История возникновения ислама

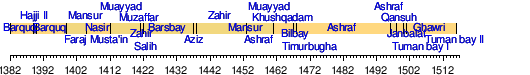

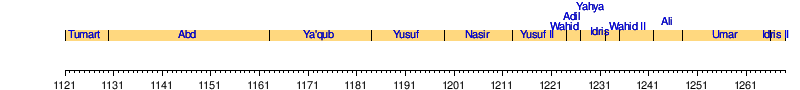

- Ислам и его источники

- Первые мусульмане

- Зарождение Ислама

- Религиозная и историческая ситуация в Аравии накануне зарождения Ислама

- Основатель ислама: пророческая деятельность Мухаммеда ﷺ

- Противостояние распространению Ислама

- Переселение мусульман

- Причина битв Пророка ﷺ

- Распространение ислама

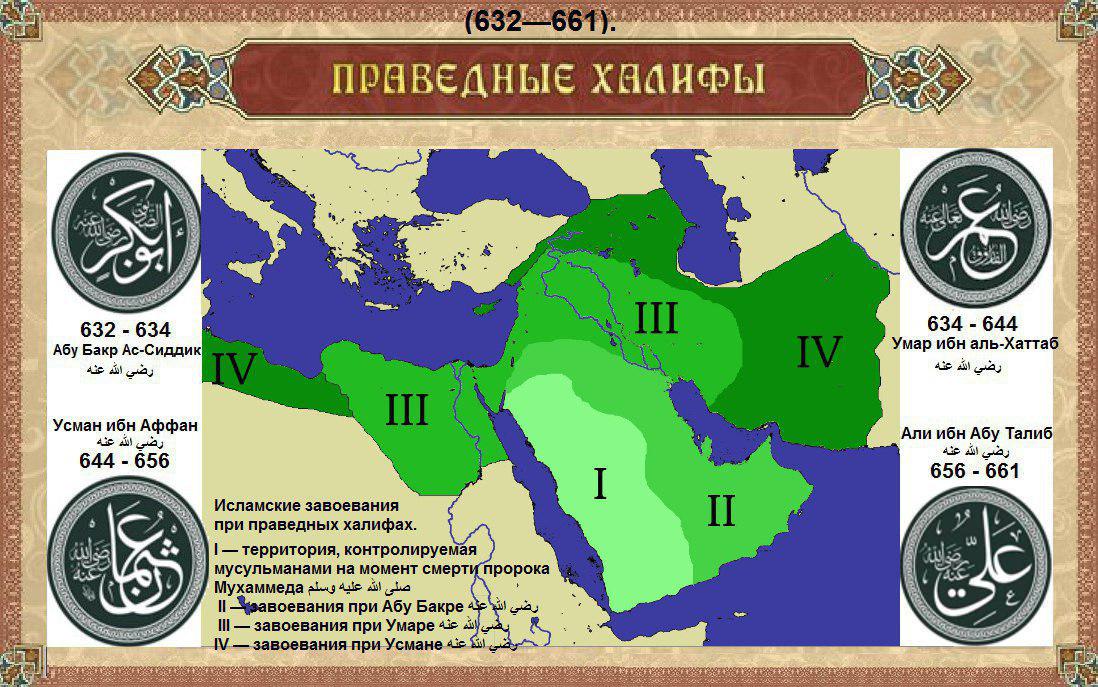

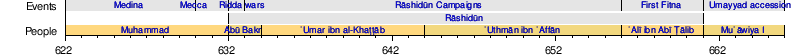

- История развития ислама после смерти Пророка Мухаммада ﷺ: Праведный халифат

- Правление Абу Бакра ас-Сиддыка

- Правление Умара ибн аль-Хаттаба

- Правление Усмана ибн Афвана

- Правление Али ибн Абу Талиба

- Развитие Халифата

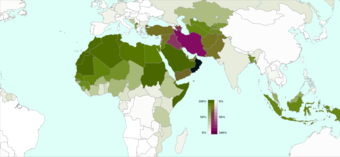

Ислам – религия, которая является самой молодой в истории человечества, а по числу приверженцев занимает в мире второе место, число приверженцев ислама составляет около двух миллиардов человек.

Мусульмане проживают в ста двадцати пяти странах по всему земному шару, и в двадцати восеми государств мира ислам является официальной государственной религией.

Мусульмане, в большинстве принадлежат к течению суннитов, составляет от 85 до 90% всех последователей ислама, а остальные подразделяются на шиитов и ибадитов.

Ислам и его источники

В переводе с арабского языка слово «ислам» означает «предание себя Единому Богу» или «покорность». Ислам является мировой монотеистической авраамической религией.

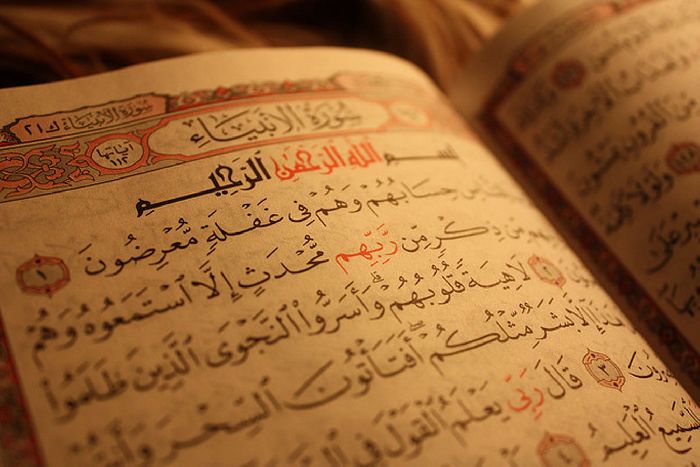

Посланник Аллаха Пророк Мухаммед ﷺ – проповедник ислама, а основным источником ислама является Священная Книга Коран, а также Сунна Пророка Мухаммеда ﷺ, которая является вторым по значению источником исламского права и вероучения. Сунна – это совокупность хадисов Пророка Мухаммеда ﷺ или преданий, рассказов, в которых сообщается о жизни Посланника Аллаха ﷺ, его изречениях и мудрых высказываниях, о его деяниях. Исламские богослужения совершаются на арабском языке.

Первые мусульмане

Ислам считает первыми мусульманами первых людей на земле Адама и Еву или Хавву. В ряду исламских пророков называют Нуха или Ноя, Ибрахима или Авраама, Давуда или Давида, Мусу или Моисея, Ису или Иисуса, а также ряд других.

Представители других авраамических религий – христиане и иудеи – называются в исламе «Людьми Писания». В Священной Книге Коран представлены истории о сотворении мира, о том, как возник первый человек на земле, о всемирном потопе и прочие.

Зарождение Ислама

Точный год возникновения ислама определить нельзя: зарождение ислама связывают с городом Меккой в Западной Аравии и началом седьмого века. В этот период истории господствующей религией было язычество, и каждое племя почитало своих богов, идолы которых были установлены в Мекке. На этом отрезке истории началось постепенное разрушение родоплеменного патриархального строя, и общество начинает разделяться на классы, в результате чего должно было появиться нечто, что объединило бы людей духовно.

В этих условиях и возникает Ислам, который является религией авраамической, как иудаизм и христианство, которые также восходят своими корнями к самым древним формам монотеизма, то есть все эти религии объединяет с исламом принципиально единая картина мира, и относится к богооткровенной или ревелятивной традиции.

Осознание монотеизма происходило на самых ранних этапах зарождения ислама, и это было выражено в проповедях, с которыми обращался к своей умме Пророк Мухаммед ﷺ, главной идеей которых была мысль о необходимости очищения единобожия или таухида от тех искажений, которые были внесены многобожниками, христианами и иудеями.

Религиозная и историческая ситуация в Аравии накануне зарождения Ислама

В преддверии возникновения ислама на Аравийском полуострове господствовала ханифия или автохтонный аравийский монотеизм, уходящий своими корнями к пророку Аврааму (Ибрахиму). Современная концепция указывает на наличие в тот период двух относительно независимых монотеистических традиций, которые в итоге объединились в аравийское пророческое движение. В период, когда возник ислам, то есть до момента прихода к пророческой миссии Мухаммеда ﷺ, в Аравии уже действовали несколько авраамических пророков, но именно на Мухаммеда ﷺ была возложена Богом миссия распространения Ислама. Пророка Мухаммед ﷺ существенно отличался от остальных пророков, как с политической, так и с идейной точки зрения, что явилось одной из главных составляющих успеха ислама.

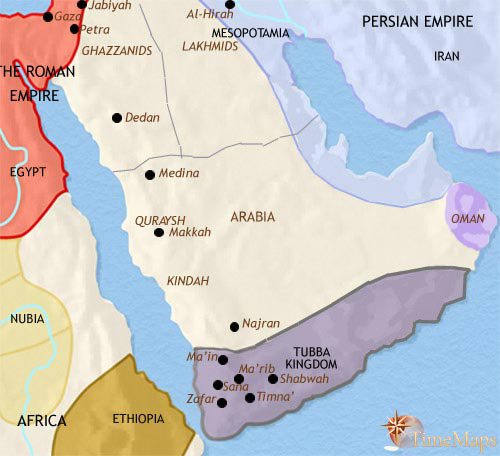

Частично население Аравийского полуострова в этот период времени приняли иудаизм, частично – приняли христианство, а в некоторых государствах, таких, как Йемен и Бахрейн, проповедовали зороастризм. Аравийский полуостров в этот исторический период делили между собой княжество Лахмидов, которое являлось союзником с Ираном, где правили Сасаниды, и княжество Гассанидов, которое являлось вассалом Византии.

Центральная же Аравия осталась свободной после того, как на Мекку совершил поход эфиопский царь, и чудесным образом мекканцам удалось спастись, а армия царя и сам эфиопский царь были уничтожены раскаленными камнями, которые скидывали на них прилетевшие с неба птицы. Данное событие было известно арабскими и мекканскими современниками и описывается в суре Корана «Слон».

Основатель ислама: пророческая деятельность Мухаммеда ﷺ

Вопреки расхожему мнению, основателем ислама не является Мухаммед ﷺ. По мнению мусульман – до него уже были пророки, и Мухаммад ﷺ – это последний пророк ислама или «Печать пророков». Мухаммед ﷺ не проповедовал новую религию, но восстановил истинную веру.

Пророк Мухаммед ﷺ, будучи мекканцем по своему происхождению и рождению, выходцем из курайшитов, вел активную деятельность мекканского ханифа: с момента рождения до начала своей пророческой миссии он вел обычную жизнь, позже занимался скотоводством и перегонял караваны. Мухаммад ﷺ принимал активное участие в восстановлении курайшитами общеарабской святыни Каабы.

Когда ему исполнилось сорок лет, в 610 году, Мухаммед ﷺ объявил, что он – расуль, то есть посланник, и наби, то есть пророк Аллаха, Единого Бога. После этого Пророк Мухаммад ﷺ начал проповедовать новую религию ислам в Мекке. Первые аяты Корана были произнесены Пророком Мухаммедом ﷺ в это же время. В его проповедях звучали призывы вернуться к монотеизму, к вере Ибрахима или Авраама, к вере пророков Мусы или Моисея и Исы или Иисуса, произносить молитвы и держать пост, давать милостыню и честно производить торговые сделки. В своих призывах во время проповедей Посланник Всевышнего говорил о необходимости веры в Единого Бога, о том, что верующие должны сплотиться в единое братство и соблюдать простые нормы морали.

По словам Мухаммеда ﷺ, всем народам были посланы пророки, появление которых было связано с тем, что они должны были наставить на истинный путь людей. Одними из главных вопросов, на которые обращал внимание Пророк Мухаммад ﷺ, был вопросы веры (имана) и неверия (куфра), вопросы загробной жизни, Ада и Рая.

Противостояние распространению Ислама

Но мекканская знать не поддержала идеи Мохаммеда ﷺ и встретила его пророческую проповедническую деятельность враждебно. История возникновения Ислама рассказывает о тех тяжелых испытаниях, которые испытывал Пророк Мухаммад ﷺ поначалу, ведь очень немногие люди приняли для себя новую веру с самого начала: только сам Пророк Мухаммад ﷺ и его жена Хадиджа приняли ислам, а также его двоюродный брат Али ибн Абу Талиб, которого он взял на воспитание, в возрасте 9 лет. Также к числу первых мусульман присоединился Абу Бакр, который был богатым купцом, а также еще сорок человек, среди которых были богатые и бедные люди преимущественно в молодом возрасте, которые впоследствии стали первыми сподвижниками Пророка Мухаммада ﷺ.

От преследований соотечественников многобожников Пророк Мухаммед ﷺ вынужден был спасаться бегством в сопровождении своих последователей.

Переселение мусульман

Первую хиджру, паломничество и переселение совершил Пророк Мухаммед ﷺ в 621 году: он переехал в Йасриб, чтобы разорвать все связи с обществом, в котором он вырос, но которое не приняло призыв к единобожию и стало преследовать его и его последователей. Позже Йасриб в честь Пророка Мухаммеда ﷺ был назван Мадинат-ун-Наби, что в переводе означает «город Пророка».

В Ясрибе (Йасрибе) люди питали надежду на то, что появление Пророка Мухаммада ﷺ положит конец войнам и междоусобицам своим справедливым судом. В Медине Пророк ﷺ и его сподвижники оказались практически без средств к существованию, и местные ансары из числа мединских мусульман помогали им.

В Медине Мухаммаду ﷺ удалось сплотить вокруг себя местное население, и в городе была создана первая мусульманская умма или община. Но религиозная борьба (газават) между мединскими мусульманами и многобожниками Мекки продолжалась еще восемь лет.

Причина битв Пророка ﷺ

Пророк Мухаммад ﷺ оправдал надежды мединцев и прекратил конфликты, которые происходили внутри, но мекканские многобожники все еще притесняли мусульман из Мекки, и с 623 года начали происходить военные столкновения мединцев и мекканцев. В 624 году произошла битва при Бадре, которая закончилась поражением мекканцев, хотя их количество превышало количество мусульман в три раза. Многие мекканцы были захвачены в плен, Пророк Мухаммад ﷺ предложил, чтобы пленные обучали грамоте детей мединцев в обмен на их свободу.

Позже в 625 году состоялась битва при Ухуде, в которой верх взяли уже мекканцы. Через год войско из Мекки совместно с племенами Аравийского полуострова пришло к городу Медине, чтобы покончить с исламом раз и навсегда. Мекканским многобожникам также помогало иудейское племя в Медине, нарушившее договор с Мухаммедом ﷺ о взаимопомощи и ненападении. Мусульмане, обладавшие армией в четыре раза меньше, но будучи более мудрыми в тактике и стратегии, сумели противостоять мекканцам, которые вынуждены были вернуться домой ни с чем.

Мухаммад ﷺ покорил Мекку в 630 году, уже установив контроль над большей частью Аравии.

Распространение ислама

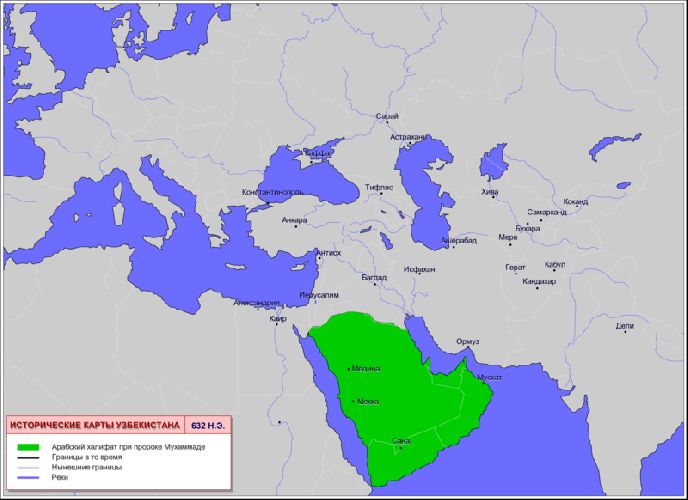

Всего за 23 года благодаря пророческой деятельности Мухаммеда ﷺ новая вера ислам быстро распространилась на территории Аравийского полуострова.

Существует предание, по которому Пророк Мухаммед ﷺ отправил письмо с призывом принять ислам тогдашним правителям Византии, Персии (Ирана), Эфиопии и Египта. Все, кроме царя Персии, приняли послов благосклонно: иранский же царь письмо разорвал, но вскоре после этого события иранский царь Хосров Парвиз умер.

Пророк Мухаммад ﷺ умер в 632 году, и к этому году почти все племена арабов приняли ислам.

Успех в распространении ислама во многом был обусловлен тем, что учение Мухаммада ﷺ осуждало неравенство между людьми, ростовщичество, несло справедливость и развитие.

Когда же мусульмане в 630 году завоевали Мекку, ислам стал общей религией всех арабов, а сама Мекка стала центром ислама. В период с пятого по седьмой века древние государства Киндитов, Гассанидов и Лахмидов, Пальмира, Саба, Химьяр и Набатея пришли в упадок и распались, и этот процесс способствовал активной исламизации региона.

История развития ислама после смерти Пророка Мухаммеда ﷺ: Праведный халифат

Появление ислама кардинально изменило всю политическую, социальную, экономическую, бытовую жизнь многих народов от Испании до берегов Индонезии.

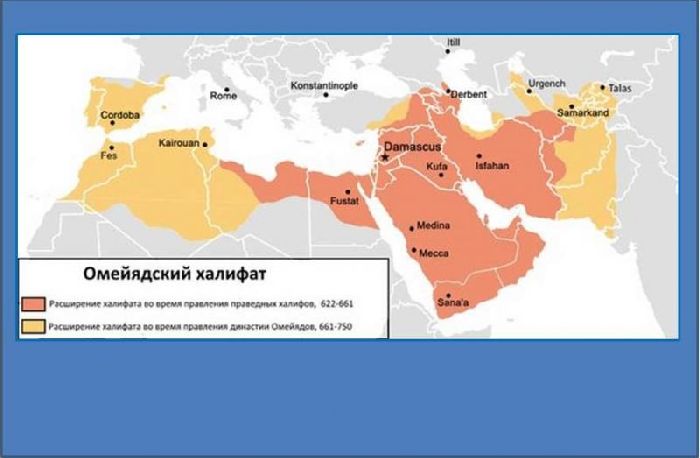

После кончины Пророка Мухаммада ﷺ образовалось первое мусульманское государство Халифат, в котором власть, как светская, так и духовная, была сосредоточена в руках халифа. Первыми халифами государства были Абу Бакр, а затем Умар, Усман, Али, после них к власти пришла династия Омейядов, а затем их сменила династия Аббасидов. В результате проводимых Халифатом завоевательных войн в течение седьмого и восьмого веков ислам распространился на Среднюю и Переднюю Азию, а также на Северную Африку, Закавказье, Индию, а затем на Балканский полуостров через Турцию.

Правление Абу Бакра ас-Сиддыка

После смерти Пророка Мухаммада ﷺ, когда встал вопрос о том, что следует избрать халифа, то есть его «заместителя», был избран на эту должность Абу Бакр. Ему удалось пробыть у власти всего два года, после чего он умер, но даже за эти два года он успел убедить племена, которые отвернулись от Ислама, чтобы они вновь вернулись в религию.

История ислама гласит, что Абу Бакр сделал многое для распространения ислама: успел начать боевые действия против Персии и Византии, которые в то время были самыми могущественными империями. Накануне своей кончины Абу Бакр назначил Умара (Омара) своим преемником.

Правление Умара ибн аль-Хаттаба

Омар (Умар) стал вторым халифом исламского государства, и он, продолжив военные походы на Византию, отвоевав Сирию, а также захватив Египет, Палестину, частично Магриб, который располагался на территории Северной Африки.

При халифе Умаре мусульмане вели военные действия и против династии Сисанидов, правившей в Персидской империи: в битве при Кадисии и Нихавенде он нанесли армии Ирана тяжелые поражения, а вскоре и заняли столицу государства Сисанидов Ктесифон, который находился неподалеку от Багдада. Мусульмане также заняли Армению, Азербайджан, Ирак, Мазендаран, Хузестан и часть Фарса, что составляло основные территории Ирана.

Во время правления Омара были проведены реформы, которые заложили основы мусульманской государственности: был определен порядок налогообложения, установлены законы. На покоренных территориях халиф Омар придерживался политики веротерпимости, христианам и иудеям была предоставлена защита и свободное вероисповедание своей религии.

Правление Усмана ибн Афвана

Следующий халифом избрали Османа (Усмана), в тот период Усман был самым достойным титула халифа человеком, и выбор членов совета был верным и справедливым.

При нем все ключевые посты в государстве занимали его родственники Омеяды, по этой причине в сторону Усмана (Османа) поступало много критики, в результате поднялся бунт, в ходе которого мятежники убили халифа. Осман сделал важный шаг в дальнейшем развитии ислама и создании основ религии – во время его правления был составлен полный канонический текст Священной Книги Коран. До этого момента текст Корана существовал только в памяти хафизов – людей, заучивших текст Священной Книги Коран наизусть в момент, когда появлялся каждый аят, будучи ниспослан Посланнику Аллаха ﷺ еще при жизни Пророка Мухаммада ﷺ. Осман отдал приказ собрать весь Коран и записать его тогда, когда сразу семьдесят хафизов погибло в одном из воинских сражений.

Правление Али ибн Абу Талиба

Следующим халифом стал Али ибн Абу Талиб, который прославился как мужественный, справедливый халиф, который внес огромный вклад в становление ислама и чьи заслуги перед исламом огромны. Во время правления халифа Али была развернута борьба с коррупцией, халиф стремился распределить государственные доходы так, чтобы разрыв между богатыми и бедными гражданами государства сократился максимально.

Четыре первые халифа вошли в историю ислама как Праведные халифы, а государство, во главе которого они стояли, получило название Праведный халифат.

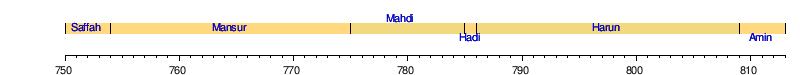

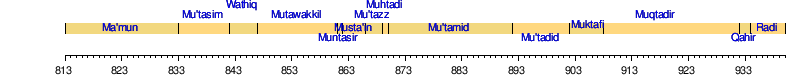

Развитие Халифата

Первые три века существования ислама, когда он зародился и распространился, вошли в историю как золотой период арабской культуры – были сформированы первые мусульманские религиозные школы, сформулированы этические, философские и правовые положения, а также сформированы правила арабского языка, было положено начало таким наукам, как литература, химия, география и медицина.

История ислама продолжилась в феодальном государстве, которое стало преемником Праведного халифата – Омейядском халифате или Дамасском халифате, во главе которого стояла династия Омеядов. Во время существования этого государства исламский мир распространился на Северную Африку, частично Пиренейский полуостров — Андалусию, а также на Табаристан, Синд, Джурджан, Среднюю Азию, Юго-Восточную Азию, включая Малайзию и Индонезию.

Ислам в современном мире играет в жизни верующих большую и важную роль: это не только религиозная идеология, дошедшая со времени возникновения ислама до наших дней, но и идеология, определяющая светскую жизнь мусульман, мерило их гражданского поведения, системы ценностей. Исламская религия, мусульманство оказывает большое влияние на все сферы жизни мусульман.

История исламского мира является отдельным направлением для многих историков и исследователей, охватывая более 14 веков жизни человечества, именно, благодаря мусульманским ученым удалось сохранить научное наследие предыдущих цивилизаций и развить новые направления в науке, культуре и искусстве.

(Протоиерей Олег Корытко)

В начале VII века н. э. на просторах Аравии появляется человек, проповедь и религиозная деятельность которого оказали огромное влияние на формирование религиозной картины всего мира. И сегодня имя Мухаммада с благоговением произносится его многочисленными последователями, составляющими почти 23% населения планеты117. В настоящее время ислам занимает второе после христианства место по количеству своих последователей.

Ислам118 – одна из мировых авраамических религий, возникшая на территории Аравийского полуострова в VII веке в результате проповеднической деятельности Мухаммада – основателя первой общины мусульман.

Арабы и Аравия в доисламский период

Во время возникновения ислама в VII веке н. э. Аравийский полуостров представлял собой территорию, крайне неоднородную по составу населения и религиозным традициям.

На полуострове проживали многочисленные кочевые семитские племена, которые принято называть арабами (самоназвание alʿarab).

Согласно представлениям арабского народа, он ведет свое происхождение от библейского патриарха Авраама (араб. Ибрахим). Первый сын Авраама Исмаил, родившийся от рабыни Агари (араб. Хаджар), почитается основателем части арабских народов. После рождения второго сына Авраама от Сарры – Исаака (см.: Быт. 16–21) – Агарь вместе с Исмаилом были изгнаны в пустыню Фаран119. Многочисленные потомки120 Исмаила заселили обширные земли от реки Евфрата до Черного моря и назвали свою страну Набатея121. По именам двенадцати сыновей Исмаила были названы и отдельные арабские племена122.

Исмаил и его потомки считаются родоначальниками североарабских племен. Родоначальником же южных арабов почитался Иоктан (араб. Кахтан) – сын Евера123, отождествляемого мусульманами с пророком Худом124, к которому восходит и род Ибрахима (Авраама). Именно потомков Кахтана (Иоктана) арабские генеалоги считали «настоящими арабами» (ал-араб ал-ариба), в то время как потомков Исмаила называли «арабизированными арабами» (ал-араб ал мутаариба, или ал-араб ал-мустариба)125.

Религиозно-социальная ситуация в Аравии в VI-VII веках н. э. Возникновение ислама

К моменту зарождения ислама религиозная картина в Аравии была довольно разнообразной. К концу VI – началу VII века н. э. на территории полуострова находились и христианские общины, и иудейские поселения, и святилища местных божеств.

Христианство в Аравии

Часть арабских племен исповедовали христианство, правда, в основном еретического направления. В частности, гассаниды и лахмиды были христианами монофизитского и несторианского толка. По верному замечанию знаменитого исследователя ислама XX века Г. Грюнебаума, «Греческая Церковь препятствовала деятельности еретических общин. Отколовшиеся группы отсылали в отдаленнейшие пограничные области, таким образом, христианство представало перед бедуинским миром в облике еретических сект»126.

Разногласия в исповедании веры приводили к тому, что аравийские христиане нередко враждовали друг с другом. В священной книге мусульман – Коране – эти споры между христианами также нашли свое отражение. Тем не менее именно христианское богословие оказало значительное влияние на мышление Мухаммада, особенно в самом начале его проповеднической деятельности. Варака ибн Науфаль, двоюродный брат первой жены пророка Хадиджи, был довольно образованным христианином. По словам авторитетного жизнеописания Мухаммада, один из ближайших родственников пророка Варака ибн Науфаль «последовал книгам, стал знатоком в религии людей, следовавших Писанию»127.

Благодаря тесным контактам с христианами128 на ранних этапах своей жизни исламский пророк получил представление об основных событиях и действующих лицах библейской истории.

Иудаизм в Аравии

На юге Аравии распространение получил иудаизм. Довольно успешной была иудейская проповедь129 в центральной и северной части Аравийского полуострова, где в оазисах возникло немало иудейских поселений.

Местные политеистические культы

Бóльшая часть арабов придерживалась все же политеистических верований и поклонялась звездам и камням-идолам.

В разных аравийских городах существовали свои святилища. Но главная святыня доисламской Аравии располагалась в районе Хиджаз130

, в городе Мекке. Здесь находилась Кааба (с араб. букв. «куб») – святилище кубической формы, в котором было собрано около 360 идолов от всех племен, населяющих полуостров.

Арабы верили в существование добрых и злых духов – джинов и шайтанов, которые играли роль посредников между богами и людьми. Эти духи внушали человеку те или иные мысли, толкали на совершение определенных поступков. К обычным людям, как считалось, духи приходят лишь иногда, но есть особые люди – аррафы (букв. «провидцы») и кахины (букв. «прорицатели»)131, через которых духи могут общаться с остальными. К аррафам и кахинам люди обращались, если хотели узнать свое будущее, найти потерянную вещь, понять смысл увиденного сна. Аррафы и кахины были в каждом арабском племени.

Святилище Мекки

Мекканское святилище принадлежало одному из самых влиятельных арабских племен – курайшитам. Они заручились поддержкой всех племен, проживающих на пути маршрутов к святилищу, дабы во время паломничеств обеспечить порядок и безопасность желающих поклониться святыням Каабы. Так лидеры курайшитов способствовали религиозному единению арабских племен, проживающих на полуострове. В Каабе были собраны священные идолы всех родов и кланов. Таким образом, здесь происходило соединение нескольких культов в один большой ритуальный конгломерат.

Мекка названа в Коране «Матерью городов»132. В этот город стекались представители многочисленных кланов практически со всего Аравийского полуострова. Они приносили с собой собственных идолов и фетишей, приобщаясь к общей святыне арабского мира.

Несмотря на обилие предметов мекканского культа, настоящим «хозяином» Каабы почитался бог-создатель Аллах133

. У него не было собственного культа. Его роль, скорее, сводилась к гарантии соглашений между арабскими племенами и мекканскими кланами, а также защите паломников, держащих путь к Каабе.

Особым почитанием в Мекке пользовались три богини – дочери Аллаха: ал-Лат (с араб. букв. «богиня»; форма женского рода от «Аллах»), аль-Узза (с араб. «великая», «могущественная») и Манат (с араб. «судьба», «рок», «время»). В некоторых аравийских регионах существовали даже храмы, посвященные этим богиням. В центре же Каабы располагался идол божества Хубала.

Поклонение святыням Каабы происходило следующим образом: паломники медленно обходили куб несколько раз и прикасались к священным камням, вмурованным в здание святилища. Самым важным из этих камней был Черный камень134

, расположенный в восточном углу здания Каабы.

Социальная организация жизни арабов

Ключевыми понятиями в общественном устроении для арабов были племя и род (араб. бану – букв. «сыновья»). Так, например, Мухаммад принадлежал к племени курайш и роду (клану) Хашим.

В древней Аравии основным принципом организации отношений между людьми были кровнородственные отношения, выстраивавшиеся по мужской линии. Но постепенно племена увеличивались не только за счет появления новых родственников, но и за счет тех, кто оказывался под покровительством того или иного племени. По давней и весьма почитаемой традиции гостеприимства это могли быть приемные дети, отпущенные на свободу рабы, примкнувшие чужаки из других земель.

Племя состояло из различных родов и семей. Во главе племени стоял вождь. Его статус был обусловлен не происхождением, но силой, благородством, храбростью, богатством и личным моральным авторитетом. Реальная власть в племени принадлежала вовсе не вождю. Вождь был, скорее, главнокомандующим во время походов или набегов. Основные наиболее важные для жизни племени решения принимал совет старейших, выбиравший вождя, объявлявший войну соседям, распределявший завоеванное богатство и земли. Старшие члены семьи, рода и племени являлись гарантами безопасности и благополучия арабского общества.

Прочность внутриплеменных связей можно было бы описать емкой формулой «все за одного». В обществе четко действовал принцип коллективной ответственности: если с одним из членов племени случалась беда, то его выручали общими усилиями. Кроме того, коллективная ответственность была еще и своего рода гарантией упорядоченности, спокойствия и нравственно здоровой обстановки жизни самого племени, поскольку никакой проступок не оставался безнаказанным. Самым же страшным наказанием считалось изгнание. В таком случае человек оказывался совершенно беззащитным и уязвимым перед лицом других людей: его могли безнаказанно оскорбить, ограбить или даже убить.

Ханифы

Кроме арабов-христиан, иудеев и последователей местных политеистических культов в доисламской Аравии существовала еще одна категория верующих людей. Ханифы веровали в некого единого бога, отвергали поклонение идолам, жили довольно аскетической жизнью, стремясь соблюдать ритуальную чистоту, но при этом убежденно отделяли себя от христианской и иудейской традиций. По всей вероятности, такой неопределенный монотеизм ханифов послужил отправной точкой для возникновения ислама.

Примечательно использование самого термина «ханиф» в арабском языке. О происхождении термина известно немного, но споров об истории его возникновения у ученых велось немало. Вероятно, сами ханифы себя так не называли. Наименование имеет внешнее происхождение. Известный западноевропейский исследователь ислама и арабской культуры Уильям Монтгомери Уотт считает, что первоначально название «ханиф» использовали сирийские иудеи и христиане применительно к арабам-язычникам135.

Однако в Коране и у исламских богословов мы находим неожиданно новую интерпретацию этого термина. Согласно словарю, значение исходного для словообразования глагола ḥanafa переводится на русский как «склоняться к чему-то»136. Резонно поинтересоваться, о каком устремлении идет речь?

В Коране ханифом называется пророк Ибрахим, само слово используется в качестве синонима термину муслим, который означает человека, принявшего ислам и явившего покорность Богу: «Ибрахим не был ни иудеем, ни христианином. А был он ханифом, предавшимся [Аллаху]137, и не был многобожником» (3:67)138.

Жажда поклонения истинному Богу, устремленность к Нему – вот основные отличительные качества настоящего ханифа в понимании Корана.

«Пророки» доисламского арабского мира

Ханифы не были закрытой религиозной общиной. Среди них были яркие проповедники, называвшие себя набú (букв. «пророк»). По их утверждению, с ними говорил сам Бог и от Него они получали свои откровения.

Так, наиболее известным проповедником был наби Масламá, который жил в центральной части Аравийского полуострова – в Йамаме. То, чему он учил, было весьма схоже с проповедью Мухаммада. Он так же, как и Мухаммад, верил в Единого Бога, которого называл «Рахман» (букв. «милостивый»), и так же собирал свои откровения в священную книгу. Как гласит предание, однажды Маслама написал письмо пророку ислама с предложением объединить усилия в проповеди и договориться действовать сообща. Но Мухаммад решительно отверг это предложение, приказав написать ответ, который начинался словами: «От посланника Аллаха Мухаммада лжецу Масламе…». Противники Мухаммада часто укоряли его в том, что его учение копирует учение Масламы. В ответ на эти укоры появляются следующие строки в Коране, в которых все «пророки» – конкуренты Мухаммада – недвусмысленно называются лицемерами и обманщиками:

«Есть ли [люди] несправедливее тех, кто возводит на Аллаха напраслину и утверждает: “Мне дано откровение”, хотя никакого откровения ему не дано, или кто говорит: “Я ниспошлю подобное тому, что ниспослал Аллах”? О, если бы ты видел, как грешники пребывают в пучинах смерти, а ангелы простирают [к ним] руки [чтобы лишить их жизни, и говорят]: “Расставайтесь ныне со своими душами! Сегодня вам воздадут унизительным наказанием за то, что вы возводили на Аллаха навет и пренебрегали Его знамениями”» (6:93).

Маслама переживет Мухаммада и будет убит его сторонниками в 633 году.

Кроме Масламы на юге полуострова – в Йемене – большое влияние и сильную политическую и военную власть приобрел другой наби – «пророк» Асвад, который подобно Мухаммаду и Масламе призывал веровать в Единого Бога.

Немалым авторитетом на севере Аравии пользовалась и «пророчица» Саджах из Месопотамии.

Были и другие менее известные наби. Но в целом можно сказать, что «пророки» не были экзотикой для доисламского арабского мира. В этом смысле появление фигуры Мухаммада на религиозном горизонте Аравии не представляется чем-то совсем уникальным. Он был далеко не первым и не единственным, кто в то время боролся за звание «пророка для всех арабов».

Мухаммад – посланник Аллаха и основатель ислама

Исторические источники о жизни Мухаммада

Описание жизни и проповеднической деятельности Мухаммада зафиксировано как в мусульманских, так и в немусульманских источниках.

Немусульманские источники представляют собой, как правило, полемические тексты, принадлежащие перу христианских авторов. Их историческая достоверность и беспристрастность вызывают немало вопросов у взыскательного читателя.

Мусульманские источники сведений о жизни Мухаммада также не всегда надежны. Связано это с тем, что даже самые ранние из них появились намного позднее времени жизни основателя ислама. Первая биография Мухаммада была составлена ибн Исхаком лишь через 130 лет после смерти основателя ислама. К сожалению историков, она сохранилась лишь в отрывках и пересказах других авторов. Современная мусульманская традиция опирается на

«Жизнеописание пророка Мухаммада», составленное

ибн Хишамом в IX веке. Таким образом, наиболее раннее и авторитетное из дошедших до нашего времени свидетельств появилось спустя почти два столетия после смерти основателя ислама.

Отдельные эпизоды из жизни Мухаммада, его поступки и слова, сказанные в определенных обстоятельствах, собраны также в сборниках хадисов139

. Наиболее ранний из них – «аль-Джами» – составлен Абдаллахом бин Вахбом спустя 130 лет после смерти Мухаммада. Из ранних общепризнанных сборников следует отметить «Аль-джами ас-сахих» имама аль-Бухари, а также «Альджами ас-сахих» имама Муслима.

Происхождение Мухаммада

Мухаммад ибн Абдаллах происходил из племени курайш и принадлежал к клану Хашим. Он родился в Мекке в небогатой, но знатной семье 20 апреля 571 года н. э.140 По представлениям мусульман, Мухаммад по прямой линии был потомком сына Ибрахима – Исмаила.

Как гласит мусульманское предание, рождению Мухаммада предшествовал ряд необычных событий и явлений. Например, во дворце персидского царя Хосроя неожиданно обрушилось несколько террас и погас горевший до того непрерывно 1000 лет священный жертвенный огонь141.

Отец Мухаммада – Абдаллах – умер еще до рождения сына во время одной из торговых поездок в Сирию. Мать Мухаммада – Амина бинт Вахб – покинула мир спустя несколько лет после мужа. Потому воспитание мальчика легло на плечи его деда Абдаль-Мутталиба, человека весьма уважаемого, пользовавшегося большим авторитетом у мекканцев.

Имя для новорожденного выбрал Абд-аль-Мутталиб. После ритуального благодарения богов Каабы младенца нарекли Мухаммадом, что буквально означает «восхваляемый», или «достойный хвалы».

Перед смертью Абд-аль-Мутталиб поручил заботиться о Мухаммаде одному из своих сыновей – Абу Талибу. На протяжении всей своей последующей жизни Абу Талиб относился к Мухаммаду как к собственному сыну.

Детство основателя ислама

В детстве Мухаммад прекрасно освоил торговое дело и нередко сопровождал торговые караваны. Однажды на пути в Шам142

юный Мухаммад повстречался с неким христианским подвижником по имени Бахира.

Увидев на спине между лопатками двенадцатилетнего мальчика родовую отметину – «печать пророчества», Бахира предсказал ему великое будущее, посоветовав дяде Мухаммада поберечь мальчика и не брать его с собой больше в опасные путешествия.

Послушав монаха, Абу Талиб отправил племянника обратно в Мекку.

Первый брак Мухаммада

Когда основателю ислама исполнилось 25 лет, одна богатая и знатная женщина по имени Хадиджа бинт Хувейлид предложила ему работу. Работа состояла в том, чтобы доставить ее товары в Шам. Поездка была более чем удачной и принесла Хадидже немалую прибыль. Служанка же рассказала ей о необычайной сообразительности, благородстве и честности юного торговца. После случившегося Хадиджа начала питать к новому работнику нежные чувства и задумалась о браке с ним.

До Мухаммада Хадиджа была замужем два раза, но оба ее мужа умерли. От предыдущих браков у нее остались трое сыновей и одна дочь. На момент знакомства с пророком женщине было 40 лет, то есть она была старше Мухаммада на 15 лет.

По инициативе Хадиджи и с разрешения дяди пророка Абу Талиба состоялся ее брак с Мухаммадом. Она стала матерью практически всех детей Мухаммада, из которых, правда, только дочь Фатима143 пережила своего отца.

Женитьба на Хадидже стала настоящим подарком судьбы для Мухаммада и позволила ему надолго обрести не только финансово-материальную стабильность и независимость, но и возможность предаваться размышлениям и духовным упражнениям.

Без сомнения, брак с Хадиджей был счастливым для Мухаммада. До самой ее смерти он не брал себе никого больше в жены, хотя многоженство было у арабов обычным явлением. Мухаммад оставался рядом со стареющей Хадиджей, продолжая испытывать к ней самые нежные чувства. После смерти Хадиджи последовали другие браки Мухаммада, но память о ней была священна для него вплоть до самой его смерти. Последняя и очень любимая жена – Аиша – с грустью признавалась, что ни к кому она так не ревновала мужа, как к его покойной первой жене.

Жизнь Мухаммада до сорока лет

Спокойное время жизни Мухаммада сопровождалось частыми прогулками в одиночестве по северным окраинам Мекки. Красота здешней природы, гористый и аскетичный ландшафт этих мест особенно располагали к размышлениям на духовные темы. Излюбленным же местом для уединения будущий пророк избрал гору Хиру с небольшой пещерой у подножия. Предварительно взяв с собой достаточный запас пищи и воды, он мог на целый месяц удалиться на гору для размышлений.

До сорока лет ничего особенного с Мухаммадом не происходило: он продолжал заведовать делами своей жены, совершал торговые поездки в разные страны и был, на первый взгляд, вполне счастливым обывателем и успешным купцом. Во время таких «деловых командировок» нередко предоставлялась возможность пообщаться с очень разными людьми, среди которых были и христианские аскеты, говорившие о скором Судном дне и воздаянии, и иудеи, рассказывавшие о ветхозаветных пророках и чаявшие прихода Мессии. В целом это не могло не оказывать влияния на Мухаммада, видевшего упадок национальной религии, превратившейся в набор диких и непонятных суеверий.

Кроме того, в окружении самого Мухаммада были люди, навсегда отказавшиеся от идолопоклонства: Зейд ибн Амр, отправившийся в сторону Шама, чтобы лучше узнать религию христиан и иудеев, но решивший остановить свои активные духовные поиски на отвлеченном деизме; а также небезызвестный Варака ибн Науфаль – двоюродный брат Хадиджи.

Первое откровение в жизни Мухаммада

Мухаммад много размышлял обо всем услышанном и увиденном, и вот его стали посещать странные сны. Однажды

в середине месяца рамадан 610 года, когда он находился на горе Хира и совершал свои аскетические подвиги, он получил свое первое откровение. Ночью к нему явился некто и заставил прочесть стихи, ставшие впоследствии частью Корана (сура 96, аяты 1–5).

Биограф Мухаммада ибн Хишам следующим образом описывает это событие:

«Пришел к нему Джабраиль [т. е. архангел Гавриил. – Прим. прот. О. К.] с приказом от Аллаха. Посланник Аллаха сказал: “Пришел ко мне Джабраиль, когда я спал, с куском шелка, а в нем книга, и сказал: “Читай!”. Я сказал: “Я не читаю”. Он начал душить меня этой книгой так, что я подумал, что это – смерть. Потом отпустил меня и сказал: “Читай!”. Я сказал: “Я не читаю”. Он начал душить меня этой книгой так, что я подумал, что это – смерть. Потом отпустил меня и сказал: “Читай!”. Я сказал: “Что мне читать?”. Я сказал это лишь для того, чтобы избавиться от него и чтобы снова не начал душить меня. Он сказал: “Читай! Во имя Господа твоего, создавшего Человека из сгустка крови. Читай! Господь твой самый милостивый, который научил каламом, научил человека тому, чего он не знал” (96:1–5). Я произнес эти слова. Потом он закончил читать и ушел от меня. Я проснулся от сна, и как будто эти слова отпечатались в моем сердце. Я пошел, и, когда дошел до середины горы, услышал голос с неба, который говорил: “О Мухаммад! Ты – Посланник Аллаха, а я – Джабраиль”. Я поднял голову к небу и посмотрел. И вот Джабраиль в образе человека, сомкнув ноги, закрыл весь горизонт и говорит: “О Мухаммад! Ты – Посланник Аллаха, а я – Джабраиль”. Я остановился и смотрел на него, не двигаясь ни вперед, ни назад. Отвернул свое лицо от него в сторону небесных горизонтов и, куда бы я ни смотрел, видел только его в таком виде. Я продолжал стоять, не двигаясь ни вперед, ни назад. Хадиджа послала людей за мной. Они дошли до вершины Мекки и вернулись к ней, а я все стою на том же месте. Потом он ушел от меня, и я ушел, возвращаясь к своей семье”»144.

После случившегося145 Мухаммад поспешил вернуться домой к своей жене Хадидже. В страхе и растерянности рассказал он ей о произошедшем с ним событии и попросил укрыть его, закутать. Спустя некоторое время после этого во сне Мухаммад снова услышал слова, воспринятые им как Божественный глас и также вошедшие в Коран (74:1–7):

«О завернувшийся!

Встань и увещевай,

превозноси своего Господа,

очисти одежды свои,

избегай скверны,

не оказывай милости в надежде получить большее и терпи [притеснения неверных] ради твоего Господа».

Хадиджа, внимательно выслушав мужа, попыталась его успокоить и отправилась к своему двоюродному брату Вараке ибн Науфалю за советом.

Узнав о том, что случилось, Варака сказал Хадидже:

«Свят, свят! Клянусь тем, в чьих руках душа Вараки, если ты мне говоришь правду, о Хадиджа, то пришел к нему Великий Намус146 – архангел Гавриил, который приходил к Мусе (Моисею). Он – Пророк этой нации. Скажи ему, пусть крепится»147.

Хадиджа поведала Мухаммаду о словах ее брата Вараки, после чего Мухаммад успокоился. Приняв все слова мужа и брата за правду, Хадиджа стала первым человеком, принявшим ислам, и «матерью» всех правоверных мусульман. Затем ислам приняли сын дяди Мухаммада Али бин Абу Талиб, вольноотпущенник Мухаммада Зайд бин Хариса, а также один из его близких друзей Абу Бакр.

После первого откровения были еще подобные видения. Но в течение трех лет Мухаммад никому, кроме близких ему людей, не рассказывал о них.

Мусульманские источники так описывают состояние пророка во время нисхождения откровений148:

«“О, посланник Аллаха, как приходят к тебе откровения?” Посланник Аллаха, да благословит его Аллах и приветствует, ответил: “Иногда приходящее ко мне подобно звону колокола, что является для меня наиболее тяжким, а когда я усваиваю сказанное, это покидает меня. Иногда же ангел предстает передо мной в образе человека и обращается ко мне со своими словами, и я усваиваю то, что он говорит”.

Аиша, да будет доволен ею Аллах, сказала: “И мне приходилось видеть, как в очень холодные дни ему ниспосылались откровения, а после завершения ниспослания со лба его всегда лился пот”».

(Сборник хадисов «Аль-джами ас-сахих» имама аль-Бухари, хадис 2)

«Посланник Аллаха, да благословит его Аллах и приветствует, всегда испытывал напряжение во время ниспослания (откровений), что заставляло его шевелить губами».

(Сборник хадисов «Аль-джами ас-сахих» имама аль-Бухари, хадис 5)

Начало проповеди в Мекке

Через три года после ниспослания первого откровения Мухаммаду было велено начать открытую проповедь в Мекке и обратить в ислам ближайших родственников. По этому поводу ему были ниспосланы соответствующие стихи Корана (26: 214–220). Обратившись к курейшитским родам Мекки, Мухаммад призвал их отказаться от идолопоклонства, признать его посланником Единого Бога и поверить в неотвратимость Судного дня. Проповедь имела ничтожный эффект, в ислам обратилось лишь несколько человек. Большинство мекканцев отвергли проповедь и потребовали от дяди Мухаммада Абу Талиба, пользовавшегося огромным авторитетом и влиянием в городе, заставить Мухаммада прекратить проповедническую деятельность.

В результате нараставшего напряжения на пятом году от начала пророческой деятельности часть мусульман совершили первую хиджру («переселение»). Они переселились в Эфиопию в 615 году, где некоторые из них приняли впоследствии христианство.

Между тем противостояние последователей Мухаммада и мекканских кланов переходило в стадию вооруженного конфликта. Кроме того, ко всем, принявшим ислам, были применены «экономические санкции»: запрещалось заключать торговые сделки и браки с родственниками пророка. Этот бойкот продолжался три года, но затем был аннулирован, поскольку многие курейшиты выражали недовольство тем, что их дальние родственники терпят лишения и подвергаются гонениям.

Вскоре после окончания бойкота, в 619 году, умер Абу Талиб – самый могущественный защитник Мухаммада. Несмотря на то что он был особенно близок со своим племянником, Абу Талиб так и не принял ислам. Еще через несколько месяцев в возрасте 65 лет скончалась Хадиджа. Этот год Мухаммад назвал годом скорби.

Выход с проповедью за пределы Мекки

Оставшись один на один с мекканцами, получившими, наконец, после смерти Абу Талиба возможность открыто преследовать основателя ислама, Мухаммад решается выйти на проповедь за пределы Мекки и отправляется в соседний город Таиф (около 70 км от Мекки). Проведя там десять дней, Мухаммад встретился с местной знатью, но никто не захотел оказать ему поддержку.

Вернувшись в Мекку, Мухаммад продолжил искать союзников в других городах, чтобы впоследствии община новообращенных могла переселиться туда. Но все племена прекрасно понимали, что тот, кто примет Мухаммада и его единоверцев, неизбежно окажется в изоляции и столкнется с враждой других племен, настроенных против пророка.

Вскоре на призыв Мухаммада ответили некоторые жители Ясриба – небольшого оазиса в 350 км от Мекки – и присягнули пророку на верность в городе Акабе.

Спустя некоторое время, в 622 году, мусульмане из Мекки начали постепенно переселяться в Ясриб (вторая хиджра), что вызывало огромное недовольство жителей Мекки, ведь Ясриб лежал на пути следования торговых караванов в Сирию и потому переход города под влияние мусульман ставил мекканцев в некоторую зависимость от последователей новой религии.

Старейшины Мекки после совещания решили пресечь на корню деятельность Мухаммада, убив пророка.

Но этим планам не суждено было сбыться. Узнав об этих намерениях, Мухаммад покинул Мекку149 вместе со своим верным другом Абу Бакром. Они направились сначала в пригород Ясриба – Кубá, где пророк основал первую в истории ислама мечеть. Затем Мухаммад въехал в сам Ясриб, который с тех пор стал называться Медина (араб. Madīnah «город»), или «город пророка» (араб. Madīnat an-Nabī). В Медине же Мухаммад обзавелся и гаремом150.

Значение Хиджры для развития ислама

Хиджра стала ключевым, поворотным моментом в истории ислама151.

Получив возможность открыто и без стеснения исповедовать свою веру, мусульмане почувствовали себя реальной силой, способной устроить общество на новых основаниях. Именно после Хиджры появились условия для формирования основ мусульманского государства и новых внутрисоциальных отношений. Мусульмане объединились в умму (общину), в которой были стерты различия по происхождению, социальному статусу или месту рождения. Верующие чувствовали в первую очередь духовное единство.

Первое время после Хиджры было крайне тяжелым и для мухáджиров – переселенцев в Медину из Мекки, и для ансáров – мусульман Медины. Курейшиты начали активно искать себе союзников для борьбы с последователями Мухаммада, подстрекая другие арабские племена на конфликт с мусульманами. Им даже удалось заручиться поддержкой некоторых жителей Медины, недовольных все возрастающим влиянием пророка и его сподвижников на жизнь города.

В результате Мухаммад вынужден был предпринять ответные действия, чтобы обеспечить содержание общины, лишившейся имущества, в том числе многих земель. Основателю ислама были ниспосланы коранические строки, позволявшие сражаться с иноверцами даже в запретные для войны месяцы:

«Они спрашивают тебя, [дозволено ли] сражаться [с мекканскими многобожниками] в запретный месяц. Отвечай: “Сражаться в запретный месяц – великий грех. Однако совращать с пути Аллаха, не пускать в Запретную мечеть152, неверие в Него и изгнание молящихся из нее [т. е. из Запретной мечети. – Прим. прот. О. К.] – еще больший грех перед Аллахом, ибо многобожие – грех больший, чем убиение. Они не перестанут сражаться с вами, пока не отвратят вас от вашей религии, если только смогут. А если кто из вас отвратится от своей веры и умрет неверным, то тщетны деяния таких людей в этой жизни и в будущей. Они – обитатели ада и пребудут в нем навеки”».

(Коран 2:217)

«Тем, которые подвергаются нападению, дозволено [сражаться], защищая себя от насилия. Воистину, во власти Аллаха помочь тем, которые беззаконно были изгнаны из своих жилищ только за то, что говорили: “Наш Господь – Аллах”. Если бы Аллах не даровал одним людям возможность защищаться от других, то непременно были бы разрушены кельи, церкви, синагоги и мечети, в которых премного славят имя Аллаха. Нет сомнения, Аллах помогает тому, кто помогает Его религии. Воистину, Аллах – сильный, великий».

(Коран 22:39–40)

Произошли множественные вооруженные столкновения между мусульманами и мекканцами. Все же, несмотря на старания уммы153

, некоторые из военных походов окончились для мусульман безрезультатно. Но в январе 624 года последователям ислама удалось захватить караван курейшитов, шедший без охраны.

Военные столкновения сторонников и противников Мухаммада

Первое крупное сражение между мекканцами и сторонниками Мухаммада произошло в марте

624 года при Бадре, расположенном на пути из Мекки в Медину. В битве приняли участие 300 мусульман, на стороне их противников, по разным оценкам – от 600 до 1000 человек. Но, несмотря на явное численное превосходство, мекканцы потерпели полное поражение. За пленных курайшитов Мухаммад решил просить выкуп. После сражения при Бадре Мухаммаду были ниспосланы очередные стихи Корана, вошедшие в восьмую суру под названием «Трофеи».

Победа при Бадре укрепила позиции Мухаммада в Медине, и потому немало людей, проживающих в городе, начали принимать ислам. Вместе с тем укрепился и моральный боевой дух самих мусульман, убежденных в том, что их победа – свидетельство милости к ним Аллаха и подтверждение их правоты. «Не вы [о верующие] убили неверных, а Аллах сразил их» (Коран 8:17), – говорится по этому случаю в Коране.

Следующая

битва при Ухуде, состоявшаяся год спустя, в 625 году, принесла мусульманам поражение, несмотря на то что Мухаммад предсказывал своим сторонникам безоговорочную победу. Сам основатель ислама получил ранение в этом сражении.

Вооруженное противостояние продолжалось много месяцев. Но очередная крупная битва все же завершилась для мусульман победой. Росло и количество приверженцев новой религии.

В 628 году сторонники Мухаммада захватили иудейское поселение Хайбар, а также заключили мирный договор с соседним оазисом Фадак. После этого Мухаммад отправил послания правителям Византии, Персии, Эфиопии, Египта и других царств с предложением уверовать в Аллаха и признать Мухаммада его пророком и посланником.

Годом позднее, в 629 году, в местечке под названием Мут мусульманская армия впервые вступила в сражение с армией Византии, во главе которой находился сам император Ираклий. Последователи Мухаммада потерпели сокрушительное поражение и были вынуждены отступить.

В

630 году Мухаммад принял решение двигаться

на Мекку. Десятитысячная армия мусульман застала врасплох курайшитов, и они не смогли оказать должного сопротивления нападавшим. Город капитулировал. Мухаммад, проявив снисхождение к побежденным, демонстративно простил своих противников. Большинство мекканцев приняли после этого ислам.

Последний год земной жизни Мухаммада

В 632 году Мухаммад объявил о своем намерении совершить большое паломничество в Мекку – хадж. Он вошел в Каабу, очищенную от идолов, и совершил поклонение черному камню. Во время хаджа у горы Арафат Мухаммад обратился к умме с последней,

прощальной проповедью, свидетелями которой стали около 120 тысяч человек. В своем слове Мухаммад призвал верующих поклоняться только Аллаху, признавать верховенство закона, хорошо относиться к своим женам; он отменил кровную месть, ростовщичество и межплеменную вражду, возложил ответственность за деяния только на человека, их совершившего. Мухаммад засвидетельствовал, что он последний из посланных Аллахом пророков и после него пророков уже не будет. Вскоре после данной проповеди Мухаммаду были ниспосланы и одни из последних стихов Корана, которые, как считается, завершили формирование шариата (религиозно-правовых норм)154 и вошли в 3 аят 5 суры:

«Сегодня Я завершил [ниспослание] вам вашей религии, довел до конца Мою милость и одобрил для вас в качестве религии ислам».

(Коран 5:3)

По окончании хаджа Мухаммад отправился в Медину.

В том же году в ряде областей Аравии, в частности, в Йемене, в Йамаме, в северных и восточных районах, арабские племена под предводительством своих пророков – Асвада, Масламы, Саджах и других – попытались собрать силы для того, чтобы расправиться со сторонниками Мухаммада. Осознавая, что столкновение неизбежно, Мухаммад принял решение готовиться к войне против

Византии, поскольку от успеха похода, по его мнению, зависел авторитет мусульман в Аравии и объединение всех арабов под знаменем ислама.

Но тяжелая болезнь, а затем и смерть не позволили ему осуществить задуманное. Мухаммад умер в Медине 8 июня 632 года.

После смерти Мухаммада его преемником (халифом) был назначен его ближайший друг и сподвижник Абу Бакр.

Коран Характеристика структуры и содержания Корана

Коран (араб. al-Qur’ān – букв. «чтение») – это главная священная книга мусульман. Представляет собой запись проповедей Мухаммада, произнесенных им в форме пророческих откровений между 610 и 632 годами.

В основном Коран изложен ритмически организованной прозой с использованием рифмы и состоит из глав – сур (араб. sūrah – букв. «стена», «высокое строение»). Всего в «канонической» версии Корана 114 сур. Каждая сура состоит из стихов – аятов (араб. āyah – букв. «знак», «знамение», «чудо»).

Речь в тексте идет от первого лица, то есть от лица Аллаха, использующего местоимения «мы» или «я». Содержание Корана весьма разнородно: в тексте тесно переплетены пересказ историй древнего мира и доисламской Аравии, повествование о некоторых библейских событиях, установления юридического и нравственного характера, попытки полемики с «неверными», эсхатологические сюжеты, описывающие Страшный суд и грядущее посмертное воздаяние.

Современные исламские ученые следующим образом формулируют отношение к Корану в мусульманской традиции:

«Коран – главный источник мусульманского вероучения, нравственно-этических норм и права. Текст этого Писания на арабском языке считается несотворенным Словом Бога по форме и содержанию. Каждое его слово соответствует записи в Хранимой Скрижали – небесном архетипе Священных Писаний, хранящем сведения обо всем происходящем во Вселенной. Аллах вкладывал Коран в уста Мухаммада, и принято говорить, что откровения были ниспосланы Пророку»155.

Итак, по убеждению последователей Мухаммада, Коран является неизменным и несотворенным словом Аллаха. Логика здесь довольно проста: если Аллах является единственным несотворенным объектом, существующим вне времени и пространства, то и все его мысли и слова, будучи его вечными атрибутами, являются несотворенными. Соответственно, и Коран, подобно Аллаху, вечен и неизменен по форме и содержанию.

Данное положение вызывало немало споров даже среди самих мусульман, не говоря уже о критике со стороны инаковерующих. В VII-IX веках в лоне ислама появляется движение мутазилитов (с араб. букв. «обособившиеся», «отделившиеся»), которые, придерживаясь строгого монотеизма (таухид), отвергали вечность атрибута речи. По их убеждению, придание Корану статуса несотворенности ставит его в один ряд с Аллахом, то есть наделяет свойствами Бога. А это, в свою очередь, равнозначно многобожию (ширк). Идеи мутазилитов были живы вплоть до XIII века. Но в исламе все же возобладала иная точка зрения, считающая Коран неизменным и вечным атрибутом Аллаха.

Специфика чтения Корана

Другой аспект, на который стоит обратить внимание: несотворенным и вечным для мусульманской традиции является лишь Коран на арабском языке.

Ислам закрепляет за арабским языком особый статус: статус сакрального языка, языка Божественного откровения. Подтверждение этому находим в следующих коранических строках:

«Воистину, Мы ниспослали его [т. е. Священное Писание. – Прим. прот. О. К.] (в виде) Корана на арабском языке в надежде, что вы поймете [его содержание]».

(Коран 12:2)

Только Коран на языке оригинала передает всю полноту и глубину смыслов, заложенных в тексте, а потому любые, даже дословные переводы не могут считаться совершенно точными и абсолютно адекватными.

Неслучайно в некоторых переводах священного писания мусульман на другие языки после слова «Коран» стоит специальное пояснение: «перевод смыслов». Согласно представлениям последователей Мухаммада, любой перевод священного текста Корана является в некотором смысле его интерпретацией. В связи с этим во время мусульманских богослужений Коран читается исключительно по-арабски156.

Чтение Корана является одной из форм богопочитания. А рецитация (чтение) отдельных частей или всего священного текста целиком в ритуальных целях называется кираáт (араб. qira’at – букв. «чтение», «рецитация»). В исламе существует несколько традиций кираата, все из которых, по убеждению мусульманских богословов, восходят к Мухаммаду и связаны с именем одного из имамов, преподававших чтение священного текста.

Восприятие Корана мусульманами

Мусульмане считают Коран уникальным явлением, настолько совершенным, что человеку невозможно написать ничего такого, что бы сравнилось по красоте и стройности с Кораном. Это представление закрепилось в мусульманской догматике, получив наименование иджаз аль-Куран, что буквально означает «неподражаемость, чудесность Корана».

Процесс формирования священного писания мусульман начался с момента первого откровения Мухаммаду в 610 году. По мусульманскому преданию, во время жизни основателя ислама многие верующие записывали его слова. Но в основном передача коранических откровений осуществлялась в устной форме.

Мухаммад, напомним, был неграмотным человеком. Его сподвижник и личный писец Зайд ибн Сабит свидетельстовал о том, что сам Мухаммад нередко проверял точность записей своих последователей. Записи делались на отдельных лоскутках, и, если какое-то слово казалось Мухаммаду не относящимся к Корану, он приказывал его стереть. Несмотря на имевшие место записи священного текста, Коран долгое время существовал в разрозненном виде.

Первые полные записи начали появляться в кругу ближайших соратников Мухаммада лишь после его смерти. Эти записи зачастую отличались друг от друга названием глав (сур), написанием некоторых слов, а также порядком и количеством откровений.

Потребность создания единого кодекса коранического текста возникла в критический для жизни уммы момент. Мусульмане были вынуждены противостоять другим арабским племенам, отказавшимся материально поддерживать последователей Мухаммада либо вовсе решившим вернуться к традициям предков, либо же примкнувшим к другим духовным лидерам и вождям, коих в Аравии было немало в то время. Более того, постепенно нарастало напряжение на границе с Византией, выливавшееся периодически в серьезные военные столкновения. Наиболее существенные потери мусульмане понесли в Йамаме, где в сражении с племенем бану ханифа в 633 году погибли около 70 знатоков Корана.

Проблемы сохранности текста Корана

Опасаясь за сохранность священного текста, праведный халиф Абу Бакр предпринял первую попытку записать текст целиком.

Первый письменный экземпляр Корана получил название мусхаф (с араб. букв. «книга», «свиток»), который до потомков, увы, не дошел.

С течением времени появилось немало разногласий в чтениях священного текста, это особенно касалось форм чтения (харф)157. Дело в том, что пророк был носителем курайшитского диалекта арабского языка. Но в арабском языке существовало несколько диалектов, и различия между ними были довольно заметны. Как пишет отечественный филолог-арабист Г. Р. Аганина, «пестрая картина говоров в Аравии, чужеродная языковая среда в районах первоначального распространения ислама <…> создавали почву для вариантного чтения Корана»158.

Как гласит исламское предание, Мухаммад, осознавая, что его проповедь может быть не понята представителями других племен, попросил Всевышнего упростить усвоение Корана для всех людей.

В ответ на мольбу пророка Аллах ниспослал своему посланнику священный текст в семи харфах. Это означало, что некоторые слова или даже целые аяты могли читаться по-разному в зависимости от диалекта. Но следует отметить, что все эти расхождения сначала воспринимались первыми мусульманами как норма, как важное и неотъемлемое свойство Божественного откровения.

Появление кодекса Усмана

После смерти пророка вопрос о разночтениях встал особенно остро среди его последователей. Чтобы примирить разногласия между верующими относительно правильного текста Корана, третий халиф Усман бин Аффан создал специальную комиссию из двенадцати знатоков священного текста, среди которых особое место занимал уже упоминавшийся выше Зайд ибн Сабит.

В результате было составлено несколько списков Корана, которые были разосланы в крупнейшие города мусульманского государства. Текст списков получил название кодекс Усмана. Первоначально текст Корана не имел огласовок. Следует заметить, что кодекс Усмана хоть и стремился помочь избежать разногласий, но все же не ограничивался лишь одним харфом, не исчерпывая вместе с тем всех возможных вариантов чтения.

Среди мусульманских корановедов также бытует мнение, что именно зайдо-усмановская версия Корана окончательно закрепила порядок расположения сур в тексте.

Кроме признанного в суннитском мире кодекса Усмана существует также версия Корана159, признаваемая «крайними» шиитами. «Крайние» шииты уверены в том, что кодекс Усмана исказил некоторые аяты Корана, в которых говорится об Али ибн Абу Талибе – двоюродном брате и зяте Мухаммада, ставшем последним из четырех праведных халифов.

Основные отличия между двумя версиями Корана заключаются в том, что в указанном списке в ряде мест вставлено имя сугубо почитаемого шиитами Али ибн Абу Талиба, а также добавлена 115 сура, которая называется «ан-Нурайн» («Два светила»), прославляющая Али ибн Абу Талиба вместе с пророком Мухаммадом. Эта сура встречалась в некоторых версиях текста Корана вплоть до XVII века. Позднее она была признана подделкой160.

В настоящее время большинство шиитов пользуется версией Корана, составленной Усманом и Зайдом ибн Сабитом. Лишь небольшие группы шиитов, проживающих в Индии и Пакистане, продолжают использовать так называемый «список Али».

Хронология коранических аятов

В целом все аяты делятся на мекканские, ниспосланные Мухаммаду в период его жизни в Мекке, и мединские, связанные с началом хиджры в Медину.

Обстоятельства жизни мусульманской уммы накладывали свой отпечаток на содержание откровений. Так, мекканские аяты отличает яркая полемичность с многобожием, призывы к поклонению только Аллаху, напоминания о грядущем воздаянии, рае и адских муках, проклятия в адрес идолопоклонников. С переселением в Медину перед общиной встали новые задачи, связанные с социально-правовой организацией жизни уммы. Соответственно меняется и пафос аятов: теперь в них больше обстоятельных и пространных прозаических периодов, раскрывающих различные стороны жизни и деятельности мусульман.

Суры могут быть составлены как полностью из мекканских (сура 2 «Завернувшийся») или мединских аятов (сура 3 «Семейство Имрана»), так и сочетать в себе и те и другие. Например, сура 6 «Скот» содержит мекканские и мединские аяты, являясь смешанной.

Относительно хронологии ниспослания тех или иных аятов у улемов161 нет единого мнения. Что касается первых ниспосланных аятов, то здесь большинство комментаторов Корана сходятся в том, что ими стали первые пять стихов, вошедшие в 96 суру «Сгусток»:

«Читай [откровение] во имя Господа твоего, который сотворил [все создания],

сотворил человека из сгустка [крови].

Возвещай, ведь твой Господь – самый великодушный,

который научил [человека письму] посредством калама,

научил человека тому, чего он [ранее] не ведал».

(Коран 96:1–5)

Интересна точка зрения исламских ученых на первую так называемую «Открывающую» суру Корана («аль-Фатиха»)1. По убеждению многих исламских ученых, эти аяты заключали каждое ниспосылаемое Мухаммаду «откровение»:

«Во имя Аллаха, Милостивого, Милосердного.

Хвала Аллаху – Господу [обитателей] миров,

милостивому, милосердному,

властителю дня Суда!

Тебе мы поклоняемся и к Тебе взываем о помощи:

веди нас прямым путем, путем тех, которых Ты облагодетельствовал, не тех, что [подпали под Твой] гнев, и не [путем] заблудших».

(Коран 1:1–7)

А вот последние ниспосланные строки вызывают немало споров среди богословов. В основном называются либо аяты о наказании за убийство мусульманина (Коран 4:93), либо о боковой линии наследования (Коран 4:176), либо о совершенстве дарованной людям через Мухаммада религии (Коран 5:3). Итак, установление точного хронологического порядка сур представляет немалую сложность для коранистики.

Суры в Коране, за исключением первой «Фатихи», расположены, как уже очевидно, не в хронологическом порядке их ниспослания, а в основном в порядке уменьшения их длины, но этот принцип соблюдается неточно. Самая длинная сура 2 «Корова» состоит из 286 аятов, а самая короткая – сура 108 «Аль-Каусар» («Обильный») – содержит только три аята.

Современный порядок сур в Коране

Нет единого мнения о том, был ли он определен при жизни Мухаммада или же сложился позднее.

Ряд авторитетных улемов, таких как ан-Наххас, аль-Кирмани, ибн аль-Анбари, склоняются к мысли, что порядок сур в первом письменном экземпляре цельного текста Корана был обусловлен указаниями самого Мухаммада. Они полагают, что именно этот экземпляр – мусхаф Абу Бакра – содержит порядок сур, который более всего угоден Аллаху.

Малик ибн Анас, Бакиллани придерживаются мнения о том, что расположение сур в священном тексте было установлено сподвижниками пророка на основании собственных суждений – иджтихада162

.

Главным доводом второй группы улемов было то, что ранние списки Корана, созданные, в частности, ’Абдаллахом ибн Мас‘удом – старейшим и авторитетнейшим сподвижником Мухаммада, содержали иной порядок сур. Более того, в списке ибн Мас‘уда было на две суры меньше: в нем отсутствовали первая и последняя суры, которые он считал не чем иным, как молитвами, предваряющими и завершающими чтение Корана.

В любом случае для самих мусульман вопрос возникновения современного порядка сур не является камнем преткновения. Как пишет об этом андалузский улем Ибн аз-Зубайр ал-Гирнати, «если порядок сур был установлен пророком, то этот вопрос не обсуждается; если же он возложил его решение на своих последователей, то каждый из сподвижников приложил все силы для этого. Они прекрасно знали этот вопрос, и тому, как они понимали его, можно доверять»163.

«Отменяющие» и «отмененные» аяты в Коране

Феномен «аннулирования определенного религиозного положения на основании более позднего священного текста»164 получил в исламе название

насх (с араб. «отмена», «упразднение»). Насх является одним из объектов критики в полемике с исламом. И потому стоит осветить точку зрения самих мусульман по указанной проблематике.

По оценкам разных улемов, в Коране насчитывается от 5 до 500 отмененных аятов165. Так, например, если в 180 аяте 2 суры «Корова» говорится, что имущество мусульманина наследуют родители или близкие родственники, то в аятах 11–13 и 176 суры 4 «Женщины» предлагается долевое деление наследства между всеми членами семьи умершего. Неоднозначно говорит Коран о вине и азартных играх. В одном месте о них сказано, что «и в том, и в другом есть великий грех, есть и некая польза для людей, но греха в них больше, чем пользы» (Коран 2:219). В двух других аятах они названы «скверными деяниями, внушаемыми шайтаном», которых должно сторониться (Коран 5:90–91).

Впрочем, для мусульман в отмене заповедей и замене их на другие нет ничего удивительного и противоречивого. Главным аргументом улемов является то, что власть Аллаха безгранична и он в своих действиях не обязан считаться с мнением или желаниями людей. Вместе с тем Аллах справедлив и знает лучше, что и в какой момент человеку полезно, а что – нет. Иными словами, Аллах позволяет людям только то, что им полезно, и запрещает только то, что наносит им вред.

Устами Мухаммада Аллах говорит в Коране:

«Мы не отменяем и не предаем забвению ни один аят, не приведя лучше его или равный ему. Разве ты не знаешь, что Аллах властен над всем сущим?»

(Коран 2:106)

«Когда Мы заменяем один аят другим – Аллах лучше знает то, что Он ниспосылает, – [неверные] говорят [Мухаммаду]:

“Воистину, ты – выдумщик”. Да, большинство неверных не знает [истины]».

(Коран 16:101)

Разногласия среди улемов относительно отмененных и действующих аятов можно объяснить и различием их отношений к тем или иным ситуациям или явлениям.

Сунна

Форма и содержание

Сунна (араб. sunnah – «обычай», «пример», «предание») – второй по важности после Корана источник исламского вероучения и правовых норм. В целом под сунной понимают совокупность сведений о поступках, изречениях, внешних и нравственных качествах Мухаммада. Пример жизни посланника Аллаха (букв. суннат расул Аллах, то есть пример посланника Аллаха) является образцом для подражания для каждого правоверного мусульманина.

Сунна поясняет смысл аятов Корана, дополняя их подробными разъяснениями о том, каким должно быть поведение мусульманина в различных сферах его жизни. Так, в Сунне Мухаммад объяснял, как именно нужно исполнять предписания Аллаха, как совершать молитву (намаз) и паломничество (хадж), как выплачивать закят (милостыню) и многое другое.

Существовавшая долгое время устно, Сунна зафиксирована в форме хадисов. В шиитской среде хадисы могут еще именоваться хабарами166

. Несмотря на то что сунниты и шииты пользуются разными сборниками преданий, Сунну одинаково почитают все направления традиционного ислама. Как и Коран, Сунна считается частью Божественного откровения. Но если Коран является таковым и по форме, и содержанию, то хадисы передают Божественное откровение лишь по содержанию.

Хадисы: структура, содержание, история записи

Хадис (араб. ḥadīth – букв. «новость», «известие», «рассказ») – краткий рассказ с описанием ситуации из жизни Мухаммада. Хадис задает верующим образец для подражания, а также восприятия различных религиозно-правовых вопросов с позиций ислама. Структурно хадис состоит из двух частей: информационной части, составляющей собственно содержание хадиса (матн), и перечисления людей, участвовавших в цепочке передачи данного хадиса (иснад).

История записи хадисов началась еще в период жизни Мухаммада, когда его верные сподвижники, а также члены уммы записывали сказанные пророком слова или же описывали его поведение в различных ситуациях.

Спустя некоторое время после смерти пророка накопилось огромное количество материала, связанного с жизнью и высказываниями Мухаммада. И очевидно, что среди этого многообразия далеко не все свидетельства соответствовали действительности. Некоторые данные и вовсе являлись фальсификацией.

Во времена первых халифов исламские ученые провели огромную работу по систематизации хадисного материала. Сподвижники Мухаммада, дабы избежать распространения в народе «лживых» хадисов, обязывали каждого, кто рассказывал тот или иной хадис, называть имя того, от кого он услышал его, и возводить цепочку передатчиков хадиса к самому пророку. Именно эта цепочка передатчиков хадиса – иснад – служила главным критерием достоверности рассказа.

Категории хадисов. Суннитские и шиитские сборники хадисов

В результате кропотливой работы исламских богословов хадисы были разделены на

достоверные (сахих),

хорошие (хасан) и

слабые (даиф). Первые две группы считаются надежными хадисами и обладают юридической силой, то есть служат доводом для вынесения того или иного религиозно-правового решения. Слабые хадисы считаются ненадежными и не являются источником права, поскольку в иснаде отсутствует какое-либо звено или же содержание хадиса противоречит другим, более надежным сообщениям. Но эти хадисы могут использоваться верующими для духовной пользы и назидания.

Особая категория хадисов – это хадисы

аль-кудси (с араб. букв. «священный», «божественный»), которые передают слова Аллаха, не вошедшие в Коран.

«Золотой век» хадисоведения наступил в VIII-IX веках, когда наука о хадисах начала активно развиваться. В это время появились так называемые «шесть сводов» хадисов, которые приобрели наибольшую известность и авторитет среди мусульман-суннитов167.

1. «Аль-джамиас-сахих’имамаМухаммадааль-Бухари. Этот сборник считается самым надежным источником. В его состав вошли только достоверные хадисы. Сборник разделен на тематические главы.

2. «Аль-джами ас-сахих» имама Муслима. Это второй по надежности сборник. Хадисы распределены по тематическим разделам. Похожие хадисы приводятся вместе, это помогает сравнивать их друг с другом.

3. «Китаб ас-сунан» имама Абу Дауда. В сборник собраны хадисы, касающиеся в основном вопросов мусульманского права. Помимо высказываний пророка в сборник имама Абу Дауда вошли также высказывания ближайших сподвижников Мухаммада и их учеников.

4. «Аль-джами ас-сахих» имама Мухаммада ат-Тирмизи. Сборник собрал хадисы, посвященные различным сторонам исламского права. Обычно подобные сборники называют также «сунан». Потому труд имама ат-Тирмизи известен как «Сунан» ат-Тирмизи.

5. «Китаб ас-сунан» имама Ахмада ан-Насаи. Этот сборник считается мусульманами самым авторитетным после сборников аль-Бухари и Муслима.

6. «Китаб ас-сунан» имама Мухаммада бин Язида, более известного как ибн Маджа. Данный сборник содержит большое количество слабых хадисов, но несмотря на это, приобрел большую популярность у верующих. Однако авторитетность и достоверность многих хадисов вызывает немало нареканий и вопросов у мусульманских ученых.

Приведем пример хадиса из сборника имама аль-Бухари.

«Нам рассказал Яхйа ибн Са’ид аль-Ансари, который сказал: Рассказал мне Мухаммад ибн Ибрахим ат-Тайми о том, что он слышал, как ‘Алькъама ибн Ваккъас аль-Лейси говорил: “Я слышал, как ‘Умар ибн аль-Хаттаб, да будет доволен им Аллах, будучи на минбаре сказал:

– Я слышал, как посланник Аллаха, да благословит его Аллах и приветствует, сказал: “Поистине, дела (оцениваются) только по намерениям и, поистине, каждому человеку (достанется) только то, что он намеревался (обрести), и поэтому (человек, совершавший) переселение к Аллаху и посланнику Его, переселится к Аллаху и посланнику Его, переселявшийся же ради чего-нибудь мирского или ради женщины, на которой он хотел жениться, переселится (лишь) к тому, к чему он переселялся””».

(Сборник аль-Бухари. Книга 1. «Начало откровений». Хадис 1)

Первая часть хадиса представляет собой иснад и указывает на то, что каждый из передатчиков данного рассказа слышал его от своего учителя-шейха. Цепочка восходит к Умару ибн аль-Хаттабу – ближайшему сподвижнику Мухаммада и второму праведному халифу исламского государства, а от аль-Хаттаба восходит к самому Мухаммаду.

Текст хадиса – матн – представляет собой слова Мухаммада, в которых пророк подчеркивает важность благих намерений для мусульманина: любое действие, совершенное не ради Аллаха, не принесет добрых плодов для совершающего это действие.

Несмотря на то что все течения ислама признают авторитет и духовное значение Сунны, мусульмане различных направлений пользуются при этом разными сборниками. У шиитов авторитет и популярность получили следующие четыре свода хадисов (хабаров):

1. «Аль-Кафи», составленный шейхом

Абу Джафаром ар-Рази. В нем содержатся хадисы, записанные со слов членов семьи пророка.

2. «Ман ла йахдуруху аль-факих» шейха Садука

аль Куми, известного также как Шейх-и Аджал и Шейх-и Таифа.

3. «Ат-Тазхиб»,составленныйшейхом

ат-Туси; 4. «Аль-Истибсар», также составленный шейхом

ат-Туси.

Значение Сунны в жизни мусульманина

Изучение Сунны имеет огромное значение для образования и воспитания настоящего мусульманина. Сунна – источник вероучения, права, этических и бытовых норм для любого правоверного. Авторитетом Сунны освящались все последующие нормы административной, религиозной, юридической и бытовой практики. Но вместе с тем историческая достоверность многих частей Сунны вызывает немало споров среди ученых-востоковедов, а также либерально настроенных мусульман. Это, впрочем, не отменяет духовной ценности хадисов для большинства последователей ислама.

Вероучение. «Шесть основ веры»

Иман

Исламская традиция имеет особый термин, обозначающий веру во всей совокупности ее аспектов, – иман (с араб. букв. «вера»). Иман включает в себя:

1) внутреннюю убежденность в истине мусульманского учения,

2) свидетельство веры делами,

3) словесное исповедание веры.

Каждый верующий мусульманин должен исповедовать определенный набор вероучительных принципов, которые получили в исламе наименование акида (с араб. букв. «убеждение»). Это закрытый список доктринальных положений, состоящий из шести пунктов и известный как

«Шесть основ веры».

Шесть основ мусульманской веры

1. Вера в Аллаха

Убежденность в существовании верховного Бога, единого и единственного, как в отношении личности, так и в отношении природы. Аллах нерожден и несотворен, Он Единственный в Своем роде, не имеет Себе равных и даже подобных Ему. Он не нуждается в помощниках и «сотоварищах». Он Творец и Судия Вселенной, существующий вне времени и пространства. Аллах открывает Себя людям через Свои писания и Своих посланниковпророков.

Коранический текст указывает:

«Аллах – нет божества, кроме Него, вечно живого, вечно сущего. Не властны над Ним ни дремота, ни сон. Ему принадлежит то, что на небесах, и то, что на земле. Кто же станет без Его соизволения заступничать перед Ним [за кого бы то ни было]? Он знает то, что было до людей и что будет после них. Люди же постигают из Его знания лишь то, что Он пожелает. Ему подвластны небеса и земля, Ему не в тягость их охранять. Он – всевышний, великий».

(Коран 2:255–257)

Первое основание веры имеет особую формулу –

шахаду (с араб. букв. «свидетельствовать»), которая выглядит следующим образом:

«Ля иляха илля-Ллах ва Мухаммадун расулю-Ллах» (букв. «Нет бога, кроме Бога, и Мухаммад – посланник Бога»).

Искреннее и убежденное произнесение шахады в присутствии свидетелей-мусульман является актом принятия ислама. Обычно шахада произносится трижды в собрании общины верующих.

Мусульманская традиция делает особый акцент на единстве и единственности Аллаха, видя в единобожии центральный стержень ислама. Это вовсе не случайно. Ислам, как было отмечено ранее, возник во многом как реакция на столкновение представителей монотеистических религий (иудаизма и христианства) с аравийским политеистическим обществом.

Исламская традиция приписывает Аллаху 99 имен, которые в совокупности называются

аль-асма аль-хусна (с араб. букв. «прекрасные имена»). В мусульманской среде считается похвальным упоминание имен Аллаха и призывание Его.

2. Вера в ангелов

Убежденность в существовании созданных Аллахом из света ангелов.

Из света Аллах создал духов с целью исполнения ими служебных функций. В зависимости от вменяемых им обязанностей ангелы разделены по классам. Они не обладают способностью к творчеству и половыми различиями. Обитают на небесах, но по повелению Аллаха могут нисходить на землю и общаться с людьми.

В Коране имеется следующее славословие Создателю мира:

«Хвала Аллаху, Творцу небес и земли, назначившему посланцами ангелов, обладающих двумя, тремя и четырьмя крыльями».

(Коран 35:1)

В рамках исламской традиции некоторые ангельские сущности выделяются особо, поскольку им принадлежит особая роль в замысле Творца. Так, существуют ангелы исполинских размеров, носящие трон Аллаха, ангелы-писцы, приставленные к каждому человеку для фиксации всех совершаемых им дел, ангелы-истязатели покойников о совершенных поступках, ангелы смерти, ангелы-хранители гор и т. п.

Поименно известны следующие ангелы:

– Джабраиль (Джибрил) – отраженный в исламе образ библейского архангела Гавриила. Служит посыльным и доверенным лицом Аллаха;

– Микаил – ответственный за рост и продуцирование растений;

– Исрафил – возвещатель грядущего Суда, для чего ему надлежит в свое время вострубить в рог.

Поскольку только Аллах достоин поклонения, мусульмане не должны поклоняться и молиться ангелам. Нельзя просить ангелов о помощи и заступничестве. Однако им надлежит оказывать уважение.

Кроме ангелов, имеющих световую природу, творениями Аллаха являются еще

джинны, созданные из пламени. Джинны, подобно людям, отличаются половым диморфизмом и могут склонять как к добру, так и ко злу. Одним из таковых был

Иблис (вероятно, от греч. δια᾿

βολος) – исламский сатана, о котором в Коране прямо сказано: «Он был из джиннов» (Коран 18:50). Иблис решился служить Аллаху, но в момент испытания не устоял: отказался по требованию Создателя поклониться человеку (Адаму), мотивировав это тем, что Адам создан из глины, а сам Иблис – из огня.

Джинны, последовавшие за возмутителем спокойствия, укоренились во зле и стали именоваться

шайтаны168

. Они постоянно вредят людям, внушая им дурные мысли и побуждая к скверным поступкам.

В то же время часть джиннов не пошла вслед за Иблисом. Более того, некоторые из них, внимая проповеди Мухаммада, обратились в ислам.

3. Вера в Писания

Уверенность в сакральности текстов, ниспосланных Аллахом отдельным своим доверенным лицам с целью наставления в истине.

Вторая сура Корана говорит о даровании письменных откровений ряду людей: