на расшифровку календаря майя. Как только не объясняют значения его символов и чисел. Кто-то связывает календарь с предсказаниями будущих событий. Кто-то видит в его расчетах движение солнца вокруг центра галактики. Остается тайной точное происхождение и назначение календаря майя. Очевидно одно, что для его создания требовались очень глубокие познания в математике и астрономии.

Самые главные памятники майя

Культура майя оставила после себя многочисленные археологические памятники: пирамиды, храмы, фрески, стелы, скульптуры и т.п. Их исследование – очень увлекательное занятие. Стоит самому совершить путешествие по ним, когда представится такая возможность. Просто дух захватывает от красоты и таинственности этих сооружений.

Храм надписей в Паленке

По сути это пирамида с небольшой постройкой на ее вершине. Пирамида получила свое название благодаря трем плитам с иероглифами на стенах храма. Расшифровкой надписей занималось несколько групп ученых, но до конца прочитать их так и не удалось. В пирамиде был обнаружен тоннель, ведущий в тайную комнату. Там археологи нашли саркофаг с погребенным в нем правителем майя Пакалем, о котором речь шла выше.

Пирамида Кукулькана в Чичен-Ице

Это уникальная пирамида высотой 30 метров. На ее вершине располагается храм, в котором древние жрецы майя совершали жертвоприношения своему верховному божеству Кукулькану. Пирамида знамениты своим необычным построением: дважды в год в дни равноденствия тень от уступов пирамиды падает на ступени, создавая впечатление ползущей змеи. Наверняка, для индейцев эта картина выглядела устрашающе. Внутри храма находится «трон ягуара», украшенный ракушками и нефритом. Предполагают, что на нем восседали правители Чичен-Ицы. Размеры этого «трона» невелики и точное его предназначение неизвестно.

Пирамида Волшебника в Ушмале

Высота пирамиды 36 метров. Эта пирамида знаменита тем, что ее основание имеет не квадратную, а овальную форму. По древней легенде майя за одну ночь ее соорудил колдун, умеющий заклинаниями переставлять камни. Пирамида имеет несколько платформ, на вершине расположен храм, посвященный богу дождя Чааку. Сама пирамида Волшебника украшена изображениями этого божества, а также змей и людей.

Тулум

Тулум – единственный портовый город майя, сохранившийся до наших дней. Его название переводится как «стена». Действительно, часть защитной стены города свидетельствует о его былом величии. Здесь также можно рассмотреть несколько впечатляющих дворцов и храмов.

Коба

Коба – это древний город майя, территорию которого невозможно обойти за один день. Город имеет площадь 70 кв. км. Для прогулок по нему можно арендовать велосипед или прокатиться на велотакси. Коба знаменита огромными пирамидами, 100 километровой дорогой и множеством других загадочных построек.

Священный сенот Чичен-Ицы

На территории археологического комплекса Чичен-Ица расположен таинственный священный сенот или природный карстовый колодец. К нему ведет трехсотметровая дорога от пирамиды Кукулькана. Индейцы майя использовали сенот во время религиозных ритуалов. Чтоб добиться благосклонности своих выдуманных божеств, они приносили в жертву не только драгоценные камни, изделия из золота и оружие, но и людей. Их просто бросали на дно колодца в надежде, что божество пошлет в ответ долгожданный дождь.

История открытий и загадок Мексики

До нас дошли весьма скудные сведения испанских колонизаторов о найденных ими древних городах майя. К тому же они больше похожи на сказочные истории о городах из золота.

На протяжении многих лет сокровища майя были затеряны в непроходимых джунглях. Начало целенаправленному исследованию памятников древней культуры майя положил американец Джон Стефенс в 1839 году. Он смог обнаружить такие города как Паленке, Ушмаль, Чичен-Ицу, Копан и др. Свои наблюдения он описал в книге, которая произвела настоящий фурор в научном мире Америки и Европы. Вслед за Стефенсоном вглубь джунглей отправились многие исследователи из разных стран, жаждущие новых открытий и разгадок тайн. Ведущую роль в археологических раскопках приняли на себя несколько исследовательских институтов США.

Вначале основное внимание уделялось изучению строений, надписей, барельефов, стел и фресок, т.е. внешних атрибутов. Со временем ученые углубились в исследования мелких предметов и деталей, а также того, что скрыто под землей.

Так, например, в конце 19-го века на полуостров Юкатан прибыл американец Э. Томпсон. Ранее к нему попали свидетельства Диего де Ланда о том, что на дне священного колодца в Чичен-Ице хранятся несметные богатства. Американец решил проверить это утверждение и, вооружившись необходимыми инструментами, достал со дна колодца настоящие сокровища. Это были драгоценности из нефрита, золота, меди, а также были обнаружены останки более 40 человек.

Еще одно нашумевшее открытие произошло в 1949 году в археологическом комплексе Паленке. Археолог А. Рус заметил, что одна из плит на полу в Храме надписей имеет отверстия, закрытые пробками. Он решил поднять эту плиту и обнаружил вход в тоннель. Тоннель требовалось расчистить от камней и земли, на что ушло несколько лет. В июне 1952 года археолог смог проникнуть в подземную комнату под пирамидой. Там он обнаружил знаменитый саркофаг с погребенным в нем, как утверждают, правителем майя Пакалем. Помимо саркофага были найдены останки людей, украшения и драгоценности. Ученые до сих пор пытаются объяснить значение изображения на пятитонной крышке саркофага.

На сегодняшний день открыта и изучена лишь малая часть культурного наследия древней цивилизации. К тому же многое просто недоступно обычным любителям древностей. Кто знает, сколько еще древних сокровищ ждут своего открытия…

Возвращаемся не спеша к темам сентябрьского стола заказов и вспоминаем тему от servus_dei : Восход и исчезновение государства майа

С майя связана одна из многочисленных тайн. Целый народ, состоявший в основном из жителей городов, внезапно покинул свои добротные и крепкие до-ма, распрощался с улицами, площадями, храмами и дворцами и переселился на далекий дикий север. Ни один из этих переселенцев никогда не вернулся на старое место. Города опустели, джунгли ворвались на улицы, сорные травы буйствовали на лестницах и ступенях; в пазы и желобки, куда ветер принес мельчайшие кусочки земли, заносило лесные семена, и они пускали здесь рост-ки, разрушая стены. Никогда уже больше нога человека не ступала на вымо-щенные камнем дворы, не поднималась по ступеням пирамид.

Но, может быть, всему виной была какая-нибудь катастрофа? И вновь мы вынуждены задать тот же самый вопрос: где следы этой катастрофы и что это, собственно, за катастрофа, которая могла заставить целый народ покинуть свою страну и свои города и начать жизнь на новом месте?

Быть может, в стране разразилась какая-нибудь страшная эпидемия? Но у нас нет никаких данных, которые бы свидетельствовали о том, что в далекий поход отправились лишь жалкие, немощные остатки некогда многочисленного и сильного народа. Наоборот, народ, выстроивший такие города, как Чичен-Ица, был, несомненно, крепким и находился в расцвете своих сил.

Может быть, наконец, в стране внезапно переменился климат, и потому дальнейшая жизнь сделалась здесь невозможной? Но от центра Древнего царства до центра Нового царства по прямой не более четырехсот километров. Перемена климата, о чем, кстати, также нет никаких данных, которая могла бы так резко повлиять на структуру целого государства, вряд ли не затронула бы и тот район, в который переселились майя.

Существуют еще много тайн древней цивилизации майя, может быть, со временем многие из них будут раскрыты, а может быть, они так и останутся тайнами.

Около 10000 лет тому назад, когда закончился последний ледниковый период, люди с севера двинулись осваивать южные земли, известные теперь под названием Латинская Америка. Они расселились на территории, составившей потом область майя, с горами и долинами, густыми лесами и безводными равнинами. В область майя входят современные Гватемала, Белиз, южная Мексика, Гондурас, Сальвадор. В течение последующих 6000 лет местное население перешло от полукочевого существования охотников-собирателей к более оседлому земледельческому образу жизни. Они научились выращивать кукурузу и бобы, с помощью разнообразных каменных приспособлений измельчали зерно и готовили еду. Постепенно возникали поселки.

Примерно в 1500 году до н. э. началось повсеместное строительство поселков сельского типа, послужившие сигналом о начале так называемого «доклассического периода», с которого начинается отсчет столетий славной цивилизации майя.

«ДОКЛАССИЧЕСКИЙ» ПЕРИОД (1500 год до н. э.–250 год н. э)

Люди приобрели некоторые сельскохозяйственные навыки, научились повышать урожайность полей. По всей области майя возникают густонаселенные поселки сельского типа. Около 1000 года до н. э. сельские жители Куэльо (на территории Белиза) изготовляли глиняную посуду и хоронили умерших. Соблюдая положенный церемониал: в могилу клали кусочки зеленого камня и другие ценные предметы. В искусстве майя этого периода заметно влияние ольмекской цивилизации, возникшей в Мексике на берегу залива и установившей торговые связи со всей Мезоамерикой. Некоторые ученые считают, что созданием иерархического общества и царской власти древние майя обязаны ольмекскому присутствию в южных районах области майя с 900 по 400 годы до н. э.

Власть ольмеков кончилась. Начинается рост и процветание южных торговых городов майя. С 300 года до н. э. по 250 год н. э. возникают такие крупные центры, как Накбе, Эль-Мирадор и Тикаль. Майя достигли значительных успехов в области научных знаний. Используются ритуальный, солнечный и лунный календари. Они представляют собой сложную систему взаимосвязанных календарей. Эта система позволяла индейцам майя фиксировать важнейшие исторические даты, делать астрономические прогнозы и смело заглядывать в столь отдаленные времена, о которых даже современные специалисты в области космологии не берутся судить. Их вычисления и записи основывались на гибкой системе счета, включавшей в себя символ для обозначения ноля, неизвестный древним грекам и римлянам, а в точности астрономических расчетов они превосходили другие современные им цивилизации.

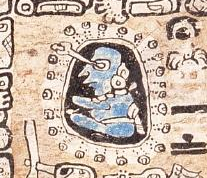

Из всех древних культур, процветавших в Северной и Южной Америке, только майя обладали развитой системой письменности. И именно в это время и начинает развиваться иероглифическая письменность майя. Иероглифы майя похожи на миниатюрные рисунки, втиснутые в крошечные квадратики. В действительности же это единицы письменной речи — одной из пяти оригинальных систем письменности, созданных независимо одна от другой. Некоторые иероглифы – слоговые, но большая их часть – это идеограммы, обозначающие фразы, слова или части слов. Иероглифы вырезали на стелах, на притолоках, на вертикальных плоскостях каменных лестниц, на стенах гробниц, а также писали на страницах кодексов, на глиняной посуде. Около 800 иероглифов уже прочитаны, и ученые с неослабивающим интересом занимаются дешифровкой новых, а также дают новые истолкования уже известным символам.

В этот же период возводятся храмы, которые украшаются скульптурными изображениями богов, а затем и правителей майя. В гробницах правителей майя этого периода находят богатые приношения.

РАННИЙ «КЛАССИЧЕСКИЙ» ПЕРИОД (250-600 годы н. э.)

К 250 году н.э. Тикаль и соседний с ним город Вашактун становятся главными городами в центральной низменной зоне на территории майя. В Тикале было все: и гигантские храмы-пирамиды, и дворцовый комплекс, и площадки для игры в мяч, и рынок, и паровая баня.

Общество разделилось на правящую элиту и подчиненный ей трудящийся класс земледельцев, ремесленников, торговцев. Благодаря раскопкам нам стало известно, что социальное расслоение в Тикале касалось в первую очередь жилища. В то время как простые общинники жили в разбросанных тут и там среди лесов поселках, правящая элита получала в свое распоряжение более или менее четко очерченное жизненное пространство Центрального акрополя, который к концу классического периода превратился в настоящий лабиринт из зданий, построенных вокруг шести просторных внутренних дворов на площади около 2,5 квадратных километров. Здания состояли из одного-двух рядов длинных помещений, разделенных поперечными стенками на ряд комнат, каждая комната имела свой выход. «Дворцы» служили жилищем для важных персон, кроме того, здесь, вероятно, размещалась городская администрация.

Начиная с III века правители, наделенные высшей властью, воздвигают храмы-пирамиды и стелы с изображениями и надписями, призванными увековечить их правление; обряд посвящения состоит из ритуала кровопускания и человеческих жертвоприношений. Самая ранняя из известных стел (датированная 292 годом) найдена в Тикале, она поставлена в честь одного из наследников правителя Яш-Мок-Шока, основавшего в начале века династия, которой суждено было править городом 600 лет. В 378 году, при девятом правителе из этой династии – Лапе Великого Ягуара, Тикаль покорил Вашактун. К тому времени Тикаль находится под влиянием племени воинов и торговцев из мексиканского центра Теотиуакана, переняв у иноземцев некоторые методы ведения войны.

ПОЗДНИЙ «КЛАССИЧЕСКИЙ» ПЕРИОД (600-900 годы н. э.)

Классическая культура майя, для которой характерно бурное строительство дворцов и храмов, в VII-VIII веках вышла на новый уровень развития. Тикаль возвращает себе былую славу, но появляются и другие, не менее влиятельные центры. На западе области майя процветает Паленке. Которым правит Пакаль, пришедший к власти в 615 году и похороненный с наивысшими почестями в 683 году. Правители Паленке отличались большим строительным рвением и создали большое количество храмов, дворцовых комплексов, царскую усыпальницу и другие постройки. Но что важнее всего – скульптурные изображения и иероглифические надписи, которыми изобилуют эти сооружения, дают нам представление о том, что правители и послушный им народ считали главным. После изучения всех памятников складывается впечатление, что в этот период произошли некоторые изменения в роли, которая отводилась правителю, и эти-то изменения косвенно указывают на причину краха такой, казалось бы, благополучной цивилизации, какой была цивилизация майя в «классический период».

Кроме того, в четырех разных местах в Паленке Пакаль и его наследник воздвигли так называемые царские реестры – стелы с записями о членах правящей династии, прослеживающими ее корни вплоть до 431 года н. э. По- видимому эти двое были очень озабочены доказательством своего законного права на власть, и причиной тому были два случая в истории города, когда правитель получал право престолонаследия по материнской линии. Так произошло с Пакалем. Поскольку у майя право на престол передавалось обычно по отцовской линии, Пакаль и его сын были вынуждены внести в это правило некоторые коррективы.

В VII веке снискал себе славу и юго-восточный город Копан. Многие надписи и стелы Копана показывают, что городом в течение 4-х столетий, с V века н. э., правила одна династия. Благодаря такой стабильности город приобрел вес и влияние. Основатель династии, правитель Яш-Кук-Мо (Голубой-Кетуаль-Попугай), пришел к власти в 426 году н. э. И можно предположить, что авторитет его был очень велик, и все последующие правители Копана считали необходимым именно от него вести отсчет своей царской линии. Из 15 его царственных потомков дольше всех прожил энергичный Дым-Ягуар, взошедший на престол в 628 году и правивший 67 лет. Прославившийся как Великий Подстрекатель, Дым-Ягуар привел Копан к небывалому расцвету, сильно расширив его владения, возможно с помощью территориальных войн. Знатные люди, служившие при нем, вероятно, становились правителями покоренных городов. За время правления Дыма-Ягуара численность городского населения достигла примерно 10000 человек.

В то время войны между городами были обычным явлением. Несмотря на то, что правители городов приходились друг другу родственниками вследствие междинастических браков, да и в культуре – искусстве и религии – этих городов было много общего.

Продолжает развиваться искусство, ремесленники снабжают знать различными изысканными поделками. Продолжается строительство церемониальных зданий и многочисленных стел, превозносящих личные заслуги правителей. Однако, начиная с VIII века, и особенно в IX веке, города центральных низменностей приходят в упадок. В 822 году политический кризис потряс Копан; последняя датированная надпись в Тикале относится к 869 году.

«ПОСТКЛАССИЧЕСКИЙ» ПЕРИОД (900-1500 годы н. э.)

Истощение природных ресурсов, упадок сельского хозяйства, перенаселенность городов, эпидемии, вторжения из вне, социальные потрясения и непрекращающиеся войны – все это как вместе, так и по отдельности могло послужить причиной заката цивилизации майя в южных равнинных областях. К 900 году н. э. Строительство на этой территории прекращается, некогда многолюдные города, покинутые жителями, превращаются в руины. Но культура майя все еще живет в северной части Юкатана. Такие прекрасные города, как Ушмаль, Кабах, Сайиль, Лабна в холмистой местности Пуук, существуют вплоть до 1000 года.

Исторические хроники кануна конкисты и данные археологии наглядно свидетельствуют о том, что в X веке н.э. На Юкатан вторглись воинственные центрально мексиканские племена – тольтеки. Но, не смотря на все это в центральной области полуострова население уцелело и быстро приспособилось к новым условиям жизни. И спустя короткое время появилась своеобразная синкретическая культура, соединяющая в себе майянские и тольтекские черты. В истории Юкатана начался новый период, получивший в научной литературе название «мексиканский». Хронологически его рамки приходятся на X – XIII века н.э.

Центром этой новой культуры становится город Чичен-Ица. Именно в это время для города наступает пора процветания, продолжающаяся 200 лет. Уже к 1200 году огромна площадь застройки (28 квадратных километров), величественная архитектура и великолепная скульптура говорит о том, что этот город был главным культурным центром майя последнего периода. Новые скульптурные мотивы и архитектурные детали отражают возросшее влияние мексиканских культур, преимущественно тольтекской, развившейся в Центральной Мексике прежде ацтекской. После внезапного и загадочного падения Чичен-Ицы главным городом на Юкатане становится Майяпан. Юкатанские майя, по-видимому, вели между собой более жестокие войны по сравнению с теми, что велись их собратьями на юге. Хотя подробные описания конкретных сражений отсутствуют, известно, что войны из Чичен-Ицы сражались против воинов из Ушмаля и Кобы, а позднее люди Майяпана напали на Чичен-Ицу и разграбили ее.

По мнения ученых, на поведении северян сказалось влияние других народов, вторгшихся на территорию майя. Не исключено что вторжение происходило мирным путем, хотя это и мало вероятно. Например, у епископа де Ланде имелись сведения о каких-то людях, пришедших с запада, которых майя назвали «ица». Эти люди, как говорили оставшиеся потомки майя епископу де Ланде, напали на Чичен-Ицу и захватили ее. После внезапного и загадочного падения Чичен-Ицы главным городом на Юкатане становится Майяпан.

Если застройка Чичен-Ицы и Ушмаля повторяет другие города майя, то Майяпан в этом случае довольно таки отличался от общей схемы. Майяпан, обнесенный стеной, был городом хаотичной застройки. Кроме того, здесь не было огромных храмов. Главная пирамида Майяпана была не очень хорошей копией пирамиды Эль-Кастильо в Чичен-Ице. Численность населения в городе достигала 12 тысяч человек. Ученые предполагают, что в Майяпане был достаточно высокий уровень экономики, и что общество майя постепенно переходило на деловые отношения, уделяя все меньше внимания древним богам.

250 лет в Майяпане правила династия Кокомов. Они сохраняли за собой власть, удерживая своих потенциальных врагов в заложниках за высокими стенами города. Еще больше укрепили свои позиции Кокомы, когда приняли к себе на службу целую армию наемников из Ах-Кануля (мексиканский штат Табаско), чья преданность была куплена посулами военной добычи. Повседневная жизнь династии большей своей частью была занята увеселениями, танцами, пирами и охотами.

В 1441 году Майяпан пал в результате кровавого восстания, поднятого вождями соседних городов, город был разграблен и сожжен.

Падение Майяпана прозвучало похоронным звоном над всей цивилизацией майя, поднявшейся из джунглей Центральной Америки до небывалой высоты и канувшей в бездну забвения. Майяпан был последним городом на Юкатане, которому удавалось подчинить себе другие города. После его падения конфедерация распалась на 16 соперничающих между собой мини-государств, каждое из которых боролось за территориальные преимущества силами собственной армии. В постоянно разгоравшихся войнах города подвергались набегам: захватывали в основном молодых мужчин, чтобы пополнить ими войско или принести их в жертву, поля поджигали, чтобы заставить земледельцев подчиниться. В непрерывных войнах архитектура и искусство были оставлены за ненадобностью.

Вскоре после падения Майяпана, всего через несколько десятилетий, на полуострове высадились испанцы, и участь майя была решена. Когда-то один пророк, слова которого приводятся в «Книгах Чилам-Балам», предсказывал появление чужестранцев и его последствия. Вот как звучало пророчество: «Принимайте ваших гостей, бородатых людей, которые идут с востока… Это начало гибели». Но те же самые книги предупреждают и о том, что не только внешние обстоятельства, но и сами майя будут виновны в том, что случится. «И не было больше счастливых дней, — гласит пророчество, — здравомыслие нас оставило». Можно подумать, что задолго до этого последнего завоевания майя знали, что слава их потускнеет и древняя мудрость забудется. И все же, словно предвидя будущие попытки ученых вызвать из небытия их мир, они высказали надежду, что когда-нибудь голоса из прошлого будут услышаны: «В конце нашей слепоты и нашего позора все откроется вновь».

Познания в науке и медицине.

Медицина. Медицинские познания у майя были на очень высоком уровне: они прекрасно знали анатомию, и очень неплохо трепанировали черепа. Однако, их представления были и достаточно противоречивы — причинами болезней они могли посчитать плохой по календарю год, или грехи, или неправильные жертвоприношения, но при этом признавали определенный образ жизни человека как первоисточник болезней. Майя знали о заразных заболеваниях, в словарном запасе майя было множество слов, которыми они характеризовали различные болезненные состояния человека. Более того, отдельно были описаны многие нервные заболевания и ментальное состояние человека. Для стимуляции и обезболивания родов применяли различные лекарственные и наркотические травы, которые выращивали в отдельных аптекарских садах.

Математика. Майя использовали двадцатеричную систему счисления, а также позиционную систему записи цифр, когда цифры стоят друг за другом от первого порядка к последующим. Эта система записи используется и нами, и называется арабской цифровой системой. Но в отличие от европейцев майя сами до этого додумались на тысячи лет раньше. Только запись цифр майя строится не горизонтально, а вертикально ( в столбик ).

Еще одним поразительным фактом математических познаний майя является использование нуля. Это означает величайший прогресс в области абстрактного мышления.

Поразительные знания процивилизации Майя отражены в календаре майя. Он известен на весь мир своей поразительной точностью и соперничает в совершенстве с современными компьютерными расчетами.

6

Загадки майя

Художники майя создавали свои бесчисленные сокровища. Ритуальные предметы должны были понравиться богам. Каменные, резные, глиняные, шлифованные или покрашенные в яркие цвета – все они имели символическое значение. Так, дырочка в расписном блюде показывает, что блюдо «убито» и что его освободившаяся душа может сопровождать умершего в загробных странствиях.

Майя не знали ни металлических инструментов, ни гончарного круга, но их глиняные вещи изящны и красивы. Шлифовальные порошки и каменные ин-струменты применялись для работ с нефритом, кремнем, раковинами. Ремес-ленники – майя знали разницу между материалами. Любимый древними майя за красоту, редкость, а также за предполагаемую волшебную силу, нефрит осо-бенно ценился древними мастерами, хотя и требовал терпения и изобретатель-ности для его обработки. Деревянными пилами или костяными сверлами дела-лись канавки, завитки, лунки и т.п. Полирование производилось с помощью твердых растительных волокон, добываемых из побегов бамбука или тыквенно-го дерева, клетки которых содержат микроскопические частицы твердых мине-ральных веществ. Огромное количество фигурок из нефрита, изображающих людей и животных, имеет форму клина: древние камнерезы использовали та-кую форму изделия, чтобы можно было при случае применить их как орудие труда. После небольшой доработки эти прекрасные каменные поделки могли превратиться в амулеты или фигурки людей и богов. Найденное изящное зеле-ное ожерелье, относящееся к доклассической эпохе, говорит нам о том, что но-сил его не простой человек, а наделенный властью и стоящий на верхней сту-пени соци¬альной лестницы.

В искусстве майя изображение часто передает действие или эмоции. Мас-тера выработали информационный стиль, вкладывая в свои произведения заряд юмора и нежности или, напротив, жестокости. Предметы, сделанные руками безымянных мастеров, до сих пор поражают людей своей красотой, помогая нашим современникам понять давно исчезнувший мир древнейшей цивилиза-ции.

Из множества городов, поднявшихся среди холмов Пуука в «поздний клас-сический период» (700−1000 годы н.э.), особенно выделяются великолепием планировки и архитектуры три города – Ушмаль, Сайиль и Лабна: массивные четырехугольники зданий по фасаду облицованы известняком, у дверных кося-ков стоят круглые колонны с квадратными капителями, верхняя часть фасада украшена изящной каменной мозаикой, сделанной из кремня.

Строгая организация пространства, пышность и усложненность архитекту-ры, сама панорама городов – все это приводит ценителей в восхищение. Высо-кие пирамиды, дворцы с рельефами и мозаичными фасадами, сложенными из плотно пригнанных друг к другу кусочков колотого камня, подземные резер-вуары, где когда-то хранились запасы питьевой воды, настенные иероглифы – все это великолепие сочеталось с ужасной жестокостью. «Главный жрец дер-жал в руке большой, широкий и острый нож, сделанный из кремня. Другой жрец держал деревянный ошейник в виде змеи. Обреченных, полностью обна-жен¬ных, по очереди проводили по лестнице вверх» Там, уложив человека на камень, надевали на него ошейник, и четыре жреца брали жертву за руки и за ноги. Затем главный жрец с удивительным проворством вспарывал жертве грудь, вырывал сердце и протягивал его к солнцу, поднося ему и сердце, и пар, исходящий из него. Затем оборачивался к идолу бросал сердце ему в лицо, по-сле чего сталкивал тело по ступеням, и оно скатывало» вниз», − писал об этом священнодействии Стефенс с ужасом.

Главные археологические изыскания производились в Чичен-Ице, послед-ней столицей майя. Руины освобождены от джунглей, остатки зданий видны со всех сторон, а та: где в свое время приходилось прорубать дорогу при помощи мачете, курсируют автобус с туристами; они видят «Храм воинов» с его колон-нами и лестницей, ведущей к пирамид они видят так называемую «Обсервато-рию» − круглое строение, окна которого прорублены таким образом, что из ка-ждого видна какая-то определенная звезда; они осматривав большие площади для древней игры в мяч, из которых самая большая имеет сто шестьдесят мет-ров в длину и сорок в ширину, − на этих площадках «золотая молодежь» майя и рала в игру, похожую на баскетбол. Они, наконец, останавливаются перед «Эль Кастилы самой большой из пирамид Чичен-Ицы. Девять уступов имеет она, и на верхней верши) ее расположен храм бога Кукулькана − «Пернатой змеи».

Вид всех этих изображений змеиных голов, богов, шествий ягуаров дейст-вует устрашающе. Пожелав проникнуть в тайны орнаментов и иероглифов, можно узнать, что здесь нет буквально ни одного знака, ни одного рисунка, ни одной скульптуры, которые не были бы связаны с астрономическими выклад-ками. Два креста на надбровных дуг; головы змеи, коготь ягуара в ухе бога Ку-кулькана, форма ворот, число «бусинок росы форма повторяющихся лестнич-ных мотивов – все это выражает время и числа. Нигде числа и время не были выражены таким причудливым образом. Но если вы захотите обнаружить здесь хоть какие-нибудь следы жизни, вы увидите, что в великолепном царстве ри-сунков майя, в орнаментике этого народа, жившего среди пышной и разнооб-разной растительности, очень редко встречаются изображения растений – лишь немногие из огромно количества цветов и ни один из восемьсот видов кактусов. Недавно в одном орнаменте разглядели цветок Bombax aquaticum – дерева, рас-тущего наполовину в воде. Если это даже действительно не ошибка, общее по-ложение все равно не меняется: в искусстве майя отсутствуют растительные мотивы. Даже обелиски, колонны, стелы, которые почти всех странах являются символическим изображением тянущегося ввысь дерева, у майя изображают тела змей, извивающиеся гадины.

Две такие змеевидные колонны стоят перед «Храмом воинов». Головы с роговидными отростком прижаты к земле, пасти широко открыты, туловища подняты кверху вместе с хвостами, некогда эти хвосты поддерживали крышу храма.

Голландец Гильермо Дюпэ, много лет прослуживший в испанской армии в Мексик-образованный и увлекающийся стариной человек получил от испанско-го короля Карла Г. поручение исследовать памятники культуры Мексики доис-панского периода.

С трудом добравшись до Паленке, Дюпэ пришел в неописуемый восторг от архитектуры, наружной отделки зданий: красочные узоры с изображением птиц, цветов, полные драматизма барельефы. «Позы очень динамичны и вместе с тем величавые. Одежды хоть и роскошны, никогда не закрывают тела. Голову обычно украшают шлемы, гребни и развевающиеся перья».

Дюпэ заметил, что у всех людей, изображенных на барельефах, голова бы-ла странной, сплющенной формы, из чего и заключил, что местные индейцы, с нормальной головой, никак не могут быть потомками строителей Паленке.

Скорее всего, по мнению Дюпэ, здесь жили когда-то люди неизвестной, исчезнувшей с лица земли расы, оставившей после себя величественные и пре-красные творения своих рук.

В Ватиканской библиотеке хранится интересное свидетельство о потопе «Коде Риос». По иронии судьбы католическое духовенство, уничтожившее подлинные рукописи майя, сохранило их редкие копии.

В «Кодексе Риос» рассказано о сотворении мира и о гибели первых людей. Остались дети, которых вскормило чудесное дерево. Образовалась новая раса людей. Но через 40 лет боги обрушили на землю потоп. Уцелела одна пара, спрятавшаяся на дереве.

После потопа возродилась другая раса. Но через 2010 лет необычный ура-ган уничтожил людей; оставшиеся в живых превратились в обезьян, которых стали грызть ягуар.

И вновь спаслась лишь одна пара: скрылась среди камней. Через 4801 год людей уничтожил великий пожар. Одна только пара спаслась, уплыв на лодке в море.

В этом предании говорится о периодических (повторяемых через 2−4−8 тысяч лет) катастрофах, одна из которых – потоп.

Если мы внимательно посмотрим на карту, то убедимся, что Древнее цар-ство занимало своего рода треугольник, углы которого образовывали Вашак-тун, Паленке и Копан. Не ускользнет от нашего внимания и то обстоятельство, что на сторонах углов или непосредственно внутри треугольника находились города Тикаль, Наранхо и Пьедрас Неграс. Теперь мы можем прийти к выводу, что, за единственным исключением (Бенке Вьехо), все последние города Древ-него царства, в частности, Сейбаль, Ишкун, Флорес, находились внутри этого треугольника.

Когда испанцы прибыли в Юкатан, у майя были тысячи рукописных книг, сделанных из природного материала, но часть их была сожжена, часть осела в частных коллекциях. Были также обнаружены надписи на стенах храмов и сте-лы. В XIX в. ученые знали о 3-х книгах — кодексах, названных по имени города, в котором каждый текст был обнаружен (Дрезденский, Парижский и Мадрид-ский кодексы; позже был найден 4-й кодекс – Кодекс Гролье). 14 лет изучал главный Королевский библиотекарь в Дрездене Эрнст Форстеманн кодекс и понял принцип действия календаря майя. А исследования Юрия Кнорозова, Генриха Берлина и Татьяны Проскуряковой открыли новый этап в современной май-янистике. Разгадано более 80 процентов всех иероглифов, а археологи сде-лали множество поразительных открытий.

Так, Юрий Кнорозов пришел к выводу, что система письма индейцев майя – смешанная. Часть знаков должна передавать морфемы, а часть – звуки и сло-ги. Такую систему письма принято называть иероглифической.

Не составила большого труда для ученых дешифровка цифровых знаков майя. Причиной тому – поразительная простота и доведенная до совершенства логичность системы их счета.

Древние майя пользовались двадцатеричной системой счисления, или сче-та. Они записывали свои цифровые знаки в виде точек и тире, причем точка всегда означала единицы данного порядка, а тире – пятерки.

Встреча Нового и Старого Света

Первый контакт двух культур происходил при участии самого Христофора Колумба: во время своего четвертого плавания в предполагаемую Индию (а он верил, что открытая им земля – Индия) его корабль проходил мимо берегов се-верной части современного Гондураса и у острова Гуанайя встретил каноэ, сде-ланное из целого ствола дерева, шириной в 1,5 м. Это была торговая лодка, и европейцам были предложены медные пластины, каменные топоры, керамиче-ские изделия, какао-бобы, одежды из хлопка.

В 1517 г. три испанских корабля, шедшие на поимку рабов, пристали к не-известному острову. Отбив атаку воинов-майя, испанские солдаты при дележе добычи нашли украшения из золота, а золото должно было принадлежать ис-панской короне. Эрнан Кортес, покорив великую империю ацтеков в централь-ной части Мексики, послал одного из своих капитанов на юг – завоевывать но-вые территории (современные государства Гватемала и Сальвадор). К 1547 г. покорение майя завершилось, хотя некоторые племена укрылись в густых лесах центральной части полуострова Юкатан, где им и их потомкам еще 150 лет удавалось оставаться непокоренными.

Эпидемии оспы, кори и гриппа, к которым у коренного населения не было иммунитета, унесли жизни миллионов майя. Испанцы жестоко искореняли их религию: рушили храмы, разбивали святыни, грабили, а тех, кто был замечен в идолопоклонстве, монахи-миссионеры растягивали на дыбе, ошпаривали ки-пятком, наказывали плетьми.

Во главе монахов прибыл на Юкатан монах-францисканец Диего де Ланда, неординарная и сложная личность. Он изучал быт, обычаи местного населения, пытался найти и ключ к тайне письменности майя, нашел тайник, в котором хранилось около 30 иероглифических книг. Это были настоящие произведения искусства: черные и красные знаки были каллиграфически выписаны на свет-лой бумаге, сделанной из нижнего слоя фигового дерева или шелковицы; бума-га была гладкой от нанесенного на ее поверхность гипсозидного состава; сами книги были сложены «гармошкой», а обложка сделана из шкуры ягуара.

Этот монах решил, что в книгах майя содержатся эзотерические знания, смущающие душу дьявольские соблазны, и велел книги эти сжечь все разом, что «повергло майя в глубокую скорбь и сильнейшие страдания».

Во время трехмесячной инквизиции под его руководством в 1562 году пыткам было подвергнуто около 5 000 индейцев, из них 158 человек погибли. Де Ланда был затребован обратно в Испанию по обвинению в превышении полномочий, но был оправдан и вернулся на Юкатан уже епископом.

Индейская культура уничтожалась всеми возможными способами. И всего сто лет спустя после прихода европейцев о славном прошлом майя не осталось и воспоминаний.

Интересные факты о майя.

1. До сих пор в своих прежних регионах живут многочисленные представители культуры майя. Фактически, есть 7 млн майя, многие из которых смогли сохранить важные свидетельства о своем древнем культурном наследии.

2. У майя были странные представления о красоте. В раннем возрасте ко лбу младенцев прикладывали доску, чтобы он был плоским. А еще им нравилось косоглазие: они одевали большую бусину на детские переносицы, чтобы те беспрестанно на нее косились. Еще один интересный факт – детей майя часто называли по тому дню, в который они родились.

3. Они любили сауны. Важным очистительным элементом для древних майя являлась потогонная ванна: на горячие камни лили воду для создания пара. Такими ваннами пользовались все, от женщин, которые недавно родили, до королей.

4. Так же они любили погонять в мяч. Мезоамериканская игра в мяч приравнивалась к ритуалу и существовала на протяжении 3000 лет. Современная версия игры, улама, все еще популярна у местного коренного населения.

5. Последняя страна майя существовала до 1697 г. (островной город Тайя). Сейчас землями под строениями в основном владеет одна семья, а правительству принадлежат сами памятники.

6. Майя не умели обрабатывать металл – их оружие было оснащено каменными наконечниками, или наконечниками из острых ракушек. Но! Воины майя использовали в качестве метательного оружия гнёзда шершней («шершневые бомбы») для создания паники в рядах противника – находчиво.

7. А еще, поговаривают, майя очень любили морских свинок. Ну, как любили…Они получали из бедняг очень вкусное мясо и великолепный пух.

Кстати, у майя был и своего рода гороскоп. Дело в том, что по календарю «Тцолькин» (он же «Цолькин», о котором сообщалось выше) каждому дню в году присвоен свой кин — своего рода частота космической энергии (Боже, что я несу?) и, в зависимости от того, какой кин ваш (какой соответствует дню вашего рождения) – можно судить о вашем характере, жизненных целях и блаблабла. А в зависимости от того, какой кин присвоен сегодняшнему дню – можно судить о вашей удачливости, самочувствии и прочей лабуде, которую обычно пишут в гороскопах.

Кстати, довольно занимательная штука. А майянские астрологические характеристики личностей по кину вполне соответствуют действительности, хотя обычно я и предпочитаю в астрологию не верить.

[источники]

источники

http://xreferat.ru/36/567-1-obshie-svedeniya-po-istorii-maiyya.html

http://www.historyworlds.ru/civiliz/mather/may/history_maya/419-istorija-majjja.html

http://www.bibliotekar.ru/skvorcova/6.htm

http://www.indiansworld.org/

http://nibler.ru/cognitive/17606-mayya.html

А я вас напомню вот еще о каких событиях и персонажах: знаете ли вы например Кто расшифровал письмена Майя ?, а помните ли такую личность как Конкистадор Кортес. Ну и конечно же древний Эль-Тахин (El Tajin)

Оригинал статьи находится на сайте ИнфоГлаз.рф Ссылка на статью, с которой сделана эта копия — http://infoglaz.ru/?p=34973

The Maya civilization () of the Mesoamerican people is known by its ancient temples and glyphs. Its Maya script is the most sophisticated and highly developed writing system in the pre-Columbian Americas. It is also noted for its art, architecture, mathematics, calendar, and astronomical system.

The Maya civilization developed in the Maya Region, an area that today comprises southeastern Mexico, all of Guatemala and Belize, and the western portions of Honduras and El Salvador. It includes the northern lowlands of the Yucatán Peninsula and the highlands of the Sierra Madre, the Mexican state of Chiapas, southern Guatemala, El Salvador, and the southern lowlands of the Pacific littoral plain. Today, their descendants, known collectively as the Maya, number well over 6 million individuals, speak more than twenty-eight surviving Mayan languages, and reside in nearly the same area as their ancestors.

The Archaic period, before 2000 BC, saw the first developments in agriculture and the earliest villages. The Preclassic period (c. 2000 BC to 250 AD) saw the establishment of the first complex societies in the Maya region, and the cultivation of the staple crops of the Maya diet, including maize, beans, squashes, and chili peppers. The first Maya cities developed around 750 BC, and by 500 BC these cities possessed monumental architecture, including large temples with elaborate stucco façades. Hieroglyphic writing was being used in the Maya region by the 3rd century BC. In the Late Preclassic a number of large cities developed in the Petén Basin, and the city of Kaminaljuyu rose to prominence in the Guatemalan Highlands. Beginning around 250 AD, the Classic period is largely defined as when the Maya were raising sculpted monuments with Long Count dates. This period saw the Maya civilization develop many city-states linked by a complex trade network. In the Maya Lowlands two great rivals, the cities of Tikal and Calakmul, became powerful. The Classic period also saw the intrusive intervention of the central Mexican city of Teotihuacan in Maya dynastic politics. In the 9th century, there was a widespread political collapse in the central Maya region, resulting in internecine warfare, the abandonment of cities, and a northward shift of population. The Postclassic period saw the rise of Chichen Itza in the north, and the expansion of the aggressive Kʼicheʼ kingdom in the Guatemalan Highlands. In the 16th century, the Spanish Empire colonised the Mesoamerican region, and a lengthy series of campaigns saw the fall of Nojpetén, the last Maya city, in 1697.