ВАЖНО!

Информацию из данного раздела нельзя использовать для самодиагностики и самолечения. В случае боли или иного обострения заболевания диагностические исследования должен назначать только лечащий врач. Для постановки диагноза и правильного назначения лечения следует обращаться к Вашему лечащему врачу.

Для корректной оценки результатов ваших анализов в динамике предпочтительно делать исследования в одной и той же лаборатории, так как в разных лабораториях для выполнения одноименных анализов могут применяться разные методы исследования и единицы измерения.

Цинга: причины появления, симптомы, диагностика и способы лечения.

Определение

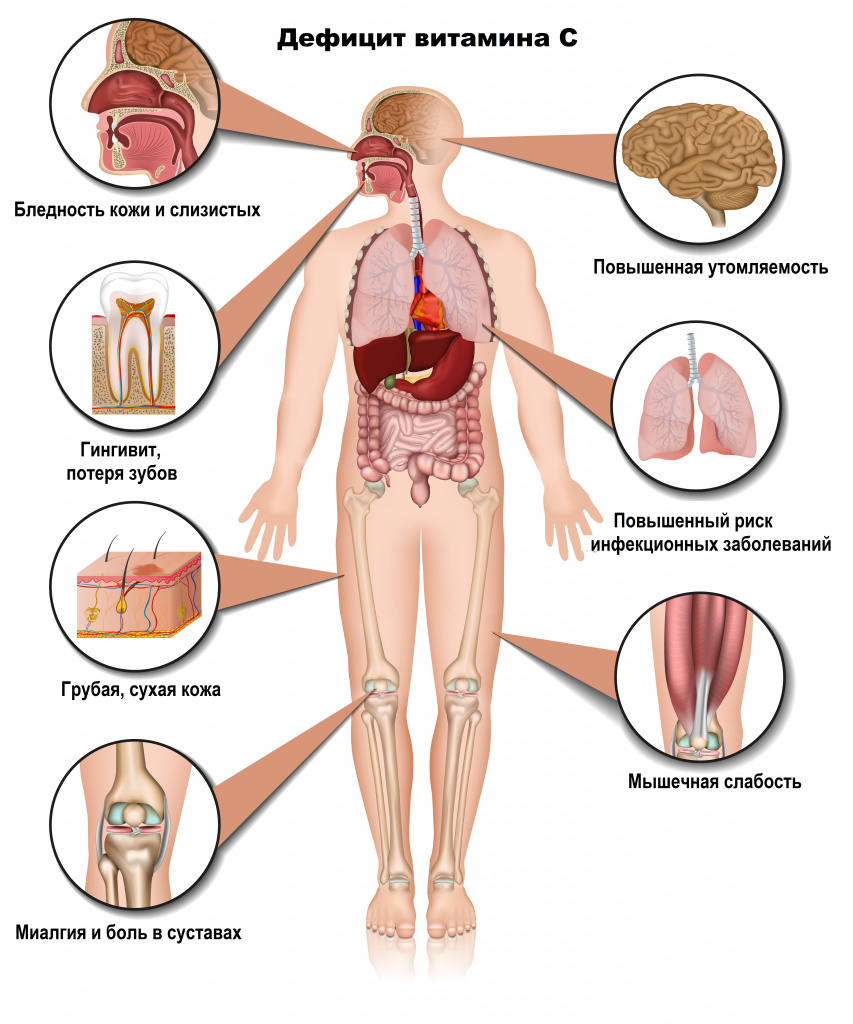

Цинга — это заболевание, развивающееся в результате острого недостатка аскорбиновой кислоты (витамина C) в в организме человека.

Первые зафиксированные случаи цинги относятся ко временам Крестовых походов. По мере развития мореплавания в эпоху географических открытий XVI—XVIII веков заболевание часто распространялось среди моряков, что объяснялось длительными плаваниями и скудным рационом питания. В XVIII веке ученые выяснили причину развития цинги, и с тех пор мореплаватели были обязаны брать с собой на борт достаточный запас цитрусовых. После этого вспышки опасной болезни, конечно, происходили, но их становилось все меньше и меньше.

Причины появления цинги

В наше время цинга стала очень редким заболеванием, единичные случаи фиксируют среди людей, в рационе которых отсутствуют сырые фрукты и овощи.

Авитаминозу С могут способствовать состояния, при которых нарушена всасывающая функция кишечника (синдром мальабсорбции). У грудных детей в редких случаях развивается цинга, если основу их питания составляют кипяченое молоко, молочные консервы и овощные пюре без добавления витамина С.

Классификация заболевания

В МКБ-10 термин «Цинга» употребляется как синоним недостаточности аскорбиновой кислоты.

Выделяют три степени тяжести цинги в зависимости от выраженности клинических проявлений: легкую, среднюю и тяжелую.

Симптомы цинги

Тяжесть проявлений заболевания определяется темпами развития авитаминоза С и его длительностью. Симптомы возникают спустя несколько месяцев после прекращения поступления в организм аскорбиновой кислоты: сначала больные отмечают общую слабость, утомляемость; возможна травматизация десен твердой пищей или зубной щеткой и их кровоточивость.

При цинге первой степени одним из ведущих симптомов заболевания становится утомляемость. Физическая нагрузка приводит к быстрой и выраженной усталости и появлению миалгии (боли в мышцах). Отмечается припухлость десен, пастозность и бледность лица; на коже нижних конечностей и туловища появляются мелкие кровоизлияния, локализующиеся преимущественно вокруг луковиц волос. Обнаруживается умеренная анемия.

На фоне приема аскорбиновой кислоты проявления цинги первой степени быстро исчезают.

Цинга второй степени характеризуется более тяжелым общим состоянием. Заметно общее похудание, вплоть до истощения. Выражен гингивит с гангреной и кровоточивостью десен. Кожа приобретает темный цвет с локальной гиперпигментацией. Отмечаются обширные кровоизлияния в мышцы, в подкожную клетчатку, иногда субпериостальные (рядом с надкостницей) и внутрисуставные кровоизлияния с артропатией (воспалением суставов).

Из-за кровоизлияний в мышцы ног и в суставы пациенты испытывают мучительную боль, значительно ограничивающую передвижение.

При цинге любой степени может наблюдаться субфебрильная (37-38оС) или даже фебрильная лихорадка (38-39оС).

Функция сердца при неосложненной цинге существенно не нарушена; иногда отмечается тахикардия, имеется тенденция к снижению артериального давления.

Для цинги характерно снижение секреторной функции желудка и поражение кишечника с клинической картиной энтероколита, протекающего как осложнение цинги (с язвенным поражением кишечника, кишечными кровотечениями).

У лиц, перенесших цингу второй и третьей степени, нередко формируются контрактуры конечностей и деформации суставов в связи с развитием плотной соединительной ткани в местах бывших кровоизлияний. Эти изменения могут приводить к резкому ограничению функции конечностей, чаще ног.

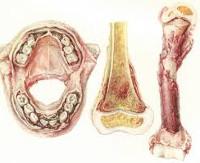

У детей грудного возраста наряду с геморрагическими проявлениями цинги отмечаются нарушения развития скелета — так называемый рахитический скорбут, или болезнь Меллера—Барлоу. Грудной ребенок, заболевший цингой, ослаблен, бледен, из-за болей в мышцах и суставах ребенок плачет, когда его пеленают, берут на руки, вынимают из кровати, купают. Вследствие дефектов процесса окостенения вблизи диафизов костей могут возникать поднадкостничные гематомы (синяки). Движения в конечностях становятся ограниченными и болезненными.

Важный симптом цинги у ребенка – цинготные четки (воспаление в местах костно-хрящевых соединений ребер), которые напоминают четки при рахите, но очень болезненны. Боль усиливается при глубоком вдохе, из-за чего дыхание становится поверхностным.

Диагностика цинги

Диагноз «недостаточность витамина С» устанавливается после лабораторного подтверждения.

Для выявления анемии назначают анализ на ферритин.

Ферритин (Ferritin)

Синонимы: Анализ крови на ферритин; Депонированное железо; Индикатор запасов железа. Serum ferritin.

Краткая характеристика определяемого вещества Ферритин

Ферритин &n…

В клиническом анализе крови у больных цингой выявляют ускорение СОЭ, в неосложненных случаях отмечается нейтропения при нормальном общем содержании лейкоцитов в крови; нейтрофильный лейкоцитоз обычно наблюдается при присоединении инфекционных осложнений.

Определение уровня витамина С в плазме крови.

В общем анализе мочи у пациентов с цингой обнаруживают эритроциты, нередко наблюдается макрогематурия.

Рентгеновское исследование скелета может помочь диагностировать цингу у детей – изменения более очевидны на концах длинных костей.

Если у пациента есть сопутствующая патология, которая могла привести к гиповитаминозу, следует провести соответствующие обследования:

- эзофагогастродуоденоскопию,

Гастроскопия

Исследование слизистой оболочки верхнего отдела желудочно-кишечного тракта с возможностью выполнения биопсии или эндоскопического удаления небольших патологич…

К каким врачам обращаться

Терапию, профилактические и реабилитационные мероприятия назначает

терапевт

или

врач общей практики

. Если болен ребенок –

педиатр

.

Консультация

гастроэнтеролога

необходима при любом подозрении на гиповитаминоз.

После постановки диагноза рекомендована консультация диетолога.

Лечение цинги

Методы лечения определяются клинической картиной, наблюдаемой у пациента. При легкой форме патологии, как правило, достаточно амбулаторного лечения под контролем специалиста. Средняя и тяжелая степени требуют госпитализации.

Диетотерапия остается основным немедикаментозным способом лечения. Врач проводит расчет суточной калорийности пищи, употребляемой пациентом, с учетом его пола, возраста и рода деятельности. Рацион включает продукты, богатые витамином C: листовые овощи, красные плоды, цитрусовые.

Большое количество аскорбиновой кислоты содержится в сухих плодах шиповника: до 1200 мг на 100 г.

Цинга средней и тяжелой степени требует медикаментозной терапии, в ходе которой купируют основные симптомы заболевания. Этиотропное лечение направлено на устранение патологий желудочно-кишечного тракта. На фоне мониторинга лабораторных показателей пациент получает ферменты (панкреатин, энзимы неживотного происхождения), аскорбиновую кислоту (перорально или парентерально).

Симптоматическое лечение направлено на остановку кровотечения. Для этого применяют лекарственные препараты, обладающие гемостатическим (кровоостанавливающим) действием.

Осложнения

При отсутствии лечения на деснах появляются язвы, присоединяется инфекционный процесс, и со временем пациент может потерять все зубы.

Тяжелое течение заболевания способно привести к поражению сердечной мышцы (тампонаде сердца) или головного мозга (кровоизлияние в желудочки).

Цинга может вызвать рецидив хронических заболеваний и ухудшить их течение. Например, на фоне цинги туберкулез приобретает тяжелые формы; снижение иммуннитета проявляется крайне медленным заживлением ран и переломов. Течение любых острых заболеваний (пневмонии, острых кишечных инфекций, ангины и др.) на фоне цинги часто принимает крайне тяжелый характер и обусловливает большинство летальных исходов.

Профилактика цинги

С целью массовой профилактики гиповитаминоза С на предприятиях пищевой промышленности производят продукты, обогащенные аскорбиновой кислотой. В детских учреждениях, а также в родильных домах и больницах проводят обязательную витаминизацию готовой пищи, добавляя аскорбиновую кислоту в первые или третьи блюда с учетом суточной потребности в витамине организма детей, подростков, мужчин, женщин, беременных женщин и кормящих матерей.

Суточная потребность в витамине С у детей первого года жизни составляет 30-40 мг, в возрасте от 1 до 6 лет — 40-50 мг, у детей школьного возраста — 60-75 мг.

Если суточная потребность в витамине не может быть в должной мере обеспечена введением в рацион достаточного количества свежих овощей и фруктов, то необходимо использовать в питании консервированные овощи (щавель, зеленый горошек), компоты, свежезамороженные ягоды (смородину, землянику), отвары из сухих ягод шиповника, а также принимать аскорбиновую кислоту. Дети второго полугодия жизни должны получать аскорбиновую кислоту с продуктами и питательными смесями, используемыми для докорма.

В экстремальных условиях для профилактики цинги могут быть использованы настои и отвары из дикого щавеля, хвои и шишек хвойных деревьев, лесные ягоды (клюква, рябина) и другие растения, содержащие аскорбиновую кислоту.

Источники:

- Чипигина Н.С., Карпова Н.Ю., Большакова М.А., Калинина Т.Ю., Асхабова Э.Д., Юзашарова Л.М., Багманян С.Д., Бадалян К.А., Юцевич О.К. Цинга — забытое заболевание под маской геморрагического васкулита // Архивъ внутренней медицины. – 2017;7 (3): 228-232. DOI: 10.20514/2226-6704-2017-7-3-228-232

- Витамины: учебное пособие для иностранных студентов / О.А. Булавинцева, И.Э. Егорова, ГБОУ ВПО ИГМУ Минздрава России, Кафедра химии и биохимии. – Иркутск : ИГМУ. – 2014. – 41 с.

- Методические руководства. Стандарты лечебного питания. Профильная комиссия по диетологии Экспертного совета в сфере здравоохранения Минздрава России, ФГБУН «Федеральный центр питания и биотехнологий». – 2017. – 313 с.

ВАЖНО!

Информацию из данного раздела нельзя использовать для самодиагностики и самолечения. В случае боли или иного обострения заболевания диагностические исследования должен назначать только лечащий врач. Для постановки диагноза и правильного назначения лечения следует обращаться к Вашему лечащему врачу.

Для корректной оценки результатов ваших анализов в динамике предпочтительно делать исследования в одной и той же лаборатории, так как в разных лабораториях для выполнения одноименных анализов могут применяться разные методы исследования и единицы измерения.

Информация проверена экспертом

Лишова Екатерина Александровна

Высшее медицинское образование, опыт работы — 19 лет

Поделитесь этой статьей сейчас

Рекомендации

-

13792

10 Января

-

13784

10 Января

-

13787

09 Января

Похожие статьи

Кандидозный стоматит

Кандидозный стоматит: причины появления, симптомы, диагностика и способы лечения.

Кровоточивость десен

Кровоточивость десен: причины появления, при каких заболеваниях возникает, диагностика и способы лечения.

Металлический привкус

Металлический привкус во рту может появляться по разным причинам. Обратить внимание на этот симптом необходимо, если он сохраняется после употребления пищи и неоднократно возникает в течение дня.

Кислый привкус во рту

Неприятный кислый привкус во рту может существенно влиять на настроение и аппетит, изменять вкусовое восприятие блюд. Причинами изменения вкуса могут быть изменения в работе желудочно-кишечного тракта и проблемы с зубами.

Цинга – это заболевание группы авитаминозов, служащее клиническим проявлением дефицита витамина C. Основные симптомы – кровоточивость и набухание десен, поражение кожных покровов (сухость, петехии на конечностях с синеватым оттенком), костно-суставной системы (гемартроз, расшатывание зубов c дальнейшим их выпадением). Диагноз устанавливается на основании характерных клинических признаков, анамнестических данных, рентгенологического исследования. Лечение заключается в заместительной терапии аскорбиновой кислотой, соблюдении диеты с достаточным содержанием данного витамина.

Общие сведения

Цинга (скорбут, болезнь Меллера-Барлоу) возникает только при недостатке аскорбиновой кислоты. Ее название происходит от греческой приставки «а», обозначающей отрицание, и латинского корня «scorbutus – «цинга». В 1932 году было доказано противоцинготное действие витамина С. Вплоть до XX века от данного заболевания гибли миллионы человек. В настоящее время цинга встречается редко, в основном среди крайне бедных и неблагополучных слоёв населения с иррациональной культурой питания. Вспышки возможны во время длительных экспедиций, военных действий, в учреждениях закрытого типа. Частота развития и степень тяжести не зависят от возраста и пола.

Цинга

Причины цинги

Аскорбиновая кислота, обладающая множеством биохимических функций, не синтезируется эндогенно в организме человека. Всасывание витамина С происходит в 12-ти перстной кишке, затем он накапливается в железистой ткани (преимущественно в мозговом слое надпочечников и щитовидной железе). Необходимые запасы данного вещества у взрослых составляют около 1500 мг. Причинами возникновения цинги могут являться:

- Нарушение всасывания витамина С. Усвоение аскорбиновой кислоты непосредственно связано с правильной работой желудочно-кишечного тракта. В условиях нарушения пристеночного переваривания (деструктивные изменения кишечного эпителия, например, при глистных инвазиях) и полостного пищеварения (панкреатит, длительная диарея) всасывание витамина снижается или полностью прекращается.

- Недостаточное поступление. Данная причина реализуется при несоблюдении ежедневного разнообразного питания, но она маловероятна, так как аскорбиновая кислота содержится практически во всех овощах, фруктах, ягодах. Суточная потребность составляет 70-100 мг для взрослых и 30-70 мг для детей. При абсолютном дефиците витамина цинга развивается в период от 4-х до 12-ти недель.

Факторы риска

К факторам риска развития цинги относятся беременность и лактация, тяжёлый физический труд, инфекционные болезни, которые приводят к чрезмерной активации симпатоадреналовой системы. В таком состоянии усиливается катаболизм (распад) всех веществ, в том числе – аскорбиновой кислоты. Алкоголизм, табакокурение снижают адаптационные возможности организма, что влечёт за собой увеличение потребности в витамине С.

Патогенез

Витамин С участвует в окислительно-восстановительных процессах, отвечает за синтез и распад многих веществ. При цинге происходят аберрации в механизме образования коллагена – фибриллярного белка, составляющего основу соединительной ткани. При его дефекте тормозится активность остеобластов, нарушается структурирование белковых матриц и, как следствие, снижаются процессы окостенения.

Эндотелиальная выстилка сосудов также представлена коллагеном, который обеспечивает её морфофункциональную целостность и отвечает за процессы гемостаза. В результате дефектов эндотелия увеличивается проницаемость сосудистой стенки, что клинически проявляется кровотечениями различной локализации.

Аскорбиновая кислота принимает участие в образовании гемоглобина, осуществляя переход трёхвалентного железа в двухвалентное, которое становится пригодным для реабсорбции (всасывания). При дефиците железа нарушается цикл образования гема, развивается микроцитарная гипорегенераторная анемия. Недостаток витамина С приводит к снижению активности кофермента тетрагидрофолата, отвечающего за метаболизм фолиевой кислоты. На фоне таких изменений наблюдаются лабораторные признаки мегалобластной анемии.

Классификация

Систематизация форм цинги осуществляется по клиническим проявлениям, этиологическому фактору. Она может быть первичной (экзогенной) – возникающей на фоне алиментарной недостаточности витамина С, вторичной (эндогенной), вызванной повышенной потребностью и нарушением всасывания. По критерию тяжести различают 3 степени:

- Лёгкая. Проявляется слабостью, утомляемостью. При осмотре кожа с бледным оттенком по типу «гусиной» в результате увеличения волосяных луковиц. Характерно поражение слизистой оболочки рта: возникает гиперемия межзубных сосочков, кровоточивость. В дальнейшем припухлость распространяется на всю поверхность дёсен, они становятся разрыхлёнными.

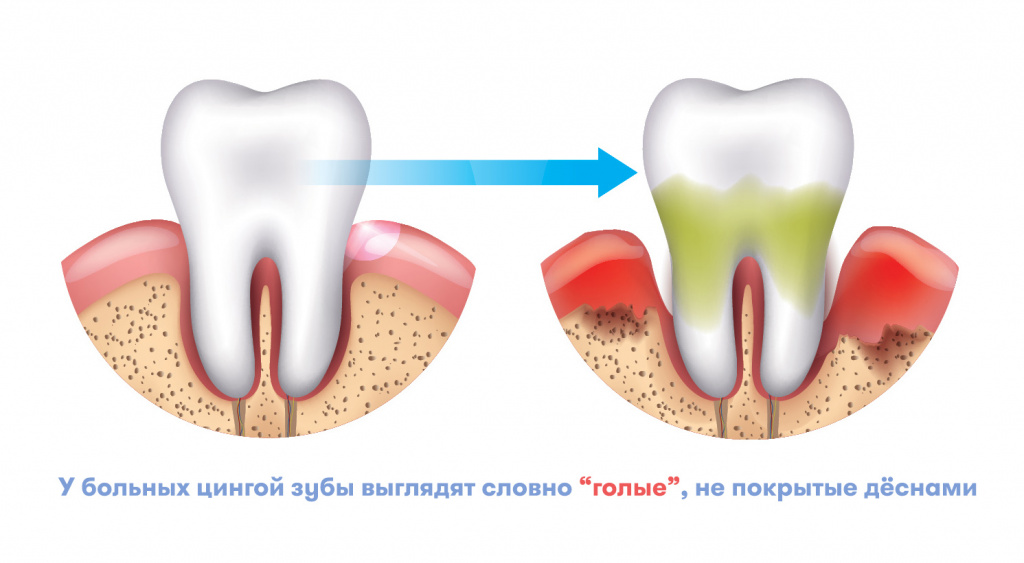

- Средняя. Клинически проявляется болью в мышцах, преимущественно нижних конечностей, гиподинамией. Кожа становится грязно-синего цвета, вокруг волосяных фолликулов визуализируется огромное количество экхимозов – кровоизлияний с диаметром больше 3 мм. Характерно развитие афтозного стоматита, дёсны приобретают сине-багровый оттенок, зубы расшатываются и выпадают.

- Тяжёлая. Развивается резкая слабость, адинамия. Наблюдаются кровоизлияния в серозные полости (перикард, плевру), полость суставов, мышцы. При данной форме возникают язвенный стоматит, гингивит. Часто отмечается артериальная гипотензия, слабость пульса.

Симптомы цинги

Клинические проявление цинги начинаются с общей слабости, утомляемости. Снижение прочности коллагена капилляров и венул служит причиной петехий на конечностях, часто сопровождающихся перифолликулярным гиперкератозом. Отмечаются кровоизлияния в слизистые оболочки (геморрагический пародонтит), толщу мышц, что клинически проявляется миалгией различной степени. При попадании крови в полость сустава развивается характерный для цинги гемартроз, преимущественно коленный. Возникают распирающие боли, сустав увеличивается в объеме, при значительном скоплении геморрагического экссудата наблюдается сглаживание контура.

В результате дефицита Fe2+ в организме происходит снижение уровня железосодержащих ферментов (цитохрома, пероксидазы), что проявляется сидеропеническим синдромом: извращением вкуса, пристрастием к острой, пикантной пище. Развиваются дистрофические изменения ногтей, они становятся тонкими, тусклыми, появляется исчерченность; волосы редеют, легко ломаются. Сниженный уровень железа приводит к анемии с её классической клиникой: головокружение, недомогание, тахикардия.

Изменения эндокринной системы представлены гипофункцией мозгового вещества надпочечников. Дефицит катехоламинов приводит к артериальной гипотензии, нарушению нервной проводимости, усиливая проявления имеющейся анемии. Частые вирусные, бактериальные инфекции возникают на фоне иммуносупрессии, всегда имеющейся при цинге. За счёт угнетения остеогенеза ослабевает фиксация зубов, что приводит к их выпадению.

В раннем детском возрасте цинга проявляется болезнью Меллера-Барлоу. Наблюдаемые нарушения окостенения выражаются деформацией грудной клетки, места перехода хрящевой ткани рёбер в костную утолщаются, образуя «чётки». Отмечаются искривления трубчатых костей, изменения в них приводят к повреждению костного мозга – этим объясняется угнетение гемопоэза и усиление кровоточивости. Как и у взрослых, имеются кожные проявления – кровоизлияния в кожу, слизистые оболочки, носовые кровотечения.

Осложнения

Как правило, осложнения связаны с присоединением вторичной инфекции, так как очаги кровоизлияний являются благоприятной средой для размножения микроорганизмов. На языке, миндалинах образуется гнойный налёт, возникает некроз слизистой оболочки. Дефекты коллагена и геморрагический выпот в суставы сопровождаются контрактурами, анкилозами. В некоторых случаях кровь из сосудов пропотевает в полость перикарда, наблюдается геморрагический перикардит с переходом в тампонаду сердца. Кровоизлияния в желудочки мозга, межоболочечные пространства сопровождаются повышением внутричерепного давлением с риском развития дислокационного синдрома.

Диагностика

Поскольку клинические проявления цинги достаточно специфичны, диагностика не представляет особых трудностей. Обследование проводят врач-гастроэнтеролог, стоматолог и специалисты других профилей в зависимости от картины заболевания. Осложнения цинги представляют реальную угрозу для жизни больного, поэтому необходима своевременная диагностика, которая имеет следующую стадийность:

- Клинический опрос и осмотр. Пациенты жалуются на проявления анемического и геморрагического синдромов: быструю утомляемость, слабость, кровоточивость различной локализации. Анамнез характеризуется наличием хронических заболеваний ЖКТ, отсутствием в рационе продуктов с высоким содержанием витамина С. Кожные покровы бледные с множеством петехий. Определяется кровоточивость десен, расшатывание зубов, деформации костей.

- Инструментальные исследования. При отсутствии чётких данных, указывающих на алиментарную недостаточность витамина С, проводится ФГДС, колоноскопия. При подозрении на панкреатит, гепатит необходимо УЗИ брюшной полости. Для исключения или подтверждения кровоизлияний в серозные и суставные полости применяется рентгенографии ОГК, суставов. Ранним рентгенологическим признаком цинги является общий остеопороз костной ткани.

- Лабораторные исследования. В анализах крови обнаруживаются изменения, характерные для железодефицитной анемии. В копрограмме ‒ признаки мальдигестии, мальабсорбции. Определение концентрации аскорбиновой кислоты в плазме является незаменимым методом в спорных случаях. Референсные значения витамина С в крови составляют 4-20 мкг/мл.

Дифференциальная диагностика

Дифференциальная диагностика требует исключения заболеваний, представленных синдромом геморрагического диатеза:

- врождённых форм дефицита факторов свёртывания крови (гемофилии, болезни Стюарта-Прауэра):

- приобретённых форм – при циррозе печени, геморрагических лихорадках (Крымской, Эбола).

Экссудативный перикардит, возникающий при цинге, необходимо дифференцировать с инфарктом миокарда.

Лечение цинги

Терапевтические мероприятия определяются степенью тяжести цинги. Лечение лёгкой степени проводится под контролем диетолога в амбулаторных условиях с соблюдением рационального питания. Средняя и тяжёлая степени требуют обязательной госпитализации в терапевтический стационар, назначения лечебного питания, постельного режима, коррекции сопутствующих расстройств.

Диетотерапия

Основным немедикаментозным методом лечения цинги является диетотерапия. Она включает обязательный расчёт суточной калорийности, соотношения основных макро-, микронутриентов с учётом возрастно-половых, профессиональных особенностей и соблюдение составленного рациона. Он представлен продуктами, богатыми витамином С, в большинстве своём растительного происхождения: листовые овощи (белокочанная и брюссельская капуста, брокколи), красный плоды (томаты, перец), цитрусовые фрукты. Рекордсмен по содержанию аскорбиновой кислоты — сухой шиповник, в 100 г которого содержится 1200 мг витамина С.

Медикаментозное лечение

При средней и тяжёлой степени тяжести наряду с диетой требуется медикаментозная терапия, целью которой является коррекция обмена витаминов, купирование болевого синдрома и неотложных состояний. Для этого используются лекарственные средства различных фармакологических групп. При цинге применяются следующие виды лечения:

- Этиотропное. Основное медикаментозное воздействие нацелено на лечение заболеваний ЖКТ. Назначаются ферментные препараты, содержащие панкреатин, компоненты желчи и энзимы неживотного происхождения. При глистных инвазиях проводится дегельминтизация в зависимости от вида возбудителя. В случае алиментарной недостаточности витамина С назначается аскорбиновая кислота в таблетках и парентерально в течение 1 месяца.

- Симптоматическое. Терапия направлена на остановку кровотечений: с этой целью применяются хлорид кальция, аминокапроновая и транексамовая кислота. В тяжёлых случаях выполняется переливание эритроцитарной массы, плазмы. Железодефицитная анемия корректируется препаратами железа. При миалгии используются местные и системные НПВС, обладающие достаточным анальгезирующим эффектом.

Прогноз

Своевременно начатая рациональная терапия неосложнённой формы авитаминоза С даёт благоприятные перспективы для жизни, выздоровления и трудоспособности. Прогноз ухудшается при цинге средней и тяжёлой степени, становясь сомнительным в случае массивных кровоизлияний в серозные полости и неблагоприятным при кровоизлиянии в мозг. Присоединение вторичной инфекции, обострение сопутствующих заболеваний существенно ухудшает прогноз.

Профилактика

Основную и главную роль в профилактике гипо-, авитаминоза составляет диета. Немаловажным аспектом является санитарно-просветительская работа, которая заключается в пропаганде здорового образа жизни, консультировании по вопросам рационального и сбалансированного питания. Компенсация соматической патологии ЖКТ, санация очагов хронической инфекции, назначение витаминных комплексов лицам из группы риска представляют собой важнейшие меры, предупреждающие развитие цинги.

Цинга: причины, особенности течения, терапия

До XX века от этой болезни умирали миллионы людей ежегодно. Цинга (скорбут) начиналась обычно с кровоточивости десен, часто преследовала путешественников и узников тюрем. В 1932 году, наконец, обнаружили, что главная ее причина — авитаминоз. Точнее, — острый дефицит аскорбиновой кислоты в организме. В настоящее время патология достаточно изучена и успешно лечится. Большинству она известна из истории и научных источников, но все еще диагностируется у скудно питающихся и страдающих пищеварительными нарушениями людей.

Содержание:

-

Факторы появления цинги

-

Механизм развития и симптомы болезни

-

Диагностика цинги

-

Методы лечения цинги

Факторы появления цинги

Витамин С не синтезируется эндогенно и должен поступать с пищей ежедневно. Во избежание дефицита детям требуется около 40–60 мг, а взрослым — около 100 мг в сутки. При курении, во время беременности, при инфекционных заболеваниях и интенсивных физических нагрузках потребность возрастает в 1,5–2 раза. Запас аскорбинки в течение нескольких суток сохраняется в железистой ткани надпочечников, излишки выводятся почками.

Гиповитаминоз, провоцирующий цингу, развивается по нескольким причинам:

-

нарушение структуры кишечного эпителия;

-

продолжительные диареи;

-

тяжело протекающие глистные инфекции;

-

нарушение выработки пищеварительных ферментов (панкреатит, гастриты).

Во всех этих случаях витамин С, поступающий с пищей, не всасывается в организм, проходя через него транзитом. Это главная причина эндогенной (вторичной) цинги. Недостаток или отсутствие аскорбиновой кислоты в рационе — более редкий фактор патологии. Общеизвестно, что витамин С содержится во всех видах свежих ягод, фруктов, овощей, корнеплодов и зелени. Поэтому к экзогенному авитаминозу и первичной цинге приводит крайне скудное питание, лишенное всех полезных продуктов. Такая ситуация характерна для экстремальных ситуаций и регионов, в которых наблюдается гуманитарная катастрофа.

Механизм развития и симптомы болезни

Недостаток витамина С вызывает появление первых симптомов цинги в течение 4–12 недель. Нарушается всасывание железа, образование гемоглобина, усвоение фолиевой кислоты. Затем следует ряд системных реакций:

-

замедляется белковый обмен;

-

увеличивается проницаемость сосудистых стенок — возникают кровотечения;

-

развивается мегабластная анемия;

-

снижаются процессы восстановления и формирование костных тканей.

В зависимости от времени возникновения и продолжительности различают несколько степеней тяжести болезни:

-

Легкая. Проявляется покраснением слизистой рта, утолщением и разрыхлением десен, кровоточивостью межзубных сосочков. Возможна точечная гиперемия и бледность кожных покровов, физическая слабость, быстрая утомляемость, сонливость.

-

Средняя. Развивается афтозный стоматит: десны и слизистая рта опухают, становятся багровыми, зубы расшатываются, могут выпадать во время еды. Кожа приобретает синюшный оттенок. В области волосяных фолликулов появляются темные очаги кровоизлияний. Резко снижается работоспособность, больные испытывают боли в мышцах, суставах. Возможны спазмы и судороги нижних конечностей, тахикардия.

-

Тяжелая. Внешне проявляется язвенным стоматитом, обильной кровоточивостью десен. Фиксируются также внутренние кровотечения: в полости суставов, плевры. У больных отмечается низкое артериальное давление, они теряют способность передвигаться, испытывают резкую слабость и головокружение. Характерные симптомы цинги на запущенной стадии: резкие распирающие боли в коленях, распухание суставов, остеопороз.

У больных цингой расслаиваются и ломаются ногти, выпадают волосы, появляется тяга к острой пище или различные извращения вкуса. У маленьких детей развивается синдром Меллера-Барлоу:

-

из-за нарушения окостенения скелета искривляются трубчатые кости, возникают сколиозы и кифозы;

-

в местах переходов в костные фрагменты реберные хрящи утолщается, образуя рельефные «четки».

Осложненное течение болезни характеризуется вторичным инфицированием и некрозом слизистых, образованием глубоких язв. Поражение суставов сопровождается ограничением или полной потерей их подвижности. В тяжелых случаях вероятно нарушение внутричерепного давления, смерть от кровоизлияния в головной мозг или геморрагического перикардита.

Диагностика цинги

Предварительный диагноз устанавливается на основе первичного осмотра, жалоб больного, изучения анамнеза. Для подтверждения и установления степени тяжести болезни проводят инструментальные обследования:

-

рентгенографию;

-

УЗИ внутренних органов;

-

ФГДС;

-

колоноскопию.

В лабораторных показателях крови косвенным признаком цинги является железодефицитная анемия. В копрограмме — диагностирование мальабсорбции. Ключевое значение имеет концентрация аскорбиновой кислоты в плазме.

Методы лечения цинги

При легкой форме первичной болезни, спровоцированной дефицитом витамина С в пище применяют диетотерапию. Помогает рацион, обогащенный зелеными овощами, различными видами фруктов и ягод. Лечение дополняют препаратами аскорбиновой кислоты, которые назначают перорально и в форме инъекций.

В зависимости от состояния организма больных проводят сопутствующую терапию соматических нарушений: назначают прием ферментов, противовоспалительных, антимикробных препаратов, НПВС. На начальной стадии проводят амбулаторное лечение. В тяжелых случаях пациентов госпитализируют, применяют инфузионную терапию, переливание плазмы крови.

Прогноз зависит от общего физического состояния, возраста больных и изменений, к которым привела болезнь. Как правило, нарушенные функции кроветворения и обменные процессы восстанавливаются успешно. С трудом поддаются лечению поражения суставов, сердца, мозга, костной системы. Необратимые нарушения чаще характерны для пожилых и страдающих системными патологиями людей.

Цинга – острое заболевание, характеризующееся недостатком или отсутствием в организме человека витамина С (аскорбиновой кислоты).

Причины

Заболевание возникает в результате острого недостатка в организме витамина С. Это приводит к нарушению образования коллагена, который является основным компонентом соединительной ткани, входящей в состав всех органов, выполняя опорную и защитную функцию. Из-за недостатка коллагена соединительная ткань она становится рыхлой и теряет свою прочность.

Главная причина возникновения заболевания – несоблюдение режима питания.

Симптомы цинги

Характерные для цинги симптомы выглядят следующим образом:

- образования геморрагической сыпи (различной интенсивности кровоизлияния на коже);

- кровоточивость десен;

- зубы начинают шататься (возможно даже их выпадение);

- боли в конечностях, суставах;

- частые кровотечения (носовые, из слизистой оболочки рта);

- общая слабость;

- быстрая утомляемость;

- снижение иммунитета;

- сильные отеки.

На поздней стадии заболевания возможны:

- переломы костей;

- примеси крови в стуле;

- резкие боли в животе;

- гангренозный гингивит (отмирание тканей десен);

- кровоизлияния во внутренние органы.

При недостатке витамина С симптомы начинают проявляться спустя 4-6 месяцев. При полном отсутствии витамина С клинические признаки возникают через 1-3 месяца.

Если Вы обнаружили у себя схожие симптомы, незамедлительно обратитесь к врачу. Легче предупредить болезнь, чем бороться с последствиями.

Диагностика

Диагностику заболевания проводит иммунолог. Чтобы установить, как лечить цингу, он:

- проводит анализ жалоб пациента и собирает анамнез;

- назначает общие анализы мочи, крови.

Возможна консультация у диетолога.

Следует исключать заболевания со схожими симптомами, например, заболевания крови.

Лечение цинги

Необходимое для цинги лечение включает в себя:

- препараты с высоким содержанием витамина С (аскорбиновая кислота, комплексные витаминные препараты);

- соблюдение диеты.

Диета

В период лечения пациентам назначается диета, включающая в рацион свежие овощи и фрукты (особенно цитрусовые).

Опасность

Отсутствие своевременного лечения заболевания может привести к осложнениям:

- сепсис;

- сильные кровотечения;

- полиорганная недостаточность;

- гиповитаминоз.

На поздних стадиях возможен летальный исход.

Группа риска

Группу риска составляют:

- асоциальные слои населения;

- участники дальних экспедиций;

- заключенные;

- солдаты армии.

Профилактика

Для заболевания «цинга» профилактика включает в себя:

- рациональное и сбалансированное питание (регулярное употребление в пищу продуктов с высоким содержанием клетчатки (овощи, фрукты) и витамина С (свежие овощи и фрукты, особенно цитрусовые));

- прием препаратов, содержащих витамин С (дозировку и длительность приема назначает врач).

Данная статья размещена исключительно в познавательных целях и не является научным материалом или профессиональным медицинским советом.

| Scurvy | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Moeller’s disease, Cheadle’s disease, scorbutus,[1] Barlow’s disease, hypoascorbemia,[1] vitamin C deficiency |

|

|

| Scorbutic gums, a symptom of scurvy. The triangle-shaped areas between the teeth show redness of the gums. | |

| Specialty | Endocrinology |

| Symptoms | Weakness, feeling tired, changes to hair, sore arms and legs, gum disease, easy bleeding[1][2] |

| Causes | Lack of vitamin C[1] |

| Risk factors | Mental disorders, unusual eating habits, homelessness, alcoholism, substance use disorder, intestinal malabsorption, dialysis,[2] voyages at sea (historic) |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms[2] |

| Treatment | Vitamin C supplements,[1] diet that contains fruit and vegetables (notably citrus) |

| Frequency | Rare (contemporary)[2] |

Scurvy is a disease resulting from a lack of vitamin C (ascorbic acid).[1] Early symptoms of deficiency include weakness, feeling tired and sore arms and legs.[1][2] Without treatment, decreased red blood cells, gum disease, changes to hair, and bleeding from the skin may occur.[1][3] As scurvy worsens there can be poor wound healing, personality changes, and finally death from infection or bleeding.[2]

It takes at least a month of little to no vitamin C in the diet before symptoms occur.[1][2] In modern times, scurvy occurs most commonly in people with mental disorders, unusual eating habits, alcoholism, and older people who live alone.[2] Other risk factors include intestinal malabsorption and dialysis.[2] While many animals produce their own vitamin C, humans and a few others do not.[2] Vitamin C is required to make the building blocks for collagen.[2] Diagnosis is typically based on physical signs, X-rays, and improvement after treatment.[2]

Treatment is with vitamin C supplements taken by mouth.[1] Improvement often begins in a few days with complete recovery in a few weeks.[2] Sources of vitamin C in the diet include citrus fruit and a number of vegetables, including red peppers, broccoli, and tomatoes.[2] Cooking often decreases the residual amount of vitamin C in foods.[2]

Scurvy is rare compared to other nutritional deficiencies.[2] It occurs more often in the developing world in association with malnutrition.[2] Rates among refugees are reported at 5 to 45 percent.[4] Scurvy was described as early as the time of ancient Egypt.[2] It was a limiting factor in long-distance sea travel, often killing large numbers of people.[5] During the Age of Sail, it was assumed that 50 percent of the sailors would die of scurvy on a major trip.[6] A Scottish surgeon in the Royal Navy, James Lind, is generally credited with proving that scurvy can be successfully treated with citrus fruit in 1753.[7] Nevertheless, it was not until 1795 that health reformers such as Gilbert Blane persuaded the Royal Navy to routinely give lemon juice to its sailors.[6][7]

Signs and symptoms[edit]

Early symptoms are malaise and lethargy. After one to three months, patients develop shortness of breath and bone pain. Myalgias may occur because of reduced carnitine production. Other symptoms include skin changes with roughness, easy bruising and petechiae, gum disease, loosening of teeth, poor wound healing, and emotional changes (which may appear before any physical changes). Dry mouth and dry eyes similar to Sjögren’s syndrome may occur. In the late stages, jaundice, generalised edema, oliguria, neuropathy, fever, convulsions, and eventual death are frequently seen.[8]

-

A child presenting a «scorbutic tongue» due to vitamin C deficiency.

-

A child with scurvy in flexion posture.

-

Photo of the chest cage with scorbutic rosaries.

Cause[edit]

Scurvy, including subclinical scurvy, is caused by a deficiency of dietary vitamin C since humans are unable to metabolically synthesize vitamin C. Provided the diet contains sufficient vitamin C, the lack of working L-gulonolactone oxidase (GULO) enzyme has no significance, and in modern Western societies, scurvy is rarely present in adults, although infants and elderly people are affected.[9] Virtually all commercially available baby formulas contain added vitamin C, preventing infantile scurvy. Human breast milk contains sufficient vitamin C, if the mother has an adequate intake. Commercial milk is pasteurized, a heating process that destroys the natural vitamin C content of the milk.[6]

Scurvy is one of the accompanying diseases of malnutrition (other such micronutrient deficiencies are beriberi and pellagra) and thus is still widespread in areas of the world depending on external food aid.[10]

Although rare, there are also documented cases of scurvy due to poor dietary choices by people living in industrialized nations.[11][12][13][14][15]

Pathogenesis[edit]

X-ray of the knee joint (arrow indicates scurvy line).

Vitamins are essential to the production and use of enzymes that are involved in ongoing processes throughout the human body.[6] Ascorbic acid is needed for a variety of biosynthetic pathways, by accelerating hydroxylation and amidation reactions. In the synthesis of collagen, ascorbic acid is required as a cofactor for prolyl hydroxylase and lysyl hydroxylase. These two enzymes are responsible for the hydroxylation of the proline and lysine amino acids in collagen. Hydroxyproline and hydroxylysine are important for stabilizing collagen by cross-linking the propeptides in collagen.

Collagen is a primary structural protein in the human body, necessary for healthy blood vessels, muscle, skin, bone, cartilage, and other connective tissues.

Defective connective tissue leads to fragile capillaries, resulting in abnormal bleeding, bruising, and internal hemorrhaging.

Collagen is an important part of bone, so bone formation is also affected. Teeth loosen, bones break more easily, and once-healed breaks may recur.[6]

Defective collagen fibrillogenesis impairs wound healing.

Untreated scurvy is invariably fatal.[16]

Diagnosis[edit]

Diagnosis is typically based on physical signs, X-rays, and improvement after treatment.[2]

Differential diagnosis[edit]

Various childhood onset disorders can mimic the clinical and X-ray picture of scurvy such as:

- Rickets

- Osteochondrodysplasias especially osteogenesis imperfecta

- Blount’s disease

- Osteomyelitis

Prevention[edit]

| Item | Vitamin C contents (mg) |

|---|---|

| Camu Camu | 2000.00 |

| Amla | 610.00 |

| Urtica | 333.00 |

| Guava | 228.30 |

| Blackcurrant | 181.00 |

| Kiwifruit | 161.30 |

| Chili pepper | 144.00 |

| Parsley | 133.00 |

| Green kiwifruit | 92.70 |

| Broccoli | 89.20 |

| Brussels sprout | 85.00 |

| Bell pepper | 80.40 |

| Papaya | 62.00 |

| Strawberry | 58.80 |

| Orange | 53.20 |

| Lemon | 53.00 |

| Cabbage | 36.60 |

| Spinach | 28.00 |

| Turnip | 27.40 |

| Potato | 19.70 |

Scurvy can be prevented by a diet that includes uncooked vitamin C-rich foods such as amla, bell peppers (sweet peppers), blackcurrants, broccoli, chili peppers, guava, kiwifruit, and parsley. Other sources rich in vitamin C are fruits such as lemons, limes, oranges, papaya, and strawberries. It is also found in vegetables, such as brussels sprouts, cabbage, potatoes, and spinach. Some fruits and vegetables not high in vitamin C may be pickled in lemon juice, which is high in vitamin C. Nutritional supplements which provide ascorbic acid well in excess of what is required to prevent scurvy may cause adverse health effects.[17]

Some animal products, including liver, muktuk (whale skin), oysters, and parts of the central nervous system, including the adrenal medulla, brain, and spinal cord, contain large amounts of vitamin C, and can even be used to treat scurvy.[citation needed] Fresh meat from animals, notably internal organs, contains enough vitamin C to prevent scurvy, and even partly treat it.[18]

Scott’s 1902 Antarctic expedition used lightly fried seal meat and liver, whereby complete recovery from incipient scurvy was reported to have taken less than two weeks.[19]

Treatment[edit]

Scurvy will improve with doses of vitamin C as low as 10 mg per day though doses of around 100 mg per day are typically recommended.[20] Most people make a full recovery within 2 weeks.[21]

History[edit]

Symptoms of scurvy have been recorded in Ancient Egypt as early as 1550 BCE.[22] In Ancient Greece, the physician Hippocrates (460-370 BCE) described symptoms of scurvy, specifically a «swelling and obstruction of the spleen.»[23][24]

In 406 CE, the Chinese monk Faxian wrote that ginger was carried on Chinese ships to prevent scurvy.[25]

The knowledge that consuming foods containing vitamin C is a cure for scurvy has been repeatedly forgotten and rediscovered into the early 20th century.[26][27]

Early modern era[edit]

In the 13th century, the Crusaders frequently developed scurvy. In the 1497 expedition of Vasco da Gama, the curative effects of citrus fruit were already known[27][28] and confirmed by Pedro Álvares Cabral and his crew in 1507.[29]

The Portuguese planted fruit trees and vegetables in Saint Helena, a stopping point for homebound voyages from Asia, and left their sick, who had scurvy and other ailments, to be taken home by the next ship if they recovered.[30]

In 1500, one of the pilots of Cabral’s fleet bound for India noted that in Malindi, its king offered the expedition fresh supplies such as lambs, chickens, and ducks, along with lemons and oranges, due to which «some of our ill were cured of scurvy».[31][32]

Unfortunately, these travel accounts did not stop further maritime tragedies caused by scurvy, first because of the lack of communication between travelers and those responsible for their health, and because fruits and vegetables could not be kept for long on ships.[33]

In 1536, the French explorer Jacques Cartier, exploring the St. Lawrence River, used the local St. Lawrence Iroquoians’ knowledge to save his men who were dying of scurvy. He boiled the needles of the arbor vitae tree (eastern white cedar) to make a tea that was later shown to contain 50 mg of vitamin C per 100 grams.[34][35] Such treatments were not available aboard ship, where the disease was most common. Later, possibly inspired by this incident, several European countries experimented with preparations of various conifers, such as spruce beer, as cures for scurvy.[36]

In February 1601, Captain James Lancaster, while sailing to Sumatra, landed on the northern coast of Madagascar specifically to obtain lemons and oranges for his crew to stop scurvy.[37] Captain Lancaster conducted an experiment using four ships under his command. One ship’s crew received routine doses of lemon juice while the other three ships did not receive any such treatment. As a result, members of the non-treated ships started to contract scurvy, with many dying as a result.[38]

During the Age of Exploration (between 1500 and 1800), it has been estimated that scurvy killed at least two million sailors.[39] Jonathan Lamb wrote: «In 1499, Vasco da Gama lost 116 of his crew of 170; In 1520, Magellan lost 208 out of 230;…all mainly to scurvy.»[40]

In 1579, the Spanish friar and physician Agustin Farfán published a book in which he recommended oranges and lemons for scurvy, a remedy that was already known in the Spanish Navy.[41]

In 1593, Admiral Sir Richard Hawkins advocated drinking orange and lemon juice as a means of preventing scurvy.[42]

A 1609 book by Bartolomé Leonardo de Argensola recorded a number of different remedies for scurvy known at this time in the Moluccas, including a kind of wine mixed with cloves and ginger, and «certain herbs.» The Dutch sailors in the area were said to cure the same disease by drinking lime juice. [43]

In 1614, John Woodall, Surgeon General of the East India Company, published The Surgion’s Mate as a handbook for apprentice surgeons aboard the company’s ships. He repeated the experience of mariners that the cure for scurvy was fresh food or, if not available, oranges, lemons, limes, and tamarinds.[44] He was, however, unable to explain the reason why, and his assertion had no impact on the prevailing opinion of the influential physicians of the age, that scurvy was a digestive complaint.

Apart from ocean travel, even in Europe, until the late Middle Ages, scurvy was common in late winter, when few green vegetables, fruits and root vegetables were available. This gradually improved with the introduction from the Americas of potatoes; by 1800, scurvy was virtually unheard of in Scotland, where it had previously been endemic.[45]: 11

18th century[edit]

James Lind, a pioneer in the field of scurvy prevention

In 2009, a handwritten household book authored by a Cornishwoman in 1707 was discovered in a house in Hasfield, Gloucestershire, containing a «Recp.t for the Scurvy» amongst other largely medicinal and herbal recipes. The recipe consisted of extracts from various plants mixed with a plentiful supply of orange juice, white wine or beer.[46]

In 1734, Leiden-based physician Johann Bachstrom published a book on scurvy in which he stated, «scurvy is solely owing to a total abstinence from fresh vegetable food, and greens; which is alone the primary cause of the disease», and urged the use of fresh fruit and vegetables as a cure.[47][48][49]

It was not until 1747 that James Lind formally demonstrated that scurvy could be treated by supplementing the diet with citrus fruit, in one of the first controlled clinical experiments reported in the history of medicine.[50][51] As a naval surgeon on HMS Salisbury, Lind had compared several suggested scurvy cures: hard cider, vitriol, vinegar, seawater, oranges, lemons, and a mixture of balsam of Peru, garlic, myrrh, mustard seed and radish root. In A Treatise on the Scurvy (1753)[2][52][50]

Lind explained the details of his clinical trial and concluded «the results of all my experiments was, that oranges and lemons were the most effectual remedies for this distemper at sea.»[6][50] However, the experiment and its results occupied only a few paragraphs in a work that was long and complex and had little impact. Lind himself never actively promoted lemon juice as a single ‘cure’. He shared medical opinion at the time that scurvy had multiple causes – notably hard work, bad water, and the consumption of salt meat in a damp atmosphere which inhibited healthful perspiration and normal excretion – and therefore required multiple solutions.[6][53] Lind was also sidetracked by the possibilities of producing a concentrated ‘rob’ of lemon juice by boiling it. This process destroyed the vitamin C and was therefore unsuccessful.[6]

During the 18th century, scurvy killed more British sailors than wartime enemy action. It was mainly by scurvy that George Anson, in his celebrated voyage of 1740–1744, lost nearly two-thirds of his crew (1,300 out of 2,000) within the first 10 months of the voyage.[6][54] The Royal Navy enlisted 184,899 sailors during the Seven Years’ War; 133,708 of these were «missing» or died from disease, and scurvy was the leading cause.[55]

Although throughout this period sailors and naval surgeons were increasingly convinced that citrus fruits could cure scurvy, the classically trained physicians who determined medical policy dismissed this evidence as merely anecdotal, as it did not conform to their theories of disease. Literature championing the cause of citrus juice, therefore, had no practical impact. The medical theory was based on the assumption that scurvy was a disease of internal putrefaction brought on by faulty digestion caused by the hardships of life at sea and the naval diet. Although this basic idea was given different emphases by successive theorists, the remedies they advocated (and which the navy accepted) amounted to little more than the consumption of ‘fizzy drinks’ to activate the digestive system, the most extreme of which was the regular consumption of ‘elixir of vitriol’ – sulphuric acid taken with spirits and barley water, and laced with spices.

In 1764, a new and similarly inaccurate theory on scurvy appeared. Advocated by Dr David MacBride and Sir John Pringle, Surgeon General of the Army and later President of the Royal Society, this idea was that scurvy was the result of a lack of ‘fixed air’ in the tissues which could be prevented by drinking infusions of malt and wort whose fermentation within the body would stimulate digestion and restore the missing gases.[56] These ideas received wide and influential backing, when James Cook set off to circumnavigate the world (1768–1771) in HM Bark Endeavour, malt and wort were top of the list of the remedies he was ordered to investigate. The others were beer, Sauerkraut (a good source of vitamin C) and Lind’s ‘rob’. The list did not include lemons.[57]

Cook did not lose a single man to scurvy, and his report came down in favour of malt and wort, although it is now clear that the reason for the health of his crews on this and other voyages was Cook’s regime of shipboard cleanliness, enforced by strict discipline, as well as frequent replenishment of fresh food and greenstuffs.[58] Another beneficial rule implemented by Cook was his prohibition of the consumption of salt fat skimmed from the ship’s copper boiling pans, then a common practice elsewhere in the Navy. In contact with air, the copper formed compounds that prevented the absorption of vitamins by the intestines.[59]

The first major long distance expedition that experienced virtually no scurvy was that of the Spanish naval officer Alessandro Malaspina, 1789–1794. Malaspina’s medical officer, Pedro González, was convinced that fresh oranges and lemons were essential for preventing scurvy. Only one outbreak occurred, during a 56-day trip across the open sea. Five sailors came down with symptoms, one seriously. After three days at Guam all five were healthy again. Spain’s large empire and many ports of call made it easier to acquire fresh fruit.[60]

Although towards the end of the century MacBride’s theories were being challenged, the medical authorities in Britain remained committed to the notion that scurvy was a disease of internal ‘putrefaction’ and the Sick and Hurt Board, run by administrators, felt obliged to follow its advice. Within the Royal Navy, however, opinion – strengthened by first-hand experience of the use of lemon juice at the siege of Gibraltar and during Admiral Rodney’s expedition to the Caribbean – had become increasingly convinced of its efficacy. This was reinforced by the writings of experts like Gilbert Blane[61] and Thomas Trotter[62] and by the reports of up-and-coming naval commanders.

With the coming of war in 1793, the need to eliminate scurvy acquired a new urgency. But the first initiative came not from the medical establishment but from the admirals. Ordered to lead an expedition against Mauritius, Rear Admiral Gardner was uninterested in the wort, malt and elixir of vitriol which were still being issued to ships of the Royal Navy, and demanded that he be supplied with lemons, to counteract scurvy on the voyage. Members of the Sick and Hurt Board, recently augmented by two practical naval surgeons, supported the request, and the Admiralty ordered that it be done. There was, however, a last minute change of plan, and the expedition against Mauritius was cancelled. On 2 May 1794, only HMS Suffolk and two sloops under Commodore Peter Rainier sailed for the east with an outward bound convoy, but the warships were fully supplied with lemon juice and the sugar with which it had to be mixed.

In March 1795, it was reported that the Suffolk had arrived in India after a four-month voyage without a trace of scurvy and with a crew that was healthier than when it set out. The effect was immediate. Fleet commanders clamoured also to be supplied with lemon juice, and by June the Admiralty acknowledged the groundswell of demand in the navy and agreed to a proposal from the Sick and Hurt Board that lemon juice and sugar should in future be issued as a daily ration to the crews of all warships.[63]

It took a few years before the method of distribution to all ships in the fleet had been perfected and the supply of the huge quantities of lemon juice required to be secured, but by 1800, the system was in place and functioning. This led to a remarkable health improvement among the sailors and consequently played a critical role in gaining the advantage in naval battles against enemies who had yet to introduce the measures.

Scurvy was not only a disease of seafarers. The only colonists of Australia suffered greatly because of the lack of fresh fruit and vegetables in the winter. There the disease was called Spring fever or Spring disease and described an often fatal condition associated with skin lesions, bleeding gums and lethargy. It was eventually identified as scurvy and the remedies already in use at sea implemented.[64]

19th century[edit]

Page from the journal of Henry Walsh Mahon showing the effects of scurvy, from his time aboard HM Convict Ship Barrosa (1841/2)

The surgeon-in-chief of Napoleon’s army at the Siege of Alexandria (1801), Baron Dominique-Jean Larrey, wrote in his memoirs that the consumption of horse meat helped the French to curb an epidemic of scurvy. The meat was cooked but was freshly obtained from young horses bought from Arabs, and was nevertheless effective. This helped to start the 19th-century tradition of horse meat consumption in France.[65]

Lauchlin Rose patented a method used to preserve citrus juice without alcohol in 1867, creating a concentrated drink known as Rose’s lime juice. The Merchant Shipping Act of 1867 required all ships of the Royal Navy and Merchant Navy to provide a daily lime ration of one pound to sailors to prevent scurvy.[66] The product became nearly ubiquitous, hence the term «limey», first for British sailors, then for English immigrants within the former British colonies (particularly America, New Zealand and South Africa), and finally, in old American slang, all British people.[67]

The plant Cochlearia officinalis, also known as «common scurvygrass», acquired its common name from the observation that it cured scurvy, and it was taken on board ships in dried bundles or distilled extracts. Its very bitter taste was usually disguised with herbs and spices; however, this did not prevent scurvygrass drinks and sandwiches from becoming a popular fad in the UK until the middle of the nineteenth century, when citrus fruits became more readily available.[68]

West Indian limes began to supplement lemons, when Spain’s alliance with France against Britain in the Napoleonic Wars made the supply of Mediterranean lemons problematic, and because they were more easily obtained from Britain’s Caribbean colonies[27] and were believed to be more effective because they were more acidic. It was the acid, not the (then-unknown) Vitamin C that was believed to cure scurvy. In fact, the West Indian limes were significantly lower in Vitamin C than the previous lemons and further were not served fresh but rather as lime juice, which had been exposed to light and air, and piped through copper tubing, all of which significantly reduced the Vitamin C. Indeed, a 1918 animal experiment using representative samples of the Navy and Merchant Marine’s lime juice showed that it had virtually no antiscorbutic power at all.[27]

The belief that scurvy was fundamentally a nutritional deficiency, best treated by consumption of fresh food, particularly fresh citrus or fresh meat, was not universal in the 19th and early 20th centuries, and thus sailors and explorers continued to have scurvy into the 20th century. For example, the Belgian Antarctic Expedition of 1897–1899 became seriously affected by scurvy when its leader, Adrien de Gerlache, initially discouraged his men from eating penguin and seal meat.

In the Royal Navy’s Arctic expeditions in the 19th century it was widely believed that scurvy was prevented by good hygiene on board ship, regular exercise, and maintaining the morale of the crew, rather than by a diet of fresh food. Navy expeditions continued to be plagued by scurvy even while fresh (not jerked or tinned) meat was well known as a practical antiscorbutic among civilian whalers and explorers in the Arctic. Criticism also focused on the fact that some of the men most affected by scurvy on Naval polar expeditions had apparently been heavy drinkers, with suggestions that this predisposed them to the condition.[69] Even cooking fresh meat did not entirely destroy its antiscorbutic properties, especially as many cooking methods failed to bring all the meat to high temperature.

The confusion is attributed to a number of factors:[27]

- while fresh citrus (particularly lemons) cured scurvy, lime juice that had been exposed to light, air and copper tubing did not – thus undermining the theory that citrus cured scurvy;

- fresh meat (especially organ meat and raw meat, consumed in arctic exploration) also cured scurvy, undermining the theory that fresh vegetable matter was essential to preventing and curing scurvy;

- increased marine speed via steam shipping, and improved nutrition on land, reduced the incidence of scurvy – and thus the ineffectiveness of copper-piped lime juice compared to fresh lemons was not immediately revealed.

In the resulting confusion, a new hypothesis was proposed, following the new germ theory of disease – that scurvy was caused by ptomaine, a waste product of bacteria, particularly in tainted tinned meat.[70]

Infantile scurvy emerged in the late 19th century because children were being fed pasteurized cow’s milk, particularly in the urban upper class. While pasteurization killed bacteria, it also destroyed vitamin C. This was eventually resolved by supplementing with onion juice or cooked potatoes. Native Americans helped save some newcomers from scurvy by directing them to eat wild onions.[71]

20th century[edit]

By the early 20th century, when Robert Falcon Scott made his first expedition to the Antarctic (1901–1904), the prevailing theory was that scurvy was caused by «ptomaine poisoning», particularly in tinned meat.[72] However, Scott discovered that a diet of fresh meat from Antarctic seals cured scurvy before any fatalities occurred.[73] But while he saw fresh meat as a cure for scurvy, he remained confused about its underlying causes.[74]

In 1907, an animal model which would eventually help to isolate and identify the «antiscorbutic factor» was discovered. Axel Holst and Theodor Frølich, two Norwegian physicians studying shipboard beriberi contracted by ship’s crews in the Norwegian Fishing Fleet, wanted a small test mammal to substitute for the pigeons then used in beriberi research. They fed guinea pigs their test diet of grains and flour, which had earlier produced beriberi in their pigeons, and were surprised when classic scurvy resulted instead. This was a serendipitous choice of animal. Until that time, scurvy had not been observed in any organism apart from humans and had been considered an exclusively human disease. Certain birds, mammals, and fish are susceptible to scurvy, but pigeons are unaffected, since they can synthesize ascorbic acid internally. Holst and Frølich found they could cure scurvy in guinea pigs with the addition of various fresh foods and extracts. This discovery of an animal experimental model for scurvy, which was made even before the essential idea of «vitamins» in foods had been put forward, has been called the single most important piece of vitamin C research.[75]

In 1915, New Zealand troops in the Gallipoli Campaign had a lack of vitamin C in their diet which caused many of the soldiers to contract scurvy. It is thought that scurvy is one of many reasons that the Allied attack on Gallipoli failed.[76]

Vilhjalmur Stefansson, an arctic explorer who had lived among the Inuit, proved that the all-meat diet they consumed did not lead to vitamin deficiencies. He participated in a study in New York’s Bellevue Hospital in February 1928, where he and a companion ate only meat for a year while under close medical observation, yet remained in good health.[77]

In 1927, Hungarian biochemist Albert Szent-Györgyi isolated a compound he called «hexuronic acid».[78] Szent-Györgyi suspected hexuronic acid, which he had isolated from adrenal glands, to be the antiscorbutic agent, but he could not prove it without an animal-deficiency model. In 1932, the connection between hexuronic acid and scurvy was finally proven by American researcher Charles Glen King of the University of Pittsburgh.[79] King’s laboratory was given some hexuronic acid by Szent-Györgyi and soon established that it was the sought-after anti-scorbutic agent. Because of this, hexuronic acid was subsequently renamed ascorbic acid.

21st century[edit]

Rates of scurvy in most of the world are low.[80] Those most commonly affected are malnourished people in the developing world and the homeless.[81] There have been outbreaks of the condition in refugee camps.[82] Case reports in the developing world of those with poorly healing wounds have occurred.[83]

Human trials[edit]

Notable human dietary studies of experimentally induced scurvy were conducted on conscientious objectors during World War II in Britain and in the United States on Iowa state prisoner volunteers in the late 1960s.[84][85] These studies both found that all obvious symptoms of scurvy previously induced by an experimental scorbutic diet with extremely low vitamin C content could be completely reversed by additional vitamin C supplementation of only 10 mg per day. In these experiments, no clinical difference was noted between men given 70 mg vitamin C per day (which produced blood levels of vitamin C of about 0.55 mg/dl, about 1⁄3 of tissue saturation levels), and those given 10 mg per day (which produced lower blood levels). Men in the prison study developed the first signs of scurvy about 4 weeks after starting the vitamin C-free diet, whereas in the British study, six to eight months were required, possibly because the subjects were pre-loaded with a 70 mg/day supplement for six weeks before the scorbutic diet was fed.[84]

Men in both studies, on a diet devoid or nearly devoid of vitamin C, had blood levels of vitamin C too low to be accurately measured when they developed signs of scurvy, and in the Iowa study, at this time were estimated (by labeled vitamin C dilution) to have a body pool of less than 300 mg, with daily turnover of only 2.5 mg/day.[85]

In other animals[edit]

Most animals and plants are able to synthesize vitamin C through a sequence of enzyme-driven steps, which convert monosaccharides to vitamin C. However, some mammals have lost the ability to synthesize vitamin C, notably simians and tarsiers. These make up one of two major primate suborders, haplorrhini, and this group includes humans.[86] The strepsirrhini (non-tarsier prosimians) can make their own vitamin C, and these include lemurs, lorises, pottos, and galagos. Ascorbic acid is also not synthesized by at least two species of caviidae, the capybara[87] and the guinea pig. There are known species of birds and fish that do not synthesize their own vitamin C. All species that do not synthesize ascorbate require it in the diet. Deficiency causes scurvy in humans, and somewhat similar symptoms in other animals.[88][89][90]

Animals that can contract scurvy all lack the L-gulonolactone oxidase (GULO) enzyme, which is required in the last step of vitamin C synthesis. The genomes of these species contain GULO as pseudogenes, which serve as insight into the evolutionary past of the species.[91][92][93]

Name[edit]

In babies, scurvy is sometimes referred to as Barlow’s disease, named after Thomas Barlow,[94] a British physician who described it in 1883.[95] However, Barlow’s disease may also refer to mitral valve prolapse (Barlow’s syndrome), first described by John Brereton Barlow in 1966.[96]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j «Scurvy». GARD. 1 September 2016. Archived from the original on 26 January 2017. Retrieved 26 September 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Agarwal, A; Shaharyar, A; Kumar, A; Bhat, MS; Mishra, M (June 2015). «Scurvy in pediatric age group — A disease often forgotten?». Journal of Clinical Orthopaedics and Trauma. 6 (2): 101–7. doi:10.1016/j.jcot.2014.12.003. PMC 4411344. PMID 25983516.

- ^ «Vitamin C». Office of Dietary Supplements. 11 February 2016. Archived from the original on 30 July 2017. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- ^ Renzaho, Andre M. N. (2016). Globalisation, Migration and Health: Challenges and Opportunities. World Scientific. p. 94. ISBN 978-1-78326-889-4. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- ^ Toler, Pamela D. (2012). Mankind: The Story of All of Us. Running Press. p. 296. ISBN 978-0762447176. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Price, Catherine (2017). «The Age of Scurvy». Distillations. Vol. 3, no. 2. pp. 12–23. Retrieved April 17, 2018.

- ^ a b Hemilä, Harri (29 May 2012). «A Brief History of Vitamin C and its Deficiency, Scurvy». Archived from the original on 9 July 2014. Retrieved 25 May 2014.

- ^ Lynne Goebel, MD. «Scurvy Clinical Presentation». Medscape Reference. Archived from the original on 23 June 2011.

- ^ Hampl JS, Taylor CA, Johnston CS (2004). «Vitamin C deficiency and depletion in the United States: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988 to 1994». American Journal of Public Health. 94 (5): 870–5. doi:10.2105/AJPH.94.5.870. PMC 1448351. PMID 15117714.

- ^ WHO (4 June 2001). «Area of work: nutrition. Progress report 2000» (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 December 2006.

- ^ Davies IJ, Temperley JM (1967). «A case of scurvy in a student». Postgraduate Medical Journal. 43 (502): 549–50. doi:10.1136/pgmj.43.502.539. PMC 2466190. PMID 6074157.

- ^ Sthoeger ZM, Sthoeger D (1991). «[Scurvy from self-imposed diet]». Harefuah (in Hebrew). 120 (6): 332–3. PMID 1879769.

- ^ Ellis CN, Vanderveen EE, Rasmussen JE (1984). «Scurvy. A case caused by peculiar dietary habits». Archives of Dermatology. 120 (9): 1212–4. doi:10.1001/archderm.120.9.1212. PMID 6476860.

- ^ McKenna KE, Dawson JF (1993). «Scurvy occurring in a teenager». Clinical and Experimental Dermatology. 18 (1): 75–7. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.1993.tb00976.x. PMID 8440062. S2CID 42245389.

- ^ Feibel, Carrie (15 August 2016). «The Return of Scurvy? Houston Neurologist Diagnoses Hundreds of Patients with Vitamin Deficiencies». Houston Public Media. University of Houston. Archived from the original on 16 August 2016. Retrieved 2016-08-17.

- ^ «Forgotten Knowledge: The Science of Scurvy». 28 November 2010. Archived from the original on 10 May 2016. Retrieved 29 April 2016.

- ^ Rivers, JM (1987). «Safety of high-level vitamin C ingestion». Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 498 (1 Third Confere): 445–54. Bibcode:1987NYASA.498..445R. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1987.tb23780.x. PMID 3304071. S2CID 1410094.

- ^ Speth, JD (2019). «Neanderthals, vitamin C, and scurvy». Quaternary International. 500: 172–184. Bibcode:2019QuInt.500..172S. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2018.11.042. S2CID 134893835.

- ^ Scott, R.F. (1905). The Voyage of the Discovery. London. pp. 541–545. [26 September 1902] [The expedition members] Heald, Mr. Ferrar, and Cross have very badly swollen legs, whilst Heald’s are discoloured as well. The remainder of the party seem fairly well, but not above suspicion; Walker’s ankles are slightly swollen. [15 October 1902] [After a fresh seal meat diet at base camp] within a fortnight of the outbreak there is scarcely a sign of it remaining […] Heald’s is the only case that hung at all […] and now he is able to get about once more. Cross’s recovery was so rapid that he was able to join the seal-killing party last week.

- ^ Manual of Nutritional Therapeutics. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2008. p. 161. ISBN 9780781768412.

- ^ «Scurvy». nhs.uk. 25 October 2017.

- ^ Bradley S, Buckler MD, Anjali Parish MD (2018-08-27). «Scurvy». EMedicine. Archived from the original on 12 February 2010.

- ^ Hippocrates described symptoms of scurvy in book 2 of his Prorrheticorum and in his Liber de internis affectionibus. (Cited by James Lind, A Treatise on the Scurvy, 3rd ed. (London, England: G. Pearch and W. Woodfall, 1772), page 285 Archived 1 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine) Symptoms of scurvy were also described by: (i) Pliny, in Naturalis historiae, book 3, chapter 49; and (ii) Strabo, in Geographicorum, book 16. (Cited by John Ashhurst, ed., The International Encyclopedia of Surgery, vol. 1 (New York, New York: William Wood and Co., 1881), page 278 Archived 5 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ Stone I (1966). «On the genetic etiology of scurvy». Acta Geneticae Medicae et Gemellologiae (Roma). 15 (4): 345–50. doi:10.1017/s1120962300014931. PMID 5971711. S2CID 32103456. Archived from the original on 10 February 2008.

- ^ Pickersgill, Barbara (2005). Prance, Ghillean; Nesbitt, Mark (eds.). The Cultural History of Plants. Routledge. pp. 163–164. ISBN 0415927463.

- ^ Cegłowski 2010.

- ^ a b c d e Maciej Cegłowski, 2010-03-06, «Scott and Scurvy». Retrieved 2016-05-31.

- ^ As they sailed farther up the east coast of Africa, they met local traders, who traded them fresh oranges. Within 6 days of eating the oranges, da Gama’s crew recovered fully and he noted, «It pleased God in his mercy that … all our sick recovered their health for the air of the place is very good.» Infantile Scurvy: A Historical Perspective Archived 4 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Kumaravel Rajakumar, MD

- ^ «Relação do Piloto Anônimo», narrativa publicada em 1507 sobre a viagem de Pedro Álvares Cabral às Índias, indicava que os «refrescos» oferecidos aos portugueses pelo rei de Melinde eram o remédio eficaz contra a doença (Nava, 2004). A medicina nas caravelas — Século XV Archived 4 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Cristina B. F. M. Gurgel I; Rachel Lewinsohn II, Marujos, Alimentação e Higiene a Bordo

- ^ On returning, Lopes’ ship had left him on St Helena, where with admirable sagacity and industry he planted vegetables and nurseries with which passing ships were marvellously sustained. […] There were ‘wild groves’ of oranges, lemons and other fruits that ripened all the year round, large pomegranates and figs. Santa Helena, A Forgotten Portuguese Discovery Archived 29 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Harold Livermore – Estudos em Homenagem a Luis Antonio de Oliveira Ramos, Faculdade de Letras da Universidade do Porto, 2004, p. 630-631

- ^ Logo que chegámos mandou-nos El Rey visitar e ao mesmo tempo um refresco de carneiros, galinhas, patos, limões e laranjas, as melhores que há no mundo, e com ellas sararam de escorbuto alguns doentes que tinhamos connosco in Portuguese, in Pedro Álvares Cabral, Metzer Leone Editorial Aster, Lisbon, p.244

- ^ Germano de Sousa (2013) História da Medicina Portuguesa Durante a Expansão, Círculo de Leitores, Lisbon, p.129

- ^ Contudo, tais narrativas não impediram que novas tragédias causadas pelo escorbuto assolassem os navegantes, seja pela falta de comunicação entre os viajantes e responsáveis pela sua saúde, ou pela impossibilidade de se disponibilizar de frutas frescas durante as travessias marítimas. A medicina nas caravelas — Século XV Archived 4 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Cristina B. F. M. Gurgel I; Rachel Lewinsohn II, Marujos, Alimentação e Higiene a Bordo

- ^ Jacques Cartier’s Second Voyage Archived 12 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine, 1535 Winter & Scurvy.

- ^ Martini E (2002). «Jacques Cartier witnesses a treatment for scurvy». Vesalius. 8 (1): 2–6. PMID 12422875.

- ^ Durzan, Don J. (2009). «Arginine, scurvy and Cartier’s «tree of life»«. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine. 5: 5. doi:10.1186/1746-4269-5-5. PMC 2647905. PMID 19187550.

- ^ Brown, Mervyn. A history of Madagascar. p. 34.

- ^ Rogers, Everett. Diffusion of Innovations. p. 7.

- ^ Drymon, M. M. (2008). Disguised As the Devil: How Lyme Disease Created Witches and Changed History. Wythe Avenue Press. p. 114. ISBN 978-0-615-20061-3. Archived from the original on 15 May 2016.

- ^ Lamb, Jonathan (2001). Preserving the self in the south seas, 1680–1840. University of Chicago Press. p. 117. ISBN 978-0-226-46849-5. Archived from the original on 24 June 2016.

- ^ «El descubrimiento español de la cura del escorbuto». 2018-02-27.

- ^ Kerr, Gordon (2009). Timeline of Britain. Canary Press.

- ^ Argensola, Bartolomé Leonardo de (1609). Conquista de las Islas Molucas. Madrid: Alonso Martín.

- ^ Bown, Stephen R (2003). Scurvy: How a Surgeon, a Mariner and a Gentleman Solved the Greatest Medical Mystery of the Age of Sail. New York: Viking. ISBN 978-0-312-31391-3.

- ^ «SCURVY and its prevention and control in major emergencies» (PDF). Unhcr.org. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- ^ «Cure for Scurvy discovered by a woman». The Daily Telegraph. 5 March 2009. Archived from the original on 10 March 2009.

- ^ Bartholomew, Michael (2002). «James Lind and scurvy: A revaluation». Journal for Maritime Research. 4 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1080/21533369.2002.9668317. PMID 20355298. S2CID 42109340.

- ^ Johann Friedrich Bachstrom, Observationes circa scorbutum [Observations on scurvy] (Leiden («Lugdunum Batavorum»), Netherlands: Conrad Wishof, 1734) p. 16. From page 16: Archived 1 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine » … sed ex nostra causa optime explicatur, quae est absentia, carentia & abstinentia a vegetabilibus recentibus, … « ( … but [this misfortune] is explained very well by our [supposed] cause, which is the absence of, lack of, and abstinence from fresh vegetables, … )

- ^ «The Blood of Nelson» by Glenn Barnett — Military History — Oct 2006.

- ^ a b c James Lind (1772). A Treatise on the Scurvy: In Three Parts, Containing an Inquiry Into the Nature, Causes, an Cure, of that Disease, Together with a Critical and Chronological View of what Has Been Published on the Subject. S. Crowder (and six others). p. 149.

(Also archived second edition (1757))

- ^ Baron, Jeremy Hugh (2009). «Sailors’ scurvy before and after James Lind — a reassessment». Nutrition Reviews. 67 (6): 315–332. doi:10.1111/j.1753-4887.2009.00205.x. PMID 19519673.

- ^ Lind 1753.

- ^ Bartholomew, M (Jan 2002). «James Lind and Scurvy: a Revaluation». Journal for Maritime Research. 4: 1–14. doi:10.1080/21533369.2002.9668317. PMID 20355298. S2CID 42109340.

- ^ «Captain Cook and the Scourge of Scurvy Archived 21 February 2011 at the Wayback Machine» BBC – History

- ^ A. S. Turberville (2006). «Johnson’s England: An Account of the Life & Manners of His Age«. ISBN READ BOOKS. p.53. ISBN 1-4067-2726-1

- ^ Vale and Edwards (2011). Physician to the Fleet; the Life and Times of Thomas Trotter 1760-1832. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press. pp. 29–33. ISBN 978-1-84383-604-9.

- ^ Stubbs, B. J. (2003). «Captain Cook’s Beer; the anti-scorbutic effects of malt and beer in late 18th century sea voyages». Asia and Pacific Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 12 (2): 129–37. PMID 12810402.

- ^ Fernandez-Armesto, Felipe (2006). Pathfinders: A Global History of Exploration. W.W. Norton & Company. p. 297. ISBN 978-0-393-06259-5.

- ^ «BBC — History — British History in depth: Captain Cook and the Scourge of Scurvy». Bbc.co.uk. Archived from the original on 3 March 2009. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- ^ Fernandez-Armesto, Felipe (2006). Pathfinders: A Global History of Exploration. W.W. Norton & Company. pp. 297–298. ISBN 978-0-393-06259-5.

- ^ Blane, Gilbert (1785). Observations on the diseases incident to seamen. London: Joseph Cooper; Edinburgh: William Creech

- ^ Thomas Trotter; Francis Milman (1786). Observations on the Scurvy: With a Review of the Theories Lately Advanced on that Disease; and the Opinions of Dr Milman Refuted from Practice. Charles Elliott and G.G.J. and J. Robinson, London.