Вега

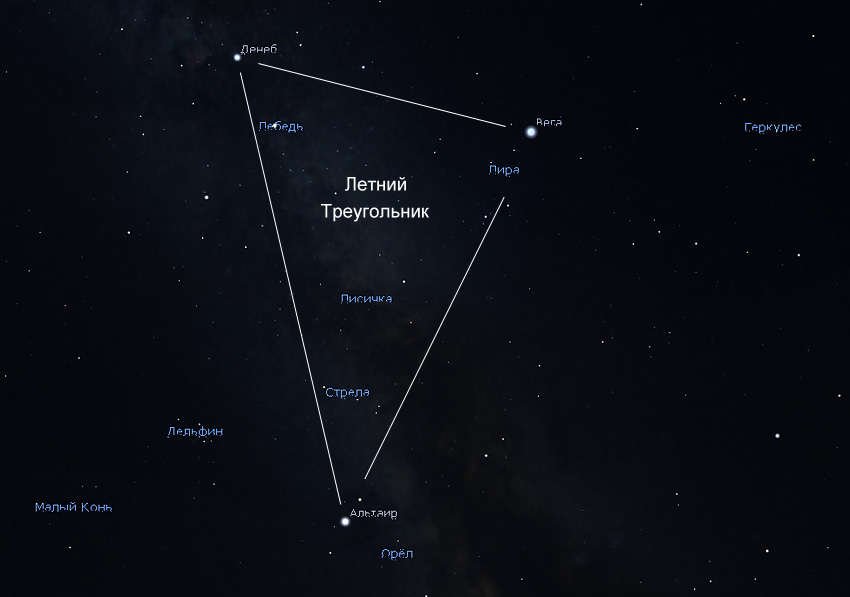

Летом и осенью, на ночном небосклоне, в северном полушарии небесной сферы можно различить так называемый Большой Летний Треугольник. Это один из самых известных астеризмов. В верхней точке Треугольника находится Вега — звезда ярко-голубого цвета, являющаяся главной в созвездии Лиры.

Содержание:

- 1 История

- 2 Как Вега помогла астрономам

- 3 Некоторые свойства Веги

- 3.1 Параметры

- 4 Материалы по теме

- 4.1 Движение

- 5 Мифическая роль голубого солнца

История

Название Вега переводится с арабского языка как «падающий орел». Другое ее название Alpha Lyrae (α Lyrae / α Lyr) – это официальное название, упоминаемое в научной литературе. По яркости для жителей России Вега третья звезда после Сириуса и Арктура. Расстояние от Солнца до Веги составляет 25,3 световых года, что считается относительно близко.

Как Вега помогла астрономам

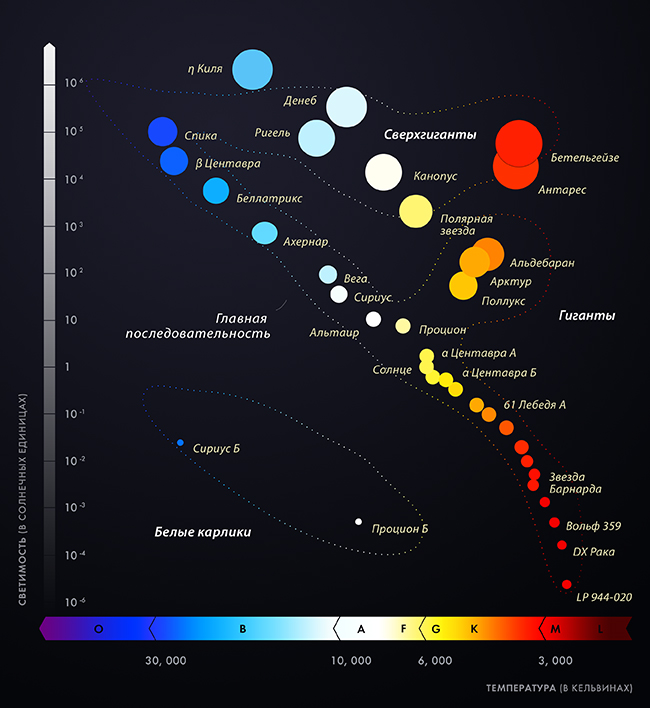

Вега на диаграмме Гершпрунга-Рассела

Вега сыграла важнейшую роль в развитии астрофизики. Она послужила отправной точкой для разработки фотометрической системы определения цвета и блеска звезд UVB. То есть ее блеск был принят за 0 (точку отсчета).

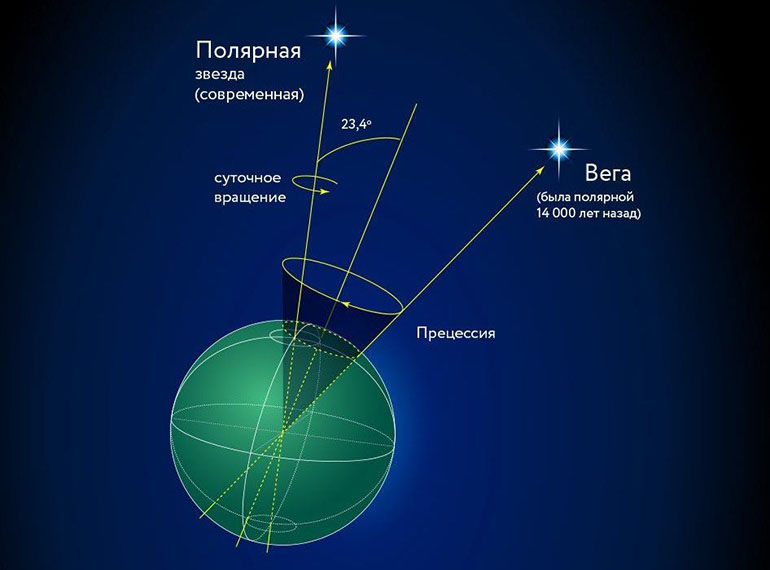

Это первая сфотографированная звезда после Солнца, а также одна из первых, расстояние до которой было определено методом параллакса. И, интересный факт, в XII веке до н.э. она являлась Полярной звездой (звездой указывающий на Северный полюс) и снова ее будет через 12 000 лет!

Некоторые свойства Веги

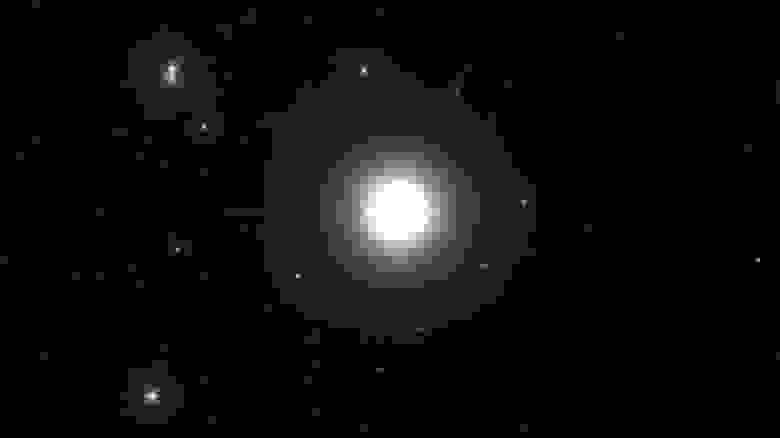

Любительский снимок

Звезда Вега — спектрального класса A0V, то есть белая звезда главной последовательности. Это означает, что источником энергии для нее является реакция термоядерного синтеза гелия из водорода. Вега тяжелее Солнца более чем в 2 раза, а ее светимость в 37 раз больше солнечной. Из-за большой массы это голубое солнце просуществует в виде белой звезды 1 миллиард лет, или 1/10 жизни Солнца. Возраст Веги равен 386-510 миллионов лет, и сейчас она находится в середине своей жизни, как и наше Солнце. Затем она превратится в красного гиганта М типа, и впоследствии станет белым карликом.

Параметры

Ее радиус был измерен и составил 2,73 ± 0,01 радиуса Солнца, однако этот факт противоречил теоретическим расчетам размера звезды. Объяснение этому лежит, вероятно, в скорости вращения объекта, этот факт был подтвержден наблюдениями в 2005 году. Действительно Вега вращается так быстро, что форма ее представляет собой эллипс. Скорость вращения Веги достигает 274 км/сек. Ее экваториальный диаметр на 23% больше полярного.

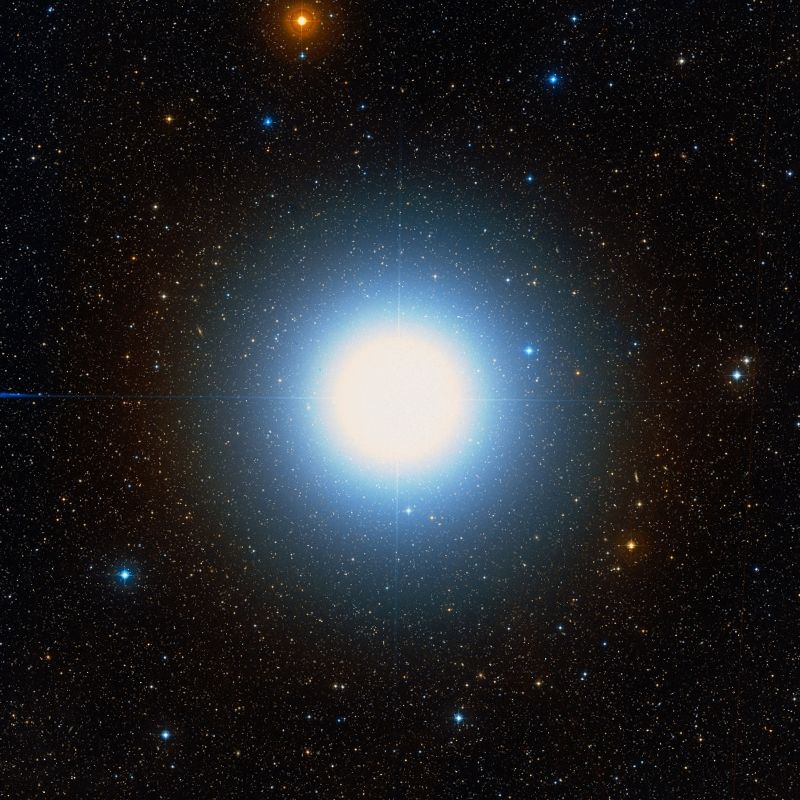

Вега, снимок ESO

В астрономии любой элемент тяжелее гелия называется металлом, в составе Веги таких металлов мало, всего 32% от такого же солнечного показателя.

Материалы по теме

Причина этого до сих пор неясна. Скорость движения звезд относительно Земли вычисляется с помощью смещения их спектра. Если цвет смещается в сторону красной части спектра, то небесный объект удаляется от Земли. Для Веги это смещение составляет − 13,9 ± 0,9 км/с, знак минуса означает, что «падающий орел» приближается к нам.

Движение

Также звезда имеет собственную скорость движения. Оно равно 202,03 ±0,63 миллисекунды дуги по прямому восхождению и 278,47 ±0,54 миллисекунд дуги по склонению. По небесной сфере на 1 градус Вега перемещается за 11 000 лет. Относительно соседних звезд голубая звезда движется приблизительно с такой же скоростью, как и Солнце, или 19 км/сек.

Астрономы изучили и другие звезды похожие на Вегу, в результате она была причислена к группе Кастора. К этой группе относится 16 звезд, в пространстве они движутся параллельно друг другу с равными скоростями. Догадка ученых состоит в том, что звездные объекты этой группы сформировались в одно время и в одном месте, но потом стали гравитационно-независимыми.

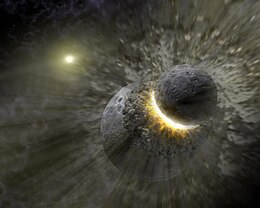

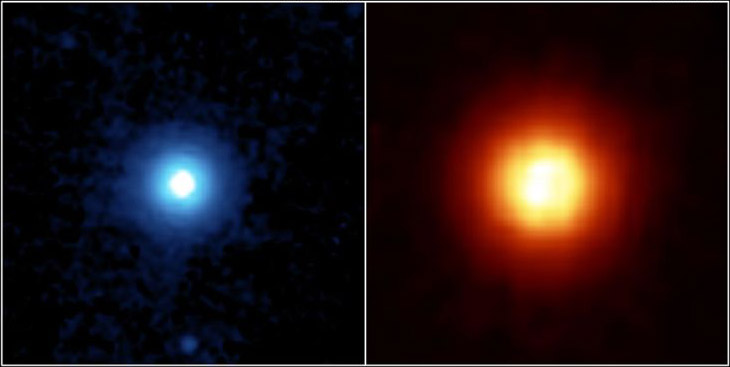

Пылевой диск вокруг планеты, снимок телескопа Спитцер на длине волны 24 (слева) и 70 микрон

В настоящее время изучается вопрос о наличии у Веги экзопланеты (или экзопланет), а также планет земной группы. Но пока вопрос остается открытым. На данный момент, вокруг Веги обнаружен лишь пылевой диск.

Путешествие к Веге

Мифическая роль голубого солнца

Благодаря своей яркости, Вега, несомненно, привлекала внимание многих людей с самых древних времен. Поэтому-то она является героиней мифов и легенд разных народов мира.

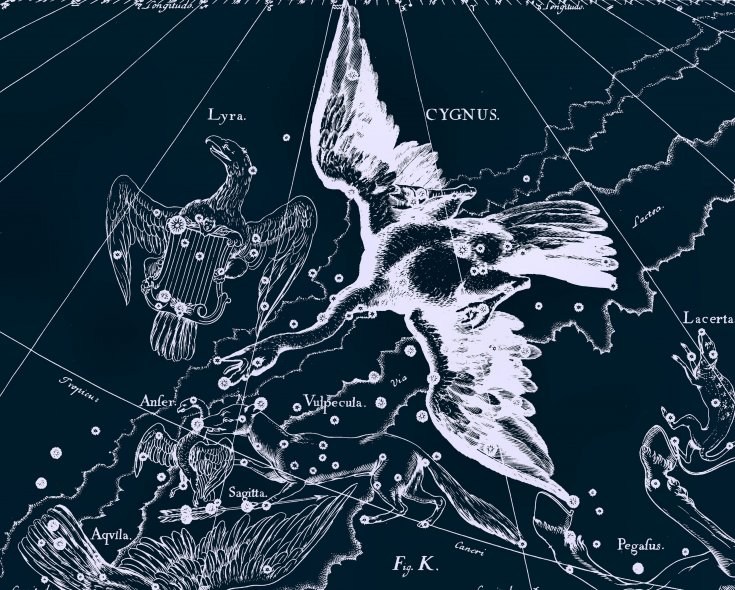

Созвездие Лиры и Лебедя, рисунок из древнего атласа звездного неба Яна Гевелия

Китайцы, например, верили, что земное воплощение Альтаира, молодой человек по имени Ню-Лан по совету своего старого вола отправляется к Серебряной реке, где находит девушку по имени Чжи-нюй (Вегу), внучку Тян-ди (небесного правителя) и женится на ней. У них рождается сын и дочь (β и γ Орла), но небесный правитель забрал свою дочь, Чжи-нюй на небо, а супругам разрешил видеться 1 раз в год. Этот день, 7-е число 7-й луны, у китайцев считается днем встречи влюбленных.

Коротко о Веге

Список самых ярких звёзд

| № | Название | Расстояние, св. лет | Видимая величина | Абсолютная величина | Спектральный класс | Небесное полушарие |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Солнце | 0,0000158 | −26,72 | 4,8 | G2V | |

| 1 | Сириус (α Большого Пса) | 8,6 | −1,46 | 1,4 | A1Vm | Южное |

| 2 | Канопус (α Киля) | 310 | −0,72 | −5,53 | A9II | Южное |

| 3 | Толиман (α Центавра) | 4,3 | −0,27 | 4,06 | G2V+K1V | Южное |

| 4 | Арктур (α Волопаса) | 34 | −0,04 | −0,3 | K1.5IIIp | Северное |

| 5 | Вега (α Лиры) | 25 | 0,03 (перем) | 0,6 | A0Va | Северное |

| 6 | Капелла (α Возничего) | 41 | 0,08 | −0,5 | G6III + G2III | Северное |

| 7 | Ригель (β Ориона) | ~870 | 0,12 (перем) | −7 | B8Iae | Южное |

| 8 | Процион (α Малого Пса) | 11,4 | 0,38 | 2,6 | F5IV-V | Северное |

| 9 | Ахернар (α Эридана) | 69 | 0,46 | −1,3 | B3Vnp | Южное |

| 10 | Бетельгейзе (α Ориона) | ~530 | 0,50 (перем) | −5,14 | M2Iab | Северное |

| 11 | Хадар (β Центавра) | ~400 | 0,61 (перем) | −4,4 | B1III | Южное |

| 12 | Альтаир (α Орла) | 16 | 0,77 | 2,3 | A7Vn | Северное |

| 13 | Акрукс (α Южного Креста) | ~330 | 0,79 | −4,6 | B0.5Iv + B1Vn | Южное |

| 14 | Альдебаран (α Тельца) | 60 | 0,85 (перем) | −0,3 | K5III | Северное |

| 15 | Антарес (α Скорпиона) | ~610 | 0,96 (перем) | −5,2 | M1.5Iab | Южное |

| 16 | Спика (α Девы) | 250 | 0,98 (перем) | −3,2 | B1V | Южное |

| 17 | Поллукс (β Близнецов) | 40 | 1,14 | 0,7 | K0IIIb | Северное |

| 18 | Фомальгаут (α Южной Рыбы) | 22 | 1,16 | 2,0 | A3Va | Южное |

| 19 | Мимоза (β Южного Креста) | ~290 | 1,25 (перем) | −4,7 | B0.5III | Южное |

| 20 | Денеб (α Лебедя) | ~1550 | 1,25 | −7,2 | A2Ia | Северное |

| 21 | Регул (α Льва) | 69 | 1,35 | −0,3 | B7Vn | Северное |

| 22 | Адара (ε Большого Пса) | ~400 | 1,50 | −4,8 | B2II | Южное |

| 23 | Кастор (α Близнецов) | 49 | 1,57 | 0,5 | A1V + A2V | Северное |

| 24 | Гакрукс (γ Южного Креста) | 120 | 1,63 (перем) | −1,2 | M3.5III | Южное |

| 25 | Шаула (λ Скорпиона) | 330 | 1,63 (перем) | −3,5 | B1.5IV | Южное |

Содержание

- 1 Происхождение наименования

- 2 История открытия и эволюция звезды

- 3 Физические параметры Веги

- 3.1 Содержание тяжелых элементов

- 4 Особенности вращения

- 5 Как найти на небе

- 5.1 Альфа Лиры

- 5.2 Вега и Большой летний треугольник

- 6 Интересные факты о Веге

- 6.1 Самая изучаемая звезда после Солнца

- 6.2 Аномальная звезда

- 6.3 Звезда-волчок

- 6.4 Вега — первая звезда, у которой был обнаружен околозвездный диск

- 6.5 Вега была и будет полярной звездой

- 6.6 В будущем Вега станет самой яркой звездой на небе после Солнца

Вега — звезда Северного полушария, наблюдаемая практически из любой точки Земли. В России она видна в начале лета как яркое светило, расположенное высоко на небе в южной его части. За такое свойство это небесное тело получило поэтическое название «Королева летних ночей».

Вега — самая яркая звезда в созвездии Лиры. Credit: syl.ru

Происхождение наименования

Название этого небесного объекта происходит от waqi — арабского слова, обозначающего «падающий», либо от устойчивого словосочетания «падающий коршун (по другим версиям — гриф, орел)». Впервые под своим именем Вега появилась в XIII в. в астрономическом трактате «Альфонсовы таблицы». Древние греки называли светило Луерой, в Древнем Риме — Лирой, а Клавдий Птолемей в своем труде «Альмагест» именовал его Аллоре.

История открытия и эволюция звезды

Нет точных исторических данных, когда была открыта звезда, когда ее координаты были нанесены на карту небосвода. Но она стала одним из первых космических объектов, которые смогли запечатлеть астрофотографы — это случилось в 1850 г.

Возраст альфы Лиры — всего около 450 млн лет, но с точки зрения эволюции она, как и Солнце, родившееся гораздо раньше, сейчас проживает середину своей жизни.

Звезда находится в состоянии устойчивого динамического равновесия: давление излучения, которое исходит из недр и выталкивает вещество в окружающее пространство, уравновешивается силой тяжести, сжимающей тело звезды.

Это обеспечивают идущие в центре объекта ядерные реакции, и так продлится еще около 500 млн лет, а затем светило постепенно станет красным гигантом, пройдет через этап планетарной туманности и превратится в сверхплотного белого карлика. Чтобы стать сверхновой, у Веги не хватит массы.

Физические параметры Веги

Вега — пятая по яркости звезда ночного неба, лишь немногим уступающая «соседу» — занимающему 4-е место Арктуру. Однако Канопус и альфа Центавра (участники №№ 2 и 3 этого рейтинга) не видны с территории России, и из тройки самых ярких видимых (круглый год или периодически) объектов — Сириуса, Арктура и Веги — последняя занимает уверенное третье место.

Вега — горячая звезда спектрального класса. Credit: spacegid.com

Эта звезда ярче Солнца и отчетливо видна в радиусе 10 пк от Земли. По своей массе она превосходит дневное светило в 2,1 раза, по диаметру — в 2,8 раза, по количеству излучаемого света — в 40 раз, но она младше Солнца примерно в 10 раз.

Основные характеристики Веги:

- тип — одиночная;

- класс спектра — A0V;

- цвет — белый с голубым оттенком;

- расстояние до Солнца — около 25 световых лет.

Содержание тяжелых элементов

Вега родилась позже, чем Солнце, но имеет необычный состав. В ней слишком мало тяжелых (тяжелее, чем гелий) химических элементов: 32% от солнечного показателя и всего 0,4-0,5% от массы самого светила, что характерно для гораздо более старых звезд.

Умирая, они выбрасывают в космическое пространство часть своей массы, и вещество, обогащенное металлами, входит в состав светил следующего поколения. Так как для Веги это нехарактерно, есть гипотеза, что она родилась из водородного облака, содержавшего минимум тяжелых элементов.

Особенности вращения

1 полный оборот вокруг своей оси Вега совершает всего за 17,5 часа, ее экваториальные участки летят в пространстве с линейной скоростью почти 250 км/с. Это значение приближается к критическому для звезды с такими параметрами, и если оно достигнет критического или превысит его, светило будет разорвано центробежными силами.

Раньше Вега являлась полярной звездой для Земли — на нее указывал северный полюс. Из-за прецессии нашей планеты, расположение звезды на небосводе изменилось. Credit: uranika.ru

Как найти на небе

Найти эту звезду на небе несложно. Это можно сделать 2 способами: как самый яркий элемент созвездия Лиры или как участницу Большого летнего прямоугольника.

Вега видна невооруженным глазом, но в бинокль или даже любительский телескоп она выглядит еще более эффектно — как голубовато-белое светило в окружении нескольких десятков маленьких тусклых звездочек-искорок.

Альфа Лиры

В любую летнюю ночь или вечером в начале сентября встаньте лицом к южному горизонту небосклона и, не поворачивая головы, поднимите глаза вверх. Ваш взгляд упрется в Вегу. На этом участке она будет не единственной, но наиболее яркой звездой.

Во второй половине осени светило нужно искать в западной части звездного неба, весной — на востоке, а зимой она будет располагаться на севере, достаточно низко над горизонтом на севере.

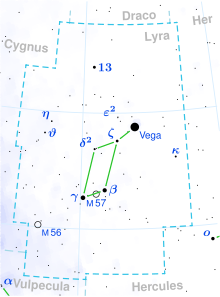

Заодно рассмотрите и созвездие Лиры, к которому звезда относится. Оно маленькое, но бросается в глаза, хотя из множества его участников хорошо видны только 5: Вега и расположенные прямо под ней в виде параллелограмма 4 светила третьей и четвертой звездной величины, более тусклые, чем альфа, но все-таки отлично различимые.

Вега и Большой летний треугольник

С мая по октябрь Вегу легко отыскать как одну из точек гигантского астеризма. Вместе со звездами Альтаир и Денеб она образует условный Большой летний (он же — Большой летне-осенний) треугольник. Его можно заметить даже при мимолетном взгляде на небо, и наиболее ярко фигура выглядит в период с начала июля до середины августа. Vega — ярчайший элемент в нем: она находится в верхнем углу астеризма.

Появляется Большой треугольник в начале лета. Credit: skygazer.ru

Интересные факты о Веге

Ученые и астрономы-любители знают множество занимательных фактов о Веге.

Самая изучаемая звезда после Солнца

Веге посвящено почти 2,5 тыс. работ (от научных статей до целых исследований), и это только то, что опубликовано после 1850 г.

Возможно, она настолько популярна из-за:

- своей яркости;

- близости к Солнечной системе;

- использования в качестве калибратора для телескопов и других измерительных (например, фотометрических) систем;

- удачного месторасположения на небосводе.

Аномальная звезда

Аномально высокие светимость и температура Веги (в 1,5 раза выше по сравнению с объектами такого же класса) были обнаружены в 1960-х гг. Сначала было высказано предположение, что у светила имеется спутник, вносящий свой вклад в общие показатели излучения, но обнаружить его никаким способом (визуальным, спектральным или иным) не удалось.

Вега — звезда с хорошо изученными характеристиками. Credit: starwalk.space

Только в середине 1980-х гг. появилась гипотеза, что разгадка — в слишком быстром вращении Веги вокруг своей оси. У быстро вращающихся звезд не бывает правильной сферической формы: они сплюснуты к своим полярным областям, и их называют волчками.

Звезда-волчок

Таковой оказалась и альфа Лиры. Она вращается быстро и потому имеет искаженную форму. Так как полюса к раскаленному ядру светила находятся ближе, чем участки на экваторе, они более яркие и горячие. Исследования 2005 г., проведенные учеными калифорнийской обсерватории Маунт-Вильсон, показали, что к земному наблюдателю Вега обращена одним из своих полюсов, и это объясняет ее аномальную светимость.

Вега — первая звезда, у которой был обнаружен околозвездный диск

Орбитальный телескоп IRAS в 1984 г. обнаружил вокруг альфа Лиры некое образование, напоминавшее по своим характеристикам и структуре пояс Койпера. Этот околозвездный диск вокруг Веги имел радиус не менее 550 а. е. и состоял из пыли и мельчайших обломков. Он стал доказательством, что за границами Солнечной системы в межзвездном пространстве также присутствует твердая материя.

Структура этого диска (2 выраженных пылевых узла) могла служить доказательством существования около светила собственной планеты, вращающейся по вытянутой орбите на расстоянии около 30 а. е. от Веги. До сих пор это гипотетическое космическое тело обнаружено не было. Кроме того, последние исследования с использованием более точной техники показали, что узлы пыли полностью рассосались.

Вега была и будет полярной звездой

Когда-то альфа Лиры являлась полярной звездой для Земли — на нее указывал северный полюс. Земная планетарная ось вращения не является статичной, она пребывает в состоянии прецессии: движется в пространстве по конусовидной траектории, описывая полный круг за 25 770 лет. Около 12,5 тыс. лет назад ось была направлена на Вегу (точнее, на точку, находящуюся в 4° от нее), и эта ситуация повторится снова через примерно 13,5 тыс. лет.

В будущем Вега станет самой яркой звездой на небе после Солнца

Солнечная система движется в космосе по направлению к Веге, и последняя постепенно будет все ближе к Земле и потому ярче. Примерно через 210 тыс. лет альфа Лиры затмит собой Сириус и станет для земного наблюдателя ярчайшим объектом на небосклоне. Расстояние между Землей и этим светилом через 290 тыс. лет станет минимальным — всего около 17,2 светового года. Затем Солнечная система начнет отдаляться, и через полмиллиона лет Вега снова потеряет статус самой яркой видимой звезды. Еще через миллион лет альфа Лиры перестанет быть видна землянам невооруженным глазом.

Вега — голубая жемчужина северных небес

Вега — удивительно красивая и притягательная звезда. Одна из ярчайших на всем небе, а в северном его полушарии она конкурирует с оранжевым Арктуром из созвездия Волопаса за право считаться ярчайшей звездой северного небосвода. В отличие от Арктура, Вега отчетливо голубого цвета.

Долгое время об этой звезде астрономы не могли сказать ничего кроме уже перечисленного выше.

Она считалась звездой-одиночкой, с постоянным блеском — не переменная, никак не связанная ни с какими другими феноменами или явлениями — не наблюдалось вокруг неё никакой туманности, и спектр звезды был в полном порядке. Но она все равно привлекала к себе пристальное внимание ученых. Ну, не может быть, чтобы такая красавица, и без какого-то секрета!

Стоит иметь в виду, что для астрономов не бывает неинтересных объектов — бывают недообследованные. И по части обследований Веге досталось поболее, чем любой другой звезде.

Когда только зарождалась астрофотография, Вегу выбрали для первого фотоснимка. История изучения звездных спектров вновь началась с Веги. Вега стала первой звездой, до которой удалось измерить расстояние методом измерения параллакса.

Разговор о том, что это за метод такой, заслуживает отдельной статьи, но если кратко, то положение Земли в пространстве постоянно меняется — Земля обращается вокруг Солнца. Это приводит к тому, что в разные сезоны мы смотрим на звезды из разных точек. В результате видимое расположение звезд несколько меняется. Те, что поближе смещаются на фоне тех, что подальше. Вега оказалась относительно недалеко. Хотя, все равно астрономы были обескуражены величиной межзвездных дистанций — 25 световых лет — это 250 000 умножить на триллион километров — и это ведь до одной из ближайших звезд.

Вега летит к нам навстречу со скоростью 20 километров в секунду. Это почти ничего не меняет, но все-таки приятно. Причем, звезда смотрит на нас одним из своих полюсов. Данное обстоятельство сильно затрудняло изучение её осевого вращения. Но потом выяснилось, что это — стремительный звездный волчок, который едва ли не разрывает себя на части своим фантастически быстрым вращением — один оборот менее чем за сутки, с линейной скоростью вращения на экваторе в 230 километров в секунду.

Относительно недавно вокруг звезды был обнаружен протопланетный диск, а сейчас ученые уже склонны подозревать, что как минимум одна планета могла успеть сформироваться. Разумеется, речи о её обитаемости нет — уж очень молода Вега и вся окружающая её экосистема.

В средних широтах северного полушария Земли Вега является незаходящим светилом. Она видна круглый год. Но лучшее время для её наблюдений — с весны по позднюю осень.

Вега возглавляет собой небольшое, но очень красивое созвездие Лиры — богатое интересными астрономическими объектами, доступными для наблюдений даже в бинокль, а уж для владельцев небольших телескопов оно являет собой буквально жемчужную россыпь, в которой Вега, бесспорно, может считаться самой красивой жемчужиной.

Много лет назад я посвятил этой звезде одну из своих мелодий. Она так и называется — «Вега». Приближался концерт, а я вдруг вспомнил, что у меня нет для этой пьесы сопровождающего её живое исполнение видеоролика. И в ночь перед концертом я в полусне нарисовал несколько картинок — очень поспешно и небрежно, собрал из этих картинок видеоролик и исполнил под него произведение. И оказалось, что именно он понравился и запомнился слушателям более всего остального. И по сей день этот ролик самый популярный на Youtube среди прочих моих видеосюжетов.

Прикрепляю ссылку на него в завершении этого небольшого рассказа о звездах.

Видеоверсия рассказа

| Вега | |

|---|---|

| Звезда | |

|

|

|

| Наблюдательные данные | |

| Тип | одиночнаяШаблон:Source-ref |

| Физические характеристики | |

| Вращение |

v = 236 ± 4 км/сШаблон:Source-ref v·sin(i) = 20,48 ± 0,11 км/сШаблон:Source-ref |

Ве́га (α Лиры, α Lyr) — самая яркая звезда в созвездии Лиры, пятая по яркости звезда ночного неба и вторая (после Арктура) — в Северном полушарии, третья по яркости звезда (после Сириуса и Арктура), которую можно наблюдать в России и ближнем зарубежье. Вега находится на расстоянии 25,3 светового года от Солнца и является одной из ярчайших звёзд в его окрестностях (на расстоянии до 10 парсек).

Этимология

Название «Вега» (WegaШаблон:Source-ref, позже — Vega) происходит от приблизительной транслитерации слова waqi («падающий») из фразы араб. النسر الواقع (an-nasr al-wāqi‘), означающей «падающий орёл»[1] или «падающий гриф»[2]. Созвездие Лиры представлялось в виде грифа в Древнем Египте[3] и в виде орла или грифа — в древней Индии[4][5]. Арабское название вошло в европейскую культуру после использования в астрономических таблицах, которые были разработаны в 1215—1270 годах по приказу Альфонсо X[6]. Вероятно, ассоциация Веги и всего созвездия с хищной птицей имело в древности свою мифологическую основу, однако этот миф был позабыт и замещён более поздней легендой о коршуне бога Зевса, выкравшем тело нимфы Кампы у титана Бриарея, и за эту услугу помещённом своим хозяином на небо[7].

Основные характеристики

Вега, иногда называемая астрономами «наверное, самой важной звездой после Солнца», в настоящее время является самой изученной звездой ночного небаШаблон:Source-ref. Вега стала первой звездой (после Солнца), которая была сфотографированаШаблон:Source-ref, а также первой звездой, у которой был определён спектр излученияШаблон:Source-ref. Кроме того, Вега была одной из первых звёзд, до которой методом параллакса было определено расстояниеШаблон:Source-ref. Яркость Веги долгое время принималась за ноль при измерении звёздных величин, то есть она была точкой отсчёта и являлась одной из шести звёзд, которые лежат в основе шкалы UBV-фотометрии (измерение излучения звезды в различных диапазонах спектра)Шаблон:Source-ref.

Вега — относительно молодая звезда с низкой, по сравнению с Солнцем, металличностью — малым содержанием элементов тяжелее гелияШаблон:Source-ref. Вега, возможно, является переменной звездой, хотя это и не доказано. Возможная причина переменности — нестабильность в недрахШаблон:Source-ref.

Вега очень быстро вращается вокруг своей оси. На её экваторе скорость вращения, вероятно, превышает 230 км/сШаблон:Source-ref. Для сравнения: скорость вращения на экваторе Солнца чуть больше двух километров в секунду (7284 км/ч). Вега вращается в сто раз быстрее и поэтому имеет форму эллипсоида вращения. Температура её фотосферы неоднородна: максимальная температура — на полюсе звезды, минимальная — на её экваторе. В настоящее время с Земли Вега наблюдается почти с полюса, и поэтому кажется яркой бело-голубой звездой.

Основываясь на значении интенсивности инфракрасного излучения Веги, которое значительно выше, чем должно быть у неё теоретически, учёные пришли к выводу, что вокруг Веги расположен пылевой диск, который вращается вокруг неё и разогревается излучением звезды. Этот диск образовался, скорее всего, в результате столкновения астероидных или кометных тел. Аналогичный пылевой диск в Солнечной системе связан с поясом КойпераШаблон:Source-ref[8].

Вега является прототипом так называемых «инфракрасных звёзд» — звёзд, у которых имеется диск из пыли и газа, излучающий в инфракрасном спектре под действием энергии звезды. Эти звёзды называются «Вега-подобные звёзды»Шаблон:Source-ref.

В последнее время в диске Веги были выявлены несимметричности, указывающие на возможное присутствие около Веги по крайней мере одной планеты, размер которой может быть примерно соизмерим с размером ЮпитераШаблон:Source-refШаблон:Source-ref.

История изучения

Созвездие Лиры в атласе «Уранометрия». Вега изображена в клюве орла, держащего лиру

Один из разделов астрономии — астрофотография, или фотографирование через телескопы небесных объектов, стал развиваться с 1840 года, когда астроном Джон Уильям Дрейпер сфотографировал Луну с помощью дагеротипииШаблон:Source-ref. Первой сфотографированной звездой стала Вега. В ночь с 16 на 17 июля 1850 года в обсерватории Гарвардского колледжа был сделан первый снимок звездыШаблон:Source-ref[9]. В 1872 году Генри Дрейпер получил первые (после Солнца) фотографии спектра Веги и впервые показал линии поглощения в этом спектреШаблон:Source-ref.

В 1879 году Уильям Хаггинс использовал фотографии спектра Веги и ещё двенадцати похожих звёзд, чтобы определить «двенадцать сильных линий», которые являются общими для этого класса звёзд. Позже эти линии были определены как линии водорода (серия Бальмера)Шаблон:Source-ref.

Расстояние до Веги может быть определено по её параллаксу относительно неподвижных звёзд во время движения Земли по орбите вокруг Солнца. Первым параллакс Веги определил Василий Струве в 1837 году. Используя 9-дюймовый рефрактор на экваториальной монтировке и нитяной микрометр, изготовленные Фраунгофером, Струве получил значение 0,125 угловой секундыШаблон:Source-ref, что очень близко к современному значению. Но Фридрих Бессель, который определил расстояние до звезды 61 Лебедя, скептически оценил полученные Струве данные, заставив его отказаться от первоначальной оценки. Струве пересмотрел свою точку зрения и после новых подсчётов получил почти вдвое большую величину параллакса (0,2169±0,0254″)Шаблон:Source-ref. Таким образом, полученные Струве данные были приняты как неверные, и первым определителем расстояния до звезды считается Бессель.

В настоящее время параллакс Веги оценивается в 0,129″Шаблон:Source-ref[10].

Яркость всех звёзд измеряется по стандартной логарифмической шкале, причём чем ярче звезда, тем меньше значение её звёздной величины. Самые тусклые звёзды, доступные наблюдению невооружённым глазом, имеют шестую звёздную величину, в то время как блеск Сириуса, ярчайшей звезды ночного неба, равен −1,47. За точку отсчёта на этой шкале астрономы первоначально решили выбрать Вегу: её видимый блеск был принят за «ноль» Шаблон:Source-refШаблон:Source-ref.

Таким образом, в течение многих лет от яркости Веги вёлся отсчёт звёздных величин. В настоящее время точка отсчёта переопределена с помощью ряда других звёзд. Однако для визуальных наблюдений Вегу и сейчас можно считать эталоном нулевой звёздной величины: при наблюдении в стандартной полосе V фотометрической системы UBV, наиболее распространённой на сегодняшний день, величина Веги равна 0,03m, что на глаз неотличимо от нуляШаблон:Source-ref. В этой фотометрической системе при определении блеска звёзд применяются три светофильтра — ультрафиолетовый (англ. ultraviolet), синий (англ. blue) и видимый (англ. visible). Они обозначаются буквами U, B и V соответственно. Вега была одной из шести звёзд класса А0V, которые использовали при разработке этой фотометрической системы. Звёздные величины со всеми тремя фильтрами измеряются таким образом, что для Веги и подобных ей белых звёзд они равны между собой: U = B = VШаблон:Source-ref.

Фотометрические измерения Веги в 1920-х годах показали, что её блеск не постоянен, а слегка изменяется. Изменения блеска звезды были очень малы (±0,03 величины), и поэтому из-за слишком несовершенной техники того времени астрономы долго не знали, является ли Вега переменной или постоянной звездой. Более поздние измерения, проведённые в 1981 году в обсерватории им. Дэвида Данлэпа, показали такое же, как в 1930-х годах, слабое изменение блеска звезды. После попытки отнести Вегу к какому-то конкретному классу переменных звёзд было высказано предположение, что Вега совершает неправильные низкоамплитудные пульсации, аналогичные пульсациям δ ЩитаШаблон:Source-ref.

Это одна из категорий переменных звёзд, изменения блеска которых вызвано собственными пульсациями из-за неустойчивости в недрах звездыШаблон:Source-ref. Однако переменность Веги по-прежнему спорна, поскольку другие астрономы не обнаружили никаких изменений в блеске Веги, хотя она относится к типу звёзд, где встречается переменность. Поэтому весьма вероятно, что неспособность зарегистрировать изменение блеска Веги вызваны несовершенством оборудования или систематическими ошибками в измеренияхШаблон:Source-refШаблон:Source-ref.

Вега — первая звезда, у которой был обнаружен пылевой диск. Это открытие было сделано в 1983 году с помощью Инфракрасной космической обсерватории (IRAS)[9]Шаблон:Source-ref.

В 2006 году с помощью оптической интерферометрии с длинной базой была обнаружена асферичность ВегиШаблон:Source-ref.

Условия наблюдения

Вега — звезда Северного полушария и имеет в настоящее время склонение +38°48′. Её можно увидеть в Северном и Южном полушариях вплоть до 51° южной широты, то есть почти в любой точке мира, кроме Антарктиды и самого юга Южной Америки (в частности, звезда никогда не восходит в городе Ушуая). Севернее 51° с. ш. Вега никогда не пересекает линию горизонта, и по этой причине в высоких и полярных широтах Северного полушария наблюдается круглый год. Точку зенита Вега проходит примерно на широте Афин. На широте Москвы Вега не заходит за горизонт, однако зимой из-за низкого положения над горизонтом её наблюдение возможно только утром или вечером. На юге России (южнее 51° северной широты) Вега скрывается за горизонтом, но глубоко под него не опускается.[11]

Вега, наряду с Денебом и Альтаиром образует известный астеризм «Летне-осенний треугольник», который виден в Северном полушарии, на экваторе и в Южном полушарии вплоть до 45-й параллели. В средних северных широтах (45° и выше) наблюдается круглый год, лучше всего в конце весны, летом, осенью и в начале зимы (с мая по декабрь). Во второй половине зимы и ранней весной (с января по апрель) Альтаир показывается после полуночи, поэтому увидеть астеризм целиком можно только под утро. В средних южных широтах Вега, как и весь Летне-осенний треугольник видна зимой и ранней весной (с июня по сентябрь).

Вега кульминирует в астрономическую полночь 1 июля и в это время наступает её противостояние с Солнцем. Именно в это время создаются наилучшие условия для наблюдения Веги с ЗемлиШаблон:Source-ref.

С течением времени северное склонение Веги увеличится. По мере приближения звезды к Северному небесному полюсу в результате прецессии Земли — примерно через 12 тыс. лет — Вега станет полярной звездой Северного полушария. Такой звездой Вега была за 13 тысяч лет до н. э. и будет в 14 000 году н. э. В этот период Вега будет приближённо указывать на север, а вид неба сильно изменится, и на широтах Харькова будут видны такие южные созвездия, как Южный Крест, Центавр, Муха, Волк. Сто тысяч лет назад самой яркой звездой неба был Канопус, а сейчас — Сириус, Вега же была и будет одной из ярчайших звёзд неба, причём в будущем её блеск возрастёт. Кроме того, в будущем увеличится блеск и Альтаира — другой яркой звезды «Летне-осеннего треугольника».Шаблон:Source-ref

Физические характеристики

Спектр Веги в диапазоне 3820—10 200 Å. В левой части видны интенсивные линии водорода, в правой — линии кислорода и воды земного происхождения

Вега относится к спектральному классу A0V, то есть является белой звездой главной последовательности. Основной источник энергии звезды — термоядерная реакция синтеза гелия из водорода в недрах при высокой температуре. Поскольку массивные звёзды расходуют водород быстрее, чем малые, продолжительность жизни Веги составит (по подсчётам 1979 года) один миллиард лет — в десять раз меньше, чем у СолнцаШаблон:Source-ref: согласно моделям развития звёзд при 1,75<M<2,7; 0,2<Y<2,7; 0,004<Z<0,001 между вхождением звезды в главную звёздную последовательность и её переходом на боковую ветвь красных гигантов проходит 0,43—1,64⋅109 лет. Однако при массе Веги 2,2 возраст Веги меньше одного миллиарда лет.

В отличие от Солнца, основным источником энергии на Веге служит не протон-протонная реакция, а так называемый CNO-цикл синтеза атомов гелия из атомов водорода с помощью посредников — углерода, азота и кислорода. Для этого необходима температура в 16 миллионов кельвин[12] — выше температуры в недрах Солнца. Этот способ является более эффективным, чем протон-протонная реакция. Цикл очень чувствителен к температуре, отвод тепла от центра звезды осуществляется не излучением, а конвекцией[13]. Поэтому в Веге зона лучистого переноса располагается над конвективной, в то время как в Солнце — наоборотШаблон:Source-ref[14][15].

Энергетический поток от Веги был точно измерен различными способами и используется как эталон. Так, при длине волны 548 нм плотность потока составляет 3650 Ян при допустимой погрешности 2 %Шаблон:Source-ref. Вега имеет относительно плоский электромагнитный спектр в видимой области спектра, 350—800 нанометров, где плотность потока составляет 2000—4000 Ян[16]. В инфракрасной части спектра плотность потока мала и равна около 100 Ян при длине волны в 5 микрометров[17]. В спектре звезды доминируют линии поглощения водородаШаблон:Source-ref. Линии других элементов относительно слабы; из них сильнейшими являются линии ионизированного магния, железа и хромаШаблон:Source-ref.

Вега стала первой одиночной звездой главной последовательности (не считая Солнца), у которой было обнаружено рентгеновское излучение (в 1979 году)[18]. Излучение Веги в рентгеновском диапазоне незначительно, что свидетельствует о том, что корона у Веги вообще отсутствует или же очень слабая[19].

Эволюция звезды

Вега образовалась 455±13 миллионов лет назадШаблон:Source-ref. Она значительно старше Сириуса, возраст которого оценивается в 240 миллионов лет. Учитывая достаточно высокую светимость Веги (по сравнению с Солнцем), исследователи предполагают, что продолжительность жизни Веги составит на стадии главной последовательности примерно 1 миллиард лет, после чего она станет субгигантом и, наконец, красным гигантом. Последней стадией эволюции Веги станет сброс её оболочек и превращение в белый карлик. Сверхновой Вега стать не сможет — для этого ей не хватит массы, которая должна составлять минимум 5 масс Солнца. В теперешнем виде Вега просуществует ещё примерно 500 миллионов лет, пока у неё не закончится водородное топливо. Другими словами, Вега находится, как и Солнце, в середине своей жизниШаблон:Source-refШаблон:Source-ref.

Вращение

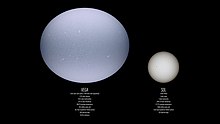

Сравнение размеров Веги с Солнцем. Вега не только больше Солнца, но и ярче, и массивнее. Обратите внимание на приплюснутость Веги

По интерферометрическим данным радиус Веги оценён в 2,73 ± 0,01 радиуса Солнца, что на 60 % больше радиуса Сириуса. В то время как по теоретическим расчётам[уточнить] он должен лишь на 12 % превышать радиус Сириуса.

Было предположено, что такая аномалия может быть вызвана большой скоростью вращения звезды вокруг своей оси. Вега, в отличие от большинства звёзд, имеет не форму шара, а форму эллипсоида вращения, и в настоящее время видима с Земли почти со стороны полюса. Телескоп CHARA подтвердил это предположениеШаблон:Source-ref.

Вега видна с Земли практически со стороны полюса — угол между осью вращения и лучом зрения составляет около 5 градусовШаблон:Source-ref. Скорость вращения звезды на экваторе была определена в пределах от 175±33 до 274±14 км/с. Для 2010 года она составляет 236±4 км/с, или 88 % первой космической (такой, при которой Вега разрушилась бы от центробежных сил)Шаблон:Source-ref. Период вращения звезды вокруг своей оси равен 17,6±0,2 часаШаблон:Source-ref.

Такое быстрое вращение Веги придаёт ей эллипсоидную форму: её экваториальный диаметр на 1/5 больше полярного. Полярный радиус равен 2,36 ± 0,01 радиуса Солнца, в то время как экваториальный — 2,82 ± 0,01 радиуса СолнцаШаблон:Source-ref.

Ускорение свободного падения на Веге также в значительной мере зависит от широты, поэтому температура поверхности на Веге сильно отличается. По теореме фон Цейпеля светимость звёзд в районе полюсов выше, что отражается в разнице температур между полюсами и экватором. В районе полюса она равна 9695 ± 20 К, в то время как вблизи экватора — на 2400 К меньшеШаблон:Source-ref.

Если бы мы могли видеть Вегу со стороны экватора, то её яркость показалась бы нам вдвое слабееШаблон:Source-ref[20].

Температурная разница может также указывать на наличие конвективной зоны вокруг экватора.Шаблон:Source-ref

Если бы Вега была медленно вращающейся, сферически симметричной звездой, то её яркость была бы эквивалентна 57 светимостям Солнца. Эта яркость значительно больше светимости типичной звезды, имеющей такую массу. Таким образом, обнаружение вращения Веги позволило устранить данное противоречие, и полная болометрическая светимость Веги превышает солнечную лишь в 37 разШаблон:Source-ref.

Вега длительное время использовалась как эталонная звезда для калибровки телескопов. Знания о скорости вращения Веги и знание того угла, под которым мы её видим, помогли при настраивании интерферометров относительно этой звезды, и теперь диаметр звезды измерен точноШаблон:Source-ref.

Металличность

Понятие «металличность» в описании звезды означает содержание в ней элементов тяжелее гелия, так как все элементы, тяжелее гелия, в астрономии называются металлами.

В фотосфере Веги мало таких элементов — всего 32 % от аналогичного солнечного показателя. Для сравнения, в фотосфере Сириуса содержится втрое больше металлов, чем в Солнце. Солнце же содержит множество элементов тяжелее гелия. Их содержание оценивается в 0,0172 ± 0,002 от общей массыШаблон:Source-ref (то есть Солнце примерно на 1,72 процента состоит из тяжёлых элементов). Вега же состоит из тяжёлых элементов всего на 0,54 %.

Необычно низкая металличность Веги позволяет отнести её к звёздам типа λ ВолопасаШаблон:Source-refШаблон:Source-ref.

Причина такой низкой металличности Веги (и других подобных звёзд спектрального класса A0-F0) остаётся неясной.

Возможно, это обусловлено потерей массы звезды. Однако такой процесс начинается лишь в конце жизни звезды, когда у неё заканчивается водородное топливо. Другой возможной причиной может быть формирование Веги из газопылевого облака с необычно низким содержанием металловШаблон:Source-ref.

Наблюдаемое соотношение гелия к водороду у Веги примерно на 40 % меньше, чем у Солнца. Это может быть вызвано исчезновением конвективной зоны гелия вблизи поверхности. Энергия из недр звезды передаётся вместо конвекции с помощью электромагнитного излучения, что может быть причиной аномалий. Ещё одной из причин таких аномалий может быть диффузияШаблон:Source-ref.

Движение в пространстве

Радиальная скорость Веги — составляющая движения звезды вдоль луча зрения наблюдателя.

Для звёзд и галактик одной из важнейших характеристик является смещение линий в их спектре. Если линии смещены в красную сторону спектра (красное смещение), то эта звезда или галактика удаляется от наблюдателя, и чем больше смещение, тем больше скорость удаления. Для звёзд это смещение невелико, но другого способа определить скорость их движения относительно Земли нет. Точные измерения красного смещения Веги дали результат в −13,9 ± 0,9 км/с.Шаблон:Source-ref Знак минус указывает на движение звезды к Земле.

Вследствие собственного движения звёзд Вега постепенно перемещается на фоне других звёзд, столь удалённых от Земли, что они кажутся неподвижными — их собственное движение столь мало, что им пренебрегают.

Тщательные измерения положения звезды позволили измерить собственное движение Веги. Собственное движение Веги за год составляет 202,03 ± 0,63 миллисекунды дуги по прямому восхождению и 287,47 ± 0,54 миллисекунды дуги по склонениюШаблон:Source-ref.

Полное собственное движение Веги равно 327,78 миллисекунды дуги в год. За 11 тыс. лет Вега перемещается приблизительно на градус по небесной сфере[21].

Относительно соседних звёзд скорость Веги такова: по координате U = −16,1 ± 0,3 км/с, по координате V = −6,3 ± 0,8 км/с, и по координате W = −7,7 ± 0,3 км/сШаблон:Source-ref. Полная скорость Веги равна 19 километрам в секунду[22], что примерно соответствует скорости движения Солнца относительно соседних звёзд.

Хотя в данный момент Вега всего лишь пятая по яркости звезда неба, с течением времени её блеск будет медленно расти из-за приближения к Солнечной системе. Примерно через 210 тысяч лет Вега станет самой яркой звездой неба. Ещё через 70 тысяч лет её блеск достигнет максимума в −0,81m, и Вега будет ярчайшей звездой на протяжении 270 тысяч летШаблон:Source-ref.

Исследуя другие звёзды, похожие по возрасту и свойствам на Вегу, а также движущиеся сходным с Вегой образом, астрономы причислили Вегу к так называемой группе Кастора. Эта небольшая группа включает около 16 звёзд, очень похожих на Вегу. К ней относятся следующие объекты: α Весов, α Цефея, Кастор, Фомальгаут и Вега. Все эти звёзды в пространстве движутся почти параллельно друг другу и с одинаковой скоростью. Когда-то все эти звёзды сформировались в одном месте и в одно время, но затем стали гравитационно независимыми, но как и в случае с Сириусом, астрономы нашли свидетельства существования в прошлом данной группыШаблон:Source-ref.

По подсчётам учёных, группа образовалась примерно 100—300 миллионов лет назад, и звёзды этой группы движутся примерно с одинаковой скоростью — около 16,5 километра в секундуШаблон:Source-ref[23].

Планетарная система

Избыток инфракрасного излучения

Одним из первых серьёзных достижений в работе Инфракрасной астрономический обсерватории (IRAS) была регистрация значительного превышения потока инфракрасного излучения от Веги по сравнению с ожидаемым. Повышенная интенсивность излучения была обнаружена на длинах волн в 25, 60 и 100 микрометров, и эти волны исходили из пространства, имеющего угловой радиус в десять угловых секунд, что соответствует источнику излучения диаметром 80 а. е. Было предложено, что источником излучения являются мелкие частички, вращающиеся вокруг Веги, с диаметром не меньше одного миллиметра и температурой около 85 КШаблон:Source-ref. Частички же более мелкого диаметра будут выдуваться из системы световым давлением или упадут на звезду в результате эффекта Пойнтинга — РобертсонаШаблон:Source-ref. Этот эффект связан с тем, что переизлучаемые частицами пыли тепловые фотоны анизотропны в системе отсчёта, неподвижной относительно звезды, и поэтому преобладает переизлучение в направлении движения пылинки. В результате пылинка теряет момент импульса и по спирали падает на звезду, а, достаточно приблизившись к ней, испаряется. Этот эффект тем более существенен, чем ближе находится пылинка к звезде[9].

Более поздние измерения потока электромагнитного излучения от Веги с длиной волны в 193 микрометра показали, что он слабее, чем ожидалось. Это означало, что размер пылевых частиц составляет 100 микрометров или меньше. Построенная на основе этих наблюдений модель предполагала, что мы наблюдаем окружающий звезду пылевой диск радиусом 120 а. е. почти сверху, так как смотрим на Вегу практически с полюса. Кроме того, в центре этого диска находится дыра радиусом почти в 80 астрономических единиц. В центре этой дыры расположена ВегаШаблон:Source-ref.

После обнаружения аномального излучения Веги были открыты и другие подобные звёзды. На 2002 год зарегистрировано порядка 400 «Вега-подобных» звёздШаблон:Source-ref, среди которых Денебола, Бета Живописца, Фомальгаут, Эпсилон Эридана и др.Шаблон:Source-ref Высказано предположение, что эти звёзды могут стать ключом к разгадке происхождения Солнечной системыШаблон:Source-ref.

Пылевой диск

Столкновение двух массивных небесных тел недалеко от Веги в представлении художника. Подобные столкновения могли вызвать образование вокруг Веги пылевого диска

В 2005 году космическим телескопом «Спитцер» были получены изображения Веги, а также окружающей звезду пыли в инфракрасном спектре, так как пыль свободно пропускает инфракрасное излучение. Было видно, что разные части пылевого диска — источники излучения разной длины волны. На длине волны 24 микрометра диск имеет размер в 43 угловые секунды, что соответствует расстоянию от Веги 330 а. е., на 70 микрометрах — 70 угловых секунд (543 а. е.), а на 160 микрометрах — 105 угловых секунд (815 а. е.). Эти широкие и далёкие от звезды части состояли из мелких частиц размером от 1 до 50 микрометров в диаметре. Расстояние внутренней границы пыли от звезды оценивается в 71—102 а. е. или 11±2 угловых секунды. Такая чёткая граница диска возникла потому, что Вега своим излучением отталкивает частицы пыли, одновременно удерживая пылевой диск за счёт притяжения, из-за чего он относительно стабиленШаблон:Source-ref.

Общая масса пыли диска составляет 0,003 массы Земли, что эквивалентно объекту радиусом порядка 1000 км. Предполагается, что разрушение и превращение в пыль тела такой массы в результате столкновения маловероятно. Более вероятным представляется её образование при столкновении объектов меньшей массы, которые запустили каскад дробления, сталкиваясь с другими аналогичными объектамиШаблон:Source-ref.

Время существования без подпитки новым материалом подобных пылевых структур — не более 10 млн лет. Если не происходит новых столкновений, они постепенно прекращают своё существованиеШаблон:Source-ref.

Наблюдения инфракрасного телескопа CHARA (обсерватория Маунт-Вильсон) в 2006 году подтвердили наличие второго пылевого диска вокруг Веги примерно на расстоянии 8 а. е. от звезды (около 1 млрд км). Эта пыль аналогична солнечному поясу астероидов, или же является результатом интенсивных столкновений между кометами или метеоритами, но может быть и формирующейся планетойШаблон:Source-ref. Возможно, пыль из этого диска служит причиной предполагаемой переменности Веги[24].

Возможная планетная система

Пылевой диск Веги в искусственных цветах. Видна открытая асимметрия. Положение звезды отмечено «∗», «+» указывает положение гипотетической планеты

Наблюдения, проведённые на телескопе Джеймса Кларка Максвелла в 1997 году, выявили вокруг Веги так называемый «продолговатый яркий центральный регион», который располагался на расстоянии 9 угловых секунд (70 а. е.) от Веги по направлению к северо-востоку. Было предположено, что это либо возмущения диска гипотетической экзопланетой, либо на орбите вокруг Веги находился какой-то небесный объект, целиком окружённый пылью. Однако изображения, полученные с телескопа «Кек» на Гавайях, привели учёных к выводу, что речь идёт об очень крупном облаке пыли и газа, который располагается вокруг Веги, и что это, очевидно, протопланетный диск, а масса объекта, который из него формируется — 12 масс Юпитера, что соответствует лёгкому коричневому карлику либо субкоричневому карлику. К выводу, что планеты Веги находятся в процессе формирования, пришли и астрономы из Калифорнийского университета в Лос-Анджелесе (UCLA)Шаблон:Source-ref[25].

В 2003 году было выдвинуто другое похожее предложение о наличии вокруг Веги планеты (возможно, нескольких планет) с массой Нептуна, которые мигрировали с расстояния 40 а.е. от звезды до 65 а.е. примерно 50 млн лет назадШаблон:Source-ref. Используя коронограф телескопа «Субару» на Гавайских островах в 2005 году, астрономы сумели ограничить верхний предел массы планет Веги 5—10 массами Юпитера. К тому же астрономы предположили, что кроме этих гипотетических планет-гигантов в системе Веги могут существовать и планеты земной группы. Весьма вероятно, что угол наклона орбит планет Веги, скорее всего, будет тесно связан с экваториальной плоскостью звезды[26]Шаблон:Source-ref.

После десяти лет наблюдений Веги методом лучевых скоростей, астрономы предположили, что у неё, возможно, есть спутник Вега b с минимальной массой не менее 20 масс Земли. Один оборот вокруг Веги планета делает за 2,43 дня, при этом, сама Вега вращается вокруг своей оси за 16 часов. Температура на поверхности планеты может достигать 3000 °C (5390 градусов по Фаренгейту[27])[28].

Ближайшее окружение звезды

Следующие звёздные системы находятся на расстоянии в пределах 10 световых лет от Веги:

| Звезда | Спектральный класс | Расстояние, св. лет |

| G 184-19 | M4,5 V / M4,5 V | 6,2 |

| μ Геркулеса | G5 IV / M3V / M4 | 7,3 |

| G 203-47 | M3,5 V | 7,4 |

| BD+43 2796 | M3,5 V | 7,8 |

| BD+45 2505 | M3 V / M3,5 V | 8,2 |

| AC+20 1463-148 A | M2 V—VI | 9,3 |

| AC+20 1463-148 B | M2 V—VI | 9,7 |

С точки зрения наблюдателя, ведущего наблюдения с любой из гипотетических планет Веги, Солнце будет находиться в созвездии Голубя, и иметь видимую звёздную величину 4,3m. Невооружённым глазом звезду такого блеска на гипотетической планете можно было бы увидеть в ясную, хорошую звёздную ночь, и для этого исключительная зоркость не требуетсяШаблон:Source-ref.

Структура Местного пузыря. Показано положение Веги, Солнца и других звёзд. Изображение ориентировано так, что звёзды, ближайшие к центру Галактики, находятся на его вершине

Вега в мифах народов мира

Являясь одной из самых ярких звёзд на небесном своде, Вега издавна привлекала внимание древних народов, которые наделяли её мифологическими свойствами. Ещё ассирийцы называли Вегу «Даян-сейм», что в переводе на русский язык означает «судья неба». Аккадцы дали звезде имя «Тир-анна», или «жизнь небес». Вавилонский Дильган («посланник света») мог быть связан с ВегойШаблон:Source-ref. Древние греки считали находящийся рядом с Вегой ромбик из четырёх звёзд лирой, созданной Гермесом и впоследствии переданной Аполлоном музыканту Орфею; это название созвездия распространено и сегодня[29].

В китайской мифологии описана любовная история Ци Си (кит. упр. 七夕, пиньинь qī xī), в которой Ню-лан (звезда Альтаир), Пастух, и его двое детей (β и γ Орла) навеки разлучены с родной матерью, небесной ткачихой Чжи-нюй (Вегой), которая находится на другой стороне реки — Млечного Пути[30]. Японский фестиваль Танабата также основан на этой легенде[31]. Древние ингушские мифы объясняют происхождение Веги, Денеба и Альтаира, составляющие на небе треугольник, легендой о дочери бога грома и молнии Села, девушкой необычайной красоты, вышедшей замуж за небожителя. Согласно этой легенде, она подготовила из теста треугольный хлеб и сунула его в золу с угольками, чтобы он испёкся. Пока она ходила за соломой, два угла хлеба сгорели, уцелел лишь один. И теперь на небе видны три звезды, из которых одна (Вега) намного ярче двух других[32]. В зороастризме Вега иногда ассоциируется с Ванантом, маленьким божеством, чьё имя означает «завоеватель»[33].

В Римской империи момент, когда Вега пересекала линию горизонта перед восходом Солнца, считался началом осениШаблон:Source-ref.

Средневековые астрологи считали Вегу одной из 15 избранных звёзд, влияние которых на человечество было наиболее велико[34]. Генрих Корнелиус Агриппа для обозначения Веги использовал каббалистический символ с подписью лат. Vultur cadens, дословным переводом арабского названия[35]. Звезду олицетворяли камень хризолит и растение чабер. Помимо имени «Вега», различные астрологи Средневековья называли эту звезду «Вагни», «Вагниехом» и «Векой»Шаблон:Source-ref.

Кроме того, Вега неоднократно упоминается в произведениях научно-фантастической литературы. В частности, к Веге была направлена 34 звёздная экспедиция звездолёта «Парус» в романе Ивана Ефремова «Туманность Андромеды», которая обнаружила лишь 4 безжизненные планеты.

См. также

- Список самых ярких звёзд

Примечания

- ↑ Cyril Glasse. Astronomy // The New Encyclopedia of Islam. — Rowman Altamira, 2001. — ISBN 0-75-910190-6.

- ↑ Harper, Douglas. Vega. Online Etymology Dictionary (ноябрь 2001). Дата обращения: 21 февраля 2008. Архивировано 25 января 2012 года.

- ↑ Gerald Massey. Ancient Egypt: the Light of the World. — Adamant Media Corporation, 2001. — ISBN 1-4021-7442-X.

- ↑ William Tyler Olcott. Star Lore of All Ages: A Collection of Myths, Legends, and Facts Concerning the Constellations of the Northern Hemisphere. — G. P. Putnam’s sons, 1911.

- ↑ Deborah Houlding. Lyra: The Lyre. Skyscript (декабрь 2005). Дата обращения: 21 февраля 2008. Архивировано 25 января 2012 года.

- ↑ Houtsma, M. Th.; Wensinck, A. J.; Gibb, H. A. R.; Heffening, W.; Lévi-Provençal. E. J. Brill’s First Encyclopaedia of Islam, 1913—1936. — E. J. Brill, 1987. — Vol. VII. — P. 292.

- ↑ Лира. Они над нами вверх ногами: Мифология созвездий. Дата обращения: 21 июля 2017. Архивировано 15 февраля 2012 года.

- ↑ С. Б. Попов. Диск вокруг Веги. Астронет. Астронет (7 апреля 2005). Дата обращения: 26 апреля 2009. Архивировано 12 января 2011 года.

- ↑ 9,0 9,1 9,2 А. И. Дьяченко. Планетная система Веги. Астронет. Астронет. Дата обращения: 18 апреля 2009. Архивировано 17 декабря 2011 года.

- ↑ Anonymous. The First Parallax Measurements. Astroprof (28 июня 2007). Дата обращения: 21 февраля 2008. Архивировано 25 января 2012 года.

- ↑ Энциклопедия для детей. Астрономия. — М.: Аванта, 2007.

- ↑ Competition between the P-P Chain and the CNO Cycle. Dept. Physics & Astronomy University of Tennessee. Архивировано 25 января 2012 года.

- ↑ Астрономия: век XXI / Ред.-сост. В. Г. Сурдин. — 2-е изд. — Фрязино: Век 2, 2008. — С. 134—135. — ISBN 978-5-85099-181-4.

- ↑ Thanu Padmanabhan. Theoretical Astrophysics. — Cambridge University Press, 2002. — ISBN 0521562414.

- ↑ Cheng, Kwong-Sang; Chau, Hoi-Fung; Lee, Kai-Ming. Chapter 14: Birth of Stars (недоступная ссылка). Nature of the Universe. Hong Kong Space Museum (2007). Дата обращения: 21 февраля 2008. Архивировано 25 января 2012 года.

- ↑ Walsh, J. Alpha Lyrae (HR7001) (недоступная ссылка). Optical and UV Spectrophotometric Standard Stars. ESO (6 марта 2002). Архивировано 4 июля 1998 года.

- ↑ McMahon, Richard G. Notes on Vega and magnitudes (Text). University of Cambridge (23 ноября 2005). Дата обращения: 21 февраля 2008. Архивировано 25 января 2012 года.

- ↑ Понятов, 2021, с. 48.

- ↑ Schmitt, J. H. M. M. Coronae on solar-like stars (англ.) // Astronomy and Astrophysics. — EDP Sciences, 1999. — Vol. 318. — P. 215—230.

- ↑ Проекция звезды со стороны полюсов — круг, со стороны экватора — эллипс. Поперечное сечение эллипса составляет только около 81 % поперечного сечения в районе полюсов, поэтому экваториальная область получает меньше энергии. Любая дополнительная светимость объясняется распределением температур. По закону Стефана — Больцмана, поток энергии от экватора Веги будет приблизительно на 33 % больше, чем от полюса:

- [math]displaystyle{ begin{smallmatrix}left( frac{T_{eq}}{T_{pole}} right)^4 = left( frac{7600}{10 000} right)^4 = 0,33end{smallmatrix} }[/math]

- ↑ Majewski, Steven R. Stellar Motions. University of Virginia (2006). Дата обращения: 22 февраля 2008. Архивировано 25 января 2012 года. — Собственное движение Веги определяется по формуле:

- [math]displaystyle{ begin{smallmatrix}mu = sqrt{ {mu_delta}^2 + {mu_alpha}^2 cdot cos^2 delta } = 327,78 end{smallmatrix} }[/math] миллисекунд дуги в год.

где [math]displaystyle{ mu_alpha }[/math] и [math]displaystyle{ mu_delta }[/math] составляющие собственного движения в прямом восхождении и, соответственно, склонении, и [math]displaystyle{ delta }[/math] — склонение.

- ↑ Полная скорость определяется следующей формулой:

- [math]displaystyle{ begin{smallmatrix}v_{text{sp}} = sqrt{16,1^2 + 6,3^2 + 7,7^2} = 19 end{smallmatrix} }[/math] км/с.

- ↑ U = −10,7 ± 3,5, V = −8,0 ± 2,4, W = −9,7 ± 3,0 км/с. Полная скорость определяется следующей формулой:

- [math]displaystyle{ begin{smallmatrix}v_{text{sp}} = sqrt{10,7^2 + 8,0^2 + 9,7^2} = 16,5 end{smallmatrix} }[/math] км/с.

- ↑ Girault-Rime, Marion. Vega’s Stardust. CNRS International Magazine (Summer 2006). Дата обращения: 21 февраля 2008. Архивировано 25 января 2012 года.

- ↑ Staff. Astronomers discover possible new Solar Systems in formation around the nearby stars Vega and Fomalhaut (недоступная ссылка). Joint Astronomy Centre (21 апреля 1998). Дата обращения: 21 февраля 2008. Архивировано 25 января 2012 года.

- ↑ Gilchrist, E.; Wyatt, M.; Holland, W.; Maddock, J.; Price, D. P. New evidence for Solar-like planetary system around nearby star (недоступная ссылка). Royal Observatory, Edinburgh (1 декабря 2003). Дата обращения: 21 февраля 2008. Архивировано 25 января 2012 года.

- ↑ A giant, sizzling planet may be orbiting the star Vega Архивная копия от 9 марта 2021 на Wayback Machine, March 8, 2021

- ↑ Spencer A. Hurt et al. A Decade of Radial-velocity Monitoring of Vega and New Limits on the Presence of Planets Архивная копия от 16 февраля 2022 на Wayback Machine, 2021 March 2. The Astronomical Journal, Volume 161, Number 4 (arXiv Архивная копия от 11 марта 2021 на Wayback Machine)

- ↑ Ян Ридпат. Звёзды и планеты. — М.: Астрель, 2004. — С. 178. — ISBN 0-271-10012-X.

- ↑ Liming Wei; Yue, L.; Lang Tao, L. Chinese Festivals. — Chinese Intercontinental Press, 2005. — ISBN 7-5085-0836-X.

- ↑ John Robert Kippax. The Call of the Stars: A Popular Introduction to a Knowledge of the Starry Skies with their Romance and Legend. — G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1919.

- ↑ Е. М. Мелетинский. Мифология. — Изд. 4-е, перепечатанное. — Большая российская энциклопедия, 1998. — С. 492.

- ↑ Mary Boyce. A History of Zoroastrianism. — N. Y.: E. J. Brill, 1996. — Vol. 1: The Early Period. — ISBN 9004088474.

- ↑ Tyson, Donald; Freake, James. Three Books of Occult Philosophy. — Llewellyn Worldwide, 1993. — ISBN 0-87-542832-0.

- ↑ Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa. De Occulta Philosophia. — 1533.

Ссылки

- Понятов, Алексей. Эталонная. Главная струна небесной лиры // Наука и жизнь. — 2021. — № 10. — С. 42—53.

- Попов С. Б. Вега крутится волчком. Астронет. Астронет (22 марта 2006). Дата обращения: 29 апреля 2009.

- Gay Yee Hill; Dolores Beasley. Spitzer Sees Dusty Aftermath of Pluto-Sized Collision (англ.) (недоступная ссылка). Spitzer Space Telescope. NASA (10 января 2005). Архивировано 11 января 2005 года.

- Astrophysical Chemistry Video Lectures by Harry Kroto (англ.). Vega Science Trust. Архивировано 25 января 2012 года.

Объекты глубокого космоса > Звезды > Вега

Вега (Альфа Лиры) – самая яркая звезда на территории созвездия Лиры и 5-я в небе. Стоит на втором месте по яркости в северном полушарии, уступив первенство Арктуру.

За ней можно наблюдать с широт севернее 51° ю. ш. Для тех, кто живет севернее, она выступает циркумполярной (никогда не опускается ниже горизонта).

Вместе с Альтаиром и Денебом формирует астеризм Летний треугольник. Наша карта звездного неба поможет отыскать Вегу самостоятельно в телескоп. Или воспользуйтесь 3D-моделями онлайн, чтобы изучить внешний вид и расположение звезды в космическом пространстве.

Современное имя получено от свободной транслитерации «wāqi’», что с арабского переводится как «падение» или «наглость» и относится к «an-nasr al-wāqi» – «нападающий орел».

Художественная интерпретация астероидного пояса вокруг яркой Веги. Доказательства присутствия осколков обнаружили телескопом НАСА Спитцер, а также Космической обсерваторией Гершеля

Созвездие Лиры отображали в виде падающего орла или стервятника в египетской и индийской культурах. Интересно, что это дает Веге «птичью» связь со звездами Летнего треугольника.

Факты

Вега относится к спектральному классу A0 V, а значит перед нами бело-голубая звезда главной последовательности, продолжающая плавить водород в гелий в ядре. В итоге, она станет красным гигантом и завершит жизнь в виде белого карлика.

Отдалена от нас на 25 световых лет, а кажущаяся величина достигает 0.03. Превосходит солнечную яркость в 40 раз и считается одной из ярчайших звезд в пределах нашей системы.

Сопоставление стремительно вращающейся Веги (слева) и меньшего Солнца (справа)

Возраст звезды Вега – 455 млн. лет, что составляет 1/10 солнечного. Но звезда в 2.1 раз крупнее, а общая длительность жизни должна охватывать миллиард лет. Для наблюдателя Веги наше Солнце казалось бы звездой 4.3 величины.

Вега стала первой чужой звездой, которую сфотографировали и записали спектр. 17 июля 1850 года это удалось Джону Адамсу и Уильяму Бондо. Спектр запечатлел Генри Дрейпер в 1872 году.

Ученые смогли найти крупный астероидный пояс вокруг Веги, отмеченный здесь слева коричневым. Кольцо скалистых осколков зафиксировали при помощи телескопа Спитцер НАСА и Космической обсерватории Гершель ЕКА. На этой диаграмме система Вега с холодным внешним кометным поясом (оранжевый) сопоставляется с нашей системой и ее астероидным поясом и Койпера. Центральный рисунок показывает сравнение масштабов. Справа – увеличенная вчетверо Солнечная система. У обеих есть астероидные пояса. Внешний пояс осколков примерно в 10 раз дальше внутреннего. Исследователи полагают, что зазор между ними в Веге может заполняться планетами

Вега также стала первой одиночной чужой звездой главной последовательности, чье рентгеновское излучение удалось зафиксировать. Она также обладает пылевым диском на орбитальном пути.

Звезда демонстрирует случайные малоамплитудные пульсации и перемены в яркости и считается подозрительной переменной Дельта Щита. Это карликовые цефеиды, показывающие перемены в яркости из-за радиальных и не радиальных поверхностных пульсаций.

Звезда Вега в созвездии Лира стремительно вращается, разгоняясь до 236.2 км/с на экваториальной линии. Из-за этого ее экватор расширяется и температура на нем выше полярной. Экваториальный радиус на 19% превышает полярный.

Космическому телескопу НАСА Спитцер удалось запечатлеть Вегу, отдаленную на 25 световых лет на территории Лиры. Спитцер способен улавливать тепловое излучение от пылевого и газового облака вокруг звезды и заметил, что диск с осколками намного крупнее, чем полагали ранее. Это параллельное сопоставление, добытое многодиапазонным фотометром телескопа, показывающее теплые ИК-свечения от пылевых частичек, выполняющих обороты вокруг звезды на длинах волн в 24 микрон (слева в синем) и 70 микрон (справа в красном). Оба кадра демонстрируют крупный и гладкий мусорный диск, который в радиусе охватывает 815 а.е. Исследователи сравнили поверхностную яркость диска на инфракрасных длинах волн, чтобы разобраться в температурном распределении. Большая часть частиц в размере достигает всего лишь несколько микрон (в 100 раз меньше земной песчинки). Они формируются из-за ударов эмбриональных планет. У них короткий срок существования, а значит замеченный диск появился относительно недавно с участием объектов размером с Плутон

Солнечная система перемещается в сторону Веги на ускорении 12 миль в секунду и через 210000 лет Вега станет ярчайшей звездой, когда ее кажущаяся величина достигнет максимума при -0.81 (через 290000 лет).

Вега обладает околозвездным орбитальным пылевым диском. На нем заметны неровности, а значит вокруг звезды есть планета, которая по размерам сходится с Юпитером.

Примерно в 12000 году до н.э. Вега была ближайшей звездой к северному небесному полюсу (полярная звезда) и снова займет это место в 13727 году.

Вега с созвездием Лиры ассоциируется с метеоритным потоком Лирид, который прибывает каждое 21-22 апреля. Между ними нет физической связи, так как объекты выступают осколками от кометы С/1861 G1 Тэтчер.

Физические характеристики и орбита

- Созвездие: Лира.

- Расположение: 18ч 36м 56.33635с (прямое восхождение), + 38° 47′ 01.2802″ (склонение).

- Спектральный класс: A0 V.

- Видимая величина: 0.03.

- Абсолютная величина: 0.58.

- Масса: 2.135 солнечных.

- Радиус: 2.362 солнечных.

- Светимость: 40.12 солнечной.

- Температурная отметка: 8152-10060 К.

- Удаленность: 25.04 световых лет.

- Тип переменной: Дельта Щита (предположительно).

- Наименования: Вега, α Лиры, 3 Лиры, GJ 721, HR 7001, BD + 38° 3238, HD 172167, GCTP 4293.00, LTT 15486, SAO 67174, HIP 91262.

Ссылки

Рубрика: Прогулки по небу

Звезда Вега, королева летнего неба

Опубликовано 16.08.2019 ·

Комментарии: 0

·

На чтение: 14 мин

·

Просмотры:

Post Views:

23 913

Наверное, многие, кто смотрел летними вечерами на небо, задавались вопросом, как называется яркая звезда, сверкающая почти в зените. Во время долгих июньских сумерек она появляется на небе первой, располагаясь высоко над южным горизонтом. Это Вега, одна из ярчайших звезд ночного неба, главное светило созвездия Лиры, «королева летних ночей».

В списке ярчайших звезд ночного неба Вега занимает 5-е место. Она сильно уступает в блеске Сириусу и Канопусу, заметно альфе Центавра и лишь немного Арктуру. При этом только две более яркие звезды, Сириус и Арктур, можно наблюдать с территории России. Но Сириус — зимняя звезда и летом не видна. Арктур «на глаз» такой же по яркости, как и Вега. У Веги даже есть небольшое преимущество над ним: на бо́льшей части территории России она наблюдается на небе круглый год.

Вега и знаменитая «двойная двойная» эпсилон Лиры на фоне звездных полей. Примерно так выглядит Вега при наблюдении в бинокль и небольшой телескоп. Фото: Alan Dyer

Как ни странно, название Вега не имеет никакого отношения к популярной в латинских странах фамилии. Оно происходит от арабского waqi («падающий») из фразы النسر الواقع (an-nasr al-wāqi‘), что означает «падающий орел». Это название впервые появилось в «Альфонсовых таблицах» (XIII в.). До этого греки называли звезду Луера, римляне — Лирой, а в «Альмагесте» одно из ее названий — Аллоре. Наконец, у Цицерона это была звезда Фидис, а у Плиния — Фидикула. В древнем Риме придавалось большое значение Веге, так как ее утренний заход совпадал с приходом осени.

Содержимое

- 1 Звезда Вега: как найти на небе

- 1.1 Вега и Большой летний треугольник

- 1.2 Альфа Лиры

- 2 Вега в телескоп

- 3 Физические характеристики Веги

- 4 Звезды наибольшей светимости в окрестностях Солнца

- 5 Интересные факты о Веге

- 5.1 Вега — самая изучаемая звезда после Солнца

- 5.2 Аномальная звезда

- 5.3 Звезда-волчок

- 5.4 Вега — первая звезда, у которой был обнаружен околозвездный диск

- 5.5 Вега была и будет полярной звездой

- 5.6 В будущем Вега станет самой яркой звездой на небе после Солнца

Звезда Вега: как найти на небе

Так как Вега яркая звезда, искать ее на небе — занятие простое. Летним вечером встаньте лицом на юг и посмотрите вверх. Вы увидите Вегу высоко в небе, недалеко от зенита! Обратите внимание: звезда не одинока на этом участке неба! Вместе с еще двумя яркими звездами Вега образует огромный треугольник, острая вершина которого направлена вниз.

Вегу часто называют летней звездой, потому что именно в летние месяцы после наступления темноты она находится в южной части неба. (Как известно, именно на юге лучше всего наблюдать любые небесные светила, будь то звезды, планеты или Луну, так как там они поднимаются выше всего над горизонтом, пересекая небесный меридиан.) Вега кульминирует на юге в полночь в середине лета. В конце августа она проходит через южный меридиан поздним вечером. Поэтому теплые вечера в августе и в начале сентября — лучшее время для наблюдения Веги!

Но Вега видна на небе не только летом — она прекрасно наблюдается весной и всю осень. А жители Москвы и Минска, Киева и Самары, Новосибирска и Петербурга, а также многих других городов, расположенных севернее 50° северной широты, могут наблюдать Вегу на небе круглый год. Если летом и в начале осени по вечерам она наблюдается высоко в небе на юге, а во вторую половину осени на западе, то зимой Вега плывет низко над горизонтом на севере. Весной звезду легко найти в восточной части неба.

Вега и Большой летний треугольник

Три яркие звезды, Вега, Денеб и Альтаир образуют на небе Большой летний треугольник, гигантский астеризм, который наблюдается с мая по октябрь. Это главный звездный рисунок на летнем небе. Он притягивает к себе внимание уже при первом мимолетном взгляде на вечерний небосклон июля или августа.

Вега находится в правом верхнем углу треугольника и является в ней ярчайшей звездой. Летний треугольник — очень полезная фигура: он выполняет роль ориентира, отталкиваясь от которого можно довольно просто найти все летние созвездия. Через летний треугольник проходит полоса Млечного Пути.

Восход летнего треугольника. Вега находится вверху. Фото: frankastro

Альфа Лиры

Одновременно Вега возглавляет маленькое, но бросающееся в глаза созвездие Лиры. Основной рисунок этого созвездия — параллелограмм из звезд 3-й и 4-й зв. вел., расположенный непосредственно под Вегой. Вместе со звездами эпсилон и дзета Вега образует крошечный равносторонний треугольник, «сидящий» на вершине параллелограмма.

Созвездие Лиры. Рисунок: Stellarium

Интересно, что греческая буква «альфа» утвердилась за Вегой задолго до выхода знаменитого атласа Иоганна Байера «Уранометрия», в котором наиболее ярким звездам созвездий были впервые присвоены буквы греческого алфавита. Ярчайшая звезда именовалась буквой альфа (α), следующая за ней по яркости — бета (β) и так далее, вплоть до омеги (ω). В издании Альмагеста 1551 года звезда именовалась как α Лиры. Этому, по-видимому, способствовала ее необыкновенная яркость в сравнении с окружающими светилами.

Вега в телескоп

Если у вас есть телескоп или бинокль, не упустите возможности посмотреть на Вегу! Бинокль обладает более широким полем зрения, чем телескоп, и покажет прекрасные звездные поля, окружающие Вегу. В телескоп Вега предстанет далеким голубовато-белым солнцем в окружении десятков тусклых звезд-искорок. Если присмотреться, то рядом со звездой на расстоянии 57″ к югу можно увидеть спутник 9,5m. Спутник Веги — оптический: звезды случайно оказались на небе поблизости друг от друга, в реальности же их разделяют многие световые года. Для того, чтобы увидеть пару во всей красе, понадобится телескоп с объективом не менее 150 мм. Тогда перед вами предстанет купающаяся в потоках света главной звезды маленькая искорка. Примерно в 1′ к западу от Веги есть еще одна звездочка, но увидеть ее в сиянии звезды — задача гораздо более сложная, достижимая только для продвинутых любительских телескопов (блеск спутника всего 11m).

Когда смотришь на Вегу в телескоп, то при хороших атмосферных условиях кажется, будто звезда имеет крохотный голубой диск. В XVII-XVIII веках астрономы считали, что и вправду способны видеть в свои телескопы диски звезд. Только в XIX веке астроном Эри доказал, что такие диски кажущиеся и обусловлены дифракцией света. Однако, к примеру, для Галилея наблюдаемый феномен был еще одним доказательством того, что звезды — это далекие солнца. «Сверх того, у Солнца нет решительно никаких свойств, по которым мы могли бы выделить его из всего стада неподвижных звезд»… — писал он в то время, когда большинство просвещенных людей все еще полагало, будто звезды прикреплены к хрустальной сфере…

Физические характеристики Веги

Вега — горячая звезда спектрального класса A0V. Она больше и гораздо ярче Солнца: ее масса в 2,1 раза превосходит массу нашей звезды, диаметр — в 2,8 раза, Вега излучает в 40 раз больше света, чем наше дневное светило. Цвет звезды — белый, с голубоватым оттенком.

Вега является одной из ближайших звезд к Солнцу: расстояние до нее составляет 25,3 световых лет или 7,67 пк. В радиусе 10 пк от Солнца это звезда наибольшей светимости.

Звезды наибольшей светимости в окрестностях Солнца

| Звезда | Спектр | Масса | Радиус | Светимость | Расстояние пк | Расстояние св. г. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Вега | A0V | 2.13 | 2,36 х 2,82 | 40.10 | 7.68 | 25.00 |

| Сириус А | A1V | 2.06 | 1.71 | 25.40 | 2.64 | 8.60 |

| Фомальгаут | A3V | 1.92 | 1.84 | 16.60 | 7.70 | 25.10 |

| Альтаир | A7 IV-V | 1.79 | 1.63 | 10.60 | 5.13 | 16.73 |

| Процион | F5 IV-V | 1.50 | 2.05 | 6.93 | 3.51 | 11.46 |

| δ Эридана | K0IV | 1.33 | 2.33 | 3.00 | 9.04 | 19.49 |

| π³ Ориона | F6V | 1.24 | 1.32 | 2.82 | 8.07 | 26.32 |

| γ Зайца | F6V | 1.23 | 1.33 | 2.29 | 8.93 | 29.12 |

| α Центавра А | G2V | 1.10 | 1.22 | 1.52 | 1.32 | 4.37 |

| γ Павлина | F9V | 1.21 | 1.15 | 1.52 | 9.26 | 30.21 |

Масса, радиус и светимость звезд даны в единицах Солнца. Расстояние указано в парсеках (пк) и в световых годах (св. г.).

Возраст Веги оценивается в 450 миллионов лет — она примерно в 10 раз младше Солнца. Несмотря на это, эволюционно Вега, как и Солнце, находится примерно в середине жизни. Как и Солнце, Вега пребывает на Главной последовательности диаграммы Герцшпрунга-Рессела. Это означает, что звезда находится в состоянии динамического равновесия между силой тяжести, стремящейся сжать тело, и давлением излучения, идущим из недр, которое расталкивает вещество в стороны.

Равновесие поддерживается ядерными реакциями в ядре звезды, где при температуре 16 миллионов градусов из атомов водорода синтезируются атомы гелия (CNO-цикл). Эта реакция сможет удерживать звезду на Главной последовательности еще в течение примерно 500 миллионов лет, после чего водород в ядре исчерпается, и звезда начнет превращаться в красный гигант. Конечная стадия эволюции Веги аналогична солнечной — прохождение через стадию планетарной туманности с образованием сверхплотного белого карлика.

Интересный момент: несмотря на то, что звезда родилась гораздо позже Солнца, в ее составе наблюдается недостаток химических элементов тяжелее гелия, что характерно для звезд старше Солнца! Последнее неудивительно, ведь все элементы тяжелее гелия рождаются в недрах звезд, которые, умирая, выбрасывают часть своего вещества, обогащенного металлами, в космос. В результате следующее поколение звезд должно содержать больше тяжелых элементов. Но в случае с Вегой это не так. Очевидно, звезда образовалась из водородного облака, бедного металлами и космической пылью.

Интересные факты о Веге

Вега — самая изучаемая звезда после Солнца

В той или иной степени этой звезде посвящены 2466 научных работ и статей, опубликованных после 1850 года. Здесь сыграли свою роль и яркость Веги, и ее близость к Солнцу, и то, что Вега долгое время использовалась в качестве фундаментального калибратора для различных фотометрических систем. Но все же этого было бы недостаточно, если бы Вега не занимала свое сверхудачное место на небесной сфере. В разное время года она проходит близко от зенита для большинства обсерваторий северного полушария Земли, что делает ее гораздо более удобным объектом для наблюдений, чем похожий на нее Сириус.

Аномальная звезда

С Вегой связана любопытная история. В 60-е годы XX века выяснилось, что альфа Лиры имеет аномально большую светимость и температуру для звезд своего класса. (Светимость можно вычислить, если знать блеск звезды и точно измерить расстояние до нее.) По всем расчетам выходило, что звезда излучает почти в 1,5 раза больше света, чем другие подобные ей звезды класса A0V. Некоторое время астрономы пытались объяснить это наличием у Веги звезды-спутника, который мог бы вносить свой вклад в общее излучение звезды. Однако все попытки обнаружить такой спутник (визуально, спектрально или астрометрически) дали отрицательный результат.

Наконец, в 1980-х годах было высказано предположение, что разгадка аномальной светимости Веги кроется… в ее чрезвычайно быстром вращении вокруг своей оси! Как это связано, спросите вы? Разве звезды светят ярче из-за того, быстрее или медленнее они вращаются?

Конечно, нет! Но дело тут вот в чем. Если тело вращается вокруг своей оси достаточно быстро, его форма не может быть идеальной сферой — оно будет сплюснуто к полюсам! Причиной тому — действие центробежных сил, которые стремятся растащить вещество на экваторе, где линейная скорость вращения максимальна. Из-за этого полярный диаметр Земли на 21 километр меньше экваториального. А если посмотреть на фотографии Юпитера или Сатурна, сутки на которых длятся 10 и 9 часов соответственно, то там эта «сплюснутость» буквально бросается в глаза!

Солнце представляется нам почти идеальной сферой, так как вращается чрезвычайно медленно: на один оборот вокруг своей оси у него уходит 25,4 суток — почти целый месяц! Но не все звезды такие, как Солнце. Многие массивные горячие звезды вращаются гораздо быстрее и потому их форма должна быть эллипсоидальной. Такие светила астрономы называют звездами-волчками.

А что Вега?

Звезда-волчок

Долгое время считалось, что Вега вращается почти так же медленно, как и Солнце. Тут надо пояснить: астрономы измеряют скорость вращения звезд косвенным путем по доплеровским сдвигам линий в их спектрах. При вращении звезды одна ее часть приближается к наблюдателю, а другая часть, наоборот, удаляется. Соответственно и линии поглощения в спектре исследуемой звезды смещаются в сторону фиолетового или красного цветов. Измеряя степень отклонения линий, можно найти скорость вращения звезды. Однако этот метод хорош, если звезда обращена к нам экватором. Тогда мы можем измерить действительную скорость ее вращения. Однако как быть со звездой, которая обращена к нам полюсом? Ведь тогда все части звезды не приближаются к Земле, но и не удаляются, так как вращение происходит в перпендикулярной плоскости! Соответственно, мы не наблюдали бы никаких доплеровских сдвигов вне зависимости от того, с какой скоростью вращается звезда!

Итак, в случае Веги спектральный анализ показывал весьма умеренные сдвиги линий, соответствовавшие периоду в 5 дней, и ничто не указывало на обратное. Кроме… аномальной светимости!

Карта температур на поверхности Веги, синтезированная по наблюдениям на интерферометре CHARA. Температура на полюсе составляет 10150 К, а на экваторе только 7900 К. Полярный радиус Веги в 2,2 раза больше солнечного, а экваториальный в 2,8 раз! Источник: J. P. Aufdenberg et al., 2006

Если Вега вращается достаточно быстро, ее форма искажена. Центробежные силы вытягивают звезду вдоль экватора, и со стороны она становится похожей на дыню или мяч для регби.

Но тогда полюса находятся ближе к горячему ядру звезды и потому сами становятся горячее и ярче. Экваториальные области, наоборот, гораздо холоднее, чем у аналогичной, но медленно вращающейся звезды, так как располагаются дальше от ядра звезды. Теперь, имея в виду эти соображения, не кажется ли уместным предположить, что Вега — настоящая звезда-волчок, обращенная к нам горячим и ярким полюсом? Эта гипотеза прекрасно объясняет аномальную светимость звезды (ведь мы смотрим на ее сплюснутые области, которые горячее, чем у аналогичных звезд сферической формы), а заодно показывает, почему стандартная процедура измерения скорости вращения Веги давала столь малые величины (именно потому, что звезда вращается для нас «плашмя» и ее вещество практически не двигается по отношению к земному наблюдателю).