Восстание Пугачева — один из знаменитых и важных общественных бунтов в ответ на происходящие события в стране и мире. Это один из острых сюжетов политической полемики, который является до сих пор актуальным. Кто такой Емельян Пугачев, каковы причины восстания, цели и основные события? Об этом расскажем в кратком содержании далее.

Краткая биография Емельяна Пугачева

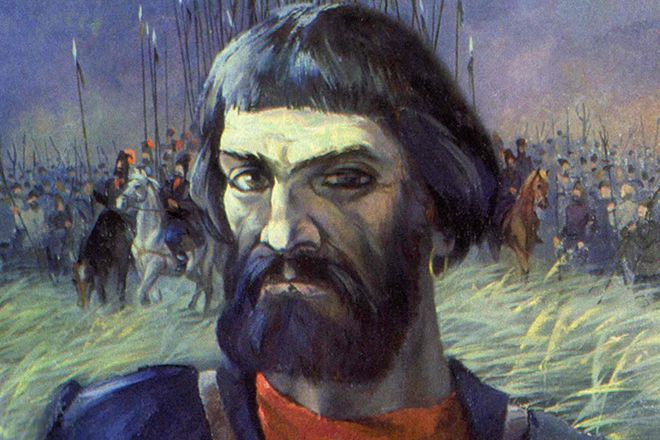

Емельян Иванович Пугачев родился в 1742 году (официальная дата) в Зимовейской станице. Он рос лидером и харизматичным человеком. О нем в свое время даже писал Пушкин в своей повести «Капитанская дочка». В 18 лет Емельян отправился в армию, а на следующий год женился на Софье Недюжевой, которая жила по соседству.

С 1756 года был участником семилетней войны, а затем был военным в польском походе и русско-турецкой войне. После этого начинается его противозаконная деятельность, в ходе которой он помогал свояку скрываться от службы и сам постоянно скрывался.

Когда его задержали, Пугачев был направлен в Черкасск. Там его друг помог ему сбежать в старообрядческий скит. Оттуда Емельян направился в Яицк, где встретился с соратниками и организовал крестьянское шествие против власти под своим предводительством.

Однако оно было повержено, а Емельян был отправлен на сибирскую каторгу. В 1773 г. он сбежал и представился всем как Петр III, подняв бунт. В 1774 г. он был арестован. В 1775 г. в столице его четвертовали на глазах у всех.

Причины и предпосылки восстания

Основная причина пугачевщины — нестабильность социальной финансовой и политической сферы, ограничение прав и свобод казачества и коренных уральских народов. К тому же, крестьяне, которые работали на уральском заводе, работали сверхурочно. В итоге вся сила сконцентрировалась на беглом каторжнике Емельяне Пугачеве, назвавшемся Петром III, который был сослан императрицей.

Другими причинами бунта под руководством каторжника стали:

-

Большие коммуникации с малой эффективностью госуправления, в результате которых случался произвол властей и происходили нарушения законов.

-

Чиновничьи злоупотребления властью из-за отсутствия должного контроля за действиями властей.

-

Дискредитации беззакония низших сословий в гражданских судах.

-

Распоряжения крестьянами в своих интересах со стороны помещиков с дворянами в результате проигрыша в карты и других игр.

-

Незаинтересованность улучшения в управлении государством со стороны служащих и чиновников.

-

Приумножение капиталов властей и бесправие на социальном уровне.

-

Злоупотребления со стороны духовенства, дворянства и мещан властью.

-

Неограниченность богатств и эксплуатация крестьянства духовенством, дворянством и мещанством.

-

Массовый голод каждые несколько лет, в результате которого умирали несколько сотен человек.

-

Ненормированный график работы крестьян (5 дней крестьяне работали на хозяев, а 2 дня на себя).

Цели и требования восставших

Основные цели восстания заключались в:

-

возвращении былой вольности;

-

свободной рыбной ловле с солевой добычей;

-

требовании прекращения беспредела местных властей;

-

уравнивании в правах крестьян с мещанами и возвращении им воли с участком земли;

-

улучшении условий труда уральских рабочих и увеличении привилегий национальных окраин.

Восставшие требовали разные вещи, в зависимости от рода их занятий. Например, рабочие требовали повысить зарплату, передать заводы из частных владений в общую кассу. Крестьяне заявляли о том, чтобы ослабить крепостничество, отменить сибирскую ссылку, отменить продажу крестьянских земель, снизить налоги и барщину с месячиной.

Малые народности хотели, чтобы прекратился чиновничий произвол, остановилось взяточничество со скупкой земель и прекратилось насильственное христианское обращение.

Казаки требовали возвратить бывшие вольности и иметь возможность самостоятельно выбирать себе атамана.

История пугачевского бунта — основные события и даты

Пугачевский исторический бунт был начат в сентябре 1773 г. в области хутора Толкачевых в Яицком городке. Бунт продолжался три этапа. Пугачев объявил себя Петром III, который чудом спасся после восшествия Екатерины на престол как главы государства. Затем он начал распространять письмена и рассказы, где обещал людям даровать свободу с землей и освободить их от рекрутов, поскольку выдавал себя за царя.

В октябре Пугачев стал собирать войско и набрал около 2500 человек. В ходе осаждения Оренбурга к нему присоединились 15000 человек и продолжили движение к столице. К тому же, его сподвижники обзавелись 86 пушками. Подобно Емельяну, в то же время Юлаев поднял восстание в Башкирии, Зарубин — в Уфе, Овчинников — в Яицке, а Арапов — в Самаре.

В январе 1774 г. восстание охватило Нижнее Поволжье с Южным Уралом. Чтобы подавить бунт, Екатерина выслала армию во главе с Бибиковым. Восстание дошло до крепости Татищево Оренбургской области, где состоялось сражение в марте, как и в Уфе. Армия Пугачева потерпела ряд неудач. В апреле Емельян затаился в горах Урала, чтобы с ним ничего не произошло, и вновь собрал войско для осады других городов.

В период с 12 по 17 июля Пугачеву удается взять Казань, Нижегородскую, Воронежскую, Пензенскую и Тамбовскую губернии. Он продолжает свой ход к родине донских казаков в надежде на помощь. К 31 июлю он захватывает Саранск с Пензой, Саратовым, Камышиным и Царицыным. Донские казаки его не поддерживают. В августе Пугачев издает царский манифест, где освобождает крестьян от их обязанностей. В начале осени яицкие казаки арестовывают Пугачёва и ведут его к Михельсону, где против восставших выступает Суворов. 10 января 1775 г. всех глав бунтовщиков казнят.

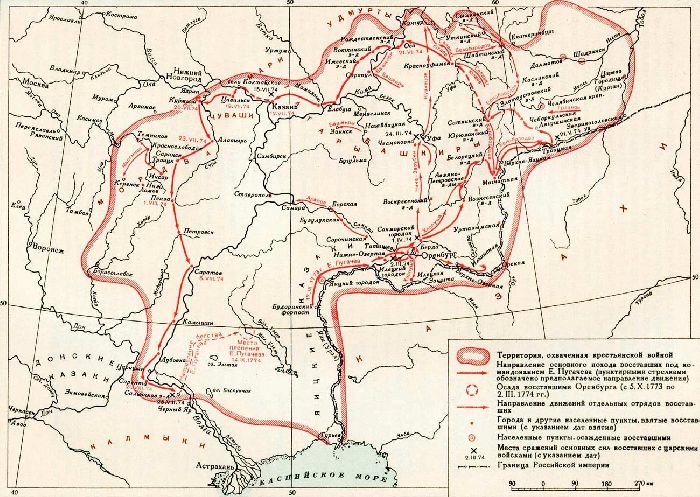

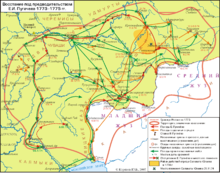

Основные действия и события, передвижения бунтовщиков показаны на исторических картах.

Причины поражения бунтовщиков

Пугачевские бунтовщики не смогли закончить начатое дело с успехом из-за стихийности и неорганизованности характера восстания, отсутствия четко выработанной программы работы с организацией, вооружением и дисциплиной. Также все мечтали о государе, который бы отпустил всех крестьян, дал бы им землю и права. Однако они не пытались свергнуть самодержавие.

Итоги и значение крестьянской войны

В итоге восстание было жестоко подавлено в России, Пугачев был казнен, как и многие восставшие. Восстание значительным образом дестабилизировало положение в стране и превратило его в стихийное бедствие. Императрица запретила упоминать о главе восстания, попыталась стереть из памяти все, что с ним было связано. Даже казачество было названо уральским.

Крестьянское восстание не смогло улучшить ситуацию, репрессии продолжились и усилились. Кроме того, положение работников на заводе не было улучшено.

Восстание стало значимым в обществе из-за того, что пугачевский бунт был самым крупным в народе за всю историю, и впервые была проведена борьба с крепостничеством. Императрица обратила внимание на крестьянский вопрос и усилила полицейский режим, поняв, насколько страшным может быть бунт общества, и к чему он может привести.

В целом, восстание Пугачева — реакция общества на происходящие изменения во власти, притеснение крестьян вследствие государственных реформ и один из самых кровопролитных гражданских бунтов. Оно показало, что обществу нужны изменения и в дальнейшем это послужило толчком к реформированию страны.

Главной причиной народных волнений, включая восстание под предводительством Емельяна Пугачева, было усиление крепостного права и рост эксплуатации всех слоев черного населения. Казаки были недовольны наступлением правительства на их традиционные привилегии и права. Коренные народы Поволжья и Приуралья испытывали притеснения и от властей, и от действия русских помещиков и промышленников. Войны, голод, эпидемии также способствовали народным восстаниям. (Например, московский чумной бунт 1771 г. возник вследствие эпидемии чумы, занесенной с фронтов русско-турецкой войны.)

МАНИФЕСТ «АМПЕРАТОРА»

«Самодержавного амператора, нашего великого государя, Петра Федоровича Всероссийского и прочая… Во имянном моем указе изображено Яицкому войску: как вы, други мои, прежным царям служили до капли своей крови… так вы послужите за свое отечество мне, великому государю амператору Петру Федоровичу… Будити мною, великим государем жалованы: казаки и калмыки и татары. И которые мне… винные были… в всех винах прощаю и жаловаю вас: рякою с вершины и до устья и землею, и травами, и денежным жалованием, и свиньцом, и порохам, и хлебным правиянтам».

САМОЗВАНЦЫ

В сентябре 1773 г. яицкие казаки могли слышать этот манифест «чудом спасенного царя Петра III». Тень «Петра III» в предшествующие 11 лет не раз являлась в России. Некоторые смельчаки назывались государем Петром Федоровичем, объявляли, что хотели они вслед за вольностью дворянству дать волю крепостным да жаловать казаков, работных людей и прочий весь простой люд, но дворяне вознамерились их убить, и пришлось им скрываться до времени. Самозванцы эти быстро попадали в Тайную экспедицию, открытую при Екатерине II взамен распущенной канцелярии тайных розыскных дел, и жизнь их обрывалась на плахе. Но появлялся вскоре где-нибудь на окраине живой «Петр III», и народ хватался за слух о новом «чудесном спасении амператора». Из всех самозванцев лишь одному — донскому казаку Емельяну Ивановичу Пугачеву удалось разжечь пламя крестьянской войны и возглавить беспощадную войну простолюдинов против господ за «мужицкое царство».

В своей ставке и на поле битвы под Оренбургом Пугачев отлично играл «царскую роль». Он издавал указы не только от себя лично, но и от имени «сына и наследника» Павла. Часто при людях Емельян Иванович доставал портрет великого князя и, глядя на него, говорил со слезами: «Ох, жаль мне Павла Петровича, как бы окаянные злодеи его не извели!» А в другой раз самозванец заявлял: «Сам я царствовать уже не желаю, а восстановлю на царствие государя цесаревича».

«Царь Петр III» пытался внести порядок в мятежную народную стихию. Повстанцы были поделены на «полки», возглавляемые выборными или назначенными Пугачевым «офицерами». В 5 верстах от Оренбурга в Берде сделал он свою ставку. При императоре из его охраны образовалась «гвардия». На пугачевские указы ставили «большую государственную печать». При «царе» действовала Военная коллегия, сосредоточившая военную, административную и судебную власть.

Еще Пугачев показывал сподвижникам родимые пятна — в народе тогда все были убеждены, что цари имеют на теле «особые царские знаки». Красный кафтан, дорогая шапка, сабля и решительный вид завершали образ «государя». Хотя внешность Емельяна Ивановича была непримечательная: это был казак тридцати с небольшим лет, среднего роста, смугловатый, волосы стрижены в круг, лицо обрамляла небольшая черная борода. Но он был таким «царем», каким желала видеть царя мужицкая фантазия: лихим, безумно отважным, степенным, грозным и скорым на суд над «изменниками». Он казнил и жаловал…

Казнил помещиков да офицеров. Жаловал простых людей. Например, появился в его лагере мастеровой Афанасий Соколов по прозвищу «Хлопуша», видя «царя» упал в ноги и повинился: сидел он, Хлопуша, в оренбургской тюрьме, но был выпущен губернатором Рейнсдорфом, пообещав за деньги убить Пугачева. «Ампера-тор Петр III» прощает Хлопушу, да еще назначает его полковником. Вскоре Хлопуша прославился как решительный и удачливый предводитель. Другого народного вожака Чику-Зарубина, Пугачев произвел в графы и звал не иначе, как «Иваном Никифоровичем Чернышевым».

Среди пожалованных вскоре оказались прибывшие к Пугачеву работные люди и приписные горнозаводские крестьяне, а также восставшие башкиры во главе со знатным молодым богатырем-поэтом Салаватом Юлаевым. Башкирам «царь» возвращал их земли. Башкиры принялись поджигать русские заводы, построенные в их крае, при этом уничтожались деревни русских поселенцев, жители вырезались чуть ли не поголовно.

ЯИЦКИЕ КАЗАКИ

Восстание началось на Яике, что было не случайно. Волнения начались еще в январе 1772 г., когда яицкие казаки с иконами и хоругвями явились в свою «столицу» Яицкий городок просить царского генерала сместить угнетавшего их атамана и часть старшины да восстановить прежние привилегии яицких казаков.

Правительство в то время изрядно потеснило казаков Яика. Их роль пограничной стражи упала; казаков стали отрывать от дома, отправляя в дальние походы; выборность атаманов и командиров была отменена еще в 1740-е гг.; в устье Яика рыбопромышленники поставили, по царскому дозволению, заграждения, которые затрудняли продвижение рыбы вверх по реке, что больно ударило по одному из основных казачьих промыслов — рыболовству.

В Яицком городке шествие казаков было расстреляно. Солдатский корпус, прибывший чуть позже, подавил казацкое возмущение, зачинщиков казнили, «непослушные казаки» разбежались и затаились. Но спокойствия на Яике не было, казачий край по-прежнему напоминал пороховой погреб. Искрой, которая его взорвала, и стал Пугачев.

НАЧАЛО ПУГАЧЕВЩИНЫ

17 сентября 1773 г. он зачитал свой первый манифест перед 80 казаками. На другой день у него уже было 200 сторонников, а на третий — 400. 5 октября 1773 г. Емельян Пугачев с 2,5 тыс. сподвижников начал осаду Оренбурга.

Пока «Петр III» шел к Оренбургу, весть о нем облетела всю страну. По крестьянским избам шептались, как везде «амператора» встречают «хлебом-солью», торжественно гудят в его честь колокола, казаки и солдаты гарнизонов небольших пограничных крепостиц без боя распахивают ворота и переходят на его сторону, «кровопийц-дворян» «царь» без промедления казнит, а их вещами жалует восставших. Сначала некоторые храбрецы, а потом целые толпы крепостных с Волги побежали к Пугачеву в его лагерь у Оренбурга.

ПУГАЧЕВ У ОРЕНБУРГА

Оренбург был хорошо укрепленным губернским городом, его защищали 3 тыс. солдат. Пугачев стоял под Оренбургом 6 месяцев, но взять его так и не сумел. Однако войско восставших выросло, в некоторые моменты восстания его численность достигала 30 тыс. человек.

На выручку осажденному Оренбургу с верными Екатерине II войсками спешил генерал-майор Кар. Но его полуторатысячный отряд был разгромлен. То же произошло и с воинской командой полковника Чернышева. Остатки правительственных войск отступили в Казань и вызвали там панику среди местных дворян. Дворяне уже были наслышаны о свирепых расправах Пугачева и начали разбегаться, бросая дома и имущество.

Положение складывалось нешуточное. Екатерина, чтобы поддержать дух поволжских дворян, объявила себя «казанскою помещицей». К Оренбургу стали стягиваться войска. Для них требовался главнокомандующий — человек талантливый и энергичный. Екатерина II ради пользы могла поступаться убеждениями. Вот в этот решающий момент на придворном бале императрица обратилась к А.И. Бибикову, которого не любила за близость к своему сыну Павлу и «конституционные мечтания», и с ласковой улыбкой попросила его стать главнокомандующим армией. Бибиков отвечал, что посвятил себя службе отечеству и, конечно, принимает назначение. Надежды Екатерины оправдались. 22 марта 1774 г. в 6-часовом сражении под Татищевой крепостью Бибиков разгромил лучшие силы Пугачева. 2 тыс. пугачевцев были убиты, 4 тыс. ранены или сдались в плен, у повстанцев захватили 36 пушек. Пугачев был вынужден снять осаду Оренбурга. Казалось, бунт подавлен…

Но весной 1774 г. началась вторая часть пугачевской драмы. Пугачев двигался на восток: в Башкирию и на горнозаводской Урал. Когда он подошел к Троицкой крепости, самой восточной точке продвижения повстанцев, в его армии насчитывалось 10 тыс. человек. Восстание захлестывала разбойная стихия. Пугачевцы жгли заводы, отнимали у приписных крестьян и работных людей скот и другое имущество, чиновников, приказчиков, пленных «господ» уничтожали без жалости, иногда самым изуверским способом. Часть простолюдинов пополняла отряды пугачевских полковников, другие сбивались в отряды вокруг заводовладельцев, раздавших своим людям оружие, чтобы защитить их и свою жизнь и собственность.

ПУГАЧЕВ В ПОВОЛЖЬЕ

Войско Пугачева росло за счет отрядов поволжских народов — удмуртов, марийцев, чувашей. С ноября 1773 г. манифесты «Петра III» призывали крепостных расправляться с помещиками — «возмутителями империи и разорителями крестьян», а дворянские «дома и все их имение брать себе в награждение».

12 июля 1774 г. император» с 20-тысячным войском взял Казань. Но в казанском кремле заперся правительственный гарнизон. К нему на помощь подоспели царские войска во главе с Михельсоном. 17 июля 1774 г. Михельсон разбил пугачевцев. «Царь Петр Федорович» бежал на правый берег Волги, и там крестьянская война развернулась вновь с большим размахом. Пугачевский манифест 31 июля 1774 г. даровал крепостным волю и «освободил» крестьян от всех повинностей. Везде возникли повстанческие отряды, которые действовали на свой страх и риск, часто вне связи друг с другом. Интересно, что обычно восставшие громили усадьбы не своих хозяев, а соседних помещиков. Пугачев с главными силами двигался к Нижней Волге. Он с легкостью брал маленькие города. К нему пристали отряды бурлаков, поволжских, донских и запорожских казаков. На пути восставших стояла мощная крепость Царицын. Под стенами Царицына в августе 1774 г. пугачевцы потерпели крупное поражение. Поредевшие отряды мятежников начинали отступать туда, откуда пришли, — на Южный Урал. Сам Пугачев с группой яицких казаков переплыл на левый берег Волги.

12 сентября 1774 г. бывшие соратники предали своего предводителя. «Царь Петр Федорович» превратился в беглого бунтовщика Пугача. Не действовали уже гневные окрики Емельяна Ивановича: «Кого вы вяжете? Ведь если я вам ничего не сделаю, то сын мой, Павел Петрович, ни одного человека из вас живым не оставит!» Связанного «царя» верхом и отвезли к Яицкому городку и там сдали офицеру.

Главнокомандующего Бибикова уже не было в живых. Он умер в разгар подавления бунта. Новый главнокомандующий Петр Панин (младший брат воспитателя цесаревича Павла) имел ставку в Симбирске. Туда Михельсон и приказал отправить Пугачева. Конвоировал его отозванный с турецкой войны прославленный екатерининский полководец А.В. Суворов. Пугачева везли в деревянной клетке на двухколесной телеге.

Тем временем не сложившие еще оружия соратники Пугачева распустили слух, что арестованный Пугачев к «царю Петру III» отношения не имеет. Некоторые крестьяне вздыхали облегченно: «Слава Богу! Какого-то Пугача поймали, а царь Петр Федорович на воле!» Но в целом силы повстанцев были подорваны. В 1775 г. были затушены последние очаги сопротивления в лесной Башкирии и в Поволжье, подавили отголоски пугачевского бунта на Украине.

А.С. ПУШКИН. «ИСТОРИЯ ПУГАЧЕВА»

«Суворов от него не отлучался. В деревне Мостах (во ста сорока верстах от Самары) случился пожар близ избы, где ночевал Пугачев. Его высадили из клетки, привязали к телеге вместе с сыном, резвым и смелым мальчиком, и во всю ночь; Суворов сам их караулил. В Коспорье, против Самары, ночью, в волновую погоду, Суворов переправился через Волгу и пришел в Симбирск в начале октября… Пугачева привезли прямо на двор к графу Панину, который встретил его на крыльце… «Кто ты таков?» — спросил он у самозванца. «Емельян Иванов Пугачев», — отвечал тот. «Как же смел ты, юр, назваться государем?» — продолжал Панин. — «Я не ворон» — возразил Пугачев, играя словами и изъясняясь, по обыкновению, иносказательно. «Я вороненок, а ворон-то еще летает». Панин, заметя, что дерзость Пугачева поразила народ, столпившийся около дворца, ударил самозванца по лицу до крови и вырвал у него клок бороды…»

РАСПРАВЫ И КАЗНИ

Победа правительственных войск сопровождалась зверствами, не меньшими, чем творил Пугачев над дворянами. Просвещенная императрица заключила, что «в теперешнем случае казнь нужна для блага империи». Склонный к конституционным мечтаниям Петр Панин реализовал призыв самодержицы. Тысячи людей были казнены без суда и следствия. На всех дорогах восставшего края валялись трупы, выставленные в назидание. Невозможно было счесть крестьян, наказанных кнутом, батогами, плетьми. У многих отрезали носы или уши.

Емельян Пугачев сложил свою голову на плахе 10 января 1775 г. при большом стечении людей на Болотной площади в Москве. Перед смертью Емельян Иванович поклонился соборам и попрощался с народом, повторяя прерывающимся голосом: «Прости, народ православный; отпусти мне, в чем я согрубил перед тобою». Вместе с Пугачевым были повешены несколько его сподвижников. Знаменитого атамана Чику увезли для казни в Уфу. Салават Юлаев оказался на каторге. Пугачевщина кончилась…

Пугачевщина не принесла облегчения крестьянам. Правительственный курс в отношении крестьян ожесточился, а сфера действия крепостного права расширилась. По указу 3 мая 1783 г. в крепостную неволю переходили крестьяне Левобережной и Слободской Украины. Крестьяне здесь лишались права перехода от одного владельца к другому. В 1785 году казацкая старшина получила права российского дворянства. Еще ранее, в 1775 г., была уничтожена вольная Запорожская Сечь. Запорожцев переселили на Кубань, где они составили казачье кубанское войско. Помещики Поволжья да и других областей не сократили оброки, барщину и другие крестьянские повинности. Все это взыскивалось с прежней строгостью.

«Матушке Екатерине» хотелось, чтобы память о Пугачевщине стерлась. Она даже велела переименовать реку, где начался бунт: и стал Яик — Уралом. Яицких казаков и Яицкий городок приказано было звать уральскими. Станицу Зимовейскую, родину Стеньки Разина и Емельяна Пугачева, окрестили по-новому — Потемкинской. Однако Пугач запомнился народу. Старики всерьез рассказывали, что Емельян Иванович — это оживший Разин, и вернется он еще не раз на Дон; по Руси звучали песни и ходили легенды о грозном «императоре и его детушках».

ВОССТАНИЕ ПУГАЧЕВА В ХУДОЖЕСТВЕННОЙ ЛИТЕРАТУРЕ

«Сказка про Пугачева и про вдову Харлову» — первое фольклорно-поэтическое произведение о крестьянской войне 1773-1775 гг. под предводительством Е. И. Пугачева

А.С. Пушкин. «История Пугачева»

А.С. Пушкин. «Капитанская дочка»

С.А. Есенин. «Пугачев»

В.Я. Шишков. Емельян Пугачев

Восстание Пугачева

4.7

Средняя оценка: 4.7

Всего получено оценок: 2928.

4.7

Средняя оценка: 4.7

Всего получено оценок: 2928.

Восстание Пугачева в 1773-1775 годах стало крупнейшим антиправительственным выступлением в истории России XVIII века. Его отличием от предыдущих народных восстаний был тот факт, что предводитель повстанцев выдавал себя за императора Петра III, погибшего 11 годами ранее. Оно охватило огромную территорию, от южного Зауралья до нижнего Поволжья.

Опыт работы учителем истории — 29 лет.

Начало восстания

К началу 1770-ых годов в Российской империи накопилось немало проблем, в том числе особо остро они стояли на южном Урале и Поволжье. Это и привело к восстанию под руководством Емельяна Пугачева. Среди его участников были представители разных слоев общества: коренные народы Урала и Волго-Камского региона, крепостные и приписанные к уральским заводам крестьяне, казачество, старообрядцы.

Ситуацию ухудшало появление в стране самозванцев, выдававших себя за Петра III, чье правление стало коротким, но из-за Манифеста о вольности дворянства породило в крестьянской среде ожидания на освобождение от крепостного права.

Сам Емельян Пугачев был родом из донских казаков, из станицы Зимовейской, где в XVII веке родился другой известный вождь повстанцев – Степан Разин. В конце ноября 1772 года, находясь на землях Яицких казаков (они жили вдоль берегов современных реки Урал), Пугачев назвал себя Петром III. Весной 1773 года его арестовали и сослали в Казань, но Емельян бежал и осенью 1773 собрал на Яике отряд из нескольких сотен человек и начал издавать указы от лица царя Петра Федоровича.

К октябрю 1773 года Пугачев захватил ряд крепостей вблизи Оренбурга, его войско выросло до 2500 человек с несколькими десятками пушек, а к концу года его численность составляла порядка 25-40 тыс. Предводитель восстания занялся организацией управления подконтрольной ему территорией. У него появилась Военная коллегия, а своих атаманов он именовал как высших сановников Екатерины 2.

Таким образом, появились самозванцы вроде “графа Орлова” или “графа Панина”.

Боевые действия на Урале

К концу 1773 года вторым центром восстания стала деревня Чесноковка вблизи Уфы. Ряды повстанцев пополнили башкиры, их лидером стал Салават Юлаев. Он вел борьбу с правительственными войсками до ноября 1774 года. В январе 1774 восстание охватило территорию от городов Оса и Екатеринбург на севере и до низовьев Яика (город Гурьев) на юге.

Пугачев пытался привлечь к участию в восстании казахских ханов, но заметных успехов это не принесло. Несмотря на тяжелую осаду, гарнизон Оренбурга продержался полгода, до марта 1774 года. Именно тогда повстанцы потерпели первые серьезные поражения: одно у крепости Татищевой, другие на территории южного Зауралья, под Шадринском и Курганом. В апреле-июне 1774 войско Емельяна Пугачева совершило поход по Уралу, от Магнитной крепости (ныне – Магнитогорск) до Кунгура и далее до низовьев Камы, откуда вышло к Волге.

Бои с повстанцами в Поволжье

Под Казанью армия повстанцев неожиданно одержала победу над правительственными силами и взяла под контроль почти весь город, кроме Кремля. Вскоре к городу подошло войско подполковника Михельсона, который одержал победу над Пугачевым и вытеснил его на правый берег Волги, в район города Кокшайска (ныне – республика Марий Эл). Оттуда в июле 1774 повстанцы совершили поход на города Цивильск, Алатырь, Саранск и Пензу. В этой части Российской империи восстание стало в большей степени крестьянским по составу участников. В августе Емельян Пугачев взял Саратов, но продержался в городе всего несколько дней, так как его преследовали правительственные войска, направленные на подавление восстания.

На финальном этапе восстания тактика самозванца заключалась в том, чтобы прорваться на юг страны и пополнить войско калмыками и донскими казаками. Этого не вышло, так как войско Емельяна Пугачева потерпело подряд два поражения – под Царицыном и Солениковой ватаги. В сентябре он был схвачен казаками и выдан властям. Бои с мелкими отрядами повстанцев продолжилась до лета 1775 года.

Что мы узнали?

Кратко о восстании под предводительством Пугачева необходимо знать для лучшего понимания событий XVIII века.

Следует отметить, что восстание сочетало несколько факторов: религиозный, политический (самозванец), социальный, территориальный. На разгром повстанцев императрице Екатерине II потребовалось почти два года.

Тест по теме

Доска почёта

Чтобы попасть сюда — пройдите тест.

-

Никита Лымарев

10/10

-

Айка Абдиева

4/10

-

Далер Аллаяров

9/10

-

Анастасия Казаринова

8/10

-

Юля Воропаева

10/10

-

Даниил Сапунов

9/10

-

Андрей Смирнов

9/10

-

Антон Родин

9/10

-

Даниил Ларшин

10/10

-

Уран Белеков

10/10

Оценка доклада

4.7

Средняя оценка: 4.7

Всего получено оценок: 2928.

А какая ваша оценка?

| Pugachev’s Rebellion | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| Belligerents | ||||||

|

|

Coalition of Cossacks, Russian Serfs, Old Believers, and non-Russian peoples | |||||

| Commanders and leaders | ||||||

|

Catherine the Great Grigory Potemkin Petr Panin Alexander Suvorov Johann von Michelsohnen |

Yemelyan Pugachev Salawat Yulayev |

|||||

| Strength | ||||||

| 5,000+ men[2] |

1773:

1774:

|

|||||

| Casualties and losses | ||||||

| 3,500 killed[2] |

|

Pugachev’s Rebellion (Russian: Восстание Пугачёва, Vosstaniye Pugachyova; also called the Peasants’ War 1773–1775 or Cossack Rebellion) of 1773–1775 was the principal revolt in a series of popular rebellions that took place in the Russian Empire after Catherine II seized power in 1762. It began as an organized insurrection of Yaik Cossacks headed by Yemelyan Pugachev, a disaffected ex-lieutenant of the Imperial Russian Army, against a background of profound peasant unrest and war with the Ottoman Empire. After initial success, Pugachev assumed leadership of an alternative government in the name of the late Tsar Peter III and proclaimed an end to serfdom. This organized leadership presented a challenge to the imperial administration of Catherine II.

The rebellion managed to consolidate support from various groups including the peasants, the Cossacks, and Old Believers priesthood. At one point, its administration claimed control over most of the territory between the Volga River and the Urals. One of the most significant events of the insurrection was the Battle of Kazan in July 1774.

Government forces failed to respond effectively to the insurrection at first, partly due to logistical difficulties and a failure to appreciate its scale. However, the revolt was crushed towards the end of 1774 by General Michelsohn at Tsaritsyn. Pugachev was captured soon after and executed in Moscow in January 1775. Further reprisals against rebel areas were carried out by General Peter Panin.

The events have generated many stories in legend and literature, most notably Pushkin’s historical novel The Captain’s Daughter (1836). It was the largest peasant revolt in the history of the Russian Empire.

Background and aims[edit]

As the Russian monarchy contributed to the degradation of the serfs, peasant anger ran high. Peter the Great ceded entire villages to favored nobles, while Catherine the Great confirmed the authority of the nobles over the serfs in return for the nobles’ political cooperation. The unrest intensified as the 18th century wore on, with more than fifty peasant revolts occurring between 1762 and 1769. These culminated in Pugachev’s Rebellion, when, between 1773 and 1775, Yemelyan Pugachev rallied the peasants and Cossacks and promised the serfs land of their own and freedom from their lords.

There were various pressures on Russian serfs during the 18th century, which induced them to follow Pugachev. The peasantry in Russia were no longer bound to the land, but tied to their owner. The connecting links that had existed between the peasant community and the tsar, which had been diminishing, was broken by the interposition of the serf owners; these private lords or agents of the Church or state who owned the land blocked serfs’ access to the political authority. Many nobles returned to their estates after 1762 and imposed harsher rules on their peasants. The relationship between peasant and ruler was cut off most dramatically in the decree of 1767, which completely prohibited direct petitions to the empress from the peasantry. The peasants were also subject to an increase in indirect taxes due to the increase in the state’s requirements. In addition, a strong inflationary trend resulted in higher prices on all goods.[4] The peasants felt abandoned by the «modern» state.[5] They were living in desperate circumstances and had no way to change their situation, having lost all possibilities for political redress.

There were natural disasters in Russia during the 18th century, which also added strain on the peasants. Frequent recurrence of crop failures, plagues and epidemics created economic and social instability. The most dramatic was the 1771 epidemic in Moscow, which brought to the surface all the unconscious and unfocused fears and panics of the populace.[6]

Each ruler altered the position of the Church, which created more pressure. Peter the Great gave the Church new obligations, while its administration assimilated to a department of the secular state. The Church’s resources, or the means of collection, could not meet the new obligations and as a consequence, they heavily exploited and poorly administered their serfs. The unrest spurred constant revolt among Church serfs.[6]

Leadership and strategy[edit]

Pugachev’s image according to folk memory and contemporary legends was one of a pretender-liberator. As Peter III, he was seen as Christ-like and saintly because he had meekly accepted his dethronement by his evil wife Catherine II and her courtiers. He had not resisted his overthrow, but had left to wander the world. He had come to help the revolt, but he did not initiate it; according to popular myth, the Cossacks and the people did that.[7]

The popular mythology of Peter III linked Pugachev with the Emancipation Manifesto of 1862 and the serf’s expectations of further liberalizations had he continued as ruler. Pugachev offered freedom from the poll tax and the recruit-levy, which made him appear to follow in the same vein as the emperor he was impersonating.

Pugachev attempted to reproduce the St. Petersburg bureaucracy. He established his own College of War with quite extensive powers and functions. It is important to emphasize that he did not promise complete freedom from taxation and recruitment for the peasants; he granted only temporary relief. His perception of the state was one where soldiers took the role of Cossacks, meaning they were free, permanent, military servicemen. Pugachev placed all other military personnel into this category as well, even the nobles and officers who joined his ranks. All peasants were seen as servants of the state, they were to become state peasants and serve as Cossacks in the militia. Pugachev envisioned the nobles returning to their previous status as the czar’s servicemen on salary instead of estate and serf owners. He emphasized the peasants’ freedom from the nobility. Pugachev still expected the peasants to continue their labor, but he granted them the freedom to work and own the land. They would also enjoy religious freedoms and Pugachev promised to restore the bond between the ruler and the people, eradicating the role of the noble as the intermediary.[8]

Under the guise of Peter III, Pugachev built up his own bureaucracy and army, which copied that of Catherine. Some of his top commanders took on the pseudonyms of dukes and courtiers. Zarubin Chaika, Pugachev’s top commander, for example, took the guise of Zakhar Chernyshev. The army Pugachev established, at least at the very top levels of command, also mimicked Catherine’s. The organizational structure Pugachev set up for his top command was extraordinary, considering Pugachev defected as an ensign from Catherine’s army. He built up his own War College and a fairly sophisticated intelligence network of messengers and spies. Even though Pugachev was illiterate, he recruited the help of local priests, mullahs, and starshins to write and disseminate his «royal decrees» or ukases in Russian and Tatar languages. These ukazy were copied, sent to villages and read to the masses by the priests and mullahs. In these documents, he begged the masses to serve him faithfully. He promised to grant to those who followed his service land, salt, grain, and lowered taxes, and threatened punishment and death to those who didn’t. For example, an excerpt from a ukase written in late 1773:

From me, such reward and investiture will be with money and bread compensation and with promotions: and you, as well as your next of kin will have a place in my government and will be designated to serve a glorious duty on my behalf. If there are those who forget their obligations to their natural ruler Peter III, and dare not carry out the command that my devoted troops are to receive weapons in their hands, then they will see for themselves my righteous anger, and will then be punished harshly.[9]

Recruitment and support[edit]

From the very beginning of the insurgency, Pugachev’s generals carried out mass recruitment campaigns in Tatar and Bashkir settlements, with the instructions of recruiting one member from every or every other household and as many weapons as they could secure. He recruited not only Cossacks, but Russian peasants and factory workers, Tatars, Bashkirs, and Chuvash. Famous Bashkir hero Salawat Yulayev joined him. Pugachev’s primary target for his campaign was not the people themselves, but their leaders. He recruited priests and mullahs to disseminate his decrees and read them to the masses as a way of lending them credence.

Priests in particular were instrumental figures in carrying out Pugachev’s propaganda campaigns. Pugachev was known to stage “heroic welcomes” whenever he entered a Russian village, in which he would be greeted by the masses as their sovereign. A few days before his arrival to a given city or village, messengers would be sent out to inform the priests and deacons in that town of his impending arrival. These messengers would request that the priests bring out salt and water and ring the church bells to signify his coming. The priests would also be instructed to read Pugachev’s manifestos during mass and sing prayers to the health of the Great Emperor Peter III. Most priests, although not all, complied with Pugachev’s requests. One secret report of Catherine’s War College, for example, tells of one such priest, Zubarev, who recruited for Pugachev in Church under such orders. “[Zubarev], believing in the slander-ridden decree of the villainous-imposter, brought by the villainous Ataman Loshkarev, read it publicly before the people in church. And when that ataman brought his band, consisting of 100 men, to their Baikalov village, then that Zubarev met them with a cross and with icons and chanted prayers in the Church; and then at the time of service, as well as after, evoked the name of the Emperor Peter III for suffrage.” (Pugachevshchina Vol. 2, Document 86. Author’s translation)

Pugachev’s army was composed of a diverse mixture of disaffected peoples in southern Russian society, most notably Cossacks, Bashkirs, homesteaders, religious dissidents (such as Old Believers) and industrial serfs. Pugachev was very much in touch with the local population’s needs and attitudes; he was a Don Cossack and encountered the same obstacles as his followers. It is noticeable that Pugachev’s forces always took routes that reflected the very regional and local concerns of the people making up his armies. For example, after the very first attack on Yaitsk, he turned not towards the interior, but instead turned east towards Orenburg which for most Cossacks was the most direct symbol of Russian oppression.

The heterogeneous population in Russia created special problems for the government, and it provided opportunities for those opposing the state and seeking support among the discontented, as yet unassimilated natives.[10] Each group of people had problems with the state, which Pugachev focused on in order to gain their support.

Non-Russians, such as the Bashkirs, followed Pugachev because they were promised their traditional ways of life, freedom of their lands, water and woods, their faith and laws, food, clothing, salaries, weapons and freedom from enserfment. (Madariaga, 250) Cossacks were similarly promised their old ways of life, the rights to the river Iaik (now the Ural River) from source to sea, tax-free pasturage, free salt, twelve chetvi of corn and 12 roubles per Cossack per year.[11]

Map of the Pugachev’s Rebellion

Pugachev found ready support among the odnodvortsy (single homesteaders). In the westernmost part of the region swept by the Pugachev rebellion, the right bank of the middle Volga, there were a number of odnodvortsy. These were descendants of petty military servicemen who had lost their military function and declined to the status of small, but free, peasants who tilled their own lands. Many of them were also Old Believers, and so felt particularly alienated from the state established by Peter the Great. They were hard-pressed by landowners from central provinces who were acquiring the land in their area and settling their serfs on it. These homesteaders pinned their hopes on the providential leader who promised to restore their former function and status.[12]

The network of Old Believer holy men and hermitages served to propagandize the appearance of Pugachev as Peter III and his successes, and they also helped him recruit his first followers among the Old Believer Cossack of the Iaik.[13]

The Iaik Cossack host was most directly and completely involved in the Pugachev revolt. Most of its members were Old Believers who had settled among the Iaik River. The Cossacks opposed the tide of rational modernization and the institutionalization of political authority. They regarded their relationship to the ruler as a special and personal one, based on their voluntary service obligations. In return, they expected the czar’s protection of their religion, traditional social organization, and administrative autonomy. They followed the promises of Pugachev and raised the standard of revolt in the hope of recapturing their previous special relationship and securing the government’s respect for their social and religious traditions.[14]

Factory workers supported Pugachev because their situation had worsened; many state-owned factories had been turned over to private owners, which intensified exploitation. These private owners stood as a barrier between the workers and the government; they inhibited appeals to the state for improvement of conditions. Also, with the loss of Russia’s competitive advantage on the world market, the production of the Ural mines and iron-smelting factories declined. This decline hit the workers the hardest because they had no other place to go or no other skill to market. There was enough material to support rebellion against the system. By and large the factories supported Pugachev, some voluntarily continuing to produce artillery and ammunition for the rebels.[15]

Challenge to the Russian state[edit]

In 1773 Pugachev’s army attacked Samara and occupied it. His greatest victory came with the taking of Kazan, by which time his captured territory stretched from the Volga to the Ural mountains. Though fairly well-organized for a revolt at the time, Pugachev’s main advantage early on was the lack of seriousness about Pugachev’s rebellion. Catherine the Great regarded the troublesome Cossack as a joke and put a small bounty of about 500 rubles on his head. But by 1774, the threat was more seriously addressed; by November the bounty was over 28,000 rubles. The Russian general Michelson lost many men due to a lack of transportation and discipline among his troops, while Pugachev scored several important victories.

Pugachev launched the rebellion in mid-September 1773. He had a substantial force composed of Cossacks, Russian peasants, factory serfs, and non-Russians with which he overwhelmed several outposts along the Iaik and early in October went into the capital of the region, Orenburg. While besieging this fortress, the rebels destroyed one government relief expedition and spread the revolt northward into the Urals, westward to the Volga, and eastward into Siberia. Pugachev’s groups were defeated in late March and early April 1774 by a second relief corps under General Bibikov, but Pugachev escaped to the southern Urals, Baskiria, where he recruited new supporters. Then, the rebels attacked the city of Kazan, burning most of it on July 23, 1774. Though beaten three times at Kazan by tsarist troops, Pugachev escaped by the Volga, and gathered new forces as he went down the west bank of the river capturing main towns. On September 5, 1774, Pugachev failed to take Tsaritsyn and was defeated in the steppe below that town. His closest followers betrayed him to the authorities. After a prolonged interrogation, Pugachev was publicly executed in Moscow on 21 January [O.S. 10 January] 1775.[16]

Indigenous involvement[edit]

Pugachev’s vague rhetoric inspired not only Cossacks and peasants to fight, but also indigenous tribes on the eastern frontier. These indigenous groups made up a comparatively small portion of those in revolt, but their role should not be underestimated. Each group had a distinct culture and history, which meant that their reasons for following Pugachev were different.

Bashkir riders from the Ural steppes

The Mordovians, Mari, Udmurts, and Chuvash (from the Volga and Kama basin) for example, joined the revolt because they were upset by Russian attempts to convert them to Orthodoxy. These groups lived within Russia’s borders, but held onto their language and culture. During the Pugachev Rebellion, these natives responded by assassinating Orthodox clergy members.[citation needed] Because the natives professed allegiance to Pugachev, the rebel leader had no choice but to implicitly condone their actions as part of his rebellion.[17]

The Tatars (from the Volga and Kama basin) were the indigenous group with the most complex political structure. They were most closely associated with Russian culture because they had lived within the empire’s borders since the 16th century. Many Tatars owned land or managed factories. As more integrated members of the Russian Empire, the Tatars rebelled in objection to the poll tax and their military and service obligations. The Tatars were closely associated with the Cossacks and were a crucial part of Pugachev’s recruitment efforts.

As a group, the Bashkirs had the most unified involvement in the rebellion. The Bashkirs were nomadic herdsman, angered by newly arrived Russian settlers who threatened their way of life. Russians built factories and mines, began farming on the Bashkir’s former land, and tried to get the Bashkirs to abandon their nomadic life and become farmers too. When fighting broke out, Bashkir village leaders preached that involvement in the rebellion would end Russian colonialism, and give the Bashkirs the political autonomy and cultural independence they desired. The Bashkirs were crucial to Pugachev’s rebellion. Some of the memorable leaders of the rebellion, like Salavat Yulaev were Bashkirs, and historian Alan Bodger argues that the rebellion might have died in the beginning stages were it not for the Bashkir’s involvement. But important to note is in spite of their integral role, Bashkirs fought for different reasons than many of the Cossacks and peasants, and sometimes their disparate objectives disrupted Pugachev’s cause. There are accounts of Bashkirs, upset over their lost land, taking peasant land for themselves. Bashkirs also raided factories, showing their aggression towards Russian expansion and industrialization. Pugachev thought that these raids were ill-advised and not helpful towards his cause.

While the Bashkirs had a clear unified role in the rebellion, the Buddhist Kalmyks and Muslim Kazakhs, neighboring Turkic tribes in the steppe, were involved in a more fragmented way. The Kazakhs were nomadic herdsman like the Bashkirs, and were in constant struggle with neighboring indigenous groups and Russian settlers over land. Pugachev tried hard to get Kazakh leaders to commit to his cause, but leaders like Nur-Ali would not do so fully. Nur-Alit engaged in talks with both Pugachev’s and Tsarist forces, helping each only when it was advantageous for him. The Kazakhs mostly took advantage of the rebellion’s chaos to take back land from Russian peasants and Bashkir and Kalmyk natives. Historian John T. Alexander argues that these raids, though not directly meant to help Pugachev, ultimately did help by adding to the chaos that the Imperial forces had to deal with.[18]

The early Volga German settlements were attacked during the Pugachev uprising.

The Kalmyks’ role in the rebellion was not unified either, but historians disagree about how to classify their actions. Historian Alan Bodger argues that the Kalmyks’ role was minimal. They helped both sides in the conflict, but not in a way that changed the results. John T. Alexander argues that the Kalmyks were a significant factor in the rebel’s initial victories. He cites the Kalmyk campaign led by II’ia Arapov which, though defeated, caused a total uproar and pushed the rebellion forward in the Stavropol region.[19]

Defeat[edit]

By late 1774 the tide was turning, and the Russian army’s victory at Tsaritsyn left 9,000-10,000 rebels dead. Russian General Panin’s savage reprisals, after the capture of Penza, completed their discomfiture. By 21 August 1774, Don Cossacks recognize that Pugachev is not Peter III. By early September, the rebellion was crushed. Yemelyan Pugachev was betrayed by his own Cossacks when he tried to flee in mid-September 1774, and they delivered him to the authorities.[20] He was beheaded and dismembered on 21 January 1775, in Moscow.

After the revolt, Catherine cut Cossack privileges further and set up more garrisons across Russia. Provinces became more numerous, certain political powers were broken up and divided among various agencies, and elected officials were introduced.[21]

Assessments[edit]

The popular interpretation of the insurgency was that Pugachev’s men followed him out of the desire to free themselves from the oppression of Catherine’s reign of law. However, there are documents from Pugachev’s war college and eye witness accounts that contradict this theory. While there were many who believed Pugachev to be Peter III and that he would emancipate them from Catherine’s harsh taxes and policies of serfdom, there were many groups, particularly of Bashkir and Tatar ethnicity, whose loyalties were not so certain. In January 1774, for example, Bashkir and Tatar generals led an attack on the City of Kungur. During the revolt the nomadic Kazakhs took the opportunity to raid the Russian settlements.[22] Pugachev’s troops suffered from a lack of food and gunpowder. Many fighters deserted, including one general who left the battle and took his entire unit with him. One general wrote in a report to his superior, V. I. Tornova, «For the sake of your eminence, we humbly request that our Naigabitskiaia Fortress be returned to us with or without a detachment, because there is not a single Tatar or Bashkir detachment, since they have all fled, and the starshins, who have dispersed to their homes, are presently departing for the Naigabanskaia fortress.» (Dokumenty i Stavki E. I. Pugacheva, povstancheskikh vlastei i ucherezhdenii, 1773-1774. Moskva, Nauka, 1975. Document number 195. Author’s translation)

The concept of freedom was applied to the movement in regard to being free from the nobility. A peasant was to be free to work and own the land he worked. Pugachev’s followers idealized a static, simple society where a just ruler guaranteed the welfare of all within the framework of a universal obligation to the sovereign. The ruler ought to be a father to his people, his children; and power should be personal and direct, not institutionalized and mediated by land- or serf owner. Such a frame of mind may also account for the strong urge to take revenge on the nobles and officials, on their modern and evil way of life.[23]

Pugachev’s followers were particularly frightened by apparent economic and social changes. They wished to recapture the old ideals of service and community in a hierarchy ordained by God. They needed a palpable sense of direct relationship with the source of sovereign power. The Cossacks were most keenly aware of the loss of their special status and direct contact with the czar and his government.

The Imperial government endeavored to keep the matter of the rebellion strictly secret or, failing that, to portray it as a minor outbreak that would soon be quelled. The absence of an independent Russian press at the time, particularly in the provinces, meant that foreigners could read only what the government chose to print in the two official papers, or whatever news they could obtain from correspondents in the interior. (Alexander, 522) Russian government undertook to propagate in the foreign press its own version of events and directed its representatives abroad to play down the revolt.[24]

The Russian government favored the use of manifestos to communicate with the people of Russia. Catherine thought that exhortations to abandon him would excite popular antipathy for his cause and elicit divisions within rebel ranks. Her printed pronouncements were widely distributed in the turbulent areas; they were read on the public squares and from the parish pulpits. In the countryside local authorities were instructed to read them to gatherings of the people, who were then required to sign the decree. These government proclamations produced little positive effect. They actually added more confusion and even provoked unrest when the peasantry refused to believe or sign them.[25]

Much of the blame for the spread of the insurrection must be laid on the local authorities in Russia. “They were lax, timid, and indecisive; their countermeasures were belated, futile, and lost lives needlessly.”[26] Catherine herself recognized this assessment. As Catherine said “I consider the weak conduct of civil and military officials in various localities to be as injurious to the public welfare as Pugachev and the rabble he has collected.”[27] The weakness could not have been entirely the fault of the officials. The local bureaucracy in Russia was too remote and too inefficient to adequately deal with even the most basic administrative matters.

Pugachev’s success in holding out against suppression for over a year proved to be a powerful incentive for future reforms. It made apparent to the government several problems with their treatment of the provinces. They were left weakly controlled and consequently, susceptible to outbreaks of peasant violence. The most crucial lesson Catherine II drew from the Pugachev rebellion, was the need for a firmer military grasp on all parts of the Empire, not just the external frontiers. For instance, when the governor of the Kazan guberniya called for assistance against the approaching Pugachev, there was no force available to relieve him. The revolt did occur at a sensitive point in time for the Russian government because many of their soldiers and generals were already engaged in a difficult war on the southern borders with Ottoman Turkey. However, the professional army available outside the gates of Kazan to counter the Cossack-based army of Pugachev only consisted of 800 men.[11]

Media[edit]

- The Captain’s Daughter (1836 historical novel by Alexander Pushkin) Imperial officer Pyotr Grinyov is sent to a remote outpost. While traveling he is lost in a snowstorm, where he encounters a stranger who guides him to safety. He gratefully gives the stranger his fur coat and they part ways when the storm ends. Later his outpost is attacked by Pugachev’s forces, led by the stranger — who turns out to be Pugachev himself. Pugachev, impressed with the young man’s integrity, offers him a place in his army. The officer has to choose between loyalty to his commission or following the charismatic Pugachev.

- Tempest (1958 film) An adaptation of The Captain’s Daughter produced by Dino de Laurentis and directed by Alberto Lattuada. It starred Geoffrey Horne as Piotr Grinov, Silvana Mangano as Masha Miranov and Van Heflin as Emelyan Pugachov.

Notes[edit]

- ^ «Catherine the Great». Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 9 October 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f Tucker, Spencer C. (2017). The Roots and Consequences of Civil Wars and Revolutions: Conflicts that Changed World History. ABC-CLIO. p. 140. ISBN 9781440842948. Retrieved 9 October 2019.

- ^ (in Russian) К. Амиров. Казань: где эта улица, где этот дом, Казань, 1995., стр 214–220

- ^ Forster, Preconditions of Revolution p 165-72.

- ^ Forster, Robert (1970). Preconditions of Revolution in Early Modern Europe. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins. pp. 163. ISBN 9780801811760.

- ^ a b Forster, Preconditions of Revolution p 169.

- ^ Forster, Robert. p. 195.

- ^ Forster, Robert. p. 197.

- ^ Pugachevshchina vol. 1 document 7, author’s translation from Russian.

- ^ Forster, Robert. p. 181.

- ^ a b Madariaga, Isabel De (1981). Russia in the Age of Catherine the Great. New Haven: Yale UP. p. 250.

- ^ Forster, Robert. 176. CS1 maint: location (link)

- ^ Forster, Robert. p. 179.

- ^ Forster, Robert. p. 190.

- ^ Forster, Robert. p. 180.

- ^ Alexander, John T (October 1970). «Western Views of the Pugachev Rebellion». The Slavonic and East European Review. No. 113. 48: 520–536.

- ^ Bodger, Alan. “Nationalities in History: Soviet Historiography and the Pugačëvščina.” Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas, Vol. 39, No. 4 (1991): 563.

- ^ Bodger, Alan. “Nationalities in History: Soviet Historiography and the Pugačëvščina.” Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas, Vol. Bd. 39, No. 4 (1991): 564.

- ^ John T. Alexander, The Emperor of the Cossacks (Lawrence, Kan: Colorado Press, 1973), 100.

- ^ Longley, David (2014-07-30). Longman Companion to Imperial Russia, 1689-1917. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-88220-6.

- ^ Christine Hatt (2002). Catherine the Great. Evans Brothers. pp. 28–29. ISBN 9780237522452.

- ^ NUPI — Centre for Russian Studies Archived 2007-02-14 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Forster, Robert. p. 198.

- ^ Alexander, John T. : 528. ;

- ^ Alexander, John T (1969). Autocratic Politics in a National Crisis; the Imperial Russian Government and Pugachev’s Revolt, 1773-1775. Bloomington: Indiana UP. p. 95.

- ^ Alexander, John T (1969). Autocratic Politics in a National Crisis; the Imperial Russian Government and Pugachev’s Revolt, 1773-1775. Bloomington: Indiana UP. p. 144.

- ^ Jones, Robert Edward (1973). The Emancipation of the Russian Nobility, 1762-1785. Princeton: Princeton UP. pp. 207. ISBN 9780691052083.

References[edit]

- Alexander, John T. Autocratic politics in a national crisis: the Imperial Russian government and Pugachev’s revolt, 1773-1775 (Indiana University Press, 1969).

- Alexander, John T. «Recent Soviet Historiography on the Pugachev Revolt: A Review Article.» Canadian-American Slavic Studies 4#3 (1970): 602-617.

- Alexander, John T. «Western Views of the Pugachev Rebellion». Slavonic and East European Review (1970) 48#113: 520–536.

- Avrich, Paul. Russian Rebels, 1600-1800 (1972).

- Bodger, Alan. The Kazakhs and the Pugachev uprising in Russia, 1773-1775(No. 11. Research Institute for Inner Asian Studies, Indiana University, 1988).

- Commercio, Michele E. «The “Pugachev rebellion” in the context of post‐Soviet Kazakh nationalization.» Nationalities Papers 32.1 (2004): 87-113. Online

- De Madariaga, Isabel. Russia in the Age of Catherine the Great (1981) pp 239-55.

- Kagan, Donald, Ozment, Steven, Turner, Frank. The Western Heritage, Eighth Edition. Prentice Hall Publishing, New York, New York. 2002. Textbook website

- Longworth, Ph. «The last great cossack-peasant rising». Journal of European Studies. 3#1 (1973)

- Longworth, Ph. «The Pretender Phenomenon in Eighteenth Century Russia». Past and Present. 66 (1975): 61—84

- Pushkin, Aleksandr Sergeevich. The Complete Works of Alexander Pushkin: History of the Pugachev Rebellion (Milner, 2000).

- Raeff, Marc. «Pugachev’s rebellion.» in Robert Forster, ed., Preconditions of revolution in early modern Europe (1972) pp 197+

- Raeff, Marc. «Pushkin’s The History of Pugachev: Where Fact Meets the Zero-Degree of Fiction.» in David M. Bethea ed. The Superstitious Muse: Thinking Russian Literature Mythopoetically (Academic Studies Press. (2009) 301-322. Online

- Yaresh, Leo. «The» Peasant Wars» in Soviet Historiography.» American Slavic and East European Review 16.3 (1957): 241-259. in JSTOR

In Other languages[edit]

- AN SSSR, In-t istorii SSSR, TSentr. gos. arkhiv drev. aktov (Rus. Moscow, 1975.)

- Pugachevshchina. Moscow : Gosizdat, 1926-1931.

- Palmer, Elena. Peter III — Der Prinz von Holstein. Sutton Publishing, Germany 2005 ISBN 978-3-89702-788-6

External links[edit]

- World History at KMLA

- Stavropol and Pugachyov’s rebellion

| Pugachev’s Rebellion | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| Belligerents | ||||||

|

|

Coalition of Cossacks, Russian Serfs, Old Believers, and non-Russian peoples | |||||

| Commanders and leaders | ||||||

|

Catherine the Great Grigory Potemkin Petr Panin Alexander Suvorov Johann von Michelsohnen |

Yemelyan Pugachev Salawat Yulayev |

|||||

| Strength | ||||||

| 5,000+ men[2] |

1773:

1774:

|

|||||

| Casualties and losses | ||||||

| 3,500 killed[2] |

|

Pugachev’s Rebellion (Russian: Восстание Пугачёва, Vosstaniye Pugachyova; also called the Peasants’ War 1773–1775 or Cossack Rebellion) of 1773–1775 was the principal revolt in a series of popular rebellions that took place in the Russian Empire after Catherine II seized power in 1762. It began as an organized insurrection of Yaik Cossacks headed by Yemelyan Pugachev, a disaffected ex-lieutenant of the Imperial Russian Army, against a background of profound peasant unrest and war with the Ottoman Empire. After initial success, Pugachev assumed leadership of an alternative government in the name of the late Tsar Peter III and proclaimed an end to serfdom. This organized leadership presented a challenge to the imperial administration of Catherine II.

The rebellion managed to consolidate support from various groups including the peasants, the Cossacks, and Old Believers priesthood. At one point, its administration claimed control over most of the territory between the Volga River and the Urals. One of the most significant events of the insurrection was the Battle of Kazan in July 1774.

Government forces failed to respond effectively to the insurrection at first, partly due to logistical difficulties and a failure to appreciate its scale. However, the revolt was crushed towards the end of 1774 by General Michelsohn at Tsaritsyn. Pugachev was captured soon after and executed in Moscow in January 1775. Further reprisals against rebel areas were carried out by General Peter Panin.

The events have generated many stories in legend and literature, most notably Pushkin’s historical novel The Captain’s Daughter (1836). It was the largest peasant revolt in the history of the Russian Empire.

Background and aims[edit]

As the Russian monarchy contributed to the degradation of the serfs, peasant anger ran high. Peter the Great ceded entire villages to favored nobles, while Catherine the Great confirmed the authority of the nobles over the serfs in return for the nobles’ political cooperation. The unrest intensified as the 18th century wore on, with more than fifty peasant revolts occurring between 1762 and 1769. These culminated in Pugachev’s Rebellion, when, between 1773 and 1775, Yemelyan Pugachev rallied the peasants and Cossacks and promised the serfs land of their own and freedom from their lords.

There were various pressures on Russian serfs during the 18th century, which induced them to follow Pugachev. The peasantry in Russia were no longer bound to the land, but tied to their owner. The connecting links that had existed between the peasant community and the tsar, which had been diminishing, was broken by the interposition of the serf owners; these private lords or agents of the Church or state who owned the land blocked serfs’ access to the political authority. Many nobles returned to their estates after 1762 and imposed harsher rules on their peasants. The relationship between peasant and ruler was cut off most dramatically in the decree of 1767, which completely prohibited direct petitions to the empress from the peasantry. The peasants were also subject to an increase in indirect taxes due to the increase in the state’s requirements. In addition, a strong inflationary trend resulted in higher prices on all goods.[4] The peasants felt abandoned by the «modern» state.[5] They were living in desperate circumstances and had no way to change their situation, having lost all possibilities for political redress.

There were natural disasters in Russia during the 18th century, which also added strain on the peasants. Frequent recurrence of crop failures, plagues and epidemics created economic and social instability. The most dramatic was the 1771 epidemic in Moscow, which brought to the surface all the unconscious and unfocused fears and panics of the populace.[6]

Each ruler altered the position of the Church, which created more pressure. Peter the Great gave the Church new obligations, while its administration assimilated to a department of the secular state. The Church’s resources, or the means of collection, could not meet the new obligations and as a consequence, they heavily exploited and poorly administered their serfs. The unrest spurred constant revolt among Church serfs.[6]

Leadership and strategy[edit]

Pugachev’s image according to folk memory and contemporary legends was one of a pretender-liberator. As Peter III, he was seen as Christ-like and saintly because he had meekly accepted his dethronement by his evil wife Catherine II and her courtiers. He had not resisted his overthrow, but had left to wander the world. He had come to help the revolt, but he did not initiate it; according to popular myth, the Cossacks and the people did that.[7]

The popular mythology of Peter III linked Pugachev with the Emancipation Manifesto of 1862 and the serf’s expectations of further liberalizations had he continued as ruler. Pugachev offered freedom from the poll tax and the recruit-levy, which made him appear to follow in the same vein as the emperor he was impersonating.

Pugachev attempted to reproduce the St. Petersburg bureaucracy. He established his own College of War with quite extensive powers and functions. It is important to emphasize that he did not promise complete freedom from taxation and recruitment for the peasants; he granted only temporary relief. His perception of the state was one where soldiers took the role of Cossacks, meaning they were free, permanent, military servicemen. Pugachev placed all other military personnel into this category as well, even the nobles and officers who joined his ranks. All peasants were seen as servants of the state, they were to become state peasants and serve as Cossacks in the militia. Pugachev envisioned the nobles returning to their previous status as the czar’s servicemen on salary instead of estate and serf owners. He emphasized the peasants’ freedom from the nobility. Pugachev still expected the peasants to continue their labor, but he granted them the freedom to work and own the land. They would also enjoy religious freedoms and Pugachev promised to restore the bond between the ruler and the people, eradicating the role of the noble as the intermediary.[8]

Under the guise of Peter III, Pugachev built up his own bureaucracy and army, which copied that of Catherine. Some of his top commanders took on the pseudonyms of dukes and courtiers. Zarubin Chaika, Pugachev’s top commander, for example, took the guise of Zakhar Chernyshev. The army Pugachev established, at least at the very top levels of command, also mimicked Catherine’s. The organizational structure Pugachev set up for his top command was extraordinary, considering Pugachev defected as an ensign from Catherine’s army. He built up his own War College and a fairly sophisticated intelligence network of messengers and spies. Even though Pugachev was illiterate, he recruited the help of local priests, mullahs, and starshins to write and disseminate his «royal decrees» or ukases in Russian and Tatar languages. These ukazy were copied, sent to villages and read to the masses by the priests and mullahs. In these documents, he begged the masses to serve him faithfully. He promised to grant to those who followed his service land, salt, grain, and lowered taxes, and threatened punishment and death to those who didn’t. For example, an excerpt from a ukase written in late 1773:

From me, such reward and investiture will be with money and bread compensation and with promotions: and you, as well as your next of kin will have a place in my government and will be designated to serve a glorious duty on my behalf. If there are those who forget their obligations to their natural ruler Peter III, and dare not carry out the command that my devoted troops are to receive weapons in their hands, then they will see for themselves my righteous anger, and will then be punished harshly.[9]

Recruitment and support[edit]

From the very beginning of the insurgency, Pugachev’s generals carried out mass recruitment campaigns in Tatar and Bashkir settlements, with the instructions of recruiting one member from every or every other household and as many weapons as they could secure. He recruited not only Cossacks, but Russian peasants and factory workers, Tatars, Bashkirs, and Chuvash. Famous Bashkir hero Salawat Yulayev joined him. Pugachev’s primary target for his campaign was not the people themselves, but their leaders. He recruited priests and mullahs to disseminate his decrees and read them to the masses as a way of lending them credence.

Priests in particular were instrumental figures in carrying out Pugachev’s propaganda campaigns. Pugachev was known to stage “heroic welcomes” whenever he entered a Russian village, in which he would be greeted by the masses as their sovereign. A few days before his arrival to a given city or village, messengers would be sent out to inform the priests and deacons in that town of his impending arrival. These messengers would request that the priests bring out salt and water and ring the church bells to signify his coming. The priests would also be instructed to read Pugachev’s manifestos during mass and sing prayers to the health of the Great Emperor Peter III. Most priests, although not all, complied with Pugachev’s requests. One secret report of Catherine’s War College, for example, tells of one such priest, Zubarev, who recruited for Pugachev in Church under such orders. “[Zubarev], believing in the slander-ridden decree of the villainous-imposter, brought by the villainous Ataman Loshkarev, read it publicly before the people in church. And when that ataman brought his band, consisting of 100 men, to their Baikalov village, then that Zubarev met them with a cross and with icons and chanted prayers in the Church; and then at the time of service, as well as after, evoked the name of the Emperor Peter III for suffrage.” (Pugachevshchina Vol. 2, Document 86. Author’s translation)

Pugachev’s army was composed of a diverse mixture of disaffected peoples in southern Russian society, most notably Cossacks, Bashkirs, homesteaders, religious dissidents (such as Old Believers) and industrial serfs. Pugachev was very much in touch with the local population’s needs and attitudes; he was a Don Cossack and encountered the same obstacles as his followers. It is noticeable that Pugachev’s forces always took routes that reflected the very regional and local concerns of the people making up his armies. For example, after the very first attack on Yaitsk, he turned not towards the interior, but instead turned east towards Orenburg which for most Cossacks was the most direct symbol of Russian oppression.

The heterogeneous population in Russia created special problems for the government, and it provided opportunities for those opposing the state and seeking support among the discontented, as yet unassimilated natives.[10] Each group of people had problems with the state, which Pugachev focused on in order to gain their support.

Non-Russians, such as the Bashkirs, followed Pugachev because they were promised their traditional ways of life, freedom of their lands, water and woods, their faith and laws, food, clothing, salaries, weapons and freedom from enserfment. (Madariaga, 250) Cossacks were similarly promised their old ways of life, the rights to the river Iaik (now the Ural River) from source to sea, tax-free pasturage, free salt, twelve chetvi of corn and 12 roubles per Cossack per year.[11]

Map of the Pugachev’s Rebellion

Pugachev found ready support among the odnodvortsy (single homesteaders). In the westernmost part of the region swept by the Pugachev rebellion, the right bank of the middle Volga, there were a number of odnodvortsy. These were descendants of petty military servicemen who had lost their military function and declined to the status of small, but free, peasants who tilled their own lands. Many of them were also Old Believers, and so felt particularly alienated from the state established by Peter the Great. They were hard-pressed by landowners from central provinces who were acquiring the land in their area and settling their serfs on it. These homesteaders pinned their hopes on the providential leader who promised to restore their former function and status.[12]

The network of Old Believer holy men and hermitages served to propagandize the appearance of Pugachev as Peter III and his successes, and they also helped him recruit his first followers among the Old Believer Cossack of the Iaik.[13]

The Iaik Cossack host was most directly and completely involved in the Pugachev revolt. Most of its members were Old Believers who had settled among the Iaik River. The Cossacks opposed the tide of rational modernization and the institutionalization of political authority. They regarded their relationship to the ruler as a special and personal one, based on their voluntary service obligations. In return, they expected the czar’s protection of their religion, traditional social organization, and administrative autonomy. They followed the promises of Pugachev and raised the standard of revolt in the hope of recapturing their previous special relationship and securing the government’s respect for their social and religious traditions.[14]

Factory workers supported Pugachev because their situation had worsened; many state-owned factories had been turned over to private owners, which intensified exploitation. These private owners stood as a barrier between the workers and the government; they inhibited appeals to the state for improvement of conditions. Also, with the loss of Russia’s competitive advantage on the world market, the production of the Ural mines and iron-smelting factories declined. This decline hit the workers the hardest because they had no other place to go or no other skill to market. There was enough material to support rebellion against the system. By and large the factories supported Pugachev, some voluntarily continuing to produce artillery and ammunition for the rebels.[15]

Challenge to the Russian state[edit]

In 1773 Pugachev’s army attacked Samara and occupied it. His greatest victory came with the taking of Kazan, by which time his captured territory stretched from the Volga to the Ural mountains. Though fairly well-organized for a revolt at the time, Pugachev’s main advantage early on was the lack of seriousness about Pugachev’s rebellion. Catherine the Great regarded the troublesome Cossack as a joke and put a small bounty of about 500 rubles on his head. But by 1774, the threat was more seriously addressed; by November the bounty was over 28,000 rubles. The Russian general Michelson lost many men due to a lack of transportation and discipline among his troops, while Pugachev scored several important victories.

Pugachev launched the rebellion in mid-September 1773. He had a substantial force composed of Cossacks, Russian peasants, factory serfs, and non-Russians with which he overwhelmed several outposts along the Iaik and early in October went into the capital of the region, Orenburg. While besieging this fortress, the rebels destroyed one government relief expedition and spread the revolt northward into the Urals, westward to the Volga, and eastward into Siberia. Pugachev’s groups were defeated in late March and early April 1774 by a second relief corps under General Bibikov, but Pugachev escaped to the southern Urals, Baskiria, where he recruited new supporters. Then, the rebels attacked the city of Kazan, burning most of it on July 23, 1774. Though beaten three times at Kazan by tsarist troops, Pugachev escaped by the Volga, and gathered new forces as he went down the west bank of the river capturing main towns. On September 5, 1774, Pugachev failed to take Tsaritsyn and was defeated in the steppe below that town. His closest followers betrayed him to the authorities. After a prolonged interrogation, Pugachev was publicly executed in Moscow on 21 January [O.S. 10 January] 1775.[16]

Indigenous involvement[edit]

Pugachev’s vague rhetoric inspired not only Cossacks and peasants to fight, but also indigenous tribes on the eastern frontier. These indigenous groups made up a comparatively small portion of those in revolt, but their role should not be underestimated. Each group had a distinct culture and history, which meant that their reasons for following Pugachev were different.

Bashkir riders from the Ural steppes

The Mordovians, Mari, Udmurts, and Chuvash (from the Volga and Kama basin) for example, joined the revolt because they were upset by Russian attempts to convert them to Orthodoxy. These groups lived within Russia’s borders, but held onto their language and culture. During the Pugachev Rebellion, these natives responded by assassinating Orthodox clergy members.[citation needed] Because the natives professed allegiance to Pugachev, the rebel leader had no choice but to implicitly condone their actions as part of his rebellion.[17]

The Tatars (from the Volga and Kama basin) were the indigenous group with the most complex political structure. They were most closely associated with Russian culture because they had lived within the empire’s borders since the 16th century. Many Tatars owned land or managed factories. As more integrated members of the Russian Empire, the Tatars rebelled in objection to the poll tax and their military and service obligations. The Tatars were closely associated with the Cossacks and were a crucial part of Pugachev’s recruitment efforts.