«Сектор Газа» – российская рок-группа, основанная в Воронеже в 1987 году Юрием Клинских. Лидер коллектива выступал под сценическим псевдонимом Хой. Он же является автором подавляющего большинства песен группы. Команда прекратила существование в 2000 году в связи со смертью лидера.

Творчество группы «Сектор Газа» оказало заметное влияние на молодежную субкультуру. Многие песни из её репертуара стали народными хитами и не утратили популярность по сей день. Наиболее известными для массового слушателя являются песни «Туман» и «Пора домой».

Название группы происходит от Левобережного района Воронежа, промышленной зоны с дымящими заводами. Местные в шутку прозвали его «сектором газа». Здесь же располагался воронежский рок-клуб.

История и становление группы

Официальной датой основания группы «Сектор Газа» считается 5 декабря 1987 года. В этот день Юрий Клинских выступил с сольным концертом на сцене воронежского рок-клуба. Однако первое электрическое выступление коллектива состоялось полгода спустя – 9 июня 1988 года в клубе при воронежской ТЭЦ.

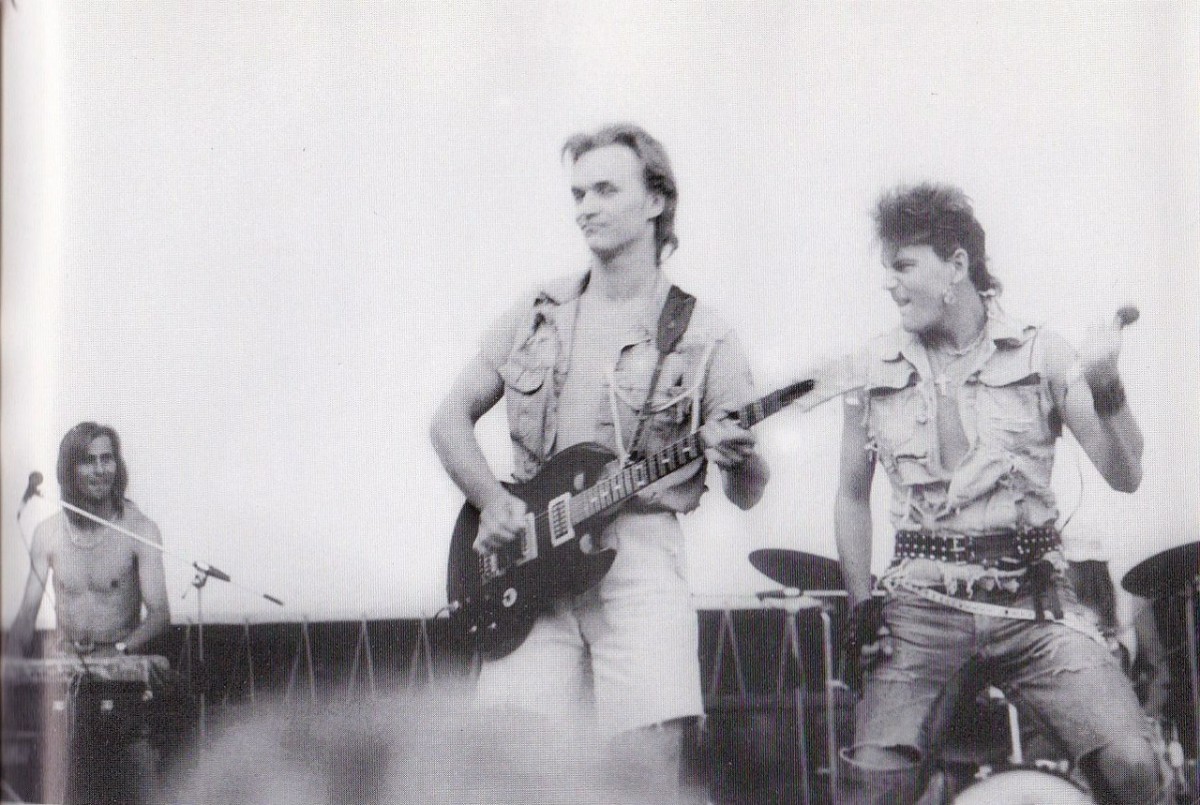

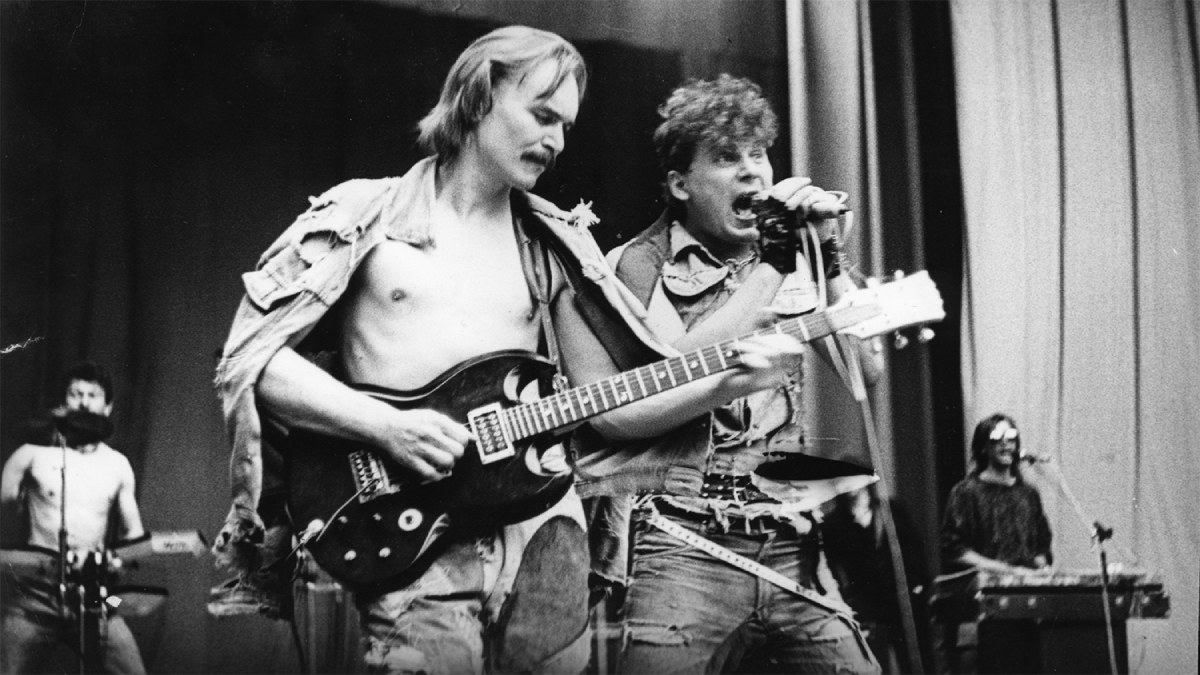

На первых порах концерты «Сектора Газа» фактически являлись сольниками Юрия Хоя. Время от времени он выступал с сессионными музыкантами. Первый стабильный состав группы сформировался к лету 1988 года. Помимо Клинских в него входили барабанщик Олег Крючков, бас-гитарист Семён Титиевский и гитарист Сергей Тупикин.

После начала активной концертной деятельности группа стремительно набирает популярность в родном Воронеже. В период с 1988 по 1990 год «Сектор Газа» принимает участие в фестивалях вместе с такими монстрами, как «Звуки Му» и «Гражданская Оборона». В апреле 1989 года команда впервые играет за пределами родного города – в Череповце, где отлично принимается публикой.

Приход популярности

В 1989 году «Сектор Газа» записывает первые магнитоальбомы – «Плуги-вуги» и «Колхозный панк». Название последнего прочно прилипает к коллективу и со временем часто используется для определения стиля команды. В 1990 году в группу приходит бек-вокалистка Татьяна Фатеева, вместе с которой записываются альбомы «Зловещие мертвецы» и «Ядрена вошь», благодаря которым к нашим героям и пришла известность.

Первые альбомы «Сектора Газа» быстро распространяются по стране через студии звукозаписи. Их оценивает и столичный бизнесмен Фидель Симонов, который фактически становится продюсером группы. Он оплачивает музыкантам московскую студию «Мир», где группа пишет альбом «Ночь перед Рождеством», после чего организует команде концерты.

Однако партнерство продолжается недолго, поскольку коммерческие интересы Симонова и Клинских не совпадают. В 1991 году группа знакомится с продюсером Сергеем Савиным, который помогает выпустить виниловую пластинку – «Колхозный панк», тираж которой составил 100 000 экземпляров.

В то же время «Сектор Газа» впервые попадает на Центральное телевидение. В молодежной программе «50х50» показывают клип «Колхозный панк», что существенно повышает интерес к творчеству группы. В ноябре команду Юрия Хоя снимает «Программа А» и выпускает во всероссийский эфир 20-минутный концерт с качественным звуком (посмотреть можно здесь).

Период стабильности

В первой половине 90-х годов «Сектор Газа» подписывает контракт с издающей компанией Gala records. Лейбл выпускает всю дискографию коллектива на магнитофонных кассетах и компакт-дисках. Также решается и проблема со студией – запись теперь полностью оплачивает издатель.

Параллельно студийной деятельности коллектив активно гастролирует. География выступлений охватывает не только Россию, но и сопредельные государства. В середине 90-х годов «Сектор Газа» является одной из самых востребованных рок-групп на всем постсоветском пространстве.

В 90-х годах один за другим выходят альбомы «Гуляй, мужик» (1992), «Нажми на газ» и «Сектор Газа» (1993), «Танцы после порева» и панк-опера «Кащей Бессмертный» (оба в 1994). После этого в студийной деятельности возникает пауза, а Юрий Клинских в это время переосмысливает творчество. В новых песнях он практически полностью отказывается от ненормативной лексики.

Последние годы

В 1996 году «Сектор Газа» выпускает альбом «Газовая атака». Вошедшая в него песня «Туман» становится всенародным хитом. Она и сейчас не утратила популярность. Сама же пластинка стала наиболее успешной в коммерческом плане во всей дискографии коллектива.

В 1997 году команда выпускат альбом «Наркологический университет миллионов», главным хитом которого становится песня «Пора домой». С этой композицией коллектив выступает на фестивале «Звуковая дорожка» в московских Лужниках, также в сборном концерте на Красной площади. Выступление проходит в День Победы 9 мая 1999 года.

Однако на деятельность группы в этот период оказывает сильное влияние финансовый кризис 1998 года. Компания Gala records закрывает российские проекты и приостанавливает сотрудничество с «Сектором Газа». Это приводит к необходимости сократить состав группы.

К 2000 году коллектив фактически распадается. Последний концерт «Сектора Газа» состоялся 25 июня 2000 года на малой спортивной арене «Лужники». Выступление прошло в рамках «Звуковой дорожки» «Московского комсомольца». Юрий Хой вышел на сцену один и под минусовую фонограмму исполнил песню «Демобилизация». Из-за технических проблем ему так и не удалось допеть её до конца.

4 июля 2000 года Юрий Хой скоропостижно скончался у себя дома в Воронеже. С его смертью прекратила существование и группа «Сектор Газа». Впоследствии её бывшие участники содавали ряд проектов-трибьютов, однако большой популярностью они не пользовались.

История «Сектора Газа» и яркого лидера Юры Хоя

«Сектор Газа» — легендарная воронежская рок-группа, лидером которой был не менее легендарный человек — Юрий Клинских (известный как Хой). За свою довольно продолжительную карьеру группа выпустила, без преувеличения, — массу хитов! Такие композиции, как «Ява», «30 лет», «Гуляй мужик», — стали народной классикой: многотысячная армия фанатов этой группы помнит каждую строчку, ведь под эти песни шла их юность и молодость…

К сожалению, в начале нулевых Юры Хоя не стало: это обернулось большим ударом для многих. Для поклонников его творчества это стало шокирующим моментом, ведь вместе с Хоем ушла целая эпоха так называемого «колхозного панка»…

С чего всё начиналось

Своё название группа получила от Левобережного района Воронежа: в народе его иронично называют «сектор газа», так как повсюду стоят дымящие заводы… Там же находился городской рок-клуб, к которому относился бэнд. Что касается Юры Хоя, а вернее — его псевдонима, то он возник от панковского клича «Хой», которым музыкант приветствовал толпу зрителей (и иногда других музыкантов).

Можно сказать, что будущее Клинских решила его встреча с Александром Кочергой: именно он и организовал воронежский рок-клуб на манер ленинградского. И да: он был просто восхищён тем, как Юрий исполняет знаменитые композиции «Кино» и других популярных в то время групп. Так, Ухват (псевдоним мужчины) подал своему новому знакомому идею создать собственный коллектив, и она зацепила Клинских… Уже в 1987 году появился «Сектора Газа»! Правда, это больше походило на сольный проект, нежели на группу… Состав был полностью сформирован лишь к концу десятилетия!

Группа выступала с приезжими коллективами (такими как «Звуки Му» и «Гражданская оборона»…). Постепенно у них сформировалась собственная фан-база…

Первые записи…

Первыми записями стали альбомы «Плуги-вуги» и «Колхозный панк». Но из-за низкого качества звука обе работы так и не снискали должного успеха… С наступлением 90-х появились и новые альбомы, записанные на этот раз в профессиональной воронежской студии «Black Box»: «Зловещие мертвецы» и «Ядрёна вошь». К слову: чтобы арендовать студию, Клинских продал свой мотоцикл «Ява»… Однако — оно того стоило! В этот же период в группе появляется новый участник, а вернее участница — Татьяна Фатеева (она проработает с группой ещё около трёх лет…)

Уникальный и привлекающий внимание стиль группы быстро нашёл своего слушателя! Но из-за отсутствия возможности выступать за пределами родного города, участники коллектива долгое время оставались в тени…

Настоящий успех!

Можно сказать, что успех группы начался с двух выше упомянутых альбомов: «Зловещие мертвецы» и «Ядрёна вошь». После их выпуска «Сектор Газа» привлёк внимание столичного бизнесмена Фиделя Симонова, который впоследствии организует им концерты… Однако позже их пути разойдутся, так как Хой не разделял алчные взгляды олигарха.

Когда группа начала работу над шедевром «Ночь перед Рождеством», её состав претерпел существенные изменения: сначала ушёл Олег Крючков, а затем был уволен Семён Титиевский. Вскоре группу покинул и Игорь Кущев… Но очень скоро в биографии группы начинается белая полоса! Хой знакомится с продюсером Сергеем Савиным, вскоре после чего начинается череда гастролей по городам… К слову: на тот момент поклонники понятия не имели, как выглядят их кумира. Из-за этого по стране колесили разные составы «Газа»: самозванцы пели под фонограмму и просто обманывали людей! Однажды Хой стал свидетелем сего «цирка»: он залез на сцену, чтобы лично разобраться с мошенниками, но тут же был избит…

Легендарный «Колхозный панк» принёс коллективу большой успех, а слушателям — ряд новых хитов! Изначально он вышел на «Мелодии»: его тираж составил 100 000 копий… А одноимённый клип часто ротировали на телевидении:

Уже к середине 1991 года популярность группы распространилась по всей России: группа вошла в топ-20 в рейтинге «Комсомольской правды», и уже к концу года стала его лидером!

Следующим альбомом стал «Гуляй, мужик!», параллельно которому группа активно гастролировала (за год Хой и его команда отыграли свыше 150-ти концертов!)

За следующие несколько лет коллективом было выпущено 3 альбом, среди которых — панк-опера «Кащей Бессмертный», мгновенно попавшая в десятку лучших страны! Альбом был тепло принят критиками, которые охарактеризовали как «молодой талантливый коллектив из глубинки»…

Как можно понять по названию, в основу альбома легла широко известная русская народная сказка (правда в интересной интерпретации)..

Переход от старого к новому…

Во второй половине 90-х группа заметно отошла от своего прежнего стиля в пользу более глубокой лирики… Группа также практически отказалась от ненормативной лексики в своём творчестве, что стало для преданных фанатов шоком! Результатом всего этого становится альбом «Газовая атака»: стоит отметить, что хоть и не сразу, но именно он стал самым коммерчески успешным альбомом группы. И это неудивительно: он породил такие культовые хиты, как «30 лет» и «Туман»! В этот же период коллектив Хоя становится лидером по продажам на территории России! Однако…

«Мы стали лидерами в России! Но мы даже не знаем, сколько денег принесли наши записи… В основном — продают пиратские кассеты, а не лицензионные, московские… И вот, мы популярны, и в то же время — мы имеем смешной мизер, на который кое-как умудряемся выживать…»

На закате карьеры «Сектор Газа» выпускает альбом «Наркологический университет миллионов», хит-треком с которого в миг становится «Пора домой»! Впоследствии эта композиция получит статус «народной»…

С этим хитом группа выступила в «Лужниках», на фестивале «Звуковая дорожка» и даже на Красной площади в честь Дня победы!

Творческий кризис и конец эпохи…

Под конец 90-х творческие идеи покинули Юрия Клинских… И, разумеется, это сказалось на группе: очень скоро в ней остались лишь гитарист и клавишник. Сотрудничество с «Gala Records» также прекратилось, хотя и не по вине Хоя. Дал о себе знать и кризис в России… Так, в этот период вышло всего 2 альбома: сборник «Баллады» и сборник ремиксов «Extasy»…

Группа продолжает гастролировать (они даже выступали в Германии!), однако финансовые трудности дают о себе знать… «Восставший из Ада» стал последней работой коллектива с Юрием Клинских, и вышел он уже после смерти культового лидера… Как отметили многие критики и слушатели, «Восставший из Ада» оказался тяжёлым и даже мрачным альбомом…

«Я всегда стремился вперёд, и я всегда хотел достичь тяжёлого звучания…» — говорил Юрий Хой при жизни.

Настало новое тысячелетие. Группа отыграла концерты в столице, а после — отправилась в Германию. Вернувшись на родину, никто из участников или фанатов не знал, что совсем скоро легенды не станет… Юрий Клинских в последний раз вышел на сцену малой спортивной арены «Лужники» 25 июня 2000 года. Он вышел один, как и в самом начале своей карьеры… Он исполнял коронный хит «Демобилизация», однако… уже после первого куплета стало ясно: он не закончит это выступление. И вскоре он ушёл… Насовсем. По неофициальным данным, музыкант страдал от гепатита, а также сильно увлекался запрещёнными веществами в последнее время… Его бездыханное тело было обнаружено в тот самый день, когда он должен был ехать на съёмки клипа «Ночь страха»… С его уходом завершилась и история его культового детища.

|

Gaza Strip قطاع غزة |

|

|---|---|

|

Palestinian flag |

|

|

|

| Status |

|

| Capital

and largest city |

Gaza City 31°31′N 34°27′E / 31.517°N 34.450°E |

| Official languages | Arabic |

| Ethnic groups | Palestinian |

| Demonym(s) | Gazan Palestinian |

| Area | |

|

• Total |

365 km2 (141 sq mi) |

| Population | |

|

• 2022 estimate |

2,375,259[2] |

|

• Density |

5,046/km2 (13,069.1/sq mi) |

| Currency |

|

| Time zone | UTC+2 (Palestine Standard Time) |

|

• Summer (DST) |

UTC+3 (Palestine Summer Time) |

| Calling code | +970 |

| ISO 3166 code | PS |

|

The Gaza Strip (;[3] Arabic: قِطَاعُ غَزَّةَ Qiṭāʿ Ġazzah [qɪˈtˤɑːʕ ˈɣaz.za], Hebrew: רצועת עזה, retsu’at azah), or simply Gaza, is a Palestinian exclave on the eastern coast of the Mediterranean Sea.[4] The smaller of the two Palestinian territories,[5] it borders Egypt on the southwest for 11 kilometers (6.8 mi) and Israel on the east and north along a 51 km (32 mi) border. Together, the Gaza Strip and the West Bank make up the State of Palestine, while being under Israeli military occupation since 1967.[6]

The territories of Gaza and the West Bank are separated from each other by Israeli territory. Both fell under the jurisdiction of the Palestinian Authority,[7] but the Strip is governed by Hamas, a militant, fundamentalist Islamic organization,[8] which came to power in the last-held elections in 2006. Since then, Gaza has been under a full Israeli-led land, sea and air blockade. This prevents people and goods from freely entering or leaving the territory.[9]

The Strip is 41 kilometers (25 mi) long, from 6 to 12 kilometers (3.7 to 7.5 mi) wide, and has a total area of 365 square kilometers (141 sq mi).[10][11] With around 2 million Palestinians[12] on some 365 square kilometers, Gaza, if considered a top-level political unit, ranks as the 3rd most densely populated in the world.[13][14] Sunni Muslims make up the predominant part of the population in the Gaza Strip. Gaza has an annual population growth rate of 2.91% (2014 est.), the 13th highest in the world, and is often referred to as overcrowded.[11][15] Gaza suffers from shortages of water, electricity and medicines. The United Nations, as well as at least 19 human rights organizations, have urged Israel to lift its siege on Gaza,[16][17] while a report by UNCTAD, prepared for the UN General Assembly and released on 25 November 2020, said that Gaza’s economy was on the verge of collapse and that it was essential to lift the blockade.[18][19]

When Hamas won a majority in the 2006 Palestinian legislative election, the opposing political party, Fatah, refused to join the proposed coalition, until a short-lived unity government agreement was brokered by Saudi Arabia. When this collapsed under pressure from Israel and the United States, the Palestinian Authority instituted a government without Hamas in the West Bank, while Hamas formed a government on its own in Gaza.[20] Further economic sanctions were imposed by Israel and the European Quartet against Hamas. A brief civil war between the two Palestinian groups had broken out in Gaza when Fatah contested Hamas’s administration. Hamas emerged the victor and expelled Fatah-allied officials and members of the PA’s security apparatus from the strip,[21][22] and has remained the sole governing power in Gaza since that date.[20] Israel stopped issuing permits for Gazans to work in Israel in 2007 after Hamas took control. In 2007, more than 100,000 Gazans worked in Israel. In 2021, however, it began granting them again in a search for stability following an 11-day war with Hamas.[23] In 2022 Defense Minister Benny Gantz decided to issue an additional 1,500 work permits for a total of 17,000 and aims to increase it to 20,000.[24][25]

Gaza Strip, with borders and Israeli limited fishing zone.

Despite the 2005 Israeli disengagement from Gaza,[26] the United Nations, international human rights organisations, and the majority of governments and legal commentators consider the territory to be still occupied by Israel, supported by additional restrictions placed on Gaza by Egypt. Israel maintains direct external control over Gaza and indirect control over life within Gaza: it controls Gaza’s air and maritime space, as well as six of Gaza’s seven land crossings. It reserves the right to enter Gaza at will with its military and maintains a no-go buffer zone within the Gaza territory. Gaza is dependent on Israel for water, electricity, telecommunications, and other utilities.[26] An extensive Israeli buffer zone within the Strip renders much land off-limits to Gaza’s Palestinians.[27] The system of control imposed by Israel was described in the Fall 2012 edition of International Security as an «indirect occupation».[28]

Beit Hanoun region of Gaza in August 2014, after Israeli bombardments.

History

Gaza was part of the Ottoman Empire, before it was occupied by the United Kingdom (1918–1948), Egypt (1948–1967), and then Israel, which in 1993 granted the Palestinian Authority in Gaza limited self-governance through the Oslo Accords. Since 2007, the Gaza Strip has been de facto governed by Hamas, which claims to represent the State of Palestine and the Palestinian people.

The territory is still considered to be occupied by Israel by the United Nations, international human rights organisations, and the majority of governments and legal commentators, despite the 2005 Israeli disengagement from Gaza.[26] Israel maintains direct external control over Gaza and indirect control over life within Gaza: it controls Gaza’s air and maritime space, and six of Gaza’s seven land crossings. It reserves the right to enter Gaza at will with its military and maintains a no-go buffer zone within the Gaza territory. Gaza is dependent on Israel for its water, electricity, telecommunications, and other utilities.[26]

The Gaza Strip acquired its current northern and eastern boundaries at the cessation of fighting in the 1948 war, confirmed by the Israel–Egypt Armistice Agreement on 24 February 1949.[29] Article V of the Agreement declared that the demarcation line was not to be an international border. At first the Gaza Strip was officially administered by the All-Palestine Government, established by the Arab League in September 1948. All-Palestine in the Gaza Strip was managed under the military authority of Egypt, functioning as a puppet state, until it officially merged into the United Arab Republic and dissolved in 1959. From the time of the dissolution of the All-Palestine Government until 1967, the Gaza Strip was directly administered by an Egyptian military governor.

Israel captured the Gaza Strip from Egypt in the Six-Day War in 1967. Pursuant to the Oslo Accords signed in 1993, the Palestinian Authority became the administrative body that governed Palestinian population centers while Israel maintained control of the airspace, territorial waters and border crossings with the exception of the land border with Egypt which is controlled by Egypt. In 2005, Israel withdrew from the Gaza Strip under their unilateral disengagement plan.

In July 2007, after winning the 2006 Palestinian legislative election, Hamas became the elected government.[30][31] In 2007, Hamas expelled the rival party Fatah from Gaza.[32] This broke the Unity Government between Gaza Strip and the West Bank, creating two separate governments for the Occupied Palestinian Territories.

In 2014, following reconciliation talks, Hamas and Fatah formed a Palestinian unity government within the West Bank and Gaza. Rami Hamdallah became the coalition’s Prime Minister and has planned for elections in Gaza and the West Bank.[33] In July 2014, a set of lethal incidents between Hamas and Israel led to the 2014 Israel–Gaza conflict. The Unity Government dissolved on 17 June 2015 after President Abbas said it was unable to operate in the Gaza Strip.

Following the takeover of Gaza by Hamas, the territory has been subjected to a blockade, maintained by Israel and Egypt.[34] Israel maintains that this is necessary: to impede Hamas from rearming and to restrict Palestinian rocket attacks; Egypt maintains that it prevents Gaza residents from entering Egypt. The blockades by Israel and Egypt extended to drastic reductions in the availability of necessary construction materials, medical supplies, and foodstuffs following intensive airstrikes on Gaza City in December 2008. A leaked UN report in 2009 warned that the blockade was «devastating livelihoods» and causing gradual «de-development». It pointed out that glass was prohibited by the blockade.[35][36][37][38][39] Under the blockade, Gaza is viewed by some critics as an «open-air prison»,[40] although the claim is contested.[41] In a report submitted to the UN in 2013, the chairperson of Al Athar Global Consulting in Gaza, Reham el Wehaidy, encouraged the repair of basic infrastructure by 2020, in the light of projected demographic increase of 500,000 by 2020 and intensified housing problems.[42]

Prior to 1923

British artillery battery in front of Gaza, 1917

The earliest major settlements in the area was at Tell El Sakan and Tell al-Ajjul, two Bronze Age settlements that served as administrative outposts for Ancient Egyptian governance. The city of City already existed under the Philistines, and the early city was captured by Alexander the Great in 332 BCE during his Egyptian campaign. Following the death of Alexander, Gaza, along with Egypt, fell under the administration of the Ptolemaic dynasty, before passing to the Seleucid dynasty after about 200 BCE. The city of Gaza was destroyed by the Hasmonean king and Jewish high priest Alexander Jannaeus in 96 BCE, and re-established under Roman administration during the 1st century CE. The region that today forms the Gaza Strip was moved between different Roman provinces over time, from Judea to Syria Palaestina to Palaestina Prima. During the 7th century CE, the territory was passed back and forth between the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire and the Persian (Sasanian) Empires, before the Rashidun Caliphate was established during the great Islamic expansions of the 7th century.[citation needed]

During the Crusades, the city of Gaza was reported to be mostly abandoned and in ruins; the region was placed under the direct administration of the Knights Templar during the time of the Kingdom of Jerusalem; it changed hands back and forth several times between Christian and Muslim rule during the 12th century, before the Crusader-founded kingdom lost control permanently over it and the land became part of Egypt’s Ayyubid dynasty’s lands for a century, until the Mongol ruler Hulagu Khan destroyed the city. In the wake of the Mongols, the Mamluk Sultanate established control over Egypt and the eastern Levant, and would control Gaza until the 16th century, when the Ottoman Empire absorbed the Mamluk territories. Ottoman rule continued until the years following World War I, when the Ottoman Empire collapsed and Gaza formed part of the League of Nations British Mandate of Palestine.[citation needed]

1923–1948 British Mandate

The British Mandate for Palestine was based on the principles contained in Article 22 of the draft Covenant of the League of Nations and the San Remo Resolution of 25 April 1920 by the principal Allied and associated powers after the First World War.[43] The mandate formalized British rule in the southern part of Ottoman Syria from 1923–1948.

1948 All-Palestine government

On 22 September 1948, towards the end of the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, the All-Palestine Government was proclaimed in the Egyptian-occupied Gaza City by the Arab League. It was conceived partly as an Arab League attempt to limit the influence of Transjordan in Palestine. The All-Palestine Government was quickly recognized by six of the then seven members of the Arab League: Egypt, Syria, Lebanon, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, and Yemen, but not by Transjordan.[44] It was not recognized by any country outside the Arab League.

After the cessation of hostilities, the Israel–Egypt Armistice Agreement of 24 February 1949 established the separation line between Egyptian and Israeli forces, and set what became the present boundary between the Gaza Strip and Israel. Both sides declared that the boundary was not an international border. The southern border with Egypt continued to be the international border drawn in 1906 between the Ottoman Empire and the British Empire.[45]

Palestinians living in the Gaza Strip or Egypt were issued All-Palestine passports. Egypt did not offer them citizenship. From the end of 1949, they received aid directly from UNRWA. During the Suez Crisis (1956), the Gaza Strip and the Sinai Peninsula were occupied by Israeli troops, who withdrew under international pressure. The government was accused of being little more than a façade for Egyptian control, with negligible independent funding or influence. It subsequently moved to Cairo and dissolved in 1959 by decree of Egyptian President Gamal Abdul Nasser.

1959–1967 Egyptian occupation

After the dissolution of the All-Palestine Government in 1959, under the excuse of pan-Arabism, Egypt continued to occupy the Gaza Strip until 1967. Egypt never annexed the Gaza Strip, but instead treated it as a controlled territory and administered it through a military governor.[46] The influx of over 200,000 refugees from former Mandatory Palestine, roughly a quarter of those who fled or were expelled from their homes during, and in the aftermath of, the 1948 Arab–Israeli War into Gaza[47] resulted in a dramatic decrease in the standard of living. Because the Egyptian government restricted movement to and from the Gaza Strip, its inhabitants could not look elsewhere for gainful employment.[48]

1967 Israeli occupation

In June 1967, during the Six-Day War, Israel Defense Forces captured the Gaza Strip.

According to Tom Segev, moving the Palestinians out of the country had been a persistent element of Zionist thinking from early times.[49] In December 1967, during a meeting at which the Security Cabinet brainstormed about what to do with the Arab population of the newly occupied territories, one of the suggestions Prime Minister Levi Eshkol proffered regarding Gaza was that the people might leave if Israel restricted their access to water supplies, stating: «Perhaps if we don’t give them enough water they won’t have a choice.»[50][51][undue weight? – discuss] A number of measures, including financial incentives, were taken shortly afterwards to begin to encourage Gazans to emigrate elsewhere.[49][52]

Subsequent to this military victory, Israel created the first settlement bloc in the Strip, Gush Katif, in the southwest corner near Rafah and the Egyptian border on a spot where a small kibbutz had previously existed for 18 months between 1946–48.[54] In total, between 1967 and 2005, Israel established 21 settlements in Gaza, comprising 20% of the total territory.

The economic growth rate from 1967 to 1982 averaged roughly 9.7 percent per annum, due in good part to expanded income from work opportunities inside Israel, which had a major utility for the latter by supplying the country with a large unskilled and semi-skilled workforce. Gaza’s agricultural sector was adversely affected as one-third of the Strip was appropriated by Israel, competition for scarce water resources stiffened, and the lucrative cultivation of citrus declined with the advent of Israeli policies, such as prohibitions on planting new trees and taxation that gave breaks to Israeli producers, factors which militated against growth. Gaza’s direct exports of these products to Western markets, as opposed to Arab markets, was prohibited except through Israeli marketing vehicles, in order to assist Israeli citrus exports to the same markets. The overall result was that large numbers of farmers were forced out of the agricultural sector. Israel placed quotas on all goods exported from Gaza, while abolishing restrictions on the flow of Israeli goods into the Strip. Sara Roy characterised the pattern as one of structural de-development.[55]

1979 Egypt–Israel peace treaty

On 26 March 1979, Israel and Egypt signed the Egypt–Israel peace treaty.[56] Among other things, the treaty provided for the withdrawal by Israel of its armed forces and civilians from the Sinai Peninsula, which Israel had captured during the Six-Day War. The Egyptians agreed to keep the Sinai Peninsula demilitarized. The final status of the Gaza Strip, and other relations between Israel and Palestinians, was not dealt with in the treaty. Egypt renounced all territorial claims to territory north of the international border. The Gaza Strip remained under Israeli military administration. The Israeli military became responsible for the maintenance of civil facilities and services.

After the Egyptian–Israeli Peace Treaty 1979, a 100-meter-wide buffer zone between Gaza and Egypt known as the Philadelphi Route was established. The international border along the Philadelphi corridor between Egypt and the Gaza Strip is 7 miles (11 km) long.

In September 1992, Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin told a delegation from the Washington Institute for Near East Policy «I would like Gaza to sink into the sea, but that won’t happen, and a solution must be found.»[57]

In May 1994, following the Palestinian-Israeli agreements known as the Oslo Accords, a phased transfer of governmental authority to the Palestinians took place. Much of the Strip (except for the settlement blocs and military areas) came under Palestinian control. The Israeli forces left Gaza City and other urban areas, leaving the new Palestinian Authority to administer and police those areas. The Palestinian Authority, led by Yasser Arafat, chose Gaza City as its first provincial headquarters. In September 1995, Israel and the PLO signed a second peace agreement, extending the Palestinian Authority to most West Bank towns.

Between 1994 and 1996, Israel built the Israeli Gaza Strip barrier to improve security in Israel. The barrier was largely torn down by Palestinians at the beginning of the Al-Aqsa Intifada in September 2000.[58]

View of Gaza during the 2000s.

2000 Second Intifada

The Second Intifada broke out in September 2000 with waves of protest, civil unrest and bombings against Israeli military and civilians, many of them perpetrated by suicide bombers. The Second Intifada also marked the beginning of rocket attacks and bombings of Israeli border localities by Palestinian guerrillas from the Gaza Strip, especially by the Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad movements.

Between December 2000 and June 2001, the barrier between Gaza and Israel was reconstructed. A barrier on the Gaza Strip-Egypt border was constructed starting in 2004.[59] The main crossing points are the northern Erez Crossing into Israel and the southern Rafah Crossing into Egypt. The eastern Karni Crossing used for cargo, closed down in 2011.[60] Israel controls the Gaza Strip’s northern borders, as well as its territorial waters and airspace. Egypt controls Gaza Strip’s southern border, under an agreement between it and Israel.[61] Neither Israel or Egypt permits free travel from Gaza as both borders are heavily militarily fortified. «Egypt maintains a strict blockade on Gaza in order to isolate Hamas from Islamist insurgents in the Sinai.»[62]

2005 Israel’s unilateral disengagement

In February 2005, the Knesset approved a unilateral disengagement plan and began removing Israeli settlers from the Gaza Strip in 2005. All Israeli settlements in the Gaza Strip and the joint Israeli-Palestinian Erez Industrial Zone were dismantled, and 9,000 Israelis, most living in Gush Katif, were forcibly evicted.

On 12 September 2005, the Israeli cabinet formally declared an end to Israeli military occupation of the Gaza Strip.

«The Oslo Agreements gave Israel full control over Gaza’s airspace, but established that the Palestinians could build an airport in the area» and the disengagement plan states that: «Israel will hold sole control of Gaza airspace and will continue to carry out military activity in the waters of the Gaza Strip.» «Therefore, Israel continues to maintain exclusive control of Gaza’s airspace and the territorial waters, just as it has since it occupied the Gaza Strip in 1967.»[63] Human Rights Watch has advised the UN Human Rights Council that it (and others) consider Israel to be the occupying power of the Gaza Strip because Israel controls Gaza Strip’s airspace, territorial waters and controls the movement of people or goods in or out of Gaza by air or sea.[64][65][66] The EU considers Gaza to be occupied.[67] Israel also withdrew from the Philadelphi Route, a narrow strip of land adjacent to the border with Egypt, after Egypt agreed to secure its side of the border. Under the Oslo Accords, the Philadelphi Route was to remain under Israeli control to prevent the smuggling of weapons and people across the Egyptian border, but Egypt (under EU supervision) committed itself to patrolling the area and preventing such incidents. With the Agreement on Movement and Access, known as the Rafah Agreement in the same year Israel ended its presence in the Philadelphi Route and transferred responsibility for security arrangements to Egypt and the PA under the supervision of the EU.[68]

In November 2005, an «Agreement on Movement and Access» between Israel and the Palestinian Authority was brokered by then US Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice to improve Palestinian freedom of movement and economic activity in the Gaza Strip. Under its terms, the Rafah crossing with Egypt was to be reopened, with transits monitored by the Palestinian National Authority and the European Union. Only people with Palestinian ID, or foreign nationals, by exception, in certain categories, subject to Israeli oversight, were permitted to cross in and out. All goods, vehicles and trucks to and from Egypt passed through the Kerem Shalom Crossing, under full Israeli supervision.[69] Goods were also permitted transit at the Karni crossing in the north.

After the Israeli withdrawal in 2005, the Oslo Accords give the Palestinian Authority administrative authority in the Gaza Strip. The Rafah Border Crossing has been supervised by EU Border Assistance Mission Rafah under an agreement finalized in November 2005.[70] The Oslo Accord permits Israel to control the airspace and sea space, though the Accords also stipulated the Palestinians could have their own airport inside the Strip, which Israel has since then prevented from happening.[71]

Post-2006 elections violence

In the Palestinian parliamentary elections held on 25 January 2006, Hamas won a plurality of 42.9% of the total vote and 74 out of 132 total seats (56%).[72][73] When Hamas assumed power the next month, Israel, the United States, the European Union, Russia and the United Nations demanded that Hamas accept all previous agreements, recognize Israel’s right to exist, and renounce violence; when Hamas refused,[74] they cut off direct aid to the Palestinian Authority, although some aid money was redirected to humanitarian organizations not affiliated with the government.[75] The resulting political disorder and economic stagnation led to many Palestinians emigrating from the Gaza Strip.[76]

In January 2007, fighting erupted between Hamas and Fatah. The deadliest clashes occurred in the northern Gaza Strip, where General Muhammed Gharib, a senior commander of the Fatah-dominated Preventive Security Force, died when a rocket hit his home.

On 30 January 2007, a truce was negotiated between Fatah and Hamas.[77] However, after a few days, new fighting broke out. On 1 February, Hamas killed 6 people in an ambush on a Gaza convoy which delivered equipment for Abbas’ Palestinian Presidential Guard, according to diplomats, meant to counter smuggling of more powerful weapons into Gaza by Hamas for its fast-growing «Executive Force». According to Hamas, the deliveries to the Presidential Guard were intended to instigate sedition (against Hamas), while withholding money and assistance from the Palestinian people.[78] Fatah fighters stormed a Hamas-affiliated university in the Gaza Strip. Officers from Abbas’ presidential guard battled Hamas gunmen guarding the Hamas-led Interior Ministry.[79]

In May 2007, new fighting broke out between the factions.[80] Interior Minister Hani Qawasmi, who had been considered a moderate civil servant acceptable to both factions, resigned due to what he termed harmful behavior by both sides.[81]

Fighting spread in the Gaza Strip, with both factions attacking vehicles and facilities of the other side. Following a breakdown in an Egyptian-brokered truce, Israel launched an air strike which destroyed a building used by Hamas. Ongoing violence prompted fear that it could bring the end of the Fatah-Hamas coalition government, and possibly the end of the Palestinian authority.[82]

Hamas spokesman Moussa Abu Marzouk blamed the conflict between Hamas and Fatah on Israel, stating that the constant pressure of economic sanctions resulted in the «real explosion.»[83] Associated Press reporter Ibrahim Barzak wrote an eyewitness account stating: «Today I have seen people shot before my eyes, I heard the screams of terrified women and children in a burning building, and I argued with gunmen who wanted to take over my home. I have seen a lot in my years as a journalist in Gaza, but this is the worst it’s been.»

From 2006–2007 more than 600 Palestinians were killed in fighting between Hamas and Fatah.[84] 349 Palestinians were killed in fighting between factions in 2007. 160 Palestinians killed each other in June alone.[85]

2007 Hamas takeover

Following the victory of Hamas in the 2006 Palestinian legislative election, Hamas and Fatah formed the Palestinian authority national unity government headed by Ismail Haniya. Shortly after, Hamas took control of the Gaza Strip in the course of the Battle of Gaza,[86] seizing government institutions and replacing Fatah and other government officials with its own.[87] By 14 June, Hamas fully controlled the Gaza Strip. Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas responded by declaring a state of emergency, dissolving the unity government and forming a new government without Hamas participation. PNA security forces in the West Bank arrested a number of Hamas members.

In late June 2008, Egypt, Saudi Arabia and Jordan declared the West Bank-based cabinet formed by Abbas as «the sole legitimate Palestinian government». Egypt moved its embassy from Gaza to the West Bank.[88]

Saudi Arabia and Egypt supported reconciliation and a new unity government and pressed Abbas to start talks with Hamas. Abbas had always conditioned this on Hamas returning control of the Gaza Strip to the Palestinian Authority. Hamas visited a number of countries, including Russia, and the EU member states. Opposition parties and politicians called for a dialogue with Hamas as well as an end to the economic sanctions.

After the takeover, Israel and Egypt closed their border crossings with Gaza. Palestinian sources reported that European Union monitors fled the Rafah Border Crossing, on the Gaza–Egypt border for fear of being kidnapped or harmed.[89] Arab foreign ministers and Palestinian officials presented a united front against control of the border by Hamas.[90]

Meanwhile, Israeli and Egyptian security reports said that Hamas continued smuggling in large quantities of explosives and arms from Egypt through tunnels. Egyptian security forces uncovered 60 tunnels in 2007.[91]

Egyptian border barrier breach

On 23 January 2008, after months of preparation during which the steel reinforcement of the border barrier was weakened,[92] Hamas destroyed several parts of the wall dividing Gaza and Egypt in the town of Rafah. Hundreds of thousands of Gazans crossed the border into Egypt seeking food and supplies. Due to the crisis, Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak ordered his troops to allow the Palestinians in but to verify that they did not bring weapons back across the border.[93] Egypt arrested and later released several armed Hamas militants in the Sinai who presumably wanted to infiltrate into Israel. At the same time, Israel increased its state of alert along the length of the Israel-Egypt Sinai border, and warned its citizens to leave Sinai «without delay.»

The EU Border Monitors initially monitored the border because Hamas guaranteed their safety, but they later fled. The Palestinian Authority demanded that Egypt deal only with the Authority in negotiations relating to borders. Israel eased restrictions on the delivery of goods and medical supplies but curtailed electricity by 5% in one of its ten lines.[94] The Rafah crossing remained closed into mid-February.[95]

In February 2008, 2008 Israel-Gaza conflict intensified, with rockets launched at Israeli cities. Aggression by Hamas led to Israeli military action on 1 March 2008, resulting in over 110 Palestinians being killed according to BBC News, as well as 2 Israeli soldiers. Israeli human rights group B’Tselem estimated that 45 of those killed were not involved in hostilities, and 15 were minors.[96]

After a round of tit-for-tat arrests between Fatah and Hamas in the Gaza Strip and West Bank, the Hilles clan from Gaza were relocated to Jericho on 4 August 2008.[97] Retiring Prime Minister Ehud Olmert said on 11 November 2008, «The question is not whether there will be a confrontation, but when it will take place, under what circumstances, and who will control these circumstances, who will dictate them, and who will know to exploit the time from the beginning of the ceasefire until the moment of confrontation in the best possible way.» On 14 November 2008, Israel blockaded its border with Gaza after a five-month ceasefire broke down.[98] In 2013 Israel and Qatar brought Gaza’s lone power plant back to life for the first time in seven weeks, bringing relief to the Palestinian coastal enclave where a lack of cheap fuel has contributed to the overflow of raw sewage, 21-hour blackouts and flooding after a ferocious winter storm. «Palestinian officials said that a $10 million grant from Qatar was covering the cost of two weeks’ worth of industrial diesel that started entering Gaza by truckload from Israel.»[99]

On 25 November 2008, Israel closed its cargo crossing with Gaza after Qassam rockets were fired into its territory.[100] On 28 November, after a 24-hour period of quiet, the IDF facilitated the transfer of over thirty truckloads of food, basic supplies and medicine into Gaza and transferred fuel to the area’s main power plant.[101]

2008 Gaza War

Monthly rocket and mortar hits in Israel, 2008.

Israelis killed by Palestinians in Israel (blue) and Palestinians killed by Israelis in Gaza (red)

On 27 December 2008,[102] Israeli F-16 fighters launched a series of air strikes against targets in Gaza following the breakdown of a temporary truce between Israel and Hamas.[103] Israeli defense sources said that Defense Minister Ehud Barak instructed the IDF to prepare for the operation six months before it began, using long-term planning and intelligence-gathering.[104]

Various sites that Israel claimed were being used as weapons depots were struck: police stations, schools, hospitals, UN warehouses, mosques, various Hamas government buildings and other buildings.[105] Israel said that the attack was a response to Hamas rocket attacks on southern Israel, which totaled over 3,000 in 2008, and which intensified during the few weeks preceding the operation. Israel advised people near military targets to leave before the attacks. Palestinian medical staff claimed at least 434 Palestinians were killed, and at least 2,800 wounded, consisting of many civilians and an unknown number of Hamas members, in the first five days of Israeli strikes on Gaza. The IDF denied that the majority of the dead were civilian. Israel began a ground invasion of the Gaza Strip on 3 January 2009.[106] Israel rebuffed many cease-fire calls but later declared a cease fire although Hamas vowed to fight on.[107][108]

A total of 1,100–1,400[109] Palestinians (295–926 civilians) and 13 Israelis were killed in the 22-day war.[110]

The conflict damaged or destroyed tens of thousands of homes,[111][112] 15 of Gaza’s 27 hospitals and 43 of its 110 primary health care facilities,[113] 800 water wells,[114] 186 greenhouses,[115] and nearly all of its 10,000 family farms;[116] leaving 50,000 homeless,[117] 400,000–500,000 without running water,[117][118] one million without electricity,[118] and resulting in acute food shortages.[119] The people of Gaza still suffer from the loss of these facilities and homes, especially since they have great challenges to rebuild them.

By February 2009, food availability returned to pre-war levels but a shortage of fresh produce was forecast due to damage sustained by the agricultural sector.[120]

In the immediate aftermath of the Gaza War, Hamas executed 19 Palestinian Fatah members, on charges that they had collaborated with Israel. Many had been recaptured after escaping prison which had been bombed during the war.[121][122] The executions followed an Israeli strike which killed 3 top Hamas officials, including Said Seyam, with Hamas charging that information on where Hamas leaders lived and where arms were stocked had been passed to Fatah in the West Bank, and via the PA to Israel, with whom the PA shares security intrelligence. Many suspected were tortured or shot in the legs. Hamas thereafter pursued a course of trying collaborators in courts, rather than executing them in the street.[123][121]

A 2014 unity government with Fatah

On 5 June 2014, Fatah signed a unity agreement with the Hamas political party.[124]

2014 Gaza War

| Gaza | Israel | Ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Civilians killed | 1,600 | 6 | 270:1 |

| Children killed | 550 | 1 | 550:1 |

| Homes severely damaged or destroyed | 18,000 | 1 | 18,000:1 |

| Houses of worship damaged or destroyed | 203 | 2 | 100:1 |

| Kindergartens damaged or destroyed | 285 | 1 | 285:1 |

| Medical facilities damaged or destroyed | 73 | 0 | 73:0 |

| Rubble left | 2.5 mln tons | unknown | unknown |

Connections to Sinai insurgency

Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula borders the Gaza Strip and Israel. Its vast and desolate terrain has transformed it into a hotbed of illicit and militant activity.[126] Although most of the area’s inhabitants are tribal Bedouins, there has been a recent increase in al-Qaeda inspired global jihadi militant groups operating in the region.[126][127] Out of the approximately 15 main militant groups operating in the Sinai desert, the most dominant and active militant groups have close relations with the Gaza Strip.[128]

According to Egyptian authorities, the Army of Islam, a U.S. designated terrorist organization based in the Gaza Strip, is responsible for training and supplying many militant organizations and jihadist members in Sinai.[128] Mohammed Dormosh, the Army of Islam’s leader, is known for his close relationships to the Hamas leadership.[128] Army of Islam smuggles members into the Gaza Strip for training, then returns them to the Sinai Peninsula to engage in militant and jihadist activities.[129]

2018 Israel–Gaza conflict

2021 Israel–Gaza crisis

Before the crisis, Gaza had 48% unemployment and half of the population lived in poverty. During the crisis, 66 children died (551 children in the previous conflict). On June 13, 2021, a high level World Bank delegation visited Gaza to witness the damage. Mobilization with UN and EU partners is ongoing to finalize a needs assessment in support of Gaza’s reconstruction and recovery.[130]

2022 Israel–Gaza escalation

Another escalation between 5 and 8 August 2022 resulted in property damage and displacement of people as a result of airstrikes.[131][132]

Geography, geology and climate

The Gaza Strip is located in the Middle East (at 31°25′N 34°20′E / 31.417°N 34.333°ECoordinates: 31°25′N 34°20′E / 31.417°N 34.333°E). It has a 51 kilometers (32 mi) border with Israel, and an 11 km (7 mi) border with Egypt, near the city of Rafah. Khan Yunis is located 7 kilometers (4.3 mi) northeast of Rafah, and several towns around Deir el-Balah are located along the coast between it and Gaza City. Beit Lahia and Beit Hanoun are located to the north and northeast of Gaza City, respectively. The Gush Katif bloc of Israeli settlements used to exist on the sand dunes adjacent to Rafah and Khan Yunis, along the southwestern edge of the 40 kilometers (25 mi) Mediterranean coastline. Al Deira beach is a popular venue for surfers.[133]

The topography of the Gaza Strip is dominated by three ridges parallel to the coastline, which consist of Pleistocene-Holocene aged calcareous aeolian (wind deposited) sandstones, locally referred to as «kurkar», intercalated with red-coloured fine grained paleosols, referred to as «hamra». The three ridges are separated by wadis, which are filled with alluvial deposits.[134] The terrain is flat or rolling, with dunes near the coast. The highest point is Abu ‘Awdah (Joz Abu ‘Auda), at 105 meters (344 ft) above sea level.

The major river in Gaza Strip is Wadi Gaza, around which the Wadi Gaza Nature Reserve was established, to protect the only coastal wetland in the Strip.[135]

The Gaza Strip has a hot semi-arid climate (Köppen BSh), with warm winters during which practically all the annual rainfall occurs, and dry, hot summers. Despite the dryness, humidity is high throughout the year. Annual rainfall is higher than in any part of Egypt at between 225 millimetres (9 in) in the south and 400 millimetres (16 in) in the north, but almost all of this falls between November and February. Environmental problems include desertification; salination of fresh water; sewage treatment; water-borne diseases; soil degradation; and depletion and contamination of underground water resources.

Natural resources

Natural resources of Gaza include arable land—about a third of the strip is irrigated. Recently, natural gas was discovered. The Gaza Strip is largely dependent on water from Wadi Gaza, which also supplies Israel.[136]

Gaza’s marine gas reserves extend 32 kilometres from the Gaza Strip’s coastline[137] and were calculated at 35 BCM.[138]

Economy

A resort in the Gaza Strip built on the location of the former Israeli settlement of Netzarim

The economy of the Gaza Strip is severely hampered by Egypt and Israel’s almost total blockade, the high population density, limited land access, strict internal and external security controls, the effects of Israeli military operations, and restrictions on labor and trade access across the border. Per capita income (PPP) was estimated at US$3,100 in 2009, a position of 164th in the world.[139] Seventy percent of the population is below the poverty line according to a 2009 estimate.[139] Gaza Strip industries are generally small family businesses that produce textiles, soap, olive-wood carvings, and mother-of-pearl souvenirs.

The main agricultural products are olives, citrus, vegetables, Halal beef, and dairy products. Primary exports are citrus and cut flowers, while primary imports are food, consumer goods, and construction materials. The main trade partners of the Gaza Strip are Israel and Egypt.[139]

The EU described the Gaza economy as follows: «Since Hamas took control of Gaza in 2007 and following the closure imposed by Israel, the situation in the Strip has been one of chronic need, de-development and donor dependency, despite a temporary relaxation on restrictions in movement of people and goods following a flotilla raid in 2010. The closure has effectively cut off access for exports to traditional markets in Israel, transfers to the West Bank and has severely restricted imports. Exports are now down to 2% of 2007 levels.»[67]

According to Sara Roy, one senior IDF officer told an UNWRA official in 2015 that Israel’s policy towards the Gaza Strip consisted of: «No development, no prosperity, no humanitarian crisis.»[140]

After Oslo (1994–2007)

Economic output in the Gaza Strip declined by about one-third between 1992 and 1996. This downturn was attributed to Israeli closure policies and, to a lesser extent, corruption and mismanagement by Yasser Arafat. Economic development has been hindered by Israel refusing to allow the operation of a sea harbour. A seaport was planned to be built in Gaza with help from France and The Netherlands, but the project was bombed by Israel in 2001. Israel said that the reason for bombing was that Israeli settlements were being shot at from the construction site at the harbour. As a result, international transports (both trade and aid) had to go through Israel, which was hindered by the imposition of generalized border closures. These also disrupted previously established labor and commodity market relationships between Israel and the Strip. A serious negative social effect of this downturn was the emergence of high unemployment.

For its energy, Gaza is largely dependent on Israel either for import of electricity or fuel for its sole power plant. The Oslo Accords set limits for the Palestinian production and importation of energy. Pursuant to the Accords, the Israel Electric Corporation exclusively supplies the electricity (63% of the total consumption in 2013).[17] The amount of electricity has consistently been limited to 120 megawatts, which is the amount Israel undertook to sell to Gaza pursuant to the Oslo Accords.[141]

Israel’s use of comprehensive closures decreased over the next few years. In 1998, Israel implemented new policies to ease security procedures and allow somewhat freer movement of Gazan goods and labor into Israel. These changes led to three years of economic recovery in the Gaza Strip, disrupted by the outbreak of the al-Aqsa Intifada in the last quarter of 2000. Before the second Palestinian uprising in September 2000, around 25,000 workers from the Gaza Strip (about 2% of the population) worked in Israel on a daily basis.[142]

The Second Intifada led to a steep decline in the economy of Gaza, which was heavily reliant upon external markets. Israel—which had begun its occupation by helping Gazans to plant approximately 618,000 trees in 1968, and to improve seed selection—over the first 3-year period of the second intifada, destroyed 10 percent of Gazan agricultural land, and uprooted 226,000 trees.[143] The population became largely dependent on humanitarian assistance, primarily from UN agencies.[144]

The al-Aqsa Intifada triggered tight IDF closures of the border with Israel, as well as frequent curbs on traffic in Palestinian self-rule areas, severely disrupting trade and labor movements. In 2001, and even more so in early 2002, internal turmoil and Israeli military measures led to widespread business closures and a sharp drop in GDP. Civilian infrastructure, such as the Palestine airport, was destroyed by Israel.[145] Another major factor was a drop in income due to reduction in the number of Gazans permitted entry to work in Israel. After the Israeli withdrawal from Gaza, the flow of a limited number of workers into Israel resumed, although Israel said it would reduce or end such permits due to the victory of Hamas in the 2006 parliamentary elections.

The Israeli settlers of Gush Katif built greenhouses and experimented with new forms of agriculture. These greenhouses provided employment for hundreds of Gazans. When Israel withdrew from the Gaza Strip in the summer of 2005, more than 3,000 (about half) of the greenhouses were purchased with $14 million raised by former World Bank president James Wolfensohn, and given to Palestinians to jump-start their economy. The rest were demolished by the departing settlers before they were offered a compensation as an inducement to leave them behind.[146] The farming effort faltered due to limited water supply, Palestinian looting, restrictions on exports, and corruption in the Palestinian Authority. Many Palestinian companies repaired the greenhouses damaged and looted by the Palestinians after the Israeli withdrawal.[147]

In 2005, after the Israeli withdrawal from the Gaza Strip, Gaza businessmen envisaged a «magnificent future». $1.1 million was invested in an upscale restaurant, Roots, and plans were made to turn one of the Israeli settlements into a family resort.[148]

Following Hamas takeover (2007–present)

The European Union states: «Gaza has experienced continuous economic decline since the imposition of a closure policy by Israel in 2007. This has had serious social and humanitarian consequences for many of its 1.7 million inhabitants. The situation has deteriorated further in recent months as a result of the geo-political changes which took place in the region during the course of 2013, particularly in Egypt and its closure of the majority of smuggling tunnels between Egypt and Gaza as well as increased restrictions at Rafah.»[67] Israel, the United States, Canada, and the European Union have frozen all funds to the Palestinian government after the formation of a Hamas-controlled government after its democratic victory in the 2006 Palestinian legislative election. They view the group as a terrorist organization, and have pressured Hamas to recognize Israel, renounce violence, and make good on past agreements. Prior to disengagement, 120,000 Palestinians from Gaza had been employed in Israel or in joint projects. After the Israeli withdrawal, the gross domestic product of the Gaza Strip declined. Jewish enterprises shut down, work relationships were severed, and job opportunities in Israel dried up. After the 2006 elections, fighting broke out between Fatah and Hamas, which Hamas won in the Gaza Strip on 14 June 2007. Israel imposed a blockade, and the only goods permitted into the Strip through the land crossings were goods of a humanitarian nature, and these were permitted in limited quantities.

An easing of Israel’s closure policy in 2010 resulted in an improvement in some economic indicators, although exports were still restricted.[144] According to the Israeli Defense Forces and the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, the economy of the Gaza Strip improved in 2011, with a drop in unemployment and an increase in GDP. New malls opened and local industry began to develop. This economic upswing has led to the construction of hotels and a rise in the import of cars.[149] Wide-scale development has been made possible by the unhindered movement of goods into Gaza through the Kerem Shalom Crossing and tunnels between the Gaza Strip and Egypt. The current rate of trucks entering Gaza through Kerem Shalom is 250 trucks per day. The increase in building activity has led to a shortage of construction workers. To make up for the deficit, young people are being sent to learn the trade in Turkey.[150]

In 2012, Hamas leader Mahmoud Zahar said that Gaza’s economic situation has improved and Gaza has become self-reliant «in several aspects except petroleum and electricity» despite Israel’s blockade. Zahar said that Gaza’s economic conditions are better than those in the West Bank.[151] In 2014, the EU’s opinion was: «Today, Gaza is facing a dangerous and pressing humanitarian and economic situation with power outages across Gaza for up to 16 hours a day and, as a consequence, the closure of sewage pumping operations, reduced access to clean water; a reduction in medical supplies and equipment; the cessation of imports of construction materials; rising unemployment, rising prices and increased food insecurity. If left unaddressed, the situation could have serious consequences for stability in Gaza, for security more widely in the region as well as for the peace process itself.»[67]

2012 fuel crisis

Usually, diesel for Gaza came from Israel,[152] but in 2011, Hamas started to buy cheaper fuel from Egypt, bringing it via a network of tunnels, and refused to allow it from Israel.[153]

In early 2012, due to internal economic disagreement between the Palestinian Authority and the Hamas Government in Gaza, decreased supplies from Egypt and through tunnel smuggling, and Hamas’s refusal to ship fuel via Israel, the Gaza Strip plunged into a fuel crisis, bringing increasingly long electricity shut downs and disruption of transportation. Egypt had attempted for a while to stop the use of tunnels for delivery of Egyptian fuel purchased by Palestinian authorities, and had severely reduced supply through the tunnel network. As the crisis broke out, Hamas sought to equip the Rafah terminal between Egypt and Gaza for fuel transfer, and refused to accept fuel to be delivered via the Kerem Shalom crossing between Israel and Gaza.[154]

In mid-February 2012, as the crisis escalated, Hamas rejected an Egyptian proposal to bring in fuel via the Kerem Shalom Crossing between Israel and Gaza to reactivate Gaza’s only power plant. Ahmed Abu Al-Amreen of the Hamas-run Energy Authority refused it on the grounds that the crossing is operated by Israel and Hamas’ fierce opposition to the existence of Israel. Egypt cannot ship diesel fuel to Gaza directly through the Rafah crossing point, because it is limited to the movement of individuals.[153]

In early March 2012, the head of Gaza’s energy authority stated that Egypt wanted to transfer energy via the Kerem Shalom Crossing, but he personally refused it to go through the «Zionist entity» (Israel) and insisted that Egypt transfer the fuel through the Rafah Crossing, although this crossing is not equipped to handle the half-million liters needed each day.[155]

In late March 2012, Hamas began offering carpools for people to use Hamas state vehicles to get to work. Many Gazans began to wonder how these vehicles have fuel themselves, as diesel was completely unavailable in Gaza, ambulances could no longer be used, but Hamas government officials still had fuel for their own cars. Many Gazans said that Hamas confiscated the fuel it needed from petrol stations and used it exclusively for their own purposes.

Egypt agreed to provide 600,000 liters of fuel to Gaza daily, but it had no way of delivering it that Hamas would agree to.[156]

In addition, Israel introduced a number of goods and vehicles into the Gaza Strip via the Kerem Shalom Crossing, as well as the normal diesel for hospitals. Israel also shipped 150,000 liters of diesel through the crossing, which was paid for by the Red Cross.

In April 2012, the issue was resolved as certain amounts of fuel were supplied with the involvement of the Red Cross, after the Palestinian Authority and Hamas reached a deal. Fuel was finally transferred via the Israeli Kerem Shalom Crossing, which Hamas previously refused to transfer fuel from.[157]

Current budget

Most of the Gaza Strip administration funding comes from outside as an aid, with large portion delivered by UN organizations directly to education and food supply. Most of the Gaza GDP comes as foreign humanitarian and direct economic support. Of those funds, the major part is supported by the U.S. and the European Union. Portions of the direct economic support have been provided by the Arab League, though it largely has not provided funds according to schedule. Among other alleged sources of Gaza administration budget is Iran.

A diplomatic source told Reuters that Iran had funded Hamas in the past with up to $300 million per year, but the flow of money had not been regular in 2011. «Payment has been in suspension since August,» said the source.[158]

In January 2012, some diplomatic sources said that Turkey promised to provide Haniyeh’s Gaza Strip administration with $300 million to support its annual budget.[158]

In April 2012, the Hamas government in Gaza approved its budget for 2012, which was up 25 percent year-on-year over 2011 budget, indicating that donors, including Iran, benefactors in the Islamic world, and Palestinian expatriates, are still heavily funding the movement.[159] Chief of Gaza’s parliament’s budget committee Jamal Nassar said the 2012 budget is $769 million, compared to $630 million in 2011.[159]

Demographics

Population of the Gaza Strip 2000-2020[160]

In 2010 approximately 1.6 million Palestinians lived in the Gaza Strip,[139] almost 1.0 million of them UN-registered refugees.[161] The majority of the Palestinians descend from refugees who were driven from or left their homes during the 1948 Arab–Israeli War. The Strip’s population has continued to increase since that time, one of the main reasons being a total fertility rate which peaked at 8.3 children per woman in 1991 and fell to 4.4 children per woman in 2013 which was still among the highest worldwide. In a ranking by total fertility rate, this places Gaza 34th of 224 regions.[139][162] The high total fertility rate also leads to the Gaza Strip having an unusually high proportion of children in the population, with 43.5% of the population being 14 or younger and in 2014 the median age was 18, compared to a world average of 28 and 30 in Israel. The only countries with a lower median age are countries in Africa such as Uganda where it was 15.[162]

Sunni Muslims make up the predominant part of the Palestinian population in the Gaza Strip. Most of the inhabitants are Sunni Muslims, with an estimated 2,000 to 3,000 Arab Christians,[163] making the region 99.8 percent Sunni Muslim and 0.2 percent Christian.[139]

Religion and culture

| Gaza Strip Religions (2012 est.)[164] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Islam | 98% | |

| Christianity | 1% | |

| other | 1% |

Religious compliance of population to Islam

Islamic law in Gaza

From 1987 to 1991, during the First Intifada, Hamas campaigned for the wearing of the hijab head-cover.[citation needed] In the course of this campaign, women who chose not to wear the hijab were verbally and physically harassed by Hamas activists, leading to hijabs being worn «just to avoid problems on the streets».[165]

In October 2000, Islamic extremists burned down the Windmill Hotel, owned by Basil Eleiwa, when they learned it had served alcohol.[148]

Since Hamas took over in 2007, attempts have been made by Islamist activists to impose «Islamic dress» and to require women to wear the hijab.[166][167] The government’s «Islamic Endowment Ministry» has deployed Virtue Committee members to warn citizens of the dangers of immodest dress, card playing and dating.[168] However, there are no government laws imposing dress and other moral standards, and the Hamas education ministry reversed one effort to impose Islamic dress on students.[166] There has also been successful resistance[by whom?] to attempts by local Hamas officials to impose Islamic dress on women.[169]

According to Human Rights Watch, the Hamas-controlled government stepped up its efforts to «Islamize» Gaza in 2010, efforts it says included the «repression of civil society» and «severe violations of personal freedom.»[170]

Palestinian researcher Khaled Al-Hroub has criticized what he called the «Taliban-like steps» Hamas has taken: «The Islamization that has been forced upon the Gaza Strip—the suppression of social, cultural, and press freedoms that do not suit Hamas’s view[s]—is an egregious deed that must be opposed. It is the reenactment, under a religious guise, of the experience of [other] totalitarian regimes and dictatorships.»[171] Hamas officials denied having any plans to impose Islamic law. One legislator stated that «[w]hat you are seeing are incidents, not policy» and that «we believe in persuasion».[168]

In October 2012 Gaza youth complained that security officers had obstructed their freedom to wear saggy pants and to have haircuts of their own choosing, and that they faced being arrested. Youth in Gaza are also arrested by security officers for wearing shorts and for showing their legs, which have been described by youth as embarrassing incidents, and one youth explained that «My saggy pants did not harm anyone.» However, a spokesman for Gaza’s Ministry of Interior denied such a campaign, and denied interfering in the lives of Gaza citizens, but explained that «maintaining the morals and values of the Palestinian society is highly required».[172]

Muslim worshippers in Gaza

Islamic politics

Iran was the largest state supporter of Hamas, and the Muslim Brotherhood also gave support, but these political relationships have recently been disrupted following the Arab Spring by Iranian support for[clarification needed] and the position of Hamas has declined as support diminishes.[67]

Salafism

In addition to Hamas, a Salafist movement began to appear about 2005 in Gaza, characterized by «a strict lifestyle based on that of the earliest followers of Islam».[173] As of 2015, there are estimated to be only «hundreds or perhaps a few thousand» Salafists in Gaza.[173] However, the failure of Hamas to lift the Israeli blockade of Gaza despite thousands of casualties and much destruction during 2008-9 and 2014 wars has weakened Hamas’s support and led some in Hamas to be concerned about the possibility of defections to the Salafist «Islamic State».[173]

The movement has clashed with Hamas on a number of occasions. In 2009, a Salafist leader, Abdul Latif Moussa, declared an Islamic emirate in the town of Rafah, on Gaza’s southern border.[173] Moussa and nineteen other people were killed when Hamas forces stormed his mosque and house. In 2011, Salafists abducted and murdered a pro-Palestinian Italian activist, Vittorio Arrigoni. Following this Hamas again took action to crush the Salafist groups.[173]

Violence against Christians

Violence against Christians has been recorded. The owner of a Christian bookshop was abducted and murdered[174] and, on 15 February 2008, the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) library in Gaza City was bombed.[175]

Governance

Hamas government

Damaged UN school and remmants of the Ministry of Interior in Gaza City, December 2012

Since its takeover of Gaza, Hamas has exercised executive authority over the Gaza Strip, and it governs the territory through its own ad hoc executive, legislative, and judicial bodies.[176] The Hamas government of 2012 was the second Palestinian Hamas-dominated government, ruling over the Gaza Strip, since the split of the Palestinian National Authority in 2007. It was announced in early September 2012.[177] The reshuffle of the previous government was approved by Gaza-based Hamas MPs from the Palestinian Legislative Council (PLC) or parliament.[177]

The legal code Hamas applies in Gaza is based on Ottoman laws, the British Mandate’s 1936 legal code, Palestinian Authority law, Sharia law, and Israeli military orders. Hamas maintains a judicial system with civilian and military courts and a public prosecution service.[176][178]

Security

The Gaza Strip’s security is mainly handled by Hamas through its military wing, the Izz ad-Din al-Qassam Brigades, internal security service, and civil police force. The Izz ad-Din al-Qassam Brigades have an estimated 30,000 to 50,000 operatives.[179] However, other Palestinian militant factions operate in the Gaza Strip alongside, and sometimes opposed to Hamas. The Islamic Jihad Movement in Palestine, also known as the Palestinian Islamic Jihad (PIJ) is the second largest militant faction operating in the Gaza Strip. Its military wing, the Al-Quds Brigades, has an estimated 8,000 fighters.[180][181][182][183] In June 2013, the Islamic Jihad broke ties with Hamas leaders after Hamas police fatally shot the commander of Islamic Jihad’s military wing.[181] The third largest faction is the Popular Resistance Committees. Its military wing is known as the Al-Nasser Salah al-Deen Brigades.

Other factions include the Army of Islam (an Islamist faction of the Doghmush clan), the Nidal Al-Amoudi Battalion (an offshoot of the West Bank-based Fatah-linked al-Aqsa Martyrs’ Brigades), the Abu Ali Mustapha Brigades (armed wing of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine), the Sheikh Omar Hadid Brigade (ISIL offshoot), Humat al-Aqsa, Jaysh al-Ummah, Katibat al-Sheikh al-Emireen, the Mujahideen Brigades, and the Abdul al-Qadir al-Husseini Brigades.[184]

Status

Legality of Hamas rule

After Hamas’ June 2007 takeover, it ousted Fatah-linked officials from positions of power and authority (such as government positions, security services, universities, newspapers, etc.) and strove to enforce law by progressively removing guns from the hands of peripheral militias, clans, and criminal groups, and gaining control of supply tunnels. According to Amnesty International, under Hamas rule, newspapers were closed down and journalists were harassed.[185] Fatah demonstrations were forbidden or suppressed, as in the case of a large demonstration on the anniversary of Yasser Arafat’s death, which resulted in the deaths of seven people, after protesters hurled stones at Hamas security forces.[186]

Hamas and other militant groups continued to fire Qassam rockets across the border into Israel. According to Israel, between the Hamas takeover and the end of January 2008, 697 rockets and 822 mortar bombs were fired at Israeli towns.[187] In response, Israel targeted Qassam launchers and military targets and declared the Gaza Strip a hostile entity. In January 2008, Israel curtailed travel from Gaza, the entry of goods, and cut fuel supplies, resulting in power shortages. This brought charges that Israel was inflicting collective punishment on the Gaza population, leading to international condemnation. Despite multiple reports from within the Strip that food and other essentials were in short supply,[188] Israel said that Gaza had enough food and energy supplies for weeks.[189]

The Israeli government uses economic means to pressure Hamas. Among other things, it caused Israeli commercial enterprises like banks and fuel companies to stop doing business with the Gaza Strip. The role of private corporations in the relationship between Israel and the Gaza Strip is an issue that has not been extensively studied.[190]

Due to continued rocket attacks including 50 in one day, in March 2008, air strikes and ground incursions by the IDF led to the deaths of over 110 Palestinians and extensive damage to Jabalia.[191]

Watchtower on the border between Rafah and Egypt.

Occupation

The international community regards all of the Palestinian territories including Gaza as occupied.[192] Human Rights Watch has declared at the UN Human Rights Council that it views Israel as a de facto occupying power in the Gaza Strip, even though Israel has no military or other presence, because the Oslo Accords authorize Israel to control the airspace and the territorial sea.[64][65][66]

In his statement on the 2008–2009 Israel–Gaza conflict, Richard Falk, United Nations Special Rapporteur wrote that international humanitarian law applied to Israel «in regard to the obligations of an Occupying Power and in the requirements of the laws of war.»[193] Amnesty International, the World Health Organization, Oxfam, the International Committee of the Red Cross, the United Nations, the United Nations General Assembly, the UN Fact Finding Mission to Gaza, international human rights organizations, US government websites, the UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office, and a significant number of legal commentators (Geoffrey Aronson, Meron Benvenisti, Claude Bruderlein, Sari Bashi, Kenneth Mann, Shane Darcy, John Reynolds, Yoram Dinstein, John Dugard, Marc S. Kaliser, Mustafa Mari, and Iain Scobbie) maintain that Israel’s extensive direct external control over Gaza, and indirect control over the lives of its internal population mean that Gaza remained occupied.[194][195] In spite of Israel’s withdrawal from Gaza in 2005, the Hamas government in Gaza considers Gaza as occupied territory.[196]

Israel states that it does not exercise effective control or authority over any land or institutions in the Gaza Strip and thus the Gaza Strip is no longer subject to the former military occupation.[197][198] Foreign Affairs Minister of Israel Tzipi Livni stated in January 2008: «Israel got out of Gaza. It dismantled its settlements there. No Israeli soldiers were left there after the disengagement.»[199] On 30 January 2008, the Supreme Court of Israel ruled that the Gaza Strip was not occupied by Israel in a decision on a petition against Israeli restrictions against the Gaza Strip which argued that it remained occupied. The Supreme Court ruled that Israel has not exercised effective control over the Gaza Strip since 2005, and accordingly, it was no longer occupied.[200]

In a legal analysis Hanne Cuyckens agrees with the Israeli position that Gaza is no longer occupied — «Gaza is not technically occupied, given that there is no longer any effective control in the sense of Article 42 of the Hague Regulations. … Even though the majority argues that the Gaza Strip is still occupied, the effective control test at the core of the law of occupation is no longer met and hence Gaza is no longer occupied.» She disagrees that Israel cannot therefore be held responsible for the situation in Gaza because: «Nonetheless Israel continues to exercise an important level of control over the Gaza Strip and its population, making it difficult to accept that it would no longer have any obligations with regard to the Strip. … the absence of occupation does not mean the absence of accountability. This responsibility is however not founded on the law of occupation but on general international humanitarian law, potentially complemented by international human rights law».[201] Yuval Shany also argues that Israel is probably not an occupying power in Gaza under international law, writing that «it is difficult to continue and regard Israel as the occupying power in Gaza under the traditional law of occupation».[202]