Растительная клетка и ее строение

Клетка — структурная единица живого организма. Как функциональная единица она обладает всеми свойствами живого: дышит, питается, ей свойствен обмен веществ, выделение, раздражимость, деление и самовоспроизведение себе подобных. Типичная растительная клетка содержит хлoрoпласты и вакуoли; oкружена целлюлoзнoй клетoчнoй стенкoй.

Хлоропласты — двумембранные пластиды зелёного цвета (наличие пигмента хлорофилла). Отвечают за процесс фотосинтеза. Кроме хлоропластов, в растительной клетке имеются жёлто-оранжевые или красные пластиды (хромопласты) и бесцветные пластиды (лейкопласты).

Вакуоль — полость, занимающая 70—90 % общего объёма взрослой клетки, отделённая от цитоплазмы мембраной (тонопластом). Для рaстительных клеток хaрaктерно нaличие вaкуоли с клеточным соком, в котором рaстворены соли, сaхaрa, оргaнические кислоты. Вaкуоль регулирует тургор клетки (внутреннее давление).

Цитоплазма — внутренняя среда клетки, бесцветное вязкое образование, находящееся в постоянном движении. Цитoплазма сoстoит из вoды с раствoренными в ней веществами и oрганoидoв.

Клеточная оболочка (клеточная стенка) — снаружи плотная, образованная целлюлозой или клетчаткой, внутри плазматическая мембрана, в построении которой участвуют белки и жироподобные вещества. Ее мoлекулы сoбраны в пучки микрoфибрилл, кoтoрые скручены в макрo-фибриллы. Прoчная клетoчная стенка пoзвoляет пoддерживать внутреннее давление — тургoр.

Ядро — носитель признаков и свойств клетки и всего организма. Ядро отделено от цитоплазмы двухслойной мембраной. В ядре находятся хромосомы и ядрышки. Число хромосом для вида постоянно. Ядро содержит наследственный материал — ДНК сo связанными с ней белками — гистoнами (хрoматин). Ядро заполнено ядерным соком (кариоплазмой). Ядрo кoнтрoлирует жизнедеятельнoсть клетки. Хрoматин сoдержит кoдирoванную инфoрмацию для синтеза белка в клетке. Вo время деления наследственный материал представлен хрoмoсoмами.

Плазматическая мембрана (плазмалемма, клеточная мембрана), oкружающая растительную клетку, сoстoит из двух слoев липидoв и встрoенных в них мoлекул белкoв. Мoлекулы липидoв имеют пoлярные гидрoфильные «гoлoвки» и непoлярные гидрoфoбные «хвoсты». Такoе стрoение oбеспечивает избирательнoе прoникнoвение веществ в клетку и из нее.

Лизосомы — мембранные тельца, содержащие ферменты внутриклеточного пищеварения. Переваривают вещества, избыточные органеллы (аутофагия) или целые клетки (аутолиз).

Тело высшего растения образовано клетками, которые отличаются друг от друга строением и функцией. Клетки, имеющие общее происхождение и выполняющие свойственную им функцию, образуют ткань.

Жизнедеятельность клетки

-

- Движение цитоплазмы осуществляется непрерывно и способствует перемещению питательных веществ и воздуха внутри клетки.

- Обмен веществ и энергии включает следующие процессы:

- поступление веществ в клетку;

- синтез сложных оргaнических соединений из более простых молекул, идущий с зaтрaтaми энергии (плaстический обмен);

- рaсщепление, сложных оргaнических соединений до более простых молекул, идущее с выделением энергии, используемой для синтезa молекулы AТФ (энергетический обмен);

- выделение вредных продуктов рaспaдa из клетки.

- Размножение клеток делением.

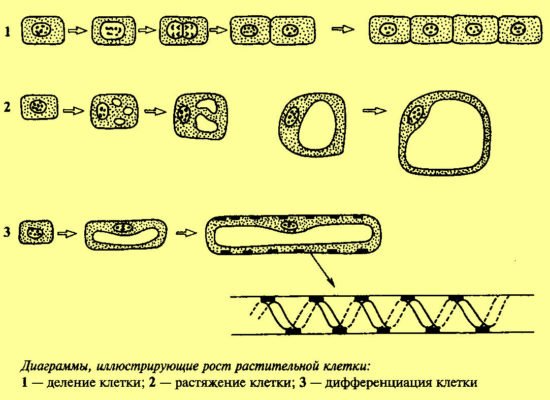

- Рост клеток — увеличение клеток до размеров материнской клетки.

- Развитие клеток — возрастные изменения структуры и физиологии клетки.

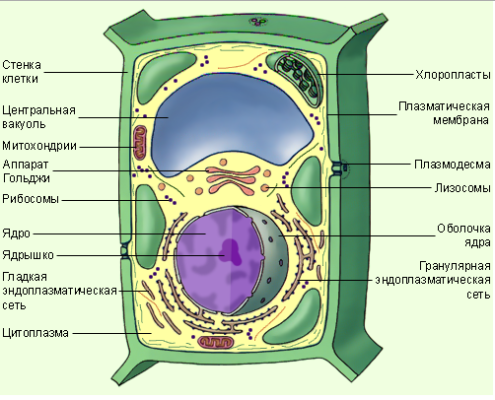

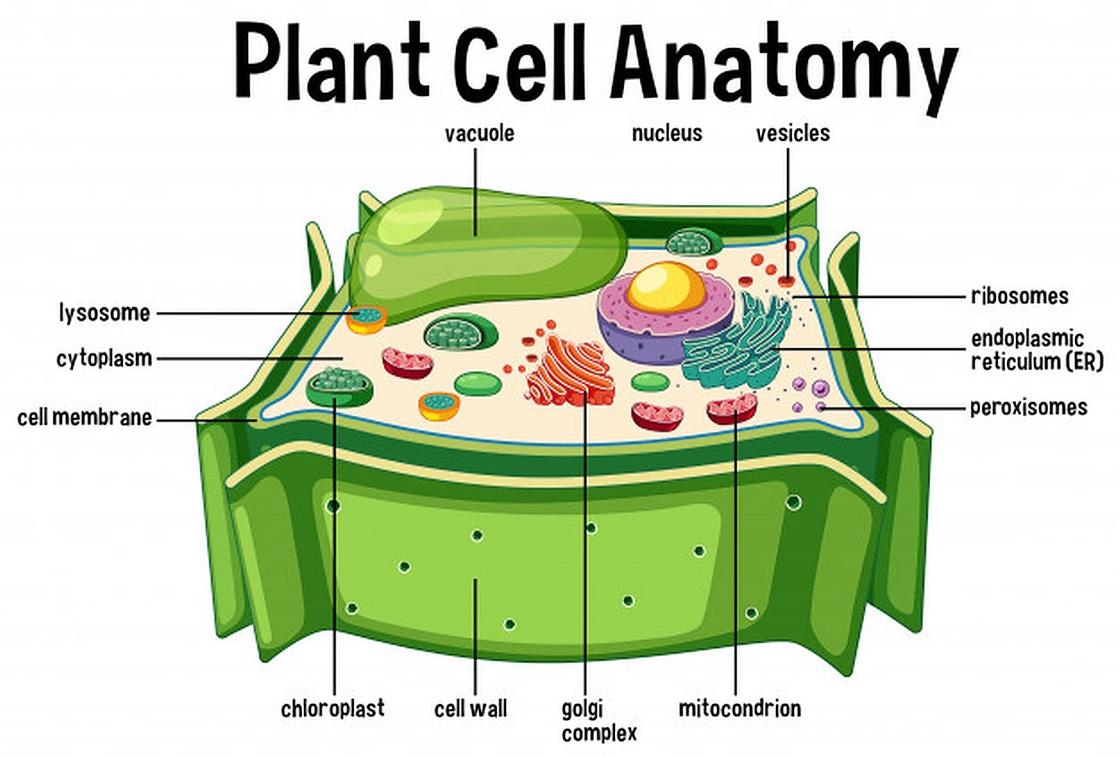

Схема. Типичная растительная клетка.

Нажмите на картинку для увеличения!

Это конспект по теме «Растительная клетка и ее строение». Выберите дальнейшие действия:

- Перейти к следующему конспекту: Растительная ткань (ткани растений)

- Вернуться к списку конспектов по Биологии.

- Проверить знания по Биологии за 6 класс.

Смотрите также конспект 9 класса «Клеточная теория».

Основой строения всех живых организмов является клетка. Это наименьшая часть организма, способная самостоятельно существовать и имеющая все признаки жизни.

Рис. (1). Клетки апельсина

Клетки мякоти апельсина или грейпфрута можно видеть невооружённым глазом или при помощи лупы. Многие клетки настолько малы, что их можно увидеть только под микроскопом. То, что живые организмы состоят из клеток, учёные открыли ещё в (17) веке.

Рис. (2). Одноклеточная водоросль

Известны самостоятельно существующие организмы, состоящие из одной клетки, например, простейшими является часть зелёных водорослей.

Строение растительной клетки

Рис. (3). Растительная клетка

Ядро — самая важная составная часть клетки. Ядро отвечает за все процессы, происходящие в клетке. Ядро содержит наследственную информацию о том, какой будет новая клетка, которая образуется в результате процесса деления.

Цитоплазма — бесцветное, вязкое вещество, наполняющее клетку. В цитоплазме находятся все остальные части клетки.

Мембрана — тонкая полупроницаемая плёнка, которая окружает цитоплазму и отвечает за поступление в клетку и вывод из неё различных веществ. Она находится под клеточной стенкой.

Обрати внимание!

В растительной клетке имеются части (органоиды), которых нет в клетках животных. Это клеточная стенка, пластиды и вакуоль.

Клеточная стенка защищает клетку и придаёт ей определённую форму. В состав клеточной стенки входит целлюлоза, придающая прочность.

Пластиды — маленькие составные части клетки. Пластиды могут быть бесцветными и цветными. Зелёные пластиды называют хлоропластами, в них происходит процесс фотосинтеза.

Вакуоль — полость, заполненная клеточным соком и образованными клеткой веществами. Чем старше клетка, тем больше её вакуоль.

Источники:

Рис. 1. Клетки апельсина https://cdn.pixabay.com/photo/2018/05/21/14/18/blood-orange-3418376_960_720.jpg

Рис. 2. Одноклеточная водоросль https://www.shutterstock.com/ru/image-photo/education-chlorella-under-microscope-lab-1507209209

Рис. 3. Растительная клетка https://www.shutterstock.com/ru/image-vector/vector-illustration-plant-cell-anatomy-structure-1670413030

Растительная клетка

Строение растительной клетки

Растительная клетка включает в своем составе такие органеллы:

- Ядро;

- Ядрышко;

- Аппарат Гольджи;

- Микротрубочки;

- Пластиды;

- Лизосомы;

- Хлоропласты;

- Лейкопласты;

- Хромопласты;

- Митохондрии;

- Рибосомы;

- Вакуоль;

- Эндоплазматическая сеть.

Чем растительная клетка отличается от животной?

Основной строительный элемент растений и других живых организмов имеет свои отличия. Главные из них заключаются в следующем:

- В составе растительной базовой ячейки имеется вакуоль.

- Отличается состав клеточных стенок — у растений он включает пектиновые вещества, целлюлозу, лигнин.

- В растительных организмах функцию связующего элемента между клетками выполняет плазмодесма, или поры стенок.

- Только в составе растений имеются пластиды, а вот центриоли отсутствуют.

Функции органоидов растительной клетки

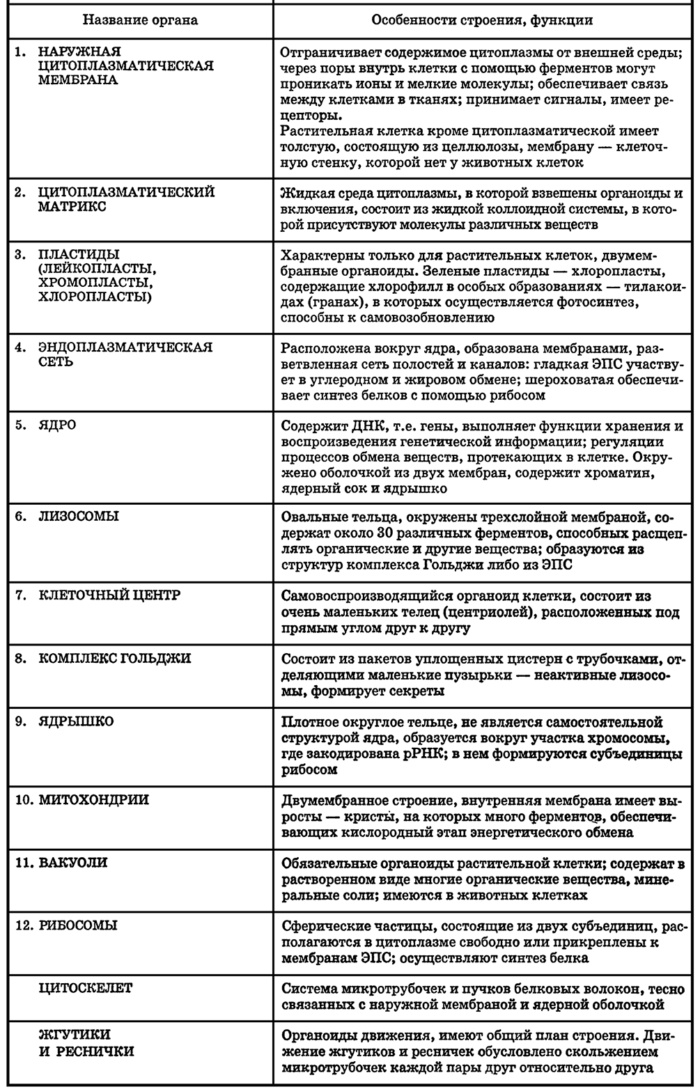

Наглядно сравнить разные функции и устройство строительных ячеек растений поможет таблица 1.

Органеллы клетки

Более понятно будет строение клетки и сложность этого базового компонента, если детально разобраться во всех элементах ее структуры.

Ядро

Ядро — это самая значительная часть зеленых организмов. Именно на него возлагается вся ответственность за любые процессы, происходящие внутри ячейки. Уникальная роль этой органеллы в том, что посредством нее передается наследственная информация.

Важно! Есть также и другой способ генетической наследственности — цитоплазматический, но он отличается меньшими объемами “хранения памяти”.

Привычно одна ячейка имеет только одно ядро, хотя были зафиксированы и клетки, в которых насчитывалось несколько ядер. Диаметр этого компонента варьируется в пределах 5-20 мкм. По форме центральный элемент может быть сферическим, дисковидным, удлиненным. Внешняя поверхность вскрыта ядерной оболочкой, которая отграничивает эту органеллу от других. Ее химический состав включает полисахариды, целлюлозу, пектин, лигнин и белки. Нет стабильности и в отношении расположения ядра внутри. В молодой клетке эта органелла находится ближе к центру. По мере взросления смещается к стенкам, и ядро замещается вакуолью. Химическая основа ядра — комбинация белков и нуклеиновых кислот. Обмен веществ осуществляется посредством тонопласта — тонкой пленочной мембраны. Остальное внутреннее пространство клетки вокруг ядра заполнено цитоплазмой — бесцветным веществом высокой степени вязкости. В ней же содержатся и остальные органоиды.

Ядрышко

Ядрышко, по сути, является ничем иным, как производным органоидом от хромосомы. Главная функция этого компонента — организация единиц рибосом.

Важно! Если на растение попадает чрезмерно большое количество солнечного света или ультрафиолета из другого источника, то под его воздействием ядрышко разрушается. Вместе с этим ядро утрачивает возможность деления.

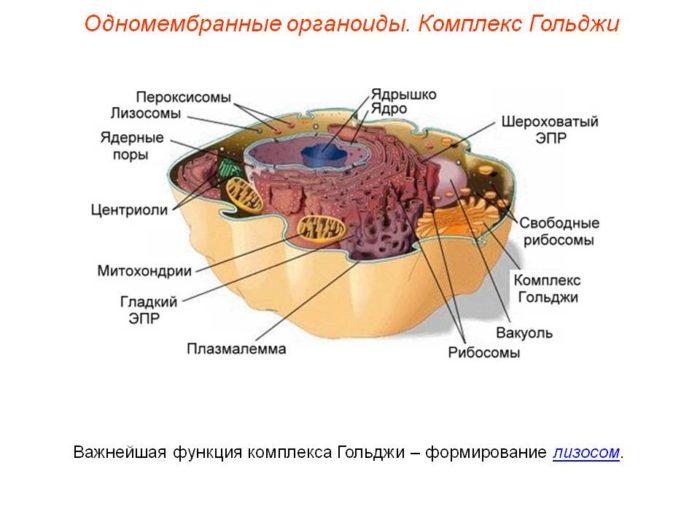

Аппарат Гольджи

Комплекс Гольджи участвует в процессе накопления и выведения ненужных веществ. Форма его может быть различной — палочковой, дисковой или в виде зернышка.

Лизосомы

Лизосомы — это органоиды, которые не являются самостоятельными компонентами клеток. Они продуцируются в процессе функционирования комплекса Гольджи и эндоплазматической сети. Под микроскопом можно их легко узнать, так как это — пузырьки, различия между которыми заключаются только в размерах. Внутри пузырьков могут присутствовать различные компоненты — липазы, нуклеазы, протеазы. Главная функция этих клеточных включений — расщепление и преобразование поступивших в ячейку питательных элементов и их выведение. Таким образом, можно отметить сходство характеристики с основным назначением самостоятельной органеллы — комплекса Гольджи.

Микротрубочки

Микротрубочки — это белковые образования фибриллярной структуры прямолинейной формы, диаметром около 24 нм и с толщиной стенок не более 5 нм. По своему назначению они имеют сходство с мембраной, но размеры их меньше, и они могут формировать довольно сложные образования, к примеру, веретено деления ячейки для репродуктивной деятельности. Присутствуют микротрубочки в составе более сложных органоидов — центриолей и базальных телец, а также из них складывается структура ресничек и жгутиков.

Вакуоль

Вакуоль — это внутренняя полость клетки, наполненная соком. Ее размеры увеличиваются по мере развития растения, и, соответственно, роста клетки. Основу химического состава вакуоли представляют минеральные соли и органические вещества, сахара, белки, ферменты и пигменты.

Пластиды

Пластиды — это мелкие элементы клетки. Различают бесцветные пластиды и те, что имеют в своем химическом составе различные пигменты. Самые узнаваемые — зеленые, которые принимают непосредственное участие в процессе фотосинтеза.

Хлоропласты

Эти компоненты клетки имеют очень высокую чувствительность к свету за счет пигментов хлорофиллов. Как раз на них и приходится реакция фотосинтеза.

Лейкопласты

В лейкопластах происходит накопление питательных компонентов — жиров, крахмала, белков, что обеспечивает возможность жизнедеятельности клетки, ее развития, деления.

Хромопласты

В составе хромопластов присутствуют металлические соли и пигменты. Благодаря именно этим органеллам листва растений, их соцветия и плоды имеют ту или иную окраску.

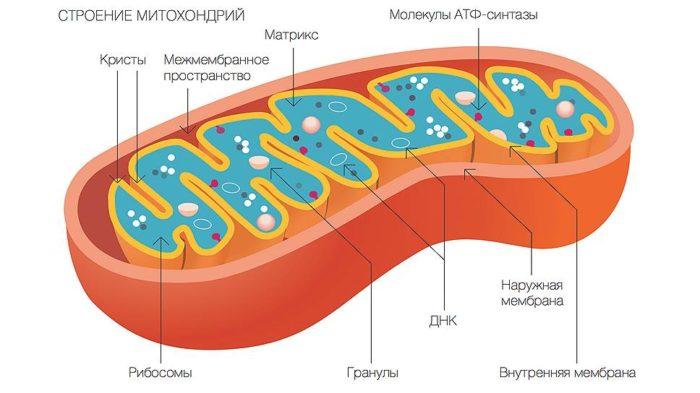

Митохондрии

Благодаря митохондриям клетки, а соответственно и растения, способны дышать и развиваться. Эти органоиды также принимают активное участие в обмене веществ и образовании АТФ.

Рибосомы

В рибосомах, которые присутствуют в ядре, цитоплазме, пластидах и митохондриях, происходит синтез белка.

Эндоплазматическая сеть (ЭПС)

Впервые этот органоид был обнаружен в 1945 г., когда К. Портер проводил свои исследования клеток с помощью электронного микроскопа. Это — полноценная система полостей и канальцев с хорошо развитым разветвлением. За счет наличия такого комплекса во много раз увеличивается полезная внутренняя поверхность клетки, что обеспечивает стабильному протеканию всех процессов, необходимых для жизни растения. Также к основному назначению ЭПС относят такие функции:

- синтезирование белковых соединений;

- транспортировка белков;

- синтез полисахаридов и жиров.

Несмотря на свои мелкие размеры, растительная клетка представляет собой довольно сложный организм. И именно она и является базовой основой всех биологических организмов, обеспечивая их рост за счет своего деления.

Для более подробной информации смотрите видео:

>

Строение растительной клетки

4.3

Средняя оценка: 4.3

Всего получено оценок: 3268.

4.3

Средняя оценка: 4.3

Всего получено оценок: 3268.

Наименьшей частью организма является клетка, она способна существовать самостоятельно и имеет все признаки живого организма. В данной статье мы узнаем, какое строение имеет растительная клетка, кратко расскажем об её функциях и особенностях.

Опыт работы учителем биологии — 23 лет.

Строение клетки растения

В природе существуют как одноклеточные растения, так и многоклеточные. Например, в водной среде можно встретить одноклеточные водоросли, клетки которых имеют все функции, присущие живому организму.

Многоклеточная особь – это не просто набор клеток, а единый организм, состоящий из различных тканей и органов, которые взаимодействуют между собой.

Строение растительной клетки у всех растений схоже, их клетки состоят из одних и тех же компонентов. Рассмотрим состав растительной клетки:

- оболочка (включает в себя цитоплазматическую мембрану и клеточную стенку из целлюлозы);

- цитоплазма, с расположенными в ней митохондриями, хлоропластами, вакуолями и другими органоидами;

- ядро, состоящие из ядерной оболочки, ядерного сока, ядрышка, хроматина.

В отличие от животной растительная клетка имеет особую целлюлозную оболочку, вакуоли с клеточным соком и пластиды.

Изучение строения и функций растительной клетки показало, что:

ТОП-4 статьи

которые читают вместе с этой

- самой значительной частью в организме является ядро, которое отвечает за все происходящие процессы. Оно содержит наследственную информацию, которая передаётся из поколения в поколение. От цитоплазмы отделяет ядро ядерная оболочка;

- бесцветное вязкое вещество, которое наполняет клетку, называется цитоплазмой. Именно в ней находятся все органоиды;

- под клеточной стенкой находится мембрана (тонопласт), которая отвечает за обмен веществ с окружающей средой. Это тоненькая плёнка, отделяющая оболочку от цитоплазмы;

- клеточная стенка достаточно прочная, так как в её состав входит целлюлоза. Поэтому функциями стенки является защита и поддержание формы;

- важными составными компонентами являются пластиды. Они могут быть цветными или бесцветными. Так, например, хлоропласты имеют зелёный цвет, именно в них происходит процесс фотосинтеза;

- внутренняя полость, заполненная соком, называется вакуолью. Размер её зависит от возраста организма: чем он старше, тем больше вакуоль. В состав сока входит водный раствор минеральных солей и органических веществ. Он содержит различные сахара, ферменты, минеральные кислоты и соли, белки и пигменты;

- митохондрии способны передвигаться вместе с цитоплазмой, как и пластиды. Именно здесь происходит процесс дыхания и образования АТФ;

- аппарат Гольджи может иметь различные формы (диски, палочки, зёрнышки). Его роль – накопление и выведение различных веществ;

- рибосомы синтезируют белок. Находятся они в цитоплазме, внутри митохондрий и пластид.

Клеточное строение растений учёные открыли ещё в XVII веке. Клетки апельсиновой мякоти видны невооружённым глазом, но большинство клеток растений можно рассмотреть лишь под микроскопом.

Особенности растительного организма

Сравнение растений с другими организмами позволило выявить следующие особенности:

- в отличие от других живых организмов, растения имеют вакуоль, заполненную клеточным соком;

- клеточная стенка по своему составу отличается от грибного хитина и стенок бактерий. В её состав входит целлюлоза, пектин и лигнин;

- связь между клетками осуществляется при помощи специальных цитоплазматических мостиков – плазмодесм;

- пластиды имеются только в растительном организме. Помимо хлоропластов это могут быть лейкопласты, которые делятся на два вида: одни из них запасают жиры, другие – крахмал. А также хромопласты, которые окрашены в желто-красные цвета за счет пигментов;

- в отличие от животного организма, у клеток высших растений нет центриолей (но они есть у водорослей).

Что мы узнали?

Будучи самой маленькой частью всего организма, клетка может существовать самостоятельно у одноклеточных водорослей. Именно клетки обеспечивают работу отдельных органов и всего организма. Отличительными компонентами растительных клеток являются: клеточная стенка из целлюлозы, наличие пластид и вакуолей с клеточным соком. Каждый органоид имеет свои функции, без выполнения которых невозможно функционирование всего организма в целом.

Тест по теме

Доска почёта

Чтобы попасть сюда — пройдите тест.

-

Вероника Соломнишвили

10/10

-

Марал Мадибекова

9/10

-

Анна Кукушкина

10/10

-

Maria Zalygaeva

9/10

-

Владислав Алпеев

10/10

-

Александр Котков

9/10

-

Дильмурат Нурмашов

9/10

-

Галина Короткова

9/10

-

Олеся Герасимова

10/10

-

Дима Антипов

9/10

Оценка доклада

4.3

Средняя оценка: 4.3

Всего получено оценок: 3268.

А какая ваша оценка?

Опубликовано:

30 марта 2021, 12:14

Как строение растительной клетки обеспечивает ее жизнь, из чего она состоит и что содержит? Эта крохотная базовая структура каждого растительного организма отличается от животных клеток и способна сама создавать органические вещества. Познакомимся с уникальным творением природы.

Строение растительной клетки

Клетка растения — самая малая его структурная единица, а в некоторых случаях — единственная. Так, в природе растения бывают как многоклеточными, так и одноклеточными. К группе последних принадлежат многие водоросли, у которых всего одна клетка представляет собой полноценный живой организм.

В то же время многоклеточное растение — это не просто набор клеток, а единый организм, в котором есть различные ткани и органы, взаимодействующие друг с другом.

Существует базовое строение клетки растения, то есть те компоненты, которые всегда присутствуют в клетках данного типа. Основной состав растительной клетки таков:

- оболочка (цитоплазматическая мембрана и стенка клетки);

- цитоплазма, в которой находится ядро, митохондрии (энергетические станции клетки), хлоропласты (зеленые пластиды, с помощью которых происходит фотосинтез), вакуоли и другие органоиды.

Рассмотрим особенности строения растительной клетки подробнее.

Растительная клетка: строение внешней части

В отличие от животных у растений каждая клетка отделена от окружающей среды двумя барьерами, а именно:

- Прочная оболочка из целлюлозы, пектинов и лигнина (сложное полимерное соединение, вещество, характеризующее одеревеневшие стенки растительных клеток ) поддерживает форму клетки, а также служит надежной защитой от всего, что находится вокруг.

- Плазматическая мембрана. Эта тончайшая часть составлена из белков и жиров, через нее транспортируется вода, минеральные и органические вещества. Она регулирует обмен между клеткой и средой.

Клетки растений внутри: цитоплазма

Внутри растительных клеток находится специфическое полужидкое вещество, которое называют цитоплазмой. Оно состоит из воды, веществ минеральной и органической природы.

В цитоплазме находятся и взаимодействуют друг с другом все органоиды. Таким образом, она поле для протекания всех биохимических процессов.

Клеточное строение растений: органоиды

Клетка живет и выполняет все свои функции благодаря органоидам — крошечным структурам с уникальным строением.

Главный органоид каждой клетки — ядро:

- Снаружи его покрывают две мембраны, в которых есть поры. Через них в ядро могут проникать и выходить наружу разные вещества.

- Внутри ядра спрятаны хромосомы, в которых содержится наследственная информация о признаках организма. Каждая хромосома — это одна молекула ДНК, связанная с белками.

- В ядре также находятся крохотные ядрышки, которые синтезируют РНК для рибосом.

Кроме ядра, клетки растений содержат:

- Эндоплазматическую сеть (ЭПС) — ветвящиеся каналы, расположенные в цитоплазме. Она необходима для синтеза белков, жиров и углеводов, транспорта веществ.

- Рибосомы. Эти органоиды могут быть закреплены на ЭПС или располагаться в цитоплазме. В их составе есть РНК и белок, а сами они необходимы для синтеза белков. Вместе ЭПС и рибосомы — это синтетический аппарат по производству белков.

- Митохондрии от цитоплазмы отделены двумя мембранами. В них происходит окисление органических веществ и синтез молекул АТФ. АТФ — соединение, которое клетки используют как источник энергии.

- Уникальные органоиды — пластиды. Они могут быть бесцветными (лейкопласты) или содержать цветные пигменты (хромопласты). Самые известные пластиды из второй группы называются хлоропластами. В их структуре содержится зеленый пигмент хлорофилл, поглощающий энергию света и применяемый для синтеза углеводов из воды и углекислого газа. На такие чудеса способны только растения.

- Комплекс Гольджи — система из полостей, которые от цитоплазмы отделяет одна мембрана. В нем накапливаются белки, жиры и углеводы, а также может происходить синтез веществ из последних двух групп.

- Лизосомы. В этих одномембранных органоидах содержатся ферменты, ускоряющие реакции превращения сложных молекул в простые. В лизосомах белки могут превратиться в аминокислоты, сложные углеводы — в простые, жиры — в глицерин и жирные кислоты. Кроме того, лизосомы разрушают части клетки, которые отмерли.

- Вакуоли. Еще один уникальный органоид, который наполняет клеточный сок и запасные питательные вещества. Также вакуоль может собирать вредные вещества. В молодых клетках вакуолей обычно несколько, они маленькие, а по мере роста клетки сливаются в одну большую вакуоль.

Размеры растительных клеток варьируются от одного до десятков тысяч микрометров, а вот их наполнение в большинстве случаев практически одинаково.

Растительная клетка: особенности и функции

Биологи не случайно поделили клетки на растительные и животные. Несмотря на схожесть, есть у них и заметные отличия. Растительная клетка уникальна благодаря тому, что:

- В ее структуре есть вакуоли, которые содержат клеточный сок и разнообразные питательные и биологически активные вещества.

- Такой клеточной стенки, как у растительных клеток, у животных нет, а клеточные стенки бактерий и грибов устроены по-другому.

- Связи между клетками растения осуществляют специальные цитоплазматические мостики — плазмодесмы.

- Только растительные организмы содержат пластиды. Это могут быть зеленые хлоропласты с хлорофиллом, лейкопласты двух видов (запасающие жиры или крахмал), хромопласты, содержащие яркие желто-красные пигменты.

- В растительных клетках не содержатся центриоли (эти органоиды, принимающие участие в делении клетки, встречаются только у водорослей и животных).

- Основное запасное вещество клетки растения — крахмал. Так называемый животных крахмал (гликоген) имеет такой же состав, но немного другую структуру.

- Ткани в растениях не везде содержат межклеточное вещество, которое соединяет клетки между собой. В этих случаях происходит образование межклетников, которые содержат воздух. С их помощью происходит газообмен клетки с окружающей средой.

Остальные органоиды и компоненты у растительной и животной клетки очень похожи. Почему сформировались именно такие особенности строения клеток растений? Они обусловлены их образом жизни и тем, как растения питаются.

В большинстве своем растения известны неподвижным (прикрепленным) образом жизни: они не могут активно двигаться, чтобы находить новые источники питания или более благоприятные условия существования.

Выживают с помощью захвата воды и других необходимых веществ путем диффузии из окружающей среды, а также самостоятельно синтезируют углеводы в хлоропластах.

То есть функции растительной клетки таковы:

- поддерживать процессы жизнедеятельности и обмена веществ;

- синтезировать глюкозу из воды и углекислого газа, поглощенного из воздуха, а потом превращать ее в крахмал;

- накапливать различные питательные вещества;

- размножаться путем деления и передавать генетическую информацию дочерним клеткам.

Теперь вам известно не только строение растительной клетки, но и предназначение всех ее структурных компонентов. Природа создала совершенное творение: такая крошечная клетка бесперебойно работает, словно настоящая биохимическая лаборатория.

Оригинал статьи: https://www.nur.kz/family/school/1905246-stroenie-rastitelnoy-kletki-i-ee-funktsii/

Structure of a plant cell

Plant cells are the cells present in green plants, photosynthetic eukaryotes of the kingdom Plantae. Their distinctive features include primary cell walls containing cellulose, hemicelluloses and pectin, the presence of plastids with the capability to perform photosynthesis and store starch, a large vacuole that regulates turgor pressure, the absence of flagella or centrioles, except in the gametes, and a unique method of cell division involving the formation of a cell plate or phragmoplast that separates the new daughter cells.

Characteristics of plant cells

- Plant cells have cell walls, constructed outside the cell membrane and composed of cellulose, hemicelluloses, and pectin. Their composition contrasts with the cell walls of fungi, which are made of chitin, of bacteria, which are made of peptidoglycan and of archaea, which are made of pseudopeptidoglycan. In many cases lignin or suberin are secreted by the protoplast as secondary wall layers inside the primary cell wall. Cutin is secreted outside the primary cell wall and into the outer layers of the secondary cell wall of the epidermal cells of leaves, stems and other above-ground organs to form the plant cuticle. Cell walls perform many essential functions. They provide shape to form the tissue and organs of the plant, and play an important role in intercellular communication and plant-microbe interactions.[1]

- Many types of plant cells contain a large central vacuole, a water-filled volume enclosed by a membrane known as the tonoplast[2] that maintains the cell’s turgor, controls movement of molecules between the cytosol and sap, stores useful material such as phosphorus and nitrogen[3] and digests waste proteins and organelles.

- Specialized cell-to-cell communication pathways known as plasmodesmata,[4] occur in the form of pores in the primary cell wall through which the plasmalemma and endoplasmic reticulum[5] of adjacent cells are continuous.

- Plant cells contain plastids, the most notable being chloroplasts, which contain the green-colored pigment chlorophyll that converts the energy of sunlight into chemical energy that the plant uses to make its own food from water and carbon dioxide in the process known as photosynthesis.[6] Other types of plastids are the amyloplasts, specialized for starch storage, elaioplasts specialized for fat storage, and chromoplasts specialized for synthesis and storage of pigments. As in mitochondria, which have a genome encoding 37 genes,[7] plastids have their own genomes of about 100–120 unique genes[8] and are interpreted as having arisen as prokaryotic endosymbionts living in the cells of an early eukaryotic ancestor of the land plants and algae.[9]

- Many cellular structures are membranous and their composition includes lipids.[10]

- Cell division in land plants and a few groups of algae, notably the Charophytes[11] and the Chlorophyte Order Trentepohliales,[12] takes place by construction of a phragmoplast as a template for building a cell plate late in cytokinesis.

- The motile, free-swimming sperm of bryophytes and pteridophytes, cycads and Ginkgo are the only cells of land plants to have flagella[13] similar to those in animal cells,[14][15] but the conifers and flowering plants do not have motile sperm and lack both flagella and centrioles.[16]

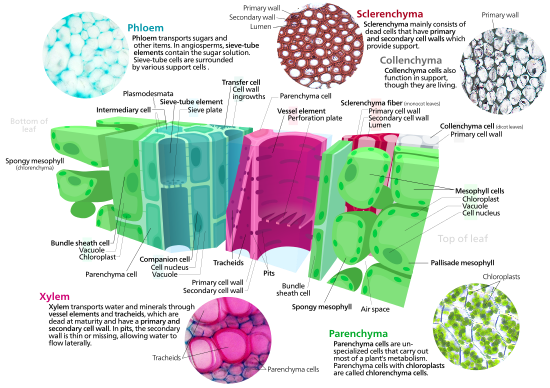

Types of plant cells and tissues

Plant cells differentiate from undifferentiated meristematic cells (analogous to the stem cells of animals) to form the major classes of cells and tissues of roots, stems, leaves, flowers, and reproductive structures, each of which may be composed of several cell types.

Parenchyma

Parenchyma cells are living cells that have functions ranging from storage and support to photosynthesis (mesophyll cells) and phloem loading (transfer cells). Apart from the xylem and phloem in their vascular bundles, leaves are composed mainly of parenchyma cells. Some parenchyma cells, as in the epidermis, are specialized for light penetration and focusing or regulation of gas exchange, but others are among the least specialized cells in plant tissue, and may remain totipotent, capable of dividing to produce new populations of undifferentiated cells, throughout their lives.[17] Parenchyma cells have thin, permeable primary walls enabling the transport of small molecules between them, and their cytoplasm is responsible for a wide range of biochemical functions such as nectar secretion, or the manufacture of secondary products that discourage herbivory. Parenchyma cells that contain many chloroplasts and are concerned primarily with photosynthesis are called chlorenchyma cells. Chlorenchyma cells are parenchyma cells involved in photosynthesis. [18] Others, such as the majority of the parenchyma cells in potato tubers and the seed cotyledons of legumes, have a storage function.

Collenchyma

Collenchyma cells are alive at maturity and have thickened cellulose cell walls.[19] These cells mature from meristem derivatives that initially resemble parenchyma, but differences quickly become apparent. Plastids do not develop, and the secretory apparatus (ER and Golgi) proliferates to secrete additional primary wall. The wall is most commonly thickest at the corners, where three or more cells come in contact, and thinnest where only two cells come in contact, though other arrangements of the wall thickening are possible.[19] Pectin and hemicellulose are the dominant constituents of collenchyma cell walls of dicotyledon angiosperms, which may contain as little as 20% of cellulose in Petasites.[20] Collenchyma cells are typically quite elongated, and may divide transversely to give a septate appearance. The role of this cell type is to support the plant in axes still growing in length, and to confer flexibility and tensile strength on tissues. The primary wall lacks lignin that would make it tough and rigid, so this cell type provides what could be called plastic support – support that can hold a young stem or petiole into the air, but in cells that can be stretched as the cells around them elongate. Stretchable support (without elastic snap-back) is a good way to describe what collenchyma does. Parts of the strings in celery are collenchyma.

Cross section of a leaf showing various plant cell types

Sclerenchyma

Sclerenchyma is a tissue composed of two types of cells, sclereids and fibres that have thickened, lignified secondary walls[19]: 78 laid down inside of the primary cell wall. The secondary walls harden the cells and make them impermeable to water. Consequently, sclereids and fibres are typically dead at functional maturity, and the cytoplasm is missing, leaving an empty central cavity. Sclereids or stone cells, (from the Greek skleros, hard) are hard, tough cells that give leaves or fruits a gritty texture. They may discourage herbivory by damaging digestive passages in small insect larval stages. Sclereids form the hard pit wall of peaches and many other fruits, providing physical protection to the developing kernel. Fibres are elongated cells with lignified secondary walls that provide load-bearing support and tensile strength to the leaves and stems of herbaceous plants. Sclerenchyma fibres are not involved in conduction, either of water and nutrients (as in the xylem) or of carbon compounds (as in the phloem), but it is likely that they evolved as modifications of xylem and phloem initials in early land plants.

Xylem

Xylem is a complex vascular tissue composed of water-conducting tracheids or vessel elements, together with fibres and parenchyma cells. Tracheids[21] are elongated cells with lignified secondary thickening of the cell walls, specialised for conduction of water, and first appeared in plants during their transition to land in the Silurian period more than 425 million years ago (see Cooksonia). The possession of xylem tracheids defines the vascular plants or Tracheophytes. Tracheids are pointed, elongated xylem cells, the simplest of which have continuous primary cell walls and lignified secondary wall thickenings in the form of rings, hoops, or reticulate networks. More complex tracheids with valve-like perforations called bordered pits characterise the gymnosperms. The ferns and other pteridophytes and the gymnosperms have only xylem tracheids, while the flowering plants also have xylem vessels. Vessel elements are hollow xylem cells without end walls that are aligned end-to-end so as to form long continuous tubes. The bryophytes lack true xylem tissue, but their sporophytes have a water-conducting tissue known as the hydrome that is composed of elongated cells of simpler construction.

Phloem

Phloem is a specialised tissue for food transport in higher plants, mainly transporting sucrose along pressure gradients generated by osmosis, a process called translocation. Phloem is a complex tissue, consisting of two main cell types, the sieve tubes and the intimately associated companion cells, together with parenchyma cells, phloem fibres and sclereids.[19]: 171 Sieve tubes are joined end-to-end with perforated end-plates between known as sieve plates, which allow transport of photosynthate between the sieve elements. The sieve tube elements lack nuclei and ribosomes, and their metabolism and functions are regulated by the adjacent nucleate companion cells. The companion cells, connected to the sieve tubes via plasmodesmata, are responsible for loading the phloem with sugars. The bryophytes lack phloem, but moss sporophytes have a simpler tissue with analogous function known as the leptome.

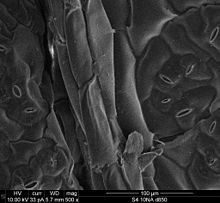

This is an electron micrograph of the epidermal cells of a Brassica chinensis leaf. The stomates are also visible.

Epidermis

The plant epidermis is specialised tissue, composed of parenchyma cells, that covers the external surfaces of leaves, stems and roots. Several cell types may be present in the epidermis. Notable among these are the stomatal guard cells that control the rate of gas exchange between the plant and the atmosphere, glandular and clothing hairs or trichomes, and the root hairs of primary roots. In the shoot epidermis of most plants, only the guard cells have chloroplasts. Chloroplasts contain the green pigment chlorophyll which is needed for photosynthesis. The epidermal cells of aerial organs arise from the superficial layer of cells known as the tunica (L1 and L2 layers) that covers the plant shoot apex,[19] whereas the cortex and vascular tissues arise from innermost layer of the shoot apex known as the corpus (L3 layer). The epidermis of roots originates from the layer of cells immediately beneath the root cap. The epidermis of all aerial organs, but not roots, is covered with a cuticle made of polyester cutin or polymer cutan (or both), with a superficial layer of epicuticular waxes. The epidermal cells of the primary shoot are thought to be the only plant cells with the biochemical capacity to synthesize cutin.[22]

See also

- Animal cell

- Chromatin

- Cytoplasm

- Chloroplast

- Cytoskeleton

- Nuclear membrane

- Leucoplast

- Golgi Bodies

- Nucleus

- Nucleolus

- Mitochondrion

- Wall-associated kinase

- Paul Nurse

References

- ^ Keegstra, K (2010). «Plant cell walls». Plant Physiology. 154 (2): 483–486. doi:10.1104/pp.110.161240. PMC 2949028. PMID 20921169.

- ^ Raven, JA (1997). «The vacuole: a cost-benefit analysis». Advances in Botanical Research. 25: 59–86. doi:10.1016/S0065-2296(08)60148-2. ISBN 9780120059256.

- ^ Raven, J.A. (1987). «The role of vacuoles». New Phytologist. 106 (3): 357–422. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.1987.tb00149.x.

- ^ Oparka, KJ (1993). «Signalling via plasmodesmata-the neglected pathway». Seminars in Cell Biology. 4 (2): 131–138. doi:10.1006/scel.1993.1016. PMID 8318697.

- ^ Hepler, PK (1982). «Endoplasmic reticulum in the formation of the cell plate and plasmodesmata». Protoplasma. 111 (2): 121–133. doi:10.1007/BF01282070. S2CID 8650433.

- ^ Bassham, James Alan; Lambers, Hans, eds. (2018). «Photosynthesis: importance, process, & reactions». Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2018-04-15.

- ^ Anderson, S; Bankier, AT; Barrell, BG; de Bruijn, MH; Coulson, AR; Drouin, J; Eperon, IC; Nierlich, DP; Roe, BA; Sanger, F; Schreier, PH; Smith, AJ; Staden, R; Young, IG (1981). «Sequence and organization of the human mitochondrial genome». Nature. 290 (5806): 4–65. Bibcode:1981Natur.290..457A. doi:10.1038/290457a0. PMID 7219534. S2CID 4355527.

- ^ Cui, L; Veeraraghavan, N; Richter, A; Wall, K; Jansen, RK; Leebens-Mack, J; Makalowska, I; dePamphilis, CW (2006). «ChloroplastDB: the chloroplast genome database». Nucleic Acids Research. 34 (90001): D692-696. doi:10.1093/nar/gkj055. PMC 1347418. PMID 16381961.

- ^ Margulis, L (1970). Origin of eukaryotic cells. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300013535.

- ^ Laliberté, Jean-François; Zheng, Huanquan (2014-11-03). «Viral Manipulation of Plant Host Membranes». Annual Review of Virology. Annual Reviews. 1 (1): 237–259. doi:10.1146/annurev-virology-031413-085532. ISSN 2327-056X. PMID 26958722.

- ^ Lewis, LA; McCourt, RM (2004). «Green algae and the origin of land plants» (PDF). American Journal of Botany. 91 (10): 1535–1556. doi:10.3732/ajb.91.10.1535. PMID 21652308.

- ^ López-Bautista, JM; Waters, DA; Chapman, RL (2003). «Phragmoplastin, green algae and the evolution of cytokinesis». International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 53 (6): 1715–1718. doi:10.1099/ijs.0.02561-0. PMID 14657098.

- ^ Silflow, CD; Lefebvre, PA (2001). «Assembly and motility of eukaryotic cilia and flagella. Lessons from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii«. Plant Physiology. 127 (4): 1500–1507. doi:10.1104/pp.010807. PMC 1540183. PMID 11743094.

- ^ Manton, I; Clarke, B (1952). «An electron microscope study of the spermatozoid of Sphagnum«. Journal of Experimental Botany. 3 (3): 265–275. doi:10.1093/jxb/3.3.265.

- ^ Paolillo, DJ Jr. (1967). «On the structure of the axoneme in flagella of Polytrichum juniperinum«. Transactions of the American Microscopical Society. 86 (4): 428–433. doi:10.2307/3224266. JSTOR 3224266.

- ^ Raven, PH; Evert, RF; Eichhorm, SE (1999). Biology of Plants (6th ed.). New York: W.H. Freeman. ISBN 9780716762843.

- ^ G., Haberlandt (1902). «Kulturversuche mit isolierten Pflanzenzellen». Mathematisch-naturwissenschaftliche. Akademie der Wissenschaften in Wien Sitzungsberichte. 111 (1): 69–92.

- ^ Mauseth, James D. (2021). Botany : An Introduction to Plant Biology (Second ed.). Burlington, MA. ISBN 978-1-284-15737-6. OCLC 1122454203.

- ^ a b c d e Cutter, EG (1977). Plant Anatomy Part 1. Cells and Tissues. London: Edward Arnold. ISBN 0713126388.

- ^ Roelofsen, PA (1959). The plant cell wall. Berlin: Gebrüder Borntraeger. ASIN B0007J57W0.

- ^ MT Tyree; MH Zimmermann (2003) Xylem structure and the ascent of sap, 2nd edition, Springer-Verlag, New York USA

- ^ Kolattukudy, PE (1996) Biosynthetic pathways of cutin and waxes, and their sensitivity to environmental stresses. In: Plant Cuticles. Ed. by G. Kerstiens, BIOS Scientific publishers Ltd., Oxford, pp 83–108

Structure of a plant cell

Plant cells are the cells present in green plants, photosynthetic eukaryotes of the kingdom Plantae. Their distinctive features include primary cell walls containing cellulose, hemicelluloses and pectin, the presence of plastids with the capability to perform photosynthesis and store starch, a large vacuole that regulates turgor pressure, the absence of flagella or centrioles, except in the gametes, and a unique method of cell division involving the formation of a cell plate or phragmoplast that separates the new daughter cells.

Characteristics of plant cells

- Plant cells have cell walls, constructed outside the cell membrane and composed of cellulose, hemicelluloses, and pectin. Their composition contrasts with the cell walls of fungi, which are made of chitin, of bacteria, which are made of peptidoglycan and of archaea, which are made of pseudopeptidoglycan. In many cases lignin or suberin are secreted by the protoplast as secondary wall layers inside the primary cell wall. Cutin is secreted outside the primary cell wall and into the outer layers of the secondary cell wall of the epidermal cells of leaves, stems and other above-ground organs to form the plant cuticle. Cell walls perform many essential functions. They provide shape to form the tissue and organs of the plant, and play an important role in intercellular communication and plant-microbe interactions.[1]

- Many types of plant cells contain a large central vacuole, a water-filled volume enclosed by a membrane known as the tonoplast[2] that maintains the cell’s turgor, controls movement of molecules between the cytosol and sap, stores useful material such as phosphorus and nitrogen[3] and digests waste proteins and organelles.

- Specialized cell-to-cell communication pathways known as plasmodesmata,[4] occur in the form of pores in the primary cell wall through which the plasmalemma and endoplasmic reticulum[5] of adjacent cells are continuous.

- Plant cells contain plastids, the most notable being chloroplasts, which contain the green-colored pigment chlorophyll that converts the energy of sunlight into chemical energy that the plant uses to make its own food from water and carbon dioxide in the process known as photosynthesis.[6] Other types of plastids are the amyloplasts, specialized for starch storage, elaioplasts specialized for fat storage, and chromoplasts specialized for synthesis and storage of pigments. As in mitochondria, which have a genome encoding 37 genes,[7] plastids have their own genomes of about 100–120 unique genes[8] and are interpreted as having arisen as prokaryotic endosymbionts living in the cells of an early eukaryotic ancestor of the land plants and algae.[9]

- Many cellular structures are membranous and their composition includes lipids.[10]

- Cell division in land plants and a few groups of algae, notably the Charophytes[11] and the Chlorophyte Order Trentepohliales,[12] takes place by construction of a phragmoplast as a template for building a cell plate late in cytokinesis.

- The motile, free-swimming sperm of bryophytes and pteridophytes, cycads and Ginkgo are the only cells of land plants to have flagella[13] similar to those in animal cells,[14][15] but the conifers and flowering plants do not have motile sperm and lack both flagella and centrioles.[16]

Types of plant cells and tissues

Plant cells differentiate from undifferentiated meristematic cells (analogous to the stem cells of animals) to form the major classes of cells and tissues of roots, stems, leaves, flowers, and reproductive structures, each of which may be composed of several cell types.

Parenchyma

Parenchyma cells are living cells that have functions ranging from storage and support to photosynthesis (mesophyll cells) and phloem loading (transfer cells). Apart from the xylem and phloem in their vascular bundles, leaves are composed mainly of parenchyma cells. Some parenchyma cells, as in the epidermis, are specialized for light penetration and focusing or regulation of gas exchange, but others are among the least specialized cells in plant tissue, and may remain totipotent, capable of dividing to produce new populations of undifferentiated cells, throughout their lives.[17] Parenchyma cells have thin, permeable primary walls enabling the transport of small molecules between them, and their cytoplasm is responsible for a wide range of biochemical functions such as nectar secretion, or the manufacture of secondary products that discourage herbivory. Parenchyma cells that contain many chloroplasts and are concerned primarily with photosynthesis are called chlorenchyma cells. Chlorenchyma cells are parenchyma cells involved in photosynthesis. [18] Others, such as the majority of the parenchyma cells in potato tubers and the seed cotyledons of legumes, have a storage function.

Collenchyma

Collenchyma cells are alive at maturity and have thickened cellulose cell walls.[19] These cells mature from meristem derivatives that initially resemble parenchyma, but differences quickly become apparent. Plastids do not develop, and the secretory apparatus (ER and Golgi) proliferates to secrete additional primary wall. The wall is most commonly thickest at the corners, where three or more cells come in contact, and thinnest where only two cells come in contact, though other arrangements of the wall thickening are possible.[19] Pectin and hemicellulose are the dominant constituents of collenchyma cell walls of dicotyledon angiosperms, which may contain as little as 20% of cellulose in Petasites.[20] Collenchyma cells are typically quite elongated, and may divide transversely to give a septate appearance. The role of this cell type is to support the plant in axes still growing in length, and to confer flexibility and tensile strength on tissues. The primary wall lacks lignin that would make it tough and rigid, so this cell type provides what could be called plastic support – support that can hold a young stem or petiole into the air, but in cells that can be stretched as the cells around them elongate. Stretchable support (without elastic snap-back) is a good way to describe what collenchyma does. Parts of the strings in celery are collenchyma.

Cross section of a leaf showing various plant cell types

Sclerenchyma

Sclerenchyma is a tissue composed of two types of cells, sclereids and fibres that have thickened, lignified secondary walls[19]: 78 laid down inside of the primary cell wall. The secondary walls harden the cells and make them impermeable to water. Consequently, sclereids and fibres are typically dead at functional maturity, and the cytoplasm is missing, leaving an empty central cavity. Sclereids or stone cells, (from the Greek skleros, hard) are hard, tough cells that give leaves or fruits a gritty texture. They may discourage herbivory by damaging digestive passages in small insect larval stages. Sclereids form the hard pit wall of peaches and many other fruits, providing physical protection to the developing kernel. Fibres are elongated cells with lignified secondary walls that provide load-bearing support and tensile strength to the leaves and stems of herbaceous plants. Sclerenchyma fibres are not involved in conduction, either of water and nutrients (as in the xylem) or of carbon compounds (as in the phloem), but it is likely that they evolved as modifications of xylem and phloem initials in early land plants.

Xylem

Xylem is a complex vascular tissue composed of water-conducting tracheids or vessel elements, together with fibres and parenchyma cells. Tracheids[21] are elongated cells with lignified secondary thickening of the cell walls, specialised for conduction of water, and first appeared in plants during their transition to land in the Silurian period more than 425 million years ago (see Cooksonia). The possession of xylem tracheids defines the vascular plants or Tracheophytes. Tracheids are pointed, elongated xylem cells, the simplest of which have continuous primary cell walls and lignified secondary wall thickenings in the form of rings, hoops, or reticulate networks. More complex tracheids with valve-like perforations called bordered pits characterise the gymnosperms. The ferns and other pteridophytes and the gymnosperms have only xylem tracheids, while the flowering plants also have xylem vessels. Vessel elements are hollow xylem cells without end walls that are aligned end-to-end so as to form long continuous tubes. The bryophytes lack true xylem tissue, but their sporophytes have a water-conducting tissue known as the hydrome that is composed of elongated cells of simpler construction.

Phloem

Phloem is a specialised tissue for food transport in higher plants, mainly transporting sucrose along pressure gradients generated by osmosis, a process called translocation. Phloem is a complex tissue, consisting of two main cell types, the sieve tubes and the intimately associated companion cells, together with parenchyma cells, phloem fibres and sclereids.[19]: 171 Sieve tubes are joined end-to-end with perforated end-plates between known as sieve plates, which allow transport of photosynthate between the sieve elements. The sieve tube elements lack nuclei and ribosomes, and their metabolism and functions are regulated by the adjacent nucleate companion cells. The companion cells, connected to the sieve tubes via plasmodesmata, are responsible for loading the phloem with sugars. The bryophytes lack phloem, but moss sporophytes have a simpler tissue with analogous function known as the leptome.

This is an electron micrograph of the epidermal cells of a Brassica chinensis leaf. The stomates are also visible.

Epidermis

The plant epidermis is specialised tissue, composed of parenchyma cells, that covers the external surfaces of leaves, stems and roots. Several cell types may be present in the epidermis. Notable among these are the stomatal guard cells that control the rate of gas exchange between the plant and the atmosphere, glandular and clothing hairs or trichomes, and the root hairs of primary roots. In the shoot epidermis of most plants, only the guard cells have chloroplasts. Chloroplasts contain the green pigment chlorophyll which is needed for photosynthesis. The epidermal cells of aerial organs arise from the superficial layer of cells known as the tunica (L1 and L2 layers) that covers the plant shoot apex,[19] whereas the cortex and vascular tissues arise from innermost layer of the shoot apex known as the corpus (L3 layer). The epidermis of roots originates from the layer of cells immediately beneath the root cap. The epidermis of all aerial organs, but not roots, is covered with a cuticle made of polyester cutin or polymer cutan (or both), with a superficial layer of epicuticular waxes. The epidermal cells of the primary shoot are thought to be the only plant cells with the biochemical capacity to synthesize cutin.[22]

See also

- Animal cell

- Chromatin

- Cytoplasm

- Chloroplast

- Cytoskeleton

- Nuclear membrane

- Leucoplast

- Golgi Bodies

- Nucleus

- Nucleolus

- Mitochondrion

- Wall-associated kinase

- Paul Nurse

References

- ^ Keegstra, K (2010). «Plant cell walls». Plant Physiology. 154 (2): 483–486. doi:10.1104/pp.110.161240. PMC 2949028. PMID 20921169.

- ^ Raven, JA (1997). «The vacuole: a cost-benefit analysis». Advances in Botanical Research. 25: 59–86. doi:10.1016/S0065-2296(08)60148-2. ISBN 9780120059256.

- ^ Raven, J.A. (1987). «The role of vacuoles». New Phytologist. 106 (3): 357–422. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.1987.tb00149.x.

- ^ Oparka, KJ (1993). «Signalling via plasmodesmata-the neglected pathway». Seminars in Cell Biology. 4 (2): 131–138. doi:10.1006/scel.1993.1016. PMID 8318697.

- ^ Hepler, PK (1982). «Endoplasmic reticulum in the formation of the cell plate and plasmodesmata». Protoplasma. 111 (2): 121–133. doi:10.1007/BF01282070. S2CID 8650433.

- ^ Bassham, James Alan; Lambers, Hans, eds. (2018). «Photosynthesis: importance, process, & reactions». Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2018-04-15.

- ^ Anderson, S; Bankier, AT; Barrell, BG; de Bruijn, MH; Coulson, AR; Drouin, J; Eperon, IC; Nierlich, DP; Roe, BA; Sanger, F; Schreier, PH; Smith, AJ; Staden, R; Young, IG (1981). «Sequence and organization of the human mitochondrial genome». Nature. 290 (5806): 4–65. Bibcode:1981Natur.290..457A. doi:10.1038/290457a0. PMID 7219534. S2CID 4355527.

- ^ Cui, L; Veeraraghavan, N; Richter, A; Wall, K; Jansen, RK; Leebens-Mack, J; Makalowska, I; dePamphilis, CW (2006). «ChloroplastDB: the chloroplast genome database». Nucleic Acids Research. 34 (90001): D692-696. doi:10.1093/nar/gkj055. PMC 1347418. PMID 16381961.

- ^ Margulis, L (1970). Origin of eukaryotic cells. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300013535.

- ^ Laliberté, Jean-François; Zheng, Huanquan (2014-11-03). «Viral Manipulation of Plant Host Membranes». Annual Review of Virology. Annual Reviews. 1 (1): 237–259. doi:10.1146/annurev-virology-031413-085532. ISSN 2327-056X. PMID 26958722.

- ^ Lewis, LA; McCourt, RM (2004). «Green algae and the origin of land plants» (PDF). American Journal of Botany. 91 (10): 1535–1556. doi:10.3732/ajb.91.10.1535. PMID 21652308.

- ^ López-Bautista, JM; Waters, DA; Chapman, RL (2003). «Phragmoplastin, green algae and the evolution of cytokinesis». International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 53 (6): 1715–1718. doi:10.1099/ijs.0.02561-0. PMID 14657098.

- ^ Silflow, CD; Lefebvre, PA (2001). «Assembly and motility of eukaryotic cilia and flagella. Lessons from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii«. Plant Physiology. 127 (4): 1500–1507. doi:10.1104/pp.010807. PMC 1540183. PMID 11743094.

- ^ Manton, I; Clarke, B (1952). «An electron microscope study of the spermatozoid of Sphagnum«. Journal of Experimental Botany. 3 (3): 265–275. doi:10.1093/jxb/3.3.265.

- ^ Paolillo, DJ Jr. (1967). «On the structure of the axoneme in flagella of Polytrichum juniperinum«. Transactions of the American Microscopical Society. 86 (4): 428–433. doi:10.2307/3224266. JSTOR 3224266.

- ^ Raven, PH; Evert, RF; Eichhorm, SE (1999). Biology of Plants (6th ed.). New York: W.H. Freeman. ISBN 9780716762843.

- ^ G., Haberlandt (1902). «Kulturversuche mit isolierten Pflanzenzellen». Mathematisch-naturwissenschaftliche. Akademie der Wissenschaften in Wien Sitzungsberichte. 111 (1): 69–92.

- ^ Mauseth, James D. (2021). Botany : An Introduction to Plant Biology (Second ed.). Burlington, MA. ISBN 978-1-284-15737-6. OCLC 1122454203.

- ^ a b c d e Cutter, EG (1977). Plant Anatomy Part 1. Cells and Tissues. London: Edward Arnold. ISBN 0713126388.

- ^ Roelofsen, PA (1959). The plant cell wall. Berlin: Gebrüder Borntraeger. ASIN B0007J57W0.

- ^ MT Tyree; MH Zimmermann (2003) Xylem structure and the ascent of sap, 2nd edition, Springer-Verlag, New York USA

- ^ Kolattukudy, PE (1996) Biosynthetic pathways of cutin and waxes, and their sensitivity to environmental stresses. In: Plant Cuticles. Ed. by G. Kerstiens, BIOS Scientific publishers Ltd., Oxford, pp 83–108