|

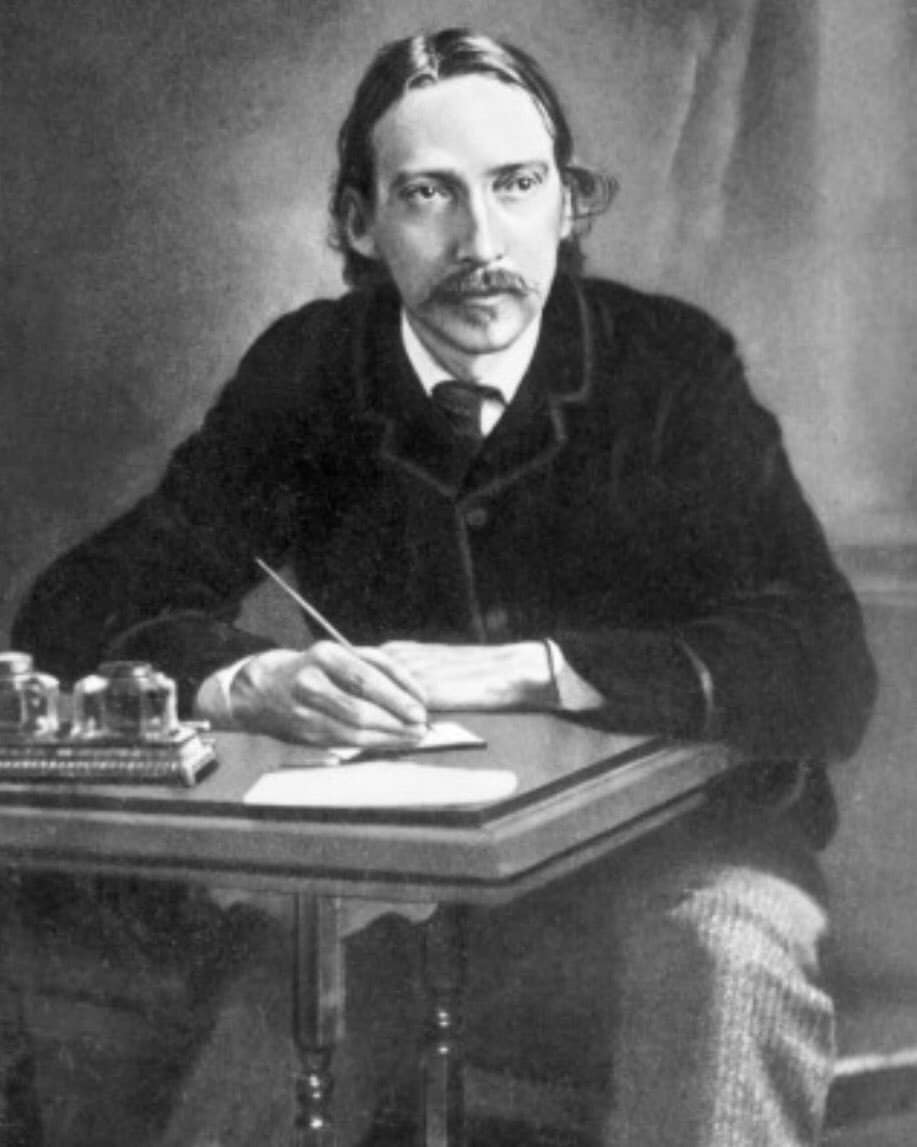

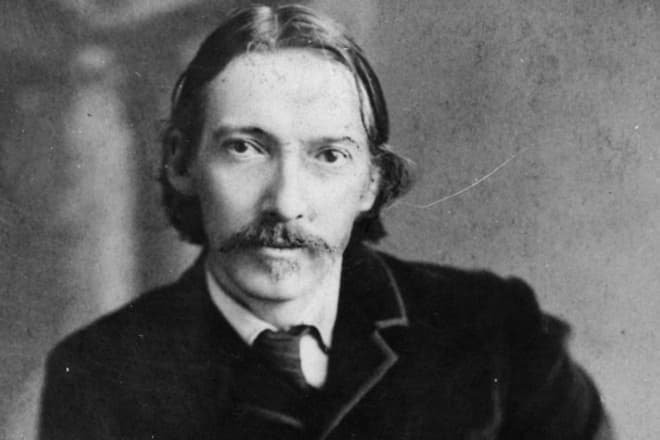

Robert Louis Stevenson |

|

|---|---|

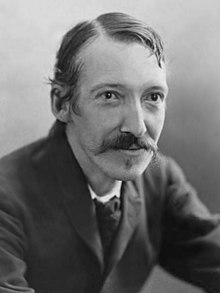

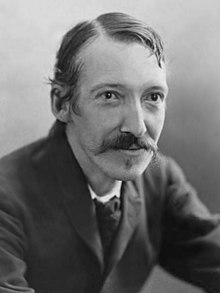

Stevenson in 1893 |

|

| Born | Robert Lewis Balfour Stevenson 13 November 1850 Edinburgh, Scotland |

| Died | 3 December 1894 (aged 44) Vailima, Samoa |

| Occupation |

|

| Alma mater | University of Edinburgh |

| Notable works |

|

| Spouse |

Fanny Van de Grift Osbourne (m. 1880–1894) |

| Parents | Thomas Stevenson (father) |

| Relatives | Robert Stevenson (paternal grandfather) Lloyd Osbourne (stepson) Isobel Osbourne (stepdaughter) Edward Salisbury Field (stepson-in-law) |

| Signature | |

Bound set of many of Stevenson’s works, 1909

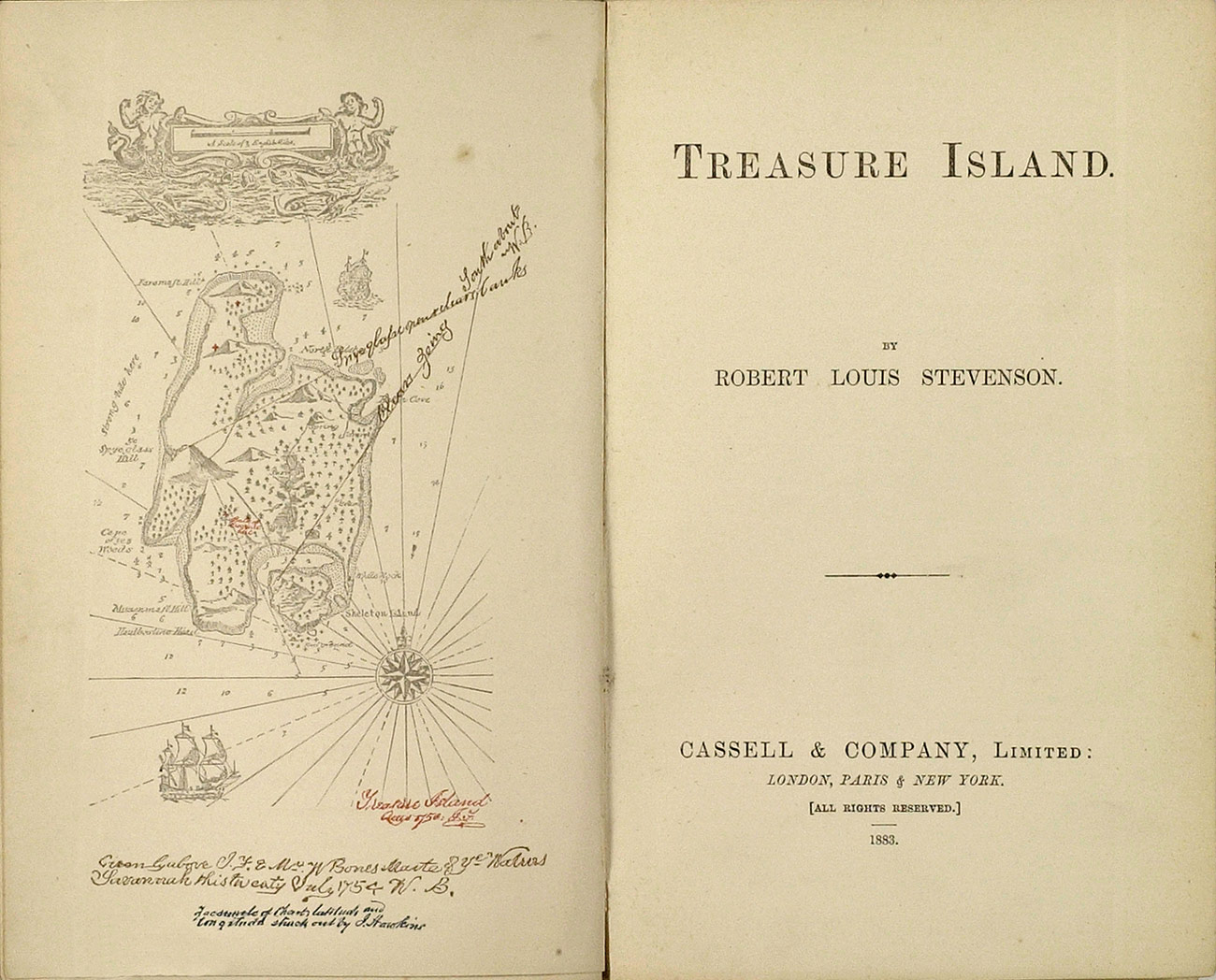

Robert Louis Stevenson (born Robert Lewis Balfour Stevenson; 13 November 1850 – 3 December 1894) was a Scottish novelist, essayist, poet and travel writer. He is best known for works such as Treasure Island, Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, Kidnapped and A Child’s Garden of Verses.

Born and educated in Edinburgh, Stevenson suffered from serious bronchial trouble for much of his life, but continued to write prolifically and travel widely in defiance of his poor health. As a young man, he mixed in London literary circles, receiving encouragement from Andrew Lang, Edmund Gosse,[1] Leslie Stephen and W. E. Henley, the last of whom may have provided the model for Long John Silver in Treasure Island. In 1890, he settled in Samoa where, alarmed at increasing European and American influence in the South Sea islands, his writing turned away from romance and adventure fiction toward a darker realism. He died of a stroke in his island home in 1894 at age 44.[2]

A celebrity in his lifetime, Stevenson’s critical reputation has fluctuated since his death, though today his works are held in general acclaim. In 2018 he was ranked, just behind Charles Dickens, as the 26th-most-translated author in the world.[3]

Family and education[edit]

Childhood and youth[edit]

Stevenson’s childhood home in Heriot Row

Stevenson was born at 8 Howard Place, Edinburgh, Scotland, on 13 November 1850 to Thomas Stevenson (1818–1887), a leading lighthouse engineer, and his wife, Margaret Isabella (born Balfour, 1829–1897). He was christened Robert Lewis Balfour Stevenson. At about age 18, he changed the spelling of «Lewis» to «Louis», and he dropped «Balfour» in 1873.[4][5]

Lighthouse design was the family’s profession; Thomas’s father (Robert’s grandfather) was civil engineer Robert Stevenson, and Thomas’s brothers (Robert’s uncles) Alan and David were in the same field.[6] Thomas’s maternal grandfather Thomas Smith had been in the same profession. However, Robert’s mother’s family were gentry, tracing their lineage back to Alexander Balfour who had held the lands of Inchrye in Fife in the fifteenth century.[7] His mother’s father Lewis Balfour (1777–1860) was a minister of the Church of Scotland at nearby Colinton,[8] and her siblings included physician George William Balfour and marine engineer James Balfour. Stevenson spent the greater part of his boyhood holidays in his maternal grandfather’s house. «Now I often wonder what I inherited from this old minister,» Stevenson wrote. «I must suppose, indeed, that he was fond of preaching sermons, and so am I, though I never heard it maintained that either of us loved to hear them.»[9]

Lewis Balfour and his daughter both had weak chests, so they often needed to stay in warmer climates for their health. Stevenson inherited a tendency to coughs and fevers, exacerbated when the family moved to a damp, chilly house at 1 Inverleith Terrace in 1851.[10] The family moved again to the sunnier 17 Heriot Row when Stevenson was six years old, but the tendency to extreme sickness in winter remained with him until he was 11. Illness was a recurrent feature of his adult life and left him extraordinarily thin.[11] Contemporaneous views were that he had tuberculosis, but more recent views are that it was bronchiectasis[12] or even sarcoidosis.[13]

«My second mother, my first wife. The angel of my infant life— From the sick child, now well and old, Take, nurse, the little book you hold!» Dedication of «A Child’s Garden of Verses»: »To Alison Cunningham. From her Boy.»[14]

Stevenson’s parents were both devout Presbyterians, but the household was not strict in its adherence to Calvinist principles. His nurse Alison Cunningham (known as Cummy)[15] was more fervently religious. Her mix of Calvinism and folk beliefs were an early source of nightmares for the child, and he showed a precocious concern for religion.[16] But she also cared for him tenderly in illness, reading to him from John Bunyan and the Bible as he lay sick in bed and telling tales of the Covenanters. Stevenson recalled this time of sickness in «The Land of Counterpane» in A Child’s Garden of Verses (1885),[17] dedicating the book to his nurse.[18]

Stevenson was an only child, both strange-looking and eccentric, and he found it hard to fit in when he was sent to a nearby school at age 6, a problem repeated at age 11 when he went on to the Edinburgh Academy; but he mixed well in lively games with his cousins in summer holidays at Colinton.[19] His frequent illnesses often kept him away from his first school, so he was taught for long stretches by private tutors. He was a late reader, learning at age 7 or 8, but even before this he dictated stories to his mother and nurse,[20] and he compulsively wrote stories throughout his childhood. His father was proud of this interest; he had also written stories in his spare time until his own father found them and told him to «give up such nonsense and mind your business.»[6] He paid for the printing of Robert’s first publication at 16, entitled The Pentland Rising: A Page of History, 1666. It was an account of the Covenanters’ rebellion which was published in 1866, the 200th anniversary of the event.[21]

Education[edit]

In September 1857, when he was six years old, Stevenson went to Mr Henderson’s School in India Street, Edinburgh, but because of poor health stayed only a few weeks and did not return until October 1859, aged eight. During his many absences, he was taught by private tutors. In October 1861, aged ten, he went to Edinburgh Academy, an independent school for boys, and stayed there sporadically for about fifteen months. In the autumn of 1863, he spent one term at an English boarding school at Spring Grove in Isleworth in Middlesex (now an urban area of West London). In October 1864, following an improvement to his health, the 13-year-old was sent to Robert Thomson’s private school in Frederick Street, Edinburgh, where he remained until he went to university.[22] In November 1867, Stevenson entered the University of Edinburgh to study engineering. He showed from the start no enthusiasm for his studies and devoted much energy to avoiding lectures. This time was more important for the friendships he made with other students in The Speculative Society (an exclusive debating club), particularly with Charles Baxter, who would become Stevenson’s financial agent, and with a professor, Fleeming Jenkin, whose house staged amateur drama in which Stevenson took part, and whose biography he would later write.[23] Perhaps most important at this point in his life was a cousin, Robert Alan Mowbray Stevenson (known as «Bob»), a lively and light-hearted young man who, instead of the family profession, had chosen to study art.[24]

Each year during the holidays, Stevenson travelled to inspect the family’s engineering works: to Anstruther and Wick in 1868, with his father on his official tour of Orkney and Shetland islands lighthouses in 1869, and for three weeks to the island of Erraid in 1870. He enjoyed the travels more for the material they gave for his writing than for any engineering interest. The voyage with his father pleased him because a similar journey of Walter Scott with Robert Stevenson had provided the inspiration for Scott’s 1822 novel The Pirate.[25] In April 1871, Stevenson notified his father of his decision to pursue a life of letters. Though the elder Stevenson was naturally disappointed, the surprise cannot have been great, and Stevenson’s mother reported that he was «wonderfully resigned» to his son’s choice. To provide some security, it was agreed that Stevenson should read law (again at Edinburgh University) and be called to the Scottish bar.[26] In his 1887 poetry collection Underwoods, Stevenson muses on his having turned from the family profession:[27]

Say not of me that weakly I declined

The labours of my sires, and fled the sea,

The towers we founded and the lamps we lit,

To play at home with paper like a child.

But rather say: In the afternoon of time

A strenuous family dusted from its hands

The sand of granite, and beholding far

Along the sounding coast its pyramids

And tall memorials catch the dying sun,

Smiled well content, and to this childish task

Around the fire addressed its evening hours.

Rejection of church dogma[edit]

In other respects too, Stevenson was moving away from his upbringing. His dress became more Bohemian; he already wore his hair long, but he now took to wearing a velveteen jacket and rarely attended parties in conventional evening dress.[28] Within the limits of a strict allowance, he visited cheap pubs and brothels.[29] More significantly, he had come to reject Christianity and declared himself an atheist.[30] In January 1873, when he was 22, his father came across the constitution of the LJR (Liberty, Justice, Reverence) Club, of which Stevenson and his cousin Bob were members, which began: «Disregard everything our parents have taught us». Questioning his son about his beliefs, he discovered the truth.[31] Stevenson no longer believed in God and had grown tired of pretending to be something he was not: «am I to live my whole life as one falsehood?» His father professed himself devastated: «You have rendered my whole life a failure.» His mother accounted the revelation «the heaviest affliction» to befall her. «O Lord, what a pleasant thing it is», Stevenson wrote to his friend Charles Baxter, «to have just damned the happiness of (probably) the only two people who care a damn about you in the world.»[32]

Stevenson’s rejection of the Presbyterian Church and Christian dogma, however, did not turn into lifelong atheism or agnosticism. On February 15, 1878, the 27-year-old wrote to his father and stated:[33]

Christianity is among other things, a very wise, noble and strange doctrine of life … You see, I speak of it as a doctrine of life, and as a wisdom for this world … I have a good heart, and believe in myself and my fellow-men and the God who made us all … There is a fine text in the Bible, I don’t know where, to the effect that all things work together for good for those who love the Lord. Strange as it may seem to you, everything has been, in one way or the other, bringing me nearer to what I think you would like me to be. ‘Tis a strange world, indeed, but there is a manifest God for those who care to look for him.

Stevenson did not resume attending church in Scotland. However, he did teach Sunday School lessons in Samoa, and prayers he wrote in his final years were published posthumously.[34]

«An Apology for Idlers»[edit]

Justifying his rejection of an established profession, in 1877 Stevenson offered «An Apology for Idlers». «A happy man or woman», he reasoned, «is a better thing to find than a five-pound note. He or she is a radiating focus of goodwill» and a practical demonstration of «the great Theorem of the Liveableness of Life». So that if they cannot be happy in the «handicap race for sixpenny pieces», let them take their own «by-road».[35]

Early writing and travels[edit]

Literary and artistic connections[edit]

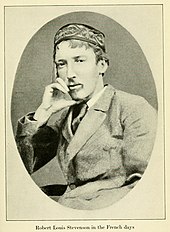

Stevenson at age 26 in 1876 at Barbizon, France

Stevenson was visiting a cousin in England in late 1873 (Stevenson was 23) when he met two people who became very important to him: Sidney Colvin and Fanny (Frances Jane) Sitwell. Sitwell was a 34-year-old woman with a son, who was separated from her husband. She attracted the devotion of many who met her, including Colvin, who married her in 1901. Stevenson was also drawn to her, and they kept up a warm correspondence over several years in which he wavered between the role of a suitor and a son (he addressed her as «Madonna»).[36] Colvin became Stevenson’s literary adviser and was the first editor of his letters after his death. He placed Stevenson’s first paid contribution in The Portfolio, an essay titled «Roads».[37]

Stevenson was soon active in London literary life, becoming acquainted with many of the writers of the time, including Andrew Lang, Edmund Gosse[38] and Leslie Stephen, the editor of The Cornhill Magazine who took an interest in Stevenson’s work. Stephen took Stevenson to visit a patient at the Edinburgh Infirmary named William Ernest Henley, an energetic and talkative poet with a wooden leg. Henley became a close friend and occasional literary collaborator, until a quarrel broke up the friendship in 1888, and he is often considered to be the inspiration for Long John Silver in Treasure Island.[39]

Stevenson was sent to Menton on the French Riviera in November 1873 to recuperate after his health failed. He returned in better health in April 1874 and settled down to his studies, but he returned to France several times after that.[40] He made long and frequent trips to the neighbourhood of the Forest of Fontainebleau, staying at Barbizon, Grez-sur-Loing and Nemours and becoming a member of the artists’ colonies there. He also travelled to Paris to visit galleries and the theatres.[41] He qualified for the Scottish bar in July 1875, aged 24, and his father added a brass plate to the Heriot Row house reading «R.L. Stevenson, Advocate». His law studies did influence his books, but he never practised law;[42] all his energies were spent in travel and writing. One of his journeys was a canoe voyage in Belgium and France with Sir Walter Simpson, a friend from the Speculative Society, a frequent travel companion, and the author of The Art of Golf (1887). This trip was the basis of his first travel book An Inland Voyage (1878).[43]

Stevenson had a long correspondence with fellow Scot J.M. Barrie. He invited Barrie to visit him in Samoa, but the two never met.[44]

Marriage[edit]

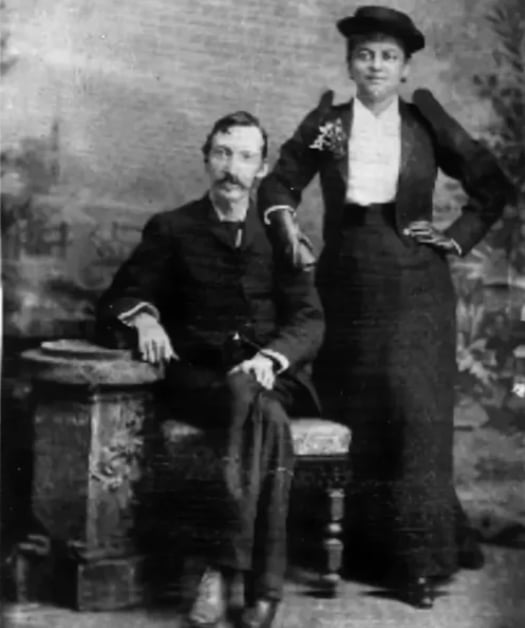

Fanny Van de Grift Osbourne, c. 1876

The canoe voyage with Simpson brought Stevenson to Grez-sur-Loing in September 1876, where he met Fanny Van de Grift Osbourne (1840–1914), born in Indianapolis. She had married at age 17 and moved to Nevada to rejoin husband Samuel after his participation in the American Civil War. Their children were Isobel (or «Belle»), Lloyd and Hervey (who died in 1875). But anger over her husband’s infidelities led to a number of separations. In 1875, she had taken her children to France where she and Isobel studied art.[45] By the time Stevenson met her, Fanny was herself a magazine short-story writer of recognized ability.[46]

Stevenson returned to Britain shortly after this first meeting, but Fanny apparently remained in his thoughts, and he wrote the essay «On falling in love» for The Cornhill Magazine.[47] They met again early in 1877 and became lovers. Stevenson spent much of the following year with her and her children in France.[48] In August 1878, she returned to San Francisco and Stevenson remained in Europe, making the walking trip that formed the basis for Travels with a Donkey in the Cévennes (1879). But he set off to join her in August 1879, aged 28, against the advice of his friends and without notifying his parents. He took a second-class passage on the steamship Devonia, in part to save money but also to learn how others travelled and to increase the adventure of the journey.[49] He then travelled overland by train from New York City to California. He later wrote about the experience in The Amateur Emigrant. It was a good experience for his writing, but it broke his health.

Family in 1893: Wife Fanny, Stevenson, his stepdaughter Isobel, and his mother Margaret Balfour

He was near death when he arrived in Monterey, California, where some local ranchers nursed him back to health. He stayed for a time at the French Hotel located at 530 Houston Street, now a museum dedicated to his memory called the «Stevenson House». While there, he often dined «on the cuff,» as he said, at a nearby restaurant run by Frenchman Jules Simoneau, which stood at what is now Simoneau Plaza; several years later, he sent Simoneau an inscribed copy of his novel Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1886), writing that it would be a stranger case still if Robert Louis Stevenson ever forgot Jules Simoneau. While in Monterey, he wrote an evocative article about «the Old Pacific Capital» of Monterey.

By December 1879, aged 29, Stevenson had recovered his health enough to continue to San Francisco where he struggled «all alone on forty-five cents a day, and sometimes less, with quantities of hard work and many heavy thoughts,»[50] in an effort to support himself through his writing. But by the end of the winter, his health was broken again and he found himself at death’s door. Fanny was now divorced and recovered from her own illness, and she came to his bedside and nursed him to recovery. «After a while,» he wrote, «my spirit got up again in a divine frenzy, and has since kicked and spurred my vile body forward with great emphasis and success.»[51] When his father heard of his 28-year-old son’s condition, he cabled him money to help him through this period.

Fanny and Robert were married in May 1880. She was 40; he was 29. He said that he was «a mere complication of cough and bones, much fitter for an emblem of mortality than a bridegroom.»[52] He travelled with his new wife and her son Lloyd[53] north of San Francisco to Napa Valley and spent a summer honeymoon at an abandoned mining camp on Mount Saint Helena (today designated Robert Louis Stevenson State Park). He wrote about this experience in The Silverado Squatters. He met Charles Warren Stoddard, co-editor of the Overland Monthly and author of South Sea Idylls, who urged Stevenson to travel to the South Pacific, an idea which returned to him many years later. In August 1880, he sailed with Fanny and Lloyd from New York to Britain and found his parents and his friend Sidney Colvin on the wharf at Liverpool, happy to see him return home. Gradually, his wife was able to patch up differences between father and son and make herself a part of the family through her charm and wit.

England, and back to the United States[edit]

The Stevensons shuttled back and forth between Scotland and the Continent, finally settling in 1884 in the Westbourne district of the English seaside town of Bournemouth in Dorset. They lived in a house Stevenson named ‘Skerryvore’ after a Scottish lighthouse built by his uncle Alan.[54]

From April 1885, 34-year-old Stevenson had the company of the novelist Henry James. They had met previously in London and had recently exchanged views in journal articles on the “art of fiction” and thereafter in a correspondence in which they expressed their admiration for each other’s work. After James had moved to Bournemouth to help support his invalid sister, Alice, he took up the invitation to pay daily visits to Skerryvore for conversation at the Stevensons’ dinner table.[55]

Largely bedridden, Stevenson described himself as living «like a weevil in a biscuit.» Yet, despite ill health, during his three years in Westbourne, Stevenson wrote the bulk of his most popular work: Treasure Island, Kidnapped, Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (which established his wider reputation), A Child’s Garden of Verses and Underwoods.

Thomas Stevenson died in 1887 leaving his 36-year-old son feeling free to follow the advice of his physician to try a complete change of climate. Stevenson headed for Colorado with his widowed mother and family. But after landing in New York, they decided to spend the winter in the Adirondacks at a cure cottage now known as Stevenson Cottage at Saranac Lake, New York. During the intensely cold winter, Stevenson wrote some of his best essays, including Pulvis et Umbra. He also began The Master of Ballantrae and lightheartedly planned a cruise to the southern Pacific Ocean for the following summer.[56]

Reflections on the art of writing[edit]

Stevenson’s critical essays on literature contain «few sustained analyses of style or content».[57] In «A Penny Plain and Two-pence Coloured» (1884) he suggests that his own approach owed much to the exaggerated and romantic world that, as a child, he had entered as proud owner of Skelt’s Juvenile Drama—a toy set of cardboard characters who were actors in melodramatic dramas. «A Gossip on Romance» (1882) and «A Gossip on a Novel of Dumas’s» (1887) imply that it is better to entertain than to instruct.

Stevenson very much saw himself in the mould of Sir Walter Scott, a storyteller with an ability to transport his readers away from themselves and their circumstances. He took issue with what he saw as the tendency in French realism to dwell on sordidness and ugliness. In «The Lantern-Bearer» (1888) he appears to take Emile Zola to task for failing to seek out nobility in his protagonists.[57]

In «A Humble Remonstrance», Stevenson answers Henry James’s claim in «The Art of Fiction» (1884) that the novel competes with life. Stevenson protests that no novel can ever hope to match life’s complexity; it merely abstracts from life to produce a harmonious pattern of its own.[58]

Man’s one method, whether he reasons or creates, is to half-shut his eyes against the dazzle and confusion of reality…Life is monstrous, infinite, illogical, abrupt and poignant; a work of art, in comparison, is neat, finite, self-contained, rational, flowing, and emasculate…The novel, which is a work of art, exists, not by its resemblances to life, which are forced and material … but by its immeasurable difference from life, which is designed and significant.

It is not clear, however, that in this there was any real basis for disagreement with James.[55] Stevenson had presented James with a copy of Kidnapped, but it was Treasure Island that James favoured. Written as a story for boys, Stevenson had thought it in “no need of psychology or fine writing», but its success is credited with liberating children’s writing from the «chains of Victorian didacticism».[59]

Politics: «The Day after Tomorrow»[edit]

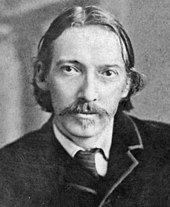

Photographic portrait, c. 1887

Bibliography frontispiece

During his college years, Stevenson briefly identified himself as a «red-hot socialist». But already by age 26 he was writing of looking back on this time «with something like regret. … Now I know that in thus turning Conservative with years, I am going through the normal cycle of change and travelling in the common orbit of men’s opinions.»[60] His cousin and biographer Sir Graham Balfour claimed that Stevenson «probably throughout life would, if compelled to vote, have always supported the Conservative candidate.»[61] In 1866, then 15-year-old Stevenson did vote for Benjamin Disraeli, the Tory democrat and future Conservative Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, for the Lord Rectorship of the University of Edinburgh. But this was against a markedly illiberal challenger, the historian Thomas Carlyle.[62] Carlyle was notorious for his anti-democratic and pro-slavery views.[63][64]

In «The Day after Tomorrow», appearing in The Contemporary Review (April 1887),[65][66] Stevenson suggested: «we are all becoming Socialists without knowing it». Legislation «grows authoritative, grows philanthropical, bristles with new duties and new penalties, and casts a spawn of inspectors, who now begin, note-book in hand, to darken the face of England».[67] He is referring to the steady growth in social legislation in Britain since the first of the Conservative-sponsored Factory Acts (which, in 1833, established a professional Factory Inspectorate). Stevenson cautioned that this «new waggon-load of laws» points to a future in which our grandchildren might «taste the pleasures of existence in something far liker an ant-heap that any previous human polity».[68] Yet in reproducing the essay his latter-day libertarian admirers omit his express understanding for the abandonment of Whiggish, classical-liberal notions of laissez faire. «Liberty», Stevenson wrote, «has served us a long while» but like all other virtues «she has taken wages».

[Liberty] has dutifully served Mammon; so that many things we were accustomed to admire as the benefits of freedom and common to all, were truly benefits of wealth, and took their value from our neighbour’s poverty…Freedom to be desirable, involves kindness, wisdom, and all the virtues of the free; but the free man as we have seen him in action has been, as of yore, only the master of many helots; and the slaves are still ill-fed, ill-clad, ill-taught, ill-housed, insolently entreated, and driven to their mines and workshops by the lash of famine.[69]

In January 1888, aged 37, in response to American press coverage of the Land War in Ireland, Stevenson penned a political essay (rejected by Scribner’s magazine and never published in his lifetime) that advanced a broadly conservative theme: the necessity of «staying internal violence by rigid law». Notwithstanding his title, «Confessions of a Unionist», Stevenson defends neither the union with Britain (she had «majestically demonstrated her incapacity to rule Ireland») nor «landlordism» (scarcely more defensible in Ireland than, as he had witnessed it, in the goldfields of California). Rather he protests the readiness to pass «lightly» over crimes—»unmanly murders and the harshest extremes of boycotting»—where these are deemed «political». This he argues is to «defeat law» (which is ever a «compromise») and to invite «anarchy»: it is «the sentimentalist preparing the pathway for the brute».[70]

Final years in the Pacific[edit]

Pacific voyages[edit]

Stevenson playing a flageolet in Hawaii ca. 1889

Stevenson and King Kalākaua of Hawaii, c. 1889

The author with his wife and their household in Vailima, Samoa, c. 1892

Stevenson’s birthday fete at Vailima, November 1894

Stevenson on the veranda of his home at Vailima, c. 1893

His tomb on Mount Vaea, c. 1909

In June 1888, Stevenson chartered the yacht Casco and set sail with his family from San Francisco. The vessel «plowed her path of snow across the empty deep, far from all track of commerce, far from any hand of help.»[71] The sea air and thrill of adventure for a time restored his health, and for nearly three years he wandered the eastern and central Pacific, stopping for extended stays at the Hawaiian Islands, where he became a good friend of King Kalākaua. He befriended the king’s niece Princess Victoria Kaiulani, who also had Scottish heritage. He spent time at the Gilbert Islands, Tahiti, New Zealand and the Samoan Islands. During this period, he completed The Master of Ballantrae, composed two ballads based on the legends of the islanders, and wrote The Bottle Imp. He preserved the experience of these years in his various letters and in his In the South Seas (which was published posthumously).[72] He made a voyage in 1889 with Lloyd on the trading schooner Equator, visiting Butaritari, Mariki, Apaiang and Abemama in the Gilbert Islands.[73] They spent several months on Abemama with tyrant-chief Tem Binoka, whom Stevenson described in In the South Seas.[73]

Stevenson left Sydney, Australia, on the Janet Nicoll in April 1890 for his third and final voyage among the South Seas islands.[74] He intended to produce another book of travel writing to follow his earlier book In the South Seas, but it was his wife who eventually published her journal of their third voyage. (Fanny misnames the ship in her account The Cruise of the Janet Nichol.)[75] A fellow passenger was Jack Buckland, whose stories of life as an island trader became the inspiration for the character of Tommy Hadden in The Wrecker (1892), which Stevenson and Lloyd Osbourne wrote together.[76][77] Buckland visited the Stevensons at Vailima in 1894.[78]

Political engagement in Samoa[edit]

In December 1889, 39-year-old Stevenson and his extended family arrived at the port of Apia in the Samoan islands and there he and Fanny decided to settle. In January 1890 they purchased 314+1⁄4 acres (127.2 ha) at Vailima, some miles inland from Apia the capital, on which they built the islands’ first two-storey house. Fanny’s sister, Nellie Van de Grift Sanchez, wrote that “it was in Samoa that the word ‘home’ first began to have a real meaning for these gypsy wanderers”.[79] In May 1891, they were joined by Stevenson’s mother, Margaret. While his wife set about managing and working the estate, 40-year-old Stevenson took the native name Tusitala (Samoan for «Teller of Tales»), and began collecting local stories. Often he would exchange these for his own tales. The first work of literature in Samoan was his translation of The Bottle Imp,[79] which presents a Pacific-wide community as the setting for a moral fable.

Immersing himself in the islands’ culture, occasioned a «political awakening»: it placed Stevenson «at an angle» to the rival great powers, Britain, Germany and the United States whose warships were common sights in Samoan harbours.[80][81] He understood that, as in the Scottish Highlands (comparisons with his homeland «came readily»), an indigenous clan society was unprepared for the arrival of foreigners who played upon its existing rivalries and divisions. As the external pressures upon Samoan society grew, tensions soon descended into several inter-clan wars.[82]

No longer content to be a «romancer», Stevenson became a reporter and an agitator, firing off letters to The Times which «rehearsed with an ironic twist that surely owed something to his Edinburgh legal training», a tale of European and American misconduct.[82] His concern for the Polynesians is also found in the South Sea Letters, published in magazines in 1891 (and then in book form as In the South Seas in 1896). In an effort he feared might result in his own deportation, Stevenson helped secure the recall of two European officials. A Footnote to History: Eight Years of Trouble in Samoa (1892) was a detailed chronicle of the intersection of rivalries between the great powers and the first Samoan Civil War.

As much as he said he disdained politics—»I used to think meanly of the plumber», he wrote to his friend Sidney Colvin, «but how he shines beside the politician!»[83]—Stevenson felt himself obliged to take sides. He openly allied himself with chief Mataafa, whose rival Malietoa was backed by the Germans whose firms were beginning to monopolise copra and cocoa bean processing.[81]

Stevenson was alarmed above all by what he perceived as the Samoans’ economic innocence—their failure to secure their claim to proprietorship of the land (in a Lockean sense)[84] through improving management and labour. In 1894 just months before his death, he addressed the island chiefs:[85]

There is but one way to defend Samoa. Hear it before it is too late. It is to make roads, and gardens, and care for your trees, and sell their produce wisely, and, in one word, to occupy and use your country… if you do not occupy and use your country, others will. It will not continue to be yours or your children’s, if you occupy it for nothing. You and your children will, in that case, be cast out into outer darkness».

He had «seen these judgments of God», not only in Hawaii where abandoned native churches stood like tombstones «over a grave, in the midst of the white men’s sugar fields», but also in Ireland and «in the mountains of my own country Scotland».

These were a fine people in the past brave, gay, faithful, and very much like Samoans, except in one particular, that they were much wiser and better at that business of fighting of which you think so much. But the time came to them as it now comes to you, and it did not find them ready…

Five years after Stevenson’s death, the Samoan Islands were partitioned between Germany and the United States.[86]

Last works[edit]

Stevenson wrote an estimated 700,000 words during his years on Samoa. He completed The Beach of Falesá, the first-person tale of a Scottish copra trader on a South Sea island. Wiltshire is heroic in terms neither of his actions nor a preoccupation with his own soul. Rather he is a man of limited understanding and imagination, comfortable with his own prejudices: where, he wonders, can he find «whites» for his «half caste» daughters. The villains are white, their behaviour towards the islanders ruthlessly duplicitous.

Stevenson saw «The Beach of Falesá» as the ground-breaking work in his turn away from romance to realism. Stevenson wrote to his friend Sidney Colvin:

It is the first realistic South Seas story; I mean with real South Sea character and details of life. Everybody else that has tried, that I have seen, got carried away by the romance, and ended in a kind of sugar candy sham epic, and the whole effect was lost… Now I have got the smell and look of the thing a good deal. You will know more about the South Seas after you have read my little tale than if you had read a library.[87]

The Ebb-Tide (1894), the misadventures of three deadbeats marooned in the Tahitian port of Papeete, has been described as presenting «a microcosm of imperialist society, directed by greedy but incompetent whites, the labour supplied by long-suffering natives who fulfil their duties without orders and are true to the missionary faith which the Europeans make no pretence of respecting».[88] It confirmed the new Realistic turn in Stevenson’s writing away from romance and adolescent adventure. The first sentence reads: «Throughout the island world of the Pacific, scattered men of many European races and from almost every grade of society carry activity and disseminate disease». No longer was Stevenson writing about human nature «in terms of a contest between Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde»: «the edges of moral responsibility and the margins of moral judgement were too blurred».[82] As with The Beach of Falesà, in The Ebb Tide contemporary reviewers find parallels with several of Conrad’s works: Almayer’s Folly, An Outcast of the Islands, The Nigger of the ‘Narcissus’’, Heart of Darkness, Lord Jim.[89][90][81]

With his imagination still residing in Scotland and returning to earlier form, Stevenson also wrote Catriona (1893), a sequel to his earlier novel Kidnapped (1886), continuing the adventures of its hero David Balfour.[91]

Although he felt, as a writer, that «there was never any man had so many irons in the fire».[92] by the end of 1893 Stevenson feared that he had «overworked» and exhausted his creative vein.[93] His writing was partly driven by the need to meet the expenses of Vailima. But in a last burst of energy he began work on Weir of Hermiston. «It’s so good that it frightens me,» he is reported to have exclaimed.[94] He felt that this was the best work he had done.[95] Set in eighteenth century Scotland, it is a story of a society that (however different), like Samoa is witnessing a breakdown of social rules and structures leading to growing moral ambivalence.[82]

Death[edit]

On 3 December 1894, Stevenson was talking to his wife and straining to open a bottle of wine when he suddenly exclaimed, «What’s that?», then asked his wife, «Does my face look strange?», and collapsed.[2] He died within a few hours, at the age of 44, due to a stroke. The Samoans insisted on surrounding his body with a watch-guard during the night and on bearing him on their shoulders to nearby Mount Vaea, where they buried him on a spot overlooking the sea on land donated by British Acting Vice Consul Thomas Trood.[96] Based on Stevenson’s poem Requiem,[97] the following epitaph is inscribed on his tomb:[98]

-

- Under the wide and starry sky

- Dig the grave and let me lie

- Glad did I live and gladly die

- And I laid me down with a will

- This be the verse you grave for me

- Here he lies where he longed to be

- Home is the sailor home from the sea

- And the hunter home from the hill

Stevenson was loved by Samoans, and his tombstone epigraph was translated to a Samoan song of grief.[99] The requiem appears on the eastern side of the grave. On the western side the biblical passage of Ruth 1:16-17 is inscribed:

-

- Whither thou goest, I will go; and where thou lodgest, I will lodge:

- And thy people shall be my people, and thy God shall be my God:

- Where thou diest will I die, and there will I be buried.[100]

Artistic reception[edit]

Half of Stevenson’s original manuscripts are lost, including those of Treasure Island, The Black Arrow and The Master of Ballantrae. His heirs sold his papers during World War I, and many Stevenson documents were auctioned off in 1918.[101]

Stevenson was a celebrity in his own time, being admired by many other writers, including Marcel Proust, Arthur Conan Doyle, Henry James, J. M. Barrie,[102] Rudyard Kipling, Emilio Salgari, and later Cesare Pavese, Bertolt Brecht, Ernest Hemingway, Jack London, Vladimir Nabokov,[103] and G. K. Chesterton, who said that Stevenson «seemed to pick the right word up on the point of his pen, like a man playing spillikins.»[104]

Stevenson was seen for much of the 20th century as a second-class writer. He became relegated to children’s literature and horror genres,[105] condemned by literary figures such as Virginia Woolf (daughter of his early mentor Leslie Stephen) and her husband Leonard Woolf, and he was gradually excluded from the canon of literature taught in schools.[105] His exclusion reached its nadir in the 1973 2,000-page Oxford Anthology of English Literature where he was entirely unmentioned, and The Norton Anthology of English Literature excluded him from 1968 to 2000 (1st–7th editions), including him only in the eighth edition (2006).[105]

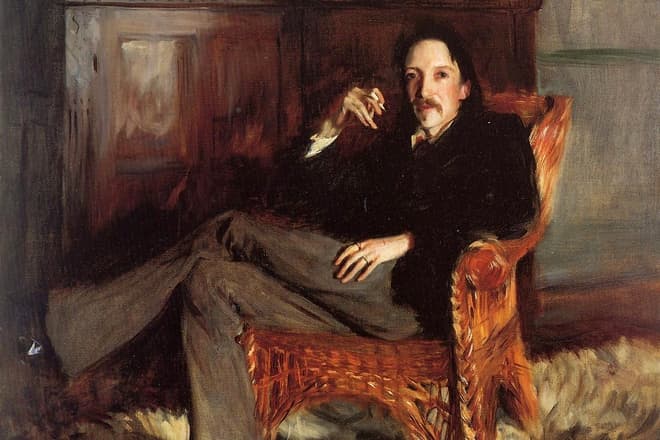

Portrait in 1893 by Barnett

The late 20th century brought a re-evaluation of Stevenson as an artist of great range and insight, a literary theorist, an essayist and social critic, a witness to the colonial history of the Pacific Islands and a humanist.[105] He was praised by Roger Lancelyn Green, one of the Oxford Inklings, as a writer of a consistently high level of «literary skill or sheer imaginative power» and a pioneer of the Age of the Story Tellers along with H. Rider Haggard.[106] He is now evaluated as a peer of authors such as Joseph Conrad (whom Stevenson influenced with his South Seas fiction) and Henry James, with new scholarly studies and organisations devoted to him.[105] Throughout the vicissitudes of his scholarly reception, Stevenson has remained popular worldwide. According to the Index Translationum, Stevenson is ranked the 26th-most-translated author in the world, ahead of Oscar Wilde and Edgar Allan Poe.

On the subject of Stevenson’s modern reputation, American film critic Roger Ebert wrote in 1996,

I was talking to a friend the other day who said he’d never met a child who liked reading Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island.

Neither have I, I said. And he’d never met a child who liked reading Stevenson’s Kidnapped. Me neither, I said. My early exposure to both books was via the Classics Illustrated comic books. But I did read the books later, when I was no longer a kid, and I enjoyed them enormously. Same goes for Stevenson’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.

The fact is, Stevenson is a splendid writer of stories for adults, and he should be put on the same shelf with Joseph Conrad and Jack London instead of in between Winnie the Pooh and Peter Pan.[108]

Monuments and commemoration[edit]

United Kingdom[edit]

The Writers’ Museum near Edinburgh’s Royal Mile devotes a room to Stevenson, containing some of his personal possessions from childhood through to adulthood.

A bronze relief memorial to Stevenson, designed by the American sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens in 1904, is mounted in the Moray Aisle of St Giles’ Cathedral, Edinburgh.[109] Saint-Gaudens’ scaled-down version of this relief is in the collection of the Montclair Art Museum.[110] Another small version depicting Stevenson with a cigarette in his hand rather than the pen he holds in the St. Giles memorial is displayed in the Nichols House Museum in Beacon Hill, Boston.[111]

In the West Princes Street Gardens below Edinburgh Castle a simple upright stone is inscribed: «RLS – A Man of Letters 1850–1894» by sculptor Ian Hamilton Finlay in 1987.[112] In 2013, a statue of Stevenson as a child with his dog was unveiled by the author Ian Rankin outside Colinton Parish Church.[113] The sculptor of the statue was Alan Herriot, and the money to erect it was raised by the Colinton Community Conservation Trust.[113]

Stevenson’s house Skerryvore, at the head of Alum Chine, was severely damaged by bombs during a destructive and lethal raid in the Bournemouth Blitz. Despite a campaign to save it, the building was demolished.[114] A garden was designed by the Bournemouth Corporation in 1957 as a memorial to Stevenson, on the site of his Westbourne house, «Skerryvore», which he occupied from 1885 to 1887. A statue of the Skerryvore lighthouse is present on the site. Robert Louis Stevenson Avenue in Westbourne is named after him.

In 1994, to mark the 100th anniversary of Stevenson’s death, the Royal Bank of Scotland issued a series of commemorative £1 notes which featured a quill pen and Stevenson’s signature on the obverse, and Stevenson’s face on the reverse side. Alongside Stevenson’s portrait are scenes from some of his books and his house in Western Samoa.[115] Two million notes were issued, each with a serial number beginning «RLS». The first note to be printed was sent to Samoa in time for their centenary celebrations on 3 December 1994.[116]

United States[edit]

The Stevenson House at 530 Houston Street in Monterey, California, formerly the French Hotel, memorializes Stevenson’s 1879 stay in «the Old Pacific Capital», as he was crossing the United States to join his future wife, Fanny Osbourne. The Stevenson House museum is graced with a bas-relief depicting the sickly author writing in bed.

Spyglass Hill Golf Course, originally called Pebble Beach Pines Golf Club, was renamed «Spyglass Hill» by Samuel F. B. Morse (1885–1969), the founder of Pebble Beach Company, after a place in Stevenson’s Treasure Island. All the holes at Spyglass Hill are named after characters and places in the novel.

The Robert Louis Stevenson Museum in St. Helena, California, is home to over 11,000 objects and artifacts, the majority of which belonged to Stevenson. Opened in 1969, the museum houses such treasures as his childhood rocking chair, writing desk, toy soldiers and personal writings among many other items. The museum is free to the public and serves as an academic archive for students, writers and Stevenson enthusiasts.

In San Francisco there is an outdoor Robert Louis Stevenson Memorial in Portsmouth Square.

At least six US public and private schools are named after Stevenson, in the Upper West Side of New York City,[117] in Fridley, Minnesota,[118] in Burbank, California,[119] in Grandview Heights, Ohio (suburb of Columbus), in San Francisco, California,[120] and in Merritt Island, Florida.[121] There is an R. L. Stevenson middle school in Honolulu, Hawaii and in Saint Helena, California. Stevenson School in Pebble Beach, California, was established in 1952 and still exists as a college preparatory boarding school. Robert Louis Stevenson State Park near Calistoga, California, contains the location where he and Fanny spent their honeymoon in 1880.[122]

A street in Honolulu’s Waikiki District, where Stevenson lived while in the Hawaiian Islands, was named after his Samoan moniker: Tusitala.[123]

Samoa[edit]

Stevenson’s former home in Vailima, Samoa, is now a museum dedicated to the later years of his life. The Robert Louis Stevenson Museum presents the house as it was at the time of his death along with two other buildings added to Stevenson’s original one, tripling the museum in size. The path to Stevenson’s grave at the top of Mount Vaea starts at the museum.[124]

France[edit]

The Chemin de Stevenson (GR 70) is a popular long-distance footpath in France that approximately follows Stevenson’s route as described in Travels with a Donkey in the Cévennes. There are numerous monuments and businesses named after him along the route, including a fountain in the town of Saint-Jean-du-Gard where Stevenson sold his donkey Modestine and took a stagecoach to Alès.[125]

Gallery[edit]

-

With Kalakaua in the King’s boathouse

-

-

Stevenson paces in his dining room in an 1885 portrait by John Singer Sargent. His wife Fanny, seated in an Indian dress, is visible in the lower right corner.

-

Alternate portrait in 1893 by Barnett, subtly different from the more familiar shot.

-

Bibliography[edit]

Novels[edit]

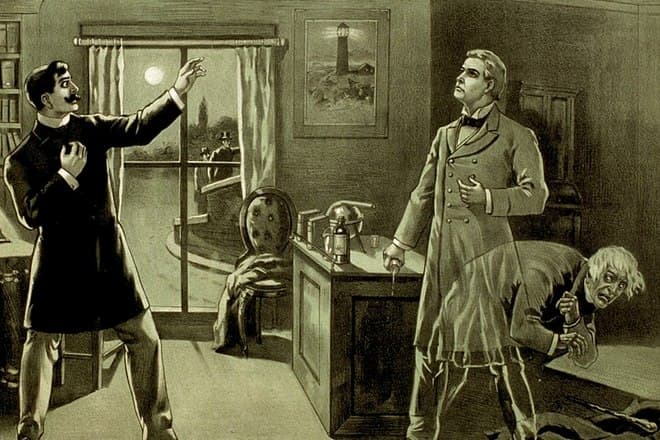

Illustration from Kidnapped. Caption: «Hoseason turned upon him with a flash» (chapter VII, «I Go to Sea in the Brig «Covenant» of Dysart»)

- The Hair Trunk or The Ideal Commonwealth (1877) – unfinished and unpublished.[126] An annotated edition of the original manuscript, edited and introduced by Roger G. Swearingen, was published as The Hair Trunk or The Ideal Commonwealth: An Extravaganza in August 2014.

- Treasure Island (1883) – his first major success, a tale of piracy, buried treasure and adventure; has been filmed frequently. In an 1881 letter to W. E. Henley, he provided the earliest-known title, «The Sea Cook, or Treasure Island: a Story for Boys».

- Prince Otto (1885) – Stevenson’s third full-length narrative, an action romance set in the imaginary Germanic state of Grünewald.

- Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1886) – a novella about a dual personality; much adapted in plays and films; also influential in the growth of understanding of the subconscious mind through its treatment of a kind and intelligent physician who turns into a psychopathic monster after imbibing a drug intended to separate good from evil in a personality.

- Kidnapped (1886) – a historical novel that tells of the boy David Balfour’s pursuit of his inheritance and his alliance with Alan Breck Stewart in the intrigues of Jacobite troubles in Scotland.

- The Black Arrow (1888) – a historical adventure novel and romance set during the Wars of the Roses.

- The Master of Ballantrae (1889) – a tale of revenge set in Scotland, America and India.

- The Wrong Box (1889) – co-written with Lloyd Osbourne. A comic novel of a tontine; filmed in 1966 starring John Mills, Ralph Richardson and Michael Caine.

- The Wrecker (1892) – co-written with Lloyd Osbourne and filmed in 1957 as a television series episode of Maverick starring James Garner and Jack Kelly, with full credit to Stevenson and Osbourne.

- Catriona (1893) – also known as David Balfour; a sequel to Kidnapped, telling of Balfour’s further adventures.

- The Ebb-Tide (1894) – co-written with Lloyd Osbourne.

- Weir of Hermiston (1896) – unfinished at the time of Stevenson’s death; considered to have promised great artistic growth.

- St Ives (1897) – unfinished at the time of Stevenson’s death; completed by Arthur Quiller-Couch.

Short story collections[edit]

- New Arabian Nights (1882) (11 stories)

- More New Arabian Nights: The Dynamiter (1885) (co-written with Fanny Van de Grift Stevenson)

- The Merry Men and Other Tales and Fables (1887) (6 stories)

- Island Nights’ Entertainments (1893) (3 stories)

- Fables (1896) (20 stories: «The Persons of the Tale», «The Sinking Ship», «The Two Matches», «The Sick Man and the Fireman», «The Devil and the Innkeeper», «The Penitent», «The Yellow Paint», «The House of Eld», «The Four Reformers», «The Man and His Friend», «The Reader», «The Citizen and the Traveller», «The Distinguished Stranger», «The Carthorse and the Saddlehorse», «The Tadpole and the Frog», «Something in It», «Faith, Half Faith and No Faith at All», «The Touchstone», «The Poor Thing» and «The Song of the Morrow»)

- Tales and Fantasies (1905) (3 stories)

Short stories[edit]

List of short stories sorted chronologically.[127] Note: does not include collaborations with Fanny found in More New Arabian Nights: The Dynamiter.

| Title | Date | Collection | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| «An Old Song» | 1875 | Uncollected | Stevenson’s first published fiction, in London, 1877. Anonymous. Republished in 1982 by R. Swearingen. |

| «When the Devil Was Well» | 1875 | Uncollected | First published in 1921, by the Boston Bibliophile Society. |

| «Edifying Letters of the Rutherford Family» | 1877 | Uncollected | Unfinished. Not truly a short-story. First published in 1982 by R. Swearingen. |

| «Will o’ the Mill» | 1877 | The Merry Men and Other Tales and Fables, 1887 | First published in The Cornhill Magazine, 1878 |

| «A Lodging for the Night» | 1877 | New Arabian Nights, 1882 | First published in Temple Bar in 1877 |

| «The Sire De Malétroits Door» | 1877 | New Arabian Nights, 1882 | First published in Temple Bar in 1878 |

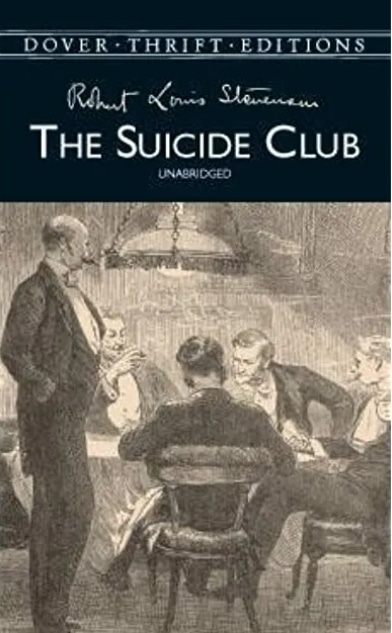

| «The Suicide Club» | 1878 | New Arabian Nights, 1882 | First published in London in 1878. Three interconnected stories: «Story of the Young Man with the Cream Tarts», «Story of the Physician and the Saratoga Trunk» and «The Adventure of the Hansom Cab». Part of the Later-day Arabian Nights. |

| «The Rajah’s Diamond» | 1878 | New Arabian Nights, 1882 | First published in London in 1878. Four interconnected stories: «Story of the Bandbox», «Story of the Young Man in Holy Orders», «Story of the House with the Green Blinds» and «The Adventure of Prince Florizel and a Detective». Part of the Later-day Arabian Nights. |

| «Providence and the Guitar» | 1878 | New Arabian Nights, 1882 | First published in London in 1878 |

| «The Story of a Lie» | 1879 | Tales and Fantasies, 1905 | First published in New Quarterly Magazine in 1879. |

| «The Pavilion on the Links» | 1880 | New Arabian Nights, 1882 | First Published in The Cornhill Magazine in 1880. Told in 9 mini-chapters. Later included with a few suppressions in New Arabian Nights. Conan Doyle in 1890 called it the first English short story. |

| «Thrawn Janet» | 1881 | The Merry Men and Other Tales and Fables, 1887 | First published in The Cornhill Magazine, 1881 |

| «The Body Snatcher» | 1881 | Tales and Fantasies, 1905 | First published in the Christmas 1884 edition of The Pall Mall Gazette. |

| «The Merry Men» | 1882 | The Merry Men and Other Tales and Fables, 1887 | First published in The Cornhill Magazine in 1882. Later included with changes in The Merry Men and Other Tales and Fables. |

| «Diogenes» | 1882 | Uncollected | Two sketches: «Diogenes in London» and «Diogenes at the Savile Club». |

| «The Treasure of Franchard» | 1883 | The Merry Men and Other Tales and Fables, 1887 | First published in Longman’s Magazine, 1883 |

| «Markheim» | 1884 | The Merry Men and Other Tales and Fables, 1887 | First published in the Broken Shaft. Unwin’s Annual., 1885 |

| «Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde» | 1885 | Standalone, 1886 | Novella. Also referred to, more rarely, as a short novel.[128] |

| «Olalla» | 1885 | The Merry Men and Other Tales and Fables, 1887 | First published in The Court and Society Review, 1885 |

| «The Great North Road» | 1885 | Uncollected | Unfinished. First published in Illustrated London News/The Cosmopolitan, 1895 |

| «The Story of a Recluse» | 1885 | Uncollected | Unfinished. First published by the Boston Bibliophile Society, 1921. Later completed by Alasdair Gray. |

| «The Misadventures of John Nicholson» | 1887 | Tales and Fantasies, 1905 | Novella. With the subtitle: «A Christmas Story». First published in Yule Tide, 1887 |

| «The Clockmaker» | 1880s | Uncollected | One of two fables not included in the 1896 collection.[129] |

| «The Scientific Ape» | 1880s | Uncollected | One of two fables not included in the 1896 collection. |

| «The Enchantress» | 1889 | Uncollected | First published in the Fall 1989 issue of The Georgia Review. |

| «Adventures of Henry Shovel» | 1891 | Uncollected | Unfinished. First published in the Vailima Edition, Vol. 25. Published alongside three other short fragments: «The Owl», «Cannonmills» and «Mr Baskerville and His Ward». |

| «The Bottle Imp» | 1891 | Island Nights’ Entertainments, 1893 | First published in Black and White, 1891 |

| «The Beach of Falesá» | 1892 | Island Nights’ Entertainments, 1893 | Novella. First published in The Illustrated London News in 1892 |

| «The Isle of Voices» | 1892 | Island Nights’ Entertainments, 1893 | First published in National Observer, 1883 |

| «The Waif Woman» | 1892 | Uncollected | Unfinished. First published in the Scribner’s Magazine, 1914 |

| «The Young Chevalier» | 1893 | Uncollected | Unfinished. First published in the Edinburgh Edition, Vol. 26, 1897 |

| «Heathercat» | 1894 | Uncollected | Unfinished. First published in the Edinburgh Edition, Vol. 20, 1897 |

Non-fiction[edit]

- «Béranger, Pierre Jean de» . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911. – first published in the 9th edition (1875–1889).

- Virginibus Puerisque, and Other Papers (1881), contains the essays Virginibus Puerisque i (1876); Virginibus Puerisque ii (1881); Virginibus Puerisque iii: On Falling in Love (1877); Virginibus Puerisque iv: The Truth of Intercourse (1879); Crabbed Age and Youth (1878); An Apology for Idlers (1877); Ordered South (1874); Aes Triplex (1878); El Dorado (1878); The English Admirals (1878); Some Portraits by Raeburn (previously unpublished); Child’s Play (1878); Walking Tours (1876); Pan’s Pipes (1878); A Plea for Gas Lamps (1878).

- Familiar Studies of Men and Books (1882) containing Preface, by Way of Criticism (not previously published); Victor Hugo’s Romances (1874); Some Aspects of Robert Burns (1879); The Gospel According to Walt Whitman (1878); Henry David Thoreau: His Character and Opinions (1880); Yoshida-Torajiro (1880); François Villon, Student, Poet, Housebreaker (1877); Charles of Orleans (1876); Samuel Pepys (1881); John Knox and his Relations to Women (1875).

- Memories and Portraits (1887), a collection of essays.

- On the Choice of a Profession (1887)

- The Day After Tomorrow (1887)

- Memoir of Fleeming Jenkin (1888)

- Father Damien: an Open Letter to the Rev. Dr. Hyde of Honolulu (1890)

- A Footnote to History: Eight Years of Trouble in Samoa (1892)

- Vailima Letters (1895)

- Prayers Written at Vailima (1904)

- Essays in the Art of Writing (1905)

- The New Lighthouse on the Dhu Heartach Rock, Argyllshire (1995) – based on an 1872 manuscript, edited by R. G. Swearingen. California. Silverado Museum.

- Sophia Scarlet (2008) – based on an 1892 manuscript, edited by Robert Hoskins. AUT Media (AUT University).

Poetry[edit]

- A Child’s Garden of Verses (1885), written for children but also popular with their parents. Includes such favourites as «My Shadow» and «The Lamplighter». Often thought to represent a positive reflection of the author’s sickly childhood.

- Underwoods (1887), a collection of poetry written in both English and Scots.

- Ballads (1891), included Ticonderoga: A Legend of the West Highlands (1887). Based on a famous Scottish ghost story.

- Songs of Travel and Other Verses (1896)

- Poems Hitherto Unpublished, 3 vol. 1916, 1916, 1921, Boston Bibliophile Society, republished in New Poems

Plays[edit]

- Three Plays (1892), co-written with William Ernest Henley. Includes the theatre pieces Deacon Brodie, Beau Austin and Admiral Guinea.

Travel writing[edit]

Stevenson with native Chief Tui-Ma-Le-Alh-Fano

- An Inland Voyage (1878), travels with a friend in a Rob Roy canoe from Antwerp (Belgium) to Pontoise, just north of Paris.

- Edinburgh: Picturesque Notes (1878) — a paean to his birthplace, it provides Stevenson’s personal introduction to each part of the city and some history behind the various sections of the city and its most famous buildings.

- Travels with a Donkey in the Cévennes (1879), two weeks’ solo ramble (with Modestine as his beast of burden) in the mountains of Cévennes (south-central France), one of the first books to present hiking and camping as recreational activities. It tells of commissioning one of the first sleeping bags.

- The Silverado Squatters (1883). An unconventional honeymoon trip to an abandoned mining camp in Napa Valley with his new wife Fanny and her son Lloyd. He presciently identifies the California wine industry as one to be reckoned with.

- Across the Plains (written in 1879–80, published in 1892). Second leg of his journey, by train from New York to California (then picks up with The Silverado Squatters). Also includes other travel essays.

- The Amateur Emigrant (written 1879–80, published 1895). An account of the first leg of his journey to California, by ship from Europe to New York. Andrew Noble (From the Clyde to California: Robert Louis Stevenson’s Emigrant Journey, 1985) considers it to be his finest work.

- The Old and New Pacific Capitals (1882). An account of his stay in Monterey, California in August to December 1879. Never published separately. See, for example, James D. Hart, ed., From Scotland to Silverado, 1966.

- Essays of Travel (London: Chatto & Windus, 1905)

- Sawyers, June Skinner (ed.) (2002), Dreams of Elsewhere: The Selected Travel Writings of Robert Louis Stevenson, The In Pin, Glasgow, ISBN 1-903238-62-5

Island literature[edit]

Although not well known, his island fiction and non-fiction is among the most valuable and collected of the 19th century body of work that addresses the Pacific area.

- In the South Seas (1896). A collection of Stevenson’s articles and essays on his travels in the Pacific.

- A Footnote to History, Eight Years of Trouble in Samoa (1892).

See also[edit]

- Robert Louis Stevenson State Park

- People on Scottish banknotes

- Victorian literature

- Salvation Army Waiʻoli Tea Room (Robert Louis Stevenson Memorial Grass House on premises)

- Writers’ Museum

References[edit]

- ^ Gosse, Edmund William (1911). «Stevenson, Robert Lewis Balfour» . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 25 (11th ed.). pp. 907–910.

- ^ a b Balfour, Graham (1906). The Life of Robert Louis Stevenson London: Methuen. 264

- ^ Osborn, Jacob. «49 most-translated authors from around the world». Stacker. Stacker. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- ^ Mehew (2004). The spelling «Lewis» is said to have been rejected because his father violently disliked another person of the same name, and the new spelling was not accompanied by a change of pronunciation (Balfour (1901) I, 29 n. 1.

- ^ Furnas (1952), 23–4; Mehew (2004)).

- ^ a b Paxton (2004).

- ^ The Life of Robert Louis Stevenson by Sir Graham Balfour — Delphi Classics (Illustrated). Delphi Classics. 17 July 2017. ISBN 9781786568007.

- ^ Balfour (1901), 10–12; Furnas (1952), 24; Mehew (2004).

- ^ Memories and Portraits (1887), Chapter VII. The Manse Archived 3 August 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ «A Robert Louis Stevenson Timeline (born Nov. 13th 1850 in Edinburgh, died Dec. 3rd 1894 in Samoa)». robert-louis-stevenson.org. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- ^ Furnas (1952), 25–8; Mehew (2004).

- ^ Holmes, Lowell (2002). Treasured Islands: Cruising the South Seas with Robert Louis Stevenson. Sheridan House, Inc. ISBN 1-57409-130-1.

- ^ Sharma, O. P. (2005). «Murray Kornfeld, American College of Chest Physician, and sarcoidosis: a historical footnote: 2004 Murray Kornfeld Memorial Founders Lecture». Chest. 128 (3): 1830–35. doi:10.1378/chest.128.3.1830. PMID 16162793.

- ^ Robert Louis Stevenson: A Bookman Extra Number, 1913, Hodder & Stoughton, 1913

- ^ «Stevenson’s Nurse Dead: Alison Cunningham («Cummy») lived to be over 91 years old» (PDF). The New York Times. 10 August 1913. p. 3.

- ^ Furnas (1952), 28–32; Mehew (2004).

- ^ Available at Bartleby Archived 9 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine and elsewhere.

- ^ Furnas (1952), 29; Mehew (2004).

- ^ Furnas (1952), 34–6; Mehew (2004). Alison Cunningham’s recollection of Stevenson balances the picture of an oversensitive child, «like other bairns, whiles very naughty»: Furnas (1952), 30.

- ^ Mehew (2004).

- ^ Balfour (1901) I, 67; Furnas (1952), pp. 43–45.

- ^ Stephenson, Robert Louis (1850–1894) – Childhood and schooling Archived 9 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Retrieved: 1 August 2013.

- ^ Furnas (1952), 51–54, 60–62; Mehew (2004)

- ^ Balfour (1901) I, 86–8; 90–4; Furnas (1952), 64–9

- ^ Balfour (1901) I, 70–2; Furnas (1952), 48–9; Mehew (2004)

- ^ Balfour (1901) I, 85–6

- ^ Underwoods (1887), Poem XXXVIII

- ^ Furnas (1952), 69–70; Mehew (2004)

- ^ Furnas (1952), 53–7; Mehew (2004.

- ^ Theo Tait (30 January 2005). «Like an intelligent hare – Theo Tait reviews Robert Louis Stevenson by Claire Harman». The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 4 August 2013.

A decadent dandy who envied the manly Victorian achievements of his family, a professed atheist haunted by religious terrors, a generous and loving man who fell out with many of his friends – the Robert Louis Stevenson of Claire Harman’s biography is all of these and, of course, a bed-ridden invalid who wrote some of the finest adventure stories in the language. […] Worse still, he affected a Bohemian style, haunted the seedier parts of the Old Town, read Charles Darwin and Herbert Spencer, and declared himself an atheist. This caused a painful rift with his father, who damned him as a «careless infidel».

- ^ Furnas (1952), 69 with n. 15 (on the club); 72–6

- ^ Stevenson, Robert Loui (2001). Selected Letters of Robert Louis Stevenson. New Have CT: Yale University Press. p. 29. ISBN 0-300-09124-9. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- ^ Colvin, Sidney, ed. (1917). The Letters of Robert Louis Stevenson, Vol. 1: 1868–1880. New York: Scribner’s. pp. 259–260.

- ^ Stevenson, Robert Louis (8 December 1912). «Prayers written at Vailima». New York, : C. Scribner’s sons. Retrieved 8 December 2022 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ «Robert Louis Stevenson «An Apology for Idlers» (first appeared in Cornhill Magazine, July 1877)». Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Retrieved 18 March 2021.

- ^ Furnas (1952), 81–2; 85–9; Mehew (2004)

- ^ Furnas (1952), 84–5

- ^ Furnas (1952), 95; 101

- ^ Balfour (1901) I, 123-4; Furnas (1952) 105–6; Mehew (2004)

- ^ Furnas (1952), 89–95

- ^ Balfour (1901) I, 128–37

- ^ Furnas (1952), 100–1

- ^ Balfour (1901) I, 127

- ^ Shaw, Michael (ed.) (2020), A Friendship in Letters: Robert Louis Stevenson & J.M. Barrie, Sandstone Press, Inverness ISBN 978-1-913207-02-1

- ^ Furnas (1952), 122–9; Mehew (2004)

- ^ Van de Grift Sanchez, Nellie (1920). The Life of Mrs. Robert Louis Stevenson. New York: C. Scribner’s Sons. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- ^ Balfour (1901) I, 145–6; Mehew (2004)

- ^ Furnas (1952), 130–6; Mehew (2004)

- ^ Balfour (1901) I, 164–5; Furnas (1952), 142–6; Mehew (2004)

- ^ Letter to Sidney Colvin, January 1880, The Letters of Robert Louis Stevenson, Volume 1, Chapter IV

- ^ «To Edmund Gosse, Monterey, Monterey Co., California, 8 October 1879,» The Letters of Robert Louis Stevenson, Volume 1, Chapter IV

- ^ «To P. G. Hamerton, Kinnaird Cottage, Pitlochry [July 1881],» The Letters of Robert Louis Stevenson, Volume 1, Chapter V

- ^ Isobel was married to artist Joseph Strong.

- ^ «Bournemouth | Robert Louis Stevenson». robert-louis-stevenson.org. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- ^ a b O’Hagan, Andrew (2020). «Bournemouth». The London Review of Books. 42 (10). ISSN 0260-9592.

- ^ «To W.E. Henley, Pitlochry, if you please, [August] 1881,» The Letters of Robert Louis Stevenson, Volume 1, Chapter V

- ^ a b «Robert Louis Stevenson Biography». people.brandeis.edu. Brandeis University. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- ^ Stevenson, Robert Louis. «A Humble Remonstrance» (PDF). Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- ^ Livesey, Margot (November 1994). «The Double Life of Robert Louis Stevenson». The Atlantic. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- ^ Stevenson, Robert Louis (1907) [originally written 1877]. «Crabbed Age and Youth». Crabbed Age and Youth and Other Essays. Portland, Maine: Thomas B. Mosher. pp. 11–12.

- ^ Terry, R. C., ed. (1996). Robert Louis Stevenson: Interviews and Recollections. Iowa City: U of Iowa P. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-87745-512-7.

- ^ Reginald Charles Terry (1996). «Robert Louis Stevenson: Interviews and Recollections». p. 49. University of Iowa Press,

- ^ Goldberg, David Theo (2008). «Liberalism’s Limits: Carlyle and Mill on «the Negro Question’,» Nineteenth-Century Contexts, Vol. XX, No. 2, pp. 203–216.

- ^ Cumming, Mark (2004). The Carlyle Encyclopedia. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, p. 223 ISBN 978-0-8386-3792-0

- ^ Stevenson, Robert Louis (1887), The Contemporary Review, Vol. LI, April, pp. 472-479.

- ^ «Robert Louis Stevenson — National Library of Scotland». digital.nls.uk. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ Collected Works pp. 286-287

- ^ Collected Works pp. 288

- ^ Collected Works pp. 287-288

- ^ Stevenson, Robert Louis (1921). Confessions of a Unionist. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Privately Printed by G.G. Winchip. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- ^ Quoted from Stevenson’s diary in Overton, Jacqueline M. The Life of Robert Louis Stevenson for Boys and Girls Archived 12 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1933

- ^ In the South Seas (1896) & (1900) Chatto & Windus; republished by The Hogarth Press (1987). A collection of Stevenson’s articles and essays on his travels in the Pacific

- ^ a b In the South Seas (1896)& (1900) Chatto & Windus; republished by The Hogarth Press (1987)

- ^ The Cruise of the Janet Nichol Among the South Sea Islands, Mrs Robert Louis Stevenson, Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, 1914

- ^ The Cruise of the Janet Nichol among the South Sea Islands A Diary by Mrs Robert Louis Stevenson (first published 1914), republished 2004, editor, Roslyn Jolly (U. of Washington Press/U. of New South Wales Press)

- ^ Selected Letters of Robert Louis Stevenson, ed. by Ernest Mehew (New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 2001) p. 418, n. 3

- ^ Robert Louis Stevenson, The Wrecker, in Tales of the South Seas: Island Landfalls; The Ebb-Tide; The Wrecker (Edinburgh: Canongate Classics, 1996), ed. and introduced by Jenni Calder

- ^ ‘Memories of Vailima’ by Isobel Strong & Lloyd Osbourne, Archibald Constable & Co: Westminster (1903)

- ^ a b Farrell, Joseph (8 September 2019). «The story of Samoa’s love for Robert Louis Stevenson». The National. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ^ Jamie, Kathleen (20 August 2017). «Scot of the South Seas: Robert Louis Stevenson in Samoa». New Statesman. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ^ a b c Farrell, Joseph (2017). Robert Louis Stevenson in Samoa. London: Maclehose Press. ISBN 978-0-85705-995-6.

- ^ a b c d Jenni Calder, Introduction, Stevenson, Robert Louis (1987). Island Landfalls. Edinburgh: Cannongate. ISBN 0-86241-144-0.

- ^ Letter to Sidney Colvin, 17 April 1893, Vailima Letters, Chapter XXVIII

- ^ Graeber, David; Wengrow, David (19 October 2021). The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity. Penguin Books Limited. p. 149. ISBN 978-0-241-40245-0.

- ^ Lang, Andrew (1911). The Works of Robert Louis Stevenson Vol 25, Appendix II. London: Chatto and Windus. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- ^ «German Colonies in the Pacific | National Library of Australia». www.nla.gov.au. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- ^ Roslyn Jolly (editor). Robert Louis Stevenson: South Sea Tales. The World’s Classics. Oxford University Press. 1996. See «Introduction».

- ^ Roslyn Jolly, «Introduction» in Robert Louis Stevenson: South Sea Tales (1996)

- ^ Tabachnick, Stephen (January 2011). «Robert Louis Stevenson and Joseph Conrad: Writers of Transition (review)». English Literature in Transition 1880-1920. 54 (2): 247–250. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ^ Sandison, Alan (1996). Robert Louis Stevenson and the Appearance of Modernism. London: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 317–368. ISBN 978-1-349-39295-7.

- ^ «Robert Louis Stevenson – Bibliography: Detailed list of works». robert-louis-stevenson.org. Retrieved 20 April 2008.

- ^ Letter to Sidney Colvin, 3 January 1892, Vailima Letters, Chapter XIV.

- ^ Letter to Sidney Colvin, December 1893, Vailima Letters, Chapter XXXV

- ^ Stevenson, Robert Louis (2006). Robert Allen Armstrong (ed.). An Inland Voyage, Including Travels with a Donkey. Cosimo, Inc. p. xvi. ISBN 978-1-59605-823-1.

- ^ «To H. B. Baildon, Vailima, Upolu [undated, but written in 1891].,» The Letters of Robert Louis Stevenson, Volume 2, Chapter XI

- ^ «Stevenson’s tomb». National Library of Scotland. Archived from the original on 8 December 2008. Retrieved 20 October 2008.

- ^ Stevenson, Robert Louis (1887). Underwoods. London: Chatto and Windus. p. 43.

- ^ Mattix, Micah (4 November 2018). «Wide and Starry Sky». Washington Examiner. Retrieved 21 November 2022.

- ^ Jolly, Roslyn (2009). Robert Louis Stevenson in the Pacific: Travel, Empire, and the Author’s Profession. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 160. ISBN 978-0-7546-6195-5.

- ^ Harry J. Moors, With Stevenson in Samoa, Boston: Small, Maynard, 1910, page 214. [1]

- ^ «Bid to trace lost Robert Louis Stevenson manuscripts». BBC News. 9 July 2010. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- ^ Chaney, Lisa (2006). Hide-and-seek with Angels: The Life of J. M. Barrie. London: Arrow Books. ISBN 0-09-945323-1.

- ^ Dillard, R. H. W. (1998). Introduction to Treasure Island. New York: Signet Classics. xiii. ISBN 0-451-52704-6.

- ^ Chesterton, Gilbert Keith (1913). The Victorian Age in Literature. London: Henry Holt and Co. p. 246.

- ^ a b c d e Stephen Arata (2006). «Robert Louis Stevenson». David Scott Kastan (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of British Literature. Vol. 5: 99–102

- ^ introduction to 1965 Everyman’s Library edition of the one-volume The Prisoner of Zenda and Rupert of Hentzau

- ^ «Muppet Treasure Island». Chicago Sun Times. 16 February 1996. Retrieved 7 May 2019.

- ^ «Robert Louis Stevenson Memorial». St Giles’ Cathedral. Archived from the original on 28 August 2008. Retrieved 20 October 2008.

- ^ [50.199.148.5:8081/view/objects/asitem/45/97/primaryMaker-asc?t:state:flow=92095637-f394-4ee3-9846-f82e8985400e Saint-Gaudens, Augustus (American, 1848–1907): Robert Louis Stevenson, 1887–88 (cast after 1895)], accessed 26 February 2015

- ^ Petronella, Mary Melvin, ed., Victorian Boston Today: Twelve Walking Tours (Lebanon, N.H.: University Press of New England, 2004), p. 107.

- ^ «Robert Louis Stevenson Memorial Grove». City of Edinburgh Council. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 27 October 2013.

- ^ a b (27 October 2013) Robert Louis Stevenson statue unveiled by Ian Rankin Archived 28 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine BBC News Scotland, Retrieved 27 October 2013

- ^ Sean O’Connor (27 February 2014). Handsome Brute: The True Story of a Ladykiller. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4711-0135-9.

- ^ «Royal Bank Commemorative Notes». Rampant Scotland. Retrieved 14 October 2008.

- ^ «Our Banknotes: Commemorative Banknote». The Royal Bank of Scotland. Archived from the original on 15 October 2007. Retrieved 20 October 2008.

- ^ «Robert Louis Stevenson School». stevenson-school.org. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- ^ «R. L. Stevenson Elementary School Archived 19 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine». Fridley Public Schools. Retrieved 26 January 2014.

- ^ «Robert Louis Stevenson Elementary School», Burbank Unified School District. Retrieved 27 December 2022.

- ^ «Robert Louis Stevenson Elementary». robertlouisstevensonschool.org. Retrieved 29 October 2016.

- ^ «Stevenson Elementary School: FAQ’s». Edline. Retrieved 26 March 2018.

- ^ «Robert Louis Stevenson SP Archived 15 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine». California Department of Parks and Recreation. Retrieved 18 July 2014.

- ^ Farrell, Joseph. «Robert Louis Stevenson and his meeting with a princess in Hawaii». The National. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- ^ «Robert Louis Stevenson Museum». Atlas Obscura. Retrieved 16 May 2021.

- ^ Castle, Alan (2007). The Robert Louis Stevenson Trail (2nd ed.). Cicerone. ISBN 978-1-85284-511-7.

- ^ McCracken, Edd (20 March 2011). «Found: Louis Stevenson’s missing masterpiece». Sunday Herald. Glasgow. Retrieved 20 March 2011.

- ^ «Robert Louis Stevenson». robert-louis-stevenson.org. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde and Other Tales, Robert Louis Stevenson. Oxford World’s Classics.

- ^ Parfect, Ralph. «Robert Louis Stevenson’s «The Clockmaker» and «The Scientific Ape»: Two Unpublished Fables.» English Literature in Transition, 1880-1920, vol. 48 no. 4, 2005, p. 387-400. Project MUSE, doi:10.2487/Y008-J320-0428-0742.

Biographies of Stevenson[edit]

- Graham Balfour, The Life of Robert Louis Stevenson, London: Methuen, 1901

- Calder, Jenni, RLS: A Life Study, London: Hamish Hamilton, 1980, ISBN 0-241-10374-6

- Callow, Philip (2001). Louis: A Life of Robert Louis Stevenson. London: Constable. ISBN 0-09-480180-0.

- John Jay Chapman «Robert Louis Stevenson», Emerson, and Other Essays. New York: AMS Press, 1969, ISBN 0-404-00619-1 (reprinted from the edition of 1899)

- David Daiches, «Robert Louis Stevenson and his World», London: Thames and Hudson, 1973, ISBN 0-500-13045-0

- Farrell, Joseph, Robert Louis Stevenson in Samoa. London: Maclehose Press, 2017. ISBN 978-0-85705-995-6.

- J.C. Furnas, Voyage to Windward: The Life of Robert Louis Stevenson, London: Faber and Faber, 1952

- Claire Harman, Robert Louis Stevenson: A Biography, HarperCollins, ISBN 0-00-711321-8 [reviewed by Matthew Sturgis in The Times Literary Supplement, 11 March 2005, page 8]

- Rosaline Masson, Robert Louis Stevenson. London: The People’s Books, 1912

- Rosaline Masson, The life of Robert Louis Stevenson. Edinburgh & London: W. & R. Chambers, 1923

- Rosaline Masson (editor), I can remember Robert Louis Stevenson. Edinburgh & London: W. & R. Chambers, 1923

- Ernest Mehew, «Robert Louis Stevenson», Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford: OUP, 2004. Retrieved 29 September 2008

- Roland Paxton, «Stevenson, Thomas (1818–1887)», Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford: OUP, 2004. Retrieved 11 October 2008

- Pinero, Arthur Wing (1903). Robert Louis Stevenson: the dramatist . London: Philosophical Institution of Edinburgh.

- James Pope-Hennessy, Robert Louis Stevenson – A Biography, London: Cape, 1974, ISBN 0-224-01007-7

- Eve Blantyre Simpson, Robert Louis Stevenson’s Edinburgh Days, London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1898

- Eve Blantyre Simpson, The Robert Louis Stevenson Originals, [With illustrations and facsimiles], London & Edinburgh: T. N. Foulis, 1912

- Stephen, Leslie (1902). «Robert Louis Stevenson» . Studies of a Biographer. Vol. 4. London: Duckworth & Co. pp. 206–246.

Further reading[edit]

- Clunas, Alex, R.L. Stevenson, Precursor of the Post-Moderns?, in Murray, Glen (ed.), Cencrastus No. 6, Autumn 1981, pp. 9 – 11

- Gosse, Edmund William (1911). «Stevenson, Robert Lewis Balfour» . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 25 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 907–910.

- Hubbard, Tom (1996), «Debut at Antwerp: The Flanders Chapters of Robert Louis Stevenson’s An Inland Voyage, in Hubbard, Tom (2022), Invitation to the Voyage: Scotland, Europe and Literature, Rymour, pp. 48 — 52, ISBN 9-781739-596002

- Hubbard, Tom (2009), «Writing Scottishly on Non-Scottish Matters», in Hubbard, Tom (2022), Invitation to the Voyage: Scotland, Europe and Literature, Rymour, pp.135 — 138, ISBN 9-781739-596002

- Shaw, Michael (ed.), A Friendship in Letters: Robert Louis Stevenson & J.M. Barrie, Sandstone Press, Inverness, 2020, ISBN 978-1-913207-02-1

External links[edit]

|

Robert Louis Stevenson |

|

|---|---|

Stevenson in 1893 |

|

| Born | Robert Lewis Balfour Stevenson 13 November 1850 Edinburgh, Scotland |

| Died | 3 December 1894 (aged 44) Vailima, Samoa |

| Occupation |

|

| Alma mater | University of Edinburgh |

| Notable works |

|

| Spouse |

Fanny Van de Grift Osbourne (m. 1880–1894) |

| Parents | Thomas Stevenson (father) |

| Relatives | Robert Stevenson (paternal grandfather) Lloyd Osbourne (stepson) Isobel Osbourne (stepdaughter) Edward Salisbury Field (stepson-in-law) |

| Signature | |

Bound set of many of Stevenson’s works, 1909

Robert Louis Stevenson (born Robert Lewis Balfour Stevenson; 13 November 1850 – 3 December 1894) was a Scottish novelist, essayist, poet and travel writer. He is best known for works such as Treasure Island, Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, Kidnapped and A Child’s Garden of Verses.

Born and educated in Edinburgh, Stevenson suffered from serious bronchial trouble for much of his life, but continued to write prolifically and travel widely in defiance of his poor health. As a young man, he mixed in London literary circles, receiving encouragement from Andrew Lang, Edmund Gosse,[1] Leslie Stephen and W. E. Henley, the last of whom may have provided the model for Long John Silver in Treasure Island. In 1890, he settled in Samoa where, alarmed at increasing European and American influence in the South Sea islands, his writing turned away from romance and adventure fiction toward a darker realism. He died of a stroke in his island home in 1894 at age 44.[2]

A celebrity in his lifetime, Stevenson’s critical reputation has fluctuated since his death, though today his works are held in general acclaim. In 2018 he was ranked, just behind Charles Dickens, as the 26th-most-translated author in the world.[3]

Family and education[edit]

Childhood and youth[edit]

Stevenson’s childhood home in Heriot Row