Характеристики Балтийского моря

Координаты: 58.786668 северной широты, 20.044074 восточной долготы

Площадь: 419000 км²

Размеры: 1610 × 193 км

Объем: 21500 км³

Береговая линия: 8000 км

Абсолютная высота: 470 м

Максимальная глубина: 470 м

Средняя глубина: 51 м

Солёность: до 30 ‰

Впадающие реки: Нева, Западная Двина, Нарва, Висла, Неман, Одер и др.

Климат: переходный от морского к умеренно континентальному

Местное время:

Погода:4 °Cоблачно с прояснениямиОщущается как: -2 °C

Давление: 756 мм рт.ст.Влажность: 87%Ветер: 12.62 м/c

Происхождение и история Балтийского моря

История образования Балтийского моря начинается с ледникового периода. Огромная ледяная глыба двигалась со Скандинавских гор и покрывала европейскую часть суши. Около 13 тыс. лет назад море было покрыто толстой (в несколько километров) коркой льда. В период глобального потепления солнце с максимальной активностью обнажило дно будущего моря. Его заполнили воды тающих ледников.

Чаша моря быстро заполнялась, поток перетекал по проливам. Воды проложили один из путей через Южную Швецию к бассейну Северного моря. Другое направление к Атлантическому океану через Среднюю Швецию было заблокировано ледником. Когда пресноводный гигант был растоплен, уровень воды в Иольдиевом озере поравнялся с уровнем Атлантического океана. В нижней области образовался противоток со стороны океана.

Примерно 10 тыс. лет назад водоём ещё подпитывался пресными водами ледника. Но поток тяжёлой солёной воды, хлынувший в нижней части, был мощнее. Постепенно ледниковое озеро превратилось в море. Позднее открылись датские проливы, в то время Скандинавский полуостров, Дания и современный остров Готланд имели сухопутное сообщение. Уровень воды в море был на 50 метров ниже современного значения.

«Первичное» море существовало не более 600—700 лет. Тектонические изменения, поднятия земной коры отрезали его от океанов. За счёт впадающих рек солёность Балтийского моря понизилась. На дне нашли пресноводного моллюска анцилюса, и озеро получило название Анциловое. Оно существовало не более 1000 лет. Перемены наступили 7 тыс. лет назад, после открытия датских проливов и пути к океану через Среднюю Швецию.

Проливы в нижней области водоёма встретили противотечение солёных вод. В тот период дно заселяли микроорганизмы и растения, характерные для океанических глубин. Солёность вод моря была выше, чем сегодня, а климат на побережье был более мягким. Современные очертания берега Балтийское море приобрело 2—3 тыс. лет назад. Поднятия земной коры повлияли на характер береговой линии и дна водоёма.

Балтийскому морю посвящали произведения русские писатели, художники. Более полувека назад известный поэт Валерий Брюсов сочинил стихотворение «К Северному морю». Среди исторических личностей Балтийское море посещали Вильгельм Оранский, Юлий Цезарь и другие. Побережье Балтийского моря омывает берега Швеции, Финляндии, России, Эстонии, Латвии, Германии, Литвы, Дании и Польши.

Древние славяне на Руси назвали море Варяжским в честь народов, населявших его побережье. Современное название — Балтийское или Балтика — появилось в XIX веке. Во многих языках оно имеет аналогичное название: Bałtyk — в польском, Baltijas jūra — на языке латышей и т.д. Но германцы, датчане и шведы называют море Восточным, а эстонцы — Западным. Впервые обозначение Балтийского моря встречается у Адама Бременского.

Берега Балтики населяло множество племён. Их описание встречается в летописях. Многочисленные народы территории Волго-Балтийского пути называли «варягами». Среди других племён в XI веке здесь проживали норманны (норвежцы), англы, венецианцы, генуезцы, римляне, волохи, немцы, готы, свевы (шведы), русь и др. Народы развивались, зарождалась торговля. Керамика с южного побережья распространилась вплоть до Новгорода.

Географические особенности и климат Балтийского моря

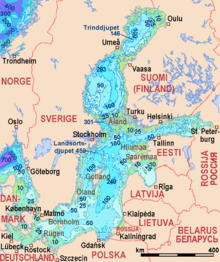

Водоём заключён в пределах материкового шельфа. Дно Балтийского моря имеет неровный рельеф с множеством банок, отмелей у островов и котловин. Они имеют разные отметки, до 12 м у берегов и 200 м на глубине. Самая низкая точка — Ландсортская котловина у берегов Швеции с максимальной отметкой в 470 метров. Средняя глубина водоёма составляет 50—60 м. В настоящее время она изменяется за счёт нестабильности земной коры.

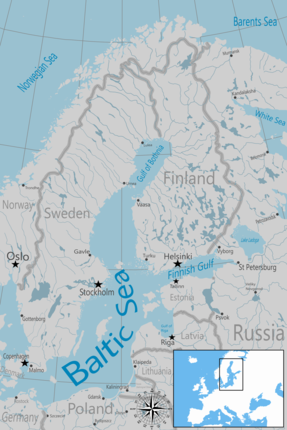

Границы моря: 53—66° северной широты и 20—26° восточной долготы. Балтика тянется через островную Данию и захватывает пролив Каттегат, разделяющий страну от юго-западной части Швеции. На востоке расположились мелководные заливы — Рижский и Финский. Крупнейший архипелаг — Аландские острова, площадью в 1,5 тыс. км², объединяет 20 тыс. объектов. Известные острова: наименьший Хиддензе, Фемарн, треугольный Пёль и курортный Рюген.

Протяжённость моря с севера на юг — 1610 км и с запада на восток — 193 км. Его площадь — около 420000 км², относительно Мирового океана это 0,1%. Объём — 21500 км³. Протяжённость береговой линии — 8000 км. Более 200 пресноводных рек наполняют море и местами понижают его солёность до 2‰. Ежегодно 1/40 часть моря замещают солёные и пресные воды. Средняя температура воды равна +17—19°C.

Из-за близкого расположения к Северному полярному кругу северные воды моря зимой покрываются льдом. Толщина ледяной корки — около 70 см. Полностью Балтика замерзала около 20 раз. В истории сохранились случаи с 1720 по 1987 годы. Несмотря на большую площадь, объём воды меньше, чем в Байкале, на 2000 км³. Крайние границы моря представлены заливами: Ботаническим — на севере и Селькямери — на юге. Куршский залив отделён косой.

Искусственные водные пути — Беломорканал и Кильский канал — соединяют Балтику с Белым и Северным морями соответственно. С Санкт-Петербургом море соединено Финским заливом. По дну моря проложен газопровод «Северный поток». Начиная с XII века на побережье находили янтарные и золотые месторождения. Большие месторождения встречаются у южных берегов. На 15 верфях 7 государств по-прежнему занимаются судостроением.

Линия берегов Балтийского моря охватывает материковую часть Европейского континента. К Балтике относятся Датские острова и Скандинавский полуостров. После событий Второй мировой войны на дне моря захоронили химическое оружие. Спустя годы оболочки контейнеров постепенно разрушаются. Медленно ядовитые химикаты просачиваются в воды моря, и поэтому экологическая обстановка сегодня требует вмешательства.

Один из самых интересных участков моря — побережье города Скаген — граница Балтийского и Северного морей. Они отличаются по плотности воды и её химическому составу. Поэтому их волны бьются друг об друга и создают уникальное явление природы. На дне Балтики покоятся более 100 тыс. кораблей. Самая древняя лодка относится к каменному веку и датирована 5200 г. до н.э. Она выполнена из полого дерева.

Флора и фауна Балтийского моря

Из-за низкого содержания кислорода в воде животный мир не отличается большим разнообразием. В водах Балтики обитают пресноводные и морские представители фауны. Из морских рыб встречаются сельдь, камбала, хек, лосось, палтус, треска, килька, гигантская акула и колюшка. К пресноводным обитателям относятся щука, карась, судак, карп, сиг, плотва и окунь. По берегам можно видеть кольчатых нерп и европейских выдр.

Кроме рыб, в водах Балтики обитают кальмары, моллюски, мелкие ракообразные. Совсем недавно в море появился мохнаторукий краб. Широко распространены медузы и крупная волосистая цианея. Данный вид обитает вблизи берегов Дании. На других участках моря встречаются аурелия и несколько видов тюленей, включая нерпу и тевяка. В Датских проливах из крупных млекопитающих встречается безобидная акула катран.

Представители животного царства находятся под угрозой исчезновения. Это морские свиньи и белые дельфины Атлантики. Раньше в море обитали афалины, полосатики, касатки, белухи и клюворыловые. Помимо уменьшения популяции млекопитающих, снижается с каждым годом миграция финвалов и горбатых китов. Из птиц встречаются журавли, цапли, скопы, белые аисты. Распространены рептилии и амфибии: тритоны, черепахи и лягушки.

Под водой археологи находят останки обитателей каменного века и затопленные леса, существовавшие 15 тыс. лет назад. На датском побережье высажен Лес Троллей. Сосны, растущие здесь, имеют причудливо изогнутую форму. В толще воды с низким уровнем кислорода произрастают простейшие растения. Среди них саргасс, бурые, циановые, планктоновые, перидиниевые водоросли, растения групп Charophyta, Zostera, Potamogeton.

В 2010 году зафиксировано распространение сине-зелёных водорослей на отмелях. Они представляют собой ярко-зелёные капли на поверхности воды. В этом месте уровень кислорода сильно снизился. Образование водорослей происходит при эвтрофикации. Этот участок моря непригоден для обитания и считается «мёртвой зоной». Здесь зафиксированы бактериальные вспышки из-за насыщения водоёма биогенными организмами.

Отдых на Балтийском море

На карте Балтийское море расположено выше 53° северной широты. Климат на побережье не отличается теплотой, как в южных российских регионах. Но жителей и туристов не смущает температура воды +17—19°C, они купаются и загорают. Белоснежные песчаные пляжи Калининградской области считаются самыми широкими в России. Туристы стремятся к свежему балтийскому воздуху, в санатории и лечебницы под открытым небом.

Морской мягкий климат, оздоровительные процедуры полезны людям с заболеваниями лёгких и сердца. Все это благоприятно влияет на нервную систему. Пляжи моря отличаются в зависимости от расположения. Например, в курортных городах Зеленоградске и Светлогорске зона отдыха представлена узкой полосой берега. Каждый год её укрепляют, чтобы море не размыло песчаные пляжи.

Янтарный — посёлок, песчаные берега которого имеют ширину около 100 м. За ним следует Балтийск, но он является основной базой Балтийского флота РФ. Поэтому локация мало популярна у отдыхающих. Неподалёку от мыса Таран на пляже посёлка Донское сохранился немецкий старинный маяк. Береговая линия резко переходит в обрывистую возвышенность, на плато которого произрастает лес. Пейзаж напоминает остров Гозо на Мальте.

Чтобы провести время с комфортом и не кутаться в тёплые куртки, следует приехать к Балтийскому морю с середины июля по середину августа. На Балтике купальный сезон длится недолго. Воды медленно прогреваются до +19—22°C и быстро остывают. Воздух в летний период прогревается до +24—26°C, иногда до +30°C. Дожди в этот период — явление редкое. Наибольший поток туристов наблюдается в августе.

Если на июнь приходятся все дожди и холодная погода, то август — солнечный и тёплый. В бархатный сезон до середины сентября посетители нежатся на «сковородках» — открытых песчаных пляжах, защищённых от ветра. По берегу распределены пансионаты и санатории. Самый крупный — «Янтарный берег». Туристы посещают это место даже в несезон. Менее посещаемые санатории находятся в Зеленоградске и Светлогорске.

Для семейного отдыха подходят два курорта: Янтарный и Зеленоградск. Чистые пляжи и мелководные морские лагуны любят взрослые и дети. Вода здесь прогревается на 3—5°C выше. Зеленоградск интересен не только пологими входами в воду, но и необычном оформлением города. Жители особо почитают кошек и заботятся о бездомных животных. В городе множество статуй в виде пушистых зверей, даже установлены светофоры для котов.

Массаж, гидромассаж, лечебные процедуры, солнечные и янтарные ванны предлагают ведущие санатории региона: «Зеленоградск», «Отрадное», «Волна» и «Янтарь». Специализация лечебниц: профилактика и лечение нервной, сердечно-сосудистой и лёгочной систем организма. Также здесь лечат заболевания органов пищеварения, гинекологии, опорно-двигательного аппарата. В городах-курортах создана туристическая инфраструктура.

Остановиться можно в комфортных номерах отелей. Многие предпочитают пятизвёздочные отели, напоминающие отдых на Лазурном берегу. В Светлогорске можно снять на время отдыха виллу в немецком стиле. Большие компании останавливаются в хостелах. В Зеленоградске, Янтарном и других курортах Калининградской области на выбор предлагают несколько крупных отелей средней ценовой категории.

Хотя Балтийское море омывает российскую границу, чтобы попасть в Калининград, нужно получить разрешение. Для поездки на поезде обязательным условием является наличие загранпаспорта. В случае отсутствия шенгенской визы нужно получить упрощённый проездной документ. На автомобиле нужно пересечь границы соседних государств. Только для перелёта на самолёте достаточно российского паспорта.

Даже в летний сезон погода у моря переменчива. Перед поездкой нужно приготовить тёплые вещи, дождевик или зонт. Вероятность того, что пойдут проливные дожди, высока. Цены в магазинах и кафе мало отличаются от московских, но ассортимент невысок. Если нужно соблюдать диету, необходимые продукты лучше взять с собой. Балтийское море содержит на глубине много янтаря, и кусочки минерала туристы нередко находят после штормов.

Что посмотреть в окрестностях

Куршская коса

Туристический объект встречает туристов пустынными дюнами и девственными смешанными лесами из берёзы и сосны. Полоса суши протянулась на 98 км вдоль моря. Ширина Куршской косы варьируется от 400 м до 4 км. Полуостров, на котором расположен туристический объект, разделён между Россией (на юге) и Литвой (на севере). Сегодня Куршская коса входит в состав одноимённого национального парка, посещение локации платное.

Здесь можно поселиться в отеле, коттедже или на базе отдыха с видом на море. Туристы купаются по обеим сторонам (в том числе в Куршском заливе) косы. В связи со статусом места разведение костров, установка палаток, парковка и установка мангала разрешены на специально отведённых территориях. Знаменитый Танцующий лес ежегодно привлекает тысячи посетителей. На его территории запрещены охота, сбор грибов и ягод.

Выборг

Город основанный шведами, а перед закреплением территории за Россией был частью Финляндии. Расположен на берегу Финского залива в 130 км от Санкт-Петербурга. Часть Выборга занимают полуострова, а другая распределена по островам. Посередине пролива на скалистом островке сохранилась «Святая крепость», или Выборгский замок. Он был построен в 1293 году во время похода шведских крестоносцев.

Его стены шелушатся и открывают взору кирпичную кладку. Завершают композицию треугольные крыши и шпили. В центре архитектурного ансамбля высится башня Святого Олафа — 7-этажная цитадель шведских воинов-крестоносцев. Со смотровой площадки открывается вид на старинные улочки города в окружении четырёх заливов: Выборгского, Южного, Салакка-Лахти и Северного. Современный вид замок получил после реставрации в конце XIX века.

В Выборге сохранилась боевая башня Ратуши. Четырёхугольное каменное сооружение являлось частью средневековой городской стены. Часовая башня на улице Крепостная является колокольней Кафедрального собора. На его вершине по указу Екатерины II установили набатный колокол, ранее башня служила пожарной каланчой. Ещё один памятник архитектуры — костёл Гиацинта. Здание в готическом стиле — одно из самых старинных в городе.

Куршская коса

Как добраться до моря

На песчаных пляжах можно позагорать, искупаться, побродить и поискать древний янтарь. На побережье Балтийского моря со стороны России расположены несколько курортных городов и посёлков Калининградской области. Среди них Балтийск, Зеленоградск, Янтарный, Светлогорск. Добраться до Калининграда можно на самолёте (без виз и загранника), поездом и на автомобиле из Москвы, Санкт-Петербурга и других российских городов.

От областного центра Калининграда до побережья Балтики 40 км пути. До туристических мест можно добраться на общественном транспорте и личном автомобиле. До Балтийска ехать около часа, протяжённость пути — 39 км. До Зеленоградска дорога составит 36 км. Калининград и Янтарный соединяет трасса длиной в 48 км. Расстояние по трассе до Светлогорска — 52 км. В любом направлении можно заказать такси или арендовать автомобиль.

От Калининграда до Светлогорска ходит рейсовый автобус №118 с периодичностью в 20 минут. До Зеленоградска можно доехать на автобусах №114, №140, №141 и №114А. От вокзала Калининграда к прибрежным Балтийским городам ходит электричка. По направлению к Янтарному автобус №120 едет через каждый час. До Балтийска два способа отправления: на автобусе №107 с периодичностью рейсов в 20 минут и рельсобусе.

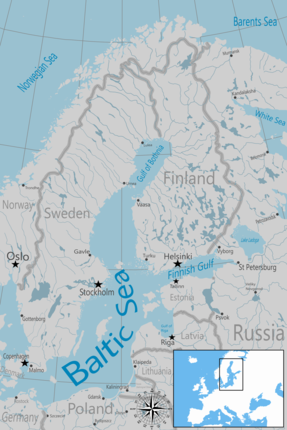

БАЛТИ́ЙСКОЕ МО́РЕ (позднелатинское Mare Balticum, у древних славян – Варяжское море или Свейское), внутриматериковое море Атлантического океана, между Скандинавским полуостровом и материковыми берегами Северо-Западной Европы. Омывает берега Швеции, Финляндии, России, Эстонии, Латвии, Литвы, Польши, Германии, Дании. На юго-западе соединяется с Северным морем Датскими проливами. Морская граница Б. м. проходит по южным входам проливов Эресунн, Большой Бельт и Малый Бельт. Площадь 419 тыс. км2, объём 21,5 тыс. км3. Наибольшая глубина 470 м. Глубины над порогами Датских проливов: Дарсер – 18 м, Дрогден – 7 м. Поперечное сечение над порогами соответственно 0,225 и 0,08 км2, что лимитирует водообмен с Северным морем. Б. м. глубоко вдаётся в материк Евразия. Сильно изрезанная береговая линия образует многочисленные заливы и бухты. Наиболее крупные заливы: Ботнический залив, Финский залив, Рижский залив, Куршский залив, Щецинский залив, Гданьский залив. Берега Б. м. на севере высокие, скалистые, преимущественно шхерного и фьордового типов, на юге и юго-востоке – большей частью низменные, лагунного типа, с песчаными и галечными пляжами. Наиболее крупные острова: Готланд, Борнхольм, Сааремаа, Муху, Хийумаа, Эланд и Рюген. Много небольших скалистых островков – шхер, расположенных вдоль северных берегов (в группе Аландских островов свыше 6 тыс.).

Рельеф и геологическое строение дна

Фото А. И. Нагаева

Пролив Эресунн.

Балтийское море мелководное, полностью лежит в пределах шельфа, глубины до 200 м занимают 99,8% его площади. Наиболее мелководны Финский, Ботнический и Рижский заливы. Их участки дна имеют выровненный аккумулятивный рельеф и хорошо развитый покров рыхлых отложений. Бóльшая же часть дна Б. м. характеризуется сильно расчленённым рельефом. Дно его котловины имеет впадины, разграниченные возвышенностями и основаниями островов: на западе – Борнхольмская (105 м) и Арконская (53 м), в центре – Готландская (249 м) и Гданьская (116 м); к северу от острова Готланд с северо-востока на юго-запад протянулась наиболее глубокая впадина – Ландсортская (до 470 м). Многочисленные каменные гряды, в центральной части моря прослежены уступы – продолжения глинтов, тянущихся от северного берега Эстонии к северной оконечности острова Эланд, подводные долины, затопленные морем ледниково-аккумулятивные формы рельефа.

Ботнический залив. Аландские острова.

Фото А. И. Нагаева

Б. м. занимает депрессию на западе древней Восточно-Европейской платформы. Северная часть моря располагается на южном склоне Балтийского щита; центральная и южная части принадлежат крупной отрицательной структуре древней платформы – Балтийской синеклизе. Крайняя юго-западная часть моря входит в пределы молодой Западно-Европейской платформы. Дно на севере Б. м. сложено преимущественно комплексами докембрийского возраста, перекрытыми прерывистым чехлом ледниковых и современных морских отложений. В центральной части моря в строении дна принимают участие осадки силура и девона. Прослеживающиеся здесь уступы образованы кембрийско-ордовикскими и силурийскими породами. Палеозойские комплексы на юге перекрыты толщей ледниковых и морских осадков значительной мощности.

В последнюю ледниковую эпоху (в позднем плейстоцене) впадина Б. м. была полностью перекрыта ледниковым щитом, после таяния которого образовалось Балтийское ледниковое озеро. В конце позднего плейстоцена, ок. 13 тыс. лет назад, произошло соединение озера с океаном и впадину заполнили морские воды. Связь с океаном прерывалась в интервале 9–7,5 тыс. лет назад, после чего последовала морская трансгрессия, отложения которой известны на современном побережье Б. м. В северной части Б. м. продолжается поднятие, скорость которого достигает 1 см в год.

Донные осадки на глубинах свыше 80 м представлены глинистыми илами, под которыми залегает ленточная глина на ледниковых отложениях, на меньших глубинах ил смешан с песком, в прибрежных районах распространены пески. Встречаются валуны ледникового происхождения.

Климат

Для Б. м. характерен умеренный морской климат с чертами континентальности. Его сезонные особенности определяются взаимодействием барических центров: Исландского минимума и Азорского максимума на западе и Сибирского максимума на востоке. Циклоническая деятельность достигает наибольшей интенсивности в осенне-зимние месяцы, когда циклоны приносят пасмурную, дождливую погоду с сильными западными и юго-западными ветрами. Средняя температура воздуха в феврале от –1,1 °C на юге, –3 °C в центральной части моря до –8 °C на севере и востоке и до –10 °C в северной части Ботнического залива. Редко и на короткое время проникающий на Балтику холодный арктический воздух понижает температуру до –35 °C. Летом дуют также ветры западных направлений, но небольшой силы, приносящие с Атлантики прохладную, влажную погоду. Температура воздуха в июле 14–15 °C в Ботническом заливе и 16–18 °C в остальных районах моря. Редкие поступления тёплого средиземноморского воздуха вызывают кратковременные повышения температуры до 22–24 °C. В год выпадает осадков от 400 мм на севере до 800 мм на юге. Наибольшее число дней с туманами (до 59 дней в году) отмечается на юге и в центральной части Б. м., наименьшее (22 дня в году) – на севере Ботнического залива.

Гидрологический режим

Фото А. И. Нагаева

Финский залив.

Гидрологические условия Б. м. определяются его климатом, значительным поступлением пресных вод и ограниченным водообменом с Северным морем. В Б. м. впадает ок. 250 рек. Речной сток в среднем составляет 472 км3 в год. Наиболее крупные реки: Нева – 83,5 км3, Висла – 30, Неман – 21, Западная Двина – 20 км3 в год. По территории пресный сток распределяется неравномерно. В Ботнический залив поступает 181, в Финский – 110, в Рижский – 37, в центральную часть Б. м. – 112 км3 в год. Количество пресной воды атмосферных осадков (172 км3 в год) равно испарению. Водообмен с Северным морем в среднем составляет 1660 км3 в год. Более пресные воды с поверхностным стоковым течением уходят из Б. м. в Северное море, солёная североморская вода с придонным течением поступает через проливы из Северного моря. Сильные западные ветры обычно усиливают приток, восточные – сток воды из Б. м. через Датские проливы.

Гидрологическая структура Б. м. в большинстве районов представлена поверхностной и глубинной водными массами, разделёнными тонким промежуточным слоем. Поверхностная водная масса занимает слой от 20 до (местами) 90 м, температура её в течение года колеблется от 0 до 20 °C, солёность обычно в пределах 7–8‰. Эта водная масса образуется в самом море как результат взаимодействия морских вод с пресными водами атмосферных осадков и речного стока. Она имеет зимнюю и летнюю модификации, отличающиеся в основном по температуре. В тёплом сезоне отмечается наличие холодного промежуточного слоя, что связано с летним прогревом воды на поверхности. Глубинная водная масса занимает слой от 50–100 м до дна, её температура изменяется от 1 до 15 °C, солёность – от 10,0 до 18,5‰. Глубинная вода образуется в придонном слое в результате перемешивания с водой высокой солёности, поступающей из Северного моря. Обновление и вентиляция придонных вод сильно зависят от поступления североморской воды, которое подвержено межгодовой изменчивости. При сокращении притока солёной воды в Б. м. на больших глубинах и во впадинах рельефа дна создаются условия для появления заморных явлений. Сезонные изменения температуры воды захватывают слой от поверхности до 50–60 м и глубже обычно не проникают.

Ветровое волнение особенно сильно развивается в осенне-зимнее время при продолжительных и сильных юго-западных ветрах, когда отмечаются волны высотой 5–6 м и длиной 50–70 м. Наиболее высокие волны наблюдаются в ноябре. Зимой развитию волнения препятствует морской лёд.

В Б. м. всюду прослеживается циклоническая (против часовой стрелки) циркуляция вод, осложнённая вихревыми образованиями разных масштабов. Скорости постоянных течений обычно ок. 3–4 см/с, но на некоторых участках временами возрастают до 10–15 см/с. Из-за малых скоростей течения неустойчивы, их картина часто нарушается под действием ветров. Штормовые ветры вызывают сильные ветровые течения со скоростями до 150 см/с, быстро затухающие после шторма.

Приливы в Б. м. из-за незначительной связи с океаном выражены слабо, высота 0,1–0,2 м. Сгонно-нагонные колебания уровня достигают значительных величин (в вершинах заливов до 2 м). Совместное действие ветра и резких перепадов атмосферного давления вызывает сейшевые колебания уровня с периодом 24–26 часов. Величина таких колебаний от 0,3 м в открытом море до 1,5 м в Финском заливе. Сейшевые волны при нагонных западных ветрах иногда вызывают повышение уровня в вершине Финского залива до 3–4 м, что задерживает сток Невы и приводит к наводнениям в Санкт-Петербурге, иногда катастрофического характера: в ноябре 1824 около 410 см, в сентябре 1924 – 369 см.

Температура воды на поверхности Б. м. сильно изменяется от сезона к сезону. В августе в Финском заливе вода прогревается до 15–17 °C, в Ботническом заливе – 9–13 °C, в центральной части моря – 14–18 °C, в южных районах достигает 20 °C. В феврале в открытой части моря температура воды на поверхности 1–3 °C, в заливах и бухтах ниже 0 °C. Солёность воды на поверхности составляет 11‰ у выхода из Датских проливов, 6–8‰ в центральной части моря, 2‰ и меньше в вершинах Ботнического и Финского заливов.

Б. м. относится к т. н. солоноватым бассейнам, в которых температура наибольшей плотности выше температуры замерзания, что приводит к интенсификации процесса образования морского льда. Льдообразование начинается в ноябре в заливах и у берегов, позднее – в открытом море. В суровые зимы ледяной покров занимает всю северную часть моря и прибрежные воды центральной и южной его частей. Толщина припайного (неподвижного) льда достигает 1 м, дрейфующего – от 0,4 до 0,6 м. Таяние льда начинается в конце марта, распространяется с юго-запада на северо-восток и заканчивается в июне.

История исследования

Первые сведения об исследованиях Б. м. связаны с норманнами. В сер. 7 в. они проникли в Ботнический залив, открыли Аландские острова, во 2-й пол. 7–8 вв. достигли западного побережья Прибалтики, открыли Моонзундский архипелаг, впервые проникли в Рижский залив, в 9–10 вв. использовали для торговой и пиратской деятельности побережье от устья Невы до Гданьской бухты. Гидрографические и картографические работы производились русскими в Финском заливе в начале 18 в. В 1738 Ф. И. Соймонов издал атлас Б. м., составленный по отечественным и иностранным источникам. В сер. 18 в. многолетние исследования проводил А. И. Нагаев, который составил подробную лоцию Б. м. Первые глубоководные гидрологические исследования в сер. 1880-х гг. были выполнены С. О. Макаровым. С 1920 проводились гидрологические работы Гидрографическим управлением военно-морского флота, Государственным гидрологическим институтом (Ленинград), а со 2-й пол. 20 в. были развёрнуты широкие комплексные исследования под руководством Ленинградского (Санкт-Петербургского) отделения Государственного океанографического института РАН.

Хозяйственное использование

Фото А. И. Нагаева

Порт в г. Турку (Финляндия).

Рыбные ресурсы складываются из пресноводных видов, обитающих в распреснённых водах заливов (карась, лещ, щука, судак, голавль), балтийского стада сёмги и чисто морских видов, распространённых преимущественно в центральной части моря (треска, салака, корюшка, ряпушка, шпрот). В Б. м. ведётся рыбный промысел салаки, шпрота, сельди, корюшки, речной камбалы, трески, окуня и др. Уникальный объект рыбного промысла – угорь. На побережье Б. м. распространены россыпи янтаря, добыча ведётся близ Калининграда (Россия). На дне моря обнаружены запасы нефти, начата промышленная разработка. Добыча железной руды ведётся у берегов Финляндии. Велико значение Б. м. как транспортной артерии. По Б. м. осуществляются большие перевозки жидких, навалочных и генеральных грузов. Через Б. м. осуществляется значительная часть внешней торговли Дании, Германии, Польши, России, Литвы, Латвии, Эстонии, Финляндии, Швеции. В грузообороте преобладают нефтепродукты (из портов России и со стороны Атлантического океана), уголь (из Польши, России), лесоматериалы (из Финляндии, Швеции, России), целлюлоза и бумага (из Швеции и Финляндии), железная руда (из Швеции); важную роль играют также машины и оборудование, крупными производителями и потребителями которых являются страны, расположенные на берегах и в бассейне Б. м.

По дну Б. м. между Россией и Германией проложен газопровод (2 нити, диаметром по 1220 мм каждая) «Северный поток» («Nord Stream»). Проходит от бухты Портовая близ Выборга (Ленинградская область) до Лубмина близ Грайфсвальда (Германия, федеральная земля Мекленбург – Передняя Померания); длина 1224 км (самый протяжённый подводный газопровод в мире). Пропускная способность (мощность) газопровода 55 млрд. м³ газа в год. Максимальная глубина моря в местах прохождения трубы 210 м. В строительстве было задействовано 148 морских судов. Общая масса стали, использованной при строительстве газопровода, – 2,42 млн. т.

На подготовительном этапе на исследования в области экологии по всему будущему маршруту трубопровода компания «Nord Stream» потратила ок. 100 млн. евро. В 1997 начались подготовительные работы по строительству морского участка: проведены научные исследования, на основе которых определён примерный маршрут газопровода. В 2000 решением комиссии Европейского союза по энергетике и транспорту проекту был присвоен статус TEN («Трансъевропейские сети»). Строительство газопровода началось 9 апреля 2010. Первая нить газопровода введена в эксплуатацию 8 ноября 2011, вторая – 8 октября 2012.

В сентябре 2015 было подписано Соглашение акционеров по реализации проекта, получившего название «Северный поток – 2». 8 июля 2016 компания «Nord Stream 2» завершила тендер по выбору подрядчика для нанесения утяжеляющего бетонного покрытия на трубы газопровода.

В портах Б. м. зарегистрированы 344 судна суммарной грузоподъёмностью 1196,6 тыс. т дедвейта. Крупнейшие порты: Санкт-Петербург, Калининград, Выборг, Балтийск (все – Россия); Таллин (Эстония); Рига, Лиепая, Вентспилс (все – Латвия); Клайпеда (Литва); Гданьск, Гдыня, Щецин (все – Польша); Росток – Варнемюнде, Любек, Киль (все – Германия); Копенгаген (Дания); Мальмё, Стокгольм, Лулео (все – Швеция); Турку, Хельсинки и Котка (все – Финляндия). Развито морское пассажирское и паромное сообщение: Копенгаген – Мальмё, Треллеборг – Засниц (железнодорожные паромы), Нортелье – Турку (автомобильный паром) и др. Переправы через проливы: Большой Бельт (1998; длина 6790 м), Малый Бельт (оба – Дания; 1970; 1700 м), Эресунн (Дания – Швеция; 2000; 16 км); планируется возведение переправы через Фемерский пролив (Дания – Германия; 2018; 19 км). Из-за небольших глубин многие места недоступны судам со значительной осадкой, однако самые крупные круизные лайнеры проходят через Датские проливы в Атлантический океан.

На южном и юго-восточном побережьях множество курортных мест: Сестрорецк, Зеленогорск, Светлогорск, Пионерский, Зеленоградск, Куршская коса (все – Россия); Пярну, Нарва-Йыэсуу (оба – Эстония); Юрмала, Саулкрасты (оба – Латвия); Паланга, Неринга (оба – Литва); Сопот, Хель, Колобжег, Кошалин (все – Польша); Альбек, Бинц, Хайлигендамм, Тиммендорф (все – Германия); остров Эланд (Швеция).

Экологическое состояние

Б. м., имеющее затруднённый водообмен с Мировым океаном (обновление вод длится около 30 лет), окружено индустриально развитыми странами и испытывает чрезвычайно интенсивную антропогенную нагрузку. Основные экологические проблемы связаны с захоронением на дне моря химического оружия, сбросом в море сточных вод крупных городов, смывом химических удобрений, используемых в сельском хозяйстве, и особенно с судоходством – одним из самых интенсивных в мире (преимущественно нефтеналивные танкеры). После вступления в силу в 1980 Конвенции по защите морской среды Б. м. экологическая ситуация улучшилась за счёт введения в строй большого количества очистных сооружений сточных вод, сокращения использования химических удобрений, контроля за техническим состоянием судов. Уменьшилась концентрация токсических веществ типа ДДТ и полихлорбифенила, нефтяных углеродов. Содержание диоксинов в балтийской сельди в 3 раза ниже ПДК, восстановилась популяция серого тюленя. Рассматривается вопрос о придании Б. м. статуса особо уязвимого морского района.

22 марта в Европе празднуют День Балтийского моря.

- Энциклопедия

- География

- Балтийское море

Балтийское море — одно из самых молодых морей на планете. Его история насчитывает примерно десять тысяч лет. Ледники, которые надвинулись на Европу со стороны Скандинавии, заняли всю ее основную территорию. То место, где сейчас расположилось море, было покрыто очень толстым слоем льда. Но когда ледники начали свое отступление, открылась огромная часть земли, которая и стала дном будущего моря. Таянье льдов привело к быстрому заполнению водой открывшейся чаши. Но поток воды был настолько стремителен, что наполнив озеро, хлынул к Северному морю, которое является частью Атлантического океана.

Во время образования моря его пресная вода от тающих ледников сильно смешалось с водами океана и стала очень соленой. В нем обитали животные и растительный мир присущий соленым водоемам. Но с прошествием времени, претерпев очень многие географические изменения, связанные со многими факторами, воды моря стали совсем не солеными. Огромное количество пресноводных рек впадающих в море очень сильно снижают соленость его воды. И даже в месте, где Балтийское море соединяется с Северным морем, вода в котором достаточно соленая, из-за разной плотности не происходит смешивания вод этих двух морей.

Вода в море достаточно холодная. И только в южной его части, на побережьях Литвы, летом она может прогреться до 23 градусов. В некоторых заливах моря, зимой температура может опуститься ниже нулевой отметки, и воды заливов замерзают.

В водах Балтийского моря очень активно развивается рыбный промысел. Здесь водятся такие промышленные виды как атлантическая сельдь, салака, треска и много другой рыбы. Так же добывают огромное количество водорослей. В северной его части водятся Балтийские тюлени.

Недра Балтики богаты полезными ископаемыми. Одними из самых крупных являются месторождения нефти и газа. Очень славится Балтийское море добычей янтаря. В качестве строительного материала используют песок и гравий поднятые со его дна.

В водах Балтики очень сильно развито судоходство. Благодаря постоянно осуществляющимся морским перевозкам различных грузов, многочисленные страны расположившиеся на его побережье, поддерживает очень тесные отношения в экономике и торговле. На его побережье расположилось большое количество грузовых и пассажирских портов. На Балтийском море также много живописных курортов, в том числе и литовские курорты Паланга и Неринга.

Так как это море является внутренним, водообмен с водами Атлантического океана происходит очень медленно. Из-за этого в нем скапливается огромное количество загрязняющих веществ. Это привело к тому, что Балтийское море стало считаться одним из самых загрязненных морей. Сейчас ситуация изменилась. Многочисленные программы по очищению его вод привели к хорошим результатам.

Строятся многочисленные очистные сооружения, на сельскохозяйственных поля расположившихся рядом с побережьем не используют минеральные удобрения.

Балтийское море имеет поразительной красоты суровые северные пейзажи.

4 класс

Балтийское море

Популярные темы сообщений

- Цветок Астранция

Астранция – великолепнейший цветок, который подарила нам щедрая природа. В народе его также называют звездовкой. Это травянистое растение. Относится к многолетним растениям,

- Таблицы менделеева (история и создания)

Один из обязательных предметов в школе является химия. Большинство знаний, полученных по этой дисциплине, в жизни не применяются. Но знаменитую таблицу Менделеева знает каждый человек. Мало кто догадывается, как она была создана.

- Балет Ярославна

Впервые драматическая танцующая труппа «Ярославна», в исполнении хореографии и симфонии, произошла в 1974 г. Спектакль прошел в Ленинградском академическом малом театре. Представление было задумано,

- Достопримечательности Краснодарского края

Красивых мест в Краснодарском крае довольно много и все их охватить невозможно. Кубань является древней территорией с давней историей. К замечательным местам Краснодарского края относится Кавказ, красивейший берег Черного моря

- Творчество Мольера

Мольер – Жан-Батист Мольер – это известный человек 17 столетия. Таинственная, своеобразная, необыкновенная личность. В его биографии очень много различных моментов касающихся его стремительной,

| Baltic Sea Region | |

|---|---|

Map of the Baltic Sea region |

|

| Location | Europe |

| Coordinates | 58°N 20°E / 58°N 20°ECoordinates: 58°N 20°E / 58°N 20°E (slightly east of the north tip of Gotland Island) |

| Type | Sea |

| Primary inflows | Daugava, Kemijoki, Neman (Nemunas), Neva, Oder, Vistula, Lule, Narva, Torne |

| Primary outflows | The Danish Straits |

| Catchment area | 1,641,650 km2 (633,840 sq mi) |

| Basin countries | Coastal: Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden Non-coastal: Belarus, Czech Republic, Norway, Slovakia, Ukraine[1] |

| Max. length | 1,601 km (995 mi) |

| Max. width | 193 km (120 mi) |

| Surface area | 377,000 km2 (146,000 sq mi) |

| Average depth | 55 m (180 ft) |

| Max. depth | 459 m (1,506 ft) |

| Water volume | 21,700 km3 (1.76×1010 acre⋅ft) |

| Residence time | 25 years |

| Shore length1 | 8,000 km (5,000 mi) |

| Islands | Abruka, Aegna, Archipelago Sea Islands (Åland), Bornholm, Dänholm, Ertholmene, Falster, Fårö, Fehmarn, Gotland, Hailuoto, Hiddensee, Hiiumaa, Holmöarna, Kassari, Kesselaid, Kihnu, Kimitoön, Kõinastu, Kotlin, Laajasalo, Lauttasaari, Lidingö, Ljusterö, Lolland, Manilaid, Mohni, Møn, Muhu, Poel, Prangli, Osmussaar, Öland, Replot, Ruhnu, Rügen, Saaremaa, Stora Karlsö, Suomenlinna, Suur-Pakri and Väike-Pakri, Ummanz, Usedom/Uznam, Väddö, Värmdö, Vilsandi, Vormsi, Wolin |

| Settlements | Copenhagen, Gdańsk, Gdynia, Haapsalu, Helsinki, Jūrmala, Kaliningrad, Kiel, Klaipėda, Kuressaare, Kärdla, Lübeck, Luleå, Mariehamn, Oulu, Paldiski, Pärnu, Riga, Rostock, Saint Petersburg, Liepāja, Stockholm, Tallinn, Turku, Ventspils |

| References | [2] |

| 1 Shore length is not a well-defined measure. |

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden and the North and Central European Plain.

The sea stretches from 53°N to 66°N latitude and from 10°E to 30°E longitude. A marginal sea of the Atlantic, with limited water exchange between the two water bodies, the Baltic Sea drains through the Danish Straits into the Kattegat by way of the Øresund, Great Belt and Little Belt. It includes the Gulf of Bothnia, the Bay of Bothnia, the Gulf of Finland, the Gulf of Riga and the Bay of Gdańsk.

The «Baltic Proper» is bordered on its northern edge, at latitude 60°N, by Åland and the Gulf of Bothnia, on its northeastern edge by the Gulf of Finland, on its eastern edge by the Gulf of Riga, and in the west by the Swedish part of the southern Scandinavian Peninsula.

The Baltic Sea is connected by artificial waterways to the White Sea via the White Sea–Baltic Canal and to the German Bight of the North Sea via the Kiel Canal.

Definitions[edit]

Danish Straits and southwestern Baltic Sea

Administration[edit]

The Helsinki Convention on the Protection of the Marine Environment of the Baltic Sea Area includes the Baltic Sea and the Kattegat, without calling Kattegat a part of the Baltic Sea, «For the purposes of this Convention the ‘Baltic Sea Area’ shall be the Baltic Sea and the Entrance to the Baltic Sea, bounded by the parallel of the Skaw in the Skagerrak at 57°44.43’N.»[3]

Traffic history[edit]

Historically, the Kingdom of Denmark collected Sound Dues from ships at the border between the ocean and the land-locked Baltic Sea, in tandem: in the Øresund at Kronborg castle near Helsingør; in the Great Belt at Nyborg; and in the Little Belt at its narrowest part then Fredericia, after that stronghold was built. The narrowest part of Little Belt is the «Middelfart Sund» near Middelfart.[4]

Oceanography[edit]

Geographers widely agree that the preferred physical border of the Baltic is a line drawn through the southern Danish islands, Drogden-Sill and Langeland.[5] The Drogden Sill is situated north of Køge Bugt and connects Dragør in the south of Copenhagen to Malmö; it is used by the Øresund Bridge, including the Drogden Tunnel. By this definition, the Danish Straits is part of the entrance, but the Bay of Mecklenburg and the Bay of Kiel are parts of the Baltic Sea.

Another usual border is the line between Falsterbo, Sweden, and Stevns Klint, Denmark, as this is the southern border of Øresund. It’s also the border between the shallow southern Øresund (with a typical depth of 5–10 meters only) and notably deeper water.

Hydrography and biology[edit]

Drogden Sill (depth of 7 m (23 ft)) sets a limit to Øresund and Darss Sill (depth of 18 m (59 ft)), and a limit to the Belt Sea.[6] The shallow sills are obstacles to the flow of heavy salt water from the Kattegat into the basins around Bornholm and Gotland.

The Kattegat and the southwestern Baltic Sea are well oxygenated and have a rich biology. The remainder of the Sea is brackish, poor in oxygen, and in species. Thus, statistically, the more of the entrance that is included in its definition, the healthier the Baltic appears; conversely, the more narrowly it is defined, the more endangered its biology appears.

Etymology and nomenclature[edit]

Tacitus called it Mare Suebicum after the Germanic people of the Suebi,[7] and Ptolemy Sarmatian Ocean after the Sarmatians,[8] but the first to name it the Baltic Sea (Medieval Latin: Mare Balticum) was the eleventh-century German chronicler Adam of Bremen. The origin of the latter name is speculative and it was adopted into Slavic and Finnic languages spoken around the sea, very likely due to the role of Medieval Latin in cartography. It might be connected to the Germanic word belt, a name used for two of the Danish straits, the Belts, while others claim it to be directly derived from the source of the Germanic word, Latin balteus «belt».[9] Adam of Bremen himself compared the sea with a belt, stating that it is so named because it stretches through the land as a belt (Balticus, eo quod in modum baltei longo tractu per Scithicas regiones tendatur usque in Greciam).

He might also have been influenced by the name of a legendary island mentioned in the Natural History of Pliny the Elder. Pliny mentions an island named Baltia (or Balcia) with reference to accounts of Pytheas and Xenophon. It is possible that Pliny refers to an island named Basilia («the royal») in On the Ocean by Pytheas. Baltia also might be derived from «belt», and therein mean «near belt of sea, strait».

Others have suggested that the name of the island originates from the Proto-Indo-European root *bʰel meaning «white, fair»,[10] which may echo the naming of seas after colours relating to the cardinal points (as per Black Sea and Red Sea).[11] This ‘*bʰel’ root and basic meaning were retained in Lithuanian (as baltas), Latvian (as balts) and Slavic (as bely). On this basis, a related hypothesis holds that the name originated from this Indo-European root via a Baltic language such as Lithuanian.[12] Another explanation is that, while derived from the aforementioned root, the name of the sea is related to names for various forms of water and related substances in several European languages, that might have been originally associated with colors found in swamps (compare Proto-Slavic *bolto «swamp»). Yet another explanation is that the name originally meant «enclosed sea, bay» as opposed to open sea.[13]

In the Middle Ages the sea was known by a variety of names. The name Baltic Sea became dominant only after 1600. Usage of Baltic and similar terms to denote the region east of the sea started only in the 19th century.

Name in other languages[edit]

The Baltic Sea was known in ancient Latin language sources as Mare Suebicum or even Mare Germanicum.[14] Older native names in languages that used to be spoken on the shores of the sea or near it usually indicate the geographical location of the sea (in Germanic languages), or its size in relation to smaller gulfs (in Old Latvian), or tribes associated with it (in Old Russian the sea was known as the Varanghian Sea). In modern languages, it is known by the equivalents of «East Sea», «West Sea», or «Baltic Sea» in different languages:

- «Baltic Sea» is used in Modern English; in the Baltic languages Latvian (Baltijas jūra; in Old Latvian it was referred to as «the Big Sea», while the present day Gulf of Riga was referred to as «the Little Sea») and Lithuanian (Baltijos jūra); in Latin (Mare Balticum) and the Romance languages French (Mer Baltique), Italian (Mar Baltico), Portuguese (Mar Báltico), Romanian (Marea Baltică) and Spanish (Mar Báltico); in Greek (Βαλτική Θάλασσα Valtikí Thálassa); in Albanian (Deti Balltik); in Welsh (Môr Baltig); in the Slavic languages Polish (Morze Bałtyckie or Bałtyk), Czech (Baltské moře or Balt), Slovenian (Baltsko morje), Bulgarian (Балтийско море Baltijsko More), Kashubian (Bôłt), Macedonian (Балтичко Море Baltičko More), Ukrainian (Балтійське море Baltijs′ke More), Belarusian (Балтыйскае мора Baltyjskaje Mora), Russian (Балтийское море Baltiyskoye More) and Serbo-Croatian (Baltičko more / Балтичко море); in Hungarian (Balti-tenger).

- In Germanic languages, except English, «East Sea» is used, as in Afrikaans (Oossee), Danish (Østersøen [ˈøstɐˌsøˀn̩]), Dutch (Oostzee), German (Ostsee), Low German (Oostsee), Icelandic and Faroese (Eystrasalt), Norwegian (Bokmål: Østersjøen [ˈø̂stəˌʂøːn]; Nynorsk: Austersjøen), and Swedish (Östersjön). In Old English it was known as Ostsǣ; also in Hungarian the former name was Keleti-tenger («East-sea», due to German influence). In addition, Finnish, a Finnic language, uses the term Itämeri «East Sea», possibly a calque from a Germanic language. As the Baltic is not particularly eastward in relation to Finland, the use of this term may be a leftover from the period of Swedish rule.

- In another Finnic language, Estonian, it is called the «West Sea» (Läänemeri), with the correct geography (the sea is west of Estonia). In South Estonian, it has the meaning of both «West Sea» and «Evening Sea» (Õdagumeri).

History[edit]

Classical world[edit]

At the time of the Roman Empire, the Baltic Sea was known as the Mare Suebicum or Mare Sarmaticum. Tacitus in his AD 98 Agricola and Germania described the Mare Suebicum, named for the Suebi tribe, during the spring months, as a brackish sea where the ice broke apart and chunks floated about. The Suebi eventually migrated southwest to temporarily reside in the Rhineland area of modern Germany, where their name survives in the historic region known as Swabia. Jordanes called it the Germanic Sea in his work, the Getica.

Middle Ages[edit]

Cape Arkona on the island of Rügen in Germany, was a sacred site of the Rani tribe before Christianization.

In the early Middle Ages, Norse (Scandinavian) merchants built a trade empire all around the Baltic. Later, the Norse fought for control of the Baltic against Wendish tribes dwelling on the southern shore. The Norse also used the rivers of Russia for trade routes, finding their way eventually to the Black Sea and southern Russia. This Norse-dominated period is referred to as the Viking Age.

Since the Viking Age, the Scandinavians have referred to the Baltic Sea as Austmarr («Eastern Lake»). «Eastern Sea», appears in the Heimskringla and Eystra salt appears in Sörla þáttr. Saxo Grammaticus recorded in Gesta Danorum an older name, Gandvik, -vik being Old Norse for «bay», which implies that the Vikings correctly regarded it as an inlet of the sea. Another form of the name, «Grandvik», attested in at least one English translation of Gesta Danorum, is likely to be a misspelling.

In addition to fish the sea also provides amber, especially from its southern shores within today’s borders of Poland, Russia and Lithuania. First mentions of amber deposits on the South Coast of the Baltic Sea date back to the 12th century.[15] The bordering countries have also traditionally exported lumber, wood tar, flax, hemp and furs by ship across the Baltic. Sweden had from early medieval times exported iron and silver mined there, while Poland had and still has extensive salt mines. Thus, the Baltic Sea has long been crossed by much merchant shipping.

The lands on the Baltic’s eastern shore were among the last in Europe to be converted to Christianity. This finally happened during the Northern Crusades: Finland in the twelfth century by Swedes, and what are now Estonia and Latvia in the early thirteenth century by Danes and Germans (Livonian Brothers of the Sword). The Teutonic Order gained control over parts of the southern and eastern shore of the Baltic Sea, where they set up their monastic state. Lithuania was the last European state to convert to Christianity.

An arena of conflict[edit]

In the period between the 8th and 14th centuries, there was much piracy in the Baltic from the coasts of Pomerania and Prussia, and the Victual Brothers held Gotland.

Starting in the 11th century, the southern and eastern shores of the Baltic were settled by migrants mainly from Germany, a movement called the Ostsiedlung («east settling»). Other settlers were from the Netherlands, Denmark, and Scotland. The Polabian Slavs were gradually assimilated by the Germans.[16] Denmark gradually gained control over most of the Baltic coast, until she lost much of her possessions after being defeated in the 1227 Battle of Bornhöved.

The burning Cap Arcona shortly after the attacks, 3 May 1945. Only 350 survived of the 4,500 prisoners who had been aboard

In the 13th to 16th centuries, the strongest economic force in Northern Europe was the Hanseatic League, a federation of merchant cities around the Baltic Sea and the North Sea. In the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, Poland, Denmark, and Sweden fought wars for Dominium maris baltici («Lordship over the Baltic Sea»). Eventually, it was Sweden that virtually encompassed the Baltic Sea. In Sweden, the sea was then referred to as Mare Nostrum Balticum («Our Baltic Sea»). The goal of Swedish warfare during the 17th century was to make the Baltic Sea an all-Swedish sea (Ett Svenskt innanhav), something that was accomplished except the part between Riga in Latvia and Stettin in Pomerania. However, the Dutch dominated the Baltic trade in the seventeenth century.

In the eighteenth century, Russia and Prussia became the leading powers over the sea. Sweden’s defeat in the Great Northern War brought Russia to the eastern coast. Russia became and remained a dominating power in the Baltic. Russia’s Peter the Great saw the strategic importance of the Baltic and decided to found his new capital, Saint Petersburg, at the mouth of the Neva river at the east end of the Gulf of Finland. There was much trading not just within the Baltic region but also with the North Sea region, especially eastern England and the Netherlands: their fleets needed the Baltic timber, tar, flax, and hemp.

During the Crimean War, a joint British and French fleet attacked the Russian fortresses in the Baltic; the case is also known as the Åland War. They bombarded Sveaborg, which guards Helsinki; and Kronstadt, which guards Saint Petersburg; and they destroyed Bomarsund in Åland. After the unification of Germany in 1871, the whole southern coast became German. World War I was partly fought in the Baltic Sea. After 1920 Poland was granted access to the Baltic Sea at the expense of Germany by the Polish Corridor and enlarged the port of Gdynia in rivalry with the port of the Free City of Danzig.

After the Nazis’ rise to power, Germany reclaimed the Memelland and after the outbreak of the Eastern Front (World War II) occupied the Baltic states. In 1945, the Baltic Sea became a mass grave for retreating soldiers and refugees on torpedoed troop transports. The sinking of the Wilhelm Gustloff remains the worst maritime disaster in history, killing (very roughly) 9,000 people. In 2005, a Russian group of scientists found over five thousand airplane wrecks, sunken warships, and other material, mainly from World War II, on the bottom of the sea.

Since World War II[edit]

Since the end of World War II, various nations, including the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom and the United States have disposed of chemical weapons in the Baltic Sea, raising concerns of environmental contamination.[17] Today, fishermen occasionally find some of these materials: the most recent available report from the Helsinki Commission notes that four small scale catches of chemical munitions representing approximately 105 kg (231 lb) of material were reported in 2005. This is a reduction from the 25 incidents representing 1,110 kg (2,450 lb) of material in 2003.[18] Until now, the U.S. Government refuses to disclose the exact coordinates of the wreck sites. Deteriorating bottles leak mustard gas and other substances, thus slowly poisoning a substantial part of the Baltic Sea.

After 1945, the German population was expelled from all areas east of the Oder-Neisse line, making room for new Polish and Russian settlement. Poland gained most of the southern shore. The Soviet Union gained another access to the Baltic with the Kaliningrad Oblast, that had been part of German-settled East Prussia. The Baltic states on the eastern shore were annexed by the Soviet Union. The Baltic then separated opposing military blocs: NATO and the Warsaw Pact. Neutral Sweden developed incident weapons to defend its territorial waters after the Swedish submarine incidents.[19] This border status restricted trade and travel. It ended only after the collapse of the Communist regimes in Central and Eastern Europe in the late 1980s.

Since May 2004, with the accession of the Baltic states and Poland, the Baltic Sea has been almost entirely surrounded by countries of the European Union (EU). The remaining non-EU shore areas are Russian: the Saint Petersburg area and the Kaliningrad Oblast exclave.

Winter storms begin arriving in the region during October. These have caused numerous shipwrecks, and contributed to the extreme difficulties of rescuing passengers of the ferry M/S Estonia en route from Tallinn, Estonia, to Stockholm, Sweden, in September 1994, which claimed the lives of 852 people. Older, wood-based shipwrecks such as the Vasa tend to remain well-preserved, as the Baltic’s cold and brackish water does not suit the shipworm.

Storm floods[edit]

Storm surge floods are generally taken to occur when the water level is more than one metre above normal. In Warnemünde about 110 floods occurred from 1950 to 2000, an average of just over two per year.[20]

Historic flood events were the All Saints’ Flood of 1304 and other floods in the years 1320, 1449, 1625, 1694, 1784 and 1825. Little is known of their extent.[21] From 1872, there exist regular and reliable records of water levels in the Baltic Sea. The highest was the flood of 1872 when the water was an average of 2.43 m (8 ft 0 in) above sea level at Warnemünde and a maximum of 2.83 m (9 ft 3 in) above sea level in Warnemünde. In the last very heavy floods the average water levels reached 1.88 m (6 ft 2 in) above sea level in 1904, 1.89 m (6 ft 2 in) in 1913, 1.73 m (5 ft 8 in) in January 1954, 1.68 m (5 ft 6 in) on 2–4 November 1995 and 1.65 m (5 ft 5 in) on 21 February 2002.[22]

Geography[edit]

Geophysical data[edit]

Baltic drainage basins (catchment area), with depth, elevation, major rivers and lakes

An arm of the North Atlantic Ocean, the Baltic Sea is enclosed by Sweden and Denmark to the west, Finland to the northeast, and the Baltic countries to the southeast.

It is about 1,600 km (990 mi) long, an average of 193 km (120 mi) wide, and an average of 55 metres (180 ft) deep. The maximum depth is 459 m (1,506 ft) which is on the Swedish side of the center. The surface area is about 349,644 km2 (134,998 sq mi) [23] and the volume is about 20,000 km3 (4,800 cu mi). The periphery amounts to about 8,000 km (5,000 mi) of coastline.[24]

The Baltic Sea is one of the largest brackish inland seas by area, and occupies a basin (a Zungenbecken) formed by glacial erosion during the last few ice ages.

| Sub-area | Area | Volume | Maximum depth | Average depth |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| km2 | km3 | m | m | |

| Baltic proper | 211,069 | 13,045 | 459 | 62.1 |

| Gulf of Bothnia | 115,516 | 6,389 | 230 | 60.2 |

| Gulf of Finland | 29,600 | 1,100 | 123 | 38.0 |

| Gulf of Riga | 16,300 | 424 | > 60 | 26.0 |

| Belt Sea/Kattegat | 42,408 | 802 | 109 | 18.9 |

| Total Baltic Sea | 415,266 | 21,721 | 459 | 52.3 |

Extent[edit]

The International Hydrographic Organization defines the limits of the Baltic Sea as follows:[26]

- Bordered by the coasts of Germany, Denmark, Poland, Sweden, Finland, Russia, Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, it extends north-eastward of the following limits:

- In the Little Belt. A line joining Falshöft (54°47′N 9°57.5′E / 54.783°N 9.9583°E) and Vejsnæs Nakke (Ærø: 54°49′N 10°26′E / 54.817°N 10.433°E).

- In the Great Belt. A line joining Gulstav (South extreme of Langeland Island) and Kappel Kirke (54°46′N 11°01′E / 54.767°N 11.017°E) on Island of Lolland.

- In the Guldborg Sound. A line joining Flinthorne-Rev and Skjelby (54°38′N 11°53′E / 54.633°N 11.883°E).

- In the Sound. A line joining Stevns Lighthouse (55°17′N 12°27′E / 55.283°N 12.450°E) and Falsterbo Point (55°23′N 12°49′E / 55.383°N 12.817°E).

Subdivisions[edit]

The northern part of the Baltic Sea is known as the Gulf of Bothnia, of which the northernmost part is the Bay of Bothnia or Bothnian Bay. The more rounded southern basin of the gulf is called Bothnian Sea and immediately to the south of it lies the Sea of Åland. The Gulf of Finland connects the Baltic Sea with Saint Petersburg. The Gulf of Riga lies between the Latvian capital city of Riga and the Estonian island of Saaremaa.

The Northern Baltic Sea lies between the Stockholm area, southwestern Finland, and Estonia. The Western and Eastern Gotland basins form the major parts of the Central Baltic Sea or Baltic proper. The Bornholm Basin is the area east of Bornholm, and the shallower Arkona Basin extends from Bornholm to the Danish isles of Falster and Zealand.

In the south, the Bay of Gdańsk lies east of the Hel Peninsula on the Polish coast and west of the Sambia Peninsula in Kaliningrad Oblast. The Bay of Pomerania lies north of the islands of Usedom/Uznam and Wolin, east of Rügen. Between Falster and the German coast lie the Bay of Mecklenburg and Bay of Lübeck. The westernmost part of the Baltic Sea is the Bay of Kiel. The three Danish straits, the Great Belt, the Little Belt and The Sound (Öresund/Øresund), connect the Baltic Sea with the Kattegat and Skagerrak strait in the North Sea.

Temperature and ice[edit]

Satellite image of the Baltic Sea in a mild winter

Traversing Baltic Sea and ice

On particularly cold winters, the coastal parts of the Baltic Sea freeze into ice thick enough to walk or ski on.

The water temperature of the Baltic Sea varies significantly depending on exact location, season and depth. At the Bornholm Basin, which is located directly east of the island of the same name, the surface temperature typically falls to 0–5 °C (32–41 °F) during the peak of the winter and rises to 15–20 °C (59–68 °F) during the peak of the summer, with an annual average of around 9–10 °C (48–50 °F).[28] A similar pattern can be seen in the Gotland Basin, which is located between the island of Gotland and Latvia. In the deep of these basins the temperature variations are smaller. At the bottom of the Bornholm Basin, deeper than 80 m (260 ft), the temperature typically is 1–10 °C (34–50 °F), and at the bottom of the Gotland Basin, at depths greater than 225 m (738 ft), the temperature typically is 4–7 °C (39–45 °F).[28] Generally, offshore locations, lower latitudes and islands maintain maritime climates, but adjacent to the water continental climates are common, especially on the Gulf of Finland. In the northern tributaries the climates transition from moderate continental to subarctic on the northernmost coastlines.

On the long-term average, the Baltic Sea is ice-covered at the annual maximum for about 45% of its surface area. The ice-covered area during such a typical winter includes the Gulf of Bothnia, the Gulf of Finland, the Gulf of Riga, the archipelago west of Estonia, the Stockholm archipelago, and the Archipelago Sea southwest of Finland. The remainder of the Baltic does not freeze during a normal winter, except sheltered bays and shallow lagoons such as the Curonian Lagoon. The ice reaches its maximum extent in February or March; typical ice thickness in the northernmost areas in the Bothnian Bay, the northern basin of the Gulf of Bothnia, is about 70 cm (28 in) for landfast sea ice. The thickness decreases farther south.

Freezing begins in the northern extremities of the Gulf of Bothnia typically in the middle of November, reaching the open waters of the Bothnian Bay in early January. The Bothnian Sea, the basin south of Kvarken, freezes on average in late February. The Gulf of Finland and the Gulf of Riga freeze typically in late January. In 2011, the Gulf of Finland was completely frozen on 15 February.[29]

The ice extent depends on whether the winter is mild, moderate, or severe. In severe winters ice can form around southern Sweden and even in the Danish straits. According to the 18th-century natural historian William Derham, during the severe winters of 1703 and 1708, the ice cover reached as far as the Danish straits.[30] Frequently, parts of the Gulf of Bothnia and the Gulf of Finland are frozen, in addition to coastal fringes in more southerly locations such as the Gulf of Riga. This description meant that the whole of the Baltic Sea was covered with ice.

Since 1720, the Baltic Sea has frozen over entirely 20 times, most recently in early 1987, which was the most severe winter in Scandinavia since 1720. The ice then covered 400,000 km2 (150,000 sq mi). During the winter of 2010–11, which was quite severe compared to those of the last decades, the maximum ice cover was 315,000 km2 (122,000 sq mi), which was reached on 25 February 2011. The ice then extended from the north down to the northern tip of Gotland, with small ice-free areas on either side, and the east coast of the Baltic Sea was covered by an ice sheet about 25 to 100 km (16 to 62 mi) wide all the way to Gdańsk. This was brought about by a stagnant high-pressure area that lingered over central and northern Scandinavia from around 10 to 24 February. After this, strong southern winds pushed the ice further into the north, and much of the waters north of Gotland were again free of ice, which had then packed against the shores of southern Finland.[31] The effects of the afore-mentioned high-pressure area did not reach the southern parts of the Baltic Sea, and thus the entire sea did not freeze over. However, floating ice was additionally observed near Świnoujście harbor in January 2010.

In recent years before 2011, the Bothnian Bay and the Bothnian Sea were frozen with solid ice near the Baltic coast and dense floating ice far from it. In 2008, almost no ice formed except for a short period in March.[32]

Piles of drift ice on the shore of Puhtulaid, near Virtsu, Estonia, in late April

During winter, fast ice, which is attached to the shoreline, develops first, rendering ports unusable without the services of icebreakers. Level ice, ice sludge, pancake ice, and rafter ice form in the more open regions. The gleaming expanse of ice is similar to the Arctic, with wind-driven pack ice and ridges up to 15 m (49 ft). Offshore of the landfast ice, the ice remains very dynamic all year, and it is relatively easily moved around by winds and therefore forms pack ice, made up of large piles and ridges pushed against the landfast ice and shores.

In spring, the Gulf of Finland and the Gulf of Bothnia normally thaw in late April, with some ice ridges persisting until May in the eastern extremities of the Gulf of Finland. In the northernmost reaches of the Bothnian Bay, ice usually stays until late May; by early June it is practically always gone. However, in the famine year of 1867 remnants of ice were observed as late as 17 July near Uddskär.[33] Even as far south as Øresund, remnants of ice have been observed in May on several occasions; near Taarbaek on 15 May 1942 and near Copenhagen on 11 May 1771. Drift ice was also observed on 11 May 1799.[34][35][36]

The ice cover is the main habitat for two large mammals, the grey seal (Halichoerus grypus) and the Baltic ringed seal (Pusa hispida botnica), both of which feed underneath the ice and breed on its surface. Of these two seals, only the Baltic ringed seal suffers when there is not adequate ice in the Baltic Sea, as it feeds its young only while on ice. The grey seal is adapted to reproducing also with no ice in the sea. The sea ice also harbors several species of algae that live in the bottom and inside unfrozen brine pockets in the ice.

Due to the often fluctuating winter temperatures between above and below freezing, the saltwater ice of the Baltic Sea can be treacherous and hazardous to walk on, in particular in comparison to the more stable fresh water-ice sheets in the interior lakes.

Hydrography[edit]

Depths of the Baltic Sea in meters

The Baltic Sea flows out through the Danish straits; however, the flow is complex. A surface layer of brackish water discharges 940 km3 (230 cu mi) per year into the North Sea. Due to the difference in salinity, by salinity permeation principle, a sub-surface layer of more saline water moving in the opposite direction brings in 475 km3 (114 cu mi) per year. It mixes very slowly with the upper waters, resulting in a salinity gradient from top to bottom, with most of the saltwater remaining below 40 to 70 m (130 to 230 ft) deep. The general circulation is anti-clockwise: northwards along its eastern boundary, and south along with the western one .[37]

The difference between the outflow and the inflow comes entirely from fresh water. More than 250 streams drain a basin of about 1,600,000 km2 (620,000 sq mi), contributing a volume of 660 km3 (160 cu mi) per year to the Baltic. They include the major rivers of north Europe, such as the Oder, the Vistula, the Neman, the Daugava and the Neva. Additional fresh water comes from the difference of precipitation less evaporation, which is positive.

An important source of salty water is infrequent inflows of North Sea water into the Baltic. Such inflows, important to the Baltic ecosystem because of the oxygen they transport into the Baltic deeps, used to happen regularly until the 1980s. In recent decades they have become less frequent. The latest four occurred in 1983, 1993, 2003, and 2014 suggesting a new inter-inflow period of about ten years.

The water level is generally far more dependent on the regional wind situation than on tidal effects. However, tidal currents occur in narrow passages in the western parts of the Baltic Sea. Tides can reach 17 to 19 cm in the Gulf of Finland.[38]

The significant wave height is generally much lower than that of the North Sea. Quite violent, sudden storms sweep the surface ten or more times a year, due to large transient temperature differences and a long reach of the wind. Seasonal winds also cause small changes in sea level, of the order of 0.5 m (1 ft 8 in) .[37] According to the media, during a storm in January 2017, an extreme wave above 14m has been measured and significant wave height of around 8m has been measured by the FMI. A numerical study has shown the presence of events with 8 to 10m significant wave heights. Those extreme waves events can play an important role in the coastal zone on erosion and sea dynamics.[39]

Salinity[edit]

The Baltic Sea is the world’s largest inland brackish sea.[40] Only two other brackish waters are larger according to some measurements: The Black Sea is larger in both surface area and water volume, but most of it is located outside the continental shelf (only a small fraction is inland). The Caspian Sea is larger in water volume, but—despite its name—it is a lake rather than a sea.[40]

The Baltic Sea’s salinity is much lower than that of ocean water (which averages 3.5%), as a result of abundant freshwater runoff from the surrounding land (rivers, streams and alike), combined with the shallowness of the sea itself; runoff contributes roughly one-fortieth its total volume per year, as the volume of the basin is about 21,000 km3 (5,000 cu mi) and yearly runoff is about 500 km3 (120 cu mi).[citation needed]

The open surface waters of the Baltic Sea «proper» generally have a salinity of 0.3 to 0.9%, which is border-line freshwater. The flow of freshwater into the sea from approximately two hundred rivers and the introduction of salt from the southwest builds up a gradient of salinity in the Baltic Sea. The highest surface salinities, generally 0.7–0.9%, are in the southwesternmost part of the Baltic, in the Arkona and Bornholm basins (the former located roughly between southeast Zealand and Bornholm, and the latter directly east of Bornholm). It gradually falls further east and north, reaching the lowest in the Bothnian Bay at around 0.3%.[41] Drinking the surface water of the Baltic as a means of survival would actually hydrate the body instead of dehydrating, as is the case with ocean water.[note 1][citation needed]

As saltwater is denser than freshwater, the bottom of the Baltic Sea is saltier than the surface. This creates a vertical stratification of the water column, a halocline, that represents a barrier to the exchange of oxygen and nutrients, and fosters completely separate maritime environments.[42] The difference between the bottom and surface salinities varies depending on location. Overall it follows the same southwest to east and north pattern as the surface. At the bottom of the Arkona Basin (equalling depths greater than 40 m or 130 ft) and Bornholm Basin (depths greater than 80 m or 260 ft) it is typically 1.4–1.8%. Further east and north the salinity at the bottom is consistently lower, being the lowest in Bothnian Bay (depths greater than 120 m or 390 ft) where it is slightly below 0.4%, or only marginally higher than the surface in the same region.[41]

In contrast, the salinity of the Danish straits, which connect the Baltic Sea and Kattegat, tends to be significantly higher, but with major variations from year to year. For example, the surface and bottom salinity in the Great Belt is typically around 2.0% and 2.8% respectively, which is only somewhat below that of the Kattegat.[41] The water surplus caused by the continuous inflow of rivers and streams to the Baltic Sea means that there generally is a flow of brackish water out through the Danish Straits to the Kattegat (and eventually the Atlantic).[43] Significant flows in the opposite direction, salt water from the Kattegat through the Danish Straits to the Baltic Sea, are less regular. From 1880 to 1980 inflows occurred on average six to seven times per decade. Since 1980 it has been much less frequent, although a very large inflow occurred in 2014.[28]

Major tributaries[edit]

The rating of mean discharges differs from the ranking of hydrological lengths (from the most distant source to the sea) and the rating of the nominal lengths. Göta älv, a tributary of the Kattegat, is not listed, as due to the northward upper low-salinity-flow in the sea, its water hardly reaches the Baltic proper:

| Name | Mean Discharge (m3/s) |

Length (km) | Basin (km2) | States sharing the basin | Longest watercourse |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neva | 2500 | 74 (nominal) 860 (hydrological) |

281,000 | Russia, Finland (Ladoga-affluent Vuoksi) | Suna (280 km) → Lake Onega (160 km) → Svir (224 km) → Lake Ladoga (122 km) → Neva |

| Vistula | 1080 | 1047 | 194,424 | Poland, tributaries: Belarus, Ukraine, Slovakia | Bug (774 km) → Narew (22 km) → Vistula (156 km) total 1204 km |

| Daugava | 678 | 1020 | 87,900 | Russia (source), Belarus, Latvia | |

| Neman | 678 | 937 | 98,200 | Belarus (source), Lithuania, Russia | |

| Kemijoki | 556 | 550 (main river) 600 (river system) |

51,127 | Finland, Norway (source of Ounasjoki) | longer tributary Kitinen |

| Oder | 540 | 866 | 118,861 | Czech Republic (source), Poland, Germany | Warta (808 km) → Oder (180 km) total: 928 km |

| Lule älv | 506 | 461 | 25,240 | Sweden | |

| Narva | 415 | 77 (nominal) 652 (hydrological) |

56,200 | Russia (Source of Velikaya), Estonia | Velikaya (430 km) → Lake Peipus (145 km) → Narva |

| Torne älv | 388 | 520 (nominal) 630 (hydrological) |

40,131 | Norway (source), Sweden, Finland | Válfojohka → Kamajåkka → Abiskojaure → Abiskojokk (total 40 km) → Torneträsk (70 km) → Torne älv |

Islands and archipelagoes[edit]

- Åland (Finland, autonomous)

- Archipelago Sea (Finland)

- Pargas

- Nagu

- Korpo

- Houtskär

- Kustavi

- Kimito

- Blekinge archipelago (Sweden)

- Bornholm, including Christiansø (Denmark)

- Falster (Denmark)

- Gotland (Sweden)

- Hailuoto (Finland)

- Kotlin (Russia)

- Lolland (Denmark)

- Kvarken archipelago, including Valsörarna (Finland)

- Møn (Denmark)

- Öland (Sweden)

- Rügen (Germany)

- Stockholm archipelago (Sweden)

- Värmdön (Sweden)

- Usedom or Uznam (split between Germany and Poland)

- West Estonian archipelago (Estonia):

- Hiiumaa

- Muhu

- Saaremaa

- Vormsi

- Wolin (Poland)

- Zealand (Denmark)

Coastal countries[edit]

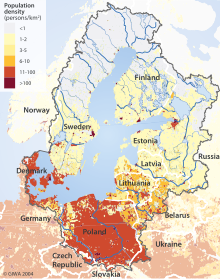

Population density in the Baltic Sea catchment area

Countries that border the sea: Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden.

Countries lands in the outer drainage basin: Belarus, Czech Republic, Norway, Slovakia, Ukraine.

The Baltic Sea drainage basin is roughly four times the surface area of the sea itself. About 48% of the region is forested, with Sweden and Finland containing the majority of the forest, especially around the Gulfs of Bothnia and Finland.

About 20% of the land is used for agriculture and pasture, mainly in Poland and around the edge of the Baltic Proper, in Germany, Denmark, and Sweden. About 17% of the basin is unused open land with another 8% of wetlands. Most of the latter are in the Gulfs of Bothnia and Finland.

The rest of the land is heavily populated. About 85 million people live in the Baltic drainage basin, 15 million within 10 km (6 mi) of the coast and 29 million within 50 km (31 mi) of the coast. Around 22 million live in population centers of over 250,000. 90% of these are concentrated in the 10 km (6 mi) band around the coast. Of the nations containing all or part of the basin, Poland includes 45% of the 85 million, Russia 12%, Sweden 10% and the others less than 6% each.[44]

Cities[edit]

The biggest coastal cities (by population):

- Saint Petersburg (Russia) 5,392,992 (metropolitan area 6,000,000)

- Stockholm (Sweden) 962,154 (metropolitan area 2,315,612)

- Helsinki (Finland) 658,864 (metropolitan area 1,536,810)

- Riga (Latvia) 614,618 (metropolitan area 1,070,00)

- Gdańsk (Poland) 462,700 (metropolitan area 1,041,000)

- Tallinn (Estonia) 435,245 (metropolitan area 542,983)

- Kaliningrad (Russia) 431,500

- Szczecin (Poland) 413,600 (metropolitan area 778,000)

- Gdynia (Poland) 255,600 (metropolitan area 1,041,000)

- Espoo (Finland) 257,195 (part of Helsinki metropolitan area)

- Kiel (Germany) 247,000[45]

- Lübeck (Germany) 216,100

- Rostock (Germany) 212,700

- Klaipėda (Lithuania) 194,400

- Oulu (Finland) 191,050

- Turku (Finland) 180,350

Other important ports:

- Estonia:

- Pärnu 44,568

- Maardu 16,570

- Sillamäe 16,567

- Finland:

- Pori 83,272

- Kotka 54,887

- Kokkola 46,809

- Port of Naantali 18,789

- Mariehamn 11,372

- Hanko 9,270

- Germany:

- Flensburg 94,000

- Stralsund 58,000

- Greifswald 55,000

- Wismar 44,000

- Eckernförde 22,000

- Neustadt in Holstein 16,000

- Wolgast 12,000

- Sassnitz 10,000

- Latvia:

- Liepāja 85,000

- Ventspils 44,000

- Lithuania:

- Palanga 17,000

- Poland:

- Kołobrzeg 44,800

- Świnoujście 41,500

- Police 34,284

- Władysławowo 15,000

- Darłowo 14,000

- Russia:

- Vyborg 79,962

- Baltiysk 34,000

- Sweden:

- Norrköping 84,000

- Gävle 75,451

- Trelleborg 26,000

- Karlshamn 19,000

- Oxelösund 11,000

Geology[edit]

Much of modern Finland is former seabed or archipelago: illustrated are sea levels immediately after the last ice age.

The Baltic Sea somewhat resembles a riverbed, with two tributaries, the Gulf of Finland and Gulf of Bothnia. Geological surveys show that before the Pleistocene, instead of the Baltic Sea, there was a wide plain around a great river that paleontologists call the Eridanos. Several Pleistocene glacial episodes scooped out the river bed into the sea basin. By the time of the last, or Eemian Stage (MIS 5e), the Eemian Sea was in place. Instead of a true sea, the Baltic can even today also be understood as the common estuary of all rivers flowing into it.

From that time the waters underwent a geologic history summarized under the names listed below. Many of the stages are named after marine animals (e.g. the Littorina mollusk) that are clear markers of changing water temperatures and salinity.