Детские и юношеские годы

Томас Мор родился 7 февраля 1478 года в столице Англии. Его отец Джон был известным судьей. Этот человек славился своими моральными ценностями, а также честностью. Во многом его воспитание предопределило мировосприятие Томаса. Первым образовательным учреждением для него стала школа Святого Антония. В 13 лет мальчику была доверена должность пажа при кардинале Мортоне.

Этому человеку сразу понравился любознательный и веселый парнишка. Мортон стал первым, кому удалось разглядеть большой потенциал Мора. В шестнадцатилетнем возрасте Томас становится студентом Оксфордского университета. Его наставниками были лучшие юристы Англии того времени:

- Томас Линакр;

- Вильям Гросин.

В университете Томас изучал законодательство, а также его внимание привлекли труды гуманистов. По настоянию отца через 2 года с момента поступления в университет Томас возвращается домой. Сэр Джон хотел, чтобы его сын улучшил свои знания в области права. Томас быстро разобрался со всеми тонкостями законодательства Англии.

Одновременно он заинтересовался философией и социологией. В первую очередь его внимание привлекли работы древних классиков Платона и Лукиана. Для этого Мору пришлось улучшить знания латыни и греческого. Еще во время учебы в Оксфорде он начал собственную литературную деятельность, которая продолжилась и после возвращения в Лондон.

Ориентиром в мире гуманизма для него стал Эразм Роттердамский. Знакомство автора «Утопии» с этим человеком состоялось во время приема лорд-мэра. Именно в доме Моров Роттердамский написал сочинение «Похвала глупости». Историки считают, что период с 1500 по 1504 год Томас провел в картезианском монастыре Лондона. Однако молодого философа не привлекла идея посвятить всю оставшуюся жизнь служению Богу, поэтому он остается в миру.

Проведенное в монастыре время не прошло для Мора бесследно, поскольку многие привычки, полученные в этот период, не были им забыты. Философия Томаса Мора — христианский гуманизм и материализм — прослеживается во всех трудах автора.

Политическая деятельность

Вскоре после возвращения из монастыря Томас избирается в парламент страны. Уже в начале политической карьеры он предлагает снизить налоги в королевскую казну. Месть со стороны монарха оказалась быстрой — отец философа был арестован и заключен в тюрьму. Освободили его лишь после того, как Мор отказался от политической деятельности и выплатил большой выкуп.

Томас возвращается в политику лишь после смерти монарха в 1509 году. Спустя год он занимает должность младшего шерифа Лондона. Политические взгляды Томаса Мора и его честность приводили в восторг жителей столицы. Обратил внимание на него и Генрих VIII, занявший трон в то время.

В 1515 году Мор по приказу короля отправляется во Фландрию в качестве посла. Следующие несколько лет оказали серьезное влияние на его жизнь:

- В 1517 г. автор «Утопии» помогает усмирить бунт жителей Лондона.

- На следующий год Томас входит в состав Тайного совета — могущественного учреждения Британии.

- Через 2 года философ сопровождает монарха Англии во время его встречи с королем Франции.

- В 1521 году Мор был посвящен в рыцари благодаря своим заслугам перед Отечеством.

- В 1529 году автор «Утопии» назначен королем на пост лорд-канцлера. Мор оказался первым представителем класса буржуазии на этой должности.

Личная жизнь

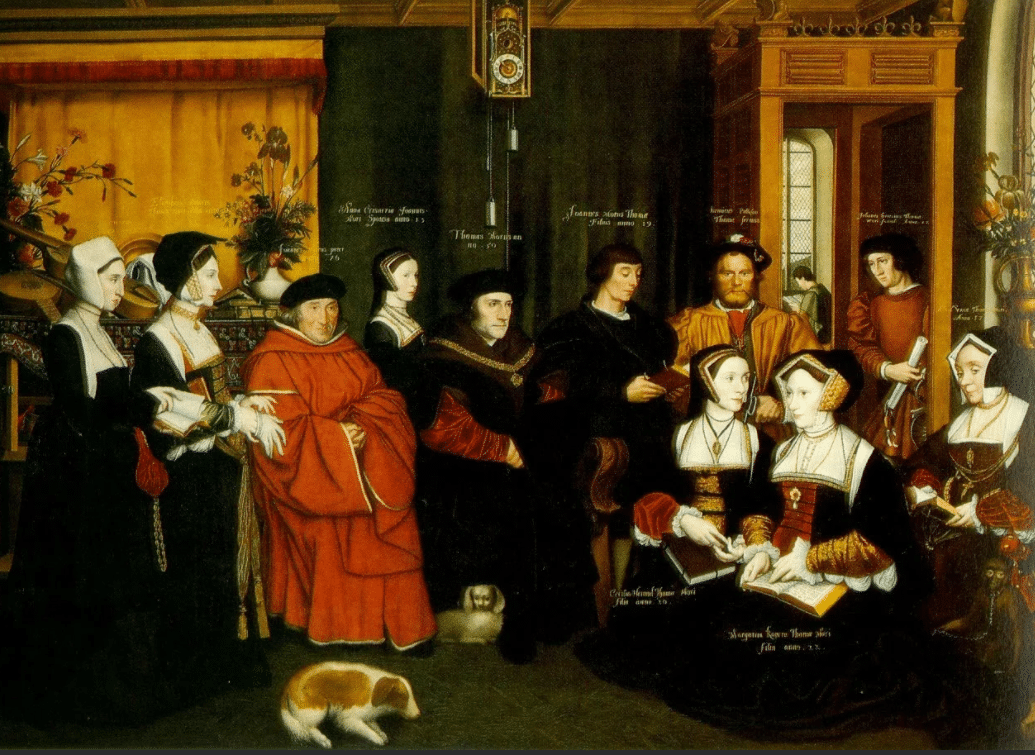

В 1505 году состоялось бракосочетание Мора и Джейн Кольт. Эта женщина была старшей дочерью состоятельного и известного английского эсквайра. Историкам удалось найти информацию, что Томас был влюблен в младшую дочь семейства Кольтов. Но будучи учтивым человеком, он все же сделал предложение Джейн. Избранница Мора отличалась тихим нравом и получила неплохое домашнее образование. Эразм Роттердамский, близкий товарищ и единомышленник Томаса, предложил Джейн не бросать обучение. Обладая педагогическим талантом, он лично учил ее музыке и литературе.

У Томаса и Джейн родилось 4 ребенка — Маргарет, Сесиль, Джон и Элизабет. К сожалению, семейное счастье не продлилось долго. В 1511 году супруга Мора умерла от лихорадки. Томас не хотел, чтобы его дети оставались без матери и вскоре после похорон вступил в брак с Элис Мидлтон. Эта женщина оказалась прямой противоположностью Джейн. По мнению друзей Мора, несмотря на поспешность и расчетливость, второй брак философа стал счастливым. Супруги прожили в мире и согласии до последних мгновений жизни.

Отсутствие собственных детей с новой супругой совершенно не тяготило Мора. Он относился к дочери Элис от первого брака, как к родной, и дал ей отличное воспитание. Томас был хорошим и любящим отцом. Когда он уезжал из дома, то всегда писал детям письма и с нетерпением ждал их ответа. Мор в течение всей своей жизни особое внимание уделял вопросам образования женщин. Он был уверен, что они способны совершать такие же открытия, как и мужчины. Ему удалось воплотить в жизнь свою мечту — дать хорошее образование не только сыну, но и дочерям.

Арест и смерть

Серьезные разногласия с королем у Мора возникли из-за сильной религиозности Томаса. Когда английский монарх Генрих VIII решил расторгнуть свой брак, автор «Утопии» был уверен, что дать согласие на это может только Папа Римский. Однако Климент VII, руководивший в те времена Ватиканом, также возражал против расторжения брака. В результате Генрих VIII принял решение разорвать все связи с Ватиканом и начал создавать в своей стране новую церковь.

Вскоре новой супругой монарха стала Анна Болейн. Это переполнило чашу терпения Мора. Он оставляет пост лорд-канцлера и оказывает посильную помощь монахине Элизабет Бартон в публичном осуждении поступка монарха.

Однако парламент принимает новый «Акт о престолонаследии», согласно которому все рыцари страны должны признать детей Генриха VIII и Анны. Мор отказался давать присягу и попал в тюрьму. В 1535 году он был казнен за измену государству. Спустя ровно 400 лет Ватиканом было принято решение причислить Томаса Мора к лику католических святых.

Литературные произведения

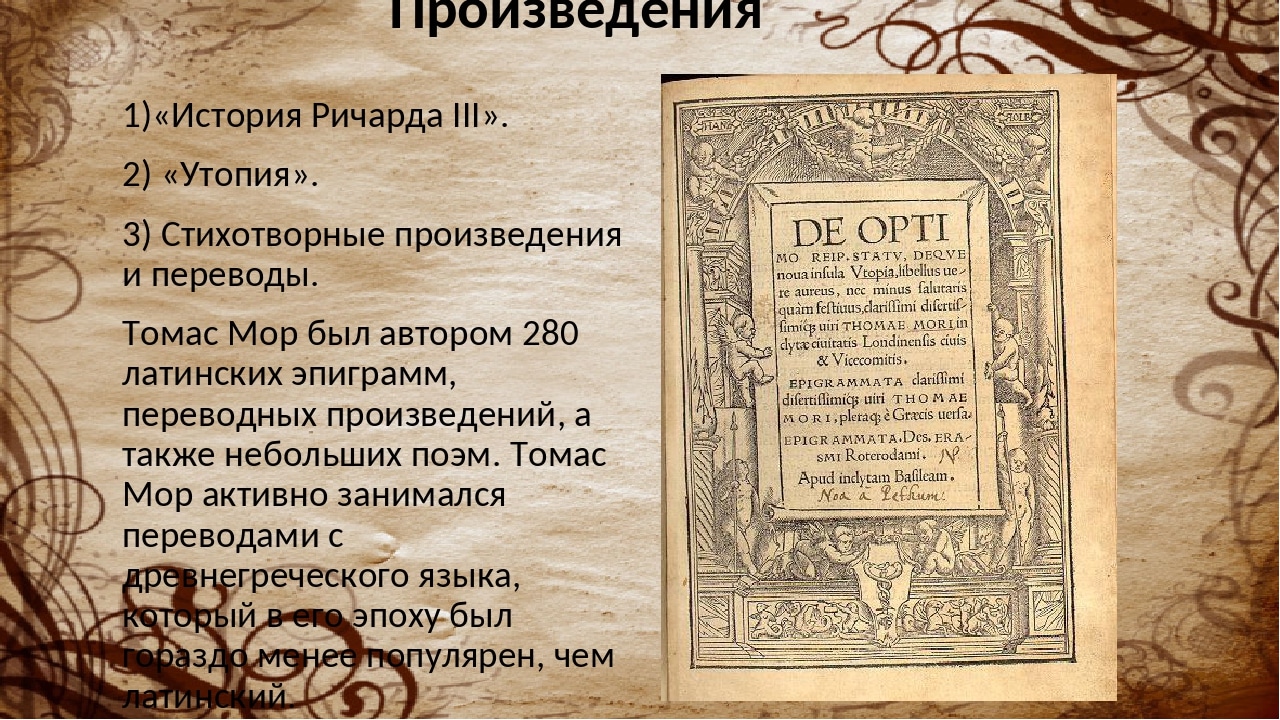

Самой известной книгой писателя является «Утопия». В список работ Мора входят 280 небольших поэм, эпиграмм, а также переводов произведений других писателей. Он активно переводил труды философов Древней Греции. Главной темой всех произведений Томаса Мора является образ идеального правителя.

История Ричарда III

Все еще не утихают споры о том, историческое это произведение или все же художественное. Основные сюжетные линии книги совпадают с многочисленными хрониками и историческими изысканиями. В частности, «История Ричарда III» во многом соответствует запискам Кармилиано, Вергилия, Манчини, Андре.

Различия между работой Томаса и других хронистов наблюдаются в несущественных деталях. Автор «Истории Ричарда III» не ограничился описанием известных исторических событий, а дает им собственную оценку. Также специалисты в области литературы отмечают, что Мор довольно часто ссылается на весьма сомнительные источники.

Роман Утопия

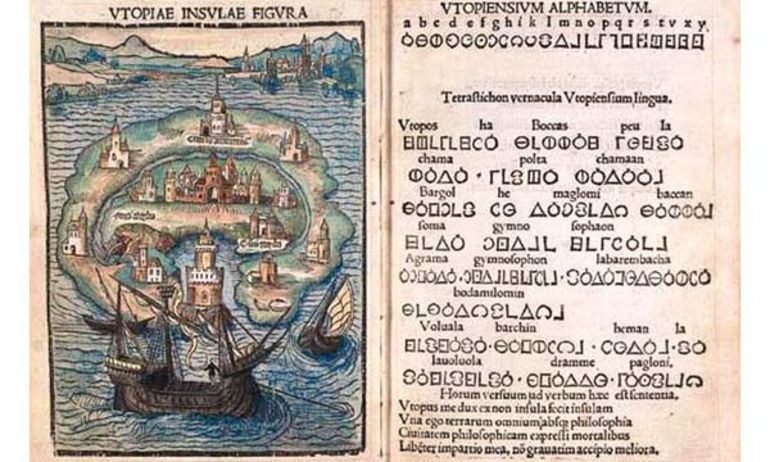

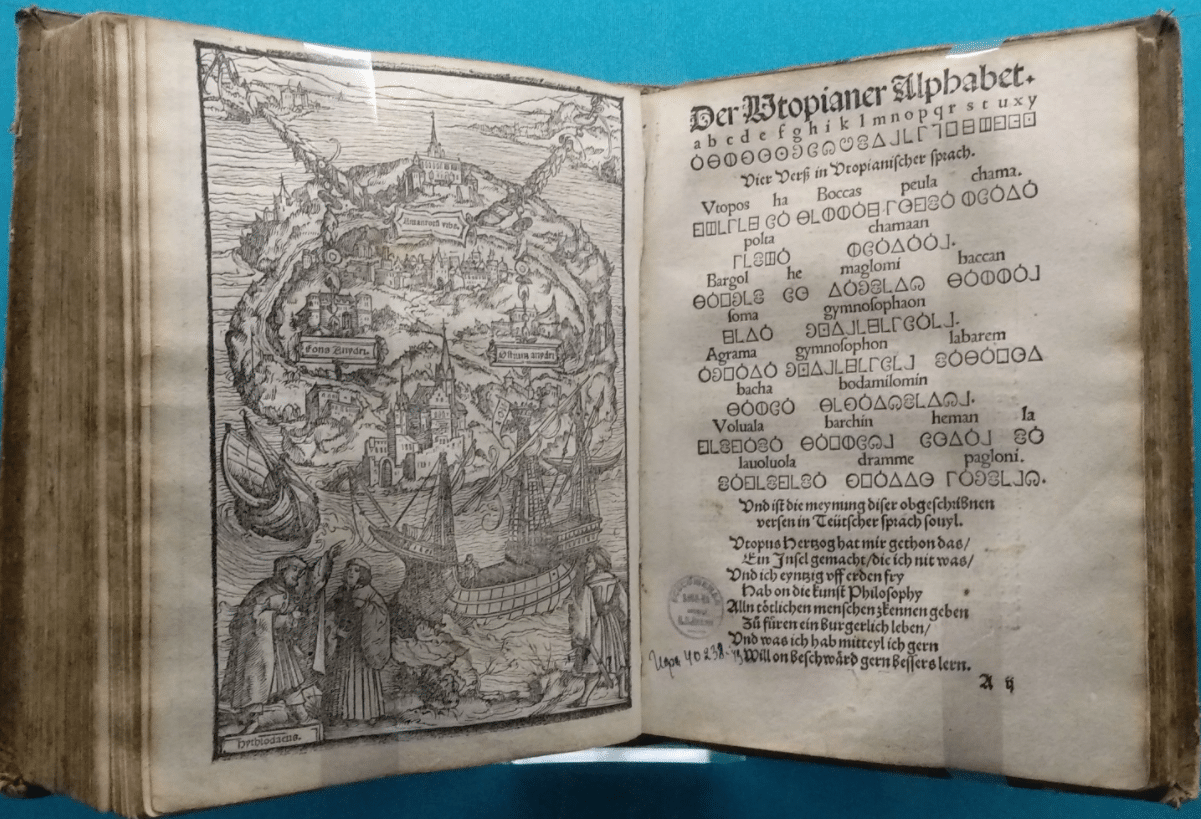

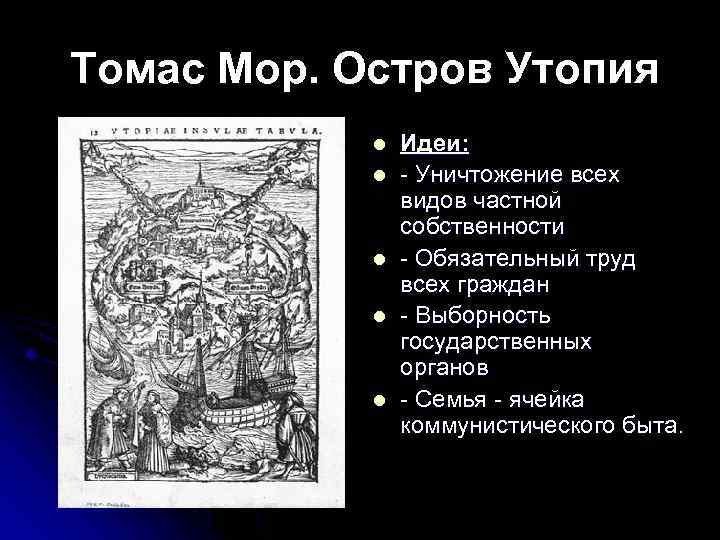

Работать над своим главным произведением Томас начал во время поездки во Фландрию в составе английской делегации. Впервые книга была опубликована в 1516 году и предназначалась для просвещенных монархов, а также ученых-гуманистов. Сам автор называл ее «Золотой книжечкой, одинаково полезной и забавной».

Произведение состоит из 2 частей, содержание которых имеет существенные отличия, но логически они неотделимы. В первой книге автор высказывает свои мысли о несовершенстве политической и социальной системы. Мор подвергает критике смертную казнь, высмеивает тунеядство духовных деятелей, а также разврат, царящий в обществе. При этом автор предлагает собственную программу реформ, которые помогут изменить ситуацию.

Вторая книга «Утопии» содержит гуманистические черты учения Мора. По мнению автора, во главе государства должен стоять мудрый монарх, а труд должен стать обязательным для всех слоев общества, но при этом не быть изнуряющим. Философия Мора предполагает равноправие и демократию даже при наличии короля. Именно эта работа сыграла большую роль в дальнейшем развитии утопической теории. Среди основных идей «Утопии» Томаса Мора кратко можно отметить:

- деньги следует использовать только для торговли с другими государствами;

- частная собственность должна быть заменена общественным производством;

- монарх должен обладать мудростью;

- несмотря на наличие короля, в стране должны царить равноправие и демократия;

- все продукты следует распределять только в зависимости от потребностей людей.

Мор был одним из самых выдающихся людей своего времени. Написанные им литературные работы имели важное значение для становления последователей. Современники считали его умным и добрым человеком. Он мог быть веселым и радоваться каждому мгновению жизни, но при определенных обстоятельствах становился серьезным и сосредоточенным на деле. Мор до последнего мгновения жизни придерживался своих принципов и не отказывался от сказанных слов. Его влияние на развитие философии и литературы высоко оценивается современными учеными.

Томас Мор (1478-1535) – известный английский философ, общественный деятель, писатель-гуманист, юрист. В течение трёх лет занимал пост лорд-канцлера Англии. Наиболее известен произведением «Утопия», в нём философ привёл пример вымышленного островного государства, на котором изложил своё видение идеальной общественно-политической системы.

Детство

Томас появился на свет в Лондоне 7 февраля 1478 года. Его папа, сэр Джон Мор, был знаменитым в стране юристом, занимал должность судьи королевской скамьи, в период правления Эдуарда IV получил дворянский титул, прославился своею честностью и неподкупностью.

Получать образование Томаса отправили в лучшую в Лондоне грамматическую школу Святого Антония. Здесь он среди прочих предметов в совершенстве овладел латинским языком.

Когда Томасу было тринадцать лет, благодаря своим связям отец определил мальчика на службу в качестве пажа к духовному главе английской церкви Кентерберийскому архиепископу – кардиналу Джону Мортону. Это был очень просвещённый человек, ранее занимавший пост лорд-канцлера Англии. Подросток уважал кардинала, что впоследствии нашло отображение в его произведениях «Утопия» и «История Ричарда III».

Джон Мортон действительно оказал неоценимую роль в образовании и воспитании Томаса. Мальчик рос весёлым, обладал остроумием и стремился к знаниям, что произвело на кардинала хорошее впечатление. Позже он сказал о Томасе, что из него в будущем получится «изумительный человек».

Образование

В 1492 году Томас поступил на учёбу в Кентербери-колледж при Оксфордском университете, его наставниками были знаменитые юристы того времени – Вильям Гросин и Томас Линакр.

Учился парень с лёгкостью, но уже в тот период сухие формулировки законов стали привлекать его меньше, чем произведения современных гуманистов. Во время учёбы Томас Мор увлёкся работами мыслителя эпохи Возрождения – итальянца Пико делла Мирандола, юноша переводил на английский язык его биографию и произведение «Двенадцать мечей».

В 1494 году Томас покинул учебное заведение в Оксфорде по настоянию отца и вернулся в Лондон. Сэр Джон Мор хотел, чтобы сын продолжил его дело, и нанял ему для изучения права опытных законоведов. Томас был способным учеником, из него действительно получился превосходный юрист.

Начало юридической карьеры

Он начал свою карьеру в лондонской адвокатской корпорации «Нью Инн». В начале 1496 года молодой человек перешёл в контору с более высоким статусом «Линкольнз Инн».

Наряду с юридической практикой юный Мор стал изучать философские труды древних классиков, особенный интерес у него вызывали сочинения Лукиана и Платона. Также Мор продолжил совершенствовать латинский и греческий языки и работал над собственными произведениями, которые начал ещё в Оксфорде.

В 1497 году Томас Мор получил приглашение на торжественный обед к лорд-мэру. Здесь он познакомился с крупнейшим учёным Северного Возрождения Эразмом Роттердамским, который в это время находился в Англии с визитом.

Между ними завязалась дружба, в результате чего Мор вступил в кружок Эразма и сблизился с гуманистами. Они много и плодотворно работали вместе, оказывали друг другу поддержку в литературных замыслах, переводили труды Лукиана. Позднее, в 1509 году, Роттердамский гостил у Мора дома и сочинил сатирическое произведение «Похвала глупости».

В 1501 году Томасу присвоили адвокатскую категорию высшего ранга – барристер.

Сложный выбор между церковью и миром

Однако Мор никак не мог определиться, посвящать ли всю жизнь карьере юриста? В какой-то период, под влиянием декана лондонского собора Святого Павла Джона Колета, Томас склонился к тому, чтобы связать своё будущее с церковным служением. Долгое время он выбирал между церковной и гражданской службой. В итоге всё-таки принял решение стать монахом и поселиться в картузианском монастыре. Здесь он провёл около четырёх лет.

Тем не менее, желание быть полезным своей стране перевесило над монастырскими устремлениями, и Томас решил оставаться в миру. При этом до конца жизни Мор сохранил привычки, приобретённые в монашеской обители. Всегда очень рано пробуждался и длительно молился, носил власяницы, постоянно соблюдал посты, самобичевался.

Политическая деятельность

В 1504 году Томас был избран в английский Парламент. Начав здесь свою трудовую деятельность, Мор сразу же выступил за то, чтобы уменьшить налоговые сборы в пользу казны английского короля Генриха VII.

За это последовала месть – король арестовал и заключил в тюрьму отца Томаса Мора. Освобождение последовало только после того, как Томас самоустранился от общественной деятельности и заплатил за родителя внушительный выкуп.

В 1509 году Генрих VII скончался, и Мор вернулся к политике. И уже в следующем 1510 году его назначили младшим шерифом Лондона. Все восторгались его красноречием, честностью и справедливостью. На Томаса сразу же обратил внимание пришедший к власти король Генрих VIII, тем более что Мор воспел его в своих изящных латинских стихотворениях. В 1515 году правитель назначил Томаса послом во Фландрию вести переговоры по поводу торговли английской шерстью.

В 1517 году Мор оказал помощь в усмирении Лондона, когда народ поднял против иностранцев бунт.

В 1518 году Томас был избран в члены почтеннейшего органа британского королевства – Тайного Совета.

В 1520 году вблизи города Кале состоялась встреча Генриха VIII с французским королём Франциском I, Томас Мор входил в состав свиты правителя Англии.

В 1521 году Томас получил к своему имени почётную приставку «сэр», за заслуги перед страной и королём его посвятили в рыцари.

В 1529 году впервые в английской истории на должность лорд-канцлера был назначен выходец из буржуазной среды, по рекомендации короля им стал Томас Мор.

«Утопия»

Во время поездки во Фландрию Томас начал работу над первой частью своего самого знаменитого произведения «Утопия». Он завершил её, когда вернулся домой.

Это произведение состоит из двух частей, которые по содержанию мало похожи, но по логике неотделимы друг от друга. Здесь автор поделился своими взглядами, насколько несовершенны политическая и социальная системы. Томас высмеивал разврат и духовное тунеядство, критиковал смертную казнь и кровавые законы о рабочих. Здесь же он предлагал программу реформ, с помощью которых можно было изменить положение.

Вторая часть «Утопии» – это, по сути, и есть гуманистическое учение Томаса Мора. Его основные идеи:

- Полное равноправие и демократия, несмотря на наличие короля.

- Глава государства – это, прежде всего, мудрый монарх.

- Продукты распределяются только по потребностям.

- Эксплуатацию и частную собственность следует заменить общественным производством.

- Деньги надо использовать лишь при торговле с другими странами.

- Труд обязателен для всех, но он не должен изнурять.

Семейная жизнь

В 1505 году Томас женился. Избранницей Мора стала Джейн Кольт – старшая дочь почётного чиновника (эсквайра) с юго-восточного английского графства Эссекса. Согласно некоторым биографическим данным Томас был влюблён в младшую дочь, но из учтивости сделал предложение Джейн. Девушка была тихая и с добрым нравом. Она получила домашнее образование, но друг Томаса, Эразм Роттердамский, предложил ей продолжить обучение и лично занимался с Джейн литературой и музыкой. У супругов родилось четверо детей – три девочки Маргарет, Элизабет, Сесиль и мальчик Джон.

Однако счастье их было не долгим, в 1511 году Джейн скончалась от лихорадки. Томас хотел, чтобы у детей была мать, поэтому в течение месяца после похорон Джейн он женился на обеспеченной вдове Элис Мидлтон. В отличие от Джейн это была прямая, сильная и властная женщина. По свидетельству друзей Томаса брак, несмотря на какой-то расчёт и поспешность, оказался счастливым. Супруги прожили вместе до самой смерти. Общих детей они не имели, Томас воспитывал дочку Элис от предыдущего мужа, как свою родную.

Мор был очень любящим отцом, если уезжал, то всегда писал своим детям письма и просил их обязательно отвечать. Он особенно был заинтересован проблемами образования женщин, считал, что они способны на такие же открытия, как и мужчины. Именно поэтому настаивал на том, чтобы не только сын получил достойное образование, но и дочери.

Казнь

У глубоко религиозного Томаса Мора возникли разногласия с королём Англии Генрихом VIII, когда правитель решил расторгнуть брак со своей супругой. Мор настаивал на том, что это подвластно лишь Папе Римскому. Правящий на тот момент в Ватикане Климент VII тоже был против расторжения брака. Тогда Генрих VIII разорвал все связи с Ватиканом и встал на путь создания в стране англиканской церкви. В результате чего в скором времени была коронована новая супруга короля Анна Болейн.

Это вызвало негодование у Томаса Мора, причём настолько сильное, что он оставил пост лорд-канцлера и оказал помощь монахине Элизабет Бартон в публичном осуждении короля.

Но Парламент проголосовал о принятии «Акта о престолонаследии». Согласно этому документу все рыцари Англии обязаны были присягнуть и признать законными детей Генриха VIII и Анны Болейн. Томас Мор отказался давать такую присягу и его заключили в Тауэр.

В 1535 году его казнили как государственного изменника. Спустя четыре столетия, в 1935 году, его причислили к лику католических святых.

Современники отзывались о Томасе Море как о человеке учёном и ангельски умном. Говорили, что ему нет равных среди людей. Где ещё можно было увидеть мужчину подобной скромности и приветливости, такого высочайшего благородства? Если надо, он радовался жизни и веселился, при иных обстоятельствах был серьёзным и грустным. Это был человек на все времена. Такое название получила и картина, которую сняли о Томасе Море в 1966 году. В 1967 году фильм получил множество наград, в том числе шесть «Оскаров». Томаса Мора играл английский актёр Пол Скофилд.

Томас Мор — биография

Томас Мор – философ, юрист, писатель-гуманист. Автор известной книги «Утопия», где описывается наилучшая система общественного устройства, примером которого послужило вымышленное островное государство. В 1935-м канонизирован католической церковью.

История Англии знает не так много людей, которых казнили за их убеждения. Томас Мор один из них. Формально причиной вынесения такого приговора назвали государственную измену Мора, на самом же деле он поплатился жизнью из-за того, что не согласился с новой избранницей короля. С тех пор имя общественного деятеля олицетворяет образ человека, отдавшего жизнь, но не изменившего своим убеждениям.

Детство и юность

Родился Томас Мор 7 февраля 1478 года в Лондоне. Его отец – судья Высшего королевского суда Англии сэр Джон Мор, был очень честным, неподкупным, имел высокие моральные принципы. Эти черты характера отца наложили отпечаток на формировании мировоззрения Томаса, он старался быть похожим на папу. Вначале мальчика отдали на обучение в грамматическую школу Святого Антония.

В тринадцать лет Томаса назначили пажом кардинала Джона Мортона, занимавшего в то время должность лорд-канцлера Англии. Мортон остался доволен своим новым помощником – остроумным, веселым и очень любознательным подростком. Кардинал всем говорил, что из Мора получится «изумительный человек».

В шестнадцатилетнем возрасте молодой человек стал студентом Оксфордского университета. Он учился у величайших юристов Британии 15-го века – Томаса Линакра и Вильяма Гросина. Мор легко справлялся с учебным процессом, и кроме сухих формулировок различных законов начал пристально изучать работы гуманистов того периода. К слову, Томас сделал самостоятельный перевод произведения итальянского гуманиста Пико делла Мирандола под названием «Двенадцать мечей».

Прошло два года, и отец Томаса настоял на том, чтобы он вернулся домой, в Лондон. Мор-старший хотел, чтобы сын совершенствовал свои знания в английском праве. Молодой человек оказался достаточно способным, и вскоре разбирался во всех подводных камнях законодательства Англии, познакомиться с которыми ему помогли опытные юристы. После этого из Томаса Мора получился блистательный адвокат. Одновременно с этим, Томаса интересовала философия, древние классики, такие, как Платон и Лукиан. Молодой адвокат продолжал шлифовать свои навыки в греческом и латинском языках, писал свои труды. Некоторые из его сочинений датируются еще студенческими годами.

Большую роль в биографии Томаса сыграл Эразм Роттердамский, ставший для него своеобразным проводником к миру гуманистов. Их знакомство состоялось во время торжественного приема у лорда-мэра. Дружба с Эразмом открыла Томасу дверь в круг гуманистов, он стал одним из членов кружка Роттердамского. Когда Эразм гостил у Мора дома, он написал сатирическое произведение «Похвала глупости».

Историки утверждают, что в 1500-1504-м годах Мор жил в картезианском монастыре Лондона. Но вскоре понял, что служение Богу это не его удел в жизни, и отбросил затею остаться в монастыре до конца своих дней. Однако время, проведенное в стенах монастыря, наложило свой отпечаток на образ жизни молодого адвоката, он придерживался привычек, выработанных за эти годы. Томас вставал очень рано, много времени проводил в молитвах, соблюдал все посты, устраивал себе самобичевание и не расставался с власяницей. Наряду с этими привычками были и другие стремления – молодой человек хотел быть нужным своей стране, оказывать ей всяческую помощь.

Политика

После ухода из монастыря Мор вел адвокатскую практику и преподавал право. В 1504-м он вошел в Парламент, представлял купечество Лондона. За время работы в Парламенте Томас выказывал свое негативное отношение к налоговому произволу короля Генриха VII, от которого страдали англичане. По этой причине его невзлюбили высшие эшелоны английской власти, и Мору пришлось прервать на некоторое время свою политическую карьеру. Он полностью занялся адвокатской работой.

Параллельно с участием в судовых процессах, Мор все больше времени уделяет литературному творчеству. В 1510 году к власти в Англии пришел новый правитель, Генрих VIII, он начал созывать новый высший законодательный орган страны, в котором нашлось место и Томасу Мору, на тот момент уже достаточно известному юристу и литератору. Одновременно с этим Томаса назначают помощником шерифа города Лондона. В 1515-м, спустя пять лет, Мор вошел в число делегатов от посольства Англии, которые отправились во Фландрию на переговоры.

Это же время считается началом работы Томаса над самой известной своей книгой – «Утопией». Работу над первой книгой Мор начал во время пребывания во Фландрии, он закончил ее по возвращению домой. Вторая, основная книга произведения, была частично написана еще раньше, а когда Мор закончил работу над первой, то ему оставалось только систематизировать и немного подкорректировать материал. Во второй части писатель представляет читателю выдуманный остров в океане, якобы недавно открытый путешественниками. Третью книгу Мор издал в 1518-м, и в нее вошли его «Эпиграммы» в виде обширного собрания рифмованных произведений. Это были стихотворения, поэмы и непосредственно сами эпиграммы.

Основной аудиторией «Утопии» должны были стать ученые-гуманисты и просвещенные монархи. Книга оказала неоценимое влияние на развитие утопистской идеологии, в ней есть упоминание о том, что нужно ликвидировать частную собственность, добиться равенства потребления и обобществления производства. Кроме работы над «Утопией» Мор начал писать и другую книгу – «Историю Ричарда III».

Королю Генриху VIII очень понравилась «Утопия», и в 1517-м он утвердил талантливого адвоката на должность своего личного советника. Так Мор стал членом Королевского совета и королевским секретарем, он выполнял все дипломатические поручения Генриха VIII. С 1521 года Томас Мор вошел в «Звездную палату» — высший английский судебный орган.

Одновременно с этим Мор удостоился рыцарского титула, земельных пожалований и получил должность помощника казначея. Политическая карьера Томаса развивалась очень успешно и быстро, но, несмотря на это, он был такой же честный и скромный, как раньше. Мор всегда стремился к справедливости, и об этом было известно каждому англичанину. В 1529-м верный королевский советник получил от Генриха VIII новое назначение, стал лорд-канцлером. Мор был первым представителем класса буржуазии, которому удалось оказаться на высшем государственном посту.

Могут быть знакомы

Произведения

Среди многочисленных трудов Томаса наибольшую популярность получила «Утопия», состоящая из двух книг. Первая – в виде литературно-политического памфлета, в котором отражены взгляды автора на несовершенство политической и социальной систем. Мор выступает с критикой смертной казни, в открытую смеется над развратом и тунеядством представителей духовенства, выказывает жесткий протест против огораживания общинных людей, протестует против «кровавых» законов о рабочих. Однако писатель не просто критикует, он предлагает разработанную им программу реформирования, направленную на исправление этой несправедливости.

Вторая часть произведения знакомит читателя с гуманистическим учением великого утописта. Главные идеи этой книги выглядят так – государство должно управляться «мудрым монархом», обобществленное производство должно прийти на смену частной собственности и эксплуатации, трудиться должны все без исключения, причем труд не должен изнурять человека. Мор призывал использовать деньги только как средство платежа другим странам, и осуществлять такую торговлю могло только государство, продукты должны быть распределены в соответствии с потребностями. Томас предлагал модель общества, в основе которого полная демократия и равноправие, несмотря на то, что на троне сидел король.

На основе «Утопии» в последующем развивались всевозможные утопические учения. Гуманистическая позиция одного из самых известных философов – Томмазо Кампанелла строилась на основе «Утопии» Томаса Мора.

Еще одно значимое произведение утописта – «История Ричарда III», хотя вокруг него дебаты не утихают спустя несколько веков. Причина споров – правдоподобность изложенной в произведении истории. Одни исследователи видят в нем историческое произведение, другим кажется, что это просто художественный вымысел. Перу Томаса Мора принадлежат множество стихов и переводов.

Личная жизнь

Томас Мор устроил свою личную жизнь задолго до того, как стал известным философом и юристом. Он взял в жены 17-летнюю Джейн Кольт, отец которой был богатым эсквайром из Эссекса. Зять Томаса, Уильям Ропер, опубликовал биографию Мора, из которой следует, что философ отдавал предпочтение младшей сестре, но он был учтивым человеком, и сделал предложение Джейн. Друзья Томаса характеризовали девушку как добрую и тихую нравом. Эразм Роттердамский настаивал на дополнительном образовании Джейн, сам лично учил ее литературе и музыке. Джейн родила супругу четырех детей – дочерей Маргарет, Элизабет, Сесиль, и сына Джона.

Джейн не стало в 1511 году, ее жизнь унесла лихорадка. Томас вдовствовал недолго, на протяжении месяца привел в дом новую жену. Его избранницей стала богатая вдова Элис Мидлтон. Она была прямой противоположностью Джейн, отличалась сильным и прямым характером. Однако это не помешало супругам быть счастливыми, во всяком случае, Эразм Роттердамский утверждал, что его друг обрел семейное счастье. В этом браке не было общих детей, но Томас стал настоящим отцом дочери Элис от первого брака. Помимо этого, Мор опекал молодую девушку – Алису Кресакр, ставшую впоследствии женой его сына Джона. Томас очень любил своих детей, часто писал им письма, если вынужденно уезжал по делам государства, просил, чтобы и они ему чаще писали. Философ уделял большое внимание проблеме женского образования, и в те годы это вызывало только изумление. А Мор был уверен, что женщина тоже способна сделать научное открытие, равно как и мужчина. Он настаивал, чтобы не только у сына, но и у его дочерей было высшее образование.

Смерть

Сам философ не считал свои произведения вымыслом, все, о чем в них говорилось, было его жизнью, к тому же, он отличался неимоверной религиозностью. Когда стало известно, что король Генрих VIII собрался развестись со своей женой Екатериной Арагонской, Мор выступил против этого расторжения брака. Он свято верил, что это под силу только Папе Римскому – Клименту VII. Папа тоже не приветствовал этот бракоразводный процесс.

Генрих не стал слушать никого, он принял решение жениться на Анне Болейн, и ради этого брака решился разорвать все связи с Римом. Он пошел своим путем и создал англиканскую церковь в собственной стране. Анну Болейн вскоре короновали, она стала второй супругой короля. Томас Мор был так сильно возмущен поведением монарха, что без сожаления сложил свои полномочия на посту лорда-канцлера. Помимо этого, он подговорил монахиню Элизабет Бартон осудить короля публично, и оказал ей всяческую поддержку.

Спустя некоторое время Парламент утвердил документ под названием «Акт о престолонаследии», на основании которого всем английским рыцарям предписывалось принести присягу, признать детей, рожденных в браке Генриха VIII и Анны Болейн законными престолонаследниками. Кроме этого, в этом документе говорилось, что в Англии признается власть исключительно представителей династии Тюдоров. Мор отказался присягать под этим документом, и 17 апреля 1534 года его заключили в Тауэр. 6 июля 1535 года ему зачитали «Акт об измене» и обезглавили на Тауэр-Хилле. Томас Мор не просил пощады, он держался очень мужественно накануне казни, даже шутил.

Верность Томаса Мора католицизму оценили спустя несколько столетий. В 1935 году Римско-католическая церковь причислила его к лику святых.

Произведения

- «История Ричарда III»

- «Утопия»

- Стихи и переводы

Ссылки

- Страница в Википедии

Для нас важна актуальность и достоверность информации. Если вы обнаружили ошибку или неточность, пожалуйста, сообщите нам. Выделите ошибку и нажмите сочетание клавиш Ctrl+Enter.

|

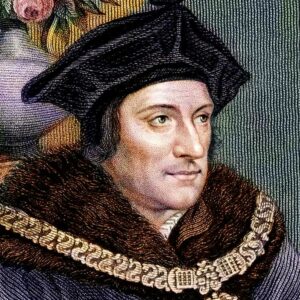

The Right Honourable Sir Thomas More |

|

|---|---|

Sir Thomas More (1527) |

|

| Lord Chancellor | |

| In office October 1529 – May 1532 |

|

| Monarch | Henry VIII |

| Preceded by | Thomas Wolsey |

| Succeeded by | Thomas Audley |

| Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster | |

| In office 31 December 1525 – 3 November 1529 |

|

| Monarch | Henry VIII |

| Preceded by | Richard Wingfield |

| Succeeded by | William FitzWilliam |

| Speaker of the House of Commons | |

| In office 15 April 1523 – 13 August 1523 |

|

| Monarch | Henry VIII |

| Preceded by | Thomas Nevill |

| Succeeded by | Thomas Audley |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 7 February 1478 City of London, England |

| Died | 6 July 1535 (aged 57) Tower Hill, London, England |

| Spouses |

Jane Colt (m. 1505; died 1511) Alice Middleton (m. 1511) |

| Children | Margaret, Elizabeth, Cicely, and John |

| Parent(s) | Sir John More Agnes Graunger |

| Education | University of Oxford Lincoln’s Inn |

| Signature |  |

|

Philosophy career |

|

| Notable work | Utopia (1516) Responsio ad Lutherum (1523) A Dialogue of Comfort against Tribulation (1553) |

| Era | Renaissance philosophy 16th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy, Catholic |

| School | Christian humanism[1] Renaissance humanism |

|

Main interests |

Social philosophy Criticism of Protestantism |

|

Notable ideas |

Utopia |

|

Influences

|

|

|

Influenced

|

|

Sir Thomas More (7 February 1478 – 6 July 1535), venerated in the Catholic Church as Saint Thomas More,[7][8] was an English lawyer, judge,[9] social philosopher, author, statesman, and noted Renaissance humanist. He also served Henry VIII as Lord High Chancellor of England from October 1529 to May 1532.[10] He wrote Utopia, published in 1516,[11] which describes the political system of an imaginary island state.

More opposed the Protestant Reformation, directing polemics against the theology of Martin Luther, Huldrych Zwingli, John Calvin and William Tyndale. More also opposed Henry VIII’s separation from the Catholic Church, refusing to acknowledge Henry as supreme head of the Church of England and the annulment of his marriage to Catherine of Aragon. After refusing to take the Oath of Supremacy, he was convicted of treason and executed. On his execution, he was reported to have said: «I die the King’s good servant, and God’s first».

Pope Pius XI canonised More in 1935 as a martyr. Pope John Paul II in 2000 declared him the patron saint of statesmen and politicians.[12][13][14]

Early life[edit]

Born on Milk Street in the City of London, on 7 February 1478, Thomas More was the son of Sir John More,[15] a successful lawyer and later a judge,[9] and his wife Agnes (née Graunger). He was the second of six children. More was educated at St. Anthony’s School, then considered one of London’s best schools.[16][17] From 1490 to 1492, More served John Morton, the Archbishop of Canterbury and Lord Chancellor of England, as a household page.[18]: xvi

Morton enthusiastically supported the «New Learning» (scholarship which was later known as «humanism» or «London humanism»), and thought highly of the young More. Believing that More had great potential, Morton nominated him for a place at the University of Oxford (either in St. Mary Hall or Canterbury College, both now gone).[19]: 38

More began his studies at Oxford in 1492, and received a classical education. Studying under Thomas Linacre and William Grocyn, he became proficient in both Latin and Greek. More left Oxford after only two years—at his father’s insistence—to begin legal training in London at New Inn, one of the Inns of Chancery.[18]: xvii [20] In 1496, More became a student at Lincoln’s Inn, one of the Inns of Court, where he remained until 1502, when he was called to the Bar.[18]: xvii

Spiritual life[edit]

According to his friend, the theologian Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam, More once seriously contemplated abandoning his legal career to become a monk.[21][22] Between 1503 and 1504 More lived near the Carthusian monastery outside the walls of London and joined in the monks’ spiritual exercises. Although he deeply admired their piety, More ultimately decided to remain a layman, standing for election to Parliament in 1504 and marrying the following year.[18]: xxi

More continued ascetic practices for the rest of his life, such as wearing a hair shirt next to his skin and occasionally engaging in self-flagellation.[18]: xxi A tradition of the Third Order of Saint Francis honours More as a member of that Order on their calendar of saints.[23]

Family life[edit]

More married Jane Colt in 1505. In that year he leased a portion of a house known as the Old Barge (originally there had been a wharf nearby serving the Walbrook river) on Bucklersbury, St Stephen Walbrook parish, London. Eight years later he took over the rest of the house and in total he lived there for almost 20 years, until his move to Chelsea in 1525.[19]: 118, 271 [24][25] Erasmus reported that More wanted to give his young wife a better education than she had previously received at home, and tutored her in music and literature.[19]: 119 The couple had four children: Margaret, Elizabeth, Cicely, and John. Jane died in 1511.[19]: 132

Going «against friends’ advice and common custom,» within 30 days, More had married one of the many eligible women among his wide circle of friends.[26][27] He chose Alice Middleton, a widow, to head his household and care for his small children.[28] The speed of the marriage was so unusual that More had to get a dispensation from the banns of marriage, which, due to his good public reputation, he easily obtained.[26]

More had no children from his second marriage, although he raised Alice’s daughter from her previous marriage as his own. More also became the guardian of two young girls: Anne Cresacre who would eventually marry his son, John More;[19]: 146 and Margaret Giggs (later Clement) who was the only member of his family to witness his execution (she died on the 35th anniversary of that execution, and her daughter married More’s nephew William Rastell). An affectionate father, More wrote letters to his children whenever he was away on legal or government business, and encouraged them to write to him often.[19]: 150 [29]: xiv

More insisted upon giving his daughters the same classical education as his son, an unusual attitude at the time.[19]: 146–47 His eldest daughter, Margaret, attracted much admiration for her erudition, especially her fluency in Greek and Latin.[19]: 147 More told his daughter of his pride in her academic accomplishments in September 1522, after he showed the bishop a letter she had written:

When he saw from the signature that it was the letter of a lady, his surprise led him to read it more eagerly … he said he would never have believed it to be your work unless I had assured him of the fact, and he began to praise it in the highest terms … for its pure Latinity, its correctness, its erudition, and its expressions of tender affection. He took out at once from his pocket a portague [A Portuguese gold coin] … to send to you as a pledge and token of his good will towards you.[29]: 152

More’s decision to educate his daughters set an example for other noble families. Even Erasmus became much more favourable once he witnessed their accomplishments.[19]: 149

A portrait of More and his family, Sir Thomas More and Family, was painted by Holbein; however, it was lost in a fire in the 18th century. More’s grandson commissioned a copy, of which two versions survive.

Early political career[edit]

In 1504 More was elected to Parliament to represent Great Yarmouth, and in 1510 began representing London.[30]

From 1510, More served as one of the two undersheriffs of the City of London, a position of considerable responsibility in which he earned a reputation as an honest and effective public servant. More became Master of Requests in 1514,[31] the same year in which he was appointed as a Privy Counsellor.[32] After undertaking a diplomatic mission to the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V, accompanying Thomas Wolsey, Cardinal Archbishop of York, to Calais and Bruges, More was knighted and made under-treasurer of the Exchequer in 1521.[32]

As secretary and personal adviser to King Henry VIII, More became increasingly influential: welcoming foreign diplomats, drafting official documents, and serving as a liaison between the King and Lord Chancellor Wolsey. More later served as High Steward for the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge.

In 1523 More was elected as knight of the shire (MP) for Middlesex and, on Wolsey’s recommendation, the House of Commons elected More its Speaker.[32] In 1525 More became Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, with executive and judicial responsibilities over much of northern England.[32]

Chancellorship[edit]

After Wolsey fell, More succeeded to the office of Lord Chancellor in 1529. He dispatched cases with unprecedented rapidity.

Campaign against the Protestant Reformation[edit]

Sir Thomas More is commemorated with a sculpture at the late-19th-century Sir Thomas More House, Carey Street, London, opposite the Royal Courts of Justice.

More supported the Catholic Church and saw the Protestant Reformation as heresy, a threat to the unity of both church and society. More believed in the theology, argumentation, and ecclesiastical laws of the church, and «heard Luther’s call to destroy the Catholic Church as a call to war.»[33]

His early actions against the Protestant Reformation included aiding Wolsey in preventing Lutheran books from being imported into England, spying on and investigating suspected Protestants,[34] especially publishers, and arresting anyone holding in his possession, transporting, or distributing Bibles and other materials of the Protestant Reformation. Additionally, More vigorously suppressed Tyndale’s English translation of the New Testament.[35]

The Tyndale Bible used controversial translations of certain words that More considered heretical and seditious; for example, «senior» and «elder» rather than «priest» for the Greek presbyteros, and «congregation» instead of «church.»[36] He also pointed out that some of the marginal glosses challenged Catholic doctrine.[37] It was during this time that most of his literary polemics appeared.

Many accounts circulated during and after More’s lifetime regarding persecution of the Protestant «heretics» during his time as Lord Chancellor. The popular sixteenth-century English Protestant historian John Foxe was instrumental in publicising accusations of torture in his Book of Martyrs, claiming that More had often personally used violence or torture while interrogating heretics.[38] Later authors such as Brian Moynahan and Michael Farris cite Foxe when repeating these allegations,[39] although Diarmaid MacCulloch, while acknowledging More’s «relish for burning heretics», finds no evidence that he was directly involved.[40] During More’s chancellorship, six people were burned at the stake for heresy; they were Thomas Hitton, Thomas Bilney, Richard Bayfield, John Tewkesbury, Thomas Dusgate, and James Bainham.[19]: 299–306 Moynahan argued that More was influential in the burning of Tyndale, as More’s agents had long pursued him, even though this took place over a year after his own death.[41]

Peter Ackroyd also lists claims from Foxe’s Book of Martyrs and other post-Reformation sources that More «tied heretics to a tree in his Chelsea garden and whipped them», that «he watched as ‘newe men’ were put upon the rack in the Tower and tortured until they confessed», and that «he was personally responsible for the burning of several of the ‘brethren’ in Smithfield.»[19]: 305 Richard Marius records a similar claim, which tells about James Bainham, and writes that «the story Foxe told of Bainham’s whipping and racking at More’s hands is universally doubted today».[42] More himself denied these allegations:

Stories of a similar nature were current even in More’s lifetime and he denied them forcefully. He admitted that he did imprison heretics in his house – ‘theyr sure kepynge’ – he called it – but he utterly rejected claims of torture and whipping… ‘as help me God.’[19]: 298–299

More instead claimed in his «Apology» (1533) that he only applied corporal punishment to two heretics: a child who was caned in front of his family for heresy regarding the Eucharist, and a «feeble-minded» man who was whipped for disrupting the mass by raising women’s skirts over their heads at the moment of consecration.[43]: 404

Burning at the stake had been a standard punishment for heresy: 30 burnings had taken place in the century before More’s elevation to Chancellor, and burning continued to be used by both Catholics and Protestants during the religious upheaval of the following decades.[44] Ackroyd notes that More zealously «approved of burning».[19]: 298 Marius maintains that More did everything in his power to bring about the extermination of the Protestant «heretics».[42]

John Tewkesbury was a London leather seller found guilty by the Bishop of London John Stokesley[45] of harbouring English translated New Testaments; he was sentenced to burning for refusing to recant. More declared: he «burned as there was neuer wretche I wene better worthy.»[46] After Richard Bayfield was also executed for distributing Tyndale’s Bibles, More commented that he was «well and worthely burned».[19]: 305

Modern commentators are divided over More’s religious actions as Chancellor. Some biographers, including Ackroyd, have taken a relatively tolerant view of More’s campaign against Protestantism by placing his actions within the turbulent religious climate of the time and the threat of deadly catastrophes such as the German Peasants’ Revolt, which More blamed on Luther,[47][48][49] as did many others, such as Erasmus.[50] Others have been more critical, such as Richard Marius, an American scholar of the Reformation, believing that such persecutions were a betrayal of More’s earlier humanist convictions, including More’s zealous and well-documented advocacy of extermination for Protestants.[43]: 386–406

Some Protestants take a different view. In 1980, More was added to the Church of England’s calendar of Saints and Heroes of the Christian Church, despite being a fierce opponent of the English Reformation that created the Church of England. He was added jointly with John Fisher, to be commemorated every 6 July (the date of More’s execution) as «Thomas More, scholar, and John Fisher, Bishop of Rochester, Reformation Martyrs, 1535».[13] Pope John Paul II honoured him by making him patron saint of statesmen and politicians in October 2000, stating: «It can be said that he demonstrated in a singular way the value of a moral conscience … even if, in his actions against heretics, he reflected the limits of the culture of his time».[12]

Resignation[edit]

As the conflict over supremacy between the Papacy and the King reached its peak, More continued to remain steadfast in supporting the supremacy of the Pope as Successor of Peter over that of the King of England. Parliament’s reinstatement of the charge of praemunire in 1529 had made it a crime to support in public or office the claim of any authority outside the realm (such as the Papacy) to have a legal jurisdiction superior to the King’s.[51]

In 1530, More refused to sign a letter by the leading English churchmen and aristocrats asking Pope Clement VII to annul Henry’s marriage to Catherine of Aragon, and also quarrelled with Henry VIII over the heresy laws. In 1531, a royal decree required the clergy to take an oath acknowledging the King as Supreme Head of the Church of England. The bishops at the Convocation of Canterbury in 1532 agreed to sign the Oath but only under threat of praemunire and only after these words were added: «as far as the law of Christ allows».[52]

This was considered to be the final Submission of the Clergy.[53] Cardinal John Fisher and some other clergy refused to sign. Henry purged most clergy who supported the papal stance from senior positions in the church. More continued to refuse to sign the Oath of Supremacy and did not agree to support the annulment of Henry’s marriage to Catherine.[51] However, he did not openly reject the King’s actions and kept his opinions private.[54]

On 16 May 1532, More resigned from his role as Chancellor but remained in Henry’s favour despite his refusal.[55] His decision to resign was caused by the decision of the convocation of the English Church, which was under intense royal threat, on the day before.[56]

Indictment, trial and execution[edit]

In 1533, More refused to attend the coronation of Anne Boleyn as the Queen of England. Technically, this was not an act of treason, as More had written to Henry seemingly acknowledging Anne’s queenship and expressing his desire for the King’s happiness and the new Queen’s health.[57] Despite this, his refusal to attend was widely interpreted as a snub against Anne, and Henry took action against him.

Shortly thereafter, More was charged with accepting bribes, but the charges had to be dismissed for lack of any evidence. In early 1534, More was accused by Thomas Cromwell of having given advice and counsel to the «Holy Maid of Kent,» Elizabeth Barton, a nun who had prophesied that the king had ruined his soul and would come to a quick end for having divorced Queen Catherine. This was a month after Barton had confessed, which was possibly done under royal pressure,[58][59] and was said to be concealment of treason.[60]

Though it was dangerous for anyone to have anything to do with Barton, More had indeed met her, and was impressed by her fervour. But More was prudent and told her not to interfere with state matters. More was called before a committee of the Privy Council to answer these charges of treason, and after his respectful answers the matter seemed to have been dropped.[61]

On 13 April 1534, More was asked to appear before a commission and swear his allegiance to the parliamentary Act of Succession. More accepted Parliament’s right to declare Anne Boleyn the legitimate Queen of England, though he refused «the spiritual validity of the king’s second marriage»,[62] and, holding fast to the teaching of papal supremacy, he steadfastly refused to take the oath of supremacy of the Crown in the relationship between the kingdom and the church in England. More furthermore publicly refused to uphold Henry’s annulment from Catherine. John Fisher, Bishop of Rochester, refused the oath along with More. The oath reads:[63]

…By reason whereof the Bishop of Rome and See Apostolic, contrary to the great and inviolable grants of jurisdictions given by God immediately to emperors, kings and princes in succession to their heirs, hath presumed in times past to invest who should please them to inherit in other men’s kingdoms and dominions, which thing we your most humble subjects, both spiritual and temporal, do most abhor and detest…

In addition to refusing to support the King’s annulment or supremacy, More refused to sign the 1534 Oath of Succession confirming Anne’s role as queen and the rights of their children to succession. More’s fate was sealed.[64][65] While he had no argument with the basic concept of succession as stated in the Act, the preamble of the Oath repudiated the authority of the Pope.[54][66][67]

His enemies had enough evidence to have the King arrest him on treason. Four days later, Henry had More imprisoned in the Tower of London. There More prepared a devotional Dialogue of Comfort against Tribulation. While More was imprisoned in the Tower, Thomas Cromwell made several visits, urging More to take the oath, which he continued to refuse.

The site of the scaffold at Tower Hill where More was executed by decapitation

A commemorative plaque at the site of the ancient scaffold at Tower Hill, with Sir Thomas More listed among other notables executed at the site

The charges of high treason related to More’s violating the statutes as to the King’s supremacy (malicious silence) and conspiring with Bishop John Fisher in this respect (malicious conspiracy) and, according to some sources, included asserting that Parliament did not have the right to proclaim the King’s Supremacy over the English Church. One group of scholars believes that the judges dismissed the first two charges (malicious acts) and tried More only on the final one, but others strongly disagree.[51]

Regardless of the specific charges, the indictment related to violation of the Treasons Act 1534 which declared it treason to speak against the King’s Supremacy:[68]

If any person or persons, after the first day of February next coming, do maliciously wish, will or desire, by words or writing, or by craft imagine, invent, practise, or attempt any bodily harm to be done or committed to the king’s most royal person, the queen’s, or their heirs apparent, or to deprive them or any of them of their dignity, title, or name of their royal estates …

That then every such person and persons so offending … shall have and suffer such pains of death and other penalties, as is limited and accustomed in cases of high treason.[69]

The trial was held on 1 July 1535, before a panel of judges that included the new Lord Chancellor, Sir Thomas Audley, as well as Anne Boleyn’s uncle, Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk, her father Thomas Boleyn and her brother George Boleyn. Norfolk offered More the chance of the king’s «gracious pardon» should he «reform his […] obstinate opinion». More responded that, although he had not taken the oath, he had never spoken out against it either and that his silence could be accepted as his «ratification and confirmation» of the new statutes.[70]

Thus More was relying upon legal precedent and the maxim «qui tacet consentire videtur» («one who keeps silent seems to consent»[71]), understanding that he could not be convicted as long as he did not explicitly deny that the King was Supreme Head of the Church, and he therefore refused to answer all questions regarding his opinions on the subject.[72]

Thomas Cromwell, at the time the most powerful of the King’s advisors, brought forth Solicitor General Richard Rich to testify that More had, in his presence, denied that the King was the legitimate head of the Church. This testimony was characterised by More as being extremely dubious. Witnesses Richard Southwell and Mr. Palmer (a servant to Southwell) were also present and both denied having heard the details of the reported conversation.[73] As More himself pointed out:

Can it therefore seem likely to your Lordships, that I should in so weighty an Affair as this, act so unadvisedly, as to trust Mr. Rich, a Man I had always so mean an Opinion of, in reference to his Truth and Honesty, … that I should only impart to Mr. Rich the Secrets of my Conscience in respect to the King’s Supremacy, the particular Secrets, and only Point about which I have been so long pressed to explain my self? which I never did, nor never would reveal; when the Act was once made, either to the King himself, or any of his Privy Councillors, as is well known to your Honours, who have been sent upon no other account at several times by his Majesty to me in the Tower. I refer it to your Judgments, my Lords, whether this can seem credible to any of your Lordships.[74]

Beheading of Thomas More, 1870 illustration

The jury took only fifteen minutes, however, to find More guilty.

After the jury’s verdict was delivered and before his sentencing, More spoke freely of his belief that «no temporal man may be the head of the spirituality» (take over the role of the Pope). According to William Roper’s account, More was pleading that the Statute of Supremacy was contrary to the Magna Carta, to Church laws and to the laws of England, attempting to void the entire indictment against him.[51]

He was sentenced to be hanged, drawn, and quartered (the usual punishment for traitors who were not the nobility), but the King commuted this to execution by decapitation.[75]

The execution took place on 6 July 1535 at Tower Hill. When he came to mount the steps to the scaffold, its frame seeming so weak that it might collapse,[76][77] More is widely quoted as saying (to one of the officials): «I pray you, master Lieutenant, see me safe up and [for] my coming down, let me shift for my self»;[78] while on the scaffold he declared «that he died the king’s good servant, and God’s first.»[79][80][81] After More had finished reciting the Miserere while kneeling,[82][83] the executioner reportedly begged his pardon, then More rose up merrily, kissed him and gave him forgiveness.[84][85][86][87]

Relics[edit]

Sir Thomas More family’s vault

Another comment he is believed to have made to the executioner is that his beard was completely innocent of any crime, and did not deserve the axe; he then positioned his beard so that it would not be harmed.[88] More asked that his foster/adopted daughter Margaret Clement (née Giggs) be given his headless corpse to bury.[89] She was the only member of his family to witness his execution. He was buried at the Tower of London, in the chapel of St Peter ad Vincula in an unmarked grave. His head was fixed upon a pike over London Bridge for a month, according to the normal custom for traitors.

More’s daughter Margaret later rescued the severed head.[90] It is believed to rest in the Roper Vault of St Dunstan’s Church, Canterbury,[91] perhaps with the remains of Margaret and her husband’s family.[92] Some have claimed that the head is buried within the tomb erected for More in Chelsea Old Church.[93]

Among other surviving relics is his hair shirt, presented for safe keeping by Margaret Clement.[94] This was long in the custody of the community of Augustinian canonesses who until 1983 lived at the convent at Abbotskerswell Priory, Devon. Some sources, including one from 2004, claimed that the shirt, made of goat hair was then at the Martyr’s church on the Weld family’s estate in Chideock, Dorset.[95][96] It is now preserved at Buckfast Abbey, near Buckfastleigh in Devon.[97][98]

Scholarly and literary work[edit]

History of King Richard III[edit]

Between 1512 and 1519 More worked on a History of King Richard III, which he never finished but which was published after his death. The History is a Renaissance biography, remarkable more for its literary skill and adherence to classical precepts than for its historical accuracy.[99] Some consider it an attack on royal tyranny, rather than on Richard III himself or the House of York.[100] More uses a more dramatic writing style than had been typical in medieval chronicles; Richard III is limned as an outstanding, archetypal tyrant—however, More was only seven years old when Richard III was killed at the Battle of Bosworth in 1485 so he had no first-hand, in-depth knowledge of him.

The History of King Richard III was written and published in both English and Latin, each written separately, and with information deleted from the Latin edition to suit a European readership.[101] It greatly influenced William Shakespeare’s play Richard III. Modern historians attribute the unflattering portraits of Richard III in both works to both authors’ allegiance to the reigning Tudor dynasty that wrested the throne from Richard III in the Wars of the Roses.[101][102] According to Caroline Barron, Archbishop John Morton, in whose household More had served as a page (see above), had joined the 1483 Buckingham rebellion against Richard III, and Morton was probably one of those who influenced More’s hostility towards the defeated king.[103][104] Clements Markham asserts that the actual author of the chronicle was, in large part, Archbishop Morton himself and that More was simply copying, or perhaps translating, Morton’s original material.[105][106]

Utopia[edit]

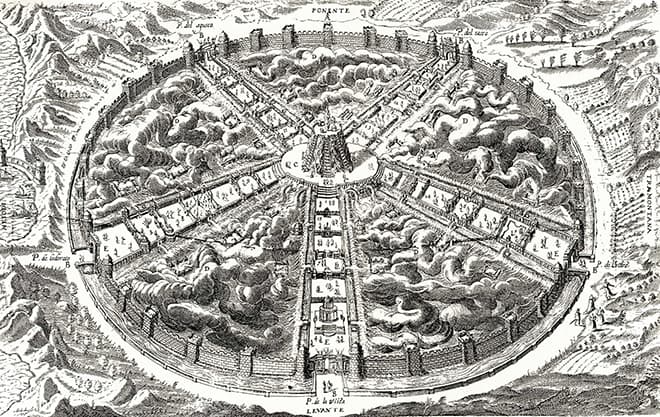

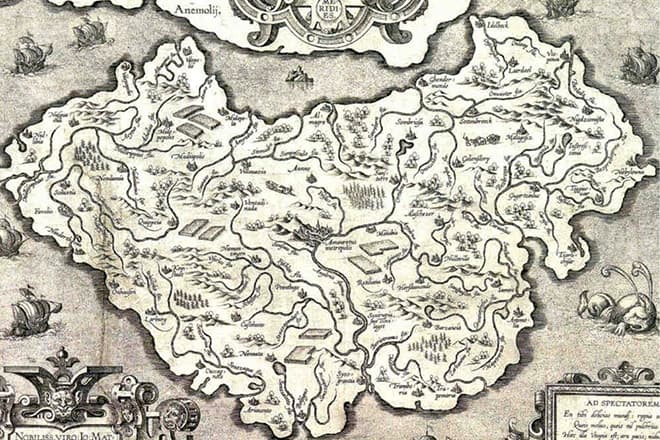

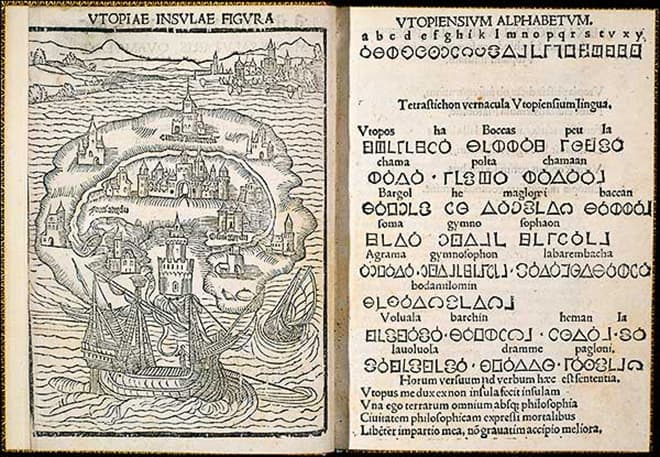

A 1516 illustration of Utopia

More’s best known and most controversial work, Utopia, is a frame narrative written in Latin.[107] More completed and theologian Erasmus published the book in Leuven in 1516, but it was only translated into English and published in his native land in 1551 (16 years after his execution), and the 1684 translation became the most commonly cited. More (also a character in the book) and the narrator/traveller, Raphael Hythlodaeus (whose name alludes both to the healer archangel Raphael, and ‘speaker of nonsense’, the surname’s Greek meaning), discuss modern ills in Antwerp, as well as describe the political arrangements of the imaginary island country of Utopia (a Greek pun on ‘ou-topos’ [no place] and ‘eu-topos’ [good place]) among themselves as well as to Pieter Gillis and Hieronymus van Busleyden.[108] Utopia’s original edition included a symmetrical «Utopian alphabet» omitted by later editions, but which may have been an early attempt or precursor of shorthand.

Utopia contrasts the contentious social life of European states with the perfectly orderly, reasonable social arrangements of Utopia and its environs (Tallstoria, Nolandia, and Aircastle). In Utopia, there are no lawyers because of the laws’ simplicity and because social gatherings are in public view (encouraging participants to behave well), communal ownership supplants private property, men and women are educated alike, and there is almost complete religious toleration (except for atheists, who are allowed but despised).

More may have used monastic communalism as his model, although other concepts he presents such as legalising euthanasia remain far outside Church doctrine. Hythlodaeus asserts that a man who refuses to believe in a god or an afterlife could never be trusted, because he would not acknowledge any authority or principle outside himself.

Some take the novel’s principal message to be the social need for order and discipline rather than liberty. Ironically, Hythlodaeus, who believes philosophers should not get involved in politics, addresses More’s ultimate conflict between his humanistic beliefs and courtly duties as the King’s servant, pointing out that one day those morals will come into conflict with the political reality.

Utopia gave rise to a literary genre, Utopian and dystopian fiction, which features ideal societies or perfect cities, or their opposite. Early works influenced by Utopia included New Atlantis by Francis Bacon, Erewhon by Samuel Butler, and Candide by Voltaire. Although Utopianism combined classical concepts of perfect societies (Plato and Aristotle) with Roman rhetorical finesse (cf. Cicero, Quintilian, epideictic oratory), the Renaissance genre continued into the Age of Enlightenment and survives in modern science fiction.

Religious polemics[edit]

In 1520 the reformer Martin Luther published three works in quick succession: An Appeal to the Christian Nobility of the German Nation (Aug.), Concerning the Babylonish Captivity of the Church (Oct.), and On the Liberty of a Christian Man (Nov.).[19]: 225 In these books, Luther set out his doctrine of salvation through grace alone, rejected certain Catholic practices, and attacked abuses and excesses within the Catholic Church.[19]: 225–6 In 1521, Henry VIII formally responded to Luther’s criticisms with the Assertio, written with More’s assistance.[109] Pope Leo X rewarded the English king with the title «Fidei defensor» («Defender of the Faith») for his work combating Luther’s heresies.[19]: 226–7

Martin Luther then attacked Henry VIII in print, calling him a «pig, dolt, and liar».[19]: 227 At the king’s request, More composed a rebuttal: the Responsio ad Lutherum was published at the end of 1523. In the Responsio, More defended papal supremacy, the sacraments, and other Church traditions. More, though considered «a much steadier personality»,[110] described Luther as an «ape», a «drunkard», and a «lousy little friar» amongst other epithets.[19]: 230 Writing under the pseudonym of Gulielmus Rosseus,[32] More tells Luther that:

- for as long as your reverend paternity will be determined to tell these shameless lies, others will be permitted, on behalf of his English majesty, to throw back into your paternity’s shitty mouth, truly the shit-pool of all shit, all the muck and shit which your damnable rottenness has vomited up, and to empty out all the sewers and privies onto your crown divested of the dignity of the priestly crown, against which no less than the kingly crown you have determined to play the buffoon.[111]

His saying is followed with a kind of apology to his readers, while Luther possibly never apologized for his sayings.[111] Stephen Greenblatt argues, «More speaks for his ruler and in his opponent’s idiom; Luther speaks for himself, and his scatological imagery far exceeds in quantity, intensity, and inventiveness anything that More could muster. If for More scatology normally expresses a communal disapproval, for Luther, it expresses a deep personal rage.»[112]

Confronting Luther confirmed More’s theological conservatism. He thereafter avoided any hint of criticism of Church authority.[19]: 230 In 1528, More published another religious polemic, A Dialogue Concerning Heresies, that asserted the Catholic Church was the one true church, established by Christ and the Apostles, and affirmed the validity of its authority, traditions and practices.[19]: 279–81 In 1529, the circulation of Simon Fish’s Supplication for the Beggars prompted More to respond with the Supplycatyon of Soulys.

In 1531, a year after More’s father died, William Tyndale published An Answer unto Sir Thomas More’s Dialogue in response to More’s Dialogue Concerning Heresies. More responded with a half million words: the Confutation of Tyndale’s Answer. The Confutation is an imaginary dialogue between More and Tyndale, with More addressing each of Tyndale’s criticisms of Catholic rites and doctrines.[19]: 307–9 More, who valued structure, tradition and order in society as safeguards against tyranny and error, vehemently believed that Lutheranism and the Protestant Reformation in general were dangerous, not only to the Catholic faith but to the stability of society as a whole.[19]: 307–9

Correspondence[edit]

Most major humanists were prolific letter writers, and Thomas More was no exception. As in the case of his friend Erasmus of Rotterdam, however, only a small portion of his correspondence (about 280 letters) survived. These include everything from personal letters to official government correspondence (mostly in English), letters to fellow humanist scholars (in Latin), several epistolary tracts, verse epistles, prefatory letters (some fictional) to several of More’s own works, letters to More’s children and their tutors (in Latin), and the so-called «prison-letters» (in English) which he exchanged with his oldest daughter Margaret while he was imprisoned in the Tower of London awaiting execution.[33] More also engaged in controversies, most notably with the French poet Germain de Brie, which culminated in the publication of de Brie’s Antimorus (1519). Erasmus intervened, however, and ended the dispute.[37]

More also wrote about more spiritual matters. They include: A Treatise on the Passion (a.k.a. Treatise on the Passion of Christ), A Treatise to Receive the Blessed Body (a.k.a. Holy Body Treaty), and De Tristitia Christi (a.k.a. The Agony of Christ). More handwrote the last in the Tower of London while awaiting his execution. This last manuscript, saved from the confiscation decreed by Henry VIII, passed by the will of his daughter Margaret to Spanish hands through Fray Pedro de Soto, confessor of Emperor Charles V. More’s friend Luis Vives received it in Valencia, where it remains in the collection of Real Colegio Seminario del Corpus Christi museum.

Veneration[edit]

|

Saint Thomas More |

|

|---|---|

Portrait of Saint Thomas More, executed on Tower Hill (London) in 1535, apparently based on the Holbein portrait. |

|

| Reformation Martyr, Scholar | |

| Venerated in | Catholic Church Anglican Communion |

| Beatified | 29 December 1886, Florence, Kingdom of Italy, by Pope Leo XIII |

| Canonized | 19 May 1935, Vatican City, by Pope Pius XI |

| Major shrine | Church of St Peter ad Vincula, London, England |

| Feast | 22 June (Catholic Church) 6 July (Church of England) 9 July (Catholic Extraordinary Form) |

| Attributes | dressed in the robe of the Chancellor and wearing the Collar of Esses; axe |

| Patronage | Statesmen and politicians; lawyers; Ateneo de Manila Law School; Diocese of Arlington; Diocese of Pensacola-Tallahassee; Kerala Catholic Youth Movement; University of Malta; University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Arts and Letters |

Catholic Church[edit]

Pope Leo XIII beatified Thomas More, John Fisher, and 52 other English Martyrs on 29 December 1886. Pope Pius XI canonised More and Fisher on 19 May 1935, and More’s feast day was established as 9 July.[113] Since 1970 the General Roman Calendar has celebrated More with St John Fisher on 22 June (the date of Fisher’s execution). On 31 October 2000 Pope John Paul II declared More «the heavenly Patron of Statesmen and Politicians».[12] More is the patron of the German Catholic youth organisation Katholische Junge Gemeinde.[114]

Anglican Communion[edit]

In 1980, despite their opposition to the English Reformation, More and Fisher were added as martyrs of the reformation to the Church of England’s calendar of «Saints and Heroes of the Christian Church», to be commemorated every 6 July (the date of More’s execution) as «Thomas More, scholar, and John Fisher, Bishop of Rochester, Reformation Martyrs, 1535».[13][115] The annual remembrance of 6 July, is recognized by all Anglican Churches in communion with Canterbury, including Australia, Brazil, Canada, and South Africa.[116]

In an essay examining the events around the addition to the Anglican calendar, Scholar William Sheils links the reasoning for More’s recognition to a «long-standing tradition hinted at in Rose Macaulay’s ironic debating point of 1935 about More’s status as an ‘unschismed Anglican’, a tradition also recalled in the annual memorial lecture held at St. Dunstan’s Church in Canterbury, where More’s head is said to be buried.»[116] Sheils also noted the influence of the 1960s popular play and film A Man for All Seasons which gave More a ‘reputation as a defender of the right of conscience».[116] Thanks to the play’s depiction, this «brought his life to a broader and more popular audience» with the film «extending its impact worldwide following the Oscar triumphs».[116] Around this time the atheist Oxford historian and public intellectual, Hugh Trevor-Roper held More up as «the first great Englishman whom we feel that we know, the most saintly of Humanists…the universal man of our cool northern Renaissance.»[116] By 1978, the quincentenary of More’s birth Trevor-Roper wrote an essay putting More in the Renaissance Platonist tradition, and claim his reputation was «quite independent of his Catholicism.»[116] (Only, later on, did a more critical view arise in academia, led by Professor Sir Geoffrey Elton, which «challenged More’s reputation for saintliness by focusing on his dealings with heretics, the ferocity of which, in fairness to him, More did not deny. In this research, More’s role as a prosecutor, or persecutor, of dissidents has been at the center of the debate.»)[116]

Legacy[edit]

The steadfastness and courage with which More maintained his religious convictions, and his dignity during his imprisonment, trial, and execution, contributed much to More’s posthumous reputation, particularly among Roman Catholics. His friend Erasmus defended More’s character as «more pure than any snow» and described his genius as «such as England never had and never again will have.»[117] Upon learning of More’s execution, Emperor Charles V said: «Had we been master of such a servant, we would rather have lost the best city of our dominions than such a worthy councillor.»[118]

G. K. Chesterton, a Roman Catholic convert from the Church of England, predicted More «may come to be counted the greatest Englishman, or at least the greatest historical character in English history.»[119] Hugh Trevor-Roper called More «the first great Englishman whom we feel that we know, the most saintly of humanists, the most human of saints, the universal man of our cool northern renaissance.»[120]

Jonathan Swift, an Anglican, wrote that More was «a person of the greatest virtue this kingdom ever produced».[121][122][123] Some consider Samuel Johnson that quote’s author, although neither his writings nor Boswell’s contain such.[124][125] The metaphysical poet John Donne, also honoured as a hero by Anglicans,[126] was More’s great-great-nephew.[127] US Senator Eugene McCarthy had a portrait of More in his office.[128]

Roman Catholic scholars maintain that More used irony in Utopia, and that he remained an orthodox Christian. Marxist theoreticians such as Karl Kautsky considered the book a critique of economic and social exploitation in pre-modern Europe and More is claimed to have influenced the development of socialist ideas.[129]

In 1963, Moreana, an academic journal focusing on analysis of More and his writings, was founded.[130]

In 2002, More was placed at number 37 in the BBC’s poll of the 100 Greatest Britons.[131]

In literature and popular culture[edit]

William Roper’s biography of More was one of the first biographies in Modern English.

Sir Thomas More is a play written circa 1592 in collaboration between Henry Chettle, Anthony Munday, William Shakespeare, and others. In it More is portrayed as a wise and honest statesman. The original manuscript has survived as a handwritten text that shows many revisions by its several authors, as well as the censorious influence of Edmund Tylney, Master of the Revels in the government of Queen Elizabeth I. The script has since been published and has had several productions.[132][133]

The 20th-century agnostic playwright Robert Bolt portrayed Thomas More as the tragic hero of his 1960 play A Man for All Seasons. The title is drawn from what Robert Whittington in 1520 wrote of More:

More is a man of an angel’s wit and singular learning. I know not his fellow. For where is the man of that gentleness, lowliness and affability? And, as time requireth, a man of marvelous mirth and pastimes, and sometime of as sad gravity. A man for all seasons.[120]

In 1966, the play A Man for All Seasons was adapted into a film with the same title. It was directed by Fred Zinnemann and adapted for the screen by the playwright. It stars Paul Scofield, a noted British actor, who said that the part of Sir Thomas More was «the most difficult part I played.»[134] The film won the Academy Award for Best Picture and Scofield won the Best Actor Oscar. In 1988 Charlton Heston starred in and directed a made-for-television film that restored the character of «the common man» that had been cut from the 1966 film.

In the 1969 film Anne of the Thousand Days, More is portrayed by actor William Squire.

Catholic science fiction writer R. A. Lafferty wrote his novel Past Master as a modern equivalent to More’s Utopia, which he saw as a satire. In this novel, Thomas More travels through time to the year 2535, where he is made king of the world «Astrobe», only to be beheaded after ruling for a mere nine days. One character compares More favourably to almost every other major historical figure: «He had one completely honest moment right at the end. I cannot think of anyone else who ever had one.»

Karl Zuchardt’s novel, Stirb du Narr! («Die you fool!»), about More’s struggle with King Henry, portrays More as an idealist bound to fail in the power struggle with a ruthless ruler and an unjust world.

In her 2009 novel Wolf Hall, its 2012 sequel Bring Up the Bodies, and the final book of the trilogy, her 2020 The Mirror and the Light, the novelist Hilary Mantel portrays More (from the perspective of a sympathetically portrayed Thomas Cromwell) as an unsympathetic persecutor of Protestants and an ally of the Habsburg empire.

Literary critic James Wood in his book The Broken Estate, a collection of essays, is critical of More and refers to him as «cruel in punishment, evasive in argument, lusty for power, and repressive in politics».[135]

Aaron Zelman’s non-fiction book The State Versus the People includes a comparison of Utopia with Plato’s Republic. Zelman is undecided as to whether More was being ironic in his book or was genuinely advocating a police state. Zelman comments, «More is the only Christian saint to be honoured with a statue at the Kremlin.»[citation needed] By this Zelman implies that Utopia influenced Vladimir Lenin’s Bolsheviks, despite their brutal repression of religion.

Other biographers, such as Peter Ackroyd, have offered a more sympathetic picture of More as both a sophisticated philosopher and man of letters, as well as a zealous Catholic who believed in the authority of the Holy See over Christendom.

The protagonist of Walker Percy’s novels, Love in the Ruins and The Thanatos Syndrome, is «Dr Thomas More», a reluctant Catholic and descendant of More.

More is the focus of the Al Stewart song «A Man For All Seasons» from the 1978 album Time Passages, and of the Far song «Sir», featured on the limited editions and 2008 re-release of their 1994 album Quick. In addition, the song «So Says I» by indie rock outfit The Shins alludes to the socialist interpretation of More’s Utopia.

Jeremy Northam depicts More in the television series The Tudors as a peaceful man, as well as a devout Roman Catholic and loving family patriarch. He also shows More loathing Protestantism, burning both Martin Luther’s books and English Protestants who have been convicted of heresy. The portrayal has unhistorical aspects, such as that More neither personally caused nor attended Simon Fish’s execution (since Fish actually died of bubonic plague in 1531 before he could stand trial), although More’s The Supplication of Souls, published in October 1529, addressed Fish’s Supplication for the Beggars.[136][137] Indeed, there is no evidence that More ever attended the execution of any heretic. The series also neglected to show More’s avowed insistence that Richard Rich’s testimony about More disputing the King’s title as Supreme Head of the Church of England was perjured.

More is depicted by Andrew Buchan in the television series The Spanish Princess.

In the years 1968–2007 the University of San Francisco’s Gleeson Library Associates awarded the annual Sir Thomas More Medal for Book Collecting to private book collectors of note,[138] including Elmer Belt,[139] Otto Schaefer,[140] Albert Sperisen, John S. Mayfield and Lord Wardington.[141]

Institutions named after More[edit]

Communism, socialism and resistance to communism[edit]

Having been praised «as a Communist hero by Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, and Karl Kautsky» because of the Communist attitude to property in his Utopia,[14] under Soviet Communism the name of Thomas More was in ninth position from the top of Moscow’s Stele of Freedom (also known as the Obelisk of Revolutionary Thinkers),[142] as one of the most influential thinkers «who promoted the liberation of humankind from oppression, arbitrariness, and exploitation.»[143] This monument was erected in 1918 in Aleksandrovsky Garden near the Kremlin at Lenin’s suggestion.[14][144][143]