За всю историю человечества было огромное множество войн, от локальных стычек и княжеских междоусобиц до кошмарных ужасов двух мировых войн прошлого ХХ века. Война – это всегда страшное и горестное событие, влекущее за собой смерть и разрушение, в ней нет места красоте и поэзии. Тем более странно выглядит, пожалуй, самое поэтическое название, какое только можно было дать войне – война алой и белой розы. Случилась эта война в средневековой Англии, в куртуазную эпоху рыцарей и королей, а столь поэтичное название ей присвоил шотландский историк, более известный как писатель-прозаик – сер Вальтер Скот. Итак, что это была за такая война, кто с кем воевал и за что, и какое ее значение для истории, как Англии, так и общемировой истории, обо всем этом читайте дальше.

Причины войны

В 1412-1422 году королем Англии был Генрих V Ланкастер. Он был талантливым правителем и не менее талантливым полководцем, как и его предшественники с успехом громил французов на полях сражений столетней войны. В результате его правления англичане смогли занять значительные французские территории, а сам английский король женился на французской принцессе – Екатерине Валуа. Их сын Генрих VI Ланкастер должен был стать королем, как Англии, так и Франции, примирив оба воющие государства.

Гербом королевского рода Ланкастеров была алая роза.

Но не все случилось, как того хотелось Генриху V: вскоре французы усилили свое сопротивление, во главе которого стала героиня французского народа, Орлеанская Дева – Жанна Д’арк. Сам же Генрих V подхватил болезнь, как полагают историки, это была дизентерия, от которой и скончался в молодом 35-летнем возрасте (состояние медицины в Средние века оставляло желать лучшего). Его же сын, наследник престола – Генрих VI оказался душевнобольным.

В результате Англия потеряла все свои прежние завоевания во Франции (за исключением города Кале), и потерпела поражение в столетней войне. В самой Англии состояние дел также оставляло желать лучшего: страна была истощена столетней войной, к тому же назревал кризис феодальной системы, недовольные постоянными поборами английские крестьяне устроили целый ряд восстаний, наибольшим из которых было крестьянское восстание Уотта Тайлера, охватившее почти всю Англию.

Новый английский король Генрих VI Ланкастер периодически впадал в приступы безумия, и в это время Англией пыталась управлять его жена, также француженка, королева Маргарита Анжуйская. Она хотя и была властной и умной женщиной, однако не пользовалась популярностью среди английских дворян от слова совсем (еще бы, «женщина, да еще и француженка будет нам тут управлять Англией, да никогда!», примерно так, наверное, думали они). Поэтому вскоре недовольные дворяне решили назначить душевнобольному королю регента, на эту роль выбрали двоюродного брата короля – Ричарда Плантагенета, герцога Йоркского, вокруг него уже долгое время собиралась сильная дворянская партия.

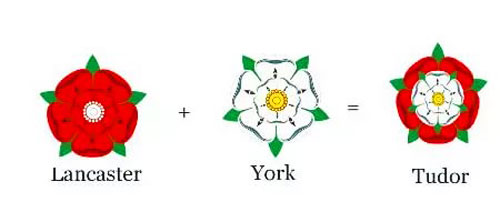

И вот, несмотря на протесты королевы, Ричард Плантагенет, представитель родственной династии Йорков, гербом которой была белая роза, становится регентом больного короля и одновременно получает высокий титул лорда-протектора Англии.

Герб династии Йорков.

Королева, разумеется, вовсе не рада такому повороту событий, она вполне не безосновательно опасается, что их с Генрихом сын, принц Эдуард, который должен был стать новым королем Англии, теперь может пролететь мимо престола как фанера над Лондоном. Поэтому воспользовавшись тем, что королю стало легче, а его душевное состояние улучшилось, она подговаривает супруга сместить регента и самому взять на себя управление страной, а партию Йорков и вовсе изгнать из большого королевского совета. Что король и делает.

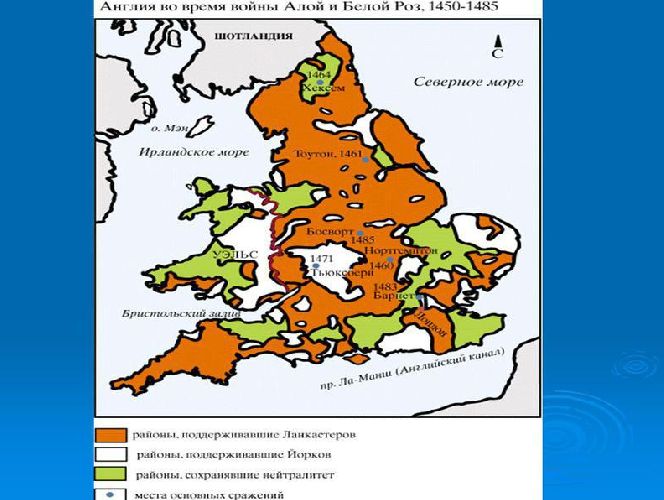

Вот только Ричард Йоркский не желает лишаться столь высокого титула и начинает собирать войска, его поддерживают могущественные графы Уорвик и Солсбери. Ланкастеры также в свою очередь собирают войска и верных сторонников, их поддержали северные бароны, убежденные консерваторы, правящие в наиболее экономично отсталом районе Англии, в то время как к Йоркам примкнули жители более экономически продвинутой Южной Англии, купцы, прогрессивные дворяне. Так начинается гражданская война между двумя аристократическими английскими династиями: Йорками и Ланкастерами, война, которую по цвету гербов воюющих сторон веками позднее сер Вальтер Скот поэтически назовет «войной алой и белой розы».

Итак, подведем итоги, касательно причин начала войны алой и белой розы:

- Поражение Англии в столетней войне. Оно подорвало авторитет королевской власти и сделало возможным сам факт, того, что дворяне могут столь открыто выступить против короля.

- Плохое отношение англичан к королеве, француженке Маргарите Анжуйской, по сути эта война в немалой степени ее заслуга (да, порой войны начинались из-за женщин, и эта война одна из них).

- Политическая нестабильность, связанная с душевным здоровьем короля.

- Наличие разных ветвей Плантагенетов (напомним, Ричард и Генрих были двоюродными братьями) в равной степени претендующих на власть.

- Общий кризис феодального землевладения, массовое недовольство устаревшими феодальными порядками.

История войны

Итак, война началось, первое столкновение между Ланкастерами и Йорками произошло в мае 1455 года в битве при Сент-Олбансе. Королевские войска Ланкастеров оказались хуже подготовленными и поэтому потерпели сокрушительное поражение, многие знатные сторонники Ланкастеров были убиты в той битве. Еще более сокрушительно поражение Ланкастеры получили в битве при Нортгемптоне, после которой король попал в плен к Йоркам, а Ричард Йорк смог беспрепятственно войти в Лондон. Казалось, вот она победа. Но борьба продолжилась, королева Маргарита Анжуйская избежала плена, она собрала остатки верных Ланкастерам войск и в битве при Уэйкфилде нанесла сокрушительное поражение уже Йоркам. Ричард Йорк погиб в этой битве, так и не став королем.

После смерти Ричарда Йорков возглавил его старший сын – Эдуард. Вместе со сподвижником графом Уорвиком они нанесли ряд поражений Ланкастерам, вследствие которых Маргарита Анжуйская вместе с сыном были вынуждены бежать из страны. Старый король, душевнобольной Генрих VI Ланкастер был заключен в лондонский Тауэр, а Эдуард объявил себя новым королем Англии – Эдуардом IV. Первым же указом нового короля все Ланкастеры объявлялись предателями Англии. Казалось вот она, победа Йорков, но и это еще далеко был не конец.

Эдуард IV на английском престоле оказался весьма жестким, упрямым и своевольным королем, лишенным дипломатической гибкости, он вскоре разругался со многими своими сторонниками, среди которых был младший брат короля – герцог Кларенс и уже упомянутый нами граф Уорвик, которого англичане прозвали «деятелем королей» (так как в победе Йорков была его немалая заслуга). Кларенс и Уорвик перешли на сторону Ланкастеров, и война алой и белой розы возобновилась с новой силой.

Войскам Ланкастеров вновь улыбнулась военная удача, Эдуард IV теснимый своими противниками вынужден отступить в Бургундию. В том числе Уорвик освободил из Тауэра старого короля Генриха VI.

Однако честолюбивый граф Уорвик вовсе не собирался помогать Ланкастерам, у него были свои планы на корону, так на английский трон он собирался посадить своего брата Джорджа, и для этого якобы под предлогом защиты пленил старого короля Ланкастера в своем замке.

В это время Эдуард IV помирился со своим братом Кларенсом и вновь перешел в наступление, нанеся войскам Ланкастеров ряд сокрушительных поражений, наиболее значимым из которых была битва при Тьюксбери, получившая название «кровавый луг». В ней погибли все видные сторонники Ланкастеров, включая наследного принца Эдуарда, сына Генриха VI и Маргариты Анжуйской. Сам Генрих VI пережил своего сына лишь на несколько дней, всем было объявлено, что старый король скончался от горя, узнав от смерти сына. Хотя как современниками, так и поздними историками было высказано сомнение в природности смерти Генриха, скорее всего он был убит по приказу Эдуарда IV, желавшего устранить последнего законного претендента на английскую корону.

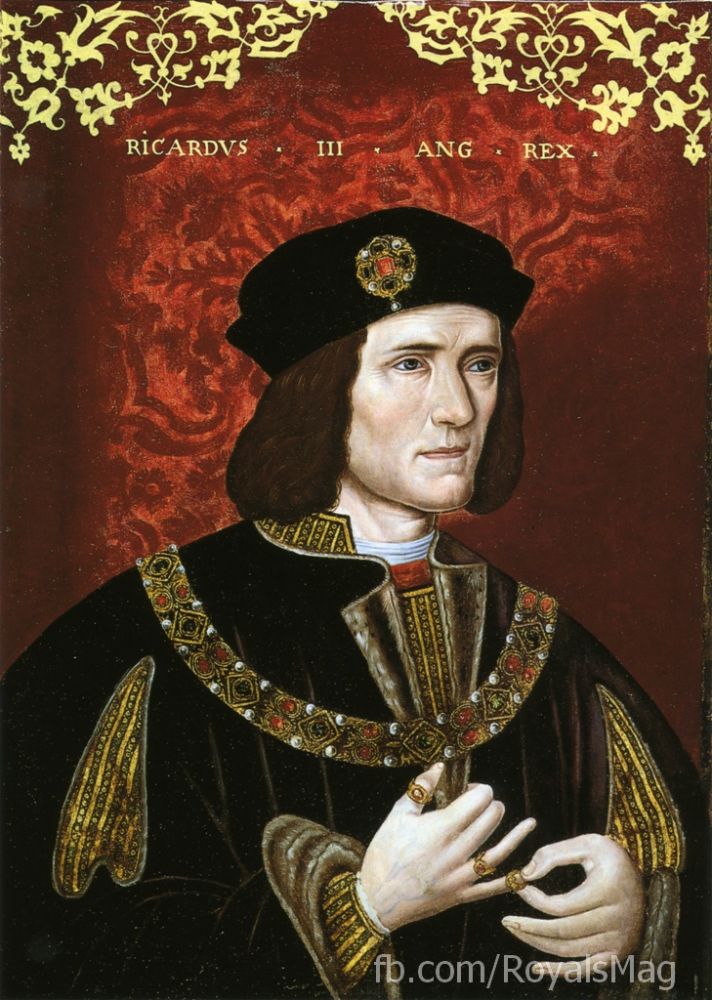

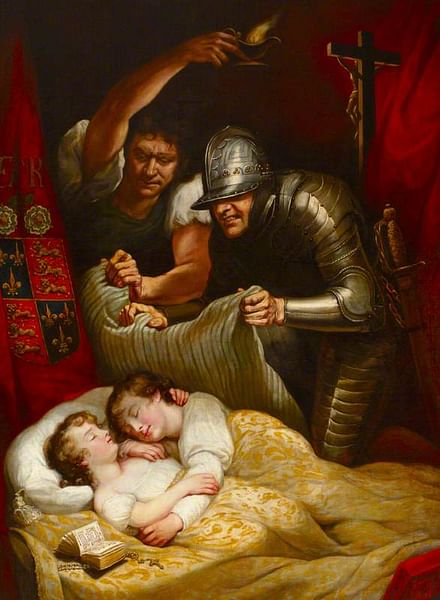

После этих событий на определенное время в Англии воцарился мир, Эдуард IV Йорк спокойно правил страной до самой своей смерти в 1483 году. После этого престол по закону должен был перейти его малолетнему сыну, Эдуарду V Йорку. Но тут вмешался один из младших братьев умершего короля – Ричард Глостер. Он объявил своих племянников незаконнорожденными, заточил в Тауэр, где те вскоре были убиты по приказу дядюшки, а сам стал новым королем Англии под именем Ричарда ІІІ.

Однако новым королем были недовольны, как представители династии Йорков, так и казалось бы уже полностью сломленные Ланкастеры. Оппозицию новому королю возглавил Генрих Тюдор, внук Екатерины Валуа и племянник Генриха VI. Оставшись вдовой после смерти Генриха V Ланкастера, будучи еще совсем молодой женщиной, Екатерина завела роман с уельским дворянином Огюстом Тюдором, от которого родила шестеро детей, включая отца Генриха Тюдора.

И вот в августе 1485 года, Генрих Тюдор, который до этого всю жизнь жил во Франции вместе с войском высаживается в Англии. Ричард ІІІ пытается оказать сопротивление, но многие дворяне, включая родственников из династии Йорков, переходят на сторону Генриха Тюдора. Ричард гибнет в битве, а Генрих Тюдор становится новым английским королем под именем Генриха VII, в истории Англии начинается новый яркий период. На знак примирения двух враждебных династий Генрих в качестве своего герба объединяет алую и белую розы.

Герб Тюдоров.

Таковы вкратце события войны алой и белой розы.

Итоги

- Генрих VII установил мир в стране, для примирения даже женился на дочери Эдуарда Йорка, таким образом, две враждующие династии оказались связанными династическим браком.

- Династия Тюдоров воцарилась в Англии, а при последующих правителях из этой династии: Генрихе VIIІ и в особенности Елизавете І Тюдор Англия получила огромное политическое и экономическое развитие.

- Многие старинные дворянские роды в Англии были истреблены в ходе этой жестокой войны, произошел упадок дворянство, но с другой стороны, произошло усиление купечества, именно купцы, а не дворяне, стали основной социальной опорой Тюдоров.

Вскоре политика новых просвещенных правителей Англии привела к экономическому росту, развитию экономики, науки, (Тюдоры, понимая важность знаний, активно покровительствовали английским университетам, и не зря, ведь сейчас они одни из лучших в мире), общему возвышению Англии. А для общемировой истории последствия хотя бы в том, что сейчас все мы учим именно английский язык, как язык международного общения, а не любой другрй, и это все не в последнюю очередь, потому, что после династической гражданской войны к власти в Англии все же пришли правильные люди.

Видео

И в завершение интересный документальный фильм об этой войне.

Автор: Павел Чайка, главный редактор исторического сайта Путешествия во времени

При написании статьи старался сделать ее максимально интересной, полезной и качественной. Буду благодарен за любую обратную связь и конструктивную критику в виде комментариев к статье. Также Ваше пожелание/вопрос/предложение можете написать на мою почту pavelchaika1983@gmail.com или в Фейсбук, с уважением автор.

История войны Алой и Белой розы

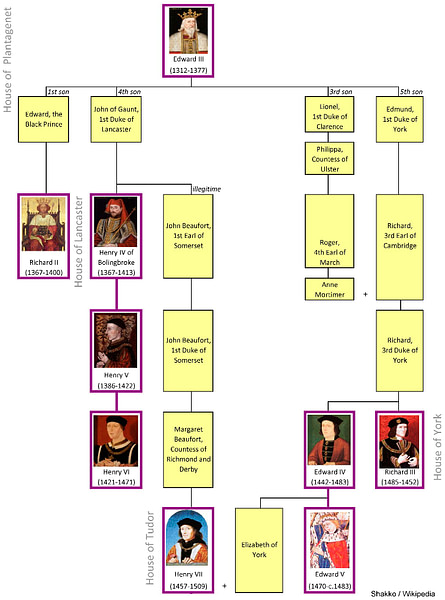

Точную дату начала Войны Роз определить нельзя: споры длятся уже 5 столетий. Непосредственной причиной конфликта стал династический кризис — следствие сверхплодовитости короля Эдуарда III (1327−1377 гг.). Борьба за престол между наследниками двух его сыновей — Джона Гонта и Эдмунда Йорка — вылилась почти в полувековую вооружённую борьбу двух самых могущественных и богатых феодальных домов Англии. Но к концу XV столетия они почти полностью истребили друг друга: мужская линия Ланкастеров пресеклась ещё в 1471 году после смерти принца Эдуарда, сына Генриха VI и Маргариты Анжуйской, а последний Йорк, Ричард III, был убит в битве при Босворте в 1485 году.

Елизавета Йорк и Генрих VII Тюдор. (wikipedia.org)

Итогом продолжительных распрей придворных группировок стало воцарение новой династии Тюдоров, основателем которой был Генрих VII. Он являлся дальним родственником Ланкастеров и для легализации своих прав на престол взял в жены последнюю оставшуюся в живых представительницу Йорков — дочь Эдуарда IV Елизавету.

Именно на королевской свадьбе впервые появляется знаменитая эмблема двух соединённых роз — Алой и Белой. До этого никто даже не задумывался о знаменитой метафоре, которая позже найдёт своё место на страницах произведений Шекспира и Вальтера Скотта.

Ланкастеры и Йорки

Влияние Войн Роз на историю Англии огромно: эта серия конфликтов привела к воцарению новой династии и утверждению абсолютизма. И все же называть это полномасштабной гражданской войной будет неправильно. Для этой эпохи больше подходит термин «немирье» (архаизм, означающий немирное или военное время. — Толковый словарь В. И. Даля).

Борьба придворных партий за английскую корону не могла не отразиться на жизни в провинции. Мелкие дворяне были вынуждены вступать в войну, чтобы не потерять расположение лорда-покровителя. Сами джентри (так называли «новое дворянство» Англии той эпохи) не имели никаких предпочтений в правящих династиях. Мирная обстановка и стабильность являлись для них куда более важными, чем соблюдение очерёдности престолонаследия. Во время политической борьбы в центре на местах также происходили волнения, но до убийств дворян дело доходило редко, обычно враждовавшие стороны ограничивались угоном скота, запугиванием и в крайнем случае убийством слуг.

Битва при Таутоне, 29 марта 1461. (wikipedia.org)

Количество павших дворян в самих битвах придворных партий сравнительно невелико. Тот факт, что джентри бились не за свои убеждения, а за покровительство лорда-протектора, доказывает, что никакой кровавой гражданской войны в сознании современников не было и не могло быть. Для людей, далёких от двора, это была серия затянувшихся конфликтов в высших кругах.

Выступления третьего сословия в войнах и вовсе было лишь несколько раз, самое знаменитое — восстание Джека Кеда в 1450 году. Однако многие современники называют это движение «грабительским»: никаких благородных целей, кроме разбоя, восставшие не преследовали.

Ричард Йорк. Начало мифологизации

Создание мифа о войне Алой и Белой Роз началось ещё во время восстания Ричарда Йорка в 1452 году. Герцог активно пользовался достижениями пропаганды той эпохи. В своих призывах к восстанию он начал делать упор на незаконность приобретения власти Генрихом VI — ведь дед короля получил престол, свергнув своего дядю, Ричарда II еще в 1399 году.

Ричард III Плантагенет. (wikipedia.org)

Этот вариант мифа быстро набирал популярность в среде английских аристократов, которые были недовольны правлением Генриха и всевластием партии Ланкастеров во главе с королевой Маргаритой, которую противники прозвали «Королевой шипов»

Ричард III и Генрих VII. Гравюра Уильяма Фейторна, 1640. (wikipedia.org)

Второй вариант мифа был создан уже в конце династической войны, сразу после женитьбы Генриха VII Тюдора на наследнице Йорков. Именно в это время начали демонизировать образ Ричарда III: он стал кровожадным тираном, дето- и братоубийцей. Остальные участники конфликта вырисовывались в нейтральных тонах. В этом мифе упор делался не на критику Ланкастеров, чьим дальним предком был Генрих, а на жесткие обвинения в адрес предшествовавшего правителя.

Распространению этой версии в народной среде способствовала противоречивость, которой окутано восхождение Ричарда на престол: после смерти Эдуарда IV, своего старшего брата, он стал регентом при малолетних детях короля — принцах Эдуарде и Ричарде. Однако уже через полгода Ричард Глостер объявил мальчиков бастардами, а себя — законным наследником. Получив согласие парламента, он короновался в июле 1483 года. Судьба сыновей Эдуарда так и осталась неизвестной: по одной версии, «принцев из Тауэра» убил собственный дядя, по другой, — им удалось сбежать во Францию. Первая версия оказалась гораздо более привлекательной для пропагандистской машины Тюдоров.

Вскоре после укрепления своей власти Генрих VII начал забывать о том, что половиной короны он обязан жене. Началась третья переработка истории, в которой было принято критиковать Йорков и прославлять Ланкастеров, а также представлять эпоху не как серию конфликтов придворных партий, а как непрерывную войну, избавителем от которой выступал юный Тюдор.

Четвертая стадия трансформации мифа была при Генрихе VIII. В нем текла кровь двух династий, поэтому критиковать одну из них не было необходимости. Предки короля, как Ланкастеры, так и Йорки (кроме Ричарда III), теперь стали жертвами обстоятельств. Всю вину за развязывание гражданской войны возложили на иноземку Маргариту Анжуйскую. А образ последнего из династии Йорков в труде известного гуманиста Томаса Мора «История Ричарда III» приобрел новые черты: автор приписывает горе-королю знаменитый горб и высохшую левую руку.

Маргарита Анжуйская, королева Англии. (wikipedia.org)

В царствование Елизаветы миф был переработан в пятый раз. Целью тюдоровской пропаганды стало утверждение идиллии елизаветинской эпохи на фоне ужасных и темных времён феодальных распрей. Тут появляются знаменитые «Исторические хроники» Шекспира. Перу великого драматурга принадлежит знаменитая сцена, где в саду Тауэра Ланкастеры и Йорки прикалывают себе алые и белые розы в знак непримиримой борьбы до победного конца. Именно Шекспир создал образ темной и кровожадной эпохи беспрерывных братоубийственных войн, привлекающий своей трагичностью и героизмом.

Созданные Шекспиром стереотипы на два столетия закрепили в сознании англичан образ масштабной кровопролитной войны. Наконец, в XVIII веке Вальтер Скотт предложил термин «Война Алой и Белой Роз», который показался современникам настолько удачным, что он используется в науке до сих пор.

Развенчание тюдоровского мифа началось только в XX веке. Пошёл процесс повальной реабилитации героев истории. Доходило до крайностей: были созданы многочисленные общества Ричарда III, члены которых убеждены, что не было у Англии короля лучше. События Войн Роз изучаются и сегодня, но многие вопросы так и остаются без ответов.

Война Алой и Белой розы

4.5

Средняя оценка: 4.5

Всего получено оценок: 471.

4.5

Средняя оценка: 4.5

Всего получено оценок: 471.

В мировой военной истории мало войн, которые имеют почти поэтические названия. Одной из таких стала война Алой и Белой розы. Она произошла в Англии во второй половине XV века и датируется 1455-1485 годами, а иногда датой ее окончания считают 1487 год.

Причины конфликта и его особенности

В 1453 году завершилась 117-летняя Столетняя война между Англией и Францией. Английский король Генрих VI Ланкастер ее проиграл и утратил все владения в континентальной Европе, кроме небольшого города Кале. Его политика не пользовалась поддержкой аристократии, тем более король находился под влиянием королевы и фаворитов.

Лидером оппозицию правящей династии Ланкастеров стал герцог Ричард Йоркский. Он, как и Генрих VI был потомком короля Эдуарда III правившего Англией в середине XIV века. Масла в огонь подливали и солдаты, которые остались без работы после неудачного окончания Столетней войны.

Термин “Война Роз” впервые появился в 1762 году у философа Дэвида Юма в “Истории Англии”. Во время самой войны ее так не называли. Ланкастеры и Йорки имели мало общего с одноименными городами и графствами. Их замки были разбросаны по всей Англии.

В ходе войны розы не всегда использовать как символ. Ланкастеры вступали в бой под знаменем с красным драконом, а Йорки – под флагом белого вепря.

Армии состояли из представителей феодальной аристократии и их слуг. Представители низших социальных слоев, которые пополняли ряды пехоты – лучников и алебардистов. Кавалерия использовалась в основном для передвижения, а в бой воины шли пешими. В этой войне обе стороны использовали огнестрельное оружие.

Основные события и результат

Первое сражение в 1455 году выиграл Ричард Йорк и парламент Англии объявил его наследником, но спустя пять лет он погиб и в 1461 году в Лондоне был коронован его сын, который вошел в историю как король Эдуард IV.

В 1470 году он был свергнут Генрихом VI и графом Уориком, а в следующем 1471 году Эдуард VI вернулся на престол. В битвах 1471 года погиб граф Уорик и принц Эдуард Ланкастер, а вскоре и сам Генрих VI скончался, что по сути означало конец этой династии.

Эдуард IV правил в Англии до 1483 года. После его смерти престол унаследовал Эдуард V, который вошел в истории страны как один из трех некоронованных монархов. Его правление оказалось кратким. Одним из актов парламента он был лишен прав на престол. В результате, престол занял представитель мужской линии Плантагенетов – Ричард III (брат покойного Эдуарда IV). В 1485 году против него выступил Генрих Тюдор. Он одержал победу при Босворте и был коронован как Генрих VII Тюдор, положив начало новой династии. Уже после коронации, в 1487 году, он разгромил последнего сторонника Йорков – графа Линкольна.

Война Красной и Белой розы отражена не только в английских исторических источниках и хрониках, но и в мемуарах французского дипломата Филиппа де Коммина и бургундского военного историка Жана де Энена.

Что мы узнали?

Война Белой и Алой розы в Англии стала одним из крупнейших военных конфликтов в Европе XV века. Она имела такие последствия: смена правящей династии вместо Плантагенетов – Тюдоры. Ослабли позиции феодальной знати, зато укрепились позиции торгового класса. Генрих VII стал держать баронов под жестким контролем, уменьшилась их военная власть. Погибло много представителей аристократии.

Тест по теме

Доска почёта

Чтобы попасть сюда — пройдите тест.

-

Марианна Бендерская

4/5

-

Ludmila Matvejeva

5/5

-

Полина Михеева

5/5

-

Жека Корташов

3/5

Оценка доклада

4.5

Средняя оценка: 4.5

Всего получено оценок: 471.

А какая ваша оценка?

Эдуард IV и Ланкастеры в битве у аббатства Тьюксбери Jappalang (Public Domain)

Война Алой и Белой Розы (1455-1485) – династический конфликт между английскими монархами и дворянством, который продолжался четыре десятилетия непрекращающихся военных действий, казней, и заговоров. Английское дворянство поделилось на 2 противоборствующих королевской семьи, каждая из которых была потомками Эдуард III (1327-1377) из династии Плантагенетов – Ланкасетров и Йорков.

Название этой войны происходит от изображения гербов каждой из сторон, хотя в то время они так часто не использовались: белая роза Йорков и красная роза Ланкастеров. Ричард, 3-й герцог Йоркский (1411-1460) объявляет свои права на престол и смещает Генриха 4, страдавшего внезапными приступами гнева, в последствии, сын Ричарда, Генрих VI (1422-1470(71)) становится королем Англии (1461-70; 1471-1483). После него на престол восходит его брат, Ричард III (1483-1485), чье имя печально известно убийством наследников Эдуарда IV, «принцев Тауэра», что и возмутило дворянство. Ричард вскоре погибает на Битве при Босворте в 1485г., и таким образом, престол короля Англии занимает Генрих VII (1485-1509) из династии Тюдоров. Женившись на Елизавете, дочери Эдуарда IV, он объединил династии Ланкастеров и Йорков. Образовав новую — Тюдор. Вероятно, весь этот династический конфликт не так сильно повлиял на широкие слои населения, как на английское дворянство и весьма шаткое положение английских семей. Именно этот этап английской истории вдохновил на написание многих творений художественной литературы, начиная от Шекспира, заканчивая романами Дж.Р.Р.Мартина и телесериала «Игра Престолов».

Происхождение названия

Романтизированные названия династических расприй, впервые были упомянуты писателем-романистом Сэром Вальтером Скоттом (1771-1832) в честь двух гербов 2 королевских семей, хотя во время своего правления, ни одна из них не пользовалась авторитетом: белая роза Йорков и красная Ланкастеров. Такое разделение имело гораздо больший политический контекст, поскольку у каждой из семей были свои союзники и враги, и, таким образом, поле битвы разделилось на 2 большие группы: Ланкастеры и Йорки. Нередко союзники каждой из семей переходили на сторону соперника, если видели слабость или смерть короля, а также ввиду каких-либо других возможностей и личных мотивов. Отличительной чертой этого конфликта были периодические военные столкновения, мелкие стычки и осады, казни и заговоры. Но с трудом можно считать эту династическую войну, затрагивающую обычный люд XV века как часть масштабных исторических событий, которые имеют гордое название «Война Алой и Белой Розы».

Причины войны

Причин для войны было множество, и в ходе разрастания конфликта, в нем участвовали как все новые участники, так и рождались все новые мотивы для конфликта. Вероятно, зачинщиком был Генрих Болинброк, который в 1399г. захватил трон короля Англии и провозгласил себя как Генрих IV (1399-1413) и затем убил своего предшественника Ричарда II (1377-1399). Генрих был первым королем из дома Ланкастеров (его отец был Джон Гонт, герцог Ланкастерский, основатель дома Ланкастеров). Цареубийство было шоком для всей Англии, но вполне приемлемой политической борьбой.

Сцена выбора герба Красной и Белой Розы Live Auctioneers (Public Domain)

Поводом для начала войны стало неспособность Генриха VI править страной. Король был окружен беспринципными и жаждой власти герцогами и придворными; его правление часто сопровождалось беззаконием и упадком экономики в некоторых районах Англии. Когда Генрих достиг совершеннолетия, Франция победила в Столетней Войне. В английском дворянстве стояли ожесточенные споры, как быть с французскими землями: продолжить военную кампанию, как это делал Генрих V, пойти на переговоры или вовсе отказаться от материковых владений. Одной из проблем Англий был тот факт, что стране очень дорого обходились военные действие на материке. Генрих легко поддавался на советы своих придворных и был нерешителен в государственных вопросах, когда это требовалось на самом деле.

У Ричарда, герцога Йоркского были две сильные стороны: он был правнуком Эдуарда III и то, что он был самым богатым человеком во всей Англии.

Что касается Генриха VI, он был не очень осмотрителен, безынициативен, не способен принять ни одного решения самостоятельно и не хотел ввязываться в противоречия со своими подданными, что еще больше разозлило дворянство. Ситуация еще сильней ухудшилась в 1445г., когда он решается жениться на Маргарите Анжуйской (1430-1482), племянницей Карла VII (1422-1461), второй дочери Рене I Доброго, герцога Анжуйского (1409-1480), и Изабеллы Лотарингской (1400-1453). Дворянство посчитало такую смелость как пособничество и полная капитуляция перед Францией, а очевидное влияние Маргариты на покладистого и миролюбивого короля стало еще одним поводом для разногласий. Поскольку авторитет Генриха уже и так был низким, и его отношения с низкоранговыми графами как Уильям де ла Поль и Граф Саффолк привнесли еще большую враждебность дворянства. Даже обычные граждане не особо уважали короля, вследствие чего произошло восстание Джэка Кэда в 1450г; люди были недовольны высокими налогами, отсутствием справедливости и высоким уровнем коррупции. Хотя волнения в обществе мало как повлияли на короля, но это дало еще один повод дворянству, чтобы начать активные действие по свержению власти, не ограничиваясь собственными интересами. Учитывая все эти проблемы и психическую болезнь его дедушки Карла V (1422-1461), неудивительно, что у Генриха случается нервный срыв в 1453г., скорее всего вызванный поражением в Столетней Войне и утрата всех земель во Франции, за исключением Кале. Болезнь так сильно подкосила его здоровье, что он не мог ходить, говорить, а также были серьезные проблемы с памятью. Стало очевидно, что королю нужен регент, а государственный проблемы ослабевали власть с еще большей силой, и дворянство разделилось на 2 противоборствующего лагеря.

Герцоги Йоркские

Бароны и герцоги значительно обогатилось и приобрели еще больше привилегий вследствие упадка власти. Историки ознаменовали этот период как «феодализм бастардов», во время которого, дворянство получает еще больше земель, богатств и политической власти на местном уровне. Крупные землевладельцы управляют своими землями как короли и создают собственные армии из наемников, которые будут преданны только им, а некоторые из них вспоминая успех Генриха Болинброка, и даже считали достойны быть Королем Англии. Имея небольшое родство с королевской семьей, они могли объединиться с другими баронами, которые были не в милости у короля. Вследствие таких союзов появились «сверхвластные» бароны и по мнению некоторых историков, могли свергнуть короля. В 1453г. Столетняя Война окончилась, и такие «сверхвластные» бароны могли управлять целыми армиями и огромным богатством в угоду удовлетворения своих личных амбиций.

Семейное древо Ланкастеров и Йорков Shakko (CC BY-SA)

Самым влиятельным таким бароном был Ричард, Герцог Йоркский. У него было 2 преимущества: он был правнуком Эдуарда III и племянником Графа Марч; он заявлял, что он законный наследник короля Ричарда II (1377-1399), а также был богатейшим человеком во всей Англии. Учитывая амбиции короля и его военных опыт, он являлся самой опасной угрозой для короны, учитывая, что Генрих и так был не в самом выгодном положении. Когда у короля случается первых приступ гнева, ввиду неспособности управлять страной при такой болезни, его регентом и защитником государства становится Ричард в 1454г.

Войны в значительной степени повлияли на дворянство, убив тем самым половину лордов из 60 знатных семей Англии.

Любопытно, что авторитет Генриха был настолько низок, что Ричарда считали настоящим реформатором Англии. Он стремился очистить двор и навести порядок в королевстве и в итоге ему удается заполучить корону. Сначала, Ричард, хотел чтобы его именовали истинным наследником Генриха, несмотря на то, что у него не было детей. Герцога поддерживали могущественные союзники – семья Невилли из Мидлхэма, которые хотели заручиться поддержкой в войне против своего заклятого врага – семьи Перси, но у самого Ричарда было только два врага – Маргарита Анжуйская, которая терпеть не могла герцога и Эдмунд Бофорт, 2-й герцог Сомерсет, давний родственник Эдуарда 3, полон амбиций и решительности, но к несчастью погибает в битве при Сент-Олбанс 22 мая 1455г. Королева Маргарет проявила себя как опытный стратег и полководец; смогла взять верх над своим супругом и повела свое войско против Ричарда. При сражении в г.Лудлоу у Лудфордского моста, Ричард потерпел поражение и был вынужден бежать в Ирландию. В 1459г. парламент признал его предателем и лишил наследства всех его наследников.

Вернувшись в Англию, его сын Эдуард одержал победу над королевой Маргарет в битве при Нортгемтоне, 10 июля 1460г. Ричард убедил Генриха, который на тот момент содержался в Тауре Лондона, признать его истинным наследником Англии; это решение было узаконено Актом Согласия от 24 октября 1460г. Но, когда корона должна уже была перейти Ричарду, тот погибает в битве при Уэйкфилде, 30 декабря 1460г. от руки придворных королевы. Его голову с бумажной короной насадили на пику на всеобщее обозрение в Миклгейте, г.Йорке, чтобы все знали, что его правление было ничтожным. Однако, это бы еще не конец Йорков, а только начало их возвышения.

Эдвард, сын Ричарда взял на себя роль лидера дома Йорков и стал самым главным врагом короля и королевы. У Эдварда был свой козырь в рукаве, его влиятельные союзники – богатейший человек Англии, Ричард Невилли, граф Варвик (1428-1471), который получил прозвище «Создатель Королей». Эдуард смог выиграть самую кровавую и продолжительную битву за всю английскую историю, сражение при Таутоне, которое закончилось в марте 1461г. Генрих 6 был окончательно свергнут и на престол восходит Эдвард 28 июня 1461г., коронованный как Эдуард VI. В этот момент, ход войны приобретает мрачный окрас, когда его правление ненадолго прерывается, его давний союзник Варвик выступает против него и восстанавливает Генриха 6 вновь на престол в 1470г. Однако такая перестановка длилась не долго. Во время битвы при Текесбери, 4 мая 1470г., Эдвард возвращает себе корону, а граф Варвик и единственный сын Генриха погибают в сражении. Королева Маргарита заключается в тюрьму, а самого короля Генриха 6 убивают в Тауре Лондона 21 мая 1471г. Казалось в такой ожесточенном и кровавом соперничестве Йорки побеждают, но ненадолго.

Ричард III и Генрих Тюдор

Эдуард IV, младший брат Ричарда, герцога Глостера (1452-?), который становится следующей главной персоной этой кровавой войны за престол Англии. Ричард отважно сражался вместе со своим братом еще до того, как он станет королем и вскоре внезапно умирает, вероятно от инсульта в 1483г. Для Ричарда появляется возможность заполучить корону Англии. Эдуарда сменяет другой его 12-летний сын Эдуард (1470-?). В этот момент дворянство концентрируют все свое внимание на малолетнем короле, строя козни и заговоры, и самым коварным врагом для них становится его дядя — Ричард.

Молодой и все еще некоронованный Эдуард V и его брат Ричард (1473-?) были заключены в тюрьму Тауэра Лондона,впоследствии стали именоваться «принцами Тауэра». Тем временем, королевством управляет Защитник Государства, Ричард, герцог Глостера. Принцев несколько раз видели на территории Тауэра, но вскоре они вовсе исчезли. Согласно наиболее распространённой до последнего времени версии, их убил Ричард III. Историки эпохи Тюдоров также признают это обвинение. Уильям Шекспир (1564-1616) также изобразил Ричарда в гораздо мрачных красках, чем в действительности – пьесе Ричард III. Интересен тот факт, что, человеку, кто смог извлечь выгоду из смерти Эдуарда V был его дядя, короновавший Ричарда III 6 июля 1483 года в Вестминстерском аббатстве. Однако, захватить трон прибегая к такому ужасному преступлению могло навлечь одни неприятности. Даже Йорки были в шоке, и Война Роз принимает еще более неожиданный поворот.

Ричард III и Генрих VII, витражное стекло John Taylor (CC BY)

Несмотря на то, что, в ходе династических расприй, почти всех Ланкастеров перебили люди Эдуарда IV, династия все еще была жива и единственным претендентом на престол оказался Генрих Тюдор. В его крови были королевские примеси, которые протекают через незаконнорожденную линию Бофоров, исходящая от Джона Гонта, сына Эдуарда III. Хотя этот факт не означал королевскую принадлежность, и не смотря на легитимазацию Бофортской линии в 1407г., это было самое лучшее, чем могли апеллировать Ланкастеры, когда Генрих VI не оставил ни одного наследника. Генриху Тюдору все же удалось привлечь несколько сильных союзников, кроме безумных переметнувшихся йорксистов, также удалось заручиться поддержкой Элизаветы Вудвилл, супруга короля Эдуарда IV, герцога Букингемского и на континенте – короля Франции Карла VII (1483-1498), которой хотел дестабилизировать положение Англии и отгородить свои территории как можно дальше от англичан.

Смерть наследника Ричарда III (еще один Эдуард) породила все новые стычки в войне Алой и Белой Розы. Теперь между Генрихом Тюдором стояло одно препятствие чтобы стать королем Англии. В августе 1985г. армия Генриха проходит через Милфорд Хэйвен в Южном Уэльсе вместе со своей армией из французских наемников и 22 августа 1485г. вступают в противостояние с армией Ричарда на поле Босфорт в Лейчестшире. В этот момент, от Ричарда уходят главные его союзники – Сэр Уильям Стэнли и Сэр Генри Перси), а он сам умирает во время битвы. Новым королем Англии становится Генрих Тюдор (1485-1509), коронованный 30 октября 1485г. Однако, Йорки, в лице Ламберта Симнела, отчаянно пытаются этому противостоять, но терпят поражение в битве при Стоук-Филд в июне 1487г. И на этом история Алой и Белой Роз заканчивается, но стоит отметить что в течении следующей половины столетия происходят незначительные стычки и локальные конфликты, которые не оказывают на ход истории никакого значения.

Последствия Войны Роз

Не считая очевидного противоборства семей Йорков и Ланкастеров, одно из самых значительных последствий этой войны — создание дома Тюдоров. В 1486г. Генрих VI женился на Елизавете Йоркской, дочери Эдуарда IV, таким образом объединив 2 семьи. Король даже учредил новую эмблему для новой династии – Роза Тюдоров, в которой присутствовали розы Ланкастеров и Йорков. Сын Генриха стал его приемником как Генрих VIII (1509-1547), и династия Тюдоров правила до 1603г., что в последствии ознаменовано в истории как Золотая Век Англии.

Убиство принцев в Тауэре Art UK (Public Domain)

Воина не коснулась широких слоев населения, а только ограничилась королевскими семьями и дворянством, несмотря не тот факт, что некоторые сражения причинили смерть, разрушение и хаос. За всю историю войны, было проведено 13 военных кампаний, которые в совокупности длились около 2 лет. Конфликт не затронул большую часть территории Англии, а только сосредоточился вокруг знати и дворянства, истребив больше половины знатных баронов из 60 дворянских семей. Много веков назад, многие усобицы с участием дворянства зачастую происходили путем похищения людей и требование за них выкуп, но теперь эта тактика уже не работала, поскольку люди не хотели платить или имели недостаточно денег для выкупа, а соперников надо было как-то устранять. В дальнейшем, многие бароны смогли сколотить хорошее состояние на этой войне, но к концу конфликта, король твердо контролировал королевство, устанавливая высокие налоги, конфисковал земли и поместья угасших семей и своих соперников. Для большинства людей, живших в то время, такой круговорот имущества абсолютно ничего не значил. По окончании войны имена семей могли изменятся, но одно останется неизменным – 3% дворян будут владеть 95% богатств всего королевства.

В итоге, Война Алой и Белой Розы оставила неизгладимый след в истории и культуры Англии, а многочисленные козни, заговоры, интриги, казни, взлеты и падения королевских семей и по сей день вдохновляют на написание произведений художественной литературы. Как известно «историю пишут победители», так и Тюдоры пытались приукрасить свой триумф и изобразить Йорков в неблагоприятном свете, а своих королей — победителями. Уильям Шекспир (1564-1616) много писал про тот период, что и стало поводом для написания таких исторических пьес как «Генрих VI» и «Ричард III», в которых присутствуют одноименные персонажи, а строчки этих пьес цитируются и по сей день. Даже в XXI веке, Война Роз вдохновляет Джорджа Р.Р.Мартина на написание современных романов в стиле фэнтези, а также известного телесериала «Игра Престолов».

|

Не дай вам Бог родиться |

| А. Городницкий, «Песня крестьян» |

Война Алой и Белой розы, или попросту Война роз — гражданская заваруха, имевшая место в Англии XV века (1455—1468, буквально через пару лет после Столетней войны, так что ветераны последнего этапа Столетней войны в солидных количествах махались на обеих сторонах) между двумя ветвями рода Плантагенетов за английской престол. Алая роза была символом дома Ланкастеров[1], белая — дома Йорков. По итогам заварухи Плантагенеты кончились вообще, а на английский трон сели Тюдоры[2].

Поскольку на территории Англии было существенно меньше войн, чем в не таких островных европейских странах, эта произвела на англичан глубочайшее впечатление и отразилась во многих произведениях массовой культуры. К тому же в этой войне полностью погибло больше половины английских аристократических родов (и тут у нее нет равных среди любых европейских), что, помимо усиления впечатления («выбиты» оказались те, кто создавал общественное мнение), привело к существенному изменению структуры английского общества (для средневековых войн тоже весьма нехарактерное явление).

Как всё начиналось[править]

Жил да был король Эдуард III. Он начал Столетнюю войну и основал Орден Подвязки, но песня не об этом. А о том, что он был счастливо женат и со своей милой женой Филиппой Геннегау родил семерых сыновей:

- Эдуард «Чёрный принц» — вырос, стал лихим воякой, родил сына Ричарда, умер раньше отца.

- Лионель Антверпентский[3] — вырос, уехал в Ирландию, родил дочь Филиппу.

- Джон Гентский (ака Джон Гонт) — вырос, женился на Бланш Ланкастер, получил через неё, соответственно, герцогство Ланкастерское. Как уже догадался проницательный читатель, он и стал основателем ветви Ланкастеров. Прославился как выдающийся полководец — потерпел поражение аж в самой Испании.

- Эдмунд Лэнгли — вырос, стал герцогом Йоркским. Да, проницательный читатель, ты прав, от него пошёл дом Йорков.

- Томас Видзорский (умер ребёнком).

- Вильям Виндзорский (умер ребёнком).

- Томас Вудстокский — вырос, поссорился со своим племянником королём Ричардом (сыном Чёрного принца), был убит, возможно, по его приказу.

Там ещё и дочки были, но заваруха началась не из-за них.

В общем, вроде начиналось всё чинно-благородно: есть старший сын Чёрный принц, законный наследник престола, у него тоже есть сын Ричард, законный наследник престола, но если случится какая беда и эта линия пресечётся, то есть младшая ветвь — Лионель и его дочь Филиппа (да, в Англии женщина могла унаследовать корону, если осталась единственной наследницей), а если и она пресечётся, то есть Джон Гонт, который женился три раза и, помимо старшего сына Генриха, умудрился сообразить нескольких дочерей и сыновей-бастардов от любовницы Катерины Суинфорд, которых он в конце концов узаконил под фамилией Бофоров. То есть, кроме просто Ланкастеров, были ещё и Ланкастеры-Бофоры. Это важно[4]. Затем идет Эдмунд и двое его сыновей, Эдуард Йоркский и Ричард Кембриджский. Потом — Томас и его сын Хамфри.

В общем, казалось бы, генеалогическое древо Плантагенетов весьма раскидисто, и усыхание ему не грозит.

Вся Европа в XIV-м веке переживала весёлое времечко, известное как Катастрофа Позднего Средневековья. В начале столетия Европу поразили резкие климатические изменения, сильно ударившие по сельскому хозяйству, а вслед за ними пришёл и голод 20-х годов. Добивающий удар нанесла Чёрная Смерть, свирепствовавшая всю вторую половину века. Англия потеряла от трети до половины своего населения, в основном крестьян, что привело к краху сервитута — местного варианта крепостного права — и неожиданному росту заработной платы. Лорды и рыцари, которые прежде содержали себя за счёт аграрной ренты, внезапно обнаружили, что денег у них попросту нет. Единственным способом хоть как-то поддерживать свой статус была война: там можно было всласть пограбить, получить выкупы за пленников и, отличившись в бою, пробиться ко двору. Вскоре каждый мужчина, способный владеть оружием, мечтал отправить во Францию и стать там рутьером — солдатом удачи. А поскольку феодальная иерархия, вследствие вышеописанных событий, развалилась, то особой разницы между чеширским йоменом-лучником и помазанным рыцарем не осталось. Они все теперь принадлежали к так называемым men-at-arms, и воевали не ради присяги, а за деньги и патронаж. Крупные английские феодалы от вассальных отношений перешли к институт клиентеллы: богатый граф или герцог оказывал покровительство землевладельцам поменьше, а те в обмен служили ему на войне, и создавали, что называется, политическую партию. Именно так родился «бастардный феодализм», как его иногда называют историки. Английские лорды на абсолютно законных основаниях получили право содержать целые армии вооружённых до зубов профессиональных солдат. Именно эти частные армии и будут сражаться на полях Войн Роз.

Почему же это не волновало короля? Да потому, что иных способов собрать армию для войн с французами попросту не было. Традиционно английская корона получала средства на ведение войн от Парламента, но эти чрезвычайные налоги были непопулярны, плохо собирались и порой приводили к бунтам. В качестве альтернативы, правительство Эдуарда III предложило систему военных подрядчиков. Крупный магнат собирал войско из своих клиентов и родственников, и подряжался воевать во Франции в обмен на добычу. Часть добычи потом передавалась Казначейству в обмен на выплату жалований армии из государственной казны. Так что частные армии были в Англии не просто законными, но и прямо поощряемыми правительством, да, и в общем-то, безальтернативными. Всё это накладывалось на состояние перманентной военной истерии, нагнетаемой как реальной угрозой французского вторжения, так и пропагандой, повальное увлечение мифами о короле Артуре, которые при Эдуарде стали чуть ли не государственной идеологией, и стремительно обнищание английского джентри. К XV-му веку война с Францией стала для англичан не просто святым делом, но и основным источником доходов. Нетрудно догадаться, что в таких условиях популярность правящего короля и правительства напрямую зависело от военных успехов. Поражения и утрата территорий на континенте приводили к восстаниям и гражданским войнам. В чём, в общем-то, и лежат истоки Войн Роз.

Беда подкралась незаметно[править]

В 1369-м году Франция возобновила Столетнюю Войну, начав наступление на английскую Аквитанию, отданную Чёрному Принцу по договору в Бретиньи в 1360-м году. Сам Чёрный Принц, да и его отец к тому времени были стареющими, сломленными людьми, чей золотой век давно прошёл. Остальные английские военачальники в подмётки им не годились, а в правительстве засела клика коррупционеров во главе с первым министром Уильямом Латимером, фламандским финансистом Ричардом Лайонсом и фавориткой короля Алисой Перрерз. Эта сладкая компашка де факто монополизировала военный бюджет (в одном знаменитом случае выплатив цену кампании самим себе из королевской казны), чем настроила против себя Церковь, лондонских купцов и значительную часть аристократии. Лидером недовольных формально стал Чёрный Принц, но, будучи в последние годы жизни прикованным к постели инвалидом, политику он доверил Эдмунду Мортимеру, графу Марчу, зятю покойного Лайонелла Антверпенского. Джон Гонт, с другой стороны, поддерживал правительство, изрядно навариваясь на участии в их схемах. Можно сказать, что в общих чертах будущие враждебные фракции Войн Роз начали оформляться ещё в 1376-м году.

В том же году состоялся так называемый «Хороший» Парламент, объявивший импичмент правительству, и отменивший Статут о Рабочих, ограничивавший размеры заработной платы в стране. Однако стоило только Парламенту разойтись, как Гонт тут же отменил все его решения и восстановил коррумпированных министров на их должностях, а ведущие реформаторы были арестованы. В следующем году он созвал новый Парламент, получивший прозвище «Плохой». Этот Парламент тут же подмахнул все решения герцога Ланкастера и заново ввёл Статут о Рабочих. Это привело к бунтам в Лондоне, по итогам которых правительству пришлось пойти на уступки. Джон Гонт, грозившийся покарать лондонцев, вышел в отставку и уехал из столицы, а Латимер и Лайонс попали под суд. В декабре умирает Эдуард III (Чёрный Принц умер ещё раньше, в 76-м), и новым королём становится Ричард Бордосский, сын Чёрного Принца, которому тогда было всего 10 лет.

Ричард II был так себе король[5]. Как только он достиг совершеннолетия, тут же начал ссориться со своими дядями-регентами, Джоном Гонтом и Томасом Вудстоком, и даже вроде как заказал дядю Тома. А когда умер Джон Гонт, он лишил наследства его сына, своего кузена Генриха Болингброка. Генрих не стерпел, восстал, а поскольку воевал он лучше Ричарда, то сумел его спихнуть с престола и заточить в тюрьму, где Ричард довольно скоро помер.

Итак, Генрих захватил корону и стал не просто Генрихом, а Генрихом IV… Но мы-то помним, что он старший сын третьего сына! И впереди его в очереди на трон — Филиппа, дочь Лионеля, а точней, её сын — Роджер Мортимер! А у Роджера есть сыновья — Эдмунд и опять же Роджер!

Узурпатор, сказали люди добрые Генриху. Ага, узурпатор, попробуй меня скинь, ответил Генрих.

И попробую, сказал Генри «Горячая шпора» Перси, женатый на сестре Роджера Мортимера. Спихну тебя и посажу на трон законного наследника, моего племянника Эдмунда.

Умри, сказал Генрих будущий Пятый. И Перси умер в битве при Шрусбери, а Эдмунда взяли воспитанником-заложником к королевскому двору. Что интересно, ни травить его, ни морить каким-то другим образом не стали, и это характеризует Ланкастеров как людей, в общем и целом, порядочных. Со своей стороны Эдмунд платил лояльностью.

А вот Ричард, который Кембриджский, который сын герцога Йоркского, лояльным не был. Он был женат на сестре Эдмунда и мутил заговор в его пользу[6], чем поставил его в страшно неловкое положение. За этот заговор Ричарду сняли голову, но у него остался четырёхлетний сын, тоже Ричард, за которым сохранили титул и земли (что опять-таки характеризует Ланкастеров как людей в основном порядочных). А Эдмунд умудрился так и не сообразить детей, так что его права на английский престол перешли после его смерти к его сестре, а через неё — к вот этому самому Ричарду, сыну мятежного обезглавленного Ричарда Йоркского.

И получилось, что Ричард, 3-й герцог Йоркский, через отца — правнук Эдуарда ІІІ, а через маму — его же праправнук. И прав на престол у него таким образом вроде как больше, чем у Генриха VI, внука узурпатора-Ланкастера.

Но качать эти права он начал далеко не сразу, а только после того, как оказалось, что Генрих VI нетвёрд мозгами, а других наследников у Ланкастеров нет. Так вышло, что все четверо сыновей узурпатора Болингброка оказались не шибко плодовиты. Прямо скажем, не в дедушку.

На беду Ричарда, с мозгами (а также волей и характером) всё в порядке было у жены Генриха VI, Маргариты Анжуйской. И она не собиралась сидеть за пяльцами, пока её мужа сгоняют с престола.

И всё заверте…[править]

Ричард поначалу вовсе не хотел бодаться за корону. Он через браки и удачные смерти старших родичей унаследовал кучу земель ещё ребенком и со школьной скамьи стал одним из выдающихся магнатов Англии. С таким «приданым» его воспитатель Ральф Невилл, граф Уэстморленд, его никуда не отпустил, а женил на своей младшей дочери Сесиль. С таким воспитателем Ричард вырос верным продолжателем дела Ланкастеров, воевал во Франции десять лет безвылазно. А пока он воевал, Ланкастеры, которые просто Ланкастеры, умудрились поссориться с Ланкастерами, которые Бофоры. Точнее, не так — собственно Ланкастеры умерли все, кроме младшего Хамфри, а его Бофоры быстренько оттеснили от власти, состряпав донос на его жену — мол, занимается ведьмовством и мутит против короля. Бофоров на тот момент возглавлял кардинал Генри Бофор, который осудил Жанну: опыт по обращению с ведьмами у него был. Сжечь леди Элеанор не сожгли, но приговорили к разводу и пожизненному заключению. Хамфри не вынес такого несчастья и умер. Теперь ничто не мешало Бофорам петь молодому королю в оба уха о мире с Францией, а француженке-королеве — им подпевать.

Ричард, узнав про такие дела, вернулся из Франции и накатил на родичей: что за фигня, Бофоры? Бофоры посоветовались с Тюдорами (см. раздел «Бофоры и Тюдоры») и заслали Йорка усмирять вечно бузящую Ирландию.

Пока тот был в отъезде, с королём случился приступ кататонии, и срочно начали назначать регентский совет. Бофоры категорически не хотели пускать туда Йорка, что было совсем уже свинством: как это не пускать такого магната, наследника престола (сыновей у Генриха всё никак не получалось) и лорда-протектора Англии? Йорк качнул права, его пустили в Совет, и оказалось, что его поддерживает большинство, потому что Бофоры-Тюдоры всем как-то надоели.

А потом у короля случилось просветление, а у королевы — беременность. И когда родился мальчик, Йорка погнали — не нужен.

Вот тут Йорк обиделся всерьёз и взялся за оружие. Нет, на корону он всё ещё не претендовал, а просто хотел восстановления в правах.

Битва при Сент-Олбансе[править]

Считается первой битвой Войны роз, но на самом деле стычки между родичами и сторонниками Ричарда Йорка и родичами-сторонниками Бофоров начались раньше. Поскольку они носили характер обычных феодальных потасовок из-за мельницы у брода (пользуясь раздором в королевском семействе, остальное дворянство принялось выяснять отношения), никто им особого значения не придавал. И битва при Сент-Олбансе планировалась как такая потасовка из-за мельницы у брода: Ричард собирался захватить короля и заставить его восстановить себя в правах. Ну что, получилось. Захватил и восстановил. После чего несколько расслабился.

Реванш: битва при Ладфордском Мосту[править]

Но Маргарита Анжуйская не собиралась сидеть сложа руки. Она созвала под свои знамёна Перси, которые давно враждовали с Невиллами, роднёй по жене и сторонниками Йорка. Перси были кланом многочисленным и воинственным, а вековая вражда усугубилась тем, что двое Перси погибли при Сент-Олбансе. В общем, при Ладлоу Йорки-Невиллы получили по шее и удрали в Кале, коннетаблем которого на тот момент был Ричард Варвик, будущий делатель королей. Там они собрали силы и вернулись в Англию. Вот с этого момента Йорк начинает уже бороться за корону.

Битва при Нортхэмптоне[править]

При Ладлоу Йорки проиграли из-за массового перебежничества войска и отдельных командиров на сторону Ланкастеров. При Нортхэмптоне перебежчик лорд Грей, командующий правым флангом, помог им выиграть. Йорк опять взял короля в плен и заставил подписать Акт Согласия, по которому он так и быть, остается королём, но вот передать корону сыну уже не может, а передаст её Йорку и его потомкам.

Битва при Уэйкфилде[править]

Королева с маленьким сыном убежала в Уэльс к Тюдорам и опять собрала там войска против Йорков. И в битве при Уэйкфилде Ричард Йорк был убит, Ричард Невилл, граф Солсбери, был убит, его сына взяли в плен и казнили. Отрубленные головы в бумажных коронах выставили людям на посмотрение (кто сказал «Джоффри»?). Всё, после этого война пошла на полное уничтожение противника.

Битва при Мортимерс-Кросс[править]

Сын Ричарда Йорка, юный Эдуард, в битве при Уэйкфилде не участвовал, так как шёл на перехват войску Тюдоров из Уэльса. Перехватил, разбил, взял в плен Оуэна Тюдора, а когда узнал о смерти отца — отрубил ему голову.

Битва при Таутоне[править]

Это было самое большое и кровопролитное сражение всей Войны роз. Эдуард спешился и лично рубился в первых рядах, чтобы воодушевить солдат. Лучники осыпали противника градом стрел, спровоцировали наступление, а когда оно захлебнулось, стали наступать сами, продолжая обстрел выдернутыми из земли вражескими стрелами. Ланкастерцы бросились бежать, началась давка, йоркисты дорезали бегущих, а при попытке переправиться через реку утонуло столько народу, что река оказалась запружена. Маргарита с сыном бежали, короля заточили в Тауэр, Эдуард короновался в Лондоне как Эдуард IV.

Битва при Хексеме[править]

Остатки сопротивления Ланкастеров возглавил Генри Бофор, герцог Сомерсет. Сначала он получил королевское прощение и перешёл на сторону Йорков, но потом снова переменил знамёна. Этого ему уже не простили и после того, как Варвик разбил его и захватил в плен, его казнили.

Битва при Барнетте[править]

Тут Эдуард IV сам себе подгадил так, как ни один враг бы не сумел. Пока Варвик вёл переговоры с французским королём насчет женить его на савойской принцессе, Эдуард взял и женился на Элизабет Вудвилл, вдове лорда Грея (которая потому и стала вдовой, что её муж погиб, воюя за Ланкастеров). Что Эдуард в принципе не умеет ходить застёгнутым, все знали (кто сказал «Роберт Баратеон»?), но вот так чтобы взять и жениться — это было внезапно (Кто сейчас крикнул «Робб Старк»?).

- С другой стороны, это мог быть и рассчитанный политический ход. Во-первых, король проявил патриотизм — взял в жёны англичанку. У нас тут уже недавно была королева-француженка (ну как была — собственно, и до сих пор никуда не делась) — спасибо, больше не надо. Во-вторых, она из ланкастерского лагеря — тем самым Эдуард показал, что гражданская война закончена, и для него нет разницы между бывшими йоркистами и ланкастерцами, они все в равной мере его подданные. В-третьих, король подчеркнул: он женится, на ком августейше соблаговолил жениться, а не на ком велел Уорвик. Так что не всё так однозначно.

Варвик обиделся и перешёл на сторону Ланкастеров. У Эдуарда все верные войска были в разгоне, так что пришлось ему с младшим братом Ричардом (ага, тем самым) бежать в Гаагу. Но Эдуард не остался в долгу и в битве при Барнете разбил войско своего бывшего верного союзника. Варвика зарубили при попытке к бегству.

- Точнее, по поводу скандальной женитьбы Эдуарда у них с Уорвиком действительно состоялся крупный разговор. Но до окончательного разрыва дошло позже, когда Эдуард поддержал бургундского герцога Карла Смелого в конфликте с Людовиком XI. Молодой воинственный король надеялся отыграться за Столетнюю войну, а Уорвик выступал за соблюдение мира с Францией. Делатель Королей зашёл так далеко, что публично отрицал законность происхождения Эдуарда, утверждая, что мать родила его от связи с простым солдатом. Таким образом, права на престол переходят к брату Эдуарда Джорджу, герцогу Кларенсу, а он — так уж случайно совпало — женат на старшей дочери Уорвика. После такого возможности для примирения у обеих сторон были отрезаны.

Битва при Тьюксбери[править]

Через две недели после битвы при Барнете Маргарита Анжуйская решила дать последний и решительный бой йоркистам. Всё кончилось для неё плохо: юный сын, наследник престола Ланкастеров, погиб в этом бою, последний из Бофоров был взят в плен и казнён, сама она тоже попала в плен, но, как даму, её казнить не стали. В целом со смертью юного Эдуарда, принца Уэльского, дело Ланкастеров казалось окончательно проигранным и потеряло смысл. Вскоре умер в заточении и Генрих VI (или, что представляется более вероятным, его умерли).

Последствия[править]

Эдуард наконец-то прочно уселся на трон, и все выдохнули. Есть король, есть два младших брата, Джордж герцог Кларенс, и Ричард герцог Глостер. Казалось бы, династической чехарде конец. А вот фиг.

Во-первых, брат короля герцог Кларенс в очередной раз решил сыграть в престолы в свою пользу. Но поскольку он был непроходимый дурак, то запалился, попался и был приговорён к смертной казни, которую провели в тихой семейной обстановке. По легенде, Кларенса утопили в бочке с мальвазией.

Во-вторых, сам Эдуард с окончанием войны расслабился, запил, начал опять бегать по бабам и как-то внезапно ещё не старым преставился.

После него остались двое здоровых крепких сыновей, но вот незадача: едва их батюшка преставился, как епископ Шоу объявил, что они и их старшая сестра Элизабет являются незаконными, поскольку до женитьбы на их матери их отец уже был женат на леди Элеонор Батлер, дочери графа Шрусбери. С одной стороны, это слишком смахивало на интригу Ричарда, который решил, что королём быть лучше, чем регентом, а с другой — с Эдуарда бы сталось. Он, чтобы забраться под желанную юбку, не останавливался ни перед чем, даже перед женитьбой.

- К тому же, по имеющимся документам, Ричард был совершенно не готов к такой новости — на коронацию племянника он явился с небольшой свитой и после заявления Шоу вынужден был срочно собирать войска с бору по сосенке — его собственные части находились на севере и не могли прибыть в Лондон быстро.

- Однако тонкость в том, что действия Ричарда в любом случае были узурпацией. Да, Эдуард действительно женился на Элизабет Вудвилл без предварительного оглашения, и вполне возможно, что он тогда уже был обручён (а не женат — этого никто и не утверждал) с Элеонор Батлер. Но, извините, вопросы законности браков и деторождений относились к ведению церковных инстанций, а вопросы очерёдности престолонаследия — к ведению парламента. Однако Ричард даже не обращался ни туда, ни туда (да парламента тогда и не было, его новый состав собрался только в 1484 году, уже после коронации Ричарда). Нужно ведь было всесторонне рассмотреть дело, дать возможность другой стороне представить свои аргументы. А вот так просто заявить: «Я король, и всё тут!» (между прочим, наплевав на свою недавнюю присягу на верность Эдуарду V) — это и есть узурпация.

- По уму, насчёт законности королевского брака следовало бы запросить Рим. Но Ричард (который после разгрома клана Вудвиллов фактически уже правил Англией), видимо, не рискнул это сделать, поскольку тогдашний папа Сикст IV был товарищем весьма непредсказуемым.

Принцев до выяснения отправили в Тауэр (бывший в то время не столько тюрьмой, сколько резиденцией), и как-то они совсем пропали из виду. Ричард тем временем короновался. И вскоре умерли от туберкулёза его жена и маленький сын. Нет, никаких шекспировских инсинуаций мы тут не потерпим, жену он любил и очень горевал.

И тут на сцену выходит Генрих Тюдор. Кто он вообще такой и откуда взялся?

Тюдоры + Бофоры[править]

Про Бофоров мы помним: это внебрачные дети Джона Гонта и Катерины Суинфорд. Ричард ІІ их узаконил, Генрих IV подтвердил этот акт, с поправкой: на престол они права не имеют и из линии престолонаследия исключаются.

- Джон Бофор, 1-й граф Сомерсет.

- Генри Бофор, епископ Винчестерский и кардинал, тот самый, который осудил Жанну и затравил своего двоюродного племянника Хамфри.

- Томас Бофор, герцог Эксетер — его линия прервалась, аминь.

- Джоанна Бофор, вышла замуж за Ричарда Невилла, графа Уэстморленда. Сесили, жена Ричарда Йоркского и мать королей Эдуарда IV и Ричарда III — её дочь. Варвик, «делатель королей» — её внук от старшего сына Ричарда.

Но нас больше интересует Джон Бофор, старшенький. Он женился на племяннице короля Маргарет Холланд и зачал с ней шестерых детей. Первый его сын, Генри, погиб на Столетней войне, не оставив детишек, и титул графа Сомерсета унаследовал второй его сын, тоже Джон. Его кузены-Ланкастеры подняли до герцога, он тоже принял участие в Столетней войне — неудачно, как полководец был ни то ни сё, попал в плен, выкупился — и женился на Маргарет Бошан из Блетсо. Она уже была вдовой с семью детьми, в т. ч. сыновьями, которые наследовали всё имущество отца, так что тут, наверное, была большая любовь. Но продлилась она недолго, Джон Бофор впал в немилость, был обвинён в измене и то ли покончил с собой, то ли умер от болезни. От него у Маргарет была единственная дочь, тоже Маргарет.

Когда Маргарет Бофор достигла то ли 12, то ли 14 лет, её выдали замуж за Эдмунда Тюдора, графа Ричмонда.

Кто такой был Эдмунд Тюдор?

В 1421 году, когда Генрих V заключил «мир в Труа», по которому его признавали королем Англии и Франции, он для подкрепления своих претензий женился на Екатерине Валуа, дочери окончательно спятившего к тому времени Карла. От этого брака родился Генрих VI, злополучный последний король ветви Ланкастеров. Но Генрих V вскорости помре, и Екатерина осталась одна при английском дворе, всем чужая и никому не нужная. От воспитания сына её устранили, вернуться на родину не позволили, замуж во второй раз выйти не дали, и утешил её только молодой красивый камерист Оуэн Тюдор, валлиец, а не англичанин. Вот от этого утешения и родились Эдмунд и его брат Джаспер. Сначала Ланкастеры держали обоих в отдалении от двора, но потом они все закончились, на первые места выдвинулись Бофоры, и братьев призвали ко двору короля (их брата по маме), признали законными, пожаловали титулами и сосватали им выгодных невест. Так Эдмунд Тюдор стал графом Ричмондом и мужем Маргарет Бофор.

Своего первого и единственного ребенка Генриха она родила то ли в 13, то ли в 14 лет. Роды были тяжёлыми, она чуть не умерла, Генрих чуть не умер, а тут ещё беда случилась — Эдмунд, воевавший на стороне Ланкастеров, попал в плен и умер в заточении от чумы.

Когда дело Ланкастеров провалилось окончательно, Тюдор вместе со своим дядей Джаспером эмигрировал во Францию. Про престол он тогда и думать не думал: и по отцовской, и по материнской линии он происходил от незаконных связей, хоть и узаконенных постфактум. Но когда и Йорки сошли на нет, остался один бездетный Ричард с его паршивой репутацией (впрочем, в стране короля любили и можно найти в хрониках отображение этого факта), мама, оставшаяся в Англии и снова вышедшая замуж, начала усиленно подталкивать Генриха: а давай! Ничего лучше, чем этот дважды потомок бастардов, у Ланкастеров всё равно не было.

Ну, Генрих и дал. Высадился в Уэльсе, набрал сторонников, разбил Ричарда III (личная эмблема — кабан) в битве при Босворте, где тот стал одним из трёх королей Англии, погибших в бою (после Гарольда II, убитого при Гастингсе, и Ричарда I Львиное Сердце), женился на последней наследнице Йорков, принцессе Элизабет, и стал королём Генрихом VII. В гербе он поместил розу с алыми и белыми лепестками — типа, в своей особе примирил Ланкастеров с Йорками. Причем для пущей законности он отменил парламентский акт о признании детей Эдуарда IV незаконнорожденными (без чтения). Конечно, эта отмена автоматически делала старшего из мальчиков королем, так что есть вполне логичная версия, что это Генрих сперва тихомолком убрал обоих принцев, а потом уже были отмена акта и женитьба на Элизабет. Точных данных нет — ну не доверять же Томасу Мору, который в качестве источника информации ссылается на случившуюся два десятка лет спустя исповедь…

Есть, кстати, информация, что Генрих провернул такой финт — объявил постфактум начало своего правления за день до Босвортской битвы. Что дало повод объявить ВСЕХ, кто сражался на стороне законного на тот момент короля Ричарда изменниками, конфисковать имущество и так далее.

Прочие последствия[править]

То, что в войне перебили цвет рыцарства, дало шанс части йоменов получить дворянство, дававшееся им с целью быстрого восполнения потерь рыцарства. Сами йомены были недобитыми при норманнском завоевании потомками англо-саксонской знати, и как следствие занимали промежуточное положение между дворянами и простолюдинами. Так что до войны Роз дворянство и аристократия состояли из норманнов, а англо-саксы были простолюдинами и йоменами. После же, англо-норманнская аристократия наконец-то стала английской в полном смысле слова — ушли в прошлое галломания и презрение ко всему «не-норманнскому», вместо этого появились патриотизм и национальное самосознание.

Кроме того, резкое ослабление и уменьшение численности аристократии, с одной стороны, стало причиной усиления королевской власти и началом английского абсолютизма, а с другой — открыло новые возможности для т. н. «третьего сословия», особенно его верхушки — купцов и буржуазии, которые начали усиливать своё влияние на власть с каждым годом. Тем самым, было положено начало процессу смены общественного строя с феодального на капиталистический, конечным этапом которого полтора столетия спустя станет Английская революция. Неудивительно, что англичане оценивают Войну Роз как событие, окончательно подведшее черту под Средневековьем в Англии.

Список норманских фамилий переживших эту войну: w:en:Anglo-Normans#Anglo-Norman families. И это на всю многомиллионную Англию!

Тропы[править]

- Бастард — Бофоры и Тюдоры.

- Если епископ Шоу сказал правду — Тауэрские принцы и их сестра.

- Безумный король — Генрих VI.

- На взгляд автора правки, он ближе к глупому королю. Особых безумств на троне Генрих не творил, зато его глупость была очевидна всем, и не вертел им только ленивый.

- Безумие бывает разным. Не все безумные буйные, многие (и даже большинство) тихие.

- На взгляд автора правки, он ближе к глупому королю. Особых безумств на троне Генрих не творил, зато его глупость была очевидна всем, и не вертел им только ленивый.

- Вечная загадка — судьба Тауэрских принцев.

- Выиграть войну, проиграть мир — Эдуард Йорк, кодификатор. Не успел толком сесть на трон, как пьянками-гулянками свел себя в могилу.

- С прикрученным фитильком, поскольку в качестве короля мирного времени Эдуард показал себя более чем недурственно — особенно после реставрации 1471 года, Барнета и Тьюксбери, когда он окончательно утвердился на троне. Тогда в стране настал прочный мир, Англия переживала экономический и культурный расцвет (помимо прочего, именно во второй период царствования Эдуарда началась история английского книгопечатания). Но насчёт пьянок-гулянок — святая правда. Кто знает, как сложилась бы история Англии, если бы Эдуард вёл более здоровый образ жизни и протянул ещё десяток-другой лет?

- Делатель королей — Ричард Невилл, граф Варвика. Он реально звался «Warwick Kingmaker».

- Злая королева — во многих произведениях Маргарита Анжуйская.

- Маргарите Бофор в книгах тоже досталось. Гнобила и Елизавету Йорк, и Маргарет Поул-Кларенс (кузину этой самой Елизаветы), и Екатерину Арагонскую (на тот момент — еще инфанту Каталину). По версии Филиппы Грегори, именно по ее приказу убили Тауэрских Принцев.

- Историю пишут победители: Ричарда III изрядно очернили историографы Тюдоров. Да и Шекспир подсобил.

- А вот Филиппа Грегори ему наоборот, польстила. Хотя лестью это не назовешь — скорее, отрицание приевшихся исторических мифов. Объективно, резона убивать принцев у Ричарда не было, так как к моменту коронации они оба были изолированы от родни королевы, Риверсов и Греев, а также исключены из линии наследования как бастарды. Узурпация трона, бессудная расправа над Уильямом Гастингсом и родственниками королевы — всё это никуда не делось (да и не могло деться, поскольку эти события описаны в исторических источниках и ни у кого сомнений не вызывают).

- Среди историков существует мнение, что и сама Война Роз по масштабам жертв и разрушений была сильно преувеличена тюдоровской пропагандой XVI века: «Вот от какого кошмара Тюдоры спасли несчастную страну!». На самом же деле особого кошмара не было: большинство англичан как жило до начала войны, так и продолжало жить, не слишком обращая внимание на эту верхушечную разборку.

- Кармическое возмездие — исход этой войны именно этим и выглядит. Династия Плантагенетов предъявила претензию на престол Франции после смертей бездетных сыновей Филиппа IV Красивого и в течение более 100 лет её представители грабили и пытались расчленить Францию. Сначала закончились Плантагенеты, потом — их побочные ветви, и престол заняли «седьмая вода на киселе» Тюдоры, попутно же в ходе междоусобных воин была вырезана львиная доля англо-норманнской аристократии.

- Ловелас нарвался: Эдуард IV нарвался сначала на Элизабет Вудвилл, потребовавшую «Сначала свадьба, а потом остальное», а потом на Варвика, которому он обгадил этой свадьбой дипломатическую победу.

- Самозванец: после интронизации Генриха Тюдора было несколько выдававших себя за «выживших тауэрских принцев».

- Самоуверенный мерзавчик — Варвик.

- Серый кардинал — не такой уж серый, если говорить о Генри Бофоре.

- Хроническое спиннокинжальное расстройство — герцог Кларенс.

- Варвик же!

Произведения по мотивам[править]

- Шекспир, «Генрих VI» и «Ричард III».

- А в других пьесах-хрониках Шекспира описана предыстория всего этого безобразия. Например, в «Ричарде II» Генри Болингброк, он же будущий Генрих IV Ланкастерский, свергает Ричарда II и сам восходит на трон. А в пьесе «Генрих IV, часть первая» принц Хэл, будущий Генрих V, побеждает мятежного Генри «Горячую Шпору» Перси. В 2011-2016 годах по этим пьесам был снят цикл фильмов «Пустая корона».

- Джозефина Тэй, «Дочь времени».

- Р. Л. Стивенсон, «Чёрная стрела».

- Есть мнение, что Вестерос времён игры престолов — СФК Англии эпохи Войны роз. А Старки и Ланнистеры — толстый намёк на Йорков и Ланкастеров соответственно. Мартин сам признался, что имел в виду Войну роз. В любом интервью.

- Юрий Нестеренко, «Приговор»: Йорлинги и Лангедарги — очевидная отсылка к Йоркам и Ланкастерам, а некоторые эпизоды войны Льва и Грифона дублируют реальные события войны Алой и Белой Розы.

- Цикл Филиппы Грегори «Война кузенов», а также его экранизации «Белая королева» (BBC One) и «Белая принцесса» (Starz). ПоВы книг — Жакетта Риверс, Елизавета Вудвилл, Анна Невилл, Маргарита Бофор, Елизавета Йорк, Маргарет Поул.

- Алькор, «Война Роз». Субверсия: сеттинг — эклектика, присутствуют как минимум пираты и гражданская война в России, а возможно, и Октябрьская революция и Одесса.

- «Свет и тень» — противостояние между Макгрегорами и Дюкайнами, произошедшие за триста лет до событий основной истории, явно списывалось с войны Роз.

- Кир Булычёв, «Принцы в башне» — Алиса Селезнева на машине времени отправляется в прошлое, чтобы выяснить судьбу Тауэрских принцев.

Примечания[править]

- ↑ На самом деле алую розу как символ Ланкастеров придумали задним числом — в хрониках того времени алая роза не упоминается, этот символ прославил Шекспир.

- ↑ Впрочем, поскольку жена первого короля из династии Тюдоров была дочерью Эдуарда IV Йоркского и стала вдобавок прапрабабушкой Якова I из династии Стюартов, строго говоря, и нынешняя королевская семья — очень дальние потомки Плантагенетов по нескольким женским линиям (по мужской линии они саксонского происхождения), а если учесть что и сами Плантагенеты по женской линии происходят от Вильгельма Завоевателя, то все династии Англии находятся с ним в некотором родстве. Во Франции же все монархи по мужской линии являлись потомками Гуго Капета (династии Капетингов, Валуа, Бурбонов), за исключением, разумеется, Бонапартов.

- ↑ По тогдашней традиции всем английским принцам давали прозвище по месту рождения. Ричард II был Бордоским, а Генрих IV — Болингброком в этом же смысле.

- ↑ Папа и король узаконили Бофоров при условии, что они и их потомки никогда не будут претендовать на английский престол. Ага, щас.

- ↑ С точки зрения автора правки, вопрос дискуссионный. Всё-таки не каждый способен в 14 лет выйти к толпе повстанцев и заявить, что, хотя Уот Тайлер и убит, но он, король, выполнит все его обещания. Если бы у парня получилось в полной мере это реализовать, он мог бы войти в историю как Ричард II Великий. Увы — король переоценил свои возможности.

- ↑ В свою он не мог мутить, потому что был сыном четвёртого сына, а Генрих Пятый — внуком третьего сына.

|

[изменить] Армия и военное дело |

||

|---|---|---|

| Основы | Армия • Армия из одного человека • Бог войны • Война • Гвардия • Солдаты (Суперсолдаты) • Флот • … Варгейм • Вторая мировая война • Искусство на военную тематику • Шкала силы армий |

|

| Сословия | Амазонки • Викинги (берсерки) • Дикарь • Дикие варвары (Герой-варвар) • Казак • Рыцарь • Самурай • … | |

| Воинские части | Армия воров и шлюх • Армия магов • Армия Чудовищ • Боевая организация пацифистов • Боевые рабы • Бригада амазонок • Великая армия • Военная полиция • Желудочная рота • Иностранный легион • Космодесант • Крошечная армия • Крутая армия • Ксерокс-армия • Линейная пехота • Пушечное мясо/Грузовик с пушечным мясом • Частная армия • Штрафбат • Штурмовая группа • Элитная армия • Янычары • … | |

| Полководцы | War Lord • Адмирал • Вояка и дипломат • Генерал-вундеркинд • Завоеватель • Кондотьер • Крутой генерал (Генерал-рубака vs Генерал-шахматист) • Неопытный генерал • Плохой генерал (Генерал Горлов • Генерал Потрошиллинг • Генерал Фейлор • ЛИИИРОООЙ ДЖЕЕЕНКИИИИИИНС!) • Полевой командир • Слаб в бою, но отличный тактик vs Крутой вояка, но никудышный командир • Стратег vs Тактик • Стратег vs Дипломат | |

| Военнослужащие обычные | Боевой садомазохист • Боевой феминист • Военный социопат • Воин vs солдат • Гусар • (крылатый гусар) • Дезертир • Зелёный лейтенант (Такой молодой, а уже лейтенант) • Камикадзе • Арбалетчик/Пращник • Магистр Ордена/Гроссмейстер Ордена • Мародёр • Мушкетёр • Наёмник (Псих-наёмник) • Неуставные взаимоотношения (Деды, черпаки, слоны и ду́хи) • Номинальный командир • Отец солдатам • Паладин • Прагматичный боец • Рыцарь щита • Сержант Зверь • Сержант Кремень • Следопыт • Тупой солдафон • Хвастливый воин • Центурион | |

| Военнослужащие крутые | Ас • Боевой монах • В каждой руке по оружию • Воин и музыкант • Воин и ремесленник • Вояка и дипломат • Вынул ножик из кармана (Фанат ножей) • Ганфайтер • Девушка с молотом • Колдун и воин • Крутой генерал (Генерал-рубака vs Генерал-шахматист) • Крутой копейщик • Крутой лучник • Крутой фехтовальщик • Лечит и калечит • Лучник и рубака • Любитель взрывчатки • Мастер клинка и пули • Мастер боевых искусств (Боевая гимнастика) • Мечник с арбалетом • Не любит пушки vs Ствол — великий уравнитель • Настоящий полковник • Носить кучу пистолетов • Однорукий воин • Офицер и джентльмен/Леди-воительница • Поэт и воин • Слепой самурай • Снайпер (Снайперская дуэль • Попадание через прицел) • Универсальный солдат • Учёный и офицер | |

| Полувоенные | Ассасин • Бретёр • Военный маг • Гладиатор • Госбезопасность (Всемогущая спецслужба • несколько спецслужб • ЧК-НКВД-КГБ-ФСБ • Нечисть на госслужбе) • Дети-солдаты • Диверсант • Из силовиков в бандиты vs Из криминала в армию • Из силовиков в повстанцы • Из наёмников в дворяне • Капеллан/Политрук • Маньяк-милитарист • Ниндзя/Куноити • Орда • Орден • Партизаны (Городской партизан) vs Злые партизаны • Пират (Космический пират) • Преторианцы • Торговец и воин (Торговец оружием) • Шпион (Воин vs шпион • Двойной агент • Манчжурский агент • Спящий агент • Супер-агент) • Эскадроны смерти • … | |

| Оружие | «Авада Кедавра» • Атомная бомба (Атомная хлопушка vs Килотонный армагеддец, Бог из атомной бомбы, Неатомные аналоги, Грязный вариант) • Бластер • Боевой электромагнитный излучатель • Вундервафля • Выходила на берег Катюша (Перехвачены ракеты) • Луч смерти (Дезинтегратор) • Ускоритель массы (пушка Гаусса • рельсотрон) • Многоствольный пулемёт • Массового поражения (атомное • биологическое • химическое • супероружие в RTS) • Непороховое оружие • Оружие на чёрный день • Плазмомёт • Планетоубийца • Проблема пистолета • Психотронное оружие • Пучковое оружие • Пушка-боксёр • Суповой набор фантастического оружия • Удар из ножен • Электрическая пушка

Холодное: Алебарда • Метательное оружие (Бумеранг vs Не бумеранг) • Молот • Рапира • Трезубец • Штык • Щит Конкретные виды: AR-15 • FN FAL • Mauser C96 • M1911 • Luger P.08 • Пистолет Макарова • Автомат Калашникова (Автомат Ералашникова) • Пистолет-пулемёт Томпсона • Пистолет Токарева • Пушки Дикого Запада |

|

| Техника | Авиация (бомбардировщик • вертолёт • Воздушный командный пункт • истребитель/истребители не нужны • штурмовик) • Бронетехника (бронепоезда • бронетранспортёр • танки (крутые vs ненужные • летающие) • Командно-штабная машина • шагоход (боевой многоножник • куроход) • Импровизированная (Техничка • Гантрак • Ганшип) • Флот (авианосец • дредноут • линкор • крейсер • крутой корабль • москитный флот • подлодка • романтика парусов • Эсминцы и миноносцы) • … | |

| Стратегия | casus belli (DEUS VULT • Война за наследство • Маленькая победоносная война • Объединительная война) • Блицкриг (Раш) • Асимметричный конфликт • Бабы новых нарожают • Война на истребление (Тараканья война • Убить всех человеков) • Война чужими руками • Герилья • Господство на море • Доктрина Дуэ • Неограниченная подводная война • Обезглавленная армия • Окопная война • Победить миром • Рокош • Сменить сторону (Напасть на своих) • Стратегия непрямых действий (Fleet in Being • Тактика выжженной земли) • Уличные бои • Холодная война (Флирт с Третьим Миром) • Частная корпоративная война… | |