|

Parliament of England |

|

|---|---|

Royal coat of arms of England, 1558–1603 |

|

| Type | |

| Type |

Unicameral |

| Houses | Upper house: House of Lords (1341–1649 / 1660–1707) House of Peers (1657–1660) Lower house: House of Commons (1341–1707) |

| History | |

| Established | c. 1236[1] |

| Disbanded | 1 May 1707 |

| Preceded by | Curia regis |

| Succeeded by | Parliament of Great Britain |

| Leadership | |

|

Lord Keeper of the Great Seal |

William Cowper1 |

|

Speaker of the House of Commons |

John Smith1 |

| Structure | |

|

|

|

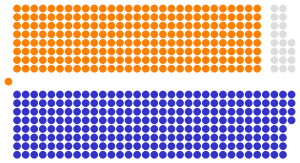

House of Commons political groups |

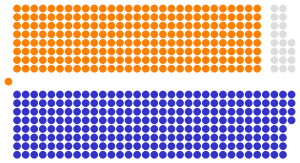

Final composition of the English House of Commons: 513 Seats Tories: 260 seats Whigs: 233 seats Unclassified: 20 seats |

| Elections | |

|

House of Lords voting system |

Ennoblement by the Sovereign or inheritance of an English peerage |

|

House of Commons voting system |

First past the post with limited suffrage1 |

| Meeting place | |

|

|

| Palace of Westminster, Westminster, London | |

| Footnotes | |

| 1Reflecting Parliament as it stood in 1707.

See also: Parliament of Scotland, |

The Parliament of England was the legislature of the Kingdom of England from the 13th century until 1707 when it was replaced by the Parliament of Great Britain. Parliament evolved from the great council of bishops and peers that advised the English monarch. Great councils were first called Parliaments during the reign of Henry III (r. 1216–1272). By this time, the king required Parliament’s consent to levy taxation.

Originally a unicameral body, a bicameral Parliament emerged when its membership was divided into the House of Lords and House of Commons, which included knights of the shire and burgesses. During Henry IV’s time on the throne, the role of Parliament expanded beyond the determination of taxation policy to include the «redress of grievances,» which essentially enabled English citizens to petition the body to address complaints in their local towns and counties. By this time, citizens were given the power to vote to elect their representatives—the burgesses—to the House of Commons.

Over the centuries, the English Parliament progressively limited the power of the English monarchy, a process that arguably culminated in the English Civil War and the High Court of Justice for the trial of Charles I.

Predecessors (pre-13th century)[edit]

Witan[edit]

The origins of Parliament can be traced to the 10th century when a unified Kingdom of England was forged from several smaller kingdoms. In Anglo-Saxon England, the king would hold deliberative assemblies of nobles and prelates called witans. These assemblies numbered anywhere from twenty-five to hundreds of participants, including bishops, abbots, ealdormen, and thegns. Witans met regularly during the three feasts of Christmas, Easter and Whitsun and at other times. In the past, kings interacted with their nobility through royal itineration, but the new kingdom’s size made that impractical. Having nobles come to the king for witans was an important alternative to maintain control of the realm.[2]

Witans served several functions. They appear to have had a role in electing kings, especially in times when the succession was disputed. They were theatrical displays of kingship in that they coincided with crown-wearings. They were also forums for receiving petitions and building consensus among the magnates. Kings dispensed patronage, such as granting bookland, and these were recorded in charters witnessed and consented to by those in attendance. Appointments to offices, such as to bishoprics or ealdormanries, were also made during witans. In addition, important political decisions were made in consultation with witans, such as going to war and making treaties. Witans also helped the king to produce Anglo-Saxon law codes and acted as a court for important cases (such as those involving the king or important magnates).[3]

Magnum Concilium[edit]

After the Norman Conquest of 1066, William the Conqueror (r. 1066–1087) continued the tradition of summoning assemblies of magnates to consider national affairs, conduct state trials, and make laws; although legislation now took the form of writs rather than law codes. These assemblies were called magnum concilium (Latin for «great council»).[4] While kings had access to familiar counsel, this private advice could not replace the need for consensus building, and overreliance on familiar counsel could lead to political instability. Great councils were valued because they «carried fewer political risks, allowed responsibility to be more broadly shared, and drew a larger body of prelates and magnates into the making of decisions».[5]

The council’s members were the king’s tenants-in-chief. The greater tenants, such as archbishops, bishops, abbots, earls, and barons were summoned by individual writ, but sometimes lesser tenants[note 1] were also summoned by sheriffs.[7] Politics in the period following the Conquest (1066–1154) was dominated by about 200 wealthy laymen, in addition to the king and leading clergy. High-ranking churchmen (such as bishops and abbots) were important magnates in their own right. According to Domesday Book, the English church owned between 25% and 33% of all land in 1066.[8]

Traditionally, the great council was not involved in levying taxes. Royal finances derived from land revenues, feudal aids and incidents, and the profits of royal justice. This changed near the end of Henry II’s reign (1154–1189) due to the levying of national taxation to finance the Third Crusade, ransom Richard I, and pay for the series of Anglo-French wars fought between the Plantagenet and Capetian dynasties. In 1188, Henry II set a precedent when he applied to the great council for consent to levy the Saladin tithe.[9]

The burden imposed by national taxation and the likelihood of resistance made consent politically necessary. It was convenient for kings to present the great council of magnates as a representative body capable of consenting on behalf of all within the kingdom. Increasingly, the kingdom was described as the communitas regni (Latin for «community of the realm») and the barons as their natural representatives. But this development also created more conflict between kings and the baronage as the latter attempted to defend what they considered the rights belonging to the king’s subjects.[10]

King John (r. 1199–1216) alienated the barons by his partiality in dispensing justice, heavy financial demands and abusing his right to feudal incidents, reliefs, and aids. In 1215, the barons forced John to abide by a charter of liberties similar to charters issued by earlier kings (see Charter of Liberties).[11] Known as Magna Carta (Latin for «Great Charter»), the charter was based on three assumptions important to the later development of Parliament:[12]

- the king was subject to the law

- the king could only make law and raise taxation (except customary feudal dues) with the consent of the community of the realm

- that the obedience owed by subjects to the king was conditional and not absolute

While the clause stipulating no taxation «without the common counsel» was deleted from later reissues, it was nevertheless adhered to by later kings. Magna Carta transformed the feudal obligation to advise the king into a right to consent. While it was the barons who made the charter, the liberties guaranteed within it were granted to «all the free men of our realm».[13] The charter was promptly repudiated by the king, which led to the First Barons’ War,[14] but Magna Carta would gain the status of fundamental law during the reign of John’s successor.[15]

Early development (1216–1307)[edit]

Henry III and the first parliaments[edit]

Henry III (r. 1216–1272) became king at nine years old after his father, King John, died during the First Barons’ War. During the king’s minority, England was ruled by a regency government that relied heavily on great councils to legitimise its actions. Great councils even consented to the appointment of royal ministers, an action that normally was considered a royal prerogative. Historian John Maddicott writes that the «effect of the minority was thus to make the great council an indispensable part of the country’s government [and] to give it a degree of independent initiative and authority which central assemblies had never previously possessed».[16]

The regency government officially ended when Henry turned sixteen in 1223, and the magnates demanded the adult king confirm previous grants of Magna Carta made in 1216 and 1217 to ensure their legality. At the same time, the king needed money to defend his possessions in Poitou and Gascony from a French invasion. At a great council in 1225, a deal was reached that saw Magna Carta and the Charter of the Forest reissued in return for a fifteenth tax on movable property (personal property and rents). This set a precedent that taxation was granted in return for the redress of grievances.[17]

In the mid-1230s, the word parliament came into common use for meetings of the great council.[18] The word parliament comes from the French parlement first used in the late 11th century with the meaning of parley or conversation (compare to the parlements of Ancien Régime France).[19] It was in Parliament, and with its assent, that the king declared law and where national affairs were deliberated. It granted or refused the king’s request for extraordinary taxation (as opposed to ordinary feudal or customary taxes), and it served as England’s highest court of justice.[20]

After the 1230s, the normal meeting place for Parliament was fixed at Westminster. Parliament tended to meet according to the legal year so that the courts were also in session. It often met in January or February for the Hilary term, in April or May for the Easter term, in July, and in October for the Michaelmas term.[21] In the 13th century, most parliaments had between forty to eighty attendees.[22] Meetings of Parliament always included:[1][23]

- the king

- chief ministers and other ministers (great officers of state, justices of the King’s Bench and Common Bench, and barons of the exchequer)

- members of the king’s council

- ecclesiastical magnates (archbishops, bishops, abbots, priors)

- lay magnates (earls and barons)

Other groups were occasionally summoned. The lesser tenants-in-chief (or knights) were regularly summoned to consent to taxation; though, they were summoned on the basis of their status as tenants of the Crown rather than as representatives of a wider class. The lower clergy (deans, cathedral priors, archdeacons, parish priests) were occasionally summoned when papal taxation was on the agenda. Beginning around the 1220s, the concept of representation, summarised in the Roman law maxim quod omnes tangit ab omnibus approbetur (Latin for «what touches all should be approved by all»), gained new importance among the clergy, and they began choosing proctors to represent them at church assemblies and, when summoned, at Parliament.[24]

Tension over ministers and finances[edit]

In 1232, Peter des Roches became the king’s chief minister. His nephew, Peter de Rivaux, accumulated a large number of offices, including keeper of the privy seal and keeper of the wardrobe; yet, these appointments were not approved by the magnates as had become customary during the regency government. Under Roches, the government revived practices used during King John’s reign and that had been condemned in Magna Carta, such as arbitrary disseisins, revoking perpetual rights granted in royal charters, depriving heirs of their inheritances, and marrying heiresses to foreigners.[25]

Both Roches and Rivaux were foreigners from Poitou. The rise of a royal administration controlled by foreigners and dependent solely on the king stirred resentment among the magnates, who felt excluded from power. Several barons rose in rebellion, and the bishops intervened to persuade the king to change ministers. At a great council in April 1234, the king agreed to remove Rivaux and other ministers. This was the first occasion in which a king was forced to change his ministers by a great council or parliament. The struggle between king and Parliament over ministers became a permanent feature of English politics.[26]

Thereafter, the king ruled in concert with an active Parliament, which considered matters related to foreign policy, taxation, justice, administration, and legislation. January 1236 saw the passage of the Statute of Merton, the first English statute. Among other things, the law continued barring bastards from inheritance. Significantly, the language of the preamble describes the legislation as «provided» by the magnates and «conceded» by the king, which implies that this was not simply a royal measure consented to by the barons.[27][28] In 1237, Henry asked Parliament for a tax to fund his sister Isabella’s dowry. The barons were unenthusiastic, but they granted the funds in return for the king’s promise to reconfirm Magna Carta, add three magnates to his personal council, limit the royal prerogative of purveyance, and protect land tenure rights.[29]

But Henry was adamant that three concerns were exclusively within his royal prerogative: family and inheritance matters, patronage, and appointments. Important decisions were made without consulting Parliament, such as in 1254 when the king accepted the throne of the Kingdom of Sicily for his younger son, Edmund Crouchback.[30] He also clashed with Parliament over appointments to the three great offices of chancellor, justiciar, and treasurer. The barons believed these three offices should be restraints on royal misgovernment, but the king promoted minor officials within the royal household who owed their loyalty exclusively to him.[31]

Parliament’s main tool against the king was to deny consent to national taxation, which they consistently withheld after 1237. Nevertheless, this proved ineffective at restraining the king as he was still able to raise lesser amounts of revenue from sources that did not require parliamentary consent:[32][33]

- county farms (the fixed sum paid annually by sheriffs for the privilege of administering and profiting from royal lands in their counties)

- profits from the eyre

- tallage on the royal demesne, the towns, foreign merchants, and most importantly English Jews

- scutage

- feudal dues and fines

- profits from wardship, escheat, and vacant episcopal sees

In 1253, while fighting in Gascony, Henry requested men and money to resist an anticipated attack from Alfonso X of Castile. In a January 1254 Parliament, the bishops themselves promised an aid but would not commit the rest of the clergy. Likewise, the barons promised to assist the king if he was attacked but would not commit the rest of the laity to pay money.[34] For this reason, the lower clergy of each diocese elected proctors at church synods, and each county elected two knights of the shire. These representatives were summoned to Parliament in April 1254 to consent to taxation.[35] The men elected as shire knights were prominent landholders with experience in local government and as soldiers.[36] They were elected by barons, other knights, and probably freeholders of sufficient standing, illustrating the increasing importance of the gentry as a class.[37] Summoning elected knights to Parliament would not become a regular occurrence until the reign of Edward I. However, the events of 1254 reveal that the barons were no longer viewed as the sole representatives of the realm.[38]

Baronial reform movement[edit]

By 1258, the relationship between the king and the baronage had reached a breaking point over the «Sicilian Business», in which Henry had promised to pay papal debts in return for the pope’s help securing the Sicilian crown for his son, Edmund. At the Oxford Parliament of 1258, reform-minded barons forced a reluctant king to accept a constitutional framework known as the Provisions of Oxford:[39]

- The king was to govern according to the advice of an elected council of fifteen barons.

- The baronial council appointed royal ministers (justiciar, treasurer, chancellor) to serve for one-year terms.

- Parliament met three times a year on the octave of Michaelmas (October 6), Candlemas (February 3), and June 1.

- The barons elected twelve representatives (two bishops, one earl and nine barons) who together with the baronial council could act on legislation and other matters even when Parliament was not in session as «a kind of standing parliamentary committee».[40]

Parliament now met regularly according to a schedule rather than at the pleasure of the king. The reformers hoped that the provisions would ensure parliamentary approval for all major government acts. Under the provisions, Parliament was «established formally (and no longer merely by custom) as the voice of the community».[41]

The theme of reform dominated later parliaments. During the Michaelmas Parliament of 1258, the Ordinance of Sheriffs was issued as letters patent that forbade sheriffs from taking bribes. At the Candlemas Parliament of 1259, the baronial council and the twelve representatives enacted the Ordinance of the Magnates. In this ordinance, the barons promised to observe Magna Carta and other reforming legislation. They also required their own bailiffs to observe similar rules as those of royal sheriffs, and the justiciar was given power to correct abuses of their officials. The Michaelmas Parliament of 1259 enacted the Provisions of Westminster, a set of legal and administrative reforms designed to address grievances of freeholders and even villeins, such as abuses related to the murdrum fine.[42]

Henry III made his first move against the baronial reformers while in France negotiating peace with Louis IX. Using the excuse of his absence from the realm and Welsh attacks in the marches, Henry ordered the justiciar, Hugh Bigod, to postpone the parliament scheduled for Candlemas 1260. This was an apparent violation of the Provisions of Oxford; however, the provisions were silent on what should happen if the king were outside the kingdom. The king’s motive was to prevent the promulgation of further reforms through Parliament. Simon de Montfort, a leader of the baronial reformers, ignored these orders and made plans to hold a parliament in London but was prevented by Bigod. When the king arrived back in England he summoned a parliament which met in July, where Montfort was brought to trial though ultimately cleared of wrongdoing.[43][44]

In April 1261, the pope released the king from his oath to adhere to the Provisions of Oxford, and Henry publicly renounced the Provisions in May. Most of the barons were willing to let the king reassume power provided he ruled well. By 1262, Henry had regained all of his authority, and Montfort left England. The barons were now divided mainly by age. The elder barons remained loyal to the king, but younger barons coalesced around Montfort, who returned to England in the spring of 1263.[45]

Montfortian parliaments[edit]

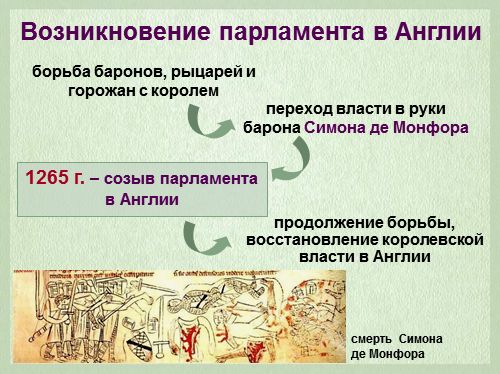

The royalist barons and rebel barons fought each other in the Second Barons’ War. Montfort defeated the king at the Battle of Lewes in 1264 and became the real ruler of England for the next twelve months. Montfort held a parliament in June 1264 to sanction a new form of government and rally support. This parliament was notable for including knights of the shire who were expected to deliberate fully on political matters, not just assent to taxation.[46]

The June Parliament approved a new constitution in which the king’s powers were given to a council of nine. The new council was chosen and led by three electors (Montfort, Stephen Bersted, Bishop of Chichester, and Gilbert de Clare, 7th Earl of Gloucester). The electors could replace any of the nine as they saw fit, but the electors themselves could only be removed by Parliament.[46][47]

Montfort held two other Parliaments during his time in power. The most famous—Simon de Montfort’s Parliament—was held in January 1265 amidst threat of a French invasion and unrest throughout the realm. For the first time, burgesses (elected by those residents of boroughs or towns who held burgage tenure, such as wealthy merchants or craftsmen)[48] were summoned along with knights of the shire.[49]

Montfort was killed at the Battle of Evesham in 1265, and Henry was restored to power. In August 1266, Parliament authorised the Dictum of Kenilworth, which nullified everything Montfort had done and removed all restraints on the king.[50] In 1267, some of the reforms contained in the 1259 Provisions of Westminster were revised in the form of the Statute of Marlborough passed in 1267. This was the start of a process of statutory reform that continued into the reign of Henry’s successor.[51]

Edward I[edit]

Edward I (r. 1272–1307) learned from the failures of his father’s reign the usefulness of Parliament for building consensus and strengthening royal authority.[52] Parliaments were held regularly throughout his reign, generally twice a year at Easter in the spring and after Michaelmas in the autumn.[53]

Membership continued to include lay and ecclesiastical magnates. However, individuals were no longer summoned exclusively because of their status as tenants-in-chief. It is unclear what principles determined who was summoned, except that the great and powerful needed to be present. The numbers varied. In 1283, 110 lay magnates were summoned but only 41 in 1296. The numbers for heads of religious houses also varied, sometimes as many as 73 were summoned while at other times as few as 44 were called.[54]

As feudalism declined, the shires and boroughs were recognised as communes (Latin communitas) with a unified constituency capable of being represented by shire knights and burgesses in Parliament.[55] Edward summoned knights and burgesses when requesting new taxation. It was important that the representatives of the communes (or «the Commons») report back to their communities that taxes were lawfully granted. This was an acknowledgement of the growing influence and prosperity of the gentry and merchant classes.[56]

Burgesses and shire knights were not regularly summoned until the 1290s,[57] after the so-called «Model Parliament» of 1295. Of the thirty parliaments between 1274 and 1294, knights only attended four and burgesses only two. This is explained by the low level of taxation during the early years of Edward’s reign.[58]

Edward also summoned specialists to Parliament to provide expert advice. For example, Roman law experts were summoned from Cambridge and Oxford to the Norham parliament of 1291 to advise on the disputed Scottish succession. At the Bury St Edmunds parliament of 1296, burgesses «who best know how to plan and lay out a certain new town» were summoned to advise on the rebuilding of Berwick after its capture by the English.[59]

In this period, the first major statutes amending the common law were passed by Parliament:[60][59]

- Statute of Westminster I (1275)

- Statute of Gloucester (1278)

- Statute of Mortmain (1279)

- Statute of Westminster II (1285)

- Statute of Winchester (1285)

- Statute Quia Emptores (1290)

- Statute Quo Warranto (1290)

Laws, however, «were not made by the King in Parliament».[60] The actual work of law-making was done by the king and council, especially the judges. Completed legislation was then presented to Parliament for ratification.[61]

Large numbers of petitions were submitted to the king and his council during Parliament, which coincided with sessions of the king’s council, exchequer, and chancery. As the number of petitions increased, they came to be directed to particular departments (chancery, exchequer, the courts) leaving the king’s council to concentrate on the most important business. Parliament had become «a delivery point and a sorting house for petitions».[62]

Crisis of 1297[edit]

Upon his return from crusade, Edward was in debt to the Riccardi of Lucca. In 1275, Parliament took advantage of England’s wealthy wool trade, granting the king a half-mark tax (6s 8d) on each sack of wool exported. This tax, the so called magna et antiqua custuma (Latin for «great and ancient custom»), produced around £8,800[note 2] per year. In Edward’s early reign, extraordinary taxation was rare. Royal undertakings were financed through normal sources, which amounted to £26,828[note 3] in 1284. In the 1290s, however, Edward’s military campaigns in Wales, Scotland, and Gascony placed the king under crushing fiscal pressures. Between 1294 and 1298, total military spending was around £750,000.[note 4][66]

Taxes on moveable property became more prevalent and unpopular. At the parliament of November 1296, the clergy refused to pay a tax citing the papal bull Clericis Laicos, which forbade secular rulers from taxing the church. Ultimately, most clergy paid the tax when threatened with the confiscation of their property. In 1297, lay opposition also increased with new taxes on wool (the maltolt) and the use of prises. The king also ordered the Exchequer to collect a levy on moveable property regardless of parliamentary consent. Opposition was led by Roger Bigod, Earl of Norfolk, and Humphrey de Bohun, Earl of Hereford, who presented the king with a list of grievances known as the Remonstrances, which among other things complained about the amount of taxation and violations of Magna Carta. As Edward left the country for a military campaign on the Continent, civil war was a real possibility.[67]

The outbreak of the First War of Scottish Independence necessitated that both the king and his opponents put aside their differences. At the October parliament held during the king’s absence, the king’s council agreed to concessions in the Confirmatio Cartarum in exchange for Parliament’s consent to new taxes. This confirmation of Magna Carta formally recognised that «aids, mises, and prises» needed the consent of Parliament.[68]

Formal separation of Lords and Commons[edit]

Between 1352 and 1396, the House of Commons met in the chapter house of Westminster Abbey.[69]

One of the moments that marked the emergence of parliament as a true institution in England was the deposition of Edward II in January 1327. Even though it is debatable whether Edward II was deposed in parliament or by parliament, this remarkable sequence of events consolidated the importance of parliament in the English unwritten constitution. Parliament was also crucial in establishing the legitimacy of the king who replaced Edward II: his son Edward III.

In 1341 the Commons met separately from the nobility and clergy for the first time, creating what was effectively an Upper Chamber and a Lower Chamber, with the knights and burgesses sitting in the latter. This Upper Chamber became known as the House of Lords from 1544 onward, and the Lower Chamber became known as the House of Commons, collectively known as the Houses of Parliament.

The authority of parliament grew under Edward III; it was established that no law could be made, nor any tax levied, without the consent of both Houses and the Sovereign. This development occurred during the reign of Edward III because he was involved in the Hundred Years’ War and needed finances. During his conduct of the war, Edward tried to circumvent parliament as much as possible, which caused this edict to be passed.

The Commons came to act with increasing boldness during this period. During the Good Parliament (1376), the Presiding Officer of the lower chamber, Peter de la Mare, complained of heavy taxes, demanded an accounting of the royal expenditures, and criticised the king’s management of the military. The Commons even proceeded to impeach some of the king’s ministers. The bold Speaker was imprisoned, but was soon released after the death of Edward III.

During the reign of the next monarch, Richard II, the Commons once again began to impeach errant ministers of the Crown. They insisted that they could not only control taxation, but also public expenditure. Despite such gains in authority, however, the Commons still remained much less powerful than the House of Lords and the Crown.

This period also saw the introduction of a franchise which limited the number of people who could vote in elections for the House of Commons. From 1430 onwards, the franchise was limited to Forty Shilling Freeholders, that is men who owned freehold property worth forty shillings or more. The Parliament of England legislated the new uniform county franchise, in the statute 8 Hen. 6, c. 7. The Chronological Table of the Statutes does not mention such a 1430 law, as it was included in the Consolidated Statutes as a recital in the Electors of Knights of the Shire Act 1432 (10 Hen. 6, c. 2), which amended and re-enacted the 1430 law to make clear that the resident of a county had to have a forty shilling freehold in that county to be a voter there.

King, Lords and Commons[edit]

Queen Elizabeth I presiding over Parliament, between c. 1580 – c. 1600

During the reign of the Tudor monarchs, it is often argued that the modern structure of the English Parliament began to be created. The Tudor monarchy, according to historian J. E. Neale, was powerful, and there were often periods of several years when parliament did not sit at all. However, the Tudor monarchs realised that they needed parliament to legitimise many of their decisions, mostly out of a need to raise money through taxation legitimately without causing discontent. Thus they consolidated the state of affairs whereby monarchs would call and close parliament as and when they needed it. However, if monarchs did not call Parliament for several years, it is clear the Monarch did not require Parliament except to perhaps strengthen and provide a mandate for their reforms to Religion which had always been a matter within the Crown’s prerogative but would require the consent of the Bishopric and Commons.

By the time of the Tudor monarch Henry VII’s 1485 coronation, the monarch was not a member of either the Upper Chamber or the Lower Chamber. Consequently, the monarch would have to make his or her feelings known to Parliament through his or her supporters in both houses. Proceedings were regulated by the presiding officer in either chamber.

From the 1540s the presiding officer in the House of Commons became formally known as the «Speaker», having previously been referred to as the «prolocutor» or «parlour» (a semi-official position, often nominated by the monarch, that had existed ever since Peter de Montfort had acted as the presiding officer of the Oxford Parliament of 1258). This was not an enviable job. When the House of Commons was unhappy it was the Speaker who had to deliver this news to the monarch. This began the tradition whereby the Speaker of the House of Commons is dragged to the Speaker’s Chair by other members once elected.

A member of either chamber could present a «bill» to parliament. Bills supported by the monarch were often proposed by members of the Privy Council who sat in parliament. For a bill to become law it would have to be approved by a majority of both Houses of Parliament before it passed to the monarch for royal assent or veto. The royal veto was applied several times during the 16th and 17th centuries and it is still the right of the monarch of the United Kingdom and Commonwealth realms to veto legislation today, although it has not been exercised since 1707 (today such an exercise might precipitate some form of constitutional crisis).

When a bill was enacted into law, this process gave it the approval of each estate of the realm: the King, Lords and Commons. The Parliament of England was far from being a democratically representative institution in this period. It was possible to assemble the entire peerage and senior clergy of the realm in one place to form the estate of the Upper Chamber.

The voting franchise for the House of Commons was small; some historians[who?] estimate that it was as little as three per cent of the adult male population; and there was no secret ballot. Elections could therefore be controlled by local grandees, because in many boroughs a majority of voters were in some way dependent on a powerful individual, or else could be bought by money or concessions. If these grandees were supporters of the incumbent monarch, this gave the Crown and its ministers considerable influence over the business of parliament.

Many of the men elected to parliament did not relish the prospect of having to act in the interests of others.[citation needed] So a law was enacted, still on the statute book today, whereby it became unlawful for members of the House of Commons to resign their seat unless they were granted a position directly within the patronage of the monarchy (today this latter restriction leads to a legal fiction allowing de facto resignation despite the prohibition, but nevertheless it is a resignation which needs the permission of the Crown). However, while several elections to parliament in this period would be considered corrupt by modern standards, many elections involved genuine contests between rival candidates, even though the ballot was not secret.

Establishment of permanent seat[edit]

It was in this period that the Palace of Westminster was established as the seat of the English Parliament. In 1548, the House of Commons was granted a regular meeting place by the Crown, St Stephen’s Chapel. This had been a royal chapel. It was made into a debating chamber after Henry VIII became the last monarch to use the Palace of Westminster as a place of residence and after the suppression of the college there.

This room was the home of the House of Commons until it was destroyed by fire in 1834, although the interior was altered several times up until then. The structure of this room was pivotal in the development of the Parliament of England. While most modern legislatures sit in a circular chamber, the benches of the British Houses of Parliament are laid out in the form of choir stalls in a chapel, simply because this is the part of the original room that the members of the House of Commons used when they were granted use of St Stephen’s Chapel.

This structure took on a new significance with the emergence of political parties in the late 17th and early 18th centuries, as the tradition began whereby the members of the governing party would sit on the benches to the right of the Speaker and the opposition members on the benches to the left. It is said that the Speaker’s chair was placed in front of the chapel’s altar. As Members came and went they observed the custom of bowing to the altar and continued to do so, even when it had been taken away, thus then bowing to the Chair, as is still the custom today.

The numbers of the Lords Spiritual diminished under Henry VIII, who commanded the Dissolution of the Monasteries, thereby depriving the abbots and priors of their seats in the Upper House. For the first time, the Lords Temporal were more numerous than the Lords Spiritual. Currently, the Lords Spiritual consist of the Archbishops of Canterbury and York, the Bishops of London, Durham and Winchester, and twenty-one other English diocesan bishops in seniority of appointment to a diocese.

The Laws in Wales Acts of 1535–42 annexed Wales as part of England and this brought Welsh representatives into the Parliament of England, first elected in 1542.

Rebellion and revolution[edit]

The interior of Convocation House, which was formerly a meeting chamber for the House of Commons during the English Civil War and later in the 1660s and 1680s.

Parliament had not always submitted to the wishes of the Tudor monarchs. But parliamentary criticism of the monarchy reached new levels in the 17th century. When the last Tudor monarch, Elizabeth I, died in 1603, King James VI of Scotland came to power as King James I, founding the Stuart monarchy.

In 1628, alarmed by the arbitrary exercise of royal power, the House of Commons submitted to Charles I the Petition of Right, demanding the restoration of their liberties. Though he accepted the petition, Charles later dissolved parliament and ruled without them for eleven years. It was only after the financial disaster of the Scottish Bishops’ Wars (1639–1640) that he was forced to recall Parliament so that they could authorise new taxes. This resulted in the calling of the assemblies known historically as the Short Parliament of 1640 and the Long Parliament, which sat with several breaks and in various forms between 1640 and 1660.

The Long Parliament was characterised by the growing number of critics of the king who sat in it. The most prominent of these critics in the House of Commons was John Pym. Tensions between the king and his parliament reached a boiling point in January 1642 when Charles entered the House of Commons and tried, unsuccessfully, to arrest Pym and four other members for their alleged treason. The Five Members had been tipped off about this, and by the time Charles came into the chamber with a group of soldiers they had disappeared. Charles was further humiliated when he asked the Speaker, William Lenthall, to give their whereabouts, which Lenthall famously refused to do.

From then on relations between the king and his parliament deteriorated further. When trouble started to brew in Ireland, both Charles and his parliament raised armies to quell the uprisings by native Catholics there. It was not long before it was clear that these forces would end up fighting each other, leading to the English Civil War which began with the Battle of Edgehill in October 1642: those supporting the cause of parliament were called Parliamentarians (or Roundheads), and those in support of the Crown were called Royalists (or Cavaliers).

Battles between Crown and Parliament continued throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, but parliament was no longer subservient to the English monarchy. This change was symbolised in the execution of Charles I in January 1649.

In Pride’s Purge of December 1648, the New Model Army (which by then had emerged as the leading force in the parliamentary alliance) purged Parliament of members that did not support them. The remaining «Rump Parliament», as it was later referred to by critics, enacted legislation to put the king on trial for treason. This trial, the outcome of which was a foregone conclusion, led to the execution of the king and the start of an 11-year republic.

The House of Lords was abolished and the purged House of Commons governed England until April 1653, when army chief Oliver Cromwell dissolved it after disagreements over religious policy and how to carry out elections to parliament. Cromwell later convened a parliament of religious radicals in 1653, commonly known as Barebone’s Parliament, followed by the unicameral First Protectorate Parliament that sat from September 1654 to January 1655 and the Second Protectorate Parliament that sat in two sessions between 1656 and 1658, the first session was unicameral and the second session was bicameral.

Although it is easy to dismiss the English Republic of 1649–60 as nothing more than a Cromwellian military dictatorship, the events that took place in this decade were hugely important in determining the future of parliament. First, it was during the sitting of the first Rump Parliament that members of the House of Commons became known as «MPs» (Members of Parliament). Second, Cromwell gave a huge degree of freedom to his parliaments, although royalists were barred from sitting in all but a handful of cases.

Cromwell’s vision of parliament appears to have been largely based on the example of the Elizabethan parliaments. However, he underestimated the extent to which Elizabeth I and her ministers had directly and indirectly influenced the decision-making process of her parliaments. He was thus always surprised when they became troublesome. He ended up dissolving each parliament that he convened. Yet it is worth noting that the structure of the second session of the Second Protectorate Parliament of 1658 was almost identical to the parliamentary structure consolidated in the Glorious Revolution Settlement of 1689.

In 1653 Cromwell had been made head of state with the title Lord Protector of the Realm. The Second Protectorate Parliament offered him the crown. Cromwell rejected this offer, but the governmental structure embodied in the final version of the Humble Petition and Advice was a basis for all future parliaments. It proposed an elected House of Commons as the Lower Chamber, a House of Lords containing peers of the realm as the Upper Chamber. A constitutional monarchy, subservient to parliament and the laws of the nation, would act as the executive arm of the state at the top of the tree, assisted in carrying out their duties by a Privy Council. Oliver Cromwell had thus inadvertently presided over the creation of a basis for the future parliamentary government of England. In 1657 he had the Parliament of Scotland (temporarily) unified with the English Parliament.

In terms of the evolution of parliament as an institution, by far the most important development during the republic was the sitting of the Rump Parliament between 1649 and 1653. This proved that parliament could survive without a monarchy and a House of Lords if it wanted to. Future English monarchs would never forget this. Charles I was the last English monarch ever to enter the House of Commons.

Even to this day, a Member of the Parliament of the United Kingdom is sent to Buckingham Palace as a ceremonial hostage during the State Opening of Parliament, in order to ensure the safe return of the sovereign from a potentially hostile parliament. During the ceremony the monarch sits on the throne in the House of Lords and signals for the Lord Great Chamberlain to summon the House of Commons to the Lords Chamber. The Lord Great Chamberlain then raises his wand of office to signal to the Gentleman Usher of the Black Rod, who has been waiting in the central lobby. Black Rod turns and, escorted by the doorkeeper of the House of Lords and an inspector of police, approaches the doors to the chamber of the Commons. The doors are slammed in his face—symbolising the right of the Commons to debate without the presence of the monarch’s representative. He then strikes three times with his staff (the Black Rod), and he is admitted.

Parliament from the Restoration to the Act of Settlement[edit]

The revolutionary events that occurred between 1620 and 1689 all took place in the name of parliament. The new status of parliament as the central governmental organ of the English state was consolidated during the events surrounding the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660.

After the death of Oliver Cromwell in September 1658, his son Richard Cromwell succeeded him as Lord Protector, summoning the Third Protectorate Parliament in the process. When this parliament was dissolved under pressure from the army in April 1659, the Rump Parliament was recalled at the insistence of the surviving army grandees. This in turn was dissolved in a coup led by army general John Lambert, leading to the formation of the Committee of Safety, dominated by Lambert and his supporters.

When the breakaway forces of George Monck invaded England from Scotland, where they had been stationed without Lambert’s supporters putting up a fight, Monck temporarily recalled the Rump Parliament and reversed Pride’s Purge by recalling the entirety of the Long Parliament. They then voted to dissolve themselves and call new elections, which were arguably the most democratic for 20 years although the franchise was still very small. This led to the calling of the Convention Parliament which was dominated by royalists. This parliament voted to reinstate the monarchy and the House of Lords. Charles II returned to England as king in May 1660. The Anglo-Scottish parliamentary union that Cromwell had established was dissolved in 1661 when the Scottish Parliament resumed its separate meeting place in Edinburgh.

The Restoration began the tradition whereby all governments looked to parliament for legitimacy. In 1681 Charles II dissolved parliament and ruled without them for the last four years of his reign. This followed bitter disagreements between the king and parliament that had occurred between 1679 and 1681. Charles took a big gamble by doing this. He risked the possibility of a military showdown akin to that of 1642. However, he rightly predicted that the nation did not want another civil war. Parliament disbanded without a fight. Events that followed ensured that this would be nothing but a temporary blip.

Charles II died in 1685 and he was succeeded by his brother James II. During his lifetime Charles had always pledged loyalty to the Protestant Church of England, despite his private Catholic sympathies. James was openly Catholic. He attempted to lift restrictions on Catholics taking up public offices. This was bitterly opposed by Protestants in his kingdom. They invited William of Orange,[70] a Protestant who had married Mary, daughter of James II and Anne Hyde to invade England and claim the throne.

William assembled an army estimated at 15,000 soldiers (11,000 foot and 4000 horse)[71] and landed at Brixham in southwest England in November, 1688. When many Protestant officers, including James’s close adviser, John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough, defected from the English army to William’s invasion force, James fled the country. Parliament then offered the Crown to his Protestant daughter Mary, instead of his infant son (James Francis Edward Stuart), who was baptised Catholic. Mary refused the offer, and instead William and Mary ruled jointly, with both having the right to rule alone on the other’s death.

As part of the compromise in allowing William to be King—called the Glorious Revolution—Parliament was able to have the 1689 Bill of Rights enacted. Later the 1701 Act of Settlement was approved. These were statutes that lawfully upheld the prominence of parliament for the first time in English history. These events marked the beginning of the English constitutional monarchy and its role as one of the three elements of parliament.

Union: the Parliament of Great Britain[edit]

After the Treaty of Union in 1707, Acts of Parliament passed in the Parliament of England and the Parliament of Scotland created a new Kingdom of Great Britain and dissolved both parliaments, replacing them with a new Parliament of Great Britain based in the former home of the English parliament. The Parliament of Great Britain later became the Parliament of the United Kingdom in 1801 when the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was formed through the Acts of Union 1800.

Acts of Parliament[edit]

Specific Acts of Parliament can be found at the following articles:

- List of Acts of the Parliament of England to 1483

- List of Acts of the Parliament of England, 1485–1601

- List of Acts of the Parliament of England, 1603–1641

- List of Acts of the Parliament of England, 1642–1660

- List of Acts of the Parliament of England, 1660–1699

- List of Acts of the Parliament of England, 1700–1706

Locations[edit]

Other than London, Parliament was also held in the following cities:

- York, various

- Lincoln, various

- Oxford, 1258 (Mad Parliament), 1681

- Kenilworth, 1266

- Acton Burnell Castle, 1283[72]

- Shrewsbury, 1283 (trial of Dafydd ap Gruffydd), 1397 (‘Great’ Parliament)

- Carlisle, 1307

- Oswestry Castle, 1398

- Northampton 1328

- New Sarum (Salisbury), 1330

- Winchester, 1332, 1449

- Leicester, 1414 (Fire and Faggot Parliament), 1426 (Parliament of Bats)

- Reading Abbey, 1453

- Coventry, 1459 (Parliament of Devils)

See also[edit]

- Duration of English parliaments before 1660

- History of local government in England

- Lex Parliamentaria

- List of English ministries

- List of parliaments of England

- Modus Tenendi Parliamentum

Notes[edit]

- ^ These were small landholders, perhaps owning no more than one or two manors, and were often described as knights in the sources.[6]

- ^ The Bank of England’s inflation calculator estimates that £8,800 in 1275 would be worth £7,547,835.26 in 2022 money.[63]

- ^ The Bank of England’s inflation calculator estimates that £26,828 in 1284 would be worth £24,069,339.27 in 2022 money.[64]

- ^ The Bank of England’s inflation calculator estimates that £750,000 in 1298 would be worth £676,716,265.88 in 2022 money.[65]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c Brand 2009, p. 10.

- ^ Maddicott 2010, pp. 2–6 & 11–12.

- ^ Maddicott 2010, pp. 22, 25–26, 28, 30 & 33.

- ^ Maddicott 2010, pp. 57, 61 & 75.

- ^ Maddicott 2010, pp. 91 & 96.

- ^ Maddicott 2010, p. 83.

- ^ Maddicott 2010, pp. 76–80.

- ^ Huscroft 2016, pp. 47 & 76.

- ^ Maddicott 2009, p. 6.

- ^ Maddicott 2010, pp. 123 & 140–143.

- ^ Lyon 2016, pp. 58 & 62–63.

- ^ Butt 1989, p. 60.

- ^ Maddicott 2009, pp. 6–7.

- ^ Lyon 2016, p. 63.

- ^ Maddicott 2010, p. 152.

- ^ Maddicott 2010, pp. 149–151 & 153.

- ^ Butt 1989, p. 73.

- ^ Maddicott 2010, p. 157.

- ^ Richardson & Sayles 1981, p. I 146.

- ^ Butt 1989, p. 65.

- ^ Maddicott 2010, pp. 162 & 164.

- ^ Maddicott 2009, p. 3.

- ^ Maddicott 2010, p. 187.

- ^ Maddicott 2010, pp. 202, 205 & 208.

- ^ Maddicott 2010, pp. 167–168.

- ^ Butt 1989, pp. 75–77.

- ^ Sayles 1974, p. 40.

- ^ Maddicott 2010, pp. 168–169.

- ^ Maddicott 2010, p. 173.

- ^ Maddicott 2010, p. 178.

- ^ Butt 1989, p. 90.

- ^ Butt 1989, p. 91.

- ^ Maddicott 2010, pp. 174–175.

- ^ Butt 1989, pp. 93–94.

- ^ Sayles 1974, p. 44.

- ^ Maddicott 2010, pp. 216–217.

- ^ Butt 1989, p. 95.

- ^ Maddicott 2010, p. 218.

- ^ Lyon 2016, pp. 67–70.

- ^ Butt 1989, p. 100.

- ^ Maddicott 2010, p. 239.

- ^ Maddicott 2010, pp. 239–240 & 243.

- ^ Butt 1989, pp. 105–106.

- ^ Maddicott 2010, p. 249.

- ^ Butt 1989, p. 107.

- ^ a b Butt 1989, pp. 108–109.

- ^ Maddicott 2010, p. 255.

- ^ Butt 1989, p. 123.

- ^ Sayles 1974, pp. 60 & 63.

- ^ Butt 1989, pp. 113–114.

- ^ Jones 2012, p. 241.

- ^ Butt 1989, p. 117.

- ^ Sayles 1974, p. 71.

- ^ Maddicott 2010, p. 287.

- ^ Jolliffe 1961, p. 331.

- ^ Butt 1989, pp. 121–122.

- ^ Brand 2009, p. 11.

- ^ Maddicott 2010, pp. 287–288.

- ^ a b Maddicott 2010, p. 282.

- ^ a b Lyon 2016, p. 79.

- ^ Maddicott 2010, p. 283.

- ^ Maddicott 2010, pp. 295–296.

- ^ «Inflation Calculator». www.bankofengland.co.uk. Bank of England. 14 December 2022. Retrieved 6 January 2023.

- ^ «Inflation Calculator». www.bankofengland.co.uk. Bank of England. 14 December 2022. Retrieved 6 January 2023.

- ^ «Inflation Calculator». www.bankofengland.co.uk. Bank of England. 14 December 2022. Retrieved 6 January 2023.

- ^ Lyon 2016, pp. 82 & 88.

- ^ Lyon 2016, pp. 88–90.

- ^ Lyon 2016, pp. 90–91.

- ^ Butt 1989, p. xxiii.

- ^ Troost 2005, p. 191.

- ^ Troost 2005, pp. 204–205.

- ^ Virtual Shropshire Archived 30 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine

Bibliography[edit]

- Brand, Paul (2009). «The Development of Parliament, 1215–1307». In Jones, Clyve (ed.). A Short History of Parliament: England, Great Britain, the United Kingdom, Ireland and Scotland. The Boydell Press. pp. 10–15. ISBN 978-1-843-83717-6.

- Butt, Ronald (1989). A History of Parliament: The Middle Ages. London: Constable. ISBN 0-0945-6220-2.

- Huscroft, Richard (2016). Ruling England, 1042–1217 (2nd ed.). Routledge. ISBN 978-1-138-78655-4.

- Jolliffe, J. E. A. (1961). The Constitutional History of Medieval England from the English Settlement to 1485 (4th ed.). Adams and Charles Black.

- Jones, Dan (2012). The Plantagenets: The Warrior Kings and Queens Who Made England (revised ed.). Penguin Books. ISBN 978-1-101-60628-5.

- Lyon, Ann (2016). Constitutional History of the UK (2nd ed.). Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-20398-8.

- Maddicott, John (2009). «Origins and Beginnings to 1215». In Jones, Clyve (ed.). A Short History of Parliament: England, Great Britain, the United Kingdom, Ireland and Scotland. The Boydell Press. pp. 3–9. ISBN 978-1-843-83717-6.

- Maddicott, J. R. (2010). The Origins of the English Parliament, 924-1327. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-199-58550-2.

- Powell, J. Enoch; Wallis, Keith (1968). The House of Lords in the Middle Ages: A History of the English House of Lords to 1540. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 0-2977-6105-6.

- Richardson, H. G.; Sayles, G. O. (1981). The English Parliament in the Middle Ages. London: Hambledon Press. ISBN 0-9506-8821-5.

- Sayles, George O. (1974). The King’s Parliament of England. Historical Controversies. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-3930-9322-0.

- Troost, Wouter (2005). William III, the Stadholder-King: A Political Biography. Translated by Grayson, J. C. Ashgate. ISBN 0-7546-5071-5.

Further reading[edit]

- Blackstone, William (1765). Commentaries on the Laws of England. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Chisholm, Hugh (1911). «Parliament» . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 20 (11th ed.). pp. 835–849.

- Fryde, E. B.; Miller, Edward, eds. (1970). Historical Studies of the English Parliament. Vol. 1, Origins to 1399. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-09610-3.

- Fryde, E. B.; Miller, Edward, eds. (1970). Historical Studies of the English Parliament. Vol. 2, 1399 to 1603. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-09611-1.

- Spufford, Peter (1967). Origins of the English Parliament. Problems and Perspectives in History. Barnes & Noble, Inc.

- Thompson, Faith (1953). A Short History of Parliament: 1295-1642. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 9780816664672. OCLC 646750148.

External links[edit]

- Birth of the English Parliament. UK Parliament

- Parliament and People. British Library

- Origins and growth of Parliament. National Archives

| Parliament of England | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by

Curia regis |

Parliament of England c. 1215–1707 |

Succeeded by

Parliament of Great Britain |

|

Parliament of England |

|

|---|---|

Royal coat of arms of England, 1558–1603 |

|

| Type | |

| Type |

Unicameral |

| Houses | Upper house: House of Lords (1341–1649 / 1660–1707) House of Peers (1657–1660) Lower house: House of Commons (1341–1707) |

| History | |

| Established | c. 1236[1] |

| Disbanded | 1 May 1707 |

| Preceded by | Curia regis |

| Succeeded by | Parliament of Great Britain |

| Leadership | |

|

Lord Keeper of the Great Seal |

William Cowper1 |

|

Speaker of the House of Commons |

John Smith1 |

| Structure | |

|

|

|

House of Commons political groups |

Final composition of the English House of Commons: 513 Seats Tories: 260 seats Whigs: 233 seats Unclassified: 20 seats |

| Elections | |

|

House of Lords voting system |

Ennoblement by the Sovereign or inheritance of an English peerage |

|

House of Commons voting system |

First past the post with limited suffrage1 |

| Meeting place | |

|

|

| Palace of Westminster, Westminster, London | |

| Footnotes | |

| 1Reflecting Parliament as it stood in 1707.

See also: Parliament of Scotland, |

The Parliament of England was the legislature of the Kingdom of England from the 13th century until 1707 when it was replaced by the Parliament of Great Britain. Parliament evolved from the great council of bishops and peers that advised the English monarch. Great councils were first called Parliaments during the reign of Henry III (r. 1216–1272). By this time, the king required Parliament’s consent to levy taxation.

Originally a unicameral body, a bicameral Parliament emerged when its membership was divided into the House of Lords and House of Commons, which included knights of the shire and burgesses. During Henry IV’s time on the throne, the role of Parliament expanded beyond the determination of taxation policy to include the «redress of grievances,» which essentially enabled English citizens to petition the body to address complaints in their local towns and counties. By this time, citizens were given the power to vote to elect their representatives—the burgesses—to the House of Commons.

Over the centuries, the English Parliament progressively limited the power of the English monarchy, a process that arguably culminated in the English Civil War and the High Court of Justice for the trial of Charles I.

Predecessors (pre-13th century)[edit]

Witan[edit]

The origins of Parliament can be traced to the 10th century when a unified Kingdom of England was forged from several smaller kingdoms. In Anglo-Saxon England, the king would hold deliberative assemblies of nobles and prelates called witans. These assemblies numbered anywhere from twenty-five to hundreds of participants, including bishops, abbots, ealdormen, and thegns. Witans met regularly during the three feasts of Christmas, Easter and Whitsun and at other times. In the past, kings interacted with their nobility through royal itineration, but the new kingdom’s size made that impractical. Having nobles come to the king for witans was an important alternative to maintain control of the realm.[2]

Witans served several functions. They appear to have had a role in electing kings, especially in times when the succession was disputed. They were theatrical displays of kingship in that they coincided with crown-wearings. They were also forums for receiving petitions and building consensus among the magnates. Kings dispensed patronage, such as granting bookland, and these were recorded in charters witnessed and consented to by those in attendance. Appointments to offices, such as to bishoprics or ealdormanries, were also made during witans. In addition, important political decisions were made in consultation with witans, such as going to war and making treaties. Witans also helped the king to produce Anglo-Saxon law codes and acted as a court for important cases (such as those involving the king or important magnates).[3]

Magnum Concilium[edit]

After the Norman Conquest of 1066, William the Conqueror (r. 1066–1087) continued the tradition of summoning assemblies of magnates to consider national affairs, conduct state trials, and make laws; although legislation now took the form of writs rather than law codes. These assemblies were called magnum concilium (Latin for «great council»).[4] While kings had access to familiar counsel, this private advice could not replace the need for consensus building, and overreliance on familiar counsel could lead to political instability. Great councils were valued because they «carried fewer political risks, allowed responsibility to be more broadly shared, and drew a larger body of prelates and magnates into the making of decisions».[5]

The council’s members were the king’s tenants-in-chief. The greater tenants, such as archbishops, bishops, abbots, earls, and barons were summoned by individual writ, but sometimes lesser tenants[note 1] were also summoned by sheriffs.[7] Politics in the period following the Conquest (1066–1154) was dominated by about 200 wealthy laymen, in addition to the king and leading clergy. High-ranking churchmen (such as bishops and abbots) were important magnates in their own right. According to Domesday Book, the English church owned between 25% and 33% of all land in 1066.[8]

Traditionally, the great council was not involved in levying taxes. Royal finances derived from land revenues, feudal aids and incidents, and the profits of royal justice. This changed near the end of Henry II’s reign (1154–1189) due to the levying of national taxation to finance the Third Crusade, ransom Richard I, and pay for the series of Anglo-French wars fought between the Plantagenet and Capetian dynasties. In 1188, Henry II set a precedent when he applied to the great council for consent to levy the Saladin tithe.[9]

The burden imposed by national taxation and the likelihood of resistance made consent politically necessary. It was convenient for kings to present the great council of magnates as a representative body capable of consenting on behalf of all within the kingdom. Increasingly, the kingdom was described as the communitas regni (Latin for «community of the realm») and the barons as their natural representatives. But this development also created more conflict between kings and the baronage as the latter attempted to defend what they considered the rights belonging to the king’s subjects.[10]

King John (r. 1199–1216) alienated the barons by his partiality in dispensing justice, heavy financial demands and abusing his right to feudal incidents, reliefs, and aids. In 1215, the barons forced John to abide by a charter of liberties similar to charters issued by earlier kings (see Charter of Liberties).[11] Known as Magna Carta (Latin for «Great Charter»), the charter was based on three assumptions important to the later development of Parliament:[12]

- the king was subject to the law

- the king could only make law and raise taxation (except customary feudal dues) with the consent of the community of the realm

- that the obedience owed by subjects to the king was conditional and not absolute

While the clause stipulating no taxation «without the common counsel» was deleted from later reissues, it was nevertheless adhered to by later kings. Magna Carta transformed the feudal obligation to advise the king into a right to consent. While it was the barons who made the charter, the liberties guaranteed within it were granted to «all the free men of our realm».[13] The charter was promptly repudiated by the king, which led to the First Barons’ War,[14] but Magna Carta would gain the status of fundamental law during the reign of John’s successor.[15]

Early development (1216–1307)[edit]

Henry III and the first parliaments[edit]

Henry III (r. 1216–1272) became king at nine years old after his father, King John, died during the First Barons’ War. During the king’s minority, England was ruled by a regency government that relied heavily on great councils to legitimise its actions. Great councils even consented to the appointment of royal ministers, an action that normally was considered a royal prerogative. Historian John Maddicott writes that the «effect of the minority was thus to make the great council an indispensable part of the country’s government [and] to give it a degree of independent initiative and authority which central assemblies had never previously possessed».[16]

The regency government officially ended when Henry turned sixteen in 1223, and the magnates demanded the adult king confirm previous grants of Magna Carta made in 1216 and 1217 to ensure their legality. At the same time, the king needed money to defend his possessions in Poitou and Gascony from a French invasion. At a great council in 1225, a deal was reached that saw Magna Carta and the Charter of the Forest reissued in return for a fifteenth tax on movable property (personal property and rents). This set a precedent that taxation was granted in return for the redress of grievances.[17]

In the mid-1230s, the word parliament came into common use for meetings of the great council.[18] The word parliament comes from the French parlement first used in the late 11th century with the meaning of parley or conversation (compare to the parlements of Ancien Régime France).[19] It was in Parliament, and with its assent, that the king declared law and where national affairs were deliberated. It granted or refused the king’s request for extraordinary taxation (as opposed to ordinary feudal or customary taxes), and it served as England’s highest court of justice.[20]

After the 1230s, the normal meeting place for Parliament was fixed at Westminster. Parliament tended to meet according to the legal year so that the courts were also in session. It often met in January or February for the Hilary term, in April or May for the Easter term, in July, and in October for the Michaelmas term.[21] In the 13th century, most parliaments had between forty to eighty attendees.[22] Meetings of Parliament always included:[1][23]

- the king

- chief ministers and other ministers (great officers of state, justices of the King’s Bench and Common Bench, and barons of the exchequer)

- members of the king’s council

- ecclesiastical magnates (archbishops, bishops, abbots, priors)

- lay magnates (earls and barons)

Other groups were occasionally summoned. The lesser tenants-in-chief (or knights) were regularly summoned to consent to taxation; though, they were summoned on the basis of their status as tenants of the Crown rather than as representatives of a wider class. The lower clergy (deans, cathedral priors, archdeacons, parish priests) were occasionally summoned when papal taxation was on the agenda. Beginning around the 1220s, the concept of representation, summarised in the Roman law maxim quod omnes tangit ab omnibus approbetur (Latin for «what touches all should be approved by all»), gained new importance among the clergy, and they began choosing proctors to represent them at church assemblies and, when summoned, at Parliament.[24]

Tension over ministers and finances[edit]

In 1232, Peter des Roches became the king’s chief minister. His nephew, Peter de Rivaux, accumulated a large number of offices, including keeper of the privy seal and keeper of the wardrobe; yet, these appointments were not approved by the magnates as had become customary during the regency government. Under Roches, the government revived practices used during King John’s reign and that had been condemned in Magna Carta, such as arbitrary disseisins, revoking perpetual rights granted in royal charters, depriving heirs of their inheritances, and marrying heiresses to foreigners.[25]

Both Roches and Rivaux were foreigners from Poitou. The rise of a royal administration controlled by foreigners and dependent solely on the king stirred resentment among the magnates, who felt excluded from power. Several barons rose in rebellion, and the bishops intervened to persuade the king to change ministers. At a great council in April 1234, the king agreed to remove Rivaux and other ministers. This was the first occasion in which a king was forced to change his ministers by a great council or parliament. The struggle between king and Parliament over ministers became a permanent feature of English politics.[26]

Thereafter, the king ruled in concert with an active Parliament, which considered matters related to foreign policy, taxation, justice, administration, and legislation. January 1236 saw the passage of the Statute of Merton, the first English statute. Among other things, the law continued barring bastards from inheritance. Significantly, the language of the preamble describes the legislation as «provided» by the magnates and «conceded» by the king, which implies that this was not simply a royal measure consented to by the barons.[27][28] In 1237, Henry asked Parliament for a tax to fund his sister Isabella’s dowry. The barons were unenthusiastic, but they granted the funds in return for the king’s promise to reconfirm Magna Carta, add three magnates to his personal council, limit the royal prerogative of purveyance, and protect land tenure rights.[29]

But Henry was adamant that three concerns were exclusively within his royal prerogative: family and inheritance matters, patronage, and appointments. Important decisions were made without consulting Parliament, such as in 1254 when the king accepted the throne of the Kingdom of Sicily for his younger son, Edmund Crouchback.[30] He also clashed with Parliament over appointments to the three great offices of chancellor, justiciar, and treasurer. The barons believed these three offices should be restraints on royal misgovernment, but the king promoted minor officials within the royal household who owed their loyalty exclusively to him.[31]

Parliament’s main tool against the king was to deny consent to national taxation, which they consistently withheld after 1237. Nevertheless, this proved ineffective at restraining the king as he was still able to raise lesser amounts of revenue from sources that did not require parliamentary consent:[32][33]

- county farms (the fixed sum paid annually by sheriffs for the privilege of administering and profiting from royal lands in their counties)

- profits from the eyre

- tallage on the royal demesne, the towns, foreign merchants, and most importantly English Jews

- scutage

- feudal dues and fines

- profits from wardship, escheat, and vacant episcopal sees

In 1253, while fighting in Gascony, Henry requested men and money to resist an anticipated attack from Alfonso X of Castile. In a January 1254 Parliament, the bishops themselves promised an aid but would not commit the rest of the clergy. Likewise, the barons promised to assist the king if he was attacked but would not commit the rest of the laity to pay money.[34] For this reason, the lower clergy of each diocese elected proctors at church synods, and each county elected two knights of the shire. These representatives were summoned to Parliament in April 1254 to consent to taxation.[35] The men elected as shire knights were prominent landholders with experience in local government and as soldiers.[36] They were elected by barons, other knights, and probably freeholders of sufficient standing, illustrating the increasing importance of the gentry as a class.[37] Summoning elected knights to Parliament would not become a regular occurrence until the reign of Edward I. However, the events of 1254 reveal that the barons were no longer viewed as the sole representatives of the realm.[38]

Baronial reform movement[edit]

By 1258, the relationship between the king and the baronage had reached a breaking point over the «Sicilian Business», in which Henry had promised to pay papal debts in return for the pope’s help securing the Sicilian crown for his son, Edmund. At the Oxford Parliament of 1258, reform-minded barons forced a reluctant king to accept a constitutional framework known as the Provisions of Oxford:[39]

- The king was to govern according to the advice of an elected council of fifteen barons.

- The baronial council appointed royal ministers (justiciar, treasurer, chancellor) to serve for one-year terms.

- Parliament met three times a year on the octave of Michaelmas (October 6), Candlemas (February 3), and June 1.

- The barons elected twelve representatives (two bishops, one earl and nine barons) who together with the baronial council could act on legislation and other matters even when Parliament was not in session as «a kind of standing parliamentary committee».[40]

Parliament now met regularly according to a schedule rather than at the pleasure of the king. The reformers hoped that the provisions would ensure parliamentary approval for all major government acts. Under the provisions, Parliament was «established formally (and no longer merely by custom) as the voice of the community».[41]

The theme of reform dominated later parliaments. During the Michaelmas Parliament of 1258, the Ordinance of Sheriffs was issued as letters patent that forbade sheriffs from taking bribes. At the Candlemas Parliament of 1259, the baronial council and the twelve representatives enacted the Ordinance of the Magnates. In this ordinance, the barons promised to observe Magna Carta and other reforming legislation. They also required their own bailiffs to observe similar rules as those of royal sheriffs, and the justiciar was given power to correct abuses of their officials. The Michaelmas Parliament of 1259 enacted the Provisions of Westminster, a set of legal and administrative reforms designed to address grievances of freeholders and even villeins, such as abuses related to the murdrum fine.[42]

Henry III made his first move against the baronial reformers while in France negotiating peace with Louis IX. Using the excuse of his absence from the realm and Welsh attacks in the marches, Henry ordered the justiciar, Hugh Bigod, to postpone the parliament scheduled for Candlemas 1260. This was an apparent violation of the Provisions of Oxford; however, the provisions were silent on what should happen if the king were outside the kingdom. The king’s motive was to prevent the promulgation of further reforms through Parliament. Simon de Montfort, a leader of the baronial reformers, ignored these orders and made plans to hold a parliament in London but was prevented by Bigod. When the king arrived back in England he summoned a parliament which met in July, where Montfort was brought to trial though ultimately cleared of wrongdoing.[43][44]

In April 1261, the pope released the king from his oath to adhere to the Provisions of Oxford, and Henry publicly renounced the Provisions in May. Most of the barons were willing to let the king reassume power provided he ruled well. By 1262, Henry had regained all of his authority, and Montfort left England. The barons were now divided mainly by age. The elder barons remained loyal to the king, but younger barons coalesced around Montfort, who returned to England in the spring of 1263.[45]

Montfortian parliaments[edit]

The royalist barons and rebel barons fought each other in the Second Barons’ War. Montfort defeated the king at the Battle of Lewes in 1264 and became the real ruler of England for the next twelve months. Montfort held a parliament in June 1264 to sanction a new form of government and rally support. This parliament was notable for including knights of the shire who were expected to deliberate fully on political matters, not just assent to taxation.[46]

The June Parliament approved a new constitution in which the king’s powers were given to a council of nine. The new council was chosen and led by three electors (Montfort, Stephen Bersted, Bishop of Chichester, and Gilbert de Clare, 7th Earl of Gloucester). The electors could replace any of the nine as they saw fit, but the electors themselves could only be removed by Parliament.[46][47]

Montfort held two other Parliaments during his time in power. The most famous—Simon de Montfort’s Parliament—was held in January 1265 amidst threat of a French invasion and unrest throughout the realm. For the first time, burgesses (elected by those residents of boroughs or towns who held burgage tenure, such as wealthy merchants or craftsmen)[48] were summoned along with knights of the shire.[49]

Montfort was killed at the Battle of Evesham in 1265, and Henry was restored to power. In August 1266, Parliament authorised the Dictum of Kenilworth, which nullified everything Montfort had done and removed all restraints on the king.[50] In 1267, some of the reforms contained in the 1259 Provisions of Westminster were revised in the form of the Statute of Marlborough passed in 1267. This was the start of a process of statutory reform that continued into the reign of Henry’s successor.[51]

Edward I[edit]

Edward I (r. 1272–1307) learned from the failures of his father’s reign the usefulness of Parliament for building consensus and strengthening royal authority.[52] Parliaments were held regularly throughout his reign, generally twice a year at Easter in the spring and after Michaelmas in the autumn.[53]

Membership continued to include lay and ecclesiastical magnates. However, individuals were no longer summoned exclusively because of their status as tenants-in-chief. It is unclear what principles determined who was summoned, except that the great and powerful needed to be present. The numbers varied. In 1283, 110 lay magnates were summoned but only 41 in 1296. The numbers for heads of religious houses also varied, sometimes as many as 73 were summoned while at other times as few as 44 were called.[54]

As feudalism declined, the shires and boroughs were recognised as communes (Latin communitas) with a unified constituency capable of being represented by shire knights and burgesses in Parliament.[55] Edward summoned knights and burgesses when requesting new taxation. It was important that the representatives of the communes (or «the Commons») report back to their communities that taxes were lawfully granted. This was an acknowledgement of the growing influence and prosperity of the gentry and merchant classes.[56]

Burgesses and shire knights were not regularly summoned until the 1290s,[57] after the so-called «Model Parliament» of 1295. Of the thirty parliaments between 1274 and 1294, knights only attended four and burgesses only two. This is explained by the low level of taxation during the early years of Edward’s reign.[58]

Edward also summoned specialists to Parliament to provide expert advice. For example, Roman law experts were summoned from Cambridge and Oxford to the Norham parliament of 1291 to advise on the disputed Scottish succession. At the Bury St Edmunds parliament of 1296, burgesses «who best know how to plan and lay out a certain new town» were summoned to advise on the rebuilding of Berwick after its capture by the English.[59]

In this period, the first major statutes amending the common law were passed by Parliament:[60][59]

- Statute of Westminster I (1275)

- Statute of Gloucester (1278)

- Statute of Mortmain (1279)

- Statute of Westminster II (1285)

- Statute of Winchester (1285)

- Statute Quia Emptores (1290)

- Statute Quo Warranto (1290)

Laws, however, «were not made by the King in Parliament».[60] The actual work of law-making was done by the king and council, especially the judges. Completed legislation was then presented to Parliament for ratification.[61]