Биография Гоголя

1 Апреля 1809 – 4 Марта 1852 гг. (42 года)

4.4

Средняя оценка: 4.4

Всего получено оценок: 22897.

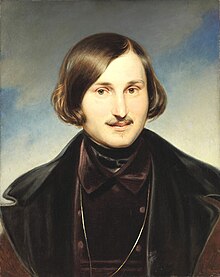

Николай Васильевич Гоголь (1809 – 1852) – классик русской литературы, писатель, драматург, публицист, критик. Самыми известными произведениями Гоголя можно назвать сборник «Вечера на хуторе близ Диканьки», посвященный обычаям и традициям украинского народа, а также величайшую поэму “Мертвые души”.

Опыт работы учителем русского языка и литературы — 27 лет.

Детство и юность писателя

Родился 20 марта (1 апреля)1809 года в селе Сорочинцы Полтавской губернии в семье помещика. Гоголь был третьим ребенком, а всего в семье было 12 детей.

В биографии Гоголя нельзя не сказать об обучении его в Полтавском училище. Затем в 1821 году он поступил в Нежинскую гимназию высших наук, где изучал юстицию. В школьные годы писатель не отличался особыми способностями в учебе. Хорошо ему давались только уроки рисования и изучение русской словесности. Ещё в детстве Гоголь полюбил театр, и в училище он был участником почти каждой театральной постановки. Что касается его ранних литературных трудов, то судить о них мы можем только по поэме «Ганц Кюхельгартен», изданной уже в Петербурге. Других ранних произведений Гоголя не сохранилось.

Начало литературного пути

В 1828 году в жизни Гоголя случился переезд в Петербург. Там он служил чиновником, пробовал устроиться в театр актером и занимался литературой. Актерская карьера не ладилась, а служба не приносила Гоголю удовольствия, а порою даже тяготила. И писатель решил проявить себя на литературном поприще.

Произведение Гоголя «Басаврюк» было опубликовано первым. Позднее повесть переработана в «Вечер накануне Ивана Купала». Именно она подарила писателю известность. Ведь до этого творчество не приносило Гоголю успеха.

Произведения Гоголя «Ночь перед Рождеством», «Майская ночь», «Сорочинская ярмарка», «Страшная месть» и прочие из того же цикла поэтично воссоздают образ Украины. Также Украина была ярко описана в произведении Гоголя «Тарас Бульба».

В 1831 году Гоголь знакомится с представителями литературных кругов Жуковским и Пушкиным, бесспорно эти знакомства сильно повлияли на его дальнейшую судьбу и литературную деятельность.

Гоголь и театр

Интерес к театру у Николая Васильевича Гоголя проявился еще в юности, после смерти отца, замечательного драматурга и рассказчика.

Осознавая всю силу театра, Гоголь занялся драматургией. Произведение Гоголя «Ревизор» было написано в 1835 году, а в 1836 впервые поставлено. Из-за отрицательной реакции публики на постановку «Ревизора» писатель покидает страну.

Последние годы жизни

1836 год – очень важный период в биографии Николая Гоголя: в это время им были совершены поездки в Швейцарию, Германию, Италию, а также во Францию (некоторое время он пребывал в Париже). Затем, с марта 1837, в Риме продолжалась работа над первым томом величайшего произведения Гоголя «Мертвые души», который был задуман автором еще в Петербурге. После возвращения на родину из Рима писатель издает первый том поэмы. Во время работы над вторым томом у Гоголя наступил духовный кризис. Даже поездка в Иерусалим не помогла исправить ситуацию.

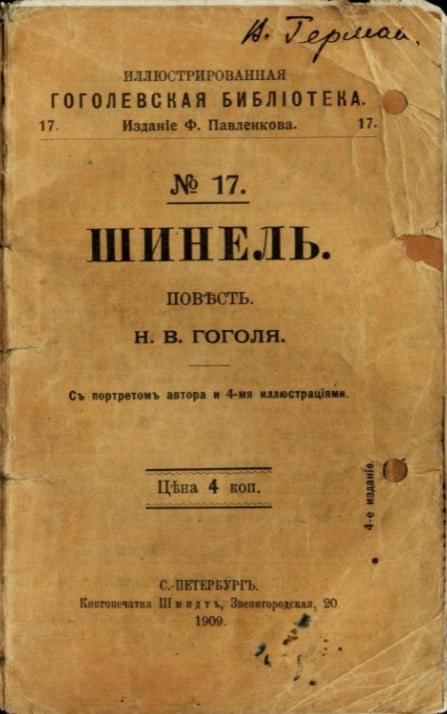

В начале 1843 года была впервые напечатана одна из самых главных, может быть, повестей Гоголя – «Шинель».

Ночью 11 февраля 1852 года Гоголь сжег второй том “Мертвых душ”, а 21 февраля скончался.

Хронологическая таблица

Другие варианты биографии

Более сжатая для доклада или сообщения в классе

Вариант 2

Интересные факты

- Писатель увлекался мистикой и религией. Самым загадочным произведением Гоголя считается повесть «Вий», созданная, по словам самого автора, на основе народного украинского предания. Однако литературоведы и историки до сих пор не могут найти доказательств этому, что указывает на эксклюзивное авторство писателя-мистификатора.

- Принято также считать, что за несколько дней до своей смерти великий писатель сжег второй том «Мертвых душ». Некоторые ученые считают это недостоверным фактом, но правду уже никто никогда не узнает.

- До сих пор доподлинно не известно, как именно умер писатель. Одна из основных версий гласит, что Гоголь был похоронен заживо. Доказательством тому было изменение положения его тела при перезахоронении.

Все интересные факты из жизни Гоголя

Тест по биографии

Чтобы проверить свои знания краткой биографии Гоголя ответьте на несколько вопросов теста:

Доска почёта

Чтобы попасть сюда — пройдите тест.

-

奥莱斯亚 库兹涅佐娃

12/12

-

Lili Belova

7/12

-

Татьяна Санникова

10/12

-

Никита Поветкин

11/12

-

Арина Старичевская

9/12

-

Миша Тимонин

12/12

-

Елена Юрьева

12/12

-

Вика Никитина

12/12

-

Виктория Битюкова

10/12

-

Диана Каримова

12/12

Оценка по биографии

4.4

Средняя оценка: 4.4

Всего получено оценок: 22897.

А какая ваша оценка за эту биографию?

Роль и место в литературе

Роль и место в литературе

Николай Васильевич Гоголь – выдающийся классик русской литературы XIX столетия. Он внес большой вклад в драматургию и публицистику. По мнению многих литературных критиков, Гоголь основал особое направление, названное «натуральной школой». Писатель своим творчеством повлиял на развитие русского языка, делая акцент на его народности.

Происхождение и ранние годы

Н.В. Гоголь появился на свет 20 марта 1809 года в Полтавской губернии (Украина) в селе Великие Сорочинцы. Николай родился третьим ребенком в семье помещика (всего было 12 детей).

Будущий писатель принадлежал к старинному казацкому роду. Возможно, что предком был сам гетман Остап Гоголь.

Дом в Сорочинцах, в котором родился Гоголь

Отец – Василий Афанасьевич Гоголь-Яновский. Он занимался сценической деятельностью и привил сыну любовь к театру. Когда Николаю было всего 16 лет, его не стало.

Мать – Мария Ивановна Гоголь-Яновская (в девичестве Косяровская). Она вышла замуж в юном возрасте (14 лет). Ее красивой внешностью восхищались многие современники. Николай стал ее первым ребенком, который родился живым. И поэтому его назвали в честь Святителя Николая.

Детство Николай провел в деревне в Украине. Традиции и быт украинского народа сильно повлияли на будущую творческую деятельность писателя. А религиозность матери передалась сыну и тоже отобразилась во многих его работах.

Образование и работа

Гоголь читает “Ревизора”

Когда Гоголю было десять лет, его отправили в Полтаву для подготовки к учебе в гимназии. Учил его один местный педагог, благодаря которому, Николай в 1821 году поступает в Гимназию высших наук в Нежине. Успеваемость Гоголя оставляла желать лучшего. Он был силен только в рисовании и русской словесности. Хотя в том, что успехи в учебе Гоголя были не велики, виновата и сама Гимназия. Методы преподавания были устаревшими и не приносили пользы: зубрежка и розги. Поэтому Гоголь занялся самообразованием: выписывал вместе с товарищами журналы, увлекался театром.

После окончания учебы в гимназии Гоголь переезжает в Петербург, надеясь на светлое будущее здесь. Но реальность несколько его разочаровала. Его попытки стать актером провалились. В 1829 году он становится мелким чиновником, писцом в отделе министерства, но работает там не долго, разочаровавшись в этом деле.

Творчество

Работа чиновником не принесла радости Николаю Гоголю, поэтому он пробует себя в литературной деятельности. Первое опубликованное произведение – «Вечер накануне Ивана Купала» (вначале имело другое название). С этой повести началась известность Гоголя.

Одна из комнат Дома-музея Гоголя

Популярность произведений Гоголя объяснялась интересом петербургской публики к малороссийской (так ранее называли некоторые регионы Украины) бытности.

В своем творчестве Гоголь часто обращался к народным легендам, поверьям, использовал народную простую речь.

Ранние произведения Николая Гоголя относят к направлению романтизма. Позже он пишет в своем самобытном стиле, многие соотносят его с реализмом.

Главные произведения

Первый труд, который принес ему известность – это сборник «Вечера на хуторе близ Диканьки». Эти рассказы относят к главным произведениям Гоголя. В них автор потрясающе точно отобразил традиции украинского народа. А волшебство, которое таится на страницах этой книги, и сейчас удивляет читателей.

Дом-музей Гоголя в Москве

Памятник Гоголю в Полтаве

К важным произведениям относят историческую повесть «Тарас Бульба». Она входит в цикл повестей «Мирогород». Драматическая судьба героев на фоне настоящих событий производит сильное впечатление. По мотивам повести сняты фильмы.

Одним из великих достижений в сфере драматургии Гоголя стала пьеса «Ревизор». Комедия смело разоблачала пороки российских чиновников.

Последние годы

1836 год стал для Гоголя временем путешествий по Европе. Он работает над первой частью «Мертвых душ». Вернувшись на родину, автор ее издает.

В 1843 году Гоголь издал повесть «Шинель».

Существует версия, что Гоголь 11 февраля 1852 года сжег второй том «Мертвых душ». А в том же году его не стало.

Хронологическая таблица (по датам)

| Год (годы) | Событие |

| 1809 | Год рождения Н.В. Гоголя |

| 1821-1828 | Годы учебы в Нежинской гимназии |

| 1828 | Переезд в Петербург |

| 1830 | Повесть «Вечер накануне Ивана Купала» |

| 1831-1832 | Сборник «Вечера на хуторе близ Диканьки» |

| 1836 | Закончена работа над пьесой «Ревизор» |

| 1848 | Поездка в Иерусалим |

| 1852 | Не стало Николая Гоголя |

Интересные факты из жизни писателя

- Увлечение мистикой привело к написанию самого загадочного произведения Гоголя – «Вий».

- Существует версия, что автор сжег второй том «Мертвых душ».

- Николай Гоголь имел страсть к миниатюрным изданиям.

Музей писателя

В 1984 году было открытие музея в селе Гоголево в торжественной обстановке.

Ирина Зарицкая | Просмотров: 14.9k

Николай Гоголь — биография

Николай Гоголь – известный писатель, драматург, критик, публицист, один из выдающихся классиков русской литературы, оказавший большое влияние не только на русскую, но и на мировую литературу.

Он прожил такую обширную и многогранную жизнь, что ученым-историкам до сих пор хватает работы по исследованию его биографии и эпистолярных материалов. Творчество Николая Гоголя знают во всем мире, по его произведениям сняты картины и поставлены спектакли. Интерес к его личности не утрачен на протяжении двух веков не только благодаря его литературной деятельности, но еще и по той причине, что Гоголь – самая мистическая фигура в русской литературе XIX века.

Детство

Родился Николай Гоголь (фамилия при рождении Гоголь-Яновский) 20 марта (1 апреля) 1809 года в небольшой деревеньке Сорочинцы Полтавской губернии. В то время это была территория Российской империи. Он выходец из древнего рода Гоголей-Яновских. Семейное предание гласит, что он потомок Остапа Гоголя, гетмана Правобережного войска Запорожского Речи Посполитой. Его дед – Афанасий Гоголь-Яновский, указывал свою принадлежность к польской нации, хотя многие биографы сходятся во мнении, что Гоголи все же были малороссами.

Отец будущего писателя – Василий Гоголь-Яновский, коллежский асессор, служащий почты. Вышел в отставку в 1805-м, женился и принялся вести домашнее хозяйство. Среди его друзей появился экс-министр Дмитрий Трощинский, живший в соседней деревне. Вдвоем они организовали домашний театр. Основываясь на народных сказках, Василий Гоголь-Яновский писал комедии на украинском языке, которые ставили на сцене этого театра. Его жена, Мария Косяровская, вышла замуж в четырнадцать лет, рожала детей и занималась домом. Она никогда не участвовала ни в каких собраниях и балах, женщина наслаждалась тихим семейным счастьем, находя его в заботах о муже и детях. Мария скучала во время разлук с супругом, поэтому они старались как можно больше времени проводить вместе. Василий брал жену с собой, когда объезжал хозяйство на маленьких дрожках.

Николай родился третьим, но первые двое младенцев умерли еще при рождении. Мальчик получил свое имя в честь святого Николая, ведь именно ему мать молилась перед самыми родами. Потом она родит еще восемь детей, но выжить удастся только девочкам – Марии, Анне, Елизавете и Ольге. Николай любил проводить с сестрами почти все свое время, он даже увлекся чисто девчоночьим занятием – рукоделием. Он осилил крой, шил платья и занавески, умел вышивать и вязать на спицах шарфы. Спустя годы Ольга напишет в своих воспоминаниях, что Николай просил шерсть у бабушки, чтобы выткать поясок. Сочинительство увлекло мальчика с ранних лет. Вместе с отцом он часто выезжал в поля, и по дороге тот просил сына подобрать рифмы словам «солнце», «степь», «небеса». В пятилетнем возрасте Николай уже записывал свои сочинения самостоятельно. На становление мировоззрения Гоголя большую роль оказала суеверность матери. Каждый вечер она рассказывала детишкам истории, главными героями которых были домовые, лешие, и прочая нечисть.

Гоголь вспоминал, как в сумерках он прижимался в уголке дивана, и слушал, как отбивает время маятник на старинных стенных часах. И только мяуканье кошки нарушало этот монотонный бой. Он описывал ее походку, медлительное потягивание, стук мягких лап о половицы и искристые зеленые глаза. Мальчик испытывал сильный страх под ее недобрым взглядом. Он поймал ее, схватил и бросился в сад. Швырнул в пруд, и не давал животному выплыть, отталкивал шестом от берега.

В возрасте десяти лет Николай оказался в Полтаве. Родители отправили отпрыска на обучение к преподавателю местной гимназии. Он жил в доме преподавателя, учил арифметику, историю, работал с картами. Таким образом учитель готовил будущего писателя к поступлению в пансион.

Гимназия – первая поэма и школьный театр

В 1821-м Гоголь стал учеником Нежинской гимназии высших наук. Прилежность была не его характерной особенностью, он невнимательно слушал уроки, прилагал усилия исключительно накануне экзаменов. По воспоминаниям учителя латыни Ивана Кулжинского, Гоголь даже после трех лет обучения латыни ничему не научился. На лекциях он часто отвлекался на чтение книги, которую неизменно держал под скамьей. Больше всего Николай увлекался рисованием и русской словесностью, ему нравилось творчество Александра Пушкина. После того, как в 1825-м опубликовали первые главы поэмы «Евгений Онегин», Николай Гоголь перечитывал их так часто и с удовольствием, что вскоре мог рассказать наизусть. Он и сам занимался сочинительством. В это время из-под его пера вышла поэма «Разбойники» и повесть под названием «Братья Твердиславичи», которые и положили начало его творческой биографии. Эти произведения Гоголь опубликовал в своем журнале «Звезда», издававшемся в рукописном виде.

По мнению драматурга Николая Сушкова, который учился вместе с Гоголем в гимназии, никто не верил, что из Николая получится писатель, потому, что во время учебы в лицее, он был самым нерадивым и ленивым среди всех слушателей. Но он мог увлечь своими рассказами так, что в классе начинался сумасшедший хохот, даже несмотря на присутствие директора или учителя.

Именно стараниями Гоголя в гимназии появился театр. Он сам занимался подбором пьес, выполнял декорации и находил подходящих «артистов». Актеры – обычные ученики гимназии, тащили из дома все, что могло пригодиться в «театральном гардеробе». Среди самых популярных постановок был «Недоросль» Фонвизина. Николаю Гоголю доставалась роль госпожи Простаковой. Один из его сокурсников – Тимофей Пащенко, позже вспоминал, что Гоголю пророчили актерское будущее, так как он действительно обладал недюжинным талантом и имел все те качества, которые нужны настоящему артисту.

В 1825-м не стало отца Николая, и он очень тяжело переживал утрату родного человека. Мать говорила, что не могла сама сообщить детям о случившемся, и просила директора гимназии подготовить к такому известию Николая. Молодой человек получил такой удар, что чуть не выбросился из окна на верхнем этаже. После того, как умер отец, семью настигли материальные трудности. Мама совершенно ничего не смыслила в хозяйстве. Николай предложил ей продать лес, принадлежащий ему по завещанию. Спустя некоторое время Гоголь отказался от своего наследства, и оно перешло к сестрам.

В 1827-м Николай стал автором поэмы под названием «Ганц Кюхельгартен». Главный герой – юноша, который отказался от любви ради того, чтобы побывать в Греции. В следующем году Гоголь получил документ об окончании Нежинской гимназии и принял решение о переезде в Петербург. В письме своему дяде по материнской линии Петру Косяровскому молодой человек объясняет причину своего нежелания возвращаться в родной дом. Он говорит, что не может видеть, как живут его родные, как мать считает каждую копейку. Но он заверял, что со своей стороны сделал все, что было в его силах, и что денег с собой берет минимум, лишь бы только хватило на проезд и на первое время в Петербурге.

Могут быть знакомы

Петербург

В декабре 1828-го Гоголь прибыл в Петербург в надежде найти себе какую-нибудь службу. В своих воспоминаниях он писал, что город был совершенно не таким, как он видел в своих мечтах, не такой великолепный и красивый, как он думал ранее. И что жизнь в этом городе оказалась несравненно дороже, чем он мог себе представить. По этой причине Гоголь был вынужден ограничивать себя во многом, в том числе и в походах в театр. Только так можно было хоть раз в день позволить себе съесть щи и кашу. Николаю не удавалось найти хоть какую-то работу, его либо не брали, либо предлагали совершенно мизерное жалование.

В 1829-м молодой человек сочинил стих под названием «Италия», и отправил его в журнал «Сын Отечества», не указав ни своего имени, ни фамилии. Стихотворение напечатали, и это вселило Гоголю уверенность в своих силах. Он принял решение опубликовать и поэму «Ганц Кюхельгартен», написанную им еще в Нежинской гимназии. Николай не поставил свое имя под произведением, подписался псевдонимом В.Алов. Но на этот раз его ждала неудача, книгу не хотели покупать, критики посчитали ее наивной и лишенной композиции. Тогда начинающий писатель выкупил все книги этого тиража, и сжег их без сожаления. После этого расстроенный писатель решил попробовать силы в актерском мастерстве и пришел к директору Имперских театров Сергею Гагарину. Однако получил отказ. Гоголь написал в своих воспоминаниях, что неудачи преследовали его на каждом шагу, причем там, где он совершенно не ждал. Он считал такое положение вещей ужасным наказанием, жесточе которого трудно и представить. Летом 1829-го Николай Гоголь отправился в Германию путешествовать.

Осенью того же года писатель вернулся в Петербург. Отсутствие денег стало катастрофическим. Наконец-то Николай нашел себе хоть какую-то работу, его приняли на должность помощника к столоначальнику департамента уделов. Должность коллежского асессора считалась самым младшим чином в Табели о рангах. В одном из писем матери Николай писал, что ему очень долго не везло с работой, но и это место нельзя считать удачей. Но другого выхода он не видел. В обязанности писателя входил прием жалоб, подшив документов и выполнение незначительных поручений руководства. Когда появлялось свободное время, Гоголь писал, в основном, о жизни в Украине. Чтобы произведения выглядели достоверно, Николай попросил мать описывать обычаи, нравы, поверья, а также наряды разных слоев населения, от сотников с их женами до тысячников. А также ткани, из которых шились эти наряды, причем, во всех подробностях. В 1830-м журнал «Отечественные записки» издал произведение Гоголя под названием «Бисаврюк, или Вечер накануне Ивана Купалы». Текст очень отличался от оригинала, потому что издателю Павлу Свиньину захотелось переделать его по своему вкусу.

Гоголь все интенсивнее сотрудничал с журналами. В 1831-м он отправил в Литературную газету свои произведения «Женщина» и «Несколько мыслей о преподавании детям географии». Альманах «Северные цветы» опубликовал несколько глав исторического романа Николая «Гетьман». Эти издания принадлежали Антону Дельвигу, с помощью которого Гоголь вошел в литературный круг Петербурга. Среди новых знакомых Гоголя появились Петр Плетнев и Василий Жуковский, с помощью которых ему удалось устроиться на новую работу. Николая Гоголя приняли на должность учителя женского Патриотического института. По выходным писатель занимался с детьми богатых дворян. Одновременно с этим, Гоголь писал серию повестей об Украине.

Самые известные произведения Николая Гоголя

В 1831-м писатель опубликовал свою книгу «Вечера на хуторе близ Диканьки», состоящую из четырех рассказов – «Сорочинская ярмарка», «Вечер накануне Ивана Купала», «Майская ночь, или Утопленница», «Пропавшая грамота». В своих рассказах Гоголь переносит читателя на свою родину – в Полтавскую губернию. Герои произведений – обычные люди украинского села с их повседневной жизнью, но приукрашенной мистическими мотивами, которые так любили селяне. Сборник получил большую популярность и хвалебные отзывы читательской аудитории. Его произведение произвело впечатление на Евгения Баратынского, Александра Пушкина, Ивана Киреевского, и многих других известных литераторов. По мнению Баратынского, Гоголь стал первым автором на севере, обладающим «такой веселостью», живым, оригинальным, красочным слогом и чувством вкуса.

Пушкин тоже восторгался творчеством Гоголя, в одном из своих писем Александру Воейкову он писал, что «Вечера на хуторе близ Диканьки» просто изумили его. В них присутствует настоящее веселье, непринужденное, искреннее, полностью лишенное чопорности и жеманства. Он вспоминал, что где-то слышал, что те, кто набирал этот текст в печать, просто умирали со смеху.

В 1832-м вышел второй том «Вечеров», в который опять вошло четыре повести – «Страшная месть», «Ночь перед Рождеством», «Заколдованное место», «Иван Федорович Шпонька и его тетушка». Книга стала такой же популярной, как и первая. Николай Гоголь начал получать приглашения для участия во всех литературных вечерах, где зачастую присутствовал и Александр Пушкин. Летом того же года Гоголь отправился на родину, хотел повидаться с родными. По пути он заехал в Москву, где его представили публицистам Михаилу Погодину и Сергею Аксакову, а также актеру Михаилу Щепкину. Прибыв домой, писатель отметил, что имение почти пришло в упадок, у родни накопилось множество неоплаченных долгов, которые нет возможности погасить.

В 1834-м Гоголя пригласили на работу в Санкт-Петербургский университет, на кафедру истории. Писатель стал адъюнкт-профессором, читал студентам лекции на тему Средневековья и о Великом переселении народов. По вечерам занимался изучением истории крестьянско-казацких восстаний на территории Украины. Все свое свободное время посвящал сочинительству новых произведений. Буквально год спустя выпустил новый сборник, получивший название «Арабески», объединивший в своем составе разно жанровые произведения. Самую большую популярность получила одна из статей этого сборника – «Несколько слов о Пушкине», в которой автор анализирует творчество известного поэта, и называет его «первый русский национальный поэт». В этом сборнике вышли и первые повести Гоголя, написанные им по приезду в Петербург – «Записки сумасшедшего», «Портрет», «Невский проспект». Помимо этого, в сборник вошли и статьи на исторические темы – «О преподавании всеобщей истории», «Взгляд на составление Малороссии», «Ал Мамун».

Буквально спустя месяц после выхода «Арабесок» Гоголь издал еще одну свою книгу, которую назвал «Миргород». Она являлась своеобразным продолжением «Вечеров», в ней также использован украинский фольклор, а местом действия автор выбрал Запорожье. Сборник «Миргород» состоял из повестей «Тарас Бульба», «Вий», «Старосветские помещики», «Повесть о том, как поссорился Иван Иванович с Иваном Никифоровичем». В работе над этими произведениями писатель пользовался собственными научными наработками. В повести «Тарас Бульба» он использовал материал, посвященный крестьянскому восстанию 1637-1638-го годов. Образ главного героя повести автор писал из атамана Охрима Макухи.

Оба сборника были раскуплены до последней книги. По мнению критика Виссариона Белинского, талант Гоголя не упадал, а постепенно возвышался, его новые сборники отличались оригинальностью и игривостью фантазии, и являлись самыми необыкновенными явлениями, случившимися в литературе того периода. Он считал, что они вполне заслуживают тех хвалебных отзывов, которыми осыпает их восторженная публика.

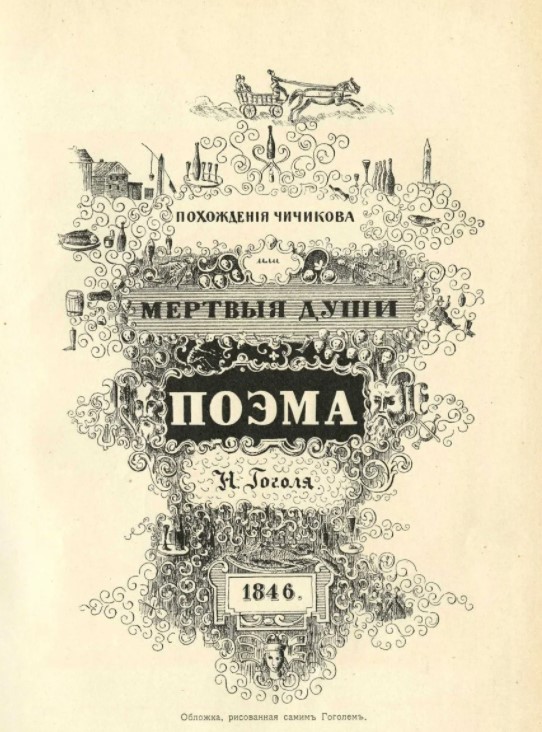

В 1835-м Николай Гоголь принялся за написание «Мертвых душ». Сюжетом этого произведения поделился с Гоголем поэт Александр Пушкин. Однажды, находясь в кишиневской ссылке, он услышал, что есть такой помещик, который умерших записывал беглецами.

Буквально через несколько месяцев Гоголь уже читал Пушкину первые главы своего романа. По мере прочтения, улыбка исчезала с лица поэта, а к концу он стал очень мрачным. Когда Гоголь окончил читать, Пушкин отметил, как же грустна Россия. После этого Николай Гоголь прекратил работу над «Мертвыми душами».

Сам писатель отмечал, что в его произведениях присутствует веселость, и она вызвана, в первую очередь, его душевными потребностями. Он так часто впадал в тоску, причины которой и сам не мог объяснить, (возможно, это состояние вызывалось болезненным состоянием автора), что ему приходилось развлекать самого себя при помощи чего-то смешного.

«Ревизор»

Осенью 1835-го Николай Гоголь оставляет службу в университете. Он решил, что литературой нужно заниматься профессионально, и задумался над тем, чтобы сочинить пьесу. Он написал письмо Пушкину, в котором попросил подсказать какой-либо сюжет, можно даже и не очень смешной, но чисто русский. Говорил, что горит желанием создать комедию из пяти актов. При этом отметил, что не только его ум, но и желудок изголодались. Пушкин поведал другу историю о том, как некий господин представился высокопоставленным чиновником, и приехал в город под видом ревизора. Именно по этому сюжету и написана комедия «Ревизор». Судьба занесла коллежского регистратора Хлестакова в уездный город, а перед этим, он сильно проигрался в карты. Его принимают за ревизора, и всем должностным лицам приходится «прогибаться» перед ним, давать взятки, чтобы скрыть недостатки своей работы и скрыть истинное положение дел в городе.

Позже Гоголь напишет, что в этой комедии он собрал все, что было дурного в России в те времена, всю несправедливость, творящуюся в таких вот уездных городках, и высмеял это на весь мир.

Работа над комедией подошла к концу в 1836 году. Гоголь прочитал ее полностью гостям, собравшимся у Василия Жуковского – Петру Вяземскому, Александру Пушкину, Ивану Тургеневу. Ему посоветовали обязательно поставить ее на сцене театра, но очень долго писатель не мог получить разрешение на спектакль. Цензура не пропускала это крамольное произведение, и если бы не Василий Жуковский, лично обратившийся к императору, то возможно, зрители так и не увидели бы эту постановку. Через несколько месяцев начались репетиции комедии в петербургском Александринском театре под руководством Гоголя. Он сам занимался разработкой схем расположения на сцене артистов, руководил режиссером и художником, создающим костюмы. Премьера спектакля состоялась в мае 1836 года, на ней присутствовал Николай I и его сын Александр. Он был в восторге от этой комедии, и приказал всем министрам обязательно ее посмотреть.

Реакция зрителей на «Ревизор» оказалась очень неоднозначной. Писатель вспоминал, что все против него, что он слышит от пожилых и почтенных чиновников об отсутствии у него уважения к служащим людям. Против него ополчились полицейские и литераторы, которые ругают его пьесу, но все равно продолжают на нее ходить. Все билеты на спектакль раскупались мгновенно, четыре представления прошли при полном аншлаге. Писатель понимал, что если бы за него не заступился государь, то его пьесу никогда бы не поставили на сцене театра. Спустя несколько недель комедию увидели москвичи, там ее постановкой занимался друг автора – Михаил Щепкин.

В тот же период начал выходить и журнал «Современник», который издавал Александр Пушкин. В первом его номере вышла повесть Гоголя «Нос». Главный герой произведения – чиновник, потерявший нос в одно утро, и теперь он никак не мог рассчитывать на повышение. Вслед за этим на страницах журнала напечатали «Коляску» Гоголя, где помещик по фамилии Чертокуцкий вечером расхваливает экипаж перед генералом с целью его продажи, а утром ему приходится прятаться от покупателя, так как его хваленая карета оказалась ни на что негодной.

«Мертвые души» и «Шинель»

Буквально сразу после премьерного показа «Ревизора» Гоголь отправился в Германию. Он объяснял свое решение тем, что ему просто необходимо собраться с мыслями, которые очень рассеяны «от разных досад и волнений», а также размыкать тоску, навеянную соотечественниками. Он говорил, что стоит вывести на сцену нескольких плутов, как тысячи честных людей начинают сердиться, и говорить, что они не такие. Писатель отправился в Германию, потом в Швейцарию, а затем побывал в Париже. В столице Франции он снова принялся за работу над романом «Мертвые души», который забросил в Петербурге от нехватки времени. В феврале 1837-го на дуэли погибает Пушкин. Эта трагедия доставила Гоголю много переживаний. По мнению полковника Андрея Карамзина, известие о гибели поэта сильно подкосило Гоголя, он затосковал и думал, что пора возвращаться в Петербург, который опустел для него после смерти друга. Но вместо того, чтобы вернуться в Россию, писатель отправился в Италию. В 1841-м ему удалось закончить работу над первым томом «Мертвых душ», и чтобы отдать его в печать, Гоголь приехал в Москву. В этот период он жил в доме Михаила Погодина, известного историка.

Весной 1842 года удалось получить разрешение цензуры на публикацию «Мертвых душ». Дизайн обложки этого издания разработал сам Гоголь. История помещика Чичикова, разъезжавшего по России в поисках бумаг на мертвых душ, вызвала разную реакцию читательской аудитории. Сергей Аксаков вспоминал, что очень многим нравилось произведение, но были и такие, кто относился к Гоголю с нескрываемой ненавистью. По задумке Гоголя «Мертвые души» должны были выйти в трех томах, причем в конце главный герой меняется, переосмысливает свое отношение к жизни и понятие о нравственных ценностях.

В том же, 1842-м Гоголь представил на суд читателей новую повесть под названием «Шинель». Действие разворачивается в Петербурге, главного героя зовут Акакий Башмачкин, он мелкий чиновник, целыми днями корпящий над переписыванием бумаг за мизерное жалование. В один из дней у него случилась неприятность – порвалась шинель, и он начал собирать деньги, чтобы купить новую. Для этого ввел режим тотальной экономии, отказался от чая, носил дома только халат, чтобы другая одежда не изнашивалась. А когда его мечта сбылась, и он смог купить себе обновку, то тут же ее потерял, ее отобрали какие-то люди на улице.

Летом 1842-го писатель снова отправился за границу. Он побывал в Риме, Дюссельдорфе, Ницце, Париже. Он продолжал писать второй том «Мертвых душ». Спустя три года, в 1845-м, Гоголь оказался под властью душевного кризиса. Поддавшись нахлынувшему порыву, он сжигает второй том романа «Мертвые души», и все рукописи. Писатель отказался от общения с друзьями, перестал писать им письма. В 1848-м Николай Васильевич уехал в Иерусалим, и только там в полной мере ощутил, как много в нем «холода сердечного, как много себялюбия и самолюбия».

На следующий год Гоголь возвращается на родину, и пытается восстановить сожженный том повести по памяти. Но спустя некоторое время его снова накрывает тоска и отчаяние.

Личная жизнь

От отца писатель унаследовал не только любовь к литературе, но и страх ранней смерти, который впервые проявился еще в юности. У Гоголя с детства обнаружился маниакально-депрессивный психоз. Из веселого и задорного молодого человека он мог мгновенно превратиться в угрюмого и отчаянного. Часто впадал в депрессию.

Это состояние не давало покоя писателю до самой смерти. В письмах друзьям он часто признавался, что слышит голоса, куда-то зовущие его. Жизнь в постоянном страхе превратила его в аскета и затворника. Николай любил женщин, но на расстоянии. Иногда он говорил матери, что отправляется за границу к какой-то даме.

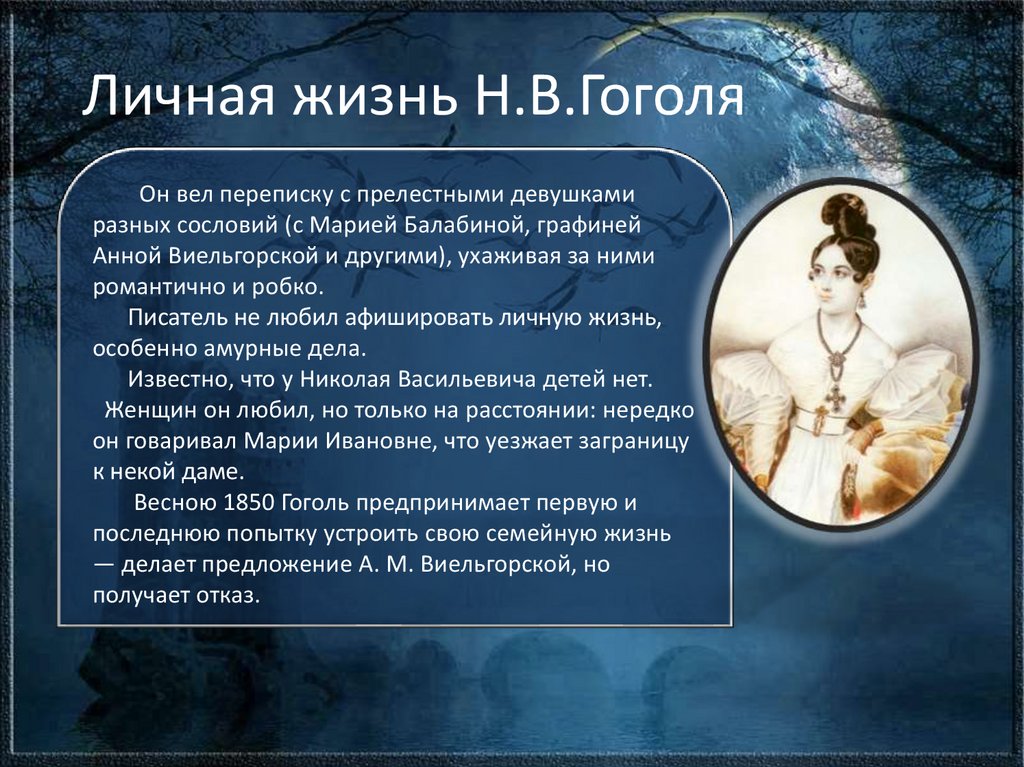

Гоголь переписывался с милыми барышнями самых разных сословий. Сохранились письма, отправленные писателем Марии Балабиной, графине Анне Виельгорской. Его ухаживания были робкими и романтичными. Николай никогда не афишировал свою личную жизнь, возможно, по причине ее отсутствия. Гоголь никогда не был женат, и не оставил после себя наследников. Некоторые утверждают, что писатель имел нетрадиционную ориентацию, другие говорят, что он имел отношения с женщинами, но чисто платонические.

Смерть

В январе 1852 года не стало его давней хорошей знакомой Екатерины Хомяковой. Это новое потрясение привело к тому, что писатель отказался от пищи, он чувствует страх приближающейся смерти, и признается в этом своему духовнику. Забросил Гоголь и работу над вторым томом романа.

В ночь с 11-го на 12-е февраля 1852 года Гоголь приказал своему слуге Семену зажечь камин, и в этом огне сжег все свои произведения, включая и «Мертвых душ», работа над которыми только что завершилась. Незадолго до смерти писатель перестал выезжать из дома, а 21 февраля 1852 года умер у себя в постели, не приходя в сознание. Местом упокоения Николая Гоголя стало Даниловское кладбище Москвы, и только в 1931 году его останки перезахоронили на Новодевичьем кладбище.

Интересные факты

- Фамилия Гоголя при рождении – Гоголь-Янковский, но писателю не нравилось, что она слишком длинная, и он убрал вторую часть. Мировая слава пришла к нему под фамилией Гоголь.

- Мать писателя всегда считала, что ее сын – гений. Она говорила, что это именно он изобрел паровую машину, железную дорогу, и другие полезные новшества тех лет.

- Студентам не нравились лекции Гоголя по истории, они считали, что преподаватель из него никудышный. Он не мог увлечь их живым и одушевленным рассказом, от того и прошедшие события в его рассказах казались скучными и отжившими.

- Николай Гоголь всегда жил в долгах, и это несмотря на то, что его произведения пользовались большой популярностью.

- Писатель не расставался с Евангелием, он считал, что выше этой книги придумать ничего невозможно. Помимо этого, Гоголь каждый день читал одну главу Ветхого Завета.

Известные произведения

- Мёртвые души

- Ревизор

- Женитьба

- Вечера на хуторе близ Диканьки

- Вий

- Повесть о том, как поссорился Иван Иванович с Иваном Никифоровичем

- Старосветские помещики

- Тарас Бульба

- Невский проспект

- Нос

- Шинель

- Записки сумасшедшего

- Портрет

- Коляска

- Выбранные места из переписки с друзьями

Ссылки

- Страница в Википедии

Для нас важна актуальность и достоверность информации. Если вы обнаружили ошибку или неточность, пожалуйста, сообщите нам. Выделите ошибку и нажмите сочетание клавиш Ctrl+Enter.

|

Nikolai Gogol |

|

|---|---|

Daguerreotype of Gogol taken in 1845 by Sergei Lvovich Levitsky (1819–1898) |

|

| Born | Nikolai Vasilyevich Yanovsky 20 March 1809[1] (OS)/1 April 1809 (NS) Sorochyntsi, Poltava Governorate, Russian Empire |

| Died | 21 February 1852 (aged 42) Moscow, Russian Empire |

| Resting place | Novodevichy Cemetery |

| Occupation | Playwright, short story writer, novelist |

| Language | Russian |

| Period | 1840–51 |

| Notable works |

Petersburg Tales [fr] (1833–1842)

|

| Signature | |

|

Portrait of Nikolai Gogol (early 1840s)

Nikolai Vasilyevich Gogol[a] (1 April [O.S. 20 March] 1809[1] – 4 March [O.S. 21 February] 1852) was a Russian novelist, short story writer and playwright of Ukrainian origin.[3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11]

Gogol was one of the first to use the technique of the grotesque, in works such as «The Nose», «Viy», «The Overcoat», and «Nevsky Prospekt». These stories, and others such as «Diary of a Madman», have also been noted for their proto-surrealist qualities. According to Viktor Shklovsky, Gogol’s strange style of writing resembles the «ostranenie» technique of defamiliarization.[12] His early works, such as Evenings on a Farm Near Dikanka, were influenced by his Ukrainian upbringing, Ukrainian culture and folklore.[13][14] His later writing satirised political corruption in the Russian Empire (The Government Inspector, Dead Souls). The novel Taras Bulba (1835), the play Marriage (1842), and the short stories «The Tale of How Ivan Ivanovich Quarreled with Ivan Nikiforovich», «The Portrait» and «The Carriage», are also among his best-known works.

Many writers and critics have recognized Gogol’s huge influence on Russian, Ukrainian and world literature. Gogol’s influence was acknowledged by Mikhail Bulgakov, Fyodor Dostoevsky, Ryūnosuke Akutagawa, Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin, Flannery O’Connor, Franz Kafka and others.[15][16]

Early life

Gogol was born in the Ukrainian Cossack town of Sorochyntsi,[17] in the Poltava Governorate of the Russian Empire. His mother was descended from Leonty Kosyarovsky, an officer of the Lubny Regiment in 1710. His father Vasily Gogol-Yanovsky, who died when Gogol was 15 years old, was supposedly a descendant of Ukrainian Cossacks (see Lyzohub family) and belonged to the ‘petty gentry’. His father wrote poetry in Ukrainian as well as Russian, and was an amateur playwright in his own theatre. As was typical of the left-bank Ukrainian gentry of the early nineteenth century, the family spoke Ukrainian as well as Russian. As a child, Gogol helped stage plays in his uncle’s home theater.[18]

In 1820, Nikolai Gogol went to a school of higher art in Nezhin (Nizhyn) (now Nizhyn Gogol State University) and remained there until 1828. It was there that he began writing. He was not popular among his schoolmates, who called him their «mysterious dwarf», but with two or three of them he formed lasting friendships. Very early he developed a dark and secretive disposition, marked by a painful self-consciousness and boundless ambition. Equally early he developed a talent for mimicry, which later made him a matchless reader of his own works and induced him to toy with the idea of becoming an actor.

On leaving school in 1828, Gogol went to Saint Petersburg, full of vague but ambitious hopes. He desired literary fame, and brought with him a Romantic poem of German idyllic life – Hans Küchelgarten, and had it published at his own expense, under the pseudonym «V. Alov.» The magazines he sent it to almost universally derided it. He bought all the copies and destroyed them, swearing never to write poetry again.

Literary development

In 1831, the first volume of Gogol’s Ukrainian stories (Evenings on a Farm Near Dikanka) was published, and met with immediate success.[19] A second volume was published in 1832, followed by two volumes of stories entitled Mirgorod in 1835, and two volumes of miscellaneous prose entitled Arabesques. At this time, Russian editors and critics such as Nikolai Polevoy and Nikolai Nadezhdin saw Gogol as a regional Ukrainian writer, and used his works to illustrate the specific of Ukrainian national characters.[18] The themes and style of these early prose works by Gogol, as well as his later drama, were similar to the work of Ukrainian-language writers and dramatists who were his contemporaries and friends, including Hryhory Kvitka-Osnovyanenko. However, Gogol’s satire was much more sophisticated and unconventional.[20]

At this time, Gogol developed a passion for Ukrainian Cossack history and tried to obtain an appointment to the history department at Saint Vladimir Imperial University of Kiev. Despite the support of Alexander Pushkin and Sergey Uvarov, the Russian minister of education, the appointment was blocked by a bureaucrat on the grounds that Gogol was unqualified.[21] His fictional story Taras Bulba, based on the history of Zaporozhian Сossacks, was the result of this phase in his interests. During this time, he also developed a close and lifelong friendship with the historian and naturalist Mykhaylo Maksymovych.[22]

In 1834, Gogol was made Professor of Medieval History at the University of St. Petersburg, a job for which he had no qualifications. The academic venture proved a disaster:

He turned in a performance ludicrous enough to warrant satiric treatment in one of his own stories. After an introductory lecture made up of brilliant generalizations which the ‘historian’ had prudently prepared and memorized, he gave up all pretence at erudition and teaching, missed two lectures out of three, and when he did appear, muttered unintelligibly through his teeth. At the final examination, he sat in utter silence with a black handkerchief wrapped around his head, simulating a toothache, while another professor interrogated the students.[23]

Gogol resigned his chair in 1835.

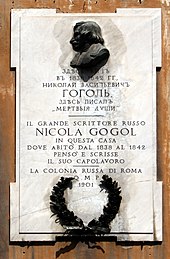

Commemorative plaque on his house in Rome

Between 1832 and 1836, Gogol worked with great energy, and had extensive contact with Pushkin, but he still had not yet decided that his ambitions were to be fulfilled by success in literature. During this time, the Russian critics Stepan Shevyrev and Vissarion Belinsky, contradicting the earlier critics, reclassified Gogol from a Ukrainian to a Russian writer.[18] It was only after the presentation of his comedy The Government Inspector (Revizor) at the Saint Petersburg State Theatre, on 19 April 1836,[24] that he finally came to believe in his literary vocation. The comedy, a violent satire of Russian provincial bureaucracy, was staged thanks only to the intervention of the emperor, Nicholas I.

From 1836 to 1848, Gogol lived abroad, travelling through Germany and Switzerland. Gogol spent the winter of 1836–37 in Paris,[25] among Russian expatriates and Polish exiles, frequently meeting the Polish poets Adam Mickiewicz and Bohdan Zaleski. He eventually settled in Rome. For much of the twelve years from 1836, Gogol was in Italy, where he developed an adoration for Rome. He studied art, read Italian literature and developed a passion for opera.

Pushkin’s death produced a strong impression on Gogol. His principal work during the years following Pushkin’s death was the satirical epic Dead Souls. Concurrently, he worked at other tasks – recast Taras Bulba (1842)[26] and The Portrait, completed his second comedy, Marriage (Zhenitba), wrote the fragment Rome and his most famous short story, «The Overcoat».

In 1841, the first part of Dead Souls was ready, and Gogol took it to Russia to supervise its printing. It appeared in Moscow in 1842, under a new title imposed by the censorship, The Adventures of Chichikov. The book established his reputation as one of the greatest prose writers in the language.

Later life and death

After the triumph of Dead Souls, Gogol’s contemporaries came to regard him as a great satirist who lampooned the unseemly sides of Imperial Russia. They did not know that Dead Souls was but the first part of a planned modern-day counterpart to the Divine Comedy of Dante.[citation needed] The first part represented the Inferno; the second part would depict the gradual purification and transformation of the rogue Chichikov under the influence of virtuous publicans and governors – Purgatory.[27]

In April 1848, Gogol returned to Russia from a pilgrimage to Jerusalem and passed his last years in restless movement throughout the country. While visiting the capitals, he stayed with friends such as Mikhail Pogodin and Sergey Aksakov. During this period, he also spent much time with his old Ukrainian friends, Maksymovych and Osyp Bodiansky. He intensified his relationship with a starets or spiritual elder, Matvey Konstantinovsky, whom he had known for several years. Konstantinovsky seems to have strengthened in Gogol the fear of perdition (damnation) by insisting on the sinfulness of all his imaginative work. Exaggerated ascetic practices undermined his health and he fell into a state of deep depression. On the night of 24 February 1852 he burned some of his manuscripts, which contained most of the second part of Dead Souls. He explained this as a mistake, a practical joke played on him by the Devil.[citation needed] Soon thereafter, he took to bed, refused all food, and died in great pain nine days later.

Gogol was mourned in the Saint Tatiana church at the Moscow University before his burial and then buried at the Danilov Monastery, close to his fellow Slavophile Aleksey Khomyakov. His grave was marked by a large stone (Golgotha), topped by a Russian Orthodox cross.[28]

Post-2009 gravesite of Nikolai Gogol in Novodevichy Cemetery, Moscow, Russia

In 1931, Moscow authorities decided to demolish the monastery and had Gogol’s remains transferred to the Novodevichy Cemetery.[29] His body was discovered lying face down, which gave rise to the story that Gogol had been buried alive. The authorities moved the Golgotha stone to the new gravesite, but removed the cross; in 1952 the Soviets replaced the stone with a bust of Gogol. The stone was later reused for the tomb of Gogol’s admirer Mikhail Bulgakov. In 2009, in connection with the bicentennial of Gogol’s birth, the bust was moved to the museum at Novodevichy Cemetery, and the original Golgotha stone was returned, along with a copy of the original Orthodox cross.[30]

The first Gogol monument in Moscow, a Symbolist statue on Arbat Square, represented the sculptor Nikolay Andreyev’s idea of Gogol rather than the real man.[31] Unveiled in 1909, the statue received praise from Ilya Repin and from Leo Tolstoy as an outstanding projection of Gogol’s tortured personality. Joseph Stalin did not like it, however, and the statue was replaced by a more orthodox Socialist Realist monument in 1952. It took enormous efforts to save Andreyev’s original work from destruction; as of 2014 it stands in front of the house where Gogol died.[32]

Style

D. S. Mirsky characterizes Gogol’s universe as «one of the most marvellous, unexpected – in the strictest sense, original[33] – worlds ever created by an artist of words».[34]

A characteristic of Gogol’s writing is his ‘impressionist’ vision of reality and people.[citation needed] He saw the outer world strangely metamorphosed, a singular gift particularly evident from the fantastic spatial transformations in his Gothic stories, «A Terrible Vengeance» and «A Bewitched Place». His pictures of nature are strange mounds of detail heaped on detail, resulting in an unconnected chaos of things: «His people are caricatures, drawn with the method of the caricaturist – which is to exaggerate salient features and to reduce them to geometrical pattern. But these cartoons have a convincingness, a truthfulness, and inevitability – attained as a rule by slight but definitive strokes of unexpected reality – that seems to beggar the visible world itself.»[35] According to Andrey Bely, Gogol’s work influenced the emergence of Gothic romance, and served as a forerunner for absurdism and impressionism.[36]

The aspect under which the mature Gogol sees reality is expressed by the Russian word poshlost’, which means something similar to «triviality, banality, inferiority», moral and spiritual, widespread in some group or society. Like Sterne before him, Gogol was a great destroyer of prohibitions and of romantic illusions. He undermined Russian Romanticism by making vulgarity reign where only the sublime and the beautiful had before.[37] «Characteristic of Gogol is a sense of boundless superfluity that is soon revealed as utter emptiness and a rich comedy that suddenly turns into metaphysical horror.»[38]

His stories often interweave pathos and mockery, while «The Tale of How Ivan Ivanovich Quarreled with Ivan Nikiforovich» begins as a merry farce and ends with the famous dictum, «It is dull in this world, gentlemen!»

Politics

The first Gogol memorial in Russia (an impressionistic statue by Nikolay Andreyev, 1909).

Gogol burning the manuscript of the second part of Dead Souls, by Ilya Repin

It stunned Gogol when critics interpreted The Government Inspector as an indictment of tsarism despite Nicholas I’s patronage of the play. Gogol himself, an adherent of the Slavophile movement, believed in a divinely inspired mission for both the House of Romanov and the Russian Orthodox Church. Like Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Gogol sharply disagreed with those Russians who preached constitutional monarchy and the disestablishment of the Orthodox Church.

After defending autocracy, serfdom, and the Orthodox Church in his book Selected Passages from Correspondence with his Friends (1847), Gogol came under attack from his former patron Vissarion Belinsky. The first Russian intellectual to publicly preach the economic theories of Karl Marx, Belinsky accused Gogol of betraying his readership by defending the status quo.[39]

Influence and interpretations

Even before the publication of Dead Souls, Belinsky recognized Gogol as the first Russian-language realist writer and as the head of the Natural School, to which he also assigned such younger or lesser authors as Goncharov, Turgenev, Dmitry Grigorovich, Vladimir Dahl and Vladimir Sollogub. Gogol himself appeared skeptical about the existence of such a literary movement. Although he recognized «several young writers» who «have shown a particular desire to observe real life», he upbraided the deficient composition and style of their works.[40] Nevertheless, subsequent generations of radical critics celebrated Gogol (the author in whose world a nose roams the streets of the Russian capital) as a great realist, a reputation decried by the Encyclopædia Britannica as «the triumph of Gogolesque irony».[41]

The period of literary modernism saw a revival of interest in and a change of attitude towards Gogol’s work. One of the pioneering works of Russian formalism was Eichenbaum’s reappraisal of «The Overcoat». In the 1920s a group of Russian short-story writers, known as the Serapion Brothers, placed Gogol among their precursors and consciously sought to imitate his techniques. The leading novelists of the period – notably Yevgeny Zamyatin and Mikhail Bulgakov – also admired Gogol and followed in his footsteps. In 1926 Vsevolod Meyerhold staged The Government Inspector as a «comedy of the absurd situation», revealing to his fascinated spectators a corrupt world of endless self-deception. In 1934 Andrei Bely published the most meticulous study of Gogol’s literary techniques up to that date, in which he analyzed the colours prevalent in Gogol’s work depending on the period, his impressionistic use of verbs, the expressive discontinuity of his syntax, the complicated rhythmical patterns of his sentences, and many other secrets of his craft. Based on this work, Vladimir Nabokov published a summary account of Gogol’s masterpieces.[42]

The house in Moscow where Gogol died. The building contains the fireplace where he burned the manuscript of the second part of Dead Souls.

Gogol’s impact on Russian literature has endured, yet various critics have appreciated his works differently. Belinsky, for instance, berated his horror stories as «moribund, monstrous works», while Andrei Bely counted them among his most stylistically daring creations. Nabokov especially admired Dead Souls, The Government Inspector, and «The Overcoat» as works of genius, proclaiming that «when, as in his immortal ‘The Overcoat’, Gogol really let himself go and pottered happily on the brink of his private abyss, he became the greatest artist that Russia has yet produced.»[43] Critics traditionally interpreted «The Overcoat» as a masterpiece of «humanitarian realism», but Nabokov and some other attentive readers argued that «holes in the language» make the story susceptible to interpretation as a supernatural tale about a ghostly double of a «small man».[44] Of all Gogol’s stories, «The Nose» has stubbornly defied all abstruse interpretations: D.S. Mirsky declared it «a piece of sheer play, almost sheer nonsense». In recent years, however, «The Nose» became the subject of several postmodernist and postcolonial interpretations.

Some critics have paid attention to the apparent anti-Semitism in Gogol’s writings, as well as in those of his contemporary, Fyodor Dostoyevsky.[45] Felix Dreizin and David Guaspari, for example, in their The Russian Soul and the Jew: Essays in Literary Ethnocentrism, discuss «the significance of the Jewish characters and the negative image of the Ukrainian Jewish community in Gogol’s novel Taras Bulba, pointing out Gogol’s attachment to anti-Jewish prejudices prevalent in Russian and Ukrainian culture.»[46] In Léon Poliakov’s The History of Antisemitism, the author mentions that

«The ‘Yankel’ from Taras Bulba indeed became the archetypal Jew in Russian literature. Gogol painted him as supremely exploitative, cowardly, and repulsive, albeit capable of gratitude. But it seems perfectly natural in the story that he and his cohorts be drowned in the Dniper by the Cossack lords. Above all, Yankel is ridiculous, and the image of the plucked chicken that Gogol used has made the rounds of great Russian authors.»[47]

Despite his portrayal of Jewish characters, Gogol left a powerful impression even on Jewish writers who inherited his literary legacy. Amelia Glaser has noted the influence of Gogol’s literary innovations on Sholem Aleichem, who

«chose to model much of his writing, and even his appearance, on Gogol… What Sholem Aleichem was borrowing from Gogol was a rural East European landscape that may have been dangerous, but could unite readers through the power of collective memory. He also learned from Gogol to soften this danger through laughter, and he often rewrites Gogol’s Jewish characters, correcting anti-Semitic stereotypes and narrating history from a Jewish perspective.»[48]

In music and film

Gogol’s oeuvre has also had an impact on Russia’s non-literary culture, and his stories have been adapted numerous times into opera and film. The Russian composer Alfred Schnittke wrote the eight-part Gogol Suite as incidental music to The Government Inspector performed as a play, and Dmitri Shostakovich set The Nose as his first opera in 1928 – a peculiar choice of subject for what was meant to initiate the great tradition of Soviet opera.[49] More recently, to celebrate the 200th anniversary of Gogol’s birth in 1809, Vienna’s renowned Theater an der Wien commissioned music and libretto for a full-length opera on the life of Gogol from Russian composer and writer Lera Auerbach.[50]

More than 135 films[51] have been based on Gogol’s work, the most recent being The Girl in the White Coat (2011).

Legacy

Gogol has been featured many times on Russian and Soviet postage stamps; he is also well represented on stamps worldwide.[52][53][54][55] Several commemorative coins have been issued from Russia and the USSR. In 2009, the National Bank of Ukraine issued a commemorative coin dedicated to Gogol.[56] Streets have been named after Gogol in various towns, including Moscow, Sofia, Lipetsk, Odessa, Myrhorod, Krasnodar, Vladimir, Vladivostok, Penza, Petrozavodsk, Riga, Bratislava, Belgrade, Harbin and many other towns and cities.

Gogol is mentioned several times in Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s Poor Folk and Crime and Punishment and Chekhov’s The Seagull.

Ryūnosuke Akutagawa considered Gogol along with Edgar Poe his favorite writers.

Adaptations

BBC Radio 4 made a series of six Gogol short stories, entitled Three Ivans, Two Aunts and an Overcoat (2002, adaptations by Jim Poyser) starring Griff Rhys-Jones and Stephen Moore. The stories adapted were «The Two Ivans», «The Overcoat», «Ivan Fyodorovich Shponka and His Aunt», «The Nose», «The Mysterious Portrait» and «Diary of a Madman».

Gogol’s short story «Christmas Eve» (literally the Russian title «Ночь перед Рождеством» translates as «The Night before Christmas») was adapted into operatic form by at least three East Slavic composers. Ukrainian composer Mykola Lysenko wrote his Christmas Eve («Різдвяна ніч», with libretto in Ukrainian by Mykhailo Starytsky) in 1872. Just two years later, in 1874, Tchaikovsky composed his version under the title Vakula the Smith (with Russian libretto by Yakov Polonsky) and revised it in 1885 as Cherevichki (The Tsarina’s Slippers). In 1894 (i.e., just after Tchaikovsky’s death), Rimsky-Korsakov wrote the libretto and music for his own opera based on the same story. «Christmas Eve» was also adapted into a film in 1961 entitled The Night Before Christmas. It was adapted also for radio by Adam Beeson and broadcast on BBC Radio 4 on 24 December 2008[57] and subsequently rebroadcast on both Radio 4 and Radio 4 Extra on Christmas Eve 2010, 2011 and 2015.[58]

Gogol’s story «Viy» was adapted into film by Russian filmmakers four times: the original Viy in 1967; the horror film Vedma (aka The Power of Fear) in 2006; the action-horror film Viy in 2014; and the horror film Gogol Viy released in 2018. It was also adapted into the Russian FMV video game Viy: The Story Retold (2004). Outside of Russia, the film loosely served as the inspiration for Mario Bava’s film Black Sunday (1960) and the South Korean horror film Evil Spirit: Viy (2008).

Gogol’s short story «The Portrait» is being made into a feature film The Portrait by fine artists Anastasia Elena Baranoff and Elena Vladimir Baranoff.[59][60][61][62][63][64]

The Russian TV-3 television series Gogol features Nikolai Gogol as a lead character and presents a fictionalized version of his life that mixes his history with elements from his various stories.[65] The episodes were also released theatrically starting with Gogol. The Beginning in August 2017. A sequel entitled Gogol: Viy was released in April 2018 and the third film Gogol: Terrible Revenge debuted in August 2018.

In 1963 an animated version of Gogol’s classic surrealist story «The Nose» was made by Alexandre Alexeieff and Claire Parker, using the pinscreen animation technique, for the National Film Board of Canada.[66]

A definitive animated movie adaptation of Gogol’s The Nose released in January 2020. The Nose or Conspiracy of Mavericks has been in production for about fifty years.[67]

Bibliography

Notes

- ^ (;[2] Russian: Никола́й Васи́льевич Го́голь, IPA: [nʲɪkɐˈlaj vɐˈsʲilʲjɪvʲɪdʑ ˈɡoɡəlʲ]; Ukrainian: Мико́ла Васи́льович Го́голь, romanized: Mykola Vasyliovych Hohol; né Yanovsky (Russian: Яновский; Ukrainian: Яновський, romanized: Yanovskyi)

Citations

- ^ a b Some sources indicate he was born 19/31 March 1809.

- ^ «Gogol». Random House Webster’s Unabridged Dictionary.

- ^ Bojanowska, Edyta M. (2007). «Introduction». Nikolai Gogol: Between Ukrainian and Russian Nationalism. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. pp. 1–13. ISBN 9780674022911.

- ^ Lavrin, Janko (27 March 2021). «Nikolay Gogol: Ukrainian-born writer». Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

Ukrainian-born humorist, dramatist, and novelist whose works, written in Russian, significantly influenced the direction of Russian literature. His novel Myortvye dushi (1842; Dead Souls) and his short story «Shinel» (1842; «The Overcoat») are considered the foundations of the great 19th-century tradition of Russian realism . . . member of the petty Ukrainian gentry and a subject of the Russian Empire

- ^ Fanger, Donald (30 June 2009). The Creation of Nikolai Gogol. Harvard University Press. pp. 87–88. ISBN 9780674036697. pp. 87–88:

Romantic theory exalted ethnography and folk poetry as expressions of the Volksgeist, and the Ukraine was particularly appealing to a Russian audience in this respect, being, as Gippius observes, a country both ‘»ours» and «not ours,» neighboring, related, and yet lending itself to presentation in the light of a semi-realistic romanticism, a sort of Slavic Ausonia.’ Gogol capitalized on this appeal as a mediator; by embracing his Ukrainian heritage, he became a Russian writer.

- ^ Vaag, Irina (9 April 2009). «Gogol: russe et ukrainien en même temps» [Gogol: Russian and Ukrainian at the same time]. L’Express (Interview with Vladimir Voropaev) (in French). Retrieved 2 April 2021.

Il ne faut pas diviser Gogol. Il appartient en même temps à deux cultures, russe et ukrainienne…Gogol se percevait lui-même comme russe, mêlé à la grande culture russe…En outre, à son époque, les mots «Ukraine» et «ukrainien» avaient un sens administratif et territorial, mais pas national. Le terme «ukrainien» n’était presque pas employé. Au XIXe siècle, l’empire de Russie réunissait la Russie, la Malorossia (la petite Russie) et la Biélorussie. Toute la population de ses régions se nommait et se percevait comme russe.

[We must not divide Gogol. He belongs at the same time to two cultures, Russian and Ukrainian…Gogol perceived himself as Russian, mingled with the great Russian culture…Furthermore, in his era, the words «Ukraine» and «Ukrainian» had an administrative and territorial meaning, but not national. The term «Ukrainian» was almost never used. In the nineteenth century, the Russian Empire comprised Russia, Malorossia (Little Russia) and Byelorussia. The whole population of these regions called themselves, and perceived themselves as, Russian.] - ^ Gippius, V. V. (1989). Robert A. Maguire (ed.). Gogol. Translated by Robert A. Maguire. Duke University Press. p. 7. ISBN 9780822309079. p. 7:

Gogol is the one great Russian writer who has most puzzled English-speaking readers.

- ^ Joe Andrew (1995). Writers and society during the rise of Russian realism. The Macmillan Press LTD. pp. 13, 76. ISBN 9781349044214. p. 76:

He was to remain the least educated of all great Russian writers.

- ^ Fanger, Donald (2009). The Creation of Nikolai Gogol. Harvard University Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-674-03669-7. Retrieved 25 August 2016. p. 24:

Gogol left Russian literature on the brink of that golden age of fiction which many deemed him to have originated, and to which he did, very clearly, open the way. The literary situation he entered, however, was very different, and one cannot understand the shape and sense of Gogol’s career—the peripeties of his lifelong devotion to being a Russian writer, the singularity and depth of his achievement—without knowing something of that situation.

- ^ Amy C. Singleton (1997). Noplace Like Home: The Literary Artist and Russia’s Search for Cultural Identity. SUNY Press. p. 65. ISBN 978-0-7914-3399-7. p. 65:

In 1847 Gogol wrote that Russian literature would call forth a truly ‘Russian Russia.’ The clarity of this image would unite the country ‘in one voice’ to proclaim its long-awaited homecoming. ‘[Our literature] will call forth our Russia for us—our Russian Russia[…] It will elicit [Russia] from us and thus show that all of us to a man, no matter that we be of different minds, upbringing, and opinions, will say in one voice «This is our Russia; we are comfortable [priiutno] and warm here, and now we are truly at home [u sebia doma], under our native roof, and not in a foreign land.»‘

- ^ Postoutenko, Kirill (Summer 2000). «Gogol’s eloquentia corporis: Einverleibung, Identitaet und die Grenzen der Figuration by Natasha Drubek-Meyer». The Slavic and East European Journal. 44 (2): 319–320. doi:10.2307/309969. JSTOR 309969. Retrieved 5 October 2022. p. 319:

Natasha Drubek-Meyer applies this reconstructive approach (mostly in its psychological version) to a widely known yet barely explained phenomenon of Russian culture — the retreat of the main Russian writers (Gogol, Tolstoy, Dostoevsky) from literature.

- ^ Viktor Shklovsky. String: On the dissimilarity of the similar. Moscow: Sovetsky Pisatel, 1970. — p. 230.

- ^ Ilnytzkyj, Oleh. «The Nationalism of Nikolai Gogol’: Betwixt and Between?», Canadian Slavonic Papers Sep–Dec 2007. Retrieved 15 June 2008.

- ^ Karpuk, Paul A. «Gogol’s Research on Ukrainian Customs for the Dikan’ka Tales». Russian Review, Vol. 56, No. 2 (April 1997), pp. 209–232.

- ^ «Natural School (Натуральная школа)». Brief Literary Encyclopedia in 9 Volumes. Moscow. 1968. Retrieved 1 December 2013.

- ^ Nikolai Gogol // Concise Literary Encyclopedia in 9 volumes.

- ^ «Nikolay Gogol». Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 31 December 2010.

- ^ a b c Bojanowska, Edyta M. (2007). Nikolai Gogol: Between Ukrainian and Russian Nationalism. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. pp. 78–88. ISBN 9780674022911.

- ^ Krys Svitlana, “Allusions to Hoffmann in Gogol’s Ukrainian Horror Stories from the Dikan’ka Collection.” Canadian Slavonic Papers: Special Issue, devoted to the 200th anniversary of Nikolai Gogol’’s birth (1809–1852) 51.2–3 (June–September 2009): 243–266.

- ^ Richard Peace (30 April 2009). The Enigma of Gogol: An Examination of the Writings of N.V. Gogol and Their Place in the Russian Literary Tradition. Cambridge University Press. pp. 151–152. ISBN 978-0-521-11023-5. Retrieved 15 April 2012.

- ^ Luckyj, G. (1998). The Anguish of Mykola Ghoghol, a.k.a. Nikolai Gogol. Toronto: Canadian Scholars’ Press. p. 67. ISBN 1-55130-107-5.

- ^ «Welcome to Ukraine». Wumag.kiev.ua. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- ^ Lindstrom, T. (1966). A Concise History of Russian Literature Volume I from the Beginnings to Checkhov. New York: New York University Press. p. 131. LCCN 66-22218.

- ^ «The Government Inspector» (PDF). American Conservative Theater. 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2020. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- ^ RBTH (24 June 2013). «Le nom de Nikolaï Gogol est immortalisé à la place de la Bourse à Paris» (in French). Retrieved 30 August 2016.

- ^ Ilnytzkyj, Oleh S. (2010–2011). «Is Gogol’s 1842 Version of Taras Bul’ba really ‘Russified’?». Journal of Ukrainian Studies. 35–36: 51–68.

- ^ Gogol declared that «the subject of Dead Souls has nothing to do with the description of Russian provincial life or of a few revolting landowners. It is for the time being a secret which must suddenly and to the amazement of everyone (for as yet none of my readers has guessed it) be revealed in the following volumes…»

- ^ Могиле Гоголя вернули первозданный вид: на нее поставили «Голгофу» с могилы Булгакова и восстановили крест.(in Russian)

- ^ «Novodevichy Cemetery». Passport Magazine. April 2008. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- ^ Могиле Гоголя вернули первозданный вид: на нее поставили «Голгофу» с могилы Булгакова и восстановили крест.(in Russian) Retrieved 23 September 2013

- ^ Российское образование. Федеральный образовательный портал: учреждения, программы, стандарты, ВУЗы, тесты ЕГЭ. Archived 4 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine (in Russian)

- ^ For a full story and illustrations, see Российское образование. Федеральный образовательный портал: учреждения, программы, стандарты, ВУЗы, тесты ЕГЭ. Archived 17 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine (in Russian) and Москва и москвичи Archived 13 December 2018 at the Wayback Machine (in Russian)

- ^ This does not mean that numerous influences cannot be discerned in his work. The principle of these are: the tradition of the Ukrainian folk and puppet theatre, with which the plays of Gogol’s father were closely linked; the heroic poetry of the Cossack ballads (dumy), the Iliad in the Russian version by Gnedich; the numerous and mixed traditions of comic writing from Molière to the vaudevillians of the 1820s; the picaresque novel from Lesage to Narezhny; Sterne, chiefly through the medium of German romanticism; the German romanticists themselves (especially Tieck and E.T.A. Hoffmann); the French tradition of Gothic romance – a long and yet incomplete list.[citation needed]

- ^ D.S. Mirsky. A History of Russian Literature. Northwestern University Press, 1999. ISBN 0-8101-1679-0. p. 155.

- ^ Mirsky, p. 191

- ^ Andrey Bely (1934). The Mastery Of Gogol (in Russian). Leningrad: Ogiz.

- ^

According to some critics[which?], Gogol’s grotesque is a «means of estranging, a comic hyperbole that unmasks the banality and inhumanity of ambient reality». See: Fusso, Susanne. Essays on Gogol: Logos and the Russian Word. Northwestern University Press, 1994. ISBN 0-8101-1191-8. p. 55. - ^ «Russian literature.» Encyclopædia Britannica, 2005.

- ^ «Letter to N.V. Gogol». marxists.org. February 2008. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ^ «The structure of the stories themselves seemed especially unskilful and clumsy to me; in one story I noted excess and verbosity, and an absence of simplicity in the style». Quoted by Vasily Gippius in his monograph Gogol (Duke University Press, 1989, p. 166).

- ^ The latest edition[which?] of the Britannica labels Gogol «one of the finest comic authors of world literature and perhaps its most accomplished nonsense writer.» See under «Russian literature.»[citation needed]

- ^ Nabokov, Vladimir (2017) [1961]. Nikolai Gogol. New York: New Directions. p. 140. ISBN 0-8112-0120-1

- ^ Nabokov, Vladimir (2017) [1961]. Nikolai Gogol. New York: New Directions. p. 140. ISBN 978-0-8112-0120-9.

- ^ Dostoevsky appears to have had such a reading of the story in mind when he wrote The Double. The quote, often apocryphally attributed to Dostoevsky, that «we all [future generations of Russian novelists] emerged from Gogol’s Overcoat«, actually refers to those few who read «The Overcoat» as a ghost story (as did Aleksey Remizov, judging by his story The Sacrifice).

- ^ Vladim Joseph Rossman, Vadim Rossman, Vidal Sassoon. Russian Intellectual Antisemitism in the Post-Communist Era. p. 64. University of Nebraska Press. Google.com

- ^ «Antisemitism in Literature and in the Arts». Sicsa.huji.ac.il. Archived from the original on 26 September 2013. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- ^ Léon Poliakov. The History of Antisemitism. p. 75. University of Pennsylvania Press, Google.com

- ^ Amelia Glaser. «Sholem Aleichem, Gogol Show Two Views of Shtetl Jews.» The Jewish Journal, 2009. Journal: Jewish News, Events, Los Angeles

- ^ Gogol Suite, CD Universe

- ^ «Zwei Kompositionsaufträge vergeben» [Two Compositions Commissioned]. wien.orf.at (in German). Archived from the original on 25 July 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) Alt URL - ^ «Nikolai Gogol». IMDb.

- ^ «ru:200 лет со дня рождения Н.В.Гоголя (1809–1852), писателя» [200 years since the birth of Nikolai Gogol (1809–1852), writer] (in Russian). marka-art.ru. 1 April 2009. Archived from the original on 22 March 2009. Retrieved 3 April 2009.

- ^ К 200-летию со дня рождения Н.В. Гоголя выпущены почтовые блоки [Stamps issued for the 200th anniversary of N.V. Gogol’s birthday]. kraspost.ru (in Russian). 2009. Archived from the original on 17 March 2012. Retrieved 3 April 2009.

- ^ Зчіпка 200-річчя від дня народження Миколи Гоголя (1809–1852) [Coupling for the 200th anniversary of the birth of Mykola Hohol (1809–1852)]. Марки (in Ukrainian). Ukrposhta. Retrieved 3 April 2009.[dead link]

- ^ Украина готовится достойно отметить 200-летие Николая Гоголя [Ukraine is preparing to celebrate the 200th anniversary of Nikolai Gogol’s birth] (in Russian). otpusk.com. 28 August 2006. Archived from the original on 19 August 2014. Retrieved 24 August 2016.

- ^ Events by themes: NBU presented an anniversary coin «Nikolay Gogol» from series «Personages of Ukraine», UNIAN-photo service (19 March 2009)

- ^ «Christmas Eve». BBC Radio 4. 24 December 2008. Archived from the original on 10 January 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Gogol, Nikolai (24 December 2015). «Nikolai Gogol – Christmas Eve». BBC Radio 4 Extra. Retrieved 24 August 2016.

- ^ «Patrick Cassavetti boards Lenin?!».

- ^ «Gogol’s short story The Portrait to be made into feature film». russianartandculture.com. 4 July 2014. Archived from the original on 10 April 2016. Retrieved 24 August 2016.

- ^ Screen International [1], Berlin Film Festival, 12 February 2016.

- ^ Russian Art and Culture “Gogol’s “The Portrait” adapted for the screen by an international team of talents” Archived 1 July 2016 at the Wayback Machine, London, 29 January 2016.

- ^ Kinodata.Pro [2] Archived 3 May 2019 at the Wayback Machine Russia, 12 February 2016.

- ^ Britshow.com [3] Archived 29 August 2018 at the Wayback Machine 16 February 2016.

- ^ «Сериал о Гоголе собрал за первые выходные в четыре раза больше своего бюджета». Vedomosti.

- ^ Nowell-Smith, Geoffrey, ed. (1996). The Oxford History of World Cinema. Oxford University Press. p. 274. ISBN 978-0-19-874242-5. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- ^ «Если бы речь шла только об отрицании, пароход современности далеко бы не уплыл». Коммерсантъ. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

References

- Townsend, Dorian Aleksandra, From Upyr’ to Vampire: The Slavic Vampire Myth in Russian Literature, Ph.D. Dissertation, School of German and Russian Studies, Faculty of Arts & Social Sciences, University of New South Wales, May 2011.

This article incorporates text from D.S. Mirsky’s «A History of Russian Literature» (1926-27), a publication now in the public domain.

External links

|

Nikolai Gogol |

|

|---|---|

Daguerreotype of Gogol taken in 1845 by Sergei Lvovich Levitsky (1819–1898) |

|

| Born | Nikolai Vasilyevich Yanovsky 20 March 1809[1] (OS)/1 April 1809 (NS) Sorochyntsi, Poltava Governorate, Russian Empire |

| Died | 21 February 1852 (aged 42) Moscow, Russian Empire |

| Resting place | Novodevichy Cemetery |

| Occupation | Playwright, short story writer, novelist |

| Language | Russian |

| Period | 1840–51 |

| Notable works |

Petersburg Tales [fr] (1833–1842)

|

| Signature | |

|

Portrait of Nikolai Gogol (early 1840s)

Nikolai Vasilyevich Gogol[a] (1 April [O.S. 20 March] 1809[1] – 4 March [O.S. 21 February] 1852) was a Russian novelist, short story writer and playwright of Ukrainian origin.[3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11]

Gogol was one of the first to use the technique of the grotesque, in works such as «The Nose», «Viy», «The Overcoat», and «Nevsky Prospekt». These stories, and others such as «Diary of a Madman», have also been noted for their proto-surrealist qualities. According to Viktor Shklovsky, Gogol’s strange style of writing resembles the «ostranenie» technique of defamiliarization.[12] His early works, such as Evenings on a Farm Near Dikanka, were influenced by his Ukrainian upbringing, Ukrainian culture and folklore.[13][14] His later writing satirised political corruption in the Russian Empire (The Government Inspector, Dead Souls). The novel Taras Bulba (1835), the play Marriage (1842), and the short stories «The Tale of How Ivan Ivanovich Quarreled with Ivan Nikiforovich», «The Portrait» and «The Carriage», are also among his best-known works.

Many writers and critics have recognized Gogol’s huge influence on Russian, Ukrainian and world literature. Gogol’s influence was acknowledged by Mikhail Bulgakov, Fyodor Dostoevsky, Ryūnosuke Akutagawa, Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin, Flannery O’Connor, Franz Kafka and others.[15][16]

Early life

Gogol was born in the Ukrainian Cossack town of Sorochyntsi,[17] in the Poltava Governorate of the Russian Empire. His mother was descended from Leonty Kosyarovsky, an officer of the Lubny Regiment in 1710. His father Vasily Gogol-Yanovsky, who died when Gogol was 15 years old, was supposedly a descendant of Ukrainian Cossacks (see Lyzohub family) and belonged to the ‘petty gentry’. His father wrote poetry in Ukrainian as well as Russian, and was an amateur playwright in his own theatre. As was typical of the left-bank Ukrainian gentry of the early nineteenth century, the family spoke Ukrainian as well as Russian. As a child, Gogol helped stage plays in his uncle’s home theater.[18]

In 1820, Nikolai Gogol went to a school of higher art in Nezhin (Nizhyn) (now Nizhyn Gogol State University) and remained there until 1828. It was there that he began writing. He was not popular among his schoolmates, who called him their «mysterious dwarf», but with two or three of them he formed lasting friendships. Very early he developed a dark and secretive disposition, marked by a painful self-consciousness and boundless ambition. Equally early he developed a talent for mimicry, which later made him a matchless reader of his own works and induced him to toy with the idea of becoming an actor.

On leaving school in 1828, Gogol went to Saint Petersburg, full of vague but ambitious hopes. He desired literary fame, and brought with him a Romantic poem of German idyllic life – Hans Küchelgarten, and had it published at his own expense, under the pseudonym «V. Alov.» The magazines he sent it to almost universally derided it. He bought all the copies and destroyed them, swearing never to write poetry again.

Literary development

In 1831, the first volume of Gogol’s Ukrainian stories (Evenings on a Farm Near Dikanka) was published, and met with immediate success.[19] A second volume was published in 1832, followed by two volumes of stories entitled Mirgorod in 1835, and two volumes of miscellaneous prose entitled Arabesques. At this time, Russian editors and critics such as Nikolai Polevoy and Nikolai Nadezhdin saw Gogol as a regional Ukrainian writer, and used his works to illustrate the specific of Ukrainian national characters.[18] The themes and style of these early prose works by Gogol, as well as his later drama, were similar to the work of Ukrainian-language writers and dramatists who were his contemporaries and friends, including Hryhory Kvitka-Osnovyanenko. However, Gogol’s satire was much more sophisticated and unconventional.[20]

At this time, Gogol developed a passion for Ukrainian Cossack history and tried to obtain an appointment to the history department at Saint Vladimir Imperial University of Kiev. Despite the support of Alexander Pushkin and Sergey Uvarov, the Russian minister of education, the appointment was blocked by a bureaucrat on the grounds that Gogol was unqualified.[21] His fictional story Taras Bulba, based on the history of Zaporozhian Сossacks, was the result of this phase in his interests. During this time, he also developed a close and lifelong friendship with the historian and naturalist Mykhaylo Maksymovych.[22]

In 1834, Gogol was made Professor of Medieval History at the University of St. Petersburg, a job for which he had no qualifications. The academic venture proved a disaster: