Александр Суворов — биография

Александр Суворов — русский полководец, ставший основоположником российской военной теории, генералиссимус. Награжден всеми известными российскими орденами того времени, и семью иностранными.

Александра Суворова называют великим полководцем, гением военного дела, победным генералиссимусом. Но как бы не звучали эпитеты в его адрес, он был и остается одним из самых великих стратегов в мировой истории. Все шестьдесят боев, в которых принимала участие его армия, закончились безоговорочной победой. Его опыт ведения военных действий уникален, он ни разу не держал оборону, все его сражения были исключительно наступательными. Ему удалось укрепить границы России так, что ни один из агрессоров не рисковал их нарушить.

Помимо воинского таланта, Суворов обладал и высокими моральными качествами. Он чувствовал ответственность за своих солдат, поэтому старался сделать их жизнь хоть немного легче и комфортней. Именно Суворову принадлежит идея обновления обмундирования для военных, их форма стала более удобной и практичной. Кроме этого он стал автором нового устава и правил воспитания.

Он был ярким человеком во всех отношениях, и остался в памяти потомков не только как победитель, но и как неординарный человек.

Детство

Родился Александр Суворов 24 ноября 1730 года в Москве. Его отцом был генерал Василий Суворов, крестник самого великого Петра I. В начале своей карьеры был обычным денщиком, потом занял должность царского переводчика. В годы правления Екатерины II переведен в тайную канцелярию, где за долгие годы службы и выдающиеся заслуги получил звание генерала. Перед самой отставкой был избран сенатором. Маму Александра Суворова звали Авдотья Манукова, ее предки принадлежали к старинному дворянскому роду. Дед Суворова по материнской линии занимал должность вице-президента в Вотчинной коллегии.

Вероятнее всего предками Суворова были не только русские, но и шведы и даже армяне. Согласно семейной легенде родоначальником Суворовых был швед Сувор, получивший русское подданство в 1622 году. А по материнской линии он скорее всего получил в наследство армянскую кровь, потому что ее фамилия на армянском звучит как «ребенок».

Точную дату рождения великого полководца до сих пор устанавливают все мировые историки, и в этом есть часть его вины. Когда он написал свою автобиографию, то указал, что поступил на службу в 1742 году, когда ему исполнилось 15. С помощью простого арифметического действия легко сосчитать, что годом его рождения был 1727-й. Согласно второй записки Суворов родился в 1730-м, а согласно полкового журнала, он родился в 1729 году.

Назвать сына Александром решил его отец, который написал первый в России военный словарь. Свое имя мальчик получил не просто так. Именно древнерусский полководец Александр Невский вдохновил Василия Суворова дать сыну такое же имя. Военным делом мальчик увлекся с детства, этому способствовала шикарнейшая библиотека, которую Василий Суворов собрал в своем имении. Только-только научившись читать, Саша интересовался не детскими сказками и рассказами, а артиллерийским и фортификационным делом. Благо, пособий по этим наукам в библиотеке было более, чем достаточно.

Отец всегда мечтал, что его сын продолжит военную биографию их семьи. Однако глядя на болезненного и хилого отпрыска, не верил, что он сумеет воплотить его мечты в жизнь. Василий решил, что из него получится хороший гражданский служащий. Он даже не предполагал, что в таком хилом теле может жить такой сильный дух, что мальчик уже давно для себя решил продолжить военную карьеру. Будучи подростком, он владел такими знаниями военного дела, которыми не всегда могли похвастаться опытные военные. По этой причине Суворов решил укреплять здоровье, ежедневно, до полного изнеможения, он выполнял физические упражнения.

Во время пребывания в их доме генерала Абрама Ганнибала, Саша развлекал гостя игрой в солдатики. Опытный генерал сумел рассмотреть, насколько грамотными были действия мальчика в отношении ведения «боя», и именно он посоветовал старшему Суворову отдать сына в военные.

Военная служба

Военная карьера Александра Суворова началась в 1742 году, когда его взяли в Семеновский полк мушкетером. Спустя шесть лет, уже в чине офицера, он поступил на действующую военную службу. В те годы Суворов занялся совершенствованием своих знаний в этой области и поэтому записался на курсы Санкт-Петербургского кадетского корпуса. Помимо этого он вплотную занялся изучением иностранных языков.

В самом начале карьеры военного в жизни Суворова произошло событие, о котором он не забывал никогда. Во время несения караульной службы в Петергофе мимо юного Суворова проследовала Елизавета II. Она подошла к молодому военному, поинтересовалась тем, кто его родители, и узнав, что он сын верноподданного ей Суворова, одарила его серебряным рублем. Однако Александр не принял этот дар, сказал, что часовой не имеет права брать деньги во время несения службы. Царица похвалила его за рвение, и оставила рубль на земле у его ног. Она сказала, что он может забрать его после смены караула. Эта монета хранилась у Суворова до самой смерти.

В 1754 году поручик Александр Суворов получил назначение в Ингерманландский полк пехоты. Спустя год он стал служащим Военной коллегии, где находился вплоть до 1758-го. В самом начале Семилетней войны Александр проходил службу в одном из тыловых подразделений. Сразу он был провиантмейстером, прошел весь карьерный путь и стал премьер-майором. Это стало хорошим опытом в изучении работы служб, отвечающих за обеспечение тыла и снабжения армии.

В 1758 году Суворов оказывается в действующей армии. Через год он принял боевое крещение — во главе драгунского эскадрона он сумел разбить такой же эскадрон драгун из Германии. Те с позором бежали.

Это сражение датируется 1759 годом и проходило под Кунесдорфом. Оно знаменито тем, что переломило ход Семилетней войны и стало завершающим аккордом в победе над прусской армией. Зарекомендовав себя как талантливый военный, Суворов получил назначение на должность дежурного офицера при Виллиме Ферморе, который в то время был главнокомандующим. Потом в военной карьере Александра была не менее успешная Берлинская операция.

В 1760 году непосредственным командиром Суворова становится генерал фон Берг. Александра ставят во главе драгунских и гусарских отрядов, которые должны были прикрывать русскую дивизию, отходящую к Бреславлю.

Помимо этого они занимались уничтожением запасов продуктов вражеской армии. В 1762 году Суворову присвоили звание полковника, и он получил в подчинение Астраханский полк. Его усердие в воинской службе не осталось незамеченным императрицей, которая вознаградила его собственным портретом. Именно это время стало настоящим переломом в биографии Суворова, с этого момента он стал знаменитым.

В 1763-1769-м годах Александр Васильевич возглавлял Суздальский полк, местом дислокации которого была Новая Ладога. Именно этими годами датируется написание «Полкового учреждения», своеобразного устава, по которому велась воспитательная работа с солдатами, их боевая подготовка и условия внутренней службы. В 1768 году Суворов удостоился звания бригадир.

Войны

Настоящим полководцем Суворов стал именно во времена правления Екатерины II. Этому способствовали и две Русско-турецкие войны, которые он выиграл. В 1770 году Суворова произвели в генерал-майоры. После того, как он разгромил турков в Туртукайском и Козлуджинском сражениях, ему присвоили звание генерал-поручика. Это были годы, когда непосредственным командиром Суворова был Петр Румянцев. То, что Суворов постепенно становится настоящим полководцем, стало видно во время второй Русско-турецкой войны. В 1788-м имя Суворова прогремело во время битвы за город Кинбурн. Именно там он был впервые серьезно ранен.

Эта победа принесла полководцу серьезную награду, он получил орден Андрея Первозванного. Второе ранение Александр Васильевич получил во время сражения в Очакове, где войска под его руководством штурмовали турецкую крепость. В перерыве между этими двумя войнами Суворов участвовал в подавлении пугачевского бунта. За это он получил персональную награду от императрицы, которая измерялась двумя тысячами червонцев. Осенью 1789-го Суворов снова принимает участие в сражении. В этот раз при Рымнике, когда 25-тысячная армия русско-австрийских военных разгромила превышающее их в четыре раза войско турецкого Юсуф-паши. И снова во главе армии-победителя был непобедимый Суворов.

Эта победа лишний раз продемонстрировала величие русской армии, и стратегическая обстановка выгодно изменилась в пользу России. В 1790-м Суворов снова подтвердил свое звание выдающегося полководца, когда перед ним пала турецкая крепость Измаил, до этого абсолютно неприступная. Это сражение стало историческим, по важности оно не уступает Полтавскому и Бородинскому.

В 1796-м на престол вместо умершей Екатерины взошел Павел I, отношения с которым у Суворова никак не складывались. В 1797 году император издает указ об отставке Александра Васильевича. В начале того года он оказался в ссылке в родовом имении, однако, когда политическая ситуация в Европе накалилась, о нем немедленно вспомнили. Павел Первый получил прошение правителей Британии и Австрии, чтобы он поставил именно Суворова командовать союзными войсками.

Он провел Итальянскую кампанию, причем так, что она до сих пор является гордостью воинского мастерства.

Суворов смог провести несколько блистательных боев, закончившихся сокрушительным разгромом противника. Войска под руководством Суворова вскоре гордо шагали по Милану и Турину, сокрушительное поражение французской армии произошло и на речке Треббия. После этого сражения от вражеской армии осталась половина.

Остатки французской армии под руководством генерала Жубера отправилась на Пьемонт. В августе того же года они оккупировали город Нови-Лигуре. Армия союзников под руководством Суворова приняла этот вызов. Сражение длилось на протяжении восемнадцати часов, французы потерпели полное фиаско. Семь тысяч их солдат навечно остались на этом поле боя. Смерть настигла и командующего Жубера. Это сражение имело решающее значение для окончания Итальянского похода. Император Павел I был просто в шоке от блестящей победы, и отдал распоряжение чтить Суворова на уровне особ императорской фамилии.

В 1799 году Суворов предпринял переход через Альпы, который с тех пор навечно внесен историю побед российского оружия. Император был в полном восхищении, ведь Суворову удалось выйти победителем в сражении с самой природой. После покорения горных хребтов Швейцарии и в память о его былых заслугах, Суворову присваивают звание генералиссимуса. Выше этого звания военная иерархия не знает.

Полководец стал создателем абсолютно новой военной доктрины. Используя личный опыт ведения боя, он сумел создать революционную стратегию и тактику ведения боя. Его книгу под названием «Наука побеждать» держали на столе самые известные русские военные начальники. Среди лучших воспитанников генералиссимуса можно назвать Николая Раевского, Михаила Кутузова, Петра Багратиона. Суворов имеет все существующие высшие военные награды, причем орден Святого Георгия всех 3-х степеней.

Заслуги Суворова отмечены еще при его жизни. В России начали появляться суворовские училища, где растили достойные кадры для армии. Орден Суворова доставался исключительно за проявленный героизм на фронтах Великой Отечественной войны. Имя Александра Суворова носят морские суда, среди которых есть и боевые.

Образ выдающегося полководца импонировал и режиссерам, которые сняли о нем не один десяток картин. Воплощать его роль на экране посчастливилось Юрию Катину-Ярцеву, Николаю Черкасову, Вадиму Демчогу, Валерию Золотухину.

Личная жизнь

Если на полях военных сражений Суворова ждал успех, то в личной жизни он потерпел полное фиаско. Военное ремесло настолько увлекло молодого Суворова, что он посвятил ему лучшие годы, когда приходит любовь, создается семья, рождаются дети. К сорока годам у Суворова не было ничего, кроме службы и побед в военных сражениях. Эта ситуация очень не нравилась его отцу, который и решил заняться устройством личной жизни любимого отпрыска. Он нашел для сына подходящую партию и сумел обвенчать их. В итоге Александр женился на Варваре Прозоровской, 23 лет от роду, дочери обедневших дворян.

В конце 1773-го они помолвились, а в начале следующего года поженились. Они были абсолютно разными — маленький тщедушный 40-летний жених и пышущая здоровьем красавица-невеста.

Но не только внешне они отличались друг от друга. Александр имел отличное образование, он владел пятью языками, тогда как его избранница не могла написать слово, чтобы не сделать в нем ошибку. Ее интересовали исключительно наряды и светские приемы.

В семье царили напряженные отношения. Когда родилась дочь Наталья, они уже ссорились постоянно. Суворов много времени пропадал на войне, а его супруга развлекалась, как могла.

Узнав о том, что супруга ему изменяет, Александр не стал это терпеть и подал прошение развестись. Однако расторжение брака оказалось не таким легким, против него была императрица. Она наградила Суворова очередной медалью и просила оставить все, как есть.

В 1784-м полководец опять заговорил о разводе, причем во всеуслышание назвал имя человека, с которым ему изменяет жена. Но тут родился сын Аркадий, которого Александр не собирался признавать своим. Только спустя двенадцать лет он признал его сыном. Расторгнуть брак снова не удалось, но с тех пор супруги жили каждый своей жизнью. Суворов давал на содержание жены 1200 рублей, дочь отправил на воспитание в Смольный институт и запретил ей встречаться с мамой.

После признания Аркадия своим сыном в 1796 году Александр определил его в юнкера. Сын полководца прожил короткую жизнь, утонул, когда ему исполнилось 26. Однако успел четыре раза сделать Суворова дедом. У дочери Суворова родилось шесть наследников. Суворов и его жена так и прожили каждый в своем одиночестве до самой смерти.

Смерть

После героического перехода через Альпы Суворов серьезно заболел. Вернувшись в свое имение в Кобрине, он слег. А в это время его ждали в Петербурге, чтобы оказать положенные почести. К полководцу направили доктора, который смог поставить его на ноги.

По приезде в Петербург Суворов снова почувствовал резкое недомогание и слег, чтобы больше уже не подняться. 18 мая 1800 года его не стало. На церемонии прощания император отсутствовал. Местом упокоения Александра Суворова стала Благовещенская церковь Александро-Невской лавры.

Ссылки

- Страница в Википедии

Для нас важна актуальность и достоверность информации. Если вы обнаружили ошибку или неточность, пожалуйста, сообщите нам. Выделите ошибку и нажмите сочетание клавиш Ctrl+Enter.

Суворов Александр Васильевич: русский полководец

Полководец, не проигравший ни одного сражения.

Драма в личной жизни и триумф на поле боя.

Александр Васильевич Суворов (1730-1800) — великий русский полководец, основоположник русской военной теории, кавалер не только всех российских орденов своего времени, но и нескольких иностранных.

- Известен тем, что не проиграл ни одного сражения, включая те, где силы противника значительно превосходили российскую армию по численности.

- Участвовал в более, чем 60 сражениях.

- Был не только великим стратегом, но и справедливым человеком. Старался, чтобы солдаты, участвовавшие в боях, имели хорошую униформу, ни в чем не нуждались.

Детство Суворова

Александр Суворов родился в уважаемой семье. Его отец, генерал Василий Суворов приходился крестником самому Петру I. По некоторым источникам он служил в тайной канцелярии и отличался строгостью. Василий Суворов прошел долгий и трудный путь от простого денщика до сенатора. Мать Александра Суворова Авдотья Манукова принадлежала дворянскому роду. Считается, что в роду у будущего великого полководца были шведы и армяне. Свое имя Александр Васильевич получил в честь Александра Невского.

Александр Суворов не отличался крепким здоровьем и телосложением, однако с малых лет был очарован рассказами о военном деле и грезил соответствующей карьерой. Его первыми детскими книгами были не сказки, а труды о военном искусстве. При этом родители, зная о болезненности сына, не питали особых надежда на то, что он сможет продолжить военную династию. Александр Суворов не сдавался. До изнеможения он занимался физическими упражнениями, много читал и продолжать мечтать о военной карьере.

Однажды, когда в доме Суворовых гостил генерал Абрам Ганнибал, маленький Саша стал играть при нем в солдатики. Генерал был поражен точностью действий ребенка и восхитился его стратегией ведения боя.

Военная карьера

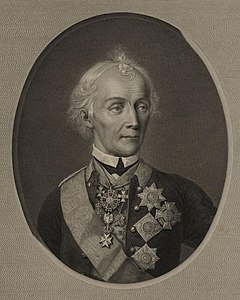

Портрет работы Н. И. Уткина, гравированный с портрета 1800 года. 1818 год.

В 1742 году Суворов стал мушкетером Семеновского полка, где он добился чина офицера. Поступив на военную службу, Суворов записался на курсы Санкт-Петербургского кадетского корпуса и активно учил иностранные языки, зная, что это пригодится для его карьеры.

В 1754 году Александр Васильевич получил опыт работы в тылу. Во время семилетней войны он проходил службу в тыловом подразделении, откуда вышел в должности премьер-майора. Этот опыт одарил его знаниями о том, как должно быть обеспечено снабжение армии.

Победы на поле боя

В 1758 году Суворов получил опыт военных действий. Выступая главой драгунского эскадрона, он разбил эскадрон из Германии в сражении под Кунесдорфом, одержав свою первую победу. Именно эта битва определила дальнейший ход Семилетней войны и поражение прусской армии.

В 1762 году Суворов выступал уже в звании полковника Астраханского полка. Он стал знаменит, его узнавали. В дальнейшем Суворов возглавлял Суздальский полк. Тогда же он написал свой труд «Полковое учреждение» о воспитательной работе с солдатами.

Благодаря навыкам ведения боя Суворова были выиграны две Русско-турецкие войны. В 1770 году он стал генерал-майором.

В 1788 году великий полководец был серьезно ранен в битве за город Кинбурн, но армия все равно одержала победу, а Суворову вручили орден Андрея Первозванного. Известно также, что он помогал подавить Пугачевский бунт, за что получил награду и персональную благодарность от императрицы.

В 1789 году Суворов вновь оказался на поле боя, где русско-австрийская армия разгромила многотысячное турецкое войско, несмотря на то, что Турция имела численное преимущество. В 1790 году Суворов взял турецкую крепость Измаил, считавшуюся абсолютно неприступной.

В 1796 году в жизни Суворова произошел перелом. На престол взошел Павел I, который не так благоволил Александру Васильевичу, как императрица Екатерина. В 1797 году Суворов получил отставку и отправился фактически в ссылку в свое родовое имение. Однако изгнание было недолгим. Политическая обстановка в Европе оказалась напряженной и Суворова призвали возглавить Итальянскую кампанию. Разгром противника и победа были настолько грандиозными, что Павел I изменил свое мнение о Суворове и призвал чтить его на уровне императорских особ.

В 1799 году Суворов вместе с возглавляемой им армией совершил переход через Альпы, оказавшись сильнее самой природы в глазах императора. Тогда же он получил высшее военное звание и стал генералиссимусом.

Свой военный опыт Александр Васильевич Суворов изложил в книге «Наука побеждать», которая стала обязательным чтением для всех военных экспертов и военных начальников.

Переход через Альпы

Жена Александра Суворова

Александр Васильевич Суворов отдавал все силы военному делу. О подходящей партии для него подумал его отец. Василий Суворов сосватал ему молодую дочь обедневших дворян Варвару Прозоровскую. Помолвка состоялась в 1773 году. Суворов был значительно старше невесты, но разнился не только их возраст. У юной Варвары не было такого блестящего образования, она интересовалась больше светскими приемами, что вполне соответствовало образу жизни девушек ее возраста в те времена. Брак нельзя было назвать счастливым, хоть супруги и воспитывали дочь Наталью. Впоследствии у Варвары родился сын Аркадий, которого Суворов отказывался признавать, утверждая, что жена ему неверна. Его прошение о разводе отклонили дважды, но жить с молодой супругой полководец не стал. При этом он выделял средства на воспитание дочери. Однако с матерью общаться запретил, выслав Наталью в Смольный институт.

В 1796 году Суворов все же признал и сына Аркадия. Молодой человек утонул в возрасте 26 лет, и о его судьбе мало что известно.

Смерть русского полководца

Переход через Альпы подорвал здоровье Александра Суворова. Однако его ждали в Петербурге, чтобы оказать военные почести. Там его здоровье настолько ослабло, что Александр Васильевич слег, несмотря на все усилия докторов. 18 мая 1800 года Суворов скончался. Великий русский полководец покоится в Благовещенской церкви Александро-Невской Лавры.

Читайте также:

- Так говорил Суворов

- Имя победы — Суворов

Поскольку вы здесь…

У нас есть небольшая просьба. Эту историю удалось рассказать благодаря поддержке читателей. Даже самое небольшое ежемесячное пожертвование помогает работать редакции и создавать важные материалы для людей.

Сейчас ваша помощь нужна как никогда.

290 лет тому назад родился Александр Васильевич Суворов, один из самых успешных и любимых полководцев в отечественной истории. В эти дни давайте вместе вспомним самые интересные факты из его биографии.

По духу своему Суворов был подлинный «птенец гнезда Петрова», хоть они с Петром Первым и разминулись чуть-чуть в ленте времени. Если бы эта встреча произошла, то они явно поладили бы друг с другом. Государь Петр Алексеевич был дружен и запросто захаживал в гости к деду будущего великого полководца – Ивану Григорьевичу, служившему генеральным писарем лейб-гвардии Преображенского полка (немалая должность в то время!). На карте Москвы, в районе Преображенской площади, есть улица под названием Суворовская, большинство современных горожан думает, что названа она в честь Александра Васильевича, но, на самом деле, она получила название по имени его деда – Ивана;

* Петр I стал крёстным отцом сына Ивана Григорьевича – Василия. И позже следил за судьбой мальчика, определив его в царские денщики. Что влекло за собой и автоматическое зачисление в гвардию. Когда у мальчика обнаружились явные способности к языкам, он был назначен переводчиком. Интересовался техническими науками – изучал инженерное дело, искусство фортификации. Именно в таких юных тянущихся к знаниям мальчишках, видел Петр настоящее будущее России. Известно его письмо, где он предлагал отправить Василия Суворова за границу, чтобы он посмотрел, как «делают каналы, доки, гавани… присмотреться к машинам и …мог бы у тех фабрик учиться». Точных сведений о его зарубежных поездках не сохранилось, но карьеру Василий Иванович сделал достойную – стал генералом, сенатором, известным при дворе человеком;

* Женился Василий на Авдотье Мануковой, происходившей из обрусевшего армянского рода. Отец жены дослужился до вице-президента Вотчинной коллегии, занимался делами дворянского землевладения. После своей смерти оставил дочери дом в районе Арбатских переулков, где, возможно и появился на свет будущий полководец; * Младенец, появившийся на свет 13 ноября (24 ноября) был наречён Александром в честь святого Александра Невского, память которого отмечается 23 ноября; * Мальчиком Саша Суворов был болезненным и слабым. Но зато сильным духом, и уже в раннем детстве пришел к мысли, что «нужно преодолевать себя». Главным врагом он назначил лень, и считал, что «если я буду её побеждать, то мне уже никто страшным не будет»; * Решив следовать спартанскому образу жизни, он приказал убрать прочь все мягкие перины и теплые шубы. Стал заниматься физическими упражнениями. И хоть богатырем не вырос, зато серьезно прибавил себе здоровья и выносливости, а, позднее, и жизненных лет; * Аскетизм стал его второй натурой. Всю свою жизнь он вставал за два часа до рассвета, делал зарядку и обливался холодной водой. Во время утренней пробежки стремился не терять времени — учил и повторял иностранные слова. Уже в зрелые годы случилась с ним забавная история: увидев, как он ходит зимой полураздетым, Екатерина II, опасаясь за его здоровье, отправила ему в подарок роскошную шубу. Узнав, что и этот подарок полководец не носит, при встрече она лично приказала ему не выходить без неё в плохую погоду. Суворов подчинился, но опять по-своему: отправляясь куда-нибудь на лошади или в карете, подаренную шубу имел при себе, но не надевал, а держал рядом, на коленях; * Второй важный шаг, намеченный им ещё в юности – учиться у великих полководцев прошлого. Любимым местом у Саши в доме была библиотека, где он до ночи зачитывался книгами о военных подвигах прошлого. Это был мир великих свершений, гораздо более увлекательный, чем тот, который окружал его в действительности. Как-то раз в гости к отцу – Василию Ивановичу – приехал старинный друг, сподвижник Петра, легендарный генерал Ибрагим Ганнибал – «Арап Петра Великого» и прадед Александр Сергеевича Пушкина. Однажды генерал вошел в библиотеку и с трудом разглядел за стопкой толстенных фолиантов маленького мальчика, увлеченно штудировавшего том по военному искусству. Отметив после разговора проявленные собеседником не по годам знания стратегии и тактики, Ганнибал растроганно прибавил, что вот уж кто порадовался бы такому молодцу, так это Петр Алексеевич! И обязательно держал бы его при себе. А еще именно Ганнибал настоял, чтобы мальчика непременно стали готовить к военной службе, пророчески разглядев в нём задатки выдающегося военачальника;

* Отец учил сына всему, что знал: языкам, математике, военным дисциплинам. Сам он в это время переводил труд выдающегося французского инженера – маркиза де Вобана, посвященный искусству укрепления городов от нападений врага. Вот по этой книге, вместе с отцом юный Александр Суворов и познавал азы фортификации;

* В юности Александр долго колебался, кого именно – Петра Великого или его шведского соперника Карла XII — выбрать в качестве героя для подражания. Фигура Карла интересовала мальчика еще и потому, что в семье была легенда, что род их идет от шведа Сувора, приехавшего на службу к русскому государю после великой Смуты начала XVII века. История типичная — в те времена не только в России, но и других странах было принято выводить свое происхождение от какого-нибудь иноземного предка. Но сегодня более убедительной считается версия, что фамилия Суворовых имеет русское происхождение. В словаре Даля указано, что в сибирском диалекте есть слово «суворый», т. е. суровый, серьезный. Судя по жизни Александра Васильевича, в военных делах фамилия оказалась пророческой. Ну а в остальных, по-разному бывало; * В источниках упоминается один из реальных предков Александра Васильевича – в рассказе про казанский поход 1544 года присутствует Михаил Суворов, служивший при Иване Грозном четвертым воеводою полка правой руки; * Кстати, в «битве героев» в душе юного Александра победил Петр Первый. Мальчик пришел к выводу, что тот сражался для блага государства, тогда как шведский король думал, прежде всего, о личной славе. Уже, будучи знаменитым полководцем часто учил Суворов своих солдат: «Выбери героя, бери пример с него, подражай ему в геройстве, догони его, перегони – слава тебе!» И, самое главное, сам жил по этому принципу! * В самом начале службы в Семеновском полку, молодой Суворов стоял часовым в дворцовом карауле, когда его заметила проходившая мимо императрица Елизавета. Поинтересовавшись, кто он и откуда, и узнав, что он сын генерала Василия Суворова, она дала ему серебряный рубль, но, часовой, к её удивлению, отказался, заявив, что принимать подарки на посту устав не позволяет. Императрице это так понравилось, что она похвалила его за усердие и положила рубль на землю, чтобы взял позже. Эту серебряную монету полководец сохранил на всю жизнь, как свой талисман.

* Принято считать, что Суворов — единственный полководец в истории, выигравший абсолютно все сражения, в которых принимал участие. Это не совсем так – была одна неудача, пусть и не сыгравшая большой роли ни в ходе войны, ни в судьбе полководца. Этой единственной военной «досадой» полководца стали события под польским городком Ланцкороной в феврале 1771 года, когда Суворов не добился успеха в штурме крепости. Но совсем отступать было явно не в его характере. Вскоре он вернулся к городу с новыми силами, и, хотя гарнизон за это время получил подкрепление, полностью решил поставленную боевую задачу; * Его достижения на военном поприще были так велики, что ещё при жизни коллеги по военному делу отзывались о нём исключительно в превосходной степени. «Суворов имеет врагов, но не соперников» — утверждал итальянский генерал Сент-Андре. Австрийцы прозвали его “Генерал Вперёд”, намекая на его «фирменную», всегда успешную тактику, основанную на стремительном натиске. «Герой всех веков и всех народов» — так отозвался о нем австрийский генерал Цах. Австрийцы знали, о чем говорили: весьма неудачливые в самостоятельных боевых действиях, в союзе с Суворовым они всегда одерживали победу. Что не раз отмечал и острый на язык Суворов: «С нами и австрийцы победители!». В другой раз, австрийские военачальники, после совместно выигранной битвы, попросили у Суворова забрать половину пушек. Александр Васильевич тут же решил отдать все. «Мы-то себе новые добудем, а им то, где взять!», — откомментировал он с улыбкой.

* Суворов всю жизнь имел особый дар находить и возвышать таланты. Порой он высказывал удивительные по меркам своей эпохи, созвучные, скорей, времени Петра Первого, мысли, призывая ценить личные качества человека превыше других его жизненных обстоятельств: «Дарование в человеке — бриллиант в глине. Отыскав его, надо тотчас очистить и показать блеск. Талант, выхваченный из толпы, превосходит многих других, ибо он обязан не породе, не учению и не старшинству, а самому себе»;

* Каждого солдата, отличившегося храбростью или другим достойным поступком, он приказывал привести к себе. Так, после сражения при Требии, представили ему солдата Митрофанова, взявшего в плен трех французов и защитившего их от самосуда однополчан, заявив, что простил их совсем. «Пусть и француз знает, что русское слово твердо». Суворов полюбопытствовал, кто же научил его быть великодушным к врагу. И услышал: «Русская азбука — С.Т. (игра слов, в которой обыгрывается название букв «слово», «твердо») и словесное Вашего Сиятельства… поучение. Солдат — христианин, а не разбойник». Обнял его Суворов и тут же произвел в унтер-офицеры;

* Много осталось любопытных свидетельств, касающихся наружности фельдмаршала. Сам он, как считается, не был особенно доволен своей внешностью. Есть легенда, что не терпел в доме зеркал и приказывал их всегда занавесить, где бы ни останавливался. Но современники были далеко не так критичны в оценке его внешности. Один из французских маркизов, перешедших на службу в русскую армию, отмечал, что наружность полководца отлично подходит оригинальности его характера. И пусть он слабого сложения, но взгляд его полон огня и пронизывает насквозь, до самой глубины души. Кстати, роста Суворов, даже по современным меркам, был вполне приличного (от 170 до 175 см). Так что разговоры о его «малости и слабом сложении» слегка преувеличены;

* Гениальный военачальник сохранил на всю жизнь искреннее, почти детское восприятие происходящего. Известно, что многие генералы были недовольны резким взлетом талантливого полководца – в частности, назначением его фельдмаршалом, поскольку сами претендовали на эту должность и были выше его рангом. «Свежеиспеченный» фельдмаршал, получив весть о назначении, расставил в зале стулья и скакал через них, как в детской игре, выкрикивая при этом фамилии генералов, которых оставил не у дел! «Долгорукий — позади, Салтыков- позади!…А мы — впереди!» А если говорить серьезно, то можно отметить, что Суворов знал справедливую цену своим победам: получение фельдмаршальского звания он ожидал ещё в 1790 году, после успешного штурма Измаила. Но в тот раз не случилось. Когда в 1794 году он покорил мятежную Варшаву, то отправил императрице, возможно, самый лаконичный и, уж бесспорно, блестящий военный доклад в истории. Он состоял всего из трех слов: «Ура! Варшава наша!». Екатерина не уступила своему полководцу в краткости и остроумии, ответив со значением: «Ура, фельдмаршал Суворов!»;

* Рассказывали, что великий военачальник любил переодеваться в солдатский мундир и радовался, когда его не узнавали. Один солдат, не признав Суворова во встречном пожилом солдате, даже хотел его поколотить, когда услышал, что тот без почтения отзывается о своем командире (а на самом деле, о себе самом): «где сейчас, никто не знает,наверное, горланит где-то петухом или мертвецки пьян». Еле убежав от грозного защитника-обидчика, Суворов вскоре встретился с ним в штабе. Сержант, с изумлением узнав в «дерзком солдате» великого Суворова, бросился ему в ноги, а тот обнял его и сказал: «Ты доказал любовь ко мне на деле: хотел поколотить меня за меня же!» и от души угостил чаркой водки. * Окружающих поражало наличие у Александра Васильевича глубоких познаний в самых неожиданных областях. На это он отвечал, что всегда ценил и был особенно бережлив с самым дорогим, «драгоценнейшим» сокровищем на земле – временем. Он любил продемонстрировать свою образованность, но только перед теми, кого считал способными оценить её. Рассказывали, что однажды Потемкин услышал, как тонко, умно, с каким глубоким знанием предмета, Суворов говорил с Екатериной. И удивился, почему часто он прикрывается «маской» шутника. В ответ Суворов резонно заметил: «с государыней говорю на её языке, с иными — иным«. * Была ему свойственна бережливость, и в самом прямом смысле слова. Тут, по-видимому, сыграло свою роль отцовское воспитание. Он не терпел никакой роскоши и излишеств ни в чем, сам довольствовался, да и других приучал к простой «полезной» жизни, не чурался хозяйственных вопросов, досконально изучая экономику своих поместий. * Но, главная, достойная всякого подражания и самая ценная для Отечества, черта Суворова – его бережливость в отношении к русскому солдату. Известно, что он всегда стремился избежать излишних потерь. Заботился о солдатской жизни, вникая в мельчайшие детали быта. И ценил тех, кто уже не мог служить – по возрасту или по ранению. Сам выделял из своего кармана на содержание вышедших на пенсию солдат по 10 рублей в год. Это сумма, эквивалентная той, что они получали за действительную армейскую службу. У себя дома он и вовсе организовал пансионат на несколько человек для вышедших в отставку или по ранению;

* Самым жестким образом Суворов пресекал насилие по отношению к местным жителям и военнопленным, независимо от национальности. «Крайне остерегаться и от малейшего грабежа. В поражениях сдающимся в полон давать пощаду» — такие инструкции получали от него подчиненные во время походов; * Едва ли не больше, чем своими легендарными победами, Суворов гордился тем, что за всю карьеру не подписал ни одного смертного приговора. *За свои заслуги генерал Суворов был удостоен всех высших степеней российских орденов, которые мог получить мужчина в восемнадцатом столетии. А также был обладателем коллекции из 7 иностранных наград. В его эпоху такое больше не удалось никому. Получение отличий было чрезвычайно важно для него, так, в письме к дочери — «любезной Наташе-Суворочке» — после очередного награждения орденами Св. Андрея Первозванного и Св. Георгия Первого класса он писал : «Вот каков твой папенька. Чуть, право, от радости не умер».

* В противовес этому, на надгробной плите Суворова не указано никаких титулов и орденов, вся эпитафия состоит из одной фразы — “Здесь лежит Суворов.” Говорят, что ещё при жизни эту строку предложил самому полководцу знаменитый поэт Гаврила Державин, приведя его этим в совершеннейший восторг;

* Как известно, отношения Павла I и Суворова были очень непростыми. И, все же, именно Павел повелел в 1799 году поставить Александру Васильевичу памятник. Еще при жизни, что было редчайшим случаем в российской истории; * Этот памятник Суворову в Ленинграде не закрывали и не убирали даже во время блокады – считали, и совершенно правильно, как показало время, что «Великий победитель» обязательно принесет победу и в этот раз!

Биография Александра Суворова

24 Ноября 1730 – 18 Мая 1800 гг. (69 лет)

4.5

Средняя оценка: 4.5

Всего получено оценок: 2519.

Александр Васильевич Суворов (1730–1800 гг.) – великий полководец, князь Италийский, граф Рымникский, генералиссимус, генерал-фельдмаршал. Обладатель всех русских военных орденов того времени, а также многих иностранных наград. Надолго смог обезопасить страну от агрессии соседей, победил более чем в 60 сражениях.

Опыт работы учителем истории и обществознания — 11 лет.

Ранние годы

Дата и место рождения Александра Суворова достоверно неизвестно, однако многие ученые считают, что он родился 13 (24) ноября 1730 года в Москве в семье генерала. Получил свое имя в честь князя Александра Невского.

Детство его прошло в деревне, в имении отца.

Военная семья еще с детства оставила свой отпечаток на судьбе Суворова. Несмотря на то, что Александр был слабым и часто болеющим ребенком, он хотел стать военным. Суворов стал заниматься изучением военного дела, укреплял свою физическую подготовку. В 1742 году пошел служить в Семеновский полк, где провел 6,5 лет. В это же время обучался в Сухопутном кадетском корпусе, учил иностранные языки, занимался самообразованием. На дальнейшую судьбу Суворова большое влияние оказал генерал Абрам Ганнибал, который был другом семьи Суворовых и прадедом Александра Пушкина.

Краткая биография Суворова для детей и учащихся разных классов представляет собой небольшой, но содержательный и интересный рассказ о его подвигах и заслугах перед Родиной.

Начало военной карьеры

Во время Семилетней войны (1756–1763 гг.) находился в военном тылу (майор, премьер-майор), затем был переведен в действующую армию. Первые военные действия, в которых Суворов принял участие, произошли в июле 1759 года (атаковал немецких драгун). Затем Суворов занимал должность дежурного при главнокомандующем, в 1762 году получил чин полковника, командовал Астраханским и Суздальским полками.

Военные походы

В 1769 – 1772 гг. во время войны с Барской конфедерацией Суворов командовал бригадами нескольких полков. В январе 1770 года Суворову было присвоено звание генерал-майора. Он выиграл несколько битв против поляков, получил свою первую награду – орден Св. Анны (1770 г.).

А в 1772 году награжден самым почетным военным орденом Св. Георгия третьей степени. Польская кампания закончилась победой русских во многом благодаря действиям Суворова.

Во время русско-турецкой войны принял решение захватить гарнизон, за что был осужден, а позже помилован Екатериной II. Затем Суворов оборонял Гирсово, участвовал в бою у Козлуджи. После этого в биографии Александра Суворова наступает период преследования Емельяна Пугачева, восстание которого к тому времени уже подавлено.

В сентябре 1786 года получил звание генерал-аншефа. Во время второй русско-турецкой войны (1787–1792 гг.) полководец Суворов принял участие в Кинбурнской битве, Измаильском сражении, а также битве при Рымнике. В период польского восстания 1794 года войска Суворова штурмовали Прагу. При Павле I полководец выступил в Итальянском походе в 1799 году, затем в Швейцарском походе.

Смерть

В январе 1800 года Суворов по распоряжению Павла I вместе с войском возвращается в Россию. По пути домой он заболел, а 6 (18) мая 1800 года Александр Васильевич Суворов скончался в Санкт-Петербурге. Похоронен великий полководец в Благовещенской церкви Александро-Невской лавры.

Другие варианты биографии

Более сжатая для доклада или сообщения в классе

Вариант 2

Тест по биографии

После прочтения краткой биографии Суворова – обязательно пройдите этот тест:

Доска почёта

Чтобы попасть сюда — пройдите тест.

-

Максим Кормушкин

14/14

-

Иван Сложнев

13/14

-

Надежда Братских

10/14

-

Наталья Тайшина

14/14

-

Даниил Глушко

11/14

-

Наталья Шевцова

7/14

-

Ольга Смирнова

14/14

-

Роман Роман

9/14

-

Артём Теплов

12/14

-

Ольга Федорук

13/14

Оценка по биографии

4.5

Средняя оценка: 4.5

Всего получено оценок: 2519.

А какая ваша оценка за эту биографию?

Александр Суворов.

Александр Васильевич Суворов – один из самых великих полководцев Российской империи XVIII века.

Юность и начало карьеры.

Родился будущий полководец в 1730 году в Москве, в семье военной. Поступил Александр на службу в возрасте 15 лет, но по некоторым источникам в 12 лет.

И в 1742 году поступил Семеновский полк, в 1754 году получил чин поручика. До 1758 года служил в Военной коллегии.

Начало его боевой карьеры относят к Семилетней войне. Многие историки считают, что именно во время боевых действий этого периода и началась распространятся его военная слава.

Заслуги и достижения

Александр Суворов участвовал в около 60 сражениях и ни в одном не проиграл, хотя преимущество противников достигало и в 60 раз больше чем армия Суворова. Суворов принимал решающие и верные решения в критический ситуациях и эти решения вели за собой только позитивные последствия для Российской империи. Александр Васильевич был на службе у Екатерины II и Павла I.

1789 год знаменовался для Суворова великим достижениям, за сражения при р. Рымник, он разгромил 100 тысячную турецкую армию (великий подвиг) и получил за это титул граф Суворов-Рымникский. Здесь полководец продемонстрировал врожденных талант военного теоретика и блистательного стратега. Потери при Рымнике были минимальными, тогда как турки утратили десятки тысяч, а их боевой дух был подорван.

Большие сражения и военные кампании

Одни из самых больших и стратегических сражений и военных кампаний были: (другие значимые подвиги) война с Барной конфедерацией, русско-турецкая войны, Фокшанское сражение (1789 г.), сражение при Рымнике (1789 г.), взятие Измаила (1791 г.), подавление польского восстания (1794 г.) и штурм Праги.

Смерть

Скончался Александр Суворов в два часа дня в Санкт-Петербурге, оставив после себя великое наследия военного дела и стратегии ведения боя. Были также созданы военные суворовские училища и имя полководца носили военные корабли.

Краткий рассказ о Суворове (вариант 2)

Краткий рассказ о Суворове (вариант 3)

|

Field Marshal Generalissimo The Count Suvorov |

|

|---|---|

Alexander Suvorov by Joseph Kreutzinger |

|

| Born | 24 November 1730 Moscow, Moscow Governorate, Russian Empire |

| Died | 18 May 1800 (aged 69) Saint Petersburg, Russian Empire |

| Buried |

Annunciation Church, Alexander Nevsky Lavra, Saint Petersburg |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/branch | |

| Years of service | 1746–1800 |

| Rank | Field Marshal and Generalissimo of the Russian Empire. |

| Battles/wars | Seven Years’ War

War of the Bar Confederation

First Russo-Turkish War

Kuban Nogai Uprising

Kościuszko Uprising

War of the Second Coalition

|

| Awards |

|

Alexander Vasilyevich Suvorov (Russian: Алекса́ндр Васи́льевич Суво́ров, tr. Aleksándr Vasíl’yevich Suvórov, IPA: [ɐlʲɪkˈsandr vɐˈsʲilʲjɪvʲɪtɕ sʊˈvorəf]; 24 November [O.S. 13 November] 1729 or 1730 – 18 May [O.S. 6 May] 1800) was a Russian general in service of the Russian Empire. He was Count of Rymnik, Count of the Holy Roman Empire, Prince of the Kingdom of Sardinia, Prince of the Russian Empire and the last Generalissimo of the Russian Empire. Suvorov is considered one of the greatest military commanders in Russian history and one of the great generals of the early modern period.[1] He was awarded numerous medals, titles, and honors by Russia, as well as by other countries. Suvorov secured Russia’s expanded borders and renewed military prestige and left a legacy of theories on warfare. He was the author of several military manuals, the most famous being The Science of Victory, and was noted for several of his sayings. He never lost a single battle he commanded.[2][3] Several military academies, monuments, villages, museums, and orders in Russia are dedicated to him.

Born in Moscow, he studied military history as a young boy and joined the Imperial Russian Army at the age of 17. During the Seven Years’ War he was promoted to colonel in 1762 for his success on the battlefield. When war broke out with the Bar Confederation in 1768, Suvorov captured Kraków and defeated the Poles at Lanckorona and Stołowicze, bringing about the start of the Partitions of Poland. He was promoted to general and next fought in the Russo-Turkish War of 1768–1774, winning a decisive victory at the Battle of Kozludzha. Becoming the General of the Infantry in 1786, he commanded in the Russo-Turkish War of 1787–1792 and won crushing victories at the Battle of Rymnik and Siege of Izmail.

For his accomplishments, he was made a Count of both the Russian Empire and Holy Roman Empire. Suvorov put down a Polish uprising in 1794, defeating them at the Battle of Maciejowice and storming Warsaw.

While a close associate of Empress Catherine the Great, Suvorov often quarreled with her son and heir apparent, Paul. After Catherine died of a stroke in 1796, Paul I was crowned Emperor and dismissed Suvorov for disregarding his orders. However, he was forced to reinstate Suvorov and make him a field marshal at the insistence of the coalition allies for the French Revolutionary Wars.[4]

Suvorov was given command of the Austro-Russian army, captured Milan, and drove the French out of Italy through his triumphs at Cassano d’Adda, Trebbia, and Novi.[5] Suvorov was made a Prince of Italy for his deeds. Afterwards, he was ordered to head to Switzerland to assist allied operations. He was cut off by André Masséna and later became surrounded in the Swiss Alps by the French after an allied Russo-Austrian army he was supposed to reinforce suffered defeat at Zurich. Suvorov led the strategic withdrawal of Russian troops dealing with French forces four times the size of his own and returned to Russia with minimal casualties.[citation needed] For this exploit, he became the fourth Generalissimo of Russia. He died in 1800 of illness in Saint Petersburg.

Early life and career[edit]

Alexander Suvorov was born into a noble family originating from Novgorod at the Moscow mansion of his maternal grandfather, Fedosey Manukov. His father, Vasiliy Suvorov, was a general-in-chief and a senator in the Governing Senate, and was credited with translating Vauban’s works into Russian.[6] His mother, Avdotya Fyodorovna (née Manukova), was the daughter of Fedosey Manukov. According to a family legend his paternal ancestor named Suvor[7] had emigrated from Karelia, Sweden with his family in 1622 and enlisted at the Russian service to serve Tsar Mikhail Feodorovich (his descendants became Suvorovs).[8][6] Suvorov himself narrated for the record the historical account of his family to his aide, colonel Anthing, telling particularly that his Swedish-born ancestor was of noble descent, having engaged under the Russian banner in the wars against the Tatars and Poles. These exploits were rewarded by Tsars with lands and peasants.[9] This version, however, was questioned recently by prominent Russian linguists, professors Nikolay Baskakov and Alexandra Superanskaya [ru], who pointed out that the word Suvorov more likely comes from the ancient Russian male name Suvor based on the adjective suvory, an equivalent of surovy, which means «severe» in Russian. Baskakov also pointed to the fact that the Suvorovs’ family coat of arms lacks any Swedish symbols, implying its Russian origins.[10] Among the first of those who pointed to the Russian origin of the name were Empress Catherine II, who noted in a letter to Johann von Zimmerman in 1790: «It is beyond doubt that the name of the Suvorovs has long been noble, is Russian from time immemorial and resides in Russia», and Count Semyon Vorontsov in 1811, a person familiar with the Suvorovs.[11] Their views were supported by later historians: it was estimated that by 1699 there were at least 19 Russian landlord families of the same name in Russia, not counting their namesakes of lower status, and they all could not descend from a single foreigner who arrived only in 1622.[11] Moreover, genealogy studies indicated a Russian landowner named Suvor mentioned under the year 1498, whereas documents of the 16th century mention Vasily and Savely Suvorovs, with the last of them being a proven ancestor of General Alexander Suvorov.[11] The Swedish version of Suvorov’s genealogy had been debunked in the Genealogical book of Russian nobility by V. Rummel and V. Golubtsov (1887) tracing Suvorov’s ancestors from the 17th-century Tver gentry.[12] In 1756 Alexander Suvorov’s first cousin, Sergey Ivanovich Suvorov, in his statement of background (skazka) for his son said that he did not have any proof of nobility; he started his genealogy from his great-grandfather, Grigory Ivanovich Suvorov, who ‘served as a dvorovoy boyar scion at Kashin.[12]

As a boy, Suvorov was a sickly child and his father assumed he would work in civil service as an adult. However, he proved to be an excellent learner, avidly studying mathematics, literature, philosophy, and geography, learning to read French, German, Polish, and Italian, and with his father’s vast library devoted himself to intense study of military history, strategy, tactics, and several military authors including Plutarch, Quintus Curtius, Cornelius Nepos, Julius Caesar, and Charles XII. This also helped him develop a good understanding of engineering, siege warfare, artillery, and fortification.[5] He tried to overcome his physical ailments through rigorous exercise and exposure to hardship.[13] His father, however, insisted that he was not fit for the military. When Alexander was 12, General Gannibal, who lived in the neighborhood, overheard his father complaining about Alexander and asked to speak to the child. Gannibal was so impressed with the boy that he persuaded the father to allow him to pursue the career of his choice.[6]

Suvorov entered the army in 1748 and served in the Semyonovsky Life Guard Regiment for six years. During this period he continued his studies attending classes at Cadet Corps of Land Forces. He gained his first battle experience fighting against the Prussians during the Seven Years’ War (1756–1763). After repeatedly distinguishing himself in battle Suvorov became a colonel in 1762, aged around 33.

Suvorov next served in Poland during the Confederation of Bar, dispersed the Polish forces under Pułaski, and captured Kraków (1768), paving the way for the first partition of Poland between Austria, Prussia and Russia,[14] and reached the rank of major-general.

The Russo-Turkish War of 1768–1774 saw his first successful campaigns against the Turks in 1773–1774, and particularly in the Battle of Kozluca, he laid the foundations of his reputation, becoming a lieutenant-general in 1774. His later earned victories against the Ottomans bolstered the morale of his soldiers who were usually outnumbered. His astuteness in war was uncanny and he also proved a self-willed subordinate who acted upon his own initiative. For «unauthorized actions against the Turks,» Suvorov was tried and sentenced to death but Tsarina Catherine the Great refused to uphold the verdict, proclaiming «winners can’t be judged.»[13]

In 1774, Suvorov was dispatched to suppress Pugachev’s Rebellion, whose leader claimed to be the assassinated Tsar Peter III. Suvorov arrived at the scene only in time to conduct the first interrogation of the rebel leader, who had been betrayed by his fellow Cossacks and was eventually beheaded in Moscow. The next year, he married into the influential Golitsyn family.[5]

Battles against the Ottoman Empire[edit]

From 1774 to 1786, Suvorov served in the Kuban, the Crimea, the Caucasus, Finland, and Russia itself. He became General of the Infantry in 1786, upon completion of his tour of duty in the Caucasus. In 1778, he prevented a Turkish landing in the Crimea, thwarting another Russo-Turkish war.[5] He commanded the Russian troops in the Crimea from 1782 to 1784. In 1783 he suppressed the Kuban Nogai Uprising. On behalf of Empress Catherine II, he organized the resettlement of Armenian migrants displaced from Crimea and gave them permission to establish a new city, named Nor Nakhichevan by the Armenians.

From 1787 to 1791 he again fought the Turks during the Russo-Turkish War of 1787–1792 and won many victories; he was wounded twice at Kinburn (1787), took part in the siege of Ochakov, and in 1789 won two great victories at Focșani and by the river Rymnik, where a Russo-Austrian force of 25,000 routed 100,000 Turks within a few hours, losing only 500 men in the process. In both these battles an Austrian corps under Prince Josias of Saxe-Coburg participated, but at the battle of Rymnik, Suvorov was in command of the whole allied forces. For the latter victory, Catherine the Great made Suvorov a count with the name «Rymniksky» in addition to his own name, and the Emperor Joseph II made him a count of the Holy Roman Empire.

Suvorov led the Siege of Izmail in Bessarabia on 22 December 1790. His capture of the reputedly unconquerable fortress played a vital role in Russia’s victory in the war.[13] Turkish forces inside the fortress had the orders to stand their ground to the end and haughtily declined the Russian ultimatum. Their defeat was seen as a major catastrophe in the Ottoman empire. An unofficial Russian national anthem in the late 18th and early 19th centuries «Grom pobedy, razdavaysya!» (Let the thunder of victory sound!) commemorates Suvorov’s victory and 24 December is today commemorated as a Day of Military Honour in Russia. Suvorov announced the capture of Ismail in 1791 to the Empress Catherine in a doggerel couplet.[15]

Battles against Polish uprising[edit]

Suvorov entering Warsaw in 1794

Immediately after signing the Treaty of Jassy with the Ottoman Empire, Suvorov was transferred to Poland where he assumed the command of one of the corps and took part in the Battle of Maciejowice. There, he captured the Polish commander-in-chief Tadeusz Kościuszko. On November 4, 1794, Suvorov’s forces stormed Warsaw and captured Praga, one of its boroughs.

The massacre of approximately 20,000 civilians in Praga[16] broke the spirits of the defenders and soon put an end to the Kościuszko Uprising. According to some sources[17] the massacre was the deed of Cossacks who were semi-independent and were not directly subordinate to Suvorov. The Russian general supposedly tried to stop the massacre and even went to the extent of ordering the destruction of the bridge to Warsaw over the Vistula River[18] with the purpose of preventing the spread of violence to Warsaw from its suburb. Other historians dispute this,[19] but most sources make no reference to Suvorov either deliberately encouraging or attempting to prevent the massacre.[20][21][22]

Suvorov sent a report to his sovereign consisting of only three words: «Hurrah, Warsaw’s ours!» (Ура, Варшава наша!). Catherine replied in two words: «Hurrah, Field-Marshal!» (rus. Ура, фельдмаршал!—that is, awarding him this title). The newly appointed field marshal remained in Poland until 1795, when he returned to Saint Petersburg. But his sovereign and friend Catherine died in 1796, and her son and successor Paul I dismissed the veteran in disgrace.[4]

Suvorov’s Italian campaign[edit]

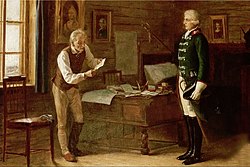

An exiled Suvorov receiving orders to lead the Russian Army against Napoleon

Suvorov remained a close confidant of Catherine, but he had a negative relationship with her son and heir apparent Paul. As a prince, Paul became fanatically interested in the flashy but dysfunctional uniforms, parades, drills, and common corporal punishments of the Prussian Army. He even had his own regiment of Russian soldiers whom he dressed up in Prussian-style uniforms and paraded around. Suvorov was strongly opposed to these uniforms and had fought hard for Catherine to get rid of similar uniforms that were used by Russians up until 1784.[4]

When Catherine died of a stroke in 1796, Paul I was crowned Emperor and brought back these outdated uniforms. Suvorov was not happy with this and disregarded Paul’s orders to train new soldiers in this Prussian manner, which he considered cruel and useless.[5] Paul was infuriated and dismissed Suvorov, exiling him to his estate Konchanskoye near Borovichi and kept under surveillance. His correspondence with his wife, who had remained at Moscow for his marriage relations had not been happy, was also tampered with. It is recorded that on Sundays he tolled the bell for church and sang among the rustics in the village choir. On week days he worked among them in a smock-frock.[4]

In February 1799, Paul I, worried about the victories of France in Europe during the French Revolutionary Wars and at the insistence of the coalition leaders, was forced to reinstate Suvorov as field marshal.[4] Suvorov was given command of the Austro-Russian army and sent to drive France’s forces out of Italy. Suvorov and Napoleon never met in battle because Napoleon was campaigning in Egypt at the time. However, Suvorov erased practically all of the gains Napoleon had made for France during 1796 and 1797, defeating some of the republic’s top generals: Moreau at Cassano d’Adda, MacDonald at Trebbia, and Joubert at Novi.[5] He went on to capture Milan and became a hero to those opposed to the French Revolution. French troops were driven from Italy, save for a handful in the Maritime Alps and around Genoa. Suvorov himself gained the rank of «Prince of the House of Savoy» from the King of Sardinia.

After the victorious Italian theater, Suvorov planned to march on Paris, but instead was ordered to Switzerland to join up with the Russian forces already there and drive the French out. The Russian army under General Korsakov was defeated by Masséna at Zürich before Suvorov could reach and unite with them. Surrounded by Masséna’s 80,000 French troops, Suvorov with a force of 18,000 Russian regulars and 5,000 Cossacks, exhausted and short of provisions, led a strategic withdrawal from the Alps while fighting off the French. His host hoped to make its way over the Swiss passes to the Upper Rhine and arrive at Vorarlberg, where the army, much shattered and almost destitute of horses and artillery, went into winter quarters.[4] When Suvorov battled his way through the snow-capped Alps his army was checked but never defeated. Suvorov refused to call it a retreat and commenced a trek through the deep snows of Panix Pass and into the 9,000-foot mountains of the Bündner Oberland, by then deep in snow. Thousands of Russians slipped from the cliffs or succumbed to cold and hunger, eventually escaping encirclement and reached Chur on the Rhine, with the bulk of his army intact at 16,000 men.[23] For this marvel of strategic retreat, earning him the nickname of the Russian Hannibal, Suvorov became the fourth Generalissimo of Russia.

He was officially promised a military triumph in Russia, but Emperor Paul cancelled the ceremony and recalled the Russian armies from Europe. Early in 1800, Suvorov returned to Saint Petersburg. Paul refused to give him an audience, and, worn out and ill, the old veteran died a few days afterwards on 18 May 1800, at Saint Petersburg. Suvorov was meant to receive the funeral honors of a Generalissimo, but was buried as an ordinary field marshal due to Paul’s direct interference. Lord Whitworth, the British ambassador, and the poet Gavrila Derzhavin were the only persons of distinction present at the funeral.[4] Suvorov lies buried in the Church of the Annunciation in the Alexander Nevsky Monastery, the simple inscription on his grave stating, according to his own direction, «Here lies Suvorov.»

Progeny and titles[edit]

In 1792, Suvorov founded Tiraspol, today the capital city of Transnistria. An equestrian statue of Suvorov sits in the central square of the city.

Suvorov’s full name and titles (according to Russian pronunciation), ranks and awards are the following: «Aleksandr Vasiliyevich Suvorov, Prince of Italy, Count of Rymnik, Count of the Holy Roman Empire, Prince of Sardinia, Generalissimo of Russia’s Ground and Naval forces, Field Marshal of the Austrian and Sardinian armies». Seriously wounded six times, he was the recipient of the Order of St. Andrew, the Apostle First Called, Order of St. George the Bringer of Victory First Class, Order of St. Vladimir First Class, Order of St. Alexander Nevsky, Order of St. Anna First Class, Grand Cross of the Order of St. John of Jerusalem, (Austria) Order of Maria Theresa First Class, (Austria) Order of the Black Eagle, Order of the Red Eagle, the Pour le Mérite, (Prussia) Order of the Revered Saints Maurice and Lazarus, (Sardinia) Order of St. Gubert, the Golden Lioness, (France) United Orders of the Carmelite Virgin Mary and St. Lazarus (on 20. April 1800), (Poland) Order of the White Eagle, the Order of Saint Stanislaus.

Suvorov was married to Varvara Ivanovna Prozorovskaya of the Golitsyn family and had a son and daughter, but his family life was not happy and he had an unpleasant relationship with his wife due to her infidelity. Suvorov’s son, Arkadi Suvorov (1783–1811) served as a general officer in the Russian army during the Napoleonic and Turkish wars of the early 19th century, and drowned in the same river Rymnik in 1811 that had brought his father so much fame. The drowning of his son in the river is supported by Aleksey Yermolov’s memoirs,[24][self-published source?] as well as by the military historian Christopher Duffy.[25] His grandson Alexander Arkadievich (1804–1882) served as Governor General of Riga in 1848–61 and Saint Petersburg in 1861–66. Suvorov’s daughter Natalia Alexandrovna (1775–1844) known under her name Suvorochka married Count Nikolay Zubov.

Assessment[edit]

Russians have long cherished the memory of Suvorov as a great general. While on a campaign, he reportedly lived as a private soldier, sleeping on straw and contenting himself with the humblest fare.[26] Suvorov considered victory dependent on the morale, training, and initiative of the front-line soldier. In battle he emphasized speed and mobility, accuracy of gunfire and the use of the bayonet, as well as detailed planning and careful strategy. He abandoned traditional drills, and communicated with his troops in clear and understandable ways. Suvorov also took great care of his army’s supplies and living conditions, reducing cases of illness among his soldiers dramatically, and earning their loyalty and affection.[4]

He was seriously wounded six times in his military career. Suvorov’s guiding principle was to detect the weakest point of an enemy and focus an attack upon that area. He would send forth his units in small groups as they arrived on the battlefield in order to sustain momentum. Suvorov utilized aimed fire instead of repeated barrages from line infantry and applied light infantrymen as skirmishers and sharpshooters. He used a variety of army sizes and types of formations against different foes: squares against the Turks, lines against Poles, and columns against the French.[5]

According to D. S. Mirsky, Suvorov «gave much attention to the form of his correspondence, and especially of his orders of the day. These latter are highly original, deliberately aiming at unexpected and striking effects. Their style is a succession of nervous staccato sentences, which produce the effect of blow and flashes. Suvorov’s official reports often assume a memorable and striking form. His writings are as different from the common run of classical prose as his tactics were from those of Frederick or Marlborough.»[27]

Suvorov monument in the Swiss Alps

Mikhail Ivanovich Dragomirov (1830–1905) declared that he based his teaching on Suvorov’s practice, which he held as representative of the fundamental truths of war and of the military qualities of the Russian nation.[28]

Suvorov considered Hannibal, Alexander the Great, Julius Caesar, and Napoleon Bonaparte to be the greatest military commanders of all time. His high regard for Napoleon is interesting because he did not live to see the Napoleonic Wars. Suvorov is often compared to Napoleon, whom he was on opposing sides of during the late French Revolutionary Wars and desired to face in battle, but never did so because Napoleon was campaigning in Egypt while Suvorov was campaigning in Italy. Military historians often debate between Suvorov and Napoleon as to who was the superior commander.[5]

His political views were centered around enlightened monarchy. However, Suvorov had no interest in pursuing politics and made his disdain for the court lifestyle and tendencies of aristocrats well known: he lacked diplomacy in his dispatches, and his sarcasm triggered enmity among some courtiers.[5]

Legacy[edit]

Suvorov was buried in Saint Petersburg in the Alexander Nevsky Lavra. His gravestone states simply: «Here lies Suvorov». Within a year after his death, Paul I was murdered in his bedroom for his disastrous leadership by a band of dismissed officers and his son and successor Alexander I erected a statue to Suvorov’s memory in the Field of Mars.

He was famed for his military writings, the most well-known being The Science of Victory and Suzdal Regulations, and lesser-known works such as Rules for the Kuban and Crimean Corps, Rules for the Conduct of Military Actions in the Mountains (written during his Swiss campaign), and Rules for the Medical Officers. Suvorov was also noted for several of his sayings, including «What is difficult in training will become easy in a battle,» «The bullet is a mad thing; only the bayonet knows what it is about,» and «Perish yourself but rescue your comrade!» He taught his soldiers to attack instantly and decisively: «Attack with the cold steel! Push hard with the bayonet!» He joked with the men, calling common soldiers «brother,» and shrewdly presented the results of detailed planning and careful strategy as the work of inspiration.[29]

A «Suvorov school» of generals who had apprenticed under him played a prominent role in the Russian military. Among them was future Field Marshal Mikhail Kutuzov who led the Imperial Russian Army against Napoleon during the Napoleonic Wars, including the French invasion of Russia.[5]

The Suvorov Museum opened in Saint Petersburg in 1900 to commemorate the centenary of the general’s death.[30] Apart from in St. Petersburg, other Suvorov monuments have feature in Focșani, Ochakiv (1907), Sevastopol, Tulchin, Kobrin, Novaya Ladoga, Kherson, Timanovka, Simferopol, Kaliningrad, Konchanskoye, Rymnik, Elm, Switzerland and in the Swiss Alps.

During World War II, the Soviet Union revived the memory of many pre-1917 heroes in order to raise patriotism. Suvorov was the Tsarist military figure most often referred to by Joseph Stalin, who also received (but did not personally use) the rank of Generalissimo that Suvorov had previously held. The Order of Suvorov was established by the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet on 29 July 1942 and is awarded to senior army personnel for exceptional leadership in combat operations against superior enemy forces.[31]

The town of Suvorovo in Varna Province, Bulgaria, was named after Suvorov, as was the Russian ship which discovered Suwarrow Island in the Pacific in 1814.

Various currency notes of the Transnistrian ruble depict Suvorov.[32][33]

There is a Square in Tiraspol, Transnistria named after Suvorov, and another in Saint Petersburg.

His prowess, military wisdom, and daring remain in high regard. Another of his many utterances, «Achieve victory not by numbers, but by knowing how» and «Train hard, fight easy. Train easy and you will have hard fighting» are well known in the Russian military. «Train hard, fight easy» became a Russian proverb.[5]

A bust of the Generalissimo is prominently displayed in the office of the Russian Minister of Defense.[citation needed]

In Russia, there are 12 secondary-level military schools called Suvorov Military School that were established during the USSR. There is also a military school in Minsk named after Suvorov.[34]

Russia’s defence minister Sergei Shoigu has proposed that Suvorov be made a saint in the Russian Orthodox Church.[35]

Ukraine[edit]

Due to «decommunization policies» the street named after Suvorov in (Ukraine’s capital) Kyiv was renamed after Mykhailo Omelianovych-Pavlenko in 2016.[36]

In September 2022 a street that was named after Suvorov in Dnipro (Ukraine) was renamed to honor Alan Shepard.[37]

In October 2022, during the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Russian troops captured a monument to Suvorov in Kherson and took it with them as they fled the city.[38]

In December 2022 another street in Kyiv that was still named after Suvorov was renamed to Serhiy Kotenko Street.[39]

In January 2023 an image of Suvorov on a monument was removed in Odesa.[40]

Literary references[edit]

Poet Alexander Shishkov devoted an epitaph to Suvorov, while Gavrila Derzhavin mentioned him in Snigir (Bullfinch) and other poems, calling Suvorov «an Alexander by military prowess, a stoic by valor». Suvorov was mentioned by Alexander Pushkin and Mikhail Lermontov and in the numerous works of other Russian poets of the 18th and 19th centuries, such as Ivan Dmitriev, Apollon Maykov, Dmitry Khvostov, Kondraty Ryleyev, Vasili Popugaev. In 1795 poet and soldier Irinarkh Zavalishin [ru], who had fought under the command of Alexander Suvorov, wrote a heroic poem titled «Suvoriada», celebrating Suvorov’s victories. Suvorov is one of the characters in the drama «Antonio Gamba, Companion of Suvorov in the Alpine Mountains» by Sergey Glinka which commemorates the Swiss expedition of 1799.[41][42] In British literature, Byron caricatured Suvorov in the seventh canto of Don Juan. In Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace, old Prince Nicholas Bolkonski says: «Suvorov couldn’t manage them so what chance has Michael Kutuzov?» Tolstoy also refers to Suvorov later on in the book. Suvorov is also mentioned by Capt. Ryków in Adam Mickiewicz’s poem Pan Tadeusz.

See also[edit]

- Suvorov Military School

- Suvorov military canals

- Suvorov Museum

- Order of Suvorov

- Medal of Suvorov

- Aleksandr Suvorov (ship)

- Russian battleship Knyaz Suvorov

References[edit]

- ^ Peter Paret, Gordon A. Craig, Felix Gilbert. Makers of Modern Strategy from Machiavelli to the Nuclear Age. Princeton University Press, 1986, p. 356

- ^ Fuller, William C. Jr. «Suvorov, Alexander» in The Reader’s Companion to Military History. Ed. by Robert Cowley & Geoffrey Parker. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. 1996. p. 457

- ^ Goodwin, J. Lords of the Horizons, p. 244. Henry Holt and Company, 1998.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Chisholm 1911.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Isinger, Russell (October 1996). «Aleksandr Suvorov: Count of Rymniksky and Prince of Italy». Military History.

- ^ a b c Spalding (1888). «Suvóroff». Illustrated Naval and Military Magazine. VII: 328–340. Retrieved June 29, 2009.

- ^ Chamber’s repository, 1857, v. 6, p. 3.

- ^ Mandich, Donald R. Russian Heraldry and Nobility, 1992, p. 271

- ^ History of the Life and Campaigns of Count A. Suworow Rymnikski by Fr. Anthing, 1799, P. 6.

- ^ «Наука и жизнь. №8, 2005». Nauka i Zhizn magazine. 2005. Retrieved May 28, 2018.

- ^ a b c Осипов К. (И. М. Куперман). Александр Васильевич Суворов. Изд. 3-е, испр. М.: 1955. С. 3-5

- ^ a b В. Могильников. Новая версия происхождения полководца А. В. Суворова//Генеалогический вестник. №13, 2003.

- ^ a b c K. Osipov. Alexander Suvorov. A Biography. London, 1944.[page needed]

- ^ Cowley, Robert; Parker, Geoffrey, eds. (July 10, 2001). The Reader’s Companion to Military History. Houghton Mifflin Books. p. 457. ISBN 978-0-618-12742-9. Retrieved 2006-09-10.

- ^ J. Goodwin, Lords of the Horizons, p. 244, 1998, Henry Holt and Company, ISBN 978-0-8050-6342-4

- ^ : Ledonne, 2003, p.144 Google Print and Alexander, 1989, p.317 Google Print

- ^ (in Russian) Alexander Bushkov Russia that never existed, cites Adam Jerzy Czartoryski’s memoirs that Suvorov was trying to prevent the massacre Archived September 27, 2007, at archive.today

- ^ Petrushevsky, Alexandr Fomich (2005) [1884]. «17. Польская война: Прага; 1794.» [Polish war: Prague; 1794.]. Генералиссимус князь Суворов [Generalissimo Prince Suvorov] (in Russian). Русская Симфония. ISBN 978-5-98447-010-0. Retrieved 9 October 2016.

- ^ (in Polish) Janusz Tazbir, Polacy na Kremlu i inne historyje (Poles on Kreml and other stories), Iskry, 2005, ISBN 978-83-207-1795-2, fragment online Archived March 25, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Davies, Norman (1996). Europe: A History. Oxford University Press. p. 722. ISBN 0060974680.

- ^ Dixon, Simon (1999). The Modernisation of Russia, 1676-1825. Cambridge University Press. p. 41. ISBN 052137961X.

- ^ John Leslie Howard, Soldiers of the Tsar: Army and Society in Russia, 1462–1874, Keep, Oxford University Press, 1995, ISBN 978-0-19-822575-1, Google Print, p.216

- ^ Latimer, Jon (December 1999). «War of the Second Coalition». Military History: 62–69.

- ^ Mikaberidze, Alexander (2011). Alexey Yermolov’s Memoirs. Lulu.com. p. 211. ISBN 978-1105258183.[self-published source]

- ^ Duffy, Christopher (1999). Eagles Over the Alps: Suvorov in Italy and Switzerland, 1799. Emperor’s Press. p. 86. ISBN 1883476186.

- ^ Ross, Steven T.; Ross, P. Stewart Michael (2010). The A to Z of the Wars of the French Revolution (Volume 203 of The A to Z Guide Series). Rowman & Littlefield. p. 159. ISBN 978-0810876323.

- ^ Mirsky, D.S. (1999). A History of Russian Literature. Northwestern University Press. pp. 60–61. ISBN 978-0-8101-1679-5.

- ^ Keegan, John; Wheatcroft, Andrew (2014). Who’s Who in Military History: From 1453 to the Present Day. Routledge. p. 79. ISBN 978-0415260398.

- ^ Goodwin, J. Lords of the Horizons, p. 244. Henry Holt and Company, 1998.

- ^ Giangrande, Cathy; Norwich, John Julius (2003). Saint Petersburg: Museums, Palaces, and Historic Collections. Bunker Hill Publishing, Inc. p. 71. ISBN 1593730004.

- ^ «Decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR of July 7, 1942» (in Russian). Legal Library of the USSR. 1942-07-29. Retrieved 2012-03-26.

- ^ Brezianu, Andrei; Spânu, Vlad (2010). The A to Z of Moldova. Scarecrow Press. p. 109. ISBN 9781461672036.

- ^ King, Charles (2009). Extreme Politics: Nationalism, Violence, and the End of Eastern Europe. Oxford University Press. p. 120. ISBN 9780199708246.

- ^ «Minsk Suvorov Military School». Archived from the original on 5 August 2014. Retrieved 18 Dec 2014.

- ^ «Russian defender of 18th-century Crimea proposed for sainthood». Reuters. 24 May 2022.

- ^ (in Ukrainian) Bandera Avenue in Kyiv to be — the decision of the Court of Appeal, Ukrayinska Pravda (22 April 2021)

- ^ «In the center of Dnipro, the street of Stepan Bandera appeared — the mayor». Ukrayinska Pravda (in Ukrainian). 21 September 2022. Retrieved 18 October 2022.

- ^ «Occupiers steal monuments to Suvorov and Ushakov when fleeing Kherson». Ukrayinska Pravda. 24 October 2022. Retrieved 3 December 2022.

- ^ Oleksandr Shumilin (8 December 2022). «n Kyiv, 32 more streets were de-Russified, including Druzhby Narodiv Boulevard». Ukrayinska Pravda (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ Oleksandr Shumilin (3 January 2023). «In Odessa, the images of the Russian tsar and admiral were dismantled». Istorychna Pravda («Historical Truth») (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ Замостьянов А. А. Гений войны Суворов. «Наука побеждать». М. Эксмо, 2013, ISBN 978-5-699-62465-2 / 9785699624652

- ^ Суворовский сборник. Статьи и исследования. ред. А. В. Сухомлин, генерал-лейтенант. М. АН СССР. 1951

Attribution:

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). «Suvárov, Alexander Vasilievich». Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 26 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 172–173.

- Ledonne, John P. (2003). The Grand Strategy of the Russian Empire. Oxford University Press US. ISBN 978-0-19-516100-7.

- Alexander, John T. (1990). Catherine the Great: Life and Legend. Oxford University Press US. ISBN 978-0-19-506162-8.

Further reading[edit]

- Longworth, Philip. 1965. The Art of Victory. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston

- J.F. Anthing, Versuch einer Kriegsgeschichte des Grafen Suworow (Gotha, 1796–1799)

- Clausewitz, Carl von (2020). Napoleon Absent, Coalition Ascendant: The 1799 Campaign in Italy and Switzerland, Volume 1. Trans and ed. Nicholas Murray and Christopher Pringle. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-3025-7

- Clausewitz, Carl von (2021). The Coalition Crumbles, Napoleon Returns: The 1799 Campaign in Italy and Switzerland, Volume 2. Trans and ed. Nicholas Murray and Christopher Pringle. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-3034-9

- Macready, Edward Nevil (1851). A sketch of Suwarow and his last campaign : with observations on Mr. Alison’s opinion of the Archduke Charles as a military critic, and a few objections to certain military statements in Mr. Alison’s History of Europe. London: Smith, Elder.

- G. von Fuchs, Suworows Korrespondenz, 1799 (Glogau, 1835)

- Von Reding-Biberegg, Der Zug Suworows durch die Schweiz (Zürich 1896)

- F. von Smut, Suworows Leben und Heerzüge (Vilna, 1833–1834) and Suworow and Polens Untergang (Leipzig, 1858,)

- Lieut.-Colonel Spalding, Suvorof (London, 1890)

- Souvorov en Italie by Gachot, Masséna’s biographer (Paris, 1903)

- The standard Russian biographies of Polevoi (1853; Ger. trans., Mitau, 1853); Rybkin (Moscow, 1874), Vasiliev (Vilna, 1899), Meshcheryakov and Beskrovnyi (Moscow, 1946), and Osipov (Moscow, 1955).

- The Russian examinations of his martial art, by Bogolyubov (Moscow, 1939) and Nikolsky (Moscow, 1949).

- «1799 le baionette sagge» by Marco Galandra and Marco Baratto (Pavia, 1999).

- «SUVOROV – La Campagna Italo-Svizzera e la liberazione di Torino nel 1799» by Maria Fedotova ed. Pintore (Torino, 2004).

External links[edit]

- Alexander V. Suvorov: Russian Field Marshal, 1729–1800

- Speed, Assessment, and Hitting Power: Suvorov’s Art of Victory

- Suvorov military museum in Saint Petersburg

- Suvorov’s home and family

- Suvorov – the one man who could have stopped Bonaparte

- Aleksandr Suvorov: Count of Rymniksky and Prince of Italy

- Alexander Suvorov: The Science of Victory (Untranslated)

|

Field Marshal Generalissimo The Count Suvorov |

|

|---|---|

Alexander Suvorov by Joseph Kreutzinger |

|

| Born | 24 November 1730 Moscow, Moscow Governorate, Russian Empire |