4.5

Средняя оценка: 4.5

Всего получено оценок: 128.

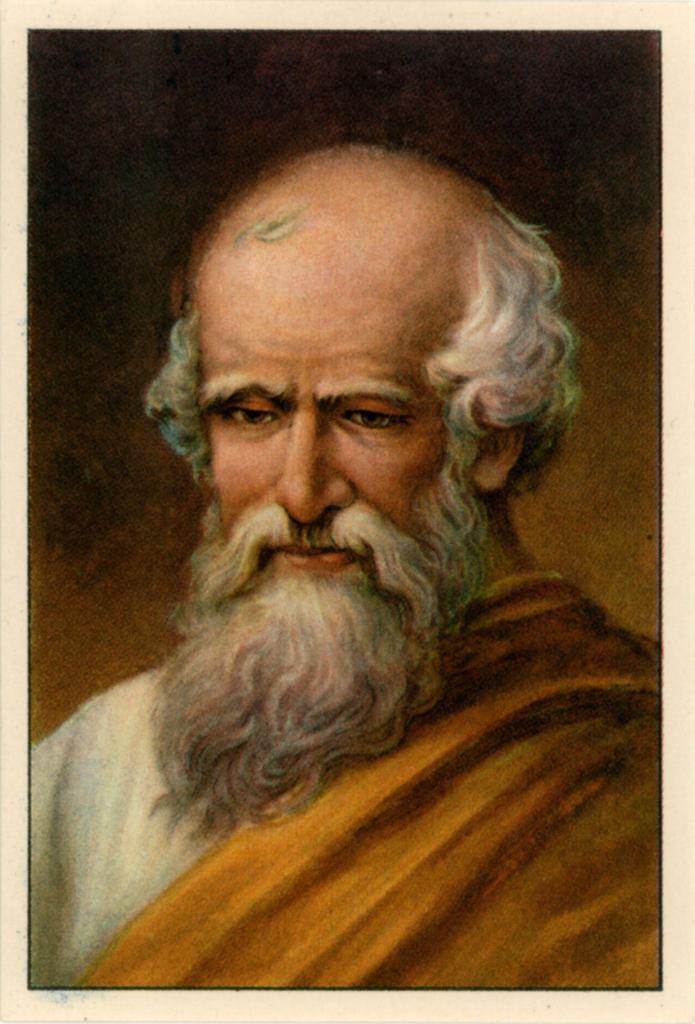

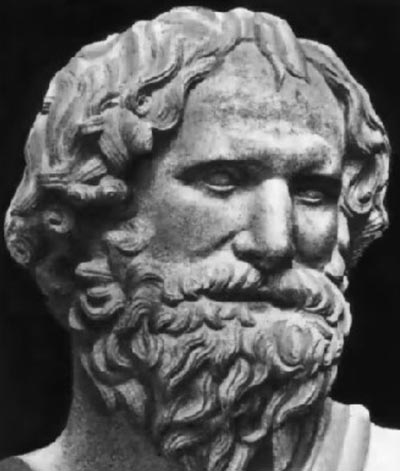

Архимед (287–212 гг. до н.э.) – великий древнегреческий учёный, физик и изобретатель. Является основоположником гидростатики и теоретической механики. Биография Архимеда богата интересными фактами: например, он впервые вычислил число «пи».

Опыт работы учителем математики — более 33 лет.

Юношество

Архимед родился в 287 г. до н.э., в Сиракузах. Родственником будущего учёного был Гиерон, впоследствии ставший правителем Сиракуз Гиероном II. Отец Архимеда Фидий, выдающийся астроном и математик, состоял при дворе. По этой причине мальчик получил приличное образование.

Осознавая, что ему не хватает теоретических знаний, юноша вскоре отправился на обучение в Александрию, где в то время трудились самые светлые умы древности.

Большую часть своего времени Архимед проводил в Александрийской библиотеке. Там он занимался изучением трудов Демокрита и Евдокса. Во время обучения, Архимед сблизился с Эратосфеном и Кононом. Дружба сохранилась на долгие годы.

Труды и достижения

Закончив обучение, Архимед вернулся в родные Сиракузы и вступил в должность астронома при дворе Гиерона II. Но не только звёзды привлекали его внимание.

Должность астронома не была обременительной. Архимед имел возможность заниматься механикой, физикой и математикой. В это время для решения нескольких задач по геометрии исследователем был применён принцип рычага.

Выводы были подробно изложены в работе “О равновесии плоских фигур”. Немногим позже, Архимед написал сочинение “Об измерении круга”. Ему удалось вычислить отношение диаметра окружности к её длине.

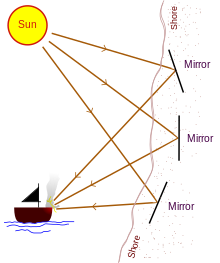

Изучая краткую биографию Архимеда, следует знать, что также он уделял внимание геометрической оптике. Им было проведено несколько интересных экспериментов по преломлению света. Теорема дошла и до наших дней. Она доказывает, что на фоне отражения луча света от зеркальной поверхности, угол падения равняется углу отражения.

Дары Сиракузам

Архимед сделал немало полезных открытий. Все они были посвящены родному городу учёного. Архимед активно развивал идеи применения рычага. В сиракузском порту ему удалось создать целую систему рычагово-блочных механизмов, ускоряющих процесс перевозки тяжелых, крупногабаритных грузов.

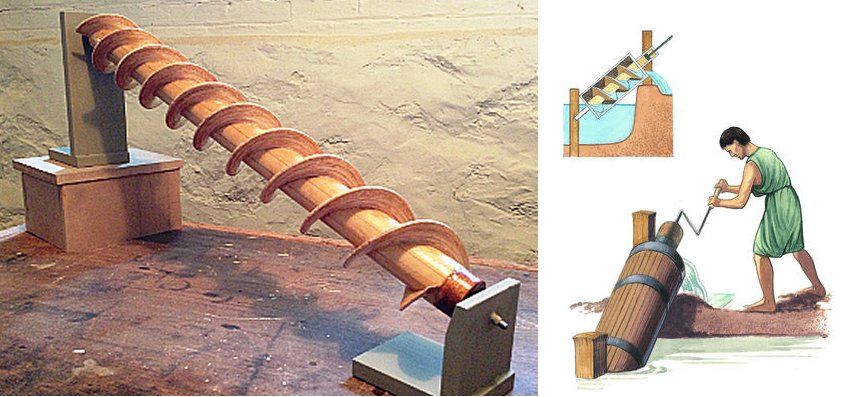

При помощи архимедова винта, или шнека, стала возможной добыча воды из низколежащих водоёмов. Благодаря этому, оросительные каналы стали получать влагу бесперебойно.

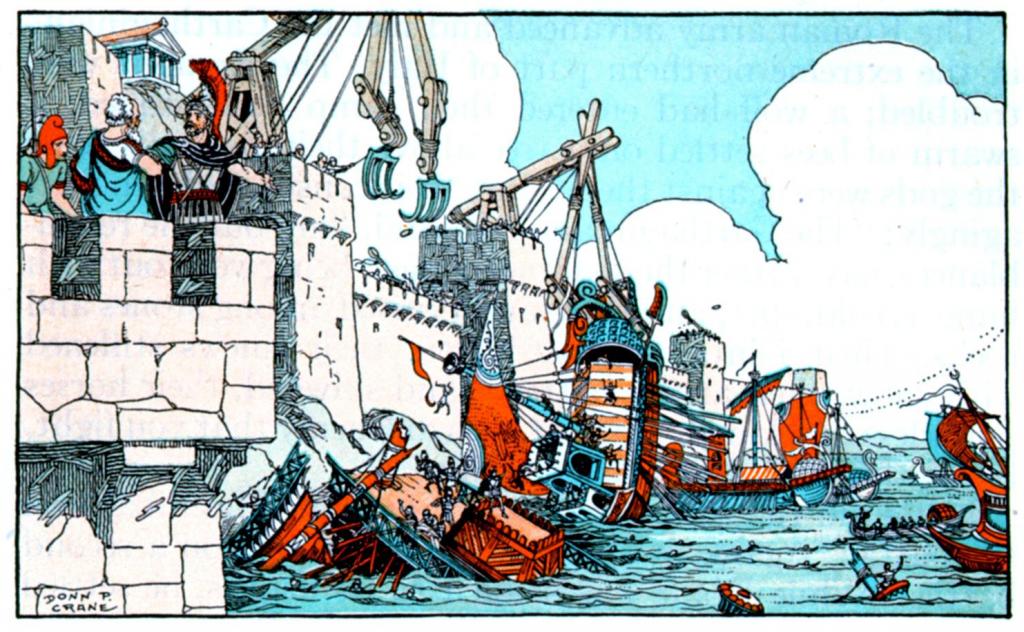

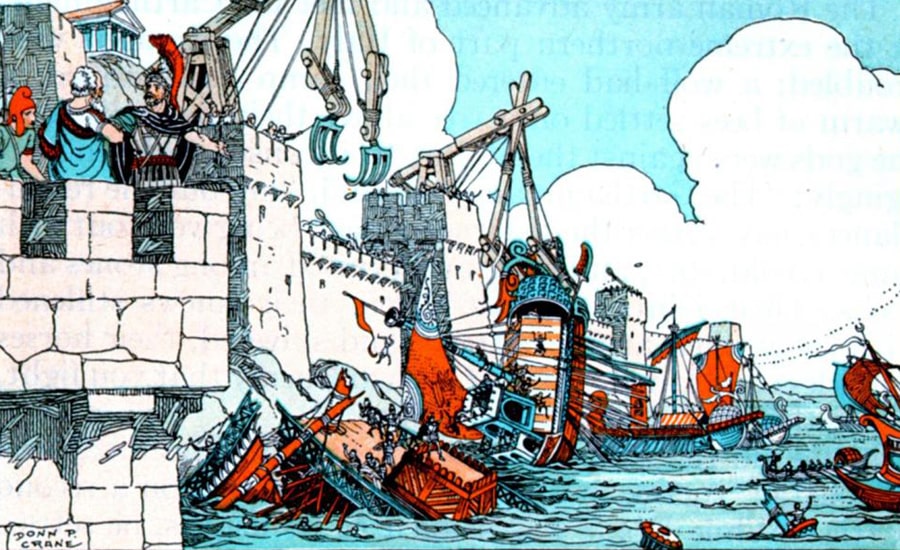

Главная услуга Сиракузам была оказана Архимедом в 212 г. Учёный принял активнейшее участие в обороне Сиракуз, которые были осаждены римскими войсками. Архимеду удалось создать несколько мощнейших метательных машин. Когда римляне ворвались в город, многие из них пали под ударами камней, пущенных из этих машин.

Архимедовы краны с лёгкостью переворачивали корабли римлян. Это привело к тому, что римские воины отказались от штурма города и приступили к продолжительной осаде.

К сожалению, в итоге, город был взят.

Смерть учёного

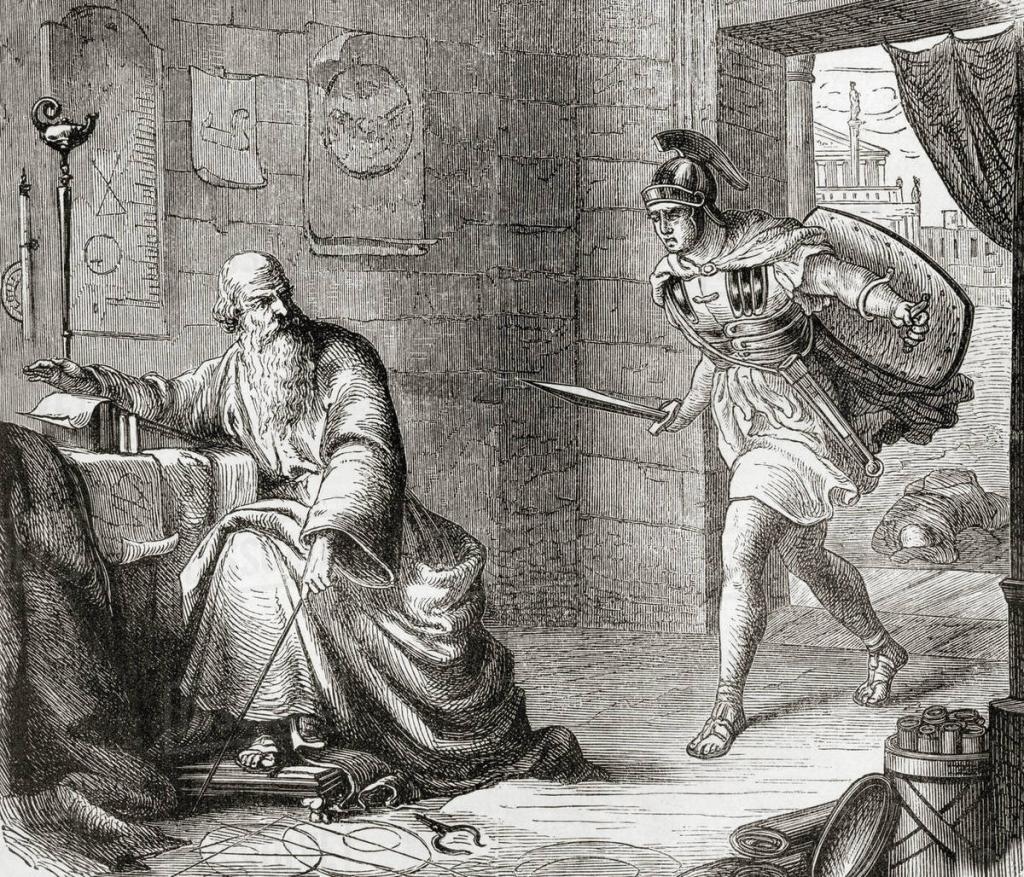

Рассказ о смерти Архимеда был передан Иоанном Цецем, Плутархом, Диодором Сицилийским и Титом Ливием. Детали гибели великого учёного разнятся. Общим является одно: Архимед был убит неким римским солдатом. По одной из версий, римлянин не стал дожидаться, пока Архимед завершит чертеж, и за отказ следовать к консулу, заколол его мечом.

Другая версия гласит, что учёный был убит на пути к Марцеллу. Римским солдатам показались подозрительными приборы для измерения Солнца, которые нёс в руках Архимед.

Консул Марцелл, узнав о гибели учёного, был огорчён. Тело Архимеда было погребено с большими почестями, а его родственникам оказано “великое уважение”.

Другие варианты биографии

Более сжатая для доклада или сообщения в классе

Вариант 2

Интересные факты

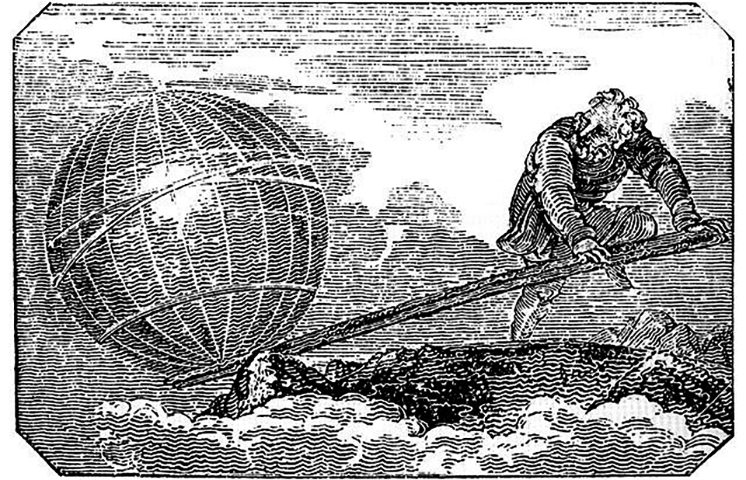

- Однажды Архимед воскликнул: “Дайте мне точку опоры, и я сдвину Землю!” В глазах современников выдающийся учёный был практически полубогом.

- По легенде, сиракузцам удалось сжечь несколько римских кораблей. Это было сделано при помощи огромных зеркал, удивительные свойства которых также были открыты Архимедом.

Тест по биографии

Доска почёта

Чтобы попасть сюда — пройдите тест.

-

Светлана Ермашкевич

10/10

-

Василиса Зотова

9/10

Оценка по биографии

4.5

Средняя оценка: 4.5

Всего получено оценок: 128.

А какая ваша оценка за эту биографию?

| Полное имя: | Архимед |

| Дата рождения: | 287 г. до н. э. |

| Место рождения: | Сиракузы, Италия |

| Деятельность: | Ученый, математик, физик, астроном, инженер, изобретатель |

| Дата смерти: | 212 г. до н. э. (≈75 лет) |

Ранние годы и молодость

Архимед родился в 287 году до н. э. в колонии Сиракузы на греческом острове Сицилия. По неподтвержденной информации отец его, Фидий, был учителем астрономии и математики. Семья, в которой воспитывался Архимед, была бедной. Отец не мог дать сыну достойное образование, которым в то время считались занятия литературой и философией. Он сам его потихоньку обучал тому, что знал. Поэтому и проявилась ранняя тяга Архимеда к математике.

Архимед являлся родственником царя Сиракуз, Гиерона. Благодаря этому будущий ученый смог поехать в главный научный центр Античности — Александрию.

Архимед стал общаться с другими учеными Александрийского мусейона. Здесь он часто приходил в знаменитую библиотеку, который содержал более 700 тысяч рукописей. Архимед много читал, знакомился с трудами ученых. Среди них Демокрит, Евдокс, о которых он много упоминал в своих записях. Ученый до конца жизни дружил с астрономом Кононом, ученым Эратосфеном. Две свои работы он даже начал со слов «посвящается Эратосфену». Это известные его труды «Метод механических теорем» и «Задача о быках».

Смерть Конона в 220 году до н. э. очень огорчила Архимеда. Однако он активно продолжал общение с его учеником Досифеем, и многие сохранившиеся трактаты ученого тех лет начинаются с фразы: «Архимед приветствует Досифея».

Будущий великий ученый стремился на родину и, завершив учебу, вернулся на Сицилию. Царь Сиракуз поощрял своего родственника к занятию наукой и создавал ему все условия для этого. Он хотел, чтобы Архимед применял свои достижения и открытия на практике. Именно он способствовал созданию Архимедом механизмов, работа которых повергла в шок современников и принесла всемирную славу ученому уже при жизни. Благодаря его изобретениям, о нем слагались легенды. Царь Сиракуз очень гордился достижениями Архимеда.

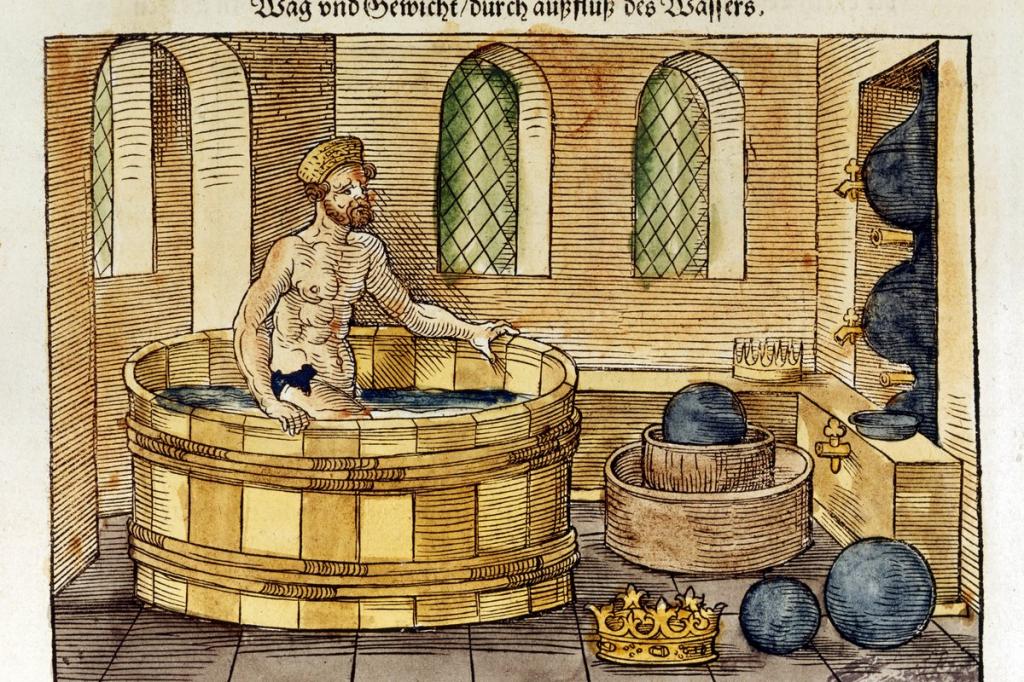

Громко об Архимеде заговорили после истории с короной царя. До Гиерона дошла информация, что золото в короне, которую он приказал сделать для себя, частично заменили серебром. Он разгневался и поручил Архимеду определить, правда ли это. Масса короны соответствовала количеству выделенного на её изготовление чистого золота. Архимед согласился выполнить приказ царя, но перед этим решил помыться ванной. Зайдя в воду, он увидел, как из неё вытекает вода. В эту секунду его осенила идея, и он с криком «Эврика!» выскочил из ванны и побежал к царю. Вот так внезапная мысль Архимеда стала началом развития гидростатики. Таким образом был доказан и обман ювелира.

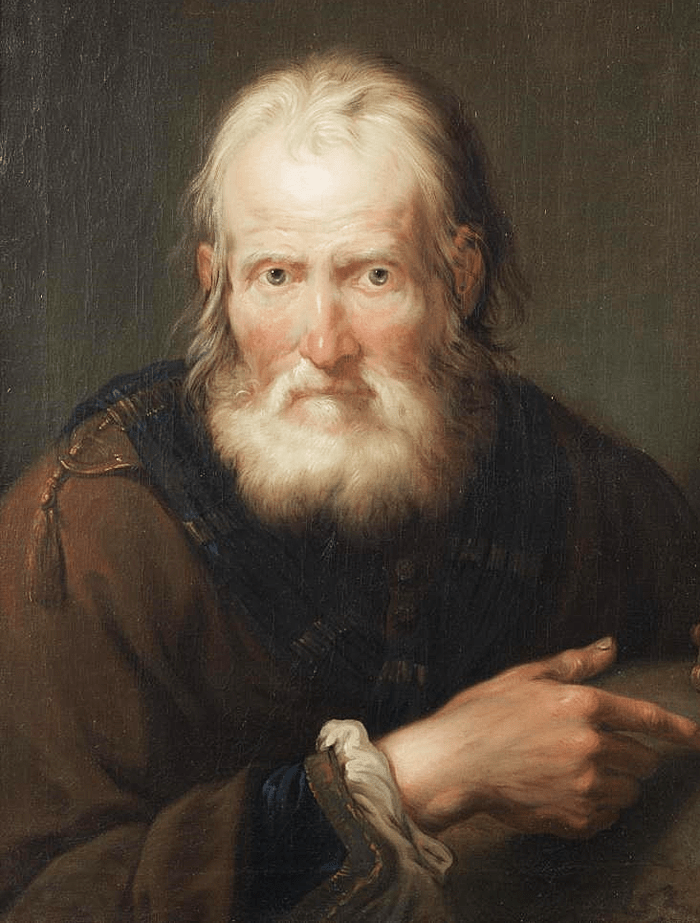

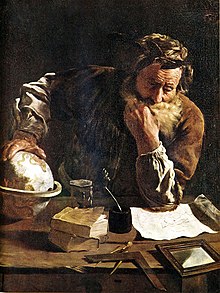

«Архимед с криком „Эврика“ бежит к царю». Худ. Г. Маззучелли (1737 г.)

Еще одна легенда про Архимеда гласит, что он написал Гиерону, что сможет сдвинуть с места любой груз, и что если бы он распоряжался другой землей, на которую можно было бы опереться, он сдвинул бы с места и эту землю. В ответ на вызов Архимеда царь поручил вытащить на берег большой грузовой корабль. Его трюм наполнили грузом и посадили на корму много матросов. Сев неподалеку, Архимед начал тянуть прикреплённый к кораблю канат. Корабль сдвинулся с места и стал медленно перемещаться.

В современном звучании известная фраза Архимеда означает: «Дайте мне точку опоры, и я переверну Землю».

«Архимед переворачивает Землю». Гравюра (1824 г.)

Основные достижения

Главные достижения и идеи Архимеда приходятся на 3 век до н. э., а именно:

- Основание механики и гидростатики.

- Обоснование понятия «центр тяжести».

- Расчет числа пи. Верхний предел (22⁄7).

- Открытие формулы для вычисления объема и площади поверхности сферы.

- Введение способа записи очень больших чисел.

- Применение физических принципов (закон рычага) в решении математических задач.

- Изобретение высокоточной катапульты.

- Развитие науки в Греции.

- Изобретение «архимедова винта».

Греческий ученый Архимед, благодаря которому были сделаны многочисленные открытия, стал одним из лучших умов нашего мира. Его труды пересматривались из века в век после его смерти. Ученым, которые не сомневались в правдивости его открытий, все же приходилось гадать, каким путем он к ним пришел. В особенности их волновали математические открытия Архимеда.

Долгое время математические способности Архимеда не были известны. Лишь в 1906 году профессор Йохан Хейберг обнаружил в турецком городе Константинополе книгу, содержащую семь трактатов под авторством Архимеда, включая «Метод», который считался утерянным на протяжении тысячелетия.

Этот труд положен в основу почти всем математическим новшествам двадцатого века.

К известным трактатам Архимеда, написанным на греческом языке, относятся:

- Измерение круга.

- О коноидах и сфероидах.

- О шаре и цилиндре.

- Квадратура параболы.

- О счислении песчинок.

- О равновесии плоских фигур.

- Метод механических теорем.

- О плавающих телах.

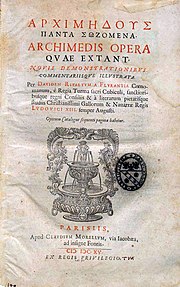

Важным событием является выход в печать работ Архимеда в 1544 году. До этого времени их не печатали.

Архимед провел большую часть жизни в Сиракузах. Он активно защищал город во время осады его римлянами в 213 году до н. э. Позже, когда Сиракузы все же были захвачены римлянами под предводительством полководца Марка Клавдия Марцеллы в 212 году до н. э., Архимед был убит римским солдатом. Он убил Архимеда вопреки приказу своего командования не убивать ученого.

Смерть Архимеда худ. Томас Деджордж (1815 г.)

Личная жизнь

Единственный человек, который подробно описал биографию Архимеда – его друг Гераклид. К сожалению, записи были утеряны, в связи с чем до наших дней дошла лишь часть информации из жизни Архимеда. Биография Архимеда известна из трудов Цицерона, Тита, Полибия, Ливия и других авторов, которые жили позже него и, в основном, представлена его достижениями. О личной жизни, семье, детях ничего не известно.

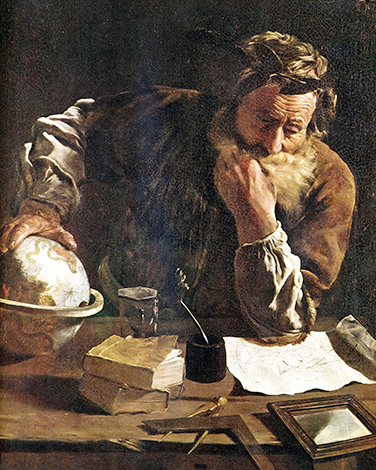

В биографии Архимеда, написанной знаменитым Плутархом, упоминается, что он был настолько увлечен наукой, что ничего вокруг себя не замечал. Он забывал есть, менять одежду и приводить себя в порядок.

Архимед, как сообщается, будучи в молодом возрасте, любил посещать библиотеки. В особенности Александрийскую библиотеку с ее просторными залами, которая стала центром науки для ученых древнего мира. Архимед пополнял свои знания ежедневно и мечтал о новых открытиях в науке.

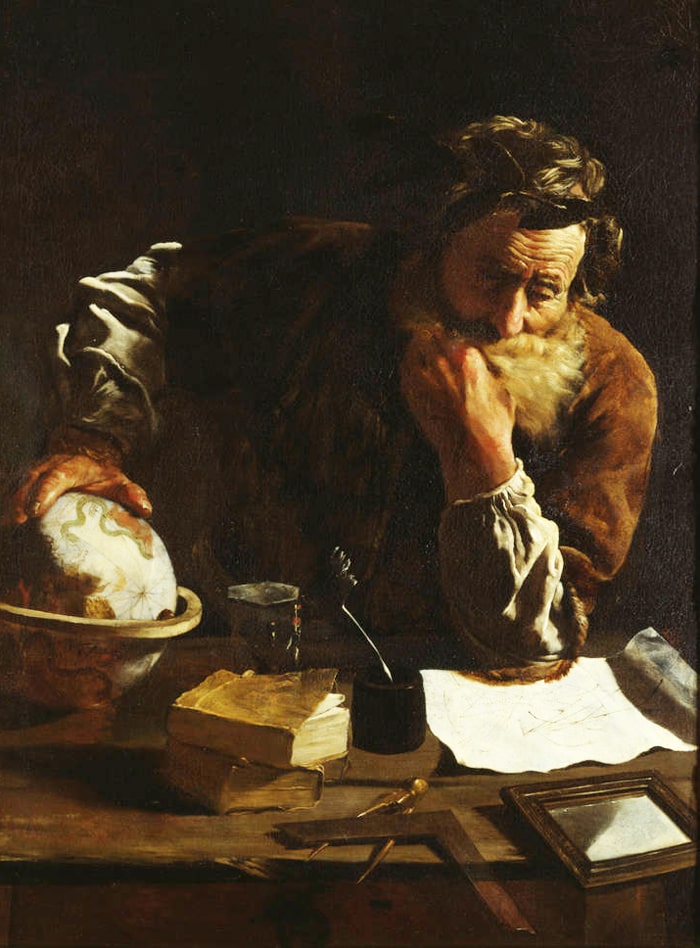

Задумчивый Архимед. Худ. Доменико Фетти (1620 г.)

След в истории

Архимед был, без преувеличения, величайшим ученым. Он был математиком, астрономом, физиком, инженером, изобретателем, а также выдающимся представителем своего времени, благодаря трудам и изобретениям которого мир опередил время.

Памятник Архимеду в Сиракузах (Сицилия, Италия)

Вклад Архимеда в науку бесценен. Он сделал для прогресса науки больше, чем большинство учёных до него, и после. Его выдающийся ум принёс беспрецедентную пользу человечеству и заставил говорить о нем все последующие поколения.

Архимед: биография, открытия и интересные факты из жизни математика

- 1 Июля, 2019

- Наука и Техника

Архимед был, пожалуй, величайшим ученым в мире и, безусловно, величайшим ученым классической эпохи. Он был математиком, физиком, астрономом, инженером, изобретателем и разработчиком оружия. Это был не только выдающийся представитель своей эпохи, благодаря трудам и изобретениям он намного опередил свое время, о чем расскажет краткая биография Архимеда и его открытия, описанные в статье.

Родился он в греческом городе-государстве Сиракузы, на острове Сицилия, примерно в 287 году до нашей эры. Его отец Фидий был астрономом. Возможно, Архимед также был связан с Гиероном II, королем Сиракуз.

Величайшие достижения

Долгое время ученые не могли понять, как же были сделаны все его открытия. И биография Архимеда включает описание его достижений и идей, которые только в 18-м веке были развиты и продолжены. В 3-м веке до нашей эры он совершил множество новаторских вещей, а именно:

- Изобрел такие науки, как механика и гидростатика.

- Определил законы рычага и блока, которые позволяют нам перемещать тяжелые предметы, используя небольшую силу.

- Стал автором одного из самых фундаментальных понятий физики — центра тяжести.

- Рассчитал число пи до наиболее точного из известных значений. Его верхний предел для него составлял 22⁄7.

- Открыл и математически обосновал формулы для объема и площади поверхности сферы.

- Ввел способ записи очень больших чисел.

- Вдохновил Галилео Галилея и Исаака Ньютона на исследование математики движения. Сохранившиеся до наших дней работы Архимеда (к сожалению, многие из них были утеряны) наконец вышли в печать в 1544 году. Леонардо да Винчи посчастливилось увидеть некоторые из произведений Архимеда, скопированные вручную, еще до того, как они были напечатаны.

- Был одним из первых в мире ученых, применивших свои передовые математические методы в физическом мире.

- Был первым, кто применил физические принципы, например закон рычага, для решения математических задач.

- Изобрел военные машины, такие как высокоточная катапульта, которая долгие годы не давала римлянам покорить Сиракузы. Он мог сделать это на основании математических расчетов и понимания траектории снаряда.

Развитие науки в Греции

Чтобы лучше узнать жизнь и биографию Архимеда, нужно представить, в какую эпоху он жил. Древние греки были первыми, кто занялся настоящей наукой и признал ее дисциплиной, изучающей саму себя. Хотя в других культурах также делались научные открытия, это происходило по вполне практическим причинам, например, с целью постройки более крепких храмов или для предсказания, когда наступит период, наиболее подходящий для посадки культур или для вступления в брак.

Древние греки же исследовали мир просто ради удовольствия, расширяя свои знания. Они изучали геометрию ради ее логики и красоты. Не имея каких-либо практических целей, Демокрит предположил, что вся материя состоит из крошечных частиц, называемых атомами и что эти атомы не могут быть разделены на более мелкие частицы. Он привел логические аргументы в пользу своей идеи.

Краткая биография

Архимед, вероятно, провел некоторое время в Египте в начале своей карьеры, но большую часть своей жизни он прожил в Сиракузах, главном греческом городе-государстве на Сицилии, где он был в близких отношениях с его королем. Архимед опубликовал свои работы в форме переписки с выдающимися математиками своего времени, включая александрийских ученых Конона Самосского и Эратосфена Киренского. Он сыграл важную роль в защите Сиракуз от осады римлян в 213 г. до н. э. Когда Сиракузы в конце концов были захвачены римским полководцем Марком Клавдием Марцеллом осенью 212 года или весной 211 года до н. э., Архимед был убит во время разграбления города.

Жизнеописание ученого

В биографии Архимеда сказано, что он родился и жил в условиях развития греческой научной культуры. В своей работе «О счислении песчинок» он рассказывает о том, что его отец был астрономом. В своем письме об оценках размера Солнца Архимед говорит: «Фидий, мой отец, сказал, что Солнце было в двенадцать раз больше».

В молодости он проводил время в египетском городе Александрии, где преемник Александра Великого, Птолемей I Сотер, построил величайшую библиотеку мира. Александрийская библиотека с ее лекционными и конференц-залами стала центром внимания ученых древнего мира.

Некоторые работы Архимеда сохранились в копиях писем, которые он отправил из Сиракуз своему другу Эратосфену. Тот руководил Александрийской библиотекой и сам был ученым (математиком, астрономом, географом и филологом). Он был первым человеком, который точно рассчитал размер нашей планеты.

Архимед, погруженный в научную культуру Древней Греции, стал одним из лучших умов нашего мира. Спустя две тысячи лет после смерти Архимеда, в эпоху Возрождения и в 1600-х годах, математики снова пересмотрели его труды. Они знали, что результаты, полученные Архимедом, были правильными, но не могли понять, как этот ученый смог получить их.

Находка в стиле Индианы Джонса

Тайна математических изысканий Архимеда в биографии не была раскрыта до 1906 года, когда профессор Йохан Хейберг обнаружил в городе Константинополе (теперь Стамбул), в Турции, книгу. Это был христианский молитвенник, написанный в тринадцатом веке, когда город был последним форпостом Римской империи. В стенах Константинополя хранились многие великие произведения, написанные в Древней Греции. Найденная Хейбергом книга теперь называется Палимпсест Архимеда.

Хейберг обнаружил, что молитвы были написаны поверх математических расчетов. Монах, который написал молитвы, попытался удалить оригинальную работу, от которой после этого остались только еле заметные следы. Оказалось, что на самом деле это были копии работ Архимеда, сделанные с оригинального текста в 10-м веке.

Неожиданное открытие

Эта книга содержала семь трактатов, автором которых был Архимед, включая «Метод», который считался утраченным на протяжении многих веков. Согласно биографии математика, Архимед написал эту работу, чтобы показать, как именно он занимался математикой. Этот труд был отправлен Эратосфену в Александрийскую библиотеку. Он предполагал, что впоследствии другие ученые, используя его «Метод», смогут сделать новые открытия.

Благодаря этому труду математики двадцатого века узнали, насколько далеко опередил свое время Архимед, и изучили методы, которые он использовал для решения разных проблем. Именно благодаря им были сделаны его открытия и изобретения. Сохранилось 9 трактатов Архимеда, написанных на греческом языке.

«О шаре и цилиндре»

Основные результаты этой работы в двух книгах заключаются в том, что площадь поверхности любой сферы радиуса r в четыре раза больше площади ее наибольшего круга (в современных обозначениях S = 4πr2), а объем сферы равен двум третям того цилиндра, в который она вписана (что сразу приводит к формуле для объема, V = 4 / 3πr3). Архимед был очень горд последним открытием и оставил инструкции для создания своей могилы, которая должна была представлять собой сферу, вписанную в цилиндр. Марк Туллий Цицерон (106–43 гг. до н. э.) обнаружил гробницу, заросшую растительностью, спустя полтора столетия после смерти Архимеда.

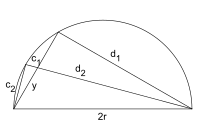

«Измерение круга»

Это фрагмент более длинной работы, в которой π (пи), отношение длины окружности к диаметру круга, лежит в пределах 310/71 и 31/7. Подход Архимеда к определению πи, который заключается во вписывании и описании правильных многоугольников с большим количеством сторон, использовался всеми до развития бесконечных серийных расширений в Индии в 15-м веке и в Европе в 17-м веке. Эта работа также содержит точные приближения (выраженные как отношения целых чисел) к квадратным корням из 3 и нескольким большим числам.

«О коноидах и сфероидах»

В этой работе представлено определение объемов сегментов твердых тел, образованных вращением конического сечения (окружность, эллипс, парабола или гипербола) вокруг его оси. В современных условиях это проблемы интеграции. В «Спиралях» развивается множество свойств касательных и областей, связанных со спиралью Архимеда, то есть местоположения точки, движущейся с одинаковой скоростью вдоль прямой линии, которая сама вращается с постоянной скоростью вокруг фиксированной точки.

«О равновесии плоских фигур»

Здесь главным образом рассматривается установление центров тяжести различных прямолинейных плоских фигур и сегментов параболы и параболоида. В первой книге рассматривается «закон рычага» (баланс величин на расстояниях от точки опоры в обратном отношении к их весам), и именно на основе этого трактата Архимед был назван основателем теоретической механики. Однако большая часть этой книги, несомненно, не является подлинной и состоит из неумелых более поздних дополнений или переделок, и представляется вероятным, что базовый принцип закона рычага и, возможно, концепция центра тяжести были установлены учеными раньше, чем это сделал Архимед. Биографы считают, что его вклад заключался, скорее, в распространении этих понятий на конические сечения.

«Квадратура параболы»

Эта работа демонстрирует при помощи «механических» средств, а затем обычных геометрических методов, что площадь любого сегмента параболы составляет 4/3 от площади треугольника, имеющего такое же основание и высоту, как этот сегмент.

«О счислении песчинок»

Это небольшой трактат, написанный для обывателя, который адресован Гелону, сыну Гиерона. Его цель состоит в том, чтобы исправить недостатки греческой системы числовых обозначений, показав, как выразить огромное число на примере песчинок, которые потребуются для заполнения всей вселенной. По сути, Архимед создает целочисленную систему обозначений с базой в 100 000 000. Работа также представляет интерес, поскольку она дает наиболее подробное сохранившееся описание гелиоцентрической системы Аристарха Самосского (310–230 гг. до н. э.). Также в ней содержится описание гениальной процедуры, которую Архимед использовал для определения видимого диаметра Солнца путем наблюдения с помощью инструмента.

«Метод механических теорем»

Он касается механических теорем и описывает процесс открытия в математике. В нем Архимед рассказывает, как он использовал «механический» метод для достижения некоторых своих ключевых открытий, включая площадь параболического сегмента, площадь поверхности и объем сферы.

«О плавающих телах»

Этот труд (в двух книгах) сохранился лишь частично на греческом языке, остальное — в средневековом латинском переводе с греческого. Это первая известная работа по гидростатике, основателем которой признан Архимед. Он определял положения, которые различные твердые тела будут занимать при плавании в жидкости, в соответствии с их формой и изменением их удельного веса. В первой книге изложены различные общие принципы, в частности то, что стало известно как принцип Архимеда: твердое вещество, более плотное, чем жидкость, при погружении в эту жидкость будет легче на вес вытесняемой ею жидкости. Во второй книге Архимед определяет различные положения устойчивости в соответствии с геометрическими и гидростатическими вариациями.

Другие труды

Как известно из биографии Архимеда и упоминаний более поздних авторов, ученый написал ряд других работ, которые не сохранились. Особый интерес представляют трактаты о катоптрике, в которых он среди прочего обсуждает явление рефракции; на 13 полурегулярных (архимедовых) многогранниках (те тела, ограниченные правильными многоугольниками, не обязательно все одного типа, которые могут быть вписаны в сферу). В дополнение к этим, в арабском переводе сохранились несколько работ, приписанных Архимеду, которые он не мог бы составить в их нынешнем виде, хотя они могут содержать «архимедовы» элементы. К ним относятся работы по вписанию правильного семиугольника в круг; коллекция лемм (предположения, которые считаются истинными и используемые для доказательства теоремы) и книга «О касающихся кругах» — обе они имеют отношение к геометрии элементарной плоскости; и «Стомахион», содержащий описание загадки в виде головоломки (квадрат, разделенный на 14 частей).

Архимедов винт

Этот водяной винт похож на штопор, размещенный в трубе. С его помощью можно поднимать воду из реки, озера или колодца. Традиционно его изобретение приписывают Архимеду. Стефани Далли из Оксфордского университета обнаружила ассирийские клинописные письмена, датированные около 680 до н. э. и содержащие описания того, что очень напоминает водяной винт и использовалось для орошения садов в городе Ниневии в Месопотамии. Она считает, что эти сады на самом деле были знаменитыми Висячими садами, когда-то связанными с Вавилоном. В месопотамской культуре изобретатели оставались анонимными или их изобретения приписывались королю, который заплатил за работу.

Возможно, имя Архимеда связано с водяным винтом по одной из этих причин:

- Устройство было забыто, после того как Ниневия была завоевана вавилонянами, а Архимед изобрел его с нуля.

- Устройство могло достичь Египта, который находился под властью Ассирии в 680 году до нашей эры. Архимед, возможно, видел его в действии четыре столетия спустя, когда Египет был под властью греков. Вполне возможно, что он значительно улучшил конструкцию, сделав ее более удобной и дешевой в использовании.

История о золотой короне

Это один из самых интересных фактов в биографии Архимеда. Король Гиерон II отдал золото ремесленнику, чтобы сделать из него корону. Готовая, она весила столько же, сколько и золото, данное мастеру, но король был подозрительным. Он решил, что мастер украл часть золота, заменив его серебром. Решить проблему он поручил Архимеду.

Было известно, что золото плотнее серебра, поэтому один кубический сантиметр золота будет весить больше, чем один кубический сантиметр серебра. Проблема заключалась в том, что корона была неправильной формы, поэтому, хотя ее вес был известен, ее объем — нет.

Считается, что Архимед измерил уровень воды в чашке, сравнив изменения при погружении килограмма золота и килограмма серебра. Если бы мы сделали это измерение с использованием современного оборудования, мы обнаружили бы, что 1 кг золота повысит уровень воды на 51,8 мл, а 1 кг серебра — на 95,3 мл.

Как говорится в биографии, Архимед обнаружил, что корона была смесью золота и серебра. Считается, что идея, как решить эту проблему, появилась, когда Архимед принимал ванну, заметив при этом, как меняется уровень воды. Он был так взволнован, что вскочил и побежал голым по улицам Сиракуз, выкрикивая: «Эврика!» — что значит: «Нашел!»

Астрономия

В биографии великого математика Архимеда есть упоминание о том, что он также был известен как выдающийся астроном: его наблюдения солнцестояний использовались Гиппархом, одним из выдающихся астрономов II века до н. э. Об этой стороне деятельности Архимеда известно очень мало, хотя работа «О счислении песчинок» раскрывает его интерес к этой науке и практические наблюдательные способности. Однако сохранился ряд чисел, которые приписываются ему, указывающих расстояния между Землей и различными небесными телами, которые, как было показано, основаны не на наблюдаемых астрономических данных, а на «пифагорейской» теории. Удивительно, что эти метафизические предположения можно найти в работах практикующего астронома, но есть все основания полагать, что их верно приписывают Архимеду.

Архимед (287-212 гг. до н. э.) – древнегреческий ученый и инженер. Автор множества открытий в сфере геометрии, предвосхитил многие идеи математического анализа. Сделал множество открытий в области геометрии, предвосхитил многие идеи математического анализа. Заложил основы механики, гидростатики, был автором ряда важных изобретений.

С именем Архимеда связаны многие математические понятия. Наиболее известно приближение числа π, которое называется Архимедовым числом. Кроме того, имя Архимеда носят граф, ещё одно число, копула, аксиома, спираль, тело, закон и другие.

В биографии Архимеда есть много интересных фактов, о которых мы расскажем в данной статье.

Итак, перед вами краткая биография Архимеда.

Биография Архимеда

О биографии Архимеда нам известно из упоминаний Полибия, Цицерона, Плутарха, Витрувия и других древних авторов. Поскольку все они жили гораздо позже его, достоверность их сведений оценить сложно.

В своих трудах биографы Архимеда упоминают его достижения в науках, открытия, изобретения и другие интересные факты из жизни ученого. Известно, что Архимед появился на свет 287 г. до н.э. в эллинской колонии Сиракузы, находящейся на востоке Сицилии.

Считается, что отцом Архимеда был астроном и математик Фидий. По словам Плутарха, изобретатель приходился родственником Гиерону II – главе Сиракуз. Очевидно, что его детские годы прошли в этой колонии, после чего он отправился обучаться наукам в Александрию.

Стоит отметить, что Архимед сам указывал в своих работах, что обучался математике в Александрии. При этом начальное образование он, по-видимому, получил у отца. Спустя какое-то время ученый вернулся в Сиракузы и жил там до самой смерти.

Механика

Архимед проявлял большой интерес к механике, вследствие чего сконструировал немало разных устройств. Он детально описал способ действия рычага, который многократно использовал на практике.

И хотя о «рычаге» было известно задолго до Архимеда, именно ему удалось популяризировать его и продемонстрировать его эффективность в разных областях. В частности, ему удалось сконструировать ряд различных блочно-рычажных механизмов в порту Сиракуз.

Посредством таких приспособлений соотечественники Архимеда смогли быстрее и проще перемещать тяжелые грузы. Также он является автором известного механизма, названного его именем – «Архимедов винт». С помощью данного устройства человек мог в одиночку выкачивать воду.

Такой винт позже начали использовать в самых разных сферах, включая перекачку жидкостей и сыпучих веществ, как, например, уголь и зерно. Важно не забывать и теоретические разработки Архимеда.

Опираясь на все тот же закона рычага, изобретатель издал научную работу «О равновесии плоских фигур». Здесь он обосновал доказательство того, что на равных плечах, равные тела по необходимости уравновесятся. В другом труде – «О плавании тел», он описал подобный принцип.

Математика

На протяжении всей биографии Архимед проявлял огромный интерес к точным наукам. По воспоминаниям Плутарха, когда он начинал работать, то забывал о еде и полностью погружался в вычисления. В сфере математики его больше всего интересовали вопросы математического анализа.

Архимед нашел новые эффективные способы подсчета объемов и площадей. Ему удалось усовершенствовать метод исчерпывания Евдокса Книдского, вследствие чего он мастерски применял его на практике. И хотя еще до Архимеда была сформулирована теория интегрального исчисления, именно его труды легли в основу данной теории.

Одновременно с этим, Архимед заложил базу для дифференциальных вычислений. Он смог определить, что объемы конуса и шара, вписанных в цилиндр, и самого цилиндра имеют соотношение – 1:2:3. До этого еще никому не удавалось вычислить поверхность и объем шара.

Интересен факт, что Архимед завещал выбить на собственном надгробии шар, вписанный в цилиндр. Кроме этого, математик смог узнать площадь поверхности для сегмента шара и витка открытой им «спирали Архимеда».

Отдельного внимания заслуживает вычисленное Архимедом отношение длины окружности к диаметру. В труде «Об измерении круга» он подробно описал свое легендарное приближение для числа «Пи» (π).

Чтобы доказать свои предположения, Архимед построил для круга вписанный и описанный 96-угольники, после чего определил длины их сторон. Параллельно с этим, он научно обосновал, что площадь круга равна числу π, умноженному на квадрат радиуса круга. Именно так появилось знаменитая формула – πr².

Закон Архимеда

Под законом Архимеда подразумевается следующее: на тело, погруженное в жидкость или газ, действует выталкивающая или подъемная сила, равная массе объема жидкости или газа, вытесненного частью тела, погруженной в жидкость или газ.

Согласно известной легенде, Архимед якобы открыл свой закон, когда выполнял просьбу Гиерона. Правитель хотел узнать, не обманывает ли его работник, выполнявший заказ на изготовление золотой короны. Он понимал, что работник мог присвоить себе часть предоставленного золота, а вместо желтого метала подмешать серебро.

Чтобы решить эту непростую задачу, Архимед отлил 2 равноценных по весу слитка из серебра и золота. Затем он поочередно опустил слитки в емкость, до краев заполненную водой, что позволило ему узнать какое количество воды вытеснил каждый из слитков.

Благодаря этому, Архимед вычислил сколько воды вытесняет золото. Потом он просто поместил корону в емкость с водой и узнал, соответствует ли ее вес вытесняемой жидкости. Опасения Гиерона оправдались, ювелир действительно смошенничал, присвоив часть золота.

По легенде, математик сделал свое открытие во время нахождения в ванной. Когда Архимед садился в воду он заметил, что вес его тела поднял ее уровень. С громким возгласом «Эврика», мужчина выскочил из ванны и нагим помчался к правителю.

Астрономия

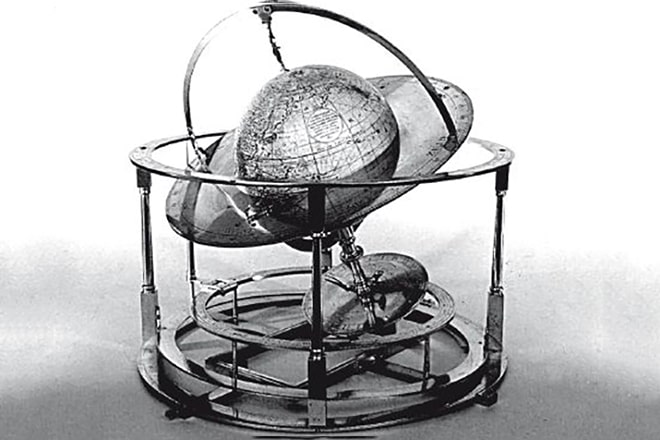

Архимед стал автором не менее 3-х работ по астрономии. Он пытался узнать размеры Вселенной, и был первым изобретателем планетария. При движении данного устройства можно наблюдать следующие явления:

- восход Луны и Солнца;

- вращение 5 планет;

- исчезновение Луны и Солнца за горизонтом;

- фазы и затмения Луны.

Архимед стремился определить максимально точные расстояния до планет. Современные ученые полагают, что Землю он считал центром мироздания. Изобретатель думал, что Венера, Марс и Меркурий двигаются вокруг Солнца, а уже вся эта система движется вокруг Земли.

Личная жизнь

О личной биографии Архимеда мы практически ничего не знаем. Еще при жизни о нем начали слагать легенды. По одной из них, когда Гиерону не удавалось спустить на воду многопалубное судно «Сиракузия», он решил обратиться за помощью к математику.

Из нескольких блоков Архимед якобы сконструировал механизм, который позволил спустить корабль на воду одним касанием руки. Бытует мнение, что именно тогда он сказал свою популярную фразу: «Дайте мне точку опоры, и я переверну мир».

Смерть

В 212 г. до н.э. в разгар Второй Пунической войны Сиракузы были осаждены римскими войсками. Архимед постоянно задействовал свой инженерный талант, чтобы оказать помощь соотечественникам. К примеру, он соорудил метательные машины, посредством которых римлян забрасывали крупными камнями.

Тогда же Архимед сконструировал огромные краны, с помощью которых греки могли цеплять крючьями вражеские корабли и отбрасывать их обратно в море. Римские судна переворачивались набок и нередко шли на дно.

Когда римляне поняли, что вряд ли смогут взять город штурмом, они избрали тактику осады. Осенью 212 г. до н.э. Сиракузы пали вследствие измены. Во время захвата колонии Архимед был убит. Есть несколько версий смерти гениального ученого.

Согласно одной их них Архимеда убили в его лаборатории. Он якобы был так сильно увлечен работой, что отказался сразу следовать за римским воином, которому надлежало доставить пленника к начальству. В результате, разгневанный неподчинением солдат заколол Архимеда.

Фото Архимеда

Если вам понравилась краткая биография Архимеда – поделитесь ею в соцсетях. Если же вам нравятся биографии известных людей или интересные истории из их жизни, – подписывайтесь на сайт InteresnyeFakty.org.

Понравился пост? Нажми любую кнопку:

Краткая биография Архимеда

Пожалуй, при слове изобретатель или каком-то подобном довольно часто в уме появляется имя Архимеда. Этот древний мыслитель действительно был выдающимся изобретателем и оставил существенное количество открытий, которые повлияли на развитие всего человечества в дальнейшем.

Архимед родился в 287 году до новой эры на территории острова Сицилия в столице – Сиракузы. Он родился в довольно знатной семье, отец его сам был математиком, а также он был известен тирану того города Гиерону Второму. Оба они с ранних лет заметили в мальчике склонность к познаниям и отправили в подростковом возрасте Архимеда учиться в Александрию Египетскую, именно там была крупнейшая библиотека, которую потом сжег Герострат, чтобы прославиться.

После обучения, за период которого он познакомился со множеством ученых мужей своего времени и усвоил передовые идеи, Архимед возвращается на родину и фактически поступает на службу к Гиерону. Тиран всячески хочет, чтобы Архимед начал разрабатывать всяческие военные новшества для острова, а молодой ученый придерживается миролюбивых воззрений и хочет заняться только изучением мира. Итак, Архимед остается на острове и начинает совершать свои открытия, многие из которых оказываются итогом работы с Гиероном, к примеру, именно он хотел чтобы молодой математик определил состав короны, но, не повреждая сам предмет.

Именно тогда и появилось изобретение о вытеснении телами разного объема воды, при идентичной массе. Помимо этого Архимед сделал множество открытий в математике, которые не много ни мало опередили эпоху на пару тысяч лет. Именно так, некоторые идеи, такие как полуправильные многогранники или использование парабол и гипербол для решения уравнений, ученые смогли по достоинству оценить и развить только в новом времени, после средневековья.

В 212 году Сиракузы оказались под натиском римских войск. Тогда шла вторая Пуническая война и Сицилия была в невыгодном положении между империей и Карфагеном. Архимед сделал немало военных изобретений для того чтобы отстоять собственный город (метательные орудия, отражающие медные пластины и многое другое) тем не менее Сиракузы пали, а Архимед погиб от руки римского солдата.

Биография 2

Точная биография Архимеда, к сожалению, неизвестна. Учёными и археологами разных эпох были приведены разные факты из его жизни, но и они основаны на трудах людей, живших много позднее Архимеда. Согласно самой распространённой версии, будущий математик родился в 287 году до н.э. Местом рождения были Сиракузы (остров Сицилия). Отец мальчика, астроном и математик, отправил сына обучаться в Александрию. Излюбленным местом будущего физика и математика стала библиотека Александрии, где он изучал труды и сочинения Демокрита, Евдокса и многих других учёных. Там же Архимед заводит знакомства, которые пронесёт через всю жизнь.

Молодой человек с юности любил математику. Всё время он посвящал разработкам в области арифметики, алгебры и геометрии. Специалисты этих областей смогли понять, классифицировать и развить его идеи только к 17 веку. Архимед решал сложнейшие уравнения, находя решения графически. Вычислял площади, объёмы разного рода геометрических фигур. Собирал и обобщал в единые принципы и формулы уже известные методы вычисления. Выводил и доказывал постулаты и аксиомы, которые мало того, что не опровергнуты, но и взяты за основу современными учёными. Одно из важнейших его достижений в геометрии, по его же словам, заключалось в нахождении площади поверхности и объёма сферы. Также он вывел формулы расчетов объёмов параболоида, гиперболоида вращения и эллипсоида. До Архимеда этих вычислений не совершал ни один математик.

Помимо арифметики, алгебры и столь любимой им геометрии, Архимед применял свои знания в области механики и физики, изобретая и совершенствуя уже существующие конструкции и механизмы. К примеру, известный до его рождения рычаг Архимед усовершенствовал, рассчитав его возможности и применив на практике в порту Сиракуз. Некоторые приспособления и механизмы, основанные на принципе рычага, с тех пор существенно облегчали тяжёлую работу.

Астрономия также не оставила его равнодушным. Учёный занимался определением расстояния между космическими объектами, хотя и делал это с ошибочной точки зрения. Ведь в 3 веке до н.э. была распространена геоцентрическая теория существования мира. Впрочем, позднее Архимед преподнёс в одном из своих трудов гелиоцентрическую теорию.

В его честь названы цепь гор и кратер на поверхности Луны, астероид, улицы в нескольких городах России и она улица в Амстердаме. Погиб Архимед во время военных действий при наступлении римлян на Сиракузы. Для победы своей Родины учёный создал метательные механизмы. Римские войска существенно пострадали от этих машин. Решено было держать город в осаде. В 212 году до н.э. Сиракузы сдались, а Архимед был убит.

Биография по датам и интересные факты. Самое главное.

Другие биографии:

- Карл Брюллов

Брюллов родился в Петербурге в 1799 году и оставил мир неподалеку от города Лацио и Рима в коммуне Манциана в 1852 году. Он был третьим сыном в семье преподавателя Академии художеств

- Александр Федорович Керенский

Керенский родился не в самой богатой семье, но и не в очень бедной, 1881 года, в мае, в городе Симбирск. Кроме того, в этом городе также родился Ленин. Родители Александра хорошо дружили с родителями Ленина.

- Винсент Ван Гог

Ван Гог родился в 1853 году, а умер в 1890. Он вдохновлялся такими велики художниками, как Миле и Сардо и ориентироваться на них в своём творчестве. Как художник Ван Гог начал с зарисовки различных сцен из жизни

- Василий Белов

Василий Иванович Белов — писатель, сценарист, публицист и прозаик. Появился на свет 23 октября в 1932 году в селе Тимониха Волгоградской области в Российской империи.

- Александр III

Александр III – Всероссийский император, правивший страной в период с 1 марта 1881 по 20 октября 1894 года. Известен как Царь-Миротворец, так как за все время его правления страна не знала сражений и войн.

- Биографии

- Архимед

/

Краткая биография Архимеда самое главное

Знаменитый учёный эпохи Античности, Архимед родился в 287 году до н.э. на Сицилии, в городе Сиракузы. Об этом рассказал миру в своих трудах Иоанн Цеце. Сам Архимед не оставил потомкам автобиографию, воспоминания, мемуары. Он полностью посвятил свою жизнь математике, физике, геометрии, инженерии. Талантом писателя пользовался, но для других целей.

По площади Сиракузы были самым крупным населённым пунктом античного мира. Самыми крупными культурными центрами были, конечно же, Афины, Рим. Но и в Сиракузах цивилизация процветала: у будущего учёного в детстве была возможность получить хорошее образование, много времени уделять урокам, притом предметам в чём-то абстрактным, философским. Ораторское искусство, популярное в те времена, не увлекло его. Скорее всего, потому что Сиракузы находились вдали от столицы. Он не стал великим архитектором, не разбогател за счёт торговых сделок, земледелия. Восхищённый миром чисел и идей, его призрачностью и реалистичностью, он изобретал, открывал невидимые законы.

Большинство исследователей считают, что его отец – математик, астроном Фидий. Сам Архимед упоминает его в трактате «Исчисление песчинок». Больше нигде, из найденных документов той эпохи, это имя не звучит. Но понять, о ком именно идёт речь сложно – текст можно перевести по-разному. В одной интерпретации в нём о Фидии написано, что тот был сыном Акупатра, а в другой – отцом Архимеда. Плутарх утверждал, что Архимед был родом из весьма влиятельной семьи: правитель Сиракуз, Гиерон II был его родственником.

В юности будущий великий учёный отправился в Египет, город Александрию, чтобы начать свою карьеру в области науки. Он многого не знал, было чему поучиться. Здесь располагалась великолепная библиотека, с огромным количеством рукописей. В этом городе также проживали многие известные учёные. В Александрии Архимед подружился с небезызвестным астрономом Кононом Самосским, поэтом, математиком, географом Эратосфеном Киренским.

После обучения он снова приехал в Сиракузы. Очень быстро создал себе имя, репутацию гения. Успех ему принесли, однако, не рассуждения. Его открытия были полезными государству. Он, не стесняясь, применял их на практике. Например, считается, что он открыл закон Архимеда, измеряя корону короля, пытаясь выяснить, сколько в ней золота, а сколько примесей. Впрочем, вёл он и переписку с другими учёными, обсуждал достижения, делился своими успехами.

В те времена постоянно шла война между разными государствами за территорию. Но это не мешало цивилизации развиваться. Древняя Греция была серьёзным противником. В ней жили славные воины, трудолюбивые земледельцы. Архимеду же была свойственна фанатичность, он без ума был влюблён в науку, служил истине. В 212 году до н.э. началась война за Сиракузы с римлянами. Именно Архимед придумал грозное оружие, метательные машины с прицельным огнём. Благодаря его усилиям атаки были отражены. Но город взяли в осаду, и вскоре, всё в том же 212 году, он был захвачен хитростью – помог предатель. Архимед погиб в той битве. Ему было 75 лет. О сражении за Сиракузы, изобретениях учёного рассказано в трудах Плутарха, Тита Ливия, Анфимия Траллийского.

Самое важное. Для детей и школьников и его открытие

Биография Архимеда о главном

Архимед является выдающимся древнегреческим математиком, инженером и изобретаем своего времени. Родился он в 287 году до н.э. в городе Сиракузы на Сицилии. Отец Фидий был физиком и математиком, находящийся при дворе.

Архимед получил превосходное образование, но он понимал, что всё-таки ему недостаёт теоретических знаний, которые были даны ранее. Поэтому проводил в Александрийской библиотеке всё своё свободное время. После окончания учёбы стал работать при дворе – астрономом, создал планетарий. Так как в то время было модно изучать астрономию, то все считали, что Солнце и Луна вращаются вокруг Земли, но только Архимед предположил, что именно все планеты кружатся вокруг Солнца. Помимо этого он изучал механику, физику и математику свои труды он изложил в своих работах «О равновесии плоских фигур», далее последовало сочинение «Об изменении круга».

У ученого много открытий, который он посветил своей родине. Ему удалось воссоздать целую рычагово-блочных механизмом, которые позволяют перевозить тяжелые грузы намного быстрее.

Так же у Архимеда существуют множество работ связанных с алгеброй, геометрией, арифметикой. Разработал всесторонний метод вычисления площадей разнообразных фигур. Создал теорию об уравновешивании равных тел.

Одной из версий смерти является, что убили великого ученого в период Второй Пунической войны, когда после продолжительной обороны взяли Сиракузы. Марк Клавдий Марцелл отдал приказ разыскать Архимеда и привести к нему. За ним послали солдата, он направился в дом ученого, который в этот период производил математические расчёты. Солдат потребовал явиться к римлянам, на что Архимед ответил, только после того как закончу расчёты, но разозлившись солдат зарезал мечом самого гениального человека такого времени. Он прожил всего лишь 75 лет.

Самое важное. Для детей и школьников и его открытие

Интересные факты и даты из жизни

- Станиславский Константин Сергеевич

Константин Сергеевич Станиславский был рожден зимой 1863 года в столице России. Кроме мальчика в семье было девять детей. Их отец был промышленником. Семья была творческой. Один из братьев Кости стал режиссером, другой брат – историком.

- Чехов

Антон Павлович Чехов- литератор, драматург, академик. Почти все произведения Чехова- это классика глобальной публицистики, а его прелюдии ставятся на сценах по всему миру. Чехов появился на свет 17 января 1860г. в городе Таганрог в купеческой семье.

- Боголюбский Андрей

На сегодняшний день точная дата появления на свет Боголюбского никому не известна. Примерно называют две даты. Это 1111 и 1113 годы. Очень скудны сведения о детстве и юности Боголюбского Андрея. Доподлинно известно, что мальчик получил достойное

- Тихона Патриарха

Патриарх Тихон считается величайшей фигурой в православии. Он искренне верил в дела Господа, помогал людям, когда те, даже этого не просили. Василий Иванович Белавин, его настоящее имя, родился 19 января 1865 года в Псковской губернии, в деревне Клин.

- Верн Жюль

Жюль Верн появился на свет 8 февраля 1828 года во Франции в семье юристов. Он был старшим из пяти детей и, уважая своего отца, решил посвятить себя адвокатуре. Но страсть к книгам и сочинению постоянно отвлекали его от учёбы в университете.

- Уайльд Оскар

Драматург и писатель Оскар Уайльд родился в 1854 году в богатой и интеллектуальной ирландской семье. Его отец, Уильям Уайльд, один из ведущих викторианских окулистов и хирургов в Ирландии, имел свою клинику. Среди его пациентов были особы

- Энциклопедия

- Люди

- Архимед

Архимед — доклад сообщение

Архимед – ученый родом из Сиракуз, который прожил свой век, начиная с 287 до 212 года до новой эры. Еще мальчиком он проявлял способности к познанию мира и царь Сиракуз отправил его «на большую землю» учиться к лучшим умам того времени, в частности с 272 года Архимед учится у Эвклида и пользуется Александрийской библиотекой.

В 20 лет молодому ученому требуется возвращаться обратно на родину, хотя Эвклид и отговаривал его от служения царю, ведь он станет использовать его знания для того чтобы упрочить собственную власть, а не для того чтобы упрочить и распространить знания.

По дороге обратно корабль Архимеда терпит крушение, и он чудом спасается. После чего он изобретает так называемый архимедов винт – полую трубу с винтом, благодаря которой возможно откачивать существенные объемы воды из тонущего корабля, этот винт потом использовали не только для кораблей, но и в оросительных системах.

Далее царь Сиракуз дал ученому задание: узнать из какого металла сделана его корона. Он сказал не разламывать корону и не повреждать изделие, но узнать, из чего сделан предмет. Тогда и родилась известная легенда с криком «Эврика» (в переводе «нашел») и пониманием как измерить состав изделия через объем вытесняемой воды.

Архимед помимо этого занимался и астрономическими исследованиями, которые были довольно современными для его времени. Он измерял дистанции от Солнца до Земли, придерживался мнения о наличии солнечной системы, которое расходилось с распространенным мнением о Земле, вокруг которой вращаются остальные планеты.

Царь Геирон предоставил ему возможность выполнять изыскания в области математики и других областей знаний. Архимед стал великим ученым и сделал открытия, которые стали базой для математических изысканий следующих времен. Он является создателем ряда фундаментальных математических теорем.

Тем не менее, со временем ученому пришлось отказаться от мирной деятельности. Сиракузы были довольно богатым островом и в Пунические войны выступали против Карфагена, и во второй войне Карфаген во главе с Ганнибалом направил свои корабли к Сиракузам. Поэтому Архимеду предстояло создать множество оборонительных сооружений, которые смогли бы сохранить неприкосновенность острова.

В итоге Архимед создал множество механизмов, но произошел переворот, сына Геирона предали и в итоге город стал союзником Карфагена и против него выступил Рим. Войска империи продолжали атаковать город, хотя Сиракузы отлично оборонялись благодаря изобретениям Архимеда. В итоге житель Сиракуз предал свой город и впустил римские войска, а Архимед погиб от руки римских солдат.

Вариант 2

Многие ученые древности не были поняты своими современниками, так как они родились слишком рано. Чтобы общество могло понять их труды и должным образом оценить их, этим людям следовало бы появиться на свет на много столетий позже. Самым ярким, самым выдающимся ученым древности по праву считается Архимед из Древней Греции.

Он родился в Сиракузах, дату можно назвать лишь примерно – 287 год до нашей эры. Мальчик получил хорошее образование, но все же решил поехать в Александрию, которая была тогда крупным культурным и образовательным центром. Архимед изучал там разные науки, однако больше всего времени он посвятил математике. После окончания учебы он вернулся в Сиракузы.

В родном городе Архимед получил хорошую должность, он стал придворным астрономом. Имея достаточно свободного времени, занялся научной работой. Этот человек был гениален во многих областях, и свидетельством этого являются труды, которые дошли до нас.

Ученому было уже более 70 лет, когда он был назначен ответственным за оборону Сиракуз, так как город пытались захватить римляне. И Архимед выполнил эту задачу блестяще, очередной раз подтвердив свою гениальность. Он изобрел мощную метательную машину и создал несколько образцов. Более трех лет римляне не могли захватить город, а когда это случилось, то первых солдат, вступивших в Сиракузы, встретил град камней из метательных машин Архимеда.

Так что великий ученый был не только теоретиком, но и практиком, инженером. Он использовал рычаги для перемещения тяжестей в порту, во время войны по его приказанию греки поджигали корабли римлян с помощью зеркал, все его изобретения были полезными и нужными, а некоторыми мы пользуемся до сих пор.

Научные труды Архимеда на много веков опередили свое время, например, его работы по математике стали понятны ученым лишь в 17 веке, тогда они и получили свое развитие и продолжение. Математика была любимой наукой Архимеда. Он заложил основу интегрального исчисления и математического анализа, с помощью его формулы мы считаем радиус окружности, площадь и объем разных фигур. Он изобрел немало механизмов, построил планетарий. Архимед был первым во многих науках. И сейчас ученые используют закон Архимеда, правило Архимеда, теорему Архимеда.

К сожалению, не все труды ученого дошли до наших времен. Но и то, что должно, бесценно для науки.

Умер Архимед в 212 году до нашей эры. Его убили римляне, против которых он так долго воевал. Но имя его помнят до сих пор, как имя одного из самых выдающихся и гениальных людей за всю историю.

3, 5, 6, 7 класс по физике, математике.

Архимед

Интересные темы

- История создания Ревизора — комедии Гоголя

Идея комедии Ревизор зародилась у Николая Васильевича Гоголя в начале 1830-ых гг., во время написания повести Мертвые души. Автор хотел написать произведение, в котором полностью бы раскрывались

- История открытия и изучения «Слова о полку Игореве» доклад сообщение

Слово о полку Игореве считается своеобразным литературным и историческим памятником культуры Древней Руси. Слово могло к нам не дойти, как и не дошли другие великие повести и сказания

- Жизнь и творчество Карло Гоцци

Карло Гоцци (1720-1806 гг.) является известным итальянским драматургом и писателем, из-под пера которого вышло большое количество сказочных пьес, именуемых фьябами, основанных на фольклорных элементах сюжетной линии

- Доклад сообщение на тему Гриб Лисичка

Гриб является популярным грибом, широко известным как лисички, имя которое также может относиться к видам типа «cibarius». Это грибы, которые образуют симбиотические ассоциации с растениями, что делает их очень трудными для эволюционирования

- Доклад на тему Футбол (сообщение по физкультуре)

Самый популярный в мире командный вид спорта — футбол. Сегодня в него играет огромное количество парней и даже девушек. До сих пор неизвестно точного года и места зарождения этого вида спорта.

|

Archimedes of Syracuse |

|

|---|---|

|

Ἀρχιμήδης |

|

Archimedes Thoughtful |

|

| Born | c. 287 BC

Syracuse, Sicily |

| Died | c. 212 BC (aged approximately 75)

Syracuse, Sicily |

| Known for |

List

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Mathematics Physics Astronomy Mechanics Engineering |

| Influences | Eudoxus |

| Influenced | Apollonius[2] Hero Pappus Eutocius |

Archimedes of Syracuse (;[3][a] c. 287 – c. 212 BC) was a Greek mathematician, physicist, engineer, astronomer, and inventor from the ancient city of Syracuse in Sicily.[4] Although few details of his life are known, he is regarded as one of the leading scientists in classical antiquity. Considered the greatest mathematician of ancient history, and one of the greatest of all time,[5] Archimedes anticipated modern calculus and analysis by applying the concept of the infinitely small and the method of exhaustion to derive and rigorously prove a range of geometrical theorems.[6][7] These include the area of a circle, the surface area and volume of a sphere, the area of an ellipse, the area under a parabola, the volume of a segment of a paraboloid of revolution, the volume of a segment of a hyperboloid of revolution, and the area of a spiral.[8][9]

Archimedes’ other mathematical achievements include deriving an approximation of pi, defining and investigating the Archimedean spiral, and devising a system using exponentiation for expressing very large numbers. He was also one of the first to apply mathematics to physical phenomena, working on statics and hydrostatics. Archimedes’ achievements in this area include a proof of the law of the lever,[10] the widespread use of the concept of center of gravity,[11] and the enunciation of the law of buoyancy or Archimedes’ principle.[12] He is also credited with designing innovative machines, such as his screw pump, compound pulleys, and defensive war machines to protect his native Syracuse from invasion.

Archimedes died during the siege of Syracuse, when he was killed by a Roman soldier despite orders that he should not be harmed. Cicero describes visiting Archimedes’ tomb, which was surmounted by a sphere and a cylinder that Archimedes requested be placed there to represent his mathematical discoveries.

Unlike his inventions, Archimedes’ mathematical writings were little known in antiquity. Mathematicians from Alexandria read and quoted him, but the first comprehensive compilation was not made until c. 530 AD by Isidore of Miletus in Byzantine Constantinople, while commentaries on the works of Archimedes by Eutocius in the 6th century opened them to wider readership for the first time. The relatively few copies of Archimedes’ written work that survived through the Middle Ages were an influential source of ideas for scientists during the Renaissance and again in the 17th century,[13][14] while the discovery in 1906 of previously lost works by Archimedes in the Archimedes Palimpsest has provided new insights into how he obtained mathematical results.[15][16][17][18]

Biography

Archimedes was born c. 287 BC in the seaport city of Syracuse, Sicily, at that time a self-governing colony in Magna Graecia. The date of birth is based on a statement by the Byzantine Greek historian John Tzetzes that Archimedes lived for 75 years before his death in 212 BC.[9] In the Sand-Reckoner, Archimedes gives his father’s name as Phidias, an astronomer about whom nothing else is known.[20] A biography of Archimedes was written by his friend Heracleides, but this work has been lost, leaving the details of his life obscure. It is unknown, for instance, whether he ever married or had children, or if he ever visited Alexandria, Egypt, during his youth.[21] From his surviving written works, it is clear that he maintained collegiate relations with scholars based there, including his friend Conon of Samos and the head librarian Eratosthenes of Cyrene.[b]

The standard versions of Archimedes’ life were written long after his death by Greek and Roman historians. The earliest reference to Archimedes occurs in The Histories by Polybius (c. 200–118 BC), written about 70 years after his death. It sheds little light on Archimedes as a person, and focuses on the war machines that he is said to have built in order to defend the city from the Romans.[22] Polybius remarks how, during the Second Punic War, Syracuse switched allegiances from Rome to Carthage, resulting in a military campaign under the command of Marcus Claudius Marcellus and Appius Claudius Pulcher, who besieged the city from 213 to 212 BC. He notes that the Romans underestimated Syracuse’s defenses, and mentions several machines Archimedes designed, including improved catapults, crane-like machines that could be swung around in an arc, and other stone-throwers. Although the Romans ultimately captured the city, they suffered considerable losses due to Archimedes’ inventiveness.[23]

Cicero (106–43 BC) mentions Archimedes in some of his works. While serving as a quaestor in Sicily, Cicero found what was presumed to be Archimedes’ tomb near the Agrigentine gate in Syracuse, in a neglected condition and overgrown with bushes. Cicero had the tomb cleaned up and was able to see the carving and read some of the verses that had been added as an inscription. The tomb carried a sculpture illustrating Archimedes’ favorite mathematical proof, that the volume and surface area of the sphere are two-thirds that of the cylinder including its bases.[24][25] He also mentions that Marcellus brought to Rome two planetariums Archimedes built.[26] The Roman historian Livy (59 BC–17 AD) retells Polybius’ story of the capture of Syracuse and Archimedes’ role in it.[22]

Plutarch (45–119 AD) wrote in his Parallel Lives that Archimedes was related to King Hiero II, the ruler of Syracuse.[27] He also provides at least two accounts on how Archimedes died after the city was taken. According to the most popular account, Archimedes was contemplating a mathematical diagram when the city was captured. A Roman soldier commanded him to come and meet Marcellus, but he declined, saying that he had to finish working on the problem. This enraged the soldier, who killed Archimedes with his sword. Another story has Archimedes carrying mathematical instruments before being killed because a soldier thought they were valuable items. Marcellus was reportedly angered by Archimedes’ death, as he considered him a valuable scientific asset (he called Archimedes «a geometrical Briareus») and had ordered that he should not be harmed.[28][29]

The last words attributed to Archimedes are «Do not disturb my circles» (Latin, «Noli turbare circulos meos«; Katharevousa Greek, «μὴ μου τοὺς κύκλους τάραττε»), a reference to the mathematical drawing that he was supposedly studying when disturbed by the Roman soldier. There is no reliable evidence that Archimedes uttered these words and they do not appear in Plutarch’s account. A similar quotation is found in the work of Valerius Maximus (fl. 30 AD), who wrote in Memorable Doings and Sayings, «… sed protecto manibus puluere ‘noli’ inquit, ‘obsecro, istum disturbare’» («… but protecting the dust with his hands, said ‘I beg of you, do not disturb this‘«).[22]

Discoveries and inventions

Archimedes’ principle

A metal bar, placed into a container of water on a scale, displaces as much water as its own volume, increasing the mass of the container’s contents and weighing down the scale.

The most widely known anecdote about Archimedes tells of how he invented a method for determining the volume of an object with an irregular shape. According to Vitruvius, a votive crown for a temple had been made for King Hiero II of Syracuse, who had supplied the pure gold to be used; Archimedes was asked to determine whether some silver had been substituted by the dishonest goldsmith.[30] Archimedes had to solve the problem without damaging the crown, so he could not melt it down into a regularly shaped body in order to calculate its density.

In Vitruvius’ account, Archimedes noticed while taking a bath that the level of the water in the tub rose as he got in, and realized that this effect could be used to determine the crown’s volume. For practical purposes water is incompressible,[31] so the submerged crown would displace an amount of water equal to its own volume. By dividing the mass of the crown by the volume of water displaced, the density of the crown could be obtained. This density would be lower than that of gold if cheaper and less dense metals had been added. Archimedes then took to the streets naked, so excited by his discovery that he had forgotten to dress, crying «Eureka!» (Greek: «εὕρηκα, heúrēka!, lit. ‘I have found [it]!’).[30] The test on the crown was conducted successfully, proving that silver had indeed been mixed in.[32]

The story of the golden crown does not appear anywhere in Archimedes’ known works. The practicality of the method it describes has been called into question due to the extreme accuracy that would be required while measuring the water displacement.[33] Archimedes may have instead sought a solution that applied the principle known in hydrostatics as Archimedes’ principle, which he describes in his treatise On Floating Bodies. This principle states that a body immersed in a fluid experiences a buoyant force equal to the weight of the fluid it displaces.[34] Using this principle, it would have been possible to compare the density of the crown to that of pure gold by balancing the crown on a scale with a pure gold reference sample of the same weight, then immersing the apparatus in water. The difference in density between the two samples would cause the scale to tip accordingly.[12] Galileo Galilei, who in 1586 invented a hydrostatic balance for weighing metals in air and water inspired by the work of Archimedes, considered it «probable that this method is the same that Archimedes followed, since, besides being very accurate, it is based on demonstrations found by Archimedes himself.»[35][36]

Archimedes’ screw

A large part of Archimedes’ work in engineering probably arose from fulfilling the needs of his home city of Syracuse. The Greek writer Athenaeus of Naucratis described how King Hiero II commissioned Archimedes to design a huge ship, the Syracusia, which could be used for luxury travel, carrying supplies, and as a naval warship. The Syracusia is said to have been the largest ship built in classical antiquity.[37] According to Athenaeus, it was capable of carrying 600 people and included garden decorations, a gymnasium and a temple dedicated to the goddess Aphrodite among its facilities. Since a ship of this size would leak a considerable amount of water through the hull, Archimedes’ screw was purportedly developed in order to remove the bilge water. Archimedes’ machine was a device with a revolving screw-shaped blade inside a cylinder. It was turned by hand, and could also be used to transfer water from a low-lying body of water into irrigation canals. Archimedes’ screw is still in use today for pumping liquids and granulated solids such as coal and grain. Described in Roman times by Vitruvius, Archimedes’ screw may have been an improvement on a screw pump that was used to irrigate the Hanging Gardens of Babylon.[38][39] The world’s first seagoing steamship with a screw propeller was the SS Archimedes, which was launched in 1839 and named in honor of Archimedes and his work on the screw.[40]

Archimedes’ claw

Archimedes is said to have designed a claw as a weapon to defend the city of Syracuse. Also known as «the ship shaker«, the claw consisted of a crane-like arm from which a large metal grappling hook was suspended. When the claw was dropped onto an attacking ship the arm would swing upwards, lifting the ship out of the water and possibly sinking it.[41]

There have been modern experiments to test the feasibility of the claw, and in 2005 a television documentary entitled Superweapons of the Ancient World built a version of the claw and concluded that it was a workable device.[42]

Heat ray

Archimedes may have written a work on mirrors entitled Catoptrica,[c] and later authors believed he might have used mirrors acting collectively as a parabolic reflector to burn ships attacking Syracuse. Lucian wrote, in the second century AD, that during the siege of Syracuse Archimedes destroyed enemy ships with fire. Almost four hundred years later, Anthemius of Tralles mentions, somewhat hesitantly, that Archimedes could have used burning-glasses as a weapon.[43] The presumed device, often called the «Archimedes heat ray«, focused sunlight onto approaching ships, causing them to catch fire. In the modern era, similar devices have been constructed and may be referred to as a heliostat or solar furnace.[44]

Archimedes’ purported heat ray has been the subject of an ongoing debate about its credibility since the Renaissance. René Descartes rejected it as false, while modern researchers have attempted to recreate the effect using only the means that would have been available to Archimedes, mostly with negative results.[45][46] It has been suggested that a large array of highly polished bronze or copper shields acting as mirrors could have been employed to focus sunlight onto a ship, but the overall effect would have been blinding, dazzling, or distracting the crew of the ship rather than fire.[47]

Lever

While Archimedes did not invent the lever, he gave a mathematical proof of the principle involved in his work On the Equilibrium of Planes.[48] Earlier descriptions of the lever are found in the Peripatetic school of the followers of Aristotle, and are sometimes attributed to Archytas.[49][50] There are several, often conflicting, reports regarding Archimedes’ feats using the lever to lift very heavy objects. Plutarch describes how Archimedes designed block-and-tackle pulley systems, allowing sailors to use the principle of leverage to lift objects that would otherwise have been too heavy to move.[51] According to Pappus of Alexandria, Archimedes’ work on levers caused him to remark: «Give me a place to stand on, and I will move the Earth» (Greek: δῶς μοι πᾶ στῶ καὶ τὰν γᾶν κινάσω).[52] Olympiodorus later attributed the same boast to Archimedes’ invention of the baroulkos, a kind of windlass, rather than the lever.[53]

Archimedes has also been credited with improving the power and accuracy of the catapult, and with inventing the odometer during the First Punic War. The odometer was described as a cart with a gear mechanism that dropped a ball into a container after each mile traveled.[54]

Astronomical instruments

Archimedes discusses astronomical measurements of the Earth, Sun, and Moon, as well as Aristarchus’ heliocentric model of the universe, in the Sand-Reckoner. Without the use of either trigonometry or a table of chords, Archimedes describes the procedure and instrument used to make observations (a straight rod with pegs or grooves),[55][56] applies correction factors to these measurements, and finally gives the result in the form of upper and lower bounds to account for observational error.[20] Ptolemy, quoting Hipparchus, also references Archimedes’ solstice observations in the Almagest. This would make Archimedes the first known Greek to have recorded multiple solstice dates and times in successive years.[21]

Cicero’s De re publica portrays a fictional conversation taking place in 129 BC, after the Second Punic War. General Marcus Claudius Marcellus is said to have taken back to Rome two mechanisms after capturing Syracuse in 212 BC, which were constructed by Archimedes and which showed the motion of the Sun, Moon and five planets. Cicero also mentions similar mechanisms designed by Thales of Miletus and Eudoxus of Cnidus. The dialogue says that Marcellus kept one of the devices as his only personal loot from Syracuse, and donated the other to the Temple of Virtue in Rome. Marcellus’ mechanism was demonstrated, according to Cicero, by Gaius Sulpicius Gallus to Lucius Furius Philus, who described it thus:[57][58]

|

Hanc sphaeram Gallus cum moveret, fiebat ut soli luna totidem conversionibus in aere illo quot diebus in ipso caelo succederet, ex quo et in caelo sphaera solis fieret eadem illa defectio, et incideret luna tum in eam metam quae esset umbra terrae, cum sol e regione. |

When Gallus moved the globe, it happened that the Moon followed the Sun by as many turns on that bronze contrivance as in the sky itself, from which also in the sky the Sun’s globe became to have that same eclipse, and the Moon came then to that position which was its shadow on the Earth when the Sun was in line. |

This is a description of a small planetarium. Pappus of Alexandria reports on a treatise by Archimedes (now lost) dealing with the construction of these mechanisms entitled On Sphere-Making.[26][59] Modern research in this area has been focused on the Antikythera mechanism, another device built c. 100 BC that was probably designed for the same purpose.[60] Constructing mechanisms of this kind would have required a sophisticated knowledge of differential gearing.[61] This was once thought to have been beyond the range of the technology available in ancient times, but the discovery of the Antikythera mechanism in 1902 has confirmed that devices of this kind were known to the ancient Greeks.[62][63]

Mathematics

While he is often regarded as a designer of mechanical devices, Archimedes also made contributions to the field of mathematics. Plutarch wrote that Archimedes «placed his whole affection and ambition in those purer speculations where there can be no reference to the vulgar needs of life»,[28] though some scholars believe this may be a mischaracterization.[64][65][66]

Method of exhaustion

Archimedes calculates the side of the 12-gon from that of the hexagon and for each subsequent doubling of the sides of the regular polygon.

Archimedes was able to use indivisibles (a precursor to infinitesimals) in a way that is similar to modern integral calculus.[6] Through proof by contradiction (reductio ad absurdum), he could give answers to problems to an arbitrary degree of accuracy, while specifying the limits within which the answer lay. This technique is known as the method of exhaustion, and he employed it to approximate the areas of figures and the value of π.

In Measurement of a Circle, he did this by drawing a larger regular hexagon outside a circle then a smaller regular hexagon inside the circle, and progressively doubling the number of sides of each regular polygon, calculating the length of a side of each polygon at each step. As the number of sides increases, it becomes a more accurate approximation of a circle. After four such steps, when the polygons had 96 sides each, he was able to determine that the value of π lay between 31/7 (approx. 3.1429) and 310/71 (approx. 3.1408), consistent with its actual value of approximately 3.1416.[67] He also proved that the area of a circle was equal to π multiplied by the square of the radius of the circle (

Archimedean property

In On the Sphere and Cylinder, Archimedes postulates that any magnitude when added to itself enough times will exceed any given magnitude. Today this is known as the Archimedean property of real numbers.[68]

Archimedes gives the value of the square root of 3 as lying between 265/153 (approximately 1.7320261) and 1351/780 (approximately 1.7320512) in Measurement of a Circle. The actual value is approximately 1.7320508, making this a very accurate estimate. He introduced this result without offering any explanation of how he had obtained it. This aspect of the work of Archimedes caused John Wallis to remark that he was: «as it were of set purpose to have covered up the traces of his investigation as if he had grudged posterity the secret of his method of inquiry while he wished to extort from them assent to his results.»[69] It is possible that he used an iterative procedure to calculate these values.[70][71]

The infinite series

In Quadrature of the Parabola, Archimedes proved that the area enclosed by a parabola and a straight line is 4/3 times the area of a corresponding inscribed triangle as shown in the figure at right. He expressed the solution to the problem as an infinite geometric series with the common ratio 1/4:

If the first term in this series is the area of the triangle, then the second is the sum of the areas of two triangles whose bases are the two smaller secant lines, and whose third vertex is where the line that is parallel to the parabola’s axis and that passes through the midpoint of the base intersects the parabola, and so on. This proof uses a variation of the series 1/4 + 1/16 + 1/64 + 1/256 + · · · which sums to 1/3.

Myriad of myriads

In The Sand Reckoner, Archimedes set out to calculate a number that was greater than the grains of sand needed to fill the universe. In doing so, he challenged the notion that the number of grains of sand was too large to be counted. He wrote:

There are some, King Gelo (Gelo II, son of Hiero II), who think that the number of the sand is infinite in multitude; and I mean by the sand not only that which exists about Syracuse and the rest of Sicily but also that which is found in every region whether inhabited or uninhabited.

To solve the problem, Archimedes devised a system of counting based on the myriad. The word itself derives from the Greek μυριάς, murias, for the number 10,000. He proposed a number system using powers of a myriad of myriads (100 million, i.e., 10,000 x 10,000) and concluded that the number of grains of sand required to fill the universe would be 8 vigintillion, or 8×1063.[72]

Writings

Frontpage of Archimedes’ Opera, in Greek and Latin, edited by David Rivault (1615).

The works of Archimedes were written in Doric Greek, the dialect of ancient Syracuse.[73] Many written works by Archimedes have not survived or are only extant in heavily edited fragments; at least seven of his treatises are known to have existed due to references made by other authors.[9] Pappus of Alexandria mentions On Sphere-Making and another work on polyhedra, while Theon of Alexandria quotes a remark about refraction from the now-lost Catoptrica.[c]

Archimedes made his work known through correspondence with the mathematicians in Alexandria. The writings of Archimedes were first collected by the Byzantine Greek architect Isidore of Miletus (c. 530 AD), while commentaries on the works of Archimedes written by Eutocius in the sixth century AD helped to bring his work a wider audience. Archimedes’ work was translated into Arabic by Thābit ibn Qurra (836–901 AD), and into Latin via Arabic by Gerard of Cremona (c. 1114–1187). Direct Greek to Latin translations were later done by William of Moerbeke (c. 1215–1286) and Iacobus Cremonensis (c. 1400–1453).[74][75]

During the Renaissance, the Editio princeps (First Edition) was published in Basel in 1544 by Johann Herwagen with the works of Archimedes in Greek and Latin.[76]

Surviving works

The following are ordered chronologically based on new terminological and historical criteria set by Knorr (1978) and Sato (1986).[77][78]

Measurement of a Circle

This is a short work consisting of three propositions. It is written in the form of a correspondence with Dositheus of Pelusium, who was a student of Conon of Samos. In Proposition II, Archimedes gives an approximation of the value of pi (π), showing that it is greater than 223/71 and less than 22/7.

The Sand Reckoner

In this treatise, also known as Psammites, Archimedes finds a number that is greater than the grains of sand needed to fill the universe. This book mentions the heliocentric theory of the solar system proposed by Aristarchus of Samos, as well as contemporary ideas about the size of the Earth and the distance between various celestial bodies. By using a system of numbers based on powers of the myriad, Archimedes concludes that the number of grains of sand required to fill the universe is 8×1063 in modern notation. The introductory letter states that Archimedes’ father was an astronomer named Phidias. The Sand Reckoner is the only surviving work in which Archimedes discusses his views on astronomy.[79]

On the Equilibrium of Planes

There are two books to On the Equilibrium of Planes: the first contains seven postulates and fifteen propositions, while the second book contains ten propositions. In the first book, Archimedes proves the law of the lever, which states that: