[mybigtext]Шумерская цивилизация считается одной из древнейших в мире, однако так ли их общество отличалось от современного? Сегодня мы расскажем о некоторых деталях быта шумеров и о том, что мы у них переняли.[/mybigtext]

Начнем с того, что время и место происхождения шумерской цивилизации до сих пор остаются вопросом научной дискуссии, ответ на который вряд ли будет найден, ведь количество сохранившихся источников крайне ограниченно. К тому же, из-за современной свободы слова и информации Интернет заполнен множеством конспирологических теорий, что многократно усложняет процесс поиска истины научным сообществом. По принятым же большей частью научного сообщества данным шумерская цивилизация уже существовала в начале VI тысячелетия до нашей эры в Южной Месопотамии.

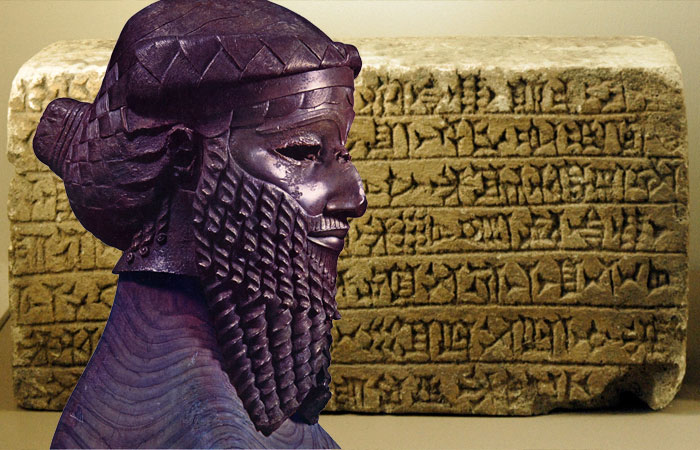

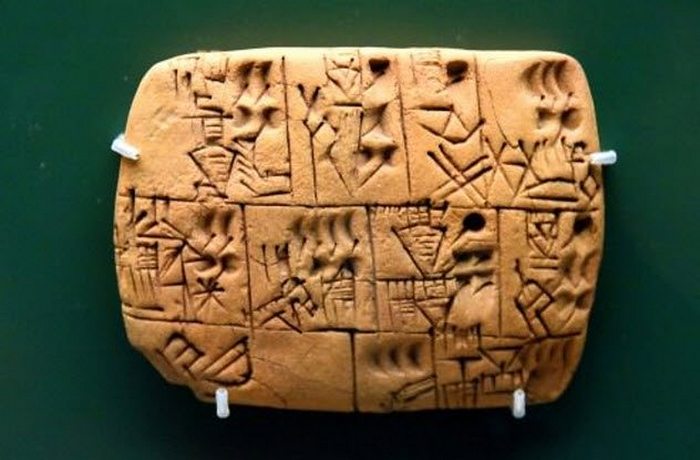

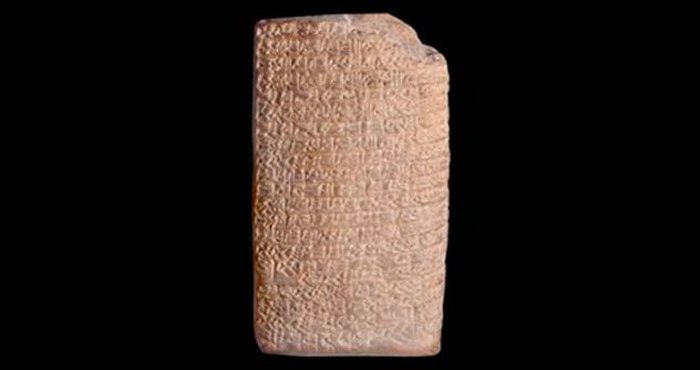

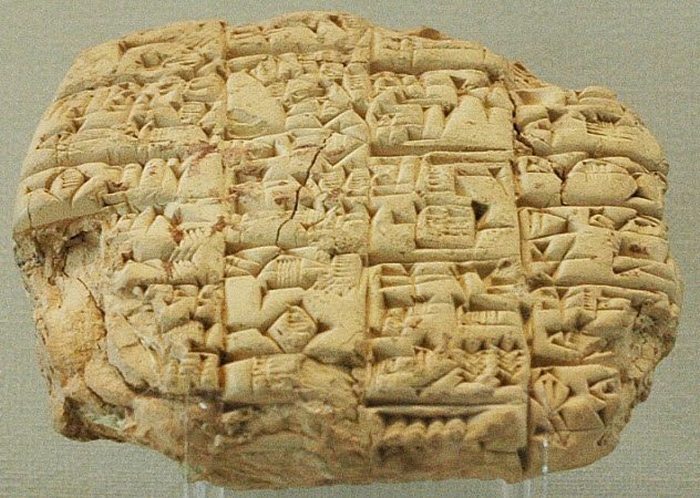

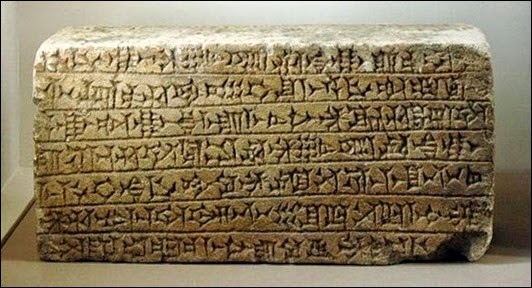

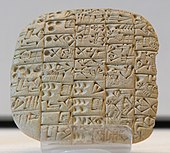

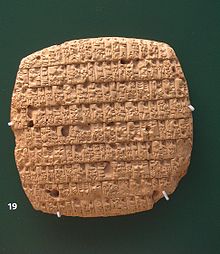

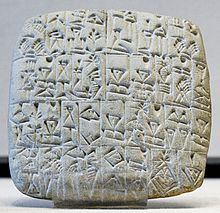

[myline]Основным источником информации о шумерах являются клинописные таблицы, а наука, которая их исследует, называется ассириологией.[/myline] Как самостоятельная дисциплина она оформилась только к середине XIX века на основе английских и французских раскопок на территории Ирака. С самого момента зарождения ассириологии ученым приходилось сражаться с невежеством и ложью как личностей, не имеющих отношения к науке, так и со своими собственными коллегами. В частности, книга русского этнографа Платона Акимовича Лукашевича «Чаромутие» повествует о том, что шумерский язык произошел от общего христианского языка «истотного» и является прародителем русского языка. Мы же с вами попытаемся избавиться от назойливых свидетелей инопланетной жизни и будем опираться на конкретные работы исследователей Самюэля Крамера, Василия Струве и Вероники Константиновны Афанасьевой.

Образование

Начнем с основы всего — с образования и истории. Шумерская клинопись — это крупнейший вклад в историю современной цивилизации. Интерес к обучению у шумеров появляется с III тыс. до н.э. Во второй половине III тыс. до н.э. происходит расцвет школ, в которых насчитывается тысяча писцов. Школы, помимо образовательных, были и литературными центрами. Они отделились от храма и представляли собой элитарное заведение для мальчиков. Во главе стоял учитель, или «отец школы» — уммиа. Изучались ботаника, зоология, минералогия, грамматика, но лишь в виде списков, то есть опора делалась на зубрежку, а не на выработку системы мышления.

[mydoubleline]Среди работников школы были некие «владеющие хлыстом», видимо, для мотивации учеников, которые должны были обязательно посещать занятия каждый день.[/mydoubleline] К тому же, сами учителя не гнушались рукоприкладством и наказывали за каждую оплошность. Благо, всегда можно было откупиться, ведь учителя получали мало и были совсем не против «подарков».

Важно отметить, что обучение медицине проходило фактически без вмешательства религии. Так, на найденной табличке с 15 рецептами медицинских препаратов не было ни одной магической формулы или религиозного отступления.

Повседневная жизнь и ремесло

Если брать за основу ряд дошедших повестей о жизни шумеров, то можно сделать вывод, что трудовая деятельность стояла на первом месте. Считалось, что если ты не работаешь, а гуляешь по паркам, то ты не только не мужчина, но и не человек. То есть идея труда как основного фактора эволюции воспринималась на внутреннем уровне даже древнейшими цивилизациями.

Для шумеров было принято уважать старших и помогать своей семье в ее деятельности, будь то работа в поле или торговля. Родители должны были правильно воспитать своих детей, чтобы те позаботились о них в старости. Именно поэтому так ценилась устная (через песни и сказания) и письменная передача информации, а вместе с ней и передача опыта из поколения в поколение.

Шумерская цивилизация была аграрной, отчего сельское хозяйство и ирригация развивались относительно быстрыми темпами. Существовали специальные «календари землевладельца», которые содержали советы по правильному ведению хозяйства, пахоты и управлению работниками. Сам документ не мог быть написан земледельцем, так как они были неграмотными, следовательно, он был издан в образовательных целях. Многие исследователи придерживаются мнения, что мотыга обычного земледельца пользовалась не меньшим уважением, чем плуг зажиточных горожан.

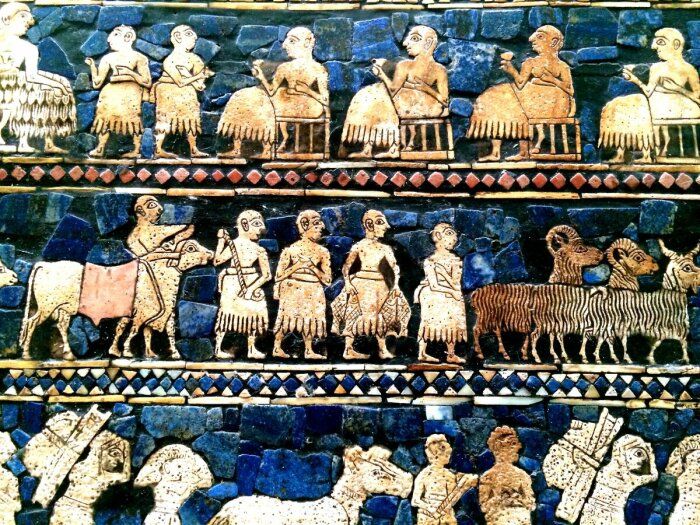

[myline]Большой популярностью пользовались ремесла: шумеры изобрели технологию гончарного круга, ковали инструменты для сельского хозяйства, строили парусные лодки, владели искусством литья и пайки металлов, а также инкрустации драгоценных камней. К женским ремеслам относилось умение искусно ткать, варить пиво и заниматься садоводством.[/myline]

Политика

Политическая жизнь древних шумеров была весьма активной: интриги, войны, манипуляции и вмешательства божественных сил. Полный набор для хорошего исторического блокбастера!

Касательно внешней политики сохранилось немало сюжетов, связанных с войнами между городами, которые являлись самой крупной политической ячейкой шумерской цивилизации. Особый интерес представляет повествование о конфликте между легендарным правителем города Урука Эн-Меркаром и его оппонентом из Аратты. Победу в так и не начавшейся войне удалось одержать с помощью настоящей психологической игры с использованием угроз и манипуляций сознанием. Каждый правитель загадывал другому загадки, пытаясь показать, что боги на его стороне.

Внутренняя политика была не менее интересна. Существует доказательство того, что в 2800 году до н.э. состоялось первое собрание двухпалатного парламента, который состоял из совета старейшин и низшей палаты — из граждан мужского пола. На нем обсуждались вопросы войны и мира, что говорит о его ключевом значении для жизни города-государства.

Городом управлял либо светский, либо религиозный правитель, который при отсутствии парламентской власти сам решал ключевые вопросы: ведение войны, законотворчество, сбор налогов, борьба с преступностью. Однако его власть не считалась священной и могла быть свергнута.

Законодательная система, по признанию современных судей, в том числе и членом Верховного суда США, была весьма проработанной и справедливой. Закон и правосудие шумеры считали основой своего общества. Именно они первые заменили варварский принцип «глаз за глаз и зуб за зуб» на денежный штраф. Помимо правителя, судить обвиняемого могло собрание граждан города.

Философия и этика

Как писал Самюэль Крамер, пословицы и поговорки «лучше всего взламывают панцирь культурных и бытовых наслоений общества». На примере шумерских аналогов можно сказать, что беспокоящие их вопросы не слишком отличались от наших: траты и экономия средств, оправдания и поиск виноватого, бедность и богатство, моральные качества.

Что касается натурфилософии, у шумеров к III тысячелетию сложился ряд метафизических и теологических понятий, оставивших след в религии древних евреев и христиан, однако четко сформулированных принципов не было. Основные представления касались вопросов мироздания. Так, Земля для них представлялась плоским диском, а небо — пустым пространством. Мир же произошел из океана. Шумеры обладали достаточным интеллектом, но им не хватало научных данных и критического мышления, поэтому они воспринимали свой взгляд на мир как правильный, не подвергая его сомнению.

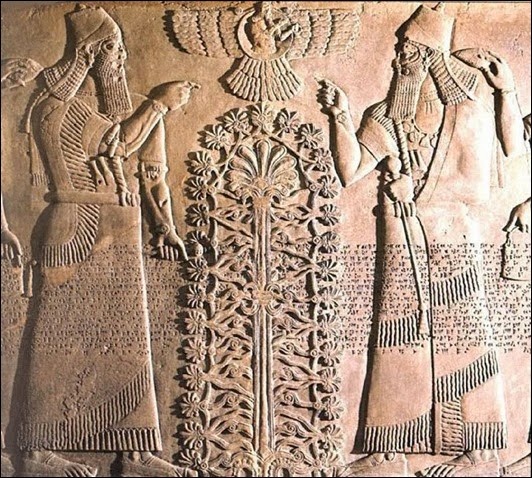

Шумеры признавали созидательную силу божественного слова. Для источников о пантеоне богов характерна красочная, но нелогичная манера повествования. Сами шумерские боги — антропоморфны. Считалось, что человек создан богами из глины для удовлетворения их потребностей. [myline]Божественные силы признавались идеальными и добродетельными. Зло же, причиной которого были люди, казалось неизбежным.[/myline] После своей смерти они попадали в потусторонний мир, по-шумерски он назвался Кур, в который их переправлял «человек лодки». Сразу видна тесная связь с греческой мифологией.

В произведениях шумеров можно уловить отзвуки библейских мотивов. Одним из таких является идея небесного рая. У шумеров рай носил название Дильмун. Особенно интересна связь с библейским сотворением Евы из ребра Адама. Существовала богиня Нин-Ти, что можно перевести и как «богиня ребра», и как «богиня, дарующая жизнь». Хотя исследователи считают, что именно из-за схожести мотивов имя богини было изначально переведено неверно, так как «Ти» означает одновременно и «ребро», и «дарующая жизнь». Также в шумерских легендах имелся великий потоп и смертный человек Зиусудра, который строил по указанию богов огромный корабль.

Часть ученых видит в шумерском сюжете убийства дракона связь со святым Георгием, пронзающим змея.

Незримый вклад шумеров

Какой же можно сделать вывод о быте древних шумеров? Они не только внесли неоценимый вклад в дальнейшее развитие цивилизации, но по некоторым аспектам своей жизни вполне понятны современному человеку: они имели представление о морали, уважении, любви и дружбе, обладали хорошей и справедливой судебной системой, ежедневно сталкивались с вполне знакомыми нам вещами.

Сегодня подход к культуре шумеров как к многогранному и уникальному явлению, предусматривающий тщательный анализ связей и преемственности, дает возможность по-другому взглянуть на известные нам современные явления, осознать их значимость и глубокую, увлекательную историю.

Шумерские народы считаются древней и, возможно, первой высокоразвитой цивилизацией на Земле. Хотя ведь была и Лемурия. Странно, что весь мир узнал об их существовании только после XIX века. Человечеству шумеры подарили много открытий. Например, колесо и кирпичи, письменность и деньги, налоги и законы. Они строили города, проводили операции на высоком уровне, поклонялись своим богам. Несмотря на такие высокие достижения, эта цивилизация просто бесследно исчезла с лица земли.

Где и когда появились шумеры, есть ли подтверждение этому

О древней цивилизации шумеров последнее время говорят часто. Ведь они изобрели большое количество вещей, которыми большинство людей пользуются сегодня. Сейчас о шумерах упоминают, как о величественной цивилизации Ближнего Востока, жившей в середине III тысячелетия до н. э. Хотя до XIX века об этом народе ничего не было известно. Есть гипотеза, что это первая развитая нация в мире были именно шумеры. Хотя этот вопрос спорный. Если брать мифы и легенды разных народов мира, то многие из них рассказывают о таинственной Лемурии. Эта высокоразвитая цивилизация человекоподобных обезьян проживала в районе Индийского океана много миллионов лет назад.

Где жил шумерский народ. / Фото: infourok.ru

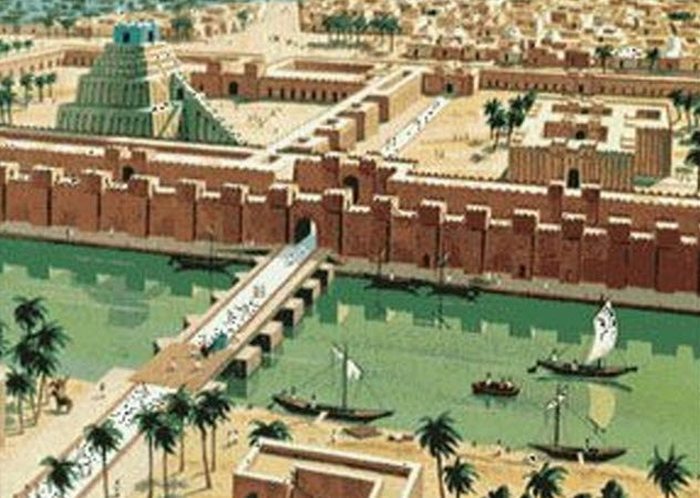

Шумеры предположительно жили на юге Месопотамии (территория долин рек Евфрата и Тигра). Историки утверждают, что они обосновались на территории, где сейчас расположено современное государство Ирак. Это древний народ называли «черноголовыми».

ЧИТАЙТЕ ТАКЖЕ: 9 изобретений шумеров, которые стали основой современных инноваций

Интересно, что эти народы владели ценными знаниями в области астрономии и математики. Их год делился на 12 месяцев и 4 сезона. Они знали о секундах, минутах и часах, о знаках зодиака и умели измерять углы. Их медицина, в частности хирургия, психотерапия и траволечение, были на высшем уровне. Также шумеры считаются основателями судопроизводства. Их законодательные акты только способствовали развитию правовых отношений на всей территории Древнего мира.

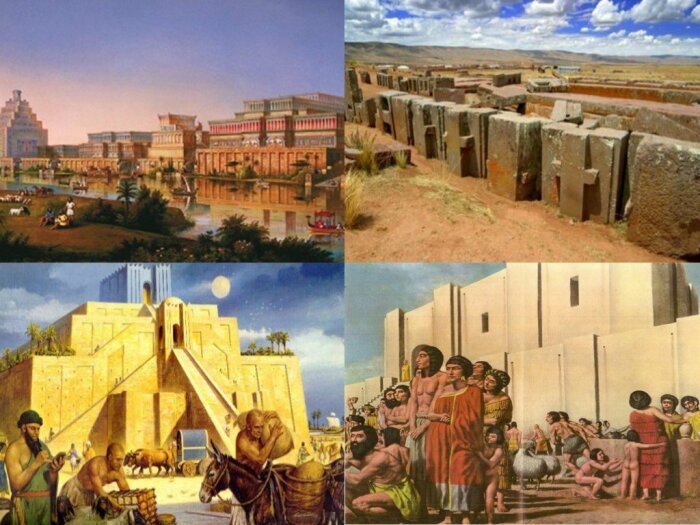

Шумеры строили целые города. / Фото: prezentacii.org

Кто были первые шумеры до сих пор до конца непонятно. Известно, что такие города, как Вавилон, Ниневия и Урук построил именно этот древний народ. Археологи нашли при раскопках большое количество документов, которые датируются III тысячелетием до н.э. Это подтвердило, что в Месопотамии действительно жили шумерские цари, и народ, который многого достиг. Там даже были описаны, как развивались и со временем приходили в упадок целые города и династии.

Необычные факты о жизни и достижениях шумерского народа

Ученые предполагают, что шумеры имели невысокий рост и крепкое телосложение. Преимущественно они были кареглазые с темным цветом волос. Однако на древних шумерских статуях глаза всегда были голубого цвета. Скорее всего, так этот народ подчеркивал свою связь с божествами.

Земледелие было их основным занятием. / Фото: zen.yandex.ru

Шумерский народ изысканно и красиво одевался. Главной одеждой была юбка и туника, которая отличалась у женщин и мужчин. Много одежды шили из шерсти, а вытканное полотно окрашивали в разные цвета. Чем богаче был человек, тем длиннее его юбка. Чтобы одежда не падала и держалась, ее фиксировали ремнем.

Чем длиннее была юбка, тем богаче шумер. / Фото: yael-shoshany.livejournal.com

Среди женских нарядов была найдена бахрома, которую сделали из пучков шерсти или тонких кожаных ремешков.Шумеры очень трепетно относились к личной гигиене и чистой одежде. Именно они первыми изобрели мыло, которое использовали для стирки, мытья и ритуалов. У знати были свои ванны, а бедные брали воду из каналов или рек. Этот народ даже использовал косметики и создал необычные духи.

Шумеры изобрели колесо. / Фото: am-world.ru

Основной город шумерской цивилизации считался Урук. Там проживало более 100 тыс. человек. Толстые стены защищали город, а из сторожевых башен хорошо просматривались все окрестности и возможная опасность. Основным видом работы у шумеров было земледелие. Воды не хватало для полива, поэтому для орошения полей использовались специальные насосы. Все делалось вручную. Позже начали создавать систему каналов шириной до 20 метров, источником воды которых были ближайшие реки.

ЧИТАЙТЕ ТАКЖЕ: 10 малоизвестных фактов о шумерах – представителях первой цивилизации человечества

Считают, что именно шумерский народ является первооткрывателем многих предметов и идей. Например, образовательные учреждения, колесо, первые деньги, налогообложение и законодательная система. Кроме того, у шумеров была своя письменность и высокий уровень грамотности даже среди простого народа. Некоторые историки считают, что шумерская цивилизация стала основоположником первой письменности на Земле. Также шумерам принадлежит создание первых фабрик по производству текстиля и кирпичи. Это позволило им строить дома и обеспечить многих жильем.

Кому поклонялись шумеры

Кому поклонялся шумерский народ. / Фото: septener.ru

Древний народ шумеры имел отличную логику и здравый смысл, а еще определенные знания, которые помогли сформировать единую для них систему мироздания. Небо и земля – это главные элементы, а все, что находилось между ними – это жизнь. Все шумеры почитали нескольких главных богов. Они были общими для племен и городов:

• Энлиль – главный над всеми, владыка людей и богов. Его называли богом земли и воздуха;

• Ану – бог неба;

• Энки – бог подземных вод;

• Нинхурсаг – богиня земли и жена Энки.

Согласно одной из древнейших легенд, богиню Намму считали созидательницей и праматерью всех главных богов. Кроме того, некоторые шумеры поклонялись и другим богам. Например, богине любви и плотских утех Иштар или богу болезни Эру.

Куда исчезла цивилизация шумеров

Этот народ считался высокоразвитой цивилизацией, которая могла просуществовать долгое время. Однако она неожиданно для всех бесследно исчезла. Некоторое время ученые предполагали, что к гибели целого народа привело объединение всех в Аккадскую империю во главе с Саргоном Великим. Благодаря группе исследователей во главе со Стэйси Кэролин из Оксфордского университета, появилась другая теория исчезновения шумеров.

Вероятно, шумерскую цивилизацию погубила засуха. / Фото:naurok.com.ua

Дело в том, что ученым удалось найти на берегу Оманского залива и Красного моря доказательства того, что причиной гибели шумеров стала климатическая катастрофа. Вероятно, из-за сильных пылевых бурь и затянувшейся засухи, цивилизация лишилась самого дорогого, что у них было – воды. Возможно, по этой же причине погибли и другие цивилизации, проживавшие в Древнем Египте и Индии. Помогли разгадать эту тайну сталактиты, которые были найдены рядом с городом Иран (Демавенда) в пещере Голь-и-Зард. А ведь эти образования формируются на протяжении многих тысяч лет. Возраст сталактитов в пещере Голь-и-Зард около 5 тыс. лет.

Результаты анализа показали, что в состав сталактитов входит магний и кальций. Скорее всего, в пещеру попадало много песка из-за мощных пылевых бурь. Кроме того, годичные кольца на этих пещерных созданиях показывают количество воды, выпавшее в виде осадков и колебания температур. У сталактитов пещеры Голь-и-Зард отмечено замедление роста, что повлияло на их форму. Это произошло из-за длительного отсутствия осадков и засухи. Многих волнует и другой вопрос. Можно ли на карте отыскать Шамбалу и существовала ли она на самом деле.

Понравилась статья? Тогда поддержи нас, жми:

Zefirka > Интересности > Любопытное о жизни шумеров

Любопытное о жизни шумеров

Шумер был одной из древнейших цивилизаций на Земле. Более 7000 лет назад шумеры построили дороги и стены своего первого города. Они первыми в истории человечества покинули свои насиженные места, отказавшись от привычных земледелия и скотоводства, и переехали жить в настоящий город. Сохранилось мало артефактов, которые бы могли что-то рассказать о жизни в 5000 году до н.э., тем не менее учёные могут рассказать кое-что о жизни шумеров.

1.

У женщин был свой собственный язык

Мужчины и женщины в Шумере не были равны. Когда наступало утро, мужчина был уверен, что жена уже приготовила ему завтрак. Когда у семьи были дети, то они отправляли мальчиков в школу, а девочек оставляли дома. Жизнь мужчин и женщин была настолько разной, что женщины даже разработали свой собственный язык.

Основной шумерский язык назывался «эмегир», но у женщин был свой отдельный диалект под названием «эмзаль» («женский язык»), и о нем не сохранилось никаких записей. Некоторые звуки в женском языке произносились по-другому, также представительницы слабого пола использовали некоторые слова и несколько гласных, которых не было в эмегире.

2.

Шумеры платили налоги, прежде чем они изобрели деньги

Натурпродукт как средство уплаты налогов.

Налоги существуют дольше, чем деньги для их оплаты. Еще до того, как в Месопотамии появились первые монеты и серебряные сикли, народ должен отдавать правителю часть своих доходов. Часто шумерские налоги не отличались от современных. Вместо денег правитель взимал процент от того, что производили люди. Фермеры отправляли урожай или скот, в то время как торговцы могли платить кожей или древесиной.

Богатые люди облагались гораздо большим налогом – в некоторых случаях приходилось отдавать правителю половину того, что они заработали. Однако это был не единственный способ оплаты налогов. Шумеры практиковали работу в общественных проектах. В течение месяца каждый год мужчина должен был покинуть свой дом, чтобы работать на ферме, копать оросительные каналы или воевать. От подобной повинности могли откупиться (заплатить кому-то другому, чтобы отработали вместо него) только богатые люди.

3.

Жизнь вращалась вокруг пива

Шумерская табличка с рецептом приготовления пива.

Есть теория, что цивилизация началась из-за пива. Якобы люди начали заниматься сельским хозяйством, только, чтобы иметь возможность напиться. А в город их «заманили» только обещанием большего количества пива. Правда это или нет, пиво было, безусловно, важной частью жизни в Шумере. Оно подавалось на стол при каждом приеме пищи, от завтрака до ужина, и его не рассматривали как основной напиток в жизни любого человека.

Конечно, шумерское пиво отличалось от современного. Оно было по консистенции чем-то вроде каши, с грязным осадком внизу, слоем пены сверху и небольшими кусками хлеба, оставшимися от ферментации, плавающих на поверхности. Его можно было пить только через соломинку. Но оно того стоило. В шумерском пиве было достаточно зерна, чтобы оно считалось питательной частью сбалансированного завтрака. Когда рабочие приходили на работу в общественные проекты, очень часто им платили пивом. Именно так правитель «заманивал» фермеров работать над своими строительными проектами: у него было лучшее пиво.

4.

Использование опиума

Пиво не было единственным способом «расслабиться» в Шумере. У шумеров был опиум, и они определенно использовали это вещество. Шумеры выращивали опийный мак по меньшей мере с 3000 г. до н.э. Сегодня нет большого количества информации о том, что они с ним сделали, но название, которое дали маку шумеры, явно говорит само за себя — они называли его «растением радости». Существуют теории, что шумеры использовали эти растения для медицины, в частности, в качестве болеутоляющего средства.

5.

Новая жена для правителя ежегодно

Документ о вступлении в брак.

Каждый год правитель женился на новой женщине. Он должен был жениться на одной из жриц – группе девушек-девственниц, выбранных для того, чтобы быть «совершенными телом» – и заниматься с ней любовью. В противном случае боги якобы сделали бы землю и женщин Шумера бесплодными. Правитель и его избранная невеста должны были бы «отображать акт занятий любовью богов в земном мире». В день ее свадьбы невесту купали, окуривали благовониями и одевали в самые красивые одеяния, в то время как правитель и его окружение шли к ее храму.

В храме же ждала толпа священников и жриц, которые начинали петь песни любви. Когда прибывал правитель, он вручал подарки невесте, а затем они отправлялись вместе в комнату, обкуренную дымом благовоний и занимались любовью на церемониальной кровати, которую делали на заказ исключительно для этого события.

6.

Жрицы были врачами и стоматологами

Шумерская жрица.

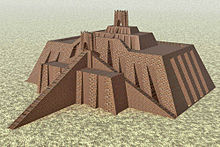

Жрицы были не только гаремом правителя – они были одними из самых полезных людей в шумерском обществе. Это были поэты, книжники и некоторые из первых врачей в истории. Шумерские города всегда строили вокруг храмового комплекса. В центре располагался великий зиккурат, окруженный зданиями, в которых жили священники и жрицы, а ремесленники работали над общественными проектами. Это было огромное пространство, которое занимало треть города, и оно использовалось не только для проведения церемоний.

Здесь также были детские дома, астрономические центры и крупные деловые организации. Однако именно снаружи комплекса проделывалась самая исторически важная работа. Сюда приходили больные и просили жриц осмотреть их. Эти женщины выходили наружу и проверяли здоровье пациентов. Они диагностировали больных и готовили для них лекарства для них.

7.

Грамотность – это богатство

Табличка с шумерской клиинописью.

Чтение и письмо были довольно новыми понятиями в древнем Шумере, но они были уже тогда невероятно важны. Люди никогда не становились богатыми, работая руками. Обычно торговцы и фермеры принадлежали к низшему классу. Если кто-то хотел разбогатеть, то он становился управляющим или жрецом. И обязательным условием была грамотность. Шумерские мальчики могли начинать учебу, как только им исполнялось семь лет, но это было дорого. Только самые богатые люди в городе могли позволить себе отправить детей в школу, где их учили математике, истории и грамотности. Обычно дети просто копировали то, что пишет учитель, до тех пор, пока они не могли точно имитировать его.

8.

Бедняки, живущие за пределами города

Стены шумерского города.

Не каждый шумер был частью подобного «верхнего эшелона общества». Большинство из них относились к нижнему классу, живя на фермах за пределами городских стен или помогая низкооплачиваемым рабочим-ремесленникам в городе. Пока богатые жили в глинобитных домах с мебелью, окнами и лампами, бедные должны селиться в тростниковых палатках. Они спали на соломенных матах на земле, и в таких условиях жили все их семьи. За пределами городских стен жизнь была тяжелой. Но люди могли двигаться вверх. Трудолюбивая семья могла торговать некоторыми из своих культур, чтобы купить больше земли, или сдавать свои земли с прибылью.

9.

Армия завоевателей

Шумеры-завоеватели.

И все же жизнь бедняков Шумера была намного лучше, чем жизнь рабов. Шумерские правители постоянно использовали порабощенных рабочих в своих городах, а набирали рабов просто – проводя набеги на людей, которые жили в горах. Налетчики уводили с собой этих людей в плен и отбирали у них все имущество. Шумерские правители считали, что если боги даруют им победу, то божественная воля заключается в том, чтобы сделать из жителей гор рабов.

Обычно рабами-мужчинами руководили женщины, а женщины-рабыни часто становились полностью бесправными наложницами. Хотя, стоит отметить, что были и варианты обрести свободу. Женщина-рабыня могла выйти замуж только за свободного мужчину, хотя ей пришлось бы отдать своего первенца своему хозяину в качестве оплаты. Мужчина-раб мог сделать достаточно, чтобы купить свою свободу и даже получить свою землю. Но здесь была и обратная сторона – никто не был застрахован от рабства. Если свободный человек попадал в долговую кабалу или совершал преступление, то его делали рабом.

10.

Ритуальные погребения

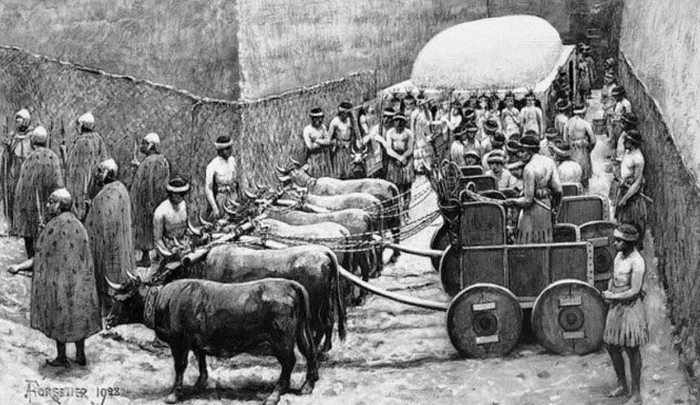

В Шумере смерть была настоящим таинством. Мертвые якобы отправлялись в то, что шумеры называли «землей без возврата», но при этом никто не знал, что находится там. Поэтому шумеры верили в то, что им понадобятся все земные блага, которыми они владели, в загробной жизни. Они были в ужасе от возможности провести вечность в одиночестве и голоде, поэтому мертвых хоронили с украшениями, золотом, едой и даже с их домашними собаками. Правители же «забирали» с собой в мир иной всех своих слуг и «придворных», а иногда и свои семьи.

Интересности

10 июля, 2017

2 443 просмотра

На юге современного Ирака, в междуречье Тигра и Евфрата, почти 7000 лет назад поселился загадочный народ – шумеры. Они внесли весомый вклад в развитие человеческой цивилизации, но мы до сих пор не знаем, откуда шумеры пришли и на каком языке говорили…

Загадочный язык

Долину Месопотамии издавна населяли племена семитов-скотоводов. Именно их вытеснили на север пришельцы-шумеры. Сами шумеры не состояли в родстве с семитами, более того, их происхождение по сей день неясно. Неизвестна ни прародина шумеров, ни языковая семья, к которой принадлежал их язык.

На наше счастье, шумеры оставили много письменных памятников. Из них мы и узнаем, что «шумерами» этот народ называли соседние племена, а сами они именовали себя «санг-нгига» — «черноголовые».

Язык же свой они называли «благородным языком» и считали единственным пригодным для людей (в отличие от не столь «благородных» семитских языков, на которых разговаривали их соседи).

Но шумерский язык не был однородным. Были в нем особые диалекты для женщин и мужчин, рыбаков и пастухов. Как звучал шумерский язык, неизвестно по сей день. Большое количество омонимов позволяет предположить, что язык этот был тоновым (как, например, современный китайский), а значит смысл сказанного часто зависел от интонации.

После заката шумерской цивилизации, язык шумеров еще долго изучался в Месопотамии, так как на нем были написаны большинство религиозных и литературных текстов.

Прародина шумеров

Одной из главных загадок остается прародина шумеров. Ученые строят гипотезы, основываясь на археологических данных и сведеньях, полученных из письменных источников.

Эта неизвестная нам азиатская страна должна была располагаться на море. Дело в том, что шумеры попали в Месопотамию по руслам рек, а первые их поселения появляются на юге долины, в дельтах Тигра и Евфрата.

Сначала шумеров в Месопотамии было совсем немного – и не удивительно, ведь корабли могут вместить не так уж много переселенцев. Видимо, они были хорошими мореплавателями, раз смогли подняться вверх по незнакомым рекам и найти подходящее место, чтобы пристать к берегу.

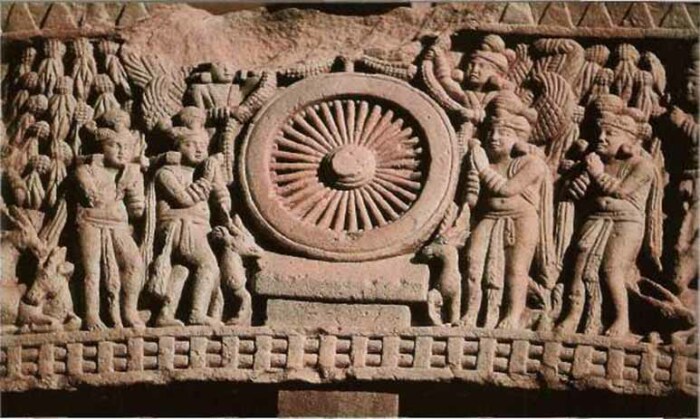

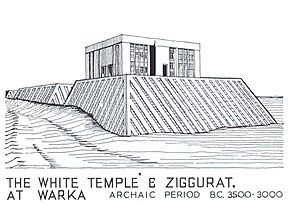

Кроме того, ученые считают, что шумеры происходят из гористой местности. Не зря в их языке слова «страна» и «гора» пишутся одинаково. Да и шумерские храмы «зиккураты» по своему виду напоминают горы – это ступенчатые сооружения с широким основанием и узкой пирамидальной вершиной, где и находилось святилище.

Еще одно важное условие – эта страна должна была обладать развитыми технологиями. Шумеры были одним из наиболее продвинутых народов своего времени, они первые на всем Ближнем Востоке начали использовать колесо, создали ирригационную систему, изобрели уникальную письменность.

По одной из версий, эта легендарная прародина располагалась на юге Индии.

Пережившие потоп

Шумеры не зря избрали своей новой родиной долину Междуречья. Тигр и Евфрат берут начало в Армянском нагорье, и несут в долину плодородный ил и минеральные соли. Из-за этого почва в Месопотамии чрезвычайно плодородная, там в изобилии росли фруктовые деревья, злаки и овощи.

Кроме того, в реках водилась рыба, на водопой стекались дикие звери, а на заливных лугах было вдоволь пищи для скота.

Но у всего этого изобилия была и обратная сторона. Когда в горах начинали таять снега, Тигр и Евфрат несли в долину потоки воды. В отличие от разливов Нила, разливы Тигра и Евфрата нельзя было предсказать, они не были регулярными.

Сильные разливы превращались в настоящее бедствие, они уничтожали все на своем пути: города и деревни, колосящиеся поля, животных и людей. Наверно, впервые столкнувшись с этим бедствием, шумеры и создали легенду об Зиусудре.

На собрание всех богов были принято страшное решение – уничтожить все человечество. Лишь один бог Энки пожалел людей. Он явился во сне к царю Зиусудре и велел ему построить огромный корабль. Зиусудра выполнил волю бога, на корабль он погрузил своё имущество, семью и родичей, различных мастеров для сохранения знаний и технологий, домашний скот, зверей и птиц. Двери корабля были засмолены снаружи.

Наутро начался страшный потоп, которого испугались даже боги. Дождь и ветер свирепствовали шесть дней и семь ночей. Наконец, когда вода начала отступать, Зиусудра покинул корабль и принес жертвы богам. Тогда в награду за его верность, боги даровали Зиусудре и его жене бессмертие.

Эта легенда не просто напоминает предание о Ноевом ковчеге, скорее всего библейская история является заимствованием из шумерской культуры. Ведь первые дошедшие до нас поэмы о потопе восходят аж к XVIII веку до нашей эры.

Цари-жрецы, цари-строители

Шумерские земли никогда не являлись единым государством. По сути дела это была совокупность городов-государств, каждый со своим законом, своей казной, своими правителями, своей армией. Общими были лишь язык, религия и культура. Города-государства могли враждовать между собой, могли обмениваться товарами или вступать в военные союзы.

В каждом городе-государстве правили три царя. Первый и самый главный назывался «эн». Это был царь-жрец (впрочем, эном могла быть и женщина). Главной задачей царя-эна было проведение религиозных церемоний: торжественных процессий, жертвоприношений. Кроме того, он заведовал всем храмовым имуществом, а иногда – имуществом всей общины.

Важной сферой жизни в древней Месопотамии было строительство. Шумерам приписывают изобретение обожженного кирпича. Из этого более прочного материала строились городские стены, храмы, амбары. Заведовал возведением этих сооружений жрец-строитель энси. Кроме того, энси следил за оросительной системой, ведь каналы, шлюзы и плотины позволяли хоть немного контролировать нерегулярные разливы.

На время ведения войны шумеры избирали еще одного предводителя – военного вождя – лугаля. Самым известным военным вождем был Гильгамеш, подвиги которого увековечены в одном из самых древних литературных произведений – «Эпосе о Гильгамеше». В этой истории великий герой бросает вызов богам, побеждает чудовищ, привозит в родной город Урук драгоценное кедровое дерево и даже спускается в загробный мир.

Шумерские боги

В Шумере существовала развитая религиозная система. Особым почитанием пользовались три бога: бог неба Ану, бог земли Энлиль и бог воды Энси. Помимо этого, у каждого города был свой бог-покровитель. Так, Энлиль особенно почитался в древнем городе Ниппуре.

Жители Ниппура считали, что Энлиль подарил им такие важные изобретения как мотыга и плуг, а также научил строить города и возводить вокруг них стены.

Важными богами для шумеров были солнце (Уту) и луна (Наннар), сменявшие друг друга на небосклоне. И, конечно, одной из важнейших фигур шумерского пантеона была богиня Инанна, которую ассирийцы, позаимствовавшие религиозную систему у шумеров, станут именовать Иштар, а финикийцы – Астартой.

Инанна была богиней любви и плодородия и, одновременно, богиней войны. Она олицетворяла прежде всего плотскую любовь, страсть. Не зря во многих шумерских городах существовал обычай «божественного брака», когда цари, чтобы обеспечить плодородие свом землям, скоту и людям, проводили ночь с верховной жрицей Инанну, воплощавшей саму богиню.

Подобно многим древним богам, Инанну была капризна и непостоянна. Она часто влюблялась в смертных героев, и горе было тем, кто отвергал богиню!

Шумеры считали, что боги сотворили людей, смешав свою кровь с глиной. После смерти души попадали в загробный мир, где также не было ничего, кроме глины и пыли, которой и питались мертвые. Чтобы сделать жизнь своих умерших предков чуть лучше, шумеры приносили им в жертву еду и напитки.

Клинопись

Шумерская цивилизация достигла удивительных высот, даже после завоевания северными соседями, культура, язык и религия шумеров были заимствованы сначала Аккадом, потом Вавилонией и Ассирией.

Шумерам приписывают изобретение колеса, кирпичей и даже пива (хотя ячменный напиток они, скорее всего, изготавливали по другой технологии). Но главным достижением шумеров была, конечно, уникальная система письма – клинопись.

Клинопись получила свое название из-за формы значков, которые оставляла тростниковая палочка на мокрой глине – самом распространенном материале для письма.

Шумерское письмо произошло от системы подсчета различных товаров. Например, когда человек подсчитывал свое стадо, для обозначения каждой овцы он делал шарик из глины, потом эти шарики складывал в коробочку, а на коробочке оставлял пометки – количество этих шариков. Но ведь все овцы в стаде разные: разного пола, возраста. На шариках появлялись пометки, соответственно животному, которое они обозначали.

И, наконец, овцу стали обозначать рисунком – пиктограммой. Рисовать тростниковой палочкой было не очень удобно, и пиктограмма превращалась в схематичное изображение, состоящее из вертикальных, горизонтальных и диагональных клинышков. И последний шаг – эта идеограмма стала обозначать не только овцу (по-шумерски «уду»), но и слог «уду» в составе сложных слов.

Сначала клинопись использовалась для составления хозяйственных документов. От древних жителей Месопотамии до нас дошли обширные архивы. Но позднее шумеры стали записывать и художественные тексты, и появились даже целые библиотеки из глиняных табличек, которым были не страшны пожары – ведь после обжига глина становилась только прочнее.

Именно благодаря пожарам, в которых гибли шумерские города, захваченные воинственными аккадцами, до нас и дошли уникальные сведения об этой древней цивилизации.

Вера Потопаева

Шумеры — первая цивилизация на земле.

Шумеры — древний народ, некогда населявший территорию долины рек Тигра и Евфрата на юге современного государства Ирак (Южная Месопотамия или Южное Двуречье). На юге граница их обитания доходила до берегов Персидского залива, на севере — до широты современного Багдада.

На протяжении целого тысячелетия шумеры были главными действующими лицами на древнем Ближнем Востоке.

Шумерская астрономия и математика были точнейшими на всем Ближнем Востоке. Мы до сих пор делим год на четыре сезона, двенадцать месяцев и двенадцать знаков зодиака, измеряем углы, минуты и секунды в шестидесятках — так, как это впервые стали делать шумеры.

Идя на прием к врачу, мы все… получаем рецепты лекарств или совет психотерапевта, совершенно не задумываясь о том, что и траволечение, и психотерапия впервые развились и достигли высокого уровня именно у шумеров. Получая повестку в суд и рассчитывая на справедливость судей, мы также ничего не знаем об основателях судопроизводства — шумерах, первые законодательные акты которых способствовали развитию правовых отношений во всех частях Древнего мира. Наконец, задумываясь о превратностях судьбы, сетуя на то, что при рождении нас обделили, мы повторяем те же самые слова, которые впервые занесли на глину философствующие шумерские писцы, — но вряд ли даже догадывается об этом.

Шумеры — «черноголовые». Этот народ, появившийся на юге Месопотамии в середине III-го тысячелетия до нашей эры неизвестно откуда, сейчас называют «прародителем современной цивилизации» , а ведь до середины 19-го века никто о нём даже не подозревал. Время стерло Шумер из анналов истории и, если бы не лингвисты, возможно мы бы никогда не узнали о Шумере.

Но начну я , наверное, с 1778-м года, когда датчанин Карстен Нибур, возглавлявший экспедицию в Месопотамию 1761-м года, опубликовал копии клинописной царской надписи из Персеполя. Он первый предположил, что 3 колонки в надписи — это три разных вида клинописи, содержащих один и тот же текст.

В 1798-м году ещё один датчанин, Фридрих Христиан Мюнтер высказал гипотезу что письмена 1-го класса — это алфавитная староперсидская письменность (42 знака), 2-го класса — слоговое письмо, 3-го — идеографические знаки. Но первым удалось прочесть текст не датчанину а немцу, преподавателю латыни в Геттингене, Гротенфенду. Внимание его привлекла группа из семи клинописных знаков. Гротенфенд предположил что это слово Царь, а остальные знаки были подобраны исходя из исторических и лингвистических аналогий. В конце концов Гротенфенд сделал следующий перевод :

Ксеркс, царь великий, царь царей

Дария, царя, сын, Ахеменид

Однако только через 30 лет француз Эжен Бюрнуф и норвежец Кристианн Лассен нашли правильные эквиваленты для почти всех клинописных знаков 1-й группы. В 1835-м году была найдена вторая многоязычная надпись на скале в Бехистуне и в 1855-м году Эдвину Норрису удалось дешифровать 2-й тип письменности, состоявший из сотни слоговых знаков. Надпись оказалась на эламском языке (кочевые племена называемые в Библии амореями или аморитянами).

С 3-м типом оказалось ещё сложнее. Это был совершенно забытый язык. Один знак там мог обозначать и слог и целое слово. Согласные выступали только в составе слога, тогда как гласные могли фигурировать и как отдельные знаки. Например звук «р» мог быть передан шестью различными знаками, в зависимости от контекста. 17 января 1869-го года лингвист Жюль Опперт заявил , что язык 3-й группы является…. шумерским… А значит должен существовать и шумерский народ… Но была ещё и теория , что это лишь искусственный — «сакральный язык» жрецов Вавилона. В 1871м году Арчибальд Сайс пуликует первый шумерский текст, царскую надпись Шульги. Но только в 1889-м году определение шумерский принимается повсеместно.

РЕЗЮМЕ : То, что мы сейчас называем шумерским языком — фактически искусственная конструкция, построенная на аналогиях с надписями народов, перенявших шумерскую клинопись — эламскими, аккадскими и староперсидскими текстами. А теперь вспомните как древние греки коверкали иностранные имена и оцените возможную достоверность звучания «восстановленного шумерского». Странно, но у шумерского языка нет ни предков, ни потомков. Иногда шумерский называют «латынью древнего Вавилона» — но надо отдавать себе отчёт, что шумерский не стал прародителем мощной языковой группы, от него остались только корни нескольких десятков слов.

Появление Шумеров.

Надо сказать, что южная Месопотамия не самое лучшее место в мире. Полное отсутствие леса и полезных ископаемых. Заболоченность, частые наводнения сопровождаемые изменением русла Евфрата из-за низких берегов и, как следствие, полное отсутствие дорог. Единственное чего там было в достатке это тростника, глины и воды. Однако , в сочетании с плодородной почвой, удобренной наводнениями, этого оказалось достаточно чтобы в самом конце III-го тысячелетия до нашей эры там расцвели первые города-государства древнего Шумера.

Мы не знаем откуда пришли Шумеры, но когда они появились в Месопотамии там уже жили люди. Племена, населявшие в глубочайшей древности Месопотамию, жили на островах, возвышавшихся среди болот. Свои поселения они строили на искусственных земляных насыпях. Осушая окружающие болота, они создали древнейшую систему искусственного орошения. Как указывают находки в Кише, они пользовались микролитическими орудиями.

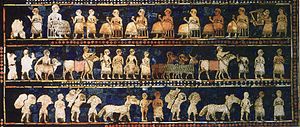

Оттиск шумерийской цилиндрической печати с изображением плуга. Наиболее раннее поселение, открытое в Южной Месопотамии, находилось около Эль-Обеида (близ Ура), на речном острове, который возвышался над болотистой равниной. Население, жившее здесь, занималось охотой и рыболовством, но уже переходило к более прогрессивным видам хозяйства: к скотоводству и земледелию

Культура Эль-Обеида существовала очень долго. Своими корнями она уходит в древние местные культуры Верхней Месопотамии. Однако уже появляются и первые элементы шумерийской культуры.

По черепам из погребений определили, что шумеры не были однорасовым этносом: встречаются и брахицефалы («круглоголовые») и долихоцефалы ( «длинноголовые» ). Впрочем это могло стать и результатом смешения с местным населением. Так что мы даже не можем с полной уверенностью отнести их к определённой этнической группе. В настоящее время с некоторой уверенностью можно утверждать лишь то, что семиты Аккада и шумерийцы Южной Месопотамии резко отличались друг от друга как по своему внешнему облику, так и по языку.

В древнейших общинах южной части Месопотамии в третьем тысячелетии до н. э. почти все производившиеся здесь продукты потреблялись на месте и царило натуральное хозяйство. Широко использовалась глина и тростник. В древнейшие времена из глины лепили сосуды — сначала от руки, а впоследствии на специальном гончарном круге. Наконец, из глины делали в большом количестве важнейший строительный материал — кирпич, который приготовлялся с примесью камыша и соломы. Этот кирпич иногда просушивался на солнце, а иногда обжигался в специальной печи. К началу третьего тысячелетия до н. э., относятся древнейшие здания, построенные из своеобразных крупных кирпичей, одна сторона которых образует плоскую поверхность, а другая — выпуклую. Крупный переворот в технике произвело открытие металлов. Одним из первых металлов, известных народам южной части Месопотамии, была медь, название которой встречается как в шумерийском, так и в аккадском языках. Несколько позднее появилась бронза, которая делалась из сплава меди со свинцом, а впоследствии — с оловом. Последние археологические открытия указывают на то, что уже и середине третьего тысячелетия до н. э. в Месопотамии было известно железо, очевидно, метеоритное.

Следующий период шумерийской архаики носит название периода Урука по месту наиболее важных раскопок. Для этой эпохи характерен новый вид керамики. Глиняные сосуды, снабжённые высокими ручками и длинным носиком, возможно, воспроизводят древний металлический прототип. Сосуды сделаны на гончарном круге; однако по своей орнаментации они гораздо скромнее, чем раскрашенная керамика времени Эль-Обеида. Однако, хозяйственная жизнь и культура получают в эту эпоху своё дальнейшее развитие. Появляется необходимость в составлении документов. В связи с этим возникает ещё примитивная картинная (пиктографическая) письменность, следы которой сохранились на цилиндрических печатях того времени. Надписи насчитывают в общей сложности до 1500 картинных знаков, из которых постепенно выросла древнешумерийская письменность.

После шумеров осталось огромное количество глиняных клинописных табличек. Возможно это была первая бюрократия в мире. Самые ранние надписи относятся к 2900 году до Р.Х. и содержат хозяйственные записи. Исследователи жалуются, что Шумеры оставили после себя огромное количество «хозяйственных» записей и «списков богов» но так и не удосужились записать «философскую основу» своей системы верований. Поэтому наши знания лишь интерпретация «клинописных» источников, в большинстве своём переведённых и переписанных жрецами более поздних культур, например Эпоса о Гильгамеше или поэмы «Энума элиш» датируемых началом II-го тысячелетия до нашей эры. Так что, возможно, мы читаем своеобразный дайджест, подобный адаптивному варианту библии для современных детей. Особенно учитывая, что большинство текстов скомпилированы из нескольких отдельных источников ( из-за плохой сохранности).

Имущественное расслоение, происходившее внутри сельских общин, приводило к постепенному распаду общинного строя. Рост производительных сил, развитие торговли и рабства, наконец, грабительские войны способствовали выделению из всей массы общинников небольшой группы рабовладельческой аристократии. Аристократы, владевшие рабами и отчасти землёй, называются “большими людьми” (лугаль), которым противостоят “маленькие люди”, т. е. свободные малоимущие члены сельских общин.

Древнейшие указания на существование рабовладельческих государств на территории Месопотамии относятся к началу третьего тысячелетия до н. э. Судя по документам этой эпохи, это были очень маленькие государства, вернее, первичные государственные образования, во главе которых стояли цари. В княжествах, потерявших свою независимость, правили высшие представители рабовладельческой аристократии, носившие древний полужреческий титул “цатэси” (эпси). Экономической основой этих древнейших рабовладельческих государств был централизованный в руках государства земельный фонд страны. Общинные земли, обрабатывавшиеся свободными крестьянами, считались собственностью государства, и население их было обязано нести в пользу последнего всякого рода повинности.

Разобщённость городов-государств создало проблему с точной датировка событий в Древнем Шумере. Дело в том, что каждый город-государство имел свои летописи. А дошедшие до нас списки царей, в основном, написаны не ранее аккадского периода и представляют собой смесь обрывков различных «храмовых списков» что привело к путанице и ошибкам. Но в общем всё выглядит так :

2900 — 2316 г. до Р.Х. — период расцвета шумерских городов-государств

2316 — 2200 г. до Р.Х — объединение шумера под властью аккадской династии (семитских племен северной части Южного Междуречья перенявших шумерскую культуру)

2200 — 2112 г. до Р.Х — Междуцарствие. Период раздробленности и нашествий кочевников -кутиев

2112 — 2003 г. до Р.Х — Шумерский Ренессанс, период расцвета культуры

2003 г. до Р.Х — падение Шумера и Аккада под натиском амореев (эламитов). Анархия

1792 — возвышение Вавилона при Хаммурапи (Старовавилонское царство)

После своего падения шумеры оставило то, что подхватило множество других народов, пришедших на эту землю — Религию.

Религия Древнего Шумера.

Давайте коснёмся Религии Шумеров. Похоже в Шумере истоки религии имели чисто материалистические , а не «этические», корни . Культ Богов имел целью не «очищение и святость» а призван был обеспечить хороший урожай, военные успехи и т.д…. Самые древние из Шумерских Богов , упомянутые в древнейших табличках «со списками богов» ( середина III -го тысячелетия до н.э.), олицетворяли силы природы — небо, море, солнце, луну, ветер и т.д., затем появились боги — покровители городов, земледельцев, пастухов и т.п. Шумеры утверждали , что всё в мире принадлежит богам — храмы были не местом пребывания богов, обязанных заботится о людях, — а житницей богов — амбарами.

Главными божествами Шумерского Пантеона были АН (небо — мужское начало) и КИ (земля — женское начало). Оба этих начала возникли из первозданного океана, который породил гору, из прочно связанных неба и земли.

На горе небес и земли Ан зачал [богов] Ануннаков. От этого союза родился и бог воздуха — Энлиль, разделивший небо и землю.

Существует гипотеза, что в начале поддержание порядка в миря являлись функциями Энки, бога мудрости и моря. Но затем, по мере возвышения города-государства Ниппура, богом которого считался Энлиль, именно он занял руководящее место среди богов.

К сожалению до нас не дошёл ни один шумерский миф о сотворении мира. Ход событий представленный в аккадском мифе «Энума Элиш», по мнению исследователей не соответствует концепции Шумеров, несмотря на то, что большинство богов и сюжетов в нём заимствовано из шумерских верований . Тяжело поначалу жилось богам, всё приходилось делать самим, некому было им служить. Тогда они и создали людей, для услужения себе. Казалось бы, Ан, подобно другим богам-творцам должен был иметь ведущую роль в шумерской мифологии. И , действительно, его почитали, правда скорее всего символически. Его храм в Уре назывался E.ANNA — «Дом AN». Первое царство называли «Царство Ану». Однако по представлениям Шумеров, Ан практически не вмешивается в дела людей и поэтому основная роль в «повседневной жизни» перешла к другим богам, во главе с Энлилем. Однако и Энлиль был не всесилен, ведь верховная власть принадлежала совету из пятидесяти главных богов, среди которых особо выделялись семь главных богов «вершащие судьбу».

Считается что структура совета богов повторяла «земную иерархию» — где правители , энси, правили совместно с «советом старейшин», в котором выделялась группа наиболее достойных..

Одной из основ шумерской мифологии, точный смысл которой не установлен, являются «МЕ» игравшие в религиозно-этической системе Шумеров огромную роль. В одном из мифов названо более ста «МЕ», из которых удалось прочесть и расшифровать меньше половины. Здесь такие понятия как правосудия, доброта, мир, победа, ложь, страх, ремесла и т.д. , всё так или иначе связанное с общественной жизнью Некоторые исследователи считают что «ме» — это прототипы всего живого, излучаемые богами и храмами, «Божественные правила».

Вообще в Шумере Боги были как Люди. В их взаимоотношениях встречаются сватовство и войны, изнасилование и любовь, обман и гнев. Существует даже миф о человеке, овладевшем во сне богиней Инанной. Примечательно, но весь миф проникнут симпатией к человеку.

Интересно, что шумерский рай не предназначен для людей — это обитель богов, где неизвестны печали , старости, болезни и смерть и единственная проблема, волнующая богов — это проблема пресной воды. Кстати в Древнем Египте концепции рая не было вообще. Шумерский ад — Кур — мрачный тёмный подземный мир, где на пути куда стояло три служителя — «человек двери», «человек подземной реки», «перевозчик». Напоминает древнегреческий Аид и Шеол древних евреев. Это пустое пространство, отделяющее землю от первозданного океана наполнено тенями умерших, блуждающих без надежды на возврат и демонами.

Вообще взгляды Шумеров, нашли отражение во многих более поздних религиях, но сейчас нам гораздо более интересен их вклад в техническую сторону развития современной цивилизации.

История начинается в Шумере.

Один из крупнейших экспертов по Шумеру, профессор Сэмюел Ноа Крамер, в своей книге «История начинается в Шумере» перечислил 39 предметов, в которых шумеры были первооткрывателями. Помимо первой системы письменности, о чем мы уже говорили, он включил в этот список колесо, первые школы, первый двухпалатный парламент, первых историков, первый «альманах земледельца»; в Шумере впервые возникли космогония и космология, появился первый сборник пословиц и афоризмов, впервые велись литературные дебаты; впервые был создан образ «Ноя»; здесь появился первый книжный каталог, получили хождение первые деньги (серебряные шекели в виде «слитков на вес»), впервые стали вводиться налоги, были приняты первые законы и проведены социальные реформы, появилась медицина, и впервые делались попытки добиться мира и гармонии в обществе.

В области медицины у шумеров с самого начала были очень высокие стандарты. В найденной Лайярдом в Ниневии библиотеке Ашшурбанипала был четкий порядок, в ней был большой медицинский отдел, в котором насчитывались тысячи глиняных табличек. Все медицинские термины основывались на словах, заимствованных из шумерского языка. Медицинские процедуры описывались в специальных справочниках, где содержались сведения о гигиенических правилах, об операциях, например об удалении катаракты, о применении спирта для дезинфекции при хирургических операциях. Шумерская медицина отличалась научным подходом к постановке диагноза и предписанию курса лечения, как терапевтического, так и хирургического.

Шумеры были превосходными путешественниками и исследователями — им приписывается также изобретение первых в мире судов. В одном аккадском словаре шумерских слов содержалось не менее 105 обозначений различных типов судов — по их размерам, назначению и по виду грузов. В одной надписи, раскопанной в Лагаше, говорится о возможностях ремонта судов и перечисляются виды материалов, которые местный правитель Гудея привозил для строительства храма своего бога Нинурта приблизительно в 2200 году до РХ. Широта ассортимента этих товаров поразительна — начиная от золота, серебра, меди — и до диорита, сердолика и кедра. В некоторых случаях эти материалы перевозились более чем за тысячи миль.

Первая печь для обжига кирпича также была построена в Шумере. Применение такой большой печи позволяло обжигать изделия из глины,, что придавало им особую прочность за счет внутреннего напряжения, без отравления воздуха пьлью и золой. Такая же технология применялась для выплавки металлов из руды, например меди — для этого руда нагревалась до температуры свыше 1500 градусов по Фаренгейту в закрытой печи с малой подачей кислорода. Этот процесс, именуемый плавкой, стал необходим уже на ранних этапах, как только был исчерпан запас натуральной самородной меди. Исследователи древней металлургии были крайне удивлены тем, как быстро шумеры выучились методам обогащения руды, плавки металла и литья. Эти передовые технологии были освоены ими всего лишь несколько столетий спустя после возникновения шумерской цивилизации.

Еще более поразительным было то, что шумеры овладели способами получения сплавов — процессом, при помощи которого различные металлы химически соединяются при нагреве в печи. Шумеры научились производить бронзу — твердый, но хорошо поддающийся обработке металл, который изменил весь ход истории человечества. Умение сплавлять медь с оловом было величайшим достижением по трем причинам. Во-первых, было необходимо подобрать очень точное соотношение меди и олова (анализ шумерской бронзы показал оптимальное соотношение — 85% меди на 15% олова). Во-вторых, в Месопотамии совсем не было олова.( В отличии , например, от Тиауанако ) В-третьих, олово вообще не встречается в природе в натуральном виде. Для его извлечения,из руды — оловянного камня — необходим довольно сложный процесс. Это не такое дело, которое можно открыть случайно. У шумеров было около тридцати слов для обозначения различных видов меди разного качества, для обозначения же олова они пользовались словом AN.NA, что означает буквально «Небесный камень» — что многие рассматривают как свидетельствует о том, что шумерская технология была даром богов.

Были найдены тысячи глиняных табличек, содержавших сотни астрономических терминов. В некоторых из этих табличек содержались математические формулы и астрономические таблицы, при помощи которых шумеры могли предсказывать солнечное затмение, различные фазы Луны и траектории движения планет. Изучение древней астрономии обнаружило замечательную точность этих таблиц (известных под названием эфемерид). Никто не знает, каким образом они были рассчитаны, но мы можем задаться вопросом — зачем это было нужно?

«Шумеры измеряли восход и закат видимых планет и звезд относительно земного горизонта, пользуясь той же гелиоцентрической системой, которая применяется сейчас. Мы переняли от них также разделение небесной сферы на три сегмента — северный, центральный и южный (соответственно у древних шумеров — «путь Энлиля», «путь Ану» и «путь Эа»). В сущности, все современные понятия сферической астрономии, включая полную сферическую окружность в 360 градусов, зенит, горизонт, оси небесной сферы, полюса, эклиптику, равноденствие и пр. — все это внезапно возникло в Шумере.

Все познания шумеров относительно движения Солнца и Земли были объединены в созданном ими первом в мире календаре созданном в городе Ниппуре— солнечно-лунном календаре, начинавшемся в 3760 году до Р.Х.. Шумеры считали 12 лунных месяцев, составлявших приблизительно 354 дня, а затем прибавляли еще 11 дополнительных дней, чтобы получить полный солнечный год. Эта процедура, называемая интеркаляцией, проделывалась ежегодно, пока, через 19 лет, солнечный и лунный календарь не совмещались. Шумерский календарь был составлен очень точно, чтобы ключевые дни (например, Новый год всегда приходился на день весеннего равноденствия) . Удивительно то, что такая развитая астрономическая наука совсем не была необходима этому только что народившемуся обществу.

Вообще математика шумеров имела «геометрические» корни и очень необычна. Лично я вообще не понимаю как такая система счисления могла зародится у примитивных народов. Но лучше судите об этом сами…

Математика Шумеров.

Шумеры пользовались шестидесятеричной системой счисления. Для изображения чисел использовались всего два знака: «клин» обозначал 1; 60; 3600 и дальнейшие степени от 60; «крючок» — 10; 60 х 10; 3600 х 10 и т. д. В основу цифровой записи был положен позиционный принцип, но если Вы , исходя из основы счисления, думаете, что числа в Шумере отображали как степени 60-ти, то ошибаетесь.

За основание в Шумерской системе берется не 10, а 60, но затем это основание странным образом заменяется числом 10, затем, 6, а затем снова на 10 и т.д. И таким образом, позиционные числа выстраиваются в следующий ряд:

1, 10, 60, 600, 3600, 36 000, 216 000, 2 160 000, 12 960 000.

Эта громоздкая шестидесятеричная система позволяла шумерам вычислять дроби и перемножать числа до миллионов, извлекать корни и возводить в степень. Во многих отношениях эта система даже превосходит применяющуюся нами в настоящее время десятичную систему. Во-первых, число 60 имеет десять простых делителей, в то время как 100 — всего 7. Во-вторых, это единственная система, идеально подходящая для геометрических вычислений, и именно этим объясняется то, что она продолжает применяться и в наше время отсюда, например, деление круга на 360 градусов.

Мы редко осознаем, что не только нашей геометрией, но также и современному способу исчисления времени мы обязаны шумерской системе счисления с шестидесятеричным основанием. Деление часа на 60 секунд было совсем не произвольным — оно основывается на шестидесятеричной системе. Отголоски шумерской системы счисления сохранились и в делении суток на 24 часа, года на 12 месяцев, фута на 12 дюймов, и в существовании дюжины как меры количества. Они обнаруживаются также в современной системе счета, в которой выделяются отдельно числа от 1 до 12, а затем следуют числа типа 10+3, 10+4 и т.д.

Теперь нас уже не должно удивлять, что зодиак также был еще одним изобретением шумеров, изобретением, которое в дальнейшем было усвоено другими цивилизациями. Но шумеры не пользовались знаками зодиака, привязывая их к каждому месяцу, как мы делаем сейчас в гороскопах. Они использовали их в чисто астрономическом смысле — в смысле отклонения земной оси, движение которой делит полный цикл прецессии в 25 920 лет на 12 периодов по 2160 лет. При двенадцатимесячном движении Земли по орбите вокруг Солнца картина звездного неба, образующего большую сферу в 360 градусов, меняется. Понятие зодиака возникло путем разделения этой окружности на 12 равных сегментов (сферы зодиака) по 30 градусов каждый. Затем звезды в каждой группе объединялись в созвездия, и каждое из них получало свое наименование, соответствующее современным их наименованиям. Таким образом, не остается сомнения в том, что впервые понятие зодиака использовалось в Шумере. Начертания знаков зодиака (представляющие воображаемые картины звездного неба), а также произвольное деление их на 12 сфер доказывают, что соответствующие знаки зодиака, применяющиеся в других, более поздних культурах, не могли появиться в результате самостоятельного развития.

Исследования шумерской математики, к большому удивлению ученых, показали, что их числовая система тесно связана с прецессионным циклом. Необычный подвижной принцип шумерской шестидесятеричной системы счисления акцентирует внимание на числе 12 960 000, что в точности равняется 500 больших прецессионных циклов, совершающихся за 25 920 лет. Отсутствие каких бы то ни было иных, кроме астрономических, возможных приложений для произведений чисел 25 920 и 2160 может означать лишь одно — эта система разработана специально для астрономических целей.

Похоже на то, что ученые уклоняются от ответа на неудобный вопрос, который заключается в следующем: каким образом шумеры, чья цивилизация длилась всего 2 тысячи лет, могли заметить и зафиксировать цикл небесных движений, продолжающийся 25 920 лет? И почему начало их цивилизации относится к середине периода между сменами зодиака? Не свидетельствует ли это о том, что они унаследовали астрономию от богов?

Not to be confused with Summer.

|

Sumer General location on a modern map, and main cities of Sumer with ancient coastline. The coastline was nearly reaching Ur in ancient times. |

|

| Geographical range | Mesopotamia, Near East, Middle East |

|---|---|

| Period | Late Neolithic, Middle Bronze Age |

| Dates | c. 4500 – c. 1900 BC |

| Preceded by | Ubaid period |

| Followed by | Akkadian Empire |

Sumer () is the earliest known civilization in the historical region of southern Mesopotamia (south-central Iraq), emerging during the Chalcolithic and early Bronze Ages between the sixth and fifth millennium BC. It is one of the cradles of civilization in the world, along with ancient Egypt, Elam, the Caral-Supe civilization, Mesoamerica, the Indus Valley civilisation, and ancient China. Living along the valleys of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, Sumerian farmers grew an abundance of grain and other crops, the surplus from which enabled them to form urban settlements. Proto-writing dates back before 3000 BC. The earliest texts come from the cities of Uruk and Jemdet Nasr, and date to between c. 3500 and c. 3000 BC.[ambiguous]

Name

The term «Sumer» (Sumerian: 𒅴𒄀 eme-gi or 𒅴𒂠 eme-ĝir15, Akkadian: 𒋗𒈨𒊒 šumeru)[5] is the name given to the language spoken by the «Sumerians», the ancient non-Semitic-speaking inhabitants of southern Mesopotamia, by their successors the East Semitic-speaking Akkadians.[6][7][8] The Sumerians referred to their land as Kengir, the ‘Country of the noble lords’ (𒆠𒂗𒄀, k-en-gi(-r), lit. ‘country’ + ‘lords’ + ‘noble’) as seen in their inscriptions.[6][9][10]

The origin of the Sumerians is not known, but the people of Sumer referred to themselves as «Black Headed Ones» or «Black-Headed People»[6][11][12][13] (𒊕 𒈪, saĝ-gíg, lit. ‘head’ + ‘black’, or 𒊕 𒈪 𒂵, saĝ-gíg-ga phonetically /saŋ ɡi ɡa/, lit. ‘head’ + ‘black’ + ‘carry’).[1][2][3][4] For example, the Sumerian king Shulgi described himself as «the king of the four quarters, the pastor of the black-headed people».[14] The Akkadians also called the Sumerians ‘black-headed people’, or ṣalmat-qaqqadi, in the Semitic Akkadian language.[2][3]

The Akkadian word Šumer may represent the geographical name in dialect, but the phonological development leading to the Akkadian term šumerû is uncertain.[15] Hebrew שִׁנְעָר Šinʿar, Egyptian Sngr, and Hittite Šanhar(a), all referring to southern Mesopotamia, could be western variants of Sumer.[15]

Origins

Most historians have suggested that Sumer was first permanently settled between c. 5500 and 4000 BC by a West Asian people who spoke the Sumerian language (pointing to the names of cities, rivers, basic occupations, etc., as evidence), a non-Semitic and non-Indo-European agglutinative language isolate.[16][17][18][19][20] In contrast to its Semitic neighbours, it was not an inflected language.[16]

Others have suggested that the Sumerians were a North African people who migrated from the Green Sahara into the Middle East and were responsible for the spread of farming in the Middle East.[21] However, with evidence strongly suggesting the first farmers originated from the Fertile Crescent, this suggestion is often discarded.[22] Although not specifically discussing Sumerians, Lazaridis et al. 2016 have suggested a partial North African origin for some pre-Semitic cultures of the Middle East, particularly Natufians, after testing the genomes of Natufian and Pre-Pottery Neolithic culture-bearers.[22][23] Alternatively, a recent (2013) genetic analysis of four ancient Mesopotamian skeletal DNA samples suggests an association of the Sumerians with Indus Valley Civilization, possibly as a result of ancient Indus-Mesopotamia relations.[24] According to some data, the Sumerians are associated with the Hurrians and Urartians, and the Caucasus is considered their homeland.[25][26][27]

A prehistoric people who lived in the region before the Sumerians have been termed the «Proto-Euphrateans» or «Ubaidians»,[28] and are theorized to have evolved from the Samarra culture of northern Mesopotamia.[29][30][31][32] The Ubaidians, though never mentioned by the Sumerians themselves, are assumed by modern-day scholars to have been the first civilizing force in Sumer. They drained the marshes for agriculture, developed trade, and established industries, including weaving, leatherwork, metalwork, masonry, and pottery.[28]

Some scholars contest the idea of a Proto-Euphratean language or one substrate language; they think the Sumerian language may originally have been that of the hunting and fishing peoples who lived in the marshland and the Eastern Arabia littoral region and were part of the Arabian bifacial culture.[33] Reliable historical records begin much later; there are none in Sumer of any kind that have been dated before Enmebaragesi (Early Dynastic I). Juris Zarins believes the Sumerians lived along the coast of Eastern Arabia, today’s Persian Gulf region, before it was flooded at the end of the Ice Age.[34]

Sumerian civilization took form in the Uruk period (4th millennium BC), continuing into the Jemdet Nasr and Early Dynastic periods.

The Sumerians progressively lost control to Semitic states from the northwest. Sumer was conquered by the Semitic-speaking kings of the Akkadian Empire around 2270 BC (short chronology), but Sumerian continued as a sacred language. Native Sumerian rule re-emerged for about a century in the Third Dynasty of Ur at approximately 2100–2000 BC, but the Akkadian language also remained in use for some time.[35]

The Sumerian city of Eridu, on the coast of the Persian Gulf, is considered to have been one of the oldest cities, where three separate cultures may have fused: that of peasant Ubaidian farmers, living in mud-brick huts and practicing irrigation; that of mobile nomadic Semitic pastoralists living in black tents and following herds of sheep and goats; and that of fisher folk, living in reed huts in the marshlands, who may have been the ancestors of the Sumerians.[35]

City-states in Mesopotamia

In the late 4th millennium BC, Sumer was divided into many independent city-states, which were divided by canals and boundary stones. Each was centered on a temple dedicated to the particular patron god or goddess of the city and ruled over by a priestly governor (ensi) or by a king (lugal) who was intimately tied to the city’s religious rites.

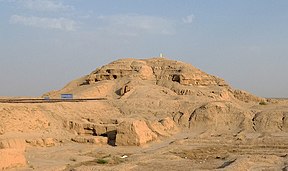

Anu ziggurat and White Temple at Uruk. The original pyramidal structure, the «Anu Ziggurat» dates to around 4000 BC, and the White Temple was built on top of it c. 3500 BC.[36] The design of the ziggurat was probably a precursor to that of the Egyptian pyramids, the earliest of which dates to c. 2600 BC.[37][38]

The five «first» cities, said to have exercised pre-dynastic kingship «before the flood»:

- Eridu (Tell Abu Shahrain)

- Bad-tibira (probably Tell al-Madain)

- Larak 1

- Sippar (Tell Abu Habbah)

- Shuruppak (Tell Fara)

Other principal cities:

- Uruk (Warka)

- Kish (Tell Uheimir and Ingharra)

- Ur (Tell al-Muqayyar)

- Nippur (Afak)

- Lagash (Tell al-Hiba)

- Girsu (Tello or Telloh)

- Umma (Tell Jokha)

- Hamazi 1

- Adab (Tell Bismaya)

- Mari (Tell Hariri) 2

- Akshak 1

- Akkad 1

- Isin (Ishan al-Bahriyat)

- Larsa (Tell as-Senkereh)

- (1location uncertain)

- (2an outlying city in northern Mesopotamia)

Minor cities (from south to north):

- Kuara (Tell al-Lahm)

- Zabala (Tell Ibzeikh)

- Kisurra (Tell Abu Hatab)

- Marad (Tell Wannat es-Sadum)

- Dilbat (Tell ed-Duleim)

- Borsippa (Birs Nimrud)

- Kutha (Tell Ibrahim)

- Der (al-Badra)

- Eshnunna (Tell Asmar)

- Nagar (Tell Brak) 2

(2an outlying city in northern Mesopotamia)

Apart from Mari, which lies full 330 kilometres (205 miles) north-west of Agade, but which is credited in the king list as having «exercised kingship» in the Early Dynastic II period, and Nagar, an outpost, these cities are all in the Euphrates-Tigris alluvial plain, south of Baghdad in what are now the Bābil, Diyala, Wāsit, Dhi Qar, Basra, Al-Muthannā and Al-Qādisiyyah governorates of Iraq.

History

Portrait of a Sumerian prisoner on a victory stele of Sargon of Akkad, c. 2300 BC.[39] The hairstyle of the prisoners (curly hair on top and short hair on the sides) is characteristic of Sumerians, as also seen on the Standard of Ur.[40] Louvre Museum.

The Sumerian city-states rose to power during the prehistoric Ubaid and Uruk periods. Sumerian written history reaches back to the 27th century BC and before, but the historical record remains obscure until the Early Dynastic III period, c. 23rd century BC, when a now deciphered syllabary writing system was developed, which has allowed archaeologists to read contemporary records and inscriptions. The Akkadian Empire was the first state that successfully united larger parts of Mesopotamia in the 23rd century BC. After the Gutian period, the Ur III kingdom similarly united parts of northern and southern Mesopotamia. It ended in the face of Amorite incursions at the beginning of the second millennium BC. The Amorite «dynasty of Isin» persisted until c. 1700 BC, when Mesopotamia was united under Babylonian rule.

- Ubaid period: 6500–4100 BC (Pottery Neolithic to Chalcolithic)

- Uruk period: 4100–2900 BC (Late Chalcolithic to Early Bronze Age I)

- Uruk XIV–V: 4100–3300 BC

- Uruk IV period: 3300–3100 BC

- Jemdet Nasr period (Uruk III): 3100–2900 BC

- Early Dynastic period (Early Bronze Age II–IV)

- Early Dynastic I period: 2900–2800 BC

- Early Dynastic II period: 2800–2600 BC (Gilgamesh)

- Early Dynastic IIIa period: 2600–2500 BC

- Early Dynastic IIIb period: c. 2500–2334 BC

- Akkadian Empire period: c. 2334–2218 BC (Sargon)

- Gutian period: c. 2218–2047 BC (Early Bronze Age IV)

- Ur III period: c. 2047–1940 BC

Ubaid period

Pottery jar from Late Ubaid Period

The Ubaid period is marked by a distinctive style of fine quality painted pottery which spread throughout Mesopotamia and the Persian Gulf. The oldest evidence for occupation comes from Tell el-‘Oueili, but, given that environmental conditions in southern Mesopotamia were favourable to human occupation well before the Ubaid period, it is likely that older sites exist but have not yet been found. It appears that this culture was derived from the Samarran culture from northern Mesopotamia. It is not known whether or not these were the actual Sumerians who are identified with the later Uruk culture. The story of the passing of the gifts of civilization (me) to Inanna, goddess of Uruk and of love and war, by Enki, god of wisdom and chief god of Eridu, may reflect the transition from Eridu to Uruk.[41]

Uruk period

The archaeological transition from the Ubaid period to the Uruk period is marked by a gradual shift from painted pottery domestically produced on a slow wheel to a great variety of unpainted pottery mass-produced by specialists on fast wheels. The Uruk period is a continuation and an outgrowth of Ubaid with pottery being the main visible change.[42][43]

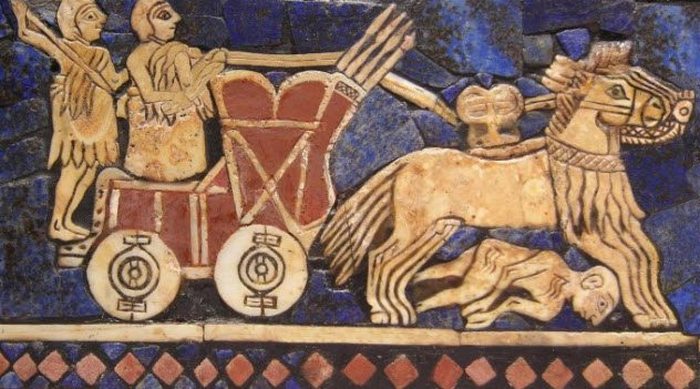

The king-priest and his acolyte feeding the sacred herd. Uruk period, c. 3200 BC

By the time of the Uruk period (c. 4100–2900 BC calibrated), the volume of trade goods transported along the canals and rivers of southern Mesopotamia facilitated the rise of many large, stratified, temple-centered cities (with populations of over 10,000 people) where centralized administrations employed specialized workers. It is fairly certain that it was during the Uruk period that Sumerian cities began to make use of slave labour captured from the hill country, and there is ample evidence for captured slaves as workers in the earliest texts. Artifacts, and even colonies of this Uruk civilization have been found over a wide area—from the Taurus Mountains in Turkey, to the Mediterranean Sea in the west, and as far east as western Iran.[44]: 2–3

The Uruk period civilization, exported by Sumerian traders and colonists (like that found at Tell Brak), had an effect on all surrounding peoples, who gradually evolved their own comparable, competing economies and cultures. The cities of Sumer could not maintain remote, long-distance colonies by military force.[44][page needed]

Sumerian cities during the Uruk period were probably theocratic and were most likely headed by a priest-king (ensi), assisted by a council of elders, including both men and women.[45] It is quite possible that the later Sumerian pantheon was modeled upon this political structure. There was little evidence of organized warfare or professional soldiers during the Uruk period, and towns were generally unwalled. During this period Uruk became the most urbanized city in the world, surpassing for the first time 50,000 inhabitants.

The ancient Sumerian king list includes the early dynasties of several prominent cities from this period. The first set of names on the list is of kings said to have reigned before a major flood occurred. These early names may be fictional, and include some legendary and mythological figures, such as Alulim and Dumizid.[45]

The end of the Uruk period coincided with the Piora oscillation, a dry period from c. 3200–2900 BC that marked the end of a long wetter, warmer climate period from about 9,000 to 5,000 years ago, called the Holocene climatic optimum.[46]

Early Dynastic Period

The dynastic period begins c. 2900 BC and was associated with a shift from the temple establishment headed by council of elders led by a priestly «En» (a male figure when it was a temple for a goddess, or a female figure when headed by a male god)[47] towards a more secular Lugal (Lu = man, Gal = great) and includes such legendary patriarchal figures as Dumuzid, Lugalbanda and Gilgamesh—who reigned shortly before the historic record opens c. 2900 BC, when the now deciphered syllabic writing started to develop from the early pictograms. The center of Sumerian culture remained in southern Mesopotamia, even though rulers soon began expanding into neighboring areas, and neighboring Semitic groups adopted much of Sumerian culture for their own.

The earliest dynastic king on the Sumerian king list whose name is known from any other legendary source is Etana, 13th king of the first dynasty of Kish. The earliest king authenticated through archaeological evidence is Enmebaragesi of Kish (Early Dynastic I), whose name is also mentioned in the Epic of Gilgamesh—leading to the suggestion that Gilgamesh himself might have been a historical king of Uruk. As the Epic of Gilgamesh shows, this period was associated with increased war. Cities became walled, and increased in size as undefended villages in southern Mesopotamia disappeared. (Both Enmerkar and Gilgamesh are credited with having built the walls of Uruk.)[48]

1st Dynasty of Lagash

The dynasty of Lagash (c. 2500–2270 BC), though omitted from the king list, is well attested through several important monuments and many archaeological finds.

Although short-lived, one of the first empires known to history was that of Eannatum of Lagash, who annexed practically all of Sumer, including Kish, Uruk, Ur, and Larsa, and reduced to tribute the city-state of Umma, arch-rival of Lagash. In addition, his realm extended to parts of Elam and along the Persian Gulf. He seems to have used terror as a matter of policy.[49] Eannatum’s Stele of the Vultures depicts vultures pecking at the severed heads and other body parts of his enemies. His empire collapsed shortly after his death.

Later, Lugal-Zage-Si, the priest-king of Umma, overthrew the primacy of the Lagash dynasty in the area, then conquered Uruk, making it his capital, and claimed an empire extending from the Persian Gulf to the Mediterranean. He was the last ethnically Sumerian king before Sargon of Akkad.[35]

Akkadian Empire

Sumerian prisoners on a victory stele of the Akkadian king Sargon, c. 2300 BC.[39][40] Louvre Museum.

The Akkadian Empire dates to c. 2234–2154 BC (middle chronology). The Eastern Semitic Akkadian language is first attested in proper names of the kings of Kish c. 2800 BC,[49] preserved in later king lists. There are texts written entirely in Old Akkadian dating from c. 2500 BC. Use of Old Akkadian was at its peak during the rule of Sargon the Great (c. 2334–2279 BC), but even then most administrative tablets continued to be written in Sumerian, the language used by the scribes. Gelb and Westenholz differentiate three stages of Old Akkadian: that of the pre-Sargonic era, that of the Akkadian empire, and that of the Ur III period that followed it. Akkadian and Sumerian coexisted as vernacular languages for about one thousand years, but by around 1800 BC, Sumerian was becoming more of a literary language familiar mainly only to scholars and scribes. Thorkild Jacobsen has argued that there is little break in historical continuity between the pre- and post-Sargon periods, and that too much emphasis has been placed on the perception of a «Semitic vs. Sumerian» conflict.[50] However, it is certain that Akkadian was also briefly imposed on neighboring parts of Elam that were previously conquered, by Sargon.

Gutian period

c. 2193–2119 BC (middle chronology)

2nd Dynasty of Lagash

Gudea of Lagash, the Sumerian ruler who was famous for his numerous portrait sculptures that have been recovered.

c. 2200–2110 BC (middle chronology)

Following the downfall of the Akkadian Empire at the hands of Gutians, another native Sumerian ruler, Gudea of Lagash, rose to local prominence and continued the practices of the Sargonic kings’ claims to divinity.

The previous Lagash dynasty, Gudea and his descendants also promoted artistic development and left a large number of archaeological artifacts.

«Neo-Sumerian» Ur III period