Время чтения 3 мин.Просмотры 11k.Обновлено 2021-10-25

Содержание

- Основные характеристики тропического леса

- Классификация тропических лесов

- Животные тропических лесов

Тропические леса – это леса которые растут в тропических и субтропических регионах. Тропические леса занимают около шести процентов поверхности суши Земли. Есть два основных типа тропических лесов: влажные тропические леса (например, те, что в бассейне Амазонки или бассейна реки Конго) и сухие тропические леса (например, те, что на юге Мексики, равнинах Боливии и западных регионах Мадагаскара).

Тропические леса, как правило, имеют четыре различных яруса, которые определяют структуру леса. Ярусы включают в себя лесную подстилку, подлесок, верхний навес (полог леса) и верхний ярус. Лесная подстилка, самое темное место в тропическом лесу, куда проникает мало солнечного света. Подлесок – это слой леса между землей и до высоты около 20 метров. Он включает в себя кустарники, травы, небольшие деревья и стволы крупных деревьев. Полог леса – представляет навес из крон деревьев на высоте от 20 до 40 метров. Этот ярус состоит из переплетных крон высоких деревьев на которых обитает множество животных тропического леса. Большинство продовольственных ресурсов в тропическом лесу находятся в верхнем навесе. Верхний ярус тропического леса включает в себя кроны самых высоких деревьев. Этот ярус расположен на высоте около 40-70 метров.

Основные характеристики тропического леса

Ниже приведены основные характеристики тропических лесов:

- тропические леса расположены в тропических и субтропических регионах планеты;

- богаты видовым разнообразием флоры и фауны;

- здесь выпадает большое количество осадков;

- тропические леса находятся под угрозой исчезновения из-за вырубки для древесины, земледелия и выпаса скота;

- структура тропического леса состоит из четырех слоев (лесная подстилка, подлесок, полог, верхний ярус).

Классификация тропических лесов

- Влажные тропические леса, или тропические дождевые леса – лесные местообитания, которые получают обильные осадки в течение всего года (обычно более 200 см в год). Влажные леса расположены близко к экватору и получают достаточное количество солнечного света, чтобы поддерживать среднегодовую температуру воздуха на достаточно высоком уровне (между 20° и 35° С). Тропические дождевые леса являются одними из самых богатых видами местообитаний на Земле. Они растут в трех основных областях по всему миру: Центральной и Южной Америке, Западной и Центральной Африке и Юго-Восточной Азии. Из всех регионов влажных тропических лесов, бассейн Амазонки в Южной Америке является крупнейшим в мире: он охватывает около 6 миллионов квадратных километров.

- Сухие тропические леса – леса, которые получают меньшее количество осадков, чем дождевые тропические леса. Сухие леса, как правило, имеют сухой сезон и сезон дождей. Хотя количество осадков достаточно, чтобы поддержать рост растительности на должном уровне, деревья должны быть способны выдерживать длительные периоды засухи. Многие виды деревьев, которые растут в сухих тропических лесах лиственные и сбрасывают свои листья во время засушливого сезона. Это позволяет деревьям сократить свои потребности в воде во время сухого сезона.

Животные тропических лесов

Примеры нескольких животных, которые населяют тропические леса:

- Ягуар (Panthera onca) – крупный представитель семейства кошачьих, который обитает в тропических лесах Центральной и Южной Америки. Ягуар единственный вид пантер обитающий в новом мире.

- Капибара, или водосвинка (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris) – полуводное млекопитающее, которое населяет леса и саванны Южной Америки. Капибары являются крупнейшим живущими сегодня представителями отряда грызунов.

- Ревуны (Aloautta) – род обезьян, который включает в себя пятнадцать видов населяющих тропические леса на всей территории Центральной и Южной Америки.

Узнать больше информации о животных дождевых лесов Амазонки можно в статье “Животные Амазонии – млекопитающие, птицы и пресмыкающиеся дождевого леса“.

Гугломаг

Спрашивай! Не стесняйся!

Задать вопрос

Не все нашли? Используйте поиск по сайту

Contents

- 1 Что такое тропические леса

- 2 Где находятся тропические леса

- 3 Значение тропических лесов

- 4 Климат тропических лесов

- 5 Почвы тропических лесов

- 6 Растения тропических лесов

- 7 Животные тропических лесов

- 8 Тропические леса Америки

- 9 Тропические леса Африки

- 10 Тропические леса Евразии

- 11 Экологические проблемы тропических лесов

Что такое тропические леса

Тропические леса характеризуется повышенной влажность. Места их «обитания» это тропики и субтропики. Несмотря на большое количество осадков, вы падающих в таких районах, существуют как влажные тропики, так и сухие.

Тропические леса укомплектованы 4-мя ярусами: лесной подстилкой, подлеском, пологом леса и верхним ярусом. Вначале идёт лесная подстилка, она меньше всего освещена. Затем подлесок – это кустарники, травы, деревья до 20-ти метров. Полог леса следующий ярус до 40 метров, включающий кроны достаточно высоких деревьев. А после него начинается верхний ярус с кронами самых высоких деревьев.

Влажные тропические леса или, как их ещё называю дождевые, получают более 200 см осадков за год. Их относят к самым густонаселенным ареалом обитания многих видов. А благодаря близкой расположенности к экватору поддерживается достаточно высокая температура, порядка 30°.

Сухие тропические леса не так богаты на осадки, как дождевые. Но, несмотря на это, количество выпавших осадков поддерживает обитателей и растительность этих лесов. Здесь есть сезон дождей и сезон засухи. Многие лиственные деревья в периоды засухи сбрасывают листву, сокращая тем самым потребление воды.

Где находятся тропические леса

Тропические леса окутывают экватор земли, их часто называют «лёгкие земли». Самые внушительные леса распростерлись по территориям Центральной и Южной Америки, Африки, Юго-Восточной Азии.

Большие реки на южноамериканском, африканском континентах и субконтиненте Австралии уносят большую часть воды, которая «высыпается» на леса с избытком.

Сухие субтропики типичны для полуострова Индостан и небольшой части Австралии. Для остальных территорий характерны влажные тропические леса.

Значение тропических лесов

По различным данным около 50% кислорода на Земле производится тропическими лесами. Живое дерево потребляет углекислый газ для роста. Дерево, которое погибло, наоборот, испускает углекислый газ. Поэтому необходимо следить за балансом газов в атмосфере.

Трудно представить какую роль тропики играют в создании климатических условий. А ведь она огромна! В первую очередь они контролируют циркуляцию водяного пара в атмосфере. Тем самым леса защищают нашу Землю от парникового эффекта.

Леса создают благоприятную атмосферу для обитания животных, а последние, тем временем служат санитарами.

Для здоровья человека тропики играют неоценимую роль. Воздух лесов производит множество химических соединений, поглащая углеводы, пыль, промышленную грязь. А некоторые вещества благотворно влияют на нервную систему, сердечно-сосудистую, иммунитет.

Климат тропических лесов

Тропический климат, как уже говорилось ранее, делится на сухой и влажный. Влажный тропический климат характерен для территорий вблизи океана на низких широтах, сухой включает в себя практически все пустыни.

Влажные тропические леса находятся под постоянным воздействием дождей и высоких температур. Большое влияние на климат оказывают муссоны. В лесах не выделяются времена года, постоянная температура воздуха 25-35°. Осадков выпадает огромное количество (2000 мм, не меньше). Поэтому влажность здесь может достигать и 100%.

Сухой тропический климат отличается незначительными осадками (50-60 мм в год). А самое удивительное явление, характерно для «сухих» тропиков это большой перепад температур днем и ночью (20-30° днем и 0° ночью). Да, ночи здесь достаточно холодные. Особенно явно это явление наблюдается в пустынях.

Почвы тропических лесов

Тропические леса имеют в своём составе жёлтые, красные и красно-жёлтые почвы. Их окутывает древесная листва, опавшая за ненадобностью. Такие почвы обладают скудными запасами микроэлементов. Из-за сильнейших осадков все питательные вещества впитываются в почву или в корни деревьев. Эта особенность позволяет новым деревьям расти на месте вырубленных.

Земледелием в таких районах заниматься крайне проблематично. Почву нужно постоянно удобрять или пользоваться землёй максимум 2 года и искать новый участок.

Самое интересное в таком виде почв – это медленное изменение структуры. Вещества, которые вымывает дождь являются тому причиной.

Гумуса в тропических лесах практически нет, хотя сложно в это поверить, глядя на буйство растительности. Зато здесь предостаточно разных обитателей флоры и фауны. Столь огромное разнообразие видов (составляет две трети Земли) , что многие из них ещё не изучены.

Растения тропических лесов

Все тропические леса имеют ярусное расположение растительности, благодаря этому на самом нажнем ярусе отсутствует травяной покров. Это делает леса более проходимыми для их обитателей.

Очень трудно описать то количество растительности, которое растёт в этих местах. Давайте попробуем рассмотреть ярусы леса и их обитателей.

Итак, первый и самый «низкий » ярус – лесная подстилка. Солнечный свет здесь не появляется. В таких условиях светолюбивые растения просто не могут существовать. В связи с этим этот слой населяют насекомые и животные.

Следующий ярус – подлесок. Здесь есть недостаток солнечного света, но не такой критичны как в лесной подстилке. Повышенная влажность воздуха создаёт благоприятную среду для папоротников, лиан, кустов и деревьев. Всё растения, которые ниже 20-ти метров «живут» именно здесь.

Поднимаемся выше и видим верхний ярус, некий лесной потолок. Он образован из деревьев с широкими листьями, из-за которых, кстати, и не проникает солнечный свет вниз. Все эти деревья составляют важное жизнеобеспечения леса.

Новый ярус составляют кроны деревьев и все остальные деревья выше 30-ти метров. Здесь многие обитатели леса нашли свой дом.

Для человека тропики оказывают неоценимую услугу, производят на свет лекарственные растения. Эта «природная аптечка» содержит растения, из которых производят более четверти всех лекарств мира.

Животные тропических лесов

Тропические леса занимают малую часть суши, около 6%, но при всем этом здесь обитают животные, которых больше нигде не встретить. 50% всех видов нашли свой дом именно в тропиках. Благодаря повышенной влажности некоторые редкие животные сохранили свою популяцию.

А из-за густо сплетенных ветвей деревьев многие птицы даже разучились летать, зато искусно лазают по деревьям.

А теперь давайте поподробнее рассмотрим наиболее удивительных жителей джунглей, начнём с ярусности. Итак, поехали.

Лесная подстилка

Не будем в сотый раз вдаваться в подробности описания этого яруса, лучше сразу начнём с его обитателей. Здесь живут тапир, кубинский щелезуб, казуар, окапи, западная горилла, суматранский носорог.

Тапир – это близкий родственник лошади и носорога. Своим внешним видом он напоминает свинью с хоботом. Это животное около 2-х метров ведёт преимущественно ночной образ жизни.

Кубинский щелезуб – насекомоядное животное с вытянутой мордочкой. Напоминает землеройку или крысу.

Казуар – это птица относится к нелетающим. Является самой опасной для человека. Рост около 2-х метров.

Окапи – внешне есть схожесть с зеброй и жирафом. Животное небольшое, отличается длинным языком (35см), который помогает доставать листья с деревьев.

Западная горилла является самой крупной в Африке. Их осталось немного. Гориллы умеют ходить на задних лапах, но передвигается на четырёх.

Суматранский носорог это самый древний и самый маленький носорог. Длина его около 2, 5 метров.

Подлесок

Обитатели данного яруса не выше 3-х метров. Здесь встречаются: ягуар, бинтуронг, южноамериканская носуха, лягушка-древолаз, обыкновенный удав, летающий дракон.

Ягуар – это самая большая особь из кошачьих, обитающая в Америке. Отличительной особенностью ягуар является его окрас (у каждой особи он индивидуальный). Эти кошки отлично плавают.

Бинтуронг это хищное животное обитает в Азии. Внешне есть схожесть с енотом.

Южноамериканская носуха это зверёк из семейства енотовых. Обладает вытянутой мордочкой и длинным носом. Отлично лазает по деревьям благодаря цепким лапам.

Лягушка-древолаз является одним из ярких животных джунглей. Её яркий окрас как бы предупреждает о неприкосновенности. Дело в том, что лягушка-древолаз очень ядовита.

Обыкновенный удав может добывать себе пропитание как в воде так и на земле, и даже на деревьях. Удавы приносят большую пользу, поедая грызунов.

Летающий дракон. Несмотря на устрашающее название это обыкновенная ящерица с выростами кожи с боков. При прыжке с дерева эти выросты раскрываются.

Полог леса

Жителями этого яруса являются членистоногие и птицы. Одними из них являются: кинкажу, малайский медведь, жако, коата, тукан, златошлемый калао, ленивец.

Кинкажу – довольно интересный зверёк из семейства енотовых с длинным и цепким хвостом. Благодаря своему хвостик он передвигается по деревьям. Кинкажу большие любители мёда, иногда их сравнивают с медведями.

Малайский медведь является самым маленьким в своём виде, с очень короткой шерстью. Обитает в основном на деревьях. С другими данными в тропиках на такой высоте ему пришлось бы тяжело. Отличительная особенность медведя очень длинные когти и язык.

Жако – это, пожалуй, самая умная птица. Оперение у него серое, обитает в тропических лесах Африки. Сейчас многие птицы приручены людьми.

Коата это маленькая обезьянка с довольно длинным хвостом. Её часто сравнивают с пауком. Коата может передвигаться среди деревьев цепляясь и конечности и хвостиком.

Тукан крупная птичка, весом до 500 гр. У тукана очень массивный клюв с ярким раскрасом. Нужен он для того, чтобы добывать плоды деревьев.

Златошлемый калао. Птица обитает в Африканских джунглях. Калао практически самая большая из птиц этого региона, около 2 кг весом. На голове у неё вырост вроде лат (древние доспехи), очень массивный клюв.

Ленивец. Это животное полностью оправдывает свое название. Самое медлительное из всех видов. У ленивцев очень размеренная жизнь. Большую часть времени они спят вниз головой, а в остальное время неспешно жуют листья. Ленивцы хорошие пловцы.

Верхний ярус

Сложно добраться до высоты 50-ти метров, а уж тем более там жить. Но, несмотря на трудности, немногие животные выбрали для себя такой образ жизни. Вот основные из них: венценосный орёл, гигантская летучая лисица, королевский колобус.

Венценосный орёл является самой крупной хищной птицей. Свое название получил из-за хохолка на голове, который раскрываются во время опасности. Это парные птицы, редко когда обитают по одиночке.

Гигантская летучая лисица. Свое название рукокрылый зверёк получил из-за схожесть с лисой. Лисицы живут стаями.

Королевский колобус обитает в тропиках Африки. Это животное из семейства мартышковых. Небольшой зверёк с очень длинным хвостом. Не спускается на землю, питается фруктами с верхушек деревьев.

Очень и очень много видов обитает на просторах тропических лесов. Всё их не перечислить. Думаю, многие виды вы узнали впервые из этой статьи. Тем и интересно познавать джунгли и саванны.

Тропические леса Америки

Южная Америка является самой густонаселенной лесами территорией. Влажный тропический лес занимает практически всю территорию Амазонки. Такие леса называют гилей.

Гилей богат растительность и густые леса. Огромная территория просто окутана паутиной непроходимых джунглей. Здесь «живут» растения, которых больше нигде не встретишь на всем Земном шаре. Где ещё можно увидеть дерево, высотой 100 метров? А для тропиков это обыденно.

Но богатством отличается не только флора, но и фауна. Животные тропических лесов Южной Америки очень своеобразны. Многие из них проживают на большой высоте или в труднопроходимых местах.

Огромное количество обезьян разных видов нашли свой дом здесь, в тропиках. Например, игрунковые обезьяны. Это очень маленькие обезьянки, около 15 см длиной. Или цебиды – это тоже обезьянки, но уже побольше, с длинным цепким хвостом.

Хищные млекопитающих также не являются редкостью джунглей. В основном это ягуар, оцелоты, кустовая собака.

Грызуны, земноводные, пресмыкающиеся – все эти виды заселились в джунглях. А главной особенностью влажных тропических лесов является большое количество пауков и насекомых.

Тропические леса Африки

Африканские тропические леса также богаты на растительность. Здесь находятся мангровые джунгли.

В джунглях растут около 3000 видов деревьев. В связи с низким содержанием микроэлементов и отсутствием солнечного света на самом нижнем ярусе, некоторые виды цветов и кустарников растут прямо на стволах деревьев.

Животные мангровых лесов обитают в основном на деревьях. Здесь также как и в лесах гилей обитает очень много различных видов обезьян. От самых маленьких до горилл. Питаются они плодами деревьев. Среди копытных животных антилопы, окапи, дикие кабаны. Все они пугливы, прячутся в зарослях.

Огромное количество дивных птиц можно встретить в джунглях Африки. Ярко окрашенные попугаи, павлин, нектарницы.

Пресмыкающиеся мангровых лесов в большинстве случаев ядовиты. Нередко они имеют яркий окрас, им некого бояться.

Тропические леса Евразии

Так как Евразия является самым крупным материком, необходимо обозначить точное местонахождение тропических лесов или гилей. П-ов Малакка, о-ов Сумантра и Калимантан, Западные и восточные районы Индии, Таиланд, юг Китая.

Гилеи Евразии мало чем отличаются от остальных. Здесь так же насыщенные флорой и фауной леса, такая же ярусность.

Но все же растительное богатство Евразии больше, чем в тропиках Америки и Африки. Одних только цветочных растений насчитывается более 20 тысяч видов. Эти леса наполняют бамбук, пальмы, являющиеся важным строительным материалом у некоторых народов.

Обитатели фауны такие же как и в других тропиках. Единственное, гилеи Евразии представлены большим числом лягушек и жаб.

Экологические проблемы тропических лесов

Тропические леса, «лёгкие Земли», гилеи, мангровые леса, под всеми этими названиями кроется одна огромная проблема – вырубка тропиков. 80% всех видов фауны, 50% всей растительности планеты — все это тропические леса.

На сегодняшний день вырубка леса идёт губительно быстрыми темпами. Конечно новые деревья тоже растут, но это как капля в море.

Изменение климата, круговорот воды, исчезновение животных и растений, усиление парникового эффекта — это лишь малая часть проблем, к которым приводит «убийство» тропиков. Если погибнет один вид, за ним по цепной реакции начнут исчезать и другие, от него зависящие. А на месте уже мёртвого участка образуются пустыни, болота, полупустыни.

Конечно люди уже предлагают пути выхода из сложившейся ситуации, но пока что действий недостаточно. Коренным образом на вырубку лесов действуют государства, на границах которых они расположены. Истребление гилей для стран, к сожалению, играет экономически важную роль.

Тропические дождевые леса — это леса вокруг экватора с большим количеством вечнозеленой растительности. Здесь очень тепло, и дождь идет круглый год.

Хотя только 7% поверхности суши покрыто тропическими лесами, здесь обитает более половины всех видов растений и животных в мире.

Тропические леса очень важны для человека. Заводы производят продукты питания и лекарства, а мы получаем промышленные продукты из некоторых из них. Деревья производят древесину, помогают контролировать климат Земли и снабжают нас свежим воздухом.

Несмотря на эти преимущества, люди ежегодно вырубают тысячи квадратных километров тропических лесов.

Климат

Температура остается неизменной круглый год — около 20-30 градусов по Цельсию.

Вокруг экватора есть два сезона дождей с обильными осадками-до 10 метров. Когда вы удаляетесь от экватора, он становится немного суше в некоторые месяцы, но все еще есть более 2 метров дождя в год.

Погода почти не меняется от одного дня к другому. Утром все ясно. Солнце начинает нагревать землю, и теплый, влажный воздух начинает подниматься. После полудня облака становятся еще чернее, и в течение часа или двух, прежде чем они снова начинают проясняться, идут грозы.

Большая часть дождя остается в тропическом лесу. Он испаряется, создает облака и снова падает вниз.

Почвы дождевых лесов не очень плодородны, потому что дождь вымывает большую часть питательных веществ.

Структура тропического леса

Тропические леса имеют четыре слоя.

- Верхний слой — это навес. Он состоит из самых высоких деревьев тропического леса. Их высота может достигать более 50 метров. Но лишь очень немногие достигают этой высоты. Это та часть, которая получает большую часть солнечного света.

- Подканопа — это слой деревьев, который находится под пологом леса. Более 70 % видов животных и растений тропических лесов обитают в кронах деревьев и подканопах. Лианы часто лазают вокруг деревьев.

- Подлесок-это темная нижняя область. В нем есть молодые деревья и растения, такие как папоротники или пальмы, которые не нуждаются в большом количестве света. Только 1-2% солнечного света попадает в подлесок.

- На полу лежит тонкий слой листьев, семян или плодов и веток, которые падают с деревьев. Он быстро разлагается, и на его место приходит новый материал.

Когда большие, высокие деревья умирают и падают на землю, они оставляют брешь в тропическом лесу. Очень быстро меньшие деревья занимают это место, и их кроны становятся больше. Вот почему слои тропического леса всегда меняются.

Растения и животные

Около половины мировых видов растений можно встретить в тропических лесах. Из-за того, что здесь тепло и весь год идут дожди, леса остаются зелеными. Деревья теряют свои листья и сразу же вырастают новые. Тропический лес является домом для многих растений: лиан, папоротников, орхидей и многих видов тропических деревьев.

Рыбы, пресмыкающиеся, птицы и насекомые также живут в тропических лесах и реках. Растения и животные нуждаются друг в друге, чтобы выжить. Насекомые опыляют цветы тропического леса. Животные получают пищу из цветочного нектара. Семена с деревьев часто забирают другие животные и птицы и роняют в отдаленных районах.

Ценность тропического леса

Люди извлекают пользу из тропического леса во многих отношениях:

1. Экономическая ценность

Древесина — самый важный продукт тропического леса. Около 80 % его используется для производства энергии, а 20 % продается для производства мебели. Леса производят другие ценные товары, такие как фрукты, орехи, различные виды масел и резины.

2. Научная ценность

Ученые изучают тропический лес как экосистему. Они многое узнают о том, как растения и животные живут вместе. Тропические растения используются для лечения таких заболеваний, как малярия.

3. Экологическая ценность

Дождевые леса помогают регулировать нашу окружающую среду. Деревья контролируют воду, которая достигает Земли. Они также занимают много дождя. Большая часть этой воды испаряется и снова попадает в атмосферу в виде пара. Затем он превращается в дождь и спускается на землю. Без дождевых лесов наводнения и засухи были бы очень сильными. Тропические леса также помогают нашей атмосфере не становиться слишком теплой.

Люди тропического леса

Большая часть тропических лесов мира населена коренными жителями. Это люди, которые живут там уже тысячи лет. Их выживание зависит от тропических лесов. Некоторые люди живут в местах, куда можно добраться только на лодке.

Многие люди собирают фрукты, орехи и дрова. Они охотятся и ловят рыбу, чтобы выжить. Они сжигают небольшие участки тропических лесов и выращивают там урожай. Когда почва становится слишком плохой, они уходят в другие места и сажают новые культуры. Этот способ земледелия называется сдвиговым культивированием.

Сегодня жилые районы этих коренных племен находятся в опасности, потому что другие люди пришли сюда рубить деревья, разводить скот или добывать золото и серебро.

Вырубка леса

Люди уничтожают тропические леса в мире очень быстрыми темпами. Одна из причин — вырубка лесов. С каждым годом вырубается все больше деревьев, потому что

- население планеты нуждается во все большем количестве древесины

- люди в тропическом лесу нуждаются в энергии. Они не могут купить нефть или газ, потому что это слишком дорого.

- правительства находят в этих районах ценное сырье — железную руду, золото или серебро.

- вдоль тропических рек строятся плотины.

- крупные компании получают землю для выращивания мяса и производства продуктов питания.

Как мы можем спасти тропические леса

Многие экологические организации, такие как Всемирный фонд дикой природы, работают над сохранением тропических лесов во всем мире. Они помогают создавать национальные парки или другие охраняемые территории. Но это стоит больших денег, и не все правительства хотят их тратить.

Также важно рассказать общественности, насколько ценны тропические леса и что произойдет, если они будут полностью уничтожены.

Животные и растения тропического леса

Пальма

Пальмы растут в жарком и влажном климате тропиков. Они дают нам пищу, питье и иногда строительный материал. Большинство пальм встречается в Юго-Восточной Азии, Южной Америке и на островах Тихого океана.

Существует более 2000 видов пальм. Они растут прямыми и высокими, и большинство из них несут плоды, такие как кокосовый орех, который может быть до двух футов в высоту.

Каучуковое дерево

Резина — одно из наших важнейших сырьевых материалов. Натуральный каучук получают из сока каучукового дерева. Лучше всего он растет в жарком климате. Дерево может быть около 20 метров высотой. У него гладкие, блестящие листья. Белая, молочная жидкость выходит из коры, если ее разрезать. Это называется латекс.

Сегодня большая часть каучука поступает с плантаций в Юго-Восточной Азии.

Орхидея

Дикие орхидеи растут в местах с большим количеством осадков. Большинство видов растут на стволах или ветвях деревьев. В более прохладных регионах орхидеи выращивают в теплицах. Большинство из них растут в смеси завораживающих цветов.

Пиранья

Пиранья-рыба с острыми зубами, обитающая в озерах и реках долины Амазонки. Он нападает и поедает других рыб и водных животных. В некоторых случаях он даже нападает на людей. Пираньи имеют плоские тела и могут вырасти до 30 см в длину.

Тукан

Туканы — типичные птицы тропических лесов. У них большие и длинные клювы, которые ярко окрашены, так что они могут привлечь других птиц. Самые крупные туканы могут достигать 65 см в длину. Большинство из них живут в дуплах деревьев.

Горилла

Гориллы — самые крупные представители семейства обезьяньих. У них огромные плечи, длинные руки и короткие ноги. Они могут весить до 200 кг.

Гориллы живут в Африке недалеко от экватора. Хотя большинство из них живут в низинах, есть некоторые высокогорные типы.

Люди уже давно охотятся на горилл. В результате они стали очень редкими, и только около 1000 горилл живут сегодня в дикой природе.

Влажный тропическим лес представляет собой гигантское сообщество растений и животных. От остального мира со всех сторон он огражден зеленой до шести метров в высоту стеной из множества переплетенных друг с другом деревьев, кустарников и лиан, а сверху — плотной крышей из крон гигантских деревьев. Над тропическим лесом светит яркое солнце, но внутри него всегда стоит полумрак, расцвеченный яркой окраской бабочек и птиц. Здесь тепло и много влаги — исключительное сочетание для буйного роста растений. Температура воздуха круглый год держится на уровне + 26 ºС.

Растительность тропического леса

По образному выражению Арнольда Ньюмена, влажные тропические леса — это «легкие» нашей планеты. Благодаря этим огромным массивам деревьев, лиан и трав наша атмосфера постоянно получает новые порции кислорода, жизненно необходимого для любого живого организма, а углекислый газ, выделяемый животными в процессе дыхания, поглощается зеленой массой растений и трансформируется путем фотосинтеза в органическую структуру, которая служит пищей многим миллионам живых существ.

Тропические леса — «легкие» нашей планеты

В тропических лесах встречается гораздо больше видов животных, чем в умеренном климате, хотя число особей в отдельных видах в среднем незначительное. Большое число видов животных можно объяснить отчасти разнообразием растительности, ведь она является пищей и жильем для многих и многих видов животных. Смешанные леса Центральной Европы по богатству видов не выдерживают никакого сравнения с богатством форм и разнообразием видов растений тропического леса.

Влажные тропические леса еще называют влажным экваториальным лесом, тропическим дождевым лесом, гилеей и джунглями. «Гилея» —древнегреческое слово, означающее «лес». «Джунгли» в переводе с санскрита означают «пустыня», т.е. слово имеет совсем противоположное значение. Просто оно очень понравилось на слух европейцам, и они назвали им влажные тропические леса.

Влажные тропические леса отличаются обилием древесных форм животных, богатством видового состава даже на небольшой площади. Теплый и мягкий климат экваториальной зоны джунглей создает условия для круглогодичной активности живых существ. Животные размножаются здесь практически круглый год.

Влажные тропические леса занимают около восьми процентов земной суши. Они произрастают в тропической Азии, в Африке в бассейне реки Конго, в Габоне, Центральноафриканской республике.

Самый крупный массив тропических лесов находится в Южной Америке, в бассейне Амазонки. Здесь обитают уникальные животные, названные за особенности зубной системы неполнозубыми. Их вы не встретите ни в Евразии, ни в Африке, ни в Австралии, не говоря уже об Антарктиде, а в Северную Америку они попали из Южной. Представители этого отряда — ленивцы, муравьеды и броненосцы — своего рода зоологическая «визитная карточка» Южной Америки.

Муравьед

Вся эта группа животных, как легко догадаться по их названию, отличается недоразвитием зубов: зубы у них или отсутствуют, как у муравьедов, или лишены эмали, обладают постоянным ростом и почти недифференцированы, как у ленивцев и броненосцев.

Муравьеды получили свое название из-за пристрастия к муравьям и термитам. На передних лапах у них находятся длинные и острые когти, способные разрушать прочные стенки термитников, а голова вытянута в длинную узкую трубку, на конце которой имеется небольшое ротовое отверстие. Благодаря такой голове и длинному клейкому языку муравьед легко достает муравьев и термитов из их убежищ.

Современные представители неполнозубых — лишь остатки некогда богатой и очень своеобразной фауны. Когда-то в Южной Америке обитали большие броненосцы величиной с носорога и гигантские ленивцы величиной со слона. В настоящее время сохранились лишь относительно мелкие животные с длиной тела от 12 до 120 сантиметров.

Ленивцы растительноядны, пищей им служат молодые листья, побеги и почки деревьев. Медлительность ленивца, затрачивающего незначительное количество энергии на свою жизнедеятельность, отразилась и на внутренних процессах организма ленивца. Переваривание пищи в пищеварительной системе ленивца происходит медленно, иногда несколько дней. Желудок ленивца (на него приходится почти одна треть массы животного) всегда набит пищей. Свое название животные получили за удивительно малоподвижный образ жизни, большую часть которой они проводят на деревьях, цепляясь за ветви с помощью мощных когтей-крючков. В тропическом лесу очень много влаги, поэтому в густой и всегда мокрой шерсти ленивца поселяются водоросли, придающие коричневому цвету шерсти этих медлительных животных зеленоватый оттенок.

Броненосец

Броненосцы своим названием обязаны наружному панцирю, состоящему из покрытых роговым слоем костных пластин. Панцирь гигантского броненосца по твердости не уступает камню и служит надежной защитой животному. Броненосцы имеют мощные когти, которые они используют для рытья. Броненосцы неприхотливы в еде: питаются насекомыми, грызунами, змеями, а также падалью и растениями.

Очень много в Южной Америке летучих мышей. Большинство из них относится к так называемым листоносам: их название связано с носовым выростом в виде листочка. Разные виды листоносов питаются насекомыми, плодами, нектаром и цветочной пыльцой. Есть среди них и «настоящие вампиры», высасывающие кровь у домашнего скота, а иногда и у человека.

Все обезьяны тропических лесов Южной Америки всю жизнь проводят на деревьях и обладают приспособлениями для древесного образа жизни, например очень цепкий хвост, помогает им передвигаться по древесным «этажам» тропического леса (своеобразная «пятая конечность»).

В лесах Южной Америки живут игрунки — самые маленькие обезьяны нашей планеты. Их вес обычно не превышает 500 г. Живут они высоко в кронах деревьев и благодаря своим цепким коготкам чувствуют себя на высоте довольно уверенно и уютно. Карликовая игрунка имеет длину тела 13-15, а иногда 10 сантиметров, хвост у нее довольно длинный по сравнению с телом — его длина 20-21 см. Глаза большие, а, как пишут натуралисты, наблюдавшие за этими обезьянками, выражение мордочки вполне осмысленное. Мордочка карликовой игрунки покрыта волосами, маленькие ушки скрыты в густой шерсти. Вокруг глаз светлые окружности. Шерсть густая, шелковистая, ее окраску можно описать как «перец с солью». Обезьянка легко и непринужденно передвигается по ветвям, хорошо прыгает. Удивляет то, что такое маленькое существо может прыгать на расстояние до двух метров.

Игрунка

Беременность у карликовой игрунки длится 134—140 дней. Рождается обычно два, реже три детеныша. На протяжении нескольких месяцев малыши висят на животе у матери. В пять месяцев они становятся самостоятельными, а в два-три года достигают половой зрелости. Бывает так, что самец полностью берет на себя воспитание детеныша, всюду таская его, и возвращает матери лишь на время кормления. Описаны случаи, когда самец игрунки хлопочет возле самочки при родах, всячески пытаясь ей помочь.

Южноамериканские обезьяны отличаются от своих сородичей из Старого Света очень широкой носовой перегородкой и широко расставленными ноздрями, за что вся группа обезьян Нового Света получила название широконосых.

Латинское название игрунок — «каллитрициды» происходит от греческого слова «каллос», означающего «красивый».

В Южной Америке обитают многочисленные грызуны. Самые крупные из них — капибары живут в бассейнах рек Бразилии и Парагвая. Они достигают в длину полутора метров. Между пальцами ног у капибар натянуты перепонки, помогающие этим пятидесятикилограммовым животным передвигаться по топким болотистым местам и быстро плавать в воде. Питается капибара сочными плодами и водными растениями.

Капибары

В южноамериканских тропических лесах живут мелкие копытные — мазамы. Самая крупная из них — большая мазама достигает в высоту 75 см и весит 25 кг, а самые маленькие мазамы весят всего лишь 10 кг. Южноамериканскую свинку зовут пекари, он отличается наличием большой железы на спине, выделяющей сильно пахнущий секрет. Здесь представлены два вида — белобородый и ошейниковый пекари.

Ревун — самая большая обезьяна Южной Америки. Самцы весят не менее 6-7 кг, самки — несколько меньше. На подбородке и горле у ревунов имеются гортанные мешки, служащие резонаторами, усиливающими звуки.

В густых зарослях тропических лесов возле болот живут далекие родственники лошадей — тапиры. Это весьма своеобразные животные размером со свинью и маленьким хоботом. В Южной Америке обитают три вида тапиров. Самый крупный — тапир Бэйруа — весит до 300 килограммов. Равнинный тапир весит до 250 кг. В горных лесах встречается самый мелкий и стройный — горный тапир.

Копытные, обезьяны и многочисленные грызуны Южной Америки — отличная пища для многочисленной группы хищных млекопитающих. Ягуар — король среди них.

Ягуар

Рацион ягуара весьма разнообразен. В него входят грызуны, рыба, черепахи, крокодилы, обезьяны. Но больше всего этим «гурманам» нравятся пекари и капибара.

Приемы охоты ягуара зависят от выбранной жертвы. Так, на каймана ягуар прыгает прямо с берега, ломает ему шею, после чего вспарывает кожу. Черепаху хищник переворачивает на спину и выдирает из панциря. А вообще ягуар — универсальный охотник, который хорошо лазает по деревьям, прекрасно плавает и может успешно преследовать добычу и в воде, и на суше.

Слово «ягуар» пришло из древнеиндейского языка и означает «убийца, справляющийся с жертвой одним прыжком».

Южная Америка самый богатый материк по числу видов птиц. Только в бассейне Амазонки живет каждый пятый из известных на Земле вид птиц. А всего тут обитает около 2,5 тысячи видов пернатых, из которых около 90% эндемичны для этой области. Это — цапли, ибисы, аисты, пастушки, дневные хищники, совы, перепела, голуби, попугаи, дрозды, чибисы, дятлы-туканы и другие широко распространенные и хорошо знакомые нам птицы. Два отряда птиц — нандуобразные (южноамериканские страусы) и скрытохвостые (43 вида тинаму) характерны только для Южной Америки.

Гоацин

Но, пожалуй, самая удивительная птица этих мест — гоацин. Взрослые птицы похожи на фазана. Селятся они в кронах деревьев, но летают плохо, да и то не летают, а скорее перепархивают с ветки на ветку. Питаются гоацины жесткими листьями каучуконосных растений. Основное бремя по перевариванию пищи лежит на зобе. Он у гоацина большой, раз в пятьдесят больше желудка, и расположен на груди, как раз там, где у нормальных птиц, умеющих хорошо летать, расположены кости, к которым прикрепляется грудная, или летательная, мускулатура. Вот это обстоятельство и мешает гоацину хорошо летать.

У птенцов гоацинов на крыльях имеются по два подвижных пальца с острыми коготками. Благодаря им птенцы могут спокойно ползать на четвереньках, не опасаясь упасть с высоких деревьев. Однако когда маленькие гоацины взрослеют и у них отрастают маховые перья, пальцы теряют способность двигаться.

Для любителей птичьих песен Южная Америка не представляет интереса: большинство тропических птиц кричат, а не поют. Природа, щедро одарив их ярким, красочным оперением, решила, что одного подарка будет более чем достаточно, и лишила этих красавиц вокального таланта.

Птенцы гоацина — отличные специалисты по прыжкам в воду. Если их настигает опасность, они не раздумывая ныряют с дерева в воду. Благо родители позаботились и построили гнездо на дереве, растущем прямо над водой. Нырнув в воду, птенец благополучно добирается до берега вплавь. Может и нырнуть, если надо. А уже с берега и до родного гнезда недалеко, лазать-то по деревьям они хорошо умеют.

Высокая влажность тропического леса создала определенные условия для жизни группам животных, которые в других климатических зонах живут в водоемах: лягушкам, ракообразным, моллюскам и пиявкам. Тропические земноводные откладывают икру не в водоемы, как это делают их родственницы из более сухих климатических зон, а в скопившуюся влагу дупел и пазух листьев.

Паук-птицеед

Необычайно богата и интересна фауна насекомых Южной Америки: пауки-птицееды величиной больше мужского кулака; под пологом леса по лесной подстилке ползают огромные жуки, а в воздухе порхают ярко окрашенные бабочки с крыльями величиной больше 10 см.

В тропических лесах Южной Америки живут сухопутные лягушки древолазы, обладающие сильнодействующим ядом. Индейцы в свое время смазывали им свои стрелы. Живет здесь и жаба ага — самая большая жаба в мире. Питается она мышами.

Тело паука-птицееда покрыто волосками. Живет он в норе глубиной 15-20 см. Стенки своей «квартиры» паук-птицеед обрабатывает слюной, которая, смешиваясь с землей, становится очень твердой и делает нору водонепроницаемой. Паук этот ядовитый, для него не составит большого труда убить птицу или жабу, опасен он и для человека. Однако в период линьки эти пауки теряют агрессивность.

Это самая интересная и мало исследованная природная зона на планете, которая появилась 100 млн. лет назад.

Здесь, в жарком и влажном климате, растёт 80 % известной растительности и обитает 50 % видов наземно – воздушных животных.

Все типы тропических лесов имеют общий облик. Это реликтовая флора, не изменившая видового состава, и представляющая 40 видов тропических лесов. Главные группы образованы влажным (дождевым) и сезонным лесами.

болотистый тропический лес фото

Виды влажного тропического леса:

- Мангровым лесом занята приливно-отливная зона побережья в тропиках.

- Тропическим горным вечнозелёным лесом покрыты склоны на высоте от 1500 до 1800 м. Эти растения привыкли к температуре 10-12 градусов и холоднее.

- Болотистый лес – затопленный лес на равнине. Занимает меньшую площадь, чем не затопленный лес на равнинах.

мангровые леса фото

Другие тропические леса:

- вечнозелёные сезонные леса;

- полу вечнозелёные леса (в верхнем ярусе листопадные виды, а внизу вечнозелёные растения);

- светлыми разрежёнными лесами (чаще однопородные деревья).

Тропический сезонный листопадный лес:

- Муссонным лесом поросли места, где действуют муссоны, а сухой период длится по 5 месяцев.

- Саванновый лес — в тропиках, где сухой сезон ярко выражен.

- Колючим ксерофильным лесом покрыты места с засухой по полгода.

саванновые леса фото

Широкий пояс тропического леса, от 25 градусов с. ш. до 30 градусов ю. ш., охватывает Землю вдоль экватора. Влажный экваториальный, сухой тропический и умеренный субэкваториальный пояса, по которым проходит чёткая линия тропических лесов, составляя 50 % лесных массивов Земли.

Муссонный лес расположен на африканском и южноамериканском западе, на юге и юго-востоке Азии.

Саванновый лес растёт в восточной части этих материков, на Кубе с близлежащими островами. Индия, Китай и Австралия так же имеют массивы такого леса.

тропические горные леса фото

Влажные тропические леса занимают Центральную Африку, юго-восток Азии и австралийский северо-восток.

Южная Америка располагает самыми большими площадями влажного тропического леса (сельвас), находящимся в бассейне Амазонки.

Суша планеты, тропических и субтропических регионов, на 6 % занята тропическим лесом с ценящимися древесными породами. Дикие тропические растения считаются прародителями культурных растений таких, как кофе, бананы, цитрусы и другие.

«Дождевой» лес, на протяжении года, в избытке получает влагу и тепло, освещения недостаточно, но она постоянная для каждого яруса.

слоны фото

Продолжительность светового дня – 12 ч., сумерки длятся полчаса.

Тропический лес разделён ярусами:

Верх образован вечнозелёными 70 м деревьями.

2-й ярус называется пологом, здесь 45-м деревья.

3-й ярус – подлесок.

4-я — лесная подстилка.

В южноамериканском лесу только три яруса.

В тропическом лесу постоянное пониженное давление воздуха, обильные ливни и жара.

Отличия тропического леса:

- многообразие растительности и животных;

- сложное 4-х ярусное строение;

- влажный и тёплый климат;

- у вечнозелёных древовидных растений слабая кора, цветы и плоды вырастают из ствола дерева;

- выделение малого количества кислорода;

- фильтрование воздуха влагой и очищение от загрязнения.

Тропический лес расположен в тропической, экваториальной и субэкваториальной природных зонах различающихся составом флоры и фауны.

В экваториальной зоне разросся влажный тропический лес. На побережьях с приливами и отливами в экваториальных и тропических зонах распространён мангровый лес.

Экваториальные и тропические леса занимают рыхлые красно-желтые ферралитные почвы. Эти почвы сформированы на породах коры выветривания поверхностного отложения, чему помогло обильное тепло и влага.

Из-за быстро разлагающейся органики и вымывания, почва стала кислой, заминирилизованной и малоплодородной.

Обширное заболачивание леса ведёт к образованию торфа. Надпойменные террасы песчаные с иллювиально-гумусовыми подзолами.

Расположение в природном поясе влияет на климат леса. Тропики характеризуются повышенной температурой и влажностью, на субэкваториальный пояс влияют муссоны.

Температура в тропических лесах постоянная – 20-35 градусов жары.

бегемоты фото

Времена года не различаются. Горные леса обволакиваются туманами, дневное тепло сменяется резким ночным похолоданием, местами до нуля градусов. Влажность, в среднем, 80%. Осадков выпадает неравномерное количество, но не менее 2000 мм.

Дождевой лес:

- осадки 2000-12 000 мм, распределение за год равномерное;

- влажность 80-100 %;

- «сухие паузы» длятся не дольше 2-3 недель;

- температура неизменная – 24-35 градусов.

В сезонном лесу отмечаются сухие и влажные сезоны. Осадки составляют 3000 мм. Во время сухого сезона листья с деревьев опадают.

За год уничтожается 20 млн. гектаров тропического леса.

Главные причины уничтожения:

- Смена огородов через 1-2 года использования.

- Освобождение площадей для пастбищ выжиганием.

- Лесоразработки.

пума фото

Последствия уничтожения леса:

- почвенная эрозия;

- сокращение разнообразия видов растений и животных;

- смещённый экологический баланс сообществ и биосферы.

Исчезающий тропический лес замещается вторичным лесом, или травянистым сообществом, постепенно становящимся пустыней.

Сформированный животный мир изолированно от других материков, различается. Так, обитание лемуров и хамелеонов — Мадагаскар и Коморские о-ва. Южная Америка — обитание броненосцев, носух, обыкновенного удава и муравьедов. Центральная Африка – встреча с Западной гориллой. Обитание ягуара — Центральная Америка.

малая панда фото

Сходные условия обитания создали одинаковый тип фауны, здесь много архаичных, древних животных. В тропиках обитают все крупные млекопитающие (кроме северных обитателей):

- слон и носорог;

- бегемот и буйвол;

- лев и тигр;

- пума, пантера, ягуар;

Многим небольшим животным никогда не приходилось спускаться, некоторые приспособились к другой пище. Много бабочек дивной красоты, райских птиц, древесных лягушек различной окраски. Насекомые, ящерицы и жабы, хамелеоны, крокодилы и др.

Тропические леса населены внешне не привычными, с ярким оперением птицами. На каждом материке обитает «свой» вид.

В азиатских тропиках живёт турач, похожий на куропатку, кустарниковая курица, фазан, царственный павлин.

туканы фото

В американских тропиках обитают бегающая птица тинаму и попугаи. В Латинской Америке — радужный тукан. Африка – родина серого попугая жако, Златошлемного калао и Венценосного орла — жестокой хищной птицы.

Живущие в густых кронах птицы — носороги, птицы — турако и туканы умеют прыгать и лазать по деревьям, но не летать.

Леса экватора населены пёстрыми голубями, трогонами, дятлами, мухоловками, птицами-носорогами и другими пернатыми обитателями.

В тропическом лесу ярусное расположение:

- 1-й ярус — одиночные многолетние, 60 м деревья — гиганты, с обширной кроной и гладким стволом.

- Во 2-м ярусе 20-30 м деревья.

- В 3-м ярусе 10-20 метровые пальмы.

- 4-й ярус из 3 м подлеска: бамбук, кустарники, травы, папоротники и плауны. Здесь широколистные растения.

орхидеи фото

Мангровым растениям не обязателен кислород и им не вредит солёная почва. В сухом тропическом лесу преобладание низкорослых растений.

В джунглях под пологом мало света, поэтому нет травянистого покрова.

Травы растут, где появляется просвет, остальные селятся на деревьях (орхидея). Из тенелюбивых растений комфортно папоротникам, бегониям и широколиственным злакам. Так же сапрофитным и растениям – паразитам, например раффлезии.

В тропических лесах насчитывается 400 видов отличающихся деревьев:

- Стволы прямые, цилиндрические, утолщённые внизу или похожие на склеенные свечи.

- Корни поверхностные и сильные придаточные корни, дыхательные, похожие на ходули или доски – подпорки.

- Тонкая и светлая кора.

- Годичные кольца отсутствуют.

- Маленькие кроны начинают формирование вверху.

- У кожистых и жёстких листьев размер средний. Сбрасывание листьев одиночное и постепенное.

- Место появления невзрачных цветков, а после и плодов — стволы и толстые ветви.

рамбутан фото

Среди тропических деревьев много таких, которые снабжают человека пищей, лекарственным сырьём и нужными в хозяйстве материалами.

Рамбутан

Гуава

Кумкват

Гибискус-дерево жизни.

Лес в тропиках отличается сложной, видоразнообразной и уязвимой экосистемой.

Отличие экосистемы — не чёткие границы между ярусами. Встречается 6 м трава, доходящая до среднего яруса. Папоротниками занято 3 этажа. «Размывают» границы лианы, эпифиты, плотно опутывающие растительность.

Второе отличие: животные – потребители живут на кормовой базе, на деревьях. Сухопутных животных мало, но они больших размеров (слон, носорог, бегемот и др.).

Редуценты, как и везде — термиты и грибы.

Джунгли не дают распространяться углекислому газу, удерживая в лесном массиве. Влажный лес охлаждает воздушные массы, проходящие сквозь него. Тропики – центры появления новых видов живой природы.

Тропическими лесами, исчезающими по вине человека, занято 6 % земной суши, которая погибнет, если их не станет.

Location of tropical (dark green) and temperate/subtropical (light green) rainforests in the world.

Tropical rainforest climate zones (Af).

Tropical rainforests are rainforests that occur in areas of tropical rainforest climate in which there is no dry season – all months have an average precipitation of at least 60 mm – and may also be referred to as lowland equatorial evergreen rainforest. True rainforests are typically found between 10 degrees north and south of the equator (see map); they are a sub-set of the tropical forest biome that occurs roughly within the 28-degree latitudes (in the equatorial zone between the Tropic of Cancer and Tropic of Capricorn). Within the World Wildlife Fund’s biome classification, tropical rainforests are a type of tropical moist broadleaf forest (or tropical wet forest) that also includes the more extensive seasonal tropical forests.[3]

Overview

Tropical rainforests are characterized by two words: hot and wet. Mean monthly temperatures exceed 18 °C (64 °F) during all months of the year.[4] Average annual rainfall is no less than 1,680 mm (66 in) and can exceed 10 m (390 in) although it typically lies between 1,750 mm (69 in) and 3,000 mm (120 in).[5] This high level of precipitation often results in poor soils due to leaching of soluble nutrients in the ground.

Tropical rainforests exhibit high levels of biodiversity. Around 40% to 75% of all biotic species are indigenous to the rainforests.[6] Rainforests are home to half of all the living animal and plant species on the planet.[7] Two-thirds of all flowering plants can be found in rainforests.[5] A single hectare of rainforest may contain 42,000 different species of insect, up to 807 trees of 313 species and 1,500 species of higher plants.[5] Tropical rainforests have been called the «world’s largest pharmacy», because over one quarter of natural medicines have been discovered within them.[8][9] It is likely that there may be many millions of species of plants, insects and microorganisms still undiscovered in tropical rainforests.

Tropical rainforests are among the most threatened ecosystems globally due to large-scale fragmentation as a result of human activity. Habitat fragmentation caused by geological processes such as volcanism and climate change occurred in the past, and have been identified as important drivers of speciation.[10] However, fast human driven habitat destruction is suspected to be one of the major causes of species extinction. Tropical rain forests have been subjected to heavy logging and agricultural clearance throughout the 20th century, and the area covered by rainforests around the world is rapidly shrinking.[11][12]

History

Tropical rainforests have existed on earth for hundreds of millions of years. Most tropical rainforests today are on fragments of the Mesozoic era supercontinent of Gondwana.[13] The separation of the landmass resulted in a great loss of amphibian diversity while at the same time the drier climate spurred the diversification of reptiles.[10] The division left tropical rainforests located in five major regions of the world: tropical America, Africa, Southeast Asia, Madagascar, and New Guinea, with smaller outliers in Australia.[13] However, the specifics of the origin of rainforests remain uncertain due to an incomplete fossil record.

Other types of tropical forest

Several biomes may appear similar-to, or merge via ecotones with, tropical rainforest:

- Moist seasonal tropical forest

Moist seasonal tropical forests receive high overall rainfall with a warm summer wet season and a cooler winter dry season. Some trees in these forests drop some or all of their leaves during the winter dry season, thus they are sometimes called «tropical mixed forest». They are found in parts of South America, in Central America and around the Caribbean, in coastal West Africa, parts of the Indian subcontinent, and across much of Indochina.

- Montane rainforests

These are found in cooler-climate mountainous areas, becoming known as cloud forests at higher elevations. Depending on latitude, the lower limit of montane rainforests on large mountains is generally between 1500 and 2500 m while the upper limit is usually from 2400 to 3300 m.[14]

- Flooded rainforests

Tropical freshwater swamp forests, or «flooded forests», are found in Amazon basin (the Várzea) and elsewhere.

Forest structure

Rainforests are divided into different strata, or layers, with vegetation organized into a vertical pattern from the top of the soil to the canopy.[15] Each layer is a unique biotic community containing different plants and animals adapted for life in that particular strata. Only the emergent layer is unique to tropical rainforests, while the others are also found in temperate rainforests.[16]

Forest floor

The forest floor, the bottom-most layer, receives only 2% of the sunlight. Only plants adapted to low light can grow in this region. Away from riverbanks, swamps and clearings, where dense undergrowth is found, the forest floor is relatively clear of vegetation because of the low sunlight penetration. This more open quality permits the easy movement of larger animals such as: ungulates like the okapi (Okapia johnstoni), tapir (Tapirus sp.), Sumatran rhinoceros (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis), and apes like the western lowland gorilla (Gorilla gorilla), as well as many species of reptiles, amphibians, and insects. The forest floor also contains decaying plant and animal matter, which disappears quickly, because the warm, humid conditions promote rapid decay. Many forms of fungi growing here help decay the animal and plant waste.

Understory layer

The understory layer lies between the canopy and the forest floor. The understory is home to a number of birds, small mammals, insects, reptiles, and predators. Examples include leopard (Panthera pardus), poison dart frogs (Dendrobates sp.), ring-tailed coati (Nasua nasua), boa constrictor (Boa constrictor), and many species of Coleoptera.[5] The vegetation at this layer generally consists of shade-tolerant shrubs, herbs, small trees, and large woody vines which climb into the trees to capture sunlight. Only about 5% of sunlight breaches the canopy to arrive at the understory causing true understory plants to seldom grow to 3 m (10 feet). As an adaptation to these low light levels, understory plants have often evolved much larger leaves. Many seedlings that will grow to the canopy level are in the understory.

Canopy layer

The canopy is the primary layer of the forest, forming a roof over the two remaining layers. It contains the majority of the largest trees, typically 30–45 m in height. Tall, broad-leaved evergreen trees are the dominant plants. The densest areas of biodiversity are found in the forest canopy, as it often supports a rich flora of epiphytes, including orchids, bromeliads, mosses and lichens. These epiphytic plants attach to trunks and branches and obtain water and minerals from rain and debris that collects on the supporting plants. The fauna is similar to that found in the emergent layer, but more diverse. It is suggested that the total arthropod species richness of the tropical canopy might be as high as 20 million.[17] Other species inhabiting this layer include many avian species such as the yellow-casqued wattled hornbill (Ceratogymna elata), collared sunbird (Anthreptes collaris), grey parrot (Psitacus erithacus), keel-billed toucan (Ramphastos sulfuratus), scarlet macaw (Ara macao) as well as other animals like the spider monkey (Ateles sp.), African giant swallowtail (Papilio antimachus), three-toed sloth (Bradypus tridactylus), kinkajou (Potos flavus), and tamandua (Tamandua tetradactyla).[5]

Emergent layer

The emergent layer contains a small number of very large trees, called emergents, which grow above the general canopy, reaching heights of 45–55 m, although on occasion a few species will grow to 70–80 m tall.[15][18] Some examples of emergents include: Balizia elegans, Dipteryx panamensis, Hieronyma alchorneoides, Hymenolobium mesoamericanum, Lecythis ampla and Terminalia oblonga.[19] These trees need to be able to withstand the hot temperatures and strong winds that occur above the canopy in some areas. Several unique faunal species inhabit this layer such as the crowned eagle (Stephanoaetus coronatus), the king colobus (Colobus polykomos), and the large flying fox (Pteropus vampyrus).[5]

However, stratification is not always clear. Rainforests are dynamic and many changes affect the structure of the forest. Emergent or canopy trees collapse, for example, causing gaps to form. Openings in the forest canopy are widely recognized as important for the establishment and growth of rainforest trees. It is estimated that perhaps 75% of the tree species at La Selva Biological Station, Costa Rica are dependent on canopy opening for seed germination or for growth beyond sapling size, for example.[20]

Ecology

Climates

Artificial tropical rainforest in Barcelona

Tropical rainforests are located around and near the equator, therefore having what is called an equatorial climate characterized by three major climatic parameters: temperature, rainfall, and dry season intensity.[21] Other parameters that affect tropical rainforests are carbon dioxide concentrations, solar radiation, and nitrogen availability. In general, climatic patterns consist of warm temperatures and high annual rainfall. However, the abundance of rainfall changes throughout the year creating distinct moist and dry seasons. Tropical forests are classified by the amount of rainfall received each year, which has allowed ecologists to define differences in these forests that look so similar in structure. According to Holdridge’s classification of tropical ecosystems, true tropical rainforests have an annual rainfall greater than 2 m and annual temperature greater than 24 degrees Celsius, with a potential evapotranspiration ratio (PET) value of <0.25. However, most lowland tropical forests can be classified as tropical moist or wet forests, which differ in regards to rainfall. Tropical forest ecology- dynamics, composition, and function- are sensitive to changes in climate especially changes in rainfall.[21]

Soils

Soil types

Soil types are highly variable in the tropics and are the result of a combination of several variables such as climate, vegetation, topographic position, parent material, and soil age.[22] Most tropical soils are characterized by significant leaching and poor nutrients, however there are some areas that contain fertile soils. Soils throughout the tropical rainforests fall into two classifications which include the ultisols and oxisols. Ultisols are known as well weathered, acidic red clay soils, deficient in major nutrients such as calcium and potassium. Similarly, oxisols are acidic, old, typically reddish, highly weathered and leached, however are well drained compared to ultisols. The clay content of ultisols is high, making it difficult for water to penetrate and flow through. The reddish color of both soils is the result of heavy heat and moisture forming oxides of iron and aluminium, which are insoluble in water and not taken up readily by plants.

Soil chemical and physical characteristics are strongly related to above ground productivity and forest structure and dynamics. The physical properties of soil control the tree turnover rates whereas chemical properties such as available nitrogen and phosphorus control forest growth rates.[23] The soils of the eastern and central Amazon as well as the Southeast Asian Rainforest are old and mineral poor whereas the soils of the western Amazon (Ecuador and Peru) and volcanic areas of Costa Rica are young and mineral rich. Primary productivity or wood production is highest in western Amazon and lowest in eastern Amazon which contains heavily weathered soils classified as oxisols.[22] Additionally, Amazonian soils are greatly weathered, making them devoid of minerals like phosphorus, potassium, calcium, and magnesium, which come from rock sources. However, not all tropical rainforests occur on nutrient poor soils, but on nutrient rich floodplains and volcanic soils located in the Andean foothills, and volcanic areas of Southeast Asia, Africa, and Central America.[24]

Oxisols, infertile, deeply weathered and severely leached, have developed on the ancient Gondwanan shields. Rapid bacterial decay prevents the accumulation of humus. The concentration of iron and aluminium oxides by the laterization process gives the oxisols a bright red color and sometimes produces minable deposits (e.g., bauxite). On younger substrates, especially of volcanic origin, tropical soils may be quite fertile.

Nutrient recycling

This high rate of decomposition is the result of phosphorus levels in the soils, precipitation, high temperatures and the extensive microorganism communities.[25] In addition to the bacteria and other microorganisms, there are an abundance of other decomposers such as fungi and termites that aid in the process as well. Nutrient recycling is important because below ground resource availability controls the above ground biomass and community structure of tropical rainforests. These soils are typically phosphorus limited, which inhibits net primary productivity or the uptake of carbon.[22] The soil contains microbial organisms such as bacteria, which break down leaf litter and other organic matter into inorganic forms of carbon usable by plants through a process called decomposition. During the decomposition process the microbial community is respiring, taking up oxygen and releasing carbon dioxide. The decomposition rate can be evaluated by measuring the uptake of oxygen.[25] High temperatures and precipitation increase decomposition rate, which allows plant litter to rapidly decay in tropical regions, releasing nutrients that are immediately taken up by plants through surface or ground waters. The seasonal patterns in respiration are controlled by leaf litter fall and precipitation, the driving force moving the decomposable carbon from the litter to the soil. Respiration rates are highest early in the wet season because the recent dry season results in a large percentage of leaf litter and thus a higher percentage of organic matter being leached into the soil.[25]

Buttress roots

A common feature of many tropical rainforests is the distinct buttress roots of trees. Instead of penetrating to deeper soil layers, buttress roots create a widespread root network at the surface for more efficient uptake of nutrients in a very nutrient poor and competitive environment. Most of the nutrients within the soil of a tropical rainforest occur near the surface because of the rapid turnover time and decomposition of organisms and leaves.[26] Because of this, the buttress roots occur at the surface so the trees can maximize uptake and actively compete with the rapid uptake of other trees. These roots also aid in water uptake and storage, increase surface area for gas exchange, and collect leaf litter for added nutrition.[26] Additionally, these roots reduce soil erosion and maximize nutrient acquisition during heavy rains by diverting nutrient rich water flowing down the trunk into several smaller flows while also acting as a barrier to ground flow. Also, the large surface areas these roots create provide support and stability to rainforests trees, which commonly grow to significant heights. This added stability allows these trees to withstand the impacts of severe storms, thus reducing the occurrence of fallen trees.[26]

Forest succession

Succession is an ecological process that changes the biotic community structure over time towards a more stable, diverse community structure after an initial disturbance to the community. The initial disturbance is often a natural phenomenon or human caused event. Natural disturbances include hurricanes, volcanic eruptions, river movements or an event as small as a fallen tree that creates gaps in the forest. In tropical rainforests, these same natural disturbances have been well documented in the fossil record, and are credited with encouraging speciation and endemism.[10] Human land use practices have led to large-scale deforestation. In many tropical countries such as Costa Rica these deforested lands have been abandoned and forests have been allowed to regenerate through ecological succession. These regenerating young successional forests are called secondary forests or second-growth forests.

Biodiversity and speciation

Tropical rainforests exhibit a vast diversity in plant and animal species. The root for this remarkable speciation has been a query of scientists and ecologists for years. A number of theories have been developed for why and how the tropics can be so diverse.

Interspecific competition

Interspecific competition results from a high density of species with similar niches in the tropics and limited resources available. Species which «lose» the competition may either become extinct or find a new niche. Direct competition will often lead to one species dominating another by some advantage, ultimately driving it to extinction. Niche partitioning is the other option for a species. This is the separation and rationing of necessary resources by utilizing different habitats, food sources, cover or general behavioral differences. A species with similar food items but different feeding times is an example of niche partitioning.[27]

Pleistocene refugia

The theory of Pleistocene refugia was developed by Jürgen Haffer in 1969 with his article Speciation of Amazonian Forest Birds. Haffer proposed the explanation for speciation was the product of rainforest patches being separated by stretches of non-forest vegetation during the last glacial period. He called these patches of rainforest areas refuges and within these patches allopatric speciation occurred. With the end of the glacial period and increase in atmospheric humidity, rainforest began to expand and the refuges reconnected.[28] This theory has been the subject of debate. Scientists are still skeptical of whether or not this theory is legitimate. Genetic evidence suggests speciation had occurred in certain taxa 1–2 million years ago, preceding the Pleistocene.[29]

Human dimensions

Habitation

Tropical rainforests have harboured human life for many millennia, with many Indian tribes in South- and Central America, who belong to the Indigenous peoples of the Americas, the Congo Pygmies in Central Africa, and several tribes in South-East Asia, like the Dayak people and the Penan people in Borneo.[30] Food resources within the forest are extremely dispersed due to the high biological diversity and what food does exist is largely restricted to the canopy and requires considerable energy to obtain. Some groups of hunter-gatherers have exploited rainforest on a seasonal basis but dwelt primarily in adjacent savanna and open forest environments where food is much more abundant. Other people described as rainforest dwellers are hunter-gatherers who subsist in large part by trading high value forest products such as hides, feathers, and honey with agricultural people living outside the forest.[31]

Indigenous peoples

Members of an uncontacted tribe encountered in the Brazilian state of Acre in 2009

A variety of indigenous people live within the rainforest as hunter-gatherers, or subsist as part-time small scale farmers supplemented in large part by trading high-value forest products such as hides, feathers, and honey with agricultural people living outside the forest.[30][31] Peoples have inhabited the rainforests for tens of thousands of years and have remained so elusive that only recently have some tribes been discovered.[30] These indigenous peoples are greatly threatened by loggers in search for old-growth tropical hardwoods like Ipe, Cumaru and Wenge, and by farmers who are looking to expand their land, for cattle(meat), and soybeans, which are used to feed cattle in Europe and China.[30][32][33][34] On 18 January 2007, FUNAI reported also that it had confirmed the presence of 67 different uncontacted tribes in Brazil, up from 40 in 2005. With this addition, Brazil has now overtaken the island of New Guinea as the country having the largest number of uncontacted tribes.[35] The province of Irian Jaya or West Papua in the island of New Guinea is home to an estimated 44 uncontacted tribal groups.[36]

Pygmy hunter-gatherers in the Congo Basin in 2014

The pygmy peoples are hunter-gatherer groups living in equatorial rainforests characterized by their short height (below one and a half meters, or 59 inches, on average). Amongst this group are the Efe, Aka, Twa, Baka, and Mbuti people of Central Africa.[37] However, the term pygmy is considered pejorative so many tribes prefer not to be labeled as such.[38]

Some notable indigenous peoples of the Americas, or Amerindians, include the Huaorani, Ya̧nomamö, and Kayapo people of the Amazon. The traditional agricultural system practiced by tribes in the Amazon is based on swidden cultivation (also known as slash-and-burn or shifting cultivation) and is considered a relatively benign disturbance.[39][40] In fact, when looking at the level of individual swidden plots a number of traditional farming practices are considered beneficial. For example, the use of shade trees and fallowing all help preserve soil organic matter, which is a critical factor in the maintenance of soil fertility in the deeply weathered and leached soils common in the Amazon.[41]

There is a diversity of forest people in Asia, including the Lumad peoples of the Philippines and the Penan and Dayak people of Borneo. The Dayaks are a particularly interesting group as they are noted for their traditional headhunting culture. Fresh human heads were required to perform certain rituals such as the Iban «kenyalang» and the Kenyah «mamat».[42] Pygmies who live in Southeast Asia are, amongst others, referred to as «Negrito».

Resources

Cultivated foods and spices

Yam, coffee, chocolate, banana, mango, papaya, macadamia, avocado, and sugarcane all originally came from tropical rainforest and are still mostly grown on plantations in regions that were formerly primary forest. In the mid-1980s and 1990s, 40 million tons of bananas were consumed worldwide each year, along with 13 million tons of mango. Central American coffee exports were worth US$3 billion in 1970. Much of the genetic variation used in evading the damage caused by new pests is still derived from resistant wild stock. Tropical forests have supplied 250 cultivated kinds of fruit, compared to only 20 for temperate forests. Forests in New Guinea alone contain 251 tree species with edible fruits, of which only 43 had been established as cultivated crops by 1985.[43]

Ecosystem services

In addition to extractive human uses, rain forests also have non-extractive uses that are frequently summarized as ecosystem services. Rain forests play an important role in maintaining biological diversity, sequestering and storing carbon, global climate regulation, disease control, and pollination.[44] Half of the rainfall in the Amazon area is produced by the forests. The moisture from the forests is important to the rainfall in Brazil, Paraguay, Argentina[45] Deforestation in the Amazon rainforest region was one of the main reason that cause the severe Drought of 2014–2015 in Brazil[46][47] For the last three decades, the amount of carbon absorbed by the world’s intact tropical forests has fallen, according to a study published in 2020 in the journal Nature. In 2019 they took up a third less carbon than they did in the 1990s, due to higher temperatures, droughts and deforestation. The typical tropical forest may become a carbon source by the 2060s.[48]

Tourism

Despite the negative effects of tourism in the tropical rainforests, there are also several important positive effects.

- In recent years ecotourism in the tropics has increased. While rainforests are becoming increasingly rare, people are travelling to nations that still have this diverse habitat. Locals are benefiting from the additional income brought in by visitors, as well areas deemed interesting for visitors are often conserved. Ecotourism can be an incentive for conservation, especially when it triggers positive economic change.[49] Ecotourism can include a variety of activities including animal viewing, scenic jungle tours and even viewing cultural sights and native villages. If these practices are performed appropriately this can be beneficial for both locals and the present flora and fauna.

- An increase in tourism has increased economic support, allowing more revenue to go into the protection of the habitat. Tourism can contribute directly to the conservation of sensitive areas and habitat. Revenue from park-entrance fees and similar sources can be utilised specifically to pay for the protection and management of environmentally sensitive areas. Revenue from taxation and tourism provides an additional incentive for governments to contribute revenue to the protection of the forest.

- Tourism also has the potential to increase public appreciation of the environment and to spread awareness of environmental problems when it brings people into closer contact with the environment. Such increased awareness can induce more environmentally conscious behavior. Tourism has had a positive effect on wildlife preservation and protection efforts, notably in Africa but also in South America, Asia, Australia, and the South Pacific.[50]

Conservation

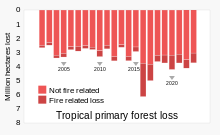

Loss of primary (old-growth) forest in the tropics has continued its upward trend, with fire-related losses contributing an increasing portion.[51]

Threats

Deforestation

Mining and drilling

Deposits of precious metals (gold, silver, coltan) and fossil fuels (oil and natural gas) occur underneath rainforests globally. These resources are important to developing nations and their extraction is often given priority to encourage economic growth. Mining and drilling can require large amounts of land development, directly causing deforestation. In Ghana, a West African nation, deforestation from decades of mining activity left about 12% of the country’s original rainforest intact.[52]

Conversion to agricultural land

With the invention of agriculture, humans were able to clear sections of rainforest to produce crops, converting it to open farmland. Such people, however, obtain their food primarily from farm plots cleared from the forest[31][53] and hunt and forage within the forest to supplement this. The issue arising is between the independent farmer providing for his family and the needs and wants of the globe as a whole. This issue has seen little improvement because no plan has been established for all parties to be aided.[54]

Agriculture on formerly forested land is not without difficulties. Rainforest soils are often thin and leached of many minerals, and the heavy rainfall can quickly leach nutrients from area cleared for cultivation. People such as the Yanomamo of the Amazon, utilize slash-and-burn agriculture to overcome these limitations and enable them to push deep into what were previously rainforest environments. However, these are not rainforest dwellers, rather they are dwellers in cleared farmland[31][53] that make forays into the rainforest. Up to 90% of the typical Yanamomo diet comes from farmed plants.[53]

Some action has been taken by suggesting fallow periods of the land allowing secondary forest to grow and replenish the soil.[55] Beneficial practices like soil restoration and conservation can benefit the small farmer and allow better production on smaller parcels of land.

Climate change

The tropics take a major role in reducing atmospheric carbon dioxide. The tropics (most notably the Amazon rainforest) are called carbon sinks.[citation needed] As major carbon reducers and carbon and soil methane storages, their destruction contributes to increasing global energy trapping, atmospheric gases.[citation needed] Climate change has been significantly contributed to by the destruction of the rainforests. A simulation was performed in which all rainforest in Africa were removed. The simulation showed an increase in atmospheric temperature by 2.5 to 5 degrees Celsius.[56]

Declining populations

Some species of fauna show a trend towards declining populations in rainforests, for example, reptiles that feed on amphibians and reptiles. This trend requires close monitoring.[57] The seasonality of rainforests affects the reproductive patterns of amphibians, and this in turn can directly affect the species of reptiles that feed on these groups,[58] particularly species with specialized feeding, since these are less likely to use alternative resources.[59]

Protection

Efforts to protect and conserve tropical rainforest habitats are diverse and widespread. Tropical rainforest conservation ranges from strict preservation of habitat to finding sustainable management techniques for people living in tropical rainforests. International policy has also introduced a market incentive program called Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD) for companies and governments to outset their carbon emissions through financial investments into rainforest conservation.[60]

See also