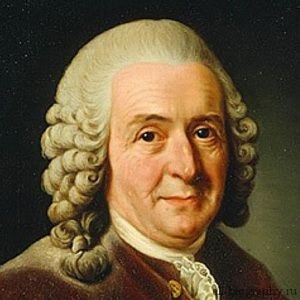

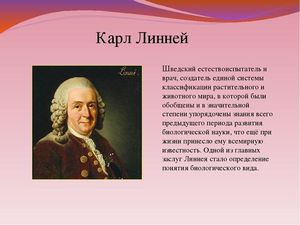

Карл Линней — биография

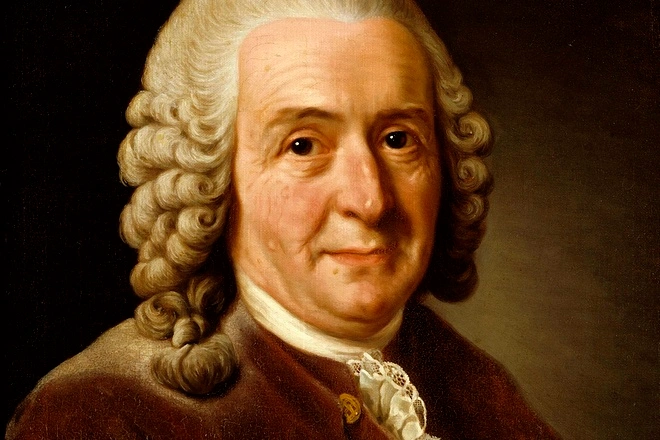

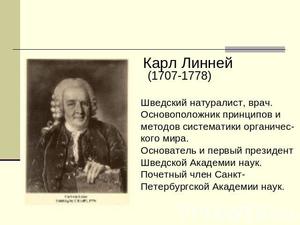

Достижения шведского ученого Карла Линнея трудно переоценить. Ботаники всего мира считают его создателем этой науки. Но он преуспел не только в данном направлении, ученый много сил и времени посвятил работе над литературным шведским языком. По сути, он является создателем литературного шведского языка в его нынешнем виде. Академик и профессор Линней считал, что в систему университетского образования обязательно должно войти преподавание естественных наук. Он много сделал для воплощения своей идеи в жизнь.

Детство

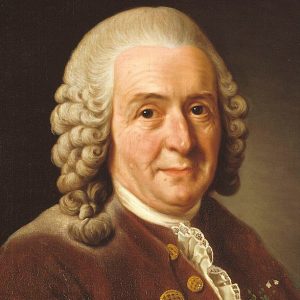

Карл Линней родился в шведском селении Росхульт 23 мая 1707 года в семье небогатого священника, Николауса Линнеуса. Отец будущего ученого происходил из крестьянского сословия. Но его родители сделали все возможное, чтобы Николаус получил образование. Молодому человеку удалось несколько лет проучиться в Лундском университете, но денег на завершение образования и получение ученой степени ему не хватило. Николаус возвратился в родную деревню, где стал служить помощником местного пастора. После он принял духовный сан, женился на дочери священника, пастора Бродерсониуса, под началом которого работал.

Карл был первенцем, всего же в семье Николауса Линнеуса было пятеро детей. Вскоре после рождения Карла его дедушка скончался. Через два года Николауса назначили священником взамен умершего тестя, и разрешили его семье занять дом, где жил дед Карла. Молодая семья очень радовалась улучшению своего материального положения, просторному дому. Пастор Николаус с воодушевлением взялся за благоустройство приусадебного участка. Он решил разбить возле дома большой сад, занялся огородом и цветниками. Карл с увлечением помогал отцу, занимался посадками, и уходом за растениями. Он был очень любознательным, трудолюбивым, имел прекрасную память.

К восьми годам мальчик знал название большинства растений, которые можно было увидеть в Росхульте.

Внимательный и мудрый отец заметил, что его старший сын испытывает неподдельный интерес к растениеводству, выделил для мальчика опытный участок. Этот небольшой клочок находился рядом с домом, Карл выращивал на нем цветы и травы. Он учился в той же низшей грамматической школе, которую когда-то окончил его отец. После 8-ми лет обучения юноша поступил в гимназию. Город Векше, где учился юный Линней, располагался далеко от родной деревни. Родители видели Карла только на каникулах, и не могли контролировать процесс его обучения.

Карл не был успешным гимназистом, имел весьма посредственные знания по многим предметам. Но зато он увлекался математикой и биологией. Педагоги были крайне недовольны успехами юного Линнея, и даже предлагали родителям прекратить обучение, рекомендуя занять подростка ремеслом. Но в дело вмешался доктор, преподававший в гимназии логику и медицину. Он предложил Карлу учиться на доктора. Линней поселился у этого врача для индивидуального обучения. Кроме основных занятий, доктор обучал его и любимому предмету Карла – ботанике.

Вклад в науку

В 1749 году после окончания гимназии Карл поступает в Лундский университет. В стенах этого учебного заведения Линней знакомится с профессором Стобеусом. Ученый муж помог студенту с жильем, поселил его в своем доме. Это принесло большую пользу Карлу, кроме удобного жилья он получил доступ к богатейшей библиотеке профессора. У преподавателя в доме была прекрасная коллекция морских, речных обитателей, замечательный гербарий. Лекции профессора тоже имели огромное значение для становления ботаника Линнея.

Через год Линней перешел учиться в Уппсальский университет. Это был осознанный выбор. Учебное заведение в Уппсале предоставляло гораздо больше возможностей для изучения медицины, здесь работала целая когорта талантливых профессоров. Студенты здешнего университета были чрезвычайно активными и знающими, в свободное от занятий время они самостоятельно изучали те предметы, которые их интересовало больше всего.

Линней подружился со студентом, который тоже живо интересовался ботаникой. Тандем увлеченных молодых людей вместе работал над пересмотром естественноисторических классификаций, которые существовали в то время. Линней занялся изучением растений. После знакомства с Уолофом Цельсием, преподавателем теологии, в жизни Линнея наступил новый этап. Финансовое положение Карла всегда оставляло желать лучшего, Цельсий поселил его в своем доме, предоставил доступ к собственной солидной библиотеке.

На досуге молодой человек занялся написанием научной работы, где были включены главные идеи его будущей половой классификации растений. Это научное исследование вызвало в университете большой интерес. Труд Линнея высоко оценил Рудбек-младший, университетский профессор. Он дал возможность Карлу стать преподавателем-демонстратором ботанического сада в Уппсальском университете.

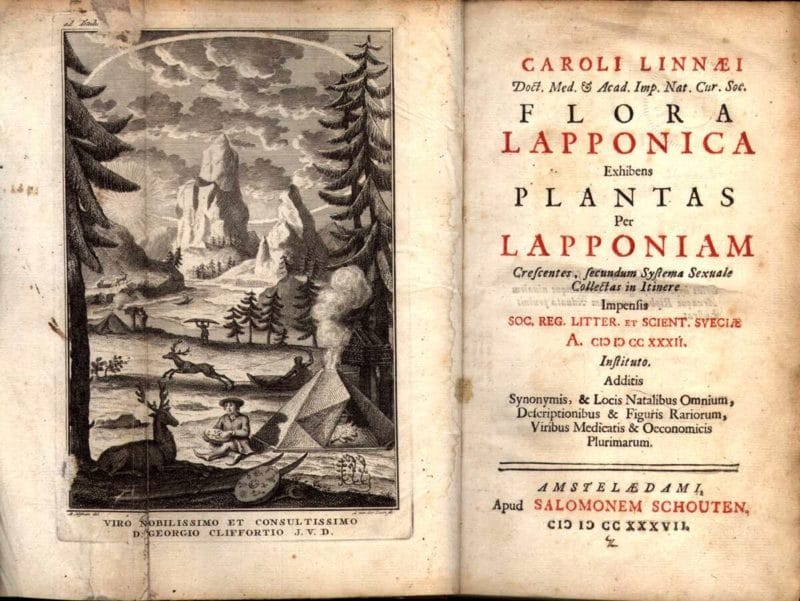

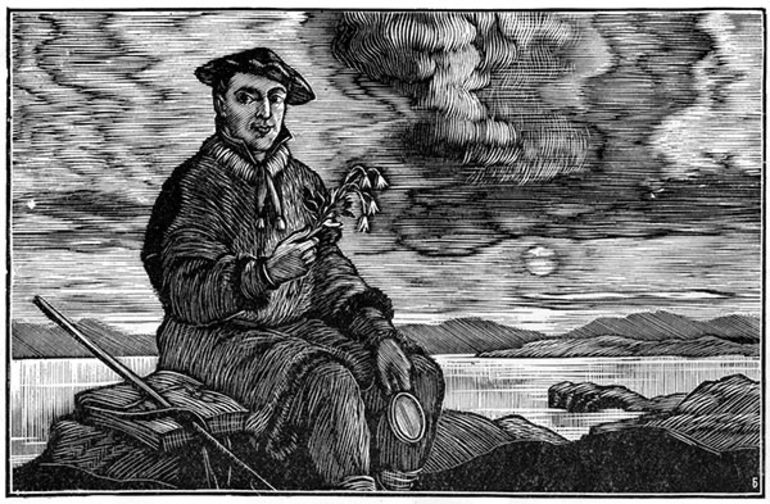

В 1732 году Линней отправился в экспедиционную поездку по Лапландии. Его финансовые возможности были очень скромны, по этой причине учебное заведение полностью оплатило поездку. Карл посетил Скандинавский полуостров, где в течение шести месяцев изучал минералы, животный, растительный мир, условия жизни местных аборигенов-саамов. Он очень скрупулезно отнесся к своей миссии. Не желая пропустить ни единой детали, ученый шел пешком, и только самые трудные участки пути преодолевал с помощью лошади. Он привез в Швецию богатейшую коллекцию, состоящую из собранных образов естественной науки и предметов быта саамов.

Карл передал отчет о своей экспедиции в Уппсальское королевское научное общество. Он надеялся, что эти записи будут полностью опубликованы, однако дождался лишь короткого отчета о флоре Лапландии, представляющего собой каталог разных видов растений.

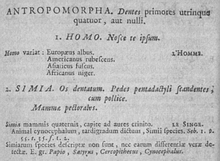

Первой опубликованной работой ученого стала статья Florula Lapponica, где он знакомит читателей с половой системой классификации растений. Он делит растения на классы, утверждая, что у них есть пол, который можно определить по принципу наличия пестиков или тычинок. Классы ученый делит на отряды в зависимости от особенностей строения пестиков. Иногда Линней допускал ошибки, но в целом его система вызвала большой интерес в среде ученых, послужила новым витком в развитии ботаники.

Наблюдения за жизнью саамов, подчерпнутые из дневника Линнея, впервые появились в печати только в 1811 году. Поскольку ни один из современников великого ботаника не занимался подобными трудами, дневник Линнея представляет собой огромную ценность для этнографов.

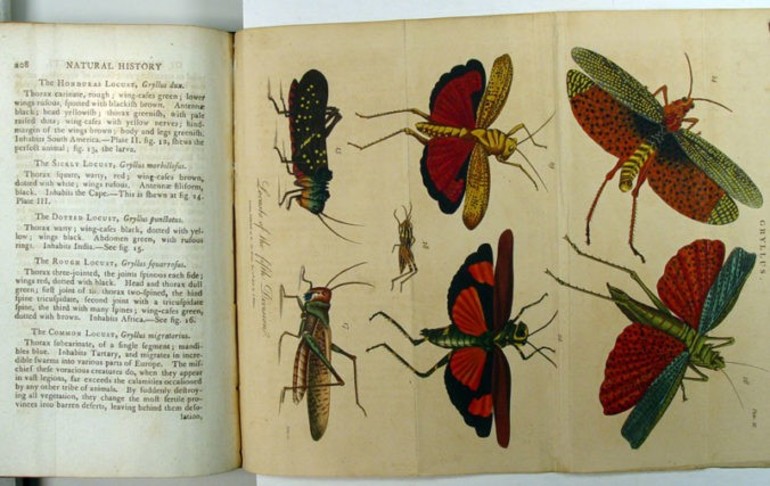

В 1735 году ученый отправляется в Голландию, где он защитил диссертацию по медицине. В Лейдене был опубликован научный труд Линнея под названием «Система природы». Карл жил в этом городе два года, время, проведенное в Голландии, было очень плодотворным для ученого. Он издал множество научных трудов. Классы животных Линней поделил на виды – птиц и млекопитающих, рыб и амфибий, червей и насекомых. Человека ученый относит к млекопитающим, беспозвоночных – к червям, земноводных и пресмыкающихся – к амфибиям.

За эти два года Линней успел описать и классифицировать большую коллекцию растений, которые были собраны в разных странах. В голландский период своей жизни он опубликовал основные труды, изменившие биологию, прославившую его среди других ученых мужей. Линней занимался не только научными трудами. Он написал автобиографию, поделился с читателями интересными фактами, историями, которые случались с ним во время экспедиций.

Вернувшись на родину, ученый поселился в Стокгольме, затем перебрался в Уппсалу. Профессор занимался врачебной практикой, был главой кафедры ботаники, участником многих экспедиций. Многочисленные открытия Линнея в области ботаники и биологии поражали современников. Еще при своей жизни он опубликовал целый ряд статей, некоторые труды были напечатаны после кончины большого ученого. В Швеции и во всем мире высоко ценили и ценят заслуги профессора.

Могут быть знакомы

Личная жизнь

Имя супруги великого ученого – Сара Лиза Морея. Она была дочерью врача. Линней познакомился с ней в Фалуне, через две недели сделал предложение. Отец девушки благословил молодых. Их свадьба состоялась только через три года, до этого времени молодые люди побывали за границей. Торжественное бракосочетание проходило на хуторе, в фамильном имении Сары Лизы.

Первого сынишку молодожены назвали Карлом в честь его знаменитого отца. Он тоже стал известным ботаником, Карлом Линнеем-младшим. Кроме Карла, Сара Лиза подарила любимому супругу еще шестерых детей, двое из которых скончались во младенческом возрасте.

Жизнь ученого была настоящим примером для подражания. Он добился огромных успехов в научной деятельности, был счастливым семьянином. Фамилией своей супруги и ее отца знаменитый ученый назвал цветок из семейства ирисовых, растущий в Южной Африке. В 1758 году счастливое и дружное семейство Линнеев переехало в поместье, расположенное в десяти километрах от Уппсалы.

Причина смерти

В последние годы жизни Линней пережил два инсульта. Первый случился в 1774 году. После частичного паралича профессор уже не мог читать лекции, этим занялся его старший сын. Через два года ученый пережил второй инсульт, после которого потерял память. Он умер в 1778 году, перед этим доставив родным немало хлопот. Ученый уже не узнавал близких, делал попытки уйти из дома. Прах знаменитого профессора покоится в кафедральном соборе Уппсалы.

Своему старшему сыну ученый оставил огромную коллекцию книг и гербариев. Однако вдова профессора Сара Лиза настояла на продаже этих ценностей. И хотя научный мир Швеции протестовал против такого положения вещей, собрание было продано и вывезено за пределы государства. Так страна лишилась великого наследия, который собрал для нее знаменитый ученый.

Труды

- «Система природы»

- «Роды растений»

- «Флора Лапландии»

- «Виды растений»

Ссылки

- Страница в Википедии

Для нас важна актуальность и достоверность информации. Если вы обнаружили ошибку или неточность, пожалуйста, сообщите нам. Выделите ошибку и нажмите сочетание клавиш Ctrl+Enter.

Происхождение и ранние годы

Родина Карла Линнея – шведская деревенька Росхульт, где он появился на свет 23 мая 1707 года. Мальчик был старшим ребенком в семье, после него родилось еще четверо детей – три его младшие сестры и брат. Семейство принадлежало к небогатому сословию – отец, Нильс Линнеус, был обычным сельским пастором, мать, Кристина Бродерсония – дочерью простого священника. В год рождения Карла умер его дедушка по материнской линии, служивший в соседнем приходе. Когда Мальчику исполнилось два года, семья переехала в Стенброгульт и поселилась в доме деда, а Нильс занял место тестя в местном приходе. Здесь, в живописном местечке Швеции проходило детство Карла Линнея.

Родители Карла Линнея

После переезда на новое место, отец Карла разбил прекрасный сад, где произрастали редкие, благоухающие цветы и душистые травы. Этот сад поистине был уникальным в своем роде и тут же стал предметом гордости всех жителей провинции. Мальчику нравилось помогать отцу ухаживать за прекрасными растениями, и тот выделил сыну маленький участок в несколько грядок, который назвали «садиком Карла».

Образование

В десятилетнем возрасте Карл поступил в начальную школу, которая находилась в городе Вексис. Учился он плохо, домашние задания выполнял с большой неохотой. Причиной этому было все то же увлечение ботаникой. Отец, видя, что учеба с трудом дается сыну, принял решение забрать его из школы, но в дело вмешался случай. Однажды Нильс Линней познакомился с одним доктором по фамилии Ротман, который предложил индивидуально позаниматься с Карлом. В процессе подготовки Ротман постепенно знакомил мальчика с медициной и даже заставил по-другому взглянуть на латынь, с которой у Карла всегда были большие проблемы.

Студенческие годы

Следующим этапом обучения был университет Лунда, куда Карл поступил после окончания гимназии. Проучившись там некоторое время, он перевелся в более престижный университет в Уппсале. Способности юноши и его стремление к познанию естественных наук не остались незамеченными: профессор ботаники Улоф Цельсий предложил Карлу стать его помощником. Так, в двадцать три года Линней, еще будучи студентом, начал преподавать в университете.

В 1732 году Линней решил отправиться в одиночное путешествие в Лапландию. В то время Лапландия считалась неизведанной, полной опасностей дикой страной, поэтому решение Карла вызывало очень большие сомнения. Но юноша настаивал на своем, утверждая, что он, молодой и выносливый, легко справится со всеми трудностями. Целью Линнея было знакомство с животным и растительным миром и с местным населением саамами, их бытом, образом жизни, особенностями питания и лечения.

Преодолев пешком почти 700 километров пути, основная часть которого проходила по бездорожью, включающему горные тропы, стремительные реки и зыбкие болота, Линней привез из путешествия огромную коллекцию, представлявшую большую ценность для науки того времени. Итогом этой экспедиции стала первая книга молодого ученого «Флора Лапландии». В ней давалось разделение растений по полу, который определяло наличие пестиков или тычинок. Также Линней делил растения на классы, которые, в свою очередь, подразделялись на отряды. Это была первая попытка ученого провести классификацию растений, в ходе которой он допускал некоторые ошибки. Но, тем не менее, она представляла собой большой научный интерес и сыграла значительную роль в развитии ботаники.

Дом Линнея в Уппсале

В 1735 году Линней защитил диссертацию в одном из университетов Голландии и получил степень доктора медицинских наук. Затем он отправился в Лейден, где опубликовал свою работу «Система природы». Этот труд состоял из четырнадцати страниц большого формата, которые содержали сгруппированные данные в виде таблиц с описанием растений, животных и минералов. За два года, проведенные в Лейдене, у Линнея появилось множество новых идей, которые он воплотил в последующих работах. Так, он провел деление животных на классы, которые состояли из следующих видов: млекопитающие и птицы, рыбы и амфибии, насекомые и черви. За этот же период им была проведена классификация и описание огромного числа растений, которые привозили со всех концов света.

Научная деятельность

Голландский период в биографии Линнея был самым плодотворным в плане его научной карьеры. За это время появилось много новых публикаций, а также первая автобиография, в которой ученый описывал не только свою жизнь, но и интересные случаи из экспедиций. В трудах Линнея, появившихся в 1736-1737 годах, содержались уже более оформленные мысли по классификации видов и родов, а также применялась новая, усовершенствованная терминология.

Первая научная работа Линнея

В этот же период Линней получил предложение стать личным врачом одной важной персоны. Ему пообещали жалованье в 1000 гульденов и полное содержание. Этой персоной был Георг Клиффорд – бургомистр Амстердама и один из управляющих Ост-Индской компании. В те времена эта компания была довольно успешной и процветающей и вливала в Голландию огромные средства. Страстью Клиффорда было разведение и акклиматизация экзотических растений из разных стран мира. На это он не жалел ни времени, ни денег. В его знаменитом саду, разбитом в собственном имении в Гартекампе, помимо растений, завезенных из Африки, Азии, Южной Америки, была огромная ботаническая библиотека и обширный гербарий. Не удивительно, что все эти условия полностью устраивали Линнея и благоприятствовали его научным исследованиям.

Несмотря на идеальную обстановку, в которой жил и работал Линней, все чаще давала о себе знать тоска по родине. В 1738 году Карл вернулся в Швецию но неожиданно для себя понял, что здесь он лишен того уважения, почитания и знаков внимания, которыми был окружен в Голландии. Здесь он был обычным врачом, безработным и безденежным, а его научные заслуги мало кого интересовали. Линнею на некоторое время пришлось забыть о науке и заняться врачебной практикой.

Но уже в следующем, 1739 году сейм Швеции предоставил Линнею ежегодную ассигнацию в размере ста дукатов с условием, что он будет преподавать ботанику и минералогию. Еще одним приятным моментом стало присвоение ему титула «королевского ботаника» и назначение на должность адмиралтейским врачом в столице. За время жизни в Стокгольме Линней не только стал свидетелем основания академии наук, но и сам активно участвовал в этом процессе. В начале своего существования в академии насчитывалось всего шесть действительных членов, которые единогласным голосованием поддержали кандидатуру Линнея на пост ее президента.

Сад Линнея в Уппсале

В 1742 году Линней получил долгожданное звание профессора ботаники в университете Уппсалы. Кафедра ботаники, которую он возглавил, в прямом смысле расцвела под его руководством. Все последующие тридцать лет Карл посвятил работе в родном университете, а кафедра оставалась под его началом практически до самой его смерти.

Вместе с удовлетворением от работы улучшилось и финансовое положение ученого. Наконец, он смог приобрести небольшое имение Гаммарба недалеко от Уппсалы. Наступил период торжества его идей, которые получали всё большее распространение и признание. Имя Линнея занимало одно из первых мест наряду с великими учеными того времени, он был окружен уважением и почестями. Оказывали ему любезности и первые люди государства, включая короля Фредрика Первого Гессенского.

Отныне все свое время Линней посвящал науке. Наконец, ему удалось осуществить задуманное: не просто сделать описание всех существующих лекарственных растений, но и проанализировать действие лекарственных средств, полученных на их основе. Оставалось у Линнея время и на другие научные разработки. В этот же период (1744) он изобрел ртутный термометр, который в 1745 году подарил Шведской академии наук. За основу была взята температурная шкала Цельсия, но теперь она показывала нулевую температуру для таяния льда и сто градусов для кипения воды, что было намного удобнее в практическом использовании.

Усадьба Линнея в Хаммарбрю

В планах Линнея была систематизация всего растительного мира нашей планеты. Еще в тот период, когда ученый только начал заниматься своими исследованиями, ботаника, как и зоология, представляла собой науку, которая лишь изучала и описывала виды, но делалось это бессистемно и хаотично. Многие авторы не утруждали себя достаточно точным описанием новых растений или животных, не говоря уже о какой-либо их классификации, о которой практически никто не задумывался. Гениальность Линнея заключалась в том, что он, видя эти недостатки, не отрицал ту научную платформу, которую создали его предшественники, а провел ее грандиозную реформу. Не являясь первооткрывателем новых наук или законов, он сумел навести порядок там, где ранее царили неразбериха и путаница. Его метод отличался простотой и логикой и стал тем толчком, без которого невозможен научный прогресс.

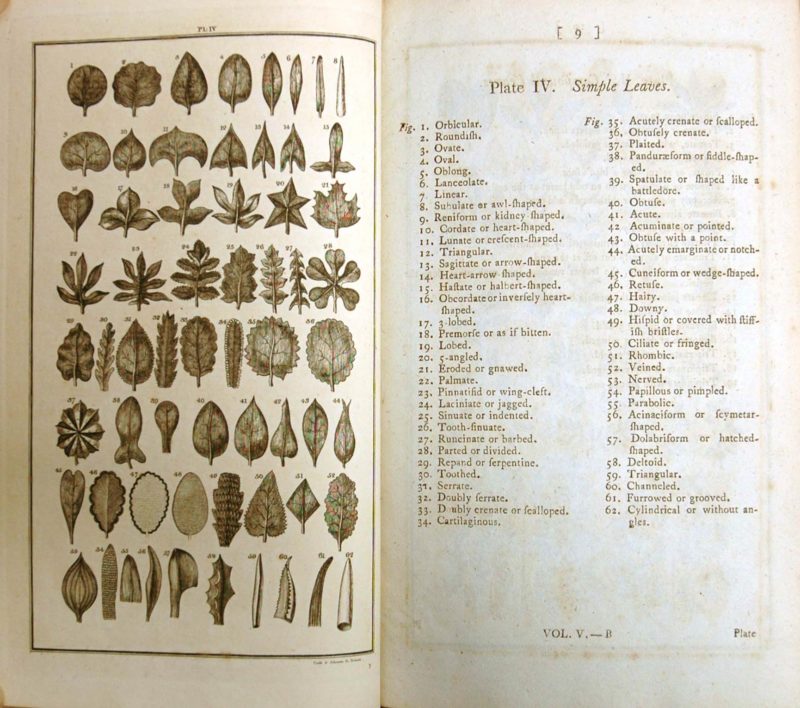

Линнеем была создана совершенно новая система научных названий животных и растений. Взяв за основу особенности их строения, все растения были поделены им на 24 класса с выделением родов и видов. Он предложил именовать растения двумя словами (бинарная номенклатура), первым из которых была принадлежность к роду, вторым – к виду.

Памятник в Стокгольме

Этот принцип, несмотря на некоторую искусственность, оказался настолько удобным, что не потерял своего значения и в наши дни. Но для его плодотворной работы необходимо было самое точное и подробнейшее описание каждого вида, такое, чтобы конкретный вид имел максимальное число характерных признаков и его невозможно было перепутать с другими видами того же рода. Линней был первым, кто ввел ботаническую терминологию, при помощи которой можно было точнейшим образом описывать различные признаки. В практическом отношении система Линнея оказалась необыкновенно удобной и полезной: теперь каждому вновь открытому растению находилось в ней свое место.

Что касается зоологической систематизации, то она не получила такого широкого распространения и признания, как ботаническая. Во многом причиной явилось то, что Линней брал за основу внешние сходства и различия животных, так как не очень хорошо разбирался в их анатомии и физиологии.

Основные достижения и вклад в науку

В 1753 году Карл Линней стал членом Лондонского Королевского общества, что явилось свидетельством его признания английскими учеными. Не оставлял Линней и преподавательскую деятельность. Его лекции в Ботаническом саду собирали до двухсот пятидесяти студентов, о чем он с гордостью писал в биографии этого периода.

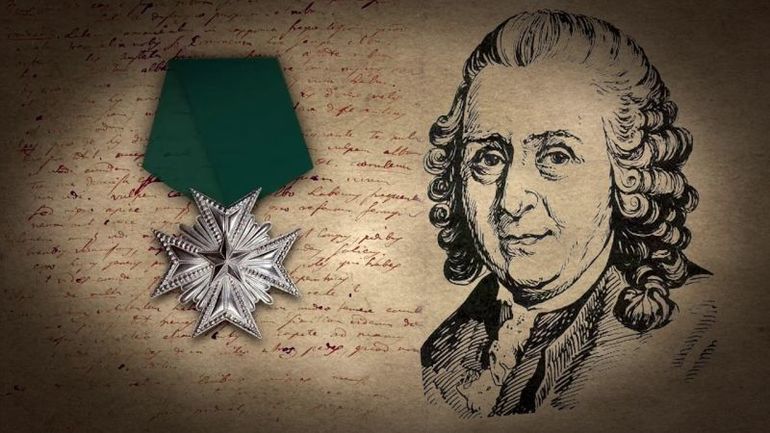

Медаль Линнея

В 1754 году Линней был награжден медалью за работу «Рассуждение о возделывании полезных растений в горах Лапландии». В сентябре того же года он был избран почетным членом Академии наук Петербурга и членом Академии Флоренции.

Труды Линнея сыграли огромную роль в развитии естественных наук 18 века. Не ограничиваясь классификацией растений и животных, позже Линней применил свой метод и к классификации минералов и горных пород. Он был первым, кто отнес человека и обезьяну к одной группе приматов. Результаты своих исследований ученый изложил в многотомном труде «Система природы», который выдержал двенадцать изданий.

Среди других важных работ Линнея нельзя не отметить «Философию ботаники (1751), в которой впервые была применена бинарная номенклатура и учение о виде. Об этом труде Жан Жак Руссо писал, что это самое философское произведение, из тех, что он знает. Заслуживает внимания и работа по вопросу пола у растений, получившая премию Петербургской Академии наук. Одна из важнейших работ Линнея «Виды растений» увидела свет в 1753 году. В ней впервые были систематизированы все растения Земли, известные на тот период.

Последние годы

Место захоронения в кафедральном соборе

В первой половине семидесятых годов у Линнея обозначились проблемы со здоровьем, а в 1774 году он перенес первый инсульт. Ученый выжил, но остался частично парализованным и уже был не в состоянии читать лекции. Эту работу он передал своему сыну, Карлу Линнею-младшему. Второй инсульт случился в 1777 году. Он протекал гораздо тяжелее и оставил после себя необратимые последствия: Карл перестал узнавать близких, порывался покидать дом, почти полностью потерял память. Смерть наступила 10 января 1778 года в имении Линнея недалеко от Уппсалы. После кончины близкие обнаружили запечатанный конверт, в котором содержались распоряжения насчет похорон. Дословно они звучали так: «Положить меня в гроб небритого, немытого, неодетого, завернутого в простыню. Гроб закрыть совсем, так, чтобы никто не мог видеть меня в таком плохом виде. Пусть звонит большой соборный колокол… Пусть вознесут благодарение богу, давшему мне долгие годы… Пусть мои земляки снесут меня к могиле; дать каждому из них по малой медали с моим изображением. Не устраивать поминок на моих похоронах и не принимать соболезнований». За особые заслуги перед наукой и как почетного гражданина города, Линнея похоронили с почестями в Уппсальском кафедральном соборе.

Личная жизнь

Женой Карла Линнея стала дочь врача Сара Лиза Морея. Через две недели после знакомства Линней сделал восемнадцатилетней Саре предложение, и она с радостью его приняла. Получив благословение отца невесты, влюбленные решили отложить свадьбу и уехали за границу. После возвращения Карл и Сара официально обручились, но свадьба состоялась лишь в 1739 году, через пять лет после знакомства. У супругов родилось семеро детей. Старшего сына, появившегося на свет в 1741 году, так же, как и отца, нарекли Карлом. Двое детей умерли еще в младенческом возрасте.

После смерти отца Карл Линней-младший возглавил кафедру ботаники в Уппсальском университете. Молодой человек подавал большие надежды как ученый, но преждевременная смерть в 41 год не позволила им осуществиться. Огромная коллекция гербариев и солидная библиотека, которую всю жизнь собирал Линней-старший, была продана его вдовой и вывезена за пределы Швеции.

Хронологическая таблица

| Год (годы) | Событие |

| 23.05.1707 | Родился Карл Линней |

| 1727 | Учеба в Лундском университете |

| 1728 | Учеба в Уппсальском университете |

| 1732 | Экспедиция в Лапландию |

| 1734 | Путешествие в провинцию Даларна |

| 1735 | Присвоение степени доктора медицины в голландском университете Хардервейк. Первое издание Системы природы |

| 1735-1738 | Путешествие в Данию, Германию, Голландию, Англию и Францию |

| 1736 | Выход «Основ ботаники» |

| 1737 | Выход «Флоры Лапландии» |

| 1739 | Работа врачом в Стокгольме. Линней – один из основателей Академии наук и ее первый президент. Женитьба на Саре Лисе Морее |

| 1741 | Профессор медицины в Уппсале. Путешествие на острова Эланд и Готланд |

| 1744 | Секретарь Уппсальского научного общества |

| 1745 | Издание «Флоры Швеции» |

| 1746 | Путешествие в Вестгёту. Издание «Фауны Швеции» |

| 1749 | Путешествие в провинцию Сконе |

| 1751 | Выход труда «Философия ботаники» |

| 1753 | Выход научной работы «Виды растений» |

| 1758 | Приобретение имения Хаммарбю. 10-е издание «Системы природы»

|

| 1761 | Получение дворянского титула |

| 1766-1768 | Последнее прижизненное издание Линнеем «Системы природы» |

| 10.01.1778 | Дата смерти Карла Линнея |

Интересные факты

- Единая классификация растений, созданная Линнеем, в несколько измененном виде используется во всем мире по сегодняшний день;

- несмотря на простое происхождение, за научные достижения Линней получил статус дворянина. После этого его имя стало звучать так: Карл фон Линней;

- из-за плохой учебы руководство гимназии предлагало отцу забрать Карла и отдать в ремесленники;

- первая работа, принесшая известность молодому Линнею, называлась «Введение к помолвкам растений» и была посвящена их рамножению;

- Линней преобразовал шкалу температур Цельсия. С тех пор точкой замерзания стал ноль, а +100° – точкой кипения;

- Карл Линней был первым, кто добился отмены запрета на вскрытие тел умерших, став, по сути, первым шведским патологоанатомом;

- у Линнея было множество учеников. Тех из них, кто прославился на научном поприще, называют «апостолами Линнея»;

- за всю жизнь Линней написал пять своих автобиографий. Над ними он работал в разные периоды жизни. Последняя автобиография является самой объемной;

- Линнеевское общество, расположенное в Лондоне, является одним из крупнейших научных центров мира.

Память

Имя Линнея носят некоторые роды и виды животных и растений. В честь него названы географические и астрономические объекты, печатные издания, ботанические сады. Об ученом написано множество книг, в числе которых романы и рассказы. Во многих странах мира установлены памятники Линнею.

Цитаты

«Из маленькой хижины может выйти великий человек»

«В естественной науке принципы должны подтверждаться наблюдениями»

«С помощью искусства природа творит чудеса»

«Минералы существуют, растения живут и растут, животные живут, растут и чувствуют»

Ссылки

https://www.hmong.press/wiki/Linnaeus%27_Garden Сад Линнея

Литература

- Бобров Е. Г. Карл Линней. 1707–1778–Л. : Наука, 1970.

- Бруберг Г. Карл фон Линней. – Стокгольм : Шведский институт, 2006.

- Скворцов А. К. У истоков систематики. К 300-летию Карла Линнея//

- Природа: журнал. – 2007. – № 4.

- Шапаренко К. К. К вопросу о роли Линнея в развитии ботаники

- //Природа: журнал. – 1935. – № 7.

- Комаров В. Л. Жизнь и труды Карла Линнея. 1707—1778// Избр. соч. – М.–Л., 1945.

Ирина Зарицкая | Просмотров: 1.5k

Биография Карла Линнея

23 Мая 1707 – 10 Января 1778 гг. (70 лет)

4.6

Средняя оценка: 4.6

Всего получено оценок: 1011.

Карл Линней (1707–1778 гг.) — исследователь, биолог, натуралист шведского происхождения, который приложил много усилий, чтобы систематизировать по родам и видам растения и животных, а также поделил весь мир на три царства. Благодаря его трудам биология стала полноценной наукой. Карл Линней также основал Королевскую академию наук и заслужил звание «отца ботаники».

Юные годы

Карл Линней, биография которого наполнена исследованиями и важными открытиями, родился 23 мая 1707 года в деревне Росхульт, что в Южной Швеции, в семье пастора. Отец, Ниль Линней, мечтал, что он пойдёт по его стопам. Стоит отметить, что изначально у главы семьи была другая фамилия (Ингемарсон), которую он поменял, следуя христианской моде.

Несмотря на все старания Ниля, Карла с ранних лет тянуло к природе, интерес к которой проснулся тогда, когда отец посадил сад. Из-за этого интереса страдала его успеваемость в учебных учреждениях.

В 1727 году началось его погружение в мир флоры и фауны. Линней обучался вначале в Лундском институте, затем в Уппсальском. Там он приобрёл необходимые знания о природе, начал заниматься медициной, а также познакомился с Цельсием и Артеди.

Научные исследования

В 1732 году Карл Линней поехал в Лапландию, чтобы исследовать природу этой страны. Экспедиция продлилась около 5 месяцев, а после на её основе он создал небольшой доклад. Это первый вклад в биологию, который Линней принёс миру.

В 1735 году учёный издал брошюру, состоящую из 14 страниц. Она называлась «Systema naturae» и содержала в себе систему природы, которую создал Линней. Изучение многих научных сочинений и трудов привело его к мысли о том, что такая систематизация поможет другим учёным. Исследования, заложенные в этом издании, стали самыми важными в жизни Линнея. Он всю жизнь проработал над их усовершенствованием, и к её окончанию переизданное издание составляло 4 тома, а это в общей сложности 2335 страниц.

В 1738 году Линней получил возможность работать врачом и создал Королевскую академию наук. Созданную им классификация организмов начали брать за основу современной науки биологии. Так, флору и фауну стали обозначать, исходя из двоичной системы, то есть по роду и виду.

Популярность

Изучая краткую биографию Карла Линнея, необходимо отметить и то, что со временем он собрал вокруг себя множество последователей и учеников, приобрёл славу, благодаря которой его звали преподавать во многие институты. Но Карл, в 1742 году возглавивший кафедру ботаники в Уппсальском институте, до конца своей жизни остался работать там. В 1750 году Линней занял должность ректора в институте.

Личная жизнь

К не менее интересным фактам относятся и личные отношения исследователя. В 1734 году Карл Линней познакомился со своей будущей супругой, а спустя 4 года женился на ней. Сара Лиза Моррея была дочерью врача. Она родила своему знаменитому супругу 7 детей, двое из которых умерли в очень раннем возрасте.

По мнению его современников, супруга Линнея не проявляла интереса к его исследованиям, очень любила дочерей, но не слишком жаловала сына. Она часто жаловалась на Карлу на последнего, пытаясь настроить мужа против него. Но учёный очень любил его и привлекал к своим исследованиям.

Смерть

В 1774 году у учёного случилось несчастье: из-за кровоизлияния в мозг он оказался частично парализован. После этого ему пришлось часть дел передать сыну. Через несколько лет произошло второе кровоизлияние, из-за которого он потерял память. Умер великий исследователь 10 января 1778 года. После себя он оставил ценные труды и огромное наследие, которое помогло современникам в изучении биологии.

Другие варианты биографии

Более сжатая для доклада или сообщения в классе

Вариант 2

Тест по биографии

Доска почёта

Чтобы попасть сюда — пройдите тест.

-

Mmm Mmm

10/10

-

Мбдоу-Детский-Сад Красногорск

10/10

-

Sergey Klygin

10/10

-

David Kamalov

10/10

Оценка по биографии

4.6

Средняя оценка: 4.6

Всего получено оценок: 1011.

А какая ваша оценка за эту биографию?

Карл Линней (швед. Carl Linnaeus, 1707-1778) — выдающийся шведский ученый, естествоиспытатель и медик, профессор Упсальского университета. Он заложил принципы классификации природы, разделив ее на три царства. Заслугами великого ученого стали оставленные им подробные описания растений и одна из наиболее удачных искусственных классификаций растений и животных. Он ввел в науку понятие таксоны и предложил метод бинарной номенклатуры, а также построил систему органического мира на основе иерархического принципа.

Детство и юность

Карл Линней родился 23 мая 1707 года в шведском городе Росхульте в семье сельского пастора Николаса Линнеуса. Он был настолько увлеченным цветоводом, что поменял свою прежнюю фамилию Ингемарсон на латинизированный вариант Линнеус от названия огромной липы (по шведски Lind), которая росла неподалеку от дома. Несмотря на большое желание родителей видеть своего первенца священником, его с юных лет привлекали естественные науки, а в особенности ботаника.

Когда сыну было два года, семья перебралась в соседний город Стенброхульт, но учился будущий ученый в городке Векше — сначала в местной грамматической школе, а затем в гимназии. Основные предметы — древние языки и богословие ─ давались Карлу нелегко. Зато молодой человек с головой был увлечен математикой и ботаникой. Ради последней он нередко прогуливал занятия, чтобы в естественных условиях изучать растения. Латынь он также освоил с большим трудом, и то ради возможности прочесть в оригинале «Естественную историю» Плиния. По совету доктора Ротмана, преподававшего у Карла логику и медицину, родители решились отдать учиться сына на врача.

Учеба в университете

В 1727 году Линней успешно сдал экзамены в Лундский университет. Здесь наибольшие впечатления на него произвели лекции профессора К. Стобеуса, который помог пополнить и систематизировать знания Карла. В течение первого года обучения он скрупулезно изучал флору окрестностей Лунда и создал каталог редких растений. Однако проучился в Лунде Линней недолго: по совету Ротмана он перевелся в Упсальский университет, имевший больший медицинский уклон. Впрочем, уровень преподавания в обоих учебных заведениях был ниже возможностей студента Линнея, поэтому большую часть времени он занимался самообразованием. В 1730 году он начал преподавать в ботаническом саду в качестве демонстратора и имел среди слушателей большой успех.

Однако польза от пребывания в Упсале все же была. В стенах университета Линней знакомится с профессором О. Цельсием, иногда помогавшему бедному студенту деньгами и профессором У. Рудбеком-младшим, по совету которого отправился в путешествие по Лапландии. Кроме того, судьба его свела со студентом П. Артеди, в соавторстве с которым будет пересмотрена естественно-историческая классификация.

В 1732 году Карл побывал в Лапландии с целью детального изучения трех царств природы — растений, животных и минералов. Также он собрал большой этнографический материал, в том числе о быте аборигенов. По итогам поездки Линней написал краткую обзорную работу, которая в 1737 году вышла в развернутом варианте под названием «Flora Lapponica». Свою исследовательскую деятельность начинающий ученый продолжил в 1734 году, когда по приглашению местного губернатора отправился в Делекарлию. После этого он переехал в Фалун, где занимался пробирным делом и изучением минералов.

Голландский период

В 1735 году Линней отправляется на берега Северного моря как соискатель диплома доктора медицины. Эта поездка состоялась в том числе по настоянию его будущего тестя. Защитив диссертацию в университете Гардервейка, Карл с упоением изучал естественнонаучные кабинеты Амстердама, а затем отправился в Лейден, где увидел свет один из его фундаментальных трудов «Systema naturae». В нем автор представил распределение растений по 24 классам, заложив основу классификации по количеству, величине, расположению тычинок и пестиков. Позднее работа будет постоянно дополняться, и при жизни Линнея будет выпущено 12 изданий.

Созданная система оказалась очень доступной даже для непрофессионалов, позволяя без труда идентифицировать растения и животных. Ее автор осознавал свое особенное предназначение, называя себя избранником Творца, призванного дать толкование его планов. Кроме того, в Голландии он пишет «Bibliotheca Botanica», в которой систематизирует литературу по ботанике, «Genera plantraum»с описанием родов растений, «Classes plantraum» — сопоставление различных классификаций растений с системой самого автора и ряд других произведений.

Возвращение на родину

Вернувшись в Швецию, Линней занялся медицинской практикой в Стокгольме и довольно быстро вошел в королевский двор. Причиной стало излечение нескольких фрейлин отваром тысячелистника. Он широко использовал в своей деятельности целебные растения, в частности, ягодами земляники лечил подагру. Ученый приложил немало усилий для создания Королевской академии наук (1739), стал первым ее президентом и был удостоен звания «королевского ботаника».

В 1742 году Линней осуществляет давнюю мечту и становится профессором ботаники в своей альма-матер. При нем кафедра ботаники в Упсальском университете (Карл возглавлял ее более 30 лет) приобрела огромное уважение и авторитет. Важную роль в проводимых им занятиях играл Ботанический сад, где произрастали несколько тысяч растений, собранных буквально со всего света. «В естественных науках принципы должны подтверждаться наблюдениями», — говорил Линней. В это время к ученому пришли настоящий успех и известность: Карлом восхищались многие выдающиеся современники, в том числе Руссо. В век Просвещения ученые, подобные Линнею, были в моде.

Поселившись в своем имении Гаммарба вблизи Упсала, Карл отошел от медицинской практики и с головой окунулся в науку. Ему удалось описать все известные на тот момент лекарственные растения и изучить воздействие на человека произведенных из них лекарств. В 1753 году он публикует свой главный труд «Система растений», над которым работал четверть века.

Научный вклад Линнея

Линнею удалось исправить существующие недостатки ботаники и зоологии, чья миссия ранее сводилась к простому описанию объектов. Ученый заставил всех по-новому взглянуть на цели этих наук, проведя классификацию объектов и разработав систему их распознавания. Главная заслуга Линнея связана с областью методологии — он не открыл новых законов природы, зато смог упорядочить уже накопленные знания. Ученый предложил метод бинарной номенклатуры, в соответствии с которым животным и растениям присваивались названия. Он разделил природу на три царства и применил четыре ранга для ее систематизации — классы, отряды, виды и роды.

Линней распределил все растения на 24 класса в соответствии с особенностями их строения и выделил их род и вид. Во втором издании книги «Виды растений» он представил описание 1260 родов и 7540 видов растений. Ученый был убежден, что у растений есть пол и положил в основу классификации выделенные им особенности строения тычинок и пестиков. При употреблении названия растений и животных было необходимо использовать родовое и видовое наименование. Такой подход положил конец хаосу в классификации флоры и фауны, а со временем стал важным инструментом определения родства отдельных видов. Чтобы новая номенклатура была удобна в использовании и не вызывала двусмысленности, автор подробнейшим образом описал каждый вид, введя в науку точный терминологический язык, который подробно изложил в работе «Фундаментальная ботаника».

В конце жизни Линней попытался применить свой принцип систематизации для всей природы, в том числе горных пород и минералов. Он стал первым, кто отнес человека и обезьян к общей группе приматов. При этом шведский ученый никогда не был сторонником эволюционного направления и считал, что первые организмы были созданы в некоем райском уголке. Он резко критиковал сторонников идеи изменчивости видов, называя это отступлением от библейских традиций. «Природа не делает скачка», — не раз повторял ученый.

В 1761 году после четырехлетних ожиданий Линней получил дворянский титул. Это позволило ему несколько видоизменить фамилию на французский манер (von Linne) и создать собственный герб, центральными элементами которого стали три символа царств природы. Линнею принадлежит идея изготовления термометра, для создания которого он применил шкалу Цельсия. За свои многочисленные заслуги в 1762 году ученый был принят в ряды Парижской Академии наук.

В последние годы жизни Карл тяжело болел и перенес несколько инсультов. Он скончался в собственном доме в Упсале 10 января 1778 года и был захоронен в местном кафедральном соборе.

Научное наследство ученого было представлено в виде огромной коллекции, включающей в себя собрание раковин, минералов и насекомых, два гербария и огромную библиотеку. Несмотря на возникшие семейные споры, она досталась старшему сыну Линнея и его полному тезке, который продолжил дело отца и сделал все, чтобы сохранить эту коллекцию. После его преждевременной смерти она попала к английскому натуралисту Джону Смиту, основавшему в британской столице «Лондонское Линнеевское общество».

Личная жизнь

Ученый был женат на Саре Лизе Морене, с которой познакомился в 1734 году, дочерью городского врача Фалуна. Роман протекал очень бурно, и через две недели Карл решился сделать ей предложение. Весной 1735 года они довольно скромно обручились, после чего Карл уехал в Голландию защищать диссертацию. В силу разных обстоятельств их свадьба состоялась только спустя 4 года в фамильном хуторе семьи невесты. Линней стал многодетным отцом: у него родилось два сына и пять дочерей, из которых двое детей умерли во младенчестве. В честь своей супруги и тестя ученый назвал Moraea род многолетних растений из семейства Ирисовых, произрастающих в Южной Африке.

|

Carl Linnaeus |

|

|---|---|

Carl von Linné by Alexander Roslin, 1775 |

|

| Born | 23 May 1707[note 1]

Råshult, Stenbrohult parish (now within Älmhult Municipality), Sweden |

| Died | 10 January 1778 (aged 70)

Hammarby (estate), Danmark parish (outside Uppsala), Sweden |

| Resting place | Uppsala Cathedral 59°51′29″N 17°38′00″E / 59.85806°N 17.63333°E |

| Nationality | Swedish |

| Alma mater |

|

| Known for |

|

| Spouse |

Sara Elisabeth Moræa (m. 1739) |

| Children | 7 |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields |

|

| Institutions | Uppsala University |

| Thesis | Dissertatio medica inauguralis in qua exhibetur hypothesis nova de febrium intermittentium causa (1735) |

| Notable students |

|

| Author abbrev. (botany) | L. |

| Author abbrev. (zoology) | Linn. |

| Signature | |

Carl Linnaeus (;[1][2] 23 May[note 1] 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after his ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné[3] (Swedish pronunciation: [ˈkɑːɭ fɔn lɪˈneː] (listen)), was a Swedish botanist, zoologist, taxonomist, and physician who formalised binomial nomenclature, the modern system of naming organisms. He is known as the «father of modern taxonomy».[4] Many of his writings were in Latin; his name is rendered in Latin as Carolus Linnæus and, after his 1761 ennoblement, as Carolus a Linné.

Linnaeus was born in Råshult, the countryside of Småland, in southern Sweden. He received most of his higher education at Uppsala University and began giving lectures in botany there in 1730. He lived abroad between 1735 and 1738, where he studied and also published the first edition of his Systema Naturae in the Netherlands. He then returned to Sweden where he became professor of medicine and botany at Uppsala. In the 1740s, he was sent on several journeys through Sweden to find and classify plants and animals. In the 1750s and 1760s, he continued to collect and classify animals, plants, and minerals, while publishing several volumes. He was one of the most acclaimed scientists in Europe at the time of his death.

Philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau sent him the message: «Tell him I know no greater man on earth.»[5] Johann Wolfgang von Goethe wrote: «With the exception of Shakespeare and Spinoza, I know no one among the no longer living who has influenced me more strongly.»[5] Swedish author August Strindberg wrote: «Linnaeus was in reality a poet who happened to become a naturalist.»[6] Linnaeus has been called Princeps botanicorum (Prince of Botanists) and «The Pliny of the North».[7] He is also considered one of the founders of modern ecology.[8]

In botany and zoology, the abbreviation L. is used to indicate Linnaeus as the authority for a species’ name.[9] In older publications, the abbreviation «Linn.» is found. Linnaeus’s remains constitute the type specimen for the species Homo sapiens following the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature, since the sole specimen that he is known to have examined was himself.[note 2]

Early life

Childhood

Linnaeus was born in the village of Råshult in Småland, Sweden, on 23 May 1707. He was the first child of Nicolaus (Nils) Ingemarsson (who later adopted the family name Linnaeus) and Christina Brodersonia. His siblings were Anna Maria Linnæa, Sofia Juliana Linnæa, Samuel Linnæus (who would eventually succeed their father as rector of Stenbrohult and write a manual on beekeeping),[10][11][12] and Emerentia Linnæa.[13] His father taught him Latin as a small child.[14]

One of a long line of peasants and priests, Nils was an amateur botanist, a Lutheran minister, and the curate of the small village of Stenbrohult in Småland. Christina was the daughter of the rector of Stenbrohult, Samuel Brodersonius.[15]

A year after Linnaeus’s birth, his grandfather Samuel Brodersonius died, and his father Nils became the rector of Stenbrohult. The family moved into the rectory from the curate’s house.[16][17]

Even in his early years, Linnaeus seemed to have a liking for plants, flowers in particular. Whenever he was upset, he was given a flower, which immediately calmed him. Nils spent much time in his garden and often showed flowers to Linnaeus and told him their names. Soon Linnaeus was given his own patch of earth where he could grow plants.[18]

Carl’s father was the first in his ancestry to adopt a permanent surname. Before that, ancestors had used the patronymic naming system of Scandinavian countries: his father was named Ingemarsson after his father Ingemar Bengtsson. When Nils was admitted to the University of Lund, he had to take on a family name. He adopted the Latinate name Linnæus after a giant linden tree (or lime tree), lind in Swedish, that grew on the family homestead.[10] This name was spelled with the æ ligature. When Carl was born, he was named Carl Linnæus, with his father’s family name. The son also always spelled it with the æ ligature, both in handwritten documents and in publications.[16] Carl’s patronymic would have been Nilsson, as in Carl Nilsson Linnæus.[19]

Early education

Linnaeus’s father began teaching him basic Latin, religion, and geography at an early age.[20] When Linnaeus was seven, Nils decided to hire a tutor for him. The parents picked Johan Telander, a son of a local yeoman. Linnaeus did not like him, writing in his autobiography that Telander «was better calculated to extinguish a child’s talents than develop them».[21]

Two years after his tutoring had begun, he was sent to the Lower Grammar School at Växjö in 1717.[22] Linnaeus rarely studied, often going to the countryside to look for plants. At some point, his father went to visit him and, after hearing critical assessements by his preceptors, he decided to put the youth as an apprentice to some honest cobbler.[23] He reached the last year of the Lower School when he was fifteen, which was taught by the headmaster, Daniel Lannerus, who was interested in botany. Lannerus noticed Linnaeus’s interest in botany and gave him the run of his garden.

He also introduced him to Johan Rothman, the state doctor of Småland and a teacher at Katedralskolan (a gymnasium) in Växjö. Also a botanist, Rothman broadened Linnaeus’s interest in botany and helped him develop an interest in medicine.[24][25] By the age of 17, Linnaeus had become well acquainted with the existing botanical literature. He remarks in his journal that he «read day and night, knowing like the back of my hand, Arvidh Månsson’s Rydaholm Book of Herbs, Tillandz’s Flora Åboensis, Palmberg’s Serta Florea Suecana, Bromelii’s Chloros Gothica and Rudbeckii’s Hortus Upsaliensis».[26]

Linnaeus entered the Växjö Katedralskola in 1724, where he studied mainly Greek, Hebrew, theology and mathematics, a curriculum designed for boys preparing for the priesthood.[27][28] In the last year at the gymnasium, Linnaeus’s father visited to ask the professors how his son’s studies were progressing; to his dismay, most said that the boy would never become a scholar. Rothman believed otherwise, suggesting Linnaeus could have a future in medicine. The doctor offered to have Linnaeus live with his family in Växjö and to teach him physiology and botany. Nils accepted this offer.[29][30]

University studies

Lund

Rothman showed Linnaeus that botany was a serious subject. He taught Linnaeus to classify plants according to Tournefort’s system. Linnaeus was also taught about the sexual reproduction of plants, according to Sébastien Vaillant.[29] In 1727, Linnaeus, age 21, enrolled in Lund University in Skåne.[31][32] He was registered as Carolus Linnæus, the Latin form of his full name, which he also used later for his Latin publications.[3]

Professor Kilian Stobæus, natural scientist, physician and historian, offered Linnaeus tutoring and lodging, as well as the use of his library, which included many books about botany. He also gave the student free admission to his lectures.[33][34] In his spare time, Linnaeus explored the flora of Skåne, together with students sharing the same interests.[35]

Uppsala

Pollination depicted in Praeludia Sponsaliorum Plantarum (1729)

In August 1728, Linnaeus decided to attend Uppsala University on the advice of Rothman, who believed it would be a better choice if Linnaeus wanted to study both medicine and botany. Rothman based this recommendation on the two professors who taught at the medical faculty at Uppsala: Olof Rudbeck the Younger and Lars Roberg. Although Rudbeck and Roberg had undoubtedly been good professors, by then they were older and not so interested in teaching. Rudbeck no longer gave public lectures, and had others stand in for him. The botany, zoology, pharmacology and anatomy lectures were not in their best state.[36] In Uppsala, Linnaeus met a new benefactor, Olof Celsius, who was a professor of theology and an amateur botanist.[37] He received Linnaeus into his home and allowed him use of his library, which was one of the richest botanical libraries in Sweden.[38]

In 1729, Linnaeus wrote a thesis, Praeludia Sponsaliorum Plantarum on plant sexual reproduction. This attracted the attention of Rudbeck; in May 1730, he selected Linnaeus to give lectures at the University although the young man was only a second-year student. His lectures were popular, and Linnaeus often addressed an audience of 300 people.[39] In June, Linnaeus moved from Celsius’s house to Rudbeck’s to become the tutor of the three youngest of his 24 children. His friendship with Celsius did not wane and they continued their botanical expeditions.[40] Over that winter, Linnaeus began to doubt Tournefort’s system of classification and decided to create one of his own. His plan was to divide the plants by the number of stamens and pistils. He began writing several books, which would later result in, for example, Genera Plantarum and Critica Botanica. He also produced a book on the plants grown in the Uppsala Botanical Garden, Adonis Uplandicus.[41]

Rudbeck’s former assistant, Nils Rosén, returned to the University in March 1731 with a degree in medicine. Rosén started giving anatomy lectures and tried to take over Linnaeus’s botany lectures, but Rudbeck prevented that. Until December, Rosén gave Linnaeus private tutoring in medicine. In December, Linnaeus had a «disagreement» with Rudbeck’s wife and had to move out of his mentor’s house; his relationship with Rudbeck did not appear to suffer. That Christmas, Linnaeus returned home to Stenbrohult to visit his parents for the first time in about three years. His mother had disapproved of his failing to become a priest, but she was pleased to learn he was teaching at the University.[41][42]

Expedition to Lapland

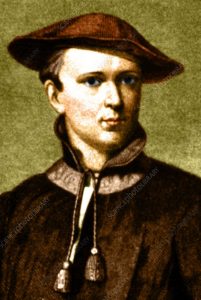

Carl Linnaeus in Laponian costume (1737)

During a visit with his parents, Linnaeus told them about his plan to travel to Lapland; Rudbeck had made the journey in 1695, but the detailed results of his exploration were lost in a fire seven years afterwards. Linnaeus’s hope was to find new plants, animals and possibly valuable minerals. He was also curious about the customs of the native Sami people, reindeer-herding nomads who wandered Scandinavia’s vast tundras. In April 1732, Linnaeus was awarded a grant from the Royal Society of Sciences in Uppsala for his journey.[43][44]

Wearing the traditional dress of the Sami people of Lapland, holding the twinflower, later known as Linnaea borealis, that became his personal emblem. Martin Hoffman, 1737.

Linnaeus began his expedition from Uppsala on 12 May 1732, just before he turned 25.[45] He travelled on foot and horse, bringing with him his journal, botanical and ornithological manuscripts and sheets of paper for pressing plants. Near Gävle he found great quantities of Campanula serpyllifolia, later known as Linnaea borealis, the twinflower that would become his favourite.[46] He sometimes dismounted on the way to examine a flower or rock[47] and was particularly interested in mosses and lichens, the latter a main part of the diet of the reindeer, a common and economically important animal in Lapland.[48]

Linnaeus travelled clockwise around the coast of the Gulf of Bothnia, making major inland incursions from Umeå, Luleå and Tornio. He returned from his six-month-long, over 2,000 kilometres (1,200 mi) expedition in October, having gathered and observed many plants, birds and rocks.[49][50][51] Although Lapland was a region with limited biodiversity, Linnaeus described about 100 previously unidentified plants. These became the basis of his book Flora Lapponica.[52][53] However, on the expedition to Lapland, Linnaeus used Latin names to describe organisms because he had not yet developed the binomial system.[45]

In Flora Lapponica Linnaeus’s ideas about nomenclature and classification were first used in a practical way, making this the first proto-modern Flora.[54] The account covered 534 species, used the Linnaean classification system and included, for the described species, geographical distribution and taxonomic notes. It was Augustin Pyramus de Candolle who attributed Linnaeus with Flora Lapponica as the first example in the botanical genre of Flora writing. Botanical historian E. L. Greene described Flora Lapponica as «the most classic and delightful» of Linnaeus’s works.[54]

It was also during this expedition that Linnaeus had a flash of insight regarding the classification of mammals. Upon observing the lower jawbone of a horse at the side of a road he was travelling, Linnaeus remarked: «If I only knew how many teeth and of what kind every animal had, how many teats and where they were placed, I should perhaps be able to work out a perfectly natural system for the arrangement of all quadrupeds.»[55]

In 1734, Linnaeus led a small group of students to Dalarna. Funded by the Governor of Dalarna, the expedition was to catalogue known natural resources and discover new ones, but also to gather intelligence on Norwegian mining activities at Røros.[51]

Years in the Dutch Republic (1735–38)

The Hamburg Hydra, from the Thesaurus (1734) of Albertus Seba. Linnaeus identified the hydra specimen as a fake in 1735.

View of Hartekamp, where Carl von Linné lived and studied for three years, from 1735 until 1738

Doctorate

Cities where he worked; those outside Sweden were only visited during 1735–1738.

His relations with Nils Rosén having worsened, Linnaeus accepted an invitation from Claes Sohlberg, son of a mining inspector, to spend the Christmas holiday in Falun, where Linnaeus was permitted to visit the mines.[56]

In April 1735, at the suggestion of Sohlberg’s father, Linnaeus and Sohlberg set out for the Dutch Republic, where Linnaeus intended to study medicine at the University of Harderwijk[57] while tutoring Sohlberg in exchange for an annual salary. At the time, it was common for Swedes to pursue doctoral degrees in the Netherlands, then a highly revered place to study natural history.[58]

On the way, the pair stopped in Hamburg, where they met the mayor, who proudly showed them a supposed wonder of nature in his possession: the taxidermied remains of a seven-headed hydra. Linnaeus quickly discovered the specimen was a fake, cobbled together from the jaws and paws of weasels and the skins of snakes. The provenance of the hydra suggested to Linnaeus that it had been manufactured by monks to represent the Beast of Revelation. Even at the risk of incurring the mayor’s wrath, Linnaeus made his observations public, dashing the mayor’s dreams of selling the hydra for an enormous sum. Linnaeus and Sohlberg were forced to flee from Hamburg.[59][60]

Linnaeus began working towards his degree as soon as he reached Harderwijk, a university known for awarding degrees in as little as a week.[61] He submitted a dissertation, written back in Sweden, entitled Dissertatio medica inauguralis in qua exhibetur hypothesis nova de febrium intermittentium causa,[note 3] in which he laid out his hypothesis that malaria arose only in areas with clay-rich soils.[62] Although he failed to identify the true source of disease transmission, (i.e., the Anopheles mosquito),[63] he did correctly predict that Artemisia annua (wormwood) would become a source of antimalarial medications.[62]

Within two weeks he had completed his oral and practical examinations and was awarded a doctoral degree.[59][61]

That summer Linnaeus reunited with Peter Artedi, a friend from Uppsala with whom he had once made a pact that should either of the two predecease the other, the survivor would finish the decedent’s work. Ten weeks later, Artedi drowned in the canals of Amsterdam, leaving behind an unfinished manuscript on the classification of fish.[64][65]

Publishing of Systema Naturae

One of the first scientists Linnaeus met in the Netherlands was Johan Frederik Gronovius, to whom Linnaeus showed one of the several manuscripts he had brought with him from Sweden. The manuscript described a new system for classifying plants. When Gronovius saw it, he was very impressed, and offered to help pay for the printing. With an additional monetary contribution by the Scottish doctor Isaac Lawson, the manuscript was published as Systema Naturae (1735).[66][67]

Linnaeus became acquainted with one of the most respected physicians and botanists in the Netherlands, Herman Boerhaave, who tried to convince Linnaeus to make a career there. Boerhaave offered him a journey to South Africa and America, but Linnaeus declined, stating he would not stand the heat. Instead, Boerhaave convinced Linnaeus that he should visit the botanist Johannes Burman. After his visit, Burman, impressed with his guest’s knowledge, decided Linnaeus should stay with him during the winter. During his stay, Linnaeus helped Burman with his Thesaurus Zeylanicus. Burman also helped Linnaeus with the books on which he was working: Fundamenta Botanica and Bibliotheca Botanica.[68]

George Clifford, Philip Miller, and Johann Jacob Dillenius

In August 1735, during Linnaeus’s stay with Burman, he met George Clifford III, a director of the Dutch East India Company and the owner of a rich botanical garden at the estate of Hartekamp in Heemstede. Clifford was very impressed with Linnaeus’s ability to classify plants, and invited him to become his physician and superintendent of his garden. Linnaeus had already agreed to stay with Burman over the winter, and could thus not accept immediately. However, Clifford offered to compensate Burman by offering him a copy of Sir Hans Sloane’s Natural History of Jamaica, a rare book, if he let Linnaeus stay with him, and Burman accepted.[69][70] On 24 September 1735, Linnaeus moved to Hartekamp to become personal physician to Clifford, and curator of Clifford’s herbarium. He was paid 1,000 florins a year, with free board and lodging. Though the agreement was only for a winter of that year, Linnaeus practically stayed there until 1738.[71] It was here that he wrote a book Hortus Cliffortianus, in the preface of which he described his experience as «the happiest time of my life». (A portion of Hartekamp was declared as public garden in April 1956 by the Heemstede local authority, and was named «Linnaeushof».[72] It eventually became, as it is claimed, the biggest playground in Europe.[73])

In July 1736, Linnaeus travelled to England, at Clifford’s expense.[74] He went to London to visit Sir Hans Sloane, a collector of natural history, and to see his cabinet,[75] as well as to visit the Chelsea Physic Garden and its keeper, Philip Miller. He taught Miller about his new system of subdividing plants, as described in Systema Naturae. Miller was in fact reluctant to use the new binomial nomenclature, preferring the classifications of Joseph Pitton de Tournefort and John Ray at first. Linnaeus, nevertheless, applauded Miller’s Gardeners Dictionary,[76] The conservative Scot actually retained in his dictionary a number of pre-Linnaean binomial signifiers discarded by Linnaeus but which have been retained by modern botanists. He only fully changed to the Linnaean system in the edition of The Gardeners Dictionary of 1768. Miller ultimately was impressed, and from then on started to arrange the garden according to Linnaeus’s system.[77]

Linnaeus also travelled to Oxford University to visit the botanist Johann Jacob Dillenius. He failed to make Dillenius publicly fully accept his new classification system, though the two men remained in correspondence for many years afterwards. Linnaeus dedicated his Critica Botanica to him, as «opus botanicum quo absolutius mundus non-vidit«. Linnaeus would later name a genus of tropical tree Dillenia in his honour. He then returned to Hartekamp, bringing with him many specimens of rare plants.[78] The next year, 1737, he published Genera Plantarum, in which he described 935 genera of plants, and shortly thereafter he supplemented it with Corollarium Generum Plantarum, with another sixty (sexaginta) genera.[79]

His work at Hartekamp led to another book, Hortus Cliffortianus, a catalogue of the botanical holdings in the herbarium and botanical garden of Hartekamp. He wrote it in nine months (completed in July 1737), but it was not published until 1738.[68] It contains the first use of the name Nepenthes, which Linnaeus used to describe a genus of pitcher plants.[80][note 4]

Linnaeus stayed with Clifford at Hartekamp until 18 October 1737 (new style), when he left the house to return to Sweden. Illness and the kindness of Dutch friends obliged him to stay some months longer in Holland. In May 1738, he set out for Sweden again. On the way home, he stayed in Paris for about a month, visiting botanists such as Antoine de Jussieu. After his return, Linnaeus never left Sweden again.[81][82]

Return to Sweden

When Linnaeus returned to Sweden on 28 June 1738, he went to Falun, where he entered into an engagement to Sara Elisabeth Moræa. Three months later, he moved to Stockholm to find employment as a physician, and thus to make it possible to support a family.[83][84] Once again, Linnaeus found a patron; he became acquainted with Count Carl Gustav Tessin, who helped him get work as a physician at the Admiralty.[85][86] During this time in Stockholm, Linnaeus helped found the Royal Swedish Academy of Science; he became the first Praeses of the academy by drawing of lots.[87]

Because his finances had improved and were now sufficient to support a family, he received permission to marry his fiancée, Sara Elisabeth Moræa. Their wedding was held 26 June 1739. Seventeen months later, Sara gave birth to their first son, Carl. Two years later, a daughter, Elisabeth Christina, was born, and the subsequent year Sara gave birth to Sara Magdalena, who died when 15 days old. Sara and Linnaeus would later have four other children: Lovisa, Sara Christina [sv], Johannes and Sophia.[83][88]

In May 1741, Linnaeus was appointed Professor of Medicine at Uppsala University, first with responsibility for medicine-related matters. Soon, he changed place with the other Professor of Medicine, Nils Rosén, and thus was responsible for the Botanical Garden (which he would thoroughly reconstruct and expand), botany and natural history, instead. In October that same year, his wife and nine-month-old son followed him to live in Uppsala.[89]

Öland and Gotland

Ten days after he was appointed Professor, he undertook an expedition to the island provinces of Öland and Gotland with six students from the university to look for plants useful in medicine. First, they travelled to Öland and stayed there until 21 June, when they sailed to Visby in Gotland. Linnaeus and the students stayed on Gotland for about a month, and then returned to Uppsala. During this expedition, they found 100 previously unrecorded plants. The observations from the expedition were later published in Öländska och Gothländska Resa, written in Swedish. Like Flora Lapponica, it contained both zoological and botanical observations, as well as observations concerning the culture in Öland and Gotland.[90][91]

During the summer of 1745, Linnaeus published two more books: Flora Suecica and Fauna Suecica. Flora Suecica was a strictly botanical book, while Fauna Suecica was zoological.[83][92] Anders Celsius had created the temperature scale named after him in 1742. Celsius’s scale was inverted compared to today, the boiling point at 0 °C and freezing point at 100 °C. In 1745, Linnaeus inverted the scale to its present standard.[93]

Västergötland

In the summer of 1746, Linnaeus was once again commissioned by the Government to carry out an expedition, this time to the Swedish province of Västergötland. He set out from Uppsala on 12 June and returned on 11 August. On the expedition his primary companion was Erik Gustaf Lidbeck, a student who had accompanied him on his previous journey. Linnaeus described his findings from the expedition in the book Wästgöta-Resa, published the next year.[90][94] After he returned from the journey, the Government decided Linnaeus should take on another expedition to the southernmost province Scania. This journey was postponed, as Linnaeus felt too busy.[83]

In 1747, Linnaeus was given the title archiater, or chief physician, by the Swedish king Adolf Frederick—a mark of great respect.[95] The same year he was elected member of the Academy of Sciences in Berlin.[96]

Scania

In the spring of 1749, Linnaeus could finally journey to Scania, again commissioned by the Government. With him he brought his student, Olof Söderberg. On the way to Scania, he made his last visit to his brothers and sisters in Stenbrohult since his father had died the previous year. The expedition was similar to the previous journeys in most aspects, but this time he was also ordered to find the best place to grow walnut and Swedish whitebeam trees; these trees were used by the military to make rifles. While there, they also visited the Ramlösa mineral spa, where he remarked on the quality of its ferruginous water.[97] The journey was successful, and Linnaeus’s observations were published the next year in Skånska Resa.[98][99]

Rector of Uppsala University

Summer home at his Hammarby estate

In 1750, Linnaeus became rector of Uppsala University, starting a period where natural sciences were esteemed.[83] Perhaps the most important contribution he made during his time at Uppsala was to teach; many of his students travelled to various places in the world to collect botanical samples. Linnaeus called the best of these students his «apostles».[100] His lectures were normally very popular and were often held in the Botanical Garden. He tried to teach the students to think for themselves and not trust anybody, not even him. Even more popular than the lectures were the botanical excursions made every Saturday during summer, where Linnaeus and his students explored the flora and fauna in the vicinity of Uppsala.[101]

Philosophia Botanica

Linnaeus published Philosophia Botanica in 1751.[102] The book contained a complete survey of the taxonomy system he had been using in his earlier works. It also contained information of how to keep a journal on travels and how to maintain a botanical garden.[103]

Nutrix Noverca

Cover of Nutrix Noverca (1752)

During Linnaeus’s time it was normal for upper class women to have wet nurses for their babies. Linnaeus joined an ongoing campaign to end this practice in Sweden and promote breast-feeding by mothers. In 1752 Linnaeus published a thesis along with Frederick Lindberg, a physician student,[104] based on their experiences.[105] In the tradition of the period, this dissertation was essentially an idea of the presiding reviewer (prases) expounded upon by the student. Linnaeus’s dissertation was translated into French by J. E. Gilibert in 1770 as La Nourrice marâtre, ou Dissertation sur les suites funestes du nourrisage mercénaire. Linnaeus suggested that children might absorb the personality of their wet nurse through the milk. He admired the child care practices of the Lapps[106] and pointed out how healthy their babies were compared to those of Europeans who employed wet nurses. He compared the behaviour of wild animals and pointed out how none of them denied their newborns their breastmilk.[106] It is thought that his activism played a role in his choice of the term Mammalia for the class of organisms.[107]

Species Plantarum

Linnaeus published Species Plantarum, the work which is now internationally accepted as the starting point of modern botanical nomenclature, in 1753.[108] The first volume was issued on 24 May, the second volume followed on 16 August of the same year.[note 5][110] The book contained 1,200 pages and was published in two volumes; it described over 7,300 species.[111][112] The same year the king dubbed him knight of the Order of the Polar Star, the first civilian in Sweden to become a knight in this order. He was then seldom seen not wearing the order’s insignia.[113]

Ennoblement

Linnaeus felt Uppsala was too noisy and unhealthy, so he bought two farms in 1758: Hammarby and Sävja. The next year, he bought a neighbouring farm, Edeby. He spent the summers with his family at Hammarby; initially it only had a small one-storey house, but in 1762 a new, larger main building was added.[99][114] In Hammarby, Linnaeus made a garden where he could grow plants that could not be grown in the Botanical Garden in Uppsala. He began constructing a museum on a hill behind Hammarby in 1766, where he moved his library and collection of plants. A fire that destroyed about one third of Uppsala and had threatened his residence there necessitated the move.[115]

Since the initial release of Systema Naturae in 1735, the book had been expanded and reprinted several times; the tenth edition was released in 1758. This edition established itself as the starting point for zoological nomenclature, the equivalent of Species Plantarum.[111][116]

The Swedish King Adolf Frederick granted Linnaeus nobility in 1757, but he was not ennobled until 1761. With his ennoblement, he took the name Carl von Linné (Latinised as Carolus a Linné), ‘Linné’ being a shortened and gallicised version of ‘Linnæus’, and the German nobiliary particle ‘von’ signifying his ennoblement.[3] The noble family’s coat of arms prominently features a twinflower, one of Linnaeus’s favourite plants; it was given the scientific name Linnaea borealis in his honour by Gronovius. The shield in the coat of arms is divided into thirds: red, black and green for the three kingdoms of nature (animal, mineral and vegetable) in Linnaean classification; in the centre is an egg «to denote Nature, which is continued and perpetuated in ovo.» At the bottom is a phrase in Latin, borrowed from the Aeneid, which reads «Famam extendere factis«: we extend our fame by our deeds.[117][118][119] Linnaeus inscribed this personal motto in books that were given to him by friends.[120]

After his ennoblement, Linnaeus continued teaching and writing. His reputation had spread over the world, and he corresponded with many different people. For example, Catherine II of Russia sent him seeds from her country.[121] He also corresponded with Giovanni Antonio Scopoli, «the Linnaeus of the Austrian Empire», who was a doctor and a botanist in Idrija, Duchy of Carniola (nowadays Slovenia).[122] Scopoli communicated all of his research, findings, and descriptions (for example of the olm and the dormouse, two little animals hitherto unknown to Linnaeus). Linnaeus greatly respected Scopoli and showed great interest in his work. He named a solanaceous genus, Scopolia, the source of scopolamine, after him, but because of the great distance between them, they never met.[123][124]

Final years

Linnaeus was relieved of his duties in the Royal Swedish Academy of Science in 1763, but continued his work there as usual for more than ten years after.[83] In 1769 he was elected to the American Philosophical Society for his work.[125] He stepped down as rector at Uppsala University in December 1772, mostly due to his declining health.[82][126]

Linnaeus’s last years were troubled by illness. He had had a disease called the Uppsala fever in 1764, but survived due to the care of Rosén. He developed sciatica in 1773, and the next year, he had a stroke which partially paralysed him.[127] He had a second stroke in 1776, losing the use of his right side and leaving him bereft of his memory; while still able to admire his own writings, he could not recognise himself as their author.[128][129]

In December 1777, he had another stroke which greatly weakened him, and eventually led to his death on 10 January 1778 in Hammarby.[130][126] Despite his desire to be buried in Hammarby, he was buried in Uppsala Cathedral on 22 January.[131][132]

His library and collections were left to his widow Sara and their children. Joseph Banks, an eminent botanist, wished to purchase the collection, but his son Carl refused the offer and instead moved the collection to Uppsala. In 1783 Carl died and Sara inherited the collection, having outlived both her husband and son. She tried to sell it to Banks, but he was no longer interested; instead an acquaintance of his agreed to buy the collection. The acquaintance was a 24-year-old medical student, James Edward Smith, who bought the whole collection: 14,000 plants, 3,198 insects, 1,564 shells, about 3,000 letters and 1,600 books. Smith founded the Linnean Society of London five years later.[132][133]

The von Linné name ended with his son Carl, who never married.[6] His other son, Johannes, had died aged 3.[134] There are over two hundred descendants of Linnaeus through two of his daughters.[6]

Apostles

During Linnaeus’s time as Professor and Rector of Uppsala University, he taught many devoted students, 17 of whom he called «apostles». They were the most promising, most committed students, and all of them made botanical expeditions to various places in the world, often with his help. The amount of this help varied; sometimes he used his influence as Rector to grant his apostles a scholarship or a place on an expedition.[135] To most of the apostles he gave instructions of what to look for on their journeys. Abroad, the apostles collected and organised new plants, animals and minerals according to Linnaeus’s system. Most of them also gave some of their collection to Linnaeus when their journey was finished.[136] Thanks to these students, the Linnaean system of taxonomy spread through the world without Linnaeus ever having to travel outside Sweden after his return from Holland.[137] The British botanist William T. Stearn notes, without Linnaeus’s new system, it would not have been possible for the apostles to collect and organise so many new specimens.[138] Many of the apostles died during their expeditions.

Early expeditions

Christopher Tärnström, the first apostle and a 43-year-old pastor with a wife and children, made his journey in 1746. He boarded a Swedish East India Company ship headed for China. Tärnström never reached his destination, dying of a tropical fever on Côn Sơn Island the same year. Tärnström’s widow blamed Linnaeus for making her children fatherless, causing Linnaeus to prefer sending out younger, unmarried students after Tärnström.[139] Six other apostles later died on their expeditions, including Pehr Forsskål and Pehr Löfling.[138]

Two years after Tärnström’s expedition, Finnish-born Pehr Kalm set out as the second apostle to North America. There he spent two-and-a-half years studying the flora and fauna of Pennsylvania, New York, New Jersey and Canada. Linnaeus was overjoyed when Kalm returned, bringing back with him many pressed flowers and seeds. At least 90 of the 700 North American species described in Species Plantarum had been brought back by Kalm.[140]

Cook expeditions and Japan

Daniel Solander was living in Linnaeus’s house during his time as a student in Uppsala. Linnaeus was very fond of him, promising Solander his eldest daughter’s hand in marriage. On Linnaeus’s recommendation, Solander travelled to England in 1760, where he met the English botanist Joseph Banks. With Banks, Solander joined James Cook on his expedition to Oceania on the Endeavour in 1768–71.[141][142] Solander was not the only apostle to journey with James Cook; Anders Sparrman followed on the Resolution in 1772–75 bound for, among other places, Oceania and South America. Sparrman made many other expeditions, one of them to South Africa.[143]

Perhaps the most famous and successful apostle was Carl Peter Thunberg, who embarked on a nine-year expedition in 1770. He stayed in South Africa for three years, then travelled to Japan. All foreigners in Japan were forced to stay on the island of Dejima outside Nagasaki, so it was thus hard for Thunberg to study the flora. He did, however, manage to persuade some of the translators to bring him different plants, and he also found plants in the gardens of Dejima. He returned to Sweden in 1779, one year after Linnaeus’s death.[144]

Major publications

Systema Naturae

The first edition of Systema Naturae was printed in the Netherlands in 1735. It was a twelve-page work.[145] By the time it reached its 10th edition in 1758, it classified 4,400 species of animals and 7,700 species of plants. People from all over the world sent their specimens to Linnaeus to be included. By the time he started work on the 12th edition, Linnaeus needed a new invention—the index card—to track classifications.[146]