|

Thor Heyerdahl |

|

|---|---|

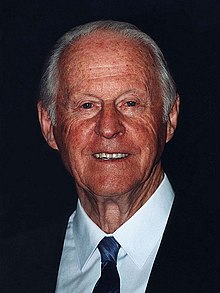

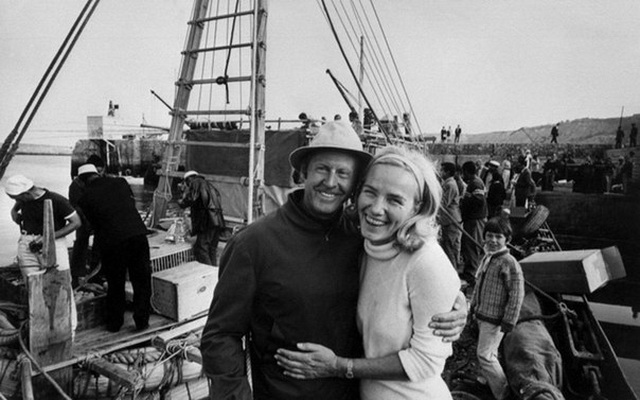

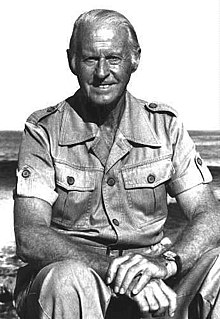

Heyerdahl circa 1980 |

|

| Born | 6 October 1914

Larvik, Norway |

| Died | 18 April 2002 (aged 87)

Colla Micheri, Italy |

| Alma mater | University of Oslo |

| Spouses |

Liv Coucheron-Torp (m. 1936; div. 1947) Yvonne Dedekam-Simonsen (m. 1949; div. 1969) Jacqueline Beer (m. 1991) |

| Children | 5 |

| Awards | Mungo Park Medal (1950) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields |

|

| Doctoral advisor |

|

Thor Heyerdahl KStJ (Norwegian pronunciation: [tuːr ˈhæ̀ɪəɖɑːɫ]; 6 October 1914 – 18 April 2002) was a Norwegian adventurer and ethnographer with a background in zoology, botany and geography.

Heyerdahl is notable for his Kon-Tiki expedition in 1947, in which he sailed 8,000 km (5,000 mi) across the Pacific Ocean in a hand-built raft from South America to the Tuamotu Islands. The expedition was designed to demonstrate that ancient people could have made long sea voyages, creating contacts between societies. This was linked to a diffusionist model of cultural development.

Heyerdahl made other voyages to demonstrate the possibility of contact between widely separated ancient peoples, notably the Ra II expedition of 1970, when he sailed from the west coast of Africa to Barbados in a papyrus reed boat. He was appointed a government scholar in 1984.

He died on 18 April 2002 in Colla Micheri, Italy, while visiting close family members. The Norwegian government gave him a state funeral in Oslo Cathedral on 26 April 2002.[1]

In May 2011, the Thor Heyerdahl Archives were added to UNESCO’s Memory of the World Register.[2] At the time, this list included 238 collections from all over the world.[3] The Heyerdahl Archives span the years 1937 to 2002 and include his photographic collection, diaries, private letters, expedition plans, articles, newspaper clippings, and original book and article manuscripts. The Heyerdahl Archives are administered by the Kon-Tiki Museum and the National Library of Norway in Oslo.

Youth and personal life[edit]

Heyerdahl was born in Larvik, Norway, the son of master brewer Thor Heyerdahl (1869–1957) and his wife, Alison Lyng (1873–1965). As a young child, Heyerdahl showed a strong interest in zoology, inspired by his mother, who had a strong interest in Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution. He created a small museum in his childhood home, with a common adder (Vipera berus) as the main attraction.

He studied zoology and geography at the faculty of biological science at the University of Oslo.[4] At the same time, he privately studied Polynesian culture and history, consulting what was then the world’s largest private collection of books and papers on Polynesia, owned by Bjarne Kroepelien, a wealthy wine merchant in Oslo. (This collection was later purchased by the University of Oslo Library from Kroepelien’s heirs and was attached to the Kon-Tiki Museum research department.)

After seven terms and consultations with experts in Berlin, a project was developed and sponsored by Heyerdahl’s zoology professors, Kristine Bonnevie and Hjalmar Broch. He was to visit some isolated Pacific island groups and study how the local animals had found their way there.

On the day before they sailed together to the Marquesas Islands in 1936, Heyerdahl married Liv Coucheron-Torp (1916–1969), whom he had met at the University of Oslo, and who had studied economics there. He was 22 years old and she was 20 years old. Eventually, the couple had two sons: Thor Jr. and Bjørn. The marriage ended in divorce shortly before the 1947 Kon-Tiki expedition, which Liv had helped to organize.[5]

After the occupation of Norway by Nazi Germany, he served with the Free Norwegian Forces from 1944, in the far north province of Finnmark.[6][7]

In 1949, Heyerdahl married Yvonne Dedekam-Simonsen (1924–2006). They had three daughters: Annette, Marian, and Helene Elisabeth. They were divorced in 1969. Heyerdahl blamed their separation on his being away from home and differences in their ideas for bringing up children. In his autobiography, he concluded that he should take the entire blame for their separation.[8]

In 1991, Heyerdahl married Jacqueline Beer (born 1932) as his third wife. They lived in Tenerife, Canary Islands, and were very actively involved with archaeological projects, especially in Túcume, Peru, and Azov until his death in 2002. He had still been hoping to undertake an archaeological project in Samoa before he died.[9]

Fatu Hiva[edit]

In 1936, on the day after his marriage to Liv Coucheron Torp, the young couple set out for the South Pacific Island of Fatu Hiva. They nominally had an academic mission, to research the spread of animal species between islands, but in reality they intended to «run away to the South Seas» and never return home.[10]

Aided by expedition funding from their parents, they nonetheless arrived on the island lacking «provisions, weapons or a radio». Residents in Tahiti, where they stopped en route, did convince them to take a machete and a cooking pot.[5]

They arrived at Fatu Hiva in 1937, in the valley of Omo‘a, and decided to cross over the island’s mountainous interior to settle in one of the small, nearly abandoned, valleys on the eastern side of the island. There, they made their thatch-covered stilted home in the valley of Uia.[10]

Living in such primitive conditions was a daunting task, but they managed to live off the land, and work on their academic goals, by collecting and studying zoological and botanical specimens. They discovered unusual artifacts, listened to the natives’ oral history traditions, and took note of the prevailing winds and ocean currents.[5]

It was in this setting, surrounded by the ruins of the formerly glorious Marquesan civilization, that Heyerdahl first developed his theories regarding the possibility of pre-Columbian trans-oceanic contact between the pre-European Polynesians, and the peoples and cultures of South America.[10]

Despite the seemingly idyllic situation, the exposure to various tropical diseases and other difficulties caused them to return to civilisation a year later. They worked together to write an account of their adventure.[5]

The events surrounding his stay on the Marquesas, most of the time on Fatu Hiva, were told first in his book På Jakt etter Paradiset (Hunt for Paradise) (1938), which was published in Norway but, following the outbreak of World War II, was never translated and remained largely forgotten. Many years later, having achieved notability with other adventures and books on other subjects, Heyerdahl published a new account of this voyage under the title Fatu Hiva (London: Allen & Unwin, 1974). The story of his time on Fatu Hiva and his side trip to Hivaoa and Mohotani is also related in Green Was the Earth on the Seventh Day (Random House, 1996).

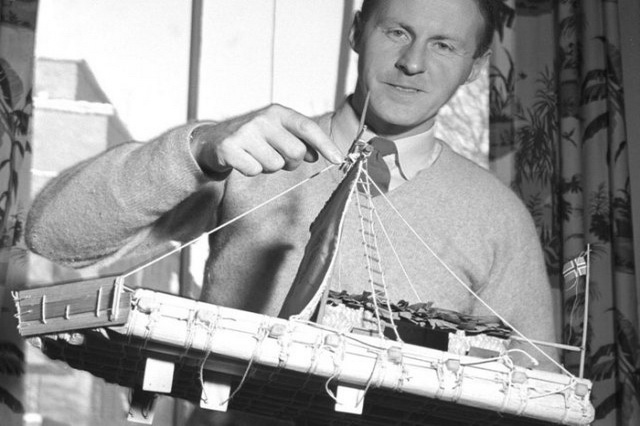

Kon-Tiki expedition[edit]

In 1947 Heyerdahl and five fellow adventurers sailed from Peru to the Tuamotu Islands, French Polynesia in a pae-pae raft that they had constructed from balsa wood and other native materials, christened the Kon-Tiki. The Kon-Tiki expedition was inspired by old reports and drawings made by the Spanish Conquistadors of Inca rafts, and by native legends and archaeological evidence suggesting contact between South America and Polynesia. The Kon-Tiki smashed into the reef at Raroia in the Tuamotus on 7 August 1947 after a 101-day, 4,300-nautical-mile (5,000-mile or 8,000 km)[11] journey across the Pacific Ocean. Heyerdahl had nearly drowned at least twice in childhood and did not take easily to water; he said later that there were times in each of his raft voyages when he feared for his life.[12]

Kon-Tiki demonstrated that it was possible for a primitive raft to sail the Pacific with relative ease and safety, especially to the west (with the trade winds). The raft proved to be highly manoeuvrable, and fish congregated between the nine balsa logs in such numbers that ancient sailors could have possibly relied on fish for hydration in the absence of other sources of fresh water. Other rafts have repeated the voyage, inspired by Kon-Tiki.

Heyerdahl’s book about The Kon-Tiki Expedition: By Raft Across the South Seas has been translated into 70 languages.[13] The documentary film of the expedition entitled Kon-Tiki won an Academy Award in 1951. A dramatised version was released in 2012, also called Kon-Tiki, and was nominated for both the Best Foreign Language Oscar at the 85th Academy Awards[14] and a Golden Globe Award for Best Foreign Language Film at the 70th Golden Globe Awards.[15] It was the first time that a Norwegian film was nominated for both an Oscar and a Golden Globe.[16]

Anthropologists continue to believe that Polynesia was settled from west to east, based on linguistic, physical, and genetic evidence, migration having begun from the Asian mainland. In response to the linguistic evidence, Heyerdahl observed, by analogy, that African Americans originated in Africa despite the fact that they today speak a language that originated in England.[17] Other evidence supports Heyerdahl’s hypothesis of South American/Polynesian contact. For example, the South American sweet potato is served as a dietary staple throughout much of Polynesia. Moreover, blood samples taken in 1971 and 2008 from Easter Islanders without any European or other external descent were analysed in a 2011 study, which concluded that the evidence supported some aspects of Heyerdahl’s hypothesis.[18][19][20] This result has been questioned because of the possibility of contamination by South Americans after European contact with the islands.[21] A study published in 2020, purports to find «conclusive evidence for prehistoric contact of Polynesian individuals with Native American individuals» in «a single contact event» about AD 1200 with a «Native American group most closely related to the indigenous inhabitants of present-day Colombia.»[22]

Theory on Polynesian origins[edit]

Heyerdahl claimed that in Incan legend there was a sun-god named Con-Tici Viracocha who was the supreme head of the mythical fair-skinned people in Peru. The original name for Viracocha was Kon-Tiki or Illa-Tiki, which means Sun-Tiki or Fire-Tiki.[citation needed]

Kon-Tiki was high priest and sun-king of these legendary «white men» who left enormous ruins on the shores of Lake Titicaca. The legend continues with the mysterious bearded white men being attacked by a chief named Cari, who came from the Coquimbo Valley. They had a battle on an island in Lake Titicaca, and the fair race was massacred. However, Kon-Tiki and his closest companions managed to escape and later arrived on the Pacific coast. The legend ends with Kon-Tiki and his companions disappearing westward out to sea.

When the Spaniards came to Peru, Heyerdahl asserted, the Incas told them that the colossal monuments that stood deserted about the landscape were erected by a race of white gods who had lived there before the Incas themselves became rulers. The Incas described these «white gods» as wise, peaceful instructors who had originally come from the north in the «morning of time» and taught the Incas’ primitive forebears architecture as well as manners and customs. They were unlike other Native Americans in that they had «white skins and long beards» and were taller than the Incas. The Incas said that the «white gods» had then left as suddenly as they had come and fled westward across the Pacific. After they had left, the Incas themselves took over power in the country.

Heyerdahl said that when the Europeans first came to the Pacific islands, they were astonished that they found some of the natives to have relatively light skins and beards. There were whole families that had pale skin, hair varying in colour from reddish to blonde. In contrast, most of the Polynesians had golden-brown skin, raven-black hair, and rather flat noses. Heyerdahl claimed that when Jacob Roggeveen discovered Easter Island in 1722, he supposedly noticed that many of the natives were white-skinned. Heyerdahl claimed that these people could count their ancestors who were «white-skinned» right back to the time of Tiki and Hotu Matua, when they first came sailing across the sea «from a mountainous land in the east which was scorched by the sun». The ethnographic evidence for these claims is outlined in Heyerdahl’s book Aku-Aku: The Secret of Easter Island.

Tiki people[edit]

Heyerdahl proposed that Tiki’s neolithic people colonised the then uninhabited Polynesian islands as far north as Hawaii, as far south as New Zealand, as far east as Easter Island, and as far west as Samoa and Tonga around 500 AD. They supposedly sailed from Peru to the Polynesian islands on pae-paes—large rafts built from balsa logs, complete with sails and each with a small cottage. They built enormous stone statues carved in the image of human beings on Pitcairn, the Marquesas, and Easter Island that resembled those in Peru. They also built huge pyramids on Tahiti and Samoa with steps like those in Peru.

But all over Polynesia, Heyerdahl found indications that Tiki’s peaceable race had not been able to hold the islands alone for long. He found evidence that suggested that seagoing war canoes as large as Viking ships, and lashed together two by two, had brought Stone Age Northwest American Indians to Polynesia around 1100 AD, and they mingled with Tiki’s people. The oral history of the people of Easter Island, at least as it was documented by Heyerdahl, is completely consistent with this theory, as is the archaeological record he examined (Heyerdahl 1958).

In particular, Heyerdahl obtained a radiocarbon date of 400 AD for a charcoal fire located in the pit that was held by the people of Easter Island to have been used as an «oven» by the «Long Ears, » which Heyerdahl’s Rapa Nui sources, reciting oral tradition, identified as a white race that had ruled the island in the past (Heyerdahl 1958).

Heyerdahl further argued in his book American Indians in the Pacific that the current inhabitants of Polynesia migrated from an Asian source, but via an alternative route. He proposes that Polynesians travelled with the wind along the North Pacific current. These migrants then arrived in British Columbia. Heyerdahl called contemporary tribes of British Columbia, such as the Tlingit and Haida, descendants of these migrants. Heyerdahl claimed that cultural and physical similarities existed between these British Columbian tribes, Polynesians, and the Old World source.

Controversy[edit]

Heyerdahl’s theory of Polynesian origins has not gained acceptance among anthropologists.[23][24][25] Physical and cultural evidence had long suggested that Polynesia was settled from west to east, migration having begun from the Asian mainland, not South America. In the late 1990s, genetic testing found that the mitochondrial DNA of the Polynesians is more similar to people from south-east Asia than to people from South America, showing that their ancestors most likely came from Asia.[26]

Anthropologist Robert Carl Suggs included a chapter titled «The Kon-Tiki Myth» in his 1960 book on Polynesia, concluding that «The Kon-Tiki theory is about as plausible as the tales of Atlantis, Mu, and ‘Children of the Sun.’ Like most such theories, it makes exciting light reading, but as an example of scientific method it fares quite poorly.»[27]

Anthropologist and National Geographic Explorer-in-Residence Wade Davis also criticised Heyerdahl’s theory in his 2009 book The Wayfinders, which explores the history of Polynesia. Davis says that Heyerdahl «ignored the overwhelming body of linguistic, ethnographic, and ethnobotanical evidence, augmented today by genetic and archaeological data, indicating that he was patently wrong.»[28]

A 2009 study by the Norwegian researcher Erik Thorsby[29] suggested that there was some merit to Heyerdahl’s ideas and that, while Polynesia was colonised from Asia, some contact with South America also existed.[30][31] Some critics suggest, however, that Thorsby’s research is inconclusive because his data may have been influenced by recent population contact.[32]

A 2014 research project [33] indicates that the South American component of the Easter Island people’s genomes pre-dates European contact. The research team, including Anna-Sapfo Malaspinas (from the Natural History Museum of Denmark), analysed the genomes of 27 native Rapanui people and found that their DNA was on average 76 per cent Polynesian, 8 per cent Native American and 16 per cent European. Analysis showed that «although the European lineage could be explained by contact with white Europeans after the island was ‘discovered’ in 1722 by Dutch sailors, the South American component was much older, dating to between about 1280 and 1495, soon after the island was first colonised by Polynesians in around 1200.» Together with ancient skulls found in Brazil – with solely Polynesian DNA – this does suggest some pre-European-contact travel to and from South America from Polynesia.

A study based on over one hundred Rapanui DNA sequences published in Nature in July 2020 showed that a genetic contact event occurred, circa 1200 AD, between Polynesian individuals and a Native American group most closely related to the indigenous inhabitants of present-day Colombia.[34]

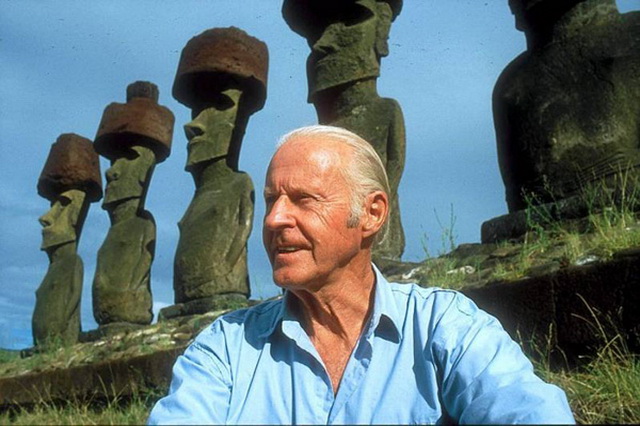

Expedition to Easter Island[edit]

In 1955–1956, Heyerdahl organised the Norwegian Archaeological Expedition to Easter Island. The expedition’s scientific staff included Arne Skjølsvold, Carlyle Smith, Edwin Ferdon, Gonzalo Figueroa[35] and William Mulloy. Heyerdahl and the professional archaeologists who travelled with him spent several months on Easter Island investigating several important archaeological sites. Highlights of the project include experiments in the carving, transport and erection of the notable moai, as well as excavations at such prominent sites as Orongo and Poike. The expedition published two large volumes of scientific reports (Reports of the Norwegian Archaeological Expedition to Easter Island and the East Pacific) and Heyerdahl later added a third (The Art of Easter Island). Heyerdahl’s popular book on the subject, Aku-Aku was another international best-seller.[36]

In Easter Island: The Mystery Solved (Random House, 1989), Heyerdahl offered a more detailed theory of the island’s history. Based on native testimony and archaeological research, he claimed the island was originally colonised by Hanau eepe («Long Ears»), from South America, and that Polynesian Hanau momoko («Short Ears») arrived only in the mid-16th century; they may have come independently or perhaps were imported as workers. According to Heyerdahl, something happened between Admiral Roggeveen’s discovery of the island in 1722 and James Cook’s visit in 1774; while Roggeveen encountered white, Indian, and Polynesian people living in relative harmony and prosperity, Cook encountered a much smaller population consisting mainly of Polynesians and living in privation.

Heyerdahl notes the oral tradition of an uprising of «Short Ears» against the ruling «Long Ears.» The «Long Ears» dug a defensive moat on the eastern end of the island and filled it with kindling. During the uprising, Heyerdahl claimed, the «Long Ears» ignited their moat and retreated behind it, but the «Short Ears» found a way around it, came up from behind, and pushed all but two of the «Long Ears» into the fire. This moat was found by the Norwegian expedition and it was partly cut down into the rock. Layers of fire were revealed but no fragments of bodies.

As for the origin of the people of Easter Island, DNA tests have shown a connection to South America.[37] But critics conjecture that this was a result of recent events. Still, whether this is inherited from a person coming in later times is hard to know. If the story that almost all Long Ears were killed in a civil war is true, as the islanders’ story goes, it would be expected that the statue-building South American bloodline would have been nearly utterly destroyed, leaving for the most part the invading Polynesian bloodline.

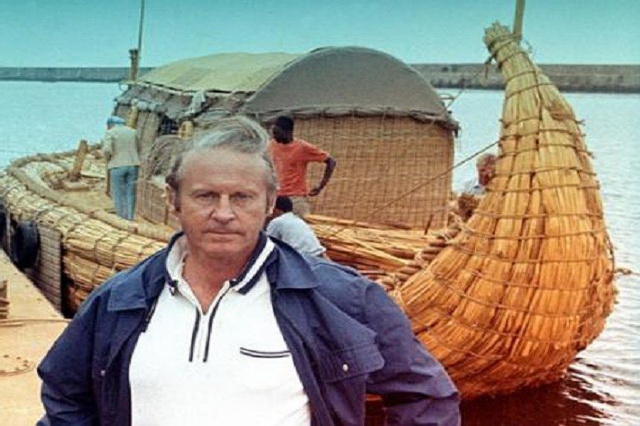

Boats Ra and Ra II[edit]

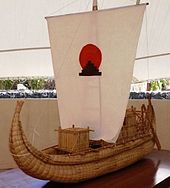

The Ra II in the Kon-Tiki Museum

In 1969 and 1970, Heyerdahl built two boats from papyrus and attempted to cross the Atlantic Ocean from Morocco in Africa. Based on drawings and models from ancient Egypt, the first boat, named Ra (after the Egyptian Sun god), was constructed by boat builders from Lake Chad using papyrus reed obtained from Lake Tana in Ethiopia and launched into the Atlantic Ocean from the coast of Morocco. The Ra crew included Thor Heyerdahl (Norway), Norman Baker (US), Carlo Mauri (Italy), Yuri Senkevich (USSR), Santiago Genovés (Mexico), Georges Sourial (Egypt), and Abdullah Djibrine (Chad). Only Heyerdahl and Baker had sailing and navigation experience. Genovés would go on to head the Acali Experiment.

After a number of weeks, Ra took on water. The crew discovered that a key element of the Egyptian boatbuilding method had been neglected, a tether that acted like a spring to keep the stern high in the water while allowing for flexibility.[38] Water and storms eventually caused it to sag and break apart after sailing more than 6,400 km (4,000 miles). The crew was forced to abandon Ra, some hundred miles (160 km) before the Caribbean islands, and was saved by a yacht.

The following year, 1970, a similar vessel, Ra II, was built from Ethiopian papyrus by Bolivian citizens Demetrio, Juan and José Limachi of Lake Titicaca, and likewise set sail across the Atlantic from Morocco, this time with great success. The crew was mostly the same; though Djibrine had been replaced by Kei Ohara from Japan and Madani Ait Ouhanni from Morocco. The boat became lost and was the subject of a United Nations search and rescue mission. The search included international assistance including people as far afield as Loo-Chi Hu of New Zealand. The boat reached Barbados, thus demonstrating that mariners could have dealt with trans-Atlantic voyages by sailing with the Canary Current.[39] The Ra II is now in the Kon-Tiki Museum in Oslo, Norway.

The book The Ra Expeditions and the film documentary Ra (1972) were made about the voyages. Apart from the primary aspects of the expedition, Heyerdahl deliberately selected a crew representing a great diversity in race, nationality, religion and political viewpoint in order to demonstrate that, at least on their own little floating island, people could co-operate and live peacefully. Additionally, the expedition took samples of marine pollution and presented its report to the United Nations.[40]

Tigris[edit]

Heyerdahl built yet another reed boat in 1977, Tigris, which was intended to demonstrate that trade and migration could have linked Mesopotamia with the Indus Valley civilization in what is now Pakistan and western India. Tigris was built in Al Qurnah Iraq and sailed with its international crew through the Persian Gulf to Pakistan and made its way into the Red Sea.[41]

After about five months at sea and still remaining seaworthy, the Tigris was deliberately burnt in Djibouti on 3 April 1978 as a protest against the wars raging on every side in the Red Sea and Horn of Africa. In his Open Letter to the UN Secretary-General Kurt Waldheim, Heyerdahl explained his reasons:[42]

Today we burn our proud ship … to protest against inhuman elements in the world of 1978 … Now we are forced to stop at the entrance to the Red Sea. Surrounded by military airplanes and warships from the world’s most civilised and developed nations, we have been denied permission by friendly governments, for reasons of security, to land anywhere, but in the tiny, and still neutral, Republic of Djibouti. Elsewhere around us, brothers and neighbours are engaged in homicide with means made available to them by those who lead humanity on our joint road into the third millennium.

To the innocent masses in all industrialised countries, we direct our appeal. We must wake up to the insane reality of our time … We are all irresponsible, unless we demand from the responsible decision makers that modern armaments must no longer be made available to people whose former battle axes and swords our ancestors condemned.

Our planet is bigger than the reed bundles that have carried us across the seas, and yet small enough to run the same risks unless those of us still alive open our eyes and minds to the desperate need of intelligent collaboration to save ourselves and our common civilisation from what we are about to convert into a sinking ship.

In the years that followed, Heyerdahl was often outspoken on issues of international peace and the environment.

The Tigris had an 11-man crew: Thor Heyerdahl (Norway), Norman Baker (US), Carlo Mauri (Italy), Yuri Senkevich (USSR), Germán Carrasco (Mexico), Hans Petter Bohn (Norway), Rashad Nazar Salim (Iraq), Norris Brock (US), Toru Suzuki (Japan), Detlef Soitzek (Germany), and Asbjørn Damhus (Denmark).

«The Search for Odin» in Azerbaijan and Russia[edit]

Background[edit]

Heyerdahl made four visits to Azerbaijan in 1981,[43] 1994, 1999 and 2000.[44] Heyerdahl had long been fascinated with the rock carvings that date back to about 8th–7th millennia BCE at Gobustan (about 30 miles/48 km west of Baku). He was convinced that their artistic style closely resembled the carvings found in his native Norway. The ship designs, in particular, were regarded by Heyerdahl as similar and drawn with a simple sickle-shaped line, representing the base of the boat, with vertical lines on deck, illustrating crew or, perhaps, raised oars.

Based on this and other published documentation, Heyerdahl proposed that Azerbaijan was the site of an ancient advanced civilisation. He believed that natives migrated north through waterways to present-day Scandinavia using ingeniously constructed vessels made of skins that could be folded like cloth. When voyagers travelled upstream, they conveniently folded their skin boats and transported them on pack animals.

Snorri Sturluson[edit]

On Heyerdahl’s visit to Baku in 1999, he lectured at the Academy of Sciences about the history of ancient Nordic Kings. He spoke of a notation made by Snorri Sturluson, a 13th-century historian-mythographer in Ynglinga Saga, which relates that «Odin (a Scandinavian god who was one of the kings) came to the North with his people from a country called Aser.»[45] (see also House of Ynglings and Mythological kings of Sweden). Heyerdahl accepted Snorri’s story as literal truth, and believed that a chieftain led his people in a migration from the east, westward and northward through Saxony, to Fyn in Denmark, and eventually settling in Sweden. Heyerdahl claimed that the geographic location of the mythic Aser or Æsir matched the region of contemporary Azerbaijan – «east of the Caucasus mountains and the Black Sea». «We are no longer talking about mythology,» Heyerdahl said, «but of the realities of geography and history. Azerbaijanis should be proud of their ancient culture. It is just as rich and ancient as that of China and Mesopotamia.»

In September 2000 Heyerdahl returned to Baku for the fourth time and visited the archaeological dig in the area of the Church of Kish.[46]

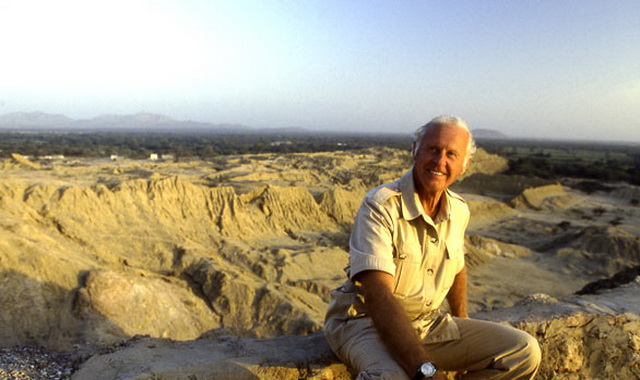

Revision of hypothesis[edit]

One of the last projects of his life, Jakten på Odin, ‘The Search for Odin’, was a sudden revision of his Odin hypothesis, in furtherance of which he initiated 2001–2002 excavations in Azov, Russia, near the Sea of Azov at the northeast of the Black Sea.[47] He searched for the remains of a civilisation to match the account of Odin in Snorri Sturlusson, significantly further north of his original target of Azerbaijan on the Caspian Sea only two years earlier. This project generated harsh criticism and accusations of pseudoscience from historians, archaeologists and linguists in Norway, who accused Heyerdahl of selective use of sources, and a basic lack of scientific methodology in his work.[48][49]

His central claims were based on similarities of names in Norse mythology and geographic names in the Black Sea region, e.g. Azov and Æsir, Udi and Odin, Tyr and Turkey. Philologists and historians reject these parallels as mere coincidences, and also anachronisms, for instance the city of Azov did not have that name until over 1,000 years after Heyerdahl claims the Æsir dwelt there. The controversy surrounding the Search for Odin project was in many ways typical of the relationship between Heyerdahl and the academic community. His theories rarely won any scientific acceptance, whereas Heyerdahl himself rejected all scientific criticism and concentrated on publishing his theories in popular books aimed at the general public.[citation needed]

As of 2021, Heyerdahl’s Odin hypothesis has yet to be validated by any historian, archaeologist or linguist.

Other projects[edit]

Heyerdahl also investigated the mounds found on the Maldive Islands in the Indian Ocean. There, he found sun-orientated foundations and courtyards, as well as statues with elongated earlobes. Heyerdahl believed that these finds fit with his theory of a seafaring civilisation which originated in what is now Sri Lanka, colonised the Maldives, and influenced or founded the cultures of ancient South America and Easter Island. His discoveries are detailed in his book The Maldive Mystery.

In 1991 he studied the Pyramids of Güímar on Tenerife and declared that they were not random stone heaps but pyramids. Based on the discovery made by the astrophysicists Aparicio, Belmonte and Esteban, from the Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias that the «pyramids» were astronomically orientated and being convinced that they were of ancient origin, he claimed that the ancient people who built them were most likely sun worshippers. Heyerdahl advanced a theory according to which the Canaries had been bases of ancient shipping between America and the Mediterranean.

Heyerdahl was also an active figure in Green politics. He was the recipient of numerous medals and awards. He also received 11 honorary doctorates from universities in the Americas and Europe.

In subsequent years, Heyerdahl was involved with many other expeditions and archaeological projects. He remained best known for his boatbuilding, and for his emphasis on cultural diffusionism.[50]

Death[edit]

Heyerdahl died on 18 April 2002 in Colla Micheri, Liguria, Italy, where he had gone to spend the Easter holidays with some of his closest family members. He died, aged 87, from a brain tumour.[51] After receiving the diagnosis, he prepared for death, by refusing to eat or take medication.[52]

The Norwegian government honored him with a state funeral in the Oslo Cathedral on 26 April 2002. He is buried in the garden of the family home in Colla Micheri.[1] He was an atheist.[53][54]

Legacy[edit]

Despite the fact that, for many years, much of his work was not accepted by the scientific community, Heyerdahl, nonetheless, increased public interest in ancient history and anthropology. He also showed that long-distance ocean voyages were possible with ancient designs. As such, he was a major practitioner of experimental archaeology. The Kon-Tiki Museum on the Bygdøy peninsula in Oslo, Norway houses vessels and maps from the Kon-Tiki expedition, as well as a library with about 8,000 books.

The Thor Heyerdahl Institute was established in 2000. Heyerdahl himself agreed to the founding of the institute and it aims to promote and continue to develop Heyerdahl’s ideas and principles. The institute is located in Heyerdahl’s birth town of Larvik, Norway. In Larvik, the birthplace of Heyerdahl, the municipality began a project in 2007 to attract more visitors. Since then, they have purchased and renovated Heyerdahl’s childhood home, arranged a yearly raft regatta in his honour at the end of summer and begun to develop a Heyerdahl centre.[55]

Heyerdahl’s grandson, Olav Heyerdahl, retraced his grandfather’s Kon-Tiki voyage in 2006 as part of a six-member crew. The voyage, organised by Torgeir Higraff and called the Tangaroa Expedition,[56] was intended as a tribute to Heyerdahl, an effort to better understand navigation via centreboards («guara[57]«) as well as a means to monitor the Pacific Ocean’s environment.

A book about the Tangaroa Expedition[58] by Torgeir Higraff was published in 2007. The book has numerous photos from the Kon-Tiki voyage 60 years earlier and is illustrated with photographs by Tangaroa crew member Anders Berg (Oslo: Bazar Forlag, 2007). «Tangaroa Expedition»[59] has also been produced as a documentary DVD in English, Norwegian, Swedish and Spanish.

Paul Theroux, in his book The Happy Isles of Oceania, criticises Heyerdahl for trying to link the culture of Polynesian islands with the Peruvian culture. Recent scientific investigation that compares the DNA of some of the Polynesian islands with natives from Peru suggests that there is some merit to Heyerdahl’s ideas and that while Polynesia was colonised from Asia, some contact with South America also existed; several papers have in the last few years confirmed with genetic data some form of contacts with Easter Island.[30][31][60]

More recently, some researchers published research confirming a wider impact on genetic and cultural elements in Polynesia due to South American contacts.[61]

Decorations and honorary degrees[edit]

Bust of Thor Heyerdahl. Güímar, Tenerife.

Asteroid 2473 Heyerdahl is named after him, as are HNoMS Thor Heyerdahl, a Norwegian Nansen class frigate, along with MS Thor Heyerdahl (now renamed MS Vana Tallinn), and Thor Heyerdahl, a German three-masted sail training vessel originally owned by a participant of the Tigris expedition. Heyerdahl Vallis, a valley on Pluto, and Thor Heyerdahl Upper Secondary School in Larvik, the town of his birth, are also named after him. Google honoured Heyerdahl on his 100th birthday by making a Google Doodle.[62]

Heyerdahl’s numerous awards and honours include the following:

Governmental and state honours[edit]

- Grand Cross of the Royal Norwegian Order of St Olav (1987) (Commander with Star: 1970; Commander: 1951)[63]

- Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of Peru (1953)[63]

- Grand Officer of the Order of Merit of the Italian Republic (21 June 1965)[63][64]

- Knight in the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem[65]

- Knight of the Order of Merit, Egypt (1971)[63]

- Grand Officer of the Order of Ouissam Alaouite (Morocco; 1971)

- Officer, Order of the Sun (Peru) (1975) and Knight Grand Cross

- International Pahlavi Environment Prize, United Nations (1978)[63]

- Knight of the Order of the Golden Ark, Netherlands (1980)[63]

- Commander, American Knights of Malta (1970)[63]

- Civitan International World Citizenship Award[66]

- Austrian Decoration for Science and Art (2000)[67]

- St. Hallvard’s Medal

Academic honours[edit]

- Retzius Medal, Royal Swedish Society for Anthropology and Geography (1950)[63][68]

- Mungo Park Medal, Royal Scottish Society for Geography (1951)[63]

- Bonaparte-Wyse Gold Medal, Société de Géographie de Paris (1951)[63]

- Elisha Kent Kane Gold Medal, Geographical Society of Philadelphia (1952)[63]

- Honorary Member, Geographical Societies of Norway (1953), Peru (1953), Brazil (1954)[63]

- Elected Member Norwegian Academy of Sciences (1958)[63]

- Fellow, New York Academy of Sciences (1960)[63]

- Vega Gold Medal, Swedish Society for Anthropology and Geography (1962)[63]

- Lomonosov Medal, Moscow State University (1962)[63]

- Gold Medal, Royal Geographical Society, London (1964)[63]

- Distinguished Service Award, Pacific Lutheran University, Tacoma, Washington, US (1966)[63]

- Member American Anthropological Association (1966)[63]

- Kiril i Metodi Award, Geographical Society, Bulgaria (1972)[63]

- Honorary Professor, Instituto Politécnico Nacional, Mexico (1972)[63]

- Bradford Washburn Award, Museum of Science, Boston, US, (1982)[63]

- President’s Medal, Pacific Lutheran University, Tacoma, US (1996)[63]

- Honorary Professorship, Western University, Baku, Azerbaijan (1999)[69]

Honorary degrees[edit]

- Doctor Honoris Causa, University of Oslo, Norway (1961)[63]

- Doctor Honoris Causa, USSR Academy of Science (1980)[63]

- Doctor Honoris Causa, University of San Martin, Lima, Peru, (1991)[63]

- Doctor Honoris Causa, University of Havana, Cuba (1992)[63]

- Doctor Honoris Causa, University of Kyiv, Ukraine (1993)[63]

- Doctor Honoris Causa, University of Maine, Orono (1998)

Publications[edit]

- På Jakt efter Paradiset (Hunt for Paradise), 1938; Fatu-Hiva: Back to Nature (changed title in English in 1974).

- The Kon-Tiki Expedition: By Raft Across the South Seas (Kon-Tiki ekspedisjonen, also known as Kon-Tiki: Across the Pacific in a Raft), 1948.

- American Indians in the Pacific: The Theory Behind the Kon-Tiki Expedition (Chicago: Rand McNally, 1952), 821 pages.

- Aku-Aku: The Secret of Easter Island, 1957.

- Sea Routes to Polynesia: American Indians and Early Asiatics in the Pacific (Chicago: Rand McNally, 1968), 232 pages.

- The Ra Expeditions ISBN 0-14-003462-5.

- Early Man and the Ocean: The Beginning of Navigation and Seaborn Civilizations, 1979

- The Tigris Expedition: In Search of Our Beginnings

- The Maldive Mystery, 1986

- Green Was the Earth on the Seventh Day: Memories and Journeys of a Lifetime

- Pyramids of Tucume: The Quest for Peru’s Forgotten City

- Skjebnemøte vest for havet [Fate Meets West of the Ocean], 1992 (in Norwegian and German only) the Native Americans tell their story, white and bearded Gods, infrastructure was not built by the Inkas but their more advanced predecessors.

- In the Footsteps of Adam: A Memoir (the official edition is Abacus, 2001, translated by Ingrid Christophersen) ISBN 0-349-11273-8

- Ingen Grenser (No Boundaries, Norwegian only), 1999[70]

- Jakten på Odin (Theories about Odin, Norwegian only), 2001

See also[edit]

- M/S Thor Heyerdahl – a ferry named after him

- List of notable brain tumor patients

- Pre-Columbian trans-oceanic contact

- Pre-Columbian rafts

- Vital Alsar

- Kitín Muñoz

- The Viracocha expedition

References[edit]

- ^ a b J. Bjornar Storfjell, «Thor Heyerdahl’s Final Projects,» in Azerbaijan International, Vol. 10:2 (Summer 2002), p. 25.

- ^ «New collections come to enrich the Memory of the World». Portal.unesco.org. Archived from the original on 14 July 2012. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ^ «Memory of the World Register Application form from Kon-Tiki Museum for Thor Heyerdahl Archives» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ^ Thor Heyerdahl, In the Footsteps of Adam: A Memoir, London: Abacus Books, 2001, p. 78.

- ^ a b c d «‘Kon-Tiki’ and me — The Boston Globe». BostonGlobe.com. Archived from the original on 11 June 2020. Retrieved 18 July 2020.

- ^ Obituary, Jo Anne Van Tilburg, 19 April 2002, The Guardian

- ^ «Explorer Thor Heyerdahl dies», 18 April 2002, BBC

- ^ Thor Heyerdahl, «In the Footsteps of Adam». Christophersen translation (ISBN 0-349-11273-8), London: Abacus, 2001, p. 254.

- ^ J. Bjornar Storfjell, «Thor Heyerdahl’s Final Projects». in Azerbaijan International, Vol. 10:2 (Summer 2002), p. 25.

- ^ a b c Copied content from Fatu Hiva (book);see that page history for attribution

- ^ «Quick Facts: Comparing the Two Rafts: Kon-Tiki and Tangaroa,» in Azerbaijan International, Vol. 14:4 (Winter 2006), p. 35.

- ^ Personal correspondence via fax on 2 February 1995 to Editor Betty Blair, Azerbaijan International magazine for article «Kon-Tiki Man», Azerbaijan International, Vol. 3:1 (Spring 1995), pp. 62–63.

- ^ Heyerdahl’s Kon-Tiki has been translated into 71 languages, according to the Director of Kon-Tiki Museum, September 2013. Azerbaijani language being the 70th.

- ^ «Oscars: Hollywood announces 85th Academy Award nominations». BBC News. 10 January 2013. Retrieved 10 January 2013.

- ^ Finke, Nikki (13 December 2012). «lasse_hallstrom.jpg». Deadline.

- ^ Ryland, Julie (11 January 2013). «Norwegian film «Kon Tiki» nominated for Oscar». The Norway Post. Retrieved 11 January 2013.

- ^ «Avax News». 2011. Retrieved 26 December 2022.

- ^ «Early Americans helped colonise Easter Island». New Scientist. 6 June 2011. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ^ Alleyne, Richard (17 June 2011). «Kon-Tiki explorer was partly right – Polynesians had South American roots». Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 19 June 2011. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ^ «Påskeøya: Heyerdahl kan ha hatt litt rett» (in Norwegian). Apollon. Archived from the original on 30 September 2011. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ^ «Did Easter Islanders Mix It Up With South Americans?». sciencemag.org. 7 February 2012.

- ^ Ioannidis, Alexander G.; et al. (2020). «Native American gene flow into Polynesia predating Easter Island settlement,» Nature«. Nature. 583 (7817): 572–577. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2487-2. PMC 8939867. PMID 32641827.

- ^ Robert C. Suggs The Island Civilizations of Polynesia, New York: New American Library, pp. 212–224.

- ^ Kirch, P. (2000). On the Roads to the Wind: An archaeological history of the Pacific Islands before European contact. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000.

- ^ Barnes, S.S.; et al. (2006). «Ancient DNA of the Pacific rat (Rattus exulans) from Rapa Nui (Easter Island)» (PDF). Journal of Archaeological Science. 33 (11): 1536–1540. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2006.02.006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 July 2011.

- ^ Friedlaender, J.S.; et al. (2008). «The genetic structure of Pacific Islanders». PLOS Genetics. 4 (1): e19. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0040019. PMC 2211537. PMID 18208337.

- ^ Robert C. Suggs, The Island Civilizations of Polynesia, New York: New American Library, p.224.

- ^ Wade Davis, The Wayfinders: Why Ancient Wisdom Matters in the Modern World, Crawley: University of Western Australia Publishing, p.46.

- ^ Thorsby, E; Flåm, S. T.; Woldseth, B; Dupuy, B. M.; Sanchez-Mazas, A; Fernandez-Vina, M. A. (June 2009). «Further evidence of an Amerindian contribution to the Polynesian gene pool on Easter Island». Tissue Antigens. 73 (6): 582–5. doi:10.1111/j.1399-0039.2009.01233.x. PMID 19493235.

- ^ a b Thorsby, E.; Flåm, S. T.; Woldseth, B.; Dupuy, B. M.; Sanchez-Mazas, A.; Fernandez-Vina, M. A. (2009). «Further evidence of an Amerindian contribution to the Polynesian gene pool on Easter Island». Tissue Antigens. 73 (6): 582–585. doi:10.1111/j.1399-0039.2009.01233.x. PMID 19493235.

- ^ a b Marshall, Michael (6 June 2011). «Early Americans helped colonise Easter Island». New Scientist. Retrieved 25 August 2012.

- ^ Lawler, Andrew. «Did Easter Islanders Mix It Up With South Americans?» Science News, Washington, 6 February 2012. Retrieved on 7 January 2014.

- ^ Moreno-Mayar, J. Víctor; Rasmussen, Simon; Seguin-Orlando, Andaine; Rasmussen, Morten; Liang, Mason; Flåm, Siri Tennebø; Lie, Benedicte Alexandra; Gilfillan, Gregor Duncan; Nielsen, Rasmus; Thorsby, Erik; Willerslev, Eske; Malaspinas, Anna-Sapfo (3 November 2014). «Genome-wide Ancestry Patterns in Rapanui Suggest Pre-European Admixture with Native Americans». Current Biology. 24 (21): 2518–2525. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2014.09.057. ISSN 0960-9822. PMID 25447991. S2CID 13439165.

- ^ Ioannidis, Alexander G.; Blanco-Portillo, Javier; Sandoval, Karla; et al. (2020). «Native American gene flow into Polynesia predating Easter Island settlement». Nature. 583 (7817): 572–577. Bibcode:2020Natur.583..572I. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2487-2. PMC 8939867. PMID 32641827.

- ^ Coad, Malcolm (4 September 2008). «Gonzalo Figueroa». Guardian. London. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ^ «Kon-Tiki Museet : Thor Heyerdahls Forskningsstiftelse».

- ^ Alleyne, Richard (2011). «Thor Heyedahl». Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022.

- ^ Heyerdahl, Thor (1972). The Ra Expeditions. p. 197.

- ^ Ryne, Linn. [1]. Retrieved 13 January 2008.

- ^ «Heyerdahl award». Norges Rederiforbund. Retrieved 29 November 2013.

- ^ Pathé, British. «Bahrain: Noted Explorer Thor Heyerdahl Prepares To Continue His Reed-Boat Voyage To India». www.britishpathe.com. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ^ Heyerdahl, Betty Blair, Bjornar Storfjell, «25 Years Ago, Heyerdahl Burns Tigris Reed Ship to Protest War,» in Azerbaijan International, Vol. 11:1 (Spring 2003), pp. 20–21.

- ^ Forecoming 2014: Thor Heyerdahl and Azerbaijan, to be published jointly by University of Oslo and Azerbaijan University of Languages, Editor Vibeke Roeggen et al.

- ^ «Thor Heyerdahl in Azerbaijan». Azer.com. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ^ Stenersens, J. (trans.) (1987). Snorri, The Sagas of the Viking Kings of Norway. Oslo: Forlag, 1987.

- ^ «8.4 The Kish Church – Digging Up History – An Interview with J. Bjornar Storfjell».

- ^ Storfjell, «Thor Heyerdahl’s Final Projects,» in Azerbaijan International, Vol. 10:2 (Summer 2002).

- ^ «Thor Heyerdahl og Per Lillieström. Jakten på Odin. På sporet av vår fortid.Oslo: J.M. Stenersens forlag, 2001. 320 s» [Thor Heyerdahl and Per Lillieström. The hunt for Odin. On the trail of our past. Oslo: J.M. Stenersen’s publishing house, 2001. 320 p.] (PDF). Reviews. Maal og Minne 1 (2002) (in Norwegian): 98–109. 2002. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 July 2011. Retrieved 8 October 2022.

- ^ Stahlsberg, Anne (13 March 2006). «Ytringsfrihet og påstått vitenskap – et dilemma? (Freedom of expression and alleged science – a dilemma?)». Retrieved 20 June 2012. (pdf at [2])

- ^ J. Bjornar Storfjell, «Thor Heyerdahl’s Final Projects Archived 2020-07-14 at the Wayback Machine,» in Azerbaijan International, Vol. 10:2 (Summer 2002), p. 25.

- ^ Harris M. Lentz III (2003). Obituaries in the Performing Arts, 2002: Film, Television, Radio, Theatre, Dance, Music, Cartoons and Pop Culture. McFarland. pp. 134–. ISBN 978-0-7864-1464-2.

- ^ Radford, Tim (19 April 2002). «Thor Heyerdahl dies at 87». The Guardian. London. Retrieved 6 July 2009.

- ^ «Thor Heyerdahl». 18 April 2002. Retrieved 27 March 2017.

- ^ «Kon-Tiki – World». Retrieved 27 March 2017.

- ^ (in Bokmål) Heyerdahl-byen. op.no. Retrieved on 5 March 2011.

- ^ Torgeir Saeverud Higraff with Betty Blair, «Tangaroa Pacific Voyage: Testing Heyerdahl’s Theories about Kon-Tiki 60 Years Later», Azerbaijan International, Vol. 14:4 (Winter 2006), pp. 28–53.

- ^ «21st Century». 21stcenturysciencetech.com.

- ^ Tangaroa Expedition, available only in Norwegian (ISBN 978-82-8087-199-2), 363 pages. The book has photos related to the Kon-Tiki expedition 60 years earlier and is lavishly illustrated with Tangaroa photos by Swedish crew member Anders Berg.

- ^ «AS Videomaker». 25 October 2017. Archived from the original on 25 October 2017.

- ^ Moreno-Mayar, J. Víctor; Rasmussen, Simon; Seguin-Orlando, Andaine; Rasmussen, Morten; Liang, Mason; Flåm, Siri Tennebø; Lie, Benedicte Alexandra; Gilfillan, Gregor Duncan; Nielsen, Rasmus; Thorsby, Erik; Willerslev, Eske; Malaspinas, Anna-Sapfo (2014). «Genome-wide Ancestry Patterns in Rapanui Suggest Pre-European Admixture with Native Americans». Current Biology. 24 (21): 2518–2525. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2014.09.057. PMID 25447991.

- ^ Callaway, Ewen (8 July 2020). «Ancient voyage carried Native Americans’ DNA to remote Pacific islands». Nature. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-02055-4. PMID 32641794. S2CID 220439360.

- ^ «Heyerdahl Google Doodle». 6 October 2014. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab (in Bokmål) nrk.no. Retrieved on 7 July 2011.

- ^ «Presidenza della Republica; ONORIFICENZE» (in Italian). Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- ^ Heyerdahl paid 50,000 dollars for this honour. De Telegraaf (16 November 1971)

- ^ Armbrester, Margaret E. (1992), Armbrester, Margaret E. (1992). The Civitan Story. Birmingham, AL: Ebsco Media. p. 95.

- ^ «Reply to a parliamentary question» (PDF) (in German). p. 1381. Retrieved 16 November 2012.

- ^ «Thor Heyerdahl». Retrieved 12 January 2011.

- ^ «Thor Heyerdahl: Beyond Borders, Beyond Seas: Links to Azerbaijan,» Western University, Book VII: Exploration Series, 2011, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Gibbs, Walter (19 December 2000). «Did the Vikings Stay? Vatican Files May Offer Clues». The New York Times. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

Further reading[edit]

- Heyerdahl, Thor. Kon-Tiki. Rand McNally & Company. 1950.

- Heyerdahl, Thor. Aku-Aku: The Secret of Easter Island. Rand McNally. 1958.

- Heyerdahl, Thor. Archaeology of Easter Island vol. 1 (1961)

- Heyerdahl, Thor. Archaeology of Easter Island vol. 2 (1965)

- Heyerdahl, Thor. Fatu Hiva. Penguin. 1976.

- Heyerdahl, Thor. Early Man and the Ocean: A Search for the Beginnings of Navigation and Seaborne Civilizations, February 1979.

- Heyerdahl, Thor. In the Footsteps of Adam: A Memoir, translated by Ingrid Christophersen, 2001 (English)

External links[edit]

- Maal og minne 1, 2002 at the Wayback Machine (archived 13 September 2009) a scientific critique of his Odin project, in English

- Thor Heyerdahl in Baku Azerbaijan International, Vol. 7:3 (Autumn 1999), pp. 96–97.

- Thor Heyerdahl Biography and Bibliography

- Thor Heyerdahl expeditions

- The ‘Tigris’ expedition, with Heyerdahl’s war protest Azerbaijan International, Vol. 11:1 (Spring 2003), pp. 20–21.

- Bjornar Storfjell’s account: A reference to his last project Jakten på Odin Azerbaijan International, Vol. 10:2 (Summer 2002).

- Biography on National Geographic

- Forskning.no Biography from the official Norwegian scientific webportal (in Norwegian)

- Thor Heyerdahl on Maldives Royal Family website

- Biography of Thor Heyerdahl

- Sea Routes to Polynesia Extracts from lectures by Thor Heyerdahl

- The home of Thor Heyerdahl Useful information on Thor Heyerdahl and his hometown, Larvik

- Thor Heyerdahl – Daily Telegraph obituary

- Works by or about Thor Heyerdahl at Internet Archive

|

Thor Heyerdahl |

|

|---|---|

Heyerdahl circa 1980 |

|

| Born | 6 October 1914

Larvik, Norway |

| Died | 18 April 2002 (aged 87)

Colla Micheri, Italy |

| Alma mater | University of Oslo |

| Spouses |

Liv Coucheron-Torp (m. 1936; div. 1947) Yvonne Dedekam-Simonsen (m. 1949; div. 1969) Jacqueline Beer (m. 1991) |

| Children | 5 |

| Awards | Mungo Park Medal (1950) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields |

|

| Doctoral advisor |

|

Thor Heyerdahl KStJ (Norwegian pronunciation: [tuːr ˈhæ̀ɪəɖɑːɫ]; 6 October 1914 – 18 April 2002) was a Norwegian adventurer and ethnographer with a background in zoology, botany and geography.

Heyerdahl is notable for his Kon-Tiki expedition in 1947, in which he sailed 8,000 km (5,000 mi) across the Pacific Ocean in a hand-built raft from South America to the Tuamotu Islands. The expedition was designed to demonstrate that ancient people could have made long sea voyages, creating contacts between societies. This was linked to a diffusionist model of cultural development.

Heyerdahl made other voyages to demonstrate the possibility of contact between widely separated ancient peoples, notably the Ra II expedition of 1970, when he sailed from the west coast of Africa to Barbados in a papyrus reed boat. He was appointed a government scholar in 1984.

He died on 18 April 2002 in Colla Micheri, Italy, while visiting close family members. The Norwegian government gave him a state funeral in Oslo Cathedral on 26 April 2002.[1]

In May 2011, the Thor Heyerdahl Archives were added to UNESCO’s Memory of the World Register.[2] At the time, this list included 238 collections from all over the world.[3] The Heyerdahl Archives span the years 1937 to 2002 and include his photographic collection, diaries, private letters, expedition plans, articles, newspaper clippings, and original book and article manuscripts. The Heyerdahl Archives are administered by the Kon-Tiki Museum and the National Library of Norway in Oslo.

Youth and personal life[edit]

Heyerdahl was born in Larvik, Norway, the son of master brewer Thor Heyerdahl (1869–1957) and his wife, Alison Lyng (1873–1965). As a young child, Heyerdahl showed a strong interest in zoology, inspired by his mother, who had a strong interest in Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution. He created a small museum in his childhood home, with a common adder (Vipera berus) as the main attraction.

He studied zoology and geography at the faculty of biological science at the University of Oslo.[4] At the same time, he privately studied Polynesian culture and history, consulting what was then the world’s largest private collection of books and papers on Polynesia, owned by Bjarne Kroepelien, a wealthy wine merchant in Oslo. (This collection was later purchased by the University of Oslo Library from Kroepelien’s heirs and was attached to the Kon-Tiki Museum research department.)

After seven terms and consultations with experts in Berlin, a project was developed and sponsored by Heyerdahl’s zoology professors, Kristine Bonnevie and Hjalmar Broch. He was to visit some isolated Pacific island groups and study how the local animals had found their way there.

On the day before they sailed together to the Marquesas Islands in 1936, Heyerdahl married Liv Coucheron-Torp (1916–1969), whom he had met at the University of Oslo, and who had studied economics there. He was 22 years old and she was 20 years old. Eventually, the couple had two sons: Thor Jr. and Bjørn. The marriage ended in divorce shortly before the 1947 Kon-Tiki expedition, which Liv had helped to organize.[5]

After the occupation of Norway by Nazi Germany, he served with the Free Norwegian Forces from 1944, in the far north province of Finnmark.[6][7]

In 1949, Heyerdahl married Yvonne Dedekam-Simonsen (1924–2006). They had three daughters: Annette, Marian, and Helene Elisabeth. They were divorced in 1969. Heyerdahl blamed their separation on his being away from home and differences in their ideas for bringing up children. In his autobiography, he concluded that he should take the entire blame for their separation.[8]

In 1991, Heyerdahl married Jacqueline Beer (born 1932) as his third wife. They lived in Tenerife, Canary Islands, and were very actively involved with archaeological projects, especially in Túcume, Peru, and Azov until his death in 2002. He had still been hoping to undertake an archaeological project in Samoa before he died.[9]

Fatu Hiva[edit]

In 1936, on the day after his marriage to Liv Coucheron Torp, the young couple set out for the South Pacific Island of Fatu Hiva. They nominally had an academic mission, to research the spread of animal species between islands, but in reality they intended to «run away to the South Seas» and never return home.[10]

Aided by expedition funding from their parents, they nonetheless arrived on the island lacking «provisions, weapons or a radio». Residents in Tahiti, where they stopped en route, did convince them to take a machete and a cooking pot.[5]

They arrived at Fatu Hiva in 1937, in the valley of Omo‘a, and decided to cross over the island’s mountainous interior to settle in one of the small, nearly abandoned, valleys on the eastern side of the island. There, they made their thatch-covered stilted home in the valley of Uia.[10]

Living in such primitive conditions was a daunting task, but they managed to live off the land, and work on their academic goals, by collecting and studying zoological and botanical specimens. They discovered unusual artifacts, listened to the natives’ oral history traditions, and took note of the prevailing winds and ocean currents.[5]

It was in this setting, surrounded by the ruins of the formerly glorious Marquesan civilization, that Heyerdahl first developed his theories regarding the possibility of pre-Columbian trans-oceanic contact between the pre-European Polynesians, and the peoples and cultures of South America.[10]

Despite the seemingly idyllic situation, the exposure to various tropical diseases and other difficulties caused them to return to civilisation a year later. They worked together to write an account of their adventure.[5]

The events surrounding his stay on the Marquesas, most of the time on Fatu Hiva, were told first in his book På Jakt etter Paradiset (Hunt for Paradise) (1938), which was published in Norway but, following the outbreak of World War II, was never translated and remained largely forgotten. Many years later, having achieved notability with other adventures and books on other subjects, Heyerdahl published a new account of this voyage under the title Fatu Hiva (London: Allen & Unwin, 1974). The story of his time on Fatu Hiva and his side trip to Hivaoa and Mohotani is also related in Green Was the Earth on the Seventh Day (Random House, 1996).

Kon-Tiki expedition[edit]

In 1947 Heyerdahl and five fellow adventurers sailed from Peru to the Tuamotu Islands, French Polynesia in a pae-pae raft that they had constructed from balsa wood and other native materials, christened the Kon-Tiki. The Kon-Tiki expedition was inspired by old reports and drawings made by the Spanish Conquistadors of Inca rafts, and by native legends and archaeological evidence suggesting contact between South America and Polynesia. The Kon-Tiki smashed into the reef at Raroia in the Tuamotus on 7 August 1947 after a 101-day, 4,300-nautical-mile (5,000-mile or 8,000 km)[11] journey across the Pacific Ocean. Heyerdahl had nearly drowned at least twice in childhood and did not take easily to water; he said later that there were times in each of his raft voyages when he feared for his life.[12]

Kon-Tiki demonstrated that it was possible for a primitive raft to sail the Pacific with relative ease and safety, especially to the west (with the trade winds). The raft proved to be highly manoeuvrable, and fish congregated between the nine balsa logs in such numbers that ancient sailors could have possibly relied on fish for hydration in the absence of other sources of fresh water. Other rafts have repeated the voyage, inspired by Kon-Tiki.

Heyerdahl’s book about The Kon-Tiki Expedition: By Raft Across the South Seas has been translated into 70 languages.[13] The documentary film of the expedition entitled Kon-Tiki won an Academy Award in 1951. A dramatised version was released in 2012, also called Kon-Tiki, and was nominated for both the Best Foreign Language Oscar at the 85th Academy Awards[14] and a Golden Globe Award for Best Foreign Language Film at the 70th Golden Globe Awards.[15] It was the first time that a Norwegian film was nominated for both an Oscar and a Golden Globe.[16]

Anthropologists continue to believe that Polynesia was settled from west to east, based on linguistic, physical, and genetic evidence, migration having begun from the Asian mainland. In response to the linguistic evidence, Heyerdahl observed, by analogy, that African Americans originated in Africa despite the fact that they today speak a language that originated in England.[17] Other evidence supports Heyerdahl’s hypothesis of South American/Polynesian contact. For example, the South American sweet potato is served as a dietary staple throughout much of Polynesia. Moreover, blood samples taken in 1971 and 2008 from Easter Islanders without any European or other external descent were analysed in a 2011 study, which concluded that the evidence supported some aspects of Heyerdahl’s hypothesis.[18][19][20] This result has been questioned because of the possibility of contamination by South Americans after European contact with the islands.[21] A study published in 2020, purports to find «conclusive evidence for prehistoric contact of Polynesian individuals with Native American individuals» in «a single contact event» about AD 1200 with a «Native American group most closely related to the indigenous inhabitants of present-day Colombia.»[22]

Theory on Polynesian origins[edit]

Heyerdahl claimed that in Incan legend there was a sun-god named Con-Tici Viracocha who was the supreme head of the mythical fair-skinned people in Peru. The original name for Viracocha was Kon-Tiki or Illa-Tiki, which means Sun-Tiki or Fire-Tiki.[citation needed]

Kon-Tiki was high priest and sun-king of these legendary «white men» who left enormous ruins on the shores of Lake Titicaca. The legend continues with the mysterious bearded white men being attacked by a chief named Cari, who came from the Coquimbo Valley. They had a battle on an island in Lake Titicaca, and the fair race was massacred. However, Kon-Tiki and his closest companions managed to escape and later arrived on the Pacific coast. The legend ends with Kon-Tiki and his companions disappearing westward out to sea.

When the Spaniards came to Peru, Heyerdahl asserted, the Incas told them that the colossal monuments that stood deserted about the landscape were erected by a race of white gods who had lived there before the Incas themselves became rulers. The Incas described these «white gods» as wise, peaceful instructors who had originally come from the north in the «morning of time» and taught the Incas’ primitive forebears architecture as well as manners and customs. They were unlike other Native Americans in that they had «white skins and long beards» and were taller than the Incas. The Incas said that the «white gods» had then left as suddenly as they had come and fled westward across the Pacific. After they had left, the Incas themselves took over power in the country.

Heyerdahl said that when the Europeans first came to the Pacific islands, they were astonished that they found some of the natives to have relatively light skins and beards. There were whole families that had pale skin, hair varying in colour from reddish to blonde. In contrast, most of the Polynesians had golden-brown skin, raven-black hair, and rather flat noses. Heyerdahl claimed that when Jacob Roggeveen discovered Easter Island in 1722, he supposedly noticed that many of the natives were white-skinned. Heyerdahl claimed that these people could count their ancestors who were «white-skinned» right back to the time of Tiki and Hotu Matua, when they first came sailing across the sea «from a mountainous land in the east which was scorched by the sun». The ethnographic evidence for these claims is outlined in Heyerdahl’s book Aku-Aku: The Secret of Easter Island.

Tiki people[edit]

Heyerdahl proposed that Tiki’s neolithic people colonised the then uninhabited Polynesian islands as far north as Hawaii, as far south as New Zealand, as far east as Easter Island, and as far west as Samoa and Tonga around 500 AD. They supposedly sailed from Peru to the Polynesian islands on pae-paes—large rafts built from balsa logs, complete with sails and each with a small cottage. They built enormous stone statues carved in the image of human beings on Pitcairn, the Marquesas, and Easter Island that resembled those in Peru. They also built huge pyramids on Tahiti and Samoa with steps like those in Peru.

But all over Polynesia, Heyerdahl found indications that Tiki’s peaceable race had not been able to hold the islands alone for long. He found evidence that suggested that seagoing war canoes as large as Viking ships, and lashed together two by two, had brought Stone Age Northwest American Indians to Polynesia around 1100 AD, and they mingled with Tiki’s people. The oral history of the people of Easter Island, at least as it was documented by Heyerdahl, is completely consistent with this theory, as is the archaeological record he examined (Heyerdahl 1958).

In particular, Heyerdahl obtained a radiocarbon date of 400 AD for a charcoal fire located in the pit that was held by the people of Easter Island to have been used as an «oven» by the «Long Ears, » which Heyerdahl’s Rapa Nui sources, reciting oral tradition, identified as a white race that had ruled the island in the past (Heyerdahl 1958).

Heyerdahl further argued in his book American Indians in the Pacific that the current inhabitants of Polynesia migrated from an Asian source, but via an alternative route. He proposes that Polynesians travelled with the wind along the North Pacific current. These migrants then arrived in British Columbia. Heyerdahl called contemporary tribes of British Columbia, such as the Tlingit and Haida, descendants of these migrants. Heyerdahl claimed that cultural and physical similarities existed between these British Columbian tribes, Polynesians, and the Old World source.

Controversy[edit]

Heyerdahl’s theory of Polynesian origins has not gained acceptance among anthropologists.[23][24][25] Physical and cultural evidence had long suggested that Polynesia was settled from west to east, migration having begun from the Asian mainland, not South America. In the late 1990s, genetic testing found that the mitochondrial DNA of the Polynesians is more similar to people from south-east Asia than to people from South America, showing that their ancestors most likely came from Asia.[26]

Anthropologist Robert Carl Suggs included a chapter titled «The Kon-Tiki Myth» in his 1960 book on Polynesia, concluding that «The Kon-Tiki theory is about as plausible as the tales of Atlantis, Mu, and ‘Children of the Sun.’ Like most such theories, it makes exciting light reading, but as an example of scientific method it fares quite poorly.»[27]

Anthropologist and National Geographic Explorer-in-Residence Wade Davis also criticised Heyerdahl’s theory in his 2009 book The Wayfinders, which explores the history of Polynesia. Davis says that Heyerdahl «ignored the overwhelming body of linguistic, ethnographic, and ethnobotanical evidence, augmented today by genetic and archaeological data, indicating that he was patently wrong.»[28]

A 2009 study by the Norwegian researcher Erik Thorsby[29] suggested that there was some merit to Heyerdahl’s ideas and that, while Polynesia was colonised from Asia, some contact with South America also existed.[30][31] Some critics suggest, however, that Thorsby’s research is inconclusive because his data may have been influenced by recent population contact.[32]

A 2014 research project [33] indicates that the South American component of the Easter Island people’s genomes pre-dates European contact. The research team, including Anna-Sapfo Malaspinas (from the Natural History Museum of Denmark), analysed the genomes of 27 native Rapanui people and found that their DNA was on average 76 per cent Polynesian, 8 per cent Native American and 16 per cent European. Analysis showed that «although the European lineage could be explained by contact with white Europeans after the island was ‘discovered’ in 1722 by Dutch sailors, the South American component was much older, dating to between about 1280 and 1495, soon after the island was first colonised by Polynesians in around 1200.» Together with ancient skulls found in Brazil – with solely Polynesian DNA – this does suggest some pre-European-contact travel to and from South America from Polynesia.

A study based on over one hundred Rapanui DNA sequences published in Nature in July 2020 showed that a genetic contact event occurred, circa 1200 AD, between Polynesian individuals and a Native American group most closely related to the indigenous inhabitants of present-day Colombia.[34]

Expedition to Easter Island[edit]

In 1955–1956, Heyerdahl organised the Norwegian Archaeological Expedition to Easter Island. The expedition’s scientific staff included Arne Skjølsvold, Carlyle Smith, Edwin Ferdon, Gonzalo Figueroa[35] and William Mulloy. Heyerdahl and the professional archaeologists who travelled with him spent several months on Easter Island investigating several important archaeological sites. Highlights of the project include experiments in the carving, transport and erection of the notable moai, as well as excavations at such prominent sites as Orongo and Poike. The expedition published two large volumes of scientific reports (Reports of the Norwegian Archaeological Expedition to Easter Island and the East Pacific) and Heyerdahl later added a third (The Art of Easter Island). Heyerdahl’s popular book on the subject, Aku-Aku was another international best-seller.[36]

In Easter Island: The Mystery Solved (Random House, 1989), Heyerdahl offered a more detailed theory of the island’s history. Based on native testimony and archaeological research, he claimed the island was originally colonised by Hanau eepe («Long Ears»), from South America, and that Polynesian Hanau momoko («Short Ears») arrived only in the mid-16th century; they may have come independently or perhaps were imported as workers. According to Heyerdahl, something happened between Admiral Roggeveen’s discovery of the island in 1722 and James Cook’s visit in 1774; while Roggeveen encountered white, Indian, and Polynesian people living in relative harmony and prosperity, Cook encountered a much smaller population consisting mainly of Polynesians and living in privation.

Heyerdahl notes the oral tradition of an uprising of «Short Ears» against the ruling «Long Ears.» The «Long Ears» dug a defensive moat on the eastern end of the island and filled it with kindling. During the uprising, Heyerdahl claimed, the «Long Ears» ignited their moat and retreated behind it, but the «Short Ears» found a way around it, came up from behind, and pushed all but two of the «Long Ears» into the fire. This moat was found by the Norwegian expedition and it was partly cut down into the rock. Layers of fire were revealed but no fragments of bodies.

As for the origin of the people of Easter Island, DNA tests have shown a connection to South America.[37] But critics conjecture that this was a result of recent events. Still, whether this is inherited from a person coming in later times is hard to know. If the story that almost all Long Ears were killed in a civil war is true, as the islanders’ story goes, it would be expected that the statue-building South American bloodline would have been nearly utterly destroyed, leaving for the most part the invading Polynesian bloodline.

Boats Ra and Ra II[edit]

The Ra II in the Kon-Tiki Museum

In 1969 and 1970, Heyerdahl built two boats from papyrus and attempted to cross the Atlantic Ocean from Morocco in Africa. Based on drawings and models from ancient Egypt, the first boat, named Ra (after the Egyptian Sun god), was constructed by boat builders from Lake Chad using papyrus reed obtained from Lake Tana in Ethiopia and launched into the Atlantic Ocean from the coast of Morocco. The Ra crew included Thor Heyerdahl (Norway), Norman Baker (US), Carlo Mauri (Italy), Yuri Senkevich (USSR), Santiago Genovés (Mexico), Georges Sourial (Egypt), and Abdullah Djibrine (Chad). Only Heyerdahl and Baker had sailing and navigation experience. Genovés would go on to head the Acali Experiment.

After a number of weeks, Ra took on water. The crew discovered that a key element of the Egyptian boatbuilding method had been neglected, a tether that acted like a spring to keep the stern high in the water while allowing for flexibility.[38] Water and storms eventually caused it to sag and break apart after sailing more than 6,400 km (4,000 miles). The crew was forced to abandon Ra, some hundred miles (160 km) before the Caribbean islands, and was saved by a yacht.

The following year, 1970, a similar vessel, Ra II, was built from Ethiopian papyrus by Bolivian citizens Demetrio, Juan and José Limachi of Lake Titicaca, and likewise set sail across the Atlantic from Morocco, this time with great success. The crew was mostly the same; though Djibrine had been replaced by Kei Ohara from Japan and Madani Ait Ouhanni from Morocco. The boat became lost and was the subject of a United Nations search and rescue mission. The search included international assistance including people as far afield as Loo-Chi Hu of New Zealand. The boat reached Barbados, thus demonstrating that mariners could have dealt with trans-Atlantic voyages by sailing with the Canary Current.[39] The Ra II is now in the Kon-Tiki Museum in Oslo, Norway.

The book The Ra Expeditions and the film documentary Ra (1972) were made about the voyages. Apart from the primary aspects of the expedition, Heyerdahl deliberately selected a crew representing a great diversity in race, nationality, religion and political viewpoint in order to demonstrate that, at least on their own little floating island, people could co-operate and live peacefully. Additionally, the expedition took samples of marine pollution and presented its report to the United Nations.[40]

Tigris[edit]

Heyerdahl built yet another reed boat in 1977, Tigris, which was intended to demonstrate that trade and migration could have linked Mesopotamia with the Indus Valley civilization in what is now Pakistan and western India. Tigris was built in Al Qurnah Iraq and sailed with its international crew through the Persian Gulf to Pakistan and made its way into the Red Sea.[41]

After about five months at sea and still remaining seaworthy, the Tigris was deliberately burnt in Djibouti on 3 April 1978 as a protest against the wars raging on every side in the Red Sea and Horn of Africa. In his Open Letter to the UN Secretary-General Kurt Waldheim, Heyerdahl explained his reasons:[42]

Today we burn our proud ship … to protest against inhuman elements in the world of 1978 … Now we are forced to stop at the entrance to the Red Sea. Surrounded by military airplanes and warships from the world’s most civilised and developed nations, we have been denied permission by friendly governments, for reasons of security, to land anywhere, but in the tiny, and still neutral, Republic of Djibouti. Elsewhere around us, brothers and neighbours are engaged in homicide with means made available to them by those who lead humanity on our joint road into the third millennium.

To the innocent masses in all industrialised countries, we direct our appeal. We must wake up to the insane reality of our time … We are all irresponsible, unless we demand from the responsible decision makers that modern armaments must no longer be made available to people whose former battle axes and swords our ancestors condemned.

Our planet is bigger than the reed bundles that have carried us across the seas, and yet small enough to run the same risks unless those of us still alive open our eyes and minds to the desperate need of intelligent collaboration to save ourselves and our common civilisation from what we are about to convert into a sinking ship.

In the years that followed, Heyerdahl was often outspoken on issues of international peace and the environment.

The Tigris had an 11-man crew: Thor Heyerdahl (Norway), Norman Baker (US), Carlo Mauri (Italy), Yuri Senkevich (USSR), Germán Carrasco (Mexico), Hans Petter Bohn (Norway), Rashad Nazar Salim (Iraq), Norris Brock (US), Toru Suzuki (Japan), Detlef Soitzek (Germany), and Asbjørn Damhus (Denmark).

«The Search for Odin» in Azerbaijan and Russia[edit]

Background[edit]

Heyerdahl made four visits to Azerbaijan in 1981,[43] 1994, 1999 and 2000.[44] Heyerdahl had long been fascinated with the rock carvings that date back to about 8th–7th millennia BCE at Gobustan (about 30 miles/48 km west of Baku). He was convinced that their artistic style closely resembled the carvings found in his native Norway. The ship designs, in particular, were regarded by Heyerdahl as similar and drawn with a simple sickle-shaped line, representing the base of the boat, with vertical lines on deck, illustrating crew or, perhaps, raised oars.

Based on this and other published documentation, Heyerdahl proposed that Azerbaijan was the site of an ancient advanced civilisation. He believed that natives migrated north through waterways to present-day Scandinavia using ingeniously constructed vessels made of skins that could be folded like cloth. When voyagers travelled upstream, they conveniently folded their skin boats and transported them on pack animals.

Snorri Sturluson[edit]

On Heyerdahl’s visit to Baku in 1999, he lectured at the Academy of Sciences about the history of ancient Nordic Kings. He spoke of a notation made by Snorri Sturluson, a 13th-century historian-mythographer in Ynglinga Saga, which relates that «Odin (a Scandinavian god who was one of the kings) came to the North with his people from a country called Aser.»[45] (see also House of Ynglings and Mythological kings of Sweden). Heyerdahl accepted Snorri’s story as literal truth, and believed that a chieftain led his people in a migration from the east, westward and northward through Saxony, to Fyn in Denmark, and eventually settling in Sweden. Heyerdahl claimed that the geographic location of the mythic Aser or Æsir matched the region of contemporary Azerbaijan – «east of the Caucasus mountains and the Black Sea». «We are no longer talking about mythology,» Heyerdahl said, «but of the realities of geography and history. Azerbaijanis should be proud of their ancient culture. It is just as rich and ancient as that of China and Mesopotamia.»

In September 2000 Heyerdahl returned to Baku for the fourth time and visited the archaeological dig in the area of the Church of Kish.[46]

Revision of hypothesis[edit]

One of the last projects of his life, Jakten på Odin, ‘The Search for Odin’, was a sudden revision of his Odin hypothesis, in furtherance of which he initiated 2001–2002 excavations in Azov, Russia, near the Sea of Azov at the northeast of the Black Sea.[47] He searched for the remains of a civilisation to match the account of Odin in Snorri Sturlusson, significantly further north of his original target of Azerbaijan on the Caspian Sea only two years earlier. This project generated harsh criticism and accusations of pseudoscience from historians, archaeologists and linguists in Norway, who accused Heyerdahl of selective use of sources, and a basic lack of scientific methodology in his work.[48][49]